Progress on hafnium oxide-based emerging ferroelectric materials and applications

Abstract

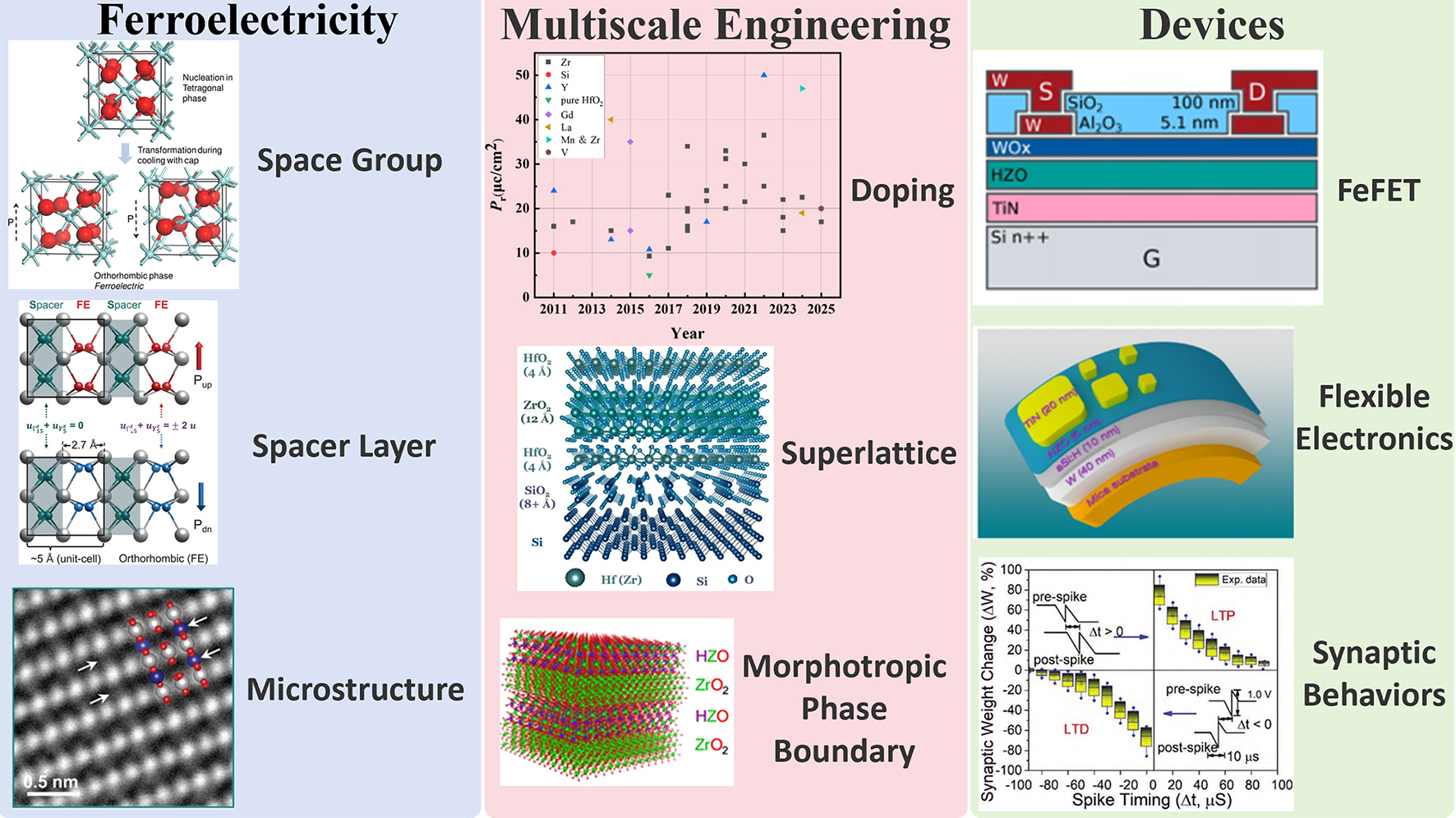

Since the discovery of ferroelectricity in Si-doped HfO2 in 2011, HfO2-based materials have attracted extensive interest from researchers. Their various advantages provide a broad research prospect in the field of ferroelectric materials and devices. Researchers have conducted effective studies on the origin of ferroelectricity, the wake-up effect, the fatigue effect, and the potential for device applications. These studies contribute to a better understanding of the properties and applications of HfO2-based materials. This article provides a comprehensive review of the origin and influencing factors of ferroelectricity in HfO2, advantages in material applications, and limitations in applications from multiple perspectives. It also introduces the currently mature methods for preparing HfO2-based ferroelectric materials and cutting-edge applications in different device fields. Finally, the future development prospects of HfO2-based materials are also discussed.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Ferroelectric materials have attracted significant attention due to their potential applications in information storage and optical devices. The electric polarization in ferroelectrics can be switched by applying an external electric field, enabling their use in various technologies such as nonvolatile memory devices[1], field-effect transistors (FeFETs)[2], and ferroelectric tunnel junctions (FTJs)[3]. Since the discovery of ferroelectricity in HfO2 in 2011[4], considerable research has focused on understanding its origin and exploring its applications. Early studies revealed that the stable phase of HfO2 at room temperature and 1 atm is the monoclinic phase (space group P21/c), which has inversion symmetry and is thus non-ferroelectric. Therefore, the researchers turned their attention to other metastable phases. Currently, many researchers agree that the ferroelectricity of HfO2 originates from its orthorhombic phase (O-phase, space group Pca21). Meanwhile, some scholars propose that the ferroelectricity arises from the rhombohedral phase (space group R3m)[5]. Guo et al., using density functional theory (DFT) calculations, discovered that Mn doping contributes to stabilizing the rhombohedral R3 ferroelectric phase[6]; furthermore, they successfully grew epitaxial Mn-doped Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 (HZO) thin films exhibiting a ferroelectric phase with space group R3[6]. Continued investigation into the origin of ferroelectricity in HfO2-based materials remains critical for advancing their practical applications.

Compared to traditional materials, HfO2 has shown great advantages in many aspects. Owing to their excellent compatibility with complementary-metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technologies, high dielectric permittivity (high-k), and high thermal stability, HfO2-based films can overcome key bottlenecks in the development of ferroelectric devices. For example, the application of FeFET, one of the most promising high-density nonvolatile random-access memories, was once impeded by limited CMOS compatibility, insufficient scalability, and unsatisfactory retention properties. However, the emergence of HfO2 may bring new vitality to the applications of ferroelectric materials[7]. The dielectric capacitor primarily stores energy in the form of an electrostatic field, but its relatively low energy density has continuously limited its widespread application[8]. Hafnium oxide-based materials, with their high dielectric constant and breakdown field, offer the potential for significant improvements in energy storage density.

There are several excellent articles[9-14] that summarize the progress in HfO2-based materials, focusing on their performance, preparation methods, and applications. This article is organized into the following sections. The first section introduces the origin of ferroelectricity in HfO2-based materials, along with the effects of factors such as stress and doping on its ferroelectric properties. It also discusses specific characteristics of HfO2-based ferroelectrics, including wake-up and fatigue effects, as well as metastable phase boundaries and superlattice structures. The second section mainly introduces methods for preparing HfO2-based ferroelectric thin films, especially the latest advances in atomic layer deposition (ALD) and pulsed laser deposition (PLD). It provides a detailed overview of the properties of HfO2-based films prepared using different techniques. The third section highlights advanced applications of HfO2-based materials.

PROPERTIES AND CHARACTERISTICS

Ferroelectricity

During the early research on HfO2 thin films, the majority of reported HfO2 phases were monoclinic (M-phase), tetragonal (T-phase), or cubic (C-phase). In the temperature range from room temperature to

Subsequent work extensively discussed whether the ferroelectricity in HfO2 originates from the polar orthorhombic phase Pca21. Sang et al. utilized a combination of high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction (PACBED) to provide support for the assertion that the Pca21 phase is the source of the ferroelectric structure of the Gd:HfO2 films[22]. Based on space groups that are most likely to cause the ferroelectric behavior, Sang et al. observed the crystal structures of five HfO2 phases along the four major zone axes, as shown in Figure 2A and B[22]. Two structures, P21/c and Pnm21, were initially ruled out by comparing the atomic column projections. As shown in Figure 2C-G, the PACBED pattern observed in the experiments lacks mirrors perpendicular to the [001] axis and is almost identical to the simulated pattern of the Pca21 phase. The absence of mirrors in the PACBED pattern also excludes the presence of centrosymmetric Pbcm and Pbca phases.

Figure 2. (A) Crystal structure projections of five HfO2 phases along the four major zone axes; (B) HAADF-STEM images of four different grains (from the perspective zone axes); (C) STEM image of Gd:HfO2 film; (D) PACBED pattern. Simulated PACBED patterns for the (E) Pca21, (F) Pbca, and (G) Pbcm phases[22]. Reprinted from Ref.[22], with permission from AIP Publishing.

The research team of Huan[19] first utilized a first-principles-based structure search algorithm to identify the low free energy phases under different pressures and temperatures. As shown in Figure 3A, it was discovered that the space groups Pca21 and Pmn21 are the most likely ferroelectric phases in HfO2, which can transform into other equilibrium phases due to the lower free energy of the two polar orthorhombic phases. As shown in Figure 3B, the T-phase of HfO2 thin films formed under high temperature and high pressure, and after cooling and annealing, it transformed into two polar phases that can generate switchable polarization. The M-phase under normal temperature and pressure conditions may transform into the T-phase through conditions such as heating and higher pressure, as shown in Figure 3C. Afterward, polarization occurred through stress and other methods, causing the T-phase to transform into the O-phase, which became the main crystal phase in the thin film after annealing[19]. Whether the Pca21 phase can exist stably at normal temperature and pressure, and how to induce this phase have become new questions.

Figure 3. (A) Equilibrium phase diagram of HfO2. (B) Regimes showing the free energy difference between the Pca21 and Pmn21 phases. (C) Possible pathways for the formation of the polar phase[19]. Reprinted figures with permission from Ref.[19] Copyright by the American Physical Society. (D) Phase diagram illustrating the relationship between grain radius and temperature for HZO thin films. (E, G, I, K, M) Illustrative schematic figures; (F, H, J, L, N) Corresponding free energy curves[23]. Figures reprinted with permission from Ref.[23] Copyright by the Wiley Company.

Figure 3D-N collectively shows the conditions in films before and throughout the accelerated thermal process utilized for film crystallization. Figure 3D presents a conceptual representation of the temperature-dependent phase stability of a columnar HZO crystal[23]. The green region represents that the stable phase is the M-phase, while the crystalline phases inside the parentheses (T-phase and O-phase) are the second stable phases. The red dashed line indicates that at these points, the second stable phase can change between the T-phase and the O-phase[23]. Therefore, the stable phase at high temperatures becomes the T-phase. The thermodynamically stable phase becomes the M-phase at low temperature. However, due to the high kinetic energy barrier, the transition from the T-phase to the M-phase is suppressed so that the metastable T-phase can be retained. If the temperature and time are enough to overcome the high kinetic barrier, a stable M-phase can be formed in this step[24]. After a rapid thermal anneal process, the stability of the O-phase increases if the formation of the m-phase is kinetically suppressed, as shown in Figure 3K and L, and the second stable phase transforms from the T-phase to the O-phase at low temperature. Fan et al. investigated the structure and polarization response of HfO2 with an applied electric field, and then elucidated how the metastable phase can exist stably at room temperature and normal pressure[25]. As a result, when the lattice parameter and lattice strain are within a certain range, the hafnium oxide lattice phase is dominated by the Pca21 phase even at room temperature and normal pressure.

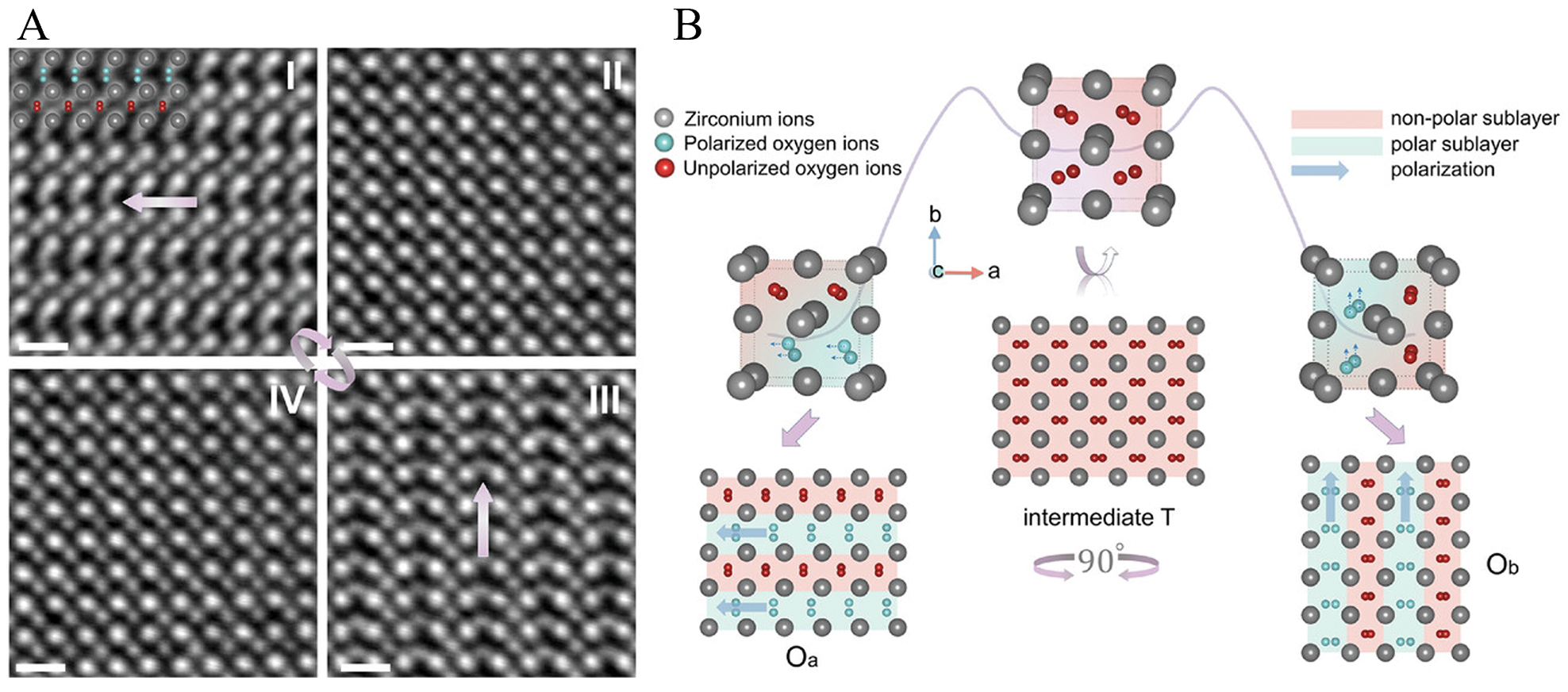

The ferroelectricity origin in hafnium oxide is intrinsically linked to its polarization switching pathways. First-principles calculations reveal that oxygen atom-mediated cross-unit-cell switching pathways dominate during domain nucleation and domain wall motion, creating asymmetric energy barriers that lead to inhomogeneous nucleation-propagation characteristics during polarization reversal[26,27]. Peng et al. further reveal the spacer layer mechanism in the ferroelectric domain switching dynamics of HZO thin film through phase-field simulations[28]. The dynamic evolution process of ferroelectric domain structures reveals that 180° polarization reversal is governed by the nucleation of new domains with high nucleation density. Under ultrafast electric fields, polarization switching is governed by high-density nucleation events, with new domains preferentially forming at grain boundaries or defects and propagating rapidly via domain wall migration. Moreover, the isolation layer leads to significantly weakened interactions between adjacent domains. The scale-free independent switching capability of nanoscale polar domains (with 1 nm lateral dimensions and atomically sharp domain walls) originates precisely from this weak inter-domain coupling. This decoupling effect enables individual domains to switch polarization states without triggering collective responses from neighboring regions[28]. This mechanism fundamentally differs from the uniform polarization switching observed in conventional perovskite materials. Furthermore, researchers have revealed a novel 90° ferroelectric/ferroelastic switching dynamics in fluorite-structured oxides through in-situ visualization of oxygen migration phenomena[29,30]: the polarization transition involves a transformation from the horizontal polarized O-phase with (Oa) to the non-polar T-phase, followed by a subsequent shift from the T-phase to the vertically polarized O-phase (Ob), with the non-polar T-phase acting as the intermediate stage, as shown in Figure 4A and B. The structural transformation from the O-phase to the T-phase mutually locks polarization and strain, generating a ferroelectric-ferroelastic coupled domain state. The non-polar T-phase provides a lower energy barrier for this ferroelectric/ferroelastic switching. This polarization switching and phase transition process provides deeper insights into the ferroelectric behavior of HfO2-based materials.

Wei et al. also found that the ferroelectricity of hafnium oxide may originate from other phases[5]. After analyzing the prepared ferroelectric HfO2 films in terms of lattice structure and symmetry, they concluded that the ferroelectricity of their prepared films did not originate from the Pca21 phase, but from the rhombohedral phase (R-phase) with higher symmetry. Shortly from the first-principles perspective, Qi et al. argued that the observation is due to the application of in-plane shear strain on the tetragonal phase, transforming it into the polar phase Pnm21 phase, which is another polar orthorhombic phase[31]. There are also some subsequent reports about the R-phase in HZO ferroelectric materials. In their work, Wang et al. also reported the discovery of the ferroelectric R-phase in HfZr1+xO2 materials[32]. They studied a method to construct the R-phase in HfO2 materials by increasing the concentration of Hf and O atoms. They confirmed the excess structure of Hf/Zr through HAADF images. Density functional theory calculations showed that the formation energy of the R-phase in HZO films is lower than that of the O-phase and M-phase when the ratio of Hf/Zr to O is greater than 1.079:2, which favors the formation of the R-phase[32]. However, some researchers have raised different opinions regarding the conclusions of this work. In response to the significantly reduced coercive field observed in this work, Zhu et al. provided further mechanistic insights[27]. They systematically investigated how interstitial Hf doping lowers the coercive field in ferroelectric HfO2. The results revealed that Hf doping diminishes the energy difference between the polar orthorhombic Pca21 phase and the intermediate tetragonal P42/nmc phase, thereby reducing both the switching energy barrier and coercive field[27]. So far, the origin of the ferroelectricity of HfO2 still remains to be further investigated.

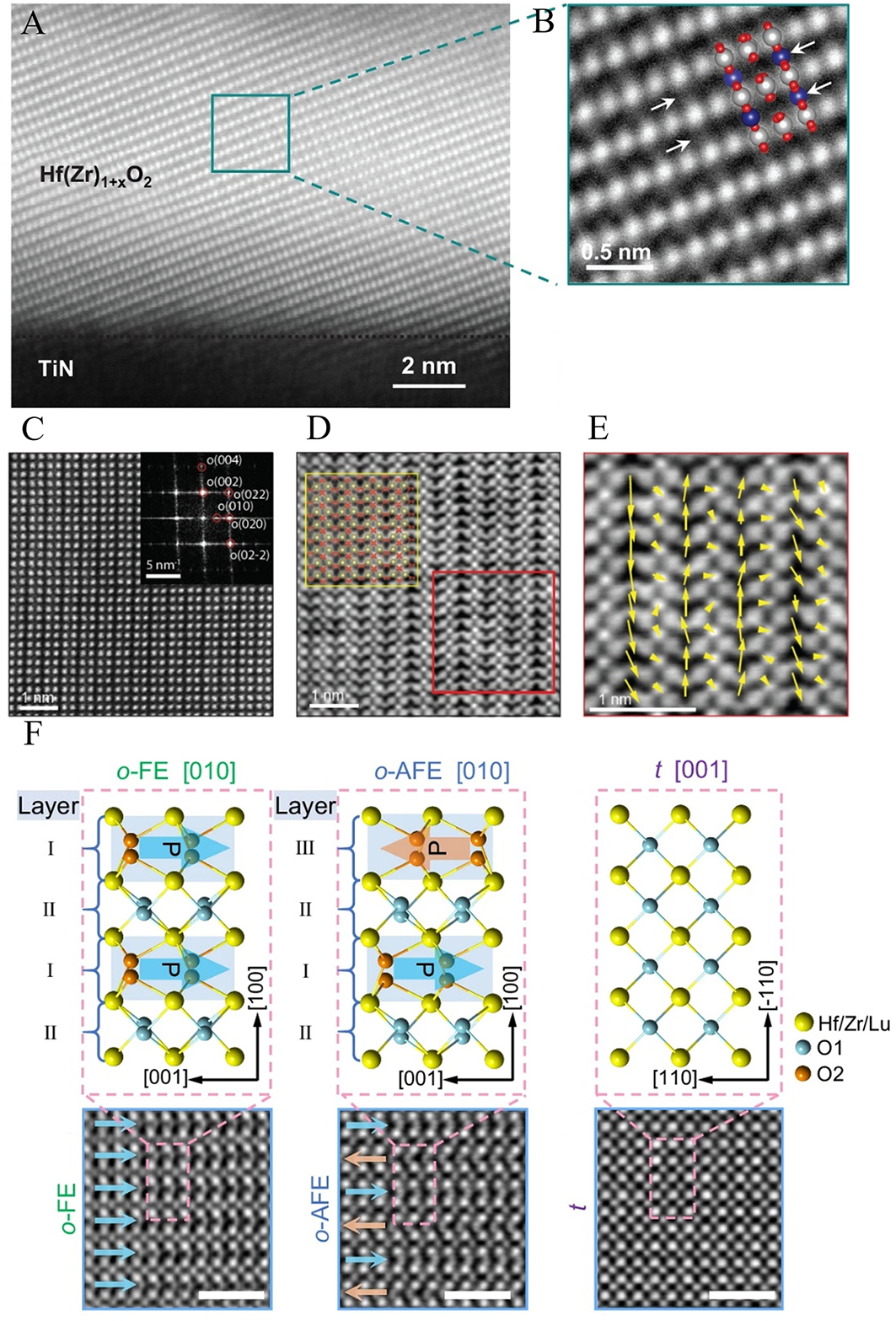

Through the research process, STEM technology plays a pivotal role in elucidating the mechanism of hafnium oxide-based ferroelectric materials, particularly in atomic-scale phase structure characterization and visualization of phase transition pathways. Figure 5A displays the HAADF-STEM image of HfZr1+x O2 thin films, while Figure 5B further reveals the insertion of excess Hf/Zr atoms into the lattice[32]. By combining STEM imaging with HAADF image simulations and DFT calculations, researchers confirmed the phase structure and demonstrated that excess Hf/Zr atoms expand the lattice of HfZr1+xO2, generating enhanced in-plane and out-of-plane stresses that effectively stabilize ferroelectricity. Clear O-phase features were observed in Y:HfO2 films, as shown in Figure 5C. Figure 5D presents Integrated Differential Phase Contrast (iDPC)-STEM images revealing distinct non-centrosymmetric polar structures, with Figure 5E highlighting oxygen atom displacements within the marked regions (red boxes), providing microscopic evidence for the in-plane switchable polarization in Y:HfO2 films[33]. In studies of HfO2-based crystals, STEM enabled precise discrimination among orthorhombic ferroelectric (o-FE), orthorhombic antiferroelectric (o-AFE), and tetragonal non-polar phases (t) [Figure 5F], while fully mapping the dynamic migration trajectories of Hf and O atoms during the metastable tetragonal-to-orthorhombic phase transition[34]. By directly observing the motion and structural changes of different atoms, the complex mechanisms of the phase transition process between the t-phase and o-phase have been effectively explained. The application of STEM for microstructural characterization of HfO2-based ferroelectric materials, complemented by atomic-scale observations of these systems, has established a crucial experimental framework for advancing mechanistic understanding of ferroelectricity in HfO2-based material systems.

Figure 5. (A) STEM-HAADF image of HfZr1+xO2 thin film, (B) The enlarged inset of (A)[32]. Reprinted from Ref.[32], with permission from AAAS. (C) STEM-HAADF image of the Y:HfO2 film. The inset shows the fast Fourier transformation of (C). (D) iDPC-STEM image of the Y:HfO2 film, (E) Polarization direction mapping of the red box in (D)[33]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[33]. Copyright (2024) American Chemical Society. (F) iDPC-STEM results of hafnium oxide crystals[34]. Reprinted from Ref.[34], with permission from Springer Nature.

Doping

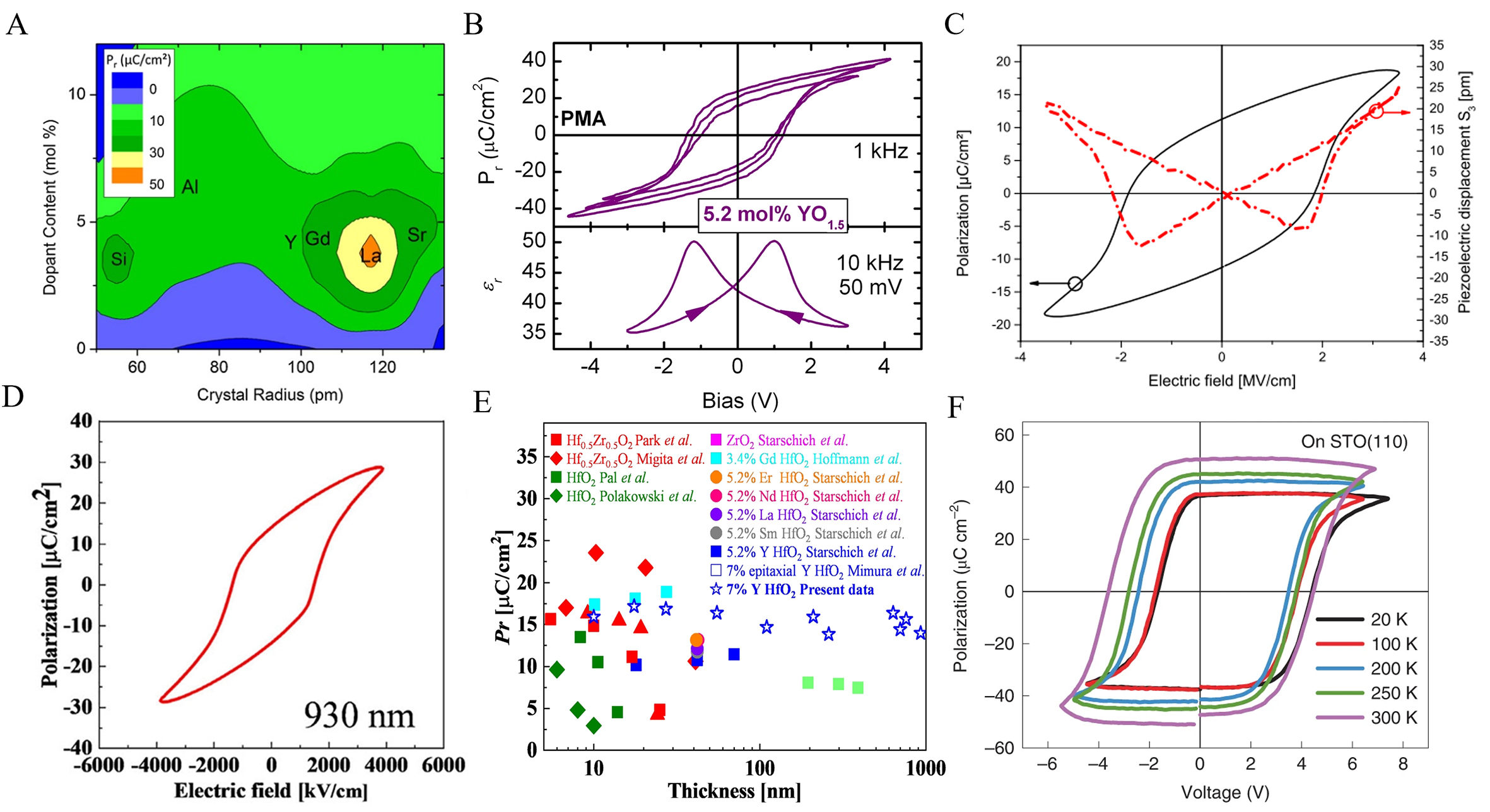

Many studies have shown that the ferroelectricity of HfO2-based thin films can be affected by extrinsic factors, such as doping[24,35-37], strain[38-41], defects[42,43], surface energy and electric field[11], with the effect of doping being particularly pronounced. The contour plots of the variation of Pr with crystal radius and doping for different doping systems are given in Figure 6A. Böscke et al. have induced ferroelectricity in HfO2 by using CVD-deposited TiN electrodes on top of Si-doped HfO2 films[4]. Schroeder et al. in their study found that different Si doping concentrations in HfO2 films caused the HfO2 films to exhibit different properties[44]; in the work of Kirbach, it was found that the Si:HfO2 films exhibited the strongest ferroelectric properties when the Si doping concentration was 3.8%, within the studied range of 2.7%-5.6%[45]. Doping affects the lattice structure of HfO2 films by changing the bond lengths between metal-oxygen bonds in HfO2 films and increasing the asymmetry of their lattice structure. Doping elements can stabilize either the T-phase or C-phase at appropriate doping concentrations, promote the generation of the O-phase, and inhibit the conversion of the T-phase to the M-phase.

Figure 6. (A) Contour plots of the variation of Pr value with crystal radius and doping amount[44]. Reprinted figures with permission from Ref.[44] Copyright by IOP Publishing, Ltd. (B) P-V curve and C-V curve[46]. Reprinted from[46], with permission from AIP Publishing. (C) Piezoelectric measurement and P-V curve of 70 nm Y:HfO2 capacitor[47]. Reprinted from[47], with permission from AIP Publishing. (D) P-E loops for Y:HfO2 films with a thickness of 930 nm[48]. (E) Thickness dependence of Pr for doping HfO2-based films[48]. Reprinted from[48], with permission from AIP Publishing. (F) Typical P-V loops of Y:HfO2 films measured from 20 to 300 K[49]. Reprinted from Ref.[49], with permission from Springer Nature.

In recent studies, Y-doped HfO2 thin films have also demonstrated excellent ferroelectricity[33]. As shown in Figure 6B, Müller investigated Y-doped HfO2 films and found that Y:HfO2 films have low annealing temperatures and are able to exhibit strong ferroelectricity without top electrode clamping[46].

Recent studies on doped ferroelectric HfO2-based thin films have shown increasing diversity. Among those doping systems, the atomic radius of Zr is similar to that of Hf, and ZrO2 and HfO2 have almost equivalent crystal structures, similar lattice parameters and exhibit similar physical and chemical properties.

Compound structure

In recent years, research on HfO2-ZrO2 superlattices has been increasing[42]. In 2017, Weeks et al. investigated the relationship between the ferroelectric properties of HfO2-ZrO2 superlattices and the thickness and deposition temperature[58]. Thin films prepared at low temperatures exhibited a pseudo-antiferroelectric response, while films prepared at higher temperatures showed ferroelectric behavior. This difference arises because temperature influences the stability of the polar orthorhombic phase. At higher deposition temperatures, microcrystalline nucleation occurred within the film, stabilizing the orthorhombic phase. In 2019, Park et al. studied the structure and electrical properties of HfO2 and ZrO2 nanolayers and superlattices with four different layer combinations and thicknesses[77]. The results showed that for ZrO2 nanolayers with thickness exceeding 1.1 nm, the fraction of the monoclinic phase was higher compared to solid solutions with the same HfO2/ZrO2 ratio or HfO2-starting samples. This is due to the biaxial tensile strain conditions in the thin film, which promote the phase transition from the T-phase to the M-phase. In the work by Peng et al. in 2022, the HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice capacitors exhibited stronger ferroelectricity, better durability, and retention characteristics[78]. Compared to the HZO capacitor, the HfO2-ZrO2 SL MFM capacitor exhibits a significantly improved retention rate. The endurance of SL capacitors exceeds 1012 cycles per fatigue cycle, which is three orders of magnitude higher than HZO. The HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice structure effectively improves the durability of capacitors.

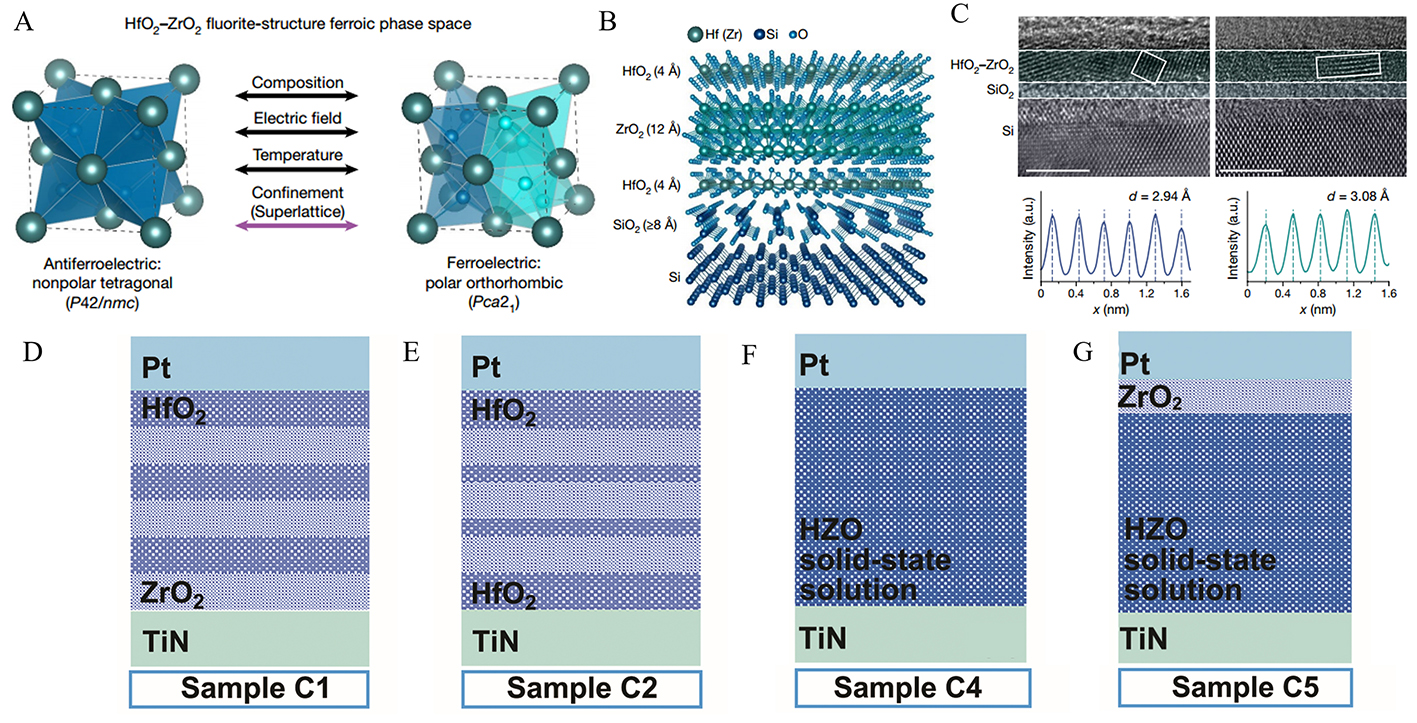

In 2022, Cheema et al. discovered that the capacitive properties of the HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice grown on the Si substrate could be enhanced by the negative capacitance effect[79]. In this work, they proposed an ultra-thin HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice gate stack, as shown in Figure 8A. A superlattice thin film with a thickness of

Figure 8. (A) HfO2-ZrO2 fluorite-structure system. (B) Schematic of the HZH fluorite-structure multilayer. (C) High-resolution TEM images of HZH tri-layer (top) and extracted d-lattice spacings[79]. Reprinted from Ref.[79], with permission from Springer Nature. The superlattice structures of (D) sample C1, (E) sample C2, (F) sample C4, (G) sample C5[80]. Reprinted from Ref.[80], with permission from Wiley.

In 2023, Bai et al. designed a special ferroelectric capacitor based on HfO2/ZrO2 superlattice. They reduced the leakage current of the thin film and enhanced the ferroelectricity through one-sided rapid thermal annealing[80]. The samples with the same compositions as C1 and C2 (shown in Figure 8D and E) were subjected to top heating at 500 °C during the annealing process (named sample C1L and sample C2L, respectively). There is a certain amount of spontaneous polarization observed after 1,000 cycles, indicating the presence of a wake-up effect, which was not observed in the samples annealed at 600 °C.

Morphotropic phase boundary of HfO2-ZrO2

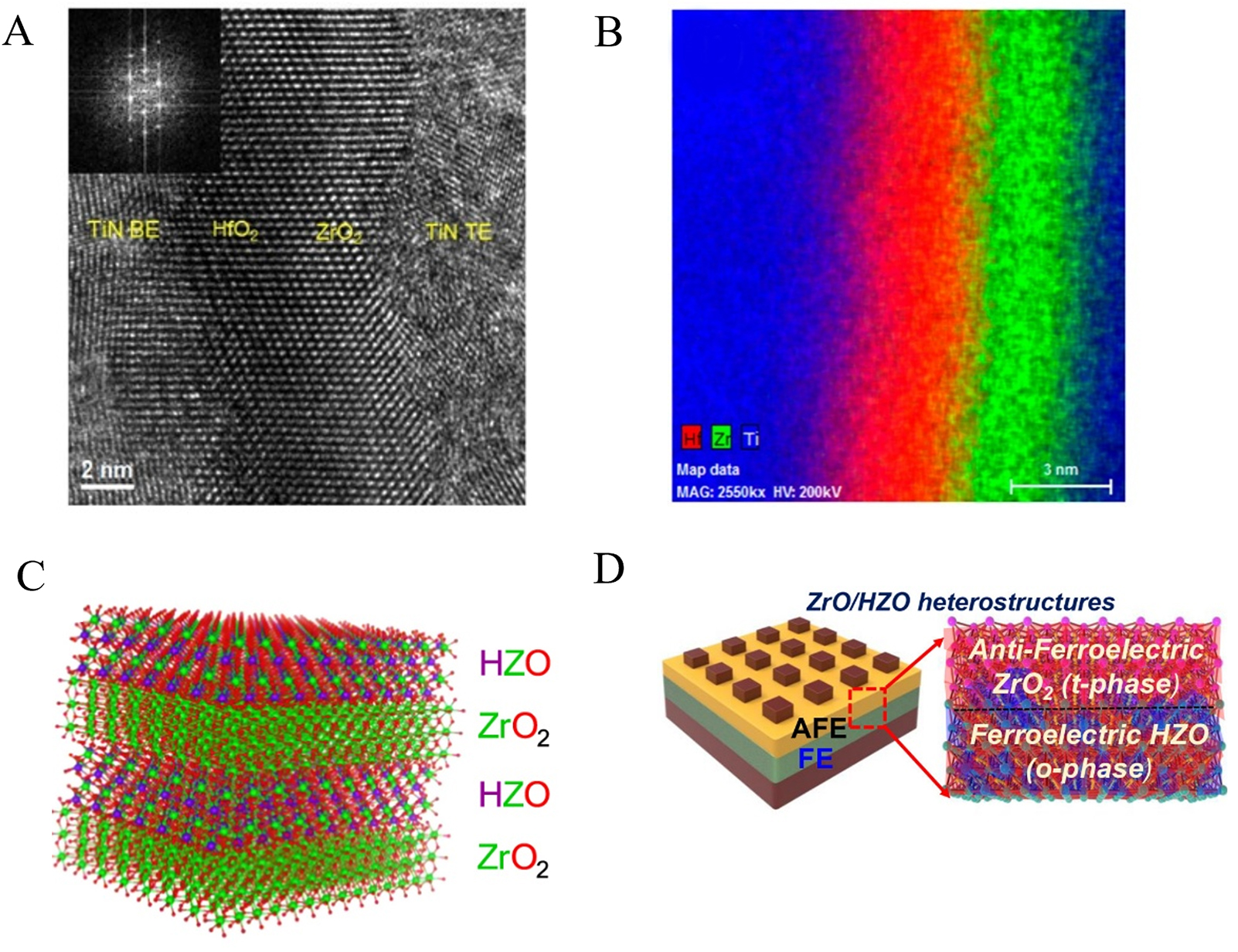

Morphotropic phase boundary (MPB) refers to the boundary between two crystal phases with different chemical compositions. Using MPB can enhance the κ value of advanced unit capacitors in dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) and reduce the Equivalent oxide thickness (EOT) of gate stacks. The HRTEM and EDS mappings in Figure 9A and B characterize a prototypical MPB microstructure[42]. The properties and structure of the MPB region will differ from the original HfO2 and ZrO2 film. In the work of Kim et al., the MPB was achieved in HZO thin films by adjusting the thermal budget during annealing[82]. It was found that by adjusting the process, MPB could be achieved by overcoming the energy barrier through low-temperature annealing. Das et al. achieved MPB in HZO thin films through high-pressure annealing and rapid cooling processes[83]. The HZO film they prepared exhibited a maximum dielectric constant of approximately 49 and an EOT of 4.8 Å, which were reported to be the optimal performance at that time[83]. Kashir et al. achieved a greater formation of MPB region by intertwining ZrO2 and HfO2 layers to create HZZ-type devices, as depicted in Figure 9C[84]. The dielectric constant of the HZZ nanolayers is larger than that of HZO and ZrO2 films, which is attributed to the formation of the MPB region[84]. They also prepared HZO films with different proportions of the T-phase by adjusting the oxygen content and heat treatment conditions[85]. The results showed that the relative dielectric constant decreased with decreasing T-phase content[85]. This may be due to the different densities of the MPB region. Oh et al. also found that a higher proportion of the T-phase helps achieve optimal MPB conditions[86]. Gaddam et al. obtained the MPB through ZrO2/HZO bilayer AFE/FE capacitor films, as depicted in Figure 9D[87]. The devices they fabricated also exhibited excellent performance (higher κ of ~56 and the lower EOT of 3.8 Å) and could withstand up to 1012 cycles[87]. The MPB is of great importance for improving the dielectric performance of HZO film and further applications.

Figure 9. (A) The HRTEM and (B) EDS mappings of the TiN/ZrO2/HfO2/TiN capacitor[42]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[42]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society. (C) HZO/ZrO2 supercell[84]. Reprinted from Ref.[84], with permission from IOP Publishing. (D) Schematic of heterostructure[87]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[87]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society.

Wake-up and fatigue

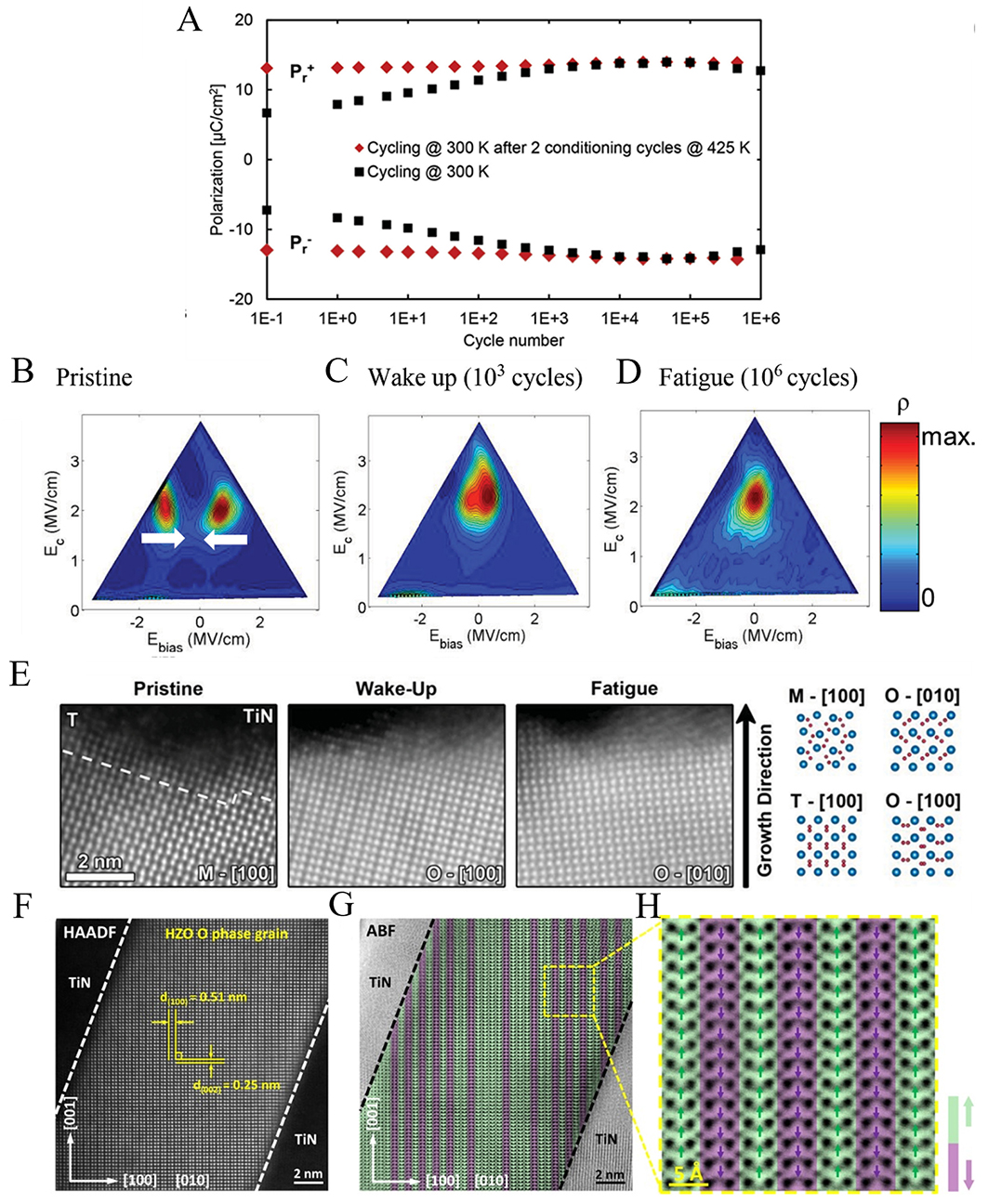

In practical applications of HfO2-based ferroelectric materials, there are phenomena of wake-up and fatigue[9,88-90]. The HZO ferroelectric thin film exhibits a “wake-up effect”, where Pr of the material increases with the number of electric field cycles. Fatigue, on the other hand, refers to a decrease in Pr as the number of cycles increases beyond a certain threshold. The classic wakefulness and fatigue phenomenon is shown in Figure 10A. In Pešic’s 2016 work, it was proposed that defects are the fundamental cause of the increase in remanent polarization during the wake-up stage and the subsequent degradation of polarization with further cycling[91]. As shown in Figure 10B-D, the wake-up and fatigue processes primarily involve the redistribution of existing defects within the device. In Figure 10E, phase transitions inside the HZO thin film under different states are observed through HAADF-STEM images, which are caused by defect rearrangement. The degradation of dielectric reduces the ferroelectric switching, and trap density increases with device cycling, indicating that trap generation is the main mechanism leading to the degradation of ferroelectric performance, apart from domain pinning.

Figure 10. (A) Wake-up and fatigue behaviors of HZO devices. In (B) 1, (C) 1,000, and (D) 106 cycles. (E) HAADF-STEM images with HfO2 doping in the pristine, wake-up, and fatigue states, along with theoretical schematic diagrams of different phases[91]. Reprinted from Ref.[91], with permission from Wiley. (F) HAADF cross-sectional image of TiN/HZO/TiN device after 107 cycles of fatigue. (G) Corresponding ABF image of (F). (H) Magnified ABF image obtained from the green square region in (G)[92]. Reprinted from Ref.[92], with permission from Springer Nature.

In 2021, McMitchell et al. found reversible tetragonal-orthorhombic, orthorhombic-monoclinic, and other phase transitions during HfO2 formation[93]. The low energy barrier of these phase transitions leads to cycle wake-up. They also established a model by describing grain reorientation to explain the changes in the orthorhombic unit cell during the wake-up process. The rotation of the orthorhombic unit cell aligns the polarization direction with the electric field direction, thereby enhancing the remnant polarization. Rushchanskii et al. suggested that in the wake-up cycle, randomly distributed oxygen vacancies are rearranged into the lowest energy configuration, allowing them to transform into the orthorhombic phase[94]. The monoclinic phase could be seen as domain boundaries between orthorhombic domains with opposite polarization. The increase in polarization may be due to the growth of the orthorhombic phase at the monoclinic phase boundaries. The decrease in polarization could result from the reverse transformation from the orthorhombic phase to the monoclinic phase or from the growth of orthorhombic phases with polarization in the opposite direction, leading to a decrease in the proportion of the monoclinic phase[94]. In 2022, Cheng et al. conducted detailed studies on the crystal structure of the O-phase grains in HZO ferroelectric films during different processes such as initial state, wake-up, fatigue, and recovery using STEM-HAADF and scanning transmission electron microscopy in annular bright-field mode (STEM-ABF) techniques[92]. The generation of the interfacial T-phase was observed during the fatigue cycling process affected by oxygen vacancies, but the wake-up, fatigue, and recovery processes were mainly dominated by the reversible transformation between the ferroelectric phase Pca21 (OFE phase) and the antiferroelectric phase Pbca (OAFE phase). Under low electric fields, these two phases could mutually convert in

PREPARATION OF HFO2 THIN FILMS

Hafnium oxide has attracted significant interest due to its unique ferroelectric properties, which has prompted extensive efforts to fabricate HfO2-based ferroelectric thin films through diverse methods. The ferroelectricity of hafnium oxide is closely related to its specific doping ratios, crystal structure, and thickness. Pulsed laser deposition can precisely replicate the atomic ratios of different elements in the target material, avoiding compositional deviations caused by the preparation method. Thickness significantly impacts the ferroelectric properties of HfO2-based thin films, and atomic layer deposition enables atomic-scale control over film growth, ensuring precise thickness regulation. Both preparation methods are highly suitable for growing ultrathin, uniform ferroelectric HfO2-based thin films.

Atomic layer deposition

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) is a chemical vapor deposition technique consisting of cyclic gas-solid reactions. The main process is that gas-phase precursors are alternately pulsed into the reaction chamber and undergo a gas-solid phase chemisorption reaction on the surface of the substrate to form a thin film[95]. Nowadays, literature regarding the production of ferroelectric HfO2-based films via ALD has become increasingly prevalent. This subsection describes some cutting-edge work on the ALD preparation of hafnium oxide thin films, as well as the improvement of the ALD preparation process for the preparation of HfO2-based thin films.

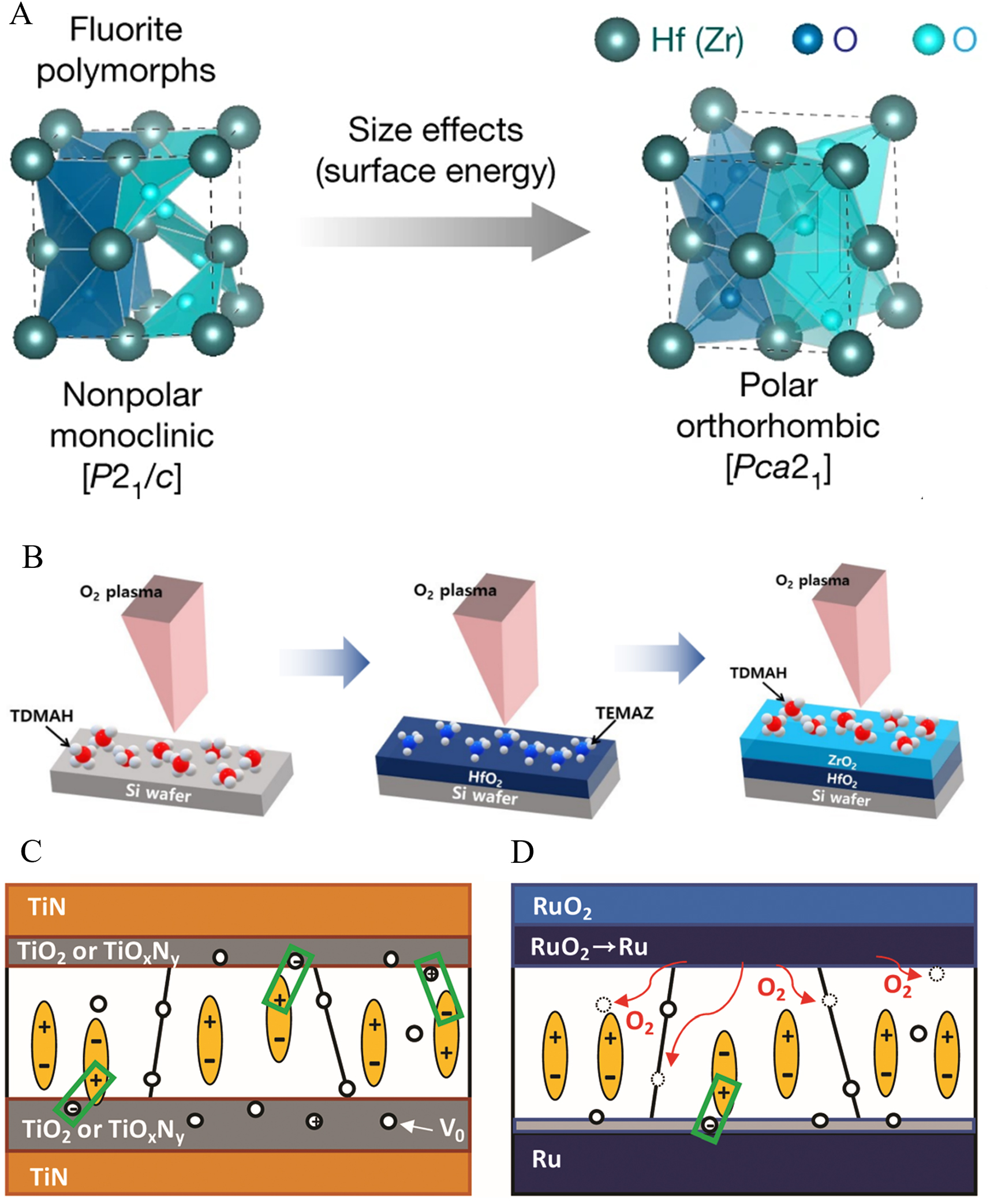

Cheema et al. grew ultra-thin HfO2 on silicon using ALD and confirmed the presence of inversion-symmetry breaking and switchable polarization using second harmonic generation and advanced scanning probe techniques, respectively[96]. HfO2 not only has no critical thickness for ferroelectricity, but its polar distortion is also enhanced as the film thickness decreases. At reduced dimensions, higher symmetry phases are energetically favorable. In the classical perovskite, the size effect driven by surface energy favors the higher symmetry ferroelectric phase (cubic phase) rather than the lower symmetry paraelectric phase (tetragonal phase) upon dimensional reduction. In contrast, in the fluorite structure, the non-centrosymmetric phase (orthorhombic Pca21, O-phase) has higher symmetry compared to the bulk-stable centrosymmetric phase (P21/c, M-phase)[96]. As shown in Figure 11A, the surface energy promotes the transformation from M-phase to O-phase. Yu et al. grew HZO ferroelectric thin films on Si substrates by the ALD technique[97], and the 20-nm-thick HZO films exhibited good ferroelectricity. Liang et al. prepared HZO thin films and HfO2-ZrO2 superlattices by ALD, which exhibit enhanced ferroelectricity, better durability and retention properties[98]. This is due to the lower defect density of the HfO2-ZrO2 superlattice suppresses the fatigue condition during electric field cycling.

Figure 11. (A) Size effects in fluorite-structure ferroelectrics[96]. Reprinted from Ref.[96], with permission from Springer Nature. (B) PEALD process for growing HZO films on a Si wafer[103]. Reprinted from Ref.[103], Copyright (2023), with permission from Elsevier (C) TiN/HZO/TiN and (D) RuO2/HZO/RuO2 are shown[65]. Reprinted from Ref.[65], with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Appropriate process conditions can effectively improve the performance of HfO2-based thin films. Lee et al. prepared HZO ferroelectric capacitors with metal-ferroelectric-metal (MFM) structures using an ALD technique incorporating a Sequential No-Atmosphere Process (SNAP)[99]. The SNAP process can effectively maintain a clean interface between TiN and HZO layers under vacuum conditions, which could effectively suppress the growth of harmful passivation layers and enhance Pr[99]. Plasma-enhanced atomic layer deposition (PEALD) employs a highly reactive plasma during the reaction, enhancing the deposition rate and the film's quality effectively[100-102]. The process of PEALD is shown in Figure 11B[103]. The relationship between the crystallization of HfO2 films and the leakage current was investigated in the work of

Factors in the preparation process, such as the oxygen content[69], insertion layer[57,71,106-109], and capping layer[38,56,59,68,110-113], also affect the properties of HfO2-based films. Oxygen vacancies in HfO2-based films are formed due to interfacial reactions between the film and the bottom electrode during deposition and post annealing. Kim et al. used ozone as an oxidizing agent during ALD to oxidize the TiN; the ferroelectricity and durability of the films were significantly improved and Pr was increased by ~1.6 times, with no wake-up effect and no significant fatigue effect, of which the number of cycling is more than 108[69]. Inserting the TaOx layer can well improve the conductivity linearity and durability of HfO2 devices[114]. Wang et al. improved the crystallinity and ferroelectricity of 4 nm HZO films by monolayer engineering, and the HZO films can show better crystallinity even at 400 °C[72]. They replaced one layer of HfO2 with one layer of ZrO2 during the ALD process of preparing HZO thin films. The test results showed that this structure can effectively enhance the ferroelectricity of HZO thin films, which provides a feasible solution for the realization of good ferroelectricity below 5 nm[72].

Goh et al. systematically investigated the effects of metal oxides on the wake-up effect and ferroelectricity of HZO ferroelectric thin films using two electrode materials, TiN and RuO2[64,65]. The results indicate that the RuO2/HZO/RuO2 capacitor has a smaller wake-up effect and better endurance than the TiN/HZO/TiN capacitor, up to more than 108 cycles. Figure 11C shows that the TiN transition metal electrode reacts with oxygen in the HZO layer, producing oxygen vacancies and defects in the HZO layer. The electron traps on the vacancies generate a built-in electric field and an unswitched pinning domain. Figure 11D explains that, unlike the TiN electrode, the RuO2 metal oxide electrode can provide oxygen to the HZO layer through its own reduction reaction, thereby suppressing the formation of oxygen vacancies. Therefore, the RuO2/HZO/RuO2 device has fewer interface layers, a smaller wake-up effect, and better reliability[65]. In the RuO2/HZO/TiN device, the Ec value increases linearly as f increases from 250 Hz to 250 kHz. However, in the TiN/HZO/TiN device, the Ec value is independent of logf. This is attributed to the reaction between the TiN transition metal electrode and oxygen in the HZO layer, whereas the RuO2 oxide metal electrode supplies oxygen to the HZO layer to inhibit the formation of oxygen vacancies[64].

Furthermore, top electrodes with different thermal expansion coefficients α and work functions also have an impact on the ferroelectric performances of HfO2-based films[59]. It can be observed that the Pr value of ferroelectric capacitors with Au, Pt, TiN, Ta, and W as the top electrode increases continuously. This phenomenon may be due to the beneficial effects of in-plane tensile strain on the phase transition from the T-phase to the O-phase along the c-axis[55,59]. As α decreases, the in-plane strain changes from compressive strain to tensile strain, and the proportion of the ferroelectric phase increases accordingly[59,115]. These factors all indicate the importance of fully considering various factors in improving the quality of HfO2-based thin films during the ALD preparation process.

Pulsed laser deposition

Pulsed laser deposition (PLD) is a highly effective deposition technique that involves subjecting the surface of a target to intense laser pulses, altering the arrangement of atoms on its surface. The high-energy laser pulse causes the target atoms to melt, resulting in the generation of a plasma plume, which subsequently sputters onto the substrate. The preparation of HfO2-based thin films using PLD is able to obtain high-quality epitaxial films with homogeneous compositions and few impurities, and the quality of the films can be improved quickly and efficiently by adjusting the growth parameters[116].

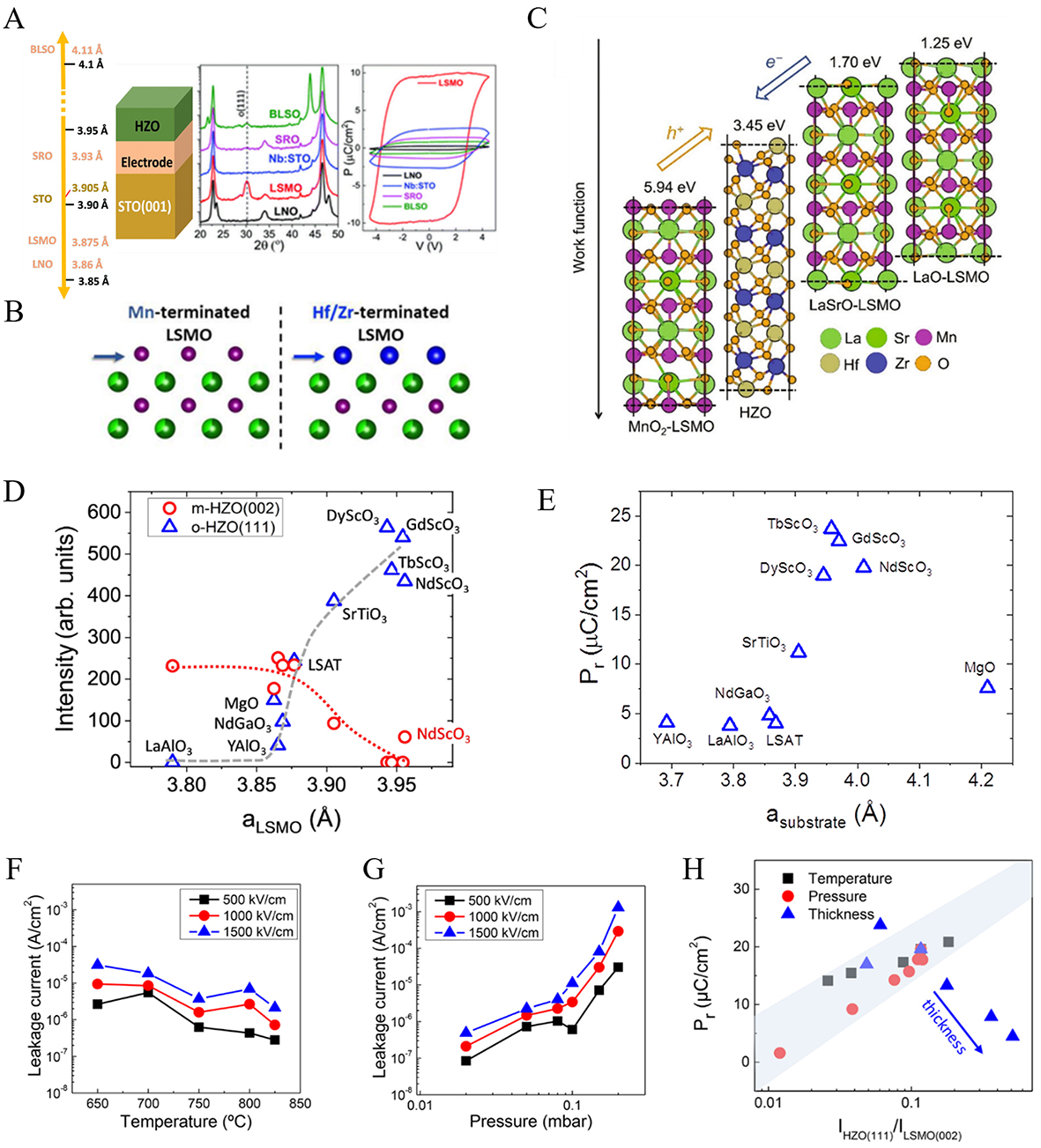

There are several crucial factors that require careful attention in preparing HZO thin film with PLD, including oxygen pressure, laser energy density, temperature, bottom electrode, and so on. It has been reported that the use of bottom electrodes with different lattice constants also greatly affects the generation of the O-phase in HZO films[11,63,117,118]. Estand et al. pointed out that different bottom electrodes, even on the same substrate, have different effects on the formation of ferroelectric O-phase and ferroelectric polarization of the HZO films[118]. The ferroelectric loops plot on the right side of Figure 12A shows that the HZO films on LSMO bottom electrode exhibit the largest ferroelectric polarization, which might be due to the epitaxial stress of LSMO on the HZO film stabilizes the O-phase. However, some researchers have suggested that it is the interfacial interaction between the LSMO and the HZO film[117]. As shown in Figure 12B, under oxygen-deficient conditions, the Hf/Zr atoms take the place of the Mn at the LSMO/HZO interface, replacing the Mn cations at the MnO2 interface. This chemical remodeling may have led to the stabilizing effect of LSMO on the ferroelectric O-phase, but the mechanism of this is still under discussion.

Figure 12. (A) XRD images and ferroelectric loops of HZO films grown on different bottom electrodes[118]. Reprinted from Ref.[118], with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry. (B) Substitution of Mn by Hf/Zr in the interface between LSMO and HZO[117]. Reprinted figures with permission from Ref.[117] Copyright by the American Physical Society. (C) The work functions of o-HZO, MnO2-LSMO, LaSrO-LSMO, and LAO-LSMO[119]. Reprinted from Ref.[119], with permission from Springer Nature. (D) Intensity of the o-HZO(111) and m-HZO(002) peaks, (E) Pr as a function of the lattice parameter of the substrate[63]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[63]. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society. Dependence of Pr and Vc on (F) temperature, (G) pressure, and (H) thickness[120]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[120]. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society.

Shi et al. demonstrated a crucial interface engineering strategy to stabilize and enhance the ferroelectric orthorhombic phase of HZO thin films by controlling the termination of the underlying LSMO[119]. In their study, the results showed that MnO2 termination promoted and stabilized the ferroelectric phase of HZO. As shown in Figure 12C, the work function of MnO2-terminated LSMO is larger than the work function of o-HZO, leading to the attraction of electrons from o-HZO to MnO2-terminated LSMO, resulting in a hole-rich condition for HZO. At low hole concentrations, the m-HZO phase is more stable, while at hole concentrations greater than 0.17 h/u.c., the o-HZO phase is more stable. These observations strongly indicate that hole doping and MnO2 termination in LSMO favor the stability of the o-HZO phase.

Substrate also has an effect on the polarization of HfO2-based films[63]. The researchers grew epitaxial bilayer films of HZO and LSMO electrodes on a series of substrates and demonstrated the critical effect of epitaxial stress on the stabilization of the ferroelectric orthorhombic phase. As shown in Figure 12D and E, the lattice strain of LSMO electrodes plays a crucial role in stabilizing the HZO orthorhombic phase, as it is determined by the lattice mismatches with the substrate. When subjected to tensile strain, the majority of HZO films exhibit an orthorhombic phase. As a result, HZO films on TbScO3 and GdScO3 substrates exhibit enhanced ferroelectric polarization compared to films on other substrates[63,121]. Lyu et al. used PLD to grow HZO thin films, and investigated the effects of other factors, temperature, oxygen pressure, and thickness, on the structure and ferroelectricity of the HZO films[120]. As shown in Figure 12F-H, their work indicated the relationship between coercive field (VC) and temperature, pressure, and film thickness.

Other fabrication methods

In addition to the ALD and PLD methods mentioned above, magnetron sputtering can also be used to prepare high-quality ferroelectric HZO thin films. Bouaziz et al. used magnetron sputtering to prepare two different structure samples: non-mesa structure (NM) and mesa structure (M)[62]. These two samples exhibit different electrical characteristics. Under low-stress conditions, the M sample has a higher maximum Pr, while under high-stress conditions, it is the opposite. During the annealing process, different microcrystalline structures are formed in the HZO layer due to the different coverage of the top electrode on the HZO layer. Mittermeier et al. also used RF magnetron sputtering technology to prepare ferroelectric HZO thin films with a thickness of 4 nm and quantitatively studied the neurobehavior of the TiN/HZO/Pt ferroelectric tunnel junction[122]. Chen et al. prepared hafnium oxide nanocrystals via the hydrothermal method and successfully achieved synaptic behavior[123,124], further expanding the application prospects of HfO2in artificial synaptic devices. There are still many unexplored aspects regarding the preparation process of HfO2-based ferroelectric thin films. For further details, please refer to the corresponding references.

APPLICATIONS OF HAFNIUM OXIDE

With the advantages of ferroelectric hafnium oxide fabricated via different preparation methods, researchers further investigated the possibility of their application in devices. Hafnium oxide could be used in various situations, such as nonvolatile memory, intelligent sensing and edge computing, low-power logic devices. This review primarily focuses on its applications in neuromorphic devices, including ferroelectric tunnel junctions (FTJs), memristors, and FeFETs.

FTJ

The reversal of spontaneous polarization in the ferroelectric tunneling junctions combined with the different charge shielding properties of the two metallic electrodes alters the internal electric field distribution of the FTJ, which in turn alters the tunneling currents to produce two different resistive states[125,126]. Hafnium oxide has no size effect, and remains ferroelectric even at a thickness of 3-5 nm[67] with high CMOS compatibility. The work of Bégon-Lours et al. demonstrates the nonvolatile resistive switching behavior of ferroelectric HZO with a thickness of 4.5 nm[127]. The resistive switching behavior of the films is significantly enhanced after wake-up. The effect of different coefficients of thermal expansion of the bottom electrode on the ferroelectricity of ultrathin HZO films was systematically investigated by Goh et al.[66]. The 2Pr values of the capacitor decrease gradually in the order of bottom electrodes: W, Mo, Pt, TiN, and Ni, indicating a corresponding reduction in their ferroelectricity. This is attributed to the film undergoing an effective phase transition from the T-phase to the O-phase under the effect of in-plane tensile stresses during annealing at room temperature.

In the work of Prasad et al., ferroelectric HZO thin films with a thickness of up to 2.5 nm were prepared. When applying this thin film to FTJs, the devices showed a significantly high Tunneling Electroresistance ratio[128]. Specifically, with a 1 nm HZO layer at zero bias voltage, the Roff/Ron ratio reached 135. FTJs with a HZO layer thickness of 2.5 nm demonstrated switch ratios above 102 at different bias voltages, and the

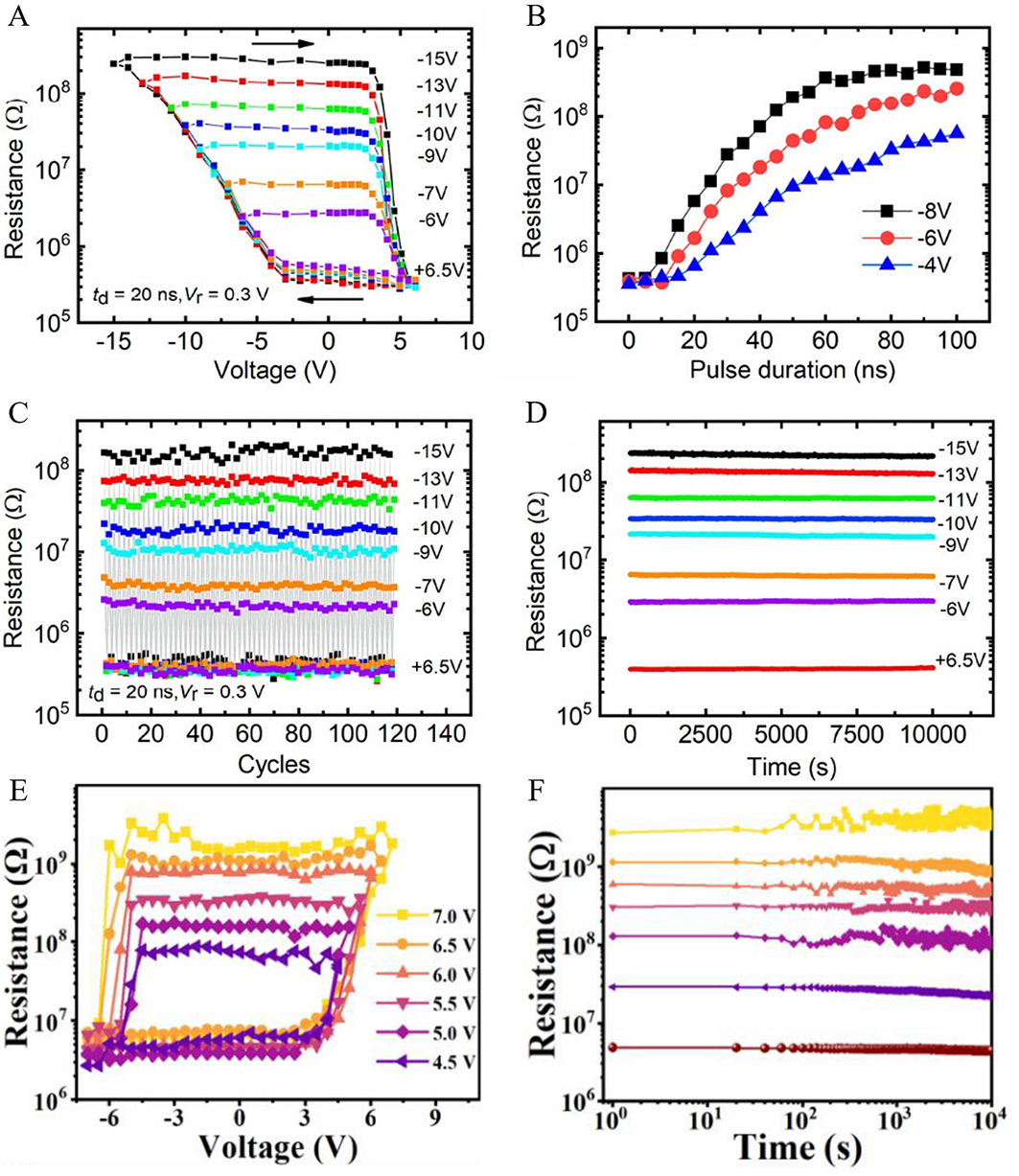

In 2018, Chen et al. prepared a three-dimensional vertical HZO-based FTJ array that meets the requirements of high-density HNN applications[60]. The FTJ had high integration density and low power consumption (1.8 pJ/pulse). It could simulate synaptic behaviors such as long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), and Spike Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP), and demonstrated good repeatability (> 1,000 cycles). In 2022, Du et al. prepared a single-phase orthorhombic epitaxial HZO-based FTJ with an MFS structure[129]. They grew a 1uc LSMO and a 4.5 nm HZO film on NSTO. Figure 13A shows the eight resistance states of the FTJ device, while Figure 13B demonstrates the response of the FTJ under different pulse voltages. Figure 13C and D illustrates the cycling endurance and retention performance of the FTJ, respectively. The FTJ device achieves over 1,000 switching cycles and retention times exceeding

Figure 13. (A) R-V loops measured at different voltages. (B) Relationship between resistance and pulse voltage duration. (C) Resistance switching cycles. (D) Retention time corresponding to the resistance states in (A)[129]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[129]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society. (E) Multilevel R-V property, (F) Retention examinations[70]. Reprinted from Ref.[70], Copyright (2022), with permission from Elsevier.

Wang et al. further fabricated FTJ devices based on epitaxial HZO and simulated synaptic behavior. The study first investigated the parameters such as crystallinity, strain, interface, and electrical properties of FTJs[70]. As shown in Figure 13E and F, the HZO-based FTJ can achieve multiple resistance states and retain for over 104 s. Figure 14A-C clearly illustrates its ability to implement various Hebbian rules, exhibiting excellent synaptic plasticity. The researchers have also applied this device to an artificial neural network depicted in Figure 14D. Figure 14E and F presents the relative frequency of the conductance distribution for the optimal weight matrix and mapping matrix, respectively. The recognition rate achieved by this FTJ is 93.7%, slightly lower than the 97.3% achieved by software training, demonstrating great potential for applications. Cao et al. effectively increased the tunneling current and residual polarization of the FTJ by adding ZrO2 (ZO) and Al2O3 (AO) layers to the HZO ferroelectric layer, while reducing leakage current[73]. Devices with only the AO layer and devices with both AO and ZO layers inserted exhibited larger ferroelectric polarization and better durability and reliability than the original devices. The optimized FTJ also achieved synaptic behavior. The calculated power consumption of the FTJ was found to be as low as 10.44 fJ/spike. The HZO-based FTJ device designed in this work has excellent prospects in the field of artificial synapses.

Figure 14. (A) Asymmetric anti-Hebbian configuration, (B) Symmetric Hebbian configuration, (C) Symmetric anti-Hebbian configuration realized by the device. (D) Schematic diagram of the multilayer neural network used for recognition. (E and F) Weight distribution and accuracy of software training and conductance maps[70]. Reprinted from Ref.[70], Copyright (2022), with permission from Elsevier.

Memristor

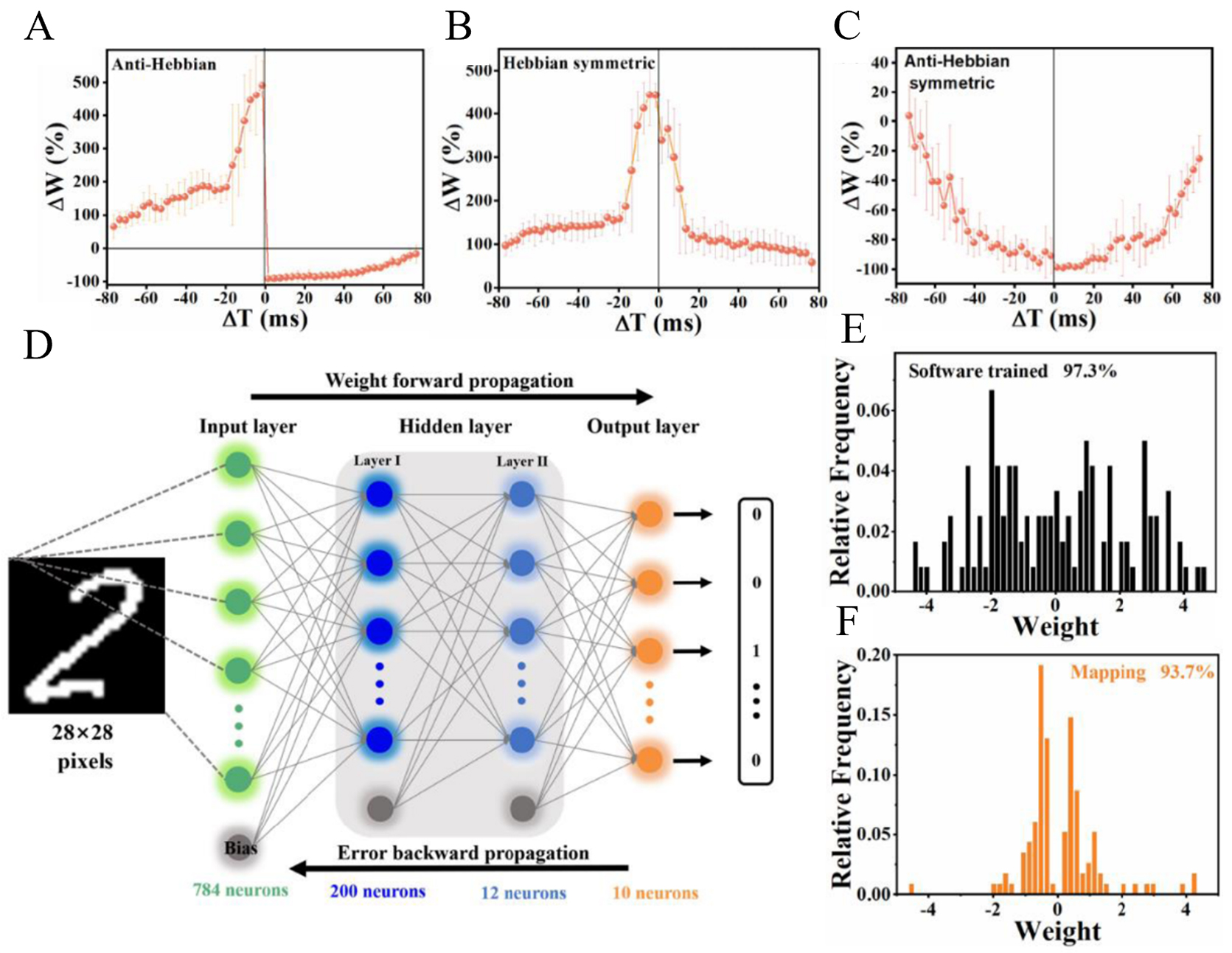

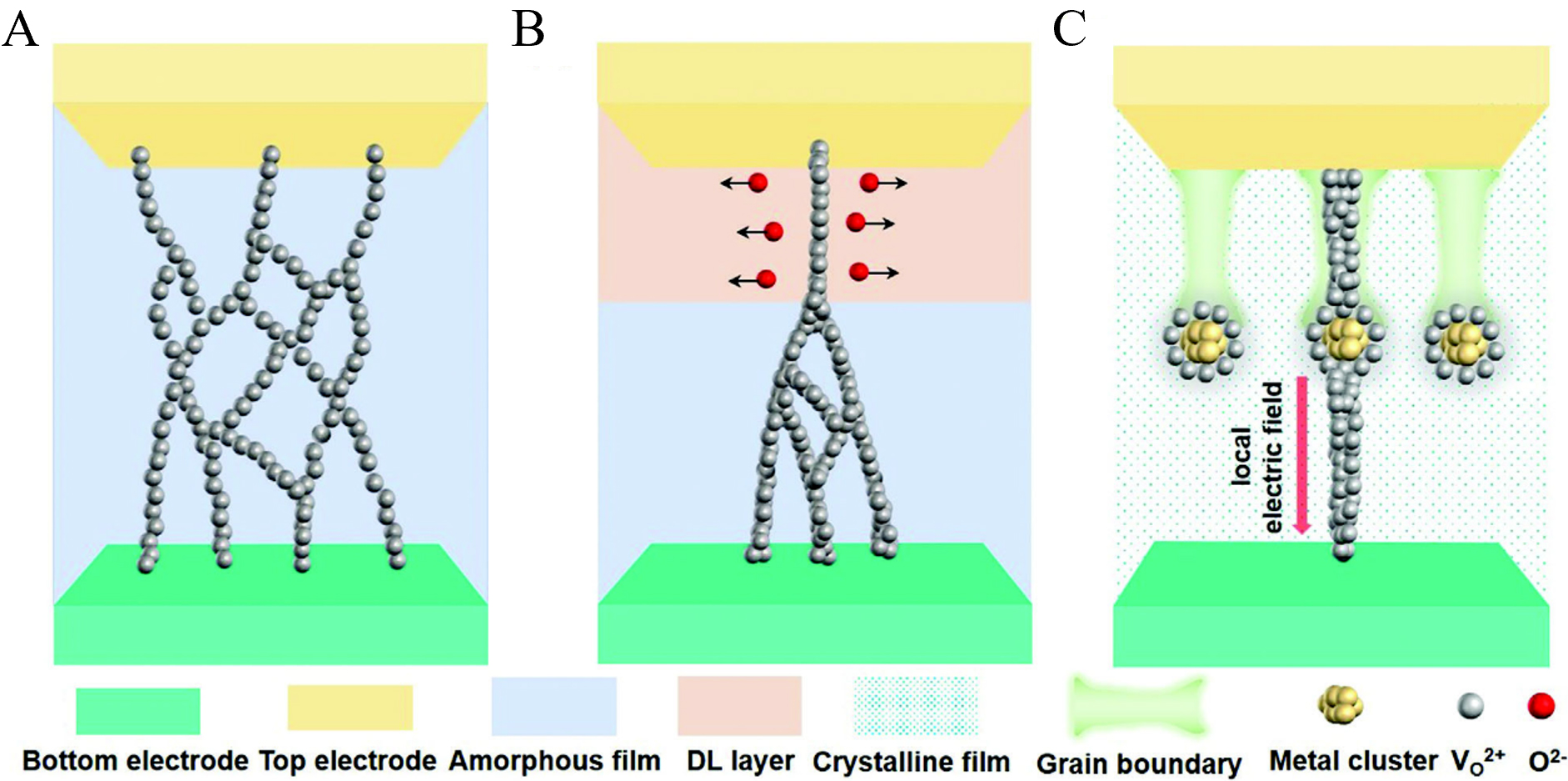

Hafnium oxide, as a binary oxide, can exhibit good RS behaviors[130-134] through the formation and dissolution of conductive filaments (CFs)[131,135,136]. The most obvious features of the CF mechanism are the sudden resistance change of SET (from HRS to LRS) and RESET (from LRS to HRS)[137]. After applying a positive voltage at the top electrode, oxygen ions leave the original lattice and move toward the bottom electrode. After the oxygen ions move, oxygen vacancies are formed in their original positions. Under the influence of the electric field, these vacancies move directionally and begin to accumulate. As they accumulate, a conductive filament channel gradually forms within the oxide film, switching the memory device from a HRS to a LRS, which is known as the SET process. When a corresponding RESET voltage is applied, the oxygen ions recombine with the oxygen vacancies, reducing their concentration within the film, breaking the conductive filaments and transforming the device from LRS to HRS; this is referred to as the RESET process.

Nonlinear behavior and high asymmetry adversely affect the synaptic behavior of memristors. Improving the linearity of memristive devices enhances their performance. The random growth of CFs formed by VO leads to stochastic CF morphologies, as shown in Figure 15A. Introducing an ion diffusion-limiting layer can regulate CF formation [Figure 15B], but these methods remain suboptimal. Zeng et al. achieved highly linear conductance modulation in HfO2-based memristors by doping metal nanoparticles during oxide film epitaxial growth, forming well-defined grain boundaries [Figure 15C], which significantly improved device linearity[138].

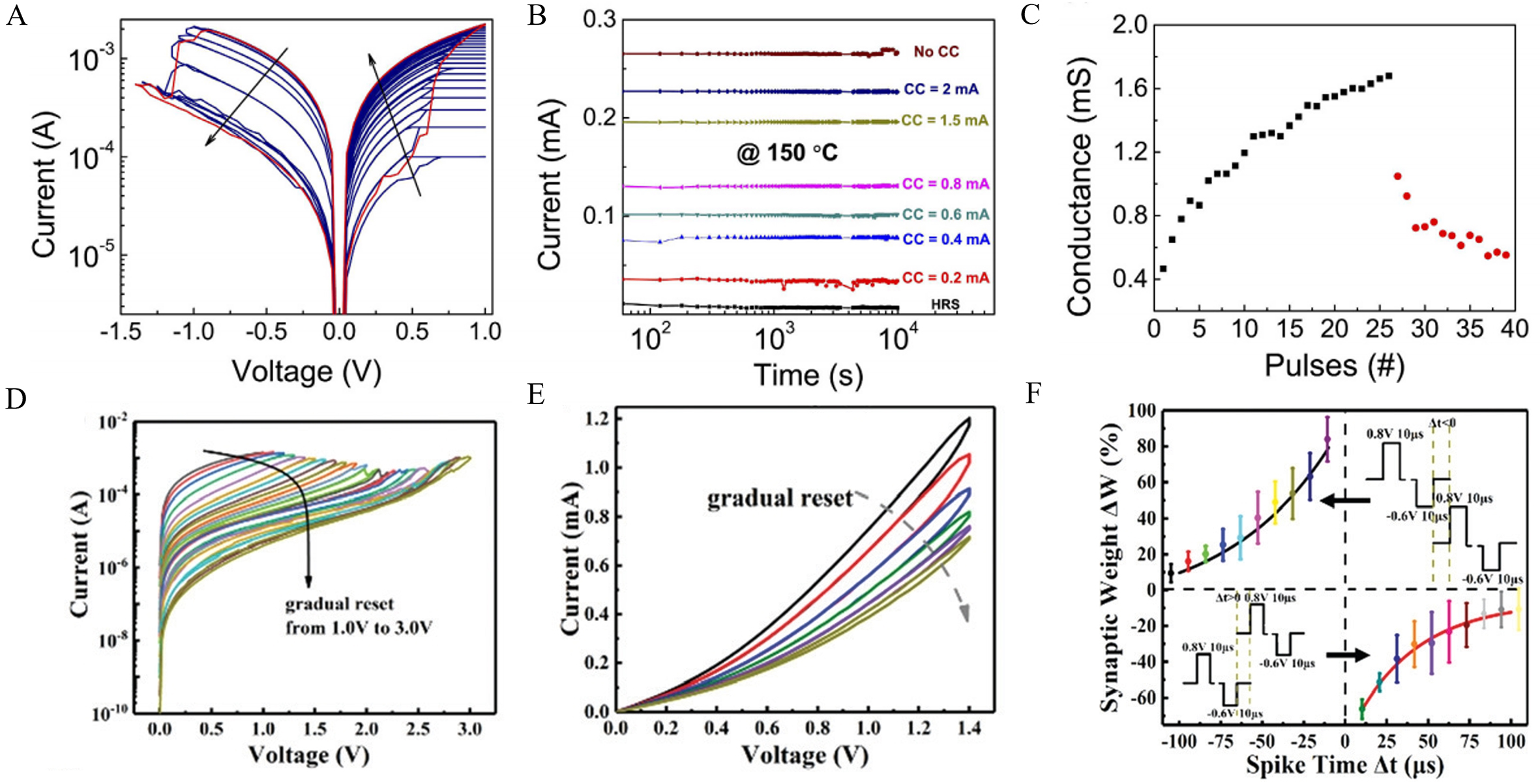

Many studies have reported on resistive switching devices with HfO2 as the functional layer. Covi et al. proposed a TiN/HfO2/Ti/TiN resistive switching device for use as an artificial synapse in neural-inspired structures[139]. This device exhibits significant resistive switching behavior, demonstrating potentiation/depression behavior under current stimulation, and has successfully achieved STDP behavior, indicating its ability to realize synaptic plasticity. Jiang et al. developed a Ta/HfO2/Pt-type resistive switching device[140]. As shown in Figure 16A, by adjusting the compliance current and testing voltage, they successfully induced 24 different resistive states in the device. Figure 16B demonstrates that these different resistive states can be maintained for more than 104 s, indicating excellent retention performance of the device. Additionally, Figure 16C shows that the device can exhibit enhanced/inhibited behavior by applying positive/negative pulses. Liu et al. fabricated a resistive switching device with a HfO2/HfOx ultrathin bilayer structure[141]. As shown in Figure 16D and E, different resistive states can be induced in the device by applying different voltages or repeating the same voltage. As an artificial synapse, the device was found to exhibit STDP behavior, as shown in Figure 16F. Additionally, the device demonstrated low power consumption, indicating excellent potential for future applications in neuromorphic computing. Zhu et al. prepared Cu/HZO/GeS/Pt and Cu/Ges/Pt memristors, and the addition of the HZO layer can effectively improve the switching ratio and reliability compared to the structure without the HZO layer[133]. Meanwhile, the memristor with the HZO layer has a switching speed as low as 10 ns, which is due to the different transport rates of copper ions in HZO and GeS, resulting in a more concentrated formation and regeneration of conductive filaments at the interface of the two layers.

Figure 16. (A) The resistance states of the device adjusted by changing the compliance current setting. (B) Retention testing of the device. (C) The simulated switching behavior of the device[140]. Reprinted from Ref.[140], with permission from Springer Nature. (D) The measured I-V curve of the resistive device with gradually increasing reset voltages from 1.0 to 3.0 V. (E) The I-V curves of the resistive device measured by applying positive 1.4 V bias voltages six times. (F) The STDP curve of the device[141]. Reprinted from Ref.[141], with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.

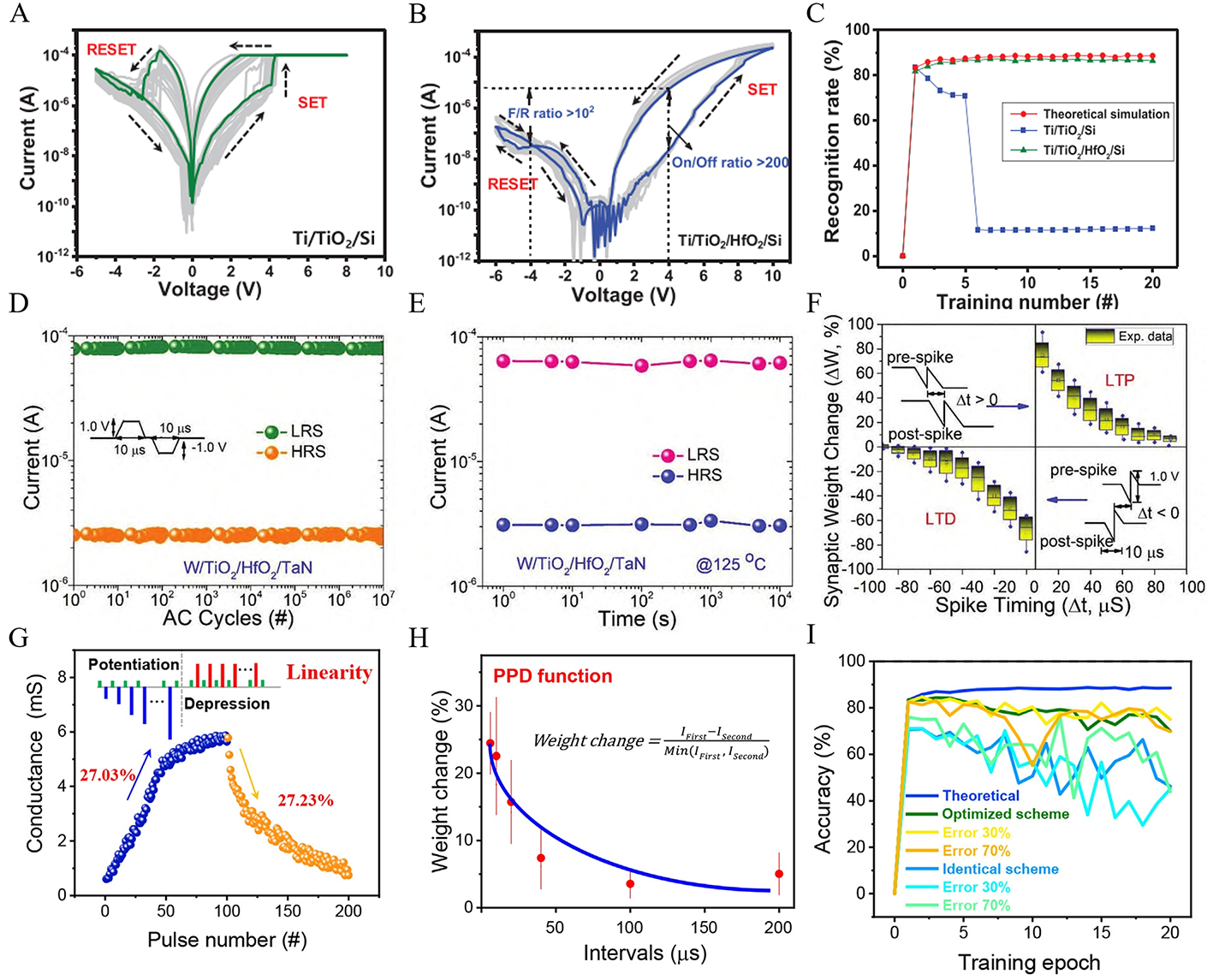

The self-correcting memristor that can be used in large synaptic array structures to reduce leakage currents in neuromorphic systems was then proposed by Ryu with Ti/TiO2/Si devices and Ti/TiO2/HfO2/Si devices[142]. As shown in Figure 17A and B, the Ti/TiO2/Si and Ti/TiO2/HfO2/Si devices exhibit different I-V characteristics. XPS analysis yielded that the HfO2 interfacial layer enhanced the interfacial switching characteristics through rectification behavior, and the current suppression by the Schottky barrier between Ti and TiO2 under negative bias facilitates the realization of high-density synaptic devices. Pattern recognition simulations with a two-layer artificial neural network found that the recognition rate of Ti/TiO2/HfO2/Si devices was higher than that of Ti/TiO2/Si devices, as depicted in Figure 17C. Ismail et al. also prepared RRAMs with TiO2 and HfO2 as the functional layers[143], which is able to achieve more than 107 cycles with retention time of more than 104 s as shown in Figure 17D and E. In addition, as shown in Figure 17F, this RRAM is capable of STDP behaviors and other synaptic behaviors, which has good potential for application in the field of nonvolatile storage and artificial synapses.

Figure 17. The I-V characteristic curves of (A) Ti/TiO2/Si and (B) Ti/TiO2/HfO2/Si devices. (C) Recognition accuracy of Ti/TiO2/Si devices and Ti/TiO2/HfO2/Si devices[142]. Reprinted from Ref.[142], Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier. (D) W/TiO2/HfO2/TaN devices withstand more than 107 switching cycles. (E) W/TiO2/HfO2/TaN devices remain unchanged for more than 104 s at

By varying the limiting current and SET voltage, the Pt/Ta2O5/HfO2/TiN memristor can achieve multiple resistance states[108]. This memristor is also capable of emulating synaptic behaviors such as LTD, LTP, and paired-pulse depression (PPD), as depicted in Figure 17G and H. Moreover, the devices demonstrated recognition performance on the Fashion MNIST dataset, as shown in Figure 17I. The inhibitory behavior of the memristor originates from the fact that the rate of accumulation of conductive defects in the switching layer is lower than the relaxation rate of these defects in the device, resulting in a decrease in conductance.

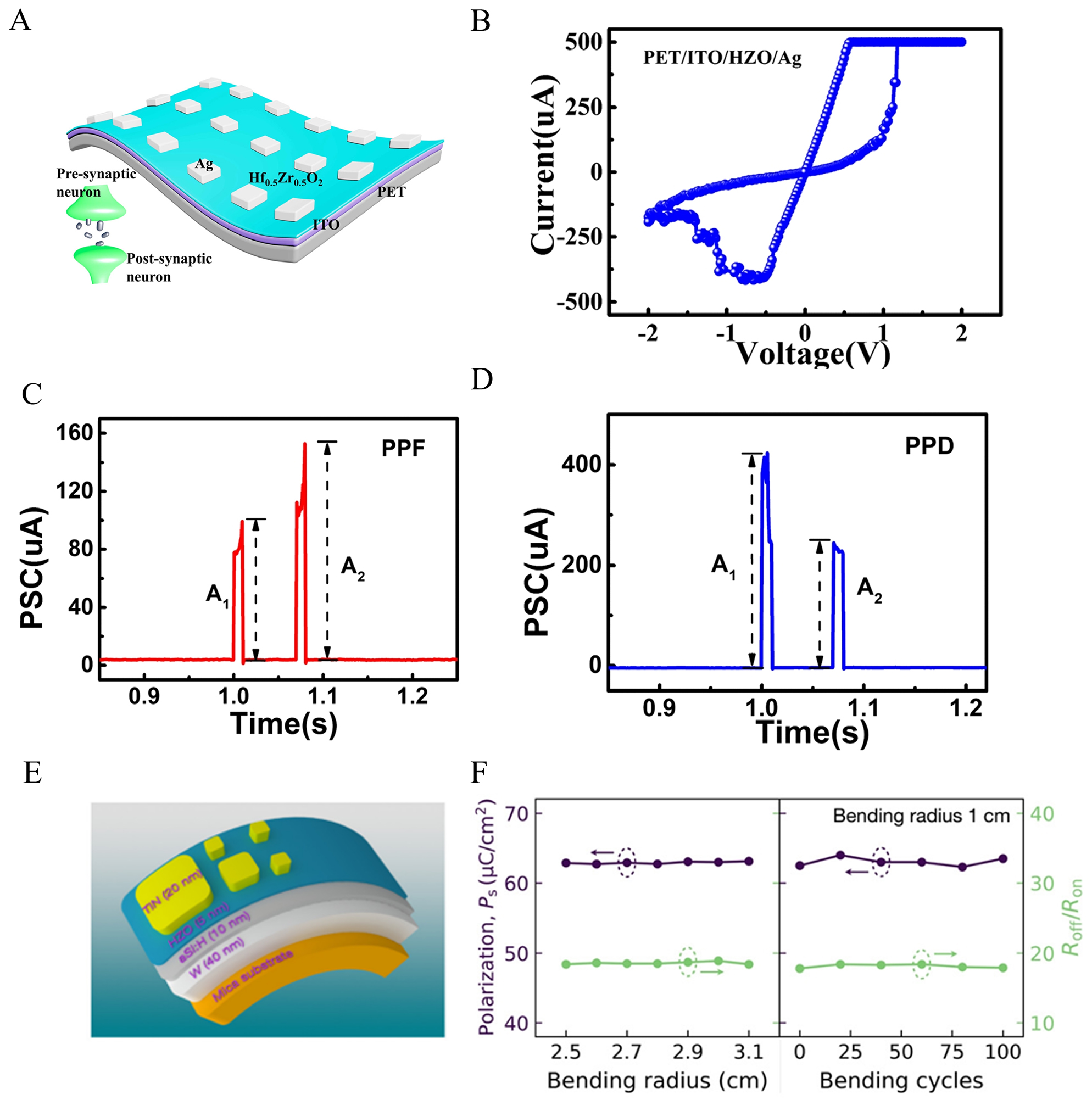

As shown in Figure 18A, a PET/ITO/HZO/Ag flexible memristor was deposited by the ALD process by Wang et al.[144]. Typical bipolar resistive switching characteristics were observed in this flexible memristor, as depicted in Figure 18B. Long-term plasticity and short-term plasticity were simulated in this artificial synapse by applying continuous pulses to the top electrode, as shown in Figure 18C and D. Gradual modulation of conductance could be attributed to the controllable Ag+ conductive filament pathway[144]. Margolin et al. achieved a W/hydrogenated amorphous silicon(aSi:H) /HZO/TiN ferroelectric memristor on a mica substrate[145]. The structure and physical image of the flexible device are shown in Figure 18E. The modulation of conductivity is achieved by gradually switching the ferroelectric domains in the structure by affecting the potential barriers. As shown in Figure 18F, even after bending at different bending radii and bending over 100 times at the same bending radius, the device can still maintain its original ferroelectric polarization and switching ratio, indicating that the device can maintain its functional characteristics under both static and repetitive bending, and the enormous potential of HZO-based devices in the field of flexible electronics.

Figure 18. (A) Schematic diagram of ITO/HZO/Ag device structure. Typical (B) I-V characteristic curve, (C) PPF curve, and (D) PPD curve of PET/ITO/HZO/Ag device[144]. Reprinted from Ref.[144], with permission from Springer Nature. (E)Schematic diagram (F) properties during bending tests of HZO-based flexible devices[145]. Reprinted from[145], with permission from AIP Publishing.

In addition to the CF mechanism, ferroelectric memristors have also received widespread attention. Unlike CF-based memristors that primarily change resistance states by the migration of oxygen vacancies to form CFs, ferroelectric memristors utilize ferroelectric materials as functional layers to switch between HRS and LRS by changing the polarization state of the ferroelectric material[13,61,146,147]. The Pd/HZO/LSMO/LAO ferroelectric memristor fabricated by Xiao et al. undergoes a transition from LRS to HRS when a positive voltage is applied to the top electrode, causing downward polarization in the ferroelectric layer and reducing the depletion layer width and barrier height at the HZO/LSMO interface[148]. Conversely, applying a negative voltage increases the depletion layer width and barrier height, transitioning the device from LRS to HRS. Yoong et al. grew HZO thin films and investigated their structure, ferroelectricity and brain-like learning behavior[61]. The device can achieve a retention time of over 6 hours, over 106 cycles, and a switching ratio of over three orders of magnitude. Zhu et al. prepared a memristor device with an Au/HZO/LSMO/STO structure and investigated the effects of cooling rate and oxygen pressure on the performance of HZO[149]. The results demonstrated that both the annealing rate and oxygen pressure influenced the proportion of the O-phase in HZO. The optimized HZO-based memory device achieved more than 15,000 cycles of high and low resistance switching. Furthermore, the impact of the O-phase on resistive behavior was discussed in this work. This study shows the great significance of the fabrication process to improve the applications of HZO ferroelectric devices in the field of artificial intelligence.

Zhao et al. prepared HZO-based ferroelectric memristors on Si substrates. The results of electrical tests showed that the memristor has typical ferroelectric polarization characteristics, stable switching behavior, and a large Roff/Ron ratio[150]. The effect of voltage on its conductance regulation was investigated using pulse voltage tests. The conduction mechanism of the HZO film in this work can be explained by the Trap-Assisted Tunneling mechanism. The ferroelectric domain polarization and charge conduction mechanisms inside the device are the key to its performance. The captured electrons are then transferred to the anode through either the Poole-Frenkel emission mechanism or trap-assisted tunneling[150]. The process of polarization modulation involves modifying the barrier height/width layer at the interface between a ferroelectric material and a semiconductor. When the ferroelectric polarization is directed toward the semiconductor, it generates a depolarizing field in the ferroelectric barrier that opposes the polarization. As a result, the barrier height decreases, leading to a higher tunneling transmittance. In this state, the device is set to LRS. On the contrary, when polarization is reversed and directed toward the metal electrode, the electrons on the semiconductor surface are depleted, increasing the barrier height and reducing the transmission rate of tunneling, causing the device to enter a high resistance state. This work has made significant contributions to explaining the conduction mechanism of the HZO ferroelectric memristor.

FeFETs

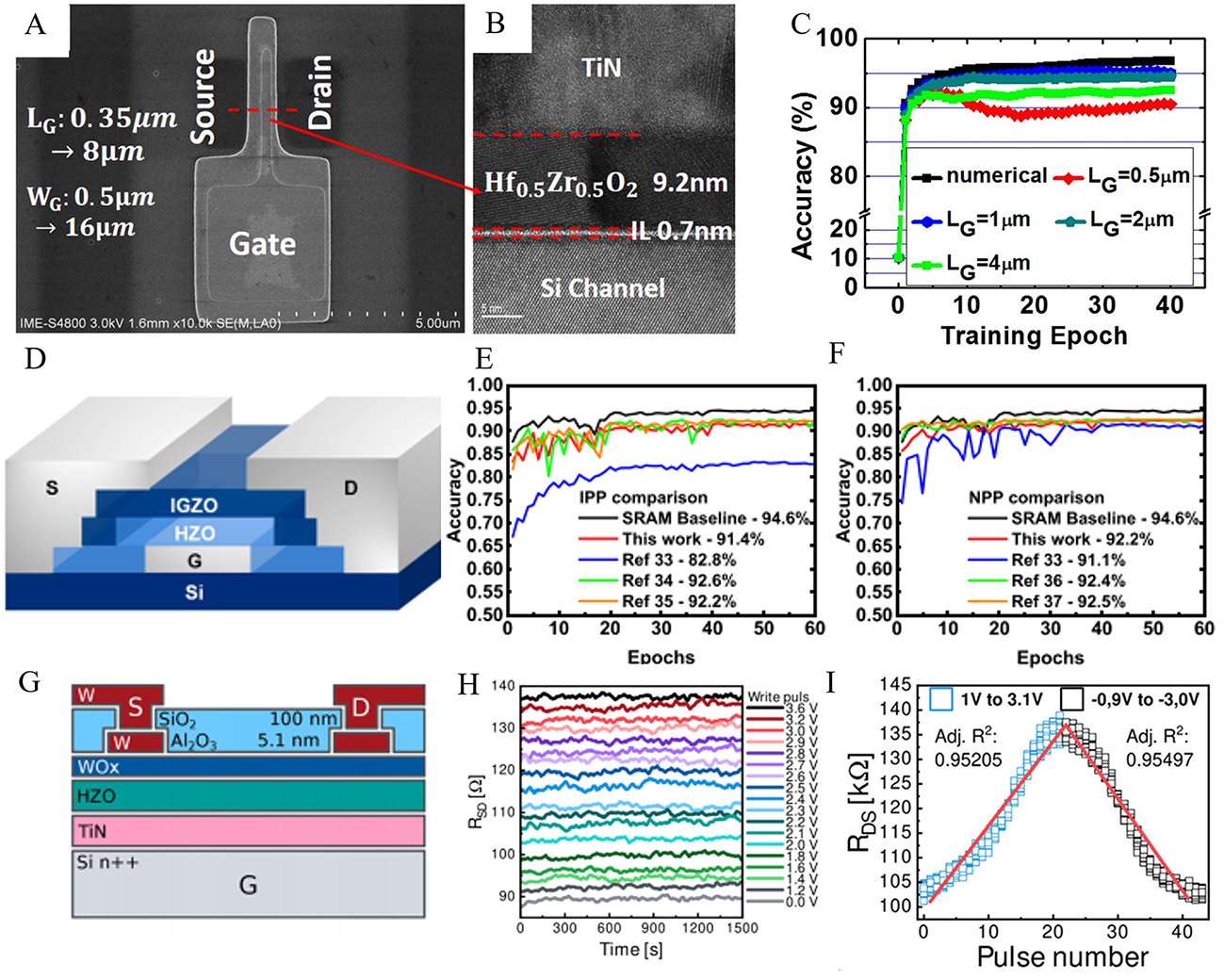

HfO2-based FeFETs with metal/ferroelectric/insulator/semiconductor (MFIS) gate stacks can be used to fabricate high-density and fast-writing nonvolatile memories. However, for practical applications, further improvements in storage window stability and device endurance are still required. Huang et al. fabricated FeFETs using alternative metal gate technology and conducted research on FeFETs with different gate lengths (Lg) and gate widths (Wg), of which the schematic diagram device is shown in

Figure 19. (A) Top-view scanning electron microscopy image, (B) HRTEM image, (C) recognition accuracy of different experimental devices and the ideal numeric values of FeFET[151]. Reprinted figures with permission from Ref.[151] Copyright by IOP Publishing, Ltd. (D) Schematic diagram of the device structure. The potentiation and depression behavior in FeFETs with (E) IPP and (F) NPP operating modes[152]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[152]. Copyright (2022) American Chemical Society. (G) Schematic illustration of the FeFET. (H) Retention tests for different resistance states. (I) The potentiation and depression behavior[153]. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[153]. Copyright (2020) American Chemical Society.

Halter et al. proposed a device concept based on FeFET[153], the structure of which is shown in Figure 19G. The device utilizes HZO gate dielectric as hardware support, which exhibits good linearity and CMOS compatibility. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 19H, each induced resistance state in the device demonstrates a retention time of over 1,500 s, showcasing excellent retention performance. It is found that the channel resistance of the device is directly coupled to the polarization of the HZO layer, and it can achieve highly symmetrical potentiation and depression, as illustrated in Figure 19I. The device's good linearity in conductivity is advantageous for its application in artificial neural networks.

In the work of Xiao et al., the storage window, retention, and durability of HZO-based FeFETs with MFIS gate stacks were studied using a fast voltage pulse measurement method[106]. The results showed that HZO-based FeFETs with an additional ZrO2 crystal seed layer exhibited longer retention and larger initial storage window. This is mainly attributed to the improved crystalline quality of the HZO layer and suppression of interface defects after inserting the ZrO2 crystal seed layer.

As shown in Table 1, compared to traditional ferroelectric materials, hafnium oxide-based devices exhibit no size effect, facilitating device miniaturization, while demonstrating strong compatibility with silicon without adverse reactions and excellent CMOS compatibility[154-159]. Currently, HfO2-based devices have already achieved diverse synaptic behaviors and hold potential for application as artificial synaptic components in artificial neural networks, with promising prospects even in the field of flexible electronics.

Statistics of devices based on HZO thin films and other ferroelectric materials

| Structure | Device | Method | Thickness | Function |

| TiN/HZO/TiN[127] | FTJ | ALD | 4.5 nm | / |

| STO/LSMO/HZO[128] | FTJ | PLD | 1-2.5 nm | / |

| STO/LSMO/HZO[70] | FTJ | PLD | 5-15 nm | LTP/LTD/STDP |

| STO/LSMO/HZO/Cu/HZO[138] | Memristor | PLD | 30 nm | PPF/STDP |

| PET/ITO/HZO/Ag[144] | Flexible Memristor | ALD | 10 nm | LTP/LTD/PPF/PPD |

| NSTO/LSMO/HZO[154] | Memristor | PLD | 10 nm | LTP/LTD/PPF/STDP |

| Si/STO/HZO[155] | Memristor | MBE(1) | 5 nm | LTP/LTD/STDP |

| NSTO/BTO/Cr/Au[156] | FTJ | PLD | 1.6 nm | PPF/PPD/STDP |

| SnS2/CuInP2S6/h-BN/Au[157] | Memristor | CVT(2) | / | PPF/STP /LTP |

| STO-SRO-BFO-BTO[158] | Memristor | PLD | / | STP/PPF/LTP |

| FTO/BFO/Ag[159] | Memristor | Sol-gel | / | LTP/LTD/PPF/STDP |

CONCLUSIONS

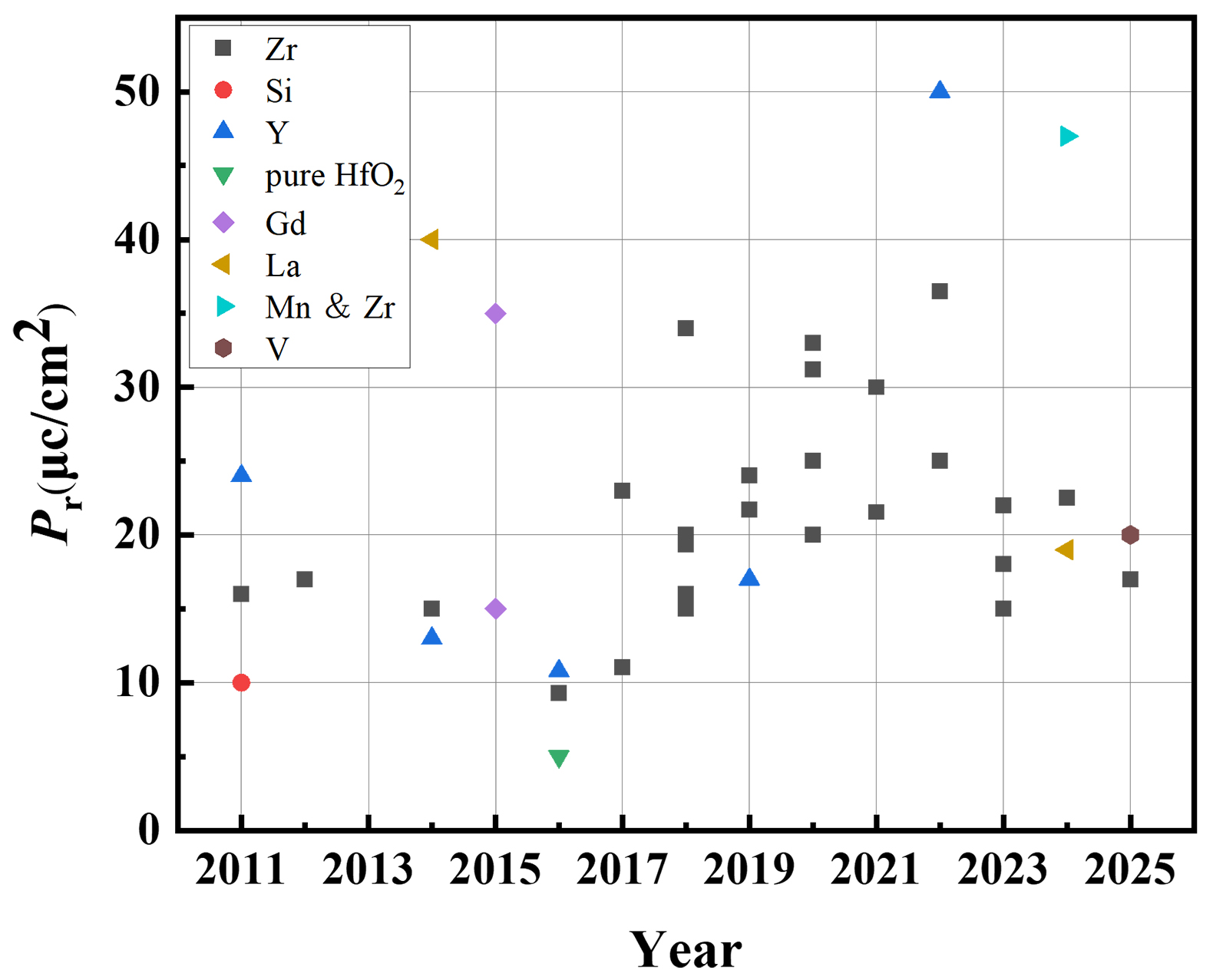

This article reviews the latest research progress on HfO2-based thin films, including the origin of their ferroelectricity, ferroelectricity in different doping systems, different preparation methods, resistive switching behavior, and practical applications of ferroelectricity. Figure 20 systematically delineates the paradigm evolution of HfO2-based ferroelectrics over the past decade, encompassing three pivotal dimensions[4,21,32,79,84,143,145,153]. Common HfO2 thin films do not exhibit ferroelectricity mainly due to their common phase, the monoclinic phase, which is a centrosymmetric non-ferroelectric phase. However, a metastable orthorhombic phase, a non-centrosymmetric ferroelectric phase, can be induced by controlling stress, doping, thermal budget, and other conditions. Currently, ferroelectric HZO films can be prepared by various means such as ALD, PLD, and magnetron sputtering, but the success rate is far from meeting the requirements for stable mass production for commercial use. In addition, although the origin of ferroelectricity in HfO2 has been explored in many aspects, there are still further possibilities for investigation.

Figure 20. Research progress in hafnium oxide-based materials[4,21,32,79,84,143,145,153]. Reprinted from Ref.[4], with permission from AIP Publishing. Reprinted from Ref.[21], with permission from AAAS. Reprinted from Ref.[32], with permission from AAAS. Reprinted from Ref.[79], with permission from Springer Nature. Reprinted from Ref.[84], with permission from IOP Publishing. Reprinted from Ref.[143], Copyright (2022), with permission from Elsevier. Copyright (2020) American Chemical Society. Reprinted from[145], with permission from AIP Publishing. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Ref.[153].

In current HfO2-based ferroelectric materials, both the wake-up effect and fatigue effect have certain adverse effects on the performance of devices, and these issues have not been completely resolved. After studying the mechanisms of wake-up and fatigue, researchers have found a significant connection between these two phenomena and the rearrangement of oxygen vacancies within the HfO2 thin film. The O-phase and M-phase are intermingled inside the HfO2, and the M-phase acts as a kind of spacing layer. During the electric field cycling process, oxygen vacancies move to the boundary between the O-phase and M-phase, causing the M-phase to undergo a phase transition to the O-phase, enhancing its ferroelectric polarization and resulting in the wake-up effect. However, after repetitions of the electric field cycling, it will transition into other phases, leading to fatigue. Understanding the mechanisms of wake-up and fatigue and reducing these effects in subsequent engineering is the next problem to be solved.

HfO2 thin films have excellent application prospects in nonvolatile devices due to their outstanding performance[154,157]. They have demonstrated a range of synaptic behaviors, including LTP/LTD, PPF, PPD, and STDP, making them suitable for use in artificial neural networks for image recognition. Moreover, their good compatibility with CMOS technology supports their integration into Si-based devices. By further exploring and developing the potential of HfO2-based devices in neuromorphic applications, these materials are expected to play an important role in advancing next-generation artificial synaptic devices.

However, numerous challenges remain to be addressed before hafnium oxide films can be commercialized in devices. For fabrication, further optimization is required, particularly to improve the uniformity and crystalline quality of ultrathin (< 10 nm) HfO2 ferroelectric films, while suppressing their wake-up effect. Additionally, interface engineering and doping strategies could be employed to regulate oxygen vacancy distributions, thereby reducing the impact of leakage currents on device performance. Furthermore, it is essential to explore the polarization switching fatigue mechanisms in HfO2-based ferroelectric films to enhance their endurance and long-term stability. Addressing these challenges will significantly increase the feasibility of integrating HfO2-based ferroelectric thin films into commercial electronic devices.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Paper writing and chart creation: Zhu, Z.

Review and editing of the paper: Zhang, B.

Guidance and review of this article: Zheng, Y.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Research Center for Magnetoelectric Physics of Guangdong Province (2024B0303390001), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 12132020 and 12427803) awarded to Zheng, Y., by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 11972382) to Zhang, B., by Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Magnetoelectric Physics and Devices (No. 2022B1212010008) to Zheng, Y., by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province of China (Grant 2023A1515010882), and the Large Scientific Facility Open Subject of Songshan Lake, Dongguan, Guangdong (Grant KFKT2022B06) to Zhang, B.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Mcadams, H.; Acklin, R.; Blake, T.; et al. A 64-Mb embedded FRAM utilizing a 130-nm 5LM Cu/FSG logic process. IEEE. J. Solid. State. Circuits. 2004, 39, 667-77.

2. Xie, L.; Chen, X.; Dong, Z.; et al. Nonvolatile photoelectric memory induced by interfacial charge at a ferroelectric PZT-gated black phosphorus transistor. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2019, 5, 1900458.

3. Sulzbach, M. C.; Estandía, S.; Long, X.; et al. Unraveling ferroelectric polarization and ionic contributions to electroresistance in epitaxial Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 tunnel junctions. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2020, 6, 1900852.

4. Böscke, T. S.; Müller, J.; Bräuhaus, D.; Schröder, U.; Böttger, U. Ferroelectricity in hafnium oxide thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 102903.

5. Wei, Y.; Nukala, P.; Salverda, M.; et al. A rhombohedral ferroelectric phase in epitaxially strained Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 1095-100.

6. Guo, J.; Tao, L.; Xu, X.; et al. Rhombohedral R3 phase of Mn-doped Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 epitaxial films with robust ferroelectricity. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2406038.

7. Eom, D.; Kim, H.; Lee, W.; et al. Temperature-driven co-optimization of IGZO/HZO ferroelectric field-effect transistors for optoelectronic neuromorphic computing. Nano. Energy. 2025, 138, 110837.

8. Yu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Z.; et al. Structure-evolution-designed amorphous oxides for dielectric energy storage. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3031.

9. Zhao, D.; Chen, Z.; Liao, X. Microstructural evolution and ferroelectricity in HfO2 films. Microstructures 2022, 2, 2022007.

10. Banerjee, W.; Kashir, A.; Kamba, S. Hafnium Oxide (HfO2) - A multifunctional oxide: a review on the prospect and challenges of hafnium oxide in resistive switching and ferroelectric memories. Small 2022, 18, e2107575.

11. Cao, J.; Shi, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J. An overview of ferroelectric hafnia and epitaxial growth. Rap. Res. Lett. 2021, 15, 2100025.

12. Breyer, E. T.; Mulaosmanovic, H.; Mikolajick, T.; Slesazeck, S. Perspective on ferroelectric, hafnium oxide based transistors for digital beyond von-Neumann computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 050501.

13. Park, M. H.; Lee, Y. H.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U.; Hwang, C. S. Review and perspective on ferroelectric HfO2-based thin films for memory applications. MRS. Commun. 2018, 8, 795-808.

14. Schroeder, U.; Park, M. H.; Mikolajick, T.; Hwang, C. S. The fundamentals and applications of ferroelectric HfO2. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 653-69.

15. Ohtaka, O.; Fukui, H.; Kunisada, T.; et al. Phase relations and volume changes of hafnia under high pressure and high temperature. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2001, 84, 1369-73.

16. Park, M. H.; Lee, Y. H.; Kim, H. J.; et al. Ferroelectricity and antiferroelectricity of doped thin HfO2-based films. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 1811-31.

17. Howard, C. J.; Kisi, E. H.; Ohtaka, O. Crystal structures of two orthorhombic Zirconias. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74, 2321-3.

19. Huan, T. D.; Sharma, V.; Rossetti, G. A.; Ramprasad, R. Pathways towards ferroelectricity in hafnia. Phys. Rev. B. 2014, 90, 064111.

20. Materlik, R.; Künneth, C.; Kersch, A. The origin of ferroelectricity in Hf1-xZrxO2: a computational investigation and a surface energy model. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 134109.

21. Lee, H. J.; Lee, M.; Lee, K.; et al. Scale-free ferroelectricity induced by flat phonon bands in HfO2. Science 2020, 369, 1343-7.

22. Sang, X.; Grimley, E. D.; Schenk, T.; Schroeder, U.; Lebeau, J. M. On the structural origins of ferroelectricity in HfO2 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 162905.

23. Park, M. H.; Lee, Y. H.; Mikolajick, T.; Schroeder, U.; Hwang, C. S. Thermodynamic and kinetic origins of ferroelectricity in fluorite structure oxides. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2019, 5, 1800522.

24. Park, M. H.; Lee, Y. H.; Kim, H. J.; et al. Understanding the formation of the metastable ferroelectric phase in hafnia-zirconia solid solution thin films. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 716-25.

25. Fan, P.; Zhang, Y. K.; Yang, Q.; et al. Origin of the intrinsic ferroelectricity of HfO2 from ab initio molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019, 123, 21743-50.

26. Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; et al. Unconventional polarization-switching mechanism in (Hf,Zr)O2 ferroelectrics and its implications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 131, 226802.

27. Zhu, T.; Ma, L.; Duan, X.; Deng, S.; Liu, S. Origin of interstitial doping induced coercive field reduction in ferroelectric hafnia. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 056802.

28. Peng, R.; Wen, S.; Cheng, X.; Chen, L.; Liao, M.; Zhou, Y. Revealing the role of spacer layer in domain dynamics of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films for ferroelectrics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403864.

29. Wang, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Unconventional ferroelectric-ferroelastic switching mediated by non-polar phase in fluorite oxides. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2415131.

30. Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, A.; et al. Ferroelastically protected reversible orthorhombic to monoclinic-like phase transition in ZrO2 nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1077-84.

31. Qi, Y.; Singh, S.; Lau, C.; et al. Stabilization of competing ferroelectric phases of HfO2 under epitaxial strain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 257603.

32. Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Guzman, R.; et al. A stable rhombohedral phase in ferroelectric Hf(Zr)1+xO2 capacitor with ultralow coercive field. Science 2023, 381, 558-63.

33. Lee, K.; Park, K.; Choi, I. H.; et al. Deterministic orientation control of ferroelectric HfO2 thin film growth by a topotactic phase transition of an oxide electrode. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 12707-15.

34. Wang, S.; Shen, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Unlocking the phase evolution of the hidden non-polar to ferroelectric transition in HfO2-based bulk crystals. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3745.

35. Materano, M.; Lomenzo, P. D.; Mulaosmanovic, H.; et al. Polarization switching in thin doped HfO2 ferroelectric layers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 262904.

36. Xu, X.; Huang, F. T.; Qi, Y.; et al. Kinetically stabilized ferroelectricity in bulk single-crystalline HfO2:Y. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 826-32.

37. Cheng, H.; Tian, H.; Liu, J. M.; Yang, Y. Structure and stability of La- and hole-doped hafnia with/without epitaxial strain. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2024, 36, 205401.

38. Zhang, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wang, D.; et al. Enhanced ferroelectric properties and insulator-metal transition-induced shift of polarization-voltage hysteresis loop in VOx-capped Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 40510-7.

39. Athle, R.; Persson, A. E. O.; Irish, A.; Menon, H.; Timm, R.; Borg, M. Effects of TiN top electrode texturing on ferroelectricity in Hf1-xZrxO2. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 11089-95.

40. Mimura, T.; Katayama, K.; Shimizu, T.; et al. Formation of (111) orientation-controlled ferroelectric orthorhombic HfO2 thin films from solid phase via annealing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 052903.

41. Liu, S.; Hanrahan, B. M. Effects of growth orientations and epitaxial strains on phase stability of HfO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2019, 3, 054404.

42. Park, J. Y.; Lee, D. H.; Yang, K.; et al. Engineering strategies in emerging fluorite-structured ferroelectrics. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 1369-80.

43. Islamov, D. R.; Zalyalov, T. M.; Orlov, O. M.; Gritsenko, V. A.; Krasnikov, G. Y. Impact of oxygen vacancy on the ferroelectric properties of lanthanum-doped hafnium oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 162901.

44. Schroeder, U.; Yurchuk, E.; Müller, J.; et al. Impact of different dopants on the switching properties of ferroelectric hafniumoxide. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 53, 08LE02.

45. Kirbach, S.; Lederer, M.; Eßlinger, S.; et al. Doping concentration dependent piezoelectric behavior of Si:HfO2 thin-films. Appl. Phy. Lett. 2021, 118, 012904.

46. Müller, J.; Schröder, U.; Böscke, T. S.; et al. Ferroelectricity in yttrium-doped hafnium oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 114113.

47. Starschich, S.; Griesche, D.; Schneller, T.; Waser, R.; Böttger, U. Chemical solution deposition of ferroelectric yttrium-doped hafnium oxide films on platinum electrodes. Appl. Phy. Lett. 2014, 104, 202903.

48. Mimura, T.; Shimizu, T.; Funakubo, H. Ferroelectricity in YO1.5-HfO2 films around 1 μm in thickness. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 115, 032901.

49. Yun, Y.; Buragohain, P.; Li, M.; et al. Intrinsic ferroelectricity in Y-doped HfO2 thin films. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 903-9.

50. Müller, J.; Böscke, T. S.; Bräuhaus, D.; et al. Ferroelectric Zr0.5Hf0.5O2 thin films for nonvolatile memory applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 112901.

51. Müller, J.; Böscke, T. S.; Schröder, U.; et al. Ferroelectricity in simple binary ZrO2 and HfO2. Nano. Lett. 2012, 12, 4318-23.

52. Yan, F.; Cao, K.; Chen, Y.; Liao, J.; Liao, M.; Zhou, Y. Optimization of ferroelectricity and endurance of hafnium zirconium oxide thin films by controlling element inhomogeneity. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1023-31.

53. Ansari, E.; Martinolli, N.; Hartmann, E.; Varini, A.; Stolichnov, I.; Ionescu, A. M. Vanadium-doped hafnium oxide: a high-endurance ferroelectric thin film with demonstrated negative capacitance. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 2702-8.

54. Zhou, C.; Ma, L.; Feng, Y.; et al. Enhanced polarization switching characteristics of HfO2 ultrathin films via acceptor-donor co-doping. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2893.

55. Park, M. H.; Kim, H. J.; Kim, Y. J.; Moon, T.; Hwang, C. S. The effects of crystallographic orientation and strain of thin Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 film on its ferroelectricity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 1243-400.

56. Karbasian, G.; dos Reis, R.; Yadav, A. K.; Tan, A. J.; Hu, C.; Salahuddin, S. Stabilization of ferroelectric phase in tungsten capped Hf0.8Zr0.2O2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 022907.

57. Onaya, T.; Nabatame, T.; Sawamoto, N.; et al. Improvement in ferroelectricity of HfxZr1-xO2 thin films using ZrO2 seed layer. Appl. Phys. Express. 2017, 10, 081501.

58. Weeks, S. L.; Pal, A.; Narasimhan, V. K.; Littau, K. A.; Chiang, T. Engineering of Ferroelectric HfO2-ZrO2 nanolaminates. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 13440-7.

59. Cao, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; et al. Effects of capping electrode on ferroelectric properties of Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films. IEEE. Electron. Device. Lett. 2018, 39, 1207-10.

60. Chen, L.; Wang, T. Y.; Dai, Y. W.; et al. Ultra-low power Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 based ferroelectric tunnel junction synapses for hardware neural network applications. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 15826-33.

61. Yoong, H. Y.; Wu, H.; Zhao, J.; et al. Epitaxial ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films and their implementations in memristors for brain-inspired computing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1806037.

62. Bouaziz, J.; Romeo, P. R.; Baboux, N.; Vilquin, B. Huge reduction of the wake-up effect in ferroelectric HZO thin films. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 1740-5.

63. Estandía, S.; Dix, N.; Gazquez, J.; et al. Engineering ferroelectric Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 thin films by epitaxial stress. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 1449-57.

64. Goh, Y.; Cho, S. H.; Park, S. K.; Jeon, S. Crystalline phase-controlled high-quality hafnia ferroelectric with RuO2 electrode. IEEE. Trans. Electron. Devices. 2020, 67, 3431-4.