Key technologies of bionic inchworm robots: a survey

Abstract

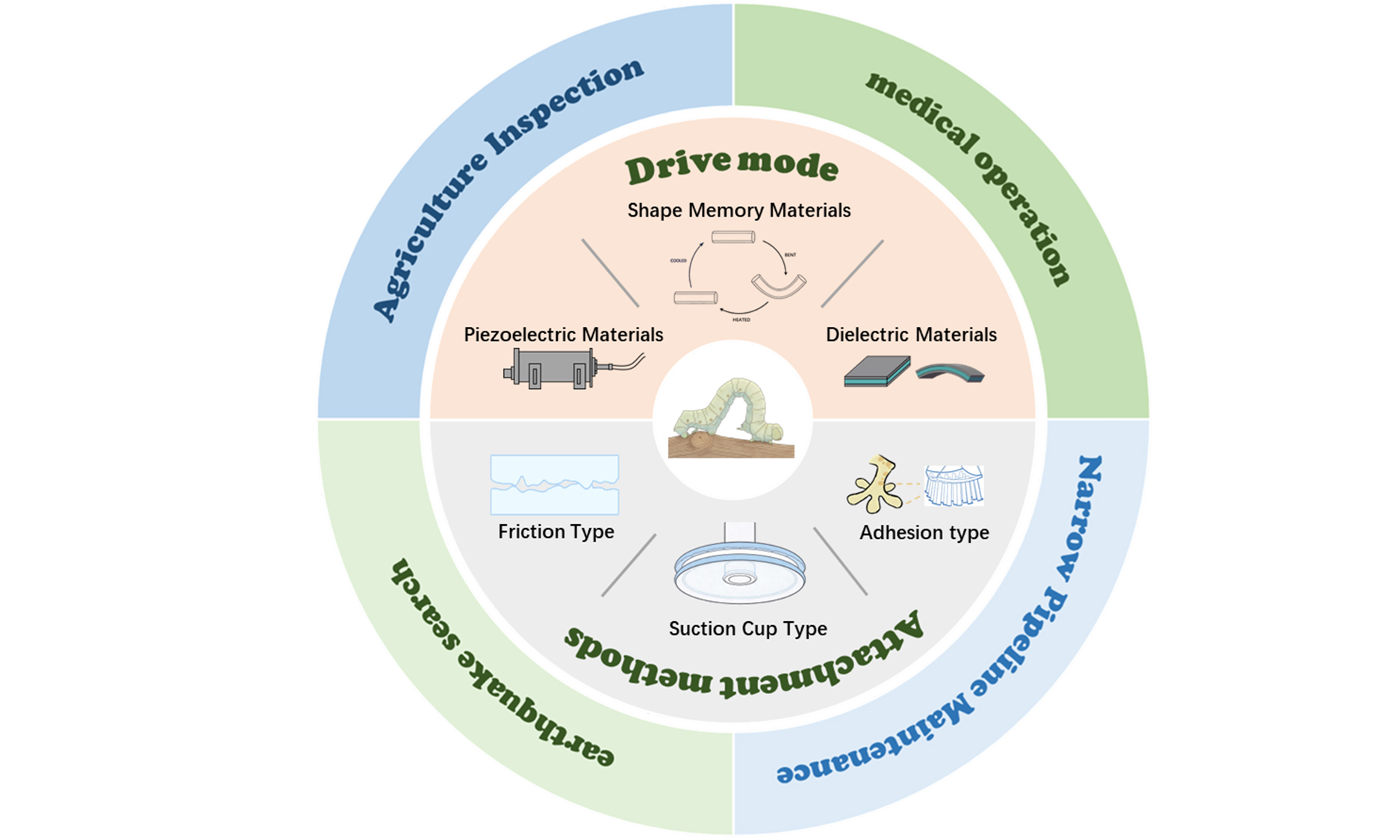

The bionic inchworm robot is known for its flexible and adaptable locomotion and has attracted growing interest in agriculture, forestry, and infrastructure inspection. This paper reviews global research on such robots, focusing on actuation mechanisms, attachment strategies, kinematic modeling, control methods and locomotion performance. By systematically comparing existing studies, it summarizes key technologies, identifies current challenges and outlines future research directions. The goal is to provide a clear perspective that supports further advances in inchworm-inspired robotic systems.

Keywords

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, soft-bodied robots have emerged as a major research focus due to their increasing relevance in medical rehabilitation, inspection and reconnaissance, underwater operations, and deep-sea exploration. Owing to their inherent flexibility, adaptability, and deformability, soft robots exhibit clear advantages when operating in complex or unstructured environments. In contrast, traditional rigid robots achieve high precision through careful mechanical design and control strategies, yet their performance is often constrained in scenarios where environmental uncertainties or irregularities dominate. Although soft robots generally exhibit lower precision because of material compliance and nonlinear dynamics, they offer distinctive benefits in tasks that prioritize adaptability over accuracy. As industrial applications continue to diversify, the demand for rigid, high-precision systems diminishes in many contexts. Soft robots effectively address several limitations of rigid systems and have therefore gained increasing prominence across a wide range of application domains.

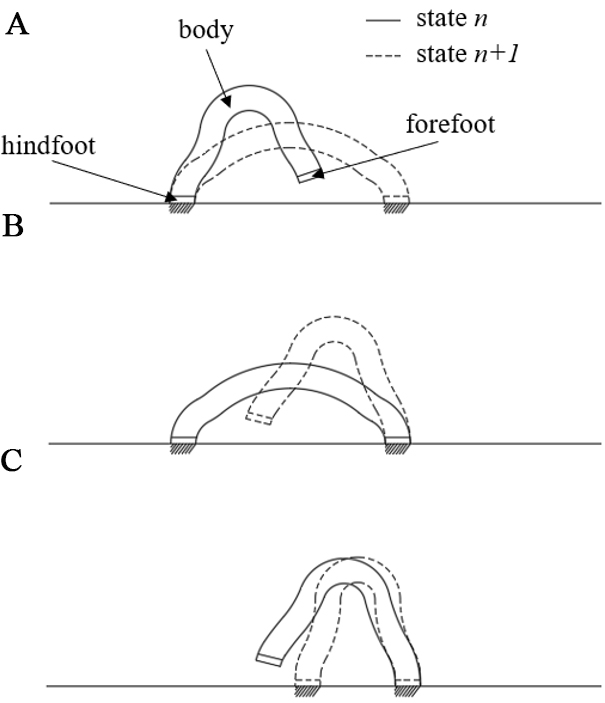

The inchworm is a soft-bodied organism with a segmented structure and multiple pairs of prolegs. Its locomotion, known as “inchworm gait,” is achieved through coordinated body bending and stretching. During movement, the inchworm first anchors the posterior prolegs, extends its body to advance the anterior prolegs [Figure 1A], then anchors the anterior prolegs and contracts its body to pull the posterior segment forward [Figure 1B and C]. The organism’s flexible, segmented morphology allows it to traverse diverse terrains by adjusting its body curvature and gripping force. Its prolegs contain specialized microstructures - such as setae and suction-like pads - that enhance friction and adhesion. Depending on the surface characteristics, the inchworm modulates its attachment strategy: on rough surfaces, the setae interlock with surface asperities, while on smooth substrates, suction-like structures may generate negative pressure to maintain stable adhesion. These biological principles provide valuable insights for the design of bionic inchworm-inspired robotic systems.

The structure and locomotion of a bionic inchworm robot should closely emulate the biological characteristics of a real inchworm. Structurally, the robot typically adopts a segmented configuration composed of multiple articulated joints linked by flexible materials, allowing body bending and stretching. The torso may be fabricated from soft materials with internal pneumatic chambers or equipped with telescopic components driven by shape-memory alloys or artificial muscles to replicate muscular contraction and extension, thereby generating propulsion.

For the feet, a biomimetic design with strong adhesion is essential. Soft materials can increase friction, while suction-cup-like structures or barbed microfeatures enhance attachment on diverse surfaces and prevent slippage.

The robot’s locomotion generally follows an alternating gait similar to that of an inchworm: one end anchors to the ground while the other advances, and the sequence then reverses to achieve forward motion. This gait ensures stability and adaptability on complex terrains. In biological inchworms, movement is realized by bending the body into an “Ω” shape and alternately anchoring the anterior and posterior prolegs to perform sequential contraction and extension. The bionic inchworm robot replicates this pattern and offers advantages in high-risk or confined environments due to its compact size, lightweight design, and flexible deformation capabilities. These features enhance the mobility of soft-bodied robots, enabling smooth transitions across multimodal surfaces and improving environmental adaptability for field exploration, monitoring, and data collection.

Research on inchworm-inspired robots has progressed rapidly worldwide. In 2014, Uenoyama and Takamura developed a microworm robot actuated by an electrically conjugated fluid[1]. In 2022, Zhang et al. proposed a multimodal soft crawling and climbing robot that mimics the “Ω” deformation of inchworms[2]. In 2023, Ding and Su developed an inchworm-inspired soft robot capable of omnidirectional steering and obstacle traversal[3]. Meanwhile, theoretical studies on soft robot dynamics have also progressed. Zhang et al. established a force and dynamic modeling framework for a soft-rigid hybrid pneumatic actuator, and applied the rigid-flexible coupling analysis to an inchworm-inspired robot, providing a theoretical basis for the dynamic performance evaluation and motion analysis of flexible bionic robots[4].

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews the major foot-end attachment strategies of bionic inchworm robots. Section 3 summarizes the main actuation methods, including smart-material, pneumatic, and electromagnetic actuation. Section 4 compares locomotion performance among robots with similar actuation but different structures. Section 5 presents representative application scenarios. Section 6 discusses key challenges and future trends in environmental adaptability and energy efficiency. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. ATTACHMENT METHOD OF FOOT END

The attachment method is a critical component in the design of inchworm robots, as it fundamentally determines locomotion stability, environmental adaptability, and task execution efficiency. This section reviews recent progress in foot-attachment strategies for bionic soft inchworm robots, discussing the underlying principles, distinctive features, and application potential of different attachment mechanisms. The aim is to provide a comprehensive reference for future research and practical applications in inchworm-inspired robotic systems.

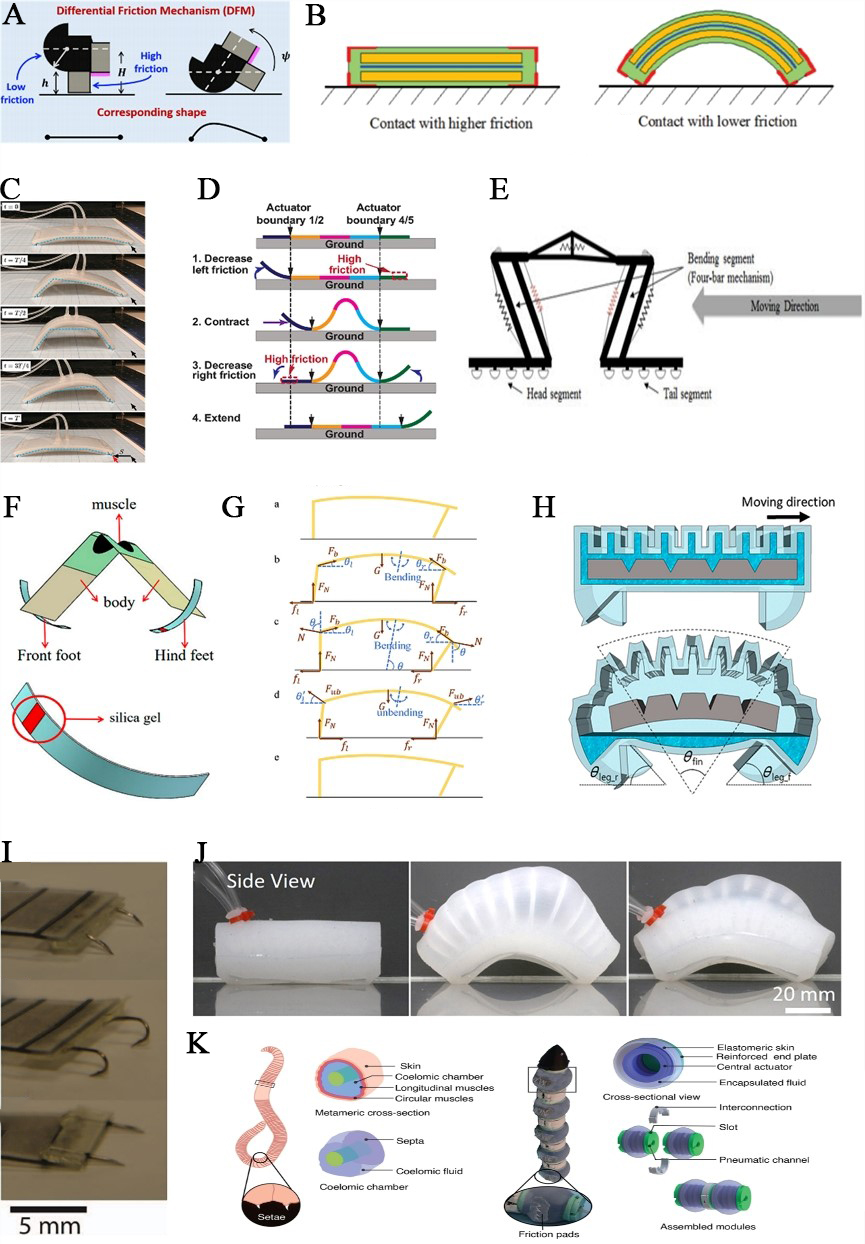

2.1. Friction attachment

Friction-based attachment is one of the most common anchoring strategies, relying primarily on the friction generated between the robot’s foot and the substrate to achieve attachment and detachment. Two typical approaches are differential-friction mechanisms and anisotropic friction pads. Differential-friction mechanisms combine materials with different friction coefficients and actively switch the foot-ground contact state, making them suitable for multidirectional locomotion and adaptable to various surface materials. In contrast, anisotropic friction pads utilize surface anisotropy to passively adjust friction according to the direction of lateral force. They enable efficient unidirectional motion but impose higher requirements on substrate conditions. Structurally, differential-friction mechanisms are relatively simple, whereas anisotropic pads often require complex micro-nano surface structures or deformable beams.

In soft inchworm-inspired robots, friction-based attachment is commonly implemented by combining materials with distinct friction properties at the foot end. As shown in Figure 2A, Chang et al. employed a differential-friction mechanism using low- and high-friction materials[5]. Xie et al.[6] and Gamus et al.[7] adopted smooth adhesive tapes in Figure 2B and C. Zheng et al. used friction films [Figure 2D][8], Koh et al. developed anisotropic pads [Figure 2E][9], and Jing et al. introduced silicone-based footpads in Figure 2F[10]. These materials generate different friction forces upon ground contact, enabling controlled attachment and detachment.

Figure 2. Friction-like attachment modes. Figure 2A-K present representative demonstrations of the friction-based attachment mechanisms discussed above: (A) differential friction mechanism (DFM) combining low- and high-friction materials.Adapted with permission[5], Copyright 2021, IEEE; (B) Smooth transparent tape. Adapted with permission[6], Copyright 2018, IEEE; (C) Smooth shielding tape. Adapted with permission[7], Copyright 2020, IEEE; (D) Friction film. Adapted with permission[8], Copyright 2022, IEEE; (E) Anisotropic friction pads. Adapted with permission[9], Copyright 2013, IEEE; (F) Silicone foot pads. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[10]; (G) Varying leg height to change the tilted posture of the robot body. Adapted with permission[11], Copyright 2019, IEEE; (H) Changing the tangential contact length of the front and rear legs with the ground. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[12]; (I) Different foot structures, such as curved and straight needles. Adapted with permission[13], Copyright 2017, IEEE; (J) Pneumatic actuation combined with silicone materials to modulate the friction coefficient. Adapted with permission[14], Copyright 2019, IEEE; (K) A pneumatic peristaltic soft actuator with pressure-induced radial expansion for friction-based attachment. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[15].

Another approach involves modifying the geometry or structure of the foot to regulate contact area and frictional force. Examples include legs of varying heights to change body inclination in Figure 2G[11], altering the tangent length of front and rear legs contacting the substrate in Figure 2H[12], or adopting different foot shapes such as curved and straight pins in Figure 2I[13], all of which influence frictional performance.

Pneumatic actuation can further enhance friction-based attachment. Duggan et al. integrated pneumatic actuation with silicone material to modulate friction: when inflated, the silicone exhibits a low friction coefficient, allowing sliding; when deflated, the increased contact length and friction provide anchoring [Figure 2J][14]. Similarly, Das et al. employed a pneumatic peristaltic soft actuator (PSA) in which the foot-end anchoring is achieved through pressure-regulated radial expansion in Figure 2K[15]. By alternately applying positive and negative pressure within a constant-volume elastomeric chamber, the actuator generates axial elongation for propulsion and circumferential expansion for anchoring. The radial expansion produces an increased normal force and frictional interaction with the surrounding surface, enabling stable attachment across planar, granular, and confined environments. This pressure-controlled friction-based anchoring mechanism effectively enhances locomotion robustness without relying on dedicated adhesive or suction components.

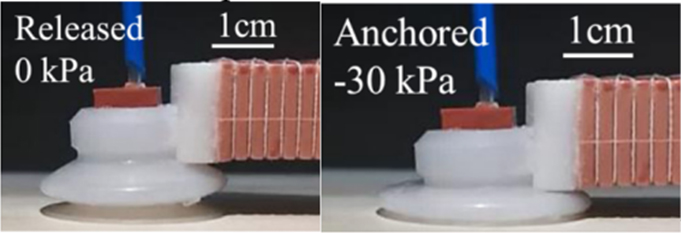

2.2. Suction cup type attachment

Suction-cup attachment is another important anchoring strategy, relying on the negative pressure generated between the cup and the substrate to achieve adhesion. In bionic soft inchworm robots, suction cups are typically fabricated from compliant elastomeric materials. As shown in Figure 3, the suction-cup foot designed by Zhang et al. adopts a double-layer silicone structure[2], which ensures effective sealing upon surface contact. When air is withdrawn, the corrugated cushioning layer is compressed, increasing the overall stiffness of the cup and improving resistance to external forces and torques. By regulating the internal pressure, the frictional interaction between the suction cup and the substrate can be controlled. In the unpressurized state, the cup exhibits low friction, enabling the robot to slide or drag across the surface. Under negative pressure, however, the tangential anchoring force increases markedly to values exceeding 10 N - sufficient to support the robot’s weight during climbing. This design enables the multimodal soft crawling-climbing robot (SCCR) to achieve stable locomotion across diverse surfaces and enhances its adaptability to complex environments[2].

Figure 3. Suction cup type of attachment. Reproduced with permission[2], Copyright 2022, IEEE.

2.3. Adhesion-type attachment

Adhesion-based attachment methods rely on interfacial adhesive forces to establish stable contact between the robot’s foot and the substrate. In bionic soft inchworm robots, various adhesive materials - such as micro-nanostructured surfaces and polymer-based adhesives - have been developed to enhance the adhesion capability at the foot end. These materials are typically flexible and deformable, enabling effective conformity to surfaces of different shapes and textures.

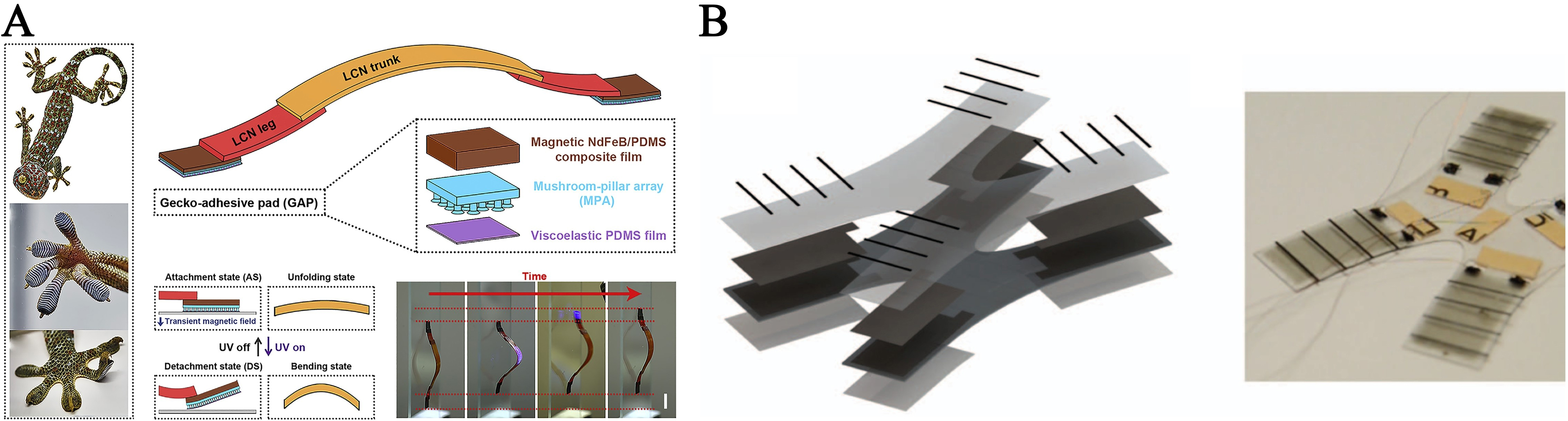

As shown in Figure 4A, the gecko-inspired adhesive pad (GAP) has attracted considerable attention in recent years[16]. Its operation is based on applying a preload force (Fpreload) that allows the micro-nanostructures - often mushroom-shaped pillars - to form intimate contact with the surface, thereby generating strong van der Waals adhesion. Once preloaded, the GAP maintains attachment until a pull-off force (Fpull-off) is applied to overcome the interfacial adhesion. The magnitude of this pull-off force depends on the adhesion strength and surface properties. Adhesion performance can be further improved by introducing a transient magnetic field to locally increase the preload. When a permanent magnet is positioned beneath the GAP, the resulting magnetic force (Fmagnet) enhances contact pressure and strengthens adhesion.

Figure 4. GAP adhesion modes. Graphical illustrations of adhesion-like attachment mechanisms are shown in Figure 4A and B: (A) Gecko adhesion mat. Adapted with permission[13], Copyright 2023, Elsevier; (B) Multilayer dielectric elastomer structure. Adapted with permission[16], Copyright 2022, Springer. GAP: Gecko-inspired adhesive pad.

Electroadhesion has also emerged as a promising technology for soft inchworm robots. Dielectric elastomer (DE) materials exhibit large deformation, high energy density, and rapid response, and their adhesion can be modulated by applied voltage. As illustrated in Figure 4B, Duduta et al. employed a multilayer DE architecture, formed by alternating elastomer and electrode layers, to construct actuators in which all four legs share the same DE-based structure[13].

2.4. Contact-type attachment

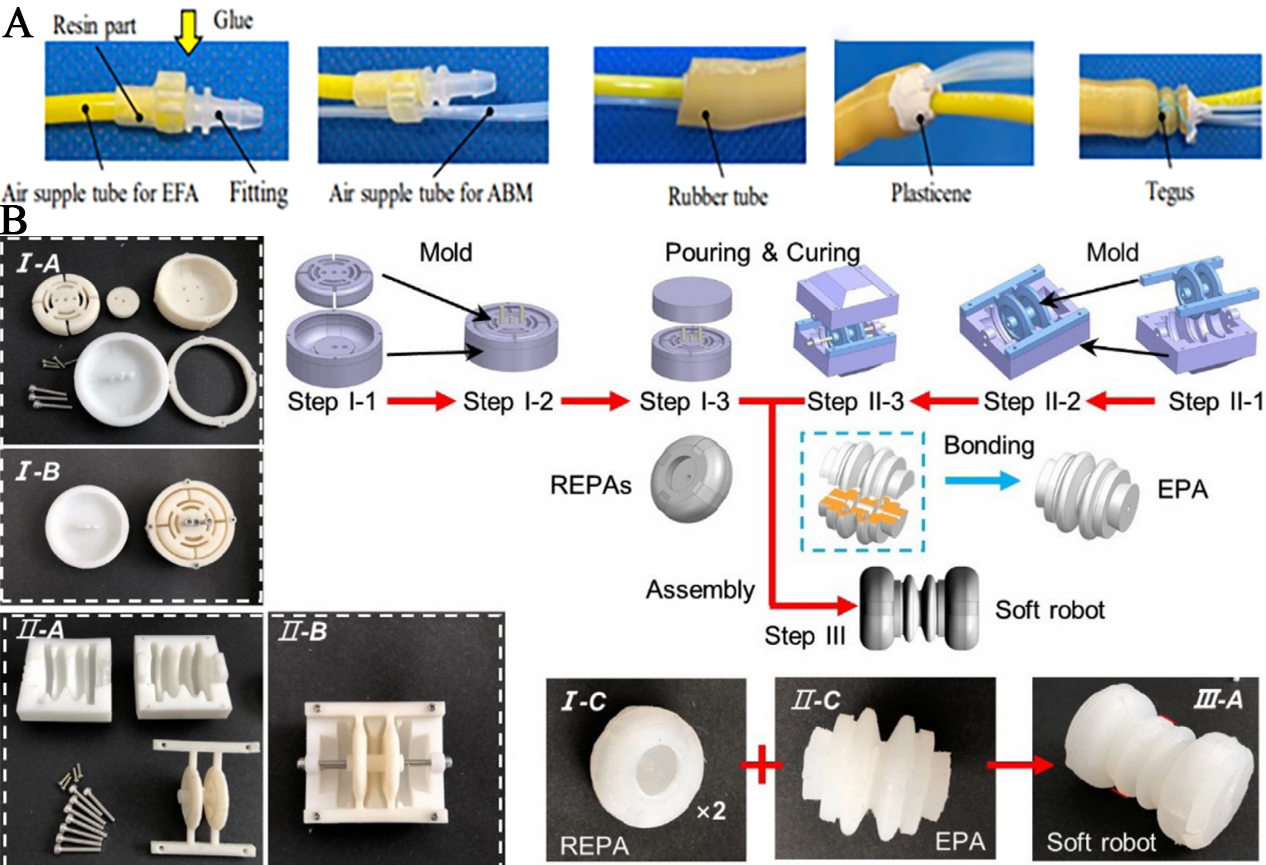

Contact-based adhesion relies on direct physical interaction between the robot’s foot and the substrate. This form of adhesion is typically achieved by increasing friction or normal pressure at the contact interface. A common approach involves the use of inflatable rubber tubes. When inflated, the tube expands, increasing its diameter and forming tight contact with the inner wall of a pipe, thereby establishing a stable attachment, as illustrated in Figure 5A. This method is simple, reliable, and easy to control, and has been widely applied in bionic soft inchworm robots[17].

Figure 5. Contact-type attachment methods. Examples of contact-type attachment methods are shown in Figure 5A and B: (A) Contact-type attachment achieved using a rubber hose that expands upon inflation. Adapted with permission[17], Copyright 2023, IEEE; (B) A REPA. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[18]. EFA: Elastic force actuator; ABM:active bending module; REPA: radial expansion pneumatic actuator; EPA: elongated pneumatic actuator.

Another implementation uses a radial expansion pneumatic actuator (REPA) as the foot module. The REPA is fabricated from an elastic material with an internal cavity; when pressurized, it expands radially and generates sufficient normal force to secure attachment to the contact surface, as shown in Figure 5B[18].

In Figure 6, a clamped winding actuator proposed by Hu et al. is illustrated[19], in which locomotion is achieved through coordinated clamping and winding motions. By alternately fixing and releasing the contact ends while generating axial contraction and extension, the actuator enables stable inchworm-like locomotion and effective force transmission in confined environments[19].

Figure 6. Clamped winding actuator. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[19].

2.5 Comparison of different attachment methods

In bionic inchworm robot design, the foot-attachment mechanism plays a central role in enabling effective locomotion and task execution. Among the four attachment strategies reviewed above, friction-based methods are widely adopted due to their structural simplicity and strong environmental adaptability, making them suitable for multidirectional and complex motion. However, their adhesion force is limited and highly sensitive to surface properties, which may compromise stability.

Suction-cup attachment generates strong adhesion through negative pressure but requires high surface flatness; sealing issues can cause performance degradation in complex environments. Adhesion-based methods offer strong interfacial bonding and excellent surface conformity, yet their effectiveness is easily influenced by environmental factors such as humidity and temperature, and detachment may leave residues. Contact-based attachment increases friction or normal pressure at the foot-surface interface, providing high reliability and stability, but often requires a large contact area or substantial pressure, leading to increased energy consumption and structural complexity.

Overall, friction-based attachment is suitable for lightweight systems requiring multidirectional mobility; suction-cup attachment performs well on smooth surfaces with high adhesion demands; adhesion-based attachment provides significant advantages on complex surfaces requiring strong adhesion; and contact-based attachment excels in applications where stability and reliability are critical. The characteristics of each attachment mode are summarized in Table 1.

Comparison of attachment methods

| Attachment method | Adhesion (N/cm2) | Responsiveness | Response time(ms) | Surface adaptability | Structural complexity | Load capacity | |||

| Smooth surface | Rough surfaces | ||||||||

| Tribology | Low | 1.5 | Fast | < 100 ms | Poor | High | Low | Low (2.3N) | |

| Suction cups | Moderate | 3.2 | Fast | < 200 ms | High | Poor | Moderate | High | |

| Adhesion class | Moderate | 4.5 | Moderate | < 300 ms | High | High | High | Moderate | |

| Contact type | High | 5 | Slow | < 500 ms | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | High (9.8N) | |

Furthermore, Jiang et al. conducted a comprehensive survey on anchoring mechanisms in inchworm-inspired robots, offering an integrated perspective that complements the classifications summarized in this section[20].Their review delineates the operational principles, advantages, and limitations of diverse anchoring strategies - including friction regulation, mechanical clamping, pneumatic expansion locking, ratchet-based unidirectional locking, magnetic adhesion, and electroadhesion - across heterogeneous environments. The authors emphasize that the effectiveness of these anchoring methods is intrinsically coupled with the actuation subsystem, as locomotion stability and gait continuity depend on the precise temporal coordination between body deformation and anchoring transitions. Importantly, the review highlights that future inchworm robot designs should adopt a co-optimization framework that jointly considers structure, actuation, and anchoring interactions to enhance environmental adaptability and ensure reliable performance in complex, unstructured settings.

3. DRIVING MODE

As a type of soft robot, the inchworm robot employs a variety of actuation strategies that can be broadly categorized into three groups: smart-material-based actuation, pneumatic actuation, and electromagnetic actuation.

3.1. Intelligent material

Research on inchworm robots driven by smart materials primarily focuses on actuation approaches based on shape memory materials (SMMs), DEs, artificial muscles, and other smart-material mechanisms.

3.1.1 Shape memory materials

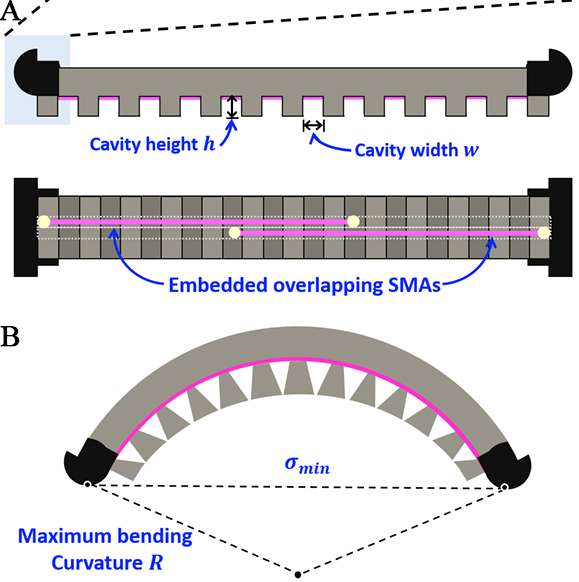

SMMs are a class of smart materials with shape memory effect (SME). In 2013, Koh et al. proposed an inchworm-inspired crawling robot driven by a new large spring index and pitch (LIP) shape memory alloy (SMA) spring actuator[9]. In 2015, Plaut et al. analyzed a mathematical model of inchworm motion to predict the bending strain required for SMA actuation[21]. As shown in Figure 6, in 2019, Shi et al. proposed an inchworm-inspired crawling soft robot driven by SMA wires, which were used as longitudinal muscle fibers to control the abdominal contraction of roundworms during locomotion[22]. In 2021, Thomas et al. constructed a mechanically intelligent oscillator based on a conventional biased-spring SMA actuator in combination with a magnetic latching system[23]. In 2021, Chang et al. fabricated a multi-material, SMA-driven embedded worm soft robot model with bi-directional locomotion[5], as shown in Figure 7. Shape memory polymers (SMPs) are intelligent polymeric materials in which a product with an initial shape can be restored to its initial shape by stimulation of external conditions (e.g., heat, electricity, magnetism, light, etc.) after it has been changed to a temporary shape and fixed under specific conditions[24]. In 2013, Felton et al. chose pre-stretched polystyrene (PSPS) as a shrinkage layer, which has a high compressive strain (50%) when heated[25].

Figure 7. SMA actuation. (A) Two overlapping SMAs are embedded in the soft body and cavity; (B) The cavity controls the bending stiffness and maximum bending curvature, and promotes cooling. Adapted with permission[5], Copyright 2021, IEEE. SMA: Shape memory alloy.

SMMs exhibit a distinctive SME and super-elasticity, along with several advantageous properties such as excellent wear resistance, corrosion resistance, high damping capacity, high power-to-weight ratio, and good biocompatibility. Although the technology associated with SMMs has become relatively mature, several critical challenges remain in practical engineering applications. These include insufficient fatigue resistance, limited response speed, high manufacturing cost, inadequate control precision, and the restricted diversity of available material systems. Such limitations hinder the performance and reliability of inchworm-inspired robots, indicating that their widespread practical deployment still requires further advancement in material technology and system integration.

3.1.2 Dielectric materials

DEs are a class of electrically activated polymers capable of undergoing mechanical deformation under an applied voltage.

In 2014, Conn et al. introduced a soft segmented embedded-worm robot that employed pneumatically coupled DE membranes to generate antagonistic actuation, enabling worm-like locomotion[26].

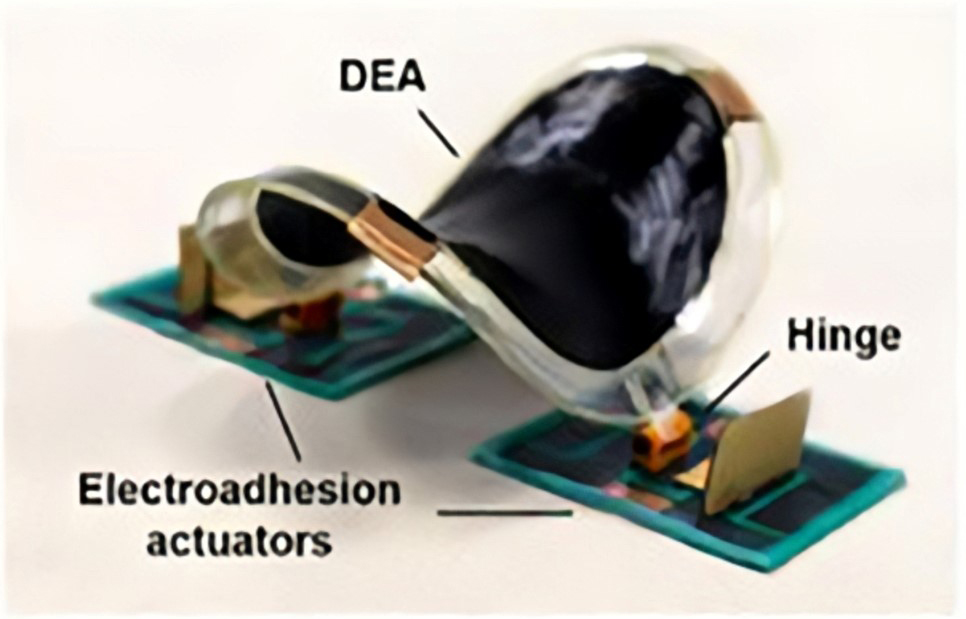

In 2020, Cao et al. developed an inchworm robot driven by a saddle-shaped DE actuator (DEA), as illustrated in Figure 8[27]. In 2022, Jing et al. demonstrated an embedded soft robot activated by simulated DEs. Their design featured high resilience, rapid response, and simple fabrication, while also achieving multimodal locomotion[10].

Figure 8. Soft crawling robot. A soft crawling robot, driven by a saddle DEA. Reproduced with permission[27], Copyright 2020, IEEE. DEA: Dielectric elastomer actuator.

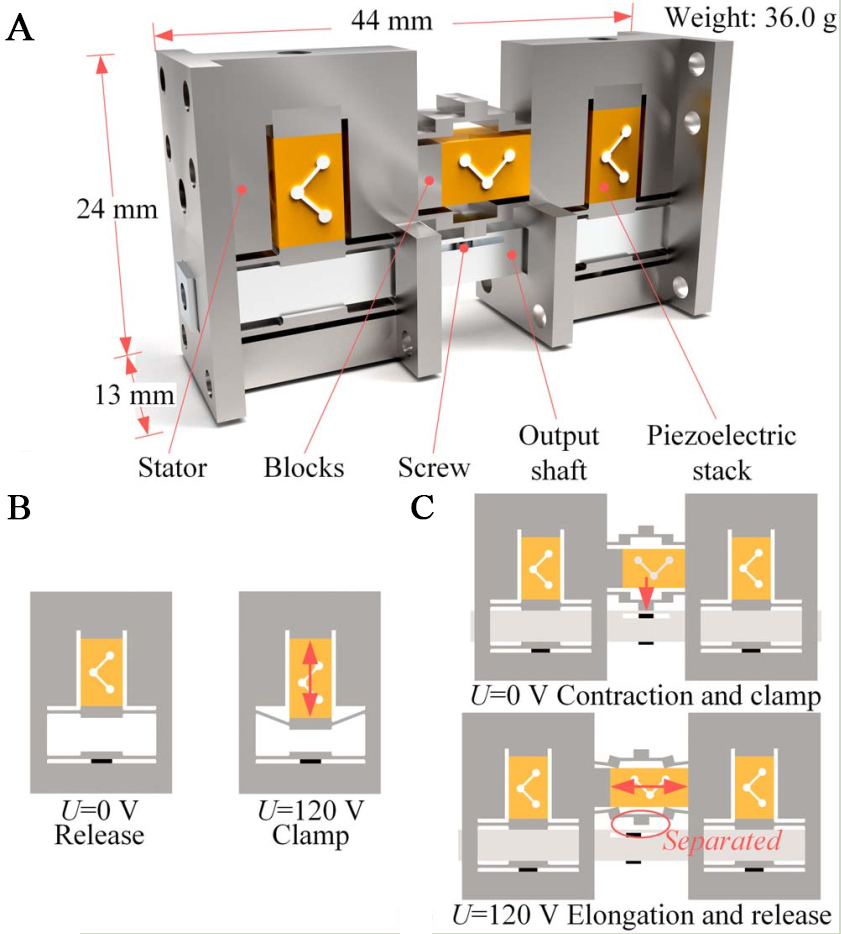

Kang et al. advanced piezoelectric inchworm actuation by introducing a shear-type piezoelectric stack (d15 mode), which differs from the conventional longitudinal stack[28] (d33 mode). They developed a coupled dynamic model that incorporates the shear electric field, preload effects, and adhesive-layer hysteresis, enabling displacement prediction at the nanometer scale with 96%-99% accuracy over millimeter-range motion. This improvement effectively suppressed shell vibration and enhanced system stability[28].

Building on this progress, Guan et al. integrated both driving and clamping functions into a single bridge-type amplification structure[29]. The design utilizes parasitic displacement in the orthogonal direction to achieve passive self-locking when unpowered. As illustrated in Figure 9, the device is highly compact (44 mm × 13 mm × 24 mm; 36 g), yet it can reach a linear speed of 1.69 mm/s and generate a thrust of 1.5 N under a 417 Hz square-wave excitation. Its thrust density of 1.09 × 1024 N/mm3 represents a substantial improvement over conventional architectures.

Figure 9. Structure of the proposed inchworm linear piezoelectric actuator. (A) Structure; (B) Clamping mechanism; (C) Driving mechanism. Adapted with permission[29], Copyright 2025, IEEE.

Wang et al. proposed an alternative strategy that employs a single piezoelectric stack together with a DC motor and a rotating permanent magnet to realize synchronous clamping[30]. This method requires only a single DC control signal, markedly simplifying the driving circuitry. Operating at 75 V and 3.2 Hz, the actuator achieved a stable step size of 0.241 μm and supported a maximum load of 19.6 N. This approach provides a practical solution for applications demanding a low number of control channels while maintaining high load capacity.

DEAs and emerging biomimetic materials have contributed substantially to recent progress in inchworm-inspired soft robots. In 2020, Pfeil et al. investigated a crawling robot driven by cylindrical DEAs as its primary actuation units[31]. Locomotion was achieved through the deformation of the DE under an applied electric field, allowing the robot to mimic inchworm- or earthworm-like crawling with high flexibility and adaptability on soft surfaces. In 2025, Wu et al. examined a braided soft robot based on Pneumatic Twisted Strips (PTS), which enables various deformations such as in-plane contraction and out-of-plane curling[32]. The design reduces structural size and complexity while improving durability and responsiveness, thereby expanding the applicability of soft robots in complex environments.

Recently, Zhong et al. proposed a dielectric-elastomer-driven biomimetic crawling robot that integrates Dielectric Elastomer Minimum Energy Structures (DEMES) with a three-dimensional scissor mechanism to achieve inchworm-like locomotion across multiple surfaces[33]. Their work not only establishes a dynamic model coupling the DEMES actuation torque with the scissor kinematics, but also systematically compares different electrostatic adhesion strategies to enhance multi-surface adaptability. The robot achieves stable crawling even after random landing postures, demonstrating that DE-based structures can extend inchworm-inspired robots from planar crawling to orientation-independent, robust locomotion in complex environments.

Recent material innovations further enhance these capabilities. Techniques such as textile compositing, variable-stiffness structures, and self-repairing materials have been introduced to improve actuator strength, controllability, and longevity. For instance, embedding fabrics (e.g., polyester, nylon, silk) into silicone matrices can significantly enhance the composite’s strength, tear resistance, and puncture resistance - critical for pneumatic soft robotic applications. This fabric-silicone composite not only maintains the silicone’s elasticity but also boosts mechanical robustness, enabling more precise crawling gaits by reducing deformation instability[34]. Newly developed DEs with tunable stiffness and self-healing properties increase resilience in unpredictable environments. Additionally, some soft robots incorporate electronics-free oscillators as artificial neural systems, enabling fully soft, autonomous locomotion without rigid electronic components.

3.1.3 Piezoelectric materials

Piezoelectric actuation is an emerging technology that converts electrical energy into mechanical motion through the inverse piezoelectric effect. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of piezoelectric semiconductor materials - such as ultrathin ZnO films - as flexible linear actuators with tunable responses, offering fast and stable actuation suitable for soft robotics.

Compared with traditional electromagnetic actuators, piezoelectric systems offer several distinct advantages, including extremely fast response speeds and the ability to execute complex maneuvers with high fluidity. In 2022, Hu et al. introduced an insect-scale piezoelectric robot with an asymmetric structure capable of operating in six vibration modes[35]. Its broad speed range and rapid response significantly expand its utility in confined spaces and precision instrumentation.

The high spatial resolution of piezoelectric actuators is particularly valuable for bionic inchworm robots. It enables precise control over step length and body configuration, ensuring stable movement in narrow or complex environments. Piezoelectric drives also exhibit excellent electromagnetic compatibility, making them resistant to external interference and free from generating electromagnetic pollution. These characteristics are essential for applications in environments with strict electromagnetic constraints, such as medical equipment or semiconductor manufacturing.

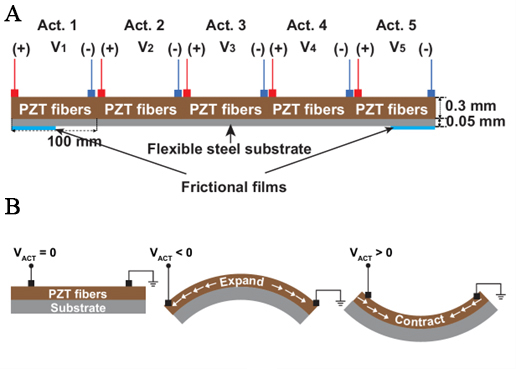

In 2001, Lobontiu et al. proposed an inchworm locomotion device capable of traversing flat surfaces[36]. It consisted of a piezoelectric single crystal paired with two custom-designed legs, and its mathematical model was constructed by superimposing compliant and rigid motion components[36]. In 2022, Zheng et al. demonstrated a five-actuator piezoelectric soft robot capable of both crawling and jumping, as shown in Figure 10[8].

Figure 10. Five-actuator piezoelectric soft robot. (A) Cross-section of the demonstrated prototype, 500 mm long and 20 mm wide, with a 50 mm-long high-friction film applied at the bottom of each end; (B) Bending mechanism based on the piezoelectric effect, in which the actuator unit bends downward (upward) due to expansion (contraction) under negative (positive) actuator voltage. Adapted with permission[8], Copyright 2022, IEEE. PZT: Lead zirconate titanate.

In 2023, Chen et al. developed a novel dual-helical soft robot, bio-mimic, fast-moving, and flippable soft piezoelectric robot (BFFSPR)[37]. Mimicking the locomotion gait of a cheetah, the BFFSPR can achieve a maximum average relative velocity of 42.8 body lengths per second (BL/s)[37]. When two BFFSPRs are connected in parallel to form a quadruped robot, it can perform rapid turning maneuvers. Moreover, the BFFSPR can move quickly even after flipping, thus demonstrating a greater adaptability to complex environments.

Due to its unique actuation principle and technical characteristics, piezoelectric drive technology has shown the following advantages in research applications: high displacement resolution, fast response speed, high force density, low speed and large thrust, diverse configurations, self-locking in case of power failure, no electromagnetic interference, good environmental adaptability, and diversified forms of motion. Restricted by the principle of operation, piezoelectric actuators have the following limitations: traditional inchworm actuators usually require multiple piezoelectric stacks and complex clamping mechanism, resulting in bulky design and control system complexity; piezoelectric stacks inherent small displacement limits the range and speed of the actuator, although it can be resolved through the amplification mechanism, but this in turn increases the complexity of the design; piezoelectric actuators under different load conditions of the stepping error control is a major challenge and requires advanced control strategies to improve stability and accuracy; integrating actuators into compact robots without sacrificing force or accuracy is difficult, especially for applications in confined spaces. The four typical drawbacks of have somewhat limited the large-scale application of piezoelectric actuators in inchworm robots.

3.1.4 Artificial muscle materials

Artificial muscle refers to a material or device that changes its shape when subjected to external physical or chemical stimuli, including not only new intelligent SMMs that mimic the structure of actual animal muscles through biotechnology, but also actuators that generate power by consuming electrical, magnetic or chemical energy to change their state.

In 2019, Yang et al. proposed a low-cost worm soft robot driven by super-helical polymer artificial muscles (SCPAM) with high power-to-weight ratio, inherent compliance, low cost, and good customizability[38]. In 2021, Xie et al. proposed a novel pneumatic artificial muscle (PAM) based on a parallel arrangement of thin-film cylinder drive units, which can be applied to flexible Exoskeletons and other human-machine interaction equipment, Xie et al. also proposed a novel pneumatic pipe crawling robot based on a tandem arrangement of thin-film cylinder drive units, which can be applied to the inspection and real-time monitoring of industrial pipeline facilities[39]. Zhang et al. used three fiber-reinforced pneumatic actuators to simulate the body parts of inchworms, which act as PAMs. This pneumatic mechanism helps precisely control the “tail”, “head” and “body” of the robot[2]. At the same time, the control system monitors the position of the actuators and coordinates the overall motion of the robot to achieve the “Ω” shape of an inchworm's wriggle as it crawls.

3.1.5 Other smart materials

The field of smart materials continues to develop, and new smart materials such as ionic polymer metal composites (IPMCs), moisture-sensitive actuated hydrogels, and magnetic SMPs, which exhibit excellent actuation properties, are also expected to be applied to bionic systems. IPMCs are electroactive polymers (EAPs) that achieve deformation based on the migration of ions under an electric field. They have advantages such as fast response and low driving voltage, but also suffer from disadvantages including easy water loss and complicated electrode preparation. Ze et al. proposed a novel magnetically driven SMP (M-SMP),which achieves remote fast reversible driving, shape memory, and reconfigurable deformation by embedding micrometer-sized magnetic particles, avoiding the IPMC’s water loss problem, and faster response to magnetic field actuation and higher deformation accuracy[40].

Hydrogel for moisture-sensitive actuation is a highly absorbent polymer network that achieves volume or shape changes based on environmental humidity changes, which has the advantages of sensitivity to humidity changes and biocompatibility, but weak mechanical properties and slow response time. Qu et al. from the University of Science and Technology of China developed a sensor based on MXene composite hydrogel[41] with excellent solvent tolerance, temperature hypersensitivity and fast response. By combining MXene and quaternized chitosan with binary polymer chains, the sensor achieves stability in high humidity and high temperature environments and significantly improves mechanical properties and strain and temperature sensing sensitivity. The hydrogel strain sensor exhibits high sensitivity, temperature/humidity tolerance (equilibrium expansion ratio of 2.5% at 80 °C), and excellent cyclic stability, enabling remote and accurate sensing of complex human motion and environmental fluctuations in underwater environments.

Magnetic SMPs are smart materials that achieve shape change through the alignment of magnetic moments of magnetic particles under an external magnetic field. They have advantages including fast response, high driving efficiency, and remote magnetic field control; however, the magnetization profile needs to be precisely controlled, and the mechanical properties and durability still need to be further improved. Aydin et al. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA, developed a muscle cell-driven micro-biobot based on muscle cells[42], which utilizes mouse muscle cell contraction and diastole to achieve locomotion. This system exhibits higher biocompatibility and environmental adaptability, but suffers from slow response speed and requires complex bioculture and maintenance conditions.

3.2 Pneumatic drive class

Pneumatic flexible actuators use gas as the working medium. The elastic chamber, under working air pressure (positive or negative), and structural constraints in a given spatial dimension (such as axial, bending, or torsion), generate directional expansion or contraction.

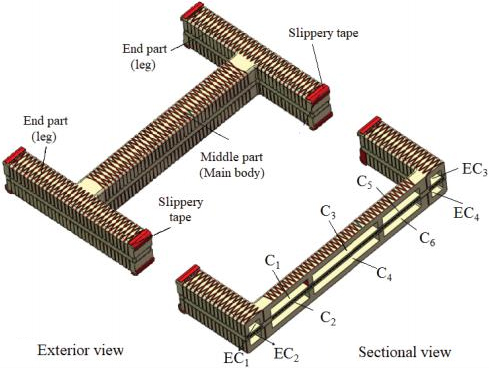

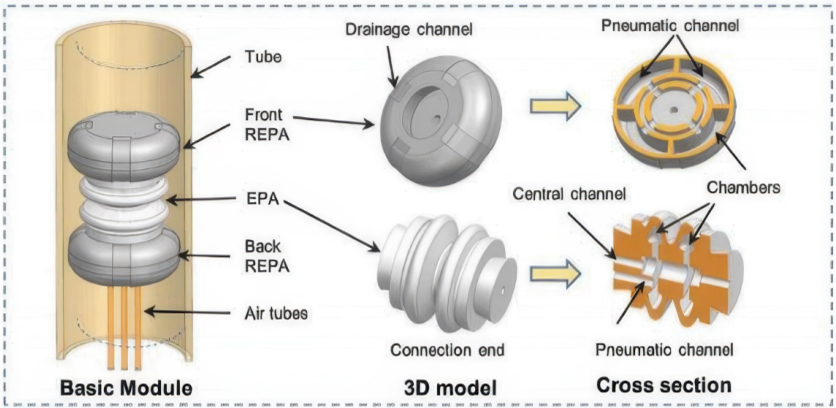

In 2000, Yeo et al. proposed a planar embedded worm gear robot with four cylinders mounted on a square crossbar frame, where the ends of the cylinders are connected to four sliding units that can move relative to the frame[43]. In 2017, Guo et al. designed an inchworm robot with a strain-limiting layer of silica gel square tubes that can bend and display an “Ω” shape when driven by gas fluid[44]. In the same year, Ning et al. designed a pneumatic inchworm robot made of a single material with a single degree of freedom, requiring only air pressure as a single-channel control signal for continuous motion[45]. In 2018, Xie et al. proposed a pneumatic soft robot, PISRob[6], shown in Figure 11, which consists of three H-shaped soft structural parts, each capable of two-dimensional bending. The middle part acts as the main body and can perform “Ω”-shaped bending, while the body and legs of the robot are actively driven by compressed air[6].

Figure 11. Configuration and structure of the robot. C1–C6 stand for the corresponding chambers. ECi stands for the ith end chamber. Reproduced with permission[6], Copyright 2018, IEEE.

In 2019, Duggan et al. presented a simple soft actuator system based on partially antagonistic fluid elastomer actuators (FEAs)[14]. They developed a mobile soft robot equipped with a compact electromechanical backpack and actuated by a gas-powered micropump, as shown in Figure 12[14].

Figure 12. (A-C) are top views of the actuator, showing structural morphologies under different working states: (A) Initial flat state without air pressure input, where the silicone matrix maintains natural relaxation; (B) Asymmetric bending state after inflation of a single-side chamber, with the strain-limiting layer (blue pattern) restricting local deformation to induce bending of the actuator to one side; (C) Transitional deformation state after alternating inflation of bilateral chambers, preparing for axial propulsion; (D) Front view of the actuator, clearly presenting the layered structure of the silicone matrix and the strain-limiting layer; (E) presents a simplified model of the actuator with varying parameters. The blue pattern indicates the strain-limiting layer. Adapted with permission[14], Copyright 2019, IEEE.

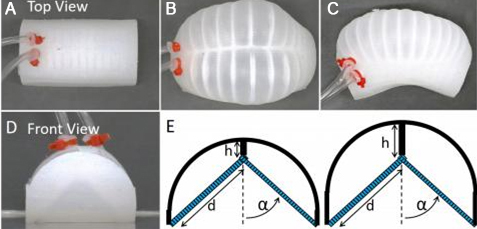

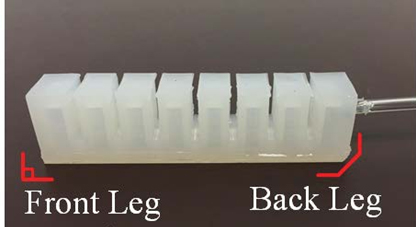

In 2019, Manfredi et al. introduced a soft pneumatic inchworm double-balloon (SPID) microrobot for colonoscopy, as shown in Figure 13[46]. In Figure 14, a representative pneumatic soft inchworm robot inspired by biological inchworm locomotion is shown by Ning et al.[45]. By regulating the internal pressure of the air cavity, the compliant body undergoes coordinated bending and stretching. Alternating frictional anchoring of the anterior and posterior legs enables stable inchworm-like locomotion on flat substrates.

Figure 13. SPID design. Explanation of the SPID design is given in Figure A-C. (A) Perspective view with distal and proximal balloons activated; (B) Cross-section showing the balloon and the available internal space of the SPA; (C) Five steps of the bionic motion, where (i) t lead-a is the time to activate the proximal balloon, (ii) t hydrotherapy center is the activation time of the SPA based on the orientation of the colonic lumen, (iii) tDB-a is the activation time of the distal balloon, (iv) tPB-D is the deactivation time of the proximal balloon, and (v) tSPA-D is the deactivation time of the SPA to allow advancement. Adapted under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[46]. DOF: Degree of freedom; SPA: soft pneumatic actuator; SPID: soft pneumatic inchworm double-balloon.

Figure 14. Pneumatic soft inchworm robot. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license[45].

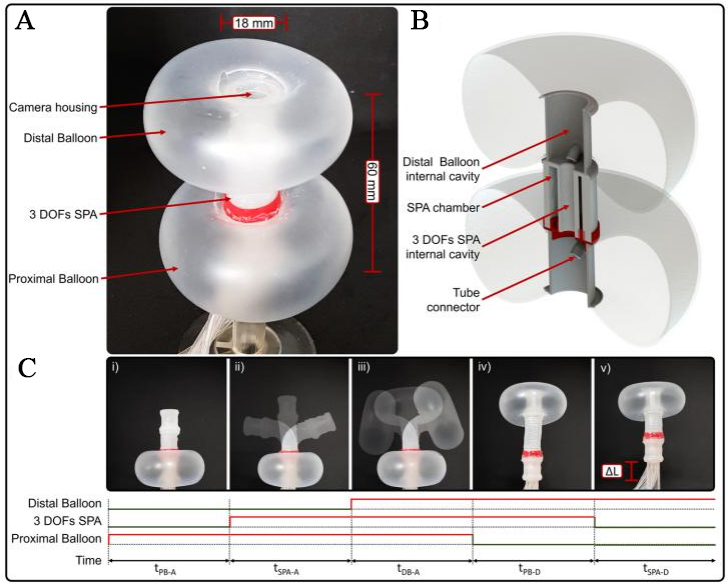

In 2021, Liu et al. designed a hose‐type robot composed of elongated pneumatic actuators (EPAs),radial expansion pneumatic actuators (REPAs), and spatially bending pneumatic actuators (SBPAs), as shown in Figure 15. This robot is capable of performing various tasks in complex pipeline and tunnel environments[18].

Figure 15. Conceptual design and fabrication of a worm-inspired soft robot: schematic diagram of the basic modules of the soft robot. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[18]. REPA: Radial expansion pneumatic actuator; EPA: elongated pneumatic actuator; 3D: three dimensional.

In 2023, Jiang et al. developed a pole-climbing robot consisting of two clamping and wrapping actuators (CWAs), which function as the thoracic and tail legs of an inchworm[3]. A steering telescopic actuator (STA) serves as the robot’s soft body. By adjusting the internal pressure of the CWAs, the robot can grasp cylindrical structures, while modifying the pressure of the STA enables stretching and bending movements[3].

Also in 2023, Jung et al. introduced an inchworm robot named WIBot, which is pneumatically driven by the expansion and contraction of methanol vapor[12]. In the same year, Shen et al. proposed a pneumatic robotic system called WATER7, designed specifically for inspecting aging water-filled pipelines. Its compact size and safe power characteristics improve adaptability to real pipeline environments[17].

The pneumatic drive mode offers several advantages, including low weight, high efficiency, environmental cleanliness, and strong adaptability to harsh conditions. Because it operates without ferromagnetic or electronic components and contains no rigid moving parts, it provides excellent flexibility and maintains high reliability in extreme environments, such as strong radiation, electromagnetic interference, dust exposure, or external crushing. However, pneumatic actuation also has notable limitations. Its relatively low working pressure results in limited output force or torque, and the necessary air purification process increases system complexity. Additionally, issues such as exhaust noise may arise, making pneumatic drive systems less suitable for applications with stringent environmental requirements.

3.3. Electromagnetic drive category

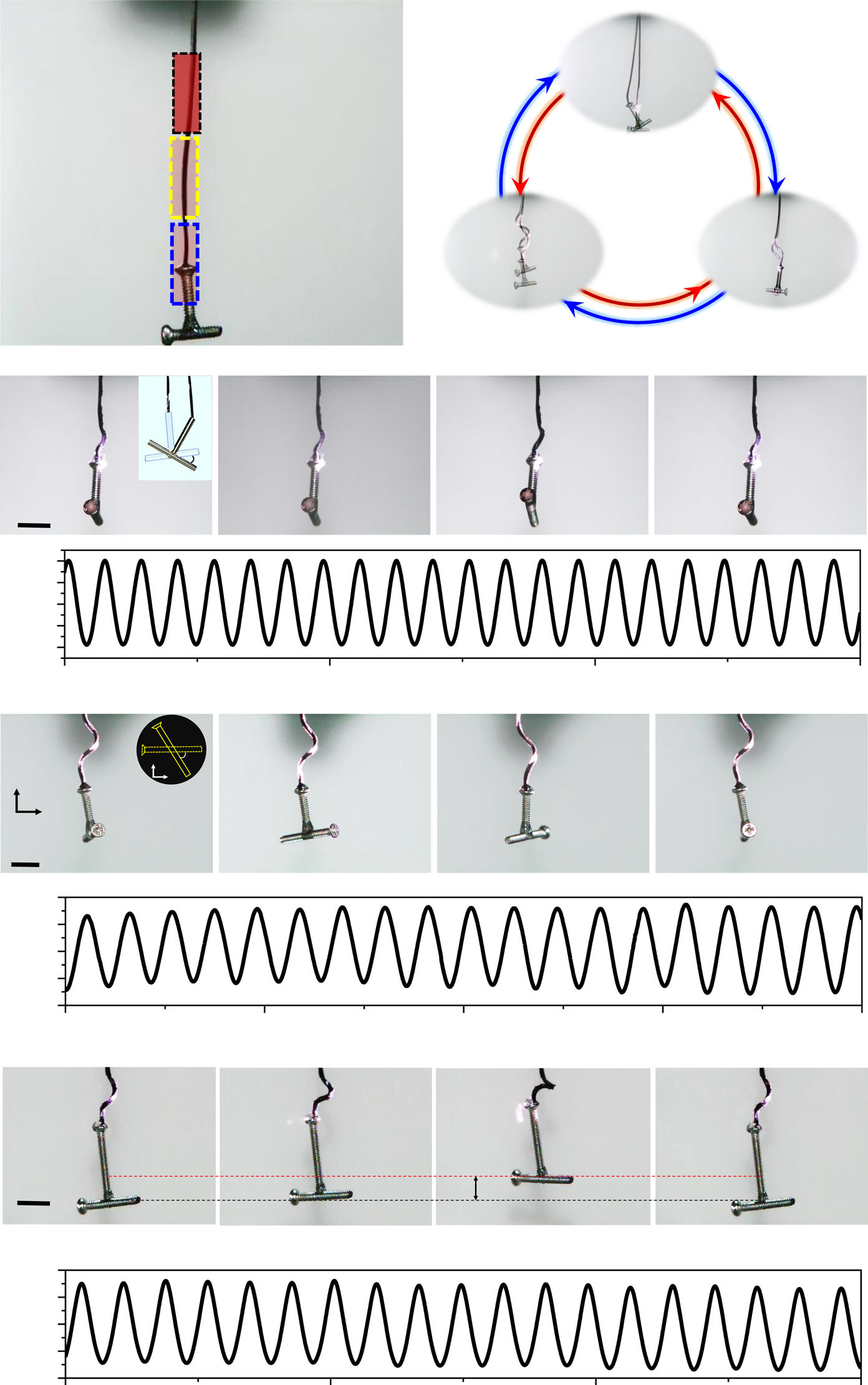

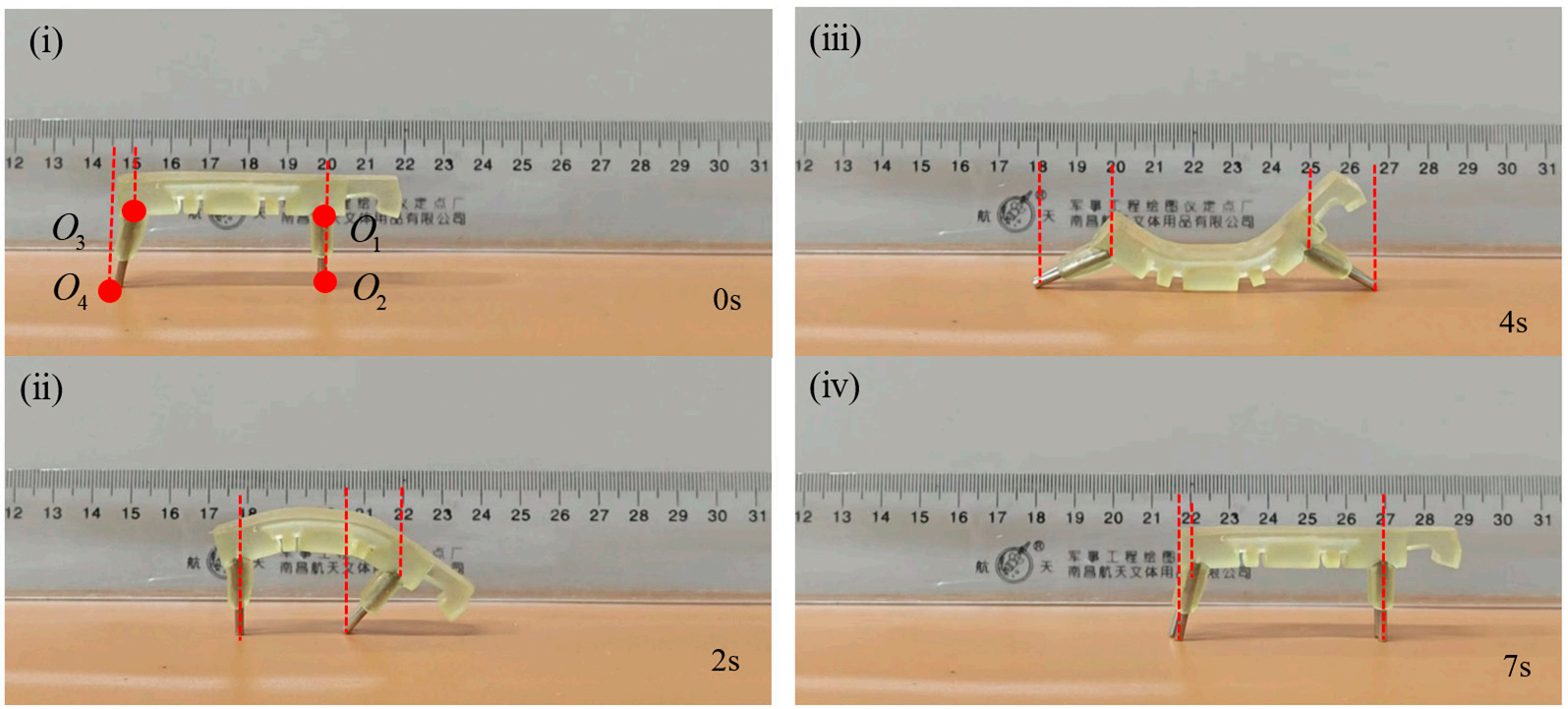

In Figure 16, the locomotion process of a magnetically actuated soft inchworm robot is illustrated over one complete gait cycle. By coordinating magnetic actuation with compliant body deformation, the robot alternates between bending and stretching states while sequentially anchoring the anterior and posterior legs. This cyclic motion enables stable inchworm-like locomotion on a horizontal surface and demonstrates the effectiveness of magnetic actuation for soft-bodied crawling robots[48].

Figure 16. Locomotion cycle of a magnetically actuated soft inchworm robot. (i) The locomotion cycle starts with the activation of the proximal balloon, which inflates and establishes firm anchoring with the surrounding lumen wall, providing a stable support for subsequent motion; (ii) After the proximal balloon is anchored, the soft pneumatic actuator (SPA) is activated. Depending on the orientation and geometry of the lumen, the SPA expands and bends, producing axial extension that advances the distal section of the robot forward; (iii) Subsequently, the distal balloon is activated and inflated, generating anchoring at the front end. At this stage, both the proximal and distal ends are temporarily fixed, ensuring positional stability during the transition phase; (iv) The proximal balloon is then deactivated and deflated, releasing the rear anchoring. With the distal end remaining fixed, the body contraction of the SPA pulls the proximal section forward, completing one inchworm-like locomotion step. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[47].

In 2018, Moreira et al. developed an inchworm robot capable of executing a double-anchored crawling gait on both horizontal surfaces and inclined planes. The innovation of their design lies in three key features: (1) a three-segment body driven by two servomotors that enables cyclic and lengthening movements, (2) passive friction pads that anchor the feet, each disengaged by a servomotor-actuated lever arm, and (3) a modular body and electronics system operated by an open-loop controller to achieve stable crawling motion, as illustrated[48].

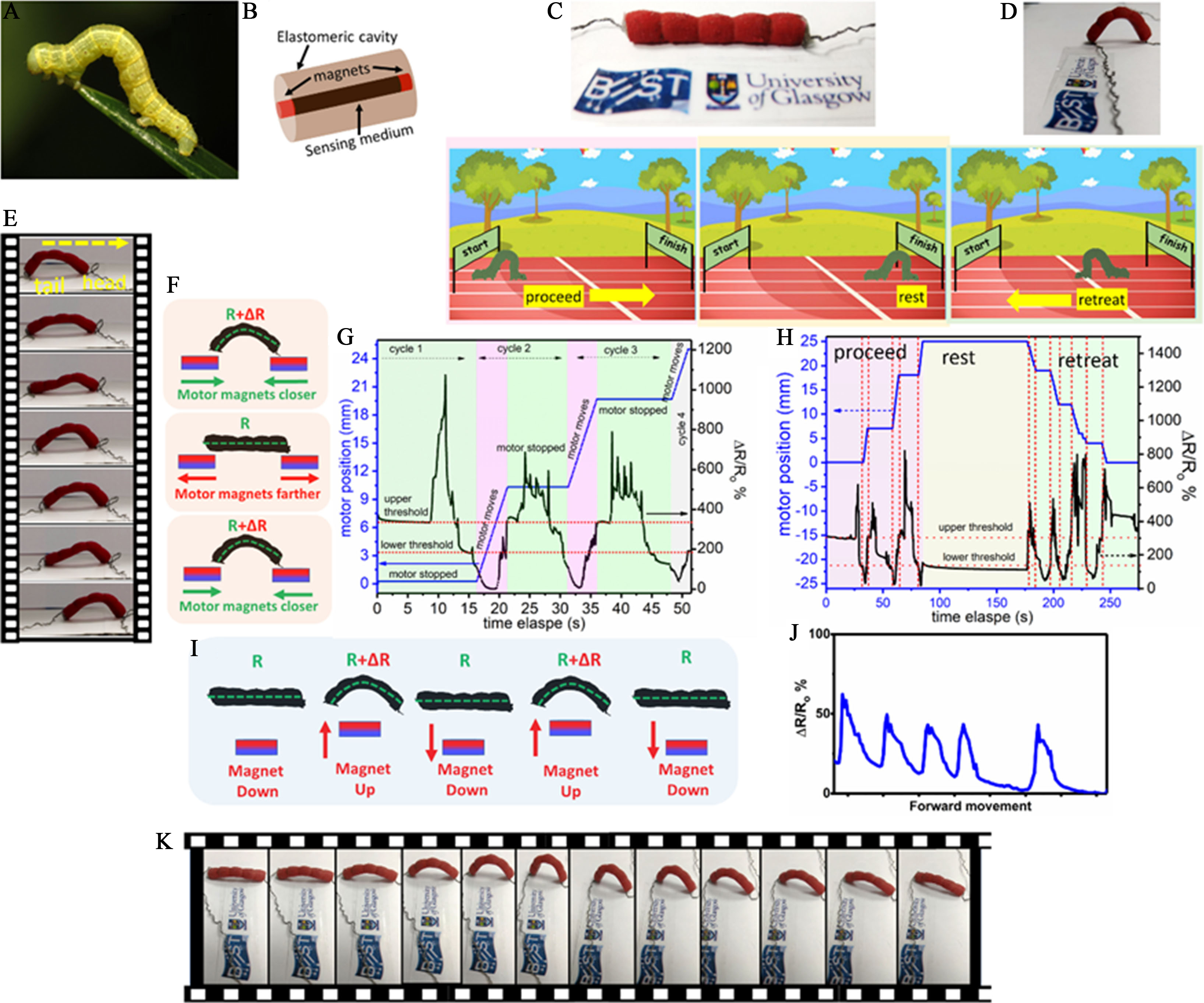

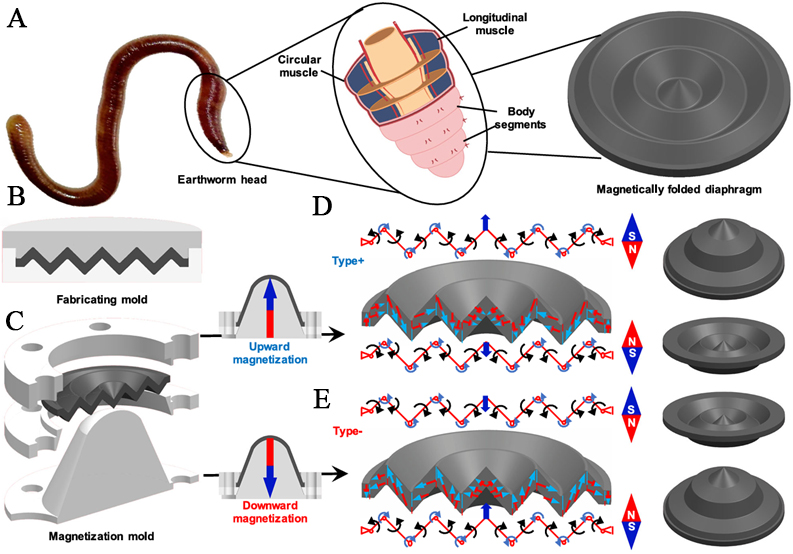

In 2022, Karipoth et al. combined the sensing capabilities of the developed graphite paste-based ultra-stretchable strain sensors, the flexibility of an elastic medium (Ecoflex), and the well-established concepts of magnetically actuated soft robots to design inchworm-type soft robots and demonstrate their externally magnetic field-driven locomotion through intrinsic sensing and closed feedback control[49]. As shown in Figure 17, two pairs of NdFeB magnet pairs embedded in the soft body can be driven forward or backward depending on the direction of the applied external magnetic field, thus enabling the embedded worm robots to move. Furthermore, Xia et al. combined 3D printing for rapid manufacturing with magnetic actuation to create an untethered soft inchworm robot capable of complex, multimodal locomotion[47], such as climbing over obstacles and moving from horizontal to vertical surfaces. Lin et al. (2023) proposed a magnetically actuated folded diaphragm with a one-piece molding[50], a simple fabrication process, and the ability to achieve large, three-dimensional, bi-directional deformations under the action of a low-strength, uniform magnetic field. This folded diaphragm with different radial magnetization characteristics is capable of large internal volume changes and high strength. The folded diaphragm can be fabricated using a simple one-piece molding method, easily customized into different shapes according to the actual requirements, and then implanted as a soft actuator into different untethered soft robotic systems, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 17. Inchworm-type soft-body robot designed by Karipoth et al.[49]. (A) Inchworm; (B) Cross-section of the inchworm-type soft-body robot; (C) Fabricated inchworm soft-body robot; (D) Bending configuration; (E) Motion sequence; (F) Kinematic mechanism under magnetic field actuation; (G) Transient strain-sensing response during motion; (H) Forward and reverse motion; (I) Schematic representation of motion under single-magnet actuation; (J) Single-sensor response during magnet actuation; (K) Motion cycle under single-magnet actuation. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[49].

Figure 18. (A) Bio-inspired magnetically driven folded diaphragm inspired by an earthworm; (B) Manufacturing mold; (C) Magnetization mold for the magnetically driven folded diaphragm; (D) Magnetization characteristics and working principle of the magnetically driven upward-magnetized folded diaphragm (Type+diaphragm); (E) Magnetization characteristics and working principle of the magnetically driven downward-magnetized folded diaphragm (Type+diaphragm). Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license[50].

Electromagnetic actuation, a traditional yet effective driving method, offers high energy efficiency, fast response, flexible control, and precise motion regulation. It supports multiple motion modes and algorithms, ensuring accurate speed and position control with broad applicability - particularly advantageous for operations in confined spaces. However, motor-based drives are relatively expensive, sensitive to voltage fluctuations, and prone to electromagnetic interference. Moreover, current magnetic programming methods are inherently linked to sequential manufacturing processes, limiting reprogrammability, throughput, and certain application scenarios.

3.4. Comparison of different drive methods

The drive modes employed in inchworm robots are well-suited to their soft materials and compliant structures, offering advantages that traditional rigid robots cannot achieve. Among the major actuation technologies, emerging soft materials - such as shape memory alloys (SMAs), DEs, piezoelectric materials, and artificial muscles - have become central research directions. These materials utilize their intrinsic characteristics to adapt to diverse environments, enhancing mobility and performance while expanding potential applications. However, their development is still constrained by limited material categories, high production costs, and performance sensitivities to environmental factors such as temperature.

Pneumatic actuation is another widely adopted approach due to its strong adaptability and environmental robustness. It provides good resistance to interference, offers precise motion control, and maintains simplicity and cost-effectiveness - making it well-suited for soft robotic systems. Current studies on pneumatic inchworm robots emphasize motion modeling, structural optimization, and performance enhancement. Despite these advantages, pneumatic actuation still faces limitations, including low working pressure, restricted stability, and the need for complex air management and control systems.

Electromagnetic actuation, as a mature and efficient technique, offers high energy conversion efficiency and rapid response, enabling precise motion tailored to specific functional requirements. However, when applied to soft-bodied robots, the integration of rigid motors and magnetic components increases system mass and reduces overall flexibility. In addition, other actuation strategies - such as light-driven mechanisms[11,13] and humidity-responsive systems - remain limited in scope and constrain broader application of inchworm robots.

The performance of different actuation modes can be evaluated based on factors such as output force, response speed, energy efficiency, mass and volume constraints, control system complexity, and motion accuracy. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of pneumatic, electromagnetic, and smart-material-based actuation methods.

Comparison of drive methods

| Driving method | driving force | responsiveness | Response time | energy efficiency | Weight/Volume limitations | Control complexity | accurate | |

| Shape Memory Alloy material driver | Small (1.2 N) | slow | About 2 s | Moderate (18%) | Light/Small | High | Moderate (0.5 mm) | |

| Dielectric material drive | Small | Fast | < 100 ms | High | Light/small | High | High | |

| Artificial muscle material drive | Moderate | Moderate | About 1 s | Moderate | Light/small | High | Low | |

| Pneumatic drive | Moderate (5 N) | Moderate | < 500 ms | Moderate | Light/Large | Low | Low (2 mm) | |

| Electromagnetic drive | Strong | Fast | < 100 ms | High (45%) | Heavy/Large | Low | High (0.3 mm) | |

| Piezoelectric materials | Moderate (4.1 N) | Fast | < 100 ms | Moderate | Light/Small | Moderate | High | |

4. MOTOR PERFORMANCE COMPARISON

In the previous section, several common actuation modes of inchworm robots were introduced, and their similarities and differences were compared. However, an inchworm robot operates as an integrated system; beyond the actuation method, factors such as body size, foot-end attachment mechanisms, and structural configuration also exert a significant influence on its kinematic performance. Therefore, the next section compares the kinematic performance of robots that employ the same actuation method but differ in structural design.

Since inchworm robots are developed not only for speed but also for exploring new materials and enabling locomotion in specific application scenarios, their kinematic performance will be evaluated in terms of robot shape, size, locomotion surface, and movement direction. A summary of these comparisons is presented in Table 3.

Comparison of locomotor performance

| Designation | Drive mode | Robot shape and size | Surface movement | Movable direction | Average movement speed (mm/s) | Movement frequency (Hz) |

| 1[22] | SMA drive | Striped | Ramp | Unidirectional motion | 0.8 | N/A |

| 2[9] | Plane | N/A | Multi-directional motion | 10 | 0.1-2 | |

| 3[3] | Pneumatic drive | Centimeter | N/A | Multi-directional motion | 0.28 | N/A |

| 4[2] | N/A | On floors, columns and other objects Bidirectional motion Slender horizontal surfaces | Bidirectional motion | 8.33 | 0.2 | |

| 5[6] | Elongate | Horizontal surfaces | Unidirectional motion | 40 | 0.5 | |

| 6[46] | Very small volume | Inside intestinal-sized tubes | Motion along tubes | 8 | N/A | |

| 7[17] | Small volume | Inside a pipe | Motion along tubes | 0.3 | 1.25 | |

| 8[45] | Small volume | Waterless surfaces | Unidirectional motion | 5 | 1.4 | |

| 9[14] | Large volume | Surfaces of different textures and inclinations Bidirectional motion | Bidirectio-nal motion | 10.65 | 1 | |

| 10[44] | N/A | Horizontal plane | Multi-dire-ctional motion | 3 | 0.5 | |

| 11[45] | Cylindrical | Horizontal surfaces | Unidirecti-onal motion | 2.2 | 2.5 | |

| 12[47] | Striped | Horizontal surfaces | Unidirecti-onal motion | 1 | 3.2 | |

| 13[38] | N/A | N/A | Unidirecti-onal motion | 0.245 | 0.025 | |

| 14[56] | Artificial muscle drive | N/A | Horizontal surfaces | Unidirecti-onal motion | 21 | N/A |

| 15[36] | Piezoelec-tric single crystal actuation | N/A | Horizontal surfaces | Bidirectio-nal motion | N/A | N/A |

| 16[36] | N/A | Horizontal surfaces | Bidirectio-nal motion | N/A | N/A |

In 2012, Koh et al. designed an inchworm robot featuring a four-link body-bending mechanism, a spherical six-bar steering mechanism, an SMA spring braker as the actuation source, and anisotropic friction pads at the foot ends[9]. This configuration enabled the robot to achieve multiple locomotion patterns at a speed of approximately 10 mm/s[9].

In 2020, Tang et al. proposed a bistable hybrid soft-tracked robot that demonstrated significantly enhanced locomotion performance[51]. Under a pressurization of 20 kPa, the robot achieved a linear velocity of 174.4 mm/s (2.49 BL/s), outperforming conventional locomotive soft robots (1.19 BL/s) and hybrid soft robots (0.53 BL/s). On wooden surfaces, its locomotion speed was 2.1 and 4.7 times that of comparable soft crawlers based on SBA actuation[51].

Among the robots listed in the table, some can only achieve unidirectional motion, whereas others are capable of bidirectional or even omnidirectional locomotion. The ability to realize bidirectional motion depends on independently controllable anchoring at the front and rear foot ends. For example, the robot designed by Lobontiu et al. employs a piezoelectric single-crystal actuator[36], two legs of different lengths, and clips connecting the legs to the body to regulate leg inclination. Its locomotion cycle consists of two phases: during the first phase, the single crystal bends, causing the front leg to self-lock via ground friction while the rear leg is dragged forward. In the second phase, the single crystal returns to its initial shape, the rear leg self-locks, and the front leg swings forward. Because the robot relies on a shorter front leg and longer rear leg, and its anchoring depends on frictional differences rather than independent actuation, it is limited to unidirectional movement.

From a comparative perspective, robots can achieve multi-surface and multi-direction locomotion by integrating foot-end adhesion strategies with appropriate locomotion gaits. Some robots adopt flat or striped structural designs to adapt to harsh environments such as rubble; others are capable of load-bearing crawling, and some can be combined to form multi-functional robotic systems.

According to the data summarized in Table 3, low locomotion speed and low actuation frequency remain common limitations of existing biomimetic inchworm robots. Although several robots exhibit speeds approaching 40 mm/s, this often results from their relatively long body lengths rather than superior locomotion performance. Such limitations inevitably restrict their practical use. Consequently, improving locomotion performance will remain a key research direction for future inchworm-inspired robotic systems.

5. APPLICATION SCENARIOS

Bionic soft inchworm robots, characterized by their flexibility and high adaptability, exhibit strong potential across a wide range of application domains. They perform effectively in both simple and complex environments and can operate in confined spaces that are inaccessible to traditional rigid robots or humans. In agriculture, these robots can navigate narrow or uneven terrains, making them suitable for monitoring and operational tasks in orchards and forests. Yuan et al. developed a bionic inchworm robot for agricultural use, demonstrating reliable mobility in complex outdoor environments[52].

In the medical field, inchworm-inspired soft robots are increasingly explored for their flexibility, controllability, and compatibility with human tissue. Shin et al. designed a centimeter-scale robot[53] consisting of two legs and a bilayer body: a moisture-responsive upper layer and an inert lower layer. When placed on wet paper, the upper layer swells and causes the body to arch upward, pulling the rear legs forward and lifting the robot into drier air. As the upper layer dries, the body contracts, allowing the front legs to advance. This alternating cycle enables inchworm-like locomotion. Similar designs could potentially be used for medical applications involving movement on wet human skin.

Yu et al. from Harbin Institute of Technology (Shenzhen) developed a biomimetic, magnetically actuated robotic shell for active locomotion of capsule endoscopes in tubular environments[54]. The robot mimics inchworm movement through dynamic telescopic deformation driven by an internal magnetic torsion spring regulated by an external magnetic field. Flexible surface hairs enhance locomotion through differential friction. The system requires no additional motors or onboard power and is compatible with commercial capsule endoscopes. Experiments demonstrated effective locomotion in complex tubular environments, with average speeds of 2.63 mm/s in vitro and 2.7 mm/s in in vivo porcine intestines. This magnetic, biomimetic design provides both safety and efficiency, offering promising potential for future gastrointestinal diagnostics.

Bionic inchworm robots also excel in inspection and detection tasks. In 2025, Chen et al. introduced an inchworm-inspired micro-inspection robot capable of autonomous operation in confined spaces of aero-engines[55], significantly improving inspection efficiency and accuracy - factors critical for engine safety. General Electric (GE) developed the “Sensitive Worm,” a soft robotic system for engine maintenance. Mimicking inchworm locomotion, it integrates a built-in power supply, microprocessor, and electronics. When placed at a turbine inlet or nozzle, it moves through the engine via push-pull motions enabled by vacuum suction cups. Traditional endoscopes often fail to reach deep internal regions of jet engines during overhauls; GE’s design overcomes this limitation, reducing maintenance difficulty and cost.

In practical applications, the selection of attachment and actuation strategies must align with the task requirements and environmental conditions. Each technique involves inherent trade-offs that influence suitability. Suction-based adhesion provides strong attachment on smooth surfaces but performs poorly on rough or porous ones. Dry adhesives and friction-based systems adapt better to irregular surfaces but produce weaker adhesion. Electrostatic adhesion provides precise, reusable control but is sensitive to humidity and surface properties.

Similarly, actuation methods exhibit distinct advantages and limitations. Pneumatic actuation can generate large deformations and forces but relies on external pumps and tubing, which limits miniaturization. Piezoelectric actuators provide high precision and fast response but produce small strokes, often requiring amplification mechanisms. Shape-memory alloys are compact and capable of generating large strains, yet they exhibit slow response and low energy efficiency.

Therefore, designers must evaluate environmental conditions and performance priorities when selecting technologies. Robots intended for wall climbing or pipeline inspection require reversible, reliable adhesion on various surfaces, making hybrid suction-friction systems advantageous. Medical and semiconductor applications demand cleanliness and precision, favoring piezoelectric or electrostatic actuation. Field exploration and rescue work emphasize adaptability and force output, making pneumatic systems particularly suitable.

Overall, bionic soft inchworm robots demonstrate broad application potential across agriculture, forestry, construction, medicine, and disaster rescue. With continued technological development, they are expected to play an increasingly important role across these diverse fields.

6. KEY ISSUES AND DEVELOPMENT TREND OF BIONIC INCHWORM ROBOT CURRENTLY FACING

6.1. Key challenges of bionic inchworm robots

The adaptability of bionic inchworm robots in complex environments remains significantly constrained. Major challenges include sensitivity to temperature and humidity, reliance on specific surface conditions, and limited cross-medium locomotion capabilities. These factors directly affect the robots’ performance and reliability in multi-environment tasks. For instance, photo-driven soft robots become inoperable when humidity falls below 15% due to material dehydration, while SMA-based robots may lose actuation capability at temperatures above 80 °C because of phase transition hysteresis. Suction-based robots experience a 60% reduction in adhesion on oily or highly rough surfaces (Ra > 10 μm), and electro-adhesive robots achieve only 30% of their typical adhesion on non-conductive surfaces. Additionally, the locomotion speed of air-liquid amphibious robots decreases by up to 72% during transitions from aquatic to terrestrial environments due to foot-end sticking effects.

Energy efficiency also presents persistent challenges. Pneumatic systems add considerable bulk and mass, piezoelectric actuators often require high driving voltages and complex structural tuning, and light-driven robots depend heavily on external energy sources. These limitations reduce autonomy and operational duration. For example, miniature air pumps provide only 0.5 W/g of power density, increasing total robot mass by more than 50%. A piezoelectric soft robot developed by Zheng et al. achieved multimodal locomotion such as inchworm crawling and jumping; however, such systems typically necessitate high driving voltages (up to 1,500 V) and rely on precise weight asymmetry optimization to overcome friction and inertia[56]. Furthermore, many light-driven robots require a continuous external optical field, making fully autonomous operation unattainable.

6.2 Emerging solutions and future directions

To address these challenges, researchers have introduced several targeted strategies. One promising direction is the development of environmentally adaptive materials. SMPs, for example, can autonomously tune stiffness and flexibility through programmed shape-memory responses, enabling stable locomotion across a wide temperature range. EAPs offer high flexibility and rapid response, and molecular structure optimization allows stable actuation even in fluctuating humidity conditions.

Surface engineering technologies also play a critical role in enhancing adaptability. Nanostructured coatings - such as nanotube layers formed via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) - significantly improve adhesion on greasy or rough surfaces by increasing contact area and reducing slip. Smart surface materials, including self-healing polymer coatings, can automatically repair micro-damage at the foot ends, thereby maintaining consistent adhesion.

In addition, multimodal sensing and intelligent control algorithms are essential for environmental adaptability. Integrating humidity sensors, temperature sensors, and surface-texture sensors enables real-time environmental monitoring. Machine learning-based control algorithms allow robots to adjust locomotion strategies dynamically. For example, humidity sensors based on fiber Bragg gratings and temperature sensors exploiting piezoelectric effects, combined with data-fusion algorithms, allow real-time tuning of locomotion parameters.

Reinforcement-learning-based controllers further enhance adaptability by enabling robots to autonomously select optimal locomotion modes in response to environmental changes, improving both efficiency and autonomy.

To improve energy efficiency, researchers have developed lightweight pneumatic systems using high-strength, low-density materials such as carbon fiber composites, reducing overall system mass. Advances in high-efficiency actuation - such as new piezoelectric materials and improved SMAs - boost energy conversion performance. Additionally, energy recovery and storage mechanisms, including mechanical-to-electrical energy reclamation during locomotion, improve overall energy utilization.

New energy-supply approaches, such as wireless charging and integrated solar cells, further enhance autonomy. Wireless inductive charging systems allow continuous recharging during operation, while high-efficiency solar cells embedded on the robot’s surface increase energy independence.

Looking forward, future research should focus on self-healing and multifunctional materials to enhance stability under extreme conditions, as well as technologies that regulate surface tension to enable seamless cross-medium transitions (e.g., water-to-land). Ultimately, interdisciplinary collaboration - spanning materials science, mechanical engineering, electronics, and biology - will be essential for solving challenges related to environmental adaptability and energy efficiency.

7. CONCLUSION

This paper provides a comprehensive overview of recent advancements in bionic inchworm robotics across several key research areas. The latest developments in actuation strategies, foot-end attachment mechanisms, and locomotion principles inspired by biological inchworms have been systematically summarized. Additionally, representative soft robot designs that highlight the intrinsic advantages of inchworm-inspired locomotion are reviewed.

In terms of actuation, current approaches can be broadly classified into three categories: smart-material-based actuation, pneumatic actuation, and electromagnetic actuation. Among them, pneumatic actuation demonstrates the widest applicability due to its strong adaptability and relatively simple implementation. Regarding foot-end attachment strategies, frictional anchoring, suction-based adhesion, and bioinspired adhesive mechanisms remain the most commonly employed, with adhesive-based techniques showing particularly promising potential as novel soft materials continue to evolve and expand applicable environments.

Despite continuous progress, several challenges persist. Future research must address key issues such as improving energy efficiency and operational endurance, enhancing sensing accuracy and control precision, and advancing locomotion performance while overcoming constraints imposed by specific surface conditions. Addressing these challenges will be essential for enabling the practical deployment of bionic inchworm robots in broader and more demanding real-world applications.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the research and investigation process, reviewed and summarized the literature, and wrote and edited the original draft: Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Q.

Reviewed and revised the manuscript structure and language, and identified and addressed missing or incomplete content: Yu, Z. (Zhengxin Yu); Li, M.

Performed oversight and leadership responsibilities for research planning and execution, and contributed to the development and evolution of the overarching research aims: Yu, Z. (Zhiwei Yu)

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52475303 and 52075248) and the Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Mechanics and Control for Aerospace Structures (Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics) (Grant No. 1005-ZAG23011).

Conflicts of interest

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Ueno, S.; Takemura, K.; Yokota, S.; Edamura, K. Micro inchworm robot using electro-conjugate fluid. Sens. Actuators. A. Phys. 2014, 216, 36-42.

2. Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Yan, P.; Zhou, P.; Zou, J.; Gu, G. Inchworm inspired multimodal soft robots with crawling, climbing, and transitioning locomotion. IEEE. Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1806-19.

3. Ding, J.; Su, H.; Nong, W.; Huang, C. An inchworm-inspired soft robot with combined functions of omni-directional steering and obstacle surmounting. Ind. Robot. 2022, 50, 456-66.

4. Jiang, Z.; Zhang, K. Force analysis of a soft-rigid hybrid pneumatic actuator and its application in a bipedal inchworm robot. Robotica 2024, 42, 1436-52.

5. Chang, A. H.; Freeman, C.; Mahendran, A. N.; Vikas, V.; Vela, P. A. Shape-centric modeling for soft robot inchworm locomotion. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, September 27 - October 1, 2021; IEEE, 2021, pp 645-52.

6. Xie, R.; Su, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, H.; Guan, Y. PISRob: A pneumatic soft robot for locomoting like an inchworm. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, May 21-25, 2018; IEEE, 2018, pp 3448-53.

7. Gamus, B.; Salem, L.; Gat, A. D.; Or, Y. Understanding inchworm crawling for soft-robotics. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 1397-404.

8. Zheng, Z.; Kumar, P.; Chen, Y.; et al. Model-based control of planar piezoelectric inchworm soft robot for crawling in constrained environments. In 2022 IEEE 5th International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Edinburgh, United Kingdom, April 4-8, 2022; IEEE, 2022, pp 693-8.

9. Koh, J.; Cho, K. Omega-shaped inchworm-inspired crawling robot with large-index-and-pitch (LIP) SMA spring actuators. IEEE/ASME. Trans. Mechatron. 2013, 18, 419-29.

10. Jing, Z.; Li, Q.; Su, W.; Chen, Y. Dielectric elastomer-driven bionic inchworm soft robot realizes forward and backward movement and jump. Actuators 2022, 11, 227.

11. Yang, Y.; Li, D.; Shen, Y. Inchworm-inspired soft robot with light-actuated locomotion. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 1647-52.

12. Jung, W.; Lee, S.; Hwang, Y. Wireless inchworm-like compact soft robot by induction heating of magnetic composite. Micromachines. (Basel). 2023, 14, 162.

13. Duduta, M.; Clarke, D. R.; Wood, R. J. A high speed soft robot based on dielectric elastomer actuators. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, Singapore, May 29 - June 3, 2017; IEEE, 2017, pp 4346-51.

14. Duggan, T.; Horowitz, L.; Ulug, A.; Baker, E.; Petersen, K. Inchworm-Inspired Locomotion in Untethered Soft Robots. In 2019 2nd IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Seoul, Korea (South), April 14-18, 2019; IEEE, 2019, pp 200-5.

15. Das, R.; Babu, S. P. M.; Visentin, F.; Palagi, S.; Mazzolai, B. An earthworm-like modular soft robot for locomotion in multi-terrain environments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1571.

16. Sun, J.; Bauman, L.; Yu, L.; Zhao, B. Gecko-and-inchworm-inspired untethered soft robot for climbing on walls and ceilings. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101241.

17. Shen, Y.; Isono, R.; Kodama, S.; et al. Design of a pneumatically driven inchworm-like gas pipe inspection robot with autonomous control. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Singapore, Singapore, April 3-7, 2023; IEEE, 2023, pp 1-6.

18. Liu, X.; Song, M.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, C. Worm-inspired soft robots enable adaptable pipeline and tunnel inspection. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 4, 2100128.

19. Hu, Z.; Li, Y.; Lv, J. A. Phototunable self-oscillating system driven by a self-winding fiber actuator. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3211.

20. Jiang, J.; Yu, Y.; Lin, C.; Sun, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, H. Robots inspired by inchworms: structural design and applications. J. Field. Robot. 2025, rob.70087.

21. Plaut, R. H. Mathematical model of inchworm locomotion. Int. J. Non-Linear. Mech. 2015, 76, 56-63.

22. Shi, Z.; Pan, J.; Tian, J.; Huang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zeng, S. An inchworm-inspired crawling robot. J. Bionic. Eng. 2019, 16, 582-92.

23. Thomas, S.; Germano, P.; Martinez, T.; Perriard, Y. An untethered mechanically-intelligent inchworm robot powered by a shape memory alloy oscillator. Sens. Actuators. A. Phys. 2021, 332, 113115.

24. Luo, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Recent advances in shape memory polymers: multifunctional materials, multiscale structures, and applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 34, 2312036.

25. Felton, S. M.; Tolley, M. T.; Onal, C. D.; Rus, D.; Wood, R. J. Robot self-assembly by folding: a printed inchworm robot. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Karlsruhe, Germany, May 6-10, 2013; IEEE, 2013, pp 277-82.

26. Conn, A. T.; Hinitt, A. D.; Wang, P. Soft segmented inchworm robot with dielectric elastomer muscles. In SPIE Smart Structures and Materials + Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring, San Diego, California, USA; Bar-cohen, Y., Eds.; pp 90562L.

27. Cao, J.; Liang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lee, H. P.; Zhu, J.; Ren, Q. Control of a soft inchworm robot with environment adaptation. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 3809-18.

28. Kang, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yu, Q.; Yang, X. Model of the longitudinal-shear piezoelectric inchworm motor in shear movement. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 269, 109033.

29. Guan, J.; Zhang, S.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y. A driving-clamping integrated inchworm linear piezoelectric actuator with miniaturization and high thrust density. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 801-10.

30. Wang, R.; Hu, Y.; Shen, D.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Wen, J. A novel piezoelectric inchworm actuator driven by one channel direct current signal. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2015-23.

31. Pfeil, S.; Henke, M.; Katzer, K.; Zimmermann, M.; Gerlach, G. A worm-like biomimetic crawling robot based on cylindrical dielectric elastomer actuators. Front. Robot. AI. 2020, 7, 9.

32. Wu, C.; Liu, H.; Lin, S.; Lam, J.; Xi, N.; Chen, Y. Shape morphing of soft robotics by pneumatic torsion strip braiding. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3787.

33. Zhong, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhu, J.; Wu, K.; Wang, C. Biomimetic crawling robot based on dielectric elastomer: design, modeling and experiment. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 9669-76.

34. Wang, Y.; Gregory, C.; Minor, M. A. Improving mechanical properties of molded silicone rubber for soft robotics through fabric compositing. Soft. Robot. 2018, 5, 272-90.

35. Hu, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, L. A new insect-scale piezoelectric robot with asymmetric structure. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8194-202.

36. Lobontiu, N.; Goldfarb, M.; Garcia, E. A piezoelectric-driven inchworm locomotion device. Mech. Mach. Theory. 2001, 36, 425-43.

37. Chen, E.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Bio-mimic, fast-moving, and flippable soft piezoelectric robots. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2023, 10, e2300673.

38. Yang, Y.; Tse, Y. A.; Zhang, Y.; Kan, Z.; Wang, M. Y. A low-cost inchworm-inspired soft robot driven by supercoiled polymer artificial muscle. In 2019 2nd IEEE International Conference on Soft Robotics (RoboSoft), Seoul, Korea (South), April 14-18, 2019; IEEE, 2019, pp 161-6.

39. Xie, D.; Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Zuo, S. Fully 3D-printed modular pipe-climbing robot. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 462-9.

40. Ze, Q.; Kuang, X.; Wu, S.; et al. Magnetic shape memory polymers with integrated multifunctional shape manipulation. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906657.

41. Qu, X.; Sun, H.; Kan, X.; et al. Temperature-sensitive and solvent-resistance hydrogel sensor for ambulatory signal acquisition in “moist/hot environment”. Nano. Res. 2023, 16, 10348-57.

42. Aydin, O.; Zhang, X.; Nuethong, S.; et al. Neuromuscular actuation of biohybrid motile bots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 19841-7.

43. Yeo, S.; Chen, I.; Senanayake, R. S.; Wong, P. S. Design and development of a planar inchworm robot. In 17th International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Taipei, Taiwan, September 18-20, 2000.

44. Guo, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Hong, J.; Li, Y. Design and control of an inchworm-inspired soft robot with omega-arching locomotion. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, Singapore, May 29 - June 3, 2017; IEEE, 2017, pp 4154-9.

45. Ning, J.; Ti, C.; Liu, Y. Inchworm inspired pneumatic soft robot based on friction hysteresis. J. Robotics. Autom. 2017, 1, 54-63.

46. Manfredi, L.; Capoccia, E.; Ciuti, G.; Cuschieri, A. A soft pneumatic inchworm double balloon (SPID) for colonoscopy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11109.

47. Xia, D.; Zhang, L.; Nong, W.; Duan, Q.; Ding, J. 3D-printed soft bionic inchworm robot powered by magnetic force. Biomimetics. (Basel). 2025, 10, 202.

48. Moreira, F.; Abundis, A.; Aguirre, M.; Castillo, J.; Bhounsule, P. A. An inchworm-inspired robot based on modular body, electronics and passive friction pads performing the two-anchor crawl gait. J. Bionic. Eng. 2018, 15, 820-6.

49. Karipoth, P.; Christou, A.; Pullanchiyodan, A.; Dahiya, R. Bioinspired inchworm- and earthworm-like soft robots with intrinsic strain sensing. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 4, 2100092.

50. Lin, D.; Yang, F.; Gong, D.; Li, R. Bio-inspired magnetic-driven folded diaphragm for biomimetic robot. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 163.

51. Tang, Y.; Chi, Y.; Sun, J.; et al. Leveraging elastic instabilities for amplified performance: Spine-inspired high-speed and high-force soft robots. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz6912.

52. Yuan, Y.; Lu, W.; Kao, C.; Hung, J.; Lin, P. Design and implementation of an inchworm robot. In 2016 International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Intelligent Systems (ARIS), Taipei, Taiwan, August 31 - September 2, 2016; IEEE, 2016, pp 1-1.