Deciphering the metallic zinc anode interface: multimodal characterization strategies for zinc-ion batteries

Abstract

Aqueous zinc ion batteries have emerged as promising candidates for next-generation energy storage systems due to their inherent advantages of cost-effectiveness, operational safety, and environmental compatibility. Nevertheless, critical challenges including zinc dendrite formation, parasitic corrosion reactions, hydrogen evolution, and unsatisfactory Zn2+ diffusion kinetics still hinder their commercial viability. To address these limitations systematically, recent research efforts have focused on developing comprehensive mechanistic analyses through advanced characterization methodologies. This review presents a critical evaluation of state-of-the-art analytical techniques for investigating aqueous zinc ion batteries, encompassing fundamental principles, operational protocols, and practical applications across various research scenarios, thereby establishing a robust methodological framework for future studies. The discussion commences with an examination of conventional characterization approaches that provide essential baseline information regarding electrode morphology and electrochemical behavior. Subsequently, we introduced in situ analytical platforms combining three-dimensional visualization techniques, multimodal spectroscopic characterization, and dynamic electrochemical monitoring systems. These advanced operando characterization tools enable real-time observation of interfacial evolution and transient reaction processes, offering unprecedented insights into battery failure mechanisms at multiple scales.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The rapid development of portable electronic devices, electric vehicles, and next-generation energy storage systems has intensified the demand for advanced storage technologies to address the global energy crisis[1-3]. Among emerging candidates, rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries (AZIBs) have garnered significant attention as promising post-lithium energy storage systems due to their intrinsic safety, environmental benignity, low cost, and high specific capacity (820 mAh g-1) and volumetric capacity (5,855 mAh cm-3)[4-6]. ZIBs are broadly classified into two categories based on electrolyte chemistry: (i) alkaline electrolyte systems (e.g., KOH-based Zn-air, Zn-Ag, and Zn-Ni batteries)[7,8]; and (ii) mild electrolyte systems (e.g., ZnSO4-based Zn-MnO2 and Zn-V2O5 batteries)[8-12]. The latter category, pioneered by Yamamoto et al.[13] in 1986, replaced the KOH electrolyte with ZnSO4, which has experienced a resurgence in research activity over the past ten years[14,15].

Despite the above advantages, Zn anode-electrolyte interface still confront many critical problem and challenges including Zn dendrite growth, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), passivation, and Zn corrosion[8,16,17]. Given the above problems, it possibly stems from the amphoteric nature and thermodynamic instability of metallic Zn in aqueous media, which compromise cycling stability and Coulombic efficiency[18,19]. Addressing these challenges necessitates the discovery of novel electrode materials, the optimization of electrolytes and separators with enhanced electrochemical performance and suppressed side reactions[20-23]. A fundamental understanding of processing-structure-property relationships at electrode interfaces during electrochemical processes is paramount, requiring advanced multimodal characterization approaches[24,25].

The Zn anode interface remains a critical bottleneck for commercial deployment, as interfacial processes govern key performance metrics. Solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation involves complex chemical, morphological, and mechanical evolution mechanisms, which directly impacts ion transport kinetics and long-term stability[26,27]. An in-depth understanding of the reaction mechanisms at this interface is crucial for addressing the problems of Zn anode side reactions. While significant progress has been made through advanced characterization techniques, systematic reviews integrating these methodologies for Zn anode analysis remain scarce. Multi methods can be used to evaluate and analyze Zn anodes, including characterizing their electronic structure, chemical composition, morphological structure, crystallinity, and electrochemical properties, which can be related to time-dependent behavior[28-30]. Modern characterization platforms span multiple length and time scales: (i) optical microscopy enables real-time observation of dendrite growth and surface morphology evolution (cm-μm scale)[31,32]; (ii) X-ray techniques [X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)] provide crystallographic, electronic structure, and elemental distribution information[33-35]; (iii) Electron microscopy (scanning electron microscope (SEM)/ transmission electron microscope (TEM)) based on the use of optical microscopes and the probing of samples with electron beams resolves nano-structural features and interfacial reactions[29,36,37]. The gaps in the work principles of different techniques can be addressed by combining multiscale technologies, which complement each other’s shortcomings in providing multiscale insights into the electrode-electrolyte interface. Recent reviews have primarily focused on the role of these techniques in studying anode issues, particularly strategies for dendrite suppression, material and structural designs of Zn anodes, and multifunctional electrolyte additives[38-40]. However, most existing reviews lack a comprehensive analysis for material design principles, interface engineering strategies, and advanced characterization methodologies[4,41,42]. This review systematically examines the challenges at the Zn anode interface, critically evaluates current mitigation strategies, and correlates these approaches with appropriate characterization techniques to establish structure-property-performance relationships.

ZINC METAL INTERFACE ISSUES

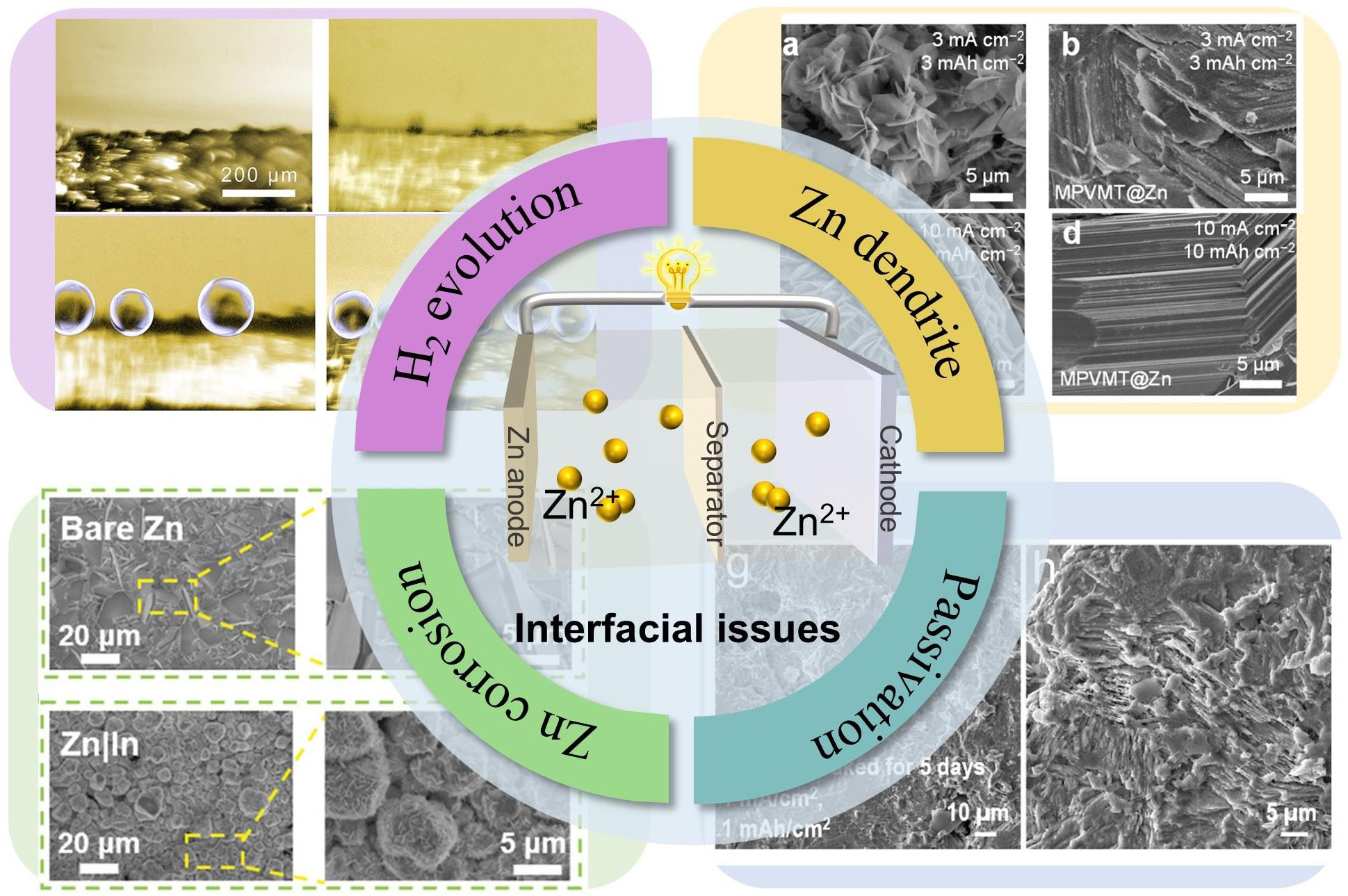

Despite considerable progress, aqueous rechargeable Zn ion batteries still face persistent challenges hindering their large-scale commercialization[43-45]. Particularly regarding interfacial instability at the Zn anode in

Figure 1. Schematics and images of the challenges on the surface of Zn anode, i.e., Zn dendrite growth[36], Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. H2 evolution reaction[62], Copyright 2022, Wiley. Zn metal corrosion[66], Copyright 2021, Wiley. Zn surface passivation[68], Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Furthermore, the inherent electrochemical properties of metallic Zn, including its low redox potential

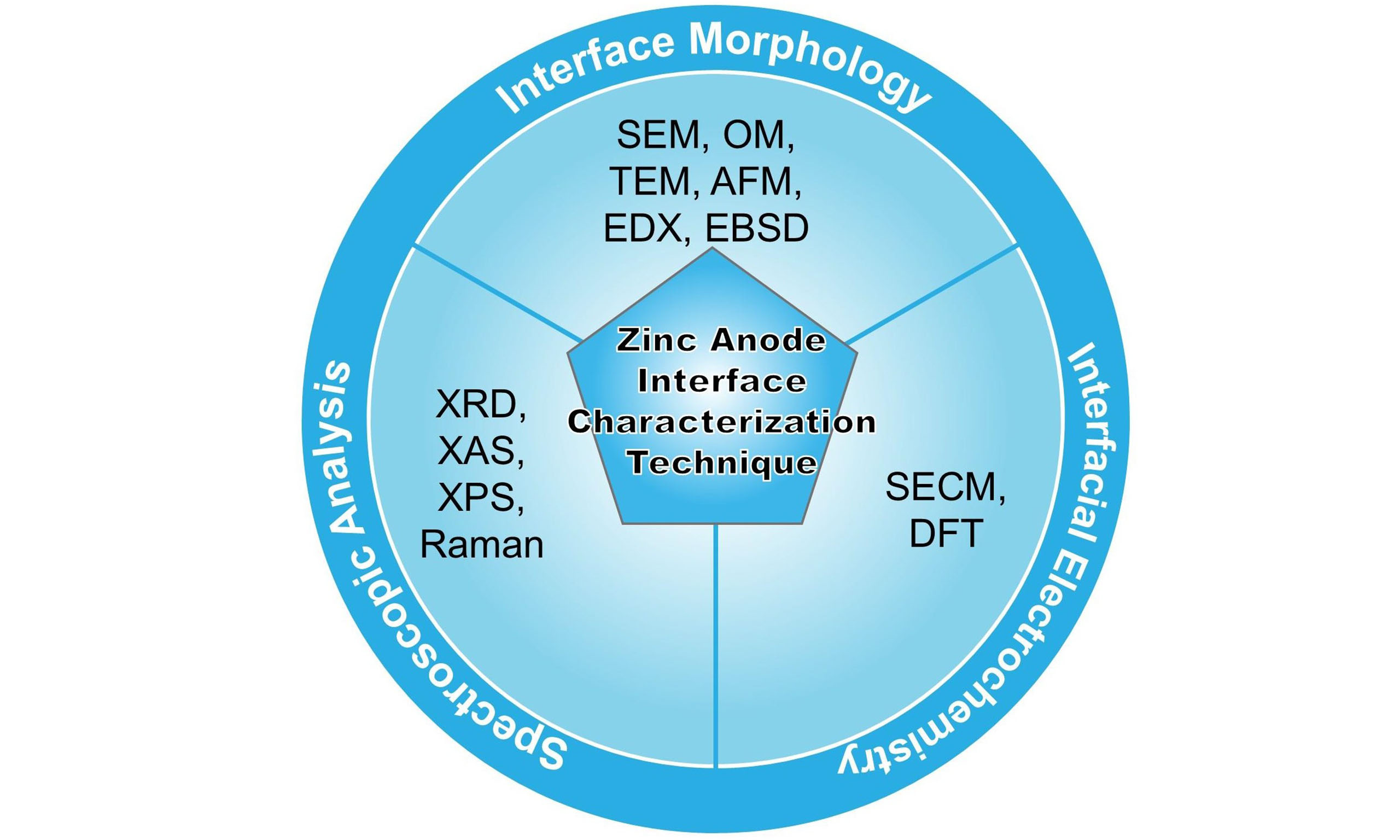

To summarize these solutions for side reactions, current reviews have extensively discussed aspects such as interfacial engineering strategies, the construction of artificial interfacial layers, and the regulation of the electrolyte microenvironment[71,72]. This review systematically evaluates advanced in situ/operando characterization techniques for decoupling the transient interfacial phenomena of the Zn anode transient interfacial phenomena. Each characterization techniques are analyzed through three critical dimensions: (i) Technical principle - methodological adaptation for aqueous real-time electrochemical operation; (ii) Multimodal correlation insights - Representative studies correlating interfacial morphology (OM, SEM, TEM, Atomic Force Microscope (AFM), SECM), crystallinity (TEM, XRD), and dynamics (SECM) with performance metrics; (iii) Comparative merits-Spatial/temporal resolution tradeoffs from macroscale morphology to atomic-scale dynamics and operational constraints; and (iv) Limitations in temporal resolution (ms - h) and sample surface sensitivity. By bridging fundamental electrochemistry with characterization science, this analysis provides a framework for the rational design of stable Zn anodes, ultimately accelerating AZIBs deployment in grid storage and mobile applications. By establishing structure-dynamics-property relationships through advanced characterization, this analysis provides a roadmap for developing Zn anodes with high Coulombic efficiency and ultra-long cycle stability critical thresholds for commercial viability.

CHARACTERIZATION TECHNIQUES FOR INTERFACE

Classification of Zn deposition morphology

Zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) have emerged as promising candidates for next-generation energy storage systems due to their inherent advantages including low environmental toxicity, natural abundance, and high theoretical energy density. Although primary Zn batteries have achieved commercial success across various applications, the development of rechargeable Zn battery systems confronts significant technical challenges, particularly regarding interfacial instability at the Zn anode[73,74]. Advanced characterization methodologies play a pivotal role in elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of parasitic side reactions and evaluating the efficiency of emerging protection strategies[75]. These advanced analytical approaches enable systematic investigation of critical parameters such as surface morphology evolution, crystalline structure transformation, and chemical composition variation during prolonged electrochemical cycling[76,77].

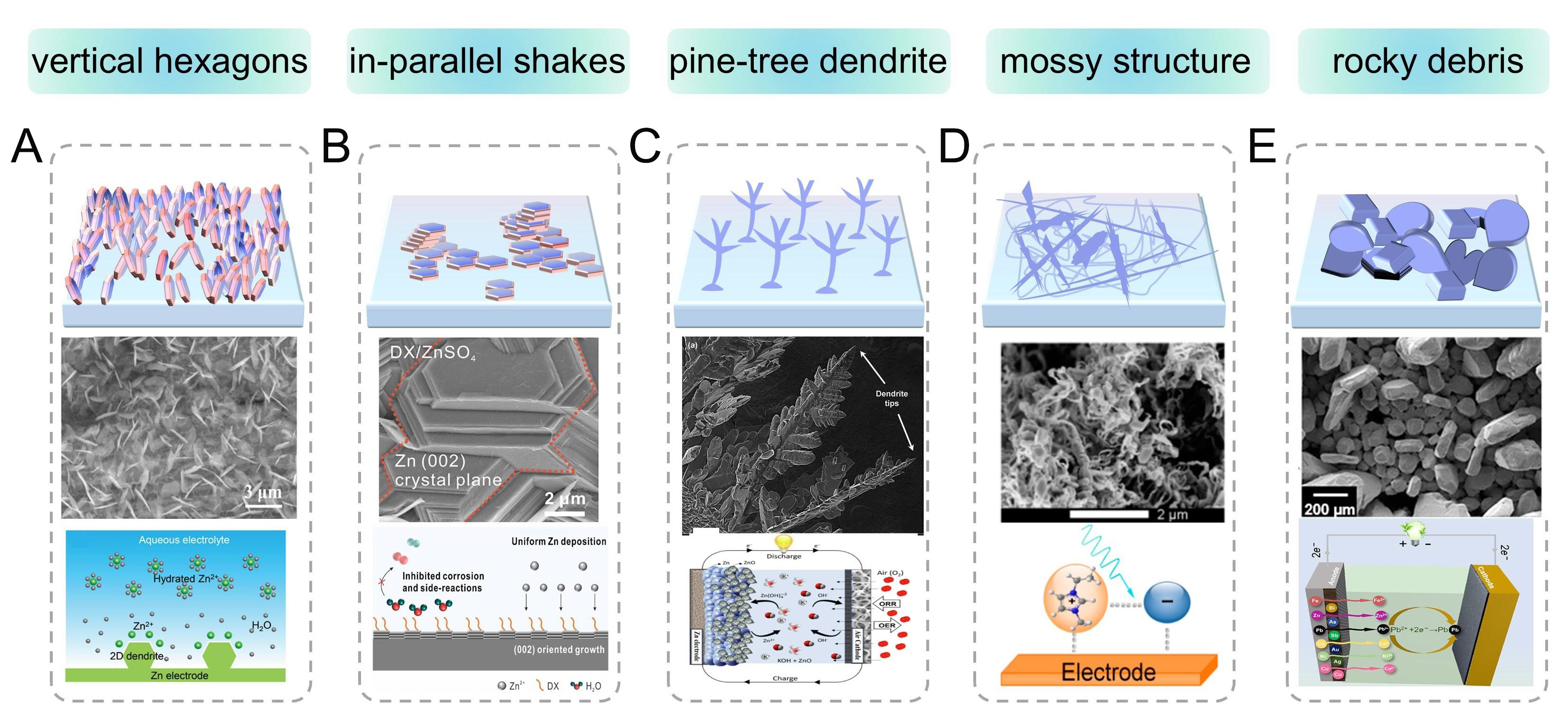

The development of alkaline ZIBs faces persistent dendritic growth issues analogous to those observed in lithium-metal systems[78]. In alkaline electrolytes, the amphoteric nature of Zn metal and high electrochemical activity induce complex interfacial reactions. The formation of zincate species [Zn(OH)42-] triggers spontaneous decomposition into ZnO passivation layers[79], which progressively impede ion diffusion and elevate interfacial impedance through resistive phase accumulation. Although dendritic growth mechanisms differ between alkaline and aqueous neutral/mildly acidic electrolytes, both systems exhibit similar morphological progression patterns under non-equilibrium deposition conditions. Comprehensive SEM image analyses revealed six distinct Zn deposition morphologies in AZIBs [Figure 2]: (i) vertical hexagonal prisms[80]; (ii) in-plane lamellar structures[81]; (iii) pine-tree dendrites[82]; (iv) mossy networks fractal branches[83]; and (v) rocky debris formations[84]. These configurations are electrolyte-dependent and governed by crystallization thermodynamics and kinetic overpotential conditions.

Figure 2. Schematics and corresponding scanning electron images of the Zn dendrite structure and ionic environment under different operation conditions. (A) Schematics and SEM images of the vertically aligned hexagonal Zn dendrites on the Zn anode[80]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (B) Schematic diagrams and SEM images of parallel flake-like Zn deposition[81]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. (C) Schematic diagrams and SEM images of pine tree-shaped Zn dendrites[82]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier. (D) Schematic illustrations and SEM images of mossy Zn deposits[83]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (E) Schematics and SEM images of Zn crystals with a rocky debris-like morphology[84]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

During the process of Zn stripping/plating, the formation of Zn dendrite concerns the fast ion diffusion kinetics and microcosmical irregular ion motions[85]. It should be noted that Zn “dendrites” in different electrolytes exhibit different morphologies, which will be discussed in detail[86]. In neutral/mildly acidic systems, Zn preferentially deposits as two-dimensional (2D) vertical hexagonal platelets and parallel flakes

Morphology characterizations of Zn deposition

Side reaction-dependent morphological evolution

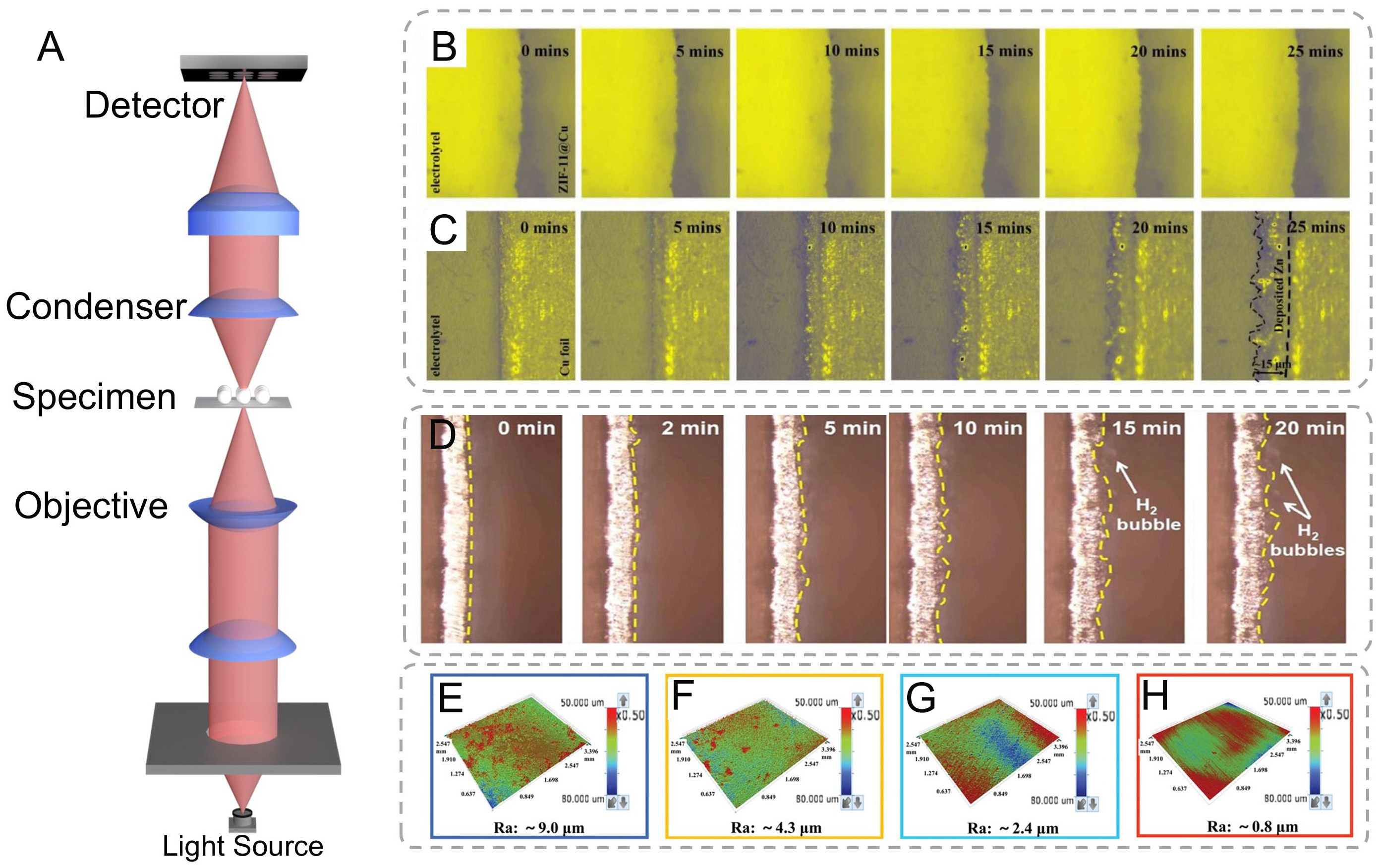

In situ optical microscopy operates on fundamental optical principles, enabling visualization of microstructure features through transmitted, reflected, or fluorescence light interactions [Figure 3A]. This technique captures and processes light-matter interactions to generate magnified representations of surface and subsurface features, offering distinct advantages over more sophisticated microscopy methods, including operational simplicity, non-destructive analysis, real-time monitoring, and broad material compatibility[90]. Recent applications in AZIB research have significantly advanced the understanding of Zn deposition morphologies and interfacial phenomena[91]. It is well-known that the interface layer can trigger uniform Zn ion decomposition. To elucidate the impact of ZIF-11 coatings on Zn electrodeposition behavior, He et al. conducted comparative in situ optical microscopy observations of bare Cu foil and ZIF-11@Cu electrodes during Zn electroplating processes [Figure 3B and C][92]. Initial imaging revealed smooth Cu foil surfaces in ZnSO4 aqueous electrolyte. Upon current application (10 mA cm-2), instantaneous Zn nucleation occurred, evolving into heterogeneous moss-like dendritic structures (~15 μm thickness) within minutes. These dendritic protrusions present critical safety risks through electrode bridging and subsequent internal short circuits. Concurrently, HER activity was observed, proceeding via either Volmer-Heyrovsky or Volmer-Tafel pathways[93]. The reaction equations are as follows:

Figure 3. (A) Schematics of the optical microscope. In situ optical microscopy images of Zn deposits on (B) ZIF-11@Cu and (C) bare Cu electrode surface at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min. (B and C) are reproduced from Ref.[92]. with permission, Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (D) In situ operando optical microscope images showing hydrogen evolution behavior[42]. Copyright 2024, Wiley. (E-H) 3D optical images of Zn foils from Zn-Zn symmetrical batteries after cycling in 2 M ZnSO4[96]. Copyright 2022, Wiley.

The HER would lead to the evolution of the Zn anode surface morphology. In situ optical microscope monitoring at 20 min deposition [Figure 3D] revealed progressive bubble accumulation on Zn surfaces, correlating with HER intensification during cycling operations[42]. Chen et al. documented analogous interfacial evolution: initial dendritic growth via tip-enhanced deposition within 2 min, followed by adherent bubble formation at 15 min, culminating in dense bubble coverage by 20 min[54]. This HER-driven process induces critical interfacial passivation and corrosion behavior - as the charge in the Helmholtz layer depletes, water molecule penetration from the outer to inner Helmholtz planes facilitates free water decomposition[94]. Moreover, to address the fundamental modulation involved in alleviating the intrinsic tradeoff between Zn nucleation/dissolution kinetics and HER inhibition, DFT calculations can be used to analyze the thermodynamic stability of the solvation sheath and the kinetics of water dissociation.

Current density-dependent morphological evolution

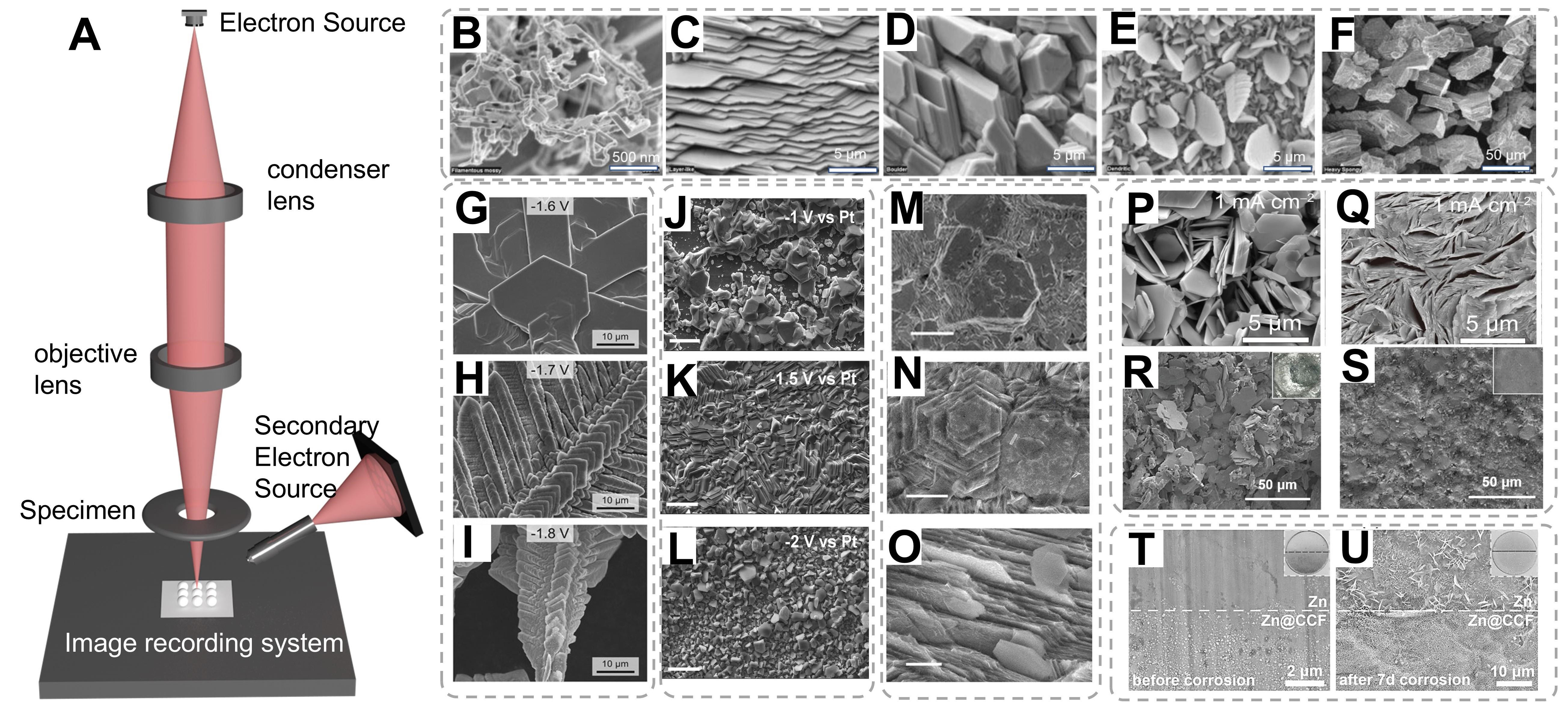

High-resolution SEM represents a cornerstone analytical technique for high-resolution surface characterization across diverse scientific disciplines, including advanced materials research, nanoscale biology, mineralogical studies, and microsystem engineering. The instrument operates through a precisely focused electron beam (accelerating voltage: 0.5-30 keV) that is electromagnetically collimated using a series of condenser and objective lenses[97,98]. Scanning coils systematically raster this nanoscale probe (< 1 to

Figure 4. (A) Schematic diagram of the SEM equipment. (B-F) SEM images of five distinct Zn deposit morphologies. (B-F) are reproduced from Ref.[99]. with permission, Copyright 2006, Electrochemical Society. (G-I) SEM images of electrodeposited Zn in alkaline solution at different voltages[100]. Copyright 2015, Springer Nature. (J-L) SEM micrographs of Zn electrodeposits at different deposition potentials from ethylene glycol solution containing 0.75 M zinc acetate and 0.5 M sodium acetate[103]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (M-O) SEM image of the (002)/(101) Zn papers after cycling in Zn(OTf)2 or ZnSO4 at 1 mA cm-2 and 10 mA cm-2, respectively[102]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (P-S) The SEM images of Zn deposits from the Zn electrodes of Zn||Zn cells with a fixed areal capacity of 1 mAh cm-2 in ZS and La3+-ZS electrolytes[106]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (T and U) Digital and SEM images of bare Zn and Zn@CCF (T) before and (U) after 7 d of corrosion[109]. Copyright 2021, Wiley.

Three distinct growth regimes were identified through chronopotentiostatic deposition on anode substrates. (i) Low current density regime (1-5 mA cm-2): Epitaxial layer-by-layer growth dominated at low overpotentials, yielding highly ordered hexagonal Zn (002) basal planes aligned parallel to the substrate surface [Figure 4B-F][99]. This regime adheres to Frank-van der Merwe growth kinetics, where sequential two-dimensional nucleation promotes atomically smooth interfaces; (ii) Intermediate regime

Overpotential-mediated morphological evolution

The morphological evolution of Zn electrodeposits exhibits pronounced dependence on cathodic overpotential regimes. Under high cathodic overpotentials (Δη = 400~500 mV, relative to the Zn2+/Zn equilibrium potential of -1.38 V vs. SHE), vertically aligned Zn pillars with nanoscale dimensions were synthesized. Statistical analysis of randomly selected particles revealed a mean diameter of

Chronopotentiostatic deposition on Pt substrates elucidated potential-dependent morphological evolution

Interface engineering for morphology regulation

Time-resolved SEM [Figure 4M-O] revealed hierarchical structural evolution: initial epitaxial boulder formation transitioned to spongiform aggregates through competitive growth between layer-by-layer stacking and lateral dendrite propagation[102,104]. Distinct morphological classes emerged under extreme polarization: (i) Hexagonal boulders; (ii) Filamentous mossy structures; and (iii) Fern-like dendrites. This regime-dependent morphological evolution underscores the critical interplay between deposition kinetics and interfacial stability. While low-current regimes enable crystallographically ordered deposition, high-current operation induces complex pattern formation through constitutional supersaturation and hydrogen co-evolution-driven interfacial turbulence. Through advanced interface engineering strategies including artificial interlayer construction and electrolyte additive modification, significant progress has been made in regulating Zn electrodeposition behavior[105]. Zhao et al. systematically investigated the morphological evolution of Zn deposits in baseline ZnSO4 and La3+-modified ZnSO4 electrolytes under varying current densities (1-20 mA cm-2) with a constant deposition capacity of 1 mAh cm-2[106].

SEM characterization revealed distinct structural differences between the two systems in Figure 4P-Figure 4Q]. Here, the porous structures observed may originate from the non-uniform distribution of the Zn nucleation on the substrate; the decreased presence of the porous structures between the Zn platelets reveals that the interactions between the Zn deposits have been successfully regulated from repulsion to attraction by adding La(NO3)3 into ZnSO4 electrolyte.

In the conventional ZnSO4 electrolyte, the deposited Zn exhibited hexagonal platelet morphology with progressively increasing platelet thickness at elevated current densities. Notably, even at 20 mA cm-2, these platelets maintained a dispersed spatial arrangement, forming loose architectures characterized by interplatelet voids. This phenomenon can be attributed to strong electrostatic repulsion forces between adjacent Zn crystallites, which impede effective particle consolidation. In striking contrast, the La3+-containing electrolyte produced densely packed Zn deposits across the entire current density range[106]. The observed porosity reduction suggests that La(NO3)3 additive effectively modulates interfacial interactions, transforming the interparticle forces from repulsive to attractive through charge redistribution mechanisms. The combined experimental evidence establishes that strategic electrolyte modification with rare-earth cations enables fundamental control over both nucleation dynamics and crystallographic growth patterns. The introduced La3+ effectively modulates interfacial charge distribution, suppresses parasitic side reactions, and promotes homogeneous Zn deposition through enhanced charge screening effects.

Corrosion mechanisms and interface passivation

The inherent reactivity of metallic Zn in aqueous environments renders it susceptible to electrochemical corrosion, particularly at structural heterogeneities such as grain boundaries and stress-induced microcracks[107]. The corrosion process proceeds via three primary pathways:[108]

Although the growth of dendrites and the corrosion of the Zn anode are weakened in the mild aqueous electrolytes, the Zn anode is still subject to corrosion due to the active water. Comparative SEM analysis reveals stark morphological contrasts between bare Zn and Zn@CCF anodes post-cycling

Crystallographic orientation and interfacial structural analysis

Crystallographic orientation analysis through high-resolution SEM demonstrated distinct growth patterns dependent on crystal plane exposure. The (002)-oriented Zn substrates exhibited perfectly aligned hexagonal basal planes parallel to the electrode surface, maintaining structural integrity even after

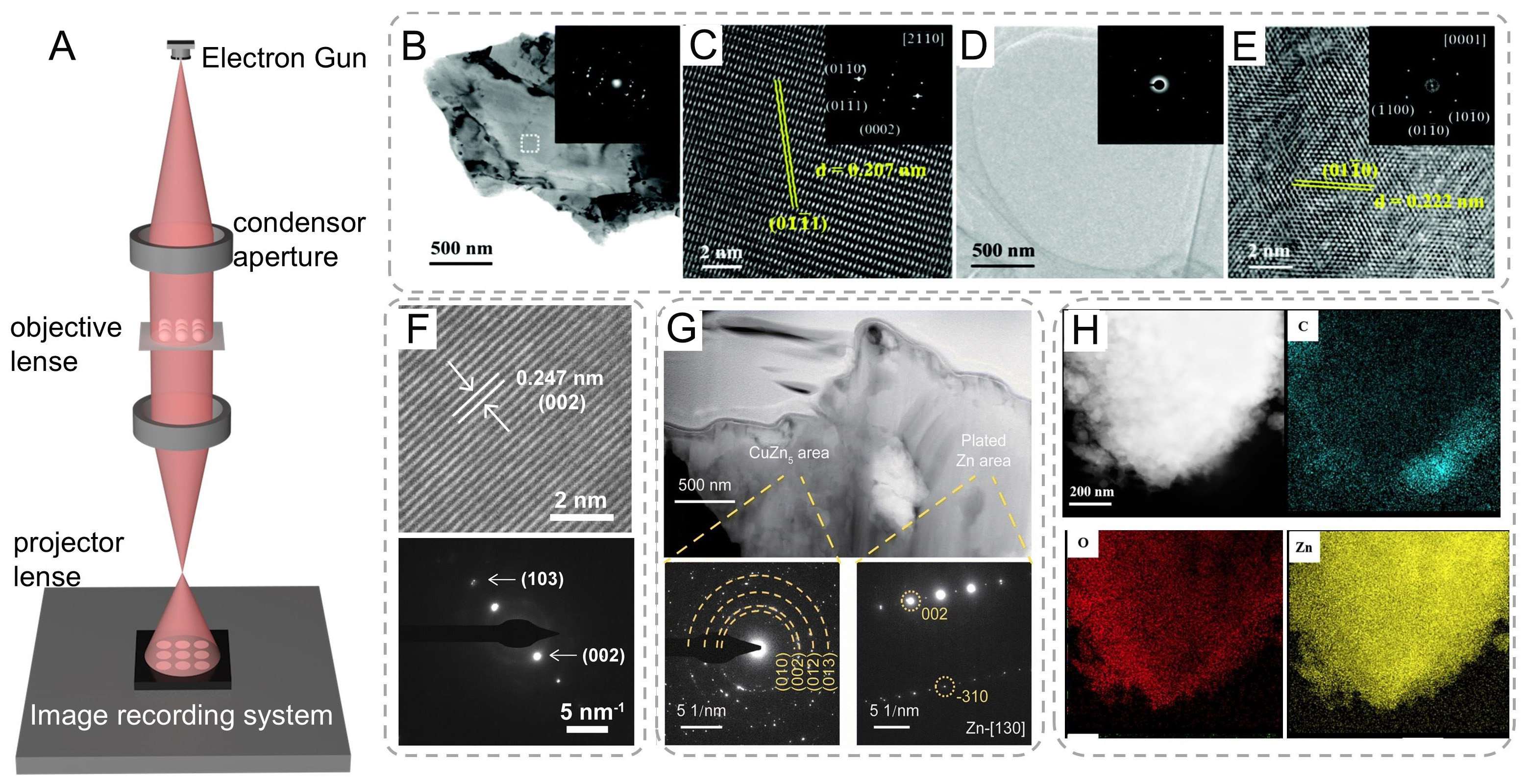

TEM is another powerful and widely used analytical tool in materials science, nanotechnology, biology, and many other research fields, complementing the capabilities of SEM[111]. While surpassing optical microscopy's diffraction-limited resolution (≈200 nm at visible wavelengths), TEM operates by passing a high-energy electron beam (usually with an accelerating voltage ranging from 80 to 300 keV or even higher in some advanced instruments) through an extremely thin specimen, typically less than 100 nm thick. The electrons interact with the atoms in the specimen, and based on the differences in the scattering and absorption of electrons by the specimen's components, a transmitted electron image is formed. The technique’s unique strength lies in its synergistic combination of: (i) Large depth of field (100× greater than optical microscopy); (ii) Wide field-of-view range (100 μm to 10 nm scales); and (iii) Multimodal analytical capabilities (morphological, compositional, crystallographic)[31,112].

TEM investigations revealed distinct microstructural differences between pristine and engineered Zn electrodes [Figure 5A]. The commercial Zn foil exhibited polycrystalline features with randomly oriented nanograins (200-500 nm, Figure 5B), as evidenced by continuous diffraction rings in the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (inset). High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) analysis of a representative grain [Figure 5C] confirmed the (002) zone axis orientation, with measured (101) lattice spacing of

Figure 5. (A) Schematics of TEM equipment. (B) BF TEM and (C) HRTEM images of commercial Zn foil; (D) BF TEM and (E) HRTEM images of the protected Zn foil after Zn plating (the corresponding SAED patterns are shown in the insets). (A-E) are reproduced from Ref.[113]. with permission, Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. (F) HRTEM image and SAED of deposited Zn in the electrolyte of 2 M Zn(TfO)2 with 0.5 M EMImTfO[39]. Copyright 2024, National Academy of Sciences. (G) The cross-sectional FIB-STEM images of Cu2+-Zn@Cu0.7Zn0.3 after 50 cycles. The corresponding SAED patterns of the CuZn5 area and plated Zn area are displayed[114]. Copyright 2025, Royal Society of Chemistry. (H) TEM image of the plated Zn electrode and the corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy mapping of carbon (C), oxygen(O), and zinc (Zn)[65]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature.

Anode interface morphology and roughness behavior analysis via AFM

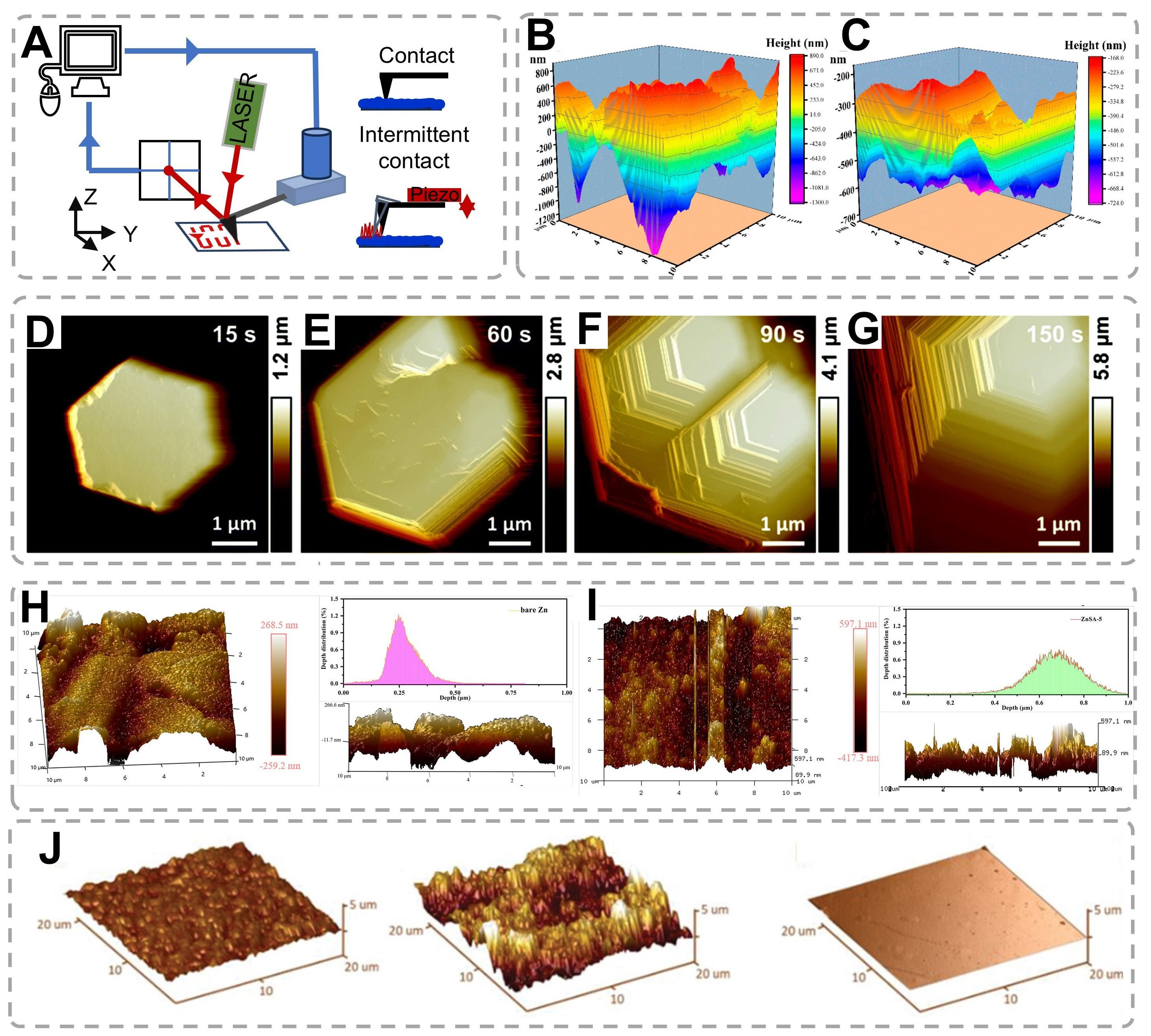

AFM, a high-resolution scanning probe technique with nanoscale lateral resolution, has emerged as a critical tool for investigating surface topology evolution during electrochemical processes [Figure 6A][115,116].

Figure 6. (A) Schematic diagram of AFM instrument. (B and C) AFM images of (B) standard Cu foil and (C) Cu (100) foi. (B and C) are reproduced from Ref.[53]. with permission, Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (D-G) In situ AFM images of Zn electrodeposits on HOPG under a current of 10 mA cm-2 in 0.5 M electrolyte[103,118]. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. (H and I) Surface and cross-sectional 3D AFM images (10 μm × 10 μm) and depth distributions of bare (H) Zn and (I) ZnSA-5[119]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (J) AFM surface profiles of Zn plated on stainless steel, Poly-Zn, and Single-Zn[120]. Copyright 2022, Wiley.

Comparative AFM characterization of electrode morphologies [Figure 6B and C] demonstrates that conventional Cu foil exhibits significant surface irregularity, whereas engineered Cu (100) substrates maintain exceptional planarity[53]. This topological contrast directly correlates with Zn deposition uniformity, as evidenced by reduced dendritic growth on flat substrates through homogeneous electric field distribution. To more comprehensively and accurately present the growth process of Zn, in situ AFM was utilized to directly observe the morphologies of Zn during the early plating stage. A highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) was selected as the working electrode, while a Zn wire served as both the counter electrode and the reference electrode. As depicted in Figure 6D-G, during the initial deposition of Zn induced by the graphite substrate, the morphologies in both 0.5 M electrolytes manifested as a hexagonal shape parallel to the substrate[118]. Three-dimensional AFM reconstructions [Figure 6H and I] provide quantitative insights into Zn electrode evolution during phosphoric acid etching[119]. Bare Zn electrodes display micro-scale inhomogeneity with characteristic depth variations of 250 ± 30 nm [Figure 6H]. Controlled etching induces distinct striped morphologies, where optimization of treatment duration proves critical: ZnSA-5 specimens exhibit limited etching depth [Figure 6I]. Cross-sectional analyses confirm that

Spectroscopic analysis of interfacial kinetic and Zn deposition behavior

Interfacial chemical composition analysis via X-ray diffraction

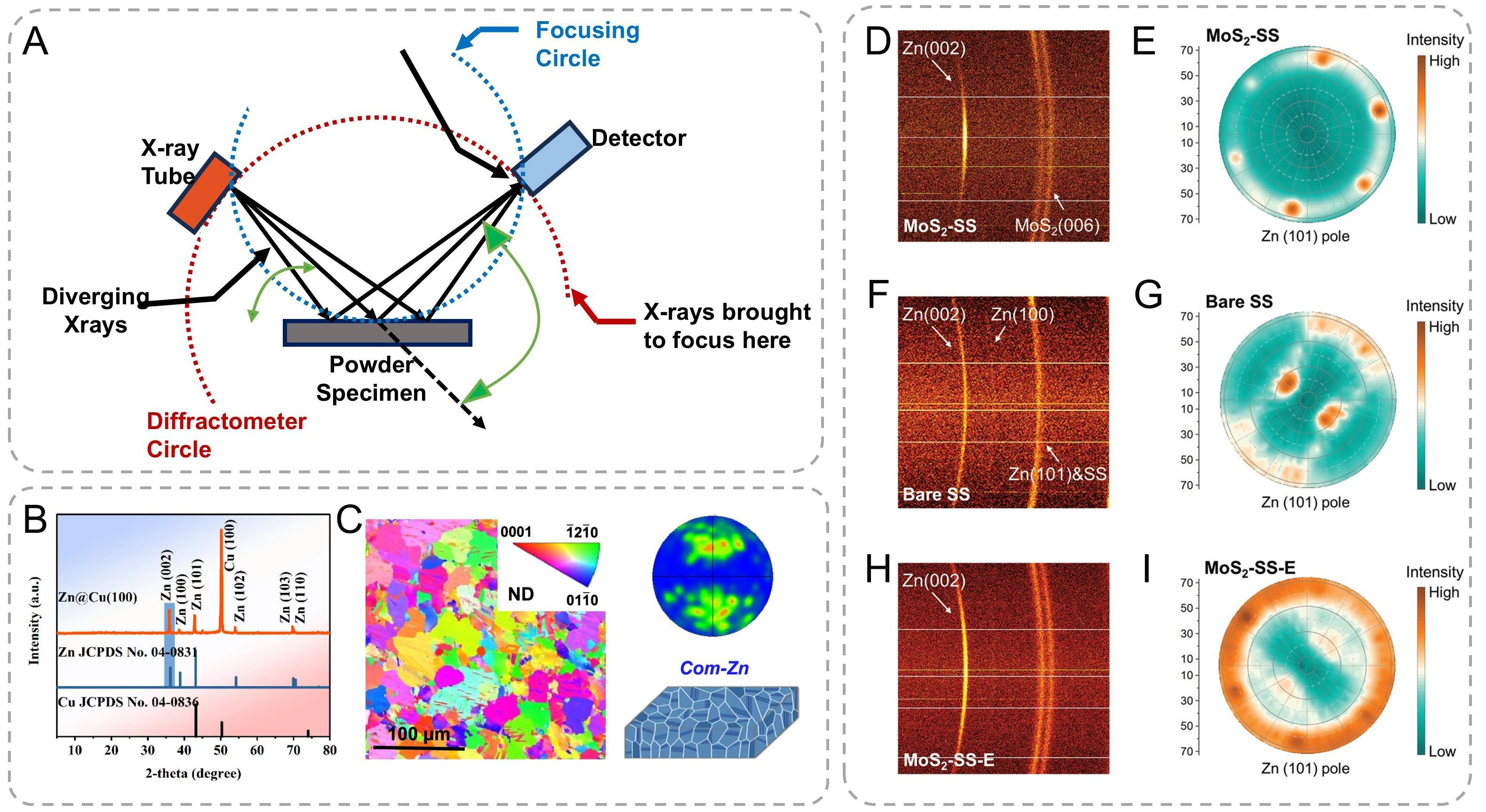

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a powerful analytical technique based on the interaction between X-rays and the crystalline structure of materials. X-rays, a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths from about 0.01-10 nanometers, have wave-particle duality [Figure 7A]. In XRD, their wave-like nature is key. When

Figure 7. (A) Schematic diagram of the principle of X-ray diffraction. XRD pattern of Zn deposited on the Cu (100) foil. X-ray diffraction pole figures of (B) Zn (002) on the Cu (100) foil[53]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (C) Plane-view EBSD maps and corresponding (0002) pole figures of (D) the com-Zn metals[33]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. (D-I) Characterizations of electrodeposited Zn films. 2D XRD patterns of (D) MoS2-SS, (F) bare SS, and (H) MoS2-SS-E deposited with a certain amount of Zn. XRD pole figures of (E) MoS2-SS, (G) bare SS, and (I) MoS2-SS-E. (D-I) are reproduced from Ref.[123]. with permission, Copyright 2022, Wiley.

XRD analysis was conducted to elucidate the epitaxial orientation relationship between electrodeposited Zn and the zincophilic Cu (100) substrate. Both Zn deposits on Cu(100) and conventional Cu foil substrates exhibited hexagonal close-packed (hcp) crystal structures, as confirmed by peak matching with the standard reference [Figure 7B][53]. Notably, a distinct inversion in relative diffraction intensities was observed between the (002) and (101) crystallographic planes of Zn on the two substrates. The Cu (100) surface induced pronounced (002) preferential orientation of Zn deposits, as evidenced by a significantly enhanced Zn (002)/Zn (101) intensity ratio, substantially exceeding both the standard reference value (5.88) and the ratio observed on conventional Cu foil substrates (7.63). This marked enhancement demonstrates strong crystallographic anisotropy during electrodeposition, with preferential growth along the Zn (002) basal plane on Cu (100) substrates. Furthermore, the com-Zn metal demonstrated a random and irregular distribution of crystal grains [Figure 7C], which was further confirmed by the Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) characterization.

Additional validation through orientation distribution functions and comparative pole figure analysis confirmed the dominant (002) texture, with the (002) pole figure exhibiting substantially sharper intensity distributions compared to (101) and (110) counterparts [Figure 7D-I][123]. These collective observations establish that Zn platelets predominantly align with their (002) planes parallel to the Cu (100) substrate surface, consistent with epitaxial growth mechanisms facilitated by lattice matching at the Zn/Cu(100) interface. XRD is mainly suitable for structural analysis of crystalline materials. For amorphous material, it is difficult to provide detailed structural and positional information due to the lack of long-range periodicity in the atomic arrangement.

Interfacial bonding analysis via X-ray spectroscopy

XAS using both hard and soft X-rays has been extensively applied to monitor element-specific evolution of oxidation states and local coordination environments in the bulk and at surfaces of active materials, electrolytes, and interfaces[124].

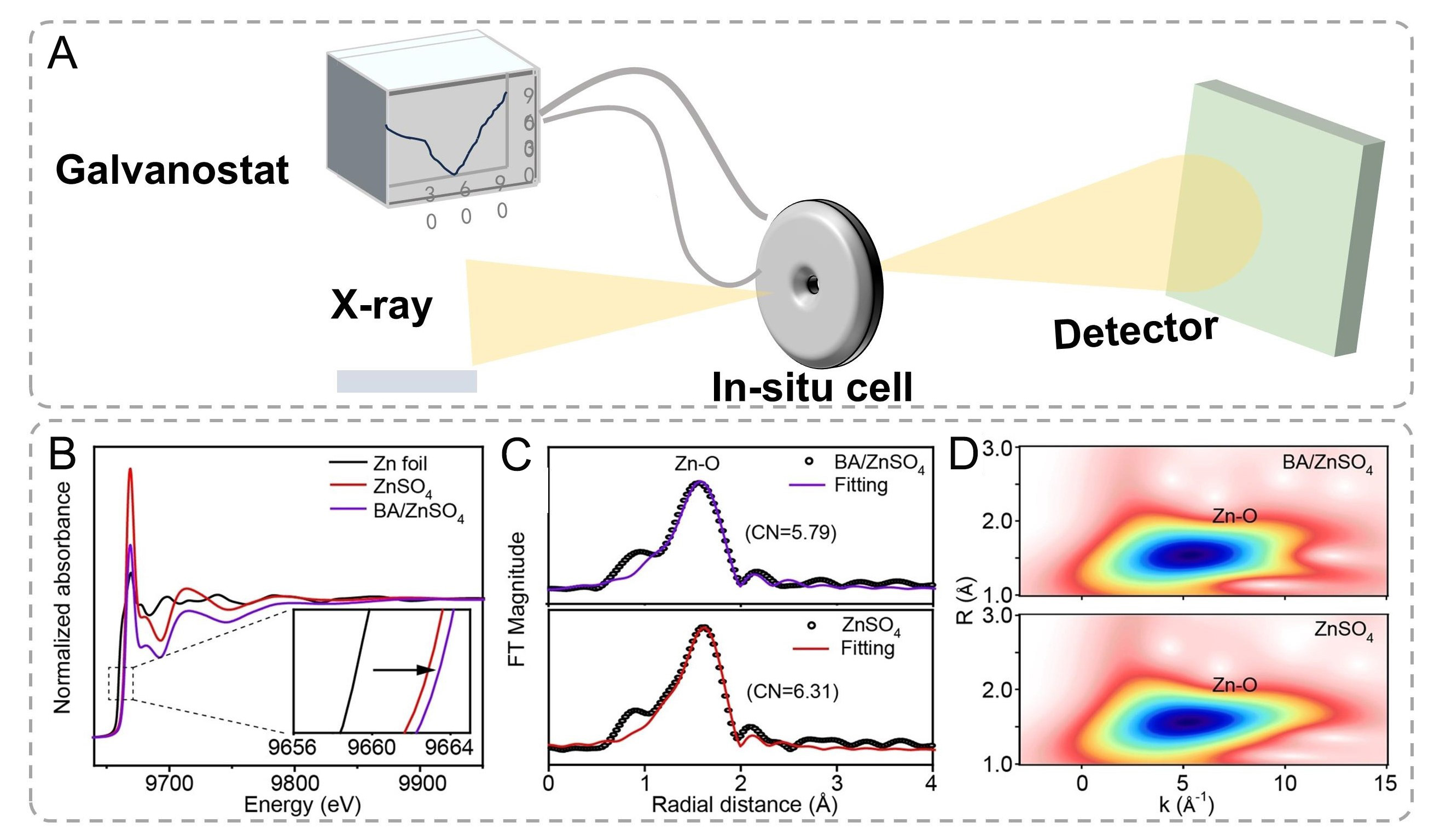

To investigate the influence of additive on the Zn2+ solvation structure, complementary characterization techniques including X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy were systematically employed. XAFS analysis proves particularly effective for probing electrolyte solvation environments, offering unique insights into first-shell coordination configurations [Figure 8A][125,126].

Figure 8. (A) Schematic illustration of X-ray adsorption spectroscopy. (B-D) The normalized Zn K-edge XANES spectra. Inset: the enlarged Zn K-edge XANES spectra. (C) The EXAFS spectra in R space. (D) Wavelet transform images of the EXAFS spectra. (B-D) are reproduced from Ref.[57]. with permission, Copyright 2022, Wiley.

The local solvation structures were further elucidated through Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) analysis in R-space [Figure 8C]. Quantitative fitting of the spectra reveals distinct coordination characteristics. The first coordination shell at ~1.60 Å (phase-uncorrected) corresponds to the Zn-O scattering path[127], while the artifact peak below 1 Å arises from low-frequency experimental noise[128]. Notably, the BA-containing electrolyte demonstrates a reduced Zn-O coordination number accompanied by slight bond elongation, suggesting partial replacement of water ligands by BA molecules in the primary solvation shell. Complementary wavelet transform (WT) EXAFS analysis

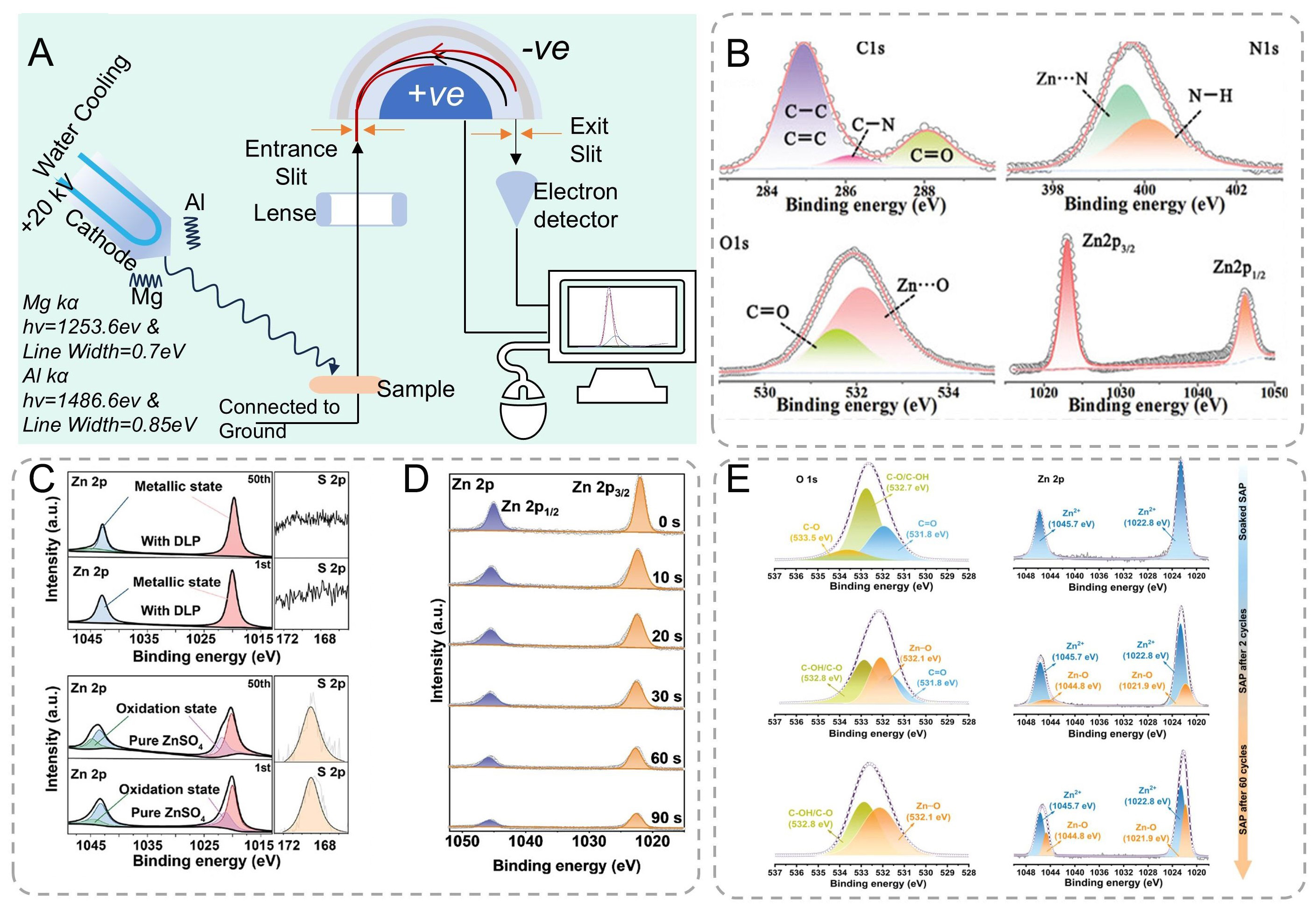

XPS operates on the photoelectric principle, where monochromatic X-rays (typically Al Kα = 1,486.6 eV) eject core-level electrons with kinetic energies (KE) defined by the equation: KE = hν - BE - Φ, where BE is electron binding energy and Φ is spectrometer work function (4-5 eV). Each element and its different chemical states have distinct electron binding energies. As a result, the ejected photoelectrons have various kinetic energies[129,130]. A detector measures these kinetic energies and the number of photoelectrons, generating a photoelectron spectrum [Figure 9A].

Figure 9. (A) Schematic illustration of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. (B) XPS of Zn foil separated from in situ GPE, showing peaks of C1s, N1s, O1s, and Zn2p[131]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (C) XPS spectra for the Zn anode after the 1st and 50th cycles in each of the DLP/ZnSO4 and pure ZnSO4 electrolytes[132]. Copyright 2024, Wiley. (D) XPS depth analysis of Zn 2p of the SEI layer on Zn metal surface at different sputtering times[133]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (E) O 1s and Zn 2p XPS spectra of SAP-GF soaked in ZnSO4 electrolyte and SAP interface after 2 and 60 cycles in Zn||Zn cells[34]. Copyright 2024, Wiley.

The in situ formed gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) exhibits enhanced interfacial adhesion (19 kPa) compared to ex-situ counterparts (11 kPa), achieving 1.7 times improvement through chemical welding at the Zn-electrolyte interface. High-resolution XPS analysis confirms covalent interactions between polyacrylamide (PAM) and Zn substrate: N 1s spectra reveal Zn-N coordination at 399.6 eV, while O 1s spectra show Zn-O bonding at 532.1 eV [Figure 9B][131]. Depth-profiling XPS with Ar+ sputtering (2 min,

Electrolyte speciation and pH-dependent behavior analysis via raman spectroscopy

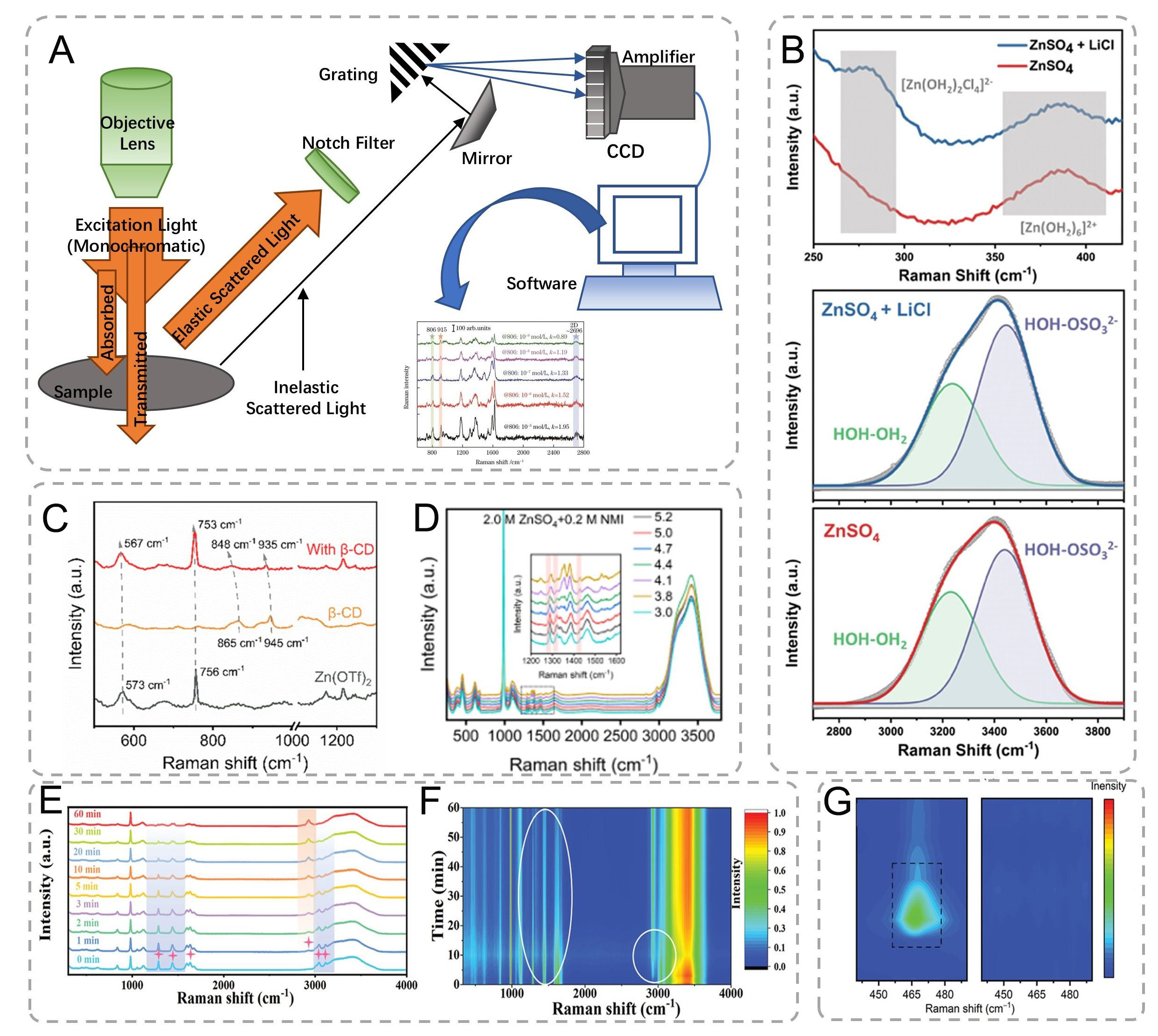

Raman spectroscopy, a powerful analytical technique based on inelastic light scattering phenomena, provides critical insights into molecular vibrations and interfacial chemistry [Figure 10A][122,134]. When interrogating Zn anode interfaces with monochromatic laser radiation (typically 532-785 nm wavelength), the majority of scattered photons undergo elastic Rayleigh scattering, while approximately 10-6-10-8 of the photons exhibit frequency shifts characteristic of Raman-active vibrational modes. These shifts

Figure 10. (A) Schematic diagram of the Raman spectroscopy setup. (B) Raman spectra of 2 M ZnSO4 and 2 m ZnSO4 containing 1.1 M LiCl electrolytes. Voltages are referenced to Zn/Zn2+[137]. Copyright 2024, Wiley (C) Raman spectra of pure Zn(OTf)2, β-CD, and β-CD@OTf- complex[9]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. (D) Raman spectrophotometry of 2.0 M ZnSO4 + 0.2 M NMI solutions at different pH values[138]. Copyright 2023, Wiley. (E) In situ Raman spectra of the GPE at various reaction times and (F) the corresponding contour map[131]. Copyright 2023, Wiley. (G) Raman spectra of Cu@Zn and MGA@Zn electrodes after first cycling[139]. Copyright 2022, Wiley.

Spectral deconvolution revealed concentration-dependent coordination chemistry: In 2 M ZnSO4 + 1.1 M LiCl, the [Zn(H2O)2Cl4]2- complex vibration emerged at 982 cm-1 [Figure 10B], while the intensity ratio of HOH-OH2/HOH-OSO32- decreased from 0.74 to 0.65 (n = 15 scans), indicating a 12% reduction in free water content[137]. β-CD@OTf- complexes exhibited 2.3 cm-1 redshift in OTf- vibration (756 cm-1, Figure 10C), confirming host-guest interactions via DFT-calculated binding energy (-23.6 kJ mol-1)[9]. Decreasing the pH from 5.2 to 3.0 caused intensity reduction at 1,235/1,350/1,422 cm-1 (NMI characteristic) with a concomitant 45% increase at 1,288/1,457 cm-1 (NMIH+ modes). These changes, consistent with the spectra observed at

As demonstrated in our ZIBs studies [Figure 10E and F], this technique achieves micrometer-scale spatial resolution with temporal resolution adjustable from seconds to minutes, depending on signal-to-noise requirements[131]. The polymerization dynamics of acrylamide to polyacrylamide were quantitatively tracked through characteristic band evolution: Initial precursor solution exhibited prominent C-H bending

Interfacial dynamic characterizations of Zn electrodeposition

Interfacial electrochemistry of Zn anode by scanning electrochemical microscopy

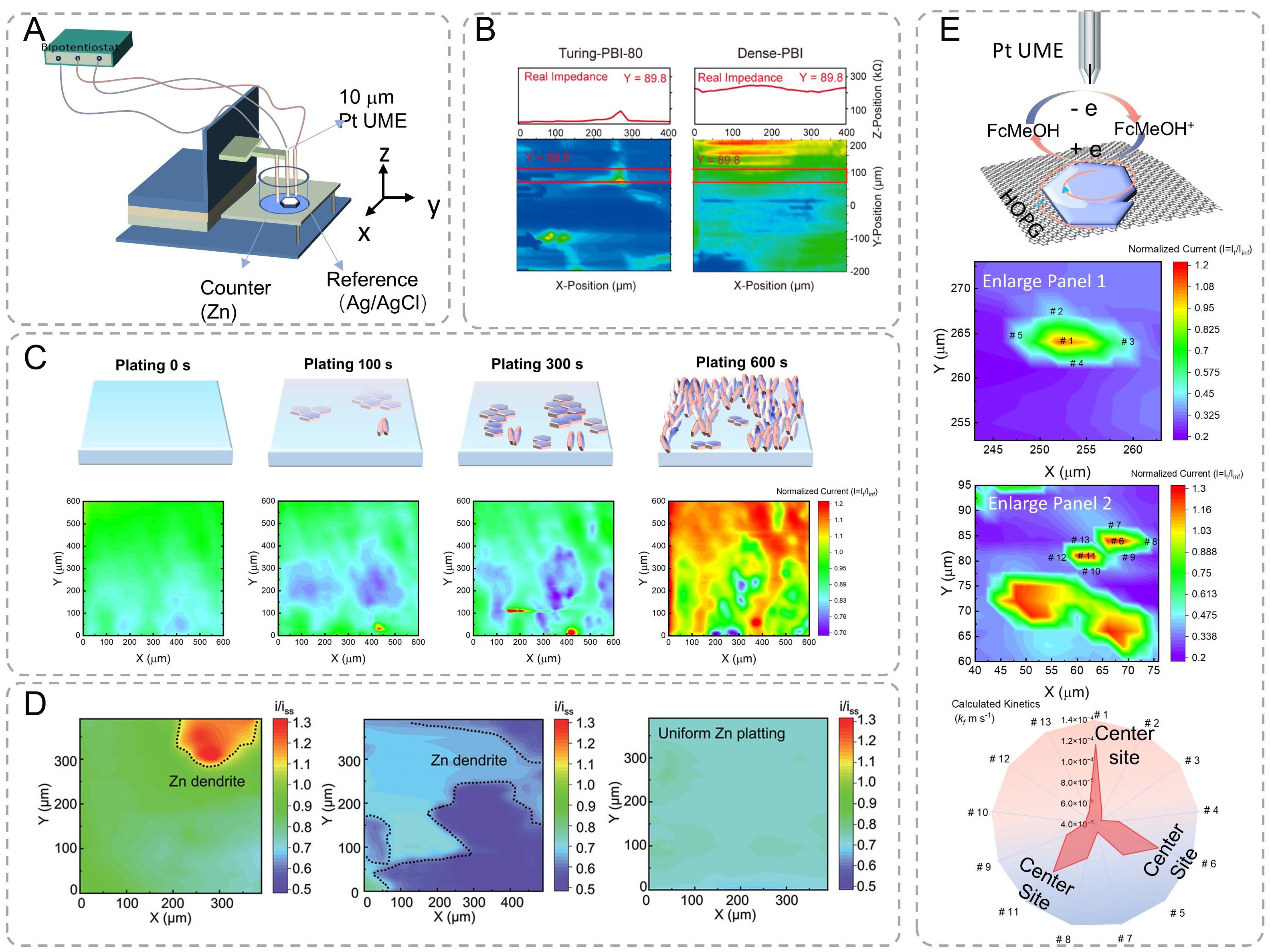

Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) is a scanning probe technique to spatially resolve electrochemical activity with exceptional resolution developed by Bard[140] and Engstrom[141] in 1989, in which a small-scale electrode is scanned across an immersed substrate while recording the current response

Figure 11. (A) Schematic diagram of scanning electrochemical microscope (SECM). (B) The membrane micro area resistance of Turing-PBI-80 and Dense-PBI was characterized by SECM[143]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (C) Schematic illustration and SECM feedback images of Fre-Zn electrodeposition behavior at various plating durations, including 0s, 100, 300, and 600 s[144]. Copyright 2023, Wiley. (D) SECM image of different after plating 300/3,600 s[145]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (E) SECM image and corresponding enlarged area of the Zn deposition sample with marked active sites and the corresponding kinetics[37]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society.

As shown in Figure 11B, localized electrochemical impedance spectroscopy revealed distinct micro-resistance distributions[143]. Dense-PBI membranes exhibited uniform but elevated real impedance, while Turing-patterned surfaces showed heterogeneous conductivity. Dense-PBI has uniform but larger real impedance, whereas the crests of Turing stripes, region B, have a higher real impedance (resistance) compared to region A, which exemplifies the hypothesis original text. As shown in Figure 11C, time-resolved SECM imaging (10 μm/s scan rate, 0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl) captured deposition evolution on Fre-Zn substrates: (i) Homogeneous surface; (ii) Emergent horizontal growth co-existing with vertical flakes; and (iii) Dominant vertical growth[144]. As a comparison in Figure 11D, Gel-coated Zn substrates exhibited suppressed dendrite detection. When the conductive Zn substrate was covered by insulating gel electrolytes (Zn + C and Zn + CWK cases), the formation of Zn dendrite beneath these gel electrolytes can only lead to a decrease in the feedback current, i.e., i/iss < 1[145]. SECM can also investigate the crystallographic-dependent charge transfer kinetics. The feedback from the substrate is reflected by the redox current fluctuation, which results from the oxidation of the redox mediator ferrocenemethanol (FcMeOH) as the tip approaches the substrate surface[37]. The SECM image distinctly reveals the differences in charge transfer activity between the HOPG surface (blue region) and the individually distributed as-deposited Zn domains (green and red regions). These heterogeneities on SECM mappings yield distinct crystal growth kinetics between center and edge regions, which means that under the influence of electrical field and electrolyte modulation, the center of the as-grown Zn domain has a higher electron transfer activity compared to the edge. To verify the relative kinetic differences between the (002)-dominant center and (100)-dominant edge sites, approach curves were conducted to quantify the heterogeneous charge transfer rate constants (kf) of several selected sites within the Zn domains [Figure 11E][37]. The approach curves clearly demonstrate a significant change in activity between the center and edge sites. Mathematically fitted values of kf further highlight the order of magnitude difference, with the center sites having a kf value of approximately 1.2 × 10-4 m s-1 and the edge sites having a kf value of 5 × 10-5 m s-1. SECM is a powerful tool for studying electrode surface properties and electrochemical reaction processes, but it has limited spatial resolution and high requirements for sample flatness and conductivity.

Interfacial evolution mechanism of Zn anode via theoretical simulations

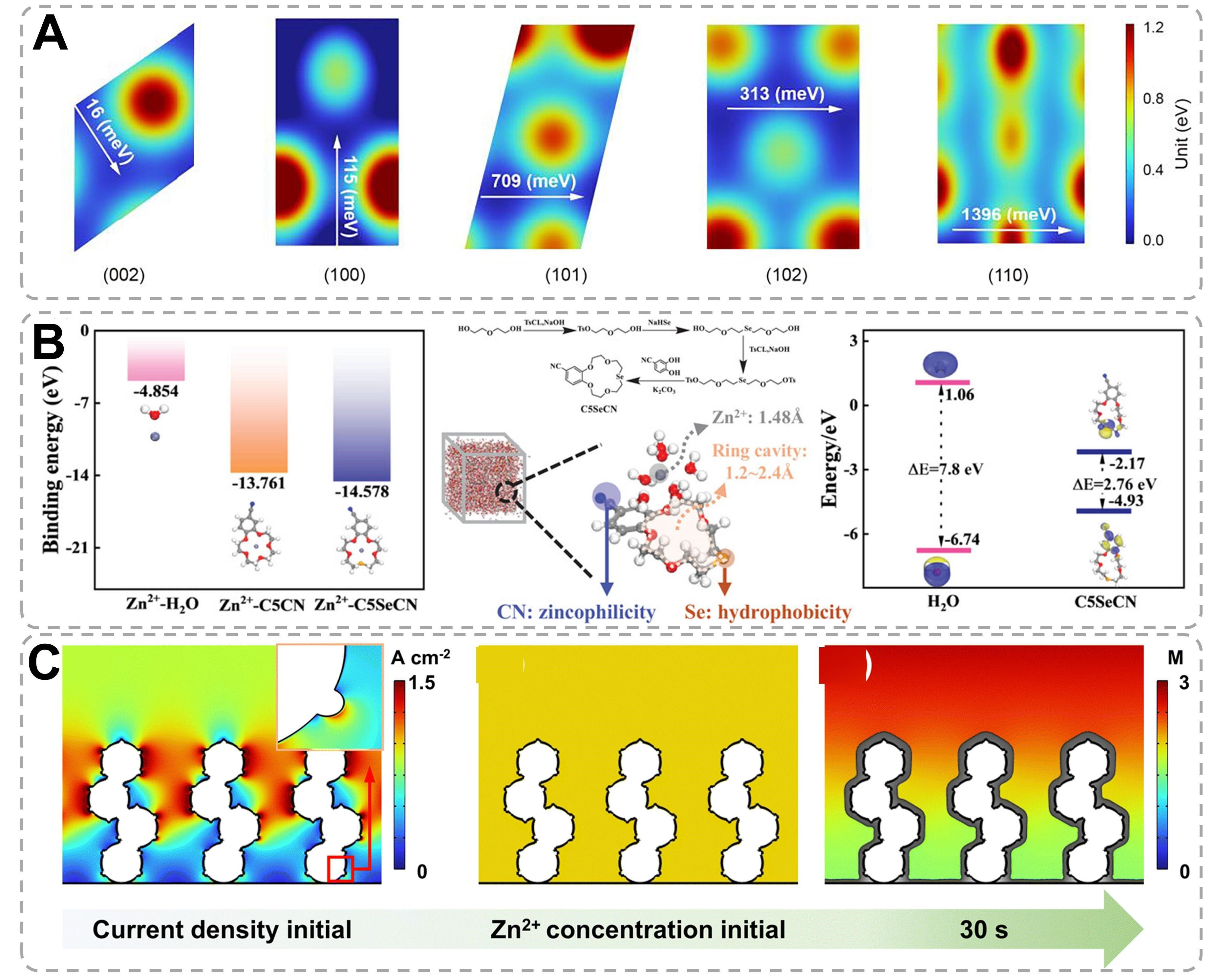

The synergistic integration of advanced computational methodologies with experimental characterization has facilitated the comprehensive understanding of dynamic interfacial processes in Zn anode systems[146]. Multiscale theoretical calculation models, including density functional theory (DFT), molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and finite element analysis, elucidate the fundamental mechanisms governing Zn electrodeposition and interface evolution[75]. Crystallographic orientation-dependent electrochemical behaviors were quantitatively analyzed through DFT calculations of surface atom self-diffusion barriers. Figure 12A demonstrates significant anisotropy in diffusion energetics, with the (002) plane exhibiting the lowest activation barrier (16 meV), followed by progressively higher barriers for (100) (115 meV), (102)

Figure 12. Theoretical calculation mode and the relevant mechanism analysis. (A) DFT calculation of the surface atom self-diffusion barrier on different Zn planes[48]. Copyright 2024, National Academy of Sciences. (B) The calculated binding energies of Zn2+-H2O, Zn2+-C5CN, and Zn2+-C5SeCN. MD snapshots of C5SeCN and [Zn(H2O)6]2+ at 2,000 ps with molecule design features illustrated. Calculated HOMO and LUMO energy levels of H2O and C5SeCN molecules[8]. Copyright 2024, Wiley. (C) COMSOL simulation of current density distribution, and Zn2+ concentration and morphology evolution of the Bi@Zn powder anode during plating[150]. Copyright 2024, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

In summary, this work provides a comprehensive overview of conventional characterization methodologies used to investigate the Zn anode interface, including visualization, spectral analysis, and electrochemical techniques. Subsequently, a detailed exploration ensues regarding a diverse array of multiple characterization techniques. Specifically, X-ray-based methodologies such as XRD and XPS, along with AFM and SECM, enable direct observation of morphological transformations and phase transitions during charge/discharge cycles. These methods include visualization methods (SEM, OM, TEM, and SECM), which offer real-time, dynamic insights into system processes; spectral characterization tools (XRD, XPS, XAS, Raman, and SECM), which provide detailed information on chemical composition and bonding states; and electrochemical approaches, which shed light on electrochemical behavior and reaction kinetics.

This review also highlights recent advancements in applying these techniques under in situ and operando conditions. While existing characterizations have predominantly focused on anode chemical structure, greater emphasis should be placed on their adaptation for studying cathode-electrolyte interfaces and solid-electrolyte interphases. Multimodal integration of complementary techniques is essential to obtain robust and comprehensive datasets. For operando analyses, innovative battery designs must be developed to ensure data fidelity while closely mimicking practical battery operating environments. High-speed data acquisition systems and advanced data mining algorithms require further refinement to elucidate dynamic interfacial kinetics. Current ex situ and in situ characterizations still exhibit significant limitations in probing ZIB mechanisms. Notably, the synergistic coupling of microscopy-spectroscopy-electrochemistry platforms - such as TEM-energy-dispersive spectroscopy (TEM-EDS), transmission X-ray microscopy-X-ray absorption near-edge structure (TXM-XANES), and SECM-AFM hybrid systems - offers unprecedented opportunities for multifaceted investigations of AZIB electrodes [Figure 13], encompassing morphological, structural, compositional, coordination chemistry, and kinetic perspectives.

Particular emphasis is placed on Zn anode interface analysis methodologies that employ surface-sensitive characterization techniques coupled with computational modeling approaches. This synergistic combination not only facilitates atomic-level understanding of interfacial phenomena but also provides predictive capabilities for material design optimization. The systematic compilation of these analytical strategies bridges critical knowledge gaps in AZIB research while establishing standardized protocols for performance evaluation and failure mechanism analysis. Ultimately, this comprehensive review aims to guide the rational development of high-performance AZIB systems through targeted material engineering and optimized operational protocols. Looking forward, continuous optimization and standardization of these operando methodologies will drive transformative breakthroughs in ZIB research. The community must prioritize updating characterization protocols to align with emerging material systems and interfacial complexities. By bridging multiscale observations with mechanistic modeling, these advanced techniques will accelerate the rational design of high-performance ZIBs for next-generation energy storage applications.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the idea and wrote the manuscript: Zhao, J.; Hui, J.

Performed schematic diagrams: Zhao, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, K.; Huang, S.

Supervised the study and manuscript writing: Tang, H.; Hui, J.; Li, Y.

All authors discussed the results.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22204115), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20220485), Suzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. ZXL2022494), start-up research grant for a distinguished professor at Soochow University (Hui, J.), the Key Scientific Research Projects for Higher Education of Henan Province (No. 25A430020), the Doctoral Start-Up Foundation of Henan Normal University (No. QD2023027), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22179089).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Li, Y.; Peng, X.; Li, X.; et al. Functional ultrathin separators proactively stabilizing zinc anodes for zinc-based energy storage. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2300019.

2. Zhu, J.; Tie, Z.; Bi, S.; Niu, Z. Towards more sustainable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202403712.

3. Liu, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, C.; et al. Zinc ion batteries: bridging the gap from academia to industry for grid-scale energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202400045.

4. Li, H.; Li, S.; Hou, R.; et al. Recent advances in zinc-ion dehydration strategies for optimized Zn-metal batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 7742-83.

5. Zhu, Y.; Liang, G.; Cui, X.; et al. Engineering hosts for Zn anodes in aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 369-85.

6. Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Xi, M.; et al. Interfacial engineering of Zn metal via a localized conjugated layer for highly reversible aqueous zinc ion battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319091.

7. Gong, S.; Sun, K.; Yang, F.; et al. Doping of magnesium ions into polyaniline enables high-performance Zn-Mg alkaline batteries. Nano. Energy. 2025, 134, 110586.

8. Han, R.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Reconfiguring Zn2+ solvation network and interfacial chemistry of Zn metal anode with molecular engineered crown ether additive. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412255.

9. Luo, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. Stable zinc anode solid electrolyte interphase via inner Helmholtz plane engineering. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6471.

10. Kim, Y.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, K. J.; Choi, J. W. Corrosion as the origin of limited lifetime of vanadium oxide-based aqueous zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2371.

11. Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Unraveling the charge storage mechanism of β-MnO2 in aqueous zinc electrolytes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2024, 9, 5801-9.

12. Gao, W.; Feng, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, S. Recent progresses of non-oxide manganese and vanadium cathode materials for aqueous zinc ion batteries. Microstructures 2025, 5, 2025018.

13. Yamamoto, T.; Shoji, T. Rechargeable Zn|ZnSO4|MnO2-type cells. Inorganica. Chimica. Acta. 1986, 117, L27-8.

14. Dai, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; et al. Fluorinated interphase enables reversible Zn2+ storage in aqueous ZnSO4 electrolytes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2023, 8, 4762-7.

15. Jesudass, S. C.; Surendran, S.; Lim, Y.; et al. Realizing the electrode engineering significance through porous organic framework materials for high-capacity aqueous Zn-alkaline battery. Small 2024, 20, e2406539.

16. Zhou, S.; Meng, X.; Chen, Y.; et al. Zinc-ion anchor induced highly reversible Zn Anodes for high performance Zn-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202403050.

17. Zhang, M.; Xu, W.; Han, X.; et al. Unveiling the mechanism of the dendrite nucleation and growth in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2303737.

18. Naveed, A.; Rasheed, T.; Raza, B.; et al. Addressing thermodynamic instability of Zn anode: classical and recent advancements. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 44, 206-30.

19. Li, M.; Wang, X.; Meng, J.; et al. Comprehensive understandings of hydrogen bond chemistry in aqueous batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2308628.

20. Yang, J.; Yang, P.; Xiao, T.; Fan, H. J. Designing single-ion conductive electrolytes for aqueous zinc batteries. Matter 2024, 7, 1928-49.

21. Wei, J.; Zhang, P.; Sun, J.; et al. Advanced electrolytes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 10335-69.

22. He, Z.; Zhu, X.; Song, Y.; et al. Separator functionalization realizing stable zinc anode through microporous metal-organic framework with special functional group. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2025, 74, 103886.

23. Sun, Y.; Jian, Q.; Wang, T.; et al. A Janus separator towards dendrite-free and stable zinc anodes for long-duration aqueous zinc ion batteries. J. Energy. Chem. 2023, 81, 583-92.

24. Zheng, J.; Huang, Z.; Ming, F.; et al. Surface and interface engineering of Zn anodes in aqueous rechargeable Zn-ion batteries. Small 2022, 18, e2200006.

25. Ziesche, R. F.; Heenan, T. M. M.; Kumari, P.; et al. Multi-dimensional characterization of battery materials. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2300103.

26. Cao, X.; Xu, W.; Zheng, D.; et al. Weak solvation effect induced optimal interfacial chemistry enables highly durable Zn anodes for aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317302.

27. Huang, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, W.; Kang, F. Transforming zinc-ion batteries with DTPA-Na: a synergistic SEI and CEI engineering approach for exceptional cycling stability and self-discharge inhibition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202409642.

28. Zheng, J.; Archer, L. A. Crystallographically textured electrodes for rechargeable batteries: symmetry, fabrication, and characterization. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 14440-70.

29. Zhang, D.; Song, Z.; Miao, L.; et al. Single exposed Zn (0002) plane and sustainable Zn-oriented growth achieving highly reversible zinc metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202414116.

30. Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, S.; Ali, N.; Kong, X.; Wang, J. High-performance organic electrodes for sustainable zinc-ion batteries: Advances, challenges and perspectives. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 71, 103544.

31. Wang, K.; Luo, D.; Ma, Q.; Lai, X.; He, L.; Chen, Z. Advanced in situ and operando characterization techniques for zinc-ion batteries. Energy. Technol. 2024, 12, 2400199.

32. Wang, J.; Tian, J. X.; Liu, G. X.; Shen, Z. Z.; Wen, R. In Situ insight into the interfacial dynamics in "water-in-salt" electrolyte-based aqueous zinc batteries. Small. Methods. 2023, 7, e2300392.

33. Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, B.; Liang, S.; Zhou, J. Single [0001]-oriented zinc metal anode enables sustainable zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2735.

34. Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, J.; et al. In situ electrochemically-bonded self-adapting polymeric interface for durable aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310995.

35. Dai, Y.; Lu, R.; Zhang, C.; et al. Zn2+-mediated catalysis for fast-charging aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 776-84.

36. Zheng, Z.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, Q.; et al. An extended substrate screening strategy enabling a low lattice mismatch for highly reversible zinc anodes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 753.

37. Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z.; et al. Epitaxy orientation and kinetics diagnosis for zinc electrodeposition. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 736-47.

38. Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Regulating Zn(002) deposition toward long cycle life for Zn metal batteries. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2023, 8, 372-80.

39. Liao, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Suppressing Zn pulverization with three-dimensional inert-cation diversion dam for long-life Zn metal batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2024, 121, e2317796121.

40. Li, J.; Azizi, A.; Zhou, S.; et al. Hydrogel polymer electrolytes toward better zinc-ion batteries: a comprehensive review. eScience 2025, 5, 100294.

41. Yang, X.; Dong, Z.; Weng, G.; et al. Crystallographic manipulation strategies toward reversible Zn anode with orientational deposition. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2401293.

42. Upreti, B. B.; Kamboj, N.; Dey, R. S. Advancing zinc anodes: strategies for enhanced performance in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Small 2025, 21, e2408138.

43. Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; et al. Ten concerns of Zn metal anode for rechargeable aqueous zinc batteries. Joule 2023, 7, 1145-75.

44. Zhang, B.; Fan, H. J. Overlooked calendar issues of aqueous zinc metal batteries. Joule 2025, 9, 101802.

45. Yang, S. J.; Zhao, L. L.; Li, Z. X.; et al. Achieving stable Zn anode via artificial interfacial layers protection strategies toward aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2024, 517, 216044.

46. Kao, C. C.; Ye, C.; Hao, J.; Shan, J.; Li, H.; Qiao, S. Z. Suppressing hydrogen evolution via anticatalytic interfaces toward highly efficient aqueous Zn-ion batteries. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 3948-57.

47. Yang, F.; Yuwono, J. A.; Hao, J.; et al. Understanding H2 evolution electrochemistry to minimize solvated water impact on zinc-anode performance. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2206754.

48. Ren, L.; Hu, Z.; Peng, C.; et al. Suppressing metal corrosion through identification of optimal crystallographic plane for Zn batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2024, 121, e2309981121.

49. Du, P.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; et al. Research progress towards the corrosion and protection of electrodes in energy-storage batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2023, 57, 371-99.

50. Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; et al. Zinc chemistries of hybrid electrolytes in zinc metal batteries: from solvent structure to interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2411802.

51. Du, D.; Zeng, L.; Lan, N.; et al. Understanding and mastering multiphysical fields toward dendrite-free aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2403153.

52. Wu, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J.; et al. Multifunctional cellulose nanocrystals electrolyte additive enable ultrahigh-rate and dendrite-free Zn anodes for rechargeable aqueous zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202319051.

53. Yan, Y.; Shu, C.; Zeng, T.; et al. Surface-preferred crystal plane growth enabled by underpotential deposited monolayer toward dendrite-free zinc anode. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 9150-62.

54. Chen, J.; Xiong, J.; Ye, M.; et al. Suppression of hydrogen evolution reaction by modulating the surface redox potential toward long-life zinc metal anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2312564.

55. Zhang, Q.; Su, Y.; Shi, Z.; Yang, X.; Sun, J. Artificial interphase layer for stabilized Zn anodes: progress and prospects. Small 2022, 18, e2203583.

56. Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Aminosilane molecular layer enables successive capture-diffusion-deposition of ions toward reversible zinc electrochemistry. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 668-77.

57. Liu, B.; Wei, C.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Regulating surface reaction kinetics through ligand field effects for fast and reversible aqueous zinc batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202212780.

58. Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Pang, W. K.; et al. Solvent control of water O-H bonds for highly reversible zinc ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2720.

59. Wang, X.; Han, C.; Dou, S.; Li, W. The protective effect and its mechanism for electrolyte additives on the anode interface in aqueous zinc-based energy storage devices. Nano. Mater. Sci. 2022.

60. Liu, Z.; Wang, R.; Ma, Q.; et al. A dual-functional organic electrolyte additive with regulating suitable overpotential for building highly reversible aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2214538.

61. Bu, F.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Bio-inspired trace hydroxyl-rich electrolyte additives for high-rate and stable Zn-ion batteries at low temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318496.

62. Guo, C.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Synergistic manipulation of hydrogen evolution and zinc ion flux in metal-covalent organic frameworks for dendrite-free Zn-based aqueous batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202210871.

64. Duan, C.; Lu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. Uniform redistribution of Zn2+ flux induced by remodeling the solvated structure to form zincophilic interfaces via sodium alginate electrolyte additive. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 487, 150413.

65. Dai, H.; Sun, T.; Zhou, J.; et al. Unraveling chemical origins of dendrite formation in zinc-ion batteries via in situ/operando X-ray spectroscopy and imaging. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8577.

66. Han, D.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. A corrosion-resistant and dendrite-free zinc metal anode in aqueous systems. Small 2020, 16, e2001736.

67. Zhao, Y.; Guo, S.; Chen, M.; et al. Tailoring grain boundary stability of zinc-titanium alloy for long-lasting aqueous zinc batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7080.

68. Xu, D.; Chen, B.; Ren, X.; et al. Selectively etching-off the highly reactive (002) Zn facet enables highly efficient aqueous zinc-metal batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 642-54.

69. Ma, L.; Chen, S.; Li, N.; et al. Hydrogen-free and dendrite-free all-solid-state Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1908121.

70. Xu, J.; Lv, W.; Yang, W.; et al. In situ construction of protective films on Zn metal anodes via natural protein additives enabling high-performance zinc ion batteries. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 11392-404.

71. He, W.; Gu, T.; Xu, X.; et al. Uniform in situ grown ZIF-L layer for suppressing hydrogen evolution and homogenizing Zn deposition in aqueous Zn-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 40031-42.

72. Zhao, R.; Feng, Z.; Kuang, R.; et al. UV-polymerized zincophilic ion-enhanced interfacial layer with high ion transference number for ultrastable Zn metal anodes. Carbon. Neutral. 2025, 4, e194.

73. He, W.; Zuo, S.; Xu, X.; et al. Challenges and strategies of zinc anode for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 2201-17.

74. Al-abbasi, M.; Zhao, Y.; He, H.; et al. Challenges and protective strategies on zinc anode toward practical aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Carbon. Neutral. 2024, 3, 108-41.

75. Ren, H.; Li, S.; Wang, B.; et al. Mapping the design of electrolyte additive for stabilizing zinc anode in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 68, 103364.

76. Lu, J.; Wu, T.; Amine, K. State-of-the-art characterization techniques for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy. 2017, 2, 201711.

77. Zhao, Y.; Feng, K.; Yu, Y. A Review on covalent organic frameworks as artificial interface layers for Li and Zn metal anodes in rechargeable batteries. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2308087.

78. Desai, D.; Turney, D. E.; Anantharaman, B.; Steingart, D. A.; Banerjee, S. Morphological evolution of nanocluster aggregates and single crystals in alkaline zinc electrodeposition. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014, 118, 8656-66.

79. Hawkins, B. E.; Turney, D. E.; Messinger, R. J.; et al. Electroactive ZnO: mechanisms, conductivity, and advances in Zn alkaline battery cycling. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2103294.

80. Zheng, G.; Wang, C.; Pei, A.; et al. High-performance lithium metal negative electrode with a soft and flowable polymer coating. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2016, 1, 1247-55.

81. Wei, T.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Addition of dioxane in electrolyte promotes (002)-textured zinc growth and suppressed side reactions in zinc-ion batteries. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 3765-75.

82. Banik, S. J.; Akolkar, R. suppressing dendritic growth during alkaline zinc electrodeposition using polyethylenimine additive. Electrochim. Acta. 2015, 179, 475-81.

83. Liu, Z.; Cui, T.; Lu, T.; Shapouri, Ghazvini. M.; Endres, F. Anion effects on the solid/ionic liquid interface and the electrodeposition of zinc. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 20224-31.

84. Khezri, R.; Rezaei, Motlagh. S.; Etesami, M.; et al. Stabilizing zinc anodes for different configurations of rechargeable zinc-air batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 449, 137796.

85. Wu, G.; Yang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H. Dendrite-free strategies for aqueous zinc-ion batteries: structure, electrolyte, and separator. J. Electrochem. 2024, 30, 2415003.

86. Sun, M.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, C. Gelation mechanisms of gel polymer electrolytes for zinc-based batteries. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109393.

87. Li, J.; Xu, K.; Yao, J.; et al. Nanofluid channels mitigated Zn2+ concentration polarization prolonged over 30 times lifespan for reversible zinc anodes. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 73, 103844.

88. Chen, C.; Long, Z.; Du, X.; et al. Interfacial ionic effects in aqueous zinc metal batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 71, 103571.

89. Zhao, P.; Cheng, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Revealing the structure/property relationships of semiconductor nanomaterials via transmission electron microscopy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2408935.

90. Chen, B.; Zhang, H.; Xuan, J.; Offer, G. J.; Wang, H. Seeing is believing: in situ/operando optical microscopy for probing electrochemical energy systems. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 2000555.

91. Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Liu, M.; Xiao, B.; Wang, P. Electrode/electrolyte interfacial engineering for aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Carbon. Neutral. 2023, 2, 186-212.

92. He, M.; Shu, C.; Hu, A.; et al. Suppressing dendrite growth and side reactions on Zn metal anode via guiding interfacial anion/cation/H2O distribution by artificial multi-functional interface layer. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 44, 452-60.

93. Seh, Z. W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C. F.; Chorkendorff, I.; Nørskov, J. K.; Jaramillo, T. F. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 2017, 355, eaad4998.

94. Dong, D.; Zhao, C. X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Aqueous electrolytes: from salt in water to water in salt and beyond. Adv. Mater. 2025, 2418700.

95. Tang, L.; Peng, H.; Kang, J.; et al. Zn-based batteries for sustainable energy storage: strategies and mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 4877-925.

96. Guan, K.; Tao, L.; Yang, R.; et al. Anti-corrosion for reversible zinc anode via a hydrophobic interface in aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2103557.

97. Cheng, X. B.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, C. Z.; Zhang, Q. Toward safe lithium metal anode in rechargeable batteries: a review. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10403-73.

98. Zhao, E.; Nie, K.; Yu, X.; et al. Advanced characterization techniques in promoting mechanism understanding for lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1707543.

99. Wang, R. Y.; Kirk, D. W.; Zhang, G. X. Effects of deposition conditions on the morphology of zinc deposits from alkaline zincate solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, C357.

100. Chamoun, M.; Hertzberg, B. J.; Gupta, T.; et al. Hyper-dendritic nanoporous zinc foam anodes. NPG. Asia. Mater. 2015, 7, e178.

101. Liu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Fan, L.; et al. Construct robust epitaxial growth of (101) textured zinc metal anode for long life and high capacity in mild aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2305988.

102. Yuan, D.; Zhao, J.; Ren, H.; et al. Anion texturing towards dendrite-free Zn anode for aqueous rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7213-9.

103. Panzeri, G.; Muller, D.; Accogli, A.; et al. Zinc electrodeposition from a chloride-free non-aqueous solution based on ethylene glycol and acetate salts. Electrochim. Acta. 2019, 296, 465-72.

104. Huang, K.; Huang, R. J.; Liu, S. Q.; He, Z. Electrodeposition of functional epitaxial films for electronics. J. Electrochem. 2022, 28, 2213006.

105. Sun, Q.; Du, H.; Sun, T.; et al. Sorbitol-electrolyte-additive based reversible zinc electrochemistry. J. Electrochem. 2024, 30, 2314002.

106. Zhao, R.; Wang, H.; Du, H.; et al. Lanthanum nitrate as aqueous electrolyte additive for favourable zinc metal electrodeposition. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3252.

107. Badwe, N.; Chen, X.; Schreiber, D. K.; et al. Decoupling the role of stress and corrosion in the intergranular cracking of noble-metal alloys. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 887-93.

108. Hao, J.; Li, B.; Li, X.; et al. An in-depth study of Zn metal surface chemistry for advanced aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2003021.

109. Deng, C.; Xie, X.; Han, J.; Lu, B.; Liang, S.; Zhou, J. Stabilization of Zn metal anode through surface reconstruction of a cerium-based conversion film. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2103227.

110. Zhao, Q.; Stalin, S.; Archer, L. A. Stabilizing metal battery anodes through the design of solid electrolyte interphases. Joule 2021, 5, 1119-42.

111. Zhang, D.; Lu, J.; Pei, C.; Ni, S. Electrochemical activation, sintering, and reconstruction in energy-storage technologies: origin, development, and prospects. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2103689.

112. Cheng, D.; Hong, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, S. Y.; Zheng, H. In situ TEM characterization of battery materials. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 1840-96.

113. Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Ultra-long-life and highly reversible Zn metal anodes enabled by a desolvation and deanionization interface layer. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3120-9.

114. Guo, R.; Liu, X.; Ni, K.; et al. Non-destructive stripping electrochemistry enables long-life zinc metal batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 2353-64.

115. Pavliček, N.; Gross, L. Generation, manipulation and characterization of molecules by atomic force microscopy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, BFs415700160005.

116. Kempaiah, R.; Vasudevamurthy, G.; Subramanian, A. Scanning probe microscopy based characterization of battery materials, interfaces, and processes. Nano. Energy. 2019, 65, 103925.

117. Lacey, S. D.; Wan, J.; von, Wald. Cresce. A.; et al. Atomic force microscopy studies on molybdenum disulfide flakes as sodium-ion anodes. Nano. Lett. 2015, 15, 1018-24.

118. Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Y.; et al. A highly reversible zinc deposition for flow batteries regulated by critical concentration induced nucleation. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 4077-84.

119. Su, T.; Wang, K.; Chi, B.; Ren, W.; Sun, R. Stripy zinc array with preferential crystal plane for the ultra-long lifespan of zinc metal anodes for zinc ion batteries. EcoMat 2022, 4, e12219.

120. Pu, S. D.; Gong, C.; Tang, Y. T.; et al. Achieving ultrahigh-rate planar and dendrite-free zinc electroplating for aqueous zinc battery anodes. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2202552.

121. Atkins, D.; Ayerbe, E.; Benayad, A.; et al. Understanding battery interfaces by combined characterization and simulation approaches: challenges and perspectives. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2102687.

122. Shadike, Z.; Zhao, E.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Advanced characterization techniques for sodium-ion battery studies. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2018, 8, 1702588.

123. Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, J.; et al. MoS2-mediated epitaxial plating of Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208171.

124. Li, H.; Guo, S.; Zhou, H. In-situ/operando characterization techniques in lithium-ion batteries and beyond. J. Energy. Chem. 2021, 59, 191-211.

125. Liu, X.; Tong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, H. In-depth mechanism understanding for potassium-ion batteries by electroanalytical methods and advanced in situ characterization techniques. Small. Methods. 2021, 5, e2101130.

126. Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Z.; Meng, X. Synchrotron-based X-ray diffraction and absorption spectroscopy studies on layered LiNixMnyCozO2 cathode materials: a review. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 49, 181-208.

127. Zhang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Designing anion-type water-free Zn2+ solvation structure for robust Zn metal anode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 23357-64.

128. Su, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, W.; et al. In-situ spectroscopic observation of dynamic-coupling oxygen on atomically dispersed iridium electrocatalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6118.

129. Pishgar, S.; Gulati, S.; Strain, J. M.; Liang, Y.; Mulvehill, M. C.; Spurgeon, J. M. In situ analytical techniques for the investigation of material stability and interface dynamics in electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical applications. Small. Methods. 2021, 5, e2100322.

130. Cheng, W.; Zhao, M.; Lai, Y.; et al. Recent advances in battery characterization using in situ XAFS, SAXS, XRD, and their combining techniques: from single scale to multiscale structure detection. Exploration 2024, 4, 20230056.

131. Qin, Y.; Li, H.; Han, C.; Mo, F.; Wang, X. Chemical welding of the electrode-electrolyte interface by Zn-metal-initiated in situ gelation for ultralong-life Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2207118.

132. Zhu, Q.; Sun, G.; Qiao, S.; et al. Selective shielding of the (002) plane enabling vertically oriented zinc plating for dendrite-free zinc anode. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2308577.

133. He, X.; Cui, Y.; Qian, Y.; et al. Anion concentration gradient-assisted construction of a solid-electrolyte interphase for a stable zinc metal anode at high rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11168-77.

134. Yi, J.; You, E. M.; Hu, R.; et al. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: a half-century historical perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 1453-551.

135. Lim, H.; Jun, S.; Song, Y. B.; Bae, H.; Kim, J. H.; Jung, Y. S. Operando electrochemical pressiometry probing interfacial evolution of electrodeposited thin lithium metal anodes for all-solid-state batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2022, 50, 543-53.

136. Strauss, F.; Kitsche, D.; Ma, Y.; et al. Operando characterization techniques for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2100004.

137. Yuan, Y.; Pu, S. D.; Pérez-Osorio, M. A.; et al. Diagnosing the electrostatic shielding mechanism for dendrite suppression in aqueous zinc batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307708.

138. Zhang, M.; Hua, H.; Dai, P.; et al. Dynamically interfacial pH-buffering effect enabled by N-methylimidazole molecules as spontaneous proton pumps toward highly reversible zinc-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208630.

139. Zhou, J.; Xie, M.; Wu, F.; et al. Encapsulation of metallic Zn in a hybrid MXene/graphene aerogel as a stable Zn anode for foldable Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2106897.

140. Bard, A. J.; Fan, F. R. F.; Kwak, J.; Lev, O. Scanning electrochemical microscopy. Introduction and principles. Anal. Chem. 1989, 61, 132-8.

141. Engstrom, R. C.; Pharr, C. M. Scanning electrochemical microscopy. Anal. Chem. 1989, 61, 1099A-104A.

142. Liu, T.; Hua, W.; Yuan, H.; et al. Direct in situ measurement of electrocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction properties using scanning electrochemical microscopy. J. Anal. Test. 2025, 9, 202-12.

143. Wu, J.; Yuan, C.; Li, T.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Dendrite-free zinc-based battery with high areal capacity via the region-induced deposition effect of Turing membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13135-44.

144. Zhao, J.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Interphase Modulated early-stage Zn electrodeposition mechanism. Small. Methods. 2023, 7, e2300731.

145. Shao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Hu, W.; et al. Regulating interfacial ion migration via wool keratin mediated Biogel electrolyte toward robust flexible Zn-ion batteries. Small 2022, 18, e2107163.

146. Wang, H.; Lai, K.; Guo, F.; et al. Theoretical calculation guided materials design and capture mechanism for Zn-Se batteries via heteroatom-doped carbon. Carbon. Neutral. 2022, 1, 59-67.

147. Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; et al. Constructing robust heterostructured interface for anode-free zinc batteries with ultrahigh capacities. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 76.

148. Zhao, K.; Fan, G.; Liu, J.; et al. Boosting the kinetics and stability of Zn anodes in aqueous electrolytes with supramolecular cyclodextrin additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 11129-37.

149. Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Organic acid etching strategy for dendrite suppression in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2102797.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].