4D-printed soft microrobots: manufacturing, materials, actuation and applications

Abstract

Four-dimensional (4D) printing couples additive manufacturing with stimuli-responsive materials to create soft microrobots that can be programmed to change their shape, properties, and functions in response to external cues. This review synthesizes the core blueprint for 4D-printed soft microrobots, encompassing printing technologies, smart materials, and stimulus modalities. It explores how these elements collectively design locomotion, manipulation, and sensing at the microscale, and investigates application frontiers including targeted drug delivery, tissue engineering, stents, sensing, and other applications. Despite rapid progress, key obstacles remain, such as resolution-throughput-multimaterial trade-offs, interlayer adhesion, long-term fidelity, limited force density, biocompatibility, near-body-temperature triggers, and closed-loop imaging and navigation. Our conclusion is that 4D printing provides a unifying platform for adaptive, reconfigurable soft microrobots, and coordinated advances in materials, manufacturing, modeling, and regulation are essential for unlocking reliable clinical and industry-relevant systems.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Three-dimensional (3D) printing, also known as additive manufacturing (AM), is a versatile, digitally guided, layer-by-layer process for directly fabricating complex 3D geometries, a paradigm first introduced in 1986 by Chuck Hull[1]. It has become a crucial method from model to device for microrobots, enabling rapid iteration, integration of different materials, and sub-millimeter-scale feature control[2-6]. However, traditional 3D-printed structures are typically geometrically fixed after curing, meaning in-situ reconfiguration, autonomous deformation, and closed-loop behavior often require additional components or external mechanisms. These limitations have spurred a shift toward temporally programmable materials[7-12]. Four-dimensional (4D) printing extends 3D printing by encoding materials with anisotropic responses and functional gradients to stimuli, enabling printed structures to predictably alter their shape, properties, or functionality. As a cutting-edge technology, 4D printing accelerates the construction of microstructures and smart functional devices for diverse applications, including targeted drug delivery[13], tissue engineering[14], stents[15], and sensing[16].

As an emerging branch of AM, 4D printing reduces design and manufacturing complexity by encoding self-transformation into simplified printable architectures that deform on demand. This significantly shortens building times and minimizes support usage, even for complex geometries[17]. With the widespread rise of AM in industrial applications, 4D printing has sparked strong interdisciplinary interest[18]. In the field of soft microrobots, this technology achieves on-demand shape transformation and multi-degree-of-freedom actuation through the unique integration of stimulus-responsive polymers with composite materials and a high-resolution fabrication process. The material library encompasses hydrogels, elastomers, and hybrid systems, which require a balance between printability, responsiveness, and robustness[19]. Specifically, liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs) can convert mesophase orientation into macroscopic motion upon thermal and optical signals[20,21]. Shape memory polymers (SMPs) provide programmable recovery capabilities for multi-material structures[22]. Magnetically controllable elastomers or hydrogel matrices enable remote torque and force transmission[23]. The selection of fabrication routes should consider the physicochemical properties of materials and their intended applications. Reported techniques for constructing soft microrobots include direct ink writing (DIW)[24], fused deposition modeling (FDM)[25], stereolithography (SLA)[26], digital light processing (DLP)[27], and two-photon polymerization (TPP)[28]. Furthermore, to achieve programmable deformation or reliable motion of microrobots, precise control through appropriate actuation schemes is essential. Energy inputs for driving soft microrobots encompass light[29], heat[30], magnetic field[31], electricity[32], ultrasound[33], and chemical stimuli[34]. In summary, materials, manufacturing, and actuation form the fundamental trinity of 4D-printed soft microrobots. Materials and manufacturing enable the physical realization of devices, while actuation endows them with mobility. Here, we adopt a broad definition of “microrobots” to include micrometer- to millimeter-scale miniaturized mechanical devices capable of controlled and programmed deformation under external stimuli; offboard actuation and control are considered sufficient, and onboard power or computation is not required. In practice, decisions across these three domains are tightly coupled, and the trade-offs between them ultimately constrain performance and determine the scope of feasible applications.

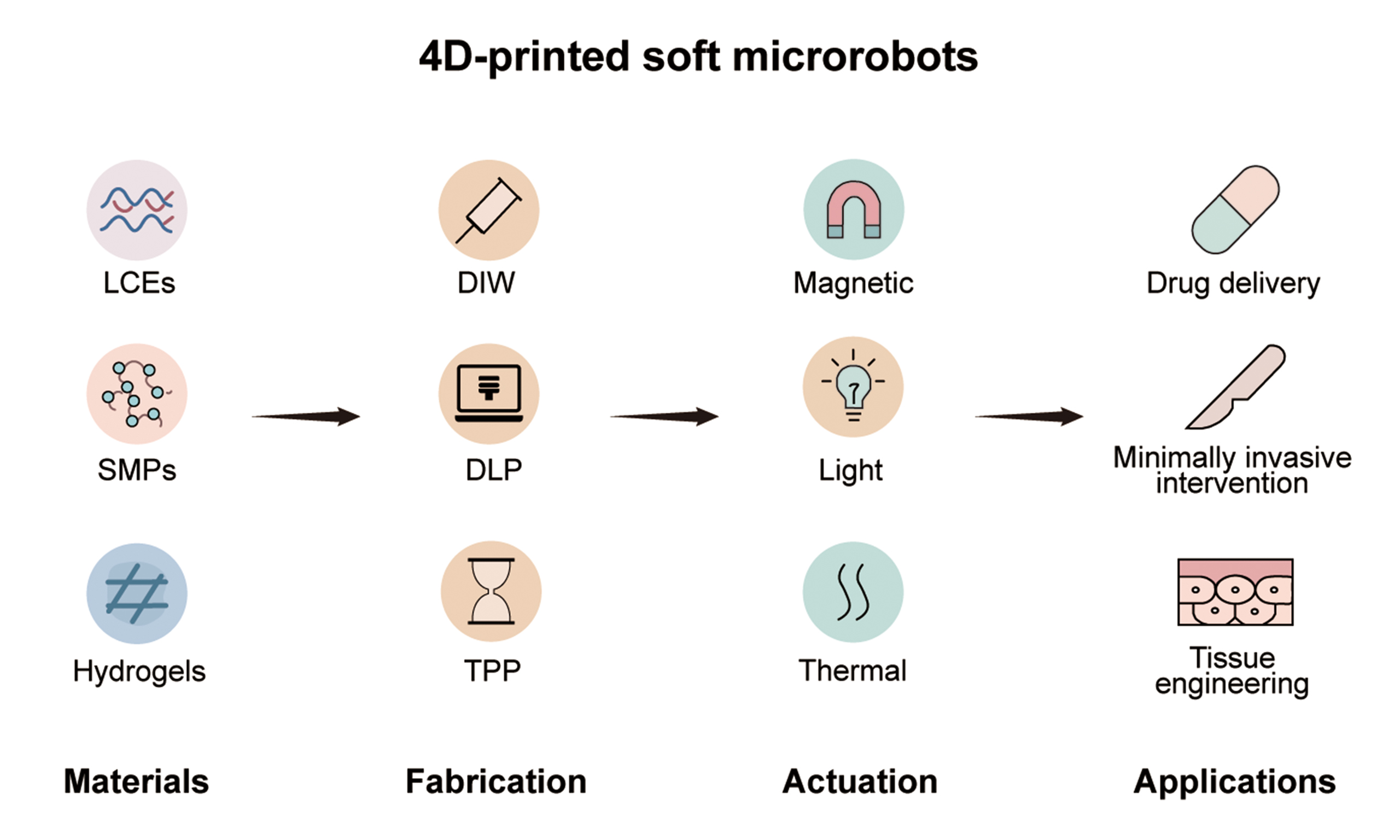

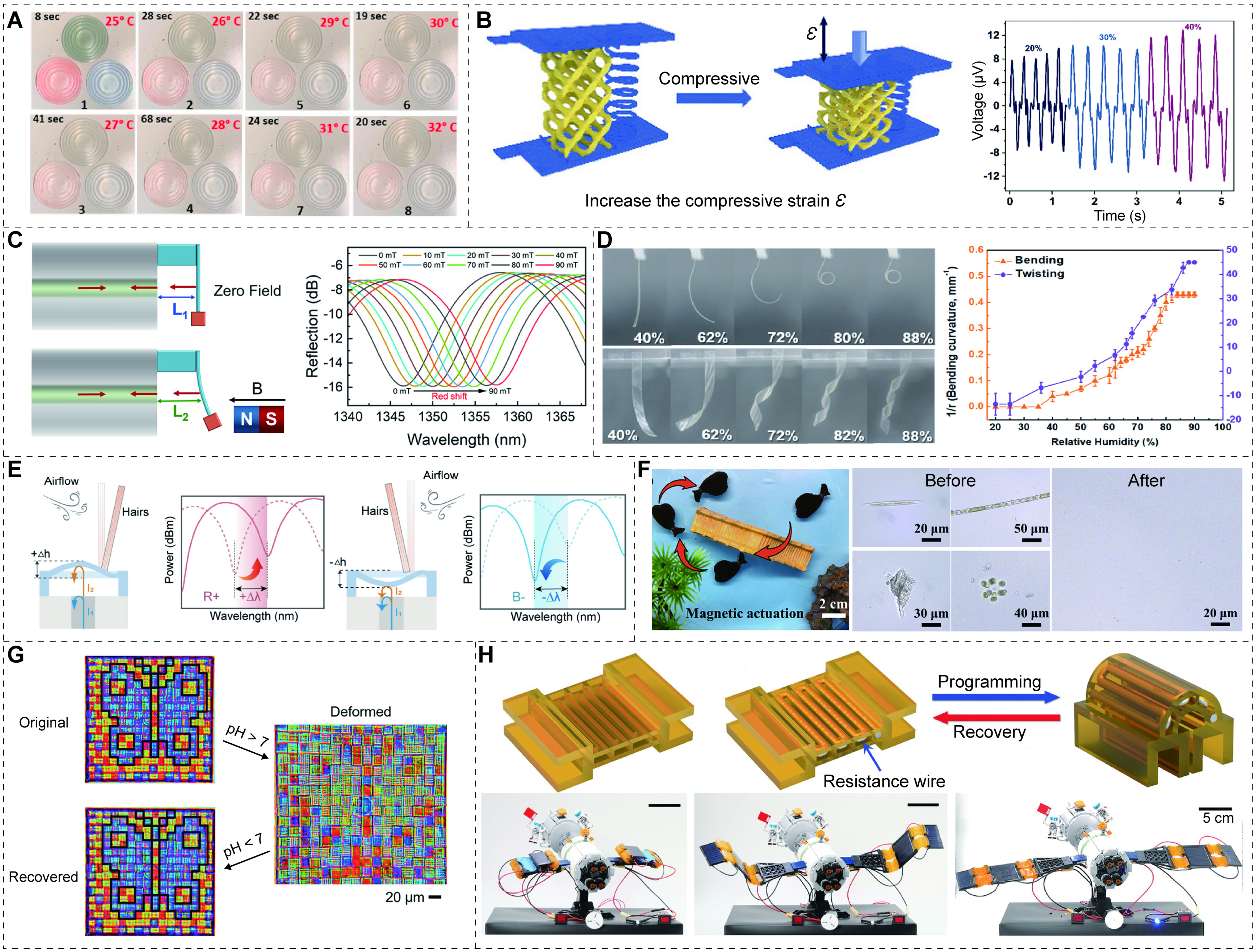

Currently, research on 4D-printed soft microrobots has been conducted in multiple areas. Some researchers focus on selecting and synthesizing suitable materials[35-37], some emphasize developing appropriate manufacturing methods[38-40], and others explore broader application scenarios[41-43]. In this review, we summarize recent advances in 4D-printed soft microrobots, covering how materials, fabrication strategies, and stimuli combine to achieve diverse functionalities, as illustrated in Figure 1. Following an overview of printing technologies and various responsive materials in Section “FABRICATION STRATEGIES” and Section “INTELLIGENT MATERIALS”, we analyze different actuation responses of 4D-printed soft microrobots in Section “STIMULI”. Then, in Section “APPLICATIONS”, we survey the applications of 4D-printed soft microrobots with outstanding behaviors in real-world scenarios. Finally, we discuss perspectives on prospective advances and their wider implications for this field in Section “CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK”.

Figure 1. Overview of 4D-printed soft microbots: materials, strategies, stimuli, and applications. 4D: Four-dimensional; LCEs: liquid crystal elastomers; SMPs: shape memory polymers; DIW: direct ink writing; FDM: fused deposition modeling; DLP: digital light processing; SLA: stereolithography; TPP: two-photon polymerization.

FABRICATION STRATEGIES

AM provides a platform for 4D printing by enabling the layered construction of complex 3D architectures. ISO/ASTM 52900:2021, Additive manufacturing-General principles-Terminology, classifies AM into seven categories: material extrusion (ME), vat polymerization (VP), powder bed fusion (PBF), material jetting (MJ), binder jetting (BJ), sheet laminating, and directed energy deposition[44]. For soft microrobots, manufacturing techniques primarily employ DIW, FDM, SLA, DLP, and TPP. To facilitate a quantitative comparison among these methods, representative key metrics (e.g., achievable feature size, layer thickness, and throughput) are summarized in Table 1. In the following sections, these fabrication technologies are described in detail.

Quantitative metrics of common AM techniques used in soft microrobotics

| Method | Representative lateral feature size | Representative layer thickness | Representative speed | Ref. |

| DIW | ~100-1,200 μm | ~10-300 μm | ~1-100 mm/s | Sol et al.[24] |

| FDM | ~200-800 μm | ~100-300 μm | mm/s-tens of mm/s | Dezaki et al.[25] |

| SLA | ~10-50 μm | ~10-100 μm | Layer-by-layer; generally higher throughput than serial micro-writing | Paunović et al.[26] |

| DLP | ~25-100 μm | ~10-100 μm | Layer-by-layer projection; often faster than scanning approaches | Chaudhary et al.[27] |

| TPP | ~0.1-1 μm | ~0.1-2 μm | Serial writing; high precision but limited throughput | Ren et al.[28] |

DIW

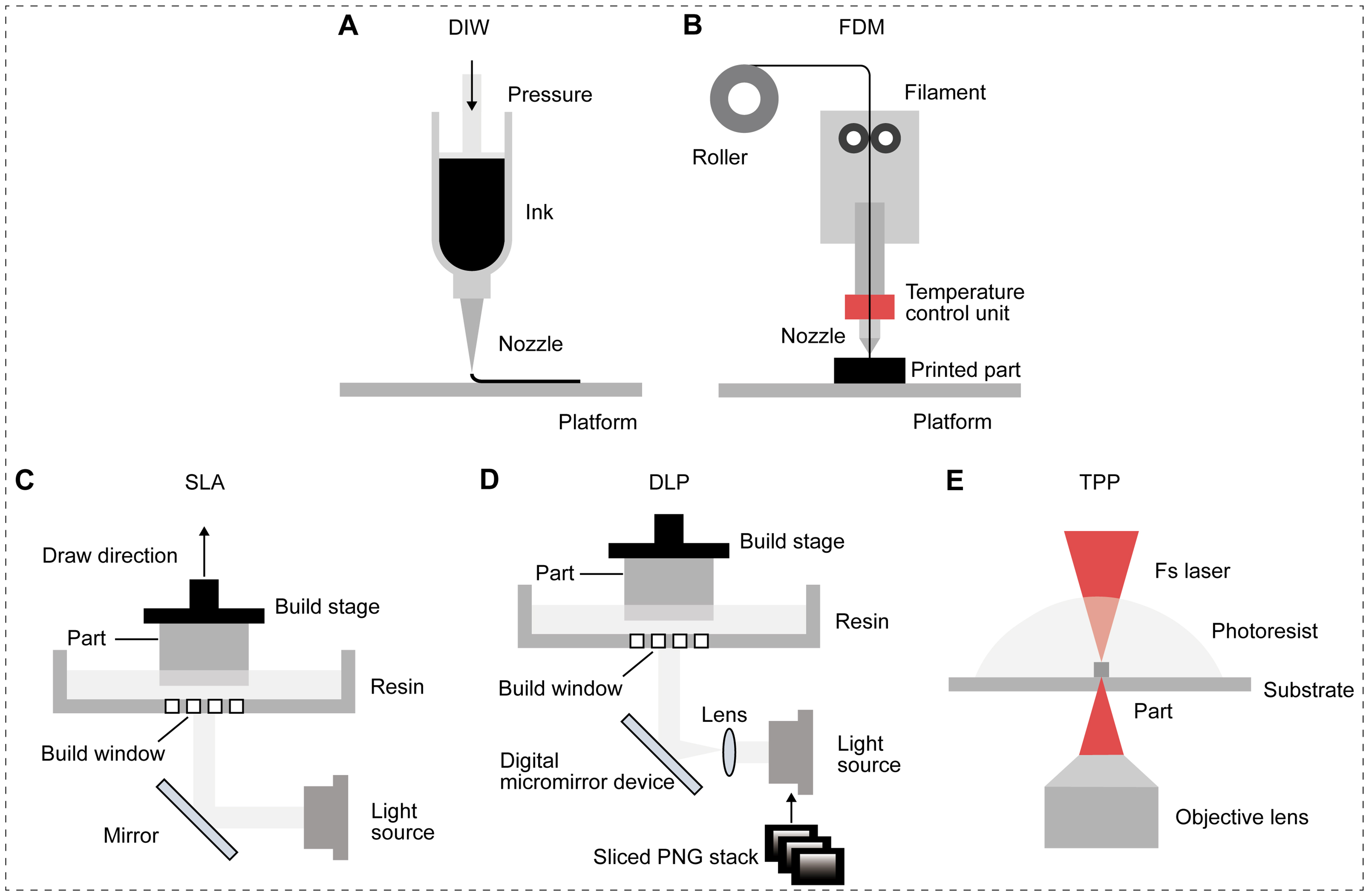

DIW originated at Sandia National Laboratories in 1996 for freeform fabrication of ceramics and composites[45]. The printing process primarily involves extruding viscoelastic and/or viscoplastic inks through a nozzle under applied pressure to build 3D structures with controlled filament geometry and composition [Figure 2A][46]. At its core, the ink formulation typically combines powdered particles with a multi-component polymer solution to produce viscous non-Newtonian fluids exhibiting shear-thinning and rapid self-healing properties[47]. Both properties are critical, with the shear-thinning behavior enabling the ink to flow under shear force for extrusion, while the rapid self-healing ability allows extruded ink to swiftly regain mechanical properties in the absence of shear force. Post-deposition, solvent removal or gelation induces further phase transitions in these inks to cure the printed structures[48].

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of (A) DIW, (B) FDM, (C) SLA, (D) DLP, and (E) TPP. DIW: Direct ink writing; FDM: fused deposition modeling; SLA: stereolithography; DLP: digital light processing; TPP: two-photon polymerization; PNG: portable network graphics.

Cheng et al. employed alginate as a biocompatible rheological modifier to fabricate free-form structures of chemically and physically crosslinked hydrogels using the DIW method, thereby overcoming fragility and mold-constrained geometries[49]. By co-tuning ink composition and tool paths, they achieved biomimetic prototypes such as moving tentacles, beating and pumping heart structures, and phototactic tendrils, collectively demonstrating geometric multifunctionality, mechanical tunability, and stimulus-response-driven behavior. Sol et al. synthesized a humidity-responsive cholesteric liquid crystal oligomer ink and demonstrated printed devices that combine structural color with processable actuation[24]. By controlling post-processing and local environments, they achieved hydrochromic coatings on complex 3D shapes and scallop-like actuators that reversibly open and close under alternating wet and dry conditions. Extending functionality toward system-level integration, Zhang et al. formulated ion-conducting, electroluminescent, and insulating inks for DIW of flexible light-emitting devices and co-printed them with soft robotic structures[50]. By integrating these devices with quadrupedal robots and sensing units, they achieved artificial camouflage that instantly adapts its displayed color to the surrounding environment.

In practice, DIW holds significant appeal for 4D printing due to its straightforward hardware and compatibility with LCEs, SMPs, hydrogels, and related composites, enabling broad applications in biomedicine, soft robots, and electronics. However, its drawbacks include limited throughput, poor surface roughness, and restricted resolution. In addition, extra solidification steps may reduce feature fidelity.

FDM

FDM, conceived by S. Scott Crump in the late 1980s and brought to market in the early 1990s through Stratasys[51], is an extrusion-based additive process where thermoplastic filament is fed into a heated nozzle, deposited layer by layer, and solidified upon cooling [Figure 2B]. Its applicability to 4D printing stems from the wide range of extrudable thermoplastics and composites, as well as the ability to program internal stresses during printing. In particular, shape-memory thermoplastics - such as polylactic acid (PLA)[52], thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)[53], and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS)[54] - have been extensively studied due to their ability to melt when heated, bond with adjacent materials, and rapidly solidify upon cooling to form robust solids. The internal stresses originate from the asynchronous cooling of sequentially deposited filaments[55].

Kačergis et al. systematically varied FDM parameters such as print speed, build plate temperature, and active layer count to preprogram deformation in PLA and TPU hinges, demonstrating that deformation can be preprogrammed through process and design choices[56]. To overcome the rigidity of traditional 4D-printed SMP hinges below their glass transition temperature, Yamamura et al. proposed a hybrid hinge design[57]. This design placed an elastic hinge adjacent to a rigid self-folding segment, enabling large elastic folding with high durability over hundreds of cycles. Extending the idea of process-encoded strain, Wang et al. proposed an economical multi-speed FDM strategy[58]. This approach embedded graded built-in strain into flat precursors to enable rapid, repeatable formation of complex 3D shapes upon heating while reducing build time and workflow complexity. From hinges to actuators, Dezaki et al. employed TPU to fabricate soft pneumatic actuators whose tip deflection, tip force, stiffness, and strength can be tuned via lattice topology and printing parameters[25]. The performance of wearable rehabilitation devices based on this actuator was validated through modeling and closed-loop pneumatic actuation.

FDM is a mature, cost-effective platform now widely adopted across automotive, aerospace, defense, biomedicine, and packaging[59]. However, it still faces key challenges including anisotropic interlayer adhesion, relatively low precision and surface quality, extended build times, and risks of delamination, shrinkage, and thermal degradation. Advancements in in-situ sensing with feedback, localized reheating, post-processing, and improved feedstocks are steadily addressing these shortcomings and propelling FDM toward the reliable fabrication of functional 4D components. Notably, rotary 4D printing has recently emerged as an extension of FDM toward continuous manufacturing, in which filaments are deposited on a rotating mandrel to directly encode circumferential or helical toolpaths, anisotropies, and gradient architectures within tubular or curvilinear structures. Compared with planar layer stacking, the rotary format can improve throughput and repeatability for axisymmetric geometries and enables efficient programming of ring- or helix-like reinforcements that are difficult to realize by conventional FDM, as demonstrated in rotary-printed programmable metamaterials[60] and architected phase-change artificial muscles[61] with encoded dynamic behaviors.

SLA

SLA is a vat photopolymerization process that transforms liquid photopolymer resin into solid components by selectively curing each layer with a focused ultraviolet (UV) laser. A typical system includes a resin vat, a recoating mechanism for creating a uniform free surface, a vertically translating build platform, beam delivery optics for precise exposure, and control electronics for printing stability [Figure 2C][62]. During printing, the laser scans a two-dimensional (2D) pattern across the resin surface, exceeding the programmed layer step height to chemically bond newly exposed resin with the partially cured layer below. The platform then inverts along the Z-axis, serially repeating this process to form a 3D object[63]. Part quality depends on machine parameters and resin formulation, particularly laser spot size, exposure dose, scan speed, layer thickness, recoating kinetics, and the resin’s absorption and reactivity. Since functional group conversion is rarely complete during layer-by-layer exposure, post-curing with UV light is typically employed to increase crosslink density and enhance mechanical properties[64]. Due to its fine in-plane resolution and smooth surfaces, SLA has become the leading approach for manufacturing complex geometries. It is increasingly utilized for 4D printing when photoswitchable or stimulus-responsive chemicals are incorporated into the resin.

Zhao et al. synthesized a polyurethane-acrylate-based photosensitive polymer for SLA and printed high-precision shape-memory components[65]. These components exhibited high fixation and recovery properties along with robust mechanical performance, establishing a material and process baseline for enabling 4D responses in SLA. Shan et al. leveraged SLA to fabricate epoxy-acrylate SMPs with high resolution and optical transparency, demonstrated tunable toughness under tension, and built a fast thermally or electrically triggered valve actuator, linking printable resin to device-level actuation[66]. Advancing toward clinical relevance, Paunović et al. used SLA to 4D-print biodegradable shape memory elastomers whose transition points are set near physiological temperature[26]. This enabled drug-loaded stents capable of room-temperature fixation, body-temperature recovery, and controlled drug release.

SLA offers multiple advantages, including high resolution and exceptional surface quality, outstanding feature fidelity, rapid fabrication of complex internal cavities and thin-walled structures, and excellent dimensional repeatability. With the advent of biodegradable and biocompatible resins, SLA has demonstrated unique appeal in biomedical applications[64]. Its limitations stem from the reliance on photocurable resins, whose toughness, heat resistance, and long-term stability often fall short of engineering thermoplastics or metals. Polymerization shrinkage and residual stress may cause warpage, dimensional deviations, and overcuring defects. Additionally, cleaning and post-curing processes are typically required, increasing time and cost. Consequently, SLA is well-suited to high-precision, high-surface-quality parts and master molds fabrication, but it proves less effective for high-temperature load-bearing components, high-toughness structures, or direct micro/nano-scale manufacturing.

DLP

DLP is a vat-based photopolymerization method similar to SLA [Figure 2D]. It projects a pixelated 2D image via a digital micromirror device or liquid crystal display, curing an entire resin layer in a single exposure[67]. This full-layer exposure reduces build time, and since curing typically occurs at the bottom of the tank, the process exhibits low sensitivity to oxygen inhibition[68]. Curing depth and lateral resolution are jointly regulated by exposure dose, resin absorption rate, initiator concentration, and layer thickness. Through parameter tuning, complex 3D components with smooth surfaces can be rapidly produced. Leveraging the advantages of DLP technology alongside optimized and expanded ink formulations, multifunctional microrobots have been developed for tasks such as targeted cargo delivery or environmental remediation[69].

TPP

TPP, as a direct laser writing technique, utilizes a highly focused femtosecond pulsed laser to induce nonlinear absorption in photosensitive resins, thereby confining polymerization reactions to a focal volume (the voxel)[70]. Typical processing setup employs a piezoelectric stage and galvanometer scanner to guide the laser focus along a preprogrammed 3D path through the resin [Figure 2E]. In negative photoresists, exposed regions undergo crosslinking and curing, while exposed areas in positive photoresists can be dissolved and removed[71]. Since excitation is confined to the voxel, printing resolutions below the optical diffraction limit (sub-100 nm) are achievable, enabling seamless free-form 3D geometries[72]. These characteristics make TPP particularly attractive for constructing micro- and nano-scale structures, such as microrobots, micro-optical devices, mechanical metamaterials, and 4D architectures, especially when the resin incorporates stimuli-responsive chemistries.

Hu et al. employed TPP to fabricate pH-responsive hydrogel microstructures at the microscopic scale, achieving sub-second actuation and multi-degree-of-freedom deformation for selective micro-object capture and release[73]. Building on microscale actuation toward richer programmable behavior, Guo et al. assembled independent, light-responsive LCE voxels with predefined 3D director fields into lines, grids, and skeletal forms, enabling optically or thermally triggered anisotropic morphing in complex geometries[74]. Extending from mechanics to functional optics and information encoding, Zhang et al. formulated a two-photon-printable shape-memory photoresist that produces submicron structural-color patterns whose colors and embedded information vanish upon flattening and rapidly recover when heated above the glass-transition temperature[75].

TPP is one of the most important 4D-printing technologies for microrobotics, but it also has drawbacks. Its primary limitations include point-by-point exposure restricting throughput and build volume, sensitivity to focus stability and optical aberrations, constraints on polymerizable resin and photoinitiator efficiency, and dimensional changes arising from polymerization shrinkage and development[76]. Practical implementation further faces challenges including high equipment costs, meticulous alignment and process control, and the typical mechanical brittleness of highly crosslinked photoresists, though advances in scan strategies, multibeam parallelization, and tailored resins continue to mitigate these issues.

Scalability for 4D-printed soft microrobots

Scalability remains a key bottleneck for translating 4D-printed soft microrobots from proof-of-concept demonstrations to reproducible, high-performance devices for mass production. Current platforms face coupled constraints in throughput, resolution, multi-material integration, and reproducibility. Serial microfabrication (TPP) enables the finest features but exhibits poor scalability in build time and volume, while projection-based photopolymerization (SLA/DLP) improves areal throughput but is constrained by pixel limits, curable materials, and curing-induced shrinkage or distortion. Material extrusion routes (DIW/FDM) offer relative scalability and cost-effectiveness, yet their minimum feature size is limited by nozzle and filament dimensions and rheology. Maintaining robust interlayer bonding and defect-free structures at small scales becomes increasingly challenging. Multi-material 4D designs further narrow the process window due to registration errors, cross-contamination, and interfacial delamination. At micro-/sub-mm scales, even minor variability in curing dose, solvent content, or filler dispersion can cause significant performance differences through changes in stiffness, transition thresholds, fatigue life, and actuation trajectories. Therefore, scalable manufacturing requires not only faster printing but also integrated quality control and standardized benchmarking to ensure cross-batch repeatability and reliable actuation in relevant environments.

INTELLIGENT MATERIALS

Intelligent materials are central to 4D printing, enabling the integration of structure and function to empower microrobots with on-demand shape transformation and the ability to perform specific tasks. Currently, researchers have developed various smart materials. In this section, we aim to outline the primary materials used for 4D-printed soft microrobots, including LCEs, SMPs, stimuli-responsive hydrogels, and magnetic nanocomposite polymers. To complement the qualitative discussion, representative quantitative properties of these material classes (e.g., modulus range, achievable actuation strain, and typical response time) are compiled in Table 2 to guide material selection. We hope this provides insights for material selection in future 4D-printed soft microrobots.

Representative quantitative metrics of major stimulus-responsive soft material classes

| Material class | Representative modulus | Representative actuation strain | Representative response time | Ref. |

| LCEs | ~0.1-10 MPa | Typically, ~10%-50% | Seconds-minutes | Ge et al.[20] |

| SMPs | ~1-1,000 MPa | Large recoverable strain is possible | Seconds-minutes | Ge et al.[22] |

| Hydrogels | ~1-200 kPa | Up to several hundred percent % | ms-min | Liu et al.[77] |

| Magnetic nanocomposite polymers | kPa-MPa | Field-driven deformation; strain depends on design and filler loading | ms-s | Chung et al.[23] |

LCEs

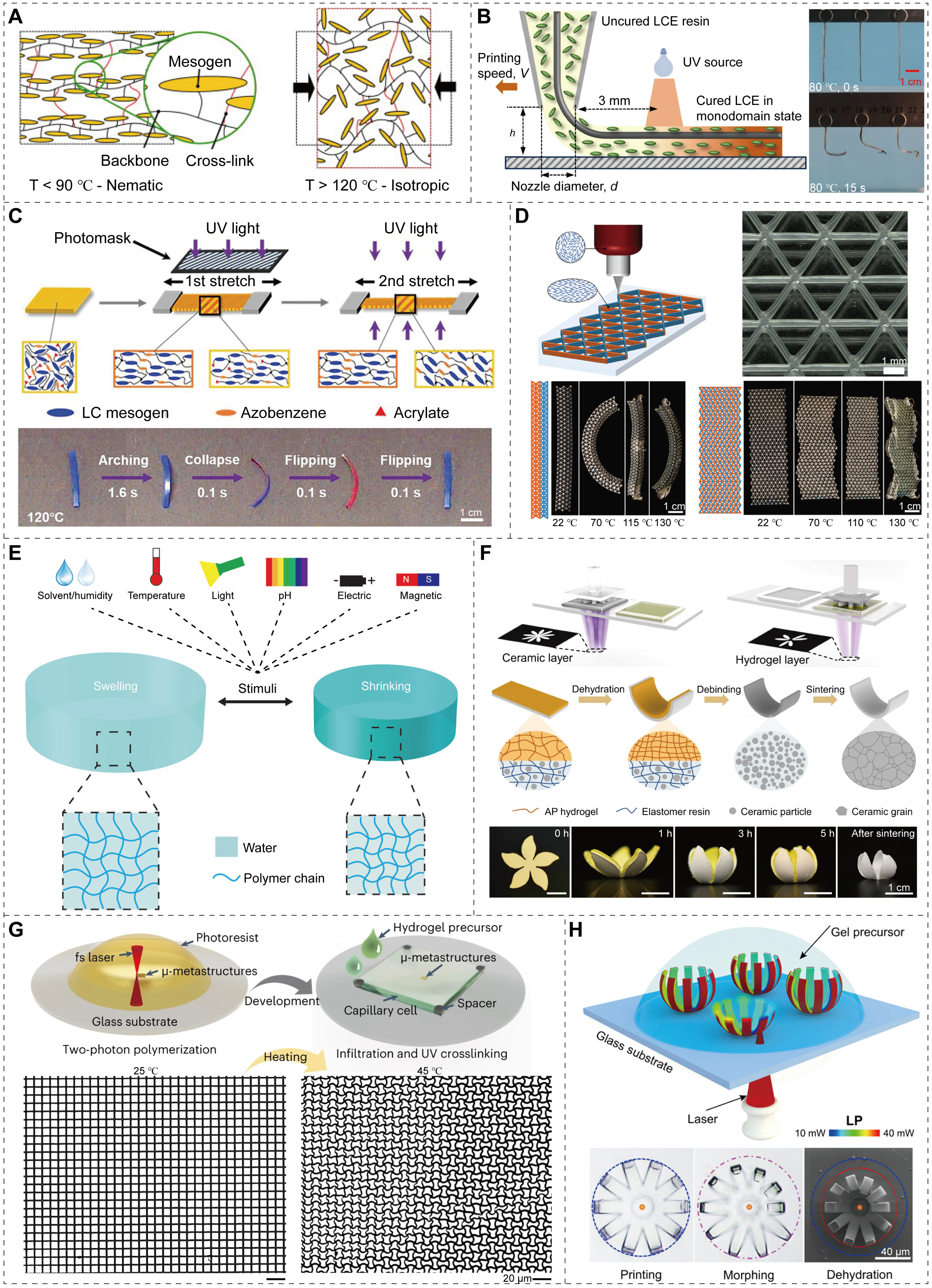

LCEs are lightly crosslinked polymer networks that combine long, flexible polymer chains with short, rigid rod-like mesomorphic units. These mesogens or liquid crystal molecules are integrated into the backbone (main chain) or attached as pendants to the backbone (side chain)[78]. Their distinct spatial alignments enable LCEs to exhibit different mesophases, including nematic, smectic, and cholesteric. Most LCEs are thermotropic, meaning that when the temperature exceeds the phase-transition temperature, the mesogens become disordered[79]. This disorder correlates with the macroscopic reversible anisotropic shape change of the LCEs, specifically manifested as contraction along the mesogenic orientation and expansion along the orthogonal direction [Figure 3A][80]. When the external stimulus is removed, the LCEs can revert to their original shape. Beyond direct heating, LCEs can be triggered by light, electro-, or magneto-joule heating, and solvent, exhibiting rapid, fully reversible deformation. This unique coupling of softness, reversibility, and programmable anisotropy positions LCEs as a cornerstone material for fabricating soft robotics, sensors, and adaptive devices.

Figure 3. 4D-printed soft microbots based on LCEs and stimuli-responsive hydrogels. (A) LCE actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[80]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier; (B) 4D-printed continuous fiber-reinforced LCE composite for programmable folding, high-force actuation, and electrical deformation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[81]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature; (C) Monolithic LCE robot with snap-trained self-sustained motion for switchable rolling and jumping with light-steered control. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[82]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (D) Multi-material LCE lattices with spatially programmed director fields for predictable reversible morphing via inverse design. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[83]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (E) Stimuli-responsive hydrogels actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[77]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; (F) DLP-printed hydrogel ceramic laminates for dehydration programmed morphing and sintered ceramic architectures. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[86]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature; (G) Thermally reconfigurable micro metastructures using transparent hydrogel artificial muscles for pixel-level information display. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[87]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (H) Stimuli-responsive hydrogel blocks assembled with DH parameters for true 3D-to-3D microscale transformers. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[88]. Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4D: Four-dimensional; LCEs: liquid crystal elastomers; DLP: digital light processing; DH: Denavit–Hartenberg; 3D: three-dimensional; UV: ultraviolet; LC: liquid crystal; AP: acid-poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate; LP: laser power.

Jiang et al. developed a 4D-printed LCE composite reinforced with continuous fibers[81]. By adjusting the printing pathway and selecting conductive or structural fibers, they programmed reversible folding, boosted actuation force and energy absorption, and achieved electrically induced shape deformation [Figure 3B]. Based on the same material, Zhou et al. fabricated a monolithic LCE robot trained to snap for self-sustained motion in a thermal gradient[82]. By modulating substrate adhesion or applying light, it switched between rolling and jumping and achieved real-time steering [Figure 3C]. Extending from devices to architected materials, Kotikian et al. printed multi-material LCE lattices with spatially programmed nematic director fields[83]. By setting local composition and using an inverse-design scheme, they realized predictable, reversible shape morphing across lattice topologies [Figure 3D].

As one of the most commonly used materials for 4D-printed microrobots, LCEs combine large reversible anisotropic strain, programmable orientation fields, and multi-stimulus actuation (heat, light, electromagnetic induction, solvents, etc.), and they exhibit excellent compatibility with printing processes such as DIW, TPP, and DLP. Their drawbacks include relatively low intrinsic modulus and force output, constrained response frequency due to thermal diffusion, hysteresis under cyclic loading, and phase-transition temperatures that are difficult to match to physiological conditions.

Stimuli-responsive hydrogels

Hydrogels are water-rich polymer networks (typically containing over 70% water by weight) formed through covalent chemical crosslinking or physical crosslinking via noncovalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic interactions, and crystallite formation[84]. The interplay of interactions fixes a 3D network that swells in water as osmotic pressure is balanced by network elasticity. Owing to their high porosity and permeability, hydrogels facilitate rapid diffusion of oxygen and nutrients and their moduli can be tuned across multiple orders of magnitude[85]. External stimuli such as humidity, temperature, light, pH, electrical, and magnetic signals can all modulate hydrogels, simultaneously inducing changes in their volume, stiffness, and shape [Figure 3E][77].

Using a photocurable ceramic elastomer slurry paired with a hydrogel precursor, Wang et al. printed hydrogel-ceramic laminates by DLP[86]. By programming dehydration of the hydrogel layer, flat patterns morphed into 3D shapes that converted to pure ceramics after sintering, guided by a curvature model accounting for both dehydration and sintering [Figure 3F]. In related work, Zhang et al. employed linearly responsive transparent hydrogel as artificial muscles to drive cooperative buckling in printed micro-metastructures[87]. By tailoring printing power, layer thickness, and unit-cell geometry, locally isotropic or anisotropic deformations were programmed, enabling thermally reconfigurable metalattices for pixel-level information display and concealment [Figure 3G]. Moving beyond planar self-folding, Huang et al. direct-laser-wrote two-photon-polymerizable, stimuli-responsive hydrogel building blocks and assembled them using Denavit-Hartenberg (DH) parameters to prescribe 3D kinematics, thereby achieving true 3D-to-3D transformations exemplified by a microscale “transformer” switching between a race car and a humanoid robot [Figure 3H][88].

For soft microrobots and 4D printing, hydrogels offer multiple advantages including biocompatibility, ease of processing, low cost, and seamless integration with other materials. However, their high-water content typically results in low tensile strength, creep, susceptibility to dehydration, and solvent-limited actuation speeds. Additional challenges include long-term stability, fatigue under cyclic loading, and maintaining fidelity in complex 3D constructions. Ongoing solutions combine graded crosslinking density architectures and multi-material design to deliver robust, biomimetic hydrogel actuators and sensors[89].

SMPs

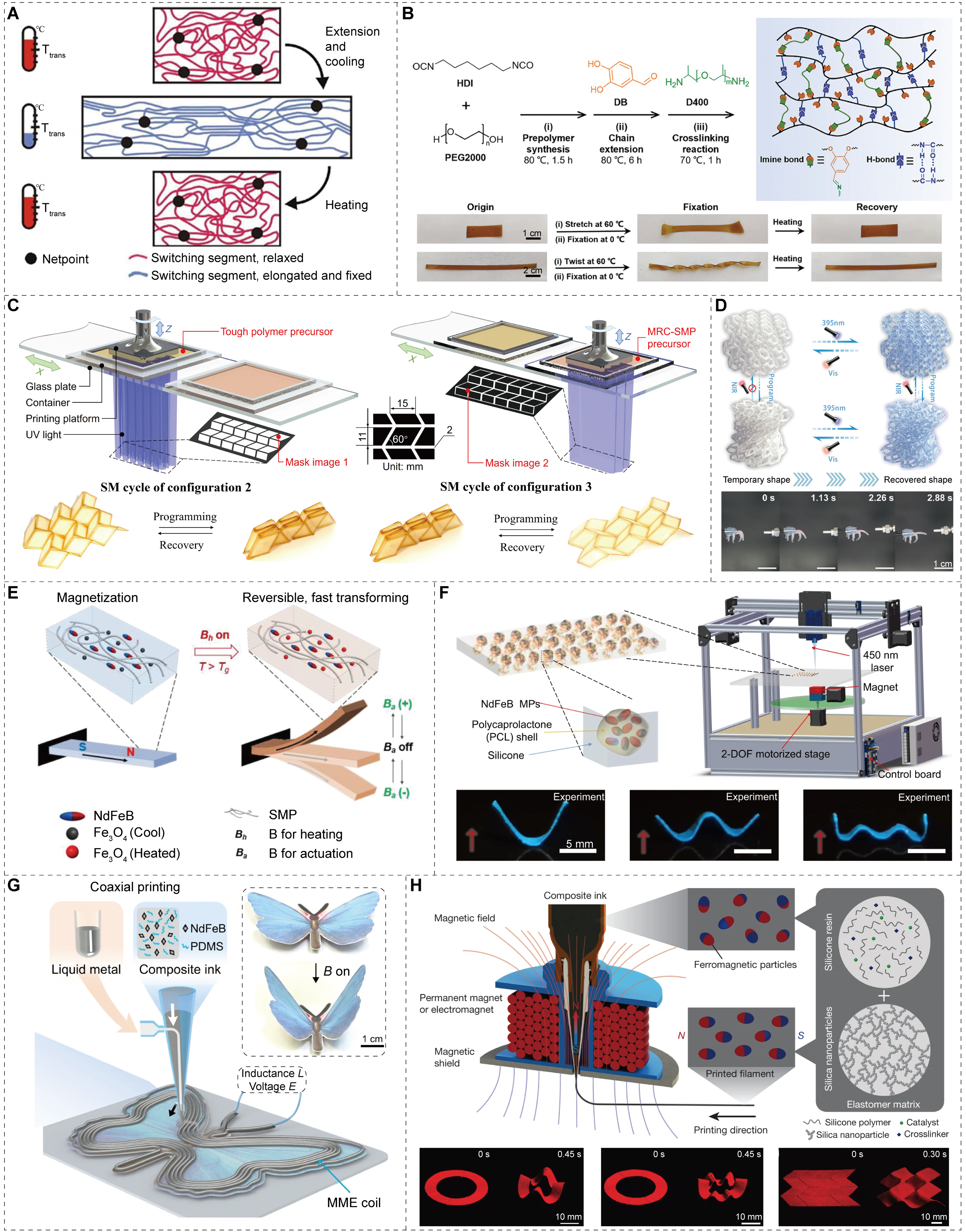

SMPs are polymer networks that can be temporarily fixed in a programmed shape and then recover their original geometry upon exposure to a stimulus, most commonly heat[90]. According to their network structure, SMPs can be primarily classified into two types: chemically crosslinked (glassy thermosets or semicrystalline rubbers) and physically crosslinked (amorphous thermoplastics or semicrystalline block copolymers)[91]. This memory effect arises from two structural elements: stable netpoints that define the permanent shape and switching segments that undergo reversible phase transitions to store and release strain. The shape-memory programming cycle typically comprises three stages: first, deforming the material to the desired shape under heating; second, fixing the temporary shape by cooling under constraint; and finally, recovering the original shape upon reheating [Figure 4A][92]. Although debates exist about classifying them as 4D printing due to the need for post-print programming, they remain a crucial component of 4D printing materials.

Figure 4. 4D-printed soft microbots based on SMPs and magnetic nanocomposite polymers. (A) SMP actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[92]. Copyright 2023, MDPI; (B) Dynamic covalent SMP artificial muscle with body temperature recovery, self-healing and recyclable biodegradable network. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[93]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (C) High-resolution DLP printed covalent adaptable SMP architecture for repeated reconfiguration. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[94]. Copyright 2024, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (D) WO2.9 nanoparticle doped SMP nanocomposite via DLP for optically addressable reversible morphing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[95]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (E) Magnetic nanocomposite polymers actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[96]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH; (F) Laser rewritable magnetic elastomer film for single field multimodal morphing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[100]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature; (G) Coaxial core sheath fiber for actuation sensing and wireless power. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[101]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (H) DIW ferromagnetic elastomer with aligned domains for rapid magnetic morphing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[102]. Copyright 2018, Springer Nature. 4D: Four-dimensional; SMPs: shape memory polymers; DLP: digital light processing; DIW: direct ink writing; HDI: hexamethylene diisocyanate; DB: 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde; UV: ultraviolet; SM: shape memory; MRC-SMP: mechanically robust covalent adaptable networks shape memory polymer; NIR: near infrared; MPs: microparticles; 2-DOF: two degrees of freedom; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; MME: magnetic-mechanical-electrical.

Kong et al. developed a dynamic covalent SMP network that transitions from rigid to pliable with heating and functions as an artificial muscle, combining reversible actuation, solvent resistance, self-healing, recyclability, and biodegradability[93]. By setting the recovery temperature close to physiological levels, the material achieves body-relevant shape recovery [Figure 4B]. Building on reconfigurability, Li et al. formulated mechanically robust covalent adaptable network SMPs for high-resolution DLP printing[94]. By leveraging extreme deformability at reconfiguration temperatures alongside a glass transition near 75 °C, one printed architecture can be reconfigured multiple times for different tasks [Figure 4C]. To introduce optical addressability, Feng et al. prepared a photoswitchable WO2.9 nanoparticle-doped SMP nanocomposite for DLP[95]. Utilizing trace amounts of WO2.9 below 0.20 wt.‰ to provide controlled photothermal absorption, the printed structures exhibited remotely and spatially controllable, reversible shape morphing with high stretchability in the rubbery state and fatigue resistance over repeated cycling [Figure 4D].

In practical applications, SMPs offer many advantages including large recoverable strains, high shape fixation, low density, and adjustable activation temperatures, broadening their applications in robotics, aerospace, and biomedicine. Key limitations include response times governed by thermal diffusion; creep and residual strain under cyclic loading; environmental sensitivity to moisture or solvents; and long-term stability of network structures and additives.

Magnetic nanocomposite polymers

Magnetic nanocomposite polymers combine a soft polymer matrix (elastomer, hydrogel, or thermoplastics/thermosets) with dispersed magnetic fillers. These magnetic materials are typically iron oxide (Fe3O4/γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles, metallic Fe/Co/Ni, or micro- to nanoscale hard magnets such as NdFeB [Figure 4E][96-98]. Their magneto-mechanical response arises from field-particle interactions. In soft-magnetic systems, field-induced magnetization generates dipole–dipole forces and torques that reconfigure the matrix. In hard-magnetic systems with remanent magnetization, preprogrammed magnetization vectors produce deterministic bending, twisting, or folding under uniform or rotating fields, while magnetic field gradients provide the net force for locomotion[99]. In this way, complex deformations and multi-degree-of-freedom behaviors are achieved at micro- to millimeter scales.

Deng et al. developed a laser-rewritable magnetic composite film consisting of an elastomer matrix and magnetic particles encapsulated by a phase-change polymer[100]. Transient laser heating melts the coating to reorient particles under a programming field, enabling a single actuation field to induce multistate switches and multimodal 3D morphing in soft robots [Figure 4F]. Using coaxial printing, Zhang et al. produced hybrid magnetic-mechanical-electrical core-sheath fibers that integrate a magnetoactive sheath with a conductive core[101]. This material system enables programmable magnetization, somatosensory feedback, magnetic actuation, and simultaneous wireless energy transfer, as demonstrated in a flexible catheter, a durable gripper, and an untethered soft robot [Figure 4G]. By applying a magnetic field during DIW of an elastomer loaded with ferromagnetic microparticles, Kim et al. aligned particles at the nozzle to program ferromagnetic domains[102]. The resulting printed composites transformed rapidly between complex 3D shapes under magnetic fields, unlocking auxetic metamaterials, reconfigurable soft electronics, and soft robots with high power density [Figure 4H].

For 4D-printed soft microrobots, magnetic nanocomposite polymers offer wireless, rapid, and deep penetration control through fluids or tissues. They are also compatible with multiple fabrication routes (DIW, DLP, SLA, TPP, and molding), and offer multifunctionality such as imaging contrast, localized heating, and embedded sensing. Key limitations include challenges with filler dispersion and sedimentation, narrowed printability windows due to increased viscosity, particle aggregation and oxidation, and trade-offs between magnetic loading and mechanical compliance or fatigue life. Other disadvantages include the scale of actuation strength with volume and with the available field or gradient, which constrains the operational range to very small spaces. Hysteresis and magnetothermal losses can cause heating and drift, and careful surface functionalization and encapsulation are required to ensure long-term biostability and minimal cytotoxicity.

Material challenges

Despite rapid progress, material selection for 4D-printed soft microrobots remains constrained by several coupled technical factors. First, printability, responsiveness, and robustness form an inherent trade-off: formulations that enable large stimulus-induced strain often exhibit lower modulus, weaker interlayer bonding, and higher susceptibility to creep, hysteresis, and fatigue, whereas mechanically robust networks frequently respond more slowly or with smaller deformation amplitudes. Second, the fidelity of anisotropy programming (e.g., director alignment, gradient formation, or multi-material interfaces) is often limited by process-induced defects, voxel-level heterogeneity, and relaxation after printing, leading to variability in shape-morphing trajectories. Third, long-term stability in aqueous or ionic environments can be compromised by hydrolytic or enzymatic degradation for biodegradable networks, stress relaxation, and solvent or ion exchange, which shift transition thresholds and reduce repeatability[103]. In addition, repeated swelling and deswelling cycles can progressively alter network morphology and mechanical properties, accelerating damage accumulation and performance drift[104]. Notably, hydrogels that appear tough under monotonic loading may still fail under cyclic actuation due to fatigue fracture, highlighting the importance of reporting fatigue-relevant metrics such as fatigue thresholds or crack propagation rate in addition to fracture energy[105]. Finally, translation requires attention to biocompatibility and safety, including potential particle leaching, residual monomers, sterilization tolerance, and predictable degradation products[106]. Addressing these issues typically demands synergistic optimization of polymer chemistry, filler-matrix interactions, and printing parameters, together with standardized mechanical and actuation characterization protocols[2].

STIMULI

Stimuli play a crucial role in inducing deformation of 4D-printed soft microrobots. They can trigger changes in composition, arrangement, phase, molecular structure, conformation, molecular/atomic packing, and other factors within smart materials, releasing stored stress/strain and converting them into deformation and motion. Currently, common actuation methods include heat, light, electric field, magnetic field, ultrasound, and chemical stimuli. Each approach presents distinct trade-offs in penetration depth, spatiotemporal addressability, energy density, environmental compatibility, and safety. Beyond qualitative pros and cons, actuation performance is ultimately governed by a set of technical limits: (i) energy coupling efficiency, namely how effectively the stimulus generates stress/strain; (ii) response time set by transport processes (diffusion/thermal conduction) or dynamic balance (torque vs. viscous drag); (iii) control bandwidth and stability (step-out, overshoot, or crosstalk in multi-field operation); and (iv) safety and compatibility constraints (thermal dose, electrochemical reactions, ultrasound intensity, and imaging/actuation interference). Therefore, the selection of an actuation scheme should align with the microrobot’s material composition and target application scenario. Detailed comparisons and recent advancements for each method are provided in the subsequent sections.

Light

Light serves as a non-contact, rapidly switchable stimulus capable of delivery with high spatiotemporal precision. By adjusting its wavelength, intensity, polarization direction, and exposure pattern, it can drive 4D-printed soft microrobots. Activation generally follows two pathways. In photothermal approaches, absorbers (e.g., dyes[107], carbon nanomaterials[108], plasmonic particles[109]) convert optical energy into heat, inducing local phase transitions, modulus changes, or differential thermal strains that bend or twist printed structures. In photochemical schemes, photoswitches (e.g., azobenzene, spiropyran) or photo-labile bonds alter molecular conformation, crosslinking density, or mesogen order [Figure 5A][110].

Figure 5. Light and heat actuation of 4D-printed soft microbots. (A) Light actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[110]. Copyright 2021, MDPI; (B) DIW TiNC/LCE photochromic actuator with near infrared photothermal bending, for reprogrammable barcode and origami/kirigami forms. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[111]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (C) Azobenzene-ink LCE swimmer with UV/green light photochemical propulsion without laser tracking. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[29]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (D) DIW supramolecular LCE light actuators with reversible morphing in air and water. The scale bars are 5, 5, and 2.5 mm, respectively. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[112]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH; (E) Heat actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[30]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society; Reproduced with permission from Ref.[115]. Copyright 2022, American Association for the Advancement of Science; Reproduced with permission from Ref.[114]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; (F) Thermally actuated 4D printed soft robot with eccentric hinges for tunable crawling, rolling, oscillating, and passive energy harvesting. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[116]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (G) Electrothermal LCE bimorph with patterned silver nanowire heaters for programmable bidirectional crawling and confined obstacle traversal. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[117]. Copyright 2023, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (H) Ambient heat powered LCE self-rolling robot with twisted and helical ends for autonomous maze navigation on granular terrain. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[118]. Copyright 2023, American Association for the Advancement of Science. 4D: Four-dimensional; DIW: direct ink writing; LCE: liquid crystal elastomer; UV: ultraviolet; NIR: near infrared; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; RGO: reduced graphene oxide; LMs: liquid metals.

Chen et al. formulated a light-driven titanium-based nanocrystal (TiNC)/LCE composite material suitable for DIW-printing[111]. UV irradiation writes and erases photochromic states, and near-infrared illumination provides photothermal bending and gripping, enabling a single printed object to be globally or locally reprogrammed into barcode patterns and origami- or kirigami-inspired 3D forms [Figure 5B]. Building upon the light-driven principle, Sartori et al. introduced azobenzene-based photopolymerizable inks to print LCE swimmers[29]. These inks rapidly responded to moderate UV and green light through a predominantly photochemical mechanism, producing synchronous lappet bending and propulsion without localized laser tracking [Figure 5C]. Extending light responsiveness while simplifying fabrication, Lugger et al. synthesized supramolecular LCE inks for DIW[112]. These inks do not require photo-crosslinking and still deliver reversible shape change under light in air and water via a combination of photothermal and photochemical triggering, allowing complex director architectures such as re-entrant honeycombs and spirals [Figure 5D].

Light stimulation offers numerous unique advantages for driving 4D-printed soft microrobots. However, limitations arise from tissue scattering or absorption of light, potential photothermal damage or drift, and photobleaching or fatigue of chromophores.

Heat

Thermal stimulation drives 4D-printed soft microrobots by coupling temperature with material phase, modulus, and internal stress. These materials include hydrogels, LCEs, SMPs, and others. Heating can be applied through direct contact via hot plates or microheaters, or generated remotely through Joule heating in conductive fillers, magnetic induction, hysteresis, or photothermal conversion in embedded nanoparticles such as carbon nanotubes or plasmonic particles [Figure 5E][113-115]. Quantitatively, the resulting temperature rise and actuation speed are often governed by transient heat transport, which can be expressed as

Ren et al. introduced a self-sustaining soft robot with eccentric hinges that exploits thermal actuation[116]. By using parameter-encoded 4D printing to preset local strain, the robot harvests a constant thermal field to deliver tunable crawling, rolling, and oscillating, with proofs-of-concept as an optical chopper and a power generator [Figure 5F]. Using electrothermal actuation, Wu et al. patterned silver-nanowire heaters within an LCE-based thermal bimorph so that programmable Joule heating sets spatial temperature and curvature profiles, enabling energy-efficient, caterpillar-inspired bidirectional crawling and traversal through confined obstacles [Figure 5G][117]. Powered solely by ambient heat, Zhao et al. crafted LCE self-rolling robots whose asymmetric twisted and helical ends endow sustained self-turning[118]. By combining with self-snapping for motion reflection, these robots navigate complex multichannel mazes on granular terrains and through narrow gaps without onboard control [Figure 5H].

Heat is highly attractive due to its ease of generation, compatibility with many printable chemicals, tunable transmission in printed parts, and the ability to be triggered within specific time frames. However, it also has some drawbacks, including slower response times due to diffusion transmission, fatigue or creep under repeated cycling, and difficulty matching physiological temperatures in in-vivo applications.

Magnetic field

Magnetic actuation in 4D-printed soft microrobots is achieved by coupling external magnetic fields to magnetically responsive particles embedded within the material. Torques generated by uniform or rotating fields induce bending, twisting, folding, or whole-body rotation, while field gradients produce net forces for translation or lifting [Figure 6A][119]. Magneto-responsive composites are formed by dispersing micro or nanoscale superparamagnetic or ferromagnetic particles into soft polymer matrices, enabling programmable deformations under remote control. Owing to their noncontact operation and deep penetration, these systems hold significant promise for biomedicine, microfluidics, and soft robotics[120].

Figure 6. Magnetic and electric field actuation of 4D-printed soft microbots. (A) Magnetic field actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[119]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature; (B) DIW printed metamaterials with neodymium microparticles for magnetically programmable multistate stiffness. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[124]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (C) UV curable ferromagnetic origami film for wireless magnetic folding and gastric delivery. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[31]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (D) Fe3O4 polymer microgripper with embedded heaters for magnetic opening and power-free shape memory closure. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[125]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (E) Electric field actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[127]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society; (F) Electrothermal PEEK SMP composite actuator with printed conductive ink for reversible shape morphing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[128]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (G) Untethered LCE soft robot with integrated Joule heating for grasping and obstacle traversal. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[32]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society; (H) Self-sensing heterogeneous polymer composites with Joule heating for high load lifting and multigait crawling. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[129]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH. 4D: Four-dimensional; DIW: direct ink writing; UV: ultraviolet; PEEK: poly(ether ether ketone); SMP: shape memory polymer; LCE: liquid crystal elastomer; EA: electro adhesive.

A magnetic soft microrobot with volume v can be viewed as a composite body possessing effective magnetization M, which is induced or programmed under an applied magnetic field B. In a spatially varying field, a net magnetic force F arises and can be expressed in

whereas in a (quasi) uniform field, the robot experiences a magnetic torque τ as expressed in

which tends to align the body’s preferred magnetization direction with the field[121]. These relations emphasize two practical trends. First, for a fixed field strength and gradient, the attainable force and torque scale approximately with the robot volume v, which explains why actuation strength quickly shrinks as devices are miniaturized unless stronger gradients or higher effective magnetization are available. Second, particle loading influences actuation mainly through M. Increasing the magnetic filler volume fraction generally enhances the effective susceptibility or magnetization, but the improvement can become less than proportional at high volume fraction due to saturation and interparticle interactions, and it is strongly affected by dispersion quality[122]. In particular, aggregation, sedimentation, or nonuniform particle distribution can reduce the effective M even at the same loading, leading to lower force density and larger variability[123]. The preferred magnetization axis is often dictated by geometry, but can also reflect crystalline anisotropy, and it can be intentionally programmed by aligning magnetic nanostructures within the matrix or by premagnetizing the composite along a prescribed direction.

Chung et al. reported magnetically tunable stiffness metamaterials in which magnetic torque served as the actuation source[124]. Using DIW of a styrene-isoprene-styrene matrix filled with neodymium microparticles and a ternary programming scheme, the metamaterial switched among soft, moderate, and stiff states with rapid response, and a 3D array enabled multi-layer stiffness control under external fields [Figure 6B]. Building on magnetic actuation, Zhang et al. 3D-printed soft magnetoactive origami films from UV curable elastomers loaded with up to 75 wt.% ferromagnetic particles[31]. Wireless magnetic fields set polarity and drove folding and locomotion for targeted gastric drug delivery and terrain adaptive locomotion [Figure 6C]. To avoid continuous magnetic fields during gripping, Wu et al. developed an electrothermal magnetic shape memory microgripper based on Fe3O4-filled polymers with embedded resistive wires[125]. The magnetic field opened the gripper while electrothermal-triggered shape memory effect closed and locked it without power, yielding about 0.9 s response and a high load-to-weight ratio [Figure 6D].

Magnetic drive is noncontact, deeply penetrating, rapidly switchable, and effective in opaque or sealed media. It requires no onboard power supply and integrates naturally with microfluidic and biomedical environments. Its main challenges include the force availability scaling proportionally with part volume and magnetic field or gradient, step-out, hysteresis or heat generation at high actuation frequencies, possible demagnetization, particle agglomeration or leaching, matrix stiffening at high filler loadings, and manufacturing issues such as sedimentation, rheology control, and print fidelity.

Electric field

The electric actuation in 4D-printed soft microrobots relies on field-charge interactions that convert electrical inputs into fluid flow, pressure gradients, or electrostatic stress. A representative mechanism is electro-osmosis[126], where an applied electric field drives cations toward the negative electrode, establishing an internal-external ion concentration gradient. This induces solvent diffusion and osmotic pressure, thereby generating programmable expansion and bending [Figure 6E][127]. By tuning electric field magnitude, frequency, phase, and electrode geometry, deformation amplitude and direction can be controlled to achieve motions such as rolling, walking, or crawling. Quantitatively, when electrostatic stress is the dominant driver, the effective Maxwell pressure P follows a compact scaling relation p = εE2, where ε is permittivity and E is the electric field, highlighting that achievable stress increases with permittivity and scales with the square of the field strength.

Wang et al. fabricated electrically activated reversible composite actuators via 4D printing that combined a conductive ink with shape memory poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK)[128]. Under electrical excitation, the electrothermal sintering of the ink and the phase transition of PEEK produced controlled and repeatable deformation, which the author validated under varied current amplitudes, circuit designs, and printing conditions [Figure 6F]. Building on electric actuation in soft systems, Xia et al. integrated 4D-printed LCE actuators with associated electronics to realize an untethered robot[32]. A modified LCE paired with a polyimide heating film and a silicone adhesive delivered tunable transition temperature and modulus and sufficient propulsive force, so the compact robot grasped objects and traversed obstacles on challenging terrains [Figure 6G]. Extending electrothermal control to higher stiffness, Morales Ferrer et al. introduced multiscale heterogeneous polymer composites with tunable electrical conductivity for Joule heating and self-sensing[129]. Electrically controllable bilayers morphed from flat sheets into a self-standing lifting robot with record weight-normalized load and actuation stress, and a printed lattice demonstrated multigait crawling while carrying up to 144 times its own weight [Figure 6H].

In summary, electric actuation offers fast response, precise spatiotemporal addressability, easy programmability, and straightforward integration with printed electrodes and conductive pathways, which is attractive for on-chip manipulation and compact soft robots. Limitations include rapid field attenuation in conductive or ionic media, electrolysis and Faradaic reactions at low frequencies, electrode fouling and delamination, safety constraints for in vivo use, and limited penetration depth compared with magnetic or ultrasound fields.

Ultrasound

Ultrasonic actuation has become an effective stimulus for inducing shape changes in smart materials. By converting acoustic energy into mechanical forces, fluid flows, or localized heating, it drives the deformation and locomotion of 4D-printed soft microrobots [Figure 7A][130]. Ultrasound-related parameters such as amplitude, frequency, and duty cycle collectively determine force output, response speed, and motion patterns. Consequently, the approach has found broad application in controlled drug release, soft robotics, and mechanosensing[131].

Figure 7. Ultrasound and chemical stimuli actuation of 4D-printed soft microbots. (A) Ultrasound actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[130]. Copyright 2024, National Academy of Sciences; (B) Acoustically activated micromachine with stiffness programmed soft hinges for millisecond folding. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[130]. Copyright 2024, National Academy of Sciences; (C) Ultrasound-driven hydrogel micromachine with variable-stiffness hinges for rapid letter-to-character morphing and fast channel navigation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[33]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier; (D) Focused ultrasound phase transition soft robot for millimeter scale selective actuation and Newton level force. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[132]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature; (E) Chemical stimuli actuation mechanism. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[119]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature; (F) TPP printed micro hinged hydrogel actuator driven by pH-responsive hydrogel muscles for programmable multi-degree of freedom folding. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[34]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (G) 3D laser lithography scaffold with β-cyclodextrin adamantane chemistry for reversible chemically actuated cell stretching. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[134]. Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (H) 4D printed humidity-actuated seed-like soft robot from biodegradable hygroscopic polymers for autonomous reshaping and soil interaction. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[135]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH. 4D: Four-dimensional; TPP: two-photon polymerization; 3D: three-dimensional; RH: relative humidity.

Zhang et al. introduced an acoustically activated micromachine that used preprogrammed soft hinges with different stiffness[130]. Under an acoustic field, the hinges concentrated acoustic energy through intensified oscillation and delivered millisecond folding with selectable morphologies by adjusting acoustic power [Figure 7B]. Building on this concept, Xiao et al. developed an acoustically actuated hydrogel micromachine with variable stiffness hinges that oscillated strongly under ultrasound and produced transformations within 500 ms[33]. The folding was preprogrammed to convert between letters and characters, and a 174 μm wide microrobot navigated narrow channels at about 800 μm/s [Figure 7C]. Extending acoustic control to spatially selective and forceful operation, Hao et al. proposed a focused ultrasound-induced phase transition strategy that inflated internal volumes to generate Newton-level forces with millimeter-scale addressability[132]. A proof-of-concept robot is proposed for transporting liquid cargo and performing biopsy and patching [Figure 7D].

Ultrasound provides remote, noninvasive and deep penetration control, and is capable of operating in opaque media with rapid response. However, Precise localization and directional control are challenging due to scattering and attenuation of acoustic fields in heterogeneous tissues, and the necessity to manage thermal side effects to meet safety constraints.

Chemical stimuli

Chemically, actuation in 4D printing converts interactions between molecules and external chemical environments into controllable shape changes. Typical triggers include pH, ionic strength changes, solvent exchange, humidity, and specific ions or ligands [Figure 7E][119]. They alter bond equilibria to modify network connectivity and stiffness. Geometric shapes and chemical stimuli must be selected together, as diffusion and reaction kinetics determine the response rate. Thin films, high porosity, and spatial patterning can accelerate reaction progress and enable directional driving. These principles have been well demonstrated in stimulus-responsive hydrogels and polymers[133].

Cao et al. developed a biomimetic micro-hinged actuator driven by stimuli-responsive hydrogel muscles[34]. A pseudo-rigid body model described large folding while maintaining high stiffness. The hinge arrays produced by multi-step TPP enable multi-degree-of-freedom and programmable shape deformation [Figure 7F]. Hippler et al. introduced a chemical actuation strategy using β-cyclodextrin and adamantane photoresist[134]. 3D laser lithography created composite scaffolds, and adding soluble competitive guests under physiological conditions triggered reversible expansion to stretch cells and then return to the initial state [Figure 7G]. To harness ambient cues for untethered operation, Cecchini et al. designed a humidity-actuated seed-like soft robot using biodegradable hygroscopic polymers patterned by 4D printing[135]. Environmental moisture changes drove reversible reshaping and soil interaction, enabling the robot to generate approximately 30 μN m of torque, about 2.5 mN of extensional force, and lift objects weighing about 100 times its own mass [Figure 7H].

Compared to physical fields, chemical stimuli are more readily accessible as they do not require specialized equipment, exhibit biocompatibility in many formulations, and can be easily integrated with microfluidics for localized delivery. Chemical stimulation requires sufficient interaction between chemicals and responsive materials, leading to key challenges such as diffusion-limited rates (typically ranging from minutes to hours), the need for sustained contact and reagent management, byproduct accumulation and leaching, and precise spatiotemporal control.

Hybrid actuation

Multi-stimulus strategies are increasingly adopted in 4D-printed soft microrobots because a single stimulus rarely satisfies the full set of requirements for navigation, reconfiguration, and task execution simultaneously. A common and practical design paradigm is to decouple functions across stimuli - for example, using magnetic fields for continuous, untethered positioning and steering - while leveraging a second stimulus, such as chemical cues or temperature, to trigger localized shape morphing, gripping, or on-demand release. A representative chemical magnetic example was reported by Xin et al., who fabricated pH-responsive, shape-morphing microrobots by laser printing, where magnetic propulsion guided the robot to the target region and a mild pH environment triggered programmed opening or closing for cargo handling and drug release[136]. Similarly, Hu et al. demonstrated a thermos-magnetic hybrid soft robot enabled by 4D printing, in which temperature-dependent material response was combined with magnetic actuation to achieve multimodal reconfiguration and motion[137]. Despite these advantages, multi-stimulus systems also introduce specific challenges, including stimulus cross-talk and calibration complexity, increased material and printing burden for multi-functional integration, and safety constraints such as thermal management or chemical compatibility in biomedical settings. Therefore, achieving robust multi-stimulus synergy typically requires careful stimulus selection with sufficient orthogonality, as well as systematic characterization and control strategies that remain reliable across realistic environments.

APPLICATIONS

The 4D printing technology transforms stimulus-responsive materials into microrobots capable of altering their shape, stiffness, and functionality on demand, making it a highly promising manufacturing technique. Previous review articles have demonstrated the significant application potential of 4D-printed soft microrobots across biomedical, defense, and electronic fields[9,138]. This section focuses on showcasing the latest representative application advancements, including targeted drug delivery, tissue engineering, stent, sensing, and other applications.

Targeted drug delivery

The 4D-printed soft microrobots offer a compelling pathway for targeted drug delivery[139]. By coupling stimuli-responsive architectures with shape-morphing mechanics, these devices can be deployed invasively, and then expand, clamp, or conform to local physiological structures to resist flushing and anchor in dynamic environments such as the stomach, bladder, airways, or vasculature. Activation and release can be driven by clinically compatible cues, including magnetic fields, ultrasound, light, temperature, pH, or enzyme activity, enabling the targeted delivery of small molecules and biologics.

Xin et al. developed environmentally adaptive shape morphing microrobots by programming differential expansion in pH-responsive hydrogels[136]. Propelled magnetically, a crab-like microrobot performed targeted microparticle gripping, transport, and release, while a fish-like microrobot encapsulated doxorubicin at pH ~7.4 and released it in mildly acidic media to treat HeLa cells in a model vascular network [Figure 8A]. Building toward gastric resident delivery, Bellinger et al. designed a swallowable capsule that deployed a star-shaped drug carrier in the stomach[140]. The carrier unfolded to maintain residence and delivered antimalarial doses for weeks before disassembly, thereby addressing compliance issue in treatment barriers [Figure 8B]. Extending organ retention to the gastrointestinal tract, Ghosh et al. created parasite-inspired mechanochemical theragrippers capable of autonomously latching onto mucosa for about twenty-four hours, extending the elimination half-life of ketorolac tromethamine by roughly sixfold[141]. This demonstrated that shape-changing microdevices can prolong drug delivery [Figure 8C].

Figure 8. Applications in targeted drug delivery, tissue engineering, and stents. (A) Magnetically propelled pH-responsive hydrogel microrobots for targeted gripping, transport, and pH-triggered doxorubicin release. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[136]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society; (B) Swallowable capsule with a star-shaped gastric carrier for multi-week antimalarial delivery and improved adherence. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[140]. Copyright 2016, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (C) Mechanochemical theragrippers for mucosal attachment and extended gastrointestinal drug release. Scale bars: 100 μm. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[141]. Copyright 2020, American Association for the Advancement of Science; (D) Biodegradable magnetic shape memory cardiac occluder for patient-specific repair. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[145]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; (E) Graphene nerve guidance conduit with reprogrammable shape morphing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[146]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH; (F) Bilayer morphing membrane for conformal scaffolds and enhanced bone formation. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[147]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (G) Shape memory tracheal stent with porous antibacterial anti-biofilm surface. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[150]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (H) Shape memory hydrogel with programmable recovery for timed stent deployment. Scale bars:

Tissue engineering

Tissue engineering aims to develop alternative tissues for regenerating and healing damaged tissues[142]. The 4D-printed soft microrobots integrate biocompatible, stimulus-responsive architectures with living cells to create scaffolds that not only support but actively guide regeneration, thereby introducing morphodynamics into tissue engineering[143]. Unlike static scaffolds, these shape-deformable structures can be invasively delivered in compact form, then unfold, bend, or self-assemble into patient-specific geometries. This enhances defect conformity, suture-free fixation, and early mechanical stability. Subsequently, their programmed transformations and tunable stiffness profiles provide time-sequenced mechanical and topographical cues that promote cell polarization, collective migration, extracellular matrix deposition, vascular ingrowth, and maturation[144].

Lin et al. demonstrated biodegradable and patient-specific shape-memory occlusion devices for cardiac defect repair, incorporating Fe3O4 into a PLA matrix for remote magnetic deployment after implantation[145]. The devices supported cell adhesion and ingrowth that promoted rapid endothelialization and offered a degradable alternative to metal occluders [Figure 8D]. Moving from cardiovascular repair to neural regeneration, Miao et al. created a multi-responsive architecture by SLA, employing stress-induced transformation and solvent relaxation to realize reprogrammable shape changes[146]. Graphene-hybridized nerve guidance conduit provided physical guidance, chemical cues, dynamic self-entubulation, and seamless integration to support nerve repair [Figure 8E]. Extending the concept to osteogenesis, You et al. fabricated a bilayer morphing membrane that combined a SMP layer and a hydrogel layer to regulate microstructure and macroscopic geometry in vivo[147]. By precisely timing the transition between stem cell proliferation and differentiation states while non-invasively conforming to defect contours, the membrane achieved over 30% greater new bone formation compared to static controls [Figure 8F]. In parallel, 4D bioprinting has enabled self-forming vascular architectures that can provide perfusable, conformal conduits for vascular tissue engineering, offering a complementary pathway for building functional tissue interfaces in situ[148].

Stent

The 4D-printed soft stents extend patient-customized 3D stents by incorporating programmable morphing and active dynamic properties. This stent achieves catheter-level compression for non-invasive delivery and on-demand expansion in response to clinically compatible signals such as body temperature, magnetic or photothermal heating, pH/ionic changes, or ultrasound. This capability allows it to resist displacement and adapt to peristalsis, maintaining lumen patency while minimizing epithelial damage[149]. Target sites span the airway, esophagus, blood vessels, ureter, and biliary ducts.

Maity et al. 3D-printed shape-memory tracheal stents using flexible photopolymerizable polypropylene glycol and polycaprolactone inks and implemented an in-situ welding strategy of thin layers to reduce the insertion profile and increase flexibility[150]. Porous architectures reduced mucus plugging, polypropylene glycol-modified surfaces and ciprofloxacin loading provided anti-biofilm and antibacterial functions. In vitro assays supported cytocompatibility and anti-adhesion properties [Figure 8G]. To address temporal control for implant deployment, Ni et al. developed a 4D printable phase-separating shape memory hydrogel that changed shape at ambient or body temperature with a programmable delay in recovery onset[15]. This naturally triggered yet actively controllable behavior supported stent concepts that required precise scheduling without external hardware [Figure 8H]. Extending toward gastrointestinal applications, Lin et al. created shape memory biocomposites triggered near body temperature and printed biodegradable biomimetic intestinal stents with tunable transition temperature[151]. The wavy network designs matched nonlinear tissue mechanics to minimize wall irritation, and biodegradability avoided the secondary endoscopic removal [Figure 8I].

Sensing

In 4D-printed soft microrobots, the integrated paradigm where the body itself functions as a sensor is replacing the traditional approach of constructing the structure first and then attaching sensors. Through multi-material co-printing, load-bearing skeletons, actuation, and sensing are synergistically designed and formed within the same configuration, thereby transforming deformation itself into readable signals[152].

Ali et al. used DLP to 3D print Fresnel lenses incorporating thermochromic pigments[153]. This optical device can both focus light and report temperature through stimulus-related color shifts, establishing a material-based sensing strategy [Figure 9A]. Transitioning from property modulation to functional conversion, Wu

Figure 9. Applications in sensing and other fields. (A) DLP printed thermochromic Fresnel lens for light focusing and temperature sensing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[153]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier; (B) 4D-printed magnetoelectric device for self-powered pressure sensing and intrusion warning. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[154]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH; (C) Fiber tip TPP printed polymer microcantilever with magnetic tip for weak field magnetic sensing. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[155]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (D) UV-assisted DIW hygroscopic LCE actuator for humidity-driven motion and environmental readout. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[156]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (E) Femtosecond laser nanoprinted all optical fiber sensilla for bidirectional airflow monitoring. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[157]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society; (F) Magnetic soft robotic fish for reusable water purification. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[158]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (G) TPP structural color lattices for reversible pH sensing and anti-counterfeiting. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[159]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH; (H) DLP printable UV curable SMP for large strain, fatigue-resistant micro actuators in aerospace. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[160]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. DLP: Digital light processing; 4D: four-dimensional; TPP: two-photon polymerization; UV: ultraviolet; DIW: direct ink writing; LCE: liquid crystal elastomer; SMP: shape memory polymer.

Other applications

The on-demand shape-changing and dynamic properties of 4D-printed structures also demonstrate significant potential in fields such as water purification, textiles, aerospace, construction, and photonics.

Qin et al. developed a magnetic soft robotic fish for water purification by combining Fe3O4 with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) and carboxymethyl chitosan. It released liquid water through phase transition, while magnetic actuation enhanced absorption and enabled remote retrieval for repeated removal of dyes, microbes, and insoluble particles [Figure 9F][158]. In the field of photonics, Liu et al. used TPP to print microscopic structural color lattices with feature resolution (98 nm), mapped full-color palette pixels, and achieved reversible pH-controlled sensors, anti-counterfeiting labels, and transformable optical devices [Figure 9G][159]. Progressing from photonics to aerospace, Zhang et al. reported a mechanically robust UV curable SMP system compatible with DLP[160]. The system enabled printing of complex micro-scale features, delivered large reversible shape changes and high fatigue resistance, and supported high-performance actuators for flight-related structures [Figure 9H].

Table 3 consolidates representative 4D-printed soft microrobot demonstrations discussed in this section and highlights their fabrication routes, materials, actuation schemes, size scales, and target applications, providing an at-a-glance summary.

Representative studies on 4D-printed soft microrobots

| Printing method | Material system | Actuation | Key function | Ref. |

| TPP | pH-responsive hydrogel and magnetic particles | Magnetic field and pH | Localized cancer therapy | Xin et al.[136] |

| FDM | Shape memory PLA with Fe3O4 magnetic particles | Magnetic field | Tissue engineering | Lin et al.[145] |

| DLP | Photo-polymerizable PPG/PCL | Heat | Stent | Maity et al.[150] |

| DLP | UV-curable resin | Heat | Sensing | Ali et al.[153] |

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This review systematically outlines the entire chain of 4D-printed soft microrobots, spanning manufacturing, materials, actuation, and applications. In fabrication, we surveyed representative routes including DIW, FDM, SLA, DLP, and TPP, along with their limits in feature size and geometric complexity. For materials, we focused on LCEs, stimuli-responsive hydrogels, SMPs, and magnetic nanocomposite polymers, and summarized stress/strain anisotropy programming via director alignment, functional gradients, and multi-material assembly. Regarding actuation, we compared light, heat, magnetic field, electrical field, ultrasound, and chemical stimuli, along with their mechanisms and applicable scenarios. On applications, we highlighted targeted drug delivery, tissue engineering, stent, sensing, and other applications.

Despite significant advancements in 4D printing, challenges and opportunities remain in three primary aspects. At the manufacturing level, there exists a triple trade-off among resolution, throughput, and multi-material coordination. Interlayer adhesion and formation fidelity limit the long-term reliability of micrometer-scale complex architectures. At the material level, it remains difficult to balance large programmable deformation, output force density, biocompatibility, and degradability, while mitigating hysteresis, creep, and environmental drift. At the system level, standardized tests, in vivo imaging, localization and navigation protocols remain lacking. In particular, closed-loop image-guided control is a central translational bottleneck. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides deep penetration, excellent soft-tissue contrast, and 3D capability (well-suited for magnetically responsive systems) but is costly and constrained by temporal resolution and hardware compatibility[161,162]; ultrasound is portable and real-time with favorable safety, yet tracking can be affected by speckle and limited visibility near gas/bone interfaces, and robust 3D state estimation often requires multi-view acquisition or advanced reconstruction[163,164]; optical coherence tomography (OCT) offers micrometer-scale resolution and fast imaging for precise state observation but is restricted to shallow depths and optically accessible scenarios[165,166]; and X-ray provides deep penetration and high frame rates with established clinical workflows but faces radiation burden, limited soft-tissue contrast, and 2D projection ambiguity[167,168]. Simulation models still fall short in capturing real-time dynamic responses and multi-physics coupling, while cross-laboratory reproducibility and ethical compliance remain underdeveloped.