Application of polymeric nanomaterials in cancer therapy: from smart delivery to precision therapy

Abstract

Although conventional modalities such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy have markedly reduced cancer incidence, they are frequently accompanied by profound adverse effects, including systemic toxicity and the emergence of multidrug resistance. While advances in immunotherapy and targeted therapy have addressed certain limitations, such as the need for precision drug delivery, cancer treatment continues to face major challenges, particularly in overcoming tumor biological barriers to enhance therapeutic efficacy and prevent acquired resistance. With the rapid advent of novel biomaterials, polymer-based nanoparticles are reshaping traditional drug delivery paradigms and accelerating the evolution of precision oncology and intelligent drug delivery platforms. Nevertheless, comprehensive and systematic investigations remain limited regarding how polymer nanoparticles can overcome the inherent drawbacks of conventional delivery strategies in oncology. This review aims to systematically synthesize recent advances in the application of polymer nanoparticles for cancer therapy. We highlight how the intrinsic properties of polymeric nanomaterials - such as chemical tunability, stimuli-responsive mechanisms, surface engineering, and multifunctional integration - enable breakthroughs in drug synergy, tumor barrier penetration, and spatiotemporally controlled delivery. Furthermore, we delineate the major challenges and future directions in this rapidly evolving field, with the aim of providing a conceptual framework and potential roadmap for the next generation of cancer therapeutics.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Cancer remains one of the most formidable global health threats, with chemotherapy and radiotherapy serving as the most commonly employed therapeutic modalities. While these conventional approaches can effectively reduce tumor burden, they are frequently associated with severe adverse effects[1]. In addition to targeting malignant cells, chemotherapeutic agents exert profound cytotoxic effects on normal tissues and organs, inducing gastrointestinal, hepatic, renal, cardiac, neurological, and hematopoietic toxicities, as well as oral mucositis, all of which substantially compromise patients’ quality of life[2]. Moreover, radiotherapy may paradoxically foster a pro-metastatic milieu by inducing the expression of metastasis-promoting factors in diverse tissues and organs, thereby elevating the risk of tumor dissemination[3]. Another critical barrier to effective cancer therapy is intratumoral heterogeneity. Given the extensive variability in chromosomal alterations, molecular characteristics, and phenotypic attributes among tumor cells, treatment regimens often yield highly unpredictable and individualized outcomes[4]. While certain subpopulations of tumor cells may be intrinsically sensitive to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, others may exhibit refractory behavior, ultimately diminishing therapeutic efficacy. Multidrug resistance further compounds this challenge, as sustained chemotherapy can drive the emergence of resistant cancer cell clones, markedly reducing treatment effectiveness[5]. For instance, tumor cells may evade therapeutic pressure by upregulating drug efflux pumps, thereby lowering intracellular drug concentrations and impairing pharmacological efficacy[6]. In addition, resistance may arise through alterations in apoptotic signaling pathways or enhanced DNA repair capacity, enabling malignant cells to withstand chemotherapeutic insult[7,8].

In recent years, innovative therapeutic strategies such as nanomedicine and targeted therapy have garnered increasing attention. Targeted therapy seeks to enhance therapeutic specificity and efficacy by selectively recognizing and attacking molecular markers unique to malignant cells. Nevertheless, its clinical effectiveness remains hindered by suboptimal targeting efficiency, largely attributable to the complexity of the tumor microenvironment and the adaptive capacity of cancer cells[9]. Consequently, a substantial fraction of the administered agents accumulates in normal tissues, thereby elevating the risk of adverse effects while attenuating antitumor efficacy[10]. In addressing multidrug resistance, nanomedicine has emerged as a promising avenue, largely propelled by advances in nanocarrier development[11].

With the advent of nanotechnology and the expanding diversity of nanoparticles, significant progress has been achieved in disease diagnosis, therapeutic delivery, and treatment[12,13]. Owing to their dimensions, which are comparable to those of biomolecules and cellular structures, nanomaterials can be precisely engineered at the nanoscale, thereby enhancing their interactions with biological systems. For example, key behaviors of nanoparticles in vivo - such as circulation time, biodistribution, and cellular uptake - can be effectively modulated by tailoring their size, shape, and surface properties[14]. Furthermore, nanomaterials can be designed to integrate multiple functions simultaneously, including therapy, imaging, and drug transport. By incorporating targeting ligands, fluorescent probes, and chemotherapeutic agents into nanocarriers, accurate tumor diagnosis and treatment can be achieved, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy while enabling real-time monitoring of therapeutic responses. For nanotechnology to be clinically effective in oncology, however, it must overcome formidable biological barriers. These barriers - including mucus layers, the blood-brain barrier, and the extracellular matrix of tumors - substantially limit therapeutic penetration and efficacy. Rationally engineered nanomaterials are capable of traversing such barriers[14-17]. For instance, liquid-core nanoparticles, owing to their mechanical flexibility and deformability, can penetrate deeply into tumor tissues, cross the blood-brain barrier, and traverse mucus layers and bacterial biofilms, thereby enhancing intratumoral drug accumulation[14].

With their highly versatile chemical and physical properties, polymer nanoparticles offer unique and powerful advantages in cancer therapy. This tunability is primarily reflected in the ability of researchers to rationally design polymer structures with tailored functions through careful monomer selection, precise adjustment of molecular weight, and modulation of the hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic balance. Such control facilitates the formation of amphiphilic architectures capable of self-assembling into micelles, thereby enabling efficient drug encapsulation and improving the delivery of hydrophobic anticancer agents[18]. Further optimization of nanoparticle size and stability enhances cellular uptake and cytotoxic activity[19], while simultaneously promoting specific interactions between drug-loaded nanoparticles and cancer cell surface receptors, thus improving the precision and efficacy of targeted delivery[20]. In addition, diverse stimuli-responsive mechanisms - including acid-labile bond cleavage, enzyme-sensitive peptide linkages, disulfide bond reduction, and photothermal or thermosensitive phase transitions - can be engineered to respond to tumor microenvironmental cues or external stimuli, enabling site-specific, on-demand drug release with high precision[21-25]. Another critical advantage of polymer nanoparticles lies in their exceptional drug-loading and delivery capacity. Through structural optimization, certain systems can achieve drug-loading efficiencies exceeding 70%[26]. Surface modification with polyethylene glycol (PEGylation), leveraging PEG’s hydrophilicity and steric hindrance, markedly extends nanoparticle half-life in systemic circulation, reduces immune clearance, and enhances tumor site accumulation[27]. Clinical applicability is further supported by superior biocompatibility and safety profiles: synthetic biodegradable polymers - such as Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and polycaprolactone (PCL) - as well as natural polymers such as chitosan and alginate, typically demonstrate excellent tissue compatibility, with their degradation products readily metabolized and eliminated[28,29]. Moreover, biomimetic surface modifications, such as red blood cell membrane coating, can substantially reduce immunogenicity while further improving biocompatibility[30]. Finally, the extensive functionalization potential of polymer nanoparticles enables versatile multifunctional integration[31]. Targeting ligands can be conjugated to the polymer surface or backbone to actively direct nanoparticles toward tumor cells[32]. Imaging probes, such as fluorescent dyes or magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents, can be incorporated to facilitate real-time monitoring of therapeutic processes[33]. In addition, multiple stimuli-responsive groups can be engineered into a single platform to create intelligent theranostic systems that seamlessly integrate diagnosis and therapy. In summary, polymeric nanomaterials hold great promise for overcoming the limitations of conventional cancer treatments by combining precise targeting, controlled drug release, high loading efficiency, prolonged systemic circulation, excellent biocompatibility, and multifunctional integration.

This review aims to illustrate how polymer nanoparticles, through precise therapeutic strategies and intelligent delivery, overcome critical challenges in cancer treatment, including drug resistance, tumor heterogeneity, and treatment-associated toxicities. It systematically traces the progression from material design to clinical translation by delineating their chemical tunability, stimuli-responsive mechanisms, and advantages of multifunctional integration. To provide a theoretical framework for next-generation cancer diagnosis and therapy, the review first examines the classification, morphological engineering, and functionalization strategies of polymeric nanomaterials. It then explores their multimodal applications in chemosensitization, gene regulation, immune modulation, and integrated theranostics. Finally, the review highlights emerging approaches such as biomimetic camouflage and in situ assembly, while addressing delivery barriers, toxicity management, and manufacturing challenges that must be resolved for successful clinical translation.

DESIGN STRATEGIES OF POLYMERIC NANOMATERIALS: FROM BASIC CONSTRUCTION TO FUNCTIONAL INNOVATION

Material sources and classification

Natural polymers

Natural polymers have unique advantages in cancer treatment, including safe sources, inherent biocompatibility, and well-defined metabolic pathways. Polysaccharide natural polymers such as chitosan, alginate, and hyaluronic acid possess good biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low immunogenicity [Table 1][34,35]. Chitosan is abundantly derived and possesses amino and hydroxyl groups in its molecular architecture, facilitating diverse chemical alterations for the fabrication of drug carriers and tissue engineering scaffolds. Chitosan nanoparticles can encapsulate nucleic acid medicines via electrostatic interactions for gene delivery[29]. Alginate presents mild gelation characteristics, creating hydrogels under gentle circumstances for cellular or medical encapsulation, facilitating prolonged release and protective benefits. Hyaluronic acid exhibits a strong affinity for CD44 receptors on the tumor cell surface, making it appropriate for nanocarriers aimed at targeting tumor cells[36].

Source and classification of polymers

| Classification | Polymer substrates | Name | Source | Refs. |

| Natural polymers | Polysaccharide | Chitosan | Crustacean exoskeletons, Cell walls of fungi | [29,34,35] |

| Alginate | Brown seaweed | [34,35] | ||

| Hyaluronic acid | Rooster combs, Umbilical cords, Microorganisms | [34-36] | ||

| Protein | Collagen | Animal tissues, Recombinant protein production systems | [37] | |

| Silk fibroin | Silkworm cocoons | [37] | ||

| Albumin | Blood plasma | [38] | ||

| Synthetic polymers | Degradable synthetic polymer | PLGA | Ring-opening polymerization of lactide and glycolide | [44] |

| PCL | Ring-opening polymerization of ε-caprolactone | [45] | ||

| Non-degradable synthetic polymer | PEI | Polymerization of ethyleneimine | [46] | |

| PS | Polymerization of styrene | [46] | ||

| TPU | Reaction of diisocyanate with polyol | [47] |

Protein-derived natural polymers, including collagen and silk fibroin, demonstrate exceptional bioactivity and biocompatibility. Collagen comprises a primary element of the extracellular matrix, facilitating cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Collagen-derived nanoparticles can create the surroundings of the extracellular matrix for use in tissue engineering and drug delivery applications. Silk fibroin displays superior mechanical features and biocompatibility and can be processed into nanofibers via electrospinning and different strategies for drug delivery in wound healing and tumor treatment[37]. Albumin nanoparticles, such as Abraxane®, generally facilitate targeted drug delivery through the ligand-binding ability on the protein surface[38].

Moreover, natural polymers can create composite materials that can address particular polymer shortcomings. The combination of alginate with pectin, chitosan, and gelatin, as well as albumin with gelatin, can strengthen the mechanical energy and discharge qualities of medicine carriers, improving the efficiency of drug delivery systems[38,39]. Using multi-polymer composites improves material targeting and discharge, reducing drug poisoning in healthy tissues[40].

With judicious design and enhancement, natural polymers could function as efficient drug delivery vehicles, significantly improving the therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects, therefore giving cancer patients safer and more effective therapy options[41,42].

Synthetic polymers

Synthetic polymer nanoparticles have a high potential for cancer treatment because of their flexible structures and properties. These materials may perform specific natural activities through the meticulous chemical design that improves the biocompatibility and transport efficiency of medications necessary for cancer therapy[43].

Degradable synthetic polymers, including polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid, and their copolymer PLGA, exhibit excellent biocompatibility and customizable degradation rates. They can progressively decompose in the body by hydrolysis or enzymatic activity into non-toxic monomers, which are ultimately metabolized and eliminated. PLGA has been extensively used in drug delivery systems, including the formulation of microspheres and nanoparticles, to facilitate sustained drug release[44]. PCL is a widely utilized degradable polymer characterized by a low glass transition temperature and melting point, enabling it to retain flexibility at body temperature, hence promoting drug release[45].

Non-degradable synthetic polymers have unique advantages in the manufacture of drug-sustained-release devices due to their excellent stability and mechanical properties. For example, polyethyleneimine (PEI) is widely used in gene therapy due to its strong nucleic acid loading capacity. However, the significant toxicity of PEI limits its clinical application, and surface functionalization is required to reduce its material toxicity. As a commonly used synthetic polymer, although polystyrene is non-biodegradable, its inherent toxicity is greatly reduced through surface functionalization, imparting specific biological functions and enabling widespread applications[46]. The thermoplastic polyurethane may be modified to meet various drug delivery requirements because of its hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties[47].

Morphology and structural engineering: physical dimensions for performance optimization

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles, a prevalent type of polymeric nanomaterials, are distinguished by their diminutive size and extensive specific surface area, enhancing medication loading capacity and cellular absorption efficiency. Optimizing the behavior of nanoparticles in vivo can be achieved by manipulating their size, shape, and surface characteristics. Smaller nanoparticles (< 100 nm) can easily pass through the capillary endothelial gaps in tumor tissues, facilitating passive targeted accumulation; conversely, larger nanoparticles

Polymeric micelles

Polymeric micelles are nanostructures created by the self-assembly of amphiphilic polymers in aqueous solutions, with a hydrophobic core and a hydrophilic shell. The hydrophobic core contains arctic pharmaceuticals, increasing their absorption and stability, and the hydrophilic shell shortens interactions with plasma proteins, thus prolonging circulation duration. PEG-PLA micelles are often used to deliver anticancer medications. Changing the ratio of PEG and PLA may regulate the size, stability, and drug release characteristics[49].

Dendrimers

Dendrimers have a highly branched three-dimensional structure since they have multiple functional groups on their surface, making them better suited for modification and drug loading. Meanwhile, the internal cavity of dendrimers is conducive to better accommodating drug molecules, thus having a higher drug loading capacity. In addition, the clear structure and size controllability are also conducive to the precise regulation of drug release by dendrimers. For example, after surface modification, polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers can better achieve targeted delivery to tumor cells and have been used to deliver a variety of drugs and genes. However, the high toxicity of PAMAM remains to be resolved[50].

Nanogels

Nanogels are polymeric entities featuring a three-dimensional network, distinguished by their hydrophilicity and swelling characteristics, which enable them to absorb substantial quantities of water while preserving a defined morphology. Nanogels can be fabricated through either physical or chemical cross-linking, with their internal network architecture providing an efficient platform for drug loading and release. Owing to their nanoscale dimensions and polymeric nature, nanogels exhibit favorable biocompatibility and tissue penetration. Moreover, in response to tumor microenvironmental cues, such as variations in temperature or pH, heat- or pH-responsive nanogels can undergo reversible swelling or contraction, thereby enabling precise, stimuli-triggered drug release[51].

Multifunctional composite structures

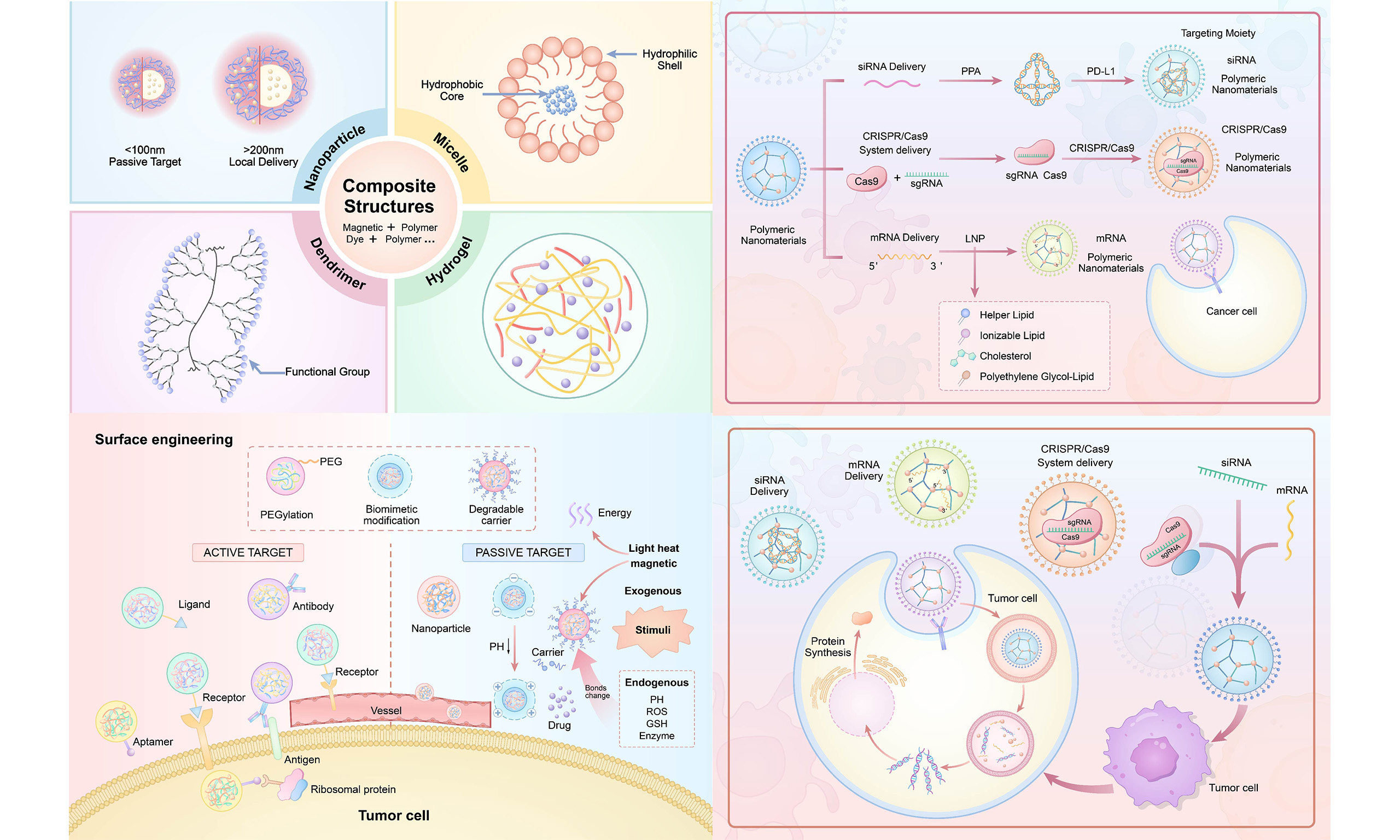

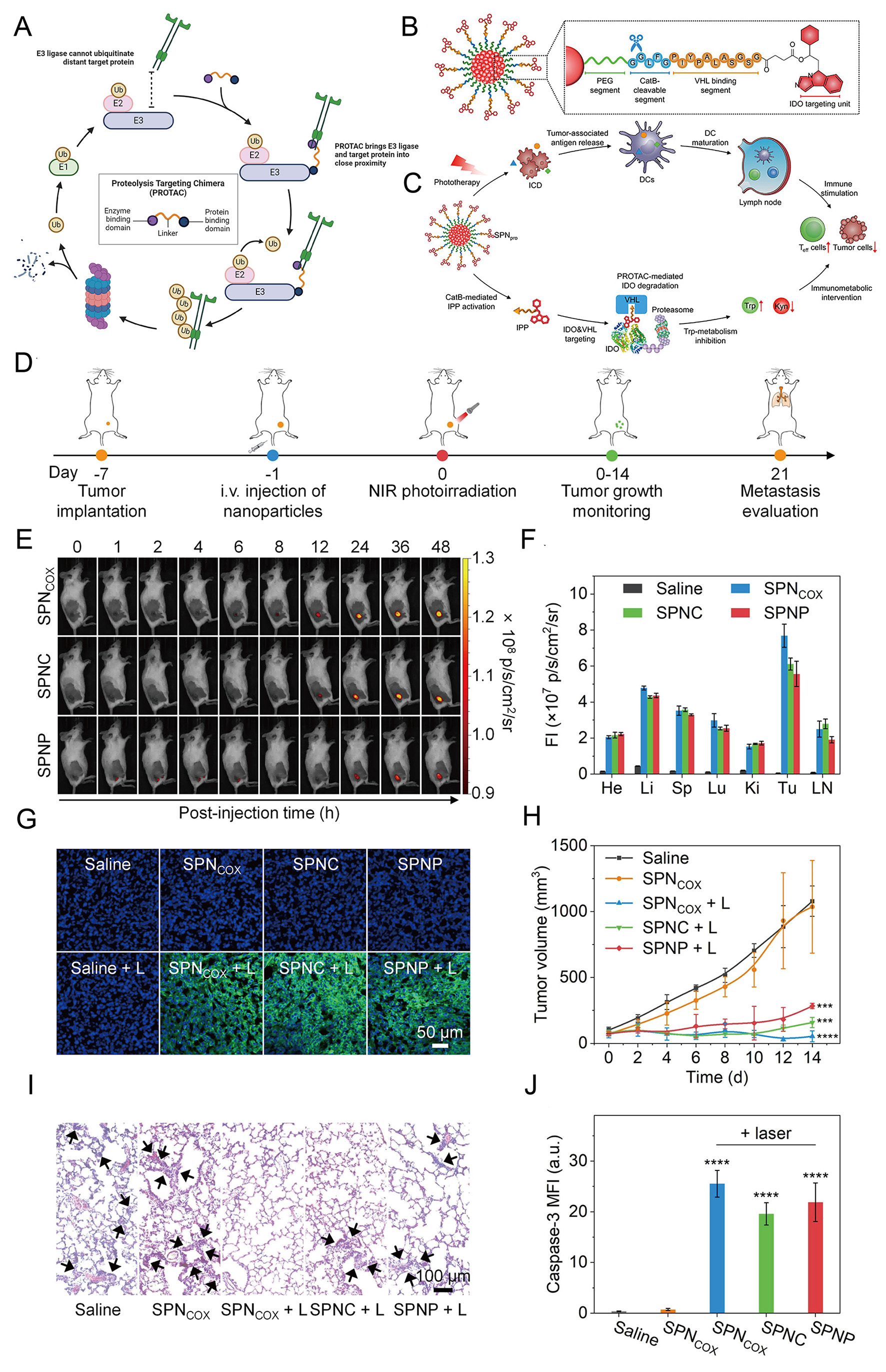

Multifunctional composite structures are designed by integrating diverse materials or architectures to achieve synergistic therapeutic and diagnostic advantages. For instance, the incorporation of magnetic nanoparticles into polymeric nanomaterials enables the fabrication of magnetically responsive composite nanostructures, suitable for magnetic-targeted drug delivery and magnetic hyperthermia. Similarly, polymers can be conjugated with quantum dots (QDs), fluorescent dyes, or other functional agents to realize integrated imaging and therapeutic applications[52]. A representative example is the development of a pH/magnetic dual-responsive hemicellulose-based nanocomposite hydrogel (Fe3O4@XH-Gel), prepared via graft polymerization of hemicellulose followed by in situ doping with Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles. This system demonstrated remarkable pH- and magnetic-responsive behavior, along with superior controlled-release properties under gastrointestinal conditions[53]. QDs conjugated with polymers exhibit significant potential for integrated tumor diagnostics and therapy. For example, poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH)-coated CdSe/ZnS QDs can simultaneously enable fluorescence imaging and drug delivery. Their synergistic functionality arises from the combination of the high fluorescence stability of QDs with the controlled-release properties of polymers, facilitating real-time tumor monitoring and therapy[54]. Similarly, polymer-extracellular vesicle (EV) hybrid systems leverage the innate targeting ability and low immunogenicity of EVs to enhance the biocompatibility and tumor-targeting efficiency of nanomedicines. Integrating EVs with synthetic nanoparticles further improves cellular uptake and drug release efficiency, thereby potentiating therapeutic outcomes[55]. Figure 1 depicts polymers with diverse architectures.

Figure 1. Polymeric nanomaterials with different structures. (A) Structure of nanoparticles. (B) Structure of micelles. (C) Structure of dentrimers. (D) Structure of nanogels. (E) Construction of polymer-based magnetic responsive nanocomposite. Copyright Elsevier, 2024[53]. (F) Construction of a pH-responsive microcapsule for the controlled release of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots. Copyright ACS Publications, 2016[54]. (G) Construction of extracellular vesicle-facilitated nanoparticles. Copyright ACS Publications, 2023[55]. Figure created by MEDGY. cNPs: Cationic polymer nanoparticles; PLGA: poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid); PEGDA: poly (ethylene glycol) diacrylate; AA: acrylic acid; MVBs: multivesicular bodies; EVs: extracellular vesicles.

Functionalization strategies: from passive targeting to intelligent response

The functionalization strategies of polymeric nanomaterials have evolved from passive targeting to intelligent response. Passive targeting mainly relies on the physiological characteristics of tumor tissues, such as the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The endothelial cell gaps in tumor vasculature are larger, and the lymphatic drainage system is imperfect, allowing nanomaterials to passively accumulate in tumor tissues through blood circulation. Polymer nanoparticles between 10 and 100 nanometers can use the EPR effect to promote tumor cell development, which increases drug accumulation at the tumor site[56].

However, passive targeting has a limited selection of efficiency and usefulness. Active targeting techniques have been developed to enhance the ability to use nanomaterials to target tumor cells. Active targeting involves changing the surface of nanomaterials with certain ligands, such as antigens, peptides, or aptamers, allowing them to specifically identify and bind to antigens or receptors overexpressed on the surface of tumor cells, achieving active identification and binding[31,32,57].

With intelligent response functionalization, nanomaterials can respond to the tumor microenvironment or external stimulation to release the drug precisely. The tumor microenvironment has distinct physical and chemical characteristics (acidic pH, high redox potential, and high expression of specific enzymes). These polymeric nanomaterials can be designed to be sensitive to these microenvironmental factors. Additionally, nanomaterials designed to respond to external stimuli, such as light, heat, and magnetic fields, can achieve spatiotemporally controlled drug release and therapy[21].

Surface engineering of polymeric nanomaterials to enhance biocompatibility

PEGylation is a method widely used in the surface engineering of polymeric nanomaterials to prolong the circulation time of nanomaterials in the bloodstream. PEG has faculties that include excellent hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and little immunogenicity. A hydrated film is formed by attaching PEG to the surface of nanomaterials, reducing the interaction between nanomaterials and plasma proteins, which decreases the likelihood of recognition and clearance by the immune system, thereby achieving extended circulation time. Simultaneously, it promotes accumulation in tumor tissues through the EPR effect[27].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that PEGylated nanoparticles significantly improve half-lives in vivo. In studies of PEGylated liposomes, polymeric vesicles exhibited markedly prolonged circulation times compared with their non-PEGylated counterparts, enhancing drug delivery to tumor tissues[58]. However, the extensive clinical use of PEGylated nanomaterials has highlighted the issue of “PEG immunogenicity”. Prolonged exposure can induce the formation of anti-PEG antibodies in some patients, which may bind to PEGylated nanocarriers and trigger the “accelerated blood clearance” (ABC) phenomenon, ultimately reducing therapeutic efficacy[59]. Scientists have explored various strategies to address this issue, including modifying PEG’s molecular weight, size, and composition, as well as experimenting with alternative polymers in place of PEG. In addition, high-molecular-weight-free PEG can be added to drug formulations to reduce the binding of anti-PEG antibodies to PEGylated drugs, thereby restoring their prolonged circulation[59].

Biomimetic modification involves covering natural cell membranes or their components onto the surface of polymeric nanomaterials, bestowing the nanomaterials with specific physiological functions. Red blood cell membranes on polymer nanoparticles exhibit immune evasion and long circulation. Several proteins are present on the surfaces of red blood cell membranes, including CD47, which acts as a “do not eat me” message and can communicate with the signal regulatory (SIR)-positive (SIRP) sensor on the surface of macrophages, preventing cells from phagocytosing nanoparticles, increasing the length of time nanoparticles remain in blood circulation. For example, Fe3O4 nanoparticles covered with red blood cell membrane have a greatly prolonged circulation time in vivo and do not arouse a notable security response[60].

Nanoparticles wrapped in tumor cell membranes exhibit strong homologous targeting and homing capabilities. On the surface of tumor cell membranes, specific proteins and antigens enable the nanoparticles to specifically recognize and bind to the surface of tumor cells, achieving homologous targeting. Coating tumor cell membranes on the surface of nanoparticles may promote preferential accumulation of nanoparticles in tumor tissues, improving drug delivery precision[61].

Nanoparticles coated with macrophage or stem cell membranes conform to the tumor surroundings and allow effective infiltration. Macrophages migrate to inflammation sites or tumor tissues. Nanoparticles encased in macrophage membranes can use this to continually infiltrate the extracellular matrix of tumor cells, thereby promoting distribution within the tumor. Because of the similar qualities of stem cell membranes, nanoparticles can better conform to the tumor microenvironment and be targeted effectively[62].

To improve cellular uptake, transmembrane peptides such as transactivating transcriptional activator (TAT) and octaarginine (R8) may be modified. Transmembrane peptides target the cell membrane, and their modification on the surface of nanomaterials may facilitate the internalization of these nanomaterials into cells. For example, nanoparticles modified with TAT have a significantly higher uptake within cells compared to unmodified nanoparticles, which helps to improve the intracellular delivery efficiency of drugs and enhance therapeutic effects[63].

In comparison, PEGylation effectively prolongs nanoparticle circulation half-life - from several hours to tens of hours - and reduces immune recognition; however, it may elicit anti-PEG antibodies, triggering the ABC phenomenon and limiting its long-term applicability[64]. Conversely, biomimetic modifications, such as coatings derived from red blood cell or tumor cell membranes, offer superior immune evasion, enhanced biocompatibility, extended circulation, and a lower risk of immune activation[65]. Nonetheless, their preparation is complex, batch-to-batch reproducibility is challenging, and clinical translation remains difficult[66]. In summary, PEGylation is better suited for short-term, high-dose therapeutic regimens, whereas biomimetic modifications hold greater promise for long-term, personalized treatment strategies.

The responsive restoration of the tumor microenvironment is a crucial method to improve the effectiveness of polymer nanoparticles in cancer treatment. Degradable carriers can disintegrate within the tumor microenvironment, facilitating profound penetration. The tumor microenvironment possesses distinct physical and chemical properties, including acidic pH, elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the presence of certain enzymes. Creating degradable carriers responsive to these parameters can elicit structural modifications at the tumor site, facilitating medication release and enhancing the infiltration of nanomaterials into tumor tissues. In some pH-sensitive polymer-carriers, acid-sensitive connections cleave in the mildly acidic environment of tumors, leading to carrier decline, drug release, and a decreased nanomaterial size, promoting diffusion inside tumor tissues[67].

Exosomes and cell membrane components allow the replication of authentic biological interfaces. Exosomes are nanoscale vesicles released by cells that contain lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins for intercellular communication. Integrating exosomes with polymer nanoparticles or simulating the cell membrane on the nanomaterial surface can improve their biocompatibility and targeting functions. Exosomes originating from tumor cells can transport tumor-specific antigens, and when integrated with polymeric nanomaterials, they can facilitate targeted delivery to tumor cells. Furthermore, nanomaterials that emulate cell membrane constituents might enhance interactions with biological systems, mitigate immunological reactions, and augment drug delivery efficacy[68].

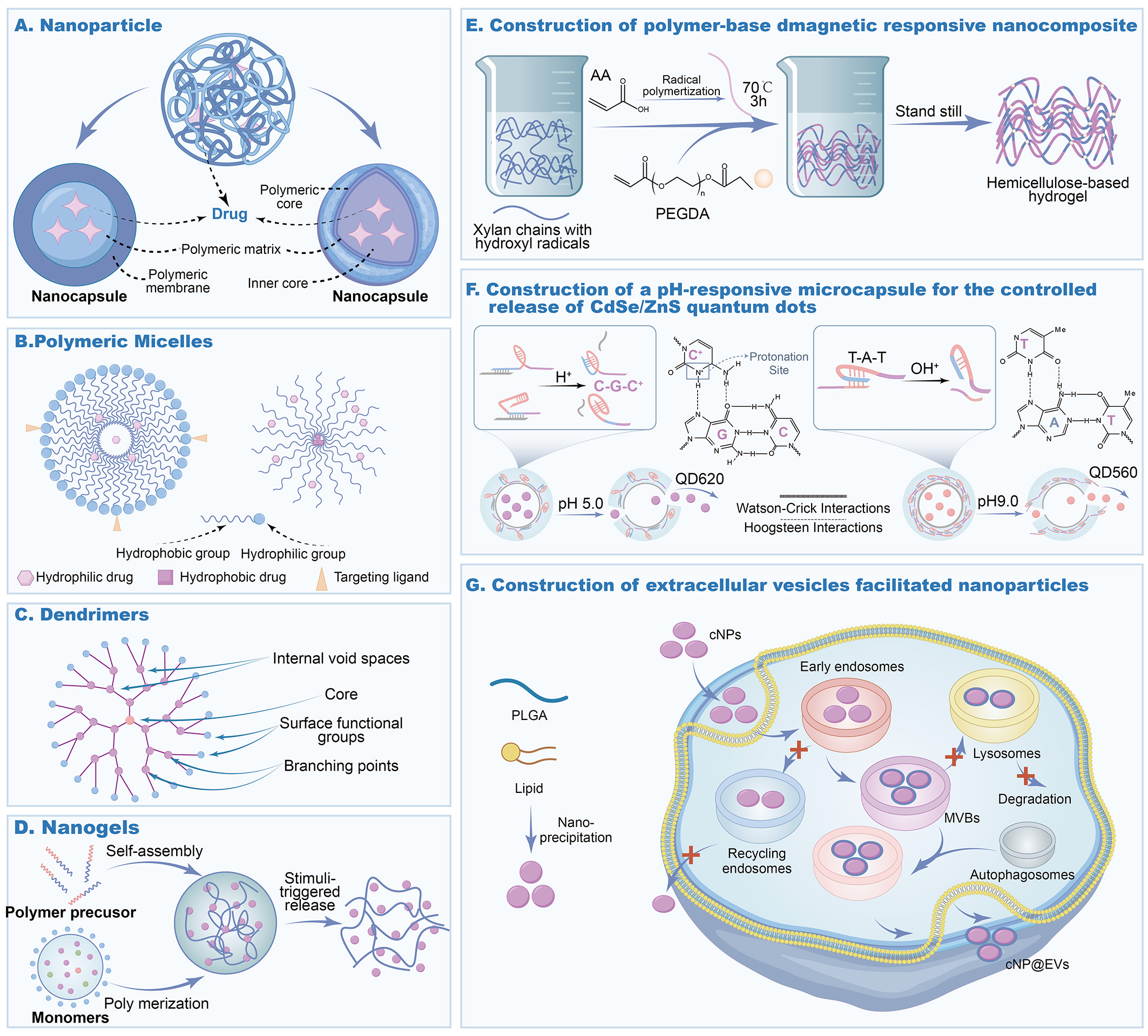

This concept of tumor microenvironment-responsive reconstruction and simulation of authentic biological interfaces enables polymeric nanomaterials to adapt more effectively to the tumor microenvironment, facilitating accurate drug administration and treatment, hence offering enhanced methods for cancer therapy [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Targeting patterns of polymers and drug release under stimuli in cancer therapy. (A) PEGylation of polymers. (B) Production of biomimetic modification of polymers. (C) Schematic presentation of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles with response. (D) Schematic description of targeting mechanisms in cancer. Figure created by MEDGY. PEG: Polyethylene glycol; GSH: glutathione; EPR: enhanced permeability and retention; PTT: photothermal therapy; PDT: photodynamic therapy.

Precise targeted design of polymeric nanomaterials

Passive targeting is accomplished through the distinctive physiological architecture and functionality of tumor tissues, with the EPR effect serving as the principal mechanism of passive targeting. The intercellular spaces of endothelial cells in tumor tissues typically range from 100 to 780 nm and the lymphatic drainage system is inadequate. This enables nanoparticles in the bloodstream to extravasate via endothelial gaps into tumor tissues and persist there, a phenomenon known as the EPR effect[56].

Polymeric nanoparticles use the EPR phenomenon for passive targeted enrichment. Nanomaterials between 10 and 100 mm are more likely to go through the tumor vasculature's spaces to facilitate passive targeting. Research on cylindrical polymer brushes found that those with lengths up to 1 μm passively target tumor cells via the EPR effect. Larger polymers with substantial aspect ratios demonstrate exceptional tumor penetration performance in smaller systems[69].

Various tumor types and locations influence the EPR effect. The blood-brain barrier limits the passive accumulation of nanomaterials in brain tumors. According to previous research, magnetic nanoparticles measuring ≤ 50 nm pass through the stroma of brain tumors. Larger nanoparticles are unable to cross the blood-brain tumor barrier. This suggests that dependence on the EPR effect for passive targeting in brain tumor therapy has inherent limitations, necessitating the integration of active targeting strategies to improve the accumulation of nanomaterials at the tumor site[56].

Active targeting modification is a crucial method to improve the targeting specificity of polymer nanoparticles towards tumor cells. Attaching particular ligands, antibodies, or aptamers to the surface of nanomaterials facilitates targeted recognition and binding to tumor cells.

Folic acid, a widely utilized ligand, possesses receptors that are abundantly expressed on the surfaces of numerous tumor cells. Research indicates that folic acid-modified nanoparticles have markedly enhanced absorption in tumor cells compared to normal cells, hence augmenting the accuracy of medication delivery[32]. Nevertheless, some studies have suggested that free folic acid may promote the initiation and progression of breast cancer, underscoring the need for careful safety evaluation when using folic acid as a targeting ligand[32]. Mannose-modified nanomaterials can selectively accumulate in tumor cells that express mannose receptors, offering an efficient targeted technique for tumor therapy[31]. Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) peptides exhibit unique binding affinity for integrin αvβ3, which is prominently expressed on the surface of tumor vascular endothelial cells and tumor cells. RGD peptide-modified nanomaterials facilitate dual targeting of tumor vasculature and tumor cells through binding to integrin αvβ3, hence augmenting drug accumulation and therapeutic efficacy at the tumor site[63].

Antibody conjugation is an important method for active targeting. Monoclonal antibodies such as anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) and anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) can specifically recognize and bind to HER2 or EGFR-positive tumor cells. Conjugating these monoclonal antibodies with polymeric nanomaterials allows the nanomaterials to precisely target tumor cells. Trastuzumab-conjugated nanoparticles can specifically accumulate in HER2-positive breast cancer cells, improving the therapeutic efficacy of the drug[57].

Aptamer AS1411 can specifically target ribosomal proteins, which are highly expressed in various tumor cells. Polymeric nanomaterials modified with AS1411 can achieve targeted delivery to tumor cells by binding to ribosomal proteins, providing a novel targeting strategy for cancer therapy[31].

Tumor microenvironment-responsive targeting is a strategy that achieves precise targeting based on the unique properties of the tumor microenvironment, with pH-sensitive charge reversal being one of the common methods. The pH value of the tumor microenvironment is usually slightly lower than that of normal tissue, ranging from pH 6.5 to 7.0. Polyhistidine coating is a commonly used pH-sensitive material. At physiological pH (pH 7.4), polyhistidine is electrically neutral or slightly negatively charged, while in the mildly acidic tumor environment (pH 6.5-7.0), its imidazole groups become protonated, exposing a positive charge on the coating. This charge reversal can enhance the electrostatic interaction between nanomaterials and the surface of tumor cells, promoting the cellular uptake of nanomaterials[50].

In addition to polyhistidine, there are other polymers that can achieve pH-sensitive charge reversal. Some nanocomposites based on poly (β-L-malic acid), by modifying their surfaces with pH-sensitive groups, exhibit a negative charge at physiological pH, which can avoid recognition and clearance by the immune system, thereby extending circulation time. In the mildly acidic tumor environment, these groups undergo hydrolysis, causing a charge reversal on the surface of the nanocomposites, enhancing cellular uptake and drug release[70]. This strategy of pH-sensitive charge reversal allows nanomaterials to remain stable in blood circulation while achieving precise targeting and drug release at tumor sites, providing an effective means for cancer treatment.

In addition to pH-responsive mechanisms, ROS-responsive strategies also exhibit strong tumor-targeting potential. Polymer nanoparticles incorporating selenium ether bonds undergo selective cleavage in the ROS-rich tumor microenvironment, facilitating precise and localized drug release[71]. Studies have demonstrated that selenium ether-modified PLGA nanoparticles markedly enhance drug accumulation while minimizing systemic toxicity in breast cancer models. Furthermore, these selenium-containing nanoparticles can potentiate the anticancer efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents by inhibiting redox enzyme activity, thereby improving overall therapeutic outcomes[72].

Enzyme-responsive strategies exploit the overexpression of proteolytic enzymes, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2/9) or cathepsin B, in tumors by incorporating enzyme-cleavable peptide linkers, thereby enabling site-specific drug release within the tumor microenvironment[73]. For instance, MMP-2-responsive peptide-PEG conjugates have demonstrated enhanced tumor penetration and superior therapeutic efficacy in vivo[74].

It should be noted that different targeting strategies have their own characteristics. pH-responsive mechanisms are applicable to most solid tumors, but have a narrow response range (pH 6.5-7.0)[75]. ROS-responsive polymeric drug delivery systems are suited for tumors exhibiting elevated oxidative stress, such as liver and lung cancers, but must be carefully designed to prevent premature drug release in normal tissues[76]. Enzyme-responsive delivery systems offer high specificity; however, the variable expression levels of target enzymes across different tumors necessitate individualized design. Additionally, the complexity of the tumor microenvironment and inherent limitations of preclinical animal models are critical considerations when selecting an appropriate targeting strategy[77].

Stimuli-responsive polymeric nanomaterials for intelligent drug release

The endogenous stimuli-responsive intelligent release mechanism of polymeric nanomaterials is designed based on the unique chemical and biological characteristics of the tumor microenvironment, enabling precise drug release at the tumor site. The acid-responsive mechanism utilizes the acidic characteristics of the tumor microenvironment. Due to vigorous metabolism, tumor cells produce a large amount of lactic acid, resulting in a slightly lower pH value in the tumor microenvironment compared to normal tissues. Acid-sensitive bonds such as hydrazone and Schiff base will break under acidic conditions, thereby triggering drug release. Some nanoparticles based on poly (γ-glutamic acid), by introducing linkers containing hydrazone bonds to bind with anticancer drugs, release the drugs from the nanoparticles in the mildly acidic tumor environment as the hydrazone bonds break, achieving effective killing of tumor cells[78]. pH response can also be achieved through the cleavage of acetal or guanidine bonds. Acetal bonds are unstable under acidic conditions and undergo hydrolysis, leading to changes in the polymer structure and drug release. Guanidine bonds are similarly sensitive to pH changes; in the mildly acidic tumor environment, the protonation state of guanidine bonds changes, triggering structural adjustments of the polymer and enabling drug release[79].

The ROS response mechanism relies on the higher oxidative stress levels within tumor cells. The concentration of ROS - such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (O2-) - is higher in tumor cells than in normal cells. Selenide bonds, thioether bonds, and others undergo oxidation reactions under high oxidative stress conditions, thereby releasing drugs and exerting therapeutic effects[80]. Redox response is primarily based on the difference in glutathione (GSH) concentration within tumor cells. The concentration of GSH in tumor cells is higher than that in normal cells, and disulfide bonds undergo reductive cleavage under high GSH concentration, achieving drug release. Many disulfide bond-based polymeric nanocarriers have been developed for tumor therapy, such as disulfide bond-crosslinked polymeric micelles, which disassemble in the high-GSH environment within tumor cells, thereby releasing their payload[80].

Enzyme-responsive mechanisms utilize the high expression of specific enzymes in tumor tissues. The activity of enzymes such as MMP-2/9 and Cathepsin B is significantly higher in tumor tissues than in normal tissues. Some peptide-based nanocarriers contain MMP-2/9 recognizable peptide sequences in their structure, and in tumor tissues, MMP-2/9 cleaves the peptide sequences, leading to structural changes in the nanocarriers and drug release[81].

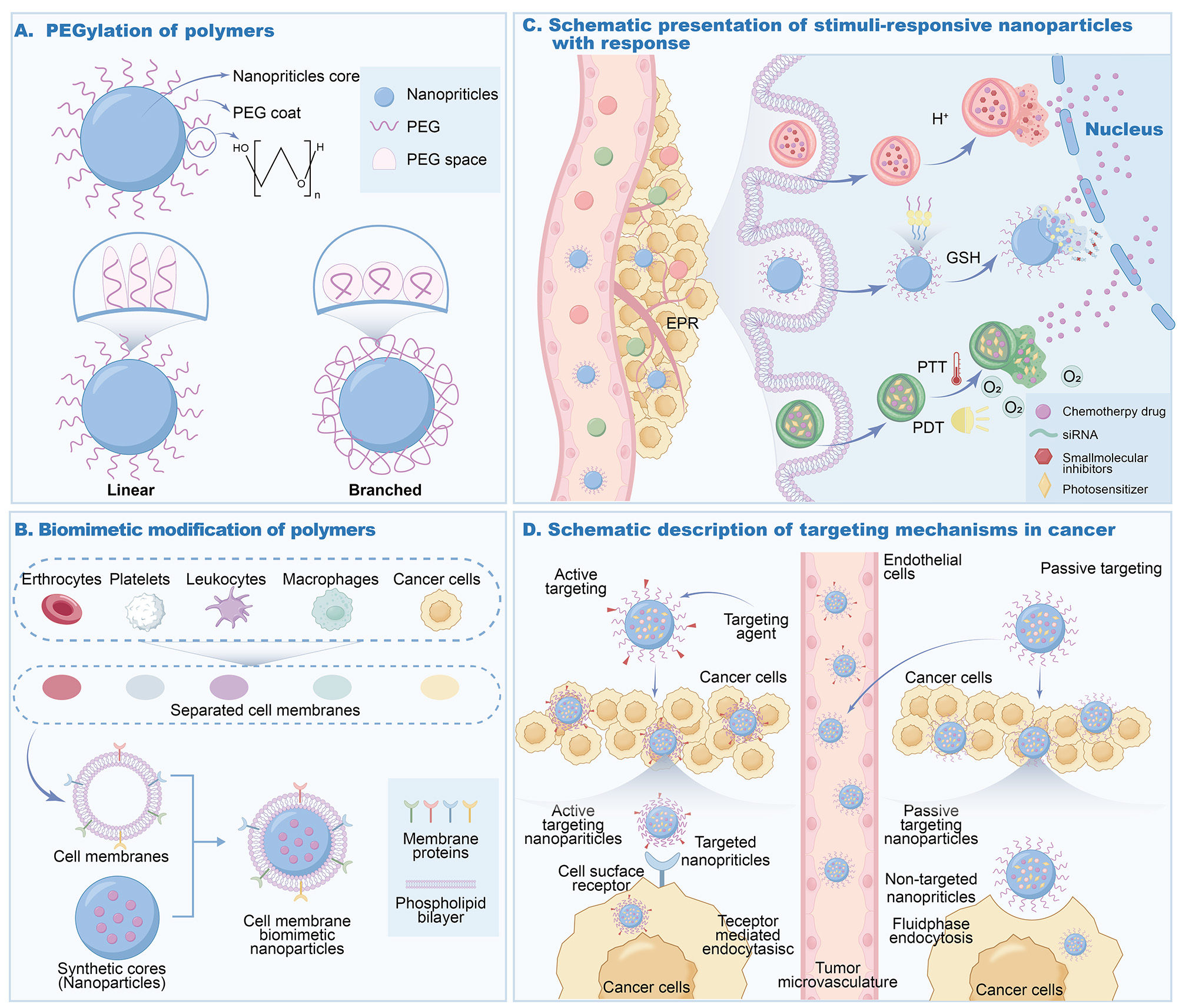

Exogenous stimuli-responsive smart release of polymeric nanomaterials provides a spatiotemporally controllable therapeutic approach for cancer treatment. The light-responsive mechanism often utilizes near-infrared (NIR) light, which has the advantages of high tissue penetration and low damage. Under NIR light irradiation, photosensitive groups undergo photochemical reactions, leading to structural changes in the polymers and rapid drug release. Simultaneously, some light-responsive materials can convert light energy into thermal energy, generating a photothermal effect to directly kill tumor cells. For instance, nanogels loaded with indocyanine green produce a photothermal effect under NIR light irradiation, while also triggering structural changes in the nanogels, enhancing the cytotoxic effect on tumor cells[21]. Nano-proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC), a sophisticated nano-proteolysis targeting chimera, features a semiconductor polymer backbone conjugated to a PROTAC peptide targeting cyclooxygenase 1/2 via a cathepsin B-cleavable linker

Figure 3. Mechanism and therapeutic evaluation of SPNpro-mediated PROTAC phototherapy in 4T1 tumors. (A) The mechanism of PROTAC was elucidated. Copyright 2024[82]. (B) The structure and activation mechanism of SPNpro, a cathepsin B-specific probe, were characterized. (C) SPNpro-mediated activatable photo-immunometabolic therapy employed a dual-action mechanism. Copyright 2021[83]. (D) The experimental timeline for 4T1 tumor implantation and treatment was outlined. (E) Post-intravenous injection, biodistribution of various formulations in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice was assessed at different time intervals. (F) Quantitative analysis of major organs was performed. (G) Confocal imaging of tumors treated with different formulations, with or without NIR irradiation, detected ROS generation via SOSG probe (green fluorescence). (H) Over 14 days of observation, tumor growth curves in 4T1-bearing mice followed various treatments. (I) H&E staining of lung tissues revealed metastatic lymph nodes. (J) Caspase-3 expression, quantified in tumors across treatment groups, showed statistical significance. Copyright 2022[84]. PROTAC: Proteolysis-targeting chimeras; SPNpro: semiconducting polymer nano-PROTAC; SPNCOX: smart nano-PROTACs. Significance thresholds were defined as follows: ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

The heat-responsive mechanism is based on thermosensitive polymers, such as poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM). PNIPAM has a lower critical solution temperature (LCST); below the LCST, the polymer chains are in an extended state with stronger hydrophilicity, while above the LCST, the polymer chains contract, enhancing hydrophobicity. This phase transition characteristic can be used to control drug release. When anticancer drugs are loaded into PNIPAM-based nanoparticles, and the local temperature rises above the LCST, the structure of the nanoparticle changes, releasing the drug. In tumor hyperthermia, external heating can raise the temperature at the tumor site, triggering the release of drugs from PNIPAM-based nanoparticles, achieving a synergistic effect of chemotherapy and hyperthermia[22].

The magnetic response mechanism can be used for targeting or hyperthermia. Magnetic nanomaterials can move directionally to the tumor site under an external magnetic field, achieving magnetic targeting. Meanwhile, magnetic nanomaterials can generate heat under an alternating magnetic field, which is used for magnetic hyperthermia of tumors. By combining magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles with polymers, a magnetically responsive nanocarrier is prepared. Under the guidance of an external magnetic field, the nanocarrier can accumulate in tumor tissues, and then the heat generated by the alternating magnetic field can kill tumor cells. Additionally, drugs can be loaded into this nanocarrier, achieving drug release concurrently with magnetic targeting and magnetic hyperthermia[52]. Figure 2 depicts various targeting patterns of polymers and drug release under stimuli.

The use of endogenous and exogenous stimuli-responsive strategies in cancer therapy offers distinct advantages and presents unique challenges. Endogenous stimuli exploit specific features of the tumor microenvironment - such as pH, redox potential, and enzyme activity - to activate therapeutic agents without external instrumentation, making them particularly suitable for treating deep-seated tumors and enabling highly specific tumor-targeted interventions[85]. Nonetheless, tumor heterogeneity may compromise the specificity and consistency of responses to endogenous stimuli[86]. In contrast, exogenous stimuli provide high spatiotemporal precision and strong controllability. By leveraging external energy sources - such as light, magnetic fields, or ultrasound - these strategies allow on-demand, remote-controlled modulation of therapeutic processes, making them especially advantageous for personalized interventions[87]. However, exogenous approaches remain largely at the preclinical stage and require further validation to facilitate clinical translation[88]. In summary, endogenous stimulation strategies offer practical benefits for clinical application due to their independence from external devices, reducing procedural complexity and cost[85]. In contrast, exogenous strategies deliver unparalleled precision and controllability, holding promise for therapies requiring tightly regulated treatment dynamics. Future research should focus on integrating both approaches to achieve more efficient and controlled tumor therapies[87].

APPLICATION OF POLYMERIC NANOMATERIALS IN CANCER THERAPY: FROM DRUG DELIVERY TO SYSTEMIC MEDICINE

Drug delivery: beyond passive carriers, multifunctional synergy

Drug resistance reversal engineering

Traditional chemotherapy drugs generally have problems such as poor solubility, low bioavailability, and acquired drug resistance[89-91]. Even though multidrug combinations have been shown to overcome single-drug resistance by reversing the expression of drug efflux transporter pumps[92], this also means that once patients develop multidrug resistance, they will be faced with very limited treatment options. New drug delivery methods mediated by polymer nanocarriers have the advantages of optimizing dosing combinations, pharmacological effects, pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and biospatial distribution[93,94], which can improve the potential efficacy of drugs, reduce the risk of drug resistance, and prolong patient survival. For example, the combination of paclitaxel and α-tocopherol (vitamin E) can generate a hydrophobic prodrug, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC 50) of which is 8 times lower than that of paclitaxel. After the prodrug was further made into polymer nanoparticles, the IC 50 concentration was reduced by 1,100 times, and the efficacy was increased by 5 times compared with single paclitaxel nanoparticles. Finally, the encapsulation combination of the prodrug nanoparticles and lapatinib achieved an excellent effect of a combination index of 0.51[94].

Time and space control release

Polymer nanoparticles can cross various biological barriers, precisely target specific parts of the body, encapsulate various therapeutic cargoes, and effectively release these cargoes according to internal and external stimuli[95]. Polymer nanoparticles are prepared by self-assembly of functionalized copolymers that are sensitive to visible light and pH. The visible light responsiveness of the nanoparticles and the synergistic effect and dual stimulation on the release of the loaded molecules eliminate the need for drug release to be stimulated by ultraviolet light or extreme pH, and can better achieve the purpose of precise release at a specific time[96]. In addition, most photoactivated pro-therapeutics only respond to ultraviolet and visible light, which limits their application in vivo. Therefore, in-depth research and development of NIR light-activated pro-therapeutics is necessary, as they also have lower phototoxicity and higher tissue permeability. NIR light-activated pro-therapeutics based on semiconductor polymeric nanomaterials can induce DNA damage, RNA degradation, protein biosynthesis inhibition or immune system activation in tumor cells through remote activation and precise release, thereby achieving the purpose of eliminating tumor growth and even completely inhibiting tumor metastasis[97].

Preclinical and clinical research progress

With good clinical efficacy and significant biological advantages, some polymer nanoparticles and micelles have entered the clinical trial stage. They mainly focus on improving the delivery methods of existing drugs[98-100] or optimizing their chemical structures[101] to enhance efficacy and reduce toxicity to the body. CALAA01 is the first small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting polymer for the treatment of cancer patients[102]. It comprises a cyclodextrin-based polymer, a transferrin-targeting ligand, and PEG, enabling targeted delivery of siRNA to human ribonucleotide reductase M2 (RRM2) while protecting it from nuclease-mediated degradation in serum[103].

Not all therapeutics successfully navigate clinical trials to achieve market approval; indeed, only a limited number of polymer-based nanoformulations have been authorized for clinical use. For instance, although the cyclodextrin-based CRLX101 demonstrated an improvement in median progression-free survival among ovarian cancer patients, its impact on median overall survival remained limited[104]. This outcome may be influenced by factors such as biological barriers, plasma stability, immune clearance, and manufacturing consistency[105,106]. Moreover, passive targeting - while a critical mechanism by which polymeric nanoformulations exert anticancer effects - is highly contingent upon tumor-specific characteristics, including vascular permeability, lymphatic drainage efficiency, extracellular matrix composition, and tumor cell density. These parameters can markedly modulate the clinical efficacy of polymer nanoformulations in certain solid tumors[95]. Therefore, optimizing the targeting strategies of polymeric nanoformulations represents a promising avenue for enhancing therapeutic outcomes. The drug-to-excipient ratio is another critical determinant of efficacy and safety in polymeric micelle-based products. Minimizing excipient content can reduce adverse toxicities associated with the formulation[100]. For example, Nanoxel-M, comprising docetaxel encapsulated in methoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(D,L-lactide) (mPEG-b-PDLLA) polymeric micelles, has demonstrated improved safety profiles in patients with advanced solid tumors[101]. Nonetheless, the influence of formulation parameters on the concentration of free drug warrants careful evaluation, particularly in equilibrium micelle systems. When polymeric micelles are diluted below their critical micelle concentration, progressive micelle dissociation can alter drug distribution in vivo, potentially affecting clinical efficacy. In summary, although polymeric nanoformulations exhibit considerable promise in preclinical cancer research, their successful translation into clinical practice necessitates ongoing optimization and investigation [Table 2].

Polymer nanoformulations entering clinical trials

| Name | Composition | Drug loading | Targeting strategy | Clinical status | Refs. |

| Genexol-PM | Paclitaxel, mPEG-b-PDLLA | Genexol-PM enables the delivery of higher doses of paclitaxel | Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, lung cancer, head and neck cancer | Approved | [107,108] |

| Nanoxel-PM | Docetaxel, mPEG-PDLLA | Stable loading of docetaxel in mPEG-PDLLA micelles demonstrates equivalent antitumor efficacy and safety to the originator drug | Lung cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer | Approved | [109,110] |

| Doxil | Doxorubicin liposome, PEG | PEGylated liposome technology significantly extends the circulation time of doxorubicin and enhances tumor-targeted delivery | Ovarian cancer, multiple myeloma | Approved | [111] |

| NC-6004 | Cisplatin, PEG-b-P(Glu) coordination complex | The optimal dosage demonstrated a favorable safety and tolerability profile while retaining antitumor activity, with no dose-limiting neurotoxicity, ototoxicity, or nephrotoxicity observed at elevated doses | Lung cancer, breast cancer, colon cancer, pancreatic cancer | Phase 3 | [112] |

| NK012 | SN-38, PEG-Pglu copolymer | Exhibited superior antitumor efficacy in orthotopically implanted human tumor xenograft models, with a favorable tolerability profile and absence of gastrointestinal toxic effects | Glioma, renal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer | Phase 2 | [113,114] |

| NK105 | Paclitaxel, PEG and polyamino acid block copolymer | It maintains potent antitumor efficacy while significantly reducing toxicity and side effects, eliminating the need for conventional premedication and enabling shorter infusion times | Breast cancer | Phase 2 | [115,116] |

| BIND-014 | Docetaxel | Efficiently loaded with docetaxel, it selectively targets and kills prostate-specific membrane antigen -positive tumor cells while significantly reducing CTCs, with concomitant reduction in systemic toxicity | Prostate cancer | Phase 2 | [117] |

| CPC634 | Docetaxel-PEG-b-P copolymer | The drug stability and therapeutic index are improved, and when combined with dexamethasone, it demonstrates controllable toxicity and sustained pharmacokinetic advantages | Ovarian cancer | Phase 2 | [118] |

| SP1049C | Doxorubicin, nonionic Pluronic block copolymer | The block copolymer enhances drug-loading stability, significantly improving antitumor activity while reducing toxicity | Esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma | Phase 2 | [119] |

| Etirinotecan pegol (EP) | Irinotecan, PEG | EP exhibits optimized pharmacokinetic properties and demonstrates potential systemic drug delivery advantages | Lung cancer, breast cancer | Phase 2 | [120] |

| PK1 | Doxorubicin, N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer | PK1 demonstrates excellent biocompatibility, low immunogenicity, and prolonged circulation of incorporated drugs. The dual combination therapy utilizing polymer-drug conjugates enables synergistic anticancer effects | Lung cancer, breast cancer | Phase 2 | [121] |

| SDX-7320 | SDX-7539 – a novel polymer-drug conjugate of METAP2 inhibitor (METAP2i) | Significantly reduces central nervous system toxicity while extending half-life, demonstrating potent antitumor and antimetastatic activity even at low doses | Obesity-associated tumors | Phase 1 | [122] |

| NK911 | Doxorubicin, PEG-b-Pcopolymer | Efficient doxorubicin loading enhanced tumor-targeted delivery and reduced systemic toxicity | Pancreatic cancer | Phase 1 | [123] |

| NC-4016 | Oxaliplatin, PEG-b-P(Glu) coordination complex | The polymeric micelle nanoformulation based on 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-platinum significantly enhances the antitumor activity of oxaliplatin while reducing its neurotoxicity | Head and neck cancer, pancreatic cancer | Phase 1 | [124,125] |

| AP5346 | Copolymer-linked 1,2-diaminocyclohexane-platinum compounds | The weekly dosing regimen demonstrated sustained-release properties of the platinum drug, with controllable tolerability and observed antitumor activity | Metastatic melanoma, ovarian cancer | Phase 1 | [126] |

| ZSYY001 | Polymeric micellar paclitaxel | No premedication with Cremophor EL is required, demonstrating favorable safety (no dose-limiting toxicity was reached even at 390 mg/m2) and antitumor activity | Solid tumor | Phase 1 | [127] |

| AP5280 | Platinum, poly-N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide | Polymer-conjugated platinum drug. It exhibits prolonged circulation and reduced bone marrow/renal toxicity | Melanoma, ovarian cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung cancer | Phase 1 | [128] |

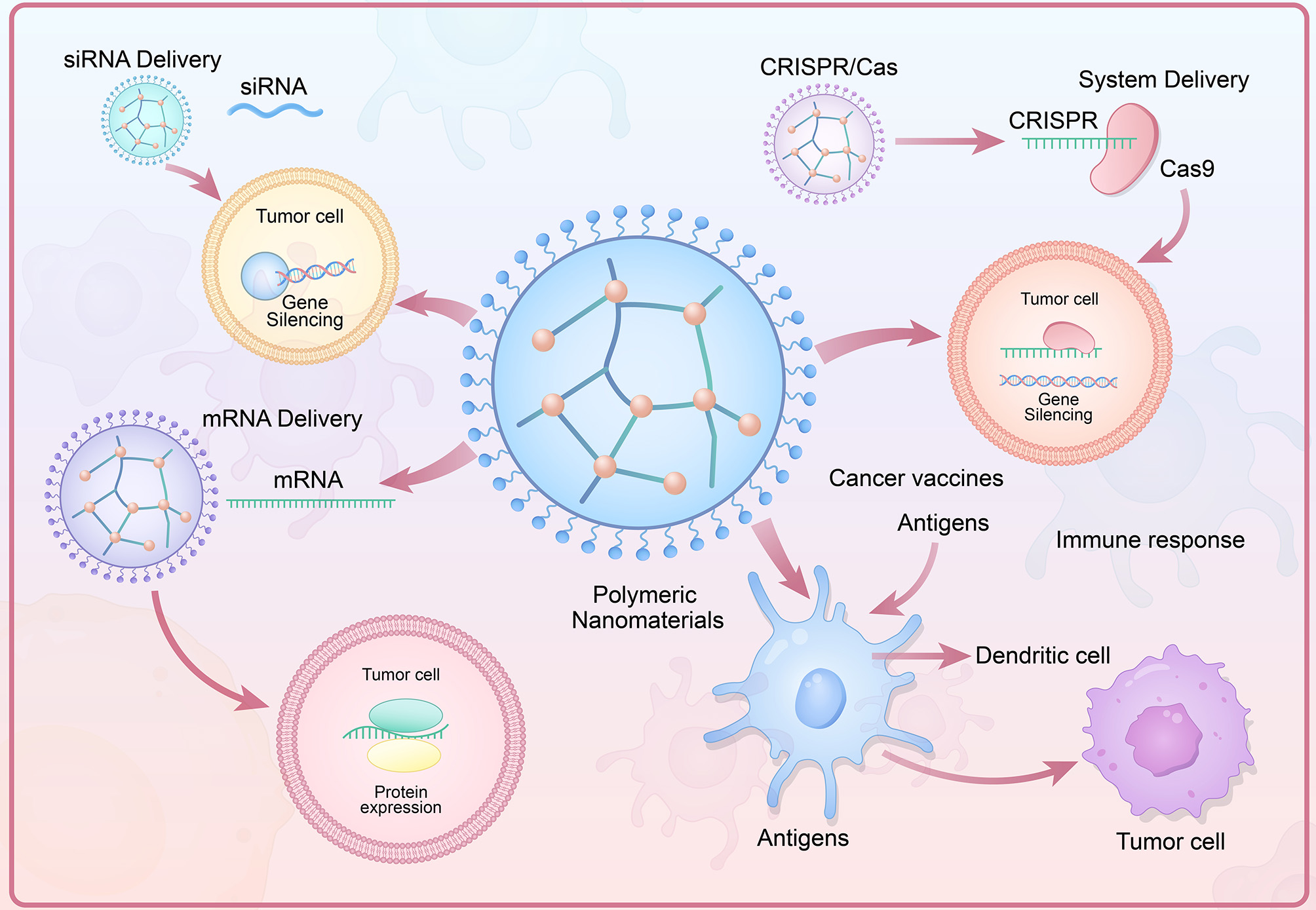

Gene therapy and nucleic acid delivery: precise regulation of tumor molecular networks

RNA interference

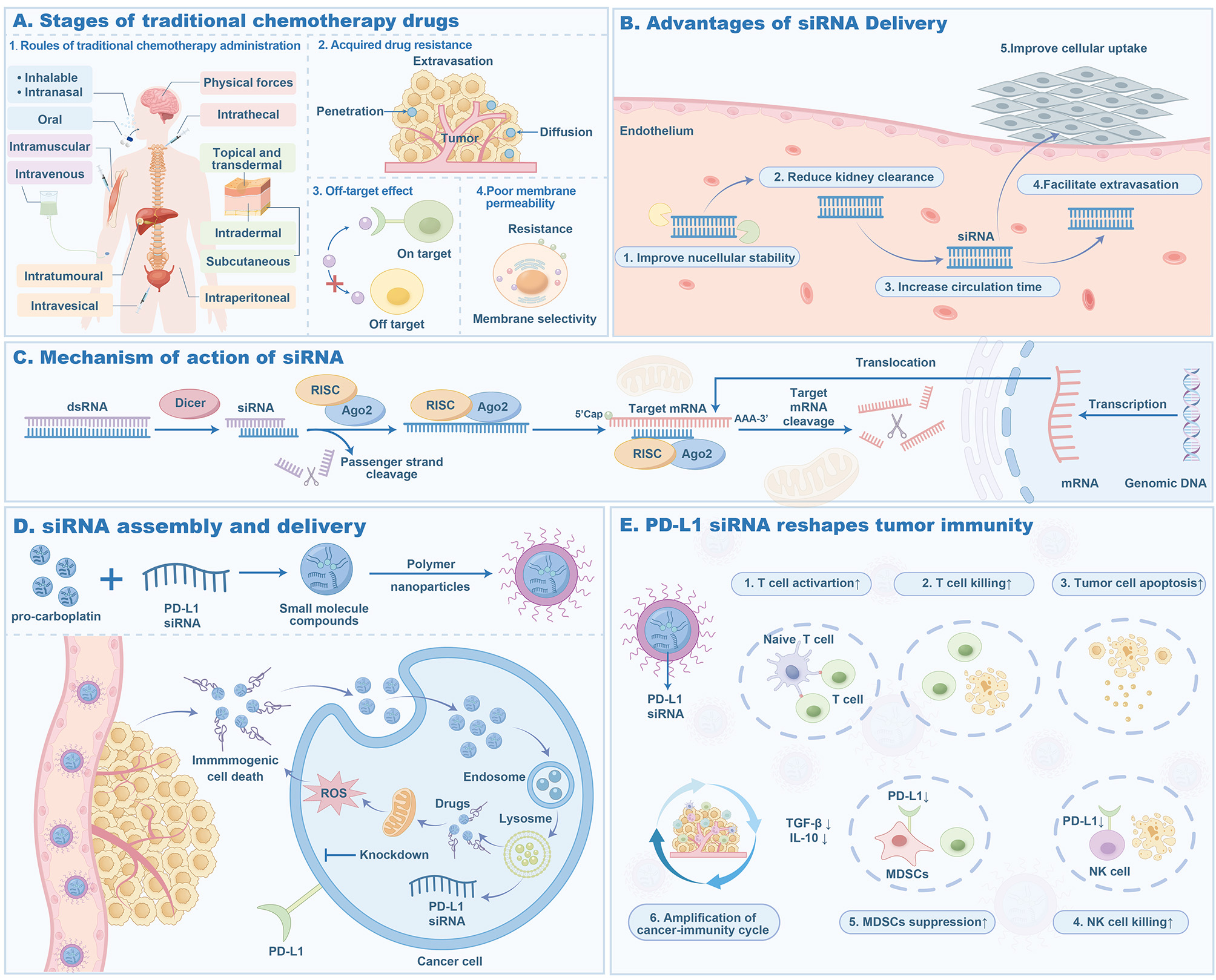

The discovery of functional small noncoding RNAs has revealed the key role of RNA interference (RNAi) in regulating gene expression in cells. RNAi can achieve sustained and long-term gene silencing by selectively manipulating gene expression, improving the stability and target selectivity of drug delivery, thereby prolonging the anti-cancer effect of RNAi [Figure 4]. However, how to deliver siRNA to the target site without toxicity is a huge challenge for researchers, and many problems need to be solved, including membrane impermeability, enzyme degradation, mononuclear phagocyte system embedding, rapid renal excretion, endosomal escape and off-target effects[129]. Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) siRNA (siPD-L1) is an acid-sensitive core-shell nanoscale coordination polymer particle whose core contains carboplatin prodrug and siRNA targeting PD-L1, while the shell contains digitoxin. This structure gives it point-source burst properties, which can generate excessive osmotic pressure in endosomes/lysosomes, thereby effectively releasing siPD-L1 into the cytoplasm, reactivating innate and adaptive immune responses, and effectively inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis[130]. A nano dual-therapeutic agent that co-delivers siRNA and hemoglobin A can selectively kill tumor cells with the aid of photodynamic therapy and induce significant immunogenic cell death. In addition, it can also silence PD-L1 expression in tumor cells and promote anti-tumor immune response, thereby enhancing anti-tumor efficacy in a synergistic manner[131].

Figure 4. siRNA delivery process of polymer nanoformulations. (A) Stages of traditional chemotherapy drugs. It illustrates the various stages and challenges of drug delivery from administration to tumor cells. (B) Enhanced systemic distribution. It describes how to improve siRNA systemic distribution by enhancing nuclear stability and reducing renal clearance. (C) RNA interference mechanism. It shows the process where dsRNA is converted into siRNA by the Dicer enzyme, followed by mRNA degradation mediated by the RISC complex. (D) Immunogenic cell death. It describes the mechanism by which pro-carboplatin, combined with PD-L1 siRNA, induces immunogenic death of tumor cells. (E) Amplification of the cancer immune cycle. It demonstrates how PD-L1 siRNA activates T cells, inhibits tumor cell apoptosis, and promotes NK cell cytotoxicity. Figure created by MEDGY. siRNA: Small interfering; dsRNA: double-stranded RNA; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

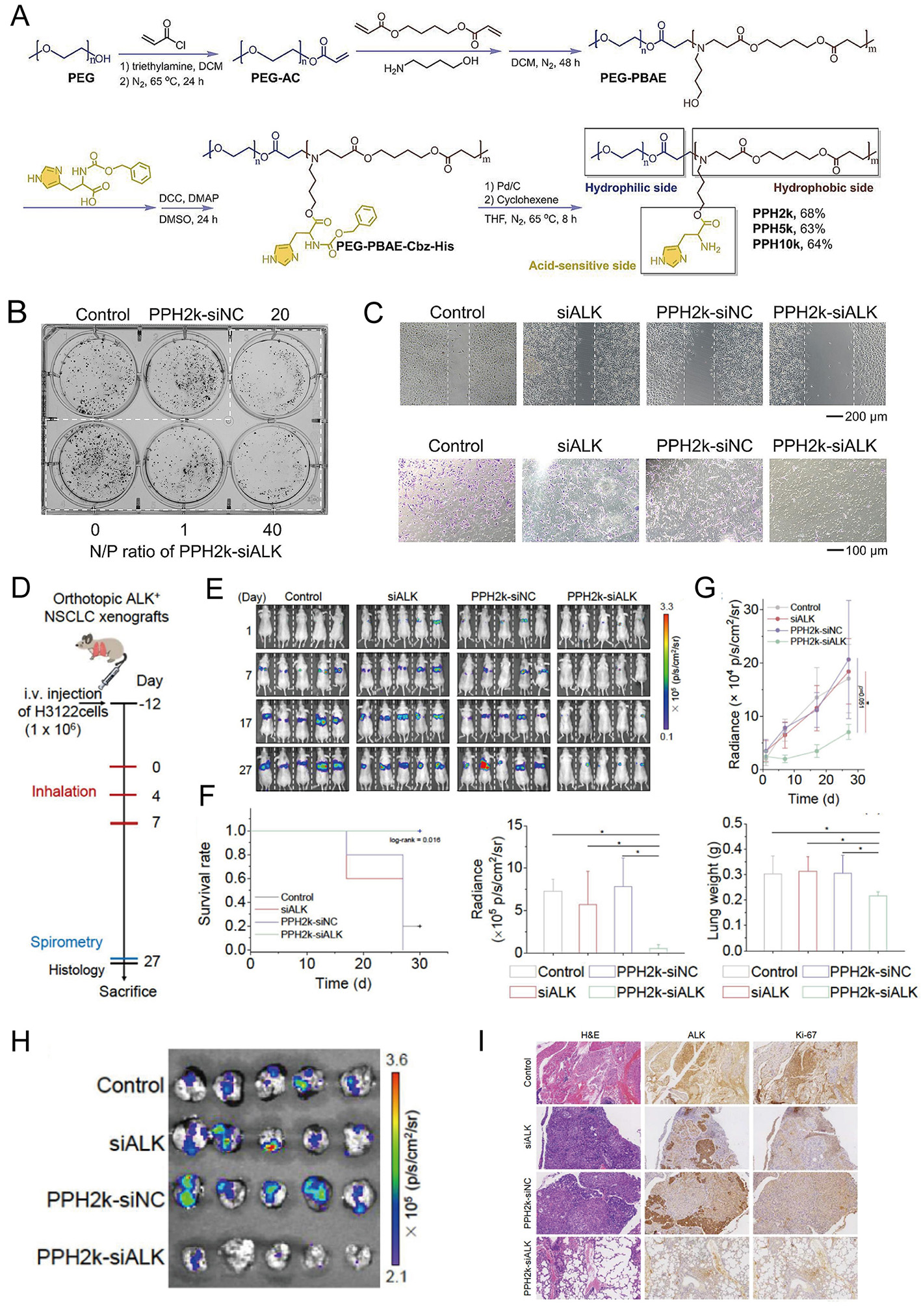

Incorporating nerve growth factor blockers into chemotherapy nanoparticles can effectively relieve peripheral neuropathic pain caused by breast cancer chemotherapy. This is because after siRNA and doxorubicin are co-encapsulated in polymer (lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles, they can better inhibit the expression of nerve growth factor after chemotherapy while enhancing the drug's tumoricidal activity. At the same time, the nanoparticles can also increase the infiltration of immune stimulatory cells into tumors, reduce the frequency of immunosuppressive cells, and stimulate the recovery of anti-tumor immune responses[132]. In addition to conventional infusion routes, investigations into alternative siRNA delivery strategies are ongoing. The polyethylene glycol-poly(β-amino esters)-histidine (PPH) inhalable system markedly enhanced siRNA stability and enabled sequence-specific knockdown of anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) in non-small-cell lung cancer NCI-H3122 cells, achieving transfection efficiencies comparable to commercial PEI while demonstrating reduced cytotoxicity [Figure 5][133].

Figure 5. Synthesis, characterization, and anti-tumor activity of PPH-siALK nanocomplexes. (A) Chemical synthesis of PPH. (B and C) PPH2k-siALK inhibited the malignant behavior of tumor cells. (D) An orthotopic ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) xenograft model was established by tail vein injection of H3122 cells, with inhalation treatment initiated at Day 0. (E-H) Mice treated with inhaled PPH2k-siALK exhibited significantly slower tumor bioluminescent growth than control groups. (I) The proliferation activity of tumor cells in mice treated with PPH2k-siALK was reduced. Copyright 2025[133]. PPH: pH-responsive charge-reversal polymer-siRNA complex; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Significance thresholds were defined as follows: *P <0.05.

Currently, more than 20 siRNA-based therapies are undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of a variety of diseases including cancer, genetic diseases, and viral infections[134]. These preclinical and clinical studies will support siRNA as a potential drug for targeted treatment of various diseases, including cancer, in the near future[135].

CRISPR/Cas system delivery

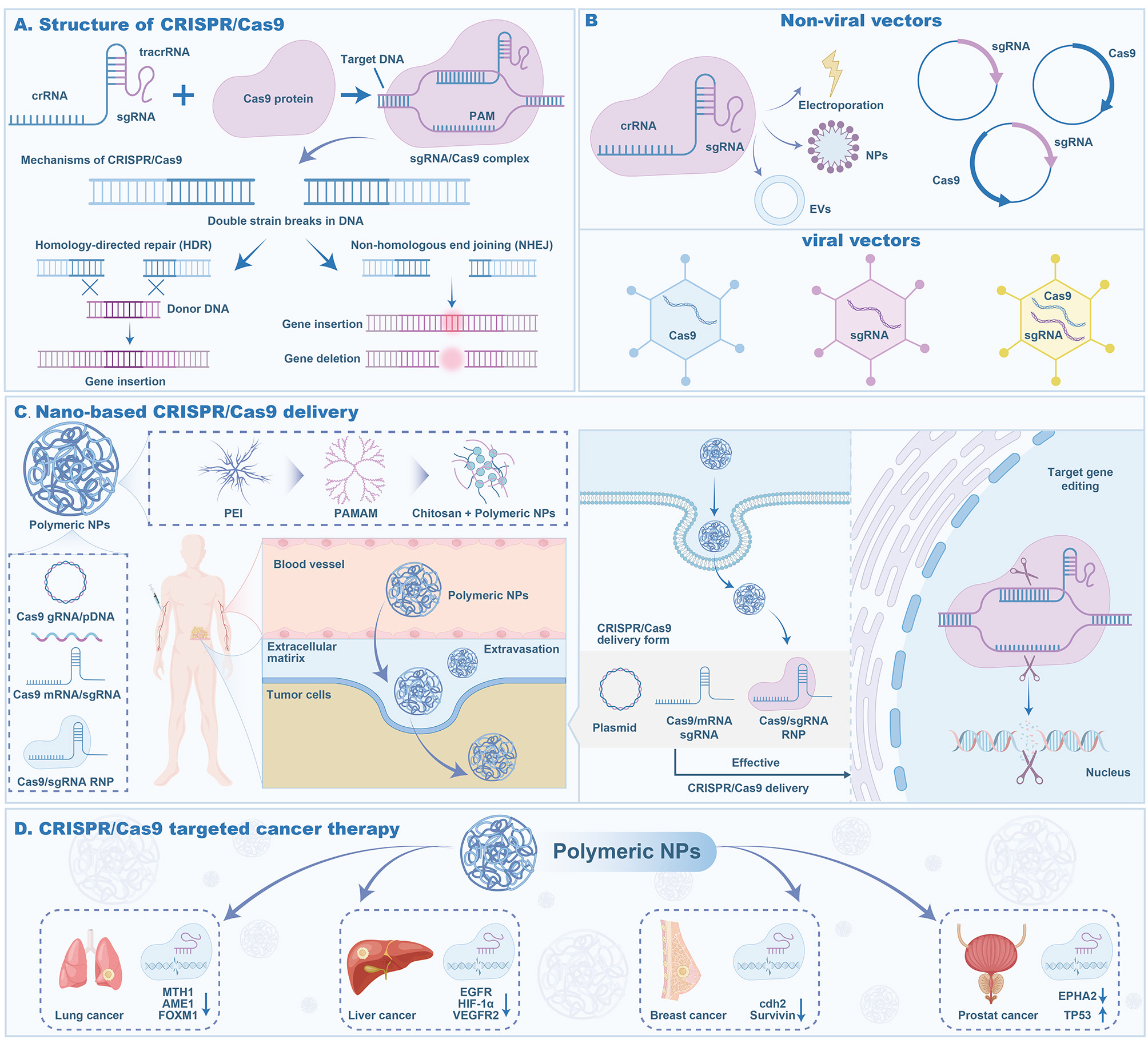

In cancer treatment, safe and efficient drug delivery is undoubtedly an important link that restricts the further application of gene therapy. Polymer nanoparticles based on clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) gene editing technology can cross the membrane through endocytosis and protect the payload from immune response and nuclease degradation. They have been widely used to deliver various types of nucleic acids, including plasmid DNA (pDNA) and messenger RNA (mRNA)[136] [Figure 6]. Viral vectors and non-viral vectors are the two main categories of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery systems. Compared with viral vectors, non-viral vectors have become a research hotspot for delivering CRISPR/Cas9 systems because of their advantages such as wide selectivity in targeted design, non-degradable delivery of drugs, large-sized drugs, low immunogenicity, no endogenous viral recombination, and easy large-scale preparation[137]. Currently, polymer nanoparticles used for CRISPR/Cas9 gene delivery mainly include PEI, PAMAM and chitosan[138].

Figure 6. CRISPR/Cas9 delivery process using polymer nanoformulations. (A) CRISPR/Cas9 structure. The composition and mechanism of action of the CRISPR/Cas9 system, including gene insertion and deletion, were demonstrated. (B) Non-viral vectors and viral vectors. Non-viral vectors describe a method for delivering sgRNA and Cas9 protein into cells via electroporation and polymer NPs. Viral vectors describe three forms. (C) Nano-based CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. The process of delivering the CRISPR/Cas9 system into tumor cells by polymeric NPs was demonstrated. (D) Applications of polymeric NPs. The application of polymeric NPs to target specific gene mutations in different cancer types is demonstrated. Figure created by MEDGY. PEI: Polyethyleneimine; PAMAM: polyamidoamine; NPs: nanoparticles; sgRNA: single-guide RNA; EVs: extracellular vesicles; crRNA: CRISPR RNA; tracrRNA: trans-activating crRNA.

As a highly cationic polymer, PEI forms electrostatically stabilized complexes with DNA. The Cas9-encoding DNA subsequently interacts with anionic residues on the cell surface, facilitating cellular uptake via endocytosis and enabling genome editing. For instance, PEI-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles have been shown to efficiently transfect human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells, achieving genome editing efficiencies comparable to lipofectamine[139]. Beyond conventional cell lines, PEI also demonstrates robust transfection in hard-to-transfect cells. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells, HeLa cells, and pheochromocytoma (PC-12) cells, PEI exhibits a 5- to 10-fold enhancement in transfection efficiency relative to standard polymeric transfection agents[140]. A notable limitation of PEI-based nanomedicines is that higher molecular weight PEI, while more effective in transfection, is often associated with increased cytotoxicity[141]. Current strategies to mitigate this toxicity involve conjugating PEI to biodegradable polymers such as heparin, PCL, dextran, chitosan, pullulan, and folic acid. For example, zwitterionic modification of lactose-grafted PEI has been shown to enhance gene transfection efficiency while reducing cytotoxicity both in vitro and in vivo[142].

PAMAM polymers possess a high density of peripheral primary amine groups, facilitating strong electrostatic complexation with nucleic acids. However, their bulky dendritic architecture can partially constrain transfection efficiency. Consequently, current applications of PAMAM in CRISPR/Cas9 gene delivery primarily involve co-delivery strategies with complementary nanomaterials[143,144]. For instance, a PAMAM-PBAE hyperbranched copolymer employed in a CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting human papillomavirus (HPV) E7 achieved a 90.3% inhibition of cervical cancer cells, demonstrating superior transfection efficiency compared to

Compared with synthetic polymeric carriers, chitosan has emerged as a prominent nanocarrier for CRISPR/Cas9 delivery owing to its inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low cytotoxicity. Studies have demonstrated that chitosan-coated PLGA nanoparticles achieve superior genome editing performance, enhancing transfection efficiency by approximately 70% relative to control groups. Notably, chitosan derivatives conjugated with low-molecular-weight PEI exhibit strong nucleic acid binding, minimal cytotoxicity, and potent antioxidant properties[146,147]. In the future, functional biomaterials and engineered synthetic vectors are poised to become leading platforms for the delivery of gene editing systems such as CRISPR/Cas.

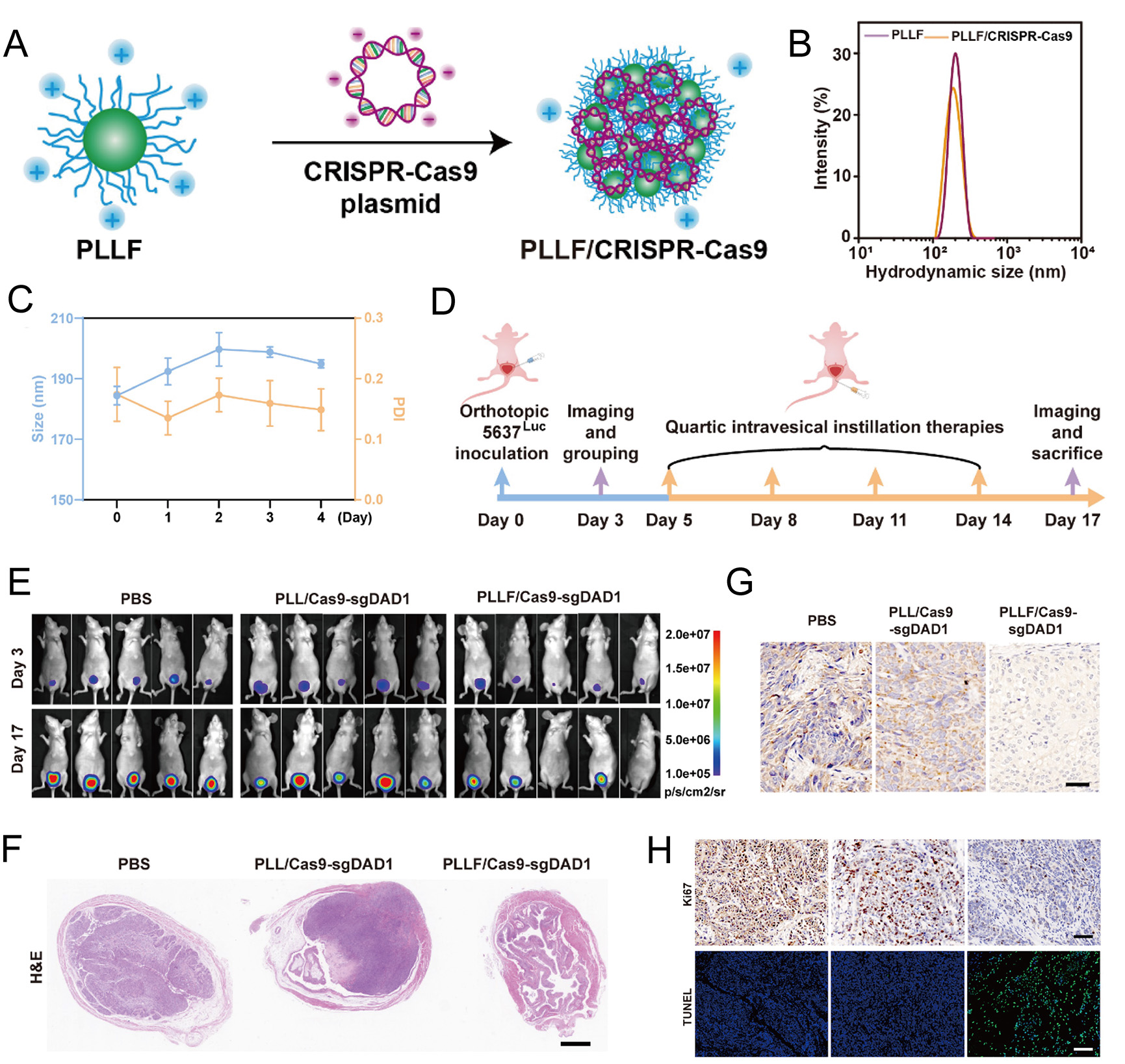

In glioblastoma, a CRISPR-Cas9 nanocapsule can promote blood-brain barrier penetration and tumor cell targeting of drugs by encapsulating a single Cas9/single-guide RNA (sgRNA) complex in a GSH-sensitive polymer shell, resulting in a polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) gene editing efficiency of up to 38.1% in brain tumors[148]. Co-delivery of nanoparticles and CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi can have a synergistic effect on breast tumors, inducing tumor microenvironment remodeling and macrophage repolarization to reactivate anti-tumor immunity[149]. The specific promoter-driven CRISPR/Cas system is composed of PAMAM dendrimers, which can achieve permanent genomic destruction of PD-L1 and immunogenic cell death by initiating specific expression of Cas9 protein, reprogramming the tumor immune microenvironment, and achieving effective cancer immunotherapy. PLLF/Cas9-single guide defender against cell death 1 (sgDAD1) nanoparticles can effectively inhibit the expression of DAD1 in breast cancer cells and induce breast cancer cell apoptosis through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway without systemic toxicity in vivo [Figure 7][150].

Figure 7. Preparation, characterization, and therapeutic efficacy of PLLF/CRISPR-Cas9 nanocomplexes in bladder tumor models. (A) Schematic illustration of the PLLF/CRISPR-Cas9 synthesis process. (B) Hydrodynamic size distribution of PLLF and PLLF/CRISPR-Cas9 NPs. (C) Stability analysis of PLLF/CRISPR-Cas9 NPs stored at room temperature, assessed by particle size and PDI over time. (D) Schematic of intravesical instillation therapy using PLLF/Cas9-sgDAD1 NPs in orthotopic bladder tumors. (E) In vivo bioluminescence images of treated mice on days 3 and 17 post-treatment. (F) H&E-stained sections of representative bladders excised from mice in each treatment group (scale bar: 1 mm). (G and H) Immunohistochemistry and fluorescence staining of each treatment group. Copyright 2024[150]. PLLF: Fluorinated polylysine micelles; PLL: polylysine; DAD1: defender against cell death 1.

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE STRATEGIES FOR CLINICAL TRANSFORMATION OF POLYMERIC NANOMATERIALS

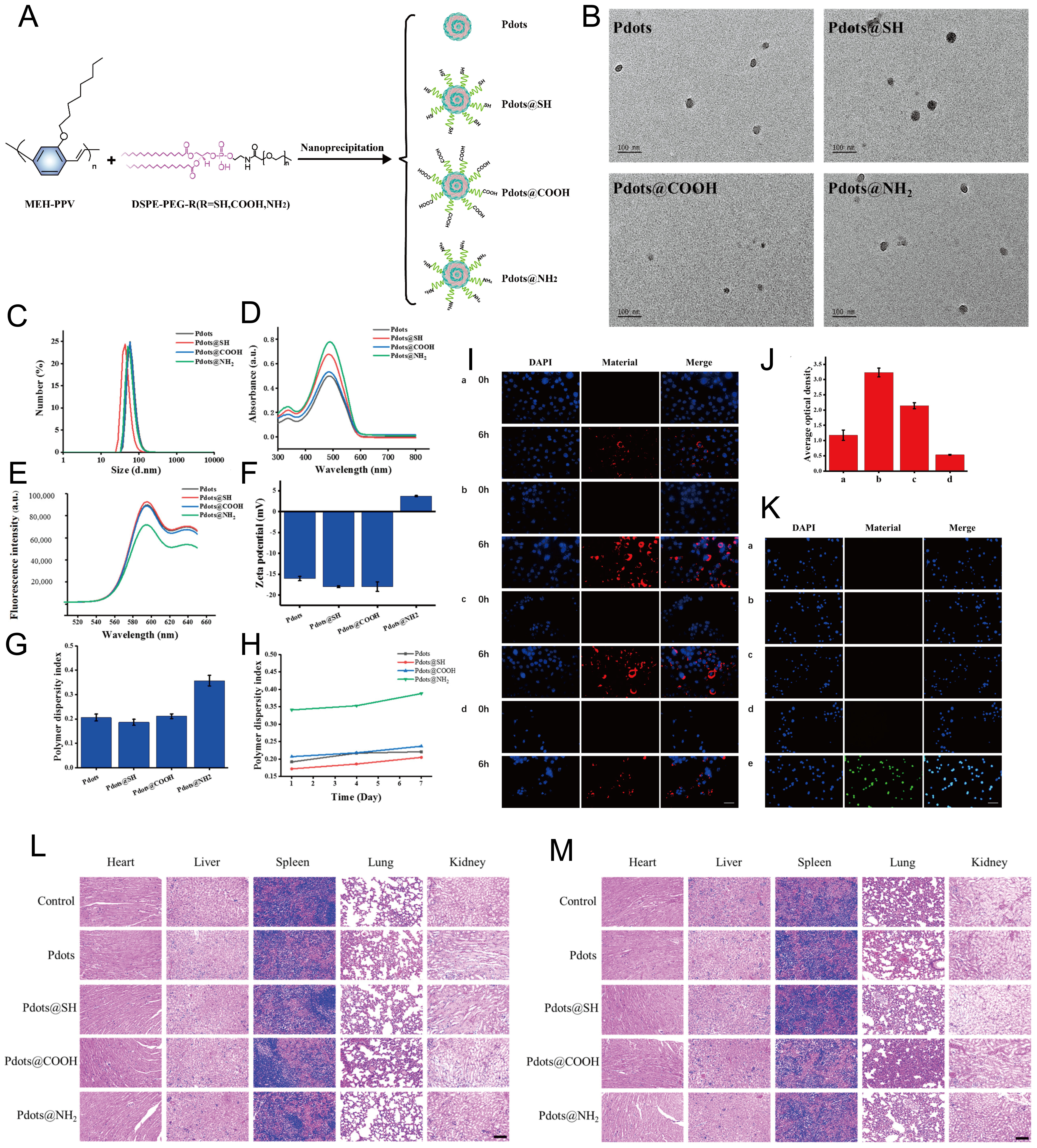

Even though cancer treatment is the most widely studied area of nanomedicine application, its clinical transformation and commercialization still face various problems and challenges, and more candidate drugs have failed in clinical trials[151]. Once polymer nanoparticles enter the body, they undergo various environmental changes, including pH changes and salt fluctuations, as well as interactions with a wide range of peptides and cells. To avoid drug leakage before reaching target cells or organs, it is desirable that the formulation maintain its structural integrity throughout the preparation process. However, the size, shape, surface potential, surface functionalization, impurities, and chemical composition of the polymers attached during the synthesis of polymer nanoparticles can directly affect the stability of the nanomaterials[152]. For example, studies have found that modifications with thiol, carboxyl, and amino groups have no significant effect on the physicochemical properties of semiconducting polymer nanoparticles (Pdots) [Figure 8], while amino modification does, to some extent, affect the stability of Pdots. Due to their instability in solution, Pdots@NH2 reduced cellular uptake and increased cytotoxicity[153]. To more comprehensively address clinical therapeutic challenges, the design of polymer nanomedicines often incorporates multiple modifications to achieve comprehensive functional coverage. However, this approach often affects functional preparation and brings many difficulties to actual clinical translation. More importantly, complex modifications at the gene level may lead to unpredictable and uncontrollable consequences[154]. This suggests that when chemically modifying polymers, we must consider the compatibility of the chemical modification, site, and carrier properties. Furthermore, the complex composition of ingredients means that unapproved ingredients may be used in the preparation of polymeric nanomaterials, resulting in uncontrollable drug safety. Therefore, simplifying drug design and using approved ingredients while meeting patients' clinical medication needs may be an effective way to accelerate the clinical translation of polymer nanomedicines in the future.

Figure 8. Figure synthesis and characterization of Pdots. (A) The synthesis protocols for Pdots, Pdots@SH, Pdots@COOH, and Pdots@NH2 were established. (B) The morphologies of Pdots, Pdots@SH, Pdots@COOH, and Pdots@NH2. (C) The hydrodynamic size distributions of all Pdot variants. (D) UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra for each functionalized Pdot. (E) Fluorescence emission spectra demonstrated the optical properties of Pdots and their derivatives. (F) Surface charge characteristics were evaluated via zeta potential measurements. (G) Polymer dispersity indices were calculated to assess colloidal stability. (H) Temporal PDI stability was monitored over time. (I) CaSki cell uptake after 0/6 h incubation with: (a) Pdots, (b) Pdots@SH, (c) Pdots@COOH, and (d) Pdots@NH2 (red = Pdots, blue = DAPI-stained nuclei; scale bar = 50 μm). (J) Quantitative analysis of cellular fluorescence intensity at 6 h. (K) ROS generation detected by DCFH-DA (green) in CaSki cells treated with (a) Pdots, (b) Pdots@SH, (c) Pdots@COOH, (d) Pdots@NH2, and (e) positive control (blue = DAPI).

This suggests that when chemically modifying polymers, we must consider the compatibility of the chemical modification, site, and carrier properties. Furthermore, the complex composition of ingredients means that unapproved ingredients may be used in the preparation of polymeric nanomaterials, resulting in uncontrollable drug safety. Therefore, simplifying drug design and using approved ingredients while meeting patients' clinical medication needs may be an effective way to accelerate the clinical translation of polymer nanomedicines in the future.

The development model driven by polymer nanomedicine and the research paradigm based on material properties can also easily lead to poor drug delivery effects[155]. Tumor heterogeneity, such as immune-desert and immune-privileged tumors, represents a significant difference in the pathophysiology of different tumors. Hyaluronic acid-conjugated, disulfide-bonded PEI-based organic polymer nanoparticles have been shown to reprogram macrophages from a pro-tumor M2 phenotype to an anti-tumor M1 phenotype within the microenvironment of immune-responsive breast cancers, simultaneously enhancing ferroptosis in cancer cells[156]. However, their efficacy in immune-desert tumors remains uncertain. In contrast, n(catalase)-second mitochondria-derived activator of caspases-polyethylene glycol (n(Cat)-Smac-PEG), a tumor-activated polymeric nanomodulator, broadly disrupts the positive feedback between tumor hypoxia and apoptotic evasion, reverses radioresistance through multiple mechanisms, and substantially augments radiotherapy efficacy, demonstrating applicability across diverse cancer types[157]. These findings highlight the necessity for future drug development to be guided by disease-specific and personalized strategies. There are also negative interactions between the immune system and nanoparticles. For example, polymer nanoparticles and macromolecules (dendritic polymers) have shown various immunosuppressive effects

Figure 9. Mechanisms of polymeric nanomaterials in promoting siRNA and mRNA delivery and CRISPR/Cas9 system gene editing in tumor cells, and the resulting immune responses. Figure created by MEDGY.

Even though polymer nanomedicines have optimized traditional drug delivery modes, they still face the obstacle of lower-than-expected targeting efficiency. For example, PEG, a common modification of polymer nanomedicines, can accelerate blood clearance but also lead to loss of efficacy[159]. By encapsulating a single Cas9/sgRNA complex within a GSH-sensitive polymer shell containing a dual-acting ligand, a novel CRISPR-Cas9 nanocapsule achieved a 38.1% PLK1 gene editing efficiency in brain tumors, with an off-target gene editing rate of less than 0.5% in high-risk tissues[160]. This suggests that appropriate cell-penetrating peptide modifications, precise drug-target binding sites, and smooth endocytic transport may be key to enhancing the deep penetration and effective targeting of polymeric nanomaterials.

In summary, although polymeric nanoformulations have garnered significant attention in nanomedicine research due to their advantages - including prolonged circulation, low immunogenicity, and minimal adverse effects - several challenges remain. These include formulation instability, difficulties in scalable production, potential nanotoxicity, suboptimal transfection efficiency, and poorly defined pharmacokinetics, all of which constrain their clinical translation and practical application[161-163].

CONCLUSION

Polymeric nanomaterials have emerged as a transformative platform for cancer diagnosis and therapy, achieving significant advancements in targeted delivery, stimuli-responsive intelligent release, and multimodal combination therapies. By utilizing precision targeting technologies, these materials substantially improve tumor accumulation efficiency. Through mechanisms responsive to the tumor microenvironment and exogenous stimuli-triggered release, they facilitate spatiotemporally controlled drug delivery. Additionally, co-delivery strategies and integrated theranostic systems work synergistically to overcome drug resistance while allowing for concurrent treatment monitoring, thereby systematically enhancing the efficacy of cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. Nonetheless, the clinical translation of these innovations faces challenges, including complex interactions at biological interfaces, considerable tumor heterogeneity, barriers to penetration, and issues related to scalable manufacturing. Addressing these challenges necessitates a profound interdisciplinary integration of materials science, biology, and clinical medicine. Future endeavors should focus on establishing a closed-loop pathway encompassing “basic research-pilot-scale production-clinical feedback” to overcome translational bottlenecks. Research strategies focus on the development of responsive programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)/PD-L1 inhibitors and other intelligent hybrid polymeric delivery systems for immunotherapy; the construction of scalable biomimetic nanocarriers to facilitate large-scale production and clinical translation; and the design of adaptive delivery platforms capable of addressing tumor heterogeneity, thereby enabling personalized treatment via multimodal responses. Collectively, these approaches are poised to advance polymeric nanomaterials from versatile drug delivery tools to foundational components of precision cancer therapy.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and writing - original draft: Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, S.

Literature investigation and Figure arrangement: Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, F.

Writing-review & editing: Wang, X.; Fang, S.; Lin, Z.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z.

Supervision and funding acquisition: Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Du, P.; Wei, Y.; Liang, Y.; et al. Near-infrared-responsive rare earth nanoparticles for optical imaging and wireless phototherapy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2305308.

2. Luo, F.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Cai, J. Efficacy of nebulized GM-CSF inhalation in preventing oral mucositis in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a retrospective study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37721.

3. Amrollahi, P.; Zheng, W.; Monk, C.; Li, C. Z.; Hu, T. Y. Nanoplasmonic sensor approaches for sensitive detection of disease-associated exosomes. ACS. Appl. Bio. Mater. 2021, 4, 6589-603.

4. Settleman, J.; Neto, J. M. F.; Bernards, R. Thinking differently about cancer treatment regimens. Cancer. Discov. 2021, 11, 1016-23.

5. Lee, L. C.; Lo, K. K. Leveraging the photofunctions of transition metal complexes for the design of innovative phototherapeutics. Small. Methods. 2024, 8, e2400563.

6. Wahnou, H.; El Kebbaj, R.; Liagre, B.; Sol, V.; Limami, Y.; Duval, R. E. Curcumin-based nanoparticles: advancements and challenges in tumor therapy. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 114.

7. Zhan, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Exosome-transmitted LUCAT1 promotes stemness transformation and chemoresistance in bladder cancer by binding to IGF2BP2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2025, 44, 80.

8. Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xia, L.; et al. LAMC3 interference reduces drug resistance of carboplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20399.