The role of selective autophagy in cardiovascular diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic potential

Abstract

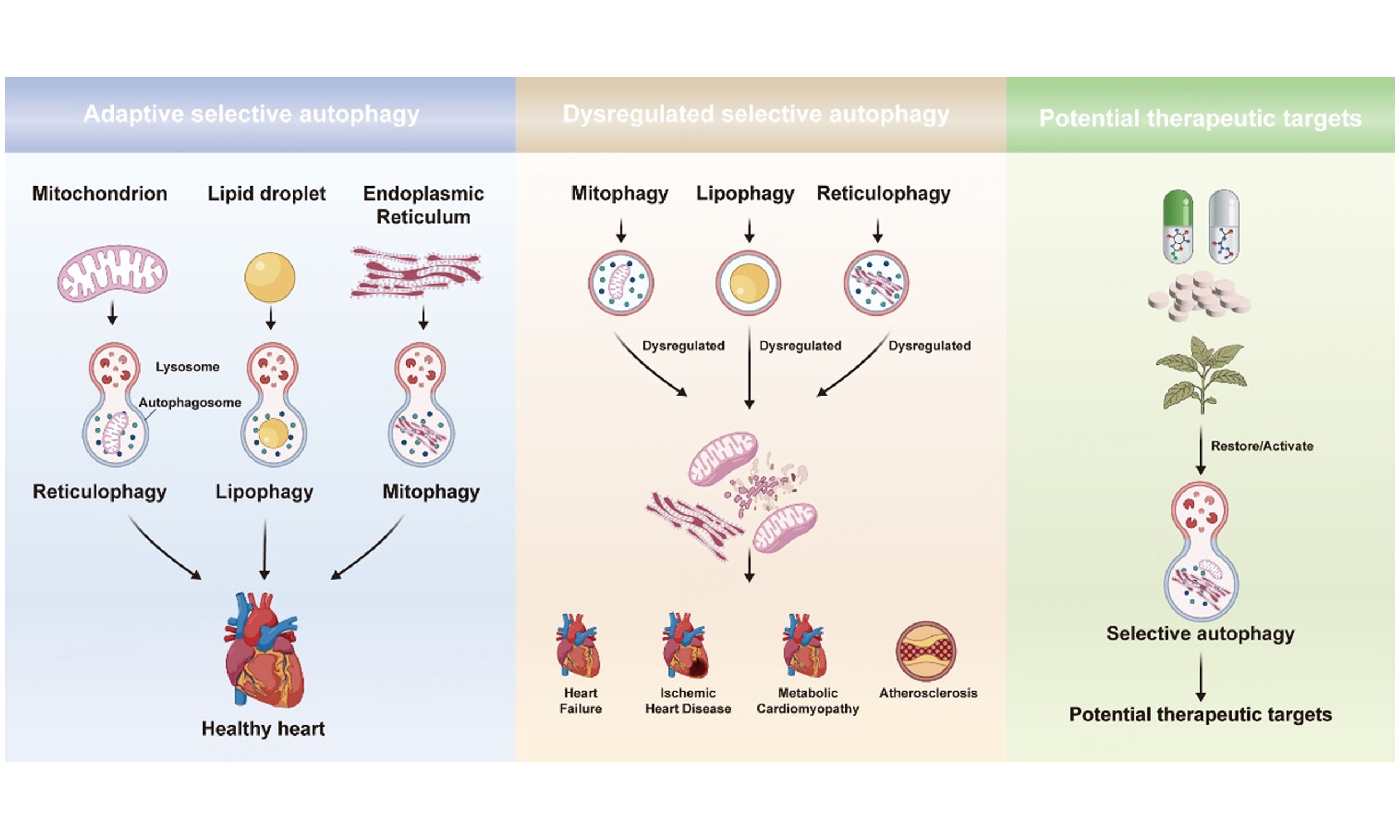

Selective autophagy, as a crucial form of cellular autophagy, plays a vital role in the degradation of specific substances or organelles in cells. Different from traditional autophagy mechanisms, it precisely identifies and removes damaged or superfluous cellular components, such as lipids, mitochondria, or endoplasmic reticulum, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis. In recent years, research has revealed a close relationship between selective autophagy and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Dysfunction in selective autophagy may promote pathological damage or disease progression in various CVDs, including atherosclerosis, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and metabolic cardiomyopathy. In this review, we focused on summarizing the mechanisms of specific selective autophagy pathways, including lipophagy, mitophagy, and reticulophagy in CVDs. Furthermore, we analyzed the potential applications and underlying mechanisms of small-molecule compounds, which could target selective autophagy for the treatment of CVDs. We aimed to provide a new theoretical foundation for the prevention and treatment of CVDs.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of death both in China and globally. The burden of CVDs is particularly heavy in low- and middle-income countries. In China, CVDs are responsible for over 40% of premature deaths, posing a significant public health burden[1]. With global population aging and lifestyle changes, the incidence and mortality rates of CVDs are rising, presenting a major challenge to global public health. Among the CVDs, heart failure (HF), myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI), and atherosclerosis (AS) are common and most lethal. Their pathophysiological mechanisms are complex and diverse, including cellular damage, inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysregulation[2-5].

Selective autophagy is a specialized form of autophagy. It refers to the process by which a specific substrate destined for degradation is directly bound to microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3, also known as autophagy-related protein 8 (Atg8) in yeast and plant cells) via specific autophagy receptors, enabling precise delivery to the autophagosome[6]. The types of selective autophagy include mitophagy, lipophagy, reticulophagy, ribophagy, aggrephagy, and others[7]. Besides its core function in maintaining cellular homeostasis, selective autophagy plays crucial roles in cell differentiation and development, maintenance of tissue homeostasis, aging delay, and immune regulation. Concurrently, selective autophagy is closely linked to the pathogenesis and progression of various human diseases, including cancer, heart disease, and neurodegenerative disorders. Evidence indicates that selective autophagy plays a critical role in cardiovascular health. We primarily focus on major CVD contexts in which selective autophagy has been most extensively investigated, including HF, ischemic heart disease (IHD), AS and metabolic cardiomyopathy (MCM). We illustrated the regulatory networks of various subtypes of selective autophagy and explored the potential therapeutic targets within these specific conditions. This review provides a theoretical foundation for deepening the understanding of the pathological mechanisms of CVDs and developing precise intervention strategies.

SELECTIVE AUTOPHAGY

Autophagy is a mechanism of self-degradation and recycling. It maintains intracellular homeostasis, recycles energy substrates, and clears potentially harmful substances by transporting damaged or unnecessary cellular components, such as protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles, to the lysosome for degradation[8]. Traditionally, autophagy was considered a non-selective and "bulk" degradation process, primarily activated under stress conditions (e.g., nutrient starvation), non-specifically degrading cytoplasmic components and providing energy and nutrients. However, as research advanced, it was reported that autophagy was not always non-selective. Cells possessed a more accurate mechanism capable of specifically recognizing and removing particular organelles or protein aggregates. This process was termed selective autophagy[9,10].

The specificity of selective autophagy primarily relies on autophagy receptors or adaptor proteins. These receptors typically contained an LC3-interacting region (LIR) domain, which could enable them to bind to LC3 family proteins on the autophagosomal membrane. Simultaneously, through other domains, receptors recognized and bound specific substrates, recruiting them to the autophagosome for degradation[11-14]. This precise recognition and recruitment mechanism ensured that only damaged or superfluous cellular components were cleared, minimizing disruption to normal cellular function.

Selective autophagy includes mitophagy, lipophagy, reticulophagy, aggrephagy, lysophagy, ribophagy, and others[7]. Research found that mitophagy, lipophagy, and reticulophagy were the most selective autophagy associated with CVDs. Mitophagy can specifically remove damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria and is crucial for maintaining mitochondrial quality control (MQC) and cellular energy metabolism[15,16]. Lipophagy could degrade intracellular lipid droplets (LDs), playing a key role in regulating lipid metabolism and maintaining energy balance[17-19]. Reticulophagy could clear damaged or excessive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in response to ER stress (ERS), thereby maintaining normal protein folding and calcium homeostasis[20,21].

In addition to the classical organelle-targeting forms of selective autophagy discussed above, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) represents a mechanistically distinct pathway that selectively degrades soluble cytosolic proteins. Unlike macroautophagy-based organelle clearance, CMA does not require autophagosome formation. Instead, substrate proteins bearing KFERQ-like pentapeptide motifs are recognized by the cytosolic chaperone heat shock cognate 70 kDa protein (HSC70) and are directly delivered to the lysosomal membrane receptor lysosome-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP-2A) for translocation and degradation[22]. Emerging evidence suggests that CMA is also implicated in cardiovascular pathology. CMA activity is dynamically induced at early stages of pro-atherogenic stress, whereas systemic CMA insufficiency exacerbates vascular pathology in mouse models of AS[23]. In myocardial ischemia-reperfusion models, CMA modulates endothelial NO signaling through regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) turnover, which in turn affects microvascular perfusion and the extent of injury[24]. Moreover, genetic manipulation of LAMP-2A indicates that CMA can modulate cardiomyocyte vulnerability under hypoxic stress[25]. These findings suggest that CMA may also contribute to the development and progression of CVDs. However, the depth of investigation and the accumulated evidence remain less extensive than for mitophagy, lipophagy, and reticulophagy. Accordingly, the following sections focus on the latter. Dysregulation of selective autophagy processes, whether excessive activation or functional impairment, could disrupt intracellular homeostasis and subsequently promote the pathogenesis and progression of CVDs[26]. Dysregulation of selective autophagy was usually a critical driver of disease progression in CVDs. Therefore, there was a scientific value and clinical significance to investigate the molecular mechanisms and explore the potential therapeutic target.

THE ROLE OF MITOPHAGY IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

The molecular mechanism of mitophagy

Mitochondria are double-membrane organelles that not only serve as the primary energy centers but also regulate processes such as cellular calcium homeostasis, signal transduction, apoptosis, and cell growth and differentiation[27]. When mitochondria were damaged or dysfunctional, cells could initiate mitophagy, a selective autophagy process, to specifically clear these impaired mitochondria, thereby maintaining the integrity of the mitochondrial network function and ensuring cell survival[28,29]. Appropriate mitophagy preserved mitochondrial homeostasis and exerted protective effects on the cardiovascular system. Conversely, insufficient or excessive mitophagy could be detrimental. Pathological processes associated with mitophagy dysregulation were observed in hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, AS, myocardial infarction (MI), HF, and MCM[30].

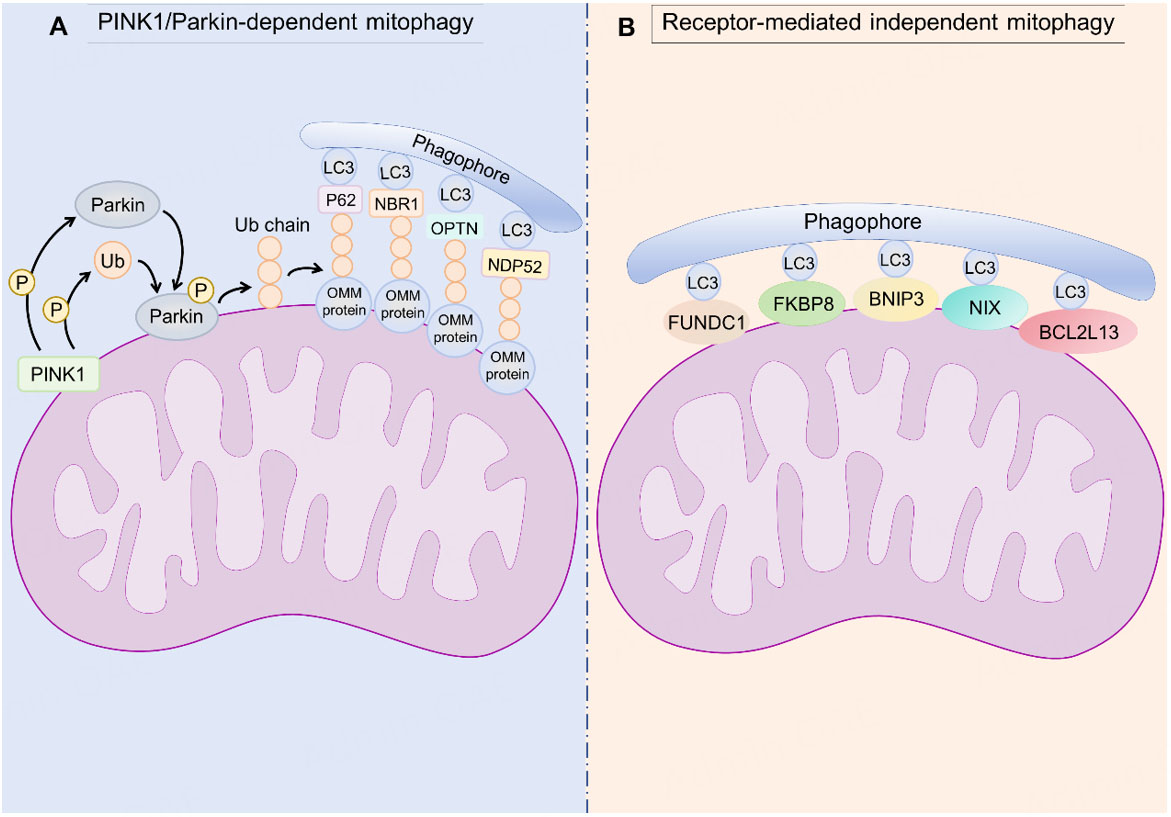

It was currently known that mitophagy primarily included the classic PINK1 [phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-induced putative kinase 1]/Parkin-dependent pathway and receptor-mediated mitophagy[31,32]. The PINK1/Parkin pathway was one of the most classic and extensively studied mitophagy mechanisms in mammalian cells. PINK1 is a serine/threonine kinase composed of 581 amino acids. Its structure includes an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting motif comprising a transmembrane domain (approximately 110 amino acids long), three N-terminal highly conserved kinase subdomains (Ins1, Ins2, and Ins3), and a C-terminal auto-regulatory sequence. Parkin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that contains an N-terminal ubiquitin-like (UBL) domain, RING0 (an extra RING-like domain N-terminal to RING1), RING1, and RING2 domains, and an In-Between-RING (IBR) domain separating RING1 and RING2. The primary function of Parkin is to ubiquitinate proteins on the outer membrane of damaged mitochondria, marking them for clearance via mitophagy[33,34]. In healthy mitochondria with normal membrane potential, PINK1 is continuously imported into the mitochondrial matrix via the TOM (translocase of the outer membrane) and TIM23 (translocase of the inner membrane 23) complexes. PINK1 is rapidly cleaved by PARL (presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protein) in the matrix, released into the cytosol, and degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), maintaining low cytosolic PINK1 levels. When mitochondrial membrane potential collapsed, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulated, or DNA damage occurred, PINK1 import failed and accumulated on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) and initiated autophosphorylation. After formation of the dimer, PINK1 phosphorylated Parkin and activated E3 ligase activity[35] [Figure 1A]. Then, activated Parkin ubiquitinated OMM proteins (e.g., voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), mitofusin 1/2 (Mfn1/2)), forming polyubiquitin chains. These ubiquitin chains served as substrates for PINK1. PINK1 phosphorylates more ubiquitin molecules, which further enhances Parkin's activity. This created a "positive feedback amplification" signal, leading to rapid and extensive ubiquitination of the damaged mitochondrion[36] [Figure 1A]. Ubiquitinated OMM proteins were recognized by autophagy receptor proteins such as p62/Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1), NBR1 (Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein), OPTN (optineurin), and NDP52 (nuclear dot protein 52). These receptors could simultaneously bind to ubiquitin chains on mitochondria and to LC3 or gamma-aminobutyric acid receptor-associated protein (GABARAP) proteins via LIR, thereby guiding mitochondria for encapsulation by autophagosomes[11-13,37] [Figure 1A]. Once encapsulated, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome. Lysosomal hydrolases degraded the mitochondrion, releasing reusable metabolic substrates such as amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleotides.

Figure 1. Principal pathways regulating mitophagy. Mitophagy proceeds mainly via the canonical PINK1/Parkin-dependent pathway (A), typically triggered by mitochondrial depolarization and leading to ubiquitin-mediated recruitment of autophagosomes, and receptor-mediated pathways that dock LC3 through LIR motifs to eliminate damaged mitochondria (B). PINK1: PTEN-induced putative kinase protein-1; Ub: ubiquitin; P: phosphorylation; OMM: outer mitochondrial membrane; LC3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B; P62: Sequestosome-1; NBR1: Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein; OPTN: optineurin; NDP52: nuclear dot protein 52; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain-containing 1; FKBP8: FK506-binding protein 8; BNIP3: B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) interacting protein 3; NIX: BNIP3L/NIP3-like protein X; BCL2L13: BCL2-like 13.

Besides the PINK1/Parkin pathway, multiple receptor-mediated mitophagy pathways exist. These receptors directly bind to proteins on the mitochondrial outer membrane and contain an LIR domain, which could target mitochondria to the autophagosome. Importantly, these pathways were ubiquitin-independent, bypassed the PINK1/Parkin pathway, and directly responded to stress signals such as hypoxia and oxidative damage, responding more rapidly and efficiently. The key receptors of the mitochondrial outer membrane include BNIP3 (B-cell lymphoma 2 interacting protein 3, BCL2 interacting protein 3)[38], BNIP3L (BCL2 interacting protein 3-like, NIP3-like protein X, NIX)[38], FUNDC1 (FUN14 domain-containing 1)[39], BCL2L13 (BCL2-like 13)[40], FKBP8 FKBP8 (FK506-binding protein 8; also known as FK506-binding protein 38, FKBP38)[41], and others. These receptors directly facilitated mitochondrial clearance by binding to LC3 via their LIR domains [Figure 1B].

Beyond the canonical PINK1/Parkin pathway and receptor-mediated mitophagy, cells can engage a set of compensatory mitochondrial clearance mechanisms under specific stress conditions or when the classical machinery is compromised, thereby establishing a multilayered quality-control network. These alternative routes can be broadly grouped into three categories. First, LC3 recruitment remains central but occurs in a Parkin-independent manner. For example, mitochondrial damage can trigger cardiolipin externalization to the OMM, which can be directly recognized by cytosolic LC3 to initiate mitophagy[42]. In addition, under certain conditions, the autophagy-related protein AMBRA1 (activating molecule in Beclin-1-regulated autophagy) can localize to mitochondria and function as an LC3 adaptor to promote mitochondrial targeting[43]. Second, alternative macroautophagy-like pathways that diverge from the canonical LC3 lipidation system have been described. During cardiac energy stress, ULK1 (Unc-51-like kinase 1)-Rab9 (Ras-related protein Rab-9)-mediated mitophagy can partially bypass ATG5 (autophagy related 5)/ATG7 (autophagy related 7)-dependent LC3 lipidation and confer cardioprotection[44]. Third, more non-canonical, ULK1-independent modes of mitochondrial handling exist. These include the formation of mitochondria-derived vesicles that deliver selected damaged components to lysosomes, or direct lysosomal engulfment and degradation via micro-mitophagy-like processes[45].

Given the substantial evidence supporting the PINK1/Parkin pathway and the receptors BNIP3/NIX and FUNDC1, and the relatively limited data on BCL2L13, FKBP8, and alternative mitophagy pathways in CVDs, this review focuses primarily on the former.

Mitophagy in HF

HF refers to a clinical syndrome characterized by abnormalities in cardiac structure and function resulting from various causes. These abnormalities impair ventricular systolic and/or diastolic function, leading to an absolute or relative inadequacy of cardiac output that fails to meet the metabolic demands of body tissues. Due to the extremely high energy demands of cardiomyocytes and the central role of mitochondria as the primary sites of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation[12], mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of HF. The accumulation of damaged mitochondria not only impairs cardiomyocyte metabolism and myocardial function, but severe mitochondrial damage can also trigger cardiomyocyte apoptosis, causing irreversible cardiac injury. Mitophagy, as a protective mechanism for clearing dysfunctional mitochondria, exerted complex and multifaceted roles in HF[46]. Under physiological conditions, mitophagy was protective for cardiomyocytes. Upregulation of mitophagy in HF could help maintain cardiomyocyte homeostasis and cardiac function. Conversely, insufficient mitophagy led to inadequate removal of damaged mitochondria and elevated the levels of ROS and peroxides, thereby exacerbating HF progression[47]. However, excessive or dysregulated mitophagy could also be detrimental, as it might cause an excessive decrease in mitochondrial quantity, impair oxidative phosphorylation, reduce ATP production, worsen myocardial energy deficiency, and further promote the development of HF[15].

PINK1/Parkin in HF

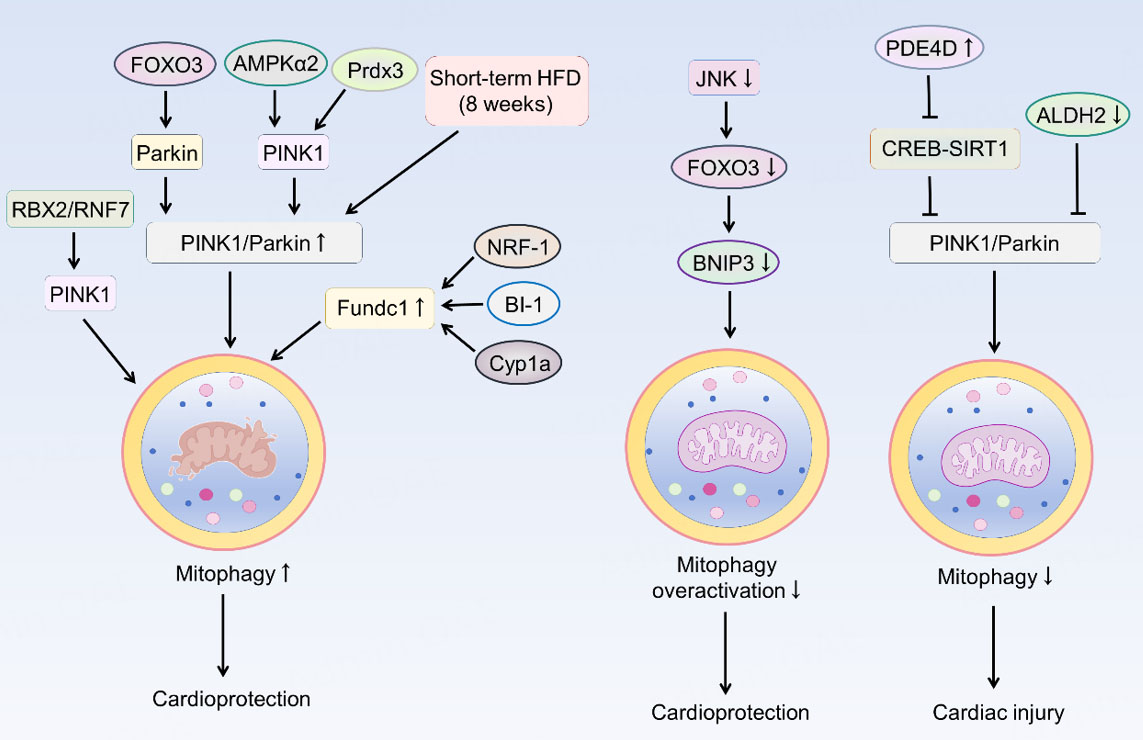

The downregulation of PINK1 contributes to impaired mitophagy in HF. Evidence indicates that patients with advanced HF exhibit significantly reduced PINK1 protein abundance, concomitant with diminished mitophagic efficiency. In contrast, normal expression of PINK1 and Parkin could mitigate cardiomyocyte injury and delay HF progression[48]. Current research on the PINK1/Parkin regulatory mechanism was extensive. In angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy models, Forkhead Box O3a (FOXO3a) directly bound to the Parkin promoter, enhancing its transcription. This activated PINK1/Parkin axis-mediated mitophagy, thereby reversing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling[49]. It was demonstrated that AMP-activated protein kinase α2 (AMPKα2) interacted with phosphorylated PINK1, augmenting PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and preventing HF progression[50]. Metabolic reprogramming and changes in enzyme activity significantly affect the efficiency of mitophagy. In HF models induced by pressure overload (transverse aortic constriction, TAC), short-term high-fat diet (HFD) for eight weeks improved mitochondrial function and suppressed hypertrophy by enhancing cardiac fatty acid utilization and activating Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Conversely, long-term HFD for 16 weeks failed to effectively activate mitophagy[51]. Another study showed that increasing fatty acid oxidation could suppress the HFD-induced decrease in mitophagic activity and reduce the accumulation of damaged mitochondria in the heart[52]. Collectively, these results highlight the time-dependent effect of HFD on cardiac mitophagy (protective in the short term, ineffective in the long term) and underscore fatty acid oxidation as a critical mediator in preserving mitophagic function and mitigating mitochondrial damage in the context of HFD-related cardiac stress. Otherwise, aberrantly elevated phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) in HF models suppressed the CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein)-SIRT1 (sirtuin 1) signaling pathway, leading to inactivation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Inhibiting PDE4D restored this pathway, reactivating mitophagy, reducing oxidative damage, and improving cardiac function[53]. Decreased aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) activity in HF rat models directly inhibited PINK1/Parkin pathway activity, causing impaired mitochondrial clearance, increased caspase-3-dependent apoptosis, and decreased cardiac function[54]. Members of the antioxidant enzyme family also play a core role in regulating mitochondrial autophagy. In aging models, peroxiredoxin 3 (Prdx3) bound to the PINK1 protein, stabilizing it on damaged mitochondria and initiating the PINK1-Parkin mitophagy pathway[55]. In HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) models, PINK1 overexpression restored peroxiredoxin 2 (Prdx2) levels, alleviated oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and improved diastolic function[56]. Additionally, studies have shown that PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy protects against pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy via inhibition of the mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA)-cGAS (cyclic GMP–AMP synthase)-STING (stimulator of interferon genes) signaling pathway, a key driver of inflammation and pathological remodeling[57,58]. Collectively, studies demonstrated that downregulation of the PINK1/Parkin signaling pathway was a major contributor to mitophagy impairment and HF pathogenesis. Targeting the upregulation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway to improve cardiac mitophagy may become a novel therapeutic approach for HF.

BNIP3/NIX in HF

BNIP3 and NIX could directly bind to LC3 proteins on the autophagosomal membrane via LIR, effectively "anchoring" damaged or superfluous mitochondria to the forming autophagosome for selective autophagic clearance. BNIP3/NIX-mediated mitophagy represented a crucial pathway independent of PINK1 kinase accumulation and Parkin ubiquitination, serving as classic examples of receptor-mediated mitophagy. However, significant controversy existed regarding the dual role of BNIP3 in HF progression. While multiple pieces of evidence implicated BNIP3 in HF pathological progression, its specific function remains contradictory. It was found that BNIP3 expression progressively increased post-aortic banding for 1week in rats, reaching its peak after developing to the stage of HF. Mitochondrial number inversely correlated with BNIP3 expression. Reducing BNIP3 expression reversed cardiac remodeling in the failing heart. Mechanistically, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling is a critical modulator of the transcription factor FOXO3a, driving the expression of its effector BNIP3 in HF, and JNK, through BNIP3, induces mitochondrial apoptosis and mitophagy[59]. In contrast, another study found decreased expression of BNIP3, PINK1, and FUNDC1 in patients with end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy and dilated cardiomyopathy HF[60]. In doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity models, doxorubicin was found to inhibit Parkin/BNIP3-mediated mitophagy, thereby exacerbating myocardial injury[61]. Another study showed that upregulated BNIP3 expression correlated with doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cardiac hypertrophy. BNIP3 knockout alleviated both mitochondrial dysfunction and hypertrophy[62]. Although studies revealed the potential involvement of BNIP3/NIX in HF, the mechanisms remain poorly understood. Therefore, future research should focus on further investigating the roles and mechanisms of BNIP3/NIX in HF pathogenesis, aiming to identify novel therapeutic targets for HF treatment.

FUNDC1 in HF

FUNDC1 is a mitophagy receptor located on the OMM and mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAM)[63]. FUNDC1 plays a critical role in cellular autophagy, particularly within the MQC system. FUNDC1 has similarities with other mitophagy receptors, which possess an LIR motif and constitute the molecular basis for its function as a mitophagy receptor[39]. FUNDC1 is widely expressed in humans, with particularly high abundance in cardiac tissue. The activity is dynamically regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Research indicated that phosphorylation of FUNDC1 at specific amino acid residues, such as Ser13[64], Ser17[65], and Tyr18[26], modulated the mitophagic activity, thereby facilitating the clearance of damaged mitochondria. Furthermore, various stimuli, including oxidative stress, hypoxia, and mitochondrial damage, could regulate the mitophagy process by influencing FUNDC1 expression levels and activity[66]. Notably, FUNDC1 expression was downregulated in HF[67]. FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy exhibited tissue-specific and bidirectional regulatory effects in hypoxia-induced CVDs. In hypoxic pulmonary hypertension models, it was found that FUNDC1 drove pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell (PASMC) proliferation by activating the ROS-hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) signaling axis, thereby promoting pulmonary vascular remodeling and disease progression[68]. Conversely, FUNDC1 demonstrated protective effects in cardiac tissue. In myocardial hypoxia injury models, the transcription factor nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1) directly bound to the FUNDC1 promoter, upregulating FUNDC1 expression, activating mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria, and protecting cardiomyocytes[69]. In doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy, the cytochrome P450 1A (Cyp1a) gene alleviated cardiac toxicity by upregulating FUNDC1 and promoting mitophagy[70]. Another study demonstrated that Bax inhibitor-1 (BI-1) overexpression protected against cardiorenal syndrome 3 (CRS-3) related myocardial injury by synergistically activating both FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy and the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6)-dependent mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) pathway, restoring mitochondrial metabolism and inhibiting cardiomyocyte apoptosis[71]. It was found that FUNDC1 exerted a crucial protective effect in septic cardiomyopathy by regulating acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4)-mediated ferroptosis[72]. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that the regulation of FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy involves complex signaling pathways. Future in-depth research into the roles of FUNDC1 across different disease models will provide vital clues for developing novel therapeutic strategies.

RBX2/RNF7 in HF

Research has systematically revealed the central role of the E3 ubiquitin ligase RBX2 (RING box protein 2)/RNF7 (RING Finger Protein 7) in maintaining cardiac mitochondrial homeostasis. The study discovered that RBX2, the catalytic subunit of the cullin-RING ligase 5 (CRL5) complex, localized to mitochondria. Knockout of RBX2 impeded mitochondrial ubiquitination, led to loss of PINK1 stability, triggered mitochondrial dysfunction, and rapidly progressed to dilated cardiomyopathy and HF. Notably, the RBX2-CRL5 complex regulated PINK1-dependent mitophagy in a manner completely independent of Parkin[73]. Subsequent research further elucidated the mechanism, confirming that even in the absence of Parkin, RNF7/RBX2 was recruited to damaged mitochondria. RNF7/RBX2 directly ubiquitinated substrates and stabilizes PINK1, thereby initiating an alternative mitophagy pathway. The study also found that cardiac-specific RNF7 knockout mice developed severe mitochondrial dysfunction and HF, which was independent of Parkin. These results indicated that RNF7 is an essential regulator for Parkin-independent MQC in the heart[74]. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that RBX2/RNF7 and its associated complex played a critical role in cardiac MQC and mitophagy. Particularly under the conditions of Parkin deficiency, RBX2/RNF7 could maintain mitochondrial function and prevent cardiac pathogenesis through an alternative pathway.

In summary, mitophagy exerts a “double-edged sword” effect in the heart: a moderate increase is generally protective, whereas insufficient or excessive mitophagy may disrupt homeostasis and lead to pathological consequences. The key lies in fine-tuned regulation that maintains mitophagy at an appropriate level. The mechanisms regulating mitophagy discussed above are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy in heart failure. RBX2/RNF7 promotes mitophagy by enhancing the stability of PINK1. Furthermore, FOXO3, AMPKα2, Prdx3, and a short-term high-fat diet (8 weeks) can augment the PINK1/Parkin pathway, thereby activating mitophagy and conferring cardioprotective effects. Meanwhile, NRF-1, BI-1, and Cyp1a promote this process by upregulating FUNDC1. Inhibiting JNK limits the overactivation of mitophagy via the FOXO3-BNIP3 axis, maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and protecting the myocardium. The aberrant elevation of PDE4D, which suppresses the CREB-SIRT1 pathway, as well as the downregulation of ALDH2, can lead to the inactivation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Consequently, reduced mitophagy leads to cardiac injury. PINK1: PTEN-induced putative kinase protein-1; RBX2: RING box protein 2; RNF7: RING Finger Protein; FOXO3: forkhead box O3; AMPKα2: AMP-activated protein kinase α2; Prdx3: peroxiredoxin 3; HFD: high-fat diet; NRF-1: nuclear respiratory factor 1; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain-containing 1; BI-1: Bax inhibitor-1; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; BNIP3: B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) interacting protein 3; PDE4D: phosphodiesterase 4D; ALDH2: aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; SIRT1: sirtuin 1; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; Cyp1a: cytochrome P450 1A.

Mitophagy and ischemic heart disease

IHD is characterized by myocardial damage, which stems from an imbalance between the heart's oxygen supply (via coronary blood flow) and its metabolic demand[75]. The heart is a high-energy-demand organ with limited myocardial energy reserves. Under ischemic stress, mitochondria sustain severe damage, releasing mediators of necrosis and apoptosis that ultimately lead to cell death[76]. The loss of cardiomyocytes plays a significant role in IHD. To prevent mitochondrial-mediated cell death pathways, damaged mitochondria are cleared via mitophagy.

PINK1/Parkin in ischemic heart disease

The PINK1/Parkin pathway plays a crucial and complex role in IHD by regulating mitophagy, exerting both damage-promoting and cardioprotective effects. Multiple studies have demonstrated that the activity of this pathway is tightly regulated by a variety of upstream signaling molecules. Studies demonstrated that PINK1, Parkin, and other mitophagy markers are significantly upregulated in rat hearts after ischemia-reperfusion, indicating activation of PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy under ischemic stress[77]. MicroRNA-23a (miR-23a) exacerbated myocardial injury by suppressing connexin 43 (Cx43) expression and hyperactivating PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy. This process was regulated by the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, and NF-κB inhibitors could block the detrimental effects of miR-23a, suggesting therapeutic potential in targeting the miR-23a-NF-κB axis[78]. Notch1 intracellular domain (N1ICD) suppressed PTEN expression during MIRI, thereby inhibiting excessive activation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway, which alleviated mitochondrial fragmentation and dysfunction[79]. Additionally, the adipokine Omentin 1 activated PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy by upregulating the Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3)/FOXO3a signaling pathway, reducing myocardial injury in mice with ischemia-induced HF[80]. Another study revealed that Ras homolog family member A (RHOA) activation stabilized PINK1 accumulation, recruited Parkin, and subsequently triggered mitochondrial ubiquitination and autophagic degradation, thereby attenuating myocardial ischemic injury. It was indicated that RHOA was a novel molecular target for enhancing mitophagy and cardioprotection[81]. Modulating the PINK1/Parkin pathway and its associated signaling networks may provide novel therapeutic strategies for ischemic heart disease.

FUNDC1 in ischemic heart disease

As a core mitophagy receptor, recent research highlighted the critical role of FUNDC1 in IHD. FUNDC1 functional status directly influenced the severity of myocardial damage. Studies in mouse MI models revealed that inhibiting bulk autophagy did not significantly impair cardiac function. However, the prognosis was determined by whether mitophagy was impeded. FUNDC1 knockout mice exhibited specific inhibition of mitophagy, leading to decreased cardiac function and exacerbated mitochondrial damage post-MI. Conversely, FUNDC1 transgenic mice demonstrated enhanced mitophagy, which significantly reversed injury. This confirmed that specifically targeting mitophagy was superior to non-selective autophagy activation[82]. Further studies demonstrated that FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy triggered the UPRmt by reducing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) levels. This subsequently activated mitochondrial antioxidant defenses, upregulated anti-apoptotic proteins, and promoted mitochondrial fusion/biogenesis, ultimately suppressing oxidative stress and apoptosis in MIRI[83]. As research progressed, the regulatory mechanisms controlling FUNDC1 function were becoming clearer, revealing novel therapeutic targets. Significantly elevated in clinical MI patients and rat/cellular MIRI models, miR-130a directly targeted and suppressed connexin gap junction protein alpha1 (GJA1), disrupting the GJA1-FUNDC1 signaling axis. It impaired mitophagy, reduced ATP synthesis, ROS accumulation, and exacerbated myocardial injury[84]. The stress-responsive transcription factor nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1) was markedly activated during MIRI. NR4A1 induced aberrant phosphorylation of FUNDC1, inhibiting mitophagic activity[74]. Overexpression of PLK1 in MIRI activated AMPK [adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase], enhancing FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy, reducing infarct size, and inhibiting apoptosis[85].

In summary, FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy exerted a significant cardioprotective effect in IHD. Modulating FUNDC1 and its associated pathways would be a novel therapeutic strategy and target for IHD treatment.

BNIP3 in ischemic heart disease

Recent research found the pivotal role of BNIP3 in MIRI. The activity of BNIP3 was elaborately regulated by a multi-layered molecular network. Multiple studies have elucidated the role of BNIP3 in myocardial injury and its regulatory mechanisms. Study discovered that MIRI specifically induced K199 crotonylation (Kcr) on the mitochondrial protein isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 alpha subunit (IDH3a). This modification attenuated myocardial apoptosis by inhibiting BNIP3-mediated mitophagy[86]. It was found that YTH domain-containing family protein 2 (YTHDF2) (an N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader protein) was downregulated during MIRI. This impaired recognition of m6A modifications on BNIP3 mRNA, leading to aberrant accumulation of BNIP3 protein, hyperactivation of mitophagy, and exacerbated myocardial injury[87]. The study demonstrated that the histone demethylase Jumonji C (JmjC) domain-containing protein 5 (JMJD5) was significantly reduced in MIRI. Overexpression of JMJD5 activated BNIP3-mediated mitophagy by upregulating HIF-1α, thereby increasing cell survival and inhibiting apoptosis[88]. Circular RNAs (circRNAs) act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), regulating BNIP3 translation by sequestering microRNAs (miRNAs), serving as key drivers of BNIP3 dysregulation in MIRI. It was found that elevated circPOSTN expression in MI models sequestered miR-96-5p, relieving its suppression of BNIP3, which resulted in aberrant BNIP3 activation and promoting cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis. Knockdown of circPOSTN significantly improved cardiac function and inhibited remodeling[89]. Besides transcriptional control, direct protein-protein interactions bidirectionally regulated mitophagy by modulating BNIP3 activity or localization. Using cardiac-specific myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) overexpression mice, it was found that Mcl-1 inhibited non-selective autophagy during starvation via the LC3-binding motif. Conversely, upon mitochondrial depolarization or post-MI mitochondrial dysfunction, enhanced Mcl-1 binding to BNIP3 triggered Parkin-independent mitophagy, accelerating clearance of damaged mitochondria and ultimately protecting cardiomyocytes[90]. The lipid regulatory protein proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) was significantly upregulated under MIRI and hypoxia-reoxygenation conditions. PCSK9 induced hyperactivated autophagy via the BNIP3-Beclin-1/LC3 axis, amplifying systemic inflammation and metabolic imbalance, which ultimately increased myocardial damage. Inhibiting PCSK9 downregulated the pathway, reducing infarct size and improving cardiac function[91].In summary, the mechanisms governing the role of BNIP3 in myocardial IHD are complex and multi-layered, involving numerous molecular pathways. Future research should focus on precisely modulating these pathways to provide novel therapeutic strategies for IHD.

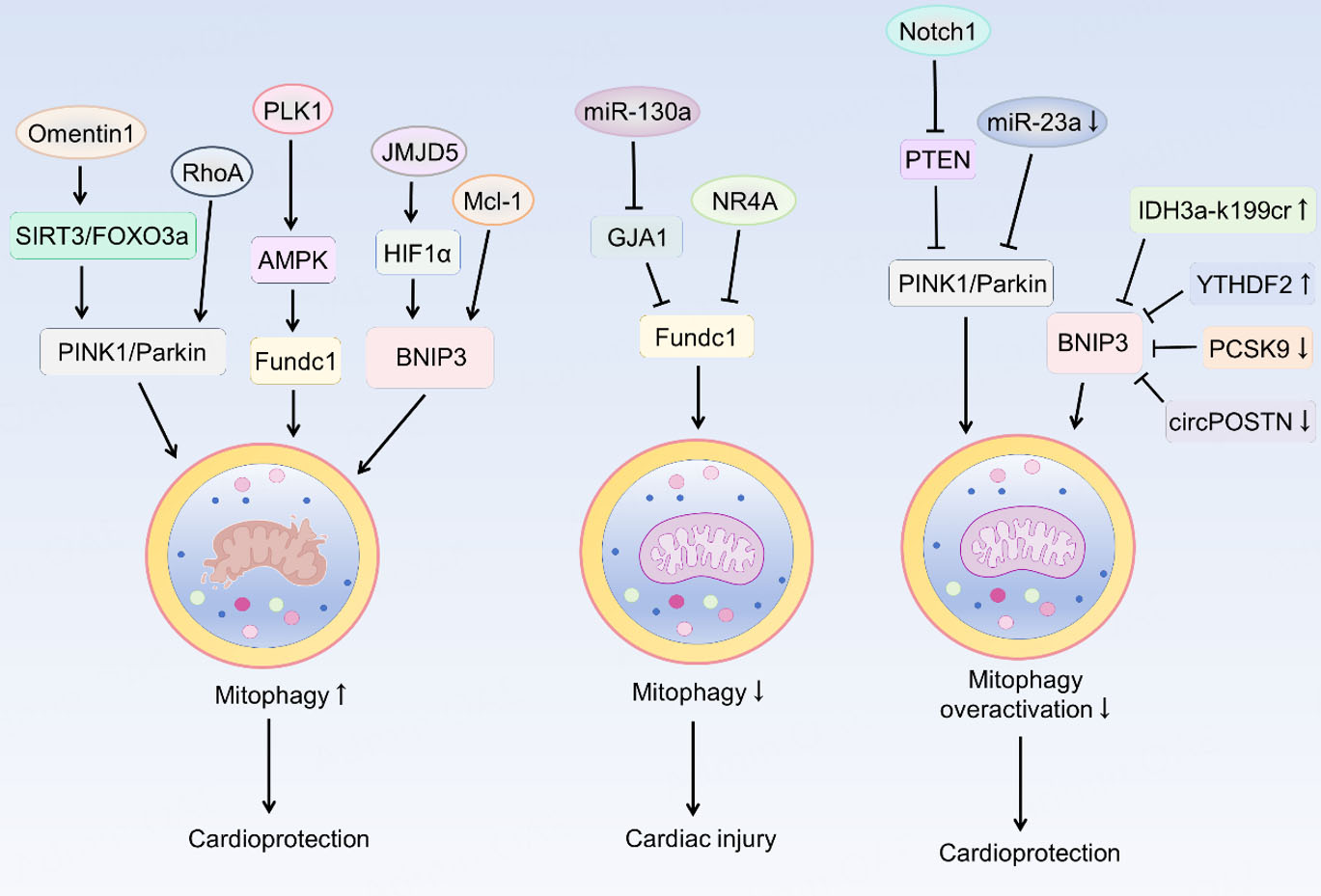

Based on the available evidence, this review summarizes the key regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy in IHD [Figure 3], aiming to provide an actionable molecular framework for the field and to lay a theoretical foundation for developing therapeutic strategies that precisely modulate autophagy.

Figure 3. Regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy in ischemic heart disease. Omentin 1 activates PINK1/Parkin-dependent mitophagy by upregulating the SIRT3/FOXO3a signaling pathway. Meanwhile, RhoA also activates this pathway to exert cardioprotective effects. PLK1 overexpression promotes FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy through AMPK activation. Overexpression of JMJD5 activates BNIP3-mediated mitophagy by upregulating HIF-1α, thereby conferring a cardioprotective effect; Mcl-1 also exerts its protective effect by activating this same pathway. Both miR-130a (by inhibiting GJA1) and NR4A can suppress FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy, ultimately leading to myocardial injury. Notch1 inhibits PTEN-PINK1-Parkin signaling-mediated mitophagy. miR-23a inhibits PINK1-Parkin signaling-mediated mitophagy. YTHDF2 inhibits BNIP3 mRNA expression and downregulates mitophagy. IDH3a-K199cr, YTHDF2, PCSK9, and circPOSTN all regulate BNIP3-mediated mitophagy, maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and conferring cardioprotection. PINK1: PTEN-induced putative kinase protein-1; FOXO3a: forkhead box O3a; SIRT3: sirtuin 3; RhoA: ras homolog family member A; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; FUNDC1: FUN14 domain-containing 1; JMJD5: jumonji-C (JmjC) domain-containing protein 5; HIF1α: hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; Mcl-1: myeloid cell leukemia-1; BNIP3: B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) interacting protein 3; GJA1: gap junction protein alpha1; NR4A1: nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1; PTEN: phosphatase and tensin homolog; IDH3a: isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 alpha subunit; YTHDF2: YTH domain-containing family protein 2; PCSK9: proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9.

Mitophagy and AS

AS, one of the most common etiologies of CVDs, involves a complex and multifactorial process including dyslipidemia, inflammation, oxidative stress, impaired autophagy, and mitochondrial dysfunction[92]. Mitophagy, as a key mechanism of MQC, is increasingly of concern for its role in the pathogenesis and progression of AS[93]. Multiple studies consistently highlighted the critical role of p62/SQSTM1-mediated selective autophagy in regulating cellular homeostasis in AS. The study demonstrated in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) that the adipokine C1q/TNF-related protein 9 (CTRP9) counteracted palmitic acid (PA)-induced inhibition of autophagy by activating AMPK, thereby restoring autophagy flux. The counteraction between CTRP9 and PA-induced autophagy accelerated p62 degradation and recovered autophagosome-lysosome fusion, evidenced by increased LC3-II levels. Consequently, it cleared damaged organelles and suppressed endothelial senescence, which indicated CTRP9 as a novel endothelial-protective target for AS prevention[94]. In monocytes/macrophages, the neuropeptide Y (NPY) not only induced M2 polarization but also significantly reduced the formation of foam cells induced by 7-ketocholesterol. This occurred by enhancing p62-mediated autophagy and concurrently activating the NRF2/heme-oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) antioxidant pathway[95]. In a co-culture model of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL)-stimulated HUVECs and THP-1 macrophages, p62-mediated autophagy was co-regulated by lysosomal dysfunction and proteasome/E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. At the same time, p62 downregulation activated alternative pathways, highlighting a compensatory interaction between the UPS and autophagy[96].

Mitophagy and MCM

MCM is a disease characterized by structural and functional impairment of the myocardium, triggered by metabolic disorders such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is typically associated with dysregulated autophagy homeostasis. Autophagy activation facilitates the degradation of damaged proteins and organelles, thereby mitigating cardiac fibrosis in MCM. Mitophagy plays a crucial role in maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis, and dysregulation of mitophagy is closely linked to metabolic diseases.

In diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), the epigenetic regulator bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) was aberrantly overexpressed. BRD4 directly bound to the PINK1 promoter, suppressing PINK1 transcription and leading to functional impairment of the PINK1/Parkin pathway, which reduced mitophagy. The BRD4 inhibitor JQ1 restored PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and alleviated HFD-induced DCM[97]. Study further demonstrated that long-term HFD suppressed PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy by upregulating acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) carboxylase 2 (ACC2)[52]. It was found that the zinc transporter [ZIP7 (transporter-like protein 7)] was significantly upregulated in type 2 diabetic hearts. ZIP7 overactivation increased mitochondrial Zn2+ efflux, leading to mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization, which inhibited PINK1 protein stability and activation, resulting in failed Parkin recruitment and inhibition of mitophagy[98]. A comparison of MIRI outcomes in rats of different ages following acute hyperglycemia revealed that hyperglycemia significantly exacerbated infarct size and reduced ejection fraction, accompanied by upregulation of autophagy proteins such as BNIP3 and Beclin-1. These results further confirmed the critical role of autophagy in cardiac injury under diabetic conditions[99]. Results revealed from an enzymatic perspective that decreased ALDH2 activity was a central defect in diabetic cardiac energy metabolism and mitochondrial damage. This decline in activity of ALDH2 suppressed the expression of multiple mitophagy receptors (Parkin, BNIP3, FUNDC1), consequently blocking mitophagy[100]. In summary, these studies demonstrated that PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy in MCM was regulated by multi-layered mechanisms. Modulating these molecular pathways may provide novel targeted therapeutic strategies for MCM.

The above studies indicate that the biological effects of mitophagy in CVDs are highly context-dependent. Mitophagy mediated by different receptors/molecular pathways exhibits non-uniform expression changes and functional outcomes across distinct pathological conditions. To more clearly delineate this complexity and identify potential patterns, we systematically reviewed and integrated the expression profiles and functional implications of key mitophagy receptors in major CVDs, and summarized the findings in Table 1.

Expression patterns and functional implications of key mitophagy receptors in major cardiovascular diseases

| Pathway/Receptor | Disease | Expression | Functional role | Reference |

| PINK1/Parkin | HF | Downregulated in advanced HF | Protective | [48] |

| IHD | Upregulated | Early adaptive activation is protective; overactivation or impaired flux is detrimental | [77-81] | |

| MCM | Downregulated | Protective | [52,97,98,100] | |

| BNIP3 | HF | Upregulated in chronic pressure overload; downregulated in end-stage HF | Context-dependent: can be protective or detrimental | [59-62] |

| IHD | Upregulated | Controlled activation can be protective; dysregulated activation is detrimental | [86-91] | |

| MCM | Upregulated | Detrimental | [99] | |

| FUNDC1 | HF | Downregulated | Protective | [67] |

| IHD | Downregulated | Protective | [82-85] | |

| MCM | Downregulated | Protective | [100] |

THE ROLE OF LIPOPHAGY IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

The molecular mechanism of lipophagy

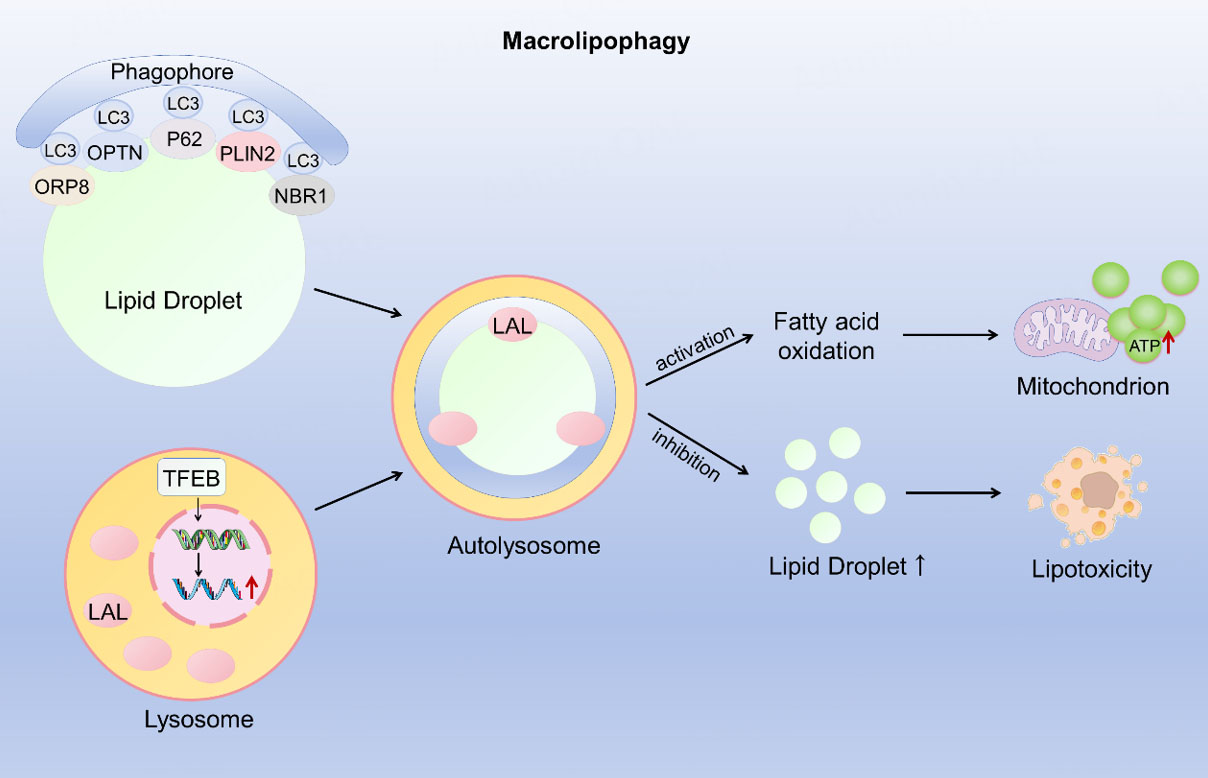

Lipophagy is a selective autophagy that specifically targets and degrades intracellular LDs. The concept of "lipophagy" was first proposed by Rajat Singh in 2009[19]. This groundbreaking work revealed that LDs, the primary intracellular lipid storage organelles, could be degraded into fatty acids by fusing with autophagosomes and subsequently undergoing hydrolysis within lysosomes. This process maintains lipid metabolic homeostasis and challenges the traditional opinion that LDs are hydrolyzed solely by neutral lipases. Lipophagy primarily occurs through two distinct mechanisms: macrolipophagy and microlipophagy. Macrolipophagy is a form of selective autophagy characterized by the engulfment of LDs by autophagosomes and their subsequent delivery to lysosomes for degradation. In contrast, microlipophagy is a more ubiquitous process in which the lysosomal membrane directly invaginates to engulf cytoplasmic components, including LDs, without the involvement of autophagosomes[101]. Similar to mitophagy, macrolipophagy initiation involves LD surface proteins or selective autophagy receptors such as oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 8 (ORP8), p62/SQSTM1, NBR1, perilipin 2 (PLIN2), and OPTN[102,103]. These proteins contain an LIR that recruits the autophagosomal membrane. Once the LD is encapsulated by the forming autophagosome, it fuses with a lysosome. Lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) then completes the hydrolysis of the LD[104]. Under lipophagy-inducing conditions, AMPK inhibits the activity of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which upregulates ULK1, inhibits p62 expression, and promotes the formation of the double-membraned autophagosome[105]. Additionally, the transcription factor EB (TFEB) enhances lipophagy by increasing lysosomal biogenesis and upregulating lysosomal function, providing essential support for the degradation process[106]. Lipophagy plays a vital role in regulating intracellular lipid storage, free fatty acid levels, and energy balance[15]. When cells are energy-deprived, lipophagy is activated to degrade LDs, releasing fatty acids as an energy source. Conversely, impaired lipophagy can lead to excessive LD accumulation, triggering lipotoxicity [Figure 4]. This makes cells more sensitive to death stimuli and contributes to the pathogenesis of various diseases. Evidence was shown that dysfunctional lipophagy was related to cancer[107,108], liver diseases[109], CVDs[110], and neurological disorders[111].

Figure 4. The mechanism of macrolipophagy. Selective autophagy receptors (e.g., p62, NBR1, OPTN) and LD surface proteins (e.g., PLIN2, ORP8) recruit LC3-positive phagophores to engulf lipid droplets, which then fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes. Within autolysosomes, lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) hydrolyzes neutral lipids to free fatty acids, while TFEB promotes lysosomal biogenesis. The liberated fatty acids are oxidized in mitochondria to generate ATP; when macrolipophagy is inhibited, lipid droplets accumulate and cause lipotoxicity. LAL: Lysosomal acid lipase; TFEB: transcription factor EB; ORP8: oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 8; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; NBR1: Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein; PLIN2: perilipin 2; OPTN: optineurin; LC3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B; P62: Sequestosome-1.

Lipophagy and AS

AS is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by lipid accumulation, inflammatory responses, and foam cell formation within the vascular wall[112]. Dysregulation of lipid metabolism is a central driver in the initiation and progression of AS, and lipophagy plays a complex and pivotal role in the process.

Macrophage lipophagy and AS

In this section, we will primarily review evidence for lipophagy and its underlying mechanisms in macrophage-derived foam cell formation. Monocyte-derived macrophages play a critical role throughout the entire continuum of AS, from initiation and progression to plaque rupture[113]. Macrophages initiate the atherosclerotic process by massively engulfing modified lipoproteins such as acetylated low-density lipoprotein (ac-LDL) and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL). As lipid uptake increases, if the lipophagic capacity of macrophages is insufficient and cholesterol efflux is impaired, intracellular accumulation of cholesterol-enriched LDs occurs. Then, macrophages are transformed into foam cells, defining the cellular component of atherosclerotic lesions[114]. Furthermore, macrophages laden with LDs trigger inflammation within the vascular wall, further promoting AS progression and even precipitating plaque rupture[115].

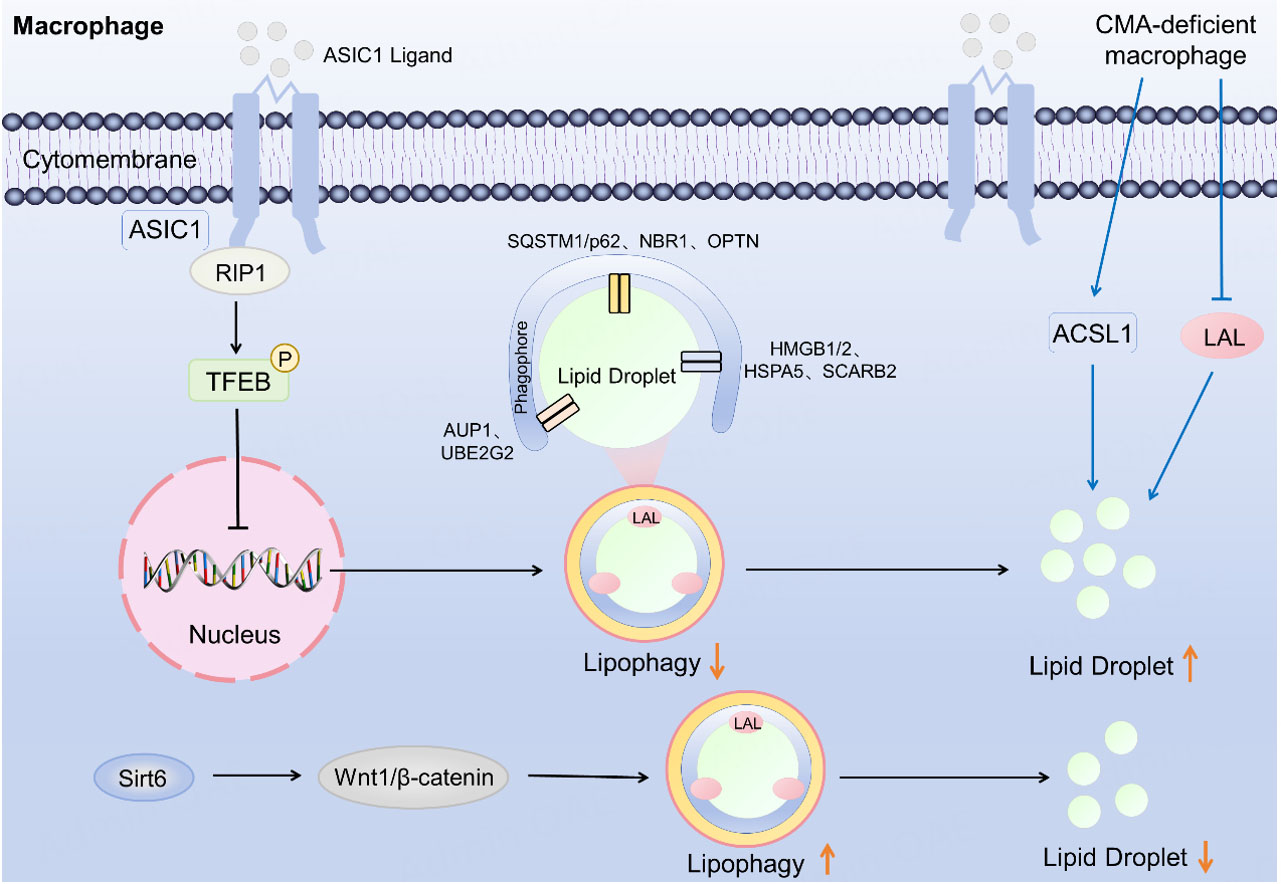

Lipophagy plays a critical role in regulating lipid accumulation within macrophages[116,117]. As a key pathway for macrophages to clear LDs, research in recent years has deeply elucidated the central position and mechanisms of lipophagy in AS [Figure 5]. By using proteomic screening and functional validation, the key protein network on LD surfaces mediating lipophagy was identified[102]. This network included ubiquitination-related proteins [ancient ubiquitous protein 1 (AUP1), ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 G2 (UBE2G2)], classical autophagy receptors (SQSTM1/p62, NBR1, OPTN) and non-canonical factors (high mobility group box proteins 1 and 2 (HMGB1/2), heat shock protein family A member 5 (HSPA5), scavenger receptor class B member 2 (SCARB2)). This work clarified the molecular basis for LD degradation via ubiquitin signaling and specific receptors, providing novel targets for promoting cholesterol clearance in foam cells by targeting lipophagy. Additionally, research found that the acid-sensing ion channel 1 (ASIC1) bound to receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1). The complex phosphorylated TFEB prevented nuclear translocation and consequently inhibited lipophagy, leading to further lipid accumulation[118]. Another study revealed that decreased CMA activity contributed to lipid accumulation. CMA exerted its effect independently of canonical lipophagy by upregulating long-chain fatty acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (ACSL1) and downregulating LAL, suggesting a distinct role for CMA in macrophage lipid homeostasis[119]. Sirtuin 6 (Sirt6) enhanced macrophage lipophagy and ameliorated lipid metabolism dysregulation in AS by modulating the Wnt family member 1 (Wnt1)/β-catenin pathway[110]. These findings provided novel insights for AS therapy and may provide a theoretical foundation for future targeted intervention strategies.

Figure 5. Regulation of lipophagy in macrophages. The binding of ASIC1 to RIP1 leads to the phosphorylation of TFEB, which prevents its nuclear translocation and ultimately inhibits lipophagy. LAL: Lysosomal acid lipase; Wnt1: wnt family member 1; Sirt6: sirtuin 6; TFEB: transcription factor EB; ASIC1: acid-sensing ion channel 1; P62: Sequestosome-1; RIP1: receptor-interacting protein 1; SQSTM1: Sequestosome-1; OPTN: optineurin; NBR1: Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein; CMA: chaperone-mediated autophagy; ACSL1: acyl-CoA synthetase 1; SCARB2: scavenger receptor class B member 2; HMGB1/2: high mobility group box proteins 1 and 2; HSPA5: heat shock protein family A member 5. AUP1: ancient ubiquitous protein 1; UBE2G2: ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 G2.

Sirt6 ameliorates AS by enhancing macrophage lipophagy via the Wnt1/β-catenin pathway. Loss of CMA in macrophages triggers a cascade of ACSL1 upregulation and LAL downregulation, driving lipid accumulation. The key protein network on LD surfaces that mediates lipophagy in macrophages includes ubiquitination-related proteins (AUP1, UBE2G2), classical autophagy receptors (SQSTM1/p62, NBR1, OPTN), and non-canonical factors (HMGB1/2, HSPA5, SCARB2).

Endothelial cell lipophagy and AS

Endothelial cells play an important role in the initiation, progression, and acute events of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Endothelial dysfunction represents the initial trigger and a key driver of AS. Under physiological conditions, the endothelium acts as a selective barrier, regulating vascular permeability and maintaining vasodilation, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant states through the release of mediators such as nitric oxide (NO). However, under the influence of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease risk factors, endothelial damage disrupts barrier function, enabling the permeation and subendothelial deposition of atherogenic lipoproteins (e.g., ox-LDL)[120]. In recent years, research on the relationship between endothelial cell autophagy and AS has deepened. Upregulation of lipophagy function in endothelial cells promotes the breakdown and clearance of lipid substrates within LDs, protecting endothelial cells from damage induced by various pro-atherosclerotic factors such as ox-LDL and advanced glycation end products (AGEs)[121]. Current studies indicated that ox-LDL could activate autophagy in endothelial cells. Following ox-LDL uptake, lipids were transported to autophagic vesicles for lysosome-mediated degradation. Simultaneously, ox-LDL might also trigger autophagy by inducing ERS[122]. However, under certain conditions such as in HUVECs, ox-LDL has been observed to impair lipophagy, resulting in disrupted lipid clearance and exacerbated lipid accumulation. This dysfunction is characterized by reduced autophagosome formation, downregulation of key autophagy-related proteins, and compromised lysosomal lipid-degrading capacity[123]. Enhancing endothelial autophagy may represent a potential therapeutic approach to reverse the atherosclerotic process, providing novel insights for future treatment strategies.

Smooth muscle cell lipophagy and AS

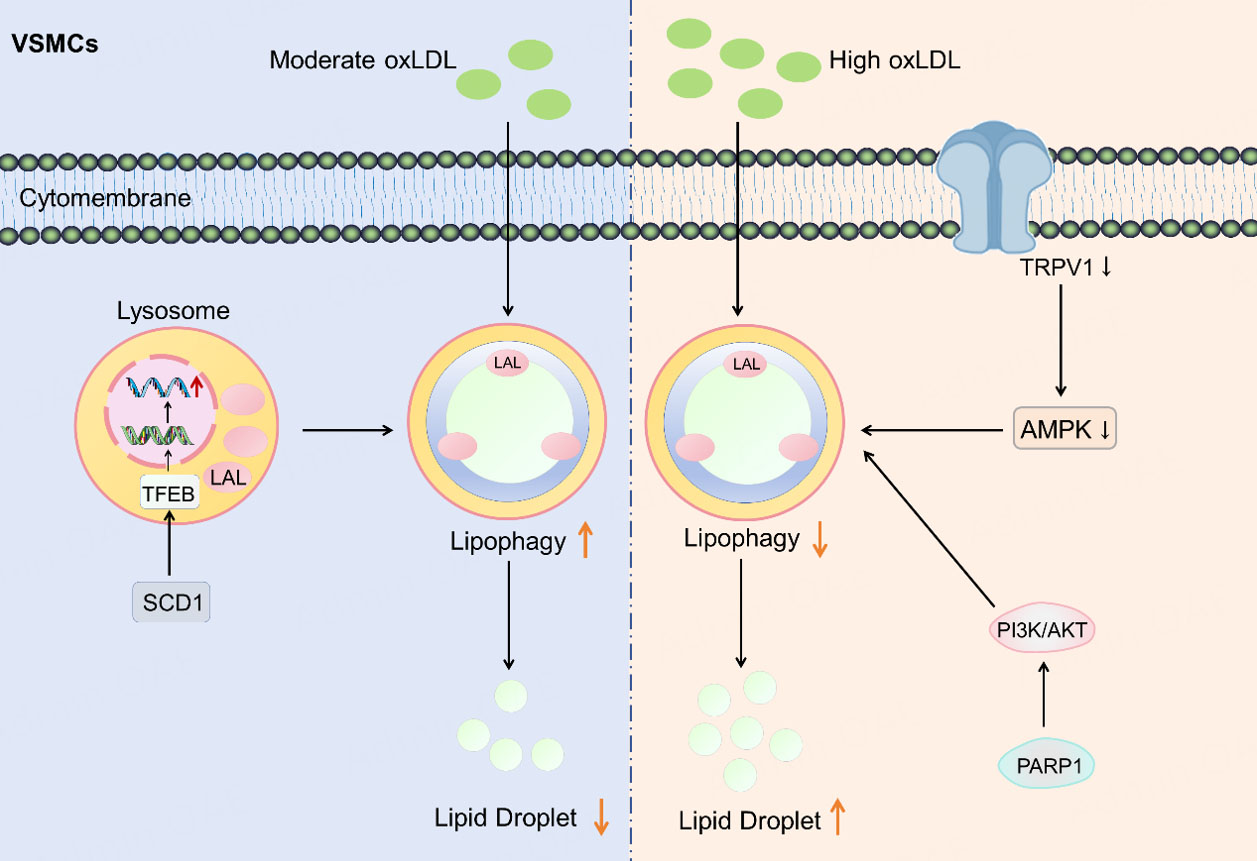

During AS progression, oxLDL plays a significant role in modulating lipid metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Research has found that in VSMCs, oxLDL downregulated stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), disrupting its binding to LDs, inhibiting LD-lysosome fusion, and ultimately reducing lipophagic flux. Further studies revealed that SCD1 overexpression reversed this lipophagy inhibition and slowed foam cell formation by activating nuclear translocation of TFEB, enhancing lysosomal biogenesis, and promoting LD-lysosome fusion[124]. Study also indicated that moderate oxLDL concentrations (10-40 μg/mL) enhanced VSMC lipophagic capacity, whereas high concentrations suppressed the lipophagy process[125]. In animal models and VSMCs experiments, geniposide alleviated the negative regulation of lipophagy by inhibiting the PARP1 (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1)/PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/AKT (protein kinase B) signaling axis. Geniposide significantly enhanced lipophagy marker expression, lysosomal activity, and lipid-autophagosome colocalization. Dependent on this pathway, geniposide inhibited lipid accumulation and inflammatory responses, ultimately reducing foam cell formation and slowing plaque progression[126]. Activating lipophagy effectively suppresses the formation of foam cells from VSMCs. Evidence demonstrates that lipophagy mediated by the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1)/AMPK pathway can protect against lipid accumulation in VSMCs induced by oxLDL[127]. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that excessive lipid accumulation inhibited lipophagy, accelerating AS development, while appropriate lipophagic activity mitigated plaque progression. To highlight VSMC lipophagy as an actionable intervention node in AS, we integrated the regulatory network of oxLDL-associated lipophagy and existing mechanistic evidence into Figure 6. This figure not only summarizes the relationship between changes in lipophagy flux and lipid accumulation under different oxLDL loads, but also indicates potential intervention directions such as activation of the TRPV1/AMPK pathway, inhibition of the PARP1/PI3K/AKT axis, and SCD1-TFEB-mediated enhancement of lysosomal biogenesis and function, thereby providing a basis for proposing subsequent targeted regulatory strategies. However, the mechanisms of VSMC lipophagy in AS remain incompletely understood and require further exploration.

Figure 6. Regulation of lipophagy in VSMCs. SCD1 activates the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor TFEB, thereby enhancing lysosomal biogenesis and ultimately increasing lipophagy. Moderate oxLDL concentrations (10-40 μg/mL) enhanced VSMC lipophagic capacity, whereas high concentrations suppressed the lipophagy process. Lipophagy in VSMCs is inhibited through the activation of the PARP1/PI3K/AKT and the inhibition of the TRPV1/AMPK signaling. LAL: Lysosomal acid lipase; TFEB: transcription factor EB; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells; OxLDL: oxidized low-density lipoprotein; SCD1: stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; TRPV1: transient receptor potential vanilloid 1; PARP1: poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B.

Lipophagy and MCM

MCM is myocardial injury triggered by metabolic disorders, and lipophagy plays an important role in the pathogenesis and progression. It was found that impaired lipophagy was a key factor in lipotoxic myocardial injury in MCM models (db/db mice and palmitate-treated H9C2 cells). SIRT3, as a crucial positive regulator of cardiomyocyte lipophagy, was downregulated in MCM. Activating SIRT3 effectively promoted lipophagy and alleviated myocardial lipotoxicity and dysfunction. Further research revealed that the natural compound berberine significantly improved cardiac function and reduced hypertrophy in diabetic model mice by activating the SIRT3-mediated lipophagy pathway. This study provided direct evidence and a potential drug candidate for targeting SIRT3 in MCM treatment[128]. Furthermore, in diabetic cardiomyopathy (DbCM) hearts, enhanced LD accumulation and lipotoxicity were found to be activated through micro-lipophagy rather than macro-lipophagy. By RNA sequencing and Rab7 conditional knockout (CKO) mouse models, it was found that Rab7 phosphorylation recruited the lysosome-associated protein Rab-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP), facilitating LD degradation. The formation of the Rab7-RILP complex was identified as the core step for LD-lysosome fusion and subsequent degradation. Treatment of DbCM mice with ML-098 (a small-molecule activator of Rab7), a Rab7-specific activator, successfully enhanced Rab7-RILP pathway activity, promoted LD degradation, and significantly improved cardiac function and pathological alterations. This finding confirmed that targeting Rab7-mediated micro-lipophagy was an effective strategy to mitigate lipotoxicity in DbCM hearts[129]. In summary, further investigation of the mechanisms of lipophagy in MCM provides novel perspectives and potential therapeutic targets for future MCM treatment.

RETICULOPHAGY

The molecular mechanism of reticulophagy

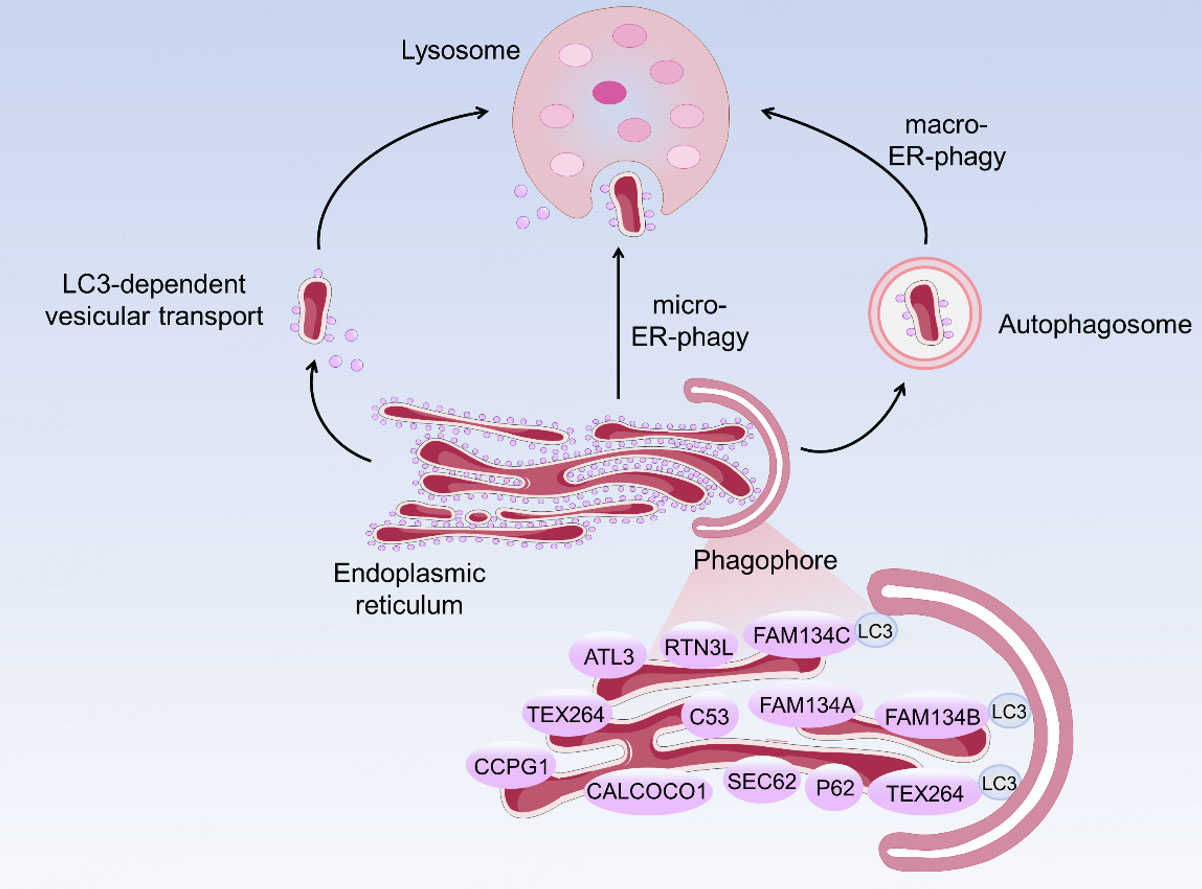

ER is the largest membrane-bound organelle in mammalian cells. It is responsible for protein processing and lipid synthesis, while also participating in calcium homeostasis, metabolic regulation, and cellular signal transduction[130]. When cells are subjected to various stresses, misfolded or unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER lumen, disrupting ER proteostasis and triggering ERS. ERS activates the unfolded protein response (UPR), which enhances the degradation capacity for misfolded proteins and stops protein translation and synthesis. If the UPR fails to effectively resolve ERS in a timely manner, cells selectively target the ER itself, initiating reticulophagy, a selective autophagy process specifically degrading the ER as substrates, to restore cellular homeostasis[131]. Reticulophagy, a form of selective autophagy targeting the ER, was first discovered in 2007[21], including macro-reticulophagy, micro-reticulophagy, and LC3-associated vesicle transport

Figure 7. Mechanism of reticulophagy. Three types of reticulophagy: macro-reticulophagy, micro-reticulophagy, and LC3-associated vesicle transport. The inset below illustrates the reticulophagy receptors identified in mammals, which tether the ER to LC3 on the phagophore, including FAM134A/B/C, RTN3L, ATL3, TEX264, SEC62, CCPG1, CALCOCO1, C53, and p62. LC3: microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; P62: Sequestosome-1; FAM134: family with sequence similarity 134; CCPG1: cell-cycle progression gene 1; TEX264: testis-expressed protein 264; ATL3: atlastin gtpase 3; RTN3L: the long isoform of reticulon 3; CALCOCO1: calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 1; SEC62: secretory 62 homolog.

Key receptors

To date, several reticulophagy receptors have been identified in mammals. These include: family with sequence similarity 134 (FAM134)A[134], FAM134B[135], FAM134C[134], p62[136], Secretory 62 homolog (SEC62)[137], the long isoform of reticulon 3 (RTN3L)[138], cell-cycle progression gene 1 (CCPG1)[139], atlastin gtpase 3 (ATL3)[140], testis-expressed protein 264 (TEX264)[141], calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 1 (CALCOCO1)[142] (also known as NDP52), and Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 regulatory subunit associated protein 3 (CDK5RAP3, C53)[143]. All these receptors contain a critical AIM (ATG8-interacting motif)/LIR/GIM (GABARAP-interacting motif) motif. Through the motif, receptors can bind to Atg8/LC3/GABARAP family proteins, thereby anchoring autophagosomes to the ER membrane and initiating the process of reticulophagy [Figure 7]. These receptors are distributed across distinct subdomains of the ER and participate in the autophagy of different ER types. For example, FAM134B localizes to ER sheets and mediates ER sheets fragmentation, whereas RTN3L, TEX264, and ATL3 are primarily involved in the degradation of tubular ER[144]. In terms of the research focus, current work has largely centered on a limited number of core ER-phagy receptors, with mechanistic studies most extensively addressing FAM134B and RTN3. Evidence indicates that its activity is largely restricted to the ER-phagy process, as FAM134B knockdown does not markedly affect other forms of selective autophagy or bulk macroautophagy[145]. Functionally, loss of FAM134B promotes ER expansion and triggers ERS, whereas its overexpression can disrupt ER-associated membrane structures and facilitate autophagosome formation[135]. RTN3 is a representative ER-phagy receptor that predominantly localizes to tubular ER domains and exhibits a strong membrane-bending capacity. RTN3L, the long isoform of RTN3, functions as a tubule-specific autophagy receptor. In contrast to FAM134B, RTN3L acts on ER tubules; its N-terminus contains six functional LIR motifs and, through oligomerization, engages LC3 and GABARAP proteins to promote the selective autophagic degradation of ER tubules[138].

The role of reticulophagy in cardiovascular diseases

Dysfunctional reticulophagy is closely associated with various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, liver diseases, and heart diseases[146]. Despite the relatively limited research on ER-phagy in CVD, some evidence indicates that it may exert context-dependent, bidirectional regulatory effects on the initiation and progression of multiple cardiovascular conditions, including cardiac hypertrophy, doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy, ischemic cardiomyopathy, and DCM. Evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies indicates that regulating FAM134B expression can attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and thereby slow the progression of HF. Mechanistically, apelin-13 has been proposed to activate the pannexin-1 hemichannel, leading to an increase in extracellular ATP. The elevated ATP subsequently stimulates the P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7) receptor and triggers FAM134B-dependent ER-phagy[147]. In the acute phase of IHD, ER-phagy is generally regarded as an adaptive ER quality-control mechanism that alleviates ERS-related cellular injury by removing damaged or excess ER components and restoring ER homeostasis. Accordingly, studies have shown that FAM134B-mediated ER-phagy can regulate the “autophagy-ERS” axis, thereby mitigating ischemia/reperfusion -induced myocardial injury[148]. On the other hand, in the context of ischemia-associated cardiac remodeling and cardiac dysfunction, RTN3 is markedly upregulated in failing human myocardium and in cardiac tissue after myocardial infarction in mice, whereas RTN3 deficiency improves post-infarction cardiac function, suggesting that this ER-shaping protein may be involved in post-ischemic structural and functional cardiac remodeling[149]. In TAC-induced HF models, the adenylyltransferase FIC domain-containing protein (FICD) alleviated pressure overload-induced HF, cardiac hypertrophy, and fibrosis by catalyzing the AMPylation of the ER chaperone binding protein (BiP). This modification inhibited the activation of the UPR and suppressed reticulophagy under stress conditions by attenuating the interaction between BiP and the reticulophagy receptor FAM134B[150]. In both septic mice and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated cardiomyocytes, FAM134B exerted a protective effect against sepsis-induced myocardial injury through the mediation of reticulophagy[151]. Furthermore, distinct isoforms of the FAM134B receptor played differential roles in regulating reticulophagy. Studies have identified both a full-length isoform (FAM134B-FL) and a truncated isoform (FAM134B-trunc), which exhibited tissue-specific distribution. The truncated FAM134B isoform was more abundantly expressed in muscle and heart tissues, particularly under starvation stress, and its deficiency led to disruptions in calcium homeostasis and protein metabolism[152]. DCM is characterized by structural and functional abnormalities resulting from hyperglycemia-induced metabolic dysregulation in the myocardium, and it is frequently accompanied by ER dysfunction and activation of ERS. Studies using high glucose-treated H9C2 cardiomyocytes and a diabetic rat model induced by a high-fat/high-fructose diet combined with streptozotocin (STZ) have revealed an imbalance in reticulophagy receptor expression. Specifically, SEC62 and RTN3 were upregulated, while FAM134B was downregulated. This imbalance led to abnormally enhanced reticulophagy, ultimately resulting in cardiac functional impairment. Further investigation demonstrated that chlorogenic acid could ameliorate high glucose/diabetes-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting ERS and restoring the balance of reticulophagy flux[153]. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of reticulophagy in DCM remain incompletely understood. Further research is needed to clarify the molecular mechanisms.

Although ER-phagy has been proposed as a potential avenue for novel interventions in CVD, the current body of evidence remains relatively limited. At the mechanistic level, the precise roles of ER-phagy receptor proteins across diverse cardiovascular pathological settings have not been fully delineated, particularly with respect to how these receptors recognize specific ER subdomains for selective degradation and whether functional redundancy or cooperation exists among them. Moreover, the spatiotemporal dynamics of ER-phagy across different stages of CVD and its crosstalk with other forms of selective autophagy remain poorly defined; the possibility that a given receptor may exert divergent, or even opposing, effects at distinct disease phases further complicates efforts toward precise therapeutic modulation. In addition, most available data are derived from cell-based and animal models, whereas clinical evidence is scarce, including limited information on ER-phagy-related biomarker patterns in human samples and their associations with patient outcomes. The lack of validated ER-phagy-specific druggable targets and standardized assessment frameworks also represents a major barrier to translation. Therefore, integrated investigations spanning molecular mechanisms, spatiotemporal regulation, and clinical translation will be instrumental in refining our understanding of ER-phagy in CVD and in laying the groundwork for its development as a potential therapeutic target.

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES TARGETING SELECTIVE AUTOPHAGY

Given the critical role of selective autophagy in the pathogenesis and progression of CVDs, accurate modulation of selective autophagy has emerged as a promising therapeutic direction. However, since selective autophagy may exert dual roles depending on the disease stage and cell type, it is crucial to develop strategies capable of precisely modulating autophagic activity rather than simply activating or inhibiting it. Currently, the majority of research on pharmacological modulation of selective autophagy focuses on mitophagy [Table 2]. In contrast, drugs that target reticulophagy and lipophagy are relatively rare. However, the importance of reticulophagy and lipophagy in physiology and pathology is gradually being recognized, particularly concerning the function of intracellular homeostasis maintenance, lipid metabolism regulation, and disease processes modulation. Consequently, further in-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying reticulophagy and lipophagy is essential to pave the way for the future development of targeted therapeutic drugs.

Mitophagy-targeted therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular diseases

| Strategy | Specific method/compound | Mechanism | Model type | Reference |

| Exercise | MRT | Activate the HIF1α-Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [155] |

| Endurance, Resistance, HIIT | Activates the PINK1/Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [156] | |

| MICT | Activate the Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [157] | |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors | Canagliflozin | ISO model: inhibits the AMPK/PINK1/Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [159] |

| Diabetic model: activates the AMPK/PINK1/Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [160] | ||

| Empagliflozin | Activates AMPKα1/ULK1/FUNDC1 pathway | Cell/Animal | [161] | |

| Traditional Chinese medicine and natural active substances | Ginsenosides | Activates the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/Mcl-1 pathway | Cell/Animal | [163] |

| C20DM | Inhibits the PINK1/Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [164] | |

| Rg3 | Activates the ULK1/FUNDC1 pathway | Cell/Animal | [165] | |

| berberine, Huangqi-Danshen decoction, Nuanxinkang, Xinyin tablets, berberine, and simvastatin | Activates the PINK1/Parkin pathway | Cell/Animal | [166-170] | |

| Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata | Activates the PI3K/AKT pathway to regulate BNIP3 | Cell/Animal | [171] | |

| Shenfuyixin | Activates SIRT3/FOXO1 pathway, promotes FOXO1 deacetylation, upregulates Bnip3 and LC3B-II | Cell/Animal | [172] | |

| DQP, XYT, α-LA | Activates FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy | Cell/Animal | [174-176] | |

| MOX | Inhibits the FUNDC1-mediated excessive mitophagy | Animal | [177] | |

| EA | Inhibits the ULK1/FUNDC1 pathway | Animal | [178] | |

| Shuangshen Ningxin | Inhibits the PINK1/Parkin and FUNDC1 | Cell/Animal | [179] |

Exercise

In recent years, the role of exercise in improving HF and MIRI has garnered increasing attention, particularly concerning the effects on MQC and autophagic mechanisms. Research indicated that aerobic exercise specifically downregulated Parkin and BNIP3 while upregulating PINK1, suggesting that it might protect the myocardium by promoting balanced selective autophagy[154]. Another study further revealed that moderate-intensity aerobic training (MRT) was the most significant benefit in improving cardiac function and enhancing mitophagy. This effect was primarily mediated through activation of the HIF1α-Parkin pathway[155]. All forms of exercise, including endurance, resistance, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT), could upregulate cardiac expression of irisin/fibronectin type III domain containing 5 (FNDC5) and could activate PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy, thereby improving myocardial function. Notably, resistance exercise was demonstrated to have the most significant effect in this process[156]. In ischemic HF, moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) provided significant improvement in cardiac function and reduction of myocardial fibrosis compared to HIIT. Conversely, in pressure-overload HF, both exercise modalities effectively improved cardiac function and suppressed pathological cardiac remodeling, depending on the Parkin-mediated autophagy pathway[157]. Exercise also protected against MIRI by enhancing parasympathetic activity/M2 muscarinic receptor (M2AChR) signaling, inhibiting ERS, and reducing excessive PINK1/Parkin-mediated autophagy[158].

SGLT2 inhibitor

In isoproterenol (ISO)-induced myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, canagliflozin significantly attenuated these pathological changes by reversing the aberrant activation of the AMPK/PINK1/Parkin pathway, inhibiting excessive mitophagy, and restoring mitochondrial homeostasis[159]. Conversely, in diabetic mice, canagliflozin directly activated AMPK, restored the PINK1-Parkin axis, and enhanced mitophagic flux, thereby ameliorating diabetic myocardial lipid deposition and fibrosis[160]. Empagliflozin protected cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMECs) by activating the AMPKα1/ULK1 pathway to enhance FUNDC1-dependent mitophagy[161]. Notably, the cardioprotective effect of empagliflozin could occur independent of Parkin protein[162]. These findings provided a novel therapeutic approach for cardiac remodeling in Parkin-deficient patients. It is worth further exploration to provide a basis for precise clinical medication.

Traditional Chinese medicine and natural active substances

Traditional Chinese medicine and natural bioactive compounds also demonstrate significant potential for cardioprotection. Extensive research indicated that ginsenosides and their derivatives protect the heart by modulating mitophagy. Specifically, ginsenosides from Panax japonicus restored mitophagy via the PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β (glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta)/Mcl-1 pathway[163]. The ginsenoside precursor 20S-O-Glc-DM (C20DM) enhanced MQC by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α) and downregulating PINK1/Parkin[164]. Ginssennoside Rg3 (Rg3) bound to ULK1 could promote phosphorylation of FUNDC1 at Ser17, and activated mitophagy[165]. Other traditional Chinese medicine constituents, including berberine[166], Huangqi-Danshen decoction[167], Nuanxinkang[168], Xinyin tablets[169] and simvastatin[170], could ameliorate myocardial remodeling and cardiac function by activating the PINK1/Parkin pathway to enhance mitophagy.

In chronic HF, the aqueous extract of Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata (Fuzi) significantly improved cardiac function and attenuated myocardial fibrosis by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway to regulate BNIP3-mediated mitophagy[171]. In MI, Shenfuyixin granule enhanced mitophagy by activating the SIRT3/FOXO1 pathway, promoting the deacetylation of FOXO1, and upregulating BNIP3 and microtubule-associated protein light chain 3B (LC3B-II). This led to improved cardiac function and reduced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis[172]. Furthermore, studies demonstrated that the marine-derived compound fucoxanthin (FX) could ameliorate high glucose-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by specifically activating the BNIP3/NIX receptors to increase mitophagy[173].

Compound Chinese medicine Danlou Tablet (DQP), the Chinese herbal compound Xinyue Tablet (XYT), and α-lipoic acid (α-LA) all could improve cardiac function by activating FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy[174-176]. In contrast, moxibustion (MOX) alleviated doxorubicin-induced HF injury by inhibiting FUNDC1-mediated excessive mitophagy and restoring mitochondrial function[177]. In MIRI, electroacupuncture (EA) reduced infarct size and apoptosis by activating mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) to inhibit the ULK1/FUNDC1 pathway, thereby suppressing mitophagy[178]. Shuangshen Ningxin capsule protected mitochondrial structure by inhibiting multiple mitophagy pathways, including PINK1/Parkin and FUNDC1[179]. Collectively, these findings demonstrated that FUNDC1-mediated mitophagy functions could act as a reparative mechanism or a contribution to pathology, which were highly dependent on the specific pathological background and upstream signals.

Despite growing preclinical evidence supporting the therapeutic potential of selective autophagy modulation in CVDs, several critical challenges must be addressed before clinical translation can be achieved. The overwhelming majority of current knowledge derives from cell-based and animal models, whereas human data characterizing selective autophagy flux, receptor activity dynamics, and their associations with clinical outcomes remain scarce. This translational gap is compounded by the absence of reliable, clinically accessible biomarkers that can accurately reflect pathway-specific autophagy activity in patients. A fundamental challenge lies in the biphasic nature of selective autophagy, wherein both insufficient and excessive activity can be detrimental, and the same pathway can exert opposing effects depending on disease stage, cell type, and underlying etiology. However, most studies fail to establish clear dose-response relationships or optimal therapeutic windows tailored to specific pathophysiological contexts. Complicating interpretation further, many autophagy-modulating interventions target upstream regulatory nodes that govern broad cellular programs beyond autophagy, making it difficult to distinguish autophagy-dependent from autophagy-independent benefits and increasing the risk of off-target effects. Safety considerations are particularly important, as systemic or prolonged perturbation of autophagy may incur unintended consequences including immune dysregulation, metabolic disturbances, or tissue injury, especially in older patients with comorbidities. Future advances will necessitate collaborative endeavors to develop and validate biomarkers, delineate therapeutic windows with precision, utilize pathway-selective tools for mechanistic dissection, establish standardized methodologies, and promote cell-type-specific or tissue-selective targeting approaches.

CONCLUSION

The role of selective autophagy in CVDs has garnered significant attention in recent years. By clearing damaged or superfluous organelles, proteins, and other cellular components, selective autophagy maintains the normal function of the cardiovascular system. It plays a crucial regulatory role in the initiation and progression of cardiac pathologies, particularly HF, AS, and MIRI. However, despite substantial progress, the mechanisms underlying selective autophagy in CVDs remain incompletely understood. Firstly, the molecular regulatory network of selective autophagy is complex and diverse, involving multiple signaling pathways and protein interactions. However, a systematic understanding of the exact functions of the individual pathways is still lacking. Secondly, although studies indicate that selective autophagy plays distinct roles in different types of CVDs, the different effects across various cardiovascular pathological states remain unclear. The dynamic changes and critical transition points during disease development, progression, and outcome are poorly defined. We propose a “stress burden-clearance capacity” dynamic balance framework to conceptualize the dual roles of selective autophagy in cardiovascular pathology. According to this framework, cardiovascular outcomes depend on whether disease-related stress is appropriately matched by the organelle clearance capacity of autophagy systems. An optimal autophagic response supports MQC and cellular homeostasis, whereas insufficient or excessive autophagy may contribute to disease progression. This model helps reconcile seemingly conflicting observations and emphasizes the importance of temporal and quantitative regulation of autophagy.