Moisture-electric generation textiles for wearable energy devices: materials, structures, manufacturing, and applications

Abstract

Moisture-electric generators, as an environmentally friendly energy-harvesting technology, operate independently of external conditions such as sunlight, water droplets, or wind, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional energy sources. Moisture from the air is captured by a functional power-generation layer, where phase transitions of water molecules occur, enabling the effective conversion of the released chemical potential energy into electrical energy. Moisture-electric generation textiles (MEGTs) inherently exhibit flexibility, breathability, and biocompatibility, demonstrating significant potential as self-sustainable power sources for wearable electronics. Through feasible integration approaches, multiple functionalities can be incorporated into a single textile-based platform, paving the way for truly intelligent wearable systems. This review summarizes recent advances in moisture-electric generation mechanisms, materials, and device architectures of MEGTs. Particular emphasis is placed on modern fiber and textile manufacturing technologies, as well as on functional enhancement strategies for power generation layers and electrodes, including wet spinning, electrospinning, screen printing, and digital printing. Besides, the latest one-, two-, and three-dimensional device configurations of MEGTs are presented. The applications of these devices are further discussed in the contexts of wearable energy supply, healthcare monitoring, and smart agriculture. Based on this comprehensive analysis, this review aims to provide guidance for the optimization and innovation of flexible moisture-electric generating devices, accelerating their deployment in intelligent electronic textiles and other wearable technologies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Against the backdrop of global focus on sustainable development, achieving carbon neutrality has become crucial for improving the environment and climate[1-3]. The carbon neutrality goal is driving the expansion of the green, clean energy industry chain[4]. Given the environmental degradation associated with fossil fuels, the development and utilization of sustainable energy technologies, such as hydropower[5,6], solar energy[7,8], and wind power[9,10], have become the forefront of energy research. Hydropower is a clean, efficient, and sustainable energy option, encompassing traditional hydroelectric power generation[11-13], evaporation power generation[14-17], and the emerging method of moisture-electric generation[18,19]. Compared to other power generation methods, such as triboelectric power generation[20,21], evaporation power generation[22,23], and solar power generation[24], they rely on friction, heat, and sunlight, respectively[25], and all exhibit dependence on external factors[14,26]. Furthermore, it is difficult for these methods to achieve continuous and stable all-weather energy supply, and their overall equipment structures are complex. Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) generate signals by coupling triboelectric and electrostatic induction effects, operating during mechanical motion or contact separation[27,28]. Moisture-electric generators (MEGs) generate electricity solely through the spontaneous, continuous adsorption and desorption of ambient moisture. Evaporative power generation relies on solar-driven interfacial evaporation processes[29], requiring liquid water sources and avoiding freezing conditions[23]. MEGs can operate directly using humidity gradients in the air and function even in environments containing only water vapor, making them suitable for a wider range of applications. MEGs are physicochemical processes that operate continuously as long as atmospheric relative humidity (RH) is not zero, offering a longer theoretical lifespan. In mild, humid, non-freezing environments year-round, they can provide sustainable energy without human intervention and with low maintenance over a wide range of environmental humidity, giving MEGs the greatest advantage in providing continuous and stable power[30,31]. Compared to the previous two systems, MEGs cannot operate under diverse climatic conditions with abundant mechanical energy such as TENGs, nor can they provide the relatively stable output of evaporation systems with guaranteed water sources. Performance is limited in extremely dry or cold conditions, where reduced ion mobility and weakened proton gradients result in significant performance degradation[32]. Some teams have designed MEGs that can operate stably in dry or low-temperature environments[33-35]. As specialized complementary energy sources for specific environments, they have the potential to form hybrid energy harvesting systems with other technologies, enabling practical applications across a wider range of scenarios. Therefore, MEGs demonstrate unique application potential in sustainable energy supply due to their advantages of being environmentally friendly, structurally simple, and independent of specific geographical conditions[36].

MEGs capture moisture from the atmosphere through hygroscopic materials, driving the dissociation and migration of ions within their functional groups[17,37], ultimately achieving highly efficient electrical energy output[38,39]. Moisture-electric generation textiles (MEGTs) have shown promising applications in energy supply, wearable technology, and health monitoring, making them a focal point of academic research. They feature a simple structure and are easy to integrate flexibly, significantly reducing system complexity and manufacturing costs[40]. They can be readily embedded into self-powered miniature electronic devices or sensors[41]. In addition, these systems demonstrate high adaptability in smart wearable textiles, reducing reliance on external power sources and opening new avenues for diversified energy applications[42,43].

The development of MEGT devices is transitioning from laboratory research to practical applications. These devices hold great promise in fields such as energy supply, smart clothing, and multifunctional integration[44]. Leveraging the diversity and intrinsic properties of material systems, researchers have successfully engineered power-generating functional layers that combine high energy conversion efficiency with environmentally friendly and safe characteristics[45,46]. Device structures include one-dimensional (1D) linear, two-dimensional (2D) thin-film, and three-dimensional (3D) multilayer gel configurations. Power generation performance can also be enhanced by constructing asymmetric heterostructures[47-49]. Fibers or fabrics with different device structures can be fabricated through processes such as wet spinning, electrospinning, and dip coating[50-52]. Research in this field has evolved from early explorations of single materials to the deep integration of power generation capabilities within fibers or fabrics through sophisticated asymmetric device design and advanced textile processes such as spinning and weaving. This approach enhances output power while improving wearable flexibility and integration. These devices can drive low-power electronic devices[53,54], serve as distributed micro-power sources in extreme scenarios[55,56], and integrate flexibly with other devices[57,58]. Although research on MEGTs has made progress, it still faces the challenge of low power density output in individual devices. During long-term operation, the ion gradient gradually dissipates, affecting the device’s energy conversion efficiency[59,60]. Equipment manufacturing is constrained by material costs, with expensive materials further driving up overall costs and hindering industrial-scale production[50,61]. Adhesion issues between the power generation layer and electrodes also remain unresolved. Further research on surface modification and enhancement of materials is needed to synergistically improve moisture absorption capacity and environmental durability[62,63]. The key to advancing current technology lies in addressing its core challenges in performance, stability, and durability. Overcoming these challenges will enable applications in medical monitoring and human-machine interaction, ultimately realizing truly self-powered, comfortable, and sustainable wearable systems.

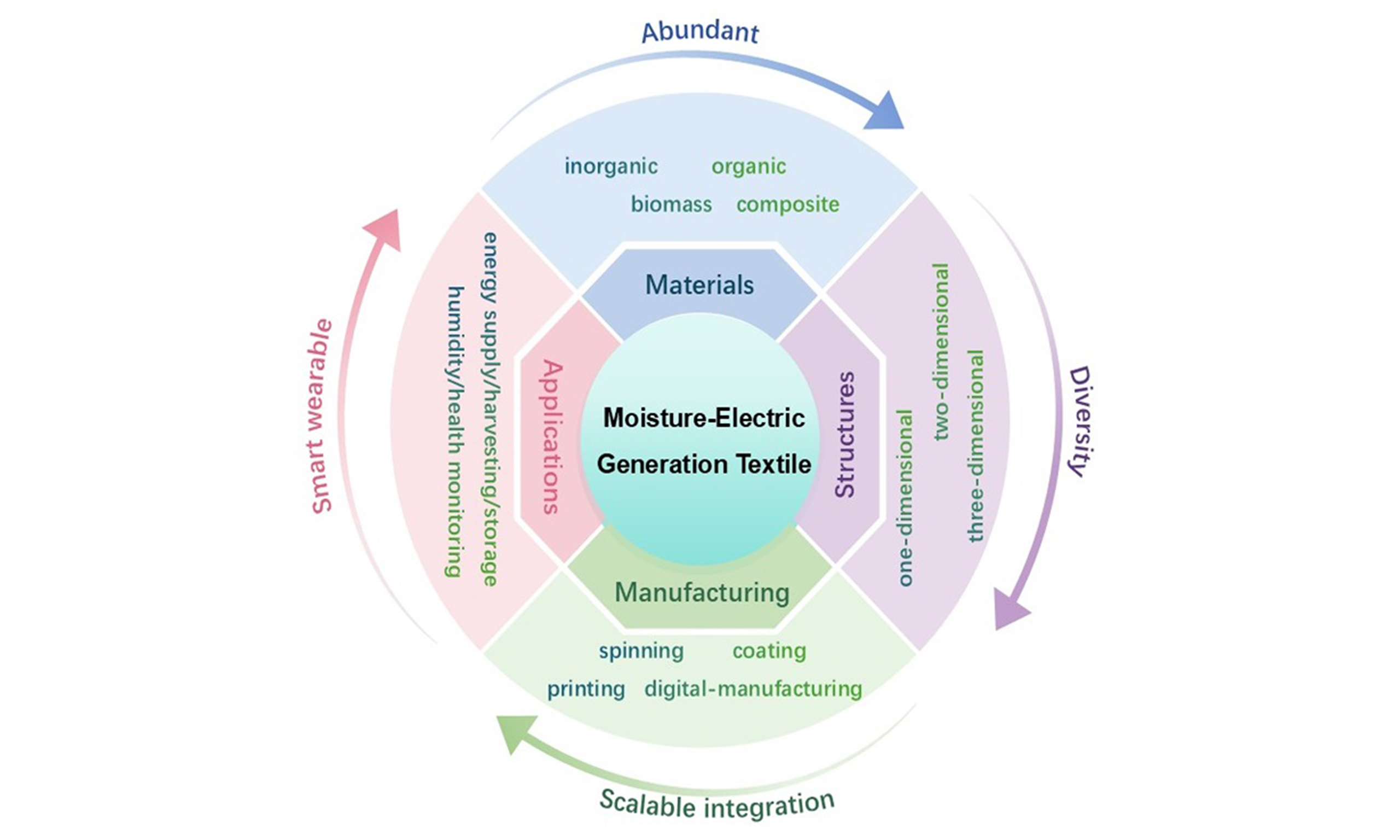

This review covers the moisture-electric generation mechanisms, materials, device structures, manufacturing processes, and application scenarios of MEGTs [Figure 1]. It focuses on exploring the potential for large-scale manufacturing and integration of these devices, as well as their applications in specific fields. To address challenges such as low power density, poor stability, and high costs, this paper proposes a synergistic development path integrating mechanisms, materials, and processes. Looking ahead, breakthroughs in these key technologies will enable MEGTs to achieve higher levels of integration and application in cutting-edge fields such as imperceptible energy replenishment, smart sensing, and personalized medicine.

MOISTURE ELECTRIC GENERATION MECHANISMS

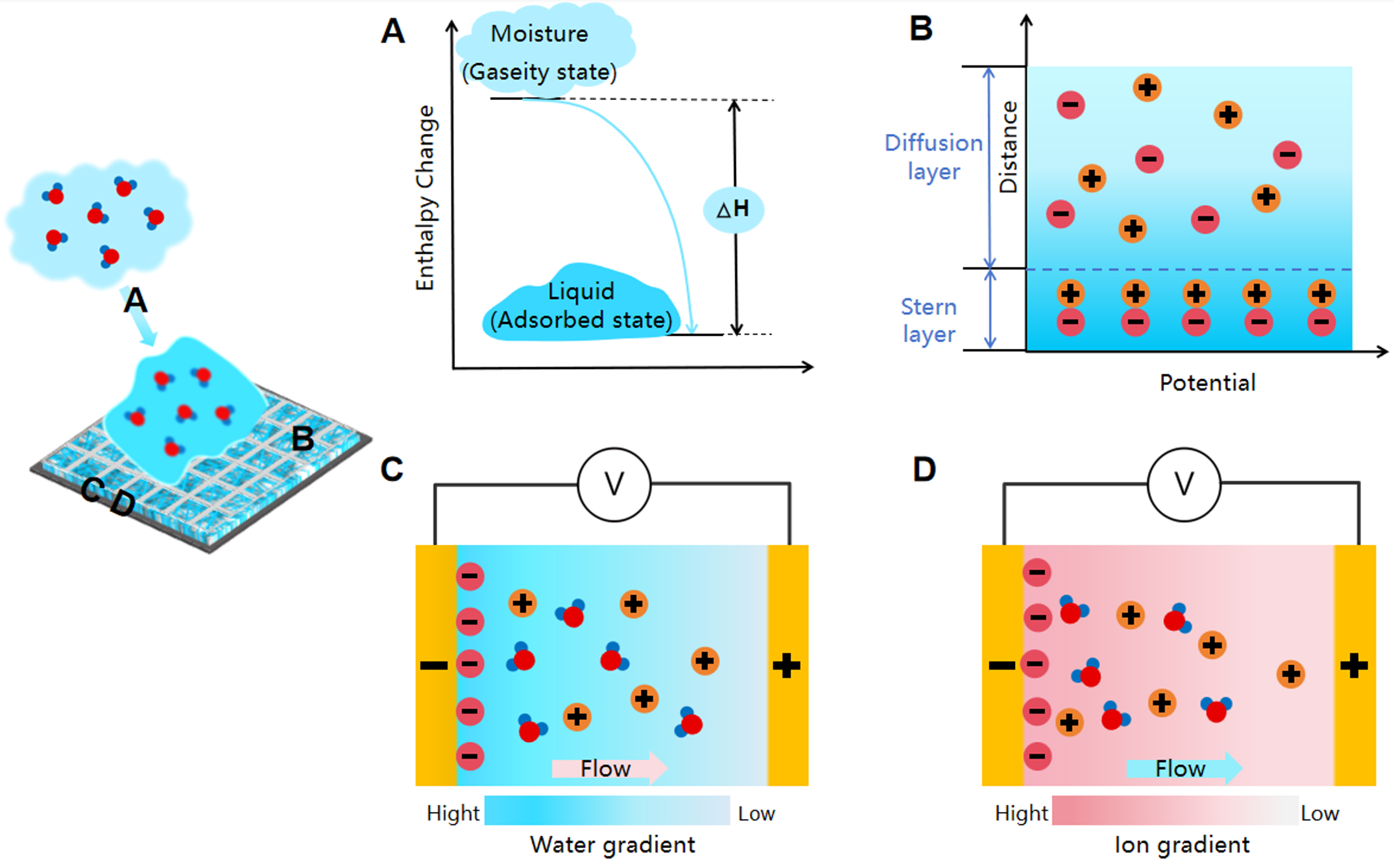

The mechanisms of MEGs primarily rely on the moisture absorption properties of materials, liquid-solid interface interactions, and ion transport mechanisms. By utilizing the adsorption of moisture by solid power-generation materials, water molecules interact with functional groups within the material and dissociate into mobile ions. The concentration gradient formed within the moisture-absorbing layer drives the directed migration of ions from regions of high to low concentration.

Interface effect

Interfacial water adsorption refers to the process whereby water molecules are captured at solid-gas or solid-liquid interfaces by surface active sites on materials, forming interfacial water films or hydration layers through physical or chemical adsorption. The atmospheric water cycle achieves efficient integration and redistribution of water and energy between the atmosphere, land surface, and subsurface through evaporation, transpiration, and precipitation[64,65]. When gaseous water molecules move freely in the atmosphere, they possess high kinetic energy[66,67]. Upon approaching the surface of a hygroscopic material, gaseous water molecules condense onto the solid surface[12]. The distance between water molecules decreases, enhancing their mutual interactions, reducing molecular kinetic energy, and increasing potential energy

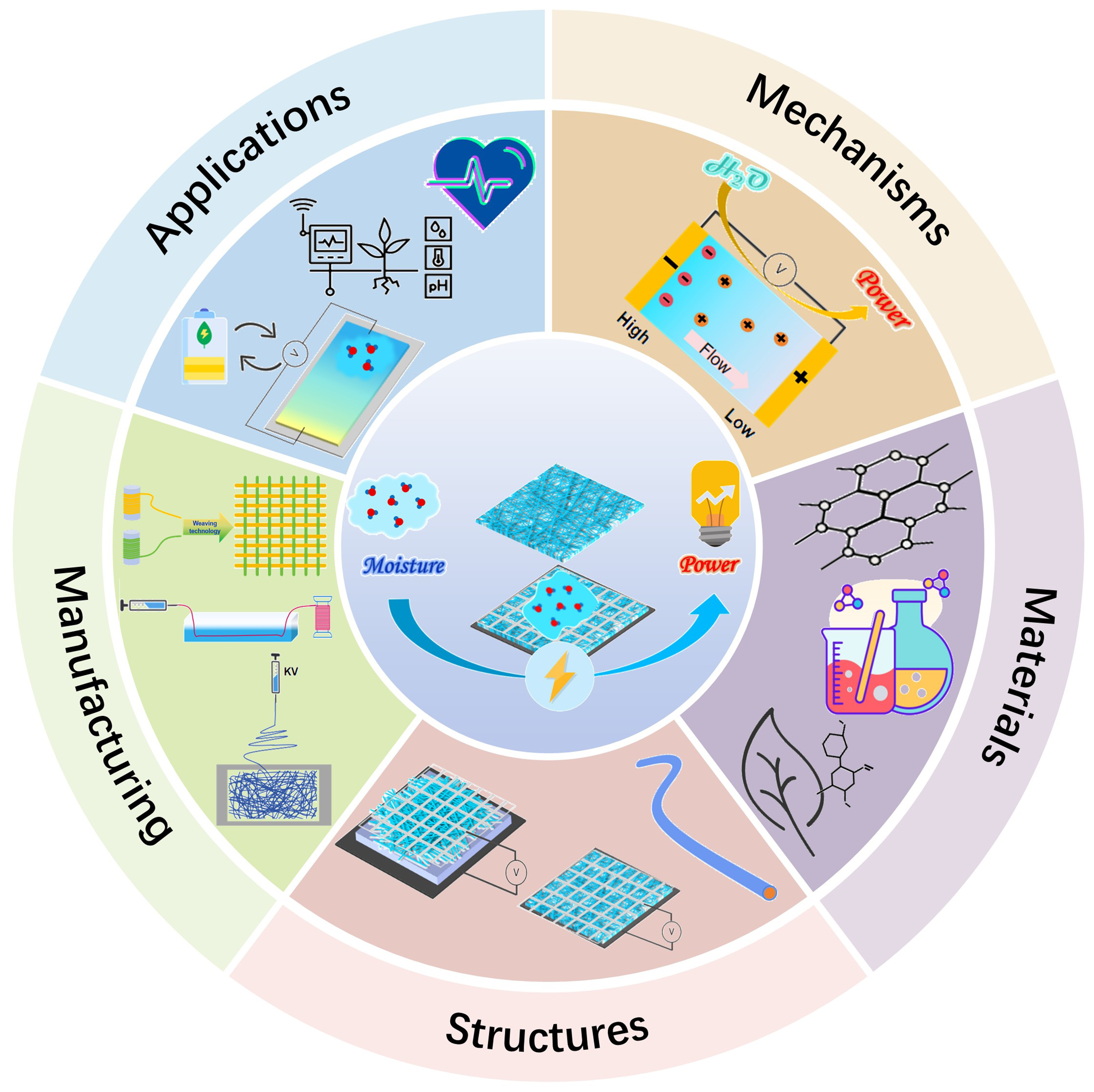

Figure 2. Mechanisms diagram of MEGs. (A) Engineering process of energy changes from gaseous water to liquid water thermodynamics; (B) The streaming potential generated by the movement of mobile counterions within the double electric layer as they are entrained by water flow; Schematic diagrams of ion diffusion and migration induced by (C) moisture gradient and (D) ion gradient in the electric generation layer. MEGs: Moisture-electric generators.

The physicochemical properties of materials in the power-generation functional layer influence device performance by regulating water-solid interactions and ion migration[32]. Pores serve as the primary pathways and sites for water molecule transport and ion migration. Multiporous structures or pore size gradients enhance the capture capacity of functional materials for water molecules while ensuring efficient ion migration channels and high migration rates[76]. Smaller pore sizes restrict ion movement, whereas excessively large pores weaken the chemical potential gradient. The chemical composition and charge distribution on the material surface are closely related to the adsorption and dissociation of water molecules. Surface defects or active sites can promote water molecule dissociation, increasing the concentration of ion carriers[62]. By optimizing these physicochemical properties, the material’s moisture absorption capacity, ionic conduction efficiency, and long-term stability can be enhanced.

Ion dissociation

When water molecules come into contact with the hygroelectric generation layer material, the interaction at their interface is a complex process. Functional groups on the material’s surface ionize or dissociate, generating surface charges. To maintain electrical neutrality at the interface, counterions in the solution accumulate at the boundary, forming a nanoscale charge distribution structure with capacitive properties. This structure constitutes the electric double layer (EDL), comprised of an inner, tightly adsorbed Stern layer and an outer, mobile diffusion layer[65,77]. Driven by external pressure or capillary action, liquids exhibit directed flow within nanoscale channels, thereby “dragging” mobile counterions (positively charged cations) within the diffusion layer of the solid-liquid interface to migrate along with them[78]. This directional charge transport induced by fluid motion forms convective currents, which manifest macroscopically as streaming currents[68]. As streaming currents develop, opposite charges gradually accumulate at opposite ends of the channel, establishing an internal potential difference related to the flow direction - the streaming potential [Figure 2B][79]. In hygroscopic power-generation materials, the adsorption and transport of water from the environment induce a dynamic response of this EDL on the material surface or within internal nanochannels, promoting the directional migration of counterions along the direction of water flow. This forms a potential gradient at both ends of the material and ultimately generates a measurable continuous current in the external circuit[13].

The material and structure of the upper and lower electrodes in MEG devices significantly influence ion dissociation within the power-generating layer. Ideal electrode materials must possess high electrical conductivity, excellent chemical stability, and ease of integration to enhance electrochemical performance and ensure long-term stability. Selecting electrode materials with high specific surface area increases adsorption sites for water molecules while simplifying the manufacturing process. In recent years, strategies for constructing asymmetric electrodes using different materials or structures have garnered significant attention[78]. By employing sandwich structures with asymmetric electrodes [such as carbon (C)/aluminum (Al) or bimetallic electrodes][80], ion concentration gradients can be significantly enhanced and ion migration pathways effectively optimized[81]. Increasing material thickness can raise voltage; however, beyond a certain limit, it impedes ion transport, leading to a decrease in current[82]. Internal ionic concentration gradients within devices are primarily achieved through two strategies[12]. First, intrinsic chemical gradients can be established within the material to form spontaneous ion diffusion pathways via asymmetric functional group modifications[83,84]. This method offers excellent stability, but precise design and controllable preparation remain challenging. Second, directional water introduction into the material, achieved through asymmetric wetting structures or unidirectional water transmission paths, can generate ion concentration gradients[34,85]. This approach imposes minimal requirements on the material itself, offering high flexibility but relying on external humidity differences for maintenance. Both strategies can be employed synergistically to enhance the device’s output performance and environmental adaptability.

Ion migration

Driven by internal water or ionic concentration gradients, freely mobile ions within the power-generating layer undergo directed migration, generating electrical output in the connected external circuit[66]. The water gradient is a core factor driving ion migration within the power generation layer, particularly during the initial moisture absorption phase and in asymmetric electrode structures. During initial moisture absorption [Figure 2C], water molecules interact with material functional groups, forming a significant water gradient that serves as the primary driving force for directed ion migration. Taking graphene oxide film (GOF) as an example, water molecules adsorb directionally and promote the dissociation of a large number of hydrogen ions (H+) from GOF. Subsequently, under the synergistic action of water gradient formation and diffusion, H+ undergoes directional movement, generating an electric current[86]. The porous structure of graphene oxide (GO) efficiently adsorbs water molecules to form a moisture gradient. Based on this principle, an asymmetric structure constructed with a moisture-proof substrate and a porous upper electrode significantly enhances this gradient[60]. The upper electrode absorbs large amounts of water and dissociates ions, while the moisture-proof substrate maintains relatively low humidity on the underside. Driven by this difference, ions migrate directionally toward the substrate, generating a stable directional current.

Establishing an ion concentration gradient is another effective strategy for driving directional ion migration [Figure 2D]. To validate this approach, Huang et al. employed directional laser irradiation technology[87]. By controlling the laser intensity to decrease with increasing GO depth, they achieved a gradient-based redistribution of oxygen-containing functional groups (Ocfgs), ultimately constructing the desired ion concentration gradient within the GO. In this asymmetric structure, Ocfgs react with water molecules, generating free ions. Due to the gradient distribution of the functional groups, the concentration of free ions also exhibits a gradient, effectively driving directional ion migration. Building upon this, the selection of electrode materials can further increase the ionic concentration gradient. For instance, replacing the top inert electrode with an Al electrode allows Al to react with water, releasing additional ions[81]. This significantly enhances the ion concentration gradient, promoting more directed ion movement and ultimately increasing voltage output. By synergistically regulating the materials and structures of the moisture-absorbing layer and electrodes, the water-ion gradient can be fully leveraged to enhance both device performance and stability.

Humidity is the core factor affecting ion migration and energy conversion efficiency. It underlies the formation of internal moisture gradients, which promote the dissociation of functional groups to produce free ions, establish ion concentration gradients, drive directional ion migration, and enhance energy conversion efficiency[45]. Humidity fluctuations can destabilize ion migration pathways, impairing charge separation efficiency. This dependence on external humidity in conventional devices can be mitigated by maintaining an internal humidity gradient through asymmetric structures[88]. Elevated temperatures accelerate the thermal motion of ions, enhancing their diffusion, but excessively high temperatures may damage material structures or cause rapid water evaporation, reducing the humidity gradient and thereby decreasing energy output. The influence of the physicochemical properties of the power generation layer on device performance has been discussed previously. Additionally, asymmetric electrode structures and robust electrode–layer interfaces promote directed ion migration[89], while highly conductive electrode materials reduce electrical resistance, further enhancing device energy output.

Streaming potential and ion diffusion are the two core mechanisms of MEG. Table 1 summarizes the key differences between them. The streaming potential mechanism converts mechanical energy into electrical energy by relying on pressure gradients to drive fluid movement within electrically charged nanochannels[45]. The viscous drag of counterions in the EDL generates flow currents, requiring an external or built-in pressure field to achieve sustained and stable electrical energy output[65]. In contrast, the ion diffusion mechanism arises from the dissipation of chemical potential gradients, enabling the direct conversion of chemical potential energy into electrical energy. Here, ions (H+) ionized by hydration undergo directed diffusion along the concentration gradient, establishing a diffusion potential[18,35]. This mechanism does not require external mechanical input and can harvest energy under static humidity conditions; however, its output typically exhibits transient or relaxation behavior and is sensitive to dynamic environmental humidity changes[12]. High-performance MEG devices can be optimized by leveraging the combined effects of both mechanisms.

Comparison of streaming potential mechanism and ion diffusion mechanism

| Mechanism | Streaming potential | Ion diffusion |

| Core principle | Liquid flow drives ion movement | Ion diffusion under chemical potential gradient |

| Material characteristics | Nanochannels, porous structures | Asymmetric hygroscopic structure |

| Output characteristics | Responsive, affected by fluid flow | High stability, long duration |

| Advantages | Stable output power, high current | Simple device structure, easy to integrate, high voltage |

| Disadvantages | Dependent on water flow or evaporation | Dependent on ambient humidity |

FUNDAMENTAL MATERIALS OF MOISTURE ELECTRIC GENERATION TEXTILES

Electric-generating materials form the core of humidity-powered devices, producing electrical output through water absorption, functional group dissociation, and ion migration. Consequently, ideal power-generating materials should combine high hygroscopicity, excellent ionic conductivity, and robust stability to ensure efficient and reliable device performance. The large specific surface area and 3D porous structure of textiles provide an excellent platform for maximizing the active interface of moisture-absorbing functional materials[90,91]. This allows nanoscale properties to be fully realized in macroscopic fabrics, significantly enhancing energy capture efficiency and output capacity[92]. Based on material type, these materials are primarily classified into four categories: inorganic, organic polymeric, biomass, and composite materials, each leveraging unique structural and performance advantages to contribute critically to the power-generating layer.

Inorganic materials

Inorganic materials, with their unique structural tunability, high electrical conductivity, and excellent thermal stability, have emerged as ideal candidates for the power-generating layer in MEGTs. Their high specific surface area provides the functional layer with abundant sites for water adsorption and ion dissociation[48]. Ions undergo directional diffusion driven by humidity gradients, while charge separation is facilitated by the ion selectivity of nanopores. The mechanical strength and chemical stability of these materials ensure that the nanostructure of the power-generating layer remains intact during prolonged cyclic moisture absorption and desorption, guaranteeing stable output performance and extending device lifespan[93]. GO as an inorganic carbon material, can form proton concentration gradients through structural regulation, making it a prominent choice for humidity-powered layers. Early studies by Zhao et al. prepared GOFs with gradient-distributed Ocfgs via a “moisture-electro-annealing” bias treatment [Figure 3A][94]. significantly enhancing proton gradient-driven effects. The team later employed directional thermal reduction to fabricate porous GOFs [asymmetric porous GO membrane (a-GOM)] with asymmetrically reconstructed functional groups, optimizing interfacial and transport behavior[95]. In the same year, laser-assisted modulation was used [Figure 3B] to selectively irradiate specific GO regions, forming a Schottky junction interface and achieving a high-performance power generation unit with output voltage up to 1.5 V[87]. Gao et al. constructed GO-reduced GO (rGO) heterostructures via localized thermal reduction of commercial GOFs, enabling efficient electricity generation by leveraging asymmetric interactions between water molecules and functional groups in distinct regions[96]. These studies exemplify a mainstream approach to enhancing device output through regulation of GO functional groups and electrode asymmetry.

Figure 3. Inorganic materials for MEGT. (A) A g-GOF prepared by MeA method[94]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2015, John Wiley & Sons; (B) Laser-directed irradiation of GO block for the preparation of heterostructure GO structure[87]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Yaxin Huang, 2018, Nature Communications; (C) MXene aerogel atmospheric moisture collection device[100]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (D) Structure of 1T-MoS2 cotton and 2H-MoS2/CSilk[98]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (E) Structure diagram of g-O-BP device[62]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons; (F) Structure of nano-structured silicon moisture generator and SEM image of cross section of SiNWs[58]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V; (G) Device based on an ion-diode-type PN junction and SEM images of top electrode and AAO side view[104]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Yong Zhang, 2022, Nature Communications. MEGT: Moisture-electric generation textile; g-GOF: gradient graphene oxide film; GO: graphene oxide; g-O-BP: oxygen defect gradient on the surface of black phosphorus aerogel; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; SiNWs: silicon nanowires; PN: positive-negative; AAO: anodized aluminum oxide; CNT: carbon nanotube.

To push the performance boundaries and expand the application potential of humidity-powered devices, researchers are exploring novel inorganic materials such as MXene[97], molybdenum disulfide (MoS2)[98,99], and black phosphorus (BP)[62], leveraging their unique structural and functional properties. MXene provides abundant active sites for ion adsorption and migration. Inspired by the “pump effect” of wood, Cai et al. fabricated a hygroscopic structure with a dual-hydrogen-bond network and wood-like channels via ice-templating and a controlled lithium chloride (LiCl) process [Figure 3C], achieving a moisture absorption capacity of 3.12 g·g-1 at 90% RH[100]. MoS2, as another class of 2D material, offers design possibilities for humidity-driven power generation[99]. Cao et al. designed a vertical heterojunction structure based on 2H-MoS2 (semiconducting) in carbonized silk (2H-MoS2/CSilk) and 1T-MoS2 (metallic) in cotton fiber (1T-MoS2 cotton) [Figure 3D], where the induced built-in electric field promotes proton migration and charge collection[98].

BP has attracted attention for its tunable band structure and catalytic activity. Liang et al. employed directional oxygen plasma irradiation to create an oxygen defect gradient on the surface of black phosphorus aerogel (g-O-BP), enabling spontaneous charge separation in humid environments [Figure 3E][62]. This flexible device, only 160 μm thick, delivered a voltage of 0.25 V and a current density of 0.16 μA·cm-2. Hydrophilic carbon cloth electrodes and tape encapsulation were incorporated, further enhancing mechanical flexibility and practical applicability.

In addition to the materials discussed above, 1D inorganic nanomaterials such as silicon nanowires (SiNWs)[101] and metal oxide nanowires[102] have attracted attention due to their unique water absorption properties and oriented nanoscale channel structures. As shown in Figure 3F, a typical device consists of a SiNWs-based power-generating layer and an asymmetric electrode. Under a humidity gradient, a directional charge transport pathway forms internally, enabling electrical signal output[58]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images reveal that the SiNWs aggregate at the top to form a dense network of nanoconductors, providing efficient pathways for water molecule permeation and ion migration. Metal oxide nanomaterials such as titanium dioxide (TiO2)[102] and aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanowires[103], possessing excellent charge transport capabilities and ordered arrangements, are also suitable for MEGT power-generating layers. Zhang et al. constructed a device based on an ion-diode-type PN junction [Figure 3G], composed of a nanoporous carbon nanotube (CNT) film and an anodized aluminum oxide (AAO) film[104]. SEM images show that the CNT film has an abundant pore structure facilitating water vapor transmission, while the AAO film exhibits well-defined nanoscale channels with excellent structural tunability. Together, these components achieve highly efficient humidity response and effective charge separation.

Organic materials

The core advantage of organic polymers lies in their exceptional molecular designability and rich interfacial interactions, enabling them to participate more precisely and efficiently in the mechanisms of the power-generating layer. Under the influence of water molecules, ionizable functional groups spontaneously dissociate, releasing a large number of ions and providing a high concentration of free charge carriers for the ion gradient diffusion mechanism[105]. The hydrophilic-hydrophobic microphase-separated structure effectively regulates the adsorption and transport kinetics of water. Upon water absorption, polymer segments exhibit flexibility and undergo swelling behavior, forming dynamically interconnected nanoscale hydration channels that facilitate rapid ion migration[106]. Furthermore, polymers can be processed into large-area, uniform, ultra-thin functional films on flexible substrates through various fabrication methods, enhancing their practical applications. Organic polymers, with their tunable molecular structures, excellent processability, and high flexibility, have become one of the ideal materials for MEGT devices. Their properties can be further optimized through chemical modification to meet the demands of diverse application scenarios. Polystyrene sulfonate (PSS), polyacrylamide (PAM), and sodium alginate (SA) are widely employed in the power-generating layers of MEGTs due to their functional characteristics[107]. Xu

Figure 4. Organic materials for MEGT. (A) PMEG based on PSSA[108]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry; (B) Schematic illustration of engineered hydrogel-based device and molecular structure and ion confinement in PGA-CA hydrogel[54]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Daozhi Shen, 2024, Advanced Science; (C) Moisture electric generation process inside BPFs structure[105]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature Limited; (D) Structure of green device based on supramolecular hydrogel[109]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Su Yang, 2024, Nature Communications; (E) Structure of electric generation hydrogel and SEM image of PAM hydrogel[55]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons; (F) Schematic diagram of device based on the IPHC structure[60]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. MEGT: Moisture-electric generation textile; PMEG: polymer moisture electric generator; PSSA: poly(4-benzenesulfonic acid); PGA-CA: polyglutamic acid-citric acid; BPFs: bilayer polymer films; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; IPHC: ionic polymer-hydrogel-carbon composite; E-PTFE: expanded polytetrafluoroethylene; PET: poly (ethylene terephthalate); PAM: polyacrylamide; PA: phytic acid; CP: carbon paper.

Organic polymer composite power-generating layers can effectively enhance the overall performance of devices through synergistic effects between materials. Compared to single-material systems, composite structures demonstrate advantages in chemical stability and environmental adaptability. Wang et al. designed a bilayer polymer film (BPF) electrolyte based on the sequential stacking of a polycationic film [poly(diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride) (PDDA)] with a polyanionic film [a mixture of PSS and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) films (PSSA)] [Figure 4C][105]. This dual-carrier system, integrated through sequential stacking, achieved a high voltage output exceeding 1,000 V, demonstrating the potential of composite structures for functional integration and performance enhancement. In the field of green material development, Yang et al. constructed a supramolecular hydrogen power-generating layer based on PVA and SA [Figure 4D][109]. This material combines biocompatibility, degradability, and processing convenience. Coupled with an asymmetric electrode structure, it enables high-performance, environmentally friendly energy devices. Through asymmetric moisture absorption and interactions between water molecules and the functional layer, a single unit can generate an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of approximately 1.30 V. These studies demonstrate significant progress in achieving high-performance, high-voltage output, and environmentally sustainable humidity-powered devices through composite polymer strategies.

To address the current limitations of most MEGT devices, which rely on a single power generation mechanism and exhibit constrained output performance, researchers have conducted a series of innovative studies employing biomimetic design and material composite strategies. Inspired by plant water uptake mechanisms, Cheng et al. synthesized a flexible, scalable PAM hydrogel-based device using acrylamide (AAm) and phytic acid (PA) as raw materials via ultraviolet polymerization with a photosensitizer [Figure 4E][55]. Its porous network structure (as shown in the SEM image) effectively promotes water absorption and transport, while the incorporation of photosensitizers further enhances electrical performance. The device maintains stable output even at low temperatures of -20 °C. Leveraging the structural similarity of amide groups, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAm) hydrogels also demonstrate application potential in power-generating layer design[110]. Liu et al. combined the ionic polymer Nafion with pNIPAm hydrogel to construct an ionic polymer-hydrogel-carbon composite (IPHC) device [Figure 4F][60]. This structure utilizes pNIPAm hydrogel as the medium and the Nafion membrane as the charge donor, enabling rapid voltage response and demonstrating strong adaptability to various practical scenarios[60]. These explorations provide new technical pathways for overcoming performance bottlenecks in high-performance devices and expanding their environmental adaptability.

Biomass materials

The core advantages of biomass materials lie in their naturally intricate multilevel structures, abundant functional groups, biodegradability, and exceptional sustainability. Their hierarchical nanostructures enable rapid adsorption and transport of water molecules via capillary action, providing efficient pathways for the diffusion and migration of water and ions[76]. The abundant intrinsic functional groups supply a continuous and biocompatible ion source for ion gradient diffusion mechanisms[111]. These groups also confer inherent surface charge to the material, facilitating the formation of an EDL. Simultaneously, their biodegradability and environmental friendliness align with sustainable development goals. Biomass materials, derived from natural plants, animals, or microorganisms, offer advantages such as renewability and wide availability[112], making them ideal candidates for MEGT power-generating layers. Common examples include lignin, proteins, and microbial cells, which can efficiently adsorb atmospheric moisture and form hydrated nanoscale channels. These channels facilitate internal ion transport, enabling highly efficient power generation. You et al. developed a low-cost, high-performance lignin sulfonate (LS-H) power-generating layer paired with graphite and zinc foil electrodes [Figure 5A][113]. The device exhibits outstanding environmental stability and mechanical flexibility, allowing continuous power generation for up to two months. Gao et al. constructed a paper-based device using natural cellulose fibers, with its structure shown in Figure 5B[114]. Its porous micro-nano architecture and abundant hydrophilic groups endow it with excellent moisture absorption and flexibility, enabling conformity to curved surfaces. These studies demonstrate the broad application potential of biomass materials in flexible, sustainable humidity-powered devices.

Figure 5. Biomass materials for MEGT. (A) Schematic of the device based on lignosulfonic acid and property[113]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society; (B) Schematic diagram of the printing paper-based device and its working mechanism[114]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry; (C) Preparation process of PNMEG[115]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V; (D) Schematic diagram of water absorption in protein-based device and optical image of protein powder[40]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry; (E) The structure of the device with a G.s-PSII hybrid film as the power-generating layer[119]. Reproduced under CC BY 4.0 license from Guoping Ren, 2022, Research. MEGT: Moisture-electric generation textile; PNMEG: protein nanofibrils-moisture electric generator; PSII: photosystem II; ITO: indium tin oxide; HPEG: hydrovoltaic-photovoltaic electricity generator.

Biological protein nanofibers, as 1D supramolecular aggregates, can be extracted from natural sources or constructed through self-assembly, providing a novel route for developing green, low-cost MEGT devices[111]. Liu et al. prepared a protein nanofiber film based on milk β-lactoglobulin via pH adjustment and hydrothermal synthesis, with the structure and preparation process shown in Figure 5C[115]. This fiber membrane exhibits excellent hydrophilicity and ionization capability, delivering a high Voc of 0.65 V and short-circuit current (Isc) of 2.9 μA. The electrical performance of the constructed device surpasses most previously reported devices. Zhu et al. further utilized inexpensive, easily processed whey protein to develop a tunable power-generating layer by modulating its surface charge and hydrophilicity through pH control [Figure 5D][40]. This protein-based film achieves a maximum voltage output of 1.45 V at 40% RH and exhibits excellent flexibility, making it suitable for applications such as wearable devices and medical patches. Protein nanofibers, as a class of biomass materials with controllable properties and sustainable sources, show great promise for the fabrication of power-generating layers.

Unlike most existing devices that generate electricity only intermittently, equipment built using microbial nano-protein wires can achieve continuous and stable electrical output. Liu et al. fabricated a thin film using nano-protein filaments extracted from Sulfuribacter, which consistently generated a voltage of 0.5 V and a current density of 17 μA·cm-2 at a thickness of only 7 μm[116]. The exceptional biocompatibility and self-assembly properties of whole-cell Geobacter sulfurreducens (G.S.) simplify device fabrication, eliminating the need for complex multilayer structures[117,118]. As shown in Figure 5E, integrating G.S. with photosystem II (PSII) enables simultaneous energy harvesting from both moisture and sunlight, providing a viable strategy for enhancing the performance of hybrid moisture-powered devices[119]. These findings demonstrate the significant potential of microbial protein wires for constructing long-term stable, environmentally adaptive power-generation systems.

Composite materials

Composite materials are created by combining components with different properties at the nano- or molecular scale, resulting in superior characteristics unattainable by any single material. This precisely meets the requirements for the humidity-powered functional layer[120,121]. By leveraging the synergistic effects of multicomponent functionality, a single functional layer simultaneously achieves multiple capabilities: efficient ion supply, rapid water transport, and stable mechanical support. Through adjustments to the proportions, morphology, and interconnection methods of composite components, high power generation performance, robust stability, and extended service life are maintained[122]. The composite construction of a multi-scale, multi-level pore network structure enables seamless integration from rapid water uptake to efficient power generation, maximizing the utilization of water’s chemical potential energy while optimizing transport pathways and charge transfer efficiency. By combining the characteristics of different materials, composite materials complement each other, efficiently adsorb water molecules from the air, and dissociate free ions[123]. This approach improves the output stability of MEGT devices across a wide range of temperatures and humidity and enhances device longevity, meeting the demands of diverse practical application scenarios[85]. Many inorganic materials have surfaces enriched with active sites that can adsorb and activate water molecules, facilitating efficient charge transport[124]. In Figure 6A, Huang et al. designed an MEG device based on a GO and sodium polyacrylate (PAAS) composite power generation layer, which operates across -25 to 50 °C and 5% RH-95% RH, enabling effective ion dissociation and transport[82]. Huang et al. developed a high-performance device integrating silica (SiO2) nanofibers, SA, and rGO substrates[125]. SA provides abundant Ocfgs with hygroscopic properties, while rGO offers a 2D nanosheet structure. SiO2 nanofibers facilitate ion migration, enabling the composite to demonstrate excellent environmental adaptability. Carbonized polymer dots (CPDs) have a polymer/carbon hybrid structure with rich functional groups. Li et al. constructed a flexible functional layer based on phosphate-rich CPDs (PA-CPDs)[47]. Figure 6B illustrates the fabrication process of the PA-CPD-based flexible device. By integrating PA-CPDs with an active liquid metal (LM) top electrode, the device achieves high voltage output and favorable current density. Liu et al. designed a water-light complementary power generation device using a hydrogel fabric composed of PSS, GO, glycerol (GI), and PVA (PSS/GO/GI/PVA@Fab) as the functional layer with asymmetric electrodes [Figure 6C][59]. The device features a vertically arranged internal gradient of oxygen functional groups. Protons dissociated from the power generation layer react with the active electrode, enhancing output performance. Based on proton-driven technology, Figure 6D shows a device composed of a hygroscopic GO/polyaniline (PANI) matrix and PDDA-modified fluorinated Nafion [F-Nafion(PDDA)], which generates spontaneous charge separation followed by directed H+ ion movement, operating reliably across a wide temperature range[36]. Its inherent flexibility and bending resistance make it particularly suitable for integration into clothing as a wearable power source.

Figure 6. Composite materials for MEGT. (A) Schematic diagram of the device assembly and its porous GO composite structure[82]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry; (B) Schematic of the preparation process for flexible device based on PA-CPD[47]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons; (C) Illustration of the fabrication process for functional electric generation layer[59]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons; (D) Working principle of polyelectrolyte double-layer devices[36]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Debasis Maity, 2023, Advanced Science; (E) Schematic diagram of the self-gradient moisture power generation device[35]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons; (F) Diagram of the LS-Al3+-PAA hydrogel structure[127]. Modified from 127, Copyright Royal Society of Chemistry, 2023. MEGT: Moisture-electric generation textile; GO: graphene oxide; PA-CPD: phytic acid-carbonized polymer dot; LS: lignin sulfonate; PAA: polyacrylic acid; PAAS: sodium polyacrylate; LM: liquid metal; PVC: polyvinyl chloride; SHMEG: self-gradient hydrogel-based moisture-induced electric generator; MBAA: N,N′-methylene-bis(acrylamide); PAM: polyacrylamide; AA: acrylic acid; APS: ammonium persulfate.

When organic polymers, inorganic materials, and biomass materials are combined to fabricate composite power generation layers, their complementary properties enable ternary composites to effectively enhance the performance of MEGT devices. Organic polymers typically provide flexibility, inorganic materials offer chemical stability in humid environments, and biomass materials are renewable and environmentally friendly. To enhance protonation or ion diffusion, Mo et al. developed a nanocellulose-based power generation layer composed of sulfated cellulose nanofibers (SCNF) and PVA[126]. This layer features an asymmetrical water permeation structure that promotes spontaneous and efficient water absorption while facilitating ion diffusion. To further extend the operating temperature range, Yu et al. designed a low-temperature-resistant power generation layer composed of PVA, polyacrylonitrile (PAN), GI, and ethyl cellulose ether (EC) pine oil[33]. This material exhibits excellent hygroscopicity and ion migration capability even at temperatures as low as -35 °C. Drawing inspiration from the gradient structure of plant root tips, Xiao et al. developed a Y-shaped microfluidic spinning technique capable of continuously producing cellulose/CNT gas-aerogel fibers (GAFs) with gradient nanoporous structures[90]. The cellulose network facilitates rapid radial liquid diffusion and efficient water transport, while CNTs, combined with quaternized cellulose nanofibrils (Q-CNF) and sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), enable the fabrication of an asymmetric, self-powered cellulose-based power generation layer via directional freeze-drying, exhibiting high humidity sensitivity and robust durability[74]. A self-gradient power generation device was also developed by self-diffusion of a pre-gel solution onto carbon black-loaded knitted fabric [Figure 6E][35]. Leveraging the electric double-layer gradient formed at the hydrogel-carbon interface and the inherent electrode properties, the device demonstrates high moisture absorption, retention, and temperature adaptability, extending its potential applications to diverse environmental and wearable devices. For flexible, low-cost, and high-performance humidity-powered electronics, Zhang et al. reported a polyacrylic acid (PAA) ionic hydrogel-based power generation layer prepared from a lignosulfonate (LS)-Al3+ composite system [Figure 6F][127]. The green Al3+ crosslinking ions interacted at room temperature, imparting the devices with excellent mechanical properties and flexibility.

DECIVE STRUCTURES OF MOISTURE ELECTRIC GENERATION TEXTILES

MEGT devices feature power-generating layers that can be categorized into three dimensional types. 1D structures integrate power generation capabilities into a single fiber or yarn, allowing the use of natural moisture-absorbing fibers as the matrix and enabling flexible functionalization. They exhibit excellent flexibility and knitability, although their power generation performance is relatively low. These structures can be seamlessly integrated into energy-harvesting textiles, making them suitable for applications that prioritize flexibility over high power output. 2D structures primarily utilize electrospun nanofiber membranes, fabrics, or nanowires as substrates. Electrospun nanofiber membranes possess high specific surface areas and porosities, ensuring thorough interaction with moisture. Their power generation performance generally surpasses that of 1D structures, making them well-suited for localized functional flexible patch electronics and miniature sensors. 3D structures are typically fabricated using biofibers or polymeric materials to form multilayer assemblies. Synergistic interactions between the functional layers maximize device performance. These structures can be produced as standalone wearable power-generating modules or integrated into clothing, capable of supplying power to devices with moderate energy demands.

1D structure

1D single-fiber structures offer many unique advantages in humidity-generating layers, such as high specific surface area, directional charge transmission, and fast response, making them highly promising for wearable devices, flexible electronics, microsensors, and related applications. GO materials, which are widely utilized, can also be fabricated into 1D power-generating layers. Liang et al. prepared a high-performance flexible graphene fiber power generator by selectively irradiating linear regions of GO fibers with a laser[128]. Building on this, Shao et al. developed a coaxial fiber-shaped hygroelectric generator (FHEG) based on GO, in which an external Ag wire is wound on the GO shell, providing excellent compatibility with woven fabrics[52]. Similarly, Zan et al. developed a novel strategy combining complex coacervation with intrinsic potential to fabricate mechanically flexible, high-performance core-shell fiber-based MEGT [Figure 7A][50]. The MEG structure consists of a poly (3,4-ethynedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) core and a shell made of oppositely charged PDDA and SA (NaAlg) coacervate (PEDOT@PDDA/NaAlg), wrapped with a copper wire electrode. When the PEDOT electrode is assembled with the copper electrode, an inherent potential is induced, providing the driving force for directional diffusion of charge carriers and thereby enhancing device performance. Inspired by natural vascular structures, Gao et al. designed a high-performance yarn-based MEGT [Figure 7B][129]. This yarn-based moisture electric generator (YMEG) uses cotton yarn as a base, with an aluminum wire as the outer electrode and a core electrode composed of PSSA/PVA and carbon fibers. The coaxial design maintains a continuous moisture gradient between the inner and outer regions. This gradient drives the directional movement of protons and Al3+ ions from the outside to the inside through moisture diffusion, optimizing device performance. To advance research on fiber-based wet electricity generation materials and their multi-scale structures, Zhang et al. prepared SA/multi-walled CNT (MWCNT) fibers with radial oxygen functional group gradients using coaxial wet spinning[130]. By adjusting the spinning and post-stretching processes and optimizing the aggregation structure of SA/MWCNT fibers, the resulting devices exhibited excellent continuous wet electricity output and temperature adaptability. Zhang et al. also designed a coaxial fiber MEGT[131], consisting of a skin layer of SA and PEDOT:PSS and a core layer of MWCNT [Figure 7C]. In addition, the SA/PEDOT:PSS–MWCNT sheath-core fiber demonstrates versatile thermoelectric and Joule heating performance.

Figure 7. 1D structure of MEGT. (A) Core-shell fiber structure[50]. Reproduced under CC-BY-NC-ND license from Guangtao Zan, 2024, Nature Communications. No modifications were made to the original work; (B) Structure of radial core electrode based on bionic design[129]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons; (C) Coaxial structure based on SA for humidity electro-optic fibers[131]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry; (D) Schematic diagram of manufacturing a biomimetic fiber structure for energy harvesting[134]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons. MEGT: Moisture-electric generation textile; SA: sodium alginate; MEG: moisture-electric generator; PEDOT: poly (3,4-ethynedioxythiophene); PDDA: poly(diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride).

To enhance the moisture-grasping efficiency of fiber-based MEGTs, Zhang et al. proposed a device based on alginate (Alg)/MWCNT coaxial fibers[132]. This device features a radial heterostructure, with the outer and inner layers exhibiting significant differences in Ocfgs and alginate-calcium (Alg-Ca) content, thereby establishing a sustained humidity gradient. Alg/MWCNT-based MEGTs can address the problem of instantaneous and low electrical output, attributed to the design of the fiber heterostructure. Building upon prior research into radial Ocfg gradients in Alg/MWCNT fibers, Zhang et al. employed a mold-forming method to fabricate SA/MWCNT fibers with Ocfgs distributed along the fiber axis[133]. The axially heterogeneous distribution of Ocfgs facilitates water condensation. These fibers exhibit high humidity-induced electrical performance, excellent environmental adaptability, and continuous energy output. At 90% RH, an axial device only 2 cm long can achieve a maximum output power density of

2D structure

The 2D planar film-like structure offers clear advantages in humidity power generation layers, featuring a large specific surface area that allows full contact with ambient moisture. Electrospun and non-woven fiber films exhibit excellent flexibility and bendability, making them easily integrable into clothing or other wearable devices. Polymer hydrogel films, with their internal cross-linked network structures, enable rapid ion migration. When combined with fabric electrodes (such as carbon fiber cloth electrodes), the power generation layer achieves both good flexibility and air permeability while maintaining electrical performance. These advantages give 2D planar film structures broad application prospects in humidity-powered devices.

Fabric-based power generation layer films usually have abundant pores and transmission channels, which facilitate ion migration. They are typically composed of electrospun fibers, bio-based fibers, or composite fibers, and can also be fabricated by immersing non-woven fabrics in functional solutions. According to different phase-structure designs, Han et al. reported a Van der Waals heterostructure based on textiles, composed of conductive 1T phase tungsten disulfide@carbonized silk (1T-WS2@CSilk) and asymmetrically distributed carbon black@cotton (CB@Cotton) fabrics[136]. The presence of Ocfgs enhances the proton concentration gradient, improving the performance of high-performance wearable hydroelectric generators (HEGs) [Figure 8A]. In this structure, the Al sheet serves as the top active electrode, the 1T-WS2@CSilk fabric functions as the bottom inert electrode, and the CB@Cotton fabric forms the intermediate power generation layer, enabling stable operation for over 10,000 s. As shown in Figure 8B, the research team first surface-modified a nonwoven fabric substrate with CB, followed by precise coating of a PSSA/LiCl/GI/PVA composite hydrogel onto predetermined areas[39]. The resulting MEGT device enhances proton dissociation efficiency through interactions between hygroscopic salts and the polyelectrolyte PSSA, driving efficient charge output. To improve device multifunctionality, Chen et al. prepared a Janus heterogeneous film based on electrospun nanofibers by directly growing one film on another[92]. The film exhibits both moisture absorption and evaporation capabilities, with two perforated electrodes made of different materials arranged on opposite sides. Both layers are composed of nanofibers, whose abundant pores provide a large specific surface area, enabling outstanding power output. To further increase performance, Xing et al. designed an asymmetric nanofiber film combining hydrophilic PVA/PA with hydrophobic polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and produced a high-efficiency wearable MEGT[91]. Using PA as a cross-linking agent, PVA nanofibers form a gel-like structure that enhances structural stability under humid conditions, while the asymmetric design ensures effective water circulation within the device. By leveraging the synergistic effects of moisture absorption and ion migration in textiles, a MEGT for wearable systems was developed using safe and environmentally friendly materials [Figure 8C][137]. PAAS served as the scaffold for water absorption and ion migration, while sodium chloride incorporation improved ionic conductivity and increased current output. As shown in Figure 8D, the MEGT device previously introduced[98] achieves sustained high-performance output through a vertically phase-engineered heteroelectrochemical bilayer. Its flexibility and body-conforming design provide an excellent foundation for wearable MEGTs as integrated self-powered devices.

Figure 8. 2D fiber film structure of MEGT. (A) 3D schematic diagram of the manufacturing of flexible HEGs[136]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons; (B) Fabrication process of all-weather MEGT devices[39]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons; (C) Green wearable MEGT based on PAAS/sodium chloride[137]. Reproduced under CC BY license from Renbo Zhu, 2025, Advanced Materials; (D) Schematic diagram of the MEGT device structure composed of 2H-MoS2/CSilk and 1T-MoS2 cotton[98]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (E) Structural composition of SS/sericin film[139]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. 2D: Two-dimensional; MEGT: moisture-electric generation textile; 3D: three-dimensional; HEGs: hydroelectric generators; PAAS: sodium polyacrylate; SS: silk fibroin/sericin; CB: carbon black; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate; NWF: non-woven fabric; PSSA: poly(4-benzenesulfonic acid); PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; UAEG: ultra-durable and all-weather energy generator; PLA: polylactic acid; SF: silk fibroin; PEO: polyethylene oxide.

Regarding the power generation layer of bio-based fiber structures, Su et al. employed an innovative approach to develop a simple manufacturing process for MEGT[138]. They constructed a 3D channel structure from biomass jute fibers (JE) loaded with lithium chloride salt. This structure significantly enhances water molecule capture from ambient air, enabling continuous and efficient electrical output. Protein nanostructures have great potential in bioelectricity generation due to their unique ion transport capabilities. He et al. studied a high-performance MEGT device with a cocoon-like structure[139]. Using electrostatic spinning, they prepared porous silk fibroin/polyethylene oxide (SF/PEO) films from a mixture of SF and PEO solutions[139]. Sericin was then applied evenly on the SF/PEO film surface via atomization spraying [Figure 8E]. The sericin adheres to the top layer, sealing pores and limiting penetration to the bottom layer. With increasing sprays, a silk fibroin/sericin (SS) composite film with uneven sericin distribution is formed. This film exhibits excellent hygroscopicity, abundant dissociated ions, and numerous micro-nano channels. To prepare devices with a simple process and high output power, Yang et al. successfully created a gradient distribution of CA in A4 paper via an asymmetric drying process[140]. When exposed to humid air, it forms a self-sustaining ion gradient, enabling efficient energy conversion. Additionally, textile-based flexible MEGTs can be prepared by soaking textiles in functional solutions. He et al. developed a textile-based MEG composed of textiles with asymmetric functional groups and a pair of flexible asymmetric electrodes[141]. This simple and low-cost process yields an Voc up to 1.0 V, opening new opportunities for self-powered and wearable electronic devices.

Polymer films usually exhibit good mechanical strength and rapid humidity response. When combined with conductive fabric electrodes, a complete device structure can be obtained, suitable for applications requiring air permeability, high stability, and wearable electronic patches. Yang et al. reported a self-sustaining wet electric generator based on 1D negatively charged nanofibers and 2D conductive nanosheets [Figure 9A], capable of continuously generating direct current from atmospheric humidity[142]. A CA-crosslinked bacterial cellulose sulfate nanofiber/rGO (CA-BCSNF/rGO) film was placed between the upper and lower electrodes. The composite power generation layer improves performance compared to single-material layers. Zhang

Figure 9. 2D structure of MEGT. (A) Structure diagram of flexible device composed of composite film[142]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (B) Flexible MEG based on PAM/AMPS/LiCl molecular-engineered hydrogels[148]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons; (C) s-MEG structure: SIG is used as power generation layer, and conductive textiles coated with Ag nanoparticles are used as electrodes[149]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (D) The dual hydrogen bond network structure within hydrogels and the ion migration process[152]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons; (E) Soft hydrophilic H-PSS film-based moisture electric generation device[153]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons. 2D: Two-dimensional; MEGT: moisture-electric generation textile; MEG: moisture-electric generator; PAM: polyacrylamide; AMPS: 2-acrylamide-2-methyl propane sulfonic acid; s-MEG: stretchable moisture electric generator; SIG: stretchable ionic gel; H-PSS: poly(4-styrene sulfonic acid); CA-BCSNF: CA-crosslinked bacterial cellulose sulfate nanofiber; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; MEH: molecular-engineered hydrogel; PET: poly (ethylene terephthalate); SA: sodium alginate; aANFs: activated aramid nanofibers; aASA: activated aramid nanofiber; ASMEG: moisture-electric generator based on the activated aramid nanofiber film.

3D structure

In the structure of MEGT electric generation layers, 3D configurations are also common, primarily including porous and heterogeneous structures. The high porosity and interconnected channels of 3D porous structures significantly enhance the material’s moisture absorption capacity and establish a stable internal humidity gradient. Multi-layer heterostructures support functional layer integration and are compatible with fibers, films, printed electrodes, and other processes, promoting the development of flexible, wearable, and miniaturized devices. Shuang et al. constructed [metal N/O] water-absorption active sites based on chemical coordination between metals and hydroxyl or amino groups, enabling efficient capture of water from air and its conversion to liquid water for storage[154]. Kim et al. developed a functional Fumion FAA-3 porous hydrogel hygroscopic electrolyte with a salt concentration gradient, leveraging the synergistic effects of water flow, auxiliary anion migration, and cationic gels[155]. Using the ultra-low density, high-efficiency water transport, and sustainability of CNF aerogels, Zhu et al. introduced Al(III) to prepare water-driven devices, improving overall hygroscopicity and stability[156]. Similarly, the porous structure of CNFs/SA@Ca/moisture adsorption complex-photothermal modification (MAC-P) aerogels prepared by Wang et al. provides strong capillary forces and effectively retains water[157]. Additionally, Zhang et al. fabricated a double-gradient aerogel power generation layer using single-walled CNTs (SWNTs) and polymer dendrimers, simultaneously enhancing power density and output duration[158].

Combined with the synergistic effect of multi-layer material structures in the 3D power generation layer, device stability is enhanced, enabling improved performance output. Zhao et al. prepared a superhydrophilic 3D GO structure based on a preformed oxygen-containing group gradient, effectively promoting the formation of an ion gradient[159]. For GO recombination, Feng et al. designed an ionic hydrogel/GO double-layer porous heterogeneous film, providing abundant channels for ion migration and achieving a wide-range, high-power device [Figure 10A][160]. For the development of highly stable devices, as shown in Figure 10B, Shin et al. used CA as a cross-linking agent to form a CNF/CNT network structure, constructing a strong, environmentally friendly, and highly stable CNF/CNT/CA (CCA) electric generation layer[161]. Through compounding with 2D materials, Zhao et al. fabricated a double-layer structure composed of hydrophilic MXene (Ti3C2Tx) aerogels with negatively charged surfaces and PAM ionic hydrogels (MAH-MEG) [Figure 10C][162]. The unique microstructure of organic polymer composites facilitates efficient ion transport. Inspired by plant transpiration, a 3D self-maintaining MEG (3D-SMEG) was developed [Figure 10D][34]. By regulating the adsorption–desorption cycle of water through a biomimetic hydrophobic microporous layer, an optimized spatial electric field forms internally, generating a strong concentration gradient of ionized radicals and significantly enhancing electrical output. In Figure 10E, Song et al. superimposed a layer of Berlin Green (BG)/GO/CNF (BGC) on a NaCl/cellulose nanofiber (NC) composite layer to create a double-layer water-induced generator, enabling high ion concentration supply, charge separation, and directional migration within the power generation layer[163]. In the PSSA-PVA aerogel double-layer device constructed by Zhao et al., micropores are oriented along the surface normal, aligning with the water evaporation direction[164]. Cao et al. designed a multilayer ionic hydrogel MEG (IH-MEG) based on PAM, LiCl, and CMC [Figure 10F]; performance can be doubled by constructing ionized hydrogel heterojunctions with cations and anions[165]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. developed a MEG using integrated ion exchange films (IEM-MEG), enhancing selective ion transport and enabling continuous energy output under low RH[166].

Figure 10. 3D structure of MEGT. (A) Internal structure diagram of two functional layers in the device[160]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons; (B) Schematic diagram of the CCA power generation layer[161]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry; (C) Internal structure diagram of MAH-MEG functional layer[162]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (D) The structural composition of 3D-SMEG unit[34]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, Royal Society of Chemistry; (E) A MEG device consisting of a BGC-NC bilayer membrane and a pair of Au@SS electrodes[163]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry; (F) Structural composition diagram of IEM-MEG device[166]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, John Wiley & Sons. 3D: Three-dimensional; MEGT: moisture-electric generation textile; CCA: CNF/CNT/CA (CNF: cellulose nanofiber; CNT: carbon nanotube; CA: citric acid); MAH-MEG: MXene aerogel-on-hydrogel moisture electric generator; 3D-SMEG: 3D self-maintaining moisture-electric generator; BGC-NC: Berlin Green (BG)/graphene oxide (GO)/cellulose nanofiber (CNF); SS: silk fibroin/sericin; IEM-MEG: ion-exchange membrane-moisture-electric generator; GO: graphene oxide; CNF: cellulose nanofiber; CNT: carbon nanotube; CA: citric acid; BG: Berlin Green; GC: graphene oxide/cellulose nanofiber; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; PA: phytic acid.

LARGE-SCALE MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGY

For the large-scale design and fabrication of MEGT, the preparation of the electric generation layer and electrodes can be considered separately. The electric generation layer can be efficiently produced over large areas using spinning processes and coating techniques, which improve uniformity and reduce cost. Electrodes can be precisely customized with complex patterns through screen printing and digital manufacturing technologies, meeting the requirements of diverse applications.

Manufacturing of electric generation layer

Wet spinning and electrostatic spinning are common technologies for preparing electric generation layers, enabling stable production of large-area fiber films. Both methods can optimize material structure and improve the hygroscopicity and ionic conductivity of fiber films through process parameter tuning. These technologies provide technical support for the industrialization of MEGT devices.

Spinning technology

Wet spinning enables continuous production via solution extrusion and solidification, making it suitable for fabricating large-area, uniform fiber films. It is compatible with various functional materials, achieving efficient and low-cost fiber production. Zan et al. prepared high-performance core-shell fibers via wet spinning, with PEDOT nanobelts as the core and complex coacervate gel formed from CaCl2 solution and PDDA/NaAlg mixture as the shell [Figure 11A][50]. The fiber device can be used in self-driven artificial synapse systems to simulate biological neuroplasticity. Using SA and PEDOT:PSS materials, Zhang et al. employed a simple coaxial wet-spinning technique to fabricate a skin-core structure: SA/(PEDOT:PSS) as the outer layer containing hygroscopic oxygen groups, and MWCNT as the inner layer [Figure 11B][131]. This design enhances internal moisture migration, providing strong charge mobility in both the radial and axial directions of the fiber. Zhang et al. also injected two solutions with different SA/MWCNT ratios into a 5% CaCl2 coagulation bath using coaxial needles to form coaxial fibers[130]. The core layer was connected to the test electrode with conductive silver glue, demonstrating excellent wet electrical properties. Liu et al. prepared a high-performance fiber by compounding PVA, MWCNTs, and sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) (PMS)[167]. A 1-cm-long fiber can continuously output voltage for more than 80 h, providing a sustainable energy solution for smart textiles and wearable technology via water-induced power generation.

Figure 11. Large-scale manufacturing of electric generation layer by spinning technology. (A) Scheme of the wet spinning to prepare PEDOT-PDDA/NaAlg core shell fiber[50]. Reproduced under CC-BY-NC-ND license from Guangtao Zan, 2024, Nature Communications. No modifications were made to the original work; (B) Schematic diagram of wet spinning process for SA-based coaxial fibers[131]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry; (C) Preparation of nanofiber membrane containing electrolyte by electrospinning and its structural schematic diagram[169]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry; (D) PAN and P(VDF-TrFE) films prepared on CNW/LiCl substrates by electrospinning[49]. Reproduced under CC-BY-NC 4.0 license from Yunhao Hu, 2024, Science Advances. PEDOT-PDDA: Poly (3,4-ethynedioxythiophene)-poly(diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride); SA: sodium alginate; PAN: polyacrylonitrile; P(VDF-TrFE): poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene); CNW: cellulose nonwoven; PSS: polystyrene sulfonate; MWCNT: multi-walled carbon nanotube; SDBS: sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate.

Electrospinning uses a high-voltage electric field to produce nanofiber films with high specific surface area and porous structures, enhancing ion transport. As a power generation layer material, nanofiber films prepared by electrospinning exhibit high moisture absorption capacity and excellent electrical properties. Sun et al. applied electrospun polymer nanofiber fabrics to wearable MEGTs, in which PEO nanofiber fabrics provided a high output voltage of 0.83 V and excellent air permeability[168]. In Figure 11C, Sun et al. prepared a nanofiber film containing electrolyte from PAN/SDBS solution[169]. This device could continuously and stably output a voltage of 0.7 V and a current of 3 mA for 120 h, demonstrating outstanding stability and durability. By optimizing its structure, Zhang et al. introduced a CA nanofiber film with a tree-like structure obtained by electrospinning[170]. A single device generated approximately 700 mV, with a maximum output power density of 2.45 μW·cm-2. Sun et al. employed coaxial conjugate electrospinning to form a core-shell structure by winding PAN nanofibers around a zinc wire[171]. The PAN nanofibers provide a high specific surface area and porous structure, while the zinc wire core electrode ensures good conductivity. Subsequently, as shown in Figure 11D, Hu et al. successively deposited PAN and poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) [P(VDF-TrFE)] nanofibers onto a cellulose nonwoven (CNW)/LiCl layer via electrospinning, constructing a multi-layer fabric structure with unidirectional moisture conductivity[49]. Owing to the structure and material properties of the nanofiber layer, the device operates stably across 15%-80% RH and -10 to 55 °C.

Coating technology

Spraying, drop-casting, and impregnation methods can be used for large-area preparation of power generation layers. The spraying method is fast and uniform; drop casting allows the solution to diffuse naturally by capillary action, and impregnation immerses the substrate in solution. These methods are convenient for integrated design, and the uniformity and performance of the power generation layer can be optimized by controlling process parameters. Wang et al. used casting and spraying strategies to combine a PDDA layer with a PSSA layer to prepare a BPF [Figure 12A][105]. The material exhibits good mechanical flexibility along with high voltage output and maintains excellent performance and stability even under bending or pressing. Poly(vinylidene fluoride)-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP) can form a network-like support structure in a nano-alumina composite film. Yao et al. therefore used patterned coating technology to prepare devices with a nano-alumina self-supporting film as the power generation layer [Figure 12B][172]. This method allows the simultaneous fabrication of hundreds of series and parallel devices, enabling scalable and customizable output voltage and current. As shown in Figure 12C, Zhu et al. evenly coated protein dispersion with an adjusted pH onto a substrate by a scraping method and dried it to form a protein film power generation layer[40]. The protein film exhibits self-healing ability, and its electrical output can be restored after scratches through water treatment. The thickness of the power generation layer is controlled by repeated dip-coating, allowing the electric output to be tuned by humidity changes. Gao et al. immersed pretreated cotton yarn in a PSSA/PVA solution[129]. Using a spinning machine, they produced high-performance MEGTs with radial PSSA/PVA gradients under centrifugal force [Figure 12D]. This structural design maintains a continuous moisture gradient between the yarn’s interior and exterior, while the use of PSS and aluminum electrodes enhances proton diffusion efficiency. Shao et al. explored a coaxial fiber based on GO material, in which a silver wire was immersed in GO suspension, allowing GO to adhere to its surface[52]. Later, He et al. developed a double asymmetric structure MEGT to optimize electrical output by varying the soaking time[141]. The device exhibits high flexibility, large-scale integrability, strong environmental adaptability, and a simple, low-cost preparation process, making it suitable for large-scale production and applications.

Figure 12. Large-scale manufacturing of electric generation layer by coating technology. (A) BPF prepared by casting and spraying process[105]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature Limited; (B) Large-scale manufacturing of array electric generation layers by scrape coating method[172]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, John Wiley & Sons; (C) Large-area protein film obtained by drop coating strategy[40]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry; (D) Preparation process of coaxial yarns with radial gradient of PSSA/PVA[129]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2025, John Wiley & Sons. BPF: Bilayer polymer film; PSSA: poly(4-benzenesulfonic acid); PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; PDDA: poly(diallyl dimethyl ammonium chloride); PSS: polystyrene sulfonic acid; PVDF-HFP: poly(vinylidene fluoride)-hexafluoropropylene; CNT: carbon nanotube; PET: poly (ethylene terephthalate); PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Manufacturing of electrodes

Electrodes need to provide electrical conductivity and strong adhesion to the power generation layer. Screen-printing and digital manufacturing technologies are important methods for achieving large-area electrode fabrication. These techniques enable efficient large-scale production of electrodes, providing critical technical support for the development and application of MEGTs.

Screen printing

Screen-printing technology has been widely used for the fabrication of flexible electrodes. Conductive materials are printed onto the substrate through a screen template, offering advantages such as reduced production cost and the ability to prepare large-area electrode patterns to meet diverse application needs. Liang et al. achieved large-scale array integration of GO-based power generation devices using screen printing, sequentially printing the bottom electrode, GO active layer, and top electrode to complete a single unit[173]. Similarly, Li et al. printed conductive silver paste and molten LM alloy successively onto a flexible paper substrate to form the bottom and top electrodes, with a PA-CPDs layer as the power generation layer[43]. He et al. further printed C and C-Al composite electrodes on a poly (ethylene terephthalate) (PET) substrate, followed by PDDA and PSSA in the inter-electrode region[174]. Printed planar device arrays not only enable scalability and customization but can also be integrated with flexible circuits. A three-step screen-printing process was employed to sequentially deposit the bottom electrode, GO active layer, and top electrode onto paper[173]. An end-to-end stacking design allowed large-scale series connection of the devices [Figure 13A]. In addition, Li et al. scrape-coated the bottom electrode, power generation layer, and top electrode in sequence onto a flexible substrate, simplifying the fabrication process and enabling large-scale production[47]. Recently, inspired by arid plants, Yu et al. developed a 3D self-sustaining device capable of continuously delivering high voltage [Figure 13B][34]. The bottom electrode was prepared via screen printing, followed by hydrogel assembly and top electrode printing, creating a series-parallel integrated system for 3D-MEG with high-performance output and minimal loss.