Diverse polymer structure design: a key enabler for advanced lithium-based batteries

Abstract

The growing demand for batteries with higher energy density and improved safety necessitates the development of advanced electrode materials beyond conventional systems. Although high-energy electrodes offer superior theoretical capacities, they encounter major challenges, including structural instability caused by volume changes and uncontrollable dissolution. These issues contribute to performance degradation and safety risks at both the electrode and cell levels. Addressing these persistent problems is therefore essential to achieving safe, high-energy-density batteries. Polymers, with their versatile functionalities, present significant opportunities in this regard. The strategic design and deployment of tailored polymer architectures can enhance structural stability and improve cell configurations. In this work, we highlight the role of polymer chemistry in governing electrochemical behavior and demonstrate how it can drive substantial improvements in both performance metrics and the critical safety features required for reliable battery operation.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

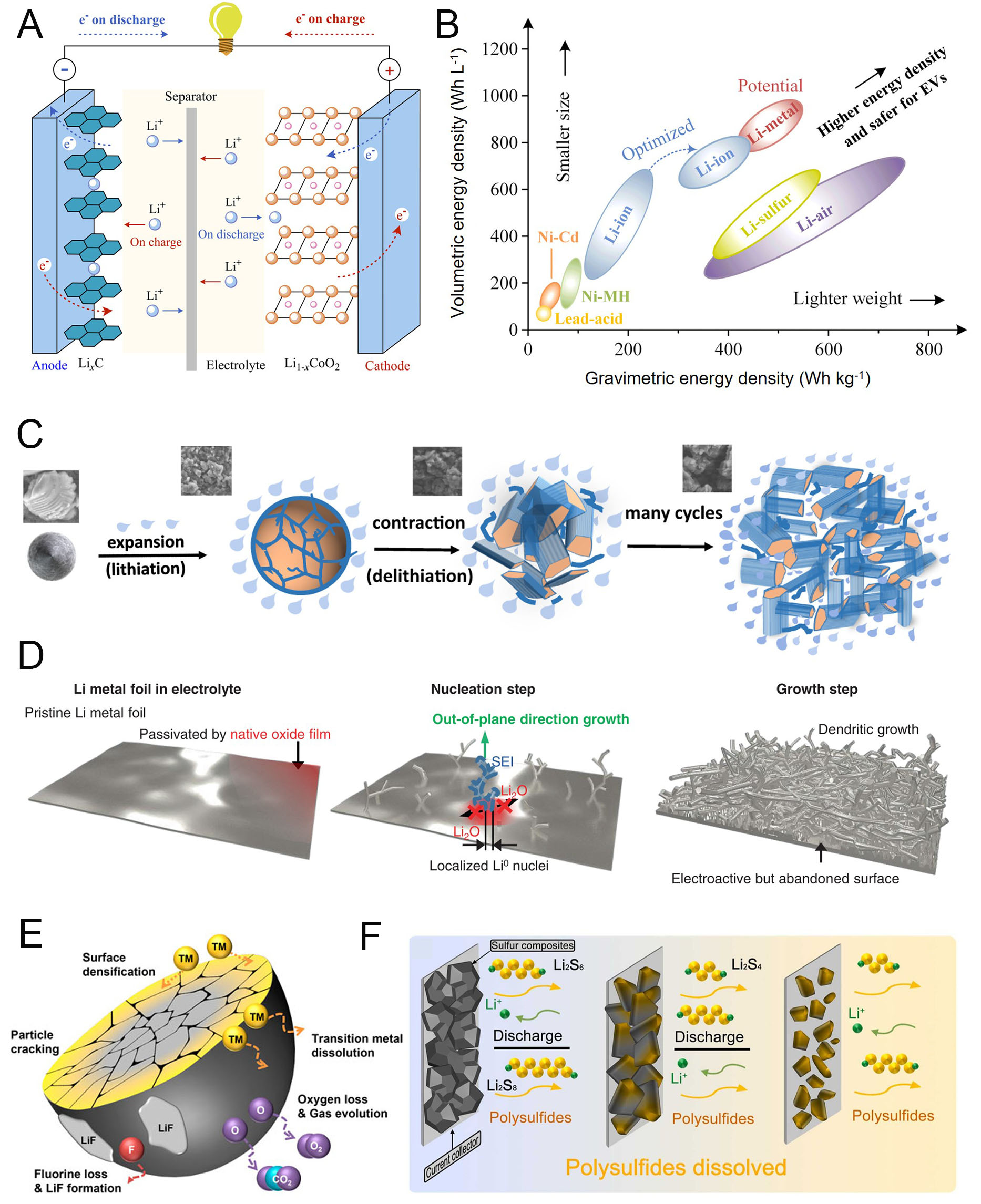

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have evolved from powering small portable electronics to serving as the dominant energy source for electric vehicles (EVs) and large-scale energy storage systems (ESSs)[1-4]. To meet the growing demand for higher energy density and safety, researchers have explored a wide range of advanced electroactive materials with greater theoretical capacities than those used in conventional systems[5-7]. Commercial LIBs typically consist of a graphite anode, a transition metal oxide cathode such as lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2, LCO), a polymer membrane separator, and an organic solvent-based electrolyte [Figure 1A][8-11]. While this configuration has proven successful for portable applications, its thermodynamic and electrochemical limitations hinder its ability to satisfy the requirements of large-scale systems. Consequently, next-generation battery chemistries, including post-LIBs, Li-metal batteries (LMBs), and lithium-sulfur (Li-S) batteries, have been proposed to surpass the performance of conventional LIBs

Figure 1. Degradation phenomena in next-generation battery materials. (A) Schematic configuration of an LIB cell. (B) Energy densities of various batteries at the cell level. Reproduced with permission[8]. (C) Schematic of SiMP electrodes cycled in conventional carbonate electrolytes, forming Si-philic organic-inorganic SEI strongly bonded to Si. Reproduced with permission[25]. (D) Nucleation and growth stages of Li metal foils. Reproduced with permission[28]. (E) Degradation pathways of cathode materials. Reproduced with permission[37]. (F) Dissolution of polysulfides in S cathodes. Reproduced with permission[44].

For high-energy-density designs, silicon (Si) and Li metal anodes have attracted considerable attention due to their exceptional theoretical capacities: 3,590 mAh g-1 (for Li3.75Si)[15,16] and 3,860 mAh g-1, respectively[17,18]. These values far exceed the 372 mAh g-1 of graphite, reflecting their fundamentally different electrochemical mechanisms of Li storage[19-22]. Si forms Li-Si alloys through alloying reactions, whereas Li metal undergoes direct electrodeposition.

Despite their advantages, both anodes face critical challenges associated with large volume changes during cycling. For Si, repeated alloying and dealloying induce severe particle expansion and contraction, leading to electrode delamination and continuous reformation of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI)

Cathode degradation also poses significant obstacles. Nickel-rich layered transition metal (TM) oxide cathodes, such as LiNixCoyMnzO2 (NCMxyz, with x > 0.8), have been developed to achieve higher reversible capacities[33,34]. However, these materials suffer from TM dissolution, cation mixing, and the formation of microcracks during prolonged cycling, which disrupt the layered crystal structure and create surface inhomogeneities [Figure 1E][35-37]. Mid-Ni cathodes (0.5 < x < 0.8), when operated at high voltages for greater energy density, further accelerate degradation through electrolyte oxidation, gas evolution, and the formation of detrimental surface byproducts[38,39]. Sulfur (S) cathodes, with a high theoretical capacity of

In this review, we summarize recent strategies employing polymers to address these persistent issues in Li-based batteries. Polymers offer diverse structural and chemical tunability, which can be leveraged to tailor electrochemical kinetics and improve stability [Table 1][47-49]. Although the general trends are outlined in the table, it is important to note that polymer properties vary significantly depending on functional groups, even within similar backbone structures. Accordingly, we focus on the design and deployment of polymers in electrodes, separators, and electrolytes, key components that define the overall performance of the battery. By highlighting the versatile roles of polymer architectures, we aim to demonstrate how their proper integration can enable structural reinforcement, interfacial engineering, and, ultimately, substantial improvements in both electrochemical performance and safety.

Comparison of polymer structures and their electrochemical implications

| Structure | Structural feature | Characteristics | Electrochemical outcomes |

| Linear | Long polymer chains | - Semi-crystalline - High mechanical strength | - High mechanical stability - Low ionic transport - Poor flexibility |

| Branched | Polymer backbone with side chains | - Amorphous - Viscoelastic - High elasticity | - High flexibility - High ionic transport - Low mechanical stability |

| Crosslinked | 3D chemical network | - High mechanical strength - High elasticity - Low solubility - Thermal stability | - High mechanical stability - High solvent durability - Low flexibility |

| Networked | Branched macromolecular structure | - Low solubility - Densely packed | - High ionic transport - Low mechanical stability |

CHRONIC ISSUES IN ADVANCED LI-BASED CELL CONFIGURATIONS

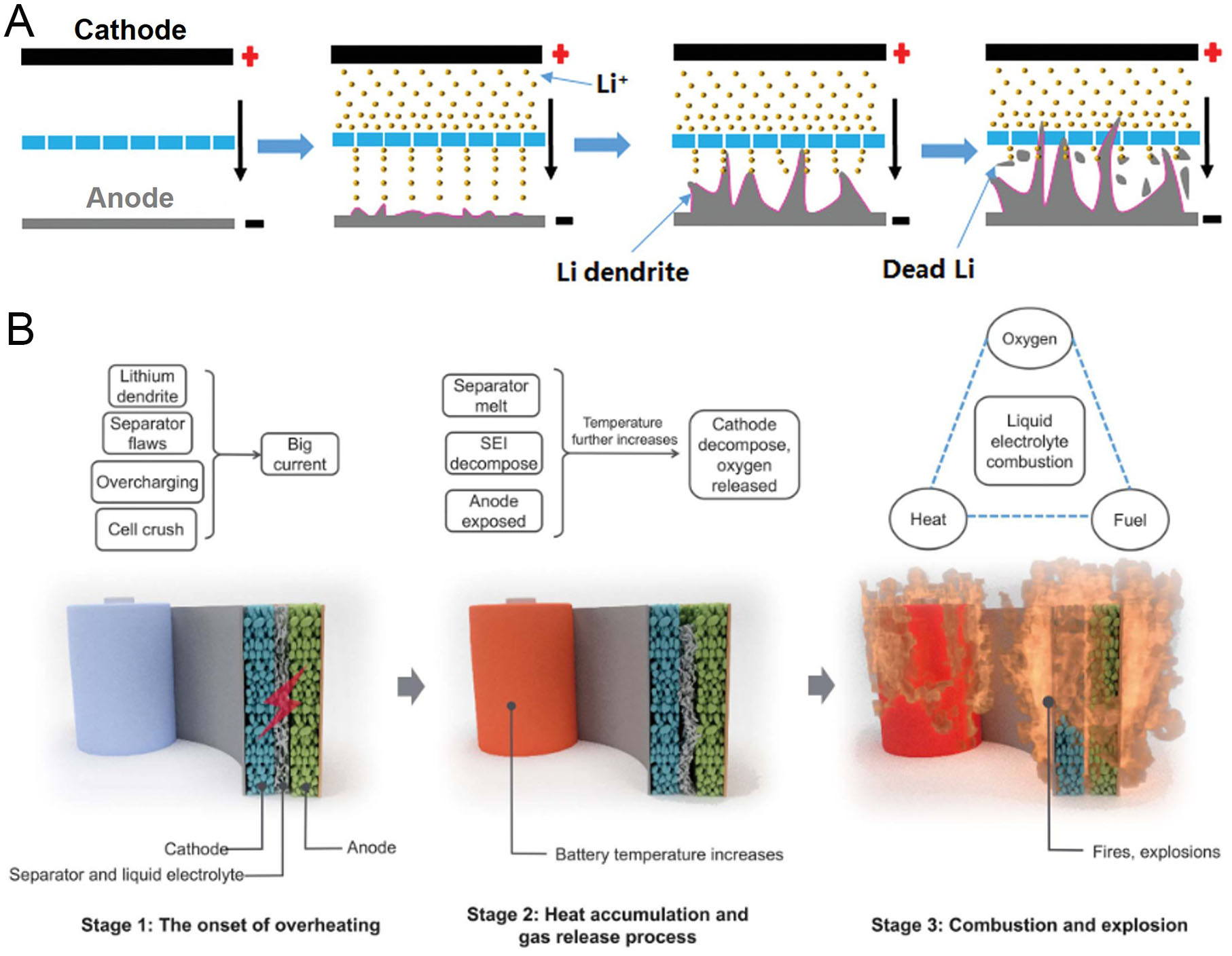

Side reactions occurring within battery electrodes pose serious threats to both electrochemical stability and overall cell safety. These processes contribute to undesirable phenomena often referred to as crosstalk between electrodes and can lead to catastrophic failures such as rollover failure [Figure 2A][50,51]. A major challenge arises from uncontrollable anode volume changes during charge-discharge cycling. The resulting mechanical stress continuously disrupts the SEI, consuming Li-ions and electrolyte while impairing mass transport due to source depletion[52,53]. This degradation leads to the loss of electrode-separator contact, severely hindering normal operation. Simultaneously, instability can originate from the cathode. Dissolved TM ions or LiPS migrate across the electrolyte and deposit on the anode surface[54]. These parasitic reactions destabilize the anode-electrolyte interface, causing uneven Li-ion flux and increasing interfacial resistance. The resulting instability accelerates structural degradation throughout the cell, exacerbates electrical contact loss, and substantially increases the risk of internal short-circuiting[55,56]. An internal short-circuit establishes a low-resistance pathway that permits uncontrolled ion and electron transport, resulting in excessive current flow. This condition poses a critical safety risk, potentially triggering thermal runaway and cell explosion [Figure 2B][57]. Therefore, mitigating electrode side reactions and preventing structural degradation are essential for ensuring the long-term safety and reliability of high-energy-density batteries. In the following sections, we review recent advances aimed at addressing these chronic challenges and systematically organize strategies developed for electrodes and other key cell components.

Figure 2. Chronic issues at the electrode and cell levels. (A) Schematic illustration of Li dendrite growth and the resulting internal short-circuit caused by electrochemical and structural degradation of the anode and/or cathode. Reproduced with permission[50]. (B) Three stages of the thermal runaway process. Stage 1: Onset of overheating, where the battery shifts from a normal to an abnormal state and internal temperature begins to rise. Stage 2: Heat accumulation and gas release, with rapid temperature increase and exothermic reactions. Stage 3: Combustion and explosion, where flammable electrolyte ignites, leading to fires and possible explosions. Reproduced with permission[57].

DESIGNING POLYMER STRUCTURES FOR ELECTRODE STABILIZATION

Accommodating volume changes in high-capacitive anodes

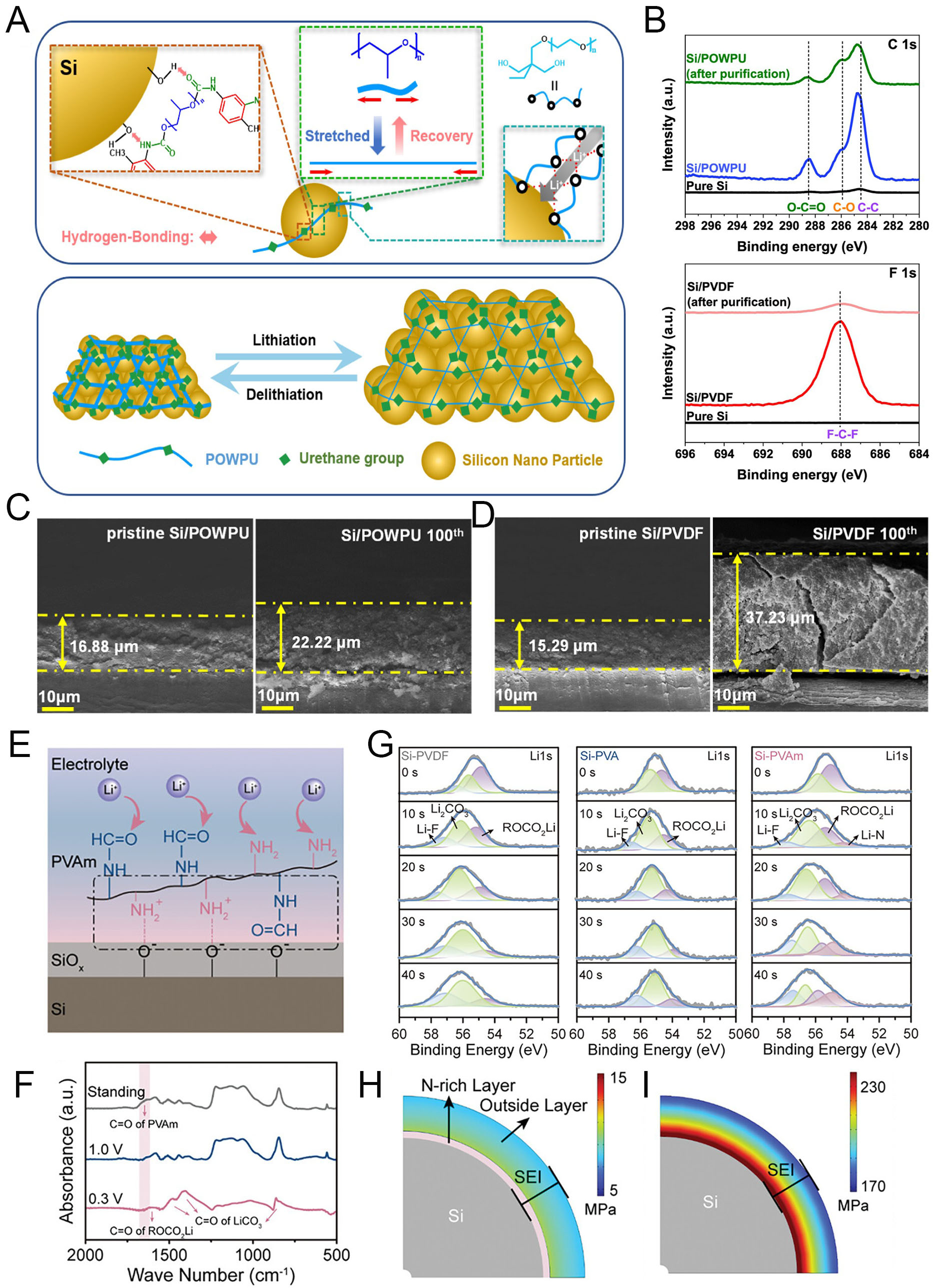

Si anodes are among the most promising candidates for next-generation LIBs owing to their exceptionally high theoretical capacity[58]. However, severe volume changes during lithiation and delithiation lead to particle pulverization, electrical isolation, unstable SEI formation, and rapid capacity fading[23,59]. To address these challenges, recent research has focused on multifunctional polymer binders capable of relieving mechanical stress through stretchable or self-healing properties[60-63]. In addition, electrochemically active binders can promote the formation of stable, ion-conductive SEI layers. Binder systems incorporating gradient mechanical modulus[64], dynamic covalent bonding[65], and ionic conductive elastic networks[66] aim to integrate chemo-mechanical functions to stabilize the electrode-electrolyte interface. These features enable efficient stress dissipation and preserve intimate contact with the Si surface under extreme volume fluctuations. As an example, Kim et al. developed a waterborne polyurethane (designated as POWPU) binder[67]. This polymer contains poly(propylene oxide) (PPO) soft segments that provide elasticity, urethane groups that form hydrogen bonds with the Si surface, and

Figure 3. Advanced polymeric binders for Si anodes: enhancing structural stability and tailoring SEI chemistry. (A) Schematic illustration of the POWPU binder structure and its role in electrode stabilization. (B) XPS spectra of C 1s (Si/POWPU) and F 1s (Si/PVDF) electrodes before and after purification. Cross-sectional SEM images of (C) POWPU and (D) PVDF electrodes, pristine and after 100 cycles. Reproduced with permission[67]. (E) Proposed mechanism of PVAm interaction with Si particles. (F) FT-IR spectra of the Si/PVAm anodes with different cutoff voltages. (G) XPS spectra of Li 1s of Si/PVDF, Si-PVA and Si/PVAm anodes. Stress distribution on Si particles in (H) Si/PVA and (I) Si/PVAm anodes. Reproduced with permission[68].

As another approach, Wang et al. proposed a poly(vinylamine) (PVAm) binder containing primary amine (-NH2) and amide (-NH-CHO) groups, which facilitate binder-derived SEI formation [Figure 3E][68]. These functional groups form strong hydrogen bonds with the native SiOx layer on the Si surface, ensuring uniform binder coverage and preventing direct contact with the electrolyte. Their strong polarity enhances electron affinity, promoting the growth of a conformal N-rich SEI with high ionic conductivity and mechanical robustness. The chemical evolution of these groups during the initial discharge process was confirmed by FT-IR analysis [Figure 3F]. After discharging to 1.0 V, the C=O stretching vibration peak at 1,660 cm-1 disappeared, indicating electrochemical decomposition of the amide group in PVAm. Upon further discharge to 0.3 V, new peaks appeared at 1,620, 1,450, and 1,400 cm-1, corresponding to ROCO2Li and Li2CO3, both typical SEI components derived from electrolyte decomposition. These results demonstrate that PVAm functional groups actively participate in SEI formation. In-depth XPS analysis further revealed SEI composition [Figure 3G]. All Si-based electrodes showed a double-layered SEI consisting of an organic-rich outer layer and an inorganic-rich inner layer. With increasing etching depth, the ROCO2Li peak (54.8 eV) decreased, while the Li2CO3 (55.5 eV) and LiF (57.0 eV) peaks became more prominent. These species, originating from electrolyte decomposition, generally exhibit low conductivity. Notably, the Si/PVAm electrode displayed an additional Li-N peak (53.5 eV), attributed to reductive decomposition of -NH2 and -NH-CHO groups, confirming the formation of an N-rich SEI. The mechanical role of the SEI was further examined through COMSOL simulations of stress distribution on Si particle surfaces. As shown in

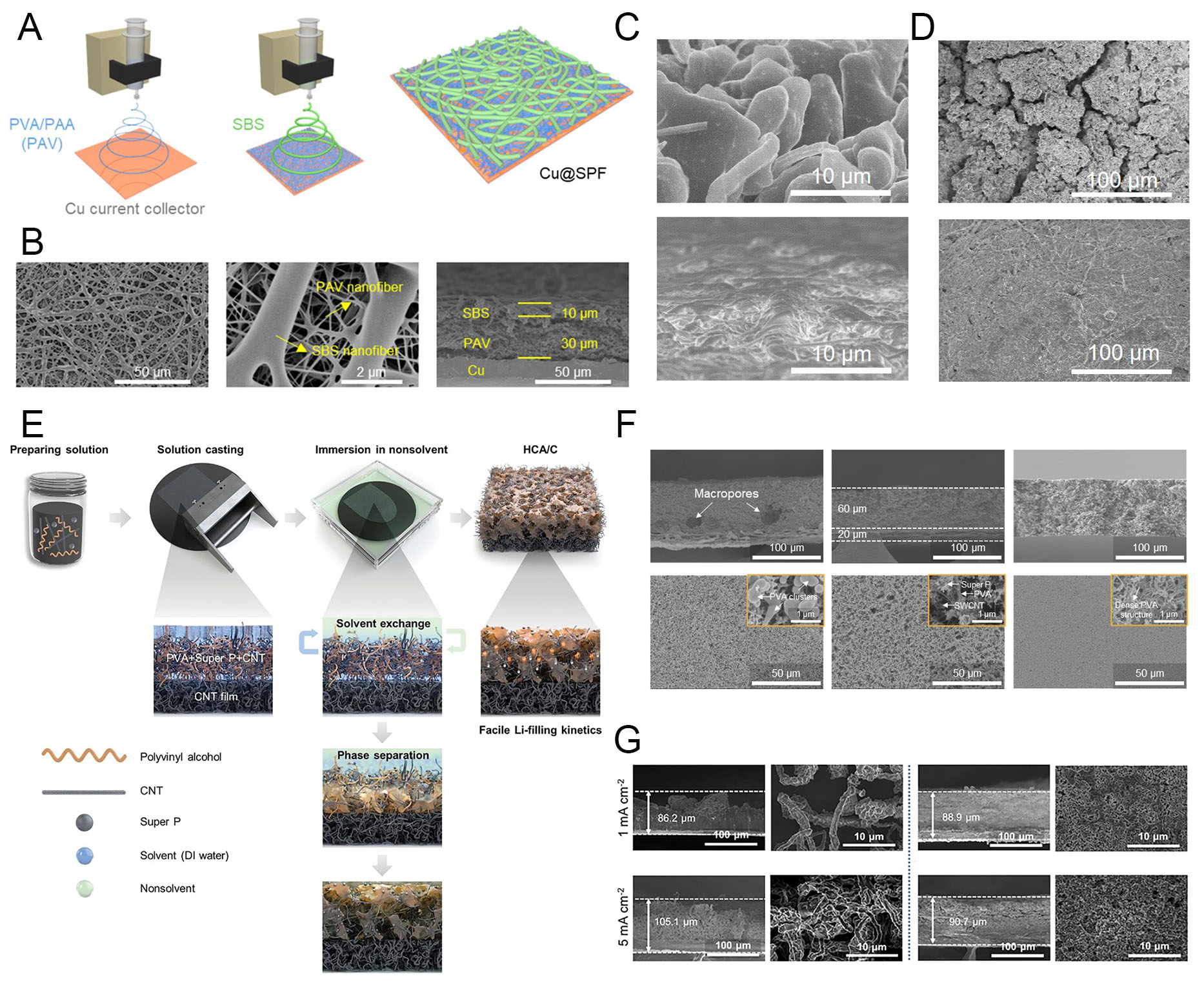

Meanwhile, LMAs experience severe electrochemical degradation due to the virtually infinite volume change caused by Li dendrite growth and isolation during repeated electrodeposition/dissolution cycles. To mitigate this, various strategies have been proposed, including the formation of artificial interphases[69,70], the construction of host structures[71-73], and LMA-tailored electrolyte engineering[74-76]. In practical cell configurations, where spatial volume within the assembled structure is a critical factor, LMAs must not only accommodate Li metal but also suppress uncontrolled anode expansion. This becomes particularly important in full cells with charge-initiating cathodes, such as transition-metal-oxide electrodes. Therefore, systematic host-structure design offers one of the most rational approaches among the various strategies to minimize volume change at both the electrode and cell levels. Han et al. developed a polymer-based 3D host structure composed of stacked polymer fibers (SPFs) fabricated by electrospinning directly onto a Cu current collector, denoted as Cu@SPF [Figure 4A][77]. The electrode featured a dual-layer configuration: a crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)/poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) composite nanofiber mat (denoted as PAV) at the bottom to provide ionic attraction, and a styrene-b-butadiene-b-styrene (SBS) block copolymer fiber mat at the top to buffer volume relaxation. As shown in SEM images, the SPF structure formed a porous fiber network uniformly covering the Cu foil with stacked PAV and SBS mats [Figure 4B]. This architecture enabled bottom-up Li filling during electrodeposition, driven by the ion-affinitive PAV layer in the SPF. By contrast, bare Cu electrodes exhibited uncontrollable dendritic Li growth after deposition of 10 mAh cm-2, as revealed by tilted-view SEM (Figure 4C, top). In sharp contrast, Cu@SPF electrodes maintained a stable Li morphology without dendrite penetration across the SPF, while electrochemically and mechanically regulating Li growth (Figure 4C, bottom). The lithiophilic PAV layer promoted uniform Li nucleation, while the SBS layer acted as a physical cushion to suppress electrode swelling under high Li loading. Electrochemical behavior was further evaluated through post-mortem SEM analysis of cycled anodes. In bare Cu electrodes, dendritic Li growth persisted due to uneven deposition, which induced continuous electrolyte consumption, reduced Sand’s time, and accelerated electrolyte depletion[78,79]. As a result, Cu-Li anodes exhibited unstable cycling behavior, with severe cracking and porous structure formation arising from uncontrollable ion flux on the bare current collector (Figure 4D, top). In contrast, Cu@SPF-Li anodes preserved their morphology without dendrite evolution, even after extended cycling, owing to the stabilizing effect of the SPF host structure (Figure 4D, bottom). These results clearly demonstrate that a well-designed polymer-based host structure can effectively preserve Li metal anodes by enabling stable volume accommodation, suppressing electrode swelling, and mitigating structural degradation. Such stabilization at both the electrochemical and mechanical levels is critical to improving the long-term operation of Li metal batteries.

Figure 4. Three-dimensional polymer architectures for Li metal accommodation. (A) Schematic of stacked polymer host structure (Cu@SPF). (B) SEM images of Cu@SPF electrode. (C) Tilted SEM images of 10 mAh cm-2 Li deposited on Cu (top) and Cu@SPF (bottom). (D) Top-view SEM images of cycled Cu-Li (top) and Cu@SPF-Li (bottom) anodes after 50 cycles. Reproduced with permission[77]. (E) Fabrication process of hyperporous/hybrid conductive architecture on CNT film (HCA/C). (F) Cross-sectional and top-view SEM images of HCA/C fabricated using ethanol, 1-propanol, and 1-butanol as nonsolvents (left to right). Insets show magnified regions confirming the structural formation of the three components. (G) Cross-sectional SEM images after Li deposition

However, additional requirements such as fast charging are difficult to achieve with the SPF structure because of limited reaction sites and the absence of a continuous electronic network. To address this limitation, Han et al. proposed a polymer-based host structure that provides both ionic and electronic charge transport by incorporating multi-dimensional conductive carbon through a nonsolvent-induced phase separation (NIPS) method, as shown in Figure 4E[80]. The NIPS method is a practical approach for fabricating porous structures, relying on the solvent-exchange rate between a good solvent and a nonsolvent of the chosen polymer[81,82]. In this system, PVA was used as the skeleton of the 3D host due to its strong ionic affinity and well-known lithiophilic properties, which promote Li-ion attraction. To establish electronic pathways, Super P carbon black and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were incorporated, resulting in a hybrid conductive architecture on the CNT current collector while simultaneously forming a porous network, denoted as HCA/C. The electrode structure was further optimized by systematically exploring different nonsolvents to balance porosity, Li accommodation, and charge conductivity. When ethanol was used as the nonsolvent, its fast solvent-exchange rate produced a macroporous structure. However, the short reaction time hindered the full development of the polymer framework, as confirmed by SEM images showing residual PVA clusters (Figure 4F, left). Consequently, this structure exhibited poor electronic conductivity, likely due to agglomeration of conductive agents and incomplete coverage of the large pore volume. On the other hand, it provided high ionic conductivity because of the large electrode/electrolyte contact area created by the macroporous network.

Conversely, when 1-butanol was used as the nonsolvent, its sluggish solvent-exchange rate with water produced a structure with smaller pores and a denser electrode morphology through controlled phase separation (Figure 4F, right). This structural feature enhanced electronic conductivity but reduced ionic conductivity in the resulting electrode. Therefore, achieving well-balanced charge conductivities requires careful porosity control through rational selection of the nonsolvent. To this end, 1-propanol, with a solubility parameter value intermediate between that of ethanol and 1-butanol, yielded optimized charge transport behavior. The electrode fabricated with 1-propanol exhibited both facile ionic and electronic transport while maintaining sufficient porosity, which facilitated efficient Li metal accumulation on the CNT current collector (Figure 4F, middle). Benefiting from these properties, the HCA/C electrode demonstrated fast-charging capability and stable Li electrodeposition. Comparative studies further highlighted these improvements. A bare Cu electrode showed severe volume expansion and rapid, uncontrolled Li growth under high current densities due to its limited reaction sites and two-dimensional film-type surface

Inhibiting chemical dissolution of high-energy cathodes

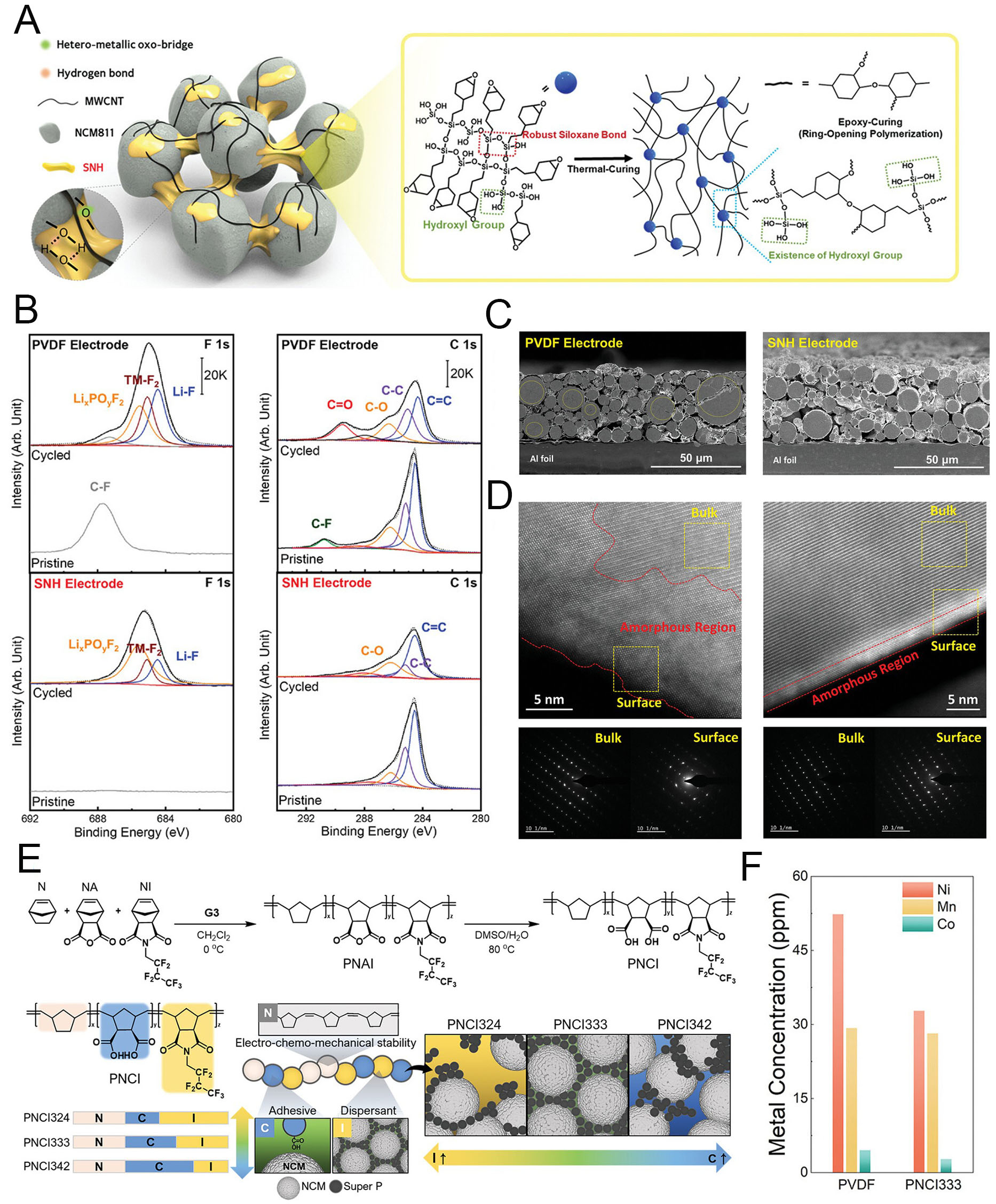

A higher Ni ratio in layered oxides accelerates structural degradation because of increased TM dissolution and unstable particle integrity[83,84]. Therefore, Ni-rich cathodes require protection strategies such as surface coatings[85,86], functional binder design[87-89], and electrolyte engineering[90,91]. In this context, rational binder design can play a vital role in enhancing electrochemical stability. Jang et al. synthesized a fluorine-free, hydroxyl-rich siloxane nanohybrid (SNH) binder to stabilize LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) cathodes[92]. As illustrated in Figure 5A, the binder’s high silanol content improved affinity with active and conductive materials, ensuring uniform distribution and stable electrochemical reactions. The silanol groups also facilitated hydrolysis, while the organic-inorganic hybrid structure helped suppress TM dissolution. As a result, the SNH-based NCM811 electrode (SNH Electrode) demonstrated greater electrochemical stability and cycling durability compared to the conventional poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) binder. Cycled SNH electrodes exhibited lower amounts of metal fluoride formation, as revealed by XPS analysis of the F 1s region (Figure 5B, left). This indicates that NCM811 cathodes stabilized with the SNH binder effectively maintain stable electrochemical reactions by suppressing uncontrolled transition-metal (TM) ion dissolution and surface degradation. Concurrently, XPS analysis of the C 1s region further confirmed the structural stability of the SNH electrode (Figure 5B, right). TM-ion dissolution can eventually induce microcracks in cathode particles, creating additional reaction sites and promoting further electrolyte decomposition. In this context, PVDF electrodes displayed a relatively higher areal ratio of C=O bonds at the surface, indicating continuous consumption of the organic solvent for cathode-electrolyte interphase (CEI) reformation. Particle degradation due to electrode instability was also investigated. SEM images of cycled PVDF electrodes revealed microcracks within the particles (Figure 5C, left). In contrast, the multifunctional SNH binder enabled enhanced stability, preserving crack-free particles even after cycling (Figure 5C, right). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) further highlighted differences in surface structure between NCM811 particles in the electrodes. Cycled PVDF electrodes exhibited unstable particle surfaces, characterized by TM-ion dissolution, cation mixing, and the formation of a thick amorphous surface layer (Figure 5D, left). By comparison, cycled SNH electrodes maintained particle stability, showing a well-preserved layered surface consistent with the bulk crystal structure and negligible surface degradation (Figure 5D, right).

Figure 5. Development of polymeric binders for Ni-rich cathodes to mitigate particle degradation. (A) Schematic illustration of the SNH-applied cathode structure. (B) XPS analyses of SNH and PVDF electrodes after charge/discharge cycling in F 1s (left) and C 1s (right) regions. (C) Cross-sectional SEM and (D) TEM images of SNH and PVDF electrodes after cycling. Reproduced with permission[92]. (E) Synthesis of PNCI terpolymers and schematic representation of the functional contributions of individual moieties in the PNCI# binder system. (F) Concentrations of Ni, Co, and Mn ions deposited on the surface of Li metal anodes in PVDF and PNCI333 cells, determined by ICP-MS. Reproduced with permission[93].

Ni-rich cathodes can improve electrochemical and structural stability at both the particle and electrode levels. Building on this concept, Jeong et al. developed another functional binder system based on poly(norbornene-co-norbornene dicarboxylic acid-co-heptafluorobutyl norbornene imide), denoted as PNCI#, synthesized via ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP)[93]. The “#” represents the feed molar ratio of the three monomers: norbornene (N), norbornene anhydride (NA), and norbornene imide (NI) [Figure 5E]. After polymerization, hydrolysis of anhydride groups yielded dicarboxylic acids, imparting multifunctionality including stability, adhesion, and dispersibility. Among the variants, PNCI333 was selected as the binder due to its balance of electrode processability and electrochemical stability. The NI component improved dispersibility, enabling uniform electrode fabrication, while the other moieties enhanced reaction homogeneity and structural robustness during cycling. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) confirmed that the PNCI333-based NCM811 cathode exhibited significantly reduced TM-ion dissolution compared to the PVDF electrode [Figure 5F]. In summary, rational binder engineering, through siloxane-based hybrids or ROMP-derived copolymers, offers an effective means to suppress particle degradation and TM dissolution in Ni-rich cathodes. While binders act indirectly compared to active cathode materials, their ability to stabilize particle surfaces, enhance electrode uniformity, and prolong cycle life demonstrates their critical role in advancing high-energy cathode performance.

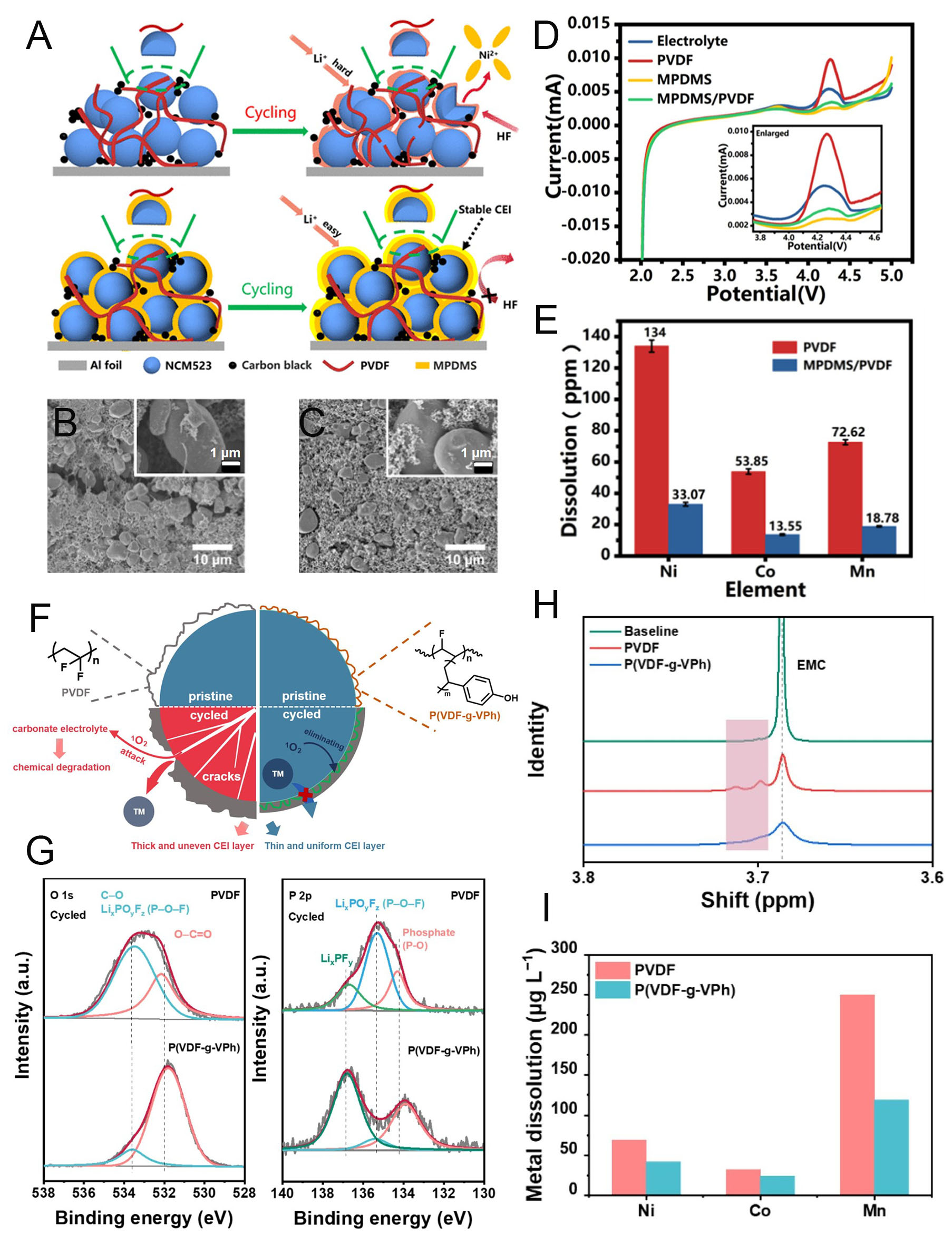

High-energy cathodes can also be achieved through high-voltage operation. Mid-Ni cathodes, such as NCM523 and NCM622, are commonly used in high-voltage systems. This approach increases energy density without changing theoretical capacity, instead relying on the optimized Ni atomic ratio within the cathode material. However, voltage elevation inevitably triggers oxidative electrolyte decomposition due to the limited electrochemical stability window of conventional electrolytes, which in turn accelerates TM dissolution[94,95]. To address this issue, Fan et al. developed a crosslinked polymer binder composed of hydroxy-terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) and methyltrimethoxysilane (MTMS), denoted as MPDMS, for use in NCM523 cathodes[96]. The elastomeric MPDMS structure provided mechanical flexibility, enabling entanglement with other electrode components and the formation of a robust coating on cathode particles. This coating effectively passivated particle surfaces and mitigated interfacial degradation during high-voltage cycling. To further improve electrode processability, PVDF was used as a co-binder. As shown in Figure 6A, incorporating MPDMS into the NCM523 slurry resulted in stable particle protection against mechanical stress and minimized direct electrolyte contact, thereby reducing oxidative decomposition at high voltage. In contrast, electrodes with a sole PVDF binder could not maintain structural stability due to mechanical failure and TM dissolution, caused by the lack of a passivated interface and a weak cohesion network. Consequently, PVDF-based electrodes exhibited structural degradation because of the difficulty in achieving uniform coverage on NCM523 particles [Figure 6B]. By comparison, the MPDMS/PVDF binder formed an interpenetrating network within the electrode, preserving structural integrity for 100 cycles without any cracks [Figure 6C]. This demonstrates that the elastomeric MPDMS binder stabilizes the NCM523 particle surface, mitigating side reactions and enhancing mechanical endurance. To further elucidate the critical role of MPDMS in suppressing electrolyte decomposition, linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements were performed [Figure 6D]. The naked NCM523 electrode exhibited clear electrolyte decomposition at the exposed electrode/electrolyte interface under high-voltage conditions, and the PVDF-based electrode showed a similar peak. In contrast, electrodes containing MPDMS or the MPDMS/PVDF combination exhibited negligible oxidative decomposition, confirming that MPDMS forms a dense interfacial layer through crosslinking of PDMS and MTMS, effectively passivating side reactions. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) further confirmed the surface stability of NCM523. Small amounts of moisture present in the electrodes and electrolyte can react with lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) to generate hydrofluoric acid (HF), which can attack the CEI and accelerate localized TM dissolution. The siloxane groups in MPDMS effectively immobilize HF by forming Si-F bonds within the polymer structure, preventing degradation of the CEI layer. As a result, the MPDMS/PVDF-based electrodes showed suppressed TM dissolution into the electrolyte compared to PVDF-based electrodes [Figure 6E].

Figure 6. Polymeric binder development for high-voltage stabilization of NCM cathodes. (A) Schematic illustration of bonding mechanisms in NCM523 cathodes using PVDF and MPDMS/PVDF binders. (B and C) SEM images of electrodes after 100 cycles with (B) PVDF and (C) MPDMS/PVDF binders (insets: high-resolution SEM). (D) LSV curves of electrodes with different binders at a scan rate of 0.5 mV s-1. (E) ICP-OES analysis of metal ions dissolved into the electrolyte from PVDF- and MPDMS/PVDF-based electrodes. Reproduced with permission[96]. (F) Schematic diagram of interfacial stabilization in NCM622 cathodes using PVDF and P(VDF-g-VPh) binders. (G) XPS spectra of O 1s and P 2p regions. (H) 1H NMR spectra of baseline and cycled electrolytes. (I) Comparison of TM dissolution in PVDF- and P(VDF-g-VPh)-based electrodes after 100 cycles. Reproduced with permission[97].

In addition to introducing new binders with tailored functions, modifying PVDF through graft polymerization can also enhance cathode interfacial stability. Liu et al. synthesized a vinylphenol-grafted PVDF polymer (P(VDF-g-VPh)) to improve the chemical stability of NCM622 during high-voltage cycling[97]. At elevated voltages, NCM622 typically releases reactive oxygen species, which attack the electrolyte and accelerate TM dissolution [Figure 6F]. The incorporation of phenolic hydroxyl groups in P(VDF-g-VPh) effectively scavenged these oxygen species, thereby preventing electrolyte degradation. In parallel, the hydroxyl groups formed strong hydrogen-bonding networks on cathode particle surfaces, improving adhesion and interfacial robustness. This dual effect preserved structural integrity and mitigated particle cracking and TM dissolution. XPS spectra of 100-cycled electrodes clearly confirmed the critical role of the grafted structure in the P(VDF-g-VPh) polymer [Figure 6G]. The P(VDF-g-VPh)-based electrode maintained a stable interphase on the cathode particles, as evidenced by reduced salt decomposition at the exposed surface, indicated by LixPOyFz detection. Meanwhile, during high-voltage operation, the carbonate electrolyte can be degraded by released oxygen species, leading to the formation of methyl carbonate derivatives. Monitoring the evolution of these derivatives provides insight into the degree of cathode degradation. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of the PVDF-based electrode after 100 cycles showed two distinct shifts at 3.69 and 3.72 ppm, corresponding to methyl carbonate derivatives [Figure 6H]. In contrast, the P(VDF-g-VPh)-based electrode showed no degradation-related peaks, demonstrating that the phenolic hydroxyl groups in the grafted structure effectively scavenged oxygen species and prevented electrolyte decomposition. Suppression of oxygen release directly enhanced the structural stability of both the CEI and the cathode particles, protecting against parasitic electrolyte reactions and preventing breakdown of the NCM622 crystal structure. As a result, TM dissolution into the electrolyte was significantly reduced in the P(VDF-g-VPh)-based electrode, as confirmed by ICP-MS analysis of cycled electrodes [Figure 6I]. Overall, the deployment of a functional binder in the cathode enables the formation of a robust interfacial layer, effectively preventing undesired side reactions. This strategy not only stabilizes mid-Ni NCM cathodes under high-voltage operation but also supports the structural and electrochemical integrity of Ni-rich NCM cathodes for high-energy applications.

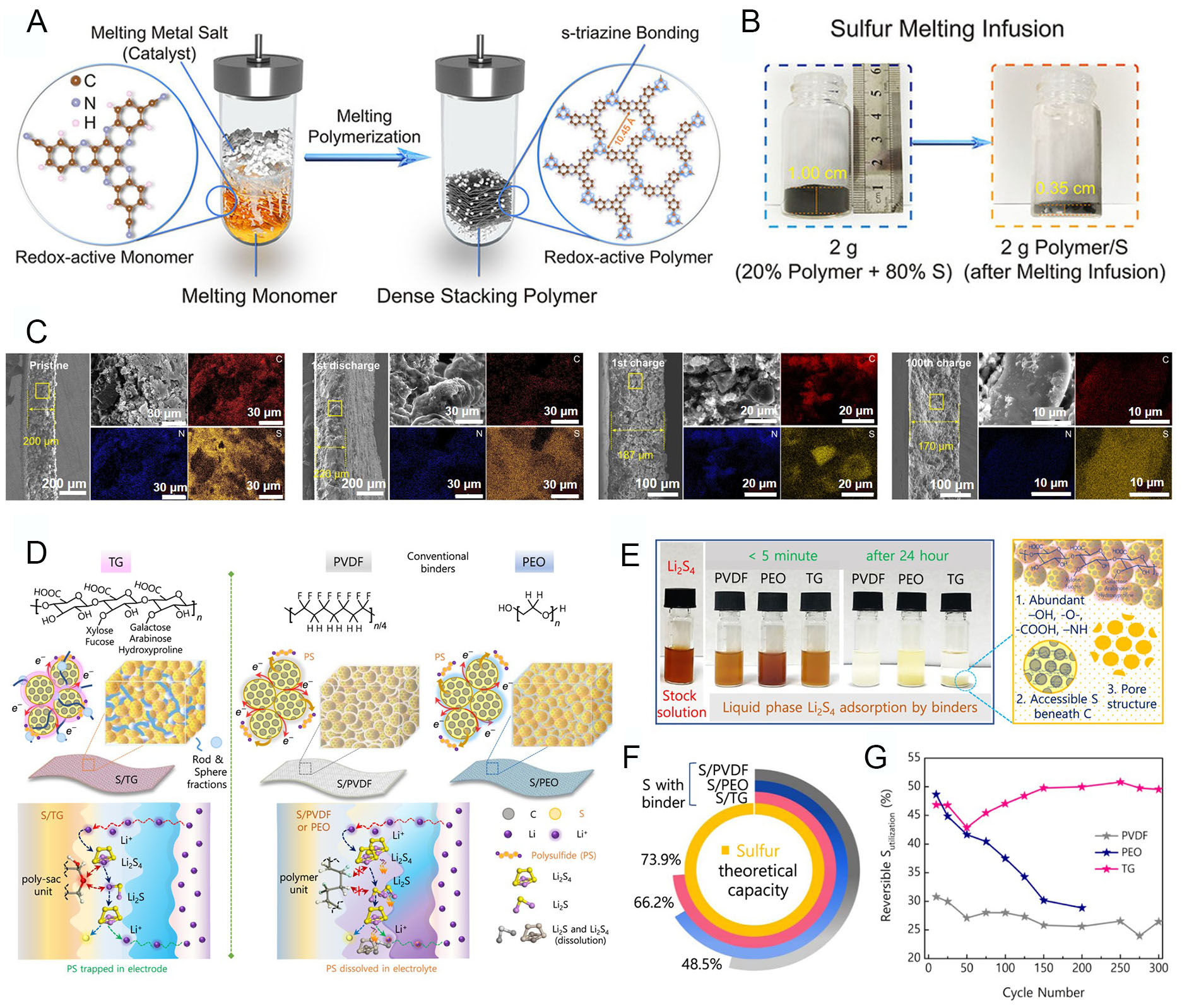

Compared to Ni-rich cathodes, S cathodes struggle to control the dissolution of LiPS compounds, which are inevitably generated during discharge[98,99]. Dissolved LiPS species migrate through the electrolyte to the LMA, where they are continuously reduced and redeposited. This so-called shuttle effect interrupts homogeneous electrochemical reactions and increases interphase resistance[100,101]. Therefore, suppressing LiPS dissolution is critical to achieving stable electrochemical performance. Several strategies have been explored to mitigate the shuttle effect, including cathode-optimized electrolytes[102], functional binders[103], and tailored host structures[104,105]. Here, we focus on polymer-based approaches that prevent LiPS migration and thereby stabilize electrode behavior. Wang et al. reported a porous polymer host with dense-stacking hexaazatrinaphthylene (HATN) as a reactive-type electrode, activated by Li2Sx[106]. This structure enabled electrochemical reactions through bidentate nitrogen atoms in HATN. To design a highly densified polymer, melting polymerization was employed via a high-temperature annealing process. As shown in Figure 7A, nanosheet-type monomers were converted into a bulky, dense redox-active polymer structure. Despite this dense stacking, numerous mesopores were formed within individual polymer sheets through s-triazine polymerization in the synthetic system. Consequently, the HATN polymer could accommodate higher amounts of S, as evidenced by the significant increase in powder density [Figure 7B]. SEM images of the cathode confirmed the chemical and structural stability derived from the designed polymer architecture [Figure 7C]. The pristine polymer/S cathode demonstrated high S loading, while the first discharged cathode showed well-distributed S atoms with minimal dissolution, due to the intimate interactions between s-triazine bonds in the polymer and LiPS. Even after the 1st charge, elemental mapping and electrode thickness measurements confirmed stable S occupancy within the HATN polymer. After 100 cycles, S remained present, and both electrode volume and thickness were maintained, reflecting a reduction in LiPS shuttle and dissolution. These results clearly highlight the structural advantages of HATN polymer, combining chemical redox activity with dense stacking features.

Figure 7. Polymer design for polysulfide shuttle suppression in S cathodes. (A) Schematic of polymer synthesis from monomers. (B) Photographs showing S infusion into dense porous polymer (cooled after 155 °C for 12 h). (C) Electrode thickness changes of polymer/S cathode (15 mg cm-2, delivering 10.5 mAh cm-2 at 1 mA cm-2) for pristine, 1st discharged, 1st charged, and 100th charged states. Reproduced with permission[106]. (D) Schematic illustration of cathode architecture with different binders: TG, PVDF, and PEO. S is loaded into Super P carbon with the respective binder. (E) Static adsorption of liquid-phase polysulfides by pristine PVDF, PEO, and TG binders. (F) S utilization for various binders at C/5 (against the theoretical capacity of S = 1,675 mAh g-1). (G) Reversible S utilization of various electrodes over selected cycle numbers. Reproduced with permission[107].

The S cathode could be further stabilized by deploying polymeric binders to counteract volume change and capacity decay caused by the LiPS shuttle. Senthil et al. proposed a functional binder using tragacanth gum (TG), a polysaccharide[107]. The diverse saccharide fractions in TG offer multiple benefits: strong attraction and coverage of S particles, effective trapping of LiPS to prevent dissolution into the electrolyte, and regulation of volume changes. As illustrated in Figure 7D, TG contains heterogeneous polysaccharide fractions that serve multiple functions as an efficient binder: polar groups restrict LiPS mobility within the cathode, while rod-like tragacanthin and sphere-like bassorin enhance mechanical strength and maintain electrode integrity. By contrast, typical PVDF and poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) binders cannot stabilize the S cathode effectively, due to a lack of ion affinity, low mechanical strength, and uncontrolled LiPS dissolution. LiPS adsorption tests further confirmed this behavior [Figure 7E]. The TG binder rendered the solution transparent through chemisorption by its abundant polar groups, whereas suspensions remained in PVDF- and PEO-containing solutions. This chemical stability of TG directly translates into improved electrochemical performance. Maintaining S content in the cathode is critical, as LiPS dissolution reduces the effective charge capacity. Figure 7F demonstrates the structural stability of the S/TG cathode, achieving 73.9% of the theoretical S capacity. Other binders showed inferior utilization, although PEO maintained moderate electrochemical activity due to its chemical structure. The differences became more pronounced over prolonged cycling [Figure 7G]. S/PVDF cathodes suffered early structural failure, with only 19.16% reversible S utilization after 200 cycles. S/PEO cathodes initially performed better but experienced rapid capacity decay due to LiPS dissolution, with 20.48% utilization after 200 cycles. In contrast, the S/TG cathode maintained high S utilization without significant decay for 300 cycles. These results clearly demonstrate the versatile advantages of functional polymer binders in improving the structural and electrochemical stability of S cathodes.

High-capacity cathodes are particularly vulnerable to structural degradation caused by side reactions and ion/compound dissolution. This section highlights how deploying functional polymers in the electrode enables structural stability and persistent electrochemical performance.

CONTROLLING SIDE REACTIONS WITH FUNCTIONAL MEMBRANES

Both anodes and cathodes can be directly stabilized by incorporating functional binders into the electrode. Meanwhile, the membrane offers an additional approach for battery stabilization through indirect modification, rather than serving solely as a structural component of the electrode. High-capacity anodes (e.g., Si and Li) and high-energy cathodes (e.g., NCM and S) often exhibit distinct degradation behaviors, which vary depending on the battery system and electrode configuration, as discussed in previous sections. In this section, we summarize the application of functional polymer-based membrane modifications, focusing on two key perspectives: (1) Shuttle issues in high-energy cathodes, related to TM and LiPS dissolution; and (2) safety risks, including the potential for short circuits caused by Li dendrite growth or operation at high voltage and elevated temperatures.

Shuttle-restraint polymer membrane

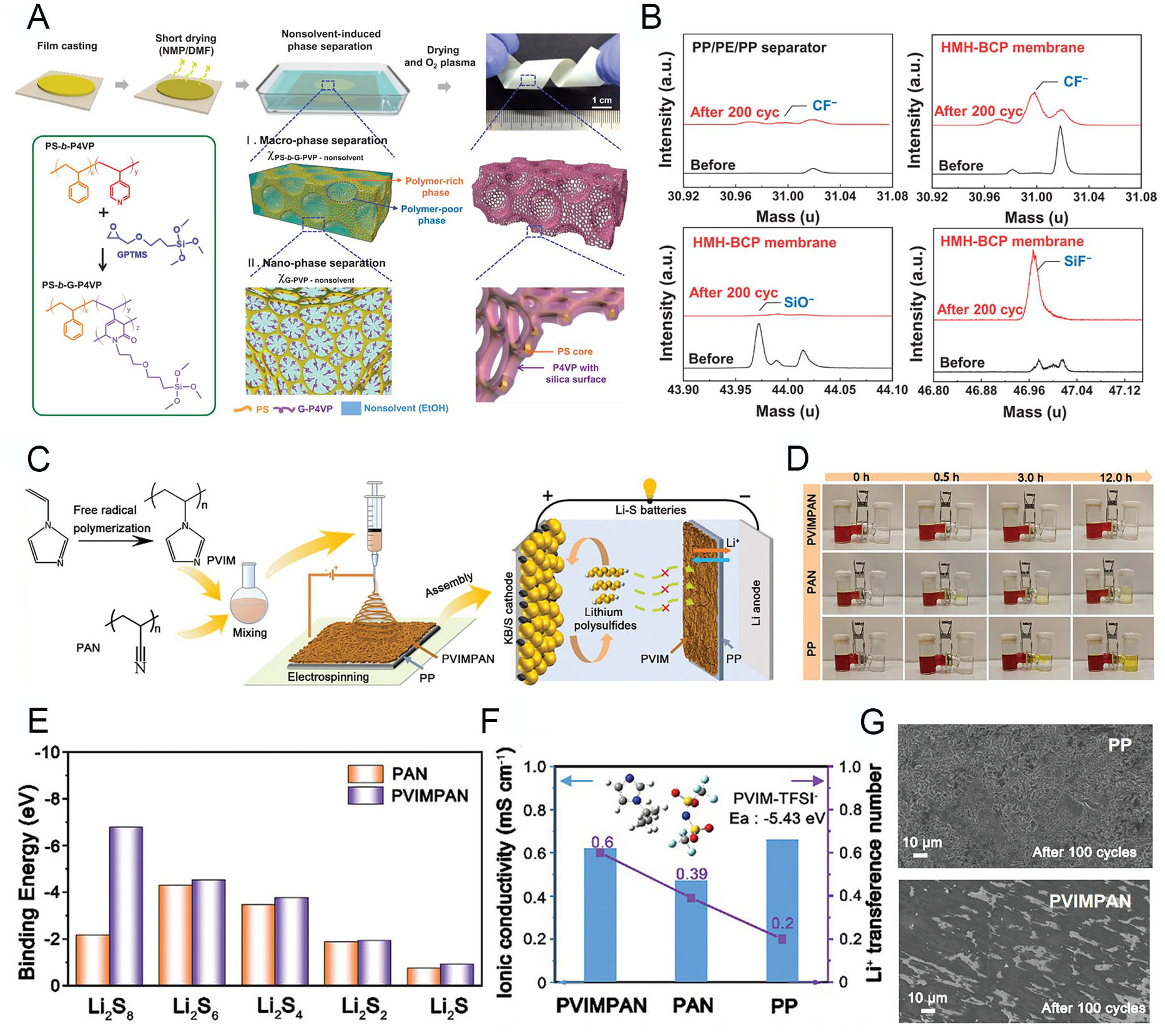

Side reactions caused by cathode dissolution can be mitigated by modifying the separator membrane, in addition to optimizing the electrode configuration. These reactions also affect the anode, leading to structural and electrochemical degradation through deposition. Although replacing the separator cannot directly eliminate the primary cause of dissolution, it can effectively suppress subsequent side reactions at the anode surface[108]. In this context, shuttle-restraint polymer membranes should be designed to minimize electrochemical degradation and enhance the cycle life of batteries. Yoo et al. synthesized a block copolymer (BCP) and fabricated a hyperporous membrane using the NIPS method, referred to as the HMH-BCP membrane[109]. An amphiphilic polystyrene-block-poly(4-vinylpyridine) (PS-b-P4VP) was used as the polymer base. Prior to preparing the polymer solution, PS-b-P4VP was chemically modified with 3-(glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) to introduce cyclic amide groups, yielding PS-b-G-P4VP [Figure 8A]. The modified polymer was then dissolved in a N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone/dimethylformamide (NMP/DMF) solvent mixture (8:2 volume ratio) and cast onto a Cu substrate. Rapid solvent evaporation was followed by immersion of the polymer film into an ethanol nonsolvent bath, generating a porous scaffold through solvent-nonsolvent exchange. Hierarchical pores were formed in the HMH-BCP membrane. Macropores resulted from phase separation between BCP-rich and BCP-poor regions, while nanopores emerged within the BCP-rich phase due to the self-assembly of PS and G-P4VP blocks into a quasi-hexagonally packed structure. This produced a multiscale hyperporous architecture. Finally, oxygen plasma treatment removed densified BCP domains and generated an inorganic silica layer. The resulting membrane functions as an advanced separator in LIBs, offering a potential replacement for conventional polyolefin separators. Moreover, the G-P4VP block provides a barrier to TM ion transport across the separator by chemically trapping the ions. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) analysis of pristine and extracted separators from cycled cells confirmed that silica compounds in the G-P4VP block act as HF scavengers, preventing interphase degradation through interactions with the electrolyte [Figure 8B]. This functional membrane preserves the structural integrity of electrodes and reduces electrochemical degradation, achieving 92% capacity retention after 200 cycles at 1 C and 50 °C. These results demonstrate the potential of indirect battery stabilization via functional polymer membranes, complementing, rather than directly modifying, the active material and electrode.

Figure 8. Shuttle-restraint polymer membranes. (A) Schematic illustration showing the fabrication process and physical appearance of HMH-BCP membranes. (B) TOF-SIMS analysis of separators before and after 200 cycles at 50 °C. Reproduced with permission[109]. (C) Schematic diagrams of PVIM synthesis, PVIMPAN separator preparation via electrospinning, and the function of PVIMPAN in Li-S batteries. (D) Digital images showing polysulfide diffusion through PP, PAN, and PVIMPAN separators in H-type cells after 0, 0.5, 3, and 12 h. (E) Binding energies of PAN and PVIMPAN with Li2Sx (x = 1, 2, 4, 6, 8). (F) Ionic conductivity and t+ of the separators at 25 °C, along with the binding energy of PVIM with TFSI-. (G) SEM images of Cu collectors after Coulombic efficiency tests of Li||Cu cells using PP (top) and PVIMPAN (bottom). Reproduced with permission[112].

Meanwhile, the use of separators with tailored functional structures, achieved through chemical and morphological modification, has been suggested for Li-S batteries. As previously mentioned, LiPS dissolution also affects the anode through unexpected deposition. In this context, controlling foreign compounds in the electrolyte can be achieved by trapping LiPS on the separator membrane via chemical and electrostatic interactions[110,111]. Lin et al. designed poly(N-vinyl imidazole) (PVIM) via a radical polymerization process[112]. The polar, electron-deficient imidazole groups in the polymer can capture dissolved LiPS in the electrolyte, thereby restraining their transport to the anode. PVIM was blended with poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN) (denoted as PVIMPAN) in DMF and subsequently processed through electrospinning to form a porous nanofiber matrix on a polypropylene (PP) separator [Figure 8C]. PAN was added to enhance mechanical strength and chemical resistance, while also enabling structural tunability during the synthetic process. As illustrated, while the PVIM cannot completely prevent LiPS leakage from the S cathode, the PVIMPAN structure effectively suppresses propagation to the anode, preventing additional degradation and improving cycle stability. The role of the imidazole group in PVIM was confirmed through a polysulfide diffusion test using an H-type cell [Figure 8D]. Cells with PP and PAN separators gradually changed color due to LiPS permeation, indicating that their functional groups interact poorly with LiPS. In contrast, PVIMPAN maintained a transparent state, confirming that dissolved LiPS were effectively blocked, thereby preventing sequential side reactions at the anode. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations further demonstrated the advantage of PVIMPAN in restraining the shuttle effect. The binding energies of various polysulfides on PVIMPAN showed that the electron-deficient imidazole groups significantly enhanced LiPS adsorption on the separator membrane [Figure 8E]. Consequently, cells with PVIMPAN membranes exhibited higher cycle retention by effectively blocking shuttle behavior between electrodes. In addition, PVIMPAN improved electrochemical performance and enabled stable, fast cycling. As shown in Figure 8F, the ionic conductivity of PVIMPAN (6.2 × 10-4 S cm-1) was comparable to that of conventional PP separators (6.6 × 10-4 S cm-1), despite the thickened electrospun matrix and reduced pore size. Moreover, immobilization of TFSI- ions by the imidazole groups in PVIM significantly increased the t+ to 0.6 compared to PAN (0.39) and PP (0.2). These electrochemical improvements indicate that PVIM enhances both kinetics and structural stability in the cell. Furthermore, PVIMPAN stabilized the surface of LMA while suppressing dendritic growth during cycling, compared to PP separators. The improved t+ facilitates uniform electrodeposition and dissolution, reducing interruptions in the electrochemical reaction [Figure 8G]. Overall, PVIMPAN-enabled Li-S cells exhibited a high capacity of 786 mAh g-1 after 500 cycles at 1 C, with a capacity retention of 80.9%. These results demonstrate that membrane modification can enhance the electrochemical stability of high-capacity cathodes by mitigating unexpected dissolution. This finding confirms the feasibility of achieving high-energy-density batteries through indirect contributions of functional cell components, even when using promising cathodes.

Fire-retardant polymer membrane

Temperature increases inside a battery, primarily caused by electrochemical side reactions within the electrodes, can trigger decomposition of the liquid electrolyte. This decomposition generates gaseous byproducts, which accelerate thermal runaway and significantly increase the risk of battery explosion[113,114]. To mitigate heat generation and ensure safe operation, thermal shutdown mechanisms are essential. To fundamentally prevent ignition, the separator blocks both heat and charge transfer between electrodes. While separators typically facilitate selective ion transport during normal operation, they should also be capable of simultaneously blocking ions and heat in critical situations, such as internal short circuits or thermal runaway. In such cases, the separator functions as an active safety component rather than merely an auxiliary part of the battery.

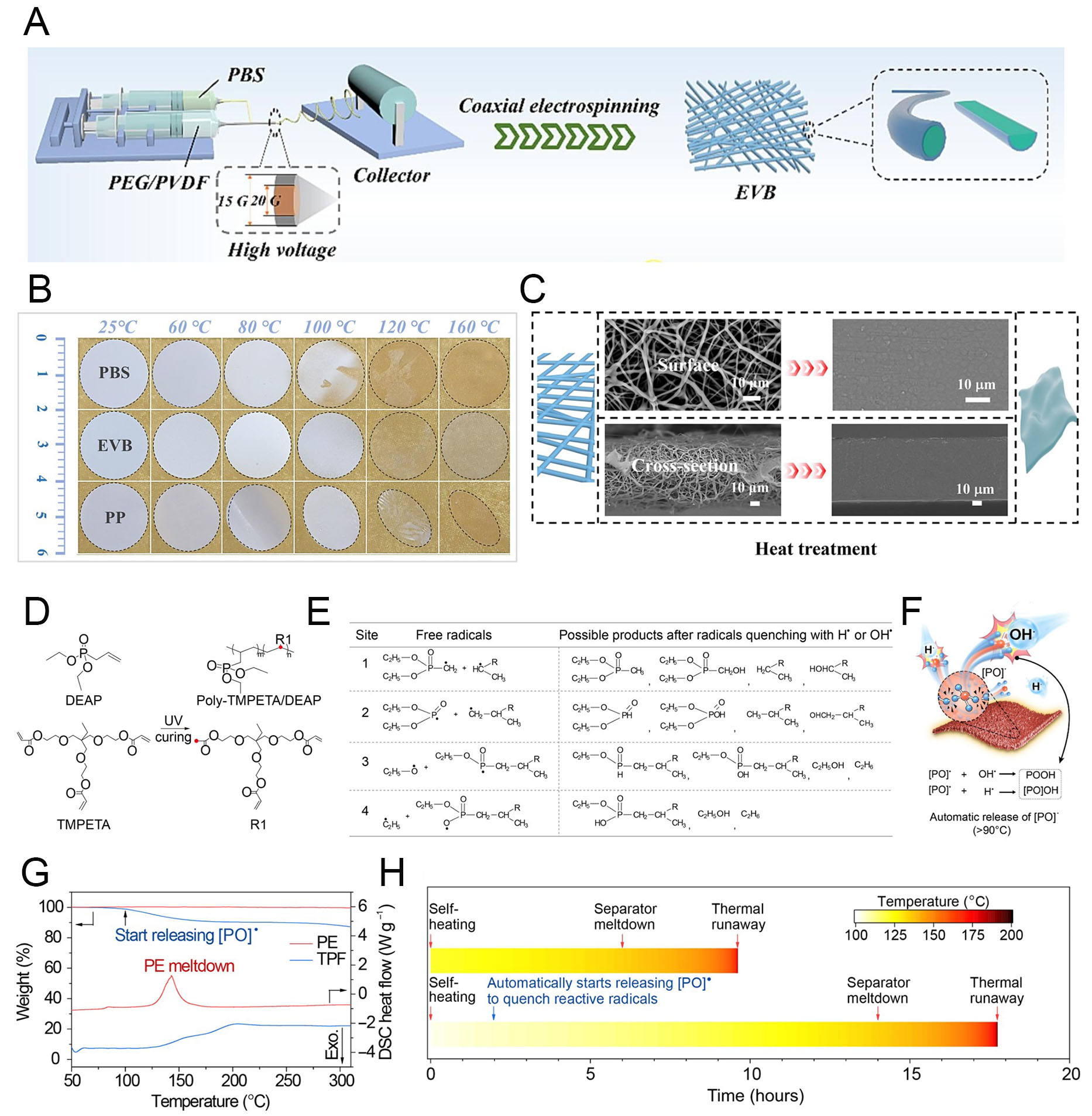

In this regard, various chemical structures have been proposed to enhance safety against thermal degradation[115,116]. Wang et al. designed an electrospun fiber matrix composed of a poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)/PVDF core and a poly(butylene succinate) (PBS) shell for individual fibers, denoted as EVB

Figure 9. Fire-retardant polymer membrane. (A) Schematic illustration of EVB membrane fabrication. (B) Optical images from thermal shrinkage tests of EVB, PBS, and PP membranes. (C) SEM images (surface and cross-section) of EVB before and after thermal shutdown. Reproduced with permission[117]. (D) Polymerization of DEAP and TMPETA monomers via ultraviolet (UV) curing. (E) Free radicals produced at different sites of the DEAP functional group and possible quenching products. (F) Illustration of thermal runaway mitigation by the TPF membrane when battery temperature exceeds 90 °C. P-containing radicals generated from TPF pyrolysis quench exothermic reactions, enhancing battery safety. (G) Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) profiles of PE and TPF membranes. (H) Timeline of thermal incidents in 1.8 Ah graphite||NCM811 pouch cells with different membranes. Reproduced with permission[118].

In addition to physical design, chemical treatment of membranes can further enhance battery safety.

ELECTROCHEMICAL/THERMAL-STABILIZED POLYMER ELECTROLYTE

Maintaining stable electrochemical performance and overall battery integrity is a critical factor for long-term cycling. Although liquid electrolytes offer high ionic conductivity (10-3-10-2) and form smooth electrode interfaces[119,120], their long-term stability remains a challenge. To address this, various solid electrolytes have been explored to enhance battery safety and prevent issues such as charge depletion and thermal runaway. Sulfide- and oxide-based inorganic solid electrolytes are attractive due to their superior thermal stability and safety; however, limitations such as low ionic conductivity, difficult processing, and poor interfacial compatibility have hindered their practical application[121,122]. As a compromise, polymer electrolytes have emerged, available in either solid or gel-like forms depending on application requirements. They combine electrochemical stability with mechanical flexibility, making them promising candidates for next-generation batteries that aim to achieve both high energy density and enhanced safety[123-125]. Among polymer-based systems, two primary forms, gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) and solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs), are employed to enable competitive electrochemical performance while improving battery safety.

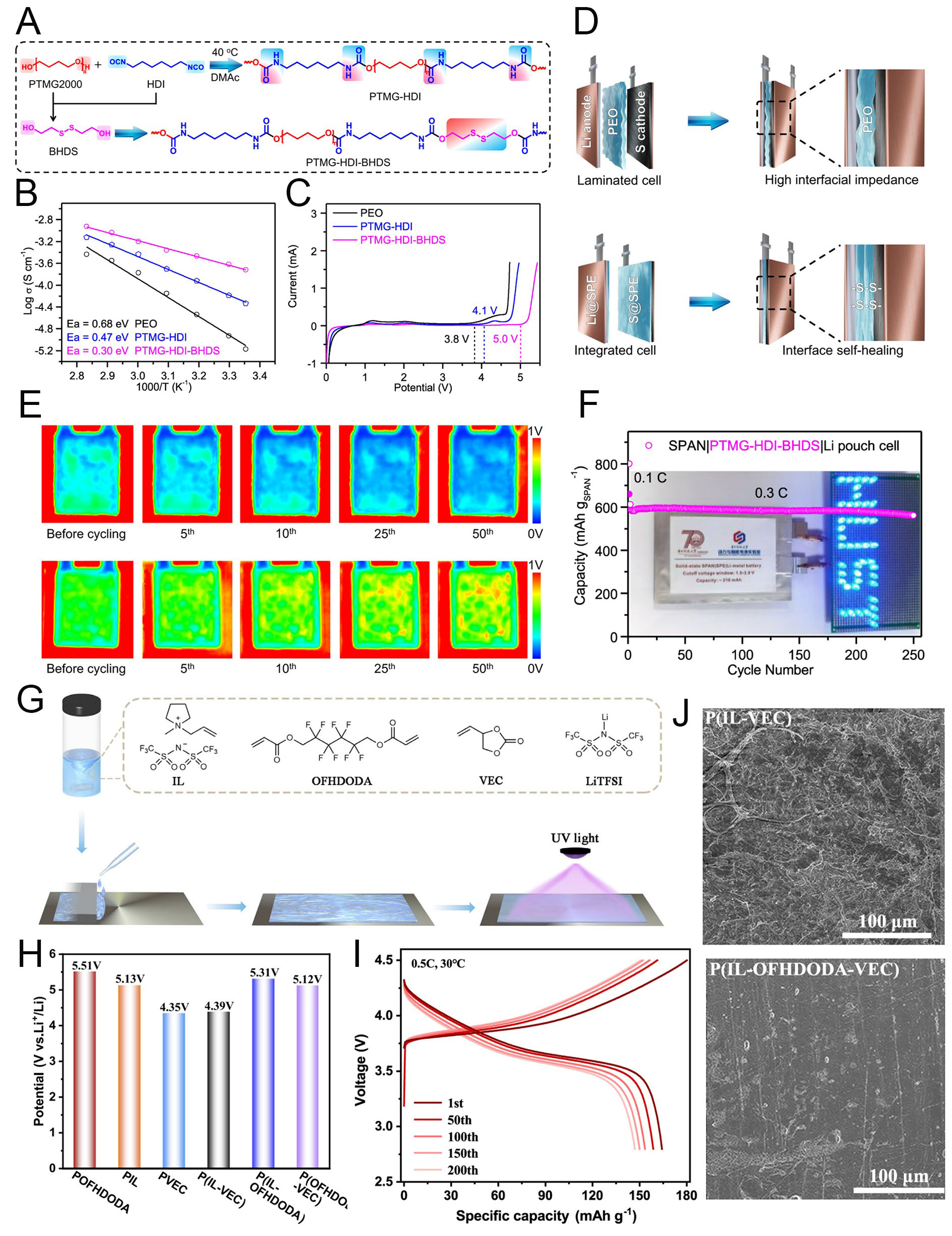

Although SPEs exclude liquid solvents and thus enhance potential stability and safety, their solid-state nature often limits intimate contact with electrodes. To overcome this, Pei et al. developed a self-healable poly(ether-urethane)-based SPE to reduce interfacial resistance in Li-S batteries[126]. The main monomers, polytetrahydrofuran (PTMG) and hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), formed the PTMG-HDI SPE framework. Additionally, 2-hydroxyethyl disulfide (BHDS) was incorporated as a chain extender with excess -N=C=O groups from HDI, yielding the PTMG-HDI-BHDS SPE [Figure 10A]. The repeated BHDS units in this SPE imparted self-healing ability through dynamic covalent disulfide bonds, allowing the polymer network to flexibly rearrange and repair interfacial contact damage during cycling. Electrochemically, PTMG-HDI-BHDS demonstrated improved ionic kinetics with lower activation energy (Ea) compared to conventional PEO and PTMG-HDI electrolytes [Figure 10B]. The SPE also exhibited higher ionic conductivity (2.4 × 10-4 S cm-1) and t+ of 0.81, confirming efficient ionic transport within the electrolyte. In comparison, PTMG-HDI and PEO showed ionic conductivities of 6.5 × 10-5 and

Figure 10. Interface stabilization and electrochemical performance enabled by SPEs. (A) Chemical structures of PTMG-HDI and PTMG-HDI-BHDS. (B) Temperature-dependent ionic conductivities of the SPEs. (C) Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) of the SPEs. (D) Structure of a conventional laminated (top) and an integrated electrode/electrolyte (bottom) solid-state Li-S battery. (E) In-situ ultrasonic transmission images during cycling for Li|PEO|SPAN (top) and Li|PTMG-HDI-BHDS|SPAN (bottom).(F) Cycling performance and optical images (inset) of the as-fabricated SPAN|SPEs|Li pouch cell. Reproduced with permission[126]. (G) Schematic illustration of the preparation of P(IL-OFHDODA-VEC). (H) Electrochemical stability window (ESW) of PIL, POFHDODA, PVEC, P(IL-OFHDODA), P(IL-VEC), and P(OFHDODA-VEC). (I) Charge/discharge curves of the Li|P(IL-OFHDODA-VEC)|NCM523 full cell. (J) SEM images of Li metal after cycling with P(IL-VEC) and P(IL-OFHDODA-VEC). Reproduced with permission[127].

Meanwhile, Tang et al. addressed another critical challenge of oxidation stability by incorporating a polyfluorinated crosslinking agent, 2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5-octafluoro-1,6-hexanediol diacrylate (OFHDODA), into the polymer network[127]. The P(IL-OFHDODA-VEC) SPE was designed using OFHDODA as a crosslinker combined with 1-allyl-1-methyl-pyrrolidinium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ionic liquid (IL), vinyl ethylene carbonate (VEC), and lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) salt through UV curing [Figure 10G]. In this structure, the difluoromethylene chain in OFHDODA exhibits strong electron-withdrawing properties, which reduce the electron density of neighboring groups. This chemical modification enhances the polymer’s resistance to oxidation, enabling high-voltage operation of the SPE while maintaining electrochemical stability for high-energy-density batteries. Compared to other combinations of ingredients, the OFHDODA-based structure showed a significantly higher electrochemical stability window (> 5 V vs. Li/Li+) [Figure 10H]. Additionally, VEC contributed to improved ionic conductivity (1.37 mS cm-1) and t+ (0.4) by enhancing segmental mobility within the polymer network and providing hopping sites for Li-ion transport. Using this optimized P(IL-OFHDODA-VEC) SPE, a

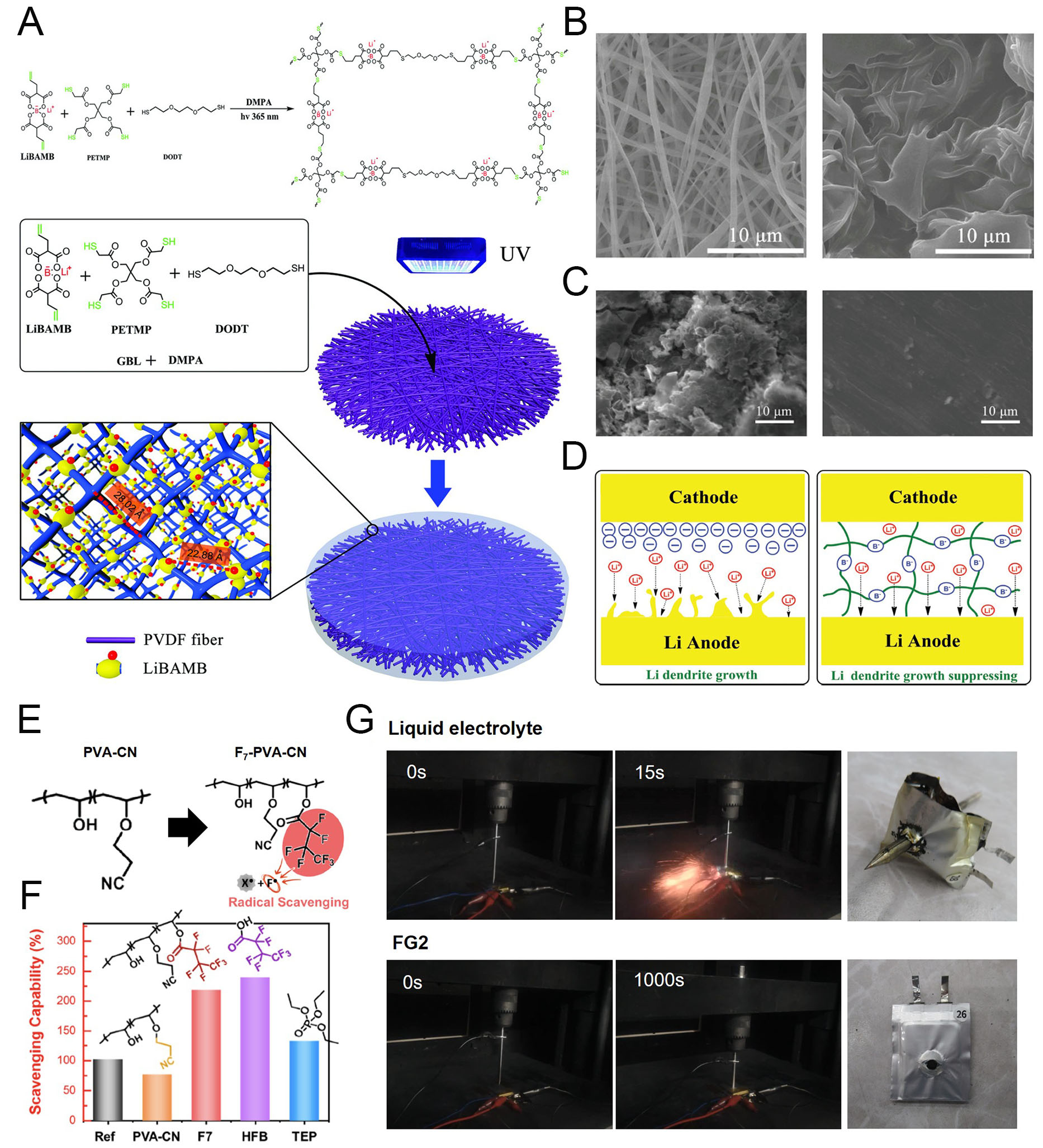

Typically, SPEs are designed without any liquid components, such as organic solvents. This limitation can restrict the ultimate electrochemical performance of the battery system. To address this, GPEs have emerged as a hybrid solution, combining the benefits of both liquid and solid electrolytes while maintaining competitive ionic conductivity, interface stability, and enhanced safety[128]. As an example of a GPE,

Figure 11. Polymer electrolyte contribution to electrochemical and thermal stabilization. (A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis and structure of LPD@PVDF SIPEs. (B) SEM images of PVDF (left) and LPD@PVDF SIPE membrane (right). (C) SEM images of cycled Li metal anode after using typical PP (left) and LPD@PVDF SIPE (right). (D) Schematic illustration of the Li metal growth mechanism depending on cell configuration. Reproduced with permission[129]. (E) Fluorine radical (F·) scavenging a flammable reactive radical (X·). F· and X· are generated from F7-PVA-CN and the electrolyte, respectively, via decomposition at elevated temperature, caused by safety issues. (F) Radical-scavenging capabilities (SR) estimated using the α-tocopherol (α-TOH) method. (G) Time-resolved photographs of nail penetration tests for 0.65 Ah pouch cells of graphite||NCM811 and the tested cells. Reproduced with permission[130].

The battery system can be evaluated not only for electrochemical stability and high energy density but also for fire safety. In this regard, fire-retardant GPEs can suppress radical-initiated chain reactions that lead to combustion or remain nonflammable even during fire exposure. Jeong et al. proposed an anti-flammable polymer by incorporating a fluorine-containing functional group as a radical-scavenging moiety into cyanoethyl poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA-CN), denoted as F7-PVA-CN [Figure 11E][130]. In the F7-PVA-CN-based GPE (FG2), cyanoethyl groups contribute to gelation via crosslinking, while the fluorine-containing moieties terminate radical chain reactions, which are primary contributors to thermal runaway. Heptafluorobutyric acid (HFB) demonstrated highly efficient radical-scavenging capability (SR > 200%), surpassing both the reference sample and the widely used flame-retardant additive triethyl phosphate (TEP, SR = 130%)

CONCLUSIONS

LIBs are increasingly critical for diverse applications, ranging from portable devices to electric vehicles and large-scale energy storage, and meet the ever-growing demand for high-energy-density systems. Promising anode materials, such as Si and Li metal, offer significantly higher theoretical capacities but face major challenges due to structural instability caused by dramatic volume changes and dendrite formation during cycling. Similarly, high-capacity and high-voltage cathode materials, including Ni-rich NCM and S, present issues such as active material loss and subsequent side reactions on the anode. This review summarizes strategic approaches focused on mitigating these challenges through the rational design and deployment of polymer structures within key battery components, including electrodes, separators, and electrolytes. By highlighting the multifaceted roles of polymers, it becomes evident that proper integration facilitates essential structural development and effective interface engineering. Consequently, polymer-centric strategies offer substantial potential to enhance both electrochemical performance and the critical safety aspects required for next-generation high-performance batteries. However, most current polymer structure designs address specific material- or electrode-level issues without considering the comprehensive battery system at the cell level. Additionally, many designs remain conceptual, with limited attention to mass production and commercial feasibility. To realize polymer-centric strategies at a practical level, future research should systematically address factors such as manufacturing cost, scalability, and comprehensive cell configuration.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Data sourcing, collection, and paper writing-original: Park, S.; Shin, H.; Song, G.

Supervision and Paper writing-review: Choi, S.; Song, G.

Funding acquisition: Song, G.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program (2410009665, Development of integrated battery cell manufacturing process and reliability evaluation technology using high-speed/low-energy curing technology) through the Korea Planning & Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Authors 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Machala, M. L.; Chen, X.; Bunke, S. P.; et al. Life cycle comparison of industrial-scale lithium-ion battery recycling and mining supply chains. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 988.

2. Song, I. T.; Kang, J.; Koh, J.; et al. Thermal runaway prevention through scalable fabrication of safety reinforced layer in practical Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8294.

3. Duan, J.; Tang, X.; Dai, H.; et al. Building safe lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles: a review. Electrochem. Energ. Rev. 2020, 3, 1-42.

4. Schmuch, R.; Wagner, R.; Hörpel, G.; Placke, T.; Winter, M. Performance and cost of materials for lithium-based rechargeable automotive batteries. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 267-78.

5. Eshetu, G. G.; Zhang, H.; Judez, X.; et al. Production of high-energy Li-ion batteries comprising silicon-containing anodes and insertion-type cathodes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5459.

6. Kim, S.; Kim, J. S.; Miara, L.; et al. High-energy and durable lithium metal batteries using garnet-type solid electrolytes with tailored lithium-metal compatibility. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1883.

7. Xu, J.; Cai, X.; Cai, S.; et al. High-energy lithium-ion batteries: recent progress and a promising future in applications. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2023, 6, e12450.

8. Liu, W.; Placke, T.; Chau, K. Overview of batteries and battery management for electric vehicles. Energy. Rep. 2022, 8, 4058-84.

9. Zeng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; et al. Extreme fast charging of commercial Li-ion batteries via combined thermal switching and self-heating approaches. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3229.

10. Frith, J. T.; Lacey, M. J.; Ulissi, U. A non-academic perspective on the future of lithium-based batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 420.

11. Zhao, S.; Guo, Z.; Yan, K.; et al. Towards high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries: Strategies for developing high-capacity lithium-rich cathode materials. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2021, 34, 716-34.

12. Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Hu, N.; et al. Tackling realistic Li+ flux for high-energy lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5431.

13. Ou, X.; Liu, T.; Zhong, W.; et al. Enabling high energy lithium metal batteries via single-crystal Ni-rich cathode material co-doping strategy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2319.

14. Lee, B. J.; Zhao, C.; Yu, J. H.; et al. Development of high-energy non-aqueous lithium-sulfur batteries via redox-active interlayer strategy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4629.

15. Huo, H.; Jiang, M.; Bai, Y.; et al. Chemo-mechanical failure mechanisms of the silicon anode in solid-state batteries. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 543-51.

16. Liang, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. Silicon-based materials as high capacity anodes for next generation lithium ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2014, 267, 469-90.

17. Li, Z.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. A 3D conducting scaffold with lithiophilic carbon nanoparticles for stable lithium metal battery anodes. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 618, 235183.

18. Long, K.; Huang, S.; Wang, H.; et al. High interfacial capacitance enabled stable lithium metal anode for practical lithium metal pouch cells. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2023, 58, 142-54.

19. Wen, Y.; He, K.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Expanded graphite as superior anode for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4033.

20. Moon, J.; Lee, H. C.; Jung, H.; et al. Interplay between electrochemical reactions and mechanical responses in silicon-graphite anodes and its impact on degradation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2714.

21. Jia, T.; Zhong, G.; Lv, Y.; et al. Prelithiation strategies for silicon-based anode in high energy density lithium-ion battery. Green. Energy. Environ. 2023, 8, 1325-40.

22. Qian, J.; Henderson, W. A.; Xu, W.; et al. High rate and stable cycling of lithium metal anode. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6362.

23. Toki, G. F. I.; Hossain, M. K.; Rehman, W. U.; Manj, R. Z. A.; Wang, L.; Yang, J. Recent progress and challenges in silicon-based anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Ind. Chem. Mater. 2024, 2, 226-69.

24. Ye, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Y. X.; Cao, F. F.; Guo, Y. G. An outlook on low-volume-change lithium metal anodes for long-life batteries. ACS. Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 661-71.

25. Li, A. M.; Wang, Z.; Pollard, T. P.; et al. High voltage electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries with micro-sized silicon anodes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1206.

26. Foss, C. E. L.; Talkhoncheh, M. K.; Ulvestad, A.; et al. Revisiting mechanism of silicon degradation in Li-ion batteries: effect of delithiation examined by microscopy combined with ReaxFF. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 2238-44.

27. Taiwo, O. O.; Paz-garcía, J. M.; Hall, S. A.; et al. Microstructural degradation of silicon electrodes during lithiation observed via operando X-ray tomographic imaging. J. Power. Sources. 2017, 342, 904-12.

28. Baek, M.; Kim, J.; Jeong, K.; et al. Naked metallic skin for homo-epitaxial deposition in lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1296.

29. Ko, S.; Obukata, T.; Shimada, T.; et al. Electrode potential influences the reversibility of lithium-metal anodes. Nat. Energy. 2022, 7, 1217-24.

30. Jiao, S.; Zheng, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Behavior of lithium metal anodes under various capacity utilization and high current density in lithium metal batteries. Joule 2018, 2, 110-24.

31. Qi, X.; Liu, B.; Pang, J.; et al. Unveiling micro internal short circuit mechanism in a 60 Ah high-energy-density Li-ion pouch cell. Nano. Energy. 2021, 84, 105908.

32. Song, Y.; Wang, L.; Sheng, L.; et al. The significance of mitigating crosstalk in lithium-ion batteries: a review. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1943-63.

33. Wu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, F.; et al. Ni-rich cathode materials for stable high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Nano. Energy. 2024, 126, 109620.

34. Cho, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; An, H.; Min, K.; Park, K. A review of problems and solutions in Ni-rich cathode-based Li-ion batteries from two research aspects: Experimental studies and computational insights. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 597, 234132.

35. Ryu, H.; Namkoong, B.; Kim, J.; Belharouak, I.; Yoon, C. S.; Sun, Y. Capacity fading mechanisms in Ni-rich single-crystal NCM cathodes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 2726-34.

36. Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Wen, Z.; et al. Cation mixing effect regulation by niobium for high voltage single-crystalline nickel-rich cathodes. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 142093.

37. Lee, G. H.; Lim, J.; Shin, J.; Hardwick, L. J.; Yang, W. Towards commercialization of fluorinated cation-disordered rock-salt Li-ion cathodes. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1098460.

38. Cai, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, L.; et al. Kinetically dormant Ni-rich layered cathode during high-voltage operation. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2419253.

39. Dong, X.; Yao, J.; Zhu, W.; et al. Enhanced high-voltage cycling stability of Ni-rich cathode materials via the self-assembly of Mn-rich shells. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 20262-73.

40. Pathak, A. D.; Cha, E.; Choi, W. Towards the commercialization of Li-S battery: from lab to industry. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 72, 103711.

41. He, B.; Rao, Z.; Cheng, Z.; et al. Rationally design a sulfur cathode with solid-phase conversion mechanism for high cycle-stable Li-S batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2003690.

42. Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ji, H.; Zhou, J.; Qian, T.; Yan, C. Unity of opposites between soluble and insoluble lithium polysulfides in lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2203699.

43. Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. Mechanism investigation of high-performance Li-polysulfide batteries enabled by tungsten disulfide nanopetals. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 9504-12.

44. Zhang, Y.; Song, H. W.; Crompton, K. R.; Yang, X.; Zhao, K.; Lee, S. A sulfur cathode design strategy for polysulfide restrictions and kinetic enhancements in Li-S batteries through oxidative chemical vapor deposition. Nano. Energy. 2023, 115, 108756.

45. Gao, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Electrolytes with moderate lithium polysulfide solubility for high-performance long-calendar-life lithium-sulfur batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2023, 120, e2301260120.

46. Kim, S. C.; Gao, X.; Liao, S. L.; et al. Solvation-property relationship of lithium-sulphur battery electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1268.

47. Zhang, Y.; Wen, J.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X. Application of anticorrosive materials in cement slurry: Progress and prospect. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1110692.

48. Pei, F.; Wu, L.; Lin, W.; et al. Progress and perspectives on molecular design of crosslinked polymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries. Rev. Mater. Res. 2025, 1, 100013.

49. Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Odent, J.; Takeoka, Y. Covalent design of ionogels: bridging with hydrogels and covalent adaptable networks. Polym. Chem. 2025, 16, 2327-57.

50. Li, Z.; Peng, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. In situ chemical lithiation transforms diamond-like carbon into an ultrastrong ion conductor for dendrite-free lithium-metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2100793.

51. Meunier, V.; Leal, De. Souza. M.; Morcrette, M.; Grimaud, A. Design of workflows for crosstalk detection and lifetime deviation onset in Li-ion batteries. Joule 2023, 7, 42-56.

52. Du, H.; Wang, Y.; Kang, Y.; et al. Side reactions/changes in lithium-ion batteries: mechanisms and strategies for creating safer and better batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2401482.

53. Xu, K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4303-417.

54. Adhitama, E.; Demelash, F.; Brake, T.; et al. Assessing key issues contributing to the degradation of NCM-622 || Cu cells: competition between transition metal dissolution and “dead Li” formation. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2303468.

55. Hogrefe, C.; Waldmann, T.; Hölzle, M.; Wohlfahrt-mehrens, M. Direct observation of internal short circuits by lithium dendrites in cross-sectional lithium-ion in situ full cells. J. Power. Sources. 2023, 556, 232391.

56. Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hu, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z. Research on internal short circuit detection method for lithium-ion batteries based on battery expansion characteristics. J. Power. Sources. 2023, 587, 233673.

57. Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, D.; Pei, A.; Cui, Y. Materials for lithium-ion battery safety. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9820.

58. Silveri, F.; Alberghini, M.; Esnault, V.; et al. Multiscale modelling of Si based Li-ion battery anodes. J. Power. Sources. 2024, 598, 234109.

59. Chae, S.; Ko, M.; Kim, K.; Ahn, K.; Cho, J. Confronting issues of the practical implementation of Si anode in high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Joule 2017, 1, 47-60.

60. Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Xie, J.; et al. An elastic cross-linked binder for silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries with a high mass loading. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 6594-602.

61. Choi, S.; Kwon, T. W.; Coskun, A.; Choi, J. W. Highly elastic binders integrating polyrotaxanes for silicon microparticle anodes in lithium ion batteries. Science 2017, 357, 279-83.

62. Jang, W.; Kim, S.; Kang, Y.; Yim, T.; Kim, T. A high-performance self-healing polymer binder for Si anodes based on dynamic carbon radicals in cross-linked poly(acrylic acid). Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143949.

63. Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Chen, Z.; McDowell, M. T.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z. Self-healing chemistry enables the stable operation of silicon microparticle anodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 1042-8.

64. Zhang, D.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. A gradient-distributed binder with high energy dissipation for stable silicon anode. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 673, 312-20.

65. Cheng, D.; Song, F.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Dynamic self-adaption supramolecular binder for silicon anodes: anhydride activation enabling practical lithium-ion battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2507041.

66. Cai, Y.; Liu, C.; Yu, Z.; et al. Slidable and highly ionic conductive polymer binder for high-performance Si anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2205590.

67. Kim, J.; Kim, E.; Lim, E. Y.; et al. Stress-dissipative elastic waterborne polyurethane binders for silicon anodes with high structural integrity in lithium-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2024, 7, 1629-39.

68. Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. N-rich solid electrolyte interface constructed in situ via a binder strategy for highly stable silicon anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301716.

69. Kozen, A. C.; Lin, C.; Zhao, O.; Lee, S. B.; Rubloff, G. W.; Noked, M. Stabilization of lithium metal anodes by hybrid artificial solid electrolyte interphase. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 6298-307.

70. Song, G.; Hwang, C.; Song, W. J.; et al. Breathable artificial interphase for dendrite-free and chemo-resistive lithium metal anode. Small 2022, 18, e2105724.

71. Hwang, C.; Song, W. J.; Song, G.; et al. A three-dimensional nano-web scaffold of ferroelectric beta-PVDF fibers for lithium metal plating and stripping. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 29235-41.

72. Lee, S.; Lee, Y.; Song, W.; et al. Integration of deformable matrix and lithiophilic sites for stable and stretchable lithium metal batteries. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2024, 73, 103850.

73. Cheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. Lithium host: advanced architecture components for lithium metal anode. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2021, 38, 276-98.

74. Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Mensi, M.; Choi, J. W.; Coskun, A. Electrolyte engineering via ether solvent fluorination for developing stable non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 299.

75. Park, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. A.; Ue, M.; Choi, N. S. Liquid electrolyte chemistries for solid electrolyte interphase construction on silicon and lithium-metal anodes. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 9996-10024.

76. Kim, K.; Ma, H.; Park, S.; Choi, N. Electrolyte-additive-driven interfacial engineering for high-capacity electrodes in lithium-ion batteries: promise and challenges. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2020, 5, 1537-53.

77. Han, D.; Song, G.; Kim, S.; Park, S. Dual-functional stacked polymer fibers for stable lithium metal batteries in carbonate-based electrolytes. Small. Struct. 2022, 3, 2200120.

78. Bai, P.; Li, J.; Brushett, F. R.; Bazant, M. Z. Transition of lithium growth mechanisms in liquid electrolytes. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3221-9.

79. Kang, H.; Kim, T.; Hwang, G.; et al. Stabilizing a lithium metal anode through the sustainable release of a multi-functional AgNO3 additive. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149510.

80. Han, D. Y.; Kim, S.; Nam, S.; et al. Facile lithium densification kinetics by hyperporous/hybrid conductor for high-energy-density lithium metal batteries. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2402156.

81. Jung, J. T.; Kim, J. F.; Wang, H. H.; di, Nicolo. E.; Drioli, E.; Lee, Y. M. Understanding the non-solvent induced phase separation (NIPS) effect during the fabrication of microporous PVDF membranes via thermally induced phase separation (TIPS). J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 514, 250-63.

82. Kim, M.; Kim, G.; Kim, J.; et al. New continuous process developed for synthesizing sponge-type polyimide membrane and its pore size control method via non-solvent induced phase separation (NIPS). Microporous. Mesoporous. Mater. 2017, 242, 166-72.

83. Park, N.; Park, G.; Kim, S.; Jung, W.; Park, B.; Sun, Y. Degradation mechanism of Ni-rich cathode materials: focusing on particle interior. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 2362-9.

84. Wen, Y.; He, Y.; Tang, Y.; et al. Mitigating fast-charging degradation in Ni-rich cathodes via enhancing kinetic-mechanical properties. J. Energy. Chem. 2025, 107, 296-304.

85. Li, X.; Liu, J.; Banis, M. N.; et al. Atomic layer deposition of solid-state electrolyte coated cathode materials with superior high-voltage cycling behavior for lithium ion battery application. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 768-78.

86. Liang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. A gradient oxy-thiophosphate-coated Ni-rich layered oxide cathode for stable all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 146.

87. Chen, L.; Yang, D.; Xin, J.; et al. High dielectric sulfonyl-containing polyimide binders optimize the long-term stability and safety of NCM811 lithium-ion batteries at high voltages. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158670.

88. Kim, J. H.; Lee, K. M.; Kim, J. W.; et al. Regulating electrostatic phenomena by cationic polymer binder for scalable high-areal-capacity Li battery electrodes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5721.

89. Kang, J.; Eom, H.; Jang, S.; et al. Bollard-anchored binder system for high-loading cathodes fabricated via dry electrode process for Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2416872.

90. Song, C.; Moon, H.; Baek, K.; et al. Acid- and gas-scavenging electrolyte additive improving the electrochemical reversibility of Ni-rich cathodes in Li-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 22157-66.

91. Zhang, D.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; et al. Lithium hexamethyldisilazide as electrolyte additive for efficient cycling of high-voltage non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6966.

92. Jang, J.; Ahn, J.; Ahn, J.; et al. A fluorine-free binder with organic-inorganic crosslinked networks enabling structural stability of Ni-Rich layered cathodes in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410866.

93. Jeong, D.; Kwon, D.; Kim, H. J.; Shim, J. Striking a balance: exploring optimal functionalities and composition of highly adhesive and dispersing binders for high-nickel cathodes in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2302845.

94. Vettori, K.; Schröder, S.; Ahrens, L.; et al. Chemical and structural degradation of single crystalline high-nickel cathode materials during high-voltage holds. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2025, 15, 2502148.

95. Dose, W. M.; Li, W.; Temprano, I.; et al. Onset potential for electrolyte oxidation and Ni-rich cathode degradation in lithium-ion batteries. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 3524-30.

96. Fan, X.; Chen, P.; Yin, X.; et al. One stone for multiple birds: a versatile cross-linked poly(dimethyl siloxane) binder boosts cycling life and rate capability of an NCM 523 cathode at 4.6 V. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 16245-57.

97. Liu, Z.; Dong, T.; Mu, P.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Cui, G. Interfacial chemistry of vinylphenol-grafted PVDF binder ensuring compatible cathode interphase for lithium batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136798.

98. Fu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Switchable encapsulation of polysulfides in the transition between sulfur and lithium sulfide. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 845.

99. Chen, H.; Zhou, G.; Boyle, D.; et al. Electrode design with integration of high tortuosity and sulfur-philicity for high-performance lithium-sulfur battery. Matter 2020, 2, 1605-20.

100. Huang, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. Recent advances and strategies toward polysulfides shuttle inhibition for high-performance Li-S batteries. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2106004.

101. Fan, Y.; Niu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, G. Suppressing the shuttle effect in lithium-sulfur batteries by a UiO-66-modified polypropylene separator. ACS. Omega. 2019, 4, 10328-35.

102. Tan, J.; Matz, J.; Dong, P.; Ye, M.; Shen, J. Appreciating the role of polysulfides in lithium-sulfur batteries and regulation strategies by electrolytes engineering. Energy. Storage. Mater. 2021, 42, 645-78.

103. Lin, X.; Wen, Y.; Ma, D.; et al. A zwitterionic polymer binder Integrating multiple dynamic interactions enables high-performance lithium - sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162808.

104. Yang, M.; Shi, D.; Sun, X.; et al. Shuttle confinement of lithium polysulfides in borocarbonitride nanotubes with enhanced performance for lithium-sulfur batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 296-304.

105. Zhou, L.; Danilov, D. L.; Eichel, R.; Notten, P. H. L. Host materials anchoring polysulfides in Li-S batteries reviewed. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2021, 11, 2001304.

106. Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Lai, C.; et al. Dense-stacking porous conjugated polymer as reactive-type host for high-performance lithium sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11359-69.

107. Senthil, C.; Kim, S. S.; Jung, H. Y. Flame retardant high-power Li-S flexible batteries enabled by bio-macromolecular binder integrating conformal fractions. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 145.

108. Dose, W. M.; Temprano, I.; Allen, J. P.; et al. Electrolyte reactivity at the charged Ni-rich cathode interface and degradation in Li-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 13206-22.

109. Yoo, S.; Kim, J. H.; Shin, M.; et al. Hierarchical multiscale hyperporous block copolymer membranes via tunable dual-phase separation. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500101.

110. Tu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z. Heteroelectrocatalyst MoS2@CoS2 modified separator for Li-S battery: unveiling superior polysulfides conversion and reaction kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 155915.

111. Dong, Q.; Zhao, X.; Ren, X.; et al. Dopamine-modified separator anchoring polysulfides via electrostatic interaction for enhanced Lithium-sulfur batteries. J. Energy. Storage. 2025, 106, 114855.

112. Lin, C.; Feng, P.; Wang, D.; et al. Safe, facile, and straightforward fabrication of poly(n-vinyl imidazole)/polyacrylonitrile nanofiber modified separator as efficient polysulfide barrier toward durable lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2411872.

113. Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Ren, D.; et al. In situ observation of thermal-driven degradation and safety concerns of lithiated graphite anode. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4235.

114. Zheng, T.; Muneeswara, M.; Bao, H.; et al. Gas evolution in Li-ion rechargeable batteries: a review on operando sensing technologies, gassing mechanisms, and emerging trends. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400065.