Research progress on liquid-solid transition under synchrotron radiation X-ray and simulation

Abstract

The structures of metallic melts are of utmost significance for understanding liquid properties, atomic dynamics, and solidification behaviors, including the formation of solidified microstructures. In recent years, with the continuous advancement of experimental techniques and numerical simulation methods, researchers have obtained deeper insights into the microscopic details of the liquid structure, the structure evolution, and the correlations between the liquid structure and the solidified microstructure. This article reviews the main experimental techniques and simulation methods employed in the study of metallic melt structures, as well as the pioneering findings in the field. High-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction and in situ X-ray imaging techniques and their applications in elucidating the liquid structure and its evolution during solidification are introduced. Special attention is given to the development of synchrotron equipment. Simulation methods for analyzing melt structures include classical molecular dynamics (MD), ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD), reversed Monte Carlo (RMC), and machine learning (ML), all of which have been applied to predict the atomic structures of metallic melts. The most recent progress in machine learning potentials or force fields is also introduced. The article also discusses future research directions, including the integration of high-resolution imaging with high-energy X-ray diffraction techniques, the application of artificial intelligence-assisted simulations to reduce computational costs, and the investigation of external factors such as pressure and cooling rates on solidification behavior. By combining advanced experimental and computational approaches, research on metallic melt structures is expected to move toward a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding, opening new opportunities for breakthroughs in metallurgy and materials science.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metallic melts play a crucial role in a wide range of material applications, including metal casting and alloy synthesis[1,2]. The structure and properties of metallic melts directly influence the quality and performance of the final products. For example, in metal casting, the viscosity and diffusion behavior of the melt affect the filling of molds and the formation of defects[3]. In alloy synthesis, the local structure of the melt determines the distribution of alloying elements and the resulting microstructure[4]. By understanding and controlling the structure of metallic melts, we can optimize the mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability of materials, which are essential for high-performance applications.

Unlike the long-range order of crystals, metallic melts exhibit an overall disordered structure, but the arrangement of atoms on a local scale tends to exhibit some degree of ordering, which is referred to as short-range order (SRO)[5]. This locally ordered structure has a significant effect on the macroscopic properties of the metallic melts. The interactions between metal atoms and the degree of structural compactness directly affect the viscosity[6], diffusion coefficient[7], and thermodynamic properties[8] of the melt, which in turn affects the flow and diffusion behaviors of the melt. The melt structure also plays an important role in the solidification process, and its local order directly determines the nucleation and crystal growth. During solidification, SRO provides the basis for initial nucleation, and its localized atomic arrangements set the stage for subsequent nucleation, which can significantly affect the morphology of the nucleus, the nucleation rate, and the subsequent crystal growth path[9]. For example, under rapid cooling conditions, metallic melts cannot transform into a crystalline structure with long-range order and instead form an amorphous solid[10]. In addition, the structural inhomogeneity in the metallic melts also affects the microstructure after solidification, such as dendrite segregation[11], and these factors together determine the mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability of metallic materials. Therefore, it is important to study the structure of the metallic melts and its evolution behavior during solidification for material design and property optimization.

However, the high temperature and reactive nature of metallic melts make it challenging to determine their local structure and how it evolves. In situ observation with simultaneous high temporal and spatial resolutions is hard to realize for the existing experimental techniques under high-temperature and rapid-cooling conditions. In addition, interactions between different elements in multicomponent systems complicate the mixing enthalpy-driven SRO and segregation behaviors, exacerbating the difficulty of description[12].

In-depth elucidation of the microscopic details of the liquid structure and the structural evolution during solidification requires breakthroughs in research methods and experimental techniques, which will help researchers paint a clearer picture of the atomic structures of the system under different temperature and pressure conditions. Therefore, the development of advanced research tools is of utmost significance. This paper summarizes the recent advances in the structural understanding of metallic melts, focusing on both the development of research methods and the enhancement of experimental techniques.

DEVELOPMENT OF EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

High energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction technique

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is one of the classical techniques for investigating the microstructure of materials. Its principle is based on the interaction between X-rays and the lattice structures of atoms or molecules in a material, resulting in diffraction phenomena. By measuring the diffraction intensity at various angles, the material’s crystal structure, lattice constants, and atomic arrangement can be directly deduced from available data[13]. In the study of metallic melts, traditional XRD faces limitations in accuracy due to thermal vibrations and structural disorder of the liquid. Thermal vibrations at high temperatures increase atomic displacement, leading to peak broadening and reduced diffraction intensity. High-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction technology overcomes many of the constraints inherent in conventional XRD for high-temperature metallic melt investigations. Specifically, the use of high-energy X-rays (typically ≥ 100 keV) provides greater penetration depth and improved scattering contrast, which mitigates the influence of thermal motion and enhances data reliability even under extreme thermal conditions. Synchrotron radiation sources, unlike traditional X-ray sources, provide much higher brightness, which enables rapid measurements with enhanced spatial resolution. Notably, electron beam energies in modern third-generation synchrotron facilities can reach several GeV, enabling the generation of typically tens to hundreds of keV X-rays with high flux, which are ideal for probing the structure of metallic melts with high sensitivity[14]. The critical angular frequency of the emitted radiation can be described by the equation[15]:

Where ωc is the critical frequency, γ is the Lorentz factor, c is the speed of light, and R is the bending radius of the electron orbit.

The structure factor, S(Q), and pair distribution function (PDF) are the two key parameters that bridge experimental diffraction techniques and theoretical structural analysis in metallic melts[16,17]. These two functions enable the conversion of reciprocal-space data into real-space atomic configurations and are essential for understanding short-range order in disordered systems. S(Q) is derived from the coherent part of the scattering intensity, Icoh(Q), normalized by the atomic form factors, and is given by[18]:

where Ci and fi(Q) represent the atomic concentration and scattering factor for element i, respectively. S(Q) describes how atomic correlations in the sample scatter X-rays, providing a reciprocal-space signature of the material’s structure. To convert this information into real space, the reduced pair distribution function G(r) is calculated from S(Q) using a Fourier transformation[19]:

Here, Q = 4πsin(θ) / λ is the momentum transfer vector, and r is the radial distance. This transformation reveals the probability of finding pairs of atoms separated by distance r, providing insight into the real-space arrangement of atoms.

In addition, the pair distribution function can be related to the local atomic number density[19]:

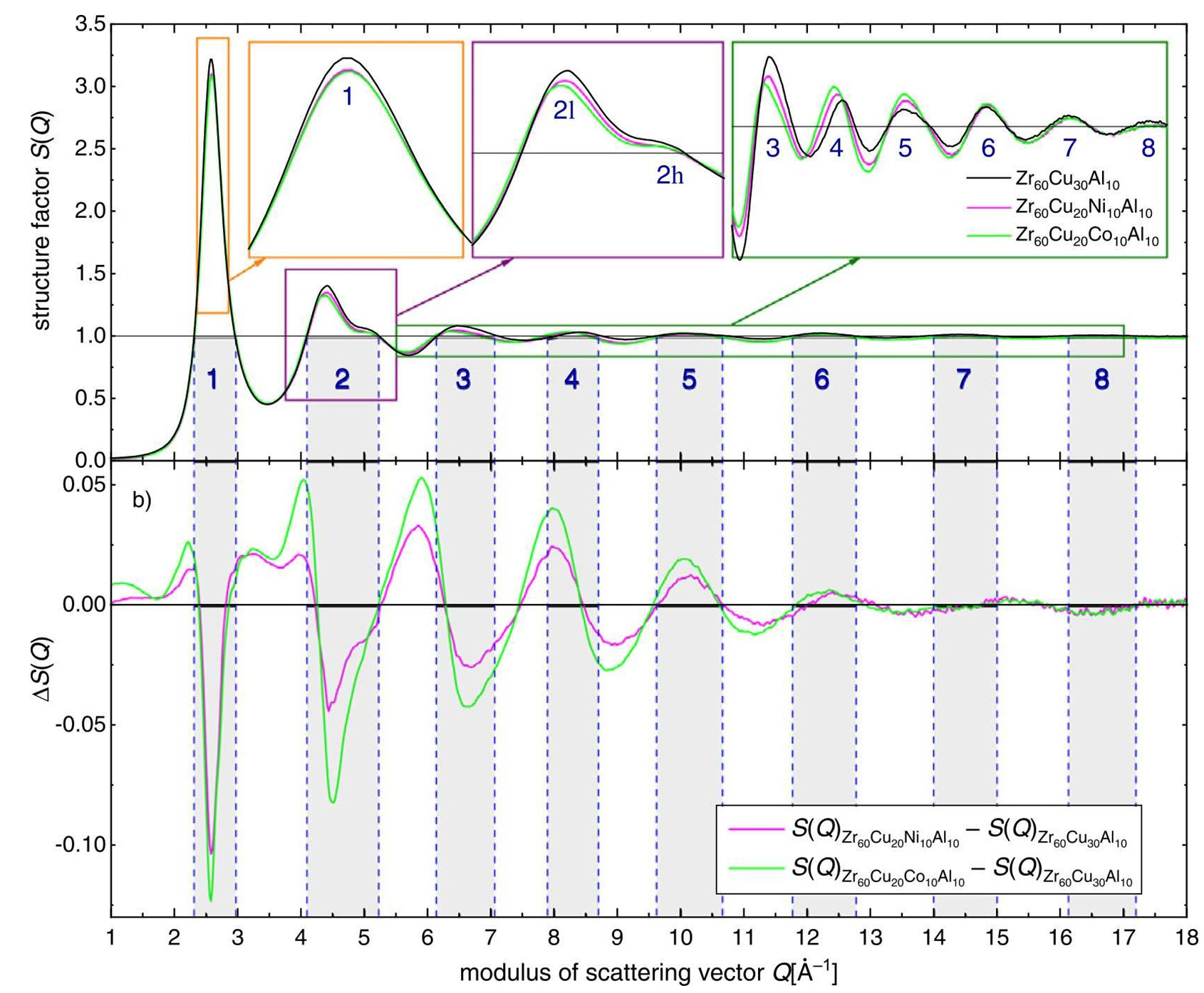

where ρ(r) and ρ0 are the local and average atomic number densities, respectively. These equations form the theoretical foundation for extracting structural information using experimental techniques such as high-energy X-ray diffraction (HEXRD). This analytical framework is particularly well-suited for disordered systems lacking long-range crystalline order, such as metallic melts and amorphous alloys, enabling the characterization of short-range atomic order at the atomic scale[20]. For instance, by measuring the diffraction peaks in the X-ray diffraction pattern, the structure factor of the metallic melt can be obtained, enabling further analysis of the local atomic arrangement within the melt. Stiehler et al.[21] employed high-energy synchrotron radiation X-ray diffraction to investigate the X-ray diffraction patterns of Zr60Cu30Al10 and its Ni- or Co-doped alloys. The structure factor S(Q) was extracted, and the pair distribution function G(r) was subsequently analyzed. Their results revealed that the incorporation of Ni or Co enhances the structural disorder in the alloys, as evidenced by the reduced intensity of the first halo in S(Q) and the diminished amplitude of the nearest-neighbor shell in G(r), accompanied by an increase in the anti-shell region of G(r) [Figure 1]. Moreover, with advancements in synchrotron radiation sources, the experimental q-values (momentum transfer) have continually increased, enabling the acquisition of more detailed short-range structural information[22].

Figure 1. Structure factors S(Q) up to 18 Å-1 of all three alloys together with several enlarged views for the first 8 halos (as numbered) and (b) the difference functions ΔS(Q) with respect to S(Q) of Zr60Cu30Al10. The vertical dotted lines and the shaded areas highlight the Q-ranges of the halos. Reprinted with permission[21]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

In situ X-ray imaging technique

By analyzing X-ray diffraction patterns, high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction provides insights into the atomic or molecular arrangement of materials, revealing both local and long-range order, particularly under high-temperature conditions. However, X-ray diffraction relies on the interpretation of diffraction data and does not directly provide information about material morphology and interfaces. In contrast, in situ X-ray imaging is an advanced technique that enables real-time observation of structural changes within a material during experimentation. This technique generates images by transmitting X-rays through a sample. Throughout the experiment, images are captured in a temporal sequence to monitor the microstructural evolution of the material under varying external conditions such as temperature, pressure, and stress[23]. These external factors can significantly influence the material’s internal structure, and continuous imaging at different time intervals enables a comprehensive and dynamic analysis of the microstructural changes, providing valuable insights into the material’s behavior under different physical stimuli. Unlike traditional X-ray imaging methods, in situ X-ray imaging provides immediate feedback during dynamic material changes, making it suitable for observing morphological and structural alterations in response to environmental changes. Its application is especially notable during solidification processes, enabling real-time monitoring of the internal morphology, structure, and interface changes before and after solidification, particularly in materials such as metals and polymers[24].

By utilizing high-throughput, high temporal and spatial resolution synchrotron X-rays in combination with in situ experimental setups, researchers can clearly observe the nucleation, growth, coarsening, and defect formation during the metal solidification process[25]. This technique not only reveals the influence of external conditions such as temperature gradients, cooling rates, and alloying elements on the solidification structure[26], but also provides insights into the mechanisms by which external physical fields, such as direct current (DC) electric fields, regulate solidification behavior[27]. Al-Cu and Cu-Sn alloys possess widespread industrial relevance and serve as classical model systems for studying solidification phenomena. They exhibit representative microstructural evolution features during solidification, such as dendritic growth and eutectic transformation, making them ideal candidates for in situ synchrotron X-ray imaging under various thermophysical conditions. For example, during the directional solidification of Al-Cu alloys, in situ X-ray imaging can capture periodic solute concentration variations, leading to intermittent nucleation and periodic grain growth. These phenomena are closely linked to thermal-solute convection and solute instability[28]. Compared to other in situ imaging techniques such as optical microscopy or neutron imaging, synchrotron X-ray imaging uniquely combines mesoscale spatial resolution with the ability to track dynamic processes in real time. This makes it a superior tool for capturing transient solidification events. Xuan et al.[27] employed synchrotron radiation real-time imaging to investigate the influence of direct current electric fields on the solidification behavior of Sn-10%Cu eutectic alloys. Their findings demonstrate that the DC electric field alters the phase transformation sequence, suppresses the precipitation of the primary phase (Cu3Sn), promotes the direct precipitation of the eutectic phase (Cu6Sn5) from the liquid phase, and affects its morphology and size. This study reveals the mechanism by which DC electric fields regulate the solidification process through alterations in electrochemical potential and Joule heating effects. These findings underscore the unique advantage of this technique in resolving interface kinetics induced by external electric fields.

In situ environment for metallic melt structure investigation

The confliction between the temperature maintenance and the observation window size restricts the measurement of liquid structure at high temperatures. With the advancement in in-situ environments, the q-value in synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments gradually increases, enabling the acquisition of the information more accurately.

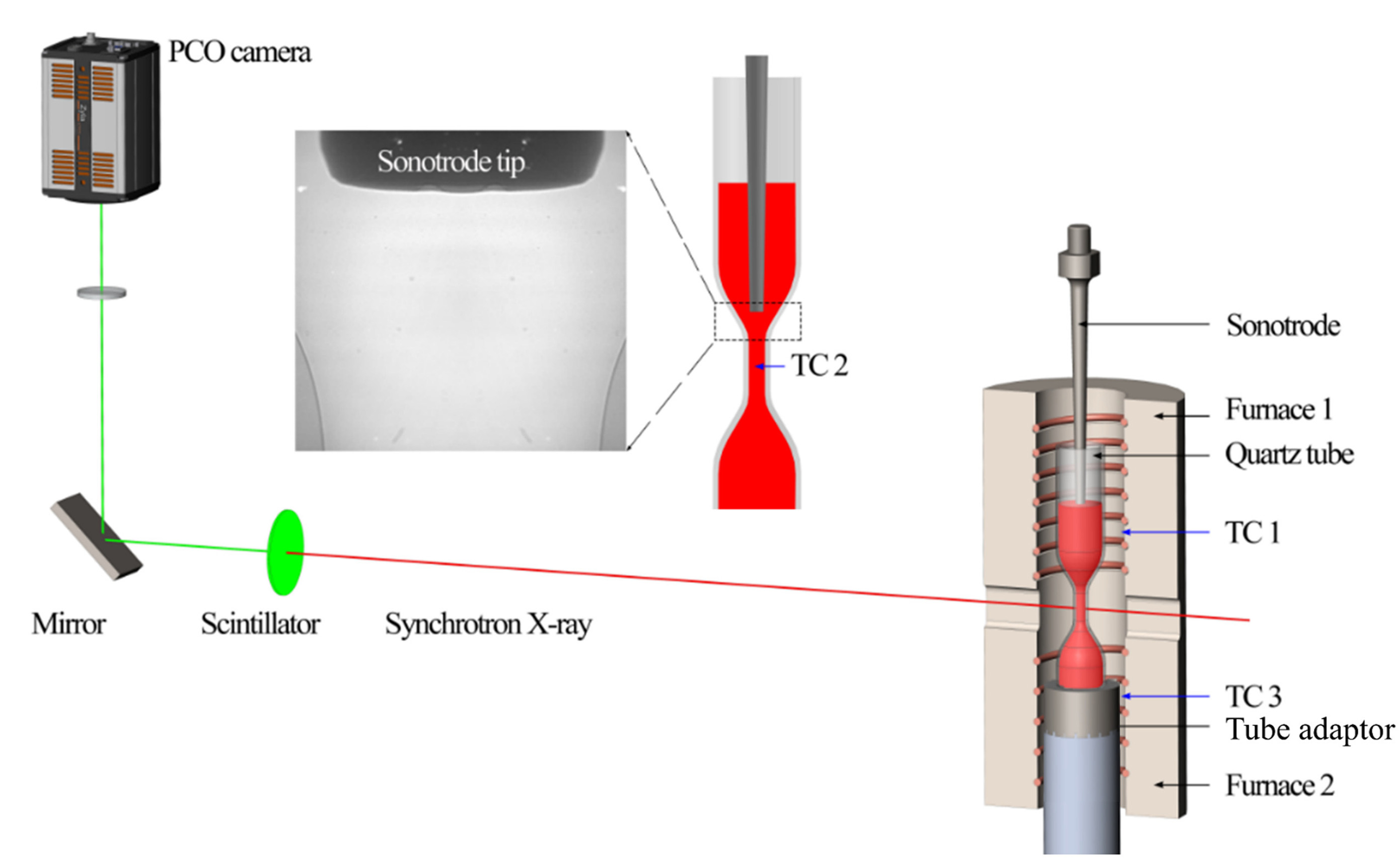

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction is an efficient technique commonly used for investigating the structure of metallic melts, while a large diffraction angle is required for finer melt structure detection. Figure 2 presents the synchrotron equipment developed by Jiawei Mi’s group at Hull University[29]. The device integrates advanced experimental and simulation techniques, enabling in-depth studies of the atomic structural evolution in metallic melts. For instance, the research group has successfully reconstructed the 3D atomic structure of metallic melts and revealed the dominant role of Zr-Zr atomic pairs in controlling elastic deformation and shear band initiation in metallic glasses[30]. This setup comprises several components, including a quartz tube, a heat source module (such as an electric furnace), a sonotrode for ultrasonic excitation, and a bottom adapter and sample holder for stabilizing the sample. The system allows for precise sample positioning via a position plate, ensuring high data accuracy through a specially designed X-ray transparent conical window. Its primary advantage lies in the ability to accommodate large samples and effectively prevent oxidation, making it suitable for studying metallic melts. However, the relatively low maximum operating temperature of the facility restricts its application to low- to moderate-temperature metallic melts. Additionally, liquid samples may be influenced by the crucible, causing signal overlap. Thus, while the system provides a stable experimental environment for studying the structure of metallic melts, temperature constraints and signal interference remain significant limitations.

Figure 2. The synchrotron equipment used by Jiawei Mi’s group at Hull University. Reprinted with permission[29]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

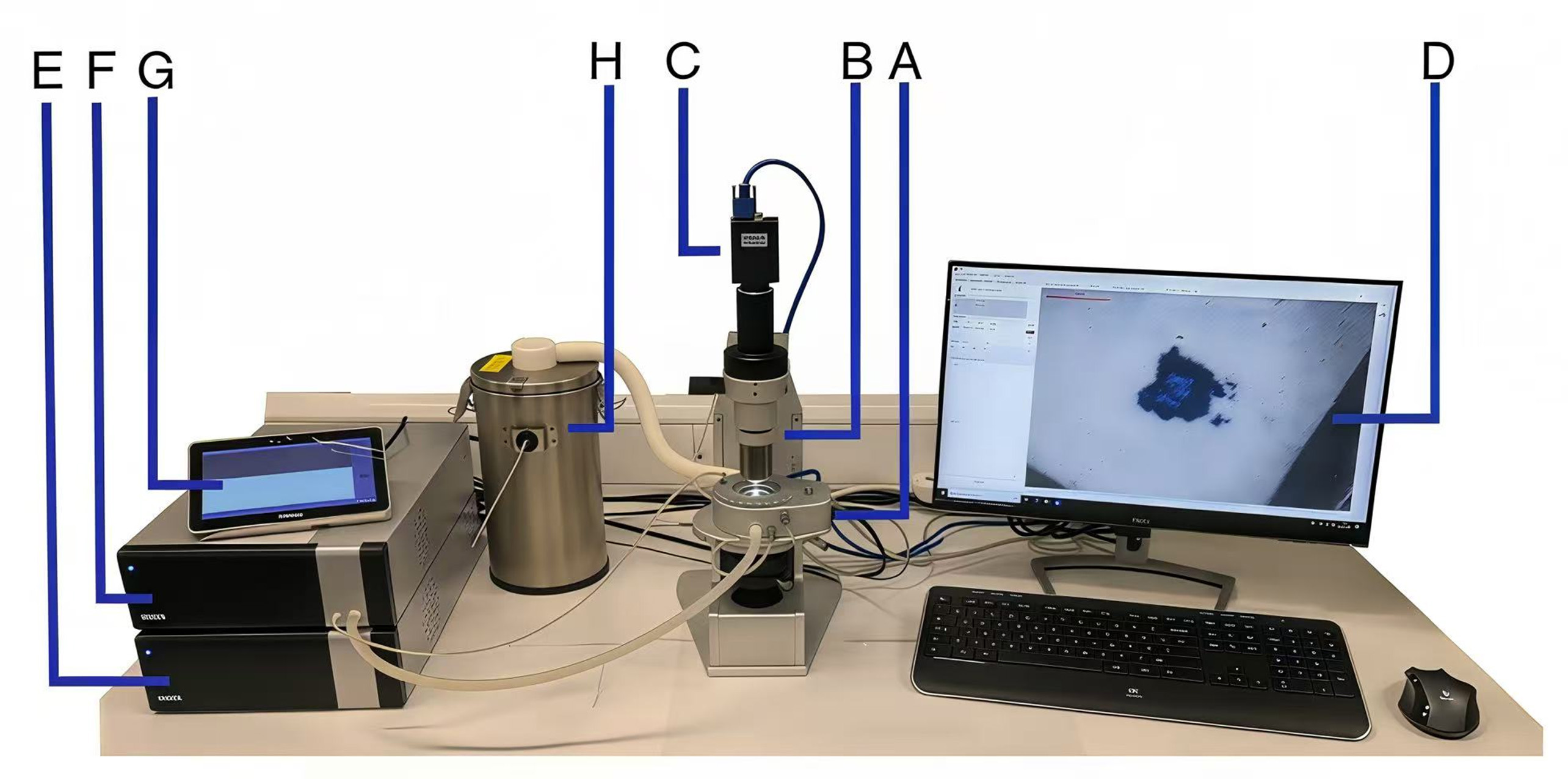

The Linkam heating stage is a widely used device for studying the physical and structural changes in materials at different temperatures under a microscope [Figure 3][31]. This device provides precise temperature control, making it suitable for the study of molten inclusions. Its compact design ensures stable experimental conditions under the microscope, particularly when precise temperature regulation is required to observe the microstructural evolution of molten inclusions during heating[32]. Otherwise, the Linkam heating stage is commonly used in studies of glass softening[33] and polymer melting[34]. However, its temperature limit is relatively low, making it unsuitable for high-temperature metallic melts, and its slower heating and cooling rates may affect experimental efficiency. Despite these limitations, the Linkam heating stage performs exceptionally well in low-temperature material behavior studies, making it an ideal temperature control device.

Figure 3. A labeled photograph of the equipment used for this study. (A) Optical DSC450, (B) Linkam imaging station (a stereoscopic microscope), (C) high-resolution digital camera, (D) PC running LINK, (E) controller unit, (F) liquid nitrogen pumping unit, (G) touchscreen control and (H) liquid nitrogen reservoir. Reprinted with permission[31]. Copyright 2021, The Author(s). PC: Personal computer; LINK: linkam instrument network kontroller.

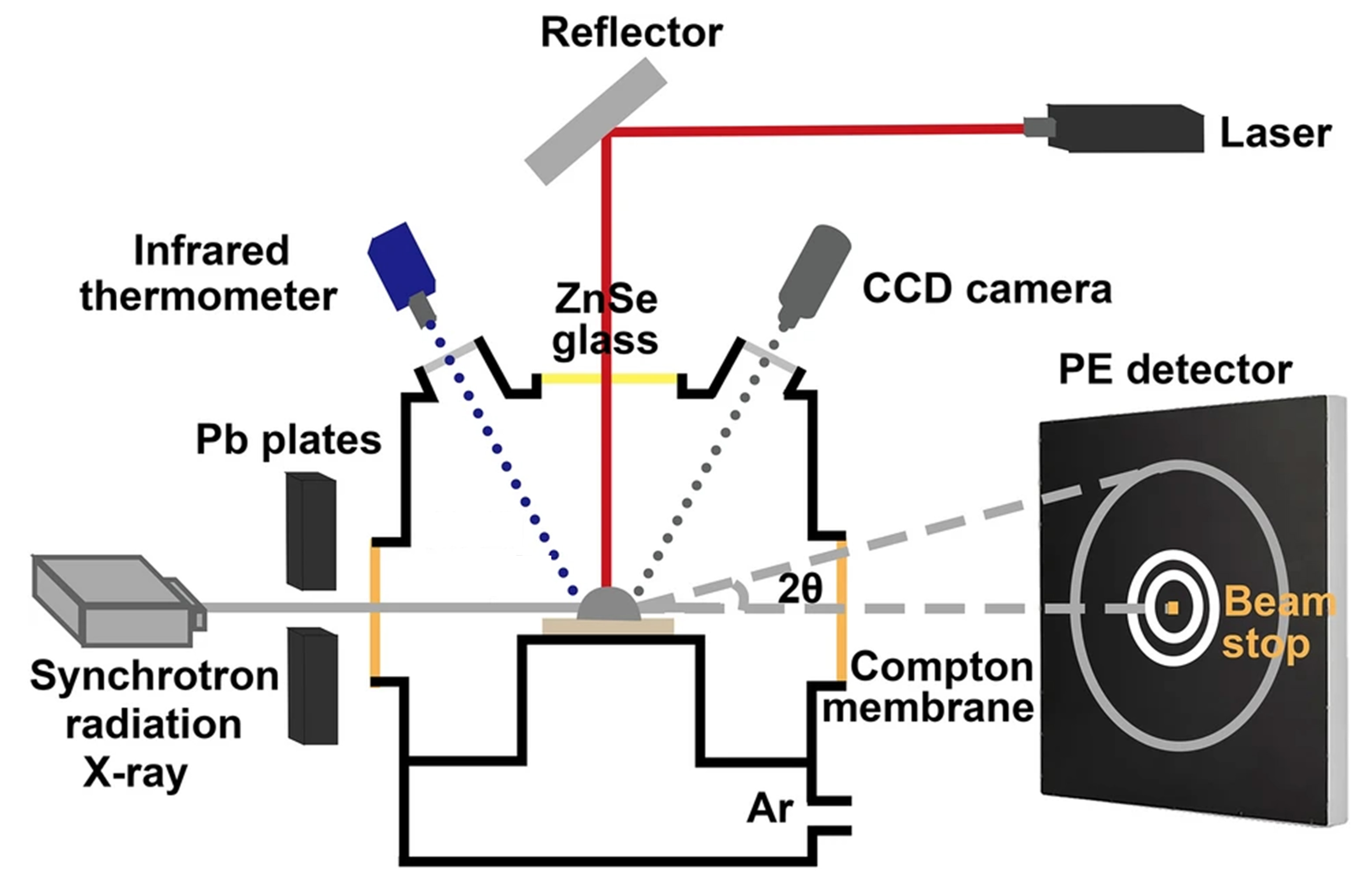

Figure 4[35] illustrates the principle of high-energy X-ray diffraction, enabling in situ and real-time observation of the solidification microstructure growth in alloy systems[36]. The system employs a substrate to support the sample and utilizes CO2 laser heating, with the laser transmitted through a ZnSe glass window. Lead plates assist in heat conduction, while an infrared thermometer continuously monitors the sample temperature. A charge coupled device (CCD) camera records the experimental process, and a perkin elmer (PE) detector is used to observe the sample’s physical phenomena. The advantages of this system include the ability to achieve high heating temperatures and controllable cooling rates, making it suitable for rapid heating and cooling experiments. However, the small sample size limits the range of materials that can be studied. In a vacuum environment, some samples may volatilize, and oxidation becomes more prominent under high-temperature conditions. Additionally, the system’s low Q factor may impact the precision of high-accuracy experiments. Overall, this heating system is ideal for high-temperature heating and rapid cooling experiments, particularly for controlled nucleation events, though attention must be paid to sample size and oxidation issues.

Figure 4. Principle diagram of high-energy X-ray diffraction. Reprinted with permission[35].Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. CCD: Charge coupled device; PE: perkin elmer.

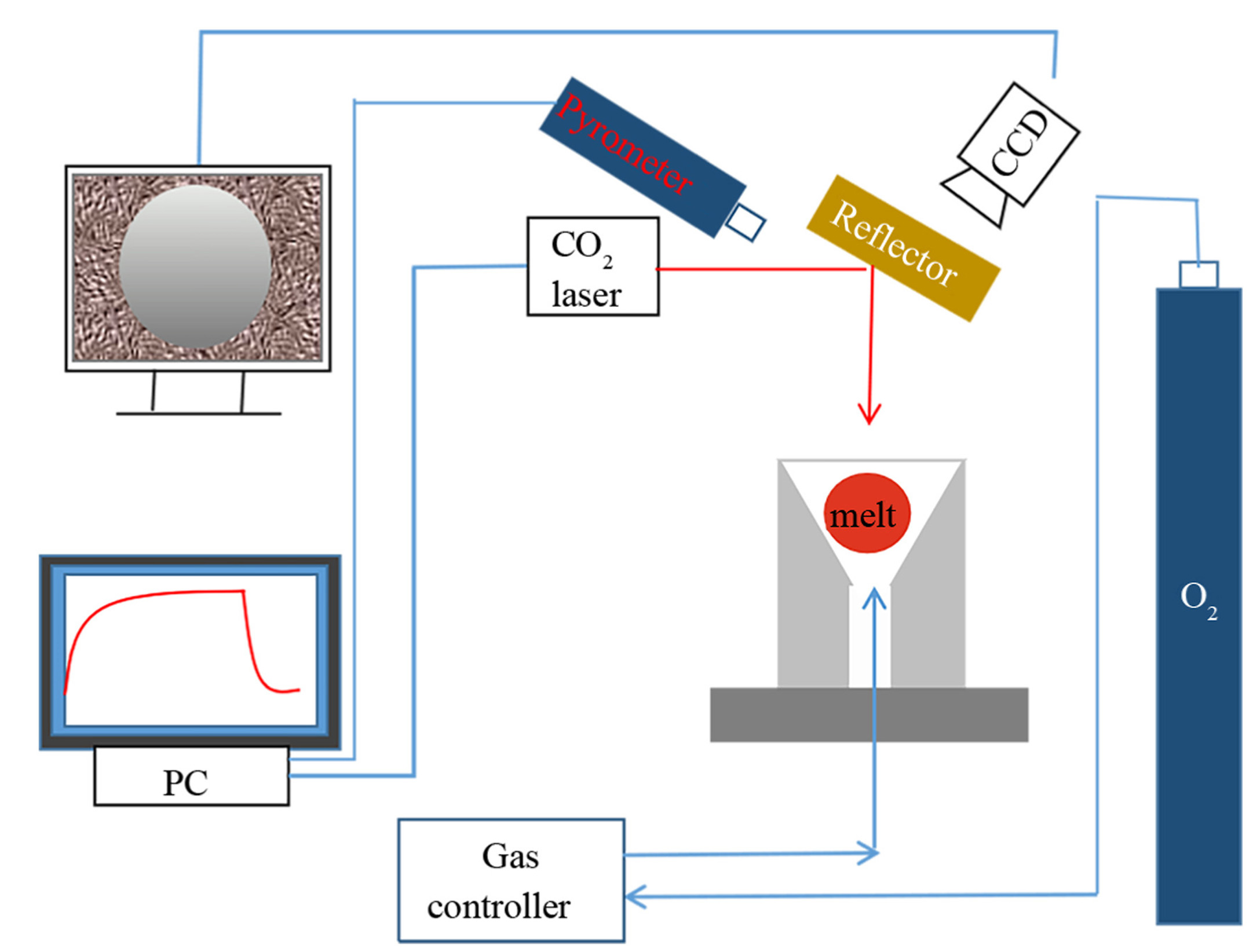

Aerodynamic levitation is an advanced experimental technique, as illustrated in Figure 5[37]. This method suspends a sample in air using aerodynamic drag from an airflow, thereby preventing contact with solid surfaces and reducing impurity contamination[38]. During experiments, the sample is typically heated using a laser, while the airflow stabilizes its position. Sample temperature is monitored in real-time with an infrared thermometer, and experimental data are captured using a CCD. Aerodynamic levitation is particularly well-suited for studying the structural evolution of liquids and metals under deeply undercooled conditions, as it provides a containerless environment that eliminates signal interference caused by wall reactions in traditional methods[38]. However, this technique also has certain limitations. For example, although sample sizes are typically small, localized temperature variations may still occur in practice due to factors such as non-uniform surface absorption. The laser heating process may, therefore, be non-uniform, leading to localized temperature fluctuations[39]. Additionally, airflow interference can affect X-ray data collection, reducing accuracy. Oxidation of metal samples, particularly under high-temperature conditions, is a significant issue that may limit the application of this technique in certain studies.

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the aerodynamic levitation device. Reprinted with permission[37]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. PC: Personal computer.

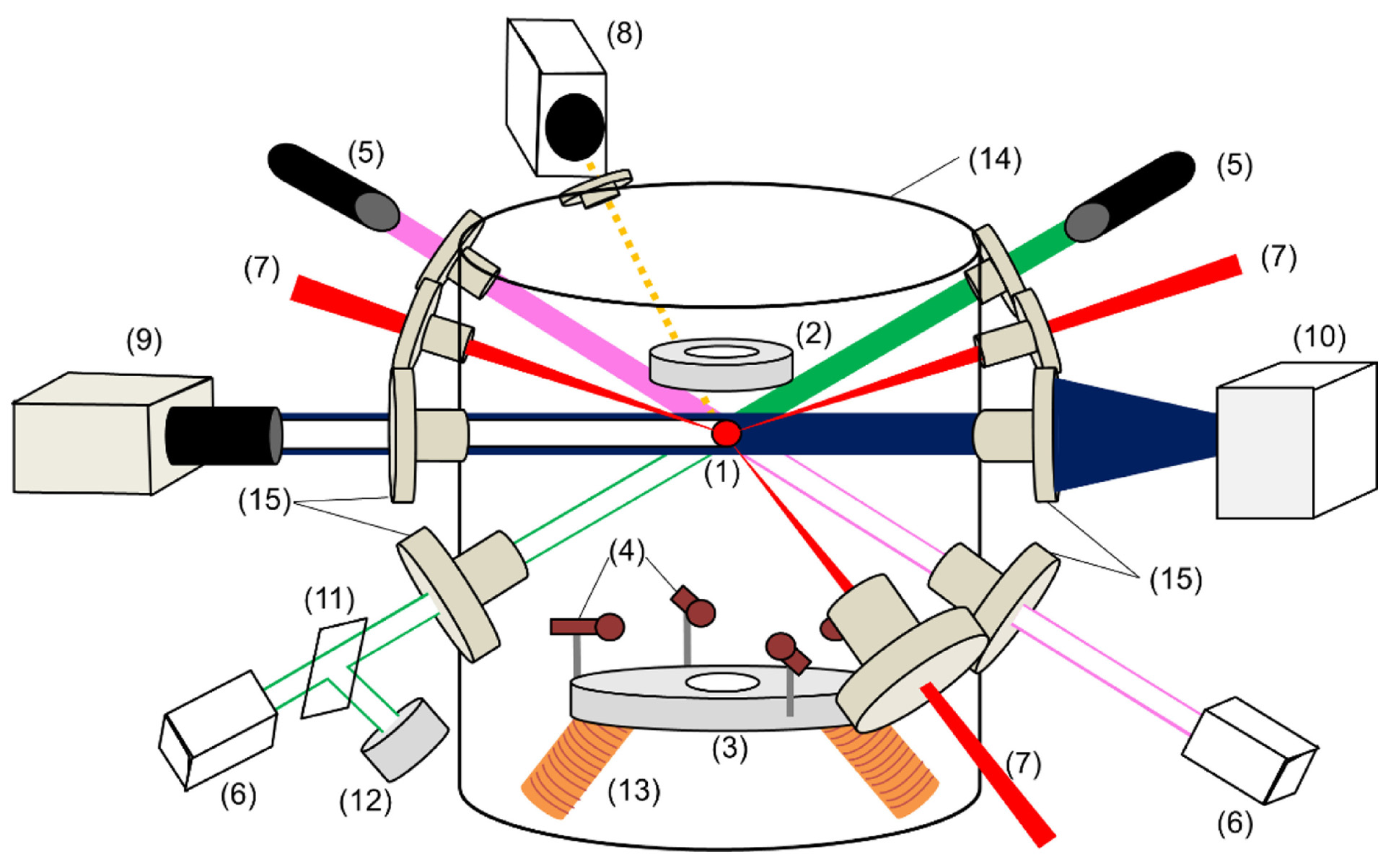

Electrostatic levitation(ESL) is another technique primarily used to study the structure of liquid samples and melts [Figure 6][40]. The system typically operates in a high-vacuum environment, where a small sample is levitated by an externally applied high voltage - usually in the range of 5-20 kV, resulting in an electric field strength of approximately 104 V/m to 105 V/m, depending on electrode configuration and spacing. The sample is heated by one or more lasers and simultaneously suspended in the electric field, thus preventing physical contact with any container or solid surface. The levitation force in ESL arises from dipole-field interactions (due to induced polarization in a non-uniform electric field) and Maxwell stresses (arising from surface charge distribution). These forces are relatively small, requiring precise feedback control systems to achieve stable suspension. Moreover, they impose restrictions on the types of materials that can be levitated, favoring those with sufficient polarizability and appropriate dielectric properties. Materials that are highly conductive or have unstable surface charge distributions may not be suitable for stable levitation. The detection system includes a helium-neon laser, a photodiode array, and thermometers, which are used to monitor the sample’s temperature, position, and shape in real time. This technique enables the measurement of multiple thermophysical properties, providing valuable data for the study of liquids[41,42].

Figure 6. Schematic of the electrostatic levitation furnace: (1): sample, (2): top electrode, (3): bottom electrode, (4): side electrode, (5): position sensing laser (semiconductor laser: 532 and He-Ne laser: 633 nm), (6): position detector, (7): CO2 laser beam, (8): pyrometer, (9): CCD camera, (10): UV lamp, (11): beam splitter, (12): power meter, (13): induction coil, (14): chamber, (15): chamber windows. Reprinted with permission[40]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. CCD: Charge coupled device; UV: ultraviolet.

The metastable liquid properties and chemical bonds beyond 2000 K remain a huge challenge for ground-based research on liquid materials chemistry[43-46]. Wang et al.[47-49] successfully performed ESL experiments in outer space and reported the strong undercooling capability, metastable liquid properties and surface wave patterns of refractory Nb-Si and Zr-V binary alloys explored in the space environment. The floating droplet of Nb82.7Si17.3 eutectic alloy superheated up to 2,338 K exhibited an extreme undercooling of 437 K, approaching the 0.2TE, where TE denotes the eutectic temperature, threshold for homogeneous nucleation of liquid-solid reaction. The microgravity state endowed alloy droplets with nearly perfect sphericity and thus ensured high accuracy in determining metastable undercooled liquid properties. Wang et al.[49] found that a special kind of swirling flow was induced for liquid alloy owing to Marangoni convection, which resulted in the spiral microstructures on the Zr64V36 alloy surface during liquid-solid phase transition. The coupled impacts of surface nucleation and surface flow resulted in a novel olivary morphology in these binary alloys.

However, the complex operation and the need for precise maintenance limit the widespread application of electrostatic levitation systems. Furthermore, research combining this technique with synchrotron radiation is relatively sparse, further restricting its scope of use.

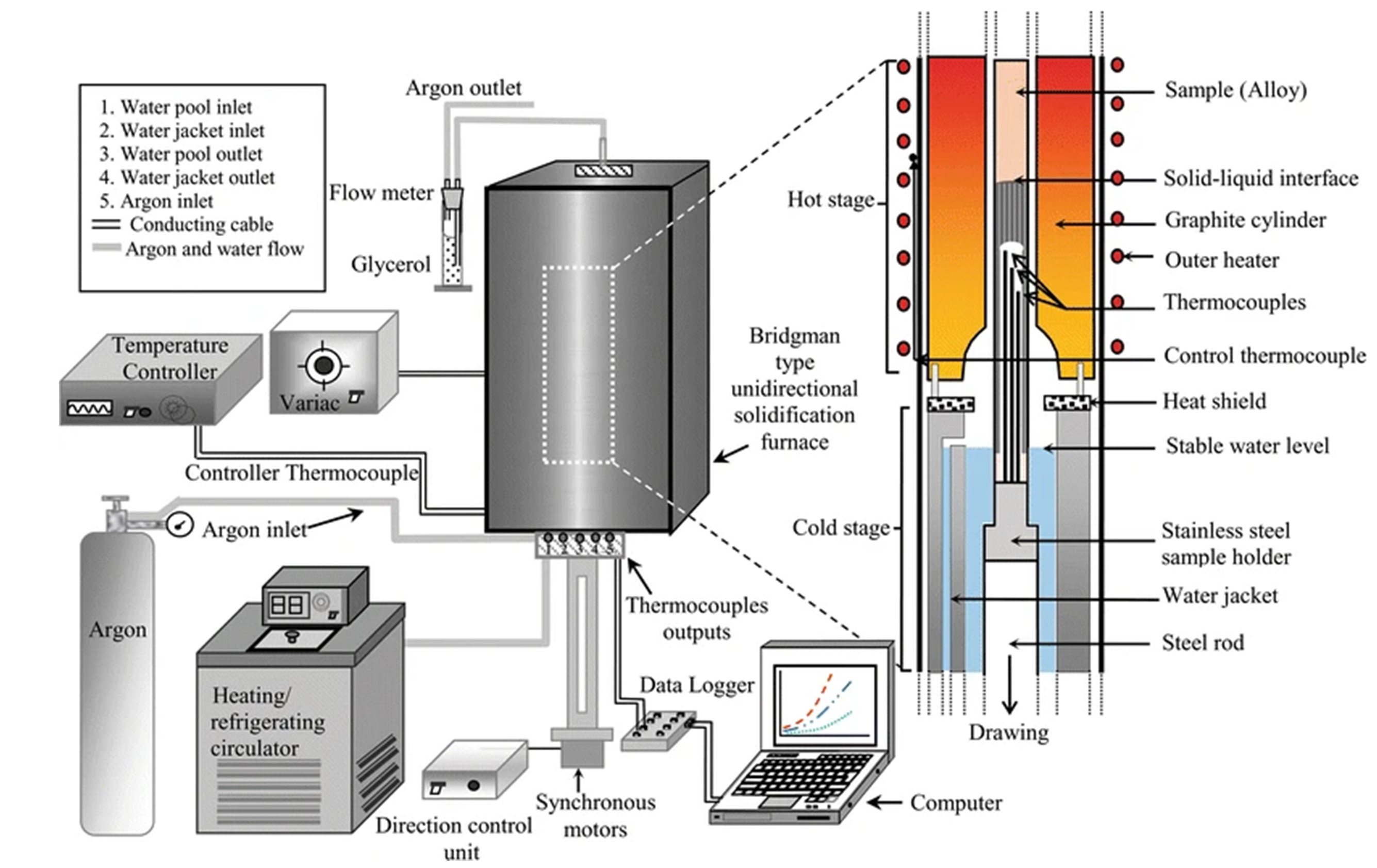

Figure 7[50] shows a Bridgman furnace primarily used for unidirectional solidification experiments of metallic melts - an apparatus for investigating the structure of metallic melts[51,52]. This device is equipped with two heating zones that provide a constant temperature gradient, enabling precise control over the solidification process of the molten metal. Furthermore, it allows real-time capture of image sequences or diffraction patterns, facilitating the observation of the microstructural evolution of the metallic melt during solidification. The furnace operates at temperatures up to 1,800 °C and supports diffraction experiments with a Q-range of less than 20 Å-1. Despite its impressive functionality and high-temperature control capabilities, the device’s large and heavy structure poses challenges for installation on beamlines. This apparatus offers researchers the opportunity to conduct in-situ studies on the microstructural changes of metallic melts, providing valuable data for materials science and metallurgical engineering.

Figure 7. Bridgman furnace. Reprinted with permission[50]. Copyright 2016, The Author(s).

With the continuous progress of technology, the advent of a wide array of in-situ devices has significantly facilitated the research on metallic melts. Techniques such as single pole diffraction environment, Linkam heating stages, pneumatic levitation, and electrostatic levitation all present unique advantages and drawbacks [Table 1]. These techniques offer diverse options for exploring the structure of metallic melts under different circumstances. Although each device has its own limitations in certain applications, when considered together, they furnish reliable experimental platforms for conducting precise measurements and studying the structural evolution of metallic melts at high temperatures. Nevertheless, overcoming these limitations remains an active area of research. Recent efforts include the integration of HEXRD with advanced data-driven modeling, such as reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD), which jointly enable real-time structural analysis with atomic-level resolution[53]. We believe that future efforts should focus on developing containerless experimental systems under microgravity conditions and AI-enhanced feedback control schemes, in order to improve levitation stability, thermal uniformity, and signal fidelity in high-temperature in-situ studies of metallic melts. These strategies promise a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of melt structure under extreme conditions.

Summary of experimental techniques for studying metallic melts: features, advantages, and limitations

| Technique | Main features | Advantages | Limitations |

| Synchrotron X-ray diffraction analytical method | High-energy X-rays; large diffraction angles | Accommodates large samples; effective oxidation prevention | Low temperature limit; signal overlap from crucible |

| Linkam heating stage + HEXRD | Stable for low-temperature studies; ideal for in-situ observation | Stable for low-temperature studies | Low temperature limit; slow heating/cooling rates |

| Aerodynamic levitation + HEXRD | Containerless environment; laser heating + airflow stabilization | Eliminates wall interference; suitable for undercooled liquids | Non-uniform heating; airflow disrupts X-ray data |

| Electrostatic levitation (ESL) + HEXRD | High-voltage suspension (5-20 kV); microgravity-compatible | No container contamination; measures thermophysical properties | Complex operation; limited material compatibility |

| Bridgman furnace + HEXRD | Dual heating zones with gradient control; Q-range < 20 Å-1 | In-situ solidification studies; high-temperature (1,800 °C) capability | Bulky design; challenging beamline integration |

DEVELOPMENT OF SIMULATION METHODS

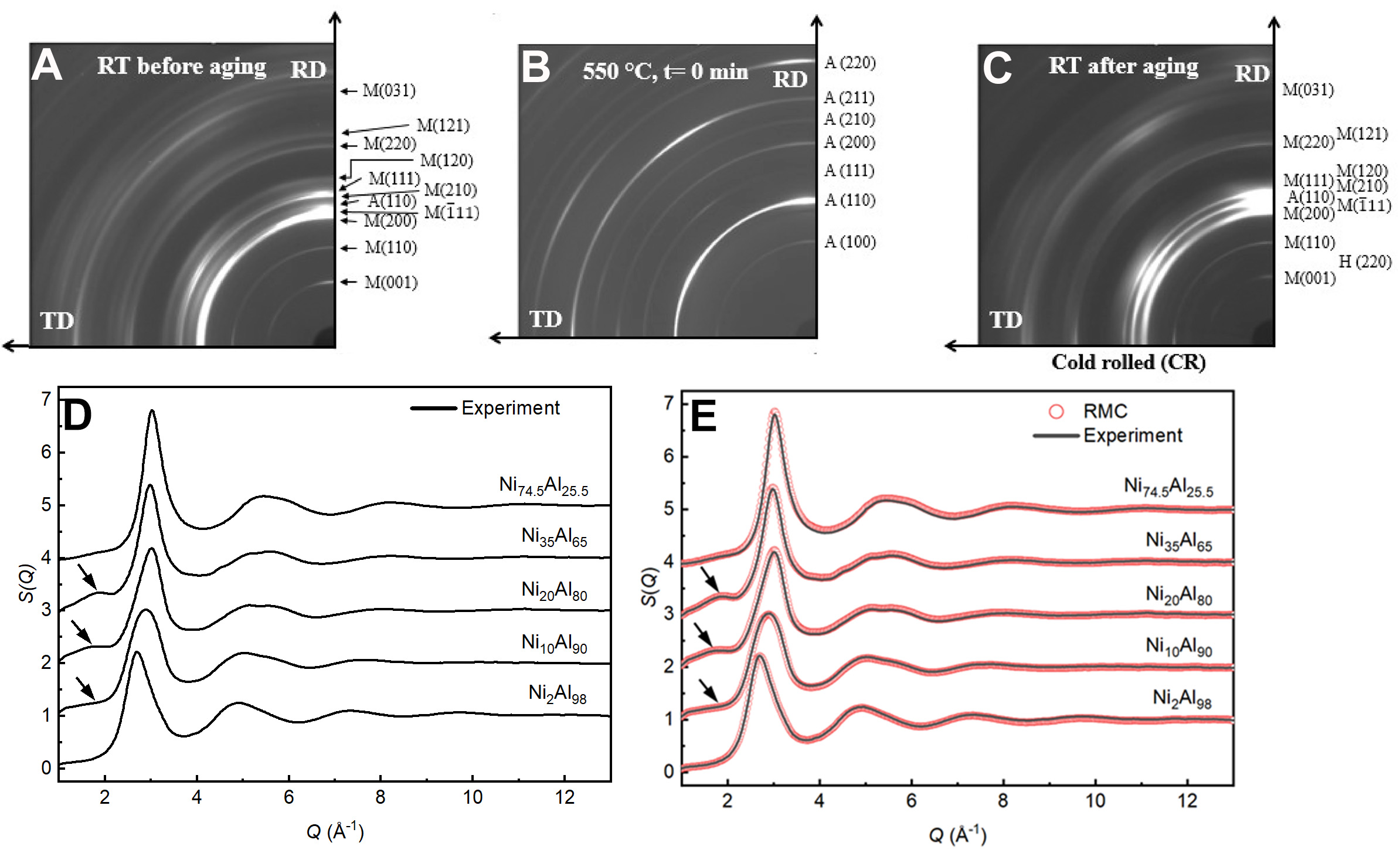

HEXRD and in situ X-ray imaging play complementary and essential roles in understanding both the liquid structure and solidification dynamics of metallic alloys. HEXRD provides detailed atomic-level structural information in the liquid state, whereas in situ X-ray imaging enables real-time visualization of solidification and microstructural evolution. For instance, Figure 8A-C[54] presents in situ X-ray radiography capturing the growth and interaction of solid phases during the solidification process. Figure 8D displays HEXRD spectra of various Ni-Al alloys at different temperatures, offering insight into short-range order and structural motifs in the melt. The structural factor data obtained from HEXRD serve as critical input for RMC simulations, enabling the reconstruction of three-dimensional atomic configurations, as illustrated in Figure 8E. These atomic models facilitate further analysis of local atomic arrangements and correlations among distinct cluster types. On the other hand, the in situ imaging results shed light on macroscopic behavior, such as solid growth rates and morphological transitions. By integrating these two approaches, a comprehensive correlation can be established between the atomic structure in the melt and the macroscopic features observed during solidification. In addition to RMC, a variety of computational techniques such as molecular dynamics (MD) and AIMD have also been employed to study metallic melts. These methods will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Figure 8. One-quarter of the Debye-Scherrer diffraction patterns of the cold rolling 550 condition at (A) room temperature (RT) before aging, (B) initially reaching 550 °C, and (C) RT after the complete aging at 550 °C; Panels A, B and C are quoted with permission from Ref.[54] . Copyright 2022, Springer Nature; (D) S(Q) curves of NixAl1-x (x = 2, 10, 20, 35, 74.5 at.%) alloy liquids obtained experimentally by HE-XRD above the liquids line temperature of 9 °C, with the arrows in the figure showing the presence of pre-peaks on the structure factor curves of Q-phase-dependent liquids, and (E) S(Q) curves at 9 °C above the liquids line temperature, where the solid lines represent experimental results and circles represent RMC simulation results. Panels D and E are quoted with permission from Ref.[35]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. HE-XRD: High-energy X-ray diffraction; RMC: reverse Monte Carlo; RD: rolling direction; TD: transverse direction.

First-principles calculation and ab initio molecular dynamics

The first-principles calculation method is a theoretical approach based on quantum mechanics that centers on the studies of the electronic structure and related properties of multi-electron systems by directly solving the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics. One of the most widely used frameworks is density-functional theory (DFT). DFT uses electron density as the fundamental variable, based on the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem[55], which states that the ground state properties of a system are uniquely determined by the electron density, thus significantly reducing the computational complexity of the many-body problem. Kohn and Sham further proposed the Kohn-Sham equations[56], which simplify the complex interactions in multi-electron systems into single-electron problems by introducing a non-interacting auxiliary electron system and an exchange-correlation energy term. This approach enables DFT to efficiently and accurately describe the structure and properties of many-electron systems. By providing detailed insights at both the atomic and electronic levels, it enables precise characterization of the electronic structure within clusters in metallic melts[57], especially the influences of chemical bonding[58] and geometric structure[59] on cluster stability. Although the first-principles calculation method offers high computational accuracy, it is extremely resource-intensive and limited to small-scale systems, which constrains its broader application.

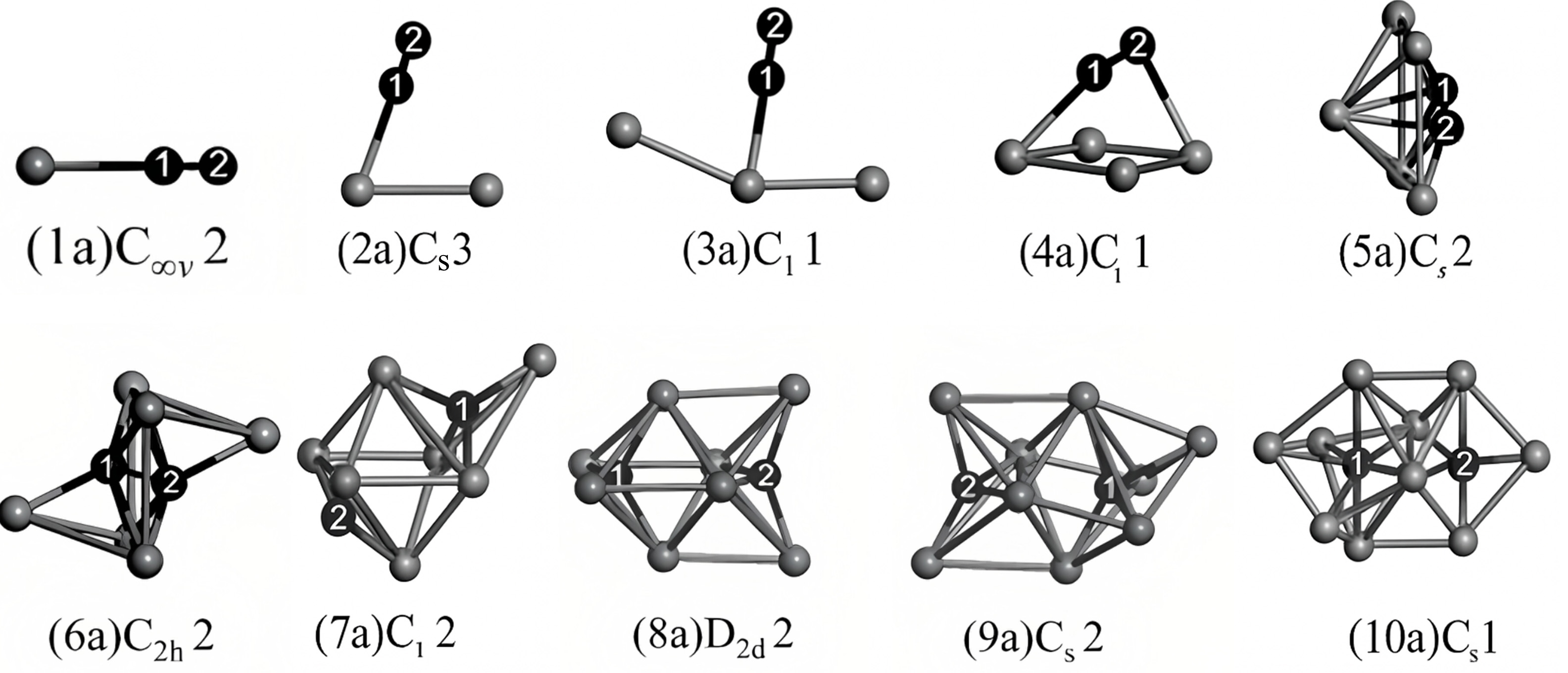

First-principles calculations revealed that the stability of clusters is typically governed by a combination of chemical bonds and electronic properties. Zhang et al.[57] showed that the partial ionic characteristic of In-N bonds and the weakening of N-N bonds in InnN2 clusters (n = 1-10) drive a structural transformation from N2-unit-based configurations to tetrahedral coordination of N atoms [Figure 9]. Jiang et al.[58] reported that Cu-Cu interactions play a crucial role in stabilizing Cu-centered Cu-Zr icosahedral clusters in CunZr13-n (n = 6, 7, 8, 9). In these highly stable icosahedral clusters, strong ionic bonds between core-shell Cu atoms and covalent bonds among shell Cu atoms contribute significantly to their stability. In Ni-rich Al-based quasicrystal clusters, 10f clusters exhibit superior stability due to their smaller energy gaps, emphasizing the importance of electronic structure[60]. Similarly, in Ni-Nb metallic glasses, the stability of clusters is precisely determined by the synergistic interplay of electronic and topological stability[61].

Figure 9. The lowest-energy structures of InnN2 clusters (n = 1 - 10). These structures illustrate the evolution of the geometric configurations of the clusters from n = 1 to n = 10. For clusters with n ≤ 6, the structures contain a distinct N2 unit. In contrast, for clusters with n ≥ 7, the nitrogen atoms gradually transform to a tetrahedral coordination, and the N-N bonds weaken and eventually disappear. Reprinted with permission[57]. Copyright 2012, Elsevier.

The works of first-principles calculation also demonstrated the important role of the geometric structure in the stability and electronic properties of clusters. Tian et al.[59] found that Au clusters exhibit diverse structural motifs, including close-packed, fullerene-like, tubular, and pyramid-based geometries. These structures display various stability characteristics, with certain clusters, such as Au32 and Au50, showing a tendency toward amorphization and unique electronic stability at specific sizes. In Mg-Zn clusters, Zn atoms preferentially substitute Mg atoms at the cluster edges, leading to reduced stability. This structural reorganization induces a redistribution of the electronic structure, particularly through the spd orbital hybridization of Zn, the sp orbital hybridization of Mg, and charge transfer from Mg to Zn, ultimately impacting the electronic properties and chemical reactivity of the clusters[62].

However, static first-principles calculations are inherently limited by high computational costs, restricting studies to relatively small system sizes and static structures, and thus cannot fully capture the melting processes and dynamic structural evolution in metallic melts. To address these limitations, AIMD integrates first-principles electronic structure calculations with MD simulations. AIMD is a computational simulation method that investigates the microscopic behavior of atomic or molecular systems by numerically integrating the Hamiltonian equations of motion. It calculates the forces acting on each atom based on interatomic potential energy and tracks their temporal evolution using Newton’s equations of motion. In AIMD, these accurate interatomic forces are directly derived from quantum mechanics, enabling the dynamic simulation of atomic trajectories.

The theoretical foundation of AIMD traces back to the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation proposed by Max Born and J. Robert Oppenheimer in 1927[63]. This approximation separates the molecular wavefunction into electronic and nuclear components, assuming that electrons can quickly relax to their ground state under fixed nuclear positions. By effectively decoupling electronic and nuclear motion, it greatly simplifies complex many-body problems. In 1985, Car and Parrinello[64] revolutionized AIMD by introducing the Car-Parrinello method, which combined the dynamics of Kohn-Sham electronic wavefunctions with atomic nuclei and incorporated dynamic pseudopotentials to reduce computational complexity. This approach significantly enhanced simulation efficiency, enabling AIMD to be applied to complex systems such as liquid metals. Subsequently, in 1993, Kresse et al.[65,66] further improved AIMD by incorporating Vanderbilt pseudopotentials[67] and conjugate gradient optimization techniques. They successfully simulated the structural and dynamic behavior of liquid Na and liquid Ge. The results demonstrated that the radial distribution function and diffusion coefficient of liquid Na closely matched experimental data [Figure 10A], while liquid Ge exhibited unique SRO and a pseudogap feature in its electronic density of states. This study highlighted the feasibility of AIMD, enhanced by improved conjugate gradient techniques and subspace-aligned wavefunction extrapolation, for investigating liquid metals.

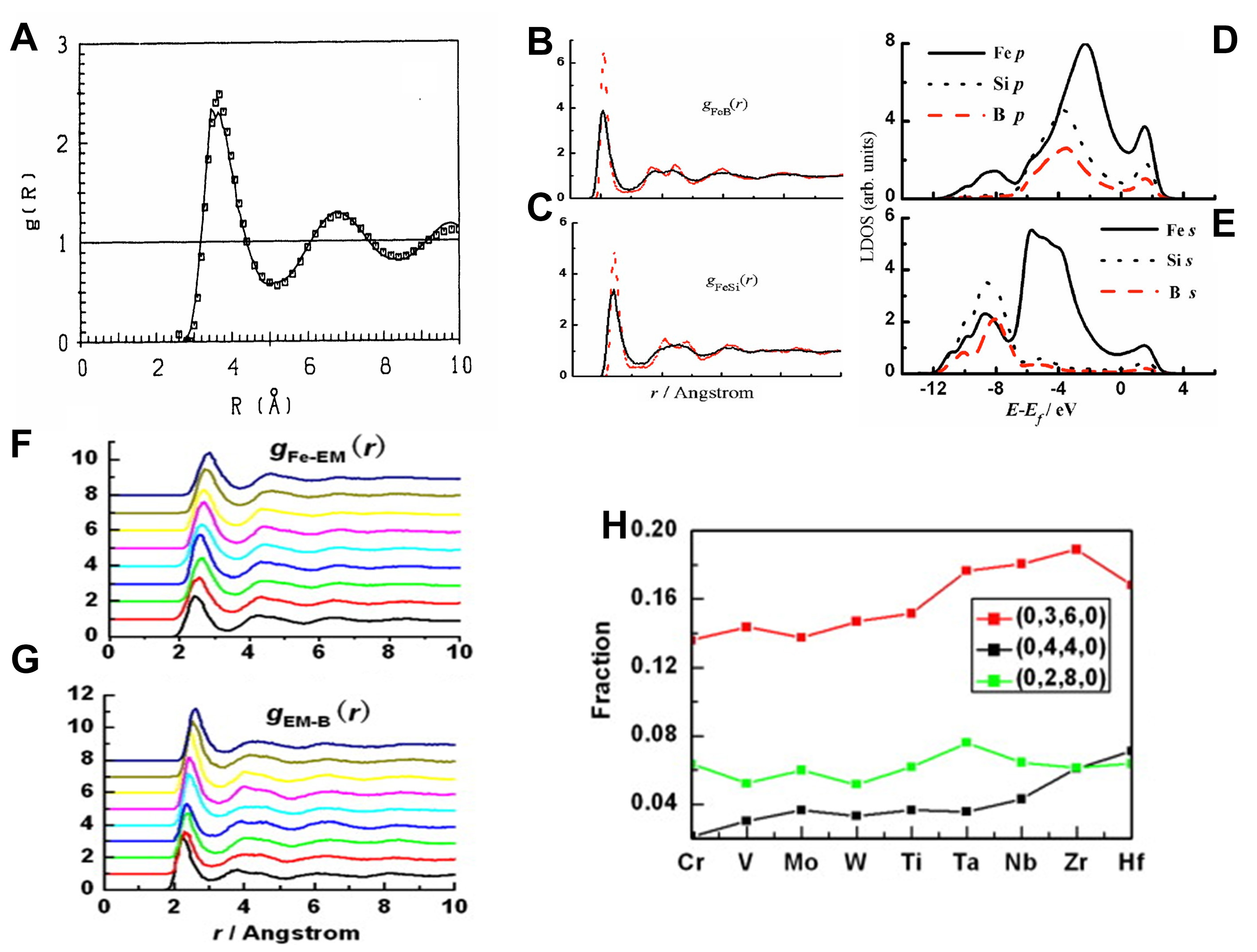

Figure 10. (A) Pair correlation function for liquid Na at T = 400 K; full curve AIMD, squares-experiment, Reprinted with permission[65]. Copyright 2012, Elsevier; (B) and (C) PDFs of both the liquid and amorphous Fe78Si9B13 alloys. The red dash is for the amorphous state and the black line for the liquid state, Panels B and C are quoted with permission from Ref.[71]. Copyright 2007, AIP Publishing; (D) and (E) local densities of states of the Fe, Si, and B atoms of the amorphous alloy, Panels D and E are quoted with permission from Ref.[71]. Copyright 2007, AIP Publishing; (F) and (G) F-Z pair correlation functions of liquid Fe70EM10B20 alloys. The curves from the bottom to the top in each panel belong to Fe70Cr10B20, Fe70V10B20, Fe70Mo10B20, Fe70W10B20, Fe70Ti10B20, Fe70Ta10B20, Fe70Nb10B20, Fe70Zr10B20 and Fe70Hf10B20, (H) Fractions of top three Kasper Voronoi polyhedra around B atoms Panels D and E are quoted with permission from Ref.[73]. Copyright 2010, Elsevier. AIMD: Ab initio molecular dynamics; PDF: pair distribution function.

With the continuous development of the AIMD method, its application in the study of static structure, dynamic behavior, and electronic properties of liquid metals is gradually expanding. Chai et al.[68] employed dynamic structure factor simulations to reveal residual tetrahedral SRO and its dynamic evolution in liquid Ge, along with the unique static and dynamic characteristics of amorphous Ge. Alemany et al.[69] found that liquid Pb exhibits SRO comparable to that of simple liquid metals, with its diffusion behavior closely linked to its complex electronic structure. In addition to single-component liquid metals, AIMD has been increasingly applied to binary and multicomponent alloy melts. Compared to unary melts, alloy melts exhibit greater structural complexity, necessitating descriptors such as partial structure factors and pair correlation functions to characterize their cluster properties[70]. Qin et al.[71] conducted AIMD simulations to investigate the relationship between Fe78Si9B13 melts and their amorphous structures. Their findings revealed that the chemical short-range order (CSRO) is predominantly governed by Fe-Si and Fe-B bonds, with Fe-Si bonds being stronger, while Si and B atoms exhibit repulsive interactions [Figure 10B-E]. During rapid cooling, (0, 3, 6, 0) polyhedra structures surrounding B atoms undergo topological distortions, ultimately resulting in amorphous features, with the glass transition temperature determined to be 873 K[72]. Pan et al.[73] further studied Fe70EM10B20 (EM = Ti, Nb, and other transition metals) alloys, discovering that EM atoms significantly enhance the stability of local (0, 3, 6, 0) polyhedra by strengthening Fe-EM and EM-B bonds [Figure 10F-H]. This stabilization effectively improves the glass-forming ability (GFA) of the alloys. These studies demonstrate the robust analytical power of AIMD in elucidating the microscopic structures and dynamics of liquid metals, providing essential theoretical insights into the understanding of complex melts.

Classical molecular dynamics and machine learning molecular dynamics

However, AIMD simulations are constrained by high computational costs, limiting their applications to small atomic systems and relatively short time scales. In contrast, classical molecular dynamics (CMD) simulations, despite lacking a direct description of electronic structures, leverage parameterized empirical potential functions to achieve lower computational costs. This enables the study of larger systems and longer time scales, offering a broader perspective for investigating the structural and dynamical properties of melts.

A significant breakthrough in CMD for metals and alloys came in 1984 when Daw and Baskes introduced the embedded atom method (EAM). This approach decomposes the total energy into embedding energy and pair potential, addressing the limitations of traditional pair potentials in capturing surface and defect behaviors. By fitting the lattice constants, elastic constants, and sublimation energies of Ni and Pd, EAM demonstrated its accuracy in describing complex defect behaviors in pure metals[74]. Subsequently, Foiles et al.[75] extended the application of EAM to investigate point defect energies, surface properties, and impurity segregation in face-centered cubic (FCC) metals and their alloys. The accuracy of the model was further validated by fitting ground-state properties and binary alloy heats of solution.

The selection of an appropriate potential function to describe interatomic interactions is fundamental to CMD simulations. Potential functions, or force fields, define the interaction energies and forces between atoms, directly governing the system’s microscopic behavior and determining the accuracy and reliability of simulation results. In recent years, advancements in computational power and the rapid development of machine learning (ML) techniques have led to significant progress in materials science, particularly in the construction of interatomic potentials.

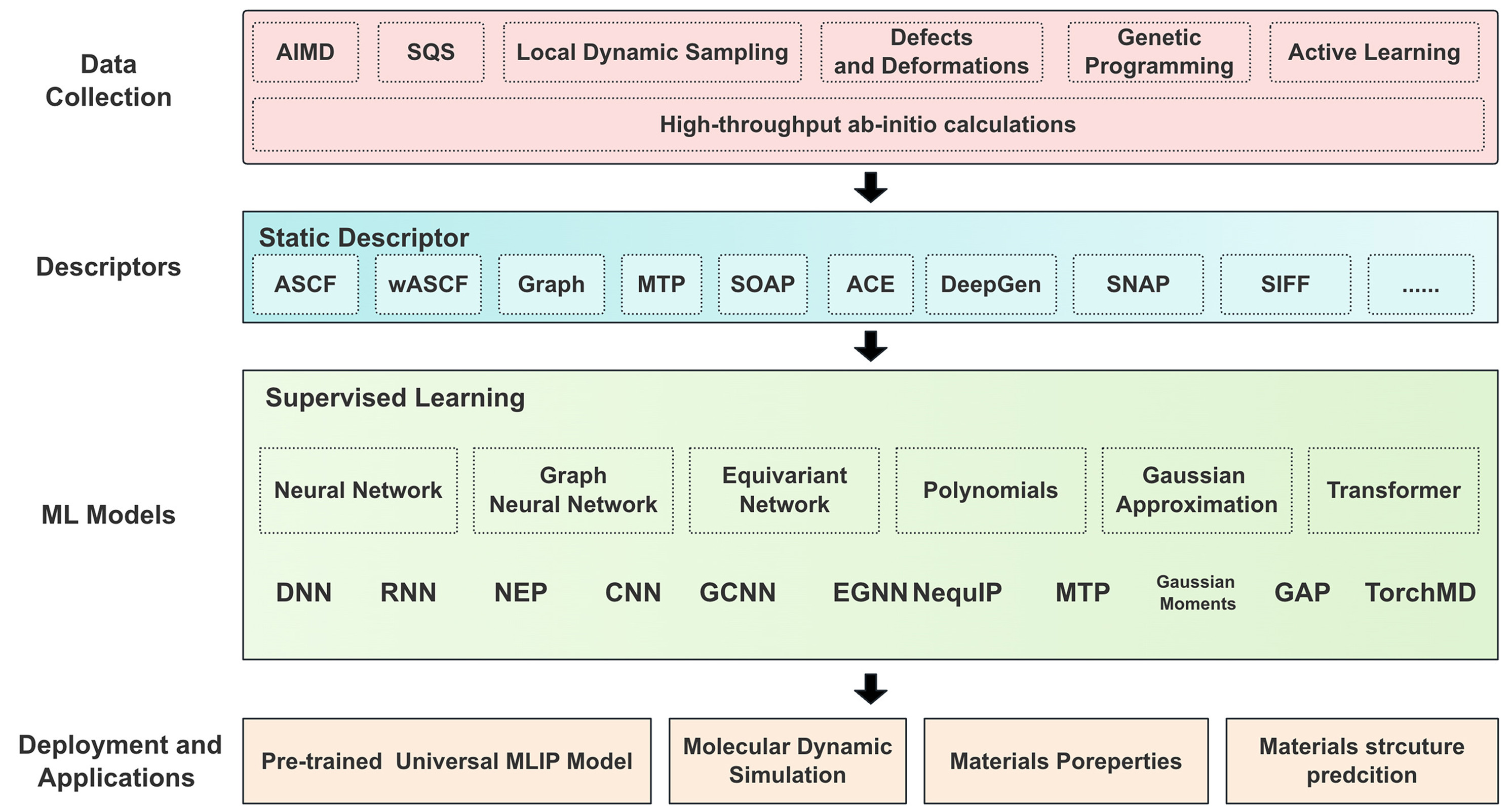

Machine learning potentials (MLPs) construct high-dimensional potential energy models to describe interatomic interactions through data-driven approaches based on first-principles data. Figure 11[76] illustrates the complete workflow for constructing MLPs. It begins with high-throughput ab initio calculations to collect atomic-level data using approaches such as AIMD, special quasirandom structures (SQS), and more. Next, spatial configurations are transformed into machine-learning-ready datasets using static descriptors such as smooth overlap of atomic positions (SOAP), atomic cluster expansion (ACE), or graph-based representations, which critically determine the model’s achievable accuracy. Then, supervised learning models - including neural networks, Gaussian approximations, and graph neural networks - are trained to fit the data. Finally, the trained models are deployed for various applications such as pre-trained universal MLP models, molecular dynamics simulations, and predictions of material properties and structures. The trained MLPs can be seamlessly integrated into molecular dynamics simulations, known as machine learning molecular dynamics (MLMD), significantly accelerating simulations and enabling efficient application from small to large-scale systems.

Figure 11. The general process of training and applying MLPs. Reprinted with permission[76]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. MLPs: Machine learning potentials; AIMD: Ab initio molecular dynamics; SQS: Special quasirandom structures; ASCF: ab initio self-consistent field; wASCF: weighted atom-centered symmetry functions; MTP: moment tensor potential; SOAP: smooth overlap of atomic positions; ACE: atomic cluster expansion; SNAP: spectral neighbor analysis potentials; DNN: deep neural network; RNN: recurrent neural network; NEP: neuroevolution potential; CNN: convolutional neural network; GCNN: graph convolutional neural network; EGNN: equivariant graph neural network; NequlP: neural equivariant interatomic potential; GAP: gaussian approximation potential; MLIP: machine learning interatomic potential.

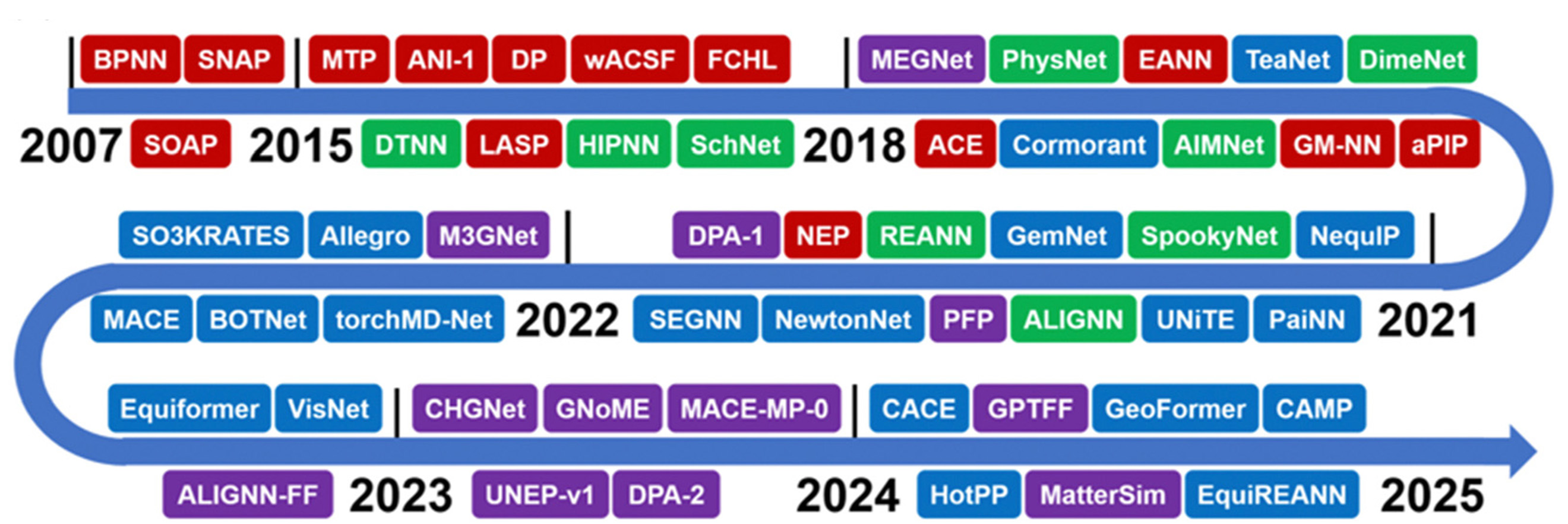

As shown in Figure 12[77], from 2007 to the present, atomistic MLPs evolved from basic local descriptor-based models to highly advanced equivariant and universal potential models, reflecting the fast-paced development and increasing complexity of machine learning approaches in atomic simulations. Early developments primarily focused on applying neural networks to study simple small-molecule-surface interaction systems[78,79]. Later, Behler et al.[80] introduced symmetry functions to describe the local geometric environment of atoms and employed a nested subnetwork architecture to sum individual atomic energy contributions into the total energy. This approach successfully constructed a potential energy surface with accuracy comparable to DFT for the Si system. In recent years, several advanced methods have emerged, including: Gaussian approximation potentials (GAPs), based on Gaussian process regression[81,82]; spectral neighbor analysis potentials (SNAPs), leveraging spectral features of local atomic environments[83]; deep potential (DP), a type of neural network potential (NNP) that employs deep neural networks to build high-accuracy potentials[84]; and moment tensor potentials (MTPs), a class of systematically improvable MLPs that employ rotationally-covariant moment tensors to describe local atomic environments and fit interatomic potentials[85].

Figure 12. The evolution of representative atomistic MLP models from 2007 to 2024, which are roughly sorted by their public release dates (e.g., an arXiv preprint if available). These MLP models are categorized as follows: strictly local descriptor-based models (red), invariant (green) and equivariant (blue) MPNN-based models, and universal potential models (purple). In recent years, the development of atomistic MLPs has accelerated significantly. Reprinted with permission[77]. Copyright 2025, RSC. MLPs: Machine learning potentials; BPNN: behler-parrinello neural network; SNAP: spectral neighbor analysis potential; MTP: moment tensor potential; DP: deep potential; wACSF: weighted atom-centered symmetry functions; FCHL: faber-christensen-huang-lilienfeld model; MEGNet: materials graph network; EANN: embedded atom neural network; SOAP: smooth overlap of atomic positions; DTNN: deep tensor neural network; LASP: large-scale atomic simulation package; HIPNN: hierarchically interacting particle neural network; ACE: atomic cluster expansion; GM-NN: gaussian moments neural network; aPIP: atomic permutationally invariant polynomial; NEP: neuroevolution potential; REANN: recursively embedded atom neural network; MACE: multi-atomic cluster expansion; SEGNN: steerable equivariant graph neural network; PFP: preferred potential; ALIGNN: atomistic line graph neural network; UNiTE: uniform neural network interatomic potential; PaiNN: polarizable atom interaction neural network; CACE: cartesian atomic cluster expansion; GPTFF: graph-based pre-trained transformer force field; CAMP: cartesian atomic moment potential; ALICNN-FF: atomistic local interaction convolutional neural network force field; HotPP: high-order tensor passing potential; CHGNet: crystal hamiltonian graph neural network; GNoME: graph networks for materials exploration.

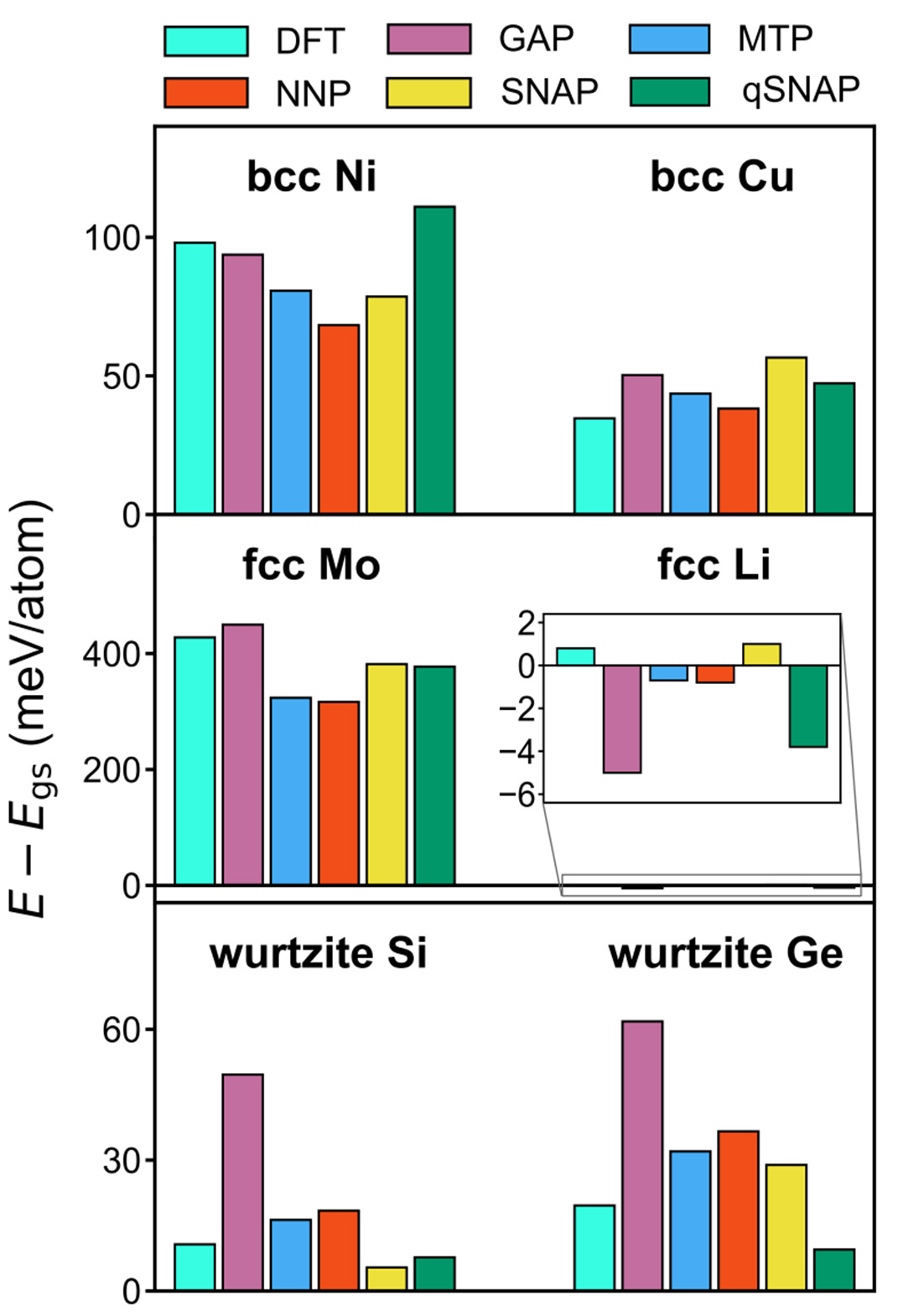

In their systematic evaluation of various MLPs across diverse elemental systems, as depicted in Figure 13, Zuo et al.[86] observed distinct characteristics for each method: GAP typically exhibited the highest computational cost, attributable to the inherent complexity of its Gaussian process regression framework. Conversely, MTP and SNAP, owing to their underlying linear or polynomial model structures, generally demonstrated superior computational efficiency. NNP, while requiring optimization of numerous neural network parameters during training, offered relatively fast inference speeds. Regarding applicability to specific material systems, SNAP or MTP were often favored for metallic systems (e.g., Cu, Ni) due to their efficient capture of metallic bond symmetries[83,87]. For semiconductors (e.g., Si, Ge), GAP or NNP were generally found to be more suitable, given their capacity to accurately represent more intricate bonding environments[81].

Figure 13. The general process of training and applying MLPs. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Zuo et al. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. Reprinted with permission[86]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. MLPs: Machine learning potentials; DFT: density functional theory; GAP: gaussian approximation potential; MTP: moment tensor potential; NNP: neural network potential; SNAP: spectral neighbor analysis potential; qSNAP: quantum-informed spectral neighbor analysis potential.

Building on this understanding of the strengths and limitations of different MLP approaches, numerous studies have successfully applied these potentials to model complex material behaviors with high accuracy. For example, Byggmästar et al.[88] developed a GAP-based high-precision interatomic potential and simulated melting points and latent heat of fusion for five body-centered cubic (BCC) metals up to 400 GPa using the liquid-solid interface method. Li et al.[87] constructed an MLP based on SNAP to model high-accuracy potential energy surfaces for FCC Ni, Cu, and Ni-Mo binary alloy systems, successfully predicting phase diagrams and melting behavior, including the FCC-to-BCC phase transition. Kondratyuk et al.[89] utilized DP to perform high-precision modeling and systematic analysis of the viscosity and microstructural characteristics of Al-Cu-Ni ternary melts. By calculating radial distribution functions (RDF) and velocity autocorrelation functions, they validated the DP model’s accuracy in reproducing the melt’s microstructural features. Furthermore, they systematically calculated the viscosity of Al-Cu-Ni melts across different compositions and temperatures, successfully reproducing the viscosity minimum near the eutectic composition. These advancements highlight the versatility and power of MLP in modeling complex atomic systems with high accuracy.

MLPs offer a promising solution for studying melt systems by combining the high accuracy of AIMD with the efficiency of CMD. Compared to AIMD, MLPs achieve quantum-mechanical accuracy in describing interatomic interactions while reducing computational costs by several orders of magnitude, making them suitable for simulations of larger systems and longer time scales[80]. In contrast to CMD, MLPs overcome the limitations of classical potentials, enabling precise descriptions of bond breaking, bond rearrangement, and localized chemical changes in melts[90]. Moreover, MLPs exhibit broader applicability, accommodating multicomponent systems, multiphase states, and complex environments. The emergence of MLP provides an efficient and accurate tool for investigating the dynamics and structure of melt systems.

Despite their remarkable capabilities, developing robust and transferable MLPs for multicomponent metallic melts presents several significant challenges. The high dimensionality of the chemical and structural space in such systems makes comprehensive data generation from first-principles calculations computationally prohibitive. Ensuring compositional, temperature, and structural transferability is particularly difficult: an MLP trained for a specific alloy composition or crystalline phase may perform poorly when simulating a melt with different elemental ratios or highly disordered structures where complex bond breaking and rearrangement events occur. Furthermore, obtaining sufficiently diverse and representative training data that accurately capture all relevant local atomic environments, including rare or transient states, remains a bottleneck.

Reverse Monte Carlo

The RMC method, a variant of the standard Metropolis-Hastings algorithm[91], is designed to solve inverse problems by iteratively adjusting a model to achieve maximum consistency between its prediction and experimental data. Its theoretical foundation combines Monte Carlo sampling with principles of statistical mechanics-based optimization. The RMC approach constructs an objective function[92]:

where Fexp and Fcal represent the experimental and calculated structural factors (e.g., from X-ray or neutron diffraction), and λ is a weighting coefficient that controls the influence of physical constraints, such as minimum interatomic distances. Atomic configurations are stochastically perturbed and optimized using the Metropolis algorithm, with a virtual temperature parameter T guiding the convergence by gradually reducing χ2. Unlike traditional forward modeling, RMC solves an inverse problem. Its core idea is to reconstruct the most probable structural distribution that satisfies experimental data by maximizing configurational entropy. This avoids the need for prior assumptions about symmetry or interaction potentials, making RMC especially suitable for disordered systems, amorphous materials, and defect-rich structures.

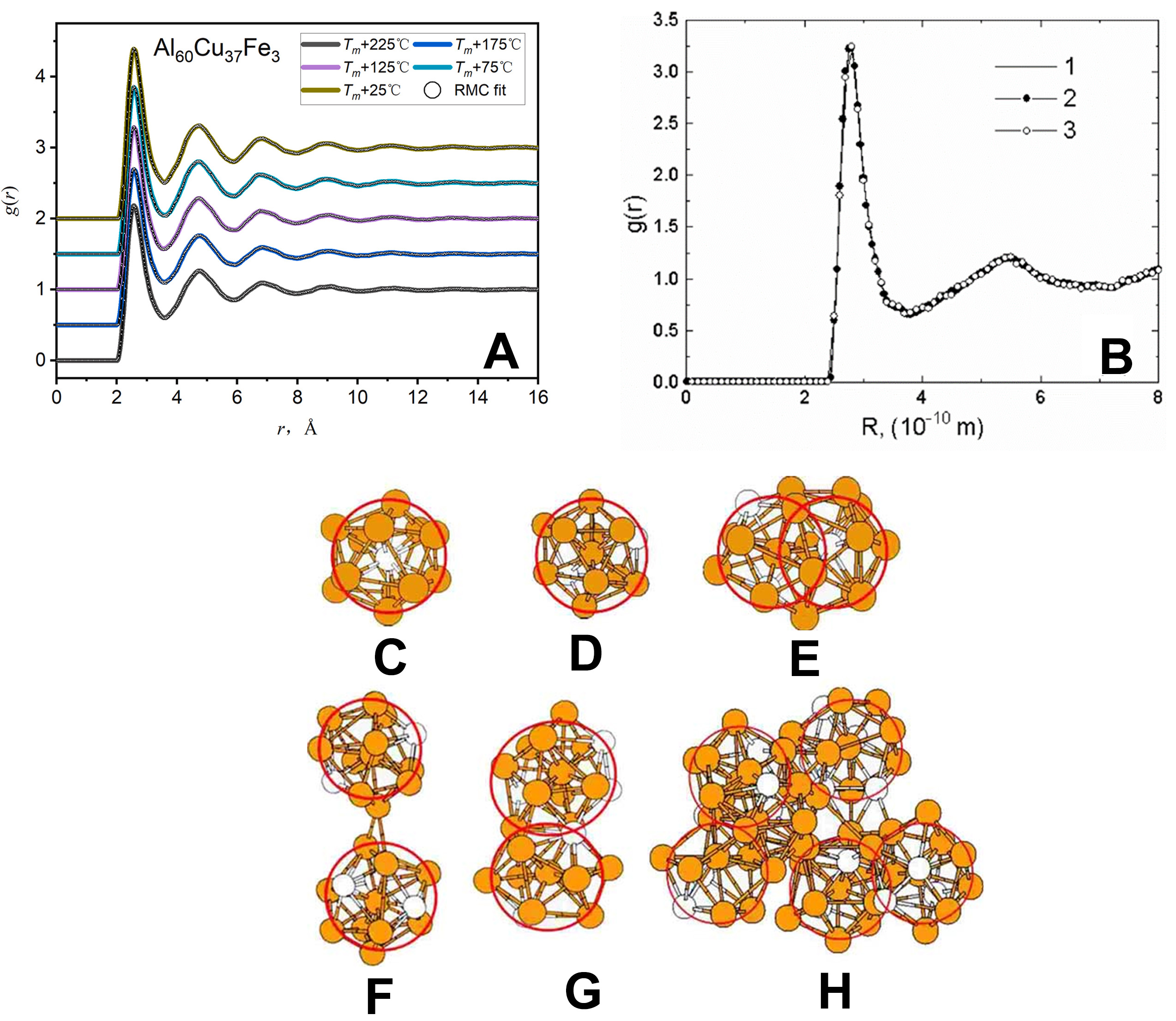

In studies of metallic melts, the RMC method refines atomic configurations to align simulation results with experimental observations, such as scattering functions or RDFs [Figure 14A]. Datafitted through RMC typically exhibits excellent agreement with experimental measurements. This approach enables the investigation of local and medium-range order structures in liquid metals and metallic glasses[10,93]. The primary advantage of the RMC method lies in its direct reliance on experimental data, eliminating the need for potential functions. However, its accuracy depends critically on the quality of the experimental input, and it has limited capability to describe structural evolution.

Figure 14. (A) Pair correlation function, g(r), of quasicrystal-forming Al60Cu37Fe3 liquid obtained from the experiment at different temperatures (solid lines) and the corresponding RMC fit (open black circles); Reprinted with permission[93]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier; (B) A comparison of the pair correlation functions of liquid gallium at 293 K: (1) the diffraction experiment (target), (2) the RMC model, and (3) the MD model, Icosahedral clusters of metallic glass alloy ZrPt from MD simulation, Reprinted with permission[95]. Copyright 2002, Elsevier; (C) Pt-centered, (D) Zr-centered, (E) interpenetrating icosahedra, (F) vertex-connected, (G) Face-sharing icosahedra, and (H) MRO made up of icosahedra in glass Zr73Pt27. Yellow and white spheres denote Zr and Pt atoms, respectively. Panels C, D, E, F, G and H are quoted with permission from Ref.[98]. Copyright 2008, American Physical Society. RMC: Reverse Monte Carlo; MD: molecular dynamics; MRO: medium-range order.

In recent years, the RMC simulation method has achieved significant breakthroughs in uncovering the atomic structures of complex materials, demonstrating strong potential for applications in the structural studies of nanoparticles, liquid metals, amorphous alloys, and metallic glasses. Harada et al.[94] utilized RMC simulations to investigate the three-dimensional atomic structures of spherical Pt and PtRh nanoparticles with diameters below 5 nm. Their work highlighted that combining HEXRD or extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) with RMC modeling offers a promising approach for resolving atomic-level structural details of nanoparticles. Additionally, studies have confirmed the validity of the RMC method in simulating the structures of liquid metals, particularly at temperatures where melts exhibit structural uniformity[95] [Figure 14B]. Kawamata et al.[96] successfully reproduced the atomic structure of amorphous Pd82Ge18 alloy through RMC simulations, revealing key features of the SRO, including variations in bond lengths and coordination numbers. Similarly, Li et al.[97] applied RMC modeling to liquid Al80Mn20 alloy and discovered a preference for Mn atoms to form fivefold symmetric structures, such as icosahedral and distorted icosahedral local orders. In Zr73Pt27 metallic glass, icosahedral-like clusters were observed to exhibit localized SRO. Furthermore, these clusters are arranged in a highly correlated manner, forming medium-range topological order through inter-cluster connections and stacking[98] [Figure 14C-H].

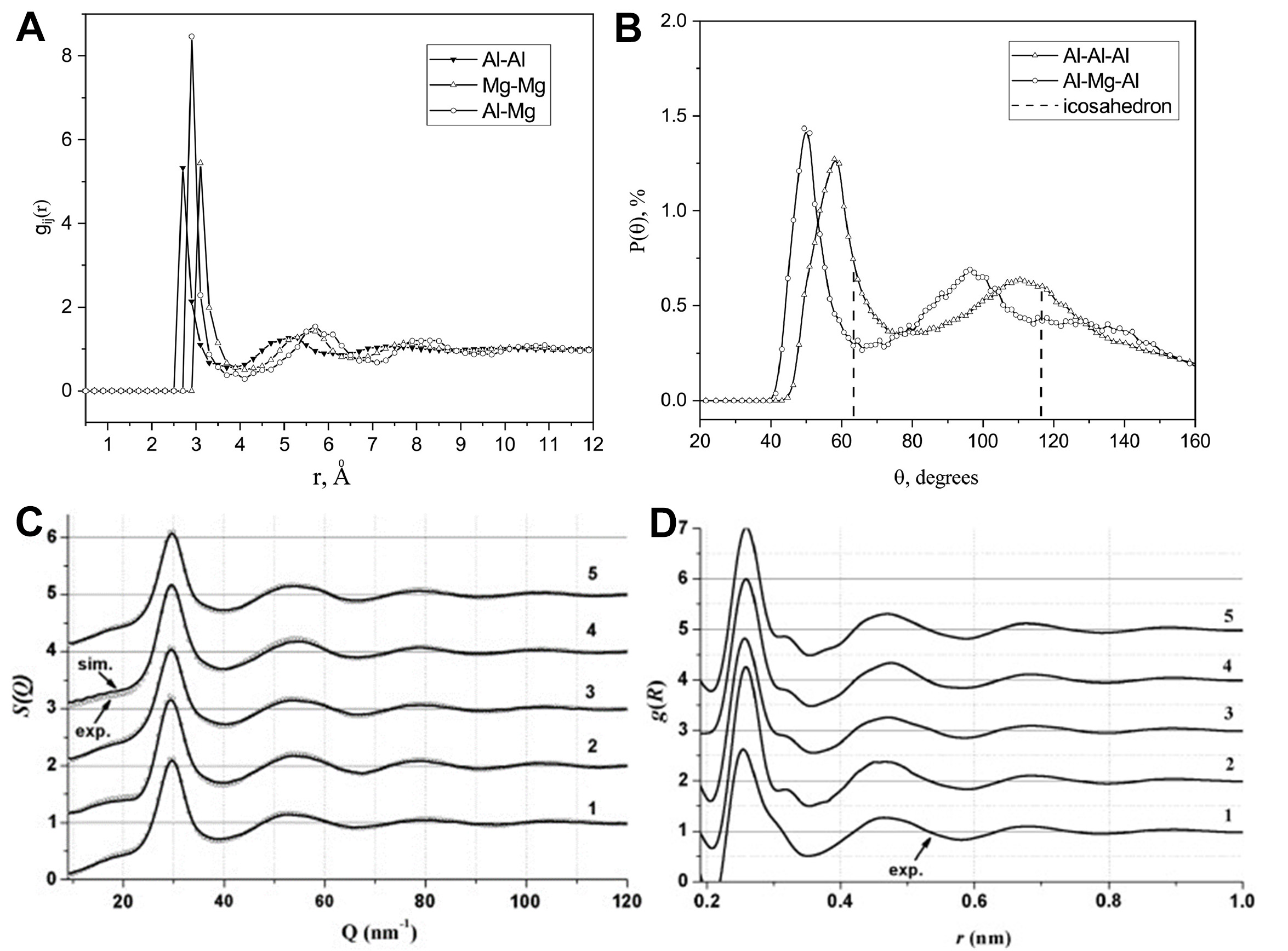

The RMC simulation method has also demonstrated exceptional capabilities in uncovering the atomic structures of liquid alloys. For instance, Kirian et al.[99] revealed in liquid Al87Mg13 alloy that different atomic species preferentially form nearest-neighbor pairs (e.g., Al-Mg), indicating the presence of CSRO. Additionally, the Al-Al-Al bond angle distribution exhibited features characteristic of icosahedral structures [Figure 15A and B]. In liquid Al-Cu-Co alloys, unique TM-TM (TM = Co, Cu) bonding and medium-range ordered structures were identified, along with a correlation between CSRO and the pre-peak phenomenon in the structure factor S(Q) [Figure 15C and D]. Both the intensity of CSRO and the pre-peak were found to decrease significantly with increasing temperature[100]. Roik et al.[101] conducted a comparative analysis of the SRO in ternary liquid alloys Al-Ge-Ni and Al-Ge-Fe, demonstrating that the strength of interatomic interactions plays a decisive role in the formation of local structures. Shtablavyi et al.[102] observed that in Al83Cu17 eutectic melts, Al-Cu clusters dominate the structural organization, whereas in Al88Si12, chemical ordering tendencies between different atomic species were negligible. Furthermore, in Al-Si eutectic liquids, the introduction of Ni was found to promote the formation of chemically ordered Al-Ni regions[103].

Figure 15. (A) Partial pair distribution functions for the liquid Al87Mg13 alloy obtained by the RMC simulation; Reprinted with permission[99]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier; (B) The bond angle distributions in the atomic configurations simulated for liquid Al87Mg13 alloy; Reprinted with permission[99]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier; The S(Q) (C) and the total PCF (D) of the liquid ternary alloys: 1-Al71Cu6Co23 at 1483 K, 2, 3, 4-Al63.9Cu19.4Co16.7 at 1373, 1443, and 1543 K, respectively, and 5-Al60Cu29Co11 at 1413 K. Panels C and D are quoted with permission from Ref.[100]. Copyright 2011, Elsevier. RMC: Reverse Monte Carlo; PCF: pair correlation function.

Machine learning method

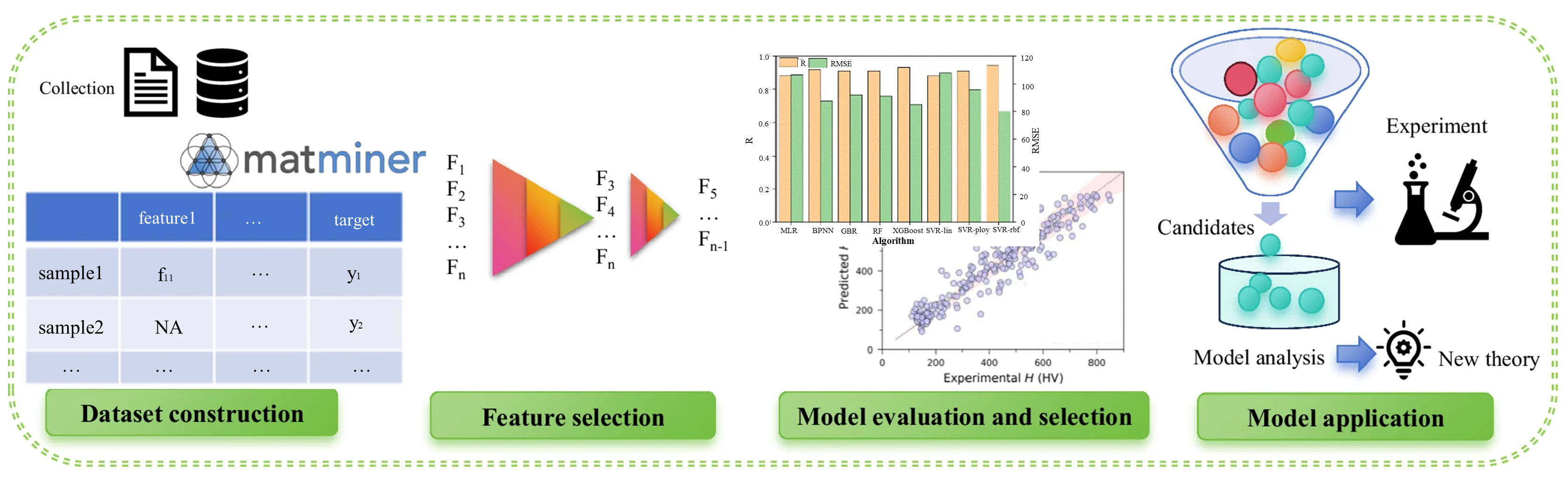

With the growing availability of material data, ML has been increasingly applied in materials science, spanning applications such as property prediction[104,105], novel material design[106], and experimental characterization analysis[107]. While much effort has focused on macroscopic data analysis, recent attention has shifted toward understanding the relationship between a material’s microscopic structure and its macroscopic properties. The MLP, mentioned in section 3.2, is based on specific models, such as neural networks, and employs ML techniques to describe atomic interactions. MD simulations using MLP can thus be employed to investigate the relationship between microscopic structure and macroscopic properties. Figure 16[108] illustrates the typical workflow of machine learning methods applied in materials science, including steps such as data collection, feature design, model training, validation, and final prediction.

Figure 16. The workflow of machine learning in materials science. Reprinted with permission[108]. Copyright 2024, The Author(s). RMSE: Root mean square error.

Yang et al.[109] effectively reduced the dimensionality of RDF using an autoencoder, mapping local atomic environments onto a two-dimensional space. This approach revealed the dynamic arrest phenomenon and its structural origins during the glass transition. By utilizing ML techniques, the study simplified the analysis of high-dimensional data, compressing the information into a two-dimensional representation that visually elucidated the evolution of clusters. The interpretability of ML methods further supported the exploration of intrinsic connections between material structure and properties. Similarly, Liu et al.[110] employed an interpretable extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) model to investigate the impact of SRO on the stability and structural heterogeneity of metallic glasses. Their research unveiled the complex mathematical relationships between structure and performance. As an efficient tool for big data analysis, machine learning can capture and characterize these intricate interactions, offering new insights into the research and design of metallic glasses.

However, studies utilizing machine learning to analyze cluster evolution[111] remain limited. Future research could employ more advanced models, such as deep learning, integrated with experimental and simulation data to investigate the evolution of clusters under various conditions. This approach holds the potential to offer valuable insights for the design of high-performance materials.

MELT STRUCTURE AND ITS EVOLUTION DURING SOLIDIFICATION

Short-range order and medium-range order

Metallic melts exhibit a structural characteristic of long-range disorder and SRO, which can be further classified into topological short-range order(TSRO) and CSRO[112]. TSRO refers to the geometric arrangement of neighboring atoms, where the spatial distribution follows specific local motifs or symmetries, such as icosahedral or polytetrahedral configurations. This type of order is typically quantified using angular distribution functions or Voronoi polyhedra analysis. CSRO, on the other hand, describes the preferential occupancy of neighboring atoms based on chemical species. It is often evaluated using the Warren-Cowley short-range order parameter, defined as[113]:

where Pαβ is the probability of finding a β-type atom adjacent to an α-type atom, and cβ is the bulk concentration of atom type β. A negative Pαβ implies a preference for heteroatomic coordination. In general, SRO is commonly characterized through the partial pair distribution function gαβ (r), which reflects the likelihood of finding a β-type atom at a distance r from an α-type atom. SRO induces local structural changes that influence the liquid’s dynamic properties and subsequent solidification behavior. Han et al.[114] in metallic melts of Cu-Zr demonstrated that the subtle change in liquid structures, especially the change in local five-fold symmetry, leads to the abnormal breakdown of the Stokes-Einstein relation at high temperatures and the slowdown of dynamics. Jakse et al.[70] conducted simulations to investigate the local structure and dynamic behavior of liquid and supercooled Cu-Zr alloys. Their study revealed that Cu64Zr36 exhibited the strongest icosahedral short-range order (ISRO), accompanied by the highest viscosity. This observation suggests that ISRO, by hindering atomic diffusion and enhancing local packing frustration, plays a key role in increasing viscosity and promoting GFA by suppressing crystallization.

In 1952, Frank[115] first proposed the icosahedral cluster in describing the liquid structure. An icosahedron consists of 20 identical tetrahedra that overlap with shared atoms. Later, Steinhardt et al.[116,117] confirmed the existence of icosahedral clusters in pure metallic melts and binary alloys through MD simulations. With the advancement of experimental techniques such as HEXRD, PDF analysis, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), it is now possible to directly probe SRO and medium-range order (MRO) in metallic melts and amorphous materials. SRO can be studied by analyzing the first coordination shell in the X-ray diffraction data, which corresponds to the nearest-neighbor atomic arrangement. MRO, on the other hand, is investigated by examining higher-order coordination shells (such as the second shell and beyond), which reflect extended atomic correlations beyond the immediate neighborhood[118]. A comprehensive understanding of icosahedral structures has since deepened with advancements in simulation techniques and synchrotron radiation methods. Li et al.[119] investigated the structural evolution in rapidly cooled Fe50Al50 liquid alloys by combining MD simulations with XRD experiments. Their work revealed that icosahedral clusters dominate under rapid cooling conditions, suppressing crystallization. They also observed corresponding structural changes in pair correlation functions and bond-pair characteristics. Guo et al.[120] explored the effect of minor Y additions on the GFA of ZrCuAl alloys through synchrotron radiation experiments combined with RMC simulations. The researchers found that the addition of Y increased the population of icosahedral-like clusters, improved atomic packing efficiency, and enhanced cluster regularity, which collectively contributed to enhanced structural stability and increased GFA. Xiao et al.[121] also discovered through experiments and AIMD simulations that increasing the Y content in Fe86-xYxB7C (x = 0, 5, 10 at.%) amorphous alloys leads to a higher proportion of icosahedral clusters, which enhances the glass-forming ability and thermal stability of the material. Analysis of the alloy’s electronic energy density and magnetic moment revealed that the addition of Y induces hybridization between Y-4d and Fe-3d orbitals, thereby weakening the ferromagnetic coupling between Fe atoms. This reduction in coupling results in decreased magnetic moments of Fe atoms and a lower total magnetic moment of the system, consistent with experimental observations. Hopur et al.[122] investigated the effects of minor Ag addition on the atomic structure, electronic valence band, and properties of Zr-Cu-Al-Ag bulk metallic glasses (BMGs) through experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. The study revealed that with increasing Ag content, the total fraction of icosahedral-like clusters slightly increased, which is positively correlated with the alloy’s GFA. Experimental results further confirmed that trace Ag addition significantly enhanced the GFA of the alloy, as evidenced by the increase in the critical casting diameter of Zr50Cu44.5Al5.5 BMG from approximately 2.5 mm to 5.0 mm. However, the ductility of the alloy decreased from 4.6% to 0.8%, indicating that Ag addition has a detrimental effect on plasticity.

Clusters can further organize into MRO through various spatial connections. MRO plays a critical role in the nucleation process of materials, acting as a structural precursor and facilitating the transition from non-equilibrium liquids to crystalline phases[123]. Wang et al.[124] demonstrated the presence of a pre-peak in the structure factor curve of Al80Fe20 melts, indicating the existence of MRO. Notably, the intensity of the pre-peak increased as the temperature decreased, demonstrating the temperature-dependent MRO behavior. Ryu et al.[125,126] employed X-ray diffraction and simulation techniques to explore correlations between SRO, MRO, and glass formation. Their study revealed distinct temperature dependences for MRO and SRO during the glass transition. Specifically, the freezing of MRO, rather than SRO, governs the dynamic slowdown and drives the glass transition. MRO structures dominate the viscosity behavior in the supercooled regime and serve as precursors for shear localization. MRO also influences material properties, such as shear instability[127], magnetic behavior[128], and local hardness[129]. These findings underscore the mechanistic link between atomic-scale structural motifs and macroscopic properties, highlighting the need to understand and tailor SRO/MRO to control viscosity, mechanical strength, and glass-forming ability. However, the complex interplay between SRO and MRO, and their combined influence on material properties, remains an area of active research, with many unresolved questions. In particular, the development of robust quantitative methods for describing SRO and MRO in multicomponent systems, as well as advances in in situ observation techniques with high temporal and spatial resolution, are critical for addressing these challenges.

Liquid-liquid phase transition

Liquid polyamorphism refers to the coexistence of two distinct phases within a liquid that share the same chemical composition and chemical potential but lack long-range order, differing in both density and structure[130]. The transition between these two liquid phases is known as a liquid-liquid phase transition (LLPT) or liquid-liquid transformation (LLT). Theoretical calculations have shown that liquids with the same composition can undergo a first-order phase transition[131]. Current studies indicate that LLPT affects properties such as GFA and thermal stability[132], making the modulation of LLPT a promising approach for optimizing material performance.

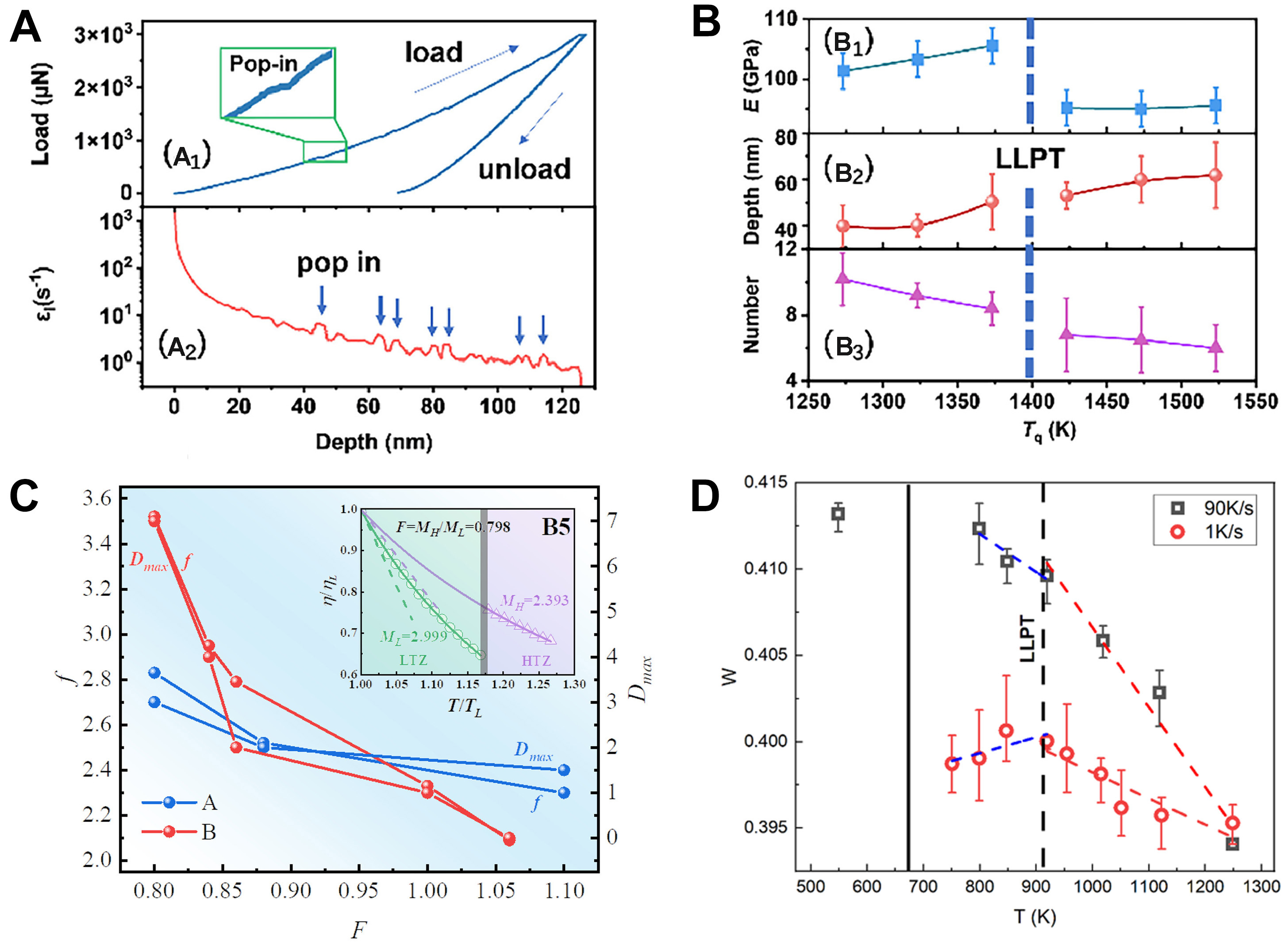

In the field of amorphous alloys, LLPT, as a unique phenomenon occurring in liquid metals or metallic glass formation, not only reveals the complex dynamic behavior of materials at high temperatures but also provides valuable insights for optimizing their properties. Recent progress has been made through case studies that integrate high-resolution experimental techniques and atomistic simulations, enabling a more accurate understanding of LLPT mechanisms. Ding et al.[133] employed a combined experimental and computational approach to investigate the influence of LLPT on the mechanical properties of Cu46Zr46Al8 metallic glass. Their findings revealed that metallic glasses quenched below the LLPT temperature exhibited a higher elastic modulus and enhanced plasticity [Figure 17A and B]. This study further demonstrates that the microscopic structural changes induced by LLPT are critical in tailoring the mechanical performance of metallic glasses. Zhai et al.[134,135] explored the correlation between LLT and the fragile-to-strong (F-S) transition in soft magnetic Fe-based metallic glasses using MD simulations and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Their findings indicate that a more pronounced LLT corresponds to a weaker F-S transition and reduced GFA [Figure 17C]. They attributed this relationship to the intrinsic evolutionary trends of crystal-like clusters in the regions associated with LLT and the F-S transition. Sengul et al.[136] observed that the structural evolution and anomalous bonding behavior during rapid solidification of Zr80Pt20 alloys under different pressures are associated with LLPT. These changes were attributed to local structural rearrangements and alterations in interatomic interactions induced by LLPT. LLPT typically manifests as a discontinuous change in the structure and properties of a liquid under varying pressures. However, accurately identifying genuine LLPT remains challenging due to the potential interference of early-stage crystallization or transient nanocluster formation. The works of Yu et al.[10,137] reported the occurrence of LLPT in the Pd40Ni40P20 alloy during the cooling process by combining experimental and simulation approaches. Using HEXRD and FDSC, they monitored structural evolution and thermal effects in real time during the cooling of the melt. HEXRD provided changes in the structure factor S(Q) and the pair distribution function g(r), while FDSC detected anomalous endothermic peaks, which are typically associated with LLPT. In parallel, AIMD and RMC simulations were employed to investigate atomic-level structural changes during LLPT, offering microscopic insights into the transition. By correlating the macroscopic structural variations observed in experiments with the atomistic details obtained from simulations, the study enabled more accurate identification of LLPT and effectively ruled out interference from early crystallization or transient nanocluster formation. Additionally, it was found that the occurrence and pathway of LLPT could be controlled by tuning the cooling rate [Figure 17D].

Figure 17. The variation in mechanical properties of MG prepared at different Tq (Quenching Temperature). (A) The representative curve of load vs displacement (A1) and strain rate sensitivity (A2) of serrated flow in nanoindentation; Reprinted with permission[133]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (B) The variation in modulus (B1), the displacement where the first pop-up occurrence (B2), and the total amount of pop-in in the entire loading phase (B3) of MG prepared at different Tq; Reprinted with permission[133]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (C) The relationship among the LLT parameter F, the F-S transition parameter f, and the critical size of MGs Dmax in A and B MGs. It is evident that the LLT parameters F is inversely proportional to both f and Dmax; Reprinted with permission[134]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (D) The evolution of five-fold local symmetries in Pd40Ni40P20 melt at different temperatures with cooling rates of 1 K/s and 90 K/s. Reprinted with permission[10]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. LLT: Liquid-liquid transformation; MG: metallic glass; LLPT: liquid-liquid phase transition.

Liquid-solid transformation

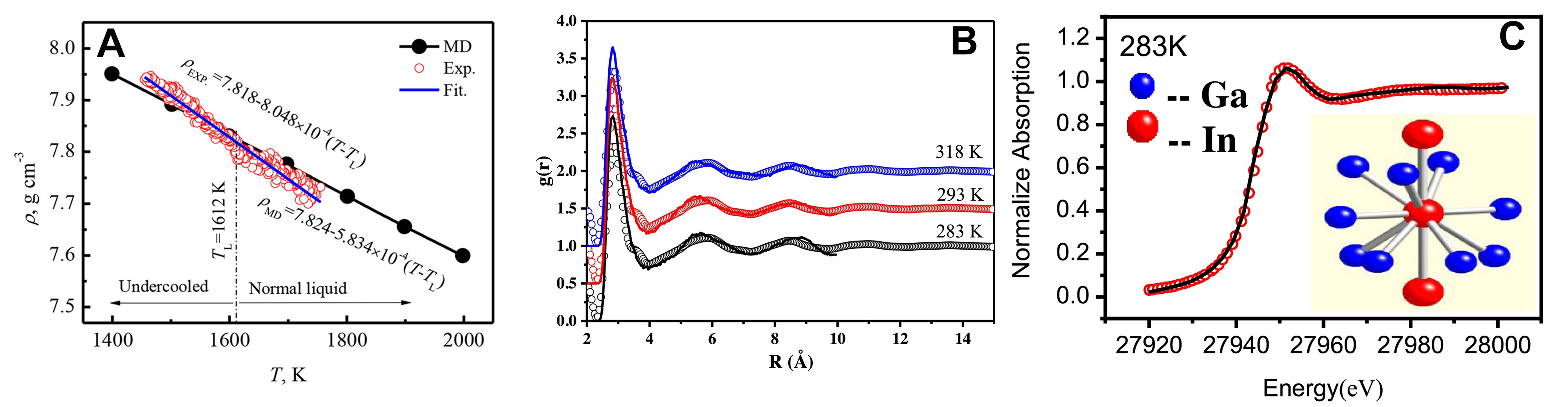

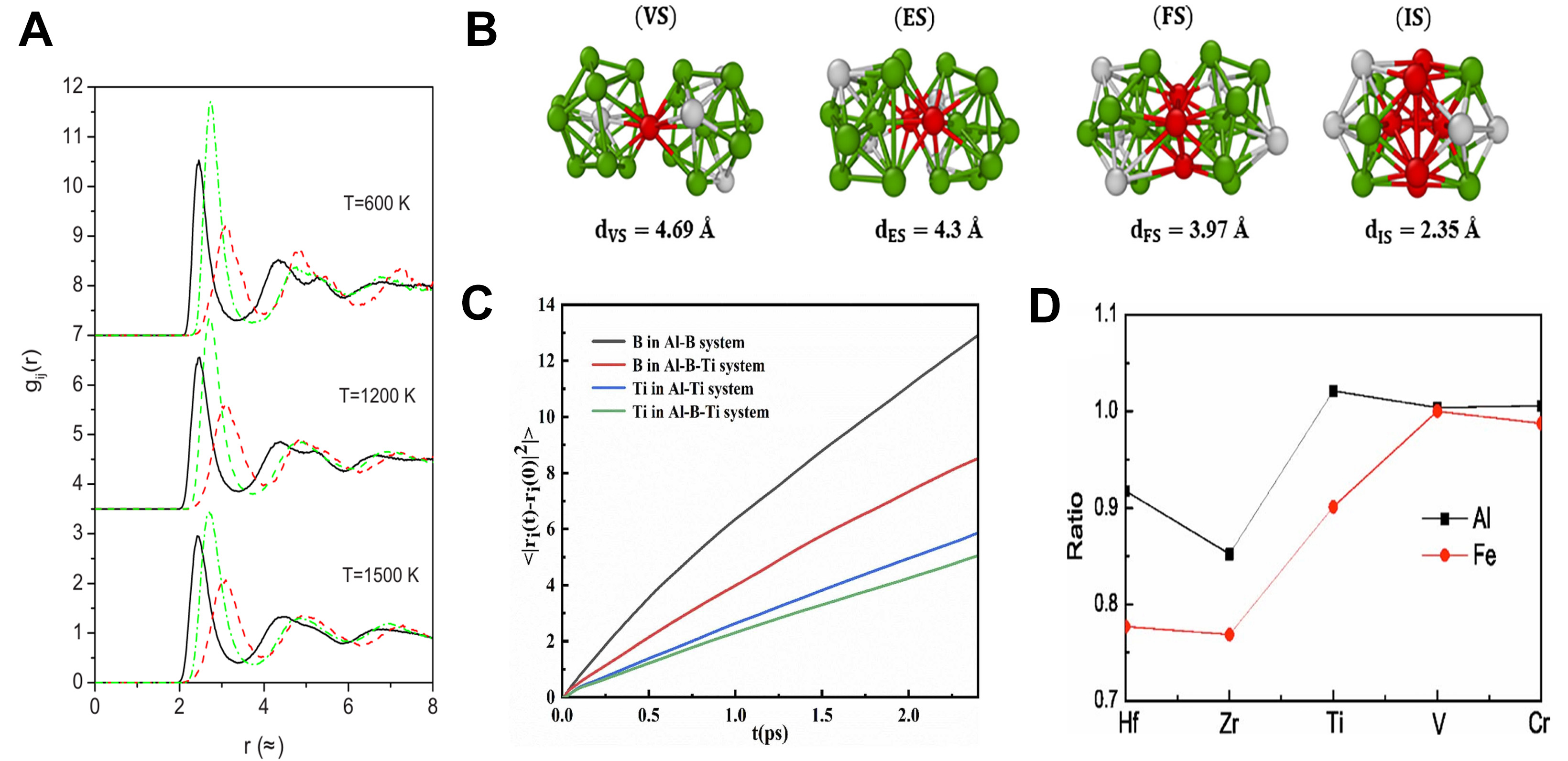

With the advancement of simulation and experimental techniques, researchers are now able to more accurately reveal the microscopic structural characteristics of metal melts during the solidification process. These advancements provide new insights into the understanding of solidification pathways, phase transition mechanisms, and material properties. For example, Lü et al.[138] combined electrostatic levitation techniques with AIMD to investigate the rapid solidification of liquid alloys, revealing that the local atomic structure notably affects phase selection. As shown in Figure 18A, the comparison between experimental measurements and AIMD simulations of the density of liquid Ni5Zr alloy further validates the accuracy of the simulations. This study highlighted the crucial role of local atomic arrangement in determining the solidification pathway. Zhao et al.[139] , using AIMD simulations during solidification, observed that in Ga90In10 alloy, atomic clusters transition from high-coordination polyhedral structures to low-coordination polyhedral structures, accompanied by a decrease in nearest-neighbor coordination and an increase in atomic distance. To further validate these observations, they compared the experimental measurements with the AIMD simulation data. The comparison results are shown in Figure 18B and C, where the experimental data are in close agreement with the simulated results, confirming the structural transitions they described. This behavior is similar to the evolution of cluster structures observed during the solidification of liquid Ni and in the Mg-Si system[140,141]. In studies of undercooled Ni melts, Ma et al.[142] found that the average lifetime of clusters increased as the temperature decreased. Numerous studies have demonstrated that ISRO significantly increases during solidification, and that icosahedral clusters and defective icosahedral clusters form MRO structures through specific connection modes, such as vertex-sharing (VS), edge-sharing (ES), face-sharing (FS), and interstitial-sharing (IS). These structures not only maintain high structural stability but also enhance the glass-forming ability of the material [Figure 19A and B][143-148].

Figure 18. (A) Density of liquid Ni5Zr peritectic alloy; Reprinted with permission[138]. Copyright 2018, AIP Publishing; (B) The pair distribution function g(r) of the Ga90In10 alloy melt under different temperatures. The solid curves are the simulated results and the curves with empty dots are the XRD experiment results; (C) Comparison between the experiments and simulations on X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) spectra at the K-edge of In for the normal and undercooled liquid Ga90In10 alloy. The curves with empty red dots are the experimental XANES spectra and the black curves are the simulated spectra based on the multiple-scattering theory. The inset figures show the models of the clusters, which contain one center In atom and other atoms on the first shell in the Ga90In10 alloy melt at the corresponding temperature. Panels B and C are quoted with permission from Ref.[139]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. XRD: X-ray diffraction; MD: molecular dynamics.

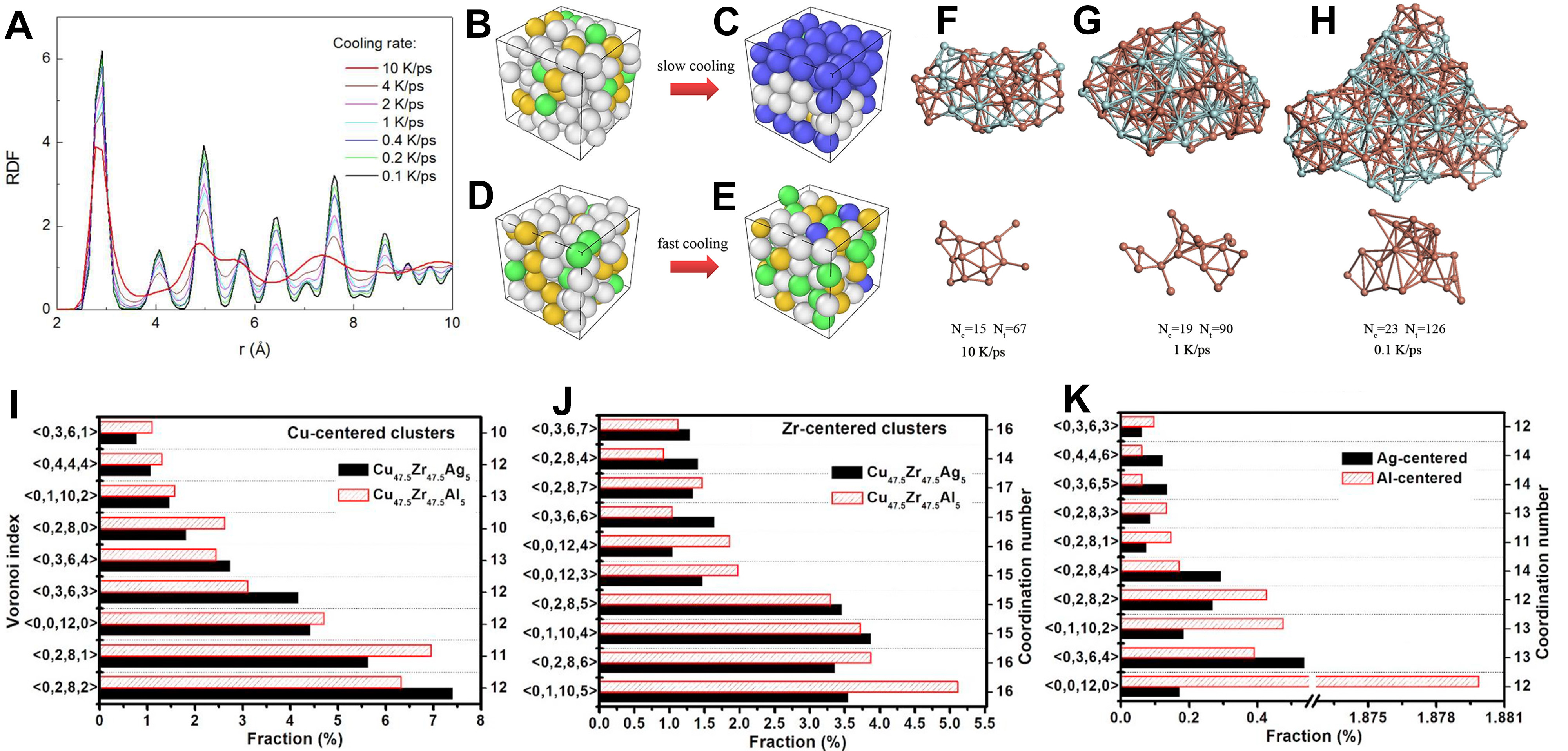

Figure 19. (A) Partial pair-correlation functions, gCu-Cu(r) solid lines, gCu-Zr(r) dashed lines, and gZr-Zr(r) dotted lines of liquid T = 1,500 K, undercooled T = 1,200 K, and amorphous T = 600 K Cu64Zr36 alloys. The curves for T = 1,200 and 600 K are shifted upward by an amount of 3.5 and 7, respectively; Reprinted with permission[143]. Copyright 2008, AIP Publishing; (B) Schematic illustrations of vertex, edge, face, and interpenetrating sharing modes of 〈0,0,12,0〉Voronoi polyhedra in the Ni3Al alloy. The average distance between the central atoms of two connected polyhedrons is shown. Grey and green represent Al and Ni atoms, respectively, while red balls indicate atoms shared by both polyhedral; Reprinted with permission[147]. Copyright 2017, Elsevier; (C) Mean square displacement curves of B and Ti atoms in Al-B, Al-Ti, and Al-B-Ti systems; Reprinted with permission[149]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (D) Ratios of DAl and DFe in Al70Fe20EM10 melts compared to those in the Al70Fe30 melt. Reprinted with permission[153]. Copyright 2007, AIP Publishing.