Smart design of Rh-based hydrogen evolution electrocatalysts: integrating DFT, machine learning, and structural optimization for sustainable hydrogen energy

Abstract

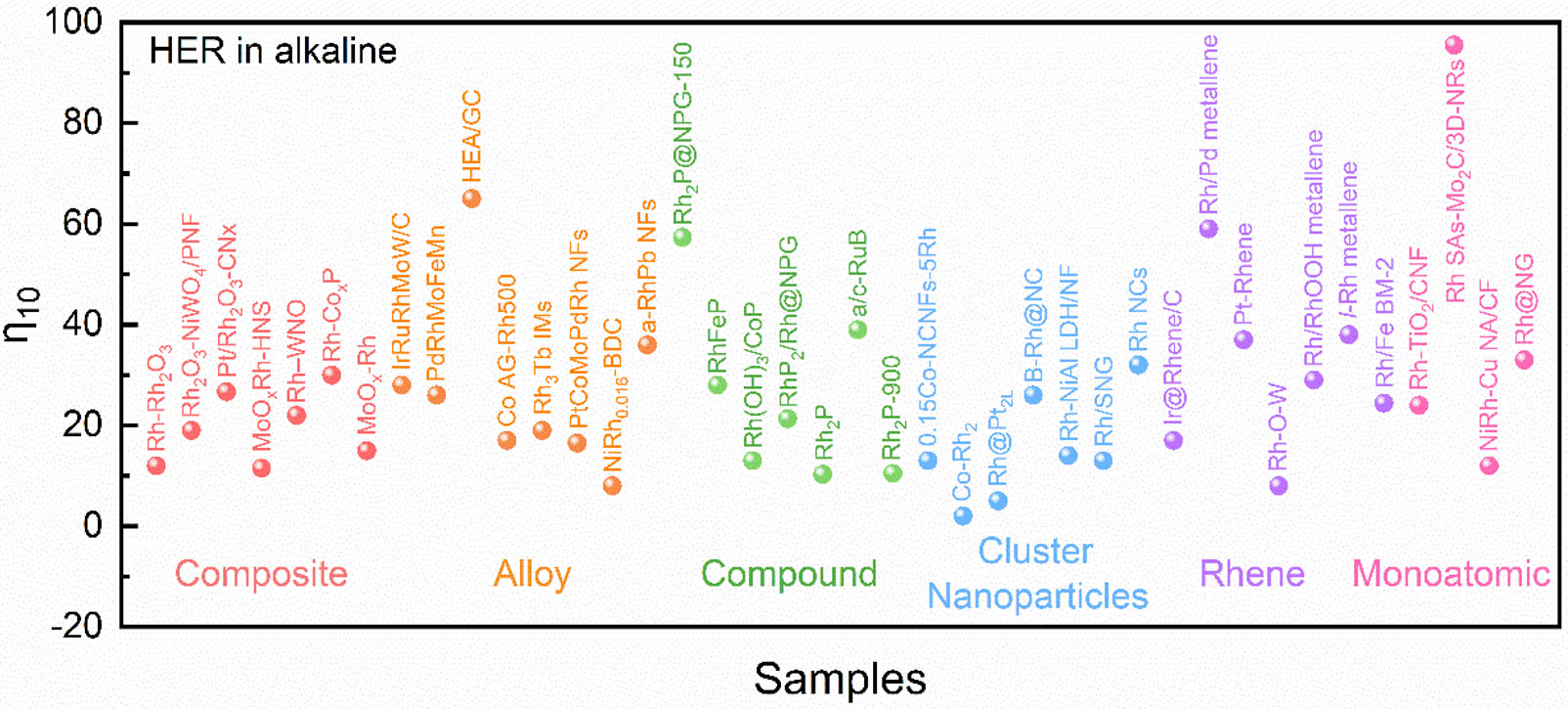

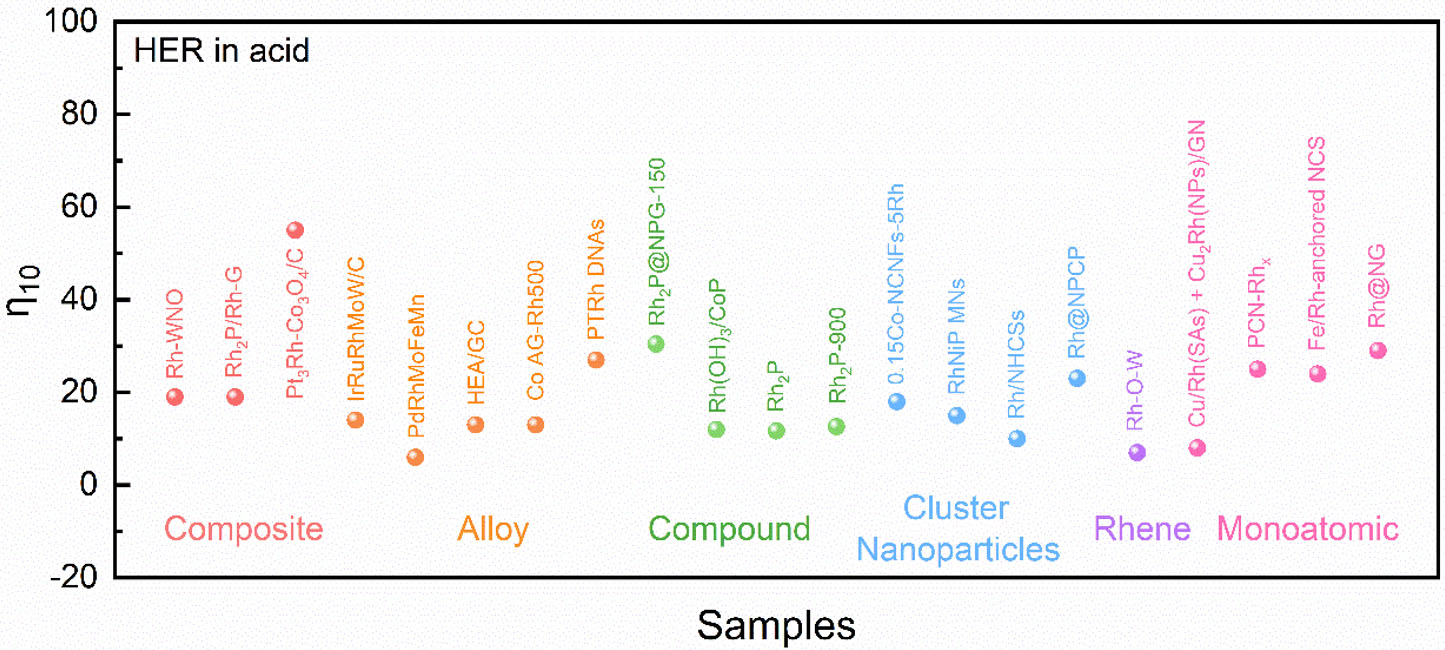

Hydrogen energy is vital for achieving carbon neutrality, with green hydrogen from water electrolysis being key. The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) critically determines system viability, driving the search for high-performance, stable and affordable electrocatalysts. Rhodium (Rh)-based catalysts are promising platinum alternatives due to near-ideal hydrogen adsorption energy, tunable electronic structure, and stable activity across all pH ranges. This review highlights recent advances in Rh-based HER catalysts, including mechanisms, descriptors, materials, and optimization strategies. Density functional theory (DFT) indicates that Rh catalysts typically follow the Volmer-Heyrovsky-Tafel pathway, with performance governed by surface geometry and electronic states. Key activity descriptors are summarized, while combining DFT with machine learning enables high-throughput screening and rational catalyst design. Experimentally, activity and stability are improved through atomic-scale modulation, interface engineering, and carrier synergy. Rh-based catalysts are categorized into single atoms, nanoclusters, 2D metallenes, nanoparticles, and compounds (phosphides, sulfides, oxides, nitrides), with synthesis methods and performance characteristics reviewed. Remaining challenges include reducing synthesis cost, ensuring long-term durability, and achieving scalable production. Future research should deepen structure-activity understanding and integrate artificial intelligence to accelerate the development of practical Rh-based HER catalysts.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Under the pressing global energy transition, hydrogen energy - as a clean, efficient, and sustainable energy carrier - is increasingly becoming a research hotspot and a pivotal player in future energy landscapes[1-4]. Water electrolysis, with its notable advantages of relatively simple processes and high product purity, is regarded as one of the most promising pathways for large-scale hydrogen production[5-10]. In water electrolysis, the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) as the core step, directly determines hydrogen production energy consumption and costs, making the development of high-performance HER catalysts critical[3,11-14]. Rhodium (Rh)-based materials have emerged as a focal point among various HER catalysts due to their unique electronic structures and exceptional catalytic properties[15]. There are some unique advantages and distinctions of Rh compared with other noble metals, such as platinum (Pt), Iridium (Ir), Ruthenium (Ru), and Palladium (Pd), when used as HER electrocatalysts. First, hydrogen binding energy: Rh exhibits an optimal hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH* ≈ 0 eV), comparable to that of Pt but with greater electronic tunability, which enables high intrinsic HER activity in both acidic and alkaline media[6,16]. Second, pH universality: Unlike Ir or Ru, which often perform well only in specific pH conditions[17], Rh-based catalysts maintain excellent stability and activity across a wide pH range. Third, anti-poisoning and durability: Rh demonstrates stronger tolerance toward surface poisoning (e.g., CO or S species) and superior corrosion resistance compared to Pt and Pd, contributing to long-term operational stability. Finally, cost-performance balance: although Rh is a noble metal, its mass-specific activity is higher and atom utilization efficiency is superior to that of Pt, allowing cost reduction through alloying or single-atom dispersion strategies[18], offering potential for cost reduction in large-scale applications[19-21]. Moreover, while significant progress has been made in developing non-precious metal catalysts (NPMCs) such as transition metal phosphides, sulfides, and carbides for the HER[22-24], these systems often face a compromise between activity, stability, and operational versatility. For instance, MoS2 exhibits notable activity primarily in acidic media[25], while many Ni-based catalysts are optimal in alkaline conditions, with their long-term durability under high current densities remaining a concern[26]. In this context, Rh emerges as a compelling alternative, presenting a unique set of catalytic properties that bridge the gap between ultra-high performance and robust stability. Theoretical and experimental studies confirm that Rh possesses a ΔGH* nearly as optimal as Pt, endowing it with superior intrinsic activity. Crucially, Rh surpasses Pt in its inherent corrosion resistance and electrochemical stability, particularly in harsh acidic environments or under oxidative potentials, suggesting potentially superior longevity[18]. When compared to NPMCs, the distinction of Rh lies in its exceptional all-rounder capability. It not only rivals the best NPMCs in intrinsic activity but, more importantly, maintains this high performance across the entire pH spectrum while exhibiting exceptional structural and chemical integrity that most earth-abundant alternatives cannot match[27].

Early studies focused on exploring the intrinsic HER activity of metallic Rh, revealing its ΔGH* close to that of Pt in acidic media, demonstrating favorable electrocatalytic performance. To reduce noble metal costs, researchers subsequently attempted to form alloys of Rh with non-noble metals such as Ni and Co (e.g., Rh-Ni, Rh-Co)[28-31], aiming to achieve synergistic catalytic effects through electronic modulation and geometric structure optimization. Entering the 21st century, advancements in nanotechnology spurred investigations into Rh-based nanostructures such as nanoparticles[32-35] and nanosheets[36]. Research emphasis shifted toward enhancing catalytic activity and atomic utilization by exposing high-index facets, tuning particle sizes, and engineering morphologies. Representative achievements during this phase included ultrafine Rh nanoparticles, polyhedral facet engineering, and carbon-supported Rh nanocomposites[34,37-39]. With the rise of single-atom catalysis (SAC) and cluster catalysis, Rh-based materials have entered a new era of atomic-level precision. Single-atom Rh catalysts, leveraging their maximal atomic utilization and unique coordination environments, have emerged as a research hotspot for achieving exceptional HER performance at ultralow loadings[18,40]. Concurrently, low-coordination Rh cluster catalysts have drawn attention due to their abundant active sites and distinctive electronic configurations[6,41]. To further enhance catalytic performance and stability, research has gradually shifted toward composite systems integrating Rh with functional materials such as MoS2, TiO2, and nitrogen (N)-doped carbon[27,42]. By harnessing carrier synergies, electronic structure modulation, and interface engineering, hierarchical porous architectures with strong interfacial coupling and high stability are being constructed. With the aid of density functional theory (DFT) calculations and machine learning algorithms, the design of Rh-based HER catalysts is progressively transitioning into an intelligent “computational-driven experimental validation” phase. Researchers utilize descriptors such as ΔGH*, d-band center, and charge transfer quantities for activity prediction, while high-throughput screening and structure-performance mapping accelerate the development of efficient, low-cost Rh-based HER materials.

In recent years, driven by rapid advancements in materials science and catalytic technologies, significant progress has been made in Rh-based HER catalyst research. From novel synthesis methods to innovative structural designs, and from mechanistic insights to practical applications, these studies continuously push the performance boundaries of Rh-based HER catalysts[43]. However, despite these achievements, challenges remain, including further improving catalyst activity and stability, optimizing synthesis processes to reduce costs, and deepening the understanding of structure-activity relationships in complex reaction environments. This review aims to comprehensively outline the current research landscape of Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts, systematically summarize recent advances in their structural features, catalytic performance, and reaction mechanisms, critically analyze existing challenges, and propose future research directions to advance the development and large-scale industrial application of Rh-based HER catalysts.

COMPARING HER MECHANISMS FOR TRADITIONAL CATALYSTS AND RH-BASED CATALYSTS

HER mechanisms of traditional catalysts

In different pH environments, HER on Rh-based catalysts follows distinct pathways. DFT calculations not only precisely resolve energy changes and electron transfer processes at each reaction stage but also elucidate the role of active sites, significantly deepening mechanistic understanding.

Acidic media

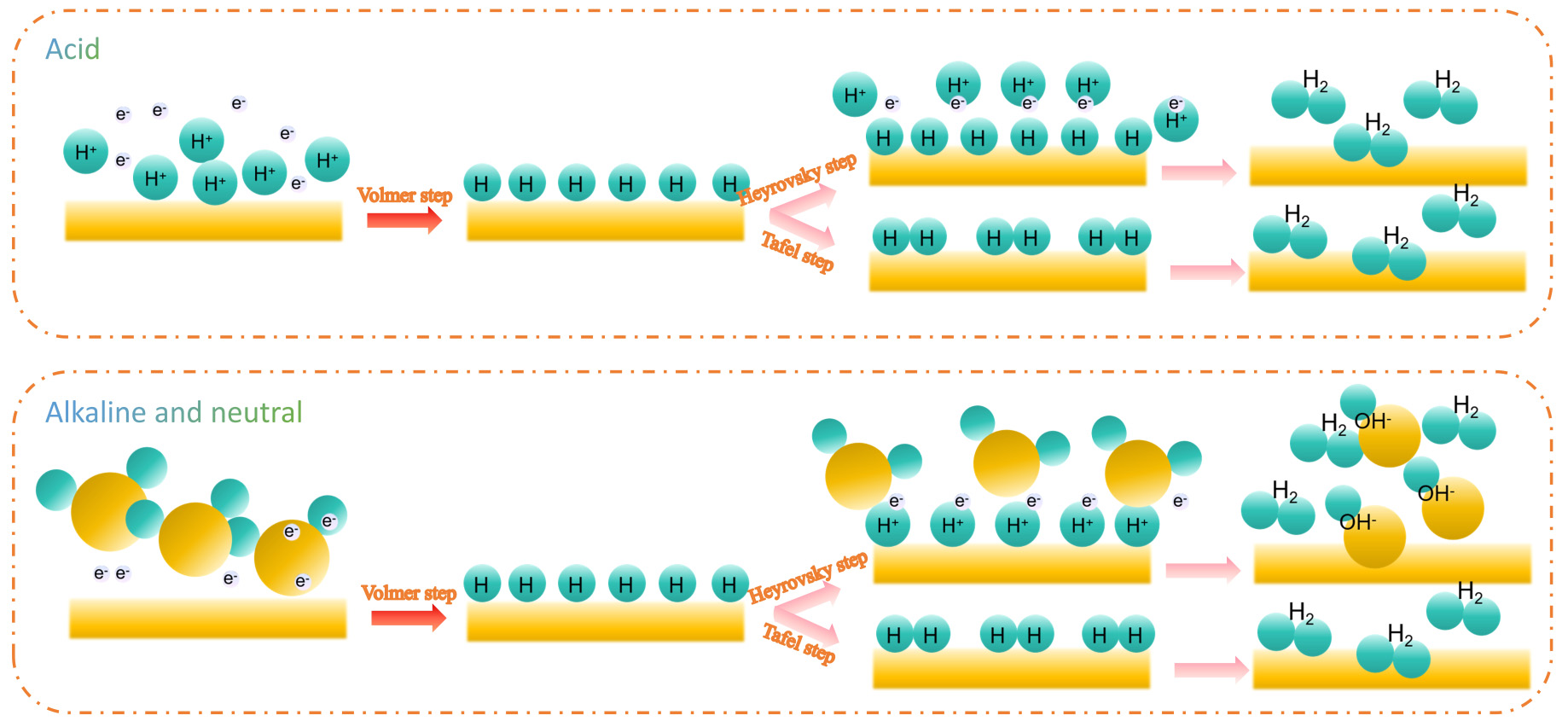

In acidic media, the HER proceeds via the Volmer, Heyrovsky and Tafel steps [Figure 1][44-46], with the overall reaction: The Volmer step under acidic conditions is H+ + e- = Hads[46], Hads is clarified as the adsorbed hydrogen intermediate on the catalyst surface during the HER. The electronic structure of the catalyst significantly affects the rate of this reaction. For example, in Rh-alloy catalysts, the addition of alloying elements changes the electron-cloud distribution around Rh atoms[47], thereby influencing the adsorption ability of the active sites. Moreover, the geometric structure of the catalyst surface also affects the Volmer step. Defects such as steps, kinks and vacancies on the catalyst surface have high activity due to the coordination unsaturation of atoms, which can lower the adsorption energy barrier and accelerate this step. The Heyrovsky step is expressed as H+ + Hads + e- = H2[46]. In this step, the catalyst surface acquires protons and electrons, which combine with the adsorbed hydrogen to form hydrogen molecules. DFT simulations show that the reaction energy barrier of this step is closely related to the hydrogen adsorption strength on the catalyst surface. When the hydrogen adsorption is too strong, the formation and desorption of H2 molecules need to overcome a high energy barrier; when the adsorption is too weak, hydrogen species may desorb from the catalyst surface before participating in the reaction. Both of these extreme situations can inhibit the progress of the HER. Through DFT calculations, Rh-based catalysts with appropriate adsorption strength can be designed to optimize the reaction kinetics of the Heyrovsky step. The Tafel step is Hads + Hads = H2; that is, two hydrogen atoms adsorbed on the catalyst surface directly combine to form hydrogen molecules[46]. DFT calculations show that the reaction energy barrier of the Tafel step is related to the H* coverage. When the H* coverage is high, the probability of two adsorbed hydrogen atoms meeting and combining increases, which is beneficial for the Tafel step[22]. However, an excessively high coverage will occupy a large number of active sites, inhibiting the Volmer step and thus reducing the overall reaction rate.

Alkaline media

In alkaline media, the HER pathway also includes the Volmer, Heyrovsky and Tafel steps [Figure 1]. The Volmer step under alkaline conditions is H2O + e- → Hads + OH-[22,46], which is the rate-controlling step; its reaction energy barrier is higher than that of the Volmer step in acidic media. By introducing metal oxide supports with oxygen vacancies[47], the adsorption and activation ability of H2O can be enhanced, and the energy barrier of the Volmer step can be lowered. Oxygen vacancies[47], as Lewis acid sites, can attract H2O molecules and promote the breaking of the H-OH bond. The reaction mechanisms of the Heyrovsky and Tafel steps in alkaline media are similar to those in acidic media. However, due to the presence of a large number of OH- in the alkaline environment, they will compete for the active sites on the catalyst surface, affecting the adsorption and reaction of H*. DFT calculations can help understand the influence of OH- ions and optimize the adsorption and desorption processes of H* by designing appropriate catalyst structures to promote the progress of these two steps.

Neutral media

In neutral media, the overall HER is also 2H2O + 2e- → H2 + 2OH-[48,49]. However, due to the lack of a large number of H+ or OH-, its reaction mechanism is more complex. Under neutral conditions, the reaction starts with the adsorption and dissociation of water molecules on the surface of Rh-based catalysts. DFT calculations show that the surface properties of the catalyst have a significant impact on the adsorption mode and adsorption energy of water molecules[50]. On the surface of Rh nanoparticles with specific crystal planes, water molecules can be adsorbed in a specific orientation, reducing the energy barrier for dissociation. In addition, introducing suitable support or doping atoms can change the electronic structure of the catalyst surface, promoting the adsorption and dissociation of water molecules. The adsorption and reaction of the dissociated hydrogen atoms on the catalyst surface determine the subsequent reaction pathway. Similar to acidic and alkaline media, appropriate adsorption energy is crucial for efficient hydrogen evolution. DFT calculations can predict the adsorption energy of different-structured Rh-based catalysts for hydrogen atoms. By optimizing the catalyst structure, the balance between adsorption and desorption can be achieved, promoting the progress of the HER. Through DFT calculations, the microscopic mechanism of the HER on Rh-based catalysts under different pH conditions can be comprehensively understood, providing a solid theoretical basis for the design of efficient Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts.

Hydrogen evolution mechanisms of Rh-based catalysts

The HER in water electrolysis has been a focal point in energy catalysis, with the mechanism of catalysts varying significantly across different electrolyte environments. Rh-based catalysts exhibit distinct catalytic behaviors in acidic, alkaline and neutral media, influenced by the ionic composition and proton transport properties of the medium, which profoundly affect reaction pathways and kinetics.

Acidic media

In acidic electrolytes (e.g., H2SO4 or HCl solutions), the HER on Rh-based catalysts proceeds with protons (H+) as the primary substrate, following the classical Volmer-Heyrovsky or Volmer-Tafel pathways[46]. The reaction initiates with the Volmer step, where H+ gains an electron on the catalyst surface to form H*. This process relies on Rh's d-band electronic structure to maintain moderate adsorption energy for H*-too strong adsorption blocks active sites, while too weak adsorption leads to rapid desorption of intermediates. The subsequent Heyrovsky step involves H* combining with H+ in the solution to generate H2, facilitated by the high proton concentration and efficient proton transport in acidic media, which accelerates kinetics. When H* coverage is high, the Tafel step (direct recombination of two H*) may dominate.

Alkaline media

The HER mechanism in alkaline environments (e.g., KOH solutions) is more complex, with water as the substrate and hydroxide (OH-) participation introducing unique kinetic features[46]. Water dissociation becomes the rate-determining step, featuring a significantly higher energy barrier than proton reduction in acidic media. Initially, water dissociates on the Rh surface into adsorbed OH* and H*, with the barrier of this step directly determining catalyst activity. The subsequent Volmer step generates H* through proton supply from water or hydronium ions, while the Heyrovsky step releases H2 via H* reacting with water, regenerating OH*. Notably, OH- adsorption on Rh exhibits dual effects: moderate adsorption promotes water dissociation via an “OH--assisted mechanism”, whereas excessive adsorption poisons active sites. Although Rh shows better oxidative stability in alkaline media than in acidic conditions, lattice distortion during long-term electrolysis can still cause activity decay, making interface engineering and structural regulation essential for enhancing stability.

Neutral media

HER in neutral media (e.g., phosphate buffer solutions (PBS) or natural water) combines features of both acidic and alkaline systems but faces dual challenges of low water dissociation and poor proton transport, leading to significantly slower kinetics[51-53]. The reaction starts with direct water dissociation into H* and OH*, requiring high energy due to the lack of high-concentration H+ or OH- assistance, thus necessitating specific active sites on the catalyst surface for water activation. Proton transfer relies on water cluster collaboration or trace H+ in solution, acting as one of the rate-determining steps. In such media, optimizing catalyst hydrophilicity and proton transport pathways is crucial.

COMPUTATIONAL MODELS AND CATALYST DESIGN OF RH-BASED CATALYSTS

Computational models

In the theoretical research of the electrocatalytic HER, the synergistic application of the computational hydrogen electrode model (CHE), the potential-correction model, and the solvation-effect model can quantitatively predict the activity trend of catalysts and reveal the reaction mechanism[54].

The computational model for Rh-based catalysts in the HER mainly predicts the catalytic activity through the synergistic simulation of the free energy of chemical adsorption (ΔGH*)[55], the potential effect, and the solvation effect. Based on the CHE, ΔGH* can be obtained by calculating the adsorption energy of hydrogen intermediates (H) on the catalyst surface using DFT, and combining it with the zero-point energy correction (ΔEZPE) and the entropy-change term (TΔSH* ≈ -0.20 eV)[56]. Its ideal value should be close to 0 eV to achieve the balance between the Volmer step and the Heyrovsky/Tafel steps. To simulate the actual electrochemical environment, a potential model needs to be introduced. The influence of the applied potential (U) is incorporated into the calculation of ΔGH* through the charge-extrapolation method or work-function correction, which can be expressed as ΔGH(U) = ΔGH*(0) + eU[57], where the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) is often used as a reference benchmark. In addition, the solvation effect corrects the interface charge distribution and adsorption energy through an implicit solvation model (such as Vienna ab initio Software Package (VASP))[58] or an explicit water-molecule layer to more realistically reflect the catalytic behavior in an aqueous-solution environment. During the calculation, the Rh(111) surface or nanoclusters are usually used as models to optimize the configuration of H* at different adsorption sites (such as top sites, bridge sites, and vacancy sites)[59], and the influence of the electronic structure on the activity is analyzed in combination with the-band center theory. However, the parameter sensitivity of the solvation model, the dynamic interface effect (requiring molecular dynamics simulation), and the strain and ligand effects of multi-component Rh-based catalysts (such as alloys or single-atom-dispersed systems) still need further optimization[40,60-62]. These theoretical methods provide important guidance for the design of Rh-based HER catalysts, but need to be verified against experimental characterization to improve the prediction reliability.

Influence factor

The theoretical computational models for Rh-based HER catalysts are influenced by multiple factors including pH[63], hydrogen coverage[64] and applied electric field effects[65]. These factors collectively regulate the catalytic activity and reaction mechanisms through complex interactions. Variations in pH directly affect the proton supply mechanism and double-layer structure at the electrode/electrolyte interface. In acidic media, HER primarily proceeds via H3O+ reduction, while in alkaline conditions, it relies on water dissociation processes. This difference leads to an increase in ΔGH* with rising pH, rendering the Volmer step the rate-limiting step in alkaline environments. Additionally, competitive adsorption of OH- under high pH conditions further occupies active sites, necessitating explicit consideration in solvation models.

Changes in hydrogen coverage (θH) significantly alter ΔGH* values through site-blocking effects and H-H repulsion. Stronger hydrogen adsorption occurs at low coverage, but adsorption energy gradually increases with higher θH. This nonlinear relationship typically optimizes HER activity at moderate coverage levels. Notably, excessive θH not only inhibits further hydrogen adsorption but may also induce surface reconstruction or phase transitions, critically influencing catalyst stability. The applied electric field modulates catalytic performance by directly modifying ΔGH* and altering interfacial electronic structures, cathodic potentials stabilize hydrogen adsorption, while anodic potentials weaken adsorption strength. Furthermore, strong electric fields induce solvent molecule alignment and interfacial charge redistribution, effects that require accurate description via self-consistent charge calculations or constant-potential DFT calculations.

Under practical reaction conditions, these factors often couple synergistically: OH- in high-pH environments may oxidize under strong electric fields to block active sites, while high hydrogen coverage partially screens electric field effects on adsorption energy. Comprehensive understanding of these interactions demands integrating first-principles calculations with multiscale simulation approaches, validated by in situ spectroscopic techniques and microkinetic modeling. This integrated strategy enables the establishment of precise theoretical frameworks to guide the design and optimization of Rh-based HER catalysts.

Descriptors

Overview of descriptors

In the study of HER mechanisms for Rh-based catalysts using DFT, descriptors serve as critical bridges linking the microscopic structure of catalysts to their macroscopic catalytic performance. Through the analysis of descriptors, researchers can rapidly screen potential high-activity catalysts, gain deep insights into catalytic reaction mechanisms, and establish theoretical guidelines for the rational design of catalysts. Common descriptors relevant to Rh-based HER catalysts include ΔGH*, d-band center, and charge transfer quantities[66].

Key descriptors and their applications

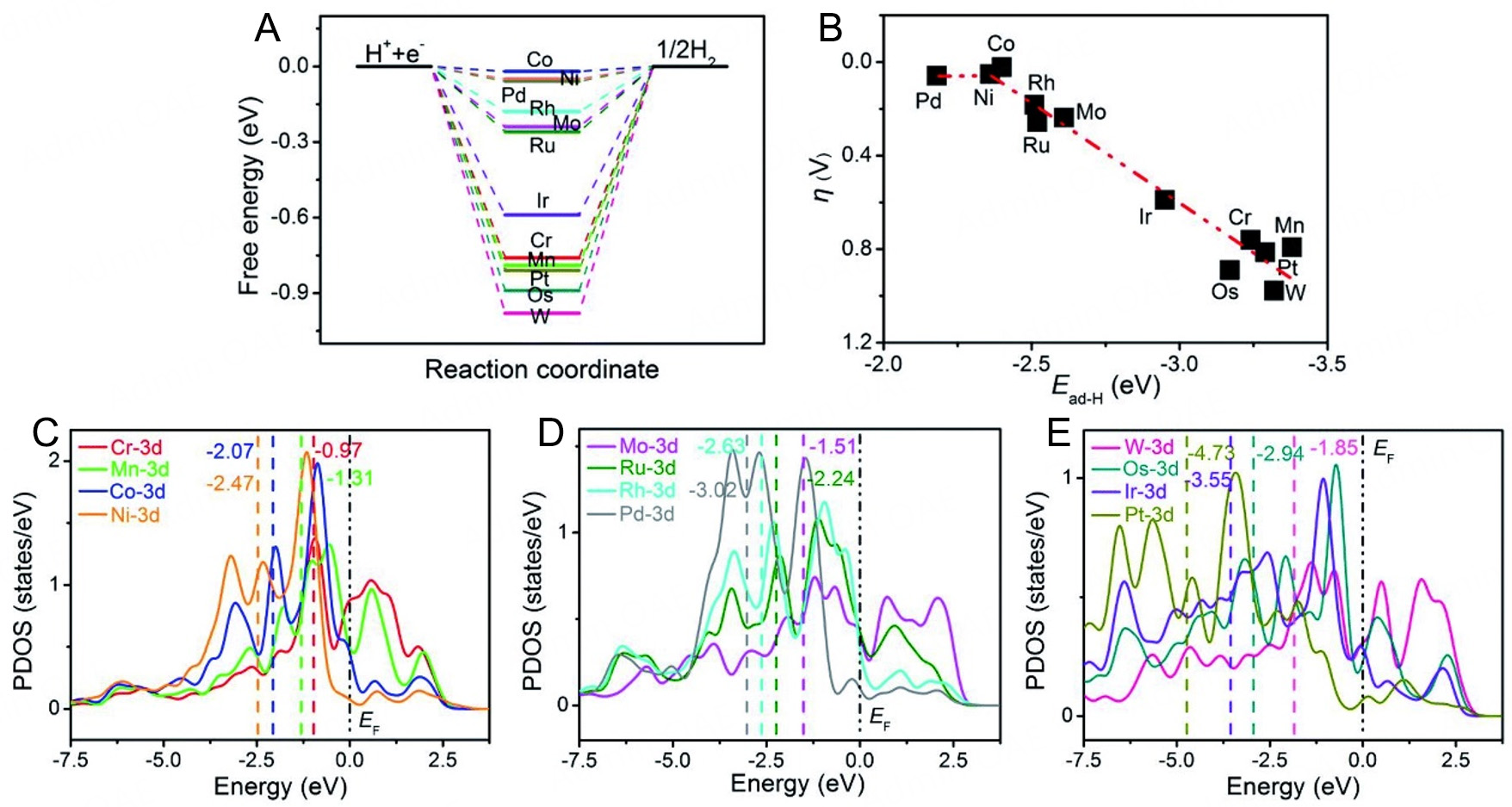

Hydrogen adsorption free energy (ΔGH*): ΔGH* is widely recognized as a critical descriptor for evaluating the activity of hydrogen evolution catalysts. Ideally, ΔGH* should approach zero[67], indicating that the catalyst exhibits neither overly strong nor weak hydrogen adsorption, thereby facilitating efficient adsorption and desorption of hydrogen atoms on the catalyst surface to promote HER [Figure 2A and B][68,69]. Through DFT calculations, Fang et al.[70] demonstrated that Rh single atoms (SAs) supported on specific substrates exhibit exceptional HER activity. They simulated the dispersion of various transition metal SAs on a C30N12Se6H12 matrix (denoted as TM@CNSeH) and evaluated hydrogen adsorption strength using ΔGH* as the descriptor. The resulting 2D and three-dimensional (3D) volcano plots revealed that HER activity peaks near the volcano summit. Notably, Rh SAs dispersed on the C30N12Se6H12 matrix exhibited the highest HER activity. This approach enables targeted design of efficient Rh-based HER catalysts by optimizing ΔGH*.

Figure 2. (A) Gibbs free energy diagram of the HER on TM-doped BNTs. (B) The volcano relationship between the Ead of H and the overpotential of HER on TM-doped BNTs. (C-E) The partial density of states (PDOS) of the transition metal-doped BNTs. This figure is reproduced from Ref.[69] with permission. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry.

d-band center: The d-band center theory, proposed by Hammer and Nørskov[71], provides a robust framework for understanding the adsorption and catalytic properties of transition metal catalysts. For Rh-based catalysts, the position of the d-band center governs the interaction strength between the catalyst and reactants. When the d-band center lies closer to the Fermi level, the interaction between the catalyst and hydrogen atoms strengthens, enhancing hydrogen adsorption[72]. However, an excessively high d-band center may result in overly strong hydrogen adsorption, impeding hydrogen desorption. DFT calculations enable precise tuning of the d-band center by modifying the composition and structure of Rh-based catalysts. For example, in Rh-based single-atom catalysts, altering the coordination environment of the central Rh atom allows fine control of the d-band center [Figure 2C-E][69,70], thereby optimizing catalytic performance for HER.

Charge transfer amount: The charge transfer amount describes the degree of charge transfer between the catalyst and reactants during a catalytic reaction. In Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts, the amount of charge transfer is closely related to the activity of the catalyst.

Descriptor-guided catalyst design strategies

Composition modulation: Optimizing the catalytic performance of Rh-based catalysts by tuning their composition based on the relationship between descriptors and catalytic properties. For instance, to achieve ΔGH* close to zero, suitable metals can be alloyed with Rh, or specific dopants can be introduced into Rh-based catalysts. Additionally, selecting supports with appropriate electronic properties (e.g., carbon materials, metal oxides) can regulate the electronic structure and descriptors of Rh-based catalysts through interfacial interactions, thereby improving the catalytic performance[18,73,74].

Structural optimization: Guiding the microstructural design of Rh-based catalysts using DFT calculations. Constructing Rh nanoparticles with specific crystallographic facets (e.g., high-index facets) adjusts the arrangement of surface atoms, modifies the d-band center position, and redistributes hydrogen adsorption sites, thereby optimizing HER performance[75]. Research demonstrates that Rh nanoparticles with high-index facets exhibit unsaturated coordination of surface atoms, unique electronic structures, and enhanced adsorption properties, leading to significantly improved HER activity[12]. Furthermore, designing nanoporous Rh-based architectures increases the specific surface area, maximizes active site exposure, and facilitates reactant adsorption and reaction[76].

Interface engineering: Constructing efficient interfaces in Rh-based composite catalysts is a critical strategy for boosting catalytic performance[77-79].

Interface engineering involves tailoring interactions at the atomic or molecular level between different components, which can include:

Heterostructure formation: Coupling Rh with metals, metal oxides/hydroxides, or carbon-based supports creates electronic interactions and charge redistribution at the interface, enhancing adsorption/desorption kinetics of reaction intermediates.

Strain and defect introduction: Interfacial strain or defects can induce lattice distortions and improved mass/charge transport, accelerating reaction dynamics.

Chemical bonding at interfaces: Covalent or coordination bonds between metal centers and heteroatom-doped carbon frameworks (e.g., Fe/Rh-anchored nitrogen-doped carbon hollow spheres (NCS)[58]) can synergistically modulate electronic structures, generate additional active sites, and stabilize reaction intermediates.

These interfacial modifications influence catalytic performance by:

Tuning electronic structures: Adjusting the d-band center of Rh or the electronic density of carbon/oxide supports, thereby optimizing adsorption energies of key intermediates.

Generating synergistic effects: Combining the advantages of different materials (conductivity of carbon, activity of metals, stability of oxides) to achieve performance superior to individual components.

Enhancing stability and durability: Reducing catalyst aggregation, leaching, or surface reconstruction to improve long-term operation under harsh conditions.

Practically, descriptor-guided strategies link interfacial structural or electronic properties (e.g., strain, charge density, coordination number) with catalytic activity[80-82], enabling rational design. Combining theoretical calculations with operando characterization facilitates identification of active sites and the precise role of interfaces, as demonstrated in Rh-carbon and Rh-metal oxide composites. Examples include tuning interfacial charge transfer in Rh-carbon composites to optimize hydrogen adsorption/desorption and introducing oxygen vacancies at Rh-oxide interfaces to promote water dissociation, thereby generating more reactive hydrogen species.

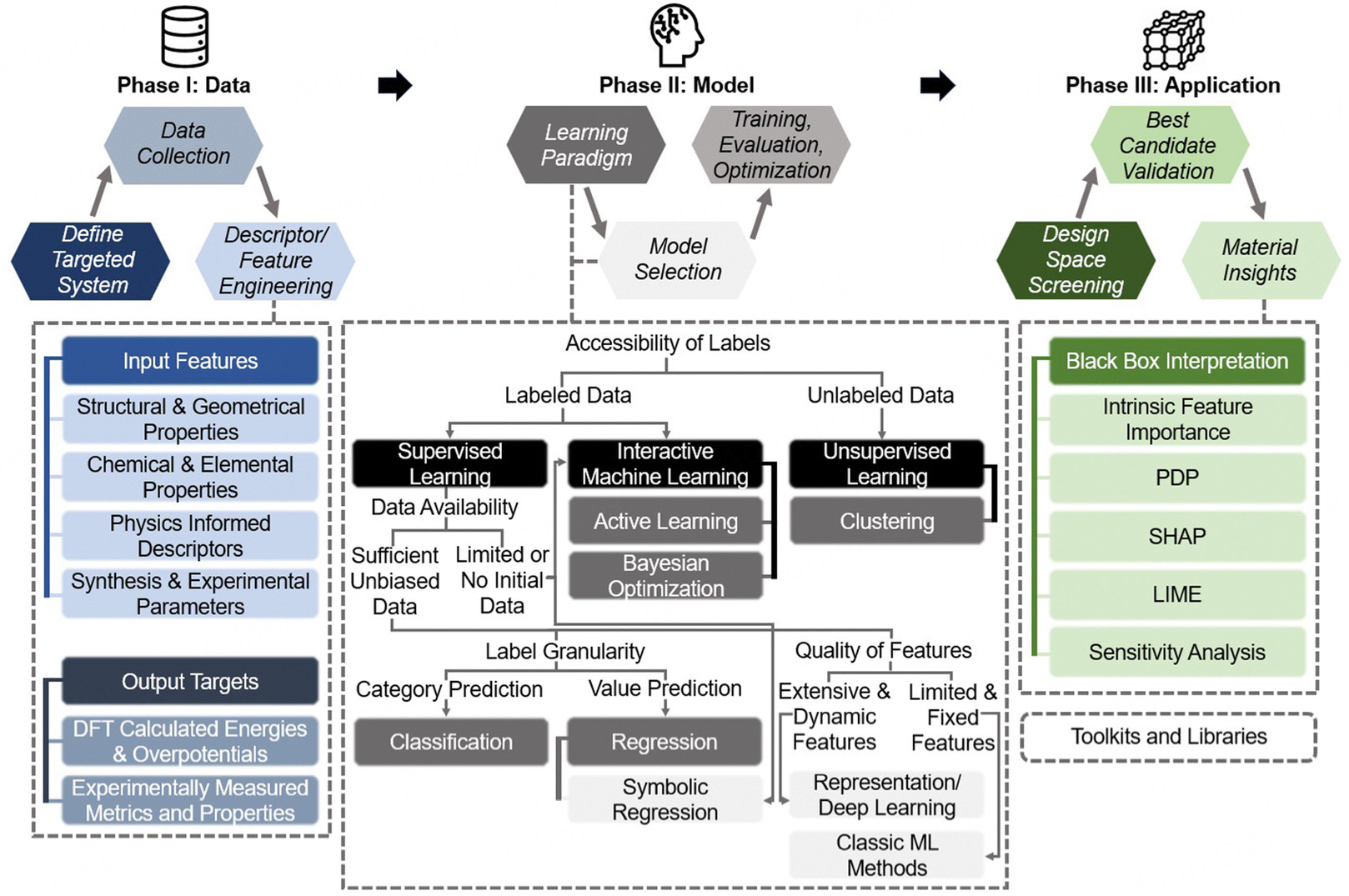

Machine learning-assisted catalyst design and screening

There are huge challenges in balancing catalytic activity (such as low overpotential), long-term stability (such as resistance to electrochemical corrosion), and cost control (reducing the loading of precious metal Rh). By integrating multi-source data (such as experimentally measured overpotential, Tafel slope, cyclic voltammetry data, as well as the ΔGH* calculated by DFT, surface electron density of states, energy barriers at alloying sites, etc.), machine learning can construct a cross-scale “structure-performance” prediction model, providing key theoretical guidance for catalyst design. The workflow of high-throughput computational screening is shown in Figure 3[83]. Therefore, machine learning has opened up an efficient and accurate data-driven path for the design and screening of Rh-based HER catalysts. For example, a model based on a graph neural network (GNN) can analyze the regulation mechanism of the local coordination environment (such as Rh-N4, Rh-S3, etc.) of Rh single-atom catalysts (Rh-SACs) on ΔGH*, while Gaussian process regression (GPR)[84] is suitable for predicting the synergistic catalytic effect of Rh-based alloys (such as Rh-Fe, Rh-Mo) with small sample data. To address the bottleneck of scarce data for Rh-based catalysts, transfer learning can leverage the known structure-activity relationships of Pt-based or transition metal sulfide catalysts and apply them to the Rh-based system[83,85,86]. Complemented by an active learning strategy to generate high-value data in a targeted manner, it significantly reduces the dependence on experimental/computational resources. In addition, multi-objective optimization algorithms (such as Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II), Bayesian optimization) can simultaneously balance the objectives of activity, stability, and cost, guiding the design of innovative systems such as core-shell structures[87,88], high-entropy alloys (diluting the Rh content)[47,89], or support interface engineering (such as Rh/MXene, Rh/N-doped carbon)[90]. Studies have shown that the Rh-Co dual-atom catalyst screened by machine learning has an overpotential[83], and its cyclic stability is increased by more than 5 times compared with pure Rh, verifying the feasibility of the data-driven strategy. In the future, a closed-loop design system that integrates cross-scale modeling (from atomic adsorption to macroscopic reaction kinetics), automated high-throughput experimental platforms (robot synthesis and in-situ characterization), and sustainability assessment (life cycle analysis) will accelerate the transformation of Rh-based HER catalysts from laboratory exploration to industrial application, providing key technical support for the large-scale preparation of green hydrogen and the achievement of the carbon neutrality goal.

Figure 3. Framework for machine learning-assisted electrocatalyst design. Reproduced with permission, Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry[83].

In conclusion, in-depth research on the descriptors of Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts using DFT calculations, combined with catalyst design based on these descriptors, provides theoretical support for developing high-performance Rh-based catalysts. These efforts can offer new insights and help advance HER technology.

ADVANTAGES OF RH-BASED CATALYSTS FOR HER

Activity aspects

Rh has unique advantages in catalytic applications for the HER. Although it has been studied less compared to Pt or Ru, it exhibits significant performance potential under specific conditions. The following includes the main advantages of Rh in HER.

Moderate hydrogen adsorption energy (ΔGH*)

The hydrogen adsorption energy is a key parameter determining hydrogen evolution activity. An ideal catalyst should have a hydrogen adsorption energy (ΔGH*) close to thermodynamic neutrality (ΔGH* ≈ 0 eV) to achieve rapid equilibrium between adsorption and desorption. Evidence from DFT calculations: The ΔGH* of the (111) crystal plane of pure Rh is approximately -0.12 eV, which is slightly stronger than that of Pt ((111) ΔGH* ≈ -0.09 eV). However, it can be further optimized through alloying or nanostructure design. For example, in the Rh3Cu1 alloy[91], electron transfer from Cu to Rh leads to an upshift of the Rh d-band center, thereby optimizing the ΔGH* and facilitating both adsorption and desorption of hydrogen intermediates. The synergistic electronic modulation between Rh and Cu effectively balances the adsorption strength of H*, significantly lowering the energy barrier for HER. As a result, the defect-rich RhCu nanotubes with the Rh3Cu1 phase exhibit superior HER performance across a wide pH range, achieving a small overpotential of

Excellent electrochemical active surface area (ECSA)

An excellent Electrochemical Active Surface Area (ECSA) is a key performance metric for Rh-based HER catalysts because it reflects the actual number of accessible active sites rather than just geometric area. Nanostructuring (nanowires, concave/tetrahedral nanoparticles, porous supports) and clean-surface synthesis routes dramatically increase the ECSA of Rh materials[37,92,93], leading to higher mass activity and lower overpotentials. For example, ultrathin wavy Rh nanowires show extremely large ECSA and correspondingly high mass activities[93], while concave/curved Rh nanoparticles and Rh nanocrystals supported on porous graphdiyne (GDY) exhibit substantially enhanced double-layer capacitance (Cdl)-derived ECSA and superior HER performance in acid[37].

Efficient water dissociation ability (in alkaline conditions)

In the alkaline HER, the dissociation of water molecules (Volmer step) is the rate-controlling step of the reaction, and Rh-based catalysts can significantly reduce the water dissociation energy barrier. DFT calculations systematically reveal the intrinsic advantages of Rh-based catalysts in the HER from the aspects of electronic structure and energy evolution. The unique d-electron configuration of Rh makes its d-band center close to the Fermi level and moderately distributed. It can effectively adsorb hydrogen intermediates (H*) while avoiding the increase in desorption energy barrier caused by overly strong adsorption, thus occupying a nearly optimal activity interval in the “volcano curve”. Through the alloying strategy, DFT simulations show that the introduction of inexpensive metals can induce lattice strain and electron redistribution in Rh, synergistically regulating the surface charge environment and significantly optimizing the ΔGH* to be close to the thermoneutral value. In addition, the interface engineering of Rh-based catalysts, through the electronic coupling between the support and the active center, can simultaneously enhance the charge transfer efficiency and inhibit surface oxidation and corrosion, providing a theoretical basis for high stability.

Stability aspects

Rh-based catalysts can undergo surface reconstruction under reaction conditions, forming dynamic active sites and avoiding activity decay caused by intermediate poisoning. DFT dynamic simulation: In the alkaline HER, metastable Rh-OH species (adsorption energy ≈ -0.3 eV) will form on the surface of Rh nanoparticles. Through periodic DFT simulations, it is found that these species can be rapidly regenerated through a water-assisted proton exchange mechanism (Rh-OH + H2O → Rh-H* + OH-), maintaining a highly active surface. Lattice distortion effect[94]: The grain boundaries of ultrafine Rh nanoparticles (~2 nm) induce lattice strain. DFT calculations confirm that the d-band broadening in the strained region enhances the adsorption-desorption cycle stability of H* (activity decay rate < 5%/100 h). In summary, Rh-based catalysts are significantly superior to traditional Pt-based or transition metal-based catalysts in terms of hydrogen evolution activity due to their moderate ΔGH*, high ECSA, efficient water dissociation ability, and dynamic stability. Combining rational design based on DFT calculations (such as alloying and interface engineering) can further break through the activity limit and promote their application in industrial water electrolysis devices.

Economic aspects

Although Rh is one of the most expensive materials among precious metals (the price of Rh was approximately ten times that of Pt in 2023), its potential low-cost substitution in HER catalysis can be achieved through multi-dimensional strategies[35,60,95,96]. In alkaline conditions, the performance advantages of Rh-based catalysts are particularly significant. To further reduce the absolute amount of Rh used, nanostructure engineering is crucial. By designing Rh nanowires, Rh metallene, or ultrathin two-dimensional (2D) materials[76,97,98], the density of active sites can be increased compared with traditional particulate catalysts, reducing Rh loading in a single cell from the milligram to the microgram level. For instance, by anchoring Rh nanocrystals on porous GDY, a minimal Rh loading of only ~0.244 wt% is sufficient to achieve excellent HER performance[37]. DFT studies indicate that the high-activity stepped surfaces and GDY-induced d-band modulation of active sites effectively accelerate both water dissociation and hydrogen recombination. As a result, this catalyst delivers a low overpotential of 65 mV at a high current density of 1,000 mA cm-2, demonstrating that even with ultralow Rh usage, high catalytic efficiency can be maintained. Such a combination of ultralow noble-metal content, high activity, and structural stability highlights a promising strategy to reduce Rh consumption while preserving HER performance, offering clear economic advantages for large-scale hydrogen production. Moreover, the recovery of precious metals plays a pivotal role in determining the total cost of ownership. Currently, Rh recovery rates can exceed 95%[99]. By combining ultralow Rh loadings, high intrinsic activity, excellent long-term stability, and closed-loop metal recovery, Rh-based catalysts emerge as a viable solution for hydrogen production in high-value or harsh-environment applications.

TYPES OF RH-BASED HYDROGEN EVOLUTION CATALYSTS

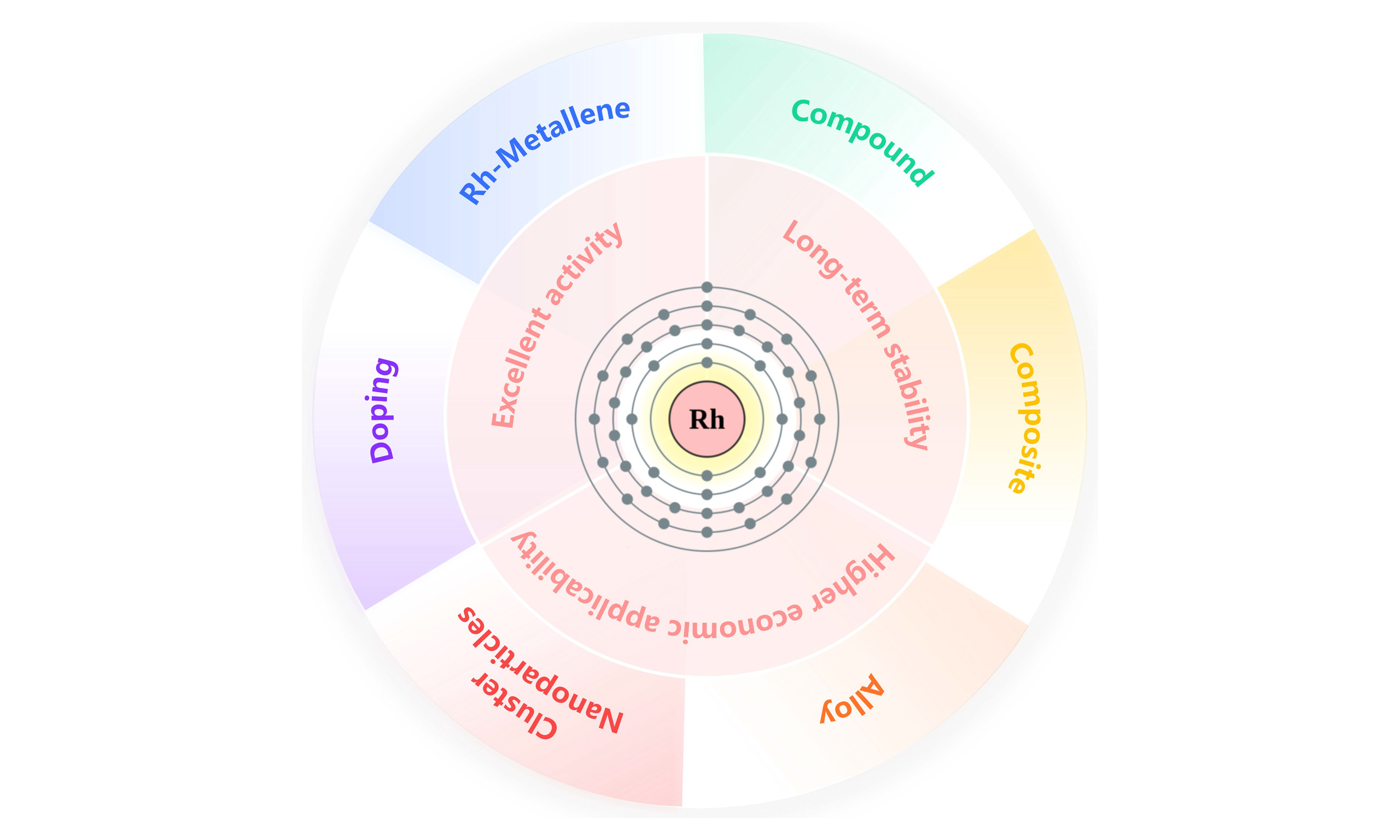

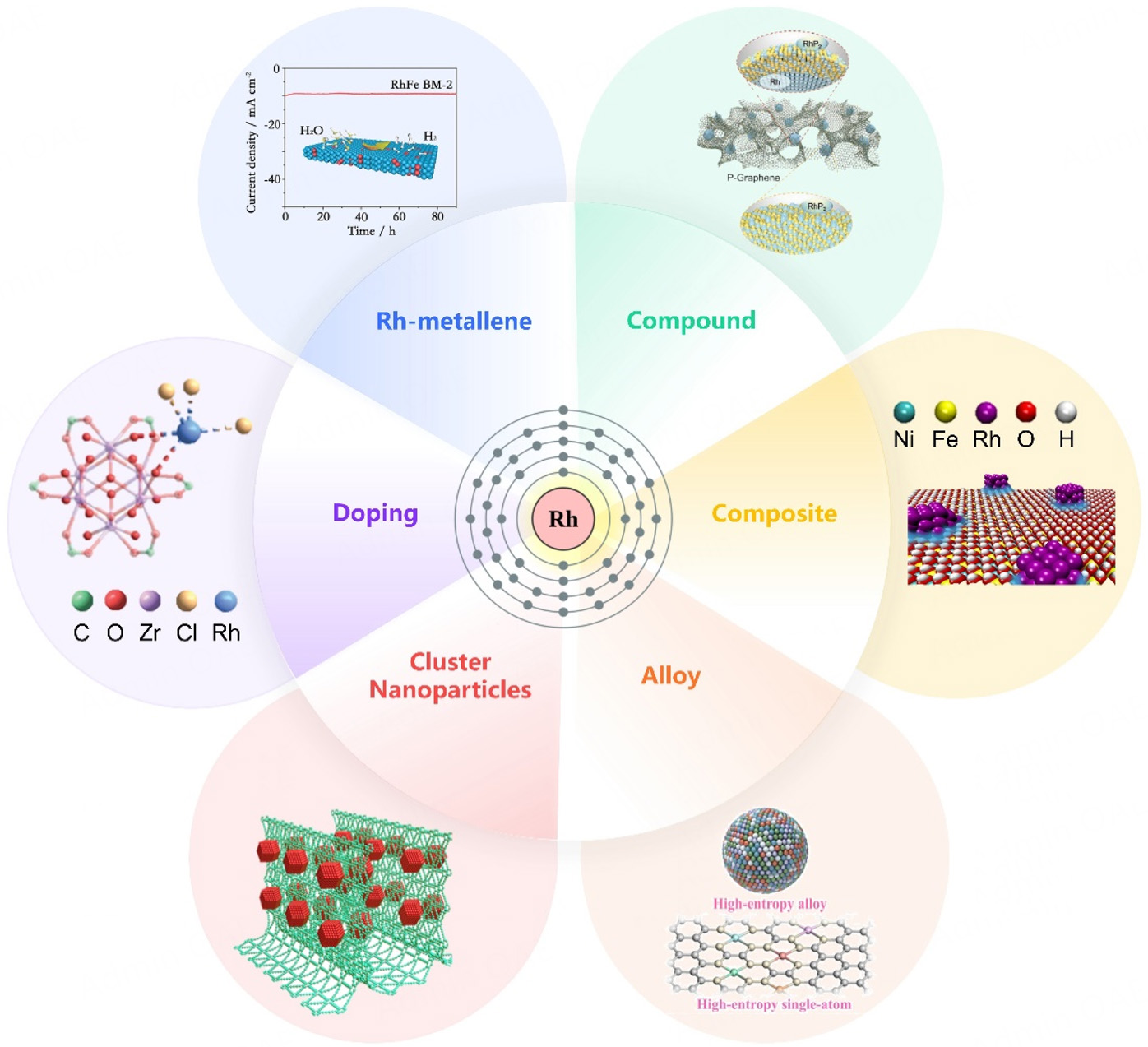

Rh-based nanomaterials exhibit great potential in the electrochemical HER due to their unique electronic structures and excellent catalytic properties. Through component regulation, structural design, and interface engineering, significant progress has been made in Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts in terms of reducing overpotential, improving stability, and enhancing intrinsic activity. In recent years, researchers have further optimized Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts from the aspects of atomic-level modification[58,100], as well as modification of graphene-like[76,101], cluster-like[6], and nanoparticle-type Rh-based materials[33,37], alloying[91,95], composite structure design[87,102], and support design[98,103] [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Classification of Rh-based HER catalysts[37,95,100-103]. Doping is reproduced from Ref.[100] with permission. Copyright 2022, Wiley. Rh-metallene is reproduced from Ref.[101] with permission. Copyright 2022, Wiley. Compound is reproduced from Ref.[103] with permission. Copyright 2023, Wiley. Composite is reproduced from Ref.[102] with permission. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. Alloy is reproduced from Ref.[95] with permission. Copyright 2024, Springer. Cluster is reproduced from Ref.[37] with permission. Copyright 2022, Springer.

Atomic-level modification

In the research of Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts, single-atom catalysts and heteroatom-doped catalysts have shown unique performance advantages, providing new ideas and methods for improving the activity, selectivity, and stability of the catalysts.

Single-atom Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts

Single-atom Rh catalysts precisely anchor isolated Rh atoms on the surface of the support, constructing highly uniform active centers. This unique atomic-level dispersion structure not only avoids the agglomeration problem of traditional nanocatalysts but also achieves precise regulation of the electronic structure through the strong interaction between the metal and the support. Under the action of the coordination environment, the electrons in the d orbitals of Rh atoms are rearranged, making the electron cloud distribution reach the optimal state, thus significantly enhancing the catalytic activity and stability. This atomic-level dispersion structure endows single-atom Rh catalysts with extremely high atomic utilization efficiency. Different from traditional nanoparticles where only surface atoms participate in the reaction, the single-atom configuration makes each Rh atom an effective active site. Through the rational design of the support material, excellent catalytic performance can be achieved with an extremely low loading of precious metals, providing new ideas for the development of resource-saving catalysts.

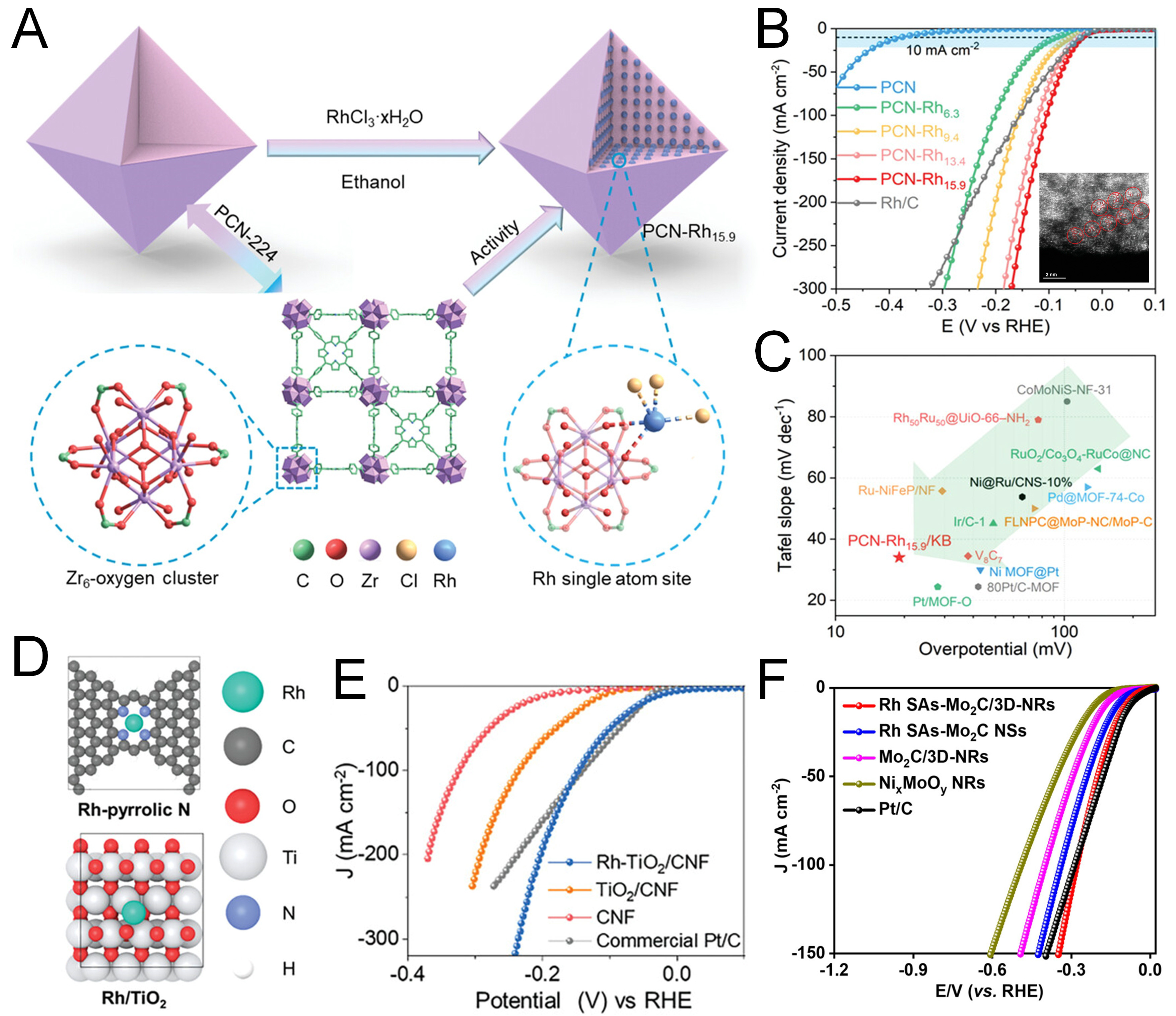

The core advantage of single-atom Rh catalysts lies in their unique coordination environment and electronic structure. The chemical bonding between the support and Rh atoms not only stabilizes the active center but also optimizes the adsorption behavior of reaction intermediates through the electron transfer effect. This precise regulation at the atomic scale enables the catalyst to maintain high activity while exhibiting excellent anti-poisoning ability and environmental adaptability, opening up new avenues for catalytic applications under complex conditions. For example, Dong et al.[100] prepared a Rh-SAC with high accessibility by loading it on the metal nodes of metal-porphyrin-based PCN metal-organic frameworks (MOFs, PCN-224) as supporting material. Notably, the PCN-Rh15.9/Ketjenblack (KB) catalyst with a high Rh content (15.9 wt%) showed excellent hydrogen evolution activity. It could reach a current density of 10 mA cm-2 at a low overpotential of 25 mV and had a mass activity of 7.7 A mg-1 Rh at an overpotential of 150 mV, far superior to the commercial Rh/C catalyst [Figure 5A-C]. Various characterizations indicated that the metal nodes with O/OHx in MOFs stabilized the Rh species, which is crucial for high loading and good activity[100]. In addition, the catalyst also showed satisfactory performance and excellent long-term stability in acidic seawater, indicating its broad application prospects in hydrogen production from seawater. Logeshwaran et al.[40] used electrospinning technology to achieve the spontaneous integration of Rh SAs on carbon nanofibers embedded with TiO2 [Figure 5D and E]. The obtained Rh-TiO2/carbon nanofibers (CNF) showed great potential as an innovative and effective electrocatalyst for HER. DFT analysis highlighted the key role of the binary-type Rh SAs promoted by the TiO2 sites. In a single-cell setup, Rh-TiO2/CNF reached an industrial-grade current density of 1 A cm-2 and exhibited extended durability of 225 h. Doan et al.[73] engineered a composite catalyst by anchoring Rh SAs onto interconnected Mo2C nanosheets, which were tightly integrated within a 3D NixMoOy nanorod array framework. This unique structure synergistically modulated the electrocatalytic properties of Mo2C, enabling broad pH adaptability and exceptional durability[73]. Remarkably, the catalyst delivered HER performance rivaling that of commercial Pt/C. Under a current density of 10 mA cm-2, it exhibited impressively low overpotentials of 31.7 mV in acidic, 109.7 mV in neutral, and 95.4 mV in alkaline media, along with favorable Tafel slopes of 42.4, 51.2, and 46.8 mV dec-1, respectively [Figure 5F][73].

Figure 5. (A) Synthesis process and the coordination environment of single Rh atom on metal nodes of PCN. (B) LSV curves of various catalysts in 0.5 M H2SO4 at 1,600 rpm. Inset: HAADF-STEM images of PCN-Rh15.9. (C) Comparative analysis of overpotentials at

The core design concept of single-atom Rh catalysts lies in precisely anchoring individual Rh atoms onto the surface of the support to achieve atomic-level dispersion and electronic structure modulation. By selecting supports with abundant metal sites or heteroatom coordination, the Rh SAs can be effectively stabilized while enabling synergistic regulation of the interfacial electronic structure.

Heteroatom-doped Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts

Regulation of Electronic Structure and Active Sites: Heteroatom doping is to introduce other elements (such as transition metals, non-metallic elements, etc.) into Rh-based catalysts to change the electronic structure and the properties of active sites of the catalysts[18]. Different heteroatoms have different electronic structures and chemical properties, and their interactions with Rh atoms will lead to changes in the electron cloud density and electronic states around Rh atoms. For example, when some non-metallic elements with high electronegativity (such as N, P, S, etc.) are doped into Rh-based catalysts, these elements will attract the electrons around Rh atoms, causing the d-band center of Rh atoms to shift, thus adjusting the adsorption energy for hydrogen atoms[18]. In addition, the introduction of heteroatoms may also form new active sites on the catalyst surface, or change the structure and properties of the original active sites, further promoting the HER.

The synergistic effect between heteroatoms and Rh atoms is one of the key factors for the performance improvement of heteroatom-doped catalysts. In some cases, heteroatoms can act as co-catalysts and participate in the HER together with Rh atoms, improving the activity and selectivity of the reaction. For example, in Rh-based alloy catalysts, the doped transition metal atoms can form an alloy phase with Rh atoms, changing the electronic structure and surface properties of the alloy, thereby enhancing the ability to adsorb and activate hydrogen. In addition, the doping of heteroatoms can also improve the stability of the catalyst, inhibit the agglomeration and loss of Rh atoms[75], and extend the service life of the catalyst. This is because heteroatoms can form stable chemical bonds with Rh atoms, restricting the migration and aggregation of Rh atoms, thus maintaining the active structure of the catalyst.

In conclusion, single-atom and heteroatom doping are effective strategies for optimizing the performance of Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalysts. By regulating the electronic structure, active sites, and atomic utilization efficiency of the catalysts, etc., they provide important approaches for the development of high-performance hydrogen evolution catalysts. Future research can further explore the mechanisms of single-atom and heteroatom doping in depth, as well as how to achieve more efficient catalyst design and preparation. Table 1 presents the key performance parameters of recently reported single-atom Rh-based HER catalysts used in acidic and alkaline environments.

Summary of the HER activity of monoatomic Rh-based materials used in acid and alkaline solutions

| Catalyst | Activity (mV@mA cm-2) | Stability | Ref. | |

| Acid | Alkaline | |||

| Rh-TiO2/CNF | 24@10 | 225 h@1 A cm-2 | [40] | |

| Rh SAs-Mo2C/3D-NRs | 31.7@10 74.6@50 | 95.4@10 199.4@50 | 40 h@50 mA cm-2 | [73] |

| PCN-Rhx | 25@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [100] | |

| Rh-Co3S4/CoOx NTs | 56.1@10 124.2@50 | 40 h@50 mA cm-2 | [60] | |

| NiRh-Cu NA/CF | 12@10 123@150 | 30 h@50 mA cm-2 | [104] | |

| Cu/Rh(SAs) + Cu2Rh(NPs)/GN | 8@10 | 500 h@10, 50 and 100 mA cm-2 | [59] | |

| Rh@NG | 29@10 | 33@10 | 25 h@25 mA cm-2 | [105] |

| Fe/Rh-anchored NCS | 24@10 | [58] | ||

Rh-metallene catalysts

Metallene is a 2D material composed of a single layer or a few atomic layers of metal atoms, typically arranged in a periodic lattice structure, analogous to graphene[106]. Due to the behavior of delocalized electrons, metallene exhibits excellent electronic transport properties. Moreover, the undercoordinated surface atoms confer high catalytic activity, making metallene highly active in catalytic reactions[107]. Rh-metallene (Rhene) materials, as a new type of catalytic material, have the following main advantages: Firstly, their unique molecular structure endows Rhene with high surface activity and electron transfer efficiency, thus showing significant advantages in the HER. Secondly, this type of material usually has good stability and can work stably for a long time under strongly alkaline or strongly acidic conditions, meeting the requirement of the durability of catalysts for the water electrolysis reaction. Thirdly, the molecular structure of Rhene can be optimized in terms of performance through functional modification, and it has a high degree of controllability. In addition, this type of material can achieve efficient hydrogen and oxygen evolution at a low overpotential, making it an ideal choice in the fields of clean energy production. However, Rhene also has some significant disadvantages. Firstly, their preparation process is complex and the cost is high, which limits their large-scale application. Secondly, the catalytic activity of this type of material may be limited under certain specific conditions, and further optimization is needed to adapt to a wider range of reaction environments. Finally, since the catalytic mechanism of Rhene has not been fully elucidated, there are still theoretical bottlenecks in improving its performance and expanding its functions. In conclusion, although Rhene has broad application prospects in water electrolysis, achieving high efficiency at low cost, along with a deeper understanding of the catalytic mechanism, remains a key research direction for the future.

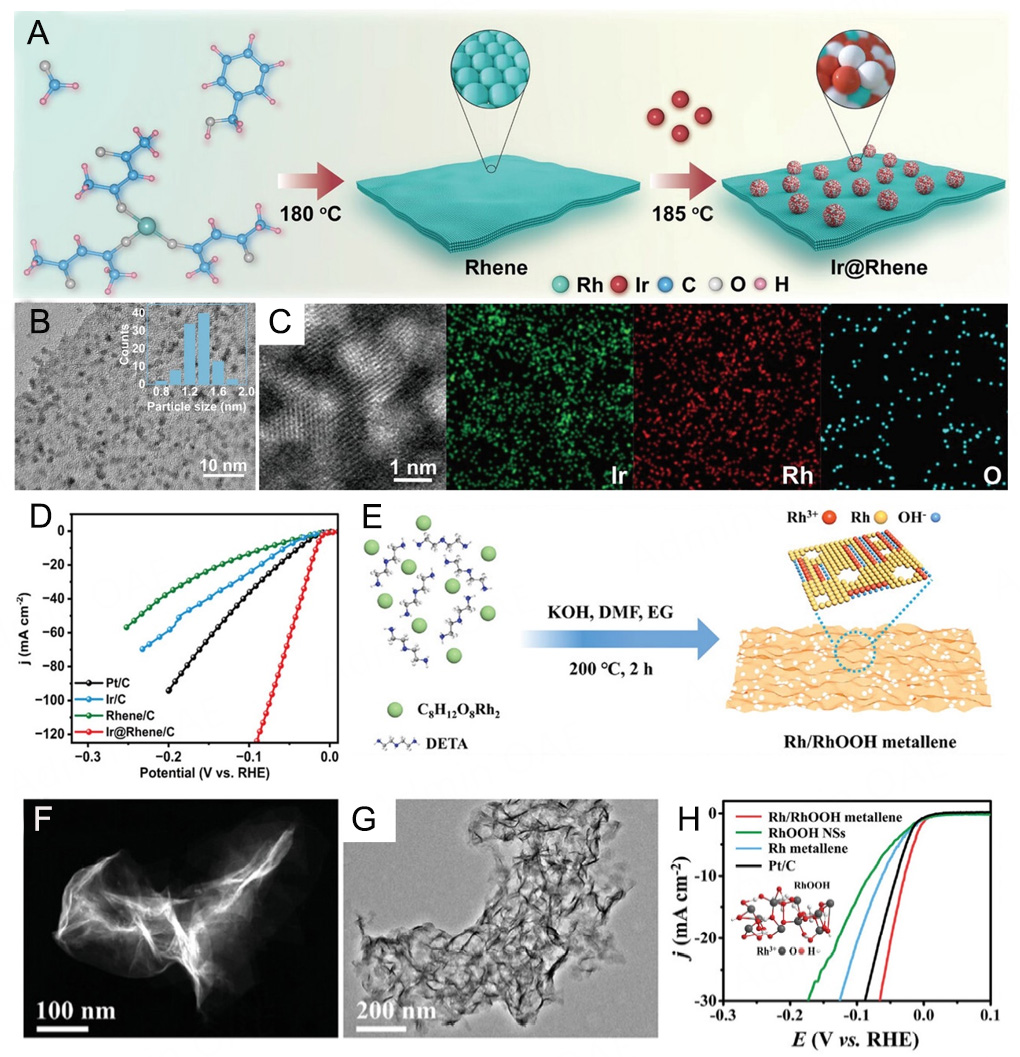

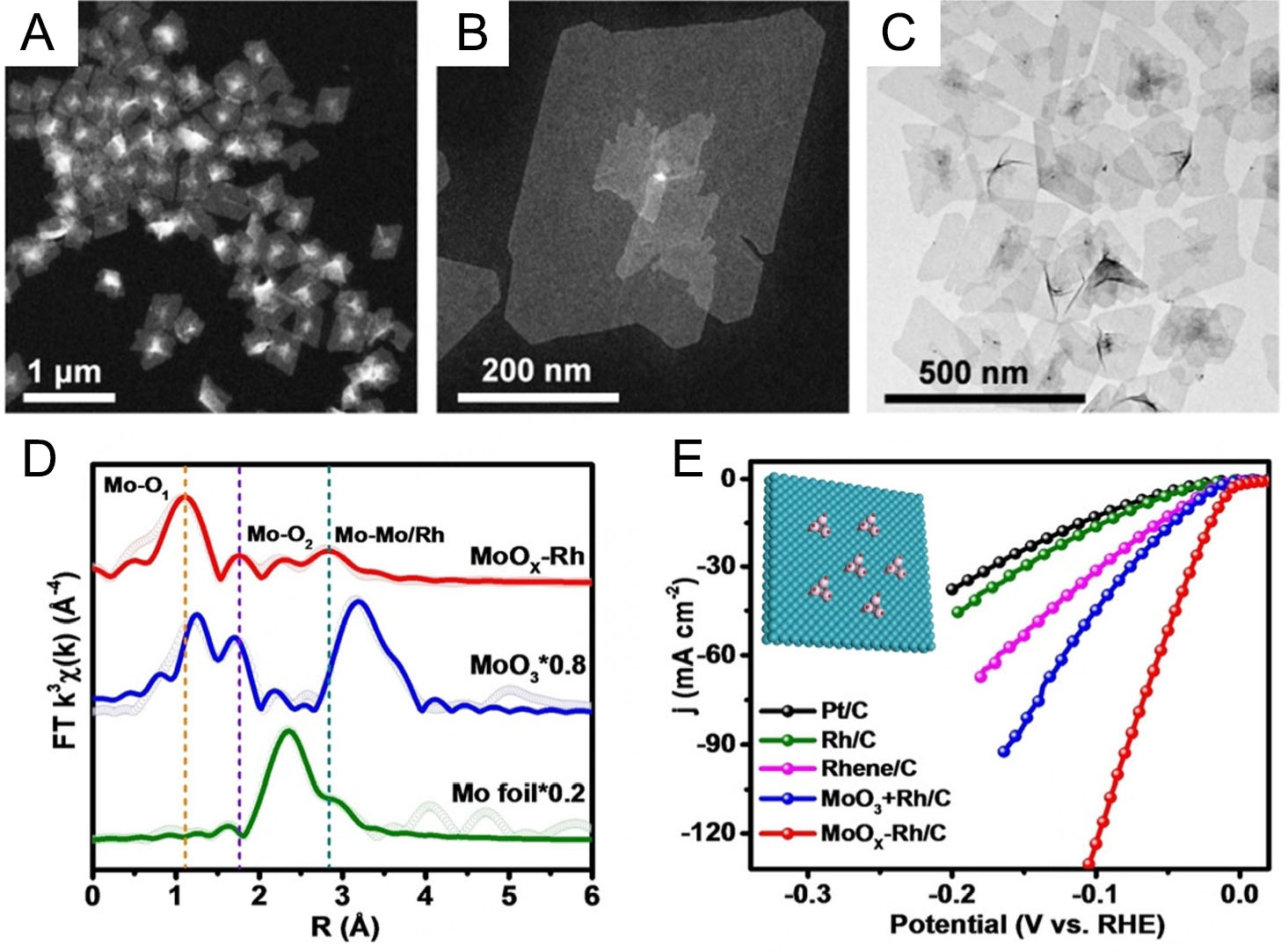

Jiang et al.[15] synthesized a novel Ir@Rhene heterojunction electrocatalyst by epitaxially confining ultra-small and low-coordinated Ir nanoclusters on an ultrathin Rh metal, accompanied by the formation of Ir/IrO2 Janus nanoparticles [Figure 6A-C]. It showed excellent alkaline HER activity, with an overpotential of only 17 mV at 10 mA cm-2 [Figure 6D]. The dual-site synergy between IrO2 and the Ir/Rh interface facilitates interfacial hydrogen spillover, effectively mitigating steric hindrance at active centers and thereby enhancing HER kinetics under alkaline conditions. Mao et al.[76] developed a partially hydroxylated Rh metallene (Rh/RhOOH metallene) featuring a porous, ultrathin framework with abundant defects and heterogeneous interfaces for ethylene glycol-assisted seawater electrolysis [Figure 6E-H]. During the electrocatalytic process, the unique interplay of RhOOH redox behavior and ethylene glycol-driven electroreduction induces dynamic in-situ reconstruction of the catalyst, generating additional active Rh species. This reconstruction enriches the active sites and optimizes surface catalytic reactions. Owing to its distinctive metallene morphology and the Rh/RhOOH heterostructure, the material demonstrates outstanding HER activity.

Figure 6. (A) Schematic diagram of the synthesis of Ir@Rhenes heterostructure, (B) typical low-magnification TEM image (inset: size distribution of the nanocluster), (C) HADDF-STEM-EDS elemental mapping images of Ir@Rhene heterostructure. (D) Polarization curves of Ir@Rhene/C, Rhene/C, and commercial Pt/C and Ir/C. (A-D) are reproduced from Ref.[15]. with permission, Copyright 2023, Wiley. (E) Schematic diagram of the synthesis process for the Rh/RhOOH metallene. (F) Low and high-magnification HAADF-STEM image and (G) low-magnification TEM image of the Rh/RhOOH metallene. (H) HER polarization curves for various electrocatalysts. Inset: local ball-and-stick model of RhOOH. (E-H) are reproduced from Ref.[76]. with permission, Copyright 2022, Wiley.

Table 2 presents the key performance parameters of recently reported graphene-like Rh-based HER catalysts used in acidic and alkaline environments.

Summary of the HER activity of metal alkene-type Rh-based materials used in acid and alkaline solutions

| Catalyst | Activity (mV@mA cm-2) | Stability | Ref. | |

| Acid | Alkaline | |||

| Ir@Rhene/C | 17@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [15] | |

| Rh/Pd metallene | 59@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [108] | |

| Pt-Rhene | 37@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [1] | |

| Rh-O-W | 7@10 | 8@10 | 48 h@10 mA cm-2 | [5] |

| Rh/RhOOH metallene | 29@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [76] | |

| l-Rh metallene | 38@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [109] | |

| Rh/Fe BM-2 | 24.4@10 34.6@100 | 90 h@10 mA cm-2 | [101] | |

Rhene catalysts achieve an organic integration of high activity, excellent stability, and high atomic utilization through the rational design of 2D atomic-layer structures, electronic state modulation, and interface engineering. Their performance enhancement mainly arises from the optimized ΔGH*, rapid charge transfer, and strain/defect-induced activation effects. Rhene provides a new design paradigm for noble-metal-based 2D electrocatalysts and exhibits broad application prospects in future hydrogen energy conversion systems.

Clusters and nanoparticles of Rh-based catalysts

In the Rh-based hydrogen evolution catalyst system, cluster and nanoparticle catalysts play an important role in the HER due to their unique physical and chemical properties, and their performance optimization strategies have also attracted much attention.

Cluster-type Rh-based catalysts

Rh clusters are usually composed of several to dozens of Rh atoms, with a size generally in the range of

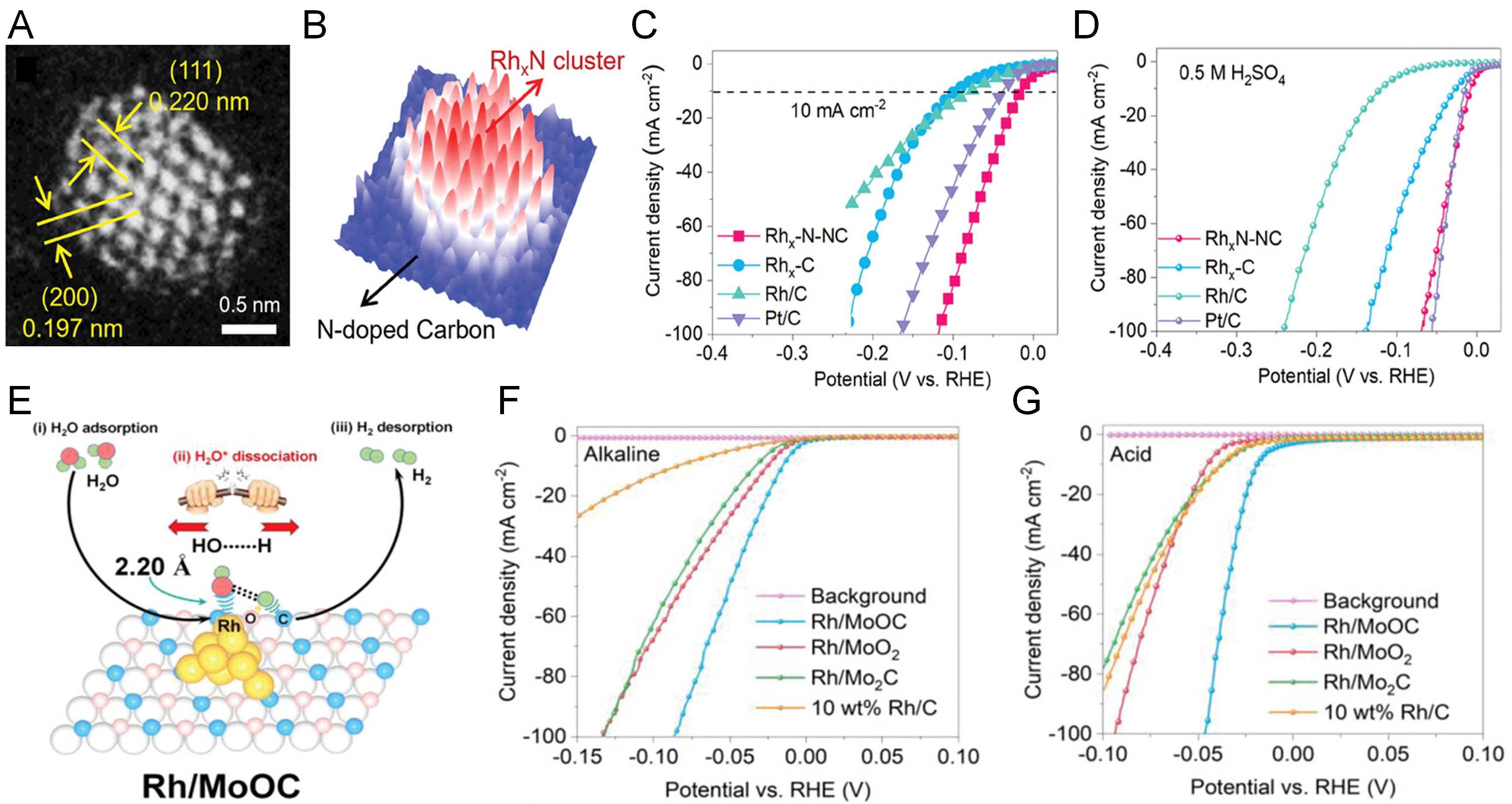

The size of the cluster has a crucial influence on its catalytic performance. As the size of the cluster decreases, the proportion of surface atoms further increases, the number of active sites increases, and the adsorption energy of hydrogen atoms also changes. Zheng et al.[6] constructed Rh nitride nanoclusters (RhxN-NC) supported on N-doped carbon using a simple molten urea method [Figure 7A and B]. The uniformly distributed RhxN clusters exhibited optimized water binding and water electrolysis effects, achieving excellent HER performance in a full pH environment. The optimized RhxN-NC catalyst exhibits remarkable activity, requiring minimal overpotentials of only 8 mV in 0.5 M H2SO4 and 12 mV in 1.0 M KOH to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm-2 [Figure 7C and D]. In a related study, Wang et al.[41] developed Rh clusters anchored on a molybdenum oxycarbide (MoOC) support to facilitate efficient hydrogen evolution for water splitting applications [Figure 7E]. Combined experimental and theoretical investigations revealed significant charge transfer from Rh to the MoOC substrate, leading to favorable modulation of the d-band center, water adsorption properties, and hydrogen binding energy-all contributing to enhanced intrinsic HER performance. Moreover, the presence of interstitial carbon and oxygen atoms within the MoOC matrix plays a pivotal role in accelerating water dissociation during the HER process. Notably, at an overpotential of

Figure 7. (A) HAADF-STEM images of RhxN-NC at different magnifications. (B) 3D intensity surface plot is shown for the Rh nanocluster in a. HER polarization curves of different catalysts in (C) 1.0 M KOH and (D) 0.5 M H2SO4. (A-D) are reproduced from Ref.[6]. with permission, Copyright 2023, Wiley. (E) Schematic illustration for alkaline HER by efficiently splitting the HO-H bond on Rh-C sites of MoOC with the O atom-tuned microenvironment and electronic structure. Performance of Rh/MoOC catalysts and control samples in a three-electrode configuration in (F) 1 M KOH and (G) 0.5 M H2SO4 at room temperature. (E-G) are reproduced from Ref.[41]. with permission, Copyright 2022, Wiley.

Rh cluster catalysts occupy an intermediate position between single-atom catalysts and nanoparticles, combining the advantages of both: they retain the high utilization of atomic-level active sites while possessing a relatively stable structural framework. Through size control, electronic structure engineering, and interface coupling, they achieve a synergistic integration of high activity, superior stability, and high atomic utilization. Their performance enhancement primarily arises from optimized hydrogen adsorption energy, synergistic electronic effects, and stable metal-support interactions. Rh clusters provide an important design strategy for developing novel, highly efficient noble-metal electrocatalysts that bridge the gap between single-atom and nanoscale systems.

Nanoparticle-type Rh-based catalysts

The size of nanoparticles has a significant impact on their catalytic performance. Nanoparticle-type Rh-based catalysts typically range from 3 to 100 nm. Smaller nanoparticles have a larger specific surface area, more surface atoms, and a higher density of active sites, which benefits the progress of the HER. For example, Rh nanoparticles with a size of about 3 nm have a lower initial hydrogen evolution potential and a larger hydrogen evolution current density in the acidic HER[113]. As the size of the nanoparticles increases, the specific surface area decreases, the proportion of internal atoms increases, and the catalytic activity gradually decreases. Water electrolysis across a wide pH range represents a promising approach for hydrogen production, necessitating the development of highly stable and active electrocatalysts for the HER.

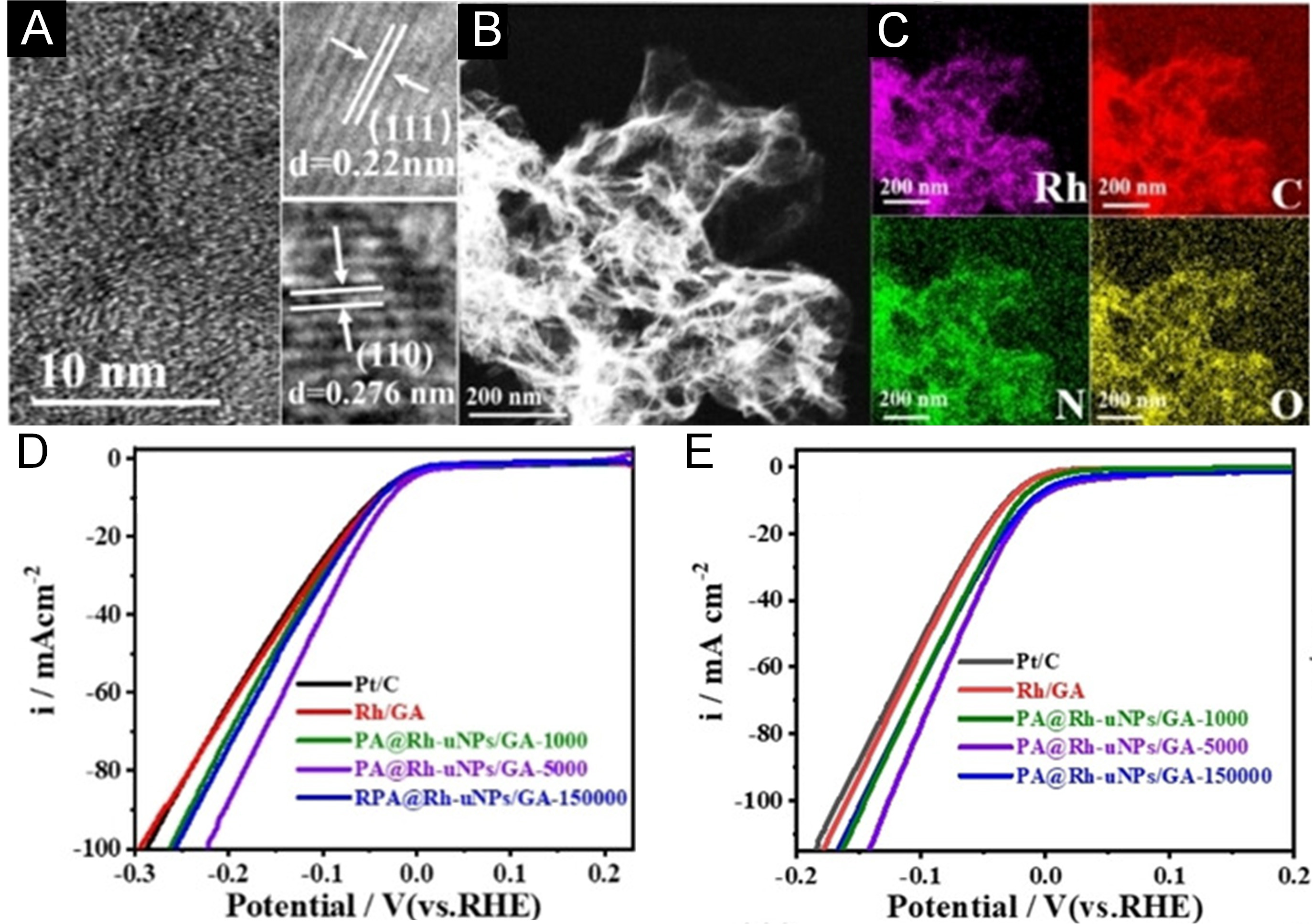

Figure 8. (A) High-resolution TEM image of PA@Rh uNPs/GA-5000 nanocomposites. (B) STEM image and (C) corresponding EDX elemental distribution maps for PA@Rh-uNPs/GA-5000. (D and E) HER polarization curves of various electrocatalysts-including PA@Rh-uNPs/GA-5000, PA@Rh-uNPs/GA-1000, PA@Rh-uNPs/GA-150000, Rh/GA nanocomposites, and commercial 20% Pt/C-measured in (D) 0.1 M HClO4 and (E) 0.1 M KOH electrolytes, respectively. This figure is reproduced from Ref.[114] with permission. Copyright 2021, Wiley.

Different crystal planes of Rh nanoparticles exhibit distinct atomic arrangements and electronic structures, leading to varying activities for the HER. Common crystal planes include (111), (100), and (110); among these, the (111) plane has a relatively dense atomic arrangement and moderate hydrogen adsorption energy, resulting in higher HER activity[75]. By controlling the synthesis conditions of the nanoparticles, their crystal plane composition and exposure ratio can be regulated. For example, using a specific surfactant-assisted synthesis method can make the Rh nanoparticles preferentially expose the (111) crystal plane, thereby improving the hydrogen evolution performance of the catalyst[115].

Surface modification of Rh nanoparticles is an important strategy for optimizing their hydrogen evolution performance. Surface modification can be achieved by changing the chemical environment and electronic structure of the nanoparticle surface. Modification can also be carried out by depositing other metal atoms or compounds on the surface of the Rh nanoparticles. For example, depositing a small amount of platinum atoms on the surface of the Rh nanoparticles to form a Rh-Pt alloy shell structure[87]. In this structure, the presence of platinum atoms changes the electronic structure and the interaction between atoms on the surface of the Rh nanoparticles, synergistically promoting the HER. Experimental results show that the catalytic activity and stability of the Rh nanoparticles modified with the Rh-Pt alloy in the acidic HER are significantly improved compared with those of the pure Rh nanoparticles.

Rh nanoparticle HER catalysts achieve high activity, superior stability, and high surface atomic utilization through nanoparticle size and morphology control, interface engineering, alloying, and surface modification. Their performance enhancement primarily arises from the abundance of low-coordinated active sites, optimized electronic structure, and synergistic interface effects. Rh nanoparticles provide an important design strategy for developing efficient and scalable noble-metal HER catalysts.

Table 3 summarizes the key performance parameters of the recently reported cluster-type and nanoparticle-type Rh-based HER catalysts for acidic and alkaline environments.

Summary of the HER activity of Rh-based materials of cluster type and nanoparticle type used in acid and alkaline solutions

| Catalyst | Activity (mV@mA cm-2) | Stability | Ref. | |

| Acid | Alkaline | |||

| Rh/SNG | 13@10 | 100 h@500 mA cm-2 (70 °C) | [19] | |

| Rh/GNPs | 76@10 | 5 h@2 mA cm-2 | [90] | |

| Pd-Rh/MoS2 | 46@10 | 30 h@10 mA cm-2 | [116] | |

| Electro-deposited Rh electrodes | 168@onset | 339@onset | 48 h@2 V | [117] |

| Au0.25Rh0.75 | 105@10 | 25 h@10 mA cm-2 | [118] | |

| Cs3Rh2I9/NC-R | 25@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [33] | |

| RhxN-NC | 8@10 | 12@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [6] |

| 0.15Co-NCNFs-5Rh | 18@10 | 13@10 | 30 h@10 mA cm-2 | [34] |

| Co-Rh2 | 2@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [12] | |

| Rh@Pt2L | 5@10 | 5 h@10 mA cm-2 | [13] | |

| B-Rh@NC | 43@10 | 26@10 | 10 h@20 mA cm-2 | [32] |

| Rh-NiAl LDH/NF | 14@10 | 70 h@38 mA cm-2 | [119] | |

| sRhNPs | 27.4@10 | [120] | ||

| Pt3NiRh NFs | 7@10 18@50 | [97] | ||

| N-Rh/CA | 65@10 210@100 | [121] | ||

| Rh2/C | 3@10 79@100 | 5 h@10 mA cm-2 | [113] | |

| Rh/MoOC | 15@10 | 80,000 s@10 mA cm-2 | [41] | |

| PA@Rh uNPs/GA | 16@10 | 28@10 | 100,000 s@10 mA cm-2 | [114] |

| MRNs | 29.4@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [122] | |

| RhNiP MNs | 15@10 | 36@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [123] |

| Rh/DNA-1 | 105@10 194@50 | 10 h@15 mA cm-2 | [124] | |

| Rh/NHCSs | 10@10 | 6@10 | 12 h@10 mA cm-2 | [17] |

| 4.2 Rh-CN | 13@10 | 46@10 | 12 h@10 mA cm-2 | [98] |

| Rh NCs/NHCAs | 7@10 48@100 | 6 h@10 mA cm-2 | [125] | |

| Rh0/TiO2-2000 | 37@10 | [126] | ||

| Rh(nP)/nC | 44@2 | [127] | ||

| P–Rh/C | 11@10 | [128] | ||

| hollow Rh nanoparticles | 28.1, 32.6, 37.6@10, 20, 40 | 3,500 s@10 mA mg-1 | [129] | |

| Rh/SiQD/CQD | 36@10 | 23 h@10 mA cm-2 | [130] | |

| Rh@NPCP | 23@10 | 20@10 | [131] | |

| Rh/Ni@NCNTs | 45@10 | 14@10 | [132] | |

| Rh-Pt-B | 31@10 | [11] | ||

| Rh NCs | 32@10 | 6 h@10 mA cm-2 | [133] | |

| Rh NP/C | 7@10 12@20 22@50 36@100 | 20 h@10 and 20 mA cm-2 | [35] | |

| W-Rh/C | 57@10 | 2 h@10 mA cm-2 | [92] | |

| Rh-NSs | 42@10 | 6,000 s@5 mA cm-2 | [36] | |

| Rh/N-CBs | 77@10 | 6,000 [email protected] | [45] | |

| 0.5Rh-GS1000 | 40@10 | 25@10 | 10 h@15 mA cm-2 | [39] |

| 29.1 wt% Rh/SiNW | 44@100 | [2] | ||

| Rh/F-graphene-2 | 46@10 | 50,000 s@10 mA cm-2 | [134] | |

| Rh NP/PC | 21@10 | [38] | ||

| Rh NSs | 43@10 | 5 h@5 mA cm-2 | [135] | |

Compounds-type Rh-based catalysts

In recent years, researchers have significantly improved the catalytic performance of Rh-based phosphides in water electrolysis by regulating their crystal structures, surface activities, and electronic properties[14,136,137]. Especially under alkaline conditions, this type of material exhibits excellent stability and efficient hydrogen evolution ability, providing a new technical pathway for clean energy production. However, its practical application still faces key challenges such as further improvement of catalytic activity, optimization of material synthesis processes, and control of large-scale preparation costs. Future research should focus on the development of new synthesis methods and the design of multifunctional materials, with the aim of more efficiently achieving the goal of hydrogen production through water electrolysis. Xin et al.[138] reported the one-step synthesis of polyhedral-shaped and morphology-controllable Rh phosphide (Rh2P) nanoparticles via high-temperature pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere. In 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1 M KOH electrolytes, the overpotentials of the polyhedral Rh2P nanoparticles at 10 mA m-2 are 12.6 mV and 10.5 mV, respectively, which are even lower than those of Pt/C[138]. Theoretical calculations show that the {200} plane of Rh2P nanoparticles has the highest catalytic activity among the {200}, {111} and {220} planes, with the lowest free energy of hydrogen adsorption. The extensive exposure of the {200} crystal plane is beneficial for achieving the high catalytic activity of Rh2P[138].

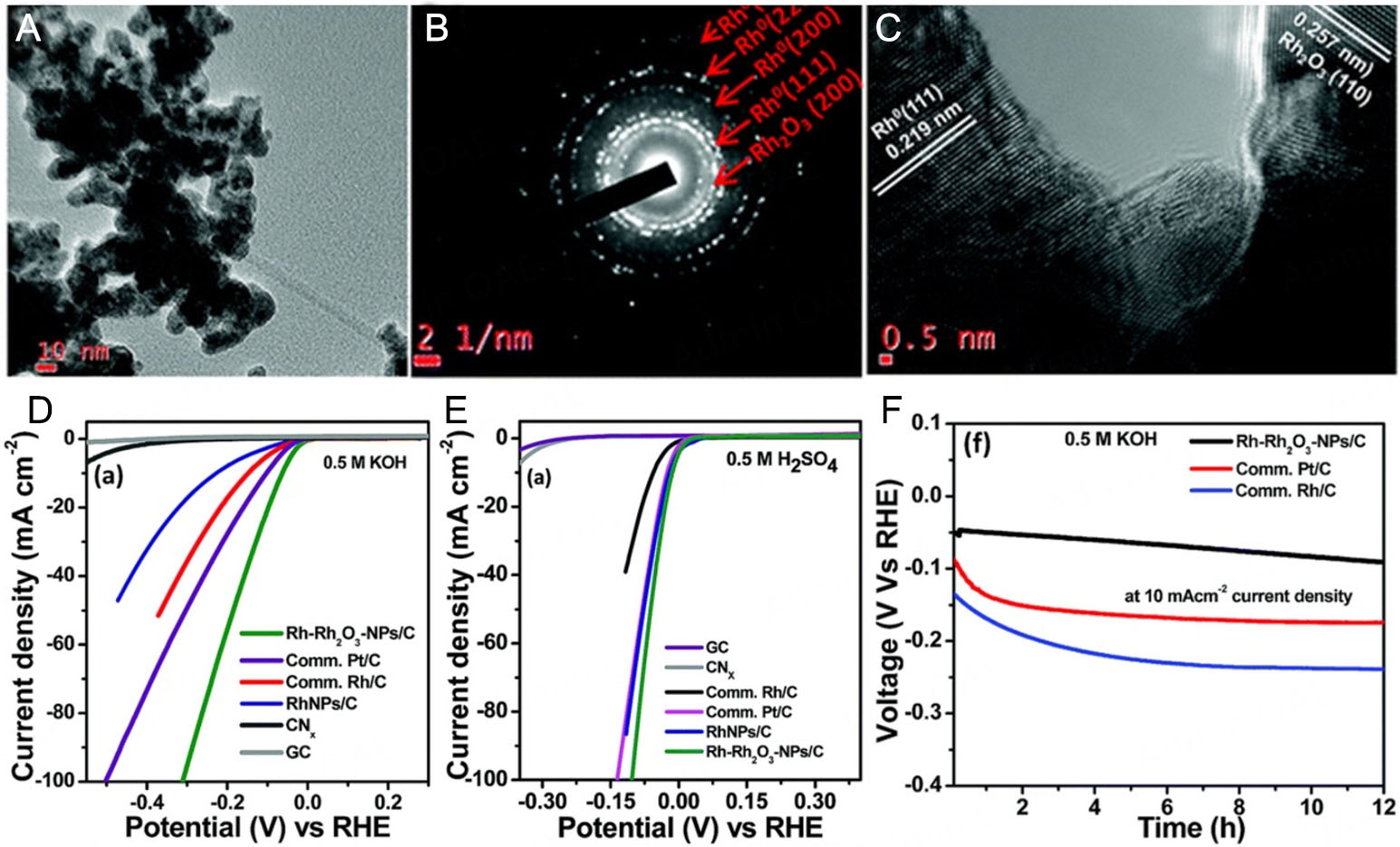

Rh oxides, such as Rh2O3, etc.[74,139], exhibit certain catalytic activity. Their crystal structure and electronic properties confer a unique mechanism of action for the HER. During the catalytic process, surface oxygen atoms can promote water dissociation by interacting with water molecules, providing a hydrogen source for subsequent hydrogen evolution steps. Simultaneously, transitions between different oxidation states of Rh ions facilitate electron transfer, further promoting HER activity. Kundu et al.[74] reported the synthesis of Rh-Rh2O3 nanoparticles/N-doped carbon composites (Rh-Rh2O3-NPs/C) for HER [Figure 9A-C]. This catalyst can achieve a current density of 10 mA cm-2 with overpotentials of only 63 mV and 13 mV in alkaline and acidic media [Figure 9D-F], respectively, and its HER activity is approximately 2.2 times and 1.43 times that of the industrial Pt/C catalyst, respectively. For the HER in an alkaline medium, water is adsorbed and dissociated at the Rh2O3 sites, and Hads is formed at the adjacent Rh sites. The recombination of Hads leads to the formation of hydrogen molecules.

Figure 9. (A) TEM, (B) SAED and (C) HRTEM images of the Rh-Rh2O3-NPs/C composite. (D) HER curves of Rh-Rh2O3-NPs/C, comm. Pt/C, comm. Rh/C, RhNPs/C, CNx and GC in 0.5 M KOH (E) 0.5 M H2SO4. (F) Chronopotentiometric stability of Rh-Rh2O3-NPs/C, Pt/C and Rh/C at 10 mA cm-2. This figure is reproduced from Ref.[74] with permission. Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Rh sulfides, such as RhS, Rh2S3, etc.[140], have been studied for HER catalysis. The sulfur atoms in these sulfides can modulate the electronic structure of Rh, optimizing hydrogen adsorption and desorption properties. Compared with oxides, sulfides may exhibit better stability under certain acidic conditions, reducing catalyst corrosion and deactivation during the reaction. Moreover, their surface structure facilitates hydrogen adsorption and recombination, thereby enhancing HER efficiency.

Nitrides usually have high hardness and stability, and can maintain good catalytic performance under some harsh reaction conditions, which helps to improve the service life of the catalyst. Meanwhile, the introduction of nitrogen atoms will change the distribution of the electron cloud of Rh, making the electronic structure of the catalyst surface more conducive to the adsorption and activation of hydrogen.

Compounds-type Rh-based HER catalysts achieve a synergistic integration of high activity, superior stability, and high atomic utilization through chemical composition tuning, crystal structure and surface coordination engineering, interface coupling, and defect/doping modulation. Their performance enhancement mechanisms mainly include optimized H* adsorption/desorption, synergistic electronic structure regulation, interface- and defect-induced activity, and enhanced environmental adaptability. Compound-type catalysts provide important design strategies for developing efficient, durable, and resource-efficient Rh-based HER catalytic systems.

Table 4 shows the key performance parameters of the recently reported Rh-based compound HER catalysts for acidic and alkaline environments.

Summary of the HER activity of Rh-based compound used in acid and alkaline solutions

| Catalyst | Activity (mV@mA cm-2) | Stability | Ref. | |

| Acid | Alkaline | |||

| Rh2P@NPG-150 | 30.4@10 | 57.3@10 | 9 h@10 mA cm-2 | [141] |

| RhFeP | 28@10 | 24 h@10 mA cm-2 | [142] | |

| NiRh2Sb CuRh2Sb | 121@10 145@10 | [143] | ||

| Rh(OH)3/CoP | 12@10 | 13@10 | 70 h@10 mA cm-2 | [7] |

| RhP2/Rh@NPG | 9@10 | 21.3@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 24 h@50 mA cm-2 | [103] |

| Rh2P | 11.7@10 | 10.3@10 | 40 h@10 mA cm-2 | [137] |

| a/c-RuB | 39@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [144] | |

| Rh2P-900 | 12.6@10 | 10.5@10 | 35 h@15 mV/13 mV | [138] |

| Rh2P | 21@50 | 14@50 | [145] | |

| R-RhFeP2CX-CNT | 15@10 | 53@10 | 7 h@130/100 mA cm-2 | [146] |

| Rh(OH)3/NiTe | 21@10 | 75 h@10 mA cm-2 | [147] | |

| Rh15/NSC YSS | 13.5@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [148] | |

| Ni2-xRhxP | 66.2@10 | 10 [email protected] V | [149] | |

| p-Rh/Fe-Ni3S2/NF | 108@100 | 50 h@100 mA cm-2 | [150] | |

| Ni1.66Rh0.34P/C | 149@10 | [151] | ||

| RhTe2/C | 47@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [152] | |

| Rh2P{200} | 22@10 | 23@10 | 10 h@1 A cm-2 | [153] |

| Rh-Pt-B | 31@10 | [11] | ||

| Rh2SbNBs/C | 39.5@10 | 20,000 [email protected] V | [154] | |

| Co0.25Rh1.75P | 58.1@10 | 10 [email protected] mA cm-2 | [155] | |

| RhRu-MPSs | 25@10 | [156] | ||

| Co0.75Rh1.25P | 90.5@10 | [157] | ||

| Rh2P-N/P-CC | 4@20 44@100 71.5@200 115@400 | [158] | ||

| RP-500 | 14.3@10 | 4.3@10 | 60,000 s@10 mA cm-2 | [159] |

| Rh/Rh2P-NFAs | 13.4@10 | 19.5@10 | [160] | |

| RhSe2 | 49.9@10 | 81.6@10 | [161] | |

| RheRh3Se4/C | 32@10 | 29@10 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [162] |

| Rh–Rh2P@C | 24@10 | 37@10 | [163] | |

| Rh2P/NPC | 40@10 | 17@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [164] |

| SLNP | 14@10 46@50 | 50 h@10 mA cm-2 | [139] | |

| Rh2S3-ThickHNP/C | 122@10 | [140] | ||

| Rh17S15/C | 340@20 | [165] | ||

| Rh2P-1@CB/Nafion | 1.5@5 | 1@5 | [145] | |

| RhNiP MNs | 15@10 | 36@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [123] |

| RhPx@NPC | 22@10 | 69@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [166] |

| RuxP/NPC | 19@10 | 20 h@-50 mV | [136] | |

| w-Rh2P NS/C | 15.8@10 | 18.3@10 | [14] | |

| Rh2P | 14@10 | 30@10 | 60,000 s@10 mA cm-2 | [167] |

| Rh3Pb2S2/C | 87.3@10 | [168] | ||

| Rh2P@NC | 9@10 | 10@10 | 10 h@10 mA cm-2 | [169] |

| Rh2P/C | 5.4@5 | [170] | ||

| RhPd-H NPs | 36.6@10 | 4 h@10 mA cm-2 | [3] | |

| Rh–Ag/SiNW-2 | 120@10 | [171] | ||

| Rh–Rh2O3-NPs/C | 13@10 | 63@10 | 12 h@10 mA cm-2 | [74] |

| Rh-Au-SiNW-2 | 62@10 | [172] | ||

Alloys-type Rh-based catalysts

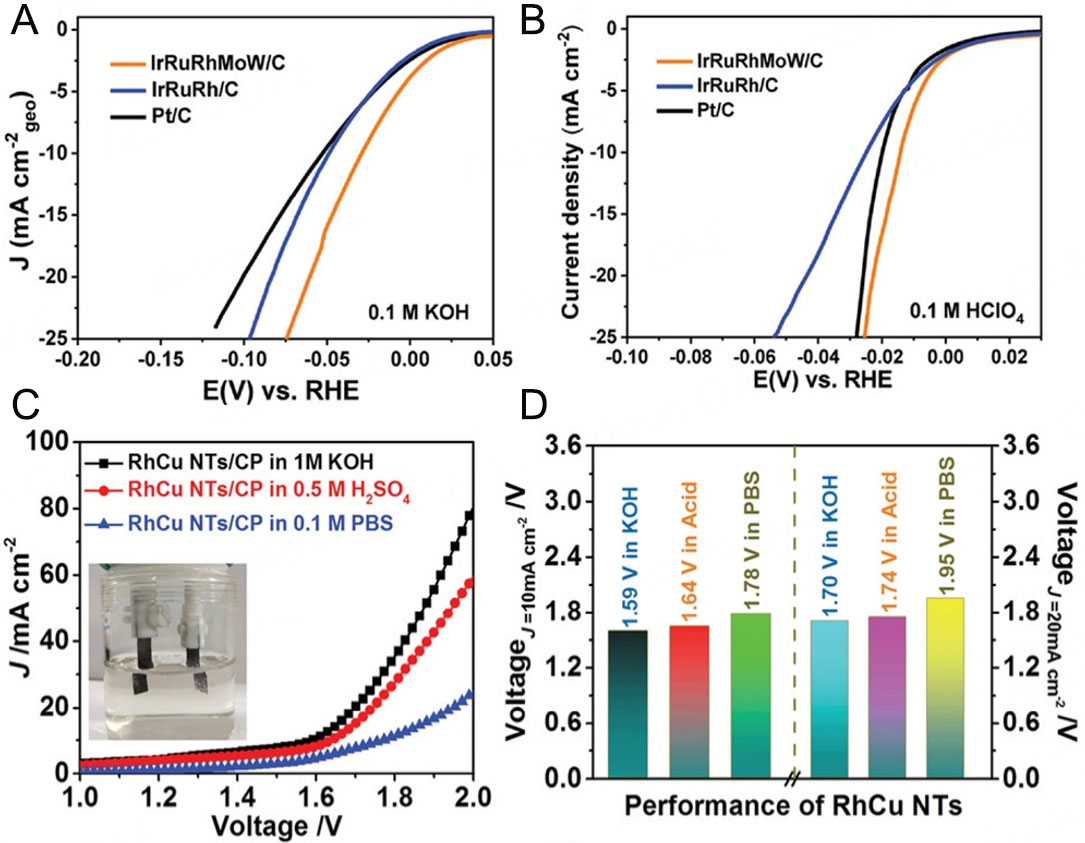

As an emerging multi-component catalytic material, Rh-based high-entropy alloy materials exhibit unique application potential in HER during water electrolysis. Due to the significant advantages of their multi-metallic composition, such as excellent mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and efficient electron transfer characteristics, Rh-based high-entropy alloys show high catalytic activity and stability in the electrochemical water splitting reaction. Researchers have further improved their catalytic performance in alkaline media by regulating the alloy composition ratio, surface modification, and multiphase structure design[62,173,174]. Especially in the HER process, this type of material shows a low overpotential and excellent long-term stability[175,176], providing a new technical means for efficient water splitting. However, although Rh-based high-entropy alloy materials perform well in laboratory research, there are still many challenges in their large-scale preparation cost, verification of stability in practical applications, and performance optimization. Future research directions should focus on developing economically viable preparation methods, deeply understanding their catalytic deactivation mechanism, and further exploring their practical applicability in industrial water splitting, with a view to achieving more efficient and large-scale clean hydrogen production. Luo et al.[47] synthesized micro-strain modulated high-entropy alloy nanoparticles (IrRuRhMoW HEA NPs) in the sub-2 nanometer range, which served as an excellent HER catalyst. Under alkaline conditions, the current density reached 10 mA cm-2 at an overpotential of only 28 mV

Figure 10. HER polarization curves of IrRuRhMoW/C, IrRuRh/C, and Pt/C in (A) 0.1 M KOH and (B) 0.1 M HClO4. (A and B) are reproduced from Ref.[47]. with permission, Copyright 2024, Wiley. (C) LSV curves for overall water splitting in a two-electrode system with RhCu nanotubes employed as both the anode and cathode. Inset: Photograph of the two-electrode system. (D) Comparison of voltage requirements at current densities of 10 and 20 mA cm-2 across various pH levels. (C and D) are reproduced from Ref.[91]. with permission, Copyright 2020, Wiley.

Rh-transition metal alloys commonly include Rh-Fe, Rh-Co, Rh-Ni and other alloys. After transition metals form alloys with Rh, they will change the electronic structure and crystal structure of the alloy. For example, in the Rh-Co alloy[177], the addition of Co atoms will affect the electronic structure around Rh atoms, causing changes in the alloy's ability to adsorb and activate hydrogen. This change may lead to the alloy having better catalytic performance in the HER[177]. Compared with pure Rh catalysts, it can reduce the overpotential of the HER and increase the reaction rate.

Rh-precious metal alloys commonly include Rh-Pt, Rh-Au, etc. Alloys formed between precious metals have good catalytic activity and stability. Taking the Rh-Pt alloy as an example[178], the addition of platinum can further improve the electron migration ability of the alloy and optimize the adsorption-desorption equilibrium of hydrogen on the catalyst surface. Since platinum itself is also an excellent hydrogen evolution catalyst, after forming an alloy with Rh, the synergistic effect of the two can give full play to their respective advantages, showing high hydrogen evolution catalytic activity in both acidic and alkaline electrolytes.

Rh-rare earth metal alloys formed by Rh and rare earth metals (such as Ln, La, Tm, etc.) have also received widespread attention[179,180]. Rare earth metals have special electronic configurations and chemical properties. Adding them to Rh-based alloys can improve the surface properties and stability of the alloys. For instance, in Rh3Ln intermetallic[179], the alloying process induces an upward shift of the d-band center and facilitates electron transfer from Ln to Rh, thereby optimizing the adsorption and dissociation energies of H2O molecules.

Precisely controlling the proportion of each element in the alloy is the key to optimizing the performance of Rh-based alloy catalysts. By changing the alloy composition, the electronic structure and crystal structure of the alloy can be adjusted, and then its catalytic performance for the HER can be optimized. For example, in the Rh-Ni alloy, when the atomic ratio of Rh to nickel reaches a certain value, a special electronic structure will form on the alloy surface, making the adsorption energy of hydrogen on the catalyst surface moderate, which is conducive to both the adsorption and activation of hydrogen and the desorption of hydrogen, thus improving the efficiency of the HER. Usually, the method of combining experimental screening with theoretical calculation is adopted to determine the optimal alloy composition. Cao et al.[91] successfully synthesized RhCu nanotubes with abundant structural defects by the mixed solvent method, which showed excellent activity and stability for the HER and the oxygen evolution reaction in all pH value ranges. In particular, under alkaline, acidic, and neutral conditions, only 8, 12, and 57 mV are required, respectively, to achieve a current density of 10 mA cm-2 for HER [Figure 10C and D]. DFT calculations revealed that exposing the appropriate composition of the highly active Rh3Cu1 alloy phase through acid etching is the key to improving the electrocatalytic performance[91], because it weakens the adsorption free energy of atomic oxygen and hydrogen and promotes the dissociation of water molecules. In addition, structural defects can also improve the catalytic performance, as the adsorption of reactants can be greatly enhanced.

Furthermore, selecting an appropriate preparation method is crucial for obtaining high-performance Rh-based alloy catalysts. Common preparation methods include physical vapor deposition, chemical coprecipitation, sol-gel method, etc. Different preparation methods will affect the particle size, morphology, crystal structure, and surface properties of the alloy. The physical vapor deposition method can prepare alloy nanoparticles with uniform particle size and good dispersion[181], which can increase the specific surface area of the catalyst and improve the exposure degree of active sites. The alloy catalyst prepared by the sol-gel method may have a more uniform element distribution and a better crystal structure, which is beneficial to improving the stability and activity of the catalyst.

Meanwhile, surface treatment of Rh-based alloy catalysts can further improve their performance. For example, methods such as surface oxidation and acid-washing (or acid leaching) can effectively remove impurities from the catalyst surface[182,183], thereby restoring clean active sites and improving catalyst performance. In addition, by using the method of surface modification, such as loading some atoms or molecules with special functions on the alloy surface, the electronic and chemical properties of the alloy surface can also be regulated to optimize its catalytic performance for the HER. Table 5 presents the key performance parameters of recently reported Rh-based alloy HER catalysts used in acidic and alkaline environments.

Summary of the HER activity of Rh-based alloy used in acid and alkaline solutions

| Catalyst | Activity (mV@mA cm-2) | Stability | Ref. | |

| Acid | Alkaline | |||

| RhNi | 40@10 197@1000 | [29] | ||

| e PtRhNiFeCu/C | 13@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [96] | |

| d-HEA NPs | 42.7@10 | 30 h@50 mA cm-2 | [89] | |

| IrRuRhMoW/C | 14@10 | 28@10 | 15 h@10 mA cm-2 | [47] |

| PdRhMoFeMn | 6@10 | 26@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [95] |

| HEA/GC | 13@10 | 65@10 | 12 h@100 mV | [184] |

| RhRu0.5-alloy wavy nanowire | 54@100 | 80 h@100 mA cm-2 | [61] | |

| Co AG-Rh500 | 13@10 | 17@10 84@100 | 20 h@100 mA cm-2 | [185] |

| Pt28Mo6Pd28Rh27Ni15 NCs | 9.7@10 57.7@100 | 30 h@10 mA cm-2 | [186] | |

| RhRuPtPdIr HEA thin film | 58@10 | 20 h@10 mA cm-2 | [187] | |

| PtPdRhRuCu MMNs | 13@10 | 10@10 | 100 h@10, 20, 50, and 100 mA cm-2 | [176] |