Innovative strategies to significantly boost photocatalytic hydrogen production: from high-performance photocatalysts to potential industrialization

Abstract

To address global energy and environmental challenges, photocatalytic hydrogen production has emerged as a clean and promising technology that utilizes solar energy to generate green hydrogen, producing only water as a byproduct. This review highlights recent advances in strategies for significantly enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen evolution to promote its industrialization. Key approaches include morphology optimization for improved light absorption and charge transport, metal hybridization or incorporation to enhance catalytic activity and selectivity, and interface engineering to facilitate charge separation and reaction kinetics. Additionally, the emerging photocatalysts, such as two-dimensional transition metal carbides, metal-organic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks, and high-entropy materials provide superior alternatives. Furthermore, this review discusses multifunctional enhancements for practical applications and showcases cutting-edge large-scale demonstrations, including 100 m2 panel arrays and compound parabolic concentrator reactors, which achieve a solar-to-hydrogen efficiency of 9% and 300 h stability in seawater splitting. These advances underscore the techno-economic potential of photocatalytic hydrogen production and bridge fundamental research with industrial implementation. Finally, the current challenges and future research trends are pointed out for designing high-performance photocatalysts and offering insight into the feasible strategies to develop the industrial application of photocatalytic hydrogen production.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the huge population and the rapidly developing economy greatly increase people’s demand for energy, which is essential to continuously improve the quality of life and establish highly developed industrial civilization[1-3]. As a result, with the increasingly frequent use of fossil fuels, environmental pollution and energy shortages have gradually become some of the most concerning issues for the general public[4-6]. To address the escalating climate change and growing energy crisis, hydrogen energy has emerged as a pivotal element in global decarbonization efforts[7-9]. Boasting an energy density of 142 MJ/kg - nearly three times that of gasoline - and producing only water upon combustion, hydrogen stands out as a promising solution for decarbonizing difficult-to-abate sectors such as heavy industry, long-haul transportation, and energy storage[10-12]. The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts a dramatic increase in hydrogen demand, from 94 million metric tons in 2023 to 650 million by 2050 under net-zero scenarios, which necessitates a 50-fold expansion in low-carbon hydrogen production capacity[13]. Steam methane reforming (SMR), which currently accounts for approximately 95% of global hydrogen production, releases 9-12 kg of CO2 per kilogram of H2[14,15]. Therefore, the conventional hydrogen production techniques remain both environmentally and economically unsustainable. Although water electrolysis is cleaner, its high production cost (~$4-6 per kg of H2) and reliance on scarce platinum-group metals (PGMs) as electrocatalysts impede its widespread adoption[16,17].

Photocatalytic water splitting, which directly converts solar energy into chemical energy to split water into H2 and O2 under ambient conditions, represents a transformative alternative to conventional methods. Unlike electrolysis, which depends on external renewable electricity infrastructure, photocatalysis integrates light absorption and fuel production into a single step, significantly reducing energy losses[18,19]. This process operates under mild conditions and can utilize diverse water sources, including seawater and wastewater, thereby improving its sustainability and potential for large-scale application[20,21]. The mechanism of photocatalytic water splitting involves three fundamental steps: (1) Photoexcitation and Charge Generation: When photons with energy equal to or greater than the bandgap energy of a semiconductor are absorbed, electrons (e-) are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), generating electron-hole (h+) pairs; (2) Charge Separation and Migration: The photogenerated electrons and holes migrate to the surface of the photocatalyst. Efficient separation and transport are crucial to mitigate recombination, as over 90% of charge carriers typically recombine prematurely, dissipating energy as heat or light[22-24]. Therefore, co-catalysts (usually nanoscale metal or metal oxide particles) are often used to significantly enhance photocatalytic performance by providing additional catalytic sites to promote charge separation and transport; (3) Surface Redox Reactions: The electrons and holes drive hydrogen and oxygen evolution reactions (HER and OER), respectively. Specifically, electrons reduce protons to H2 (2H2O + 2e- → H2+2OH-), while holes oxidize water to O2 (2H2O + 4h+ → O2 + 4H+). Due to the slow kinetics of the OER, many studies have used sacrificial agents (such as methanol and triethanolamine) to preferentially consume holes, thereby studying only the hydrogen production half-reaction. In this case, no oxygen is produced in the overall reaction. For example, the hole sacrificial reaction using methanol is: CH3OH + h+ → ⋅CH2OH + H+. To enhance charge separation and reaction kinetics, advanced material strategies such as heterojunction engineering and cocatalysts are employed. These approaches facilitate prolonged carrier lifetimes and provide active sites for HER and OER, substantially improving overall photocatalytic efficiency[20-25].

While the thermodynamic minimum bandgap for water splitting is 1.23 eV, practical systems require bandgaps of 1.8-2.0 eV to overcome kinetic barriers, necessitating novel bandgap engineering approaches[26,27]. The field has evolved through several technological periods since the seminal 1972 demonstration of TiO2 photo-electrochemistry by Fujishima and Honda [Figure 1][28]. Early research focused on wide-bandgap metal oxides and sacrificial agent systems, followed by breakthroughs in nanoscale engineering [i.e., quantum dots (QDs), 1D nanostructures] and hybrid materials [i.e., graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)/carbon composites][29-32]. The last decade has seen transformative developments, including plasmonic nanostructures, single-atom catalysts, high-entropy materials, and framework materials [metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs)] with atomic-level precision[33-36]. While laboratory-scale systems have achieved exceptional quantum efficiencies (exceeding 100% in some cases), the transition to industrial-scale applications still faces significant obstacles in optimizing broadband solar spectrum utilization, improving material stability under operational conditions, and designing scalable reactor architectures[37,38].

Figure 1. The landmark development in photocatalytic hydrogen production and the important advancements in recent years. MOF: Metal-organic framework.

Despite impressive laboratory-scale progress, photocatalytic hydrogen production is still constrained by three major bottlenecks: (1) low solar-to-hydrogen (STH) efficiency: most systems operate below 10% efficiency, far from the 15%-20% threshold necessary for economic viability[39]. Key limitations include narrow light absorption ranges [ultraviolet-visible-near infrared (UV-vis-NIR), neglecting 52% of solar infrared energy] and rapid charge recombination; (2) Material degradation: photocorrosion (e.g., CdS) and catalyst leaching (e.g., MOFs) under operating conditions undermine long-term stability[40,41]; (3) Scalability challenges: Laboratory setups often report apparent quantum yield (AQY) rates under idealized conditions (pure water, UV lamps), whereas real-world applications must contend with impurities (e.g., seawater chloride), fluctuating sunlight, and large-area reactor designs. Overcoming these challenges requires an integrated strategy that combines material innovation with system-level engineering. Typically, the strategies for designing photocatalysts, such as morphological optimization, metal modification, and interface engineering, have shown promise in enhancing photocatalytic performance and stability[42,43]. Morphological optimization primarily focuses on adjusting catalyst size and crystal facets to optimize light absorption and charge transport. Metal modifications, including the introduction of plasmonic nanoparticles (e.g., Au and Ag), extend light absorption into the near-infrared region, enhancing the utilization of solar energy[44,45]. Single-atom catalysts maximize atomic efficiency and suppress charge recombination[46]. Interface engineering focuses on constructing heterojunctions to balance strong redox potentials and facilitate efficient charge separation[37,47]. Recent innovations in core-shell interfacial catalysts have demonstrated high catalytic stability[34,48]. Additionally, system optimization often involves photothermal-photocatalytic synergy to maximize solar energy utilization, thereby enhancing reaction kinetics under full-spectrum light[29,49,50]. Further, novel reactor designs, employing micro- and nanoscale engineering, have facilitated the rejection of Cl- ions in seawater, significantly improving catalytic stability and enabling sustainable H2 production. Moreover, advances in large-scale reactor optimization, such as panel arrays and compound parabolic concentrator (CPC), have shown the potential for photocatalytic hydrogen production systems to transition from laboratory settings to real-world applications[51,52].

In recent years, advanced photocatalyst design has increasingly combined with system-level optimizations to markedly enhance photocatalytic hydrogen production. To foster a comprehensive understanding of state-of-the-art technologies and facilitate their industrial adoption, this review examines key strategies, including morphology control, metal incorporation, and interface engineering. It also specifically covers emerging materials such as two-dimensional transition metal carbides (MXenes), MOFs, COFs, and high-entropy systems. Furthermore, critical improvements essential for practical applications are discussed, including photothermal coupling, enhanced mass transfer, and corrosion resistance in seawater splitting. We also showcase recent large-scale demonstrations and assess the techno-economic potential of photocatalytic hydrogen production. These advances offer valuable insights into the role of photocatalysis in the future renewable energy mix and help bridge fundamental research with industrial implementation, accelerating the commercialization of solar-driven hydrogen technologies.

RATIONAL DESIGN OF PHOTOCATALYSTS AND THEIR SUPERIOR PERFORMANCES

As the most critical component in a photocatalytic system, the photocatalysts substantially determine the efficiency of hydrogen production via three successive processes of light absorption, charge carrier generation/separation, and surface reactions[53]. Based on these processes, various approaches have been developed for improving the performance of photocatalysts, including morphological control, ion doping, cocatalyst loading, heterostructure formation, defect construction, and so on. The effective strategies were widely investigated for several decades and some review papers comprehensively summarized them from various viewpoints. In recent years, more innovative and high-performance photocatalysts have been further exploited to significantly boost hydrogen production from photocatalytic water splitting. Typically, morphology control is vital for improving light harvesting and carrier separation efficiency through dimensional and surface modifications[54]. The loading of metal such as nanoparticles and ions/atoms induces diverse effects to greatly increase photocatalytic activity: i.e., the plasmonic enhancement from nanoparticles, the bandgap adjustments achieved through ion doping, and the atomic-level utilization of single atoms[55,56]. Interface engineering, particularly QD heterojunctions, S-type heterojunctions and organic donor-acceptor supramolecular assemblies, overcomes the traditional trade-off between charge separation and redox potential, enhancing the overall photocatalytic efficiency[57,58]. In addition, the emerging photocatalysts, including MXene-based composite catalysts, high-entropy MOFs (HE-MOFs), and three-dimensional COFs, represent cutting-edge innovations for pushing the boundaries of photocatalytic performances[35,59,60]. Undoubtedly, a deeper understanding of the shared principles and specific applications of the advanced approaches will offer invaluable insights for the development of next-generation, high-performance photocatalytic systems.

Morphology-affected photocatalytic hydrogen production

As given by the photocatalytic mechanism, the architecture of photocatalysts influences photon absorption, charge carrier dynamics, and surface reaction kinetics, which are important for improving the efficiency of hydrogen evolution. Recent advancements in synthetic approaches have enabled unprecedented precision in tailoring the morphology of catalysts across various length scales, leading to notable improvements in performance. Current strategies for regulating photocatalytic morphology primarily focus on modulating material dimensions and controlling the formation of active crystal planes to induce profound changes in the properties of the material.

For instance, in the LaNiO3/ZnCdS S-scheme heterojunction system, spherical, cubic, and rod-shaped LaNiO3 morphologies were synthesized through a meticulously optimized procedure [Figure 2A][61]. Benefiting from the facilitated directional electron flow in a one-dimensional structure, the rod-like morphology exhibited a superior activity [Figure 2B], resulting from its approximately 30% higher active component loading and enhanced resistance to aggregation during reaction cycles. Similarly, Chen et al. designed a hollow tubular g-C3N4/ZnIn2S4 system [Figure 2C-E][54], which ensured exceptional photon management with 89% absorption efficiency and provided abundant active sites due to ultrathin ZnIn2S4 nanosheets (2-5 nm). Extending beyond low-dimensional architectures, Zhang et al. demonstrated that sandwich-like hierarchical heterostructures of ZnIn2S4/P-doped hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)/ZnIn2S4 achieved a 2.35-fold increase in hydrogen evolution (~59.46 μmol·h-1) compared to pure ZnIn2S4

Figure 2. Special morphology-enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A) Schematic process for preparing spherical, rod-shaped and cubic LaNiO3 and their corresponding composite photocatalysts with ZnCdS; (B) Comparison of hydrogen evolution over different photocatalysts to indicate the largest H2 evolution by rod-shaped ones. These two figures are quoted with permission from Zhao et al. Copyright (2023) Elsevier Ltd[61]; (C) Schematic diagram of hollow tubular C3N4/ZIS composite for photocatalytic hydrogen production; (D and E) Hierarchical SEM observations of typical CN/ZIS. These three figures are quoted with permission from Chen et al. Copyright (2022) Elsevier Ltd[54]; SEM images of (F) CeO2 nanorods/CdS and (G) CeO2 nanoflower/CdS; (H) Hydrogen evolution rates of different photocatalysts. These three figures are quoted with permission from Liu et al. Copyright (2023) American Chemical Society[62]. SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; CN/ZIS: carbon nitride/ZnIn2S4.

On the other hand, the pivotal role of crystal facet engineering was demonstrated in the CeO2/CdS

Metal-facilitated photocatalytic reaction

The strategic incorporation of metallic elements into semiconductor photocatalysts has proven to be an effective approach for improving charge separation, light absorption, and surface reaction dynamics[24,65]. Depending on the nature of the metal, this strategy can generally be categorized into three main types: metal nanoparticle introduction, metal ion doping, and metal single-atom conjugation.

Metal nanostructures

In different catalytic systems, the role of incorporated metal particles can vary significantly for improving photocatalytic efficiency. Very interestingly, Chen et al. pioneered the use of Au nanoparticles as dopants, selectively growing 1.3-2.2 nm Au domains at the termini of ZnSe nanorods [Figure 3A and B][44]. Transient absorption spectroscopy confirmed the prolongation of charge separation, while density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicated enhanced proton adsorption at the Au-semiconductor interface [Figure 3C]. This localized modification promoted directional electron transfer, resulting in an 8.5-fold increase in hydrogen evolution (437.8 μmol·h-1·g-1) compared to pristine ZnSe [Figure 3D]. Alternatively, the size-dependent plasmonic near-field enhancement was demonstrated in periodic Au/TiO2 core-shell nanocrystal arrays [Figure 3E][66]. Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations [Figure 3F] revealed complex electromagnetic field distributions that maximized at the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) wavelength of 540 nm. As indicated, a 10 nm TiO2 shell achieved an optimal balance between light absorption and charge transport [Figure 3G], resulting in a 60% increase in hydrogen production compared to randomly distributed counterparts. To enable the enhanced broadband light harvesting in plasmonic nanostructure, Tsao et al. designed Au@Cu7S4 yolk-shell nanoparticles [Figure 3H and I][34], where the LSPR of Au synergized with defect-induced plasmonic activity in Cu-deficient Cu7S4. Under visible light, hot electrons from Au were injected into Cu7S4 and contributed to hydrogen production; under NIR irradiation, the hot electrons delocalized at plasmonic Cu7S4 can directly reduce protons to produce hydrogen. This dual-plasmonic system achieved quantum efficiencies of 9.4% (500 nm) and 7.3% (2,200 nm), marking a significant advancement in full-spectrum photocatalysis.

Figure 3. Gold nanoparticles-enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A and B) TEM images of single Au-tipped ZnSe and double Au-tipped ZnSe nanorods; (C) Photocatalytic mechanism of Au-ZnSe hybrid nanorods for hydrogen production; (D) Comparison of hydrogen generation rates of various samples using methanol as the sacrificial hole scavenger. These four figures are quoted with permission from Chen et al. Copyright (2019) Wiley-VCH GmbH[44]; (E) Schematic diagram of cross-section of the Au/TiO2 nanocrystal arrays; (F) The cross-section near-fields for Au-TiO2 nanocrystal arrays partially immersed in SiO2 simulated by FDTD, λ = 540 nm; (G) Amount of hydrogen generated over Au/TiO2 arrays with different coating thicknesses of TiO2 compared with bare TiO2 thin films. These three figures are quoted with permission from Wu et al. Copyright (2016) Elsevier Ltd[66]; (H) TEM and (I) HRTEM images of Au@Cu7S4. These figures are quoted with permission from Tsao et al. Copyright (2024) Springer Nature[34]. FDTD: Finite-difference time-domain; HRTEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; NPs: nanoparticles; NCAs: nanocrystal arrays.

In addition, metal nanoparticles serve as versatile cocatalysts in photocatalytic systems. For instance, Cheng et al. synthesized Ni shell-coated Mn0.3Cd0.7S with sulfur vacancies (Ni/MCS-s)[67], achieving remarkable hydrogen production (164.1 mmol h-1·g-1) in simulated seawater. The Ni coating played a dual role - facilitating hot electron injection while enhancing corrosion resistance - resulting in an outstanding AQY of 60.4% at 420 nm. In another work, Chen et al. demonstrated precise tuning of photocatalytic performance in porphyrin-based COFs through controlled metal doping (M = Co, Ni, Zn)[45]. Despite maintaining identical AA-stacked frameworks, the central metal influenced charge-carrier dynamics. The established activity trend is: Zn > Ni > Co. As revealed, the Zn-incorporated COFs exhibited optimal exciton dissociation and electron transfer kinetics, resulting in a three-fold enhancement compared to Co-containing counterparts. Overall, these findings confirm the synergistic mechanisms of metallic nanostructures to enhance photocatalytic efficiency, including plasmonic field enhancement, hot carrier injection, cocatalytic interfacial transition, and optimized surface reaction.

Metal ions

By modifying band structures and optimizing charge carrier dynamics, metal ions were incorporated into semiconductor photocatalysts to provide a powerful approach for enhancing visible-light-driven hydrogen evolution. In recent years, rare earth ions have been attracting increasing research interest owing to the unimaginable advantages of their unique 4f electrons. Typically, in the Ce/N co-doped SrTiO3, the simultaneous introduction of Ce3+ and N3- ions improved charge separation efficiency and narrowed the bandgap from 3.2 eV to 2.45 eV[68]. As revealed, this doping structure facilitated N 2p/O 2p orbital hybridization, which raised the VB maximum by 0.55 eV. In contrast, Ce 3d/Ti 3d impurity states lowered the CB minimum by 0.2 eV [Figure 4A], resulting in an impressive hydrogen production rate of

Figure 4. Metal ions-enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A) The VBM and CBM positions for different SrTiO3 samples; (B) Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of SrTiO3 samples with irradiation time. These two figures are quoted with permission from Wang et al. Copyright (2022) Elsevier Ltd[68]; (C) Spontaneous exciton dissociation in Sc-doped rutile TiO2 for photocatalytic overall water splitting; (D) Comparison of hydrogen and oxygen evolution rates for photocatalytic overall water splitting over Pt cocatalyst modified with Sc-TiO2, Al-TiO2, and undoped TiO2. These two figures are quoted with permission from Qin et al. Copyright (2025) American Chemical Society[39]; (E) Band structure of ZIS, OZIS and 10%Bi-OZIS; (F) H2 yield over each sample. These two figures are quoted with permission from Tang et al. Copyright (2025) Elsevier Ltd[70]. VBM: Valence band maximum; CBM: conduction band minimum; ZIS: ZnIn2S4; OZIS: oxygen-doped ZnIn2S4.

In pursuit of noble-metal-free catalysts, Tang et al. designed a Bi3+-doped ZnIn2S4 system (Bi-OZIS) coupled with oxygen doping[70]. Bi ions played dual roles as plasmonic sensitizers and electron sinks. Mott-Schottky analysis [Figure 4E] revealed a doping-induced positive shift in the flat-band potential (-0.73 V vs. Ag/AgCl). The optimized 10% Bi-OZIS achieved 170.22 μmol·g-1·h-1 hydrogen evolution [Figure 4F], representing an 11.8-fold improvement over undoped ZnIn2S4. Alternatively, He et al. engineered spin-polarized electrons in Mn2+-doped ZnIn2S4 (Mn0.15-ZIS), achieving a remarkable hydrogen evolution rate of 32.75 mmol·g-1·h-1 under an external magnetic field - 13.87 times higher than undoped ZnIn2S4[55]. Magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy and DFT calculations revealed that Mn2+ doping introduced spin-polarized charge carriers, while in situ X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy identified Mn sites as hole enrichment centers. These examples highlight the multifaceted role of metal ion doping in modulating light absorption, charge separation and transport, spin dynamics, and surface reaction energetics.

Metal single atom

With the rapid development of nanotechnology and the continuous upgradation of observation equipment, precise control at the atomic level [i.e., single atomic catalysts (SACs)] has been achieved to give the relatively clear catalytic centers and structure-activity relationships, which are also significant for improving photocatalytic hydrogen production[25]. Of note, significant advancements in atomic-resolution characterization techniques have laid the groundwork for these innovations. High-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) directly images metal atomic dispersions, while synchrotron X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) resolves coordination environments. For example, the Pt single atom (PtSA)/Cs2SnI6 system by Zhou et al. exemplifies electronic optimization through atomic dispersion[46]. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM [Figure 5A] confirms PtSA isolation, while DFT calculations reveal electron localization at Pt-I3 sites [Figure 5B]. This configuration establishes strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) that enhances hydroiodic acid (HI) solution tolerance and slashes reaction barriers, yielding a Pt turnover frequency (TOF) of 70.6 h-1 - 176.5× higher than Pt nanoparticle analogues

Figure 5. Single atom-enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A) High-resolution HAADF-STEM image of PtSA/Cs2SnI6; (B) Atomic structure of PtSA/Cs2SnI6 and the additional electron distribution (yellow region); (C) Superior photocatalytic activity of PtSA/Cs2SnI6 catalyst. These three figures are quoted with permission from Zhou et al. Copyright (2025) Springer Nature[46]; (D) Mechanistic study for hydrogen evolution of Pt1/def-TiO2; (E) The photocatalytic H2 production activities of Pt1/def-TiO2 and references (inset is a schematic diagram). These two figures are quoted with permission from Chen et al. Copyright (2019) Wiley-VCH GmbH[71]; (F) Hydrogen-bonding microenvironment in close proximity to single-atom sites for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production; (G) EXAFS fitting curve of Ru1/UiO-67-o-(NH2)2 (inset: the proposed coordination structure of the single Ru atom anchored on the Zr-oxo cluster); (H) Photocatalytic hydrogen production rates of Ru1/UiO-67-X and UiO-67-X for 1 h. These three figures are quoted with permission from Hu et al. Copyright (2024) American Chemical Society[72]. HAADF-STEM: High-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy; EXAFS: extended X-ray absorption fine structure.

Beyond these specialized functions, SACs can also provide bifunctional enhancements in photocatalysis. Typically, Yu et al. developed Ir-g-CN/Ru-g-CN, with single Ir and Ru atoms on mesoporous g-C3N4, optimizing both electronic structure and hydrogen adsorption properties[74]. The dual SACs-based system achieved electrocatalytic TOFs of 12.9 s-1 (0.5 M H2SO4) and 5.1 s-1 (1.0 M KOH) at 100 mV overpotential, along with photocatalytic H2 production at 489.7 mmol·gmetal-1·h-1 with stability exceeding 120 h. This synergy between electrocatalytic and photocatalytic processes highlights the versatility of SACs for integrated green hydrogen systems and demonstrates their ability to overcome the trade-off between activity and stability.

Nevertheless, the economic implications, synthetic complexity, and functional performance of these modification strategies differ substantially. For instance, noble metal nanoparticles such as gold demonstrate pronounced plasmonic effects; however, their implementation is accompanied by a substantial economic burden. Similarly, single-atom catalysts have high atomic utilization efficiency; there are also major challenges in synthesis. Precious metal single-atom catalysts (such as Pt) face the dual difficulties of cost and synthesis methods, and the popularization of practical applications needs to be further investigated.

Interface-promoted photocatalytic hydrogen production

Interfacial engineering has emerged as a pivotal strategy for optimizing photocatalytic processes by precisely modulating charge transfer dynamics and reaction kinetics at the material interfaces[23]. In recent advancements, the well-designed interfaces spanning inorganic heterojunctions, organic donor-acceptor systems, and multicomponent hybrids can effectively address the inherent limitations of conventional photocatalysts, such as rapid charge recombination and insufficient active sites[47]. Recently, the semiconductor-semiconductor interfaces have been developed to enhance charge transport, minimize recombination losses, and maximize catalytic performance. These innovations include quantum-confined heterostructures, advanced S-scheme heterojunctions and molecularly engineered organic interfaces.

One of the most promising advancements in interfacial engineering involves QD-based heterojunctions, which facilitate efficient multiple exciton generation (MEG) and subsequent extraction. A notable example is the CdTe/vanadium-doped In2S3 (V-In2S3) system developed by Zhang et al. [Figure 6A-C][37], where epitaxial alignment between CdTe QDs and V-In2S3 ensures atomic-scale coherence, as confirmed by high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging of (440) In2S3 and (411) CdTe lattice fringes [Figure 6A]. This crystallographic alignment enables a cascaded band structure [Figure 6B], with the enhanced built-in electric field by a factor of 14 after vanadium doping. The resulting charge separation efficiency ensures near-complete utilization of multiple excitons before recombination, leading to an unprecedented internal quantum efficiency (IQE) of 114% at 350 nm and stoichiometric H2/O2 evolution (2:1 ratio) under solar irradiation [Figure 6C]. Beyond QDs, other multicomponent heterostructures have also been proved as an effective approach to simultaneously enhance charge separation and improve material stability. In the CdS@MoS2/Ti3C2 system [Figure 6D-F][75], intimate interfacial contacts were formed between CdS nanoparticles, MoS2 cocatalysts, and Ti3C2 MXene sheets. The well-defined lattice fringes - (002) for CdS (0.34 nm), (004) for MoS2 (0.36 nm), and (103) for Ti3C2 (0.23 nm) - confirm a structurally integrated architecture that directs charge flow along optimized pathways [Figure 6E and F]. Electrons migrate to MoS2 for proton reduction, while holes are efficiently transferred to Ti3C2, thereby preventing CdS photocorrosion. This spatial charge separation results in a record H2 production rate of 14.88 mmol·h-1·g-1, a 6.8-fold enhancement over bare CdS, while maintaining stability for 78 hours. Similar improvements have been achieved in ultrathin 2D/2D systems such as ZnIn2S4/g-C3N4[76], where direct Z-scheme charge transfer enables Pt-free H2 evolution at 14.8 mmol·h-1·g-1.

Figure 6. Interface-enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A) HR-STEM image to determine the lattice fringe of CdTe/V-In2S3 (scale bar 2 nm); (B) Schematic illustration of the energy band structure of CdTe and V-In2S3 before and after contact. ΔΦ represents the Fermi level difference between CdTe quantum dot and V-In2S3, and W represents the depletion layer of CdTe and V-In2S3; (C) Time-dependent photocatalytic overall water splitting profiles of CdTe/V-In2S3 hybrids. These three figures are quoted with permission from Zhang et al. Copyright (2022) Springer Nature[37]; (D) Schematic for charge transfer over ternary CdS@MoS2/Ti3C2 photocatalysts during photocatalytic H2 evolution, where LA refers to lactic acid as the sacrificial agent; (E) TEM and (F) HRTEM images of CdS@MoS2/Ti3C2 composites. These three figures are quoted with permission from Wu et al. Copyright (2023) Elsevier B.V[75]; (G) HRTEM image on interface between tetra(4-sulfonatophenyl) porphyrin (TPPS) and perylene diimide (PDI); (H) Left: the frontier molecular orbital distribution of TPPS and PDI at the interface; Right: schematic diagram of interfacial interaction of co-assembly supramolecular TPPS/PDI. These two figures are quoted with permission from Yang et al. Copyright (2022) Wiley-VCH GmbH[78]. HRTEM: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; HR-STEM: high-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy; LA: lactic acid; HOMO: highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO: lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

In recent years, S-scheme heterojunctions have been developed to address the longstanding challenge of balancing charge separation with redox potential retention. Unlike conventional type-II heterojunctions, which typically compromise redox power to improve carrier separation, S-scheme designs selectively recombine low-energy electrons and holes, preserving high-potential charges for catalytic reactions. As a prime example, the CuInS2/CeO2 heterojunction was demonstrated by Wang et al.[77], where interfacial band alignment and internal electric fields synergistically enhance H2 evolution to 226.6 μmol·h-1·g-1, which is 4.6 and 9.4 times higher than pristine CuInS2 and CeO2, respectively. Similarly, the ZnCdS/CoWO4 system achieves 839.85 μmol of H2 in 5 h (a 5.2× improvement over ZnCdS alone)[47], while W18O49/polymeric carbon nitride (PCN) reaches 1,700 μmol·h-1·g-1, representing a remarkable 56-fold enhancement compared to PCN. These results underscore the S-scheme heterojunction as a versatile strategy for maintaining robust reduction potentials while minimizing recombination losses.

Another significant advancement in interfacial engineering is the development of organic donor-acceptor systems, where charge separation is governed by molecular-scale interactions rather than the traditional semiconductor band alignment. The tetra(4-sulfonatophenyl) porphyrin (TPPS)/perylene diimide (PDI) supramolecular assembly by Yang et al. exemplifies this concept[78], with high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) revealing crystalline interfaces between TPPS (0.263 nm spacing) and PDI (0.327 nm spacing). DFT calculations further support these findings, indicating localized HOMO (the highest occupied molecular orbital; TPPS) and LUMO (the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; PDI) distributions [Figure 6G and H]. This precise orbital alignment creates a substantial interfacial electric field - 3.76 times stronger than the one in pure PDI - which efficiently facilitates exciton dissociation. The enhanced charge separation, coupled with J-H type π-π stacking that prolongs exciton lifetimes, enables visible-light-driven H2 production at 30.36 mmol·h-1·g-1, with an AQY of 3.81% at 650 nm. Such an organic interface provides a new opportunity to harness low-energy photons while circumventing the limitations of inorganic semiconductors, including poor visible-light absorption and rapid charge recombination.

Important developments on new types of photocatalysts

As innovative photocatalysts that address the limitations of conventional systems, MXenes and their engineered heterostructures have emerged as particularly promising candidates. MXene-based heterostructures highlight the potential of atomic and electronic interface engineering to enhance charge separation, catalytic performance, and material stability[79,80]. A notable example is the SrTiO3/Ti3C2 Schottky junction developed by Zhang et al. [Figure 7A-C][81], which was synthesized by an in-situ alkaline etching method: Sr(OH)2 treatment induced the growth of SrTiO3 nanoparticles and bonded chemically on Ti3C2 nanosheets. This process generates Ti vacancies that serve as catalytic sites and establishes efficient electron transfer pathways [Figure 7B], resulting in a 6.8-fold increase in hydrogen evolution rate compared to pristine SrTiO3, with remarkable cycling stability [Figure 7C]. Alternatively, Gu et al. developed a CdSe/Ti3C2 nanorod-nanosheet system, utilizing hydrothermal assembly to form 1D/2D interfaces[82]. The high work function of MXene (~4.3 eV) induces upward band bending in CdSe, which effectively suppresses electron backflow, leading to a hydrogen evolution rate of 763.2 μmol·g-1·h-1, six times higher than isolated CdSe, with stable performance over five cycles.

Figure 7. Emerging semiconductor photocatalysts and their hybrid for highly-efficient hydrogen production. (A) Schematic for synthesizing the SrTiO3/Ti3C2 (STO/TC) heterostructures; (B) Mechanism for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over STO/TC Schottky heterojunction; (C) Efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution by STO/TC heterostructures. TC-36 is the Ti3C2 sample synthesized by rotating the reaction system (80 °C) at 600 rpm for 36 h. These three figures are quoted with permission from Zhang et al. Copyright (2023) Elsevier[81]; (D) Schematic diagram of Ni2P-SNO/CdS-D nanocomposite; (E) Comparison of photocatalytic H2 generation over a series of photocatalysts. These two figures are quoted with permission from Hu et al. Copyright (2020) Elsevier B.V[85]. Ni2P-SNO/CdS-D: Ni2P-SnNb2O6/CdS-diethylenetriamine.

The utilization of MXenes hybridized with wide-bandgap semiconductors is further exemplified by the mesoporous TiO2/Ti3C2 composite[83], where TiO2 nanoparticles were anchored onto conductive MXene networks via electrostatic self-assembly. This configuration reduces charge transfer resistance by 87%, resulting in a hydrogen evolution rate of 218.85 μmol·g-1·h-1 (a 5.6-fold improvement). In the work by Xu et al., g-C3N4 was first treated with HCl and then coupled with Ti3C2 to form a face-to-face Schottky junction that promotes electron redistribution. The protonated g-C3N4/MXene system achieved a hydrogen evolution rate of 2,181 μmol·g-1·h-1, 5.5 times higher than bulk g-C3N4 under visible light[84].

Currently, MXene-based photocatalysts contribute to the hydrogen evolution reaction in three primary roles, as summarized in Table 1. First, MXene can serve as an electron co-catalyst, effectively replacing Pt. Second, it can act as a hole co-catalyst, extracting and consuming holes to suppress charge recombination. Finally, it can function as a photosensitizer, enhancing light absorption.

Advanced design strategies in MXene photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution

| Catalyst classification | Catalyst | Efficiency μmol/(g·h) | AQY/STH | Reaction system | External cocatalyst | Sacrificial agents | Stability | Light source | Reference |

| Electron co-catalyst | g-C3N4-MXene | ~2,181 | 8.6% (420 nm) | H2O | No | Triethanolamine | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [84] |

| CdS/Ti3C2 | 14,342 ± 7% | 40.1% (420 nm) | H2O | No | Aqueous solution | > 7 cycles | 300 W Xe lamp | [109] | |

| Hole co-catalyst | C-TiO2/g-C3N4 | ~1,409 | - | H2O | Pt | Triethanolamine | > 3 cycles | 300 W Xe lamp | [32] |

| STO/TC | 344.1 ± 3% | - | H2O | No | Methanol | > 35 cycles | Visible light | [81] | |

| CdSe-MXene | 763.2 ± 2% | 1.3% (350 nm) | H2O | Pt | Na2SO3 and Na2S | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [82] | |

| Photosensitizers | MXene -TiO2 | ~218.85 | - | H2O | No | Methyl orange | > 3 cycles | Visible light | [83] |

Similar to MXenes, the integration of transition metal phosphides, such as Ni2P, into semiconductor photocatalysts is emerging as a promising strategy for enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen evolution, which should primarily be attributed to rapid interfacial charge kinetics and promoted multi-functional active site engineering. For instance, Hu et al. developed a ternary Ni2P-SnNb2O6/CdS-diethylenetriamine (Ni2P-SNO/CdS-D) system [Figure 7D][85] via sequential assembly. The 2D/2D S-scheme heterojunction formed between ultrathin SnNb2O6 and CdS-D nanosheets generates built-in electric fields that drive charge separation, while Ni2P nanoparticles function as electron sinks. This design achieves an impressive hydrogen production rate of 11,992 μmol·g-1·h-1 [Figure 7E], representing a 2.35-fold and 130-fold increment over binary CdS-D and pristine SnNb2O6, respectively. Similarly, Wei et al. designed a ternary ZnIn2S4-graphene-Ni2P (ZIS-GR-Ni2P) photocatalyst to address the challenge of efficient electron and hole utilization[86]. In this system, graphene acts as an electron relay, while Ni2P serves as active sites for proton reduction (TOF = 8.2 s-1) and enhances electron extraction from ZnIn2S4. This synergistic system achieves a hydrogen evolution rate of 1,287.8 μmol·g-1·h-1, a 3.3-fold improvement over pristine ZnIn2S4.

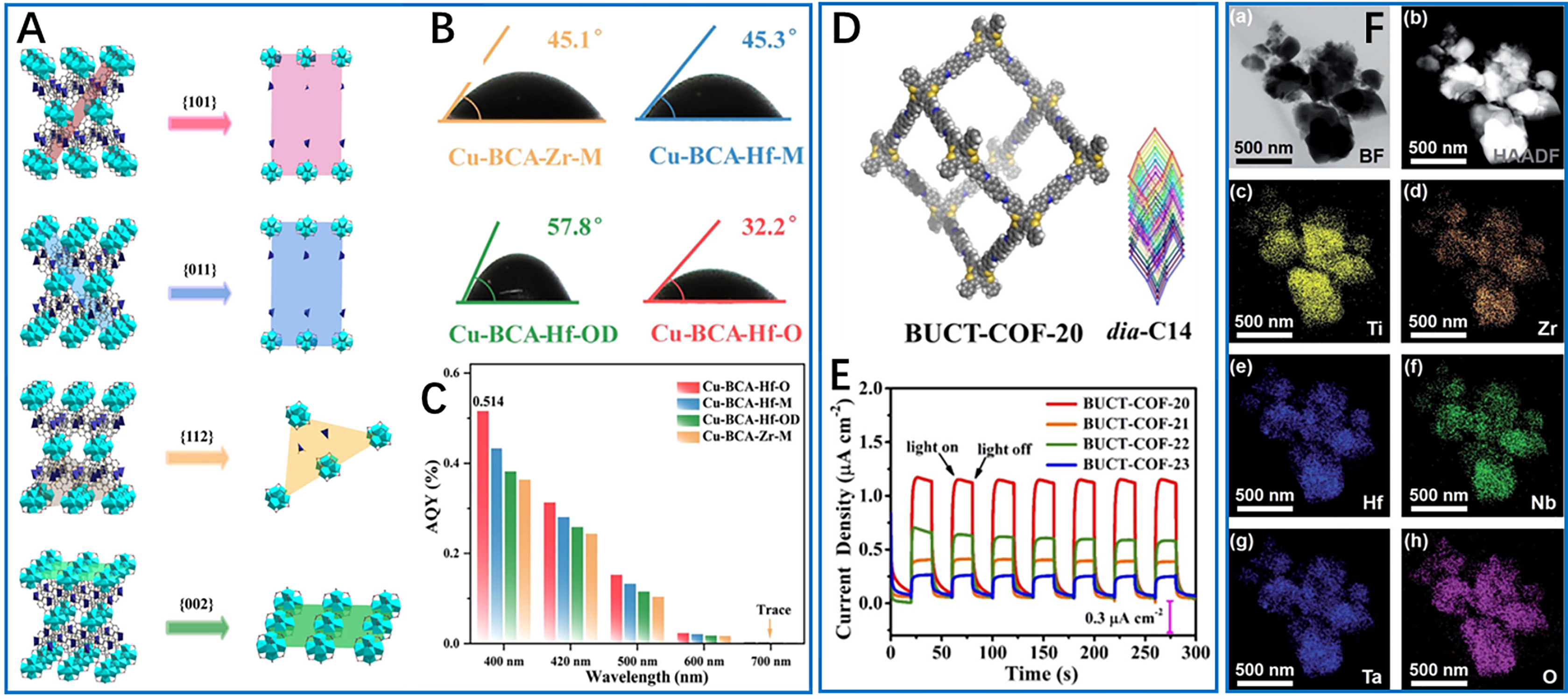

In addition to MXenes and phosphides, other emerging semiconductor materials are showing promise in photocatalysis, including MOFs, COFs, and high-entropy materials. COFs, which consist of precisely engineered active sites with tunable coordination chemistry and well-defined porous structures, have become a versatile platform for photocatalytic applications. In MOF-based photocatalysts, facet engineering enables the optimization of surface atomic arrangements to enhance catalytic performance. For instance, Lei et al. developed Cu-BCA-Hf-O MOFs with octahedral morphology exposing (101)/(011) facets [Figure 8A], which achieved a record hydrogen evolution rate of 49.8 mmol·g-1·h-1 among pristine MOFs[43]. This exceptional performance is attributed to the high density of Cu(I) active sites [Figure 8A], enhanced hydrophilicity (with a contact angle of 32.2°, Figure 8B), and efficient charge separation (AQY of 0.514% at 400 nm, Figure 8C). Further, the Hf(IV) coordination imparts structural stability, while Cu(I) functions as the catalytic center, demonstrating the ability of MOFs to integrate multiple functional components with atomic precision. However, the precise control over crystal facets and the scalable synthesis of phase-pure MOFs with high crystallinity remain great synthetic challenges. Recently, interfacial engineering in MOF composites was reported to address critical charge transfer limitations. For example, a study by Xu et al. on Pt@UiO-66-NH2 revealed that the removal of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) capping agents enables direct metal-support interactions[87], significantly boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production. Further optimization using ferrocene as a mediator (Pt-Fc@UiO-66-NH2) underscores the importance of microenvironment control in hybrid systems.

Figure 8. Multi-element photocatalysts for increasing photocatalytic hydrogen production. (A) Creation of as-cut surfaces for (101), (112), (011), and (002) facets of MOFs. Color representation: Cu, purple; Hf, cyan; N, orange; O, red; C, gray; (B) Water contact angles on the MOFs; (C) AQY efficiency of the MOFs. These three figures are quoted with permission from Lei et al. Copyright (2025) Wiley-VCH GmbH[43]; (D) Structure of fully conjugated 3D BUCT-COF-20; (E) Periodic on/off photocurrent output of BUCT-COF-20-23 cast on FTO glass (λ > 400 nm). These two figures are quoted with permission from Wang et al. Copyright (2024) Wiley-VCH GmbH[36]; (F) Mixing of elements at the atomic scale in high-entropy oxide TiZrHfNbTaO11. This figure is quoted with permission from Edalati et al. Copyright (2020) The Royal Society of Chemistry[92]. MOFs: Metal-organic frameworks; AQY: apparent quantum yield; FTO: fluorine-doped tin oxide.

In contrast to MOFs, COFs provide remarkable control over their electronic structures through crystalline porous frameworks and precise molecular engineering, which have highlighted their transformative potential in photocatalysis. In the work of Li et al., donor-π-acceptor (TCDA) COFs exhibit exceptional band structure tunability. By integrating benzotrithiophene donors and triazine acceptors via sp2 carbon linkages, they achieved a hydrogen evolution rate of 70.8 ± 1.9 mmol·g-1·h-1 under visible light. Spectroscopic analyses reveal that the full π-conjugation within the sp2 carbon-linked COF enhances both light absorption and charge separation efficiency[88]. Similarly, conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs) with defined D-π-A structures show outstanding photocatalytic performance[89]. For example, a pyrene-based D-π-A polymer (Py-TP-BTDO) achieves a remarkable hydrogen evolution rate of 115.03 mmol·g-1·h-1 under visible light (λ > 420 nm) and 312.24 mmol·g-1·h-1 under natural sunlight. The precisely engineered D-π-A framework ensures efficient charge separation and broad light absorption, where a 120 cm2 polymer film produces continuous hydrogen bubbles under sunlight in an outdoor environment to indicate the potential of structurally controlled organic polymers for practical solar-driven hydrogen production. Additionally, dimensional control has been advanced with fully conjugated 3D COFs developed by Wang et al. Using saddle-shaped cyclooctatetrathiophene building blocks, COF achieves extended π-delocalization within a diamondoid framework [Figure 8D], yielding an impressive H2 evolution rate of 40.36 mmol·g-1·h-1. Photocurrent measurements [Figure 8E] confirm enhanced charge separation efficiency, positioning 3D COFs as a new paradigm beyond 2D systems[36]. Atomic-level precision in cocatalyst integration is further demonstrated by the hydroxyl/imine-N functionalized PY-DHBD-COF [Schiff-base condensation reaction of 1,4-dihydroxybenzidine (DHBD) with 1,3,6,8-tetra(4-formylphenyl)pyrene (PY-CHO)] reported by Li et al. Periodic Pt adsorption sites enable in situ photodeposition of uniformly dispersed Pt clusters, achieving extraordinary photocatalytic activity (42,432 μmol g-1 h-1 at 1 wt% Pt loading)[90]. Notwithstanding these advances, the synthesis of highly crystalline and chemically stable COFs often requires harsh conditions and long reaction times, presenting obstacles for their large-scale fabrication.

In recent years, high-entropy materials have emerged as groundbreaking photocatalysts to offer significant advantages due to their unique multi-component synergistic effects and entropy stabilization mechanism. The incorporation of multiple metal nodes creates a “cocktail effect”[91], significantly enhancing charge transport compared to a conventional single component. These properties effectively resolve the typical challenges of traditional catalysts, such as band gap regulation, stability, and multifunctional synergy. Typically, high-entropy oxynitride (TiZrHfNbTaO6N3) overcomes the trade-off between bandgap and stability[60], maintaining excellent chemical stability with an exceptionally narrow 1.6 eV bandgap. The dual-phase structure [61% face centered cubic (FCC), 39% monoclinic] enables visible-light activity that was previously unattainable in stable oxide materials. Similarly, the high-entropy oxide (TiZrHfNbTaO11) features uniform atomic-scale mixing of five cations [Figure 8F][92], confirmed by STEM-energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis. The d0 electronic configuration leads to a visible-light-active bandgap of 2.9 eV, offering greater compositional flexibility than binary oxides. In addition, the high-entropy alloys can act both as an electron trap (via Schottky junctions) and as a thermodynamic promoter. In Pt18Ni26Fe15Co14Cu27 high-entropy-alloy (HEA) nanoparticles, when coupled with protonated g-C3N4 [holey graphitic carbon nitride (HCN)], this system achieves H2 evolution (4.825 mmol·g-1·h-1) with 958× enhancements compared to pristine HCN[59]. In the pioneering work by Qi et al., the synthesis of HE-MOFs signified a paradigm shift in photocatalytic material design[35]. By combining the structural advantages of MOFs with high-entropy principles, they address one of the major limitations of traditional MOF photocatalysts - limited charge transfer efficiency. The modulation of electronic structures from various metal centers ensures continuous charge transfer pathways, overcoming the carrier mobility challenges that limit many MOF-based photocatalysts. There are currently four main types of high-entropy catalysts used in photocatalytic hydrogen production, as shown in Table 2. The advanced electronic structures of some of these catalysts can even independently complete efficient water splitting reactions without the need for co-catalysts. However, we should notice a non-negligible problem: a primary synthesis bottleneck for these high-entropy materials lies in achieving a homogeneous distribution of multiple elements at the atomic level while simultaneously controlling phase composition and nanostructure, which often demands sophisticated and energy-intensive synthetic routes.

Advanced design strategies in high-entropy photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution

| Catalyst classification | Catalyst | Efficiency μmol/(g·h) | AQY/STH | Reaction system | External cocatalyst | Sacrificial agents | Stability | Light source | Reference |

| High entropy oxide | TiHfZrNbTaO11 | ~80 | - | H2O | Pt | Methanol | > 3 cycles | 300 W Xe lamp | [92] |

| High-entropy oxynitride | TiZrHfNbTaO6N3 | ~60 | - | H2O | Pt | Methanol | > 4 cycles | 300 W Xe lamp | [60] |

| High-entropy MOF/COF | HE-MOF-NS | ~13,240 | - | H2O | No | Ascorbic acid | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [35] |

| Cu-BCA-Hf-O | 49,825.71 ± 2% | 0.514% (400 nm) | H2O | No | Triethanolamine | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [43] | |

| High-entropy heterojunction | CuO-HEO | ~334 | - | H2O | Pt | Methanol | > 4 cycles | 300 W Xe | [110] |

| HCN/HEA | ~5,440 | 20.12% (420 nm) | H2O | No | Triethanolamine | > 20 h | Visible light | [59] | |

| ZnCdS/HEA | ~5,990 | - | H2O | No | Na2SO3 and Na2S | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [111] |

Beyond material design, the assistance from the external field represents a powerful strategy to enhance photocatalytic performance. Photoelectrocatalysis, which integrates light illumination with an applied electrical bias, is particularly effective. This approach provides a complementary pathway to overcome the intrinsic limitations of powder-based photocatalytic systems. Furthermore, the concept of using sacrificial agents can be expanded from costly pure chemicals to waste streams, enabling simultaneous hydrogen production and environmental remediation. As exemplified by the recent groundbreaking work of Hai et al., this “value-added” photoreforming process presents a highly promising and sustainable pathway for H2 production from real-world waste feedstocks[93].

Overall, recent advancements in photocatalytic materials have improved hydrogen production efficiency through morphological optimization, metal incorporation or hybridization, interface engineering, and the exploitation of outstanding material systems. These materials address fundamental challenges related to light absorption, charge separation, and surface reactions. Correspondingly, their yield for producing hydrogen was significantly increased, as summarized in Table 3.

The typical photocatalysts and their performances in hydrogen production under special conditions

| Catalyst classification | Catalyst | Efficiency μmol/(g·h) | AQY/STH | Reaction system | External cocatalyst | Sacrificial agents | Stability | Light source | Reference |

| Morphological optimization | LaNiO3/ZnCdS | ~52,091 | 11.16 % (420 nm) | H2O | No | Na2SO3 and Na2S | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [61] |

| NR-CeO2 | 444 ± 4% | - | H2O | No | Lactic acid | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [62] | |

| g-C3N4/ZnIn2S4 | ~20,738 | - | H2O | Pt | Triethanolamine | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [54] | |

| Metal modification | Au-ZnSe | ~437.8 | 1.3% (365 nm) | H2O | No | Methanol | - | Visible light | [44] |

| Au@Cu7S4 | ~27.6 | 9.4% (500 nm) | H2O | No | Methanol | 30 successive hours | Visible & NIR | [34] | |

| Ni/MCS-s | ~164,100 | 60.4% (420 nm) | Simulated seawater | No | Na2SO3 and Na2S | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [67] | |

| Ce/N-SrTiO3 | ~4,280 | - | H2O | Pt | Methanol | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [68] | |

| Sc-TiO2 | ~758 | 30.3% (360 nm), 0.34% STH | H2O | Pt | - | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [39] | |

| Bi-OZIS | ~170.22 | - | H2O | No | - | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [70] | |

| PtSA/Cs2SnI6 | ~430 | - | HI | No | H3PO2 | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [46] | |

| Pt1/def-TiO2 | ~52,720 | - | H2O | No | Methanol | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [71] | |

| Ru1/UiO-67-o-(NH2)2 | ~20,520 | - | H2O | No | Triethylamine | > 3 cycles | Visible light | [72] | |

| Interface engineering | CdTe/V-In2S3 | ~101.15 | 114% (350 nm), STH = 1.31% | H2O | No | Na2S-Na2SO3/AgNO3 | > 100 h | Solar irradiation | [37] |

| CdS@MoS2/Ti3C2 | ~14,880 | - | H2O | No | Lactic acid | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [75] | |

| TPPS/PDI | ~30,360 | 3.81% (650 nm) | H2O | Pt | Ascorbic acid | > 50 h | Visible light | [78] | |

| STO/TC | 344.1 ± 3% | - | H2O | No | Methanol | > 5 cycles | Visible light | [81] | |

| Co3O4@ZnIn2S4 | 18,900 ± 5% | - | H2O | No | Triethanolamine | > 4 cycles | AM 1.5G sunlight | [49] | |

| Ni2P-SNO/CdS-D | ~11,992 | - | H2O | No | Na2SO3 and Na2S | > 4 cycles | Visible light | [85] | |

| Other new types of photocatalysts | BUCT-COF-20 | ~40,360 | - | H2O/seawater | Pt | Ascorbic acid | > 5 cycles | λ > 400 nm | [36] |

| CDs/TCN-3.5% | ~12,940 | - | H2O | No | Triethanolamine | > 4 cycles | Full-spectrum | [50] | |

| MO@ZIS | ~33,290 | 19.93% (420 nm) | H2O | Pt | Triethanolamine | > 5 cycles | Magnetic field + photothermal | [48] |

Machine learning is increasingly pivotal in accelerating the transition of photocatalysis from laboratory discovery to practical application[94-96]. Its power lies in navigating the vast, high-dimensional design space of photocatalytic materials (e.g., composition, structure, morphology) and reaction conditions far more efficiently than traditional trial-and-error approaches. Machine learning models trained on existing experimental or theoretical data can predict promising new photocatalysts with desired properties (e.g., narrow bandgap, suitable band positions, high carrier mobility) before they are ever synthesized, dramatically reducing development time and cost. Furthermore, machine learning algorithms can optimize complex reaction parameters (light intensity, pH, catalyst loading) to maximize hydrogen evolution rates in scaled-up systems. Beyond prediction, machine learning also aids in extracting fundamental insights from complex characterization data, identifying hidden structure-property relationships that guide rational design. This data-driven paradigm is essential for solving multi-objective optimization problems inherent to practical applications, such as simultaneously maximizing activity, stability, and cost-effectiveness.

MULTI-FUNCTIONAL SYNERGISM FOR PRACTICABLE PHOTOCATALYSIS

To bridge the gap between laboratory-scale research and real-world applications, photocatalytic hydrogen production systems must address several critical challenges in solar energy utilization, mass transfer efficiency, and environmental adaptability (e.g., seawater splitting)[97,98]. This section highlights these breakthroughs and demonstrates how integrated material design and system-level optimization are paving the way for scalable and sustainable photocatalytic hydrogen production[49,99,100].

Efficient utilization of solar energy remains a fundamental challenge in photocatalysis, given the broad spectral distribution of sunlight (~5% UV, ~43% visible, and ~52% infrared) and the limited light absorption capacity of most photocatalysts. Conventional systems typically respond only to UV or visible light, thereby wasting nearly half of the available solar energy. This issue arises primarily from two factors: inadequate bandgap engineering to absorb low-energy photons (NIR/IR) and rapid charge recombination that dissipates absorbed energy as heat. To facilitate the practical application of photocatalytic hydrogen production, expanding the absorption spectrum into the NIR region is a vital approach for fully exploiting solar energy. For instance, Chen et al. developed a WO3-x/ZnIn2S4 (WO3-x/ZIS) heterojunction, where WO3-x QDs exhibited LSPR, enabling NIR photon absorption (> 800 nm)[29]. The system achieved 14.05 μmol·g-1·h-1 H2 production under NIR irradiation through efficient hot-electron transfer facilitated by an interfacial electric field. This work highlights the potential of plasmonic materials to extend light absorption beyond conventional bandgap limitations while preserving effective charge separation.

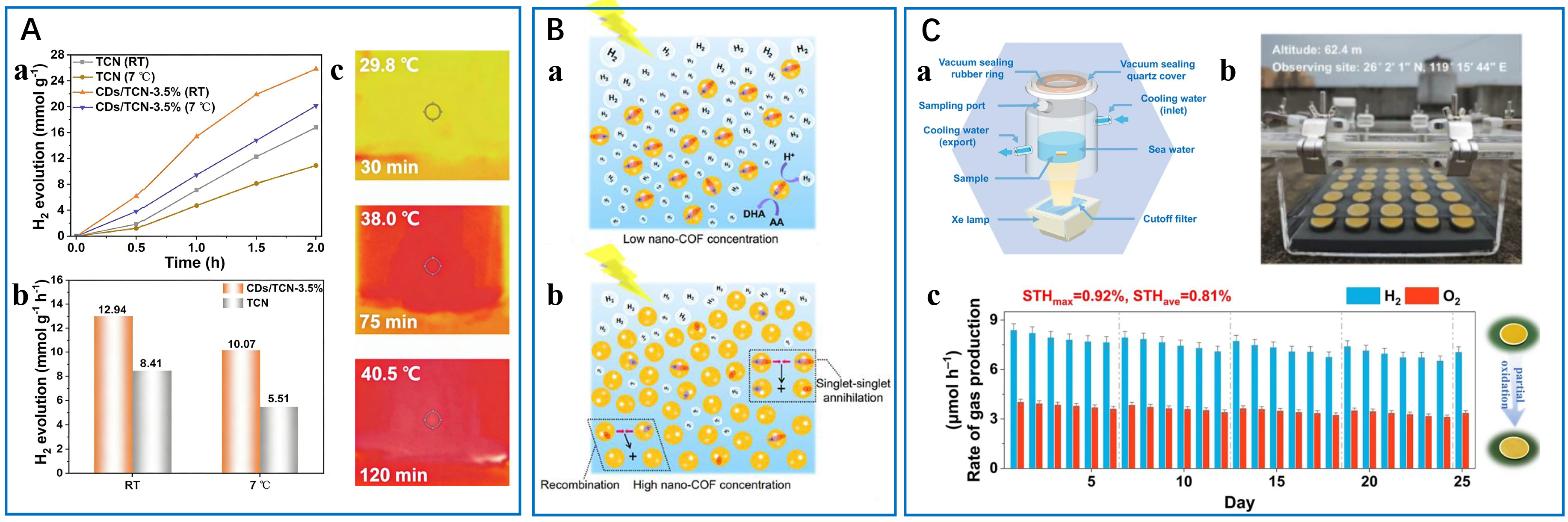

Photothermal-photocatalytic synergy offers another promising strategy by converting NIR/visible light into thermal energy to accelerate reaction kinetics. Lu et al. engineered carbon dot-modified tubular carbon nitride (CDs/TCN), where the photothermal effect of CDs elevated local temperatures to 103 °C, compared to 89.4 °C for pristine TCN[50]. This thermal enhancement boosted H2 production rates to 12.94 mmol·g-1·h-1 in water and 11.92 mmol·g-1·h-1 in seawater, with infrared imaging directly correlating higher reaction temperatures with improved activity [Figure 9A]. Similarly, a Co3O4@ZnIn2S4 system, developed by Shi et al., leveraged the photothermal effect of Co3O4 to achieve 18.9 mmol·g-1·h-1 under AM 1.5G sunlight while maintaining strong redox capabilities through an S-scheme charge transfer mechanism[49].

Figure 9. Additional optimization during photocatalytic reaction. (A) Photothermal-assisted photocatalytic water splitting into hydrogen: (a) photocatalytic H2 generation from water splitting and (b) H2 evolution rates of TCN and CDs/TCN-3.5% at different temperatures; (c) photothermal mapping images of CDs/TCN-3.5% under full-spectrum irradiation in the photocatalytic water splitting process. This figure is quoted with permission from Lu et al. Copyright (2022) Elsevier B.V[50]; (B) Free charge carriers produced in nano-COFs at (a) low concentration and (b) high concentration (ascorbic acid: AA; dehydroascorbic acid: DHA). This figure is quoted with permission from Zhao et al. Copyright (2025) Springer Nature[101]; (C) Porous microreactor chip for photocatalytic seawater splitting: (a) schematic illustration of the reaction system, (b) the optical image of an outdoor setup, and (c) stability test of as-prepared Ag3PO4/CdS chip photocatalysts. Each cycle is 12 h. This figure is quoted with permission from Zhu et al. Copyright (2025) Springer[51]. CDs/TCN: Carbon dot-modified tubular carbon nitride; COFs: covalent organic frameworks; STH: solar-to-hydrogen.

Photothermal-photocatalytic synergy effects offer an innovative solution to simultaneously address light absorption and charge separation challenges. Hao et al. designed Mn3O4@ZnIn2S4 S-scheme heterojunctions that combined magnetic field effects with photothermal activation[48]. The applied magnetic field generated Lorentz forces to drive charge separation, while the photothermal effect of Mn3O4 provided additional heating, resulting in 33.29 mmol·g-1·h-1 H2 production (19.93% AQY at 420 nm) - a 1.11-fold enhancement compared to systems without magnetic field assistance. This work exemplifies how external field modulation can synergize with other enhancement mechanisms to overcome fundamental limitations in photocatalysis. To address liquid-phase mass transfer issues, Wang et al. engineered hydrophilic carbon nitride using a salt-assisted synthesis method, significantly enhancing its dispersibility in water[100]. This surface modification created a quasi-homogeneous system, improving liquid-solid interactions and increasing hydrogen production by a factor of 16 compared to bulk PCN. Further optimization through K+ doping enhanced charge transfer, demonstrating how surface functionalization and nanostructuring can synergistically overcome liquid-phase mass transfer limitations. Similarly, Sun et al. developed an S-scheme homojunction photocatalyst by combining high-crystalline and amorphous g-C3N4 via solvothermal synthesis[99]. The efficient S-type charge transfer between the crystalline/amorphous phases, along with an increased surface area that provides more active sites, enhanced hydrophilicity, and promoted interaction between liquid-phase mass transfer and water molecules. This optimized heterostructure achieved remarkable hydrogen evolution rates of 5.534 mmol·g-1·h-1 in pure water [6.6× higher than the amorphous carbon nitride (CN)] and 3.147 mmol·g-1·h-1 in seawater. This work highlights a novel approach to maintain high activity in challenging seawater environments, offering practical potential for solar-driven hydrogen production.

In gas-phase systems, Zhao et al. developed nano-COFs to exhibit unique concentration-dependent behaviors[101]. At low concentrations [Figure 9B-a], the well-dispersed nanoparticles minimized particle collisions, promoting efficient exciton separation and proton reduction (392 mmol·g-1·h-1 H2). However, at higher concentrations [Figure 9B-b], particle collisions induced singlet-singlet annihilation, underscoring the importance of balancing catalyst loading with mass transfer efficiency. These studies illustrate that mass transfer optimization requires tailored approaches: surface modification for liquid-phase systems and precise concentration control for gas-phase reactions.

Recently, innovative solutions have been introduced to address these corrosion-related issues from seawater. For instance, Liu et al. developed a phase-transition mediated system incorporating a self-breathable, waterproof membrane, which enables in situ desalination through a liquid-gas-liquid transition[52]. The system demonstrated exceptional corrosion resistance without requiring additional energy input. Zhu et al. proposed an alternative strategy by designing a vacancy-engineered Ag3PO4/CdS porous microreactor chip [Figure 9C-a][51]. The Ag vacancies within the Ag3PO4 layer effectively repel seawater ions, preventing undesirable oxidation reactions, while S vacancies on the CdS layer selectively adsorb sulfur species, enhancing the hydrogen evolution reaction. These specific interactions between sulfur species and water promote efficient carrier transport. The optimized heterojunction design achieved a solar hydrogen production efficiency of 0.81%. When scaled to a 256 cm2 solar-driven prototype [Figure 9C-b], the device achieved a hydrogen production rate of 68.01 mmol·h-1·m-2 and displayed unprecedented stability (> 300 h) during seawater splitting, demonstrating its potential for practical outdoor applications [Figure 9C-c]. Both approaches offer efficient hydrogen production from seawater while addressing the critical corrosion challenges, advancing the development of practical marine hydrogen energy systems.

SIGNIFICANT EXPLORATION ON INDUSTRIALIZATION

The transition from laboratory-scale photocatalytic hydrogen production to industrial applications requires meticulous reactor design to address challenges related to scalability, efficiency, and safety. Three major limitations hinder the scaling of photocatalytic systems: insufficient light distribution over a large reactor area, difficulties in gas-liquid separation and hydrogen collection, and the inability to maintain catalyst activity under practical operating conditions. Although photocatalysis offers a promising low-cost route for solar hydrogen generation, conventional laboratory setups suffer from inefficient light utilization, poor mass transfer, and challenges in product separation when scaled up.

To address these challenges, researchers have proposed various novel reactor designs and solutions.

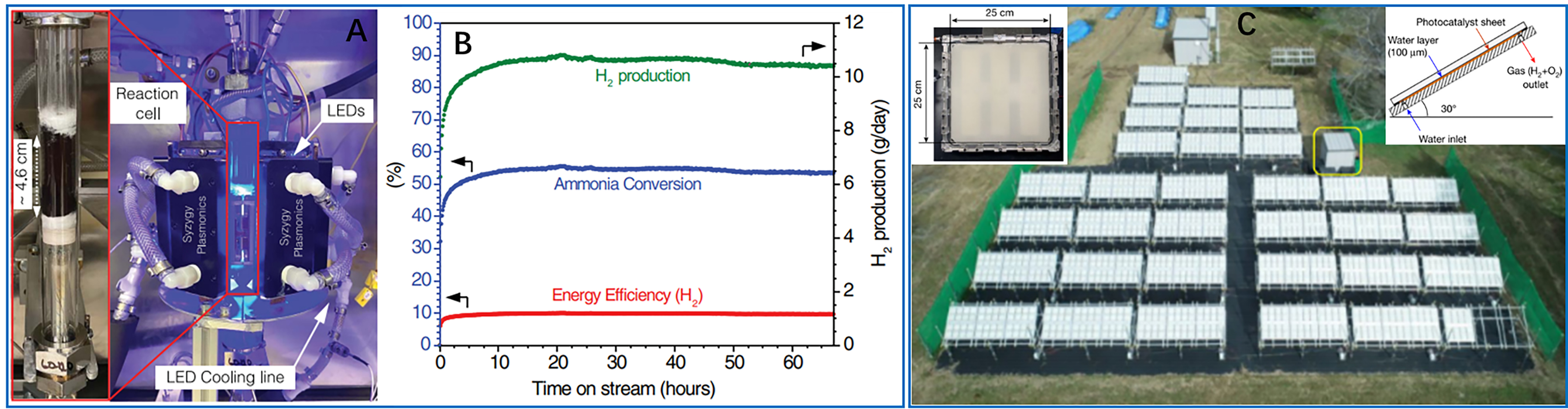

Figure 10. Practical and large-scale application. (A) Photograph of the reaction cell (left) and the photocatalytic platform (right) using LEDs at 470 nm for ammonia decomposition. The reaction cell consisted of two concentric tubes of different diameters, with the catalyst (~0.5 cm bed thickness) filled in between them; (B) Long-term photocatalytic ammonia decomposition on the Cu-Fe-AR under illumination power 137 W (light on at time = 0). These two figures are quoted with permission from Yuan et al. Copyright (2022) American Association for the Advancement of Science[102]; (C) The 100 m2 water splitting photocatalytic system consisting of 1,600 panel reactor units and a hut housing a gas separation facility (indicated by the yellow box). Left inset: a photographic image of a panel reactor unit (625 cm2). Right inset: the structure of the panel reactor unit viewed from the side. This figure is quoted with permission from Nishiyama et al. Copyright (2020) Springer Nature[104]. LED: Light-emitting diode.

Reactor safety remains a critical consideration in practical applications. Nishiyama et al. developed a 100 m2 panel array system [Figure 10C][104], consisting of 1,600 modular units with 0.1 mm reaction gaps. This ultra-compact design minimized the risk of explosive gas accumulation while enabling efficient product separation using commercial polyimide membranes. Despite a modest STH efficiency of 0.76%, the system showed exceptional stability during months of outdoor operation, demonstrating the feasibility of safe, large-scale photocatalytic water splitting.

From an economic standpoint, the reactor design is a critical factor for practical implementation. The techno-economic analysis by Pinaud et al. revealed that reactor configuration plays a significant role in determining hydrogen production costs, ranging from $1.60 to $10.40 per kg of H2[105]. Particle suspension systems, while more cost-effective, presented greater safety concerns, whereas panel-based systems offered improved control but required efficiency enhancements. The study highlighted that achieving an STH efficiency of 5%-10% could make photocatalytic systems competitive with conventional electrolysis technologies. Future research should focus on hybrid systems that combine the cost advantages of particle-based reactors with the safety benefits of panel-based designs. Additionally, incorporating advanced light management techniques and improved membrane technologies for efficient gas separation could further enhance the commercial viability of photocatalytic hydrogen production.

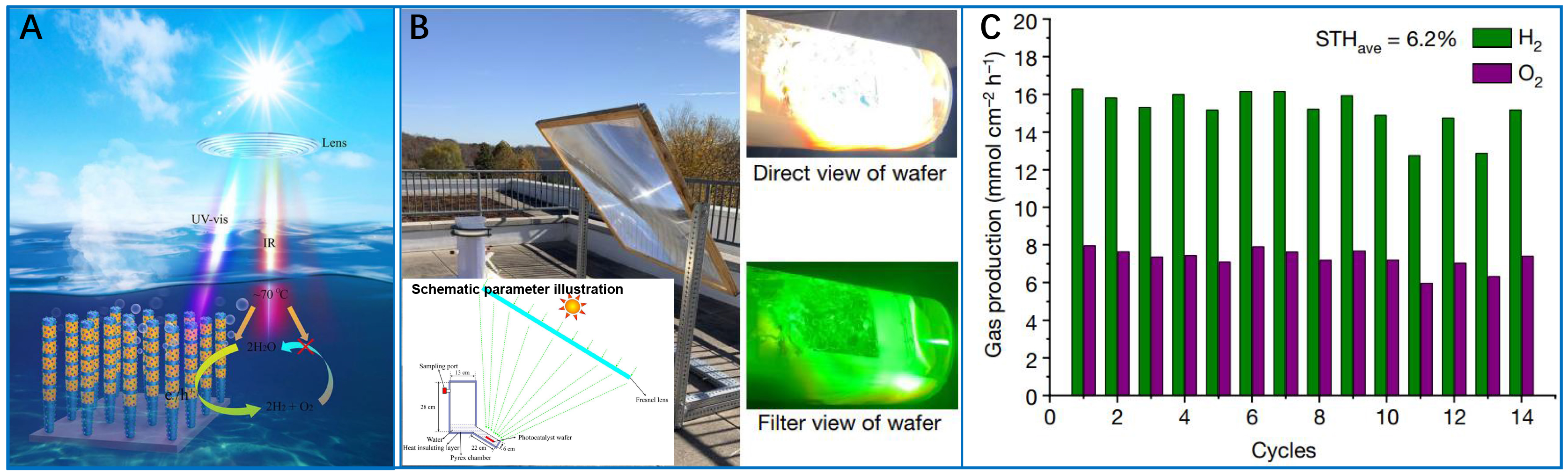

While laboratory studies consistently report impressive catalytic efficiencies, the implementation of these technologies in real-world settings encounters a range of complex obstacles that necessitate innovative engineering approaches. In the work by Guo et al., wood-based photothermal-photocatalytic systems were developed to char wood substrates for facilitating biphase interfaces (steam/photocatalyst/H2) that significantly boosted hydrogen production to 3,271.49 μmol·h-1·cm-2 - an increase of 100 times compared to traditional triphase systems[106]. This approach effectively addressed two major practical limitations: reducing water adsorption barriers and minimizing hydrogen transport resistance, demonstrating the evolution required in material engineering for large-scale deployment. Similarly, the Hydrogen Farm Project (HFP) led by Zhao et al. achieved an STH efficiency of 1.85% using BiVO4 with precisely engineered (010)/(110) facets and Fe3+/Fe2+ shuttle ions[107]; however, outdoor panel testing revealed the vulnerability of redox mediators to environmental variations. Very significantly, Zhou et al. achieved 9.2% STH efficiency using indium gallium nitride (InGaN) photocatalysts under concentrated light [Figure 11] highlighting the importance of thermal management - maintaining a temperature of 70 °C via infrared harvesting was essential to prevent H2/O2 recombination[108]. Scaling this 4 cm × 4 cm wafer system to a 257 W demonstration revealed new limitations, as the STH efficiency dropped to 6.2% [Figure 11C], underscoring the non-linear scaling effects on photon and thermal distribution.

Figure 11. STH efficiency of more than 9% in photocatalytic water splitting. (A) Synergetic effect for promoting forward hydrogen-oxygen evolution and inhibiting the reverse hydrogen-oxygen recombination in the photocatalytic overall water splitting (OWS); (B) Image of outdoor photocatalytic OWS system; (C) The corresponding STH efficiency of a 4 cm × 4 cm Rh/Cr2O3/Co3O4-loaded InGaN/GaN NW wafer under concentrated natural solar light (~16,070 mW·cm-2). These three figures are quoted with permission from Zhou et al. Copyright (2023) Springer Nature[108]. STH: Solar-to-hydrogen; IR: infrared light.

Despite promising reactor designs and high STH efficiencies, large-scale applications still face the fundamental challenge of catalyst recovery and recycling. In panel arrays or LED-driven reactors, long-term chemical and mechanical stability, including resistance to leaching, erosion, and adhesion failure, is critical. Suspended systems require efficient nanocatalyst recovery processes (e.g., microfiltration or centrifugation), which add complexity and energy cost. Future reactor designs must incorporate ease of recovery, cycling stability, and cost considerations to advance the industrialization of photocatalytic hydrogen production. Besides, these case studies demonstrate that practical deployment extends beyond catalyst optimization. Effective strategies must address temperature variations and interfacial engineering, integrating scientific and engineering insights to bridge the “efficiency cliff” between lab and field conditions. Future systems must balance scalable performance, environmental stability, and energy return on investment. The achievement of 9% STH efficiency indicates that photocatalytic water splitting is approaching economic viability. However, further advances will require co-development of catalysts, reactors, and balance-of-plant components within an integrated framework.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

As a promising approach for producing green hydrogen, photocatalytic splitting of water has gained significant attention to address both energy demand and carbon neutrality goal. This review summarizes the most significant advancements among various innovative strategies reported in the last five years for significantly boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production. Specifically, morphological optimization in materials’ dimension, structure and facets improves light absorption and enhances charge separation. Metal involvements, such as plasmonic nanoparticles, active ions and single atoms, broaden the light absorption range and increase the reaction activity to boost catalytic efficiency. Interface engineering, including S-scheme heterojunctions and QD hybrids, achieves the optimal charge transfer while maintaining the redox potential. The emergence of new photocatalysts - such as MXenes, MOFs, COFs, and high-entropy systems - offers adjustable electronic properties and multifunctional capabilities. Further, photothermal synergy enhances solar energy utilization, enabling efficient hydrogen production even under NIR irradiation. The use of hydrophilic catalysts and microreactors accelerates reaction kinetics in practical applications, while the ion-blocking membranes and vacancy engineering help mitigate corrosion and enhance long-term stability in seawater splitting. In terms of scalability and industrial potential, large-scale demonstrations, such as

Despite witnessing the remarkable advancements, we should still be aware of some challenges that need to be satisfactorily addressed in future research. As the widely-concerned progress, SACs are poised to redefine photocatalyst design through atomically precise control of electronic structure, interfacial charge transfer, and microenvironment. Although noble metals dominate current research, future efforts must focus on Earth-abundant alternatives (e.g., Fe, Co, and Ni single-atom catalysts) and scalable synthesis methods. The integration of in situ characterization, machine learning, and reactor engineering will accelerate the transition of SACs from laboratory breakthroughs to industrial-scale solar hydrogen production. The evolution of interfacial engineering in photocatalysis illustrates a clear transition from simple composite materials to precisely designed heterostructures with atomic- or molecular-level precision. Major advances involve epitaxial growth for lattice-matched interfaces, dimensional tuning to enhance charge transport, and the combination of organic and inorganic components to exploit synergistic effects. Future efforts are likely to concentrate on creating adaptive interfaces that respond to reaction environments, coupled with advanced in situ characterization techniques for real-time tracking of interfacial charge dynamics.

In addition, future research should focus on separating hydrogen/oxygen and enhancing stability under practical operating conditions and developing scalable synthesis techniques to bring these laboratory innovations into real-world applications. The integration of these material innovations with optimized reactor design marks the next frontier for achieving efficient, large-scale solar hydrogen production. Especially, the membrane-based method provides simplicity and direct integration, while the porous microreactor chip design offers flexibility for large-scale deployment. The ongoing improvements in membrane materials and microreactor chips will further enhance the commercialization potential of seawater electrolysis.

At present, computational analysis plays an important role in the theory of photocatalysis. DFT and machine learning are recommended to further investigate the relationships among the electronic structure, ion types and concentration, and hydrogen yield, thus providing theoretical support for photocatalytic hydrogen production from seawater cracking. The future lies in the development of integrated solutions that balance efficiency, stability, and cost, ultimately supporting a sustainable hydrogen economy. After in-depth investigation of photocatalytic systems and continuous optimization of photocatalysts and reactors, research on hydrogen production via photocatalytic seawater splitting is expected to make significant progress and contribute substantially to global decarbonization.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, writing - original draft: Cui, H.; Chen, C.

Data curation, figure design: Lu, X.; Wang, Q.

Conceptualization, data curation, writing - editing, supervision: Guan, G.

Writing - review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision: Han, M. Y.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2021YFF1200200) and start-up funds from Tianjin University, China.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Demski, C.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; et al. National context is a key determinant of energy security concerns across Europe. Nat. Energy. 2018, 3, 882-8.

2. Mazur, A. Does increasing energy or electricity consumption improve quality of life in industrial nations? Energy. Policy. 2011, 39, 2568-72.

4. Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Gu, B. Managing nitrogen to achieve sustainable food-energy-water nexus in China. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4804.

5. Li, X.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; Zu, X.; Sun, Y.; Xie, Y. Opportunity of atomically thin two-dimensional catalysts for promoting CO2 electroreduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2964-74.

6. Johnson, N.; Liebreich, M.; Kammen, D. M.; Ekins, P.; Mckenna, R.; Staffell, I. Realistic roles for hydrogen in the future energy transition. Nat. Rev. Clean. Technol. 2025, 1, 351-71.

7. Evro, S.; Oni, B. A.; Tomomewo, O. S. Carbon neutrality and hydrogen energy systems. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 78, 1449-67.

8. Zhu, W.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Huang, R.; Wang, Z.; Liang, H. Hydrogen production by electrocatalysis using the reaction of acidic oxygen evolution: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 3429-52.

9. Zhao, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Unveiling the mysteries of hydrogen spillover phenomenon in hydrogen evolution reaction: fundamentals, evidence and enhancement strategies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 524, 216321.

10. de Oliveira, D. S.; Costa, A. L.; Velasquez, C. E. Hydrogen energy for change: SWOT analysis for energy transition. Sustain. Energy. Technol. Assess. 2024, 72, 104063.

11. Butler, C.; Mays, T. J.; Sahadevan, V.; O’malley, R.; Graham, D. P.; Bowen, C. R. Hydrogen storage capacity of freeze cast microporous monolithic composites. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 6864-72.

12. Bhuiyan, M. M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an alternative fuel: a comprehensive review of challenges and opportunities in production, storage, and transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2025, 102, 1026-44.

13. Gomonov, K.; Permana, C. T.; Handoko, C. T. The growing demand for hydrogen: сurrent trends, sectoral analysis, and future projections. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 6, 100176.

14. Szablowski, L.; Wojcik, M.; Dybinski, O. Review of steam methane reforming as a method of hydrogen production. Energy 2025, 316, 134540.

15. Wang, B.; Shao, Y.; Guo, K.; et al. Hydrogen production with near-zero carbon emission through thermochemical conversion of H2-rich industrial byproduct gas. Energy. Conv. Manag. 2025, 332, 119777.

16. Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allen, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M. T. Technoeconomic analysis of small modular reactors decarbonizing industrial process heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713-37.

17. Rocha, F.; Georgiadis, C.; Van Droogenbroek, K.; et al. Proton exchange membrane-like alkaline water electrolysis using flow-engineered three-dimensional electrodes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7444.

18. Gunawan, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Materials advances in photocatalytic solar hydrogen production: integrating systems and economics for a sustainable future. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2404618.

19. Bie, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Challenges for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Chem 2022, 8, 1567-74.

20. Zheng, D.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Varbanov, P. S.; Klemeš, J. J.; Yin, C. Nanocatalysts in photocatalytic water splitting for green hydrogen generation: challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137700.

21. Zhang, J.; Hu, W.; Cao, S.; Piao, L. Recent progress for hydrogen production by photocatalytic natural or simulated seawater splitting. Nano. Res. 2020, 13, 2313-22.

22. Dang, V.; Nguyen, T.; Le, M.; Nguyen, D. Q.; Wang, Y. H.; Wu, J. C. Photocatalytic hydrogen production from seawater splitting: current status, challenges, strategies and prospective applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149213.

23. Li, T.; Tsubaki, N.; Jin, Z. S-scheme heterojunction in photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2024, 169, 82-104.

24. Zhang, X.; Qin, N.; Cui, H.; Guan, G.; Han, M. Y. Metal-facilitated photocatalytic nanohybrids: rational design and promising environmental applications. Chem. Asian. J. 2021, 16, 3038-54.

25. Liu, Z.; Tee, S. Y.; Guan, G.; Han, M. Y. Atomically substitutional engineering of transition metal dichalcogenide layers for enhancing tailored properties and superior applications. Nano. Micro. Lett. 2024, 16, 95.

26. Abhishek, B.; Arasalike, J.; Rao, A. S.; et al. Challenges in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution: Importance of photocatalysts and photocatalytic reactors. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 81, 1442-66.

27. Su, H.; Wang, W.; Shi, R.; et al. Recent advances in quantum dot catalysts for hydrogen evolution: synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic application. Carbon. Energy. 2023, 5, e280.

28. Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37-8.

29. Chen, Z.; Yan, Y.; Sun, K.; et al. Plasmonic coupling-boosted photothermal composite photocatalyst for achieving near-infrared photocatalytic hydrogen production. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 661, 12-22.