Nanocellulose-based bio-inks for 3D bioprinting: advances and prospects in bone and cartilage tissue engineering

Abstract

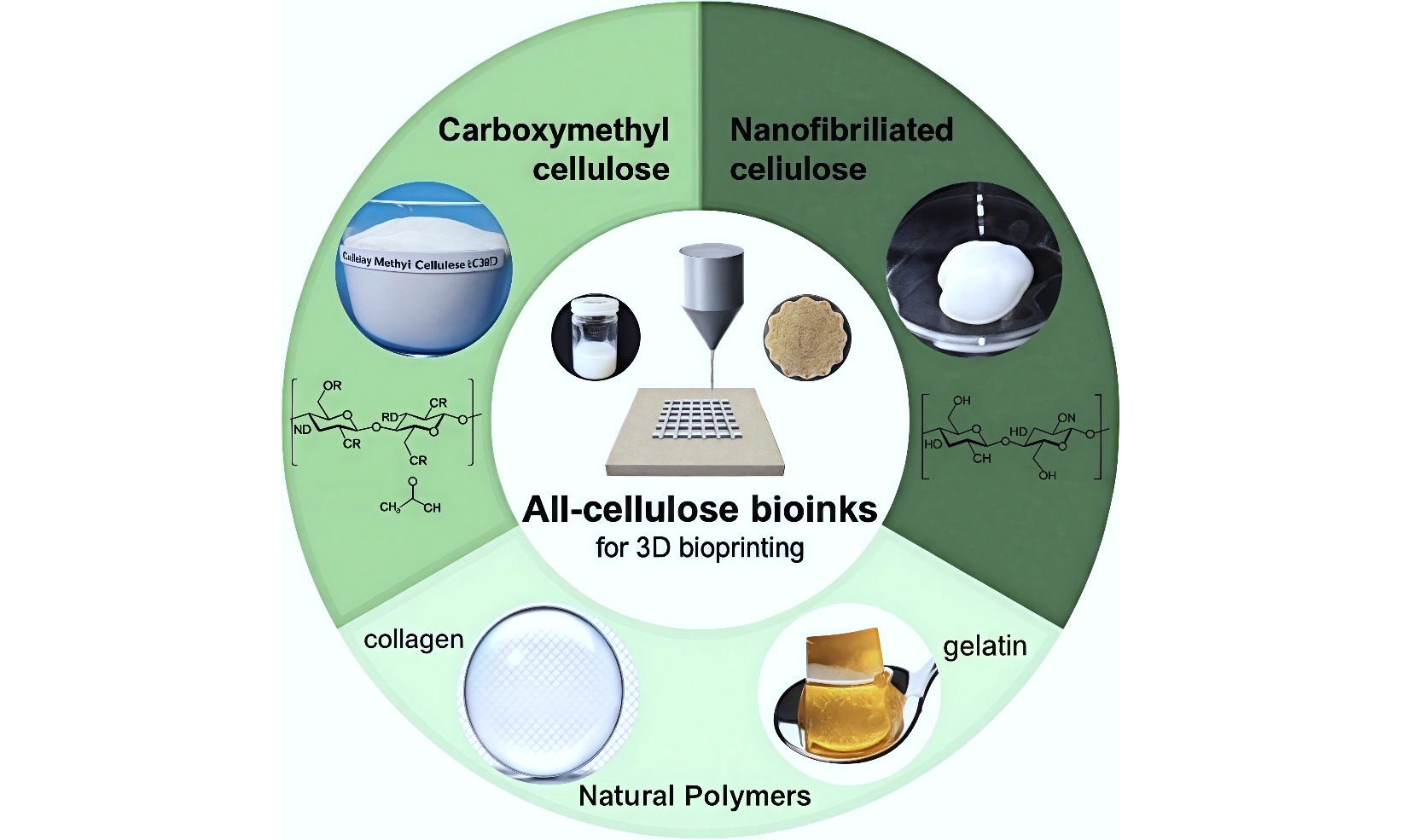

Tissue engineering offers promising regenerative alternatives to conventional medical treatments, particularly for tissues with limited self-healing capabilities such as bone and cartilage. Central to this field is three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting, an advanced fabrication technique that utilizes bio-inks to construct complex, patient-specific tissue structures. Among emerging bio-ink materials, nanocellulose and its derivatives have attracted considerable attention for their exceptional mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Derived from natural cellulose, nanocellulose exists primarily as cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) and cellulose nanofibers (CNFs), each contributing unique structural and rheological characteristics. CNCs enhance scaffold stiffness and mechanical strength, while CNFs support intricate architectures conducive to cellular infiltration and tissue growth. This review highlights recent advances in nanocellulose-based bio-inks for 3D bioprinting, emphasizing their role in improving printability and scaffold functionality for bone and cartilage tissue engineering applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

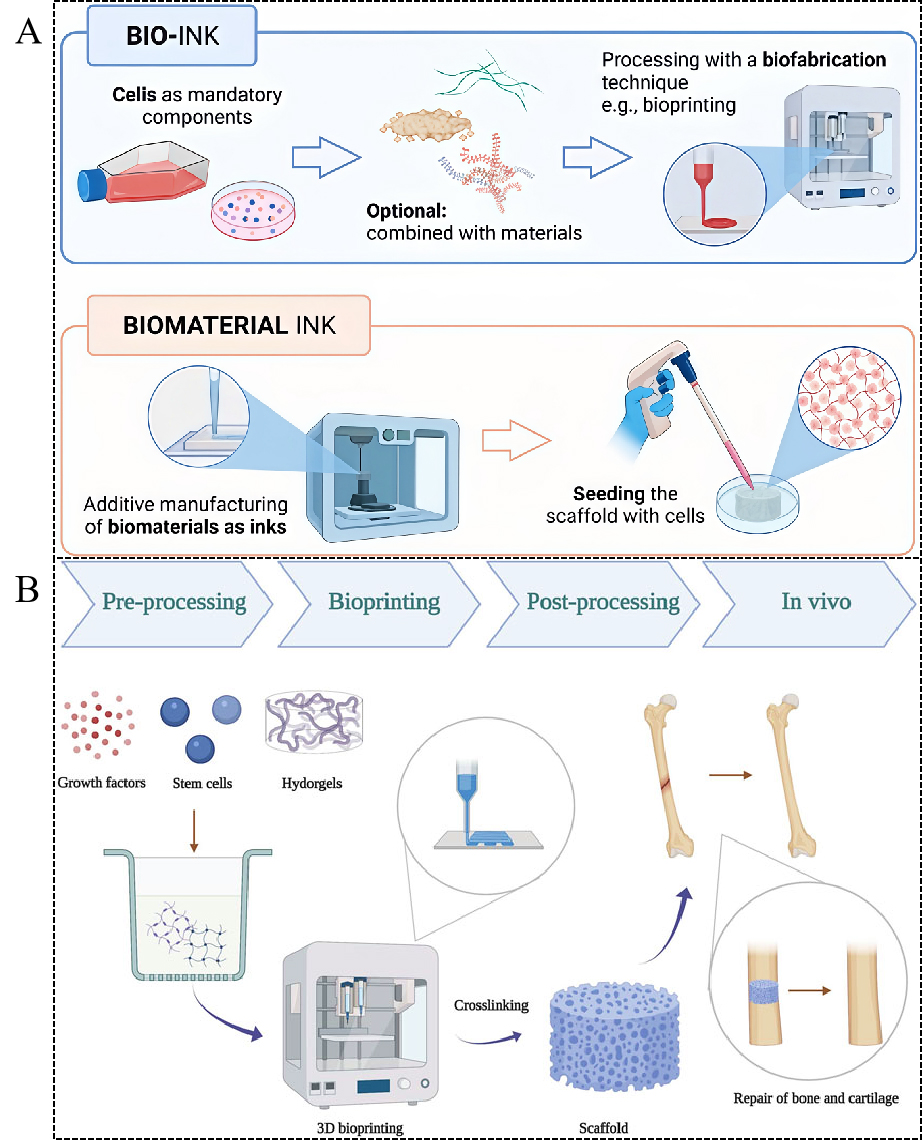

Tissue engineering has emerged as a rapidly advancing field that seeks regenerative solutions for damaged or diseased tissues[1]. The primary aim of tissue engineering is to develop functional tissue constructs that can restore or replace damaged tissues, such as bone and cartilage, which have limited self-regenerative capabilities[2]. One of the most promising technologies in this field is three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting, a technique that enables the fabrication of complex, patient-specific tissue structures using bio-inks[3]. These bio-inks are carefully selected materials that can support cell growth and mimic the mechanical properties of native tissues[4]. Here, bio-inks refer to cell-laden formulations in which living cells are incorporated during printing.

In contrast, biomaterial inks denote cell-free printable formulations that are shaped first and subsequently cellularized, as outlined in Figure 1A. In both cases, in vivo use typically refers to the application and evaluation of the printed constructs. In selected workflows, the formulation can also be printed directly into a defect site via in situ bioprinting rather than being used as an injectable “ink” in the conventional sense.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of bio-inks and biomaterial inks, and their applications in 3D bioprinting for bone and cartilage repair. (A) Bio-inks are cell-laden printing formulations in which living cells are incorporated during the printing process. In contrast, biomaterial inks are cell-free printable formulations that are shaped first and subsequently cellularized after printing. (Reproduced from Fatimi et al.[5]. Copyright @ 2022 MDPI) (B) Workflow of 3D bioprinting of hydrogel-based scaffolds for bone and cartilage repair, including pre-processing (hydrogels, stem cells, and growth factors), bioprinting, post-processing (crosslinking), and in vivo application for tissue regeneration. (Reprinted from Yang et al. (2022)[6]). 3D: Three-dimensional.

Among the various bio-ink materials explored, nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives have garnered significant attention due to their unique properties, which make them particularly suited for tissue engineering applications[7,8]. This increasing interest is also supported by practical biofabrication needs: nanocellulose-rich inks can provide shear-thinning flow with rapid structural recovery and post-print stability, which improves extrusion print fidelity while reinforcing otherwise mechanically weak hydrogel matrices; meanwhile, broader access to standardized, animal-free commercial formulations has lowered barriers to routine adoption in bioprinting workflows[9].

Nanocellulose derived from cellulose offers a versatile property space - including mechanical reinforcement and favorable rheology - that has motivated its integration into bio-inks for bone and cartilage bioprinting[10]. These attributes support both cell-laden bio-inks and cell-free “biomaterial inks” as defined in Figure 1A, and align with key requirements across the bioprinting-to-repair pipeline summarized in Figure 1B. While this review emphasizes bone and cartilage, nanocellulose-based formulations have also been explored for other tissue contexts, including skin-related constructs and liver-mimetic models, indicating broader applicability beyond musculoskeletal repair[10,11].

Nanocellulose exists in several forms, including cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) and cellulose nanofibers (CNFs)[13,14], each possessing distinct structural and mechanical features. CNCs, with their rod-like shape and high surface area, provide superior stiffness and enhance the mechanical properties of printed scaffolds[15]. Owing to their greater flexibility, CNFs enable the fabrication of intricate, highly porous architectures that support cellular infiltration and subsequent tissue growth[16]. The incorporation of nanocellulose into bio-inks significantly enhances their printability and the structural integrity of the resulting scaffolds.

Cellulose derivatives, such as carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), methyl cellulose (MC), and hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), further broaden the applicability of cellulose-based bio-inks in tissue engineering[17]. These derivatives offer the added advantage of improved solubility and gelation properties, facilitating their use in hydrogels that can encapsulate cells for controlled delivery and tissue regeneration. CMC, for instance, is known for its excellent water retention and ability to form stable gels under mild conditions, making it suitable for cartilage tissue engineering, where maintaining hydration is critical to the mechanical and functional properties of the tissue[18]. Moreover, cellulose derivatives can be easily modified to meet the specific requirements of different tissue types, enabling the development of customized bio-inks tailored to specific regenerative applications.

The application of nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives in 3D bioprinting represents a promising frontier in bone and cartilage tissue engineering. The mechanical properties of these materials, coupled with their biocompatibility and biodegradability, position them as essential components in the creation of scaffolds that not only support tissue growth but also mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM)[19]. In bone tissue engineering, where mechanical strength and osteoconductivity are crucial, nanocellulose-based scaffolds have shown significant promise in supporting osteoblast differentiation and bone regeneration[20]. Similarly, in cartilage tissue engineering, cellulose-based bio-inks are used to create hydrophilic, resilient scaffolds that replicate the unique properties of cartilage, including its ability to retain water and withstand mechanical stress.

Despite the clear potential of nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives for 3D bioprinting, several challenges remain in their application, particularly in optimizing printability, scalability, and long-term stability. This review explores the various ways these materials are being used in 3D bioprinting of bone and cartilage tissues, examining their properties, the challenges they face, and their prospects for clinical applications. The review will also provide an in-depth look at the latest advances in bio-ink formulation and the integration of nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives into tissue engineering strategies. Through this examination, we aim to highlight the significant contributions of nanocellulose-based bio-inks in the future of regenerative medicine and tissue engineering.

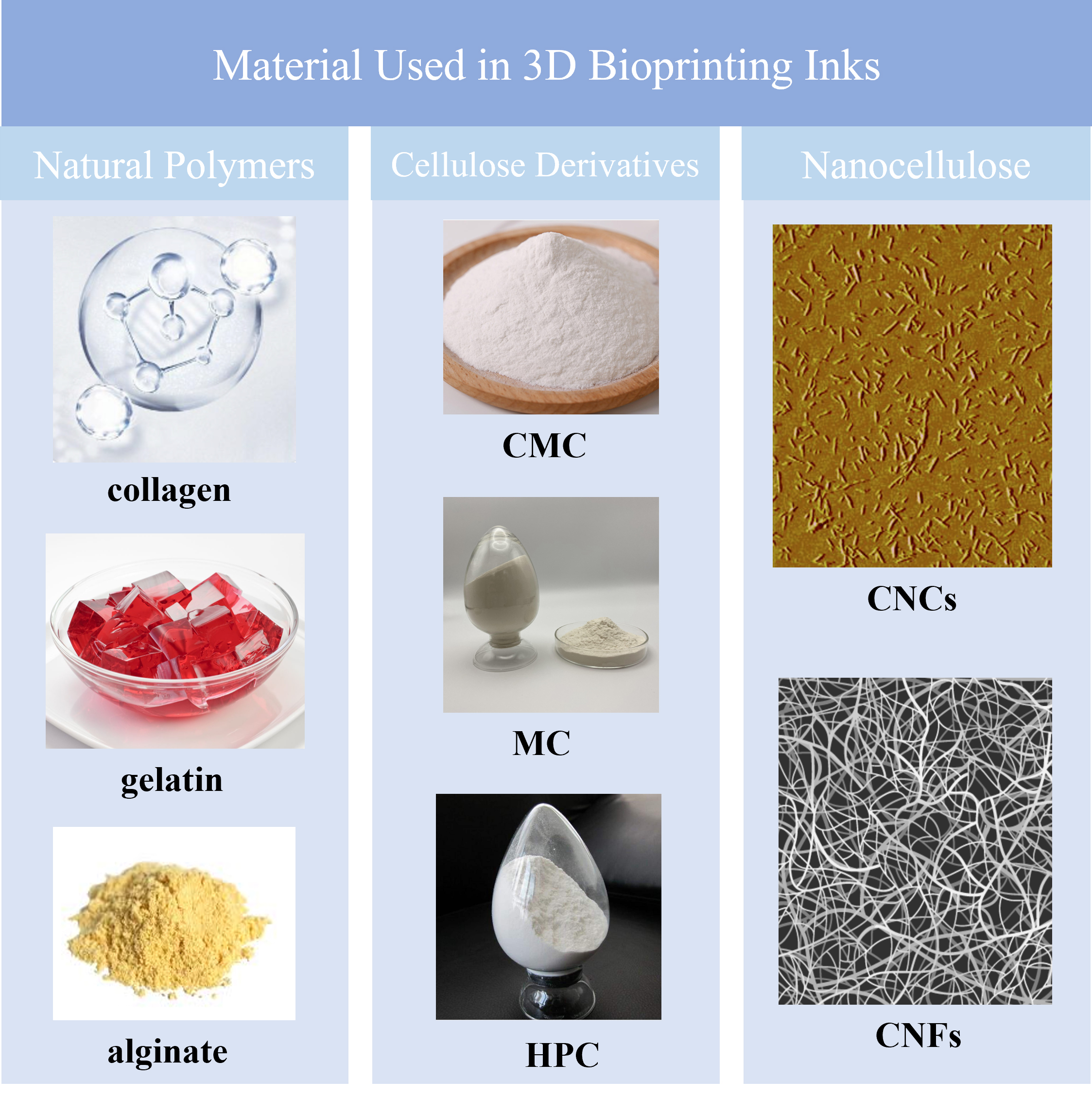

MATERIALS FOR 3D-BIOPRINTING BIO-INKS

The selection of suitable bio-inks is a fundamental aspect of successful 3D bioprinting for tissue engineering applications[21]. Bio-inks should exhibit application-appropriate rheology, biocompatibility, and mechanical properties that support cell survival, differentiation, and integration while maintaining shape fidelity after deposition. In the context of bone and cartilage tissue engineering, the material choice becomes even more critical due to the specialized mechanical and biological demands of these tissues. This section explores several key categories of bio-ink materials, with particular emphasis on natural polymers, cellulose derivatives, and nanocellulose [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Comprehensive Illustration of Material Categories Used in 3D Bioprinting Inks: Natural Polymers, Cellulose Derivatives, and Nanocellulose. Natural Polymers include collagen, gelatin, and alginate. Cellulose Derivatives include CMC, MC, and HPC. Nanocellulose includes CNCs and CNFs. (Reproduced from “Cellulose nanocrystals.jpg” by Maren Roman[22] and “202406 Cellulose Nanofiber.svg” by DataBase Center for Life Science[23].) 3D: Three-dimensional; CMC: carboxymethyl cellulose; MC: methyl cellulose; HPC: hydroxypropyl cellulose; CNC: cellulose nanocrystal; CNF: cellulose nanofiber.

Natural polymers

Natural polymers have long been favored for tissue engineering applications due to their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to mimic the natural ECM. For example, collagen, a natural polymer, demonstrated biocompatibility scores of over 90% in various cell culture models[24]. These polymers are derived from biological sources, ensuring their compatibility with human tissues and cells. However, the mechanical performance of many natural polymers remains a key limitation, as it often does not provide the structural integrity required for mechanically demanding applications such as bone tissue engineering. In particular, the compressive strength of collagen scaffolds typically ranges from 1 kPa to 2.17 MPa[25], which is insufficient for load-bearing applications in bone tissue engineering where higher mechanical strength is required. Despite this, the versatility of natural polymers continues to make them a foundational component of many bio-ink formulations.

Collagen, one of the most abundant proteins in the human body, plays a critical role in the development and maintenance of connective tissues[26]. Collagen-based bio-inks have been widely used for scaffold fabrication in both bone and cartilage tissue engineering due to their ability to facilitate cellular attachment and proliferation. The high degree of homology between collagen and the native ECMs of bone and cartilage ensures that scaffolds made from collagen promote a supportive microenvironment for regenerative processes[27]. However, collagen alone is often insufficient to create mechanically robust structures, particularly in bone tissue engineering, where the scaffold must bear significant loads. Studies have shown that combining collagen with hydroxyapatite (HA) improves its compressive strength, with composite scaffolds reaching up to 5 MPa, making them more suitable for bone tissue engineering[28].

Gelatin, a denatured form of collagen, has also been utilized in 3D bioprinting for its enhanced printability and lower cost compared to collagen. Its ability to undergo thermoreversible gelation makes it ideal for printing processes, where gelation occurs during the cooling phase[29]. Gelatin-based bio-inks have been used to create scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering, where the soft, flexible properties of the material are essential to mimic the structural characteristics of cartilage. The tensile strength of gelatin scaffolds is around 0.5 to 1 MPa[30], which is suitable for cartilage regeneration but does not support load-bearing for bone tissue applications. For context, trabecular bone typically exhibits compressive strengths in the range of 2-12 MPa, whereas cortical bone reaches 100-150 MPa, highlighting the mechanical gap that gelatin-only constructs must address for bone repair[31,32]. Additionally, the incorporation of hyaluronic acid, a key component of cartilage ECM, into gelatin bio-inks has shown to increase chondrocyte proliferation by over 50% and support the differentiation of these cells into cartilage-like tissue[33].

Alginate, derived from brown algae, is another widely employed natural polymer in 3D bioprinting. Alginate-based bio-inks form hydrogels that can be crosslinked with calcium ions, enabling the formation of stable, biocompatible scaffolds[34]. The viscosity of alginate-based inks typically ranges from 50 to 200 cP[35], enabling stable printability during 3D printing. Alginate is particularly useful in cartilage tissue engineering, as it has been shown to promote chondrocyte survival and maintain the hydration of the cartilage matrix. Studies have demonstrated that alginate scaffolds can retain up to 90% of their initial hydration over a 28-day culture period[36]. However, its limited mechanical strength (approximately 0.3 MPa in tensile strength) makes it unsuitable for bone tissue engineering on its own, necessitating the incorporation of reinforcing agents such as nanocellulose or HA[37].

Cellulose derivatives

Cellulose and its derivatives represent a distinctive class of natural polymers that offer distinct advantages beyond the general benefits of biocompatibility and biodegradability. Their abundance, renewable origin, and tunable chemical functionality enable the fabrication of bio-inks with tailored mechanical and rheological properties. In particular, nanocellulose in its various forms - CMC, MC, and HPC - offers structural reinforcement and ECM-like architectures that are especially valuable for 3D bioprinting applications.

CMC is one of the most widely studied cellulose derivatives due to its excellent water solubility and ability to form stable hydrogels. CMC-based bio-inks are particularly advantageous in cartilage tissue engineering, where the maintenance of hydration and mechanical support is critical for replicating the native cartilage environment[38]. Studies have shown that CMC-based hydrogels exhibit an elastic modulus of 10-50 kPa[39], which closely mimics native cartilage properties, providing sufficient mechanical stability while allowing cellular migration and proliferation. The incorporation of CMC into bio-inks enhances the rheological properties, enabling high-resolution printing while maintaining structural integrity post-printing. The presence of carboxyl groups in CMC also allows for the incorporation of functional groups or bioactive molecules, further enhancing the capacity of the material to promote tissue regeneration.

MC is another commonly used cellulose derivative, sharing many similarities with CMC in terms of water solubility and gelation properties. It is particularly well-suited for creating hydrogels that can encapsulate cells and provide a hydrated environment for their growth. The ability of the material to undergo reversible gelation upon temperature changes has made it a useful component in bio-inks intended for cartilage tissue engineering[40]. Studies have shown that low-molecular-weight MC (15,000 Da) gels at approximately 31-32 °C, while higher-molecular-weight MC (88,000 Da) exhibits gelation around 48 °C[41]. The thermoresponsive behavior of MC also makes it ideal for applications where temperature-induced gelation is required, providing control over the structural properties of the material during the printing process.

HPC is another cellulose derivative with excellent water retention properties. HPC-based bio-inks have been explored in bone and cartilage tissue engineering, where their ability to maintain hydration and support cell viability is crucial. The ability of the HPC to form stable hydrogels under physiological conditions has made it particularly useful in applications where long-term stability and controlled drug or growth factor release are desired[42]. When combined with other reinforcing agents, such as nanocellulose or bioactive molecules, HPC-based bio-inks can be tailored for more demanding applications, such as bone tissue regeneration, where higher mechanical strength is required[42].

Nanocellulose

Nanocellulose, a nano-engineered form of cellulose, includes CNCs and CNFs, both of which have been integrated into bio-inks to significantly enhance their mechanical properties and structural integrity. The unique properties of nanocellulose, such as high surface area, crystallinity, and tensile strength, make it an ideal component.

Importantly, nanocellulose should not be treated as a single, uniform material. Key descriptors, including particle or fibril dimensions, aspect ratio, crystallinity, and surface functional groups, are sensitive to the isolation and processing routes, and these variations can propagate into dispersion stability, ink rheology, and network formation[8,43]. For CNCs, hydrolysis conditions may alter particle size distributions and surface charge, whereas for CNFs, pretreatments and the extent of mechanical fibrillation can alter fibrillation degree and charge density[44,45]. Consequently, the printability and mechanical outcomes reported for a given formulation may not be directly transferable across different nanocellulose sources, underscoring the need to report preparation routes and core physicochemical metrics when comparing studies.

A practical consequence of this method dependence is that CNC/CNF batches can exhibit different surface chemistries and size distributions, thereby reshaping dispersion stability. For example, sulfuric acid hydrolysis commonly introduces sulfate half-ester groups, which increase colloidal stability in water. In contrast, less-charged CNC surfaces are more prone to aggregation unless additional stabilization is used. For CNFs, pretreatments [e.g., 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-mediated oxidation or enzymatic steps] and fibrillation intensity can alter fibril width/aspect ratio as well as charge density, thereby influencing network formation and water/ion sensitivity even at similar solids contents.

CNCs are rod-like nanoparticles with exceptional stiffness and a high surface area, making them effective at enhancing the mechanical properties of printed scaffolds. CNCs have been incorporated into bio-inks for bone tissue engineering, where their rigidity is essential for creating scaffolds that can withstand mechanical stresses. The integration of CNCs with natural polymers, such as alginate or gelatin, enhances the overall strength of the scaffolds without compromising cell viability[46]. For instance, CNCs significantly improve the compressive strength of composite scaffolds, with reported increases of up to 45% when combined with gelatin[47]. Furthermore, the high surface area of CNCs provides ample opportunities for functionalization, allowing the attachment of bioactive molecules such as growth factors or adhesion peptides[48].

CNFs are longer, more flexible fibers that exhibit high aspect ratios and can form networks that provide both strength and flexibility[49]. They are particularly useful for creating scaffolds that require both mechanical stability and the ability to support cellular infiltration, making them suitable for cartilage tissue engineering applications. CNF-based bio-inks have been combined with other materials, such as chitosan and gelatin, to create scaffolds that replicate the soft, hydrated nature of cartilage[50,51].

UNIQUE PROPERTIES OF NANOCELLULOSE AND CELLULOSE DERIVATIVES FOR TISSUE ENGINEERING

Nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives possess a unique combination of physical, chemical, and biological properties that make them highly suitable for tissue engineering applications. These materials offer several advantages over traditional synthetic polymers, including enhanced biocompatibility, mechanical strength, biodegradability, and the ability to mimic the native ECM. Compared with widely used bio-ink polymers such as alginate, gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), collagen/fibrin, hyaluronic acid, and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels, nanocellulose is most often leveraged for its strong rheology-building and reinforcement roles, improving shear-thinning behavior and shape fidelity while strengthening otherwise soft matrices. At the same time, unlike GelMA or collagen-rich systems, cellulose lacks intrinsic cell-adhesive motifs. It is therefore commonly used as a reinforcing or rheology-modifying phase in multi-component formulations rather than as a standalone bioactive matrix[52]. The following sections outline these key properties and their relevance to the development of advanced bio-inks for 3D bioprinting in bone and cartilage tissue engineering.

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility is a fundamental requirement for materials used in tissue engineering, as it ensures that the material does not elicit an adverse immune response and supports cellular activity, including cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. Nanocellulose derived from plant biomass is generally reported to be biocompatible, although observed responses may depend on purity, surface chemistry, and residual contaminants. Its non-toxic, non-inflammatory nature ensures a favorable environment for cell growth[53]. Additionally, cellulose derivatives, such as CMC and HPC, have been shown to facilitate cell adhesion and proliferation[42,54]. These properties are particularly valuable in cartilage tissue engineering, where chondrocyte viability within the scaffold is crucial for maintaining tissue integrity. Beyond general cytocompatibility, nanocellulose can also influence the early innate immune microenvironment, especially macrophage behavior, which can shape downstream regeneration versus fibrosis[55]. Available studies suggest that well-purified nanocellulose is often immunologically “quiet” in macrophage models and may attenuate inflammatory signaling under certain conditions. In contrast, immune activation can be strongly affected by surface chemistry and, critically, by immunogenic contaminants such as endotoxin[56,57]. Therefore, rigorous purification and contaminant control, together with basic immunoprofiling in vitro, are essential for interpreting regenerative outcomes and supporting clinical translation.

Studies have demonstrated that nanocellulose enhances the adhesion of osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and chondrocytes (cartilage-forming cells) due to its high surface area and hydroxyl-rich structure, which facilitates binding to cell-surface receptors[58]. Moreover, the compatibility of these materials with human cells has been demonstrated in numerous studies, with minimal cytotoxicity even at high concentrations. In vitro studies have shown that human lung epithelial cells, such as bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B), remain viable after exposure to nanocellulose at concentrations up to 500 µg/mL for 24 h, with no significant cytotoxicity effects observed[59].

Mechanical strength and rheological properties

In tissue engineering, particularly for bone and cartilage regeneration, the mechanical strength of scaffolds is crucial. Bone tissue requires scaffolds with sufficient stiffness and load-bearing capacity, while cartilage tissue demands materials that replicate the soft, resilient properties of native cartilage. Nanocellulose, particularly CNFs and CNCs, has been shown to possess remarkable mechanical properties suitable for these applications. CNCs exhibit high stiffness, with elastic modulus ranging from 140 to 220 GPa and tensile strengths between 5.4 and 7.2 GPa[60,61], making them ideal for bone tissue engineering, where mechanical strength is essential. On the other hand, CNFs provide flexibility and can form networks that offer both strength and flexibility, making them particularly useful for cartilage tissue engineering[62]. To better illustrate the mechanical performance of nanocellulose-based scaffolds, Table 1 summarizes representative compressive strength values reported in the literature. The wide spread in Table 1 mainly arises because the included scaffolds differ in relative density/porosity and architecture, and strength in porous/lamellar networks scales strongly with relative density rather than “nanocellulose type” alone[67]. In addition, reinforcement and network design (e.g., in situ HA coating/crosslinking or double-network formation) can shift failure modes and markedly increase peak strength, which helps rationalize the highest value (41.8 MPa) compared with more compliant hydrogels or layered constructs[66].

Tensile strength of nanocellulose-based scaffolds for bone and cartilage tissue engineering

| Material/Scaffold | Features | Compressive strength (MPa) | Reference |

| Nacre-inspired cellulose fibers/Fe3O4/HA composite scaffold | Layered nacre-like scaffold with magnetic orientation, promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis. | 1.63 | [63] |

| Double-network MCC hydrogel | Double-network hydrogel with porous structure and high-water content, supporting chondrocyte growth. | 4.53 | [64] |

| Gelatin-CNF covalently bonded composite hydrogel | Gelatin hydrogel reinforced by CNFs via Schiff-base bonding, enhancing strength and biocompatibility. | 3.40 | [65] |

| CNC/HAp/PMVEMA/PEG porous scaffold | Highly porous CNC-HAP scaffold crosslinked with PMVEMA/PEG, with strong mechanical properties. | 41.8 | [66] |

The rheological properties of nanocellulose-based bio-inks are essential for 3D bioprinting, as they affect printability and structural integrity. These properties can be adjusted by controlling nanocellulose concentration, solvent composition, and the presence of rheology modifiers[68,69]. In addition to formulation variables, extraction- and processing-dependent descriptors (e.g., aspect ratio, surface charge, and dispersion state) can shift yield stress and thixotropic recovery, which directly influence extrusion pressure, filament spreading, and layer stacking[70]. Aggregation or batch-to-batch variability can therefore narrow the printable window and reduce reinforcement efficiency, because load transfer depends on uniform nanocellulose distribution and stable interfacial interactions with the host matrix[71,72]. Reporting a minimal descriptor set alongside rheology data can improve cross-study comparability and interpretation. For instance, increasing nanocellulose concentration enhances viscosity, which supports the formation of high-resolution, complex scaffold structures[73]. This flexibility in adjusting rheological properties has been pivotal in overcoming challenges in printing high-resolution scaffolds. Moreover, incorporating cellulose derivatives such as MC and CMC further refines the rheological properties of bio-inks[74]. MC-based bio-inks enable tunable printability and stiffness, maintaining high cell viability post-printing[75]. Similarly, CMC-based bio-inks offer adjustable printability and stiffness, enhancing the viability of bioprinted cells and broadening the range of printable structures[76]. These advancements in nanocellulose-based bio-inks facilitate the development of scaffolds with mechanical and rheological properties tailored to specific tissue engineering applications, thereby improving the efficacy of bone and cartilage regeneration strategies.

Porosity and hydrophilicity

Porosity and hydrophilicity are crucial characteristics for tissue scaffolds, as they directly influence cellular infiltration, nutrient exchange, and the overall functionality of the engineered tissue. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds inherently possess high porosity due to their nanostructured nature[77]. This porosity promotes improved cell migration and vascularization, which are critical for bone regeneration. The ability to control pore size and distribution in these scaffolds enables precise engineering of their architecture, which can be tailored to more accurately mimic natural bone or cartilage tissue.

In addition to porosity, hydrophilicity plays an essential role in maintaining tissue hydration, particularly in cartilage, which is primarily composed of water. Cellulose derivatives such as CMC and HPC exhibit excellent water retention properties, making them ideal for creating hydrated environments for cell growth[78]. The high water content within the scaffold supports the mechanical properties of cartilage by preventing desiccation and promoting the formation of a gel-like matrix that mimics the ECM[79]. This ability to retain water also enhances the longevity and viability of the cells embedded in the scaffold, ensuring better integration with the surrounding tissue.

Biodegradability and environmental impact

The biodegradability of materials used in tissue engineering is essential for their successful integration within the body. As tissue regenerates, the scaffold material must degrade at a rate that matches tissue formation, thus preventing adverse effects such as chronic inflammation or mechanical mismatch[80]. In the biomedical context, this degradation - often termed resorption - is typically mediated by enzymatic cleavage, hydrolysis, and cellular activity.

Nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives exhibit tunable biodegradability, making them suitable for a range of regenerative applications. Studies have shown that their resorption rate in vivo can be modulated by chemical modifications, such as oxidation or esterification, or by varying crosslinking density, enabling tailored degradation profiles for specific tissue types[81,82]. For instance, scaffolds intended for soft tissue repair may require faster resorption (e.g., within 2-3 months)[83], while those for bone regeneration demand longer-lasting frameworks to support mineralization and mechanical load bearing.

Significantly, while cellulose is also biodegradable in environmental settings through microbial action, the mechanisms and timelines involved differ considerably from in vivo degradation. In this review, we focus specifically on biomedical resorption, rather than ecological degradation, to avoid conceptual ambiguity.

Tailorable chemical structure for functionalization

One of the key advantages of nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives is their tunable chemical structures, which enable extensive functionalization to meet specific tissue engineering needs. The hydroxyl groups present on the cellulose backbone provide reactive sites for chemical modification, allowing the attachment of bioactive molecules that can enhance cellular responses, such as growth factors, adhesion peptides, or antibiotics[84-86]. Recent functionalization work increasingly targets practical needs in biofabrication, where crosslinking should be fast, cell-friendly, and controllable during printing. Examples include light-based crosslinking for on-demand stabilization and patterning, click-type reactions that proceed efficiently under physiological conditions, and reversible linkages (or catechol-inspired adhesion) that improve injectability, shape recovery, and interface bonding[87-89]. The ability to functionalize these materials offers versatility in designing bio-inks with enhanced bioactivity, promoting specific cellular behaviors such as osteogenesis in bone tissue engineering or chondrogenesis in cartilage regeneration.

Cellulose derivatives such as CMC and HPC can be easily modified by varying the degree of substitution or by introducing additional functional groups, thereby altering their solubility, gelation properties, and bioactivity[90,91]. This tunability has led to the development of bio-inks tailored to the specific requirements of different tissue types, optimizing their use for bone, cartilage, and other regenerative applications. Functionalized nanocellulose scaffolds, when loaded with growth factors or peptides, have shown significant improvement in cell attachment, differentiation, and tissue formation, making them highly promising for clinical applications in tissue engineering.

APPLICATION IN BONE TISSUE ENGINEERING

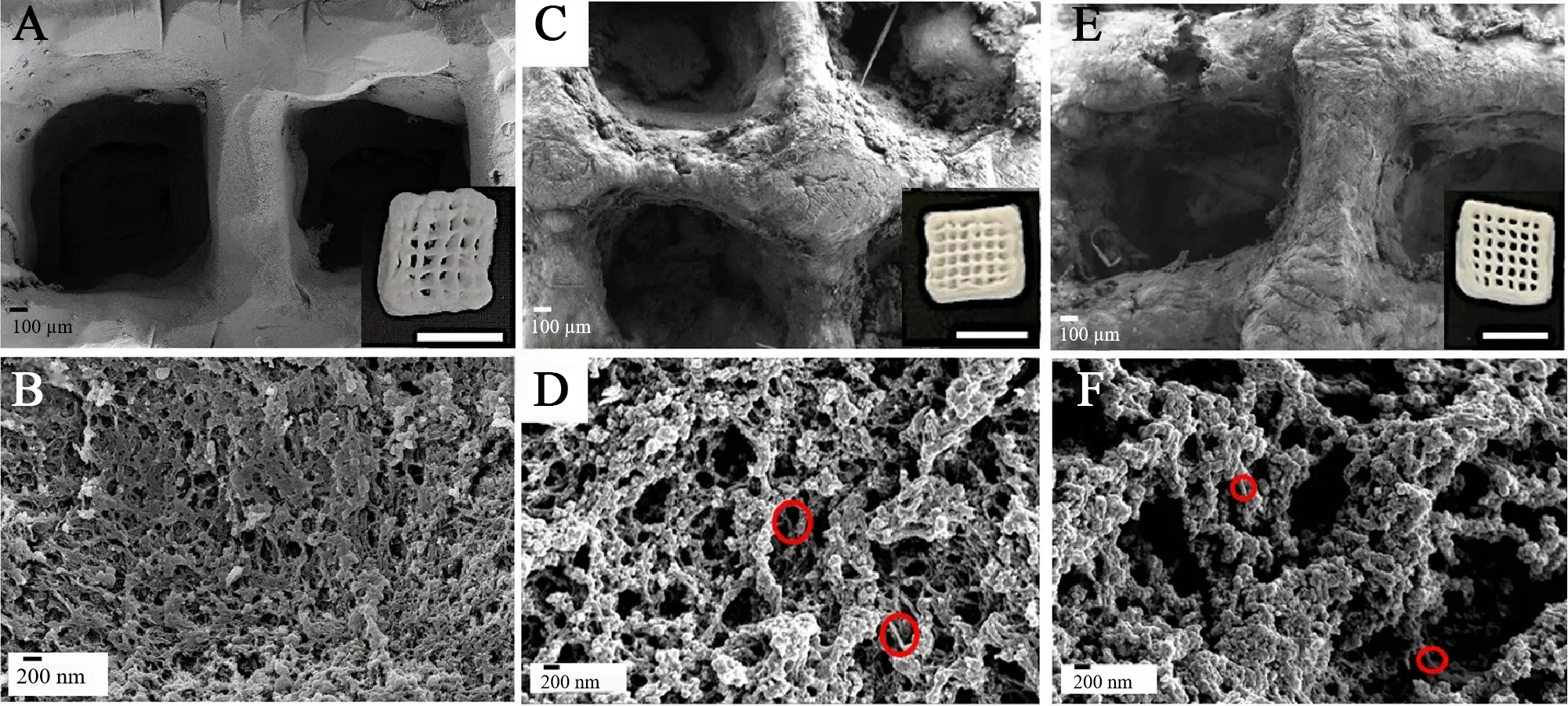

Bone tissue engineering aims to develop scaffolds that support bone tissue regeneration by providing mechanical strength, promoting cellular differentiation, and facilitating the integration of newly formed tissue with the surrounding bone. Nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives have been widely investigated for bone tissue engineering because they combine biocompatibility, mechanical reinforcement, and ECM-relevant structural features. Recent studies have demonstrated the versatility of cellulose-based systems in scaffold design. For example, cellulose-in-cellulose 3D-printed aerogels based on MC and bacterial cellulose nanofibers (BC-NF) show a well-defined macroscopic grid [Figure 3A] with a baseline porous network in MC at higher magnification [Figure 3B]; after introducing BC-NF, the construct-level morphology is retained [Figure 3C] while the filament microstructure reveals enlarged macroporosity compared with MC [Figure 3D], and at higher BC-NF loading the printed pattern appears most sharply resolved [Figure 3E] together with similarly enlarged macropores within the filaments [Figure 3F], supporting mass transport and cell infiltration [Figure 3][92]. This example underscores the potential of nanocellulose-based bio-inks to create advanced 3D scaffolds with tailored porosity and structural fidelity for bone regeneration. In the following sections, we explore how nanocellulose and cellulose-based bio-inks are further utilized in bone tissue engineering, with a focus on scaffold design, mechanical properties, and cell differentiation.

Figure 3. SEM micrographs and visual appearance of cellulose-in-cellulose aerogels. (A and B) MC; (C and D) MC NF0.5-6; (E and F) MC NF20-6. Aerogels exhibit hierarchical porous structures with well-defined 3D-printed patterns, where the incorporation of BC-NF enhances mesopore and macropore formation, favorable for nutrient diffusion and cell infiltration. (Reprinted from Iglesias-Mejuto et al.[92]. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature.). SEM: Scanning electron microscopye; MC: methyl cellulose; NF: nanofiber; 3D: three-dimensional; BC-NF: bacterial cellulose nanofibers.

Scaffold design and mechanical properties

The design of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering requires a careful balance of mechanical strength, porosity, and biodegradability. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds, particularly those made from CNCs and CNFs, exhibit excellent mechanical properties essential for bone regeneration. CNCs, with their crystalline structure, exhibit an elastic modulus of approximately 110-140 GPa, making them suitable for load-bearing applications[93]. In contrast, CNFs provide enhanced flexibility and structural integrity, with tensile strengths reported up to 1.57 GPa[94], enabling scaffold designs that can adapt to the dynamic mechanical environment of bone.

The mechanical strength of nanocellulose-based scaffolds can be fine-tuned by adjusting the nanocellulose concentration in the bio-ink formulation. For example, studies have demonstrated that increasing CNC content from 5% to 20% in bio-inks significantly enhances compressive strength from 0.5 MPa to 5.2 MPa[95], approaching the lower range of natural bone mechanical properties. Furthermore, incorporating HA into nanocellulose scaffolds improves their osteoconductivity and mechanical properties. HA-loaded CNF scaffolds exhibit a 33% increase in Young’s modulus and a 28% improvement in compressive strength[96], making them promising candidates for bone tissue engineering.

Beyond mechanical strength, nanocellulose-based scaffolds can be engineered to achieve optimal porosity, facilitating cellular infiltration and nutrient exchange. Studies have shown that scaffolds with porosity levels between 60% and 85% closely mimic the trabecular structure of bone, enhancing vascularization and promoting bone formation[97]. High porosity has also been linked to improved osteoblast proliferation, with cell viability increasing by approximately 45% compared to a non-porous structure[98].

Osteoconductivity and cell differentiation

Osteoconductivity refers to the ability of a material to support the attachment and growth of bone-forming cells, facilitating the formation of new bone tissue[99]. Nanocellulose and its derivatives have been found to promote osteoblast differentiation and mineralization, two essential processes in bone formation[100,101]. The hydroxyl groups on nanocellulose provide excellent sites for osteoblast attachment. At the same time, the nanoscale structure of the material mimics the native ECM, which is essential for cell migration and differentiation.

The incorporation of bioactive molecules, such as growth factors or peptides, into nanocellulose-based scaffolds can further enhance osteoconductivity[102]. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), for instance, are key growth factors that stimulate osteoblast differentiation. These proteins can be incorporated into cellulose-based bio-inks to promote the healing and regeneration of bone tissue[103]. Additionally, osteopontin and integrin-binding peptides can be used to facilitate cell attachment and guide stem cell differentiation into osteoblasts[103].

Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that CNCs can promote bone tissue mineralization by promoting the deposition of calcium phosphate, a critical component of bone[104]. This mineralization process not only enhances the mechanical properties of the engineered bone tissue but also accelerates the integration of the scaffold with the host bone. The controlled release of osteogenic factors from nanocellulose-based scaffolds has shown promise for inducing osteogenesis and improving overall healing.

Bone regeneration in critical-size defects

Critical-size bone defects (CSDs), which cannot heal without intervention, pose a significant challenge in regenerative medicine. In preclinical bone repair, a CSD is commonly defined in a model- and species-specific manner as the smallest defect that fails to heal spontaneously over the lifetime of the animal or within the follow-up window of the study[105]. The use of nanocellulose-based scaffolds for treating these defects has shown considerable potential. The scaffold must provide mechanical stability and facilitate bone regeneration over an extended period, while also being resorbable to allow for the eventual formation of new, natural bone tissue.

Nanocellulose-based scaffolds have been used in various animal models to treat CSDs[106], demonstrating their effectiveness in promoting bone regeneration. To be specific, commonly used validation models include rodent calvarial defects (often 8 mm in rats and 4-5 mm in mice as non-load-bearing screening models) and rabbit calvarial defects (frequently 12-15 mm depending on endpoint and protocol), with long-bone segmental defects used when load-bearing relevance is required[107]. The porosity and mechanical strength of nanocellulose scaffolds enable them to serve as effective carriers for osteoblasts and other bone-forming cells, while also facilitating the vascularization of the newly formed tissue. The biodegradability of these scaffolds ensures they will be gradually replaced by newly formed bone, thereby preventing the need for surgical removal.

Furthermore, incorporating bioactive substances, such as calcium phosphate or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), into nanocellulose scaffolds has enhanced their regenerative potential[108,109]. Studies have shown that scaffolds loaded with MSCs can improve the healing of bone defects by promoting osteogenesis, accelerating tissue regeneration, and facilitating the formation of vascularized bone tissue[110,111]. The ability of nanocellulose-based scaffolds to support cell attachment, differentiation, and mineralization makes them a promising option for the regeneration of critical-size bone defects.

Enhanced vascularization and bone integration

One of the most challenging aspects of bone tissue engineering is achieving proper vascularization within the scaffold[112]. Bone tissue is highly vascularized, and the formation of blood vessels within the scaffold is essential for providing nutrients and oxygen to the regenerating tissue[113]. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds, due to their high surface area and porosity, offer an ideal environment for promoting angiogenesis, the process by which new blood vessels form[114].

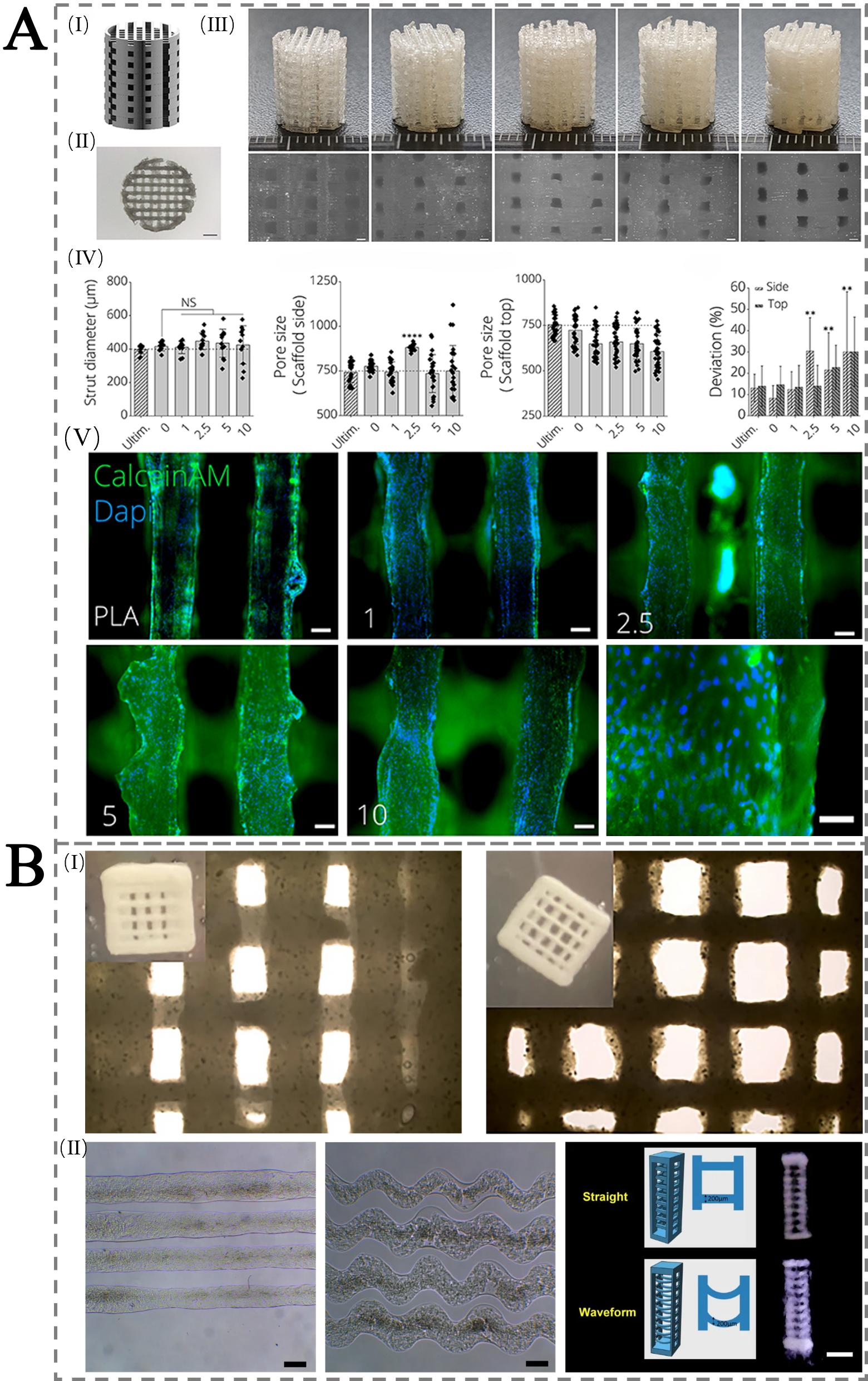

The incorporation of pro-angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), into nanocellulose scaffolds has been shown to enhance vascularization[84]. These growth factors can be released in a controlled manner, stimulating the growth of capillaries and small blood vessels within the scaffold. This vascular network is critical for supporting cell survival within the scaffold and for ensuring successful bone tissue regeneration. Studies have also highlighted the role of cellulose derivatives, such as CMC, in improving the biocompatibility of scaffolds and promoting the migration of endothelial cells, which are necessary for blood vessel formation[115]. Bakhtiary et al. further showed that a cellulose-based bioink co-delivering VEGF and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-2 promotes both vascular invasion and endochondral ossification in vivo [Figure 4A(I-IV)], with the corresponding bone-forming outcome highlighted in Figure 4A(V)[116]. Commercial bioinks such as Ink-Bone and Lifeink®200 also enable precise fabrication of microstructured constructs [Figure 4B(I)], which in turn support bone-regeneration performance [Figure 4B(II)].

Figure 4. (A) Mechanical properties of 3D-printed PLA-45S5 BG scaffolds: (I) CAD design with 750 μm pores; (II) top-view (scale bar 2 mm); (III) FDM-printed scaffolds with 0-10 wt.% BG (left to right) and microscopy images (scale bar 500 μm); (IV-VII) printability/porosity analysis vs. Ultimaker PLA, showing strut diameter, side/top porosity, and pore area deviation. (VIII) Fluorescence images of MC3T3E1 cells on scaffolds after 24 h, stained with Calcein AM (green) and DAPI (blue), at 0-10 wt.% BG (scale bars 100 μm; 200 μm for 10 wt.%). (Bakhtiary et al.[116]. Copyright 2021 MDPI.); (B) Scaffolds for bone tissue engineering 3D printed with commercial inks. The above are optical images of 3D printed scaffolds using Ink-Bone from CELLINK. The bottom is microfibers obtained with Lifeink®200 as straight and waveform along with the design models and 3D printed scaffolds. (Reprinted from Chiticaru et al.[117]. Copyright 2024 ScienceDirect.). 3D: Three-dimensional; PLA: polylactic acid; BG: Bioglass; CAD: computer-aided design; AM: acetoxymethyl; DAPI:4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

In addition to promoting vascularization, nanocellulose-based scaffolds have demonstrated enhanced integration with the surrounding host bone[118]. The ability to mimic the native bone ECM, combined with its mechanical properties, facilitates the formation of a strong bond between the engineered bone tissue and the host tissue. This integration is crucial for the long-term success of bone grafts, ensuring that the regenerated bone functions as a mechanically continuous unit with the host bone.

In conclusion, nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives offer significant advantages in bone tissue engineering, from the design of scaffolds with tailored mechanical properties to the promotion of osteoconductivity, cell differentiation, and vascularization. Their unique combination of biocompatibility, mechanical strength, biodegradability, and tunable properties positions them as key materials for the development of advanced bone regeneration scaffolds.

APPLICATION IN CARTILAGE TISSUE ENGINEERING

Following the discussion on bone regeneration, it is essential to emphasize that cartilage repair presents fundamentally different challenges. Unlike bone, which typically requires stiff, mineralized constructs for load-bearing, cartilage is avascular, highly hydrated, and relies on elastic mechanics to withstand repetitive loading. These contrasting requirements have significant implications for scaffold design, degradation behavior, and cellular interactions. To highlight these differences, Table 2 provides a comparative overview of cellulose-based bio-inks for bone versus cartilage tissue engineering, which serves as a basis for the subsequent discussion of strategies explicitly tailored for cartilage repair.

Comparison of cellulose-based bio-inks in bone and cartilage tissue engineering, highlighting distinct requirements in mechanical performance, degradation, biological additives, and structural design

| Feature | Bone regeneration | Cartilage regeneration | References |

| Mechanical requirements | Compressive yield strength: 0.06-0.61 MPa; compressive modulus: 74-127 MPa | Equilibrium Young’s modulus (unconfined compression): 0.49 ± 0.10 MPa | [119,120] |

| Degradation profile | Typical design window: 3-6 months (cranio-maxillofacial), ≥ 9 months (spinal fusion) | Example synthetic scaffold benchmark (PLGA): 6-12 months | [121,123] |

| Bioactive additives | HA, CPC, BMP-2, VEGF | TGF-β, IGF, collagen, gelatin, chondroitin sulfate | [123] |

| Cell types | Osteoblasts, MSCs, endothelial cells | Chondrocytes, MSCs (chondrogenic induction) | [121] |

| Structural features | Pore size commonly discussed for bone TE: 50-100 μm (cell attachment) and 200-400 μm (diffusion/angiogenesis) | Pore-size bins widely used in cartilage TE studies: < 150 μm, 150-300 μm, 300-500 μm | [124,125] |

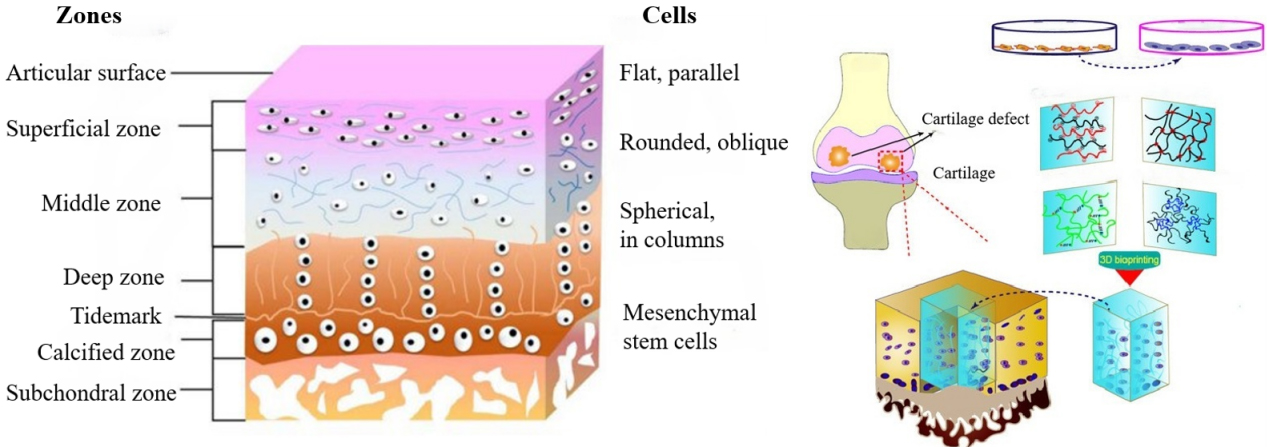

Cartilage tissue is characterized by its highly organized, multilayered structure and distinct cellular distribution, which are essential for its mechanical and biological functions. As illustrated in Figure 5, articular cartilage is composed of different zones with varying orientations and types of chondrocytes, from flat cells near the surface to columnar cells in the deeper layers, along with resident MSCs at the cartilage-bone interface. Mimicking this complex architecture using advanced fabrication techniques, such as 3D bioprinting, has become a promising strategy in regenerative medicine. Recent progress has highlighted the potential of cellulose-based bio-inks, particularly nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives, for constructing functional scaffolds that replicate the native cartilage microenvironment[128,129]. To better reflect the zonal organization of articular cartilage, nanocellulose can serve as a tunable reinforcing and rheology-modifying component, enabling layer-specific control of solids content and crosslink density during multi-material or gradient bioprinting[130,131]. In practice, this allows constructs to incorporate a more compliant, lubricious superficial region and a stiffer deep region, with an optional mineral-containing formulation positioned near the osteochondral interface; extrusion shear may further bias fibril alignment to support superficial-zone-like anisotropy[132]. These approaches collectively underscore the critical role of material design, fabrication strategy, and biological validation in advancing cellulose-based scaffold systems for cartilage tissue engineering.

Figure 5. Schematic representation of cartilage zonal architecture and hybrid bioprinting strategies for scaffold fabrication. Schematic illustration of the zonal structure of articular cartilage and chondrocyte distribution, and the strategy of fabricating functional cartilage tissue via 3D bioprinting. (Left: Reprinted from Ng et al.[126] Copyright © 2017 Shen et al., JSM Bone and Joint Diseases.);Right: Reprinted from Huang et al.[127]. © 2021 The Authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.). 3D: Three-dimensional.

Scaffold design and mechanical properties

The design of scaffolds for cartilage tissue engineering requires careful consideration of the mechanical properties of the material, particularly the ability to replicate the compressive strength and elasticity of natural cartilage. Nanocellulose, including CNFs and CNCs, exhibits remarkable mechanical properties that allow for the creation of scaffolds capable of withstanding the mechanical stresses placed on cartilage

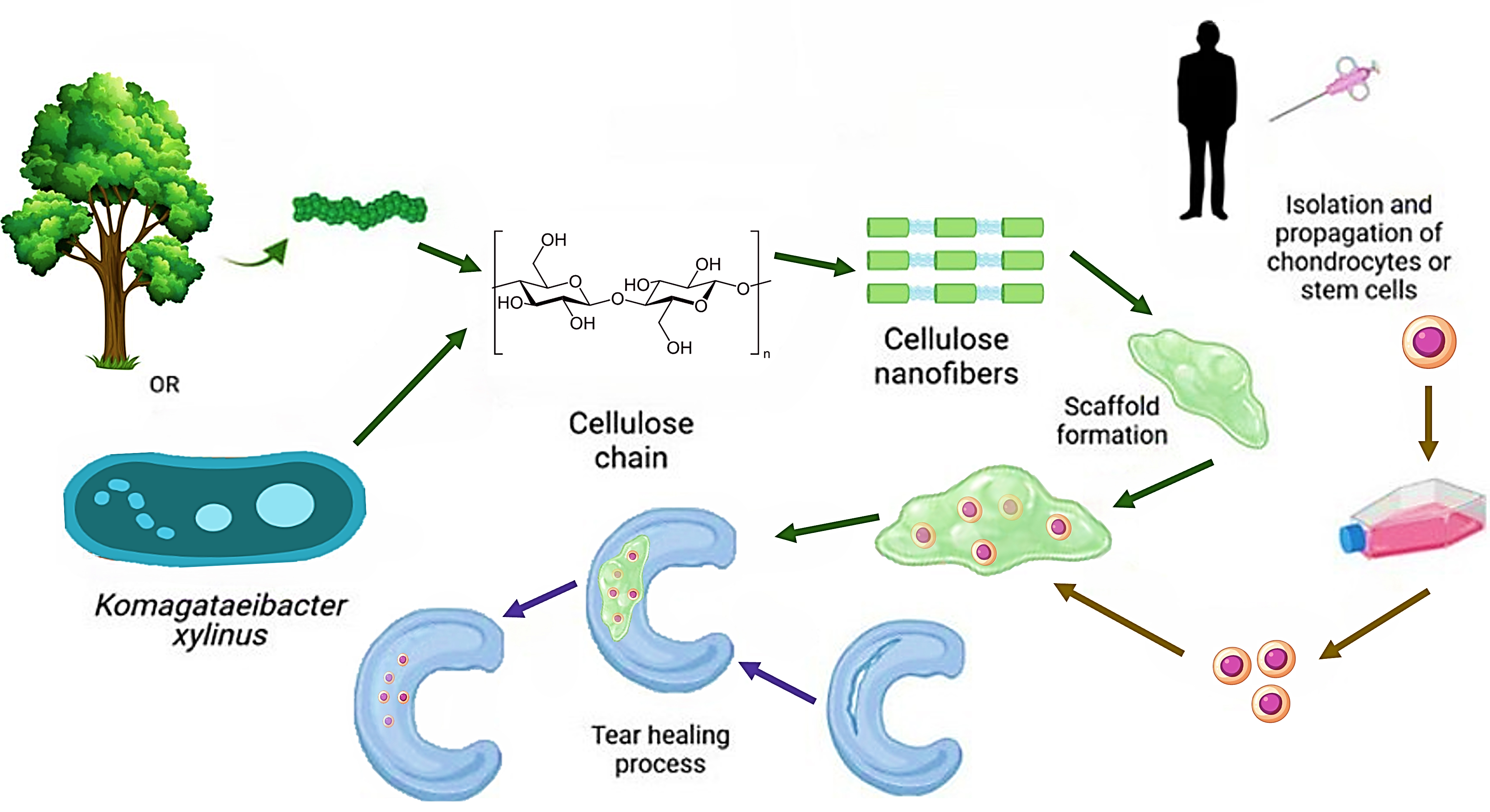

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of nanocellulose-based scaffold design for cartilage tissue engineering. Nanocellulose can be derived from plant sources or microbial synthesis and processed into cellulose nanofibers, which serve as a structural component for bioinks. These scaffolds support the isolation and expansion of chondrocytes or stem cells, facilitating extracellular matrix deposition and cartilage defect healing.

The biocompatibility of nanocellulose-based scaffolds, combined with their mechanical strength, makes them ideal for cartilage regeneration. Their ability to mimic the native ECM provides a suitable microenvironment for chondrocytes and MSCs to adhere, proliferate, and differentiate into cartilage-forming cells. Additionally, the high surface area of nanocellulose allows for the incorporation of bioactive molecules, such as growth factors, which can further enhance the effectiveness of the scaffold in cartilage regeneration.

The mechanical properties of cellulose-based scaffolds can be fine-tuned by adjusting their composition and structure. For instance, blending nanocellulose with biodegradable polymers such as polylactic acid (PLA) or polycaprolactone (PCL) has been shown to improve the mechanical performance of scaffolds[133], providing the necessary strength for cartilage repair. The addition of these polymers also allows for better control over the degradation rate of the scaffold, ensuring that it resorbs in alignment with the regeneration process of the cartilage tissue. Incorporating nanocellulose into PLA composites has been reported to increase Young's modulus by approximately 30%[134], enhancing the mechanical properties suitable for cartilage tissue engineering applications.

Chondrogenesis and cartilage cell differentiation

Chondrogenesis, the process by which undifferentiated cells transform into cartilage-forming cells (chondrocytes), is a key aspect of cartilage tissue engineering[135]. Nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives have been shown to promote chondrogenesis by providing a favorable microenvironment for cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation. The nanoscale features of cellulose-based scaffolds, including porosity and surface area, are critical for mimicking the natural ECM, which plays an essential role in guiding stem cell differentiation into chondrocytes[136].

The inclusion of bioactive molecules such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) or BMPs in cellulose-based bio-inks has been shown to enhance chondrogenic differentiation[137]. These growth factors stimulate the production of ECM components, such as collagen type II (COL II) and proteoglycans, which are crucial for the formation of hyaline cartilage. The controlled release of these growth factors from nanocellulose-based scaffolds sustains chondrogenesis, which is vital for repairing damaged cartilage.

In addition to growth factors, the use of chondroinductive peptides and ECM proteins, such as fibronectin and COL II, has also been explored to facilitate cell attachment and promote chondrogenesis[138]. These molecules help mimic the native cartilage ECM, aiding stem cell differentiation and enhancing the regenerative capacity of the scaffold. The ability to modulate the bioactivity of cellulose-based scaffolds by incorporating such molecules positions them as powerful tools for cartilage tissue engineering.

Cartilage regeneration in osteoarthritis and joint injury

Osteoarthritis (OA) and joint injuries, such as meniscus tears, often result in the loss of functional cartilage, leading to pain and impaired joint function[139]. The regeneration of cartilage in these conditions requires scaffolds that not only provide mechanical support but also promote the restoration of the biological and functional properties of the cartilage. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds, due to their mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and ability to encourage chondrogenesis, offer a promising solution for cartilage repair in OA and joint injury[140].

In OA, cartilage breakdown reduces mechanical function and increases joint friction, leading to pain and further cartilage degradation. Nanocellulose scaffolds, when combined with chondrocytes or stem cells, have shown potential to promote hyaline cartilage regeneration and alleviate OA symptoms. By incorporating bioactive factors that promote cartilage matrix synthesis, these scaffolds can stimulate the production of ECM components, restoring cartilage mechanical properties and improving joint function.

Cell selection and cell-bioink interactions are central to cartilage regeneration in OA and joint injury, where inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress can shift resident chondrocytes toward a catabolic phenotype. Primary chondrocytes remain the most direct source of matrix-producing cells, but their expansion can reduce the chondrogenic phenotype; therefore, bio-inks that preserve a rounded morphology and provide cartilage-mimetic biochemical cues are often used to support COL II/proteoglycan deposition. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells are widely employed due to their availability and trophic/immunomodulatory effects; in cellulose-based matrices, their behavior is strongly influenced by matrix stiffness, charge/functionalization, and local growth-factor presentation, which together bias chondrogenic differentiation and regulate ECM assembly. Co-culture strategies can further leverage paracrine cross-talk to enhance cartilage-like matrix production. At the same time, interactions with the joint immune environment (notably macrophage-driven signaling) motivate the use of anti-inflammatory/antioxidant formulations in OA-oriented bio-inks[142-144].

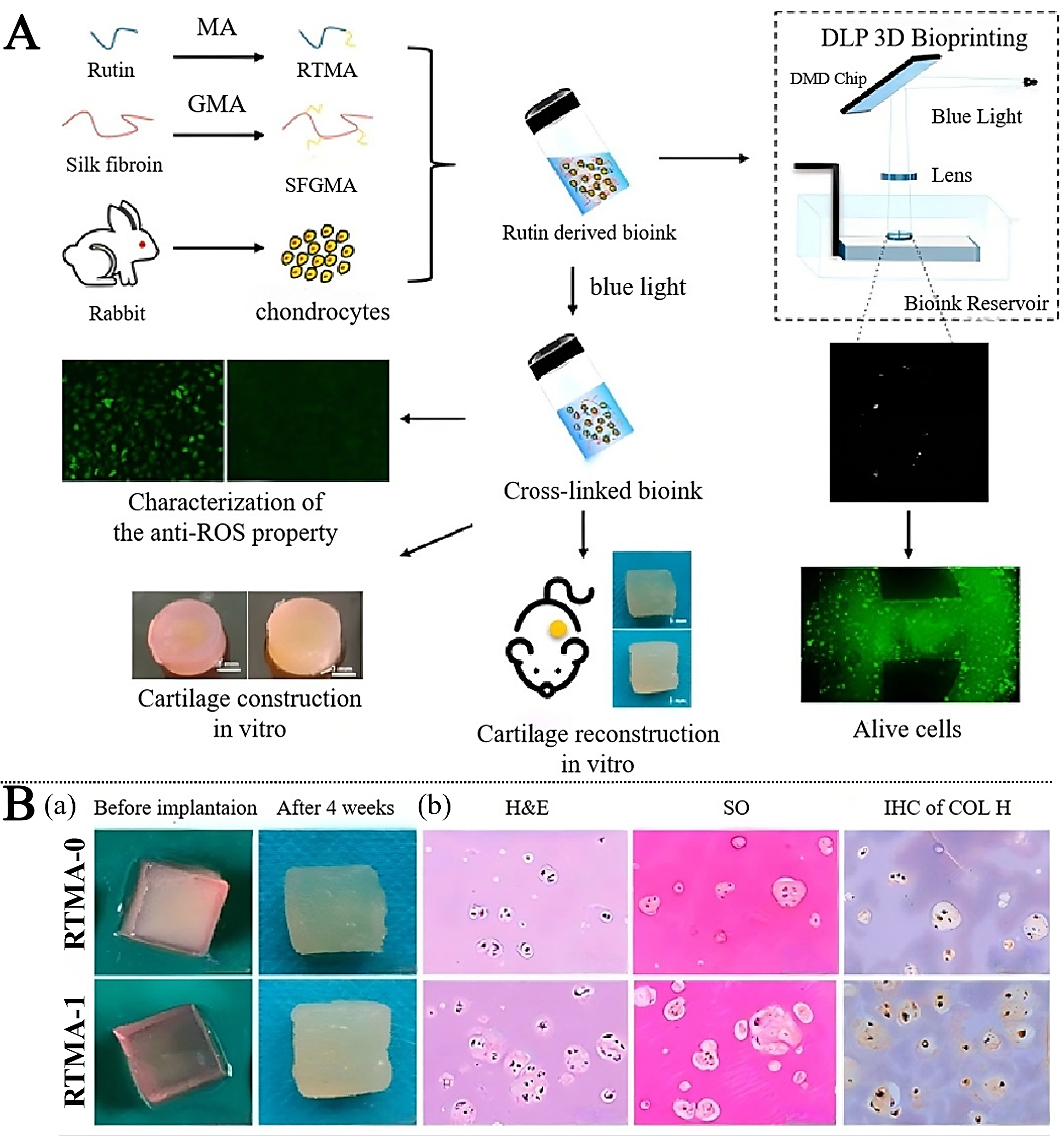

Chen et al. developed a rutin- and silk fibroin-glycidyl methacrylate (SFGMA)-based photo-crosslinkable bio-ink that exhibited strong antioxidative capacity, supported high chondrocyte viability, and effectively facilitated cartilage matrix regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Histological staining (H&E, Safranin O, COL II) confirmed cartilage-like tissue formation in a rabbit subcutaneous model [Figure 7A], consistent with the quantitative/marker readouts shown in Figure 7B.

Figure 7. (A) Anti-oxidative bioink for cartilage tissue engineering application. (B) Subcutaneous implantation in vivo. (a) Overall view of the sample before subcutaneous implantation and after subcutaneous implantation in mice for 4 weeks; (b) Histological staining, i.e., H&E, Safranin-O, and Collagen II staining, of samples implanted subcutaneously in mice for 4 weeks. (Reprinted from Chen et al.[141] Copyright 2024 Journal of Functional Biomaterials.). MA: Methacrylate; GMA: glycidyl methacrylate; RTMA: methacrylate-modified rutin; SFGMA: silk fibroin-glycidyl methacrylate; DLP: digital light processing; 3D: three-dimensional; DMD: digital micromirror device; ROS: reactive oxygen species; H&E: hematoxylin-eosin; SO: safranin O; IHC: immunohistochemistry; COL: collagen.

Joint injuries, such as meniscal tears, often require the regeneration of both cartilage and underlying bone tissue. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds have been used in preclinical models to regenerate cartilage in meniscal repair surgeries[145], demonstrating their ability to support the repair of cartilage defects and promote the integration of the engineered tissue with the surrounding tissue. The combination of nanocellulose with osteogenic factors or bone-forming cells has enhanced the regeneration of both cartilage and bone, leading to improved joint function and reduced pain.

Integration with host tissue and long-term stability

One of the most significant challenges in cartilage tissue engineering is ensuring that the regenerated cartilage integrates seamlessly with the host tissue. The engineered cartilage must bond with the surrounding tissue and exhibit mechanical properties similar to native cartilage to restore function and stability. Nanocellulose-based scaffolds, with their tunable properties and ability to mimic the ECM, have shown promise in facilitating the integration of engineered cartilage with the host tissue.

The biodegradability of nanocellulose scaffolds is a critical factor in ensuring long-term stability and integration. As the scaffold gradually degrades, it provides space for the newly formed cartilage to mature and integrate with the surrounding tissue. This gradual degradation process ensures that the scaffold does not interfere with the growth of the regenerated tissue, allowing the natural healing process to occur.

Furthermore, incorporating of hydrogels or other biomaterials that mimic the hydrated environment of cartilage can enhance the mechanical properties and stability of the engineered tissue. Hydrogels, in particular, have been shown to improve the retention of water in the scaffold, which is crucial for maintaining the mechanical properties of cartilage, such as compressive strength and elasticity[146]. The combination of nanocellulose with hydrogels has demonstrated synergistic effects in improving cartilage regeneration, providing an environment that supports cell growth, differentiation, and tissue maturation.

In conclusion, nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives offer significant potential for the development of scaffolds in cartilage tissue engineering. Their unique combination of mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and ability to promote cell differentiation makes them ideal materials for creating scaffolds that can regenerate functional cartilage. As research continues to evolve, integrating bioactive factors and advanced biomaterials into nanocellulose-based scaffolds will likely further enhance their performance in cartilage repair, offering promising solutions for the treatment of OA, joint injuries, and other cartilage-related disorders.

CELLULOSE-BASED BIO-INKS IN COMPOSITE SCAFFOLDS FOR BONE AND CARTILAGE ENGINEERING

The use of cellulose-based bio-inks in composite scaffolds has significantly advanced tissue engineering applications, allowing for their integration into more demanding regenerative treatments. By incorporating HA, synthetic polymers, bioactive molecules, and crosslinking strategies, researchers have improved the mechanical properties, bioactivity, and printability of these scaffolds. Mechanistically, these improvements are commonly attributed to nanocellulose acting as a reinforcing and rheology-building phase: a percolated fibrillar or rod-like network increases yield stress and structural recovery to support extrusion and shape fidelity, while strong interfacial interactions with the matrix (predominantly hydrogen bonding and electrostatic association, and in some systems covalent coupling) facilitate load transfer and energy dissipation, thereby enhancing stiffness and toughness[126]. Their application in bone regeneration, osteochondral repair, intervertebral disc reconstruction, and craniofacial repair has yielded biocompatible and biodegradable approaches for regenerative medicine. The following sections highlight specific clinical challenges where cellulose-based composite scaffolds are demonstrating significant potential.

3D-printed cellulose-hydroxyapatite composites for large bone defect reconstruction

Large bone defects resulting from trauma, tumor resection, or congenital abnormalities present a significant challenge in orthopedic surgery. Conventional treatments such as autografts and allografts, while commonly used, suffer from drawbacks including immune rejection, donor site morbidity, and unpredictable degradation. To address these limitations, 3D printed cellulose-HA composite scaffolds have been developed as biodegradable, mechanically stable materials that provide osteoconductive properties. These scaffolds provide structural integrity similar to cortical bone while also supporting vascularization and new bone formation.

Preclinical studies have shown that cellulose-HA composite scaffolds support bone regeneration in rabbit femoral defect models[147,148]. The porous architecture of these scaffolds enhances nutrient diffusion and vascularization, which are essential for the deposition of new bone matrix. Furthermore, the integration of bioactive molecules, such as BMP-2, enhances osteoblast differentiation, thereby accelerating bone regeneration[149].

Nanocellulose-based injectable hydrogels for osteochondral repair

Osteochondral defects involve the deterioration of both cartilage and underlying subchondral bone, requiring scaffolds that can support hydration retention and chondrogenic differentiation while maintaining mechanical support for bone repair. Injectable nanocellulose-based hydrogels have been developed as minimally invasive solutions for osteochondral regeneration, enabling localized in situ repair[150]. These hydrogels form mechanically stable and hydrated matrices at the defect site, replicating the extracellular environment of native cartilage and providing structural integrity for tissue growth.

A study conducted using rabbit knee osteochondral defect models found that nanocellulose-alginate hydrogels significantly enhanced chondrocyte proliferation and ECM deposition, thereby promoting the development of hyaline cartilage-like tissue[151]. The gradual degradation of the hydrogel sustained scaffold integrity during the critical early phases of cartilage regeneration. Additionally, nanocellulose scaffolds loaded with growth factors, such as TGF-β and VEGF, promoted healing at the bone-cartilage interface, a key factor in ensuring long-term joint function. Notably, rabbit osteochondral defect studies are most commonly evaluated at short-to-mid-term time points (typically 4-12 weeks), whereas fewer studies extend follow-up to ≥ 24 weeks, which is more informative for assessing cartilage durability, osteochondral interface stability, and remodeling under joint loading; therefore, longer-term orthotopic validation remains a key gap for translation[152,153]. Furthermore, nanocellulose-based scaffolds have been explored for early-stage OA treatment via arthroscopic administration. In this case, they serve as biolubricants while releasing bioactive molecules that reduce inflammation and support cartilage repair[154].

Cellulose-based composite scaffolds for intervertebral disc regeneration

Degenerative disc disease is a leading cause of chronic back pain and spinal instability, with limited long-term treatment success using traditional interventions such as spinal fusion and artificial disc replacement[155]. Research on cellulose-based bio-inks has supported the development of regenerative approaches for intervertebral disc repair that aim to restore biomechanical function and mitigate further degeneration. These scaffolds are designed to be biomechanically resilient, hydrophilic, and able to withstand spinal loads, making them suitable for long-term disc regeneration. For clarity, the studies summarized below include both bioprinted constructs and non-bioprinted cellulose-based systems (e.g., implantable scaffolds or injectable hydrogels); bioprinting is specified where applicable.

A rat implantation study reported a bioprinted, disc-mimetic construct combining a bacterial cellulose-based annulus component with a type II collagen-based nucleus pulposus analogue, demonstrating disc-like mechanical support and structural integration over a three-month follow-up[156]. The ability of these materials to retain hydration ensured adequate load distribution under compression, preventing further disc deterioration. Reinforcing the scaffold with CNCs increased tensile strength to approximately 2 MPa, reducing the risk of scaffold collapse while preserving its flexibility. Additionally, MSC-seeded cellulose scaffolds stimulated proteoglycan synthesis, which plays a vital role in restoring disc function[157]. In another approach, HPC-alginate hydrogels have been tested as injectable disc fillers, offering a non-surgical intervention to slow the progression of early-stage disc degeneration[158].

Load-bearing composite scaffolds for temporomandibular joint and craniofacial reconstruction

Craniofacial defects, particularly those affecting the temporomandibular joint, require scaffolds that provide both high mechanical stability and excellent biocompatibility. Conventional treatments, such as titanium implants and synthetic polymers, are associated with complications, including foreign body reactions and material degradation over time[159,160]. To address these limitations, cellulose-based composite scaffolds have been designed for patient-specific craniofacial reconstructions, offering long-term functionality and improved biological integration.

For temporomandibular joint disc replacement, 3D printed cellulose-PCL hybrid scaffolds have been engineered to replicate the properties of native fibrocartilage. These scaffolds offer tensile strength sufficient to withstand chewing forces, with reported values of approximately 5 MPa, while maintaining hydration and viscoelasticity to prevent material degradation and mechanical failure. In addition, the incorporation of fibrocartilage-derived growth factors has improved cell differentiation, promoting ECM deposition and collagen fiber alignment.

In maxillofacial reconstruction, methylcellulose-HA composite scaffolds have been investigated for their potential in mandibular defect repair. Preclinical studies have shown that these scaffolds, when combined with VEGF and BMP-7, integrate with native tissue while promoting new bone growth. Research indicates that after 12 weeks of implantation, bone healing is substantially improved compared to conventional scaffolds, demonstrating the feasibility of these materials for future clinical applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery[161].

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

The integration of nanocellulose and cellulose derivatives into bio-inks for bone and cartilage tissue engineering shows strong promise but also presents clear challenges and limitations. Addressing these barriers is essential to translate nanocellulose-based systems into regenerative medicine. To provide a more precise, structured overview of the main technical constraints discussed here, Table 3 summarizes the key challenges and corresponding engineering directions. This section then examines these issues in detail and highlights future prospects for advancing cellulose-based bio-inks in tissue engineering.

Technical challenges and engineering directions for NCF and cellulose-derivative bio-inks toward future medical and tissue re-engineering applications

| Challenge | Key impact | Direction |

| Complex and costly nanocellulose extraction; process trade-offs (energy use, yield, by-products, property changes) | Limits scale-up and consistent material quality | Improve extraction routes and process efficiency |

| Industrial scale-up with raw-source variation | Batch-to-batch property drift; weaker formulation repeatability | Strengthen control of feedstock and production to stabilize material properties |

| Rheology window for extrusion (viscosity vs. shear-thinning vs. shape retention) | Nozzle blocking or loss of structural integrity after printing | Tune rheology and printing settings to maintain stable extrusion and post-print shape |

| Blending cellulose derivatives with materials of different viscosity | Hard to reach an “optimal balance”; unstable print behavior | Optimize multi-material formulations and ratios; use hybrid designs to offset limits |

| Printing conditions that reduce cell survival (high temperature or solvents) | Narrower process window for cell-laden constructs | Refine fabrication to use milder conditions; improve crosslinking and cell compatibility |

| Bone/cartilage complexity and bioactive integration (growth factors/peptides); controlled release and activity retention remain difficult | Reduced functional regeneration if cues are unstable or poorly delivered | Develop more effective functionalization and bioactive incorporation while preserving activity through printing and in vivo |

Challenges in material sourcing and consistency

One of the significant challenges in developing cellulose-based bio-inks is sourcing and ensuring the consistency of nanocellulose materials. While cellulose is abundant in nature, the extraction process for producing nanocellulose can be complex, time-consuming, and costly. Various methods, including acid hydrolysis, enzymatic treatment, and mechanical processing, are used to obtain nanocellulose, each with its own set of advantages and drawbacks[162-164]. For instance, mechanical methods can be energy-intensive and yield low levels, while chemical treatments can introduce undesirable by-products or alter the inherent properties of cellulose.

Moreover, the scalability of nanocellulose production remains a critical issue. Although cellulose-based materials are often derived from renewable sources such as plant biomass or waste, achieving consistent nanocellulose quality on an industrial scale remains a significant challenge. Variations in raw material sources can lead to inconsistencies in the physical properties of the resulting nanocellulose, thereby affecting the reproducibility of bio-ink formulations[165]. These issues become particularly problematic when producing large quantities of bio-inks for clinical or commercial applications.

Beyond feedstock variability, scale-up is also constrained by process throughput and downstream handling. Pilot- and industrial-scale CNF production remains sensitive to solids content and energy demand, motivating process-intensified routes such as twin-screw extrusion and scalable TEMPO-type oxidation workflows[166]. For CNCs, larger-batch acid hydrolysis requires robust control of reaction conditions and surface chemistry, as well as practical acid recovery and wastewater management to keep costs and environmental burdens manageable[167]. Downstream, logistics can become decisive: transporting dilute suspensions is costly, while drying often promotes aggregation and can compromise redispersibility and rheological performance, so “never-dry” supply, concentrate handling, or validated redispersion strategies are important as one moves toward commercial bio-ink production. Finally, scale-up of biomedical-grade bio-inks benefits from defined critical quality attributes and rapid quality-control readouts linked to print performance, including rheological fingerprinting as a practical screening tool for batch-to-batch consistency[168].

Technical limitations in 3D bioprinting of cellulose-based bio-inks

Despite rapid progress in 3D bioprinting, cellulose-based bio-inks still face several technical hurdles. The rheological properties of cellulose-based bio-inks, such as viscosity and shear-thinning behavior, must be carefully tuned to ensure proper extrusion during printing. If the bio-ink is too viscous, it can block the printing nozzle; if too thin, it may not maintain the required structural integrity after deposition[169]. Achieving the optimal balance between these properties can be challenging, particularly when combining cellulose derivatives with other materials that have differing viscosities.

Furthermore, the cell viability within the bio-inks remains a significant concern. The fabrication process, particularly when using high temperatures or solvents, may negatively affect the survival of embedded cells. The printability of cellulose-based bio-inks, combined with the need for cell viability and growth within the printed structures, makes it essential to refine both the bio-ink composition and the bioprinting process itself. Research continues to focus on optimizing crosslinking methods and improving the compatibility of the bio-link with living cells, but these technical challenges remain significant limitations.

Biological complexity of bone and cartilage regeneration

Another critical challenge lies in replicating the biological complexity of bone and cartilage tissues using cellulose-based bio-inks. Both tissues possess intricate structures and cellular environments that are difficult to mimic. Bone tissue, for instance, is composed of various cell types, including osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes, all of which must interact with the ECM and mineral components to regenerate functional

Nanocellulose-based scaffolds alone cannot fully replicate this complexity. While cellulose derivatives can provide structural support and serve as a substrate for cell attachment and differentiation, additional growth factors, peptides, and bioactive molecules are often required to enhance cell behavior and promote the formation of functional tissues. In bone tissue engineering, the addition of osteogenic factors, such as BMPs and VEGF, is critical, whereas in cartilage tissue engineering, chondrogenic factors, such as TGF-β, are required[171,172]. Incorporating these bioactive molecules into cellulose-based bio-inks while ensuring controlled release and maintaining their activity throughout the printing and in vivo processes is a considerable challenge.

Regulatory considerations for clinical translation

Regulatory considerations are an essential barrier to the clinical translation of nanocellulose-based bio-inks. The regulatory pathway can change substantially when living cells or bioactive factors are incorporated, and constructs produced by additive manufacturing may face higher expectations for traceability, documentation, and process control than conventional biomaterials. These considerations should be addressed early in the translational plan rather than after material optimization[173].

From a manufacturing standpoint, clinical approval typically requires a quality management system and well-defined material specifications that control batch-to-batch variability, impurities (including endotoxin/pyrogen risk), and sterilization compatibility. Biological safety should be supported using a risk-based approach aligned with ISO 10993-1 (Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process), and nanotechnology-related guidance may be relevant when size-dependent properties are central to performance and characterization[174].

Future prospects and directions for research

Despite the current challenges, the future of nanocellulose-based bio-inks in bone and cartilage tissue engineering is auspicious. Advances in nanocellulose extraction techniques, combined with innovations in bioprinting technologies, offer significant opportunities for improving the scalability, reproducibility, and performance of cellulose-based bio-inks. In particular, the development of more efficient methods for functionalizing nanocellulose with bioactive molecules, such as growth factors and ECM proteins, could substantially enhance their regenerative potential.

Future work should clarify how nanocellulose fiber properties need to evolve for reliable bio-ink design. More consistent control over fibril size distribution, aspect ratio, and surface charge will be essential to reduce batch variability and place rheology within a predictable window for extrusion, shape retention, and cell compatibility[175,176]. In parallel, surface functionalization should shift from generic “bioactive loading” toward defined, tissue-driven functions, such as mineral affinity for bone or matrix-mimetic cue presentation for cartilage[177]. Finally, inks will benefit from crosslinking schemes that stabilize printed shapes quickly yet allow gradual remodeling and degradation as new tissue forms[178].

The integration of nanocellulose with other advanced biomaterials, such as hydrogels, synthetic polymers, and bioceramics, will continue to be a key area of research[179,180]. These hybrid systems can address the limitations of nanocellulose in terms of mechanical strength, biodegradability, and cell compatibility, creating more versatile scaffolds that can be tailored for specific tissue types and clinical applications. Moreover, research into nanocellulose-based drug delivery systems and electroactive materials for tissue regeneration holds great promise in expanding the functional applications of these bio-inks.

The future of cellulose-based bio-inks in bone and cartilage tissue engineering also involves their integration with other cutting-edge technologies, such as stem cell therapy, gene editing, and personalized medicine[11,181]. As the field moves towards more customized solutions, the ability to print scaffolds tailored to the individual anatomy of the patient and specific tissue needs will become a reality. The combination of 3D bioprinting and advanced material design is expected to drive significant breakthroughs in regenerative medicine.

Moreover, the integration of four-dimensional (4D) bioprinting represents a promising frontier in tissue engineering. Unlike traditional 3D bioprinting, which produces static structures, 4D bioprinting incorporates the dimension of time, enabling printed constructs to undergo dynamic transformations in response to physiological stimuli such as temperature, pH, moisture, or enzymes. For cellulose-based bio-inks, this could involve stimuli-responsive hydrogels or shape-memory cellulose composites that adjust their mechanical properties, degradation rates, or structural conformation over time to match tissue development better.

In conclusion, while the application of nanocellulose-based bio-inks in bone and cartilage tissue engineering faces several technical, biological, and regulatory challenges, the future prospects for these materials are promising. With ongoing research and technological advancements, nanocellulose has the potential to become a cornerstone material in regenerative medicine, enabling the creation of functional, patient-specific scaffolds for tissue repair and regeneration. The successful resolution of current limitations will pave the way for the widespread clinical application of cellulose-based bio-inks in the treatment of bone and cartilage defects.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Dai, H.

Writing: Xu, Y.; Dai, H.

Review and editing: Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, N.; Xiong, L.

Supervision: Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, N.; Xiong, L.

Project assistance: Ye, Q.

All authors contributed to the editing and approved the final version of the manuscript.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFE0204600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62305068 and 62074044), and the Shanghai 2025 "Pioneer Plan" Biological Hybrid Robot Theme Project (third batch, 25XF3201000).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.