Effect of elemental segregation and minor phase on mechanical properties of as-cast super-thick steels studied using in-situ synchrotron X-ray and neutron diffraction

Abstract

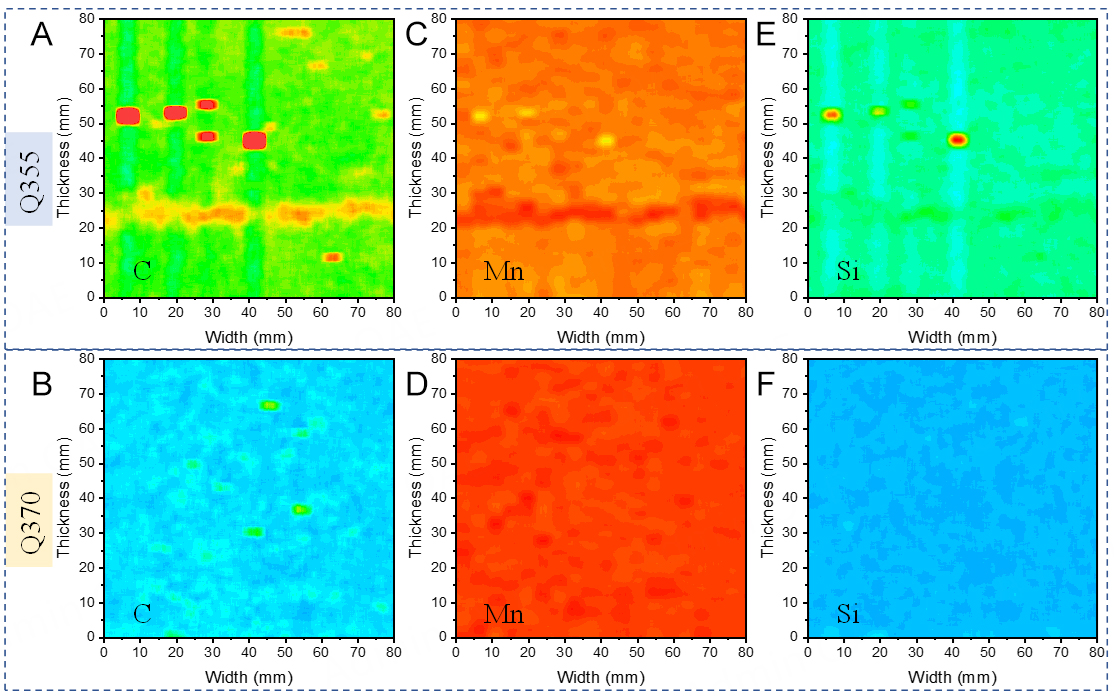

Internal defects, especially those caused by elemental segregation and minor phases in as-cast super-thick steel plates with large section sizes, can critically impact the subsequent manufacturing processes and the mechanical properties of final products, which may result in catastrophic failure during industrial applications. However, the effects of elemental segregation and the resultant phase structures on deformation behaviors and real-time microstructural evolution under tensile loading remain unexplored in as-cast super-thick steels. In this study, we employed in-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction techniques during tensile tests to investigate the relationship between internal defects and deformation behaviors of segregated and non-segregated super-thick steels. Compared to the segregated sample, the non-segregated sample exhibited improved yield and tensile strengths, increasing from 407.5 and 590.5 MPa to 515.2 and 632.8 MPa, respectively, with a significant increase in elongation from 8% to 23.4%. Strip-like elemental segregations were observed in the central core area due to final solidification, and the stress partitioning between ferrite matrix and retained austenite was revealed to be beneficial for uniform plastic deformation and necking before fracture. Both ductile and brittle fractographies were identified in segregated conditions. Our findings address a critical knowledge gap in understanding how elemental segregation and minor phases affect deformation behaviors, and offer valuable insights for optimizing processing parameters for as-cast super-thick steels.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Super-thick steel plates with thicknesses over 100 mm play a critical role in various industries, including construction and infrastructure, offshore and marine engineering, and energy sectors, due to their exceptional strength, durability, and ability to withstand extreme conditions[1]. The high thickness of the plates ensures structural integrity under massive loads, withstands wear and tear, and resists deformation under extreme stress and temperature conditions[2]. Super-thick steel slabs (> 400 mm) are manufactured by continuous casting in order to reduce nonmetallic inclusions and segregation[3]. To fabricate final commercial products, the as-cast raw steel slabs must undergo complicated processes such as tempering, rolling, machining, and welding, resulting in defects that have a negative influence on the mechanical properties, especially those internal defects that can cause catastrophic failure with safety concerns during in-service applications. Therefore, understanding the relationship between internal defects and mechanical properties is imperative for the long-term reliability of super-thick steel slabs.

Internal defects in as-cast super-thick steels, such as segregation and associated formation of minor phases, are problematic during continuous casting and difficult to eliminate in the successive manufacturing processes[4]. In the continuous casting process, molten steel flows from a ladle into the mold and freezes against the water-cooled copper mold walls to form a solid shell. This shell is further cooled by water and air mist spraying when the slab is withdrawn on rollers, until the molten core is solid[5]. The cooling and solidifying processes of molten steel vary along the thickness direction and produce thickness-dependent defects that can significantly influence mechanical properties[6]. Porosity resulting from shrinkage during final-stage solidification at the inner core is seen along the thickness cross-section but can effectively be reduced by the reduction process during the final stage of solidification[7]. However, in the steelmaking process, cracks still occur when the steel slabs are subject to various stresses and/or strains, making crack prevention and healing techniques very important[8]. For example, a deformation-assisted tempering process applied to large-size steel plates can produce a microstructure with low dislocation density and a high density of low-angle subgrain boundaries, improving crack healing and fracture resistance[9]. Hot-core heavy reduction rolling supports microstructure homogeneity and consistent mechanical properties along the thickness direction[10]. An electroslag remelting casting and roller quenching process improves the impact energy and yield strength by increasing the fraction of martensite[11].

Unfavorable residual stress and segregation generated during the manufacturing of thicker slabs increase the susceptibility of cracking during flame cutting[12]. Thermo-mechanical finite element models derived from experimental inputs have been used to simulate the improved slab center quality and enhanced compactness of rolled bars after heavy reduction[13]. After solutionizing and water quenching, lath-like bainite is observed at the quarter thickness location, while a mixture of granular and lath-like bainite appears at the center thickness location. High-angle grain boundaries resulting from as-quenched and tempered conditions amplify the thickness-dependent variation in strength and toughness[14]. Deformation parameters are optimized by combining the degree of dynamic recrystallization and flow stress for a

However, the lack of direct connection between internal defects and mechanical properties of as-cast super-thick steels creates uncertainty in subsequent processing optimization and hinders the effective strategies to achieve microstructural uniformity. There are few straightforward solutions for detecting elemental segregations of C, S, Cr, and Mo along with the cracking and guiding the applied stress modification of solidifying shells[19]. Numerical simulations remain heavily dependent on experimental verification and quantitative data inputs[20]. Destructive characterization tools of metallography and microscopies and non-destructive methods of ultrasonic and X-ray inspections fail to link macro- and micro-structural behaviors to mechanical properties in real time[21,22]. Advanced characterization techniques, such as synchrotron-based X-ray and neutron diffraction, have revolutionized the study of high-performance alloys by enabling the atomic-scale resolution and real-time complex microstructures analysis[23,24]. Nevertheless, it is challenging to investigate the deformation behaviors at the lattice scale while correlating them with internal segregation and minor phases in super-thick bulk steel samples.

In this study, we employed in-situ high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction to track the lattice strain evolution of the majority ferrite phase under tensile loading in both segregated and non-segregated conditions. In-situ neutron diffraction revealed that synergistic stress partitioning between ferrite matrix and retained austenite supports uniform plastic deformation and necking before fracture. Complementary metallography and fractography showed that strip-like elemental segregations are located in the central thickness area due to the final-stage solidification. These segregations, along with internal pores, lead to stress concentration and contribute to catastrophic fracture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As-cast super-thick steel slabs

The tested specimens were sectioned from the central core area of as-cast super-thick steel slabs measuring 4,800 mm in length, 2,070 mm in width, and 450 mm in thickness, which were continuously cast in an integrated system at the steel plant. Ultrasonic inspection identified two conditions of elemental segregation: segregation in the Q355 samples and non-segregation in the Q370 samples. The chemical compositions of super-thick steels are listed in Table 1.

Chemical composition of the investigated steel (wt.%, Fe balanced)

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Al | Nb | Ti | Cr | Ni | Cu |

| 0.12 | 0.25 | 1.33 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.032 | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| ~0.19 | ~0.34 | ~1.45 | ~0.013 | ~0.003 | ~0.035 | ~0.042 | ~0.014 | ~0.20 | ~0.4 | ~0.2 |

In-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction

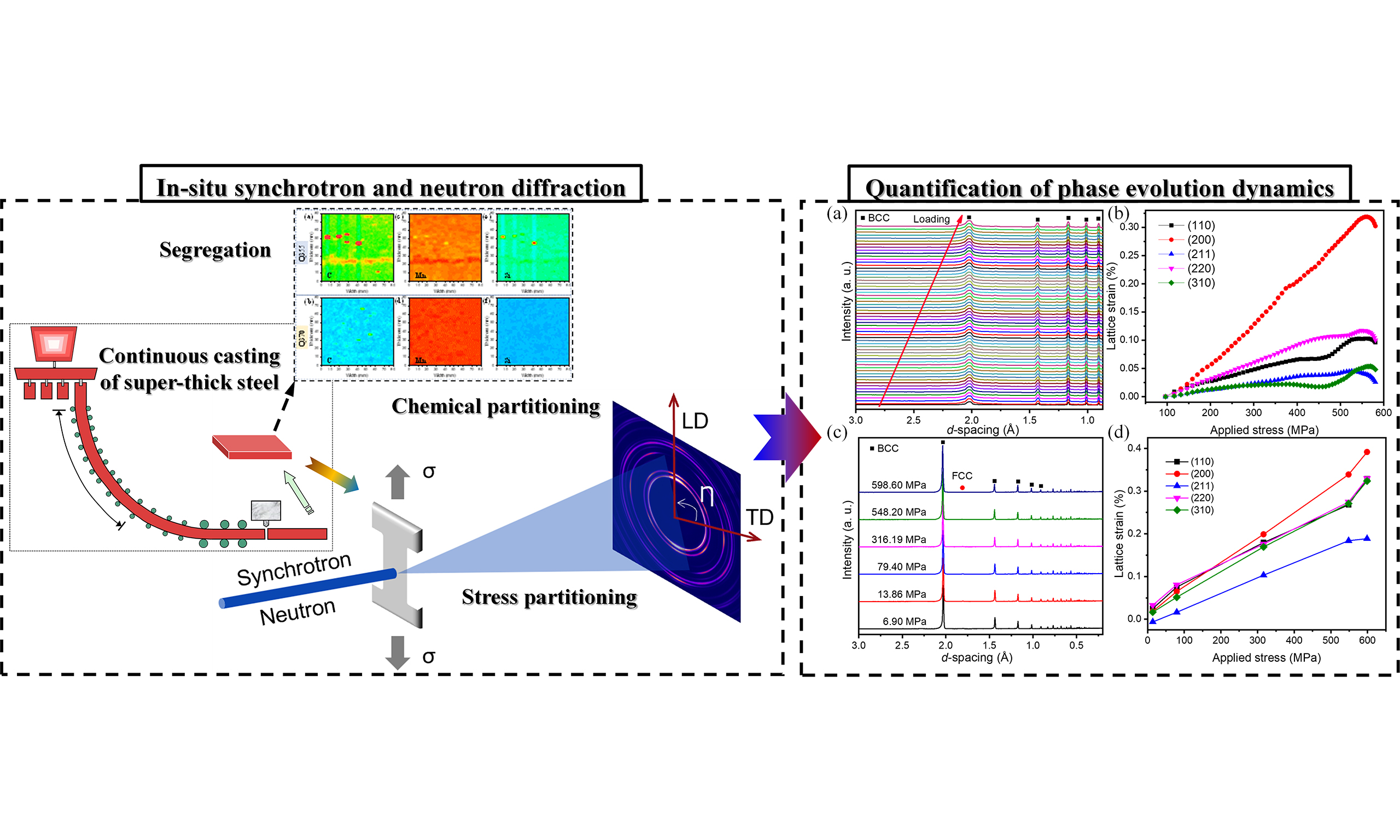

Figure 1 demonstrates the principle of in-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction monitoring of segregated and non-segregated samples under tension. Incident high-energy synchrotron X-ray beam and neutron beam interact with segregated and non-segregated samples during tensile tests and diffracted beams are captured by downstream detectors, as shown in Figure 1A. The interplanar spacing (d-spacing) of different crystallographic (hkl) planes at each tensile deformation step was obtained by tracking the two-theta angles and calculated by Bragg’s Law, as shown in Eq. (1) and Figure 1B. The lattice strain (εhkl) of each crystallographic planes at loading and transverse directions can be described by Eq. (2) by comparing the d-spacing at every applied stress step with the unloaded sample. Then, the lattice-scale stress partitioning behavior can be obtained as a function of applied stress.

Figure 1. Principle of in-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction during tensile testing of super-thick steels. (A) During the uniaxial tensile test, a high-energy synchrotron X-ray beam and a neutron beam intersect the sample, and the diffracted beams are collected by downstream detectors. (B) Representative diffraction patterns of the segregated (Q355) and non-segregated (Q370) samples. The raw as-cast super-thick steels contain a ferrite matrix along with retained austenite and carbide phases, as identified from the diffraction data.

where θ is the diffraction angle, λ is the incident beam wavelength, dhkl is the interplanar spacing of the crystallographic (hkl) plane, εhkl is the lattice strain, and dhkl0 is the interplanar spacing of the same lattice plane in the undeformed condition.

The in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments were carried out at the 3W1 beamline of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Dog-bone-shaped samples were subjected to uniaxial tensile testing at a strain rate of 1 × 10-3/s. The gauge geometry of each tensile sample was 2 mm in length, 1.5 mm in width, and 1 mm in thickness. The monochromatic synchrotron X-ray with a beam energy of 60 keV, a wavelength of 0.2062 Å, and a beam size of 0.5 × 0.5 mm2 was used. Two-dimensional diffraction patterns were captured using a large-size detector with a pixel size of 140 × 140 μm2. The 1D diffraction profile was integrated to determine the d-spacing of each set of crystallographic planes along the loading direction (using an azimuthal integration angle of 85°-95°) and the transverse direction (using an azimuthal integration angle of -5°-5°). A CeO2 powder specimen was used to calibrate experimental setups.

In-situ neutron diffraction measurements were conducted using the energy-resolved neutron imaging instrument (ERNI) at the China Spallation Neutron Source. The gauge geometry of the tensile specimen was 40 mm in length and 6 mm in diameter. The thermal neutron pulse frequency was 25 Hz. An incident neutron beam with a wavelength band of 0.1 to 4.2 Å and a beam size of 10 × 10 mm2 was used. Prior to the tensile test, the instrument was calibrated for d-spacing using Si powders contained in a vanadium can mounted on the sample stage. The instrument is equipped with six detector banks, and the detector bank positioned at 90° was used to obtain diffraction patterns with an instrumental resolution of 0.5%. The specimen was tilted to be oriented at 45° relative to the incident beam to align the diffraction vectors Q both parallel and perpendicular to the loading axis. During the tensile test, two detector banks at 90° recorded diffraction patterns corresponding to the loading direction and the transverse direction, respectively.

Microstructural characterization

Ultrasonic inspection was employed to locate the defect area along the thickness direction of the steel plate. When the ultrasonic beam propagates from the plate surface and encounters defects or the bottom surface, it generates reflected waves that form pulse waveforms, which are analyzed to determine the defects’ locations and sizes. Regions showing irregular ultrasonic patterns in the mid-thickness area were sectioned for metallographic observation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine the metallurgical microstructure. Additionally, fractured surfaces from in-situ tensile tests were analyzed using SEM to study the fracture microstructure.

Elemental segregation in large-area specimens sliced from the cross-section along the width and thickness directions was quantified by original position statistical distribution analysis. For this analysis, a linear scanning mode was used at a continuous speed of 1 mm/s along the X-axis and a step model with a 1 mm interval along the Y-axis. The exciting sparks parameters were as follows: (a) frequency, 500 Hz; (b) capacitance, 7.0 μF; (c) argon flow rate, 8 L/min; and (d) tungsten electrode with a 90° corner angle and a

RESULTS

Mechanical properties

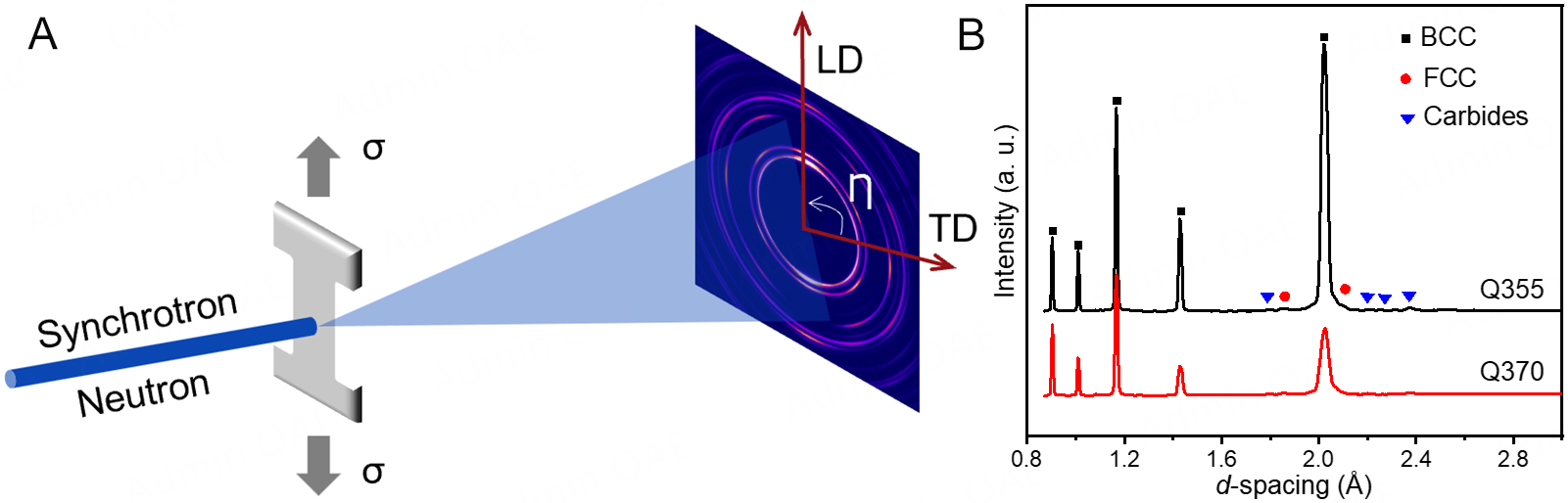

Figure 2 shows the tensile stress-strain curves of segregated (Q355) and non-segregated (Q370) samples tested at room temperature. A significant reduction in yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation was observed in the segregated samples compared to the non-segregated ones. Specifically, the yield strength decreased by 20.9%, from 515.2 MPa in the Q370 sample to 407.5 MPa in the Q355 sample. The tensile strength also slightly decreased by 6.7% from 632.8 MPa in the Q370 sample to 590.5 MPa in the Q355 sample. The most pronounced difference was in elongation: the segregated Q355 sample exhibited a substantial reduction to 8%, whereas the non-segregated Q370 sample achieved an elongation of 23.4%. The strain hardening behavior also differed markedly between the two samples. In the Q355 sample, the hardening rate dropped dramatically before 1% strain, then decreased more gradually until 6.4% strain, after which fracture occurred at 8% strain. In contrast, the Q370 sample exhibited two distinct strain hardening regimes: the hardening rate initially decreased rapidly to 3% strain, followed by an almost constant plateau until 23.4% strain. Before fracturing, clear necking was observed in the Q370 sample, indicating a fully ductile failure mode, which was markedly different from the brittle behavior of the Q355 sample. The elastic modulus, calculated from the stress-strain curves, was 48.6 GPa for the non-segregated condition and

Figure 2. Uniaxial tensile properties of the segregated (Q355) and non-segregated (Q370) samples. The Q355 samples exhibited significant reductions in yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation. Necking was observed in the Q370 samples, and the strain hardening rate was sustained over a longer strain range in the Q370 condition.

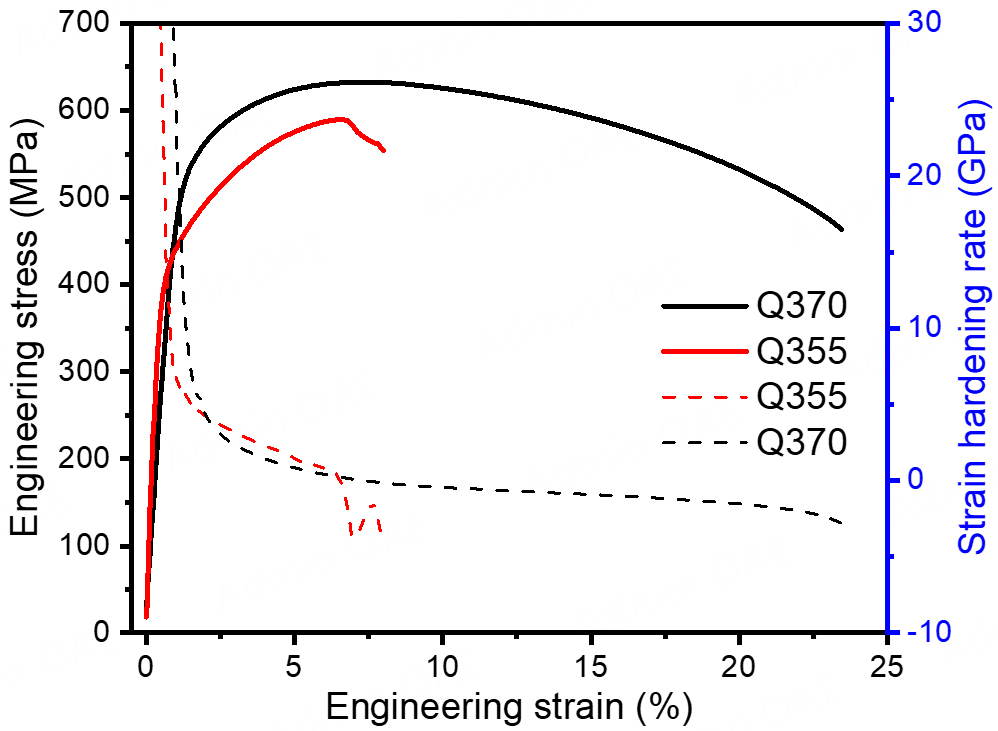

Elemental segregations

To investigate the microstructural details correlated with the significant reduction in mechanical properties in the segregated Q355 condition, an original position statistic distribution analysis was performed on large area samples (80 × 80 mm2) to examine elemental segregation. The detailed distributions of C, Mn, and Si are displayed in Figure 3. Overall, a distinct strip-like segregation was observed near the center thickness line of the Q355 sample, whereas the Q370 sample exhibited a relatively uniform elemental distribution. Specifically, the C, Mn and Si elements - added to the molten steel to reduce O and S content - showed different segregated behaviors in the Q355 and Q370 samples. In the Q355 sample, large island-like regions of C distribution, measuring on the millimeter scale, were scattered around the prominent strip line, as shown in Figure 3A. Similarly, Mn and Si also exhibited island-like segregations away from the center thickness, as seen in Figure 3C and E. These elemental segregations tended to accumulate along the thickness direction. It is important to note that the concentrated spots in Figure 3A, C, and E were induced by oxide inclusions originating from the raw steel slabs. In contrast, in the Q370 sample, although some local C enrichment was evident [Figure 3B], Mn and Si were more uniformly distributed.

Figure 3. Original position statistic distribution analysis of C, Mn, and Si over an 80 × 80 mm2 area taken from the center thickness region of Q355 and Q370 samples. Comparisons of elements C (A and B), Mn (C and D), and Si (E and F) between the Q355 and Q370 samples show the distinct strip-like segregation along the width direction and island-like segregation along the thickness direction. The heavily concentrated spots in (A, C, E) were caused by sparks from oxide inclusions.

In-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction during tensile testing

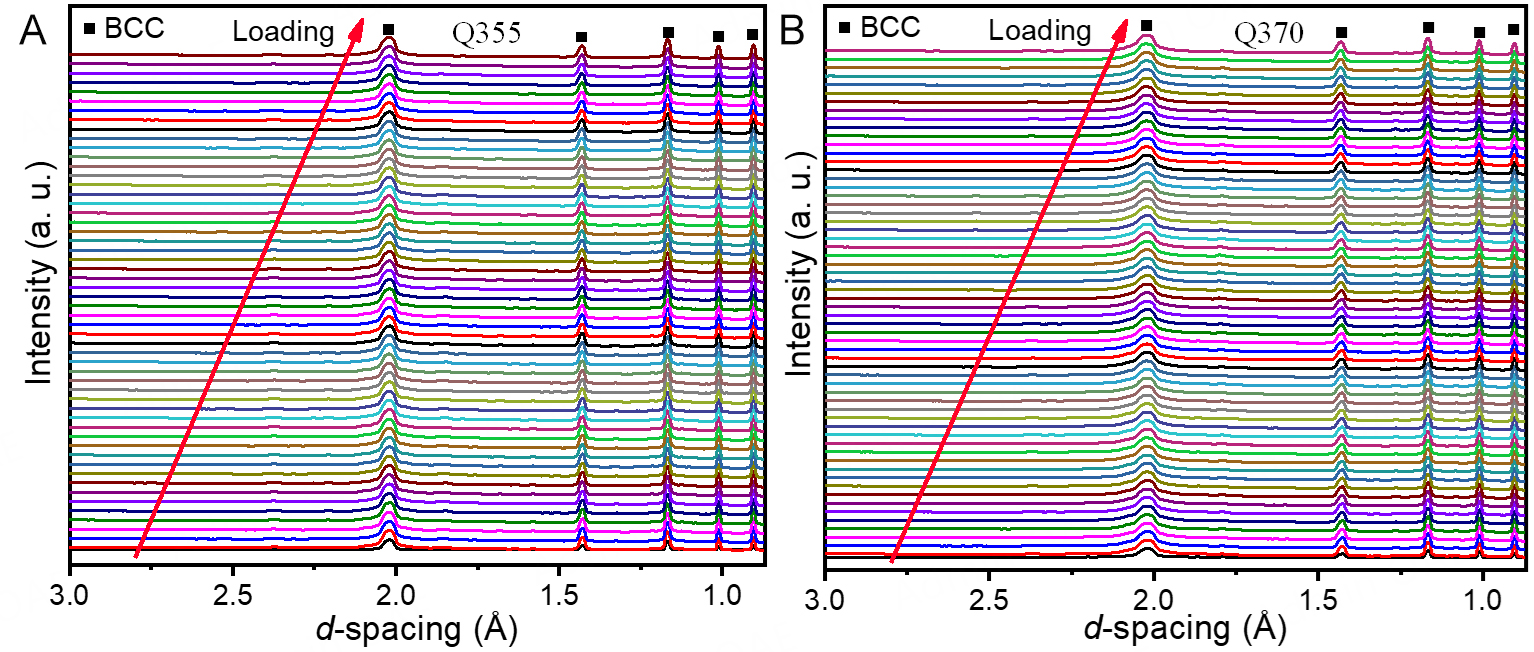

To further probe the effect of the microstructure on mechanical properties, we conducted in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements on the Q355 and Q370 samples during tensile testing, as shown in Figure 4. In the diffraction patterns obtained before the tensile tests [Figure 1B], minor phases of retained austenite and carbides can be observed. Although small peaks corresponding to these minor phases are also detectable in Figure 4, their low volume fractions (< 3%) result in very weak intensities, making them difficult to quantify under applied stress. The five (hkl) reflections of the major ferrite phase were monitored as a function of applied stress. Selected diffraction patterns along the loading direction are presented in Figure 4A for the Q355 sample and Figure 4B for the Q370 sample. The d-spacings of these five reflections shifted with increasing stress, and no new peaks were observed during the tensile tests, indicating that no phase transformation occurred.

Figure 4. In-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements of Q355 and Q370 samples during tensile testing. Diffraction patterns along the loading direction for the Q355 (A) and Q370 (B) samples during uniaxial tensile testing.

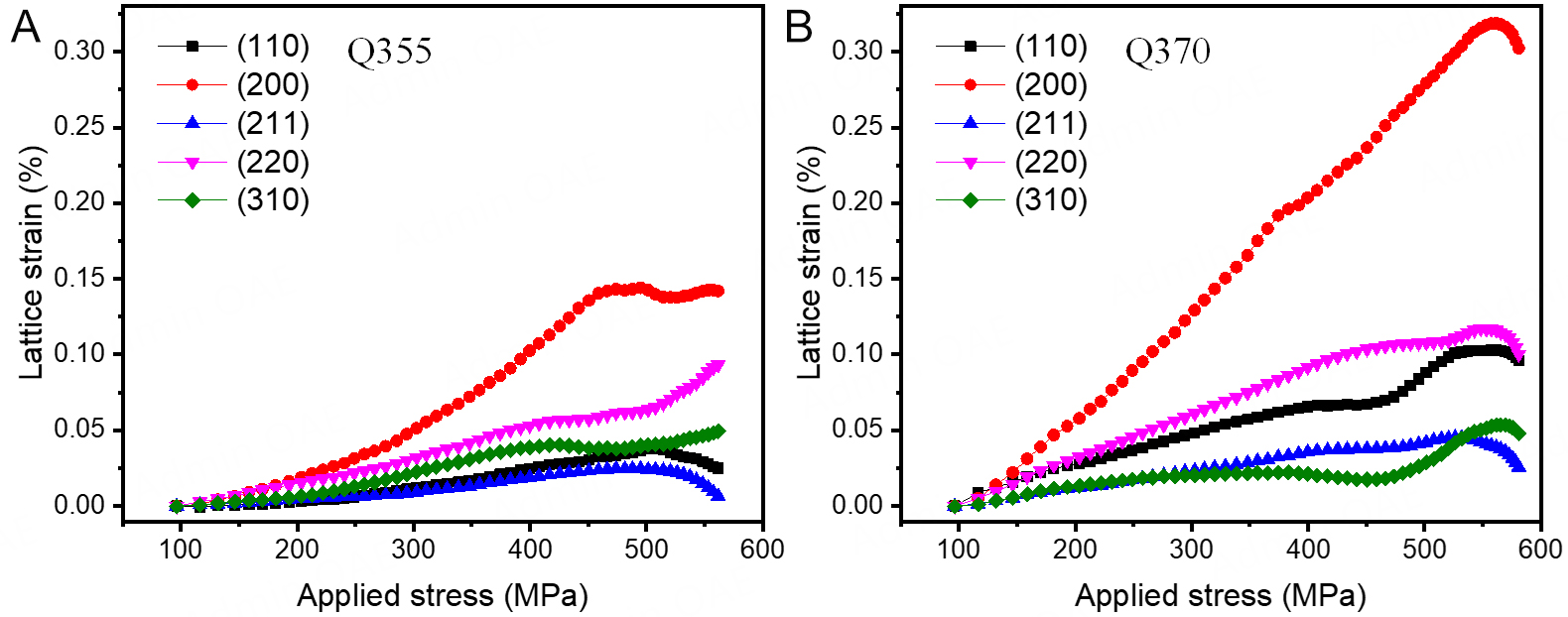

The evolution of lattice strain in the Q355 and Q370 samples during in-situ tensile testing is presented in Figure 5. The overall lattice strains vs. applied stress curves match well with the macroscopic stress-strain curves shown in Figure 2. However, the stress-strain responses of individual crystallographic planes differed significantly within each sample. All five crystallographic planes [(110), (200), (211), (220), and (310)] exhibited yielding at approximately 450 MPa for the Q355 sample and about 500 MPa for the Q370 sample, consistent with their respective macroscopic yield strengths. Among these, the (200) reflection showed the largest lattice strain in both samples, whereas the (310) reflection exhibited the lowest lattice strain in Q355 and Q370, respectively. The other reflections [(110), (211), and (220)] displayed moderate strains under tension, following trends typical for body-centered cubic (BCC) alloys. Comparing the two samples, although the (200) plane was the most compliant, the lattice strain in the Q370 sample was much higher than in the Q355 sample. This suggests superior deformation compatibility before fracture in Q370, contributing to its higher ductility.

Figure 5. Lattice strain evolution during in-situ tensile testing. Lattice strain evolution from five (hkl) reflections of the major ferrite phase along the loading direction during uniaxial tensile testing of the Q355 (A) and Q370 (B) samples, showing distinct responses of different crystallographic planes to the applied external stress.

In-situ neutron diffraction during tensile testing

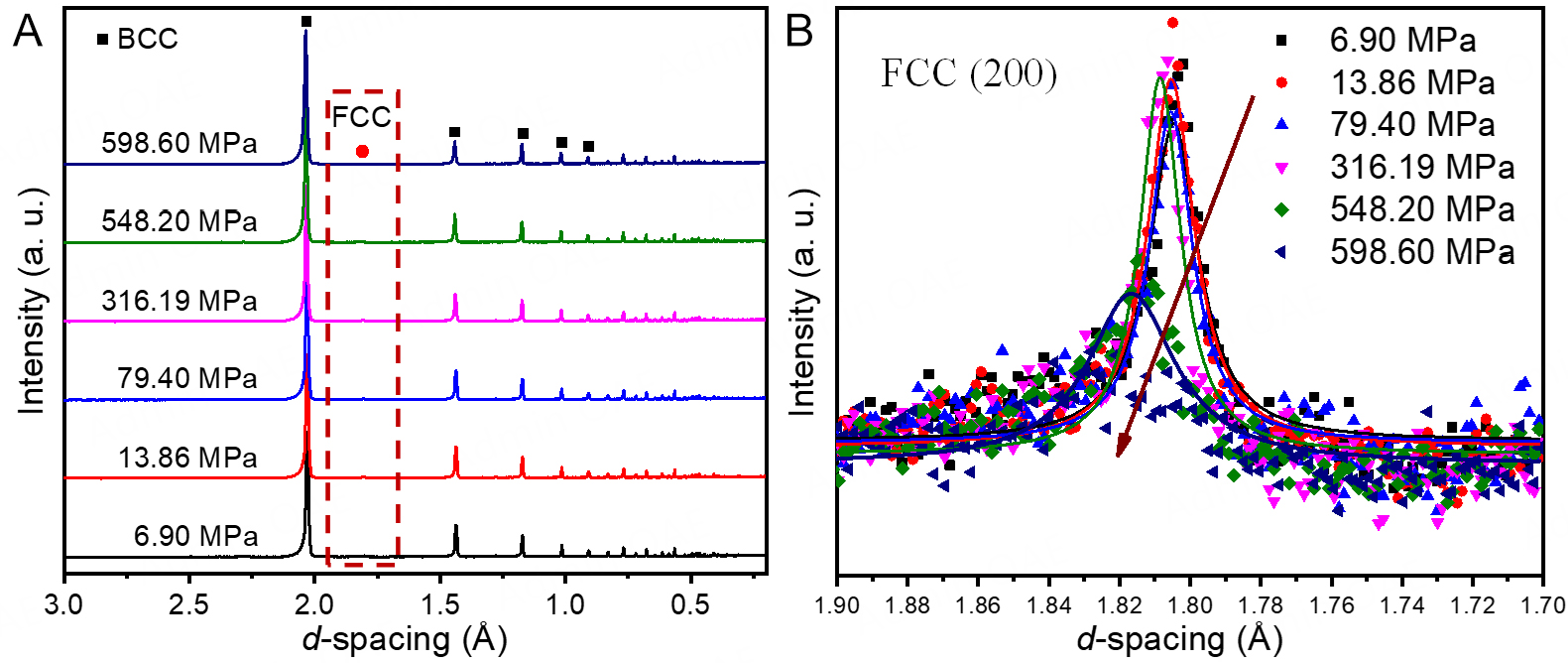

To statistically track the evolution of minor phases, we conducted in-situ neutron diffraction on the thicker Q370 sample during tensile testing, as shown in Figure 6. The diffraction patterns obtained in both axial and radial directions were nearly identical, indicating a weak texture in the as-cast steel samples[25]. The (200) peak of retained austenite is clearly visible in Figure 6A, though it is much weaker than the reflections from the predominant ferrite phase. Peaks corresponding to carbides are even weaker; therefore, this study focuses only on the major ferrite phase and the retained austenite. For ferrite, all peak positions shift to higher d-spacing values in the loading direction during the tensile tests. For retained austenite, the evolution of the (200) reflection is shown in Figure 6B, which is a magnified region of Figure 6A. The intensity of the (200) peak decreases, while the fitted peak width slightly increases with increasing applied stress.

Figure 6. In-situ neutron diffraction measurements of the Q370 sample during tensile testing: (A) Neutron diffraction patterns in the loading direction, clearly showing the (200) peak of retained austenite in the thicker specimen. (B) Evolution of the (200) reflection from retained austenite under various applied stresses.

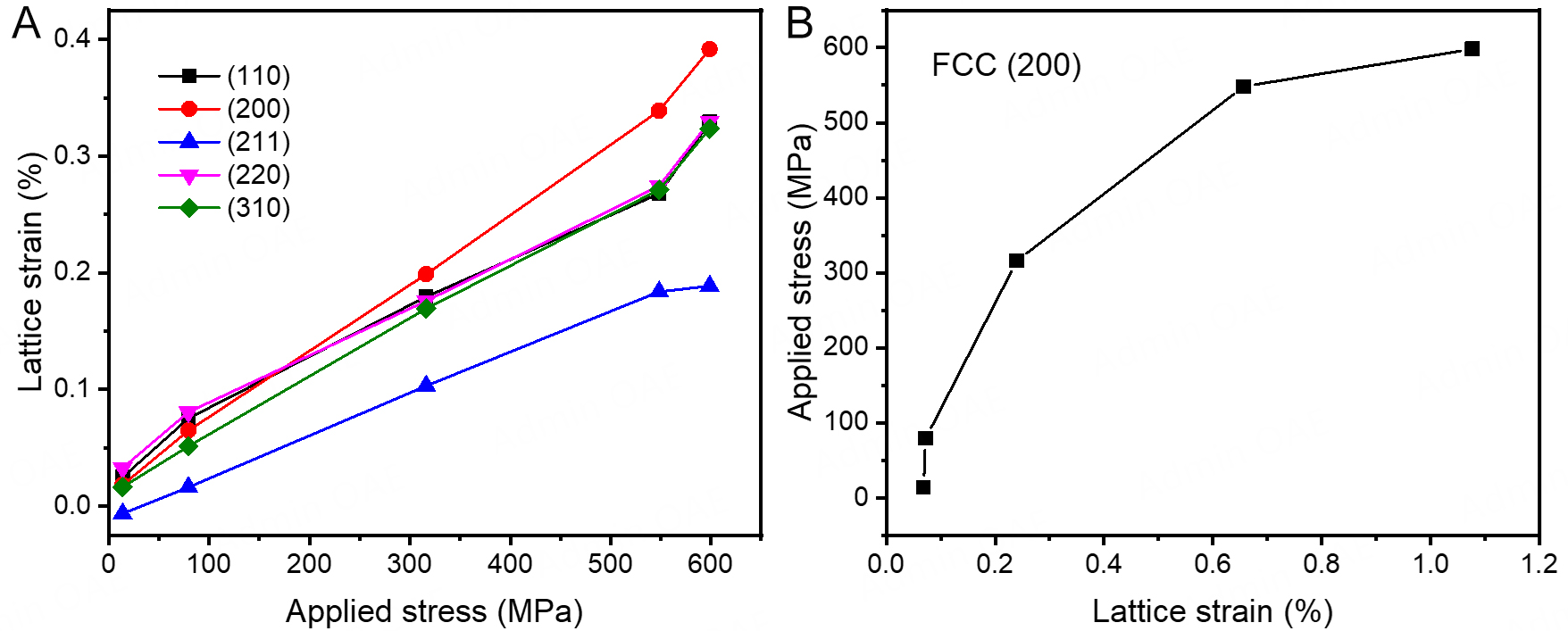

Figure 7 displays the quantitative analysis of the in-situ neutron diffraction measurements in the loading direction. Among the ferrite reflections, the(200) and (211) planes exhibit the largest and smallest lattice strains, respectively, which is consistent with in-situ synchrotron diffraction results. Reflections from the (110), (220), and (310) planes show intermediate strain values. The elastic moduli calculated from the linear region in Figure 7A for the (110), (200), (211), (220), and (310) planes are 122.2, 94.8, 156.7, 162.2, and

Fractography

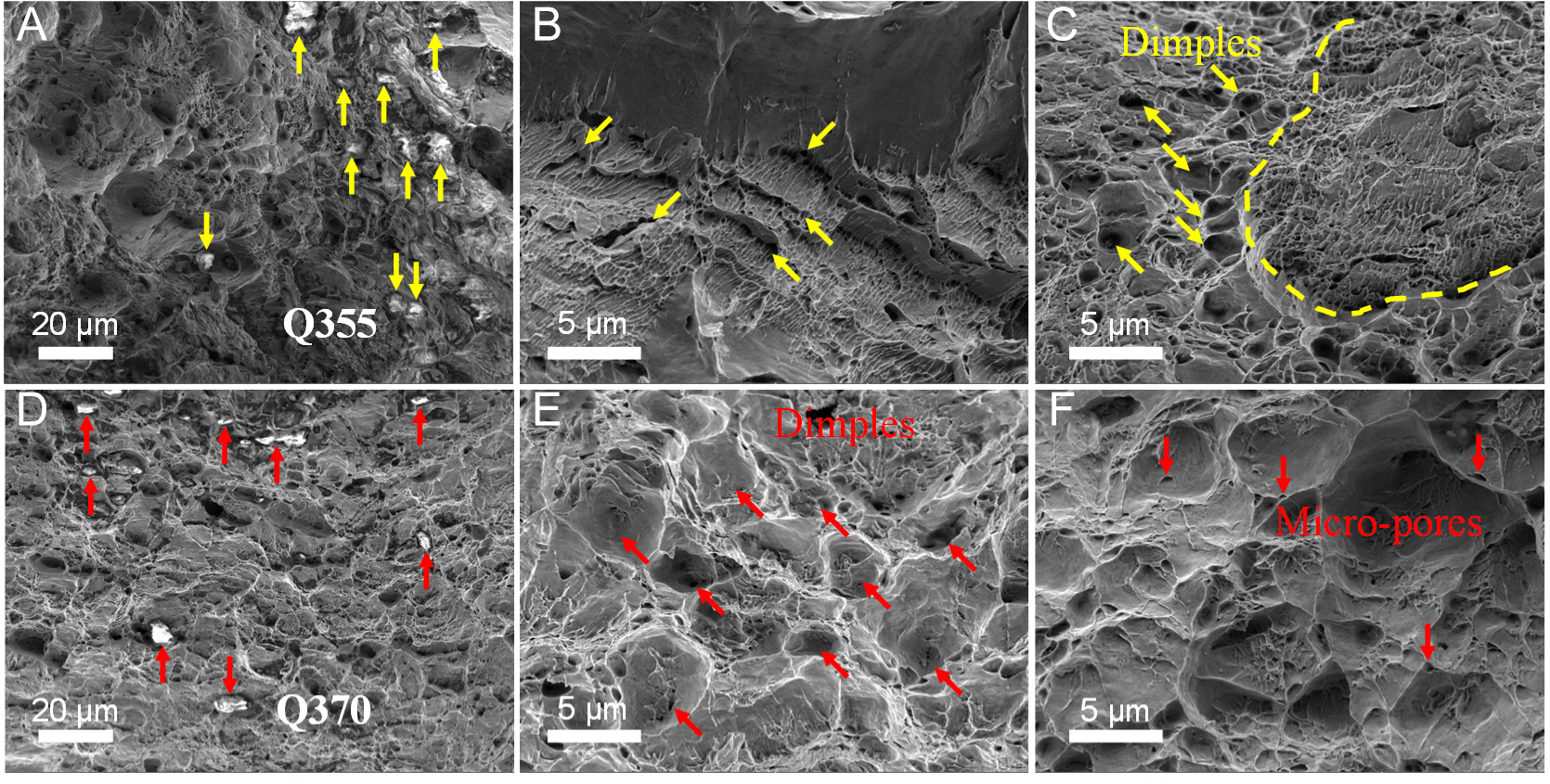

The SEM micrographs of the top surfaces of the fractured Q355 and Q370 samples are shown in Figure 8. The distinct contrast highlighted by arrows in Figure 8A and D indicates the presence of inclusions on the fracture surfaces of both samples, consistent with the segregation distributions shown in Figure 3. The river-like and layer-splitting patterns marked by arrows in Figure 8B suggest that the Q355 sample exhibited brittle behavior prior to fracture. Notably, dimples scattered around these river-like patterns were also observed in the Q355 sample, as shown in Figure 8C. In contrast, the fracture surface of the Q370 sample clearly shows numerous dimples, indicating ductile behavior under tension. Upon closer examination of the dimple edges, irregular microscale pores can be seen, as highlighted by the arrows in Figure 8F. Variations in the solidification rate during the cooling of molten steel can cause element segregation and chemical reactions, leading to a non-uniform distribution of inclusions. These inclusions not only deteriorate the mechanical properties of the steel but also exacerbate segregation effects.

Figure 8. SEM micrographs of the top-view fracture surfaces of the Q355 and Q370 samples. (A and D) Inclusions on the fracture surfaces of the Q355 and Q370 samples indicated by contrast differences. (B) River-like patterns and layer splitting in the Q355 sample. (C) Dimples around river-like features in the Q355 sample. (E) Dimples on the fracture surface of the Q355 sample. (F) Microscale pores at the edges of dimples in the Q370 sample.

DISCUSSION

Segregation remains a longstanding challenge in steelmaking, particularly during the continuous casting of ultra-thick slabs, due to the complex solidification process - from the top surface cooled by water sprays to the deep center where final solidification occurs. To reduce oxygen and sulfur content in the molten steel, appropriate amounts of carbon, manganese, and silicon were added. However, this led to problematic elemental distributions after solidification, as shown in Figure 3. Although the chemical compositions and continuous casting parameters were consistent across the as-cast samples, millimeter-scale segregation promoted the precipitation of carbides and intermetallics [Figure 1B], significantly affecting mechanical properties. Severe elemental segregation caused substantial reductions in tensile properties - including yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, and elongation - as illustrated in Figure 2. The elastic modulus also varied significantly with segregation. While the non-segregated sample exhibited ductile behavior before fracture, the segregated sample showed brittle fracture characteristics, as confirmed by the fractographic micrographs in Figure 8. Such pronounced segregation undermines the integrity of subsequent processing steps, such as rolling and forging.

The in-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction data provide valuable insights into the deformation behaviors of segregated and non-segregated samples during tensile tests[28,29]. The diffraction patterns reveal minor phases such as retained austenite and carbides. The evolving lattice strains of the various crystallographic planes were tracked and statistically quantified as a function of applied stress. Among these, the (200) reflection from primary ferrite and retained austenite phases was the most compliant compared to the stiffer (110), (211), (220), and (310) planes. The significant lattice strain observed in the BCC (200) plane is often attributed to martensitic transformation[30]. However, no obvious phase transformation was observed with increasing stress, likely due to the relatively low volume fraction of retained austenite and incomplete transformation. The lattice strains accommodated and the effective stress partitioning between ferrite and retained austenite phases contributed to uniform ductility under applied stress. In contrast, stress concentrations around pores or inclusions may have led to the abrupt fracture of segregated samples, which are more likely to contain internal defects. During tensile deformation, constituent grains develop increasing misorientations and form sub-grains, improving the diffraction statistics with increasing applied stress. The load transfer from minor phases such as carbides under external stress remains unclear and needs further investigation in future work.

The improvement in ductility due to stress partitioning between ferrite and retained austenite arises from their distinct mechanical behaviors and synergistic interactions during deformation. In multiphase steel, retained austenite plays a critical role in balancing ductility and strength through both strain and chemical partitioning. During deformation, strain is preferentially accommodated by the softer ferrite matrix, enabling early plastic flow, while retained austenite, stabilized by the chemical partitioning of elements such as carbon and manganese, resists yielding due to its higher strength. This chemical segregation (enrichment of austenite with C and Mn) enhances its metastability, enabling controlled strain-induced transformation to martensite (the TRIP effect) under increasing stress. The interplay between strain partitioning (localized deformation in ferrite) and chemical partitioning (elemental gradients stabilizing austenite) ensures progressive work hardening, delays necking, and redistributes stresses, thereby synergistically improving ductility and toughness. Furthermore, carbon plays a crucial role in affecting the stacking fault energy. When its concentration reaches a certain value, the TRIP effect can transition into the twinning-induced plasticity (TWIP) effect. The stabilization of austenite can also result from increased resistance to martensite formation, such as via the formation of carbon clusters during slow quenching. Moreover, carbon segregation at austenite boundaries can attract manganese atoms, further stabilizing the interface and inhibiting transformation[31]. Thus, segregation significantly influences localized strain compatibility and the phase stability of retained austenite, making both strain and chemical partitioning interdependent contributors to overall mechanical performance. Enhanced ductility results from the combined effects of these mechanisms, mediated by the interplay between localized strain incompatibility and phase instability. Strain incompatibility between soft ferrite and harder retained austenite creates stress gradients at phase boundaries, promoting the formation of geometrically necessary dislocations that redistribute strain and delay localized failure. Simultaneously, phase instability in retained austenite, caused by its metastable chemical composition (e.g., carbon/manganese enrichment), triggers strain-induced transformation to martensite under critical stress levels[32]. Further investigation using atomic-scale analysis will be conducted.

Interestingly, the tensile properties of as-cast super-thick steel slabs (~500 MPa yield strength and

As as-cast super-thick steel slabs are subject to rolling and forging, either by light or heavy thickness reduction, understanding the relationship between segregation-induced defects and minor phases during solidification and their deformation response is crucial for optimizing processing parameters. Future work is proposed to further investigate refined grain morphology, microstructure, and phase structure to gain a deeper understanding of the fundamental work-hardening behaviors of super-thick steels.

CONCLUSIONS

The characterization of segregated and non-segregated super-thick steel samples during tensile deformation at room temperature was performed using in-situ high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction and neutron diffraction techniques. The main conclusions are summarized below:

(1) By reducing internal defects and minimizing segregation, the yield and tensile stresses were improved from 407.5 and 590.5 MPa to 515.2 and 632.8 MPa, respectively, while the elongation increased significantly from 8% to 23.4%.

(2) Strip-like elemental segregation was found in the central core area, resulting from the final stage of solidification in super-thick steel plates. Under segregated conditions, both ductile and brittle fracture morphologies were observed. Stress concentrations around pores or inclusions may lead to fracture in segregated samples with a higher density of internal defects.

(3) At the lattice scale, uniform plastic deformation and necking before fracture were achieved in the non-segregated regions, owing to stress partitioning between the ferrite matrix and retained austenite. The combined effects of strain partitioning (localized deformation in ferrite) and chemical partitioning (elemental gradients stabilizing austenite) promote continuous work hardening, delay the onset of necking, and help redistribute stresses, thereby synergistically enhancing ductility.

This study demonstrates that in-situ synchrotron and neutron diffraction techniques provide valuable insights into the relationship between segregation and deformation behavior in super-thick steels. In future work, the stress and chemical partitioning mechanisms in these steels, which are of both scientific and industrial importance, will be further explored using atomic-scale resolution techniques.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgment

The 3W1 beamline of Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility and Energy-Resolved Neutron Imaging Instrument of China Spallation Neutron Source are greatly acknowledged.

Authors’ contributions

Design: Xiong, L.; Wen, Z.

Experiments and data collection: Tan, Z.; Shi, C.; Xu, L.

Data analysis: Xiong, L.; Wen, Z.; Shi, C.; Xu, L.

Manuscript writing: Xiong, L.; Wen, Z.

Manuscript revision and supervision: Xiong, L.; Wen, Z.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52201017), the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. J2019-VI-0004-0117), and partially sponsored by Shanghai Pujiang Program (22PJ1408000), and National Key Basic Research Program of China (grant No. 2020YFA0406101).

Conflicts of interest

Xu, L. is affiliated with Hunan Valin Xiangtan Iron & Steel Co. Ltd, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Yu, K.; Wang, M.; Fan, H.; Zhan, Z.; Ren, Z.; Xu, L. Investigation on the solidification structure of Q355 in 475 mm extra-thick slabs adopting cellular automaton-finite element model. Metals 2024, 14, 1012.

2. Guthrie, R. I. L.; Isac, M. M. Continuous casting practices for steel: past, present and future. Metals 2022, 12, 862.

3. Okayama, Y.; Kawazoe, F.; Yasui, H.; et al. Production of high quality extra heavy plates with new casting equipment. Nippon Steel Technical Report; 2004. Available from: https://www.nipponsteel.com/en/tech/report/nsc/pdf/n9012.pdf [Last accessed on 7 Jul 2025].

4. Li, H.; Gong, M.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G. Effects of hot-core heavy reduction rolling during continuous casting on microstructures and mechanical properties of hot-rolled plates. J. Mater. Proc. Technol. 2020, 283, 116708.

5. Barati, H.; Wu, M.; Kharicha, A.; Ludwig, A. Role of solidification in submerged entry nozzle clogging during continuous casting of steel. Steel. Res. Int. 2020, 91, 2000230.

6. Yang, N.; Su, C.; Wang, X.; Bai, F. Research on damage evolution in thick steel plates. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2016, 122, 213-25.

7. Cheng, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Ma, H. Comparison of porosity alleviation with the multi-roll and single-roll reduction modes during continuous casting. J. Mater. Proc. Technol. 2019, 266, 96-104.

8. Brimacombe, J. K.; Sorimachi, K. Crack formation in the continuous casting of steel. Metall. Trans. B. 1977, 8, 489-505.

9. Fan, K.; Liu, B.; Liu, T.; Yin, F.; Belyakov, A.; Luo, Z. Making large-size fail-safe steel by deformation-assisted tempering process. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22345.

10. Li, H.; Li, T.; Li, R.; Gong, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G. Effect of a novel hot-core heavy reduction rolling process after complete solidification on deformation and microstructure of casting steel. ISIJ. Int. 2019, 59, 2283-93.

11. Wang, Q.; Ye, Q.; Tian, Y.; Fu, T.; Wang, Z. Superior through-thickness homogeneity of microstructure and mechanical properties of ultraheavy steel plate by advanced casting and quenching technologies. Steel. Res. Int. 2021, 92, 2000698.

12. Jokiaho, T.; Santa-Aho, S.; Peura, P.; Vippola, M. Role of steel plate thickness on the residual stress formation and cracking behavior during flame cutting. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2019, 50, 4178-92.

13. Ji, C.; Wu, C.; Zhu, M. Thermo-mechanical behavior of the continuous casting bloom in the heavy reduction process. JOM 2016, 68, 3107-15.

14. Liu, D.; Cheng, B.; Chen, Y. Strengthening and toughening of a heavy plate steel for shipbuilding with yield strength of approximately 690 MPa. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2013, 44, 440-55.

15. Wang, W.; Ren, L.; Liu, H.; et al. Hot deformation behavior of a marine engineering steel for novel 980 MPa grade extra-thick plate. Steel. Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300642.

16. Xie, B.; Cai, Q.; Yun, Y.; Li, G.; Ning, Z. Development of high strength ultra-heavy plate processed with gradient temperature rolling, intercritical quenching and tempering. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2017, 680, 454-68.

17. Hu, J.; Du, L.; Xie, H.; Gao, X.; Misra, R. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TMCP heavy plate microalloyed steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2014, 607, 122-31.

18. Sun, X.; Yuan, S.; Xie, Z.; Dong, L.; Shang, C.; Misra, R. Microstructure-property relationship in a high strength-high toughness combination ultra-heavy gauge offshore plate steel: the significance of multiphase microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2017, 689, 212-9.

19. Chu, R.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, X. Cracking and segregation in high-alloy steel 0.4C1.5Mn2Cr0.35Mo1.5Ni produced by thick continuous casting. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01329.

20. Cao, Y.; Liu, H.; Fu, P.; et al. Distinct mechanisms for channel segregation in ultra-heavy advanced steel ingots via numerical simulation and experimental characterization. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 2023, 54, 2771-83.

21. Cameron, R.; Temple, J. Ultrasonic inspection for long defects in thick steel components. Int. J. Pres. Ves. Pip. 1985, 18, 255-76.

22. Choudhary, S.; Ganguly, S.; Sengupta, A.; Sharma, V. Solidification morphology and segregation in continuously cast steel slab. J. Mater. Proc. Technol. 2017, 243, 312-21.

23. Ying, H.; Yang, X.; He, H.; et al. Formation of strong and ductile FeNiCoCrB network-structured high-entropy alloys by fluxing. Microstructures 2023, 3, 2023018.

24. Dong, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, H.; et al. Low neutron cross-section FeCrVTiNi based high-entropy alloys: design, additive manufacturing and characterization. Microstructures 2022, 2, 2022003.

25. Wang, Y.; Tomota, Y.; Harjo, S.; Gong, W.; Ohmura, T. In-situ neutron diffraction during tension-compression cyclic deformation of a pearlite steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2016, 676, 522-30.

26. Sparks, T.; Kuksenko, V.; Gorley, M.; et al. In-situ synchrotron investigation of elastic and tensile properties of oxide dispersion strengthened EUROFER97 steel for advanced fusion reactors. Acta. Mater. 2024, 271, 119876.

27. Zhang, X.; Xu, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. High-energy synchrotron X-ray study of deformation-induced martensitic transformation in a neutron-irradiated type 316 stainless steel. Acta. Mater. 2020, 200, 315-27.

28. Chen, H.; Wang, Y. D.; Nie, Z.; et al. Unprecedented non-hysteretic superelasticity of [001]-oriented NiCoFeGa single crystals. Nat. Mater. 2020, 19, 712-8.

29. Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, T.; et al. A mechanism on multiscale heterogenous deformation of nickel-based single crystal superalloys unraveled by time-of-flight neutron diffraction technology. Acta. Mater. 2024, 281, 120430.

30. Ma, L.; Wang, L.; Nie, Z.; et al. Reversible deformation-induced martensitic transformation in Al0.6CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy investigated by in situ synchrotron-based high-energy X-ray diffraction. Acta. Mater. 2017, 128, 12-21.

31. Song, C.; Yu, H.; Lu, J.; Zhou, T.; Yang, S. Stress partitioning among ferrite, martensite and retained austenite of a TRIP-assisted multiphase steel: an in-situ high-energy X-ray diffraction study. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2018, 726, 1-9.

32. Ding, F.; Guo, Q.; Hu, B.; Luo, H. Influence of softening annealing on microstructural heredity and mechanical properties of medium-Mn steel. Microstructures 2022, 2, 2022009.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].