Flexible iontronic pressure sensing technology: advanced structural ionic layer

Abstract

Since the advent of iontronic sensing technology, this emerging field has garnered growing research attention. Its unique electric double layer (EDL) theory reveals the characteristics of the ion-electron contact interface and can significantly increase the charge density per unit area, empowering the derived pressure sensors to achieve remarkable breakthroughs in sensitivity and detection accuracy. With an increase of several orders of magnitude in force-electric response compared with traditional capacitive pressure sensors, it provides core technical support for high-performance flexible sensing applications. Studies have shown that the contact area between the ionic layer and electrodes A decisively affects relative EDL capacitance, while designing and integrating different structural ionic layers directly enhances sensing performance. Focusing on the structural features, fabrication processes, and application scenarios of different types of structural ionic layers, this review comprehensively summarizes the advances in structural ionic layer design for flexible iontronic pressure sensing technology. By systematically evaluating the function-driven strengths and limitations of various structures, this review helps readers grasp the significance and objectives of ionic layer structures. Finally, based on advanced research, it provides an outlook on the field’s development trends and explores key potential challenges.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, flexible pressure sensors, boasting superior environmental adaptability and enhanced conformability, have stably maintained high-precision sensing performance even in complex and harsh environments, relative to traditional rigid pressure sensors. Serving as indispensable core components in intelligent systems - including smart healthcare, environmental parameter monitoring, human-computer interaction, and brain-computer interfaces - their demand will continue to grow in future technological development.

Different electromechanical conversion theories underpin variations in the working principles of flexible pressure sensors. As shown in Table 1, and guided by this core relationship, these sensors are generally categorized into four main types: piezoresistive[1,2], capacitive[3,4], triboelectric[5,6], and piezoelectric[7,8]. Each type, leveraging its unique sensing mechanism, exhibits distinct strengths and weaknesses. Among these, flexible capacitive pressure sensors have emerged as a prominent research focus in the field. They show extensive application potential in areas including wearable device user experience optimization, and smart device precision integration[11]. However, the capacitance of the classic parallel-plate capacitive pressure sensor model is limited[12,13], and the measured capacitance per cm2 only remains in the picofarad (pF) range[14]. Thus, as demands for precision and stability in pressure detection across complex application scenarios grow, traditional flexible capacitive pressure sensors face inherent limitations, including low sensitivity and a narrow pressure sensing range.

Comparison of characteristics of different pressure sensor types

| Type | Mechanism | Advantage | Limitation | Ref. |

| Piezoresistive sensor | Contact resistance | Simple signal readout circuit | Poor stability | [1,2] |

| Tunneling effect | Simple device structure | |||

| Capacitive sensor | Parallel-plate capacitance modulation | Low power consumption | Poor linearity | [3,4] |

| Static-dynamic force detection | Affected by parasitic capacitance | |||

| Triboelectric sensor | Electrostatic induction | Self-powered characteristic | Difficulty in static force detection | [5,6] |

| Triboelectrification | Severe wear | |||

| Piezoelectric sensor | Piezoelectric effect | Capture transient pressure signals | Difficulty in static force detection | [7,8] |

| Poor mechanical properties | ||||

| Iontronic sensor | EDL effect | High sensitivity | Severe signal drift | [9,10] |

| High detection resolution | Poor environmental stability |

To overcome this critical challenge, flexible iontronic pressure sensing was developed, inspired by the human sensory system. In this mechanism, ion flow alters membrane potential to generate electrical signals, which are rapidly transmitted through the nervous system to perceive stimuli such as pressure, temperature, and humidity[11,15]. Pan et al., after revealing the key role of ion migration and redistribution in signal response, proposed the elastic electrolyte-electrode interface model in 2011 and developed an ultra-high-sensitivity pressure sensor based on ionic supercapacitive theory[16].

Based on the electric double layer (EDL) theory, a double layer structure composed of separated positive and negative charge layers is spontaneously formed when ions come into contact with electrodes. The capacitive performance of this structure directly depends on the interfacial charge density and charge separation distance. When pressure acts on the system, it produces two key effects: on the one hand, it drives ions in the electrolyte to accumulate more densely on the electrode surface, significantly increasing the interfacial charge density; on the other hand, it compresses the charge separation distance inside the EDL, bringing it closer to the nanoscale. The synergistic effect of these two phenomena causes the capacitance at the ion-electrode contact interface to increase exponentially, thereby inducing the generation of ultra-high interfacial capacitance[15,17]. This not only achieves order-of-magnitude improvements in sensitivity and resolution but also effectively mitigates the impacts of parasitic capacitance and environmental electromagnetic interference on detection accuracy.

Similar to the structural composition of classic parallel-plate capacitive pressure sensors, iontronic pressure sensors typically consist of electrodes and an intermediate ionic active layer, stacked in a sandwich-like manner. Researchers have made extensive attempts to optimize the sensing performance of flexible iontronic pressure sensors. These endeavors aim to achieve high-performance and stable operation of iontronic pressure sensors[16,18-22]. Among these investigations, particular emphasis is placed on the parameter A - defined as the contact area between the ionic layer and electrodes - which is critical to the calculation of the EDL capacitance (CEDL)[23-29]. This parameter is directly associated with the charge density of the EDL and interface response kinetics, so research directions have been further expanded around the physical structure design of the ionic layer.

Through the introduction of structural ionic layer design, precise regulation of the variation law of A between the electrode and the ionic layer can be achieved. This regulatory method can profoundly optimize the deformation behavior of the iontronic active layer during force application. Specifically, it can not only improve its mechanical compression efficiency under external forces but also enhance its structural stability and recovery capability during cyclic loading-unloading processes[25,30]. Advanced mainstream fabrication processes are employed in structural layer design research to engineer diverse ionic layer physical architectures, boosting overall sensor performance and meeting scenario-specific pressure-sensing requirements.

Currently, several review papers have summarized the research progress of flexible iontronic pressure sensors, all conducting systematic discussions from different research perspectives. Their content covers in-depth analysis of iontronic sensing mechanisms[31-33], screening and optimization of substrate materials and functional material[15,28,34], construction strategies for micro-nano structure][35-37], as well as expansion of application scenarios and exploration of their potentia[38-41]. However, review papers remain relatively scarce that systematically summarize iontronic pressure sensing technology, analyze its technical evolution, and focus on the deformation characteristics and working mechanisms of ionic layer structures under pressure loading, specifically taking the physical morphology of structural ionic layers as the core focus. Accordingly, this review categorizes morphologically distinct structural elements for ionic layer design, focusing on microstructure deformation modes under external forces, relevant pressure-sensing theoretical frameworks, and critical fabrication process parameters. Furthermore, it examines the scenario-specific detection performance enabled by structural ionic layer engineering for flexible iontronic pressure sensors.

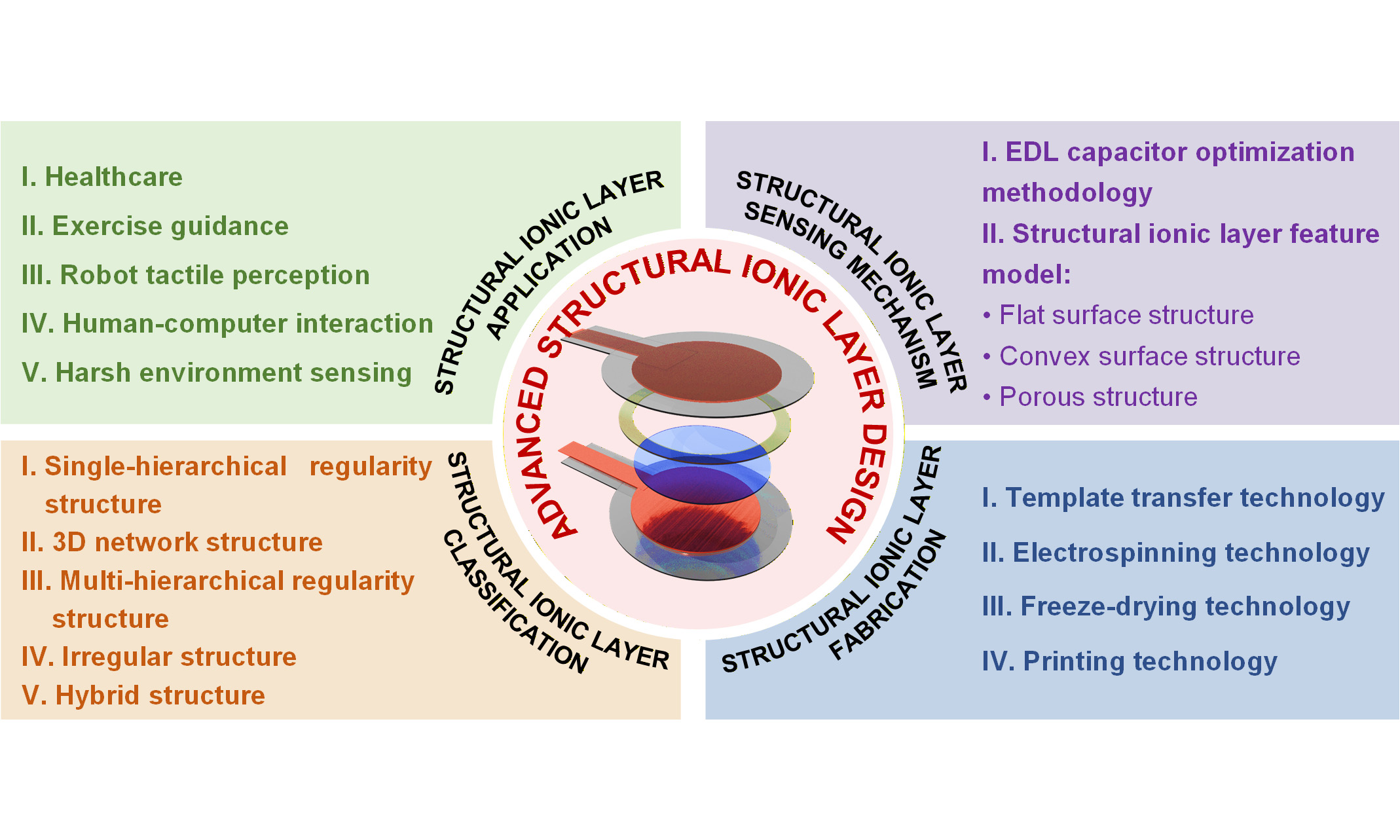

This review is organized as follows: First, the sensing mechanisms of ionic films with diverse microstructures are introduced. Subsequently, mainstream microstructure embedding methods are elaborated, with optimal fabrication processes matched to different microstructures. Drawing on representative cutting-edge studies, microstructures are classified according to their morphological characteristics and pressure-induced deformation modes; their functions in iontronic pressure sensing are systematically discussed, alongside the respective merits, demerits, and existing challenges of each type. Next, the specific applications of flexible iontronic pressure sensors empowered by these microstructures across various fields and scenarios are addressed. Finally, the full text is summarized, research prospects centered on microstructure design are proposed, and the core issues and challenges facing the current development of this technology are analyzed. Figure 1 illustrates the overall structure across the sections.

STRUCTURAL IONIC LAYER: SENSING MECHANISM

It is generally recognized in the research community that classical capacitive pressure sensors can be defined as traditional parallel-plate capacitors, and their capacitance C can be calculated using[42]

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, εr is the relative permittivity of the dielectric layer, a is the overlapping area of the electrodes, and d is the distance between the upper and lower electrodes. Under most scenarios, a is generally unaffected by the applied pressure. Furthermore, the demand for sensor miniaturization during device integration greatly limits the force-induced electrical changes provided by εr and d. Thus, their weak electrical signal output is highly susceptible to interference from parasitic capacitance and environmental magnetic fields[14,17]. Iontronic pressure sensing technology serves to address this issue[28,43,44].

EDL capacitor optimization methodology based on structural ionic layer design

The EDL effect, by optimizing the contact interface between the electrode and the ion layer, reduces the distance between electrons and ions to the nanoscale and enhances interfacial charge accumulation efficiency. This effect can significantly boost the device’s capacitance density to the µF cm-1 level[45]. The classical Gouy-Chapman-Stern (GCS) model is a key tool for explaining the EDL theory[46,47]. According to this model, the CEDL consists of the charge layer on the electrode surface and the capacitances of two series-connected components: the inner Helmholtz layer and the outer Gouy-Chapman layer[43,48-50]. Most counterions in the Helmholtz layer are confined and immobilized; in a specific system, the capacitance generated by the Helmholtz layer (CH) can be regarded as a constant. In contrast, the Gouy-Chapman layer has an almost infinite thickness, and the capacitance it generates is denoted as CD. Therefore, CEDL can be expressed as the series combination of CH and CD. Since both CH and CD are proportional to the area of the charged contact interface A, CEDL can be further derived as[11,15,48]:

where

It can be inferred from the formula that the magnitude of CEDL is strongly correlated with A (CEDL ∝ A)[16,51-54]. Accordingly, based on the functional relationship between A and CEDL validated in (2), within the operating pressure range, the slope of the area-pressure relationship A(P) determines the sensor performance, and its sensitivity (S) can be expressed as[10]:

where P is the applied pressure load, C0 is the initial capacitance in the unloaded state, A is the contact area between the iontronic layer and the electrode, and A0 is the initial contact area. Therefore, the core of performance optimization lies in the design and control of the A, aiming to increase dA/dP within the operating pressure range while delaying contact saturation to enhance sensitivity[55].

Structural ionic layer feature model

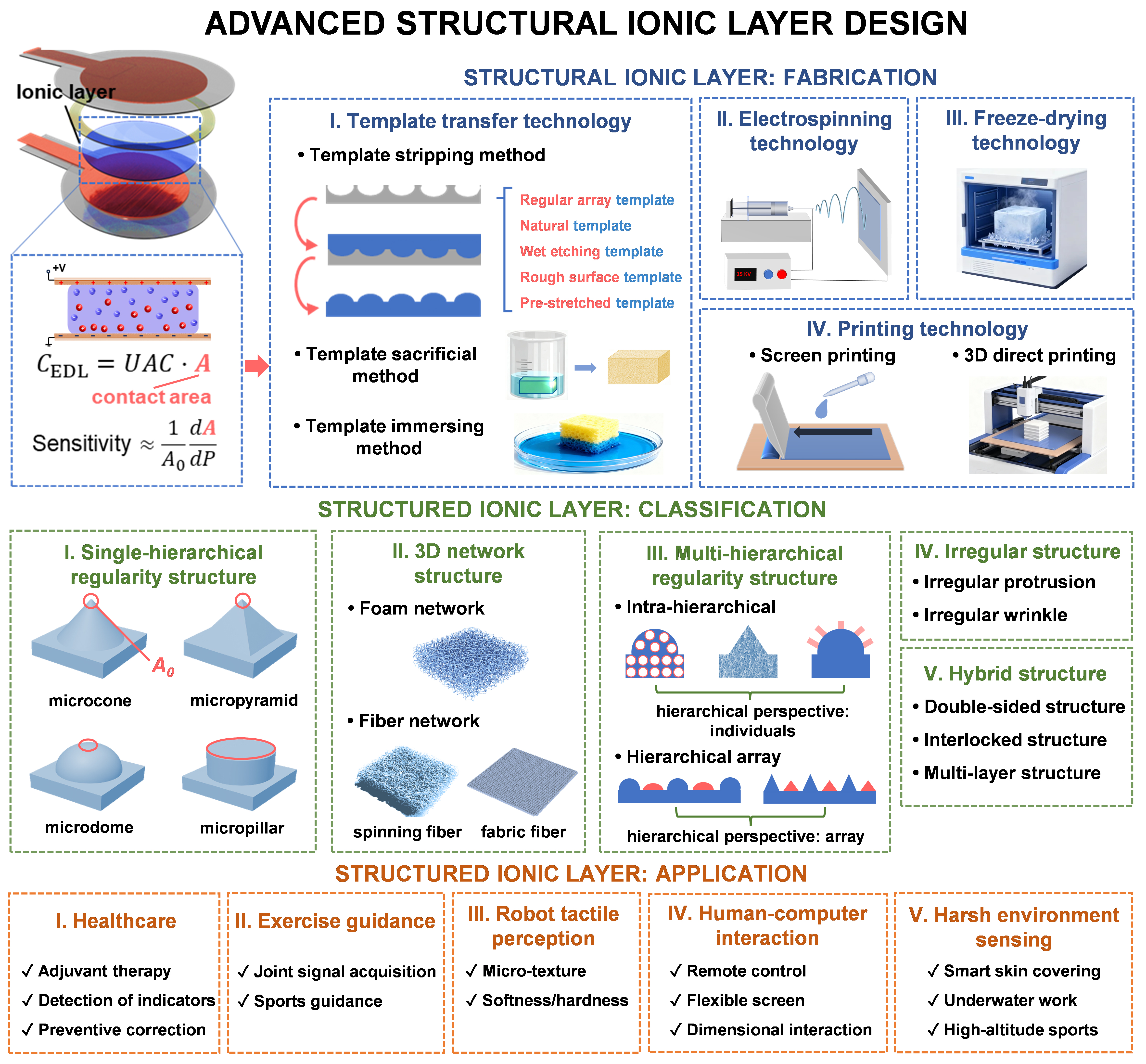

It can be concluded that rational regulation of changes in A can most directly fulfill the mapping of the corresponding performance requirements of flexible iontronic pressure sensors. As the most direct way to regulate A, the structural design of the ionic layer has become the focus of most studies in this field in recent years. As shown in Figure 2, the working mechanisms of the three main types of structural ionic layers - flat surface, convex surface, and porous - are explained, along with an analysis of their equivalent circuits.

Figure 2. The pressure sensing theories of different structural ionic layers and the corresponding equivalent circuits. (A) flat surface structure; (B) convex surface structure; (C) porous structure.

Flat surface structure

As shown in Figure 2A, according to the corresponding equivalent circuit of the solid-liquid contact interface model proposed by Chang et al.[28], it is known that the total capacitance (C) of the sensor device is determined by CTop EDL, CBottom EDL, and CE, which can be expressed by[19,28]:

where CTop EDL is the interface capacitance of the top layer, CBottom EDL is the interface capacitance of the bottom layer, and CE is the additional capacitive change primarily associated with the distance between electrodes[28]. Since CE is extremely small compared with CEDL, it can be neglected[14,56]. When a pressure is applied, owing to the incompressibility of common elastic polymer substrate materials, the deformation caused by the reduction in axial spacing under force must be compensated by strain to maintain the corresponding total volume unchanged. However, due to the strong cross-linking of polymer chains within the elastic polymer substrate, the degree of transverse strain and the resulting relative change in A are limited. With sustained loading, the ionic layer will exhibit structural hardening. Therefore, when there is a flat surface structural active layer, the achievable variation of capacitance (ΔC) is extremely limited.

Convex surface structure

The sensing mechanism in this section can be equally applied to most active layers with convex surface microstructures, and only the scenario where the ionic layer exists solely in the single-sided microstructure is considered. As illustrated in Figure 2B, Qiu et al. have proposed the corresponding model design and sensing theory by integrating the GCS model[9]: each independent protrusion structure can be regarded as a variable capacitor CTop EDLn. Thus, the capacitance of the top microstructure in the dielectric layer CTop EDL can be considered as a parallel combination of multiple independent capacitors, which is expressed by[9,19]

However, after pressure is applied, the contact area variation (ΔA) between the bottom of the ionic layer and the electrode after pressure application is very small compared to the top, which exerts little influence on the total capacitance change. In summary, the capacitance change of the dielectric layer is mainly determined by the magnitude of CTop EDL. Thus, the number and size of the top protrusion microstructures largely determine the capacitance change of the dielectric layer[57].

Porous structure

The porous structure features a large number of cavities constructed at the three-dimensional (3D) level. In current research on ionic layer structural design, the most commonly used porous structures include foams[58,59], textiles[60,61], and electrospun fibers[62,63]. When subjected to pressure loading, the collapse of these cavities can effectively buffer the transverse strain of the polymer substrate, enabling the dielectric layer to exhibit excellent large-range compressive deformation. Thus, key parameters of porous structures, such as pore size and porosity, determine the sensing performance of flexible iontronic pressure sensors with these structures as their dielectric layers. As shown in Figure 2C, in the initial stage of porous structure compression under pressure, the contact mode at the interface between the microstructures on the porous structure surface and the electrode surface is similar to that of a convex surface, and A will increase continuously[63,64]. Furthermore, sustained pressure loading will cause the uneven surface of the porous structure to collapse and compress into a flat surface, ensuring the maximum change in A.

STRUCTURAL IONIC LAYER: FABRICATION

In the research on the structural engineering of flexible ionic layers, the device fabrication process is a core step for ensuring structural effectiveness[14,15]. The fabrication process largely dictates the quality and precision of structural embedding, which not only allows microstructures to exert their maximum functionality but also mitigates errors induced by the process. Therefore, the most commonly used ionic layer fabrication methods are summarized. This section focuses on commonly used flexible materials such as thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene) [P(VDF-HFP)], as well as ionic filling materials, including ionic salts, dilute acids, and 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide ([EMIM][TFSI]), for discussion.

Template transfer technology

Template transfer technology offers the advantages of low cost and simple processing, making it the most widely used fabrication method to date. Typically, the process involves pre-designing a template with the desired morphology, followed by introducing the ionic gel precursor into the template for shaping. This procedure essentially replicates the template's features onto the ionic layer. This section focuses on the characteristics and application methods of various templates, and elaborates on three core operational modes based on their fabrication and design strategies: the template stripping method, the template sacrificial method, and the template immersion method.

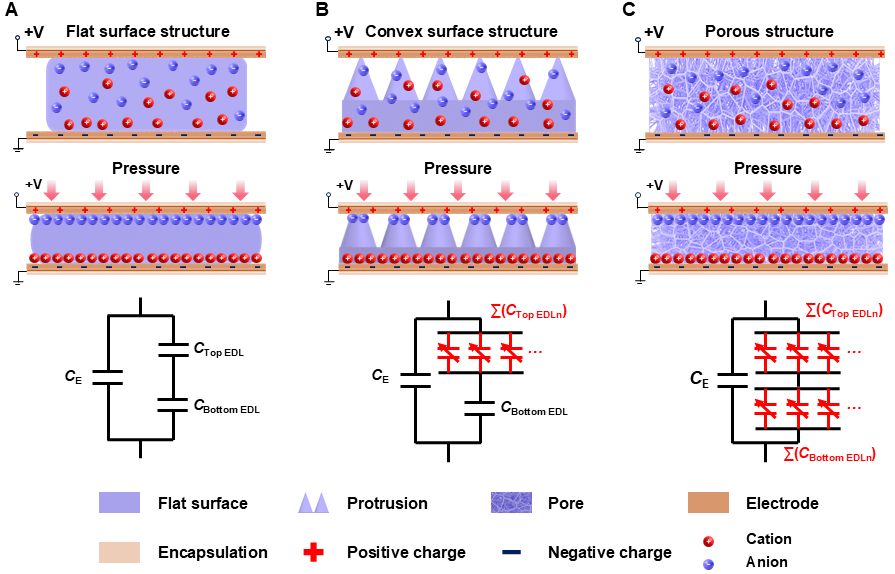

Template stripping method

The template stripping method is a technique for transferring microstructures onto the surface of ionic layers. This method achieves microstructure transfer by directly peeling the template away from the active layer. The morphology and performance of the resulting microstructures depend largely on the type and quality of the templates used.

The regular array template is an inverse mold fabricated via 3D printing, laser writing[29,65,66], or casting, based on pre-designed microstructures. These templates are typically made of easily processable materials such as silicon-based materials or polytetrafluoroethylene[67-69]. As shown in Figure 3A and B, this method is widely used to fabricate simple, regular geometric microstructure arrays[19,70]. Categorized by practical requirements into single-mold casting and secondary-mold casting, its advantages include high customization freedom and template reusability.

Figure 3. Template stripping method. (A) Secondary-mold casting and (B) single-mold casting using regular array templates. Reproduced with permission[19,70]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society and 2023 Wiley-VCH; (C) Natural template. Reproduced with permission[9] Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH; (D) Wet etching template. Reproduced with permission[71]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society; (E) Rough surface template. Reproduced with permission[10]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature; (F) Pre-stretched template[72]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. 3D: Three-dimensional; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; PET: poly(ethylene terephthalate); CNC: Computer Numerical Control; PTFE: polytetrafluoroethylene; [EMIM][TFSI]: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; P(VDF-HFP): poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene); MIG: microstructured ionic gel; PVA: poly(vinyl alcohol); PI: polyimide; GIA: graded intrafillable architecture.

As shown in Figure 3C, the key distinction of this approach is that the templates employed are directly derived from nature[9,73-75]. Specifically, the outer epidermis or specific organs of plants and animals possessing intrinsic microstructures are processed and used directly as templates for inversion molding. This process replicates these biological architectures onto the ionic layer.

Wet etching is commonly used in micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) fabrication processes[76,77]. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3D, silicon-based templates can be etched with acid to form surface relief structures[71,78,79]. However, this method is not widely adopted because the uniformity and consistency of the etched microstructures cannot be guaranteed; furthermore, the fabrication process may involve hazardous chemicals such as hydrofluoric acid and nitric acid.

Rough surface templates utilize natural or low-cost rough substrates, such as sandpaper and frosted glass, as master molds and require no complex pretreatment. As shown in Figure 3E, their random surface morphology is directly replicated via inversion molding to form the required microstructured sensing substrates[10,80,81]. The key advantages of this approach include low cost, easy accessibility, and simplified processing. The replicated rough structures optimize the ionic contact interface, improve the deformation process of A, and enhance sensing performance. However, the primary limitation is the poor control over surface roughness, as structural randomness may lead to slight deviations in sensor performance consistency.

As shown in Figure 3F, this method involves pre-stretching an elastic substrate template and then pouring the prepared polymer precursor solution onto its stretched surface[72,82,83]. Once cured, releasing the pre-stretch force allows the elastic substrate to recover via contraction. This contraction causes the attached ionic layer to shrink, thereby forming wrinkled structures. During this process, the tensile strain level must be carefully regulated: excessively high strain can trigger premature delamination of the ionic layer from the substrate during contraction, owing to discrepancies in their elastic moduli and shrinkage rates.

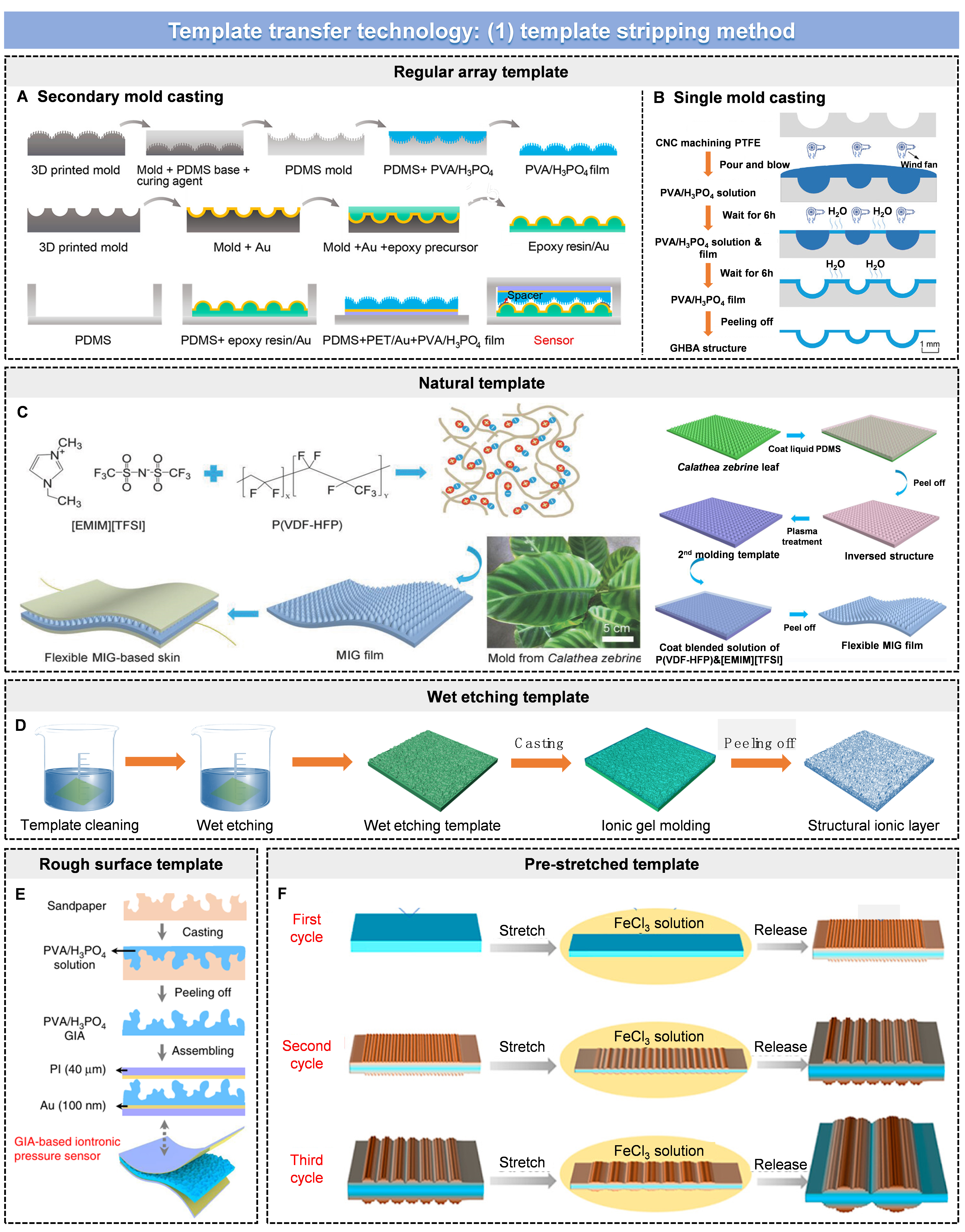

Template sacrificial method

The template sacrificial method is a technique for directly constructing a 3D network ionic layer. Preselected templates are homogeneously mixed with polymer precursors. Then, either during or after the polymer curing process, the templates are removed using a suitable method without damaging the polymer matrix. The spaces previously occupied by the templates subsequently form pores. This approach is commonly used to prepare ionic layers with porous foam structures. Commonly used templates include solid templates (e.g., sugar and NaCl)[84], liquid templates (H2O, toluene, and n-hexane; Figure 4A)[85], and gaseous templates [Figure 4B][30,88]. However, while this method is facile in operation, the inhomogeneity and randomness of the template distribution within the polymer precursor make it difficult to guarantee the performance consistency of the resulting iontronic pressure sensors.

Figure 4. Template sacrificial method. (A) Liquid template and (B) Gas template. Reproduced with permission[30,85]. Copyright 2025 American Chemical Society and 2024 Springer Nature; Template immersion method; (C) Fabric-based template. (D) Foam-based template. Reproduced with permission[86,87]. Copyright 2022 and 2024, American Chemical Society. P(VDF-HFP): Poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene); [EMIM][TFSI]: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; PVDF: poly(vinylidene fluoride); AP: atmospheric pressure; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; IL: ionic liquid; IG: ionic gel; UV: ultraviolet.

Template immersion method

The template immersion method is one of the most widely used processes for constructing structures such as 3D foams or fiber networks. Unlike the template sacrificial method, this template remains integrated with the ionic layer to form the sensing functional layer. As shown in Figure 4C and D, predefined framework templates are fully immersed in an ionic liquid (IL) precursor, followed by curing. Subsequently, the polymer layers adhere to the preformed surface[86,87]. Commonly used precursor frameworks include porous foam[87,89], nonwoven fabric[86], electrospun film[62], and fabric[90]. Currently, this process has two main limitations. First, hydrophobic frameworks struggle to stably support polymer hydrogels using H2O as the solvent, such as PVA. To address this, researchers have modified the surface of hydrophobic frameworks by polymerizing polydopamine to form a hydrophilic layer[63,91], thereby enhancing the interfacial adhesion stability. Second, the fluidity of the precursor can lead to bulk agglomeration during curing, resulting in an inhomogeneous functional layer.

Electrospinning technology

Electrospinning technology generates a strong electric field between the spinneret tip and the collector via a high-voltage power supply. As the spinning solution is pumped at a constant rate to the spinneret, charges accumulate on the liquid surface. When the electrostatic force overcomes the surface tension, a Taylor cone forms at the needle tip. The electric field then draws a charged fluid jet from the Taylor cone; as it travels toward the collector, the jet stretches and deforms. With solvent evaporation or solidification, it eventually deposits to form a nanofiber film[92]. This method enables the production of ultrathin, ultrahigh-porosity flexible ionic layers or 3D supporting frameworks[93]. Sensing devices with such structural ionic layers typically exhibit excellent breathability [Figure 5A and B][57,93]. Their ultrathin and flexible properties endow them with superior conformability, making them ideal for integration into wearable electronics and serving as a core technology for achieving lightweight devices[62,93,98,99].

Figure 5. Electrospinning technology for (A) TPU-based nanofiber and (B) PVA-based nanofiber. Reproduced with permission[57,93]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society, and 2024 Elsevier; (C) freeze-drying technology. Reproduced with permission[94]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; Printing technology. (D-E) screen printing technology, and (F) 3D direct printing technology. Reproduced with permission[95-97]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature, 2024 Wiley-VCH, and 2025 MDPI. TPU: Thermoplastic polyurethane; NFM: nanofibrous membrane; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; NF: nanofiber; GR: graphene; PVA: polyvinyl alcohol; 3D: three-dimensional; PEDOT:PSS: Poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly (styrenesulfonate); PEG(600)DMA: polyethylene glycol (600) dimethacrylate; [EMIM][TFSI]: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; PUA: photosensitive resin and polyurethane acrylate; UV: ultraviolet; BN: boron nitrideboron nitride.

Freeze-drying technology

Freeze-drying is a technique for constructing microporous structures [Figure 5C][94]. First, the homogeneous IL precursor is frozen to a solid state. Subsequently, the frozen precursor is placed in a vacuum, allowing the solid solvent to sublimate directly into gas[100]. The spaces once occupied by the solid solvent form microporous structures. Freeze-drying preserves the material’s original microstructure, minimizing shrinkage or deformation[101]. Moreover, unlike the sacrificial template method, the pore-forming medium in freeze-drying can only be a volatile liquid. A key advantage is that the liquid phase disperses more uniformly in the mixture, resulting in typically uniform and dense micropores. Notably, researchers have largely mastered directional freeze-drying, which enables the construction of gradient microporous structures by controlling the sublimation process[102-104].

Printing technology

Screen printing and 3D direct printing are the most prevalent printing processes for fabricating structural ionic layers. They enable the direct formation of ionic layers. Screen printing is typically used to print conductive pathways[105,106]. Using a mesh stencil with the target pattern, the patterned areas allow material penetration while the non-patterned areas block it. As shown in Figure 5D and E, during printing, polymer precursors are applied to the stencil as a squeegee applies pressure to force the material through the mesh openings onto the substrate, thus transferring the predefined pattern[95,96]. The pattern forms the ionic layer after curing or drying. Its advantages include low cost, high scalability for large-area fabrication, and compatibility with various substrates and materials. 3D direct printing is often used to fabricate personalized ionic layers, porous sensor scaffolds, or integrated device architectures [Figure 5F][97]. Its advantages include high design flexibility, precise control over structural parameters, and compatibility with multi-material co-deposition, making it especially suitable for developing miniaturized iontronic devices[44,107]. Notably, Zhang et al. recently reported an advanced printing strategy based on the surfactant-supported assembly of freestanding microscale hydrogel droplets and successfully fabricated a broad range of iontronic components, including iontronic diodes and npn- and pnp-type transistors[108], providing novel insights for the printing processes of iontronic devices.

STRUCTURAL IONIC LAYER: CLASSIFICATION

Diverse ionic layer morphologies generate distinct sensing responses under pressure. These structures induce stress concentration and amplification, which mitigate polymer viscosity, enhance compressibility, and, more critically, dynamically modulate interfacial area variation to optimize mechano-electrical conversion. This design strategy enables sensors to realize synergistic boosts in key performance. Hence, tailoring ionic layer structural features to target application mechanical conditions is pivotal for high-performance sensing. Synthesizing recent representative advances, this section systematically categorizes ionic layer design schemes, elucidating their unique working mechanisms, intrinsic performance merits, and characteristic compressive deformation behaviors.

Single-hierarchical regularity structure

The core design feature of single-hierarchical regular structures lies in their structural array composed of multiple micro-unit cells arranged in an ordered sequence at the contact interface between the ionic layer and the electrode. This structural design is simple to fabricate and offers high reproducibility. It significantly enhances device performance while ensuring excellent consistency. Moreover, due to its high degree of design flexibility, researchers can customize structural units according to specific application requirements. Supported by mechanical simulation technologies, this approach has become one of the most representative design paradigms for structured ionic layers.

Regarding structural units in basic geometric architectures, the commonly used ones mainly include basic 3D geometric structures such as microcones, micropyramids, microdomes, and micropillars. These structural elements, which are regularly distributed on the surface of the ionic layer, exhibit distinct deformation behaviors under pressure, and their effects on sensing performance involve different targeted optimizations.

Microcone. Microcone can optimize the initial “surface-to-surface” contact state between unstructured planar ionic layers and electrodes to a “point-to-surface” state. This state minimizes the A0, so that when iontronic pressure sensor devices are subjected to pressure load, the maximum change in A can be achieved in the early stage, realizing a significant improvement in sensitivity during the early stage of loading[109-114]. As shown in Figure 6A, Qiu et al. used the natural template Calathea zebrina leaf and employed the template stripping method to successfully transfer the microstructure[9]. They constructed a microcone array on the surface of a P(VDF-HFP)/[EMIM][TFSI] ionic gel film, which was subsequently used to fabricate high-performance iontronic e-skins. The device exhibits an effective detection range from 0.1 Pa to 115 kPa, a maximum sensitivity of 54.31 kPa-1, and a low limit of detection (LOD) of 0.1 Pa. These sensing performances are far superior to the detection capability of traditional parallel-plate capacitive pressure sensors.

Figure 6. Single-hierarchical regularity structure. (A) Constructing conical microstructural ionic layer using Calathea Zebrine Leaf as a template. Reproduced with permission[9]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH; (B) 6 × 6 iontronic pressure sensing array with micropyramid structures. Reproduced with permission[115]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH; (C) High transparency pressure sensor with microdome. Reproduced with permission[116]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature; (D) The flexible iontronic pressure sensor with a cut-corner short micropillar array ionic layer. Reproduced with permission[117]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (E) An ionic gel film with long micropillar array prepared using laser engraving templates. Reproduced with permission[29]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. [EMIM]: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium; [TFSI]: bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; ΔC: capacitance variation.

Micropyramids. Micropyramids are also widely used microstructures for enhancing early-stage sensitivity[68,115,118-122]. Although their deformation mode is similar to the initial “point-to-surface” contact state of microcones, the structural design of the edges and sharp apexes of micropyramid units usually results in a larger change in A. However, under high-pressure loads, the edges and sharp apertures are more prone to wear. This causes the sensing performance to shift, produces measurement errors, and leads to a sharp reduction in service life. As shown in Figure 6B, Niu et al. used a template obtained via 3D printing and adopted replication molding to prepare a P(VDF-HFP)/[EMIM][TFSI] ionic layer with a 6 × 6 matrix regular pyramid array[115], Furthermore, a machine learning-assisted bimodal e-skin based on a micropyramid array was developed, exhibiting an ultrahigh sensitivity of 655.3 kPa-1 within a range of 0-15 kPa and a LOD of 0.2 Pa. Additionally, inspired by the natural structure of wheat awns, Wang et al. reported a PVA/H3PO4 ionic film pressure sensor featuring an oblique pyramid design with a high aspect ratio[118]. When the pressure reaches a critical point, the high-aspect-ratio oblique pyramid undergoes axial bending deformation rather than lateral strain. High-sensitivity pressure sensing, featuring a broad range of 1 Pa to 238 kPa and a maximum sensitivity of 47.65 kPa-1, is ultimately achieved through the continuous variation in A triggered by this bending deformation.

Microdomes. In the early stage of pressure loading, the microdome can induce a large change in A, providing a significant improvement in early-stage sensitivity. Even so, as pressure continues to increase, the change in A does not show an abrupt increasing trend. Due to the structural stiffening of the microdome array under compression, the change in A tends to maintain a continuous and stable trend[123-127]. As shown in Figure 6C, Tang et al. designed an ionic layer structured with a microdome array[116]. This structure was introduced into the fabrication of an iontronic sensing device using [EMIM][TFSI] as the ionic filler and poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate/hydroxyethyl methacrylate as the flexible substrate. Benefiting from the synergy between the microdomes and the transparent substrate, the device overcomes the problem of significant transparency loss after microstructuring, while featuring high sensitivity (83.9 kPa-1) and ultrahigh transparency (96.9%). Similarly, inspired by the ionic mechanotransduction phenomena in Merkel cells, Jin et al. designed mechanically activated visco-poroelastic nanochannels based on artificial ILs and viscoelastic biocompatible polymer networks to emulate the Piezo2 nanochannels in mammalian epidermal Merkel cells[128]. They fabricated an artificial ionic mechanotransducer for pressure sensing, which achieved linear sensing in the range of 0-20 kPa by introducing a microdome array into the i-TPU/[EMIM][TFSI] functional layer.

Micropillars. Current micropillar designs are generally classified into short micropillars[117,129] and long micropillars[22,29,130] based on the aspect ratio of the columnar structure, which results in significant differences in their deformation characteristics under compression. As shown in Figure 6D, the cut-corner short micropillar array on the surface of the PVA/chitosan/gum Arabic/H3PO4 ionic layer reported by Liu et al. tends to undergo lateral strain when compressed[117], enabling a linear sensitivity response over a wide range. In contrast, as shown in Figure 6E, the long micropillar array in the P(VDF-HFP)/[EMIM][TFSI] ionic gel film reported by Zhao et al. undergoes axial bending deformation when compressed[29]. This continuously induces changes in A, achieving a highly sensitive response (maximum 14.83 kPa-1) over a wide range (0-250 kPa). Consequently, in practical applications, the morphology of the micropillar array should be tailored to meet specific sensing performance requirements.

Based on the structural design of the above-mentioned simple geometric bodies, researchers have proposed targeted structural designs for individual units based on practical sensing requirements. More complex designs and higher fabrication difficulties are usually accompanied by better sensing performance[65,70,131-134]. Li et al. reported a structural design of an ionic layer with a microcup-shaped array[131]. Due to the internal cavities, these microcup-shaped units do not undergo rapid structural stiffening when subjected to pressure, thus exhibiting a large deformation range. Finite element analysis (FEA) reveals that these units tend to undergo structural collapse deformation, which continuously induces significant changes in A. This enables highly sensitive sensing over a wide range (0-170 kPa) with a maximum sensitivity of 87.75 kPa-1. Furthermore, Huang et al. proposed a PVA/H3PO4 ionic layer film with a peanut-groove structure[133]. Linear sensitivity (R2 = 0.999) for iontronic pressure sensors in the 0-200 kPa range is effectively ensured by this microstructure. The FEA comparisons of deformation modes and contact characteristics among three microstructures (peanut groove, peanut flat, and hemisphere) under compression confirmed this stable linear performance.

3D network structure

The construction of 3D microarchitectures to regulate ion transport paths and interfacial coupling has become a major research focus for optimizing iontronic pressure sensor performance. Mainstream 3D network types in ionic layers include foam, fiber, and non-porous networks. Their structural quality relies on two key indicators: porosity and pore size. Porosity determines the compressibility limit and stress dispersion, while pore size affects ion migration and sensitivity. These 3D networks excel at dispersing pressure and enhancing ionic layer compressibility to offset the structural hardening of solid layers caused by lateral strain, thereby enabling wide-range, high-sensitivity sensing.

Foam network

Foam networks are structures with porous and interconnected characteristics in ionic layer structure design[64,135-139]. They can provide sufficient compression space and efficiently disperse pressure. Their advantages lie in the fact that high porosity can significantly enhance the compressibility of ionic layers and facilitate sensing over a wide pressure range. However, they have drawbacks. Precise control of pore size is difficult, and uniformity in batch fabrication is poor. These issues easily cause packaging problems and increase sensing hysteresis. The existence dimension of the foam network can be the loading skeleton of the ionic gel or itself. As shown in Figure 7A, Liu et al. employed the template immersion method to infiltrate polyurethane (PU) foam skeletons into 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate [BMIM]BF4 IL[59], fabricating a porous foam ionic layer with a porosity as high as 95.4% and a Young’s modulus of only 3.4 kPa. Benefiting from the changes in A brought by the foam network and the excellent mechanical properties of the PU foam, this structure design endows the iontronic pressure sensor with ultrahigh sensing performance, including a maximum sensitivity as high as 9,280 kPa-1. It also exhibits outstanding mechanical stability over 5,000 compression-release or bending-release cycles. On the other hand, Kwon et al. used the template sacrificial method, with cube sugar as the 3D pre-template, to directly construct a foam network ionic gel[84]. Sensors encapsulated with this ionic layer exhibit a high sensitivity of approximately 152.8 kPa-1 and a wide sensing pressure range up to 400 kPa, as shown in Figure 7B. Furthermore, the pressure visualization function of the sensor has also been extended.

Figure 7. 3D network structure. (A) High porosity open-cell PU foam as a continuous network skeleton, loaded with IL via one-step soaking. Reproduced with permission[59]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature; (B) Directly fabricating an ionic gel layer with a porous foam network via the sugar cube sacrificial template method. Reproduced with permission[84]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society; (C) Fabrication of IG/CP nanofiber network film ionic layer via electrospinning process. Reproduced with permission[140]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (D) A double-layer shell-core nanofiber network is constructed via coaxial electrospinning technology. Reproduced with permission[141]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature. 3D: Three-dimensional; STA: stearic acid; PDA: polydopamine; IG: ionic gel; CP: chrysanthemum pollen; P(VDF-co-HFP): poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene); [BMIM]: 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium; [TFSI]: bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; PU: polyurethane.

Fiber network

Fiber networks are formed by interwoven fibers to form the ionic layer, featuring excellent breathability and connectivity[140,142-147]. These networks with high specific surface area are proficient in enhancing the change of A to boost sensitivity, and allow for easy thickness control when prepared by electrospinning. As shown in Figure 7C, Sun et al. reported a fiber-ionic gel ionic layer system based on an open 3D porous network[140]. Benefiting from the 3D network, the sensor exhibits excellent air permeability (224.9 mm·s-1), together with an ultrahigh sensitivity of 214.92 kPa-1 and a detection range of 0-45 kPa. The porous and lightweight design of the ionic layer endows the device with outstanding flexibility, thus enabling its practical application as a sensing unit for human health status monitoring and human motion detection in intelligent wearable systems. Meanwhile, Zheng et al. reported a biocompatible, biodegradable, and high-performance flexible iontronic pressure sensor[98]. This sensor adopts conductive silver paste-coated starch gel electrodes with fingerprint-like microstructures, and uses an electrospinning process to prepare a dextran/IL nanofiber network film as the dielectric layer. Results show that the sensor achieves a sensitivity of 13.7 kPa-1 within the pressure range from 0 to 2 kPa, with a broad detection range spanning from 0 to 200 kPa. As illustrated in Figure 7D, using the electrospinning process, Li et al. successfully constructed a 3D ionic layer with shell-core structured double-layer nanofibers of TPU/P(VDF-HFP)/[BMIM][TFSI][141], which was applied to fabricate artificial ion mechanoreceptor skin. The orthogonal frequency coding successfully implemented in intelligent electronic skin combines high sensitivity and an ultra-wide pressure range, enabling ultrafast parallel readout of spatiotemporal mechanical stimuli.

Multi-hierarchical regularity structure

This section will focus on the ionic layer design of a more complex multi-hierarchical regularity structure. The multi-hierarchical regularity structure refers to the further implementation of microstructural nested design on the basis of single-hierarchical simple structural units. The aim is to integrate the advantages of different types of structures, thereby fabricating ionic layers with superior sensing performance. According to the nesting scope of multi-hierarchical regularity structures, they can be classified into two categories: intra-hierarchical structure and hierarchical arrays.

Intra-hierarchical structure

The nesting perspective of the intra-hierarchical structure focuses on a single microstructure itself. Through the multi-level nesting and synergy of multiple types of microstructures, this structure can effectively expand the functional requirements and improve the sensing performance of ionic layers[85,148-152]. However, it has notable limitations: multi-hierarchical nesting not only increases the difficulty of verifying the structural working mechanism, but also makes the design of preparation processes more complex and significantly increases preparation and processing costs. As shown in Figure 8A, Bai et al. reported a real-time, high-precision artificial sensory system for texture recognition based on a single-scale iontronic slip-sensor, and simultaneously proposed the “spatiotemporal resolution” evaluation criterion to correlate sensing performance with recognition capability[23]. The ionic layer of this slip-sensor adopts a two-level graded microstructure: periodic domes and dense fine protrusions on their surfaces. This nested structure design, by significantly increasing the specific surface area of the ionic layer, enables more abundant levels and higher-precision hierarchical changes in A. This design endows the sensor with the capability to respond to static and dynamic stimuli (0-400 Hz) and a high spatial resolution of 15 μm in spacing and 6 μm in height. Afterwards, as shown in Figure 8B, based on the nanofiber self-aggregation theory[154], Wang et al. proposed a novel spinning preparation strategy, which enables the fabrication of an electrospun ionic membrane with a surface microcone array, where the array nests on its intrinsic fiber network structure[57]. Without template assistance, the pressure sensor has a PVA/H3PO4 ionic layer featuring conical microstructures on its surface. The grown conical structures enhance ΔA, ensuring high initial sensitivity. The nested electrospun fiber 3D networks can effectively expand the detection range, thereby compensating for the limitation of the narrow sensing range of conical microstructures and enabling a broad sensing range of approximately 1 MPa.

Figure 8. Multi-hierarchical regularity structure. (A) The gel ionic layer having a two-level graded microstructure: periodic domes and dense finer protrusions on the domes. Reproduced with permission[23]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (B) Microcone array directly grown on the surface of the electrospun film ionic layer[57]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; the structural design of ionic layers for (C) Microfrustum hierarchical arrays. Reproduced with permission[153]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH. TPU: Thermoplastic polyurethane; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; PET: poly(ethylene terephthalate); PVA: poly vinyl alcohol; [TFSI]: bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide; EMI: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium; AC: alternating current; ΔC:capacitance variation.

Hierarchical array

The design philosophy of hierarchical arrays takes the perspective of the entire structure array as its basis. It centers on designing multi-hierarchical stepped structures with respect to the array gradient size and typically necessitates theoretical verification combined with FEA[67,155,156]. The multi-stage response characteristics endowed by this hierarchical array design enable its broad application in enhancing the linear response capability of iontronic pressure sensors and establish a well-defined role in optimizing sensing performance. As shown in Figure 8C, Xia et al. drew inspiration from the principle of human haptic perception and, based on the iontronic capacitive effect and triboelectric effect, developed a microfrustum ionic layer[153], which was used for the core part to assemble a multimodal, ultra-sensitive biomimetic electronic skin. The multi-stage contact characteristics yield sustained and uniform ΔA, addressing the drawbacks of narrow sensing range and poor linearity associated with single-stage microstructures. Benefiting from the gradient phase response characteristics of hierarchical micro-frustum arrays, this electronic skin achieves a highly sensitive linear response of 357.56 kPa-1 (R2 = 0.97) within the wide pressure range of 0-500 kPa. Similarly, a design strategy has also been proposed by Cheng et al.[125] The ionic gel layer is prepared using PVA/H3PO4, and the sensitivity and linearity of the iontronic pressure sensor are enhanced through the functional gradient design for the height of the domes of the gel. The fabricated iontronic pressure sensor exhibits excellent performance, with a sensitivity of 423.42 kPa-1, a wide linear sensing range of 0-400 kPa, and a LOD of 0.48 Pa. In conclusion, the morphological dimensions, distribution density, and gradient design of individual array elements largely determine the functional performance of the structure.

Irregular structure

Irregular structures serve as an important design form for optimizing the interface performance of iontronic pressure sensors. By virtue of their irregular microtopography to regulate the state of contact interfaces, they exhibit significant application potential in pressure detection scenarios. Their non-uniform topography boosts A changes under pressure, enhancing the response and sensitivity of sensing performance, especially for low-pressure weak signals. Currently, mainstream irregular structures can be roughly divided into irregular protrusions[10,21,157-160] and irregular wrinkles[72,161-163].

Irregular protrusions currently exist most widely as structures obtained via single or secondary replication using sandpaper templates. In existing studies, some works have elaborated and clearly explained the deformation characteristics and action principle of irregular protrusions obtained through replication with sandpaper templates. As illustrated in Figure 9A, Bai et al. reported a design strategy for intrafillable microstructures[10]. Intrafillable microstructural ionic layers obtained via replication using sandpaper templates possess both irregularly distributed protrusions and groove gaps. When a large pressure load is applied, the irregular protrusions are compressed to fill these grooves. This provides more deformation space for the irregular protrusions, enables continuous changes in A, effectively enhances structural compressibility and pressure response range, and thus achieves high sensitivity (≥ 220 kPa-1) pressure sensing over a wide range (0.08 Pa-360 kPa). Meanwhile, Cho et al. constructed a layer of concave randomly wrinkled microstructure (CRWM) on the surface of the ionic layer[161]. By comparing the performance of different microstructure designs and combining them with FEA, the results show that CRWM has a direct promotion effect on the change of A, which endows the pressure sensor with the CRWM-structured ionic layer as the dielectric layer with a maximum sensitivity of 56.91 kPa-1 [Figure 9B]. However, irregular structure randomness causes poor batch uniformity, hindering standardized models and combination with FEA tools, limiting mechanism verification and performance optimization.

Figure 9. Irregular structure. (A) The iontronic pressure sensor with a sandpaper reverse-molded random graded intrafillable architecture ionic layer. Reproduced with permission[10]. Copyright 2020, Springer Nature; (B) A random convex and randomly wrinkled structured ionic film. Reproduced with permission[161]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. CRWM: Concave randomly wrinkled microstructure; CM: convex microstructure; CWM: concave wrinkled microstructure.

Hybrid structure

In fact, the hybrid structure has moved beyond the scope of microstructure design and leans more towards a 3D stacking and assembly strategy, providing more innovative possibilities for the design of pressure-sensitive ionic layers. Its advantages include enhancing the stress distribution capability of ionic layers, expanding sensing performance, and also possessing the design potential for multifunctional ionic layers. However, in practical applications, ordinary packaging struggles to maintain interlayer shear force, which easily causes lateral slippage and misalignment, affecting performance consistency. Here, according to its structural characteristics, it is divided into several types: double-sided structure[164,165], interlocked structure[19,166,167], and multi-layer structure[95,168,169].

Yuan et al. reported a flexible iontronic pressure sensor with a double-sided microstructural ionic layer[164]. By adopting the simultaneous double-sided molding process, irregular microstructures and pyramid microstructures were separately constructed on the contact interfaces between the P(VDF-HFP)/[EMIM][TFSI] ionic layer and the upper and lower electrodes, respectively. Benefiting from the delicate balance between microstructure compression and mechanical alignment at the ionogel interface, the variation of A is optimized, which enables the sensor to achieve a wide-range linear response, with R2 values of 0.9975 and 0.9985 in the ranges of 100 to 760 kPa and 760 to 1000 kPa, respectively. Similarly, as shown in Figure 10A, Kou et al. reported a low-cost and facile sandpaper inversion molding method[165], and successfully fabricated a double-sided microstructural TPU/[EMIM][TFSI] ionic layer. The test results show that the sensor achieves high sensitivities of 3.744 kPa-1 and 1.689 kPa-1 in the low-pressure range (0-20 kPa) and high-pressure range (20-800 kPa), respectively. Bai et al. reported an iontronic pressure sensor with a graded interlocking structure, whose ionic layer features a coupled structure of hemispherical arrays and fine pillars[19]. The deformation of the micropillars offsets interfacial stiffening, thus maintaining linearity. Furthermore, the interlocking structure significantly increases the specific surface area of the contact region, resulting in more effective and uniform changes in the A, as shown in Figure 10B. This iontronic pressure sensor exhibits a sensitivity of 49.1 kPa-1 and a linear response (R2 > 0.995) over a wide pressure range of 485 kPa. The composite structure of the ionomeric layer also endows it with rapid response (0.61 ms) and recovery (3.63 ms) capability under a pressure load of 250 kPa. As shown in Figure 10C, Xiao et al. proposed an iontronic pressure sensor with both an ultra-wide linear operating range (0.013-2063 kPa) and high sensitivity (9.17 kPa-1)[168]. The dielectric layer consists of multiple layers of double-sided structural ionic gel films. Its multi-layer design, along with the gaps of random morphology and size between adjacent films, not only enhances the sensor’s compressibility but also distributes stress evenly across each layer, thereby achieving, for the first time, high-sensitivity pressure sensing over a load range spanning six orders of magnitude.

Figure 10. Hybrid structure. (A) Design of a pressure sensor with double-sided microstructural ionic layer fabricated via sandpaper template replication. Reproduced with permission[165]. Copyright 2025, AIP Publishing; (B) An array of hemispheres with micropillars is constructed in the ionic layer to form a double-layered graded interlocking structure. Reproduced with permission[19]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society; (C) Constructing a multilayered ionic layer enhances the sensor’s compressibility, enabling uniform stress distribution. Reproduced with permission[168]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. EDL: Electric double layer; PI: polyimide.

In summary, this chapter has comprehensively reviewed the current mainstream research on structured ionic layers: by drawing on classic literature, it has elaborated on the design advantages and disadvantages and the unique working mechanisms of various ionic layer structures. To help readers gain a clear understanding of the role of each specific structure and facilitate horizontal comparisons, we have summarized the pros and cons of all ionic layer structures discussed in this paper. Meanwhile, we have selected representative studies corresponding to these structures and outlined their impacts on the performance of iontronic pressure sensors including sensitivity, sensing range, linearity and LOD, with specific details provided in Table 2.

Structural ionic layer classification and comparison

| Structural ionic layer: Classification | Advantage | Limitation | Ref. | Sensitivity | Range | Lin-R2 | LOD | ||

| Single-hierarchical regularity structure | Basic geometric structure | Microcone | Effectively enhances early-stage sensitivity and resolution | Performance improvement is limited to the early stage | [9] | 54.31 kPa-1 30.11 kPa-1 8.42 kPa-1 1.03 kPa-1 | < 0.5 kPa ~ 10 kPa ~ 40 kPa ~ 115 kPa | -- | 0.1 Pa |

| Micropyramid | Effectively enhances early-stage sensitivity and resolution | Mircopyramid is prone to wear | [115] | 655.3 kPa-1 327.9 kPa-1 | < 0.5 kPa ~ 15 kPa ~ 150 kPa | -- | 0.2 Pa | ||

| Microdome | Improves early-stage sensitivity Broadens early-stage linear response range | Microdome is prone to strain hardening Measurement range is limited | [116] | 83.9 kPa-1 20.4 kPa-1 | < 20 kPa ~ 100 kPa | -- | 10 Pa | ||

| Micropillar | Wide linear response range | Sensitivity enhancement is limited | [117] | 37.94 kPa-1 10.16 kPa-1 1.27 kPa-1 | < 25 kPa ~ 120 kPa ~ 300 kPa | 0.969 | -- | ||

| 3D network structure | Foam network | -- | Balances high sensitivity and wide measurement range | Relatively thick Poor consistency | [30] | 321.8 kPa-1 684.8 kPa-1 338.0 kPa-1 | < 200 kPa ~ 400 kPa ~1,000 kPa | -- | 1 Pa |

| Fiber network | -- | Ultra-thin and breathable Excellent flexibility | Prone to irreversible damage Poor resilience | [141] | 3.9 kPa-1 2.2 kPa-1 1.2 kPa-1 | ~ 380 kPa ~ 1,000 kPa ~ 1,880 kPa | -- | -- | |

| Multi-hierarchical regularity structure | Intra-hierarchical structure | -- | Advantages of coupled structures | Complex structural nesting process Difficult to analyze the sensing mechanism | [23] | 519 kPa-1 | ~ 100 kPa | -- | -- |

| Hierarchical array | -- | Enhances linear response capability | Requires FEA assistance | [125] | 423.42 kPa-1 | ~ 400 kPa | 0.99 | 0.48 Pa | |

| Irregular structure | Irregular protrusion | -- | Simple preparation and low cost Significantly optimizes contact interface characteristics and efficiently enhances performance | Poor performance consistency Difficult to coordinate with FEA | [10] | 3302.9 kPa-1 671.7 kPa-1 229.9 kPa-1 | ~ 20 kPa ~ 90 kPa ~ 360 kPa | -- | 0.08 Pa |

| Irregular wrinkle | -- | [161] | 56.91 kPa-1 | ~ 80 kPa | >0.99 | 0.5 Pa | |||

| Hybrid structure | Double-sided structure | -- | Greatly enhances the variation of A, thus improving sensitivity | Complex preparation process Amplifies the effect of prestress | [164] | 0.1034 kPa-1 0.1922 kPa-1 | > 100 kPa ~ 700 kPa ~ 1,000 kPa | 0.9975 0.9985 | -- |

| Interlocked structure | -- | Balances high sensitivity and wide range Withstand large shear forces | Complex design Amplifies the effect of prestress | [19] | 48.7 kPa-1 49.2 kPa-1 49.4 kPa-1 | 485 kPa | 0.999 | -- | |

| Multi-layer structure | -- | Dissipates stress and broadens sensing range Provides multi-functional sensing design ideas | Easy relative slip between layers Difficult to package | [168] | 9.17 kPa-1 | 2063 kPa | > 0.99 | -- | |

STRUCTURAL IONIC LAYER: APPLICATION

The biomimetic perception mechanism of particle conduction in human-like skin is achieved through the structural design of the ionic layer. By constructing microstructures - such as pyramids, hemispherical arrays, and gradient interlocks - that simulate the hierarchical conduction paths of the skin’s epidermis and dermis, this approach achieves the synergistic optimization of Pa-level detection limits and kPa-level measurement ranges. Consequently, this has become a key technical direction in the field of flexible electronics. Current systematic explorations in academia center on microstructure design and integrate the regulation of ionic gel performance with multi-scenario adaptation, thus forming a multidimensional research system linked by the structure-performance-application chain.

Healthcare

The targeted design of the ionic layer microstructure in iontronic pressure sensors endows the sensing device with excellent pressure response sensitivity and enables it to possess advantages such as weak signal capture capability and high-precision signal resolution, meeting the diverse needs in the healthcare field[170]. As shown in Figure 11A, a study designed an arrayed stepped microstructure ionic layer pressure sensing array device, specifically for high-precision identification and detection of non-invasive pulse signals[96]. Benefiting from the ultra-thin thickness afforded by the screen printing process and the constructed multi-layer hybrid structural ionic layer, this device exhibits high sensing performance and excellent flexibility. It can accurately capture and identify the wavelength, beating rate, and characteristic waveform of pulse signals, and can also construct a 3D pulse cloud map to provide direct assistance for doctors' diagnosis and treatment. In addition, the nanofiber network structural ionic layer device developed by Zheng et al. achieves a 99% biocompatible cell viability by virtue of the ultra-thin and breathable properties of the electrospun 3D fiber network[98]. Combined with the convolutional neural network algorithm and relying on the significant ΔA brought about by its high specific surface area, the device exhibits both high sensing sensitivity and resolution. For the intractable disease of Parkinson’s disease, this device has successfully established a severity grading and rehabilitation assessment model, enabling direct provision of personalized diagnosis and treatment plans for patients.

Figure 11. Multi-application scenarios of structural ionic layer pressure sensors. (A) 3D visualization of pulse detection. Reproduced with permission[96]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (B) Real-time detection of joint status during movement. Reproduced with permission[57]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier; (C) Tactile perception applications of robotic hands, targeting the hardness and softness of tactile objects. Reproduced with permission[167]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH; (D) A wearable ionic textile-based touch panel with high touch sensing resolution for writing, drawing, and remote control. Reproduced with permission[171]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (E) Application of aircraft skin. Reproduced with permission[21]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature; (F) Application in wearable monitoring under high-altitude harsh environment. Reproduced with permission[172]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. EDB: Epidermis-dermis bionic; PCB: Printed Circuit Board.

Exercise guidance

In joint movement training guidance, ionic layer structure design is key for flexible iontronic pressure sensors, and with targeted design plus flexible substrates’ stretchability, the sensor gains high skin-fitting flexibility and a widened range for large limb movements. It accurately captures joint movement features, supports training posture correction and force adjustment with data, and drives movement guidance toward intelligence[173]. Figure 11B shows that a PVA/H3PO4 pressure sensor[57], with synergistic microcone arrays and electrospun nanofiber ionic layers. The 3D network structure ensures the requirement for a wide sensing range to accommodate large-amplitude movements during motion. It achieves a 1 MPa maximum effective sensing range while remaining lightweight, avoiding wearer discomfort and stably capturing large joint movements, with potential for intelligent wearables. Similarly, Wang et al. have reported that an iontronic pressure sensor maintains accurate signal acquisition over a wide range. Its hierarchical hemispherical array ensures the sensor’s multi-stage response during operation. Furthermore, the device can capture arm muscle deformations across diverse movement patterns and discriminate the tactile properties of various fruits, demonstrating considerable application potential in wearable sensing and tactile recognition scenarios[174].

Robot tactile perception

The core of refined interaction in intelligent robots lies in tactile perception. Within this, microstructure design plays a leading role. A reasonable, structural ionic layer design can significantly improve the sensor's force resolution accuracy and object texture recognition capability, ultimately enabling robots to achieve functions such as precise grasping, object perception and object classification[175]. As shown in Figure 11C, Niu et al. reported a hardware-software synergy-driven epidermis-dermis bionic (EDB) e-skin design, with the core being the proposal of a multi-layer interlocked microstructural ionic layer[167]. Based on this structural design, endowing the sensor with ultra-high resolution, researchers developed an intelligent robotic sensory system integrated into fingertips, which can autonomously and in real-time perceive materials with different hardness/softness properties with a single touch, achieving human-like perception capability with an accuracy of up to 98.25%. Bai et al. adopted a two-level graded structured ionic layer design[23]. This structure design not only endows the tactile perception system with high sensitivity sensing capability but also can accurately capture micron-level texture features of tactile objects. At a fixed sliding rate, the system can identify 20 different commercial textiles with an accuracy of 100.0%; even at random sliding rates, the accuracy remains 98.9%.

Human-computer interaction

Breakthroughs in flexible iontronic pressure sensor technology are laying the foundation for more intuitive and natural interaction between humans, computers, and other smart devices. As shown in Figure 11D, based on the in-situ growth strategy, Xu et al. developed a skin-friendly and wearable iontronic touch panel with a 3D woven fiber network[171]. The introduction of this structure endows the smart panel with excellent skin adherence and breathability. Furthermore, researchers conducted further application trials: based on user operations, the panel can implement interactive commands such as “handwriting-to-screen” conversion, simple drawing, and game control, providing support for the development of next-generation wearable interactive electronic devices. Meanwhile, iontronic pressure sensing systems have developed diversified application solutions in remote control and sensing scenarios. The iontronic dynamic sensor designed by Guo et al. achieves wide-range dynamic signal detection by virtue of the preloading strategy and micropyramid arrays on the surface of the ionic layer. This structural ionic layer design significantly enhances the device’s sensing sensitivity. In addition, the device can perform high-fidelity recording of various instrument sounds. This feature verifies the feasibility of using skin-wearable sensors in voice-controlled toy car solutions and highlights their great application potential in voice user interfaces for human-computer interaction[113].

Detection in harsh environment

One of the significant advantages of iontronic pressure sensors over other types of sensing mechanisms lies in the fact that, by virtue of the synergy of the EDL effect and rational microstructural design, they can stably achieve pressure sensing functions within a wider measurement range, further expanding the coverage capability of sensing indicators in extreme environments. As shown in Figure 11E, the interlocked sandpaper irregular protrusion structure designed by Wang et al. can map different air pressure characteristics through changes in the A[21]. The interlocking structure compresses under positive pressure, resulting in a larger A. Conversely, under negative pressure, the two interlocking layers tend to separate, which instead leads to a decrease in A. This distinct structural response characteristic endows the device with the capability to detect both positive and negative pressures. It is expected to be integrated into the smart skin on the surface of aircraft wings to achieve multi-dimensional force signal capture of positive and negative air pressures on the wing surface. Furthermore, the iontronic pressure sensor designed by Zhang et al. features a built-in intrafillable microstructure[10], which enables sensitive detection within a wide range[172]. This allows the sensor to stably detect physiological signals under environments with different altitudes and atmospheric pressures, thereby providing real-time motion assistance guidance for wearers in harsh environments [Figure 11F]. Meanwhile, Li et al. reported an electronic skin based on the ionic fiber network co-constructed by silk fibroin and glycerol[176]. The high porosity of the fiber network endows it with low evaporative resistance and high water vapor permeability, which does not impede sweat penetration and evaporation. This effectively mitigates the interference of skin’s local thermoregulation on the performance of iontronic devices, enabling stable sensing operation even in hot and humid environments[176].

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Rooted in the EDL effect-driven pressure-sensing mechanism, ionic layer structural design serves as the core arbiter of iontronic pressure sensor performance, spurring the proposal of numerous innovative microstructure strategies. Centered on the state-of-the-art in ionic layer structural design, this review systematically dissects the working models, underlying mechanisms, fabrication processes, and structural taxonomies of ionic layers, while delineating their significance for broadening application boundaries. Mainstream microstructures are first classified into three categories, with detailed exposition of their pressure detection principles, operational workflows, and matched equivalent circuits; findings corroborate prior literature that A is pivotal for structural optimization and performance enhancement. Common fabrication processes are then condensed into four groups, with analysis of their workflows, pros, cons, and corresponding microstructure preparation pathways, and advanced structural designs are further categorized into five types. Given that structural design also governs applicable scenarios, this review surveys key application fields. Ultimately, robust, advanced structural design underpins the transition of iontronic pressure sensing from lab-scale research to industrial-scale deployment. Advanced, reliable structural design establishes a robust technical foundation for iontronic pressure sensing to translate from laboratory research to industrial applications.

Despite the rapid development of ionic layer structural engineering in current iontronic pressure sensing technology, the field still faces multi-dimensional key bottlenecks that require deeper theoretical breakthroughs and technological innovations to resolve. Against this backdrop, the following outlook focuses on the future development directions and core challenges of ionic layer structural design for flexible iontronic pressure sensors.

Ambient temperature influence. Temperature fluctuations are the key factor restricting the performance stability of iontronic pressure sensors. Their impacts manifest in two aspects: on the one hand, they alter the ion migration rate and interface charge distribution of ionic conductors, directly inducing capacitive signal drift; on the other hand, they drive thermal expansion and contraction of sensing materials, undermining the contact stability between electrodes and ionic layers and even causing irreversible structural damage in severe cases. Current core challenges center on three aspects, including insufficient performance consistency within a wide temperature range, reliability degradation under long-term temperature cycling, and difficulty in decoupling temperature-pressure cross-interference. Corresponding solutions are clear. At the structural ionic layer level, flexible bionic structures are designed to offset contact deviations caused by thermal expansion. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the thermal drift of iontronic devices can also be mitigated by enhancing heat dissipation via structural design of 3D networks with high porosity and high heat dissipation efficiency[176,177].

Mechanical fatigue. The aging and irreversible degradation of flexible materials in ionic layers have become a critical bottleneck limiting the service life and performance stability of iontronic pressure sensors. Flexible substrate fatigue, molecular chain breakdown, and ionic conductor migration cause reduced sensitivity, response lag, structural damage, and failure. Key challenges include poor aging resistance under cyclic mechanical stress, difficulty in long-term ionic conductor retention, and fragile electrode ionic layer interface bonding. These issues are mitigated via targeted ionic layer structural design: a bionic micro nanoarray framework disperses external stress to cut irreversible deformation and optimizes ion transport channels (by tuning array morphology size density) to lower migration loss. Additionally, interface modification via functional layers or surface energy regulation strengthens interlayer adhesion and prevents delamination during long-term dynamic operation.

Large-scale production. Large-scale production faces a gap between laboratory-scale technologies and mass production technologies. Precision fabrication processes used in laboratories are relatively costly, making it difficult to meet the demand for low-cost mass production. Moreover, process fluctuations during mass fabrication easily cause variations in the characteristic dimensions of microstructures, affecting the signal uniformity of sensor arrays. Meanwhile, existing structures have poor compatibility with engineering scenarios, and integrating sensors with backend circuits poses significant challenges. Therefore, developing low-cost mass fabrication processes, designing scenario-specific customized structures, and addressing integration issues are key to promoting the large-scale implementation of this technology across multiple fields.

In summary, the structural design of the ionic layer takes the sensing mechanism dominated by the EDL effect as its core logic. By achieving precise regulation of A, it realizes targeted optimization of sensing performance. Meanwhile, it boasts promising commercial potential thanks to its low-cost and easily scalable fabrication processes, laying a core foundation for the technological breakthroughs of next-generation wearable and remote interactive electronic devices. Furthermore, a rational structural design of the ionic layer not only ensures the compatibility of devices with existing consumer electronics and industrial testing terminals but also meets the high-reliability commercial standards in the healthcare field. This design has facilitated the large-scale practical application of such devices in domains including healthcare and industrial testing, thereby providing key technical support for the iterative upgrading of interactive electronic technologies and removing core technical barriers to the commercialization of related technologies.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Bai, N.; Wang, W.

Made substantial contributions to writing the paper: Wang, X.

Investigation, original draft, and figure editing: Guo, C.; Su, Z.; Zhou, L.

Manuscript revision: Zhang, R.; Teng B.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52403335 and 52375573), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2024JC-YBQN-0994), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. 10251230002), and Qinchuangyuan High-Level Innovation and Entrepreneurship Talent Program of Shaanxi Province.

Conflicts of interest

Wang, W. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics. Wang, W. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Linear range enhancement in flexible piezoresistive sensors enabled by double-layer corrugated structure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e13480.

2. Gao, L.; Zhu, C.; Li, L.; et al. All paper-based flexible and wearable piezoresistive pressure sensor. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 25034-42.

3. Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Ultrawide sensing range and high-sensitivity capacitive pressure sensor based on skeleton dilution strategies for human motion and correction of poor body posture. IEEE. Sensors. J. 2024, 24, 11270-8.

4. Han, R.; Liu, Y.; Mo, Y.; et al. High anti-jamming flexible capacitive pressure sensors based on core-shell structured AgNWs@TiO2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305531.

5. Cheng, T.; Shao, J.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Rev. Methods. Primers. 2023, 3, 39.

6. Niu, S.; Wang, Z. L. Theoretical systems of triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano. Energy. 2015, 14, 161-92.

7. Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Flexible piezoelectric-induced pressure sensors for static measurements based on nanowires/graphene heterostructures. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 4507-13.