Oxygen vacancy modulation in two-dimensional metal oxides for biomedical applications

Abstract

Two-dimensional metal oxides (2D MOs), as a typical representative of 2D inorganic materials, exhibit unique physicochemical properties and have received much attention in the field of nanomedical research. However, the complex physiological environment in living organisms stimulates further research into the functionality of 2D MOs to improve their ability to assemble therapeutic, diagnostic, and regenerative devices in organisms. One promising strategy, oxygen vacancy (OV, plural: OVs) engineering, can modulate the band structure and the number of active sites of 2D MOs, giving them additional functions in biological applications. Recently, researchers have developed various types of 2D MOs containing OVs via different synthetic routes, which have been extensively studied in biomedicine. Amorphization is also an effective method to introduce OVs in 2D MOs, but currently they have not been used in biological applications. This review summarizes generation, preparation, and characterization techniques of OVs in 2D MOs, as well as the role and application of OVs-rich 2D MOs in biomedical fields. Moreover, the prospects and challenges for the development of OVs-rich 2D MOs, especially amorphous 2D MOs, are discussed to facilitate the further development of these materials for biomedical applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, Novoselov and Geim et al. at the University of Manchester successfully peeled off graphene from highly oriented graphite through micromechanical exfoliation[1]. Since the discovery of graphene, an increasing number of inorganic two-dimensional (2D) materials have been discovered and synthesized by researchers, such as hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)[2,3], graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)[4], metal sulfides (MDs)[5,6], metal oxides (MOs)[7], layered bimetallic hydroxide (LDH)[8], black phosphorus (BP)[9,10], and 2D transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides (MXenes)[11]. The emergence of these materials has greatly enriched the range of inorganic 2D nanomaterials. 2D MOs as an important inorganic 2D nanomaterials have been widely studied in typical representation. Their general formula is MxOy (M is metal, O is oxygen), and common MO nanosheets include molybdenum oxide (MoO3), tungsten oxide (WO3), titanium oxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO) and chalcocite[12,13].

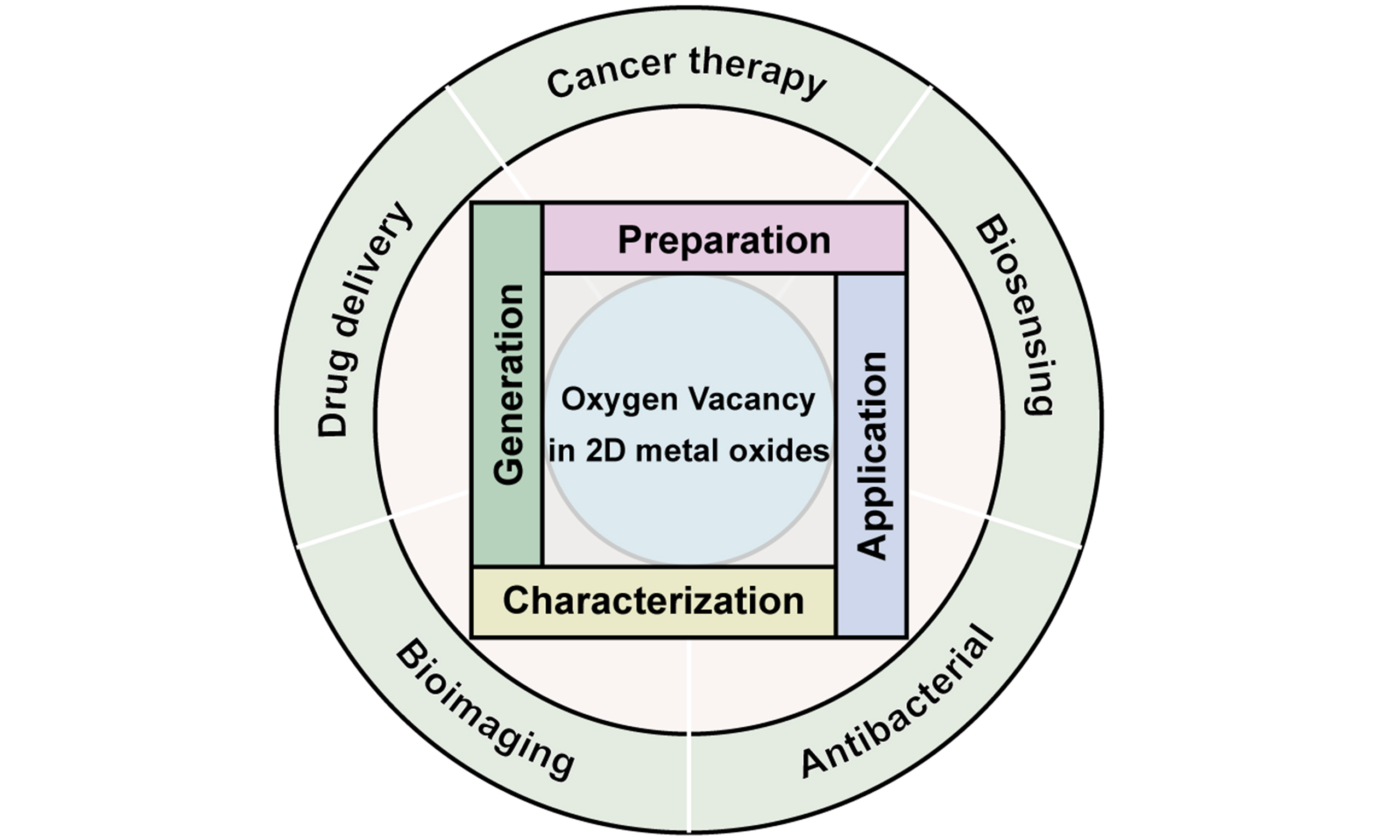

Two-dimensional MOs have unique physicochemical properties such as high photothermal response, catalytic properties, photoluminescence (PL), biocompatibility and degradability due to their large surface-to-volume ratio and finite atomic thickness, which have been widely used in electronics, optics, sensing, energy storage and biomedical fields[7,14-16]. In addition, their basic properties depend on the nature of the metal cation and its oxidation state. Indeed, by changing the stoichiometry of oxygen, the oxidation state of the metal cation is altered and the MOs layer can then exhibit different physicochemical behaviors. Oxygen vacancy (OV, plural: OVs) engineering is an effective strategy to modulate the oxidation state of metals within 2D MOs and is currently at the forefront of research. OVs are defects formed in MOs when lattice oxygen atoms are removed under specific conditions (e.g., thermal annealing or chemical reduction), generating atomic-scale vacancies that disrupt the crystal structure. The construction of OVs in MOs can regulate the band structure, introduce a large number of active sites, facilitate charge carrier transfer/separation, and improve electrical conductivity, thereby affecting their electronic and physicochemical properties[17-20]. Currently, mature techniques for introducing OVs into 2D MOs include thermal treatment, chemical reduction, ion doping, high-energy particle bombardment, interface engineering, electrochemical reduction, ultrasonic treatment, and arc-melting treatment[21]. Moreover, amorphization is also an effective method to introduce OVs, and the long-range disordered atomic arrangement of amorphous structures and the highly unsaturated coordination of surface sites can be used as a platform for the construction of OVs [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Preparation of oxygen vacancies in two-dimensional metal oxides for biomedical applications.

In recent studies, researchers have discovered that the presence of OVs endows 2D MOs with diagnostic and therapeutic functionalities, making them highly suitable for biomedical applications such as cancer therapy, biosensing, bioimaging, antibacterial activities, and so on[17]. Compared to 2D MOs without OVs, OVs-rich 2D MOs can better respond to external stimuli (such as light and sound) to generate heat or reactive oxygen species (ROS) for cancer therapy and bacteriostatic effect[22]. Moreover, they enable sensing and imaging through photoacoustic (PA) signals [Figure 1]. Therefore, this review summarizes advances in preparing OVs-rich 2D MOs and their biomedical applications. An overview of the generation of OVs in 2D MOs, introduction methods and characterization strategies are highlighted. In particular, we also discuss the preparation and characterization of OVs in 2D MOs with an amorphous structure, which extends the approach to introduce OVs in these MOs. Furthermore, we provide an overview of the advancements in the biomedical applications of OVs-rich 2D MOs, with a particular emphasis on their therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities induced by external stimuli. Finally, we outline the prospects and challenges of OVs-rich 2D MOs, especially amorphous 2D MOs, to gain a deeper understanding of the further development of these OVs-rich 2D MOs for biomedical applications and the potential for clinical translational use.

OXYGEN VACANCIES IN 2D METAL OXIDES

Generation of oxygen vacancies

Due to the synthetic constraints, it is impossible to prepare a perfect defect-free structure. OV is a common defect in oxides, especially reducible oxides. In reducible oxides, the cations possess partly filled d- or f- orbitals, which can accept the excess electrons left behind when the oxygen breaks away, thus maintaining charge balance. Such oxides often have semiconductor properties and a small band gap, making the removal of oxygen and the redistribution of excess electrons relatively easy. Common reducible oxides are TiO2, WO3, CeO2, Co3O4, MnO2, Fe2O3, V2O5, and so on[23,24]. The OVs can not only be introduced in the synthesis process of MOs, but also be generated during post-processing due to thermal effects, reduction reactions, high-energy particle irradiation, and other influences. The presence of OVs will produce many local electrons and lead to lattice distortion, which will affect the physical and chemical properties of MOs[25].

Unlike crystalline materials with ordered atomic structures, amorphous materials possess short-range order but long-range disorder[26]. Consequently, amorphous materials are isotropic and devoid of grain boundaries, possessing a higher concentration of dangling electrons, which contributes to their unique physical and chemical properties. Recent studies reveal that the disordered structure of amorphous 2D materials[27-29] generates abundant defects (e.g., OVs), which critically determine material properties. This defect-rich nature enhances their mechanical, electrochemical, and catalytic performance compared to crystalline counterparts[30-32]. However, research specifically targeting OVs in amorphous 2D MOs remains limited.

Preparation of oxygen vacancies

There are many methods to introduce OVs in MOs, which can be roughly divided into the following categories: (1) thermal treatment, (2) chemical reduction, (3) doping, (4) plasma treatment, (5) microwave-assisted method, (6) amorphization and (7) other methods. Table 1 shows the advantages and disadvantages of the various methods.

Comparative analysis of preparation methods for OVs

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Thermal treatment | Simple operation, mature technology, suitable for large-scale production, capable of introducing OVs into the bulk phase, and adjustable number of OVs | High energy consumption, prone to material phase change or structural damage |

| Chemical reduction | Simple operation, fast generation rate of OVs | Prone to introducing impurities, reduction reactions mostly occur on the surface |

| Doping | The type and concentration of dopants can precisely control the density and distribution of OVs, and the OVs are closely combined with dopant ions and are not easily annihilated | Dopants may introduce undesired defects or impurities |

| Plasma treatment | Rapid introduction of OVs, precise regulation of the generation of OVs | High equipment cost, OVs are mainly concentrated on the surface, and there are few in the bulk phase |

| Microwave-assisted method | Fast heating speed, high energy efficiency, simple operation | Local overheating or uneven reaction, limited applicable materials |

| Amorphization | Abundant defect sites, lower oxygen ion binding energy and migration barrier | Structural instability |

Thermal treatment in an anoxic atmosphere (N2, Ar, H2, etc.) or under atmospheres with varying oxygen partial pressures is a practical method to obtain OVs. Under high temperature conditions, the vibration of atoms in MO crystals intensifies, and some oxygen atoms acquire enough energy to overcome the lattice binding, escaping from the surface and subsequently forming OVs. Particularly in a reducing gas or inert gas environment, the oxygen partial pressure decreases, and the oxygen atoms exhibit greater mobility, promoting partial reduction of the metal and resulting in the formation of OVs. Therefore, in this method, the amount of OVs can be precisely controlled by adjusting temperature and atmosphere. N2[33,34] and Ar[35-38] are the most widely used inert atmospheres. Zhou et al.[33] calcined WO3·H2O nanosheets at 400 °C for 2 h under air and N2 atmosphere, and obtained crystal WO3 nanosheets and OVs-rich WO3-x nanosheets, respectively. Wu et al.[36] prepared hierarchical cobalt(II) oxide nanosheets (L-CoO) with OVs by sintering 2D Co(OH)2 at 500 °C under Ar gas flow. These indicate that the oxygen content in the annealing atmosphere is an important factor. Tu et al.[39] prepared a series of BiSmFe2O6 perovskite thin films with different OV contents in atmospheres with different oxygen-argon ratios (between 4:6 and 0:10) through thermal treatment and radio frequency magnetron sputtering deposition methods. The characterization results proved that the OV content in the films increased with the decrease of oxygen partial pressure. In addition to thermal treatment in an inert atmosphere, H2 with reducing power can also be used[40-47]. Ren et al.[41] thermally treated V2O5 nanosheets in H2 at 200 and 300 °C for 2 h to obtain H-V2O5-200 nanosheets and H-V2O5-300 nanosheets, respectively. Compared with H-V2O5-200 nanosheets, the oxygen in H-V2O5-300 nanosheets is partially removed, resulting in a higher concentration of OVs. This result shows that temperature is also important during thermal treatment.

Chemical reduction is a method in which electrons are provided to MOs by a reducing agent, leading to the reduction of metal cations and the removal of oxygen ions, thereby forming OVs. It is worth mentioning that the reduction reaction of MOs and reducing agents usually takes place in a solid or liquid state. In the liquid state, solution-phase reactions can occur directly, while in solid-state reactions an inert atmosphere is required to prevent oxidation of the substance. NaBH4 is a commonly used reducing agent[48-54]. Zhang et al.[53] reduced 2D Co3O4 with NaBH4 solutions of different concentrations at room temperature, and obtained OVs-rich 2D Co3O4 containing OVs of different concentrations. In order to prepare OVs-rich TiO2-x nanosheets, Geng et al.[54] mixed TiO2 nanosheets and NaBH4 in equal proportions and ground them, then transferred the mixture to a tube furnace, heated at 400 °C for 1 h under N2 atmosphere, and finally washed the product with hydrochloric acid, deionized water, and ethanol in turn. Ren et al.[55] adopted a facile method, that is, impregnating Di-n-butyl-magnesium (MgBu2) into TiO2 nanosheets to introduce OVs into the TiO2 nanosheets.

Doping is also a common method for preparing OVs[29,56-63]. By doping metal or non-metal ions into MOs, an unbalanced charge ambiance and lattice distortion can be created, thereby introducing OVs. When the valence state of the doping ion differs from that of the host metal ion, charge balance needs to be achieved by the formation of OVs or the alteration of the metal oxidation state. Moreover, when the radius of the dopant ion does not match that of the host ion, lattice distortion occurs, which lowers the migration barrier for oxygen ions, thereby indirectly promoting the formation of OVs. Dong et al.[56] added ZnO nanosheets to chloropalladium acid solution and calcined them under argon atmosphere to obtain Pd-decorated 2D ZnO nanosheets. Zheng et al.[58] prepared OVs-rich Mo-doped cobalt oxide (MoCoO) nanosheets by adding Na2MoO4·H2O into the cobalt carbonate hydroxide precursor solution (Co(OH)2CO3), then heating it under nitrogen flow with NaBH4 placed upstream of a tube furnace. Wang et al.[59] dispersed TiO2 nanosheets into ethanol, added Co(OAc)2·4H2O, and then used solvothermal method to obtain Co3O4-TiO2 nanosheets. Through characterization, it was found that the introduction of Co3O4 could induce a large number of OVs in TiO2 nanosheets.

Plasma is a matter state consisting of a collection of ions, electrons and non-ionized neutral particles, and the whole is electrically neutral. It is also regarded as the fourth matter state. High-energy particles in plasma bombard the material surface, directly breaking the metal-oxygen (M-O) chemical bonds, causing oxygen atoms to be sputtered off and form vacancies. Furthermore, the collisions of particles transfer energy to the lattice oxygen, enabling them to overcome the binding energy and escape from the surface. Additionally, reactive species in the plasma can chemically interact with the surface, further promoting the formation of OVs without damaging the substrate structure[64]. Plasma treatment is eco-friendly and faster than chemical or thermal methods[65]. Xu et al.[66] first reported the strategy of plasma treatment for preparing OVs. A large amount of OVs were introduced into Co3O4 nanosheets after Ar plasma treatment with a low-power of 100 W in just 120 s. Ding et al.[67] prepared 2D high-entropy FeNiCoMnVOx oxide arrays and further treated them to generate OVs on the oxide surface by Ar plasma treatment.

Microwave, characterized by rapid heating and controllable processing, has been extensively utilized in the optimal synthesis of 2D nanomaterials and MOs[68,69]. The application of microwaves to stimulate vibration and rotational motion for organic molecules possessing dipole moments facilitates the establishment of a microwave reaction system in a superheated region or “hot spot” area. The localized high temperature provides sufficient kinetic energy to oxygen ions, overcoming lattice constraints and enabling them to detach from their original positions to form OVs. Additionally, microwaves can accelerate the reaction kinetics between reducing agents and MOs, efficiently removing lattice oxygen and promoting the formation of OVs. Chen et al.[70] reported a simple microwave-assisted strategy for defect engineering of 2D WO3 that preserves the original crystal structure well. OVs-rich WO3 was synthesized by microwave treatment of WO3 with ethylene glycol as reducing agent. In the presence of Pt precursor, Pt-doped OVs-rich WO3 was prepared by the same method. Wei et al.[71] prepared OVs-rich MoO3-x nanosheets with a large aspect ratio of ~670 by microwave-assisted exfoliation method. Hu et al.[72] rapidly prepared 2D porous La0.2Sr0.8CoO3 perovskite by microwave shock method, effectively exposing its abundant active sites. In addition, the high-energy microwave shock process can precisely introduce Sr2+ into the lattice of LaCoO3, increasing the amount of OV by increasing the oxidation state of Co.

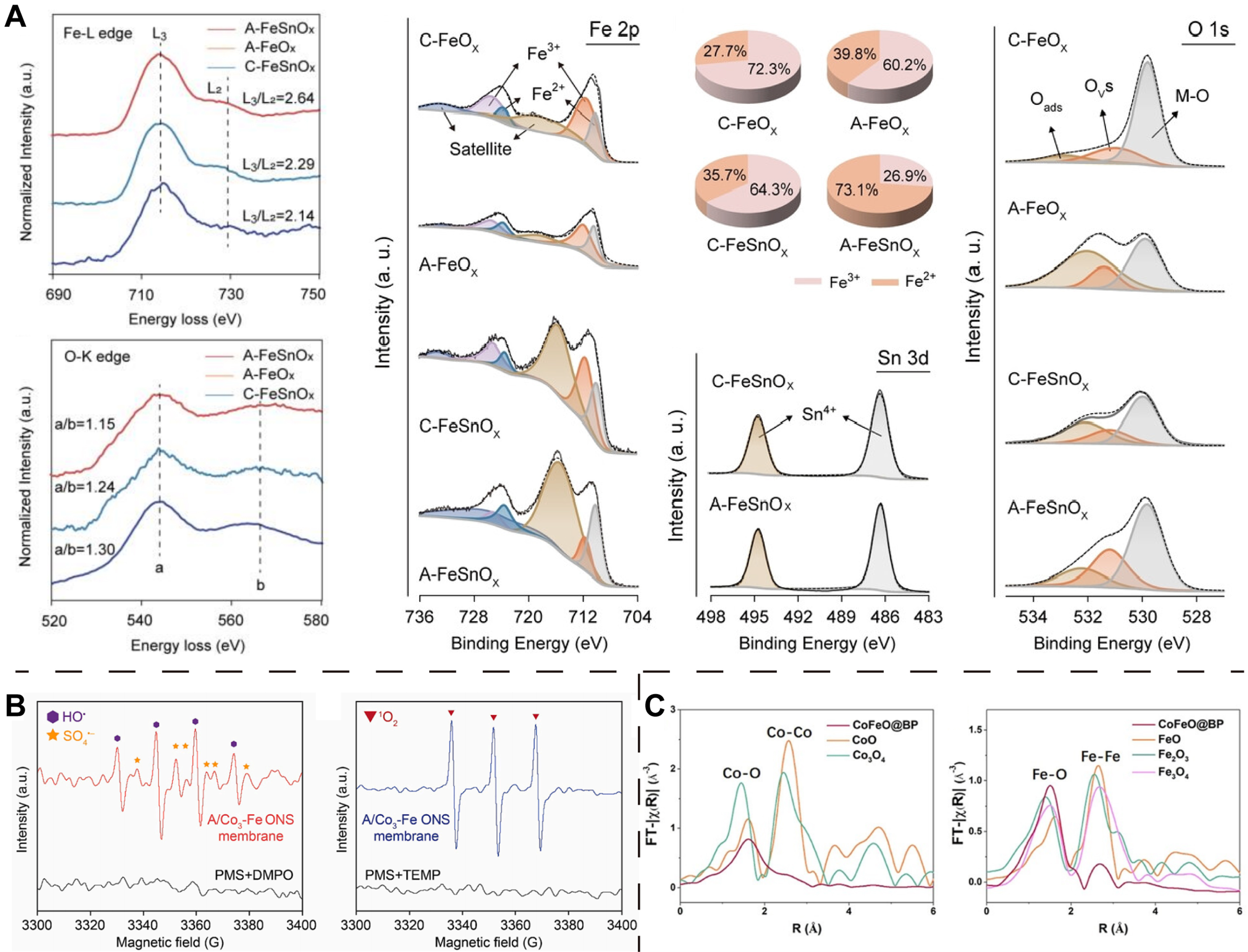

Constructing amorphous structures is also a way to introduce OVs in 2D MOs. Amorphization efficiently introduces OVs into 2D MOs by disrupting the long-range order of crystals, introducing intrinsic defects, and facilitating synergistic reduction reactions. The core mechanism lies in the fact that the disordered structure lowers the binding energy and migration barrier of oxygen ions, while also providing abundant defect sites. Sun et al.[27] synthesized OVs-rich A-FeSnOx nanosheets using a confined ion exchange and templating method. Asif et al.[73] synthesized amorphous cobalt-iron oxide nanosheets (A/Con-Fem ONS) with rich OVs using a NaBH4-based reduction method. Briefly, NaBH4 reducing agent was added to the mixed aqueous solution composed of cobalt (II) nitrate, iron (III) nitrate and cetrimonium bromide, and then the product was washed with ethanol and dried to obtain A/Con-Fem ONS powder. Li et al.[74] synthesized a hybrid CoFeO@BP electrocatalyst with amorphous CoFe oxide on 2D BP via a one-step solvothermal method. Li et al.[75] synthesized amorphous NiO nanosheets on carbon cloth via voltage-controlled electrodeposition in Ni(CH3COO)2 solution. At -1.5 V, pure amorphous NiO formed, while

In addition to the above methods, there are other methods used to prepare OVs, such as ion irradiation[76], space-confined synthesis (templating method)[77-79], sol-gel method[80], electrochemical reduction[81], etc. Ion irradiation is a method of using high-energy ion beams to produce defects on the surface of materials in a controlled manner. Zhong et al.[76] synthesized NiFe layered double hydroxides on titanium foil using a straightforward one-step hydrothermal method and subsequently subjected it to Ar+ ion irradiation to obtain a nanosheet structured NiO/NiFe2O4 heterostructure with rich OVs. Ji et al.[77] utilized angstrom-confined laminar reduced graphene oxide to drive sub-unit-cell growth of atomically thin (< 4.3 Å) 2D MOs with oxygen/metal vacancies. Prusty et al.[80] reported the colloidal synthesis of ~1 nm thick OVs-rich 2D WO3-x nanosheets.

Characterization techniques for oxygen vacancies

By characterizing OVs, one can gain insights into the physicochemical properties, catalytic activity, light absorption capabilities, and other characteristics of materials, providing crucial guidance for material design, preparation, and application. Commonly used methods for characterizing OVs include X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), scanning tunneling microscopy (STM), scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS), PL spectroscopy, and positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS), etc.[82,83]. Despite the availability of these numerous characterization techniques, no single method can unequivocally identify OVs. Therefore, to confirm the presence of OVs, it is necessary to employ multiple characterization techniques that support each other.

XPS is a surface analysis technique that provides chemical state and elemental quantification information of material surfaces. Through XPS analysis, changes in the types of chemically adsorbed oxygen resulting from OVs can be observed, thereby indirectly confirming the presence of OVs. Typically, the O1s XPS signal can be deconvoluted into lattice oxygen with binding energy ranging from 527.7 to 530.5 eV, vacancy oxygen with binding energy between 531.1 and 532 eV, and other surface-adsorbed oxygen species with binding energy greater than 532 eV[84]. Figure 2A displays the O1s XPS spectra of CoZrO2 nanosheets prepared by different methods, where the O1s peaks at 529.9, 531.8 and 533.4 eV can be attributed to lattice oxygen (Olattice), oxygen adsorbed on OVs (OV), and surface chemically adsorbed water (Oad), respectively[78]. The relative content of OVs can also be obtained by calculating the peak areas.

Figure 2. The O1s XPS spectra (A) and EPR spectra (B) of CoZrO2(0), CoZrO2(0.05), ACT-CoZrO2(0) and ACT-CoZrO2(0.05). (Reproduced with permission[78]. Copyright 2024, Wiley). XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance; ACT: amorphous-to-crystalline transformation.

EPR, a magnetic resonance technique based on the magnetic moment of unpaired electrons, can be employed for both qualitative and quantitative detection of unpaired electrons within atoms or molecules of substances. Given that most of the magnetic moment contribution originates from electron spin, EPR is also called electron spin resonance (ESR). Typical EPR signals for OVs often appear near g = 2.003, and the concentration of OVs can be determined through the intensity of these signals. As shown in Figure 2B, a typical EPR signal for OVs is observed at g = 2.003, and the concentration of OVs derived from the intensity corresponds to the results obtained by XPS[78]. Therefore, in practical applications, XPS and EPR are often used in conjunction to confirm the presence of OVs.

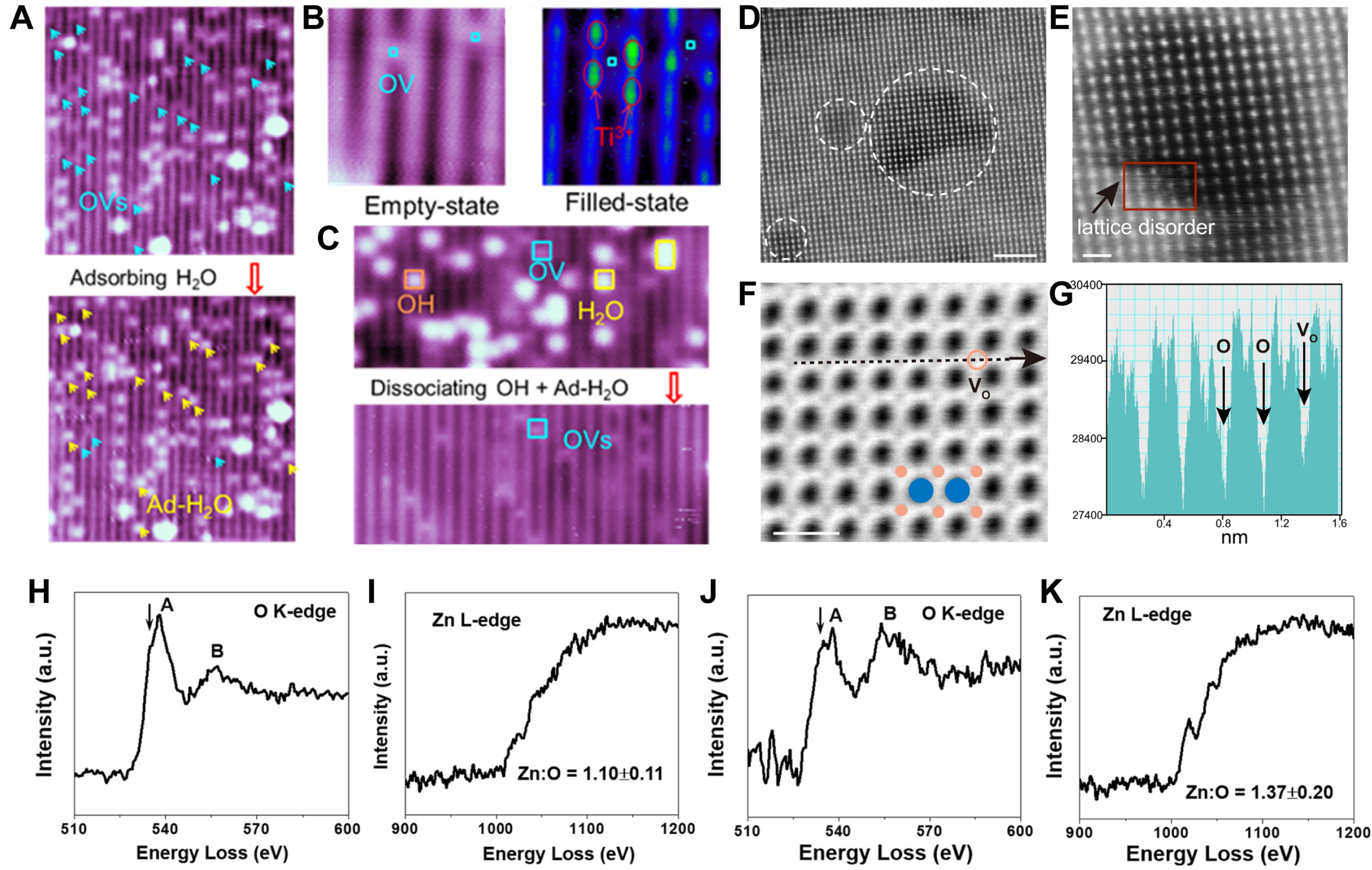

STM employs atomic-scale tips to scan samples, enabling the intuitive visualization of the distribution and morphology of OVs on material surfaces. It is primarily used for observing surface OVs and their interactions with external molecules. Feng et al.[85] utilized STM to clearly observe OVs and Ti3+ ions in TiO2 single crystals [Figure 3A and B] and employed in-situ techniques to investigate electrocatalytic dynamics occurring on the TiO2 (110) surface associated with OVs [Figure 3C].

Figure 3. (A) STM image of TiO2 (110) surface (partially reduced) pre-/post-water adsorption, highlighting OVs (light blue arrows) (

STEM and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) enable atomic-scale characterization of materials, detecting and quantifying OV-induced lattice changes and interlayer dynamics across varying OV concentrations. Chen et al.[86] used STEM to observe OVs-rich Bi2O2CO3 nanosheets. In high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images, local lattice disorder in the nanosheets caused by unsaturated coordination of metal atoms can be clearly detected [Figure 3D and E]. Angle bright-field STEM (ABF-STEM) images further identify the nonperiodic intensity of oxygen, demonstrating the presence of OVs [Figure 3F and G].

In EELS analysis, when a high-energy electron beam passes through the transmission region of a sample, it undergoes inelastic scattering with the atoms or electrons in the sample, resulting in the loss of a portion of its energy. The values of these energy losses can reveal information about the types of elements, chemical states, electronic structures, and local environments present in the sample. By collecting and analyzing these lost energies, an EELS spectrum can be obtained, which allows for an in-depth investigation of the composition and structure of the sample. Yin et al.[87] compared the EELS spectra of cross sections of ZnO nanosheets with or without Al2O3 coating [Figure 3H-K]. It is found that after coating the amorphous Al2O3 coating, the Zn:O ratio of ZnO nanosheets changes from 1.10 to 1.37. Moreover, at 534.9 eV, a significantly more intense shoulder peak is formed at the O K-edge [Figure 3J]; at 1,024.2 eV, the Zn L-edge exhibits a higher shoulder peak intensity [Figure 3K], both of which are characteristics of OVs in ZnO. These results indicate that the Al2O3 coating induces OVs in ZnO nanosheets.

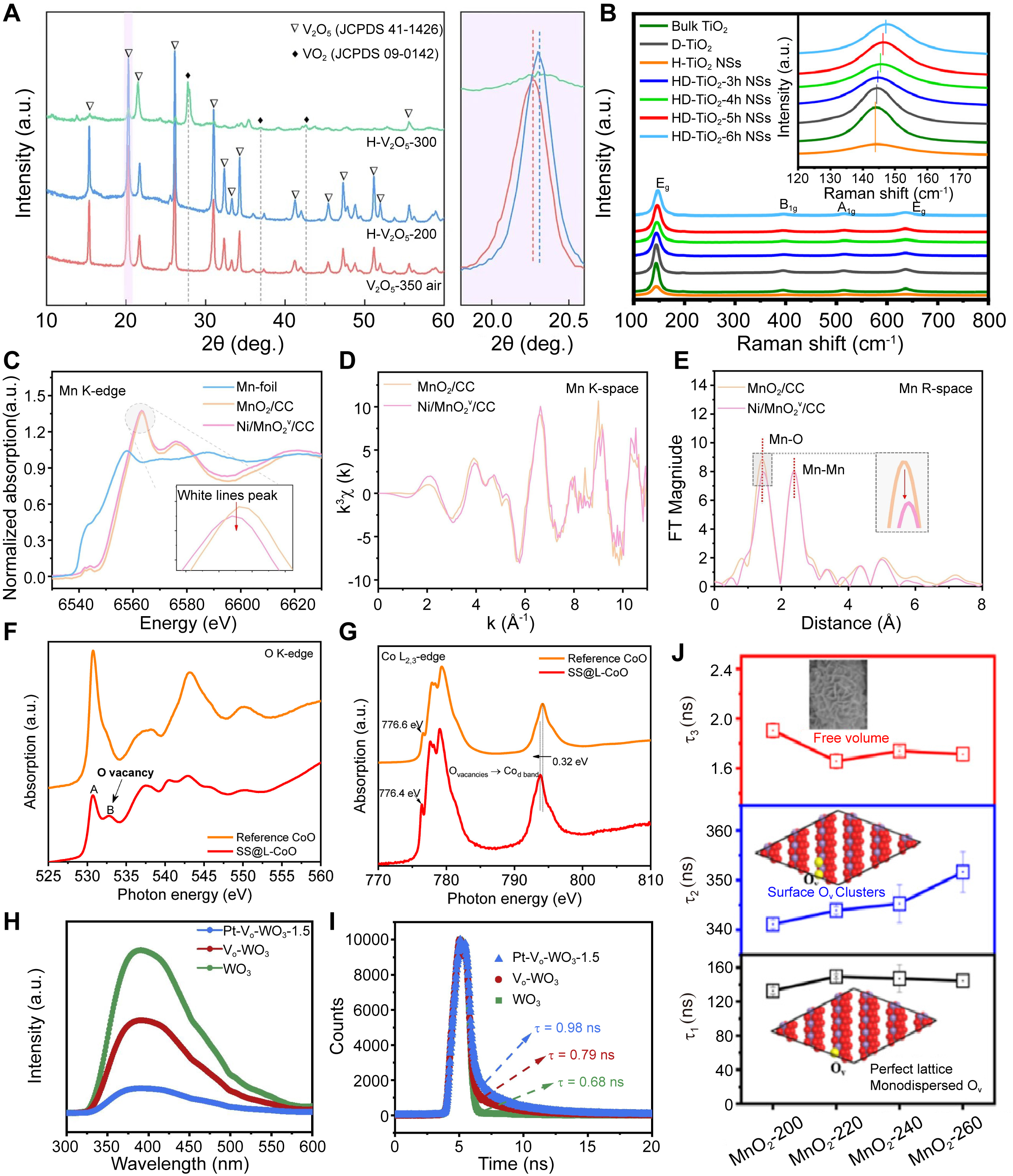

In MOs, the presence of OVs can affect the crystal structure of the material, such as altering lattice constants or inducing lattice distortions. These changes can be detected by XRD, thereby indirectly inferring the existence of OVs. For instance, Figure 4A presents the XRD patterns of H-V2O5 after annealing in hydrogen atmosphere at different temperatures. The (001) diffraction peak of H-V2O5-200 exhibits an angular shift, signifying reduced d-spacing and OVs in the crystal[41]. However, XRD has certain limitations in detecting OVs. Since XRD primarily reflects the average crystal structure of the material, it may not be sensitive enough to detect local or minute structural changes. Furthermore, the distribution and concentration of OVs in MOs may also influence the XRD detection results. Therefore, when detecting OVs in MOs, it is often necessary to combine other characterization techniques.

Figure 4. (A) XRD patterns of V2O5 nanosheets treated under different conditions[41]. (Open access); (B) Raman spectra of bulk TiO2, surface defected TiO2 (D-TiO2), holey TiO2 nanosheets (H-TiO2 NSs) and holey TiO2 nanosheets treated at 500 °C for different times (HD-TiO2 NSs). (Reproduced with permission[46]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier); (C-E) XAFS analysis of different Mn-containing materials, including Mn K-edge XANES spectra (C), Mn K-edge EXAFS spectra (D), and FT-EXAFS spectra (E). (Reproduced with permission[89]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier); (F and G) O K-edge (F) and Co L2,3-edge (G) XANES spectra of SS@L-CoO and reference CoO. (Reproduced with permission[36]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier); (H and I) PL spectra (H) and time-resolved transient PL decay (I) of WO3, Vo-WO3, and Pt-Vo-WO3-1.5. (Reproduced with permission[70]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier); (J) Positron lifetimes of different lifetime components of δ-MnO2 catalysts prepared under different hydrothermal temperatures. (Reproduced with permission[92]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society). XRD: X-ray diffraction; XAFS: X-ray absorption fine structure; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy; EXAFS: extended X-ray absorption fine structure; FT: Fourier transform; PL: photoluminescence.

Raman spectroscopy, by measuring the scattered light from molecular vibrations in MOs, can reveal the impact of OVs on the local and electronic structures, thereby enabling the detection of OVs. The incorporation of OVs alters molecular vibration modes, manifesting as Raman peak shifts, broadening, or the emergence of new peaks. Zhang et al.[46] observed that with an increase in hydrogenation duration, the intense Eg(1) mode in the Raman spectra of holey TiO2 nanosheets underwent a significant shift towards higher frequencies [Figure 4B], indicating the distortion and disruption of symmetric O-Ti-O bonds. The degree of shift of the Eg(1) mode positively correlates with the concentration of OVs.

XAFS, also known as X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), is an important spectroscopic technique that utilizes the absorption characteristics of X-rays to analyze the internal structure and elemental composition of materials. XAFS comprises XANES (X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy) and EXAFS (extended X-ray absorption fine structure). XANES reveals the absorbing atom’s electronic structure, valence state, symmetry, and orbital occupancy. On the other hand, EXAFS offers insights into the coordination atoms surrounding the absorbing atom, such as the types of coordinating atoms, bond lengths, coordination numbers, and degrees of disorder[88]. Liu et al.[89] analyzed Mn local environments in Ni/MnO2v/CC using XAFS with MnO2/CC and Mn foil references [Figure 4C-E]. The Mn absorption edge exhibited a low-energy shift alongside reduced white-line peak intensity [Figure 4C], indicating reduced Mn oxidation states post-Ni loading. EXAFS spectra showed attenuated oscillation intensities in Ni/MnO2v/CC [Figure 4D], reflecting Ni-induced distortions around Mn sites. FT K2-weighted spectra further revealed weakened Mn-O bond peaks [Figure 4E], confirming OV formation near Mn. Wu et al.[36] observed enhanced OV signatures in SS@L-CoO via O K-edge XAS [Figure 4F]: peak B (532.8 eV, OV-related Co 3d-O 2p hybridization) intensified significantly versus peak A (530.7 eV, fully coordinated Co-O). This aligns with Co L2,3-edge shifts to lower energy [Figure 4G], confirming electron transfer from OVs to the Co d-band.

The PL spectrum represents the intensity/energy distribution of emitted light wavelengths generated by electron-hole recombination under light excitation. Since the measurement of PL is directly based on the recombination of carriers, this recombination process is closely related to the nature and density of defects within the material. PL spectroscopy detection methods can be classified into continuous excitation and pulsed excitation methods based on the mode of excitation light. The continuous excitation method measures the steady-state PL spectrum of the material, while the pulsed excitation method measures the time-resolved PL spectrum. Chen et al.[70] observed through PL spectroscopy that compared to WO3, Pt-Vo-WO3-1.5 and Vo-WO3 exhibited weakened fluorescence intensity, indicating an enhanced ability to inhibit the recombination of photogenerated carriers through the enrichment of OVs and hybridization with Pt sites [Figure 4H]. Furthermore, time-resolved PL spectra revealed carrier lifetimes of 0.68 ns (WO3), 0.79 ns (Vo-WO3), and 0.98 ns (Pt-Vo-WO3-1.5) [Figure 4I], confirming OVs in Vo-WO3 and Pt-Vo-WO3-1.5.

PALS sensitively probes nanoscale defects in materials, characterizing OV types and concentrations through positron lifetime analysis. Positrons injected into materials annihilate with electrons, releasing detectable γ-rays. The emission-to-detection interval defines the positron lifetime (τ), which correlates with vacancy size/type. The lifetime comprises three components (τ1, τ2, τ3) with corresponding intensities (I1, I2, I3). Generally, smaller OV (such as monovacancies, etc.) located in the bulk of the material lead to an increase in τ1, while larger size defects (such as OV clusters) located at the surface or subsurface of the sample result in elongation of τ2. τ3 is probably assigned to the annihilation of orthopositronium atoms formed in the large voids (nanoscale) in materials[90]. Furthermore, the I1/I2 ratio quantifies the relative concentration of small versus large vacancies[91]. Lu et al.[92] synthesized a series of MnO2 nanomaterials by varying the hydrothermal reaction temperature and investigated their OVs through PALS. The τ2 value increased significantly with the elevation of the hydrothermal temperature [Figure 4J]. MnO2-260 exhibited the highest τ2 value, indicating the highest concentration of OV clusters formed among all the catalysts.

The disordered state of amorphous materials poses significant challenges for both experimental and theoretical research. For instance, despite the tremendous advancements in spherical aberration correction techniques and cryogenic electron microscopy, the most basic structure or atomic arrangement of amorphous materials remains elusive and has not been effectively elucidated. Consequently, electron microscopical analysis methods such as STM, STEM, and HRTEM, which are utilized to characterize OVs in crystalline materials, are no longer applicable in the context of amorphous materials. Fortunately, spectroscopic (Raman spectroscopy, PL, PALS, etc.) and energy spectrum (EPR, XPS, EELS, etc.) analysis remain viable for the identification and analysis of OVs in amorphous materials. For example, Zhao and co-workers[27] employed a series of characterization techniques (e.g., EELS, PALS, XPS and EPR) to confirm the existence of OVs and to analyze the relative concentration of OVs in different amorphous 2D MOs materials [Figure 5A]. Similarly, Asif et al.[73] demonstrated the presence of OVs in A/Con-Fem ONS using EPR method and O 1s XPS analysis [Figure 5B]. Li et al.[74] demonstrated the existence of OVs in CoFeO@BP by O 1s XPS and XAS analysis [Figure 5C].

Figure 5. (A) EELS of the Fe-L edge and O-K edge of A-FeSnOx, A-FeOx and C-FeSnOx; XPS spectra of C-FeOx, A-FeOx, C-FeSnOx, and A-FeSnOx: Fe 2p, corresponding +3/+2 valence ratio of Fe, Sn 3d, O 1s. (Reproduced with permission[27]. Copyright 2024, Wiley); (B) EPR spectroscopy analysis of A/Co3-Fe ONS membrane. (Reproduced with permission[73]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier); (C) EXAFS spectra of Co and Fe K-edge for CoFeO@BP together with various references. (Reproduced with permission[74]. Copyright 2020, Wiley). EELS: Electron energy loss spectroscopy; XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance; ONS: oxide nanosheets; EXAFS: extended X-ray absorption fine structure.

BIOMEDICAL APPLICATION OF OXYGEN VACANCIES-RICH 2D METAL OXIDES

Previous studies have demonstrated that the introduction of OVs may bring about changes in the electronic and chemical properties of 2D MOs: (1) modulation of the energy band structure promotes carrier separation and affects the electronic structure, (2) charge transfer regulates the reaction kinetics, and (3) affects the electrical conductivity of MOs[21]. This series of changes improves the photothermal conversion capacity of 2D MOs and enhances their ability to generate ROS, thus improving their therapeutic and diagnostic effectiveness. Therefore, OVs-rich 2D MOs possess a kind of biomedical applications, mainly in the fields of cancer therapy, drug delivery, biosensing, bioimaging, and antibacterial applications.

Cancer therapy

Traditional cancer therapies (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy) face challenges such as invasiveness and off-target toxicity[93,94], driving demand for noninvasive strategies such as photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT)[17,93]. The 2D OVs-rich MOs uniquely address these limitations by leveraging OVs to enhance both targeting and therapeutic efficacy. For example, 2D MOs with rich OVs, such as molybdenum oxide[95], tungsten oxide[96], play a pivotal role in optimizing photothermal agents (PTAs) for PTT. By narrowing the bandgap of 2D MOs, OVs extend optical absorption into the near-infrared light II (NIR-II) window, enabling deep-tissue penetration and minimizing damage to healthy cells. Under NIR irradiation, OVs suppress electron-hole recombination, converting light energy into heat (with temperature above 47 °C[97]) for tumor ablation. Simultaneously, OVs act as catalytic sites to generate ROS: photogenerated electrons reduce O2 to O2•-, while holes oxidize H2O/OH- to •OH[98]. This dual-action ROS storm (O2•- and •OH) synergizes with hyperthermia, overcoming tumor heterogeneity and resistance[99].

Despite their low toxicity, OVs-rich 2D MOs face challenges in rapid systemic excretion due to their larger size, leading to prolonged accumulation in reticuloendothelial organs (e.g., liver and spleen)[100]. The inability to effectively clear these inorganic nanomaterials may lead to long-term toxicity issues, thereby constraining their further clinical applications[101]. Ideally, OVs-rich 2D MOs can effectively accumulate and remain in the tumor after systemic administration, while being rapidly excreted by normal organs. Since the tumor microenvironment (TME) is more acidic and hypoxic than normal tissues[102,103], Song et al.[104] synthesized pH-responsive polyethylene glycol (PEG)-functionalized molybdenum oxide nanosheets (MoOx-PEG) that maintain stability in acidic TMEs while degrading at physiological pH, enabling tumor-specific accumulation and strong NIR absorption for PTT. The high surface area of the nanosheets further supports therapeutic molecule loading, facilitating combinatory drug delivery and PTT for enhanced anticancer efficacy. Liu et al.[105] developed OVs-rich MoOx@M-SN38 nanosheets by modifying MoOx nanosheets with phospholipids, tumor cell membranes, and the anticancer drug SN38 [Figure 6A], creating a dual-modality platform for PTT and chemotherapy. These biodegradable nanosheets exhibit high photothermal conversion efficiency and enhanced antitumor immunogenicity, demonstrating promising potential as a multifunctional nanomedicine system.

Figure 6. The combination of PTT and chemotherapy. (A) Preparation and antitumor mechanism of biomimetic layered MoOx@M-SN38 nanosheets. (Reproduced with permission[105]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier); (B) The fabrication and the multifunctions of PEG@WO2.9@DOX nanosheets. (Reproduced with permission[50]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier). PTT: Photothermal therapy; PEG: polyethylene glycol; DOX: doxorubicin; NIR: near-infrared; SN-38: 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin; MoOx@M-SN38: cell membrane wrapped MoOx loaded with SN38; ICD: immunogenic cell death; DAMPs: danger associated molecular patterns; DCs: dendritic cells; STING: stimulator of interferon genes; cGAS: cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase; cGAMP: 2’3’ cyclic GMP (guanosine monophosphate)-AMP (adenosine monophosphate); P-STING: phosphorylated-STING; IFN: interferon; CTLs: cytotoxic T cells; Ths: helper T cells; M2: M2 macrophages; Tregs: regulatory T cells; NSs: nanosheets; PEG@WO2.9@DOX: PEG-coated WO2.9 loaded with DOX; PA: photoacoustic; CT: computerized tomography; FL: fluorescence.

NIR light has two biowindows, namely NIR-I and NIR-II, with corresponding wavelength ranges of 700-

NIR light, even in the NIR-II region, is difficult to penetrate deep tissue, resulting in PTT and PDT being only suitable for treating superficial tumors and having limited efficacy for deep or large tumors. As a result, cancer treatments that utilize other external motivators have been developed, such as sonodynamic therapy (SDT). SDT is a cancer therapy approach that uses ultrasound (US) to activate sonosensitizers (SSs) to produce ROS to kill tumor cells[33]. One of the competitive advantages of SDT is the higher tissue penetration rate of US (10 cm), so it has greater potential in cancer clinical treatment[22,107]. Pure TiO2 nanomaterials serve as excellent inorganic SSs; however, their rapid electron-hole recombination (50 ±

Figure 7. SDT and CDT. (A) The Pt/N-CD@TiO2-x p-n junction platform integrates platinum-crosslinked nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots (Pt/N-CDs) and OVs-rich TiO2-x nanosheets, enabling glutathione (GSH) detection/depletion and enhanced sonodynamic therapy (SDT); (B) Tumor growth curves of the mice after different treatments (n = 5); (C) Survival curves of mice after various treatments. (Reproduced with permission[54]. Copyright 2021, Wiley); (D) Synthesis of OVs-rich BiO2-x nanosheets for CDT; (E) Free radical regulation of OVs-rich BiO2-x nanosheets in cancer and noncancerous cells associated with the formation of immunosuppressive TME; (F) 4T1 tumor growth curves with different treatments (n = 5); (G) Body weight changes following treatments. (Reproduced with permission[116]. Copyright 2021, Wiley); (H) Cu2-xO@TiO2-y z-scheme junctions for enhanced CDT-SDT combination tumor therapy; (I) Tumor growth curves of mice after different treatments; (J) Survival growth curves of mice after different treatments. (Reproduced with permission[49]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. OVs: Oxygen vacancies; CDT: chemodynamic therapy; ROS: reactive oxygen species; US: ultrasound; NSs: nanosheets; TME: tumor microenvironment; GSSG: glutathione disulfide.

The cancer treatment modalities discussed above all require an external energy source, while the chemodynamic therapy (CDT) first proposed by Shi et al. in 2016 requires no external excitation[114]. CDT is a novel tumor therapy technology that uses TME to activate the nanomedical Fenton or Fenton-like reactions to generate tumor-targeting •OH via strong oxidation[115]. TME biochemical features (mild acidity, high GSH, elevated H2O2) enable precise tumor-normal tissue discrimination[102,107]. Yuan et al.[116] engineered OVs-rich BiO2-x nanosheets as an environmentally adaptive CDT regulator [Figure 7D-G]. This system selectively catalyzes ROS production in cancer cells through enzymatic logic reactions while scavenging free radicals and immunosuppressive mediators in noncancerous TME cells. The mechanism study shows that both regulatory behaviors are dominated by OVs, which is very suitable for free radical catalysis kinetics.

Geng et al.[49] developed a Cu2-xO@TiO2-y Z-scheme heterojunctions to achieve tumor eradication with the combination of SDT and CDT [Figure 7H]. The narrow bandgaps of the Cu2-xO nanodots and TiO2-y nanosheets and the Z-scheme junctions between their interfaces greatly improve the spatial separation dynamics of US-generated carriers and facilitate the generation of ROS, thereby improving SDT performance. In addition, the nanomaterial has excellent redox activity, which can catalyze H2O2 to produce •OH (Fenton-like reaction) and consume endogenous GSH. The mouse model experiment proved the superiority of the combination of SDT and CDT [Figure 7I and J].

Drug delivery

The 2D MOs exhibit high specific surface areas, offering abundant anchor points. This makes them promising in drug delivery, capable of carrying large amounts of anticancer drugs[117]. Second, they have high chemical and physiological stability, ensuring that the drug is released from the carrier in a sustained manner, rather than explosive release. Third, some unique chemical components in 2D MOs can interact specifically with drug molecules and respond to external factors to achieve on-demand drug release. Fourth, the multifunction of the carrier itself can achieve collaborative therapy, such as combined PTT and chemotherapy, combined PDT and chemotherapy, etc.[99]. These unique features and functions render 2D MOs an excellent candidate for drug delivery.

These 2D MOs loaded with chemotherapy drugs can accumulate in tumor tissues through enhanced permeability and retention effects and release drugs under the influence of TME characteristics (mild acidity, high GSH concentration, elevated H2O2 level, etc.) to achieve targeted therapy. For example, MoOx nanosheets are functionalized with PEG to synthesize PEGylated nanosheets (MoOx-PEG), which exhibit pH-responsive degradation and possess the potential for targeted drug delivery. In addition, MoOx-PEG nanosheets are an effective PTA and can be loaded with a significant number of anticancer drugs, realizing the combined tumor therapy of PTT and chemotherapy[104]. PEG@WO2.9 nanosheets loaded 102% DOX, releasing 5.9% at pH 7.4 vs. 21.1% at pH 5.0 within 24 h. Under 1,064 nm laser irradiation (5 min), DOX release from PEG@WO2.9@DOX reached 57.2% (pH 7.4) and 75.6% (pH 5.0), demonstrating pH- and NIR-triggered release [Figure 6B][50].

Bioimaging

OVs-rich 2D MOs possess unique physicochemical properties, enabling them to serve as contrast agents (CAs) to enhance the imaging performance of various imaging modalities. Compared with traditional CAs, OVs-rich 2D MOs can achieve a combination of diagnostics and therapeutics, which not only has the ability to enhance cancer imaging, but also has the function of treating cancer.

OVs-rich 2D MOs for fluorescence imaging usually combine conventional organic fluorescein. Specifically, organic fluorescein is loaded onto 2D MOs to make a probe, which is then injected into the body to effectively accumulate on tumor tissue by identifying mildly acidic TME, and finally achieve fluorescence imaging under excitation of specific wavelengths of light[49,50,105]. Inorganic quantum dots vs. organic fluorophores exhibit superior fluorescence for bioimaging, including high quantum yields, tunable wavelengths, and photostability[100,118]. CD co-doped with Pt and N (Pt/N-CD) is a good fluorescent probe to detect the presence of intracellular GSH [Figure 7A]. GSH-mediated Pt2+ → Pt0 reduction in tumor cells triggers N-CD release from self-assembled NPs, restoring fluorescence.

Photothermal imaging has become one of the most commonly used biological imaging technologies due to its advantages of real-time and high sensitivity. The PTAs used in PTT, because of their excellent photothermal conversion characteristics, are also highly efficient photothermal imaging CAs, which can realize synchronous imaging monitoring during the treatment process[104,105,119]. However, the application of photothermal imaging is constrained by limitations in imaging depth, resolution, and contrast, thereby restricting its broader utilization. The emergence of PA imaging technology solves this problem perfectly. To provide high-resolution and high-contrast deep tissue imaging, PA imaging combines the high contrast of optical imaging with the great penetration depth of ultrasonic imaging[120,121]. In this technology, biological tissue is illuminated with pulsed laser light. The light absorption properties of the tissue convert the incident light energy into heat energy, triggering thermal expansion and the subsequent emission of ultrasonic waves, known as PA signals. These PA signals are then precisely detected and processed to reconstruct PA images of the illuminated tissue. In order to further improve the contrast and resolution of the PA imaging, it is necessary to develop PA imaging CAs with high PA imaging properties[121]. For PA imaging and multimodal imaging, Gong et al.[122] developed a unique, extremely stable, and effective peroxidase-like nanozyme (FeWOx nanosheets) [Figure 8A]. FeWOx nanosheets with abundant OVs and exposed Fe atoms exhibit high nanozyme activity for H2O2 decomposition into •OH. After PEG modification, FeWOx-PEG nanosheets exhibit good stability and can anchor the guest dye molecules firmly. It was found that FeWOx-PEG nanosheets can effectively trigger the catalytic oxidation of 3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine by H2O2 to generate oxidized TMB (oxTMB), which has a high absorbance for light at a wavelength of 900 nm [Figure 8B]. Subsequently, the FeWOx-PEG@TMB@IR780 (FeTIR) nanoprobe was obtained by loading TMB and near-infrared dye (IR780 as the internal reference) on the FeWOx-PEG nanosheet for H2O2 ratio-metric PA imaging. Due to the high H2O2 level (≈100 × 10-6 M) in the TME, the tumor PA signal at 900 nm rose dramatically over time following intratumoral injection of FeTIR nanoprobe, reaching its maximum intensity at 2 h, but the PA signal at 800 nm hardly changed [Figure 8C-E]. On the other hand, the opposite muscle’s PA signal barely changed over time. These findings imply that the tumor’s natural H2O2 can activate the nanozyme-based ratio-metric probe. FeTIR can also be used to image inflammatory diseases that produce excess H2O2 in tissues [Figure 8F-H]. FeWOx-PEG nanosheets can be used as promising multimodal imaging CAs for PA imaging, X-ray computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, and fluorescence imaging [Figure 8A]. Firstly, FeTIR nanoprobes containing IR 780 dyes can be used as fluorescent agents to achieve fluorescence imaging. Secondly, CT imaging is another application for FeWOx-PEG nanosheets with a substantial X-ray attenuation W element. With an increase in concentration, the CT signal of FeWOx-PEG nanosheets rose dramatically. Lastly, these nanosheets can be employed as a T2-shortening agent for MR imaging because of the iron that is present within them. Scanning by a MR scanner, FeWOx-PEG nanosheets showed a concentration-dependent enhancement of MR signals.

Figure 8. OVs-rich bimetallic oxide FeWOx nanosheets as peroxidase-like nanozyme for cancer multimodal imaging. (A) Design schematic; (B) Time-dependent TMB oxidation by FeWOx-PEG (0.5 mM) and H2O2 (100 μM); (C) PA imaging scheme for subcutaneous tumors; (D) In vivo ratiometric PA imaging of tumors post FeTIR injection; (E) PA900/PA800 ratios in tumors at various time points; (F) PA imaging scheme for LPS-induced inflammation; (G) Ratiometric PA imaging of inflamed tissues; (H) PA900/PA800 ratios in inflammation over time. (Reproduced with permission[122]. Copyright 2020, Wiley). ***P < 0.001. OVs: Oxygen vacancies; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PA: photoacoustic; MR: magnetic resonance; FeTIR: FeWOx-PEG@TMB@IR780; LPS: lipopolysaccharide.

Biosensing

In addition to their high performance in cancer treatment and diagnostic imaging, these OVs-rich 2D MOs can serve as novel biosensing platforms for detecting biomolecules and biological effects. The large surface area of the 2D planar structure allows many sensor molecules to be immobilized, and leads to short detection time and low detection limits. OVs-rich surfaces enable light-induced free carrier oscillations, driving broadband light absorption. Photoelectric chemistry (PEC) sensing integrates electrochemistry and photochemistry, offering high sensitivity, robustness, cost-effectiveness, and instrumental simplicity. Jiang et al.[123] engineered a plasma-enhanced PEC biosensor using OV-engineered dWO3·H2O nanosheets and

Antibacterial

Bacterial infections not only threaten public health, but also place a heavy burden on the economy. Antibiotics were once expected to be the terminators of all bacterial diseases[124]. However, the misuse and overuse of antibacterial drugs such as antibiotics has led to the development of resistance in many bacteria. Therefore, developing novel antimicrobial agents to combat bacterial resistance is critical for effective sterilization. Photochemical bacterial inactivation has attracted extensive attention due to its environmental friendliness, excellent stability, and high reusability[125]. The method effectively kills bacteria through the generation of ROS on photocatalysts under light irradiation. In addition, these inorganic antimicrobial agents do not cause the bacteria to develop drug resistance. Bismuth trioxide (Bi2O3) has proven to be a valuable photocatalyst and exhibits excellent photocatalytic properties under visible light. In addition, Bi2O3 photocatalysts are considered harmless to humans and the environment. Ma et al.[126] prepared OVs-rich

Figure 9. Photochemical and photoelectrochemical (PEC) bacterial inactivation. (A) Morphologic changes and synthesis of (i) pristine BWO, (ii) KCl_BWO, and (iii) IL_BWO3; (B and C) Photocatalysis of E. coli (B) and S. aureus (C) inactivated by different samples in aqueous solution under UV-vis light irradiation[127]. (Open access); (D) Diagram of Sn3Ox/Ni foam photoanode for bacterial inactivation; (E) PEC inactivation efficiency across bacterial species; (F) Bacterial colony images; (G) Pre-/post-PEC treatment (30 min) SEM and fluorescence microscopy of Chlr E. coli. (Reproduced with permission[128]. Copyright 2023, Youke Publishing Co., Ltd). SEM: Scanning electron microscope; [TBA][Cl]: tetrabutylammonium chloride; MRSA: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Compared with the photochemical method, the PEC bacterial inactivation method can utilize both light energy and electricity to drive the ROS generation process, thereby improving the charge separation efficiency and enhancing the continuous generation ability of ROS. In addition, the photocatalytic electrode that can be reused does not produce secondary pollution. Wang et al.[128] synthesized surface-amorphized OVs-rich Sn3Ox nanosheets on Ni foam via a one-step hydrothermal method, enhancing PEC bacterial inactivation [Figure 9D]. This approach offers a simpler and safer alternative to conventional H2 post-treatment for OV generation. With the improvement of PEC performance, the photoanode was 100% effective in removing drug-resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in water within 30 min

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This review describes the generation of OVs in 2D MOs nanomaterials, characterization techniques and their applications in biomedicine. In the past few decades, researchers have recognized that the presence of OVs has a significant effect or modification on the microstructure of nanomaterials and has a substantial impact on both their physical and chemical properties. Meanwhile, OVs engineering has developed greatly as an important and effective technology. Consequently, theoretical studies on the structure and characterization of OVs nanomaterials are relatively well established. In addition, OVs are now synthesized via diverse methods (e.g., ion doping, reduction), yet persistent challenges in precision and scalability demand innovative solutions. For example, amorphous 2D MOs have oxygen-rich vacancies, but the preparation and controllable regulation of corresponding OVs is currently in its infancy. Additionally, the OV characterization technique for amorphous 2D MOs is more limited. Therefore, there is a need to further advance the detection methods of OVs in amorphous 2D MOs for more accurate studies.

In this review, 2D MOs engineered with OVs exhibit multifunctional properties (optical, electrical, magnetic) for biomedical applications, including therapeutic modalities (e.g., PDT, CDT, SDT, PTT) and theranostic integration via imaging tools such as PA. Despite growing applications in nanomedicine, OV-enhanced 2D MOs remain in a nascent stage, with critical challenges in reproducibility, biosafety, and targeted delivery requiring resolution to advance clinical translation.

1. The size of OVs-rich 2D MOs should be designed and prepared to meet the requirements of practical applications. For example, the preparation of 2D MOs with sufficiently small lateral dimensions (< 100 nm) is necessary to meet the requirements for their easy transport within the vasculature and to penetrate and accumulate into the tumor tissue for therapeutic purposes. It should also be considered to transition the microscopic scale of individual OVs-rich 2D MOs to the three-dimensional macroscopic level to build larger surface-active area structures for applications in more viable therapeutic platforms, such as combining microscopic OVs-rich 2D MOs with hydrogel or inorganic scaffolds for implants for localized cancer therapy.

2. While increasing studies have demonstrated that OVs-rich 2D MOs can be used in biomedical applications, such as cancer therapy, the data on its safety conclusions for organisms are still insufficient. We need to study in depth the interactions of OVs-rich 2D MOs with the biological microenvironment to understand how they affect the increase or decrease in toxicity. The use of 2D MOs containing heavy metal elements should be avoided as much as possible in favor of OVs-rich 2D MOs with better biosecurity to further improve biosafety. There is a need to develop more specifically targeted ligands to modify OVs-rich 2D MOs to reduce their retention in normal tissues. In addition, the modification stimulates the response component to protect the OVs-rich 2D MOs, which in turn effectively improves their safety, with the active site only revealing itself and functioning after the OVs-rich 2D MOs reach the tumor and break down the protected segments. It will be a huge step for long term of biocompatibility of CAs, potential immune responses or long-term toxicity of MOs for clinical translation. The endeavor requires the collaborative participation of multidisciplinary teams to ensure the success of material development.

3. OVs-rich 2D MOs can be combined with artificial intelligence or theoretical simulations to determine the concentration and location of OVs for structural optimization of 2D MOs, thereby assisting in the synthesis of materials, improving their therapeutic efficacy, and providing an advanced platform for future translational clinical applications. Amorphization is also a good method for introducing OVs in 2D MOs, and although the characterization of crystalline OVs-rich 2D MOs can be borrowed for analyzing the presence of OVs in amorphous 2D MOs, it lacks richer characterization methods, which limits its further application. Moreover, amorphous 2D MOs have a long-range disordered structure, which exposes many OV active sites on the surface. However, their stability is easily affected by temperature, acidity and alkalinity. Thus, the stability of amorphous 2D MOs needs to be aided by structural control and surface modification, which is an urgent problem. However, the current work on amorphous 2D MOs for biomedical applications is still scarce, but the construction of amorphous 2D MOs with oxygen-rich vacancies will be an important research direction.

4. The realization of clinical applications requires the scaled-up production of nanomaterials that can be easily stored and transported, and that guarantee long-term stability of physicochemical properties. In addition, OVs-rich 2D MOs require rigorous clinical validation of biosafety and efficacy, necessitating collaboration across materials science, biology, and medicine. Their clinical translation demands time-intensive multistage processes, from material optimization to stability assessments. In addition, vacancy defects in nanomaterials are often complex and highly variable, so further studies are needed to ensure the controllability and stability of the number of vacancy defects and to avoid the complex diversity of structures and efficacy of OVs-rich 2D MOs. Insufficient consideration gap between the current work and translating medicine is obvious; more comprehensive perspective on the material’s future applications should be overcome in the following works. Therefore, simple, efficient, and controllable methods for the preparation of OVs-rich 2D MOs should be developed to maximize the efficacy of nanomedicines. In conclusion, we expect that these uniquely characterized OVs will lead 2D MOs to the clinical stage in the future.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Ding L and Zhu Y contributed equally to this work.

Conceptualization, investigation, and writing-original draft: Ding, L.

Writing-review & editing: Ding, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.

Writing-review & editing, supervision, and funding acquisition: Hou, J.; Xiao, Z.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022TQ0065), Shanghai Post-doctoral Excellence Program (2022029), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82201116), Shanghai Sailing Program (22YF1422000, 23YF1421800) and Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (24ZR1443800).

Conflicts of interest

Longjiang Ding and Yanping Li are affiliated with Jiangxi Hongdu Aviation Industry Group Co., Ltd. The other authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Novoselov, K. S.; Geim, A. K.; Morozov, S. V.; et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666-9.

2. Wang, J.; Xu, T.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Z. Miracle in “white”: hexagonal boron nitride. Small 2024, e2400489.

3. Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Kanda, H. Direct-bandgap properties and evidence for ultraviolet lasing of hexagonal boron nitride single crystal. Nat. Mater. 2004, 3, 404-9.

4. Fu, J.; Yu, J.; Jiang, C.; Cheng, B. g-C3N4-based heterostructured photocatalysts. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2018, 8, 1701503.

5. Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; et al. Coordination-precipitation synthesis of metal sulfide with phase transformation enhanced reactivity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2212655.

6. Yang, M.; Chang, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Interface modulation of metal sulfide anodes for long-cycle-life sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208705.

7. Kumbhakar, P.; Chowde, G. C.; Mahapatra, P. L.; et al. Emerging 2D metal oxides and their applications. Mater. Today. 2021, 45, 142-68.

8. Hameed, A.; Batool, M.; Liu, Z.; Nadeem, M. A.; Jin, R. Layered double hydroxide-derived nanomaterials for efficient electrocatalytic water splitting: recent progress and future perspective. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 3311-28.

9. Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Huang, G.; et al. Seeded growth of single-crystal black phosphorus nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 470-8.

10. Liu, H.; Du, Y.; Deng, Y.; Ye, P. D. Semiconducting black phosphorus: synthesis, transport properties and electronic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2732-43.

11. Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Lin, J.; Han, G.; Huang, P. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 5109-24.

12. Kalantar-zadeh, K.; Ou, J. Z.; Daeneke, T.; Mitchell, A.; Sasaki, T.; Fuhrer, M. S. Two dimensional and layered transition metal oxides. Appl. Mater. Today. 2016, 5, 73-89.

13. Ida, S.; Ogata, C.; Eguchi, M.; Youngblood, W. J.; Mallouk, T. E.; Matsumoto, Y. Photoluminescence of perovskite nanosheets prepared by exfoliation of layered oxides, K2Ln2Ti3O10, KLnNb2O7, and RbLnTa2O7 (Ln: lanthanide ion). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 7052-9.

14. Murali, A.; Lokhande, G.; Deo, K. A.; Brokesh, A.; Gaharwar, A. K. Emerging 2D nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Mater. Today. 2021, 50, 276-302.

15. Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; et al. MnO2 nanosheets based catechol oxidase mimics for robust electrochemical sensor: synthesis, mechanism and its application for ultrasensitive and selective detection of dopamine. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152656.

16. Dong, T.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; et al. Sensitive lateral flow immunoassay based on specific peptide and superior oxidase mimics with a universal dual-mode significant signal amplification. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 12532-40.

17. Bigham, A.; Raucci, M. G.; Zheng, K.; Boccaccini, A. R.; Ambrosio, L. Oxygen-deficient bioceramics: combination of diagnosis, therapy, and regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2302858.

18. Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Exploring transition metal oxide-based oxygen vacancy supercapacitors: a review. J. Energy. Storage. 2024, 80, 110350.

19. Matussin, S. N.; Harunsani, M. H.; Khan, M. M. CeO2 and CeO2-based nanomaterials for photocatalytic, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. J. Rare. Earths. 2023, 41, 167-81.

20. Ren, B.; Wang, Y.; Ou, J. Z. Engineering two-dimensional metal oxides via surface functionalization for biological applications. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020, 8, 1108-27.

21. Wei, X.; Chen, C.; Fu, X. Z.; Wang, S. Oxygen vacancies-rich metal oxide for electrocatalytic nitrogen cycle. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2024, 14, 2303027.

22. Son, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; et al. Cancer therapeutics based on diverse energy sources. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8201-15.

23. Neal, C. J.; Kolanthai, E.; Wei, F.; Coathup, M.; Seal, S. Surface chemistry of biologically active reducible oxide nanozymes. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2211261.

24. Zhang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, Z.; et al. Covalent coupling-regulated rGO/VN nanocomposite enabling nitrogen defects to remarkably boost the peroxidase-like catalytic efficiency for the ultrasensitive colorimetric assay of uric acid. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 5771-80.

25. Chen, K.; Yuan, X.; Tian, Z.; et al. A facile approach for generating ordered oxygen vacancies in metal oxides. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 835-42.

27. Sun, W.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Amorphous FeSnOx nanosheets with hierarchical vacancies for room-temperature sodium-sulfur batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202404816.

28. Moon, S.; Lee, D.; Park, J.; Kim, J. 2D amorphous GaOx gate dielectric for β-Ga2O3 field-effect transistors. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 37687-95.

29. He, C.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Defect engineered 2D mesoporous Mo-Co-O nanosheets with crystalline-amorphous composite structure for efficient oxygen evolution. Sci. China. Mater. 2022, 65, 3470-8.

30. Zhao, H.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, L. Ternary artificial nacre reinforced by ultrathin amorphous alumina with exceptional mechanical properties. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 2037-42.

31. Jamesh, M. I.; Sun, X. Recent progress on earth abundant electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in alkaline medium to achieve efficient water splitting - a review. J. Power. Sources. 2018, 400, 31-68.

32. Wang, P.; Ma, X.; Hao, X.; Tang, B.; Abudula, A.; Guan, G. Oxygen vacancy defect engineering to promote catalytic activity toward the oxidation of VOCs: a critical review. Catal. Rev. 2024, 66, 586-639.

33. Zhou, Z.; Wang, T.; Hu, T.; et al. Synergistic interaction between metal single-atoms and defective WO3-x nanosheets for enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311002.

34. Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Enhancing deep mineralization of refractory benzotriazole via carbon nanotubes-intercalated cobalt copper bimetallic oxide nanosheets activated peroxymonosulfate process: mechanism, degradation pathway and toxicity. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2022, 628, 448-62.

35. Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Xie, S. Y.; Gong, F.; Xie, K.; Zhang, Y. H. Ultrathin 2D 2D WO3-x-C3N4 heterostructure-based high-efficiency photocatalyst for selective oxidation of toluene. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 149, 111534.

36. Wu, M.; Zhang, G.; Tong, H.; et al. Cobalt (II) oxide nanosheets with rich oxygen vacancies as highly efficient bifunctional catalysts for ultra-stable rechargeable Zn-air flow battery. Nano. Energy. 2021, 79, 105409.

37. Gao, R.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.; et al. Oxygen defects-engineered LaFeO3-x nanosheets as efficient electrocatalysts for lithium-oxygen battery. J. Catal. 2020, 384, 199-207.

38. Ming, X.; Guo, A.; Wang, G.; Wang, X. Two-dimensional defective tungsten oxide nanosheets as high performance photo-absorbers for efficient solar steam generation. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2018, 185, 333-41.

39. Tu, J.; Li, H.; Liu; X; et al. Giant switchable ferroelectric photovoltage in double-perovskite epitaxial films through chemical negative strain. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads4925.

40. Zhou, X.; Zheng, X.; Yan, B.; Xu, T.; Xu, Q. Defect engineering of two-dimensional WO3 nanosheets for enhanced electrochromism and photoeletrochemical performance. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 400, 57-63.

41. Ren, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Boosting hydrogen storage performance of MgH2 by oxygen vacancy-rich H-V2O5 nanosheet as an excited H-pump. Nano-Micro. Lett. 2024, 16, 160.

42. Crowley, K.; Ye, G.; He, R.; Abbasi, K.; Gao, X. P. A. α-MoO3 as a conductive 2D oxide: tunable n-type electrical transport via oxygen vacancy and fluorine doping. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2018, 1, 6407-13.

43. Xiang, T.; Dai, D.; Li, X.; et al. In situ self-derived Co/CoOx active sites from Co-TCPP for the efficient hydrogenolysis of furfuryl alcohol to 1,5-pentanediol. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2024, 348, 123841.

44. Liu, Y.; Guo, D.; Wu, K.; Guo, J.; Li, Z. Simultaneous enhanced electrochemical and photoelectrochemical properties of α-Fe2O3/graphene by hydrogen annealing. Mater. Res. Express. 2020, 7, 025032.

45. Chang, M.; Dai, X.; Dong, C.; et al. Two-dimensional persistent luminescence “optical battery” for autophagy inhibition-augmented photodynamic tumor nanotherapy. Nano. Today. 2022, 42, 101362.

46. Zhang, Q.; Chen, D.; Song, Q.; et al. Holey defected TiO2 nanosheets with oxygen vacancies for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production from water splitting. Surf. Interfaces. 2021, 23, 100979.

47. Wang, X.; Xue, S.; Huang, M.; et al. Pressure-induced engineering of surface oxygen vacancies on metal oxides for heterogeneous photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 4945-51.

48. Ding, Q.; Dou, Y.; Liao, Y.; et al. Oxygen vacancy-rich ultrathin Co3O4 nanosheets as nanofillers in solid-polymer electrolyte for high-performance lithium metal batteries. Catalysts 2023, 13, 711.

49. Geng, B.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; et al. Cu2-xO@TiO2-y Z-scheme heterojunctions for sonodynamic-chemodynamic combined tumor eradication. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134777.

50. Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Ouyang, J.; Deng, L.; Liu, Y. N. Oxygen-deficient tungsten oxide perovskite nanosheets-based photonic nanomedicine for cancer theranostics. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133273.

51. Cao, Y.; Wu, T.; Dai, W.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. TiO2 Nanosheets with the Au nanocrystal-decorated edge for mitochondria-targeting enhanced sonodynamic therapy. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 9105-14.

52. Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Jian, P.; Wang, L. Hierarchical 0D/2D Co3O4 hybrids rich in oxygen vacancies as catalysts towards styrene epoxidation reaction. Chinese. J. Catal. 2018, 39, 1942-50.

53. Zhang, J.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. Reduced porous 2D Co3O4 enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation to form multi-reactive oxygen species: the key role of oxygen vacancies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 330, 125409.

54. Geng, B.; Xu, S.; Li, P.; et al. Platinum crosslinked carbon dot@TiO2-x p-n junctions for relapse-free sonodynamic tumor eradication via high-yield ROS and GSH depletion. Small 2022, 18, e2103528.

55. Ren, L.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Oxygen vacancy-rich 2D TiO2 nanosheets: a bridge toward high stability and rapid hydrogen storage kinetics of nano-confined MgH2. Nano-Mmicro. Lett. 2022, 14, 144.

56. Dong, H. D.; Zhao, J. P.; Peng, M. X.; et al. Pd promoted oxygen species activation of ZnO nanosheets for enhanced hydrogen sensing performance and its DFT investigation. Maters. Res. Bull. 2024, 177, 112881.

57. Zhang, Y. H.; Peng, M. X.; Yue, L. J.; et al. A room-temperature aniline sensor based on Ce doped ZnO porous nanosheets with abundant oxygen vacancies. J. Alloy. Compd. 2021, 885, 160988.

58. Zheng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, Z.; et al. High-valence Mo doping and oxygen vacancy engineering to promote morphological evolution and oxygen evolution reaction activity. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 43953-62.

59. Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Qian, R.; Wen, Z. Atomic-thick TiO2(B) nanosheets decorated with ultrafine Co3O4 nanocrystals as a highly efficient catalyst for lithium-oxygen battery. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 41398-406.

60. Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; et al. 2D electron gas and oxygen vacancy induced high oxygen evolution performances for advanced Co3O4/CeO2 nanohybrids. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1900062.

61. Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, X.; et al. 2D defect-engineered Ag-doped γ- Fe2O3/BiVO4: the effect of noble metal doping and oxygen vacancies on exciton-triggering photocatalysis production of singlet oxygen. Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138176.

62. Zhu, Y.; Guo, F.; Wei, Q.; et al. Engineering the metal/oxide interfacial O-filling effect to tailor oxygen spillover for efficient acidic water oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2421354.

63. Yu, Z.; Yu, D.; Wang, X.; et al. Photoinduced formation of oxygen vacancies on Mo-incorporated WO3 for direct oxidation of benzene to phenol by air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 13885-92.

64. Zhao, S.; Yang, Y.; Bi, F.; et al. Oxygen vacancies in the catalyst: efficient degradation of gaseous pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140376.

65. Kong, X.; Xu, Y.; Cui, Z.; et al. Defect enhances photocatalytic activity of ultrathin TiO2 (B) nanosheets for hydrogen production by plasma engraving method. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 2018, 230, 11-7.

66. Xu, L.; Jiang, Q.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Plasma-engraved Co3O4 nanosheets with oxygen vacancies and high surface area for the oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 5277-81.

67. Ding, S.; Sun, Y.; Lou, F.; et al. Plasma-regulated two-dimensional high entropy oxide arrays for synergistic hydrogen evolution: from theoretical prediction to electrocatalytic applications. J. Power. Sources. 2022, 520, 230873.

68. Siebert, J. P.; Hamm, C. M.; Birkel, C. S. Microwave heating and spark plasma sintering as non-conventional synthesis methods to access thermoelectric and magnetic materials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2019, 6, 041314.

69. Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Si, W.; Wu, H. Mass production of two-dimensional oxides by rapid heating of hydrous chlorides. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12543.

70. Chen, T.; Ma, F.; Chen, Z.; et al. Engineering oxygen vacancies of 2D WO3 for visible-light-driven benzene hydroxylation with dioxygen. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143666.

71. Wei, Z.; Gasparyan, M.; Liu, L.; et al. Microwave-exfoliated 2D oligo-layer MoO3-x nanosheets with outstanding molecular adsorptivity and room-temperature gas sensitivity on ppb level. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140076.

72. Hu, R.; Wei, L.; Xian, J.; et al. Microwave shock process for rapid synthesis of 2D porous La0.2Sr0.8CoO3 perovskite as an efficient oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Acta. Phys-Chim. Sin. 2023, 0, 2212025.

73. Asif, M. B.; Kim, S. J.; Nguyen, T. S.; Mahmood, J.; Yavuz, C. T. Highly efficient micropollutant decomposition by ultrathin amorphous cobalt-iron oxide nanosheets in peroxymonosulfate-mediated membrane-confined catalysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 149352.

74. Li, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, L.; et al. Adaptive bifunctional electrocatalyst of amorphous CoFe oxide @ 2D black phosphorus for overall water splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 21106-13.

75. Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Sequential electrodeposition of bifunctional catalytically active structures in MoO3/Ni-NiO composite electrocatalysts for selective hydrogen and oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2003414.

76. Zhong, H.; Gao, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Ion irradiation inducing oxygen vacancy-rich NiO/NiFe2O4 heterostructure for enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting. Small 2021, 17, e2103501.

77. Ji, D.; Lee, Y.; Nishina, Y.; et al. Angstrom-confined electrochemical synthesis of sub-unit-cell non-van der Waals 2D metal oxides. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2301506.

78. Yan, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, M.; et al. General and scalable synthesis of mesoporous 2D MZrO2 (M = Co, Mn, Ni, Cu, Fe) nanocatalysts by amorphous-to-crystalline transformation. Small 2024, 20, e2308016.

79. Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Xie, K.; Fang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y. Cocrystallization enabled spatial self-confinement approach to synthesize crystalline porous metal oxide nanosheets for gas sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202207816.

80. Prusty, G.; Lee, J. T.; Seifert, S.; Muhoberac, B. B.; Sardar, R. Ultrathin plasmonic tungsten oxide quantum wells with controllable free carrier densities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5938-42.

81. Fabbri, E.; Schmidt, T. J. Oxygen evolution reaction - the enigma in water electrolysis. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 9765-74.

82. Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Role of oxygen vacancy in metal oxide based photoelectrochemical water splitting. EcoMat 2021, 3, e12075.

83. Ye, K.; Li, K.; Lu, Y.; et al. An overview of advanced methods for the characterization of oxygen vacancies in materials. TrAC. Trends. Anal. Chem. 2019, 116, 102-8.

84. Wei, R.; Lu, Y.; Xu, Y. The role of oxygen vacancies in metal oxides for rechargeable ion batteries. Sci. China. Chem. 2021, 64, 1826-53.

85. Feng, H.; Xu, Z.; Ren, L.; et al. Activating titania for efficient electrocatalysis by vacancy engineering. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 4288-93.

86. Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Promoting water dissociation for efficient solar driven CO2 electroreduction via improving hydroxyl adsorption. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 751.

87. Yin, X.; Wang, Y.; Chang, T. H.; et al. Memristive behavior enabled by amorphous-crystalline 2D oxide heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2000801.

88. Kuzmin, A.; Chaboy, J. EXAFS and XANES analysis of oxides at the nanoscale. IUCrJ 2014, 1, 571-89.

89. Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Activating MnO2 nanosheet arrays for accelerated water oxidation through the synergic effect of Ni loading and O vacancies. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152644.

90. Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; et al. Characterization of oxygen vacancy associates within hydrogenated TiO2: a positron annihilation study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012, 116, 22619-24.

91. Kong, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Tuning the relative concentration ratio of bulk defects to surface defects in TiO2 nanocrystals leads to high photocatalytic efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16414-7.

92. Lu, Y.; Deng, H.; Pan, T.; Liao, X.; Zhang, C.; He, H. Effective toluene ozonation over δ-MnO2: oxygen vacancy-induced reactive oxygen species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 2918-27.

93. Sonkin, D.; Thomas, A.; Teicher, B. A. Cancer treatments: past, present, and future. Cancer. Genet. 2024, 286-287, 18-24.

94. Vachani, A.; Sequist, L. V.; Spira, A. AJRCCM: 100-YEAR Anniversary. The shifting landscape for lung cancer: past, present, and future. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2017, 195, 1150-60.

95. Zhao, B.; Ye, J.; Chen, Z.; et al. Mitochondria-targeted photoredox catalysis activates pyroptosis for effective tumor therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2417681.

96. Liang, H.; Xi, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H. Modulation of oxygen vacancy in tungsten oxide nanosheets for Vis-NIR light-enhanced electrocatalytic hydrogen production and anticancer photothermal therapy. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 18183-90.

97. Beik, J.; Abed, Z.; Ghoreishi, F. S.; et al. Nanotechnology in hyperthermia cancer therapy: from fundamental principles to advanced applications. J. Control. Release. 2016, 235, 205-21.

98. Lin, Z.; Yuan, J.; Niu, L.; et al. Oxidase mimicking nanozyme: classification, catalytic mechanisms and sensing applications. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2024, 520, 216166.

99. Kemp, J. A.; Shim, M. S.; Heo, C. Y.; Kwon, Y. J. “Combo” nanomedicine: co-delivery of multi-modal therapeutics for efficient, targeted, and safe cancer therapy. Adv. Drug. Deliv. Rev. 2016, 98, 3-18.

100. Choi, H. S.; Liu, W.; Misra, P.; et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1165-70.

101. Guo, L.; Panderi, I.; Yan, D. D.; et al. A comparative study of hollow copper sulfide nanoparticles and hollow gold nanospheres on degradability and toxicity. ACS. Nano. 2013, 7, 8780-93.

103. Zheng, X.; Wang, X.; Mao, H.; Wu, W.; Liu, B.; Jiang, X. Hypoxia-specific ultrasensitive detection of tumours and cancer cells in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5834.

104. Song, G.; Hao, J.; Liang, C.; et al. Degradable molybdenum oxide nanosheets with rapid clearance and efficient tumor homing capabilities as a therapeutic nanoplatform. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 2122-6.

105. Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Kong, X.; et al. Biomimetic layered molybdenum oxide nanosheets with excellent photothermal property combined with chemotherapy for enhancing anti-tumor immunity. Appl. Mater. Today. 2024, 36, 102027.

106. Cai, Y.; Wei, Z.; Song, C.; Tang, C.; Han, W.; Dong, X. Optical nano-agents in the second near-infrared window for biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 22-37.

107. Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-based nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4881-985.

108. Deepagan, V. G.; You, D. G.; Um, W.; et al. Long-circulating Au-TiO2 nanocomposite as a sonosensitizer for ROS-mediated eradication of cancer. Nano. Lett. 2016, 16, 6257-64.

109. You, D. G.; Deepagan, V. G.; Um, W.; et al. ROS-generating TiO2 nanoparticles for non-invasive sonodynamic therapy of cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23200.

110. Liang, S.; Deng, X.; Xu, G.; et al. A novel Pt-TiO2 heterostructure with oxygen-deficient layer as bilaterally enhanced sonosensitizer for synergistic chemo-sonodynamic cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908598.