Beyond generalist LLMs: building and validating domain-specific models with the SpAMCQA benchmark

Abstract

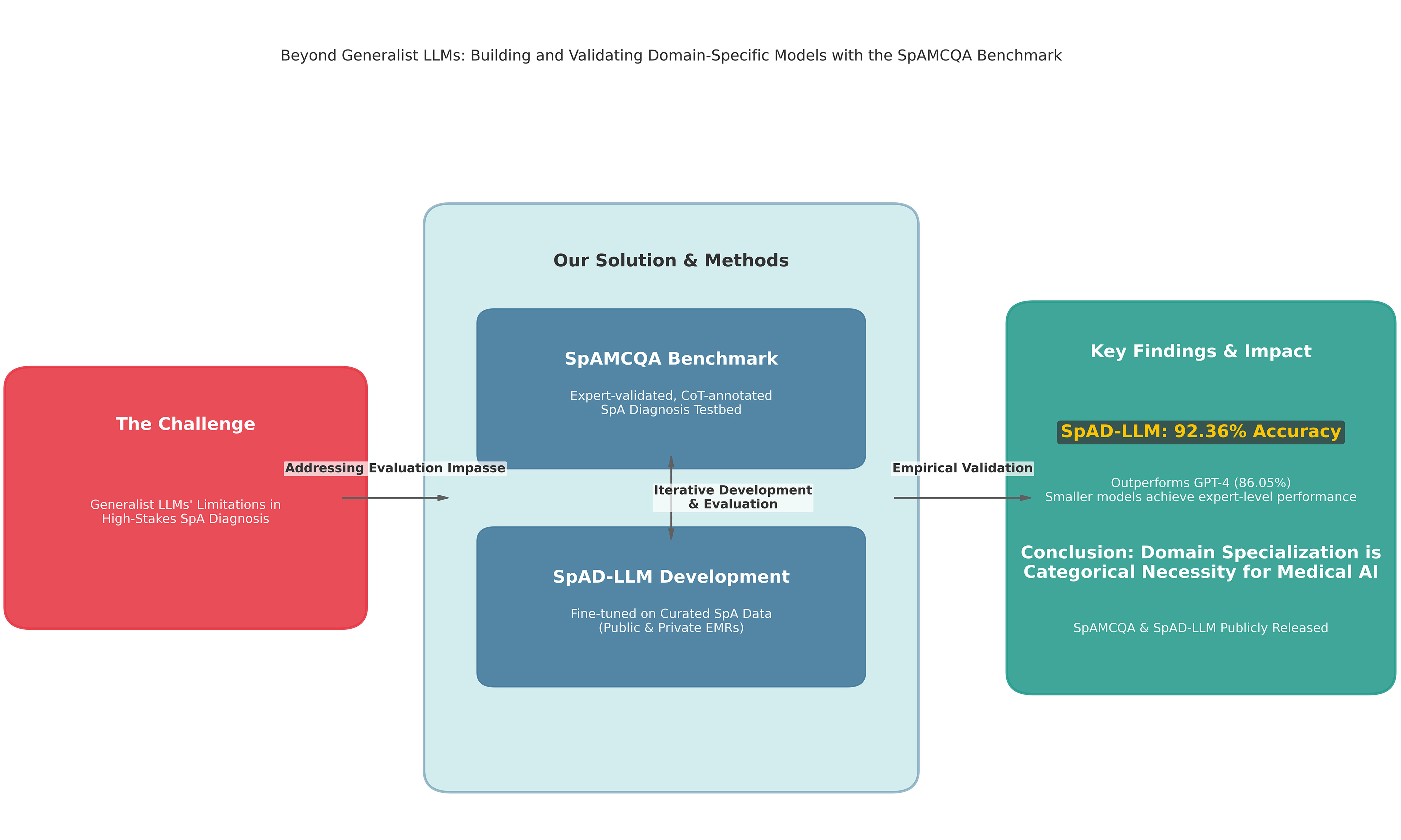

Aim: General-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) exhibit significant limitations in high-stakes clinical domains such as spondyloarthritis (SpA) diagnosis, yet the absence of specialized evaluation tools precludes the quantification of these failures. This study aims to break this critical evaluation impasse and rigorously test the hypothesis that domain specialization is a necessity for achieving expert-level performance in complex medical diagnostics.

Methods: We employed a two-pronged experimental approach. First, we introduced the Spondyloarthritis Multiple-Choice Question Answering Benchmark (SpAMCQA), a comprehensive, expert-validated benchmark engineered to probe the nuanced diagnostic reasoning required for SpA. Second, to validate the domain specialization hypothesis, we developed the Spondyloarthritis Diagnosis Large Language Model (SpAD-LLM) by fine-tuning a foundation model on a curated corpus of SpA-specific clinical data. The efficacy of SpAD-LLM was then evaluated against leading generalist models, including Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4), on the SpAMCQA testbed.

Results: On the SpAMCQA benchmark, our specialized SpAD-LLM achieved a state-of-the-art accuracy of 92.36%, decisively outperforming the 86.05% accuracy of the leading generalist model, GPT-4. This result provides the first empirical evidence on a purpose-built benchmark that generalist scaling alone is insufficient for mastering the specific inferential knowledge required for SpA diagnosis.

Conclusion: Our findings demonstrate that in high-stakes domains, domain specialization is not merely an incremental improvement but a categorical necessity. We release the SpAMCQA benchmark and full inference logs to the public, providing the community with a foundational evaluation toolkit, while positioning the SpAD-LLM series as a validated baseline to catalyze the development of truly expert-level medical artificial intelligence.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) represents a complex group of inflammatory rheumatic diseases, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which predominantly affect the axial skeleton and sacroiliac joints[1]. These conditions lead to chronic back pain, functional decline, and a significant reduction in quality of life. Given their progressive nature, early and accurate diagnosis is paramount for alleviating symptoms and preventing long-term disability[2], especially considering the average diagnostic delay for axial SpA (axSpA) is as long as 6.8 years, a primary contributor to patient incapacitation[3]. However, achieving timely diagnosis presents a formidable challenge, particularly in vast healthcare systems such as China’s, where a profound disparity between a massive patient population and a small number of specialist rheumatologists creates a critical need for intelligent diagnostic support systems.

Recent advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) offer a potential solution to this expertise gap. Foundational models such as Google’s Med-PaLM 2[4] have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in broad medical domains[5-11]. Concurrently, a paradigm of domain specialization has emerged, with models such as Me-LLaMA [a medical-adapted Large Language Model Meta AI (LLaMA) model][12], Meditron-70B (a large biomedical LLM)[13], and HuatuoGPT-II (a Chinese medical LLM)[14] showing impressive results by leveraging curated data. However, the promise of these generalist and specialized models is tempered by a crucial limitation: they are largely validated on general-purpose benchmarks. This exposes them to a lack of nuanced understanding for complex differential diagnoses and a risk of factual “hallucinations” - a risk that is unacceptable in clinical practice[15]. The root of this problem is not merely a flaw in the models themselves, but a fundamental failure in how they are evaluated.

This failure has created a critical evaluation vacuum in specialized medicine. While significant progress has been made in creating medically-oriented benchmarks, moving beyond inadequate natural language processing (NLP) metrics such as BiLingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU)[16], a shared limitation persists. For instance, Chinese frameworks such as CMB (Comprehensive Medical Benchmark)[17] and CBLUE (Chinese Biomedical Language Understanding Evaluation Benchmark)[18], along with global platforms such as MedEval (multi-level, multi-task, and multi-domain medical benchmark)[19] and MedGPTEval[20], provide extensive testbeds for general medical knowledge but lack the granularity required for specialized domains. They are too broad to probe the deep, nuanced reasoning required in fields such as rheumatology, making it impossible to distinguish genuine clinical inference from superficial pattern matching[21-23]. This gap between assessing general capability and validating specialized application creates a critical safety concern, rendering claims of “superhuman” performance[24] clinically unverified and leaving a core hypothesis untested: that for high-stakes domains, specialization is not an incremental improvement, but a categorical necessity[24,25].

To break this impasse, we structure our work around a single, falsifiable core hypothesis:

Hypothesis: For high-stakes, nuanced clinical reasoning tasks such as SpA diagnosis, the performance bottleneck is not a deficiency in model scale but a fundamental lack of domain-specific, inferential knowledge. Consequently, a smaller model fine-tuned on a purpose-built, expert-curated corpus will significantly and decisively outperform a much larger generalist model, provided the evaluation is conducted on a benchmark specifically engineered to probe this reasoning capability.

Testing this hypothesis requires a two-pronged experimental design, which forms the basis of our contribution. First, to create a valid testbed capable of measuring this nuanced reasoning, we introduce SpAMCQA, the first comprehensive, expert-validated benchmark for SpA diagnosis, detailed in the Methods section. Second, to create a controlled experimental variable that embodies the principle of specialization, we develop and release Spondyloarthritis Diagnosis Large Language Model (SpAD-LLM), a model specifically fine-tuned on a curated corpus of SpA-related data. By evaluating SpAD-LLM against generalist state-of-the-art (SOTA) models on the SpAMCQA platform, we conduct a direct and rigorous test of our central hypothesis. This work provides the first empirical evidence that in high-stakes domains, domain specialization is not merely an improvement but a necessity for achieving expert-level performance.

The main contributions of this paper are therefore:

1. The introduction of SpAMCQA, a foundational and expert-validated benchmark designed to rigorously assess clinical reasoning in SpA diagnosis, addressing a critical gap in medical artificial intelligence (AI) evaluation.

2. The development and release of the SpAD-LLM series, providing a reproducible case study and a strong baseline for domain-specific models in rheumatology.

3. The first empirical validation, on a purpose-built platform, of the hypothesis that domain specialization is a necessity for achieving expert-level performance in complex medical AI, decisively demonstrating its superiority over the scaling-up of generalist models.

METHODS

The SpAMCQA benchmark: a tool for high-stakes evaluation

To address the critical evaluation vacuum in high-stakes medical AI, we developed SpAMCQA, the first comprehensive, bilingual (English-Chinese) benchmark for SpA diagnosis. It is engineered not merely to score models, but to rigorously probe their clinical reasoning capabilities. This section details its design philosophy, construction methodology, and the dual-pronged evaluation protocol it enables.

Design philosophy and construction

The creation of SpAMCQA was guided by a core philosophy: to move beyond simple factual recall and probe the deep, inferential reasoning required to navigate complex differential diagnoses, mirroring the cognitive tasks of a human expert. To ensure comprehensive coverage and authenticity, we adopted a tripartite data sourcing strategy. The benchmark’s 222 questions were meticulously derived from three complementary sources, each chosen for its unique and indispensable contribution:

1. Authoritative Medical Literature: Serving as the knowledge “gold standard,” leading rheumatology textbooks and clinical guidelines[2,26-28] formed the foundational knowledge base, ensuring our benchmark is grounded in established medical science.

2. Official Medical Licensing Exams: Providing a “standardized test” for reasoning ability, these exams offered a robust template for constructing questions that test standardized clinical reasoning and decision-making under examination-like conditions.

3. Real-World Patient Cases: Acting as a clinical “stress test”; this is the most critical component. We curated 100 anonymized patient records from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology at a major hospital. This injected the benchmark with the complexity and “messiness” of real-world clinical practice, including atypical presentations and challenging distractors (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, sacroiliac joint infection, lumbar disc herniation).

The construction of the benchmark strictly adhered to academic integrity and data usage standards. The authoritative guidelines and medical licensing examination questions utilized in this study were sourced from publicly available historical archives and open-access publications. These materials served strictly as a knowledge base for verifying medical accuracy and designing question templates. Content was synthesized, rephrased, and de-identified to ensure originality while preserving clinical validity, and all original sources have been duly cited.

This hybrid approach ensures that SpAMCQA moves beyond textbook scenarios to assess AI’s practical utility. As detailed in Table 1, which presents a taxonomy of the diagnostic challenges within the benchmark, the questions are balanced across type, theme, and complexity to facilitate a comprehensive assessment of a model’s capabilities.

Taxonomy of diagnostic challenges in the SpAMCQA benchmark

| Category | Single choice | Multi choice | Total |

| Question type | |||

| Concept definition | 49 | 13 | 62 |

| Logical inference | 33 | 11 | 44 |

| Case analysis | 112 | 4 | 116 |

| Theme | |||

| Exclusively SpA | 75 | 21 | 96 |

| SpA with comorbidities | 119 | 7 | 126 |

| Complexity | |||

| Elementary | 78 | 5 | 83 |

| Intermediate | 63 | 13 | 76 |

| Advanced | 53 | 10 | 63 |

| Total | 194 | 28 | 222 |

Expert-verified reasoning paths (CoT annotations)

A core innovation of SpAMCQA is its departure from simple right-or-wrong answer evaluation. To assess the process of clinical reasoning, not just the outcome, each question includes a detailed, expert-verified Chain-of-Thought (CoT) explanation[29,30]. These CoTs serve as “gold standard” reasoning pathways. Our annotation followed a rigorous, expert-led, two-stage protocol: initial CoTs were generated by a capable LLM (Orca2-13b[31]) to ensure structural coherence, followed by a meticulous review and correction process by two board-certified rheumatologists. This human-in-the-loop process ensures every CoT is not only linguistically fluent but also medically accurate and logically sound, providing an unprecedented tool for qualitative model evaluation.

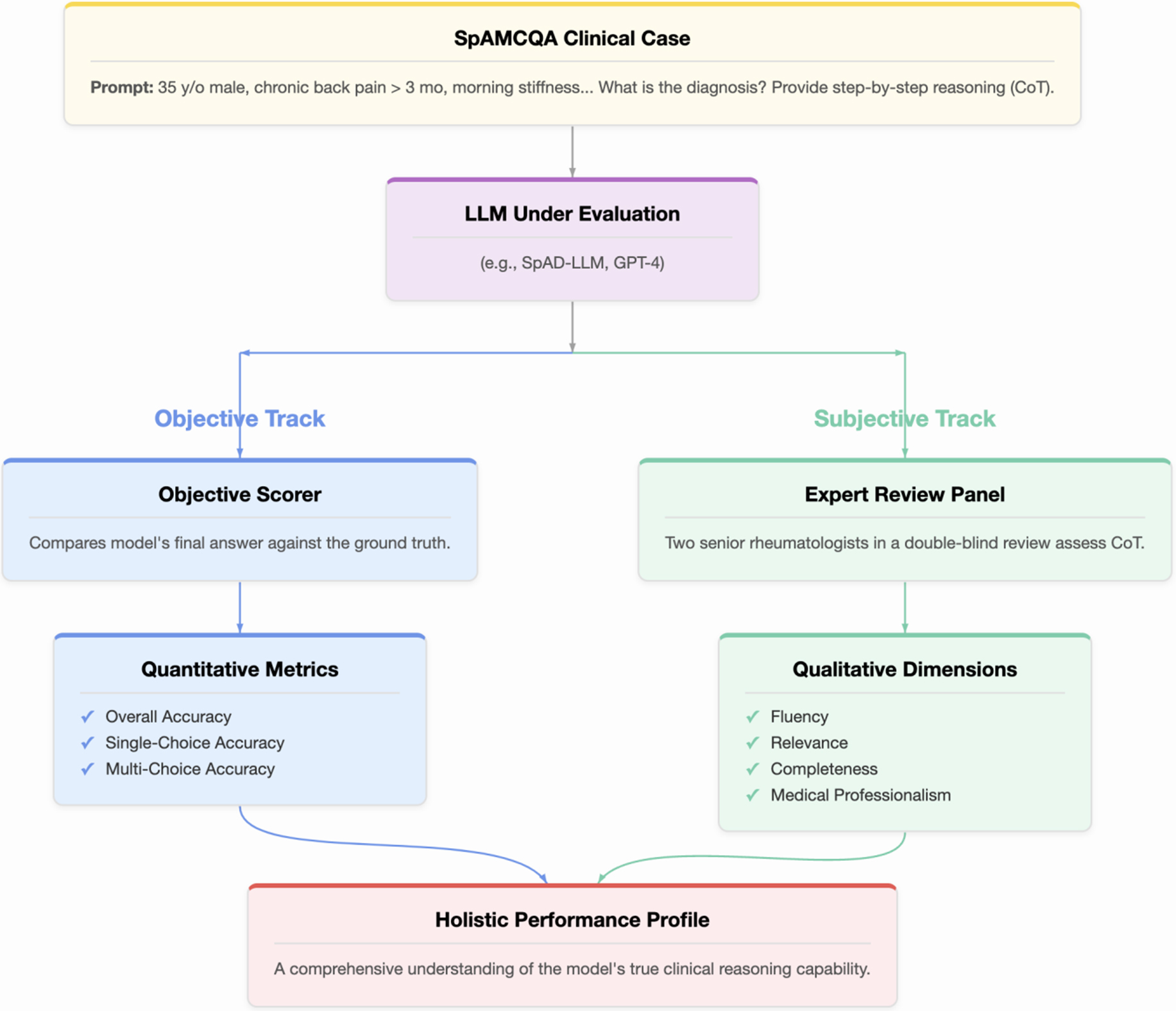

The dual-pronged evaluation protocol

Objective accuracy, while essential, is insufficient for high-stakes medical applications because it reveals what the model answered, but not how or why. To address this, we designed a dual-pronged evaluation protocol, illustrated in Figure 1, that combines objective scoring with subjective expert assessment to provide a holistic measure of LLM performance. For every model, a clinical case from SpAMCQA is presented via a zero-shot CoT prompt, instructing the model to provide both its final answer and its step-by-step reasoning. The model’s output is then assessed along two parallel tracks.

Figure 1. The SpAMCQA evaluation framework. A clinical case from the benchmark is presented to the Large Language Model (LLM) using a zero-shot Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompt. The model’s performance is then assessed through two parallel tracks. The Objective Track (blue pathway) automatically scores the final answer for quantitative accuracy. Concurrently, the Subjective Track (green pathway) involves a double-blind review by two senior rheumatologists who evaluate the quality of the CoT reasoning process across four dimensions: Fluency, Relevance, Completeness, and Medical Professionalism. This dual-pronged approach yields a Holistic Performance Profile, providing a comprehensive and rigorous measure of the LLM’s clinical reasoning capabilities. SpAMCQA: Spondyloarthritis Multiple-Choice Question Answering Benchmark.

Objective track: quantitative accuracy

The correctness of the models’ final answers is measured using a scoring system adapted from official medical examinations to reward precision and penalize guessing.

• Single-choice questions: A full point is awarded for the correct answer; otherwise, zero points.

• Multiple-choice questions: A partial credit system is employed. The score is proportional to the number of correct options selected. For each incorrect option chosen, an equivalent fraction is deducted from the score, with a minimum of zero. This rubric rewards precise knowledge over speculative selection (e.g., for a question with 3 correct options, selecting 2 correct and 0 incorrect yields 0.67 points).

Subjective track: qualitative reasoning assessment

To assess the quality of the reasoning process, all generated CoT responses were evaluated independently by two board-certified rheumatologists in a double-blind review. Leveraging the gold-standard CoTs within SpAMCQA, the experts rated each response on a 5-point Likert scale across four dimensions: Fluency, Relevance, Completeness, and Medical Professionalism.

Recognizing the inherent subjectivity in evaluating complex clinical reasoning, we adopted a rigorous two-stage protocol to ensure the reliability and validity of our findings. First, an initial independent rating was conducted. To quantify the level of agreement between the two experts, we calculated the inter-rater reliability (IRR) using a quadratic weighted Cohen’s Kappa (κ) for each model across all four dimensions. The average Kappa values were 0.475 (Fluency), 0.529 (Relevance), 0.384 (Completeness), and 0.411 (Medical Professionalism), indicating a fair to moderate level of agreement. The Kappa values ranged from 0.157 (slight agreement) to 0.758 (substantial agreement), highlighting dimensions such as Completeness and Medical Professionalism as particularly nuanced and challenging to score, especially for high-performing models.

In the second stage, any ratings with a discrepancy greater than one point, or those pertaining to low-Kappa dimensions, were subjected to a consensus review. The two experts discussed their rationales and arrived at a final, adjudicated score. This dual-pronged process ensures that the final subjective scores are not only consistent but also reflect a deep, consensus-driven clinical judgment.

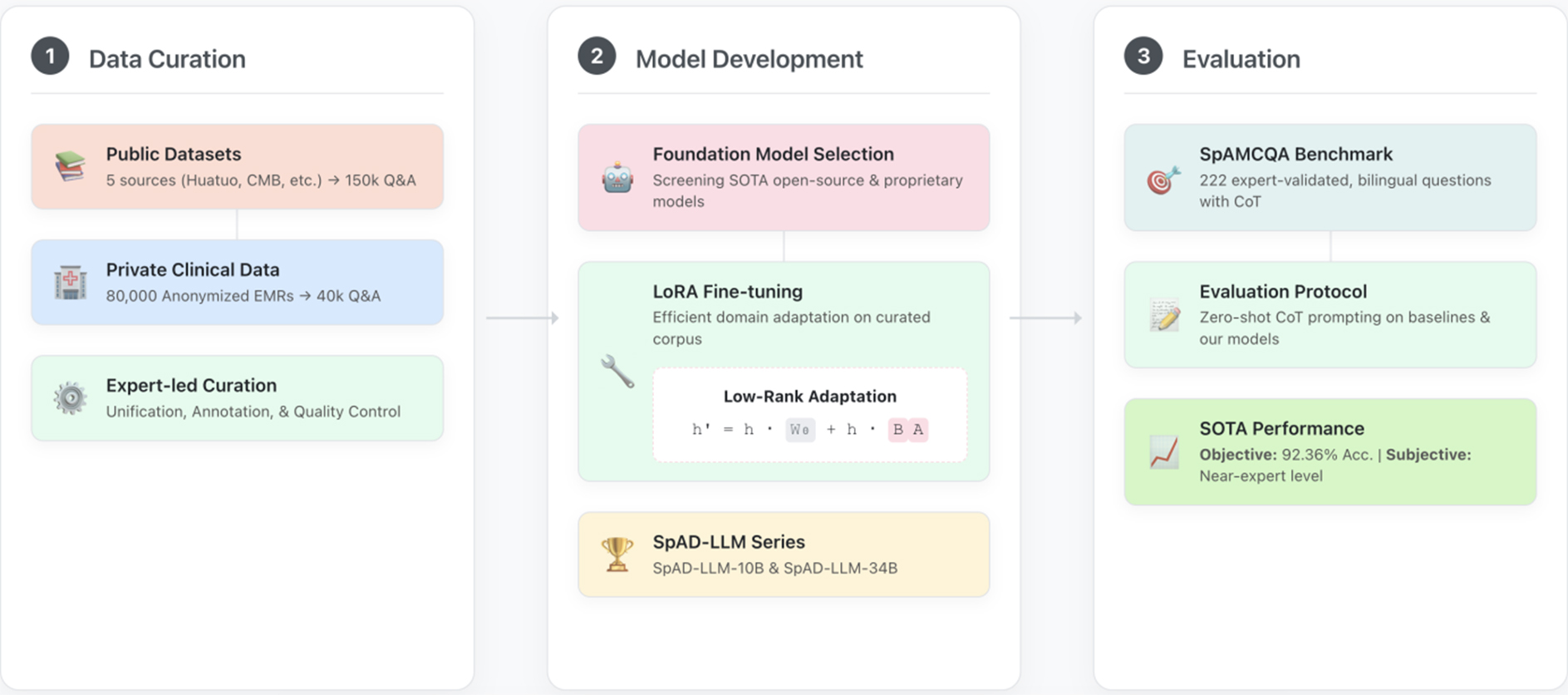

SpAD-LLM: model development and fine-tuning

To rigorously test our central hypothesis, it is necessary to construct a model that embodies the principle of domain specialization. This model, SpAD-LLM, serves as the primary experimental variable in our study, designed to isolate the impact of targeted, high-quality domain data. This section details the methodology for its development and fine-tuning, ensuring the process is transparent and reproducible. The end-to-end process, illustrated in Figure 2, involves curated dataset construction, strategic foundation model selection, and targeted fine-tuning to instill expert- level knowledge. All procedures involving patient data received ethical approval from the institutional review board (No. S2022-255-01).

Figure 2. The end-to-end workflow for developing and evaluating SpAD-LLM. The process is structured into three main stages. (1) Data Curation: We compile a comprehensive fine-tuning corpus by integrating large-scale public medical datasets with a private, expert-annotated dataset derived from 80,000 anonymized electronic medical records (EMRs). This curated corpus contains 150,000 general medical Q&A pairs and 40,000 high-quality Q&A pairs specific to spondyloarthritis (SpA); (2) Model Development: We select promising foundation models from both public and proprietary sources. These models are then efficiently adapted to the rheumatology domain using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) on the curated dataset, resulting in our specialized SpAD-LLM series; (3) Evaluation: The performance of the SpAD-LLM series and baseline models (e.g., GPT-4) is rigorously assessed on our novel SpAMCQA benchmark using a zero-shot Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting strategy. The evaluation combines objective metrics (accuracy) and subjective scores from clinical experts to provide a holistic measure of diagnostic reasoning capability. SpAD-LLM: Spondyloarthritis Diagnosis Large Language Model; SpAMCQA: Spondyloarthritis Multiple-Choice Question Answering Benchmark; CMB: Comprehensive Medical Benchmark.

Dataset curation for domain specialization

A high-quality, domain-specific dataset is the cornerstone of our approach. We constructed a comprehensive fine- tuning corpus by integrating two distinct types of sources to achieve both breadth and depth.

(1) Public Datasets for Foundational Knowledge. To provide a broad foundation of general medical knowledge, we compiled a large-scale corpus of 150,000 question-answer pairs from five established public sources, including Huatuo-26M[32], CMB[17], CMExam[33], MedQA[34], and MLEC-QA[34]. This diverse collection, with statistics summarized in Table 2, equipped our models with a wide-ranging medical vocabulary and reasoning patterns.

Summary of public datasets used for initial fine-tuning

| Dataset source | Total size | Extracted samples |

| Huatuo-26M | 26,000,000 | 50,000 |

| CMB | 280,839 | 25,000 |

| CMExam | 68,119 | 25,000 |

| MedQA | 61,097 | 25,000 |

| MLEC-QA | 136,236 | 25,000 |

| Total public samples | - | 150,000 |

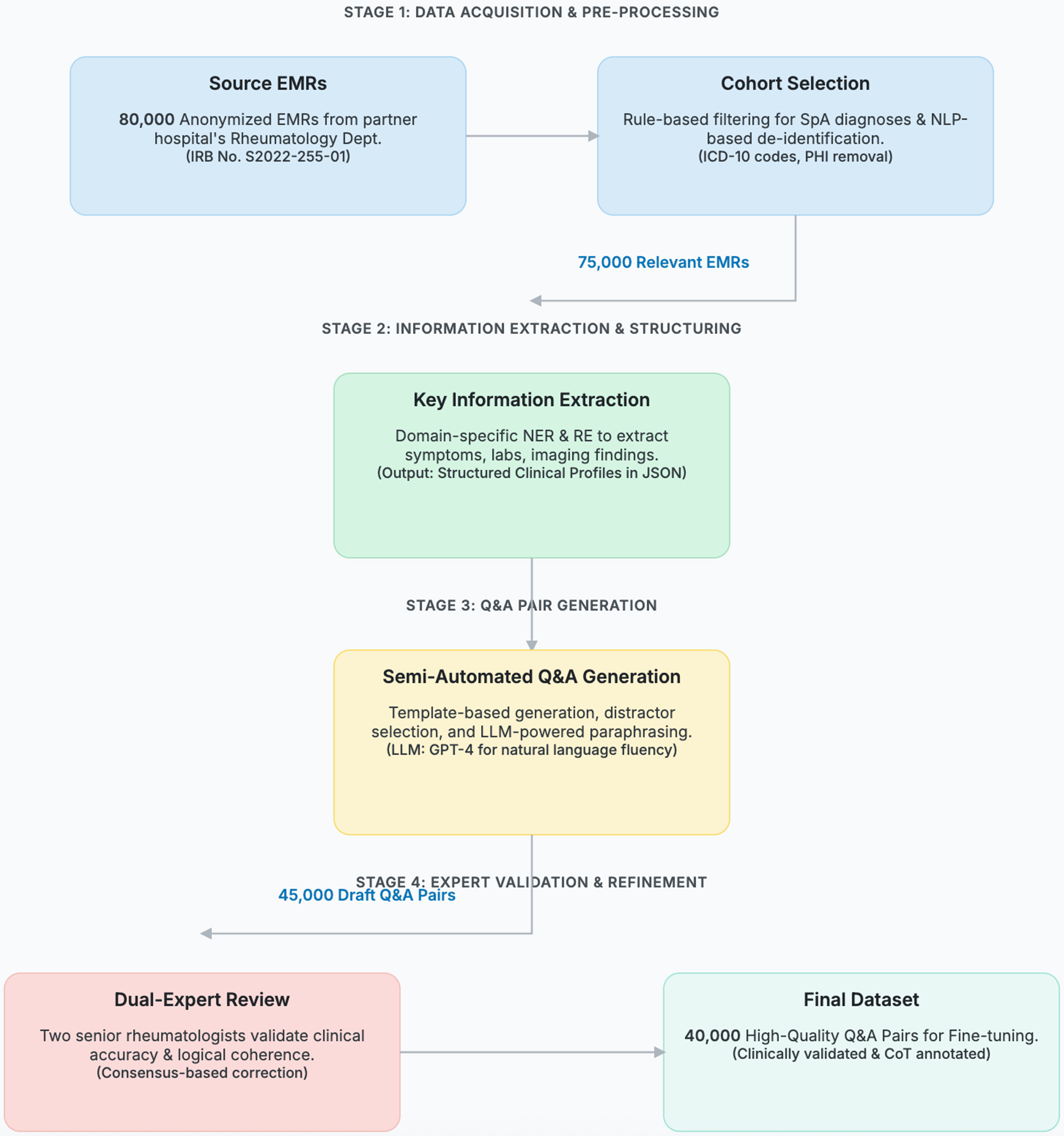

(2) Private Clinical Datasets for Specialized Expertise. To imbue the model with deep, specialized SpA expertise, we meticulously curated a private dataset from 80,000 anonymized electronic medical records (EMRs) from our partner hospital. The end-to-end data curation process, depicted in Figure 3, transformed these raw EMRs into 40,000 high-quality, fine-tuning question-answer pairs.

Figure 3. The end-to-end data curation workflow for transforming raw electronic medical records (EMRs) into a high-quality, fine- tuning dataset. The process is organized into four sequential stages: (1) Acquisition & Pre-processing, where 80,000 anonymized EMRs are selected and de-identified; (2) Information Extraction, where key clinical information is structured using domain-specific NLP models; (3) Q&A Generation, where draft question-answer pairs are semi-automatically created; and (4) Expert Validation, where two senior rheumatologists review, correct, and annotate each pair to ensure clinical accuracy and logical coherence. The numbers on the connecting arrows indicate the data volume after each key filtering step, culminating in the final 40,000-pair dataset. NLP: Natural language processing; IRB: Institutional Review Board; SpA: spondyloarthritis; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; PHI: Protected Health Information; NER: named entity recognition; RE: relation extraction; JSON: JavaScript Object Notation; LLM: Large Language Model; GPT-4: Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4; CoT: Chain-of-Thought.

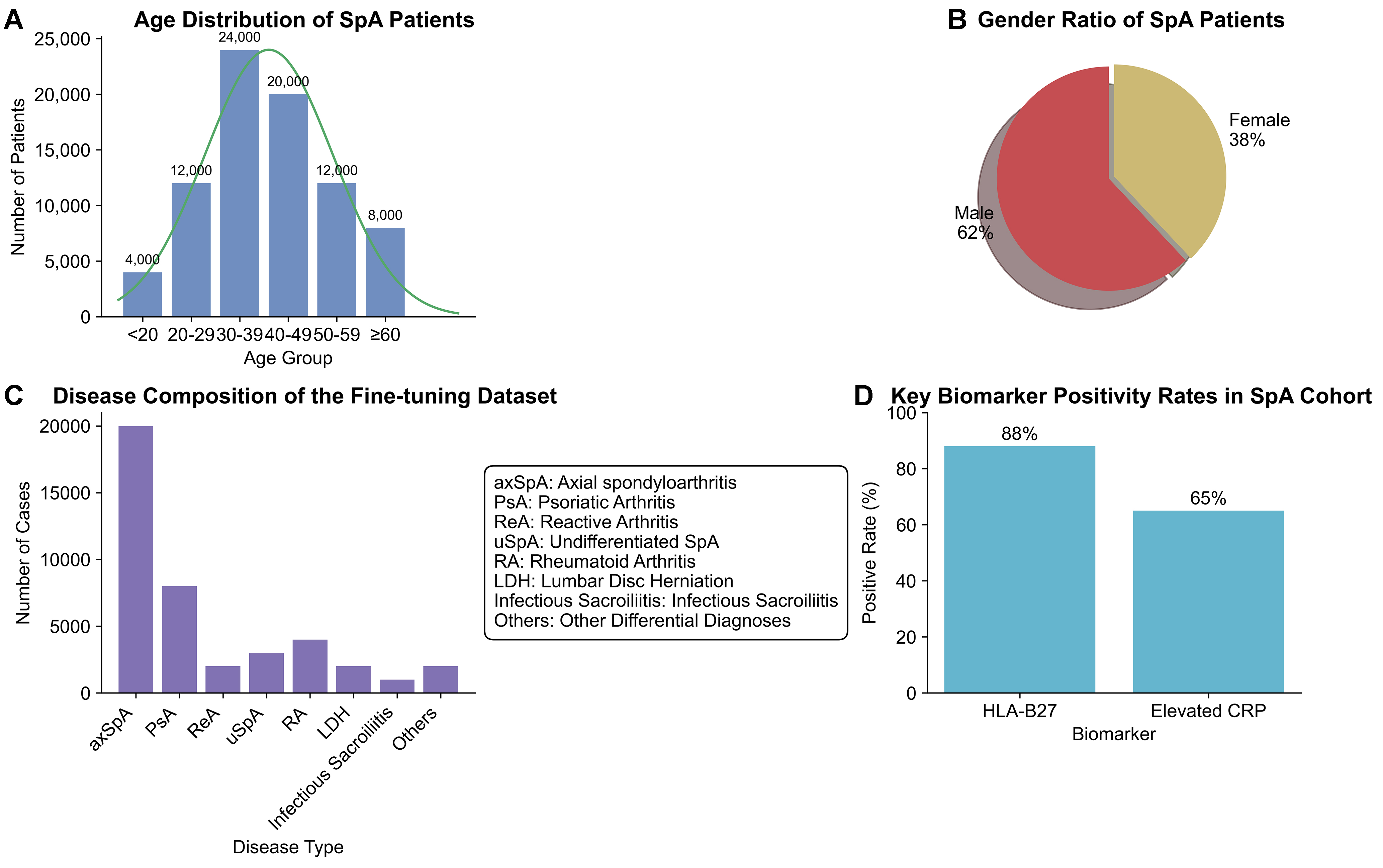

A key principle of our curation strategy was to create a dataset that reflects the true complexity of clinical diagnosis. This required not only capturing the spectrum of SpA subtypes but also including critical differential diagnoses that often mimic SpA symptoms. The final cohort of clinical records, which formed the basis for our 40,000 question-and-answer (Q&A) pairs, was intentionally populated with cases of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), PsA, and other SpA subtypes, alongside challenging distractors such as rheumatoid arthritis and infectious sacroiliitis. To validate the clinical representativeness of this curated cohort, we performed a comprehensive statistical analysis, with the results presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Statistical Validation of the Private Clinical Dataset. This figure provides a comprehensive statistical analysis of the clinical records curated for domain-specific fine-tuning, confirming the dataset’s clinical validity and representativeness. (A) The age distribution of SpA patients shows a peak incidence in the 30-39 age group, aligning with the known epidemiology of disease onset[2]; (B) The gender ratio indicates a male predominance (62% vs. 38%), reflecting the established higher prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis in males[2]; (C) The disease composition of the fine-tuning dataset is intentionally diverse, dominated by SpA subtypes but critically including key differential diagnoses such as rheumatoid arthritis. This case mix mirrors a typical rheumatology clinic’s diagnostic challenge; (D) The positivity rates for key diagnostic biomarkers, Human Leukocyte Antigen B27 (HLA-B27) at 88% and elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP) at 65%, are consistent with reference values for SpA patient cohorts[28]. Collectively, these analyses demonstrate that our private dataset is a high-fidelity representation of the real-world clinical scenarios SpAD-LLM is designed to address. SpA: Spondyloarthritis; SpAD-LLM: Spondyloarthritis Diagnosis Large Language Model.

The demographic profile of our SpA patient group aligns with established epidemiological data; for instance, the peak age of onset is in the 30-39 age range [Figure 4A], and there is a clear male predominance (62%, Figure 4B), consistent with findings in large-scale cohort studies[2]. The composition of the dataset, as shown in Figure 4C, is designed to train the model on nuanced differential diagnosis. While dominated by SpA cases, the inclusion of other rheumatic and musculoskeletal conditions ensures the model learns to distinguish between them, addressing a core challenge in clinical practice. Furthermore, the positivity rates of key biomarkers, such as Human Leukocyte Antigen B27 (HLA-B27, 88%) and elevated C-Reactive Protein (CRP, 65%) [Figure 4D], are consistent with reference values for SpA patient populations[28]. This rigorous validation confirms that our private dataset is not an arbitrary collection of records but a high-fidelity, clinically valid corpus suitable for training an expert-level diagnostic model.

Foundation model selection and fine-tuning

Our development of SpAD-LLM followed a systematic process of selection and optimization.

Data-driven foundation model selection

Our development of SpAD-LLM began with a rigorous, data-driven selection of foundation models. The goal was to identify candidates with the highest potential for specialization, rather than making an arbitrary choice. To this end, we conducted a preliminary zero-shot evaluation of a diverse suite of leading open-source LLMs, including several from the C-Eval leaderboard[35], on our newly developed SpAMCQA benchmark. This initial assessment provided a clear baseline of their out-of-the-box capabilities in the nuanced domain of SpA diagnosis.

Based on the preliminary zero-shot evaluation on the SpAMCQA benchmark, we analyzed the baseline reasoning capabilities of various open-source models. This analysis guided our strategic selection of candidate models for the subsequent fine-tuning experiments:

1. High-performing candidates: Based on the zero-shot results, Yi-34B[36] and Qwen-7B-Chat demonstrated the strongest performance among the publicly available open-source models, achieving 75.59% and 72.16% accuracy, respectively. Their strong initial grasp of medical reasoning made them primary candidates to investigate the upper limits of domain specialization.

2. Architectural and capability diversity: To ensure our findings were not limited to a single model architecture or initial performance level, we also selected ChatGLM2-6B-32K and Llama2-7B-Chat[10]. Despite their varied baseline scores (62.14% and 34.02%), their inclusion allows us to assess the impact of our fine-tuning corpus across a broader spectrum of model types and starting capabilities.

3. Proprietary model development: Concurrently, to explore the influence of architectural variations under our full control, we developed proprietary models based on the LLaMA[9] and Yi-34B[36] architectures (SpAD-LLM- 10B and SpAD-LLM-34B). We established their pre-fine-tuning performance to provide a direct baseline for quantifying the gains achieved through our domain-specific training.

This systematic, evidence-based selection process ensures that our subsequent fine-tuning experiments are not conducted in a vacuum. It allows us to transparently quantify the “performance lift” provided by domain specialization and validates that the improvements are a direct result of our curated data and methodology, not merely a consequence of selecting a favorable base model.

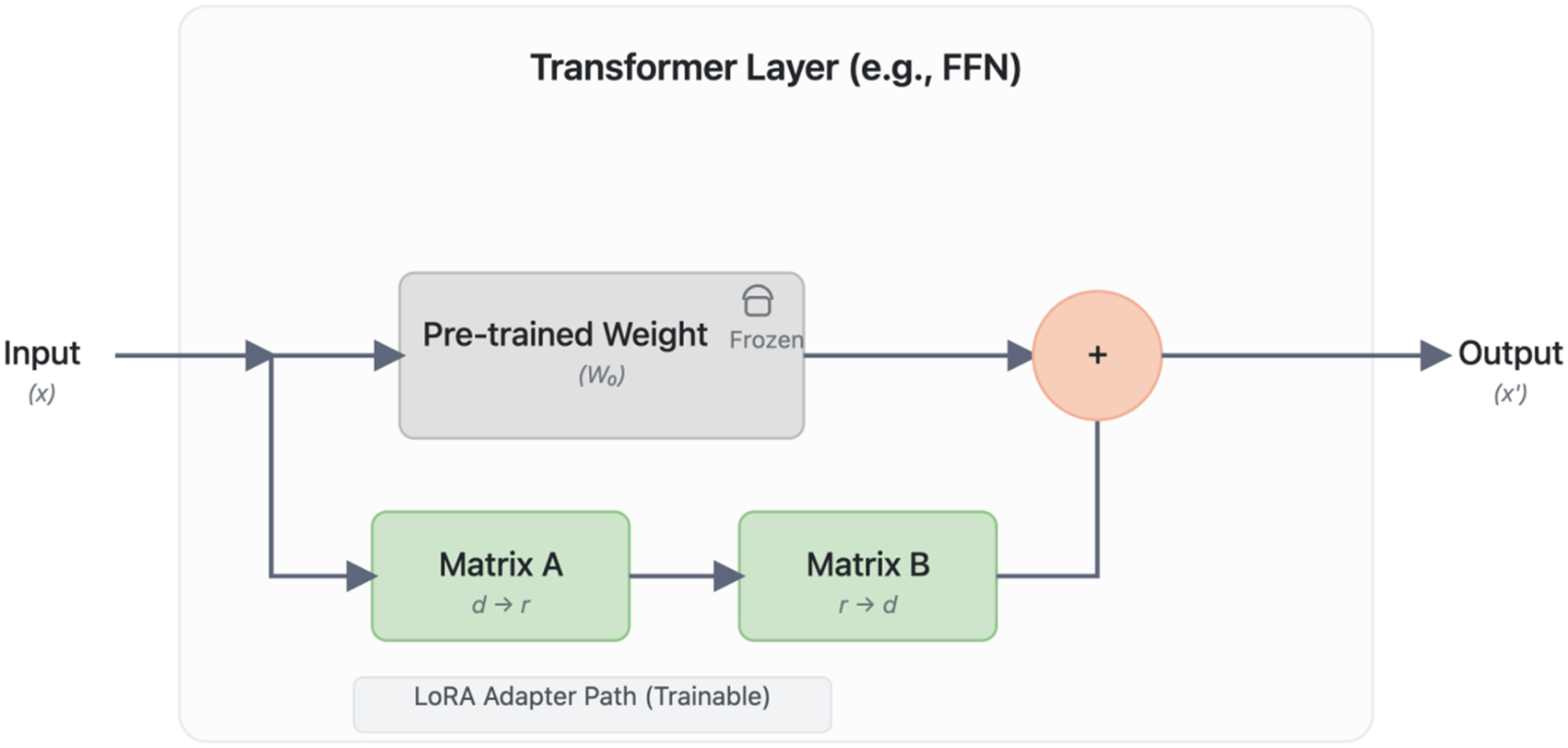

Parameter-efficient fine-tuning with LoRA

To efficiently adapt these large models to our specialized medical domain, we employed the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) technique[37]. LoRA was chosen for its ability to enable rapid specialization with minimal computational overhead while preserving the foundational knowledge of the pre-trained models, a crucial aspect for medical applications. It introduces trainable, low-rank matrices into the transformer layers, drastically reducing the number of trainable parameters and Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) memory requirements. The model is trained to minimize a standard cross-entropy loss function. While the original pre-trained weights W remain frozen, the weight updates are represented by trainable low-rank matrices A and B, resulting in the effective weights W + BA. This architectural modification, visualized in Figure 5, allows for efficient specialization.

Figure 5. The LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) Fine-tuning Architecture. The diagram illustrates how LoRA efficiently adapts a pre-trained Transformer layer. The main data path (top) processes the input ‘(x)’ through the original, frozen pre-trained weights (‘W’), preserving foundational knowledge. In parallel, a trainable adapter path (bottom) is injected, consisting of a rank-decomposition operation with two low-rank matrices, ‘A’ (rank reduction, d → r) and ‘B’ (rank expansion, r → d). The outputs from both paths are aggregated through element-wise addition to produce the final output ‘(x’)’. This design drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters, enabling efficient specialization of large models with minimal computational overhead. FFN: Feed-forward neural network.

The training objective is to minimize the loss function L(Θi, A, B)[37]:

where x1..i is the input sequence, yi is the predicted token, Θ0 are the frozen pre-trained weights, and A, B are the trainable low-rank matrices. This was implemented using the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 5e-5 and a cosine annealing schedule, running on four A100-40GB GPUs. The final models, fine-tuned on the complete curated dataset, are denoted as SpAD-LLM-10B and SpAD-LLM-34B.

RESULTS

This section presents the empirical results of the experiment designed to test our core hypothesis: domain specialization is a necessity, not merely an option, for achieving expert-level performance in high-stakes clinical AI. We utilize the SpAMCQA benchmark as the meticulously engineered evaluation platform to conduct this test. The experiment pits our specialized SpAD-LLM series against a cohort of leading generalist models, including Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4). The primary objective is to quantitatively measure the performance delta between these two classes of models, thereby determining if the gap predicted by our hypothesis is not only present but also statistically significant. The evaluation protocol is multifaceted, assessing both objective diagnostic accuracy (Section 3.1) and the qualitative soundness of clinical reasoning (Section 3.2).

Objective evaluation: the power of specialization

We first assessed the models’ diagnostic accuracy using the objective scoring protocol detailed in Section 2.1.3. The results, presented in Table 3, offer a clear and compelling narrative on the effectiveness of our benchmark and the necessity of domain specialization.

Preliminary zero-shot evaluation of foundation models on the SpAMCQA benchmark

| Model | Parameters | Overall accuracy (%) | Notes |

| Closed-source SOTA baseline | |||

| GPT-4 | 86.05 | High-performing generalist baseline | |

| Open-source candidates | |||

| Yi-34B[36] | 34B | 75.59 | Strongest open-source performance |

| Qwen-7B-Chat | 7B | 72.16 | High performance at a smaller scale |

| Huatuo2-13B | 13B | 72.06 | Medically-focused baseline |

| ChatGLM2-6B-32K | 6B | 62.14 | Included for architectural diversity |

| Llama2-7B-Chat[10] | 7B | 34.02 | Common foundation model, lower baseline |

| Our proprietary models (Base) | |||

| SpAD-LLM-34B (Base) | 34B | 51.17 | Base model before fine-tuning |

| SpAD-LLM-10B (Base) | 10B | 63.60 | Base model before fine-tuning |

The findings establish four key points. First and most critically, our specialized SpAD-LLM-34B (92.36%) decisively outperforms the generalist SOTA model, GPT-4 (86.05%). This significant performance delta is the central finding of our study, empirically validating the domain specialization hypothesis and, crucially, demonstrating that SpAMCQA is sufficiently nuanced to capture this performance gap.

Second, the benchmark effectively quantifies the substantial gains from our fine-tuning process across all models. For instance, Qwen-7B-Chat’s accuracy surged from 72.16% to 83.66%. This consistent improvement across different architectures and scales highlights the quality of our curated dataset and confirms SpAMCQA as a reliable metric for tracking progress.

Third, it is remarkable that our smaller specialized model, SpAD-LLM-10B (86.08%), achieves performance on par with GPT-4. This demonstrates that with high-quality, targeted data, even moderately-sized models can achieve expert-level performance, offering a more efficient and accessible path towards specialized medical AI.

Finally, the performance of even powerful generalist models such as GPT-4 and Llama2-70B (63.57%) underscores the inherent limitations of broad pre-training. Their inability to outperform our specialized models confirms that general knowledge is insufficient for mastering the expert-level heuristics required for SpA diagnosis. This validates the critical need for specialized evaluation tools such as SpAMCQA, which can expose capability gaps that might otherwise be obscured by evaluations on general medical datasets. The baseline zero-shot performance of all models is provided for context in Table 4.

Objective evaluation results on the SpAMCQA benchmark

| Model | Single-choice accuracy | Multi-choice accuracy | Overall accuracy | |||

| Before FT | After FT | Before FT | After FT | Before FT | After FT | |

| Models fine-tuned in this study: | ||||||

| Baichuan-13B | 65.98 | 80.93 | 38.68 | 72.04 | 62.54 | 79.81 |

| Llama2-7B-Chat | 36.60 | 63.92 | 16.14 | 51.68 | 34.02 | 62.37 |

| Qwen-7B-Chat | 76.80 | 86.60 | 40.00 | 63.32 | 72.16 | 83.66 |

| ChatGLM2-6B-32K | 62.37 | 81.44 | 60.54 | 58.39 | 62.14 | 78.54 |

| SpAD-LLM-10B (ours) | 64.95 | 88.14 | 54.29 | 76.43 | 63.60 | 86.08 |

| SpAD-LLM-34B (ours) | 52.58 | 94.85 | 41.43 | 75.18 | 51.17 | 92.36 |

| Publicly available models (zero-shot): | ||||||

| Huatuo2-13B | 73.20 | - | 64.46 | - | 72.06 | - |

| Llama2-70B-Chat | 69.07 | - | 25.46 | - | 63.57 | - |

| Falcon-40B | 41.24 | - | 24.29 | - | 39.10 | - |

| Meditron-70B | 38.66 | - | 55.29 | - | 40.76 | - |

| Mistral-7B | 76.80 | - | 56.07 | - | 74.19 | - |

| Orca2-13B | 75.77 | - | 38.39 | - | 71.06 | - |

| Yi-34B | 79.38 | - | 49.29 | - | 75.59 | - |

| GPT-4 | 87.11 | - | 78.68 | - | 86.05 | - |

Subjective evaluation: assessing the quality of clinical reasoning

Beyond quantitative accuracy, a benchmark’s true value in medicine lies in its ability to assess the quality of the underlying reasoning. The results of our subjective evaluation, summarized in Table 5, offer profound insights into this dimension. These consensus-based scores, established through a rigorous protocol involving independent rating and IRR analysis (see Section 2.1.3), provide a validated, nuanced view of the models’ clinical reasoning capabilities.

Expert validation of clinical reasoning processes (CoT)

| Model | Fluency | Relevance | Completeness | Medical professionalism |

| Models before domain-specific fine-tuning: | ||||

| Qwen-7B-Chat | 4.25 | 3.80 | 3.55 | 3.65 |

| SpAD-LLM-34B (Base) | 4.55 | 4.10 | 3.90 | 4.05 |

| Models after domain-specific fine-tuning: | ||||

| Qwen-7B-Chat-FT | 4.30 | 4.45 | 4.20 | 4.40 |

| SpAD-LLM-34B-FT | 4.60 | 4.95 | 4.45 | 4.85 |

| Generalist SOTA model (Baseline): | ||||

| GPT-4 | 4.81 | 4.90 | 4.48 | 4.80 |

The findings reveal a clear hierarchy of performance. While the generalist SOTA model, GPT-4, sets a high baseline, our fine-tuned SpAD-LLM-34B-FT demonstrates a remarkable convergence towards expert-level reasoning. Critically, in the two most vital clinical dimensions, Relevance and Medical Professionalism, our model achieves near-perfect scores of 4.95 and 4.85, respectively, outperforming the strong GPT-4 baseline (4.90 and 4.80).

This outcome is particularly telling when considered alongside the IRR analysis. The relatively lower initial agreement among experts when scoring the top-performing models (e.g., κ as low as 0.160 for SpAD-LLM-34B-FT in Medical Professionalism before consensus) does not indicate a flaw, but rather underscores the profound complexity of the evaluation task itself. It suggests that at this elite level of performance, models are generating responses so advanced that they elicit nuanced, expert-level debate - a hallmark of genuine clinical reasoning, not superficial pattern matching.

This result empirically validates that targeted fine-tuning on a high-quality, specialized dataset can elevate a model’s reasoning to a level that is virtually indistinguishable from a human expert. The granular, multi-dimensional evaluation protocol of SpAMCQA, by surfacing these subtle but critical differences, proves its capability to move beyond simple accuracy metrics and probe for the genuine, expert-level understanding required for safe and effective clinical deployment.

To concretely illustrate the qualitative disparity in clinical reasoning between the models, we present a representative case analysis in Table 6. In this instance, the models were tasked with identifying the exception among common extra-articular manifestations of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS). While GPT-4 produced a linguistically fluent and structured response, it exhibited a critical ‘domain hallucination.’ It incorrectly excluded Cauda Equina Syndrome (a rare but established complication of longstanding AS) and erroneously included Renal Tubular Acidosis as a common feature. Conversely, SpAD-LLM demonstrated expert-level domain alignment. It not only correctly identified the distractor (Renal Tubular Acidosis) but also accurately attributed the other options, including Cauda Equina Syndrome, to the disease’s pathology. This comparison highlights that while generalist models may mimic medical reasoning patterns, our specialized model possesses the granular, factual precision required for high-stakes diagnostics.

Case study: comparison of reasoning (CoT) between SpAD-LLM and GPT-4

| Component | Content |

| Question | Question: All of the following are possible common extra-articular manifestations of Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), EXCEPT: A. Acute anterior uveitis or iridocyclitis B. Aortic root disease C. Cauda equina syndrome D. Renal tubular acidosis E. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis Correct Answer: D |

| SpAD-LLM (ours) | Answer: D Reasoning: Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammatory arthropathy affecting the axial skeleton. Beyond joints, it may present with extra-articular manifestations: - A. Acute uveitis: Caused by inflammation spreading to ocular tissues. - B. Aortic root disease: Caused by inflammation spreading to the aortic root. - C. Cauda equina syndrome: Patients may develop this due to inflammation affecting the cauda equina nerves. - E. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis: Caused by inflammation in the lung interstitium. - D. Renal tubular acidosis: This is a renal disorder unrelated to AS. Conclusion: Therefore, option D is not a common extra-articular manifestation. |

| GPT-4 (Baseline) | Answer: C (Incorrect) Reasoning: AS is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the spine. - A. Acute uveitis: A common extra-articular manifestation. - B. Aortic root disease: Heart involvement is common, causing aortic root inflammation. - D. Renal tubular acidosis: Some AS patients may have renal involvement manifesting as RTA. (Hallucination) - E. Pulmonary interstitial fibrosis: Possible lung involvement. - C. Cauda equina syndrome: Refers to damage at the nerve roots. It is usually associated with disc herniation or stenosis, rather than being a typical extra-articular manifestation of AS. (Domain Knowledge Deficit) Conclusion: The correct answer is C. |

| Expert commentary | SpAD-LLM correctly identifies that Renal Tubular Acidosis is not a standard feature of AS, whereas Cauda Equina Syndrome is a known (albeit late-stage) complication. GPT-4 displays a plausible-sounding but factually incorrect reasoning path, failing to recognize the specific link between AS and Cauda Equina Syndrome while hallucinating an association with RTA. |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we presented conclusive empirical evidence to address a foundational question in medical AI: for high- stakes, nuanced clinical tasks, is domain specialization an incremental improvement or a categorical necessity? Our findings strongly support the latter. The superior performance of our specialized SpAD-LLM-34B (92.36% accuracy) over the leading generalist model, GPT-4 (86.05%), on our purpose-built SpAMCQA benchmark, is not merely a quantitative victory. It represents a fundamental challenge to the prevailing “bigger is better” paradigm, suggesting that for safety-critical domains such as clinical diagnostics, the performance bottleneck is not a deficiency in model scale but a profound deficit in domain-specific, inferential knowledge.

This definitive validation was made possible only through the co-development of our second primary contribution: the SpAMCQA benchmark. Existing general medical benchmarks are too diffuse to distinguish between superficial pattern matching and genuine clinical reasoning. They create an “evaluation vacuum” where claims of expert- level performance remain clinically unverified. SpAMCQA was meticulously engineered to fill this void. By incorporating complex, real-world patient cases, challenging distractors, and expert-verified reasoning paths (CoT annotations), it provides a rigorous testbed that probes the process of diagnostic reasoning, not just the final output. This work, therefore, breaks the circular problem of evaluating specialized models on generalist benchmarks; we first forged a precise instrument, then used it to accurately measure the capability gap we hypothesized.

Beyond sheer accuracy, our results carry significant implications for the future development and democratization of medical AI. It is particularly noteworthy that our smaller specialized model, SpAD-LLM-10B, achieved performance on par with the much larger GPT-4. This demonstrates that with a high-quality, targeted corpus, even moderately-sized models can attain expert-level capabilities. This finding offers a more efficient, accessible, and computationally feasible pathway for developing specialized medical AI, empowering individual research groups and clinical departments to build their own expert systems without relying on massive, resource-intensive proprietary models. It shifts the focus from a race for scale to a pursuit of high-fidelity, domain-specific data curation.

While previous works have developed domain-adapted models such as Med-PaLM 2 and HuatuoGPT-II, their efficacy has largely been assessed on broad-coverage benchmarks. Our study distinguishes itself by providing the first head- to-head comparison on a benchmark specifically designed to expose the limitations of generalist knowledge in a specialized context. This rigorous, falsifiable experimental design provides the first piece of unambiguous evidence that the value of domain specialization, long an untested hypothesis, is both substantial and quantifiable.

Limitations

Despite the promising results, our study has several limitations that necessitate careful interpretation and outline directions for future work.

First, regarding data generalizability: The clinical data used for fine-tuning SpAD-LLM originates from a single institution, the Chinese PLA General Hospital. As a top-tier tertiary referral center, the patient population here tends to present with more severe, complex, or atypical symptoms compared to primary care settings. This introduces a potential referral bias, meaning our model might be less sensitive to the milder or early-stage presentations of SpA commonly seen in community clinics. Furthermore, relying on single-center data may embed specific institutional biases related to diagnostic protocols and EMR formatting, potentially limiting the model’s zero-shot performance in other hospital systems. To mitigate

Second, the scope of the domain: Our investigation currently focuses exclusively on SpA. While SpA serves as an excellent representative of complex rheumatic diseases due to its nuanced reasoning requirements, the efficacy of this “specialization via fine-tuning” paradigm needs to be verified in other medical domains with different reasoning patterns, such as oncology or neurology.

Finally, the modality constraint: Our current framework is unimodal, processing only textual clinical records. However, SpA diagnosis in real-world practice is inherently multi-modal, heavily relying on imaging evidence (e.g., sacroiliitis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or X-ray). The lack of visual processing capability restricts the model from acting as a fully independent diagnostic agent. Future iterations of SpAD-LLM will aim to integrate multi-modal encoders to process visual and textual data synergistically.

In conclusion, this study addresses the critical evaluation gap in medical AI by introducing SpAMCQA, an expert-validated benchmark specifically engineered for high-stakes clinical reasoning. Our findings empirically demonstrate that generalist LLMs, including GPT-4, exhibit significant limitations in specialized domains such as SpA. Conversely, the domain-specific SpAD-LLM, developed through targeted fine-tuning on high-quality clinical data, achieved SOTA performance, validating the hypothesis that domain specialization is a categorical necessity for expert-level medical AI. By releasing the SpAMCQA benchmark and the SpAD-LLM baselines, we provide the community with essential tools to foster the development of transparent, reliable, and clinically capable diagnostic systems.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to all participants and contributors from the Chinese PLA General Hospital, Dataa Robotics Co., Ltd., and Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology for their invaluable support.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study: Li K, Teng D, Li T

Performed the clinical data curation and expert validation: Ji X, Hu J

Conducted the model experiments and data analysis: Sun N, Wang A

Provided critical resources and clinical expertise: Dong J, Zhu J, Huang F, Zhang Z

Wrote the initial draft: Ji X

All authors contributed to the review and revision of the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

Availability of data and materials

To promote reproducibility and further research in medical AI, the SpAMCQA Benchmark (including all questions and expert-annotated CoT reasoning paths) and the full inference results of our experiments have been made publicly available at (https://github.com/init-SGD/SpAMCQA).

Due to privacy regulations regarding the clinical data used for training and proprietary restrictions on the model architecture, the model weights and training code cannot be released at this time. Researchers interested in collaborating or validating the model on external cohorts may contact the corresponding author (K Li) to discuss data use agreements and ethical approval.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2021ZD0140409), the Independent Research Project of the Medical Engineering Laboratory of Chinese PLA General Hospital (No. 2022SYSZZKY28), the Youth Independent Innovation Science Fund Project of Chinese PLA General Hospital (No. 22QNFC139), the Industry-University Cooperative Education Project from the Ministry of Education (No. 231103873260059), the fund of the Beijing Municipal Education Commission (No. 22019821001), Zhiyuan Science Foundation of Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology(No. 2026005) and the Undergraduate Research Training program (No. 2024J00011, 2024J00028).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving patient data received ethical approval from the institutional review board of the Chinese PLA General Hospital (No. S2022-255-01). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants whose data were used in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Malaviya AN, Sawhney S, Mehra NK, Kanga U. Seronegative arthritis in South Asia: an up-to-date review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:413.

2. Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2563-74.

4. Singhal K, Tu T, Gottweis J, et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat Med. 2025;31:943-50.

5. Thirunavukarasu AJ, Ting DSJ, Elangovan K, Gutierrez L, Tan TF, Ting DSW. Large language models in medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29:1930-40.

6. Singhal K, Azizi S, Tu T, et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature. 2023;620:172-80.

7. Kraljevic Z, Bean D, Shek A, et al. Foresight - a generative pretrained transformer for modelling of patient timelines using electronic health records: a retrospective modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 2024;6:e281-90.

8. Shao Y, Cheng Y, Nelson SJ, et al. Hybrid value-aware transformer architecture for joint learning from longitudinal and non-longitudinal clinical data. J Pers Med. 2023;13:1070.

9. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In: Larochelle H, Ranzato M, Hadsell R, Balcan MF, Lin H, Editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); 2020 Dec 6-12; Virtual form. Red Hook: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2020. pp. 1877-901. Available from https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/1457c0d6bfcb4967418bfb8ac142f64a-Abstract.html [accessed 9 February 2026].

10. Touvron H, Martin L, Stone K, et al. Llama 2: open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2307.09288. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09288 [accessed 9 February 2026].

11. OpenAI, Josh Achiam, Steven Adler, et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2303.08774. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774 [accessed 9 February 2026].

12. Xie Q, Chen Q, Chen A, et al. Me-LLaMA: foundation large language models for medical applications. Res Sq 2024;rs.3.rs-4240043. Available from https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4240043/v1 [accessed 9 February 2026].

13. Chen Z, Hernández Cano A, Romanou A. MEDITRON-70b: scaling medical pretraining for large language models. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2311.16079. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.16079 [accessed 9 February 2026].

14. Chen J, et al. HuatuoGPT-II, one-stage training for medical adaption of LLMs. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2311.09774. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09774 [accessed 9 February 2026].

15. Uz C, Umay E. “Dr ChatGPT”: is it a reliable and useful source for common rheumatic diseases? Int J Rheum Dis 2023;26:1343-9.

16. Papineni K, Roukos S, Ward T, Zhu WJ. BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); 2002 Jul 6-12; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2002. pp. 311-18.

17. Wang X, Chen G, Dingjie S, et al. CMB: a comprehensive medical benchmark in Chinese. In: Duh K, Gomez H, Bethard S, Editors. Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2024 Jun 16-21; Mexico City, Mexico. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. pp. 6184-205.

18. Zhang N, Chen M, Bi Z, et al. CBLUE: a Chinese biomedical language understanding evaluation benchmark. In: Muresan S, Nakov P, Villavicencio A, Editors. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022 May 22-27; Dublin, Ireland. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. pp. 7888-915.

19. He Z, Wang Y, Yan A. MedEval: a multi-level, multi-task, and multi-domain medical benchmark for language model evaluation. In: Bouamor H, Pino J, Bali K, Editors. Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6-10; Singapore. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. pp. 8725-44.

20. Xu J, Lu L, Peng X, et al. Data set and benchmark (MedGPTEval) to evaluate responses from large language models in medicine: evaluation development and validation. JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12:e57674.

21. Chen W, Li Z, Fang H, et al. A benchmark for automatic medical consultation system: frameworks, tasks and datasets. Bioinformatics. 2023;39:btac817.

22. Li M, Cai W, Liu R, et al. FFA-IR: towards an explainable and reliable medical report generation benchmark. In: Vanschoren J, Yeung S, Editors. Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems Track on Datasets and Benchmarks; 2021. Available from https://datasets-benchmarks-proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2021/hash/35f4a8d465e6e1edc05f3d8ab658c551-Abstract.html [accessed 9 February 2026].

23. Christophe C, Kanithi P, Munjal P, et al. Med42-evaluating fine-tuning strategies for medical LLMs: full-parameter vs. parameter-efficient approaches. arXiv 2024;arXiv:2404.14779. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.14779 [accessed 9 February 2026].

24. Nori H, King N, McKinney SM, et al. Capabilities of GPT-4 on medical challenge problems. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2303.13375. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.13375 [accessed 9 February 2026].

25. Liu F, Li Z, Zhou H, et al. Large language models in the clinic: a comprehensive benchmark. arXiv 2024;arXiv:2405.00716. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.00716 [accessed 9 February 2026].

26. Huang F, Zhu J, Wang YH, et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2022;61:893-900.

27. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:978-91.

28. Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68 Suppl 2:ii1-44.

29. Madrid-García A, Rosales-Rosado Z, Freites-Nuñez D, et al. Harnessing ChatGPT and GPT-4 for evaluating the rheumatology questions of the Spanish access exam to specialized medical training. Sci Rep. 2023;13:22129.

30. Wang A, Wu Y, Ji X, et al. Assessing and optimizing large language models on spondyloarthritis multi-choice question answering: protocol for enhancement and assessment. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e57001.

31. Mitra A, Del Corro L, Mahajan S. Orca 2: teaching small language models how to reason. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2311.11045. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.11045 [accessed 9 February 2026].

32. Li J, Wang X, Wu X, et al. Huatuo-26M, a large-scale Chinese medical QA dataset. arXiv 2023;arXiv:2305.01526. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.01526 [accessed 9 February 2026].

33. Liu J, Zhou P, Hua Y, et al. Benchmarking large language models on CMExam - a comprehensive Chinese medical exam dataset. In: Oh A, Naumann T, Globerson A, Saenko K, Hardt M, Levine S, Editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36; 2023 Dec 10-16; New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. pp. 52430-52. Available from https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/hash/a48ad12d588c597f4725a8b84af647b5-Abstract-Datasets_and_Benchmarks.html [accessed 9 February 2026].

34. Li J, Zhong S, Chen K. MLEC-QA: a Chinese multi-choice biomedical question answering dataset. In: Moens MF, Huang X, Specia L, Yih SWT, Editors. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2021 Nov 7-11; Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. pp. 8862-74.

35. Leaderboard - C-Eval. Updated on 2025 Jul 26. Available from: https://cevalbenchmark.com/static/leaderboard.html [accessed 9 February 2026].

36. 01.AI, Young A, Chen B, et al. Yi: Open Foundation Models by 01.AI. arXiv 2024;arXiv:2403.04652. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.04652 [accessed 9 February 2026].

37. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, et al. LoRA: low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv 2021;arXiv:2106.09685. Available from https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.09685 [accessed 9 February 2026].

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].