Exploring structures of nanoclusters combining high-dimensional neural network potentials with unsupervised machine learning algorithms

Abstract

Understanding the structural evolution of catalysts with temperature is crucial for elucidating the real active sites under thermal catalytic conditions. Cerium oxides have emerged as versatile catalysts in such environments; however, the temperature-dependent stability of pristine nanoclusters remains poorly understood, creating a knowledge gap between their idealized and working structures. Herein, we developed a machine learning workflow combining high-dimensional neural network potentials and unsupervised machine learning algorithms to uncover the intrinsic structural evolution of stoichiometric CenO2n (n < 21) clusters. We first identified the most stable configurations for each cluster size and determined several magic numbers (n = 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, 20) with enhanced stability at 0 K. Nanosecond-scale neural network potential molecular dynamics simulations were then employed to explore temperature-dependent behavior, where the most frequently appearing structures extracted via K-means clustering were adopted as stability indicators. The results reveal that the temperature-sensitive stability varies with cluster size: magic-number clusters such as Ce14O28 maintain relative robust stability at elevated temperatures, while non-magic-number clusters such as Ce4O8 undergo pronounced structural fluctuations. This work not only offers new insights into temperature-induced distortion and reconstruction of oxide clusters, but also establishes an efficient workflow for high-precision structural prediction especially under high temperatures.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

With unique redox properties, cerium oxides have emerged as versatile catalysts, which are crucial for numerous reactions, such as CO2 hydrogenation, CO oxidation, the water-gas shift, and methane and alcohol reforming[1-8]. In contrast to their conventional use as support materials, the inverse configurations - where cerium oxide is supported on a metal surface - have recently attracted significant attention due to the strong metal-support interaction (SMSI), which promotes novel catalytic performance via interfacial electron transfer and dynamic reconstruction[9,10]. The application of cerium oxide nanoparticles is related to their stability and activity, which depend on their size, shape, and other structural factors[5,6,11,12]. It remains unclear whether pristine cerium oxide clusters exhibit temperature-sensitive stability. Consequently, obtaining atomically precise structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters is imperative, as this constitutes a crucial step toward understanding their thermal stability, identifying active sites, and ultimately establishing robust structure-activity relationships under realistic operating conditions.

Machine learning techniques have recently become powerful tools in nanocluster science for investigating structures and properties, achieving notable success in exploring potential energy surfaces[13,14], characterizing the local atomic environment[15-17], building reactivity descriptors[18-20], and analyzing microscopy images[21]. Recently, these methods have been extended to study the finite-temperature stability of various nanoclusters[22,23]. However, structural prediction - the first step in studying metal oxide nanoclusters - is challenging, as their numerous possible configurations lead to exponentially increasing computational costs[24-26]. This complexity is further compounded in cerium oxide nanoclusters due to their intricate electronic configurations, which necessitate high-precision potentials based on first-principles calculations for efficient structural sampling[27,28]. Consequently, determining atomically precise structures of pristine cerium oxide nanoclusters and elucidating their relative stabilities at different temperatures remains challenging.

Motivated by this, a machine learning workflow combining high-dimensional neural network potentials (HDNNPs) with unsupervised machine learning algorithms was developed to explore the structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters, systematically predicting the structures and relative stability of stoichiometric cerium oxide nanoclusters (from Ce3O6 to Ce21O42). The dataset generated through Monte-Carlo sampling and subsequent density functional theory (DFT) calculations includes atomic coordinates and corresponding energies. A well-trained neural network potential (NNP) was combined with global minimization algorithms, basin-hopping and simulated annealing algorithms, to efficiently identify the most stable structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters by searching within a broad potential energy landscape. The dynamic stability of the identified low-energy structures was confirmed through nanosecond-scale NNP molecular dynamics (NNPMD) simulations, while the K-means clustering algorithm was applied to analyze the NNPMD trajectories and assess their relative stability based on the average energies of representative structures under different temperatures.

EXPERIMENTAL

Data set based on DFT calculations

All DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)[29], with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation functional within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)[30]. The core-valence interactions were described using the projector augmented wave (PAW) potentials, treating the O (2s, 2p), Ce (5s, 5p, 4f, 5d, 6s) electrons as valence states. The cutoff energy of the plane-wave basis was set to 400 eV. The energies were converged to within 10-4 eV. To improve the description of localized excess charge in the Ce 4f orbitals, the DFT + U method[31] was employed, where U (the Hubbard parameter) was set to 5.0 eV. The random initial structures were optimized using the conjugate gradient algorithm. The atomic coordinates and corresponding energies formed the dataset for machine learning, which was randomly divided into a 90% training set and a 10% validation set to train and evaluate the accuracy of the machine learning potential.

Construction of neural network potential

A HDNNP based on the Behler-Parrinello artificial neural network was constructed using the n2p2 code[32-34]. In this framework, the total potential energy was defined as the sum of the individual atomic potential energies. Each atomic energy was trained by an atomic neural network, where symmetry functions were employed to mathematically represent the local structural and chemical environment. The symmetry functions - radial, narrow angular, and wide angular - defined by the positions of neighboring atoms within a cutoff sphere, were used to represent the local chemical environment of O and Ce atoms in Cartesian coordinates. The cutoff radius of all symmetry functions was set to 6 Å in these high-dimensional neural networks.

Each neural network architecture consists of an input layer, two hidden layers with 32 nodes each, and an output layer. The weight parameters of the neural network were optimized using the Kalman filter[35], which efficiently minimizes a cost function based on the root-mean-square error (RMSE) in energies and forces. More details about the machine learning model are provided in Supplementary Equations (1)-(6) and Supplementary Table 1 in the supporting information.

Generation of random initial structures

The initial structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters were generated through a Monte-Carlo sampling approach from a non-periodic bulk cerium oxide model, following a methodology similar to our previous work[27]. The procedure began by randomly selecting a central Ce atom and identifying its neighboring Ce and O atoms based on interatomic distances. To ensure chemical validity, isolated atoms were replaced with candidates to facilitate proper chemical bonds. Structural diversity was increased by probabilistically selecting non-nearest neighbors and adding random displacements to atomic coordinates. The generated candidate structures were evaluated using symmetry metrics derived from the eigenvalues of their interatomic distance matrices and the spatial distribution of atoms relative to the centroid. An Message-Digest Algorithm 5 (MD5) hashing algorithm applied to the atomic coordinates was used to identify and remove duplicate configurations, ensuring that only unique clusters were stored in the final database.

Global minimization based on the neural network potential

The global minimization for stable cerium oxide nanoclusters was employed by combining the NNP with the basin-hopping and simulated annealing algorithms, implemented in the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS)[36]. For each candidate structure, energy minimization was performed using the conjugate gradient algorithm based on the NNP, with an energy convergence tolerance of 10-5 eV. To thoroughly explore the vast configuration space, we initiated ten independent parallel search trajectories, each generating 1,000 structures. By integrating the results of these paths, the lowest-energy nanocluster after geometry optimization was considered as the most stable candidate. Then, using these candidates as initial solutions, the simulated annealing algorithm was incorporated to further stabilize the structures. The annealing process was carried out for 1 nanosecond (ns) with a time step of 1 femtosecond (fs), lasting 100 picosecond (ps) for both heating and cooling to ensure a gradual thermal treatment.

Molecular dynamics simulation via neural network potential

The NNPMD simulations were also performed using the LAMMPS code[36]. The most stable structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters in the range of Ce3O6 to Ce21O42, previously verified via DFT calculations, were adopted as the initial structures for NNPMD simulations. All simulations were performed in the canonical (NVT) ensemble with a time step of 1 fs, and the temperatures were set to 1, 300, 500, and 700 K, respectively. Each NNPMD simulation included a 100 ps pre-equilibration followed by a 1 ns simulation. Before the NNPMD simulations, all the initial cerium oxide structures were optimized using the conjugate gradient algorithm, with the energy tolerance set to 10-5 eV.

Analyze the MD simulation using unsupervised machine learning algorithms

Unsupervised machine learning algorithms were employed to analyze the molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories. First, the Kabsch algorithm was used to align the structure of each frame with the initial reference structure, eliminating rotational and translational effects. Subsequently, high-dimensional feature vectors were constructed from the aligned atomic coordinates, and the K-means clustering algorithm was applied to group these structures. The number of clusters was set in the range of 1 to 5, and the optimal cluster number was automatically determined using the silhouette coefficient. Additionally, to avoid over-clustering, geometrically similar clusters were further merged based on a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) threshold of 0.01 Å. This specific threshold was selected as it effectively distinguishes meaningful structural variations from negligible thermal noise, based on the typical fluctuations and numerical precision of our NNPMD trajectories. A higher threshold would risk merging distinct configurations (under-clustering), while a lower one might capture insignificant vibrational motions (over-clustering). The chosen value of 0.01 Å thus balances sensitivity and physical relevance. Finally, representative structures were selected from each cluster based on the median RMSD, and principal component analysis (PCA) was performed for dimensionality reduction to visualize the K-means clustering results. Through this workflow, the structures and relative stability of cerium oxide nanoclusters in the range of Ce3O6 to Ce21O42 at different temperatures were comprehensively elucidated.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

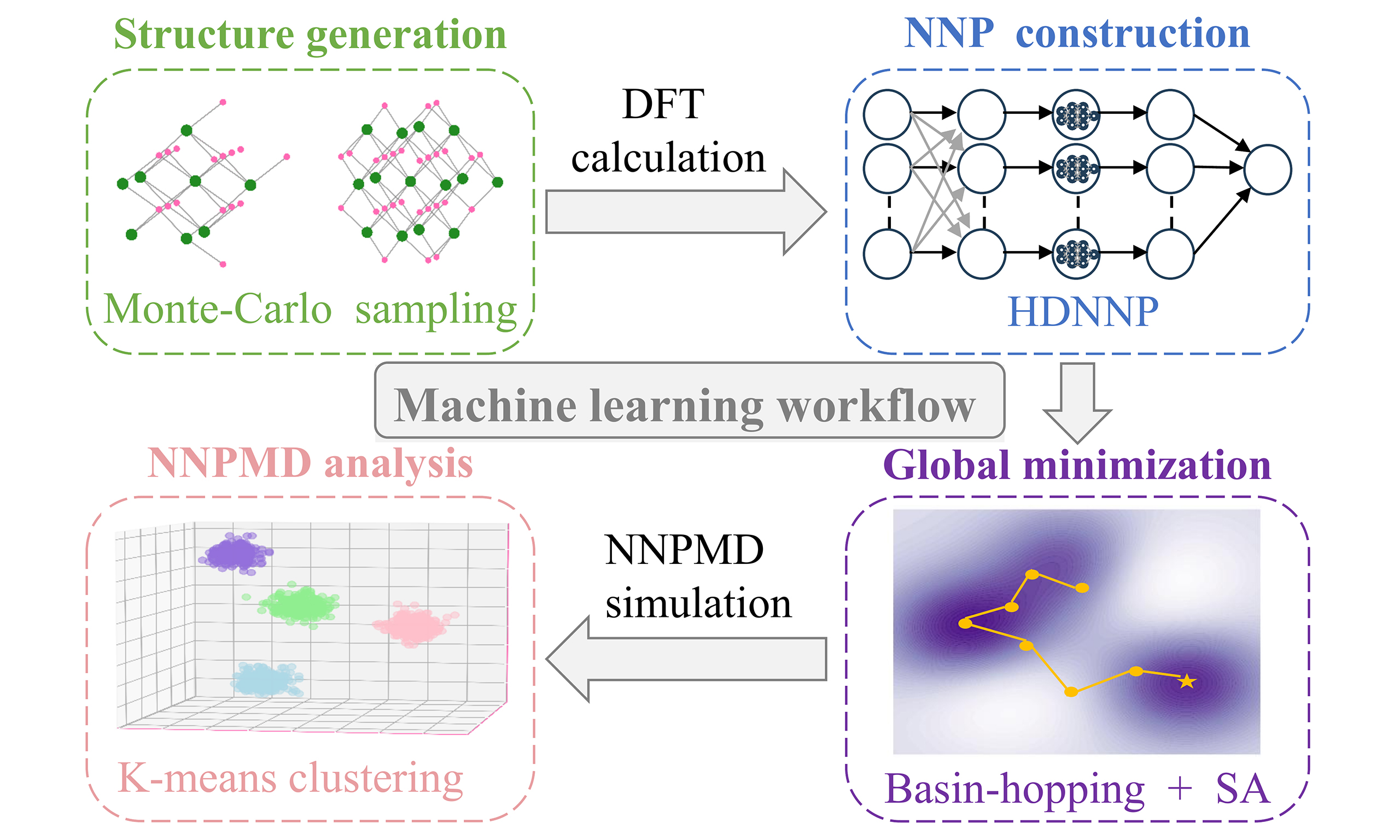

By combining HDNNPs with unsupervised machine learning algorithms, we developed a machine learning workflow to explore the structures and relative stability of cerium oxide nanoclusters under different temperatures. As illustrated in Figure 1, this workflow consists of four components: structure generation, NNP construction, global minimization, and NNPMD analysis.

Figure 1. Machine learning workflow to explore structures of cerium oxide nanocluster. (A) Structure generation: Random initial structures are generated by Monte-Carlo sampling from a large bulk cerium oxide model (Gray: bulk atoms; Green: selected Ce atoms; Red: selected O atoms); (B) NNP construction: The high-dimensional neural network potential (HDNNP) maps atomic Cartesian coordinates (Rn) to symmetry functions (Gn), which are then summed to yield the total energy (E). (n: the number of atoms); (C) Global minimization: The right panel is a schematic diagram of the two-dimensional potential energy surface (PES), where search paths (yellow lines) identify the global minimum (yellow asterisk). The color gradient (purple to white) indicates increasing energy. The left panel displays schematic diagrams of the most stable nanocluster with different sizes. (White: Ce atoms; Pink: O atoms); (D) NNPMD analysis: The right panel shows the structures of MD trajectories via principal component analysis (PCA) where different colors represent distinct clusters obtained from K-means clustering. The left panel shows schematic diagrams of representative structures from different clusters (White: Ce atoms; Pink: O atoms). DFT: Density functional theory; NNP: neural network potential; NNPMD: neural network potential molecular dynamics.

Firstly, the Monte Carlo sampling was employed to randomly generate initial structures from a large cerium oxide bulk structure, yielding a large number of random initial structures for cerium oxide nanoclusters of different sizes. These structures were calculated by DFT, after which their atomic coordinates and energies were extracted to construct the NNP. This NNP is based on the Behler-Parrinello atom-centered artificial neural network[33], which decomposes the total energy into the sum of individual atomic energies. Each atomic energy is trained and predicted by a sub-neural network. In this process, symmetry functions are utilized to transform Cartesian coordinates, enabling the description of each atom’s local chemical environment. This transformation eliminates the influence of translation and rotation of the entire structure on the structure-energy correlation.

Following the training of the NNP, we employed the basin-hopping algorithm across multiple parallel trajectories to perform global minimization and search for low-energy configurations of cerium oxide nanoclusters on the broad potential energy surface. The most stable candidates identified from this Basin-hopping search were subsequently refined using the simulated annealing algorithm to locate the global minimum with higher confidence. Once the stable structures for various sizes of cerium oxide nanoclusters were determined, we performed nanosecond-scale MD simulations using the same NNP. Each MD run totaled 1.1 ns, which included an initial 100 ps for equilibration. The subsequent 1 ns production trajectory was used for all analyses.

The NNPMD simulations revealed that the nanocluster structures undergo continuous changes, including structural distortions, chemical bond breaking and reformation, which become more pronounced at higher temperatures. To systematically analyze the structural ensembles and assess their relative stability, we employed the K-means clustering algorithm, a well-validated unsupervised machine learning method, to group geometrically similar structures from the NNPMD trajectories at different temperatures. The clustering results were visualized in a low-dimensional space using PCA. For each temperature, the centroid of the most populated cluster was identified as the most representative structure. The relative stability was then quantified by calculating the average energy of the structures within each major cluster, enabling a clear comparison of nanocluster stability across different temperatures.

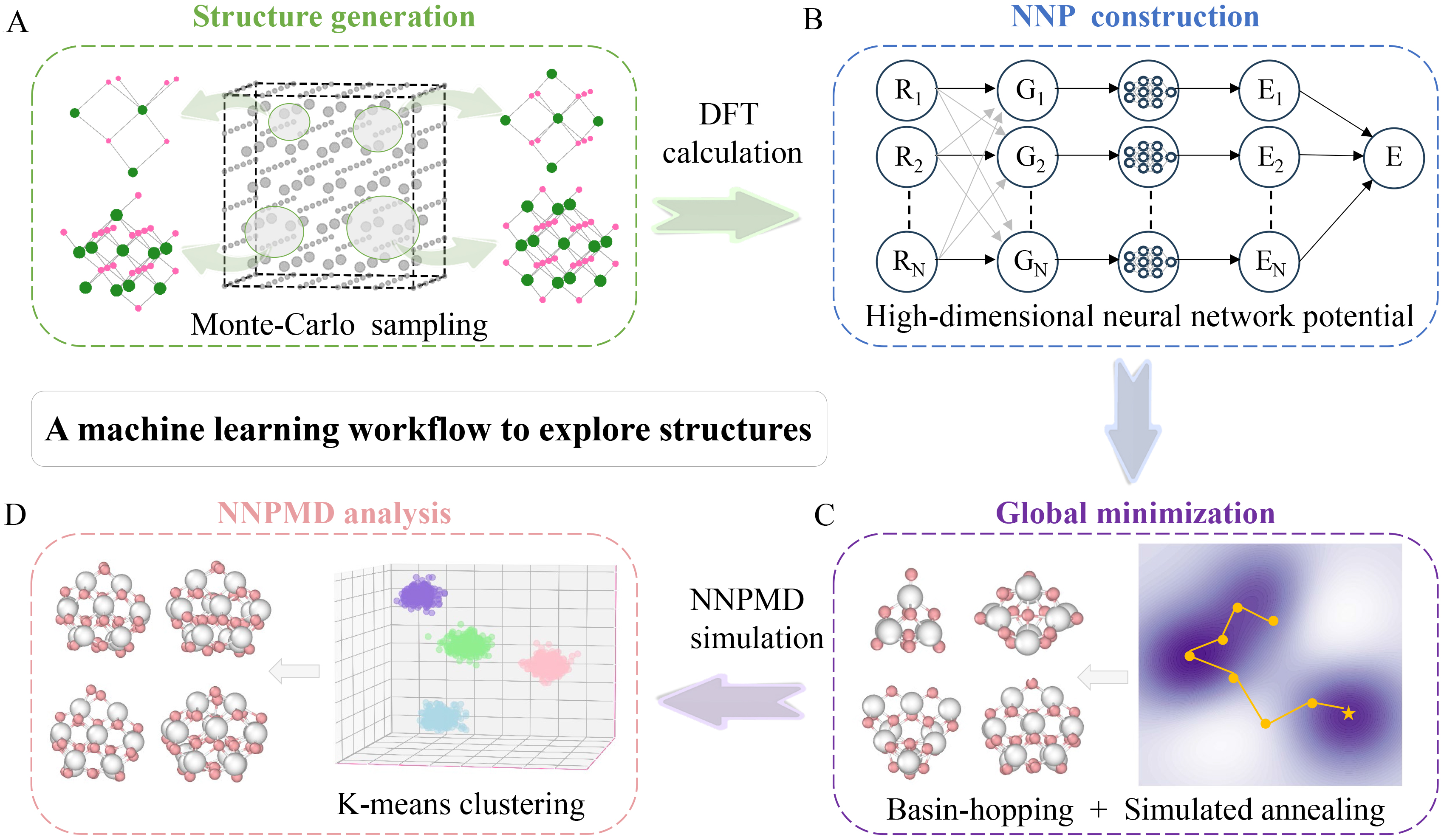

The HDNNP was trained on a dataset of 7,777 distinct cerium oxide nanocluster configurations, each with atomic coordinates and corresponding potential energies obtained from DFT calculations. These initial structures were generated via a Monte Carlo sampling approach using varied random seeds to ensure broad structural diversity. The performance of the resulting NNP is evaluated in Figure 2A and B, which directly compare NNP-predicted energies and forces with the corresponding DFT reference values. The predictions are in excellent agreement with the DFT data, as evidenced by the RMSE of approximately 4.5 meV/atom for energies and 0.089 eV/Å for forces. This high accuracy demonstrates that the NNP is robust and reliable for conducting long-time, high-precision MD simulations to investigate the atomic-scale dynamic behavior of cerium oxide nanoclusters.

Figure 2. Accuracy and performance of the neural network potential. (A and B) Parity plots comparing the energies and forces predicted by NNP versus reference DFT calculations; (C) Stability function for nanoclusters ranging from Ce3O6 to Ce21O42, as calculated by both the NNP and DFT; (D) Structures of the top six relatively stable cerium oxide clusters identified from the stability function. Color map: White, Ce atoms; Pink, O atoms. NNP: Neural network potential; DFT: density functional theory; RMSE: root-mean-square error.

The lowest-energy structures and their corresponding symmetries were shown in Supplementary Figure 1, including cerium oxide nanoclusters ranging from Ce3O6 to Ce21O42. The nanoclusters generally exhibit low symmetry, which may be attributed to their structural complexity at specific sizes, particularly when containing a certain number of atoms. With the exception of the most stable nanocluster Ce14O28, which possesses C2v symmetry, all other nanoclusters adopt either Cs or C1 (no symmetry) configurations. Notably, most stable structures across this size range share a similar pyramid-like motif, as exemplified by Ce12O24, Ce14O28, and Ce20O40. These structural features may be generalizable to other metal oxide nanoclusters. The energies of these most stable clusters are summarized in Supplementary Table 2, which lists the NNP-predicted energies, DFT-calculated energies, and the corresponding absolute errors. The NNP-predicted energies are in excellent agreement with the DFT references, with a maximum absolute error of only 0.434 eV for the nanocluster Ce13O26, corresponding to an average error of about 11 meV/atom.

The relative stability of the stoichiometric cerium oxide clusters, as evaluated using Supplementary Equation (7) of the Supporting Information, was presented in Figure 2C. The results predicted by the NNP are in excellent agreement with those obtained from DFT calculations. Among the series from Ce4O8 to Ce20O40, the nanoclusters of Ce5O10, Ce8O16, Ce10O20, Ce12O24, Ce14O28, and Ce20O40 were identified as the relatively stable structures. Their structures and corresponding symmetries were displayed in Figure 2D. The magic numbers of CenO2n within our computational scope (n ≤ 21) are 5, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 20. The most stable Ce14O28 nanocluster, which has the lowest stability function, exhibits the highest symmetry of C2v. And the nanoclusters of Ce12O24 and Ce20O40, while belonging to the asymmetric C1 point group, share a similar pyramid-like structural motif with Ce14O28. The remaining three relatively stable Ce5O10, Ce8O16 and Ce10O20 differ from those of the other three nanoclusters, but they have a relatively high symmetry of Cs symmetry.

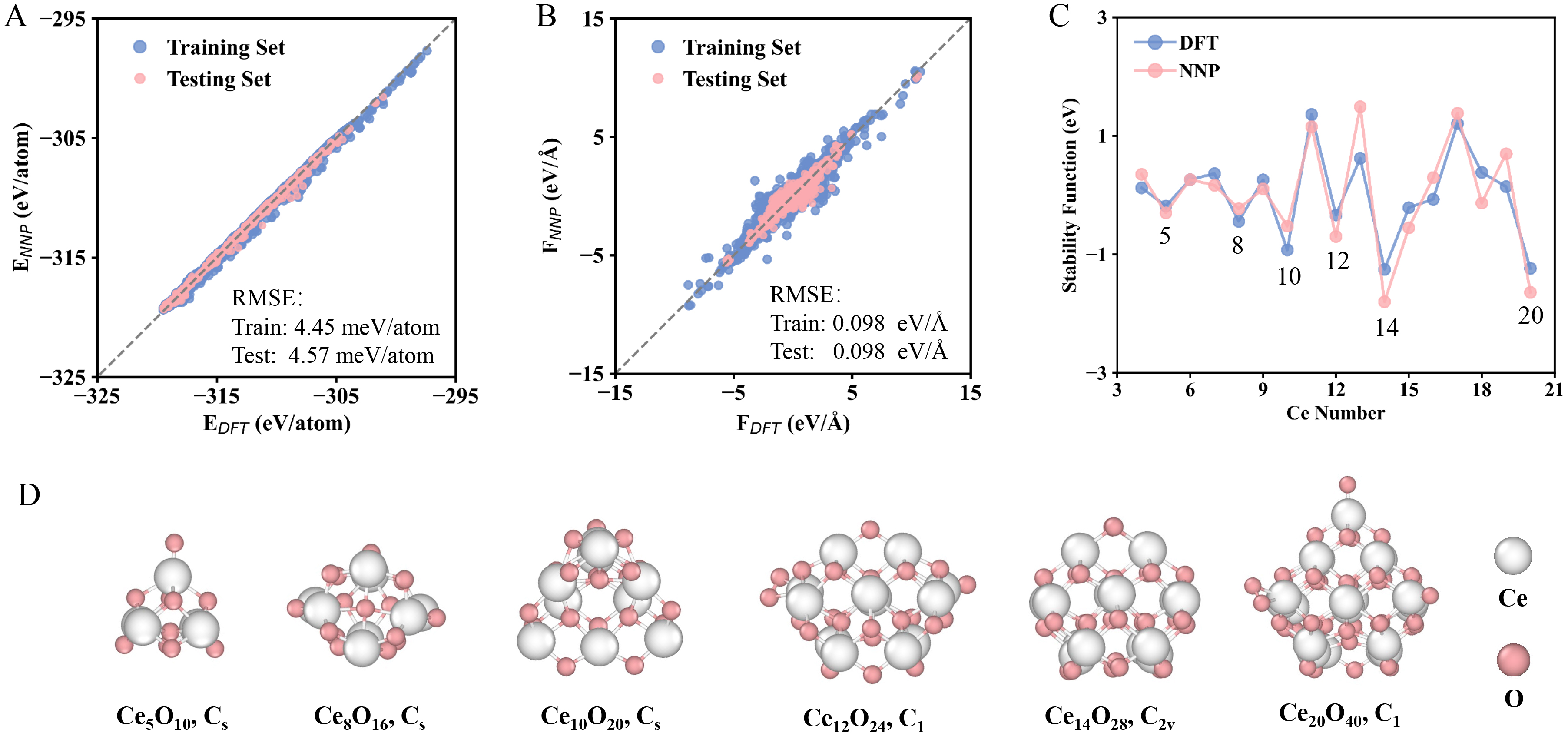

Based on the NNP, all the most stable cerium oxide nanoclusters ranging from Ce3O6 to Ce21O42 were used as initial structures to perform NNPMD simulation of 1 ns with a time step of 1 fs at 1, 300, 500, and 700 K, respectively [Figure 3 and Supplementary Figures 2-20]. We found that the structural stability of the nanoclusters indeed depends on temperature, yet the degree of temperature sensitivity varies markedly with cluster size. For instance, in the case of the non-magic-number Ce4O8 nanocluster [Figure 3A and B, Supplementary Figure 3], pronounced structural fluctuations were observed at elevated temperatures. During the NNPMD simulations, the total energy of Ce4O8 fluctuated and remained generally stable in magnitude at 1 K but increased progressively with temperature. It is likely that due to the small size of the Ce4O8 cluster, its stability is relatively poor. In the NNPMD simulation set for 1 ns, the structure had already dissociated after running for 400 ps. Therefore, data statistics and analysis were only conducted up to the 400 ps. Other relatively small clusters exhibit a similar phenomenon, as shown in Supplementary Figures 2, 5, 9, and 10. During the nanosecond-scale NNPMD simulations, the dissociation of these small clusters directly indicates their poor dynamic stability. Additionally, structural snapshots extracted at 200 ps intervals throughout the simulation reveal that the higher simulation temperatures, the more pronounced the structural distortions of the Ce4O8 nanocluster.

Figure 3. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the cerium oxide nanocluster Ce4O8 and Ce14O28 at 1 K and 700 K, including energies during the simulations and snapshots taken every 200 ps. (A and B) MD simulations of Ce4O8; (C and D) MD simulations of Ce14O28. Color map: White, Ce atoms; Pink, O atoms.

In contrast, the magic-number nanocluster exhibits smaller energy variation and maintains its configuration across the same temperature range, with snapshots showing slight structural deviation. As shown in Figure 3C and D, the Ce14O28 cluster, as the relatively most stable structure, exhibited no significant changes not only in the NNPMD simulation at 1 K but also in that at 700 K. Only slight structural distortions occurred, along with a minor shift in the positions of the oxygen atoms in the topmost layer; the overall structure remained highly stable. Furthermore, other larger magic numbers such as Ce20O40 exhibit a similar trend, as shown in Supplementary Figure 19. In addition, from the NNPMD simulation processes of Ce3O6 to Ce21O42 [Supplementary Figures 2-20], it can be observed that larger cluster structures are less likely to dissociate, undergo smaller structural changes, and demonstrate a tendency toward relatively higher dynamic stability. These results highlight that temperature sensitivity is strongly size-dependent, with magic-number clusters displaying enhanced thermal stability and resilience under high-temperature catalytic conditions.

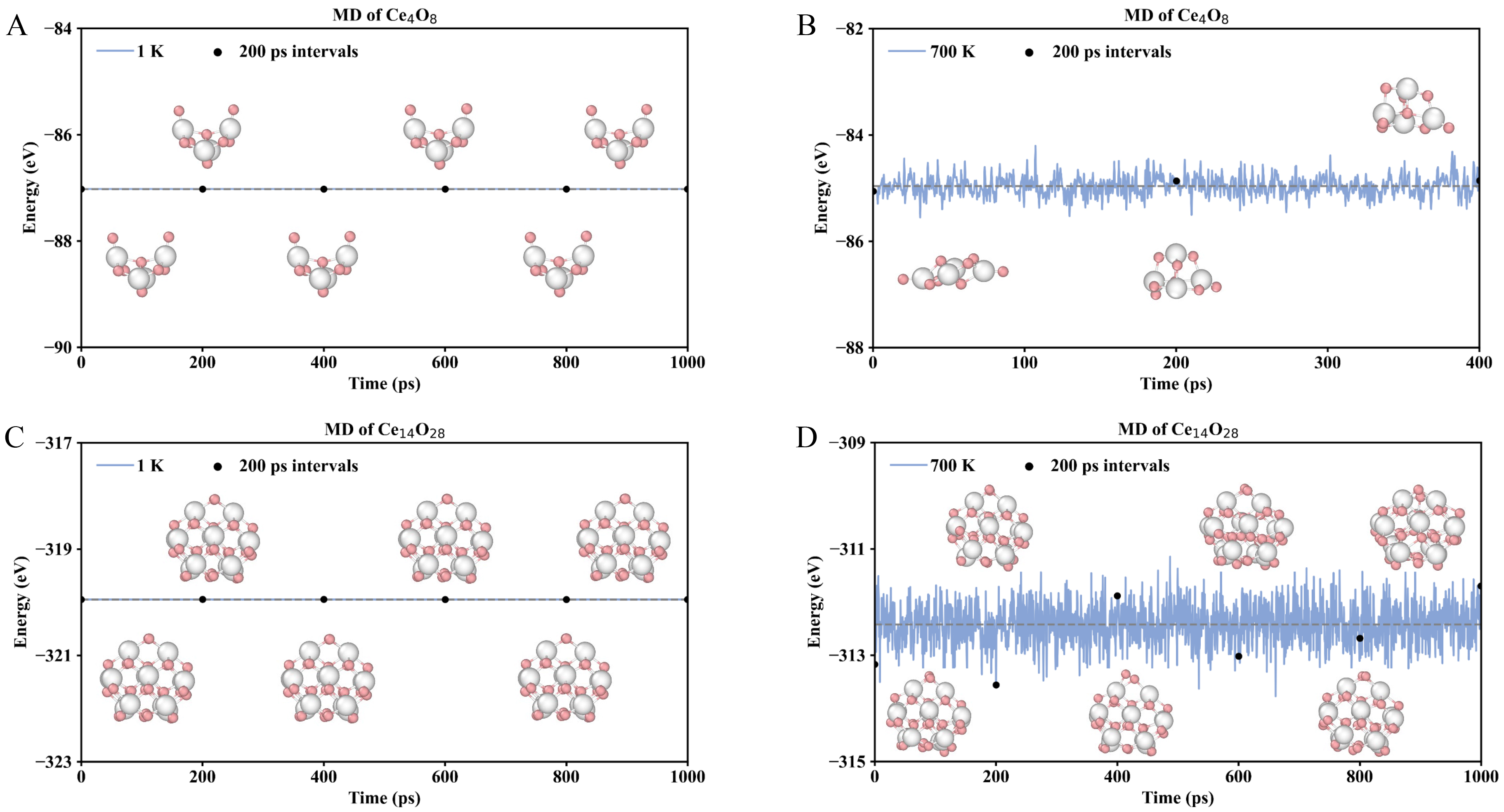

To further validate the above observations, we employed unsupervised machine learning to systematically resolve these structural changes and probe the underlying stability variations. Before analyzing the structures, all sampled structures from NNPMD trajectories were aligned to the initial most stable structures using the Kabsch algorithm to minimize the impact of rotation and translation of the pristine nanocluster structure. Subsequently, the K-means clustering algorithm was applied to classify the aligned structures based on their Euclidean distance in Cartesian space. The dataset for clustering included 1,001 structures extracted from each MD trajectory with every 1 ps interval at different temperatures.

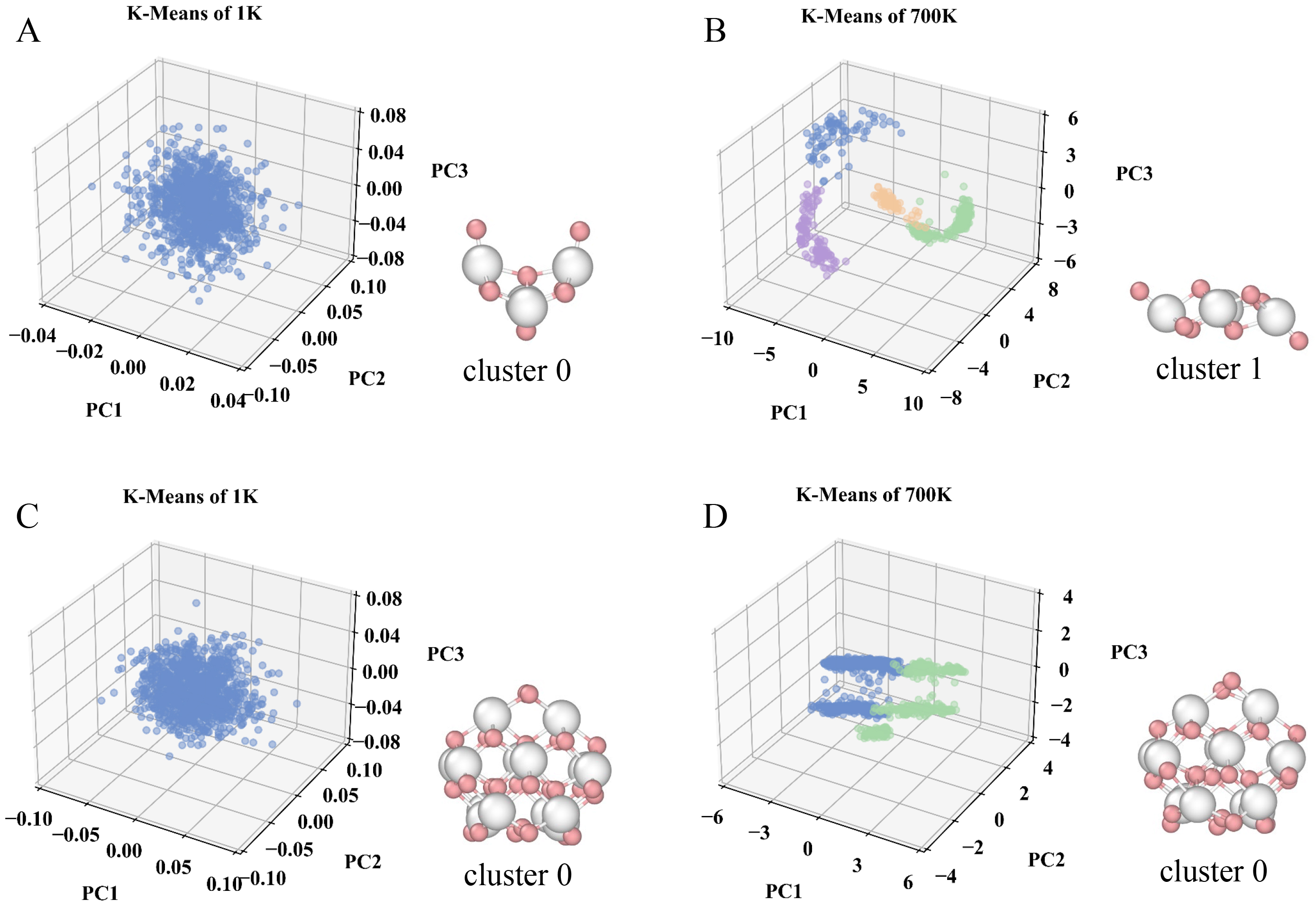

Figure 4A-D visualizes the results of the K-means clustering via PCA for Ce4O8 and Ce14O28, and the representative configurations of the most frequently appearing structures were also displayed. At 1 K, both clusters exhibit minimal structural changes, as indicated by the presence of only a single K-means cluster. In contrast, simulations at elevated temperatures yield at least two K-means clusters for each nanocluster, reflecting increased structural variability. Notably, the structural fluctuations of Ce14O28 remain smaller than those of Ce4O8, suggesting that the magic-number cluster retains higher thermal resilience. The results of other K-means clustering analyses were shown in Supplementary Figures 21-39, including the K-means clustering analyses of NNPMD simulations for Ce3O6 to Ce21O42 at 1, 300, 500, and 700 K, respectively. The details of the average energies, RMSD, and number of each cluster after clustering were shown in Supplementary Table 3. All clusters exhibited only one cluster during the simulation at 1 K. As the temperature increased, the number of clustered groups rose, indicating an increase in the structural diversity of the clusters. In particular, non-magic number clusters with relatively lower stability evolved into multiple distinguishable clusters during the NNPMD simulations, and the representative structure of the largest cluster was not necessarily identical to the most stable configuration at 0 K. The above analysis confirms the size-dependent temperature sensitivity of cerium oxide nanoclusters, and shows that clusters with magic numbers exhibit relatively high stability at elevated temperatures. We then further move to investigate if the magic number will be maintained with temperatures, to provide better guidance for experiments to prepare stable cerium oxide nanoclusters.

Figure 4. Visualization of clustered nanocluster Ce4O8 and Ce14O28 at different temperatures via PCA dimensionality reduction, along with the representative structure of the largest cluster. (A and B) Clustered Ce4O8 at 1 and 700 K; (C and D) Clustered Ce14O28 at 1 and 700 K. Color map: White, Ce atoms; Pink, O atoms; Blue: cluster 0; Green: cluster 1; Purple: cluster 2; Orange: cluster 3. PCA: Principal component analysis; PC1: principal component 1; PC2: principal component 2; PC3: principal component 3.

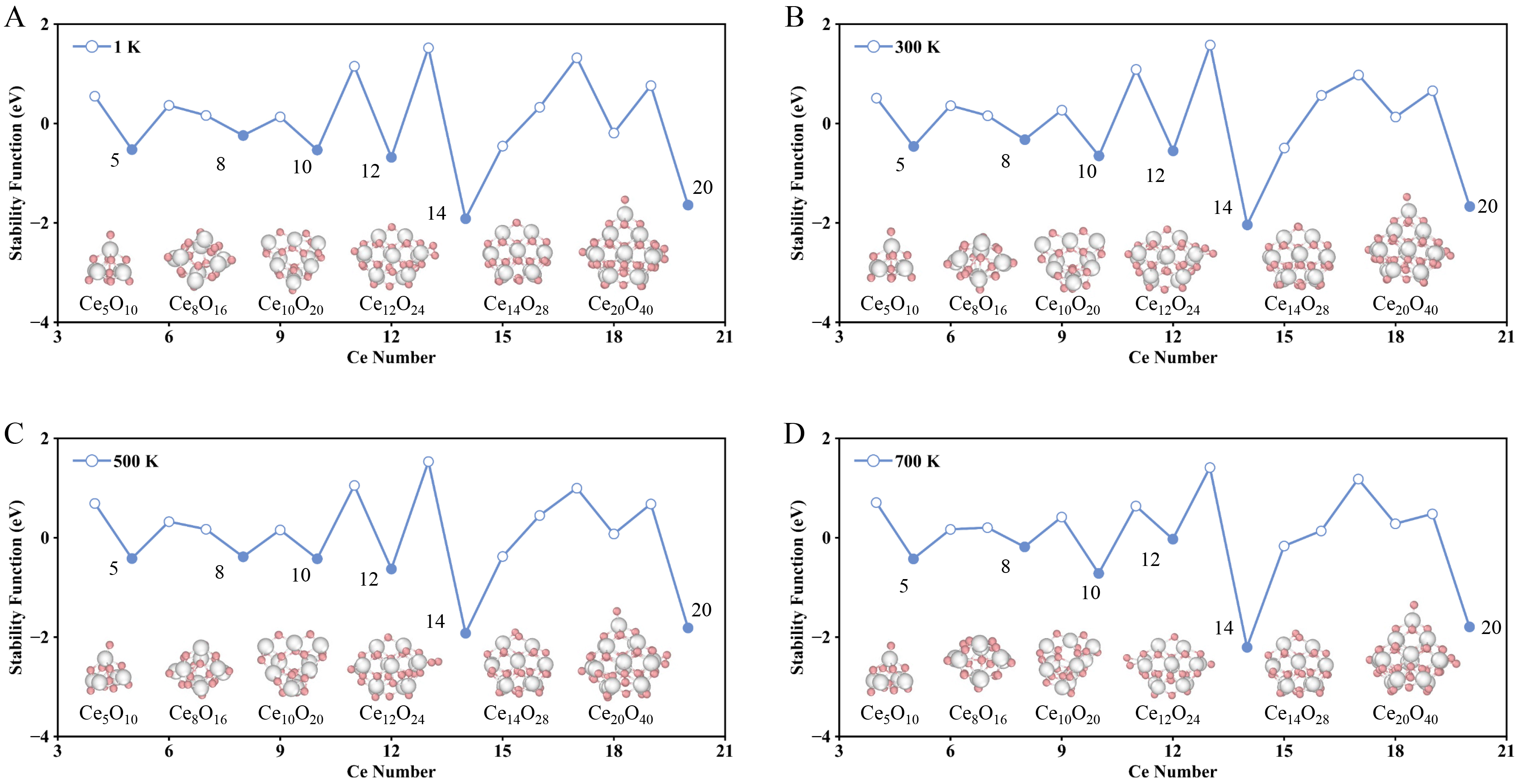

The K-means algorithm was used to cluster the cerium oxide structures in the NNPMD simulation at different temperatures. Based on the average energy of the most common structures in NNPMD simulations, the stability function between these cerium oxide cluster structures was still calculated using Supplementary Equation (7) in the Supporting Information to represent their relative stability. Figure 5A-D shows the stability functions of these most stable clusters at different temperatures, as well as the top 6 relatively most stable representative structures. As shown in Figure 2, the relatively stable cerium oxide nanoclusters were Ce5O10, Ce8O16, Ce10O20, Ce12O24, Ce14O28, and Ce20O40. In the NNPMD simulations at different temperatures, the stability functions are roughly similar to those at 0 K. Specifically, in the NNPMD simulations at 1, 300, 500, and 700 K, the Ce14O28 and Ce20O40 nanoclusters remained the two most stable structures, consistent with the results at 0 K. Particularly, Ce5O10, which exhibits lower stability at 0 K, demonstrates improved relative stability in the 1 ns MD simulations at various temperatures. In contrast, the relative stability of Ce12O24 decreases significantly in the simulation at 700 K. Therefore, the stability of the nanoclusters shows a degree of temperature sensitivity and varies under different thermal conditions, which may differ from their relative stability at 0 K.

Figure 5. Stability functions and the top 5 relatively stable nanoclusters at different temperatures. In the line chart with data points, blue solid circles represent relatively stable structures, while blue open circles denote relatively unstable ones. (A), (B), (C), and (D) correspond to 1, 300, 500, and 700 K, respectively. Color map: White, Ce atoms; Pink, O atoms.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we developed a machine learning workflow to investigate the structural evolution of cerium oxide nanoclusters under different temperatures. The most stable configurations and magic numbers of Ce3O6 to Ce21O42 were first identified at 0 K. At elevated temperatures, the structural stability becomes both temperature- and size-dependent: magic-number clusters such as Ce14O28 remain robust, whereas non-magic-number clusters such as Ce4O8 undergo pronounced structural fluctuations. These findings underscore the importance of considering thermal effects when evaluating nanocluster stability and provide critical insight into their behavior under realistic thermal conditions.

Furthermore, the developed workflow shows promising transferability for broader applications. While demonstrated for stoichiometric CenO2n clusters, the framework can be extended to non-stoichiometric systems with oxygen vacancies by expanding the training dataset to include reduced states and adapting the global minimization to sample defect configurations. For larger clusters or other reducible oxides, the main challenges involve scaling the sampling strategy and optimizing symmetry functions and DFT parameters for their specific electronic structures. Overall, the core components including HDNNP construction, global minimization, and unsupervised analysis of MD trajectories, establish a versatile foundation for exploring temperature-dependent stability across diverse nanocluster systems.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and supervised the project: Cao, A.

Carried out the calculations, data analysis and drafted the paper: Cai, H.

Revised the paper: Cao, A.

Participated in the discussions and contributed to the editing of the manuscript: Cai, H.; Xu, A.; Rajarathnam, G.; Cao, A.; Yan, J.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the "Pioneer" and "Leading Goose" R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (2025C01150), and the Industrial Catalyst Intelligent Design and Optimization Platform under the 2023 Daqingshan Laboratory Science and Technology Support Program (2023KYPT0034).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Meunier, F. C.; Cardenas, L.; Kaper, H.; et al. Synergy between metallic and oxidized Pt sites unravelled during room temperature CO oxidation on Pt/ceria. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 3799-805.

2. Montini, T.; Melchionna, M.; Monai, M.; Fornasiero, P. Fundamentals and catalytic applications of CeO2-based materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5987-6041.

3. Mudiyanselage, K.; Senanayake, S. D.; Feria, L.; et al. Importance of the metal-oxide interface in catalysis: in situ studies of the water-gas shift reaction by ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 5101-5.

4. Rodriguez, J. A.; Grinter, D. C.; Liu, Z.; Palomino, R. M.; Senanayake, S. D. Ceria-based model catalysts: fundamental studies on the importance of the metal-ceria interface in CO oxidation, the water-gas shift, CO2 hydrogenation, and methane and alcohol reforming. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1824-41.

5. Khivantsev, K.; Pham, H.; Engelhard, M. H.; et al. Transforming ceria into 2D clusters enhances catalytic activity. Nature 2025, 640, 947-53.

6. Shao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Dynamic control and quantification of active sites on ceria for CO activation and hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9620.

7. Song, I.; Kovarik, L.; Engelhard, M. H.; Szanyi, J.; Wang, Y.; Khivantsev, K. Developing robust ceria-supported catalysts for catalytic NO reduction and CO/hydrocarbon oxidation. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 18247-55.

8. Fu, N.; Liang, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Controllable conversion of platinum nanoparticles to single atoms in Pt/CeO2 by laser ablation for efficient CO oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9540-7.

9. Li, Y.; Li, S.; Bäumer, M.; Ivanova-shor, E. A.; Moskaleva, L. V. What changes on the inverse catalyst? Insights from CO oxidation on Au-supported ceria nanoparticles using ab initio molecular dynamics. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 3164-74.

10. Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, G. CeO2/Ni inverse catalyst as a highly active and stable Ru-free catalyst for ammonia decomposition. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 9927-39.

11. Esch, F.; Fabris, S.; Zhou, L.; et al. Electron localization determines defect formation on ceria substrates. Science 2005, 309, 752-5.

12. Paier, J.; Penschke, C.; Sauer, J. Oxygen defects and surface chemistry of ceria: quantum chemical studies compared to experiment. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3949-85.

13. Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; Dai, S.; Jiang, D. E. Deep learning accelerated determination of hydride locations in metal nanoclusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 12289-92.

14. Fang, C.; Wang, Z.; Guo, R.; Ding, Y.; Ma, S.; Sun, X. Machine learning potential for copper hydride clusters: a neutron diffraction-independent approach for locating hydrogen positions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 10750-7.

15. Telari, E.; Tinti, A.; Settem, M.; Maragliano, L.; Ferrando, R.; Giacomello, A. Charting nanocluster structures via convolutional neural networks. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 21287-96.

16. Boattini, E.; Dijkstra, M.; Filion, L. Unsupervised learning for local structure detection in colloidal systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 154901.

17. Zeni, C.; Rossi, K.; Pavloudis, T.; et al. Data-driven simulation and characterisation of gold nanoparticle melting. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6056.

18. Mou, L.; Jiang, G.; Wang, C.; et al. Unveiling universal reactivity descriptors of metal clusters toward dinitrogen activation: a machine learning protocol with three-level feature extraction. ACS. Catal. 2025, 15, 6618-27.

19. Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Mou, L. H.; Jiang, J. Deciphering experimental reactivity of metal clusters toward N2 activation using graph neural networks. JACS. Au. 2025, 5, 3669-78.

20. Zhao, X. G.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Y.; et al. Machine learning for experimental reactivity of a set of metal clusters toward C-H activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 12485-95.

21. Lee, B.; Yoon, S.; Lee, J. W.; et al. Statistical characterization of the morphologies of nanoparticles through machine learning based electron microscopy image analysis. ACS. Nano. 2020, 14, 17125-33.

22. Rapetti, D.; Delle Piane, M.; Cioni, M.; Polino, D.; Ferrando, R.; Pavan, G. M. Machine learning of atomic dynamics and statistical surface identities in gold nanoparticles. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 143.

23. Banik, S.; Dutta, P. S.; Manna, S.; Sankaranarayanan, S. K. Development of a machine learning potential to study the structure and thermodynamics of nickel nanoclusters. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2024, 128, 10259-71.

24. Wang, X.; Shi, K.; Peng, A.; Snurr, R. Q. Computational chemistry and machine learning-assisted screening of supported amorphous metal oxide nanoclusters for methane activation. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 18708-21.

25. Zeng, F.; Cen, W. Machine-learning-accelerated structure prediction of PtSnO nanoclusters under working conditions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 27624-32.

26. Nie, S.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, L.; et al. Active learning guided discovery of high entropy oxides featuring high H2-production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 29325-34.

27. Cai, H.; Ren, Q.; Gao, Y. Exploring the stable structures of cerium oxide nanoclusters using high-dimensional neural network potential. Nanoscale. Adv. 2024, 6, 2623-8.

28. Shi, J.; Ren, Q.; Gao, Y. Accelerating global optimization of cerium oxide nanocluster structures with high-dimensional neural network potential. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2025, 129, 2190-9.

29. Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. Condens. Matter. 1996, 54, 11169-86.

30. Perdew, J. P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865-8.

31. Dudarev, S. L.; Botton, G. A.; Savrasov, S. Y.; Humphreys, C. J.; Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B. 1998, 57, 1505-9.

32. Behler, J. Atom-centered symmetry functions for constructing high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, 074106.

33. Behler, J.; Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 146401.

34. Singraber, A.; Morawietz, T.; Behler, J.; Dellago, C. Parallel multistream training of high-dimensional neural network potentials. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2019, 15, 3075-92.

35. Blank, T. B.; Brown, S. D. Adaptive, global, extended Kalman filters for training feedforward neural networks. J. Chemom. 2005, 8, 391-407.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].