Recent advances in electrospun fiber-based flexible pressure sensors for next-gen healthcare applications: a review

Abstract

This review thoroughly evaluates the advancements and applications of electrospun functional fiber-based pressure sensors in healthcare diagnostics. Electrospinning is a versatile technique for producing micro- and nanoscale fibers with high surface-to-volume ratios and tunable porosity, making it an excellent platform for highly sensitive, flexible, and wearable sensing structures. The survey focuses on integrating piezoelectric and piezoresistive materials into electrospun fiber mats. These materials are key to transduction mechanisms, converting mechanical pressure stimuli into electrical signals by varying charge or resistance. Key healthcare applications based on pressure are critically evaluated, including wearable vital sign monitors (pulse and respiration), body motion detection for rehabilitation, gait analysis, smart prosthetics, and real-time wound-healing assessment through pressure distribution mapping. Fiber-based sensors offer high sensitivity, lower detection limits, flexibility, biocompatibility, breathability, and adaptability to complex body contours. Findings reveal that the sensitivity of the multilayer sensor (996.7 kPa-1) is far greater than that of the composite sensor (0.21 kPa-1), enabling precise detection of pulse and joint movements. Several limitations have also been addressed, including signal stability and durability, ecological interference (including humidity and temperature), scalable manufacturing, and seamless integration with electronics for continuous monitoring. Future research directions are provided for developing novel, multifunctional, and self-powered materials that enhance environmental resilience, scalable fabrication, and wireless data transmission. Finally, it is concluded that electrospun fiber sensors are poised to transform personalized, non-invasive, and continuous health monitoring, advancing next-generation, innovative healthcare systems.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The human body has a vast network of natural sensors with high 3S (stability, selectivity, and sensitivity) performance. Natural sensors have long inspired the development of artificial sensors for quick, reliable human health monitoring[1,2]. Due to advances in materials and fabrication technologies[3], sensors can be implemented with various materials and dimensions, meeting the needs of both the medical and industrial sectors[4-7]. The increasing demand for real-time health monitoring has driven the development of advanced sensing technologies that deliver accurate and timely physiological data. Among these technologies, pressure sensors stand out for their ability to measure mechanical changes associated with various health parameters, including temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate, heart rate, respiration, and physical activity[8-10].

The historical development of sensors from macro- to micro- and nanoscale technology[11] has ushered in the modern era of human-machine interfaces[12-17]. This advancement enables sensors to interface with the human body without posing health risks. Medical-grade measurements require conformal contact between the sensor and the skin. Rigid sensors have largely failed to achieve this goal, resulting in unsatisfactory comfort due to surface microtexture and skin deformation. Modern sensors are sufficiently compact and integrated to function as components of smart electronics. However, their rigid structures limit their use in healthcare wearable devices, collaborative robots, smart packaging, and building-integrated electronics. Soft and flexible sensors, on the other hand, can solve these problems and provide innovative future healthcare solutions[18,19]. Flexible sensors have garnered significant attention in the twenty-first century due to their small size, mobility, light weight, breathability, deformability, and affordability[3,20-22]. The human body performs movements that induce substantial deformations of the skin, tissues, and organs. Therefore, it is crucial to develop soft pressure sensors with exceptional mechanical flexibility and stretchability that can conformably adhere to human skin surfaces[21,23-26].

Effective wearable device frameworks have previously been designed using intricate microstructures[27,28], such as thin-layer structures[29-32], microdomes[33-35], microcones[36-39], and micropyramids[40-44]. A variety of techniques are employed to synthesize these functional microstructured devices, including three-dimensional (3D) printing[40], screen printing[45], inkjet printing[46], hydrothermal synthesis, and photolithography. However, such structures require complex production procedures and costly equipment. Notably, in recent years, numerous reviews on electrospinning technology have emerged, providing a useful platform for subsequent researchers[47-54]. Electrospinning is recognized as a high-performance technique for fabricating smart wearable sensors[24,50,55] due to its ability to create highly customizable, functional microstructures, exceptional breathability, biocompatibility, comfort, simple processing steps, high production efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

Chen et al. briefly discussed materials selection, working principles, design, and fabrication of fiber-based multifunctional sensors[49]. The electrospinning process, including its influencing parameters and technical principles, directly affects sensing performance. Numerous studies have investigated the fundamentals of electrospinning technology, the diversity of electrospun fibers, and their integration strategies in flexible electronics[21,56-59]. Electrospun electronic skin exhibits superior mechanical flexibility, breathability, self-healing properties, and high overall performance[60], highlighting the importance of electrospinning in developing wearable sensors for healthcare applications. The working principles and multiple coupling mechanisms, including piezoelectric, piezoresistive, capacitive, and triboelectric, have been analyzed by several authors[61,62]. These findings contribute to the development of more accurate and versatile sensors for diverse applications, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram illustrating the research content of flexible pressure sensors based on electrospun nanofiber membranes, the two major pressure-sensing mechanisms - (1) piezoelectric and (2) piezoresistive - and their potential applications in various healthcare areas[63-69]. Reproduced with permission from: Chang et al., RSC Advances, 2024 [The Royal Society of Chemistry]; Yue et al., ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022 [American Chemical Society]; Miaomiao et al., Nano Energy, 2020 [Elsevier]; Rongrong et al., Science Bulletin, 2023 [Elsevier]; Min et al., Applied Materials, 2023 [American Chemical Society]; Jagan et al., Materials Today Bio, 2023 [Elsevier].

The complex structures of capacitive and triboelectric sensors, such as their requirement for well-defined electrode gaps or specific surface functionalization for optimal triboelectric performance, place them outside the primary scope of this work. Therefore, the focus here is on piezoelectric and piezoresistive sensors because of their simple fundamental operating mechanisms and device architectures. Previous studies have addressed the evolution, working principles, material selection, structural design, and influencing parameters of electrospinning. However, further research is needed to investigate the application of fiber-based pressure sensors, particularly in healthcare. This article explores future directions for electrospun fiber-based flexible electronics in healthcare applications and emphasizes several pathways for flexible pressure sensors in future soft robotics and human-machine interfaces. It is expected to serve as a valuable summary and guide for future research on flexible, biocompatible electrospun pressure sensors for healthcare applications.

ELECTROSPINNING TECHNIQUE

Electrospinning is a fiber-producing technique that uses electrostatic forces to draw fibers from a solution or melt. It was first observed in 1897 by Rayleigh and studied in detail by Zeleny (1914)[70] in the context of electrospraying, and later patented by Anton in 1934[71]. Taylor’s study (1969)[72] on electrically driven jets established the concept of electrospinning. The term “electrospinning”, derived from “electrostatic spinning”, has been used relatively recently since 1994, although its origins trace back nearly 60 years[73]. Recently, electrospinning has attracted growing interest due to its versatility and potential applications across various fields, including electronics, drug delivery, textiles, energy, membrane filtration, and food packaging[74].

Electrospinning setup

Electrospinning equipment primarily consists of three components[75,76]: a high-voltage power supply, a syringe pump, and a collector. The syringe pump mechanically ejects the active material solution from a plastic syringe. The positive terminal of the high-voltage power supply is connected to the metallic needle of the syringe, and the negative terminal is connected to the fiber collector. When a voltage is applied, a high electric field generates nanofibers from the charged polymer solution between the needle tip and the collector. The electrostatic force causes the ejected solution to form fibers and move toward the collector. Electrospun fibers are then collected on the collector drum or plate[77-80]. A schematic of the electrospinning process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of a laboratory electrospinning apparatus and images of various types of electrospun fibrous membranes[81]. Adapted from Wang et al., Elsevier Books, 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

Fiber formation process

The repulsive electrostatic forces drive fiber formation during electrospinning. Coulomb interactions in the charged fluid jet lead to jet instabilities that shape the fiber architecture[82]. These instabilities cause the polymer jet to form a Taylor cone at the needle tip. Under the applied forces, the jet exits the needle and undergoes thinning. As the jet thins, the solvent evaporates, leaving behind polymer fibers deposited on a grounded collector[83]. A polymer is melted or dissolved in a volatile solvent to create a spinnable fluid with suitable conductivity and viscosity. The solution is loaded into a syringe with a metallic needle and charged by a high-voltage power supply applied to the needle[84]. Surface tension of the solution is counteracted by electrostatic repulsion. As a conductive or semi-conductive medium (due to dissolved ions or polar solvents), the solution facilitates charge buildup at the liquid-air interface (Taylor cone surface). As shown in Figure 2, a Taylor cone forms when the droplet at the needle tip deforms into a conical shape at a critical voltage. Electrostatic repulsion among similarly charged species in the solution overcomes surface tension, ejecting a charged jet from the cone tip and forming a stable flight section. The jet undergoes rapid stretching, thinning, and bending instabilities driven by charge repulsion, creating a whipping flight section. Simultaneously, the solvent evaporates, or the polymer solidifies upon cooling, reducing the jet diameter to the micro- or nanoscale and producing ultra-fine nanofibers. The solidified fibers accumulate to form a non-woven mat with adjustable alignment on the grounded collector[85-87].

Factors influencing the electrospinning process

Several parameters influencing fiber morphology during electrospinning can be categorized into three main groups: solution parameters, processing parameters, and environmental factors[88-90], as summarized in Table 1.

Factors influencing electrospinning parameters and their effects

| Category | Factors | Effects |

| Solution parameters | Polymer concentration | Controls fiber diameter and bead formation Optimum concentration for uniform nano fibers |

| Molecular weight | High molecular weight for smoother nanofibers | |

| Conductivity | Influence jet formation and fiber alignment Higher conductivity for smaller and uniform fiber diameter | |

| Viscosity | Optimal viscosity for constant ejection from the jet needle High viscosity may clog the needle | |

| Process parameters | Applied voltage | Higher voltage provided more polymer ejection Higher voltage increases jet acceleration but can destabilize the process |

| Feed rate | Controls fiber diameter and bead formation Slow flow rate enhances smooth fiber production Higher flow rate causes jet instability | |

| Tip-to-collector distance | Affects flight time and fiber drying Optimum distance for better interconnectivity | |

| Ambient parameters | Humidity | Higher humidity results in beaded, fused, or thicker fiber production |

| Temperature | Increasing temperature decreases viscosity, evaporates solvent, and generates thinner nanofibers |

This section provides an overview of electrospinning parameters and the variables that influence them. Wang and Ryan demonstrate the effects of these variables on the parameters[81].

Solution parameters

Solution parameters have a major influence on fiber formation[91]. These include polymer concentration in solution, molecular weight, viscosity, surface tension, conductivity, and volatility. Precise control of solution concentration is crucial for effective polymer chain entanglement[92]. Low concentrations can cause bead formation [Figure 2], whereas high concentrations may lead to blockages at the needle tip[93]. Appropriate surface tension promotes fiber formation and elongation, while excessively low surface tension favors bead formation[94]. Higher molecular weight generally increases viscosity[95], facilitating the formation of homogeneous fiber structures [Figure 2]. Viscosity[90,96] affects the solution flow rate and, consequently, fiber formation, with higher viscosity potentially producing thicker fibers [Figure 2][97]. Solution conductivity influences jet stability and charge dispersion[98]. Finally, fiber formation also depends on the rate of solvent evaporation, which is determined by solvent volatility.

Processing parameters

The processing parameters of electrospinning include applied voltage (~10-30 kV), solution feed rate (0.1 to 60 mL/h)[99], and nozzle tip-to-collector distance (~18-23 G)[84,95,100]. The applied voltage affects the intensity of the electric field, thereby influencing fiber diameter and morphology[101]. Increased voltage promotes stretching of the polymer solution and solvent evaporation, resulting in the formation of uniform fibers [Figure 2]. If the applied voltage is too low, the jet will not form due to insufficient electrostatic forces, whereas excessively high voltage can produce beads due to chaotic whipping[102]. Maintaining an optimal distance between the needle tip and collector is crucial for sufficient solution flight time, which facilitates solvent evaporation and improves fiber morphology by reducing bead formation[103]. When the needle-to-collector distance is too short, the solvent does not have enough time to evaporate, resulting in wet fibers that may fuse or form flat ribbons [Figure 2][104]. The nozzle diameter, also referred to as gauge size (G), affects jet initiation and fiber diameter. A smaller gauge number corresponds to a larger nozzle diameter, and vice versa. Larger diameters allow easier solution flow but produce thicker fibers, whereas smaller diameters yield thinner fibers but increase the risk of nozzle clogging during ejection. Nozzle diameter and structure also influence fiber architecture, including the formation of core-shell or hollow fibers.

Environmental parameters

In addition to solution and processing parameters, environmental parameters, such as temperature and humidity, influence the morphology of electrospun fibers[105-107]. Temperature affects both viscosity and evaporation rate[108]. Higher temperatures reduce viscosity, promote faster solvent evaporation, and consequently lead to the formation of thinner fibers. Porous fiber formation, particularly for drug delivery scaffolds, has been reported under high humidity, whereas low humidity accelerates solvent evaporation, resulting in thinner, smoother fibers.

Careful adjustment of electrospinning parameters is necessary to achieve the desired fiber characteristics. Minor changes in voltage, flow rate, distance, or collector configuration can significantly impact fiber quality. Systematic optimization of these parameters is essential for applications in wearable electronics, filtration, and biomedical scaffolds.

ELECTROSPINNING PRESSURE SENSORS

An electrospun pressure sensor consists of a nanofiber mat that serves as the primary active membrane. Sensors convert physical stimuli into data and play a foundational role in the era of digital transformation. Pressure sensors measure the force per unit area (pressure) exerted by gases, liquids, or other materials and transform this physical pressure into an electrical signal, facilitated by the unique structural properties of the fibrous network[109].

Sensors can be classified as physical, chemical, or biological based on the sensing components employed. Physical sensors are the most prevalent type and detect physical quantities through various effects, including force, heat, light, electricity, magnetism, and sound[110]. They have diverse applications, including human health monitoring, medical treatment, industrial production, and daily life[62,111,112].

Transformation of physical input into electrical output occurs through several core mechanisms, including piezoresistivity, piezoelectricity, capacitance, and triboelectric effects. The complex structures of capacitive and triboelectric sensors, which require well-defined electrode gaps or specific surface functionalization for optimal triboelectric performance, make them challenging to apply on irregularly curved body surfaces. Therefore, this study focuses primarily on piezoelectric and piezoresistive sensors due to their simple operational mechanisms and straightforward device architectures.

Piezoelectric pressure sensors

The piezoelectric effect is a fundamental property of certain materials that arises from their inherent atomic or molecular structure and enables energy conversion between mechanical and electrical forms[113-115]. Piezoelectric sensors generate an electrical (voltage) signal when subjected to mechanical deformation, such as pressure, strain, or vibration. This mechanism benefits applications that require consistent electrical signals without an external power supply, enhancing portability and durability[116]. The electrospinning process enhances the piezoelectric effect through in situ poling and β-phase enhancement, driven by the high electrostatic field and rapid stretching during fiber formation. The flexible architecture of electrospun fibers is also highly pressure-sensitive compared with films or rigid structures.

The piezoelectric effect is reversible and is characterized by both direct and indirect effects[117]. The direct piezoelectric effect refers to the generation of electric charge in certain materials when mechanical stress is applied. This occurs in asymmetric crystal structures such as quartz, lead zirconate titanate (PZT), and polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF)[118]. When compressed, the atomic lattices of these materials are distorted, resulting in a net electric dipole moment and a measurable voltage across the material. The direct piezoelectric effect is widely used in sensors and energy-harvesting devices. In contrast, when an applied electric field causes mechanical deformation in the material, it is known as the indirect piezoelectric effect. The internal dipoles in a piezoelectric material realign when a voltage is applied across it, causing expansion or contraction. This property is exploited by actuators and transducers that require precise motion control. Since this review specifically focuses on pressure sensors and applications, the primary emphasis is on the direct piezoelectric effect.

In the piezoelectric effect, mechanical-electrical coupling occurs in three principal modes (“31”, “33”, and “15”)[113,119], as shown in Figure 3. The initial subscript numeral “3” denotes the poling direction, corresponding to the output voltage direction, while the subsequent numeral indicates the direction of the applied force. These three primary modes are defined by the orientation of mechanical stress or strain relative to the material’s electrical polarization direction.

Figure 3. Schematic representation of piezoelectric modes: (A) longitudinal mode, (B) transverse mode, and (C) shear mode[113]. Reproduced from Chen et al., Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2019, with permission from Elsevier.

The shear mode (15-mode)[120] involves shear stress applied perpendicular to the poling direction (1-3 plane), which requires electrodes on parallel faces. The key piezoelectric coefficient is d15. This mode generates charge on the side electrodes and induces shear deformation. Specialized electrode configurations are required, and this mode is essential for torsional sensing, gyroscopes, and shear-horizontal wave transducers.

The transverse mode (31-mode)[121] is characterized by mechanical stress applied perpendicular to the poling direction (along the 1-axis), with electrodes oriented perpendicular to the 3-axis. The key coefficient is d31. This mode is well-suited for applications such as bimorph actuators, accelerometers, pressure sensors, and flexible energy harvesters, owing to its negative tensile stress.

The longitudinal mode (33-mode)[122] involves mechanical stress applied parallel to the poling direction (3-axis), with electrodes placed perpendicular to this axis. The piezoelectric coefficient d33 governs this mode, representing charge generation per unit force along the poling direction. It is highly efficient for applications requiring strong forces or displacements, such as stack actuators and ultrasonic transducers. To evaluate the piezoelectric properties, essential parameters include the piezoelectric charge coefficient (d33), the piezoelectric voltage factor (g33), and the electromechanical coupling coefficient (Kt)[123].

The piezoelectric phenomenon was first described by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880. Piezoelectric materials generate an electric field and change their properties when stressed or compressed. An electric dipole is created when a mechanical force deforms a material, altering the distribution of positive and negative charge centers in its anions and cations. This change generates a new equilibrium phase and develops a piezoelectric potential between the electrodes. When the material reaches maximum polarization and the electrodes are connected, mechanical energy is converted to electrical energy[124]. An alteration in electrical polarization changes the dipole-inducing environment or reorients molecular dipole moments, and consequently, induces a surface charge (voltage) on the piezoelectric material[49].

Piezoelectric pressure sensors combined with the electrospinning technique are increasingly ideal for many applications owing to their numerous benefits, including exceptional sensitivity from fiber morphology, rapid dynamic pressure capture, simplified architecture, and self-energy harvesting without an external power source[125-128]. Such sensors are known for high sensitivity and stability but are typically unable to detect static pressure[62].

Numerous piezoelectric materials have been reported for the fabrication of electrospun pressure sensors in healthcare applications. Several materials, including PVDF and its copolymers, barium titanate (BaTiO3), polylactic acid (PLLA), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), and conductive carbon fillers, have attracted significant research attention due to their potential use in energy harvesting, self-powered devices, and wearable sensors.

PVDF-based sensors

PVDF and its copolymers[129] are among the most extensively studied materials for electrospun piezoelectric sensors. PVDF exhibits five distinct crystalline phases: α, γ, β, δ, and ε[130]. The α phase is the most stable and energetically favorable due to its nonpolar nature, whereas the β phase has the highest polarity[131]. The strong piezoelectric response is attributed to β-phase crystallinity, which can be enhanced by optimizing electrospinning parameters and post-treatment processes. The incorporation of various organic and inorganic nanomaterials, including zinc oxide (ZnO), nickel oxide (NiO), BaTiO3, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene, and the emerging two-dimensional material MXene, has been reported to enhance the piezoelectric properties of electrospun fibers[132]. BaTiO3 offers a high piezoelectric coefficient while maintaining the flexibility and processability of polymers. Integrating MXenes into electrospun piezoelectric systems has opened new avenues for improving sensor performance[133]. Nanofillers, with their excellent electrical conductivity and mechanical properties, enhance the charge-transfer capabilities of composite fibers.

The β-phase concentration of raw PVDF has been reported to be 45.5%[134]. Electrospinning significantly increases β-phase content in PVDF, reaching up to 69%[135] and 70%[134]. This enhancement improves its suitability as a self-powered, flexible pressure sensor for human health monitoring, providing rapid response and recovery times, as well as high pressure sensitivity. Li et al. electrospun PVDF fibers over a steel rod, which were then rolled into a spring shape and embedded at various points in mattresses[134]. The piezoelectric PVDF fibers detected and analyzed pressure changes caused by body movements and sleep patterns, with the recorded feedback reported to aid in the early diagnosis of sleep disorders. Several studies have also shown that β-phase crystallinity can be further increased by adding nanofillers such as metal oxides (MOs), carbon family (CF) nanomaterials, MXene, and others.

PVDF-MOs

The addition of ZnO, either alone or in combination with other conductive fillers and antibacterial materials, has been reported to enhance PVDF. Incorporating metal ions into the ZnO structure can occupy central positions, induce lattice deformation, and generate permanent dipoles and ferroelectric effects. Chang et al. prepared an electrospun composite fiber membrane-based sensor by incorporating inorganic ZnO nanorods into PVDF for internal blood pressure monitoring[63]. Subsequent ZnO doping further increased crystallinity, reaching 66.3% for ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) and 73.9% for ZnO nanorods. These sensors were implanted into the femoral artery and cardiovascular walls of pigs, continuously monitoring and recording micro-pressure fluctuations across various physiological states, including heart failure, euthanasia, coma, and alertness.

Similarly, the piezoelectric effect of PVDF electrospun fibers was enhanced by adding other MOs. Amrutha et al. incorporated NiO NPs with an average size of 20 nm, increasing the β-phase content to 70% when

Furthermore, lead-free BaTiO3 ceramic particles, with tetragonal symmetry and structural diversity, exhibit high ferroelectric properties due to the displacement of Ti4+ ions along the axis of one of the oxygen ions[132,138,139]. The high crystallinity of BaTiO3 has been employed by numerous authors[140,141] to enhance the β-phase concentration in PVDF fiber membranes during electrospinning. Li et al. incorporated BaTiO3 and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to prepare PVDF composite fibers, reporting an increase in β-phase concentration from 16.46% for raw PVDF to 43.85% for the BaTiO3/PVDF composite membrane[141]. Kong et al. applied a near-field electrospinning technique to fabricate BaTiO3-doped PVDF fiber membranes[140], which were subsequently molded into a hierarchical structure, increasing the β-phase concentration to 69.7% and elastic strain by 12%. The prepared BaTiO3/PVDF-based piezoelectric sensors functioned as self-powered nanogenerators, eliminating the need for external power sources. These sensors have demonstrated high sensitivity and rapid response for various healthcare applications, particularly in monitoring physical activities and tracking vital physiological signals.

PVDF-CF piezoelectric materials

In addition to MOs, materials from the CF, including carbon dots, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and CNTs, constitute another class of highly effective fillers. Their usage is comparable to that of MOs due to strong anisotropic characteristics and excellent conductivity. Multi-filler materials have been reported to further enhance the piezoelectric performance of PVDF. This synergistic effect was demonstrated by Liu et al., who incorporated MWCNTs into PVDF-BaTiO3, successfully increasing the β-phase concentration to 76% in the resulting membrane[142]. The high β-phase content endowed the membrane with strong piezoelectricity, enabling its integration into smart wearable devices for health monitoring and fitness tracking, such as treadmilling, pedaling, and bending. It also functions as a weight sensor in security and self-powered wireless alarm systems.

In addition to MWCNTs, carbon nanomaterials, such as carbon nanoonions (CNOs), offer unique advantages. CNOs convert standard piezoelectric composites into multifunctional materials by providing a high specific surface area with numerous active sites for polymer chain entanglement. Khazani et al. developed electrospun PVDF-ZnS-CNOs composite membranes and exploited the intrinsic properties of ZnS and CNOs to harness the piezoelectric response of PVDF[143]. ZnS aligned the existing dipole moments in the β-phase of PVDF, while CNOs improved piezoelectric efficiency by facilitating charge transport at the interface[144]. Compared to PVDF fibers, the β-phase content increased to 70.03% in the composite samples containing 1 wt% ZnS nanorods and 0.15 wt% CNOs[143]. The prepared sensors effectively monitored various human movements, demonstrating their practical applications in wearable technology and self-powered devices.

PVDF-MXene

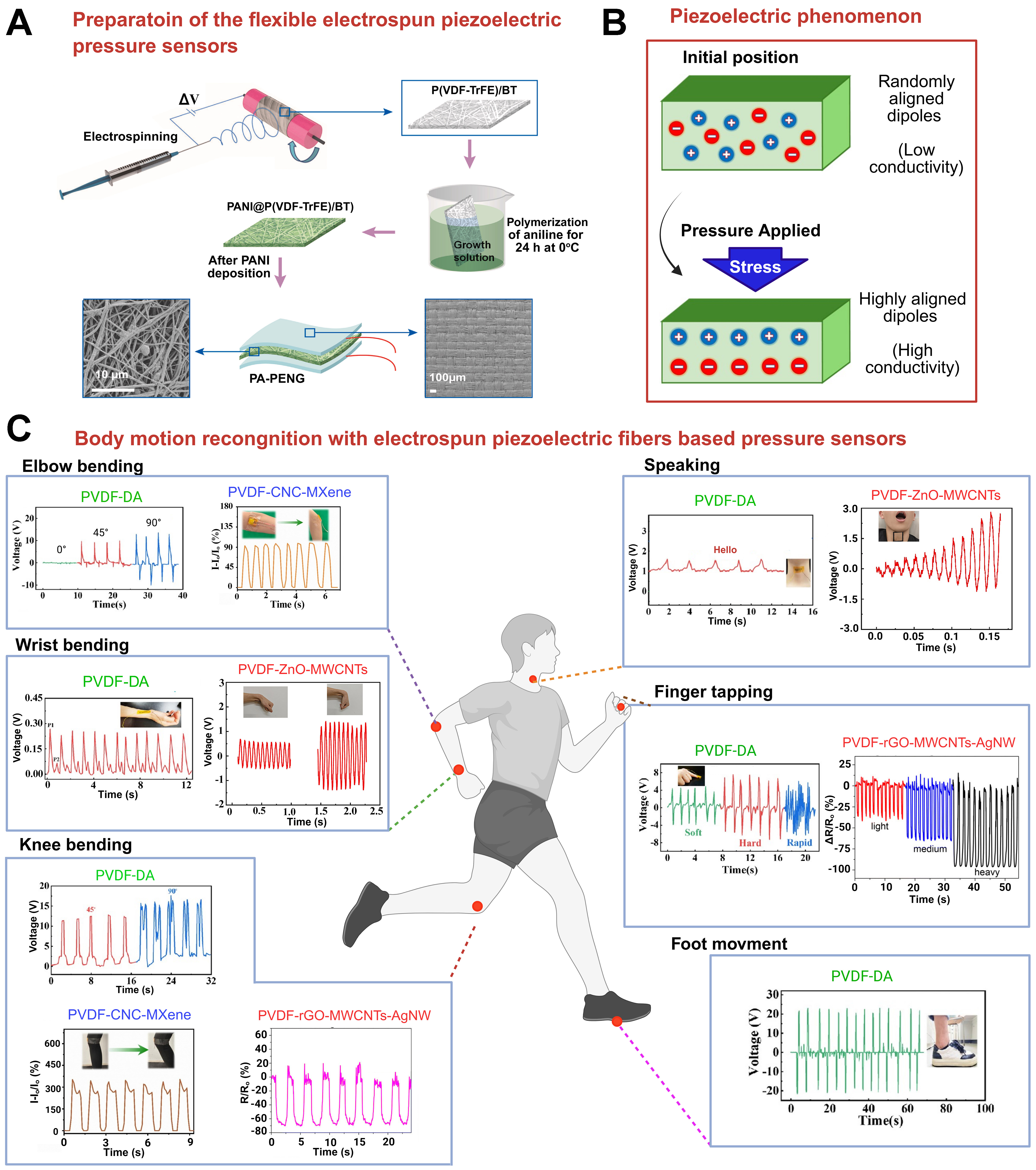

The above studies collectively indicate that leveraging the synergistic effects of multiple fillers is an effective strategy to optimize the piezoelectric properties of PVDF. In this context, the emerging two-dimensional material MXene (Ti3C2Tx) has demonstrated exceptional advantages[145]. MXene facilitates piezoelectric phase formation, promotes effective interfacial synergy, and amplifies the piezoelectric response in PVDF. Zhang et al. prepared electrospun PVDF/MXene nanofiber membranes to construct a wearable self-powered pressure sensor[146]. These sensors successfully harvested energy from pressure changes caused by human body movements. Figure 4A illustrates the sensor preparation schematic, Figure 4B depicts the piezoelectric mechanism, and Figure 4C shows the sensing response of the flexible sensors to various human body movements.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of piezoelectric pressure sensors based on electrospun fiber membranes: (A) step-by-step preparation of sensors[147]; (B) piezoelectric mechanism; (C) human body motion detection and recognition using electrospun piezoelectric sensors - PVDF-DA[137], PVDF-CNC-MXene[148], PVDF/ZnO/MWCNT[149], and PVDF-rGO-MWCNT-AgNW[150]. Reproduced with permission from: Biswajit et al., Materials Today Nano, 2023 [Elsevier]; Junpeng et al., Advanced Fiber Materials, 2024 [Springer Nature]; Yan et al., International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2025 [Elsevier]; Chuanming et al., Organic Electronics, 2025 [Elsevier]; Ravinder et al., Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2025 [Royal Society of Chemistry]. PVDF-DA: Polyvinylidene fluoride/dopamine; CNC: cellulose nonocrystal; MWCNT: multi-walled carbon nanotube; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; AgNW: Ag nanowire; P(VDF-TrFE): poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene); BT: barium titanate; PANI: polyaniline; PA-PENG: polyaniline-piezoelectric nanogenerator.

To further enhance the performance of the PVDF/MXene composite sensor, Yang et al. added ZnO, increasing the β-phase nucleation and stability to 80.57%[151]. ZnO distinctly improves the self-polarization and dipole alignment of the composite material. It facilitates the collection and transmission of internal polarized charges, thereby augmenting the piezoelectric properties of the PVDF/MXene/ZnO composite. The prepared sandwich-structured wearable sensors, with top and bottom electrodes, play a significant role in artificial intelligence electronics for smart shoes, clothing, and sports applications.

P(VDF-TrFE) based sensors

Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-trifluoroethylene) [P(VDF-TrFE)] is the most commonly used copolymer of PVDF and is recognized for its substantial piezoelectric properties, which vary significantly with processing parameters[152]. The piezoelectric performance of P(VDF-TrFE) polymers can be further improved by modifying their microstructure[153]. Techniques such as oriented electrospinning to produce aligned nanofibers have markedly enhanced the piezoelectric response, attributed to their highly ordered β-phase crystal structure and improved charge transport[154,155]. Li et al. developed flexible pressure sensors employing electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) membranes for monitoring human body movements[156]. The piezoelectric pressure sensor array was designed to explore the potential applications of flexible piezoelectric sensors in detecting human joint movements and interactions with surfaces, thereby confirming their suitability for wearable devices and electronic skin technologies. Similarly, Su et al. fabricated electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) membranes for pressure sensing applications, successfully monitoring various human movement signals and recognizing grasping movements[67].

P(VDF-TrFE)-MOs sensors

The piezoelectricity of P(VDF-TrFE) was further enhanced by utilizing the high crystallinity of BaTiO3 and polyaniline (PANI)[147]. The β-phase crystallinity of pure P(VDF-TrFE) was improved from 75% to 83% upon addition of BaTiO3. Coating PANI NPs on electrospun P(VDF-TrFE)//BaTiO3 fibers further increased the β-phase content to 92%. The applications of PANI-coated [P(VDF-TrFE)//BaTiO3] nanofibers include fitness tracking, rehabilitation, smart shoes, and wearable sensors. These pressure sensors can capture human motions, detect finger movements, and harvest biomechanical vibrations for low-power electronic devices. These applications demonstrate the adaptability and potential of PANI-coated nanocomposite fibers in advancing technologies across various fields. The crystallization of P(VDF-TrFE)/BaTiO3 is often limited by poor BaTiO3 dispersion, which results in insufficient polarization and reduced piezoelectric performance. Liu et al. used MXene to enhance the dispersion of BaTiO3 within P(VDF-TrFE), significantly increasing β-phase crystallinity up to 81.04%[157]. The BaTiO3/MXene/P(VDF-TrFE) pressure sensors were designed for wearable electronics and have been applied to various parts of the human body. These sensors can detect multiple human movements, such as finger flexion and elbow articulation, and provide instantaneous feedback on physical activity. They are also suitable for monitoring intense physical activities, including walking, running, and jumping, with a detection range of 0.2-400 kPa.

P(VDF-TrFE)-CF sensors

Similar to MOs, CF materials also significantly influence the piezoelectric performance of P(VDF-TrFE). Ahmad et al. enriched electrospun P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibers with rGO and MWCNTs and subsequently coated them with poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) to enhance β-phase crystallinity, polymer chain orientation, and the piezoelectric effect[128]. Both rGO and MWCNTs act as nucleating agents, facilitating the formation of the polar crystalline phase in P(VDF-TrFE)[158]. The prepared pressure sensors demonstrated high sensitivity for continuous health monitoring, effectively detecting physiological signals, including arterial pulse generation and pulse rate variations. They also respond to physical activity, masticatory movements, and eye blinking, making them suitable for real-time monitoring of blood pressure, pulse rate, and other physiological signals. Functional properties, including the sensitivity of electrospun fiber-based piezoelectric sensors, are summarized in Table 2.

Comparison of active materials and sensing performance of flexible piezoelectric pressure sensors prepared by the electrospinning technique

| Key material | Materials composition | Pressure range | Response recovery time (ms) | Sensitivity | d33 (%) | Applications | Ref. |

| PVDF-based sensors | PVDF | 30 N | 69 | Electronic skin, joint movement | [135] | ||

| PVDF | 5 N | 56/40 | 5.1 mV·deg-1 | 70 | Bending sensing and health monitoring | [134] | |

| PVDF-NiO | 98.07 kPa | 70 | Body movements: tapping, wrist movement, walking, running | [136] | |||

| PVDF-ZnO | 1 kPa | 73.9 | Pressure-related cardiovascular diseases (thrombus & atherosclerosis) | [63] | |||

| PVDF/ZnO | 20 N | 30.8 | 1.27 V·kPa-1 | 88.34 | Human motions, physiological signals | [159] | |

| Bamboo-PVDF | 24.68 MPa | 3,887.1 mV·N-1 | 90 | Movement monitoring of the patient | [160] | ||

| PVDF/CNF | 12.8 mV·cm-1 | 93.2 | Body movements, nanogenerators | [161] | |||

| PVDF/DA | 0-40 N | 7.29 V·N-1 | 88 | Monitoring human motion & subtle physiological signals | [137] | ||

| PVDF-BaTiO3 | 2 N | 0.07 V·N-1 | 69.7 | Monitoring human motions: joint bending, walking, jumping | [140] | ||

| PVDF-BaTiO3 | 0-100 N | 82.7/248 | 116 mV·kPa-1 | 43.85 | Monitoring human motions | [141] | |

| PVDF-BaTiO3 | 0-5 kPa | 86/57 | 25.23 mV·kPa-1 | 50.68 | Flexible electronic skin, Human motion acquisition | [162] | |

| PVDF-ZnS-CNOs | 20-80 N | 70.03 | Monitoring human motions | [143] | |||

| PVDF/ZnO@MXene | 0.01-5 N | 46/52 | 2.32 V·N-1 | 80.57 | Monitoring human motions: throat, fingers, wrist, knee | [151] | |

| PVDF/ZnONRs@Ag | 0.16-8.89 N | 0.52 V·N-1 | 85 | Monitoring human movements, nanogenerators | [163] | ||

| BaTiO3/MWCNTs/PVDF | 50-250 kPa | 390 | 101.28 V·s-1 | 76 | Monitoring human movements, self-power wireless alarm | [142] | |

| P(VDF-TrFE)-based sensors | P(VDF-TrFE) | 1 N | 2 | 0.45 V·N-1 | Human joint movements, Motion monitoring | ||

| P(VDF-TrFE) | 0-100 kPa | 26/52 | 4.05 kPa-1 | Monitoring human activity, physiological signals, soft robotic grasping movements | [67] | ||

| P(VDF-TrFE)/PVDF | 0-250 kPa | 4.45 mV·Pa-1 | 90.01 | Acoustic detection | [164] | ||

| P(VDF-TrFE): LiClO4 | 0-350 Pa | 24/27 | 6.64 kPa-1 | 76.50 | skin, wearable electronics, medical surveillance, automation systems | [165] | |

| BaTiO3/MXene/P(VDF-TrFE) | 0.2-400 kPa | 56 | 81.04 | Human joint movements | [157] | ||

| PANI@(P(VDFTrFE)/BaTiO3) | 33-85.8 kPa | 1.2 V kPa-1 | 92 | Human motions, self-powered wearable sensors capable | [147] | ||

| P(VDF-TrFE)-rGO-MWCNTs (PEDOT) | 0.001-25 kPa | 19.09 kPa-1 | Monitoring human vital signs: heartbeat and wrist pulse, masticatory movement, voice recognition, and eye blinking signals | [128] | |||

| Other composite-based sensors | PAN/BaTiO3/MXene | 2.5-15 N | 0.58 V·N-1 | Nanogenerator, monitoring human limb movement | [166] | ||

| Cellulose/PLLA | 100-500 kPa | 4.35 V·MPa-1 | Self-powered implantable electronic devices | [167] | |||

| CDA/Silica/PDA@PZT | 60-120 kPa | 36.50 mV·kPa-1 | Wearable typewriting gloves, walking posture correction shoes, smart table tennis rackets | [168] | |||

| GR/PPy@PAN | 0-80 kPa | 40/50 | 28.5 kPa-1 | Monitoring human movements | [169] |

Other piezoelectric composites

Besides PVDF and its copolymers, several other polymers and their composites have been reported to exhibit outstanding piezoelectric response under external pressure. Fu et al. synthesized an electrospun PAN/BaTiO3/MXene nanofibrous membrane by integrating BaTiO3 and MXene (Ti3C2) with PAN, resulting in substantially improved piezoelectric characteristics related to the PAN fibrous membrane[166]. PAN demonstrates remarkable piezoelectric potential, characterized by a significant dipole moment that is further amplified by the high voltage coefficient and dielectric coefficient of BaTiO3[170,171], along with the exceptional metallic conductivity and elevated surface electronegativity of MXene. The developed nanofibrous membrane enables remote monitoring of human movement and harnesses energy from pressure variations induced by these motions, making it suitable for power generation applications. Furthermore, the excellent photothermal properties of PAN/BaTiO3/MXene nanofibrous membranes suggest potential applications in photothermal therapy for human body joints.

PLLA-based piezoelectric materials typically exhibit reduced piezoelectric responses compared with PVDF and its copolymers or ceramic materials such as PZT. Nonetheless, the proportion of the β-phase can be enhanced by incorporating ferroelectric particles[172]. The high crystallinity and abundance of polar hydroxyl groups in cellulose contribute to a significant presence of dipoles, improving its capacity to donate electrons. This characteristic results in an enhanced piezoelectric effect[132]. Electrospun cellulose/PLLA composite membranes were prepared by Xu et al.[167], demonstrating significant improvements in piezoelectric performance. The device exhibited an impressive ability to detect varying airflow pressures, illustrating its potential applications in self-powered electronic skin and medical implants. The prepared sensors were also tested on shoe soles to harvest energy from human movement, further demonstrating their potential for pressure-sensing applications. PZT emerged as the first extensively utilized piezoelectric material, primarily due to its remarkable piezoelectric coefficient (d33 = 140 pm·V-1). Zhang et al. developed an electrospun hybrid nanofiber-based piezoelectric mat composed of cellulose diacetate (CDA)-silica-PZT, exhibiting exceptional homogeneity, flexibility, piezoelectric properties, and pressure sensitivity[168]. PZT NPs were surface-coated with polydopamine (PDA) through a straightforward oxidative self-polymerization process to introduce hydrophilic groups. The results highlight the potential of CDA-silica-PDA@PZT piezoelectric fibers in developing wearable electronic systems for skill detection or training. The sensor can detect activities such as walking and typing, acquiring hit position and contact force in real time and generating output voltages under various human movements, thereby supporting advances in smart clothing, footwear, and athletic gear.

Piezoresistive sensors

The operation of piezoresistive sensors relies on the piezoresistive effect, which refers to a variation in material resistance when subjected to pressure. The piezoresistive effect differs from the piezoelectric effect. The piezoelectric effect generates a voltage in response to applied mechanical strain or external force, whereas the piezoresistive effect solely involves a change in resistance. Applying mechanical stress or strain to a material deforms its atomic lattice, thereby modifying its electronic structure.

Early efforts in pressure sensor development typically exploited a single sensing mechanism, such as the piezoresistive effect. This phenomenon is commonly considered to comprise two components: the geometric effect and the resistive effect[173,174]. A piezoresistive sensor can be engineered through systematic structural design and material selection to enhance sensitivity[64,175]. Such designs are intended to produce significant variations in contact resistance while minimizing structural distortion[176]. Electrospinning enables the fabrication of structures that are highly suitable for piezoresistive sensors, as they can undergo large deformation under small applied forces. Even minimal forces can substantially increase the number of conductive contact points and enhance electron transport via tunnelling, resulting in exceptionally high sensitivity.

Piezoresistive pressure sensors, particularly those fabricated through electrospinning, have emerged as a key research focus owing to their exceptional sensitivity, flexibility, and broad range of applications. These sensors are primarily applied in healthcare, wearable technology, and human-machine interfaces. This section reviews recent advancements in electrospun piezoresistive sensors, categorized according to material composition, sensitivity, and pressure response. Integrating flexibility and conductivity in piezoresistive pressure sensors has posed challenges due to limited exploration in existing research. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes offer lightweight, tunable nanostructures, scalable manufacturing, mechanical flexibility, high porosity, and air permeability, making them highly suitable for high-performance wearable materials.

Polyimide-based sensors

Polyimide (PI) has garnered significant attention due to its lightweight nature and thermal stability and has been widely employed in the development of flexible sensors. Khuat et al. successfully synthesized PI nanofibers by electrospinning and subsequently converted them into an aerogel through multistep crosslinking[177]. This porous PI aerogel was then coated with conductive poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) to fabricate lightweight, flexible, and conductive piezoresistive pressure sensors. The calibrated sensors exhibited a sensitivity of 0.02 kPa-1 and demonstrated rapid response and recovery times of 90 and 97 ms across a broad pressure range of 250 kPa. The high conductivity of PEDOT:PSS markedly enhanced the sensitivity of the PI fiber-based aerogels. Other researchers have extended this strategy by modifying electrospun PI aerogels to create various conductive pathways. Lin et al. transformed electrospun PI fibrous aerogels into carbon nanofibrous aerogels (CNAs) via a carbonization process[178]. The resulting PI-CNA nanofibrous aerogel-based piezoresistive pressure sensors exhibited a high sensitivity of 0.07 kPa-1 over a wide pressure range of 217 kPa, with a rapid response and recovery time of 230 and 120 ms, respectively. Similarly, Lin et al. enhanced the piezoresistive performance of electrospun PI fibrous aerogels by depositing polypyrrole (PPy)[179]. The sensor sensitivity increased to 0.42 kPa-1, with response and recovery times of 300 and 80 ms, respectively, over a pressure range of 25 kPa. The fabricated wearable sensor was capable of detecting sound, capturing acoustic signals, and recognizing natural sound activities. It could also monitor respiration and diagnose obstructive sleep apnea, demonstrating high sensitivity to subtle airflow changes.

The robust nature of PI-based sensors makes them particularly suitable for harsh environments that challenge conventional technologies, prompting researchers to develop integrated temperature-pressure sensors for multifunctional sensing under extreme conditions. Various studies have reported the development of multifunctional temperature-pressure sensors[180,181]. A notable example is the work of Liu et al., who proposed a 3D platinum/PI (Pt/PI) fibrous network designed as a highly sensitive, thermally resilient, and flexible pressure sensor for harsh environments and extreme temperatures ranging from -196 to 250 °C[181]. The sensor achieved a high sensitivity of 158.23 kPa-1 at room temperature and 148 ± 10 kPa-1 under relative humidity (RH) conditions ranging from 30% to 90%. The elevated glass transition temperature (Tg) of PI, combined with the high conductivity and thermal stability of Pt, ensures reliable sensor performance in harsh environments and at elevated temperatures.

Thermoplastic polyurethane-based sensors

Building on the established use of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) as a piezoresistive material, TPU is valued for its elasticity and ability to maintain structural integrity under large deformations. Its distinctive elasticity and flexibility enable nanofiber yarns to withstand substantial deformation while preserving their structural integrity. TPU establishes a continuous conductive network within nanofibers, which is crucial for the resistance response of the sensor under strain or pressure and serves as a matrix for nanofillers[182,183]. Similarly, MXene (Ti3C2Tx), a piezoresistive filler material, plays a crucial role in enhancing sensor performance by contributing high sensitivity, electrical conductivity, and mechanical flexibility[9]. The synergy between these materials is demonstrated by the development of a high-performance wearable tactile sensor based on a hybrid nanofibrous membrane. Specifically, a wearable tactile sensor was fabricated using a hybrid nanofibrous membrane prepared by the co-electrospinning of TPU with PAN and Pluronic F127 (F127), combined with monolayer Ti3C2Tx MXene flakes[184]. The exceptional functional properties of MXene enhanced several attributes of the resulting MXene/TPU/PAN/F127 (MTPF) nanofibrous membrane, including a wide operational range, rapid response and recovery times, high sensitivity (0.21 kPa-1), and long-term durability, retaining 80% of its initial current response. The developed sensor, intended for electronic skin, real-time motion tracking, and human–machine interfaces, has been reported to be effective in wireless wearable devices and real-time health monitoring.

Further validating this material combination, Bi et al. designed a high-performance piezoresistive pressure sensor by coating MXene onto electrospun TPU/PAN fibers[185]. A pressure-sensing array was developed to map pressure distribution, demonstrating the sensor’s potential applications in robotics and healthcare. The developed sensor exhibited high sensitivity (6.7 kPa-1), a wide measurement range, and a rapid response time, making it suitable for wearable electronics, health monitoring, and human-machine interactions. The metallic nature and surface functional groups (e.g., -OH, -F, -O) of MXene create conductive networks when incorporated into TPU or PAN matrices, markedly enhancing electrical conductivity by facilitating efficient electron transport during mechanical deformation. The large surface area of two-dimensional structured MXene provides numerous sites for interaction with the polymer matrix, resulting in improved stress transfer and enhanced piezoresistive behavior.

MXene-based sensors

Based on research on TPU-based sensors, MXene, as a functional nanomaterial, has opened a new avenue for improving the performance of TPU sensors. However, MXene still faces practical challenges, including oxidation and aggregation, which degrade its performance. To address these issues, Zheng et al. developed MXene-based pressure sensors with improved environmental stability and pressure-sensing performance[186]. By anchoring MXene onto electrospun TPU fibers through hydrogen bonding, an anti-oxidized functionalized MXene (f-MXene) was electrostatically attached to the MXene layer. The functionalized f-MXene forms a hydrophobic protective layer that prevents oxidation and enhances pressure sensitivity to 40.31 kPa-1 by inhibiting stacking of the MXene layers. The developed sensor was effectively evaluated for tracking human motions and radial artery pulsations.

To ensure the environmental stability of MXene, a 3D interconnected conductive MXene network was decorated on the surface of electrospun deacetylated cellulose acetate (DCA) fiber-based piezoresistive sensors[187]. The DCA fibers, which are rich in hydroxyl groups, provide a biodegradable platform for MXene nanosheets to adhere via hydrogen bonding. The resulting MXene/DCA (MDCA) sensor exhibits exceptional sensitivity (54.62 kPa-1), linearity, and durability, making it suitable for health monitoring, human-machine interfaces, and environmental sensing applications. It can detect various physiological signals, including vocal cord vibrations, pulse vibrations, and finger movements, demonstrating its promise for wearable electronics and medical monitoring.

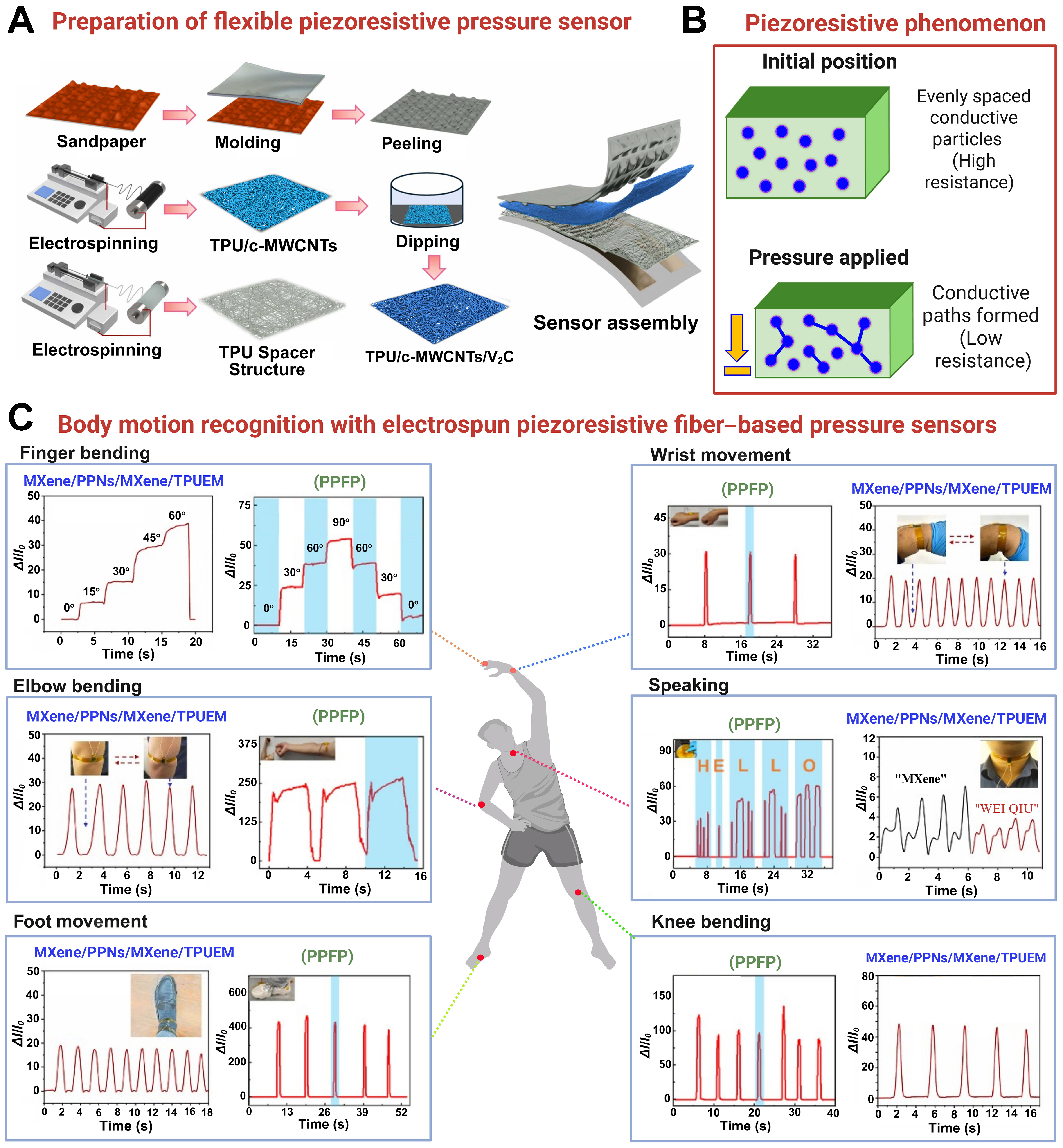

In addition to chemical modifications, microstructural engineering of the sensor also significantly enhances its sensing performance. Wang et al. developed a multilayer interlocking structure by modifying TPU with MXene and CNTs[188]. The “sandwich” structure of the sensor, comprising polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/CNT films with micro-dome arrays and TPU/MXene nanofiber films, substantially increases the contact area and sensitivity between layers. A high sensitivity of 82.17 kPa-1 was reported for the prepared PDMS/CNT-TPU/MXene pressure sensor. Similarly, Zhang et al. modified TPU with V2CTx-MXene and carboxyl multiwalled carbon nanotube (c-MWCNTs)[189]. The one-dimensional c-MWCNTs provide a consistent conductive pathway, whereas the two-dimensional MXene enhances both conductivity and mechanical performance of the sensor. The sensitivity of the developed flexible piezoresistive sensor was reported as 545.2 kPa-1 over 0-50 kPa, with a minimum detectable pressure of 5 Pa. These sensors are suitable for tracking diverse human motions, including joint flexion, gait, and gestures, making them ideal for applications in health monitoring, wearable devices, and human-computer interaction. A schematic of piezoresistive pressure sensor preparation is illustrated in Figure 5A; the working principles of the piezoresistive mechanism are presented in Figure 5B; and Figure 5C displays the sensing response of flexible piezoresistive sensors to various human body movements.

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of piezoresistive pressure sensors: (A) Step-by-step process of sensor preparation[189]; Adapted from Zhang et al., Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2024 [Elsevier], with permission; (B) Schematic of the piezoresistive phenomenon; (C) Human body motion detection and recognition using electrospun piezoresistive sensors based on MXene/PPNs/MXene/TPUEM[190]. Reproduced from Cheng et al., Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2023 [Elsevier], with permission. PPFP fiber membranes[191]. Reproduced from Wei et al., Applied Materials, 2024 [American Chemical Society], with permission. PPNs: P(St-MAA)@PPy nanospheres; TPUEM: thermoplastic polyurethane electrospun membrane; PPFP: polyvinylidene fluoride/polyacry lonitrile/polyethylene−polypropylene glycol/polypyrrole; TPU: thermoplastic polyurethane; MWCNTs: multi-walled carbon nanotubes.

MXene establishes a dense conductive network within TPU. A novel sandwich-structured multifunctional Ti3C2Tx MXene/nanospheres/Ti3C2Tx MXene/TPU electrospun membrane (MXene/PPNs/MXene/TPUEM), inspired by a bean pod-shaped structure, was developed[190]. The sensor exhibited high electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding [shielding function (SET) = 20.2 dB] and high pressure sensitivity (177.3 kPa-1). It accurately tracked human activities, including joint flexion, voice recognition, and pulse rate, making it suitable for multifunctional smart wearable devices.

The sensitivity of the electrospun polyurethane (PU) membrane was further enhanced by decorating it with MXene-embedded ZnO nanowire arrays. Incorporating MXene into ZnO nanowires improves sensor conductivity, yielding high sensitivity (236.5 kPa-1) over a low-pressure range of 0-0.2 kPa due to interlocking effects[192]. Similarly, integrating MXene onto carbonized melamine foam (CMF) and electrospun polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers creates a gradient-concentration structure that amplifies the sensor’s response to pressure changes[193]. The hydrophilic nature of MXene promotes strong bonding with the substrate, ensuring uniform distribution and durability under mechanical deformation. The resulting sensor achieved exceptional sensitivity (381.91 kPa-1) and could detect ultra-low pressures down to 0.1 Pa, making it suitable for applications such as physiological signal monitoring and human-machine interfaces.

In response to issues of sweat accumulation and limited moisture permeability in conventional electronic skins, Zhi et al. developed heterogeneous fibrous membrane-structured sensors[194]. The design comprised a hydrophobic layer of CNT-modified PVDF nanofibers, a conductive MXene/CNT layer, and a superhydrophilic PAN nanofiber layer. The sensor exhibited high pressure-sensing performance, with a sensitivity of 548.09 kPa-1. Similarly, Choi et al. fabricated MXene-coated polybutadiene-urethane (PBU) fibers as an active layer, paired with semi-cylindrical Ag nanowire (AgNW) electrodes[195]. The resulting sensor array achieved exceptional sensitivity (888.79 kPa-1) and a low-pressure detection limit of 0.4608 Pa.

CNT-based sensors

Exploring the sensing performance of TPU and MXene composites, CNTs have also been found to provide distinct advantages in enhancing flexible sensor performance, serving as another key nanomaterial. Similar to MXene, the excellent electrical conductivity of CNTs significantly improves the piezoresistive performance of pressure sensors. CNTs can be further functionalized to enhance charge-transport efficiency and pressure sensitivity. In composites, CNTs are typically not ideally connected; external pressure alters their alignment and inter-contact distances, thereby affecting the overall tunneling resistance. Numerous studies have reported the sensing responses of various functional materials integrated with CNTs.

Chang et al. developed a dual-mode piezoresistive sensor for pressure and strain by electrospinning an olefin block copolymer (OBC) into a fibrous membrane and decorating it with CNTs[196]. The CNTs form a conductive network within the highly elastic and skin-friendly OBC microfibers, enhancing the piezoresistive sensing performance up to 0.08 kPa-1 under both stretching and compression. The sensor also demonstrates air-pressure sensing to distinguish natural sounds, highlighting its potential for sound visualization applications. The piezoresistive performance of electrospun TPU fiber membranes was further improved by uniformly dispersing MWCNTs on the surface[197]. A sandwich-structured MWCNT/TPU nanofiber sensor exhibited a wide pressure detection range of approximately 364 kPa, with a high sensitivity of 0.85 kPa-1, including a low-pressure range of 0-3 kPa. Sensitivity was further enhanced by coating electrospun TPU fibers with PDA and subsequently modifying them with MWCNTs. The fabricated piezoresistive sensor employed a secondary active layer of rGO film with wrinkled microstructures. The integration of these layers enabled a high sensitivity of 8.5 kPa-1 across an extensive pressure range (0-100 kPa) with a minimal detection limit of 2 Pa[198].

CNTs have also demonstrated significant performance improvements in other polymer matrices. Luo et al. functionalized electrospun PU fibers with MWCNTs and subsequently coated them with PEDOT via in situ polymerization[176]. The resulting multifunctional PEDOT/MWCNT@PU sensor exhibited a high piezoresistive pressure sensitivity of 1.6 kPa-1 and a thermal sensitivity of 13.2 µV/K. The sensor’s ability to measure physiological signals, such as breathing rate, carotid pulse, and radial artery pulse, highlights its potential for health monitoring applications. Rather than scattering MWCNTs on the PU membrane, Sun et al. incorporated MWCNTs into PU and electrospun the composite into fibers to create a flexible pressure-sensing membrane[199]. The resulting PU/MWCNT sensor exhibited an exceptionally low-pressure detection limit of 0.1 Pa, a wide pressure detection range up to 420 kPa, and a remarkable sensitivity of 7.02 kPa-1. The sensor can detect real-time physiological signals and simulate keyboard inputs, demonstrating its potential for wearable electronics and human-machine interfaces. Polylactic acid (PLA) was electrospun and impregnated with a solution of wool keratin (WK) and CNTs to enhance piezoresistive sensitivity. The hydrophilic properties of WK, extracted from waste wool, combined with the conductive properties of CNTs, improved the biocompatibility and piezoresistive performance of the electrospun PLA fibers[200]. This combination yielded a sensor with high sensitivity (12.64 kPa-1) and a minimum detection limit of 5.64 Pa. The integration of PLA and WK ensures biocompatibility, making the sensor suitable for wearable and biomedical applications.

The sensitivity of the PAN fiber membrane was significantly enhanced by in situ polymerization of PANI and MWCNTs on its surface[201]. The resulting MWCNTs/PANI@MWCNTs/PAN sensor exhibits a high sensitivity of 61.12 kPa-1. Incorporating MWCNTs improves the sensor’s electrical properties by increasing the fiber surface area and providing additional electron transport pathways. MWCNTs also enhance the conductivity of PANI, forming a conductive layer on the PAN fiber surface during polymerization, thereby improving both sensitivity and stability. Zhu et al. developed a multilayer piezoresistive pressure sensor for intelligent recognition systems and privacy protection applications[202]. The sensor consisted of a P(VDF-TrFE)-titanium dioxide (TiO2)/single-walled CNT (SWCNT) film, a paper spacer layer, copper/nickel (Cu/Ni) electrodes, and a PI film. The pine needle-shaped TiO2 structure increases the sensor’s surface area, while SWCNTs enhance conductivity, enabling detection of minute pressure variations. The multilayer design further improves performance by increasing conductive channels and allowing greater deformation under pressure. The prepared MWCNTs/PANI@MWCNTs/PAN sensor demonstrates a sensitivity of 9,040.46 kPa-1 in the low-pressure range (0-1 kPa), substantially exceeding previously reported pressure sensors. The functional properties, including the sensitivity of electrospun fiber-based piezoresistive sensors, are summarized in Table 3.

Comparison of active materials and sensing performance of flexible piezoresistive pressure sensors prepared by the electrospinning technique

| Materials composition | Pressure range (kPa) | Response recovery time (ms) | Sensitivity (kPa-1) | Applications | Ref. | |

| PI based sensors | PEDOT:PSS@PI | 0-250 | 90/97 | 0.02 | Human motion tarcking | [177] |

| PI-CNA | 0-217 | 230/120 | 0.07 | Wearable technologies, energy conversion, electronic skin, and artificial intelligence | [178] | |

| PINA@PPy | 0-25 | 300/80 | 0.42 | Real-time respiratory monitoring | [179] | |

| PSAN/GA | 24.97 | 300/200 | 32.85 | Physiological and body movement (throat, face, fingers, elbows, knee joints, and other parts of the human body) | [180] | |

| Pt/PI | 50 | 140/120 | 158.23 | Monitor human motion, pressure detection and human–machine interactions | [181] | |

| TPU based sensors | C2AgF3O2/TPU | 0-100 | 100/70 | 7.51 | Monitoring of pulse, finger movement, Morse code | [182] |

| Carbon nanohybrid/TPU | 0.05-100 | 7.49 | Smart sports bandages and football socks | [183] | ||

| MXene/TPU/PAN/F127 | 0-160 | 60/120 | 0.21 | Monitor natural sounds and human motions | [184] | |

| TPU/PAN, MXene | 0.02-700 | 42/43 | 6.71 | Recognize subtle throat vibrations while speaking | [185] | |

| TPU/c-MWCNTs/V2C | 0-200 | 48/62 | 545.2 | Capture human physiological signals, including signals of muscle activity and pulse | [189] | |

| CA/TPU | 0-2.25 | 88/90 | 10.53 | Respiratory monitoring and smart wound dressings | [25] | |

| GO/TPU | 0-300 | 18/22 | 1.08 | Robotic hand /soft pneumatic gripper | [203] | |

| PEDOT:PSS/TPU | 0-426.7 | 152/160 | 302.9 | Recognizing respiratory strength, detecting joint movements | [44] | |

| MXene-based sensors | f-MXene/MXene/TPU | 0-120 | 180/200 | 40.31 | Monitoring human body movements | [186] |

| MXene/DCA | 0-40 | 154/125 | 54.62 | Wearable device for monitoring human activity | [187] | |

| PDMS/CNT–TPU/MXene | 0-25 | 100/100 | 82.17 | Human motion monitoring, health monitoring, wearable devices, and human–computer interaction | [188] | |

| MXene/PPNs/MXene/TPUEM | 0-30.4 | 137/163 | 177.3 | Monitor human activities: joint flexions, voice recognition, and pulses | [190] | |

| MXene/ZnO | 0-260 | 100/60 | 236.5 | Physiological signal monitoring, motion signal monitoring, tactile sensing, and pressure distribution detection | [192] | |

| MXene/CTAB/CMF | 0-3 | 100/30 | 381.91 | Physiological signals: flexion of joints, muscle movements, pulses | [193] | |

| MXene/CNTs | 0-10 | 28.4/39.1 | 548.09 | Pulse monitoring, voice recognition, and gait recognition | [194] | |

| PDMS-MXene@CNTs/TPU | 0-521.6 | 7/8 | 471.3 | Human body motion detection and health management | [204] | |

| MXene/PVP | 0-200 | 45/45 | 0.5 | Pulse, respiration, human joint motions and airflow | [205] | |

| MXene-PBU | 20 | 66/69 | 888.79 | Environmental monitoring and healthcare diagnostics | [195] | |

| CNTs based sensors | OBCs/CNTs | 0-70 | 30/60 | 0.07 | Human activities, sound visualization | [196] |

| MWCNT/TPU | 0-364 | 210/150 | 0.85 | Wearable electronic devices, as health monitoring, electronic skin, and intelligent textiles | [197] | |

| TPU/PDA/MWCNTs | 0-100 | 105/85 | 8.5 | Finger and wrist bending, beaker-holding, and fingertip-sliding on a touch screen | [198] | |

| PU/MWCNTs | 0-420 | 60/80 | 7.02 | Detection of physiological signals and mimicking keyboards | [199] | |

| PLA-WK-CNTs | 0-30 | 63/63 | 12.64 | Wearable biometric monitoring applications: finger pressure, finger bending, pulse monitoring Visual interaction: interactive blankets for infants | [200] | |

| MWCNTs/PANI@MWCNTs/PAN | 0-20 | 120/22 | 61.12 | Monitoring human sports health: knee and elbow bending, mouse clicking, beaker holding | [201] | |

| BiI3/PVP | 0-200 | 29/41 | 0.08 | Guiding shooting postures of basketball players | [206] | |

| GPU/CNTs@Ag/TPU | 0-6 | 15/35 | 0.08 | Human motion detection, smart skin, and machine haptics | [207] | |

| PEDOT/MWCNT@PU | 0-70 | 80/95 | 1.6 | Wearable health care monitoring and electronic skin | [176] | |

| C-CNTs/MXene/CCS/LS | 0-53 | 140/60 | 2.33 | Human motion detection, healthy monitoring, micro-expression identification, and speech recognition | [208] | |

| P(VDF-TrFE)-TiO2/SWCNT | 0-20 | 30/30 | 9,040.46 | Personal handwriting recognition, privacy protection and security defense applications | [202] | |

| PPy based sensors | s-PGG@PPy | 0.13-128.46 | 26/19 | 52.42 | Personal thermal management devices, human motion detection | [209] |

| PPFP | 0-1 MPa | 100/40 | 996.7 | Human movement, future health monitoring systems | [191] | |

| Other materials-based sensors | AgOCN | 0-300 | 110/340 | 2.67 | Basic human movement: finger flexion, phonation, and breathing, walking, stair climbing | [210] |

| SnO2–ZnO | 0-60 | 42/28 | 11.5 | Human motion detection: weak changes in the finger joints, wrists, and elbows | [211] | |

| GFA | 0-4 | 2/44 | 18.55 | Human health monitoring and motion detection | [212] | |

| Graphene (GAF) | 0.1-140 | 17/68 | 23.05 | Wearable electronics, feet motion monitoring, and biomedical diagnostics | [213] |

Sensor sensitivity depends on both the intrinsic performance of the sensing material and the structural design of the device. Numerous studies have demonstrated that nature-inspired microstructures can substantially enhance sensitivity[190,194]. At the microstructural level, Chen et al. introduced a novel sensor inspired by the starfish surface, featuring high- and low-spine structures to reduce rapid saturation and broaden the response range[44]. The sensor comprises a conductive nanofiber membrane of PEDOT:PSS/TPU and an insulating PVA fiber layer. This design achieves an exceptional sensitivity of 302.9 kPa-1 and a wide detection range of 0-426.7 kPa, making it suitable for precise pressure sensing in applications such as health monitoring and intelligent manufacturing.

PPy-based sensors

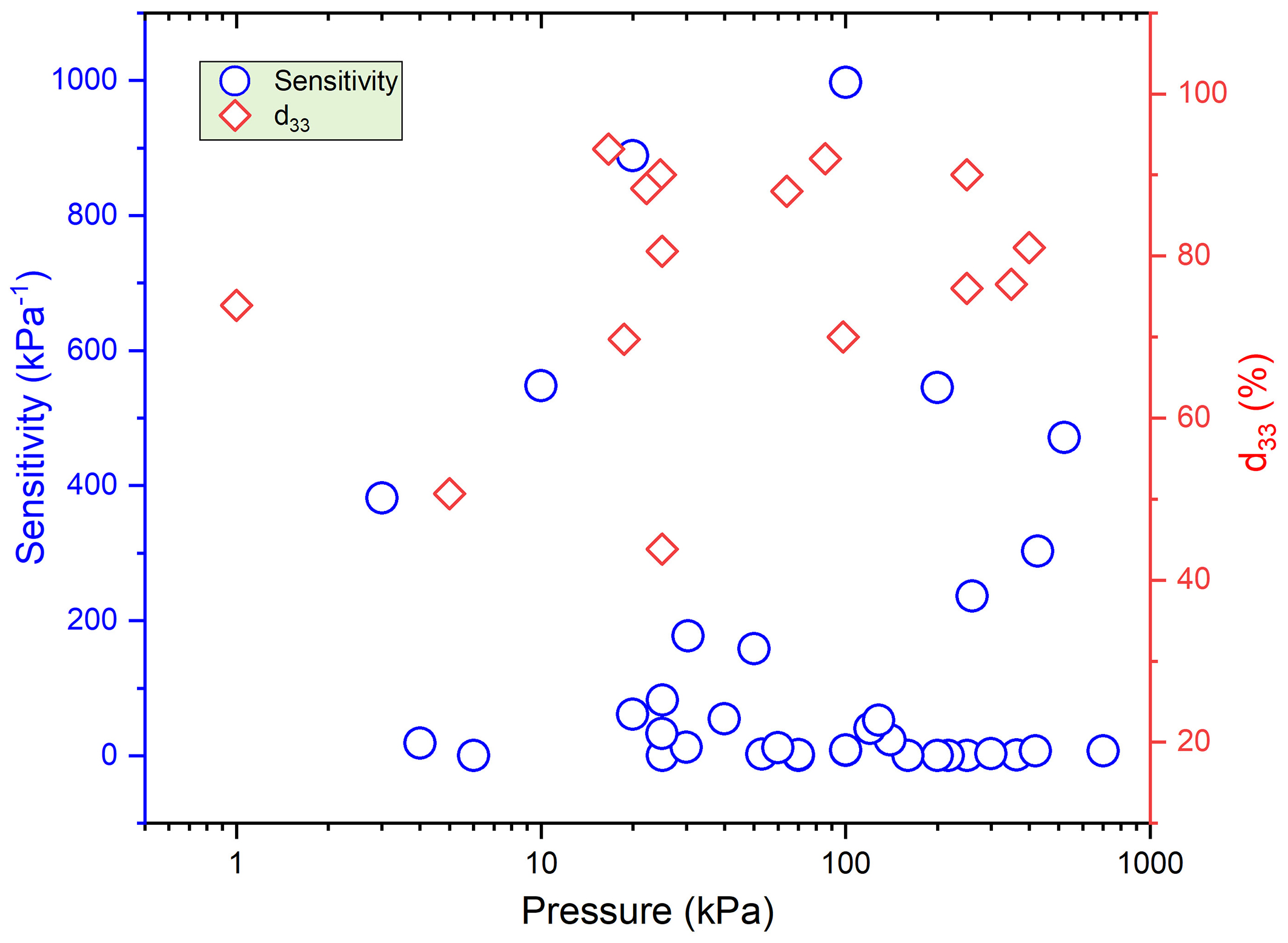

Inspired by natural biomimetic scale-like nanostructures, Su et al. developed a highly sensitive piezoresistive sensor by electrospinning polysaccharides into a fibrous membrane and subsequently coating it with PPy via in situ polymerization[209]. The PPy layer forms a 3D conductive network, enabling free π-electron movement along its carbon–carbon conjugated double bonds. This configuration enhances the electrical conductivity and piezoresistive performance of the sensor, achieving a high sensitivity of 52.42 kPa-1 and enabling a broad pressure detection range. Wei et al. designed a multilayer PVDF/PAN/polyethylene-polypropylene glycol (PPF) fibrous membrane decorated with PPy granules and anchored onto a flexible TPU substrate[191]. This sensor exhibits a remarkable sensitivity of 996.7 kPa-1 across an extensive pressure range (0-1 MPa), making it suitable for detecting diverse human motions and physiological signals. A summary of the sensitivity (kPa-1) of piezoresistive sensors and β-phase crystallinity (d33) of piezoelectric sensors is presented in Figure 6.

CONCLUSIONS

This review summarizes recent advances in electrospun piezoelectric and piezoresistive flexible pressure sensors for next-generation healthcare applications. The core findings highlight that electrospinning technology enables highly sensitive and flexible sensors by crafting unique micro/nanofiber architectures. For piezoelectric sensors, optimizing the β-phase crystallinity in polymers like PVDF and its composites is central to achieving self-powered operation and high sensitivity for detecting physiological signals. For piezoresistive sensors, constructing conductive networks with nanomaterials (e.g., MXene, CNTs) within fibrous matrices, especially through biomimetic multilayer designs, results in exceptionally high sensitivity and a broad detection range. Looking forward, continued innovation in these sensor systems is poised to enable transformative, personalized, and continuous health monitoring platforms.

FUTURE OUTLOOK

To overcome the current deficiencies, future research can be addressed through four perspectives.

Advancements in materials and structures

In future work, research should prioritize several key areas. One focus is the development of hybrid sensing systems that combine piezoelectric and piezoresistive technologies to overcome current limitations in detecting static pressure. A critical direction is the co-design of self-powered systems[214-217], where piezoelectric nanogenerators harvest energy from body movements, enabling truly autonomous, maintenance-free wearable health monitors. Another avenue is the enhancement of multilayer sensors inspired by natural structures, such as starfish surface patterns or pine needle arrangements, to improve stability and reliability. It is also essential to enhance the oxidation resistance of MXene and other active materials, including through advanced hydrophobic coatings and more precise control of PVDF β-phase crystallization - for example, by applying electric or magnetic fields during spinning. Collectively, these strategies can yield more durable, sensitive, and responsive sensing materials for next-generation healthcare applications.

Sustainable manufacturing and smart integration

Future research should also prioritize sustainable manufacturing and the integration of intelligent systems. One strategy is to develop solvent-free electrospinning and continuous roll-to-roll production methods to reduce energy consumption and environmental impact. Another approach is to embed artificial intelligence within sensor systems to simultaneously analyze multiple signal types, including pressure patterns and physiological waveforms. Such integration could enable more accurate disease detection and provide deeper insights into complex biological processes.

Expansion of application scenarios

Looking ahead, expanding the application scope of these technologies will be crucial. One objective is to develop materials that maintain reliable performance under extreme conditions, from very low temperatures (~-196 °C) to high temperatures (~250 °C), ensuring stable operation across a wide thermal range. This capability would also support sterilization and autoclaving of reusable medical devices and enable safe on-skin sensor use during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Another promising direction is the use of biodegradable materials, such as PLLA and cellulose, for implantable medical devices, including cardiovascular sensors. Additionally, integrating piezoelectric nanogenerators with microelectronic systems could enable wearable devices to self-power and operate autonomously over extended periods.

Standardization and biosafety

Future work should also prioritize establishing clear standards and ensuring biosafety. Consistent criteria for evaluating sensitivity, linearity, and durability will be essential to enable meaningful comparisons across studies. Additionally, research is needed to understand the long-term behavior of nanofillers, such as MXene and CNTs, within the body. Investigating their metabolic pathways and long-term biocompatibility is critical to ensure safety in healthcare applications, requiring close collaboration among materials scientists, toxicologists, and clinicians.

Addressing these priorities will directly support the development of robust, clinically approved devices for remote patient monitoring, advanced robotic prosthetics with sophisticated tactile feedback, and long-term implantable sensors for chronic disease management, thereby advancing human-machine interfaces. Future efforts should focus on synergistically improving long-term stability and sensitivity-linearity, promoting industrial-scale production through interdisciplinary integration of bionics, artificial intelligence, and biomedicine, and ultimately achieving holistic development of intelligent human-machine interface systems[218-221].

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com [Created in BioRender. Shahzad, A. (2026) https://BioRender.com/hhmncr8].

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, validation, writing - original draft: Shahzad, A.

Data curation, formal analysis, validation: Wei, J.; Su, X.; Zeng, X.; Luo, Y.; Liang, Z.

Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing - review and editing: Wang, L.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors acknowledge financial support from the GJYC Program of Guangzhou (No. 2024D02J0004), the Guangzhou Postdoctoral Research Fund (No. x2fkL2250020), and the Program of South China University of Technology (No. j2tw202502110).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Veeramuthu, L.; Cho, C. J.; Liang, F. C.; et al. Human skin-inspired electrospun patterned robust strain-insensitive pressure sensors and wearable flexible light-emitting diodes. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 30160-73.

2. Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Bioinspired, piezoelectrically-actuated deployable miniature robots. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2025, 166, 101054.

3. Mohamadzade, S.; Safavi-Mirmahalleh, S.; Habibzadeh, S.; Behboodi-Sadabad, F.; Salami-Kalajahi, M. A review on application of nanomaterials in flexible pressure sensors. Mater. Today. Nano. 2025, 30, 100627.

4. Kweon, O. Y.; Lee, S. J.; Oh, J. H. Wearable high-performance pressure sensors based on three-dimensional electrospun conductive nanofibers. NPG. Asia. Mater. 2018, 10, 540-51.

5. Yan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, P.; Mao, Y. Electrospun nanofibrous membrane for biomedical application. SN. Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 172.

6. Venmathi Maran, B. A.; Jeyachandran, S.; Kimura, M. A review on the electrospinning of polymer nanofibers and its biomedical applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 32.

7. Shin, Y. K.; Shin, Y.; Lee, J. W.; Seo, M. H. Micro-/nano-structured biodegradable pressure sensors for biomedical applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 952.

8. Ji, G.; Chen, Z.; Li, H.; Awuye, D. E.; Guan, M.; Zhu, Y. Electrospinning-based biosensors for health monitoring. Biosensors 2022, 12, 876.

9. Fu, X.; Li, J.; Li, D.; et al. MXene/ZIF-67/PAN nanofiber film for ultra-sensitive pressure sensors. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 12367-74.

10. Muthusamy, L.; Uppalapati, B.; Bava, M.; Koley, G. P(VDF-TrFE)/carbon black composite thin film based flexible piezoresistive pressure sensor with high sensitivity for low-pressure detection. Mater. Design. 2025, 256, 114201.

11. Luo, Y.; Abidian, M. R.; Ahn, J. H.; et al. Technology roadmap for flexible sensors. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 5211-95.

12. Wright, W. F. Early evolution of the thermometer and application to clinical medicine. J. Therm. Biol. 2016, 56, 18-30.

13. Brinkman, W.; Haggan, D.; Troutman, W. A history of the invention of the transistor and where it will lead us. IEEE. J. Solid. State. Circuits. 1997, 32, 1858-65.

14. Riordan, M.; Hoddeson, L.; Herring, C. The invention of the transistor. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1999, 71, S336-45.

15. Kane, S. K.; Morris, M. R.; Wobbrock, J. O. Touchplates: low-cost tactile overlays for visually impaired touch screen users. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Bellevue, USA, 2013. Association for Computing Machinery; 2013.

16. Pyo, S.; Lee, J.; Bae, K.; Sim, S.; Kim, J. Recent progress in flexible tactile sensors for human-interactive systems: from sensors to advanced applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2005902.

18. Han, S. T.; Peng, H.; Sun, Q.; et al. An overview of the development of flexible sensors. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1700375.

19. Feiner, R.; Dvir, T. Engineering smart hybrid tissues with built-in electronics. iScience 2020, 23, 100833.

20. Liu, E.; Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liao, H.; Yi, Y. An overview of flexible sensors: development, application, and challenges. Sensors 2023, 23, 817.

21. Banitaba, S. N.; Khademolqorani, S.; Jadhav, V. V.; et al. Recent progress of bio-based smart wearable sensors for healthcare applications. Mater. Today. Electron. 2023, 5, 100055.

22. Yan, J.; Chen, A.; Liu, S. Flexible sensing platform based on polymer materials for health and exercise monitoring. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 86, 405-14.

23. Park, J.; Lee, Y.; Cho, S.; et al. Soft sensors and actuators for wearable human-machine interfaces. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 1464-534.