The emerging pathological mechanism of coronary microvascular dysfunction: a narrative review

Abstract

Thirty to forty percent of patients undergoing angiography for chest pain and tightness show no abnormalities in the large coronary arteries. This phenomenon is particularly common among women, with more than 50% affected. Research has identified coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) as a key underlying cause; however, its pathological mechanisms remain poorly understood. In this article, we explore the relationship between CMD and coronary artery disease and summarize the current knowledge on the pathological origins of CMD, which include endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, left ventricular hypertrophy and mitochondrial abnormalities. Special emphasis is placed on pathological mechanisms contributing to the higher incidence of CMD in women.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The core pathological basis of coronary artery disease (CAD) is the narrowing and blockage of the coronary arteries. Thirty to forty percent of patients undergoing angiography for chest pain and tightness show no abnormalities of the large coronary arteries. Notably, this situation is experienced by more than 50% of female patients[1]. This paradox was described about 60 years ago, and microvascular dysfunction was considered primarily as the potential reason[2]. In the following two decades, this phenomenon was understood gradually, named “X syndrome”[3] and “microvascular angina”[4], and its association with coronary microcirculation dysfunction (CMD) was recognized.

Coronary vessels can be roughly divided into three categories: the large artery at the proximal end

Figure 1. The structure of coronary microvessels and the main mechanisms of CMD. The large artery (> 500 μm diameter) is at the proximal end, the prearteriole and the arteriole (500-10 μm diameter) are in the middle part, and the capillary (< 10 μm diameter) is at the distal end. The middle and distal arterial systems mainly provide coronary resistance, nutrient exchange and other functions. The middle and distal arterial systems and venous systems of the same magnitude constitute the coronary microvessels. The mechanisms that affect the local areas of CMD include endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, left ventricular hypertrophy, microcirculation resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. CMD: Coronary microvascular dysfunction.

In the past 20 years, CMD has gradually gained recognition and has established itself widely as the critical cause of microvascular angina. As a consequence of a myocardial blood supply:demand imbalance, microvascular dysfunction results in regional or systemic ischemic symptoms, and an adverse cardiovascular prognosis[6], which includes a nearly 4-fold increase of mortality and a 5-fold increase in major adverse cardiac events (MACE)[7]. Thanks to the development of various diagnostic technologies that have been discussed widely, CMD can now be assessed beyond having to rely solely on symptoms[8,9]. CMD is divided into CMD in patients with non-obstructive CAD, CMD in patients with obstructive CAD, CMD in patients with myocardial diseases and valvular heart diseases, and iatrogenic CMD[10]. Several drugs, such as nicorandil[11] and Danshen dripping pills[12,13], have shown certain effects on CMD in randomized controlled trials suggestively.

The pathogenesis of CMD is currently unclear and knowledge is scattered. At present, the focus is mainly on endothelial dysfunction, and a comprehensive review on multiple other pathological mechanisms such as inflammation, oxidative stress, left ventricular hypertrophy, and mitochondrial abnormalities is lacking. Moreover, the role of gender factors in those mechanisms has not been thoroughly discussed. To fill this research gap, this review aims to systematically evaluate the latest evidence for the current understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of CMD, and the role of gender factors.

Search methodology

This article aims to present a thorough and interdisciplinary analysis of the pathological mechanisms underlying CMD as a narrative review. The relevant literature was identified by searching PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar and Scopus using keyword combinations that included “microvessels”, “microcirculation”, “coronary microvascular”, “coronary microcirculation disorders”, “heart”, “coronary artery disease” and “coronary disease”. The search time frame ranged from the databases’ inception until July 2025. Studies were selected according to their relevance, timeliness (with priority given to publications from the past decade), and their contribution to clarifying microscopic mechanisms, clinical relevance, or therapeutic applications.

All types of papers related to coronary microcirculation published in the past 20 years were included, regardless of language. The papers were screened for epidemiological studies from the past decade. Next, papers related to pathological mechanisms were selected and classified according to the mechanism, and the top 5 representative mechanisms were selected. Representative papers were chosen for comprehensive discussion based on their relevance and key arguments. Research with unclear logic and incomplete focus on the topic was excluded. The selection process was completed separately by two individuals, and the results were merged after discussion.

Epidemiology of CMD

In 30%-40% of patients undergoing angiography for chest pain and tightness, no abnormalities of the large coronary arteries are found[1]. We observed that the incidence rate of CMD is higher in women[14]. In a cohort study of 686 CMD patients, 64% were female. Meanwhile, the quality of life was lower in females than in males[15]. In a 2022 meta-analysis that encompassed 56 studies involving 14,427 patients with ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA), the prevalence of CMD was 41%, and women had a 1.45-fold higher risk of testing positive for CMD than men[16]. After more than one year of follow-up, the MACE incidence was 7.7%[15]. Risk factors related to major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in CMD patients are hypertension and a history of prior CAD[15].

CMD related to revascularization is mainly manifested as no-reflow. Although the epicardial coronary artery is completely unobstructed after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), distal coronary microvascular perfusion did not fully recover in about half of the patients[17]. However, the incidence of no-reflow was 2.3% in acute myocardial infarction (MI) patients during PCI[17]. Older age, ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), prolonged time from symptom onset to admission, and cardiogenic shock were independent clinical variables of no-reflow[17]. After primary PCI, the incidence of no-reflow was higher. In elective PCI, patients with postoperative CMD have significantly increased long-term MACE[18].

No-reflow is more common in women and has a worse prognosis than in men. In an Italian registry study of STEMI patients who underwent emergency PCI, only 25.9% were female. However, females exhibited a higher incidence of 30-day mortality compared to males (4.8% vs. 2.5%). Multivariate regression analysis revealed that female patients were more susceptible to no-reflow phenomenon[19]. As mentioned above, women have a higher incidence of CMD and poorer prognosis. The ten-year mortality was about 13% in women without obstructive CAD, whereas mortality in women without ischemic symptoms was 2.8% in the same age during the same period[12,13,20].

The higher rate of morbidity may originate from female-specific risk factors associated with CMD. Estrogen has a protective effect on women’s blood vessels; therefore, a decline in estrogen levels (e.g., during menopause) increases the risk of CMD. Infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome, early or delayed menarche, adverse pregnancy outcomes (including intrauterine growth restriction, gestational hypertension, preterm birth and gestational diabetes), and insufficient breastfeeding have all been indicated as risk factors of subsequent cardiovascular diseases[21]. Although young adult women may be protected from metabolic syndrome, this situation changes after menopause, as we observe a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in older women compared with age-matched men[22]. This observation supports the use of hormone therapy for CMD in women.

CMD and CAD

The insufficient coronary microcirculation during ischemia leads to CMD. This symbiosis is particularly common in obstructive CAD. In a small sample, 60% suspected CAD patients were diagnosed as obstructive epicardial CAD. Of these patients, a portion was diagnosed as CMD, with 39%, 53%, and 32% having an abnormal index of microcirculatory resistance (IMR), coronary flow reserve (CFR), and resistive reserve ratio (RRR), respectively[23]. CMD is related to a mismatch of structure and function, and the potential of ischemia in moderate epicardial stenosis[24]. Eighty-two percent of CMD patients had induced ischemia and the overall myocardial perfusion reserve was low. Sixty-two percent of CAD patients had functional CMD. Functional and structural CMD have similar myocardial perfusion and exercise perfusion efficiency defects[25,26]. CAD and CMD are, therefore, interdependent.

Furthermore, CMD is also an important indicator of poor prognosis of CAD[27]. IMR assessed promptly following PCI could serve as a prognostic indicator for adverse events in patients with stable CAD during a 4-year follow-up[28]. Stable CAD patients undergoing PCI with left anterior descending artery stent, changes in IMR are associated with total length of stents implanted. Meanwhile, IMR probably affects post-PCI fractional flow reserve (FFR)[29]. The cardiovascular mortality is 9.7% during a 5.6-year follow-up. Positron emission tomography revealed that CFR was a more robust predictor of cardiovascular death rate compared to common cardiovascular risk factors. For patients with both reduced CFR and compromised maximal myocardial blood flow (MBF), the cardiovascular death rate is 3.3% per year, whereas those with impaired CFR but preserved maximal exhibited an intermediate mortality rate of 1.7% annually. Notably, women account for 70% of those patients[30]. Another study showed that CFR is effective to predict the risk of heart failure and MI: in the low CFR group, regardless of whether revascularization was performed, the 1-year follow-up incidence of MACE appeared higher[31]. In a large sample study of STEMI patients, of whom only 18.2% were female, severe microcirculatory dysfunction was associated with the elevated risk of long-term MACE[32]. Following a 4-year follow-up period, a positive correlation was found between cumulative MACE and IMR[28]. In a retrospective study, following a 638-day follow-up of 341 patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), myocardial perfusion reserve and stress-induced MBF were found to independently predict MACE[33]. The above studies indicate that CMD is an important prognostic indicator for patients with STEMI, PCI, and CABG.

After coronary intervention, 5%-50% of patients have achieved reperfusion of the epicardial coronary arteries, not of the myocardium, which is known as no-reflow. In fact, no-reflow has various manifestations, with particular significance placed on microvascular obstruction (MVO), CMD, and intramyocardial hemorrhage[18,34] [Figure 2][35]. Coronary MVO is an extremely serious condition compared to CMD. It is supposed that external stress, spontaneous formation of small blood clots, obstruction of blood flow by circulating cells and distal atherothrombotic embolization all contribute to MVO[18,36]. By persistent coronary occlusion with reperfusion, MVO would increase the infarct size[37]. An imbalance between endothelial vasodilating and vasoconstricting factors in CMD can lead to a no-flow or low-reflow area phenomenon[18]. Coronary MVO occurs in approximately 50% of patients who have received seemingly successful primary PCI but significantly poorer clinical outcomes[38]. Some clinical and preclinical investigations indicated that the existence and magnitude of MVO serve as a significant independent indicator of unfavorable left ventricular restructuring. Furthermore, MVO may possess greater predictive value for MACE compared to the size of the infarct itself[39].

Figure 2. No-reflow associates closely with CMD and MVO. MVO is a more severe condition than CMD, which occurs when microemboli (black block) form clogs in microvessels with inflammation, platelet aggregation and endothelial dysfunction. MVO always led to micro-infarcts (black shadow) and intramyocardial hemorrhage, which in turn aggravate MVO to form a vicious cycle[35]. CMD and MVO may result in no-reflow due to microvascular structural changes (including capillary rarefaction, endothelial dysfunction and endothelial inflammation) and microembolization (obstructive microemboli and platelet aggregation). CMD: Coronary microvascular dysfunction; MVO: microvascular obstruction; NO: nitric oxide, ET: endothelin, eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase.

THE MECHANISMS OF CMD

The pathological mechanisms underlying CMD across the entire vascular network include endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, hypertrophy, ischemia and mitochondrial abnormalities [Figure 1]. These processes impair the ability of the coronary blood vessels to increase their blood flow and disrupt the regulation of coronary vascular tone.

Endothelial dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction refers to the abnormal function of endothelial cells (ECs) under pathological stimuli (e.g., high shear stress, smoking, oxidative stress, hyperlipidemia, etc.). The inner surface of the coronary microcirculation consists of a layer of ECs, which along with immune cells and coagulation components also prevent the penetration of microorganisms[40]. Endothelial dysfunction as the primary pathological change in CMD can lead to reduced vascular dilation, enhanced vasoconstriction, and abnormal endothelial adhesion [Figure 3]. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation weakens or disappears, primarily due to abnormal secretion and reduced activity of nitric oxide (NO). A critical enzyme closely associated with the generation of NO, the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), represents a potential risk for CMD[41]. Conversely, as an adaptive response, transient ischemic episodes can delay and enhance NO generation in the coronary microcirculation by upregulating eNOS[41]. However, after decompensation of microcirculation, CMD could cause decreased eNOS activity and NO production[42]. Endothelin (ET)-1, a potent vasoconstrictor, is primarily secreted by vascular ECs. After vascular EC damage, the release of ET-1 enhances vascular constriction and smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation. The decreased biological activity of NO leads to a relative increase in ET-1, causing vascular constriction, vascular remodeling, and functional impairment[43]. The combined effects of these events result in CMD[44]. In CMD patients, ET-1 was found to be related to coronary vascular resistance, not to impaired CFR[45].

Figure 3. Endothelial dysfunction is the primary pathological change in CMD. In normal microvessels, the compensation mechanism includes eNOs and NO increase and ET-1 decrease. In CMD, the decompensation mechanism includes decreased NO and eNOS, and increased ET-1 and FFA. MVO is a more severe condition that always occurs when microemboli (small black block) clog microvessels with inflammation and platelet aggregation. MVO always leads to micro-infarcts (big black shadow). CMD: Coronary microvascular dysfunction; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; ET-1: endothelin-1; FFA: free fatty acids; MVO: microvascular obstruction.

Estrogen enhances the bioavailability of NO and reduces oxidative stress and inflammation. Firstly, estrogen binds to estrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ), thereby augmenting eNOS activity and facilitating NO production. Secondly, it interacts with estrogen response elements on DNA through classical hormonal signaling mechanisms, thereby enhancing eNOS expression[46]. The former mechanism triggers rapid vasodilation, while the latter genomic response is delayed because of the time needed to initiate gene transcription and translation[46]. ERs have also been demonstrated to localize in mitochondria. Estrogen can enhance mitochondrial function by modulating free radical production, cell apoptosis, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation and calcium influx, all related to CMD[47]. When comparing premenopausal and postmenopausal women with an age difference of < 5 years, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1, a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction, was found to be higher in postmenopausal women[48], indicating that menopausal status may affect endothelial function independently of aging. In asymptomatic postmenopausal women, CMD, manifested as low flow-mediated dilation (FMD), is associated with future cardiovascular events[49].

The mechanotransduction of shear forces is defined as endothelial wall shear stress[50]. Physiological laminar shear stress maintains the integrity of the endothelial barrier[51]. Low shear stress is associated with endothelial dysfunction, leading to increased expression of adhesion molecules and, most importantly, decreased levels of eNOS protein[41]. Continuous low shear stress promotes oxidative stress, matrix degradation, inflammation and local lipid accumulation. Plaque progression and negative vascular reconstruction mainly occur in the low shear stress region[52]. However, the overall shear stress of late plaques increases, leading to higher vulnerability of the plaques. Elevated levels of shear stress within the coronary arteries have been linked to increased susceptibility of plaque to rupture and more extensive remodeling of the arterial wall, which also improve microvascular reactivity and endothelial function[53]. Endothelial shear stress, microvascular endothelial dysfunction, and epicardial and regional blood flow dynamics are important parameters for assessment. They are related to those patients with microvascular endothelial dysfunction who are at a heightened risk of developing upstream epicardial endothelial dysfunction and the progression of plaque[54]. FFR independently predicts the area of low shear stress and maximum lesion shear stress[55]. In CMD patients, notable decreases were noted in axial/cross-sectional velocity, blood flow, wall shear rate and shear stress in the bulbar conjunctiva[56].

Numerous studies have confirmed that the coronary artery diameter shows a smaller size in women compared to men[57], whereas coronary blood flow and myocardial perfusion exhibit higher values in females. Arterioles with elevated blood flow show increased endothelial shear stress and optimized blood flow distribution patterns[58]. The impact of shear stress on CAD in women may also explain two remarkable clinical features. The first manifestation is atypical non-exertional angina, linked to diffuse-type coronary artery stenosis. In contrast to the focal stenosis typically observed in men, the increased coronary blood flow during physical exertion is related to a stenosis-induced pressure gradient that is proportional to the square of blood flow velocity. It reduces coronary perfusion pressure and leads to subendocardial hypoperfusion and angina. However, in women with diffuse disease, increased coronary blood flow correlates linearly with blood flow, resulting in less exertional angina, less subendocardial ischemia and smaller pressure gradient[59]. The second notable feature is the high death rate in postmenopausal females when focal stenosis occurs in later life. In women, late-onset stenosis occurs on top of severe diffuse coronary disease that progresses asymptomatically during middle age. A higher atherosclerotic burden in arterioles poses a greater risk than in men. Men often exhibit early-onset focal disease. With the withdrawal of estrogen, its partial protective effect against atherosclerosis in low-shear stress areas diminishes, leading to an “accelerated” clinical presentation associated with focal stenosis superimposed on diffuse disease[59].

One recently recognized characteristic of ECs is their significant plasticity, including the ability to transition from an EC state to a mesenchymal-like cell state through a process called endothelial to mesenchymal transition (EndMT). Plentiful evidence shows that EndMT is an important manifestation of endothelial dysfunction and is related to atherosclerosis[60]. The expression of related genes undergoes changes, including decrease of endothelial markers [such as vascular endothelial (VE) cadherin and platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD31)] and increase of mesenchymal or myofibroblast markers (such as SM22 α and α-smooth muscle actin)[60]. In mice prone to atherosclerosis, 32.5% and 45.5% of fibroblast-like cells in atherosclerotic plaques were derived from ECs after 8 and 30 weeks, respectively[61]. Knocking out Hdac9 specifically in ECs reduces EndMT by 20%-25% and decreases plaque volume; meanwhile, plaque stability was improved[62]. Multiple factors have been found to promote EndMT and play a role in coronary microcirculation disorders, including integrin-linked kinase (ILK)[63], and angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4)[64]. In a study exploring ECs and fibroblasts as the main cell types in a single-cell gene expression profile of CMD rats using single-cell RNA sequencing, a notable reduction was found in the proportion of ECs, accompanied by a significant increase in the quantity of fibroblasts. In addition, in the CMD group, there was an elevation in immune cell counts, a potentiated inflammatory response, and heightened oxidative stress[65].

Cellular aging is the process by which cells stop dividing and undergo structural changes that in the vascular endothelium have an impact on angiogenesis and cell proliferation[66]. These alterations involve the misregulation of the microvascular tone, increased ET-1 activity, and decreased availability of NO, which disrupt the microvascular relaxation response and cause microcirculatory disorders[67]. Redox imbalance can also lead to endothelial dysfunction in the context of endothelial aging. In elderly rats, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) marker nitrotyrosine was found to be increased, superoxide dismutase (SOD) expression decreased, and coronary artery endothelial-dependent vasodilation correspondingly impaired[68]. Research on coronary artery ECs has shown that nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) levels increase with cellular aging, which is related to enhancement in oxidative stress[69]. Sirtuin 1 (Sirt1), an enzyme responsible for deacetylating nuclear transcription factors, emerges as another mediator of age-related endothelial dysfunction. Sirt1 facilitates eNOS expression and activity, enhances NO biosynthesis, and promotes adaptive vascular remodeling[70]. However, its expression decreases with age, which can impair endothelial function. Compared with 5-7-month-old mice, the expression of Sirt1 in ECs of 30-month-old mice is reduced. Treatment with Sirt1 inhibitors in elderly and young mice leads to impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilation but does not disrupt endothelial-independent vasodilation[71]. Sirt1 can also inhibit oxidative stress, and as age increases, the decrease in Sirt1 may further impair endothelial-dependent vasomotor function[72]. Cellular aging is related to CMD. Whether regulating cellular aging factors can improve CMD is an interesting research direction.

Inflammation

The level of C-creative protein (CRP) reflects the degree of inflammation [Figure 4] and the high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) test can accurately detect low concentrations of this protein. The abundant production of CRP activates inflammatory cells, leading to vascular injury and causing vascular spasm. Patients with persistent CMD have significantly higher CRP, hs-CRP, white blood cell (WBC) count, fibrinogen and neutrophil levels[73], along with impaired CFR, FMD and IMR[74]. On exercise testing, the level of CRP in CMD patients is related to the frequency and duration of chest pain and the degree of ST-segment depression[75]. Meanwhile, in CMD patients, coronary levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) were higher. Furthermore, hs-CRP coronary levels were independently linked to CMD. Elevated levels of IL-6 and large necrotic cores with high degree of macrophage infiltration in atherosclerotic plaques correlate positively with IMR[76,77].

Figure 4. The influence of CRP on endothelium damage and CMD. CRP reflects the degree of inflammation, which damages the endothelium through a series of pathways. In CMD, several inflammatory factors change significantly. CRP and hs-CRP play roles in CMD. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, coordinating inflammatory responses, also affects the development of CMD. CMD: Coronary microvascular dysfunction; CRP: C-reactive protein; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; PAI: plasminogen activator inhibitor; WBC: white blood cell; IL-6: interleukin-6; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase-9; NLRP3: NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3.

Meanwhile, inflammasome activation coordinating inflammatory responses also affects the development of CMD. The Nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a trimeric protein complex that consists of NLRP3, the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), and the effector molecule pro-caspase-1. During its activation process, the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitates the proteolytic cleavage of pro-caspase-1 into its mature form (caspase-1), a process that subsequently initiates the activation of inflammatory mediators. The activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome is modulated by multiple molecular signaling pathways, including those involved in oxidative stress, lysosomal leakage, Ca2+ mobilization and K+ efflux. The NLRP3 inflammasome initiates the release of various pro-inflammatory factors, potentially compromising endothelial function[78,79]. Chronic inflammasome activation not only impairs cellular metabolism but also exerts detrimental effects on vascular structure and function, establishing a link between innate immune activation and endothelial dysfunction[80]. In hypertensive mice with inflammatory vascular dysfunction, NLRP3 ablation alleviated endothelial junction impairment[81].

Ischemic injury elicits a distinctive cardiac immune response marked by the persistent infiltration of immune cells. This cellular influx encompasses not only neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs) but also includes B and T lymphocytes. These cells collectively coordinate the clearance of dead myocardial cells, contribute to the formation of granulation tissue essential for scar stabilization and maturation, and modulate the subsequent stages of cardiac repair and inflammation resolution by releasing pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory mediators[82]. However, the infiltration of these immune cells presents a double-edged sword. Because the inefficient resolution of the inflammatory response can lead to chronic inflammation of the heart, it can exacerbate cardiac dysfunction via induction of coronary endothelial dysfunction and detrimental cardiac remodeling, encompassing myocardial cell hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis, which ultimately drives the progression to chronic heart failure[83]. Treatment with soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 (sVEGFR3) might attenuate antigen presentation by cardiac DCs following MI, thereby restricting the recruitment or proliferation of T cells within the infarcted region. However, it has been suggested that by limiting the recruitment of M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages, inducing beneficial inflammatory macrophages to transform into reparative macrophages, and stimulating the expansion of Tregs in cardiac draining lymph nodes, the level of cardiac DCs in the surviving left ventricle can be increased, thus protecting the remodeling of the heart after ischemia[84]. Therefore, improving the resolution of cardiac inflammation is a treatment goal for many cardiovascular diseases.

Heart-infiltrating T cells, including CD4+ helper cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, predominantly exert an inhibitory effect in the acute endogenous cardiac lymphangiogenesis response after MI. Many reports indicate that T cells, especially CD4+ helper cells, have harmful short-term and long-term cardiac effects on cardiomyocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts[85,86]. Infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells acutely decrease the survival rate of cardiac lymphatic vessels after MI, partly by secreting interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which reduces the response of blood vessels to endogenous lymphatic vessel generation stimuli[84]. It is interesting that adrenomedullin has recently been shown to increase the vascular diameter of female mice after MI[87].

The critical roles of estrogen include serving as a potent anti-inflammatory agent. The disruption of estrogen circulation patterns during the menopausal transition can trigger both adaptive and systemic innate immune responses[88]. As part of the innate immune defense, inflammasome complexes act as detectors for damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). ER silencing led to elevated levels of caspase-1, ASC, and the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the hippocampus of ovariectomized rats[89]. The presence of inflammasome complexes in the cerebrospinal fluid of postmenopausal women indicates that reduced estrogen levels induce a pro-inflammatory state[89]. Compared with men, postmenopausal women display heightened inflammatory reactions to infections, an elevated incidence of autoimmune disorders, and fluctuations in chronic inflammatory disease activity across the menstrual cycle, during pregnancy, and post-menopause[14]. All these changes relate to the role of estrogen. Reduced estrogen levels foster a pro-inflammatory, Th1-polarized milieu and exert effects on the adipose tissue, leading to increased visceral fat accumulation. This process elevates the risk of CAD in postmenopausal women[90]. Moreover, investigations conducted by multiple research groups have demonstrated that the circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) tend to increase at least after natural or surgical menopause[91]. The decline in ovarian steroid hormones during the menopausal transition coincides with higher levels of circulating interleukins IL-6, sIL-6, IL-4, IL-2, and TNF in postmenopausal women, and the latter two have been shown to be reversed by hormone therapy[91].

Oxidative stress

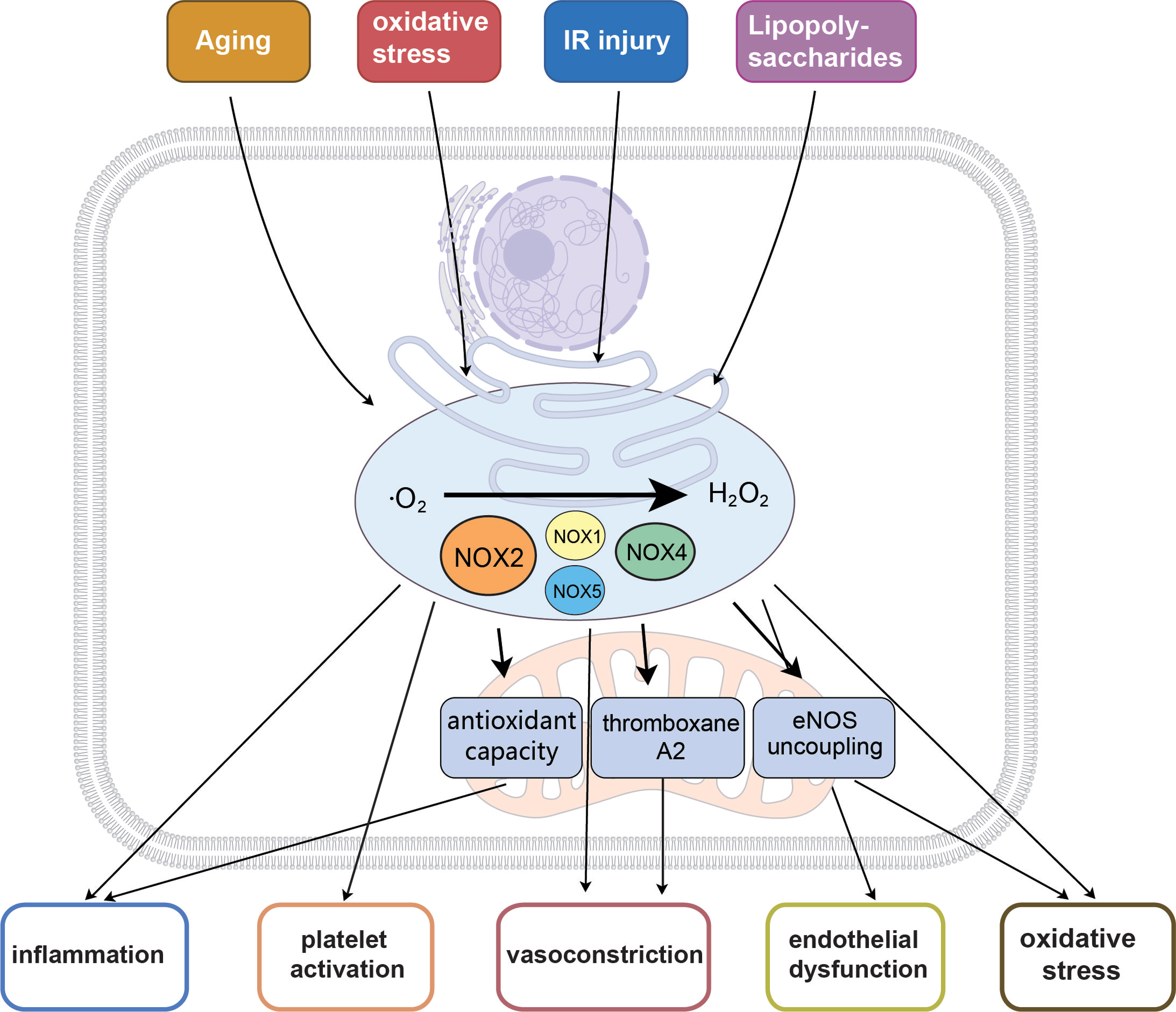

Oxidative stress represents the imbalance between the generation and the elimination of oxygen free radicals, or the excessive accumulation of ROS. The excessive intake of exogenous oxidizing substances therefore causes pathological changes in cell toxicity[44]. ROS primarily include hypochlorous acid (HOCl), hydroxyl radical (OH-), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (·O2-). They also play a crucial role in regulating cardiovascular tension and endothelial function[44] [Figure 5][92]. ROS can induce vascular leakage, which is critical in ischemia-reperfusion injury and the initiation of inflammatory responses. Meanwhile, they can inactivate NO and generate peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant. This will cause substrate protein nitrosation and further couple eNOS to produce ROS, forming a vicious cycle[44]. ROS can also mediate the release of inflammatory factors and chemokines/adhesion factors, and induce vascular inflammatory responses[5]. Furthermore, the deactivation of NO by ·O2- and the generation of the endothelial hyperpolarizing factor H2O2 collectively contribute to impaired vascular contractile function. The balance between EC proliferation and apoptosis can also be altered by ROS, potentially resulting in either loss of ECs or excessive angiogenesis[5].

Figure 5. Roles of ROS in CMD. Enzymes responsible for ROS generation mainly include NOX2, NOX4 and XO. Aging, stress overload, IR injury and the sympathetic nervous system affect the generation and accumulation of ROS, which play roles in several pathological mechanisms of CMD[92]. Moreover, ROS activation could promote pathological mechanisms related to CMD, including Ca2+ accumulation, inflammation, thrombosis, angiogenesis, apoptosis and vasoconstriction. CMD: Coronary microvascular dysfunction; ROS: reactive oxygen species; NOX2: NADPH oxidase 2; NOX4: NADPH oxidase 4; XO: xanthine oxidase; IR: ischemia/reperfusion;

In the cardiovascular system, ROS are mainly generated by certain enzymes including xanthine oxidase (XO), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) and NOS[93]. They also facilitate the transformation of xanthine dehydrogenase to XO by oxidizing thiol residues, thereby triggering further ROS generation. Additionally, ROS augment the contractile activity of coronary microvessels induced by ET-1 via activation of the RhoA/Rho kinase pathway[94].

NOX is the primary enzyme responsible for generating ROS in the blood vessels, and the development of CMD. In the microvascular system, NOX2 seems to mainly exist in the endothelium and adventitia, leading to endothelial dysfunction under disease conditions. NOX has also functional activity in human resistance SMCs[95]. In addition, NOX2 leads to CMD through excessive production of ROS, platelet activation, inhibition of artery dilation, and generation of thromboxane A2, a potent vasoconstrictor and platelet activator[96]. Meanwhile, NOX2 has a pro-inflammatory role that may induce CMD by causing extramural compression and edema[97]. CMD patients have higher levels of lipopolysaccharides, NOX2 activation, and an imbalance between the pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems[98]. It is beneficial for oxidative molecules that may potentially affect endothelial dysfunction and vascular constriction in this disease. NOX4 seems to have constitutive activity, which is most conducive to the production of H2O2 rather than ·O2-[95]. NOX4 is highly expressed in adipose tissue, coronary arteries, and small artery ECs and participates in EC proliferation[93]. NOX1 has proved to be an important source of ·O2- in certain vascular bed endothelium and SMCs[99]. Recent studies revealed that NOX1 deficiency can reduce oxidative stress and restore microvascular health in diet-induced obesity models[93,99]. In microcirculation, NOX5 isoenzymes were found in small arteries (resistance arterioles) of the coronary system of pig and human. In addition, under conditions of atherosclerosis, MI and other diseases, its expression in these microvessels is significantly enhanced[95]. In summary, NOX enzymes appear as key mediators in the pathological degradation and dysfunction of human resistant arteries.

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Left ventricular hypertrophy can lead to pathological reactions such as myocardial cell disorder, fibrosis, coronary microvascular remodeling, decreased capillary density, endothelial dysfunction, SMC dysfunction and extravascular compression[100]. The reduction of blood vessel radius has a great impact on blood flow, so these changes could greatly affect the blood perfusion of microcirculation[10]. Its characteristics are sparse capillaries and poor remodeling of intramural coronary arteries caused by thickening of the middle layer of the vascular wall, resulting in an increase in the wall-to-lumen ratio[101]. This change typically affects the entire left ventricle in a diffuse manner[100]. In the case of increased oxygen demand, repeated myocardial ischemia eventually occurs. Cardiac magnetic resonance perfusion imaging of left ventricular hypertrophy patients could identify severe local microvascular dysfunction[102]. Alcohol septal ablation, an effective surgical technique for treating ventricular hypertrophy, could enhance coronary vasodilator reserve and hyperemic MBF. Microvascular dysfunction was closely associated with decreased extravascular compression force[103]. Six months after alcohol septal ablation, microvascular dysfunction was also improved by relief of extravascular compression forces[104].

Several studies have shown that ovariectomy itself can deteriorate cardiac function or induce cardiac hypertrophy. To some extent, it explains the special pathological mechanism in ventricular hypertrophy and CMD in women. In aged rats, ovariectomy further aggravates the aging-induced decline in cardiac function, exacerbates left ventricular and endocardial collagen deposition, and amplifies these effects compared to aged non-ovariectomized counterparts. Ovariectomy also elicits a significant increase in cardiac inflammatory responses and oxidative stress[105]. In female rats, isolated ovariectomy did not result in reduced cardiac function, substantial cardiac collagen accumulation, or notable expansion of myocardial cell surface area. By contrast, ovariectomy combined with coronary artery occlusion-induced MI led to marked elevations in both collagen deposition and myocyte hypertrophy. Cardiac angiotensin receptor AT1 levels were significantly elevated in both ovariectomy-exposed and MI patients[106]. AT1 receptor activation elicits cardiac hypertrophy and promotes collagen deposition. Not only AT1 receptor expression but also aortic angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) were increased by ovariectomy, along with reduced eNOS activity and NO production[107].

Coronary microvascular resistance is not only an important mechanism but also an important index to evaluate the extent of microvascular dysfunction. When endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress and ventricular hypertrophy cause significant changes in hemodynamics, coronary microvascular resistance changes accordingly. In the absence of angiogenesis, stenosis of an epicardial artery leads to augmented resting perfusion, which could result in tissue necrosis; the self-regulating system fails to compensate, resulting in CMD[108].

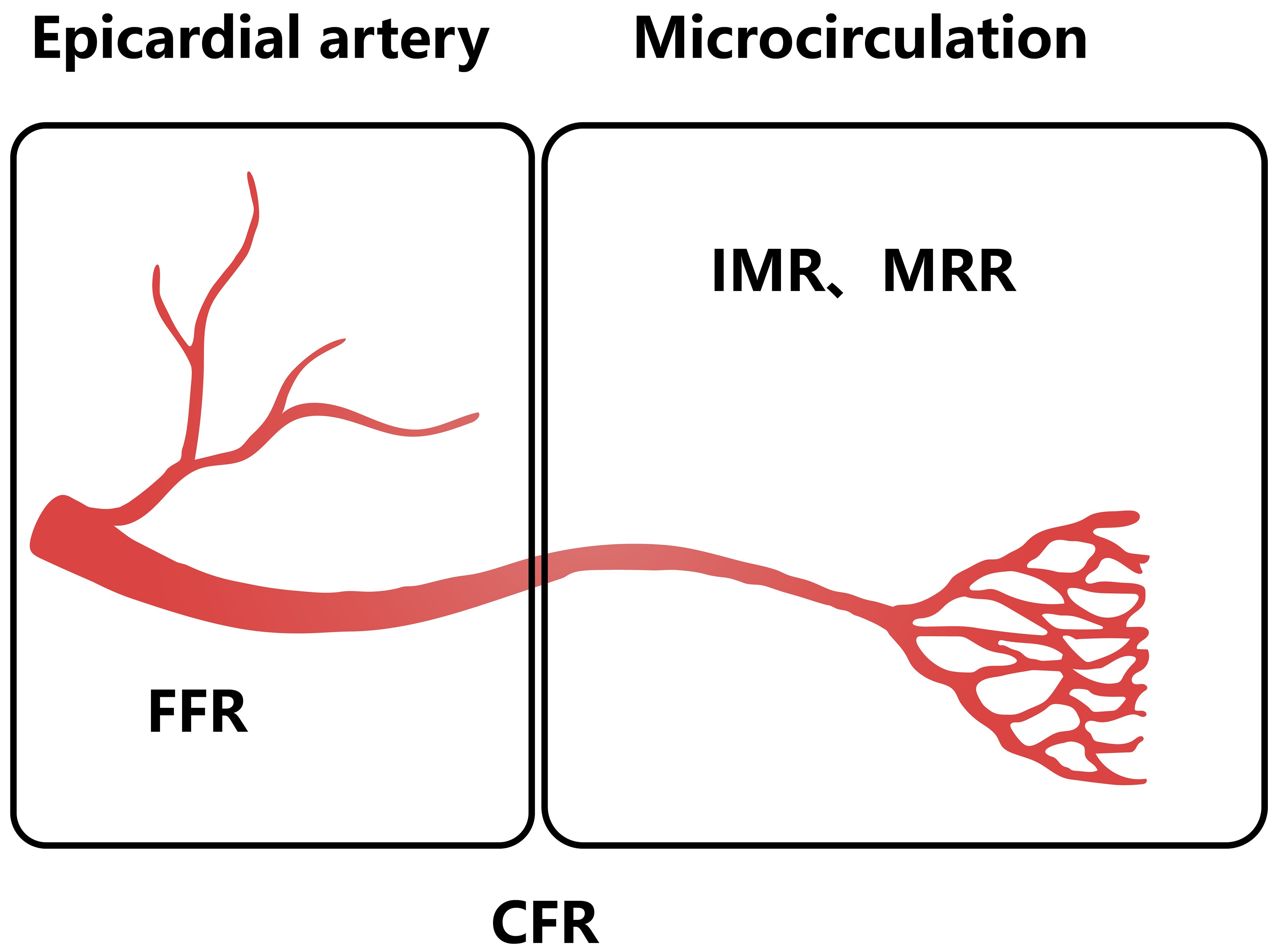

CFR, FFR, IMR and microvascular resistance reserve (MRR) are important indicators of vascular resistance [Figure 6]. A high IMR associates with poor prognosis and local microvascular damage increases the IMR in vessels of affected myocardium[109]. IMR was found to be closely related to the infarct size assessed in patients after a 6-month follow-up period[110,111]. It also predicts microvascular damage severity and left ventricular remodeling changes after primary PCI[112]. A low IMR correlated with a significantly higher recovery of left ventricular function[113,114]. Meanwhile, IMR was linked to cardiac recovery after acute MI and heart transplantation: it correlated with subsequent 1-year acute allograft rejection and associated clinical events over a 10-year period[115]. MRR equals the ratio of CFR to FFR, adjusted for driving pressures. CFR denotes the coronary circulation’s vasodilatory capacity, integrating both epicardial arterial and microvascular function[108]. MRR was found to be independent of the epicardial resistance and specific for the microvasculature, with potential as a ratio to quantify CMD[116]. MRR was independently related to MACE and target vessel failure outcomes over a 5-year follow-up period[117].

Figure 6. Vascular resistance index corresponds to different measurement areas[108]. CFR: Coronary flow reserve; FFR: fractional flow reserve; IMR: index of microcirculatory resistance; MRR: microvascular resistance reserve.

Mitochondrial abnormalities

The heart is the organ with the greatest demand for energy metabolism in the body. The ratio of mitochondrial mass relative to the cytoplasmic volume in ECs is only 2%-6%, whereas in myocytes it is 32%[40]. Under physiological conditions, the supply of ATP for the endothelial energy homeostasis is typically sustained by anaerobic metabolism. The low mitochondrial abundance in ECs suggests that as primary signal integration hubs, their mitochondria mediate responses to redox homeostasis, intracellular calcium regulation, retrograde signaling, and apoptotic pathways[118]. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to exacerbation of endothelial oxidative stress, impairment of endothelial NO metabolism, disturbance of cytoplasmic calcium homeostasis and triggers inflammatory responses. It also hastens cellular senescence, suppresses proliferative/regenerative capacity, and induces apoptotic or necrotic cell death[119]. Consequently, the duration and magnitude of mitochondrial dysfunction are intimately associated with the progression of CMD[119]. When microvascular dysfunction causes hypoxic-ischemic injury, the cell energy metabolism disorder further aggravates cell damage and necrosis. Concurrently, the supply and transport of oxygen and nutrients in the myocardium are significantly reduced, and cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction aggravates[120].

When mitochondria are damaged, the maintenance of mitochondrial structure and function relies on the activation of multiple pathways, including mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, and biogenesis. These protective mechanisms are called mitochondrial quality monitoring (MQS) systems[121,122]. Damaged MQS is the main characteristic of EC damage and dysfunction. Under physiological conditions, ECs remain in a quiescent state and constitute a barrier within the vascular intima. By contrast, stressors such as hypoxia, physical exertion, or nutrient deprivation cause angiogenic growth factors to instigate EC proliferation and differentiation, thereby facilitating tissue neovascularization, augmenting oxygen perfusion, and improving nutrient delivery[123].

Mitochondrial dynamics is the result of the combined action of mitochondrial fission and fusion. Mitochondrial fission refers to the biological process by which a mitochondrion undergoes division to form two or more separate organelles. Mitochondrial fission is central to EC dysfunction. In ECs, hypoxia acts as a physiological trigger for mitochondrial fission, which can augment mitochondrial mass and facilitate proliferation or migration[124]. The multi-stage process of mitochondrial fission, characterized by constriction and fragmentation of the mitochondrial inner membrane, is coordinately regulated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) in conjunction with its interacting proteins fission protein 1 (FIS1), mitochondrial fission factor (Mff), MiD49, and MiD51. Drp1 is a cytoplasmic guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) of the motor protein superfamily. The process of mitochondrial fission involves three steps[125]: (1) Drp1 activation; (2) Drp1 binding to its receptor; (3) GTP hydrolysis and mitochondrial fission. Abnormalities in any of the above steps will alter the mitochondrial fission process. Increased expression and phosphorylation of Mff protein can induce mitochondrial fission in CAD[126]. Silencing Drp1and FIS1 in ECs leads to decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, induced apoptosis and promoted mitochondrial fragmentation[127]. Changes in shear stress may promote the transfer of Drp1 from the cytoplasm to the mitochondrial membrane, thereby facilitating mitochondrial division in coronary ECs[40,128]. The mitochondrial fission inhibitor mdivi-1 can inhibit ET-1-induced vasoconstriction[128]. Shear stress may also promote fission of mitochondria in coronary ECs[128]. Preconditioning with mdivi-1 before myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury ameliorates cardiac dysfunction and promotes angiogenesis by upregulating gap junction protein 43, chemokine CXCL10, and endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)[129]. In myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, other mitochondrial functions (respiration, ATP production, and calcium dynamics regulation) may also be affected before mitochondrial fission is induced[130]. This suggests that there may be adaptive changes in mitochondrial function that are not dependent on mitochondrial quality control in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Mitochondrial fusion refers to fusion of two adjacent mitochondria into a longer organelle. The process is mediated by three large GTPases, mitofusins 1 and 2 (MFN1 and 2) located in the outer mitochondrial membrane, and optic nerve atrophy factor 1 (OPA1) located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and intermembrane space[118]. The mitochondrial fusion process includes two steps: outer mitochondrial membrane fusion and inner mitochondrial membrane fusion. MFN1 and MFN2 regulate mitochondrial fusion and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced angiogenesis in coronary ECs[131]. In contrast, VEGF could significantly upregulate the levels of Mfn2 and Mfn1 in cultured ECs[131]. Mfn1/2 inhibition not only facilitated mitochondrial fragmentation but also impaired VEGF-driven EC migration and differentiation[131]. Dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics in ECs has been shown to trigger mitochondria-driven apoptosis, leading to EC loss and capillary network regression[132]. Pathological defects of mitochondrial fission or fusion can induce mitochondrial ROS production, disruption of the adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-dependent relaxation response of coronary ECs, and thereby reduction of the small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel current in coronary microvascular ECs[133].

When damaged mitochondria cannot be restored by fission or fusion, their fates include mitophagy and other processes, such as mitochondria transfer[134]. Mitochondrial transfer may occur through the following ways: (1) establishment of transient cellular junctions, enabling mitochondrial translocation between cells through these connections; (2) ejection of mitochondria into extracellular vesicles for transport to recipient cells; (3) release of free mitochondria that can be internalized by recipient cells[135]. Mitophagy is activated to eliminate impaired organelles in collaboration with autolysosomes. Mitochondrial autophagy is a degradation process. Impaired mitochondrial debris undergoes selective sequestration before being decomposed with the aid of lysosomal enzymes. Thereby, toxic mitochondria are prevented from causing damage to ECs and other cells[136]. At the molecular level, damaged mitochondria are labeled with various “adaptor proteins” that can be recognized and taken up by lysosomes. Subsequently, damaged mitochondria are broken down and can be reused for synthesizing new mitochondria and other cellular constituents. Parkin and FUN14 domain containing protein 1 (FUNDC1) are two specific mitochondrial autophagy adaptor proteins. Parkin induces mitochondrial autophagy independent of mitochondrial receptors, while FUNDC1 mediates mitochondrial autophagy dependent on mitochondrial receptors[137]. Parkin in the cytoplasm of damaged mitochondria is recruited to the mitochondria, where it performs polyubiquitination modifications on various mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. P62 recognizes polyubiquitinated proteins and interacts with microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3) to facilitate autophagosome formation. Additionally, FUNDC1 functions as a mitochondrial outer membrane protein that can interact with LC3 and induce mitochondrial autophagy after dephosphorylation[138]. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) promotes EC damage that is manifested as decreased cell migration ability, impaired angiogenesis, and reduced lumen formation ability. Inducing mitochondrial autophagy can partially reverse these effects[139]. After exposure to a hypoxic environment, the mitochondrial membrane potential of ECs decreases, Parkin transfers to mitochondria and triggers induction of mitochondrial autophagy[140]. However, reoxygenation after hypoxia inhibits mitochondrial autophagy, leading to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and mediating mitochondrial apoptosis in coronary artery ECs[140] and cardiomyocytes[141].

Mild mitochondrial stress can be corrected through mitochondrial fission or fusion, while severely damaged mitochondria are cleared through mitochondrial autophagy, leading to a notable reduction in mitochondrial mass. Therefore, it is necessary to sustain sufficient mitochondrial quality and function through novel mitochondrial biogenic processes[40]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) and nuclear respiratory factor 2 (NRF2) serve as transcription factors for the majority of mitochondrial proteins. They are regarded as the primary regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis. In terms of mechanism, PGC1α can activate NRF2 and promote the synthesis of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial resident proteins. The role of PGC1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis in EC protection has been widely reported. After whole body knock out of PGC1α in mice, the arterial diameter of the mice decreased, perfusion was insufficient, and there were adhesion defects between ECs[142]. In addition, PGC1α knockout ECs exhibit an advanced aging phenotype and elevated levels of ROS[142]. Mitochondria damaged by abnormal autophagy or biological defects are more prone to overproduction of ROS[143].

CONCLUSIONS

CMD is an important pathological alteration proposed to explain the symptoms of angina pectoris in patients with non-obstructive CAD. This concept has attracted considerable attention from scholars over the past two decades. Methods for assessment of coronary microcirculation have evolved continuously, and in this review the mechanisms underlying CMD are discussed in detail. These mechanisms include endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary microcirculation resistance and mitochondrial abnormalities. In cases of ischemia, no-reflow always complicates primary PCI, and this is closely associated with CMD and MVO.

Challenges and future directions

Clinical research can answer our questions about whether, but cannot answer the questions about why and how, so animal experiments must be used. Due to the importance of coronary microcirculation research, current clinical research has received tremendous attention and achievements. However, research on the mechanism is still difficult, and many specific mechanisms cannot directly confirm the relationship with coronary microcirculation due to the limitations of experimental modelling and assessment method. Explaining the mechanism by the model of coronary endothelial cell dysfunction not coronary microcirculation is a huge constraint on the accurate mechanism research of CMD and further research on biomarkers and drugs.

Due to limitations in experimental research, current studies primarily focus on clinical diagnosis. This paper summarizes and analyzes the present research status on the mechanisms of CMD, while emphasizing the need for more basic research to better define disease classification, elucidate key mechanisms and identify effective therapeutic agents. A stepwise approach is recommended: first, obtain reliable data from animal experiments; next, conduct small-scale clinical trials to confirm efficacy; and finally, perform large-scale multicenter randomized controlled trials. This process will enable the systematic screening of clinically effective drugs for CAD.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made contributions to the conception of the study: Duan L, Wang J

Collected and analyzed all the literature: Li Z, Ren L, Liu Y, Xia P

Drafted the original review: Duan L, Wang J

Contributed to discussion of the manuscript: Wang J

Revised the manuscript: Xiong X

All authors have read and agreed to the publication of this version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81904185 and 82230124).

Conflicts of interest

Xiong X is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Duan L is a Junior Editorial Board Member of the journal Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Xiong X and Duan L were not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling and decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Pepine CJ, Ferdinand KC, Shaw LJ, et al; ACC CVD in Women Committee. Emergence of nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a woman’s problem and need for change in definition on angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1918-33.

2. Likoff W, Segal BL, Kasparian H. Paradox of normal selective coronary arteriograms in patients considered to have unmistakable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:1063-6.

3. Kaski JC. Pathophysiology and management of patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteriograms (cardiac syndrome X). Circulation. 2004;109:568-72.

4. Cannon RO 3rd, Epstein SE. “Microvascular angina” as a cause of chest pain with angiographically normal coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:1338-43.

5. Masi S, Rizzoni D, Taddei S, et al. Assessment and pathophysiology of microvascular disease: recent progress and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:2590-604.

6. Kelshiker MA, Seligman H, Howard JP, et al; Coronary Flow Outcomes Reviewing Committee. Coronary flow reserve and cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:1582-93.

7. Gdowski MA, Murthy VL, Doering M, Monroy-Gonzalez AG, Slart R, Brown DL. Association of isolated coronary microvascular dysfunction with mortality and major adverse cardiac events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014954.

8. Rehan R, Yong A, Ng M, Weaver J, Puranik R. Coronary microvascular dysfunction: a review of recent progress and clinical implications. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1111721.

9. Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF. Coronary microvascular disease pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic options: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2625-41.

10. Crea F, Montone RA, Rinaldi R. Pathophysiology of coronary microvascular dysfunction. Circ J. 2022;86:1319-28.

11. Qian G, Zhang Y, Dong W, et al. Effects of nicorandil administration on infarct size in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the CHANGE trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e026232.

12. Zhang Y, Zhao J, Ding R, Niu W, He Z, Liang C. Pre-treatment with compound Danshen dripping pills prevents lipid infusion-induced microvascular dysfunction in mice. Pharm Biol. 2020;58:701-6.

13. Kenkre TS, Malhotra P, Johnson BD, et al. Ten-year mortality in the WISE study (Women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003863.

14. Fatade YA, Dave EK, Vatsa N, et al. Obesity and diabetes in heart disease in women. Metab Target Organ Damage. 2024;4:22.

15. Shimokawa H, Suda A, Takahashi J, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients with microvascular angina: an international and prospective cohort study by the Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study (COVADIS) Group. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4592-600.

16. Mileva N, Nagumo S, Mizukami T, et al. Prevalence of coronary microvascular disease and coronary vasospasm in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023207.

17. van Kranenburg M, Magro M, Thiele H, et al. Prognostic value of microvascular obstruction and infarct size, as measured by CMR in STEMI patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:930-9.

18. Konijnenberg LSF, Damman P, Duncker DJ, et al. Pathophysiology and diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:787-805.

19. Cenko E, van der Schaar M, Yoon J, et al. Sex-specific treatment effects after primary percutaneous intervention: a study on coronary blood flow and delay to hospital presentation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011190.

20. He Z, Li N, Zhang W, et al. Efficacy and safety of Shexiang Baoxin Pill in patients with angina and non-obstructive coronary arteries: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IV clinical trial. Phytomedicine. 2025;139:156556.

21. O’Kelly AC, Michos ED, Shufelt CL, et al. Pregnancy and reproductive risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. Circ Res. 2022;130:652-72.

22. Allal-Elasmi M, Haj Taieb S, Hsairi M, et al. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence, main characteristics and association with socio-economic status in adults living in Great Tunis. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36:204-8.

23. Corcoran D, Young R, Adlam D, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with stable coronary artery disease: the CE-MARC 2 coronary physiology sub-study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:7-14.

24. Seo KW, Lim HS, Yoon MH, et al. The impact of microvascular resistance on the discordance between anatomical and functional evaluations of intermediate coronary disease. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:e185-92.

25. Rahman H, Ryan M, Lumley M, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with myocardial ischemia and abnormal coronary perfusion during exercise. Circulation. 2019;140:1805-16.

26. Barton D, Xie F, O’Leary E, Chatzizisis YS, Pavlides G, Porter TR. The relationship of capillary blood flow assessments with real time myocardial perfusion echocardiography to invasively derived microvascular and epicardial assessments. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32:1095-101.

27. AlBadri A, Eshtehardi P, Hung OY, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is associated with significant plaque burden and diffuse epicardial atherosclerotic disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1519-20.

28. Nishi T, Murai T, Ciccarelli G, et al. Prognostic value of coronary microvascular function measured immediately after percutaneous coronary intervention in stable coronary artery disease: an international multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007889.

29. Ekenbäck C, Jokhaji F, Östlund-Papadogeorgos N, et al. Changes in index of microcirculatory resistance during PCI in the left anterior descending coronary artery in relation to total length of implanted stents. J Interv Cardiol. 2019;2019:1397895.

30. Gupta A, Taqueti VR, van de Hoef TP, et al. Integrated noninvasive physiological assessment of coronary circulatory function and impact on cardiovascular mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2017;136:2325-36.

31. Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131:19-27.

32. Canu M, Khouri C, Marliere S, et al. Prognostic significance of severe coronary microvascular dysfunction post-PCI in patients with STEMI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268330.

33. Seraphim A, Dowsing B, Rathod KS, et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion predicts outcomes in patients with prior surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1141-51.

34. Robbers LF, Eerenberg ES, Teunissen PF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-defined areas of microvascular obstruction after acute myocardial infarction represent microvascular destruction and haemorrhage. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2346-53.

35. Heusch G, Andreadou I, Bell R, et al. Health position paper and redox perspectives on reactive oxygen species as signals and targets of cardioprotection. Redox Biol. 2023;67:102894.

36. Carrick D, Haig C, Ahmed N, et al. Temporal evolution of myocardial hemorrhage and edema in patients after acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: pathophysiological insights and clinical implications. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002834.

37. Skyschally A, Walter B, Heusch G. Coronary microembolization during early reperfusion: infarct extension, but protection by ischaemic postconditioning. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3314-21.

38. Niccoli G, Scalone G, Lerman A, Crea F. Coronary microvascular obstruction in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1024-33.

39. Niccoli G, Montone RA, Ibanez B, et al. Optimized treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2019;125:245-58.

40. Chang X, Lochner A, Wang HH, et al. Coronary microvascular injury in myocardial infarction: perception and knowledge for mitochondrial quality control. Theranostics. 2021;11:6766-85.

41. Bertani F, Di Francesco D, Corrado MD, Talmon M, Fresu LG, Boccafoschi F. Paracrine shear-stress-dependent signaling from endothelial cells affects downstream endothelial function and inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13300.

42. Zhang Y, Zhao J, Ren C, et al. Free fatty acids induce coronary microvascular dysfunction via inhibition of the AMPK/KLF2/eNOS signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2023;51:34.

43. Ford TJ, Corcoran D, Padmanabhan S, et al. Genetic dysregulation of endothelin-1 is implicated in coronary microvascular dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3239-52.

44. Zhang Z, Li X, He J, et al. Molecular mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in coronary microcirculation dysfunction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2023;56:388-97.

45. Theuerle J, Farouque O, Vasanthakumar S, et al. Plasma endothelin-1 and adrenomedullin are associated with coronary artery function and cardiovascular outcomes in humans. Int J Cardiol. 2019;291:168-72.

46. Kassi E, Spilioti E, Nasiri-Ansari N, et al. Vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis: the role of estrogen receptors. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:2651-65.

47. Steinberg RR, Dragan A, Mehta PK, Toleva O. Coronary microvascular disease in women: epidemiology, mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2024;102:594-606.

48. Bassuk SS, Manson JE. The timing hypothesis: do coronary risks of menopausal hormone therapy vary by age or time since menopause onset? Metabolism. 2016;65:794-803.

49. Witkowski S, Serviente C. Endothelial dysfunction and menopause: is exercise an effective countermeasure? Climacteric. 2018;21:267-75.

50. Zhou M, Yu Y, Chen R, et al. Wall shear stress and its role in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1083547.

51. Yang F, Zhang Y, Zhu J, et al. Laminar flow protects vascular endothelial tight junctions and barrier function via maintaining the expression of long non-coding RNA MALAT1. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:647.

52. Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, et al. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124:779-88.

53. Bajraktari A, Bytyçi I, Henein MY. High coronary wall shear stress worsens plaque vulnerability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Angiology. 2021;72:706-14.

54. Siasos G, Tsigkou V, Zaromytidou M, et al. Role of local coronary blood flow patterns and shear stress on the development of microvascular and epicardial endothelial dysfunction and coronary plaque. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33:638-44.

55. Wong CCY, Javadzadegan A, Ada C, et al. Fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio predict pathological wall shear stress in coronary arteries: implications for understanding the pathophysiological impact of functionally significant coronary stenoses. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023502.

56. Mailey JA, Moore JS, Brennan PF, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic indices of conjunctival microvascular function in patients with coronary microvascular dysfunction. Microvasc Res. 2023;147:104480.

57. Hiteshi AK, Li D, Gao Y, et al. Gender differences in coronary artery diameter are not related to body habitus or left ventricular mass. Clin Cardiol. 2014;37:605-9.

58. Gould KL, Johnson NP, Bateman TM, et al. Anatomic versus physiologic assessment of coronary artery disease. Role of coronary flow reserve, fractional flow reserve, and positron emission tomography imaging in revascularization decision-making. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1639-53.

59. Patel MB, Bui LP, Kirkeeide RL, Gould KL. Imaging microvascular dysfunction and mechanisms for female-male differences in CAD. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:465-82.

60. Xu Y, Kovacic JC. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition in health and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2023;85:245-67.

61. Evrard SM, Lecce L, Michelis KC, et al. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition is common in atherosclerotic lesions and is associated with plaque instability. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11853.

62. Lecce L, Xu Y, V’Gangula B, et al. Histone deacetylase 9 promotes endothelial-mesenchymal transition and an unfavorable atherosclerotic plaque phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e131178.

63. Reventun P, Sánchez-Esteban S, Cook-Calvete A, et al. Endothelial ILK induces cardioprotection by preventing coronary microvascular dysfunction and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Basic Res Cardiol. 2023;118:28.

64. Cho DI, Ahn JH, Kang BG, et al. ANGPTL4 prevents atherosclerosis by preserving KLF2 to suppress EndMT and mitigates endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2025;45:1742-61.

65. Li H, Jia Y, Chen Z, et al. Bioinformatics analysis of coronary microvascular dysfunction in rats based on single-cell RNA sequencing. Sci Rep. 2025;15:5050.

66. Sabe SA, Feng J, Sellke FW, Abid MR. Mechanisms and clinical implications of endothelium-dependent vasomotor dysfunction in coronary microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;322:H819-41.

67. Jia G, Aroor AR, Jia C, Sowers JR. Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:1802-9.

68. Clayton ZS, Hutton DA, Brunt VE, et al. Apigenin restores endothelial function by ameliorating oxidative stress, reverses aortic stiffening, and mitigates vascular inflammation with aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;321:H185-96.

69. Lee MY, Wang Y, Vanhoutte PM. Senescence of cultured porcine coronary arterial endothelial cells is associated with accelerated oxidative stress and activation of NFkB. J Vasc Res. 2010;47:287-98.

70. Man AWC, Li H, Xia N. The role of sirtuin1 in regulating endothelial function, arterial remodeling and vascular aging. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1173.

71. Donato AJ, Magerko KA, Lawson BR, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. SIRT-1 and vascular endothelial dysfunction with ageing in mice and humans. J Physiol. 2011;589:4545-54.

72. Zarzuelo MJ, López-Sepúlveda R, Sánchez M, et al. SIRT1 inhibits NADPH oxidase activation and protects endothelial function in the rat aorta: implications for vascular aging. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:1288-96.

73. Bochaton T, Lassus J, Paccalet A, et al. Association of myocardial hemorrhage and persistent microvascular obstruction with circulating inflammatory biomarkers in STEMI patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245684.

74. Long M, Huang Z, Zhuang X, et al. Association of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction with coronary microvascular resistance in patients with cardiac syndrome X. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2017;109:397-403.

75. Cosín-Sales J, Pizzi C, Brown S, Kaski JC. C-reactive protein, clinical presentation, and ischemic activity in patients with chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1468-74.

76. Suzuki M, Shimizu H, Miyoshi A, Takagi Y, Sato S, Nakamura Y. Association of coronary inflammation and angiotensin II with impaired microvascular reperfusion in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;146:254-6.

77. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685-95.

78. Dai L, Zhu L, Ma S, et al. Berberine alleviates NLRP3 inflammasome induced endothelial junction dysfunction through Ca2+ signalling in inflammatory vascular injury. Phytomedicine. 2022;101:154131.

79. Theofilis P, Sagris M, Oikonomou E, et al. Inflammatory mechanisms contributing to endothelial dysfunction. Biomedicines. 2021;9:781.

80. Karamitsos K, Oikonomou E, Theofilis P, et al. The role of NLRP3 inflammasome in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its macrovascular complications. J Clin Med. 2025;14:4606.

81. Zhang Y, Song Z, Huang S, et al. Aloe emodin relieves Ang II-induced endothelial junction dysfunction via promoting ubiquitination mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inactivation. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;108:1735-46.

82. Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161-6.

83. Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:2437-45.

84. Houssari M, Dumesnil A, Tardif V, et al. Lymphatic and immune cell cross-talk regulates cardiac recovery after experimental myocardial infarction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1722-37.

85. Laroumanie F, Douin-Echinard V, Pozzo J, et al. CD4+ T cells promote the transition from hypertrophy to heart failure during chronic pressure overload. Circulation. 2014;129:2111-24.

86. Bansal SS, Ismahil MA, Goel M, et al. Activated T lymphocytes are essential drivers of pathological remodeling in ischemic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:e003688.

87. Trincot CE, Xu W, Zhang H, et al. Adrenomedullin induces cardiac lymphangiogenesis after myocardial infarction and regulates cardiac edema via connexin 43. Circ Res. 2019;124:101-13.

88. Giannoni E, Guignard L, Knaup Reymond M, et al. Estradiol and progesterone strongly inhibit the innate immune response of mononuclear cells in newborns. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2690-8.

89. d’Adesky ND, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Bhattacharya P, et al. Nicotine alters estrogen receptor-beta-regulated inflammasome activity and exacerbates ischemic brain damage in female rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:1330.

90. Moran CA, Collins LF, Beydoun N, et al. Cardiovascular implications of immune disorders in women. Circ Res. 2022;130:593-610.

91. McCarthy M, Raval AP. The peri-menopause in a woman’s life: a systemic inflammatory phase that enables later neurodegenerative disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:317.

92. Nabeebaccus AA, Reumiller CM, Shen J, Zoccarato A, Santos CXC, Shah AM. The regulation of cardiac intermediary metabolism by NADPH oxidases. Cardiovasc Res. 2023;118:3305-19.

93. Xie Y, Nishijima Y, Zinkevich NS, et al. NADPH oxidase 4 contributes to TRPV4-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation in human arterioles by regulating protein phosphorylation of TRPV4 channels. Basic Res Cardiol. 2022;117:24.

94. Furuhashi M. New insights into purine metabolism in metabolic diseases: role of xanthine oxidoreductase activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;319:E827-34.

95. Li Y, Pagano PJ. Microvascular NADPH oxidase in health and disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;109:33-47.

96. Niccoli G, Celestini A, Calvieri C, et al. Patients with microvascular obstruction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention show a gp91phox (NOX2) mediated persistent oxidative stress after reperfusion. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2013;2:379-88.

97. Lassègue B, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: functions and pathologies in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:653-61.

98. Loffredo L, Ivanov V, Ciobanu N, et al. Low-grade endotoxemia and NOX2 in patients with coronary microvascular angina. Kardiol Pol. 2022;80:911-8.

99. Ottolini M, Hong K, Cope EL, et al. Local peroxynitrite impairs endothelial transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channels and elevates blood pressure in obesity. Circulation. 2020;141:1318-33.

100. Camici PG, Tschöpe C, Di Carli MF, Rimoldi O, Van Linthout S. Coronary microvascular dysfunction in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:806-16.

101. Giannopoulos AA, Buechel RR, Kaufmann PA. Coronary microvascular disease in hypertrophic and infiltrative cardiomyopathies. J Nucl Cardiol. 2023;30:800-10.

102. Ismail TF, Hsu LY, Greve AM, et al. Coronary microvascular ischemia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy - a pixel-wise quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance perfusion study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:49.

103. Timmer SA, Knaapen P, Germans T, et al. Effects of alcohol septal ablation on coronary microvascular function and myocardial energetics in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H129-37.

104. Soliman OI, Geleijnse ML, Michels M, et al. Effect of successful alcohol septal ablation on microvascular function in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1321-7.

105. Rouet-Benzineb P, Merval R, Polidano E. Effects of hypoestrogenism and/or hyperaldosteronism on myocardial remodeling in female mice. Physiol Rep. 2018;6:e13912.

106. Almeida SA, Claudio ER, Mengal V, et al. Exercise training reduces cardiac dysfunction and remodeling in ovariectomized rats submitted to myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115970.

107. Yung LM, Wong WT, Tian XY, et al. Inhibition of renin-angiotensin system reverses endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in estrogen deficient rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17437.

108. Rigattieri S, Barbato E, Berry C. Microvascular resistance reserve: a reference test of the coronary microcirculation? Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2870-2.

109. Lee JM, Kim HK, Lim KS, et al. Influence of local myocardial damage on index of microcirculatory resistance and fractional flow reserve in target and nontarget vascular territories in a porcine microvascular injury model. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:717-24.

110. De Maria GL, Alkhalil M, Wolfrum M, et al. The ATI score (age-thrombus burden-index of microcirculatory resistance) determined during primary percutaneous coronary intervention predicts final infarct size in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a cardiac magnetic resonance validation study. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:935-43.

111. De Maria GL, Alkhalil M, Wolfrum M, et al. Index of microcirculatory resistance as a tool to characterize microvascular obstruction and to predict infarct size regression in patients with STEMI undergoing primary PCI. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:837-48.

112. Fineschi M, Verna E, Mezzapelle G, et al. Assessing MICRO-vascular resistances via IMR to predict outcome in STEMI patients with multivessel disease undergoing primary PCI (AMICRO): rationale and design of a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2017;187:37-44.

113. Faustino M, Baptista SB, Freitas A, et al. The index of microcirculatory resistance as a predictor of echocardiographic left ventricular performance recovery in patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction undergoing successful primary angioplasty. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29:137-45.

114. Palmer S, Layland J, Carrick D, et al. The index of microcirculatory resistance postpercutaneous coronary intervention predicts left ventricular recovery in patients with thrombolyzed ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29:146-54.

115. Ahn JM, Zimmermann FM, Gullestad L, et al. Microcirculatory resistance predicts allograft rejection and cardiac events after heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:2425-35.

116. De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Gallinoro E, et al. Microvascular resistance reserve for assessment of coronary microvascular function: JACC technology corner. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1541-9.

117. Boerhout CKM, Lee JM, de Waard GA, et al. Microvascular resistance reserve: diagnostic and prognostic performance in the ILIAS registry. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:2862-9.

118. Sun D, Wang J, Toan S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of coronary microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: focus on mitochondrial quality surveillance. Angiogenesis. 2022;25:307-29.

119. Wang J, Toan S, Zhou H. New insights into the role of mitochondria in cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion injury. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:299-314.

120. Viloria MAD, Li Q, Lu W, et al. Effect of exercise training on cardiac mitochondrial respiration, biogenesis, dynamics, and mitophagy in ischemic heart disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:949744.

121. Zhu H, Toan S, Mui D, Zhou H. Mitochondrial quality surveillance as a therapeutic target in myocardial infarction. Acta Physiol. 2021;231:e13590.

122. Zhou H, Ren J, Toan S, Mui D. Role of mitochondrial quality surveillance in myocardial infarction: from bench to bedside. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;66:101250.

123. Ollauri-Ibáñez C, Núñez-Gómez E, Egido-Turrión C, et al. Continuous endoglin (CD105) overexpression disrupts angiogenesis and facilitates tumor cell metastasis. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:231-47.

124. Xian H, Liou YC. Functions of outer mitochondrial membrane proteins: mediating the crosstalk between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:827-42.

125. Whitley BN, Engelhart EA, Hoppins S. Mitochondrial dynamics and their potential as a therapeutic target. Mitochondrion. 2019;49:269-83.

126. Zhou H, Hu S, Jin Q, et al. Mff-dependent mitochondrial fission contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiac microvasculature ischemia/reperfusion injury via induction of mROS-mediated cardiolipin oxidation and HK2/VDAC1 disassociation-involved mPTP opening. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005328.

127. Liu N, Wu J, Zhang L, et al. Hydrogen sulphide modulating mitochondrial morphology to promote mitophagy in endothelial cells under high-glucose and high-palmitate. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:3190-203.

128. Chen C, Gao JL, Liu MY, et al. Mitochondrial fission inhibitors suppress endothelin-1-induced artery constriction. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:1802-11.

129. Shi Y, Fan S, Wang D, et al. FOXO1 inhibition potentiates endothelial angiogenic functions in diabetes via suppression of ROCK1/Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:2481-94.

130. Kleinbongard P, Gedik N, Kirca M, et al. Mitochondrial and contractile function of human right atrial tissue in response to remote ischemic conditioning. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009540.

131. Lugus JJ, Ngoh GA, Bachschmid MM, Walsh K. Mitofusins are required for angiogenic function and modulate different signaling pathways in cultured endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:885-93.