Tailoring mesoporous materials for catalysis: design, functionality, and future trends

Abstract

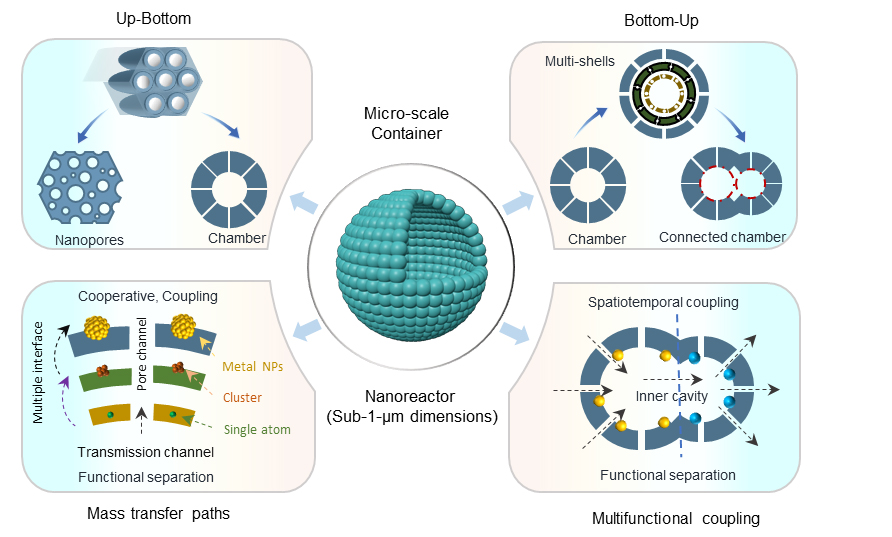

In the past five years, significant progress has been made in the synthesis of mesoporous nanoreactors through advanced interfacial engineering strategies. Researchers have explored a range of methods, both bottom-up and top-down, to achieve precise structural control, enabling the creation of functional mesoporous materials with tailored composition, morphology, pore size, and mesostructure. These developments have laid the foundation for a wide array of novel applications, particularly in catalysis, where mesoporous nanoreactors have demonstrated unprecedented performance and versatility. However, despite these advances, numerous challenges remain in both the fundamental understanding and practical application of mesoporous nanoreactors. Key challenges include improving control over single-micelle assembly, understanding the impact of “chemical scalpel” approaches on interfacial rearrangement, and developing accurate, tunable architectures for specific functions. Additionally, the structure-function relationship remains critical. Addressing these obstacles will require interdisciplinary collaboration across materials science, chemistry, and engineering, along with the integration of advanced technologies and theoretical models.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Pores, the fundamental units of porous materials at the micro- and nanoscale, serve as confined spaces within which guest molecules can be selectively adsorbed[1-3], stored[4,5], transformed[6], and diffused[7-9]. Mesoporous materials (2-50 nm) are particularly valued for their large surface areas, regular pore structures, and efficient mass transfer[10], which enhance adsorption capacity[11,12] and reduce diffusion resistance, thus altering reaction kinetics[13-15]. These unique pore structures - ranging from layered to fractal - give rise to distinctive nanoreactor effects, such as molecular recognition, confinement, synergistic coupling, and local field enhancement[16-20]. Additionally, the cooperative interaction of diverse functionalities within these mesopores modifies catalytic site distribution and interactions, influencing the selectivity and efficiency of catalytic reactions.

In catalysis, the adjustability of pore size and surface characteristics lays the foundation for efficient and selective reactions[21]. Efficient material transfer is crucial for reaction efficiency in cascade catalysis and biphasic catalysis. The pore reactor needs to be designed to promote good quality and heat transfer to support effective multi-step reactions[22]. This means the need for more complex multilevel pore structures and the ability to handle multiple reaction steps simultaneously and/or effectively separate products between different phases[23]. In the realm of electrochemical conversion, the modulation of pore sizes can increase the surface area of electrode materials, enhance ion diffusion rates[24], relieve the volume expansion effect, and thus boost the performance of batteries and supercapacitors[25].

Progress in pore engineering is guided by a design philosophy that integrates the control of pore characteristics with the functional requirements of the materials[26,27]. In 1998, Zhao et al.[28] made the initial discovery that the self-assembly of micelles between the two surfaces can lead to the controlled synthesis of mesoporous nanomaterials with chosen pore size and shape, opening a new era of designing and preparing mesoporous materials with predetermined properties using self-assembly strategies. To overcome their linear polymer micelles instability for precisely controlling the size, polymer location, and shape of the nanoreactor, Pang et al.[29] used a series of multi-arm stellate block copolymers to form thermodynamically stable single-molecule micelles by varying the length of the first P4VP block and the second PTBA block (hydrolyzed to PAA). Nanocrystals with core-shell and hollow structures can be synthesized by easily adjusting the size of core and shell materials. Since this discovery, significant progress has been achieved in the last few years toward the development of functional mesoporous materials with a variety of compositions, morphologies, mesostructured, and pore sizes[30].

Bottom-up biphasic interface template technology enables precise control over the size, shape, and distribution of nanoscale pores using micelles as templates. Through interfacial energy and steric repulsion effects, anisotropic nucleation and micelle growth can be controlled, leading to the formation of highly ordered asymmetric nanoreactors[31-33]. In parallel, top-down chemical tailoring and interfacial recombination techniques, which do not rely on specific templates, are increasingly employed[34-37]. These methods enable post-synthesis adjustments of pore connectivity, size, and functionalization, broadening the application scope of porous materials[38]. This review aims to provide an overview of mesoporous nanoreactors, highlighting interface synthesis and catalytic applications, and offering insights for future advancements in catalysis and related fields.

TAILORING AND OPTIMIZATION OF MESOPOROUS NANOREACTORS

Nanoporous materials can be synthesized through two main approaches: Bottom-up and top-down. The bottom-up approach involves assembling materials from smaller units, using either solid or liquid interfaces. When using solid interfaces, intermolecular interactions like hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces guide the formation of core-shell or asymmetric structures. In the liquid interface method, interfacial energy and steric repulsion control micelle nucleation to create ordered or anisotropic porous structures. The top-down approach involves modifying preformed materials through localized cutting and shaping, or localized reassembly and restructuring. These methods enable selective disassembly or reorganization, allowing for control over pore connectivity and size, and facilitating the incorporation of functional groups for material enhancement.

Bottom-up approach

The self-assembly interface template method is a powerful technique for fabricating nanoscale ordered structures by harnessing intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, or hydrophobic interactions, to guide the organization of building blocks into well-defined patterns at solid surfaces or at the interface of two immiscible liquids. This approach is typically categorized into two main types: using solid interfaces as the substrate and using liquid interfaces as the substrate. Each method offers distinct advantages and is suitable for different application domains.

Using solid interfaces as the substrate

To fabricate mesoporous nanoreactors, an effective strategy involves utilizing solid substrates along with intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic effects to guide self-assembly. This approach allows precise control over pore size and structural organization by adjusting factors such as solvent, concentration, temperature, and pH. At the liquid-solid interface, the surface properties of materials - including roughness, functionalization, and energy - play a crucial role in influencing both material assembly and growth.

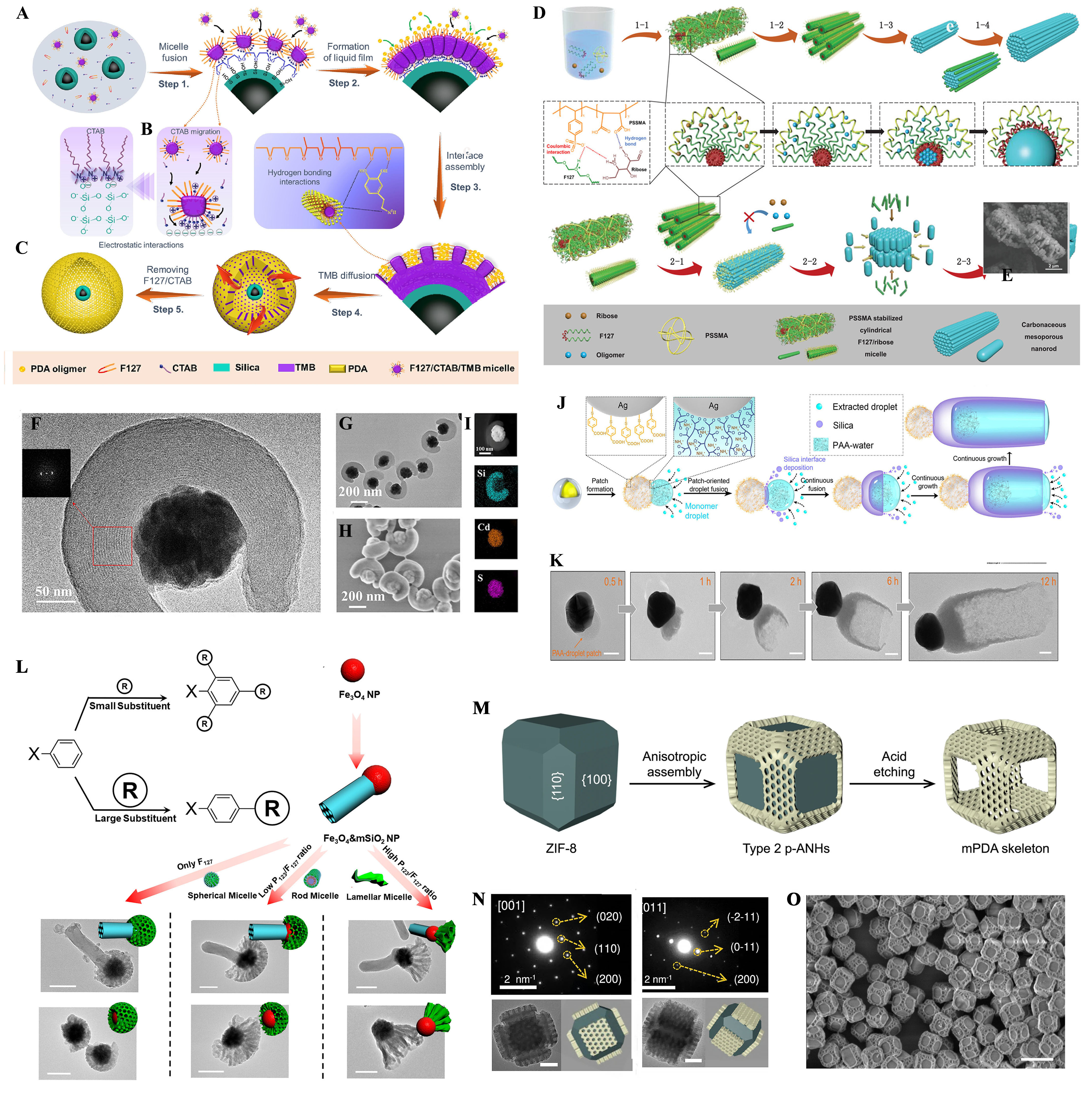

In the context of heterogeneous polymerization systems, achieving high homogeneity is essential for the successful construction of mesoporous nanoreactors. Minimizing surface free energy typically drives this homogeneity, as it stabilizes the assembly process. Pan et al.[39] investigated the interactions between dopamine oligomers and composite micelles, including Pluronic F127 and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), in a water/ethanol/1,3,5-trimethylbenzene (TMB) system [Figure 1A-C]. In this case, due to the strong electrostatic attraction between the positively charged CTAB and the negatively charged silica layer, dopamine oligomers self-assemble on the surface of Fe3O4@SiO2 solid particles through in situ polymerization, forming a mesostructured polymer layer. Afterward, the removal of the F127/CTAB organic template via acetone extraction yields hollow mesoporous nanospheres with ultra-large cavities and ultra-thin mesoporous polymer layers. Thus, this study integrates the principle of interfacial energy minimization, where the redistribution of interaction forces at the solid-liquid interface promotes the directional assembly of nanomaterials.

Figure 1. (A-C) Illustration of the formation mechanism for Yolk-shell magnetic mesoporous polydopamine (YS-MMP) vesicles: (Step 1) Micelle fusion; (Step 2) Formation of liquid film; (Step 3) Interface assembly; (Step 4) TMB diffusion; (Step 5) Removing F127/CTAB. Reproduced with permission from ref.[39]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (D) Schematic illustration of the surface energy-induced anisotropic assembly formation process of mesoporous nanorods and teeth-like superstructures; (E) SEM images of teeth-like superstructures prepared with 150 mg PSSMA. Reproduced with permission from ref.[33]. Copyright 2021 Wiley-VCH GmbH; (F and G) TEM images with different magnifications; (H and I) SEM image and element mappings of the winding-structured CdS&mSiO2 nanocomposites. Reproduced with permission from ref.[40]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; (J) Schematic of a single-capsule nanospacecraft evolved from soft patch-oriented directional fusion of monomer droplets upon collision extracted from solution. Reproduced with permission from ref.[41]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; (K) Magnified TEM images of the morphology evolution of nanospacecrafts collected at different times (t = 0.5, 1, 2, 6, and 12 h). Reproduced with permission from ref.[41]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; (L) Steric-induced anisotropic assembly of lamellar mesoporous polydopamine. Reproduced with permission from ref.[42]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (M) Schematic illustration of the selective growth of mPDA nanoplates on {110} facets of TRD ZIF-8. Reproduced with permission from ref.[43]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature; (N) TEM images. Reproduced with permission from ref.[43]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature; (O) SEM images, corresponding models, and SAED patterns taken from a single nanoparticle along the {100}, {110}, and {111} zone axes. Reproduced with permission from ref.[43]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. TMB: 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene; CTAB: etyltrimethylammonium bromide; SEM: scanning electron microscope; PSSMA: poly (4-styrenesulfonicacid-co-maleic acid) sodium salt; TEM: transmission electron microscope; PDA: polydopamine; TRD: truncated rhombic dodecahedral; ZIF-8: zeolitic imidazolate framework-8; SAED: selected area electron diffraction.

Interfacial energy minimization typically favors the formation of uniform, symmetric heterogeneous structures. However, advancements in nanoscience have enabled the creation of anisotropic mesoporous nanoreactors, which, with their high surface area and large pore volume, exhibit unique and irreplaceable properties. Xie et al.[33] introduced a surface energy-induced interfacial assembly mechanism, where hydrogen bonding and Coulomb interactions adsorb poly (4-styrenesulfonicacid-co-maleic acid) sodium salt (PSSMA) onto micelle surfaces. This reduces the surface energy of both micelles and nanoparticles in the solvent, promoting anisotropic growth and the formation of small nanorods [Figure 1D and E]. These micelles serve as solid interface templates, guiding the entry and polymerization of ribose-derived oligomers into the interior hydrophobic segment in micelles (PPO) section of cylindrical micelles. This results in the assembly of anisotropic mesoporous nanoreactors based on nanowire arrays, demonstrating the role of surface energy in driving controlled anisotropic growth.

Surface energy can also be used to control the accessibility and exposed sections of nanoreactors, enabling critical stereo-geometric features such as bending, folding, and wrapping. This approach addresses the limitations of symmetric mesoporous core-shell structures. Zhao et al.[40] introduced a surface-constrained wrapping assembly strategy [Figure 1F-I], where a higher concentration of CTAB (≥ 5 mg/mL) promotes silica oligomer crosslinking into a thin silica layer on CdS. The surface energy equation Δσ = σ micelle-solvent + σ SiO2-micelle - σ SiO2-solvent explains the process. Since the CTAB/silicate micelles and pre-deposited silica layer have similar compositions, Δσ ≈ 0, maximizing interaction between the micelles and nanoparticle surface. This causes the rod-like micelles to align parallel to the CdS surface, ensuring that mSiO2 nanorods assemble exclusively on the CdS particles.

Symmetry disruption in nanomaterials through interfacial energy relies on energy changes from substance interactions and physical/chemical changes at interfaces, often involving structural reconfiguration or phase transitions. This process is material-dependent and influenced by environmental conditions. Functionalized carriers, such as chemically modified surfaces, can disrupt nanomaterial symmetry by altering their arrangement or introducing specific chemical interactions. Yan et al.[41] demonstrated this by using 4-MPAA and PAA ligands to competitively bind to gold nanoparticle (NP) surfaces, creating Janus segregated domains [Figure 1J and K]. The PAA chains formed a PAA-NH4+ complex, promoting phase separation and droplet formation. The 4-MPAA carboxyl group reacted with silane, depositing a thin silica layer, while PAA encouraged droplet fusion to reduce surface energy. The addition of tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) facilitated continuous silica deposition, resulting in asymmetric nanocapsules with a 78 nm bottom thickness and an open, hollow structure.

The steric effect of functional group substitution plays a key role in inducing anisotropic assembly at solid-liquid interfaces. Through non-covalent interactions - such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and π-π stacking - molecules can be directed to assemble in specific orientations, resulting in anisotropic nanostructures. Zhao et al.[42] demonstrated that mesoporous mSiO2 nanorods, acting as space-occupying entities, induce a spatial repulsion effect on larger mesoporous polydopamine (mPDA) micelles, promoting the anisotropic assembly of mesoporous polydopamine (mPDA) into mesoporous cones [Figure 1L]. Increasing the P123 concentration further enhances this effect, forming larger lamellar micelles that lead to spatially isolated mesoporous nanostructures. Additionally, Liu et al.[43] developed a selective occupation strategy, where 2,3,6-trimethylphenol (TMP) small molecules were used to mask coordination sites on the {110} facets of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8). This directed the anisotropic growth of mPDA nanosheets specifically on these facets [Figure 1M]. Following architectural etching, a hollow cubic framework was obtained from the internal ZIF-8 building blocks[44] [Figure 1N and O]. This approach highlights the potential of spatial effects for site-specific anisotropic assembly, enabling the creation of structures with distinct surfaces and storage spaces for targeted applications.

This strategy offers precise control over pore size and structure, enhanced mechanical stability, and tailored interfacial interactions for efficient assembly. However, substrate dependence, potential defects, and scalability challenges may limit its versatility.

Using liquid interfaces as the substrate

The liquid-liquid interface template technique leverages the interface between two immiscible liquids, such as water and oil, as a reaction zone. This unique interface enables precise control over assembly processes by modifying or adding reactants to each phase without disturbing the interfacial stability. A notable example is the use of a continuous interface growth strategy within an oil-water biphasic reaction system, which facilitates the synthesis of hierarchical mesoporous silica nanospheres. These nanospheres feature adjustable radial and dendritic mesoporous channels, demonstrating significant advancements in material design.

Additionally, lotion droplet interfaces, created by dispersing tiny droplets of one liquid (e.g., oil) in another (e.g., water), serve as templates that dictate the size and morphology of the resulting nanomaterials. By fine-tuning the dimensions and shapes of these droplets, researchers can achieve highly diverse and hierarchically ordered structures. This approach has proven effective for constructing mesoporous nanoreactors, including mesoporous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), carbon-based nanoreactors, and silicon-based nanostructures, thus expanding the possibilities for tailored material development.

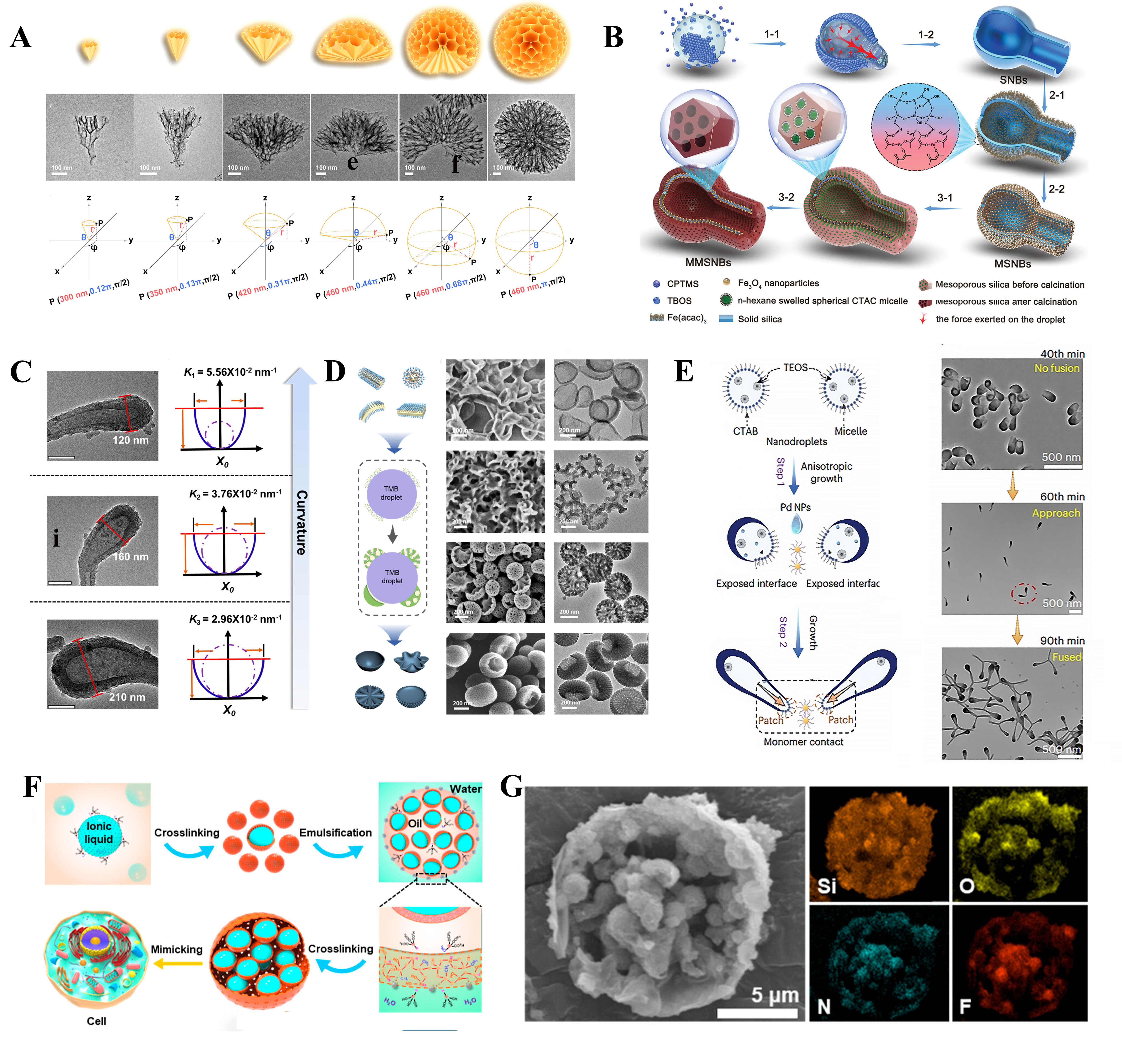

The liquid-liquid interface provides a unique platform for synthesizing porous nanoreactors by leveraging molecular assembly and reactions at the interface. Li et al.[45] demonstrated that in an oil-water system using Pluronic P123 and F127 as co-stabilizers and toluene as the oil phase, adjusting the surfactant ratio and adding hydrophobic compounds could induce various MOF structures, such as bowl-shaped, dendritic, and walnut-like particles. This process is governed by the interaction of surfactants and template stacking at the interface. Building on this, Wu et al.[46] found that increasing the P123/F127 ratio enhanced micelle stacking and pore alignment, leading to anisotropic nucleation at the interface. This directed growth resulted in MOF nanoparticles (e.g., UiO-66) with a hierarchical pore structure spanning macro-, meso-, and microporous scales [Figure 2A]. The viscosity of the emulsion system also plays a critical role. Wu et al.[46] noted that continuous stirring reduces droplet size and increases viscosity, slowing diffusion. This suppression causes precursors to accumulate on the sides of growing nanocones, accelerating their transformation from anisotropic cones to isotropic spheres[47].

Figure 2. (A) Schematic models and their corresponding TEM images of UiO-66 nanostructures prepared with different reaction durations: 11.5, 15, 19, 22, 39, and 50 min. Reproduced with permission from ref.[46]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (B) Synthesis procedure for the MMSNBs through sequentially interfacial super-assembly strategy. Reproduced with permission from ref.[49]. Copyright 2021 Wiley-VCH GmbH; (C) TEM images and the corresponding parabola model of the streamlined nanotadpoles with variable curvature prepared by using surfactants with different alkyl chain lengths. Reproduced with permission from ref.[50]. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society; (D) Schematic diagram of various micelles with different structures for the interfacial self-assembly on TMB droplets. SEM and TEM images of the asymmetry mesoporous hemispheres synthesized by using various amphiphilic Pluronic triblock copolymers as templates: eggshells, P123; lotuses, P84; jellyfishes, P105; and mushrooms. Reproduced with permission from ref.[48]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (E) Illustration of the nanodroplet fusion strategy for the synthesis of the Y-shaped mesoporous silica dimers. Representative TEM images of the formation process of dimers from 40 to 90 min. Reproduced with permission from ref.[51]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (F) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of MLMs. Reproduced with permission from ref.[54]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (G) High-resolution elemental mapping of a single MLM particle. Reproduced with permission from ref.[54]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. TEM: Transmission electron microscope; MMSNB: magnetic mesoporous silicananobottles; TMB: 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene; MLM: multicompartmentalized liquid-containing microreactor.

To further control interfacial energy and micelle behavior, Peng et al.[48] introduced ethanol (50 v/v%) into the oil-water system. This altered the total interfacial energy (Δσ > 0), inhibiting micelle diffusion and promoting anisotropic nucleation. Using different triblock copolymers (e.g., P123, P84, F127), they created unique asymmetric nanostructures, such as eggshell-like and lotus-like shapes, combining mesoporosity, large pore sizes, and high nitrogen content [Figure 2B]. Emulsion droplets offer significant flexibility, fluidity, deformability, and fusion characteristics, making them excellent templates for fabricating mesoporous nanoreactors with diverse structures. These properties enable the customization of asymmetric nanoreactors, breaking the limitations of traditional spherical symmetry. Recent advances have demonstrated the potential of liquid-liquid templated interfacial reactions for designing innovative silica nanoreactors.

In a water/n-pentanol emulsion system, Qiu et al.[49] reported the hydrolysis of CPTMS at the water-oil interface, resulting in the anisotropic deposition of silica and the formation of hollow nanobottles. These nanobottles featured a neck diameter of approximately 120 nm and an inner cavity of about 220 nm [Figure 2C]. The process leveraged CTAC-silica composite micelles to enable the superassembly of mesoporous silica on the nanobottle interior. Building on this, Ma et al.[50] introduced a method to control the surface curvature of hollow silica nanoreactors by adjusting the alkyl chain length of surfactants. Longer alkyl chains expanded the emulsion droplets, increasing their radius of curvature. This strategy allowed precise control over droplet morphology and demonstrated the adaptability of emulsion droplets for shape-controlled synthesis [Figure 2D].

Further innovations by Ma et al.[51] utilized a sequential fusion approach to create branched mesoporous silica nanostructures, termed Wedderburn-Etherington nanotrees [Figure 2E]. Using CTAB-stabilized droplets in a water-oil nanoemulsion system, excess surfactants facilitated the anisotropic growth of silica shells. The introduction of ligand-grafted palladium nanocrystals enabled droplet fusion by exposing active sites through selective CTAB removal, enhancing branching. This method adhered to the Wedderburn-Etherington pattern, providing a framework for nanoscale branching similar to macroscopic structures[52]. Pickering emulsions, stabilized by colloidal particles, offer an alternative to surfactant-based systems for creating artificial cell-like microreactors[53]. Hao et al.[54] employed ionic liquid-oil-based Pickering emulsions combined with stepwise emulsification and interfacial confinement crosslinking. Using silica particles as stabilizers and silicon precursors, they fabricated multi-layer microreactors with enhanced mechanical stability and encapsulated liquid environments [Figure 2F and G]. This approach allowed precise control over the number and size of internal subcompartments, advancing the design of robust biomimetic microreactors.

The liquid-liquid interface template technique enables precise reaction control, facilitating hierarchical and anisotropic mesostructures with tunable porosity. Its dynamic and self-regenerating nature allows for continuous material growth and modification. However, stability issues at the interface, limited scalability, and sensitivity to environmental fluctuations may impact reproducibility. Further advancements in interface engineering and phase compatibility are essential for broader applications.

Top-down approach

Localized cutting and shaping

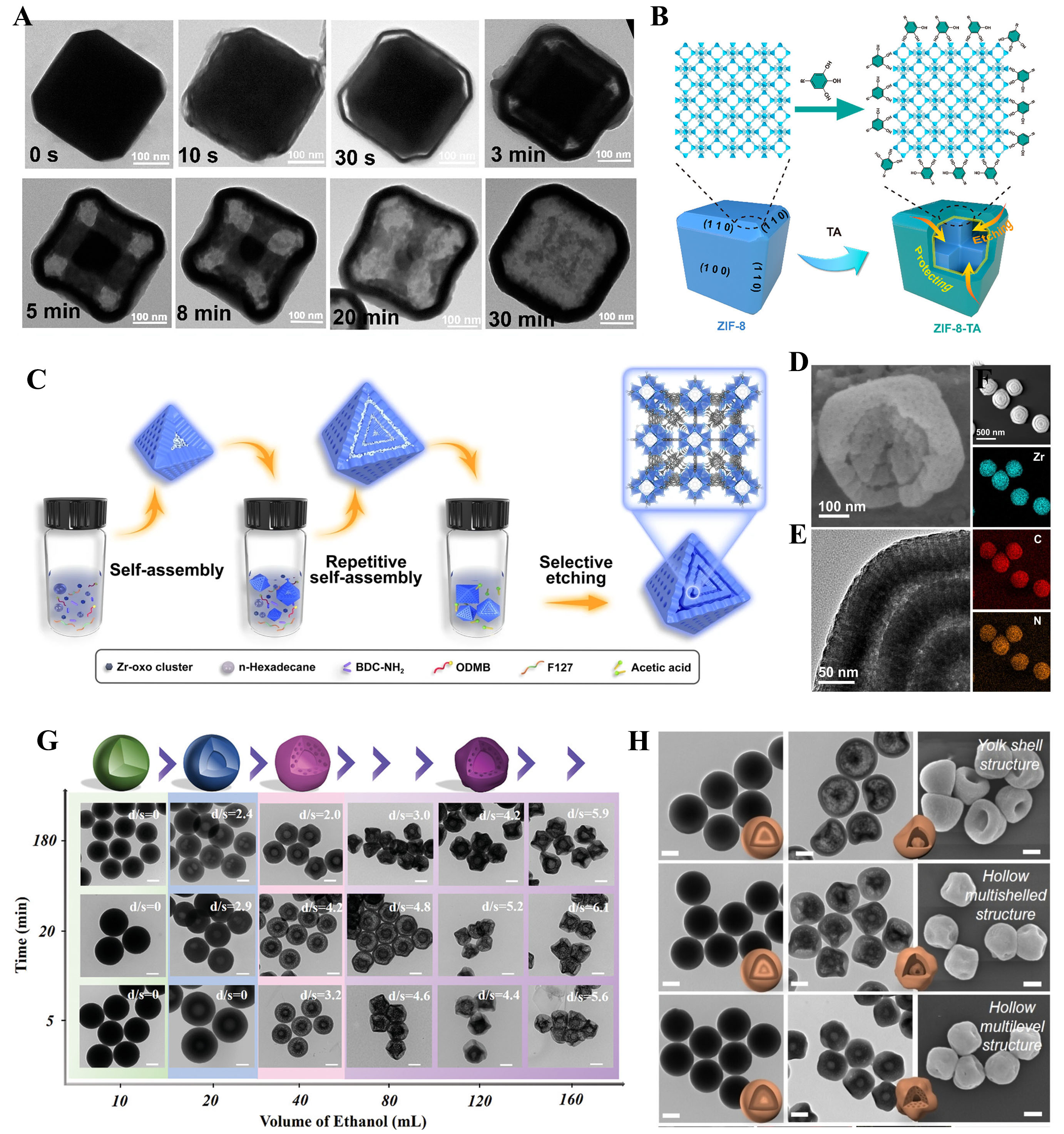

The top-down chemical tailoring method offers a highly efficient approach to preparing complex hollow carbon structures without relying on traditional templating methods or post-treatment steps. This strategy enhances synthesis efficiency by enabling precise structural control and high customization. Li et al.[34] demonstrated the potential of this method by applying tannic acid (TA) as an etching agent to selectively modify ZIF-8 cubic nanocrystals. The process intricately constructed cubic cross structures (ZIF-8-TA), which were subsequently transformed into N/O co-doped multi-cavity mesoporous carbon boxes (MCCBs) via stepwise carbonization [Figure 3A]. X-ray diffraction analysis confirmed the retention of the initial ZIF-8 crystal structure after etching, while Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy validated the successful coating of TA on the surface. When the etching duration was extended to 30 seconds, the {110} crystal planes were selectively etched, preserving the external TA-protected ZIF-8 shell [Figure 3B]. TA’s dual functionality enabled it to release protons to etch the interior structure of ZIF-8 while forming a protective layer on the surface, preventing external corrosion. This process exploits the varying Zn-N4 capping ligand densities across the truncated cubic ZIF-8, resulting in uneven etching patterns and forming intricate void structures.

Figure 3. (A) TEM images of the ZIF-8-TA at different etching times; (B) Schematic diagram of the formation mechanism for the cross-in-cube ZIF-8-TA. Reproduced with permission from ref.[34]. Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society; (C) Schematic illustration of the synthesis process; (D-F) SEM and TEM images, magnified TEM image of 3S-mesoUiO-66-NH2. Reproduced with permission from ref.[35]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature; (G) TEM images of multilevel structured APF resins with different volumes of ethanol and processing times. Scale bars = 200 nm. Reproduced with permission from ref.[56]. Copyright 2022 Yutong Pi et al. Advanced Materials published by Wiley-VCH GmbH; (H) TEM images of SPR-1, SPR-2, SPR-3, YS-PR (180), HoMS-PR (180), and HM-PR (180). SEM images of YS-PR (180), HoMS-PR (180), and HM-PR (180). Reproduced with permission from ref.[57]. Copyright 2023 Wiley-VCH GmbH. TA: tannic acid; SPR: the solid phenolicresins; YS-PR: Yolk-shell phenolic resins; HoMS-PR: hollow multi-shelled structure phenolic resins; HM-PR: hollow multi-stage phenolic resin.

Similarly, Xu et al.[35] utilized ligand density disparities to fabricate hollow multi-shell mesoporous UiO-66-NH₂ nanostructures with controllable shell numbers, large pore volumes, adjustable shell thickness, and chamber sizes [Figure 3C-F]. By combining ODMB and MOF precursors, they achieved synergistic self-assembly, initially forming mesostructured MOFs with disordered worm-like pores. As the reaction progressed, Pluronic F127 induced the formation of freely oriented mesochannels, creating MOF precursors with alternating mesostructures through repeated growth cycles. Acetic acid was then used to etch defect-rich layers selectively, yielding hollow triple-layered mesoporous MOF particles. Zheng et al.[55] employed ammonia to polymerize 3-aminophenol and formaldehyde, forming colloidal nanospheres of phenolic resin. The uneven distribution of components within the spheres was utilized to create single-shell hollow nanospheres (1S-HNs) by selectively removing the internal components using acetone. To generate multi-shell hollow carbon nanospheres (2S-HCNs and 3S-HCNs), the 1S-HNs served as a precursor, undergoing multiple growth and removal cycles. Transmission electron microscopy revealed that the MS-HCNs exhibited an onion-like hollow microstructure, with the hollow precursor nanospheres maintaining stability through the fabrication process. The increasing number of shells provided larger internal spaces for sulfur storage, demonstrating the structural adaptability of the process.

The mechanism behind this transformation relies on the precise control of the cutting process. Acetone selectively removes the internal structure of the 1S-HNs while preserving the outer shell, creating a multi-layered hollow structure. The growing number of shells is a result of controlled polymerization and selective removal, offering a scalable route to mesoporous nanoreactors. Pi et al.[56] investigated the role of ethanol in breaking chemical bonds between aromatic C and N in aminophenol formaldehyde resin (APF) spheres [Figure 3G]. The chemical cutting action of ethanol, which selectively cleaves (Ar) C-N bonds, initiates the dissolution and re-polymerization of oligomers. This “chemical scalpel” approach allows for the creation of APF spheres with multilevel hollow structures, including mesoporous layers and functional groups like hydroxymethyl and amines. Ethanol promoted selective bond cleavage within the APF matrix, facilitating the formation of hollow and porous structures by dissolving shorter-chain oligomers and driving re-polymerization. This process, involving controlled dissolution and reassembly, is essential for achieving complex hollow nanostructures with precise nanoscale functionality. In another study by Pi et al.[57], submicron particles of phenolic resin were synthesized by adjusting the molar ratio of 3-aminophenol (3-AP) and resorcinol (R). The polymerization rate differences between the two precursors were closely monitored, revealing that higher ratios of 3-AP led to faster polymerization, forming submicron particles with varying degrees of crosslinking. The submicron particles, formed through controlled polymerization, served as precursors to mesoporous nanoreactors [Figure 3H]. The top-down cutting mechanism was employed by treating these particles with ethanol to selectively remove low-polymerized regions, leaving behind hollow multi-stage phenolic resin (HM-PR) structures with distinct interlayer features. The process enabled the precise tailoring of the polymer’s internal structure, leading to the formation of yolk-shell and multi-stage hollow nanoreactors with adjustable properties.

The key mechanism in these studies centers on the selective removal of low-polymerized regions using solvents as chemical scalpels. By controlling the polymerization rate and employing selective dissolution, the researchers could engineer hollow and multi-shell structures with complex inner architectures.

Localized reassembly and restructuring

The top-down localized reassembly and restructuring method enables the preparation of various hollow nanoreactors by efficiently manipulating precursor materials at the interface, avoiding issues like poor uniformity and complex procedures. This approach typically involves two main steps: first, synthesizing mesostructured nanoparticles with tunable crosslinking distribution, followed by a second step of interfacial transformation.

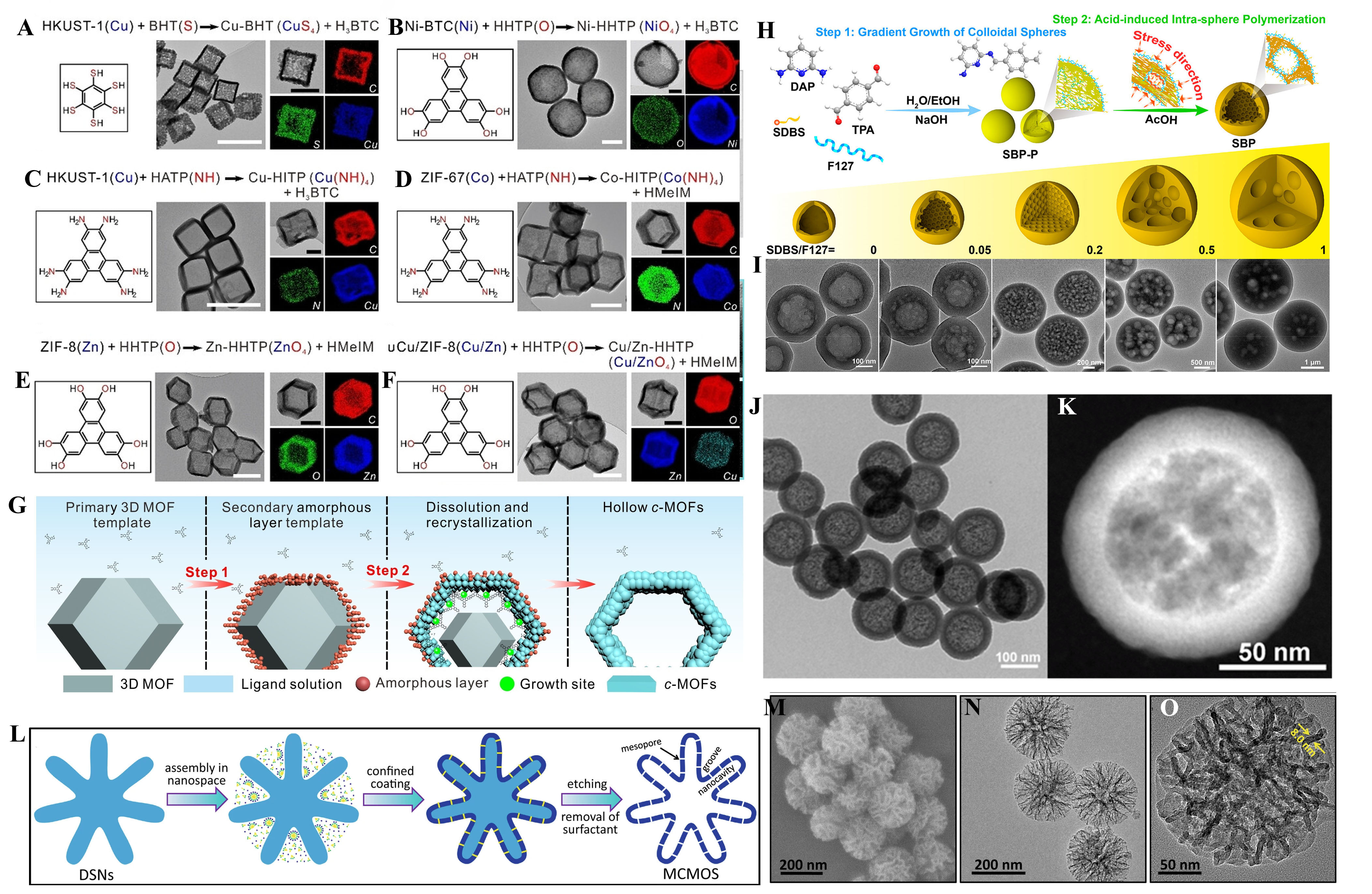

Huang et al.[36] utilized this principle to convert 3D MOFs like HKUST-1 and ZIFs into 2D conductive MOFs (c-MOFs) by first dispersing HKUST-1 nanocubes in a benzenehexathiol (BHT) solution. This reorganization occurs at the interface, forming hollow Cu-BHT nanocubes, and the same approach was applied to other metals like nickel, cobalt, and zinc. The transformation follows a two-step “template mechanism”. Initially, an amorphous interlayer forms on the 3D MOF surface, enabling subsequent heterogeneous nucleation and growth of crystalline c-MOFs while dissolving the 3D MOF core. Molecular dynamics simulations support this by showing that the amorphous layer slows down the reaction rate and serves as the primary site for material growth, emphasizing the importance of interfacial reorganization in the 3D to 2D MOF transition [Figure 4A-F]. Wang et al.[37] adopted a tandem gradient growth and confined polymerization process to create Schiff base polymer (SBP) colloidal spheres with hollow structures [Figure 4G]. This was achieved by controlling the gradient growth of monodisperse colloidal spheres using dual surfactants, Pluronic F127 and sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonate (SDBS), where electrostatic interactions between surfactants led to burst growth. The addition of glacial acetic acid further transformed the loose inner core into a hollow or multi-chamber structure [Figure 4H-I]. This approach highlights how controlled reassembly within confined spaces can yield complex nanostructures.

Figure 4. (A-F) Conjugated ligands (left), TEM images (middle) and the corresponding EELS mapping (right). Scale bars represent 500 nm for middle TEM images and 200 nm for right TEM images. Reproduced with permission from ref.[36]. Copyright 2023 The Authors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition published by Wiley-VCH GmbH; (G) Schematic overview of the two-stepped transformation mechanism of ZIF-8 NPs to hollow Zn-HHTP NPs. Reproduced with permission from ref.[36]. Copyright 2023 The Authors. Angewandte Chemie International Edition published by Wiley-VCH GmbH; (H) The synthesis of hollow SBP colloidal microspheres; Reproduced with permission from ref.[37] Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (I) TEM images of SBP-0, SBP-0.05, SBP-0.2, SBP-0.5, and SBP-1. Reproduced with permission from ref.[37] Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (J and K) TEM and HAADF-STEM images of the benzene-bridged HMOSNs synthesized via the in situ dissolution and reassembly strategy. Reproduced with permission from ref.[59]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society; (L) Schematic illustration for the fabrication of MCMOS. SEM (M) and TEM (N and O) images of DMSNs. Reproduced with permission from ref.[60]. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature. TEM: Transmission electron microscope; EELS: electron energy loss spectroscopy; HHTP: 2,3,6,7,10,11-hexahydroxytriphenylen; NP: nanoparticle; SBP: Schiff base polymer; HAADF-STEM: high angle angular dark field-scanning transmission election microscope; HMOSN: hybrid silica nanoparticle; MCMOS: multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilica; SEM: scanning electron microscope; DMSN: dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

Inorganic-organic hybrid nanoparticles were also synthesized using top-down reassembly principles. Teng et al.[58] applied interfacial reorganization techniques to reorganize low-crosslinked portions of periodic mesoporous organosilicas (PMOs) post-hydrothermal treatment. This enabled the formation of cavities and new high-crosslinked interfaces. Using a St öber solution, they incorporated TEOS and surfactant CTAB to synthesize mesoporous nanoparticles. By adding organosilicon precursors like bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane (BTSB), the silicon nanoparticles underwent hydrolysis and reorganization to form mesoporous core organosilicon/silica nanoreactors with hollow structures [Figure 4J and K]. Su et al.[59] proposed an in-situ dissolution and reorganization method to construct mesoporous hybrid silica nanoparticles (HMOSNs) with enhanced structural properties. By sequentially adding TEOS and BTSB to a CTAB-containing reaction solution, they achieved a deposition of organosilicon on preformed mesoporous silica nanoparticles, as evidenced by NMR spectroscopy, which showed 67% of silicon atoms at the T sites. This process led to the creation of mesoporous silica-organosilicon hybrid nanoreactors with hollow structures, illustrating how interface reorganization contributes to the formation of complex nanostructures [Figure 4J and K].

Zou et al.[60] applied an in-situ dissolution and reorganization mechanism to create nanochannels with nanoscale proximity between metal NPs. This approach, using dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles (DMSNs) as a template, utilized 1,2-bis(triethoxysilyl)ethane (BTEE) for a sol-gel reaction. As the mesoporous organosilica (MOS) layer grew, it dissolved the DMSNs framework, forming nanocavities within multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilica (MCMOS). The resulting structure had interconnected mesopores and nanocavities, as evidenced by High resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) images, showing how the dissolution and reassembly process created distinct nanoreactor structures with improved functionality [Figure 4L-O]. These methods emphasize how localized reassembly and restructuring at the interface can manipulate material properties, enabling the controlled formation of hollow nanoreactors with unique structures and properties.

Both approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations. The bottom-up approach provides precise control over composition, morphology, and pore architecture, enabling the design of well-ordered and tunable mesoporous materials. However, challenges include scalability, batch-to-batch variability, and the need for precise reaction conditions. In contrast, the top-down approach allows for post-synthesis modifications, offering greater flexibility in tailoring pore structures and introducing functional groups. It is often more scalable and compatible with existing material platforms, but may suffer from limited structural precision and potential defects introduced during processing. The synergy of both methods is crucial for developing advanced nanoporous materials with optimized properties.

CATALYTIC ENHANCEMENT APPLICATIONS

Mesoporous nanoreactors, due to their unique morphology, composition, and surface properties, demonstrate significant utility across a wide range of applications. The interaction of these nanomaterials with their environment - such as emulsion interfaces, electrolytes, reactants, photons, or metal activators - is notably enhanced by their specialized structures, thus offering optimized performance in various applications. In this section, we will explore several examples of the specific functional enhancements these mesoporous nanomaterials bring to fields like catalysis, energy storage, and conversion, among others.

Enhancement of hydrogenation reactions

Mesoporous nanoreactors significantly enhance hydrogenation reactions by providing a confined microenvironment that facilitates reactant enrichment without altering the activation Gibbs free energy relative to the bulk solution[61]. Within these confined spaces, substrates exhibit enhanced interaction with active sites, leading to the adsorption and concentration of reactants in the hollow structure, thereby accelerating the reaction kinetics[62,63]. The shell layer, functioning as a separator between the internal and external environments, plays a pivotal role in modulating the enrichment behavior due to its inner surface electronic properties and curvature effects[64].

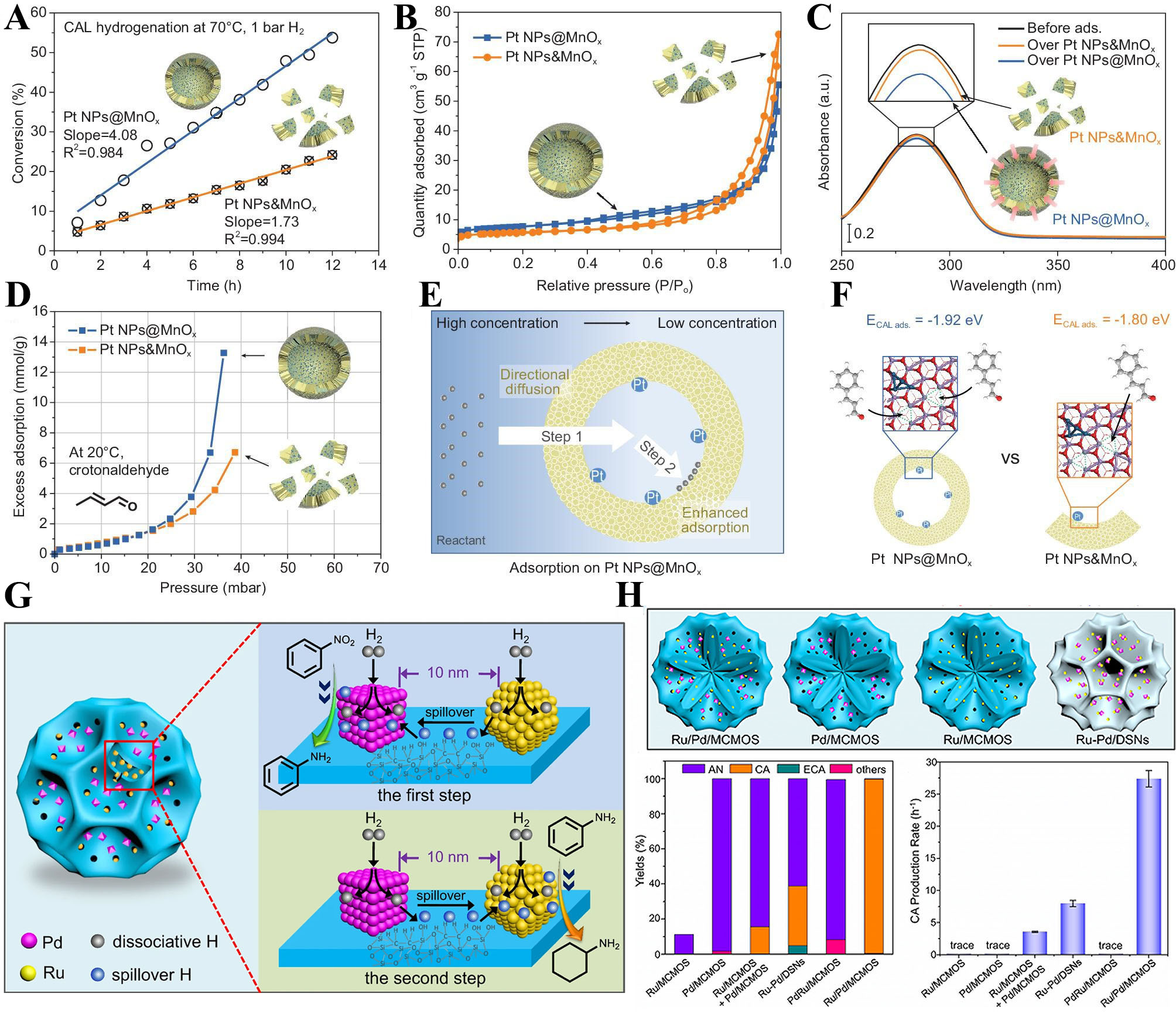

Lancet et al.[65] demonstrated that the adsorption capacity for hydrogen increases with the surface curvature of hollow SiO2, which facilitates the enrichment of hydrogen within the confined structure. Recent work by Ma et al.[66] on the catalytic performance of Pt NPs@MnOx in the hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde (CAL) further underscores the effect of confined spaces [Figure 5A-D]. The catalytic activity of the closed-structure Pt NPs@MnOx was shown to be twice as high as that of Pt NPs&MnOx [Figure 5E and F]. Through Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy, in-situ Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and in-situ gravimetric adsorption analyses, it was confirmed that the hollow structure of the nanoreactor promotes reactant adsorption, thereby increasing the local reactant concentration. Zou et al.[60] prepared a multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilicate nanoreactor, achieving Ru and Pd nanoparticles’ spatial proximity within 10 nm [Figure 5G and H]. Within the mesoporous nanoreactor, catalytically inert Ru NPs efficiently dissociate H2, generating active hydrogen atoms that migrate to nearby Pd NPs. This results in a high concentration of active hydrogen on Pd surfaces, accelerating the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene (NB) adsorbed on Pd. Similarly, catalytically inactive Pd NPs activate H2 to promote hydrogenation of aniline (AN) on Ru surfaces. This structural design enhanced hydrogen spillover, where catalytically inactive metals facilitated the transfer of activated hydrogen to nearby catalytically active metals. This proximity effect significantly accelerated hydrogenation in cascade reactions.

Figure 5. (A) Hydrogenation performance of CAL at 70 °C, 1 bar H2. Reproduced with permission from ref.[66]. Copyright 2023 National Science Review; (B-D) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K (B), Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy spectrum of CAL adsorption experiment (C) In situ gravimetric adsorption analysis profiles (D) over Pt NPs@MnOx and Pt NPs&MnOx, respectively. Reproduced with permission from ref.[66]. Copyright 2023 National Science Review; (E) Schematic illustration of reactant enrichment on Pt NPs@MnOx. Reproduced with permission from ref.[66]. Copyright 2023 National Science Review; (F) The adsorption energy of one CAL adsorbed at one OV site and that of two CAL adsorbed at two OV sites on Pt NPs&MnOx with two OV sites. Reproduced with permission from ref.[66]. Copyright 2023 National Science Review; (G) Schematic illustration for neighboring metal-assisted hydrogenation over Ru/Pd/MCMOS; (H) Schematic illustration of four catalysts including Ru/Pd/MCMOS, Pd/MCMOS, Ru/MCMOS, and Ru-Pd/DMSNs. Product distributions of the sequential hydrogenation over different catalysts. The CA production rate over different catalysts. Reproduced with permission from ref.[60]. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature. CAL: cinnamaldehyde; OV: oxygen vacancy; MCMOS: multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilica; DMSN: dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticle; CA: cyclohexylamine.

The mesoporous architecture of the nanoreactor enabled precise control over the reaction environment, promoting effective hydrogen transfer and interaction with active sites under mild reaction conditions. The sequential hydrogenation of NB to cyclohexylamine (CA) demonstrated the superior efficiency of this system, with minimal intermediate and by-product formation [Figure 5H]. This highlights the role of confined spaces and proximity effects in enhancing hydrogenation efficiency within mesoporous nanoreactors.

Enhancement of cascade catalysis

Under the framework of cascade reactions, mesoporous nanoreactors exhibit remarkable capabilities in enhancing catalytic performance by leveraging their pore and cavity structures to modulate reaction pathways. These nanoreactors rely on spatial organization and confinement effects to optimize the interaction between reactants, intermediates, and catalytic sites, thus achieving higher selectivity, improved efficiency, and reduced formation of undesired by-products.

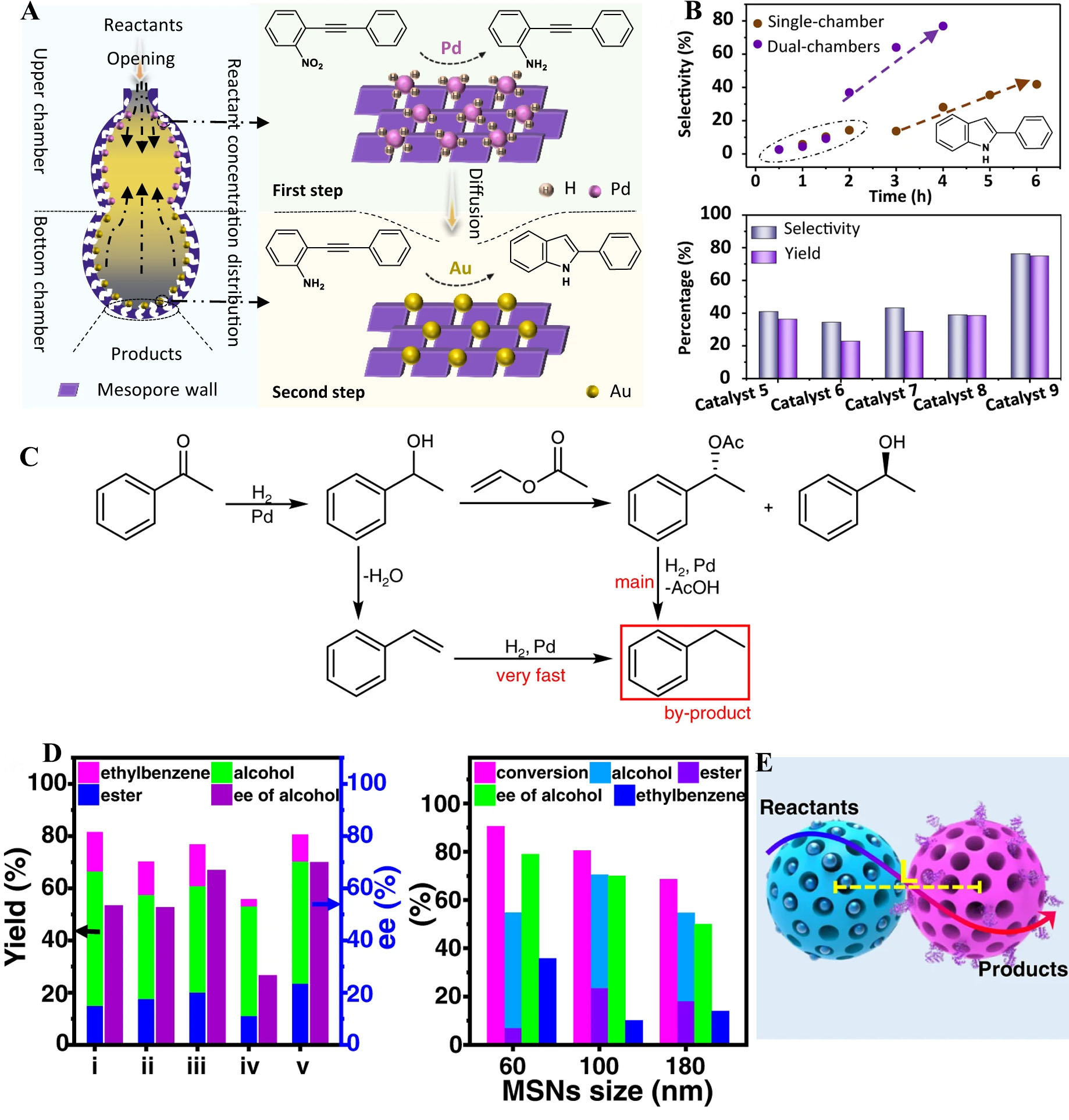

The spatial segregation of active sites within mesoporous nanoreactors is a critical factor in their effectiveness. By confining different catalytic metals or functional sites within distinct regions, these systems facilitate stepwise transformations while preventing competitive adsorption of intermediates and by-products on the same active sites. For example, the dual-chamber nanoreactor developed by Ma et al.[67]

Figure 6. (A) Schematic illustration of the concentration distribution of reactants, and kinetic plots of the cascade reaction in the dual-chambered nanoreactor (Au in the bottom chamber, Pd in the upper chamber). Reproduced with permission from ref.[67]. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature; (B) Kinetic plots of the cascade reaction in the single-chambered nanoreactor (Au and Pd loaded in the same chamber). The selectivity to 2-phenylindole as a function of time. Reproduced with permission from ref.[67]. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature; (C) Reaction network of the cascade reaction. Reproduced with permission from ref.[68]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature; (D) Results of the cascade reaction over different catalysts. Results of the cascade reactions over SPs prepared with differently sized MSNs. Reproduced with permission from ref.[68]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature; (E) Schematic illustration for proximity effects. Reproduced with permission from ref.[68]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature. SP: Supraparticle; MSN: mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

The cascade reaction of ketone hydrogenation to racemic alcohols followed by kinetic resolution is a promising method for one-pot synthesis of chiral alcohol and ester. In this process, Pd NPs catalyze the hydrogenation of acetophenone to racemic 1-phenylethanol, followed by the acylation of one enantiomer to produce chiral phenylethyl acetate [Figure 6C]. However, side reactions like debenzylation and hydrogenation of styrene have limited yields. The Pd-CALB (Candida antarctica Lipase B) /SPs catalyst, which spatially separates Pd NPs and CALB, minimizes these side reactions, improving both yield and enantiomeric excess (EE) [Figure 6D and E]. The spatial separation also enables efficient intermediate transfer between Pd and CALB. Optimizing the size of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) further improved the reaction efficiency by reducing the distance between Pd and CALB. Smaller MSNs increased conversion but led to more by-products, while larger MSNs decreased conversion and EE[68] [Figure 5D and E].

Enhancement of biphasic catalysis

Mesoporous nanoreactors exhibit distinct advantages in enhancing biphasic catalytic reactions by addressing critical limitations such as phase transfer resistance and active site accessibility. Their anisotropic wettability enables the stabilization of Pickering emulsions, which maximize the oil/water interfacial area, thereby improving the contact and transfer efficiency between immiscible phases. The hierarchical porous structure, integrating mesopores and micropores, offers abundant active sites while facilitating rapid diffusion of reactants to catalytic centers.

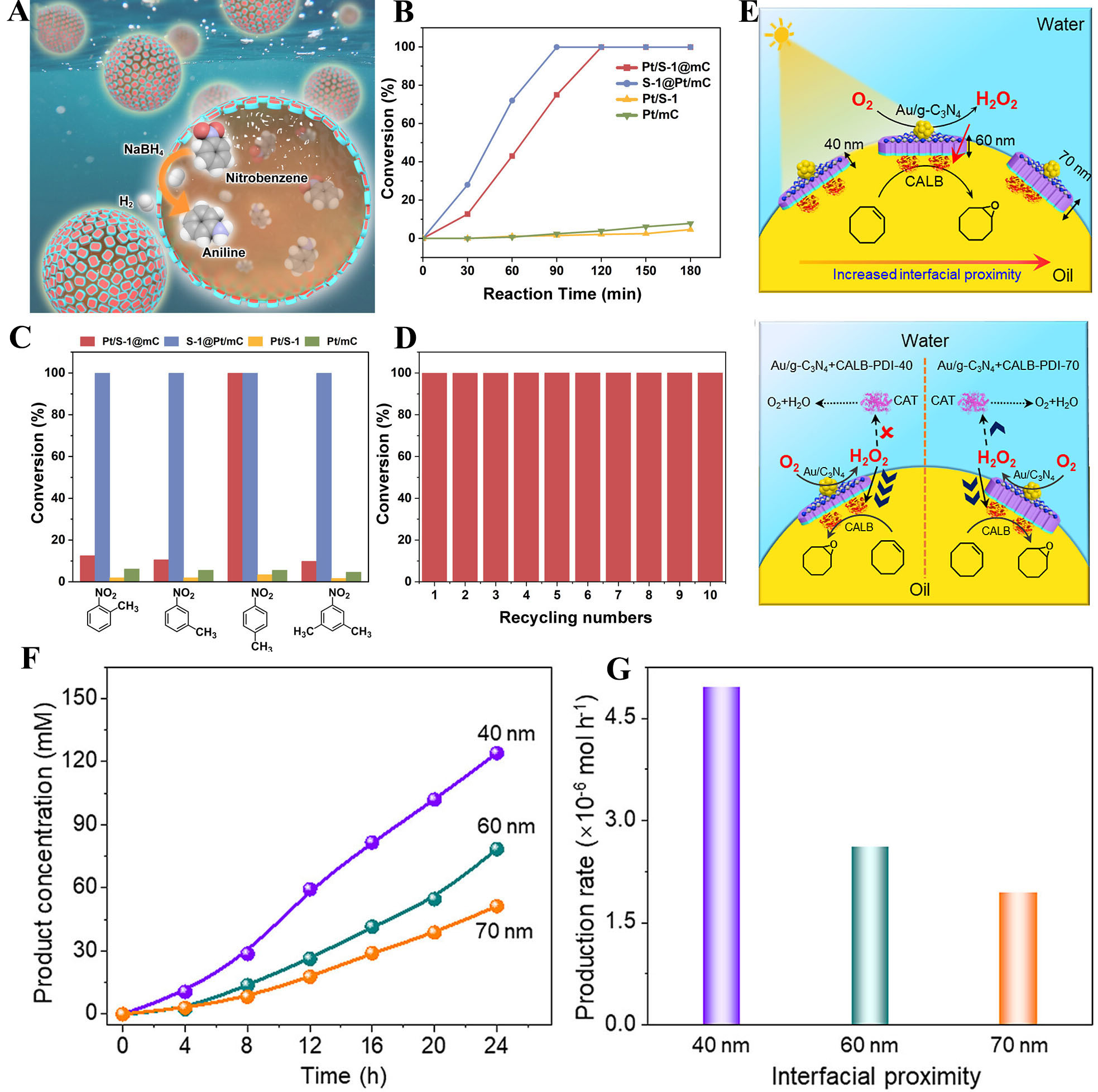

Chen et al.[69] prepared Pt/S-1@mC and S-1@Pt/mC catalysts, which were employed in a biphasic Pt-catalyzed nitroarene reduction reaction under stirring-free conditions [Figure 7A]. The nitroarene and NaBH4 were confined within toluene droplets and water phases, respectively, forming a stable Pickering emulsion. Both catalysts achieved 100% nitrobenzene conversion within 2 h, but the S-1@Pt/mC catalyst exhibited a higher reaction rate due to faster diffusion of reactants to active sites in its mesopores compared to micropores [Figure 7B-D]. The Pt/S-1@mC nanoreactor exhibits a well-defined structure-function relationship that enhances biphasic catalysis. The anisotropic wettability of the nanocomposite enables it to stabilize Pickering emulsions, increasing the oil/water interfacial area for efficient phase transfer. Pt nanoparticles are confined within the microporous zeolite matrix, allowing shape-selective catalysis by restricting access based on molecular size. For S-1@Pt/mC, Pt nanoparticles are located in mesopores, facilitating faster diffusion of reactants to active sites. The unique integration of zeolite micropores and mesopores in these nanoreactors ensures controlled reaction localization, short diffusion distances, and abundant accessible active sites, collectively promoting efficient and selective biphasic catalysis.

Figure 7. (A) Schematic illustration of NaBH4 hydrolysis combined with nitrobenzene hydrogenation in the Pickering emulsion system, catalyzed by the Pt/S-1@mC at the droplet interfaces. Reproduced with permission from ref.[69]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (B) Kinetic profile for nitrobenzene reductions over Pt/S-1@mC, S-1@Pt/mC, Pt/mC, and Pt/S-1 catalysts under stirring-free conditions. Reproduced with permission from ref.[69]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (C) Conversions of four different nitroarenes in the hydrogenation reaction under stirring-free conditions over Pt/S-1@mC, S-1@Pt/mC, Pt/mC, and Pt/S-1 catalysts. Reproduced with permission from ref.[69]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (D) Recyclability test of the Pt/S-1@mC catalyst in the nitrobenzene reduction reaction. Reproduced with permission from ref.[69]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (E) Schematic illustration for the spatial proximity between the Au/g-C3N4-NSs photocatalyst and the CALB biocatalyst at Pickering droplet interfaces. Reproduced with permission from ref.[70]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier; (F) Kinetic profiles for the photobiocatalytic cyclooctene epoxidation over Au/g-C3N4+CALB-PDI with different interfacial proximities. Reproduced with permission from ref.[70]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier; (G) Production rates of Au/g-C3N4+CALB-PDI with different interfacial proximities in the photobiocatalytic cyclooctene epoxidation. Reproduced with permission from ref.[70]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier. CALB: Candida antarctica Lipase B.

The Au/g-C3N4-NSs catalyst, prepared by Li et al.[70], enhances photocatalytic H2O2 production by immobilizing gold nanoparticles on g-C3N4 nanosheets, which significantly improves the separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs [Figure 7E]. The high interfacial activity of the catalyst enables it to stably localize at the Pickering emulsion interface, ensuring spatial separation between the photocatalyst and the enzyme, thereby preventing oxidative deactivation of the enzyme by reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, this interfacial localization effectively shortens the diffusion distance of H2O2 from the photocatalytic site to the enzymatic active site, enhancing the efficiency of the biphasic catalytic process

Enhancement of electrocatalysis

The mesoporous nanoreactor offers distinctive advantages in enhancing electrocatalytic reactions by leveraging its unique structural and compositional features. Its design enables the integration of defects and tailored interfaces, creating a synergistic environment that facilitates reaction kinetics and improves catalytic efficiency. The mesoporous structure not only ensures abundant active sites and efficient mass transport but also enhances the stability of the catalyst by mitigating deactivation mechanisms. These characteristics make mesoporous nanoreactors highly effective platforms for achieving improved activity, selectivity, and durability in a wide range of electrocatalytic processes.

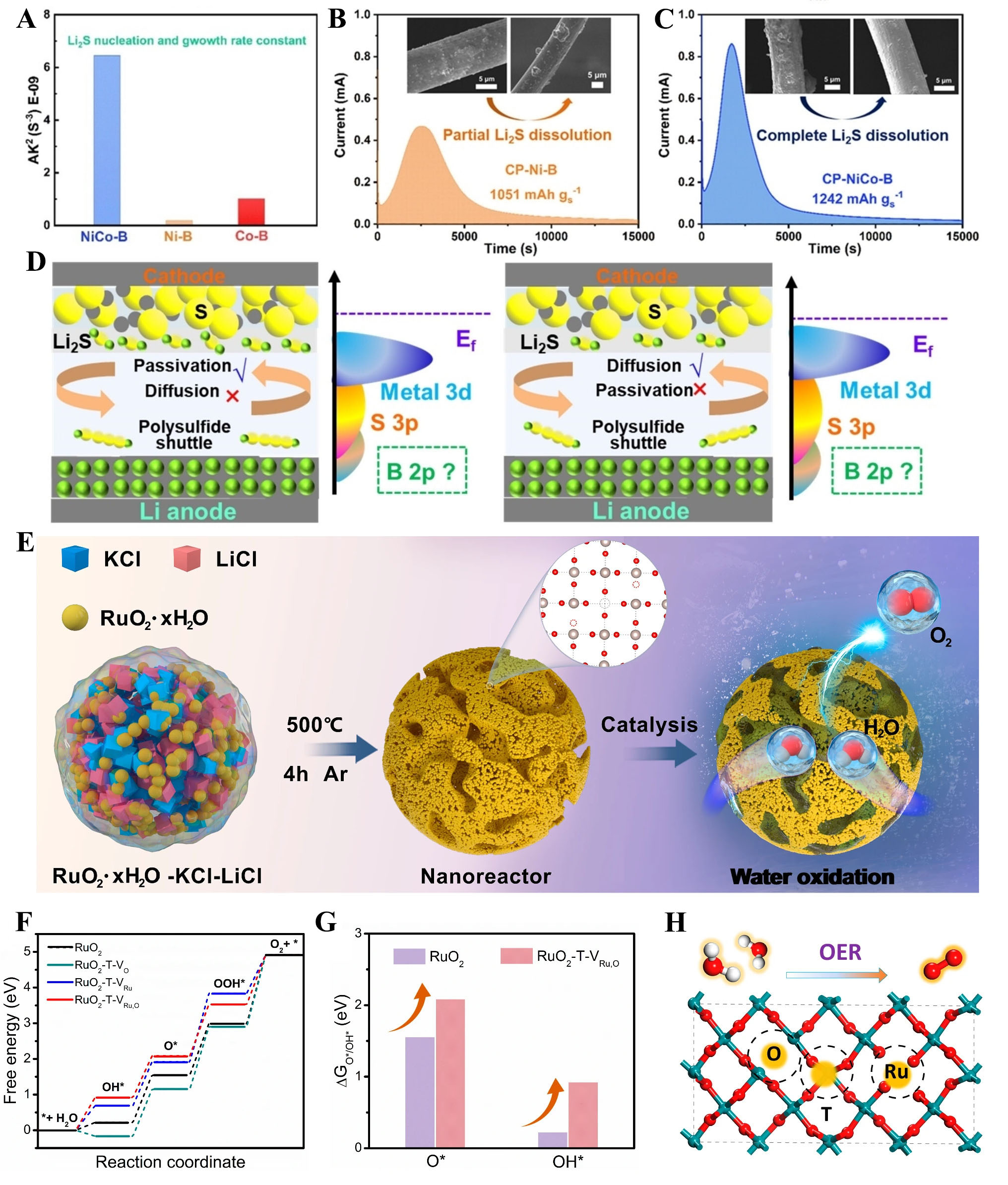

The superiority of the prepared NiCo-B nanoreactor by Wang et al.[71] lies in its unique structural advantages that effectively promote biphasic catalysis by optimizing the interplay between adsorption and catalytic conversion [Figure 8A]. The dual-cavity design of NiCo-B not only enhances the confinement of active species such as polysulfides but also suppresses the shuttle effect by facilitating their efficient conversion [Figure 8B and C]. Finite element simulations reveal that the dual-cavity structure maintains a lower polysulfide concentration and reduces stress accumulation during charge-discharge processes, ensuring better stability and suitability under high current densities [Figure 8D]. Moreover, Density functional theory (DFT)calculations demonstrate that the interaction between Ni-B and sulfur-containing species, bolstered by strong B-S bonding, leads to a balanced adsorption strength, which avoids catalyst deactivation while accelerating the nucleation and conversion of Li2S. This synergy between Ni-B and Co-B components further optimizes the electronic band structure, leveraging the complementary roles of their d-band centers to achieve efficient catalytic performance.

Figure 8. (A) Li2S nucleation and growth rate constant. Reproduced with permission from ref.[71]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH. Li2S dissolution test and SEM for (B) Ni-B. Reproduced with permission from ref.[71]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH; (C) NiCo-B. Reproduced with permission from ref.[71]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH; (D) Schematic illustration of interactions of polysulfides with Ni-B (left) and Co-B (right). Reproduced with permission from ref.[71]. Copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH; (E) Schematic illustration of the fabrication and catalytic procedure of bicontinuous nanoreactor composed of multiscale defective RuO2nanomonomers (MD-RuO2-BN). Reproduced with permission from ref.[72]. Copyright 2024, The Author(s); (F) The free energy profile of oxygen evolution reaction (OER) on twin boundary Ru sites (TB-Ru) sites. Reproduced with permission from ref.[72]. Copyright 2024, The Author(s); (G) Calculated O* and OH* adsorption energy of RuO2 and RuO2-T-VRu, O, where * denotes an adsorbed species on the catalyst surface. Reproduced with permission from ref.[72]. Copyright 2024, The Author(s); (H) The active sites (yellow highlights) on RuO2-T-VRu, O for catalyzing OER. Reproduced with permission from ref.[72]. Copyright 2024, The Author(s).

Building on the previous nanoreactor system, which demonstrated enhanced photocatalytic semi-hydrogenation through crystalline-amorphous synergy, Chen et al.[72] extend the concept to electrocatalytic oxygen evolution by introducing multiscale defects in RuO2 [Figure 8E]. The incorporation of oxygen vacancies (Vo), Ru vacancies (VRu), and twin boundaries (T) redefines the catalytic landscape, with twin boundary Ru sites (TB-Ru) playing a pivotal role in reducing the energy barrier for the OOH*-to-O2 step to an overpotential of just 0.22 V [Figure 8F-H]. Meanwhile, Vo and VRu weaken oxygenated intermediate adsorption, enhancing stability by mitigating strong binding effects. This multiscale defect synergy not only bridges the design principles across different catalytic systems but also unveils a robust mechanism for improving both activity and durability in nanoreactor engineering.

OUTLOOK & HORIZONS

In recent years, through the employment of bottom-up or top-down methods, a variety of uniquely structured mesoporous nanoreactors have been successfully fabricated to meet the demands for more specific functionalities. The bottom-up approach to constructing these unique mesoporous materials involves interface assembly at various interfaces, including liquid-liquid and liquid-solid, utilizing interface energy induction and internal tension adjustments for anisotropic growth. The top-down method leverages the heterogeneity of primary polymer density and the tunability of crosslinking density distribution for selective etching or subsequent interface transformation processes to precisely manipulate structures. These controllably fabricated functional mesoporous nanoreactors exhibit exceptional performance in catalysis. Despite the significant achievements in developing specific mesoporous structures and establishing the relationships between structure and function in applications, as well as in theoretical studies, future work still faces many challenges.

(1) The interfacial assembly behavior of primary polymers, driven by the self-assembly of micelles, is crucial for understanding and controlling the micelle-based interfacial assembly process, especially when independently manipulating the mesoporous parameters within each compartment of a nanocomposite material is critical. Emerging in situ electron microscopy techniques are well-suited for directly observing the structural evolution of micelles, the reduction of metal precursors, and the nucleation and growth of nanomaterials. In situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy and related techniques enable the tracking of oxidation states and coordination environment changes of metal active sites. In situ small-angle X-ray scattering and surface scattering techniques provide insights into the variations in size, morphology, and ordering of nanostructures during the assembly process. Moreover, in-depth studies of the dynamics of micelle self-assembly and their interactions with interfaces are facilitated through molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations. To further precisely control the interfacial assembly of single micelles, the application of external fields such as electric fields, magnetic fields, or light fields has proven to be an effective approach, guiding the assembly direction and structure of micelles. Additionally, specific chemical modifications of micelles or interfaces, by introducing functional groups, enable more refined structural and functional designs. This comprehensive application of multiple perspectives and techniques not only provides a thorough understanding of the micelle-based interfacial assembly process but also paves new pathways for designing and fabricating novel nanomaterials with specific functionalities, thereby advancing the fields of nanoscience and materials science. Since the single-micelle control approach defines the fundamental structure and functionality of nanoreactors, it serves as the foundational step and the primary challenge that must be addressed in their design.

(2) Top-down approaches often face challenges in achieving ordered and regular structures due to the inherent limitations of selectively removing material to create features. Chemical etching and trimming processes require a broader exploration of “chemical scalpels” to precisely remove or modify materials at the nanoscale. A deeper understanding of the interfacial reorganization mechanisms is crucial for enabling researchers to achieve selective and precise modifications of materials. These chemical scalpels, which include acids, bases, and other reagents, can selectively etch away specific components of a material, leaving behind the desired structure. However, to improve the accuracy and selectivity of these processes, there is a need for a more comprehensive toolkit of chemical agents that can target specific bonds or material components without damaging the rest of the structure. Understanding the interfacial reorganization mechanism involves studying how molecular rearrangements at interfaces can influence the overall structure and functionality of the material. This includes how molecules orient themselves at interfaces, how they interact with each other, and how these interactions can be manipulated to achieve desired outcomes. By gaining insights into these processes, researchers can better control the morphology and properties of materials at the nanoscale. This enhanced control can lead to the fabrication of nanostructures with highly specific functions and properties, tailored for applications in catalysis, sensors, energy storage, and more. For instance, precise etching can be used to create nanopores with specific sizes and shapes for selective filtration applications, or to modify the surface properties of nanoparticles to improve their reactivity or compatibility with different environments. Moreover, advancements in characterization techniques, such as high-resolution electron microscopy and spectroscopy methods, can provide detailed insights into the effects of chemical etching and interfacial reorganization. These techniques can help visualize the changes at the nanoscale, allowing for a more targeted approach to material design.

(3) While exploring innovative strategies and methodologies, scientists are propelling forward in the fields of nanotechnology and materials science. For instance, through precise surface chemical modification and molecular-level self-assembly processes, functional components can be introduced at specific locations within nanomaterials. This approach enables the manipulation of chemical properties and physical states at the nanoscale, facilitating highly selective and active reactions or processes. Additionally, the application of advanced nanofabrication technologies such as electron beam lithography and scanning probe lithography opens up greater flexibility and possibilities for the precise design and fabrication of nanomaterials with specific functions. These technologies offer a pathway to integrate multiple functionalities within a single nanomaterial and adjust the chemical composition and physical properties of each compartment according to specific application requirements.

(4) This bottom-up strategy is inherently scalable, as it relies on self-organization processes that can be extended to large surface areas or bulk materials. However, maintaining uniform micelle size, stability, and precise spatial arrangement at an industrial scale remains a challenge. Advances in continuous flow synthesis, templating strategies, and external field-assisted assembly (e.g., electric or magnetic fields) can enhance scalability while ensuring structural consistency. To successfully transition these approaches to industrial-scale applications, a combination of process automation, real-time monitoring, and integration with high-throughput manufacturing techniques is essential.

(4) In the realms of nanotechnology and materials science, the development of mesoporous nanoreactors with advanced structural designs is key to unlocking novel applications. These intricately designed nanostructures have proven their mettle not just in traditional areas like catalysis, energy storage, and drug delivery systems but are also making significant strides in emerging fields such as environmental remediation, biosensing, and optoelectronic materials. For instance, in environmental science, specifically designed mesoporous nanoreactors facilitate the efficient removal and decomposition of pollutants like heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants, owing to their high surface reactivity and customizable pore structures. In biomedicine, these materials, by tuning pore sizes and surface modifications, serve as efficient drug delivery platforms, enabling precise drug targeting and release, thus enhancing therapeutic effects while minimizing systemic side effects. Additionally, in the energy sector, the application of mesoporous nanoreactors as battery electrode materials shows immense potential in enhancing battery performance and lifespan. Their unique porous structures help optimize ion transport paths and charge distribution, thereby improving energy density and charge-discharge efficiency. In the field of optics, precise control over the structure of mesoporous nanoreactors has led to the creation of efficient photocatalysts and photovoltaic materials. They effectively capture and utilize light energy, opening new possibilities for the development of clean energy. Meanwhile, in sensing technology, mesoporous nanoreactors, through surface modifications, achieve high sensitivity and specificity in detecting specific chemical substances, offering new tools for environmental monitoring and early disease diagnosis. In summary, mesoporous nanoreactors based on advanced structures not only play a crucial role in enhancing the performance of existing applications but also in exploring and developing entirely new application domains. Further research and development of these materials are expected to provide a significant impetus for future scientific research and technological innovation, paving the way for breakthroughs across a wide spectrum of disciplines.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, recent years have witnessed rapid progress in the construction of mesoporous nanoreactors enabled by advanced interfacial engineering strategies. Through bottom-up and top-down approaches, substantial advances have been achieved in micelle-based interfacial assembly, chemical etching and trimming ("chemical scalpel") methodologies, and the rational design of precise and multifunctional mesoporous architectures, supported by in situ characterization techniques and theoretical simulations to elucidate structure–function relationships. These collective efforts have significantly expanded the application scope of mesoporous nanoreactors, particularly in catalysis and other emerging fields, while simultaneously revealing critical challenges related to single-micelle control, interfacial reorganization mechanisms, and scalable fabrication. Future progress is expected to rely on deeper interdisciplinary collaboration and the integration of advanced assembly strategies and manufacturing technologies to enable the precise, scalable, and application-oriented design of mesoporous nanoreactors.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conception and writing manuscript: Wang, A.; Duan, L.; Ma, Y.

Drawing the diagram: Wang, A.; Ma, Y.

All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22088101, 22375107), the "Junma" Program of Inner Mongolia University (23600-5233709, 13100-15112005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22305155), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M732323), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20231679).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Sun, C.; Bai, B. Molecular sieving through a graphene nanopore: non-equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Bull. (Beijing). 2017, 62, 554-62.

2. Gong, X.; Li, J.; Xu, K.; Wang, J.; Yang, H. A controllable molecular sieve for Na+ and K+ ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1873-7.

3. Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Understanding the chemistry of mesostructured porous nanoreactors. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 915-31.

4. Ying, Y.; Gao, R.; Hu, Y.; Long, Y. Electrochemical confinement effects for innovating new nanopore sensing mechanisms. Small. Methods. 2018, 2, 1700390.

5. Dai, J.; Zhang, H. Recent advances in catalytic confinement effect within micro/meso-porous crystalline materials. Small 2021, 17, e2005334.

6. Zhou, W.; Deng, Q. W.; Ren, G. Q.; et al. Enhanced carbon dioxide conversion at ambient conditions via a pore enrichment effect. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4481.

7. Gao, R.; Lin, Y.; Ying, Y. L.; et al. Dynamic self-assembly of homogenous microcyclic structures controlled by a silver-coated nanopore. Small 2017, 13.

8. Gu, Z.; Cai, Z.; Elmegreen, B.; et al. How water adsorbed on porous graphene affects CO2 capture and separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474;145778.

9. Blonskaya, I.; Lizunov, N.; Olejniczak, K.; et al. Elucidating the roles of diffusion and osmotic flow in controlling the geometry of nanochannels in asymmetric track-etched membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 618, 118657.

10. Gu, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, X.; et al. Mesoporous manganese oxide with large specific surface area for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitor with enhanced cycling stability. Chem. Eng. J. , 2017, 324:35-43.

11. C.; Burch, R. Mesoporous materials for water treatment processes. Water. Res. 1999, 33, 3689-94.

12. Zhao, X.; Gao, P.; Shen, B.; Wang, X.; Yue, T.; Han, Z. Recent advances in lignin-derived mesoporous carbon based-on template methods. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2023, 188, 113808.

13. Dong, Z.; Chen, W.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, F. Understanding the structure-activity relationships in catalytic conversion of polyolefin plastics by zeolite-based catalysts: a critical review. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 14882-901.

14. He, X.; Tian, Y.; Qiao, C.; et al. Acid-driven architecture of hierarchical porous ZSM-5 with high acidic quantity and its catalytic cracking performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145334.

15. Dai, L.; Zhou, N.; Cobb, K.; et al. Insights into structure-performance relationship in the catalytic cracking of high density polyethylene. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2022, 318, 121835.

16. Duan, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; et al. Interfacial assembly and applications of functional mesoporous materials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 14349-429.

17. Dong, C.; Han, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z. Scalable dealloying route to mesoporous ternary conife layered double hydroxides for efficient oxygen evolution. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 16096-104.

18. Lee, S.; Park, Y.; Choi, M. Cooperative interplay of micropores/mesopores of hierarchical zeolite in chemical production. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 2031-48.

19. Zürner, A.; Kirstein, J.; Döblinger, M.; Bräuchle, C.; Bein, T. Visualizing single-molecule diffusion in mesoporous materials. Nature 2007, 450, 705-8.

20. Calvo, A.; Yameen, B.; Williams, F. J.; Soler-Illia, G. J.; Azzaroni, O. Mesoporous films and polymer brushes helping each other to modulate ionic transport in nanoconfined environments. An interesting example of synergism in functional hybrid assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10866-8.

21. Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Gong, Q.; et al. Chemical reaction kinetics-guided size and pore structure tuning strategy for fabricating hollow carbon spheres and their selective adsorption properties. Carbon 2021, 183, 158-68.

22. Huff, C. A.; Sanford, M. S. Cascade catalysis for the homogeneous hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18122-5.

23. Xu, W.; Jiao, L.; Wu, Y.; et al. Metal-organic frameworks enhance biomimetic cascade catalysis for biosensing. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005172.

24. Mo, T.; Bi, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Ion structure transition enhances charging dynamics in subnanometer pores. ACS. Nano. 2020, 14, 2395-403.

25. Kondrat, S.; Wu, P.; Qiao, R.; Kornyshev, A. A. Accelerating charging dynamics in subnanometre pores. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 387-93.

26. Wu, D.; Zhang, P.; Yang, G.; et al. Supramolecular control of MOF pore properties for the tailored guest adsorption/separation applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 434, 213709.

27. Ji, Z.; Wang, H.; Canossa, S.; Wuttke, S.; Yaghi, O. M. Pore chemistry of metal-organic frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000238.

28. Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Huo, Q.; et al. Triblock copolymer syntheses of mesoporous silica with periodic 50 to 300 angstrom pores. Science 1998, 279, 548-52.

29. Pang, X.; Zhao, L.; Han, W.; Xin, X.; Lin, Z. A general and robust strategy for the synthesis of nearly monodisperse colloidal nanocrystals. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 426-31.

30. Zhao, Z.; Wang, X.; Jing, X.; et al. General synthesis of ultrafine monodispersed hybrid nanoparticles from highly stable monomicelles. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2100820.

31. Zhao, T.; Chen, L.; Lin, R.; et al. Interfacial Assembly directed unique mesoporous architectures: from symmetric to asymmetric. Acc. Mater. Res. 2020, 1, 100-14.

32. Kruk, M. Access to ultralarge-pore ordered mesoporous materials through selection of surfactant/swelling-agent micellar templates. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1678-87.

33. Xie, L.; Liu, J.; Bao, X.; et al. Interfacial assembly of nanowire arrays toward carbonaceous mesoporous nanorods and superstructures. Small 2022, 18, e2104477.

34. Li, D.; Gong, B.; Cheng, X.; et al. An efficient strategy toward multichambered carbon nanoboxes with multiple spatial confinement for advanced sodium-sulfur batteries. ACS. Nano. 2021, 15, 20607-18.

35. Xu, H.; Han, J.; Zhao, B.; et al. A facile dual-template-directed successive assembly approach to hollow multi-shell mesoporous metal-organic framework particles. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8062.

36. Huang, C.; Sun, W.; Jin, Y.; et al. A general synthesis of nanostructured conductive metal-organic frameworks from insulating MOF precursors for supercapacitors and chemiresistive sensors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202313591.

37. Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Gu, J.; et al. Competition among refined hollow structures in schiff base polymer derived carbon microspheres. Nano. Lett. 2022, 22, 3691-8.

38. Yan, M.; Hou, J.; Zhou, J. Effective adsorption of cyclohexene and analytically perfect separation of cyclohexene/cyclohexanol azeotropes by nonporous adaptive crystals of a Hybrid[3]arene. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 10850-6.

39. Pan, P.; Liu, Q.; Hu, L.; et al. Dual-template induced interfacial assembly of yolk-shell magnetic mesoporous polydopamine vesicles with tunable cavity for enhanced photothermal antibacterial. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144972.

40. Zhao, T.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; et al. Surface-confined winding assembly of mesoporous nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 148, 20359-67.

41. Yan, M.; Liu, T.; Li, X.; et al. Soft patch interface-oriented superassembly of complex hollow nanoarchitectures for smart dual-responsive nanospacecrafts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7778-89.

42. Zhao, T.; Lin, R.; Xu, B.; et al. Mesoporous nano-badminton with asymmetric mass distribution: how nanoscale architecture affects the blood flow dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 21454-64.

43. Liu, M.; Shang, C.; Zhao, T.; et al. Site-specific anisotropic assembly of amorphous mesoporous subunits on crystalline metal-organic framework. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1211.

44. Falkowska, M.; Bowron, D. T.; Manyar, H.; Youngs, T. G. A.; Hardacre, C. Confinement effects on the benzene orientational structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2018, 57, 4565-70.

45. Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Gu, J. Nanoemulsion-directed growth of MOFs with versatile architectures for the heterogeneous regeneration of coenzymes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1879.

46. Wu, T.; Chen, G.; Han, J.; et al. Construction of three-dimensional dendritic hierarchically porous metal-organic framework nanoarchitectures via noncentrosymmetric pore-induced anisotropic assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 16498-507.

47. Peng, L.; Hung, C. T.; Wang, S.; et al. Versatile nanoemulsion assembly approach to synthesize functional mesoporous carbon nanospheres with tunable pore sizes and architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 7073-80.

48. Peng, L.; Peng, H.; Xu, L.; et al. Anisotropic self-assembly of asymmetric mesoporous hemispheres with tunable pore structures at liquid-liquid interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 15754-63.

49. Qiu, B.; Xie, L.; Zeng, J.; et al. Interfacially super-assembled asymmetric and H2O2 sensitive multilayer-sandwich magnetic mesoporous silica nanomotors for detecting and removing heavy metal ions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010694.

50. Ma, Y.; Lan, K.; Xu, B.; et al. Streamlined mesoporous silica nanoparticles with tunable curvature from interfacial dynamic-migration strategy for nanomotors. Nano. Lett. 2021, 21, 6071-9.

51. Ma, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, R.; et al. Synthesis of branched silica nanotrees using a nanodroplet sequential fusion strategy. Nat. Synth. 2024, 3, 236-44.

52. Zhang, M.; Ettelaie, R.; Dong, L.; et al. Pickering emulsion droplet-based biomimetic microreactors for continuous flow cascade reactions. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 475.

53. Heidari, F.; Jafari, S. M.; Ziaiifar, A. M.; Malekjani, N. Stability and release mechanisms of double emulsions loaded with bioactive compounds; a critical review. Adv. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2022, 299, 102567.

54. Hao, R.; Zhang, M.; Tian, D.; et al. Bottom-up synthesis of multicompartmentalized microreactors for continuous flow catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20319-27.

55. Zheng, Z.; Hu, Z.; Lou, Y.; et al. Porosity vs carbon shell number: key factor actually affecting the performance of multi-shelled hollow carbon nanospheres in Li-S batteries. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 927, 116980.

56. Pi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Multilevel hollow phenolic resin nanoreactors with precise metal nanoparticles spatial location toward promising heterogeneous hydrogenations. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2205153.

57. Pi, Y.; Cui, L.; Luo, W.; et al. Design of hollow nanoreactors for size- and shape-selective catalytic semihydrogenation driven by molecular recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202307096.

58. Teng, Z.; Su, X.; Zheng, Y.; et al. A Facile Multi-interface transformation approach to monodisperse multiple-shelled periodic mesoporous organosilica hollow spheres. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7935-44.

59. Su, X.; Tang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Facile synthesis of monodisperse hollow mesoporous organosilica/silica nanospheres by an in situ dissolution and reassembly approach. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 12063-9.

60. Zou, H.; Dai, J.; Suo, J.; et al. Dual metal nanoparticles within multicompartmentalized mesoporous organosilicas for efficient sequential hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4968.

61. Yao, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lv, J.; Ma, X. A High-performance nanoreactor for carbon-oxygen bond hydrogenation reactions achieved by the morphology of nanotube-assembled hollow spheres. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 1218-26.

62. Pan, X.; Bao, X. The effects of confinement inside carbon nanotubes on catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 553-62.

63. Guan, J.; Pan, X.; Liu, X.; Bao, X. Syngas segregation induced by confinement in carbon nanotubes: a combined first-principles and Monte Carlo study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009, 113, 21687-92.

64. Yao, D.; Wang, Y.; Hassan-legault, K.; et al. Balancing effect between adsorption and diffusion on catalytic performance inside hollow nanostructured catalyst. ACS. Catal. 2019, 9, 2969-76.

65. Lancet, D.; Pecht, I. Spectroscopic and immunochemical studies with nitrobenzoxadiazolealanine, a fluorescent dinitrophenyl analogue. Biochemistry 1977, 16, 5150-7.

66. Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; et al. Reactant enrichment in hollow void of Pt NPs&MnOx nanoreactors for boosting hydrogenation performance. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad201.

67. Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lin, R.; et al. Remodeling nanodroplets into hierarchical mesoporous silica nanoreactors with multiple chambers. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6136.

68. Guo, X.; Xue, N.; Zhang, M.; Ettelaie, R.; Yang, H. A supraparticle-based biomimetic cascade catalyst for continuous flow reaction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5935.

69. Chen, G.; Han, J.; Niu, Z.; et al. Regioselective surface assembly of mesoporous carbon on zeolites creating anisotropic wettability for biphasic interface catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9021-8.

70. Li, K.; Zou, H.; Tong, X.; Yang, H. Enhanced photobiocatalytic cascades at pickering droplet interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 17054-65.

71. Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Mamoor, M.; et al. Manipulating atomic-coupling in dual-cavity boride nanoreactor to achieve hierarchical catalytic engineering for sulfur cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 63, e202406065.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].