Global deletion of potassium channel Kv1.5 causes biventricular heart failure

Abstract

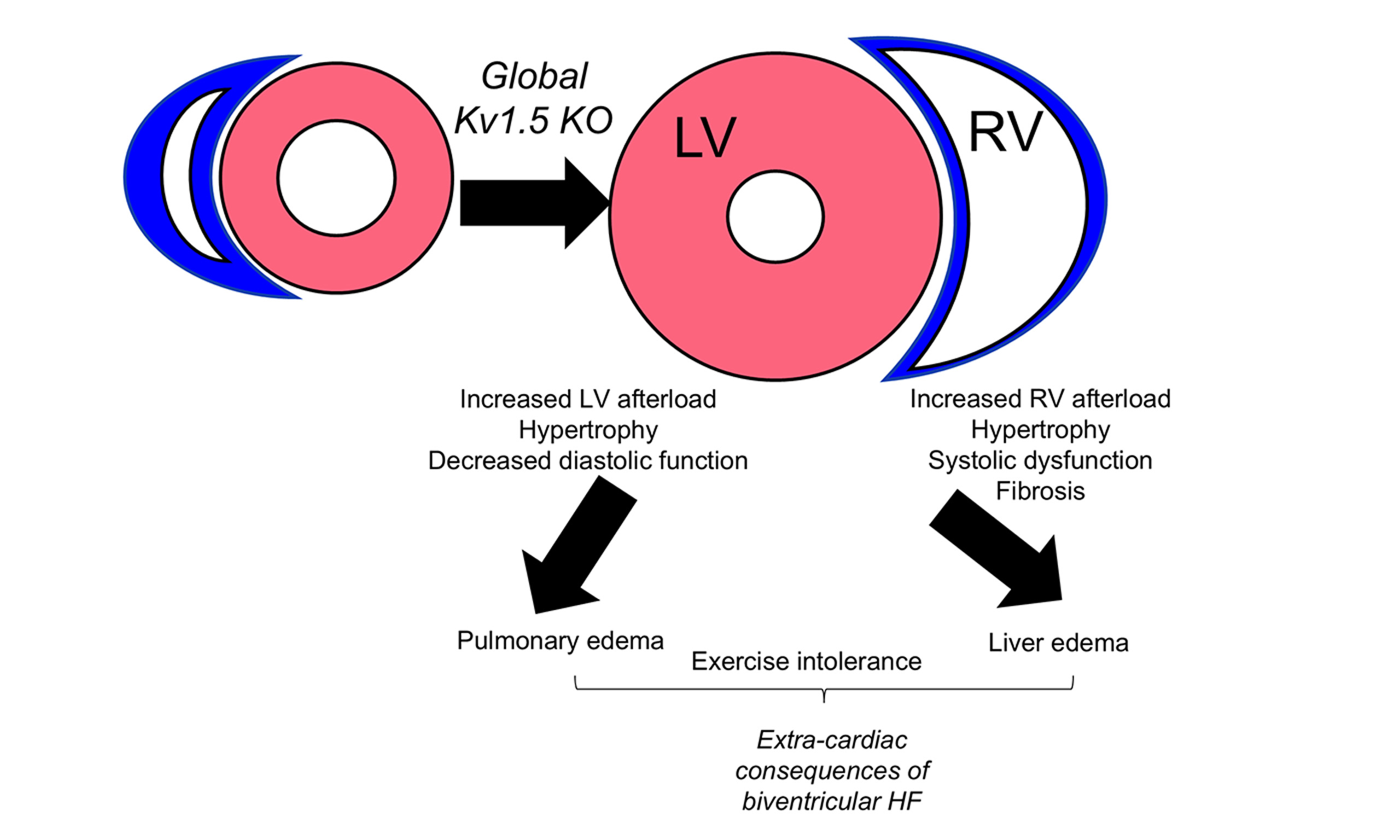

Background: Heart failure (HF) is a chronic disease with high morbidity and mortality among older populations. Chronic HF ultimately affects both the right (RV) and left (LV) ventricles and often presents with extra-cardiac outcomes including pulmonary hypertension (PH). Study of biventricular failure and its extra-cardiac consequences has been challenging in pre-clinical models, suggesting new models may be beneficial to uncover new mechanisms of disease. Potassium channels are implicit regulators of vascular tone and are strongly but independently associated with PH and LV dysfunction.

Aim: We hypothesized that deletion of the potassium rectifier channel Kv1.5 would cause biventricular HF, thus representing a new model from which to understand ventricle-specific mechanisms of HF.

Methods and Results: We used a model of global vasoconstriction by genetic deletion of potassium rectifier channel Kv1.5 (Kv1.5 KO). Male and female mice were studied at middle age (12-13 months) as this is when HF risk begins to increase with age. In response to Kv1.5 KO, both the LV and RV experienced elevated afterload. While Kv1.5 KO mice developed RV systolic dysfunction with hypertrophy and fibrosis, the LV developed mild hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. Consistent with biventricular remodeling, Kv1.5 KO mice also displayed higher liver and lung weights and exercise intolerance.

Conclusion: Deletion of Kv1.5 causes systemic and pulmonary vasoconstriction with distinct outcomes in the LV and RV. This model of biventricular dysfunction may be useful for studying extra-cardiac consequences of HF and understanding ventricle-specific mechanisms of disease.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is an enormous public health problem and continues to grow in prevalence and significance, in part due to the aging of the U.S. population[1]. Chronic HF ultimately affects both the right (RV) and left (LV) ventricles, resulting in biventricular failure, and often presents with extra-cardiac outcomes including pulmonary hypertension (PH). PH is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality in HF[2]. In both HF and PH, it is RV function that predicts survival[3,4]. However, no RV-directed therapies currently exist and those that target LV-based mechanisms are often not effective[5], underscoring the need to understand RV mechanisms distinct from those in the LV.

The diverse array of potassium (K+) channels in the cardiovascular system is an implicit regulator of vascular tone[6]. Among the types of K+ channels are voltage-regulated (Kv) channels. Kv1.5, also known as KCNA5, is an oxygen and redox sensitive member of the Kv family[7] that is widely expressed in vascular smooth muscle. The classical function of Kv1.5 is control of cell excitability. Outward K+ current flows through Kv1.5, resulting in a resting membrane potential that blocks voltage-gated calcium influx and smooth muscle contraction. Inhibition of channel activity thus results in accumulation of positively charged K+ within the cell, membrane depolarization, activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and thus vasoconstriction[8]. Loss of Kv1.5 activity results in vasoconstriction in the LV coronary supply[9] and in pulmonary artery (PA) smooth muscle cells[10]. Indeed, hypoxia-mediated loss of Kv1.5 activity has been widely described in the pulmonary vasculature[8], and it is strongly associated with pulmonary vascular remodeling and development of PH[11]. These findings suggest that Kv1.5 may be critical for regulation of vascular tone as it relates to both LV and RV function. However, the implication of loss of this channel on RV and LV remodeling is not well understood. Given that Kv1.5 is distributed throughout the systemic and pulmonic vasculature, we hypothesized that deletion of Kv1.5 would cause biventricular HF, thus representing a new model from which to understand ventricle-specific mechanisms of disease. We set out to test this hypothesis in middle-aged (12-14 months) mice. This age roughly extrapolates to 50 years in humans[12] and is the age at which HF risk begins to rise due to age-related changes to the cardiovascular system[13].

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Mouse model and overall experimental design

Male and female middle-aged (~12 months) S129 control (Con) or transgenic Kv1.5 knockout (KO) mice were used for these experiments. All protocols were approved by the University of Wyoming Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). S129 mice were purchased from Charles River. Kv1.5 KO (a model of global vasoconstriction by genetic deletion of potassium rectifier channel Kv1.5) mice were shared from Northeastern Ohio Medical University (Vahagn Ohanyan). All mice were bred and raised at the University of Wyoming with free access to standard rodent chow (Lab Diet 5001) and water. Twenty-four hours prior to euthanasia, the mice performed a graded exercise time-to-exhaustion test. Briefly, mice were first allowed to acclimate on the treadmill, followed by a beginning speed of 6 m/min at a fixed incline with gradual increases in speed until the mouse could no longer maintain speed[14]. Twenty-four hours after the treadmill test, mice underwent echocardiography followed by euthanasia by pentobarbital overdose. Total heart, LV, and RV weights were collected along with left tibia length (TL) for normalization. Liver weights and lung weights were collected to quantify edema. Tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen or preserved in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) for subsequent analysis.

Echocardiography

Cardiac function was assessed via transthoracic echocardiography using Visual Sonics Vevo 2100 with a

Histology

LV and RV were frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature immediately post-dissection and stored in -80 °C.

For assessment of fibrosis, LV and RV sections were stained using Picro-sirius red (Abcam 246832) protocols. Briefly, RV sections were hydrated using distilled water. Sufficient picro sirius red solution was added to cover tissue sections and incubated for one hour. Tissue sections were dipped in 0.5% acetic acid solution and washed in 75%, 90% and 100% ethanol. Images were acquired at 6X and processed with ImageJ[15].

qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated following the standard TRIzol protocol and reverse-transcribed using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA (complementary DNA) kit (Fisher Scientific). Gene expression was quantified by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using PowerSYBR Green PCR Master Mix on an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Ribosomal 18s was used as housekeeping control. Data are presented as fold-change within genotype and sex. Oligonucleotide sequences were as follows:

ANF Forward: GCCGGTAGAAGATGAGGTCATG,

ANF Reverse: GCTTCCTCAGTCTGCTCACTCA;

BNP Forward: CGCTGGGAGGTCACTCCTAT,

BNP Reverse: GCTCTGGAGACTGGCTAGGACTT;

α-MHC Forward: CCCAGGATCTCTGGATTGGTCT,

α-MHC Reverse: GGCAGGAAGAGGAGTAGCAGA;

β-MHC Forward: GAGCATTCTCCTGCTGTTTCCTT,

β-MHC Reverse: CTCCTCTGCTGAGGCTTCCTTT.

α-SMA Forward: GCTGGACTCTGGAGATGG;

α-SMA Reverse: GCAGTAGTCACGAAGGAATAG;

Periostin Forward: CCATTGGAGGCAAACAACTCC;

Periostin Reverse: TTGCTTCCTCTCACCATGCA;

Collagen 3 Forward: TTGGGATGCAGCCACCTTG;

Collagen 3 Reverse: CGCAAAGGACAGATCCTGAG.

Statistical analyses

Upon confirmation that the data were normally distributed, they were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA; genotype × sex), followed by Student's t-test within each sex. Significance was set a priori at P < 0.05. Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism v10. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

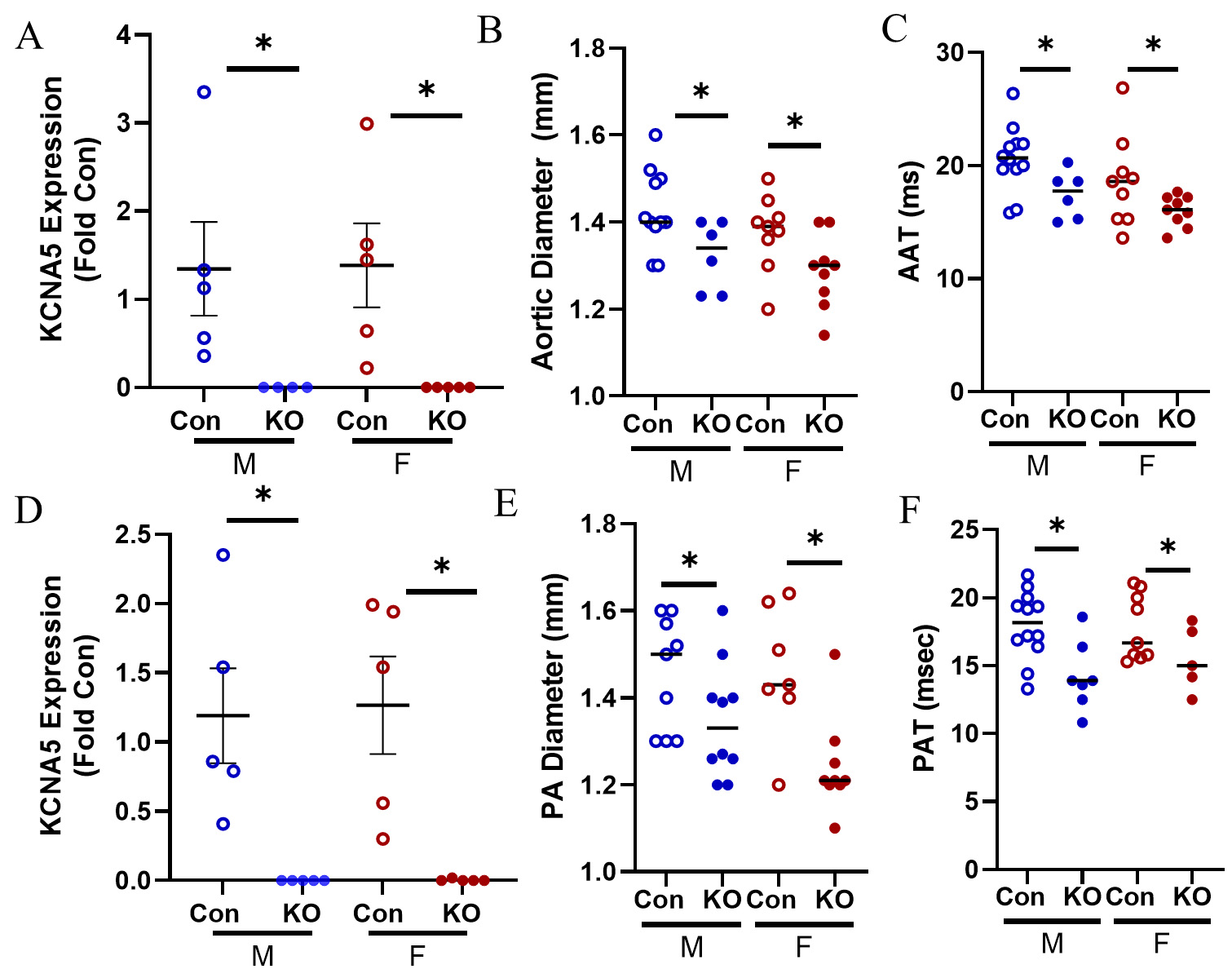

We confirmed loss of KCNA5 expression in the LV and found that it was profoundly reduced in KO mice compared to Con [Figure 1A]. As expected, KO mice had a smaller aortic diameter compared to Con

Figure 1. Model of systemic vasoconstriction by Kv1.5 KO. (A) KCNA5 expression in the LV was downregulated in male KO mice and female KO mice. (B) Aortic diameter was smaller in KO male and female mice. (C) Aortic artery acceleration time (AAT) was faster in KO male and female mice. (D) KCNA5 expression in the RV was downregulated in male KO mice and female KO mice. (E) Pulmonary artery (PA) diameter was smaller in male and female KO mice. (F) Pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAT) was lower in KO male and female mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 within sex t-test by Student’s t-test. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

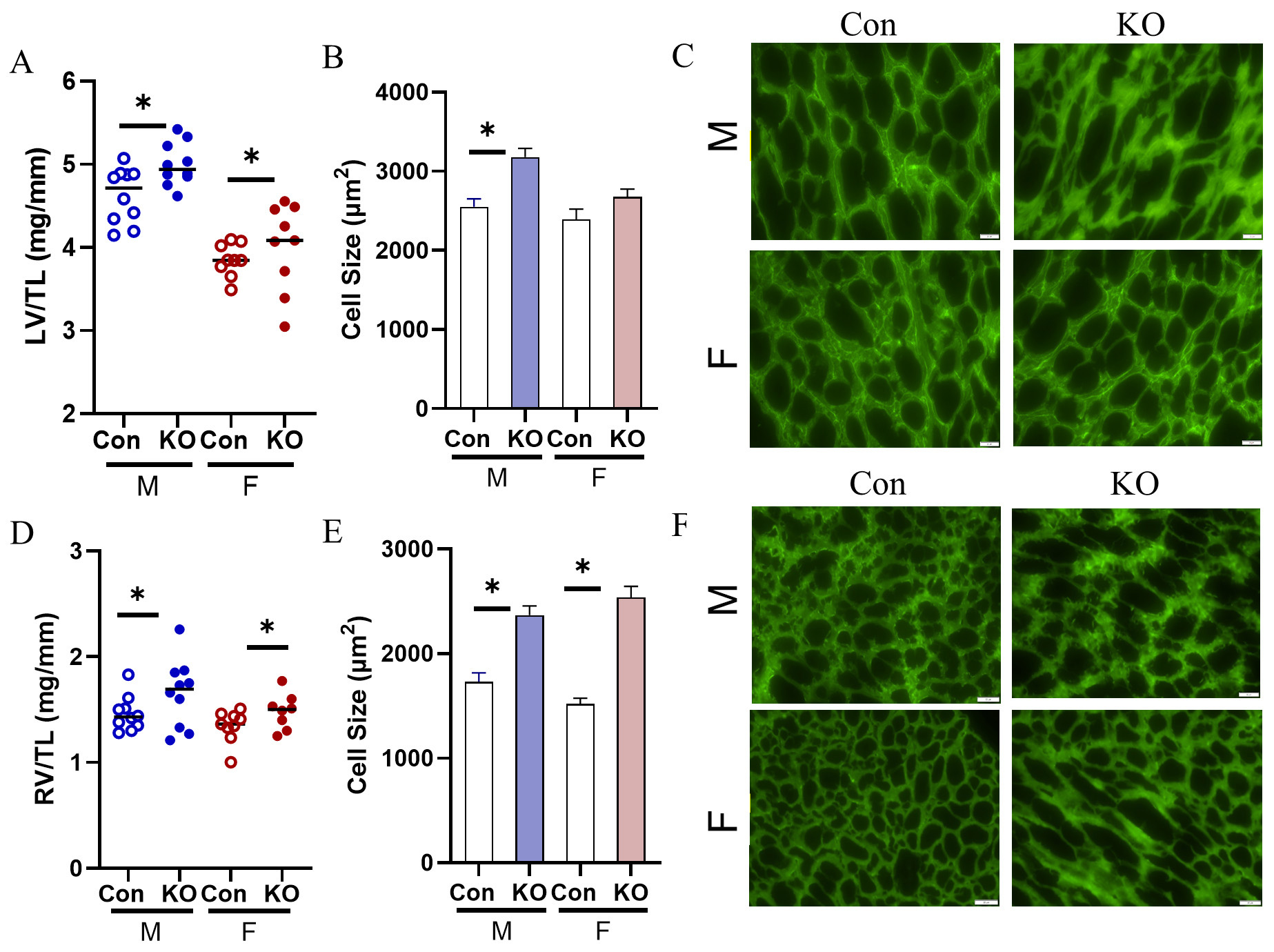

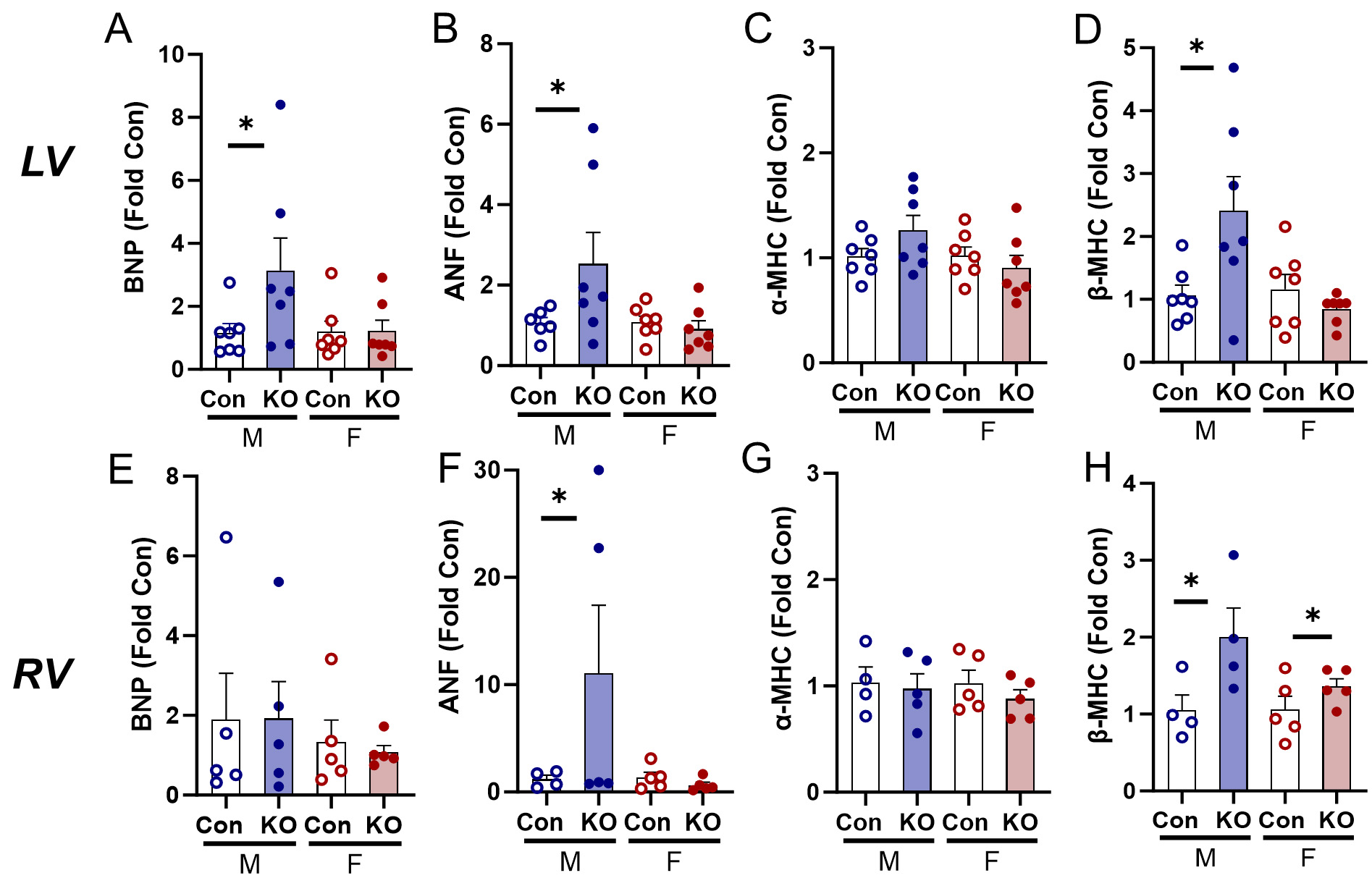

Both sexes underwent cardiac remodeling in response to global Kv1.5 KO as evidenced by higher heart weights normalized to TL (data not shown). Both sexes demonstrated higher LV weights normalized to TL (LV/TL) [Figure 2A] and LV myocyte cross-sectional area [Figure 2B and C] in male mice. RV weights were also elevated [Figure 2D] and RV myocyte cross-sectional area was larger in Kv1.5 KO, indicating RV hypertrophy in both sexes [Figure 2E and F]. We quantified expression of the hypertrophic gene program[16] and found higher expression of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the KO male LV [Figure 3A] and elevated atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) expression in the KO male LV [Figure 3B]. Although α-myosin heavy chain

Figure 2. Cardiac remodeling in response to Kv1.5 KO. (A) LV/TL was elevated in both male and female KO mice. (B) LV myocyte cell size was elevated with Kv1.5 deletion in male mice. (C) Representative images of LV lectin-stained cardiac myocytes. Scale bar: 20 mm. (D) RV/TL was elevated in male and female KO mice. (E) RV myocyte cell size was elevated in male and female KO mice. (F) Representative images of RV lectin-stained cardiac myocytes. Scale bar: 20 mm. n = 3 mice with technical triplicate for histology. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 within sex by Student’s t-test. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

Figure 3. Transcriptional activation of hypertrophic gene expression in the LV and RV in response to Kv1.5 KO. (A) Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) expression in the LV was upregulated in KO males and unchanged in females. (B) Atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) expression in the LV was upregulated in KO males and unchanged in female KO mice. (C) α-myosin heavy chain (α-MHC) expression in the LV was unchanged in male and female KO mice. (D) β- myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) expression was upregulated in KO males and unchanged in female KO mice. (E) BNP expression in the RV was unchanged. (F) ANF expression was upregulated in KO males and unchanged in females. (G) α-MHC expression in the RV was unchanged. (H) β-MHC expression in the RV was upregulated in KO male and female mice. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test to compare within-sex differences between KO and Con. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

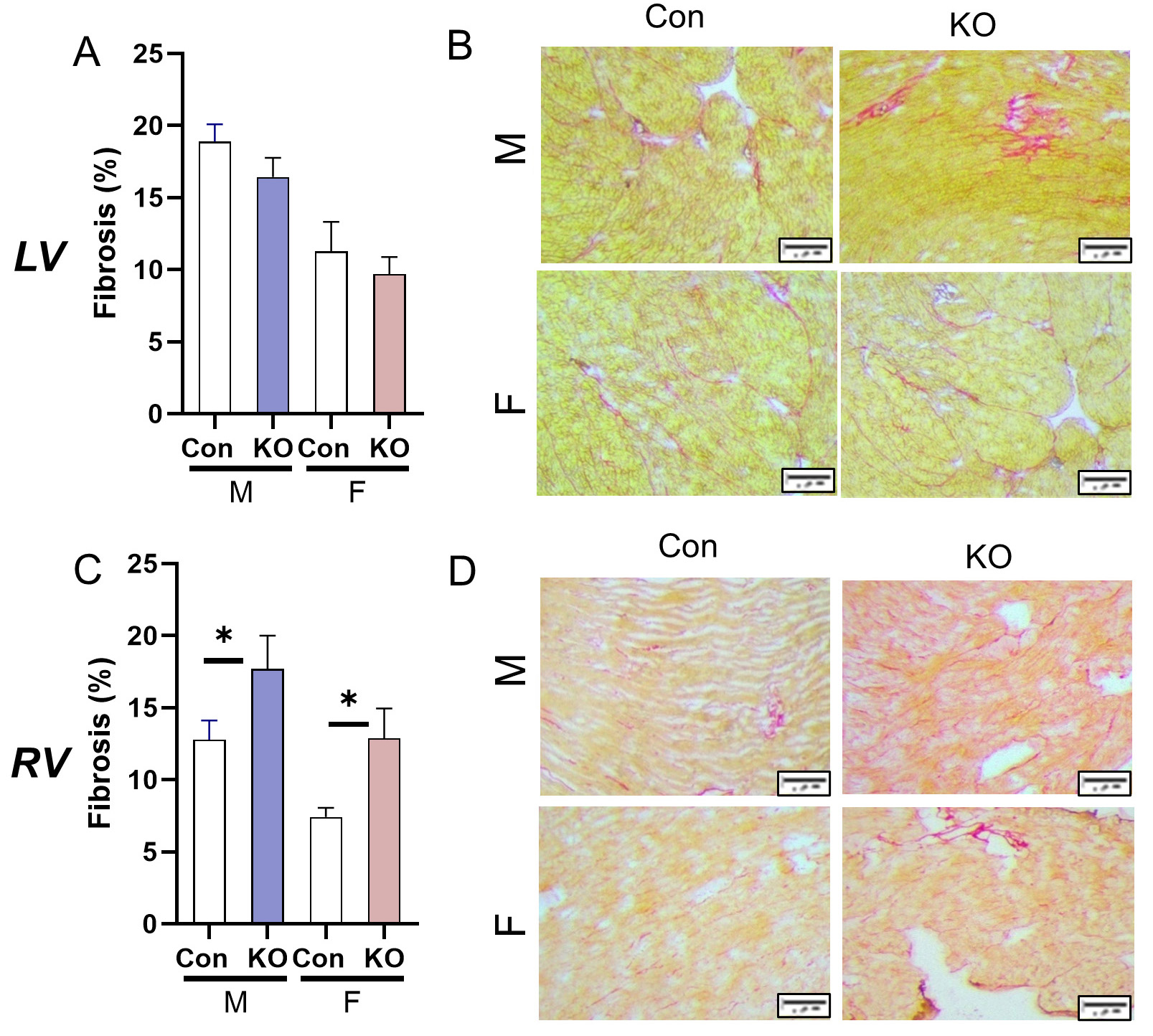

We then quantified fibrosis in both ventricles. Surprisingly, the LV did not undergo fibrotic remodeling, though Con animals at this age had relatively high collagen deposition compared to reports in younger animals [Figure 4A and B]. The RV underwent fibrotic remodeling with Kv1.5 KO with higher deposition of collagen compared to Con [Figure 4C and D]. Gene expression of pro-fibrotic markers was not different in either ventricle (data not shown).

Figure 4. Cardiac fibrotic remodeling in response to systemic Kv1.5 KO. (A) Fibrosis in the LV was unchanged by Kv1.5 KO. (B) LV picrosirius red stain representative images. Scale bar: 20 mm. (C) RV fibrosis was elevated in male and female KO mice. (D) RV picrosirius red stain representative images. Scale bar: 20 mm. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 3 mice with technical triplicate for histology,

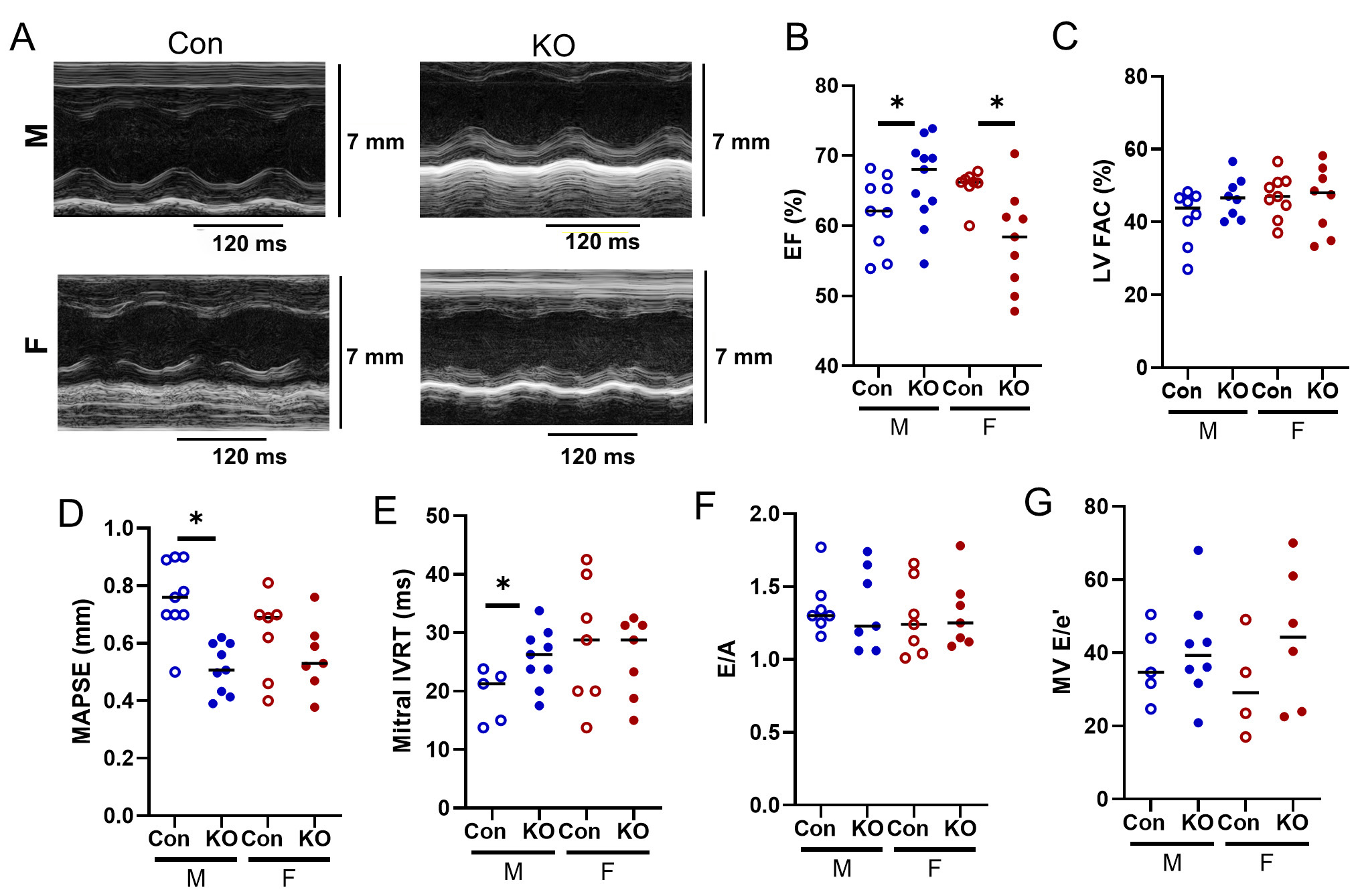

To understand changes in LV and RV function with Kv1.5 deletion, we performed comprehensive echocardiography (summarized in Table 1). While LV EF was preserved in KO male mice, EF was lower in KO female mice, albeit not clinically significant [Figure 5A and B]. LV FAC was also preserved compared to Con [Figure 5C]. Mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE), a more sensitive measure of LV systolic function, was decreased in KO males [Figure 5D]. Deletion of Kv1.5 reduced LV diastolic function by prolonged isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) in KO male mice [Figure 5E]. Although E/A and E/e’ were higher than adult control values [Figure 5F and G], Kv1.5 KO did not otherwise influence LV diastolic function.

Figure 5. LV echocardiography in Kv1.5 KO and Con mice. (A) Representative LV Ejection Fraction (EF) M-mode images. (B) LV EF was higher in KO male but mildly lower in KO female. (C) LV fractional area change (FAC) was unchanged. (D) Mitral annual plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) decreased in KO males and was unchanged in females. (E) Mitral isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT) increased in KO males and was unchanged in females. (F) Early filling divided by late filling (E/A) and G) E/e’ did not differ by genotype. *P < 0.05 as assessed by Student’s t-test to compare within-sex differences between KO and Con. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

Summary of echocardiography in male and female Con and Kv1.5 KO mice

| Female | Male | |||||

| Con | KO | Con | KO | Two-way ANOVA | ||

| HR (bpm) | 426 ± 39 | 422 ± 10 | 420 ± 12 | 435 ± 15 | ||

| LV systolic/global function | LV EF (%) | 65 ± 1 | 58 ± 2* | 62 ± 2 | 66 ± 2* | Interaction |

| LV FAC (%) | 47 ± 1 | 46 ± 3 | 45 ± 3 | 47 ± 2 | ||

| LV SV (µL) | 55.6 ± 5.4 | 48.3 ± 4.5 | 73.2 ± 7.9 | 60.2 ± 4.1 | Sex | |

| MAPSE | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 0.6 ± 0.05 | 0.8 ± 0.04 | 0.6 ± 0.04* | Genotype | |

| LV diastolic function | MV E/A | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | |

| MV IVRT | 28.2 ± 3.9 | 25.7 ± 2.6 | 19.3 ± 2 | 25.4 ± 1.7* | ||

| RV systolic/global function | RV FAC (%) | 38.3 ± 5.1 | 27.8 ± 3.2* | 45.2 ± 0.8 | 41.2 ± 2.4* | Genotype |

| RV SV (µL) | 45.5 ± 4.5 | 27.6 ± 1.3* | 48.3 ± 2.7 | 38.1 ± 3.0* | Genotype | |

| TAPSE | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.1* | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.03* | Genotype | |

| RV diastolic function | TR E/A | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.04 | |

| TR IVRT | 24.8 ± 3.7 | 20.9 ± 0.9 | 22.2 ± 6.4 | 25.6 ± 4.5 | ||

| LV/RV/vascular morphometry | LVAW (mm) | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1* | 1.4 ± 0.04 | 1.7 ± 0.1* | Genotype |

| RVFW (mm) | 0.7 ± 0.01 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.02 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | ||

| AO (mm) | 1.4 ± 0.01 | 1.3 ± 0.03* | 1.4 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.03* | Genotype | |

| PA (mm) | 1.5 ± 0.04 | 1.3 ± 0.1* | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.04 | Genotype | |

| Pulmonary/aortic vascular flow measures | PAT (ms) | 17.8 ± 0.7 | 15.5 ± 1.1 | 18.0 ± 0.7 | 14.2 ± 1.0* | Genotype |

| PET (ms) | 58.4 ± 2.4 | 60.0 ± 2.4 | 55.9 ± 2.1 | 57.6 ± 1.9 | ||

| PAT/PET | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01* | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.02* | Genotype | |

| AAT (ms) | 18.6 ± 0.8 | 16.0 ± 0.5* | 20.7 ± 0.8 | 17.5 ± 0.9* | Genotype | |

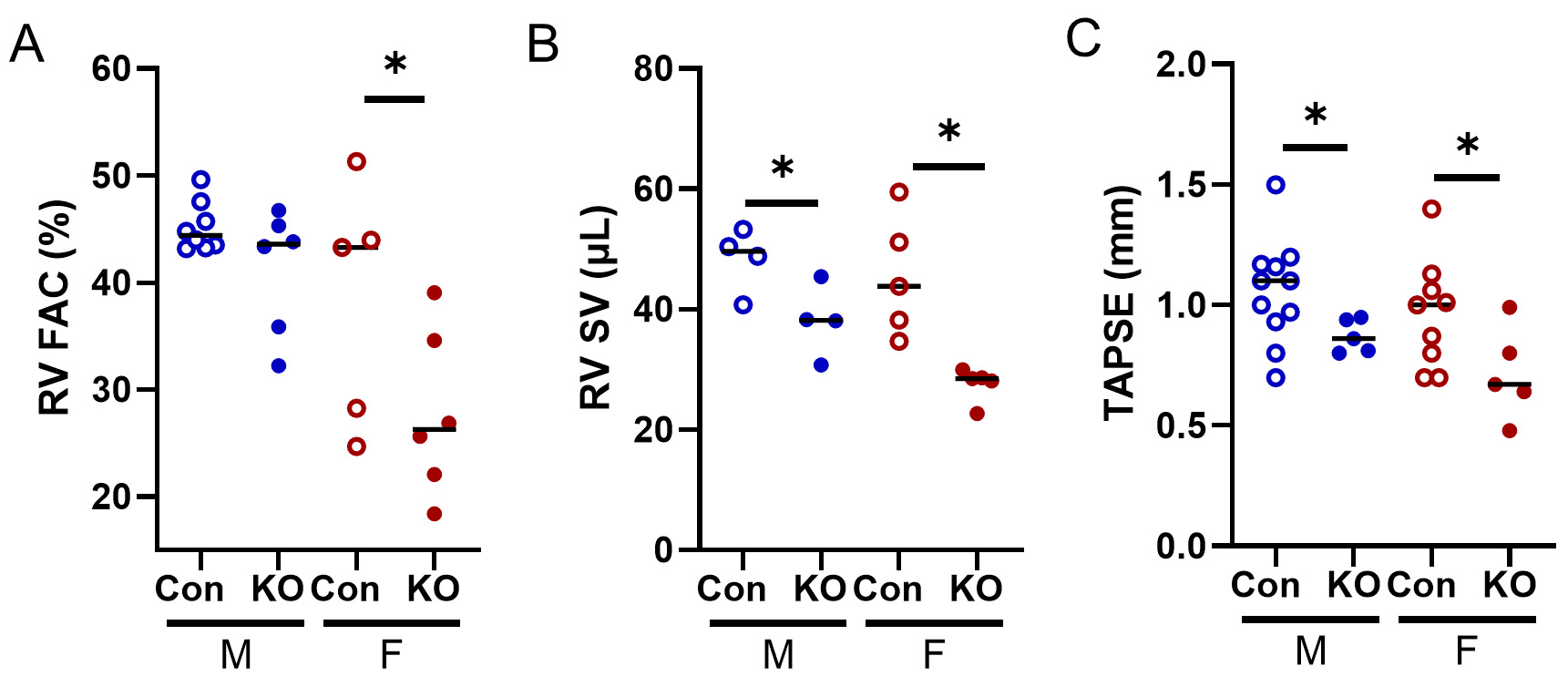

Ultrasound does not permit quantification of RV EF; thus, we quantified RV FAC, a well-accepted surrogate[17]. RV FAC was reduced in KO female mice [Figure 6A], and RV SV was reduced in both sexes

Figure 6. RV echocardiographic data from Kv1.5 KO and Con mice. (A) RV FAC was lower in KO females. (B) RV stroke volume (SV) was lower in both KO male and female mice. (C) Tricuspid annual plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was lower in Kv1.5 KO. *P < 0.05 by Student’s t-test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

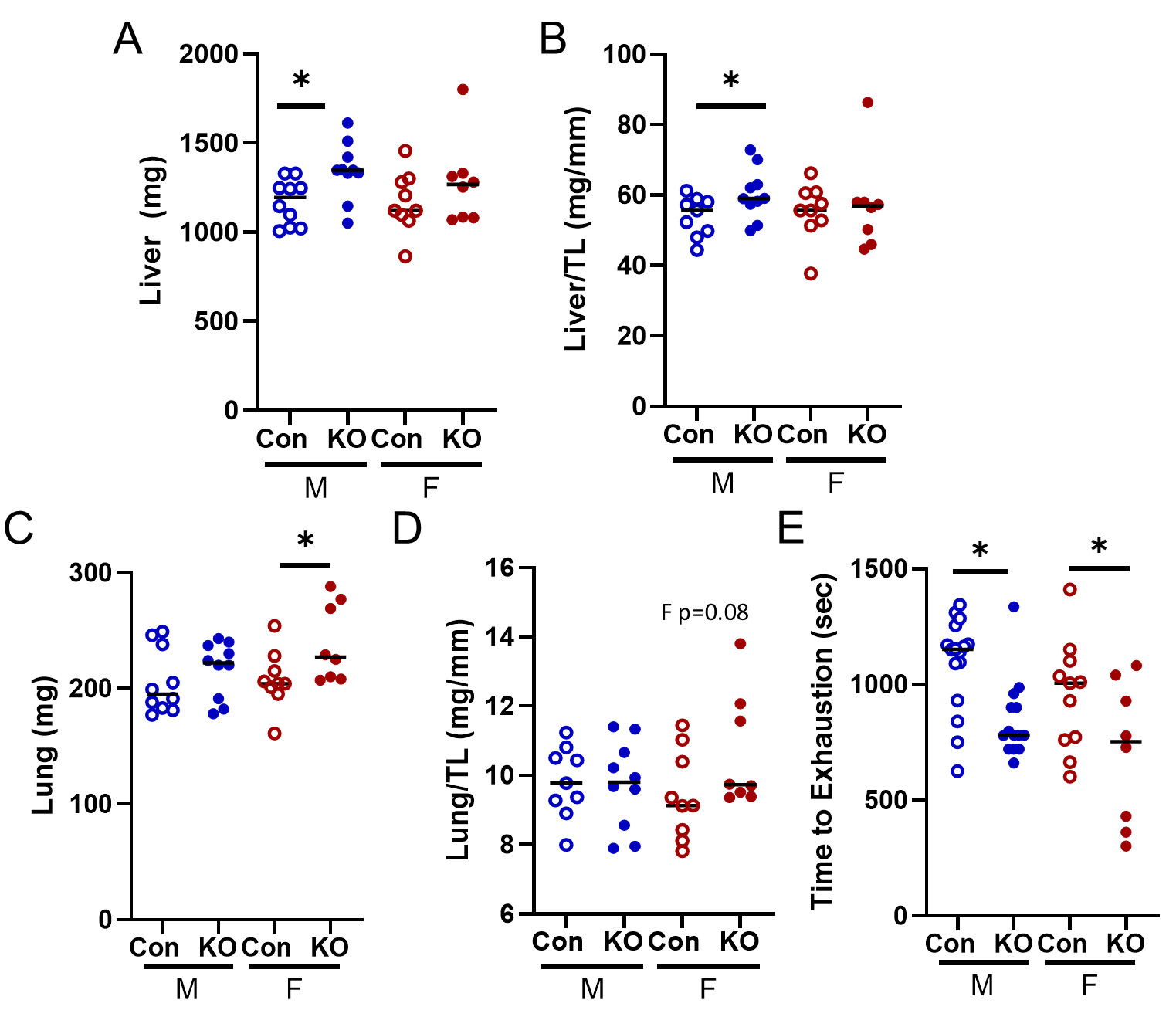

HF often affects the peripheral tissues and results in extra-cardiac outcomes; thus, we quantified lung and liver weights. Kv1.5 KO male mice had elevated liver weights and liver weight normalized to tibia length

Figure 7. Peripheral response to Kv1.5 KO. (A) Liver weight was elevated in KO males. (B) Liver weight to tibia length was elevated in male KO mice. (C) Lung weight was elevated in Kv1.5 KO female mice and (D) lung weight relative to tibia length trended towards significance in KO female mice (P = 0.08). (E) Treadmill time to exhaustion was lower in KO mice of both sexes. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 within sex by Student’s t-test. Blue: male (M), red: female (F).

DISCUSSION

HF is a chronic disease with high morbidity and mortality, especially in aging populations. Potassium channels are implicit regulators of vascular tone and may contribute to the development of HF, though the contributions of potassium channel function on both ventricles remain unclear. We set out to test the involvement of Kv1.5 in RV and LV remodeling. We demonstrate that global deletion of Kv1.5 results in biventricular remodeling that is not identical in the RV and the LV. While the RV underwent hypertrophic and fibrotic remodeling with systolic dysfunction, LV hypertrophy was milder with a diastolic dysfunction phenotype. Consistent with biventricular remodeling, Kv1.5 mice also demonstrated signs of pulmonary and liver edema as well as exercise intolerance. Together, loss of Kv1.5 affects both the RV and the LV; thus, we suggest that this model may be useful for studying the effects of biventricular remodeling and its extra-cardiac consequences.

Left ventricular failure is the most common type of HF. However, because the cardiopulmonary system is a closed-loop system, elevated pressures on either side of the heart can lead to backward pressure transmission and consequent remodeling. In the LV, high pressures backward propagate to the lungs and in the RV, high pressures result in high pressures in the vena cava and ultimately, the whole central venous system, typically manifesting as liver edema[18]. Therefore, pulmonary and systemic congestion are consequences of biventricular HF[19]. In the present work, we noted signs of both liver and pulmonary congestion as well as exercise intolerance. In the present work, loss of Kv1.5 resulted in more significant changes in RV structure and function compared to the LV, as evidenced by exacerbated RV hypertrophy and fibrotic remodeling. Further, the RV demonstrated declines in systolic dysfunction that were not evident in the LV. It is perhaps not surprising that the RV responded more robustly to Kv1.5-mediated vasoconstriction as it is well reported that the RV poorly tolerates afterload compared to the LV[20]. In response to similar percentage increases in afterload (pulmonary vs systemic pressure), RV SV declines more than the observed declines in LV SV. Therefore, while we did not perform longitudinal studies and consideration of other ages is warranted, our data strongly suggest that RV failure resulted in impaired LV function, thus contributing to the biventricular outcomes of loss of Kv1.5 and its extra-cardiac consequences.

The mechanism by which loss of Kv1.5 results in biventricular failure is of high significance and remains incompletely elucidated. Kv1.5 primarily regulates vascular tone, and we clearly demonstrate that loss of Kv1.5 results in pulmonary and systemic vasoconstriction. Thus, it is feasible that direct effects of afterload are responsible, and this is consistent with the RV remodeling occurring before, or at least more robustly than, in the LV. However, since our model was a global deletion of Kv1.5, we cannot be confident that our phenotype was due to vasoconstriction. Although KCNA5 is widely expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells[21], it is also expressed in cardiomyocytes[22]. Consistent with electrical mechanisms, adenoviral transfection of KCAN5 in myocytes shortens the duration of the action potential and rapidly excites myocytes[23]. Loss-of-function mutations in KCNA5 have been identified in patients with atrial fibrillation[24]. Thus, it is possible that deletion of Kv1.5 affects LV or RV rhythms that differentially remodel the RV and LV via non-afterload-mediated effects. Surprisingly little is known about expression of Kv1.5 in the heart in models of HF. However, in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, KCNA5 expression in the LV was low compared to controls, but unchanged in dilated cardiomyopathy[25]. In a rat model of PH, RV expression of Kv1.5 was reduced, but unchanged in the LV. In this case, downregulation of Kv1.5 decreased repolarization reserve in failing RV myocytes, thereby contributing to RV arrhythmogenesis[26]. Future work with cell-type-specific models of loss of KCNA5 will yield valuable insight into how loss of Kv1.5 results in biventricular HF through potentially distinct RV and LV mechanisms and by which cardiovascular cell types.

Chronic HF is an enormous public health burden in aging adults. Risk for HF is low at young ages, but begins to increase around age 50, reaching prevalence rates near 2% by age 60 and 10% by age 80[27]. In the present study, the mice more closely mirrored “middle-aged” rather than “aged,” yet they exhibited some signs of aging, including elevated RV and LV fibrosis and impaired LV filling, even in control animals. While not a goal of this work and, to our knowledge, not yet experimentally tested, it is possible that Kv1.5 expression changes with aging in the heart. Kv1.5 expression is reduced in the heart in models of hypertrophy[28] and the aging heart is widely established to be hypertrophic. Aging results in loss of diurnal expression of Kv1.5 in 18-20-month-old mice compared to young - a finding that the authors suggest may prime the aged animals for risk of arrhythmia[29]. Skeletal muscle arterioles have also been reported to show a non-significant trend towards lower Kv1.5 expression with age in 24-month-old rats[30]. Further study of Kv1.5 expression and activity across the aging cardiovascular system will likely yield valuable mechanistic insights into the contributions of Kv1.5 to HF risk, as well as to other cardiovascular diseases in which potassium channels play an important role.

One of the strengths of the present work was our inclusion of both male and female mice. Although we did not set out a priori to determine sex differences and did not observe profound differences between male and female mice in response to Kv1.5 deletion, we did identify subtle differences worth discussing. Male Kv1.5 KO mice had more LV hypertrophy and transcriptional activation of hypertrophic gene expression compared to female mice. On the other hand, Kv1.5 KO female mice had more RV hypertrophy and fibrosis than males. PH and RV dysfunction are well characterized by significant sex differences. Young women are more likely than men to develop PH; however, once diagnosed, female patients tend to survive longer than their male counterparts[31]. Although the precise mechanisms underlying these sex differences remain incompletely understood, estrogen undoubtedly plays a role, as it exhibits antihypertrophic and antifibrotic effects[32]. Young healthy females have superior RV systolic performance compared to males[33], likely due to the positive impact of estrogen on RV function. Given the robust protective effects of estrogen, it is interesting that loss of Kv1.5 resulted in worse RV function in females compared to male mice. However, as acknowledged, the mice in the present work were not young. With advancing age, mice undergo estropause, characterized by persistently low estrogen and estrous cycles of varying lengths, with eventual cessation of cyclicity around 12-14 months of age[34]. Thus, although we did not measure estrogen in the present work, we posit that the loss of estrogen in the setting of loss of Kv1.5 is detrimental for RV function. Future efforts to understand RV and biventricular remodeling in the setting of natural aging and underlying sex differences are warranted.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations. The mice in the present study were housed in Laramie, Wyoming, at an elevation of 7,220 ft above sea level. Therefore, our mice developed RV or LV dysfunction under mild hypoxic stress that may not be as profound in mice that reside at sea level. Our ability to use echocardiography to quantify RV function was limited. Invasive hemodynamics provide additional resolution of cardiac function and can help identify ventricular-vascular interactions, as well as load-independent systolic and diastolic measurements[35]. Although we confirmed a robust loss of Kv1.5 expression in both the LV and RV, we cannot exclude the possibility of compensatory changes in the expression of other K+ or membrane channels. KCNK3, in particular, is known to correlate with PH pathogenesis[36]. The role of this and other channels in the context of biventricular HF warrants further consideration.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that global deletion of Kv1.5 results in biventricular remodeling that is not identical in the RV and the LV. This model may be useful for studying the effects of biventricular remodeling and its extra-cardiac consequences.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conception and study design: Bruns DR, Ohanyan V, Cook RF

Data acquisition and analysis: Cook RF, Mehl ER, Polson SM, Yusifova M, Yusifov A

Writing and editing of the manuscript: Cook RF, Mehl ER, Bruns DR

Administrative, technical and material support: Bruns DR

Availability of data and materials

Data will be shared upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) K01 AG058810 and AG058810-04S1 (Bruns DR) and by the Wyoming IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE) 2P20GM103432.

Conflicts of interest

Bruns DR is an Editorial Board Member of The Journal of Cardiovascular Aging. Bruns DR was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers' selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Wyoming Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; protocol 20181008DB00324-02) on [approval date: 27 Nov 2019].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56-e528.

2. Levine AR, Simon MA, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary vascular disease in the setting of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2019;29:207-17.

3. Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3452-62.

4. van de Veerdonk MC, Kind T, Marcus JT, et al. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension responding to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2511-9.

5. Borgdorff MA, Bartelds B, Dickinson MG, Steendijk P, Berger RM. A cornerstone of heart failure treatment is not effective in experimental right ventricular failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;169:183-9.

6. Tykocki NR, Boerman EM, Jackson WF. Smooth muscle ion channels and regulation of vascular tone in resistance arteries and arterioles. Compr Physiol. 2017;7:485-581.

7. Archer SL, Souil E, Dinh-Xuan AT, et al. Molecular identification of the role of voltage-gated K+ channels, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and control of resting membrane potential in rat pulmonary artery myocytes. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2319-30.

8. Moudgil R, Michelakis ED, Archer SL. The role of K+ channels in determining pulmonary vascular tone, oxygen sensing, cell proliferation, and apoptosis: implications in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and pulmonary arterial hypertension. Microcirculation. 2006;13:615-32.

9. Ohanyan V, Yin L, Bardakjian R, et al. Requisite role of Kv1.5 channels in coronary metabolic dilation. Circ Res. 2015;117:612-21.

10. Yuan XJ. Voltage-gated K+ currents regulate resting membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Circ Res. 1995;77:370-8.

11. Vera-Zambrano A, Lago-Docampo M, Gallego N, et al. Novel loss-of-function KCNA5 variants in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2023;69:147-58.

13. Strait JB, Lakatta EG. Aging-associated cardiovascular changes and their relationship to heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2012;8:143-64.

14. Bruns DR, Yusifova M, Marcello NA, Green CJ, Walker WJ, Schmitt EE. The peripheral circadian clock and exercise: lessons from young and old mice. J Circadian Rhythms. 2020;18:7.

15. Yusifov A, Chhatre VE, Zumo JM, et al. Cardiac response to adrenergic stress differs by sex and across the lifespan. Geroscience. 2021;43:1799-813.

16. Razeghi P, Young ME, Alcorn JL, Moravec CS, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Metabolic gene expression in fetal and failing human heart. Circulation. 2001;104:2923-31.

17. Harrison A, Hatton N, Ryan JJ. The right ventricle under pressure: evaluating the adaptive and maladaptive changes in the right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension using echocardiography (2013 Grover Conference series). Pulm Circ. 2015;5:29-47.

18. Sundaram V, Fang JC. Gastrointestinal and liver issues in heart failure. Circulation. 2016;133:1696-703.

19. Hegemann N, Sang P, Kim JH, et al. Ultrasonographic assessment of pulmonary and central venous congestion in experimental heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2024;326:H433-40.

20. Haddad F, Doyle R, Murphy DJ, Hunt SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation. 2008;117:1717-31.

21. Post JM, Hume JR, Archer SL, Weir EK. Direct role for potassium channel inhibition in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C882-90.

22. Yang T, Wathen MS, Felipe A, Tamkun MM, Snyders DJ, Roden DM. K+ currents and K+ channel mRNA in cultured atrial cardiac myocytes (AT-1 cells). Circ Res. 1994;75:870-8.

23. Tanabe Y, Hatada K, Naito N, et al. Over-expression of Kv1.5 in rat cardiomyocytes extremely shortens the duration of the action potential and causes rapid excitation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345:1116-21.

24. Yang Y, Li J, Lin X, et al. Novel KCNA5 loss-of-function mutations responsible for atrial fibrillation. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:277-83.

25. Kepenek ES, Ozcinar E, Tuncay E, Akcali KC, Akar AR, Turan B. Differential expression of genes participating in cardiomyocyte electrophysiological remodeling via membrane ionic mechanisms and Ca2+-handling in human heart failure. Mol Cell Biochem. 2020;463:33-44.

26. Umar S, Lee JH, de Lange E, et al. Spontaneous ventricular fibrillation in right ventricular failure secondary to chronic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:181-90.

27. Bozkurt B, Ahmad T, Alexander K, et al. HF STATS 2024: heart failure epidemiology and outcomes statistics an updated 2024 report from the heart failure society of America. J Card Fail. 2025;31:66-116.

28. Matsubara H, Suzuki J, Inada M. Shaker-related potassium channel, Kv1.4, mRNA regulation in cultured rat heart myocytes and differential expression of Kv1.4 and Kv1.5 genes in myocardial development and hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1659-66.

29. Wang Z, Tapa S, Francis Stuart SD, et al. Aging disrupts normal time-of-day variation in cardiac electrophysiology. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2020;13:e008093.

30. Kang LS, Kim S, Dominguez JM 2nd, Sindler AL, Dick GM, Muller-Delp JM. Aging and muscle fiber type alter K+ channel contributions to the myogenic response in skeletal muscle arterioles. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:389-98.

31. Humbert M, Sitbon O, Yaïci A, et al. Survival in incident and prevalent cohorts of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:549-55.

32. Lahm T, Frump AL, Albrecht ME, et al. 17β-Estradiol mediates superior adaptation of right ventricular function to acute strenuous exercise in female rats with severe pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311:L375-88.

33. Foppa M, Arora G, Gona P, et al. Right ventricular volumes and systolic function by cardiac magnetic resonance and the impact of sex, age, and obesity in a longitudinally followed cohort free of pulmonary and cardiovascular disease: the framingham heart study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e003810.

34. Flurkey K, Randall PK, Sinha YN, Ermini M, Finch CE. Transient shortening of estrous cycles in aging C57BL/6J mice: effects of spontaneous pseudopregnancy, progesterone, L-dihydroxyphenylalanine, and hydergine. Biol Reprod. 1987;36:949-59.

35. Brener MI, Masoumi A, Ng VG, et al. Invasive right ventricular pressure-volume analysis: basic principles, clinical applications, and practical recommendations. Circ Heart Fail. 2022;15:e009101.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].