AI-empowered intelligence in industrial robotics: technologies, challenges, and emerging trends

Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) is profoundly reshaping the technological framework of industrial robotics, driving its transition from pre-programmed automation to autonomous, adaptive agents. This paper systematically reviews the key advancements of AI across three core dimensions of intelligence: perception, decision-making, and execution. Analysis indicates that AI is propelling industrial robots from tools executing predefined tasks towards intelligent partners capable of adapting to unstructured environments, autonomously planning amid dynamic changes, and engaging in nuanced interactions with the physical world. This evolution reveals a shift from optimizing specific skills towards developing rudimentary task-level cognitive reasoning capabilities. Nevertheless, fundamental challenges persist for industrial-scale deployment, including model generalization capabilities, long-term robustness, and human-machine trust. Collectively, these advancements are shaping a new generation of intelligent industrial robotic systems that are more adaptable and capable of deeper collaboration with humans.

Keywords

1. INTRODUCTION

Driven by Industry 4.0, global manufacturing is undergoing a profound transformation. This shift is from mass production to mass customization and high-mix, low-volume (HMLV) production models[1-3]. Industrial robots, as the core of traditional automation, were initially designed to execute repetitive tasks with high precision. This was intended for highly structured and predictable environments[4]. However, this inherent rigidity, optimized for scaled production, fundamentally contradicts the needs of modern manufacturing. These needs include operational flexibility, environmental adaptability, and rapid task switching. Bridging this gap, by evolving industrial robots from static tools into intelligent partners, is a core challenge in smart manufacturing[5,6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) provides the key technology to resolve this contradiction, fundamentally reshaping the core capabilities of industrial robots[7-9]. At the perception level, AI-driven vision systems are endowing robots with the ability to perform precise recognition and state understanding within unstructured environments[10-13]. At the decision-making level, AI-based adaptive strategies replace fixed algorithms, enabling robots to autonomously plan tasks and movements within dynamically changing environments[14-17]. At the execution level, AI employs learning-based control to endow robots with the dexterity to handle complex physical interactions, such as applying precise, adaptive forces during precision assembly[18-21].

Although multiple reviews have explored the intersection of AI and robotics, they provide a valuable foundation for understanding specific technologies. For example, Katona et al. systematically review the development of mobile robot obstacle avoidance and path planning[22]. This ranges from graph search algorithms to deep reinforcement learning (DRL). Ušinskis et al. focus on sensor fusion strategies for local perception and localization in complex environments[23]. Eren et al. highlight the value of AI in improving the precision of intelligent welding execution[24]. On the other hand, Fu et al. discuss intelligent coordination mechanisms for collaborative robots in human-robot interaction scenarios[25]. These studies review the application of AI in industrial robots from perspectives such as task type, robot category, or single AI technology. However, most of these studies primarily focus on specific tasks or isolated technologies. They often fail to closely link AI advancements with solving concrete, systemic industrial challenges. Therefore, a review systematically analyzing the synergistic evolution of AI in robot perception, decision-making, and execution, driven by industrial challenges, remains a critical research gap.

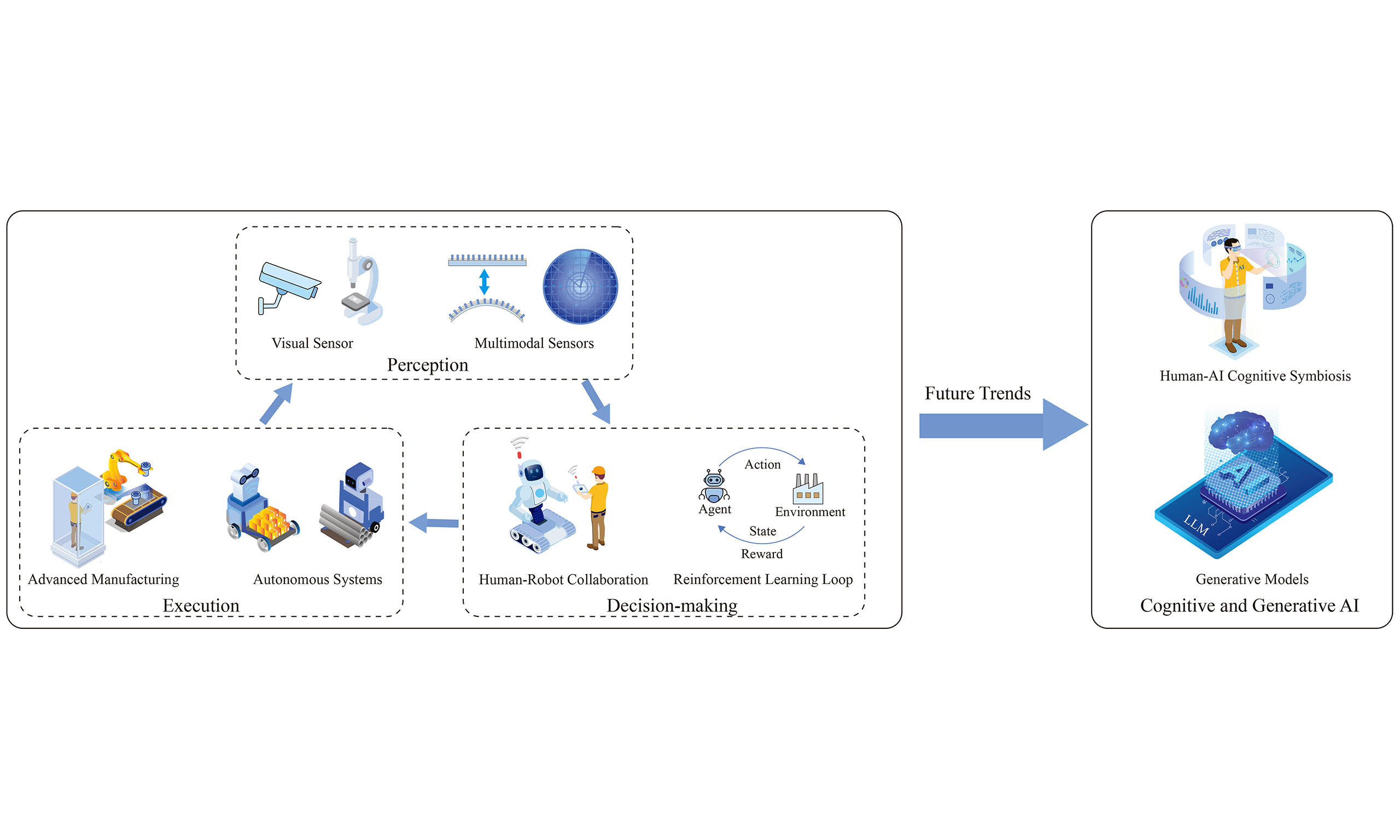

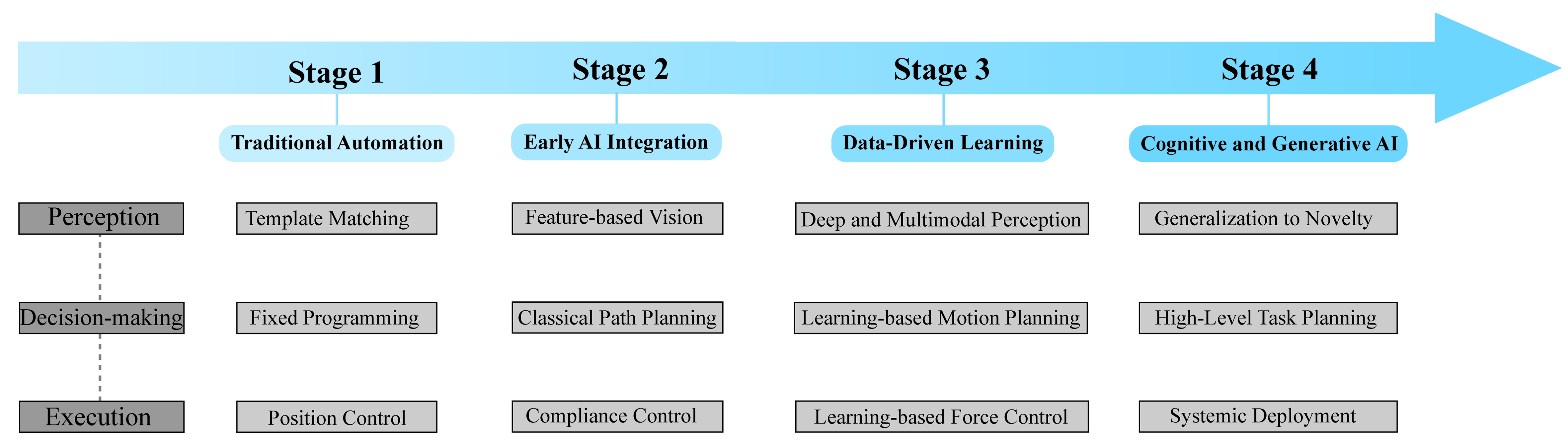

To address this, this paper systematically reviews key advancements in AI. These advancements are in shaping the core capabilities of industrial robots. Figure 1 illustrates the overall evolution of AI technologies across three levels: perception, decision-making, and execution in industrial robots. Section 2 delves into perception intelligence. It focuses on how AI addresses challenges such as unstructured object recognition and high-precision quality control (QC). Section 3 examines decision-making intelligence. It traces its evolution from rigid programming to AI-adaptive strategies. Section 4 investigates execution intelligence. It analyzes how AI enables delicate operations required for complex assembly. Section 5 systematically analyzes the fundamental challenges facing this field. Based on this, it then discusses future research directions. Section 6 concludes the entire paper.

2. PERCEPTUAL INTELLIGENCE

Perception intelligence is fundamental for industrial robots to interact with the physical world. It determines whether robots can operate effectively in complex and variable industrial environments[26]. Traditionally, robot perception capabilities were limited to highly structured scenarios. They struggled to cope with visual ambiguities caused by changes in lighting, object occlusion, and unstructured stacking[27,28]. To overcome these limitations, an important approach is to leverage AI technology. This transforms robots from passive sensor data collectors into active environment interpreters. Table 1 summarizes representative research in this domain.

Research on AI-empowered perceptual intelligence for industrial robots

| Ref. | Test platform | Baseline comparison | Key performance metric | Core capability |

| Wu et al.[29] | Aubo-i5 robot | Bidirectional RRT* | mAP: 99.5%; final success: 99.83% | High-precision construction tasks |

| Nguyen et al.[30] | Doosan robot | Low-cost 3D vision systems | Throughput: 220-250 items/hour; accuracy: 94% | High-speed adaptation |

| Wei et al.[31] | UR5 robot | GSNet (SOTA) | AP: 50.08% (+4.91%); success rate: 89.60% | Grasping visible objects |

| Huang et al.[32] | Hiwin robot | Grasp-only (VPG) | Success rate: 81.4%; training steps: -65% | Active scene manipulation before grasping |

| Wang et al.[33] | PAUT platform | ResNet152, GoogleNet | Accuracy: 99.3%; params: -75% | Volumetric non-destructive QC |

| Hassan et al.[34] | UR5 robot | Standard YOLO models | mAP: 97.49%; recall: 98.45% | Real-time multi-class identification |

| Zhou et al.[35] | UR3e robot | CNN-based methods | Recall: 94.95%; precision gain: 1.51 times | Annotation-free inspection |

| Rocha et al.[36] | ROSI robot | Human inspection | Accuracy: > 90% (thermal), 95% (acoustic) | Perception in degraded vision |

| Wong et al.[37] | ABB 6660 robot | Tool-based inspection | Classification accuracy: 100%; latency: 4 ms | In-process wear sensing |

| Chew et al.[38] | CSAM platform | RANSAC-based registration | RMS error: < 1 mm; frame rate: ~30 Hz | In-process geometric monitoring |

| Ni et al.[39] | Milling robot | No compensation | MAE and RMSE reduction: ~90% | Predictive QC |

| Chen and Lai[40] | Simulation | Baseline ZSL methods | MIoU improvement: > 5% | Adaptation to unseen objects |

2.1. Dexterous manipulation: grasping in clutter

A long-standing challenge in industrial automation is “Bin Picking”. This involves robots grasping objects from containers filled with cluttered, randomly oriented items[41,42]. Traditional industrial robots typically perform highly structured tasks from fixed fixtures. This is due to a lack of sophisticated perception capabilities to handle occlusion and pose uncertainty. Therefore, empowering robots with visual autonomy in unstructured scenarios is a core problem[43]. Therefore, enabling robots to achieve visual autonomy in unstructured environments represents the core challenge in expanding their industrial applications.

Integrating AI-powered vision systems has become a primary driver for overcoming this limitation. It transforms industrial robots from pre-programmed automated equipment into adaptive executors. By equipping robots with Red-Green-Blue-Depth (RGB-D) sensors and deep learning (DL) models, they gain a fundamental ability. This ability is to identify objects and estimate their graspable positions in cluttered bins[44,45]. This method has proven effective in various industrial sectors. In construction automation, Wu

To achieve more precise manipulation, AI models enable robots to evolve from simple object localization to full 3D spatial pose understanding. For scenarios with complex stacking or severe occlusion, Wei et al. constructed a multi-stage DL model that integrates a graspability estimation module, point feature aggregation, and six degrees of freedom (6-DoF) parameter prediction[31]. This model enables the stable and efficient generation of grasp strategies for robotic manipulation. Besides precision, operational efficiency is also a critical requirement in industrial environments. Song et al. developed a hierarchical fusion network that enables robots to complete the entire cycle from perception to prediction with real-time performance, a critical factor in maintaining production throughput[46]. This level of performance also extends to tasks requiring high-precision handling of minute components, such as the assembly of electronic components[47].

Beyond optimizing single grasping actions, AI is also enabling robots to learn multi-stage manipulation strategies. Huang et al. proposed a cooperative push-and-grasp method that combines image masking with DRL[32]. This method allows the robot to actively sort through disordered piles to isolate target objects, subsequently performing stable industrial grasping tasks.

2.2. Automated inspection: defect detection

Industrial robots are increasingly being employed as automated inspection platforms within QC processes[48,49]. However, significant challenges remain, including reliably identifying diverse and often microscopic surface defects[35], alongside addressing uncertainties arising from variations in products, lighting conditions, and background textures[50]. Such issues often lead to missed defects or elevated false-alarm rates, thereby limiting the reliability of automated inspection.

Under supervised learning (SL), robots can be trained for precise defect localization. For instance, Wang

The application of SL in QC has expanded to more diverse industries. In the traditionally labor-intensive textile industry, Hassan et al. employed an enhanced deep CNN [You Only Look Once version 8 nano (YOLOv8n)] to enable robots to identify up to 13 distinct fabric defects in real time[34]. This approach significantly enhanced detection performance while maintaining both real-time capability and operational safety. Similarly, within the automotive supply chain, Cheng et al. developed a system integrating 3D vision with DL, enabling robots to autonomously scan tire sidewalls[51]. This achieves exceptionally precise detection of minute embossed text anomalies on multi-specification tires without requiring computer aided design (CAD) models.

However, SL relies heavily on large volumes of labeled data. Consequently, model-driven and unsupervised learning approaches are addressing the issue of insufficient samples in industrial settings. Zhou et al. developed the robotic camera (RoboCam) system[35]. It integrates CAD model rendering, dual-domain pose error tuning, and visual comparison techniques, achieving the first high-precision robotic automatic detection of micro-mesh defects under unsupervised conditions. Moreover, lightweight and efficient AI models are crucial to meet real-time inspection demands on production lines. For dynamic quality sorting tasks, Lin et al. integrated a lightweight You Only Look Once version 4 (YOLOv4)-tiny model with a cascaded neural network onto a six-axis robot[52]. This system enables robots to perform multi-stage visual tasks in real time, demonstrating the potential of computationally efficient models within complex industrial inspection workflows.

2.3. Robust perception: multimodal fusion

In many industrial environments, factors such as smoke, dust, or strong light severely affect the performance of visual systems[36]. This makes single visual perception a critical point of failure. To address this challenge, researchers are employing multimodal fusion techniques. By intelligently combining data from diverse sensor types, these approaches enable robots to maintain reliable environmental awareness even under visually constrained conditions[53].

For equipment condition monitoring in extremely harsh environments such as mining sites, Rocha et al. developed the robot operating system inspection (ROSI) inspection robot system integrating multiple sensors, including vision, acoustics, and thermal imaging[36]. By employing algorithms such as CNN and random forests for multi-source data analysis, the system achieves reliable detection and assessment of various failure modes in critical equipment components[36].

Furthermore, researchers are exploring the integration of visual data with other physical signals for process monitoring and control. For instance, in robotic grinding operations, the condition of abrasive belts constitutes a critical quality-determining parameter. Research by Surindra et al. demonstrates that robots can precisely monitor belt wear by fusing data from accelerometers and force sensors[37]. Utilizing machine learning (ML) models such as decision trees and random forests, this approach achieves high-accuracy, low-latency multimodal wear recognition, providing valuable insights for intelligent industrial maintenance[37].

Multimodal perception is also extensively applied to enhance the naturalness and efficiency of human-robot collaboration in industrial settings. Effective collaboration demands that robots comprehend a range of human commands and physical cues, evolving from basic emergency stop functions to a more nuanced understanding of operator intent[54]. To this end, integrating multiple modalities such as speech and vision is considered a key technological pathway towards achieving this objective. For example, Mendez et al. developed a collaborative assembly system integrating three independent CNN models, each tasked with processing voice commands, tracking hand movements, or identifying components[55]. This multimodal approach enables operators to guide the robot through mechanical part assembly using natural language and gestures, achieving voice-controlled, contactless interaction within the collaborative assembly process.

In collaborative tasks involving substantial physical contact, a core challenge lies in managing inherent physical uncertainty, which has driven research into the fusion of vision with force/torque sensing. Bartyzel proposed a reinforcement learning (RL)-based multimodal variational deep Markov decision process (DeepMDP) approach for precision insertion tasks[56]. By learning dynamic representations through the fusion of visual and force/torque feedback, this method enables robots to perform precision assembly more robustly, enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities across varying background disturbances and object types.

2.4. In-process metrology: 3D modeling and measurement

The growing demand for in-situ, sub-millimeter precision measurement in precision manufacturing is driving the evolution of industrial robots from mere manipulator arms towards intelligent metrology platforms[57,58] As conventional offline inspection methods prove inefficient and unable to meet modern production rhythms, researchers are leveraging AI technologies to address this challenge by enhancing sensor accuracy, enabling dynamic process modeling, and optimizing measurement strategies[38].

To enhance the raw measurement accuracy of sensors, Yang et al. combined industrial 3D simulation, AI training, and multi-algorithm preprocessing to learn and correct sensor-specific error patterns[27]. This approach improved the positioning accuracy of time-of-flight cameras in industrial mobile robot vision inspection, facilitated robotic repositioning, and enhanced the stability and consistency of 3D visual inspection. This external vision-based measurement principle was also applied to the robot’s own state assessment. Simoni et al. developed the double branch semi-perspective decoupled heatmaps (D-SPDH) system, which employs depth cameras and CNNs to perform high-frequency, high-precision 3D pose estimation of robotic arms without relying on internal encoders[59]. This provides a crucial capability for safe monitoring in industrial human-robot collaboration.

In the field of robotic machining, Ni et al. developed a digital twin-based system where ML models predict final contour errors based on the numerical control (NC) code trajectory generated by robotic planning[39]. This enables pre-compensation of the path, significantly reducing machining errors. Such predictive analysis complements real-time feedback monitoring during the process. Chew et al. proposed a real-time 4D reconstruction system that employs multi-camera fusion technology to achieve object tracking and high-precision modelling in dynamic environments, providing robust support for online quality monitoring[38].

The role of industrial robots has expanded beyond passively executing measurement tasks to actively planning and optimizing measurement strategies themselves. Li et al. proposed the 3D scanning coverage prediction framework 3D scanning coverage prediction (3DSCP)-Net, which predicts the coverage of a structured light scanner on a workpiece prior to actual scanning, enabling efficient viewpoint planning[57]. Furthermore, Roos-Hoefgeest et al. proposed an end-to-end surface scanning trajectory optimization method incorporating the proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm[58]. This approach generates RL-driven transferable scanning paths based on CAD models for industrial contour measurement tasks, enabling high-quality surface acquisition.

2.5. Adaptive learning: generalization to novelty

Under the flexible manufacturing model of HMLV, traditional SL incurs high costs and time due to the frequent introduction of new products requiring extensive data collection, annotation, and model retraining[60]. Consequently, enabling industrial robots to rapidly generalize to new objects and tasks with minimal data represents a critical research challenge for achieving agile manufacturing.

To mitigate reliance on real-world data, researchers have turned to synthetic data generation techniques. Robots can be trained on large, automatically annotated virtual datasets rather than solely depending on real-world images. Mangat et al. successfully trained a You Only Look Once version 3 (YOLOv3) model for a pick-and-place task using only synthetic images generated from 3D models[60].

Beyond generating additional data, another research direction focuses on endowing models with inherent generalization capabilities. Gao et al. employed few-shot learning methods to achieve high-precision translational manipulation of novelly shaped objects under unknown friction conditions[61]. In increasingly prevalent open and dynamic industrial settings, robots frequently need to recognize and handle novel objects or categories unseen during training. Within visual systems research for assembly tasks, Chen and Lai proposed a zero-shot learning (ZSL) framework for semantic segmentation[40]. This enhances preprocessing efficiency for industrial robot operations in human-robot interaction scenarios, enabling efficient perception of unseen object categories within industrial human-robot interaction contexts.

3. DECISION-MAKING INTELLIGENCE

Effective decision-making constitutes the cognitive core that translates perception into purposeful action. However, traditional industrial robots possess limited decision-making capabilities, typically only executing pre-programmed fixed trajectories[62]. Consequently, a central challenge lies in evolving robotic decision-making from a static, offline process into a dynamic, online capability that achieves genuine operational autonomy. The primary focus centers on employing methods such as DRL and imitation learning (IL) to equip robots with the means to learn and adapt their behavior when confronting real-world complexities[63,64]. Table 2 summarizes recent research progress in this domain.

AI-powered decision-making intelligence techniques for industrial robots

| Ref. | Test platform | Baseline comparison | Key performance metric | Core capability |

| Wu et al.[65] | Franka panda and actual robot | Traditional DRL | Success rate: 78.8% | Reactive motion |

| Lindner and Milecki[66] | Mitsubishi RV-12SDL-12S | PRM algorithm | Path: -3%~10%; error: < 3.84 mm | Efficient and precise paths |

| Liu et al.[67] | ABB IRB 1200 robot | Standard DRL (DDPG, TD3) | Risk reduction: -28.7% | Intrinsically safe behavior |

| Honelign et al.[68] | Franka panda robot | PPO | Success rate: 0%-100% | Mastering high-DoF control |

| Ji et al.[69] | KUKA KR3 robot | Spiral search | Time reduction: 4-6 times | Adaptive contact manipulation |

| Men et al.[70] | UR5e robot | PPO and direct transfer | Success: +26%; force: -30 N | Cross-task knowledge transfer |

| Zhou and Lin[71] | 7-DoF Diana robot | SOTA HRL | Success: 91% (dual-task), 62% (triple-task) | Solving sparse reward tasks |

| Ghafarian Tamizi et al.[41] | UR5 and Kinova Gen3 robot | Bi-RRT | Time: -70% | Data-efficient learning |

| Koubaa et al.[72] | Multiple robots | LLaMA models | Human rating: 4.28/5 | Intuitive HRC interface |

| Gupta et al.[73] | KUKA arm | Planning w/o feedback | Success rate: 81.25% | Autonomous task decomposition |

| Faroni et al.[63] | UR5 robot | Feasibility-oriented planner | Idle time: -95%; HRC time: +74% | Synergistic HRC coordination |

| Hou et al.[74] | UR5e robot | DDQN and dueling DDQN | Success: 25%-100%; time: -28.2% | Optimized human-robot teaming |

3.1. Reactive motion planning

Deploying robots within human-centric collaborative environments presents primary safety and efficiency challenges in enabling secure navigation around dynamic and unpredictable obstacles[67]. Conventional path planning algorithms are typically computationally intensive and operate offline, struggling to respond to sudden changes[75]. DRL offers a viable solution by training an end-to-end policy that directly maps real-time sensor inputs to underlying control commands, thereby achieving responsive and fluid motion[65].

Multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of DRL in endowing industrial robots with robust dynamic obstacle avoidance capabilities. Wu et al. developed a hybrid DRL model integrating the strengths of deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) and soft actor-critic (SAC) algorithms, enabling a robot to achieve high success rates in real-world tests involving moving obstacles[65]. Beyond validating dynamic obstacle avoidance efficacy, the study further examined the quality and efficiency of DRL-generated paths. Lindner and Milecki proposed a DRL-based obstacle avoidance algorithm integrating DDPG and hindsight experience replay[66]. This approach not only achieved sub-millimeter positioning accuracy but also generated paths shorter than traditional path planning and manipulation algorithms. Furthermore, it ensured robotic behavior appeared safe and predictable to human collaborators. To this end, DRL is being employed to learn strategies that actively minimize risk, rather than relying solely on hard-coded safety rules. Liu et al. introduced an “intrinsic reward” function into the DDPG algorithm, enabling dynamic adjustment of motion trajectories based on human arm positions[67]. This allows industrial robots to simultaneously satisfy safety requirements and task efficiency, significantly enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the strategy.

3.2. Contact-rich task planning

The complexity of industrial robot decision-making is particularly evident in task and motion planning problems, especially within precision assembly tasks involving physical contact and multi-step sequences[63].

Traditional programming approaches lack the flexibility to handle such uncertainties, while standard DRL often proves inefficient due to sparse reward issues[76-79]. Consequently, recent research has focused on methods such as IL, hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL), and policy transfer, aiming to enhance robotic autonomy and dexterity in assembly tasks[41,71,80].

The foundation of complex assembly tasks lies in robotic solutions for precise positioning under high degree of freedom (DoF). Honelign et al. employed DDPG to train a seven-DoF robotic arm policy network, enabling autonomous planning and execution of end-effector movements from arbitrary initial states to target positions under continuous control[68]. This demonstrated the capability of DRL to master complex high-dimensional control without explicit kinematic modelling. This learning-based approach has also extended to optimizing underlying inverse kinematics (IK) solvers. Yu and Tan combined PPO with Damping Least Squares to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of IK solving for multiple industrial robots[81].

The complexity of tasks significantly increases when robots transition from free-space positioning to contact-rich physical interaction. For the classic “plug-in” assembly task, Ji et al. proposed a DRL approach integrated with a non-diagonal compliant controller, enabling the robot to learn how to continuously adjust its stiffness and modify its trajectory during insertion without switching between different control modes[69]. To enhance the generalizability of these learned skills, Men et al. proposed the policy fusion transfer algorithm, which enables robots to transfer acquired assembly knowledge to novel tasks by fusing source and target task policies[70]. This approach effectively enhances both generalization capability and safety in unfamiliar insertion scenarios.

Beyond task-level generalization, addressing complexity within individual tasks is equally crucial. Zhou and Lin employed the multiple goal-conditioned hierarchical learning framework to decompose complex operations into multiple subtasks[71]. Each subtask is learned by a unified policy network, with exploration guided by intermediate objectives to enhance convergence speed and robustness. This approach effectively resolves the training instability inherent in standard RL under sparse rewards. Complementing RL, IL circumvents RL’s inefficient exploration by directly learning expert policies, offering a more data-efficient pathway for complex motion planning. The path planning and collision checking network framework proposed by Ghafarian Tamizi generates paths for disordered grasping by imitating expert planners, utilizing neural networks for rapid collision detection on each path segment[41]. This approach significantly reduces the planning time required by traditional sampling algorithms.

3.3. High-level strategic planning

The decision-making capabilities of industrial robots are evolving from fundamental motion control towards higher-level task planning and strategic coordination, particularly within the framework of human-robot collaboration[82,83]. A central challenge in this evolution is enabling robots to comprehend abstract, natural language instructions from human operators[68,73]. Another is empowering robots to engage in dynamic, efficient task allocation within human-robot teams[63,74].

The advent of large language models (LLMs) has opened new avenues for robots to directly interpret high-level human commands. The robot operating system generative pre-trained transformer (ROSGPT) framework developed by Koubaa et al. integrates generative pre-trained transformer (GPT)-4 with robot operating system 2 (ROS2), enabling efficient conversion from natural language to robotic control commands[72]. Moving beyond simple instruction translation, Gupta et al. proposed a novel robotic action contextualization framework combining LLMs with dynamical system (DS) controllers[73]. This allows robots to fine-tune action parameters and correct execution errors based on task contexts, thereby enhancing autonomy and adaptability. This capability has also extended to mobile platforms. Wang et al. employed GPT-3.5-turbo to generate Python code from natural language instructions, controlling automated guided vehicles to execute navigation tasks within an intelligent workshop[84]. By integrating semantic annotation with the Pathfinder algorithm for path planning and execution, they achieved natural human-machine interaction and multimodal intelligence fusion.

However, effectively applying these general LLMs in industrial environments requires addressing their lack of domain knowledge. To this end, Li et al. constructed the inaugural industrial robot Wizard-of-Oz dialoguing dataset (IRWoZ) dialogue dataset, specifically tailored for industrial tasks such as assembly and material handling[85,86]. This provides an indispensable foundation for fine-tuning and evaluating LLM capabilities within manufacturing-specific scenarios.

Beyond interpreting instructions, higher-level decision-making involves optimizing task allocation between robots and humans to maximize team efficiency and fluidity. Faroni et al. proposed the task and motion planning framework[63]. This framework dynamically plans and assigns assembly subtasks to humans and robots by integrating timeline task modelling with multi-objective action search, effectively enhancing the execution efficiency and robustness of multi-agent systems. Furthermore, RL has been applied to this challenge. For instance, Hou et al. developed a DRL-based model for mobile collaborative robots in automotive assembly scenarios[74]. This model decomposes tasks through a hierarchical task network and utilizes the revival double deep Q-network algorithm to optimize task allocation, achieving exceptionally high success rates and efficiency in complex final assembly tasks.

4. EXECUTION INTELLIGENCE

Although perception and decision-making constitute the cognitive core of intelligent robots, executive intelligence represents their capacity to translate digital instructions into precise, robust physical actions. Even with flawless planning, successful execution in the real world remains challenged by the complexity of physical interactions, such as friction, material compliance, and unexpected contact forces[87]. Furthermore, the inherent imprecision of robotic hardware[88] and stringent safety requirements for human-robot collaboration[89] necessitate dexterity and adaptability beyond classical control. Consequently, recent research focuses on enabling robots to learn complex control strategies through data-driven approaches, thereby bridging the gap between instructions and physical reality[90,91]. Relevant studies are summarized in Table 3.

AI-powered execution intelligence techniques for industrial robots

| Ref. | Test platform | Baseline comparison | Key performance metric | Core capability contribution |

| Ma et al.[93] | UR robot | PPO, TD3, BC-SAC | Success: 93%; force: -91.7% | Low-force dexterous manipulation |

| Zhang et al.[94] | AUBO-i5 robot | Fixed admittance | Time: -9.6%; force: -26%~-45% | Adaptive compliance |

| Hu et al.[95] | UR10e robot | Manual tuning | Convergence: +33%; response: +44% | Rapid parameter tuning |

| Deng et al.[91] | KUKA iiwa | Data-driven NN | Torque accuracy: 97.1%; MSE: -72% | Interpretable dynamics learning |

| Shan and Pham[90] | Denso VS060 (industrial arm) | GMO (model-based) | Error reduction: -52% (H-guiding) | Low-cost force sensing and control |

| Zheyuan et al.[96] | HRC experiment | GTM, HAZOP | Team perf.: +8.2% | Predictive risk avoidance |

| Xin et al.[97] | UR10e and Franka Emika | 100% trust model | Fail. predict: 1.3%-79% | Confidence-aware safe action |

| Hickman et al.[98] | Grid World Sim | Gaussian process SRL | Reward: +41.7%; cost: -39.9% | Safety under data shift and outliers |

| Kana et al.[99] | KUKA iiwa | Gravity comp. mode | Chamfering error: < 0.1 mm | Virtual guidance for human operator |

| Amaya and Von Arnim[100] | KUKA iiwa | Policies w/o randomization | Success: 100% (on Loihi); latency: 1.8 ms | Zero-shot transfer via robustness |

| Mahdi et al.[101] | FANUC robot | Traditional monitoring | Defect detection AUC: 0.92 | System-level integration for QC |

| Li et al.[102] | UR5 and KUKA robot | On-site operation | Target hit rate: 98.7% | Human-in-the-loop cyber-physical system |

| Zhang et al.[103] | Fetch robot | SAC-NUR | Success rate: +20%-30% | Robust policy transfer |

| Zhang et al.[104] | UR10 robot | Direct transfer | Prediction accuracy: 94.1% | Zero-shot sim-to-real transfer |

| Liu et al.[105] | UR5 robot | Direct sim-to-real | Grasp success: 65.5%-79.5% | Fine-tuning bridge for policies |

4.1. Dexterous manipulation: precision force control

A primary operational challenge for industrial robots lies in maintaining precise force control during contact-intensive tasks such as grinding, polishing, and precision component assembly[92]. Conventional position-controlled robots cannot respond compliantly to surface variations or contact forces, posing risks of damaging both workpieces and themselves. Meanwhile, classical force control methods often struggle to model complex contact dynamics accurately. To address this challenge, researchers have begun employing DRL to directly learn end-to-end force control strategies. Ma et al. proposed a robot flexible assembly strategy system based on SAC, achieving high-precision, low-contact-force autonomous assembly of flexible components such as flexible printed circuits under simulated real-world physical constraints[93].

In industrial practice, DRL is also employed to optimize mature classical controllers, enhancing their adaptive capabilities. For instance, addressing challenging assembly tasks such as inclined holes, Zhang et al. utilized the twin delayed DDPG algorithm to optimize the virtual damping parameters of a robotic admittance controller online[94]. This approach improved mating assembly precision while reducing contact forces. To further enhance controller responsiveness in unknown or rapidly changing environments, Hu

The foundation of force control applications relies upon an accurate understanding of the robot’s dynamic model. By substituting analytical models with learned neural networks, robots can achieve more precise torque prediction. Deng et al. introduced an energy-to-neural network, embedding the structural form of the dynamic equations within the network itself[91]. This approach combines the interpretability of physical models with the flexibility of ML, enhancing the precision and robustness of robots in parameter identification and trajectory fitting.

Furthermore, research by Shan and Pham demonstrated that neural networks can learn to estimate external forces and torques directly from motor currents and joint states within the robot[90]. This breakthrough enables high-precision force control and sensitive manual guidance without any external force/torque sensors, significantly enhancing the autonomy and cost-effectiveness of industrial robots in precision manipulation scenarios.

4.2. Safe collaboration: risk management and fluent interaction

In human-robot collaboration, the challenges facing a robot’s executive intelligence extend beyond physical collision avoidance in dynamic path planning[89]. A safe and effective collaborative system not only requires robots to avoid physical contact but must also ensure their behavior appears fluid and predictable to human collaborators, as hesitant or unstable movements undermine human-robot trust and diminish team efficiency[54]. Consequently, recent research focuses on developing robotic execution systems capable of actively assessing risks and autonomously learning safe interaction strategies from data[96-98].

In safe human-robot physical interactions, industrial robots must simultaneously address external interaction risks stemming from human behavior and internal errors within their own perception systems. To mitigate external risks, Zheyuan et al. proposed the advanced human-robot collaborative model for industrial collaborative settings[94]. This model predicts interaction risks based on human behavior and semantic scene graphs, adjusting action strategies to optimize team task completion. Furthermore, ensuring safe execution necessitates accounting for uncertainties within the robot’s own perception systems. Xin et al. proposed a runtime compositional model verification framework[97]. This framework calculates trust metrics based on sensor data, updates state transition probabilities to predict system failure risks, thereby enabling runtime model verification and dynamic safety assurance.

To enable robots to autonomously learn safety policies from data, researchers are turning to safety-oriented RL (SRL). However, a core challenge for SRL in industrial applications lies in handling the common presence of outliers in data and the distribution shift between deployment environments and training data. Addressing this issue, Hickman et al. developed a SRL designed to learn policies that maximize task rewards while satisfying safety constraints[98]. By employing a student-t process instead of the standard Gaussian process, this framework better accommodates data anomalies during safety policy learning, thereby achieving a superior balance between task performance and safety constraints.

4.3. Robust deployment: sim-to-real transfer

Numerous studies have actively introduced uncertainty during the training phase to compel AI strategies to learn generalization capabilities insensitive to differences between virtual and real environments. A representative technique is domain randomization, which deliberately alters the physical and visual parameters of simulations throughout training. For instance, Amaya and Von Arnim randomized dynamic parameters such as friction within the simulation environment when training a spiking neural network controller for precision hole-punching tasks[100]. Strategies trained in this manner could be directly deployed onto physical robots controlled by Loihi neuromorphic chips without any real-world fine-tuning, while maintaining high success rates.

Beyond randomizing environments, unifying simulation and reality through “scene representation” proves equally effective. Zhang et al. proposed an end-to-end approach that avoids direct use of raw images, instead converting them into a unified 3D bounding box representation insensitive to object shape and appearance[103]. This significantly enhanced the transfer success rate of obstacle avoidance strategies. Furthermore, robustness can be bolstered by refining the learning algorithms themselves. Considering sensor noise as a primary cause of transfer failure, Wang et al. proposed the Density estimation-SAC algorithm[106]. This technique integrates density estimation into the DRL framework, enabling explicit modelling and adaptation to noisy measurements during training.

Complementary domain adaptation techniques explicitly aim to minimize feature-level discrepancies between simulated and real-world data. For instance, when investigating multimodal grasping stability assessment, Zhang et al. encountered the challenge of stark stylistic differences between simulated and real tactile images[104]. They employed a conditional GAN specifically trained to convert real tactile images into the simulated style. Following this processing, an evaluation network trained entirely on simulated data could directly process real tactile data from the physical world, achieving successful zero-shot transfer.

At the system level, high-fidelity digital twins are emerging as powerful system-level tools to bridge this gap. Rather than directly transferring strategies from general-purpose simulators to reality, an alternative approach involves utilizing digital twins as an intermediary layer. Liu et al. developed a transfer learning framework wherein grasping strategies pre-trained in simulation are first fine-tuned within a digital twin highly synchronized with the physical robot[105]. This enables final optimization of the strategy within an environment closer to reality, significantly enhancing its ultimate grasping success rate on the actual robot.

5. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

5.1. Learning and generalization

The generalization capability and data efficiency of existing AI models constitute the primary constraints limiting their adaptation to HMLV production patterns. Whilst paradigms such as meta-learning offer avenues for rapid task adaptation[107], strategy formulation under conditions of extremely sparse interactive data remains a core challenge in industrial settings. Future research must develop more robust self-SL frameworks to leverage vast amounts of unlabeled data in industrial environments for pre-training general-purpose world models. Moreover, as models grow increasingly large, efficient knowledge transfer from cloud-based large models to resource-constrained edge controllers emerges as a critical issue. Strategy distillation stands as one of the promising techniques in this field; however, establishing a mature theoretical framework remains necessary to address the issue of insufficient behavioral diversity and generalization in teacher models when strategy optimization is inadequate[108].

5.2. Robustness and reliability

The long-term robustness and self-maintenance capabilities of systems are pivotal for transitioning technology from laboratory to factory settings. Current research predominantly focuses on immediate success at the task level, with less attention given to performance degradation in robots during prolonged continuous operation due to mechanical wear or gradual environmental changes[109,110]. A significant future direction lies in developing robotic systems capable of proactive fault prediction, diagnosis, and autonomous recovery. Whilst initial explorations exist in online fault diagnosis, translating concepts such as reversible execution into robust, generalizable error recovery strategies feasible within the physical world holds substantial value for minimizing unplanned downtime on industrial production lines[111].

5.3. Cognition and interaction

Generative AI is providing novel technical pathways for long-standing challenges in robotics, such as high-level task planning and sparse perception data. At the perception level, researchers are employing models such as conditional GANs to address the simulation-to-reality domain gap. Examples include enhancing the transfer performance of perception models by learning style transfer between simulated and real tactile images[104], or directly generating kinematic solutions for robotic motions[112]. At the decision-making level, research centered on LLMs has begun exploring the autonomous decomposition of natural language instructions into robot-executable task sequences[72,73]. However, applying these technologies to industrial manufacturing, where safety and reliability demands are exceptionally high, still presents fundamental challenges. For LLMs, core issues requiring resolution in task planning include inference latency, lack of logical consistency, and insufficient understanding of physical world constraints. Regarding data generation, ensuring the fidelity and diversity of synthetic data to cover extreme conditions and long-tail problems in real industrial environments remains a key research topic requiring in-depth investigation. Consequently, future research will focus on establishing effective mechanisms to validate and constrain the outputs of generative models. It will also explore how generative models can be leveraged at scale to synthesize high-quality, diverse multimodal training data, thereby reducing the dependence of industrial AI applications on costly manual data collection and annotation.

6. CONCLUSION

This paper, driven by industrial challenges, provides a systematic review of how AI empowers industrial robots in perception, decision-making, and execution capabilities. The analysis focuses on how AI transforms robots from rigid tools on traditional automated production lines into intelligent partners capable of adapting to the dynamism and complexity of modern manufacturing. It examines the evolution and applied value of relevant AI technologies from the perspective of solving specific industrial problems.

Analysis indicates that AI applications are expanding the capabilities of industrial robots beyond optimizing predefined specific skills to handling more complex tasks that require rudimentary cognition and reasoning. At the perception level, robots no longer merely recognize known objects but are developing the capacity to generalize to unseen entities. At the decision-making level, robots are progressing from executing explicit commands to comprehending abstract natural language, decomposing complex tasks, and engaging in strategic coordination within human-robot teams. At the execution level, robots are learning to autonomously recover from errors and adapt online to dynamic changes in the physical world. This evolution from skill execution to task-level reasoning represents a core trend in the current AI-empowered industrial robotics domain.

These advances across perception, decision-making, and execution collectively form integrated robotic systems capable of navigating physical world uncertainties. Research focus is shifting from solving well-defined single tasks towards building system-level solutions that address process-level complexity, laying the groundwork for the next generation of more autonomous, adaptive industrial robots.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the overall structure of the review: Chen, Y. (Yifan Chen); Ren, T.

Conducted the literature investigation and wrote the initial draft: Chen, Y. (Yifan Chen)

Contributed to data curation, analysis, and figure design: Li, Y.; Jiang, G.; Liu, Q.

Provided technical supervision and critical revisions throughout the writing process: Chen, Y. (Yonghua Chen); Yang, S. X.

Supervised the project, finalized the manuscript, and ensured overall coherence: Ren, T.

All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 52327803, 52474004, and 52404063) and by the 2025 “AI Research Fund” of Chengdu University of Technology (Grant 2025AI004).

Conflicts of interest

Ren, T. is an Editorial Board Member of Intelligence & Robotics, and Yang, S. X. serves as the Editor-in-Chief. Neither was involved in any aspect of the editorial process for this manuscript, including reviewer selection, handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Mo, F.; Rehman, H. U.; Monetti, F. M.; et al. A framework for manufacturing system reconfiguration and optimisation utilising digital twins and modular artificial intelligence. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 82, 102524.

2. De Winter, J.; Ei Makrini, I.; Van de Perre, G.; Nowé, A.; Verstraten, T.; Vanderborght, B. Autonomous assembly planning of demonstrated skills with reinforcement learning in simulation. Auton. Robot. 2021, 45, 1097-110.

3. Ibrahim, A.; Kumar, G. Selection of Industry 4.0 technologies for Lean Six Sigma integration using fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Int. J. Lean. Six. Sigma. 2024, 15, 1025-42.

4. Zafar, M. H.; Langås, E. F.; Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergies between collaborative robotics, digital twins, augmentation, and industry 5.0 for smart manufacturing: a state-of-the-art review. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 102769.

5. Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced robotics, a review. Cogn. Robot. 2023, 3, 54-70.

6. Hao, M.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Xu, G.; Yang, H.; Liu, S. Efficient and privacy-enhanced federated learning for industrial artificial intelligence. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Inf. 2020, 16, 6532-42.

7. Velazquez, L.; Palardy, G.; Barbalata, C. A robotic 3D printer for UV-curable thermosets: dimensionality prediction using a data-driven approach. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 37, 772-89.

8. Canas-Moreno, S.; Piñero-Fuentes, E.; Rios-Navarro, A.; Cascado-Caballero, D.; Perez-Peña, F.; Linares-Barranco, A. Towards neuromorphic FPGA-based infrastructures for a robotic arm. Auton. Robot. 2023, 47, 947-61.

9. Intisar, M.; Monirujjaman Khan, M.; Rezaul Islam, M.; Masud, M. Computer vision based robotic arm controlled using interactive GUI. Intell. Autom. Soft. Comput. 2021, 27, 533-50.

10. Cazacu, C.; Iorga, I.; Parpală, R. C.; Popa, C. L.; Coteț, C. E. Optimizing assembly in wiring boxes using API technology for digital twin. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9483.

11. Ardanza, A.; Moreno, A.; Segura, Á.; de la Cruz, M.; Aguinaga, D. Sustainable and flexible industrial human machine interfaces to support adaptable applications in the Industry 4.0 paradigm. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 4045-59.

12. Tsai, Y.; Lee, C.; Liu, T.; et al. Utilization of a reinforcement learning algorithm for the accurate alignment of a robotic arm in a complete soft fabric shoe tongues automation process. J. Manuf. Syst. 2020, 56, 501-13.

13. Jeong, J. H.; Shim, K. H.; Kim, D. J.; Lee, S. W. Brain-controlled robotic arm system based on multi-directional CNN-BiLSTM network using EEG signals. IEEE. Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2020, 28, 1226-38.

14. Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, S. From junk to genius: robotic arms and AI crafting creative designs from scraps. Buildings 2024, 14, 4076.

15. Liu, Q.; Ji, Z.; Xu, W.; Liu, Z.; Yao, B.; Zhou, Z. Knowledge-guided robot learning on compliance control for robotic assembly task with predictive model. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2023, 234, 121037.

16. Cao, G.; Bai, J. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based robotic arm assembly research. PLoS. One. 2025, 20, e0311550.

17. Gao, T. Optimizing robotic arm control using deep Q-learning and artificial neural networks through demonstration-based methodologies: a case study of dynamic and static conditions. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 181, 104771.

18. Li, T.; Zeng, Q.; Li, J.; et al. An adaptive control method and learning strategy for ultrasound-guided puncture robot. Electronics 2024, 13, 580.

19. Kumar, A.; Sharma, R. Linguistic Lyapunov reinforcement learning control for robotic manipulators. Neurocomputing 2018, 272, 84-95.

20. Juarez-Lora, A.; Ponce-Ponce, V. H.; Sossa, H.; Rubio-Espino, E. R-STDP spiking neural network architecture for motion control on a changing friction joint robotic arm. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 904017.

21. Guo, C.; Luk, W. FPGA-accelerated sim-to-real control policy learning for robotic arms. IEEE. Trans. Circuits. Syst. II. 2024, 71, 1690-4.

22. Katona, K.; Neamah, H. A.; Korondi, P. Obstacle avoidance and path planning methods for autonomous navigation of mobile robot. Sensors 2024, 24, 3573.

23. Ušinskis, V.; Nowicki, M.; Dzedzickis, A.; Bučinskas, V. Sensor-fusion based navigation for autonomous mobile robot. Sensors 2025, 25, 1248.

24. Eren, B.; Demir, M. H.; Mistikoglu, S. Recent developments in computer vision and artificial intelligence aided intelligent robotic welding applications. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 4763-809.

25. Fu, J.; Rota, A.; Li, S.; et al. Recent advancements in augmented reality for robotic applications: a survey. Actuators 2023, 12, 323.

26. Rho, E.; Kim, W.; Mun, J.; Yu, S. Y.; Cho, K.; Jo, S. Impact of physical parameters and vision data on deep learning-based grip force estimation for fluidic origami soft grippers. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2487-94.

27. Yang, C.; Kang, J.; Eom, D. Enhancing ToF sensor precision using 3D models and simulation for vision inspection in industrial mobile robots. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4595.

28. Mena-Almonte, R. A.; Zulueta, E.; Etxeberria-Agiriano, I.; Fernandez-Gamiz, U. Efficient robot localization through deep learning-based natural fiduciary pattern recognition. Mathematics 2025, 13, 467.

29. Wu, H.; Zhang, W.; Lu, W.; Chen, J.; Bao, J.; Liu, Y. Automated part placement for precast concrete component manufacturing: an intelligent robotic system using target detection and path planning. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2025, 39, 04024044.

30. Nguyen, V.; Nguyen, P.; Su, S.; Tan, P. X.; Bui, T. Vision-based pick and place control system for industrial robots using an eye-in-hand camera. IEEE. Access. 2025, 13, 25127-40.

31. Wei, D.; Cao, J.; Gu, Y. Robot grasp in cluttered scene using a multi-stage deep learning model. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 6512-9.

32. Huang, C.; Su, G.; Shao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Rapid-learning collaborative pushing and grasping via deep reinforcement learning and image masking. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9018.

33. Wang, S.; Zhang, E.; Zhou, L.; Han, Y.; Liu, W.; Hong, J. 3DWDC-Net: an improved 3DCNN with separable structure and global attention for weld internal defect classification based on phased array ultrasonic tomography images. Mech. Syst. Signal. Process. 2025, 229, 112564.

34. Hassan, S. A.; Beliatis, M. J.; Radziwon, A.; Menciassi, A.; Oddo, C. M. Textile fabric defect detection using enhanced deep convolutional neural network with safe human–robot collaborative interaction. Electronics 2024, 13, 4314.

35. Zhou, S.; Le, D. V.; Jiang, L.; et al. RoboCam: model-based robotic visual sensing for precise inspection of mesh screens. ACM. Trans. Sens. Netw. 2025, 21, 1-23.

36. Rocha, F.; Garcia, G.; Pereira, R. F. S.; et al. ROSI: a robotic system for harsh outdoor industrial inspection - system design and applications. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 103, 1459.

37. Surindra, M. D.; Alfarisy, G. A. F.; Caesarendra, W.; et al. Use of machine learning models in condition monitoring of abrasive belt in robotic arm grinding process. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 3345-58.

38. Chew, S. Y.; Asadi, E.; Vargas-Uscategui, A.; et al. In-process 4D reconstruction in robotic additive manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 102784.

39. Ni, H.; Hu, T.; Deng, J.; Chen, B.; Luo, S.; Ji, S. Digital twin-driven virtual commissioning for robotic machining enhanced by machine learning. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 93, 102908.

40. Chen, Y.; Lai, C. An intuitive pre-processing method based on human–robot interactions: zero-shot learning semantic segmentation based on synthetic semantic template. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 11743-66.

41. Ghafarian Tamizi, M.; Honari, H.; Nozdryn-Plotnicki, A.; Najjaran, H. End-to-end deep learning-based framework for path planning and collision checking: bin-picking application. Robotica 2024, 42, 1094-112.

42. Arents, J.; Greitans, M. Smart industrial robot control trends, challenges and opportunities within manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 937.

43. De Roovere, P.; Moonen, S.; Michiels, N.; wyffels, F. Sim-to-real dataset of industrial metal objects. Machines 2024, 12, 99.

44. Lee, J.; Chang, C.; Cheng, E.; Kuo, C.; Hsieh, C. Intelligent robotic palletizer system. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12159.

45. Hou, R.; Yin, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H. Research on multi-hole localization tracking based on a combination of machine vision and deep learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 984.

46. Song, Y.; Wen, J.; Fei, Y.; Yu, C. Deep robotic prediction with hierarchical RGB-D fusion. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06585. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1909.06585. (accessed 3 December 2025).

47. Lin, C.; Lin, P.; Shih, C. Vision-based robotic arm control for screwdriver bit placement tasks. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 1003.

48. Lee, S. K. H.; Simeth, A.; Hinchy, E. P.; Plapper, P.; O’dowd, N. P.; Mccarthy, C. T. A vision-based hole quality assessment technique for robotic drilling of composite materials using a hybrid classification model. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 129, 1249-58.

49. Comari, S.; Carricato, M. Autonomous scanning and cleanliness classification of pharmaceutical bins through artificial intelligence and robotics. IEEE. Access. 2024, 12, 117256-70.

50. Kohut, P.; Skop, K. Vision systems for a UR5 cobot on a quality control robotic station. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9469.

51. Cheng, A.; Lu, S.; Gao, F. Anomaly detection of tire tiny text: mechanism and method. IEEE. Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 1911-28.

52. Lin, C.; Jhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, H. Vision-based robotic arm in defect detection and object classification applications. Sens. Mater. 2024, 36, 655.

53. Pereira, F. R.; Rodrigues, C. D.; Souza, H. D. S. E.; et al. Force and vision-based system for robotic sealing monitoring. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 391-403.

54. Mukherjee, D.; Gupta, K.; Chang, L. H.; Najjaran, H. A survey of robot learning strategies for human-robot collaboration in industrial settings. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102231.

55. Mendez, E.; Ochoa, O.; Olivera-Guzman, D.; et al. Integration of deep learning and collaborative robot for assembly tasks. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 839.

56. Bartyzel, G. Multimodal variational DeepMDP: an efficient approach for industrial assembly in high-mix, low-volume production. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 11297-304.

57. Li, T.; Polette, A.; Lou, R.; Jubert, M.; Nozais, D.; Pernot, J. Machine learning-based 3D scan coverage prediction for smart-control applications. Comput. Aided. Des. 2024, 176, 103775.

58. Roos-Hoefgeest, S.; Roos-Hoefgeest, M.; Alvarez, I.; González, R. C. Reinforcement learning approach to optimizing profilometric sensor trajectories for surface inspection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.03429. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.03429. (accessed 3 December 2025).

59. Simoni, A.; Borghi, G.; Garattoni, L.; Francesca, G.; Vezzani, R. D-SPDH: improving 3D robot pose estimation in Sim2Real scenario via depth data. IEEE. Access. 2024, 12, 166660-73.

60. Mangat, A. S.; Mangler, J.; Rinderle-Ma, S. Interactive process automation based on lightweight object detection in manufacturing processes. Comput. Ind. 2021, 130, 103482.

61. Gao, Z.; Elibol, A.; Chong, N. Y. Zero moment two edge pushing of novel objects with center of mass estimation. IEEE. Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 1487-99.

62. Celikel, R.; Aydogmus, O. NARMA-L2 controller for single link manipulator. In 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing (IDAP), Malatya, Turkey, September 28-30, 2018. IEEE; 2018. p. 1-6.

63. Faroni, M.; Umbrico, A.; Beschi, M.; Orlandini, A.; Cesta, A.; Pedrocchi, N. Optimal task and motion planning and execution for multiagent systems in dynamic environments. IEEE. Trans. Cybern. 2024, 54, 3366-77.

64. Calderón-Cordova, C.; Sarango, R.; Castillo, D.; Lakshminarayanan, V. A deep reinforcement learning framework for control of robotic manipulators in simulated environments. IEEE. Access. 2024, 12, 103133-61.

65. Wu, P.; Su, H.; Dong, H.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Chen, Z. An obstacle avoidance method for robotic arm based on reinforcement learning. Ind. Robot. 2025, 52, 9-17.

66. Lindner, T.; Milecki, A. Reinforcement learning-based algorithm to avoid obstacles by the anthropomorphic robotic arm. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6629.

67. Liu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, B.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y. Deep reinforcement learning-based safe interaction for industrial human-robot collaboration using intrinsic reward function. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 49, 101360.

68. Honelign, L.; Abebe, Y.; Tullu, A.; Jung, S. Deep reinforcement learning-based enhancement of robotic arm target-reaching performance. Actuators 2025, 14, 165.

69. Ji, Z.; Liu, G.; Xu, W.; Yao, B.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Z. Deep reinforcement learning on variable stiffness compliant control for programming-free robotic assembly in smart manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7073-95.

70. Men, Y.; Jin, L.; Cui, T.; Bai, Y.; Li, F.; Song, R. Policy fusion transfer: the knowledge transfer for different robot peg-in-hole insertion assemblies. IEEE. Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1-10.

71. Zhou, H.; Lin, X. Intelligent redundant manipulation for long-horizon operations with multiple goal-conditioned hierarchical learning. Adv. Robot. 2025, 39, 291-304.

72. Koubaa, A.; Ammar, A.; Boulila, W. Next-generation human-robot interaction with ChatGPT and robot operating system. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2025, 55, 355-82.

73. Gupta, S.; Yao, K.; Niederhauser, L.; Billard, A. Action contextualization: adaptive task planning and action tuning using large language models. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 9407-14.

74. Hou, W.; Xiong, Z.; Yue, M.; Chen, H. Human-robot collaborative assembly task planning for mobile cobots based on deep reinforcement learning. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C. 2024, 238, 11097-114.

75. Angelidis, A.; Plevritakis, E.; Vosniakos, G.; Matsas, E. An open extended reality platform supporting dynamic robot paths for studying human–robot collaboration in manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 3-15.

76. Zhao, D.; Ding, Z.; Li, W.; Zhao, S.; Du, Y. Cascaded fuzzy reward mechanisms in deep reinforcement learning for comprehensive path planning in textile robotic systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 851.

77. Lin, J.; Wei, X.; Xian, W.; et al. Continuous reinforcement learning via advantage value difference reward shaping: a proximal policy optimization perspective. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 151, 110676.

78. Bing, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, R.; et al. Solving robotic manipulation with sparse reward reinforcement learning via graph-based diversity and proximity. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 2759-69.

79. Yu, C.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, M. Trajectory tracking control of an unmanned aerial vehicle with deep reinforcement learning for tasks inside the EAST. Fusion. Eng. Des. 2023, 194, 113894.

80. Bartyzel, G.; Półchłopek, W.; Rzepka, D. Reinforcement learning with stereo-view observation for robust electronic component robotic insertion. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2023, 109, 1970.

81. Yu, S.; Tan, G. Inverse kinematics of a 7-degree-of-freedom robotic arm based on deep reinforcement learning and damped least squares. IEEE. Access. 2025, 13, 4857-68.

82. Amirnia, A.; Keivanpour, S. Real-time sustainable cobotic disassembly planning using fuzzy reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 3798-821.

83. Tian, B.; Kaul, H.; Janardhanan, M. Balancing heterogeneous assembly line with multi-skilled human-robot collaboration via adaptive cooperative co-evolutionary algorithm. Swarm. Evol. Comput. 2024, 91, 101762.

84. Wang, T.; Fan, J.; Zheng, P. An LLM-based vision and language cobot navigation approach for human-centric smart manufacturing. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 75, 299-305.

85. Li, C.; Chrysostomou, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H. IRWoZ: constructing an industrial robot Wizard-of-OZ dialoguing dataset. IEEE. Access. 2023, 11, 28236-51.

86. Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Chrysostomou, D.; Yang, H. ToD4IR: a humanised task-oriented dialogue system for industrial robots. IEEE. Access. 2022, 10, 91631-49.

87. Čakurda, T.; Trojanová, M.; Pomin, P.; Hošovský, A. Deep learning methods in soft robotics: architectures and applications. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025, 7, 2400576.

88. Bilancia, P.; Locatelli, A.; Tutarini, A.; Mucciarini, M.; Iori, M.; Pellicciari, M. Online motion accuracy compensation of industrial servomechanisms using machine learning approaches. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 91, 102838.

89. Bi, Z.; Luo, C.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L. Safety assurance mechanisms of collaborative robotic systems in manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102022.

90. Shan, S.; Pham, Q. Fine robotic manipulation without force/torque sensor. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 1206-13.

91. Deng, W.; Ardiani, F.; Nguyen, K. T.; Benoussaad, M.; Medjaher, K. Physics informed machine learning model for inverse dynamics in robotic manipulators. Appl. Soft. Comput. 2024, 163, 111877.

92. Zhou, H.; Ma, S.; Wang, G.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Z. A hybrid control strategy for grinding and polishing robot based on adaptive impedance control. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2021, 13, 168781402110040.

93. Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, W. Research on 3C compliant assembly strategy method of manipulator based on deep reinforcement learning. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 119, 109605.

94. Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liang, S.; Han, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, M. Research on robotic peg-in-hole assembly method based on variable admittance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2143.

95. Hu, X.; Liu, G.; Ren, P.; et al. An admittance parameter optimization method based on reinforcement learning for robot force control. Actuators 2024, 13, 354.

96. Zheyuan, C.; Rahman, M. A.; Tao, H.; Liu, Y.; Pengxuan, D.; Yaseen, Z. M. Need for developing a security robot-based risk management for emerging practices in the workplace using the advanced human-robot collaboration model. Work 2021, 68, 825-34.

97. Xin, X.; Keoh, S. L.; Sevegnani, M.; Saerbeck, M.; Khoo, T. P. Adaptive model verification for modularized industry 4.0 applications. IEEE. Access. 2022, 10, 125353-64.

98. Hickman, X.; Lu, Y.; Prince, D. Hybrid safe reinforcement learning: tackling distribution shift and outliers with the Student-t’s process. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129912.

99. Kana, S.; Lakshminarayanan, S.; Mohan, D. M.; Campolo, D. Impedance controlled human–robot collaborative tooling for edge chamfering and polishing applications. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 72, 102199.

100. Amaya, C.; von Arnim, A. Neurorobotic reinforcement learning for domains with parametrical uncertainty. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1239581.

101. Mahdi, M. M.; Bajestani, M. S.; Noh, S. D.; Kim, D. B. Digital twin-based architecture for wire arc additive manufacturing using OPC UA. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 94, 102944.

102. Li, C.; Zheng, P.; Li, S.; Pang, Y.; Lee, C. K. AR-assisted digital twin-enabled robot collaborative manufacturing system with human-in-the-loop. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 76, 102321.

103. Zhang, T.; Zhang, K.; Lin, J.; Louie, W. G.; Huang, H. Sim2real learning of obstacle avoidance for robotic manipulators in uncertain environments. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 65-72.

104. Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Huang, H.; Cao, Q. Digital twin-enabled grasp outcomes assessment for unknown objects using visual-tactile fusion perception. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 84, 102601.

105. Liu, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, L. A digital twin-based sim-to-real transfer for deep reinforcement learning-enabled industrial robot grasping. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 78, 102365.

106. Wang, R.; Tian, Y.; Kashima, K. Density estimation based soft actor-critic: deep reinforcement learning for static output feedback control with measurement noise. Adv. Robot. 2024, 38, 398-409.

107. Salehi, A.; Rühl, S.; Doncieux, S. Adaptive asynchronous control using meta-learned neural ordinary differential equations. IEEE. Trans. Robot. 2024, 40, 403-20.

108. Shin, G.; Yun, S.; Kim, W. A novel policy distillation with WPA-based knowledge filtering algorithm for efficient industrial robot control. IEEE. Access. 2024, 12, 154514-25.

109. Wang, S.; Tao, J.; Jiang, Q.; Chen, W.; Liu, C. Manipulator joint fault localization for intelligent flexible manufacturing based on reinforcement learning and robot dynamics. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102684.

110. Kim, H. Robot dynamics-based cable fault diagnosis using stacked transformer encoder layers. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 3697-708.

111. Lanese, I.; Schultz, U. P.; Ulidowski, I. Reversible execution for robustness in embodied AI and industrial robots. IT. Prof. 2021, 23, 12-7.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].