MEMS microrobots: components, applications, design challenges and perspectives

Abstract

Micro-electromechanical system (MEMS) microrobots have significant potential in various fields, including healthcare, assembly, and industrial monitoring. This paper provides a comprehensive review of microrobot components, including materials, sensing, actuation, and power systems. It also discusses microrobot classifications - such as swimming, walking, aerial types, microgrippers, and micromanipulators - and summarizes the significance and primary applications of each category. Finally, key challenges, particularly those related to sensing and powering microrobots, are examined, along with current perspectives and potential solutions.

Keywords

1. INTRODUCTION

Micro-electromechanical system (MEMS) microrobots are typically only a few centimeters in length or smaller. MEMS technologies generally refer to miniaturized electromechanical elements created through microfabrication technologies[1]. This continually evolving process allows for the development of increasingly small electrical components, such as sensors and actuators, as well as mechanical components, including reduction and linkage systems. Consequently, MEMS microrobots have been made possible through the integration of these electrical and mechanical components.

Although further development is required before microrobots become widely adopted and clinically approved, they show significant potential for social and economic impact through their ability to perform a wide variety of tasks. In most cases, the characteristic dimensions of microrobotic systems can be categorized as follows: nanoscale (< 1 μm), micro-scale (1 μm-1 mm), and meso- or insect-scale (1-50 mm). These size bands are adopted throughout this paper to ensure consistency in classification and comparative analysis across different microrobotic platforms. They also have potential applications in inspection, such as examining the interiors of engines or small pipelines, environmental monitoring, and agriculture, including crop pollination[2]. Nanoscale microrobots, also known as nanorobots, hold significant promise for medical applications due to their ability to operate inside the human body.

This paper offers a comprehensive review of MEMS microrobots from multiple perspectives. It synthesizes the current state of materials, sensing, actuation, and powering technologies, highlights representative classifications of microrobots together with their major applications, and critically discusses existing limitations and challenges. By consolidating these aspects, the paper provides a clear overview of the present landscape and outlines potential directions to address sensing and powering constraints, thereby supporting future research and development in this rapidly evolving field.

This paper is structured in the following manner. Section 2 separates the components of MEMS microrobots into categories of materials, sensing, actuation, and powering. In this section, current technologies and methods for each category are compared, and the principles of these technologies, along with their advantages and limitations, are described. Section 3 reviews classifications of microrobots, starting with mobile microrobots such as swimmers, walkers, and aerial types, and then covering microgrippers and micromanipulators. This section examines the sensing, actuation, and powering methods used for different classifications of microrobots, along with their applications and limitations. Section 4 provides the design challenge and a potential perspective for future study. Some concluding remarks are finally summarized in Section 5.

2. KEY COMPONENTS OF MEMS MICROROBOTS

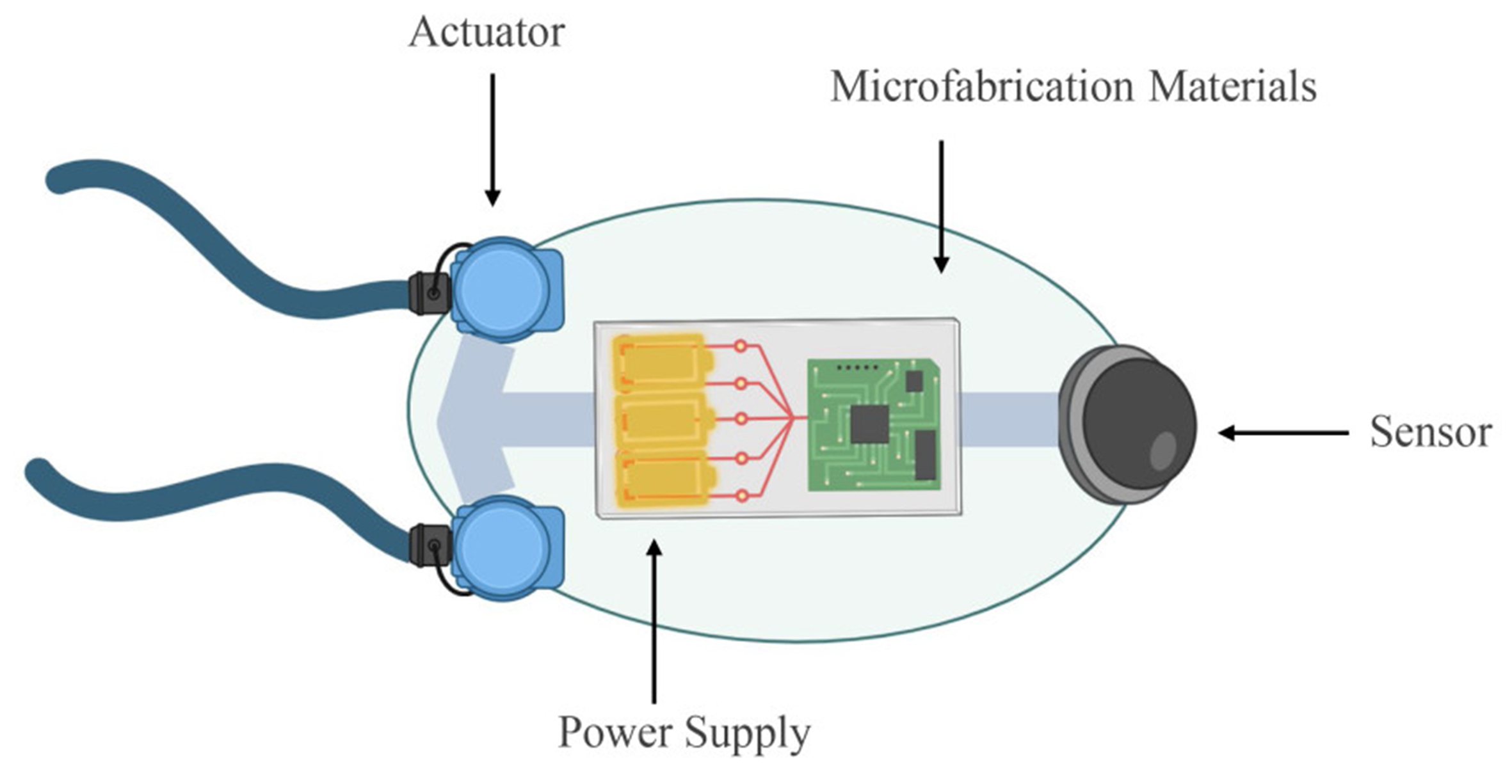

Microrobots involve many components, each with its own available technologies and methods. This section covers the microrobot components of material consideration, sensing, actuation, and powering. The microrobot illustration is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Microrobots are composed of several key components that enable their functionality: Microfabrication materials techniques allow the precise construction of microrobot structures at microscopic scales, providing the framework and intricate design necessary for operation; Sensing enables the microrobot to perceive its environment through detecting physical signals such as pressure, light, or chemicals, which inform its actions; Actuation translates these sensory inputs into movement, allowing the microrobot to perform tasks such as swimming, crawling, or gripping; and Powering supplies the necessary energy to drive the microrobot, often through micro-batteries, WPT, or chemical energy. WPT: Wireless power transfer.

2.1. Material considerations

The choice of materials plays a critical role in determining the performance, reliability, and applicability of MEMS microrobots. Due to their small scale and high integration density, these systems require materials that satisfy a unique set of mechanical, electrical, thermal, and chemical criteria. In addition, materials must be compatible with microfabrication processes to ensure manufacturability at the microscale. This section outlines the essential material requirements across several domains relevant to the design of MEMS microrobots.

2.1.1. Silicon-based materials and processes

Silicon has long been the foundational material in MEMS technology as a result of its dual role as a mechanical and electrical material[3]. Its well-established fabrication infrastructure, excellent mechanical stiffness, and compatibility with complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (CMOS) processes have made it the dominant choice for structural components in MEMS microrobots. The high dimensional stability and process precision of the silicon enable the construction of complex microscale structures with submicron resolution.

There are two primary categories of silicon micromachining: bulk micromachining and surface micromachining, as shown in Table 1. Bulk micromachining involves selectively etching into the silicon substrate to form 3D structures such as cantilevers, diaphragms, or cavities. It typically uses wet etching techniques, such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) or tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) or dry methods such as deep reactive ion etching (DRIE)[4]. DRIE enables the fabrication of high-aspect ratio structures with steep sidewalls and is especially valuable when working with silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafers[5]. SOI-based processes allow for precise control over device layer thickness and isolation, making them ideal for high-performance microrobotic actuators and sensors.

Comparison of bulk and surface micromachining for MEMS microrobots

| Category | Bulk micromachining | Surface micromachining |

| MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; SOI: silicon-on-insulator; DRIE: deep reactive ion etching; LPCVD: low-pressure chemical vapor depositio; RF: radio frequency. | ||

| Fabrication principle | Etches into the silicon substrate | Builds structures on top of the substrate using thin films |

| Substrate usage | Silicon substrate is part of the final structure | Substrate acts mainly as a base, not part of the moving structure |

| Common materials | Silicon, SOI | Polysilicon, SiO2, Si3N4 (with sacrificial layers) |

| Structure thickness | Typically tens to hundreds of microns | Usually 1-20 µm per layer (multi-layer possible) |

| Feature geometry | Deep, high-aspect-ratio structures | Planar, layered geometries |

| Process examples | Wet etching (KOH), DRIE (Bosch process) | LPCVD, photolithography, sacrificial layer release |

| Advantages | High structural strength, suitable for deep cavities or trenches | Precise multi-layer patterning, integration with electronics |

| Limitations | Limited design flexibility, more material removed | Limited structure height, possible stress or stiction issues |

| Typical applications | Pressure sensors, accelerometers, microfluidic channels | Micromotors, linkages, RF switches, microgrippers |

Surface micromachining builds structures layer by layer using deposited thin films such as polysilicon and sacrificial layers (e.g., silicon dioxide). Multi-user MEMS processes (MUMPs) and SUMMiT-V (Sandia Ultra-planar, Multi-level MEMS Technology, five-level polysilicon process) have standardized multi-layer surface micromachining, allowing for complex moving mechanisms such as linkages, gears, or electrostatic micromotors to be fabricated on a single chip. These techniques are especially useful for devices that require integrated electrical and mechanical functions in compact form factors.

Despite its strengths, silicon also has limitations. Its intrinsic brittleness and limited flexibility restrict its suitability for applications involving compliance or large deformation. Nevertheless, advances in silicon processing are continuously broadening its application range.

2.1.2. Polymer-based materials for flexible MEMS structures

Polymers play an essential role in enabling flexibility, compliance, and biocompatibility in MEMS microrobots[6]. Unlike traditional rigid materials such as silicon, polymers offer mechanical softness and high deformability, making them ideal for constructing joints, actuators, encapsulation layers, and bio-interfacing components. Commonly used polymers include SU-8, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and parylene-C, as shown in Table 2.

Comparison of common polymer materials used in flexible MEMS microrobots

| Property | SU-8 | PDMS | Parylene-C |

| MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; CVD: chemical vapor deposition. | |||

| Material type | Epoxy-based negative photoresist | Silicone elastomer | Poly-para-xylylene derivative |

| Young's modulus | 2-4 GPa | 0.36-0.87 MPa | 2.7 GPa |

| Tensile strength | 60 MPa | 2-3 MPa | 69 MPa |

| Elongation at break | 4%-10% | 100%-160% | 200% |

| Transparency (visible light) | High | High | Moderate |

| Thermal stability | Up to 200-250 °C | Up to 150 °C | Up to 290 °C |

| Biocompatibility | Moderate | Excellent | Excellent |

| Water permeability | Low | High | Very low |

| Chemical resistance | Good (limited to some solvents) | Poor (swells in organic solvents) | Excellent |

| Patterning method | Photolithography | Soft lithography, molding | CVD |

| Typical use cases | Structural layers, rigid frameworks | Soft actuators, flexible layers | Coatings, encapsulation, implantables |

SU-8 is a negative photoresist valued for its high aspect ratio patterning and structural rigidity, often used in supporting frameworks[7]. In contrast, PDMS is a soft elastomer with excellent flexibility, transparency, and biocompatibility, making it suitable for compliant mechanisms and soft microrobot bodies[8]. Parylene-C is widely applied as a conformal coating due to its biocompatibility and chemical resistance[9].

Fabrication techniques for polymer-based MEMS include soft lithography, replica molding, and increasingly additive manufacturing such as microstereolithography (μSL)[10]. These methods enable rapid prototyping of complex 3D microstructures with tunable mechanical properties. Emerging developments in 4D printing and stimuli-responsive polymers are also pushing the boundaries of polymer-based microrobotics, allowing structures to change shape in response to environmental cues. Recent advances in multiphoton lithography (MPL) have expanded the capabilities of SU-8 microstructures beyond traditional photolithography[11]. MPL enables direct fabrication of complex 3D functional microdevices in SU-8 with submicron resolution, which has been applied in microfluidics, MEMS, microrobotics, and photonics. Novel approaches have improved resolution, enabled post-fabrication functionalization, and optimized processing parameters to meet application-specific requirements. These developments, particularly in the past five years, highlight the versatility of SU-8 when combined with advanced additive manufacturing methods.

In general, polymers provide design freedom that complements the limitations of rigid microfabrication, enabling the development of flexible, adaptive, and multifunctional MEMS microrobots for biomedical, environmental, and soft robotic applications.

2.1.3. Metal and composite structures

Metallic materials play a vital role in MEMS microrobotics due to their excellent mechanical strength, high electrical and thermal conductivity, and magnetic properties[12]. Unlike silicon and polymer-based materials, metals can sustain larger mechanical loads and enable the fabrication of robust components such as linkages, frames, gears, and conductive pathways. This makes them ideal for microrobots operating under dynamic conditions, including locomotion, actuation, and wireless communication.

Among commonly used metals, nickel stands out for its ease of microfabrication through electroplating and its good mechanical resilience, as shown in Table 3. Gold and aluminum are preferred for electrodes and wiring due to their superior electrical conductivity and corrosion resistance[13]. Titanium is frequently used in biomedical applications because of its excellent biocompatibility and moderate stiffness, making it suitable for implantable microrobots[14]. For applications involving magnetic actuation or sensing, cobalt, iron, and their alloys (e.g., permalloy) are widely adopted due to their soft magnetic behavior.

Comparison of common metals used in MEMS microrobots

| Metal | Young's modulus | Electrical conductivity | Magnetic property | Biocompatibility | Typical uses in MEMS microrobots |

| MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system. | |||||

| Nickel | 200 GPa | Moderate | Soft magnetic | Moderate | Structural components, magnetic actuators |

| Gold | 78 GPa | Very high | Non-magnetic | Excellent | Electrodes, conductive paths, biocompatible interfaces |

| Aluminum | 70 GPa | High | Non-magnetic | Moderate | Wiring, thin films, lightweight structures |

| Titanium | 110 GPa | Low | Non-magnetic | Excellent | Implantable structures, corrosion-resistant frameworks |

| Iron | 210 GPa | Moderate | Ferromagnetic | Poor (unless coated) | Magnetic actuation, micromotors |

| Permalloy (Ni-Fe) | 150-200 GPa | Moderate to high | High magnetic permeability | Moderate | Magnetic sensors, field-responsive components |

Fabrication techniques for metal-based MEMS structures include electroplating, evaporation, sputtering, laser micromachining, and advanced methods such as the LIGA (lithography, electroplating, and molding) process, which enables the creation of high-aspect-ratio microstructures with precise geometry and vertical sidewalls[15]. In addition, laser micro sintering (LMS) has gained attention as a method for layer-by-layer fabrication of complex 3D metallic components, especially in prototyping and custom designs[16].

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in composite structures that integrate metals with polymers, ceramics, or biological materials[17]. These hybrid structures combine the mechanical or electrical functionality of metals with the flexibility, lightweight, or biocompatibility of other materials. For instance, metal-polymer composites are used to form flexible joints, stretchable sensors, and hybrid actuators, allowing microrobots to maintain both durability and adaptability. Furthermore, composites that incorporate magnetic nanoparticles within polymer matrices can achieve magnetically controlled deformation or navigation, which is highly desirable in targeted drug delivery or micro-manipulation tasks. However, the integration of dissimilar materials also introduces challenges such as mismatched thermal expansion coefficients, interfacial adhesion, and processing incompatibility. Careful material selection and optimized bonding strategies are essential to ensure mechanical stability and long-term reliability.

In summary, metals and composite materials significantly expand the design possibilities for MEMS microrobots. Their unique physical and functional attributes make them indispensable in developing devices that require structural integrity, conductivity, magnetic responsiveness, and multifunctional adaptability.

2.1.4. Emerging hybrid and multimaterial strategies

To meet diverse and sometimes conflicting design requirements, hybrid and multimaterial strategies have emerged as a powerful and increasingly essential approach in the development of MEMS microrobots[18]. These strategies aim to integrate the unique advantages of different classes of materials into a single microsystem. For example, combining rigid materials such as silicon or SU-8 with soft materials such as PDMS or hydrogels enables microrobots to retain structural precision and high-resolution features while achieving mechanical compliance, adaptability and safe interactions with soft or biological environments[19]. This rigid-soft integration is particularly important in applications such as microgrippers, bioinspired swimmers, and surgical tools.

Similarly, composite structures that blend metals with polymers offer benefits such as enhanced strength, stretchability, and electrical functionality. For example, nickel-PDMS composites can be used to create magnetically controllable microrobots, where the metal provides actuation while the polymer allows deformation. These metal-polymer hybrids are manufactured by a combination of electroplating, soft lithography, and lamination[20]. Another prominent direction is the development of magnetically responsive elastomers, where soft matrices such as PDMS are embedded with ferromagnetic particles (e.g., Fe3O4 or NdFeB). Such microrobots can be wirelessly actuated and steered using external magnetic fields, making them ideal for untethered biomedical or microfluidic applications[21].

Advancements in multimaterial 3D printing technologies, such as μSL, direct ink writing, and inkjet-based deposition, have enabled high-resolution layer-by-layer integration of multiple functional materials[22]. These additive processes allow the fabrication of 3D structures with spatially varying mechanical, electrical or optical properties, giving rise to "4D microrobots" that dynamically change shape or function over time in response to external stimuli such as heat, pH, or light. Emerging biohybrid strategies also explore the integration of synthetic materials with living cells or bioactive layers, enabling microrobots to sense, grow, or respond to biological cues in real time. These approaches open exciting avenues in biosensing, environmental monitoring, and precision medicine.

A comparison of representative hybrid and multimaterial strategies is summarized in Table 4. These approaches collectively point toward a future in which MEMS microrobots are no longer constrained by the limitations of individual materials but are instead empowered by the intelligent integration of multiple functional domains.

Comparison of representative hybrid and multimaterial strategies in MEMS microrobots

| Strategy type | Typical material combination | Advantages | Fabrication methods | Typical applications |

| MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane. | ||||

| Rigid-soft hybrid | Silicon + PDMS / SU-8 + hydrogel | Structural precision + flexibility + biocompatibility | Soft lithography, transfer bonding | Bio-interactive microrobots, microgrippers |

| Metal-polymer composite | Nickel + PDMS / gold + polyimide | Strength + conductivity + stretchability | Electroplating + molding, lamination | Flexible sensors, magnetic actuation |

| Magnetically responsive elastomer | PDMS + Fe3O4 / NdFeB particles | Wireless actuation + remote control | Particle dispersion + casting | Magnetic swimmers, targeted drug delivery |

| Multimaterial 3D printing | Thermoplastic elastomer + conductive polymer ink | Integrated structure + embedded functionality | μSL, inkjet printing, direct ink writing | 4D microrobots, soft electronics |

| Bio-synthetic composite | Polymer + cells or protein layers | Biofunctionality + environmental adaptation | Layer-by-layer deposition, microfluidics | Biosensing, tissue-integrated robots |

2.2. Sensing

Sensing units are integral to MEMS microrobots, enabling them to perceive environmental signals and monitor their internal states. To support autonomous behavior in microscale systems, sensors must be highly miniaturized, energy-efficient, and capable of providing accurate real-time feedback. Given the unique constraints of microscale systems, sensors are often custom-fabricated using silicon-based microfabrication techniques. Depending on the intended application, MEMS microrobots can incorporate inertial, optical, chemical, or tactile sensors into their design[23].

2.2.1. Inertial sensors

Inertial sensors are fundamental components in MEMS microrobots for motion detection, orientation tracking, and navigation. These sensors provide real-time feedback on robot linear acceleration, angular velocity, and position, allowing closed-loop control, path planning, and adaptive behavior, especially in GPS-denied or visually occluded environments.

The two primary types of inertial sensors used in MEMS are accelerometers and gyroscopes. Accelerometers measure linear acceleration along one or more axes and are typically based on a suspended proof mass that moves in response to external forces[24]. This displacement is translated into an electrical signal through capacitive, piezoresistive, or piezoelectric sensing mechanisms. In contrast, gyroscopes measure angular velocity[25]. MEMS gyroscopes commonly use vibrating structures (e.g., tuning forks or Coriolis-effect devices) to detect rotational motion. Both sensor types can be fabricated in compact, low-power forms suitable for integration into mobile microrobots.

Inertial sensors are predominantly constructed using silicon micromachining techniques. Surface micromachining allows the fabrication of intricate suspended structures such as cantilevers, comb drives, and diaphragms. These structures are typically designed with symmetrical geometries to minimize bias drift and noise. Materials such as polysilicon, silicon dioxide, and metal electrodes are used for structural, insulating, and conductive layers, respectively[26].

Integration of multi-axis inertial measurement units (IMUs), which combine tri-axis accelerometers and gyroscopes, is becoming increasingly feasible at the microscale. These integrated devices allow full 6-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) motion tracking and can be embedded directly onto microrobot substrates using wafer-level packaging or flip-chip bonding techniques.

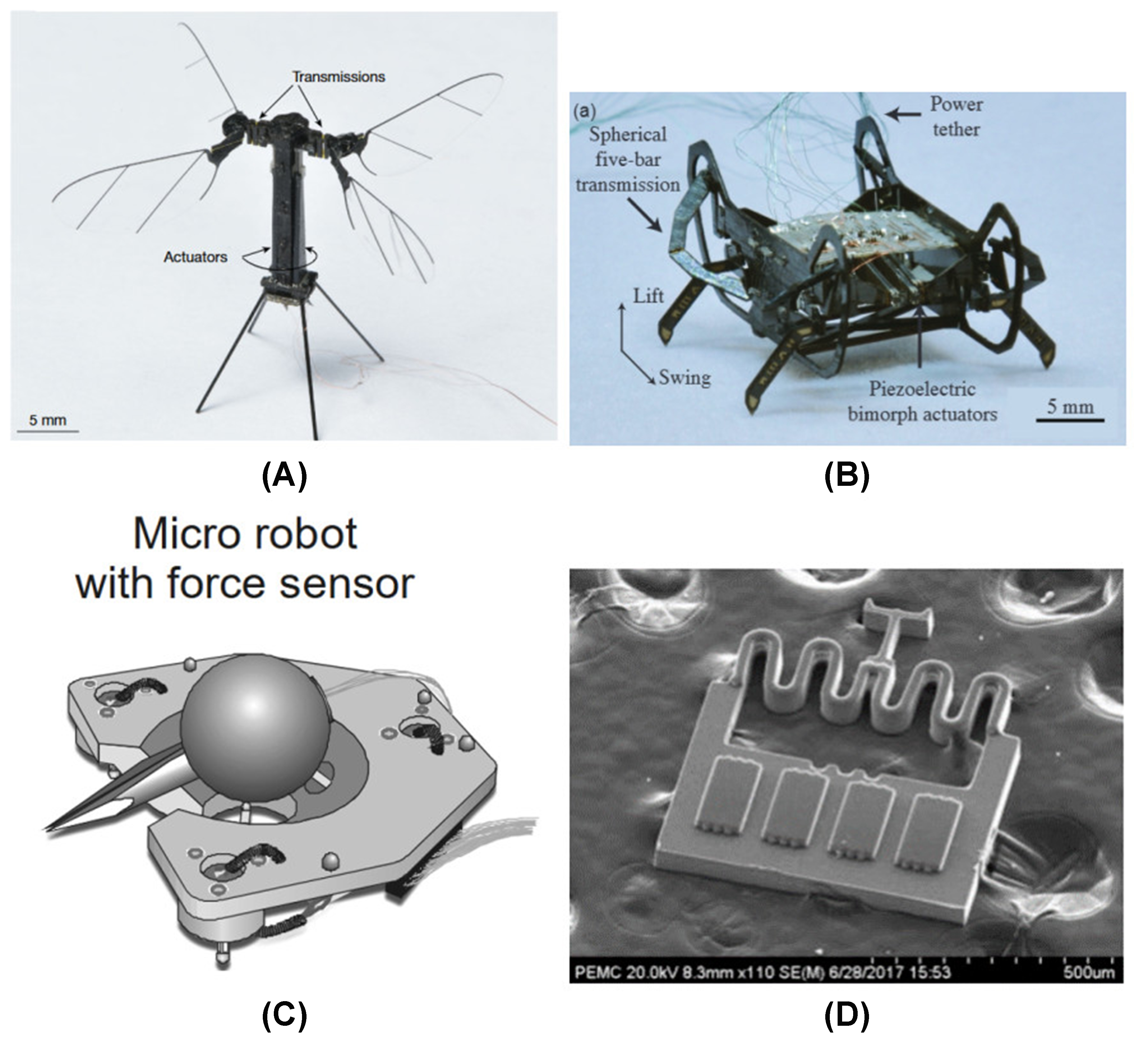

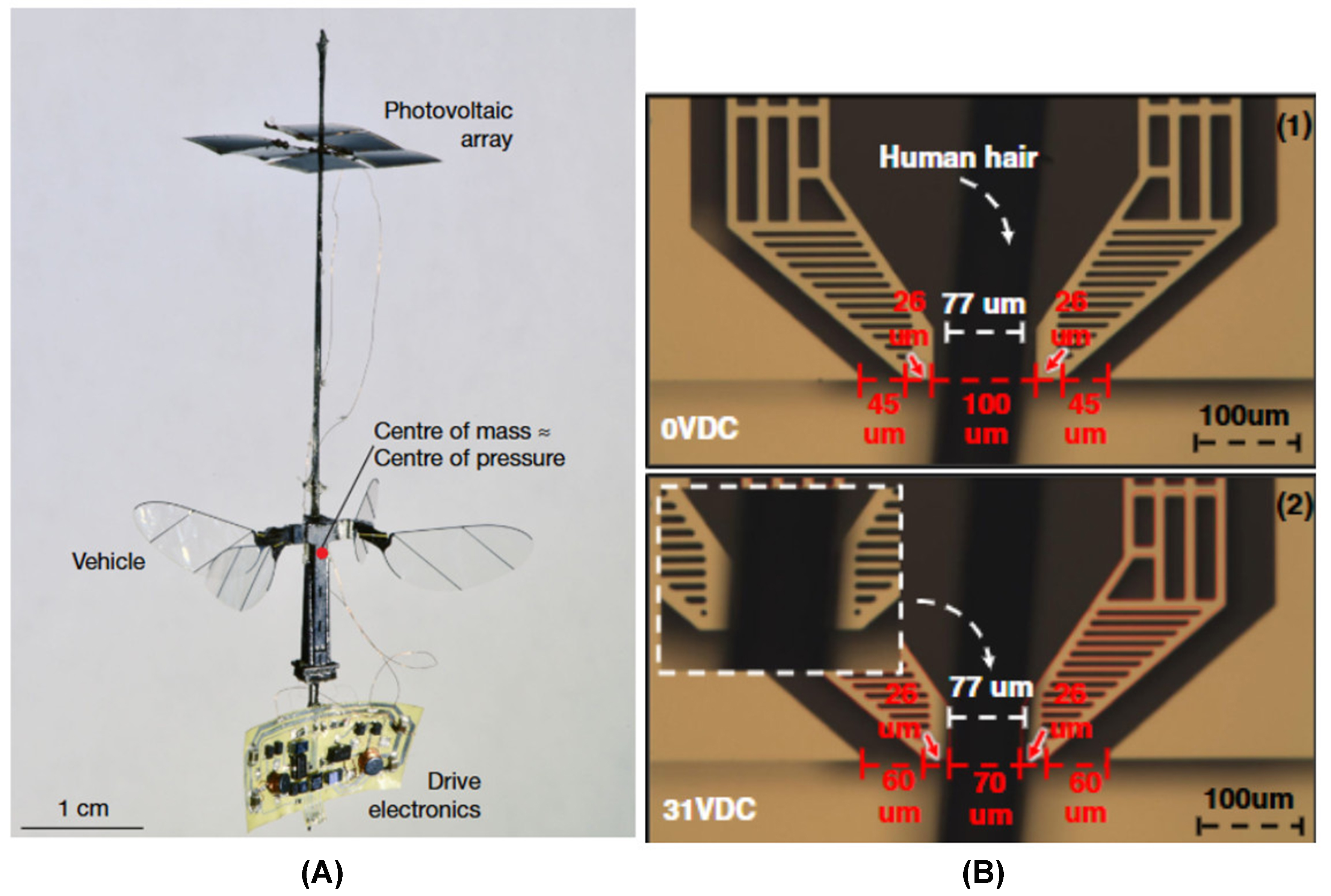

Modern microrobots utilize a technique called concomitant or self-sensing to obtain feedback on the velocity of piezoelectric actuated parts[27]. The term self-sensing refers to actuators that sense their own movements and function as piezoelectric actuators and sensors[27]. This piezoelectric sensor operates by exploiting the varying current as a function of the actuator's speed and phase. This approach is significant for miniaturization, as it enables microrobots to have sensing capabilities without the need for additional components. This sensing technology has been used in notable microrobot designs, such as RobotBee[28] and Harvard Ambulatory MicroRobot (HAMR)[2], where it provides feedback on the speed and angular position of actuators, as shown in Figure 2A and B.

Figure 2. Examples of the MEMS-based sensors. (A) Image and scale of RoboBee microrobot[28]; (B) Image and scale of HAMR microrobot with components labeled[2]; (C) Design of a microrobot with AFM-based force microsensor[29]; (D) Image and scale of microforce-sensing mobile microrobot[30]. MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; HAMR: Harvard Ambulatory MicroRobot; AFM: atomic force microscope.

2.2.2. Optical and vision sensors

Optical and vision sensors play a critical role in enabling MEMS microrobots to perceive and interact with their visual surroundings. These sensors are essential in applications where light intensity, object detection, image-based navigation, or biological tissue recognition is required[31]. Due to the stringent size and power constraints of microrobots, optical sensing systems must be highly miniaturized while still offering sufficient resolution and sensitivity.

Common types of optical sensors used in MEMS microrobots include photodiodes, phototransistors, and micro-cameras[32]. Photodiodes and phototransistors are often employed for simple tasks such as detecting ambient light, reflective surfaces, or proximity, while micro-cameras support more advanced vision functions such as image acquisition, pattern recognition, or visual feedback control. Some advanced systems integrate optical flow sensors to support real-time motion tracking or velocity estimation in autonomous microrobots.

Miniaturization of vision components remains a key challenge. Micro-cameras with integrated lenses and image processors have become increasingly compact thanks to advances in CMOS image sensor technology[32]. However, integrating these components into MEMS platforms requires careful design of optical pathways, light shielding, and data transmission interfaces, especially when operating in low-light or biologically opaque environments. To address these challenges, researchers have also explored the use of optical fibers, waveguides, or planar photonic structures to route and process light within micro-scale platforms.

Optical sensors are particularly valuable in biomedical applications. For example, vision-based endoscopic microrobots can navigate through internal tissues and provide visual feedback during minimally invasive surgery[33]. In microfluidics, optical sensors detect changes in color, transparency, or fluorescence, enabling biochemical analysis. Furthermore, light-based feedback enables closed-loop control strategies for autonomous behavior, such as target tracking, environmental mapping, and visual servoing.

Despite their advantages, optical sensors are typically more power-hungry and data-intensive than other sensor types, which limits their deployment in battery-constrained systems. Future research is focusing on event-based vision sensors, neuromorphic photodetectors, and compressive imaging techniques to enable energy-efficient visual perception at the microscale.

2.2.3. Tactile and force sensors

Tactile and force sensors are essential components in MEMS microrobots that physically interact with their environment, particularly in tasks such as object manipulation, surface exploration, and biomedical probing[34]. These sensors enable robots to detect contact events, measure applied forces or pressure distributions, and respond adaptively to external mechanical stimuli. At the microscale, the integration of compact, sensitive, and low-power tactile sensing elements is critical to maintaining robot functionality without compromising mobility or form factor. Figure 2C shows the design of a microrobot with an integrated atomic force microscope(AFM)-based force sensor[29].

Common tactile sensing mechanisms in MEMS include piezoresistive, capacitive, piezoelectric, and optical-based approaches. Piezoresistive sensors are based on changes in electrical resistance under mechanical stress and are widely used for their simplicity and compatibility with silicon-based microfabrication[35]. Capacitive sensors detect displacement or pressure by measuring changes in capacitance between two parallel plates[36]. These sensors offer high sensitivity and can be manufactured in array configurations for spatial force mapping. Piezoelectric sensors, utilizing materials such as lead zirconate titanate (PZT) or polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), generate electrical charge in response to mechanical deformation and are particularly suited for dynamic force sensing and vibration monitoring. This is because material selection plays a crucial role in tactile sensor performance. Although silicon-based devices provide structural integrity and integration with electronics, soft materials such as PDMS, polyimide, or SU-8 are often used in the sensing interface to increase compliance and sensitivity. Hybrid structures that combine rigid substrates with soft sensing layers or flexible electrodes are particularly effective for creating bio-inspired tactile skins or flexible robotic grippers.

Tactile and force sensors are widely applied in micro-manipulators, microgrippers, minimally invasive surgical tools, and bio-interfaces. In such contexts, accurate feedback on contact force not only enhances manipulation precision but also protects delicate biological tissues or structures. In addition, the integration of tactile sensing into feedback control systems facilitates adaptive grasping, slip detection, and interaction force regulation in real-time.

The measurement of force in a microrobot is achieved by understanding the physical properties, such as stiffness, of specific portions of the microrobot and then measuring the deformation of those portions using vision-based feedback to calculate the force[30]. An image of a force-sensing microrobot is shown in Figure 2D.

2.2.4. Magnetic sensors

Magnetic sensors are increasingly used in MEMS microrobots for position tracking, orientation estimation, and magnetic field interaction[37]. Their ability to function in opaque or enclosed environments, where optical or inertial sensors may be limited, makes them particularly attractive for applications in biomedical navigation, in vivo microrobotics, and wireless control systems. In magnetically actuated microrobots, magnetic sensors provide essential feedback to close the control loop and enable precise remote manipulation.

The most commonly used magnetic sensing mechanisms in MEMS include Hall effect sensors, magnetoresistive sensors, and fluxgate sensors[38]. Hall effect sensors detect magnetic fields by measuring voltage changes across a conductor due to Lorentz forces acting on charge carriers. CMOS-compatible technology is simple and suitable for low-cost applications. Magnetoresistive sensors, such as anisotropic magnetoresistance (AMR), giant magnetoresistance (GMR), and tunnel magnetoresistance (TMR) devices, offer higher sensitivity and better spatial resolution[39]. These sensors exhibit resistance changes in response to magnetic field strength and direction and are widely used in precision field detection and angular position sensing.

Magnetic sensors are often fabricated using thin-film deposition techniques such as sputtering or evaporation, followed by lithographic patterning and encapsulation. Soft magnetic materials such as NiFe (permalloy) are frequently used for their high magnetic permeability and low coercivity, allowing for sensitive, low-noise detection. For fully integrated systems, magnetic sensors can be combined with microcoils or permanent magnets to enable compact on-chip sensing and actuation.

In microrobotic systems, magnetic sensors are often used in conjunction with external magnetic fields to support closed-loop control and localization. For instance, a microrobot navigating within a human artery may rely on external magnetic guidance while internal magnetic sensors monitor its position and orientation relative to the applied field. This strategy has been used in targeted drug delivery, minimally invasive diagnostics, and micro-assembly tasks.

2.3. Actuation mechanisms

Actuation mechanisms are central to MEMS microrobots, enabling physical interaction with their surroundings through locomotion, manipulation, or deformation. At the microscale, actuators must deliver precise, efficient motion while maintaining low power consumption and compatibility with microfabrication constraints. A variety of actuation strategies have been developed to meet these demands, each with distinct advantages and limitations. To provide a clear overview of different actuation approaches, a comparative summary of representative mechanisms is presented in Table 5.

Comparative summary of actuation mechanisms

| Actuation type | Efficiency | Fabrication compatibility | Main features/remarks |

| CMOS: Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor; MUMPs: multi-user MEMS processes; PZT: lead zirconate titanate; AlN: aluminum nitride; EMI: electromagnetic interference; SMA: shape memory alloy; SEA: surface electrochemical actuator; EHD: electrohydrodynamic. | |||

| Electrostatic | High | Excellent (CMOS, MUMPs) | Fast, low power, precise; limited force and pull-in instability |

| Piezoelectric | High | Good (PZT, AlN thin films) | High precision, high force density; small displacement, high voltage |

| Electromagnetic (Motor) | Moderate | Moderate (microcoil fabrication) | Large torque, continuous motion; high current, electromagnetic interference (EMI) issues |

| Magnetic field-driven | Moderate-high | Good (magnetic thin-film, plating) | Wireless, biocompatible; bulky setup, limited precision |

| SMA/SEA | Moderate | Limited (metal or electrochemical) | Large strain, bistable; slow response, thermal fatigue |

| Dielectric elastomer | Moderate | Polymer-compatible | Lightweight, flexible; high voltage, limited accuracy |

| Acoustic | High (fuel-free) | Excellent (microfluidic integration) | Contactless, biocompatible; requires ultrasound setup |

| Electrohydrodynamic (EHD) | Low-moderate | Good (planar electrodes) | Simple design; low efficiency, fluid-dependent |

| Chemical/bubble | Moderate-high | Simple (metal deposition, microchannel) | High speed, easy fabrication; low controllability, short lifetime |

2.3.1. Electrostatic

Electrostatic actuation is one of the most widely used mechanisms in MEMS microrobotics due to its compatibility with standard microfabrication processes, fast response times, and low power consumption[40]. The principle relies on the attraction between electrically charged elements when a voltage difference is applied. This force induces the displacement or deformation of microstructures, enabling motion at very small scales.

The most common structure is the parallel-plate actuator, which consists of a movable electrode suspended over a fixed electrode. When voltage is applied, the electrostatic force pulls the movable plate downward[26]. More complex geometries, such as interdigitated comb drives, are often used to generate in-plane motion with larger travel ranges and better stability. These designs are highly scalable, and their actuation force can be precisely controlled by adjusting the spacing, surface area, and applied voltage of the electrode. Despite its simplicity and speed, electrostatic actuation typically suffers from limited output force and short displacement ranges, especially when scaled to larger loads. Furthermore, pull-in instability, a condition in which the movable electrode collapses onto the fixed one when the voltage exceeds a critical value, must be carefully managed in actuator design.

Fabrication of electrostatic actuators is highly compatible with surface micromachining and SOI processing. Materials such as doped polysilicon and silicon dioxide are commonly used to construct the structural and insulating layers. The standard MUMP process offers comb-drive and parallel-plate actuators as part of its basic fabrication modules.

Scratch-drive actuators (SDAs) are a type of electrostatic actuator commonly used in MEMS-based microrobots. They are popular for driving various microdevices due to their large output force, long travel distance, and high precision[41]. Compared to thermally actuated methods, the power requirements for generating strong forces with SDAs are much lower[42]. The actuator functions by continuously applying and then removing an electrostatic force between the substrate and a plate, causing the plate to move a step with each pulse.

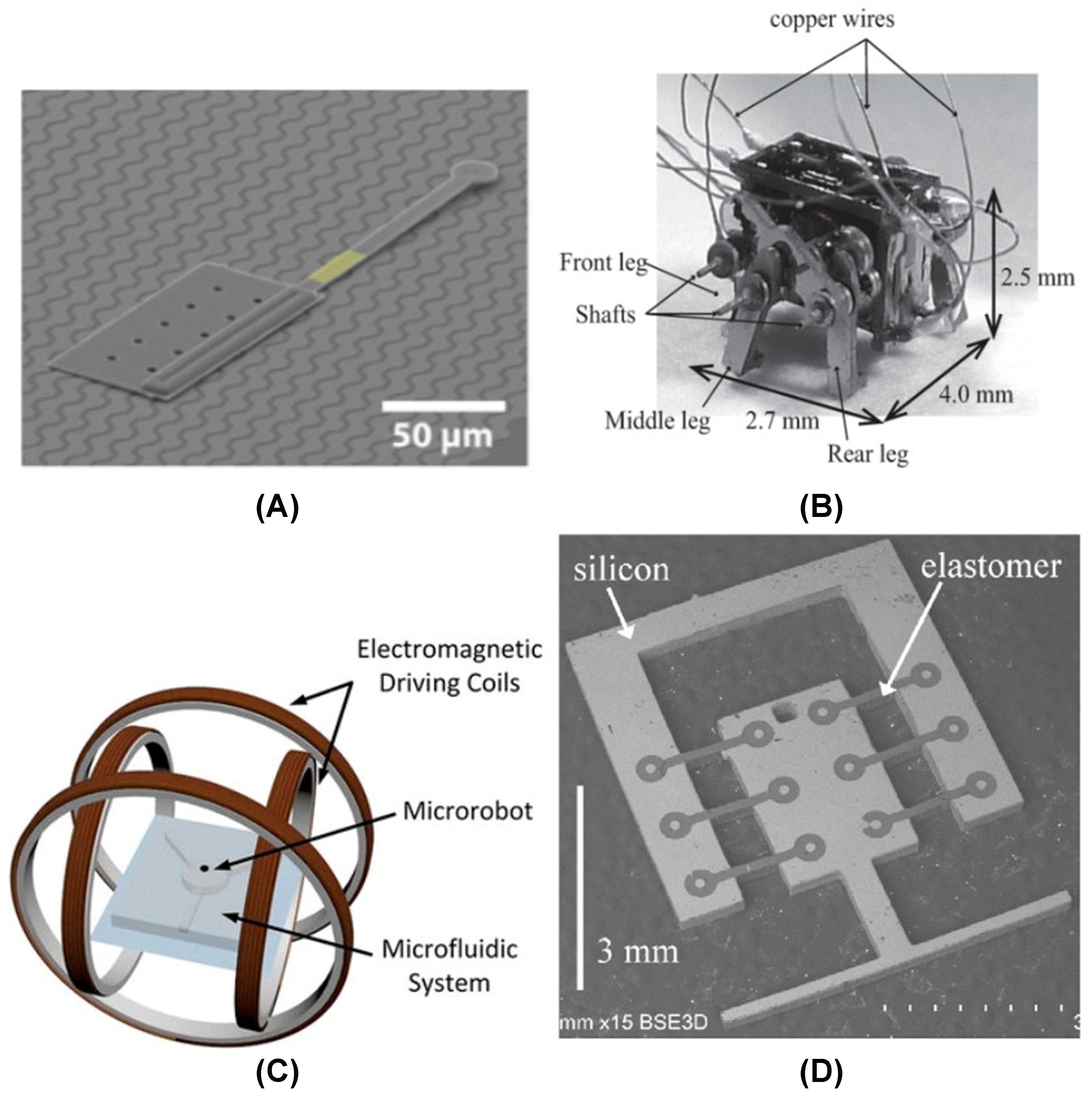

However, SDAs have some drawbacks. Since they are electrostatically actuated, they rely heavily on frictional forces to produce motion, resulting in nonlinear and unpredictable operation[43]. A more modern application of electrostatic forces as an actuation mechanism for microrobots is demonstrated in the creation of a thruster for a flying microrobot[44]. Additionally, because only a specific shape will work for SDAs, the rest of the microrobot must be designed around the SDA mechanism[45]. SDAs were used as the actuation mechanism for the design of MEMS microrobots, as shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3. Examples of the MEMS-based actuation. (A) Image and scale of a microrobot that utilizes a SDA[45]; (B) Design of remote electromagnetic actuation system[46]; (C) Design and scale of microrobot utilizing an electromagnetic motor to power a leg mechanism[47]; (D) Image of elastomer jumping mechanism[48]. MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; SDA: scratch-drive actuator.

2.3.2. Onboard electromagnetic

Electromechanical actuation refers to motor systems on board that convert electrical energy directly into mechanical motion through electromagnetic principles[49]. This actuation method encompasses stepper motors, servo motors, DC motors, and brushless motors that are widely employed in conventional robotics and have been successfully miniaturized for microrobotic applications[50,51].

The fundamental operating principle involves electromagnetic interactions between current-carrying conductors and magnetic fields to generate rotational or linear motion. At the microscale, electromechanical actuators have several advantages, including high force output, precise controllability, and compatibility with standard electronic control systems[52]. They can generate substantial torques and forces relative to their size, making them suitable for applications requiring significant mechanical work. The digital nature of stepper motor control enables precise positioning without the need for complex feedback systems, which is particularly beneficial for resource-constrained microrobotic platforms[53].

However, miniaturization introduces challenges including significant power consumption that limits battery life in untethered applications, mechanical complexity that can increase manufacturing costs and reliability issues, and potential electromagnetic interference with onboard electronics. Fabrication typically involves MEMS fabrication techniques or hybrid assembly approaches, with microcoils manufactured using photolithography and electroplating[54,55].

Applications include precision positioning systems, micromanipulators, locomotion mechanisms for wheeled microrobots and actuated joints such as arms, or legs[46,47,56,57], as illustrated in Figure 3B.

2.3.3. Piezoelectric

Piezoelectric actuation leverages the ability of certain materials to undergo mechanical deformation when subjected to an electric field[27]. In MEMS microrobots, piezoelectric actuators offer high force density, fast response, and nanometer-level resolution, making them ideal for precision positioning, rapid vibration, and high-frequency applications[28].

Piezoelectric materials, such as PZT, aluminum nitride (AlN), and zinc oxide (ZnO), are commonly used in thin-film or bulk form. When an electric field is applied across the piezoelectric layer, the material expands or contracts along specific crystallographic axes, inducing a displacement in the attached structure. This motion can be harnessed to generate bending, extension, or torsional movements depending on the actuator design.

Common MEMS configurations include cantilever beams, diaphragms, and bimorph structures, where a piezoelectric layer is sandwiched between or bonded to passive layers (e.g., silicon or metal). These multi-layer stacks convert the piezo-induced strain into amplified motion. For instance, a piezoelectric cantilever can generate vertical deflection under alternating voltage, while ring-shaped diaphragms are used in ultrasonic microrobots to produce acoustic waves for propulsion or sensing.

Piezoelectric actuators are typically fabricated using thin-film deposition techniques, such as sputtering or sol-gel processing, followed by photolithographic patterning and high-temperature annealing to activate the crystalline orientation. Integration challenges include film stress management, polarization alignment, and ensuring compatibility with CMOS processes, particularly for materials such as PZT that require high-temperature processing.

In microrobotics, piezoelectric actuators are employed in a wide range of applications: from ultrasonic propulsion in swimming microrobots, to microgrippers for cell manipulation, and resonant actuators for high-speed scanning or vibration-based locomotion. Their low power consumption in resonant modes and high stiffness enable robust and reliable operation, even in demanding environments such as inside the human body or in fluidic chambers.

However, limitations include a small displacement range, high driving voltage, and material fatigue during long-term cyclic loading[58]. Recent research addresses these issues by developing low-voltage thin-film materials, composite piezoelectric-polymer actuators, and hybrid systems that integrate piezoelectric elements with mechanical amplifiers or compliant mechanisms to expand the range of motion and reduce the voltage requirements.

2.3.4. Field-driven magnetic

Magnetic actuation is a widely adopted strategy in MEMS microrobotics, particularly for applications requiring wireless, untethered control in enclosed or non-transparent environments. It leverages the interaction between magnetic fields and magnetized materials or current-carrying elements to generate motion through magnetic torque or force. Its ability to support remote operation makes it especially attractive for biomedical microrobots, microfluidic devices, and swarm systems. Magnetic actuation can be performed using permanent magnets or electromagnets[59].

There are two main forms of electromagnetic actuation in MEMS: field-based actuation using external magnetic fields and on-chip electromagnetic actuation using integrated microcoils. In the first approach, magnetic materials (e.g., soft magnetic materials or permanent magnets) are integrated into the microrobot body. For instance, Merzaghi et al. used an external magnetic field to generate torque or translational force, allowing swimming, crawling, or rotating behaviors, as illustrated in Figure 3C[60]. In the second approach, microfabricated coils generate magnetic fields that interact with nearby magnets or magnetized structures, enabling localized motion.

Magnetic actuation offers several advantages: it enables wireless control, avoids direct electrical connections, and supports operation in fluidic or biological environments where optical or electrostatic methods may fail. It also allows for relatively large forces and long-range interaction. However, it often requires bulky external magnetic setups, such as Helmholtz coils or rotating permanent magnets, and the integration of magnetic materials can complicate fabrication processes. In addition, actuation precision depends heavily on the accuracy and stability of the external magnetic field control system.

For jumping microrobots, magnetic actuation offers a practical solution to achieve rapid energy release and controllable propulsion. By utilizing repulsive or gradient magnetic fields, these systems can store magnetic potential energy and release it instantaneously to generate a jumping motion. This approach enables wireless operation and precise timing control without the need for direct electrical connections. For instance, Gerratt et al. designed a magnetically actuated jumping microrobot, which is shown in Figure 3D[48].

2.3.5. Shape memory alloys

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) represent a unique class of smart materials that can remember and return to a predetermined shape when subjected to an external stimulus, most commonly temperature, but also electric fields, magnetic fields, or electrochemical processes[61]. This shape memory effect makes SMAs particularly attractive for microrobotics applications where maintaining a specific configuration without continuous power consumption is critical, especially in untethered systems with limited energy resources.

Traditional SMAs such as Nitinol (NiTi) and other metallic alloys have been extensively used in macroscale applications; however, their implementation at the microscale faces significant challenges, including high operating voltages, limited bending curvatures, slow response times, and specialized fabrication requirements[62]. Most conventional SMA actuators require substantial thermal energy for activation, making them unsuitable for low-power microrobotic applications.

Recent advances have introduced electrochemically-driven shape memory actuators that address many limitations of traditional SMAs[63]. Surface electrochemical actuators (SEAs) based on platinum thin films represent a breakthrough in electrically programmable shape-memory actuators for microscale applications. These actuators function through electrochemical oxidation and reduction of a platinum surface, creating strain in the oxidized layer that causes controlled bending with radii of curvature as small as 500 nanometers.

The fabrication involves atomic layer deposition (ALD) of nanometer-thick platinum films (typically 7 nm) capped with passive layers such as titanium dioxide (2 nm)[63]. The actuation mechanism relies on two distinct electrochemical regimes: at low voltages, reversible adsorption and desorption of oxygen species provide volatile actuation, while at higher positive voltages, irreversible oxidation creates a platinum oxide layer that maintains the actuated state even when power is removed[64].

Performance characteristics demonstrate significant advantages: these actuators operate at low voltages (1 volt), respond quickly (less than 100 milliseconds), and achieve submicrometer bending radii while maintaining their positions for hours without applied power[63]. They demonstrate high repeatability with only 5% variation in the actuated states after approximately 100 cycles, making them suitable for practical microrobotic applications.

Applications include electrically reconfigurable microscale grippers, origami-based three-dimensional structures, morphing metamaterials, and addressable memory arrays[63]. The ability to create bistable or multistable structures makes them particularly suitable for microrobotic systems requiring position holding without continuous power consumption. However, current limitations include the requirement for electrolyte environments and the potential for long-term degradation through electrochemical corrosion.

2.3.6. Others

Other types of microscale propulsion mechanisms have also been developed, including acoustic, chemical/bubble, and catalytic micromotors. Acoustic micromotors utilize ultrasonic waves to generate streaming flows or acoustic radiation forces, enabling precise and contactless actuation in liquid environments. This mechanism is advantageous for biocompatible applications where magnetic or electrical fields may cause interference. Ren et al. proposed a hybrid propulsion strategy that combines acoustic excitation and catalytic self-electrophoresis to overcome the inefficiency of conventional engines on the microscale[65]. This dual-mode approach enables fuel-free, biocompatible, and highly controllable motion, offering enhanced functionality. Aghakhani et al. proposed an acoustically-based microrobotic system to overcome the propulsion limitations of microrobots in non-Newtonian biological fluids[66]. By generating high shear rate microstreaming flows, the system enables effective propulsion in complex biofluids, demonstrating navigation through mucus layers and highlighting its potential for minimally invasive targeted therapy.

Chemical or bubble-driven micromotors rely on asymmetric catalytic reactions to produce bubbles that generate thrust. These systems offer high propulsion speeds and simple fabrication processes, but often suffer from limited controllability and fuel dependence. Villa et al. proposed bubble-propelled catalytic chemical microrobots that use low concentrations of chemical fuel to generate thrust for autonomous motion[67]. The proposed propulsion systems are based on chemical reactions producing bubbles to drive active movement to enable rapid and efficient disruption of dental biofilms. Wang et al. proposed bubble-propelled microrobots that operate at the air–liquid interface[68]. The propulsion systems utilized bubble collapse-induced jet flow as the primary driving force, while magnetic field modulation enables precise control of orientation, speed, and motion modes without altering fuel concentration.

Although these micromotors are not strictly MEMS-fabricated, they are frequently integrated with microfabricated sensors or microfluidic channels, forming hybrid systems for environmental monitoring, targeted drug delivery, and lab-on-chip applications. Including them provides a broader understanding of the diversity of actuation strategies at the microscale.

2.4. Power sources

Powering MEMS microrobots remains a fundamental challenge because of strict constraints on size, weight, and energy density. Unlike macroscale systems, these robots cannot carry large batteries or power electronics, necessitating compact, efficient, and sometimes unconventional energy sources that can meet functional demands without compromising mobility or integration.

2.4.1. Microbatteries and thin-film batteries

Microbatteries and thin-film batteries represent the most straightforward approach to powering MEMS microrobots, offering compact, integrated energy storage solutions[69]. These batteries are miniaturized electrochemical cells specifically designed to fit within the tight volumetric constraints of microdevices, and are capable of delivering consistent voltage and current for short-duration operations.

Thin-film batteries are typically constructed using stacked layers of electrode and electrolyte materials deposited on a substrate[70,71]. Common materials include lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO2) for the cathode, lithium metal or graphite for the anode, and solid-state electrolytes such as lithium phosphorus oxynitride (LiPON). These batteries are fabricated using techniques such as sputtering, thermal evaporation, or chemical vapor deposition, which allow precise control over thickness and patterning. Their planar structure enables integration with silicon substrates and compatibility with MEMS fabrication workflows.

The key advantages of microbatteries and thin-film batteries include predictable electrical output, good cycle stability, and on-chip integration capability, making them suitable for applications such as short-term locomotion, targeted drug delivery, and intermittent sensing tasks. Moreover, their self-contained nature simplifies system-level design, as no external energy source is required during operation.

However, significant limitations remain. Total energy storage is constrained by the extremely limited volume of the device, often resulting in operational times ranging from seconds to minutes, depending on the power load. In addition, fabrication processes for thin-film batteries can be material- and cost-intensive, and some materials (e.g., lithium) raise safety and biocompatibility concerns, especially in biomedical applications.

To address these challenges, current research is focused on developing flexible microbatteries, biocompatible electrolytes, and multifunctional structural batteries, where energy storage elements are integrated into the robot's frame. Despite their limitations, microbatteries and thin-film batteries remain a fundamental solution for MEMS microrobots that require predictable, localized, and low-noise power delivery, particularly in autonomous or semi-autonomous scenarios.

2.4.2. Energy harvesting devices

Energy harvesting offers a promising alternative to conventional batteries by enabling MEMS microrobots to generate power directly from their environment[72]. Unlike fixed-capacity microbatteries, energy harvesters can support longer operating lifetimes, reduce the need for recharging or replacement, and offer the potential for autonomous continuous operation, particularly beneficial in hard-to-reach or enclosed settings such as biological tissues, pipelines, or sealed microenvironments.

An approach widely explored is photovoltaic (PV) energy harvesting, where thin-film solar cells convert ambient light into electricity[73]. Materials such as amorphous silicon, gallium arsenide (GaAs) and perovskites are commonly used to fabricate microscale PV cells that can be integrated directly onto the robot's surface. These systems exhibit a relatively high power density under direct illumination, but are less effective in opaque or internal environments.

Piezoelectric energy harvesters utilize materials such as PZT, AlN, or PVDF, which generate charge in response to mechanical stress[72]. MEMS implementations often employ vibrating cantilever beams or membranes that resonate with ambient vibrations from movement, fluid flow, or external stimuli. Although the output power is modest, such systems are highly effective in dynamic environments with continuous mechanical excitation.

Thermoelectric generators (TEGs) offer another passive means of energy harvesting by exploiting temperature gradients[74]. When integrated onto a MEMS substrate, thermoelectric materials produce voltage in response to heat differentials between the robot and its surroundings. This method is attractive for biomedical applications, such as harvesting body heat, but suffers from low power output due to the limited temperature gradients typically available at the microscale.

Electromagnetic and radio frequency (RF) energy harvesting converts external electromagnetic fields into usable power[75]. Inductive or capacitive coupling systems can scavenge energy from nearby transmitters, while rectennas (antenna and rectifier) capture ambient RF signals from WiFi, cellular networks, or industrial devices. These methods enable complete wireless power transfer (WPT), although power levels are generally very low and highly dependent on environmental conditions.

Despite the challenges of low energy density and intermittent availability, energy harvesting remains a critical pathway toward long-term sustainable microrobotic operation. Hybrid strategies that combine multiple harvesting modalities or couple harvesters with supercapacitors and power management circuits are gaining interest. These approaches aim to smooth energy fluctuations, buffer short-term storage, and support continuous functionality across diverse and unpredictable environments.

2.4.3. WPT

WPT is a compelling approach to supply energy to MEMS microrobots without the need for storage onboard[76,77]. By transmitting energy through electromagnetic fields, WPT enables continuous or on-demand power delivery, which is especially valuable in environments where battery integration is impractical or size constraints are extreme. This approach is commonly used in biomedical, implantable, and enclosed robotic applications where external access is limited or non-existent.

Several WPT methods have been adapted for micro-scale systems, with inductive coupling being the most widely implemented. In this approach, an external transmitter coil generates a time-varying magnetic field that induces current in a miniature receiver coil embedded within the microrobot. This method provides relatively high efficiency at short distances and is compatible with standard MEMS fabrication processes to create planar microcoils. However, the power transfer efficiency drops sharply with increased separation or misalignment, limiting its range and spatial flexibility.

Capacitive coupling is another WPT method that relies on electric fields between paired electrodes[78]. While it can be implemented using ultra-thin, flexible electrodes, it typically suffers from lower efficiency and requires close proximity between the transmitter and receiver, making it more suitable for applications where robots are in direct or near contact with the power source.

Another common approach for externally powering microrobots involves using manipulated magnetic fields[79]. While this method primarily powers and controls the actuation of the microrobot and cannot provide power for other components such as sensors, it is particularly effective for controlling very small microrobots. The use of magnetic forces eliminates the need for onboard actuation mechanisms. For more details on magnetically powered microrobots, refer to the previously discussed section on electromagnetic actuation.

Despite the advantages of untethered operation and the elimination of onboard batteries, WPT systems face several practical challenges. These include limited energy transfer efficiency, susceptibility to environmental interference, and the need for precise alignment in near-field techniques. Additionally, integrating coils or antennas within microrobots adds fabrication complexity and may compete with space needed for sensing, actuation, or communication components.

To address these limitations, recent efforts focus on hybrid systems that combine WPT with local energy storage or energy harvesting modules. Advanced coil designs, adaptive impedance matching, and closed-loop power regulation are also being explored to enhance energy delivery efficiency and spatial tolerance. Overall, WPT remains a promising strategy for enabling lightweight, miniaturized microrobots with extended operational lifespans, particularly in biomedical and confined-space applications.

3. Application Scenarios of MEMS-based Microrobotics

MEMS-based microrobotics has emerged as a transformative field, enabling the creation of devices capable of performing a wide range of complex tasks at the micro-scale. These systems leverage the precision, scalability, and integration capabilities of MEMS to overcome the significant challenges of actuation, control, and power delivery in miniature robots. For this review, the diverse landscape of MEMS microrobots is categorized into three primary groups based on their function and mobility: Mobile Microrobots, MEMS-based Micromanipulators, and Autonomous and Swarm Microrobotics. A summary of key developments, their core technologies, and applications is provided in Table 6.

Summary of application scenarios of MEMS-based microrobotics

| Ref. | Year | Scenarios | Core technologies | Actuation | Service |

| MEMS: Micro-electromechanical system; SOI: silicon-on-insulator; DoF: degree-of-freedom; PCB: printed circuit board; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane; EM: electromagnetic. | |||||

| Li et al.[80] | 2019 | Walker | Oscillation amplitude/frequency optimization for control | Periodic magnetic field | Microrobot can precisely follow planned trajectories |

| Hussein et al.[81] | 2022 | Walker | Monolithic planar leg with amplifying flexures (SOI) | Electrothermal V-shaped actuators | High-force, multi-DoF locomotion (running, jumping, obstacles) |

| Hao et al.[85] | 2023 | Walkers/Swarm | 3 mm vibration-driven bristle bots; motility-based aggregation | Vibration actuation | Tunable aggregation for collective signaling/info sharing |

| Johnson et al.[86] | 2020 | Walkers/Swarm | Dual-layer printed circuit board (PCB) microcoil arrays; orientation-controllable microrobot design | Localized magnetic actuation via microcoils | Cooperative/parallel micromanipulation with multi-robot closed-loop control |

| Wang et al.[87] | 2022 | Swimmer | Piezo-driven triangular-prism swimmer (multimodal) | Piezoelectric actuation | Linear, steering, climbing, and aquatic motion under low voltage |

| Liu et al.[88] | 2022 | Swimmer | NdFeB–PDMS soft continuum robot with anti-adhesion hydrogel | Magnetic field actuation | Steering/locomotion in microchannels; intravascular micromanipulation potential |

| Giltinan et al.[89] | 2020 | Swimmer | Transchiral magnetic helices; frequency-selective control | Rotating magnetic field with frequency tuning | Selective, decoupled control of multiple swimmers |

| Jeong et al.[90] | 2020 | Swimmer | EM actuation + acoustic bubble for drug delivery | Electromagnetic actuation with acoustic bubble excitation | Targeted drug carrying, release, and penetration |

| Li et al.[91] | 2025 | Swimmer | Picoeukaryote-based self-propulsion for drug delivery | Active navigation in confined biological environments | Targeted drug delivery for kidney therapy |

| Li et al.[92] | 2024 | Swimmer | Integration of motile algae with macrophage membrane-coated nanoparticles | Active propulsion powered by algae | Neutralizing proinflammatory cytokines in the colon |

| Chen et al.[93] | 2019 | Aerial | Multi-layer dielectric elastomer actuators ("artificial muscles") | Dielectric elastomer actuation | Controlled hovering flight with collision resilience |

| Kim et al.[94] | 2025 | Aerial | 750 mg flapping-wing MAV; improved transmission/hinge | Flapping-wing actuation | Long hovering, high precision, high agility |

| Hsiao et al.[95] | 2025 | Aerial | Sub-gram flapping-wing robot with telescopic jumping leg | Hybrid flapping-wing and jumping actuation | Efficient hybrid locomotion; obstacle traversal and recovery |

| Leveziel et al.[96] | 2022 | Manipulator | Mini parallel robot; soft joints; base piezo-benders | Piezoelectric actuation | 10 pick-and-place/s with 1 μm precision |

| Zhang et al.[97] | 2023 | Manipulator | Compact laser scanner; stepper and solenoid; visual feedback | Electromagnetic and stepper motor | High-precision autonomous laser tracking in confined spaces |

3.1. Mobile MEMS microrobots

Mobile microrobots are designed for locomotion across various environments, including terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial domains. Their development is crucial for applications requiring navigation within confined or hazardous spaces.

A primary focus is on creating walkers capable of precise movement on surfaces. Li et al. demonstrated a bipedal walker whose controllability and ability to follow planned trajectories were enhanced through the optimization of magnetic field oscillation amplitude and frequency[80]. Advancing this further, Hussein et al. developed a monolithic microrobot with electrothermal V-shaped actuators on SOI wafers[81]. This design provides high-force, multi-degree-of-freedom (DoF) locomotion, enabling complex behaviors such as running, jumping, and navigating obstacles. Li et al. proposed algae-based biohybrid technology to develop inhalable, self-propelled microrobots for non-invasive pulmonary drug delivery[82]. The proposed platform can be used for the targeted treatment of respiratory infections, such as MRSA pneumonia, through inhalation rather than invasive intratracheal administration. Zhang et al. utilized green microalgae-based biohybrid technology to develop self-propelled microrobots that integrate motile algae with red blood cell membrane-coated, doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles for localized chemotherapy against lung metastasis[83]. Through autonomous propulsion and targeted intratracheal delivery, the proposed microrobots achieved deep lung penetration, enhanced drug accumulation, and superior antimetastatic efficacy, representing a significant advancement toward the clinical translation of microrobots for precision cancer therapy. Wang et al. demonstrated a magnetically actuated biohybrid microrobot system designed for precise in vivo navigation and delivery across multiple organs using an integrated endoscopy-assisted magnetic actuation with dual imaging system[84]. By combining biocompatible soft magnetic cell-based microrobots with real-time magnetic and endoscopic guidance, the study achieved high-precision, meter-scale delivery of stem cell spheroid microrobots through natural orifices into deep regions such as the bile duct, representing a major advancement toward the clinical translation of soft and magnetic microrobots for minimally invasive therapeutic interventions. Hao et al. developed a swarm of 3-mm vibration-driven bristle robots that exhibit tunable, motility-based aggregation, a primitive form of collective behavior that could be used for environmental sensing or information sharing[85]. Johnson et al. laid important groundwork by using microcoil arrays to generate localized magnetic fields, enabling the independent closed-loop control of multiple microrobots for cooperative micromanipulation[86]. Moving towards true autonomy, recent work has explored behaviors beyond direct teleoperation.

3.2. Swimming microrobots

Swimming microrobots are particularly promising for biomedical applications such as targeted drug delivery and minimally invasive surgery. Wang et al. developed a piezo-driven triangular prism structure capable of multimodal locomotion, including linear motion, steering, and climbing in both dry and wet environments under low voltage[87]. For navigating biological environments, Liu et al. created a soft continuum robot with a hydrogel coating to reduce adhesion, granting it excellent steering capabilities in microfluidic channels for potential intravascular use[88]. A significant challenge in magnetic actuation is the independent control of multiple swimmers; Giltinan et al. addressed this by fabricating transchiral magnetic helices that can be selectively and decoupled controlled via frequency modulation of a rotating magnetic field[89]. Jeong et al. developed a swimmer system that utilizes electromagnetic actuation combined with acoustic bubble excitation to achieve targeted drug transport, controlled release, and enhanced tissue penetration[90]. Hybrid actuation methods are also being explored, such as the combination of electromagnetic control with acoustic bubble excitation to enhance drug carry, release, and tissue penetration. Li et al. employed picoeukaryote-based biohybrid technology to engineer self-propelled microrobots capable of active drug navigation and delivery within confined biological environments, demonstrating significant progress toward the clinical translation of microrobots for targeted kidney therapy[91]. Li et al. used biohybrid technology based on green microalgae by integrating motile algae with macrophage membrane-coated nanoparticles to create actively moving nanoparticles capable of neutralizing proinflammatory cytokines in the colon[92].

3.3. Aerial microrobots

The domain of aerial microrobots, or micro air vehicles (MAVs), represents a major feat of engineering, requiring an exceptional power-to-weight ratio. Chen et al. utilized multi-layered dielectric elastomer actuators to create a resilient robot capable of controlled hovering flight and withstanding collisions[93]. Recent work has pushed the boundaries of endurance and agility; Kim et al. achieved a 750-mg flapping-wing MAV with a 1, 000-second hovering endurance and exceptional precision[94]. Furthermore, Hsiao et al. demonstrated a subgram hybrid robot that combines flapping-wing flight with a telescopic leg for jumping, significantly enhancing versatility and power efficiency for tasks such as obstacle traversal and collision recovery[95]. In summary, these advances illustrate a rapid convergence toward more robust, power-efficient, and multifunctional aerial microrobots, with emerging designs increasingly integrating hybrid locomotion, adaptive control strategies, and lightweight onboard sensing to support long-duration autonomous operation in real-world environments.

3.4. Micromanipulators

Micromanipulators include devices designed not for long-range mobility but for high-precision manipulation and interaction with micro-scale objects. A key design principle is to minimize inertia to enable high-speed and precise motion. The MiGriBot exemplifies high-speed and precise motion based on a parallel architecture with piezoelectric bending actuators to achieve remarkable speeds of 10 pick-and-place cycles per second with micrometer precision[96]. Beyond mechanical manipulation, other forms of precise intervention are being developed. Zhang et al. created a compact laser scanning system driven by stepper and solenoid actuators for autonomous laser tracking, demonstrating potential for high-precision applications in confined surgical spaces[97]. As shown in Figure 4A and B, these systems are vital for microassembly, cell manipulation, and microsurgery[98]. Wang et al. developed a piezoelectrically actuated spatial micromanipulator employing a three-stage displacement amplification mechanism and a deployable multi-finger structure to enable precise micro-operations[99]. Experimental validation demonstrated high precision (0.1 μm resolution), fast dynamic response (23.5 ms settling time) and large motion stroke (125 μm at 100 V), highlighting its effectiveness for high-accuracy manipulation of microscale objects. Lyu and Xu developed a bio-inspired dual-axis compliant micromanipulator that mimics the gripping and rubbing motion of the human hand to achieve millimeter-scale dexterous manipulation for fiber alignment[100]. The microrobot demonstrated large stroke motions with high precision and low slippage, enabling compact, high-dexterity manipulation at the microscale.

4. CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES

A wide range of microrobots have been designed for various functions and applications. However, several aspects of microrobots still require further development, such as energy storage, autonomy, and sensing. Advancements in these areas have the potential to enhance the capabilities and broaden the possible applications of microrobots. Despite the importance of these advancements, achieving them is a formidable task. This section concludes the challenges of current microrobots and proposes design perspectives to overcome the limitations.

4.1. Challenges of MEMS-based design

The extreme size scale of microrobots introduces fundamental design constraints that differ sharply from those of conventional robotic systems. At the microscale, physical laws make traditional engineering solutions infeasible. The following subsections outline the key obstacles that currently limit system performance and scalability, providing the basis for future innovations in microscale robotic design.

4.1.1. Long-term energy autonomy

The achievement of long-term energy autonomy remains one of the most critical bottlenecks in microrobotics. Although many microrobot designs still rely on wired power sources for research convenience, truly autonomous and wireless operation will require integrated onboard or wireless powering strategies[101]. At the insect scale (under 5 cm in length), microrobots are constrained by mechanical strength and limited payload capacity, which restricts the integration of conventional batteries.

Improvements in the power-to-weight ratio and energy efficiency are expected through hybrid designs, such as the combination of small rechargeable batteries with WPT modules. WPT has emerged as a promising solution for sustaining operation without bulky energy storage, particularly through resonant inductive coupling and mid-field electromagnetic transmission. Recent work demonstrated that optimized receiver coils can significantly reduce mass while maintaining stable power delivery, making WPT a near-term enabler for continuous microrobot activity[102].

Beyond WPT, energy harvesting and hybrid powering approaches represent promising long-term directions[103]. For instance, PV, piezoelectric, or bioelectrochemical harvesters could continuously scavenge energy from light, vibration, or biological media. However, their low power density and environmental dependency remain major obstacles. Future breakthroughs may come from integrated micro-energy networks that dynamically switch between multiple power sources depending on environmental availability and task demands.

Achieving full energy autonomy will require a paradigm shift toward co-optimized system design, where energy management, actuation, and control architectures are developed synergistically. Emerging strategies such as energy-aware AI control, adaptive power scheduling, and co-design of actuation and storage materials are expected to substantially improve energy efficiency and extend operational lifetimes. These approaches will enable microrobots to evolve from short-lived experimental prototypes into sustainably autonomous systems capable of long-duration operation in real-world environments.

4.1.2. Resource-constrained sensing

Obtaining reliable microscale sensing remains a formidable challenge due to severe constraints on payload, power, and computational capacity. In insect-scale microrobots, sensors and control units face the same payload-related limitations as onboard batteries. As a result, most microrobots still rely on externally provided feedback or global tracking systems rather than fully onboard sensing, restricting their ability to function independently in dynamic environments.

Instead of integrating independent sensors, several microrobots utilize piezoelectric materials for limbs or actuation mechanisms, taking advantage of the inherent sensing capability of these materials to obtain feedback on the speed and position of actuated parts. This approach allows microrobots to incorporate onboard sensing without additional weight[69], but the capabilities of the proposed technique remain limited in precision and response bandwidth.

Insect-scale microrobots can carry lightweight independent sensors such as vision sensors[104]; however, these still fall short of the complex multimodal perception systems used in full-sized autonomous robots. Integrating additional sensors and applying appropriate sensor fusion techniques could enable more sophisticated state estimation, thus improving control for task-specific applications[69]. Potential sensors for this purpose include accelerometers, proximity sensors, piezoelectric encoders to measure leg position, and capacitive sensors to detect actuator engagement[105].

Future progress will likely depend on multifunctional and adaptive sensing architectures. For example, combining piezoelectric self-sensing with low-power accelerometers or proximity sensors could achieve hybrid proprioceptive–exteroceptive feedback with minimal mass addition. Integration of AI-assisted sensing frameworks could further enhance performance by selectively processing salient signals, reducing computational load, while improving environmental awareness.

4.1.3. Coordination and collective control

The transition from single-unit microrobotic operation to collective swarm systems represents one of the most ambitious frontiers in microrobotics. Swarm coordination aims to exploit the emergent behavior of large numbers of microrobots to perform complex tasks collectively[106]. However, achieving robust and predictable collective behavior at the microscale is highly nontrivial due to physical coupling effects, limited communication bandwidth, and environmental uncertainties. The microscopic regime is dominated by viscous and stochastic forces, which cause the dynamics of each agent to deviate from macroscopic swarm models that assume inertial stability.

One fundamental challenge in swarm coordination lies in communication and information exchange. Unlike macroscopic robotic swarms that can rely on wireless communication or onboard processors, microrobots have extremely limited energy and computational resources. As a result, most microrobotic swarms depend on implicit communication through environmental cues such as magnetic fields, chemical gradients, or hydrodynamic interactions. Although the communication allows for scalable control, it often lacks precision and leads to unpredictable collective dynamics. Developing minimal but efficient communication architectures, such as optical or acoustic signaling, could enhance the controllability and adaptability of microrobotic collectives in dynamic environments.

Another key issue is task allocation and decentralized decision-making. In swarm microrobotics, each unit must independently determine its local action while contributing to a global objective. Current methods often rely on global field control, where all microrobots respond identically to the same external stimulus, which limits individual differentiation and task specialization. Future research should focus on AI-driven local autonomy, where microrobots equipped with minimal onboard sensing and computing can adjust their behavior based on local stimuli. Integrating reinforcement learning or neural field models into swarm control frameworks may enable adaptive coordination that scales efficiently with swarm size and task complexity.

Moreover, managing emergent dynamics remains a significant theoretical and practical challenge. Although emergent behaviors such as aggregation, dispersion, or vortex formation can be advantageous, they can also lead to instability or unintended clustering. A promising direction involves the use of digital twin systems that create real-time replicas of swarm behaviors. These digital twins can simulate collective motion under various control policies and environmental conditions, providing predictive feedback that enhances stability and responsiveness. Coupling such simulation-driven feedback with AI-based swarm controllers could enable real-time optimization and error correction during deployment.

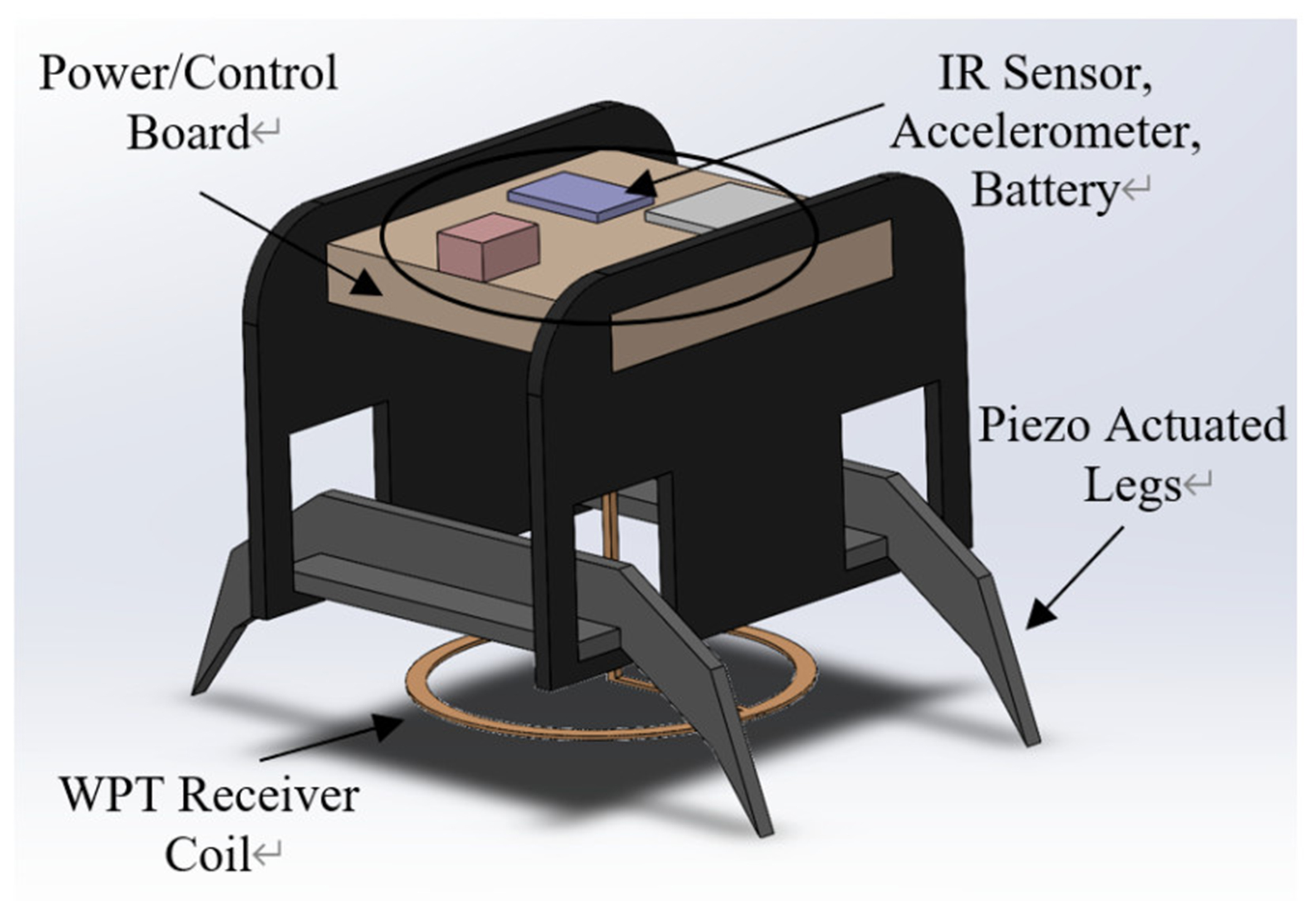

4.2. Novel design perspectives of MEMS microrobots

To overcome some of the existing challenges, a new design of MEMS-based microrobots is proposed that combines solutions for microrobot power, onboard sensing, and control, as shown in Figure 5. The WPT is used to enable the use of a smaller rechargeable battery, which can be recharged at designated charging stations. The second aspect of the design is to use the additional payload capacity made available by the smaller battery to implement additional onboard sensor devices, such as IR sensors and accelerometers. This integrated approach aims to enhance the functionality and autonomy of microrobots by addressing power constraints and improving sensing capabilities.

Figure 5. Design of WPT-enabled microrobot with advanced sensing capabilities. WPT: Wireless power transfer.