Nanofluidic neuromorphic iontronics: a nexus for biological signal transduction

Abstract

Neuromorphic iontronics is an emerging technology based on the sophisticated regulation of ions as signal carriers, demonstrating strong potential in human-machine interaction. Nanofluidic materials exhibit significant advantages in constructing iontronic neuromorphic devices due to their ability to precisely mimic the transport mechanisms of biological ion channels. By synergistically integrating multiple external stimuli, neuromorphic devices that combine perception fusion and memory behaviors are injecting new vitality into the development of artificial intelligence, including computation, neurorobotics, and healthcare. However, this field is still in its infancy and requires robust theoretical foundations, novel computational paradigms, and innovative approaches to functional material design and device integration to advance further. In this Perspective, we provide a comprehensive overview of recent advances in iontronic neuromorphic devices with respect to fabrication, integration, and applications, aiming to illustrate the rapid growth of this field. Finally, we discuss current challenges and future directions, including theoretical models based on ionic properties, neuromorphic signal simulation, and device integration.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

For millions of years, the human nervous system has evolved a sophisticated logical framework[1] that enables it to autonomously process environmental changes through perception, judgment, and decision-making. This command center system is a vast network[2] composed of a constellation of billions of neurons linked by synapses. Its distributed, parallel, and event-driven operations[3] enable humans to maintain an elegant equilibrium between past experiences and newly established patterns. Deciphering and emulating human neuromorphic mechanisms not only elucidates the workings of the nervous system but also serves as a catalyst for innovation in artificial intelligence[4].

Proposed by Mead[5] in the late 1980s to early 1990s, neuromorphic electronic systems are designed to mimic the structure, function, and plasticity of biological neural networks. Recently, silicon complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor-based neuromorphic circuits[6,7] have established a relatively mature technological framework for mimicking synaptic functions and computing. However, using electrons as the only signal carrier restricts neuromorphic electronic systems in achieving effective multimodal signal fusion and deep biological interaction. It is known that biological neural systems fundamentally rely on ionic and molecular signaling. These signals underpin all human life activities, from basic behavioral drives to complex emotional and cognitive functions[8]. The diverse species and highly tunable transport dynamics of ions allow them to carry exceptionally rich information. Iontronic neuromorphic devices, which employ precisely controlled ions as signal carriers, offer new perspectives and pathways for dynamic interactions with biological tissues, adaptive electronic interfaces, and efficient computational networks.

In this perspective, we provide an overview of the recent advancements in iontronic neuromorphic devices and their emerging applications. First, we outline the basic principles and strategies for constructing iontronic neuromorphic devices, using nanofluidics in aqueous environments or gel states. This section aims to inspire novel approaches and design paradigms for the development of such devices. Next, we explore the integration of neuromorphic principles with sensory functionalities, presenting several representative cases that achieve multifunctional fusion of perception and memory by mimicking the human five-sensory system. Additionally, we briefly explore the emerging applications in neuromorphic computing, as well as their integration with both biological and non-biological interfaces as artificial neurons. In the end, we summarize the key challenges and potential innovations of this field.

FABRICATION AND REGULATION MECHANISMS OF IONTRONIC NEUROMORPHIC DEVICES

Nanofluidic systems exhibit significant potential in emulating biological memory mechanisms, primarily through the precise modulation of solvated ion (e.g., Ca2+) transport and accumulation dynamics[9] in aqueous environments. This biomimetic approach leverages their intrinsic biocompatibility and structural resemblance to living systems, enabling the replication of fundamental processes such as signal transduction[10], synaptic plasticity[11], and information encoding computing[12] - core functionalities underlying biological memory formation.

Research in nanofluidics has uncovered unconventional transport phenomena of water and ions in nanochannels. It has been found that constructing confined nanoscale spaces, coupled with precise regulation of ion transport, holds promise for achieving processes that more closely mimic those in biological nervous systems[13-15]. The confined spaces can be broadly categorized into two main systems: aqueous environments and gel states. The iontronic neuromorphic functions in nanofluidic channels primarily arise from the following aspects: the interaction between ions and the channel walls (charged groups or functional groups) in the confined space, the hysteresis[16] and nonlinear characteristics of ion transport within the channels, and the dynamic changes in ion transport behavior under external field[17] (e.g., electric field) regulation.

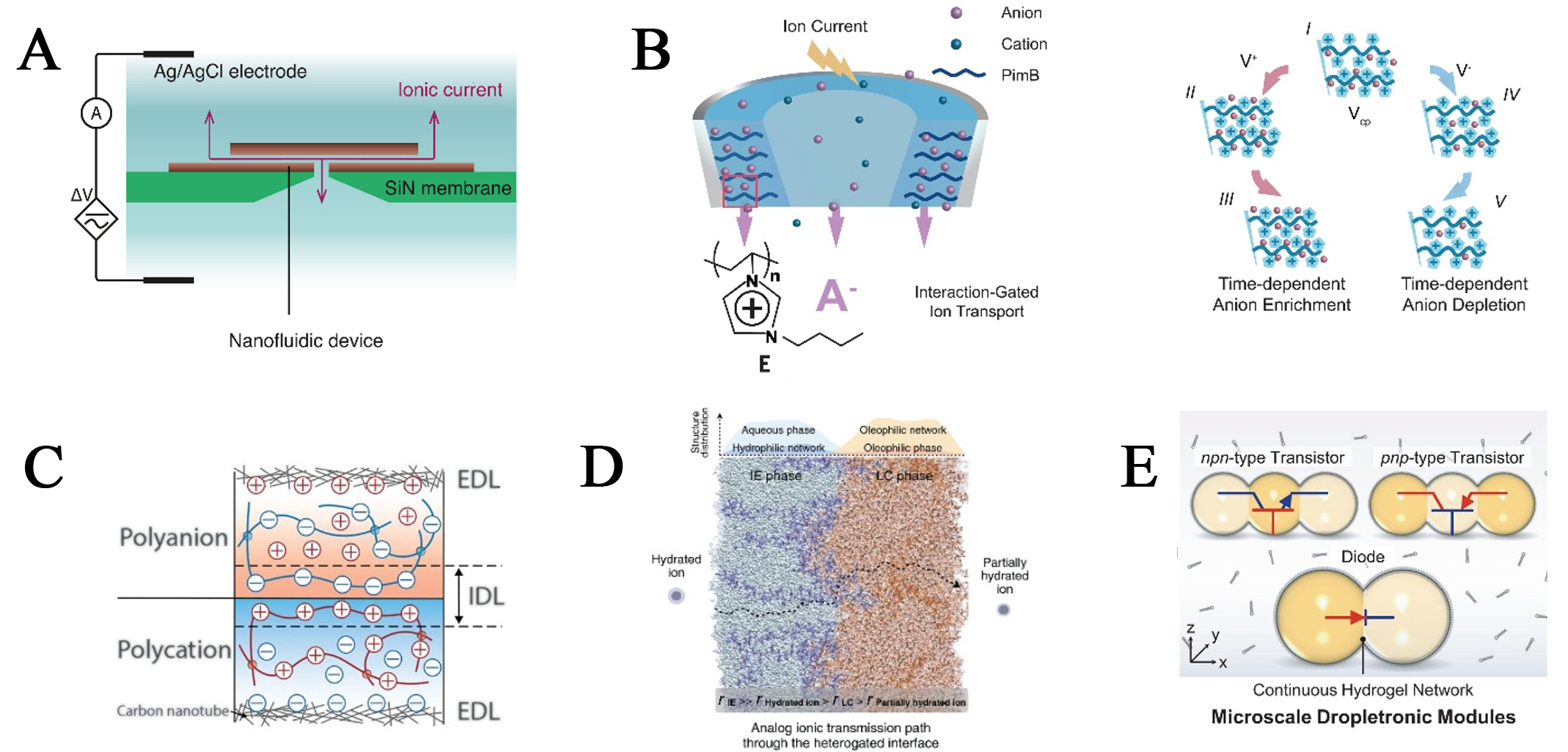

Over the past decades, aqueous-based nanofluid channels[18,19] have served as a crucial platform for studying ion transport behavior due to their unique properties. Robin et al.[20] have indicated that the channel dimensions, the ion concentration, and the asymmetry of the channels collectively influence the ion interfacial processes that give rise to memristive effects [Figure 1A]. Inspired by biological ion pumps and voltage-gated ion channels, the geometric design of nanofluid channel structures enables the regulation of ion-selective transport in specific directions, thereby inducing ion rectification and self-assembly behaviors. In this process, the accumulation and dissipation of ions are the primary origins of hysteresis[14] in iontronic devices [Figure 1B]. Based on this, by adjusting the behavior of different ions in the confined channels, the device enables electrochemical signal transduction and regulates synaptic weight changes, providing a new approach for developing low-energy neural morphology devices in aqueous environments.

Figure 1. Fabrication of nanofluid ionic neuromorphic devices. (A) Schematic diagram of the two-dimensional nanofluidic channel. Reproduced with permission from ref.[20]. Copyright 2023 American Association for the Advancement of Science; (B) Schematic illustration of time-dependent ion redistribution processes. Reproduced with permission from ref.[14]. Copyright 2023 American Association for the Advancement of Science; (C) Stretchable polyanion-polycation heterojunction. Reproduced with permission from ref.[23]. Copyright 2020 American Association for the Advancement of Science; (D) The heterogated interface and the ionic transmission path through the heterogated interface. Reproduced with permission from ref.[25]. Copyright 2023 American Association for the Advancement of Science; (E) Various assemblies of hydrogel droplets. Reproduced with permission from ref.[26]. Copyright 2024 American Association for the Advancement of Science. EDL: Electric double layer; IDL: ionic double layer.

At the same time, further considering the requirement of moduli well-matched to biological tissues in-depth human-machine interaction, soft matter-based materials[21,22] (e.g., gels, hydrogels, fibers, etc.), which are stretchable, demonstrate excellent biocompatibility at interfaces, offer unique advantages for constructing flexible iontronic devices. Inspired by the transmembrane ion transport mechanisms of biological systems, soft matter-based materials can simulate biological ion signal communication and synaptic plasticity regulation through specialized interfacial structural design. For example, the interfacial formation of an ion double layer between polyanions and polycations [Figure 1C] can serve as the foundation for a stretchable polyanion-polycation heterojunction[23], which simply enables ion current modulation. This construction of heterointerfaces provides an effective approach and means to regulate ion transport[24] (conductivity states). Further, Chen et al.[25] developed a homogeneous gel material with cascading heterointerface gating properties at the microscale [Figure 1D], which expands the ion-gating mechanism to three-dimensional intronic systems for electronic-to-multi-ion transmission, laying the foundation for neural signal transduction devices. Otherwise, to meet the demands of practical applications, there has been a persistent effort to achieve more complex functionalities in smaller devices. This approach aims to maximize the simplification of device configurations, conserve space and energy consumption, while enabling the miniaturized integration of flexible ion-based materials. In 2024, the concept of “Dropletronics”[26] has opened new possibilities for developing flexible, miniaturized iontronic module systems from both a methodology and a technical perspective. This advancement enables the realization of droplet-based diodes, transistors, and various reconfigurable logic gates, while also incorporating synthetic synapses with ion-polymer-mediated long-term plasticity [Figure 1E].

NEUROMORPHIC IONTRONIC DEVICES WITH INTEGRATED BIOSENSING

The human nervous system processes sensory stimuli through a network of neurons and synapses[1]. The integration of neuromorphic perception represents a pivotal direction in the advancement of brain-inspired computing and artificial intelligence. In recent years, researchers have sought to develop next-generation sensing platforms that combine ultralow-power processing with adaptable, high-performance sensory functions by integrating iontronic materials with neuromorphic sensing architectures.

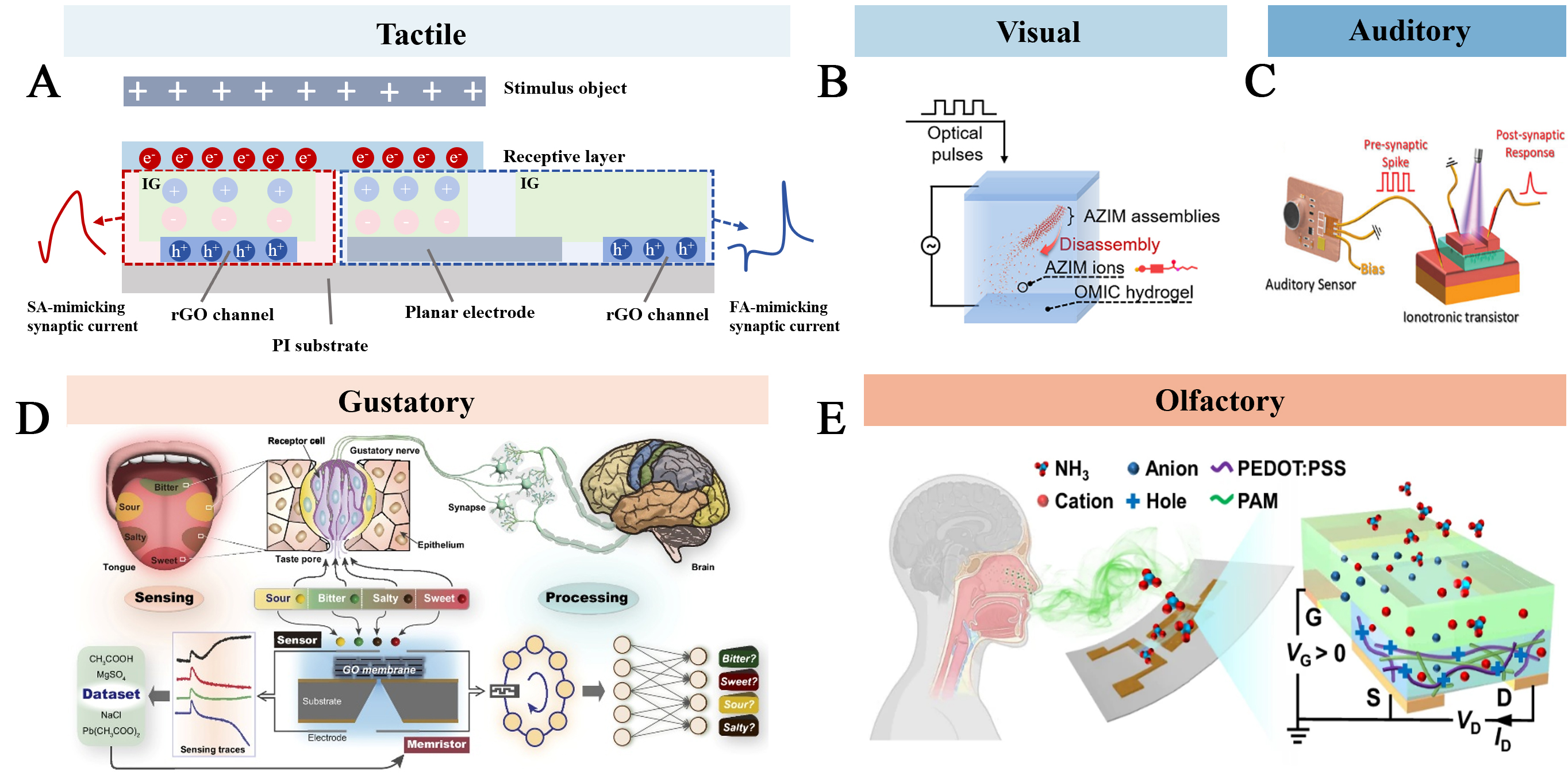

For example, human skin integrates diverse sensory receptors[27] (e.g., mechanoreceptors, nociceptors, thermoreceptors) to transduce environmental stimuli into electrical signals for neural processing. Mimicking this tactile perception is critical for advancing human-machine integration and prosthetic applications. Hong et al.[28] reported an artificial synaptic mechanoreceptor (ASMR) that processes mechanosensory signals with distinct adaptation capabilities at the single-device level, successfully emulating two types of biological mechanoreceptors connected to afferent nerve fibers via synapses [Figure 2A]. On the one hand, under self-powered triboelectric conditions, the ASMR demonstrated both slow-adaptation (SA) and fast-adaptation (FA) behaviors by directly or indirectly controlling the ion-gate dielectric layer of reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors (FETs). On the other hand, by adjusting the ionogel composition to regulate the synaptic-like connection between the sensing layer and the synaptic FET, the ASMR also achieved independent synaptic function control. This innovation provides valuable design paradigms for integrating mechanosensory signals on a simplified device platform.

Figure 2. Iontronic neuromorphic sensors for stimulus-responsive perceiving. (A) Illustration of the SA and FA ASMR structures that mimic mechanoreceptors with synapse-like connections to afferent neurons[28]; (B) Optically modulated ionic conductivity in a hydrogel. Reproduced with permission from ref.[29]. Copyright 2023, The American Association for the Advancement of Science under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (C) Schematic diagram of the bionic auditory perceptive system. Reproduced with permission from ref.[30]. Copyright 2025, The Wiley under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (D) Schemes of the biological and GO ionic sensory memristive device-based gustatory systems. Reproduced with permission from ref.[15]. Copyright 2025, The National Academy of Sciences under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (E) Mechanism diagram of gas sensing of all-gel OECT. Reproduced with permission from ref.[31]. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. IG: Ionogel; SA: slow-adaptation; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; FA: fast-adaptation; AZIM: azo-benzene functionalized imidazole; PEDOT:PSS: poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): poly(styrene sulfonate); PAM: polyacrylamide; OECT: organic electrochemical transistor.

While the development of artificial sensory systems initially focused on tactile perception, recent advancements have progressively expanded their capabilities to emulate all five human senses (tactile, auditory, visual, gustatory, and olfactory). Nowadays, researchers have developed diverse strategies to achieve response capabilities for external stimuli. For instance, photo-responsive neuromorphic devices have been employed to simulate visual perception [Figure 2B][29], while gated transistors are utilized to integrate acoustic signals for auditory processing [Figure 2C][30]. Additionally, chemical-sensitive devices (e.g., bionic tongues or gas sensors) can be integrated to detect specific analytes, thereby mimicking gustation[15] and olfaction[31] [Figure 2D and E]. It is crucial to recognize that human sensory systems are not isolated entities but rather operate through specialized yet highly collaborative mechanisms. Multimodal fusion[32] overcomes the limitations of unimodal perception by enabling comprehensive environmental information integration, thereby significantly enhancing response efficiency and recognition accuracy. This synergistic approach represents a pivotal direction for future bioinspired neuromorphic devices.

APPLICATIONS OF IONTRONIC NEUROMORPHIC DEVICES

By simulating the ion-electron signal conversion mechanism of biological nervous systems, iontronic neuromorphic devices demonstrate broad application prospects in neuromorphic computing, biomedical engineering, and intelligent interaction, laying the foundation for the development of brain-like artificial systems.

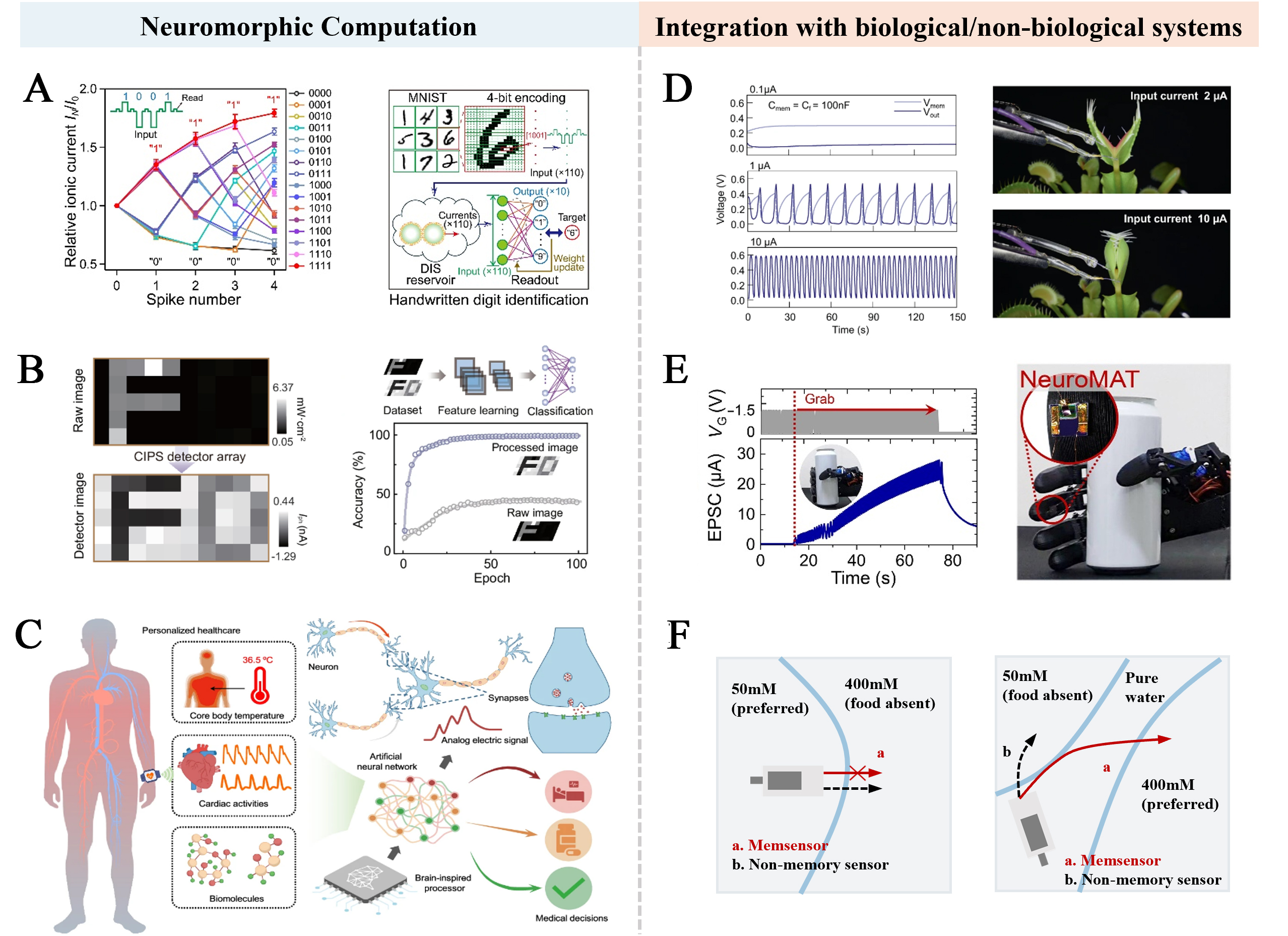

Artificial neural networks[33] (ANNs) are designed to mimic the functionality and structure of the human brain, enabling them to learn from complex datasets and make predictions. As the connecting nodes in ANNs, iontronic neuromorphic devices demonstrate deep integration with neural network algorithms, facilitating efficient execution of real-time computational tasks such as pixel recognition[34] and background noise reduction[35] [Figure 3A and B]. This novel hardware architecture of the neuromorphic paradigm also presents promising opportunities for the miniaturized integration of wearable smart medical devices. As shown in Figure 3C, recently, Choi et al. developed a chip-less wearable sensor-processor integrated neuromorphic system (CSPINS), which processes functions into a compact printed wearable device[36]. This system uses medical algorithms to simultaneously collect and analyze multiple physiological signals (core temperature, heart activity, biomolecules), enabling continuous health monitoring and medical decision support.

Figure 3. Applications of artificial neurons in neuromorphic computation and biological/non-biological interfaces. (A) Handwritten digit identification. Reproduced with permission from ref.[34]. Copyright 2025, The American Association for the Advancement of Science under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (B) Optical neuromorphic computing for high recognition accuracy of image processing. Reproduced with permission from ref.[35]. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (C) Schematic illustrations of the wearable CSPINS, designed to collect, process, and analyze multimodal physicochemical data for real-time medical decision-making. Reproduced with permission from ref.[36]. Copyright 2025, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (D) Modulation of Venus flytrap using the artificial neuron in different spiking patterns. Reproduced with permission from ref.[37]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (E) Programming process of pressure required by artificial tactile neuron integrated robotic hand to grip target object. Reproduced with permission from ref.[39]. Copyright 2023, The American Association for the Advancement of Science under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (F) Steering control of the miniature boat via chemical environment monitoring with memsensors[40]. MNIST: Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology; DIS: droplet interface synapses; CIPS: CuInP2S6; EPSC: excitatory postsynaptic current.

Through circuit design, iontronic neuromorphic devices can function as artificial sensory neurons to modulate the actuation behaviors of both biological and non-biological systems. For instance, Harikesh et al. developed an organic electrochemical neuron (OECN) with ion-modulated spiking capability, which was interfaced with the leaves of the Venus flytrap[37]. This system effectively emulated the signal transduction characteristics of biological systems and enabled precise control of spike discharge frequency, successfully inducing the closing behavior of the plant [Figure 3D]. Equally important, the integration of artificial neuron devices with actuators and feedback mechanisms paves the way for the development of biomimetic neurorobotics capable of processing and providing real-time environmental feedback. In recent years, researchers have developed various forms of memristive devices with sensing and memory capabilities[38]. These devices generate intelligent feedback signals capable of learning and self-optimization, thereby establishing a framework for artificial intelligence neurorobotics that enables applications such as regulating grasping motions of robotic hands [Figure 3E][39] and controlling the navigation of miniature boats [Figure 3F][40]. Compared to conventional iontronic sensors, iontronic neuromorphic devices can dynamically adjust synaptic weights by regulating ion migration, mimicking biological synaptic functions and adapting to different input signals. Additionally, they can simulate spiking firing and threshold transitions in biological neural networks, supporting more complex neuromorphic computing tasks. In the foreseeable future, we anticipate that iontronic neuromorphic devices will establish a distinct technological positioning and demonstrate transformative potential within the artificial intelligence domain.

OUTLOOK

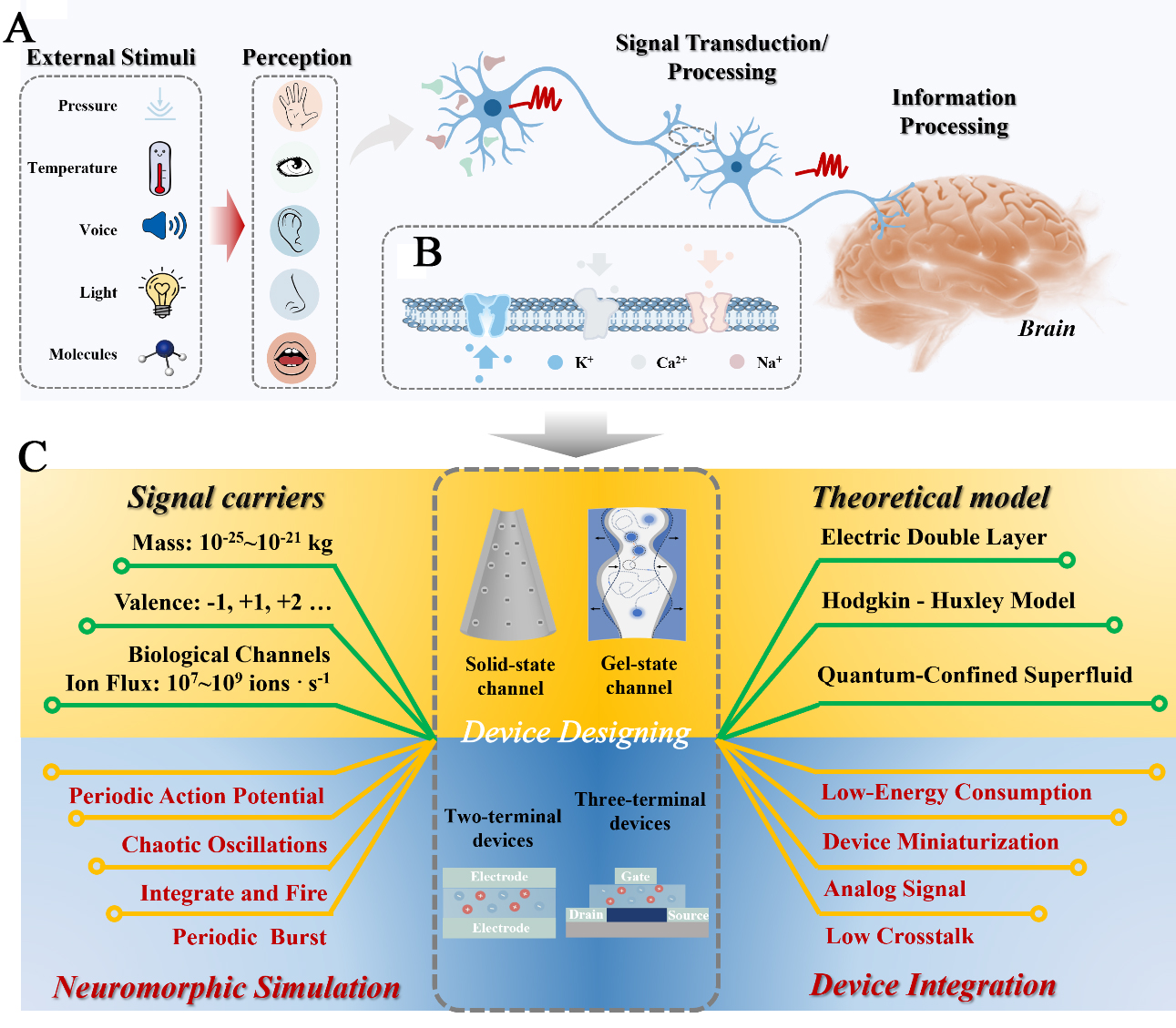

In summary, inspired by biological neural systems [Figure 4A and B], iontronic neuromorphic devices utilizing nanofluidics in aqueous environments or gel states have made rapid advancements in sensory perception and memory storage. These devices demonstrate significant potential for emerging applications in life regulation, intelligent robotics, wearable medical devices, and human-machine interfaces. However, as shown in Figure 4C, it is important to acknowledge that these ion-channel-based neuromorphic devices still exhibit significant disparities compared to biological systems, with numerous scientific questions remaining to be addressed and performance requiring further improvement.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of biological neural networks and a nanofluidic neuromorphic system. (A) Perceptual neural networks. Living organisms exhibit sensitive and intelligent perceptual abilities, including the senses of touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste. These sensory systems detect external stimuli (e.g., force, heat, light, voice, molecules) and transmit signals to the central nervous system for information processing; (B) Biological ion channels (such as K+, Ca2+, Na+ ion channels); (C) Perspective for the future of Nanofluidic Neuromorphic Iontronics based on artificial ion channels.

In terms of theoretical mechanisms, ion dynamics (such as diffusion and migration) are more complex and exhibit stronger nonlinearity compared to electron transport, making them difficult to precisely describe with traditional mathematical models. Currently, the Hodgkin-Huxley action potential propagation model[41] lays the foundation for modern computational neuroscience. In 2018, the proposal of the “quantum-confined superfluid”[42] theory provided a novel perspective to elucidate the high efficiency and precision of neural information transmission, particularly by considering the high flux of ions within channels under mild conditions. Moving forward, innovative theoretical frameworks are needed to deepen our understanding of ion-mediated signal transduction, thereby addressing the limitations of existing models. Additionally, it is important to note that ions have a much greater mass than electrons, resulting in typically slower migration speeds, which limits the device’s switching speed and operational frequency. While individual devices may consume extremely low energy, higher operating voltages are sometimes required to drive ion motion, partially offsetting the energy efficiency advantage. Therefore, it is highly necessary to further explore efficient and controllable ion-driving strategies beyond electrical stimulation (e.g., self-driven or multimodal response) to realize neuromorphic functions. Moreover, dedicated neural network architectures (e.g., spiking neural networks), learning rules, and programming paradigms tailored to exploit the parallel processing and analog computing advantages in hardware are still in early development.

In material and device design, a key challenge arises from the tendency of ions to spontaneously return to their initial state after the removal of an external stimulus, making it difficult to maintain a stable and adjustable conductance level and resulting in volatile memory behavior. Therefore, precise regulation of ion transport behavior through chemical material design is essential to achieve effective control and switching of conductance states, thereby enabling the simulation of diverse neuromorphic signal firing patterns. Additionally, researchers should focus on the flexibility and stretchability of the iontronic neuromorphic devices to enhance their compatibility and performance in various bioinspired applications. Further, in system integration, a pivotal challenge for the practical application of neuromorphic devices lies in simplifying device design to achieve miniaturization while effectively suppressing signal crosstalk. As research progresses and challenges are addressed, we believe that by then, this field will bring more intelligent experiences and services to human life through efficient and natural interaction.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

The initial draft writing: Li, L.

Supervision: Chen, W.; Kong, X. Y.; Wen, L.

Critical revision of the manuscript: Chen, W.; Kong, X. Y.; Wen, L.

All authors engaged in substantive discussions regarding the Perspective and approved the final version for publication.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this Perspective as no new datasets were generated or analyzed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22402077, 22122207, and 21988102) and the Director’s Fund of the Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E5A9Q10201).

Conflicts of interest

Wen, L. is an Associate Editor of Iontronics. Kong, X. Y.; Wen, L. are Editorial Board Members of Iontronics. Chen, W.; Kong, X. Y.; Wen, L. were not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Lohman, D. F. Human intelligence: an introduction to advances in theory and research. Rev. Educ. Res. 1989, 59, 333.

2. Colom, R.; Karama, S.; Jung, R. E.; Haier, R. J. Human intelligence and brain networks. Dialogues. Clin. Neurosci. 2010, 12, 489-501.

3. Jiang, Y.; Mi, Q.; Zhu, L. Neurocomputational mechanism of real-time distributed learning on social networks. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 506-16.

4. Capsi-Morales, P.; Barsakcioglu, D. Y.; Catalano, M. G.; Grioli, G.; Bicchi, A.; Farina, D. Merging motoneuron and postural synergies in prosthetic hand design for natural bionic interfacing. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eado9509.

6. Merolla, P. A.; Arthur, J. V.; Alvarez-Icaza, R.; et al. Artificial brains. A million spiking-neuron integrated circuit with a scalable communication network and interface. Science 2014, 345, 668-73.

7. Diorio, C.; Hasler, P.; Minch, A.; Mead, C. A single-transistor silicon synapse. IEEE. Trans. Electron. Devices. 1996, 43, 1972-80.

8. Saito, Y.; Osako, Y.; Odagawa, M.; et al. Amygdalo-cortical dialogue underlies memory enhancement by emotional association. Neuron 2025, 113, 931-948.e7.

9. Nanou, E.; Catterall, W. A. Calcium channels, synaptic plasticity, and neuropsychiatric disease. Neuron 2018, 98, 466-81.

10. Kim, W.; Lee, K.; Choi, S.; et al. Electrochemiluminescent tactile visual synapse enabling in situ health monitoring. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 925-34.

11. Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, T.; et al. Optically modulated nanofluidic ionic transistor for neuromorphic functions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202418949.

12. Wang, X.; Kerckhoffs, A.; Riexinger, J.; et al. ON-OFF nanopores for optical control of transmembrane ionic communication. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 432-40.

14. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

15. Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Qiao, Y.; Yao, T.; Zhao, X.; Yan, Y. Confinement of ions within graphene oxide membranes enables neuromorphic artificial gustation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2025, 122, e2413060122.

16. Bisquert, J. Hysteresis in organic electrochemical transistors: distinction of capacitive and inductive effects. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 10951-8.

17. Kamsma, T. M.; Boon, W. Q.; Ter Rele, T.; Spitoni, C.; van Roij, R. Iontronic neuromorphic signaling with conical microfluidic memristors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 268401.

18. Esfandiar, A.; Radha, B.; Wang, F. C.; et al. Size effect in ion transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 2017, 358, 511-3.

19. Robin, P.; Kavokine, N.; Bocquet, L. Modeling of emergent memory and voltage spiking in ionic transport through angstrom-scale slits. Science 2021, 373, 687-91.

20. Robin, P.; Emmerich, T.; Ismail, A.; et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 2023, 379, 161-7.

21. Li, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, W.; et al. Achieving tissue-level softness on stretchable electronics through a generalizable soft interlayer design. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4488.

22. Keplinger, C.; Sun, J. Y.; Foo, C. C.; Rothemund, P.; Whitesides, G. M.; Suo, Z. Stretchable, transparent, ionic conductors. Science 2013, 341, 984-7.

23. Kim, H. J.; Chen, B.; Suo, Z.; Hayward, R. C. Ionoelastomer junctions between polymer networks of fixed anions and cations. Science 2020, 367, 773-6.

24. Zhang, Z.; Sabbagh, B.; Chen, Y.; Yossifon, G. Geometrically scalable iontronic memristors: employing bipolar polyelectrolyte gels for neuromorphic systems. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 15025-34.

25. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

26. Zhang, Y.; Tan, C. M. J.; Toepfer, C. N.; Lu, X.; Bayley, H. Microscale droplet assembly enables biocompatible multifunctional modular iontronics. Science 2024, 386, 1024-30.

28. Hong, S. J.; Lee, Y. R.; Bag, A.; et al. Bio-inspired artificial mechanoreceptors with built-in synaptic functions for intelligent tactile skin. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 1100-8.

29. Tian, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Optically modulated ionic conductivity in a hydrogel for emulating synaptic functions. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd6950.

30. Wang, W. S.; Chen, X. L.; Huang, Y. J.; Huang, X.; Zhu, L. Q. Bionic visual-auditory perceptual system based on ionotronic neuromorphic transistor for information encryption and decryption with sound recognition functions. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2024, 11, 2400642.

31. Lu, L.; Liu, X.; Gu, P.; et al. Stretchable all-gel organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3831.

32. Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhao, C.; et al. An organic electrochemical transistor for multi-modal sensing, memory and processing. Nat. Electron. 2023, 6, 281-91.

33. Schmidgall, S.; Ziaei, R.; Achterberg, J.; Kirsch, L.; Hajiseyedrazi, S. P.; Eshraghian, J. Brain-inspired learning in artificial neural networks: a review. APL. Machine. Learning. 2024, 2, 021501.

34. Li, Z.; Myers, S. K.; Xiao, J.; et al. Neuromorphic ionic computing in droplet interface synapses. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6603.

35. Zhong, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Cheng, X.; et al. Ionic-electronic photodetector for vision assistance with in-sensor image processing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7096.

36. Choi, Y.; Jin, P.; Lee, S.; et al. All-printed chip-less wearable neuromorphic system for multimodal physicochemical health monitoring. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5689.

37. Harikesh, P. C.; Yang, C. Y.; Tu, D.; et al. Organic electrochemical neurons and synapses with ion mediated spiking. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 901.

38. He, K.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Su, J.; Chen, X. Artificial neuron devices. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 13796-865.

39. Kweon, H.; Kim, J. S.; Kim, S.; et al. Ion trap and release dynamics enables nonintrusive tactile augmentation in monolithic sensory neuron. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi3827.

40. Guo, R.; Feng, Q.; Ma, K.; et al. Memsensing by surface ion migration within Debye length. Nat. Mater. 2026, 25, 18-25.

41. Hodgkin, A.; Huxley, A. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. Bull. Math. Biol. 1990, 52, 25-71.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].