Synergistic photothermal engineering enables superior high-rate capability of Li4Ti5O12

Abstract

The preparation of Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) by the sol-gel method often requires a uniform distribution of metal ions in the precursor so as to obtain a uniform and fine particle feature. It can be realized via chelation and condensation reactions in the sol and gel stages. However, the molecular structure of the metal ion chelate or condensation polymer in the precursors does not easily decompose during thermal decomposition, and the LTO grains formed after calcination are relatively large and nonuniform. Herein, we propose a novel photothermal decomposition process with ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation, which could cause the cracking of the stable chelating or polymerizing structure during thermal decomposition and facilitate the formation of small and uniform LTO grains after calcination. After the UV irradiation, the Zr-doped Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 (LTZO) exhibits a smaller grain size and larger lattice parameters. As a consequence, the Li+ ion diffusion coefficient of the photothermally treated LTO with the optimum Zr dopant amount of x = 0.15 (UV-0.15LTZO) is twice that of the 0.15-LTZO sample prepared by the traditional process. The UV-0.15LTZO anode presents a specific capacity of 129 mAh·g-1 at a discharge rate of 10 C and still exhibits a capacity retention rate of 99.4% after 100 cycles, which are higher than that of the 0.15LTZO sample (95 mAh·g-1, 94.8%). The photothermal decomposition strategy proposed in this paper refines grain and expands the lattice of LTO electrodes and offers a valuable reference for controlling the properties of other electrode materials and nanomaterials.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Exploitation of more advantageous electrode materials is an important research direction for next-generation lithium-ion batteries with better cycle life, improved safety, and faster charging speeds[1-4]. Recently, several oxide materials with outstanding electrochemical performance have been widely investigated as anodes, including TiO2, VO2(B), SnOx, Fe2O3/Fe3O4, and lithium titanate (Li4Ti5O12, LTO)[5-8]. In particular, LTO is highly desirable because its spinel structure undergoes almost no strain (zero-strain feature) during the intercalation/deintercalation of lithium ions[9,10]. Thus, LTO exhibits superior stability and a long cycle life. Moreover, the unique three-dimensional ion diffusion channels of LTO grant it a distinct edge in enabling rapid charging[11]. An additional beneficial feature of LTO is its high lithiation potential (~1.55 V vs. Li+/Li), which inherently suppresses lithium dendrite formation, a common hazard in lower-potential electrode materials[12]. Consequently, battery safety can be improved. However, the low intrinsic electronic conductivity (ca. 10-8-10-13 S·cm-1) and lithium-ion diffusion coefficient (10-9-10-16 cm2·s-1) of LTO have severely limited its commercial application[13,14].

Various strategies have been evaluated to solve the inherently poor kinetics of LTO anodes, including morphological engineering[15,16], surface functionalization[17,18], and ionic doping[19,20]. Morphological tuning and surface treatments can enhance the surface conductivity of LTO materials, thereby significantly boosting electrochemical performance. These strategies cannot change the electronic conductivity and Li+ diffusivity of LTO crystals. In contrast, a small amount of ion doping can adjust the energy band structure of LTO, generate favorable lattice defects, expand lattice and even refine the LTO grains. These changes can also significantly improve the poor kinetics of LTO anodes[20,21]. Zr is a good dopant for LTO because Zr and Ti both belong to the IVB group (subgroup 4 of the periodic table) and have similar chemical properties. Zr-doped LTO materials have been widely prepared using various methods, such as the electrospinning technique[22], molten salt method[23], improved solid-state reaction[24,25], hydrothermal method[26], and ammonia-assisted mechanical ball-milling method[27]. Moreover, strategies involving the combination of Zr doping with surface modification or Na+ and Zr4+ co-doping have also been investigated by a solution method and solid phase reaction method[28-31]. Mainly, Zr doping reduces the particle size[32,33], the electrochemical impedance, and the polarization[34] of LTO while enhancing the diffusion coefficient of lithium ions in LTO[22], thereby improving the electrochemical performance. However, the advantages of Zr doping have not been fully utilized, due to insufficient optimization of the microstructure before doping. In the solid-phase reaction route, the morphology and particle size of LTO products are difficult to control, the chemical homogeneity is poor, and the reaction efficiency is low with a longer synthesis period. Meanwhile, liquid-phase methods can improve the above issues to varying degrees. However, in the preparation process of the liquid phase methods (especially the sol-gel method), the thermal decomposition process has a great impact on the morphology of the final product particles, but the relevant mechanism is still unclear, so the microstructure cannot be effectively controlled. Therefore, we need a method that can both regulate the microstructure of LTO and achieve uniform doping.

In traditional sol-gel methods, metal ions with a uniform distribution are often obtained through chelation and condensation reactions in the sol and gel stages[35]. However, the molecular structure of the precursor materials does not easily decompose during thermal decomposition, and the LTO grains formed after calcination are relatively large and nonuniform. In our previous work, we reported that applying ultraviolet (UV) irradiation during thermal decomposition had a significant effect on the microstructure and electrochemical performance of LTO[36]. To this day, there is still no clear explanation for the relevant mechanism. In this study, a novel photothermal decomposition process for producing LTO powder was proposed, and the related mechanism was discussed in depth. The chelation or polymer in the precursor often presents a stable cyclic structure, exhibiting distinct UV-sensitive characteristics. We hypothesize that irradiation with UV light of the corresponding wavelength could excite these molecules to a higher energy state, leading to the cleavage of the cyclic structures under appropriate photolysis temperature. As a result, the subsequent thermal decomposition process would yield a homogeneous and fine intermediate phase, ultimately contributing to an improved LTO microstructure after calcination. Based on the microstructure optimization induced by photothermal decomposition, Zr doping is expected to produce comprehensive advantages of more uniform doping, smaller grain size, and larger lattice expansion, further enhancing the electrochemical performance of LTO.

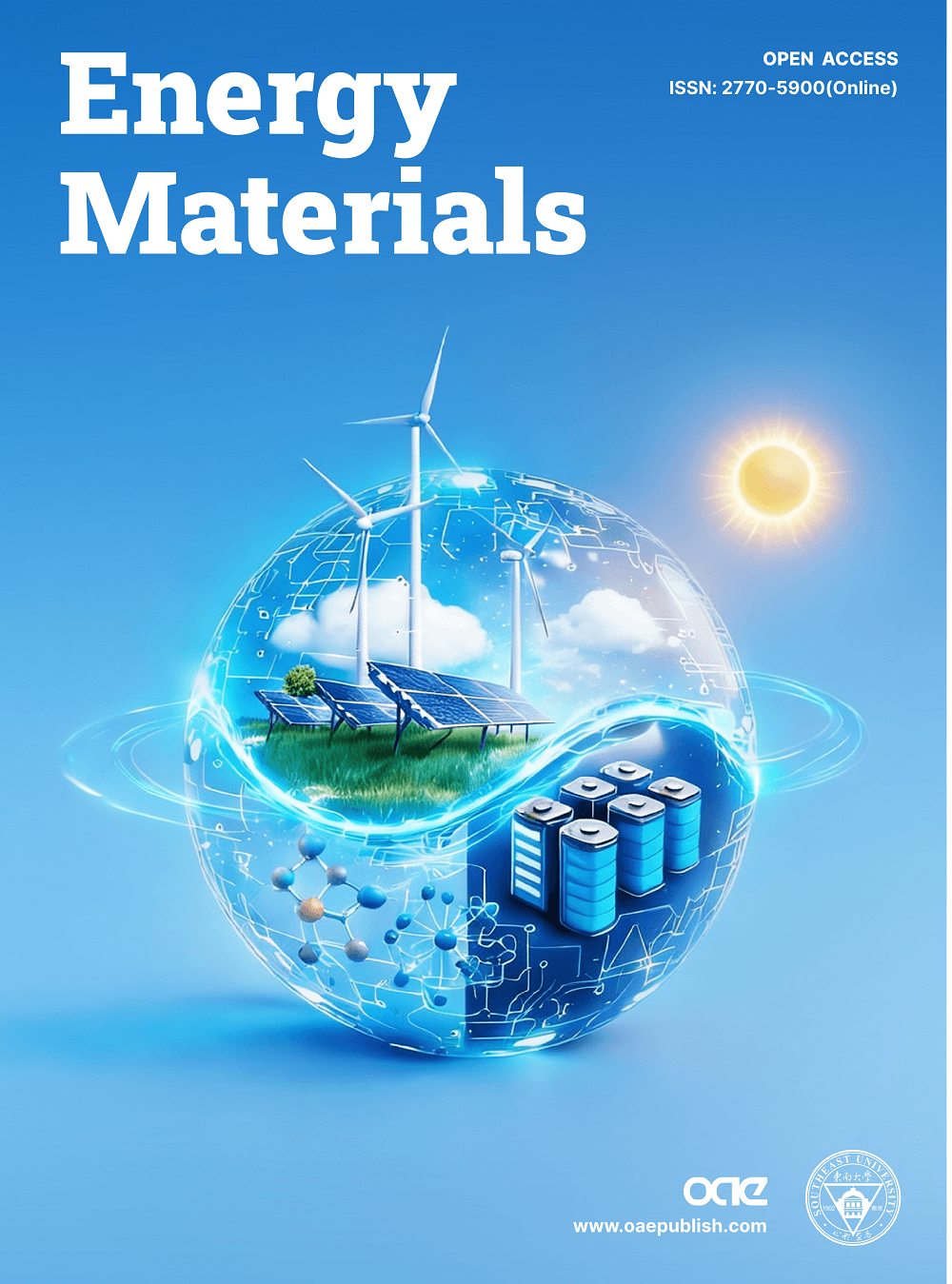

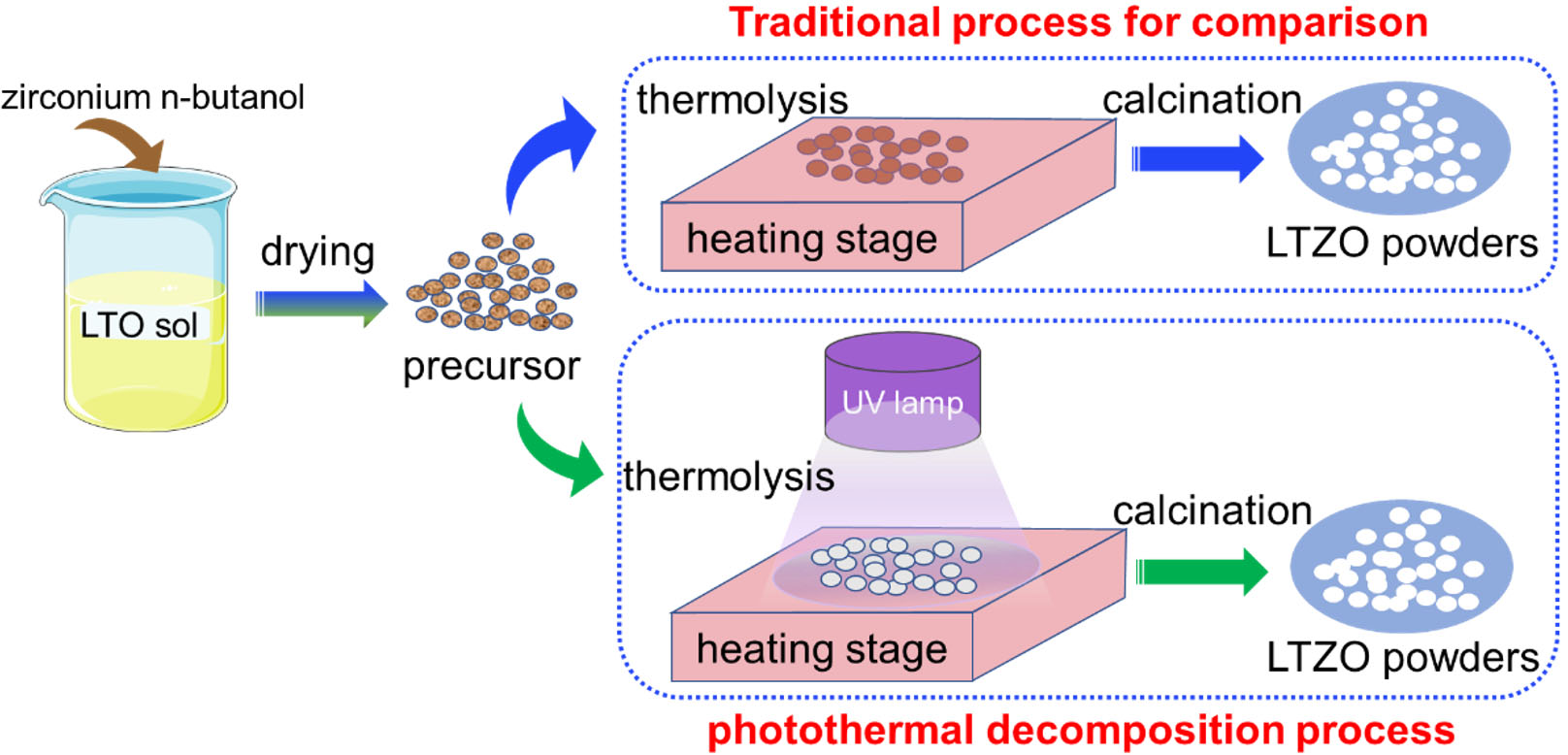

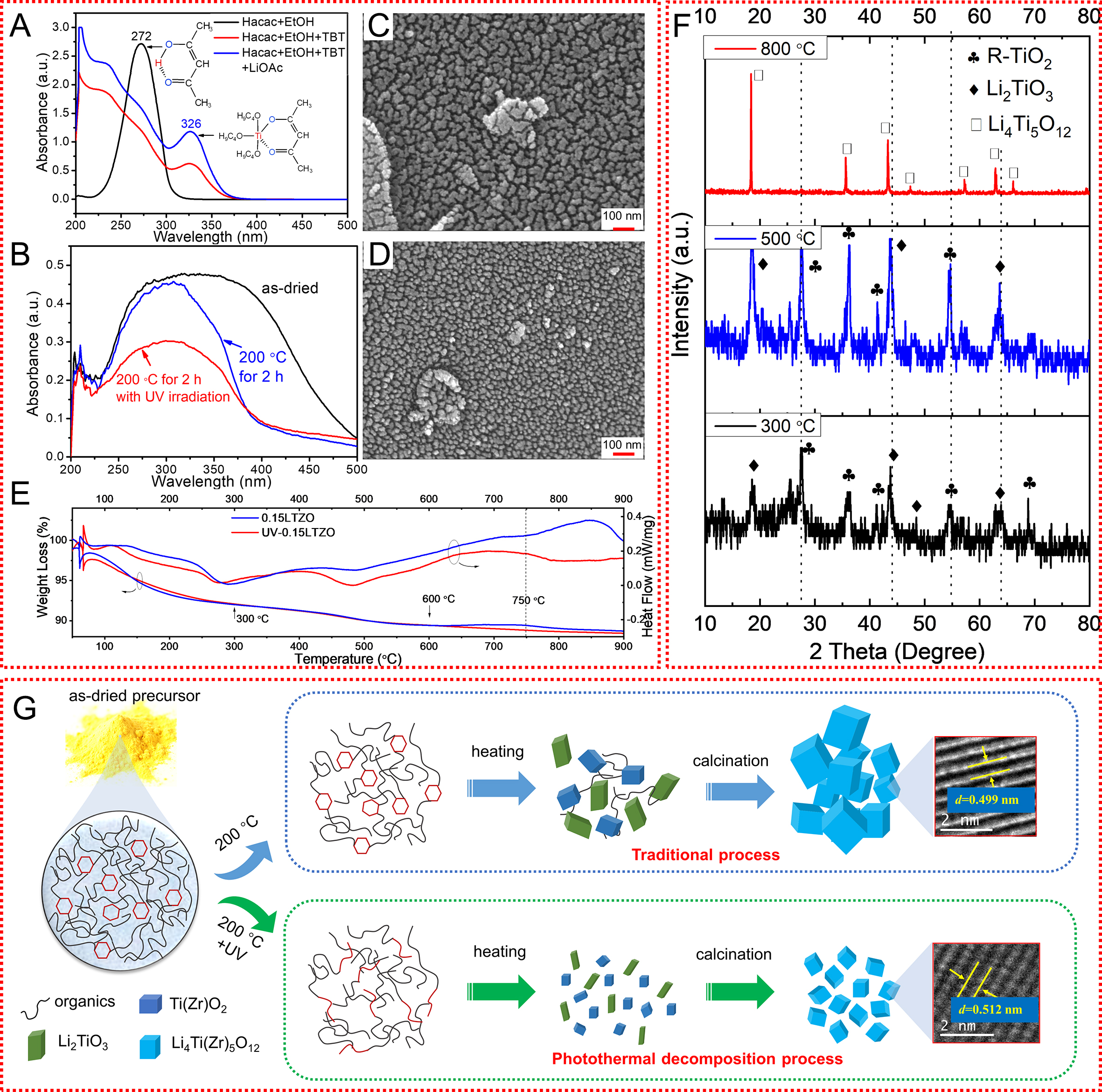

Herein, a photothermal decomposition process, as well as a traditional sol-gel process for comparison, was adopted to prepare Zr-doped LTO [Figure 1], and the combined influence of UV irradiation and Zr doping on the electrochemical performance of LTO was investigated. The use of UV radiation was confirmed to further improve the electrochemical performance of Zr-doped LTO by refining the grains and expanding the lattice. Moreover, the photothermal decomposition process shows promise as a universal modification method that could be used to improve various battery electrode materials (such as the positive and negative electrodes of lithium and sodium-ion batteries) and for the modification of other functional nanomaterials.

EXPERIMENTS

Preparation of Zr-doped LTO

Zr-doped LTO was prepared by a UV-assisted sol-gel method with a photothermal decomposition process. For comparison, a traditional sol-gel method was also employed. First, 2.47 g of acetylacetone (Hacac) and 34.55 g of absolute ethanol were placed in a 100 mL beaker. Then, 2.04 g of lithium acetate dihydrate (1% excess Li) was added to the beaker, and the mixture was magnetically stirred at room temperature for 20 min. Next, different masses of tetrabutyl titanate and zirconium (IV) butoxide (ca. 80% in 1-butanol) were slowly added to the beaker under magnetic stirring at room temperature. The masses of the tetrabutyl titanate and zirconium (IV) butoxide solution were calculated according to the molar ratio in the molecular formula Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20): 8.42, 8.34, 8.25, 8.17, and 8.08 g tetrabutyl titanate and 0, 0.12, 0.24, 0.36, and 0.48 g zirconium (IV) butoxide solution, respectively. After stirring for 2 h, a clear and bright light yellow Zr-doped LTO sol was obtained. All reagents were of analytical grade and were obtained from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (China), with the exception of absolute ethanol, which was purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (China). The Zr-doped LTO precursor sol was placed in an oil bath pan at 70 °C and stirred for about 5 h until a viscous gel formed. This gel was then dried in an oven at 70 °C for 60 h to form a yellow precursor. The precursor was pyrolyzed by using a photothermal decomposition process under UV radiation. UV irradiation was provided by a high-pressure mercury lamp (SP-9, Ushio, Japan, initial power density of 4,000 mW/cm2) with a dominant wavelength of 365 nm, and the irradiation distance was 12 cm. For comparison, each LTO precursor powder was divided into two parts, both of which were placed on a heating platform and heated at 200 °C. One part was irradiated with the UV light, and the other part was not irradiated. In this way, the UV-assisted sol-gel method was compared with traditional sol-gel synthesis. Finally, each sample was fired in a muffle furnace at 800 °C for 2 h in air to obtain Zr-doped LTO powder. For the convenience of description, the Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 (x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20) powders prepared without UV irradiation were denoted as LTO, 0.05LTZO, 0.10LTZO, 0.15LTZO, and 0.20LTZO, while the powders prepared using UV irradiation were denoted as UV-LTO, UV-0.05LTZO, UV-0.10LTZO, UV-0.15LTZO, and UV-0.20LTZO, respectively.

Material characterization

The phase structures of the Zr-doped LTO powders were characterized by a Panalytical X’Pert3 powder X-ray diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα X-ray source (λ = 1.54178 Å). The morphologies and microdomain composition distribution of the materials were observed in a field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Sigma500, ZEISS, Germany) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images of the Zr-doped LTO powders were acquired with a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-F200, JEOL, Japan). The interplanar spacing was measured with Digital Micrograph 3.4 software. The surface elements and valence states were determined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS K-Alpha, Thermo Scientific, USA), and the XPS spectra were calibrated with reference to the C 1s peak at 284.6 eV. Additionally, UV diffuse reflectance spectra (UV-DRS, UV3600 plus, Shimadzu, Japan), UV-visible (UV-vis) absorption (D-7PC, Philes, China), and thermal analysis (TG-DSC, STA449C, Netzsch, Germany) experiments were conducted to investigate the effect of UV irradiation on the thermal decomposition of the Zr-doped LTO precursor.

Electrochemical measurements

A 5 wt% binder solution was prepared by dissolving polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). Separately, 0.16 g of Zr-doped LTO powder and 0.02 g of acetylene black were mixed and ground for 30 min in a mortar. Then, 0.40 g of the binder solution and 5 drops of NMP. were quickly added to the mortar, and grinding was performed for 5 min to obtain a bright homogenate. The homogenate was coated onto a copper foil (40 μm in thickness) using a 100 μm scraper, and the coated foil was then dried under vacuum at 80° C for 12 h. After drying, each sample was cut into discs with a diameter of 14 mm. Finally, LIR2032 button half-cells were assembled in an argon glove box (< 0.01 ppm O2 and H2O). In the half-cells, Zr-doped LTO discs were used as the cathode, microporous polypropylene membranes (Celgard2400) were used as separators, commercial 1mol/L lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) in EC/DMC/EMC (ethylene carbonate/dimethyl carbonate/methyl carbonate) was used as the electrolyte, and lithium sheets were used as the anode. After standing for 12 h, the rate capacity and cycle stability of each battery were tested on a battery test system (CT-4008T, Neware, China) within the operating voltage range of 1.0-2.5 V at room temperature. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed on an electrochemical workstation (CHI760E, Chenhua, China) to study the electrochemical properties of the batteries. To ensure the electrodes remain within the single-phase region, all EIS spectra were measured at approximately 2.3 V.

Statistical analysis

The statistical distribution of grain sizes in the image field of view was analyzed with Nano Measurer 1.2 software. After confirming nonhomogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, P < 0.05) and assessing normality (Shapiro-Wilk test), group differences were analyzed using Welch’s ttest (unequal variances) with Cohen’s d for effect size. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was also applied for verification. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and all analyses were performed in Python (SciPy 1.8.0).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of Zr-doped LTO

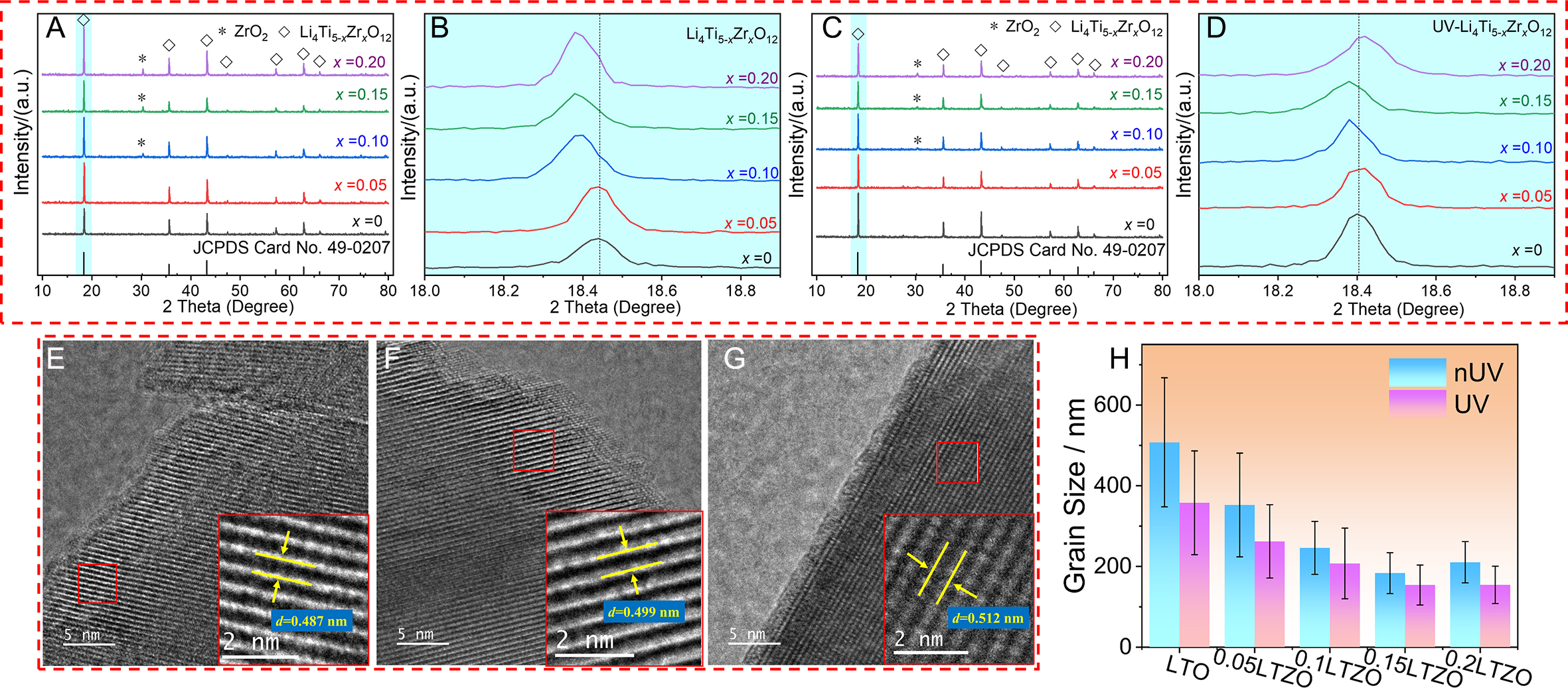

The XRD patterns of pristine and Zr-doped LTO are shown in Figure 2. Most of the diffraction peaks observed in the samples prepared with different Zr dopant ratios are ascribed to spinel LTO (Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS) Card No. 49-0207), indicating that Zr doping does not significantly change the crystal structure of LTO[25]. However, at a dopant content of x = 0.10 and above, ZrO2 diffraction peaks appear in addition to the LTO peaks, as shown in Figure 2A and C. Due to the low solubility of foreign Zr ions in the LTO lattice, excessive Zr dopant content means that some Zr ions will not be able to completely enter the LTO lattice. These Zr ions precipitate to form the ZrO2 phase, negatively affecting the capacity of LTO[22]. To compare and analyze the influence of UV irradiation on the LTO lattice, the (111) plane with the strongest peak intensity was partially enlarged, as shown in Figure 2B and D. Regardless of the presence or absence of UV irradiation during sample preparation, the (111) plane diffraction peak tends to shift to lower angles with increasing Zr dopant content. According to Bragg’s law, 2dsinθ = nλ[37], where n is the diffraction order, λ is the X-ray wavelength, d is the interplanar spacing, and θ is the Bragg angle. For a fixed n and λ, a smaller Bragg angle θ corresponds to a larger interplanar spacing d. Zr doping systematically enlarges the LTO’s lattice parameters. This enlargement is driven by the displacement of Ti4+ ions (0.068 nm) by their larger Zr4+ counterparts (0.080 nm), which mechanically expands the crystal structure[32]. Furthermore, the maximum interplanar (111) spacing is achieved with a Zr dopant content of x = 0.15. For the samples irradiated by UV, the lattice constant of the (111) plane is further increased, which is beneficial for the transport of Li+.

Figure 2. XRD patterns of pristine and Zr-doped LTO prepared without (A and B) and with (C and D) UV radiation. HRTEM images of (111) crystal planes in LTO (E), 0.15LTZO (F), and UV-0.15LTZO (G). Statistical grain size distribution based on SEM images (H). The error bars represent mean ± standard deviation (SD). The difference of grain size is highly statistically significant (Welch's t-test, P < 0.01, Cohen's

HRTEM was employed to observe the changes in the interplanar spacing of LTO after doping and UV irradiation more intuitively, as shown in Figure 2E-G. The lattice fringe reveals that the d-spacing between adjacent (111) planes in pristine LTO measures 0.487 nm, which is close to the standard 0.484 nm interplanar spacing of the standard JCPDS card. Doping with Zr (x = 0.15) expands the interplanar spacing of 0.15LTZO to 0.499 nm, and UV treatment further increases the interplanar spacing of UV-0.15LTZO to 0.512 nm. This may be due to the introduction of more Zr ion dopants via UV irradiation. Alternatively, the relaxation of residual internal stress generated during the calcination process could also explain this enlargement. Overall, these HRTEM results indicate that Zr doping under UV irradiation treatment can further enlarge the LTO lattice, surpassing conventional doping. This larger lattice structure provides wider ion diffusion channels, which is beneficial for improving the Li+ diffusion coefficient (DLi).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the Zr-doped LTO are presented in

Electrochemical properties of Zr-doped LTO

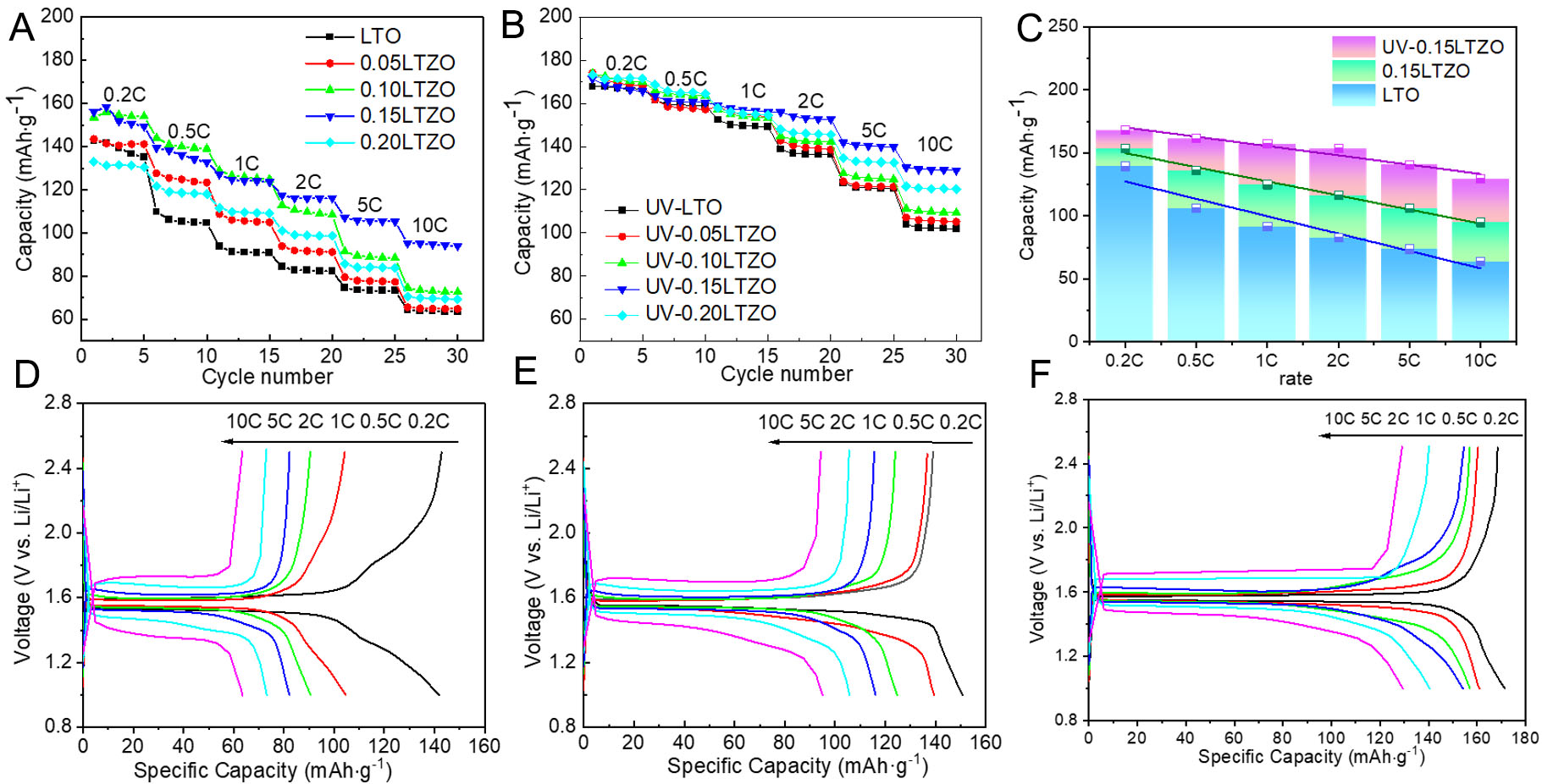

The rate performance test results are shown in Figure 3A and B. Regardless of the presence or absence of UV irradiation, increasing the Zr dopant content causes the specific capacity to first increase and then decrease, and the maximum specific capacity at high rates is achieved with a Zr dopant content of x = 0.15. The XRD and SEM analysis demonstrated that the lattice constant of LTO increased and the grain size decreased with increasing Zr dopant content. These trends are both beneficial for achieving high-rate performance. However, excessive Zr doping can generate ZrO2 impurities, reducing the electrochemical performance. Therefore, an equilibrium point is reached under a Zr dopant content of x = 0.15. This Zr dopant level maintains a larger lattice size to accelerate Li+ transport, shortens the Li+ transport distance due to the smaller grain size, and reduces the decline in specific capacity caused by the presence of ZrO2 impurities. Taking these factors into account, the optimal Zr dopant content is x = 0.15.

Figure 3. Rate performance of pristine and Zr-doped LTO prepared without (A) and with UV radiation (B). Bar graph showing the capacities of LTO, 0.15LTZO, and UV-0.15LTZO at different rates (C). Charge/discharge curves of pristine LTO (D), 0.15LTZO (E), and UV-0.15LTZO (F) at different rates. The C-rate is a normalized current parameter. An nC rate for LTO corresponds to a current of

For a more intuitive comparison, the average discharge specific capacities of the LTO samples prepared with and without UV treatment at rates of 0.2-10 C were plotted as a bar graph, as shown in Figure 3C. It is evident that at rates of 0.2C-10C, compared to pristine LTO, the discharge specific capacity of Zr-doped 0.15LTZO and UV-0.15LTZO after UV irradiation increases successively at each rate, while capacity decay gradually decreases at high rates. Figure 3D-F shows the charge-discharge curves and differential capacity dQ/dV-V curves of LTO, 0.15LTZO, and UV-0.15LTZO, with all three samples showing obvious charge and discharge plateaus at approximately 1.55 V. Among them, the specific capacity of pristine LTO reaches

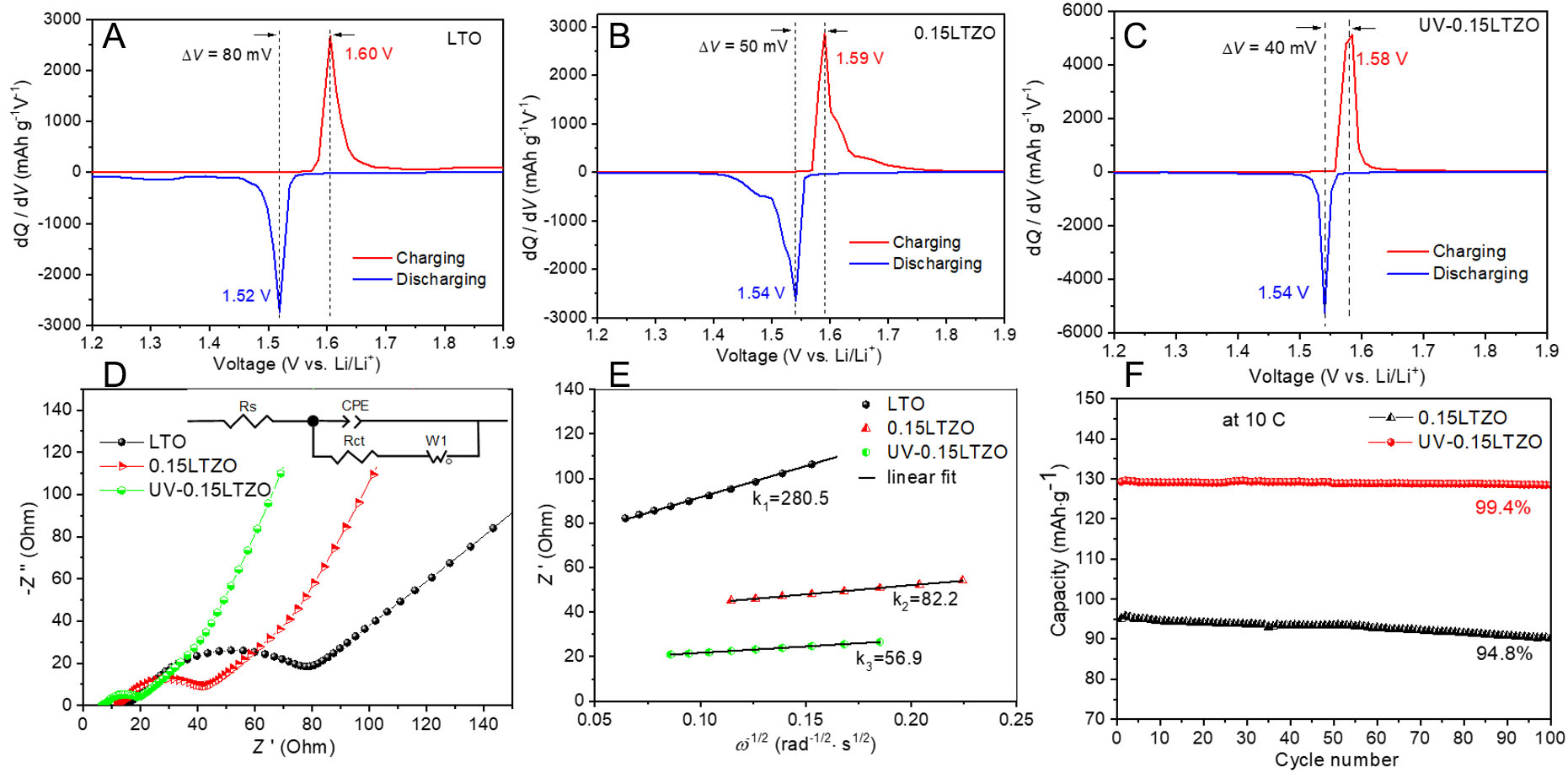

The distance between charge-discharge plateaus represents the polarization degree of each material, with a greater distance indicating greater polarization. Comparing the three samples, undoped LTO exhibits the highest polarization, while UV-0.15 LTO has the lowest polarization. According to the dQ/dV-V curves as shown in Figure 4A-C, the polarization voltages of the LTO, 0.15Zr-LTO, and UV-0.15Zr-LTO samples at 0.2 C are 80 mV, 50 mV, and 40 mV, respectively. The UV-0.15Zr LTO sample exhibits the lowest polarization voltage, consistent with its better rate performance compared with the other samples. This indicates that Zr doping and UV irradiation minimize electrode polarization and capacity degradation at high rates, which can be explained by the material characteristics. Specifically, this UV-irradiated sample has the largest lattice constant and the smallest grain size. Moreover, UV-0.15Zr-LTO also probably has fewer ZrO2 impurities than 0.15Zr-LTO. Therefore, the high-rate capacity of the material after UV irradiation is higher.

Figure 4. dQ/dV-V curves during the first charge/discharge process at 0.2 C for LTO (A), 0.15LTZO (B), and UV-0.15LTZO (C), respectively. EIS spectra (D) and Z′ - ω-1/2 curves (E) of LTO, 0.15LTZO, and UV-0.15LTZO after 100 charging-discharging cycles. To ensure the electrodes remain within the single-phase region, all EIS spectra were measured at approximately 2.3 V. The inset in (D) is the fitted equivalent circuit. Cycling stability of 0.15LTZO and UV-0.15LTZO (F).

The migration process of Li+ ions in lithium-ion batteries includes the migration of Li+ in the electrolyte, the transformation at the interface, and the solid-state diffusion process. Among these steps, the solid-state diffusion process is relatively slow. Therefore, this is the rate-controlling step of Li+ migration in lithium-ion batteries, and improving the diffusion coefficient of Li+ in the solid phase is the key to improving the high-rate performance of batteries. EIS and deuterogenic Z′ - ω-1/2 plots (where Z′ is the real part of the impedance and ω is the angular frequency) were used to evaluate the electrochemical performance of LTO, 0.15LTZO, and UV-0.15LTZO, as shown in Figure 4D and E. The impedance parameters and DLi of the three samples were obtained based on the EIS spectra and equivalent circuit model, as listed in Table 1. Clearly, the UV-0.15LTZO sample exhibits the lowest solution resistance Rs and charge transfer resistance Rct at the electrolyte/electrode interface. The DLi was calculated by analyzing the slope of the line at a low frequency, as per the equations presented in[38,39], as determined by

Impedance parameters and comparison of Li+ diffusion coefficients DLi of LTO, 0.15LTZO, and UV-0.15LTZO based on EIS spectra and equivalent circuit model

| Sample | Rs/Ω | Rct/Ω | σ/Ω cm2s-0.5 | Comparison of DLi |

| LTO | 16.4 | 66.2 | 280.5 | DLi-LTO |

| 0.15LTZO | 12.5 | 34.6 | 82.2 | 12DLi-LTO |

| UV-0.15LTZO | 6.9 | 14.4 | 56.9 | 24DLi-LTO |

where R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, A is the surface area of the electrode, n is the number of electrons transferred by the redox pair in the half-reaction, F is the Faraday constant, C is the concentration of Li-ion in the bulk, σ is the Warburg factor, Z′ is the real part of the impedance, and ω is the angular frequency.

All three samples were evaluated under the same experimental conditions. Therefore, all parameters in Eq. (1) are the same except for the Warburg factor σ, and the DLi is inversely proportional to σ2. The DLi value of 0.15LTZO is about 12 times higher than that of pristine LTO, and the DLi of UV-0.15LTZO is 24 times higher than that of pristine LTO. These results are closely related to the larger lattice constant and smaller grain size of UV-0.15LTZO.

The cyclic stability of 0.15Zr-LTO and UV-0.15Zr-LTO samples was compared, as shown in Figure 4F. The UV-irradiated sample exhibits better cyclic stability than the sample prepared without UV irradiation. At 10 C, the 0.15Zr-LTO and UV-0.15Zr-LTO samples exhibit respective capacity retentions of 94.8% and 99.4% after 100 cycles, confirming the better stability of UV-0.15Zr-LTO.

Mechanism analysis

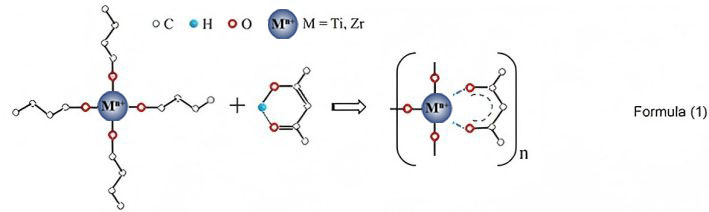

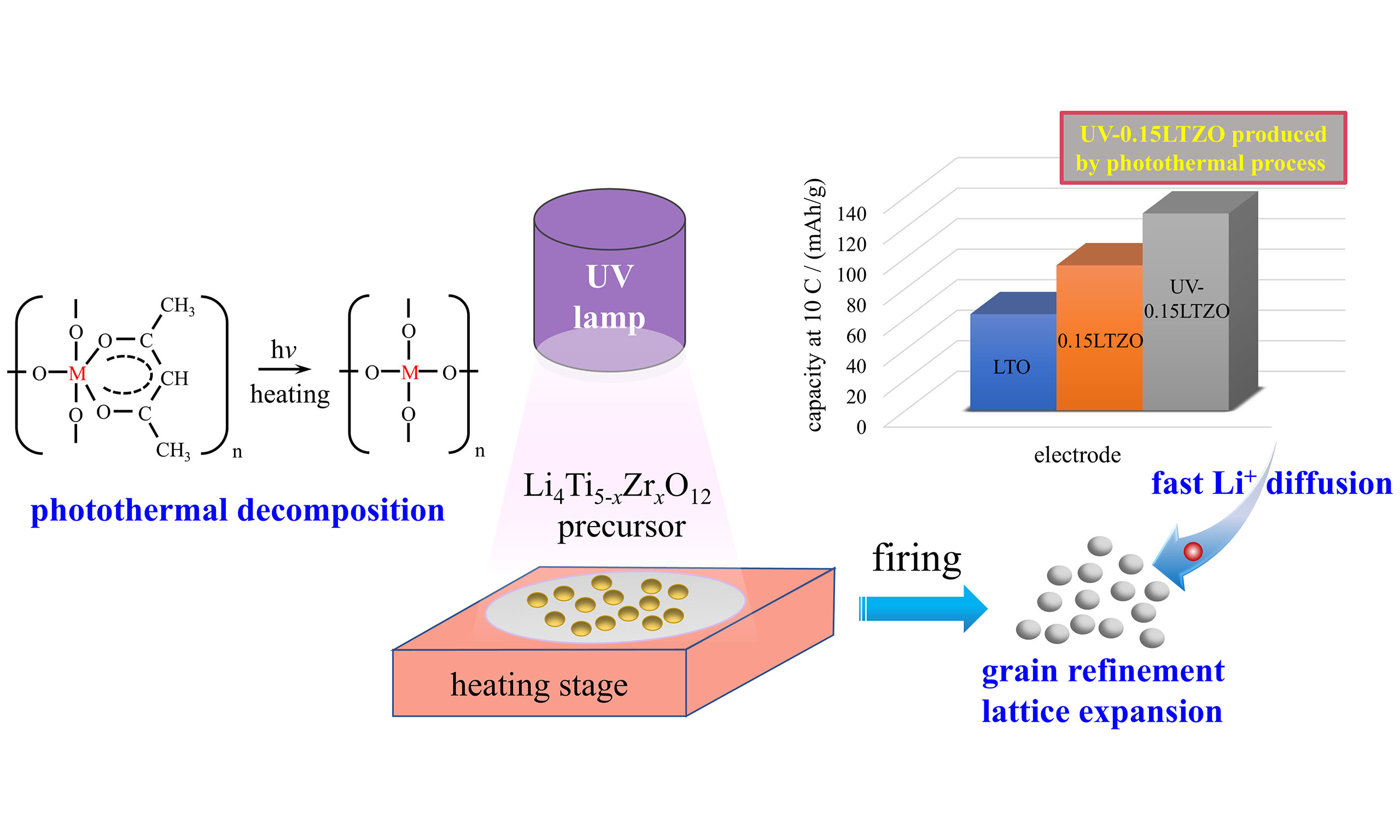

Clearly, UV irradiation treatment can further enhance the electrochemical performance of the prepared electrode materials after doping modification. To explore the mechanism of UV irradiation, a comparative analysis of the whole process was carried out for the Zr-doped LTO samples prepared with and without UV irradiation (x = 0.15). During the preparation process for obtaining the Zr-doped LTO sol, after the dissolution of Hacac in anhydrous ethanol (EtOH), a π - π conjugated system is formed by the π bond in the C=C and C=O double bonds in enol-structure Hacac[40,41]. Due to π - π* electron transition, a strong absorption peak appears at 271 nm in the UV spectrum, as shown in Figure 5A. When lithium acetate dihydrate is added to the sol, the position of this absorption peak remains unchanged, indicating that Li does not react with Hacac. However, when butyl titanate or zirconium n-butanol is added to the sol, the absorption peak undergoes a significant red shift. This is due to the coordination of the lone-pair electrons of two O atoms in Hacac with Ti or Zr, which forms a chelating ring structure[42], as given in Eq. (1).

Figure 5. UV-visible absorption spectra of different components in LTZO sol (A) and UV diffuse reflectance spectra of as-dried and

When the LTO sol is converted into a gel, the organic molecules undergo hydrolysis and polymerization, cross-linking occurs between the molecules, and the absorption peak in the UV diffuse reflectance spectra is broadened, as shown in Figure 5B. After heating the gel at 200 °C for 2 h, the solvent volatilizes, some of the organic molecules decompose, the absorption peak narrows, and the peak blue shifts to 303 nm, which corresponds to the ring structure between Hacac and Ti/Zr. This structure is stable and does not easily decompose, so the strength of the peak is almost unchanged after heating at 200 °C. However, after UV irradiation at 200 °C for 2 h, the peak intensity significantly decreases, indicating that UV light promotes the decomposition of the ring structure, as shown in Formula (2). SEM images of the intermediates of 0.15LTZO and UV-0.15LTZO obtained after further heating to 300 °C are shown in Figure 5C and D. The intermediate particles of UV-0.15LTZO prepared with UV irradiation are uniform in size, and these particles are relatively smaller compared to those of 0.15LZTO. The morphology of the uniform and small intermediate particles obtained after UV irradiation is the key to reducing the grain size of LTO.

.

.

The thermogravimetric (TG) and differential scanning calorimetric (DSC) curves of 0.15LTZO and UV-0.15LTZO are shown in Figure 5E. Although UV irradiation can decompose conjugated bonds, the energy of UV irradiation is not sufficient to cause oxidative decomposition. Instead, only the original organic macromolecules are decomposed into small molecules. Therefore, the TG curves of the two samples are similar at low temperatures. The weight loss that occurs from room temperature to approximately 300 °C corresponds to the decomposition of organic components. The second weight loss period occurs at around 300-500 °C, corresponding to the decomposition of precursor materials. Weight loss continues from

Above 750 °C, weight loss continues, corresponding to the decomposition of residual C and the formation of the LTZO crystal phase. This is confirmed by the significant endothermic peak appearing in the DSC curve. After the second weight loss period (approximately 600 °C), the UV-0.15LTZO sample immediately began the third weight loss period. This sample shows a clear endothermic DSC peak above 600 °C corresponding to the formation of LTO nuclei. These results demonstrate that UV treatment of the dried LTO precursor induces the nucleation of LTO at relatively low temperatures, which is beneficial for obtaining small grains.

To better understand the role of UV irradiation in the LTO preparation process, a UV irradiation mechanism diagram was drawn based on the analysis results, as shown in Figure 5G. The dried LTO precursor contains a large number of Ti-containing cyclic structures, which do not easily undergo low-temperature decomposition (200 °C). When UV light is applied during heating, the cyclic structure gradually decomposes (as shown in the UV diffuse reflectance spectra) to form a chain-like structure. Compared to the cyclic structure, this chain structure is more susceptible to decomposition during heating, which is conducive to the formation of a uniform oxygen-metal-oxygen (O-M-O) network structure. Thus, the small-sized intermediate products TiO2 and Li2TiO3 are formed at the early stage of heating [Figure 5F]. Eventually, TiO2 and Li2TiO3 react to form uniformly fine LTO grains, as given in Eq. (3). In summary, the application of UV irradiation during the decomposition stage of the precursor promotes the decomposition of the organic ring structure, leading to the formation of fine and uniform TiO2 and Li2TiO3 mesophases. After calcination, the as-obtained LTZO grains are finer and the lattice parameters are larger than those of the samples prepared without UV treatment. Therefore, UV-0.15LTZO exhibits an improved rate performance and cycling stability, with a specific capacity of 129 mAh·g-1 at a discharge rate of 10 C and a capacity retention rate of 99.4% after 100 cycles. Regarding the changes in microstructure, on the one hand, this may be due to the UV-induced grain refinement, which releases a certain amount of internal stress and leads to an increase in the lattice parameter. On the other hand, XRD analysis demonstrates that for the same Zr doping level, the ZrO2 diffraction peak of the UV-treated LTO is smaller than that of the LTO prepared without UV irradiation. This may be due to the photothermal decomposition process inducing the entrance of more Zr4+ ions into the lattice. These Zr4+ ions replace the smaller Ti4+ and further increase the lattice parameter. This verifies that the photothermal decomposition process significantly regulates the microstructure of these materials and is worthy of further in-depth research.

CONCLUSIONS

Zr-doped lithium titanate Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 (LTZO, x = 0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20) anodes with different Zr dopant contents were prepared by a traditional sol-gel process and a photothermal decomposition process. According to the electrochemical test results, the best rate performance and cycling stability are achieved by the LTZO prepared with Zr dopant content of x = 0.15. Overall, the photothermal decomposition technology proposed in this article improves the microstructure of LTZO electrodes and significantly enhances their electrochemical properties. In addition, this method may also provide a certain reference value for the regulation of other types of nanomaterials.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hongwei Ge, Dr. Lin Deng, Dr. Qiyuan Chen, and Dr. Xuehua Mao for their assistance with battery assembly and testing.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, formal analysis, writing - original draft: Wu, C.

Investigation, formal analysis, writing - review & editing: Pan, Z.

Resources, writing - review & editing: Ma, G.

Formal analysis, writing - review & editing: Wang, H.; Wang, X.

Writing - review & editing: Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.

Supervision, writing - review & editing: Yao, M.

Availability of data and materials

Supplementary Material is available from the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Solar Energy Utilization Technology Integration Engineering Laboratory of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 25TYNLY0001), the Sichuan Engineering Research Center for Titanium Alloy Advanced Manufacturing Technology (Grant No. TM-2023-Y-02), and the Scientific Cultivation Project of Panzhihua University (Grant No. 2022-3).

Conflicts of interest

Zhang, Y. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Energy Materials. Zhang, Y. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Khan, A.; Al Rashid, H.; Roy, P. K.; Chowdhury, S. I.; Sathi, S. A. Challenges and the way to improve lithium‐ion battery technology for next‐generation energy storage. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2025, 8, e70088.

3. Xia, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhu, X.; et al. Inorganic-organic competitive coating strategy derived uniform hollow gradient-structured ferroferric oxide-carbon nanospheres for ultra-fast and long-term lithium-ion battery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2973.

4. Wu, F.; Maier, J.; Yu, Y. Guidelines and trends for next-generation rechargeable lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 1569-614.

5. Yan, H.; Zhang, D.; Qilu, X.; Duo, X.; Sheng, X. A review of spinel lithium titanate (Li4Ti5O12) as electrode material for advanced energy storage devices. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 5870-95.

6. Wu, H. B.; Chen, J. S.; Hng, H. H.; Lou, X. W. Nanostructured metal oxide-based materials as advanced anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 2526-42.

7. Nzereogu, P.; Omah, A.; Ezema, F.; Iwuoha, E.; Nwanya, A. Anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: a review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 9, 100233.

8. Dong, C.; Dong, W.; Lin, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Huang, F. Recent progress and perspectives of defective oxide anode materials for advanced lithium ion battery. EnergyChem 2020, 2, 100045.

9. Ohzuku, T.; Ueda, A.; Yamamoto, N. Zero‐strain insertion material of Li [Li1/3Ti5/3]O4 for rechargeable lithium cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 142, 1431-5.

10. Zhang, Y.; Teeter, G.; Dutta, N. S.; Frisco, S.; Han, S. Mechanistic understanding of aging behaviors of critical-material-free Li4Ti5O12//LiNi0.9Mn0.1O2 cells with fluorinated carbonate-based electrolytes for safe energy storage with ultra-long life span. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141239.

11. Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Lu, X.; He, X. Li4Ti5O12 spinel anode: fundamentals and advances in rechargeable batteries. InfoMat 2021, 4, e12228.

12. Zhang, E.; Zhang, H. Hydrothermal synthesis of Li4Ti5O12-TiO2 composites and Li4Ti5O12 and their applications in lithium-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 7419-26.

13. Yuan, T.; Tan, Z.; Ma, C.; Yang, J.; Ma, Z. F.; Zheng, S. Challenges of spinel Li4Ti5O12 for lithium-ion battery industrial applications. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2017, 7, 1601625.

14. Bhatti, H. S.; Jabeen, S.; Mumtaz, A.; Ali, G.; Qaisar, S.; Hussain, S. Effects of cobalt doping on structural, optical, electrical and electrochemical properties of Li4Ti5O12 anode. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 890, 161691.

15. Yin, Y.; Luo, X.; Xu, B. In-situ self-assembly synthesis of low-cost, long-life, shape-controllable spherical Li4Ti5O12 anode material for Li-ion batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 904, 164026.

16. Haridas, A. K.; Sharma, C. S.; Rao, T. N. Donut-shaped Li4Ti5O12 structures as a high performance anode material for lithium ion batteries. Small 2015, 11, 290-4.

17. Roh, H.; Lee, G.; Haghighat-Shishavan, S.; Chung, K. Y.; Kim, K. Polyol-mediated carbon-coated Li4Ti5O12 nanoparticle/graphene composites with long-term cycling stability for lithium and sodium ion storages. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 385, 123984.

18. Cáceres-Murillo, J.; Díaz-Carrasco, P.; Kuhn, A.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; García-Alvarado, F. Improvement of the rate capability of the Li4Ti5O12 anode material by modification of the surface composition with lithium polysulfide. J. Alloys. Compd. 2024, 976, 173051.

19. Lakshmi-Narayana, A.; Dhananjaya, M.; Julien, C. M.; Joo, S. W.; Ramana, C. V. Enhanced electrochemical performance of rare-earth metal-ion-doped nanocrystalline Li4Ti5O12 electrodes in high-power Li-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 20925-45.

20. Ezhyeh, Z. N.; Khodaei, M.; Torabi, F. Review on doping strategy in Li4Ti5O12 as an anode material for Lithium-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 7105-41.

21. Zhang, Y. H.; Nie, Z. H.; Du, C. Q.; Zhang, J. W.; Zhang, J. W. Ultrahigh lithiation dynamics of Li4Ti5O12 as an anode material with open diffusion channels induced by chemical presodiation. Rare. Metals. 2022, 42, 471-83.

22. Kim, J. G.; Park, M. S.; Hwang, S. M.; et al. Zr4+ doping in Li4Ti5O12 anode for lithium-ion batteries: open Li+ diffusion paths through structural imperfection. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 1451-7.

23. Nithya, V. D.; Sharmila, S.; Vediappan, K.; Lee, C. W.; Vasylechko, L.; Kalai Selvan, R. Electrical and electrochemical properties of molten-salt-synthesized 0.05 mol Zr- and Si-doped Li4Ti5O12 microcrystals. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 44, 647-54.

24. Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Peng, W.; Guo, H.; Li, X. An improved solid-state reaction to synthesize Zr-doped Li4Ti5O12 anode material and its application in LiMn2O4/ Li4Ti5O12 full-cell. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 10053-9.

25. Seo, I.; Lee, C.; Kim, J. Zr doping effect with low-cost solid-state reaction method to synthesize submicron Li4Ti5O12 anode material. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2017, 108, 25-9.

26. Hou, L.; Qin, X.; Gao, X.; Guo, T.; Li, X.; Li, J. Zr-doped Li4Ti5O12 anode materials with high specific capacity for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 2019, 774, 38-45.

27. Liu, Z.; Cao, L.; He, F.; et al. Study on the possibility of diagonal line rule in elemental doping effects in Li4Ti5O12 by mechanochemical method. Electrochim. Acta. 2022, 422, 140485.

28. Gu, F.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z. Synthesis and electrochemical performances of Li4Ti4.95Zr0.05O12/C as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Solid. State. Electrochem. 2011, 16, 375-82.

29. Han, J.; Zhang, B.; Bai, X.; et al. Li 4 Li4Ti5O12 composited with Li2ZrO3 revealing simultaneously meliorated ionic and electronic conductivities as high performance anode materials for Li-ion batteries. J. Power. Sources. 2017, 354, 16-25.

30. Wang, B.; Gu, L.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W. A. High-throughput production of Zr-doped Li4Ti5O12 Modified by mesoporous Libaf3 nanoparticles for superior lithium and potassium storage. Chem. Asian. J. 2019, 14, 3181-7.

31. Lu, P.; Huang, X.; Ren, Y.; et al. Na+ and Zr4+ co-doped Li4Ti5O12 as anode materials with superior electrochemical performance for lithium ion batteries. RSC. Adv. 2016, 6, 90455-61.

32. Li, X.; Tang, S.; Qu, M.; Huang, P.; Li, W.; Yu, Z. A novel spherically porous Zr-doped spinel lithium titanate (Li4Ti5-xZrxO12) for high rate lithium ion batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 2014, 588, 17-24.

33. Li, X.; Qu, M.; Yu, Z. Structural and electrochemical performances of Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 as anode material for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 2009, 487, L12-7.

34. Yi, T.; Chen, B.; Shen, H.; Zhu, R.; Zhou, A.; Qiao, H. Spinel Li4Ti5-xZrxO12 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.25) materials as high-performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys. Compd. 2013, 558, 11-7.

35. Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Meng, Q.; Lei, S.; Song, F.; Ma, J. Synergy of a hierarchical porous morphology and anionic defects of nanosized Li4Ti5O12 toward a high-rate and large-capacity lithium-ion battery. J. Energy. Chem. 2021, 54, 699-711.

36. Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Ma, G.; Zheng, X. Enhanced rate capability of Li4Ti5O12 anode material by a photo-assisted sol-gel route for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochem. Commun. 2021, 131, 107119.

38. Bai, X.; Li, T.; Bai, Y. Dual-modified Li4Ti5O12 anode by copper decoration and carbon coating to boost lithium storage. ACS. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 17177-84.

39. Jiang, X.; Ma, G.; Ke, Y.; Deng, L.; Chen, Q. Cost-effective Li4Ti5O12/C-S prepared by industrial H2TiO3 under a carbon reducing atmosphere as a superior anode for Li-ion batteries. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 625-34.

40. Zhou, S.; Barnes, I.; Zhu, T.; Bejan, I.; Albu, M.; Benter, T. Atmospheric chemistry of acetylacetone. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 7905-10.

41. Rinaman, J. E.; Murray, C. Acetylacetone photolysis at 280 nm studied by velocity-map ion imaging. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2023, 127, 6687-96.

42. Lei, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. Micropatterning of LaCoO3 thin films through a novel photosensitive sol-gel lithography technique and their magnetic properties. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 44671-7.

43. Shen, Y.; Søndergaard, M.; Christensen, M.; Birgisson, S.; Iversen, B. B. Solid state formation mechanism of Li4Ti5O12 from an anatase TiO2 source. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 3679-86.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].