MoS2-doped polyvinyl alcohol nanofiber films via electrospinning for high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators

Abstract

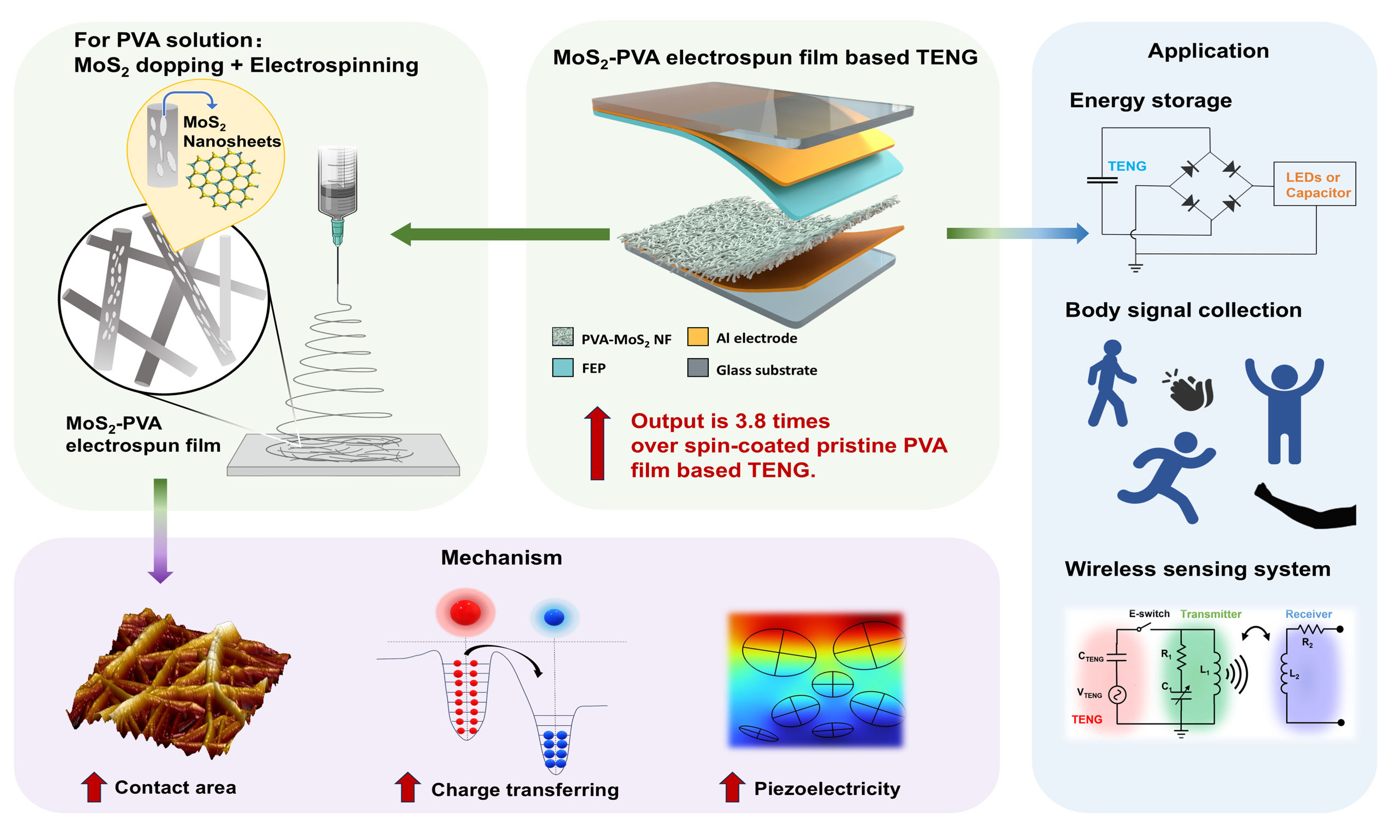

Electrospinning enables the fabrication of nanofiber films with large active surface area, high porosity, and controllable filler orientation, offering distinct advantages for fabricating high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs). Here, we develop MoS2-doped electrospun polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) films for TENG fabrication and reveal the underlying mechanisms of their enhanced triboelectric performance. Compared with spin-coated films, electrospun films intrinsically deliver higher output due to their fibrous morphology, while incorporation of MoS2 nanosheets further improves the performance. TENGs with the optimized 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA electrospun film reached 994.0 V, 111.0 mA·m-2, and

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) have attracted increasing attention as emerging energy-harvesting devices that convert ambient mechanical energy into electricity. Their operation arises from the coupled effects of contact electrification and electrostatic induction[1]. Over the past decade, TENG research has expanded from fundamental studies to diverse practical applications, showing strong potential in wearable electronics, environmental energy harvesting, and intelligent sensing systems[2-4]. Benefiting from their low cost, environmental adaptability, and high energy conversion efficiency, TENGs have been widely applied to power sensors, implantable medical devices, etc.[5-10]. With their rapidly growing application scope, TENGs are expected to play increasingly important roles in future technologies such as smart healthcare, intelligent transportation, and smart home systems.

As the performance of TENGs largely depends on the accumulation and transfer of triboelectric charges, enhancing the surface charge density and optimizing structural design of friction materials are keys to improving TENG performance. Among various strategies, electrospinning has emerged as a particularly effective technique for fabricating nanofiber-based triboelectric materials. Electrospun (ES) nanofiber films offer high specific surface area, favorable porosity, and tunable microstructures, all of which contribute to enhanced charge generation[11-13]. These properties endow the TENGs with excellent flexibility, lightweight characteristics, and stretchability, making them highly suitable for wearable electronics and self-powered sensors[14-16]. Furthermore, optimized ES architectures can maintain stable electric output under dynamic mechanical stimuli, which is crucial for real-world applications.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), although relatively neutral in the triboelectric series, has gained increasing interest as a tribopositive material due to its biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, mechanical flexibility, and chemical tunability[17,18]. Its ability to form stable nanofibers through electrospinning, combined with its compatibility with various nanomaterials, makes PVA a promising candidate for the fabrication of high-performance biocompatible TENGs. Moreover, the neutral-to-weakly positive triboelectric behavior of PVA provides a versatile platform for polarity modulation via functional fillers, enabling tunable surface potential and performance enhancement without compromising material integrity.

To further improve triboelectric performance, ES polymers are often doped with functional two-dimensional (2D) materials such as graphene[19], MXene and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) such as MoS2. For instance, MXene has been widely used as a triboelectric layer or electrode material due to its high conductivity and mechanical robustness, significantly enhancing both output power and operational durability[20-23]. Similarly, incorporating TMDs into polymer matrices can modulate interfacial electronic structures and introduce polarization effects, thereby opening new avenues for performance optimization.

In this context, MoS2 is particularly attractive due to its unique combination of electronic tunability, strong interfacial interaction capability, and piezoelectric activity in few-layer form[24,25]. These properties make MoS2 well-suited to regulate the surface potential of the host polymer matrix, facilitate charge transfer dynamics, and enhance piezoelectric polarization within composite films. Incorporating MoS2 into PVA nanofibers thus provides a promising pathway to synergistically couple morphology-driven enlargement of the effective contact area with nanosheet-induced electronic and piezoelectric contributions. However, systematic studies on MoS2-doped ES PVA composites remain scarce, and their potential for achieving high-output, stable TENGs remains underexplored[15,26-28]. Meanwhile, recent reports on MoS2-doped ES nanofiber TENGs further highlight the promise of MoS2-functionalized systems for high-performance energy harvesting[29,30].

In this study, we propose a synergistic material-structure strategy to boost the output performance and stability of TENGs by incorporating MoS2 nanosheets into PVA ES nanofiber films. This design couples three reinforcing effects: morphology-driven enlargement of the effective contact area, surface-potential modulation, and nanosheet alignment-induced piezoelectric polarization, thereby overcoming the limitations of dense spin-coated films. TENGs with the optimized 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES composite paired with fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) tribomaterial achieves an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 994.0 V, short-circuit current density (Jsc) of 111.0 mA·m-2, and transferred charge density (Qsc) of 136.3 μC·m-2, outperforming the TENG with the pristine spin-coated PVA by ~3.8, ~3.8, and ~3.0 times, respectively, and that with 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated composite by ~1.7, ~2.0, and ~1.7 times, respectively. To unravel the origins of this superior output, we combine multiscale characterization with material calculations and structural simulations. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) and Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) measurements reveal that moderate MoS2 incorporation significantly elevates the contact potential difference (VCPD) and lowers the effective work function, amplifying the potential difference with FEP. Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) quantifies a substantial rise in piezoelectric coefficient (d33) for ES composites. At the same time, COMSOL Multiphysics finite element simulations visualize strong thickness-direction polarization originating from electric field-driven nanosheet alignment. Complementary molecular dynamics (MD) simulations uncover dipole amplification and robust Mo-O interfacial interactions that stabilize this alignment against relaxation. By coherently combining experimental and theoretical evidence, this work not only clarifies the non-monotonic doping dependence but also establishes design principles for synergistic morphology-electronic-piezoelectric coupling in TENGs, offering a pathway toward durable, biocompatible, and high-output devices.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

PVA (Mowiol® 210, molecular weight 67,000), isopropyl alcohol (IPA), and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2,

Preparation of MoS2-PVA films

The fabrication procedure is illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1. MoS2 nanocrystals were dispersed in a 3:2 (v/v) IPA:deionized (DI) water mixture and ultrasonicated for 4 h in an ice bath, followed by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was vacuum-dried to obtain few-layer MoS2 nanosheets, which showed lateral sizes of 20-30 nm and thicknesses < 4 nm by an

Electrospinning was carried out for 1 h at a 0.7 mL/h feed rate and an applied voltage of 18-22 kV in 1 kV increments, under 23 ± 2 °C and 30% ± 3% RH (Relative Humidity), with a 10.5 cm needle-to-collector distance. The nanofiber mats were dried in a desiccator (20% RH) for 5 h to obtain 30 μm MoS2-PVA ES films, labeled as x wt.% MoS2-PVA ES films (x = 1, 2, 3, 4). MoS2-PVA spin-coated films (20 µm) were prepared by depositing each solution onto glass substrates using a two-step spin process (500 rpm for 10 s and 1,000 rpm for 10 s), followed by overnight drying at 20% RH and peeling to obtain freestanding films. These were designated as x wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated films and used as controls for comparison with MoS2-PVA ES film-based samples and TENGs.

Fabrication of MoS2-PVA/FEP TENG devices

MoS2-PVA composite films and FEP membranes were used as the triboelectric positive and negative layers, respectively, to assemble vertical contact-separation-mode TENGs. ES MoS2-PVA films were cut into

Materials and TENG characterization

The surface morphology and elemental distribution of the MoS2-PVA composite films were analyzed by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, HITACHI S-4800, Tokyo, Japan) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Samples were sputter-coated with a thin Au layer (KYKY SBC-12, Beijing, China) to improve conductivity. Raman spectra were obtained using a Horiba LabRAM Odyssey spectrometer (532 nm laser, Kyoto, Japan), and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded with a Nicolet 5700 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were acquired using a Shimadzu LabX XRD-6100 (Kyoto, Japan). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using a TA Instruments TGA55 (New Castle, DE, USA), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on a TA Discovery DSC25 (New Castle, DE, USA). AFM characterization, piezoelectric charge constant (d33) measurement via PFM, and KPFM surface potential mapping were carried out using a unified Bruker Multimode SPM system (Billerica, MA, USA).

Triboelectric performance was tested using a Popwil YPS-1 dynamic fatigue system (Hangzhou Popwil Physics Instrument Co., Ltd., China) to control contact force, frequency, and separation distance. Output voltage and current were measured with a Tektronix MDO 3022 oscilloscope (100 MΩ internal resistance, Beaverton, OR, USA) and a Keysight B2981A picoammeter (Santa Rosa, CA, USA), respectively. Charge density was calculated from the integration of the current. Capacitor voltages were also recorded using the Tektronix MDO 3022 oscilloscope.

A humidity-controlled environment was established using a dual-path N2 system, with one stream bubbled through DI water. Mass flow controllers (MFCs, Sevenstar Electronics Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) regulated dry/humid flow rates to adjust RH at a total flow of 5 SLM, maintaining 28 ± 0.5 °C. RH was monitored in real time with a calibrated AS847 hygrometer (Smart Sensor, Dongguan, China), and the MD1101 humidity sensor (Zave, Shenzhen, China) was tested in a sealed chamber with uniform N2 distribution.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Morphologies of MoS2-PVA ES films

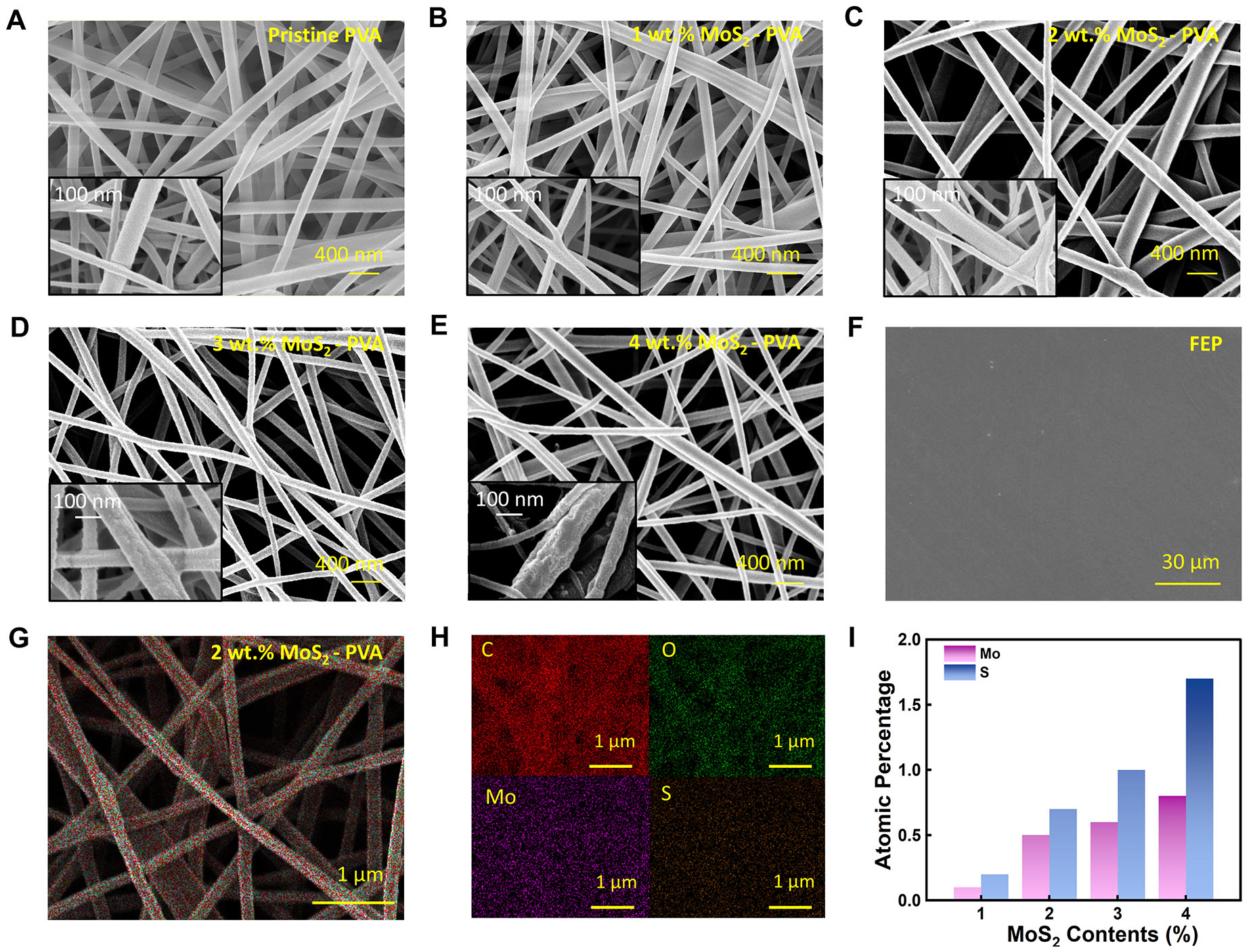

The microstructures of the MoS2-PVA ES nanofiber films were analyzed by SEM, EDS, FTIR, XRD, Raman, TGA, and DSC to establish the morphology-property relationships governing triboelectric performance. Electrospinning and MoS2 incorporation are expected to introduce structural features distinct from spin-coated films, including increased surface roughness, nanosheet-polymer interactions, and alignment-induced ordering. These detailed characterizations provide a solid foundation for correlating morphology and microstructure with surface potential modulation and piezoelectric coupling in the ES composites.

SEM images of ES nanofibers with 0-4 wt.% MoS2 [Figure 1A-E] reveal continuous, bead-free networks. Higher magnification insets reveal distinct surface protrusions at 3-4 wt.% loading, suggesting MoS2 aggregation at higher concentrations. AFM images [Supplementary Figure 4] further confirm the presence of granular features and increased surface roughness in these samples. Diameter distribution analysis (n = 35) in Supplementary Figure 5 shows a slight reduction in average diameter at 3-4 wt.% MoS2, attributed to increased solution conductivity during electrospinning[31,32]. In contrast, spin-coated MoS2-PVA films [Supplementary Figure 6A] and pristine FEP film [Figure 1F] exhibit smooth, non-fibrous surfaces. The porous ES morphology provides a larger effective contact area, beneficial for enhanced TENG output.

Figure 1. SEM morphology and elemental analysis of MoS2-PVA ES films. (A-E) SEM images of x wt.% MoS2-PVA ES films (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4). (F) An SEM image of the FEP film. (G) SEM morphology of the EDS area. (H) EDS elemental mapping of C, O, Mo and S for the 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film. (I) Elemental content variation with different MoS2 doping concentrations.

To evaluate the distribution of MoS2 within the nanofiber mat, EDS elemental mapping was conducted on

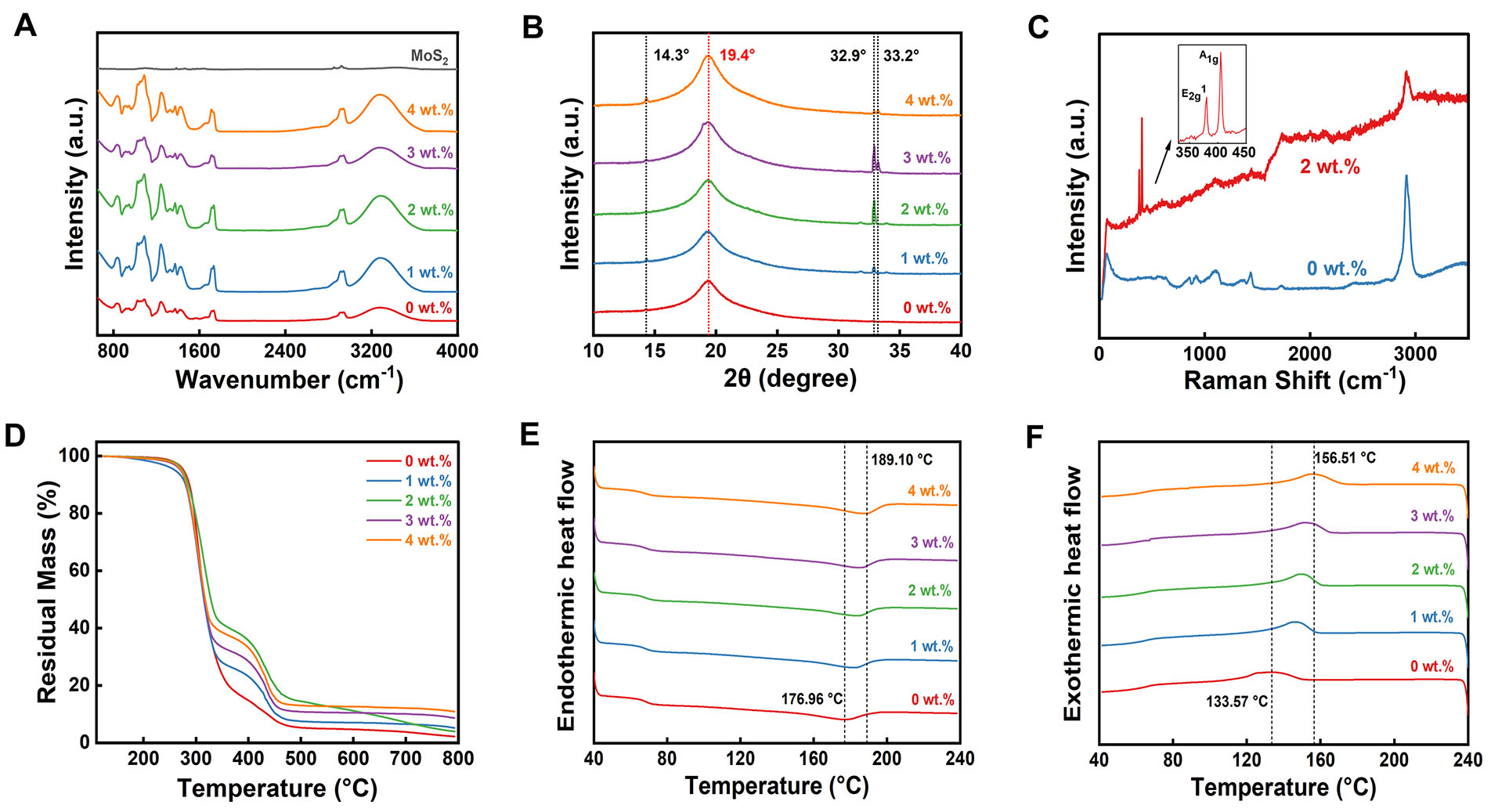

FTIR spectroscopy [Figure 2A] was used to examine the interfacial interactions between MoS2 and the PVA matrix. Pristine PVA exhibits characteristic peaks at near 3,300 cm-1 (O-H stretching), 2,924 and 2,853 cm-1 (C-H stretching), 1,717 cm-1 (C=O), 1,094 cm-1 (C-O-C), and 829 cm-1 (C-H bending)[33-35], all of which are retained in the MoS2-PVA films; no new peaks are observed, indicating no formation of new chemical bonds. A slight red shift of the O-H band to 3,304 cm-1 with reduced intensity suggests weak hydrogen bonding or physical interactions between MoS2 nanosheets and PVA chains[35]. Meanwhile, Mo-S vibrational peaks at 1,103, 1,386.6, and 1,471 cm-1 become increasingly pronounced with higher MoS2 loading[33], confirming the presence and progressive incorporation of MoS2 within the polymer matrix.

Figure 2. Structural and thermal characterization of MoS2-PVA ES films. (A) FTIR spectra. (B) XRD patterns. (C) Raman spectra. (D) TGA curves. (E) DSC endothermic thermograms. (F) DSC exothermic thermograms.

XRD analysis [Figure 2B] was used to examine the crystalline structure of the composites. Pristine MoS2 exhibits distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ ≈ 14.3°, 32.9°, and 33.2°, corresponding to the (002), (100), and (101) planes[33]. These MoS2 peaks are retained in all MoS2-PVA composites and increase in intensity with higher loading, indicating preserved MoS2 crystallinity during electrospinning. Pristine PVA shows a broad semi-crystalline peak at 2θ ≈ 19.4°[35], which remains essentially unchanged across all doped samples, suggesting minimal influence of MoS2 on PVA crystallinity.

Raman spectroscopy [Figure 2C] was used to probe the structural origin of the enhanced piezoelectric response. The 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film exhibits MoS2 E2g1 and A1g peaks at 380.0 and 404.7 cm-1, with a peak separation of ~24.7 cm-1 corresponding to approximately 5 MoS2 layers[36]. Since few-layer MoS2 shows piezoelectricity only for odd layers (1, 3, 5) due to broken inversion symmetry[36,37], the observed layer thickness indicates the likely presence of piezoelectric-active, odd-layered nanosheets within the film. The absence of major peak shifts further confirms that MoS2 retains its layered crystalline structure and is physically embedded in the PVA matrix without strong chemical disruption. Minor hydrogen bonding or weak physical interactions between MoS2 nanosheets and PVA chains remain, as shown later, though they are not easily detectable by FTIR or Raman at the low MoS2 concentrations used.

TGA analysis [Figure 2D] was conducted to evaluate the thermal stability of the MoS2-PVA ES film. All samples display three weight loss stages: adsorbed/bound water evaporation below 150 °C, PVA backbone degradation between ~220-380 °C, and carbonization above 400 °C. At 400 °C, the weight losses are 14.62% (0 wt.%), 23.73% (1 wt.%), 35.47% (2 wt.%), 28.93% (3 wt.%), and 33.93% (4 wt.%). At 800 °C, the corresponding residual masses are 2.23%, 5.22%, 4.00%, 8.67%, and 10.92%, respectively. The overall trend indicates that MoS2 incorporation increases both the decomposition onset temperature and the residual char yield, indicating enhanced thermal stability. The 2 wt.% sample decomposes most slowly at 400 °C but accelerates between 500-700 °C, yielding the lowest residue (4.00%). This behavior suggests that optimized MoS2 dispersion at moderate loading initially restricts chain scission but later promotes secondary degradation and oxidation once interfacial sites become destabilized.

DSC analysis [Figure 2E and F] reveals systematic shifts in the thermal transitions of the MoS2-PVA ES films. In the endothermic thermograms, the melting temperatures increase from 176.96 °C (0 wt.%) to 183.62 °C, 185.39 °C, 186.89 °C, and 189.10 °C for 1-4 wt.% MoS2, indicating restricted chain mobility and stabilized crystallites due to nanosheet-polymer interactions. In the exothermic thermograms, the cold-crystallization peaks shift from 133.57 °C (0 wt.%) to 145.91 °C, 149.44 °C, 151.50 °C, and 156.51 °C for 1-4 wt.% MoS2, accompanied by decreasing peak intensities. These trends suggest that MoS2 acts both as a heterogeneous nucleation site during fiber formation and as a confining agent that suppresses subsequent chain rearrangement, resulting in higher melting and crystallization temperatures and enhanced thermal robustness of the composite films.

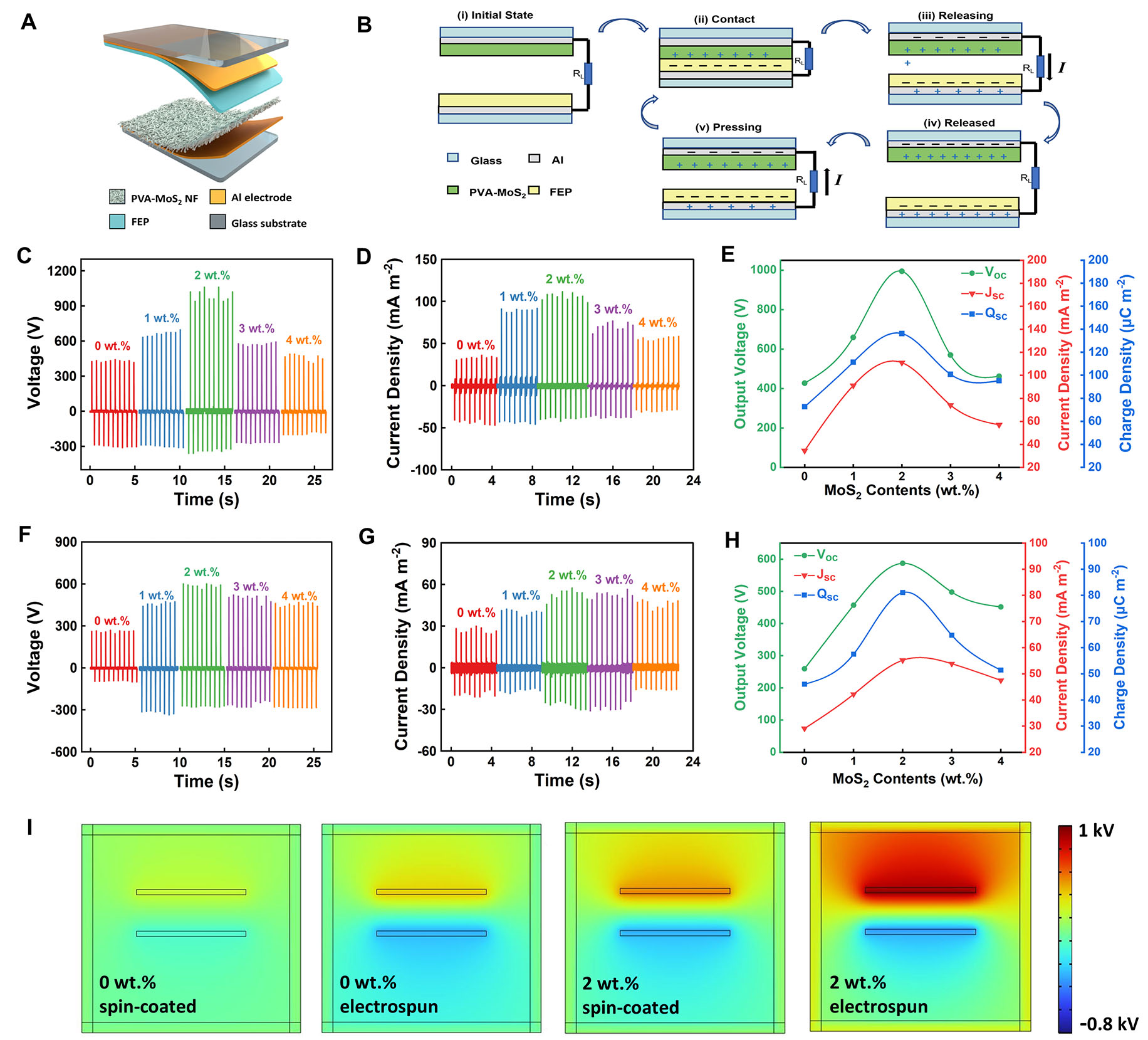

Performance of MoS2-PVA/FEP TENGs

To evaluate the triboelectric properties of the fabricated MoS2-PVA ES films, we constructed vertical contact-separation mode TENGs. Figure 3A shows the TENG configuration, using the MoS2-PVA ES film and FEP film as the positive and negative triboelectric layers, respectively. The working mechanism of the TENG device [Figure 3B] is based on contact electrification and electrostatic induction principle. During the contact stage, electrons transfer from surface of the MoS2-PVA layer to that of the FEP layer, generating charges on the surfaces of the two friction layers with opposite polarity. Upon separation, an electric potential is built up between the two triboplates which drives electron flow through the external circuit, producing an electrical output. As the separation distance increases, the potential reaches its maximum. When contact resumes, a reverse electron flow occurs, resulting in an alternating current output.

Figure 3. Structure and output performance of MoS2-PVA-based TENGs. (A) Device structure. (B) TENG working mechanism. (C-E) Output performance of 0-4 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES films: (C) open-circuit voltage; (D) short-circuit current density; (E) summary of voltage, current density, and charge density. (F-H) Output performance of 0-4 wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated films: (F) open-circuit voltage; (G) short-circuit current density; (H) summary of voltage, current density, and charge density. (I) COMSOL simulated potential distribution of spin-coated and ES MoS2-PVA films (0 and 2 wt.%).

To systematically investigate the effects of MoS2 doping concentration and film structure on the output performance of TENGs, MoS2-PVA films with varying doping levels were prepared by electrospinning and spin-coating, respectively. The tested conditions are contact force: 50 N; frequency: 2 Hz; separation distance: 3.5 mm. As illustrated in Figure 3C-E, the Voc, Jsc, and Qsc of the TENG with the MoS2-PVA ES films show a clear increasing-decreasing trend with rising MoS2 content. The pristine PVA ES film exhibits a Voc of 427.2 V, a Jsc of 34.55 mA-2, and a Qsc of 72.69 μC·m-2. Upon doping with 1 wt.% MoS2, the output of the TENG increases to 659.2 V, 91.13 mA·m-2, and 118.43 μC·m-2, respectively. The highest performance of the TENG is achieved at 2 wt.% doping, with a Voc of 994 V, Jsc of 111.03 mA·m-2, and Qsc of 136.29 μC·m-2. However, further raising the MoS2 content to 3 and 4 wt.% led to a performance decline, with Voc dropping to 569.6 and 462 V, Jsc to 74.1 and 56.98 mA·m-2, and Qsc to 106.54 and 95.37 μC·m-2, respectively. These results suggest that moderate MoS2 doping, especially at 2 wt.%, significantly enhances TENG performance. When the MoS2 concentration is higher (3 to 4 wt.%), agglomeration of the nanosheets occurs. This weakens their ability to modulate surface potential and disrupts the nanosheet alignment essential for piezoelectric enhancement, thereby diminishing TENG performance.

In comparison, the spin-coated films exhibited considerably lower performance across all doping levels [Figure 3F-H]. For instance, the spin-coated films with 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 wt.% concentrations show Voc values of 259.2, 456.9, 587.2, 497.6, and 451.6 V, Jsc values of 29.08, 42.15, 55.18, 53.85, and 47.48 mA·m-2, and Qsc values of 46.00, 57.48, 81.07, 64.75, and 51.39 μC·m-2, respectively. These results confirm that MoS2 incorporation improves the output of both film types, but the ES nanofiber structures provide a substantially greater enhancement than the dense spin-coated films.

As shown in Figure 3I, COMSOL simulations visualize the potential distribution with different film structures and MoS2 doping levels. The model used a 3.5 mm separation distance and treated the ES films as rougher effective dielectrics. Dielectric inputs (specifically the dielectric constant (ε′) and dielectric loss (D) [Supplementary Figure 7]) were taken at 4 kHz: ε′ = 3.68, D = 0.28 for pristine PVA and ε’ = 4.50, D = 0.31 for the 2 wt.% film. These values were applied to both spin-coated and ES configurations. The four panels (pristine PVA spin-coated/ES and 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated/ES) show that MoS2 incorporation and electrospinning-induced morphology both increase the potential difference between the triboelectric layers, consistent with the measured output enhancements. For the optimized 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA/FEP TENG, load-matching and power density analyses [Supplementary Figure 8] show that the output peaks at a

In summary, the MoS2-PVA/FEP TENGs exhibit significantly enhanced output performance due to the synergistic effects of MoS2 doping and ES nanofiber structure. Compared with the spin-coated pristine PVA film, the ES pristine PVA film shows increases of 1.65 times in Voc, 1.19 times in Jsc, and 1.58 times in Qsc. At 2 wt.% MoS2, the ES PVA film-based TENG delivers a Voc of 994.0 V, a Jsc of 111.0 mA·m-2, and a Qsc of 136.3 μC·m-2, corresponding to 1.69, 2.01, and 1.68 times improvements over the spin-coated 2 wt.% film, respectively. Compared with the spin-coated pristine PVA device, the ES 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA film achieves 3.8 times higher Voc, 3.8 times higher Jsc, and 3.0 times higher Qsc. These results clearly demonstrate that both MoS2 incorporation and the ES nanofiber morphology play crucial roles in boosting TENG output, offering an effective strategy for high-performance energy harvesting devices.

Influence of working conditions on TENG performance

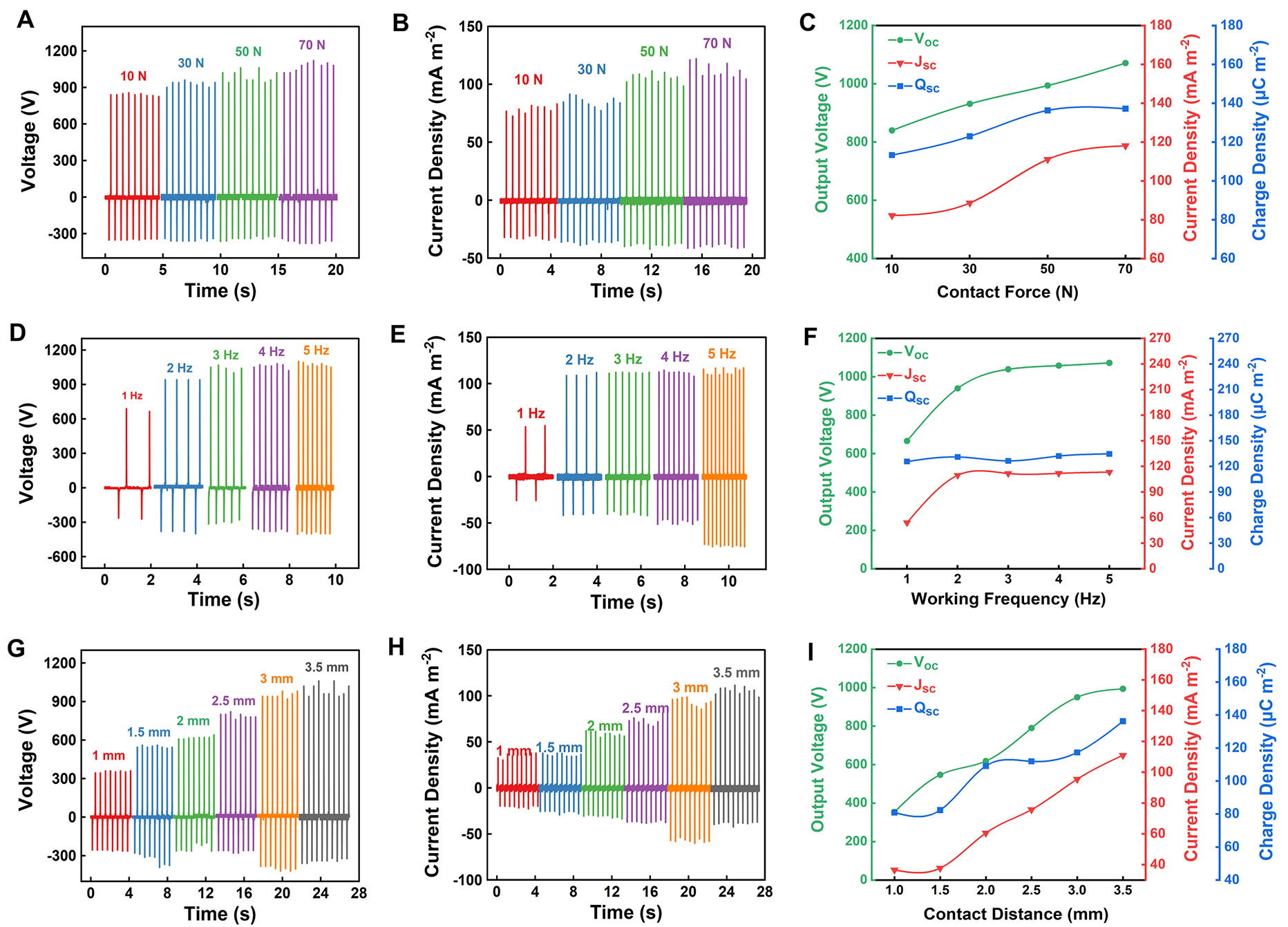

To evaluate the operational robustness and practical adaptability, 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film-based TENG was tested under varying contact force, frequency, and spacer distance [Figure 4], with all measurements conducted at 23 ± 2 °C and 30% ± 3% RH under default conditions of 50 N, 2 Hz, and 3.5 mm unless otherwise specified.

Figure 4. Influence of working conditions on output performance of MoS2-PVA-based TENG (2 wt.% MoS2 doping). (A-C) Variation of (A) open-circuit voltage, (B) short-circuit current density, and (C) Combined output with contact force. (D-F) Corresponding outputs under different working frequencies. (G-I) Corresponding outputs under different spacer distances.

As shown in Figure 4A-C, increasing the contact force from 10 to 70 N enhances the output, with Voc rising from 840.0-1,071.1 V, Jsc from 82.2-118.1 mA·m-2, and Qsc from 113.3-137.2 μC·m-2. The improvement originates from increased effective contact area and deformation-induced capacitance, confirming the good mechanical compliance of the ES fibrous structure. The improvement originates from the enlarged effective contact area at higher impact forces, which increases surface charge generation, and from deformation-induced enhancement of interfacial capacitance that promotes more efficient charge storage and transfer.

Under fixed contact force and spacer distance, raising the frequency from 1-5 Hz [Figure 4D-F] increases Voc from 666.0-1,072.5 V and Jsc from 54.1-113.4 mA·m-2, while Qsc remains nearly constant, indicating faster charge generation per unit time but unchanged charge transfer per cycle. This stability reflects the robust charge-generation mechanism of MoS2-PVA ES films.

The effect of spacer distance on device performance is depicted in Figure 4G-I. As the distance increases from 1-3.5 mm, Voc increases from 354.0-994.0 V, Jsc from 36.6-111.0 mA·m-2, and Qsc from

Durability testing further confirms device stability. After 6,000 continuous cycles at 50 N, 3.5 mm, and 3 Hz, Voc remains stable at about 1,000 V [Supplementary Figure 9A], and no cracks are observed on the glass substrate [Supplementary Figure 9B]. SEM characterizations before and after cycling

Mechanisms for performance enhancement of MoS2-PVA TENGs

To elucidate the origin of the output enhancement in ES MoS2-PVA film-based TENGs compared with those with spin-coated MoS2-PVA films, we systematically investigated the underlying mechanisms from both experimental and theoretical perspectives. Our results reveal that the performance arises from the synergistic contribution of three factors: the enlarged effective contact area associated with the fibrous porous structure, the elevated surface potential induced by MoS2 incorporation and electronic structure modulation, and the enhanced piezoelectric polarization originating from nanosheet alignment and molecular-level interactions.

Structural contribution: enlarged effective contact area by electrospinning

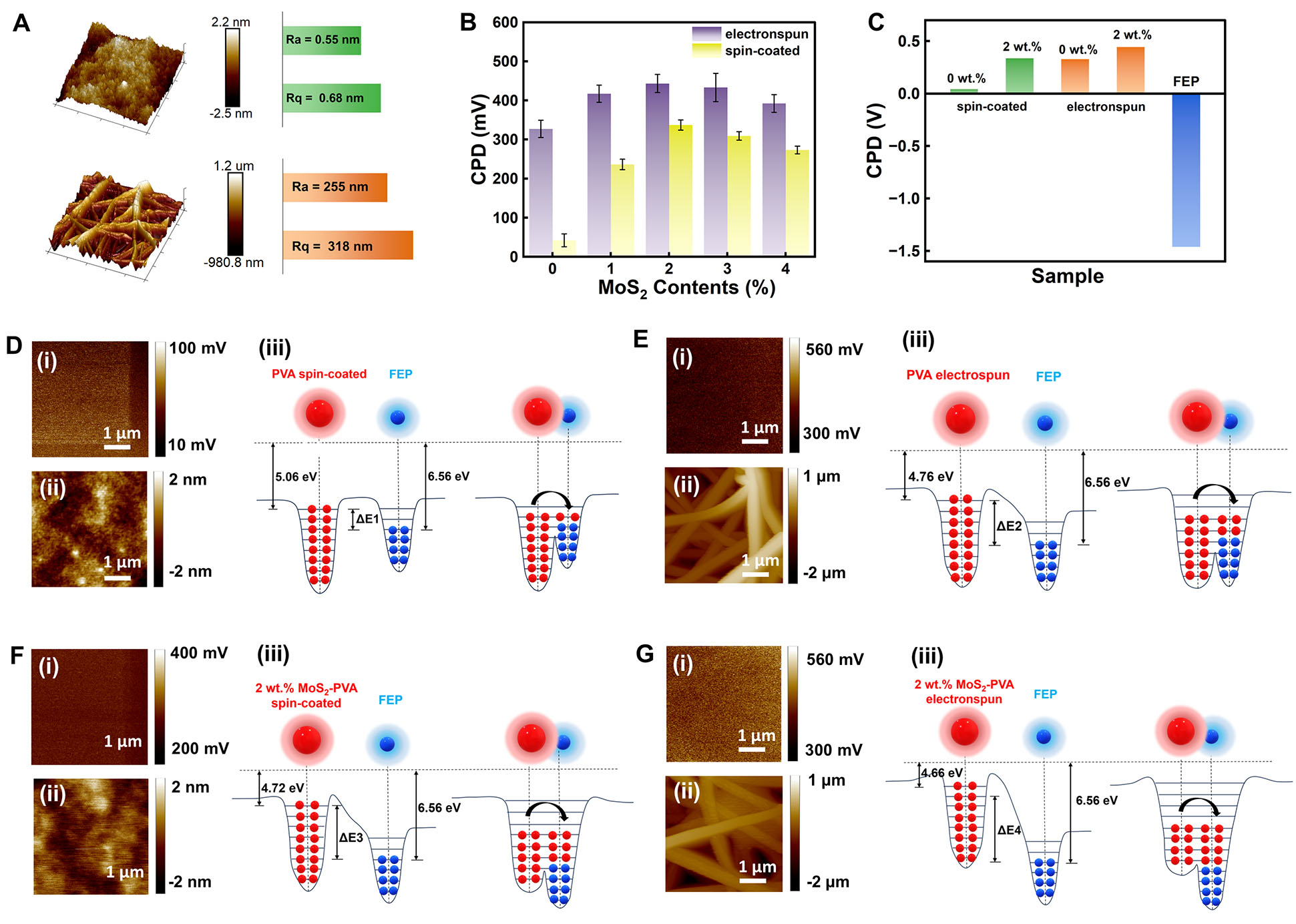

The superior triboelectric performance of TENG with ES PVA films compared with spin-coated ones can be primarily ascribed to their distinct structural characteristics. This difference underscores the decisive role of film morphology in governing triboelectric output. Spin-coated films are dense and possess a smooth surface. In contrast, ES films exhibit a three-dimensional fibrous network with a substantially rougher surface, as further evidenced by AFM analysis (Arithmetical mean surface roughness (Ra) = 0.55 nm, Root-mean-square surface roughness (Rb) = 0.68 nm for spin-coated films vs.

Figure 5. Surface morphology and surface potential analysis of pristine and MoS2-doped PVA films. (A) AFM images and corresponding roughness profiles of 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated film (top) and 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film (bottom). (B) CPD values extracted from KPFM for spin-coated and ES films. (C) Direct comparison of CPD values between pristine PVA, 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA films, and FEP. (D) KPFM results of pristine spin-coated PVA film: (i) potential energy profile, (ii) surface morphology, and (iii) schematic illustration of electron cloud distribution in the triboelectric pair before and after contact with FEP. (E) Corresponding results for pristine PVA ES film. (F) Corresponding results of 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA spin-coated film. (G) Corresponding results of 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film.

Electronic contribution: surface potential modulation by MoS2 incorporation

The TENG operates through contact electrification and electrostatic induction processes governed by surface charge accumulation and the potential difference between paired materials. Theoretical analyses indicate that the output power scales with the square of surface charge density[40]. Furthermore, advanced studies have shown that electrostatic surface potential closely reflects the distribution and magnitude of surface charges[41]. On this basis, KPFM was employed to measure the VCPD between the probe and sample surface. Since

the measured values directly reflect the relative work function of the films. Here, ϕtip is the work function of the tip, ϕsample is the work function of sample, and e is the elementary charge. A higher VCPD corresponds to a lower effective work function of the sample, indicating a stronger tendency to donate electrons and thus more positive triboelectric behavior.

As shown in Figure 5B, the pristine PVA ES film exhibits a significantly higher VCPD of 338 mV compared with only 42 mV for the spin-coated counterpart, demonstrating the inherent advantage of the porous fibrous architecture in enhancing surface potential. With MoS2 incorporation, both types of films exhibit a non-monotonic trend: VCPD increases and peaks at 2 wt.% (ES: 443 mV; spin-coated: 337 mV), followed by a slight decrease at higher contents (3-4 wt.%). The corresponding surface potential maps and topography images of all samples are provided in Supplementary Figure 10 (ES) and Supplementary Figure 11 (spin-coated), further confirming the doping-dependent modulation of electronic properties. This behavior reveals that moderate MoS2 doping optimally modulates the surface electronic structure, while excessive loading introduces recombination or screening effects that reduce the net surface potential. For reference, FEP exhibits a VCPD of -1.46 V [Figure 5C], confirming its strong electronegativity in the triboelectric series. By applying the above relation with Φtip of 5.10 eV, the effective work functions were calculated. For spin-coated films, the work function decreases from 5.058 eV (0 wt.%) to 4.763 eV (2 wt.%), while that for the ES films decreases from 4.773 eV (0 wt.%) to 4.657 eV (2 wt.%). Compared with FEP (Φ = 6.56 eV), this corresponds to an enlarged potential difference from 1.50 eV (spin-coated pristine PVA) to 1.90 eV (ES

The overlapped electron cloud (OEC) model illustrated in Figure 5D-G clarifies the charge transfer mechanism underlying the enhanced triboelectric performance. For the pristine PVA spin-coated film [Figure 5D], the relatively high work function (5.06 eV) results in a small potential difference with FEP

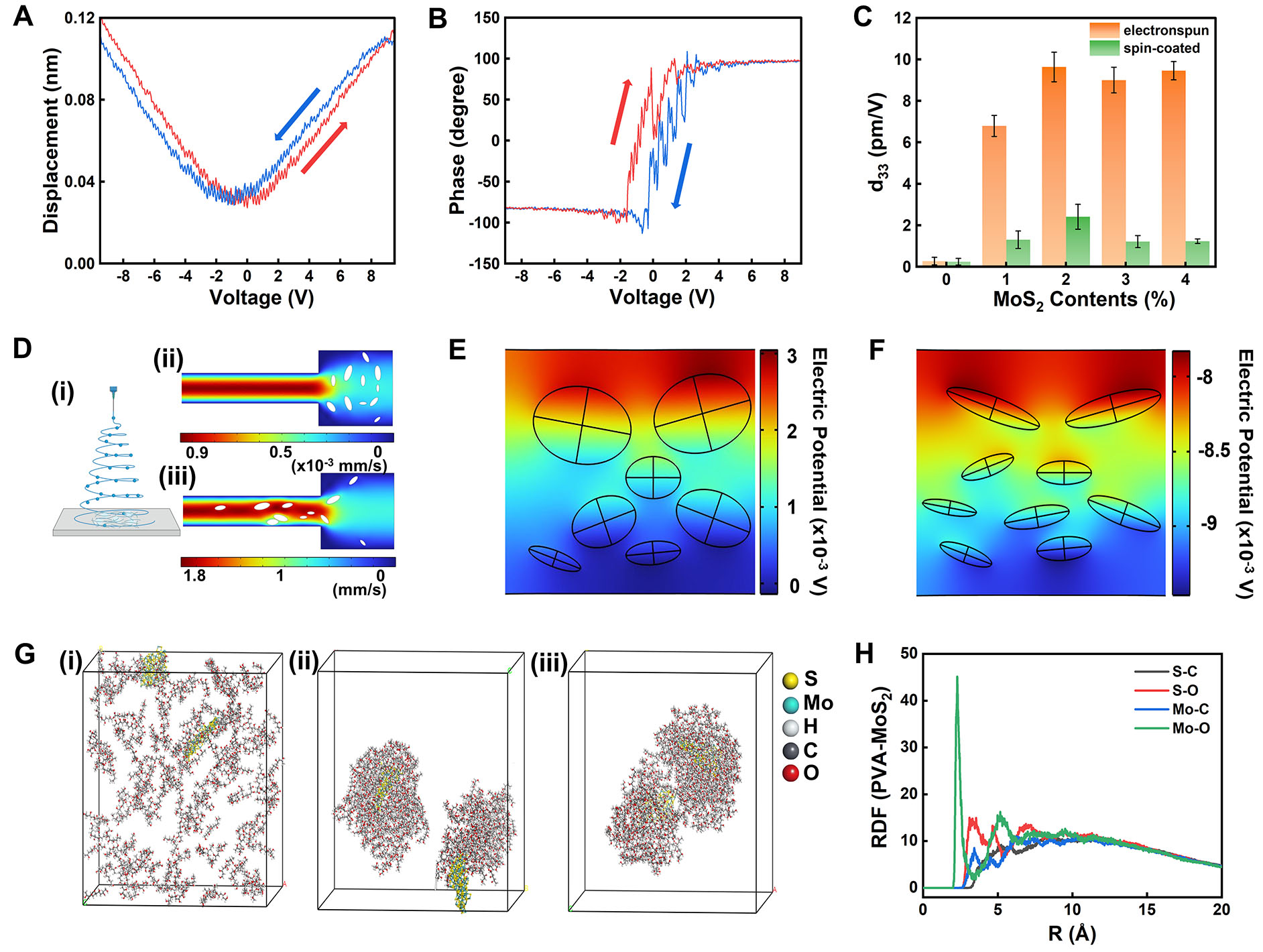

Piezoelectric contribution: nanosheet alignment and molecular-level interactions

Piezoelectric polarization plays a crucial role in enhancing TENG performance because the induced internal electric field supports surface charge separation and retention during the contact-separation cycles. In a hybrid piezoelectric-triboelectric system, the piezoelectric effect increases the effective surface charge density and thus improves overall output, mostly exceeding the sum of individual mechanisms[42,43]. MoS2 is a well-known 2D material that exhibits piezoelectricity when reduced to monolayer or few-layer form with broken inversion symmetry[37]. In this work, few-layer MoS2 nanosheets were incorporated into the PVA mat, as confirmed by Raman analysis, ensuring the retention of piezoelectric activity. Given the layered nature of the nanosheets incorporated into the PVA matrix, the resulting composite films are expected to exhibit improved piezoelectric behavior. To probe this effect, PFM was employed to characterize the piezoelectric response of the ES nanofiber films, with piezoelectric constant d33 extracted from the displacement-voltage (D-V) curves. The displacement and phase response of the 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film [Figure 6A and B] exhibit characteristic features of piezoelectric materials, including a butterfly-shaped displacement loop and a phase shift of approximately 180°, confirming a reversible polarization switching behavior. The d33 was extracted from the slope of the D-V curve using

where ΔDisplacement and ΔVoltage are the variations in displacement and applied bias voltage extracted from the D–V curve, respectively.

Figure 6. Piezoelectric response and nanosheet alignment in MoS2-PVA films. (A and B) PFM displacement and phase curves of

As shown in Figure 6C, the pristine PVA films show no piezoelectric response (0.27 pm/V for ES film and 0.24 pm/V for spin-coated film can be regarded as the experimental scattering), and the incorporation of MoS2 nanosheets markedly enhances the piezoelectric response. Upon nanosheet loading, the ES films show a sharp increase in piezoelectric coefficients, reaching 6.79, 9.63, 9.00, and 9.45 pm/V for 1, 2, 3, and 4 wt.% samples, respectively. Although the d33 values generally increase with MoS2 loading, the maximum TENG output does not coincide with the highest piezoelectric coefficient. Specifically, while the 4 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film reaches a relatively high d33 of 9.45 pm/V, its triboelectric output remains lower than that of the

Figure 6D illustrates the formation process of nanofibers during electrospinning and the corresponding orientation and alignment changes of the incorporated MoS2 nanosheets as the solution is ejected from the needle [Supplementary Figure 12]. It can be observed that the nanosheets tend to align preferentially along the longitudinal axis of the nanofiber during electrospinning, driven by the strong stretching and electric field. Although the fibers are generally arranged parallel to the film surface, the random stacking of fibrous layers introduces orientation components with non-negligible out-of-plane (thickness-direction) contributions. In contrast, in spin-coated films, centrifugal spreading causes most nanosheets to orient randomly within the substrate plane, leading to negligible thickness-direction polarization. It is noted that for each MoS2 nanosheet, a vertical potential gradient is established under mechanical deformation when oriented along the thickness direction, contributing effectively to the overall piezoelectric response of the film. The presence of partial out-of-plane components in ES films enables the establishment of vertical potential gradients under mechanical deformation, thereby contributing more effectively to the overall piezoelectric response. Consequently, the effective piezoelectric component in ES films is significantly larger than that in spin-coated films.

Figure 6E and F illustrates the COMSOL simulation results for the ES and spin-coated films with 2 wt.% MoS2 doping. They reveal a pronounced difference in the distribution and magnitude of the nanosheet-induced piezoelectric components along the film thickness. Under the COMSOL modeling conditions [Supplementary Figure 13], the maximum piezoelectric field strength in the ES film is approximately four times higher than that of the spin-coated film, consistent with the experimental observations. These findings suggest that the enhanced piezoelectric response in MoS2-PVA ES films is largely due to mechanical stretching and electric-field-driven alignment of nanosheets during electrospinning, which promotes vertical orientation of nanosheet components along the film thickness. In contrast, spin-coated films, dominated by centrifugal forces, produce randomly distributed nanosheets, resulting in a limited contribution to thickness-direction polarization.

To gain molecular-level insight into the role of MoS2 nanosheets in enhancing the piezoelectric and triboelectric response, MD simulations were performed [Figure 6G, with full simulation details provided in Supplementary Note 1]. In the initial structural model [Figure 6G-i], PVA chains and MoS2 nanosheets are randomly dispersed, with a total nanosheet dipole moment of -2.54 Debye. As the system evolves in the absence of an external electric field [Figure 6G-ii], the PVA chains gradually aggregate around the nanosheet surface due to intermolecular interactions, leading to an increase in the nanosheet dipole moment to

To further probe the nature of MoS2-PVA interactions, radial distribution function (RDF) analysis was conducted [Figure 6H]. The RDF profiles reveal the correlation between Mo and O atoms, suggesting the formation of localized interactions at the nanosheet-polymer interface. Such interfacial coupling not only facilitates charge transfer but also stabilizes the nanosheet orientation under an applied field, thereby enhancing the effective piezoelectric response of the composite film. These atomic-level insights provide a molecular explanation for the experimentally observed synergy between nanosheet incorporation and electrospinning-induced alignment.

In summary, the MD simulations revealed that PVA chains adsorb and wrap around MoS2 nanosheets, while the nanosheets undergo pronounced dipole moment amplification under an external electric field (electrospinning). Mo-O interfacial interactions further facilitate efficient polarization transfer. These molecular-level insights corroborate the COMSOL simulations and experimental results, establishing a coherent multiscale mechanism in which nanosheet alignment and interfacial coupling govern the macroscopic piezoelectric-triboelectric enhancement in MoS2-PVA film-based TENGs. Quantitative analysis [Supplementary Note 2] indicates that 40% of the total output improvement arises from structural triboelectric enhancement and 60% from MoS2-induced piezoelectricity, confirming that the overall performance gain originates from the synergistic rather than simply additive interaction of structural, electronic, and piezoelectric effects.

Applications of MoS2-PVA ES film-based TENG

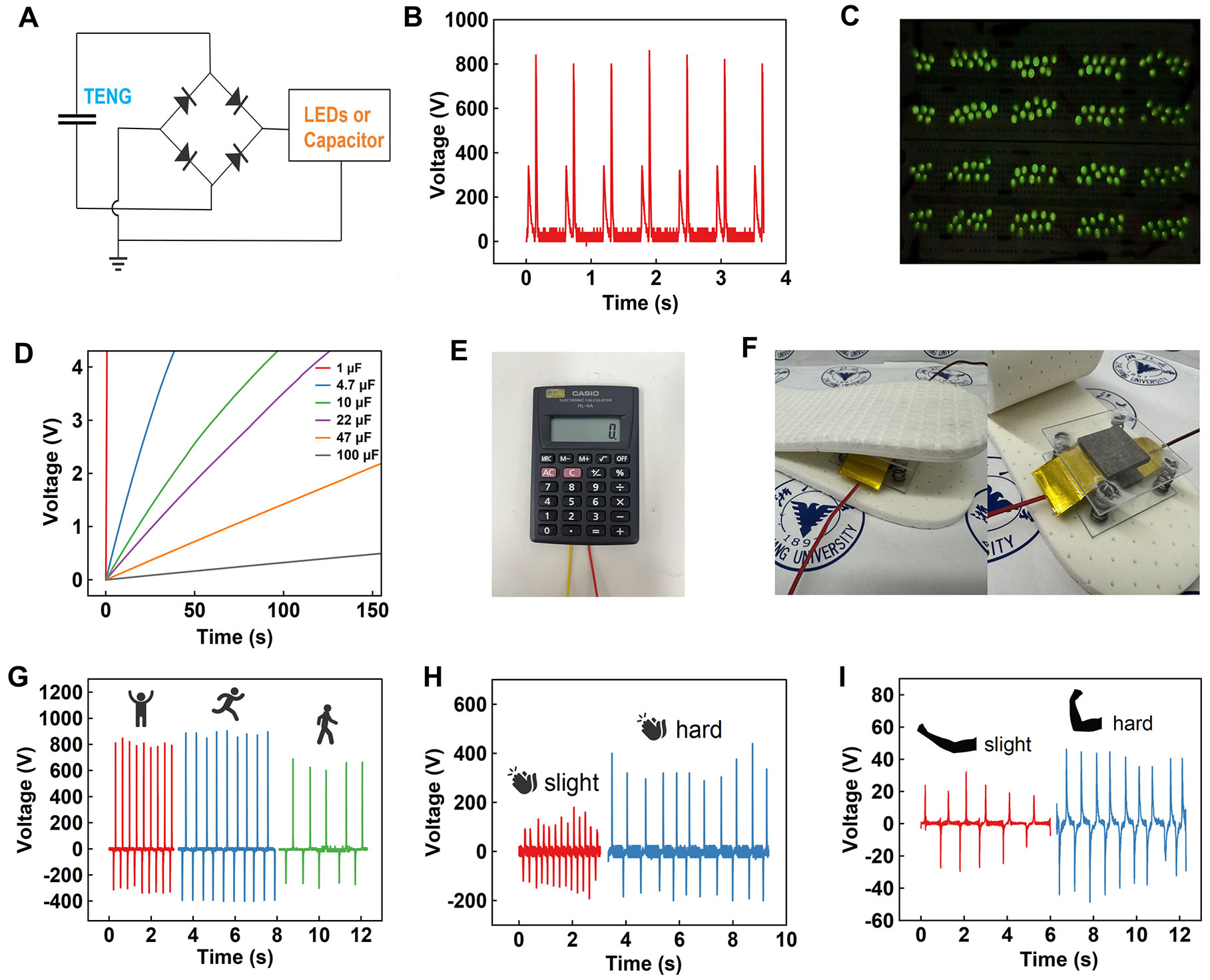

To validate the applicability of the TENG, a compact 20 × 20 mm2 device was fabricated using a 2 wt.% MoS2-PVA ES film paired with a FEP layer (same type of TENGs used hereafter unless specified). The device [Supplementary Figure 3] demonstrated excellent energy harvesting capabilities under ambient mechanical stimuli. Integrated with a full-wave rectification circuit [Figure 7A], the TENG delivered a stable rectified output voltage [Figure 7B]. Using this rectified output, 180 green light-emitting diodes (LEDs) connected in series were directly powered [Figure 7C]. In addition, the rectified electricity could be stored in commercial capacitors (1-100 μF). For example, a 47 μF capacitor was charged to 2 V within 141 s [Figure 7D], and the charged capacitor was able to drive a commercial calculator for approximately 10 seconds [Figure 7E].

Figure 7. Applications based on MoS2-PVA/FEP TENG. (A) Configuration of the TENG-based energy harvesting circuit used to power LEDs or electronic devices. (B) Output voltage of the TENG after rectification. (C) 180 green LEDs powered by the rectified TENG output. (D) Charging curves of various capacitors using the TENG output. (E) A calculator powered for 1-2 s by a charged capacitor. (F) Photograph of the energy harvesting device integrated into a shoe. (G) Energy harvesting performance during jumping, running, and walking. (H) Energy harvesting during hand clapping. (I) Energy harvesting during arm bending.

For biomechanical energy harvesting, the TENG was embedded in a shoe insole and tested under different movement modes [Figure 7F]. It generated output voltages of 647.2 V during walking, 804.4 V during jumping, and reached up to 880.9 V during running [Figure 7G]. These results highlight the TENG's robust response to various mechanical inputs and its potential for wearable energy harvesting. Furthermore, the TENG was evaluated as a self-powered motion sensor. Distinct voltage outputs were recorded in response to different human actions: 119.69 and 338.18 V for slight and forceful clapping [Figure 7H], and 22.59 and

After demonstrating the TENG’s robust response across diverse motion modes, we further confirm its sensitivity and versatility in distinguishing motion intensity and type, suggesting strong potential for gesture recognition, fitness monitoring, and interactive human-machine interfaces. In addition, the device exhibits stable performance under humidity variation, sweat exposure (with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) encapsulation), and long-term mechanical deformation, together with good cytocompatibility, as detailed in Supplementary Note 3 and 4 (containing Supplementary Figures 14-18).

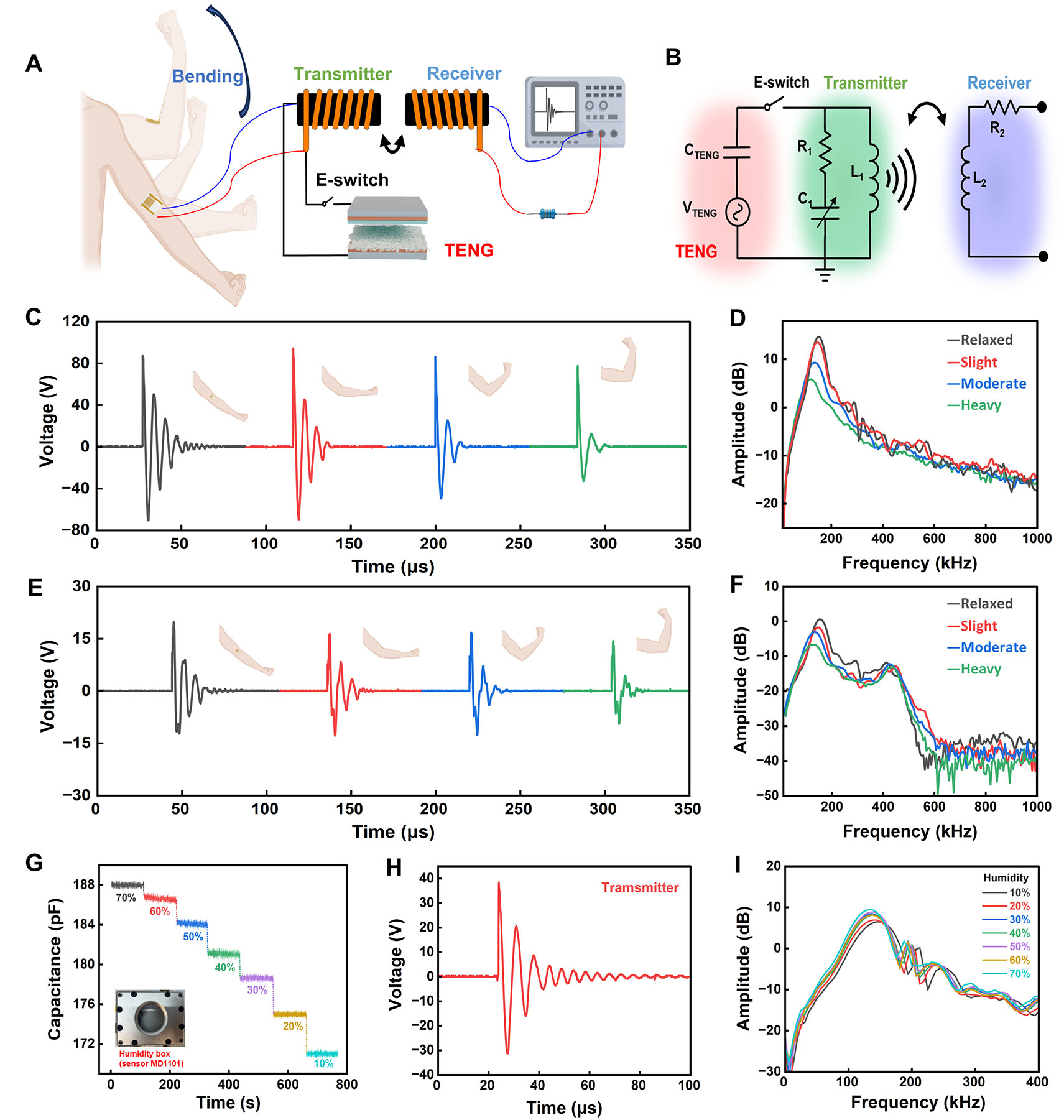

To extend the functionality of the MoS2-PVA ES film-based TENG beyond direct energy harvesting and gesture sensing, we designed a self-powered wireless sensing system in which the TENG only serves as the energy source, while capacitive sensors were used as sensors for motion and humidity monitoring. The system operates on the principle of resonant frequency modulation of an LC (inductor-capacitor) circuit[45]. When an external stimulus, such as mechanical deformation or humidity variation, alters the capacitance of the sensor, the resonant frequency of the resistor-inductor-capacitor (RLC) oscillating signal shifts accordingly. These frequency changes are wirelessly transmitted via inductive coupling and are detected at the receiver end, where Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) is employed to extract variations in frequency or amplitude. In this configuration, physical stimuli are converted into electrical signals without the need for any external power supply.

The system overview is shown in Figure 8A, and the circuit diagram is presented in Figure 8B. The system consists of a transmitter and a receiver. The transmitter consists of a capacitive sensor, an electronic switch, an inductive coil, and a TENG. For the RLC oscillation circuit, the resonant frequency, f, is governed by:

where C represents the capacitance of the sensor and L is the inductance of the transmission coil. The receiver comprises another inductive coil and a series resistor, and the output is monitored on an oscilloscope.

Figure 8. Self-powered wireless sensing system. (A) System overview. (The arm bending illustration was created with BioRender; Chen, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/z63tmpw). (B) Circuit diagram. (C) Signals of the transmitter side at different arm bending angles. (D) Corresponding transmitted signals after FFT analysis. (E) Corresponding signals of the receiver side. (F) Corresponding received signals after FFT analysis. (G) Capacitance variation of the capacitive sensor with humidity. (The inset is the box with the humidity sensor.) (H) One transmitted signal with encoded humidity information. (I) Received signals containing humidity information after FFT.

For wireless biomechanical sensing, a MoS2-PVA capacitive sensor was fabricated. The sensor consists of interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) formed on a polyethylene terephthalate substrate (100 um thickness). The

The same wireless sensing circuit was adapted for humidity detection by replacing the MoS2-PVA@IDEs sensor with a commercial humidity-sensitive capacitor (MD1101). As ambient humidity increased, the capacitance of this sensor decreased monotonically from 188 pF at 70% RH to 171 pF at 10% RH, thereby raising the resonant frequency of the RLC circuit [Figure 8G]. The transmitter signals [Figure 8H] and corresponding FFT spectra [Figure 8I] show distinct frequency shifts, confirming the reliable and uniform response of the system to humidity variation. These results demonstrate that the MoS2-PVA TENG can function not only as a power supply but also as an enabling element for flexible wireless sensing platforms, offering promising potential for wearable healthcare monitoring, environmental sensing, and low-power Internet of Things (IoT) applications.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, ES MoS2-doped PVA nanofiber films were demonstrated as high-performance positive triboelectric layers for TENGs. The ES architecture enlarged the effective contact area, while MoS2 incorporation modulated the surface electronic environment and enabled nanosheet-alignment-induced piezoelectric polarization. Together, these factors led to significantly enhanced surface potential and output performance, with KPFM and MD simulations confirming the underlying multiscale mechanisms. The optimized 2 wt.% composite exhibited stable electrical output and enabled practical applications, including LED lighting, capacitor charging, and self-powered motion sensing. These findings establish a coherent design strategy that integrates porous morphology, MoS2-mediated surface potential regulation, and piezoelectric coupling to achieve high-performance, durable, and biocompatible TENGs, offering promising potential for sustainable energy harvesting and wearable electronics.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Micro-Nano Fabrication Center at the International Campus, Zhejiang University, and the ZJU Micro-Nano Fabrication Center at the Yuquan Campus.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study: Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Yang, X.; Luo, J.

Performed data curation, acquisition, and investigation: Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Hazarika, D.; Zhang, K.; Wu, J.;

Performed validation, data analysis and interpretation: Chen, C.; Lu, J.; Wu, J.

Drafted or revised the manuscript: Chen, C.; Hazarika, D.; Li, J.; Zhuo, F.; Ye, Z.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.; Luo, J.

Provided supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: Luo, J.

Contributed to discussion and provided technical or editorial support: Luo, J.; Ye, Z.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.

Availability of data and materials

All data needed to support the conclusions in the paper are presented in the manuscript and/or the Supplementary Material. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding author upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was funded by the Zhejiang University Education Foundation Global Partnership Fund (No. 100000-11320), the Zhejiang Province High-Level Talent Special Support Plan (No. 2022R52042), the Zhejiang Province Key R&D Program (No. 2025C02165), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2025ZFJH01).

Conflicts of interest

Zhang, K. and Luo, J. are Guest Editors of special issue "Energy materials for wearable, implantable electronics and bioMEMS" of the journal Energy Materials. They were not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewers' selection, manuscript handling and decision making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Cheng, T.; Shao, J.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators. Nat. Rev. Methods. Primers. 2023, 3, 220.

2. Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as flexible power sources. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2017, 1, 7.

3. Zhu, G.; Peng, B.; Chen, J.; Jing, Q.; Lin, Wang. Z. Triboelectric nanogenerators as a new energy technology: from fundamentals, devices, to applications. Nano. Energy. 2015, 14, 126-38.

4. Pu, X.; Guo, H.; Chen, J.; et al. Eye motion triggered self-powered mechnosensational communication system using triboelectric nanogenerator. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700694.

5. Luo, J.; Gao, W.; Wang, Z. L. The triboelectric nanogenerator as an innovative technology toward intelligent sports. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2004178.

6. Kim, W. G.; Kim, D. W.; Tcho, I. W.; Kim, J. K.; Kim, M. S.; Choi, Y. K. Triboelectric nanogenerator: structure, mechanism, and applications. ACS. Nano. 2021, 15, 258-87.

7. Niu, S.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; et al. Theoretical study of contact-mode triboelectric nanogenerators as an effective power source. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3576.

8. Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Shi, B.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z. L.; Li, Z. Wearable and implantable triboelectric nanogenerators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1808820.

9. Hinchet, R.; Yoon, H. J.; Ryu, H.; et al. Transcutaneous ultrasound energy harvesting using capacitive triboelectric technology. Science 2019, 365, 491-4.

10. Han, J. H.; Moon, H. C. Monolithically integrated ionic triboelectric nanogenerators for deformable energy harvesting and self powered sensing. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 491.

11. Ge, X.; Hu, N.; Yan, F.; Wang, Y. Development and applications of electrospun nanofiber-based triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano. Energy. 2023, 112, 108444.

12. Tao, D.; Su, P.; Chen, A.; Gu, D.; Eginligil, M.; Huang, W. Electro-spun nanofibers-based triboelectric nanogenerators in wearable electronics: status and perspectives. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 357.

13. Li, Z.; Zhu, M.; Shen, J.; Qiu, Q.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. All-fiber structured electronic skin with high elasticity and breathability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908411.

14. Dong, K.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z. L. Fiber/Fabric-based piezoelectric and triboelectric nanogenerators for flexible/stretchable and wearable electronics and artificial intelligence. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1902549.

15. Chen, G.; Au, C.; Chen, J. Textile triboelectric nanogenerators for wearable pulse wave monitoring. Trends. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1078-92.

16. Kwak, S. S.; Yoon, H.; Kim, S. Textile-based triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered wearable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1804533.

17. Zhang, R.; Olin, H. Material choices for triboelectric nanogenerators: a critical review. EcoMat 2020, 2, e12062.

18. Dharmasena, R.; Silva, S. Towards optimized triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano. Energy. 2019, 62, 530-49.

19. Dai, Y.; Zhong, X.; Xu, T.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, S. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerator based on electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride-graphene oxide nanosheet composite nanofibers. Energy. Tech. 2023, 11, 2300426.

20. Yang, J.; Wang, M.; Meng, Y.; et al. High-performance flexible wearable triboelectric nanogenerator sensor by β-phase polyvinylidene fluoride polarization. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 1385-95.

21. Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Yao, N.; Shi, Y. 1.6 V nanogenerator for mechanical energy harvesting using PZT nanofibers. Nano. Lett. 2010, 10, 2133-7.

22. Han, S. A.; Lee, J.; Lin, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. H. Piezo/triboelectric nanogenerators based on 2-dimensional layered structure materials. Nano. Energy. 2019, 57, 680-91.

23. Ghorbanzadeh, S.; Zhang, W. Advances in MXene-based triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano. Energy. 2024, 125, 109558.

24. Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J. H.; Li, S.; Qiu, H.; Shi, Y.; Pan, L. Triboelectric nanogenerators based on 2D materials: from materials and devices to applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1043.

25. Mohan, R.; Ali, F. The future of energy harvesting: a brief review of MXenes-based triboelectric nanogenerators. Polym. Adv. Techs. 2023, 34, 3193-209.

26. Sardana, S.; Saddi, R.; Mahajan, A. MXene-functionalized KNN dielectric nanofillers incorporated in PVA nanofibers for high-performance triboelectric nanogenerator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 162902.

27. Jiang, C.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; et al. All-electrospun flexible triboelectric nanogenerator based on metallic MXene nanosheets. Nano. Energy. 2019, 59, 268-76.

28. Liu, Y.; Mo, J.; Fu, Q.; et al. Enhancement of triboelectric charge density by chemical functionalization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004714.

29. Amrutha, B.; Yoon, J. U.; Woo, I.; Gajula, P.; Prabu, A. A.; Bae, J. W. Performance optimization of MoS2-doped PVDF-HFP nanofiber triboelectric nanogenerator as sensing technology for smart cities. Appl. Mater. Today. 2024, 41, 102503.

30. Gajula, P.; Yoon, J. U.; Woo, I.; Oh, S.; Bae, J. W. Triboelectric touch sensor array system for energy generation and self-powered human-machine interfaces based on chemically functionalized, electrospun rGO/Nylon-12 and micro-patterned Ecoflex/MoS2 films. Nano. Energy. 2024, 121, 109278.

31. Radacsi, N.; Campos, F. D.; Chisholm, C. R. I.; Giapis, K. P. Spontaneous formation of nanoparticles on electrospun nanofibres. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4740.

32. Higashi, S.; Hirai, T.; Matsubara, M.; Yoshida, H.; Beniya, A. Dynamic viscosity recovery of electrospinning solution for stabilizing elongated ultrafine polymer nanofiber by TEMPO-CNF. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13427.

33. Vattikuti, S. V. P.; Byon, C.; Han, X. Synthesis and characterization of molybdenum disulfide nanoflowers and nanosheets: nanotribology. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 710462.

34. Chen, X.; Yusuf, A.; del, Rio. J. S.; Wang, D. A facile and robust route to polyvinyl alcohol-based triboelectric nanogenerator containing flame-retardant polyelectrolyte with improved output performance and fire safety. Nano. Energy. 2021, 81, 105656.

35. Zhou, K.; Jiang, S.; Bao, C.; et al. Preparation of poly(vinyl alcohol) nanocomposites with molybdenum disulfide (MoS2): structural characteristics and markedly enhanced properties. RSC. Adv. 2012, 2, 11695.

36. Lee, C.; Yan, H.; Brus, L. E.; Heinz, T. F.; Hone, J.; Ryu, S. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single- and few-layer MoS2. ACS. Nano. 2010, 4, 2695-700.

37. Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Piezoelectricity of single-atomic-layer MoS2 for energy conversion and piezotronics. Nature 2014, 514, 470-4.

38. Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z. Progress in textile-based triboelectric nanogenerators for smart fabrics. Nano. Energy. 2019, 56, 16-24.

39. Cheon, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, H.; et al. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerators based on electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride-silver nanowire composite nanofibers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1703778.

40. Li, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, S.; et al. Visualization and standardized quantification of surface charge density for triboelectric materials. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6004.

41. Wang, Z. L. Triboelectric nanogenerators as new energy technology for self-powered systems and as active mechanical and chemical sensors. ACS. Nano. 2013, 7, 9533-57.

42. Hussain, S. Z.; Singh, V. P.; Sadeque, M. S. B.; Yavari, S.; Kalimuldina, G.; Ordu, M. Piezoelectric-triboelectric hybrid nanogenerator for energy harvesting and self-powered sensing applications. Small 2025, 21, e2504626.

43. Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Boyer, C.; et al. Recent developments of hybrid piezo-triboelectric nanogenerators for flexible sensors and energy harvesters. Nanoscale. Adv. 2021, 3, 5465-86.

44. Kuang, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; et al. Piezoelectric boron nitride nanosheets for high performance energy harvesting devices. Nano. Energy. 2021, 80, 105561.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].