Next-gen diagnostics: artificial intelligence-powered imaging in breast cancer care

Abstract

Breast cancer is the second largest cause of mortality globally. Early detection of breast cancer may aid in better therapeutic strategies and prolong the lives of the clinical subjects. However, conventional diagnostic methods rely mainly on subjective evaluations of tumor morphology, enhancement type, and anatomic connection to the adjacent tissues. Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool in breast cancer diagnosis, particularly within medical imaging. AI-driven methods such as deep learning and radiomics have demonstrated significant improvements in mammography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasound by enhancing detection sensitivity, reducing false positives, and streamlining clinical workflows. Recent advances in convolutional neural networks and hybrid architectures have enabled more accurate tumor classification, lesion segmentation, and risk stratification. While multimodal strategies integrating imaging with clinical or genomic data show promise for personalized care, the primary impact of AI lies in its ability to improve imaging-based diagnostics. This review summarizes current advances in AI for breast cancer imaging, discusses challenges related to generalizability and clinical translation, and highlights future directions for developing clinically robust diagnostic tools. The goal is to advance the development of more accurate and efficient diagnostic tools by integrating multiple imaging modalities and other patient-specific information.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer claims the lives of nearly half a million women annually globally. It is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women[1,2]. The global incidence of breast cancer cases was estimated to be more than 2.2 million in 2020, accounting for a whopping 11.7% of the total cancer cases. Correct diagnosis of breast cancer at an early stage may increase the possibilities of implementation of successful treatment plans and dramatically prolong the survival to at least 5 years in 98% of the subjects. Artificial intelligence (AI) has demonstrated measurable benefits in breast cancer imaging[3]. For example, meta-analyses show that AI-augmented mammography increases sensitivity by ~10%-15%, while maintaining comparable specificity to radiologists[3]. Similarly, deep learning (DL) models applied to invasive carcinoma detection achieve specificity up to 0.89, reducing false-positive rates by ~20% compared to radiologists[3]. These results underscore AI’s growing clinical utility rather than speculative potential[4]. In comparison, when the disease is detected at advanced stages, the treatment regimens may only increase the survival to less than 4 years in only 26% of the patients[1,5-7].

By far, the most significant risk factor for breast cancer is gender. The incidence of breast cancer in females is 100-fold more than in males[8]. Moreover, the risk for developing breast cancer is highest up to the age of 45 to 50 years, after which the chances of breast cancer manifestation decline. This age-linked decline in breast cancer prevalence in the female population is most likely due to endocrine-related menopausal changes[8,9]. Other factors are also implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancers. Chief among these are associated with lifestyle, genomic and environmental variables[10]. Mutations in the breast cancer genes, BReast CAncer gene-2 (BRCA-2) and BReast CAncer gene-1 (BRCA-1), may be responsible for 80% of genetically-linked breast cancer cases; however, these constitute only a tiny fraction (5%-6%) of total breast cancer cases[11,12]. Genetic alterations in BRCA-1 and 2 increase the risk for development of breast cancer by 50%-85% and by 15%-65% for ovarian cancer after the age of 25 years[11,13]. The molecular mechanisms underlying breast cancer pathogenesis are extraordinarily heterogeneous; and they may involve human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2; encoded by ERBB2) and activation of hormone receptors for progesterone and estrogen, in addition to BRCA mutations[14,15]. The intrinsic categorization published in 2,000 identified four subtypes of breast cancers: luminal A, luminal B, basal-like, HER2-positive and triple-negative[6,16-21].

Breast cancer usually initiates at the lobules or channels connecting the nipples[22,23]. Although it usually initiates in cells lining the ducts of the breasts, it may also affect other areas such as the lobules, milk ducts, or occasionally between tissues[1,8]. Additionally, 95% of breast cancers are carcinomas or malignancies that develop from epithelial cells. Infiltrating or invasive carcinomas and in situ carcinomas are the two main kinds of breast cancer[10,24]. Carcinomas in situ may arise in the lobular or ductal epithelium and remain limited to that epithelium with no invasion of the underlying basement membrane[12,25]. As one might assume, the risk of metastases is minimal in such cancers[4,6,22].

In view of the molecular heterogeneity of breast cancer pathology, several therapeutic advancements have been attempted during the last few decades, including the use of biologically directed drugs with reduced treatment side effects[26-29]. However, apart from the challenges associated with the heterogeneity of pathogenic mechanisms, tumor characteristics such as the varied impact of locoregional tumor burden and differential metastatic patterns are the major hurdles in developing efficient therapies[6,30-32]. Therefore, it is essential that breast cancers are detected early, and the appropriate personalized treatment is provided[16,33]. The current gold standard for breast cancer screening is mammography, which is less effective in women under 40 years of age with thick breasts. Additionally, mammography is less sensitive to small tumors (less than 1 mm, roughly 100,000 cells) and may not be suitable for correct diagnoses in such cases[16,26,34,35]. Contrast-enhanced (CE) digital mammography (DM) may be a more precise alternative for the analysis of thick breasts; however, it is limited by its high cost and increased risk of radiation exposure[36]. Ultrasonography-based medical imaging techniques are another helpful alternative for the diagnosis of breast cancers[36,37]. Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can efficiently detect lesions that mammography may not. Positron emission tomography (PET) may be the most precise available option for breast cancer prognosis, enabling evaluation of both disease progression and regression in response to treatment[34,37-39]. However, these imaging techniques are not cost-efficient and may have low specificity, resulting in over-diagnosis[6,34,39-41]. Integration of AI technology with mammography has emerged as a novel, low-cost, accurate, and safe combinatorial technique for the diagnosis of breast cancer[38], and this review summarizes our current understanding of the various applications of AI in breast cancer theragnostics.

AI-BASED TECHNOLOGIES IN MONITORING THE MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF BREAST CANCER PATHOGENESIS

Tumor progression and responses to treatment in the clinical cases of breast cancer vary considerably depending on etiological subtypes and the differences in the underlying molecular mechanisms[30]. For instance, immunohistochemical (IHC) subtypes based on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and HER2 drive the differential responses of breast cancer patients to specific treatments[34]. The current synergistic development of AI-based analyses of breast cancer imaging focuses on risk assessment, cancer detection, diagnosis, prognosis, and response to therapy[42]. AI aids in breast cancer risk assessment targeting breast density and parenchymal cells. AI-based methods help in the assessment of the density of breast and characterization of breast parenchymal tissue, and have the potential to compare the differential risk of breast cancer development among women concerning the BRCA-1/BRCA-2 gene mutations through performance assessment of transfer learning on the distinction of their status[43].

The anti-tumorigenic cells are negatively regulated by the tumor microenvironment (TME), signaling pathways in the stromal environment, extracellular matrix (ECM) and immune cells, causing progression of breast cancer and metastasis[44]. TME plays a central role in breast cancer progression, involving complex interactions between stromal signaling pathways, ECM remodeling, and immune regulation. For example, stromal signaling events such as ER/PR overexpression can drive tumor growth, while ECM dynamics contribute to invasion and metastasis[42]. AI tools now provide powerful approaches to decode this heterogeneity. Specifically, platforms such as Immune Cell Abundance Identifier (ImmuCellAI, China) quantify the infiltration of diverse immune cell subtypes, enabling prognostic stratification based on immune signatures. By linking molecular and microenvironmental features with patient outcomes, AI offers the ability to unravel TME complexity and support the design of targeted, immune-informed therapeutic strategies[42].

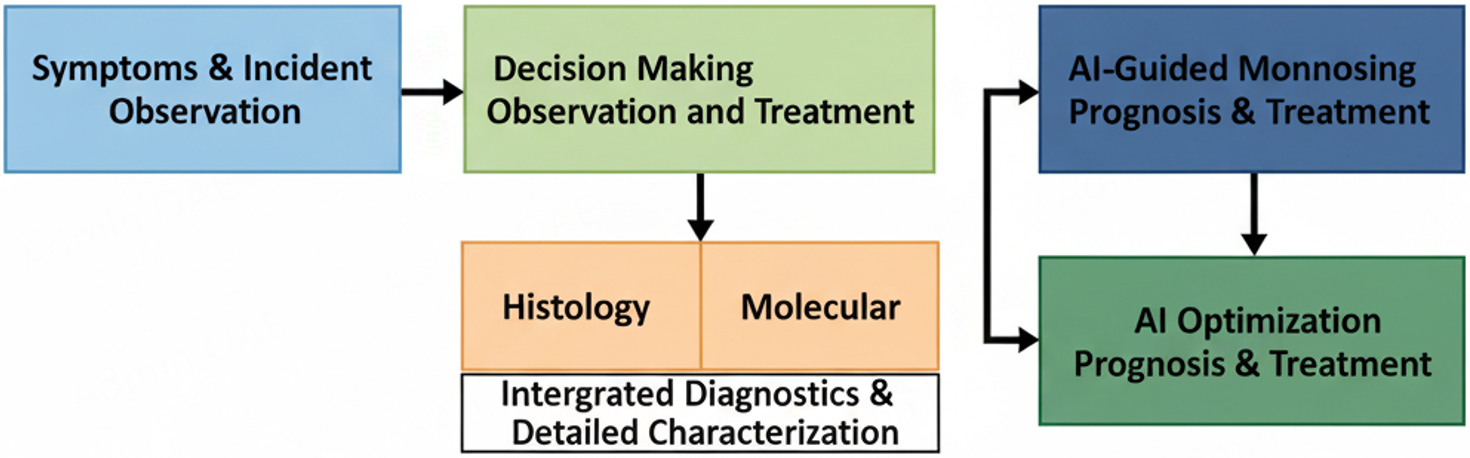

The recent approaches involving in vitro cell culture assays and in vivo mouse model studies lack information regarding the physiological outcomes in humans during drug efficacy testing[45]. The well-defined intricate relationship among breast cancer cells and stromal immune cells is the essential requirement for implementing an effective therapy in the treatment of breast cancer as shown in Figure 1. The breast cancer progression can be evaluated through stromal-to-epithelial transition with the implementation of specified features of deep machine learning (ML) subdomain of AI[46].

Figure 1. Clinical workflow of breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment modality using AI-guided models.

Breast cancer has a heterogeneous pathology, showing luminal, HER2 type, and triple negative phenotypes in the inflammatory microenvironment[34]. Resistance to trastuzumab remains a major clinical obstacle in HER2-positive breast cancer, often leading to disease recurrence. To address this, advanced drug delivery systems have been developed using nanotechnology platforms. For example, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles simultaneously loaded with chemotherapeutic agents and surface-functionalized with trastuzumab have demonstrated improved therapeutic efficacy through dual-action delivery[42]. These nanosystems enhance drug stability, enable sustained release, and promote cell-specific uptake via HER2-targeting. Notably, engineered nanocarriers tested in both 2D and 3D breast cancer models have shown improved tumor penetration and optical fiber-triggered drug release, offering spatial and temporal control of therapy[47]. Such platforms highlight the potential of nanomedicine to overcome drug resistance and improve treatment precision in HER2-positive breast cancer. A gradient tree with adaptive iterative searching AI model targets identification of different ER subtypes of breast cancers. This novel AI multifactorial data analysis approach can predict breast cancer risk based on demographic risk factors and genetic variants[48]. It may hold a promise for development into a cost-effective therapy in the future. Further, AI-based ML computational models can be applied to nuclear ER (Estrogen Receptor alpha (ERa) and Estrogen Receptor beta (ERb))[49]. Another critical element in breast cancer identification through ML is mast cell-mediated histamine production that causes hypersensitivity as a local inflammatory response to breast cancer progression and mammary carcinomas[50]. Mao et al. (2020) devised an AI-based system that predicts the molecular alterations and the inflammatory responses in the microenvironment. AI-based ImmuCellAI that runs on algorithms from various gene expression data targets T-cell subsets for cancer diagnosis and classification. However, it may lack the required spatiotemporal attributes[51].

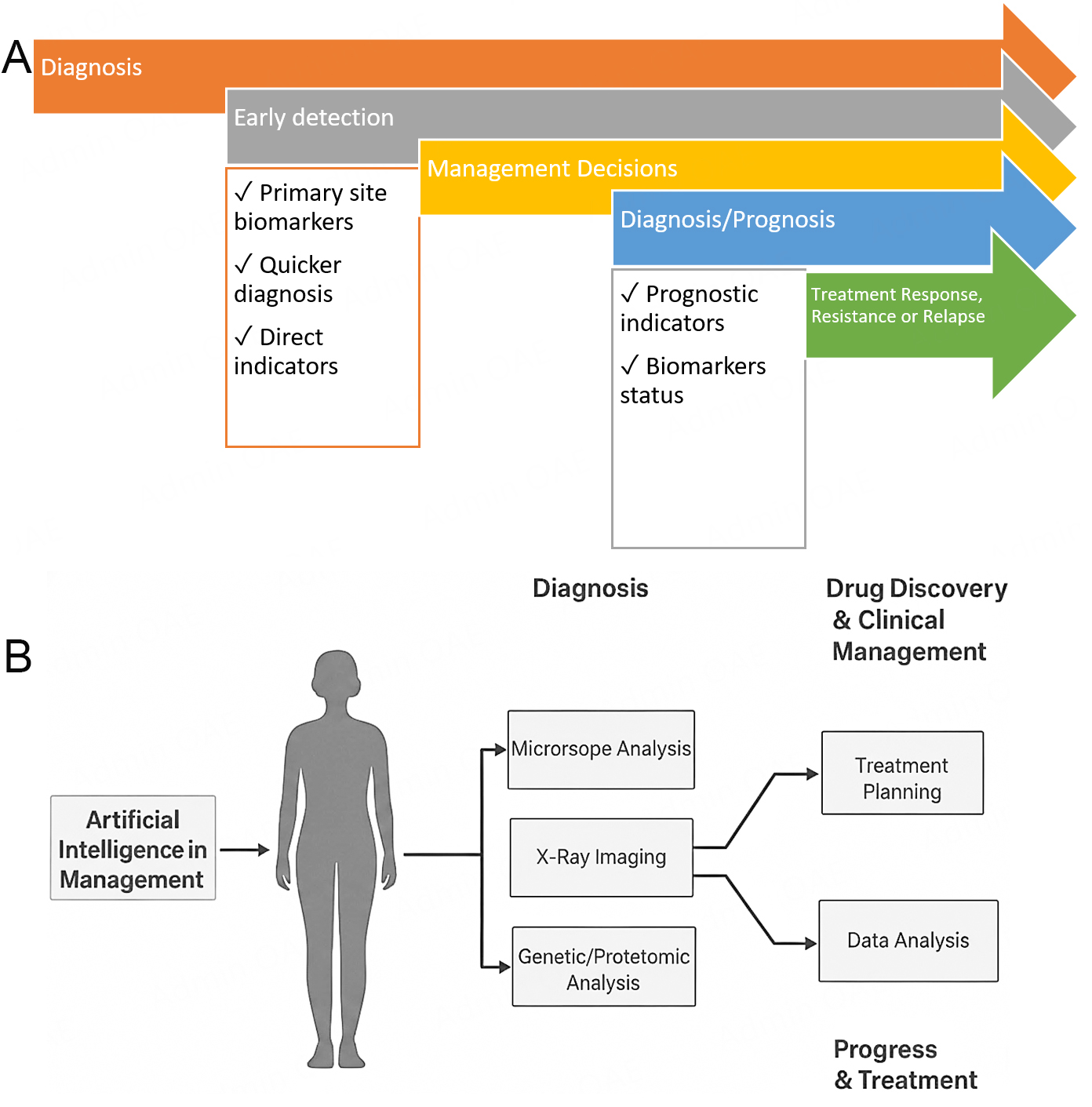

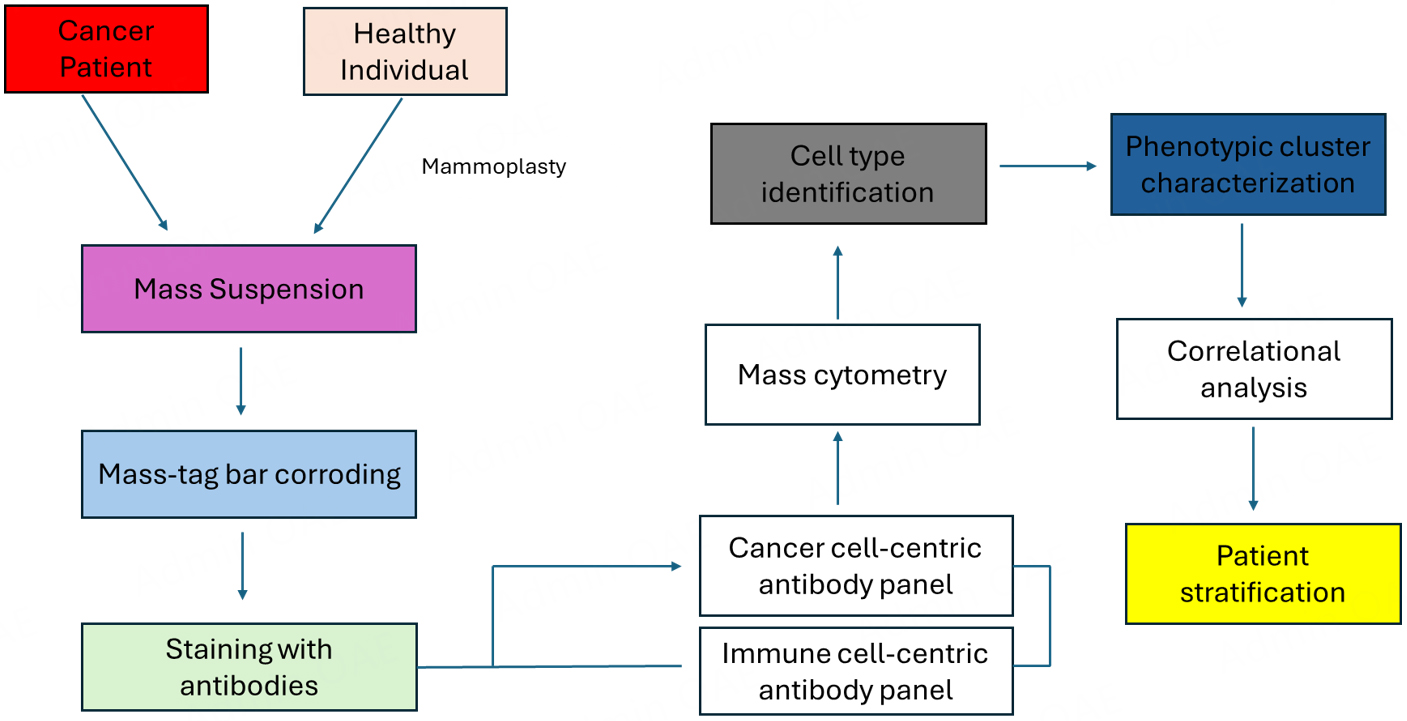

The widely used IHC staining method and the comparison of its staining intensity against a control set of biomarker-specific scoring systems result in substantial inter-observer variability in the assessment of biomarker status. This suggests the appropriateness of ML-based systems assessments. Indeed, a ML-based DL system has recently been shown to accurately predict the status of 19 biomarkers of ER and PR[52]. Osareh et al. (2010) designed a ML-based approach capable of distinguishing between malignant and benign tumors through image-based data derived from traditional biopsy-based samples, as shown in Figure 2A and B[53,54]. In other studies, classical ML methods extracted features based on biopsies and neoadjuvant responses in breast cancer cells, and an accurate, specific, concordance- and positive-predictive-value-based ML tool was developed to predict the ipsilateral recurrence risk of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) in patients undergoing lumpectomy[55,56]. The underlying mechanisms and morphological characteristics are correlated and these factors are the basis of AI application in breast cancer to predict relevant molecular variations. AI can be combined with autofluorescence or spectroscopic imaging technology to characterise breast cancer, differentiating between benign and malignant breast cancer tissues, in situ lesions, and invasive malignant lesions.

Figure 2. (A) Clinical utilities of liquid biopsy for non-invasive cancer diagnostics. Biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), tumor-educated platelets (TEPs), extracellular vesicles (EVs), as well as cancer-associated proteins, antigens, enzymes, and hormones can be identified in blood and other body fluids. Compared to conventional tissue biopsies, liquid biopsy provides a safe, less invasive alternative that allows the detection of genetic alterations, transcriptional signatures, and molecular abnormalities linked to disease progression. This strategy plays an increasingly significant role in early cancer detection and personalized therapeutic decision-making[54]. (B) Application of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data analytics in advancing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Illustration of digital mammography and digital breast tomosynthesis acquisition. Breast tissues that are only separated vertically in the mammography look overlaid, decreasing sensitivity and specificity. In digital breast tomosynthesis, this distortion is mitigated by reconstructing a pseudo-3D image from many projections, each collected with the X-ray source positioned at a different angle.

ML-based multi-omics AI approaches have elicited significant contributions to classification of breast cancer and in the determination of their subtypes using data for expression of microRNAs and Messenger RNAs (mRNAs)[55,56]. The metabolomics and proteomic data derived from 24 breast cancer patients and 61 controls with non-cancerous breast tumors have characterized healthy people into low-risk and high-risk subcategories. Several combinations of autoencoders and multiple-kernel networks in multi-omics have resulted in one of the most effective approaches for accurately predicting breast cancers and their subtypes characterization[57]. Furthermore, the expression of long non-coding RNAs was also reported to be involved in breast cancer. The interactions of AI-based ML, AI-based DL and immunomics may hold promises for diverse applications in breast cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic treatment[58].

AI encompasses a range of computational methods applied in breast cancer detection, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment optimization. Among these, ML approaches rely on handcrafted features and statistical learning[53,54]. In contrast, DL methods, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), automatically extract hierarchical features from imaging data, significantly improving classification accuracy in mammography, ultrasound, and MRI. Hybrid models combining ML with DL or incorporating clinical and genomic data have further enhanced predictive performance. While ML remains valuable for smaller, structured datasets, DL has become the dominant approach for large-scale medical imaging tasks[59].

Several studies have demonstrated the superiority of DL models over conventional computer-aided detection (CAD) systems, such as achieving a specificity of 0.847 with DNNs[59]. However, direct comparisons must be interpreted cautiously. Baseline CAD systems are often selected based on availability within the clinical setting or historical benchmarks, which may not represent the most optimized traditional methods[59]. Moreover, the composition of training datasets is a critical determinant of performance. AI systems trained on homogenous cohorts may show inflated results but fail when tested on diverse populations. Recent multicenter studies emphasize that heterogeneity in training and validation datasets significantly impacts AI performance, underscoring the need for standardized, demographically diverse benchmarking datasets before clinical claims of superiority can be fully justified[53,54].

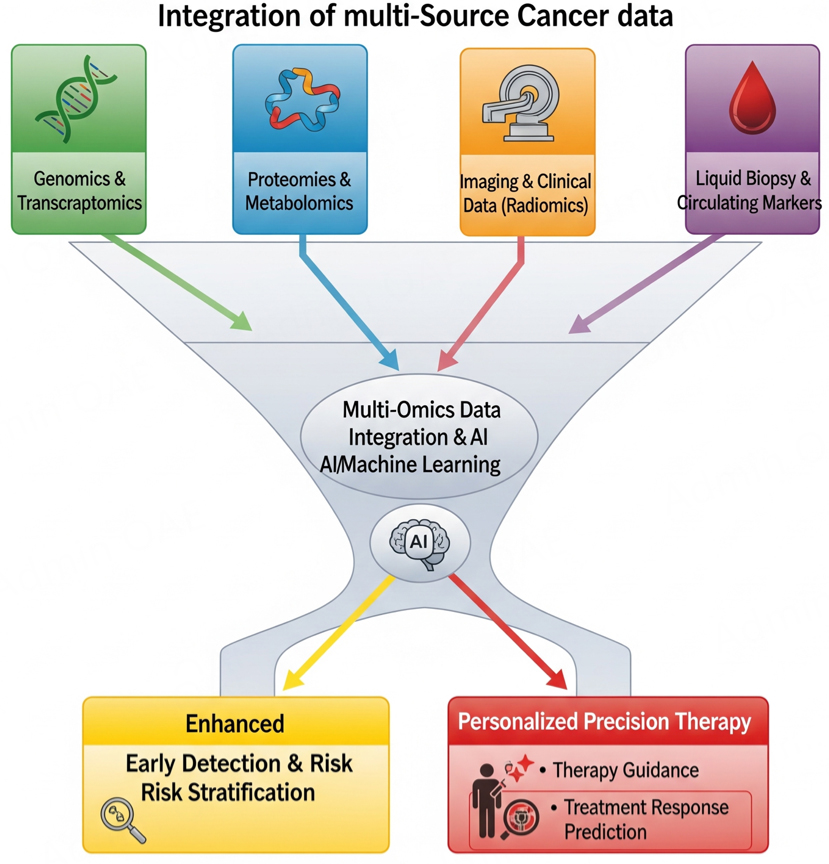

Kim et al. (2018) reported clinically significant combinatorial therapy of single-cell DNA and RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to explore human triple-negative breast cancer, about chemoresistance towards the therapeutic development in breast cancer patients[59]. Their data indicate the promising merit of scRNA-seq-based technologies. AI-based DL models assist in explicating the spatial heterogeneity of breast cancer evolution through tumorigenic antigen presentation, labeling 35 biomarkers and connecting its heterogeneity with clinical outcomes[60]. Other AI tools, such as Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) were used to develop metadata for the Decision Support and Information Management System for Breast Cancer to interpret and predict cancer pathogenesis and suggest appropriate treatment for an individual patient[61]. Figure 3 establishes the contribution of AI, Multi-Source Cancer Data and BIG DATA in cancer management[54].

Figure 3. Integrating multi-source cancer data for early detection and precision therapy in breast cancer (BC). The illustration demonstrates how information derived from diverse sources is combined to enhance the accuracy of early diagnosis and to guide personalized treatment strategies in BC.

Sandbank et al. trained an AI algorithm to specifically detect subtypes of invasive. This AI could also effectively identify stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes with an area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.965[62]. A novel AI was used for detecting pulmonary metastases in breast cancer patients using imaging data from the chest Computed Tomography (CT) of 226 subjects. Multivariate analysis showed a better correlation between nodule count and future mortality with an AUC of 0.811[62]. Furthermore, the sensitivity (0.952) and specificity (0.639) of AI-based detection were better than the reader’s assessment[63]. To improve cancer detection from high-density breast mammograms, synthetic high-density full-field digital mammograms (FFDM) can be used for data augmentation[64]. Breast cancer lesions detection using Inception V3 classified breast lesions from ultrasound images with an AUC of 0.81 and a recall rate of 0.77[65]. Recently, a deep transfer learning based DenseNet201 model was used to classify breast lesions as malignant or benign. This model used data from dynamic CE (DCE)-MRI and compared four strategies for improved model robustness[66]. DL models trained on multimodal imaging datasets have achieved diagnostic accuracies exceeding 90%, reducing unnecessary biopsies and alleviating patient anxiety.

Further, a ML-based AI algorithm relying on the “The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)” database storing individual subjects’ clinical history, transcriptomic data, and the data for cancer recurrence, prognosis, and therapeutic treatment, was reported to detect heterogeneity in triple negative breast cancer molecular subtypes for therapeutic applications[67]. The interrelation of AI-based technology and ML in breast cancer heterogeneity studies is depicted in Figure 4. Several AI models have been developed using TCGA datasets to classify breast cancer subtypes; however, their performance varies considerably[68]. For instance, autoencoder-based DL approaches achieved accuracies up to 0.885, whereas kernel learning frameworks reported lower accuracies of approximately 0.70. These discrepancies can be attributed to multiple factors. First, algorithmic architecture plays a significant role: autoencoders excel at feature compression and extraction from high-dimensional genomic data, while kernel methods may struggle with nonlinear feature interactions. Second, training dataset size and pre-processing influence outcomes, as models trained on imbalanced subtype distributions (e.g., fewer HER2+ cases) often underperform[67]. Third, validation strategies differ; studies employing cross-validation across multiple cohorts typically report higher generalizability than those using single-split validation. Collectively, these variations highlight the need for standardized benchmarking protocols to fairly evaluate AI models across datasets and architectures. The AI-based techniques in multi-omics data analysis of breast cancer and cancer cell lines are mentioned in Table 1[68,69,73,74].

Figure 4. Applications of AI and machine learning approaches in deciphering breast cancer heterogeneity. Survival prediction models integrating imaging and genomic data have improved risk stratification accuracy, allowing more personalized treatment planning and potentially enhancing long-term survival.

Features of AI-based techniques in multi-omics data analysis of breast cancer and cancer cell lines

| AI omics approach | Features of AI omics in breast cancer cells | Result of omics approach | Specificity and accuracy | Reference |

| Autoencoder and hierarchical integration deep flexible neural forest network model | mRNAs, microRNAs, DNA methylation | Classifies subtypes of breast cancer | Reads intrinsic properties and suitable for small-scale data, 0.885 accuracy | [68] |

| Autoencoder (combinations) | CNVs and mRNAs | Data integration of breast cancer types | Learned representations coupled with SVMs provide the best prediction, achieving an accuracy of 0.858 | [69] |

| Kernel learning (multiple) framework | mRNAs, microRNAs, DNA methylation | Data integration of breast cancer types with generic approach | Identification of subtypes of breast cancer and their relativity, 0.70 average cluster purity | [70] |

| Neural network (Deep learning) | Metadata, mRNAs, microRNAs, DNA methylation, CNV | Gene co-expression analysis | Predicts survival, Mean concordance. index: 0.6813 | [71] |

| Kernel learning; Bayesian efficient multiple kernel learning (BEMKL) | Proteomics, mRNAs, CNV, DNA methylation, SNP | Verifies similarities between breast cancer cell lines | Prediction of response of breast cancer drugs; False discovery rate: 2.5e-5 | [72] |

| idTRAX | Genomic and Transcriptomic data of breast cancer | Targets kinases from genes (compound data) | Identifies kinases as effective targets of anticancer drugs; Spearman correlation_0.1 | [73] |

| Capsule network-based modeling (CapsNetMMD) | mRNA, DNA, methylation, CNV | Classifies on the basis of breast cancer genes (known) | Targets breast cancer therapeutic genes P-value: 3.6e-141 | [74] |

ADVANCEMENTS IN BREAST CANCER DIAGNOSIS AND RADIOMICS

Histological and radiological assessment of biopsy samples is performed in the clinical setting to diagnose breast cancers. Four biomarkers - HER2, PR, ER, and Ki 67-Kiel, Germany, and clone number 67 antigen - are routinely analysed in biopsies and excision specimens from breast cancer cases[75]. Although such an approach allows for effective characterization, biopsy has certain associated limitations: such as problems related to tumor accessibility, risks associated with the procedures of excessively invasive focal sampling and the molecular heterogeneity of the tumor cells[76,77]. Image-guided biopsies may resolve the challenges associated with breast cancer heterogeneity owing to a high spatial resolution for cellular tissue investigation and subsequent molecular and genetic sequencing. Hence, findings can be subjected to the subjectivity of the pathologist.

Mammograms

Radiologists employ screening mammograms to monitor breast cancers by evaluating the different characteristics of lesions, and distribution and shape of the calcification clusters[77,78]. Detailed texture analyses by DBT provide better assessment of parenchymal patterns compared to DM. Hence, mammograms may result in both missed diagnoses (false negative) and misdiagnoses (false positive). AI-assisted mammography has demonstrated up to a 20%-30% reduction in false negatives compared to standard radiology, enabling earlier tumor detection and reducing the likelihood of interval cancers[79]. Although mammography is the most effective screening method for detecting early breast cancer, misdiagnosis remains a significant limitation, often due to factors such as overlapping anatomical structures, quantum mottle, suboptimal search patterns, and perceptual lapses.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another popular tool for breast cancer screening, using a magnetic field to construct accurate 3-D transverse images, which makes it highly sensitive for detecting breast cancer[80,81]. However, the relatively low screening specificity might result in a high rate of overestimation[82]. Nevertheless, alterations of the data acquisition parameters may increase spatial accuracy and permit the detection of precise changes between soft tissues. Based upon MRI scanning of subjects with different tumor characteristics such as age of the patient, tumor size, HER2 status, and texture features, it has been proposed that MRI-based radiomics signature and nomogram can be used as a reliable non-invasive tool to predict axillary lymph node metastases[83].

MRI is increasingly being recognized not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a guiding platform for therapeutic interventions in breast cancer. A notable example is the use of 3-Tesla MRI-guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (MR-HIFU), which provides a non-invasive and radiation-free option for palliative treatment of bone metastases in breast cancer patients[84]. This technique enables precise thermal ablation of metastatic lesions, effectively reducing pain while sparing surrounding healthy tissues. Importantly, the integration of AI-driven thermal mapping and treatment monitoring enhances the accuracy and safety of MR-HIFU by providing real-time feedback on ablation margins and treatment response. Furthermore, AI-based radiomics applied to MRI data can predict therapeutic outcomes, stratify patients likely to benefit from MR-HIFU, and support adaptive treatment planning. Together, these advances demonstrate how MRI serves as both a therapeutic platform and an AI-assisted monitoring system, representing a growing frontier in precision oncology for breast cancer management.

Nowadays, the textural characteristics of tumor lesions focus on the spatial arrangement of voxel intensities, including their distribution, heterogeneity, randomness, clustering patterns, and preferential signal directions[85-87]. The main goal of radiomic tumor analysis includes analyses of the TME, infiltrating cells, and inter-and intra-tumor heterogeneity. The goal retrieves qualitative and quantitative data, and subsequently for better treatment choices, resulting in better treatment outcomes and increased survival of the patients[83,88]. However, this is not often achieved. For instance, since the risk of developing carcinoma based on breast density or texture is closely related to properties of fibro-glandular tissues, such overlapping texture projections from skin or subcutaneous fatty tissues might be considered as “noise” and computed information regarding the features of texture may be affected[89,90]. AI-driven radiotherapy planning has reduced planning time by nearly 50% while maintaining accuracy, thus enabling timely initiation of treatment.

Ultrasound remains a cornerstone in breast cancer screening, especially for women with dense breast tissue where mammography sensitivity is reduced. Recent advances in AI have significantly enhanced the diagnostic performance of this modality. In particular, Automated Breast Ultrasound Systems (ABUS) integrated with DL algorithms have been shown to reduce operator dependency and improve reproducibility across centers. Deep CNNs trained on ABUS data have demonstrated higher detection sensitivity in dense breasts compared with manual interpretation, while also reducing reading time for radiologists[91]. Moreover, AI-enhanced ultrasound has been applied to lesion characterization and risk stratification, outperforming conventional Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) scoring in several studies. These advances underscore the potential of AI to transform breast ultrasound into a more standardized, accessible, and clinically reliable screening tool.

Digital breast tomosynthesis

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) provides thin section tomographic images, improving lesion visibility (structure, shape, and clearer edge of the lesion) and detecting abnormalities obscured by normal tissues[92]. The detailed texture analyses by DBT sides in better analysis of parenchymal patterns compared to DM[85]. Despite the high sensitivity of MRI, combining MRI with DM and DBT has not been shown to significantly improve sensitivity. On the other hand, the sensitivity of DBT and DM - but not MRI - may be affected by breast size and density. In breast cancer diagnosis, DBT and DM have a lower AUC and sensitivity but better specificity than DCE plus diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

Usage of radiomics nomography with CE spectral mammography (CESM) can be used to detect malignant and benign tumors of breast less than 1 cm in size[93]. Similarly, a study concluded that a model based on radiomics features extracted from diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI), antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), and quantitative DCE pharmacokinetic maps expresses a high capability to distinguish between malignant and benign breast lesions[94]. Further, a T2-weighted imaging (T2WI)-based radiomics classifier may strongly predict Ki-67 status in breast cancer patients; however, DCE-T1W1 radiomics features may not detect Ki-67 status[95]. Survival prediction models integrating imaging and genomic data have improved risk stratification accuracy, allowing more personalized treatment planning and potentially enhancing long-term survival.

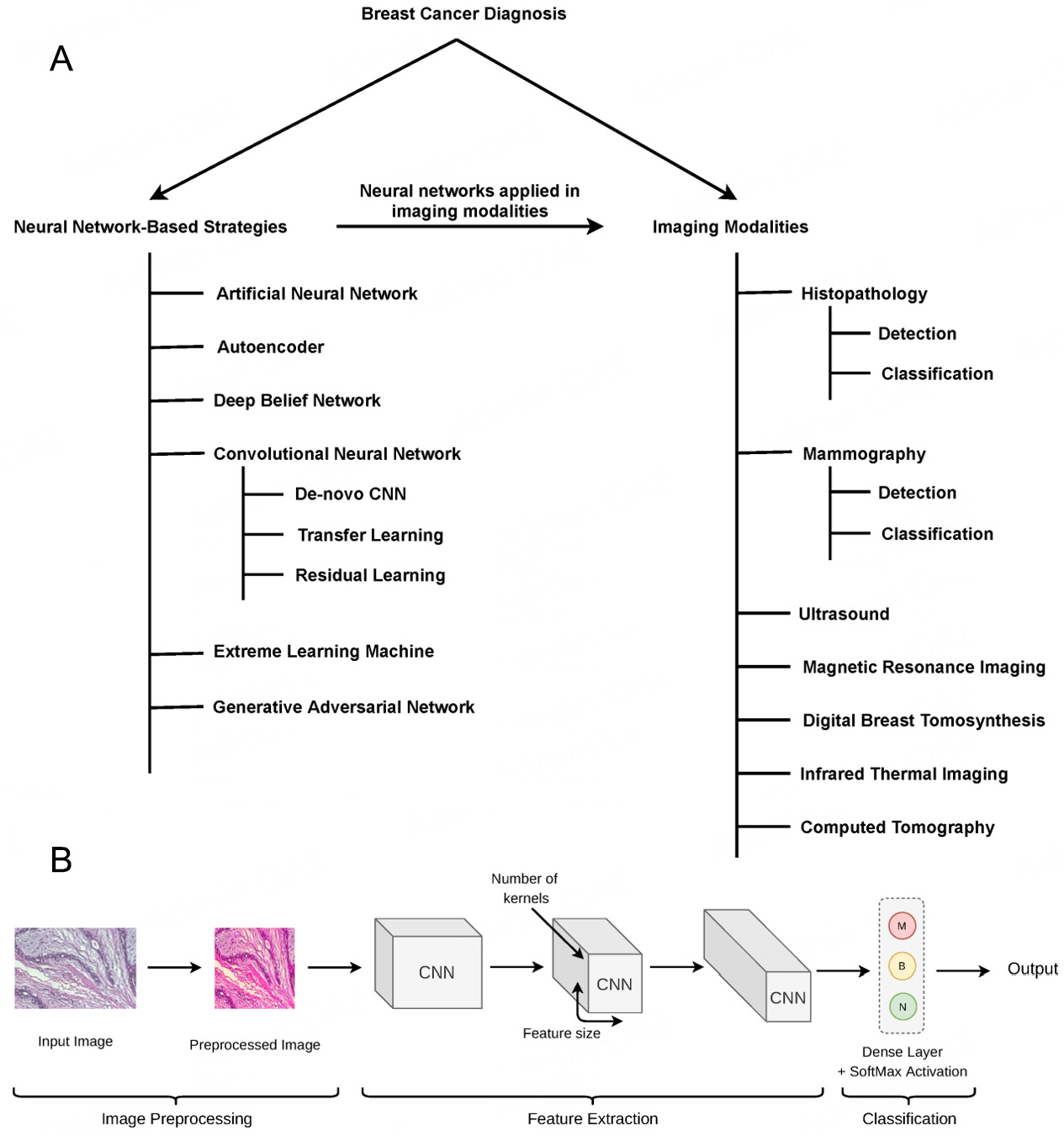

AI IN BREAST CANCER DIAGNOSIS

AI approaches may be utilized to combine the mathematical descriptors of picture characteristics into a diagnostic output[96]. AI algorithms characterized by complex logical functions, mathematical frameworks, and performance of human-like cognitive tasks are the backbone of computational radiology[97]. AI encompasses ML and DL sub-domains that can operationalize problems such as bulk identification in breast cancer[98]. ML can handle enormous datasets and recognize patterns, which could be used for prediction based on the data structure[99]. In breast cancer screening, AI performs two fundamental operations: object detection (i.e., segmentation) and categorization (e.g., malignant vs benign). To reduce differences in intensity level and brightness, images are first normalized. For image processing, DL-based CNN (DCNN), comprised of many kernels for extracting feature maps and an activation function, is extensively utilized[99]. The U-shaped network (U-Net) or Volumetric Network (V-Net) models for segmentation applications and quicker region-based CNNs (RCNNs) for object identification tasks in real-time have recently been created. Firstly, the input picture is processed by a CNN, which produces feature maps[99]. A region proposal network (RPN), which contains a classifier and regressor to separate the foreground of the image from the background, is the second component of the faster RCNN design[99].

Dheeba et al. recently examined and researched faster R-CNN for mammographic lesion identification. RPN was incorporated into the framework to conduct object-independent detection and localization operations. The CNN component was then employed to perform classification jobs which would diagnose malignant and benign lesions in full-field digital mammograms (FFDM) through a 16-layer DCNN[100].

Deep learning

Deep learning (DL) is the most progressive discipline of ML that involves a system of artificial neural networks (ANNs) that can recognize and classify tasks[102]. DL architectures automatically create the data representations required for detection or classification based on the raw data input. Raya-Povedano et al. proved that AI systems could save up to 70% of labor in breast cancer screening using DM and DBT without losing sensitivity[103]. For the objective of mass detection in DBT, Fotin et al. compared the performance of traditional CAD (CADe) to that of DL CNNs. Switching from a conventional to a DL technique increased sensitivity from 83.2% to 89.3% for regions of interest (ROIs) designated as containing suspected lesions, and from 85.2% to 93.0% for ROIs marked as containing malignant lesions[104].

Fully convolutional network

Convolutional, pooling, and up-sampling layers are entirely locally connected layers that are characteristic features of fully convolutional networks (FCNs), proposed by Long et al.[105]. This network analysis lowers the number of parameters by omitting dense layers, speeding up the training processes. FCNs additionally contain down-sampling (encoder) and up-sampling (decoder) paths for image extraction and interpretation and analysis of localization context. Images of variable sizes can be used as inputs for FCNs. To make up for the loss of fine-grained spatial information along the down-sampling path, the network additionally uses the concept of skip connections.

A fully automated DL-based approach to assess breast density from mammograms was described by Lee and Nishikawa[106]. Breast and dense fibroglandular regions were segmented using an FCN. This model has been linked to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS®) approach, which is used to evaluate breast percentage density (PD) and the fraction of dense tissue. An end-to-end FCN was set up by Hai et al.[107] to segment breast tumors. By including a multiscale picture, the authors were able to address the variability in the shapes and sizes of aberrant tumors. More recently, Xu et al.[108] suggested a multichannel and multiscale FCN for mammography-based mass segmentation. Sathyan[109] suggested a way to find anomalies such as bulk and calcification in breast cancers. A U-Net-based fully convolutional architecture has also been used to segment the irregularities[110]. Later, Lima et al. suggested a completely automated DL-based approach utilizing attention gates (AGs) and a densely connected U-Net[81]. In this system, an encoder and a decoder branch were preferred. AlGhamdi et al. created a model to find breast arterial calcifications using U-Net with dense connection. The model relied on enhancement of the gradient flow and enabled the reuse of previously completed computations, both of which increased model accuracy[111].

Generative adversarial networks

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) were first proposed as a tool for data analysis in 2014[112]. Since then, researchers have frequently used them for data augmentation and sample production[113]. For instance, Hussain et al. investigated the use of GANs for data augmentation of mammographic datasets[114]. In this study, GAN architecture relied on generator and discriminator networks and the discriminator model was trained on ground truth data, while the generator helped to produce high-quality images that attempted to refine the model[114]. Numerous GAN variations have been devised. Hence, Warnes et al. pulled out fully connected hidden layers and implemented batch normalization[115]. Similarly, ROIs in mammograms can be segmented using conditional generative adversarial networks (cGAN), and creation of binary masks relied on training of the model to represent tumor masses[116].

Wu et al. proposed the use of a class-conditional GAN to perform contextual in-filling and generate lesions on original mammography images, showing that the model was capable of producing high-quality synthetic images[117]. In a subsequent study, they introduced a data augmentation method based on a U-Net framework, incorporating self-attention and semi-supervised learning to add lesions to healthy mammography patches and remove existing lesions from affected patches[118]. Another strategy employed a progressively trained GAN to generate realistic, high-resolution synthetic mammograms[119]. Additionally, Becker et al. developed a method to insert and erase cancer features in mammograms, while also evaluating whether expert radiologists could reliably distinguish AI-generated images. Their system’s ability to detect abnormalities and estimate the likelihood of image manipulation was compared with expert performance. However, this method involved a considerable compromise between image quality and the presence of artefacts[120].

Artificial neural networks through machine learning

A computer system inspired by the biological neural network is known as an artificial neural network (ANN)[121]. One of the most popular AI techniques for developing CADe systems for mammography interpretation is the usage of ANNs. It can be used to classify the ROIs of an input mammogram in two different ways when applied to mammograms; first, as a feature extractor, and second, as a classifier[122].

In order to analyse mammograms, Wu et al. trained a three-layer feed-forward neural network using hand-labeled features from knowledgeable radiologists[123]. Fogel et al. introduced an ANN-based approach for analyzing interpreted mammographic data, achieving an average ROC area of 0.91 in detecting suspicious masses, with 62% specificity and 95% sensitivity[124]. Quintanilla-Domínguez et al. used a self-organizing map and adaptive histogram equalization to address the identification of microcalcifications in tumors[125]. Computer simulations confirmed the model’s ability and usefulness to identify microcalcifications in mammograms. An approach for identifying and classifying microcalcification clusters from digitised mammograms was also put forth by Papadopoulos et al. Cluster identification, feature extraction, and classification made up the method’s three steps, which together produced the final characterization[126]. A technique was created by García-Manso et al. to identify and categorise masses from mammograms. Blind features were extracted using the Independent Component Analysis (ICA) method, with neural networks carrying out the classification[127]. An ANN-based CAD system was created by Hupse et al. to identify abnormal bulk and architectural distortions in mammograms[128]. The CAD system performed nearly as well as qualified industry experts. Tan et al. suggest yet another CAD method for the analysis and screening of the features of mammographic images[129]. Their system used ANNs to estimate the likelihood of a mammogram being cancerous. A mass detection method built on the three steps of enhancement, characterization, and classification was introduced by Mahersia et al.[130]. For this study, the wavelet domain was utilised to segment the breast mass using a Gaussian density function. Back-propagation networks and techniques from the adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) have also been used in a comparative classification method[131].

Computer-aided detection

Computer-aided detection (CADe) systems aim to detect suspicious lesions with either masses of soft tissue and/or clusters of calcified tissues, and hence can significantly improve the detection of cancerous or metastatic tissue[95,132]. Computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) systems, on the other hand, aid in the classification of the distinct types of breast cancers. All standard CADe algorithms use the same three-step strategy; first, normalization of the image to a “reference” intensity distribution (reference intensity may be an arbitrary intensity distribution) and/or processing of the images for improving the ability to detect suspicious signals[133,134]. Second, identification of the areas in the images that contain suspicious signals, and third, reduction in the number of identified regions by predicting the likelihood of the presence of an actual lesion in each region[133]. Therefore, the core steps in a CADe system include image pre-processing, segmentation, feature extraction, and final classification into benign and malignant. Data preparation is the initial stage in making raw data more suited for future analyses. As such, image pre-processing may be an efficient strategy in CAD-aided breast cancer assessment[135]. In 1967, Winsberg et al. published the first research on computerised mammographic image analysis, which included an automated system that compared and analysed density patterns in various regions inside a single breast and between left and right breasts They found that irregularities in the conditions (tissue slice preparation, lightning conditions, etc.) under which digital images are acquired may result in changes in image colour and quality[136]. Color normalization may be used to separate colour and intensity information with the help of principal component analysis (PCA)[137]. CADx algorithms use an approach similar to the final CADe step but do not employ a threshold to determine whether a previously detected lesion is malignant or benign[2,138]. Both viable options are DL and conventional approaches to designing a CAD system. Traditional CAD methods extract features from images utilizing human-defined descriptors for classification[139]. DL CAD methods are automated learning methods that can identify data representations by translating input data into several levels of abstraction.

Design of computerized image analytical approaches for diagnosing, characterizing, and detecting lesions on breast mammograms has been on the rise in recent years[140]. These strategies take digital image data as input and then generate clinically useful information, such as the characterization and location of a suspicious lesion[141]. They predict the likelihood of malignancy of the suspicious lesions, and/or numerical indices of breast cancer risk, with the computer acting as a second reader, similar to a spell checker in the protocol of screening for breast cancers[142]. Because microcalcifications differ greatly from normal breast structures and are frequently ignored by radiologists, most automated detection systems for mammographic analyses have focused on the identification of clustered microcalcifications and mass lesions[143]. The knowledge that clinically significant microcalcifications are clustered, the spatial distribution of calcifications, the variations of individual features within a cluster, and the radiographic presentation of individual calcifications (e.g., brightness, area, and shape) are all used to create mathematical descriptors for calcifications[25,137]. Many radiologists utilize breast sonography to differentiate between solid lesions and cysts, although it might still be difficult to discern between benign solid lesions and malignant lesions. Interestingly, in one study, 55 radiologists used a commercial CAD system to examine mammographic data from 12,860 patients. They found a 19.5% increase in cancer diagnoses and an 18.5% increase in recall rate[139].

While there are many different methods for performing biological image processing tasks, the clinical recognition of ROIs from digital images is facilitated by CADe. Once suspicious regions are detected, CADe systems classify them as either masses or non-masses. In contrast, CADx approaches are designed to assess the malignancy of identified masses[144], thereby supporting radiologists in recommending biopsies, additional examinations, or treatment options[145]. Existing methods in the literature can broadly be categorized into three groups[146]. Those based on low-level image feature extraction, ML techniques, and DL models. CADe methods that rely on low-level features typically analyze characteristics such as shape, texture, and local key-point descriptors to detect suspicious regions within mammographic images.

Shape-based features and descriptors for CADe analysis

Several techniques for detecting suspicious regions in mammograms focus on analyzing shape characteristics such as compactness, fractal measures, concavity, and morphological operators. Shape-based feature analysis methods are generally grouped into two categories: One, those that perform numerical analysis of shape descriptors, and the other that utilize shape descriptors as inputs for classifiers or neural networks[146].

Fractal analysis was used by Raguso et al.[147] to address the classification of breast masses. Since breast mass contours vary in their complexity of shape, the fractal dimension is used as a distinguishing characteristic. According to Eltonsy et al., concentric layers emerge around activity regions in breast parenchyma structures due to a mass's expansion. These so-called multiple concentric layers (MCLs) may be employed to identify the activity sites[148]. The foundation of the MCL-detection technique is the morphological examination of the concentric layer model. The detection of mammography masses was tackled by using a boundary segmentation method[149]. The authors suggested a spiculation index based on the degree of spicule narrowness and the concavity fraction of a mass boundary. The spiculation index, fractional concavity, and the global shape attribute of compactness can be integrated for the boundary segmentation challenge. For the purpose of expanding on shape characteristic descriptors, Surendiran and Vadivel examined the distribution of shape features such as circularity, dispersion, standard deviation, elongatedness, eccentricity, and compactness[150]. A technique based on morphological operators and geometry was put out by Mustra et al. for precise nipple recognition in craniocaudal mammograms[151].

A technique has been developed to transform 2D breast mass contours in mammography into a 1D signature, providing a description of breast mass regularity and shape characteristics. The four local features that make up the contour descriptor were taken from subsections. The root mean square (RMS) slope served as the contour descriptor. Furthermore, benign and malignant tumors were classified using K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and ANN classifiers[152]. To distinguish between benign and malignant masses, Elmoufidi et al. suggested a multiple instance learning strategy based on the examination of combined texture and form data. They approached the classification problem utilizing features such as the ROI’s equivalent circle and bounding box[153].

To classify microcalcification, a study compared multi-wavelet, wavelet, Haralick, and form features. Using the aforementioned qualities, it provided evidence for the possibility of extraction of a number of beneficial properties concurrently, including symmetry, orthogonality, short support, and a greater number of vanishing moments[154]. Testing the utility of Zernike moments as shape descriptors for mammography classification was done by Felipe et al.[155]. The pixel values of images used to calculate Zernike moments were found to preserve shape-related pattern information. Soltanian-Zadeh et al. reported two image-processing techniques for differentiating benign from malignant microcalcifications in mammograms without the need for biopsies[156]. The authors used the first technique to extract 17 form features from each mammogram. These characteristics were connected to the clusters or individual morphologies of microcalcifications. The co-occurrence approach of Haralick, used in the second method, extracted 44 texture features from each mammogram. A genetic algorithm was then used to extract the best characteristics from each set by maximising the area under the ROC curve. A malignancy criterion and a k-nearest neighbor (kNN) classifier were used to produce this curve. In the final stage, ROCs with the biggest regions achieved using each technique were compared. A shape-based method for classifying microcalcification clusters was also presented by Zyout et al.[157]. The suggested diagnosis method used a feature selection framework called particle swarm optimization and kNN (PSO-kNN), which is an integrated method for completing the feature selection and classifier learning tasks. Sahiner et al. have developed a three-stage segmentation method based on clustering, active contour, and spiculation detection stages to address the characterization of breast masses on mammograms[158]. Following segmentation, morphological features were extracted and used to define the mass’s shape.

Texture-based features and descriptors for CADe analysis

In visual content, texture reveals visual patterns; however, the variability and diversity of natural images make the analysis and description of these textures very challenging. Haindl et al. proposed a method that utilizes textural features derived from co-occurrence matrices, wavelet, and ridgelet transforms of mammograms to identify suspicious regions in craniocaudal views[159]. In addition to these features, attributes such as entropy, energy, mean, sum variance, and cluster tendency were computed and optimized using genetic algorithms. More recently, Haindl and Remeš developed an approach aimed at enhancing suspected anomalies in breast tissue, including microcalcifications and masses, to aid radiologists in early cancer detection[159]. Their method applied a 2D adaptive causal autoregressive texture model to characterize local textural properties, integrating over 200 local cues across multiple frequency bands into a single multichannel image through the Karhunen-Loève transform[159]. A lattice-based framework in which a regular grid was applied to mammograms, with local windows centered on each lattice point to extract textural features. Building on this, an automated CADe system was developed that leverages both local and discrete textural features for the detection of mammographic masses[160]. According to this study, segmentation of adaptive square suspicious areas was found to be more informative for breast cancer diagnoses, with the suspicious regions having local textural variations and discontinuous photometric distributions which were described using the co-occurrence matrix and optical density transformation.

The idea of texture flow-field analysis was introduced to mammography analysis by

Local keypoint descriptors

Local keypoints and the descriptors that are associated with them, including Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF)[166] and the scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT)[167], have been popular in many computer vision-related fields[168]. Biomedical researchers have been using local keypoint descriptors to identify ROIs in digital pictures due to the differences in lighting conditions, spatial noise distribution, and geometric and photometric modifications in images[146]. Jiang et al. were possibly the first to specifically investigate mammographic ROIs using an approach based upon keypoint descriptors[169]. They compared language trees, all of which contained the quantized aspects of previously identified more than 11,000 mammographic ROIs and the SIFT descriptors generated from the ROIs. The main topic of Guan et al.'s study was the liability of SIFT keypoints on microcalcification segmentation in images from the Mammographic Image Analysis Society (MIAS) dataset[170]. Further, a SURF-based technique was proposed by Insalaco et al. for identifying suspicious areas in mammograms; the three primary automated steps being pre-processing, feature extraction, and selection. The technique enabled the extraction of characteristics from mammograms with varying dynamic grey intensity levels[171]. Utomo et al. tested several well-known scale- and rotation-invariant local features to identify which of these could take on the role of the convolutional layers in CNN models when applied to images from the MIAS dataset as shown in Figure 5A and B[172].

Figure 5. (A) Taxonomy of breast cancer diagnosis. (B) CNN-based model for breast cancer diagnosis. Reprinted from[173], 2021 MDPI.

According to their studies, SIFT and SURF were the best for the intended purpose. To identify ROIs in mammograms, Salazar-Licea et al. introduced a method that combines SIFT characteristics and K-means clustering. Employing picture thresholding and contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization, they improved the image quality and the detection of ROIs in mammograms[174-176].

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE

Despite substantial progress, the real-world implementation of AI in breast cancer care faces several important challenges. A major barrier is data standardization - imaging modalities, acquisition parameters, and annotation protocols vary across institutions, which complicates the training and generalizability of AI models. Related to this is the problem of bias and generalizability, as algorithms often perform well in controlled research settings but fail to replicate accuracy across diverse patient populations, particularly when underrepresented groups are excluded from training datasets. Ethical and medico-legal implications also remain unresolved. The “black box” nature of many DL algorithms raises accountability questions in clinical decision-making: if an AI system misclassifies a lesion, it is unclear whether responsibility lies with the software developers, the clinician, or the institution.

From a regulatory standpoint, Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency approvals for AI-based medical devices require rigorous validation, reproducibility, and post-market surveillance, which many experimental models currently lack. This regulatory gap slows down clinical translation and adoption. Additionally, integration into clinical workflows requires not only technical interoperability but also clinician training and acceptance, both of which remain significant barriers. Looking forward, the future of AI in breast cancer depends on collaborative, multicenter trials that validate algorithms in real-world settings, the development of explainable AI to improve transparency and trust, and clearer regulatory frameworks to ensure patient safety. Ethical frameworks addressing bias, fairness, and medico-legal liability will also be essential. With these advances, AI has the potential to evolve from a research tool into a trusted partner in personalized breast cancer care.

Despite promising results, one major issue is bias and generalizability, as models frequently inherit bias from training datasets that may underrepresent certain ethnic groups or imaging modalities, reducing their performance across diverse populations. Data privacy and security also remain pressing concerns, since the use of patient imaging and genomic data requires robust de-identification strategies and secure storage systems. Furthermore, clinical integration barriers persist, as many AI applications remain in the research phase and face hurdles related to regulatory approval, interoperability with existing hospital information systems, and the need for clinician training. Another critical limitation is the interpretability or “black box” problem, where DL models achieve high accuracy but lack transparency, making it difficult for clinicians to fully trust or understand their decision-making processes. Finally, validation and reproducibility pose significant challenges, as only a small number of AI studies have undergone large-scale, prospective, multicenter trials needed to establish their reliability and clinical utility.

CONCLUSION

Herein, we describe in detail the different techniques used to diagnose breast cancer. We discuss the pitfalls of traditional diagnostic methods such as mammography, sonography, and MRI, which rely mainly on subjective evaluations, including tumor morphology, enhancement type, and anatomical connections to adjacent tissues. The uses of computerized methods for detecting breast cancer, such as CADe and CADx, have been discussed in detail. CADe systems aim to detect suspicious lesions, either masses of soft tissue and/or clusters of calcified tissues; thus, CADe involves the detection of cancer or metastatic tissue. CADx systems help determine the distinct types of breast cancer. In addition to all combinations with imaging techniques, the authors also delineate the advantages of the application of state-of-the-art AI techniques in diagnosing breast cancer. AI approaches may be particularly suitable for combining the mathematical descriptions of image characteristics into a diagnostic output. It enables pixel-level characterization of the images allowing establishment and classification of the location of the lesion. AI encompasses ML and DL subdomains that can operationalize problems such as bulk identification in breast scan images. Scientists have observed that when trained on an extensive dataset of mammographic lesions, a DL model in the form of a CNN can outperform a state-of-the-art system in CAD, thus demonstrating an enormous potential as a promising technique. CNNs can learn from data rather than subject expertise, making development easier and faster. Multiple studies have confirmed that AI-based diagnostic methods provide better accuracy than other methods. The differences between CNN-based methods for mammographic CAD have also been discussed. Further studies in this area could explore various aspects of AI-based combinational imaging techniques, such as developing more sophisticated algorithms for image analysis and feature extraction, optimizing imaging protocols, and integrating different data sources for more comprehensive analyses.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge respective departments and institutions for providing facilities and support.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualisation and writing: Preetam S, Bhattacharjee S

Data collection and analysis: Malik S, Rustagi S

Figure preparation: Preetam S, Bora J, Malik S

Writing, editing, proofreading, critical revision, and finalisation of the manuscript: Preetam S, Bhattacharjee S, Mishra R, Muduli K, Rustagi S, Bora J, Deshwal RK, Malik S, Gundamaraju R

Coordination, revision, and supervision: Gundamaraju R, Malik S

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Bhattacharjee S is an employee of KoshKey Sciences Pvt Ltd. Gundamaraju R is a Junior Editorial Board member of Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment and was not involved in any part of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Sizilio GR, Leite CR, Guerreiro AM, Neto AD. Fuzzy method for pre-diagnosis of breast cancer from the Fine Needle Aspirate analysis. Biomed Eng Online. 2012;11:83.

2. Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. The global burden of women's cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet. 2017;389:847-60.

3. Badawy E, Elnaggar R, Soliman SAM, Elmesidy DS. Performance of AI-aided mammography in breast cancer diagnosis: does breast density matter? Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2023;54:1129.

4. Díaz O, Rodríguez-Ruíz A, Sechopoulos I. Artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection: technology, challenges, and prospects. Eur J Radiol. 2024;175:111457.

5. DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438-51.

6. Ahmad J, Akram S, Jaffar A, et al. Deep learning empowered breast cancer diagnosis: advancements in detection and classification. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0304757.

7. Al-Karawi D, Al-Zaidi S, Helael KA, et al. A review of artificial intelligence in breast imaging. Tomography. 2024;10:705-26.

8. Smith HO, Kammerer-Doak DN, Barbo DM, Sarto GE. Hormone replacement therapy in the menopause: a pro opinion. CA Cancer J Clin. 1996;46:343-63.

9. Alkayyali ZK, Taha AM, Zarandah QM, Abunasser BS, Barhoom AM, Abu-Naser SS. Advancements in AI for medical imaging: transforming diagnosis and treatment. Int J Acad Eng Res. 2024;8:8-15. Available from: https://philarchive.org/rec/ALKAIA [Last accessed on 26 Nov 2025].

10. Rojas K, Stuckey A. Breast cancer epidemiology and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;59:651-72.

11. Haber D. Prophylactic oophorectomy to reduce the risk of ovarian and breast cancer in carriers of BRCA mutations. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1660-2.

12. Malone KE, Daling JR, Thompson JD, O'Brien CA, Francisco LV, Ostrander EA. BRCA1 mutations and breast cancer in the general population: analyses in women before age 35 years and in women before age 45 years with first-degree family history. JAMA. 1998;279:922-9.

13. Feng Y, Spezia M, Huang S, et al. Breast cancer development and progression: risk factors, cancer stem cells, signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes Dis. 2018;5:77-106.

14. Ni H, Kumbrink J, Mayr D, et al. Molecular prognostic factors for distant metastases in premenopausal patients with HR+/HER2- early breast cancer. J Pers Med. 2021;11:835.

15. Wang S, Guo X, Ma J, et al. AWCDL: automatic weight calibration deep learning for detecting HER2 status in whole-slide breast cancer image. Intell Oncol. 2025;1:128-38.

16. Migowski A. [Early detection of breast cancer and the interpretation of results of survival studies]. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:1309.

17. Dai X, Li T, Bai Z, et al. Breast cancer intrinsic subtype classification, clinical use and future trends. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5:2929-43.

18. Bodily WR, Shirts BH, Walsh T, et al. Effects of germline and somatic events in candidate BRCA-like genes on breast-tumor signatures. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239197.

19. Batool Z, Kamal MA, Shen B. Advancements in triple-negative breast cancer sub-typing, diagnosis and treatment with assistance of artificial intelligence : a focused review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150:383.

20. Carriero A, Groenhoff L, Vologina E, Basile P, Albera M. Deep learning in breast cancer imaging: state of the art and recent advancements in early 2024. Diagnostics. 2024;14:848.

21. Chauhan AS, Singh R, Priyadarshi N, Twala B, Suthar S, Swami S. Unleashing the power of advanced technologies for revolutionary medical imaging: pioneering the healthcare frontier with artificial intelligence. Discov Artif Intell. 2024;4:58.

24. Makki J. Diversity of breast carcinoma: histological subtypes and clinical relevance. Clin Med Insights Pathol. 2015;8:23-31.

25. Chang J, Chaudhuri O. Beyond proteases: basement membrane mechanics and cancer invasion. J Cell Biol. 2019;218:2456-69.

26. Onega T, Goldman LE, Walker RL, et al. Facility mammography volume in relation to breast cancer screening outcomes. J Med Screen. 2016;23:31-7.

27. Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Breast cancer: a molecularly heterogenous disease needing subtype-specific treatments. Med Sci. 2020;8:18.

28. Mukherjee S, Sengupta A, Preetam S, Das T, Bhattacharya T, Thorat N. Effects of fatty acid esters on mechanical, thermal, microbial, and moisture barrier properties of carboxymethyl cellulose-based edible films. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2024;7:100505.

29. Preetam S, Mondal S, Priya S, et al. Targeting tumour markers in ovarian cancer treatment. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;559:119687.

30. Jørgensen KJ, Gyøtzsche PC. Unclear methods in estimate of screening effect in women ages 40 to 49 years. Cancer. 2012;118:1170.

31. Elahi R, Nazari M. An updated overview of radiomics-based artificial intelligence (AI) methods in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Radiol Phys Technol. 2024;17:795-818.

32. Ijaz MF, Woźniak M. Editorial: recent advances in deep learning and medical imaging for cancer treatment. Cancers. 2024;16:700.

34. Roganovic D, Djilas D, Vujnovic S, Pavic D, Stojanov D. Breast MRI, digital mammography and breast tomosynthesis: comparison of three methods for early detection of breast cancer. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2015;15:64-8.

36. Lewis TC, Pizzitola VJ, Giurescu ME, et al. Contrast-enhanced digital mammography: a single-institution experience of the first 208 cases. Breast J. 2017;23:67-76.

37. Xu P, Peng Y, Sun M, Yang X. SU-E-I-81: targeting of HER2-expressing tumors with dual PET-MR imaging probes. Med Phys. 2015;42:3260-3260.

38. Chen T, Artis F, Dubuc D, Fournie JJ, Poupot M, Grenier K. Microwave biosensor dedicated to the dielectric spectroscopy of a single alive biological cell in its culture medium. In 2013 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium Digest (MTT), Seattle, WA, USA; 2-7 June 2013.

39. Hassan AM, El-Shenawee M. Review of electromagnetic techniques for breast cancer detection. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2011;4:103-18.

40. Rentiya ZS, Mandal S, Inban P, et al. Revolutionizing breast cancer detection with artificial intelligence (AI) in radiology and radiation oncology: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024;16:e57619.

41. Uchikov P, Khalid U, Dedaj-Salad GH, et al. Artificial intelligence in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment: advances in imaging, pathology, and personalized care. Life. 2024;14:1451.

42. Andropova US, Tebeneva NA, Tarasenkov AN, et al. The effect of hafnium alkoxysiloxane precursor structure of disperse phase on the morphology of nanocomposites based on polyaryleneetherketone. Polym Sci Ser B. 2017;59:202-9.

43. Lu G, Li S, Guo Z, et al. Imparting functionality to a metal-organic framework material by controlled nanoparticle encapsulation. Nat Chem. 2012;4:310-6.

44. Makki B, Chitti K, Behravan A, Alouini M. A survey of NOMA: current status and open research challenges. IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2020;1:179-89.

45. Tsai CH, Fordyce RE. Juvenile morphology in baleen whale phylogeny. Naturwissenschaften. 2014;101:765-9.

46. Veta M, Heng YJ, Stathonikos N, et al. Predicting breast tumor proliferation from whole-slide images: the TUPAC16 challenge. Med Image Anal. 2019;54:111-21.

47. Vanni S, Caputo TM, Cusano AM, et al. Engineered anti-HER2 drug delivery nanosystems for the treatment of breast cancer. Nanoscale. 2025;17:9436-57.

48. Segovia-Mendoza M, Morales-Montor J. Immune tumor microenvironment in breast cancer and the participation of estrogen and its receptors in cancer physiopathology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:348.

49. Mansouri K, Karmaus AL, Fitzpatrick J, et al. CATMoS: collaborative acute toxicity modeling suite. Environ Health Perspect. 2021;129:47013.

50. Aponte-López A, Fuentes-Pananá EM, Cortes-Muñoz D, Muñoz-Cruz S. Mast cell, the neglected member of the tumor microenvironment: role in breast cancer. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:2584243.

51. Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683-90.

52. Bédard A, Basagaña X, Anto JM, et al. Mobile technology offers novel insights into the control and treatment of allergic rhinitis: the MASK study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:135-43.e6.

53. Osareh A, Shadgar B. Machine learning techniques to diagnose breast cancer. In 2010 5th international symposium on health informatics and bioinformatics. Ankara, Turkey; 20-22 April 2010.

54. Darbandi MR, Darbandi M, Darbandi S, Bado I, Hadizadeh M, Khorram Khorshid HR. Artificial intelligence breakthroughs in pioneering early diagnosis and precision treatment of breast cancer: a multimethod study. Eur J Cancer. 2024;209:114227.

55. Diaby V, Adunlin G, Ali AA, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of 1st through 3rd line sequential targeted therapy in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160:187-96.

56. Klimov S, Miligy IM, Gertych A, et al. A whole slide image-based machine learning approach to predict ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) recurrence risk. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:83.

57. Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1151-9.

58. Attal M, Richardson PG, Rajkumar SV, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:2096-107.

59. Kim C, Gao R, Sei E, et al. Chemoresistance evolution in triple-negative breast cancer delineated by single-cell sequencing. Cell. 2018;173:879-93.e13.

60. Alharbi J, Jackson D, Usher K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:2762-4.

61. Seroussi H, Nakayama Y, Larour E, et al. Continued retreat of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica, controlled by bed topography and ocean circulation. Geophysical Research Letters. 2017;44:6191-9.

62. Sandbank J, Bataillon G, Nudelman A, et al. Validation and real-world clinical application of an artificial intelligence algorithm for breast cancer detection in biopsies. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8:129.

63. Kocher MR, Chamberlin J, Waltz J, et al. Tumor burden of lung metastases at initial staging in breast cancer patients detected by artificial intelligence as a prognostic tool for precision medicine. Heliyon. 2022;8:e08962.

64. Garrucho L, Kushibar K, Osuala R, et al. High-resolution synthesis of high-density breast mammograms: Application to improved fairness in deep learning based mass detection. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1044496.

65. Sirjani N, Ghelich Oghli M, Kazem Tarzamni M, et al. A novel deep learning model for breast lesion classification using ultrasound images: a multicenter data evaluation. Phys Med. 2023;107:102560.

66. Meng M, Zhang M, Shen D, He G. Differentiation of breast lesions on dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) using deep transfer learning based on DenseNet201. Medicine. 2022;101:e31214.

67. Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol. 2015;19:A68-77.

68. Xu J, Wu P, Chen Y, Meng Q, Dawood H, Dawood H. A hierarchical integration deep flexible neural forest framework for cancer subtype classification by integrating multi-omics data. BMC Bioinf. 2019;20:527.

69. Simidjievski N, Bodnar C, Tariq I, et al. Variational autoencoders for cancer data integration: design principles and computational practice. Front Genet. 2019;10:1205.

70. Mariette J, Villa-Vialaneix N. Unsupervised multiple kernel learning for heterogeneous data integration. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1009-15.

71. Huang K, Xiao C, Glass LM, Critchlow CW, Gibson G, Sun J. Machine learning applications for therapeutic tasks with genomics data. Patterns. 2021;2:100328.

72. Ali M, Aittokallio T. Machine learning and feature selection for drug response prediction in precision oncology applications. Biophys Rev. 2019;11:31-9.

73. Gautam P, Jaiswal A, Aittokallio T, Al-Ali H, Wennerberg K. Phenotypic screening combined with machine learning for efficient identification of breast cancer-selective therapeutic targets. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26:970-9.e4.

74. Li M, Ni P, Chen X, Wang J, Wu FX, Pan Y. Construction of refined protein interaction network for predicting essential proteins. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2019;16:1386-97.

75. Choudhery S, Gomez-Cardona D, Favazza CP, et al. MRI radiomics for assessment of molecular subtype, pathological complete response, and residual cancer burden in breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Acad Radiol. 2022;29 Suppl 1:S145-54.

76. Dercle L, Ammari S, Bateson M, et al. Limits of radiomic-based entropy as a surrogate of tumor heterogeneity: ROI-area, acquisition protocol and tissue site exert substantial influence. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7952.

77. Prud'homme C, Deschamps F, Allorant A, et al. Image-guided tumour biopsies in a prospective molecular triage study (MOSCATO-01): what are the real risks? Eur J Cancer. 2018;103:108-19.

78. Wilkinson L, Thomas V, Sharma N. Microcalcification on mammography: approaches to interpretation and biopsy. Br J Radiol. 2017;90:20160594.

79. Qi X, Zhang L, Chen Y, et al. Automated diagnosis of breast ultrasonography images using deep neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2019;52:185-98.

80. Fischer U, Baum F, Obenauer S, et al. Comparative study in patients with microcalcifications: full-field digital mammography vs screen-film mammography. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2679-83.

81. Lima R, Del Fiol FS, Balcão VM. Prospects for the use of new technologies to combat multidrug-resistant bacteria. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:692.

82. Fischer U, Kopka L, Grabbe E. Breast carcinoma: effect of preoperative contrast-enhanced MR imaging on the therapeutic approach. Radiology. 1999;213:881-8.

83. Liu Z, Wang S, Dong D, et al. The applications of radiomics in precision diagnosis and treatment of oncology: opportunities and challenges. Theranostics. 2019;9:1303-22.

84. Bobola MS, Chen L, Ezeokeke CK, et al. A review of recent advances in ultrasound, placed in the context of pain diagnosis and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22:60.

85. Kontos D, Bakic PR, Troxel AB, Conant EF, Maidment ADA. Digital breast tomosynthesis parenchymal texture analysis for breast cancer risk estimation: a preliminary study. In: Krupinski EA, editor. Digital mammography. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2008. pp. 681-8.

86. Pesapane F, Rotili A, Agazzi GM, et al. Recent radiomics advancements in breast cancer: lessons and pitfalls for the next future. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:2351-72.

87. Limkin EJ, Reuzé S, Carré A, et al. The complexity of tumor shape, spiculatedness, correlates with tumor radiomic shape features. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4329.

88. Mariscotti G, Houssami N, Durando M, et al. Accuracy of mammography, digital breast tomosynthesis, ultrasound and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:1219-25.

89. Niu S, Wang X, Zhao N, et al. Radiomic evaluations of the diagnostic performance of DM, DBT, DCE MRI, DWI, and their combination for the diagnosisof breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:725922.

90. Chen JH, Gulsen G, Su MY. Imaging breast density: established and emerging modalities. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:435-45.

91. Smith BE, Selfe J, Thacker D, et al. Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190892.

92. Niklason LT, Kopans DB, Hamberg LM. Digital breast imaging: tomosynthesis and digital subtraction mammography. Breast Dis. 1998;10:151-64.

93. Mao N, Yin P, Li Q, et al. Radiomics nomogram of contrast-enhanced spectral mammography for prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis in breast cancer: a multicenter study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6732-9.

94. Stelzer PD, Steding O, Raudner MW, Euller G, Clauser P, Baltzer PAT. Combined texture analysis and machine learning in suspicious calcifications detected by mammography: Potential to avoid unnecessary stereotactical biopsies. Eur J Radiol. 2020;132:109309.

95. Zhou J, Tan H, Bai Y, et al. Evaluating the HER-2 status of breast cancer using mammography radiomics features. Eur J Radiol. 2019;121:108718.

96. Hosny A, Parmar C, Quackenbush J, Schwartz LH, Aerts HJWL. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:500-10.

97. Tran WT, Sadeghi-Naini A, Lu FI, et al. Computational radiology in breast cancer screening and diagnosis using artificial intelligence. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2021;72:98-108.

98. Bahl M. Artificial intelligence: a primer for breast imaging radiologists. J Breast Imaging. 2020;2:304-14.

100. Dheeba J, Albert Singh N, Tamil Selvi S. Computer-aided detection of breast cancer on mammograms: a swarm intelligence optimized wavelet neural network approach. J Biomed Inform. 2014;49:45-52.

101. Yala A, Schuster T, Miles R, Barzilay R, Lehman C. A deep learning model to triage screening mammograms: a simulation study. Radiology. 2019;293:38-46.

102. Fujioka T, Kubota K, Mori M, et al. Distinction between benign and malignant breast masses at breast ultrasound using deep learning method with convolutional neural network. Jpn J Radiol. 2019;37:466-72.

103. Raya-Povedano JL, Romero-Martín S, Elías-Cabot E, Gubern-Mérida A, Rodríguez-Ruiz A, Álvarez-Benito M. AI-based strategies to reduce workload in breast cancer screening with mammography and tomosynthesis: a retrospective evaluation. Radiology. 2021;300:57-65.

104. Fotin SV, Yin Y, Haldankar H, Hoffmeister JW, Periaswamy S. Detection of soft tissue densities from digital breast tomosynthesis: comparison of conventional and deep learning approaches. In Medical Imaging; 2016.

105. Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. EEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39:640-51.

106. Lee J, Nishikawa RM. Automated mammographic breast density estimation using a fully convolutional network. Med Phys. 2018;45:1178-90.

107. Hai J, Qiao K, Chen J, et al. Fully convolutional DenseNet with multiscale context for automated breast tumor segmentation. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:8415485.

108. Xu S, Adeli E, Cheng J, et al. Mammographic mass segmentation using multichannel and multiscale fully convolutional networks. Int J Imaging Syst Tech. 2020;30:1095-107.

109. Sathyan A, Martis D, Cohen K. Mass and calcification detection from digital mammograms using unets. In 2020 7th International Conference on Soft Computing & Machine Intelligence (ISCMI). Stockholm, Sweden; 14-15 November 2020.