Magnetic soft robots in medicine: material and structural designs for organ-specific applications

Abstract

Magnetic soft robots are emerging as biomedical tools for minimally invasive interventions. They synergize remote magnetic actuation with the compliance of soft materials to ensure safe navigation and therapy within delicate anatomical structures, such as the gastrointestinal tract, blood vessels, and urinary system. This review analyzes material-tissue toxicity and mechanical interactions and summarizes material innovations in magnetic hydrogels, elastomers, ferrofluids, and responsive composites. Organ-specific material and structural designs for clinical applications are discussed, showcasing advances of soft medical robots in targeted drug delivery, thrombus extraction, tissue sampling, thermal therapy, and in situ sensing. Furthermore, we focus on key translational challenges, including long-term biostability of materials, adaptive closed-loop control, and multifunctional system integration, which must be addressed to reach the full potential of magnetic soft robots for clinical applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Soft materials with mechanical compliance, deformability, and tunable responsiveness constitute essential components of medical soft robots[1-5]. These materials enable diverse motions, such as bending, folding, and crawling, enhancing adaptation to dynamic environments, especially in confined anatomical regions[6-10]. Their tissue-matching elastic moduli ensure safe interaction with delicate biological structures, minimizing mechanical irritation and inflammatory responses[11,12]. To achieve remote operation within the body, various actuation strategies have been explored, including magnetic[13-17], light[18-23], acoustic waves[24-29], chemical reactions[30-39], and thermal stimuli[40-43]. Among these approaches, magnetic actuation is particularly advantageous for biomedical applications[13,14,44-51]. First, biological tissues and organs exhibit high transparency to magnetic fields. Second, magnetic fields can be remotely applied without causing noticeable harmful effects on biological systems. Additionally, precise control can be achieved through tuning the parameters of magnetic fields, enabling real-time navigation and functional manipulation of soft robotic systems in vivo.

Magnetic soft robots typically consist of polymeric matrices embedded with magnetic particles[52-56]. The spatial arrangement of these particles defines the magnetization profile and governs deformation and locomotion. Advanced fabrication techniques - including template-assisted synthesis[57], 3D printing-assisted patterning[58,59] and microassembly[60-62] - optimize particle distribution to generate complex magnetization profiles. These profiles enable multimodal locomotion, such as rolling[63,64], crawling[57], walking[57,65], and swimming[66-69], and programmable shape morphing for grasping[57], folding[59,61], elongation[70], and twisting[71]. While these capabilities provide a versatile foundation for biomedical applications, their successful operation in vivo requires tailored adaptation to the specific physiological conditions of target organs. To meet these requirements, magnetic soft robots employ specific functional materials, structural designs, and programmable magnetization profiles to navigate complex physiological environments safely and effectively. For example, soft catheters with programmable magnetization profiles enable adaptive navigation through complex luminal environments, including the esophagus, blood vessels, and urethra, enhancing maneuverability while minimizing mechanical contact with surrounding tissues[72]. Moreover, the organ-specific material design of these robots further ensures biosafety and biochemical compatibility[12,73]. For gastrointestinal (GI) applications, materials such as silicone elastomers and hydrogels have been employed due to their chemical stability and resistance to acidic or alkaline fluids and enzymatic degradation[74,75]. In vascular environments, applying a lubricious hydrogel coating to the soft polymer matrix can substantially reduce mechanical trauma during navigation[76]. The stent-shaped[77] and helical-shaped[78] robots effectively reduce hydrodynamic drag and facilitate controlled locomotion within confined vascular channels when the magnetic driving force exceeds the combined resisting forces, including viscous drag from the surrounding fluid and frictional interactions at the vessel wall. Such designs allow the robot to sustain propulsion and perform controlled interventions in physiologically relevant flow conditions. Overall, integrating materials, structural architecture, and actuation strategies facilitates safer and more effective performance of magnetic soft robots in vivo.

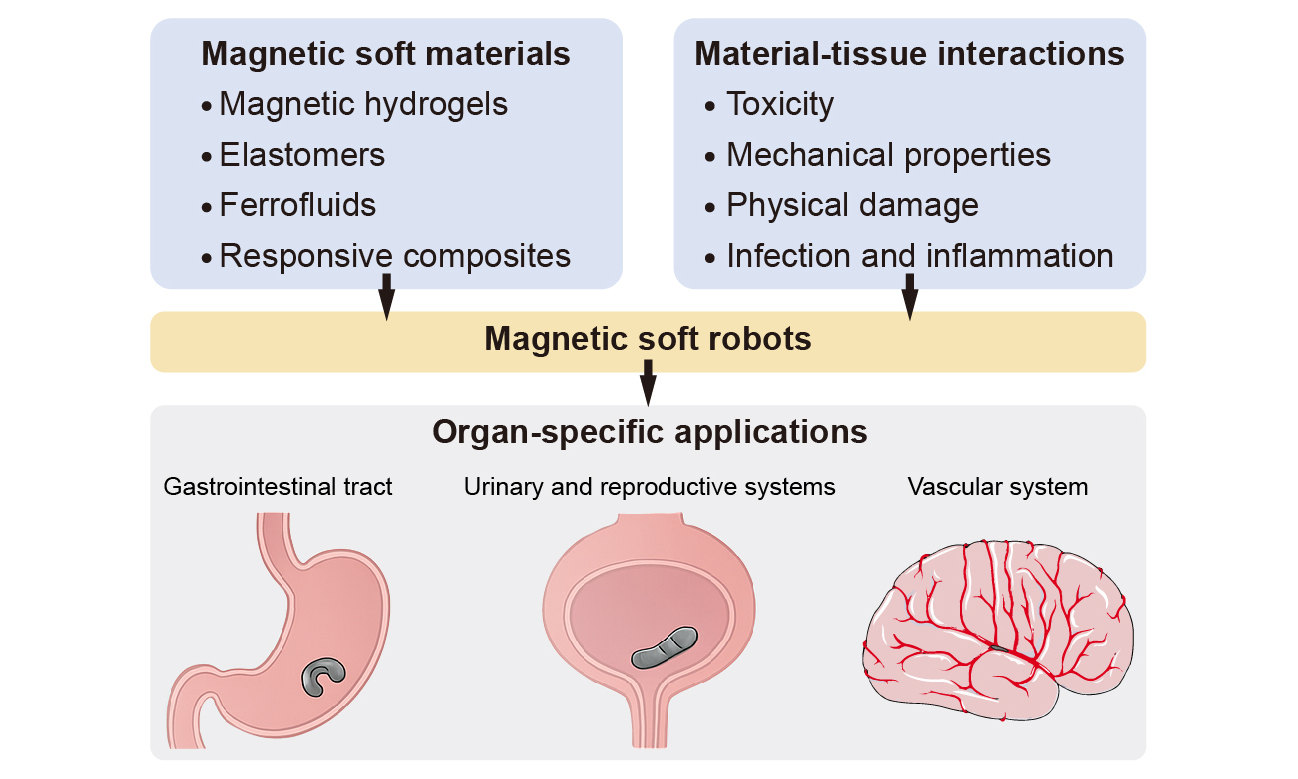

To ensure a comprehensive and unbiased synthesis of the field, we conducted a structured literature search across Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. The primary keywords used included “magnetic soft robot”, “magnetic soft materials”, “ferrofluid robot”, and “biomedical soft robot”. The results were filtered to include proceedings, articles, and review articles. We focused on peer-reviewed articles published within the past ten years, prioritizing studies that reported advances in material development, magnetic actuation strategies, organ-specific design principles, or biomedical applications in vivo or in clinically relevant models. Existing reviews focus on the actuation mechanisms and functionalization strategies[79,80] of the materials and soft components used in magnetic robots or the design, fabrication strategies, and biomedical applications of magnetic soft robots[9,81,82]. Since they lack an organ-centric perspective and clinical translation of magnetic soft robots depends on their capability to adapt to organ-specific challenges such as dynamic luminal contractions, variable biochemical milieus, and highly heterogeneous tissue-robot interface, this review discusses organ-specific materials and structural designs of magnetic soft robots [Figure 1]. We systematically discuss the development and biosafety of magnetic soft materials, focusing on four categories: magnetic hydrogels, silicone-based magnetic elastomers, ferrofluids, and magnetically responsive active composites. We analyze the chemical composition, mechanical properties, degradation behavior, and biocompatibility for in vivo implementations (Section MATERIAL DESIGN AND SAFETY ANALYSIS OF MAGNETIC SOFT ROBOTS). We also present a detailed assessment of organ-specific applications of small-scale magnetic soft robots in GI, urogenital, and vascular systems (Section ORGAN-SPECIFIC MATERIALS AND STRUCTURAL DESIGNS). We conclude the review by discussing the key challenges of the next-generation magnetic soft materials and robots for clinical translation, including the biofunctional material design, intelligent closed-loop control strategies, and multifunctional platform integration.

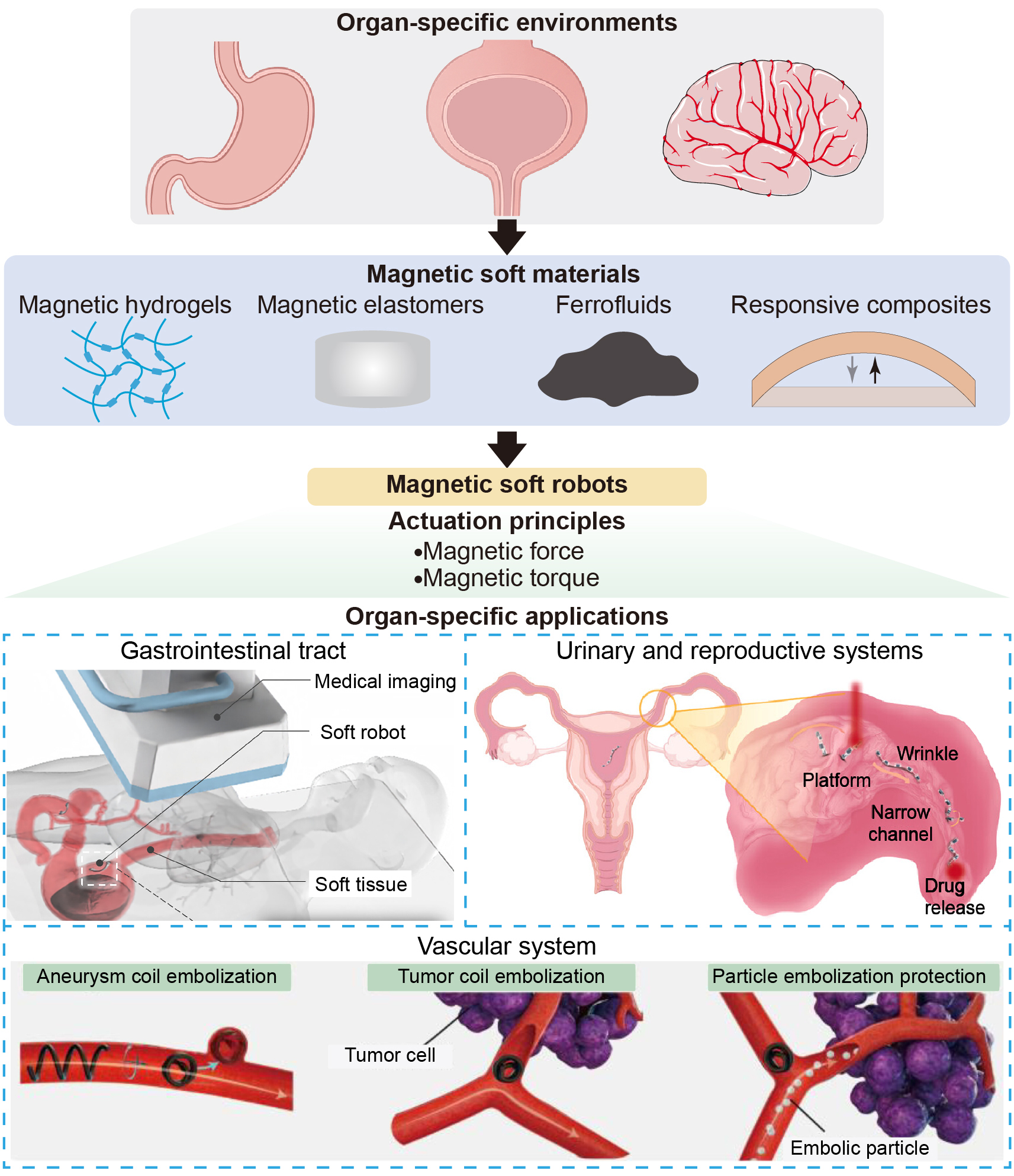

Figure 1. Schematic overview illustrating the hierarchical relationship between organ-specific environments, material properties, actuation principles, and clinical functions in magnetic soft robots. The vascular system subfigure provided by Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com).

MATERIAL DESIGN AND SAFETY ANALYSIS OF MAGNETIC SOFT ROBOTS

Magnetic soft materials govern the actuation efficiency, biocompatibility, durability, and clinical safety of soft robots[12,83]. A systematic understanding of material composition and biological responses is essential for safe and effective interactions in physiological environments. This section reviews four major categories of magnetic soft materials [Table 1] and discusses material-tissue interactions.

Classification of magnetic soft materials

| Type of magnetic soft materials | Example (Soft matrix + magnetic fillers) | Key properties | Biostability | Elastic modulus (Young’s modulus) | Main applications | Refs. | |

| Magnetic hydrogel | Alginate + Fe3O4/NdFeB | High-water content Biocompatibility Biological tissue softness Lower mechanical strength | Degrades in alkaline environments | 10-100 kPa | Cell manipulation Drug delivery | [74,85,88,97-99] | |

| Carrageenan + Fe3O4 | Degrades in alkaline environments | 40 kPa | |||||

| Gelatin + Fe3O4 | Dissolves at body temperature | 2.86 MPa | |||||

| Poly(vinyl alcohol) + NdFeB | Stable and difficult to degrade | 2.72-5.14 MPa | |||||

| Silicone-based magnetic elastomer | PDMS + NdFeB Ecoflex + NdFeB | Mechanical compliance High elastic strain Biocompatibility | Stable and difficult to degrade | 10 kPa-20 MPa | Magnetic-driven actuators Cargo delivery Minimally invasive surgeries | [57,75,76,112] | |

| Ferrofluids | Kerosene oil + Fe3O4 Mineral oil + Fe3O4 | Controlled reconfigurability Extreme deformability Toxic | NA | NA | Magnetic-driven actuators Cargo delivery | [116,119,122] | |

| Corn oil + Fe3O4 | Controlled reconfigurability Extreme deformability Biocompatibility | Degrades under lipase activity and oxidation | [125] | ||||

| Silicone oil + Fe3O4 | [128] | ||||||

| Magnetically responsive active composites | Shape memory polymers | Shape memory polymer resin + NdFeB Acrylate-based amorphous polymer + NdFeB | Shape fixation Stimuli-responsive Biocompatibility | Biodegradable | MPa (rubbery state) → GPa (glassy state) | Magnetic-driven actuators Cargo delivery | [133,134] |

| Liquid crystal elastomers + NdFeB | Shape fixation Stimuli-responsive Magnetic reprogrammed Reversible large deformation | NA | [136-138] | ||||

Magnetic soft materials

Magnetic hydrogel

Magnetic hydrogels are composed of cross-linked hydrophilic polymer networks incorporated with superparamagnetic nanoparticles[84-88] (typically iron oxide). They exhibit high water content and a low mechanical modulus, which is important for minimizing mechanical irritation at the material–tissue interface in biomedical applications[89-99]. Owing to these favorable characteristics, robots fabricated from magnetic hydrogels have been widely employed in biomedical applications, particularly in targeted delivery[100-103]. For instance, an iron gel composed of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, alginate, and adipic acid dihydrazide has been developed as a magnetically active scaffold capable of carrying therapeutic cargo or cells[84]. Similarly, a magnetic hydrogel composed of neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB), Fe3O4 nanoparticles, and alginate has been developed as a soft capsule microrobot capable of carrying therapeutic cargos[97].

Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) has also been used to develop thermoresponsive magnetic soft robots with dual actuation strategies, i.e., photothermally induced deformation for biopsy tissue and magnetically guided navigation for targeted delivery[104]. However, their inherently low mechanical strength, primarily due to high water content, limits their suitability for dynamic and high-strain environments, such as the GI or cardiovascular systems.

Silicone-based magnetic elastomer

Silicone-based magnetic elastomers, consisting of hard magnetic particles such as NdFeB and soft elastomeric materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)[75,76,105-107] and Ecoflex[106,108-112], represent a class of durable, high-performance magnetic soft materials. These elastomers exhibit tunable elastic moduli in the MPa range, excellent fatigue resistance, and long-term mechanical stability. Moreover, they can be encoded with predefined permanent magnetization patterns, enabling diverse motion modes such as rolling, jumping, and walking under low-frequency magnetic fields, as well as carrying and releasing cargo through shape morphing[57]. These multimodal motions are particularly advantageous for navigating the robots in complex geometries of the GI tract, blood vessels, or respiratory pathways.

However, their non-biodegradable nature necessitates post-operative retrieval methods, often via surgical or endoscopic means, which may limit clinical practicality. The potential cytotoxicity of ferromagnetic particles, especially under corrosive physiological conditions, further underscores the need for robust encapsulation and biocompatible coatings.

Ferrofluids

Ferrofluids are colloidal dispersions of nanoscale magnetic particles, typically Fe3O4, stabilized in polar (e.g., water) or non-polar (e.g., oil-based) carrier liquids[113-118]. Due to their liquid-like behavior and magnetic responsiveness, ferrofluids can undergo magnetically induced deformation[119], splitting[120-122], or re-merging under an applied magnetic field. These features enable reconfiguration of the soft robots in confined or torturous biological environments, such as vascular or GI lumens. Their inherently low viscosity and soft interfacial compliance enable minimally invasive and atraumatic interactions with soft tissues, making them ideal for short-term biomedical interventions[123-127].

Ferrofluid-based soft robotic systems have been engineered into diverse configurations, including liquid capsules for targeted cargo delivery, omnidirectional ciliary matrices for wireless biofluid pumping, and adaptive liquid skins for constructing microscale soft machines[123]. However, the presence of unbound magnetic nanoparticles leaked from ferrofluid raises significant concerns regarding systemic toxicity, long-term biodistribution, and accumulation in critical organs such as the liver, spleen, and brain. Moreover, physiological environments characterized by fluctuating pH, ionic strength, and protein-rich media can compromise colloidal stability, promoting aggregation, sedimentation, or magnetic shielding effects. Although ferrofluids offer excellent deformability and magnetic responsiveness, additional investigations are required to develop biocompatible oil-based ferrofluids suitable for in vivo use. One promising direction is the use of biologically compatible carrier oils to mitigate toxicity and improve physiological stability. Recent studies have demonstrated that ferrofluids formulated with corn oil[125] or silicone oil[128] and Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibit reduced cytotoxicity and improved colloidal stability, with successful in vivo validation in mouse and rabbit models, respectively.

Magnetically responsive active composites

Magnetic soft composites deform elastically under external magnetic fields and revert upon field removal, which limits their use in applications requiring semipermanent shape retention. To retain deformation or desired shapes without continuous external stimuli, thermally responsive polymers, including shape memory polymers and liquid crystal elastomers, have been widely integrated into magnetic soft matter.

Shape memory polymers typically remain stiff below their thermal transition temperature, becoming soft and deformable upon heating[129-134]. Incorporation of magnetic particles allows shape modulation through remote magnetic actuation[134]. At elevated temperatures, the composite can be reconfigured into a temporary shape, which is fixed upon cooling. Subsequent reheating induces shape recovery in the absence of magnetic fields, while heating under magnetic actuation enables deformation into alternative geometries. Such capabilities have been exploited in applications including deployable scaffolds, steerable catheters, and shape-adaptive implants. Liquid crystal elastomers[135-138], composed of loosely cross-linked polymer networks bearing anisotropic mesogens, exhibit programmable, anisotropic deformation through nematic-isotropic phase transitions. Above the critical temperature, contraction along aligned mesogens facilitates reversible motion. Patterned mesogen alignment further enables complex actuation modes such as bending and folding. Recent advances have incorporated hard magnetic particles into liquid crystal elastomers to create untethered soft robotic systems with reprogrammable magnetization profiles. These composites enable multimodal locomotion, such as walking on solid substrates and swimming via thermally induced shape changes and magnetic steering[135,136].

The multifunctional responsiveness and structural programmability of magnetically responsive active composites present a promising pathway for developing intelligent soft robotic platforms for biomedical intervention. However, their clinical translation critically depends on a deeper understanding of long-term biocompatibility, immunogenic responses, and degradation mechanisms under physiological conditions.

Magnetization programming strategies

Recent progress in fabrication technologies has enabled increasingly sophisticated magnetization control in small-scale magnetic soft robots. These approaches can be broadly classified into four categories: mold-assisted programming[57,69,134,139-141], spray-assisted programming[72], 3D-printing-assisted programming[58,59,142-145], and microassembly-assisted programming[60-62]. Each method supports distinct levels of geometric complexity, spatial magnetization resolution, and functional integration.

Mold-assisted programming represents the most established strategy, particularly for robots with simple geometries and deformation modes. A soft composite sheet containing hard-magnetic particles is first mechanically constrained into a temporary 3D shape and then magnetized to saturation under a uniform magnetic field[57,141]. After release, the planarized structure retains a programmed, spatially varying magnetization profile that drives predictable 3D deformation under external fields. Such methods have enabled millimeter-scale swimmers exhibiting travelling-wave propulsion and multimodal locomotion, including rolling, crawling, and jumping. However, the approach offers limited freedom in magnetization distribution and internal architecture.

To overcome these constraints, spray-assisted programming has been introduced as a minimalist and highly adaptable strategy[72]. A magnetically responsive coating composed of polyvinyl alcohol, gluten, and iron particles is uniformly sprayed onto diverse substrates, including 1D filaments, thin sheets, and 3D objects. The resulting magnetic film (approximately 100-250 μm thick) preserves the underlying geometry while imparting actuation capabilities several hundred times its own weight. Robots fabricated using this method can be reprogrammed and disintegrated on demand and have demonstrated potential in catheter navigation and targeted drug delivery. Three-dimensional-printing-assisted programming provides substantially greater flexibility in design and control. Extrusion-based direct ink writing enables layer-by-layer deposition of shear-thinning magnetic inks, with ferromagnetic particles reoriented in situ using a magnetic field applied at the print nozzle[142,143,145]. This allows voxel-level programming of magnetic domains throughout a 3D architecture. Light-based printing techniques, such as ultraviolet lithography and photopolymerization, offer even higher spatial resolution[59]. By orienting pre-magnetized particles before local curing, these systems can encode intricate 3D magnetization profiles capable of multi-axis bending, twisting, large-angle reconfiguration, and coupled deformation modes. These strategies have supported the development of auxetic metamaterials, reconfigurable soft electronics, and microrobots for manipulation and drug delivery.

As magnetic soft robots approach submillimeter dimensions, traditional methods become increasingly restrictive. Microassembly-assisted programming addresses this limitation by enabling bottom-up construction of complex 3D magnetic architectures from microscale components. This strategy affords arbitrary geometry, multi-material integration, and high-resolution magnetization encoding. Resulting robots can achieve sophisticated mechanical behaviors, including reversible shape reconfiguration, peristaltic pumping, targeted biopsy, and robust locomotion in curved, fluid-filled tubular environments[60]. The expanded flexibility in design offered by microassembly is particularly well-suited for biomedical microrobotics. Finally, modular strategies have begun linking advanced magnetization control with functional payload integration. Approaches based on adhesive micro-patterning or localized assembly enable the precise placement of magnetized elements alongside pH-responsive membranes, localization electronics, or therapeutic layers[61]. These developments point toward future soft robotic systems that combine high-resolution magnetic encoding with sensing, actuation, and therapeutic functionalities.

Magnetic soft material-tissue interactions

Toxicity

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles are widely employed as magnetic fillers, due to their high magnetic resonance traceability[146,147] and magnetothermal conversion efficiency in hyperthermia therapies[148-152]. However, challenges arise when ferromagnetic particles are incorporated into soft matrices[153-155]. Ferromagnetic particles such as NdFeB are prone to corrosion in the aqueous environments of hydrogels owing to their high iron content. As a result, bare NdFeB particles are generally considered to cause moderate cytotoxicity. NdFeB magnets coated with corrosion-resistant metals or metal alloys have shown good biocompatibility and have been employed in orthodontic and orthotic devices[153,156]. Similarly, a layer of biocompatible and non-cytotoxic silica can be applied to the particle surface to prevent corrosion[76,98]. Magnetic soft robots fabricated by embedding silica-coated NdFeB particles in alginate hydrogels or PDMS matrices have exhibited low cytotoxicity when co-cultured with gastric epithelial cells and mouse bone mesenchymal stem cells[66]. Notably, for intravascular applications, hemocompatibility of the magnetic soft materials must be rigorously assessed, often requiring surface modifications to prevent thrombogenesis[157,158].

Mechanical properties and physical damage

Material stability is a critical determinant of long-term biocompatibility, encompassing parameters such as mechanical stiffness, degradation kinetics, and surface morphology. One key advantage of magnetic soft materials is their low elastic modulus[8,12,159]. This property closely matches that of soft tissues such as the intestinal wall, bladder, and vasculature. The resulting mechanical compliance allows the robots to contact tissue surfaces without damage, enabling controlled navigation and targeted delivery across diverse anatomical environments. To traverse complex luminal environments, such as tortuous blood vessels or narrow esophageal passages, magnetic soft robots can be designed with specialized mechanical structures or customized magnetization patterns, allowing smooth navigation without causing tissue injury. A magnetically steered continuum robot employs helical surface protrusions and an articulating magnetic tip to translate rotational input into forward motion, thereby reducing mechanical stress on vessel walls[160]. Similarly, various magnetization patterns in multiple sections of the magnetic skin (M-skin) catheter enable controlled deformation, allowing adaptation to sharp corners and narrow passages in the throat, esophagus, and urethra[72]. This design allows rapid directional steering and reduces the risk of extrusion against delicate tissues. Beyond initial mechanical compliance, degradation dynamics must be finely tuned to maintain functional performance throughout the intended therapeutic window[161,162]. Premature degradation may impair robotic functionality, whereas delayed resorption prolongs foreign body presence, increasing the likelihood of immune activation or infection.

Surface topography further modulates tissue-material interactions. Soft and conformal interfaces are associated with attenuated immune activation, potentially reducing inflammatory responses caused by stiffness mismatches at the tissue-robot interface. In contrast, rough or irregular surfaces are more likely to trigger foreign body responses, leading to increased macrophage adhesion, fibrosis, and impaired device performance[12]. To overcome these challenges, surface engineering strategies such as hydrogel coatings have been employed to minimize interfacial irritation while preserving actuation capabilities[98,163].

Infection and inflammation

In clinical settings, device-associated infections account for a substantial proportion of healthcare-related complications and may result in severe complications such as septic shock and mortality[164]. To minimize these risks, both the fabrication of magnetic soft robots and their interventional deployment must adhere to stringent aseptic protocols. In particular, the motion or prolonged implantation of magnetic soft robotic systems in mucosal environments can compromise epithelial integrity, leading to microbial translocation and localized immune responses[165]. Moreover, inflammation may be further exacerbated by surface-induced friction and microtrauma at the robot-tissue interface. To mitigate these responses, biocompatible hydrogel-based coatings, such as polydimethylacrylamide, have been engineered to reduce interfacial shear stress and friction[76]. Experimental results have shown a 10-fold decrease in the friction coefficient as a result of the lubricious hydrogel skin, thereby improving safety and minimizing vessel-wall irritation. For clinical applications involving direct contact with circulating blood, such as magnetically guided intravascular soft robots, rigorous evaluation of hemocompatibility is essential. The blood environment is highly dynamic and protein-rich, which promotes protein adsorption on material surfaces and increases the likelihood of thrombus formation. This risk can be further exacerbated in venous circulation, where slower flow rates and longer residence times may accelerate thrombus growth compared with arteries. Careful material assessment is therefore essential to minimize hemolysis, thrombosis, and other adverse responses during therapeutic use[160,166]. Achieving immunological compatibility and mitigating the foreign-body response are therefore essential for ensuring long-term safety, functional reliability, and clinical feasibility[167].

ORGAN-SPECIFIC MATERIALS AND STRUCTURAL DESIGNS

Recent advances in biomedical applications of magnetic soft medical robots are reviewed in this section, with focused discussions on targeted drug delivery, endoluminal diagnostics, microsurgical assistance, and localized therapies. We highlight representative design strategies and performance in physiological environments, demonstrating their roles in advancing precision medicine and minimally invasive intervention [Table 2].

Summary of representative works in terms of different organ systems

| Organ system | Environmental characteristics | Typical materials | Robot size | Actuation method | Magnetic field strength | Performance metrics | In vivo model | Ref. |

| Gastrointestinal tract | Elastic modulus: 1-10 kPa; Intestine: 20-40 kPa Intestine diameter: 2.5-3.8 cm pH: Esophagus: 5-7 Stomach: 1-4 Intestine: 6.5-7 | Ecoflex/PDMS + NdFeB | Sub-millimeter | Magnetic torque | 50 mT | NA | NA | [60] |

| PDMS + NdFeB | Centimeter | Magnetic torque | 30 mT | Delivery volume: 121.6 mm3 | Rabbit | [176] | ||

| Ecoflex + NdFeB | Millimeter | Magnetic torque | 30 mT | pH ranges from 1 to 8 Viscoelasticity ranges from 0.5 to 11.3 kPa | Mouse | [177] | ||

| Urinary and reproductive systems | Bladder tissue’s Young’s modulus: 315.05 ± 49.64 kPa horizontally and 283.62 ± 57.04 kPa vertically Diameter of the oviduct: 1-4 mm | Ecoflex/Hydrogel + NdFeB | Millimeter | Magnetic torque | 3 mT | Drug release time of 14 ± 2 s | Ex vivo pig’s oviduct | [186] |

| Silicone elastomer + Co nanowire | Millimeter | Magnetic torque | 10 mT | The efficiency toward the biofilm elimination (97.22 ± 6.15% for P. aureginosa and 78.27 ± 8% for S.aureus) | NA | [187] | ||

| Ecoflex + NdFeB | Centimeter | Magnetic torque and magnetic force | A 100 mm cubic permanent magnet | Pressurize bladder ~ 37 cmH2O to voiding | Porcine | [189] | ||

| Vascular system | Diameters: 1-4 mm Dynamic viscosity: 4.4 cP Average flow speed: 11.3 cm/s to 25.5 cm/s Young’s modulus: 1-3 MPa | PDMS + NdFeB | Millimeter | Magnetic torque and magnetic force | A 50 mm cubic permanent magnet | Anchored securely against flows up to 260 mm/s Achieved ~ 0.18 mm/s under pulsatile flow | NA | [77] |

| Silicone oil + Fe3O4 | Millimeter | Magnetic force | 40 to 230 mT | Effectively remove thrombus | Rabbit | [128] | ||

| Thermoplastic elastomer + NdFeB | Millimeter | Magnetic torque and magnetic force | 40 mT | Demonstrated flow resistance up to 200 mm/s Achieved 0.32 mm/s (upstream) and 1.75 mm/s (downstream) against 100 mm/s flow The formed thrombus can resist a pressure of up to 22 kPa | Rabbit | [78] |

Gastrointestinal tract

The GI tract presents a dynamic and chemically diverse environment, comprising anatomically distinct regions such as the stomach, small intestine, and colon. Each segment poses specific challenges related to geometry, motility, and biochemical composition. Lumen diameters range from several centimeters in the stomach to just over one centimeter in the distal intestine. Moreover, peristaltic and segmental contractions continuously reshape the tract. Chemically, the environment spans a broad pH spectrum, from the highly acidic gastric lumen to the enzyme- and microbiota-rich milieu of the intestines. These region-specific physiological conditions impose stringent requirements on the design of magnetic soft robots for GI applications. To ensure safe navigation and maintain mucosal integrity, robots are typically fabricated from pH-stable materials such as elastomers and hydrogels[74,75]. Tailoring both material properties and structural features to the physiological and anatomical context of each GI segment enables magnetic soft robots to achieve site-specific drug delivery[168-176], diagnostic sampling[177-179], and localized therapy[180-182] with improved safety and therapeutic precision.

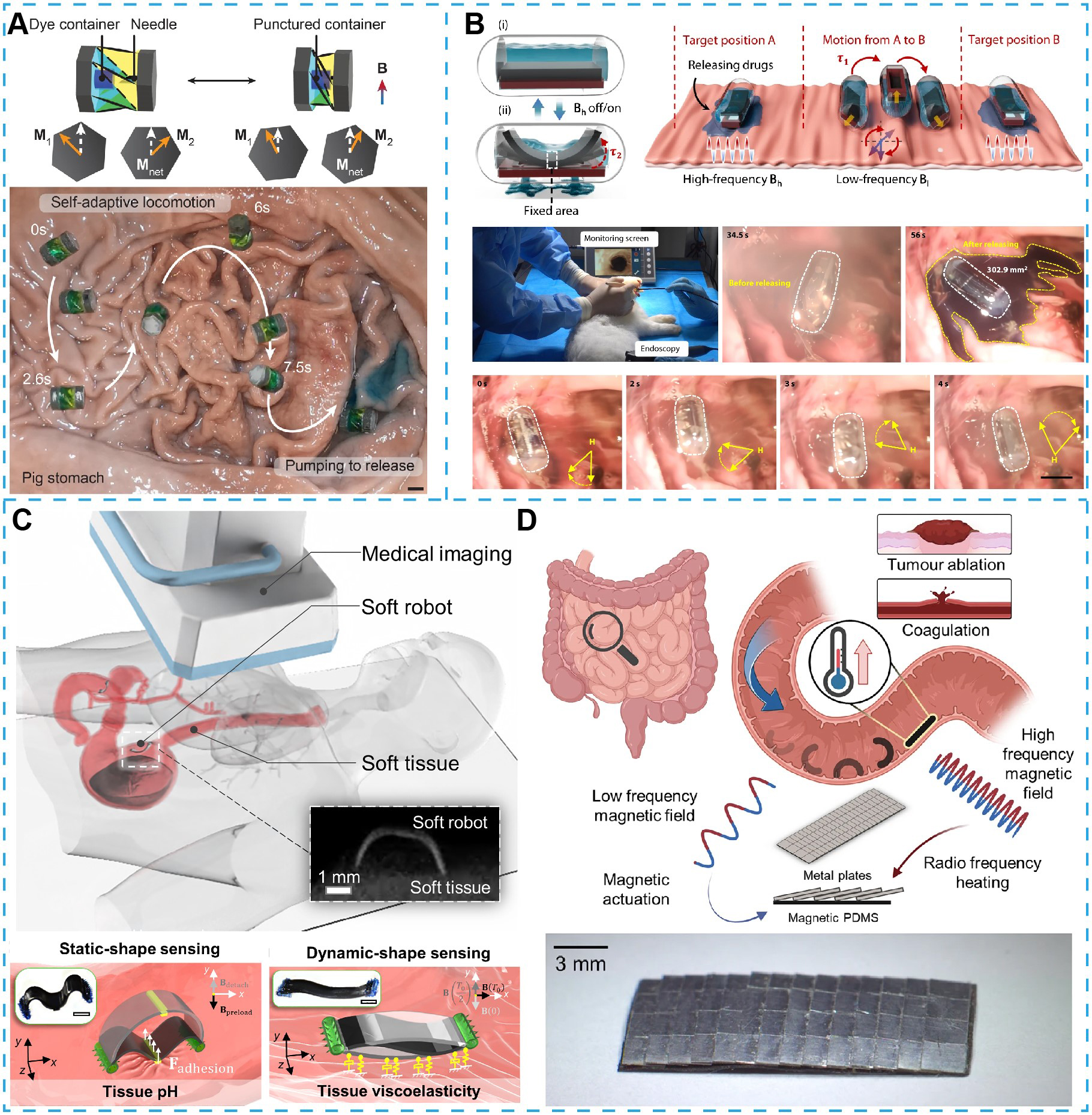

In gastric drug delivery, magnetic soft robots provide unique advantages by integrating mechanically adaptive architectures with magnetic actuation. A representative example is the magnetically actuated capsule endoscope, designed with elastomeric shells and flexible hinges that passively deform upon contact with the gastric wall[174]. This mechanical compliance minimizes mucosal irritation and enables stable locomotion through anatomical constraints. With functional components including internal magnets and localized drug reservoirs, the capsule enables rolling locomotion driven by magnetic torque for targeted drug delivery. External magnetic force then induces axial deformation of the capsule body, triggering the release of the therapeutic payload. To mitigate concerns regarding long-term magnet retention, reconfigurable miniaturized soft robots have been proposed. Voxel-based magnetic assembly permits fabrication of submillimeter-scale elastomeric capsules with embedded hard magnetic particles[60]. These microrobots realize magnetic rolling and programmable pressure-responsive liquid release. Origami-inspired structural reconfiguration strategies have enabled the development of foldable gastric robots with multimodal behaviors[173,175]. Cylindrical Kresling-pattern origami designs incorporating thin magnetic plates demonstrate reversible folding under rotating magnetic fields, which facilitates rolling locomotion, flipping movements, and targeted release [Figure 2A]. These robots can actively contract to expel liquid cargo when exposed to oppositely rotating fields. Their ability to navigate uneven terrains and achieve precise payload deployment has been validated through ex vivo studies in the porcine stomach. Peristaltic motion in the GI tract can compress soft capsules, resulting in unintended drug leakage. To address this challenge, a magnetically driven capsule has been designed with soft valve structures, whose opening and closing are actively regulated through the interplay of magnetic gradient force and torque to enable controlled drug release[176]. Meanwhile, a magnetic actuation strategy based on multifrequency response control allows decoupled regulation of global capsule locomotion and local valve response, with high-frequency fields triggering localized drug release while low-frequency fields driving overall motion. This approach minimizes unintended leakage caused by GI peristalsis while preserving multifunctional capabilities, including targeted drug delivery, selective dual-drug release, and in situ sampling. Targeted delivery with minimal mechanical disruption using this system has been demonstrated in rabbit models [Figure 2B]. To address the challenge of poor drug retention in the GI environment, magnetic soft robots with integrated bioadhesive interfaces have been developed[75,183]. Tissue adhesion is achieved via both non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces) and covalent bonding. For targeting multiple lesions, a multilayer robot has been developed for on-demand adhesion to distinct sites in the stomach of a live porcine model[75].

Figure 2. Small-scale magnetic soft robots in the GI tract for targeted delivery. (A) A wireless amphibious origami-inspired millirobot capable of self-adaptive terrestrial locomotion and remotely controlled delivery of liquid therapeutics through magnetic actuation[173]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature; (B) Magnetically actuated capsule robots exhibiting multimodal mechanical behaviors and tunable release profiles for precision-targeted therapeutic interventions[176]. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature; (C) Concept of wireless miniature soft robots for in situ assessment of gastrointestinal tissue properties, including adhesion, pH, and viscoelasticity, with an X-ray image illustrating localization within porcine small intestine[177]. Copyright 2023 American Association for the Advancement of Science; (D) Conceptual diagram and experimental demonstration of an unbounded magnetic soft robot achieving dynamic intestinal manipulation using integrated heating modules[181]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature. GI: Gastrointestinal.

Beyond drug delivery, magnetic soft robots have evolved into multifunctional platforms for complex therapeutic and diagnostic tasks in the stomach. By combining reconfigurable architectures with magnetic actuation, these devices can navigate confined gastric environments while enabling minimally invasive interventions[179,182,184]. One key application is autonomous tissue biopsy, where mechanical safety and precision are paramount. Recent capsule-type soft robots employ flexible mechanisms, such as Sarrus linkages, to regulate needle penetration force, maintain axial alignment, and incorporate intrinsic safety locks that prevent unintended puncture[180]. With anti-slip pads and localized magnetic potential energy, these robots achieve stable fixation against the gastric wall to perform controlled vertical tissue penetration. The Sarrus linkage generates a tunable force range of 0.4-0.6 N, sufficient to retract the needle from tissue while allowing full collapse under magnetic actuation, ensuring precise and safe sampling. This design has realized submucosal tissue sampling with minimal collateral damage in a gastric phantom, offering a platform for noninvasive histopathological analysis. Magnetically actuated soft robots have also been adapted for in situ mechanical and chemical sensing[177-179]. Through magnetoelastic materials and bioadhesive footpads, these robots exhibit locomotion via crawling or climbing, enabling temporary fixation at the mucosal surface[177]. Tissue contact driven by magnetic torque allows localized measurements of biomechanical properties such as detachment forces. Integration of pH-responsive adhesives further enables environmental sensing, which is useful for detecting ulceration or inflammation-associated acidity. This approach unites physical probing with biochemical diagnostics in a single system [Figure 2C].

Fluidic magnetic soft robots further expand this paradigm. By embedding magnetic microparticles in polymeric networks such as poly(vinyl alcohol), reconfigurable slime robots that combine high deformability with fast response to magnetic fields have been developed[70]. These soft-bodied systems can transform into C-shaped or toroidal configurations to encapsulate and retrieve foreign objects, such as accidentally ingested button batteries. Their high tissue compliance and extensibility reduce mucosal trauma. Additionally, magnetic soft robots with integrated heating modules have demonstrated potential for remote thermal therapy[181,185]. Bilayer designs comprising surface-mounted aluminum foil arrays for Joule heating and underlying magnetic elastomers allow robots to be navigated precisely to the site of interest[181]. Alternating magnetic fields induce localized heating at clinically relevant temperatures (> 70 °C) for coagulation or ablation in hemorrhagic lesions [Figure 2D]. This convergence of targeted navigation, adaptive locomotion, and energy delivery offers a unified approach to minimally invasive treatment.

Urinary and reproductive systems

The urinary and reproductive systems are responsible for essential physiological processes, including urine storage and excretion, gamete transport, fertilization, and childbirth. These systems feature narrow, tortuous lumens, such as the ureters and fallopian tubes, often measuring a few millimeters in diameter. They also exhibit rhythmic contractions that propel fluids and display high wall compliance, allowing substantial deformation under physiological pressure changes. The mucosa-lined walls are richly vascularized and densely innervated, making them particularly sensitive to mechanical stress and highly responsive to irritation or injury. In this environment, small-scale magnetic soft robots have emerged as promising minimally invasive surgical tools. Their intrinsic compliance and ability to morph their shape allow them to navigate and conform to confined, curvilinear spaces, minimizing the risk of tissue damage. Meanwhile, magnetic actuation offers wireless, remote control over their locomotion and functional operations, such as targeted drug release, tissue sampling, and biofilm disruption.

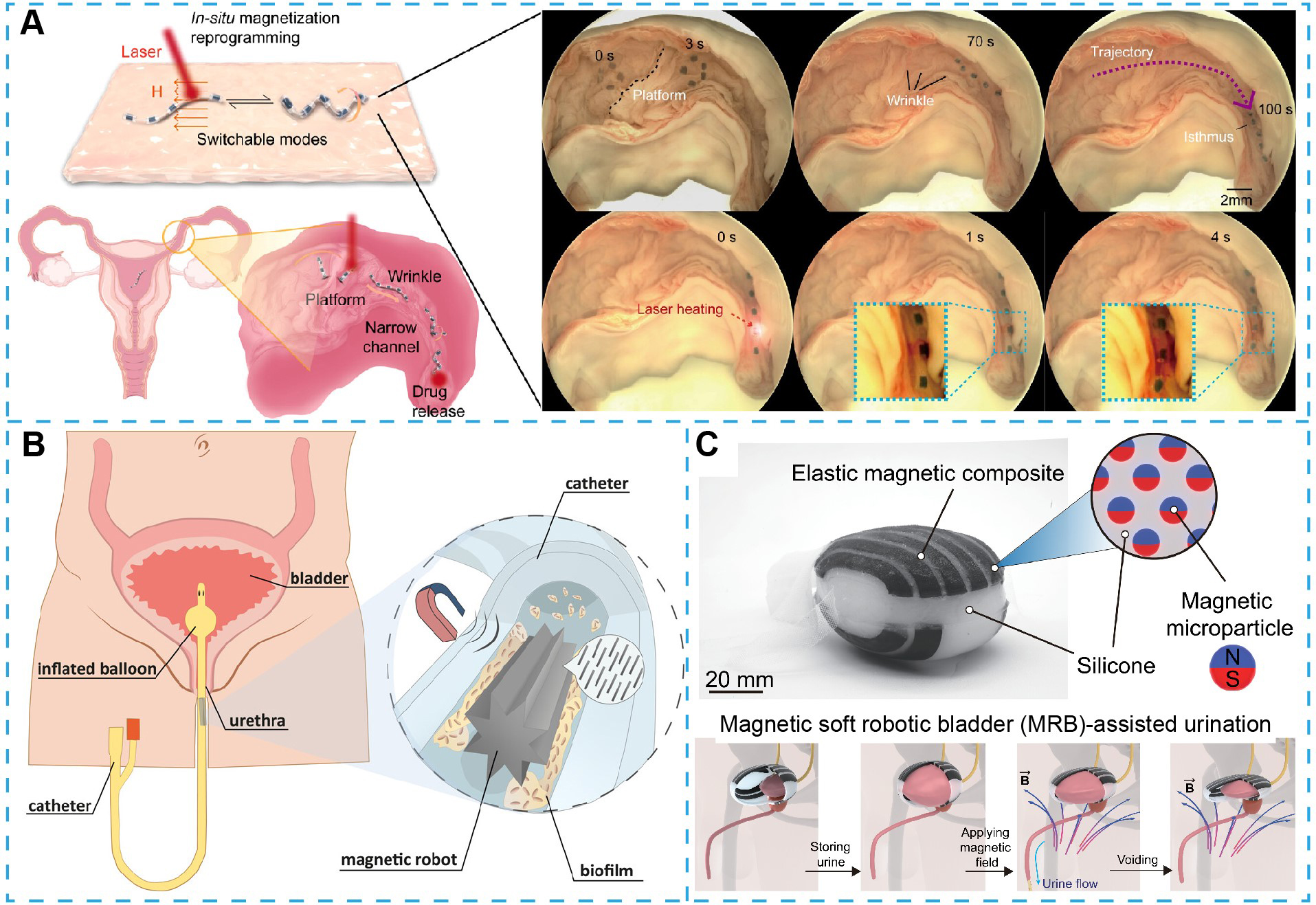

Recent advances in magnetic soft robots have demonstrated targeted intervention capabilities in the oviduct. A representative system features magnetic segments interconnected via hyperelastic linkages, with each segment embedded with photothermal-responsive hydrogels[186]. This design allows localized gel-sol transitions upon near-infrared stimulation, enabling programmable shape transformation under low-strength magnetic fields. In ex vivo porcine oviduct models, robots with dynamically transitioned locomotion modes were navigated through folded, ciliated ducts and executed photothermally triggered drug release [Figure 3A]. Beyond navigation and delivery, magnetic soft robots have been developed for biofilm disruption - an unmet clinical need in long-term urinary catheterization[187]. A star-shaped octagram soft robot, fabricated from silicone elastomer embedded with cobalt nanowires, demonstrates strong shear-force generation under rotating magnetic fields [Figure 3B]. In urethral catheter models, this motion effectively dismantled biofilm aggregates without damaging the lumen or requiring chemical agents, offering a mechanical, minimally invasive solution to catheter-associated infections.

Figure 3. Small-scale magnetic soft robots for clinical applications in the urinary and reproductive systems. (A) Schematics and experimental demonstration of magnetic millirobots with switchable locomotion modes, including woodlouse-like rolling, flipping, snake-like gliding, and sperm-like rotation, designed to actively traverse complex anatomical barriers such as platforms, folds, and narrow channels in the oviduct for targeted drug delivery[186]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society; (B) Conceptual illustration of magnetic soft robots actuated by external magnetic fields to mechanically disrupt and remove biofilms from urethral catheter surfaces, reducing the risk of infection and device failure[187]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (C) Design of a magnetically actuated soft robotic bladder-assisted urination, constructed from silicone elastomer embedded with magnetic particles, intended to generate contractile force on demand to facilitate urination in cases of an underactive bladder[189]. Copyright 2022 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

For autonomous biopsy in the upper urinary tract, thermally triggered magnetic microgrippers have emerged as a novel tool. Fabricated from stress-engineered multilayer films, these devices complete self-folding into cage-like configurations at body temperature to capture tissue samples and can be retrieved by a magnet[188]. When delivered via standard ureteral catheters, these microgrippers have demonstrated efficient tissue sampling in ex vivo porcine ureter models, showcasing the synergy between smart materials and wireless control in confined environments. In addition, magnetic soft robots have been engineered as assistive devices to address lower urinary tract dysfunctions. For underactive bladder management, a soft robot composed of silicone elastomer embedded with NdFeB particles generates torque and compression upon external activation, mimicking detrusor contractions[189]. During bladder filling, the device passively conforms to bladder expansion, thereby preserving native bladder mechanics. A hydrogel coating reduces mechanical friction and improves surface biocompatibility. Upon actuation, the device produces sufficient intravesical pressure for controlled voiding, illustrating a non-pharmacological and organ-conforming approach to bladder assistance [Figure 3C].

Vascular system

The vascular system is composed of a complex network of arteries, veins, and capillaries, each exhibiting distinct anatomical features, including variations in diameter, curvature, branching architecture, and wall elasticity. These features range from large, elastic arteries to capillaries with submillimetre lumens, presenting considerable challenges for therapeutic intervention. Clinically, vascular pathologies such as atherosclerosis, thrombosis, aneurysms, and ischemic stroke remain leading contributors to morbidity and mortality worldwide. Conventional treatment modalities, including catheter-based drug delivery, mechanical thrombectomy, and stent placement, exhibit efficacy in specific scenarios but are often constrained by limited access to distal or tortuous vasculature, procedural invasiveness, and risks of vascular perforation. Furthermore, systemic pharmacotherapies, such as anticoagulants and thrombolytics, are frequently hindered by off-target effects and an increased risk of haemorrhagic complications, highlighting the need for more precise and minimally invasive vascular interventions. Magnetic soft robots have emerged as a promising modality to address critical limitations associated with traditional catheter-based approaches and systemic pharmacological therapies[76,94,190-194]. They allow robots to access distal anatomical sites and perform localized therapeutic tasks such as targeted drug release[77,94,195], thrombus extraction[191,196], and controllable embolization[78,197].

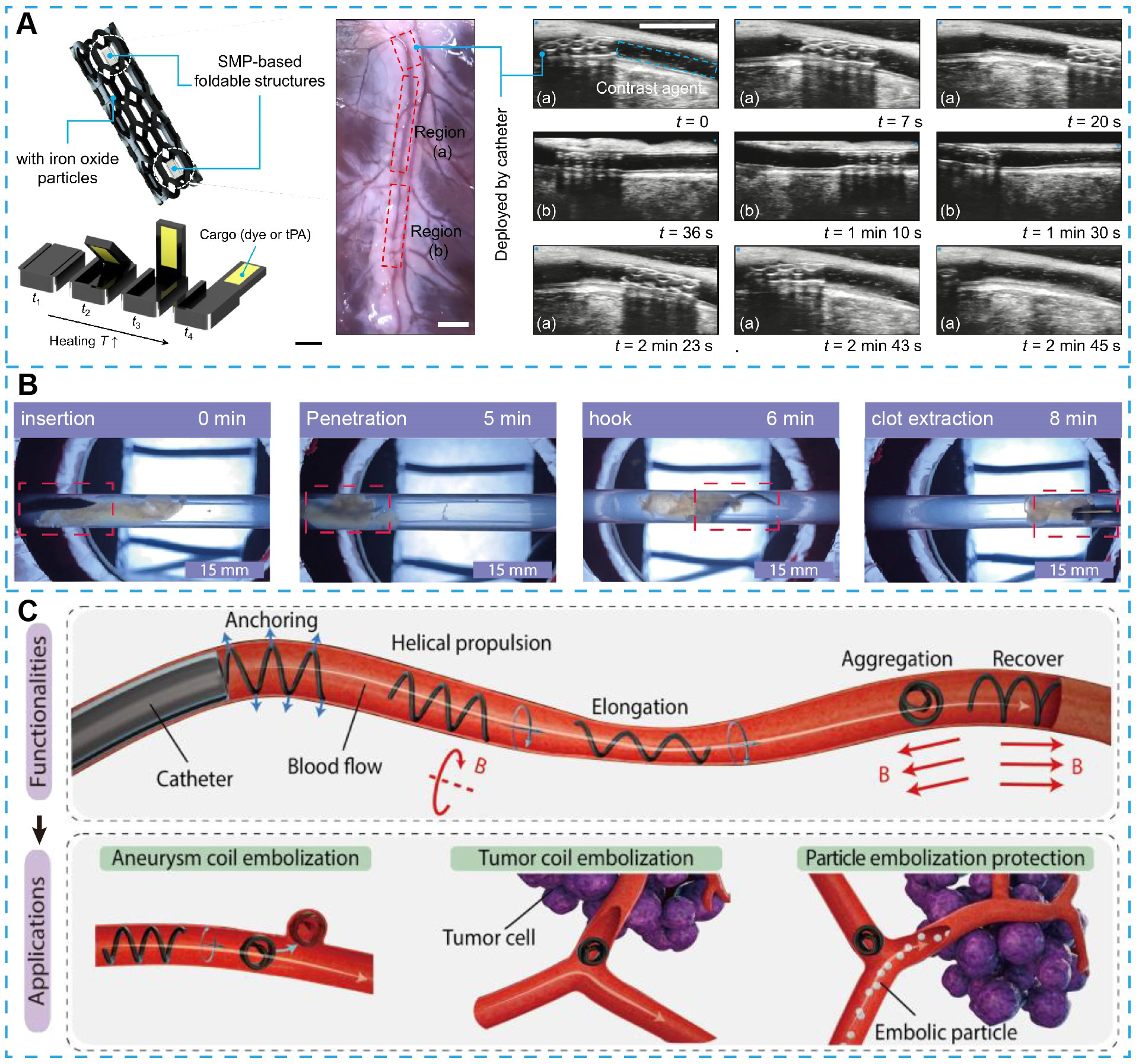

To complete targeted delivery, a stent-like magnetic soft robot has been developed for remote navigation and therapy in M4 segment of the middle cerebral artery[77]. The robot incorporates a flexible, morphologically adaptive body with shape-memory polymer components. Successful traversal through vascular phantoms, including luminal constrictions to 1.0 mm, bifurcations up to 120°, and physiologically relevant pulsatile flow velocities (~ 26 cm/s) has been demonstrated. Upon reaching the target location, wireless radiofrequency stimulation induces localized thermal activation, triggering on-demand drug release from encapsulated reservoirs [Figure 4A]. Additionally, the porous architecture enabled the device to function as a dynamic flow diverter, redirecting hemodynamics away from pathological regions such as aneurysmal sacs or malformed branches. This design integrates mechanical, therapeutic, and hemodynamic functions in a single platform.

Figure 4. Small-scale magnetic soft robots for clinical applications in the vascular system. (A) Schematic and experimental demonstration of a magnetic soft robot integrated with shape memory polymer (SMP)-based foldable structures for localized, on-demand drug delivery. Active locomotion within porcine arterial vessels has been validated through ultrasound imaging[77]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature; (B) Experimental workflow demonstrating magnetic soft robot-assisted thromboextraction[191]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (C) Conceptual schematic of a multifunctional magnetic microfiberbot capable of anchoring to vessel walls, navigating via helical propulsion, elongating to traverse narrow vasculature, and aggregating to achieve targeted flow occlusion. This system serves both as an embolic agent for coil embolization of aneurysms and tumors and as a protective device for selective particle embolization[78]. Copyright 2024 American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Thrombus formation remains a major pathological mechanism of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, contributing to high morbidity and mortality. Soft robotic systems have been developed to perform both pharmacological and mechanical thrombectomy through magnetically controlled adaptive deformation. A representative design employs ferromagnetic liquid composed of Fe3O4 nanoparticles dispersed in dimethyl silicone oil, demonstrating robust deformation and navigation through synthetic vasculature models with tortuous geometries and lumens as narrow as 0.5 mm. The robot exhibits magnetically tunable stiffness, with increasing magnetic field intensity enhancing its structural rigidity to facilitate active thrombus displacement, which has been validated in rabbit ear vein models[128]. A reconfigurable soft robot accomplishes thrombus removal through mechanically driven penetration and hooking of the clot[191] [Figure 4B]. Under rotating magnetic fields (10 mT, 40 Hz), the robot effectively engaged and removed plasma clots in a vein-mimicking phantom, achieving complete thrombus extraction in three minutes without fibrinolytic agents. Compared with conventional catheter-based or balloon-assisted thrombectomy, soft robotic approaches offer reduced procedural trauma and superior adaptability to delicate or irregular vascular anatomies.

Magnetic soft robots also show significant potential in vascular embolization to reduce blood flow in pathological regions such as aneurysms or tumors[78,197]. Microfiber-based devices, fabricated through thermal drawing of magnetic elastomer composites, demonstrate helical propulsion under rotating magnetic fields. Their design enables reversible shape transformations between elongated and aggregated states, facilitating precise modulation of embolic behavior. In addition, under physiologically relevant flow conditions, the microfiber robot demonstrated stable anchoring and effective helical propulsion within vascular environments. Driven by a 40 mT rotating magnetic field, it achieved upstream and downstream propulsion velocities of 0.32 mm/s and 1.75 mm/s, respectively, at a flow rate of 100 mm/s, confirming its capability for active locomotion and precise control under realistic blood flow. The microfiber robot also exhibited robust anchoring performance, maintaining stability against flow velocities of approximately 200 mm/s. These microfiberbots successfully performed targeted embolization in vitro inside aneurysm- and tumor-mimicking phantoms. Their efficacy has been validated through in vivo embolization of the rabbit femoral artery, guided by real-time fluoroscopic imaging[78] [Figure 4C]. This platform represents a progress in embolization strategy, allowing minimally invasive, spatiotemporally precise blood flow occlusion.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Despite the remarkable progress achieved in magnetic soft robotics, their clinical translation remains in an early stage. Bridging the gap between experimental prototypes and clinical application demands multifaceted approaches that include material innovation, intelligent control strategies, and system-level miniaturization.

Biofunctional material development

The development of magnetically responsive materials that combine strong actuation performance with high biocompatibility remains foundational[6]. Biocompatibility should extend beyond in vitro cytotoxicity assessments to include hemocompatibility, immunogenicity, fibrosis suppression, and resistance to biofilm formation[157,198]. Materials should satisfy divergent requirements based on clinical demands, exhibiting either prolonged biostability or predictable non-toxic biodegradability[199,200]. Biostable materials must preserve their structural and functional integrity under physiological conditions, including mucus-lined surfaces, variable pH, enzymatic environments, and dynamic shear flows. Biodegradability necessitates advanced chemical strategies for stable matrix-filler integration, alongside predictive degradation kinetics to ensure device safety over the intended functional lifetime. Beyond chemical strategies, future approaches are exploring the integration of patient-derived substances with magnetically actuatable materials to mitigate foreign-body responses while preserving functional performance. Gel fibers prepared from magnetic fillers and the patient's own blood have demonstrated immune evasion, controllable locomotion in physiological fluids, and on-demand drug release in large animal models[94]. Such advances suggest that personalized biohybrid materials may expand the translational potential of magnetic soft robots by enabling safer clearance pathways and facilitating targeted interventions in sensitive clinical scenarios. In addition, advanced surface engineering of the magnetic soft robot, such as the hydrogel layer and adhesion layer, can enhance retention and reduce mechanical irritation[201,202]. Ultimately, comprehensive in vivo studies over chronic durations, preferably in large animal models, are essential to evaluate immune response, tissue remodeling, and clearance or retention properties. In this context, it is also important to recognize that post-use retrieval is feasible for robots engineered from non-degradable materials. Millimeter-scale wireless non-degradable robots can be reliably retrieved after use. Depending on the target organ, they may be extracted using standard minimally invasive clinical tools such as endoscopes[12] or ureteroscopes[188]. This enables controlled removal and prevents long-term retention, complementing material-driven strategies for safe clinical deployment.

Adaptive control in vivo

To achieve clinical utility, robots must operate autonomously in dynamic and unpredictable physiological environments[50,203]. This necessitates a shift from operator-controlled open-loop systems to intelligent, sensor-integrated platforms for real-time environmental feedback. Soft embedded sensors that detect pressure, strain, temperature, or biochemical markers can provide robots with physiological awareness. Recent progress in conductive soft materials for flexible electronics has further expanded the feasibility of closed-loop magnetic soft robots[204-206]. Highly compliant and stretchable conductive polymers and hydrogels, such as those based on poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS)[207-210], offer lightweight structures with excellent electrical properties and are well-suited for incorporation into small magnetic soft robots without compromising mechanical compliance. In addition, the combination of embedded ultrasonic soft sensors with magnetic actuators has resulted in fully wireless microrobotic systems capable of feedback control, precise drug release, and real-time physiological monitoring[211]. These capabilities have already been demonstrated in rabbit and porcine models, providing concrete evidence that sensor-integrated magnetic soft robots are moving toward intelligent operation in clinically relevant environments.

When magnetic soft robots are required to perform dynamic tasks or navigate unstructured or highly constrained environments, learning-based control strategies may provide advantages over classical model-based approaches, particularly when training datasets can be efficiently collected from physical experiments. Recent work has shown that probabilistic learning frameworks can optimize gait patterns of wireless miniature magnetic soft robots using relatively small experimental datasets[201]. Although current progress remains limited, learning-driven control represents a promising avenue for enabling higher degrees of autonomy and adaptability. Moreover, effective tracking of magnetic soft robots in complex biological environments remains a significant challenge. Biological tissues, composed of heterogeneous and deformable structures, may shift or undergo dynamic changes during intervention, complicating the precise localization of robots, especially at small scales. Integrating robotic systems with clinical imaging modalities, such as X-ray fluoroscopy[78,94], ultrasound[57,77,212], and magnetic resonance imaging[213,214], is essential for establishing robust, real-time, closed-loop control. Furthermore, advances in image registration, multimodal sensor fusion, and machine learning-based perception algorithms will continue to enhance the reliability of tracking and support intelligent navigation under physiologically dynamic conditions.

Miniaturized multifunctional platforms

Magnetic soft robots require integration of actuation, sensing, and drug delivery functions within constrained sub-millimeter-scale structures[215]. This integration necessitates innovations in materials, microfabrication, and architectural design. Emerging approaches such as multimaterial 3D printing[58,59], voxel-based modular construction[60], and origami-inspired self-assembly[61] provide promising strategies for creating reconfigurable devices with hierarchical functionality. Future platforms are expected to combine magnetic propulsion components with controlled-release drug reservoirs, soft bioelectronic sensors, and environmentally responsive modules capable of autonomous operation in disease-specific microenvironments. The development of such compact, multifunctional systems is pivotal for advancing intelligent, soft robotic interventions[8,9,12].

Translational pathways toward clinical adoption

Advancing magnetic soft robots from laboratory research to clinical practice will require the establishment of clear translational pathways in two major areas: technology maturity[8,216] and ethical and regulatory governance[217-219]. From a technological perspective, future work should adopt an iterative development framework aimed at systematically raising the technology readiness level. This process involves rigorous material screening, evaluation of magnetic actuation performance, assessment of structural robustness, and refinement of multiscale manufacturing strategies. Through these steps, devices can progress from early concept validation at the laboratory level to functional verification in relevant animal models. For example, magnetically actuated GI capsules must be evaluated under acidic, mucus-rich, and peristaltic environments to confirm long-term material stability. With the increase of technical maturity, additional engineering verification is needed, including imaging compatibility, control accuracy, and manufacturing reproducibility, to ensure readiness for clinical trials.

Ethical and regulatory considerations represent the second essential component of clinical translation. Preclinical animal studies must be designed with careful selection of appropriate models; for example, microscale robots may be tested in rodent models, whereas millimeter-sized robots should be assessed in larger animals, and all studies must comply with stringent ethical review requirements[218]. Before human studies, clear procedures for informed consent, long-term management of magnetically responsive materials, and definitions of operational responsibility must be established[219]. In addition, systematic monitoring frameworks are needed to identify potential risks, including magnetic particle leakage and chronic tissue responses.

By establishing coordinated strategies that support both the advancement of technological maturity and the development of ethical and regulatory safeguards, magnetic soft robots can progress toward clinical implementation and ultimately contribute to minimally invasive and precision medicine.

CONCLUSION

This review summarizes recent advances in small-scale magnetic soft robots, focusing on material design and biomedical applications in the GI, vascular, urinary, and reproductive systems. We analyze the development of magnetically responsive soft materials, emphasizing critical requirements including mechanical compliance and tissue compatibility for safe and effective in vivo operation. We further discuss organ-specific robotic platforms that integrate locomotion with diverse biomedical functionalities, including real-time sensing, targeted drug delivery, on-demand biosampling, and localized thermal therapy.

Despite significant progress, critical barriers remain for clinical translation, such as long-term materials biostability and safety, real-time closed-loop control methods, and scalable reproducible manufacturing procedures. Overcoming these challenges requires interdisciplinary innovation across materials science, robotics, bioengineering, and regulatory science.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Designed and organized the project: Chen, Z.; Yang, S.; Law, J.; Du, X.; Sun, Y.

Manuscript writing: Chen, Z.; Yang, S.

Manuscript supervision: Law, J.; Du, X.; Sun, Y.

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52505004 and 62588301) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [DUT24RC(3)118 to Law, J.; DUT25RC(3)040 to Du, X.].

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Kim, S.; Laschi, C.; Trimmer, B. Soft robotics: a bioinspired evolution in robotics. Trends. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 287-94.

2. Yang, G. Z.; Fischer, P.; Nelson, B. New materials for next-generation robots. Sci. Robot. 2017, 2.

3. Ranzani, T.; Russo, S.; Bartlett, N. W.; Wehner, M.; Wood, R. J. Increasing the dimensionality of soft microstructures through injection-induced self-folding. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1802739.

4. Shen, Z.; Chen, F.; Zhu, X.; Yong, K. T.; Gu, G. Stimuli-responsive functional materials for soft robotics. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2020.

5. Lou, H.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, Y.; et al. Water-induced shape-locking magnetic robots. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2024, 11, e2405021.

7. Laschi, C.; Mazzolai, B.; Cianchetti, M. Soft robotics: Technologies and systems pushing the boundaries of robot abilities. Sci. Robot. 2016, 1.

10. Tang, C.; Du, B.; Jiang, S.; et al. A pipeline inspection robot for navigating tubular environments in the sub-centimeter scale. Sci. Robot. 2022, 7, eabm8597.

11. Cianchetti, M.; Laschi, C.; Menciassi, A.; Dario, P. Biomedical applications of soft robotics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2018, 3, 143-53.

12. Wang, T.; Wu, Y.; Yildiz, E.; Kanyas, S.; Sitti, M. Clinical translation of wireless soft robotic medical devices. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2024, 2, 470-85.

13. Law, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Sun, Y. Gravity-resisting colloidal collectives. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eade3161.

14. Jeon, S.; Kim, S.; Ha, S.; et al. Magnetically actuated microrobots as a platform for stem cell transplantation. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4.

15. Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Fang, K.; Liu, N.; Yu, J. Magneto-thermal hydrogel swarms for targeted lesion sealing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2403076.

16. Xie, H.; Sun, M.; Fan, X.; et al. Reconfigurable magnetic microrobot swarm: Multimode transformation, locomotion, and manipulation. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4.

17. Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Chan, K. F.; et al. tPA-anchored nanorobots for in vivo arterial recanalization at submillimeter-scale segments. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk8970.

18. Liu, Y.; Xu, B.; Sun, S.; Wei, J.; Wu, L.; Yu, Y. Humidity- and photo-induced mechanical actuation of cross-linked liquid crystal polymers. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29.

19. Lu, X.; Zhang, H.; Fei, G.; et al. Liquid-crystalline dynamic networks doped with gold nanorods showing enhanced photocontrol of actuation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1706597.

20. Lancia, F.; Ryabchun, A.; Nguindjel, A. D.; Kwangmettatam, S.; Katsonis, N. Mechanical adaptability of artificial muscles from nanoscale molecular action. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4819.

21. Liu, J. A.; Gillen, J. H.; Mishra, S. R.; Evans, E. E.; Tracy, J. B. Photothermally and magnetically controlled reconfiguration of polymer composites for soft robotics. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw2897.

22. Kuenstler, A. S.; Kim, H.; Hayward, R. C. Liquid crystal elastomer waveguide actuators. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901216.

23. Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Chang, J. K.; et al. Light-activated shape morphing and light-tracking materials using biopolymer-based programmable photonic nanostructures. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1651.

24. Ahmed, D.; Baasch, T.; Jang, B.; Pane, S.; Dual, J.; Nelson, B. J. Artificial swimmers propelled by acoustically activated flagella. Nano. Lett. 2016, 16, 4968-74.

25. Ren, L.; Nama, N.; McNeill, J. M.; et al. 3D steerable, acoustically powered microswimmers for single-particle manipulation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax3084.

26. Kaynak, M.; Dirix, P.; Sakar, M. S. Addressable acoustic actuation of 3D printed soft robotic microsystems. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2020, 7, 2001120.

27. Aghakhani, A.; Yasa, O.; Wrede, P.; Sitti, M. Acoustically powered surface-slipping mobile microrobots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 3469-77.

28. Zhu, Y.; Deng, K.; Zhou, J.; et al. Shape-recovery of implanted shape-memory devices remotely triggered via image-guided ultrasound heating. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1123.

29. Hao, B.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; et al. Focused ultrasound enables selective actuation and Newton-level force output of untethered soft robots. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5197.

30. Gladman, A. S.; Matsumoto, E. A.; Nuzzo, R. G.; Mahadevan, L.; Lewis, J. A. Biomimetic 4D printing. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 413-8.

31. Li, H.; Go, G.; Ko, S. Y.; Park, J.; Park, S. Magnetic actuated pH-responsive hydrogel-based soft micro-robot for targeted drug delivery. Smart. Mater. Struct. 2016, 25, 027001.

32. Cangialosi, A.; Yoon, C.; Liu, J.; et al. DNA sequence-directed shape change of photopatterned hydrogels via high-degree swelling. Science 2017, 357, 1126-30.

33. Shin, B.; Ha, J.; Lee, M.; et al. Hygrobot: A self-locomotive ratcheted actuator powered by environmental humidity. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3.

34. Mu, J.; Wang, G.; Yan, H.; et al. Molecular-channel driven actuator with considerations for multiple configurations and color switching. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 590.

35. Qin, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, N.; Cong, H. P.; Yu, S. H. Anisotropic and self-healing hydrogels with multi-responsive actuating capability. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2202.

36. Pena-Francesch, A.; Giltinan, J.; Sitti, M. Multifunctional and biodegradable self-propelled protein motors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3188.

37. Jiang, Y.; Korpas, L. M.; Raney, J. R. Bifurcation-based embodied logic and autonomous actuation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 128.

38. Cao, J.; Zhou, C.; Su, G.; et al. Arbitrarily 3D configurable hygroscopic robots with a covalent-noncovalent interpenetrating network and self-healing ability. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1900042.

39. Kong, L.; Ambrosi, A.; Nasir, M. Z. M.; Guan, J.; Pumera, M. Self-propelled 3D-printed “aircraft carrier” of light-powered smart micromachines for large-volume nitroaromatic explosives removal. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1903872.

40. Kotikian, A.; Truby, R. L.; Boley, J. W.; White, T. J.; Lewis, J. A. 3D printing of liquid crystal elastomeric actuators with spatially programed nematic order. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706164.

41. Jin, B.; Song, H.; Jiang, R.; Song, J.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, T. Programming a crystalline shape memory polymer network with thermo- and photo-reversible bonds toward a single-component soft robot. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaao3865.

42. Kotikian, A.; McMahan, C.; Davidson, E. C.; et al. Untethered soft robotic matter with passive control of shape morphing and propulsion. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaax7044.

43. Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Stimuli-responsive composite biopolymer actuators with selective spatial deformation behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 14602-8.

44. Kratochvil, B. E., Kummer, M. P., Erni, S., et al. MiniMag: A hemispherical electromagnetic system for 5-DOF wireless micromanipulation. In Experimental Robotics; Khatib, O., Kumar, V., Sukhatme, G., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics, Vol. 79; Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014; pp 317-29.

45. Kummer, M. P.; Abbott, J. J.; Kratochvil, B. E.; Borer, R.; Sengul, A.; Nelson, B. J. OctoMag: an electromagnetic system for 5-DOF wireless micromanipulation. IEEE. Trans. Robot. 2010, 26, 1006-17.

46. Venkiteswaran, V. K.; Tan, D. K.; Misra, S. Tandem actuation of legged locomotion and grasping manipulation in soft robots using magnetic fields. Extreme. Mech. Lett. 2020, 41, 101023.

47. Fan, X.; Hu, Q.; Sun, L.; Xie, H.; Sun, H.; Yang, Z. Large-scale swarm control of microrobots by a hybrid-style magnetic actuation system. IEEE. Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 10998-1008.

48. Sikorski, J.; Denasi, A.; Bucchi, G.; Scheggi, S.; Misra, S. Vision-based 3-D control of magnetically actuated catheter using BigMag - an array of mobile electromagnetic coils. IEEE/ASME. Trans. Mechatron. 2019, 24, 505-16.

49. Yu, J.; Jin, D.; Chan, K. F.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, L. Active generation and magnetic actuation of microrobotic swarms in bio-fluids. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5631.

50. Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Law, J.; et al. Active exploration and reconstruction of vascular networks using microrobot swarms. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2025, 7, 553-64.

51. Yan, X.; Zhou, Q.; Vincent, M.; et al. Multifunctional biohybrid magnetite microrobots for imaging-guided therapy. Sci. Robot. 2017, 2, eaaq1155.

52. Xu, C.; Yang, Z.; Lum, G. Z. Small-scale magnetic actuators with optimal six degrees-of-freedom. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2100170.

53. Huang, C.; Lai, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, T. Multimodal locomotion and cargo transportation of magnetically actuated quadruped soft microrobots. Cyborg. Bionic. Syst. 2022, 2022, 0004.

54. Wang, C.; Puranam, V. R.; Misra, S.; Venkiteswaran, V. K. A Snake-inspired multi-segmented magnetic soft robot towards medical applications. IEEE. Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 5795-802.

55. Peyer, K. E.; Zhang, L.; Nelson, B. J. Bio-inspired magnetic swimming microrobots for biomedical applications. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 1259-72.

56. Gao, Y.; Sprinkle, B.; Springer, E.; Marr, D. W. M.; Wu, N. Rolling of soft microbots with tunable traction. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg0919.

57. Hu, W.; Lum, G. Z.; Mastrangeli, M.; Sitti, M. Small-scale soft-bodied robot with multimodal locomotion. Nature 2018, 554, 81-5.

58. Li, Z.; Lai, Y. P.; Diller, E. 3D printing of multilayer magnetic miniature soft robots with programmable magnetization. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 6, 2300052.

59. Xu, T.; Zhang, J.; Salehizadeh, M.; Onaizah, O.; Diller, E. Millimeter-scale flexible robots with programmable three-dimensional magnetization and motions. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaav4494.

60. Zhang, J.; Ren, Z.; Hu, W.; et al. Voxelated three-dimensional miniature magnetic soft machines via multimaterial heterogeneous assembly. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabf0112.

61. Dong, Y.; Wang, L.; Xia, N.; et al. Untethered small-scale magnetic soft robot with programmable magnetization and integrated multifunctional modules. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn8932.

62. Zhang, S.; Ke, X.; Jiang, Q.; Ding, H.; Wu, Z. Programmable and reprocessable multifunctional elastomeric sheets for soft origami robots. Sci. Robot. 2021, 6, eabd6107.

63. Xia, N.; Jin, B.; Jin, D.; et al. Decoupling and reprogramming the wiggling motion of midge larvae using a soft robotic platform. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2109126.

64. Won, S.; Kim, S.; Park, J. E.; Jeon, J.; Wie, J. J. On-demand orbital maneuver of multiple soft robots via hierarchical magnetomotility. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4751.

65. Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, H.; Zou, Q.; Law, J.; Yu, J. Amphibious miniature soft jumping robot with on-demand in-flight maneuver. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2023, 10, e2207493.

66. Huang, H. W.; Uslu, F. E.; Katsamba, P.; Lauga, E.; Sakar, M. S.; Nelson, B. J. Adaptive locomotion of artificial microswimmers. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau1532.

67. Ren, Z.; Zhang, R.; Soon, R. H.; et al. Soft-bodied adaptive multimodal locomotion strategies in fluid-filled confined spaces. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh2022.

68. Yang, L.; Zhang, T.; Huang, H.; Ren, H.; Shang, W.; Shen, Y. An On-Wall-Rotating Strategy for Effective Upstream motion of untethered millirobot: principle, design, and demonstration. IEEE. Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 2419-28.

69. Ren, Z.; Hu, W.; Dong, X.; Sitti, M. Multi-functional soft-bodied jellyfish-like swimming. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2703.

70. Sun, M.; Tian, C.; Mao, L.; et al. Reconfigurable magnetic slime robot: deformation, adaptability, and multifunction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2112508.

71. Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Locally controllable magnetic soft actuators with reprogrammable contraction-derived motions. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo6021.

72. Yang, X.; Shang, W.; Lu, H.; et al. An agglutinate magnetic spray transforms inanimate objects into millirobots for biomedical applications. Sci. Robot. 2020, 5, eabc8191.

73. Kim, H. J.; Koo, J. H.; Lee, S.; Hyeon, T.; Kim, D. Materials design and integration strategies for soft bioelectronics in digital healthcare. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2025, 10, 654-73.

74. Sun, B.; Jia, R.; Yang, H.; et al. Magnetic arthropod millirobots fabricated by 3D-printed hydrogels. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2021, 4, 2100139.

75. Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. A magnetic multi-layer soft robot for on-demand targeted adhesion. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 644.

76. Kim, Y.; Parada, G. A.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaax7329.

77. Wang, T.; Ugurlu, H.; Yan, Y.; et al. Adaptive wireless millirobotic locomotion into distal vasculature. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4465.

78. Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Magnetic soft microfiberbots for robotic embolization. Sci. Robot. 2024, 9, eadh2479.

79. Wang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Jin, H.; Wei, R.; Bi, L.; Zhang, W. Magnetic soft robots: Design, actuation, and function. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 922, 166219.

80. Ebrahimi, N.; Bi, C.; Cappelleri, D. J.; et al. Magnetic actuation methods in bio/soft robotics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2005137.

81. Chen, J.; Jin, D.; Wang, Q.; Ma, X. Programming ferromagnetic soft materials for miniature soft robots: design, fabrication, and applications. J. Mater. Sci. &. Technol. 2025, 219, 271-87.

82. Eshaghi, M.; Ghasemi, M.; Khorshidi, K. Design, manufacturing and applications of small-scale magnetic soft robots. Extreme. Mech. Lett. 2021, 44, 101268.

83. Malappuram, K. M.; Chatterjee, K.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Nain, A. Clinical challenges in soft robotics. Adv. Robot. Res. 2025, 1, 202400018.

84. Zhao, X.; Kim, J.; Cezar, C. A.; et al. Active scaffolds for on-demand drug and cell delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011, 108, 67-72.

85. Goudu, S. R.; Yasa, I. C.; Hu, X.; Ceylan, H.; Hu, W.; Sitti, M. Biodegradable untethered magnetic hydrogel Milli-Grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004975.

86. Cezar, C. A.; Kennedy, S. M.; Mehta, M.; et al. Biphasic ferrogels for triggered drug and cell delivery. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1869-76.

87. Wang, H.; Hou, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Superparamagnetic hydrogels: Precision-driven platforms for biomedicine, robotics, and environmental remediation. Biomed. Technol. 2025, 10, 100084.

88. Ikeda, J.; Takahashi, D.; Watanabe, M.; Kawai, M.; Mitsumata, T. Particle size in secondary particle and magnetic response for carrageenan magnetic hydrogels. Gels 2019, 5, 39.

89. Zhou, C.; Wang, C.; Xu, K.; et al. Hydrogel platform with tunable stiffness based on magnetic nanoparticles cross-linked GelMA for cartilage regeneration and its intrinsic biomechanism. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 25, 615-28.

90. Zhang, H.; Hua, S.; He, C.; et al. Application of 4D-printed magnetoresponsive FOGS hydrogel scaffolds in auricular cartilage regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2404488.

91. Ge, T. J.; Roquero, D. M.; Holton, G. H.; et al. A magnetic hydrogel for the efficient retrieval of kidney stone fragments during ureteroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3711.

92. Shen, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, E.; et al. Tough hydrogel-coated containment capsule of magnetic liquid metal for remote gastrointestinal operation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf042.

93. Wu, W. S.; Yan, X.; Chen, S.; et al. Minimally invasive delivery of percutaneous ablation agent via magnetic colloidal hydrogel injection for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2309770.

94. Wang, B.; Shen, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Magnetically driven biohybrid blood hydrogel fibres for personalized intracranial tumour therapy under fluoroscopic tracking. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 9, 1471-85.

95. Londhe, P. V.; Londhe, M. V.; Salunkhe, A. B.; et al. Magnetic hydrogel (MagGel): an evolutionary pedestal for anticancer therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 522, 216228.

96. Xu, Y.; Cai, F.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Magnetically attracting hydrogel reshapes iron metabolism for tissue repair. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado7249.

97. Xu, Z.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, M.; Chen, Y.; Ge, W.; Xu, Q. Versatile magnetic hydrogel soft capsule microrobots for targeted delivery. iScience 2023, 26, 106727.

98. Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Inda, M. E.; et al. Magnetic living hydrogels for intestinal localization, retention, and diagnosis. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2010918.

99. Chen, H.; Law, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Active microgel particle swarms for intrabronchial targeted delivery. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr3356.

100. Viteri, A.; Espanol, M.; Ginebra, M.; García-Torres, J. Tailoring drug release from skin-like chitosan-agarose biopolymer hydrogels containing Fe3O4 nanoparticles using magnetic fields. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 517, 164214.

101. Li, H.; Jiang, S.; Deng, Q.; et al. Programmable magnetic hydrogel robots with drug delivery and physiological sensing capabilities. Mater. Today. 2025, 87, 66-76.

102. Hu, X.; Ge, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiao, N.; Tung, S.; Liu, L. Multifunctional thermo-magnetically actuated hybrid soft millirobot based on 4D printing. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 2022, 228, 109451.

103. Chung, H. J.; Parsons, A. M.; Zheng, L. Magnetically controlled soft robotics utilizing elastomers and gels in actuation: a review. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 3, 2000186.

104. Breger, J. C.; Yoon, C.; Xiao, R.; et al. Self-folding thermo-magnetically responsive soft microgrippers. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015, 7, 3398-405.

105. Li, X.; Fan, D.; Sun, Y.; et al. Porous magnetic soft grippers for fast and gentle grasping of delicate living objects. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2409173.

106. Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Ren, Z.; Hu, W.; Sitti, M. Creating three-dimensional magnetic functional microdevices via molding-integrated direct laser writing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2016.

107. Xia, N.; Jin, D.; Pan, C.; et al. Dynamic morphological transformations in soft architected materials via buckling instability encoded heterogeneous magnetization. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7514.

108. Chi, Y.; Evans, E. E.; Clary, M. R.; et al. Magnetic kirigami dome metasheet with high deformability and stiffness for adaptive dynamic shape-shifting and multimodal manipulation. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr8421.

109. Lin, D.; Yang, F.; Gong, D.; Li, R. Bio-inspired magnetic-driven folded diaphragm for biomimetic robot. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 163.

110. Min, H.; Bae, D.; Jang, S.; et al. Stiffness-tunable velvet worm-inspired soft adhesive robot. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp8260.

111. Zhao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; et al. Soft fibers with magnetoelasticity for wearable electronics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6755.

112. Dong, X.; Xiao, B.; Vu, H.; Lin, H.; Sitti, M. Millimeter-scale soft capsules for sampling liquids in fluid-filled confined spaces. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadp2758.

113. Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; et al. A liquid gripper based on phase transitional metallic ferrofluid. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100274.

114. Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. Wetting ridge assisted programmed magnetic actuation of droplets on ferrofluid-infused surface. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7136.

115. Ramos-sebastian, A.; Lee, J. S.; Kim, S. H. Multimodal locomotion of magnetic droplet robots using orthogonal pairs of coils. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 2300133.

116. Sun, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Versatile, modular, and customizable magnetic solid-droplet systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2024, 121, e2405095121.

117. Chen, G.; Tat, T.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Neural network-assisted personalized handwriting analysis for Parkinson’s disease diagnostics. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2025, 2, 358-68.

118. Chen, L.; Yu, H.; Yang, J.; et al. Facile synthesis of silicone oil-based ferrofluid: toward smart materials and soft robots. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 8904-15.

119. Fan, X.; Dong, X.; Karacakol, A. C.; Xie, H.; Sitti, M. Reconfigurable multifunctional ferrofluid droplet robots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 27916-26.

120. Fan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Scale-reconfigurable miniature ferrofluidic robots for negotiating sharply variable spaces. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq1677.