Management of metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular risk in patients with MASLD

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a leading global cause of chronic liver disease and is strongly linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD), which remains the primary cause of death in affected individuals. This narrative review summarizes contemporary evidence on the MASLD–CVD interface and outlines a practical framework for cardiovascular risk assessment and comorbidity management. We discuss how liver disease severity can inform cardiovascular risk stratification beyond traditional scores, including cardiovascular imaging, biomarkers of myocyte injury and stress, inflammation markers, proteomics, lipidomics, and lipid profiles. Lifestyle interventions - dietary optimization, weight loss, and increased physical activity - remain foundational and improve hepatic steatosis and key cardiometabolic parameters. Pharmacotherapies with relevance to MASLD and cardiometabolic disease - including β-selective thyromimetics, incretin-based therapies, sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, and pioglitazone - offer benefits across weight, glycemic control, and metabolic risk, while statins remain the cornerstone of dyslipidemia management and CVD prevention in MASLD. For patients who do not achieve lipid targets or are statin-intolerant, non-statin therapies such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors and bempedoic acid provide additional risk-reduction options. Bariatric surgery can achieve durable weight loss and meaningful improvements in steatohepatitis and fibrosis in carefully selected patients. Finally, we emphasize the need for integrated, multidisciplinary care pathways that coordinate hepatology, cardiology, endocrinology, and primary care to identify high-risk individuals early, tailor intensity of preventive therapies, and address the concurrent liver and CVD burden.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), is currently a leading cause of chronic liver disease globally[1-4]. MASLD encompasses a spectrum of liver lesions, ranging from isolated hepatic steatosis to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), which is characterized by an inflammatory process that can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[3,5]. The current 2023 steatotic liver disease (SLD) criteria consider hepatic steatosis and at least 1 out of 5 cardiometabolic risk factors (CMRFs) to diagnose MASLD, highlighting the relevant role that metabolic dysfunction plays in the pathophysiology of SLD [Table 1][6]. In the United States (US), 87.5% of the adults fulfill at least one cardiometabolic criterion, while around one-third of the population has SLD[7,8]. Consequently, clinicians frequently have to assess CMRFs associated with MASLD in routine clinical practice.

Definition of metabolic dysfunction according to the 2023 SLD criteria

| CMRFs: • BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (≥ 23 kg/m2 for Asian subjects); of waist circumference of > 94 cm for males, > 80 cm for females; or ethnicity adjusted equivalent • T2DM (as determined by medical history ≥ 3 months before Screening); or fasting glucose levels ≥ 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L); 2-hour post-load glucose levels 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L); or HbA1c ≥ 5.7%; or treatment for T2DM • Fasting triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (1.7 mmol/L) or on lipid lowering treatment • Fasting HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women, or on lipid lowering treatment • Hypertension or on treatment for hypertension; or ≥ 130 mmHg systolic blood pressure or ≥ 85 mmHg diastolic blood pressure |

Individuals with MASLD have an increased risk of liver complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer[9]. They also exhibit a high risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), which is a leading cause of death in these patients[4,10]. Alcohol use can also interact with these risk factors, leading to higher cardiovascular mortality[11]. Consequently, the American Heart Association (AHA) has stated that MASLD is a significant risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD)[12]. The risk of CVD in patients with MASLD parallels the severity of liver disease, with those having MASH being at greater risk than those with simple steatosis[13]. However, despite the high burden of ASCVD in MASLD, most clinicians underemphasize the prevention and management of ASCVD in this setting. Therefore, this review aims to summarize updated approaches for estimating cardiovascular risk in MASLD using validated scores and noninvasive biomarkers, as well as the management of CMRFs in MASLD. Moreover, we provide actionable recommendations for a multidisciplinary approach to ASCVD risk management in routine clinical practice.

CARDIOVASCULAR RISK STRATIFICATION IN MASLD

Most patients with MASLD should be considered for a ASCVD health check, particularly as many will be older than 40 years[4]. ASCVD risk is driven by non-modifiable factors (e.g., older age, male sex, family history of premature CVD, certain ethnicities such as South Asian ancestry, and early menopause) and modifiable factors [e.g., smoking, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet, and cardiometabolic features such as visceral adiposity, hypertension, insulin resistance, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)]. Risk is further amplified when comorbidities such as chronic kidney disease coexist, particularly in people with T2DM[14]. Beyond obtaining a thorough clinical history to assess risk factors, clinicians can use risk prediction equations, cardiac imaging, and biomarkers of myocyte injury or stress to stratify ASCVD.

Traditional equations for cardiovascular risk

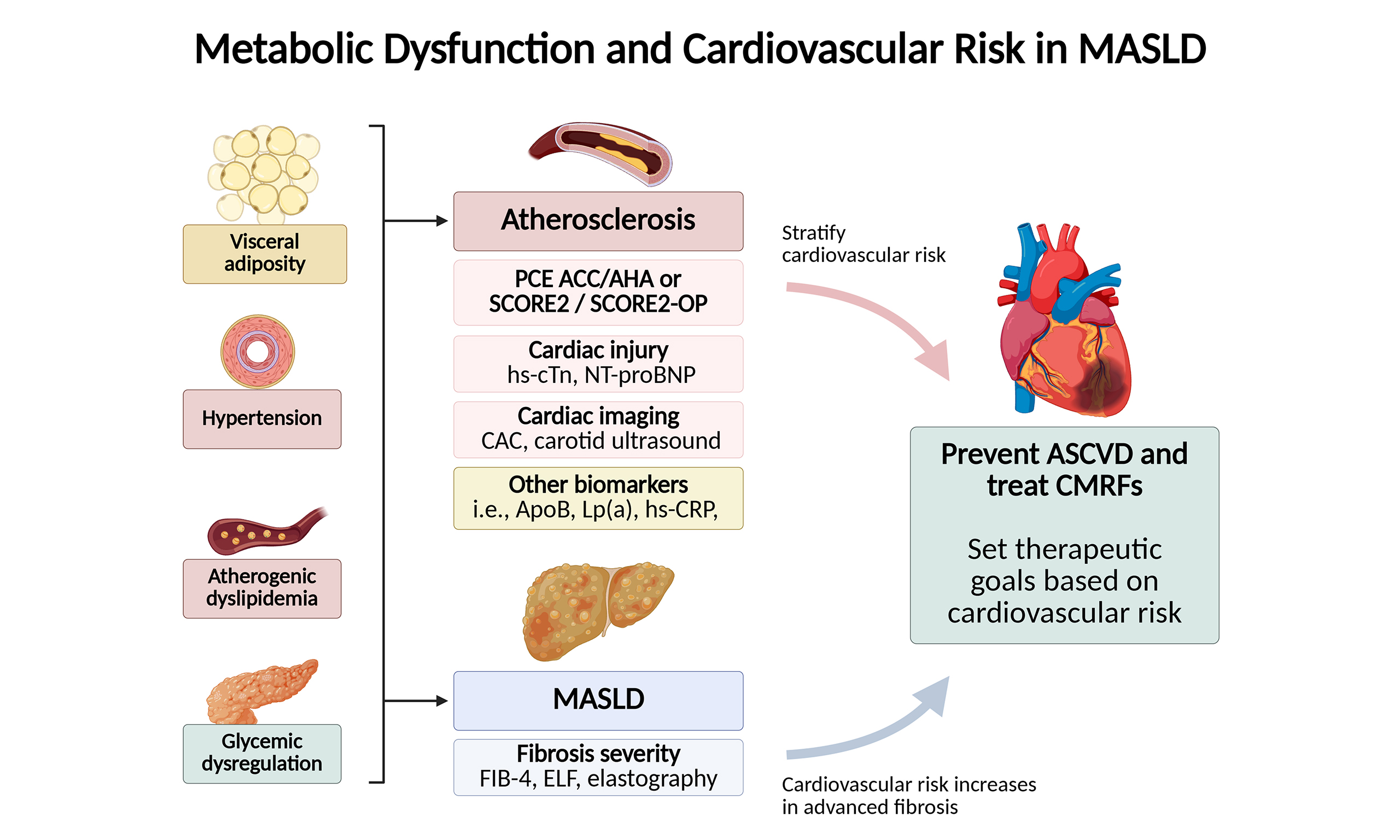

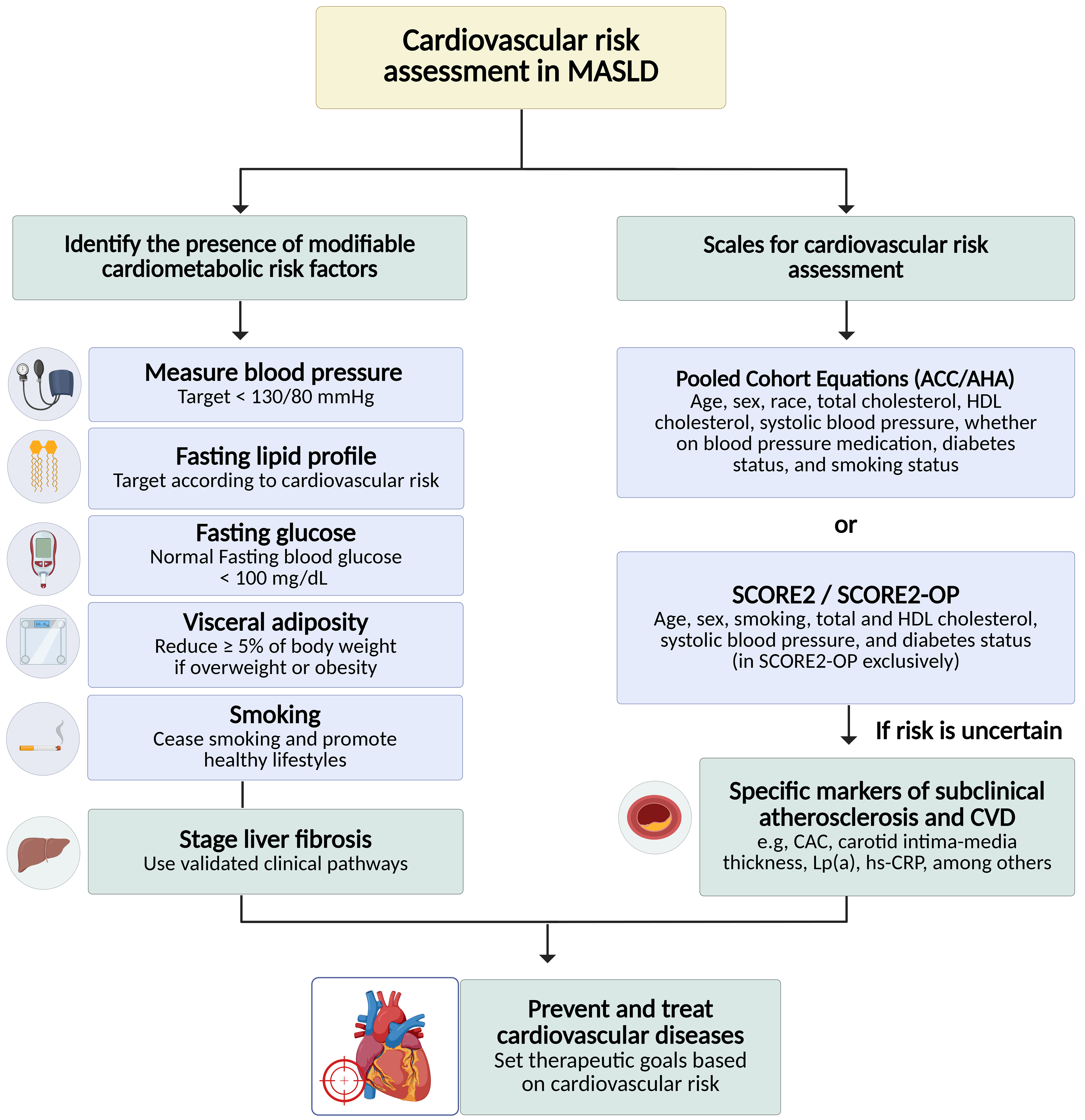

Risk stratification requires a comprehensive evaluation that integrates traditional CMRFs with disease-specific markers [Figure 1]. Instruments such as the Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE) of the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA, the Framingham General Cardiovascular Risk Profile for primary care, the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), the AHA Predicting Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Events (PREVENT), the European Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2 (SCORE2), and the Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2–Older Persons (SCORE2-OP) risk calculators are widely available to estimate 10-year cardiovascular risk [Table 2][15]. Currently, the PCE of the ACC/AHA is the instrument recommended by the ACC, AHA, and the US Preventive Services Task Force, while SCORE2 and SCORE2-OP are recommended by the European Society of Cardiology[16].

Figure 1. Main approach for the assessment of cardiovascular risk in individuals with MASLD. Current data are insufficient to recommend a specific risk calculator in MASLD, and the choice should be made based on the population (e.g., North America vs. Europe) and local guidelines. Created in BioRender. Arab, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ihth6bo. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; ACC: American College of Cardiology; AHA: American Heart Association; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; SCORE2: Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2; SCORE2-OP: Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation 2–Older Persons; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CAC: coronary artery calcium; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Most common methods to assess cardiovascular risk and their use in MASLD

| Risk calculator | Predicted outcome(s) | Key strengths | Key limitations | MASLD-specific considerations |

| ACC/AHA PCE | First ASCVD event (nonfatal MI, CHD death, fatal/nonfatal stroke) | Widely adopted in US; outcome aligns with ASCVD prevention decisions; straightforward variables; integrated into clinical workflow and tools | Calibration varies by ethnicity and contemporary cohorts; no direct measures of obesity, CKD, inflammation, family history, or liver disease | Available studies suggest underestimation and miscalibration in MASLD in some cohorts (c-statistic 0.48-0.69 in US)[17] |

| Framingham general CVD risk profile (primary care) | CVD, including CHD, stroke/TIA, PAD, heart failure | Broad composite outcome (captures HF and stroke); simple | Older derivation cohorts; tends to overestimate in contemporary lower-risk settings without recalibration; limited ethnicity-specific calibration; still omits family history, CKD, inflammatory conditions, and liver disease | Evidence suggests suboptimal discrimination (c-statistics 0.58 in US) and calibration in MASLD cohorts in some analyses[18] |

| SCORE (original) | Fatal CVD only | Very simple; regionally calibrated; focuses on mortality (high specificity for severe risk) | Understates total burden because nonfatal events excluded; limited variables; younger high-risk persons may still appear as “low risk” by 10-year fatal estimate; increasingly outdated event rates | Likely underestimates clinical burden in MASLD due to its high burden of nonfatal events (c-statistics for fatal events 0.83-0.85 in Iran)[15] |

| AHA PREVENT | Separate and combined risks for ASCVD, heart failure, and total CVD (ASCVD + HF) | Contemporary, large derivation datasets; includes BMI and kidney function; provides HF risk and longer-horizon (30-year) risk; avoids race as a required input | Newer tool with fewer external validations; still omits liver disease/fibrosis, family history, inflammatory conditions, Lp(a); greater complexity | MASLD analyses suggest that performance is poor (c-statistics 0.60 in US) and insufficiently calibrated[18] |

| SCORE2 | First fatal + nonfatal MI or stroke (country-region calibrated) | Major update over SCORE: includes nonfatal events; contemporary recalibration; improved alignment with clinical outcomes; regional calibration | Age-bounded; diabetes often separate; still limited covariates (no BMI, CKD, inflammation, liver disease); requires correct regional version | Likely improves over SCORE for MASLD because it includes nonfatal events and better lipid modeling, but still may under-estimate risk (c-statistics 0.67-0.77 in Iran)[15] |

| SCORE2-OP (70-89 year) | First fatal + nonfatal MI or stroke (older-person model; competing risk) | Specifically designed for older adults; competing-risk adjustment improves realism in elderly; includes diabetes | Many older adults will exceed thresholds largely driven by age; does not capture frailty, multimorbidity, or liver disease severity; interpretation requires patient-centered judgment | In older MASLD, risk will often be high regardless |

Recent studies have validated these instruments, showing variable performance in populations with MASLD [Table 2]. For example, a prospective study of CVD in a multiethnic cohort of 4,014 individuals from six US communities, aged 45-84 years and free of clinical CVD at enrolment, recruited between 2000 and 2002, found that discrimination of the ACC/AHA PCE was suboptimal in MASLD (c-statistic 0.69), especially in moderate-to-severe steatosis (0.65), while calibration was poor and largely driven by overestimation in the highest-risk groups[17]. In addition, a study including 1,090 participants aged ≥ 30 years with MASLD from the US showed that the Framingham risk score and the AHA PREVENT equation had poor performance in predicting incident cardiovascular events (c-statistics 0.58 and 0.60, respectively), while the PCE showed no discrimination (c-statistic 0.48)[18]. By contrast, a study of 1,431 participants with MASLD aged 40-74 years from northern Iran reported that the ACC/AHA PCE, Framingham, and SCORE2 instruments achieved the highest performance for a composite outcome of fatal and non-fatal CVD events (c-statistics 0.69-0.79, 0.68-0.77, and 0.67-0.77, respectively). Performance further improved when analyses were restricted to fatal CVD events (0.88-0.93, 0.82-0.92, and 0.83-0.87, respectively)[15]. Nonetheless, discrimination for non-fatal CVD events remained consistently lower across all instruments.

Advanced cardiovascular imaging

Cardiovascular imaging techniques offer valuable tools to detect subclinical atherosclerosis in MASLD patients [Figure 2]. Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, derived from non-contrast computed tomography (CT), is a robust predictor of coronary artery disease and provides incremental risk stratification beyond traditional scoring systems[19]. The most validated thresholds for CAC in cardiovascular risk assessment are CAC = 0, CAC = 1-99, and CAC ≥ 100 Agatston units[20]. A high CAC score is often observed in MASLD patients, even in the absence of overt cardiovascular symptoms, underscoring its utility in identifying patients who would benefit from earlier and more aggressive risk factor modification[21]. However, there are no MASLD-specific CAC thresholds recommended in the medical literature[22]. Similarly, carotid intima-media thickness measurement, a non-invasive ultrasound technique, assesses arterial wall thickening and subclinical atherosclerosis, further refining cardiovascular risk evaluation[23].

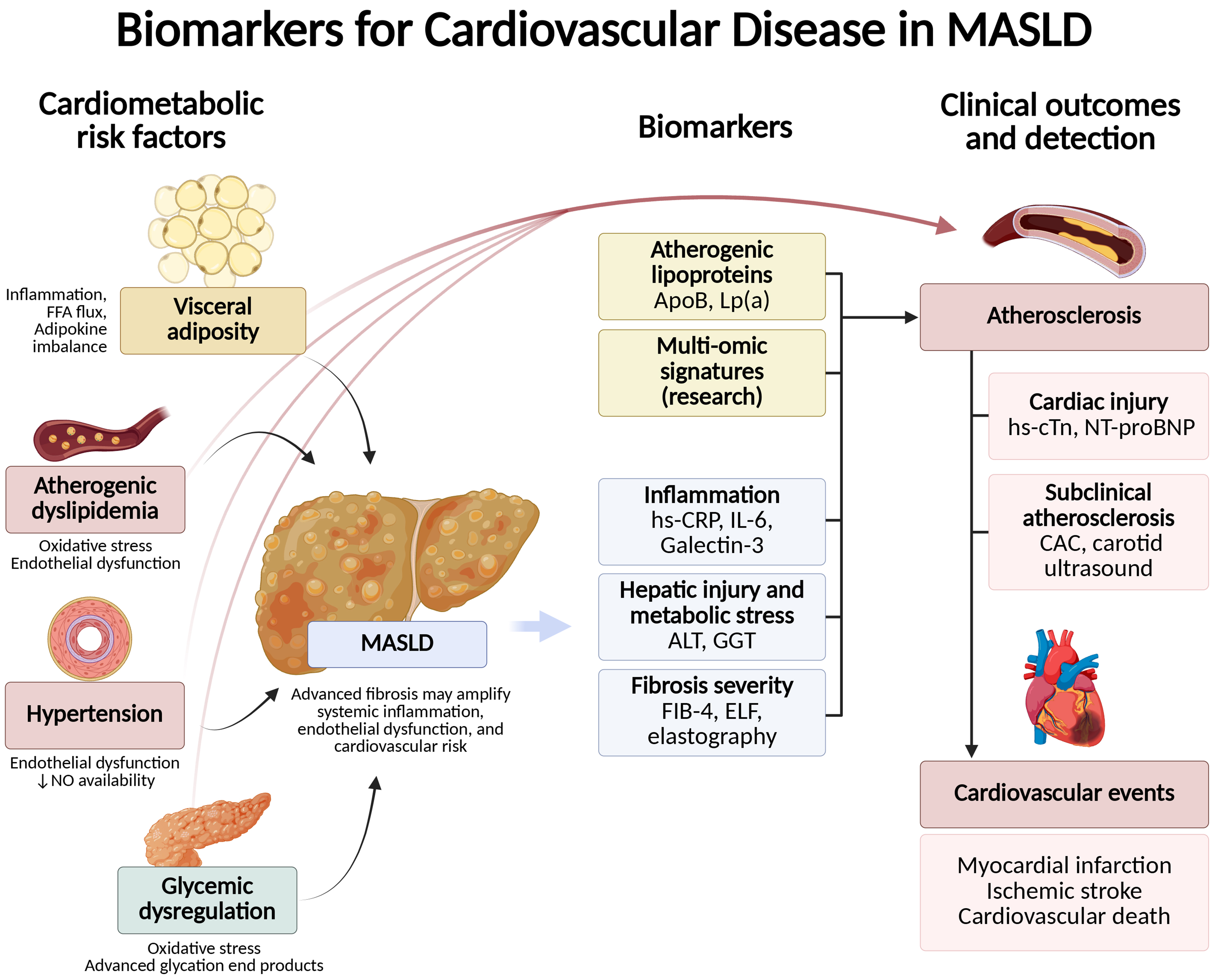

Figure 2. Pathophysiologic framework linking MASLD to CVD, and potential biomarkers. Metabolic dysfunction in MASLD, together with hepatic inflammation and advanced fibrosis, promotes systemic inflammation and vascular injury. These upstream drivers converge on core atherogenic mechanisms - endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and lipoprotein modification, macrophage activation with foam-cell formation, plaque growth with calcification, and a prothrombotic milieu - which can be captured by complementary biomarker classes. Created in BioRender. Arab, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/bka7tlp. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; FFA: free fatty acid; NO: nitric oxide; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-6: interleukin-6; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; FIB-4: Fibrosis-4; ELF: enhanced liver fibrosis; hs-cTn: high-sensitivity cardiac troponin; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; CAC: coronary artery calcium.

Biomarkers of myocyte injury and stress

High-sensitivity troponin is a cardiac biomarker assay capable of detecting very low concentrations of troponin I or T in the blood, allowing quantification in most healthy individuals and improved precision at the 99th percentile upper reference limit [Figure 2]. In the overall population, high-sensitivity troponin provides independent and incremental prognostic information for cardiovascular risk stratification beyond traditional risk factors[24]. In MASLD, a study including 5,622 participants from the US found that higher levels of high-sensitivity troponin T among individuals with MASLD were associated with progressively higher hazards of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, which remained significant after adjustment for demographic, clinical, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors[25]. N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) is another biomarker for stratifying cardiovascular risk in the general population. Elevated NT-proBNP levels are independently associated with increased risk of incident CVD, heart failure, and both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, even after adjustment for traditional risk factors and echocardiographic parameters such as left ventricular mass and function[26]. In MASLD, higher levels of NT-proBNP are associated with increased mortality[27]. However, further validation in MASLD-specific cohorts is needed before routine use.

EMERGING BIOMARKERS TO ASSESS CARDIOVASCULAR RISK

As noted above, traditional scores often fall short of accurately predicting cardiovascular risk in patients with MASLD[28-30]. These limitations stem from the unique pathophysiology of MASLD, which involves chronic hepatic and systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and lipid abnormalities, all of which amplify cardiovascular risk[31]. To address this gap, integrating traditional risk factors with liver fibrosis stage and novel biomarkers may improve risk prediction and guide personalized management [Figure 2][32,33].

Advanced fibrosis as a key risk determinant of adverse outcomes in MASLD

Advanced fibrosis (≥ F3) is one of the strongest predictors of cardiovascular events in MASLD[34]. Noninvasive tools for liver fibrosis include the Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index, the Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score, the Enhanced Liver Fibrosis test, and elastography-based methods, which typically stratify the risk as low, indeterminate, or high risk for advanced fibrosis[35,36]. Thus, the use of noninvasive biomarkers can help stratify the risk of major adverse liver outcomes, and may also help stratify cardiovascular risk. For example, a Korean study including 60,445 participants found that an indeterminate or high FIB-4 category was associated with nearly twice the incidence of CAC progression compared with those in the low-risk FIB-4 group (5.6 vs. 3.2 per 100 person-years)[37]. Moreover, studies consistently demonstrate that individuals with advanced fibrosis have a significantly higher likelihood of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure, compared with those with minimal or no fibrosis[38-41]. The fibrotic burden contributes to systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, which accelerate the development of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular complications[42,43].

Liver tests and inflammation markers

Elevated liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) can serve as surrogate markers for hepatic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, both of which correlate with cardiovascular risk[44]. Systemic markers of inflammation, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), further refine risk assessment by highlighting the pro-inflammatory state that bridges liver disease and cardiovascular pathology[45,46]. Among these biomarkers, hs-CRP has been widely studied for cardiovascular risk stratification, particularly in primary prevention and among individuals with intermediate or atypical risk profiles; however, its incremental predictive value beyond traditional risk factors is modest[47]. Importantly, hs-CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α are non-specific and can be elevated in a wide range of conditions, including acute and chronic infections, autoimmune diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus), malignancy, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic inflammatory states such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure. Consequently, IL-6 and TNF-α are not reliable standalone biomarkers of CVD[48]. Galectin-3 is another biomarker secreted by activated macrophages and other cells in response to myocardial stress, promoting fibroblast proliferation, collagen deposition, and tissue remodeling, which are central to the pathogenesis of heart failure and atherosclerosis[49]. In the overall population, increases in Galectin-3 predict future heart failure, CVD, and mortality[50]. Although Galectin-3 could be a promising biomarker, there is no validated data in patients with MASLD for predicting CVD.

Proteomics, lipidomics, and lipid profiles

Specific plasma proteomic signatures have been identified as markers of cardiovascular risk in MASLD. A recent UK Biobank study identified adrenomedullin as independently associated with CVD risk during follow-up, even after adjusting for steatosis severity and traditional CMRFs[51]. Additionally, targeted proteomic panels [e.g., Adhesion G protein-coupled receptor G1 (ADGRG1/GPR56)] have been validated as surrogates for systemic organ damage, including ischemic heart disease, during long-term follow-up, supporting their utility in risk stratification[52]. Lipidomics analyses have also revealed that specific plasma lipid species, such as docosatrienoate (22:3n6) and 2-hydroxyarachidate, mediate the relationship between SLD and coronary artery disease, independent of circulating lipoproteins[53]. Integrative omics approaches, including metabolomics and lipidomics, have further advanced biomarker discovery for CVD risk prediction in MASLD, although standardization and clinical validation remain ongoing challenges[54].

Adipokines - such as adiponectin, an anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing hormone - are often reduced in MASLD and inversely correlated with cardiovascular risk[55]. In contrast, leptin, a pro-inflammatory adipokine, is elevated and linked to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis[56]. Pro-atherogenic lipoproteins, such as small dense low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], are additional risk factors that provide insights into lipid-related cardiovascular risks. Lp(a), in particular, is genetically determined and strongly associated with atherogenesis, although levels may decrease in advanced stages of MASLD[57-59]. In MASLD, a Chinese study including 56,168 participants reported an inverse association between Lp(a) percentiles and advanced fibrosis[60]. However, patients with MASLD who had advanced liver fibrosis and high Lp(a) levels had a higher risk of MACE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56) than those with low Lp(a) levels.

EXCESS BODY WEIGHT AND ITS MANAGEMENT IN SLD

In 2021, an estimated 1.00 billion adult males and 1.11 billion adult females worldwide were overweight or had obesity[61]. In the US, the prevalence of SLD among individuals with overweight and obesity is projected to rise to 75%[62]. In parallel, up to 92.7% of individuals with MASLD have excess weight[7]. Obesity is strongly associated with liver fibrosis progression, interacting with other metabolic risk factors, alcohol use, and genetic factors[63-66]. Also, obesity is associated with shorter longevity and a significantly increased risk of CVD morbidity and mortality compared with normal body mass index (BMI)[67-69]. The assessment and management of overweight and obesity in MASLD involves a multifaceted approach focusing on lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy, and potentially surgical interventions[70]. The benefits of weight loss in MASLD have been well-documented and include the resolution of steatohepatitis, liver fibrosis regression, and reduction in CVD risk factors (i.e., blood pressure, glucose, and lipid levels)[71,72]. Although the obesity definition is evolving, in this review, we will mainly consider evidence based on the BMI-based definition as most of the evidence has been developed by using these criteria[73].

Non-pharmacological treatments

Patients with MASLD can benefit from changes in dietary composition (e.g., low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat diets, saturated vs. unsaturated fat diets, and Mediterranean diet, among others) and different intensities of caloric restriction[74]. In particular, the Mediterranean diet is one of the most effective dietary options for inducing weight loss in MASLD[75], and is characterized by high consumption of fish, monounsaturated fats from olive oil, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes/nuts[76]. In particular, fruits (such as cherries, citrus, apples, and berries) and vegetables (including artichokes, spinach, beans, and olives) are major contributors to Mediterranean diet, providing diverse polyphenol classes such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, and anthocyanins[77]. Virgin olive oil is a distinctive source, rich in tyrosol, and other phenolic compounds, being the hallmark of the Mediterranean dietary pattern[78]. Coffee consumption, regardless of caffeine content, may also be beneficial in reducing the risk of liver fibrosis[79,80]; however, the quality of evidence supporting coffee use is low[81].

Patients should be encouraged to increase their physical activity level to the extent possible independent of weight loss, as it has hepatic and cardiometabolic benefits[74]. In the case of structured and planned physical activity, aerobic exercise (i.e., walking, running, cycling, or swimming) and resistance training (i.e., weightlifting or bodyweight exercises) have been shown to be beneficial for patients with MASLD[82]. Those adults without cardiovascular or musculoskeletal contraindications should perform 150-300 min a week of moderate-intensity exercise or 75-150 min a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity[83]. Also, they should do muscle-strengthening activities at least two days a week[84]. These recommendations can even benefit individuals with cirrhosis, who usually have a hypercatabolic state and sarcopenia[85]. Importantly, a multidisciplinary care team approach is essential for the effective implementation of lifestyle modifications, as opposed to the fragmented management of individual complications[86].

Incretin-based therapies and other pharmacological strategies

In cases where lifestyle modifications alone are insufficient, pharmacotherapy can be considered[70,87,88]. Incretin-based therapies, particularly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and dual incretin-based therapies [such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) or GLP-1/glucagon receptor agonists] have shown significant promise in managing obesity in patients with MASLD[89,90]. The mechanisms by which incretin-based therapies exert these effects include signals in the central nervous system to suppress appetite, increase satiety, and thereby decrease calorie intake, improvements in insulin sensitivity, and many other extrahepatic effects[91]. Although there are multiple pharmacological therapies to treat obesity (i.e., orlistat, sympathomimetic agents, phentermine-topiramate, or bupropion-naltrexone), this review will primarily focus on GLP-1RAs due to the consistent benefits in MASH treatment including resolution and/or liver fibrosis improvement[92-94].

Liraglutide and semaglutide, two common GLP-1RAs used to treat obesity, have demonstrated substantial efficacy in reducing body weight, with semaglutide showing superior results[95,96]. GLP-1RAs can lead to weight reductions of approximately 9.6% to 17.4% of baseline body weight, which is substantially higher than what is typically achieved with lifestyle modifications alone[92,97]. Moreover, a phase 3 trial involving 800 participants with MASH-related fibrosis (F2-F3) showed that weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg compared with placebo was associated with significant MASH resolution and potential improvement in liver fibrosis[98]. Other dual or triple agonists - including tirzepatide[99,100], survodutide[101] pemvidutide[102] and retatrutide[103] - have shown promising results in MASH resolution and reduction in body weight, making them potentially attractive therapeutic agents [Table 3][104]. For instance, tirzepatide, a dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist, has shown even more pronounced effects on weight reduction than GLP1-RAs alone, with clinical trials reporting weight loss exceeding 15% from baseline.

Most common incretin-based therapies and their mechanism of action, impact on glycemic control, weight, and specific evidence in MASLD

| Drugs | Mechanism of action | HbA1c | Weight loss | Evidence in liver disease |

| Liraglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist | -0.4% to -1.0% | -3.4% to -8.4% | Significantly improved liver enzymes, improved histological features, reduced liver fat content[96] |

| Semaglutide | GLP-1 receptor agonist | -1.5 to -2.0% | -9.6% to -17.4% | Significant improvement of liver fibrosis and MASH resolution[98] |

| Tirzepatide | GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist | -1.5 to -2.5% | -15% to -20% | Resolution of MASH without worsening of fibrosis[100] |

| Survodutide | GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist | -1.5% | -10.7% to -19% | Improvement in MASH without worsening of fibrosis, decrease in liver fat content[101] |

| Pemvidutide | GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist | -0.2 to -0.4% | -3.4% to -3.9% | Significant reductions in LFC, markers of hepatic inflammation[102] |

| Retatrutide | GLP-1/GIP/glucagon receptors agonist | -2.2% | -6.3% to -17.6% | Reduction liver fat content[103] |

Incretin-based therapies provide multiple metabolic benefits beyond weight loss, including improved β-cell function, enhanced lipid metabolism, cardiovascular and renal protection, and anti-inflammatory effects[105,106]. Most cardiovascular benefits have been observed in GLP-1RAs, such as semaglutide, liraglutide, and dulaglutide. For example, in a clinical trial in patients with preexisting CVD and overweight or obesity but without T2DM, weekly subcutaneous semaglutide at a dose of 2.4 mg was superior to placebo in reducing the incidence of death from CVD, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke at long-term follow-up[107]. Side effects of incretin-based therapies are common in patients with MASLD and typically include mild-to-moderate gastrointestinal events such as nausea, diarrhea, constipation, and vomiting[5]. These effects are usually transient, dose-dependent, and more frequent at higher doses.

Bariatric procedures

Bariatric surgery can resolve steatohepatitis, improve fibrosis, and induce sustained weight loss of up to 30% with an impact on all-cause morbidity and mortality[108,109]. Currently accepted criteria for bariatric surgery are BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, irrespective of metabolic comorbid disease, or BMI between 30 and 35 kg/m2 and an obesity-related condition (i.e., T2DM, prediabetes, or uncontrolled hypertension)[110]. MASLD is increasingly accepted as a comorbid condition benefiting from bariatric surgery[111]. For example, bariatric surgery is more effective than lifestyle interventions plus medical therapy, with MASH resolution without worsening of fibrosis at 1 year achieved in 70% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery compared to 19% of those in the lifestyle intervention group[112].

In cirrhosis, bariatric surgery carries increased risks, particularly for those with portal hypertension and decompensated liver disease, including perioperative liver failure, bleeding, infection, and markedly elevated mortality rates[113]. Therefore, bariatric surgery should only be considered in carefully selected patients with compensated cirrhosis, and must be performed by experienced teams at high-volume centers. The presence of clinically significant portal hypertension is a major risk factor for complications; thus, preoperative assessment should include cross-sectional imaging and upper endoscopy[113]. Bariatric surgery is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis unless performed concurrently with or after liver transplantation.

Bariatric surgery has also been associated with a higher risk of hazardous drinking[114]. Moreover, a recent study suggests that people undergoing bariatric surgery with binge drinking are more prone to suicide and liver-related mortality[115]. Consequently, a proper psychiatric evaluation and follow-up before and after the procedure are necessary to achieve the therapeutic goals and avoid related complications[116,117]. Endoscopic bariatric procedures such as endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty are promising in the management of MASLD/MASH[118]. However, high-quality evidence on how primary endoscopic therapies compare with each other and with surgical procedures is lacking[119].

INSULIN RESISTANCE AND T2DM IN MASLD

Insulin resistance is implicated in both the pathogenesis and progression of MASLD[64]. Patients with MASLD demonstrate defects in insulin suppression of fatty acids and reduced inhibition of fatty acid oxidation[120]. Therefore, people with T2DM have both an elevated risk of developing MASLD and a more rapid progression to cirrhosis. In the US, a study with prospectively recruited patients aged ≥ 50 years with T2DM estimated a MASLD prevalence of 65%, and 14% of them had advanced fibrosis and 6% cirrhosis[121]. As liver disease progresses, insulin resistance worsens, and beta cell failure increases, making management of hyperglycemia more challenging[122]. Also, glycemic control [measured by glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)] in individuals with MASLD can predict the development of MASH, liver fibrosis, and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma[123,124]. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss the specific considerations for treating T2DM in individuals with MASLD.

Lifestyle changes

Insulin resistance in MASLD should be managed with lifestyle interventions that promote weight loss, particularly in patients with obesity[125]. In patients with T2DM, lifestyle modifications can improve glycemic control, reduce cardiovascular risk, and enhance overall quality of life[126,127]. Dietary changes focus on balanced, nutrient-dense meals with controlled portions, emphasizing low-glycemic index carbohydrates, lean protein, and healthy fats while minimizing refined sugars and processed foods[128,129]. As stated before, regular physical activity, including at least 150 min per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance training, improves insulin sensitivity and promotes weight management[130]. Behavioral interventions, such as self-monitoring of blood glucose, goal-setting, and structured T2DM education programs, empower patients to maintain adherence to lifestyle changes[131]. Weight loss can significantly improve glycemic control and reduce the need for medication. Smoking cessation and moderation of alcohol intake further contribute to mitigating complications and optimizing T2DM management[132]. Unfortunately, the majority of patients fail to achieve clinically significant lifestyle interventions alone and require treatments to achieve glycemic control[133].

Medications

Several medications have been studied in the treatment of MASLD in patients with insulin resistance and/or T2DM, with evidence supporting the use of pioglitazone and GLP-1RAs. Pioglitazone improves glucose and lipid metabolism and has demonstrated metabolic and histologic improvement in patients with MASLD[134]. A 2018 meta-analysis demonstrated that pioglitazone improved advanced fibrosis in MASLD, even in patients without T2DM[135]. The use of GLP-1RAs, discussed above in the section on the management of obesity, can contribute to achieving adequate glycemic control and reducing CVD risk in T2DM. For example, a study including adults with overweight or obesity and T2DM reported a mean reduction in HbA1c up to 1.4% with semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly, also reducing cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke[136]. However, while GLP-1RAs have shown promise in other contexts, their use in decompensated cirrhosis remains limited due to insufficient clinical experience, risk of accelerated sarcopenia, and safety data[137,138].

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), which target renal glucose reabsorption from the glomerular filtrate, are approved for the treatment of T2DM. Studies have shown that SGLT-2 inhibitors can induce weight loss of 2%-3% and may lead to improvement of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis[139,140]. Although most studies have small sample sizes, a recent Chinese trial including 154 participants with MASLD evidenced that dapagliflozin 10 mg was associated with a higher MASH resolution and fibrosis improvement[141]. Other oral hyperglycemic agents, including metformin[142] and dipeptidyl peptidase-4[143], have been studied in MASLD; however, these were not found to be consistently effective. In patients with decompensated cirrhosis and T2DM, treatment with insulin is preferred, as many of the newer diabetic medications have not been studied in cirrhosis[144].

ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION

Hypertension is a common comorbidity in patients with MASLD and contributes significantly to the progression of liver disease and the associated cardiovascular burden[145,146]. Effective blood pressure management is essential in mitigating these risks and improving long-term outcomes. The management of hypertension in MASLD should be tailored to the specific needs of these patients, considering the interplay between liver dysfunction, metabolic derangements, and cardiovascular risks.

General approach to hypertension in MASLD

The primary goal of hypertension management in MASLD is to achieve target blood pressure levels, typically < 130/80 mmHg for most patients, according to contemporary guidelines[147]. Lifestyle modifications form the foundation of therapy, including sodium restriction, weight loss, regular physical activity, moderation of alcohol intake, and a heart-healthy diet such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension or Mediterranean diet[129,148]. Pharmacological treatment should be selected carefully, taking into account the presence of hepatic dysfunction and potential drug metabolism concerns.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors, such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), are first-line agents in patients with hypertension and MASLD. These drugs not only reduce blood pressure but also provide renal and cardiovascular protection, particularly in those with T2DM or chronic kidney disease[149]. Emerging evidence suggests that RAAS inhibitors may have antifibrotic effects, which could benefit liver health. However, they should be used with caution in patients with advanced liver disease due to the risk of hyperkalemia and renal dysfunction[150]. Calcium channel blockers are effective alternatives for blood pressure control and are generally well-tolerated in MASLD. Long-acting dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, such as amlodipine, are preferred due to their favorable cardiovascular profile and minimal impact on liver metabolism. Finally, SGLT-2i and GLP1-RAs, though primarily antidiabetic agents, show promise in reducing blood pressure and improving hepatic and cardiovascular outcomes[89,151]. These agents may have a role in comprehensive MASLD management, particularly in patients with hypertension and T2DM.

Considerations for advanced liver disease and cirrhosis

In patients with cirrhosis, the management of hypertension becomes more complex, as portal hypertension and systemic hemodynamic changes often dominate. Non-selective beta-blockers (NSBBs), such as carvedilol, propranolol or nadolol, are used early in cirrhosis to manage portal hypertension and reduce the risk of variceal bleeding[152]. These agents lower portal pressure by reducing cardiac output and splanchnic blood flow. Recent guidelines support the early use of NSBBs even in patients with compensated cirrhosis and clinically significant portal hypertension, as they may delay the progression to decompensated disease[152,153]. However, careful monitoring is necessary to avoid hypotension, bradycardia, and worsening renal function, particularly in advanced cirrhosis. Selective beta-blockers, such as bisoprolol or metoprolol, may be used in MASLD patients with coexisting hypertension and cardiovascular conditions but are not recommended for managing portal hypertension. In cases of refractory ascites or hepatorenal syndrome, which often coincide with hypotension, RAAS inhibitors and diuretics should be used judiciously, with close monitoring of renal function and electrolyte balance.

DYSLIPIDEMIA AND HYPERTRIGLYCERIDEMIA

In MASLD, which shares close pathophysiology with metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance drives an increase in free fatty acid flux, leading to elevated triglycerides and very LDL, as well as triggering oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, ultimately contributing to the development of MASLD[154]. Similarly, MASLD also raises the risk of dyslipidemia. It has been shown to increase levels of oxidized LDL cholesterol[155]. A meta-analysis encompassing over 8.50 million patients with MASLD found that the overall prevalence of combined dyslipidemia was nearly 70% in patients with MASLD and MASH[156].

THERAPIES FOR LOWERING LDL CHOLESTEROL

Managing dyslipidemia, similar to other metabolic risk factors, is crucial for preventing CVD. Detailed guidance on managing dyslipidemia can be found in previous publications focused on the general population[154]. Statins, a common medication for dyslipidemia, are both safe and effective, even in individuals with decompensated liver disease[157]. Statins are typically well-tolerated in patients with Child-Pugh Class A cirrhosis. Additionally, growing evidence indicates that statins may help slow the progression of fibrosis and cirrhosis and reduce the risk of liver cancer in MASLD[158-160]. However, their role in reducing cardiovascular mortality in patients with Child-Pugh Class B or C cirrhosis remains uncertain, given the poor prognosis associated with these advanced stages of liver disease[161]. Among the various types of statins, atorvastatin is the only one proven to reduce cardiovascular risk while having a lower hepatotoxicity risk[154,162]. It is important to note that elevations in serum ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels are common in patients taking statins. However, drug-induced liver injury or acute liver failure remains rare in those on statin therapy[161]. Statin is indicated for the treatment of increased LDL levels among patients with MASLD who are at increased risk for adverse outcomes of CVD[70,163].

Non-statin therapies play a crucial role in managing LDL cholesterol in patients who do not achieve target levels with statins alone or cannot tolerate statins due to adverse effects[164]. Ezetimibe, a cholesterol absorption inhibitor, reduces LDL cholesterol by 18%-25% and has demonstrated cardiovascular risk reduction in the IMPROVE-IT trial (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial). Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, such as evolocumab and alirocumab, are monoclonal antibodies that reduce LDL cholesterol by 46%-73% and provide significant cardiovascular benefits, especially in high-risk patients. Inclisiran, an RNA interference therapy, lowers LDL cholesterol by about 50% and offers an alternative for patients unable to use PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies. Bempedoic acid, an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) citrate lyase inhibitor, reduces LDL cholesterol by 25%-38% and is particularly useful for statin-intolerant patients, as evidenced by the CLEAR OUTCOMES trial (NCT02993406)[165].

The 2022 ACC guidelines recommend PCSK9 inhibitors and bempedoic acid based on a patient’s ASCVD risk and LDL cholesterol levels, particularly those with established CVD, high cardiovascular risk, or in patients who do not achieve LDL-C targets with maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy, or who are statin-intolerant[166]. For primary dyslipidemias, aggressive treatment and early referral to specialists remain essential[167]. Although PCSK9 inhibitors have robust evidence for reducing major cardiovascular events[168], bempedoic acid has only a modest effect on cardiovascular event reduction in statin-intolerant patients[169]. Finally, PCSK9 inhibitors are well tolerated, with the main adverse event being injection-site reactions; they do not increase the risk of myalgia, neurocognitive events, or new-onset diabetes. Bempedoic acid is associated with increased risk of hyperuricemia and gout, mild increases in hepatic enzymes, and a small increase in cholelithiasis.

ADDITIONAL PHARMACOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Incorporating lipid-lowering therapies, such as statins, is a cornerstone of cardiovascular risk reduction in MASLD[170]. Statins not only decrease LDL-cholesterol but also exhibit pleiotropic effects, including anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties, which are particularly beneficial in MASLD[171,172]. Despite concerns about hepatotoxicity, the vast majority of patients tolerate statins well, even in the presence of mild to moderate liver enzyme elevations[161]. For patients at high cardiovascular risk or with advanced fibrosis, statins should be complemented by other agents, such as ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors, to achieve optimal lipid control[173]. The use of antihypertensive therapies, particularly RAAS inhibitors, and antidiabetic agents with cardiometabolic benefits, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists or SGLT-2i, further enhances risk-reduction strategies[89,174,175]. Finally, resmetirom is a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist that was recently approved as treatment for MASLD with fibrosis F2-3. Resmetirom has also been shown to significantly reduce levels of LDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and triglycerides, being a promising therapy to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients with MASLD[176].

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO RISK MANAGEMENT

Effective cardiovascular risk assessment and management in MASLD require a collaborative model that integrates hepatology, cardiology, endocrinology, diabetology, and primary care, given the bidirectional relationship between liver disease severity, cardiometabolic comorbidities, and incident cardiovascular events[4,22]. Primary care is typically best positioned to lead longitudinal prevention - screening for hypertension, T2DM, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, smoking, and alcohol use; initiating first-line therapies; and ensuring follow-up and adherence - while hepatologists contribute liver-specific phenotyping that materially affects systemic risk. In particular, staging of fibrosis may help identify patients who warrant intensified cardiovascular prevention and closer surveillance.

The interplay between liver disease and cardiovascular pathology necessitates integrated care pathways that address both hepatic and systemic risks[177]. Identifying high-risk individuals early enables targeted interventions, including lifestyle modifications, pharmacotherapy, and, where appropriate, advanced cardiovascular procedures. A practical multidisciplinary pathway begins with structured baseline phenotyping and explicit escalation thresholds. At the time of MASLD diagnosis (or first specialist contact), clinicians should document global cardiovascular risk (using ACC/AHA PCE or SCORE2), key metabolic drivers (blood pressure, lipids, glycemic status, adiposity), kidney function, and liver fibrosis stage, and subclinical atherosclerosis imaging (e.g., CAC scoring or carotid ultrasound) when risk is uncertain or when results would change management. Referral to cardiology should be prioritized for patients with established CVD, high-risk imaging findings, complex dyslipidemia requiring advanced lipid-lowering strategies, or suspected heart failure/arrhythmia.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

MASLD is strongly associated with CVD, the leading cause of mortality in these patients. Shared pathophysiological mechanisms, including metabolic dysfunction and systemic inflammation, necessitate integrated care strategies to manage both liver and cardiovascular risks effectively. Lifestyle interventions remain foundational, offering benefits for liver health and CVD risk reduction. Pharmacological therapies, including GLP-1 receptor agonists, pioglitazone, and SGLT-2i, are valuable for addressing obesity, T2DM, and cardiovascular risk. Advanced fibrosis, a key predictor of poor outcomes, underscores the importance of non-invasive diagnostics and tailored interventions. Careful management of hypertension and dyslipidemia further mitigates CVD risk. Early use of NSBBs in cirrhosis highlights the complex interplay between liver disease and systemic hemodynamics.

Future work should prioritize MASLD-specific cardiovascular risk models that integrate liver fibrosis severity, CMRFs, and biomarkers, and that are externally validated across diverse race/ethnicities and regions. Prospective studies are also needed to define when biomarkers and imaging [e.g., high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), NT-proBNP, CAC, carotid ultrasound] meaningfully reclassify risk and change management in MASLD, including identifying thresholds that trigger treatment intensification. Finally, implementation research should test scalable, multidisciplinary care pathways to determine whether structured screening and guideline-concordant therapy improve both cardiovascular and liver-related outcomes.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The Graphical Abstract was created with BioRender. Arab, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/0kcfmed.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived this review: Díaz LA, Arab JP

Wrote the first draft: Danpanichkul P, Blaney H, Perelli J, Díaz LA

All authors reviewed the manuscript, provided relevant contributions, and approved the final version: Danpanichkul P, Blaney H, Perelli J, Huerta P, Idalsoaga F, Arrese M, Arab JP, Loomba R, Díaz LA

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This manuscript was partially funded by the Chilean Government through Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico (FONDECYT Project for M.A. 1241450).

Conflicts of interest

Arab JP is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Idalsoaga F and Díaz LA are Junior Editorial Board Members of the same journal. In addition, Díaz LA is a Guest Editor of the special issue Metabolic and Alcohol-Related Dual Liver Injury: Exploring MetALD. Arab JP, Idalsoaga F, and Díaz LA were not involved in any editorial processing steps, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Arrese M consults for Inventiva and AstraZeneca and has served as a speaker for Siemens. Loomba R serves as a consultant to Aardvark Therapeutics, Altimmune, Anylam/Regeneron, Amgen, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CohBar, Eli Lilly, Galmed, Gilead, Glympse Bio, Hightide, Inipharma, Intercept, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen Inc., Madrigal, Metacrine Inc., NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Merck, Pfizer, Sagimet, Theratechnologies, 89 Bio, Terns Pharmaceuticals, and Viking Therapeutics. In addition, his institutions received research grants from Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galectin Therapeutics, Galmed Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, Intercept, Hanmi, Inventiva, Ionis, Janssen, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NGM Biopharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sonic Incytes, and Terns Pharmaceuticals. He is a co-founder of LipoNexus Inc.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77:1335-47.

2. Henry L, Paik J, Younossi ZM. Review article: the epidemiologic burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease across the world. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:942-56.

3. Huang DQ, Wong VWS, Rinella ME, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in adults. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2025;11:14.

4. Targher G, Byrne CD, Tilg H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut. 2024;73:691-702.

5. Targher G, Valenti L, Byrne CD. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2025;393:683-98.

6. Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al.; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Ann Hepatol. 2024;29:101133.

7. Díaz LA, Lazarus JV, Fuentes-López E, et al. Disparities in steatosis prevalence in the United States by Race or Ethnicity according to the 2023 criteria. Commun Med. 2024;4:219.

8. Kim D, Danpanichkul P, Wijarnpreecha K, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, Ahmed A. Current burden of steatotic liver disease and fibrosis among adults in the United States, 2017-2023. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:382-93.

9. Llovet JM, Willoughby CE, Singal AG, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:487-503.

10. Chew NWS, Mehta A, Goh RSJ, et al. Cardiovascular-liver-metabolic health: recommendations in screening, diagnosis, and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in cardiovascular disease via modified Delphi approach. Circulation. 2025;151:98-119.

11. Ciardullo S, Mantovani A, Morieri ML, Muraca E, Invernizzi P, Perseghin G. Impact of MASLD and MetALD on clinical outcomes: a meta-analysis of preliminary evidence. Liver Int. 2024;44:1762-7.

12. Duell PB, Welty FK, Miller M, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Hypertension; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42:e168-85.

13. Adams LA, Anstee QM, Tilg H, Targher G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its relationship with cardiovascular disease and other extrahepatic diseases. Gut. 2017;66:1138-53.

14. Morales J, Handelsman Y. Cardiovascular outcomes in patients with diabetes and kidney disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:161-70.

15. Motamed N, Khoonsari M, Karbalaie Niya MH, et al. External validity of cardiovascular risk assessment tools in individuals with MASLD (NAFLD): a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2025;15:33462.

16. Fegers-Wustrow I, Gianos E, Halle M, Yang E. Comparison of American and European Guidelines for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: JACC guideline comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1304-13.

17. Henson JB, Budoff MJ, Muir AJ. Performance of the Pooled Cohort Equations in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Liver Int. 2023;43:599-607.

18. Barritt AS 4th, Tapper EB, Newsome PN, et al.; TARGET-NASH Investigators. Cardiovascular risk assessment tools are insufficient for patients with metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025.

19. Cheong BYC, Wilson JM, Spann SJ, Pettigrew RI, Preventza OA, Muthupillai R. Coronary artery calcium scoring: an evidence-based guide for primary care physicians. J Intern Med. 2021;289:309-24.

20. Golub IS, Termeie OG, Kristo S, et al. Major Global Coronary Artery Calcium Guidelines. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;16:98-117.

21. Chen CC, Hsu WC, Wu HM, Wang JY, Yang PY, Lin IC. Association between the severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the risk of coronary artery calcification. Medicina. 2021;57:807.

22. Gries JJ, Lazarus JV, Brennan PN, et al. Interdisciplinary perspectives on the co-management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and coronary artery disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;10:82-94.

23. Naqvi TZ, Lee MS. Carotid intima-media thickness and plaque in cardiovascular risk assessment. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:1025-38.

24. Farmakis D, Mueller C, Apple FS. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin assays for cardiovascular risk stratification in the general population. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4050-6.

25. Kim D, Danpanichkul P, Wijarnpreecha K, Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Association of high-sensitivity troponins in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61:1785-93.

26. Haller PM, Beer BN, Tonkin AM, Blankenberg S, Neumann JT. Role of cardiac biomarkers in epidemiology and risk outcomes. Clin Chem. 2021;67:96-106.

27. Ciardullo S, Cannistraci R, Muraca E, Zerbini F, Perseghin G. Liver fibrosis, NT-ProBNP and mortality in patients with MASLD: a population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;34:963-71.

28. Kim Y, Han E, Lee JS, et al. Cardiovascular risk is elevated in lean subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut Liver. 2022;16:290-9.

29. Kuo SZ, Cepin S, Bergstrom J, et al. Clinical utility of liver fat quantification for determining cardiovascular disease risk among patients with type 2 diabetes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;58:585-92.

30. Kweon YN, Ko HJ, Kim AS, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk using nonalcoholic fatty liver disease scoring systems. Healthcare. 2021;9:899.

31. Manne V, Handa P, Kowdley KV. Pathophysiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2018;22:23-37.

32. Vilar-Gomez E, Chalasani N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J Hepatol. 2018;68:305-15.

33. Israelsen M, Rungratanawanich W, Thiele M, Liangpunsakul S. Non-invasive tests for alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2024;80:1390-407.

34. Mantovani A, Csermely A, Petracca G, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:903-13.

35. Park H, Yoon EL, Kim M, et al. Diagnostic performance of the fibrosis-4 index and the NAFLD fibrosis score for screening at-risk individuals in a health check-up setting. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7:e0249.

36. Han S, Choi M, Lee B, et al. Accuracy of noninvasive scoring systems in assessing liver fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut Liver. 2022;16:952-63.

37. Lee Y, Lee W. Time-updated FIB-4 index predicts coronary artery calcification progression in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Sci Rep. 2025;16:1459.

38. Kalligeros M, Danpanichkul P, Noureddin M. Noninvasive assessment to identify patients with at-risk metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;20:672-7.

39. Treeprasertsuk S, Björnsson E, Enders F, Suwanwalaikorn S, Lindor KD. NAFLD fibrosis score: a prognostic predictor for mortality and liver complications among NAFLD patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1219-29.

40. Takahashi T, Watanabe T, Shishido T, et al. The impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score on cardiac prognosis in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:733-9.

41. Parikh NS, VanWagner LB, Elkind MSV, Gutierrez J. Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis and stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2019;407:116524.

42. Han E, Lee YH, Lee JS, et al. Fibrotic burden determines cardiovascular risk among subjects with metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Gut Liver. 2022;16:786-97.

43. Henson JB, Simon TG, Kaplan A, Osganian S, Masia R, Corey KE. Advanced fibrosis is associated with incident cardiovascular disease in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:728-36.

44. Rahmani J, Miri A, Namjoo I, et al. Elevated liver enzymes and cardiovascular mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of more than one million participants. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:555-62.

45. Seo YY, Cho YK, Bae JC, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α as a predictor for the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a 4-year follow-up study. Endocrinol Metab. 2013;28:41-5.

46. Ding Z, Wei Y, Peng J, Wang S, Chen G, Sun J. The potential role of C-reactive protein in metabolic-dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and aging. Biomedicines. 2023;11:2711.

47. Kurt B, Reugels M, Schneider KM, et al. C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk in the general population. Eur Heart J. ;2025:ehaf937.

48. Ionescu VA, Gheorghe G, Bacalbasa N, Diaconu CC. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: pathogenetic links to cardiovascular risk. Biomolecules. 2025;15:163.

49. Seropian IM, Cassaglia P, Miksztowicz V, González GE. Unraveling the role of galectin-3 in cardiac pathology and physiology. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1304735.

50. Ghorbani A, Bhambhani V, Christenson RH, et al. Longitudinal change in galectin-3 and incident cardiovascular outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3246-54.

51. Wu J, Wu G, Li J, et al. Proteomic variation underlies the heterogeneous risk of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease for subsequent chronic diseases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2025;192:691-703.

52. Pirola CJ, Diambra L, Fernández Gianotti T, et al. Organ damage proteomic signature identifies patients with MASLD at risk of systemic complications. Hepatology. 2025.

53. Björnson E, Samaras D, Levin M, Bäckhed F, Bergström G, Gummesson A. The impact of steatotic liver disease on coronary artery disease through changes in the plasma lipidome. Sci Rep. 2024;14:22307.

54. Thiele M, Villesen IF, Niu L, et al.; MicrobLiver consortium, GALAXY consortium. Opportunities and barriers in omics-based biomarker discovery for steatotic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2024;81:345-59.

55. Shabalala SC, Dludla PV, Mabasa L, et al. The effect of adiponectin in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the potential role of polyphenols in the modulation of adiponectin signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;131:110785.

56. Luo J, He Z, Li Q, et al. Adipokines in atherosclerosis: unraveling complex roles. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1235953.

57. Huang H, Xie J, Hou L, Miao M, Xu L, Xu C. Estimated small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese populations. J Diabetes Investig. 2024;15:491-9.

58. Enkhmaa B, Berglund L. Non-genetic influences on lipoprotein(a) concentrations. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:53-62.

59. Fan H, Kouvari M, Mingrone G, et al. Lipoprotein (a) in the full spectrum of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: evidence from histologically and genetically characterized cohorts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1356-65.e5.

60. Xiao T, Liu HH, Tian N, et al.; WMU MAFLD Clinical Research Working Group. Association of plasma lipoprotein(a) with major adverse cardiovascular events in MASLD with or without advanced liver fibrosis. Liver Int. 2025;45:e70208.

61. GBD 2021 Adult BMI Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990-2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2025;405:813-38.

62. Yang AH, Tincopa MA, Tavaglione F, et al. Prevalence of steatotic liver disease, advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis among community-dwelling overweight and obese individuals in the USA. Gut. 2024;73:2045-53.

63. Kim HS, Xiao X, Byun J, et al. Synergistic associations of PNPLA3 I148M variant, alcohol intake, and obesity with risk of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2234221.

64. Díaz LA, Arab JP, Louvet A, Bataller R, Arrese M. The intersection between alcohol-related liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:764-83.

65. Marti-Aguado D, Calleja JL, Vilar-Gomez E, et al. Low-to-moderate alcohol consumption is associated with increased fibrosis in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2024;81:930-40.

66. Arab JP, Díaz LA, Rehm J, et al. Metabolic dysfunction and alcohol-related liver disease (MetALD): position statement by an expert panel on alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2025;82:744-56.

67. Khan SS, Ning H, Wilkins JT, et al. Association of body mass index with lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and compression of morbidity. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:280-7.

68. GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2133-61.

69. GBD 2021 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden and strength of evidence for 88 risk factors in 204 countries and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2162-203.

70. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542.

71. Romero-Gómez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol. 2017;67:829-46.

72. Franz MJ, Boucher JL, Rutten-Ramos S, VanWormer JJ. Lifestyle weight-loss intervention outcomes in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1447-63.

73. Rubino F, Cummings DE, Eckel RH, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13:221-62.

74. Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-835.

75. Sofi F, Casini A. Mediterranean diet and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: new therapeutic option around the corner? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7339-46.

76. Widmer RJ, Flammer AJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The Mediterranean diet, its components, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 2015;128:229-38.

77. Godos J, Marventano S, Mistretta A, Galvano F, Grosso G. Dietary sources of polyphenols in the Mediterranean healthy Eating, Aging and Lifestyle (MEAL) study cohort. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2017;68:750-6.

78. Pérez M, Dominguez-López I, Lamuela-Raventós RM. The chemistry behind the Folin-Ciocalteu method for the estimation of (poly)phenol content in food: total phenolic intake in a mediterranean dietary pattern. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71:17543-53.

79. Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Ungprasert P. Coffee consumption and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:e8-12.

80. Ebadi M, Ip S, Bhanji RA, Montano-Loza AJ. Effect of coffee consumption on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease incidence, prevalence and risk of significant liver fibrosis: systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2021;13:3042.

81. Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J. Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ. 2017;359:j5024.

82. Xue Y, Peng Y, Zhang L, Ba Y, Jin G, Liu G. Effect of different exercise modalities on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:6212.

83. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320:2020-8.

84. Hao XY, Zhang K, Huang XY, Yang F, Sun SY. Muscle strength and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:636-43.

85. Soto R, Díaz LA, Rivas V, et al. Frailty and reduced gait speed are independently related to mortality of cirrhotic patients in long-term follow-up. Ann Hepatol. 2021;25:100327.

86. Stine JG, Bradley D, McCall-Hosenfeld J, et al. Multidisciplinary clinic model enhances liver and metabolic health outcomes in adults with MASH. Hepatol Commun. 2025;9:e0649.

87. Bansal MB, Patton H, Morgan TR, Carr RM, Dranoff JA, Allen AM. Semaglutide therapy for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: November 2025 updates to AASLD Practice Guidance. Hepatology. 2025.

88. Diaz LA, Arab JP, Idalsoaga F, et al. Updated recommendations for the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) by the Latin American working group. Ann Hepatol. 2025;30:101903.

89. Nevola R, Epifani R, Imbriani S, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1703.

90. Abdelmalek MF, Harrison SA, Sanyal AJ. The role of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:2001-16.

91. Targher G, Mantovani A, Byrne CD. Mechanisms and possible hepatoprotective effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and other incretin receptor agonists in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:179-91.

92. Armstrong MJ, Okanoue T, Sundby Palle M, Sejling AS, Tawfik M, Roden M. Similar weight loss with semaglutide regardless of diabetes and cardiometabolic risk parameters in individuals with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: post hoc analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025;27:710-8.

93. Newsome PN, Buchholtz K, Cusi K, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of subcutaneous semaglutide in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1113-24.

94. Phase 3 ESSENCE trial: semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;20:6-7.

95. Giannakogeorgou A, Roden M. Role of lifestyle and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for weight loss in obesity, type 2 diabetes and steatotic liver diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2024;59 Suppl 1:S52-75.

96. Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, et al.; LEAN trial team. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387:679-90.

97. Forst T, De Block C, Del Prato S, et al. The role of incretin receptor agonists in the treatment of obesity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:4178-96.

98. Sanyal AJ, Newsome PN, Kliers I, et al.; ESSENCE Study Group. Phase 3 trial of semaglutide in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:2089-99.

99. Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, et al.; SURMOUNT-1 Investigators. Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:205-16.

100. Loomba R, Hartman ML, Lawitz EJ, et al.; SYNERGY-NASH Investigators. Tirzepatide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with liver fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:299-310.

101. Sanyal AJ, Bedossa P, Fraessdorf M, et al.; 1404-0043 Trial Investigators. A phase 2 randomized trial of survodutide in MASH and fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:311-9.

102. Harrison SA, Browne SK, Suschak JJ, et al. Effect of pemvidutide, a GLP-1/glucagon dual receptor agonist, on MASLD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Hepatol. 2025;82:7-17.

103. Sanyal AJ, Kaplan LM, Frias JP, et al. Triple hormone receptor agonist retatrutide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a randomized phase 2a trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:2037-48.

104. Chetty AK, Rafi E, Bellini NJ, Buchholz N, Isaacs D. A review of incretin therapies approved and in late-stage development for overweight and obesity management. Endocr Pract. 2024;30:292-303.

105. Badve SV, Bilal A, Lee MMY, et al. Effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on kidney and cardiovascular disease outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025;13:15-28.

106. Wu S, Gao L, Cipriani A, et al. The effects of incretin-based therapies on β-cell function and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis combining 360 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:975-83.

107. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, et al.; SELECT Trial Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in obesity without diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2221-32.

108. Mingrone G, Panunzi S, De Gaetano A, et al. Metabolic surgery versus conventional medical therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: 10-year follow-up of an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:293-304.

109. Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Goemans A, et al. Resolution of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis after bariatric surgery improves 15-year survival: a prospective cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1567-76.e9.

110. Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) indications for metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2023;33:3-14.

111. Feng G, Han Y, Yang W, et al. Recompensation in MASLD-related cirrhosis via metabolic bariatric surgery. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2025;36:118-32.

112. Verrastro O, Panunzi S, Castagneto-Gissey L, et al. Bariatric-metabolic surgery versus lifestyle intervention plus best medical care in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (BRAVES): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2023;401:1786-97.

113. Patton H, Heimbach J, McCullough A. AGA clinical practice update on bariatric surgery in cirrhosis: expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:436-45.

114. Alvarado-Tapias E, Marti-Aguado D, Kennedy K, et al. Bariatric surgery is associated with alcohol-related liver disease and psychiatric disorders associated with AUD. Obes Surg. 2023;33:1494-505.

115. Alvarado-Tapias E, Martí-Aguado D, Gómez-Medina C, et al. Binge drinking at time of bariatric surgery is associated with liver disease, suicides, and increases long-term mortality. Hepatol Commun. 2024;8:e0490.

116. Athanasiadis DI, Martin A, Kapsampelis P, Monfared S, Stefanidis D. Factors associated with weight regain post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:4069-84.

117. Lüscher A, Vionnet N, Amiguet M, et al. Impact of preoperative psychiatric profile in bariatric surgery on long-term weight outcome. Obes Surg. 2023;33:2072-82.

118. Abad J, Llop E, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty plus lifestyle intervention in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis: a multicenter, sham-controlled, randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23:1556-66.e3.

119. Aitharaju V, Ragheb J, Firkins S, Patel R, Simons-Linares CR. Endoscopic bariatric and metabolic therapies and its effect on metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a review of the current literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2025;21:175-82.

120. Syed-Abdul MM. Lipid metabolism in metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Metabolites. 2023;14:12.

121. Ajmera V, Cepin S, Tesfai K, et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of NAFLD, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in people with type 2 diabetes. J Hepatol. 2023;78:471-8.

122. Lomonaco R, Bril F, Portillo-Sanchez P, et al. Metabolic impact of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:632-8.

123. Alexopoulos AS, Crowley MJ, Wang Y, et al. Glycemic control predicts severity of hepatocyte ballooning and hepatic fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2021;74:1220-33.

124. Kramer JR, Natarajan Y, Dai J, et al. Effect of diabetes medications and glycemic control on risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2022;75:1420-8.

125. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:367-78.e5.

126. Uusitupa M, Khan TA, Viguiliouk E, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle changes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2019;11:2611.

127. Kirwan JP, Sacks J, Nieuwoudt S. The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84:S15-21.

128. Clina JG, Sayer RD, Pan Z, et al. High- and normal-protein diets improve body composition and glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Obesity. 2023;31:2021-30.

129. Zelber-Sagi S, Moore JB. Practical lifestyle management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease for busy clinicians. Diabetes Spectr. 2024;37:39-47.

130. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al.; American College of Sports Medicine, American Diabetes Association. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:e147-67.

131. Ernawati U, Wihastuti TA, Utami YW. Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education (DSME) in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients: systematic literature review. J Public Health Res. 2021;10:2240.

132. Aloke C, Egwu CO, Aja PM, et al. Current advances in the management of diabetes mellitus. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2436.

133. Madigan CD, Graham HE, Sturgiss E, et al. Effectiveness of weight management interventions for adults delivered in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2022;377:e069719.

134. Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, et al. Long-term pioglitazone treatment for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:305-15.

135. Musso G, Cassader M, Paschetta E, Gambino R. Thiazolidinediones and advanced liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:633-40.

136. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al.; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834-44.

137. Kanwal F, Shubrook JH, Adams LA, et al. Clinical care pathway for the risk stratification and management of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1657-69.

138. Castera L, Cusi K. Diabetes and cirrhosis: current concepts on diagnosis and management. Hepatology. 2023;77:2128-46.

139. Arai T, Atsukawa M, Tsubota A, et al. Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a propensity score-matched analysis of real-world data. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2021;12:20420188211000243.

140. Ong Lopez AMC, Pajimna JAT. Efficacy of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on hepatic fibrosis and steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:2122.