Sex and gender differences in MASLD: pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical implications, and future directions

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a leading and increasingly prevalent cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, with significant hepatic and extrahepatic consequences. Sex and gender are major, yet underrecognized, determinants of MASLD risk, progression, and related clinical events. This narrative review synthesizes evidence on (1) biological sex effects - including sex chromosomes, genetic variants, and the modulatory roles of estrogens and androgens on lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, immune signalling, and fibrogenesis - and (2) gendered socio-behavioral influences such as diet, physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use, health-seeking behavior, pregnancy and lactation, and gender-affirming hormone therapy. We highlight sex differences in metabolic phenotypes (fat distribution, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension), emerging sex-specific gene-microbiome interactions in the gut-liver axis, and sex-dependent patterns of extrahepatic comorbidity (cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and selected cancers). Evidence also suggests that commonly used diagnostic tools and predictive algorithms - including non-invasive fibrosis scores and machine-learning models - may misclassify risk if sex and hormonal status are not considered, and that pharmacologic, surgical, and hormone-based therapies exhibit preliminary sex-specific effects. Based on these observations, we propose a conceptual framework in which sex and gender, individually and interactively, shape the MASLD burden. Critical knowledge gaps remain, particularly for premenopausal women, transgender, and non-binary populations. Incorporating sex and gender into study design, diagnostics, risk stratification, and clinical trials is essential to advance precision prevention and equitable care for MASLD.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is now recognized as the most prevalent chronic liver condition globally, affecting nearly one-third of the adult population[1,2]. MASLD is defined by the presence of ≥ 5% hepatic steatosis in the absence of competing causes such as chronic viral hepatitis, steatogenic medications, autoimmune or genetic liver diseases (e.g., autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease), or significant alcohol consumption[3].

Closely linked to obesity, insulin resistance (IR), type 2 diabetes (T2D), and dyslipidemia, MASLD spans a disease spectrum ranging from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, advanced fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3,4]. Given its strong association with metabolic syndrome, MASLD poses a significant public health challenge and contributes substantially to global liver-related morbidity and mortality[5].

Importantly, both sex and gender influence the epidemiology and clinical course of MASLD. Sex refers to biological attributes, including chromosomes, hormones, and reproductive organs, whereas gender reflects sociocultural roles, behaviors, and expectations that shape health outcomes[6]. Together, these dimensions contribute to variability in MASLD prevalence, pathophysiology, and clinical outcomes[7]. Men generally display higher rates of MASLD, yet postmenopausal women are at increased risk for advanced fibrosis[8]. This disparity is influenced not only by hormonal changes but also by sex-specific differences in obesity patterns, insulin sensitivity, inflammatory responses, and gut microbiome composition, all of which can differentially affect MASLD development and progression[7,9]. Moreover, emerging data suggest sex-based disparities in progression to MASLD-related HCC[9].

Understanding these sex and gender differences is essential to improve risk stratification, early diagnosis, and personalized therapeutic strategies[10]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of sex-related differences in MASLD, focusing on hormonal, genetic, metabolic, and gut microbial mechanisms, and their impact on disease progression and outcomes. We also examine the role of gender, including the impact of social norms and behavioral factors. Finally, the clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

To identify relevant studies for this review, we searched PubMed and Embase using controlled vocabulary terms (including MeSH and Emtree) and free-text keywords. The search was limited to publications in English and studies conducted in adult populations (≥ 18 years), up to 11 July 2025. Detailed keywords and the search syntax for each database are provided in Table 1. We additionally reviewed supplementary materials of studies reporting MASLD-related outcomes or clinical trial results to capture sex-specific data.

Search strategies used in PubMed and Embase combining controlled vocabularies (MeSH and Emtree terms) with free-text keywords for studies on sex, gender, and MASLD

| Database | Search syntax |

| PubMed | (“Sex Characteristics”[MeSH] OR “Gender Role”[MeSH] OR “Gender Equity”[MeSH] OR “Gender-Based Violence”[MeSH] OR “Gender Dysphoria”[MeSH] OR “Sexual and Gender Minorities”[MeSH] OR “Gender-Nonconforming Persons”[MeSH] OR “Gender-Affirming Care”[MeSH] OR “Gender-Affirming Procedures”[MeSH] OR “Sexual and Gender Disorders”[MeSH] OR “Transsexualism”[MeSH] OR “Sexism”[MeSH] OR “sex differences”[tiab] OR “sex-specific”[tiab] OR “sex dimorphism”[tiab] OR gender[tiab]) AND (“non-alcoholic fatty liver disease”[MeSh] OR “NAFLD”[tiab] OR “fatty liver”[tiab] OR “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis”[tiab] OR “non-alcoholic steatohepatitis”[tiab] OR “NASH”[tiab] OR “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis”[tiab] OR “MASH”[tiab] OR “MASLD”[tiab] OR “steatotic liver”[tiab] OR “MAFLD”[tiab]) AND (“1900/01/01”[Date - Publication]: “2025/07/11”[Date - Publication]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND (english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter]) |

| Embase | (“sex difference”/de OR “sexual and gender minority”/de OR “gender identity”/de OR “transgenderism”/de OR “transgender and gender nonbinary”/de OR “sex difference*”:ab,ti OR “sex-specific”:ab,ti OR “sex dimorphism”:ab,ti OR “gender”:ab,ti) AND (“nonalcoholic fatty liver”/de OR “NAFLD”:ab,ti OR “fatty liver”:ab,ti OR “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis”:ab,ti OR “non-alcoholic steatohepatitis”:ab,ti OR “NASH”:ab,ti OR “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis”:ab,ti OR “MASH”:ab,ti OR “MASLD”:ab,ti OR “steatotic liver”:ab,ti OR “MAFLD”:ab,ti) NOT [medline]/lim AND [01-01-1900]/sd NOT [1-07-2025]/sd AND ([adult]/lim OR [aged]/lim OR [very elderly]/lim) AND [humans]/lim AND [english]/lim AND [article]/lim |

| The search was limited to studies conducted in adult humans, published in English through 11 July 2025 | |

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF MASLD BY SEX

Epidemiological data reveal consistent sex-based differences in MASLD prevalence[3,11]. For instance, in Asia, incidence rates range from 19 to 44.5 per 1,000 person-years and are higher in males than in females[12]. The overall prevalence among men spans from 4.3% to 42%, while for women it ranges between 1.6% and 24% across various cohorts[12].

These wide ranges reflect not only true population variability but also differences in diagnostic approaches. MASLD diagnosis relies on multiple methods - including liver biopsy, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), and biochemical markers - each with differing sensitivity and specificity. MRS is considered the non-invasive gold standard[12,13]. However, its limited availability and high cost restrict widespread use, leading to inconsistencies in prevalence estimates across studies. Additionally, methodological differences, such as the use of liver enzymes or administrative codes, may underestimate or overestimate MASLD prevalence depending on selection criteria and referral bias[14,15]. For example, studies based on biopsy samples may overrepresent individuals with more severe disease, while reliance on blood tests or coding data may miss asymptomatic or early-stage cases.

Geographic and demographic heterogeneity further contributes to inconsistent findings[16]. A Shanghai population study reported higher MASLD prevalence in men under 50 years of age, but a reversal of this trend in individuals over 50, with women showing higher rates[17]. Similarly, a Japanese study found MASLD prevalence increased from young adulthood to middle age in men, followed by a decline after age 50-60, while in women, rates rose sharply after menopause[18]. Another cohort revealed a MASLD prevalence of 6% in premenopausal women, compared to 24% in men and 15% in postmenopausal women[19].

HORMONAL INFLUENCES

Sex hormones play a central role in modulating susceptibility to MASLD [Figure 1] through their influence on lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, oxidative stress, immune response, and tissue repair[20,21]. Estrogens regulate key hepatic metabolic pathways. They enhance fatty acid oxidation and suppress de novo lipogenesis, mechanisms that collectively reduce hepatic fat accumulation[22]. These protective effects are largely mediated via estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), which downregulates stress pathways such as JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and upregulates antioxidant enzymes[23,24]. Estrogens also mitigate mitochondrial oxidative stress and lipid droplet accumulation by increasing mitochondrial thioredoxin 2 (TRX2) expression[25]. Animal studies confirm that estrogen deficiency - through ovariectomy or ERα deletion - leads to hepatic lipid accumulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and IR[26,27]. Restoration of estrogen improves these parameters only when liver ERα is functional[27]. Clinical data mirror these findings. In young women undergoing oophorectomy for endometrial cancer, MASLD risk significantly increased, highlighting the protective role of ovarian hormones[28]. In pediatric MASLD cohorts, higher estrone and estradiol levels were linked to lower portal inflammation in both sexes[29].

Figure 1. Hormonal and Metabolic Modulation of MASLD Risk Across Sex and Life Stages. This figure illustrates how sex hormones-estrogens, androgens, and related binding proteins-and metabolic factors collectively influence susceptibility to MASLD across life stages in both sexes. It integrates hormonal transitions (e.g., pregnancy, menopause, and aging) with sex-specific metabolic determinants such as insulin resistance, lipid metabolism, and body fat distribution, highlighting differences in pathophysiology and clinical presentation. PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome; SHBG: sex hormone-binding globulin; TRT: testosterone replacement therapy; GDM: gestational diabetes mellitus; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

The menopausal transition, characterized by estrogen decline, marks a critical risk period for the development and progression of MASLD[30-32]. During this phase, estrogen levels drop rapidly, while androgen levels decline more gradually, leading to a relative hyperandrogenic state[32]. This hormonal shift is further compounded by a reduction in circulating sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), which increases the free androgen index (FAI) and thereby amplifies androgen bioavailability[33-35]. Postmenopausal women with high bioavailable testosterone or FAI show greater fatty liver burden and reduced insulin sensitivity[36-38]. In contrast, higher SHBG levels are inversely associated with MASLD severity and metabolic dysfunction in postmenopausal women[37,39-41], indicating SHBG’s potential protective role.

Androgens show contrasting effects in men and women. In men, low serum testosterone is associated with higher MASLD risk and IR. Some evidence supports testosterone replacement therapy for reversing hepatic steatosis in hypogonadal men, although results are inconsistent[42-44]. In contrast, elevated testosterone levels in women are associated with MASLD progression, especially in those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), where androgen excess is common[45]. In premenopausal women, higher testosterone levels correlate with increased steatosis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) risk, and abdominal adiposity, but these associations diminish after menopause[46,47]. Pediatric data show that higher testosterone levels are linked to improved steatosis and fibrosis in boys, while the opposite is observed for girls-further underscoring sex-specific hormonal effects[29].

GENDER DIFFERENCES: LIFESTYLE AND BEHAVIORAL FACTORS

While biological sex governs certain physiological predispositions, gender reflects sociocultural norms, roles, and behaviors that influence an individual’s exposures and health choices. These factors shape dietary patterns, physical activity, alcohol and tobacco use, healthcare engagement, and reproductive behaviors such as pregnancy and breastfeeding, as well as decisions regarding gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) in transgender individuals. Each of these gendered determinants can modulate the onset, trajectory, and outcomes of MASLD [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Gender Differences in Lifestyle and Behavioral Factors Contributing to MASLD. This figure illustrates gender-specific influences across dietary habits, physical activity patterns, alcohol and tobacco use, health-seeking behaviors, and considerations for gender-diverse individuals. ↑Indicates an increase or higher level of a variable; ↓indicates a decrease or lower level of a variable; →indicates a relationship or influence between variables (e.g., “leads to”, “is associated with”, or “results in”). MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; FFA: free fatty acids; MetALD: metabolic and alcohol-related liver disease.

Dietary habits and nutritional exposure

Sex and gender shape both nutrient metabolism and dietary behaviors[48]. Women tend to consume more fiber-rich, nutrient-dense foods, while men favor red/processed meats, saturated fats, and sugary beverages-patterns shaped by biological and sociocultural factors, including women’s greater adherence to dietary guidelines[49,50]. Men and postmenopausal women are more susceptible to overnutrition and central adiposity, increasing liver fat[51-55]. Nutritional epidemiology indicates that high-energy, low-fiber diets are more strongly associated with MASLD in men[56], whereas women show greater hepatic lipogenic responses to fructose and high-glycemic foods[57-59]. Supporting these observations, a cohort of 2,466 MASLD patients found that both low and high total energy intake significantly increased all-cause mortality in men, with no significant effect in women[60]. Gender-related barriers-including food insecurity, cultural dietary restrictions, and caregiving responsibilities-further affect women’s nutritional quality, especially in low-resource settings, and contribute to greater MASLD vulnerability[61,62]. Sex-specific responses to dietary interventions have also been reported[63,64]; Table 2 summarizes some of these findings. Men generally achieve greater metabolic improvements from low-calorie or Mediterranean diets, whereas premenopausal women may respond better to low-glycemic index strategies[65-69]. Ketogenic diets are effective for weight loss, but estrogens appear to blunt hepatic improvements in reproductive-age women, with postmenopausal women showing the least favorable responses[68].

Sex-specific effects of lifestyle modifications on MASLD outcomes

| Author, year[Ref.] | Lifestyle modifications | Design | Method | Sex-specific results | Comment |

| Trouwborst et al., 2021[65] | Low-Calorie diet | RCT (NCT00390637) | The DiOGenes trial enrolled 782 overweight or obese adults (65% women) who followed a LCD of approximately 800 kcal/day for 8 weeks. After the initial weight-loss phase, participants entered a 6-month weight-maintenance phase on ad libitum diets that varied in protein content and glycemic index. The study assessed body weight, insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR), lipid profile, and other cardiometabolic biomarkers both after the LCD and at the end of follow-up. Results were adjusted for changes in body weight | Men lost more weight than women during the LCD phase (-12.8 ± 3.9 kg vs. -10.1 ± 2.8 kg; P < 0.001) but regained more during follow-up (1.5 ± 5.4 kg vs. -0.5 ± 5.5 kg; P < 0.001). Men had greater improvements in insulin sensitivity, triglycerides, HDL, LDL, total cholesterol, blood pressure, and adiponectin (std. β: 0.073-0.144; all q < 0.05), while women had more favorable HDL, triglyceride, and diacylglycerol rebound during follow-up (std. β: 0.114-0.164; all q < 0.05) | Men benefit more in short-term cardiometabolic improvement, while women-particularly premenopausal-appear more resilient in maintaining lipid-related benefits over time. Differences in fat distribution (visceral vs. subcutaneous), estrogen status, and metabolic adaptation likely drive this sexual dimorphism |

| Leblanc et al., 2014[67] | Mediterranean diet | Clinical trial (NCT01852721) | In a 12-week trial, 64 men and 59 premenopausal women participated in a Mediterranean diet-based nutritional intervention using motivational interviewing through individual and group sessions. Dietary intake (via food frequency questionnaire), eating behaviors (via the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire), anthropometric, and metabolic measures were assessed at baseline, post-intervention, and 3- and 6-month follow-ups | Men showed greater reductions in red and processed meat intake (P = 0.03), greater increases in whole fruit intake (P = 0.04), and more reduction in disinhibition behavior (P = 0.03). Waist circumference decreased in both sexes during the intervention, but only remained reduced in men at follow-up (P = 0.05). Improvements in total cholesterol to HDL-C ratio, triglycerides, and TG/HDL-C ratio were more pronounced in men than women (P ≤ 0.03). Despite similar initial adherence to the Mediterranean diet, dietary improvements regressed in both sexes post-intervention (P < 0.0001), with men showing more lasting metabolic benefits | Men showed more sustained metabolic improvements and behavioral changes than women, despite similar initial adherence. This suggests sex-specific physiological and behavioral responses, underscoring the importance of tailored dietary interventions |

| D’Abbondanza et al., 2020[68] | Ketogenic diet | Clinical trial (NCT03564002) | Seventy participants with severe obesity (42 females and 28 males) underwent a 25-day VLCKD. Baseline and post-intervention assessments included anthropometric measurements, bioimpedance analysis, liver steatosis grading via ultrasonography, liver function tests (including γ-glutamyl transferase), and glucose homeostasis parameters. Female participants were also stratified by menopausal status for subgroup analysis | In this 25-day VLCKD trial including 42 women and 28 men with severe obesity, men had significantly greater EBWL and γGT reduction than women. Among women, premenopausal participants had the least favorable outcomes. No sex difference was found in steatosis grade or Edmonton stage improvement | Men benefit more from short-term VLCKD in terms of weight loss and liver enzyme reduction. Female response varies by menopausal status, suggesting estrogen plays a role in modulating diet efficacy |

| Vitale et al., 2023[69] | Low glycemic index diet | RCT (NCT03410719) | This multi-national, randomized, controlled, parallel-group trial enrolled 156 adults (82 women, 74 men) with at least two metabolic syndrome traits across centers in Italy, Sweden, and the United States. Participants were randomized to consume either a low- or high-GI Mediterranean diet for 12 weeks. Both diets were isoenergetic and matched for macronutrient composition, including 270 g/day of carbohydrates and 35 g/day of fiber. The only difference was the starch source. Glucose and insulin profiles were monitored for 8 h at baseline and post-intervention, with meals replicating the assigned dietary pattern | In women, the high-GI diet led to significantly higher 8 h average plasma glucose levels than the low-GI diet as early as Day 1 (+23%, P < 0.05), increasing to +37% by Week 12 (P < 0.05). In men, no significant difference was observed between high- and low-GI diets. A significant interaction between sex and dietary GI was confirmed by two-way ANOVA (F = 7.887, P = 0.006) | This trial highlights a compelling sex-specific metabolic sensitivity to dietary glycemic index, with women showing a significantly more adverse glycemic response to high-GI foods than men. These findings reinforce the importance of sex-specific dietary recommendations, particularly in individuals at high risk for type 2 diabetes |

| Curci et al., 2024[81] | Physical activity/Exercise | Prospective cohort | A population-based prospective cohort study was conducted in Castellana Grotte, Southern Italy, enrolling 1,826 adults (> 30 years) from an eligible pool of 2,970 starting in 1985. Participants underwent anthropometric assessment, liver ultrasonography for MASLD diagnosis, and completed validated questionnaires on diet and LTPA. Vital status was tracked through municipal records to assess all-cause mortality over time | Low LTPA in individuals with MASLD was associated with significantly increased all-cause mortality risk, especially in women. Women with MASLD and low LTPA had the highest mortality risk and were 19% less likely to survive to age 82 compared to active counterparts. Physical activity mitigated mortality risk regardless of MASLD status, but the protective effect was more pronounced in women | Postmenopausal women have a higher mortality risk related to low activity levels than men; early-life inactivity in women increases later risk due to hormonal protection loss |

| Ajmera et al., 2019[139] | Lactation | Multicenter community-based longitudinal cohort | Participants from the CARDIA cohort who delivered ≥ 1 child post-baseline (Y0: 1985-1986) and underwent CT quantification of hepatic steatosis 25 years later (Y25: 2010-2011, n = 844). Lactation duration was summed across all post-baseline births. NAFLD at Y25 was defined by liver attenuation ≤ 40 Hounsfield Units after exclusion of other causes. Logistic regression (unadjusted and multivariable) adjusted for age, race, education, and baseline BMI | Longer lactation was inversely associated with NAFLD. Women with > 6 months lactation had lower odds of NAFLD vs. 0-1 month: OR 0.46 (95%CI: 0.22-0.97, P = 0.04, adjusted) | Prolonged lactation may represent a modifiable lifestyle factor with long-term hepatoprotective effects in women |

Physical activity patterns

Regular physical activity protects against MASLD by improving insulin sensitivity, enhancing fat oxidation, and reducing hepatic steatosis[70]. Both biological sex and gender roles shape activity patterns and responses. Men generally engage in more vigorous and resistance-based exercise, whereas women prefer moderate aerobic activities such as walking or group classes[71-73]. Biological differences-such as greater muscle mass and cardiorespiratory capacity in men-may lead to larger reductions in hepatic fat from resistance training, while women often derive greater glycemic and metabolic benefits from aerobic exercise[74-76]. Gender-related factors, including caregiving responsibilities, cultural norms, limited access to exercise facilities, and time constraints, disproportionately restrict women’s activity, particularly after childbirth and during midlife[77-80]. Low levels of leisure-time physical activity are associated with higher mortality in postmenopausal women, and early-life inactivity imposes long-term risks[81,82]. Additionally, obesity-related pathophysiology varies by sex: men typically present with more severe baseline steatosis and fibrosis, which may explain their greater fibrosis regression following substantial weight loss[83,84]

Alcohol consumption and smoking

Although MASLD is distinct from alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), even modest alcohol use can exacerbate steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in individuals with metabolic dysfunction, as reflected in the recently defined MetALD category[85-88]. Men generally consume more alcohol, yet women are more vulnerable to liver injury at lower doses due to differences in metabolism, body composition, and hormonal factors[89,90]. Smoking - still more common in men though narrowing globally - promotes MASLD through IR, oxidative stress, and inflammation, and may accelerate fibrosis when combined with steatosis[91-95]. Emerging evidence suggests that female smokers may face greater metabolic and liver-related harm than males[96]. Gender-related influences, including social norms, stress, and limited cessation resources, further shape alcohol and tobacco use[97-99].

Health-seeking behaviors

Timely MASLD diagnosis depends on health-seeking behavior, which varies by gender[100]. Women are generally more likely to engage with healthcare systems, attend regular check-ups, and follow preventive guidelines[100]. This pattern may lead to earlier detection of metabolic comorbidities and liver abnormalities in women. In contrast, men are less likely to seek care or follow treatment, often presenting with more advanced disease despite similar risk profiles[101]. Masculine norms (e.g., stoicism, self-reliance) contribute to delayed care and poorer outcomes in men[102]. Healthcare gender bias may downplay liver disease severity in women, especially when their metabolic profile seems less concerning[103]. Additionally, women often face competing demands related to caregiving or employment, which may hinder consistent follow-up and lifestyle modification[104].

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Women of reproductive age experience a convergence of biological and gender-related factors that shape MASLD risk and outcomes[105]. Pregnancy introduces unique metabolic demands that, when combined with preexisting liver disease, heighten the risk of gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, preterm birth, and large-for-gestational-age infants[106-123]. Gendered behaviors-including diet, physical activity, healthcare use, and prenatal care-further influence these risks. Beyond maternal biology, pregnancy-related outcomes such as delivery mode, cesarean section rates, and breastfeeding practices are strongly shaped by cultural norms, healthcare access, and social support[124-128]. Maternal MASLD also affects long-term child health by programming susceptibility to obesity and MASLD, consistent with the developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis[129-137]. Conversely, breastfeeding provides protection by improving maternal metabolic recovery and infant metabolic programming, but uptake is often lower in women with obesity or MASLD due to social, behavioral, and clinical barriers[128,138-146]. Collectively, these insights highlight that MASLD in pregnancy is driven not only by biology but also by gendered behaviors and cultural context, underscoring the importance of tailored preconception counseling, culturally sensitive care, and targeted support for nutrition, physical activity, and lactation to optimize maternal and child metabolic health[147].

Transgender individuals

Transgender individuals often pursue GAHT to align physical appearance with gender identity, relieve dysphoria, and improve mental health[148,149]. GAHT alters body composition and metabolism in ways that may influence MASLD risk, although direct liver-specific data are scarce. Systematic reviews and prospective cohorts show feminizing therapy decreases lean mass, increases fat mass, and may worsen IR, whereas masculinizing therapy increases lean mass, lowers fat mass, and generally improves or maintains insulin sensitivity, though evidence on diabetes risk is mixed[150-156]. A large study of U.S. transgender veterans found that estradiol was associated with reduced metabolic syndrome risk, while testosterone increased risk, with transmasculine individuals showing the highest burden[157]. Complementing this, a case-control study in Chinese transwomen reported that GAHT increased total and regional body fat and redistributed fat toward a feminine pattern without raising obesity or dyslipidemia prevalence, though fasting glucose rose modestly[158]. Additional work shows that GAHT modulates vascular, inflammatory, and hemostatic markers[159] and modestly shifts blood pressure[160]. HIV coinfection further compounds steatosis and IR in transfeminine populations[161]. Beyond biological effects, transgender and gender-diverse individuals experience lower physical activity, stigma, discrimination, and barriers to care, which collectively worsen cardiometabolic health[162-165]. Overall, current evidence robustly supports GAHT-mediated shifts in body composition and metabolic risk but remains indirect regarding MASLD development or progression, highlighting the need for prospective studies with standardized GAHT definitions, liver-specific endpoints, and careful consideration of behavioral and structural determinants.

METABOLIC RISK FACTORS

Sex and gender significantly influence the development, clinical presentation, and progression of MASLD through their modulation of key metabolic risk factors[166]. These include obesity and body fat distribution, IR and T2D, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Importantly, distinct sex-specific metabolic phenotypes emerge due to the interplay of sex hormones, genetics, and sociocultural factors, which may explain differences in MASLD prevalence, severity, and outcomes between women and men [Figure 1].

Men preferentially accumulate visceral fat, predisposing them to lipotoxicity, IR, and inflammation[167-170], whereas premenopausal women store fat subcutaneously, which lowers metabolic risk[171,172]. Estrogen contributes to this protective pattern by promoting subcutaneous lipid storage, improving insulin sensitivity, and enhancing lipid profiles, including higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and triglycerides[173-177]. With menopause, declining estrogen drives fat redistribution toward the visceral compartment, worsens IR and dyslipidemia, and narrows the sex gap in MASLD prevalence[178-180]. Men with testosterone deficiency also develop visceral adiposity, IR, and accelerated fibrosis progression[180]. They generally exhibit greater hepatic IR even at lower adiposity, whereas premenopausal women remain relatively insulin sensitive[181-186]. However, once T2D develops, women face higher risks of fibrosis, MASH[8,187-189], cardiovascular[190] and renal complications[191].

Sex differences also extend to triglycerides and blood pressure. Men more often present with high triglycerides and low HDL, both linked to fibrosis[192], whereas hyperandrogenism in women with PCOS promotes atherogenic lipids and MASLD risk[177,193]. Menopause worsens lipid profiles, contributing to the midlife rise in MASLD[8,177]. Hypertension, strongly associated with fibrosis[194], is more prevalent in men at younger ages but rises sharply in women after menopause, often surpassing male rates[195-197]. Postmenopausal women with MASLD frequently exhibit worse cardiometabolic profiles and suboptimal blood pressure control[198-200]. Overall, men typically present earlier with a “classic” MASLD phenotype-central obesity, IR, dyslipidemia, and hypertension[166]-while women may develop MASLD with fewer overt metabolic abnormalities, influenced by menopause, PCOS, or lean MASLD phenotypes characterized by adipose dysfunction, sarcopenia, and altered bile acid signaling[193,201,202].

GENETIC AND EPIGENETIC MODIFIERS

Sex differences in MASLD susceptibility and progression are shaped not only by hormonal influences but also by genetic and epigenetic factors, including sex chromosome complement and autosomal gene variants[203]. These biological dimensions contribute to the observed sexual dimorphism in metabolic traits and liver outcomes [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Genetic, Epigenetic, and Microbiome Modifiers of MASLD: Sex-Linked Pathways and Gut-Liver Interactions. This figure integrates genetic, epigenetic, and microbiome-related mechanisms contributing to MASLD pathogenesis, emphasizing sex-specific influences. Left side of the figure (Genetic Modifiers in MASLD): ↑Indicates an increase or higher level of a variable; ↓indicates a decrease or lower level of a variable; →indicates a relationship or influence between variables (e.g., “leads to”, “is associated with”, or “results in”). Right side of the figure (Gut-Liver Axis in MASLD): ↓Indicates a relationship or influence between variables (e.g., “leads to,” “is associated with,” or “results in”); ↕ indicates a bidirectional relationship or influence between variables. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; PNPLA3: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; HSD17B13: hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 13; Erα: estrogen receptor alpha; XX/XY: chromosomal sex complement; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; TLRs: Toll-like receptors.

Sex chromosomes and metabolic regulation

Beyond gonadal hormones, evidence from sex-chromosome aneuploidies suggests that chromosomal complement itself influences metabolic regulation and MASLD risk[204-211]. Turner syndrome (TS; 45,X) and Klinefelter syndrome (KF; 47,XXY) are both associated with increased obesity, IR, and metabolic syndrome[212-215]. While these conditions often involve hormonal abnormalities - such as hypoestrogenism in TS and hypogonadism in KF - their early metabolic manifestations, including features of metabolic syndrome in prepubertal boys with KF, support a potential hormone-independent role of sex chromosome complement[216-219].

Registry and cohort data reinforce this viewpoint. Large national registries report markedly increased liver disease in TS: for example, a Danish registry[210] identified a substantially higher incidence of fibrosis/cirrhosis in people with TS [incidence rate ratio 16.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.2-122.1 vs. age-matched controls], and another registry[208] found a similarly elevated prevalence of liver fibrosis/cirrhosis in TS. Specific karyotypes (e.g., isochromosome Xq, ring X) have been linked to a greater risk of liver dysfunction (defined by elevated liver enzymes) in multicenter analyses[220]. Importantly, these excess risks are reported to be independent of estrogen replacement[207-211,221-223] and are not clearly associated with indices of hypogonadism, such as luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)[222,224]. Data for KF are limited: a small study reported MASLD prevalence of up to 50% in individuals with KF[225], and a large population-based cohort found higher odds of liver dysfunction (OR 1.71, 95%CI: 1.30-2.25) compared with age-matched male controls, again independent of testosterone therapy[226]. Collectively, these findings support that sex chromosome complement may contribute to MASLD susceptibility through mechanisms that extend beyond gonadal hormone effects; mechanistic studies and larger, well-phenotyped cohorts are needed to disentangle chromosomal vs. hormonal drivers and to define underlying pathways.

Genetic variants influencing MASLD

The PNPLA3 (Patatin-Like Phospholipase Domain-Containing Protein 3) I148M variant (rs738409) is the strongest inherited risk factor for MASLD, with a greater effect on liver fat in women and an increased risk of liver-related events in older, non-obese women[227-229]. Estrogen receptor α (ERα) signaling may upregulate PNPLA3 expression, suggesting a sex hormone-genotype interaction in disease pathogenesis[227]. By contrast, the HSD17B13 (Hydroxysteroid 17-Beta Dehydrogenase 13) rs72613567 insertion appears protective against steatohepatitis and advanced fibrosis, with stronger effects reported in women, particularly after menopause[203,230]. This variant is also associated with lower circulating sex steroids, including 17-OH progesterone, testosterone, and androstenedione[166,203,230,231], reinforcing the interplay between genetic susceptibility and hormonal status. Emerging data further link these variants to distinct hepatic microbial DNA profiles, pointing to possible gene-microbiome interactions that may shape MASLD risk and progression[232]. Together, these findings highlight a complex network of genetic, hormonal, and microbial factors that interact in sex-specific ways to influence MASLD outcomes.

THE ROLE OF THE GUT-LIVER AXIS AND MICROBIOME

The gut-liver axis is a bidirectional communication network [Figure 3] in which microbial metabolites, bile acids, dietary components, and inflammatory mediators reach the liver through the portal circulation and influence hepatic and metabolic pathways[233]. Under physiological conditions, the gut microbiota supports nutrient metabolism, generates bioactive compounds, and maintains mucosal immune balance[234-238]. Conversely, disturbances such as dysbiosis or impaired barrier function are associated with greater translocation of microbial products [e.g., lipopolysaccharides (LPS)], which can activate hepatic toll-like receptor signaling and have been linked to inflammation, steatosis, IR, and fibrogenesis - processes central to MASLD pathogenesis[234-238].

Sex differences in gut microbial composition, diversity, and metabolic outputs have been described and appear to be shaped by a combination of genetic, hormonal, dietary, and environmental factors[239,240]. For example, premenopausal women often show greater microbial diversity and enrichment of taxa associated with metabolic resilience compared with men and postmenopausal women[241]. After menopause, microbiota profiles shift toward those observed in men, coinciding with estrogen decline and higher prevalence of IR, visceral adiposity, and MASLD in women[241]. Although these findings are observational, they suggest that endocrine-microbiome interactions may partly explain sex-specific metabolic outcomes[242].

Experimental data in animals provide additional support. In murine models, microbiota-mediated effects on steatosis and glucose metabolism vary by sex and have been shown to depend on nuclear receptor pathways such as the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a regulator of bile acid signaling[243]. Whether similar mechanisms operate in humans remains uncertain, but these data raise the possibility that sex-specific host-microbe interactions contribute to differences in MASLD risk and therapeutic response. Given the current limitations, sex-stratified human studies are needed to determine how hormonal transitions across the lifespan influence gut microbial composition, and whether microbiome-targeted strategies-including diet, probiotics, or FXR agonists-offer differential benefit by sex or hormonal status.

CARDIO METABOLIC AND EXTRAHEPATIC COMORBIDITIES

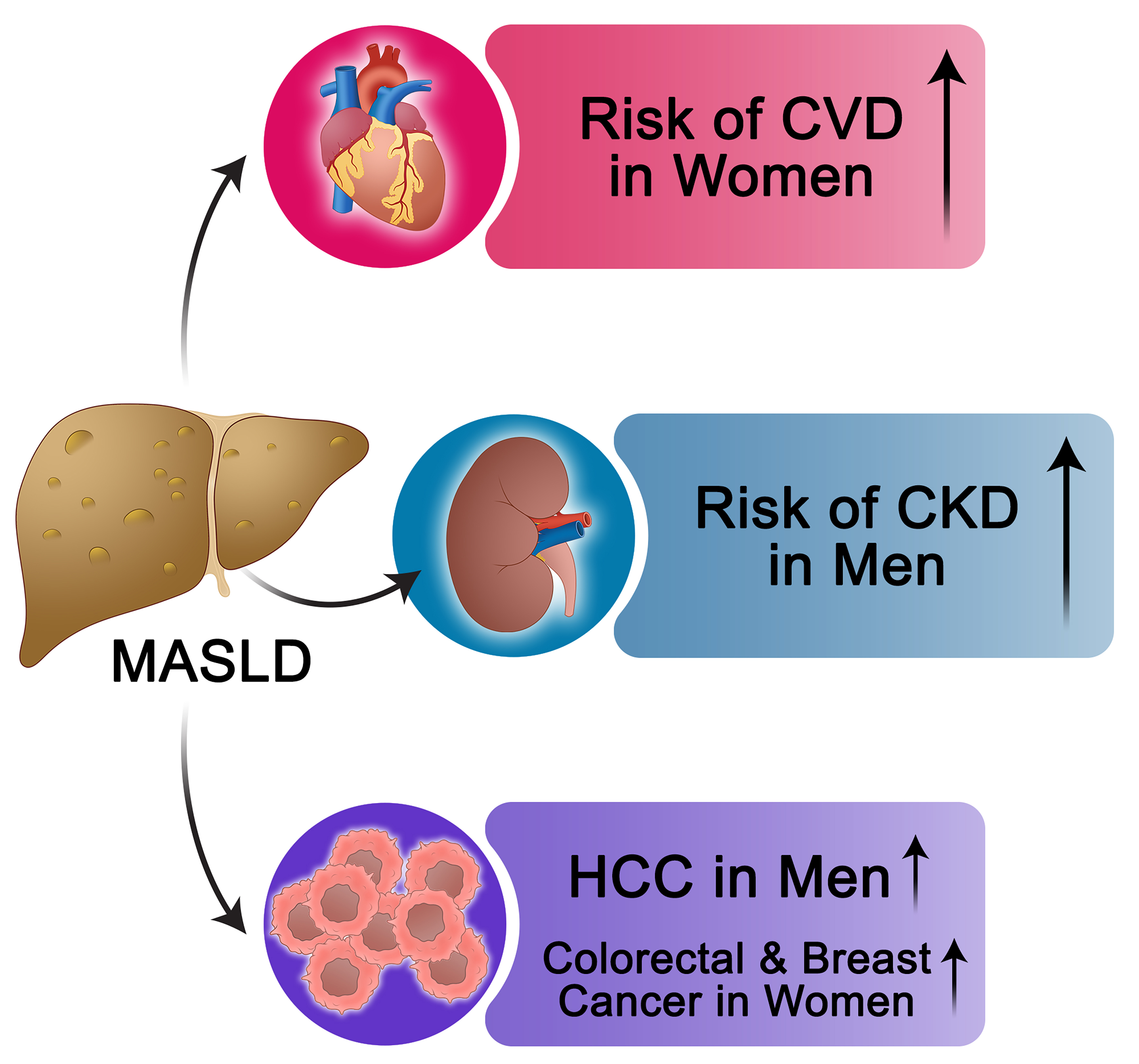

MASLD is increasingly recognized as a multisystem disease with significant comorbidities [Figure 4], including cardiovascular disease (CVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and various malignancies[244]. Notably, sex differences influence the prevalence, clinical presentation, and prognosis of these comorbidities[198,244,245].

Figure 4. Overview of Cardio-Metabolic and Extrahepatic Comorbidities in MASLD: Sex-Specific Risk Patterns. This figure provides a concise summary of the major systemic comorbidities associated with MASLD, with an emphasis on sex-related differences in risk. ↑Indicates that the risk of the specified MASLD-related complication is higher in the mentioned sex compared with the other sex. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

CVD

CVD is the leading cause of mortality among individuals with MASLD. While MASLD is more prevalent in men, women with MASLD often carry a greater burden of cardiometabolic risk factors[198], which may diminish or even reverse the natural cardiovascular advantage typically observed in premenopausal women[246-249]. A meta-analysis of 36 cohorts, including over 18.5 million individuals, reported that MASLD was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events in both sexes[250]. However, the relative risk was higher in women [pooled hazard ratio (HR) 1.59, 95%CI: 1.44-1.75] than in men (pooled HR 1.37, 95%CI: 1.27-1.48), and MASLD severity was more strongly linked to CVD risk in women (pooled HR 2.40, 95%CI: 1.73-3.32) than in men (pooled HR 1.69, 95%CI: 1.21-2.35)[250]. Importantly, these findings were independent of shared cardiometabolic risk factors such as obesity, T2D, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, underscoring the role of sex as an additional modifier of cardiovascular risk in MASLD (250).

CKD

MASLD is independently associated with an increased risk of CKD, and sex differences influence this risk[251]. A large study of over 760,000 patients reported a 16% greater CKD risk in men (adjusted HR 1.16, 95%CI: 1.13-1.18)[252]. Similarly, a Korean cohort of nearly 41,400 individuals found MASLD predicted incident CKD in men (adjusted HR 1.26, 95%CI: 1.04-1.52) but not in women (adjusted HR 1.03, 95%CI: 0.74-1.44)[175], while a U.S. study of ~263,000 adults showed a stronger risk in men (adjusted HR 1.70, 95%CI: 1.59-1.81) than in women (HR 1.47, 95%CI: 1.38-1.58)[253,254]. Notably, these associations were independent of shared cardiometabolic risk factors[252-254]. In contrast, a German database analysis found no significant sex difference in incident CKD, although men exhibited a trend toward a higher risk of requiring dialysis therapy[255]. Taken together, accumulating evidence supports a greater MASLD-related CKD burden in men, yet further research is warranted to clarify the modifiers of this sex-specific risk.

Malignancies

Sex hormones, metabolic traits, and gene expression jointly shape cancer susceptibility in MASLD[256-260]. Men with MASLD show a markedly higher risk of HCC and other malignancies[252,261]. In a large cohort study of ~600,000 patients with MASLD - balanced by sex and matched for age and cardiometabolic risk factors - men demonstrated more than double the risk of HCC (adjusted HR 2.59, 95%CI: 2.39-2.80) and a 32% higher risk of non-specific cancers compared with women (adjusted HR 1.32, 95%CI: 1.27-1.37)[252]. Beyond HCC, sex-specific differences extend to extrahepatic cancers[262]. A meta-analysis of four studies found MASLD to be associated with female-specific cancers, including breast cancer (pooled HR 1.39, 95%CI: 1.13-1.71) and gynecological cancers (pooled HR 1.62, 95%CI: 1.13-2.32)[263]. These findings highlight sex-specific patterns of MASLD-related malignancies that warrant further investigation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR DIAGNOSIS AND RISK STRATIFICATION

Accurate diagnosis and risk stratification are central to the effective management of MASLD[264]. While non-invasive tests (NITs) such as the Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4), controlled attenuation parameter (CAP), and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) using vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) have largely replaced liver biopsy in clinical practice, most diagnostic algorithms still apply uniform thresholds across sexes[265]. This risks underdiagnosis or misclassification [Table 3], particularly in women, where hormonal status, body composition, and metabolic profiles differ from those of men[264,266]. For example, CAP values may underestimate steatosis severity in women, while indices such as the fatty liver index (FLI) and hepatic steatosis index (HSI) - which use waist circumference, HDL cholesterol, and liver enzyme cut-offs-often need sex-specific adjustments to improve diagnostic accuracy.[267-271].

Sex-specific considerations in the diagnostic evaluation of MASLD

| Diagnostic tool | Sex differences consideration | Reference(s) |

| Imaging | ||

| CAP | Women exhibit earlier metabolic and vascular alterations at lower CAP values; applying uniform CAP thresholds may underestimate disease severity in women | Ramírez-Vélez et al.[267] |

| Ultrasound (Sonography) | When combined with the FLI, lower FLI cut-offs are needed in women to improve diagnostic accuracy | Crudele et al.[272] |

| MRI/CT | Significant sex-based differences in liver attenuation exist, potentially driven by differences in visceral adiposity and triglyceride levels | North et al.[274] |

| Elastography (Transient/MR Elastography) | Postmenopausal women have higher fibrosis risk despite lower MASLD prevalence; sex-adjusted liver stiffness cut-offs may enhance diagnostic precision | Balakrishnan et al.[8] |

| Blood-based biomarkers/scores | ||

| FLI | Women require ~50% lower FLI cut-offs than men for accurate MASLD detection, reflecting sex-specific metabolic and hormonal differences | Crudele et al.[272] |

| HSI | Incorporates sex as a variable; women generally have higher ALT and distinct AST/ALT ratios, leading to detection of steatosis at lower HSI values | Xu et al.[271] |

| FIB-4 Index | Postmenopausal women are at greater risk for fibrosis; sex-adjusted cut-offs could improve diagnostic accuracy, although standardized thresholds are lacking | Feng et al.[280] |

| NFS | Lean women benefit from lower NFS cut-offs for accurate fibrosis risk stratification, indicating relevant sex-based differences | Park et al.[282] |

| ELF test | Postmenopausal women show higher fibrosis risk, though sex-specific ELF thresholds are not yet established | Hinkson et al.[283] |

| APRI | Currently lacks validated sex-specific thresholds; a single cut-off is applied across sexes despite potential for sex-related variability | Xiao et al.[284] |

Imaging-based modalities also reflect sex-specific variability. Women generally display higher liver attenuation values on CT and lower visceral adiposity for the same body mass index (BMI), which may mask MASLD if male-derived thresholds are applied[272-275]. Similarly, elastography studies indicate that postmenopausal women may be at higher risk of fibrosis despite lower MASLD prevalence, suggesting the need for revised stiffness cut-offs in this group[276,277]. These findings underscore that uniform imaging thresholds may fail to capture clinically relevant sex-related risk, particularly during menopause transition when liver fat accumulation and fibrosis accelerate.

Biomarker-based NITs reveal parallel challenges. The FLI performs best when cut-offs are reduced by nearly 50% in women[272,278], while HSI incorporates sex directly as a variable but may still underestimate disease risk in premenopausal women with lower ALT and AST/ALT ratios[271,279]. Similarly, fibrosis scores such as FIB-4 and the NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) appear to overestimate risk in men and underestimate it in postmenopausal women, but sex-stratified thresholds have not been standardized[280-282]. The enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) and AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) also show promising accuracy, yet neither has validated sex-specific ranges[283,284].

Going forward, practical implementation requires integrating sex-adjusted thresholds into clinical algorithms and validating them across diverse populations. Since many NITs incorporate metabolic parameters (e.g., waist circumference, HDL, triglycerides, liver enzymes), the interaction between sex-specific metabolic phenotypes and biomarker performance should be systematically addressed. For instance, women may develop MASLD and fibrosis at lower levels of adiposity or dyslipidemia than men, necessitating tailored diagnostic scoring. Another challenge is the risk of digital amplification of existing disparities. A recent analysis of machine learning models trained on the Indian Liver Patient Dataset (ILPD) revealed that widely used classifiers systematically underperform in women, with false negative rates up to 24% higher than in men[103]. In practice, this translates into disproportionately missed diagnoses in female patients, reinforcing inequities already present in traditional diagnostic pathways. The study highlights how algorithmic approaches, unless sex-stratified, can codify and perpetuate sex bias in liver disease diagnosis.

Collectively, these observations demonstrate that diagnostic performance improves when sex-related metabolic, hormonal, and algorithmic biases are addressed, yet most tools remain calibrated for “average” populations. Large-scale, sex-stratified validation studies, coupled with fairness audits of emerging AI-based models, are essential to move from recognition of sex differences to actionable and equitable diagnostic pathways.

THERAPEUTIC AND PREVENTIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The management of MASLD requires individualized strategies that reflect sex-related differences in pathogenesis, progression, and response to interventions. While lifestyle modification remains foundational, pharmacologic therapy, bariatric surgery, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) are increasingly important[285,286], with accumulating evidence that sex-specific factors influence efficacy, safety, and long-term outcomes [Tables 4 and 5].

Sex-differentiated responses to medical interventions for MASLD

| Author, year[Ref.] | Therapeutic approach | Design | Method | Sex-specific results | comment |

| Harrison et al., 2024[290] | Thyroid hormone receptor agonists (e.g., Resmetirom) | RCT (NCT03900429) | This phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled adults with biopsy-confirmed NASH and fibrosis stages F1B to F3. Participants were randomized to receive resmetirom 80 mg, 100 mg, or placebo once daily. Primary endpoints at week 52 were: (1) NASH resolution (≥ 2-point reduction in NAFLD activity score with no fibrosis worsening); and (2) ≥ 1-stage fibrosis improvement with no worsening in activity score. Key secondary outcomes included changes in triglycerides (24 weeks), hepatic fat (16 and 52 weeks), and liver stiffness (52 weeks) | In the 100 mg group, fibrosis improvement had an EDP of 15.1% (95%CI: 7.2-23.1) in men (n = 141) and 9.6% (95%CI: 2.2-17.0) in women (n = 180). In the 80 mg group, EDP was 9.5% (95%CI: 1.9-17.1) in men (n = 137) and 10.6% (95%CI: 2.8-18.4) in women (n = 179), suggesting similar efficacy between sexes | Although efficacy was consistent in both sexes, subtle differences in drug response by dose may reflect underlying sex-based variations in lipid metabolism or thyroid hormone signaling. The slightly higher EDP in men at 100 mg and in women at 80 mg may warrant further investigation into optimal dosing strategies by sex to enhance personalized treatment for NASH |

| Loomba et al., 2023[300] | FGF21 analogue (e.g., Pegozafermin) | RCT (NCT04929483) | This multicenter, phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolled adults with biopsy-confirmed NASH and stage F2-F3 fibrosis. Participants were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous pegozafermin at 15 mg or 30 mg weekly (QW), 44 mg once every 2 weeks (Q2W), or placebo for 24 weeks. The two co-primary endpoints were: (1) ≥ 1-stage fibrosis improvement without worsening of NASH; (2) NASH resolution without fibrosis worsening | In men, pegozafermin significantly improved fibrosis in both the 30 mg QW (EDP: 30.7%; 95%CI: 8.5-52.8) and 44 mg Q2W (EDP: 33.8%; 95%CI: 7.6-60.1) groups. In women, the corresponding EDPs were lower and not statistically significant: 11.46% (95%CI: -6.1 to 29.1) for 30 mg QW and 9.6% (95%CI: -8.9 to 28.2) for 44 mg Q2W. This suggests a differential response based on sex | These results highlight a potential sex-related disparity in response to FGF21 analogues, with men showing more robust fibrosis improvement than women at the same doses. The underlying mechanisms may involve sex-specific differences in FGF21 receptor sensitivity, hepatic lipid handling, or inflammation pathways |

| Sanyal et al., 2025[297] | GLP-1 receptor agonists (e.g., Semaglutide) | RCT (NCT04822181) | In this phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 1197 patients with biopsy-confirmed MASH and fibrosis stage F2 or F3 were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo for 240 weeks. An interim analysis conducted at week 72 (part 1) involved the first 800 patients. The primary endpoints were resolution of steatohepatitis without worsening of fibrosis and improvement in fibrosis without worsening of steatohepatitis | EDP for MASH resolution was higher in women (31.4%, 95%CI: 21.4-41.4) than in men (25.8%, 95%CI: 14.4-37.1), while for fibrosis improvement, EDP was higher in men (16.9%, 95%CI: 6.7-27.1) than in women (12.4%, 95%CI: 3.2-21.8) | This large RCT reveals intriguing sex-based divergences in semaglutide efficacy: while women experienced superior resolution of steatohepatitis, men showed greater improvement in fibrosis. These opposing trends may reflect sex-specific variations in GLP-1 receptor expression, metabolic-inflammatory responses, or adipose-liver crosstalk |

| Sanyal et al., 2010[304] | Thiazolidinediones (e.g. Pioglitazone) | RCT (NCT00063622) | In a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (NCT00063622), 247 non-diabetic adults with biopsy-proven NASH were randomly assigned to receive either pioglitazone 30 mg daily (n = 80), vitamin E 800 IU daily (n = 84), or placebo (n = 83) for 96 weeks. The primary outcome was histological improvement of NASH, defined by a composite score including steatosis, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, and fibrosis | Histological improvement was greater in women than men, with an EDP of 20% for women vs. 4% for men | These findings suggest a sex-based difference in histological response to pioglitazone in NASH, with women demonstrating substantially greater benefit. Potential explanations may include differences in adipose tissue biology, insulin sensitivity, or drug metabolism between sexes |

| Lin et al., 2025[308] | SGLT2 Inhibitors (e.g., dapagliflozin) | RCT (NCT03723252) | This multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial was conducted across six tertiary hospitals in China between November 2018 and March 2023. A total of 154 adults with biopsy-confirmed MASH (with or without type 2 diabetes) were randomly assigned to receive either 10 mg dapagliflozin or a matching placebo once daily for 48 weeks. The primary endpoint was MASH improvement (≥ 2-point reduction in NAS or NAS ≤ 3) without fibrosis worsening. Secondary endpoints included MASH resolution without fibrosis worsening and fibrosis improvement without MASH worsening. Analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis | Dapagliflozin showed a greater relative benefit for MASH resolution in women (RR: 5.1, 95%CI: 0.6-39.6) compared to men (RR: 2.2, 95%CI: 0.9-5.4). Although not statistically significant, women also demonstrated a higher relative rate of fibrosis improvement (RR: 3.2, 95%CI: 0.8-12.6) than men (RR: 2.1, 95%CI: 1.2-3.6) | This study suggests a potential sex-specific response to SGLT2 inhibition in MASH, with women showing a numerically greater benefit in both histological endpoints. While confidence intervals are wide, these findings raise important questions about sex-based differences in metabolic and fibrotic response mechanisms |

| Hider et al., 2024[286] | Bariatric surgery | Retrospective cohort study | Patients who underwent gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy (June 2006-June 2022) were identified from a state-wide bariatric registry. Primary outcomes: % excess body weight loss and BMI change at 1 year. Secondary outcome: 30-day risk-adjusted complications | Among 107,504 patients (79.2% female), males were older (47.6 vs. 44.8 y), had higher baseline weight (346.6 lbs vs. 279.9 lbs) and BMI (49.9 vs. 47.2 kg/m2), and more comorbidities. Males achieved slightly greater total weight loss (105.1 lbs vs. 84.9 lbs) and excess body weight loss (60.0% vs. 58.8%) but had higher BMI at 1 year (34.0 vs. 32.8 kg/m2). Males experienced higher rates of serious complications (2.5% vs. 1.9%), leak/perforation (0.5% vs. 0.4%), VTE (0.7% vs. 0.4%), and medical complications (1.5% vs. 1.0%) compared to females | Bariatric surgery induces substantial weight loss in both sexes, which is expected to reduce MASLD risk. Men achieve slightly greater weight reduction but experience higher complication rates, likely due to greater baseline comorbidities, highlighting the need for early referral and careful perioperative management |

Impact of Hormonal Replacement Therapies on MASLD

| Author, year[Ref.] | Therapeutic approach | Design | Method | Sex-specific results | comment |

| Kim et al., 2023[313] | Estrogen replacement therapy | Observational retrospective cohort | This retrospective observational cohort study evaluated 368 postmenopausal women who received MHT over a 12-month period. Participants were categorized into two groups based on the route of estrogen administration: transdermal (n = 75) and oral (n = 293). The primary objective was to compare changes in the prevalence of NAFLD before and after 12 months of MHT between these two groups. In the oral estrogen group, the study further examined whether NAFLD progression differed based on the dose of estrogen or the type of progestogen used | After 12 months, NAFLD prevalence decreased in the transdermal group (24% to 17.3%) but increased in the oral group (25.3% to 29.4%). While the transdermal group showed no major clinical changes, the oral group had improved lipid profiles. Estrogen dose and progestogen type did not significantly affect NAFLD outcomes in the oral group | The observed improvement in hepatic outcomes with transdermal estrogen supports its potential as a liver-friendly option in MHT, likely due to its avoidance of first-pass hepatic metabolism. Despite favorable changes in lipid profiles in the oral group, the increased NAFLD prevalence raises concerns about the hepatic implications of oral estrogen |

| Shigehara et al., 2025[317] | Testosterone replacement therapy | RCT | In this randomized controlled trial, 186 hypogonadal men were enrolled and assigned to receive either TRT (n = 88) or no treatment (control; n = 98) for 12 months. The TRT group received intramuscular testosterone enanthate 250 mg every four weeks. Baseline and 12-month assessments included anthropometric measures (waist circumference, BMI, body fat volume), metabolic parameters (fasting blood sugar, HbA1c, cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL), and liver fibrosis markers (FIB-4 index based on age, AST, ALT, and platelet count). A subgroup analysis focused on patients with a baseline FIB-4 index ≥ 1.30 | At 12 months, TRT led to significant reductions in waist circumference, body fat volume, and an increase in platelet count compared to the control group, though overall FIB-4 index changes were not significant. However, in patients with elevated baseline FIB-4 (≥ 1.30), TRT significantly improved FIB-4 scores (-0.10 vs. +0.04; P = 0.0311) along with favorable changes in triglycerides, body fat, and platelet counts. This suggests TRT may improve liver fibrosis markers in men at higher fibrotic risk | These findings suggest that testosterone therapy may offer antifibrotic benefits in metabolically vulnerable hypogonadal men. Given sex-related hormonal influences on liver disease, TRT could represent a targeted strategy to mitigate fibrosis progression in men with metabolic dysfunction |

Pharmacologic therapies

Pharmacological therapies targeting liver fat, inflammation, and fibrosis are increasingly used in MASLD management, with emerging evidence for benefits beyond the liver, including improvements in the cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) profile[287]. Two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs-resmetirom and semaglutide-already provide insights into sex-specific effects. Resmetirom, a liver-specific thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist, has shown promise in reducing liver fat and fibrosis by promoting lipophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis while inhibiting fibrogenesis via transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) blockade[288,289]. In a recent phase 3 trial, resmetirom demonstrated similar antifibrotic efficacy in both sexes, though subtle dose-related differences suggest possible sex-based variations in response[290]. GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are effective for T2D and obesity, and may improve MASLD histology[291,292]. Several trials revealed that women achieved greater weight loss and glycemic responses, partly due to ~30% higher drug exposure compared to men[293-296]. In a phase 3 trial of semaglutide in biopsy-confirmed MASH, women experienced greater steatohepatitis resolution, whereas men showed more pronounced fibrosis improvement[297]. These divergent effects may reflect sex-specific differences in GLP-1 receptor expression, adipose tissue dynamics, or hepatic inflammatory signaling[296,298,299]. While these findings were encouraging, post-marketing surveillance remains essential to validate sex-specific treatment patterns and to clarify long-term effects on CKM outcomes.

Other pharmacologic agents remain investigational, and evidence is still preliminary. FGF21 (fibroblast growth factor 21) analogs such as pegozafermin have shown potential in improving liver fibrosis and resolving NASH by modulating lipid metabolism and reducing inflammation[300]. In a recent phase 2b trial, pegozafermin led to meaningful fibrosis improvement in men, while the benefits in women were less pronounced[300], potentially due to sex differences in receptor activity and hepatic lipid handling[301]. Thiazolidinediones, particularly pioglitazone, have shown benefits in steatohepatitis and insulin sensitivity, although fibrosis improvement is limited[302,303]. In a multicenter randomized trial, women demonstrated greater histological improvement than men[304], and in a Chinese cohort, pioglitazone combined with lifestyle intervention reduced liver fat more effectively in women[305]. Similarly, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors such as empagliflozin and dapagliflozin modestly reduced hepatic steatosis and ALT levels in T2D patients[306,307]. In a recent randomized trial (RCT), dapagliflozin appeared to provide greater histological benefit in women, although the difference did not reach statistical significance[308,309] . Together, these findings highlighted the importance of designing future sex-stratified trials to better define differential efficacy and to determine whether these therapies improve CKM health in a sex-specific manner.

Bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery is among the most effective interventions for severe obesity and MASLD, producing durable weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, and marked reductions in hepatic steatosis and fibrosis[310]. Both men and women benefit, but sex-specific differences have been observed. Men often achieve slightly greater absolute weight loss, yet they experience higher perioperative complication rates, which are likely explained by older age at surgery, higher baseline BMI, and greater comorbidity burden[286]. Women, on the other hand, tend to undergo surgery at younger ages and may experience more favorable improvements in metabolic risk factors, including IR and dyslipidemia[286]. These differences suggest that earlier surgical referral for men could maximize benefits while reducing complication risk. Overall, bariatric surgery improves long-term MASLD outcomes across sexes, but tailoring timing and perioperative management to sex-specific risk profiles may optimize safety and efficacy.

HRT

HRT has been investigated as a potential modifier of MASLD risk, though most studies remain observational or exploratory. In postmenopausal women, low-dose estradiol or norethisterone was associated with improved liver enzymes and reduced steatosis compared with non-users[311,312], and transdermal estrogen therapy correlated with a lower prevalence of MASLD over 12 months, whereas oral estrogen showed a modest increase, likely due to first-pass hepatic metabolism[313]. However, these findings are preliminary and require confirmation in larger RCTs. Importantly, estrogen exposure can also be harmful under certain conditions: prolonged or high-dose use, especially with synthetic formulations, has been linked to hepatotoxicity, intrahepatic cholestasis, vascular lesions, adenomas, and, rarely, hepatic vein thrombosis[314,315]. In hypogonadal men, testosterone therapy [e.g., LPCN 1144 (an oral prodrug of bioidentical testosterone)] demonstrated improvements in body fat, waist circumference, and fibrosis markers in a recent trial[316,317], suggesting possible antifibrotic benefits in metabolically vulnerable men. Still, long-term safety, particularly regarding cardiovascular outcomes, is insufficiently characterized. Overall, while physiological sex hormone replacement shows potential for modifying liver outcomes, further well-powered RCTs are needed to establish sex-specific efficacy and safety.

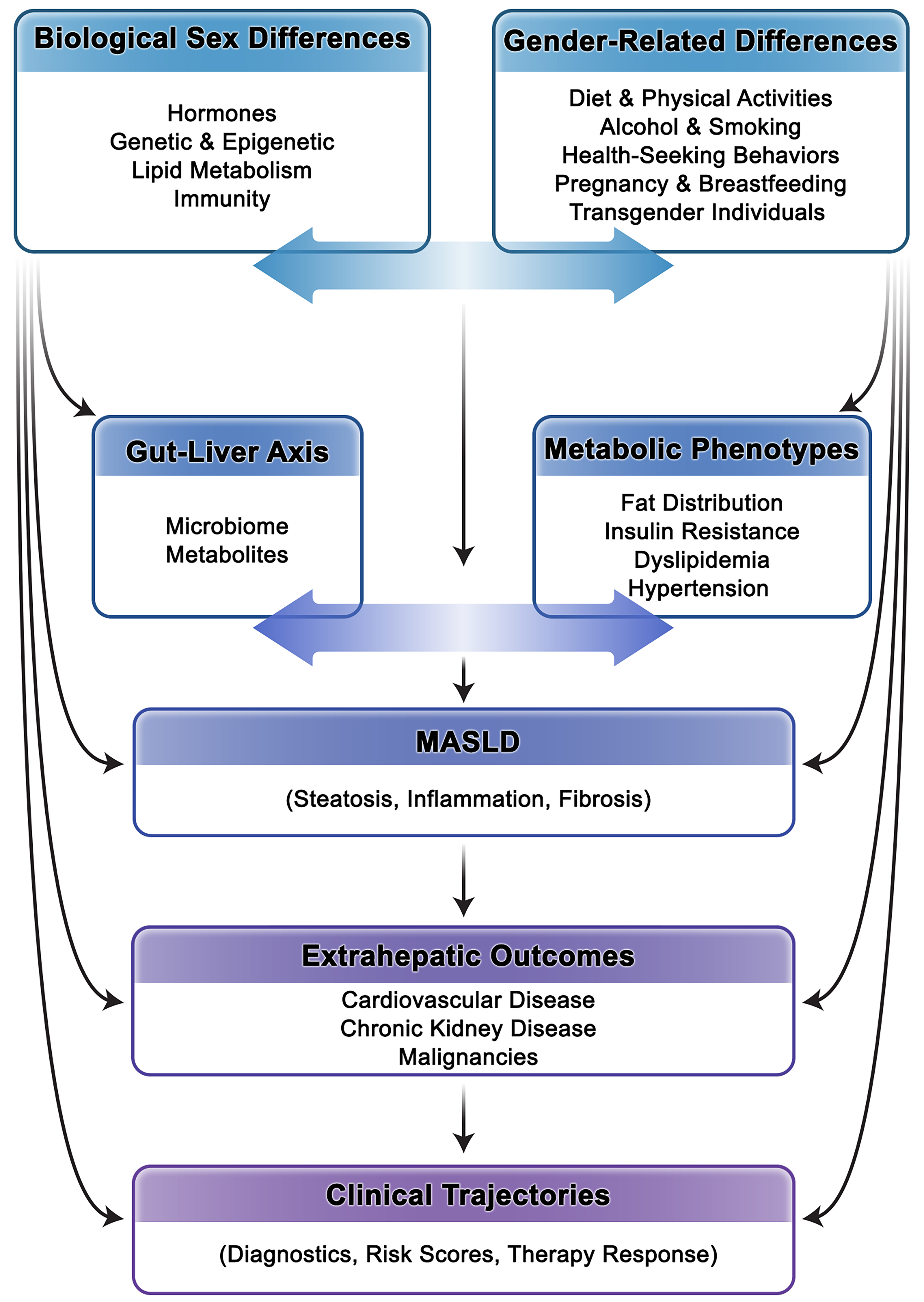

SEX-GENDER CROSSTALK IN MASLD

Considering the differences outlined in previous sections, we propose a conceptual framework in which MASLD risk emerges from the dynamic interplay between biological sex and gendered exposures, rather than from either domain alone [Figure 5]. Biological sex determines genetic background, hormonal milieu, body composition, and microbiome architecture, while gender - encompassing sociocultural norms, behaviors, and roles - shapes diet, physical activity, stress, healthcare engagement, and social responsibilities[6]. These factors interact bidirectionally. For example, caregiving burdens, occupational constraints, or limited access to exercise can influence hormonal status, amplifying metabolic and hepatic risk[6]. Similarly, reproductive events such as pregnancy and breastfeeding affect MASLD risk, but their impact is strongly mediated by gendered supports, including cultural norms, workplace policies, and social networks[105]. In men, biological susceptibility to more severe steatosis and fibrosis is often compounded by gender norms that discourage timely healthcare use, leading to delayed diagnosis and worse outcomes[102].

Figure 5. Conceptual Framework of Sex-Gender Crosstalk in MASLD. This figure illustrates how MASLD risk and disease course emerge from the dynamic, bidirectional interaction between biological sex and gender-related factors. MASLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

Gut dysbiosis - regulated in part by sex hormones - also interacts with gendered exposures, including diet, alcohol use, and stress, to influence both hepatic and extrahepatic events[239]. In transgender and gender-diverse populations, the inseparability of sex and gender is further illustrated by GAHT, which alters body composition and metabolic risk[157]. Meanwhile, stigma, discrimination, and structural barriers magnify vulnerability and reduce access to appropriate care[164]. Collectively, these interactions demonstrate that MASLD risk cannot be attributed to hormones alone but emerges from biology intersecting with gendered determinants. Effective risk stratification, diagnostics, and therapeutic approaches must therefore integrate biological mechanisms with social context to fully capture the complexity of sex-gender crosstalk in MASLD.

KNOWLEDGE GAPS AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Although significant progress has been made in understanding the pathophysiology of MASLD, substantial knowledge gaps persist regarding sex and gender differences across biological, behavioral, and clinical domains[6]. Hormonal regulation is widely recognized as a determinant of hepatic fat accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis[180]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms through which these hormones interact with immune signaling, mitochondrial function, and fibrogenesis remain incompletely understood[180]. Moreover, while metabolic abnormalities are central to MASLD, their interplay with sex-specific fat distribution, lean mass, and metabolic flexibility is not yet well defined[318]. Lean women and older individuals with sarcopenic obesity may represent a particularly vulnerable group requiring focused investigation.

Certain populations remain markedly underrepresented in MASLD research. Premenopausal women, particularly regarding long-term maternal and offspring outcomes and the effects of breastfeeding, are understudied, despite evidence that sex-gender crosstalk significantly influences metabolic trajectories. Transgender and non-binary individuals, including those undergoing GAHT, are similarly underrepresented, despite being highly affected by the interplay of biological and gendered determinants.

Genetic and epigenetic modifiers have demonstrated variable expression and impact across sexes, yet sex-stratified genomic analyses are still rare[229,319]. Additionally, the gut-liver axis, a key modulator of MASLD, has shown sexually dimorphic microbial patterns in other diseases, but its role in MASLD remains largely speculative[242]. Future studies should integrate metagenomics and metabolomics with hormonal and immunologic profiling to better define these complex interactions.

From a clinical standpoint, cardiovascular and extrahepatic outcomes of MASLD show divergence between men and women, but current diagnostic tools and risk models do not reflect these differences[250,320]. Most clinical trials still lack sex-specific subgroup analyses, limiting the generalizability of findings[321]. Collectively, advancing MASLD care will require routine incorporation of sex and gender as biological and analytical variables in both mechanistic studies and therapeutic trials[322].

CONCLUSION

Sex and gender differences are increasingly recognized as fundamental determinants in the development, progression, and clinical expression of MASLD. This review has synthesized current knowledge across multiple domains - including hormonal regulation, metabolic risk factors, genetic and epigenetic influences, microbiome profiles, and behavioral determinants - highlighting how these sex- and gender-based factors shape MASLD phenotypes.

Women and men differ not only in the distribution of traditional metabolic risk factors such as adiposity, IR, and dyslipidemia, but also in how these factors interact with sex hormones, immune responses, and lifestyle behaviors. These biological and sociocultural influences are further reflected in the burden of extrahepatic complications and response to treatment. Importantly, differences are not static and can evolve with aging, menopause, and shifting social contexts, underscoring the need for dynamic clinical assessment.

Despite growing evidence, current clinical frameworks rarely consider sex or gender when evaluating MASLD risk or guiding treatment. Integrating this perspective into clinical reasoning will improve the precision of both diagnostic assessments and therapeutic strategies. By bringing together diverse lines of evidence, this review supports a sex- and gender-informed approach to MASLD and reinforces the importance of contextualizing liver disease within the broader framework of individualized, equitable care.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualized and designed the study: Jamalinia M, Saeian S, Lankarani KB

Performed the literature review and drafted the manuscript: Jamalinia M, Saeian S, Nikkhoo N, Nazerian A

Prepared the figures and tables: Jamalinia M, Nikkhoo N, Nazerian A

All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials presented in this paper were extracted from previously published studies, which are publicly available and can be accessed through the cited sources.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Since this study is a review of previously published papers, no new ethical approval was required. All original studies included in this review obtained appropriate ethical approval and informed consent from participants.

Consent for publication

This review does not include individual-level or identifiable data; therefore, consent for publication was not required.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao YY, Zheng MH. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35:697-707.

2. Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, et al; NAFLD Nomenclature consensus group. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023;78:1966-86.

3. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64:73-84.

4. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67:328-57.

6. Jamalinia M, Lonardo A, Weiskirchen R. Sex and gender differences in liver fibrosis: pathomechanisms and clinical outcomes. Fibrosis. 2024;2:10006.

7. Joo SK, Kim W. Sex differences in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a narrative review. Ewha Med J. 2024;47:e17.

8. Balakrishnan M, Patel P, Dunn-Valadez S, et al. Women have a lower risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease but a higher risk of progression vs men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:61-71.e15.

10. Krawczyk M, Bonfrate L, Portincasa P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:695-708.

11. Moghaddasifar I, Lankarani KB, Moosazadeh M, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its related factors in iran. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2016;7:149-60.

12. Burra P, Bizzaro D, Gonta A, et al.; Special Interest Group Gender in Hepatology of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF). Clinical impact of sexual dimorphism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver Int. 2021;41:1713-33.

13. Alkaabi J, Afandi B, Alhaj O, Kanwal D, Agha A. Identifying metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using clinic-based prediction tools. Front Med. 2024;11:1425145.

14. Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77:1335-47.

15. Hayward KL, Johnson AL, Horsfall LU, Moser C, Valery PC, Powell EE. Detecting non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk factors in health databases: accuracy and limitations of the ICD-10-AM. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8:e000572.

16. Pal P, Palui R, Ray S. Heterogeneity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: implications for clinical practice and research activity. World J Hepatol. 2021;13:1584-610.

17. Fan JG, Zhu J, Li XJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for fatty liver in a general population of Shanghai, China. J Hepatol. 2005;43:508-14.

18. Eguchi Y, Hyogo H, Ono M, et al.; JSG-NAFLD. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:586-95.

19. Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Ohbora A, Takeda N, Fukui M, Kato T. Aging is a risk factor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopausal women. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:237-43.

20. Yang JD, Abdelmalek MF, Pang H, et al. Gender and menopause impact severity of fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:1406-14.

21. Shen M, Shi H. Sex hormones and their receptors regulate liver energy homeostasis. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:294278.

22. Palmisano BT, Zhu L, Stafford JM. Role of estrogens in the regulation of liver lipid metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1043:227-56.

23. Galmés-Pascual BM, Martínez-Cignoni MR, Morán-Costoya A, et al. 17β-estradiol ameliorates lipotoxicity-induced hepatic mitochondrial oxidative stress and insulin resistance. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;150:148-60.

24. Galmés-Pascual BM, Nadal-Casellas A, Bauza-Thorbrügge M, et al. 17β-estradiol improves hepatic mitochondrial biogenesis and function through PGC1B. J Endocrinol. 2017;232:297-308.

25. Smiriglia A, Lorito N, Bacci M, et al. Estrogen-dependent activation of TRX2 reverses oxidative stress and metabolic dysfunction associated with steatotic disease. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:57.

26. Ribas V, Nguyen MT, Henstridge DC, et al. Impaired oxidative metabolism and inflammation are associated with insulin resistance in ERalpha-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E304-19.

27. Zhu L, Brown WC, Cai Q, et al. Estrogen treatment after ovariectomy protects against fatty liver and may improve pathway-selective insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013;62:424-34.

28. Matsuo K, Gualtieri MR, Cahoon SS, et al. Surgical menopause and increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in endometrial cancer. Menopause. 2016;23:189-96.

29. Mueller NT, Liu T, Mitchel EB, et al. Sex hormone relations to histologic severity of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:3496-504.

30. Pafili K, Paschou SA, Armeni E, Polyzos SA, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through the female lifespan: the role of sex hormones. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:1609-23.

31. Ryu S, Suh BS, Chang Y, et al. Menopausal stages and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in middle-aged women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;190:65-70.

32. Meda C, Dolce A, Della Torre S. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease across women’s reproductive lifespan and issues. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:327-32.

33. Markopoulos MC, Kassi E, Alexandraki KI, Mastorakos G, Kaltsas G. Hyperandrogenism after menopause. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:R79-91.

34. Zaman A, Rothman MS. Postmenopausal hyperandrogenism: evaluation and treatment strategies. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2021;50:97-111.

35. Gershagen S, Doeberl A, Jeppsson S, Rannevik G. Decreasing serum levels of sex hormone-binding globulin around the menopause and temporary relation to changing levels of ovarian steroids, as demonstrated in a longitudinal study. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:616-21.

36. Lazo M, Zeb I, Nasir K, et al. Association between endogenous sex hormones and liver fat in a multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1686-93.e2.