Atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized semiconductor metal oxides for chemiresistive gas sensing

Abstract

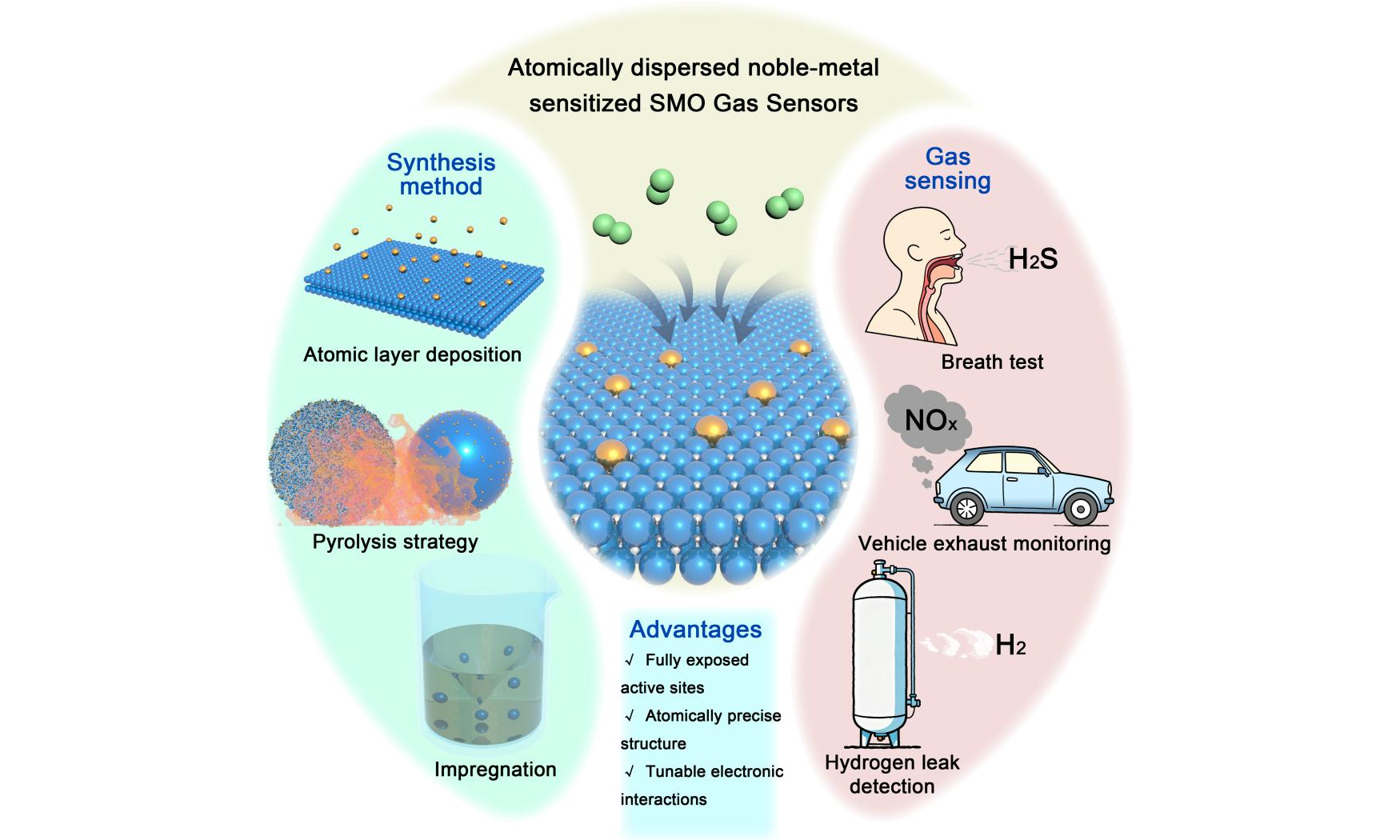

Semiconductor metal oxide (SMO) gas sensors have long been recognized for their low cost, facile fabrication, and high stability, yet conventional designs suffer from poor selectivity and limited sensitivity at trace gas levels. Recent advances in atomically dispersed noble‑metal sensitized SMO materials have increasingly enabled the transition from heterogeneous nanoparticle interfaces to more atomically defined sensitizer sites, offering enhanced atomic utilization and improved control over electronic modulation. These atomically dispersed noble metals create clear coordination environments that tailor gas adsorption, activation, and charge‑transfer dynamics, thereby enabling ultrahigh sensitivity, rapid response speed, and excellent selectivity. This review summarizes recent progress in the synthesis, characterization, and sensing applications of atomically dispersed noble‑metal sensitized SMOs, spanning hydrogen, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur‑containing gases, and some volatile organic compounds. Finally, it highlights key challenges and future directions toward mechanism‑driven design, scalable fabrication, and integration with microelectromechanical systems for next‑generation, high-performance gas sensing technologies.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Gas sensing based on semiconductor metal oxide (SMO) materials underpins a wide range of applications, from noninvasive breath diagnostics to food safety and environmental monitoring[1-4]. These chemiresistive sensors are valued for their low cost, facile fabrication, and high stability, making them the most extensively studied class of gas sensors. However, achieving reliable detection of trace gases remains challenging due to the poor selectivity and limited sensitivity of traditional SMO sensors, particularly in complex and humid environments where cross-sensitivity to multiple gases often occurs. To overcome these intrinsic limitations, the incorporation of noble-metal sensitizers has emerged as a powerful approach to enhance gas adsorption, catalytic activity, and electronic modulation in SMO-based sensing materials[5-7]. Noble metals such as Pt, Pd, and Au have long been recognized as effective sensitizers for SMO materials, owing to their superior catalytic properties, which can significantly enhance gas-sensing performance. However, traditional noble-metal sensitization strategies based on nanoparticle decoration present inherent limitations when applied to SMO gas sensors. First, noble-metal nanoparticles introduce heterogeneous active sites with broad distributions of adsorption and activation energies, which compromise chemical specificity and often lead to cross-sensitivity between structurally similar gases, such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen[8]. Second, noble-metal nanoparticle-sensitized SMOs suffer from low noble-metal utilization, as a substantial fraction of noble-metal atoms remains buried within the particle core or electronically inaccessible, thereby increasing material cost and impeding large-scale applicability[9]. Third, the lack of clear identification of active sites impedes fundamental mechanistic insight, leading to reliance on empirical optimization rather than rational, site-directed design[10]. Finally, weak interfacial coupling between noble-metal nanoparticles and SMO materials often results in structural instability, including sintering and aggregation, and induces signal drift. Furthermore, the limited electronic modulation across the nanoparticle-SMO restricts charge transfer, thereby limiting sensing sensitivity. Together, these challenges constrain the co-optimization of gas-sensing performance metrics, including sensitivity, selectivity, and stability, particularly in trace-level gas detection.

Building on the above limitations, atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers offer a site-specific approach to overcome the fundamental bottlenecks of noble-metal-modified SMO gas sensors[11,12]. First, atomically dispersed noble metals enable the formation of uniform and well-defined coordination environments, narrowing the distribution of adsorption and activation energies. This enhances chemical specificity and suppresses cross-responses among structurally similar gases. Second, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials achieve nearly maximal atom utilization, as each exposed atom functions as an active site in gas sensing. This enables superior sensing performance at ultralow target gas concentrations, even with low loadings of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. Third, the atomic-level definition of sensitizer sites enables direct mechanistic interrogation through operando spectroscopy, facilitating clear correlations between the sensitizer and gas-solid interactions, such as adsorption, charge transfer, and surface reaction pathways. This structure-function insight supports the rational, site-directed design of high-performance sensing materials. Fourth, strong interfacial interactions between the noble-metal sensitizer and SMO host enhance structural and electronic coupling, improving thermal and humidity stability, suppressing sintering, and promoting efficient charge transport, thereby boosting the sensing performance of trace target gases. While noble-metal modification of SMOs has attracted growing interest in gas sensing, existing reviews largely focus on performance enhancement via single-atom catalysts or noble-metal nanoparticles[5,8,10,12]. Studies on single-atom catalysts predominantly adopt a catalytic reactivity perspective, whereas nanoparticle sensitization is complicated by structural and interfacial heterogeneity that obscures sensing-relevant structure-property-signal relationships. In contrast, this review provides a sensor-oriented perspective on atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs, discussing their roles in gas sensor design, sensing performance, and underlying mechanisms. By clarifying how atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers regulate gas-solid interfacial processes, this review aims to inform the rational design of high-performance chemiresistive gas sensors with enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and stability.

This review summarizes recent advances in atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs for gas sensing. In contrast to earlier reviews that primarily address single-atom catalysis from a catalytic perspective, the present work adopts a gas sensor-focused framework, emphasizing how noble-metal sensitizers at the atomic scale tailor gas-solid interfacial interactions to boost sensing performance. Representative synthesis approaches are first outlined, followed by a discussion of how atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials enhance detection capabilities for a wide range of gases, including hydrogen, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur-containing species, and some volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Finally, key challenges are critically assessed, with the ultimate goal of guiding the scalable realization of next-generation, high-performance gas-sensing technologies.

SYNTHESIS AND CHARACTERIZATION OF ATOMICALLY DISPERSED NOBLE-METAL-SENSITIZED SMO MATERIALS

Representative synthetic strategies

The rational synthesis of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs is central to unlocking their full potential in gas sensing, as the spatial dispersion and local coordination of noble-metal sensitizer critically dictate adsorption dynamics, charge transfer, and catalytic enhancement at the gas-solid interface. Recent advancements have yielded a diverse array of synthetic strategies that enable precise engineering of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers on SMO materials, with each exhibiting distinct characteristics regarding loading efficiency, dispersion control, thermal stability, and scalability for gas sensing applications.

Atomic layer deposition

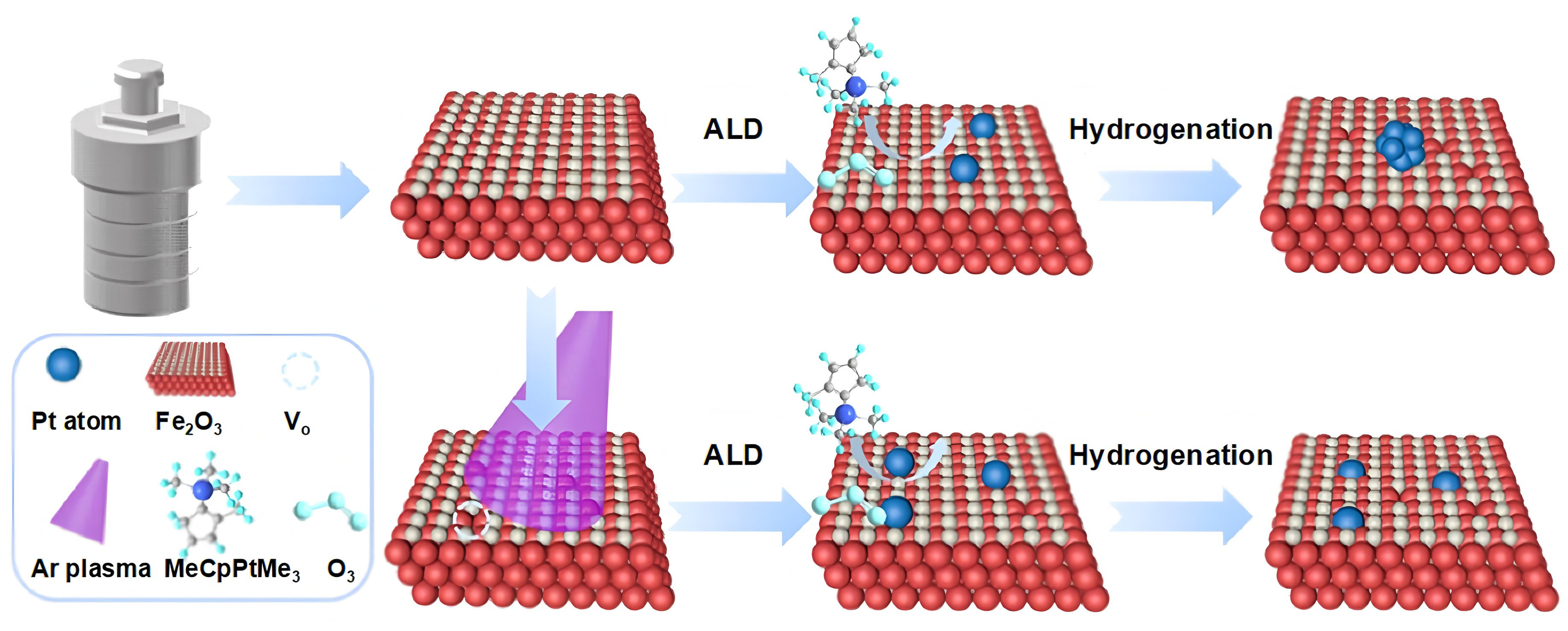

Atomic layer deposition (ALD) provides atomic-level precision in controlling noble-metal dispersion by relying on sequential, self-limiting surface reactions between gaseous precursors and reactive sites on the substrate. In a typical ALD cycle, the substrate is alternately exposed to a metal precursor and a co-reactant, separated by inert gas purging steps to remove excess reactants and by-products. Each cycle deposits less than a monolayer of material, ensuring layer-by-layer growth. This cyclic, self-saturating reaction mechanism allows for the uniform deposition of atomically dispersed noble metals that are often stabilized at defect sites such as oxygen vacancies or step edges, thereby ensuring precise control over dispersion and coordination at the atomic scale[13]. Zhou et al. developed a formaldehyde gas sensor based on atomically dispersed Rh anchored on SnO2 nanoparticles via ALD technique, using rhodium(III) with acetylacetone [Rh(acac)3] and O2 as the precursor pair[14]. To ensure uniform atomic dispersion, the SnO2 material was maintained at 150 °C during the deposition process, and the number of ALD cycles was precisely controlled (5-30 cycles) to optimize Rh loading. The resulting Rh-SnO2 nanostructures featured atomically dispersed Rh anchored on the oxide surface through surface-adsorbed functional groups generated in sequential ALD half-reactions. Besides, Zhang et al. reported the construction of a hydrogen sensor based on atomically dispersed Pt anchored on oxygen-vacancy-rich Fe2O3 nanosheets (Pt-Fe2O3-Vo) by this strategy [Figure 1][15]. First, Fe2O3 nanosheets were prepared through a hydrothermal method, followed by Ar plasma etching to generate abundant oxygen vacancies. Subsequently, five ALD cycles of Pt were carried out using a metal-organic precursor, anchoring Pt atoms onto vacancy sites. Finally, the Pt species were reduced under an Ar/H2 atmosphere to yield Pt-Fe2O3-Vo samples. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy revealed that the Pt loading increased from 1.59 wt.% in Pt-Fe2O3 to 2.59 wt.% in the oxygen-vacancy-rich Pt-Fe2O3-Vo, highlighting the critical role of surface defects in promoting the formation of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials. ALD technology also exhibits significant potential for the fabrication of atomically dispersed dual noble-metal sensitizers[16], enabling precise regulation of the local coordination environment and its correlation with gas sensing performance. However, the widespread application of ALD in sensor manufacturing remains limited by the cost and scalability, which currently confines its use to fundamental studies rather than scalable device-level production.

Figure 1. Synthesis of Pt-loaded Fe2O3 nanosheets (Pt-Fe2O3-Vo) by atomic layer deposition. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[15]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. Pt-Fe2O3-Vo: Atomically dispersed Pt anchored on oxygen-vacancy-rich Fe2O3 nanosheets; ALD: atomic layer deposition.

Impregnation

The impregnation method introduces noble-metal precursors into porous or high-surface-area materials via liquid-phase infiltration, followed by thermal decomposition and activation to yield atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials. This approach facilitates the uniform distribution of noble-metal sensitizers on the surface of SMO through a relatively simple procedure. Compared to ALD, impregnation offers advantages in operational simplicity and cost-effectiveness, making it a widely adopted technique in metal loading for gas sensing applications[17]. Xue et al. developed a step-defect engineering strategy to fabricate atomically dispersed gold on ladder-like ZnO nanostructures with abundant unsaturated step edges[18]. The ZnO was synthesized via a solution-phase layer-stacking method, forming freestanding hexagonal nanoladders with controllable lateral size (~ 100-480 nm), step thickness (5-20 nm), and a high specific surface area featuring step-rich regions. These low-coordination edge sites served as preferential anchoring centers for Au atoms. Upon hydrogen-assisted calcination, Au species were selectively anchored as single atoms on the step-rich ZnO via strong interactions with surface oxygen vacancies. The atomically dispersed state of Au was confirmed by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) imaging, where bright atomic-scale spots were observed predominantly at step edges. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy further distinguished the linear CO adsorption band at ~ 2,130 cm-1, characteristic of atomically dispersed Auδ⁺ species, with no signal at 2,100 cm-1 typical for Au nanoparticles. Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectroscopy quantified the Au loading at only 0.32 wt.%.

The high surface free energy of atomically dispersed noble metals makes them susceptible to migration and agglomeration, generating nanoclusters or nanoparticles with low surface free energy. The preparation of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers by the impregnation method suffers from the disadvantages of low loading. Thus, it is necessary to inhibit atomic aggregation while increasing the atomically dispersed noble-metal loading amount. Hai et al. prepared atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers by combining the impregnation method with the two-step annealing method[19]. A range of noble metals, including Pd, Ir, Pt, Ru, and Rh, have been incorporated into CeO2. The noble-metal loadings of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials were about 2-10 wt.%, significantly enhancing the efficiency and yield of atomic-scale sensitizer formation.

Overall, the impregnation method is distinguished by its simplicity, cost-efficiency, and suitability for large-scale implementation. When integrated with complementary approaches such as defect engineering or controlled multi-step annealing, it can substantially enhance the loading density and dispersion quality of noble-metal sensitizers, thereby enabling the practical synthesis of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials. Despite existing challenges related to site stability and spatial uniformity, this method remains a highly promising and accessible pathway for the scalable fabrication of advanced gas-sensing materials.

Pyrolysis strategy

Among the diverse synthetic strategies for constructing atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials, the pyrolysis approach is particularly notable for its ability to sequentially integrate structure-directing agent, coordination chemistry, and high-temperature treatment to yield atomically dispersed sensitizer sites[20]. This method enables the transformation of metal-ligand precursors [such as metal-phenolic networks or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)] into porous oxide scaffolds hosting atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. The thermal decomposition of organic components not only creates a high specific surface area but also facilitates the redistribution and anchoring of noble-metal atoms onto defect-rich regions with strong metal-support interactions. As a result, pyrolysis-derived materials often exhibit enhanced structural stability and tailored coordination environments, which are critical for robust gas sensing under complex operating conditions.

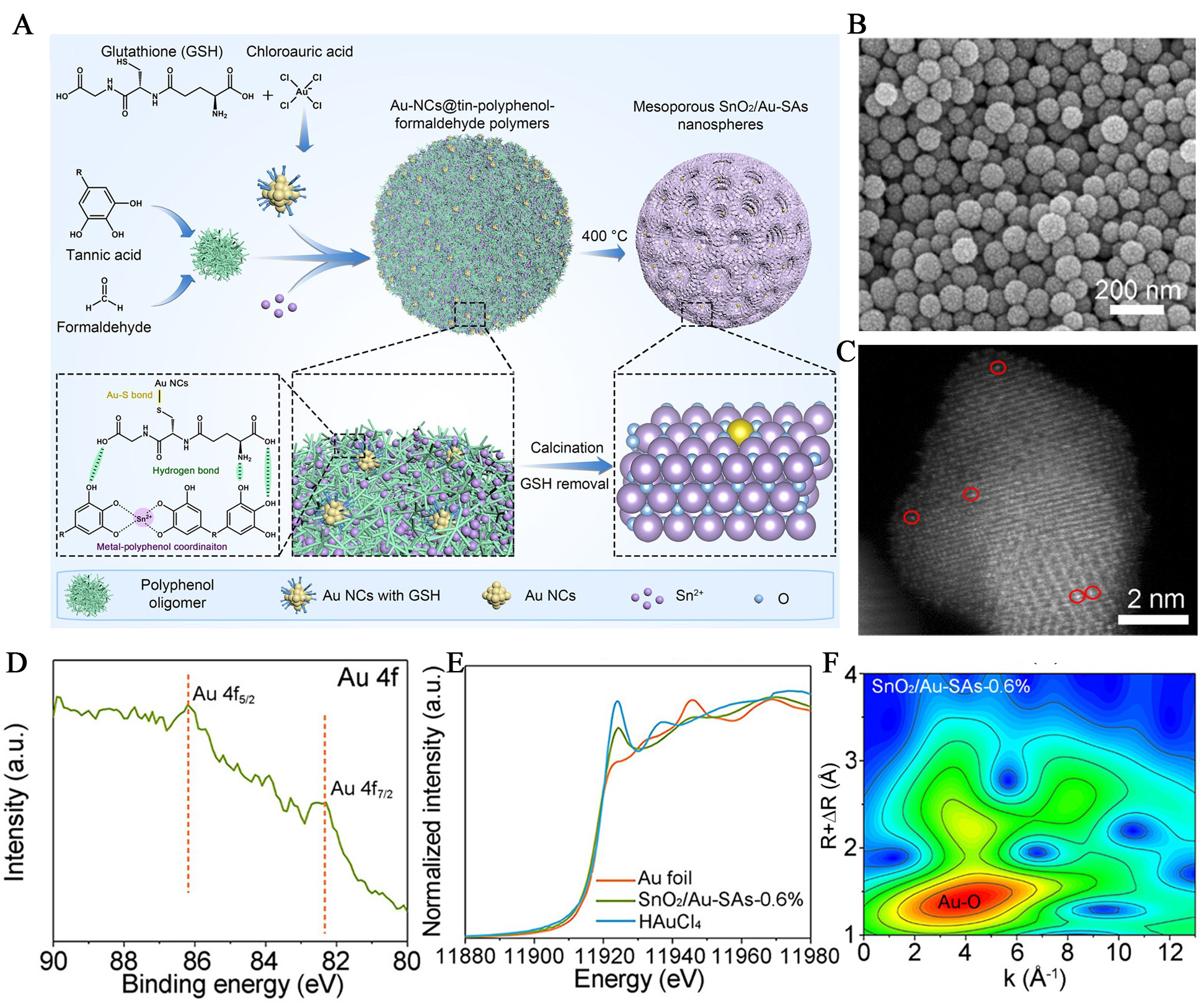

The metal-phenolic hybrids-derived mesoporous metal oxides can offer an effective strategy for fabricating atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. The polyphenol ligands coordinate with the metal, enabling the formation of well-defined structures. Upon pyrolysis, these complexes yield mesoporous SMOs, which retain their porous frameworks and facilitate the atomic-level dispersion of noble metals. This approach prevents metal agglomeration and improves the stability of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. For example, Feng et al. synthesized atomically dispersed Au-functionalized mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres via a thermal annealing approach based on metal-phenolic framework precursors [Figure 2A][21]. In this strategy, phenolic oligomers formed by the cross-linking of tannic acid served as organic scaffolds, which coordinated with Sn2+ ions to construct tin-phenolic frameworks. Pre-synthesized Au nanoclusters were incorporated into the framework through strong hydrogen-bonding interactions, ensuring the uniform dispersion. Upon thermal treatment, the organic components were removed, leading to the crystallization of SnO2 and simultaneous transformation of Au nanoclusters into atomically dispersed Au species anchored on the mesoporous structure. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Figure 2B) and HAADF-STEM [Figure 2C] images confirmed the retention of spherical morphology and the presence of atomically dispersed Au. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra [Figure 2D] revealed two characteristic peaks at 86.2 eV and 82.3 eV, confirming the presence of Au species in SnO2. X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES, Figure 2E) further indicated that the Au valence lay between 0 and +3, while Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and wavelet transform analyses [Figure 2F] identified a predominant Au-O coordination and the absence of Au-Au scattering, unequivocally demonstrating the atomically dispersed nature of Au on the mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres. In contrast to this Au nanocluster-derived single-atom Au strategy, Li et al. developed a self-template method that bypasses the need for preformed Au nanoclusters by directly employing [AuCl4]- as the metal precursor[22]. In this approach, phenolic oligomers generated from the formaldehyde-induced crosslinking of tannic acid served as chelating agents, simultaneously coordinating with Sn2+, Ce3+, and Au precursors to form homogeneous metal-phenolic colloidal spheres. Upon direct pyrolysis in air, the organic components were decomposed, forming mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres with atomically dispersed Au and lattice-incorporated Ce. Notably, this strategy allows for atomic-level rare-earth doping, which can effectively modulate the electronic structure and defect landscape of the tin dioxide scaffold.

Figure 2. Morphological and atomic-level characterization of mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres sensitized with atomically dispersed Au. (A) Schematic illustration of the formation of mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres with atomically dispersed Au; (B) SEM image and (C) HAADF-STEM image of atomically dispersed Au-functionalized mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres; (D) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra of Au 4f; (E) XANES spectra and (F) Wavelet transform analysis of EXAFS. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[21]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. NC: Nanocluster; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; HAADF-STEM: high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure; EXAFS: X-ray absorption fine structure.

In addition to metal-phenolic hybrids, MOFs provide another effective route for fabricating atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials. The intrinsic porosity of MOFs allows spatial confinement of metal precursors, which prevents aggregation and facilitates the generation of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials upon pyrolysis. High-temperature treatment of MOFs typically yields mesoporous metal oxides while preserving structural features conducive to gas sensing. For example, Liu et al. employed an indium-based MOF as a sacrificial template to synthesize atomically dispersed Pd-modified In2O3 through the pyrolysis strategy[23]. In this approach, Pd precursors were impregnated into the MOF via solution dispersion. Subsequent high-temperature calcination in air facilitated the complete decomposition of the organic ligands and the transformation of the framework into crystalline In2O3, while simultaneously anchoring atomically dispersed Pd within the In2O3 matrix. This method effectively leveraged the uniform porosity and metal-binding functionality of the MOF precursor to achieve atomic-scale dispersion of noble-metal species.

However, the pyrolysis strategy also presents several limitations. A primary challenge lies in achieving both high loading and uniform dispersion of noble metals at the atomically dispersed level. Confinement within porous structures may result in incomplete distribution or agglomeration of metal species, leading to the formation of clusters rather than atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. Moreover, the high-temperature pyrolysis or annealing processes required for stabilizing atomically dispersed configurations can induce structural changes in the SMO material, such as the collapse of porous structure or phase transformation, which may adversely affect the final sensing performance. Another concern is the relatively weak interaction between atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers and SMO materials, which can compromise the thermal and chemical stability of the atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials under operating conditions.

Photochemical strategy

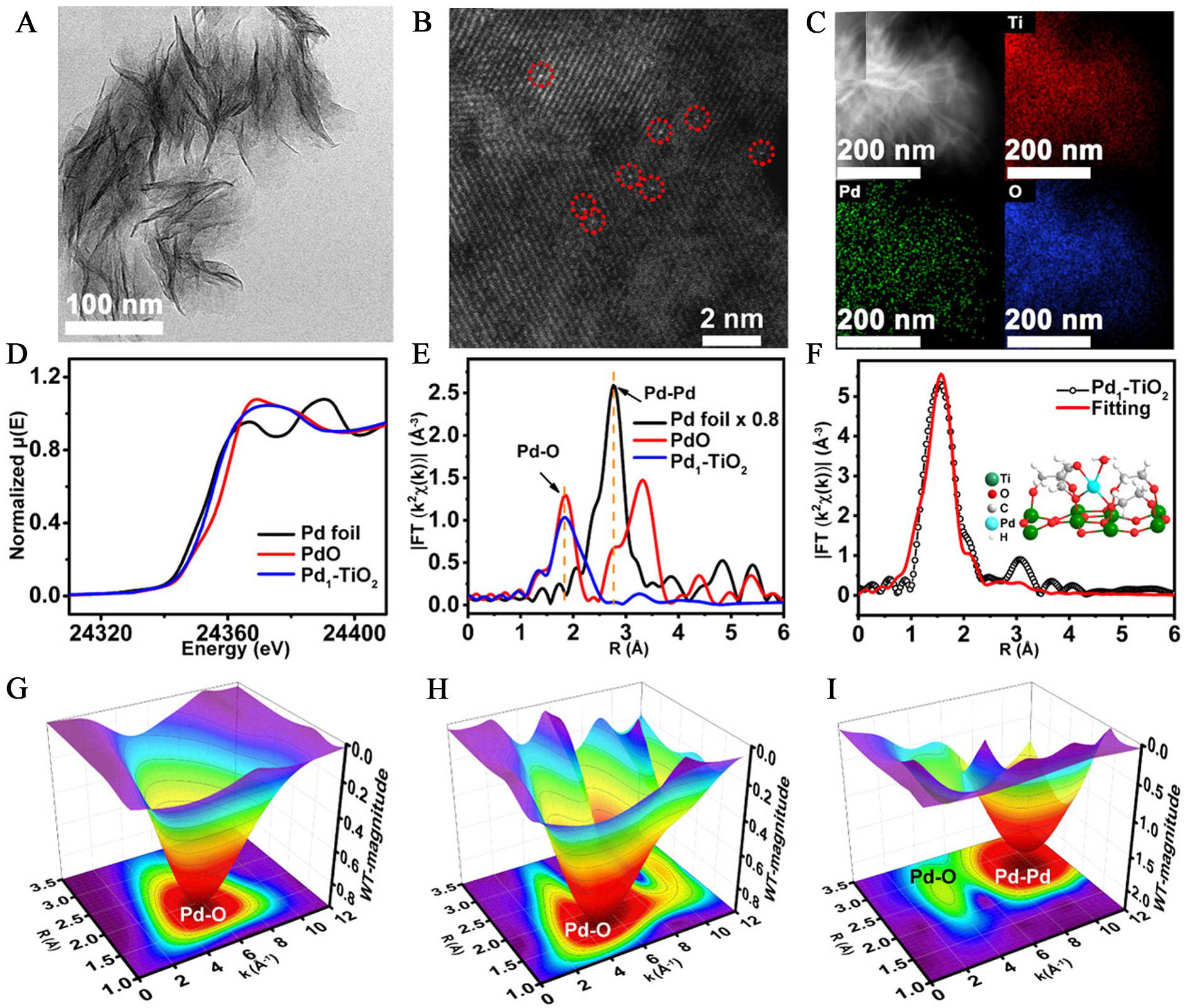

In the photochemical method, light energy excites the reducing agent, enabling it to reduce and anchor metal ions onto the sensing support material[24,25]. This method offers high loading of atomically dispersed noble-metal and easy preparation without the need for high-temperature pyrolysis, making it a mild approach. A noteworthy demonstration of this approach was performed by Liu et al., who developed a room-temperature photochemical strategy to fabricate atomically dispersed Pd on ultrathin TiO2 nanosheets[26]. The atomically dispersed Pd was dispersed on ethylene glycolate-stabilized ultrathin TiO2 nanosheets, and the Pd content was up to 1.5 wt.%. In this method, ultraviolet light irradiation induced the in situ generation of ethylene glycolate radicals on the TiO2 surface, which played a pivotal role in anchoring and stabilizing atomically dispersed Pd. Furthermore, Ye et al. synthesized atomically dispersed Pd on TiO2 nanoflowers (Pd1-TiO2, Brunauer-Emmett-Teller surface area: 326.9 m2·g-1) via a room-temperature photochemical method[9]. H2PdCl4 was anchored onto TiO2 through surface-coordinated ethylene glycol, followed by ultraviolet irradiation to immobilize Pd atoms without nanoparticle formation. No Pd nanoparticles were observed in Pd1-TiO2 from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images [Figure 3A]. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image revealed uniformly distributed bright spots corresponding to atomically dispersed Pd [Figure 3B], while elemental mapping confirmed the homogeneous distribution of Ti, O, and Pd [Figure 3C]. X-ray absorption fine structure analysis confirmed the atomically dispersed state and local coordination environment of Pd species in Pd1-TiO2. XANES spectra [Figure 3D] revealed a higher absorption edge than Pd foil, indicating a partially oxidized Pd state. The Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra [Figure 3E] exhibited a prominent Pd-O peak without Pd-Pd contributions, confirming the absence of metallic aggregation. Quantitative fitting [Figure 3F] determined a mean Pd-O bond length of ~ 1.89 Å. Wavelet transform analysis [Figure 3G-I] further supported the exclusive presence of Pd-O coordination. This mild, solution-phase strategy circumvents the need for high-temperature treatments and allows for relatively high Pd loadings while preserving atomic-level dispersion.

Figure 3. Structural characterization of atomically dispersed Pd on TiO2 using electron microscopy and synchrotron-based spectroscopy. (A) TEM; (B) HAADF-STEM; and (C) elemental mapping images of Pd1-TiO2; (D) XANES and (E) k2-weighted EXAFS spectra at the Pd K-edge of Pd1-TiO2, PdO, and Pd foil. (F) The corresponding fit of the EXAFS spectrum of Pd1-TiO2 at the R space. The inset shows the local structure of the atomically dispersed Pd on TiO2 The wavelet transform of the experimental EXAFS spectra of (G) Pd1-TiO2; (H) PdO; and (I) Pd foil. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[9]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy; HAADF-STEM: high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure; EXAFS: X-ray absorption fine structure; FT: Fourier Transform.

Nevertheless, the photochemical approach for synthesizing atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials faces several limitations. The requirement for precise control over illumination conditions poses challenges for both process optimization and reproducibility. Furthermore, insufficient control over reduction kinetics can lead to the formation of metal clusters rather than well-defined single-atom sensitizer sites, thereby diminishing the desired catalytic and sensing performance. In addition, the scalability of this method remains constrained, as factors such as limited light penetration and decreased photo reaction efficiency complicate its application in large-scale or continuous synthesis settings.

Coprecipitation

Coprecipitation is an efficient method for synthesizing atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials, with the advantages of easy operation, low cost, and suitability for large-scale production. It has great significance to control the content of loading amount. In the coprecipitation method, noble-metal ions are co-dissolved with metal-oxide precursors in solution, and a precipitant is gradually added to induce the formation of insoluble metal hydroxides or carbonates. During this process, noble-metal species are uniformly incorporated into the precursor matrix. After filtration, washing, and calcination, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials are obtained[27,28]. Qiao et al. reported the synthesis of atomically dispersed Pt species on high-surface-area FeOx nanocrystallites (290 m2·g-1) via this coprecipitation strategy[29]. Specifically, chloroplatinic acid and ferric nitrate were co-precipitated in a basic carbonate solution under controlled pH and temperature, followed by drying, calcination, and mild hydrogen reduction to yield atomically dispersed Pt anchored at defect sites on the FeOx surface. The Pt loading was precisely controlled at 0.17 wt.% to ensure sufficient separation of atomic sensitizers and avoid aggregation. The atomic dispersion of Pt was rigorously confirmed by a combination of advanced characterization techniques. Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM directly visualized isolated Pt atoms, while X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy revealed the absence of Pt-Pt coordination and the presence of Pt-O bonding environments, further supporting the atomically dispersed nature of Pt. Furthermore, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy of CO adsorption was employed to probe the chemical environment of Pt species, with the observation of a band at 2,080 cm-1 providing strong evidence for atomically dispersed Pt. Structural defects and hydroxyl groups originating from the poorly crystallized, high-surface-area support appear to play a key role in stabilizing atomically dispersed Pt. The formation of Pt-O-Fe bonding results in positively charged, high-valent Pt atoms on the metal oxide surface.

Taken together, although coprecipitation offers clear advantages in terms of cost, operational simplicity, and scalability, its inherent tendency to embed noble-metal species within the bulk matrix limits surface exposure and atomic utilization for gas sensing[30-32]. This constraint is particularly relevant for SMO gas sensors, where sensing performance relies on the ability of surface-active sites to influence charge transport through the depletion layer.

From a support perspective, SMOs offer a distinct advantage in chemiresistive sensing because they simultaneously serve as both the host for atomically dispersed noble-metal species and the electronic transducer. In SMOs, atomically dispersed noble metals are intrinsically stabilized through metal-oxygen coordination and defect-related interactions within an electronically active lattice, which is also responsible for charge transport. As a result, charge redistribution induced by atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers during gas adsorption can directly modulate band bending, depletion layers, and resistance. In comparison, SiO2 is electronically inert and generally requires additional anchoring strategies for single-atom stabilization. Carbon-based materials can function as sensing materials with high accessible surface area and abundant functional groups, which are favorable for stabilizing atomic sensitizers by heteroatom coordination or defect trapping and achieving excellent sensing performance, as exemplified by ordered mesoporous carbon sensors[33].

Although diverse supports have been reported for atomically dispersed noble-metal loading, this work focuses on SMOs. Table 1 specifically compares synthesis strategies for atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials.

Comparison of synthesis strategies for atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs

| Method | Advantage | Disadvantage |

| Atomic layer deposition | Atomic-level precision and excellent control over dispersion and coordination environment | High cost and limited scalability |

| Impregnation | Simple, low-cost, and scalable for practical material preparation | Low achievable loading and poor resistance to atomic aggregation |

| Pyrolysis strategy | Enables strong metal-support interaction and stable atomic anchoring in porous SMOs | Induction of aggregation and structural degradation by high-temperature treatment |

| Photochemical strategy | Mild conditions with relatively high atomic loading without thermal damage | Poor reproducibility and limited scalability |

| Coprecipitation | Low-cost and suitable for large-scale synthesis with controllable loading | Reduction of surface accessibility due to burial of noble-metal atoms in the bulk |

Structural and chemical characterization

Reliable identification of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers on SMOs is inherently challenging due to their ultralow metal loadings and dynamic structural characteristics. As a result, unambiguous confirmation of atomic dispersion cannot rely on a single characterization technique but requires corroborative evidence from complementary structural, chemical, and adsorption-sensitive methods.

At the structural level, electron microscopy provides direct insight into atomic-scale dispersion. While conventional TEM is effective for assessing support morphology and defect structures, its capability to directly resolve isolated noble-metal atoms is limited[34]. In contrast, scanning transmission electron microscopy in the high-angle annular dark-field mode enables direct visualization of individual noble-metal atoms through Z-contrast imaging. Element-resolved techniques such as energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy and electron energy-loss spectroscopy further strengthen spatial and chemical identification. Nevertheless, beam-induced atom migration or aggregation must be carefully considered, particularly for defect-rich SMO supports.

To elucidate local coordination environments and electronic states, X-ray absorption spectroscopy plays a central role[35,36]. XANES provides information on oxidation state and electronic configuration, while EXAFS reveals coordination numbers and bonding environments. The absence of metal-metal coordination and the dominance of metal-oxygen scattering features are widely regarded as key signatures of atomic-scale dispersion.

In addition to static structural analysis, adsorption-based spectroscopic techniques offer functional validation of atomic dispersion. Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy, using probe molecules such as CO, allows differentiation between single-atom sites and clustered species based on characteristic vibrational frequencies and adsorption behavior[37]. Consistent adsorption signatures, together with microscopy and X-ray absorption spectroscopy results, provide strong evidence for genuine atomic dispersion.

Overall, only the convergence of atomic-resolution imaging, local coordination analysis, and probe-molecule spectroscopy can reliably establish the presence of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers. This integrated characterization framework is essential for correlating atomic-scale structure with gas-sensing performance and for guiding rational material design.

ATOMICALLY DISPERSED NOBLE-METAL-SENSITIZED SMO MATERIALS FOR GAS SENSING

Atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials have emerged as a highly promising platform for advanced gas sensing. Beyond traditional catalytic functions, each atomically dispersed noble metal serves as a well-defined sensitizer site, offering precise control over local coordination environments and electronic structures to modulate adsorption strength and gas selectivity. The strong metal-support interactions with SMOs facilitate efficient charge transfer and promote rapid signal transduction, leading to enhanced sensitivity and accelerated response speed. In addition, the atomically dispersed configuration inherently resists aggregation, thereby ensuring excellent thermal and structural stability under operating conditions. Collectively, these attributes enable atomically dispersed noble metals to function as efficient sensitizers, coupling catalytic activation with electronic modulation to achieve superior performance in sensitivity, selectivity, and durability compared to conventional noble-metal nanoparticle sensitized SMO materials. The following section provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in this rapidly evolving field, with a focus on how atomic-level structural engineering governs gas-sensing behavior.

Hydrogen sensing

Hydrogen (H2) has emerged as a cornerstone in the transition to sustainable energy systems, owing to its high energy density, renewability, and zero carbon emissions during combustion[38-40]. However, its safe utilization is challenging due to its physicochemical properties. Hydrogen is colorless, odorless, and highly flammable, with an extremely low ignition energy (0.02 mJ) and a wide explosive concentration range (4%-75% in air). Even trace hydrogen leaks at sub-ppm levels can accumulate over time and pose serious explosion risks, underscoring the urgent need for gas sensors with ultrahigh sensitivity, rapid response, and long-term operational stability. While conventional SMO gas sensors offer advantages in cost and durability, they often exhibit limited sensitivity and poor selectivity toward hydrogen. The integration of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials presents a promising strategy to address these limitations. By maximizing noble-metal utilization and generating well-defined sensitizer sites, these materials enable precise modulation of gas adsorption and charge transfer processes, thereby significantly enhancing the sensing response to hydrogen.

Representative advances have demonstrated the transformative potential of this strategy. Zhang et al. synthesized Pt-Fe2O3-Vo via ALD, achieving a 17-fold response enhancement toward H2 compared to Fe2O3, with an ultrafast response time of 2 s and a detection limit down to 86 ppb[15]. Density functional theory calculations revealed that oxygen vacancies stabilized the Pt atoms through electron transfer, which simultaneously facilitated H2 dissociation and electron injection. Xiang et al. decorated SnO2 nanofibers with atomically dispersed Pd to boost the H2 sensing properties[41]. The Pd-SnO2 nanofiber sensor exhibited a response of 224 to 1,000 ppm H2 at the optimum operation temperature of 300 °C, which was 107 times higher than that of SnO2, achieving a limit of detection as low as 0.6 ppb. Moreover, a fast response time of 8.4 s, excellent selectivity, and humidity tolerance were observed. The superior H2 sensing performance of Pd-SnO2 nanofibers was ascribed to excellent catalysis of single-atom Pd and heterojunction formation.

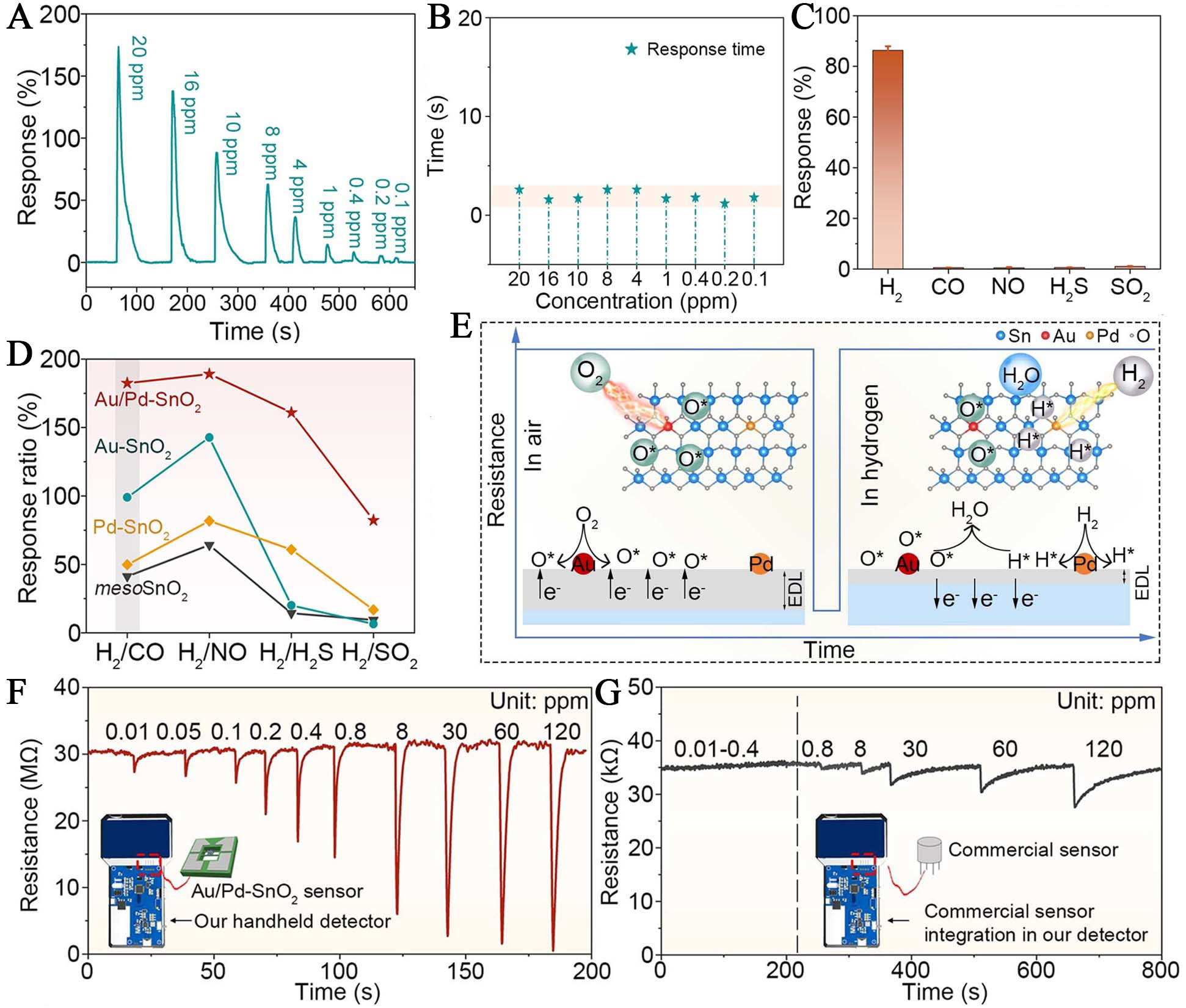

Atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials have demonstrated remarkable improvements in gas-sensing sensitivity and selectivity; however, materials incorporating only a single type of sensitizer may show limited efficiency in mediating complex multi-step surface reactions. To address this challenge, growing attention has been focused on the development of materials incorporating atomically dispersed dual noble metal sensitizers. The presence of two distinct metal species at the atomic scale enables synergistic interactions that promote cooperative adsorption and activation of target gas molecules. This strategy has shown considerable promise in overcoming the intrinsic limitations of conventional SMO-based hydrogen sensors, which are often hindered by sluggish hydrogen oxidation kinetics and inadequate hydrogen adsorption capacity. Building on this concept, atomically dispersed Au/Pd was lattice-anchored within the mesoporous SnO2 framework (Au/Pd-SnO2) for hydrogen sensing. This Au/Pd-SnO2 sensor exhibited outstanding hydrogen sensing performance, characterized by a rapid response time (~ 1 s), an ultralow detection limit down to 70 ppb, and exceptional selectivity against common interfering gases such as CO, NO, H2S, and SO2 [Figure 4A-D][42]. The performance enhancement was attributed to the synergistic sensitization effect between the atomically dispersed Au and Pd: Au atoms promoted the dissociation of O2 and stabilized reactive oxygen species, while Pd atoms activated and dissociated H2, together enabling efficient and selective redox reactions on the sensing interface [Figure 4E]. Furthermore, this material was integrated into a handheld hydrogen leakage detector, enabling sub-second H2 detection down to 0.01 ppm, outperforming commercial gas sensors [Figure 4F and G].

Figure 4. Hydrogen sensing performance of atomically dispersed Au and Pd co-sensitized SnO2 and its practical application in portable detection. (A) Dynamic response-recovery profiles of Au/Pd-SnO2 sensor toward various H2 concentrations; (B) Dependence of response time on hydrogen concentration; (C) Selectivity of the sensor against different interfering gases (10 ppm); (D) Comparative response ratios of four sensors to H2 versus interfering gases; (E) Proposed sensing mechanism involving atomically dispersed Au and Pd species, surface oxygen species (O*), and reactive hydrogen (H*); (F) Real-time response of the Au/Pd-SnO2-based handheld detector to low-level H2; (G) Performance of a commercial H2 detector (TGS2616-C00) under identical conditions. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[42]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society. EDL: Electron depletion layer.

Atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs have demonstrated remarkable potential for hydrogen sensing, offering ultrahigh sensitivity, rapid response speed, and excellent selectivity under complex conditions. Through precise engineering of active sensitizer sites at the atomic scale, these materials enable efficient hydrogen adsorption, dissociation, and charge transfer, thereby overcoming key limitations of traditional SMO-based gas sensors. Despite these advances, several challenges remain. The controlled synthesis of atomically dispersed dual noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials with defined spatial configurations and electronic structures is still nontrivial, and understanding how these sensitizers evolve under dynamic sensing conditions requires further operando investigations. Moreover, ensuring long-term stability, especially under humid or thermally fluctuating environments, continues to constrain real-world deployment.

Carbon monoxide sensing

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless, and highly toxic gas that binds with hemoglobin to form carboxyhemoglobin, thereby reducing oxygen transport in blood and causing tissue hypoxia[43-45]. Even at sub-ppm concentrations, prolonged exposure can lead to neurological impairment or even death, underscoring the importance of trace-level monitoring. In addition to its biomedical relevance, CO is also a major gaseous product released during lithium-ion battery thermal runaway, together with hydrogen, methane, and acetylene[46,47]. The rapid accumulation of CO under such conditions not only poses a direct explosion and fire hazard but also serves as an early indicator of battery failure. This dual requirement for accurate trace detection in both biomedical diagnostics and energy-storage safety monitoring highlights the pressing need for advanced sensing materials that offer both high sensitivity and strong selectivity.

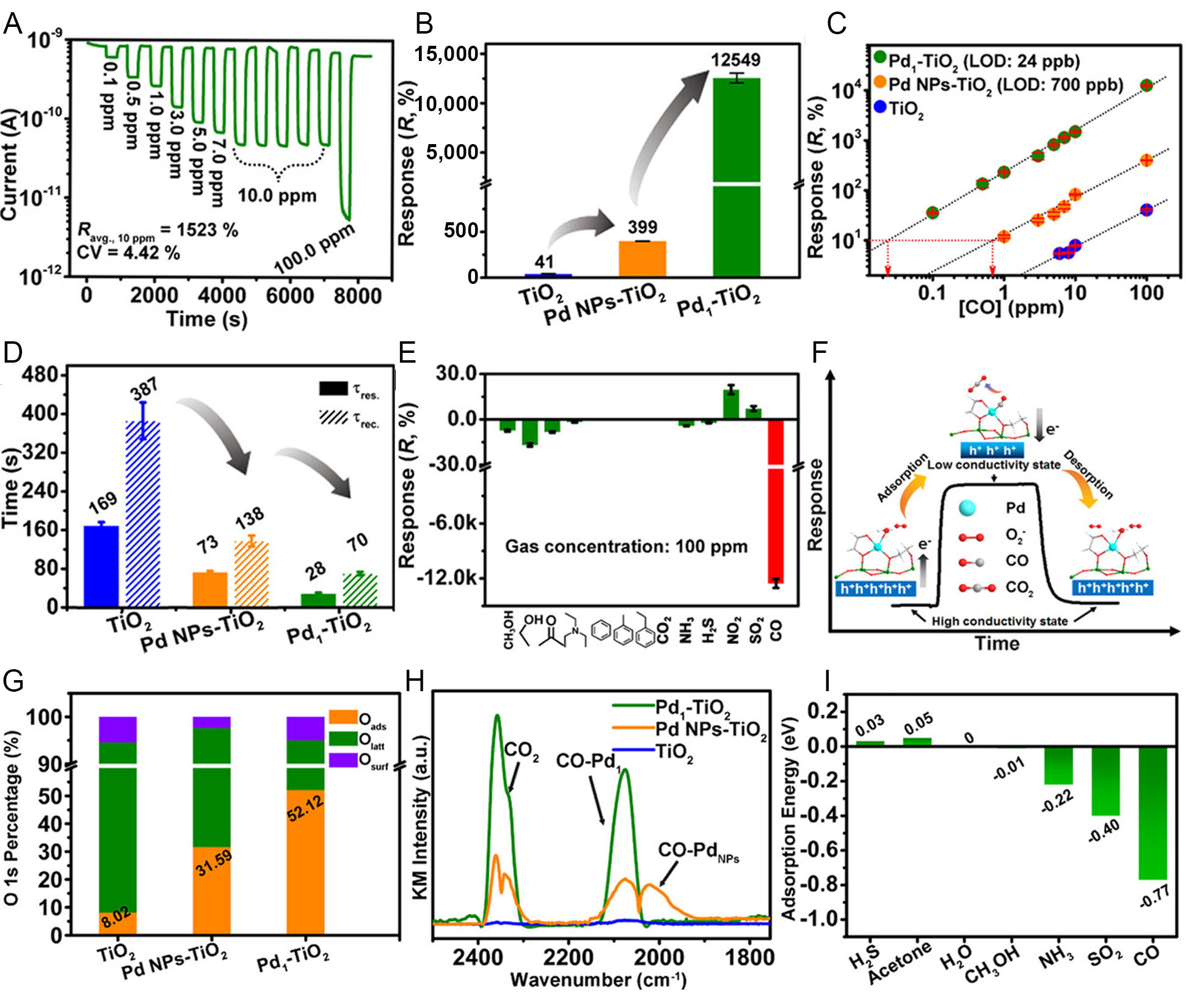

To address these challenges, several representative materials have been explored. For instance, Ye et al. constructed a Pd1-TiO2 gas sensor by anchoring atomically dispersed Pd on TiO2 nanoflowers[9]. This sensor exhibited an ultrahigh response of over 12,000% to 100 ppm CO at room temperature and a record-low detection limit of 24 ppb [Figure 5A-C]. Compared to both TiO2 and Pd nanoparticles-loaded TiO2 (Pd NPs-TiO2), the atomically dispersed Pd significantly accelerated response and recovery time [Figure 5D], while maintaining outstanding selectivity against 12 interference gases [Figure 5E]. The atomically dispersed Pd formed highly active Pd-O-Ti interfacial sites that promoted O2- generation [Figure 5F and G], enhanced CO chemisorption [Figure 5H], and enabled efficient CO oxidation even at ambient conditions. Density functional theory calculations further revealed that CO exhibited the strongest adsorption among all analytes [Figure 5I], accounting for the superior selectivity observed. Li et al. proposed an atomically dispersed Au sensitization strategy to boost the CO sensing performance of In2O3[48]. To expound it, atomically dispersed Au (Au1) was prepared from an iced photochemical reduction method and then modified on porous In2O3 nanospheres to obtain the hybrid Au1/In2O3 gas sensing material. Benefiting from the outstanding spillover and catalytic effects of Au1, the best sensing material showed superior CO sensing performances to In2O3, especially of lower optimal working temperature (360 °C vs. 380 °C), higher sensitivity (0.032/ppm vs. 0.003/ppm to 10-100 ppm CO), and faster response/recovery speed (2/10 s vs. 47/205 s). Atomically dispersed Au modification enriched surface-active oxygen via the spillover effect while lowering apparent activation energies, thereby enhancing the sensor’s sensitivity, response, and recovery speed.

Figure 5. Enhanced CO sensing performance of atomically dispersed Pd on TiO2 and underlying mechanistic insights. (A) Response-recovery curves of Pd1-TiO2 toward CO at concentrations from 0.1 to 100 ppm; (B) Comparison of CO (100 ppm) responses for TiO2, Pd nanoparticles-loaded TiO2 (Pd NPs-TiO2), and Pd1-TiO2 sensors; (C) Linear correlation between response and CO concentration for TiO2, Pd NPs-TiO2, and Pd1-TiO2; (D) Response and recovery time of different TiO2-based sensors toward 100 ppm CO; (E) Selectivity of Pd1-TiO2 toward CO against various interference gases; (F) Proposed CO sensing mechanism highlighting the Pd-O-Ti interfacial active sites; (G) Relative ratios of surface oxygen species derived from O 1s X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra; (H) In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy of different sensors; (I) Density functional theory-calculated adsorption energies of various gases on Pd1-TiO2. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[9]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. LOD: Limit of detection; CV: coefficientof variation; NP: nanoparticle; KM: Kubelka-Munk.

In conclusion, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs have shown exceptional promise for CO sensing, offering ultralow detection limits, rapid response kinetics, and robust selectivity under both ambient and elevated temperatures. The strategic incorporation of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers enables the formation of highly active interfacial sites, which facilitate the generation of reactive oxygen species, strengthen CO adsorption, and lower the energy barriers for oxidation reactions in CO sensing. These advances have significantly outperformed traditional nanoparticle-modified SMOs, underscoring the superior sensing efficiency. However, key challenges remain. The dynamic evolution of sensitizer sites under CO exposure, particularly in terms of potential aggregation or oxidation state fluctuations, is not yet fully understood and may compromise long-term stability. In addition, achieving strong and selective CO recognition under low-temperature and high-humidity conditions remains difficult, especially for materials operating near room temperature.

Nitrogen dioxide sensing

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is a highly toxic oxidizing gas released primarily from combustion sources, posing significant threats to human health and environmental safety even at sub-ppm levels[49-51]. However, its strong electron-withdrawing nature and moisture sensitivity present persistent challenges for traditional SMO gas sensors, especially under low-temperature conditions. In recent years, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials have demonstrated strong potential to overcome these limitations by enhancing NO2 chemisorption, accelerating redox kinetics, and improving signal transduction.

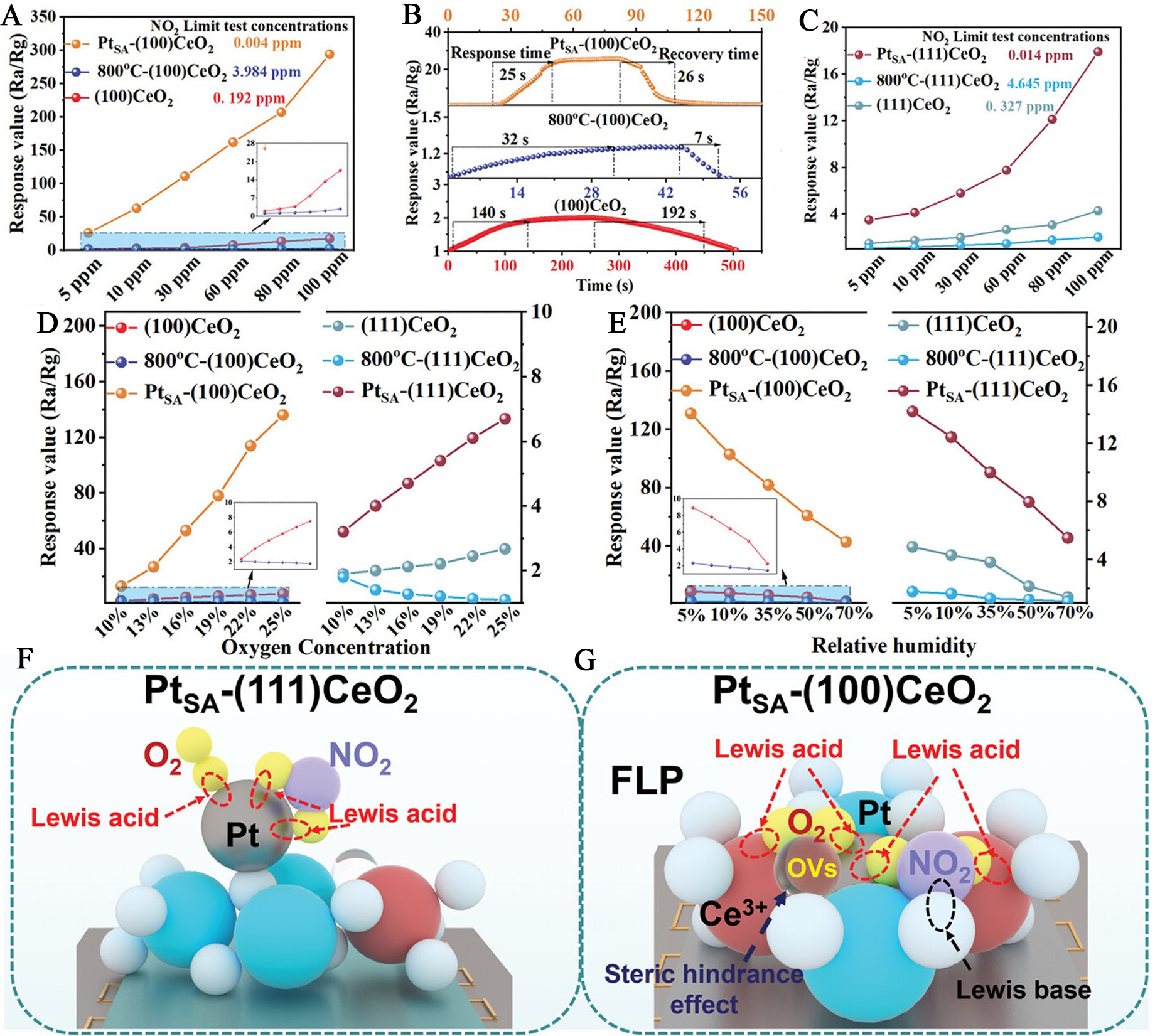

Several representative studies have exemplified how the structural tailoring of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials can markedly influence NO2 sensing behavior. Through rational engineering of surface defects, step sites, and crystallographic facets, these systems enable optimized charge transfer and adsorption energetics, leading to significantly enhanced sensitivity and selectivity under low-temperature or trace-level conditions. Xue et al. constructed step-rich ZnO ladders to selectively anchor atomically dispersed Au (Au1-ZnO), achieving a remarkable NO2 response of 12.6 at 300 ppb under 150 °C[18]. The miniaturized chemiresistor sensor (1 mm × 1 mm) integrated parallel Au electrodes and backside Pt heaters. Compared with Au nanoparticle-decorated ZnO and ZnO, the Au1-ZnO sensor exhibited significantly higher sensitivity and excellent selectivity toward NO2 over interfering gases at 300 ppb. It also maintained reproducible responses down to 10 ppb NO2 with fast, stable recovery. Density functional theory calculations revealed that atomically dispersed Au modulated the electronic structure of ZnO, as evidenced by density of states shifts and substantial charge transfer (0.68 e-) from the substrate to NO2, highlighting the role of atomic Au in enhancing electron depletion and boosting sensing performance. In another example, Ou et al. investigated atomically dispersed Pt sensitized CeO2 with distinct exposed facets, namely Pt single-atom (PtSA)-(100)CeO2 and PtSA-(111)CeO2, and revealed strong facet-dependent behavior in NO2 sensing[52]. On the CeO2(100) surface, atomically dispersed Pt served as effective sensitizers by stabilizing Ce3+ species and interacting with oxygen vacancies to generate frustrated Lewis pairs, which dramatically enhanced NO2 response from 1.8 to 27 and shortened the response/recovery time from 140-192 s to 25-26 s at 5 ppm [Figure 6A and B]. In contrast, PtSA-(111)CeO2 exhibited only limited improvement, with the response increasing from 1.6 to 3.8 [Figure 6C]. To further elucidate the underlying mechanisms, the sensing behaviors were evaluated under different oxygen concentrations and humidity levels. The response of PtSA-(100)CeO2 increased with oxygen concentration, confirming that atomically dispersed Pt sensitizers enhanced surface oxygen activation, whereas PtSA-(111)CeO2 showed a weaker variation [Figure 6D]. With rising humidity, both samples exhibited decreased responses caused by competitive water adsorption, more pronounced on the (100) facet owing to the higher density of Pt-induced frustrated Lewis pair sites [Figure 6E]. Schematic models further revealed that the absence of strong electronic interaction between Pt and Ce3+ on the (111) surface led to spatially separated adsorption sites for O2 and NO2, whereas the (100) surface enabled dual-site activation via coupled Pt-Ce3+ frustrated Lewis pairs, thereby improving sensing performance [Figure 6F and G].

Figure 6. Facet-dependent NO2 sensing performance and mechanistic illustration of atomically dispersed Pt-sensitized CeO2. (A) Sensor response of Pt single-atom (PtSA)-(100)CeO2 to varying NO2 concentrations at room temperature; (B) Response and recovery time of PtSA-(100)CeO2 for 5 ppm NO2;. (C) Response behavior of PtSA-(111)CeO2 toward different NO2 levels under identical conditions; (D and E) Sensing performance of both facet-engineered samples toward 30 ppm NO2 under varying O2 concentrations and relative humidity; (F and G) Proposed surface reaction models illustrating NO2 adsorption and activation pathways on PtSA-(100)CeO2 and PtSA-(111)CeO2, respectively. Reproduced under the terms of the CC-BY Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)[52]. Copyright 2024, The Authors, published by Wiley-VCH. Ra/Rg: Resistance in air/resistance in test gas; PtSA: atomically dispersed Pt; FLP: frustrated Lewis pair.

Overall, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs have emerged as powerful platforms for NO2 detection, enabling accelerated surface reaction kinetics, particularly under low-concentration and low-temperature conditions. By anchoring atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers at well-defined lattice sites or defect-rich SMOs, these sensitizers effectively modulate the electronic structure of the SMO, promote NO2 chemisorption, and facilitate redox reactions at the sensing interface. Nevertheless, several important challenges remain. Achieving reversible and moisture-resilient NO2 sensing at room temperature continues to be difficult, as NO2 is a strong oxidizing gas that can irreversibly bind to surface sites or induce slow desorption dynamics. Additionally, the long-term structural stability of atomic sensitizers, especially under fluctuating ambient conditions, should be further validated through operando characterization.

Sulfur-containing gas sensing

Sulfur-containing gases, such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and volatile sulfur compounds, are critical targets in both environmental monitoring and biomedical diagnostics due to their toxicity, odor, and correlation with food spoilage or disease biomarkers[53-55]. However, their strong binding affinity to sensing materials often leads to site poisoning and irreversible deactivation, making selective and durable detection particularly challenging. Recent advances have shown that atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials offer unique advantages for sulfur gas sensing by enabling strong but tunable adsorption, promoting S-H bond activation, and enhancing surface redox reactions through tailored electronic interactions.

H2S, a toxic gas with the odor of rotten eggs, can be produced in foodstuffs such as eggs, meat, vegetables, and fruits. H2S generated by sulfur-containing bacteria in garlic and meat is a key indicator of spoilage, making it a valuable marker for assessing food freshness[56]. H2S is also recognized as a diagnostic breath biomarker for halitosis, and its quantification in exhaled air contributes to the noninvasive diagnosis of disease-related conditions through breath analysis[57]. Hence, a reliable H2S sensor with high sensitivity and low limit of detection is very significant. Liu et al. investigated atomically dispersed Pd on In2O3 (In2O3/Pdatom) and demonstrated that atomically dispersed Pd markedly improved sensitivity (6.728 ppm-1), selectivity, and lowered the detection limit to 100 ppb[23]. The design relies on atomically dispersed Pd that increases H2S adsorption affinity and facilitates H-S bond cleavage, effectively reducing the reaction barrier and accelerating charge transfer. While the performance gains are notable, this sensor still requires elevated operation temperature and long-term durability under humid or mixed-gas conditions remains to be demonstrated, limiting immediate applicability. Building on this strategy, Zheng et al. introduced atomically dispersed Ru on SnO2, achieving ppb-level H2S detection with a detection limit of 100 ppb and an exceptionally high response (~ 310 for 20 ppm H2S) alongside sub-second response time at 160 °C[58]. Operando synchrotron radiation Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and density functional theory analyses confirmed that atomically dispersed Ru promoted the formation of reactive surface oxygen species and generated abundant active sites for H2S dissociation.

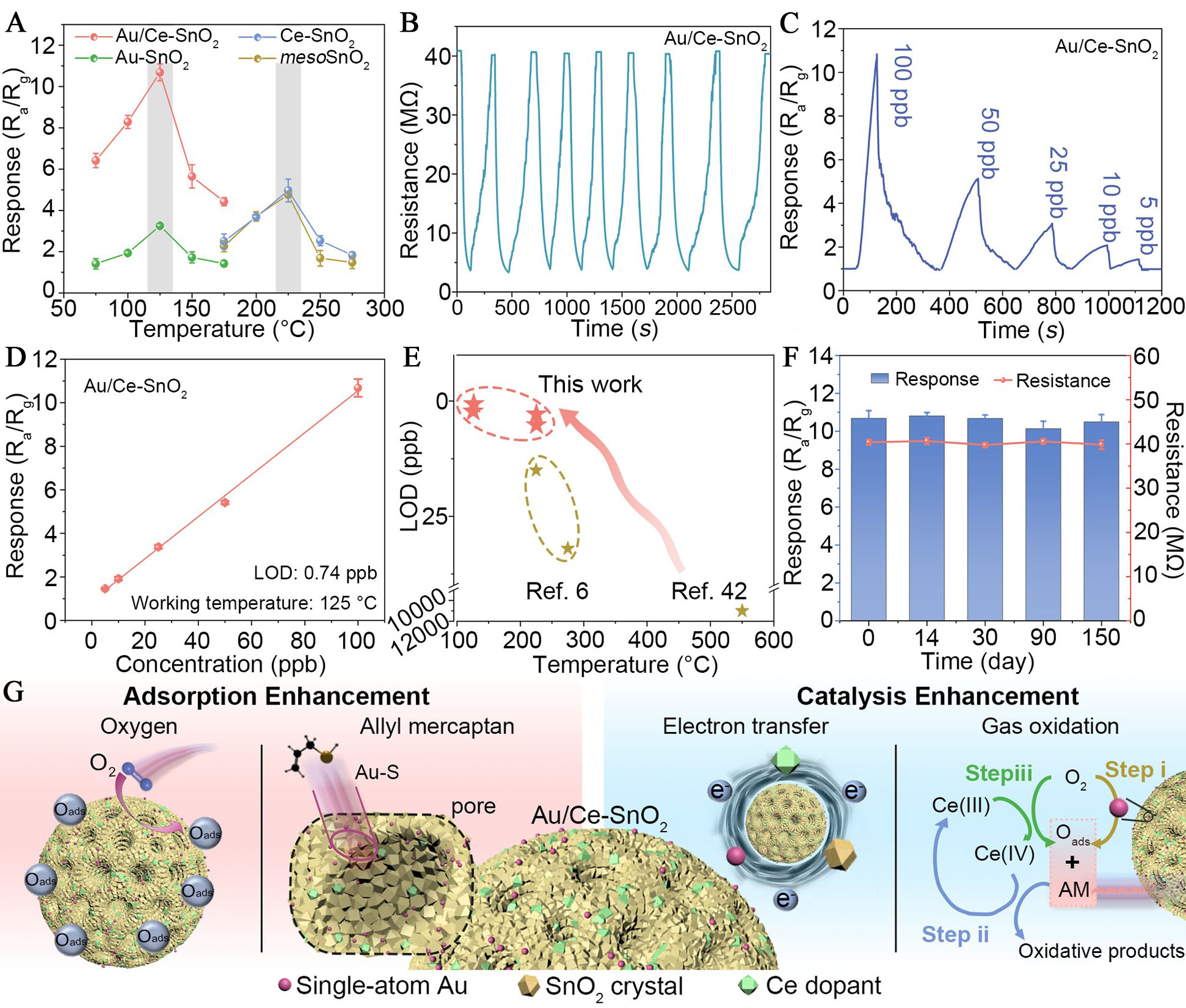

Allyl mercaptan, identified as a biomarker of psychological stress[59], has been effectively detected at the ppb level and low temperatures using mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres co-functionalized with atomically dispersed Au and Ce dopant (Au/Ce-SnO2)[60]. The Au/Ce-SnO2 sensor exhibited a peak response of 10.7 at 125 °C for 100 ppb allyl mercaptan, with a detection limit as low as 0.74 ppb and excellent linearity across 5-100 ppb [Figure 7A-D]. Compared to atomically dispersed Au-sensitized SnO2 (Au-SnO2), Ce-doped SnO2 (Ce-SnO2), and mesoporous SnO2 (mesoSnO2), the Au/Ce-SnO2 sensor demonstrated superior response/recovery dynamics, long-term operational stability over 150 days, and anti-interference capability against high-concentration coexisting gases [Figure 7E and F]. Mechanistically, atomically dispersed Au facilitated O2 dissociation and target gas adsorption, while Ce dopants accelerated surface redox via a Ce3+/Ce4+ cycle, synergistically enhancing electron transfer and catalytic oxidation of thiol species [Figure 7G].

Figure 7. Gas-sensing characteristics and mechanistic understanding of Au/Ce-SnO2 toward allyl mercaptan; (A) Sensor responses of Au/Ce-SnO2, Au-SnO2, Ce-SnO2, and mesoporous SnO2 (mesoSnO2) to 100 ppb allyl mercaptan across a temperature range of 75-275 °C; (B) Response-recovery repeatability of the Au/Ce-SnO2 sensor upon cyclic exposures to 100 ppb allyl mercaptan; (C) Dynamic sensing curves and (D) corresponding response values of Au/Ce-SnO2 for allyl mercaptan concentrations from 5 to 100 ppb; (E) Evaluation of the anti-interference performance of the Au/Ce-SnO2 sensor. Ethanol and acetone were used as interfering gases at equal concentrations. AM represents 100 ppb allyl mercaptan; Mix-1, Mix-2, and Mix-3 refer to mixtures containing 100 ppb AM with 8, 16, and 32 ppm interfering gases, respectively; (F) Long-term operational stability of Au/Ce-SnO2 evaluated over a five-month period; (G) Schematic illustration of the proposed synergistic sensitization mechanism, involving Au-mediated selective adsorption and Ce-induced interfacial electron modulation. Oads denotes surface-adsorbed oxygen species. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[60]. Copyright 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry. LOD: Limit of detection; AM: allyl mercaptan; Ra/Rg: resistance in air/resistance in test gas.

Atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs represent a highly promising class of materials for the detection of sulfur-containing gases due to the improved gas adsorption, activation, and electrical conduction. Despite these notable advancements, several critical challenges remain. The strong chemisorption of sulfur-containing analytes, along with their tendency to poison active sites, may result in irreversible deactivation of sensitizer sites, particularly under chemically complex environments. Furthermore, many existing gas sensors still rely on elevated operating temperatures, which restricts their integration into portable or breath-based sensing applications. To fully exploit the capabilities of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized materials for sulfur gas detection, future research should focus on elucidating the dynamic behavior of sensitizer-gas interactions and developing stable, low-temperature sensing systems suitable for deployment in real-world conditions.

Formaldehyde sensing

Formaldehyde (HCHO), a toxic VOC widely emitted from building materials, furniture, and consumer products, is a major indoor air pollutant with well-established links to respiratory diseases and carcinogenicity[61-63]. Even at very low concentrations, formaldehyde poses serious health risks, prompting the World Health Organization to establish a stringent indoor exposure limit of approximately 80 ppb. Given its low safety threshold and pervasive presence in enclosed environments, the development of sensors capable of detecting formaldehyde at the ppb level under humid conditions and in the presence of interfering gases remains a critical priority. Incorporating atomically dispersed noble metals onto SMOs offers a powerful strategy to overcome these limitations, as atomically dispersed noble metals maximize catalytic efficiency, tune the electronic structure of the SMOs, and create uniform active sites for selective formaldehyde adsorption and oxidation.

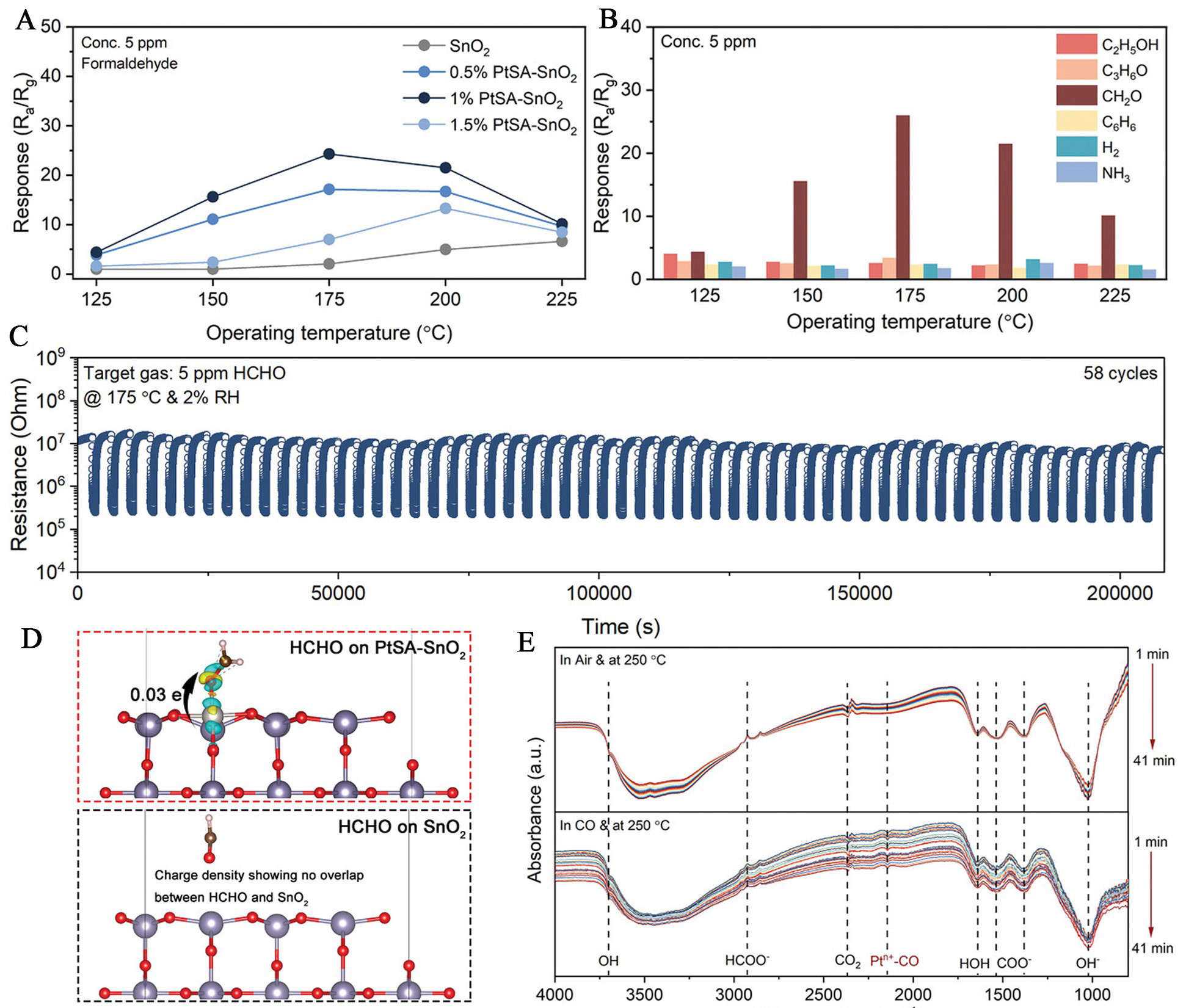

One effective strategy to enhance formaldehyde sensing performance involves electronic structure modulation through atomic-level doping, which can simultaneously tune the band structure and strengthen gas-solid interactions[64]. Wang et al. prepared SnO2 sensitized with atomically dispersed Pt [Pt single-atom (PtSA)-SnO2] to modulate the bandgap and Fermi-level position for enhanced HCHO sensing[65]. Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy analyses revealed that atomically dispersed Pt incorporation narrowed the bandgap and increased the work function (from 3.39 to 4.26 eV), indicating a downward shift of the Fermi level and improved charge transport. These electronic structure modifications led to improved electrical conductivity, thereby achieving selective and sensitive gas detection. The 1% PtSA-SnO2 (mass ratios of Pt to SnO2: 1 wt.%) exhibited a maximum response at a reduced operating temperature of 175 °C [Figure 8A]. In addition, 1% PtSA-SnO2 also imparted excellent selectivity to HCHO over various interfering gases such as ethanol, acetone, benzene, and ammonia, with a response ratio (formaldehyde-to-interferants) exceeding 6.5 across temperatures [Figure 8B]. The 1%PtSA-SnO2 sensor maintained robust stability over 58 continuous exposure-recovery cycles under 5 ppm HCHO, indicating long-term repeatability [Figure 8C]. First-principles calculations revealed that the enhanced sensing performance stemmed from strong electronic interactions between HCHO and atomically dispersed Pt. Charge density analysis [Figure 8D] showed a transfer of ~ 0.03 e at the HCHO/PtSA-SnO2 interface, compared to negligible redistribution on pristine SnO2, indicating that atomically dispersed Pt sensitizers strengthened HCHO chemisorption. Furthermore, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy detected a characteristic vibrational band at 2,144 cm-1, assigned to Pt-bound carbonyl species, thereby confirming the involvement of atomically dispersed Pt sensitizers in molecular activation [Figure 8E].

Figure 8. Enhanced HCHO sensing performance and mechanistic insights of PtSA-SnO2 sensors. (A) Sensor responses of SnO2 and PtSA-SnO2 as a function of operating temperature; (B) Selectivity profile of 1% PtSA-SnO2 toward various gases across temperatures; (C) Stability and repeatability of 1% PtSA-SnO2 under 5 ppm HCHO at 175 °C; (D) Charge density difference upon HCHO adsorption on SnO2 and PtSA-SnO2 surfaces; (E) In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy spectra. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[65]. Copyright 2024, John Wiley and Sons. HCHO: Formaldehyde; PtSA: atomically dispersed Pt; Ra/Rg: resistance in air/resistance in test gas; RH: relative humidity.

Beyond tuning the electronic structure of the sensing material, atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers can also serve as catalytic sites that directly enhance gas adsorption affinity and surface reaction kinetics. In this context, Zhou et al. achieved atomically dispersed Rh functionalization of SnO2 (SnO2/Rh) via ALD for formaldehyde sensing[14]. Compared to SnO2, the SnO2/Rh sensor showed over 20-fold enhancement in response to 50 ppm HCHO (2.2 vs. 80.5) with a low detection limit of 55 ppb. The SnO2/Rh sensor maintained excellent selectivity towards formaldehyde, butanol, triethylamine, benzene, acetone, dimethylamine, trimethylamine and ammonia. Besides, the SnO2/Rh sensor showed consistent responses over eight consecutive cycles to 20 ppm formaldehyde, indicating excellent repeatability and stability. Long-term tests confirmed stable operation over 30 days with minimal baseline drift. Density functional theory calculations reveal that atomically dispersed Rh increased the adsorption and charge transfer between HCHO and SnO2. The SnO2/Rh material was further embedded into a wireless sensing platform capable of real-time data transmission to mobile phones, enabling on-site HCHO monitoring with high reliability and no false signals from water interference.

Another strategy emphasizes optimizing surface reaction pathways to improve catalytic efficiency and selectivity. Bu et al. dispersed atomic Pt on MOF-derived In2O3 via a N-doped graphene sacrificial templating route[66]. This approach increased specific surface area, oxygen-vacancy content, and adsorbed-oxygen species, thereby raising the density of active sites at the sensing interface. The resulting Pt1-In2O3 sensor showed high response (750.4 at 100 ppm), good selectivity, rapid response speed (2 s at 100 ppm), and a low theoretical limit of detection (8.4 ppb). The performance set highlights the role of enriched active oxygen in reinforcing gas-solid interactions and accelerating HCHO oxidation. Complementing this, Gu et al. fabricated atomically dispersed Au on In2O3 nanosheets using an ultraviolet-assisted reduction method, achieving ppb-level sensitivity with only 0.01 wt.% Au[67]. Based on this design, the sensor exhibited a high response (85.67) to 50 ppm HCHO at a low operating temperature of 100 °C, with a detection limit as low as 1.42 ppb. Atomically dispersed Au provides more active sites for the adsorption reaction and reduces the activation energy, endowing the Au/In2O3 sensors with high sensitivity to HCHO at a low operating temperature.

Overall, the recent progress in formaldehyde detection clearly underscores the advantages of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs, which have enabled ppb-level formaldehyde detection, fast response speed, and reliable long-term performance under realistic indoor conditions. By tailoring the electronic structure and surface chemistry of SMOs through the incorporation of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers, researchers have achieved enhanced charge transfer, strengthened HCHO adsorption, and efficient catalytic oxidation in HCHO sensing. Nevertheless, key issues remain unresolved. The mechanistic correlation between electronic structure modulation and the density or accessibility of noble-metal sensitizers remains inadequately defined, limiting predictive sensor design. Additionally, maintaining the dispersion stability of single-atom sensitizers over extended operational periods, particularly in complex indoor environments with high humidity and multiple interfering VOCs, continues to be a technical bottleneck.

Sensing of other gases

While atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers have shown outstanding performance in detecting inorganic gases such as H2, CO, NO2, and H2S, their application in VOC sensing remains scarce. VOCs, including microbial metabolites and biomarkers related to disease or spoilage, play crucial roles in clinical diagnostics, food safety, and environmental monitoring[68,69]. Detecting VOCs poses greater challenges due to their structural diversity, low concentrations, and complex gas-solid interactions. Recent studies have begun extending atomically dispersed noble-metal modified SMO sensors to VOC gas, demonstrating promising ppb-level sensitivity, fast dynamics, and strong selectivity.

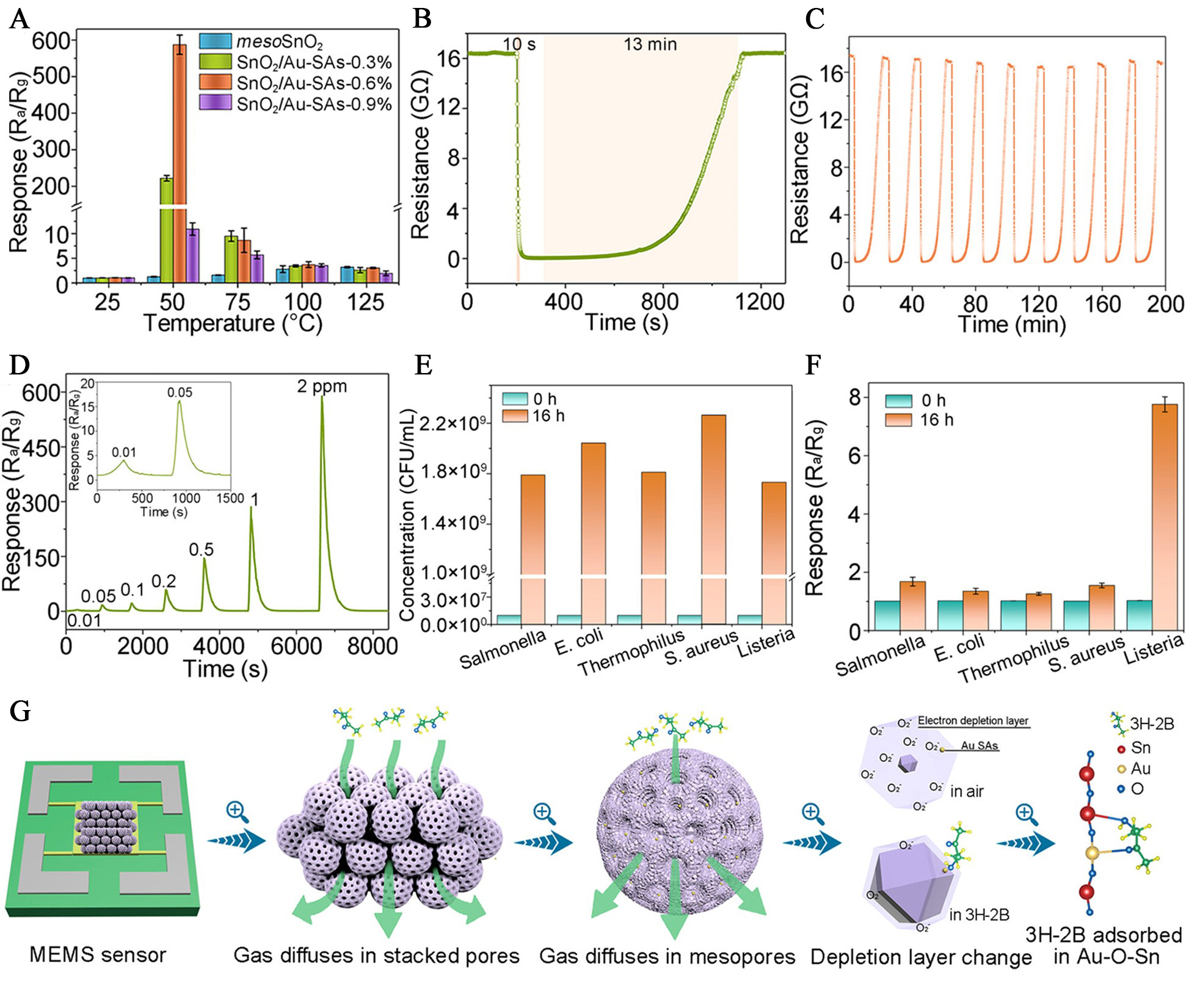

Listeria monocytogenes is a highly virulent foodborne pathogen, and its volatile metabolite 3-hydroxy-2-butanone (3H-2B) has been identified as a reliable biomarker for early-stage infection monitoring[70]. To address the limitations of conventional SMO gas sensors, Feng et al. developed a low-temperature gas sensor based on mesoporous SnO2 nanospheres, where atomically dispersed Au was anchored into the SnO2 lattice to form uniformly distributed Au-O-Sn active sites[21]. The resulting sensor demonstrated outstanding gas-sensing performance toward 3H-2B at a low working temperature (50 °C), achieving a high sensitivity of 291.5 ppm-1, a rapid response time of 10 s, and an ultralow detection limit of 10 ppb [Figure 9A-D]. Beyond its impressive sensitivity metrics, the sensor exhibited strong selectivity, successfully differentiating Listeria monocytogenes from other bacterial strains such as Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Staphylococcus aureus [Figure 9E and F]. The performance was attributed to the synergetic effect of the mesoporous architecture and the lattice-confined atomically dispersed Au, which together enhanced gas diffusion, adsorption, and surface reaction kinetics [Figure 9G]. Furthermore, the integration of this material into a microelectromechanical system-based wireless platform enabled real-time, low-power detection of 3H-2B vapor, underscoring the potential of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO materials for practical, point-of-care pathogen diagnostics.

Figure 9. Gas-sensing performance and biological application of atomically dispersed Au-sensitized mesoporous SnO2 toward 3H-2B. (A) Sensor responses of mesoSnO2 and SnO2 loaded with 0.3%, 0.6%, and 0.9% atomically dispersed Au, denoted as SnO2/Au SAs-0.3%, SnO2/Au SAs-0.6%, and SnO2/Au SAs-0.9%, respectively, toward 2 ppm 3H-2B at various temperatures; (B) Dynamic response-recovery curve of the SnO2/Au-SAs-0.6% sensor to 3H-2B; (C) Repeatability performance of SnO2/Au-SAs-0.6% under eight successive cycles at 50 °C; (D) Concentration-dependent response curves of SnO2/Au-SAs-0.6% for 3H-2B; (E) Bacterial growth profiles; (F) Sensor responses of SnO2/Au-SAs-0.6% to bacterial VOCs emitted at 0 h and 16 h; (G) Proposed sensing mechanism involving atomically dispersed Au-mediated adsorption and activation of 3H-2B on mesoporous SnO2. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[21]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. mesoSnO2: Mesoporous SnO2; MEMS: microelectromechanical systems; 3H-2B: 3-hydroxy-2-butanone; SA: single atom; Ra/Rg: resistance in air/resistance in test gas; CFU: colony-forming unit; VOC: volatile organic compound.

As a well-established biomarker for diabetes, acetone requires reliable ppb-level detection for noninvasive medical diagnostics. Normally, the concentration of breath acetone from healthy individuals is below 1 ppm (0.3-0.9 ppm), which increases to ~ 2.2 and ~ 1.7 ppm for those from type 1 and 2 diabetic patients, respectively[71-73]. Yuan et al. introduced atomically dispersed Pt onto defective tungsten oxide (WO3-x) nanosheets (SA-Pt/WO3-x)[74]. The sensor exhibited a high response (Ra/Rg = 43.4 at 5 ppm), excellent selectivity (Sbest/Ssecond = 2.8), and a detection limit down to 0.1 ppm. By anchoring on WO3-x defects, atomically dispersed Pt maximizes catalytic efficiency by providing uniform adsorption sites, lowering activation energy, and ensuring higher sensitivity and selectivity toward acetone compared to nanoparticles.

Beyond biomedical biomarkers, atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitization has also been applied to the detection of toxic amine vapors relevant to environmental and industrial safety. Xu et al. synthesized atomically dispersed Pt-functionalized SnO2 ultrathin films via ALD and investigated the effect of film thickness on the gas sensing performance[75]. The optimized 9 nm SnO2 film exhibited the strongest baseline response to triethylamine due to its thickness being comparable to the Debye length, while thinner films (4 nm) suffered from low carrier concentration. Introducing atomically dispersed Pt onto the 9 nm SnO2 further boosted the response value, reducing the working temperature from 260 to 200 °C and delivering a maximum response of 136.2 to 10 ppm triethylamine. The Pt/SnO2 sensor achieved ultrahigh sensitivity (8.76 ppm-1), ultralow limit of detection (7 ppb), and ultrafast dynamics (3 s/6 s). The sensing performances originate from the synergistic combination of the optimized film thickness comparable to the Debye length of SnO2 and the spillover activation of oxygen by atomically dispersed Pt, as well as the oxygen vacancies in the SnO2 films.

In summary, atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs have demonstrated exceptional potential for advanced gas sensing applications [Table 2]. Their superior performance arises from the atomic-scale integration of noble-metal sensitizers, which enables precise modulation of the SMO electronic structure, enhances gas adsorption affinity, and promotes interfacial redox kinetics. However, several critical challenges remain. First, current research is overwhelmingly focused on n-type semiconductors, while studies involving p-type SMOs functionalized with atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers are extremely limited, despite their distinct transport characteristics and sensing mechanisms. Beyond support type, the support architecture, particularly heterojunction formation, critically influences sensing performance by regulating band alignment and interfacial charge transfer, thereby determining how atomic-scale sensitization is converted into measurable resistance modulation[76,77]. However, the use of heterojunction architectures as supports for stabilizing and activating atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers remains largely unexplored in current gas sensing studies. Second, while extensive efforts have been devoted to atomically dispersed single noble-metal sensitizers, the exploration of atomically dispersed dual noble-metal sensitizers, which may enable cooperative adsorption and generate complementary sensitizer functions, is still at a very early stage in gas sensing studies. Third, the range of target gases remains limited, with insufficient exploration of more diverse or complex gases that are relevant to real-world applications. In particular, food- and health-related gases such as ethylene (a ripening-related plant hormone), trimethylamine (a key indicator of seafood spoilage), and methanethiol (a sulfur‑containing biomarker linked to halitosis) have received little attention in the context of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO gas sensors. In particular, the detection of benzene-series VOCs, which are common carcinogenic gases, remains underexplored due to their high chemical stability and the lack of suitable single-atom-based sensing materials[78,79]. Addressing these limitations through expanded types of SMO materials, sensitizers, and broader analyte scopes will be essential to fully realize the potential of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs for next-generation gas sensing technologies[75].

Summary of recent advances in atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO gas sensors

| Sensing materials | Target gas | Response definition | Response/Concentration (ppm) | Working temperature (°C) | Detection limit (ppb) | Response/Recovery time (s) | Reference |

| Pt-Fe2O3-Vo | Hydrogen | Ra/Rg | 25.5/50 ppm | 240 | 86 | 2/43 | [15] |

| Pd-SnO2 | Hydrogen | Ra/Rg | 224/1,000 ppm | 300 | 0.6 | 8.4/500 | [41] |

| Au/Pd-SnO2 | Hydrogen | Ra/Rg | 1.87/10 ppm | 200 | 70 | 1/44 | [42] |

| Pd-TiO2 | Carbon Monoxide | Ra/Rg | 126/100 ppm | Room Temperature | 24 | 28/70 | [9] |

| Au/In2O3 | Carbon Monoxide | Ra/Rg | 3.98/70 ppm | 360 | 0.28 | 2/10 | [48] |

| Au1-ZnO | Nitrogen Dioxide | Rg/Ra | 12.6/0.3 ppm | 150 | 10 | -/- | [18] |

| PtSA-(100)CeO2 | Nitrogen Dioxide | Rg/Ra | 27/5 ppm | 25 | 4 | 25/26 | [52] |

| In2O3/Pdatom | Hydrogen Sulfide | Ra/Rg | 78.24/10 ppm | 100 | 100 | 19.52/ | [23] |

| Ru@SnO | Hydrogen Sulfide | Ra/Rg | 310.1/20 ppm | 160 | 100 | 1/47 | [58] |

| Au/Ce-SnO2 | Allyl Mercaptan | Ra/Rg | 10.7/0.1 ppm | 125 | 0.74 | 108/166 | [60] |

| PtSA-SnO2 | Formaldehyde | Ra/Rg | 27/5 ppm | 175 | 10 | 24/1,110 | [65] |

| Rh-SnO2 | Formaldehyde | Ra/Rg | 80.5/50 ppm | 250 | 55 | 4/29 | [14] |

| Pt1-In2O3 | Formaldehyde | Ra/Rg | 750.4/100 ppm | 200 | 8.4 | 2/373 | [59] |

| Au-In2O3 | Formaldehyde | Ra/Rg | 85.67/50 ppm | 100 | 1.42 | 25/198 | [67] |

| SnO2/Au-SAs | 3-Hydroxy-2-Butanone | Ra/Rg | 587.3/2 ppm | 50 | 10 | 10/780 | [20] |

| SA-Pt/WO3-x | Acetone | Ra/Rg | 43.4/5 ppm | 350 | 100 | 8/24 | [74] |

| Pt/SnO2 | Triethylamine | Ra/Rg | 80.1/5 ppm | 200 | 7 | 3/6 | [75] |

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This review summarizes recent advances in atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO chemiresistive sensors, emphasizing how atomic-scale sensitizers regulate local electronic structures, adsorption selectivity, and interfacial redox kinetics to improve sensing performance. Moving from proof-of-concept demonstrations to practical technologies will require progress in three aspects.

(1) Synthesis methodology. A central challenge is to simultaneously achieve high loading, robust stabilization, and accessible isolated sites without aggregation. Future strategies should integrate defect engineering, lattice confinement, and coordination modulation to simultaneously maximize single-atom loading, stabilize atomic dispersion, and precisely tune the local electronic structure of noble-metal sensitizers for optimized sensing selectivity and sensitivity. Data-driven strategies, including machine learning-assisted materials design and high-throughput computational screening, are expected to accelerate the rational optimization of single-atom sites by correlating atomic-scale descriptors with sensing performance.

(2) Mechanism-driven discovery. Despite notable advances, the sensing behavior of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO gas sensors remains largely optimized empirically, owing to the difficulty of isolating and quantifying atomic-scale sensing mechanisms. Integrating operando spectroscopies with first-principles calculations is essential to track the dynamic evolution of atomically dispersed noble-metal sensitizers and to extract physically meaningful descriptors, such as oxidation state, coordination number, charge transfer, and adsorption energetics. On this basis, data-driven models can be used to evaluate the relative contribution of these descriptors to sensing performance, thereby disentangling coupled sensing pathways and enabling mechanism-guided optimization rather than empirical tuning.

(3) Application expansion. To date, most atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMO sensors have focused on small redox-active gases under laboratory conditions, whereas practical applications demand selective detection of structurally complex VOCs in realistic environments. The chemical diversity and multi-electron reaction pathways of these gases impose stringent requirements on sensing materials to maintain both sensitivity and selectivity in complex atmospheres. The integration of atomically dispersed noble-metal-sensitized SMOs into wearable and flexible sensing platforms offers opportunities for low-power, portable, and real-time gas monitoring, further extending their application scope beyond conventional rigid devices.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Investigation: Li, P. (Ping Li); Yu, Y.;

Methodology: Li, P. (Ping Li);

Formal analysis: Li, P. (Ping Li); Yu, Y.; Wei, M.; Deng, Y.;

Writing - original draft preparation: Li, P.;

Writing - review & editing: Yu, Y.; Li, P. (Peizhen Li); Wei, M.; Deng, Y.; Wei, J.

Supervision: Deng, Y.; Wei, J.

Project administration: Deng, Y.; Wei, J.

Funding acquisition: Deng, Y.; Wei, J.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22475161), the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (No. 2024GX-YBXM-317), the Science and Technology Plan Project of Xi'an (No. 24NYGG0108), the S&T Program of Energy Shaanxi Laboratory (No. ESLB202439), and the Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Disciplines Breakthrough Plan of the Ministry of Education of China (JYB2025XDXM408).

Conflicts of interest

Deng, Y. is Editor-in-Chief of the journal Micro Nano Science. Deng, Y. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Park, S.; Ahn, J.; Kim, I. D. Materials engineering for light-activated gas sensors: insights, advances, and future perspectives. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e08204.

2. Bulemo, P. M.; Kim, D. H.; Shin, H.; et al. Selectivity in chemiresistive gas sensors: strategies and challenges. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 4111-83.

3. Sharma, A.; Eadi, S. B.; Noothalapati, H.; Otyepka, M.; Lee, H. D.; Jayaramulu, K. Porous materials as effective chemiresistive gas sensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2530-77.

4. Wen, J.; Wang, S.; Feng, J.; et al. Recent progress in polyaniline-based chemiresistive flexible gas sensors: design, nanostructures, and composite materials. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 6190-210.

5. Zhu, L. Y.; Ou, L. X.; Mao, L. W.; Wu, X. Y.; Liu, Y. P.; Lu, H. L. Advances in noble metal-decorated metal oxide nanomaterials for chemiresistive gas sensors: overview. Nanomicro. Lett. 2023, 15, 89.

6. Li, Z.; Li, H.; Wu, Z.; et al. Advances in designs and mechanisms of semiconducting metal oxide nanostructures for high-precision gas sensors operated at room temperature. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 470-506.

7. Yang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Functionalization of mesoporous semiconductor metal oxides for gas sensing: recent advances and emerging challenges. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2022, 10, e2204810.

8. Li, Z.; Tian, E.; Wang, S.; et al. Single-atom catalysts: promotors of highly sensitive and selective sensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 5088-134.

9. Ye, X. L.; Lin, S. J.; Zhang, J. W.; et al. Boosting room temperature sensing performances by atomically dispersed pd stabilized via surface coordination. ACS. Sens. 2021, 6, 1103-10.

10. Chu, T.; Rong, C.; Zhou, L.; Mao, X.; Zhang, B.; Xuan, F. Progress and perspectives of single-atom catalysts for gas sensing. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2206783.

11. Park, C.; Shin, H.; Jeon, M.; Cho, S. H.; Kim, J.; Kim, I. D. Single-atom catalysts in conductive metal-organic frameworks: enabling reversible gas sensing at room temperature. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 26066-75.