Advances on piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis in energy conversion field: performance, mechanisms, applications and beyond

Abstract

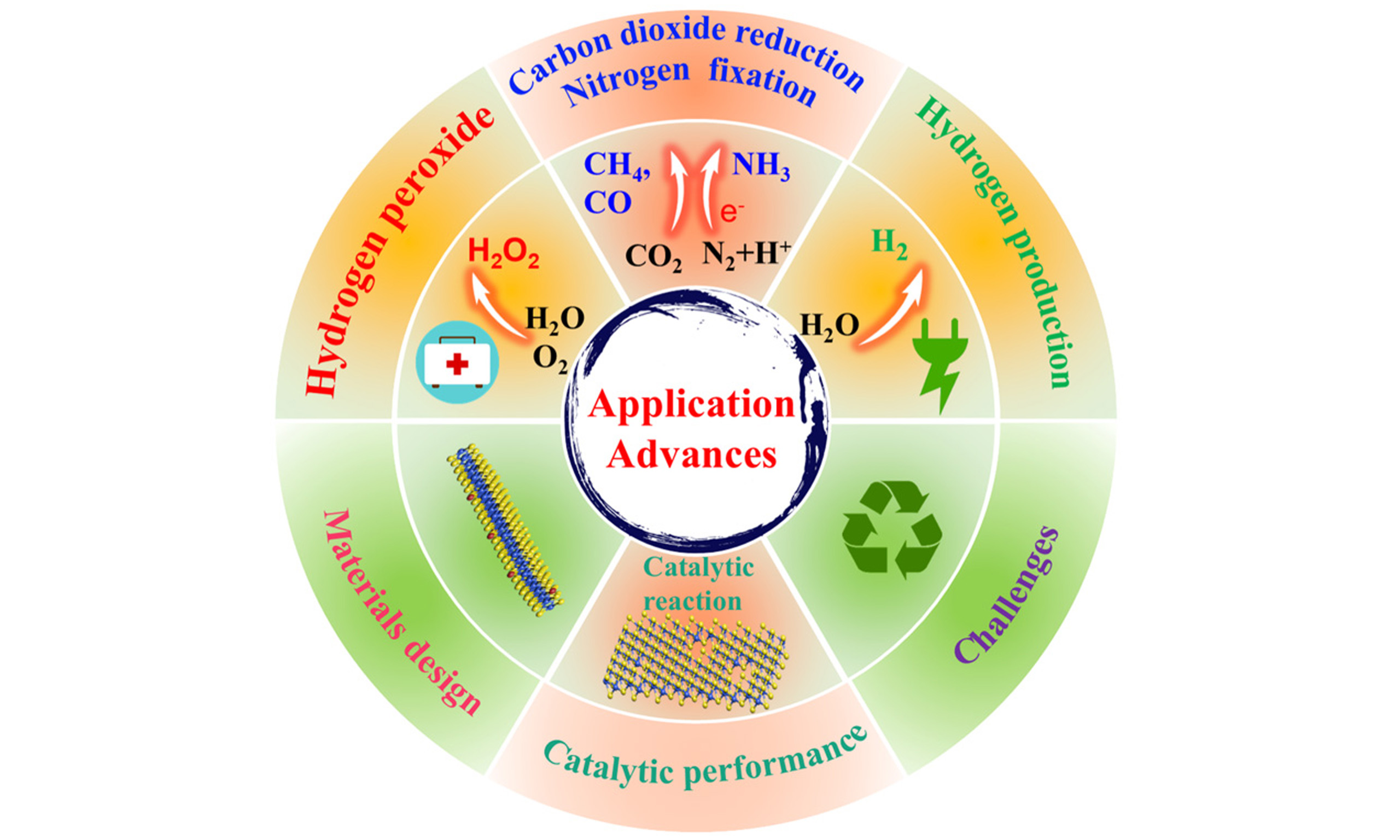

This review summarizes the latest advances in piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis for energy conversion, describing the challenges, potential development directions, and prospects. First, it overviews the evolution and development trends of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, the types of mechanical energy, the synthesis methods used to prepare piezocatalysts and tribocatalysts, and the underlying microscopic catalytic mechanisms. Second, it categorizes the catalytic applications, emphasizing recent breakthroughs in key areas such as water splitting for hydrogen production, nitrogen fixation for ammonia synthesis, carbon dioxide reduction, and hydrogen peroxide generation. This section highlights challenges across different application sectors, strategies for catalyst design, and methods for enhancing catalytic performance through microstructure control. Finally, this review discusses recent advances and the development roadmap of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, addressing current challenges and outlining potential trajectories for future research.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

At present, with the continued progress of industrialization, the energy crisis has become a major challenge. The combustion of fossil fuels remains the main energy source, but it rapidly depletes resources, causes serious environmental pollution, poses risks to human health, and hinders the sustainable development of society[1-3]. Considerably, various catalytic technologies have been explored, such as electrocatalysis, photocatalysis and biocatalysis, which have addressed energy shortages[4-6].

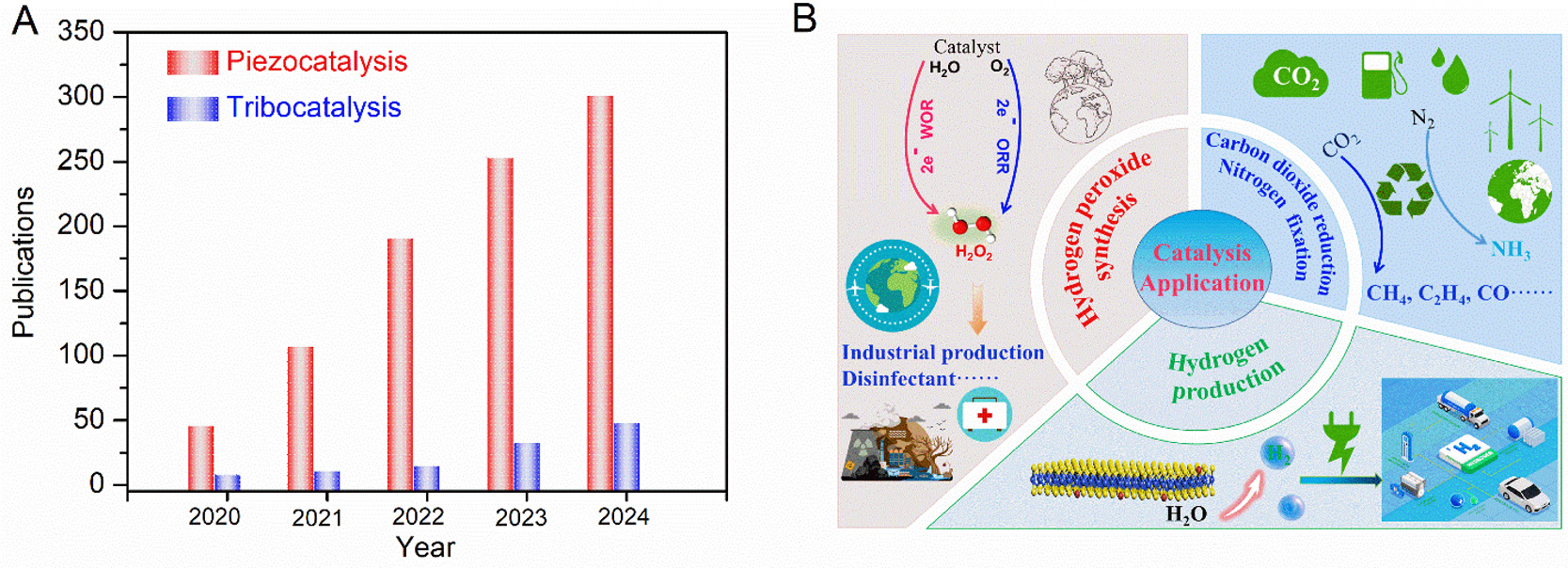

In this context, catalysis driven by mechanical energy - an abundant and ubiquitous clean energy source - represents a promising advance, as it does not require external inputs such as light or electricity. This approach employs mechanochemical activation to enhance catalytic activity; specifically, mechanical stimuli act as the driving force to facilitate physical or chemical electron transfer processes. The conversion of mechanical energy into chemical energy has been demonstrated through diverse mechanisms, including those based on piezoelectric and triboelectric effects[7-9]. Consequently, piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis have emerged as advanced, green, and environmentally friendly new catalytic technologies, attracting widespread attention[10-12]. Figure 1A shows that the number of publications on piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis has steadily increased in the past five years. As shown in Figure 1B, piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis are mainly applied to hydrogen (H2) production, carbon dioxide (CO2) reduction, nitrogen (N2) fixation and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) synthesis. However, research on tribocatalysis remains in its infancy, and further advances are needed for practical applications.

Figure 1. (A) Publications on piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis from 2020 to 2024. The publication numbers were collected from the “webofscience.com” using the keywords “piezocatalysis or piezocatalytic” and “tribocatalysis or tribocatalytic”. (B) Application fields of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis.

Piezocatalysis can effectively harness various types of mechanical energy from nature, such as vibrational, wind, and tidal energies, to drive catalytic reactions, showing promising applications potential in energy conversion and environmental remediation[13,14]. Initially, research on piezocatalysis focused on the degradation of organic pollutants and hydrogen production via water splitting, later evolving to applications in the energy and environmental sectors. Consequently, piezocatalysis has shown good application prospects in areas of energy conversion processes, such as carbon dioxide reduction, nitrogen fixation to synthesize ammonia and peroxide synthesis[15,16]. As an emerging technology, tribocatalysis has also garnered considerable scientific and technological attention. However, relatively few comprehensive reviews have summarized the applications of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis in energy conversion.

This review addresses this gap by outlining recent research progress, key challenges, development directions, and future prospects. First, the development of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis is briefly introduced, with particular attention to the underlying microscopic catalytic mechanisms. Second, their applications are reviewed, highlighting advances in energy-related processes such as H2 production via water splitting, N2 fixation to synthesise ammonia, CO2 reduction, and H2O2 synthesis. This section emphasizes key scientific and application challenges, catalyst design, microstructure control and modification strategies for enhancing the catalytic activity. Finally, future perspectives are described.

Overview of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis

Piezocatalysis is closely associated with the positive piezoelectric effect. In 1880, the Curie brothers observed that applying mechanical stress to certain materials generated positive and negative polarization charges, thereby transforming mechanical energy into electrical energy; this phenomenon was termed the piezoelectric effect. Generally, the positive piezoelectric effect occurs in non-centrosymmetric crystals. Due to structural asymmetry, when an external force is applied to a piezoelectric material in a specific direction, deformation such as compression, stretching, or bending induces polarization charges and generates a built-in electric field. The resulting piezoelectric potential provides sufficient driving force for charge carrier separation, modulation of band bending, and carrier transport, thereby enabling subsequent redox reactions[13,16-18]. In 2010, Hong et al. first employed zinc oxide (ZnO) and barium titanate (BaTiO3) micro/nanofibers to harvest ultrasonic vibrational energy for hydrogen production via water splitting, introducing the concept of the piezoelectric electrochemical effect, later termed the "piezoelectric catalytic effect"[19]. In 2012, Hong et al. demonstrated the effective degradation of Acid Orange 7 dye using BaTiO3-mediated piezocatalysis, marking the first expansion of piezocatalysis applications to environmental remediation[20]. Since then, numerous studies have investigated the piezocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants. More recently, applications of piezocatalysis have expanded beyond environmental remediation to include nitrogen fixation for ammonia synthesis, carbon dioxide reduction, and hydrogen peroxide synthesis[21-25].

Currently, the application of piezocatalysis in energy conversion is gradually gaining attention, offering new perspectives for addressing the energy crisis. Despite its promising potential, piezocatalysis still faces limitations such as slow reaction dynamics, low activity, and unclear microscopic mechanisms. To overcome these challenges, various design and modification strategies have been explored in recent years, including the development of novel piezocatalytic material systems, optimization of traditional piezoelectric materials, and microstructural engineering to enhance catalytic performance[13,16]. Moreover, the applications of piezocatalysis have expanded from initial hydrogen production to diverse fields such as nitrogen fixation for ammonia synthesis, carbon dioxide reduction, hydrogen peroxide synthesis, organic synthesis, and biomass conversion, demonstrating significant practical value in energy storage and conversion. However, systematic reviews of catalyst design, modification strategies, and recent advances in piezocatalysis across different application areas remain limited. Therefore, analyzing and summarizing the latest progress, challenges, and development directions of piezocatalysis in energy conversion will provide valuable guidance and reference for both industry and the scientific community.

Besides, triboelectricity has fascinated researchers for millennia, largely because it can be readily observed in everyday phenomena such as rubbing a balloon on hair[26]. Building on this foundation, recent insights into tribocatalysis integrate simple electrification processes with advanced catalytic applications. Unlike piezocatalysis, tribocatalysis enables the harnessing of mechanical energy through material contact and separation to drive chemical reactions, without the stringent material requirements of piezoelectric systems. This distinction underscores its versatility, as tribocatalysis can employ a wide range of materials, thereby broadening opportunities for innovative applications. The recent surge in research interest is likely a response to global challenges such as environmental pollution and the demand for sustainable energy solutions. Tribocatalysis has been investigated for pollutant degradation and energy-related processes including water splitting and CO2 reduction. The catalytic activity generated by charge transfer at material surfaces can lower the activation energy of chemical reactions, potentially enhancing efficiency[27,28]. Despite these promising directions, tribocatalysis remains at an early stage of development. Comprehensive reviews and systematic syntheses of findings are needed to advance both understanding and practical applications. As interdisciplinary collaborations among materials science, electrochemistry, and environmental science expand, rapid progress in tribocatalysis can be anticipated. Furthermore, the broad range of applicable materials opens new opportunities for designing and engineering next-generation catalytic systems.

Types of mechanical energy and synthesis methods for piezocatalyst and tribocatalyst

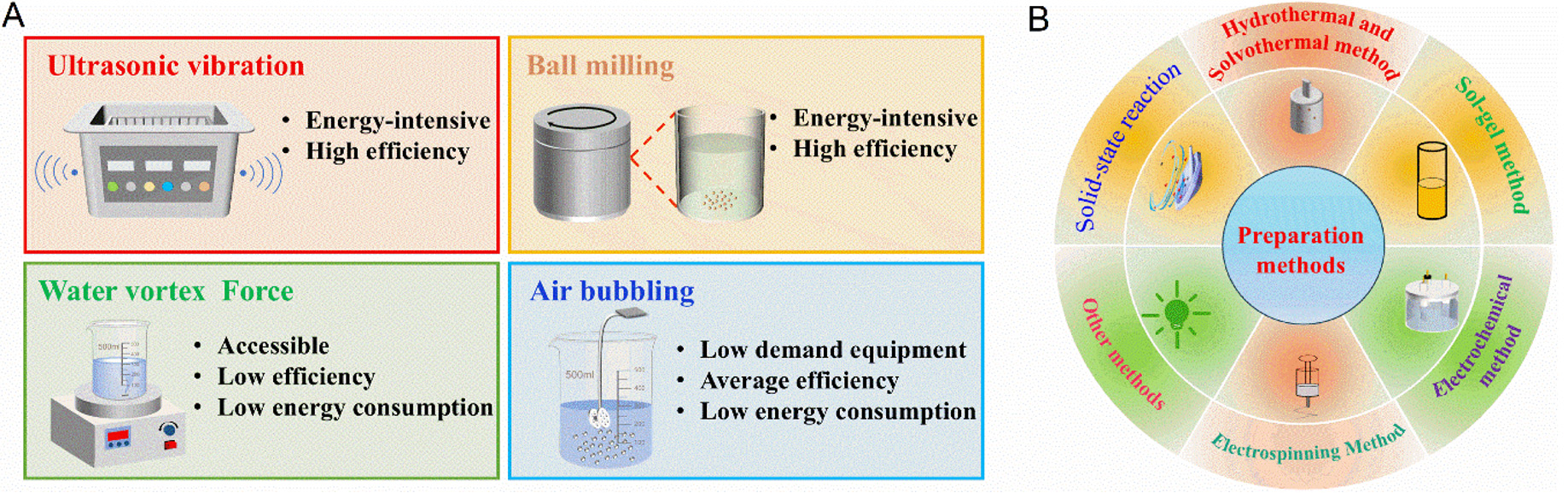

Various forms of mechanical energy - including ultrasound waves, water flow, atmospheric pressure, and wind - can induce periodic deformation of materials[16]. Predominantly employed methods inducing piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic reactions are ultrasonic vibration, ball milling, air-water vortex force, and air bubbling (see Figure 2A). Ultrasonic vibration, characterized by its high frequency, excellent directionality, robust penetration, and extended transmission distance in water, produces continuous cavitation bubble collapse pressure and ultrasonic wave pressure on materials, leading to periodic deformation[13,16]. In ultrasonic vibration-driven catalytic systems, several parameters, including ultrasonic power and frequency, profoundly influence the piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic activity. Ultrasonic vibration can effectively trigger these catalytic processes; however, its occurrence in natural settings is rare and its artificial generation is energy-intensive. Despite these drawbacks, research on ultrasonic vibration-driven catalysis has developed sonocatalysis, which leverages sonochemistry by integrating a heterogeneous catalyst into the ultrasonic field. This solid catalyst interacts with ultrasound-induced radicals and absorbs cavitation energy, facilitating chemical reaction control. The underlying mechanism of sonocatalysis is acoustic cavitation, which is dynamic process, encompassing the formation, expansion and subsequent collapse of bubbles. This method enhances the product yield by promoting charge separation and improves product selectivity by modulating the adsorption and desorption of reactants and intermediates. Therefore, sonocatalysis provides a synergistic combination of sonochemical and heterogeneous catalytic effects activated by ultrasound. Its primary applications span wastewater treatment, medical therapies, biomass conversion, and various fields of green and sustainable chemistry[29]. Notably, the mechanical input for piezocatalysis involves ultrasound, which may obscure the contributions of sonocatalysis to the overall piezocatalytic process. Consequently, sonocatalysis contributes to the piezocatalytic process during ultrasonic activation.

Figure 2. (A) Schematic diagrams of types of mechanical energy for piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis. (B) Preparation methods of piezocatalyst and tribocatalyst.

Ball milling is another viable source of mechanical energy that generates frictional heat, which can rapidly elevate local temperatures to hundreds or even thousands of degrees Celsius, subsequently facilitating various chemical reactions, such as bond formation and cleavage[30]. Thus, ball milling has been leveraged in piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis. In contrast, air bubbling, which drives bubble rupture, represents a low-frequency mechanical force. The bursting of air bubbles provides gentle stimuli with reduced energy consumption, resulting in abrupt changes and chemical energy release at the gas-liquid interface. Air flotation processes facilitate the practical application of bubbling-driven catalysis, rendering air bubbling a promising method for reducing energy usage while enhancing catalytic efficiency. Meanwhile, the water vortex force, another naturally occurring low-frequency mechanical force, can serve as a sustainable and eco-friendly energy source for catalytic reactions. However, the pressure exerted by a water vortex on the catalyst surface is substantially lower than that produced by ultrasonic vibration, further reducing the catalytic efficiency[30]. In summary, although ultrasonic vibration and ball milling trigger catalytic reactions owing to their higher mechanical energy supply, they are energy-intensive and less suitable for large-scale wastewater treatment. Conversely, water vortex force and air bubbling, as prevalent forms of mechanical energy, are promising driving forces of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis for practical applications. As a consequence, improving efficiency of low-frequency force-driven catalysis is a challenging but encouraging research task.

The catalytic performance of piezocatalysts and tribocatalysts is intricately linked to various factors, including microstructure, crystal structure, surface state, and internal charge distribution, depending on the catalyst synthesis methods[31]. Figure 2B illustrates the frequently used preparation methods for piezocatalysts and tribocatalysts. For example, the solid-state reaction strategy involves the simple processing of raw materials to obtain ultra-fine powders, subsequently subjected to high-temperature treatment. This classical approach is favored for its low cost, high yield, and relatively straightforward and stable preparation process. High-temperature solid-state sintering furnishes piezocatalysts with excellent piezoelectric properties. In addition, this process facilitates the incorporation of doping elements into the catalyst lattice, thereby enabling catalyst modification. However, despite being well-established and easy to implement, the solid-state sintering process has some drawbacks: high energy consumption and excessive use of organic solvents during raw material mixing. Consequently, developing solvent-free solid-state processes matching the performance of traditional methods is a focus of research[31].

Additionally, numerous traditional material systems have been explored for piezocatalysts and tribocatalysts. The hydrothermal method, which involves inorganic synthesis and material treatment in a closed reactor using an aqueous solution, creates a relatively high-temperature and high-pressure reaction environment by heating and pressurizing the reaction system, allowing for the dissolution and recrystallization of insoluble substances. This method produces samples that are well-developed and uniformly distributed, minimizing impurity introduction and maintaining catalyst activity[28,31]. A multitude of catalytic materials systems has been successfully synthesized via hydrothermal methods, demonstrating the high applicability and reliability of this technique. Key system parameters in hydrothermal reaction, including reaction time, temperature, pH value, precursor characteristics and concentration, are crucial determinants of catalyst synthesis. Similarly, solvothermal synthesis follows the same principle as the hydrothermal method, but utilizes organic or non-aqueous solvents (e.g., organic amines, alcohols, ammonia, or benzene) in place of water. This approach is particularly beneficial for the preparation of materials that cannot be synthesized in aqueous solution due to their susceptibility to oxidation, hydrolysis, or water-related issues. The choice of solvents influences the material performance of the synthesized products. Furthermore, because organic solvents typically possess a lower boiling point, they can achieve higher pressure than those attainable in hydrothermal synthesis under similar conditions, promoting favorable crystallization of the products. In addition, the functional groups of these solvents may interact with the reactants or products, resulting in the formation of new materials with potential applications in catalysis and energy storage.

Fundamental principles of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis

To effectively enhance the performance of piezocatalytic materials, a deep understanding of the microscopic mechanisms is crucial for their design and optimization. However, despite over a century of development in piezoelectric materials, research in the field of catalysis is still in its infancy. The dominant theories of piezocatalytic mechanisms currently include energy band theory and the screening charge effect[32,33]. Energy band theory, similar to the mechanisms of photocatalysis, asserts that the ability to undergo catalytic reactions primarily depends on the energy levels of the band structure [valence band (VB) and conduction band (CB)]. In contrast, the screening charge effect highlights the interaction between the piezoelectric potential and external screening charges from adsorbed species. Energy band theory, derived from established photocatalytic and piezoelectric electronics theories, is more comprehensive[32,34]. It is generally believed that the source of charge carriers in piezocatalytic reactions primarily arises from stress or the excitation of intrinsic free charges in the material. In this theory, the band structure of the piezoelectric catalyst and the excitation state of electrons are key determinants of catalytic activity. The piezocatalytic reaction occurs due to internal piezoelectric potential induced by the deformation of the piezoelectric material, which can exert control over the band structure, thereby favorably adjusting the energy levels towards oxidative and reductive reactions. Established band theory can explain the structure-activity relationships in different redox reactions[35,36].

Unlike band theory, the screening charge effect mechanism focuses on the dominant effect of piezoelectric potential and surface screening charge behavior in piezoelectric materials. The accumulation and release of surface charges generated during the polarization process of piezoelectric materials are key processes that promote piezocatalytic reactions, with the piezoelectric potential regarded as the main driver of redox reactions. The magnitude of the piezoelectric potential should fully match the chemical energy required for redox reactions, thereby determining the capability of the piezocatalyst to drive these reactions[31,37]. Furthermore, the charge carrier sources in the reaction processes of the two mechanisms are also different. Energy band theory posits that the primary source of reaction charges is internal charges excited by mechanical vibrational energy or defects, while the screening charge effect mechanism attributes the oxidative and reductive catalytic reactions to externally induced screening charge. Overall, both mechanisms have certain similarities and differences in specific aspects[13,16,38]. Both energy band theory and screening charge effect can be used independently to explain relevant piezocatalytic experimental results. However, it has been reported that most piezoelectric materials possess a wide band gap greater than 2.0 eV. On the one hand, this characteristic of highly insulating materials supports the screening charges theory. On the other hand, if free charge carriers are available, the conduction and VB positions can be suitable for many catalytic reactions. Therefore, both mechanisms do most probably exist simultaneously in most piezoelectric materials, which is fundamentally the reason for the ongoing debate regarding piezocatalytic mechanisms. Furthermore, it is important to differentiate between piezocatalysis and flexocatalysis. The driving force behind flexocatalysis is flexoelectricity, a fundamental electromechanical property characterized by the electrical polarization of a material under inhomogeneous strain, such as mechanical bending. Unlike the piezoelectric effect, flexoelectricity can occur in both centrosymmetric materials - via the breaking of local centrosymmetry - and in materials with asymmetric structures. Flexocatalysis has the advantage of being applicable to a wide range of non-piezoelectric and piezoelectric materials. However, it is worth noting that flexocatalysis can also contribute to the piezocatalysis process under certain conditions. Clarifying the mechanisms of piezocatalysis is therefore crucial for designing efficient piezocatalysts. To this end, advanced in situ experimental characterization techniques and theoretical methods (e.g., first-principles calculations and multiphysics simulations) should be employed to study variations of charges and carriers during piezocatalytic processes. These approaches can elucidate how factors such as piezoelectric potential, charge and carrier separation and migration, electronic structure, and active sites influence the performance of piezocatalytic materials, thereby enabling the design of high-performance piezocatalysts.

Currently, researchers have elucidated two primary mechanisms for tribocatalysis reactions: electron transfer across atoms and electron transition[39]. In the electron transfer mechanism, mechanical force induces friction between the catalyst and the surrounding solid or liquid environment, facilitating electron transfer. The transferred electrons participate directly in the chemical reactions that characterize tribocatalysis. Materials that either gain or lose electrons contribute to the generation of active species, which are essential for subsequent redox reactions. Conversely, the electron transition mechanism involves mechanical energy exciting electrons from the VB to the CB, resulting in the formation of holes in the VB and free electrons in the CB[28,39]. This process generates free radicals that interact with water and oxygen in the environment to drive tribocatalytic reactions. The generation of electrons and holes is primarily dictated by the energy band structure of the catalyst. Electron transfer across atoms is commonly invoked to explain tribocatalysis in polymer catalytic materials, which exhibit a strong capacity to acquire electrons through friction. In contrast, the electron transition mechanism is utilized in the analysis of tribocatalytic performance for semiconductor catalysts with well-defined energy band structures[26,39]. As for whether the electron transition is through the direct action of friction energy or the action of thermal energy, there is no clear conclusion yet. Kajdas proposed a theory that the flash point temperature during friction causes electron emission. Although it still lacks quantitative analysis and experimental verification, it provides a possible theoretical support for the tribocatalysis theory[40]. Thus, a deeper investigation into the relationship between these two mechanisms is essential for a more accurate understanding of the overall tribocatalysis mechanism.

Tribocatalysis represents an emerging technology capable of converting mechanical energy into chemical energy, offering a promising solution for environmental and energy crises and contributing to the pursuit of a sustainable society. Nevertheless, further advances in tribocatalysis are necessary for practical applications. A comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms is critical, as it would assist researchers in identifying key factors involved in material selection and system design. The proposed mechanistic models approach tribocatalysis from different angles, yet these mechanisms may coexist within a single tribocatalytic process. Clarifying them will help researchers identify the predominant processes in specific material systems and simplify the complex aspects of tribocatalysis into manageable components. Addressing these complexities systematically is crucial for the continued development of tribocatalysis and will significantly advance the progress and practical applications of this promising technology.

PIEZOCATALYSIS AND TRIBOCATALYSIS FOR ENERGY CONVERSION APPLICATIONS

Application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis in water splitting for hydrogen production

Hydrogen energy, as a clean, efficient, safe, and sustainable renewable energy source, is beneficial for alleviating current issues such as the energy crisis. However, hydrogen is mainly synthesized via fossil fuels such as coal and oil, which leads to the over-consumption of non-renewable energy and causes serious environmental pollution problems. Therefore, developing new environmentally friendly, readily available and cost-effective hydrogen production strategies is crucial[41]. Recently, various hydrogen production technologies have been explored, including electrocatalysis, photocatalysis and photo-electrocatalysis, which are based on the conversion of different types of energy, such as electrical and solar energy, into chemical energy through a series of reactions[42-44].

Piezocatalysis has recently attracted increasing attention for hydrogen production under environmentally friendly and mild reaction conditions[16]. To date, research has led to the development of numerous piezocatalysts for hydrogen production, including single or composite perovskite-based materials (e.g., BaTiO3 and SrTiO3), bismuth-based materials (e.g., BiFeO3 and Bi2WO6), metal sulphide/selenide-based materials (e.g., MoS2 and Au@MoS2) and polymer-based materials (e.g., UiO-66(Zr) and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF)) and more[45-54]. For instance, You et al. found that the limitation of the CB position in traditional BiFeO3 nanosheets could be overcome by inducing band bending via ultrasonic vibration, achieving a high hydrogen production rate of 124.1 µmol g-1 h-1[47]. Our group also reported various materials exhibiting excellent hydrogen production (e.g., O-MoS2, Ce-BiOBr and BiOCl/UiO-66)[49,55,56]. These studies confirm the promising applications of piezocatalysis for hydrogen production.

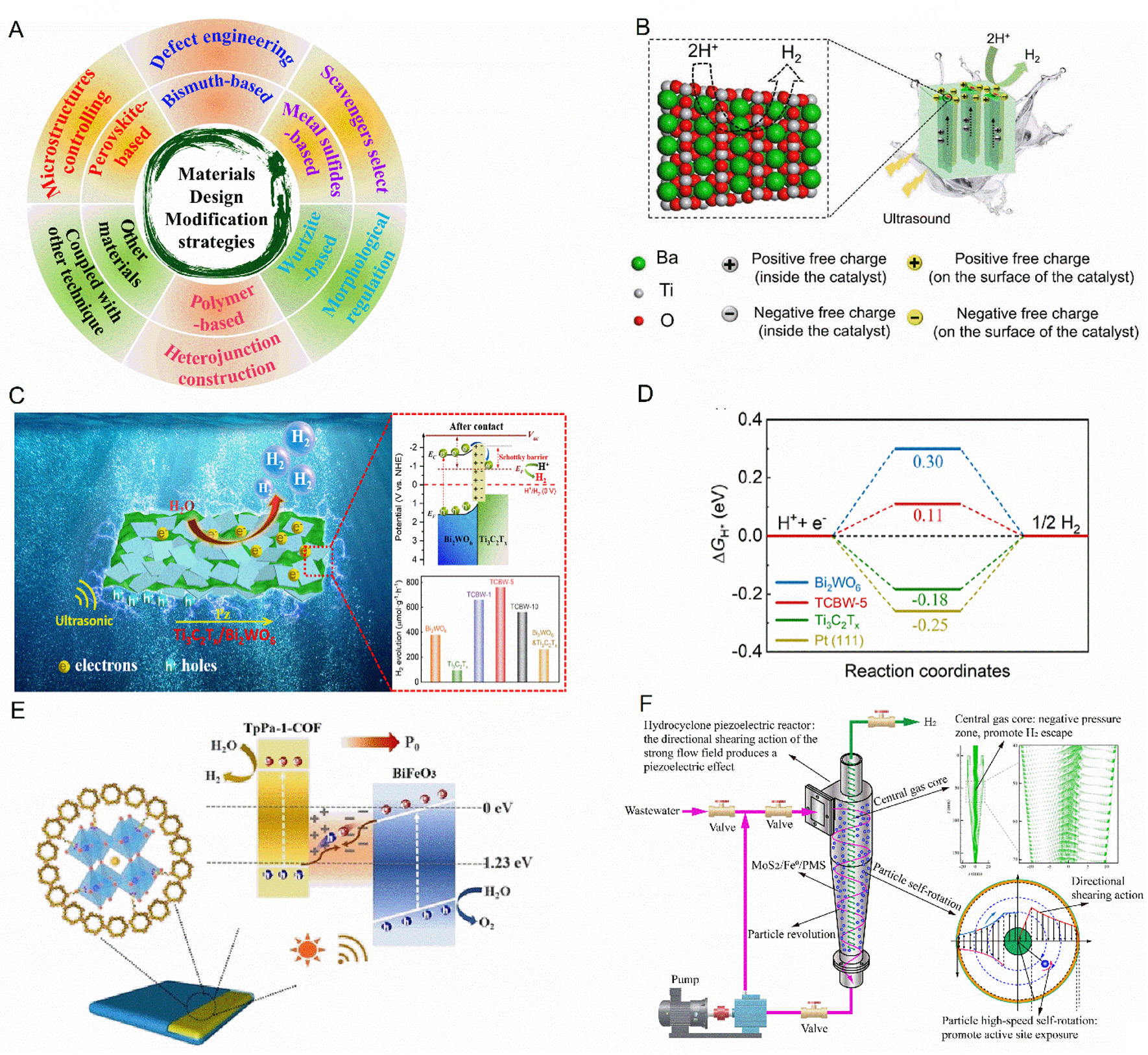

However, further advances in hydrogen production via piezocatalysis are limited by issues such as low activity, poor stability, and challenges in recycling and reuse of the piezocatalyst. To address these limitations, various strategies have been employed to enhance piezocatalyst performance, including optimization of sacrificial agents, doping engineering, loading of co-catalysts, construction of composite or heterojunction materials, and coupling with other catalytic technologies such as photocatalysis. Figure 3A summarizes material design approaches and modification strategies for hydrogen production, while Table 1 presents relevant performance metrics[57-70].

Figure 3. (A) The summary of typical piezocatalytic materials design and modification strategies for H2 production. (B) Piezocatalytic mechanism for H2 production of the deformed BaTiO3 crystals. This figure is quoted with permission[76]. (C and D) Piezocatalytic mechanism for H2 production in Ti3C2Tx/Bi2WO6 and Gibbs free energy changes of intermediate states involved in HER processes. This figure is quoted with permission[77]. (E) A schematic illustration of piezo-photocatalysis mechanism with the different directions of polarization for BiFeO3@TpPa-1-COF Z-scheme heterojunction. This figure is quoted with permission[86]. (F) The designed cyclonic piezocatalytic reactor using MoS2/Fe0/PMS ternary system for achieving substantial H2 generation from various types of wastewater. This figure is quoted with permission[91].

Summary of the energy conversion for H2 production application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis

| Catalyst | Application type | Sacrificial agent | Conditions | H2 evolution (µmol g-1 h-1) | Ref. |

| Bi2Fe4O9 | Piezocatalysis | None | 200 W, 40 kHz | 1,058 | [57] |

| O-MoS2 | Piezocatalysis | None | 100 W, 40 kHz | 47.8 | [58] |

| V-NaNbO3 | Piezocatalysis | None | 192 W, 68 kHz | 346.2 | [59] |

| Au-Bi4Ti3O12 | Piezocatalysis | None | 100 W, 40 kHz | 194.7 | [60] |

| RbBiNb2O7/PTFE | Piezocatalysis | None | 240 W, 68 kHz | 260.8 | [61] |

| SrTiO3 | Piezocatalysis | None | 300 W, 40 kHz | 540 | [62] |

| La2NiO4 | Piezocatalysis | None | 300 W Xe lamp + 100 W, 40 kHz | 1,097 | [63] |

| g-C3N4 | Piezocatalysis | None | λ ≥ 420 nm + 240 W, 40 kHz | 12,160 | [64] |

| CH3NH3PbI3 | Piezocatalysis | HI | 70W | 2.2 | [65] |

| CH3NH3PbI3 | Piezocatalysis | HI | 500 W lamp + 70 W | 23.3 | [65] |

| BaTi0.89Sn0.11O3 | Piezocatalysis | Triethanolamine | 120 W, 40 kHz | 141.1 | [66] |

| Ag-BaTi0.89Sn0.11O3 | Piezocatalysis | Triethanolamine | 120 W, 40 kHz | 360.2 | [66] |

| Li-BaTiO3 | Piezocatalysis | Triethanolamine | 300 W Xe lamp + 100 W, 40 kHz | 3,704 | [67] |

| CaTiO3 | Piezocatalysis | Methanol | 250 W, 40 kHz | 3,440 | [68] |

| BaTiO3 | Piezocatalysis | Methanol | 180 W, 35 kHz | 305 | [69] |

| ZnSnO3 | Piezocatalysis | Methanol | 250 W, 40 kHz | 3,453.1 | [70] |

| Ba0.75Sr0.25Nb1.9Ta0.1O6 | Tribocatalysis | None | Magnetic stirring | 200 | [95] |

Selecting appropriate modification strategies is crucial for developing and designing highly active piezocatalysts for hydrogen production[16,71]. First, in the absence of sacrificial agents, tuning the piezocatalyst size to obtain ultra-thin structures can substantially shorten charge migration pathways. This adjustment not only provides abundant surface dangling bonds conducive to the separation and reaction of surface charges during piezocatalytic reactions but also induces the creation of active catalytic sites, enhancing the performance compared with other modification strategies[72,73]. For instance, Su et al. found that the hydrogen production rate increased approximately by 130-fold when the BaTiO3 particle size was decreased from 200 to 10 nm, achieving rates as high as 655 µmol g-1 h-1[72]. Furthermore, the construction of composite structures can greatly enhance the hydrogen production activity of piezoelectric materials. For example, Feng and colleagues encapsulated MoC quantum dots in nitrogen-doped graphene film bubbles (NG) to create a MoC@NG structure, achieving a hydrogen production rate of up to 1,690 µmol g-1 h-1[74]. This is currently the highest reported rate for piezocatalytic water splitting under sacrificial agent-free conditions, even outperforming similar photocatalytic material systems. Moreover, crystal defects, which considerably influence the physical and chemical properties of materials, can modify the electronic structure, enhance the dynamic transport of charge carriers and create highly active sites, thereby improving the catalytic performance[75]. Furthermore, introducing vacancies or dislocations typically results in distortion of the lattice structure, which in turn enhances the catalytic performance[31,76]. Zhang et al. successfully prepared high-dislocation density materials by introducing defects into single crystals of BaTiO3 at elevated temperatures[76]. These deformed BaTiO3 crystals exhibited enhanced piezoelectric response, improved charge carrier transport capabilities, and an optimal hydrogen adsorption free energy, remarkably boosting water splitting efficiency for hydrogen production (53.8 mmol h-1 m-2). Additionally, the dislocations served as catalytically active centers, with the stress and strain fields surrounding the dislocations considerably contributing to the activity. Figure 3B illustrates the hydrogen production mechanisms in the deformed crystals[76].

To suppress the electron-hole recombination, hole scavengers such as methanol (CH3OH), triethanolamine (TEOA), sodium sulfide (Na2S), and sodium sulfite (Na2SO3) are usually added as sacrificial agents to trap the generated holes, thereby enhancing the piezocatalytic performance[16,31]. For example, Du et al. found that the hydrogen production rate over Bi2Fe4O9 nanosheets was 1,058 µmol g-1 h-1 under sacrificial agent-free conditions but increased to 5,723 µmol g-1 h-1 when using methanol as a sacrificial agent[57]. Our group also constructed the Ti3C2Tx/Bi2WO6 Schottky junction and demonstrated a good piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution rate of 764.4 μmol g-1 h-1 for optimal content Ti3C2Tx/Bi2WO6 under appropriate sacrificial agents, which is nearly eight times higher than that of pure Ti3C2Tx and twice that of Bi2WO6. Furthermore, experimental results and density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that this Schottky junction created unique pathways for an efficient electron transfer, enhances the piezoelectric properties, optimizes the Gibbs free energy of water adsorption, lowers the activation energy for hydrogen atoms and ensures an efficient charge carrier separation [Figure 3C and D][77]. Collectively, these factors enhance the efficiency of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Therefore, selecting sacrificial agents is an effective method for improving the hydrogen production performance of piezocatalysts.

A heterojunction is typically defined as the interface between two distinct semiconductors with different band structures and, consequently, specific band alignments. Heterojunction catalysts can be divided into four types: straddling gap (type-I), staggered gap (type-II), zigzag scheme (Z-scheme) and step scheme

Moreover, the loading or deposition of metal nanoparticles can remarkably promote the generation and interfacial transfer of carriers, thereby lowering the activation energy barrier for the piezocatalytic interfacial reaction and improving the catalytic efficiency[88-90]. For instance, loading metal nanoparticles such as Pt, Pd, and Au onto the surface of piezocatalysts can endow them with higher carrier concentration and charge separation efficiency, effectively adjusting the band structure between catalyst and metal. This further enhances the electronic transfer at the material interface, increasing the piezocatalysts activity, as confirmed for relevant material systems such as BiFeO3/Pd, Au@MoS2, Au/ZnO and Ag@BaTi0.99Sn0.11O3[66,88-90]. Notably, combining the aforementioned individual modification methods with other strategies such as doping engineering, defect engineering and photocatalysis can greatly enhance the hydrogen production activity of piezocatalysts[31,86,90].

Towards the industrialization of piezocatalysis application, Liu et al. coupled piezocatalysis with advanced oxidation processes using the MoS2/Fe0/peroxymonosulfate (PMS) ternary system, achieving a substantial H2 production rate of (901.0 µmol g-1 h-1) from various types of wastewater[91]. Moreover, a cyclonic piezocatalytic reactor was designed to replace the ultrasonic action in the induction of the piezoelectric effect [Figure 3F]. This strategy offers a valuable pathway for wastewater recycling via fuel production and concurrent advanced treatment, contributing to carbon neutrality in energy conversion and environmental remediation. Compared with the investigation of piezocatalytic hydrogen production, reports on tribocatalysis are scarce. For example, Zhu et al. utilized Ba0.75Sr0.25Nb1.9Ta0.1O6 powder to generate hydrogen via tribocatalysis, reaching a 15,892.8 µmol g-1 after 72 h of stirring, with an average production rate of

Overall, the piezocatalytic hydrogen production technology has rapidly developed over the past decade, considerably improving the piezocatalytic activity using optimized design strategies and achieving important research advances. However, further fundamental knowledge on the microscopic processes and intrinsic mechanisms of piezocatalysis is still required to enhance the piezocatalytic hydrogen production performance. Therefore, advanced in situ characterization techniques should be developed to delve into the complex catalytic reaction steps and charge transfer mechanisms to clarify the roles of charges and carriers in piezocatalytic reactions and the microscopic mechanisms. Further research on the tribocatalytic H2 production will enable the development of improvement strategies towards practical applications. Notably, predictive models for catalytic materials, performance and modification strategies can be scientifically established using machine learning algorithms based on existing data on piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic performance. This approach will help select, predict and design high-performance catalysts and new catalyst systems.

Application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis for nitrogen fixation to ammonia synthesis

Ammonia is an important chemical raw material and a primary component of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. Additionally, it is considered a sustainable fuel for achieving a global transition to clean energy[93-95]. Currently, the primary method for synthetic ammonia production is the Haber-Bosch process, which catalytically combines hydrogen and nitrogen under high temperature and pressure conditions to produce ammonia gas. This method produces approximately 450 million tons of ammonia annually worldwide; however, it demands very stringent conditions and results in high energy consumption and pollutant emissions, which is not conducive to sustainable development strategies. Therefore, searching for a green, energy-efficient, and effective method for ammonia synthesis is crucial for sustainability.

Currently reported photocatalytic nitrogen fixation offers advantages such as being green and sustainable, operating under mild reaction conditions, and featuring low energy consumption and cost. However, it still faces challenges, including complex mass transfer steps of nitrogen gas reactants, limitations imposed by the oxidation-reduction capabilities of photogenerated electrons and holes, and low efficiency of charge carrier utilization[96]. Electrocatalytic nitrogen fixation also offers low energy consumption, controllable reaction conditions, simple equipment, and environmental friendliness, but it faces limitations such as low Faradaic efficiency, low ammonia conversion efficiency, and susceptibility to external contamination[97,98]. Thus, finding a more suitable nitrogen fixation for ammonia synthesis is vital for advancing the industrial development of green synthetic ammonia.

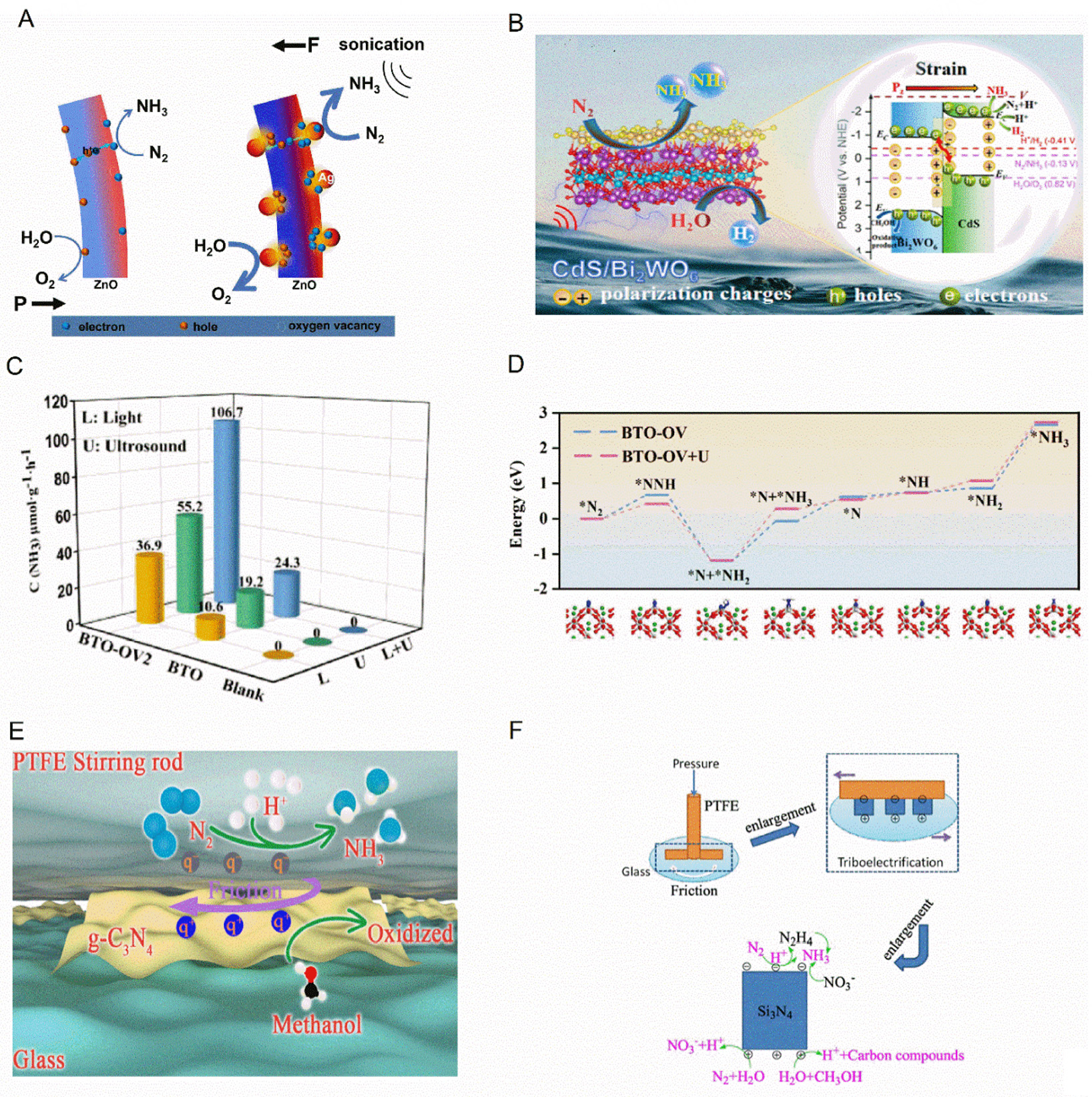

In recent years, with the extensive reporting of piezocatalysis in the field of energy conversion and water splitting applications, research on the application of piezocatalytic nitrogen fixation has gradually attracted increasing attention[24]. Utilizing piezocatalysis for nitrogen fixation can break through the constraints of material band structures and energy level positions through the generated piezoelectric potential, effectively overcoming the thermodynamic energy barriers of chemical reactions, thus achieving effective nitrogen fixation. Currently, research related to piezocatalytic nitrogen fixation is limited, primarily focusing on material systems such as KTa0.75Nb0.25O3 (KTN), ZnO, Bi5O7I and Bi2WO6[24,99-104]. However, the main challenges faced by most piezocatalysts in nitrogen fixation include weak adsorption of N2 on the catalyst surface, a lack of sufficient reactive active sites during ammonia synthesis, and low charge carrier utilization efficiency. Thus, it is essential to design nitrogen fixation materials that possess excellent piezocatalytic performance alongside high catalytic activity. Typically, some methods such as composite formation, defect engineering, nanoparticle modification and heterojunction are employed to enhance the performance of piezocatalytic nitrogen fixation, as summarized in Table 2[24,100-103]. For example, Chen et al. (2021) prepared 0.25% Bi2S3/KTN nanocomposites and found that the ammonia synthesis rate via piezocatalysis was

Figure 4. (A) Mechanism diagram of piezoelectric nitrogen fixation for ZnO-based catalysts. This figure is quoted with permission[100]. (B) Piezocatalytic N2 reduction for NH4+ yield versus time and schematic illustration for piezocatalytic mechanism of CdS/Bi2WO6. This figure is quoted with permission[103]. (C and D) NH3 production rate of blank, BTO, and BTO-OV under L, U, and L + U irradiation in the presence of sodium sulfide/sodium sulfite as sacrificial agent and reaction free energy diagrams of BTO-OV and BTO-OV + U. This figure is quoted with permission[105]. (E) Schematic diagram of tribocatalytic nitrogen fixation by g-C3N4. This figure is quoted with permission[106]. (F) Schematic diagram of tribocatalytic nitrogen fixation by Si3N4. This figure is quoted with permission[107].

Summary of the energy conversion for N2 fixation, CO2 reduction and H2O2 production applications of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis

| Catalyst | Reaction condition | Application | Reaction product and rate | Ref. |

| Bi2S3/KTa0.75Nb0.25O3 | Piezocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 14.9 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [24] |

| ZnO | Piezocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 21.4 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [100] |

| CuS/KTa0.75Nb0.25O3 | Piezocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 36.2 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [101] |

| Ag/Bi5O7I | Piezocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 99.1 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [102] |

| Ag2S/KTN | Piezocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 225.2 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [104] |

| g-C3N4 | Tribocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 100.56 µmol g-1 h-1 | [106] |

| Si3N4 | Tribocatalysis | N2 fixation | NH3, 254.68 µmol g-1 h-1 | [107] |

| (K0.5Na0.5)0.97Li0.03NbO3 (KNLN) | Piezocatalysis | CO2 reduction | CO, 438 µmol g-1 h-1 | [115] |

| BiFeO3 | Piezocatalysis | CO2 reduction | CH4, 17.9 µmol g-1 h-1 | [116] |

| BiFeO3 | Piezo-photocatalysis | CO2 reduction | CO, 28.7 µmol g-1 h-1 | [116] |

| Nb@Pb0.99 (Zr0.95Ti0.05)0.98Nb0.02O3 | Piezocatalysis | CO2 reduction | CO, 789 µmol g-1 h-1 | [117] |

| BiTiO3 | Piezocatalysis | CO2 reduction | CO, 31.7 µmol g-1 h-1 | [118] |

| Cd0.5Zn0.5S | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 151.6 µmol g-1 h-1 | [129] |

| C3N5-x-O | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 615 µmol g-1 h-1 | [131] |

| BaCaZrTi | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 692 µmol g-1 h-1 | [134] |

| Ag-Bi0.5Na0.5TiO3- AgNbO3 | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 469 µmol g-1 h-1 | [135] |

| g-C3N4 | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 34 µmol g-1 h-1 | [136] |

| Bi3TiNbO9 | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 407.1 µmol g-1 h-1 | [137] |

| BaTiO3:Nb:CDs | Piezocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 628 µmol g-1 h-1 | [139] |

| BaTiO3:Nb:CDs | Piezo-photocatalysis | H2O2 production | H2O2, 1,360 µmol g-1 h-1 | [139] |

| FEP | Tribozocatalysis | H2O2 production | 58.87 mmol L-1 g-1 h-1 | [141] |

| PTFE | Tribozocatalysis | H2O2 production | 313 μmol L-1 h-1 | [142] |

Moreover, coupling individual modification strategies with photocatalyis can significantly enhance the performance of piezoelectric nitrogen fixation[99,101,104]. Recently, Chen et al. synthesized Ag2S/KTN composites and studied their piezocatalytic, photocatalytic, and piezo-photocatalytic nitrogen fixation performance[104]. They found that under illumination and ultrasonic vibration conditions, the ammonia synthesis rate for 0.5% Ag2S/KTN reached 225.2 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1, which is much higher than the combined activities of photocatalysis and piezocatalysis (167.7 µmol L-1 g-1 h-1), indicating a significant synergistic effect[104]. This outstanding performance is attributed to Ag2S nanoparticles improving the charge carrier separation on the KTN surface through type II mechanism. This finding illustrates the effectiveness of employing multiple strategies in enhancing piezocatalytic nitrogen fixation performance. Moreover,

Compared to research on piezocatalytic nitrogen fixation, relatively few studies have focused on harnessing mechanical energy via tribocatalysis for nitrogen reduction to produce ammonia[106,107]. For the first time,

Generally, piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic nitrogen fixation, as newly developed technologies, have broad application prospects and significant development potential but currently remain underexplored. Notably, the enhancement of their performance still requires attention, with insufficient investigation into N2 adsorption and activation sites, and the microscopic reaction mechanisms remain unclear. To address these challenges, DFT calculations can be employed to study the structure-activity relationships of piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic nitrogen fixation materials, clarifying the effects of defects, heterostructures, chemical bonding, carriers, and active sites on ammonia synthesis performance. Simultaneously, advanced characterization techniques such as in situ infrared spectroscopy X-ray absorption spectroscopy should be employed to elucidate the key reaction steps and carrier variation patterns in piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis during the nitrogen fixation process, clarifying the contributions of active sites and intermediate products related to piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic reactions, therefore scientifically guiding the design and development of high-activity catalytic nitrogen fixation materials.

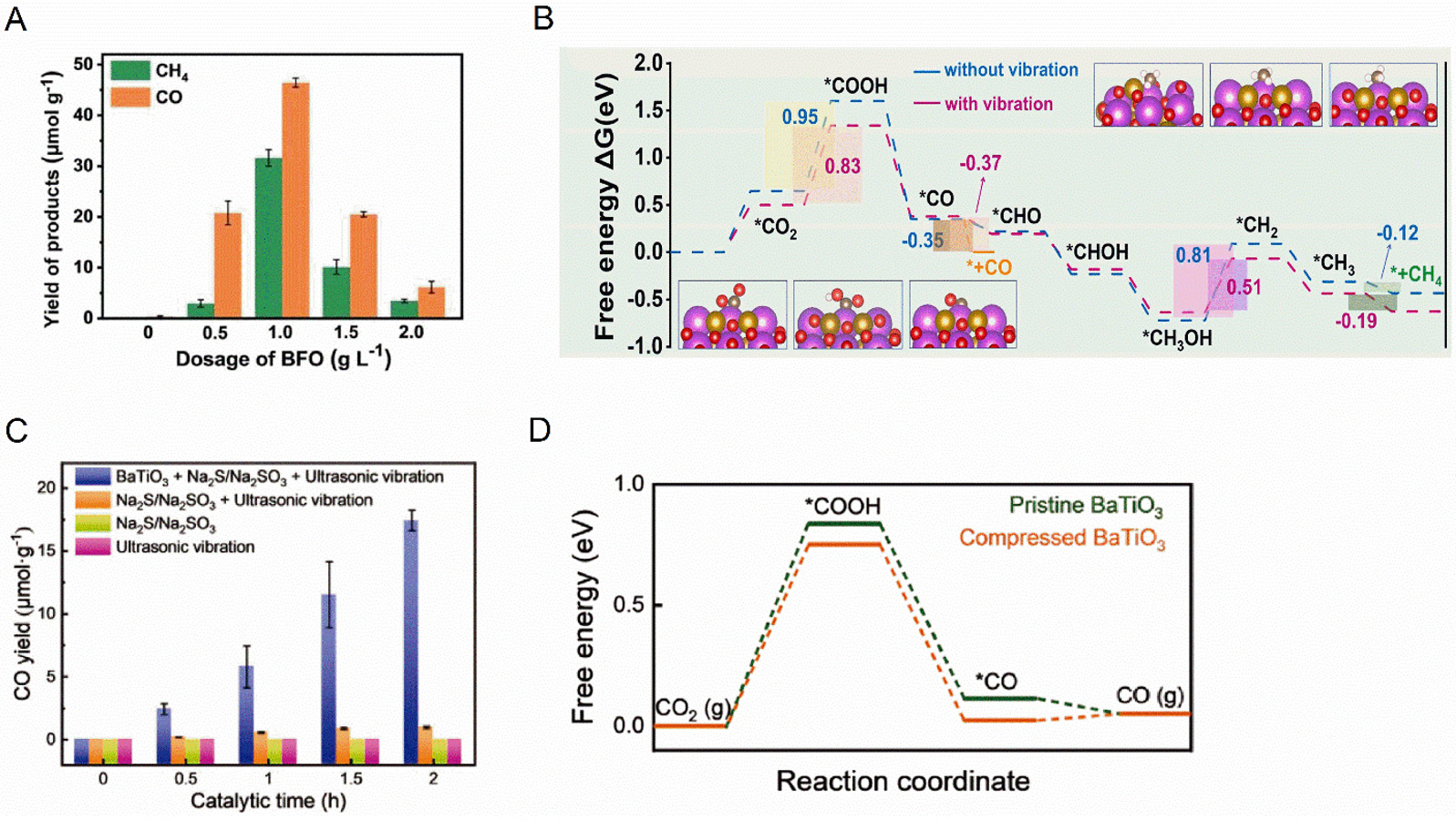

Application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis for carbon dioxide reduction

In today's society, the extensive consumption of fossil fuels has led to a continuous increase in CO2 emissions, triggering a series of global climate and environmental problems that severely threaten the green, low-carbon, and sustainable development of human society. Recently, there has been a surge in global research on the conversion of CO2 into high-value-added chemical products using catalytic technologies such as photocatalysis, electrocatalysis, and photo-electrocatalysis, driven by renewable solar energy and electrical energy. This aligns with China's development strategy of “carbon peak and carbon neutrality", highlighting the significance of converting renewable energy sources into high-value chemical fuels[108-114]. Compared to the aforementioned technologies, piezocatalysis can achieve CO2 reduction in the absence of light by harvesting vibrational energy from the environment. Similar to electrocatalytic technologies, piezocatalysts can generate appropriate piezoelectric potential to overcome reaction barriers and facilitate corresponding CO2 catalytic reactions[115]. In 2022, the piezocatalytic reduction of CO2 was reported for the first time, sparking significant research interest. Initial studies conducted by Phuong et al. synthesized lead-free lithium-doped (K,Na)NbO3 (KNN) ferroelectric ceramic particles and applied them to piezocatalytic CO2 reduction, demonstrating for the first time that lithium-doped KNN can achieve the piezocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO, with a conversion rate of 438 µmol g-1 h-1[115]. Additionally, He et al. discovered that the piezocatalytic reduction rate of CO2 on BiFeO3 was 28.7 µmol g-1 h-1 for CO and

Figure 5. (A) Yield of CO2 reduction products at different doses of BiFeO3 and (B) ΔG plots of methane and CO production during catalytic reduction of CO2. This figure is quoted with permission[116]. (C) CO yield using BaTiO3 with the addition of Na2S/Na2SO3 as sacrificial agent and (D) Free energy and structures of CO2 reduction to CO on the BaO-terminated (001) surface of BaTiO3 diagram of CO2 reduction to CO on BaTiO3 (001) by DFT calculations. This figure is quoted with permission[118].

Despite the ability of piezocatalysis to reduce CO2 into high-value-added chemicals, its reduction efficiency and selectivity remain relatively low. To address this issue, researchers have employed strategies such as doping, coupling with photocatalytic technique, and constructing heterostructure to enhance the performance of piezocatalytic CO2 reduction, as summarized in Table 2[115-118]. For example, Zhang et al. synthesized niobium-doped lead zirconate titanate piezocatalytic materials, investigating the effects of ultrasound power, particle agglomeration, and Curie temperature on the performance of piezocatalytic CO2 reduction. Under optimal conditions, the piezocatalytic CO2 reduction rate reached

Tribocatalysis also has the potential to convert carbon dioxide into combustible gases such as methane, carbon monoxide, etc.[120-123]. For example, Li et al. examined the generation of methane (CH4) at 2.45 ppm, carbon monoxide (CO) at 22.00 ppm, and hydrogen (H2) at 1.78 ppm through the use of TiO2 dispersed in water under magnetic stirring for a duration of 50 h[120]. For comparison, in the absence of TiO2 nanoparticles, only 2.17 ppm of CH4, 1.78 ppm of CO, and 0.33 ppm of H2 were produced under the same conditions. When the number of stirring rods was increased to four, the production rates significantly improved. After 50 h, 2.61 ppm of CH4, 30.04 ppm of CO, and 8.98 ppm of H2 were generated. Notably, the production of H2 and CO increased by 11 times and 36.7%, respectively, compared to the scenario using a single stirring bar[120]. Moreover, Jia et al. enhanced the experimental setup by dispersing Co3O4 nanoparticles in water and placing them in a reactor under 1 atm of CO2, along with a Teflon magnetic rotary disk[121]. After 5 h of stirring, concentrations of 0.15 µmol L-1 CH4, 57.41 µmol L-1 H2, and 0.21 µmol L-1 CO were measured. A significant improvement in CO2 reduction efficiency was observed when the reactor's bottom was switched from glass to various metal covers (Ni, SUS316, Ti, and Nb), leading to the detection of ethylene (C2H4) and ethane (C2H6). Particularly, Ti coating increased CH4 and H2 concentrations by 26 and 2 times, respectively, compared to the glass substrate. This research not only offers a valuable method to enhance the efficiency of tribocatalysis but also confirms the potential for C2+ products to be produced through this process. Furthermore, tribocatalytic materials are not limited to semiconductors; metals also exhibit excellent performance in CO2 reduction[121]. Lei et al. utilized homemade magnets with a metal Ni bottom along with a glass reactor featuring coatings of various materials on the bottom to convert CO2 and H2O into chemical fuels (CO, CH4, C2H6, and H2) through magnetic stirring[122]. Their findings demonstrated the promising potential of metals in converting H2O and CO2 into chemical fuels using mechanical energy. Notably, when Cu replaced Ni and the bottom of the quartz glass reactor was covered with Al2O3, Cu, and Ti disks, tribocatalysis also generated H2, CO, CH4, C2H4 and C2H6[122]. The material of the beaker bottom significantly influences the composition of the generated combustible gas, particularly with Ti bottoms yielding much higher concentrations of CO and CH4 than other materials. The authors proposed a tribocatalysis mechanism in which the elastic deformation of the copper disk applies pressure to water trapped in the micropores of the beaker bottom, resulting in a temporary and substantial pressure increase that enhances the efficiency of tribocatalysis. Recently, Tang et al. demonstrated that C-H and C=O bonds are more readily cleaved under a high triboelectric field generated by Ni(OH)2/Ag0.72Ga0.28 and Ga. This facilitates the efficient catalytic conversion of methane and carbon dioxide[123].

In summary, the reduction of CO2 to high-value chemical fuels through piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis opens up a new pathway for the development of mechanically driven catalytic technology and holds significant potential for application. However, research on piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic CO2 reduction remains in its infancy, particularly regarding the microscopic mechanisms behind this process, which require further exploration to achieve more significant breakthroughs. Since the multi-step reduction of CO2 is more challenging than water splitting and faces certain technical barriers, it is crucial to effectively regulate the reduction activity and selectivity of catalytic materials. This needs to be achieved through a combination of theoretical calculations and advanced characterization techniques such as aberration-corrected microscopy and synchrotron radiation to detect and analyze the evolution of catalytic active sites, electronic states, band structures, and the changes in reaction intermediates. A deeper understanding of the relationship between the reaction mechanisms of piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic CO2 reduction, energy barrier variations, and performance-enhancing modification strategies is essential. Selecting and designing more suitable catalytic materials and reaction systems remains a key direction needing exploration within the piezocatalytic and tribocatalytic CO2 reduction process.

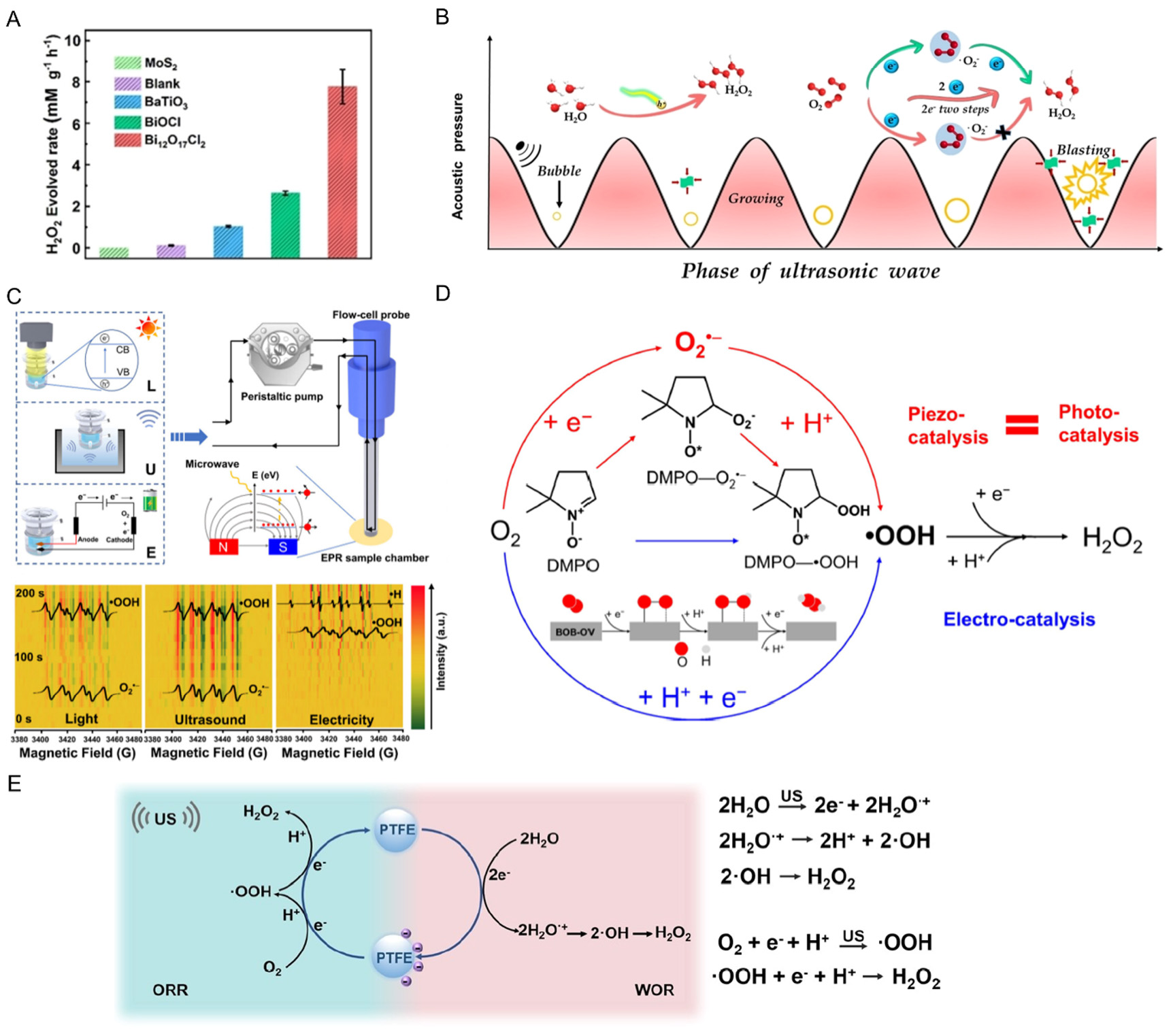

Application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis for hydrogen peroxide synthesis

Hydrogen peroxide is an emerging energy source and green oxidant widely used in industrial production and everyday life, such as in paper bleaching, wastewater treatment, and organic synthesis. The traditional anthraquinone process for producing H2O2 requires high energy consumption and generates toxic by-products, contributing to environmental pollution. Therefore, synthesizing clean H2O2 using renewable energy sources has become a focal point of research[124,125]. Among the current catalytic technologies for synthesizing H2O2, electrocatalytic redox synthesis utilizes O2 as a reactant and H2O or H+ as a proton source, gathering electrons from the cathode to selectively convert O2 into H2O2 through a proton-electron co-transfer process. This reaction offers advantages such as operation under ambient temperature and pressure, environmental friendliness, and simplicity and controllability, indicating promising prospects. However, electrocatalysts for H2O2 synthesis face drawbacks such as low selectivity, low activity, and poor long-term operational stability, limiting their practical applications[126]. Currently, due to the ability of piezocatalysis to harness vibrational energy from nature, and because the position of energy bands can effectively meet the redox potential requirements of active species (e.g., ·O2- and ·OH) while the piezoelectric potential promotes the effective separation of charge carriers, piezocatalysis represents a highly promising approach for H2O2 synthesis[127,128].

Recently, although some reports on piezoelectric materials for H2O2 synthesis have shown promising results, classical piezocatalysts still exhibit relatively low activity. Consequently, various modification strategies have been employed, including designing novel materials, doping engineering, defect engineering, constructing heterostructures, and integrating with other photocatalysis, as shown in Table 2[129-137]. Wu et al. have rationally designed the Bi12O17Cl2 piezocatalyst, incorporating multiple [Bi-O]n interlayers to achieve highly efficient H2O2 production[128]. The presence of [Bi3O4.25] enhances the electric field, accelerates charge separation, optimizes the band gap structure, and increases the adsorption energy for both O2 and H2O, thereby facilitating a higher rate of electron transfer. This is attributed to the availability of sufficient active sites, which enable the simultaneous occurrence of 2e- water oxidation reactions (WOR) and 2e- oxygen reduction reactions (ORR) to produce H2O2. Consequently, Bi12O17Cl2 demonstrates an exceptionally high

Figure 6. (A) Piezocatalytic H2O2 production, time courses of H2O2 evolved rate over different piezocatalysts and (B) mechanism of

Compared to piezocatalysis, tribocatalysis has the advantages of a wide selection of materials and high triboelectric potential for hydrogen peroxide synthesis[141,142]. Berbille et al. reported that hydrogen peroxide is generated from air and deionized water through ultrasound-driven tribocatalytic conversion, utilizing fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) as the catalyst[141]. With a catalyst-to-solution mass ratio of 1:10,000 at 20 °C, the kinetic rate of H2O2 production reaches 58.87 mmol L-1 g-1 h-1. EPR studies indicate that electrons are emitted into the solution by the charged FEP during ultrasonication. Additionally, EPR and isotope labeling experiments demonstrate that H2O2 is formed from hydroxyl radicals or two superoxide radicals generated by tribocatalytic process. Traditionally, it has been believed that these radicals migrate in the solution via Brownian diffusion prior to undergoing reactions. Moreover, Ab-initio molecular dynamics calculations reveal that the radicals can react by exchanging protons and electrons through the hydrogen bond network of water, attributed to the Grotthuss mechanism[141,142]. Fan et al. also demonstrated the tribocatalytic H2O2 synthesis through a catalytic pathway that involves contact charging at a two-phase interface under room temperature and normal pressure [Figure 6E][142]. Notably, mechanical force facilitates electron transfer during the physical interaction between PTFE particles and the deionized water/O2 interfaces, leading to the generation of reactive free radicals (·OH and ·O2-). These free radicals can subsequently react to form H2O2, achieving a production rate of up to 313 μmol L-1 h-1. Furthermore, the novel reaction device demonstrates long-term stability in H2O2 production[142]. This work presents an innovative method for the efficient synthesis of H2O2 and may inspire further investigations into tribocatalytic induced chemical processes. Overall, the synthesis of high-value-added chemicals such as

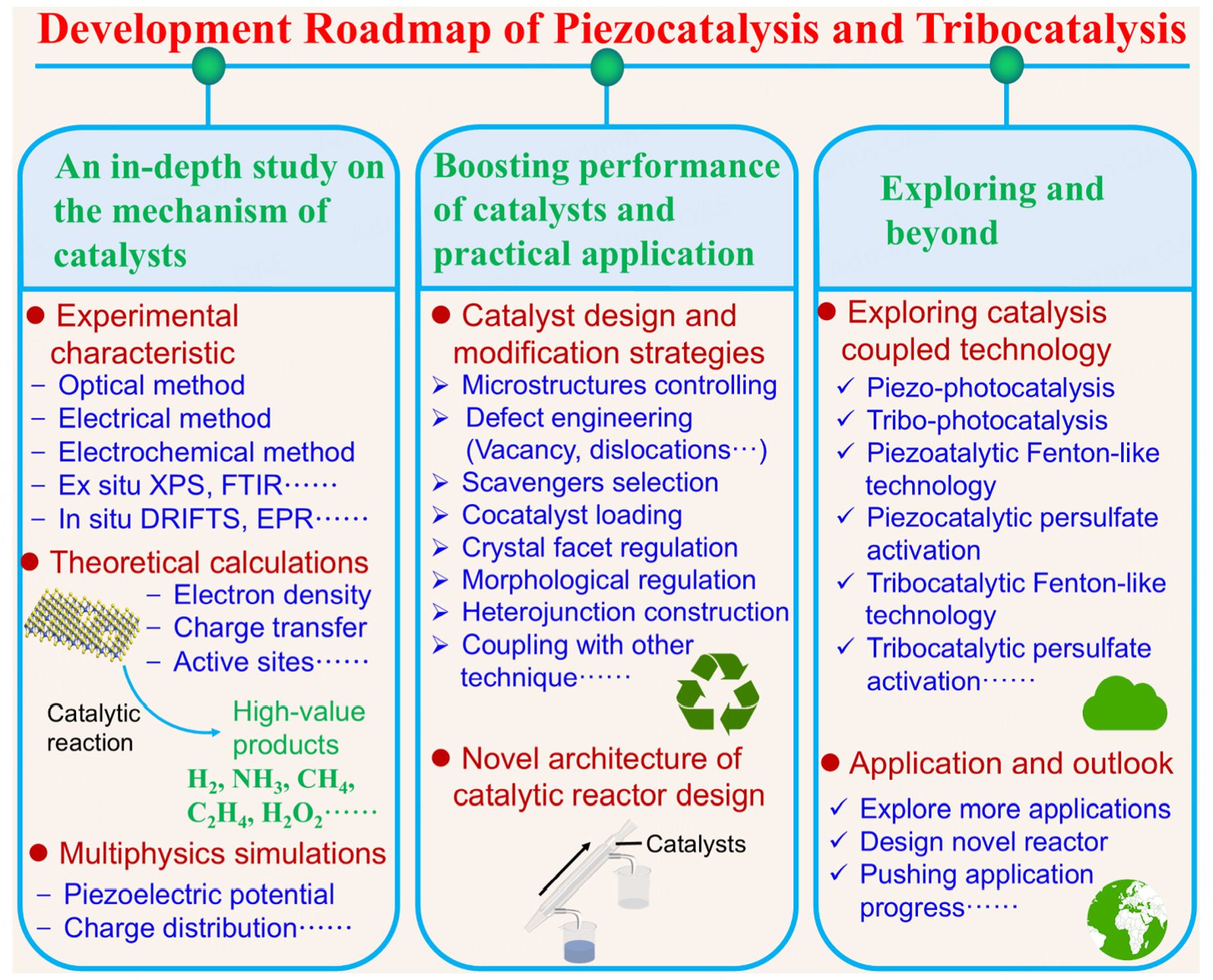

CONCLUSIONS

This review briefly summarises the research development of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, focusing on the latest advances in energy conversion applications. Effective strategies for enhancing the catalyst performance and exploring the microscopic mechanisms are discussed. This provides necessary guidance for the design and performance optimization of novel catalysts and enhances the understanding of the microscopic catalytic mechanisms, which can lead to new applications. Overall, piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis hold considerable potential for energy conversion applications to address energy shortage issues. However, further advances are still required to realise practical applications. Continuous contributions from the scientific community are essential for the development and maturation of this research field. Figure 7 depicts the development roadmap of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, including future research directions aligning with the objectives of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality in industry and society.

Despite the remarkable progress made in the fields of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, several issues remain to be addressed for obtaining high-performance catalysts:

(1) There is still a lack of understanding of the microscopic mechanisms of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis and their coupling with other catalytic technologies. In particular, the evolution and mechanisms of action of the active sites during the catalytic process have not been adequately studied. Furthermore, the contributions of charges and carriers remain unclear, leading to a lack of theoretical guidance for the exploration of new catalysts.

(2) The efficiency of piezocatalysts and tribocatalysts remains relatively low, with the catalytic reaction kinetics being relatively slow. Moreover, catalytic processes often require high-frequency and power vibrations for smooth operation, limiting their practical applications. To accelerate the development and application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis, the following efforts should be prioritized:

Advanced characterization techniques such as aberration-corrected microscopy, synchrotron radiation technology and in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy should be utilized to identify and analyse key factors such as the evolution of catalytic active sites, electronic states, energy band structures, and reaction intermediates, which will deepen the understanding of the catalytic reaction mechanisms. A systematic investigation of the separation and migration of charges and carriers should be conducted to elucidate these mechanisms and guide the development of high-performance catalytic materials. Moreover, theoretical calculations would help clarify aspects such as electronic structures, charge separation and transfer, and the thermodynamics and kinetics of catalytic reactions. The use of machine learning algorithms and genome technologies to establish predictive models would facilitate the identification of high-performance materials, further promoting the development and application of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis.

The transition from laboratory-scale to industrial-scale applications still presents notable challenges, particularly concerning energy efficiency, cost, and safety in catalytic processes. Although ultrasonic-driven catalysis is suitable for small-scale applications, its high energy consumption and equipment costs render it impractical for large-scale, continuous operations. Thus, research should focus on alternative catalytic processes with lower energy requirements. In addition, the integration of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis with other innovative technologies could enhance the overall effectiveness and economic viability. Thorough assessments of their environmental impact and sustainability are also required. To guide the future development of more environmentally friendly materials and methods. Finally, strengthening the collaboration between industry and academia would help realise the industrialization of piezocatalysis and tribocatalysis.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Talent Introduction Project of Sichuan University of Science and Engineering, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Salt City Millions of Talents Program-Leading Team, and Scientific Research and Innovation Team Program of Sichuan University of Science and Technology.

Authors’ contributions

Literature search, organization, and manuscript drafting: Hao, A.; Ye, Y.; Qiu, X.

Manuscript revision: Hao, A.; Ye, Y.; Liu, X.

Project supervision: Hao, A.; Liu, X.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the Talent Introduction Project of Sichuan University of Science and Engineering (No. 2024RC044), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12064042), Salt City Millions of Talents Program-Leading Team (No. H8012001), and Scientific Research and Innovation Team Program of Sichuan University of Science and Technology (No. SUSE652A003).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Yi, H.; Huang, D.; Qin, L.; et al. Selective prepared carbon nanomaterials for advanced photocatalytic application in environmental pollutant treatment and hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 239, 408-24.

2. Dong, W.; Xiao, H.; Jia, Y.; et al. Engineering the defects and microstructures in ferroelectrics for enhanced/novel properties: an emerging way to cope with energy crisis and environmental pollution. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2105368.

3. Xia, M.; zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; et al. Magnetic field induced synthesis of (Ni, Zn)Fe2O4 spinel nanorod for enhanced alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2023, 33, 172-7.

4. Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. Photo-/electro-/piezo-catalytic elimination of environmental pollutants. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A. Chem. 2023, 437, 114435.

5. Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Yu, X. Recent progress in graphitic carbon nitride-based materials for antibacterial applications: synthesis, mechanistic insights, and utilization. Microstructures 2024, 4, 2024017.

6. Pyser, J. B.; Chakrabarty, S.; Romero, E. O.; Narayan, A. R. H. State-of-the-art biocatalysis. ACS. Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 1105-16.

7. Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; et al. Piezoelectric materials and techniques for environmental pollution remediation. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 869, 161767.

8. Hao, A.; Ning, X.; Liu, X.; Zhan, L.; Qiu, X. Phosphorus heteroatom doped BiOCl as efficient catalyst for photo-piezocatalytic degradation of organic pollutant and unveiling the mechanism: experiment and DFT calculation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 155823.

9. Xu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Xiang, X.; et al. Modulating low-frequency tribocatalytic performance through defects in uni-doped and bi-doped SrTiO3. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 1153-63.

10. Liang, Z.; Yan, C.; Rtimi, S.; Bandara, J. Piezoelectric materials for catalytic/photocatalytic removal of pollutants: recent advances and outlook. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2019, 241, 256-69.

11. Dai, J.; Fan, Z.; Xie, H.; et al. Versatile BiFeO3 shining in piezocatalysis: from materials engineering to diverse applications. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 14, 9221046.

12. Liu, N.; Wang, R.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, J.; Fan, F. R. Piezoelectricity and triboelectricity enhanced catalysis. Nano. Res. Energy. 2024, 3, e9120137.

13. Tu, S.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Piezocatalysis and piezo-photocatalysis: catalysts classification and modification strategy, reaction mechanism, and practical application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2005158.

14. Liu, J.; Qi, W.; Xu, M.; Thomas, T.; Liu, S.; Yang, M. Piezocatalytic techniques in environmental remediation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202213927.

15. Sudrajat, H.; Rossetti, I.; Carra, I.; Colmenares, J. C. Piezocatalytic reduction: an emerging research direction with bright prospects. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2024, 45, 101043.

16. Wang, C.; Hu, C.; Chen, F.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Design strategies and effect comparisons toward efficient piezocatalytic system. Nano. Energy. 2023, 107, 108093.

17. Starr, M. B.; Wang, X. Coupling of piezoelectric effect with electrochemical processes. Nano. Energy. 2015, 14, 296-311.

18. Su, C.; Li, C.; Wang, W. Efficient piezocatalytic activation of peroxydisulfate over Bi2Fe4O9: thickness-dependent synergy effect between peroxydisulfate activation and piezocatalysis. Rare. Met. 2023, 42, 4005-14.

19. Hong, K.; Xu, H.; Konishi, H.; Li, X. Direct water splitting through vibrating piezoelectric microfibers in water. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 997-1002.

20. Hong, K.; Xu, H.; Konishi, H.; Li, X. Piezoelectrochemical effect: a new mechanism for azo dye decolorization in aqueous solution through vibrating piezoelectric microfibers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012, 116, 13045-51.

21. Ali, A.; Chen, L.; Nasir, M. S.; Wu, C.; Guo, B.; Yang, Y. Piezocatalytic removal of water bacteria and organic compounds: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1075-92.

22. Zhou, L. L.; Yang, T.; Wang, K.; et al. Efficient piezo-catalytic dye degradation using piezoelectric 6H-SiC under harsh conditions. Rare. Met. 2024, 43, 3173-84.

23. Karmakar, S.; Pramanik, A.; Kole, A. K.; Chatterjee, U.; Kumbhakar, P. Syntheses of flower and tube-like MoSe2 nanostructures for ultrafast piezocatalytic degradation of organic dyes on cotton fabrics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127702.

24. Chen, L.; Dai, X.; Li, X.; et al. A novel Bi2S3/KTa0.75Nb0.25O3 nanocomposite with high efficiency for photocatalytic and piezocatalytic N2 fixation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 13344-54.

25. Hu, J.; Zhao, R.; Ni, J.; et al. Enhanced ferroelectric polarization in Au@BaTiO3 yolk-in-shell nanostructure for synergistic boosting visible-light- piezocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2410357.

26. Fan, F.; Xie, S.; Wang, G.; Tian, Z. Tribocatalysis: challenges and perspectives. Sci. China. Chem. 2021, 64, 1609-13.

27. Che, J.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. Review on tribocatalysis through harvesting friction energy for mechanically-driven dye decomposition. J. Alloys. Compd. 2024, 1002, 175413.

28. Zhao, B.; Chen, N.; Xue, Y.; et al. Challenges and perspectives of tribocatalysis in the treatment for dye wastewater. J. Water. Proc. Eng. 2024, 63, 105455.

29. Trinh, Q. T.; Golio, N.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Sonochemistry and sonocatalysis: current progress, existing limitations, and future opportunities in green and sustainable chemistry. Green. Chem. 2025, 27, 4926-58.

30. Pickhardt, W.; Grätz, S.; Borchardt, L. Direct mechanocatalysis: using milling balls as catalysts. Chemistry 2020, 26, 12903-11.

31. Jia, P.; Li, J.; Huang, H. Piezocatalysts and piezo-photocatalysts: from material design to diverse applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2407309.

32. Wang, K.; Han, C.; Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Sunarso, J.; Liu, S. The mechanism of piezocatalysis: energy band theory or screening charge effect? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202110429.

33. Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, W.; et al. Recent advances in piezocatalytic hydrogen production and prospects. Surf. Interfaces. 2024, 54, 105245.

34. Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Niu, S.; Wang, Z. Fundamental theories of piezotronics and piezo-phototronics. Nano. Energy. 2015, 14, 257-75.

35. Tu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y. Controllable synthesis of multi-responsive ferroelectric layered perovskite-like Bi4Ti3O12: photocatalysis and piezoelectric-catalysis and mechanism insight. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2017, 219, 550-62.

36. Tian, W.; Qiu, J.; Li, N.; et al. Efficient piezocatalytic removal of BPA and Cr(VI) with SnS2/CNFs membrane by harvesting vibration energy. Nano. Energy. 2021, 86, 106036.

37. Jiang, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhuo, F.; et al. Unveiling mechanically driven catalytic processes: beyond piezocatalysis to synergetic effects. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 18037-74.

38. Du, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, X.; et al. Mechanocatalytic hydrogen generation in centrosymmetric barium dititanate. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2404483.

39. Li, X.; Tong, W.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; An, Q. Tribocatalysis mechanisms: electron transfer and transition. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023, 11, 4458-72.

40. Kajdas, C. K. Importance of the triboemission process for tribochemical reaction. Tribol. Int. 2005, 38, 337-53.

41. Hu, C.; Huang, H. Advances in piezoelectric polarization enhanced photocatalytic energy conversion. Acta. Phys. Chim. Sin. 2023, 2212048.

42. Li, L.; Kang, P.; Feng, D.; et al. High temperature liquid shock manufacturing of RuNi catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2024, 34, 985-9.

43. Zhang, B.; Sun, B.; Liu, F.; Gao, T.; Zhou, G. TiO2-based S-scheme photocatalysts for solar energy conversion and environmental remediation. Sci. China. Mater. 2024, 67, 424-43.

44. Brereton, K. R.; Bonn, A. G.; Miller, A. J. M. Molecular photoelectrocatalysts for light-driven hydrogen production. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2018, 3, 1128-36.

45. Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Vijayakumar, A.; et al. Hydrogen generation and degradation of organic dyes by new piezocatalytic 0.7BiFeO3-

46. Chen, Z.; Liu, W.; Zheng, L.; et al. Enhancing production of hydrogen and simultaneous degradation of ciprofloxacin over Sn doped SrTiO3 piezocatalyst. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128307.

47. You, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Harvesting the vibration energy of BiFeO3 nanosheets for hydrogen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11779-84.

48. Xu, X.; Xiao, L.; Wu, Z.; et al. Harvesting vibration energy to piezo-catalytically generate hydrogen through Bi2WO6 layered-perovskite. Nano. Energy. 2020, 78, 105351.

49. Ning, X.; Jia, D.; Li, S.; Khan, M. F.; Hao, A. Oxygen-incorporated MoS2 catalyst for remarkable enhancing piezocatalytic H2 evolution and degradation of organic pollutant. Rare. Met. 2023, 42, 3034-45.

50. Mondal, S.; Dilly Rajan, K.; Patra, L.; Rathinam, M.; Ganesh, V. Sulfur vacancy-induced enhancement of piezocatalytic H2 production in MoS2. Small 2025, 21, e2411828.

51. Chou, T.; Chan, S.; Lin, Y.; et al. A highly efficient Au-MoS2 nanocatalyst for tunable piezocatalytic and photocatalytic water disinfection. Nano. Energy. 2019, 57, 14-21.

52. Zhao, S.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Harvesting mechanical energy for hydrogen generation by piezoelectric metal-organic frameworks. Mater. Horiz. 2022, 9, 1978-83.

53. Su, P.; Kong, D.; Zhao, H.; et al. SnFe2O4/ZnIn2S4/PVDF piezophotocatalyst with improved photocatalytic hydrogen production by synergetic effects of heterojunction and piezoelectricity. J. Adv. Ceram. 2023, 12, 1685-700.

54. Wang, J.; Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Engineering piezoelectricity and strain sensitivity in CdS to promote piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chin. J. Catal. 2022, 43, 1277-85.

55. Zhan, L.; Hu, J.; Cao, Y.; et al. Ce-regulating defect and morphology engineering for efficiently enhancing the piezocatalytic performances of BiOBr. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 1892-5.

56. Qiu, X.; Xie, J.; Ning, X.; et al. Enhancing the piezocatalytic performance for H2 evolution by constructing BiOCl/UiO-66 heterostructure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 670, 160694.

57. Du, Y.; Lu, T.; Li, X.; et al. High-efficient piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution by centrosymmetric Bi2Fe4O9 nanoplates. Nano. Energy. 2022, 104, 107919.

58. Lei, R.; Gao, F.; Yuan, J.; et al. Free layer-dependent piezoelectricity of oxygen-doped MoS2 for the enhanced piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution from pure water. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 576, 151851.

59. Li, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, F.; et al. Robust route to H2O2 and H2 via intermediate water splitting enabled by capitalizing on minimum vanadium-doped piezocatalysts. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 7986-93.

60. Lei, R.; Fu, X.; Chen, N.; Chen, Y.; Feng, W.; Liu, P. Cocatalyst engineering to weaken the charge screening effect over

61. Ma, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhong, Y.; et al. Bifunctional RbBiNb2O7/poly(tetrafluoroethylene) for high-efficiency piezocatalytic hydrogen and hydrogen peroxide production from pure water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136958.

62. He, Y.; Tian, N.; An, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Morphology regulation and oxygen vacancy construction synergistically boosting the piezocatalytic degradation and pure water splitting of SrTiO3. Small 2024, 20, e2407624.

63. Ma, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, B.; et al. Enhanced charge separation in La2NiO4 nanoplates by coupled piezocatalysis and photocatalysis for efficient H2 evolution. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 7083-95.

64. Hu, C.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. Exceptional cocatalyst-free photo-enhanced piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution of carbon nitride nanosheets from strong in-plane polarization. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101751.

65. Wang, M.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Remarkably enhanced hydrogen generation of organolead halide perovskites via piezocatalysis and photocatalysis. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2019, 9, 1901801.

66. Zhao, Q.; Xiao, H.; Huangfu, G.; et al. Highly-efficient piezocatalytic performance of nanocrystalline BaTi0.89Sn0.11O3 catalyst with Tc near room temperature. Nano. Energy. 2021, 85, 106028.

67. Yu, C.; He, J.; Tan, M.; et al. Selective enhancement of photo-piezocatalytic performance in BaTiO3 via heterovalent ion doping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2209365.

68. Zhou, H.; Cao, J.; Ji, Y.; Xia, M.; Yao, W. Twin boundaries-induced centrosymmetric breaking of hollow CaTiO3 nanocuboids for piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Small 2024, 20, e2402679.

69. Tang, Q.; Wu, J.; Kim, D.; et al. Enhanced piezocatalytic performance of BaTiO3 nanosheets with highly exposed {001} facets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2202180.

70. Wang, Y.; Wu, J. M. Effect of controlled oxygen vacancy on H2-production through the piezocatalysis and piezophototronics of ferroelectric R3C ZnSnO3 nanowires. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1907619.

71. Ma, J.; Xia, L.; Ruan, L.; et al. Sacrificial agent effect in piezo-electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2023, 122, 203902.

72. Su, R.; Hsain, H. A.; Wu, M.; et al. Nano-ferroelectric for high efficiency overall water splitting under ultrasonic vibration. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15076-81.

73. Feng, W.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Atomically thin ZnS nanosheets: facile synthesis and superior piezocatalytic H2 production from pure H2O. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 277, 119250.

74. Feng, W.; Yuan, J.; Gao, F.; et al. Piezopotential-driven simulated electrocatalytic nanosystem of ultrasmall MoC quantum dots encapsulated in ultrathin N-doped graphene vesicles for superhigh H2 production from pure water. Nano. Energy. 2020, 75, 104990.

75. Tian, J.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, B.; Li, J. Oxygen vacancy mediated bismuth-based photocatalysts. Adv. Powder. Mater. 2024, 3, 100201.

76. Zhang, Y.; Feng, K.; Song, M.; et al. Dislocation-engineered piezocatalytic water splitting in single-crystal BaTiO3. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 602-12.

77. Ning, X.; Hao, A.; Cao, Y.; et al. Construction of MXene/Bi2WO6 schottky junction for highly efficient piezocatalytic hydrogen evolution and unraveling mechanism. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 3361-8.

78. Low, J.; Yu, J.; Jaroniec, M.; Wageh, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A. A. Heterojunction photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1601694.

79. Zhang, K.; Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Ma, Y.; Huang, H.; Ma, T. Interfacial engineering of Bi2MoO6-BaTiO3 type-I heterojunction promotes cocatalyst-free piezocatalytic H2 production. Nano. Energy. 2024, 121, 109206.

80. Shi, M.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Li, C. Unlocking the key to photocatalytic hydrogen production using electronic mediators for

81. Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Yu, J. Emerging S-scheme photocatalyst. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2107668.

82. Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; et al. Acid-engineering combined heterojunction formation for high efficient piezo-catalytic FeCo-LDH@ZnO. Nano. Energy. 2025, 144, 111333.

83. Lee, G.; Lyu, L.; Hsiao, K.; et al. Induction of a piezo-potential improves photocatalytic hydrogen production over ZnO/ZnS/MoS2 heterostructures. Nano. Energy. 2022, 93, 106867.

84. Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; et al. Synthesis of ternary ZnO/ZnS/MoS2 piezoelectric nanoarrays for enhanced photocatalytic performance by conversion of dual heterojunctions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 556, 149695.

85. Kuru, T.; Sarilmaz, A.; Aslan, E.; Ozel, F.; Hatay Patir, I. Rational design of ZnO/SrTiO3 S-scheme heterojunction for photo-enhanced piezocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 682, 161704.