Advances in graph neural networks for alloy design and properties predictions: a review

Abstract

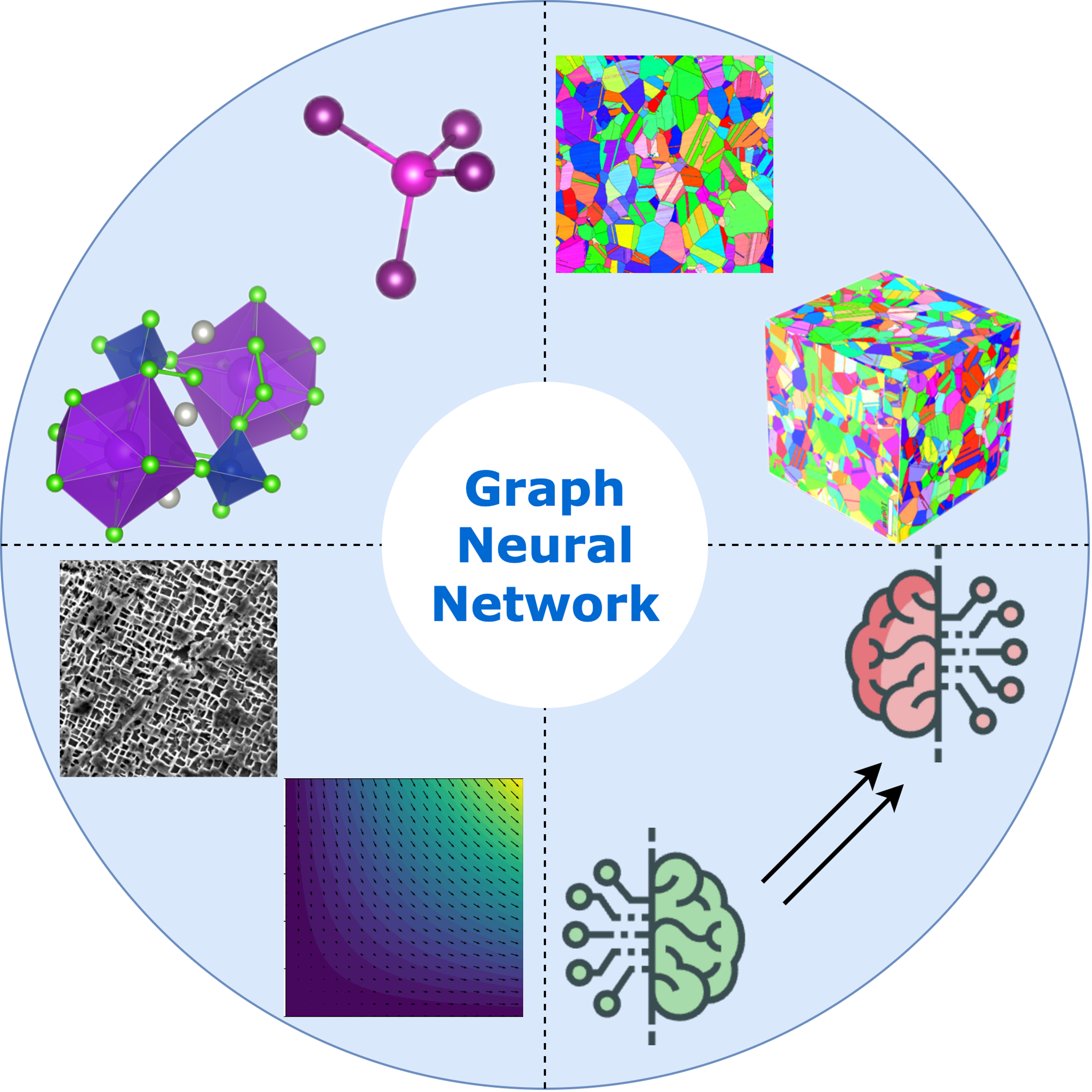

Graph neural networks (GNNs) have become a transformative modeling paradigm in materials science, offering a data-efficient and structure-aware approach for learning from complex material systems. This review focuses on the recent progress of GNNs in alloy design and property prediction. We begin by introducing the foundational concepts of graph representations and the general architecture of GNNs, including node embeddings, message passing, and pooling strategies. The review then categorizes major types of GNNs, including supervised and unsupervised learning, with a focus on the achievements and applications of GNNs in materials modeling, and discusses their strengths and inherent limitations in the context of materials modeling. Particular emphasis is placed on the application of GNNs in the alloy domain, covering a diverse range of data types, from atomic structures and compositions to microstructural images, and target properties, such as mechanical strength, thermal stability, and phase stability. We highlight how GNNs are integrated into alloy composition optimization, multi-property prediction, and frontier research workflows. The review concludes with a summary of multi-model and multiscale approaches and outlines key challenges and future directions for constructing generalizable, physics-informed GNN frameworks for alloy discovery.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

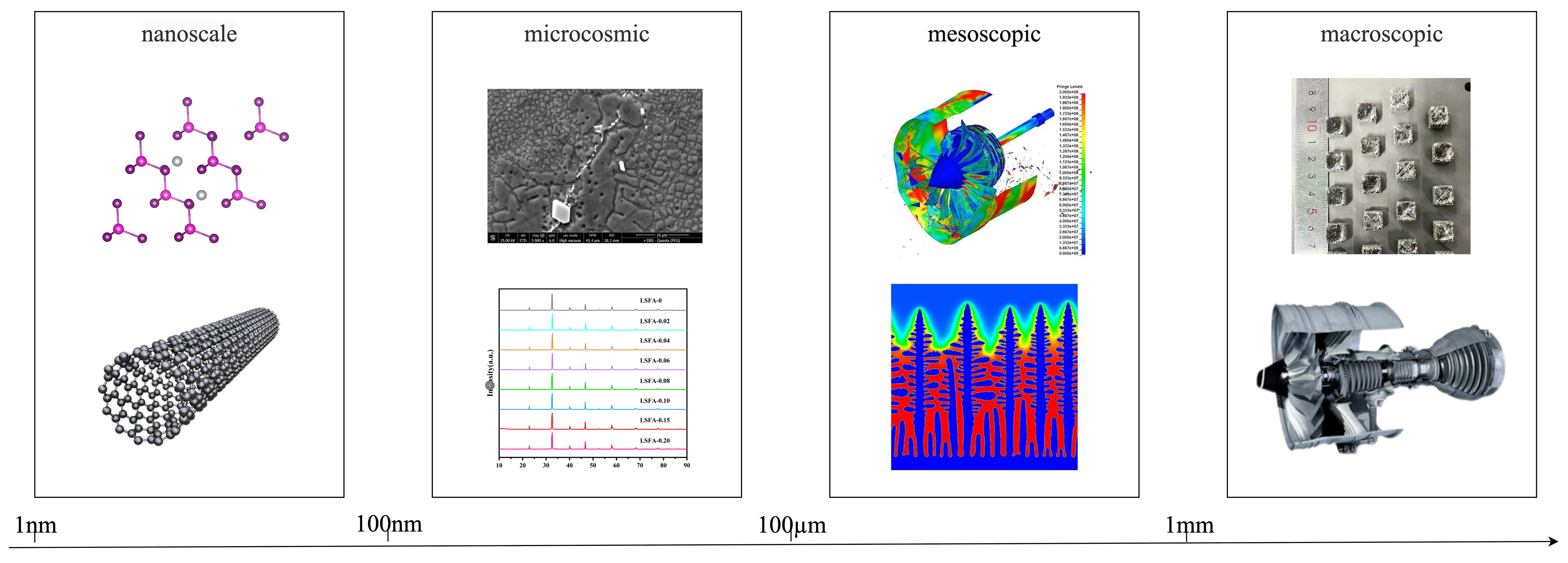

Materials science is fundamental to the advancement of modern technologies, with alloys representing a critical class of materials due to their diverse and tunable properties[1]. The design of alloys is a key aspect of contemporary engineering and materials science, enabling precise optimization of material behavior through control over composition and microstructure[2]. In the aerospace sector, nickel-based superalloys have significantly improved strength and oxidation resistance at high temperatures, thereby enhancing engine efficiency and extending operational lifespan[3]. Similarly, aluminum alloys are extensively used in the automotive industry to reduce weight, lower fuel consumption, and improve recyclability[4]. The emergence of high-entropy alloys (HEAs) has further broadened application possibilities, opening new frontiers in materials science[5]. Alloy performance is determined by the intricate interplay between composition and microstructure. Conventional experimental and theoretical approaches often suffer from limited efficiency and high cost when exploring alloy properties[6,7]. In recent years, progress in computational technologies, data science, and machine learning (ML) has provided researchers with powerful tools to expedite the material design process[8]. In particular, ML techniques provide data-driven methodologies that facilitate the rapid prediction of alloy properties, thus mitigating the inefficiencies and uncertainties associated with traditional trial-and-error approaches[9,10].

Conventional ML models [support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB)] remain competitive in the small-data regime (< 500 entries), thanks to hand-crafted compositional or thermodynamic descriptors, offering fast central processing unit (CPU)-level training and straightforward feature attribution[11-13]. By contrast, state-of-the-art GNNs [e.g., crystal graph convolutional neural network (CGCNN), materials graph network (MEGNet), global attention graph neural network (GATGNN)] learn directly from crystal or grain-scale graphs and can lower prediction errors by a further 20%-30% once datasets exceed ~1,000 samples, albeit at higher GPU cost and with still-maturing interpretability[14-16].

Graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a promising branch of ML for graph-structured data[17]. Unlike traditional neural networks, GNNs are capable of propagating information and capturing complex relationships between nodes within a graph structure, making them particularly suited to handle non-Euclidean structured data[18]. Beyond materials science, GNNs have also proved effective in biology, chemistry and network analysis, underscoring their general versatility[19]. In bio-informatics, they have been applied to tasks such as protein structure prediction[20], genetic structure design[21] and drug discovery[22]. In materials science, GNNs predict properties and guide new-material development[23]. At the atomic and molecular level, a material system can be represented as a graph whose nodes correspond to atoms (with features such as atomic number, mass, radius) and edges to chemical bonds[24]. In multi-atom systems, more complex graphs capture extended structures. Researchers have also introduced the concept of compositional genetics, mapping interpretable molecular-structure models onto macroscopic properties. GNNs, by handling non-Euclidean data, provide novel insights into alloy design across scales[25,26].

The complex microstructure and multiscale properties of alloys present considerable challenges to traditional experimental and simulation methods[1]. GNNs hold great potential in capturing the intricate relationships between a material’s microstructure and its macroscopic properties, thus offering an innovative and effective approach to alloy design. Research on the application of GNNs in alloy design aims to enhance material design efficiency and accuracy through ML methods.

This review aims to offer an overview of the recent advancements in the application of GNNs in alloy design, demonstrating their potential to model complex relationships between composition, microstructure, and macroscopic properties. It then examines how GNNs are applied for property prediction, microstructure characterization, and composition design in the context of alloy development and the application of unsupervised GNNs. Lastly, we address the latest advances in integrating GNNs with traditional alloy design methods, emphasizing the importance of multiscale modeling and data integration. By synthesizing recent research, this review aims to offer insights into how GNNs can enhance alloy design and drive the discovery of new materials with optimized properties.

BASIC CONCEPT OF GNNS

Basic definition and characteristics of graphs

A graph is widely used in discrete mathematics for representing objects and their relationships. A graph is typically denoted as G = (V, E), where V represents the set of vertices (or nodes) and E denotes the set of edges, which represent the connections between vertices[27,28]. Nodes represent specific objects (e.g., atoms), while the edges represent the relationships between these objects (e.g., bonding interactions). Therefore, there are typically three types of tasks in graph learning:

• Node-level tasks focus on the individual nodes in a graph. These tasks include node classification, which aims to assign each node to a specific category, node regression, which involves predicting a continuous value for each node, and node clustering, aimed at grouping nodes into several clusters such that similar nodes are placed together in the same group.

• Edge-level tasks involve edge classification and link prediction, which aim to determine the type of an edge or predict the presence of an edge between two specific nodes. Edge classification assigns labels to edges based on the relationship they represent, while link prediction estimates whether an edge will exist between two nodes in the future.

• Graph-level tasks include graph classification, graph regression, and graph matching, all of which require the model to learn representations of entire graphs. These tasks aim to assign labels, predict continuous values, or find correspondences between graphs by capturing global graph structures and properties.

Depending on the directionality of the edges, graphs can be classified into directed and undirected graphs. Since bonding interactions in materials science are typically undirected, undirected graphs are frequently used to represent material structures. The connectivity between vertices can be represented using an adjacency matrix or an incidence matrix. These vertices and their connections are input into GNNs as feature vectors and adjacency matrices for computation and analysis. Figure 1 converts the Ni3Al crystal into an undirected graph whose adjacency list and matrix encode atom connections - matrix zeros mark absent self-links, while off-diagonal values 1, 2 and 3 label Ni–Ni, Ni–Al and Al–Al bonds, respectively. For other types of graphs, please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1. Various representations of the Ni3Al crystal structure. (A) Schematic diagram of the Ni3Al crystal structure, showing the arrangement of Ni and Al atoms in a cubic lattice; (B) Undirected graph representation of Ni3Al, where nodes represent atoms and edges represent ionic bonds; (C) Adjacency list representation of the Ni3Al structure, depicting the connections between atoms; (D) Adjacency matrix representation of Ni3Al, illustrating the connectivity between atoms in matrix form.

The structure of GNN models

Input representation

• Node Features: Each node in the graph represents an entity. The features of each node describe the properties of the corresponding entity. Some of the features used in node representation are shown in Table 1.

Graph structural features stratified by different levels

| Level | Attributes | GNN role |

| Node | Element type | Encoded as node identity |

| Node | Atomic number[23] | Defines elemental identity; essential node input |

| Node | Atomic mass | Linked to density and vibrations; used for modeling physical trends |

| Node | Electronegativity | Correlates with bonding; helps model chemical reactivity |

| Node | Coordination number[29] | Reflects local environment; encoded as node feature of auxiliary edge info |

| Node | Lattice type[30] | Used to differentiate structure symmetry; often embedded and fed to node or graph input |

| Node | Atomic position[31] | Required for geometry-aware GNNs (ALIGNN, etc.); improves spatially dependent property predictions |

| Node | Density | Related to material mass and stiffness; helps with mechanical and thermal prediction |

| Node | Melting point | Correlates with thermal stability; relevant as input in temperature-aware models |

| Node | Thermal conductivity | Used as a label or contextual feature; important in heat transport tasks |

| Node | Electrical conductivity | Target or input for conductive materials; improves charge transport prediction |

| Node | Elastic modulus | Typically a target; can enhance multi-task learning for mechanical properties |

| Node | Yield strength | Associated with plasticity; used in property design tasks for strength |

| Node | Gibbs free energy[32] | Relates to deformation resistance; used in MEGNet as node input or supervised label in stability prediction |

| Node | Valence electron density | Supports modeling of conductivity; improves electronic predictions; key physics-inspired input |

| Node | Diffusion coefficient | Important in kinetics modeling; improves predictions under varying conditions |

| Node | Metal price[33] | Used in cost-performance models; aids in design under economic constraints |

| Node | Voronoi information[34] | Describes atomic environment; improves local structure representation; encoded as local geometric descriptors |

| Edge | Type of chemical bond | Encodes bonding category; improves modeling in molecule-oriented GNNs |

| Edge | Bonding energy[35] | Reflects bond strength; improves predictions of reactivity and stability |

| Edge | Atomic spacing[36] | Primary edge input in crystal GNNs (CGCNN); essential for structural property learning |

| Edge | Atomic exchange energy | Enhance physics-informed GNNs; relates to defect behavior |

| Edge | Bond angle[37] | Used in directional GNNs (ALIGNN, etc.); improves angular-dependent predictions |

| Graph | Ambient temperature | Affects diffusion and stability; enhances condition-aware prediction accuracy |

| Graph | Applied pressure | Encoded as graph-level input in MEGNet-like models for phase transitions |

| Graph | Chemical environment | Modeled as categorical condition or background descriptor at graph level |

| Graph | Applied electric field | Added as vector graph feature in electronic property prediction |

| Graph | Applied magnetic field | Added as vector graph feature in electronic property prediction |

• Edge Features: Edges in the graph represent relationships between nodes, such as atomic bonds or interactions between different atoms in the alloy. These relationships can also carry features as shown in Table 1.

• Graph Features: In addition to node and edge features, graph-level features capture global information about the entire graph structure.

Table 1 presents typical attributes used as node, edge, or graph-level features in GNN-based alloy modeling. These features are essential for encoding atomic identities, interatomic interactions, and external conditions, thereby enabling GNNs to learn complex structure–property relationships. A more detailed description of each attribute is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Message passing

GNNs operate by recursively aggregating and transforming information from neighboring nodes, thereby learning expressive representations of graph-structured data. Each GNN layer can be viewed as a message-passing process, where each node receives messages from its neighbors and updates its own state accordingly. This concept, generalized by Google through identifying shared principles across various GNN models, extends the forward and backward propagation mechanisms of conventional neural networks to graph structures[38]. The key lies in defining rules for inter-node message passing: during the forward pass [Figure 2], the features of each node are integrated with those of its neighbors to form a refined local representation. In the context of alloy design, such a mechanism can model interactions among different atoms or elements within an alloy, revealing how these interactions collectively shape the material’s macroscopic properties.

Figure 2. Schematic of the message passing mechanism in GNNs. The input layer contains the original attributes. In the hidden layer, each node gathers information from its immediate neighbors and transforms it, creating an updated feature that fuses its own data with local context. The output layer repeats the aggregation, allowing every node to integrate signals from a wider neighborhood and produce a final, more informative representation. GNNs: Graph neural networks.

Update mechanism

The update mechanism in GNNs allows nodes, representing elements or structural features, to iteratively refine their features based on relational information. In the context of alloy design, node updates can be categorized into three distinct strategies, each suited for different complexity levels of material interactions:

• Linear Transformation Update: The simplest form, involving only a linear transformation of the node’s own features without explicitly aggregating neighboring node information. For node v with feature vector hv, the update rule is:

Here W is a learnable weight matrix, and b is the bias term. This method captures the fundamentals of first-order properties of alloy elements and is most suitable for basic linear relationships.

• Non-linear Transformation: Extends the linear model by applying a non-linear activation function [such as rectified linear unit (ReLU)] after the linear transformation, enabling the network to model more intricate, non-linear material behaviors (e.g., predicting alloy phase transitions or mechanical property variations):

Introducing non-linearity allows the GNN to capture higher-order element interactions within alloys, essential for realistic materials modeling.

• Gated Mechanism[39]: An advanced method explicitly integrating neighboring node information through a learned gating function. It selectively aggregates neighboring information, deciding the importance of each neighbor’s contribution when updating node features.

The gating function filters less relevant signals, emphasizing critical interactions, for instance, highlighting how carbon significantly influences steel strength and ductility. It is best suited for modeling complex alloy systems with highly interdependent elemental properties.

In short, Equation (1) is a pure self-projection suited to nearly linear composition–property trends, Equation (2) adds a non-linear activation to capture higher-order interactions, while Equation (3) inserts a gate that blends the node’s own signal with selectively weighted neighbor messages, making it effective for alloy systems with strongly coupled elemental effects. Besides, selecting an appropriate update method depends on the complexity of the material system and desired prediction accuracy.

Pooling and fully connected layers

In alloy design, pooling and fully connected (FC) layers in GNNs play a pivotal role in aggregating node-level features into a comprehensive global representation of the alloy’s properties. By consolidating information from individual elements or microstructural features, these layers effectively capture how local characteristics collectively influence the material’s overall behavior.

Pooling layers combine node-level information (representing elements or phases) into a more compact form, which is crucial for deriving the alloy’s global properties. By reducing the graph’s complexity while retaining key features, pooling facilitates effective global property prediction. Common pooling techniques include:

• Global Pooling: Aggregates features from all nodes, typically by taking their average.

• Max Pooling: Selects the maximum value among node features, particularly useful when certain elements or phases exert a dominant influence on material properties.

• Sort Pooling[40]: Sort node features and selects the top features, emphasizing the alloy’s most critical components.

Pooling reduces the complexity of the graph while retaining essential information for global property prediction.

In GNNs, the FC layer typically appears at the final stage, converting graph-based features extracted by preceding layers into the final output. The layer applies a linear transformation to the high-dimensional input features via weighted sums and biases, and often introduces non-linear activation functions to capture complex relationships. In alloy design, the FC layer can process the node-level (e.g., elements) and edges-level (e.g., interactions between elements) features learned by earlier graph convolutional layers. Its output may then be used to predict specific alloy properties or assign categorical labels. For example, the FC layer can model intricate relationships among composition, microstructure, and performance, enabling more accurate predictions of an alloy’s behavior under different conditions[40].

Overview and main types of GNNs

GNNs are deep learning architectures specifically designed to process graph-structured data. They can learn representations of both nodes and overall graph structures, enabling tasks such as regression, classification, and clustering. While conventional deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), target Euclidean domains (e.g., images or text), GNNs extend these techniques to non-Euclidean entities such as atoms, ions, or molecules. In this way, graphs representations provide a flexible framework for capturing spatial coordinates and connectivity patterns that significantly influence material properties. From the perspective of supervision, graph learning tasks can be categorized into three main training paradigms:

• Supervised Learning: In the supervised setting, sufficient labeled data is provided for training, commonly used for tasks such as node classification and link prediction.

• Semi-supervised Learning: A small subset of labeled nodes coexists with a large number of unlabeled nodes. During testing, transductive approaches predict labels for unlabeled nodes in the same graph, while inductive approaches require the model to generalize to previously unseen nodes from the same distribution. This setting is particularly common in node and edge classification tasks.

• Unsupervised Learning: Only unlabeled data is available, and the model must discover latent patterns from the graph structure. A typical example is node clustering, where the model groups nodes based on their similarities without any labeled supervision.

In conclusion, GNNs provided a flexible and robust framework for processing graph-structured data under diverse learning settings, enabling the effective modeling of complex relationships and structures across a wide range of domains.

GNNs encompass various specialized architectures tailored to different applications. For the complete description of the message-passing mechanism, see Section “Message passing”. Hereafter, we will refer to that section and only briefly remind the reader of differences among variants. Recursive GNNs (RecGNNs) iteratively aggregate neighborhood information, emphasizing the hierarchical structure of graphs. This property makes them particularly well-suited for materials science tasks such as predicting the properties of complex alloy networks, where atomic interactions follow nested or hierarchical patterns. In contrast, graph autoencoders (GAEs) are unsupervised models designed to learn efficient graph representations, making them ideal for clustering material structures. Spatial-temporal GNNs (ST-GNNs) extend GNN functionality to data that varies across both space and time-an essential capability for modeling how materials respond dynamically to varying conditions (e.g., thermal or mechanical stress over time).

These GNN variants enable more nuanced and predictive analyses in material design, helping to discover new materials with optimized properties. Several GNN variants are commonly adopted in materials chemistry research, each tailored to capture the unique structural and compositional complexities inherent to different material systems. Supplementary Table 3 provides a summary of several GNN variants and their typical applications. Below is an introduction to the three most basic GNNs.

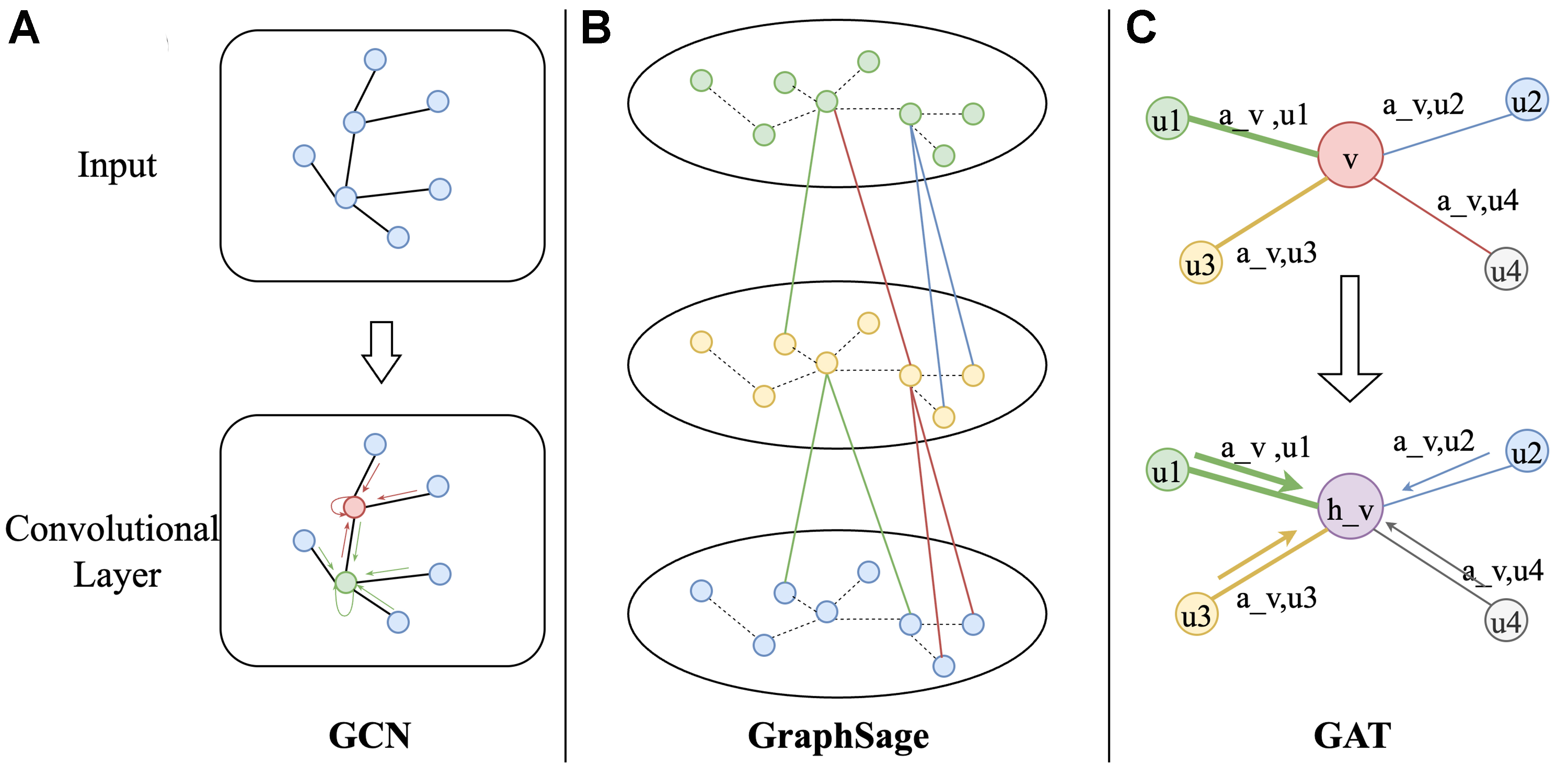

Graph convolutional networks

Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) are a class of neural network architectures designed for graph-structured data[41]. Figure 3A illustrates this iterative process. In the first layer, each node updates its feature by referencing its immediate neighbors, as indicated by the adjacency matrix. As subsequent layers are added, the receptive field of each node expands, allowing it to aggregate information from increasingly distant neighbors. By propagating features through successive layers, GCNs effectively capture both local and global dependencies in the graph, facilitating powerful learning from graph data.

Figure 3. Illustration of common GNN architectures. (A) GCN performs spectral convolution, aggregating normalized features from neighboring nodes with shared trainable weights; (B) GraphSAGE samples a fixed-size set of neighbors and aggregates their features (e.g., mean or max-pool) to build updated node representations; (C) GAT assigns attention coefficients to each neighbor, enabling the model to weigh their contributions adaptively during aggregation. GNN: Graph neural network; GCN: graph convolutional network; GAT: graph attention network.

Enhancements to GCNs: GraphSAGE

GraphSAGE employs sampling techniques to efficiently handle large-scale graphs[42]. Instead of aggregating information from all neighbors, GraphSAGE randomly samples a subset of neighbors for each node, substantially reducing computational overhead. Additionally, it supports multiple aggregation methods - such as mean, max, and long short-term memory (LSTM)-based approaches - offering flexible ways to combine node features and improving adaptability to diverse graph structures.

Figure 3B illustrates how GraphSAGE diverges from traditional GCNs: while standard GCNs incorporate information from every adjacent node, GraphSAGE’s sampling mechanism limits the number of neighbors considered at each layer. By enabling different aggregation strategies, GraphSAGE can better accommodate the varying dynamics and data distributions, significantly expanding its utility in domains where scalability is paramount. Similarly, it can be applied to modeling large-scale alloy structures, such as investigations of microscopic mechanisms at metal solid-liquid phase interfaces.

Graph attention networks: an improvement to GCNs

In addition to GCNs, graph attention networks (GATs) represent another significant advancement in the field of GNNs[43]. GATs introduce an attention mechanism that assigns different weights to each neighbor, automatically learned by the model. This approach allows the network to more precisely capture the varying importance of neighbors in heterogeneous graphs, resulting in enhanced performance. Moreover, GATs employ a multi-head attention mechanism, wherein multiple attention heads are applied in parallel and subsequently combine, boosting both the model’s stability and expressive power. Figure 3C illustrates how the attention mechanism functions in GATs. In each layer, GATs compute dynamic, learnable attention weights using a self-attention mechanism that considers both the features of the node itself and its neighbors. The multi-head attention setup aggregates the outputs of multiple attention heads, improving robustness and capturing a richer set of features. Consequently, GATs excel in tasks such as node classification, link prediction, and recommendation systems, where varying node importance plays a critical role.

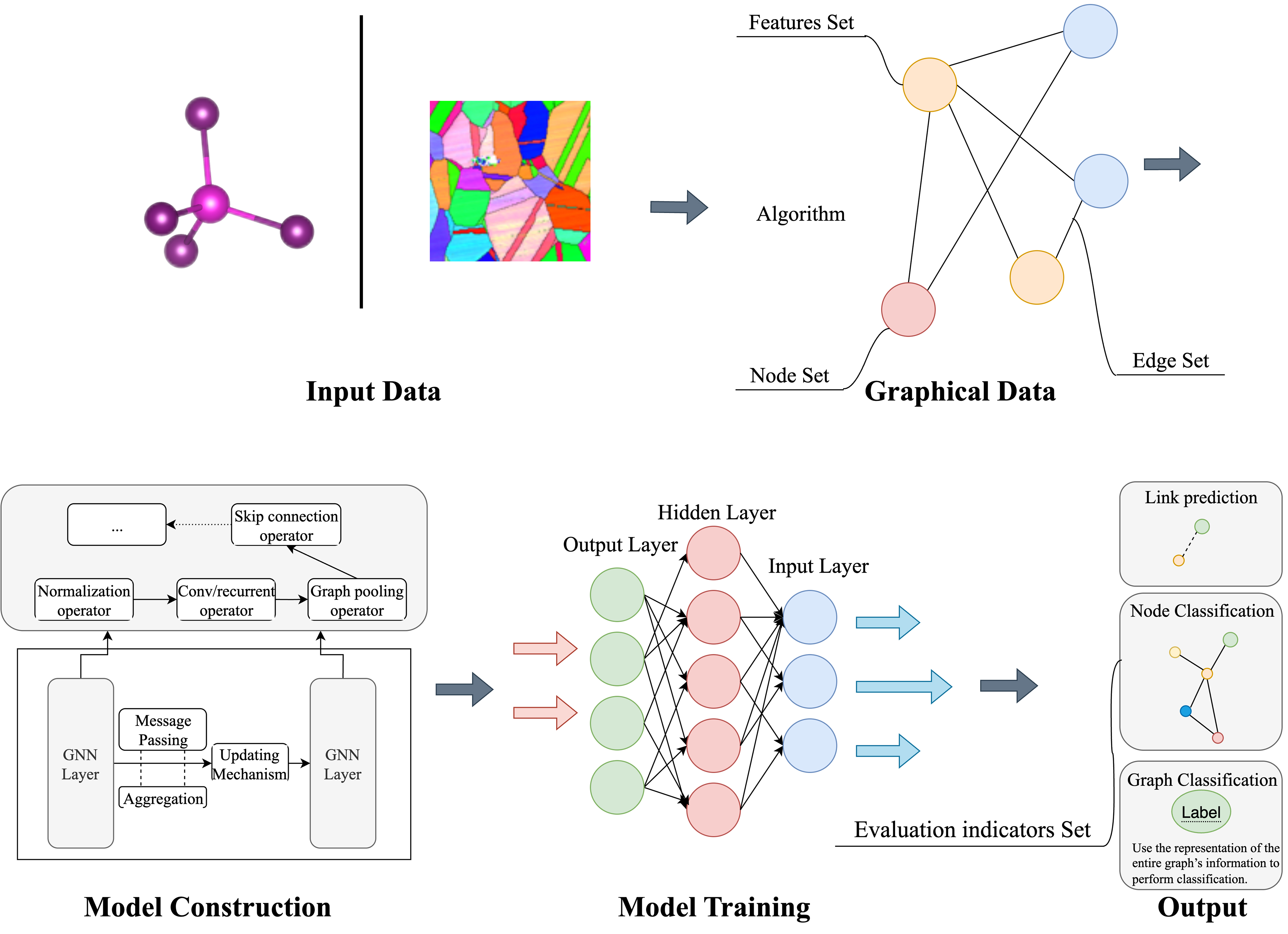

Workflow for constructing GNN tasks

Figure 4 illustrates the entire workflow of a GNN model from input data to final output predictions. Initially, the raw data is divided into training and testing sets, typically at a ratio of 4:1, and k-fold cross-validation can be employed to enhance model robustness. The data is then converted into a graph structure using specific algorithms, which involves defining nodes, edges, and their corresponding features. Feature selection usually emphasizes attributes highly correlated with the target task; for example, the stability of crystals is closely related to their structural features. Next, the GNN architecture is constructed, starting with normalization layers, followed by 3-5 graph convolutional layers. Dropout layers are added to prevent overfitting, and pooling layers are used for extracting essential features. Finally, during training, suitable optimizers, learning rates, and loss functions are established. Predictions are generated through forward propagation for each batch, and the differences between predictions and actual values (losses) drive parameter adjustments via back-propagation until the model converges.

Characteristics and constraints of GNNs

GNNs offer clear advantages for material research, especially in modeling structure-property relationships. However, the predictive accuracy of state-of-the-art GNNs is still constrained by several inherent architectural and data-related limitations. They naturally model graph-structured data (such as atoms and grain boundaries) by message passing[23] and aggregating features along edges, which lets them capture the complex relationships that govern material behavior. This end-to-end framework eliminates the need for manual feature engineering[36], speeding up development. Its multilayer design integrates information from local atomic arrangements all the way up to global microstructural patterns, yielding more accurate property predictions.

Although four key method-level hurdles remain, as shown in Table 2, each has now been met with promising solutions.

Method-level constraints of GNNs and their emerging remedies

| Core constraint | Why it matters | Typical remedies (recent progress) |

| High computational cost for large or dense graphs[44] | Full neighbor aggregation scales poorly | Neighborhood sampling (GraphSAGE), subgraph batching, sparse attention; GPU/TPU- friendly libraries |

| Feature degradation (over-smoothing) in deep stacks[45] | Node embeddings lose discriminative power | Residual or skip connections, normalization, positional encodings, hierarchical or attention-based pooling |

| Limited interpretability[46] | “Black-box” predictions hinder trust and deployment | Attention heat maps, GNNExplainer, gradient-based saliency, physics-guided constraints to expose decisive substructures |

| Heavy data demand and domain heterogeneity | Large labeled graphs are costly to curate | Self-supervised or contrastive pretraining, transfer learning across domains, data augmentation, federated or physics-informed training to boost sample efficiency |

Among these constraints, interpretability has received increasing attention. While GNNs offer strong predictive performance, their internal reasoning processes are often opaque. To improve transparency, several techniques have been developed. Attention-based models such as GAT and SAGNN learn importance weights for neighboring nodes, helping identify which parts of the graph most influence predictions. Additionally, methods such as GNNExplainer, gradient-based saliency maps, and feature masking reveal critical substructures or features responsible for specific outcomes. These techniques not only improve trust and understanding but also support model validation and refinement.

Continued advances in these four areas (scalability, representation quality, interpretability, and data efficiency) are the key to unlocking broader, more reliable GNN applications, including material discovery. Yet a critical gap remains: existing architectures rarely achieve all four goals while staying faithful to underlying physics across multiple length scales. The remainder of this review is therefore structured to confront this gap by mapping recent methodological progress, benchmarking their performance on alloy-relevant tasks, and distilling actionable guidelines that can steer the development of future, physics-consistent GNN frameworks for alloy modeling.

APPLICATION OF GNN IN MATERIALS SCIENCE

Since Kipf and Welling introduced the simplified and efficient GCN model in 2016, GNNs have found wide-ranging applications across various disciplines. Researchers in materials science have promptly embraced these methods for crystal structure analysis and material property prediction, thereby propelling materials research into a new data-driven era.

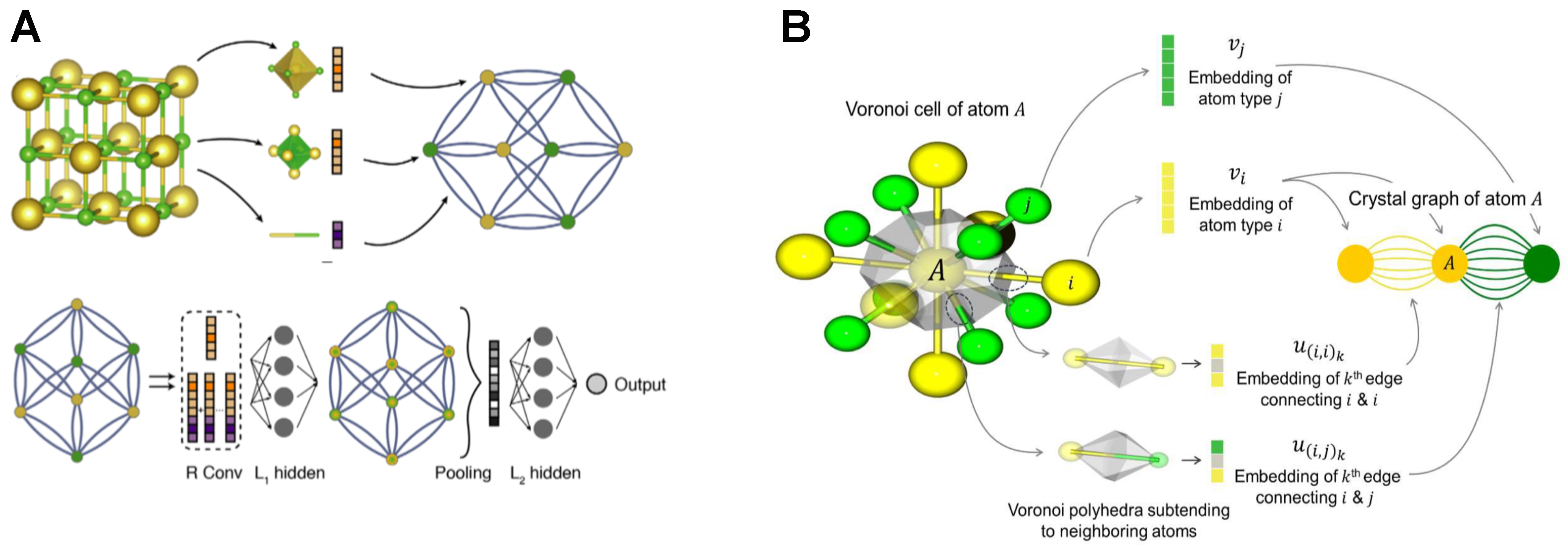

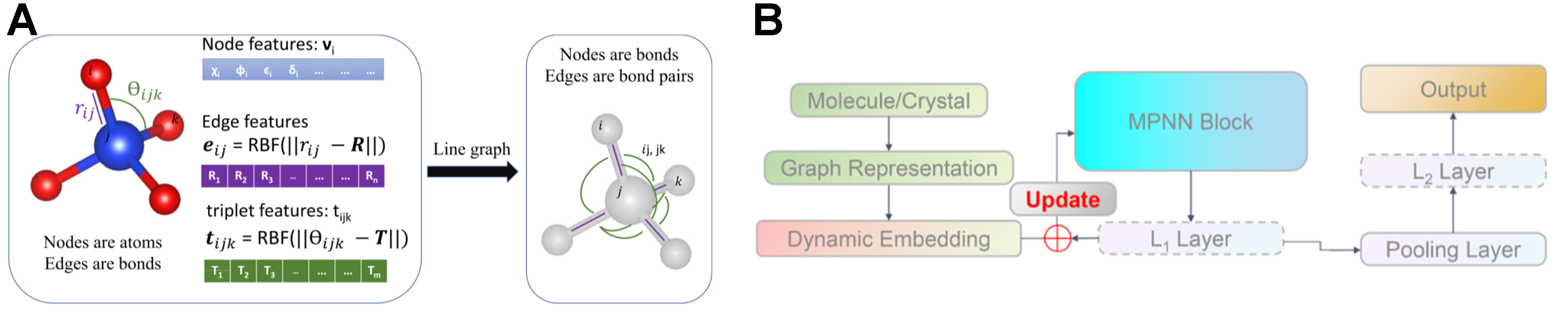

Among these advances, Xie and Grossman proposed the CGCNN[23], marking the first attempt to represent crystalline materials as graph structures for predicting their physical and chemical properties. The model uses graph layers, as illustrated in Figure 5A. In this approach, atoms in a crystal serve as graph nodes, while the chemical bonds among them form the edges. By capturing both local and global information, CGCNN achieves remarkable accuracy in predicting material properties. This pioneering framework has laid a robust foundation for subsequent research, offering scalability for tackling more complex problems.

Figure 5. Comparison of graph-conversion workflows and node-feature construction in (A) the original CGCNN and (B) its improved variant iCGCNN. (A and B) are reproduced from Refs.[23,34] with permission. Copyright © 2018 and © 2020, respectively, American Physical Society. CGCNN: Crystal graph convolutional neural network.

Building on CGCNN, Park et al. developed iCGCNN (Improved variant of the CGCNN)[34], which incorporates additional structural descriptors-such as Voronoi tessellations and atomic correlations-to refine the original framework. By integrating these features, iCGCNN reports roughly a 20% higher accuracy than CGCNN in predicting thermodynamic stability. Figure 5B illustrates how these enriched structural descriptors integrate into GNN. By integrating geometric features-such as bond angle information-into crystal representations within a GNN framework and optimizing the CGCNN architecture, these advancements show that GNNs can capture more microscopic details of materials, thereby enhancing their ability to predict material properties. This method also provides a clear roadmap for other researchers to optimize their own GNN models by incorporating additional structural descriptors (including local coordination) encouraging systematic exploration of how diverse physical features can further improve predictive performance across various material classes.

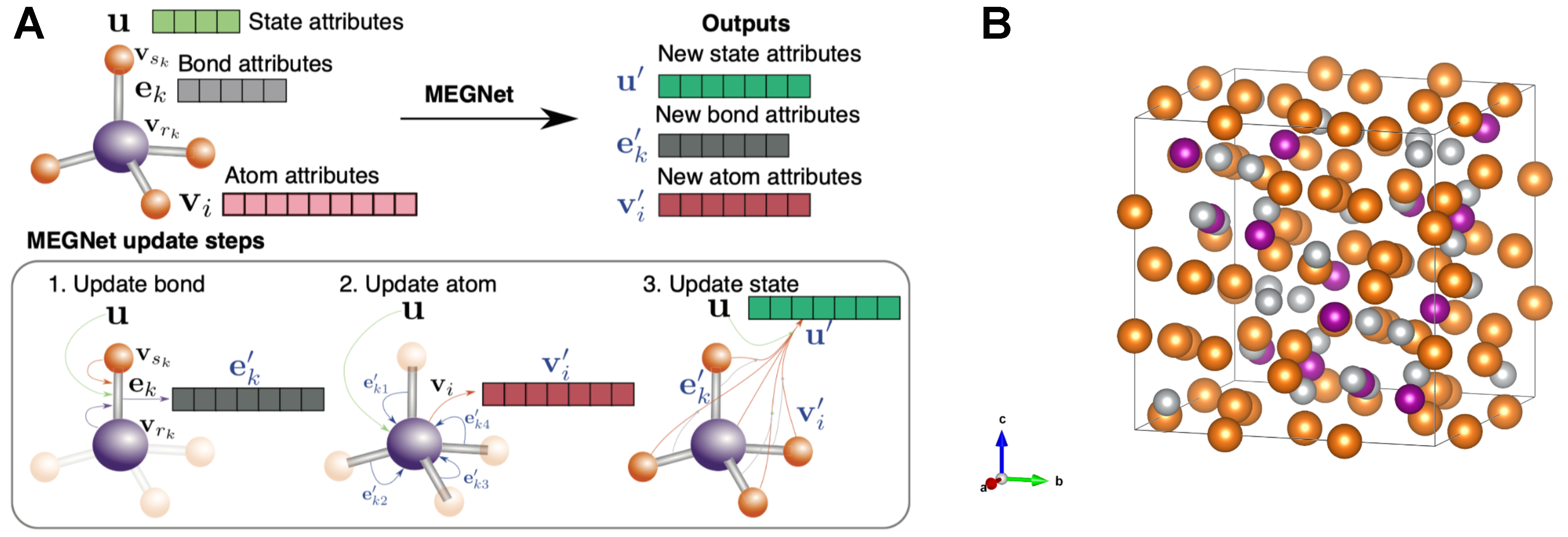

Chen et al. introduced the MEGNet[24], which builds on CGCNN by unifying molecular and crystalline systems within a single GNN framework and adding explicit edge-state and global-state updates. Instead of updating atom embeddings solely via neighbor aggregation, MEGNet applies three steps illustrated in Figure 6A: (i) refine each edges using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) on its connected atom features; (ii) update each atom by aggregating these refined bond messages; and (iii) update a global vector by pooling atom and bond information. By including physical state variables (e.g., temperature, pressure, entropy) in the global state, MEGNet can predict properties under specific conditions, whereas CGCNN is limited to static crystal representations. By treating the global context as a learnable feature, MEGNet offers a clear template for building condition-aware GNNs and invites the integration of additional environmental factors (e.g., electric or magnetic fields) to further boost predictive accuracy and accelerate materials discovery.

Figure 6. (A) Schematic of the MEGNet workflow: atoms are nodes, bonds are edges, and iterative message passing updates their features. Reproduced with permission from Ref.[24]. Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society; (B) Crystal structures of Mg-Ni-M ternary intermetallics studied here (M = Mn, Ti, Al, Ge); colors distinguish the three element types. MEGNet: Materials graph network.

Building on the MEGNet framework, Batalović et al. refined the network through transfer-learning to create MetalHydEnth[47], a task-specific model for predicting hydride-formation enthalpies in Mg-Ni-M (M = Mn, Ti, Al, Ge) ternary intermetallics. They kept MEGNet’s edge-node-global update cycle but (i) re-optimized weights on a curated hydride-enthalpy dataset; (ii) augmented the global state with composition-dependent descriptors that capture hydrogen content; and (iii) introduced a loss term that penalizes large deviations from experimentally known values. This specialization cut the mean-absolute error to ~5 kJ·mol-1 H2-comparable to density functional theory (DFT) accuracy and markedly lower than the generic MEGNet baseline. Leveraging this accuracy, the authors high-throughput-screened hundreds of Mg-Ni-M phases, swiftly pinpointing compositions whose predicted enthalpies fall in the thermodynamic “sweet spot” for reversible hydrogen storage [Figure 6B]. Their study exemplifies how MEGNet’s modular architecture can be adapted to new property targets and shows a clear path for extending GNN, driving discovery to other materials classes-such as catalysts or electronic compounds, by retraining on appropriate data and tailoring the global feature set.

Choudhary et al. advanced the field further by formulating the atomistic line GNN (ALIGNN)[48], which advances GCN-based models by incorporating bond angle information for more detailed structural analysis in complex materials. Figure 7A demonstrates how ALIGNN enhances the local geometric description using bond angles as additional features. This work underscores the importance of fine-grained geometric factors, such as bond angles and local atomic arrangements. And ALIGNN achieves superior accuracy compared to earlier models (such as CGCNN and MEGNet), especially when modeling and predicting properties of sophisticated material systems.

Figure 7. (A) ALIGNN architecture, which augments the atom-level graph with a line graph so that bond and bond-angle information is captured through coupled message-passing updates of atoms, bonds, and angles; (B) Efficiency-optimized graph neural model developed by Dong, featuring radial-basis edge encodings and adaptive interaction blocks that accelerate training while preserving accuracy. (A) reproduced from Ref.[48], copyright © 2021. (B) reproduced with permission from Ref.[49], copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society. ALIGNN: Atomistic line graph neural network.

Building upon previous messages-passing frameworks, Dong et al. subsequently optimized the message-passing mechanism within GNN models by integrating InforMax and dynamic embedding layers[49]. This approach reduced the number of message-passing layers while preserving prediction accuracy, addressing a critical limitation of earlier GNN models: computational efficiency at scale[50]. The streamlined message-passing structure depicted in Figure 7B illustrates how dynamic embeddings and information maximization strategies help balance efficiency and accuracy.

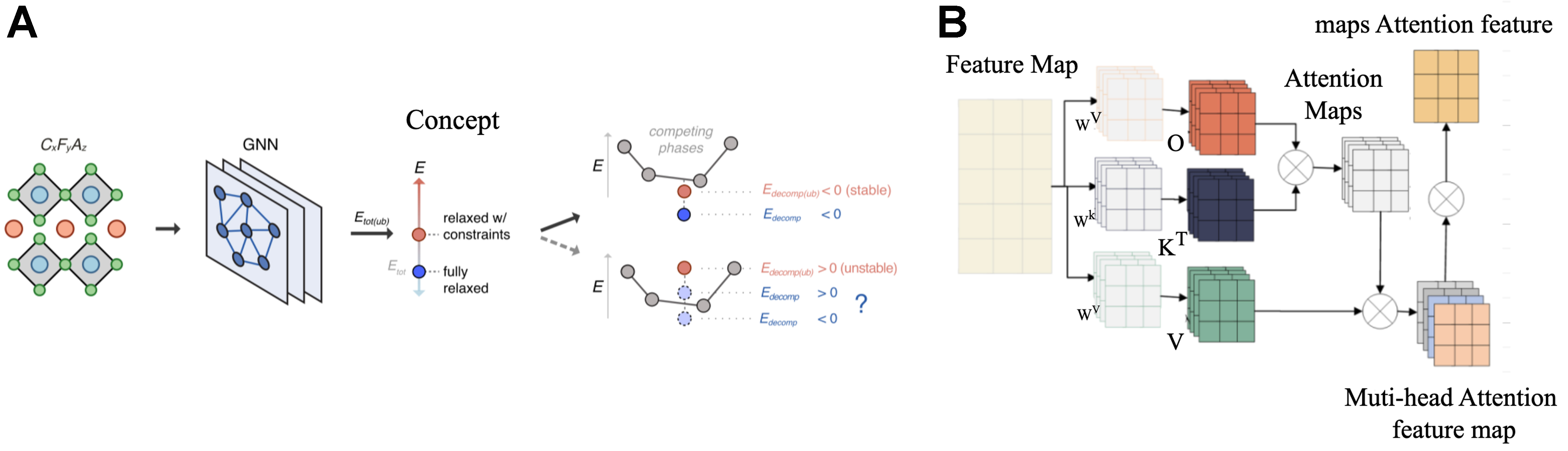

Law et al. made significant progress in investigating inorganic functional materials through GNN-based approaches[51]. By training models on data derived from DFT, Law’s team achieved over 99% accuracy in identifying novel stable structures, greatly shortening the screening time for materials and highlighting GNNs’ potential to accelerate materials research. This advancement is expected to guide ML-driven materials design, especially for effectively sifting through large-scale materials databases. Figure 8A demonstrates how the model is trained using DFT data. The model develops two-stage and GNN-driven pipeline that bypasses full DFT relaxations yet still pinpoints thermodynamically stable inorganic structures with remarkable fidelity.

Extending these approaches, Cui et al. presented the self-attention GNN (SAGNN)[52], which leverages multi-head self-attention mechanisms (MHSA) to enhance feature extraction capabilities. SAGNN substantially improved the prediction accuracy of band gaps, absorption energies, and formation energies by more effectively highlighting critical local structural features compared to traditional convolution-based methods. Figure 8B shows the architecture of SAGNN and the flow of data, showcasing how self-attention mechanisms enable nuanced modeling of complex relationships in materials, outperforming earlier convolutional GNNs such as CGCNN.

Chen et al. leveraged the materials graph network with 3-body interactions (M3GNet) model, a universal interatomic potential based on GNNs[53]. Unlike earlier GNN models designed primarily for specific materials or applications, M3GNet handles diverse multi-component systems uniformly by encoding elemental information into learnable embedding vectors. Trained on energy, force, and stress data, M3GNet accurately predicts various physical properties of materials. This universal and efficient solution for interatomic potentials spans all periodic-table elements, and the solution surpasses earlier models in terms of flexibility and applicability to materials discovery.

Lastly, Batatia et al. presented materials adaptive convolutional equivariants (MACE), a high-order message-passing neural network that was specifically designed to capture complex four-body interactions more explicitly than previous models[54]. This enhanced representation reduces iteration counts and accelerates computational convergence, delivering accuracy comparable to or exceeding state-of-the-art methods such as M3GNet. Empirical tests show that MACE meets or exceeds state-of-the-art accuracy on multiple benchmark tasks, while also accelerating convergence. Both M3GNet and MACE exemplify models that integrate many-body physics with GNN approaches for interatomic potentials; similar methods have also been adopted for structure-property studies[53-55].

Table 3 offers a compact snapshot of each model’s core upgrade, benchmark task, and reported improvement, making the evolutionary path from CGCNN to MACE immediately clear.

Comparative snapshot of milestone GNN architectures for materials modeling

| Model (year) | Key innovation(s) | Extra descriptors | Main target property and dataset | Reported performance gain* | Ref. |

| CGCNN (2018) | First graph representation of crystals message-passing GCN | - | Multi-property prediction - Materials Project 2018 | Baseline for later work | [23] |

| iCGCNN (2020) | Adds Voronoi tessellation and atomic-correlation descriptors | Local coordination geometry | Formation energy - MP + OQMD | ≈ 20 % ↓ MAE vs. CGCNN | [34] |

| MEGNet (2019) | Node–edge–global triplet updates; explicit global state (T, P, S) | Physical state vector | Energy, moduli, band gap - QM9 + MP | 10%-30% better than CGCNN | [24] |

| MetalHydEnth (2022) | MEGNet fine-tuned; H-content global feature; extra penalty loss | H-fraction, composition entropy | Hydride-formation enthalpy - curated Mg-Ni-M set | MAE ≈ 5 kJ·mol-1 H2 (≈ DFT) | [47] |

| ALIGNN (2021) | Line-graph message passing; explicit bond-angle features | Bond angles, 2nd-neighbor info | Elastic and electronic properties - MP-2020 | ≤ 25 % ↓ MAE vs. CGCNN/MEGNet | [48] |

| InforMax-GNN (2023) | InforMax loss + dynamic embeddings; fewer MP layers | - | Multi-property - AFLOW set | Same accuracy with 1/2 layers | [50] |

| Law pipeline (2022) | Two-stage GNN + DFT-based stability classifier | Pre-relax E, stoichiometry | Formation-energy hull - 90 k structures | > 99% stable-phase recall | [51] |

| SAGNN (2024) | Multi-head SAGNN | Attention weights on bonds | Band gap, absorption, formation E - MP | 5%-15% ↑ vs. conv-based GNN | [52] |

| M3GNet (2023) | Universal interatomic potential; element embeddings; predicts E/F/σ | All-element embeddings | Energies, forces, stresses - ≈ 7 M configs | DFT-level MAE; universal | [53] |

| MACE (2024) | High-order (4-body) message passing; fewer iterations | N-body tensors | Forces/energies MD, QM9 | SoTA accuracy, faster conv. | [54] |

APPLICATIONS OF GNN IN ALLOY DESIGN

High-throughput experiments and multiscale simulations now supply abundant data for data-driven alloy design. The main task is to uncover reliable structure- and composition-property links without losing speed or physical realism. First, we show how GNNs embed grain topology, crystallographic orientation and multiphysics fields into graphs, replacing finite-element, phase-field and DFT calculations in milliseconds with near-ab-initio accuracy. Next, we review composition-driven design, where GNNs and generative models traverse vast compositional spaces, optimize multiple objectives and steer targeted experiments. Together these routes form a data–model–property triad that makes GNNs a key accelerator for alloy discovery and microstructure control.

Material property prediction and microstructure characterization

In alloy design, predicting material properties is a critical task. Traditional methods for prediction typically rely on extensive experimental data and complex physical models, which are often inadequate for multi-component alloys with intricate interactions. With the advent of GNNs, researchers have started to explore more efficient and accurate ways to map alloy composition to performance, particularly in forecasting key properties such as mechanical performance.

Polycrystal-scale elasticity

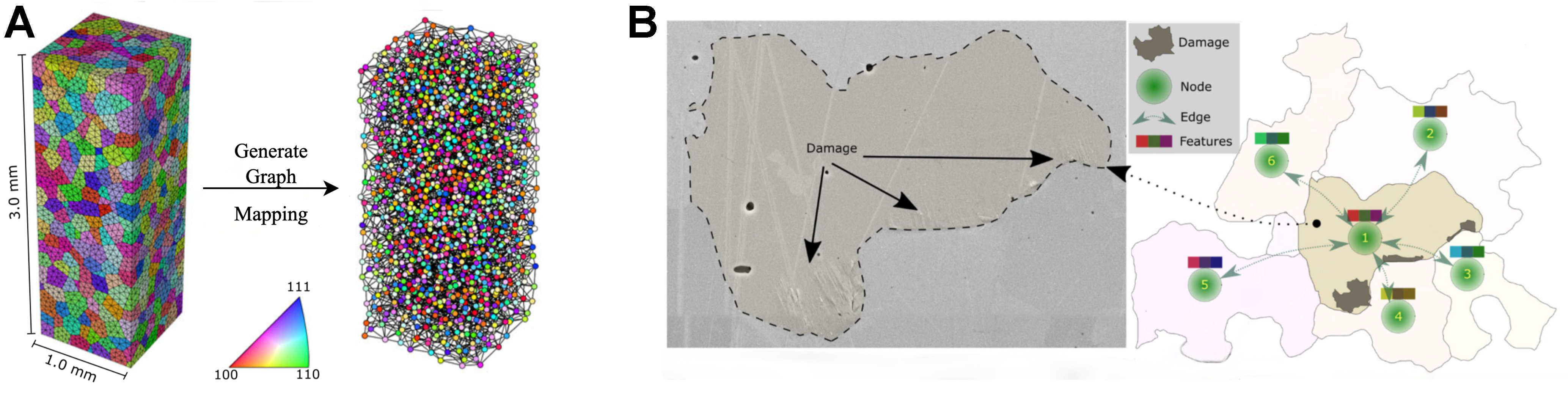

Pagan et al. laid the groundwork for grain-level GNN surrogates by training a message-passing network on crystal-elastic finite element method (FEM) data and fine-tuning it with high-energy X-ray diffraction microscopy (HEDM) measurements [Figure 9A]; using grain orientation, directional modulus and volume as node features and shared boundaries as edges. Then their model reproduced the anisotropic stiffness of a low-solvus, high-refractory (LSHR) alloy and Ti-7Al with 5%-10% error[56].

Figure 9. (A) Pipeline for mapping crystallographic graphs to direction-dependent elastic constants; grains are treated as nodes and grain-boundary misorientations as weighted edges, enabling anisotropic elastic behavior to be learned directly from the topology; (B) Graph-transformation scheme for ferritic steel, in which microstructural snapshots are converted into time-evolving graphs whose updated edge weights capture damage accumulation and allow high-cycle fatigue life to be predicted. These examples illustrate how bespoke graph representations can be tailored to very different mechanical-property targets. Reproduced with permission from Refs.[56,63]. © 2022 and © 2023 The Authors.

Building on this grain-scale graph representation, Hu et al. introduced AnisoGNN, which augments every node with symmetry aware descriptors such as Schmid factors; a single network therefore recovers elastic moduli and initial yield strength for nickel superalloys and aluminum alloys under arbitrary loading directions with high fidelity[57]. In parallel, Hestroffer et al. transferred the same architecture to crystal plasticity finite element data for α-titanium[58], achieving accurate single-axis predictions of yield strength and Young’s modulus while cutting computational cost by orders of magnitude. To explore coupled fields, Dai et al. combined phase field snapshots with a graph network to capture effective magnetostriction in ferromagnetic polycrystals[59] and later used Fourier perturbation data to predict ionic conductivity together with elastic moduli along three principal directions[60]. Vlassis et al. advanced the framework further by training a graph network to output a differentiable hyperelastic energy functional, allowing downstream continuum solvers to derive stresses directly from the learned potential[61]. Finally, Hu et al. added edges to construct a temporal GNN (TGNN) that tracks grain growth and texture evolution across time, successfully reproducing microstructural kinetics at a fraction of the phase field cost[62].

Taken together, these studies trace an explicit upgrade path-static elasticity, plasticity, multi-physics tensors, energy functional learning, and microstructure dynamics-while retaining the grain graph backbone established by Pagan, underscoring the versatility and scalability of GNNs for polycrystal property prediction.

Fatigue and hardness from EBSD graphs

In the seminal study by Thomas et al., electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) orientation maps of ferritic steel were transcribed into grain-boundary graphs (grains became nodes and shared boundaries became edges) so that a GNN could learn which grains initiate slip traces and micro-cracks during high-cycle fatigue[63]. The model outperformed support-vector machines and multilayer perceptrons in classifying damaged grains, proving that message-passing on an EBSD graph captures the essential crystallographic interactions that drive local fatigue behavior; Figure 9B visualizes this EBSD-to-graph encoding and its mapping to microstructural patterns.

Subsequent studies preserved this graph backbone while enriching the mechanical targets and widening practical utility. Karimi et al. predicted continuous nano-hardness values in 310S stainless steel using only grain orientation and neighbor information, achieving < 10% error and demonstrating regression capability on the same EBSD graph[64]. FIP-GNN - Graph neural networks for scalable prediction of grain-level fatigue indicator parameters - then introduced physics-based fatigue-indicator parameters as labels and a tiling strategy that scales predictions to microstructures far larger than those seen in training, addressing volume-size limitations[65]. Finally, Hansen et al. coupled GNN outputs with symbolic-regression techniques to derive closed-form expressions linking grain features to fatigue driving forces, supplying the interpretability needed for engineering adoption[66].

Together these works chart a coherent progression-from binary damage detection to quantitative hardness, physics-consistent fatigue metrics and human-readable design rules - showcasing how GNNs systematically translate EBSD-encoded microstructure into ever richer and more actionable mechanical insights.

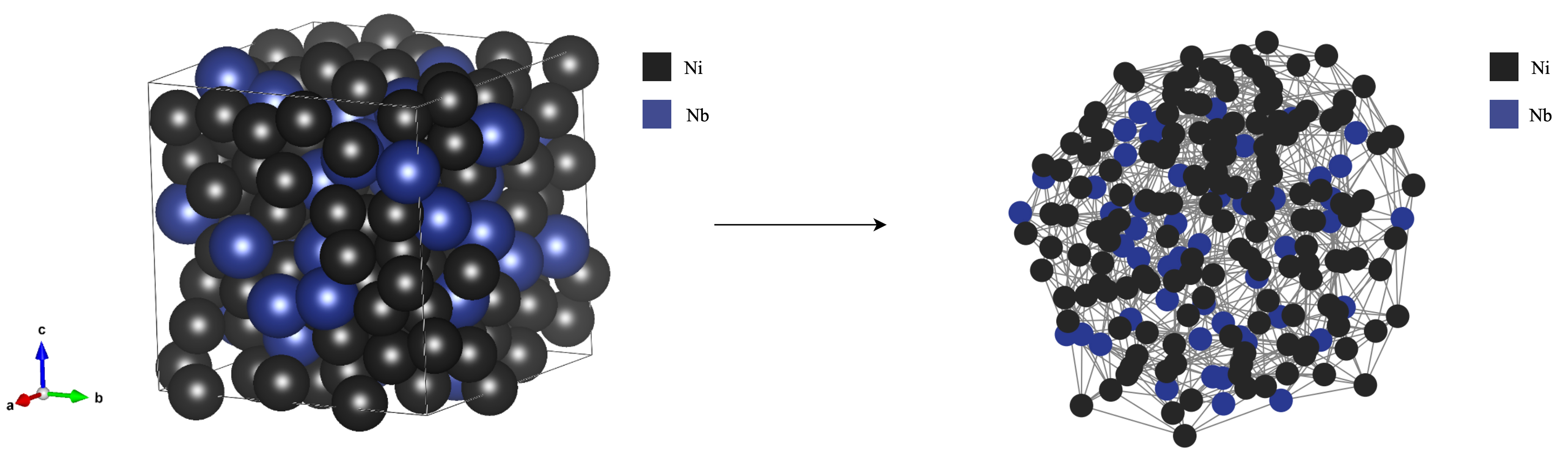

Crystal-structure graphs for formation energy

The graph-based representation pioneered by Lupo Pasini et al. begins with a rigorously constructed CGCNN that encodes the Ni-Nb binary alloy as an atomistic graph, where each atom is a node and each chemical interaction is an edge; Figure 10 illustrates this conversion in detail. Training on density-functional-theory data, the model reproduces formation energies and bulk moduli with near-DFT accuracy while running three orders of magnitude faster, thereby demonstrating that a properly designed GNN can replace brute-force quantum calculations for routine screening of crystal prototypes[67,68]. This binary proof-of-concept validates the sufficiency of simple node and edge attributes-atomic number, fractional coordinates and bond distances-to capture the essential physics governing cohesive energy and elasticity.

Figure 10. Binary-alloy structure conversion to a graph representation. The crystalline super-cell is first tiled to expose periodicity, after which each atom is mapped to a node carrying its element type, and every pair of atoms within a chosen cutoff radius is mapped to an edge weighted by inter-atomic distance. The resulting graph preserves both chemical identity and local geometry, providing a compact input for GNNs that predict alloy properties while remaining agnostic to cell size. GNNs: Graph neural networks.

Building on that foundation, subsequent studies progressively expand both chemical scope and task specificity. MEGNet couples the original node-edge graph with a learnable global state vector, enabling a single network to predict more than a dozen properties across most of the periodic table[69]. Intermetallics graph neural network (IGNN) then fine-tunes this backbone with a density-focused loss to reduce errors on heterogeneous intermetallic datasets[70]. Building on CGCNN[23], a variant tailored to battery research integrates electrochemical labels and high-throughput databases to identify over one hundred low-voltage alloy anodes without additional DFT relaxations[71].

Works above trace a coherent trajectory from a binary demonstrator to a universal backbone and, ultimately, to specialized discovery tools, underscoring the pivotal role of GNNs in converting atomic connectivity into reliable, scalable predictors for alloy design.

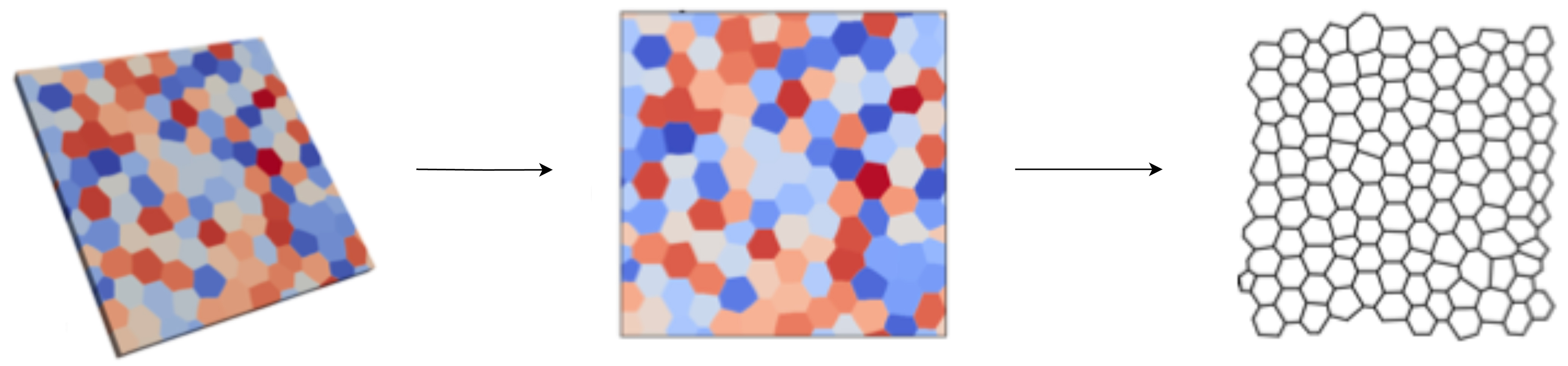

Dynamic microstructure evolution

Qin et al. introduced GrainGNN, a dynamic graph-neural surrogate that tracks grain coarsening during rapid solidification by representing every time step as a graph whose nodes are grains and whose edges are shared boundaries[72]. Grains that merge or vanish are handled through a classifier predicting topological events, while a separate regressor updates boundary motion; the network reproduces phase-field statistics with > 80% pointwise fidelity yet runs 102-103 × faster. To visualize these predictions, Figure 11 explains the compression of grain evolution during solidification to a 2D graph representation.

Figure 11. Compression of grain-evolution data during solidification into a two-dimensional graph representation. Successive 3D microstructure snapshots are projected onto a plane; each grain becomes a node whose color encodes crystallographic orientation, while shared grain boundaries are converted to edges weighted by boundary length. This 2D graph retains the essential topological information needed to track grain coalescence and growth kinetics with greatly reduced storage and computational cost. Adapted from Ref.[72], copyright © 2024 Elsevier Inc.

Meantime, Hu et al. proposed a TGNN that keeps the grain graph fixed but augments each node with time-series features such as orientation tensors[62]; stacked time-convolution and recurrent units propagate history-dependent information, enabling accurate cross-scale forecasts of texture evolution under mechanical loading. Together, GrainGNN and TGNN cover the two principal facets of microstructural kinetics: GrainGNN excels when grains appear, merge or disappear, whereas TGNN excels when grain identities persist but properties evolve continuously. Used sequentially-first GrainGNN for the as-solidified state, then TGNN for service-time evolution, the two frameworks outline a fully GNN-driven pipeline for process-to-performance alloy design.

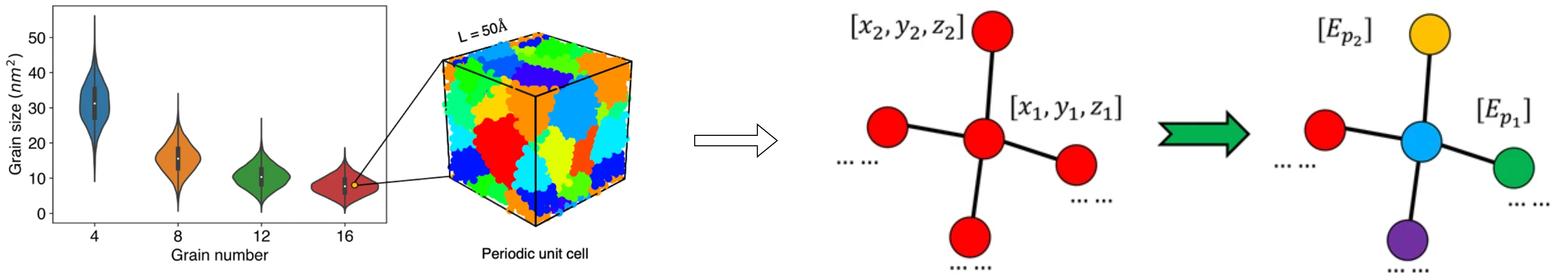

High-entropy and multi-component alloys

Wang et al. applied GNNs to predict solidus and liquidus temperatures, introducing an efficient and accurate model (AlloyGCN)[73] that makes predictions based on the alloys’ microstructural features. By incorporating explainable AI techniques, AlloyGCN provides an in-depth view of its decision-making process and demonstrates predictive accuracy comparable to CALculation of PHAse Diagrams (CALPHAD) methods, significantly reducing dependence on thermodynamic databases. In a similar vein, Beaver et al. proposed a GNN (ALIGNN-FF)-based approach for rapid, reliable, and cost-effective structure determination of single-phase HEAs[74]. Tested on 132 distinct alloys, their model notably surpassed traditional valence electron concentration (VEC)-based methods in accuracy, successfully predicting the stable body-centered cubic (BCC) structure of a cobalt-free 3D HEA-a result later validated by experiments. Complementing these efforts, another team represented short range atomic environments as local environment sets and trained the LESets graph network to link these motifs with mechanical properties such as yield strength and hardness, yielding an interpretable pathway from chemical complexity to macroscopic performance[75]. Collectively, these studies show that GNNs now support every stage of high entropy alloy discovery, from phase boundary estimation through structure selection to property ranking, while offering transparent descriptors and marked gains in computational efficiency.

Studies suggest that by integrating material-specific physical attributes within GNN architectures[57], it is possible to effectively elucidate the linkage between microstructure and macroscopic performance.

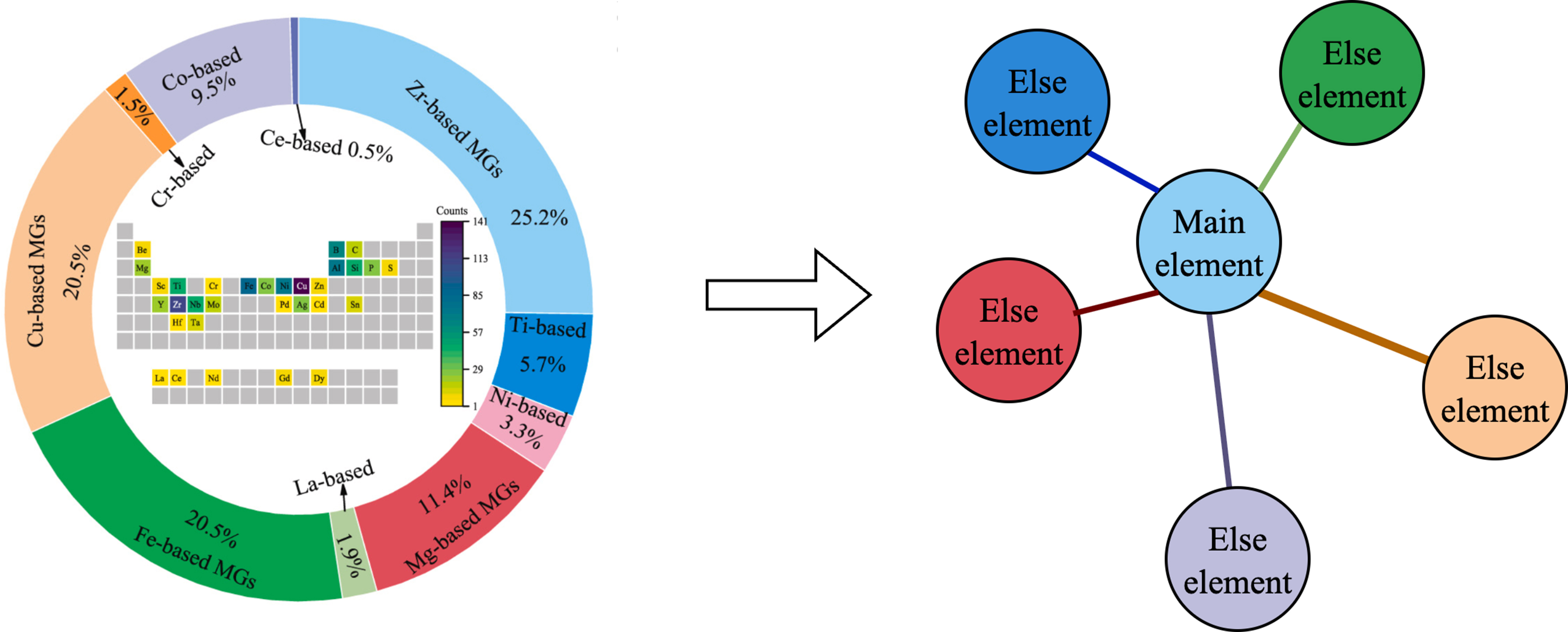

Composition design

Scholars have utilized GNNs to assist in alloy composition design. In particular, Long et al. presented a composition-to-property network for bulk metallic glasses (BMGs) that converts an alloy formula into a graph, whose nodes carry elemental descriptors and whose edges encode bond strength[76]. The end-to-end model learns latent correlations between short-range atomic topology and macroscopic mechanical strength, providing quantitative guidance where empirical rules fail. Figure 12 shows the graph construction pipeline and illustrates how the learned edge features highlight critical element-element interactions that govern BMG toughness.

Figure 12. Graph representation of alloy composition for mechanical-property prediction. Each node denotes an alloying element, and each edge represents the correlation between a pair of elements and the target property. Edge color encodes correlation strength - lighter tones indicate weaker relationships, while darker tones mark stronger ones - and edge width scales with the same metric to aid visual comparison. Adapted from Ref.[76], copyright © 2024 Elsevier Ltd.

Additionally, Yang et al. extended the paradigm to crystalline systems containing defects[77]. Using 2,000 graphene biocrystals and three-dimensional Al polycrystals generated by molecular dynamics simulation (MD), they trained a graph network to regress per-atom stresses from connectivity alone, achieving a 5.5% test error. Coupling the trained surrogate with a genetic algorithm enabled inverse design of stress-mitigating local structures, opening a route to defect-centric optimization. Figure 13 depicts the edge-only graph representation and the resulting stress-field prediction around grain boundaries.

Figure 13. Graph-neural model for atomic-stress prediction in defect-containing crystals. Atoms serve as nodes tagged by grain ID, nearest-neighbor bonds form edges, and message passing embeds grain-boundary and defect context before stress read-out. Adapted from Ref.[77]. © 2022 The Authors.

Furthermore, leveraging density-functional datasets, Zhou et al. built the adsorbate-site GCN (ASGCNN) to model nitrogen adsorption on Heusler surfaces[78]. Trained on 6,000 active-learning-selected structures, the network ranks candidate surfaces by binding free energy, then filters them with a desorption criterion to expose alloys suited for electrochemical nitrogen reduction. Subsequent DFT verification confirmed the catalytic promise of the top-ranked compositions, underscoring the synergy between graph learning and first-principles data in composition screening.

Unsupervised and self-supervised GNN techniques for alloy design

Beyond representation learning, recent developments have explored generative GNNs that directly synthesize alloy structures with desired properties, forming a natural extension to unsupervised encoders.

Contrastive learning for graph embeddings in small-sample alloy datasets

Contrastive learning enables robust representation learning from limited labeled data by leveraging large-scale unlabeled crystal structure datasets in a self-supervised manner. CrystalCLR, for instance, applies domain-specific augmentations-such as bond perturbations, and unit-cell rotations-to generate positive pairs from the same crystal graph and employs an NT-Xent objective to draw these representations closer while repelling those of different materials. During pretraining, a shared GNN encoder (e.g., CGCNN) processes each augmented view to produce node- or graph-level embeddings, which are then projected into a contrastive space via a two-layer MLP projection head. Because no property labels are required at this stage, the encoder learns generalized atomic- and crystal-level features purely from the structural graph topology and chemical attributes[79].

Designing augmentations that reflect true chemical and crystallographic variations is essential. Common strategies include masking atomic sites to mimic defects, perturbing bond weights to simulate thermal fluctuations, cropping local subgraphs to capture grain boundary effects, and randomly rotating the unit cell to enforce rotational invariance. When selecting negatives, treating every other crystal as a negative can cause “sampling collapse” if alloys share similar compositions; avoiding this involves excluding chemically close structures, using a memory bank to enlarge the negative pool, or filtering by composition distance based on phase-diagram data. Such measures preserve meaningful chemical relationships and prevent over-separation of related alloys.

For evaluation under data-scarce regimes, practitioners typically employ k-fold cross-validation (k = 5-10) or leave-one-alloy-out testing. Across multiple studies, GNNs pretrained with contrastive learning outperform randomly initialized models, yielding lower mean absolute error (MAE) on tasks such as formation energy, density, and band-gap prediction. Moreover, recent multimodal frameworks that link crystal graphs with textual descriptors have shown zero-shot generalization to new composition spaces after fine-tuning on as few as ~100 labeled samples. These results confirm that contrastive learning effectively addresses data scarcity by producing transferable, high-quality embeddings from large unlabeled crystal datasets[80].

GAEs and masked-node prediction for feature extraction

GAEs learn compact node or graph representations by reconstructing input graphs through encoder–decoder pipelines in an unsupervised manner. Variational graph autoencoders (VGAEs) impose a probabilistic Gaussian prior over node embeddings, enabling robust modeling of uncertainty in node features and graph connectivity; although VGAEs were originally demonstrated on citation-network benchmarks, they can be adapted to crystal graphs to capture structural variability[81]. Masked-node prediction methods such as GraphMAE randomly hides node attributes during encoding and train decoders to recover these masked features, resulting in enriched structural representations from material graphs[82]. MaskGAE extends this paradigm by masking edges instead, reconstructing adjacency relations and thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture global topology in crystal and microstructural graphs[83].

In alloy design, crystal diffusion variational autoencoder (CDVAE) adopts a VGAE-inspired architecture for periodic crystal graphs: its encoder learns to denoise perturbed atomic coordinates via equivariant networks, while its decoder reconstructs stable lattice configurations through Langevin dynamics[84]. Pretraining a GAE on large unlabeled alloy crystal databases - such as HEA structures - produces embeddings that cluster similar phases, which downstream regression or classification models can fine-tune with limited labeled data[36]. GraphMAE2’s multi-view re-mask decoding strategy regularizes reconstructions in both feature and embedding spaces, mitigating over-smoothing and improving discriminability for tasks[85]. Hierarchical masked autoencoders such as Hi-GMAE mask nodes at coarser graph hierarchies and progressively reconstruct finer-scale features, effectively fusing global and local topology information in multi-component alloys[86].

Limitations of self-supervised/unsupervised GNNs and future directions

Although self-supervised and unsupervised GNN methods help mitigate the scarcity of labeled alloy data, they still encounter several obstacles. Contrastive learning often treats every other crystal as a negative sample, which can inadvertently push apart chemically similar alloy compositions and degrade feature quality. Without chemistry-aware sampling rules, the model may emphasize superficial differences rather than meaningful atomic motifs. Likewise, GAEs and masked-node approaches typically rely on high masking rates to learn robust representations, but masking too many atoms or bonds in a crystal graph risks over-smoothing: the decoder may reconstruct only coarse approximations of microstructural details, especially at grain boundaries or defect sites that crucially influence alloy behavior. Moreover, there is no standardized benchmark for comparing these unsupervised methods across different alloy datasets-studies frequently use distinct sources, splits, and metrics-so a model pretrained on one corpus may lose effectiveness when fine-tuned on another alloy system.

Finally, most existing work lacks interpretability: little effort has been made to explain how self-supervised features correlate with actual physical properties, which limits industrial adoption. Moving forward, integrating chemistry-aware negative sampling (for example, filtering negatives by phase-diagram proximity), adopting hierarchical masking that preserves local context, and pretraining on large, multi-source collections of crystal and microstructure graphs-followed by few-shot fine-tuning or meta-learning, could improve transferability and reduce over-smoothing. Embedding physics or thermodynamic constraints directly into self-supervised objectives, as well as incorporating multi-task goals such as reconstructing local strain fields alongside topology, will further enhance interpretability. By addressing these challenges, future self-supervised and unsupervised GNNs can yield more reliable, generalizable representations that accelerate data-efficient alloy discovery.

To offer a concise overview, Table 4 summarizes key developments in terms of application areas, alloy types, GNN models, and their respective outcomes.

Summary of application of GNN in alloy design

| GNN application domain | Alloy/system types | Representative models | Key outcomes |

| Polycrystal elasticity domain | Ti-7Al, Ni superalloys, Al alloys | AnisoGNN, GrainGNN, TGNN | 5%-10% error in stiffness prediction[56,57] |

| Fatigue and hardness from EBSD graphs | Ferritic steel, stainless steel | FIP-GNN, symbolic-GNN | < 10% error in nano-hardness; interpretable fatigue models[50,51,53] |

| Crystal structure energy prediction | Ni-Nb binaries, intermetallic | CGCNN, MEGNet, IGNN | Nearly DFT accuracy; 1,000× faster screening[54,55,69,70] |

| Dynamic microstructure evolution | Polycrystalline microstructure (solidification) | GrainGNN, TGNN | 80%+ fidelity, 100-1,000× speed-up vs. phase-field[72] |

| High-entropy and multi-component alloys | HEAs, medium-entropy | AlloyGCN, ALIGNN-FF, LESets | Improved accuracy vs. CALPHAD/VEC; interpretable[73-75] |

| Composition design | BMGs, defective crystals, heusler | Graph-based property networks, ASGCNN | Composition-to-strength correlation; inverse design[63,78,76] |

| Unsupervised/self-supervised learning | Crystal graphs, HEA databases | CrystalCLR, GraphMAE, CDVAE | Improved low-data performance; generalizable embeddings[79-86] |

| Universal alloy property prediction | Binary alloys[69,70] | MEGNet, IGNN | Generalizable prediction across alloy families; supports high-throughput screening |

| Micro-mechanism characterization | Crystal grain boundaries[49,72] | GrainGNN, TGNN | Grain evolution and phase transition simulation; boundary-level quantitative insights |

| Specialized architecture design | Polycrystalline and atomic systems | GCNN, GrainGNN, ALIGNN | Scenario-specific GNNs improve structural resolution and scale flexibility |

| First-principles data integration | DFT-based alloy systems[56,75,78] | MEGNet, CDVAE, ALIGNN-FF | 1-3 orders of magnitude speed-up while maintaining DFT-level accuracy |

| Physics-informed design in manufacturing | Additively manufactured alloys | Physics-constrained GNNs | High predictive fidelity + domain knowledge → better microstructure control |

CUTTING-EDGE GNN APPLICATIONS IN MATERIALS AND ALLOY RESEARCH

Recent advances demonstrate that GNNs now support the entire computational pipeline for alloy discovery-from generative design and rapid property evaluation to multiscale simulation and domain knowledge-driven optimization.

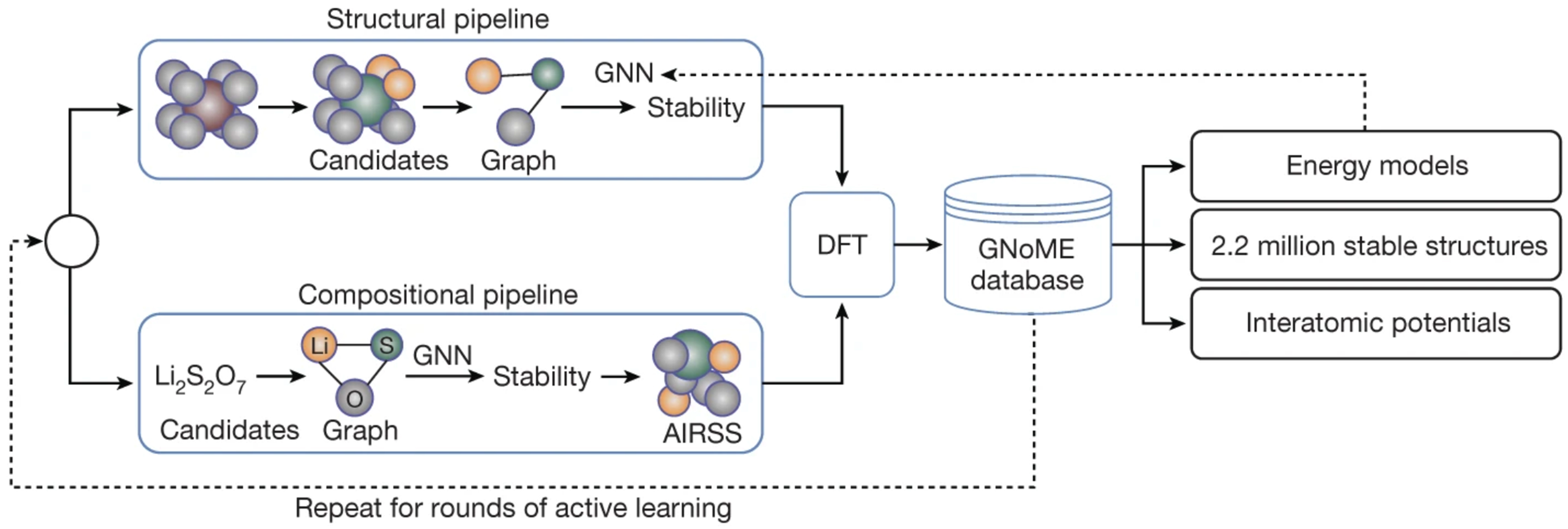

Generative and inverse design

Google DeepMind, in collaboration with the Berkeley Lab, developed the advanced active-learning deep learning tool - graph networks for materials exploration (GNoME)[87], aiming to expedite material discovery by predicting the structure and stability of novel materials-effectively addressing the time- and cost-intensive nature of conventional experimental approaches. The latest public release enumerates > 3.8 × 105 stable phases, expanding the Materials Project catalogue by almost an order of magnitude. Figure 14 illustrates how GNNs, by representing intricate atomic structures as graphs, capture the complex interatomic relationships necessary to accurately forecast material stability. The trained GNN model rapidly generates large volumes of candidate materials without requiring real-world experimentation, drastically reducing the initial screening phase.

Figure 14. GNoME framework. GNNs are employed to efficiently predict both the properties and structural stability of candidate crystals. Reproduced from Ref.[87], copyright © 2023, The Author(s). GNoME: Graph networks for materials exploration; GNNs: graph neural networks.

Moreover, the AI4S group from Microsoft introduced MatterGen[88], a framework that employs a diffusion-based generative process to iteratively refine atomic types, coordinates, and periodic lattices to construct crystal structures. In this approach, GNNs represent and process the crystal lattice, enabling MatterGen to generate new structures that meet specified property constraints; the model can then be fine-tuned for particularly performance requirements, functioning as a form of high-throughput virtual experimentation. In parallel, discriminative GNNs which are exemplified by the CGCNN[23] remain invaluable for rapid post-generation triage; recent work achieved a true-positive rate of 95% when predicting the synthesizability of double-halide perovskites[89].

GNN surrogates for quantum calculations

Beyond generation, GNNs increasingly substitute conventional quantum calculations. The universal interatomic potential M3GNet attains near-DFT accuracy across the periodic table while being three orders of magnitude faster, enabling large-scale molecular-dynamics simulations that were previously infeasible[53]. Comparable all-periodic-table performance has recently been reported for the equivariant CHGNet potential[90]. Park et al. further demonstrated that a direct-force GNN architecture delivers ab-initio-quality forces while outperforming classical potentials in both accuracy and scalability for large systems[91]. Finally, M3GNet-guided cluster-expansion workflows have been applied to multi-component and HEAs, reducing the configurational-averaging cost by roughly an order of magnitude without sacrificing phase-stability predictions[92].

High-throughput discovery and screening with GNNs

High-throughput methods accelerate materials discovery by enabling automated evaluation of vast design spaces, and their integration with GNNs offers a scalable solution for predicting materials properties with near-DFT accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost.

Wu et al. coupled CGCNN with van-der-Waals DFT screening to evaluate 5,000+ 2D monolayers for catalytic and electronic properties[93]. Elrashidy et al. combined ALIGNN with a variational autoencoder to generate 11,000 magnetic candidates, successfully validating 167 new 2D magnets[94]. Sibi et al. used ALIGNN to predict work functions for thousands of 2D materials, achieving high accuracy and transferability to MXenes[95]. Rahman et al. applied GNNs to screen over 10,000 bulk and surface structures for defect information energies using a DFT-trained surrogate model[96]. Google DeepMind’s GNoME framework predicted stability for over 390,000 hypothetical inorganic crystals, expanding the Materials Project database by nearly 10 times[87]. Microsoft’s MatterGen used a GNN-guided diffusion model to generate crystal structures matching predefined property constraints. Vazquez et al. integrated GNN surrogates with cluster expansion methods for HEA phase screening, reducing DFT computation time by an order of magnitude[92].

Multiscale dynamics and physics-informed models

Graph-based surrogates are now being extended beyond static property prediction to capture time-dependent phenomena across multiple length scales, thereby complementing or replacing computationally intensive physics solvers.

At the mesoscale, Qin et al. encoded the evolving grain topology that arises during rapid solidification of HEAs as a dynamic graph and trained GrainGNN on phase-field trajectories; the network reproduces grain-growth kinetics while delivering speed-ups of two to three orders of magnitude relative to conventional phase-field integrations[72]. Moving to the atomistic regime, Ehsan et al. coupled hybrid Monte-Carlo/MD simulations with a graph-convolutional network that predicts the potential energy landscape of medium-entropy alloys, demonstrating that a local chemical ordering signal extracted from GCNN embeddings can faithfully track thermodynamic equilibration over a wide temperature range[97]. At still larger scales, Tian

Taken together, these studies illustrate a coherent progression: graph surrogates first replicate mesoscale grain evolution, then atomistic energetics, and finally bridge to continuum-scale constitutive behavior through physics-aware loss functions.

Knowledge integration and autonomous agents

Recent studies highlight how graph-based surrogates can be embedded in higher-level reasoning frameworks to unlock autonomous decision-making in alloy research. Ghafarollahi and Buehler coupled a property-predicting GNN with a suite of large-language-model (LLM) agents[99]; the LLMs handle task planning and hypothesis generation, while the GNN supplies rapid estimates of Peierls barriers and dislocation–solute interactions, enabling the multi-agent system to chart the Nb–Mo–Ta design space with a fraction of the computational cost required by direct atomistic simulation. Complementing this top-down strategy, Qi et al. introduced knowledge-driven graph convolutional network (KD-GCN)[100], which embeds steel-making heuristics in a knowledge graph and feeds them into a GCN encoder; the model attains high predictive fidelity on limited data, showing that domain ontology can compensate for sparse labels when mapping composition-process variables to mechanical properties At the catalyst scale, the deconstruction and reconstruction (DR-Label) supervision scheme by Wang decomposes node-wise labels into edge-wise constraints before reconstruction[101], tightening the learning signal and yielding state-of-the-art adsorption-energy predictions on OC20 and Cu single-atom-alloy benchmarks.

A summary of recent cutting-edge GNN applications in alloy design is provided in Table 5.

Recent GNN advances in materials and alloy research

| Focus area | Representative models/tools | Key contributions |

| Generative and inverse design (materials-wide) | GNoME[87], MatterGen[88], CGCNN[23] | Structure generation and stability prediction; expands candidate crystal space |

| GNN surrogates for quantum calculations (materials-wide) | M3GNet[53], CHGNet[90], direct-force GNN[91] | DFT-level accuracy and 1,000× speed-up in force/energy prediction; |

| High-throughput discovery of 2D materials | CDVAE, etc.[93-95] | Accurate discovery of magnetic/catalytic 2D materials; electronic and catalytic property prediction |

| Multiscale dynamics and physics-informed models | GrainGNN[72], GCNN[97], physics-informed GNN[98] | Captures multiscale alloy dynamics with uncertainty quantification |

| Knowledge integration and autonomous agents | LLM-GNN[99], KD-GCN[100], DR-Label[101] | Autonomous alloys design via domain knowledge graphs, LLMs, and symbolic constraints |

DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY

GNNs integrating different alloy design data and models to build graphs

Below are several approaches for data representation:

(1) Converting images to graph-structured data: (a) Three-dimensional phase field patterns. Researchers spatially compress 3D phase-field pattern transitions and material microstructural characteristics[72]. These images typically describe phase transition processes and the microstructure of materials. By converting them into abstract graphs, the model can effectively capture the spatial distribution and evolutionary behavior between different phases; (b) EBSD and SEM images. By combining EBSD images and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images[60,63,64,66], grain orientation and alloy microstructure can be further characterized.

(2) Directly abstracting grain or alloy phase structures using graph structure. Each grain is treated as a node in the graph, while edges reflect grain boundaries or phase boundaries, thus depicting microscopic topological relations[67,69-71,74]. Furthermore, mapping these graph structures to first-principles models allows for atomic-level insights into materials behavior. Incorporating DFT results into GNN training can significantly boost the accuracy of alloy property predictions.

(3) Graph-based representation of elastic FEM data. In FEM, this allows the model to capture the material’s localized stress concentration and relaxation effects[56,57,61,62,65]. Some researchers have also converted phase field data into graph-structured data for the prediction of material properties[59].

(4) Transfer learning method. The graph-based model is pretrained on material datasets that are related to the target task but have different data distributions, and then fine-tuned on a specific material system. This method enables the model to learn general microstructural representations from different material systems and transfer this knowledge to new material design and prediction tasks. However, it is worth noting that careful consideration is required to avoid the negative transfer, which occurs when knowledge from general datasets impacts model performance on specific alloys. Approaches such as domain adaptation techniques or selective transfer learning can mitigate this risk.

(5) Computational data and experimental data. Some researchers have improved model accuracy through multi-source data fusion. Certain studies have integrated thermodynamic data from widely used phase diagram handbooks with first-principles calculation results to construct prediction models for alloy solid-liquid phase boundary temperatures[73]. Other researchers have incorporated process data, such as tempering temperature and cooling rate from the steel processing industry, into the input features of GNNs, achieving correlation analysis between processing parameters and material phase transformation behaviors. Verification results indicate that this approach, which fuses physics-based data with practical engineering information, yields predictions that closely match experimental data[100].

(6) Incorporating equivariance through equivariant graph neural networks (EGNNs). EGNNs embed rotational and translational symmetry directly into their architecture, ensuring that predictions remain consistent under spatial transformations[102,103]. This is critical for alloy design, where capturing structure-property relationships necessitates robust invariance[104]. By distinguishing genuine compositional or bonding effects from mere orientation artifacts, EGNNs improve data-efficiency and predictive accuracy[103]. For example, MatTen accurately predicts entire elasticity tensors across crystal classes by preserving rotational frame independence, enabling the discovery of alloys with exceptional mechanical performance[105]. Overall, by incorporating physical symmetry constraints, EGNNs yield predictions that align more closely with underlying laws, significantly accelerating the search for high-performance alloys.

Overall, these strategies underscore the flexibility and efficacy of GNNs in alloy design. By adapting their graph representations to heterogeneous data-including images, phase-field simulations, FEM and process parameters, as illustrated in Figure 15, so that researchers can more accurately model, predict, and optimize the complex interplay of phases and properties in advanced alloy systems.

The role of multiscale modeling and data integration in GNNs and alloy design