Biotic iontronics: foundations for the direct biotic-abiotic communication and modulation

Abstract

Electronic signals form the basis of modern bioelectronics; however, they lack the biochemical complexity required to fully emulate or interface with the ionic and molecular signaling inherent to living systems. Biotic iontronics employs ions and molecules as direct information carriers, enabling authentic biotic-abiotic communication and offering a pathway to monitor and modulate physiological activities through signals that are natively intelligible to biological tissues. Current biotic iontronics faces limitations in achieving high-precision sensing and response, as well as restrictions in the types of output ionic and molecular signals. Elucidating fundamental biological principles and specific structures within living systems will provide the basis for breakthroughs in next-generation biotic iontronics.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

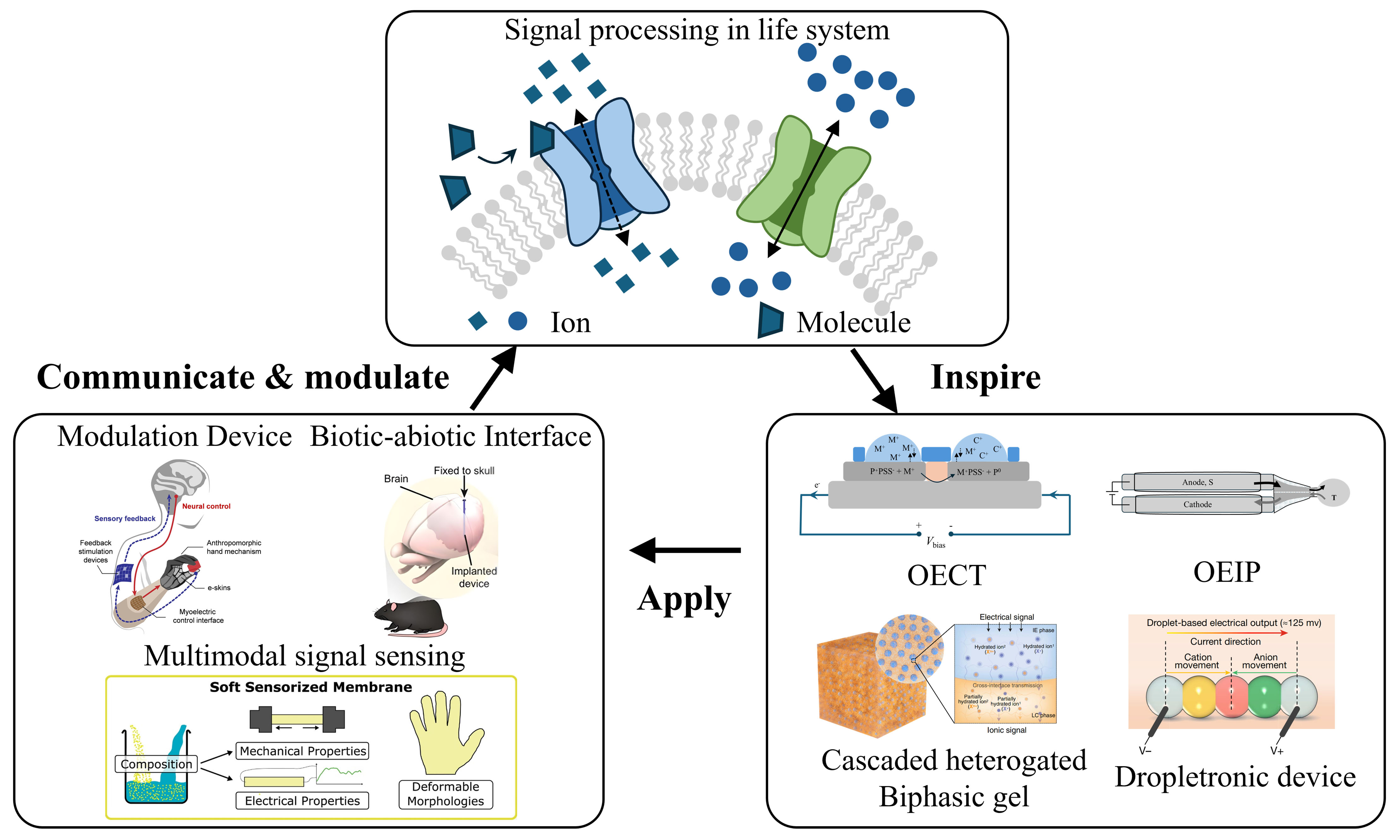

Ions and molecules are vital for physiological functions. For instance, Na+ and K+ gradients establish neuronal resting potentials, and Ca2+ binding to troponin regulates muscle contraction[1,2]. Additionally, molecules such as dopamine, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and acetylcholine modulate diverse biological processes[3]. As shown in Figure 1A, molecularly regulated ion channels facilitate signaling and transport via unique gating, selectivity, and ultrafast permeation[4]. Mimicking the geometry and surface properties of these biological models, artificial 0D-3D nanofluidic channels [Figure 1B] show robust potential in energy harvesting[5-7], neuromorphic computing[8], biosensing[9], and physiological regulation[10,11]. Based on the channel, iontronic devices are developed. Analogous to biological ion channels, iontronic devices regulate physiological activities via ionic and molecular signaling. Key technologies developed for monitoring and modulating these signals include the organic electrochemical transistors[12], organic electronic ion pumps (OEIPs)[13-15], dropletronic devices[16], and cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics[17]. These devices directly interface with living systems by utilizing biological ionic and molecular signals, referred to as biotic iontronics, showing promise in physical monitoring, healthcare, perception augmentation, functional substitution, and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) [Figure 1B]. Currently, biotic iontronics enables precise, controllable ion release to modulate a wide range of physiological processes[18], most of which are governed by ions and molecules, featuring low energy consumption and inherent feedback regulation. Iontronic devices can use the same “language” as biological systems, offering high spatiotemporal resolution, low operating voltage, and biocompatible modes of actuation. In contrast, conventional electronics rely on electrical stimulation and the measurement of resulting signals, which are external representations of the spatiotemporal variations of ions in living systems, to modulate and monitor physiological processes[19,20]. They also lack the ability to selectively and specifically regulate ions and molecules. However, existing biotic iontronic platforms are still limited to the release of inadequate ion species, restricting their ability to manipulate complex physiological activities.

Figure 1. Living systems and biotic iontronic systems regulate physiological processes through ion channels. (A) The biological system utilizes natural ion channels to perceive and transmit multiple ion signals, achieving low energy consumption and feedback regulation; (B) Biotic iontronics employs artificial ion channels to process single-ion signals, with the potential to enable multimodal signal processing, multisensory enhancement, biotic-abiotic communication, and closed-loop regulation.

In this perspective, we trace the development of biotic iontronic devices. We begin with a brief overview of recent advances in using these devices to modulate physiological processes, followed by a comparison between electronic signals and ionic and molecular signals. Finally, we outline potential future directions and discuss feasible applications.

BIOTIC IONTRONIC DEVICE FOR THE REGULATION OF LIFE PROCESS

Ionic and molecular signals serve as the interaction medium and form the basis of communication between biotic iontronic devices and living systems. This interaction requires the transduction of easily modulated and encoded electrical signals into ionic or molecular signals to regulate physiological activities. The key design principle is to enable on-demand, spatiotemporally controlled release of ions and molecules while maintaining a biocompatible and stable biotic-abiotic interface to support efficient bidirectional bioinformation exchange. Based on this principle, biotic iontronics requires advances in modeling studies of ion and molecule release, practical strategies and demonstrations for regulating living tissues, and the imitation of physiological processes mediated by ionic and molecular signaling.

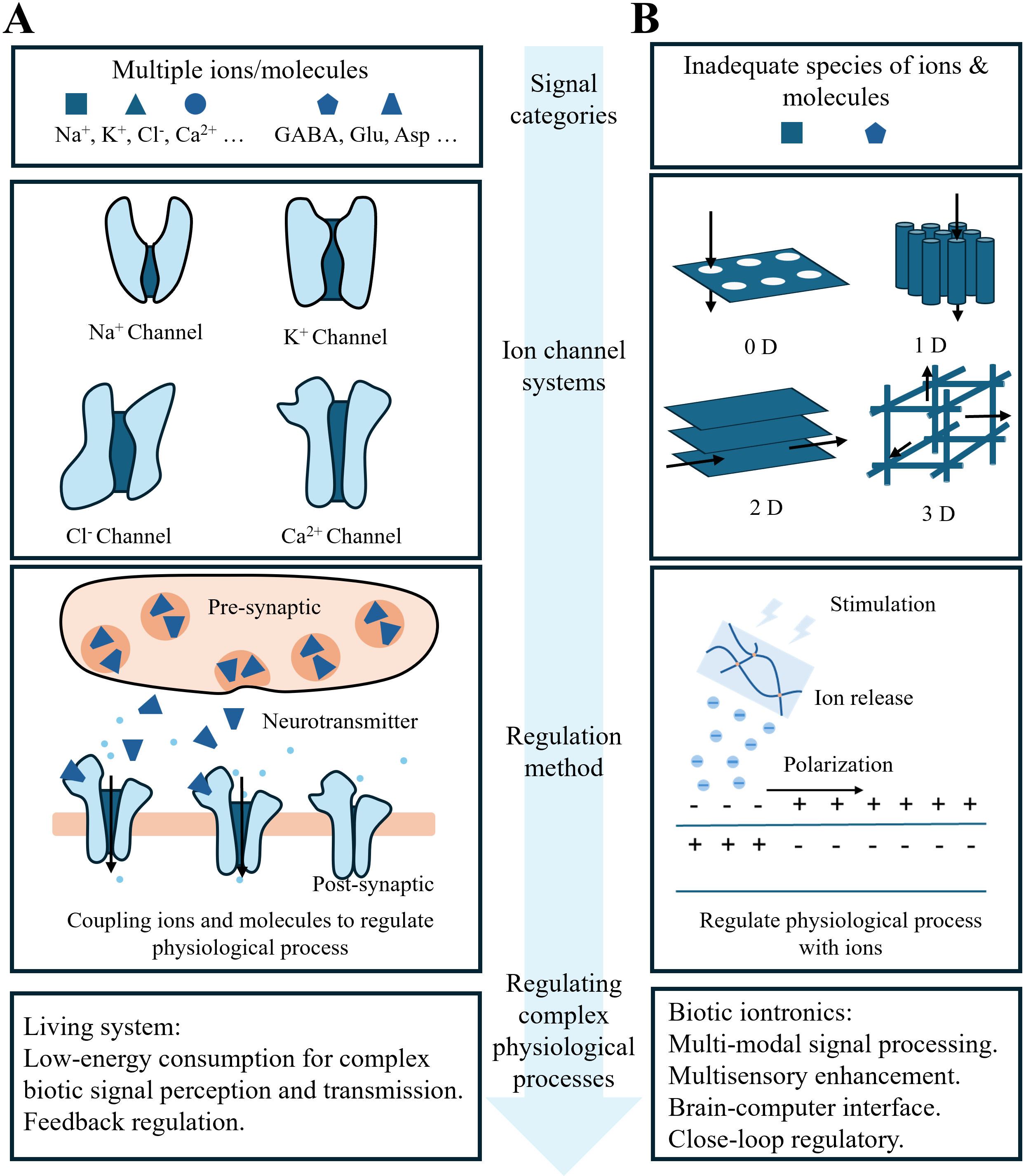

As shown in Figure 2A, in 2007, Isaksson et al.[13] developed the first OEIP, which consisted of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) doped with poly(styrene sulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) and enabled high-efficiency, electrically regulated cation transport, subsequently inducing biological signaling events at the single-cell level. Furthermore, Simon et al.[14] demonstrated precise neurotransmitter delivery, thereby specifically stimulating neurons. Positively charged molecules, including aspartate, glutamate, and GABA, were stored in the cathode region [Figure 2B] and released into targeted regions through electrophoresis under electrochemical activation. The OEIP is a groundbreaking model for ion and molecule release, taking advantage of controllable switching, non-volumetric interference, and precise dose control. However, it suffers from limitations including high activation voltage, low biocompatibility, and restricted release capacity. To explore its practicality in regulating living tissues, a series of studies on biological systems has been carried out. Zhao et al. developed a hydrogel iontronic device with an all-aqueous connective interface, achieving local muscle stimulation in vivo under low voltage[18]. Additionally, Uguz et al. developed an implantable neuronal modulation device based on a microfluidic ion pump (µFIP), enabling long-term drug delivery through microfluidic channels[19]. A series of studies on the selective modulation of specific ions or charged molecules to stimulate or regulate biological activities has demonstrated the feasibility of biotic iontronics, including a conformable neural interface based on ionogel assemblies for neurostimulation[20] [Figure 2C] and the µFIP implanted into the brain for on-demand drug delivery[21] [Figure 2D]. To match the sophisticated ion release patterns of living systems and establish intimate communication, biotic iontronic devices must achieve multi-stage, complex ion transport behavior and be miniaturized to minimize interference with host tissues. Chen et al. developed a cascade-heterogated biphasic gel, enabling selective transport of cations with different chemical valences[17]. As shown in Figure 2E, during transmission, intrinsic differences in ion mobility were amplified through cascade-heterogated effects, achieving selective transport of multiple ions. The biphasic gel is promising for coupled release of ions and molecules. As a pioneering effort toward device miniaturization, Zhang et al. developed a microflexible battery based on a nanoliter dropletronic device, matching the microscopic scale of physiological activities and functioning as a power source[16]. As shown in Figure 2F, the device could generate a voltage output of approximately 125 mV and modulate neural network activity following substitution of a low-salinity droplet with one containing neural organisms.

Figure 2. Advances in biotic iontronic devices. (A) The OEIP device utilizes electrochemical reactions at the cathode to drive the transport of ions from the left side to the targeted area on the right[13]; (B) The OEIP device is applied for transporting molecules[14]; (C) Implantable Ionogel assembly as a soft neural interface[20]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 20, Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (D) μFIP for charged molecular release, where the central region releases the neurotransmitter under a small voltage[21]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 21, Copyright 2018, The American Association for the Advancement of Science under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/; (E) The biphasic gel is applied for selective transmission of multiple ionic signals[17]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 17, Copyright 2023, The American Association for the Advancement of Science; (F) The dropletronic device of a micrometer- scale gel generates the voltage output[16]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 16, Copyright 2023, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. PSS: Poly(styrene sulfonate; Vbias: applied bias voltage; 4AP: 4-amoniopyridine; μFIP: microfluidic ion pump; OEIP: organic electronic ion pump; IE phase: ion-enriched internal phase; LC phase: low-conductive continuous phase.

THE ADVANTAGES, DISADVANTAGES, AND DEVELOPMENT ORIENTATION OF THE BIOTIC IONTRONICS

Ionic and molecular signals are the intrinsic signals of living systems, which, compared to electronic signals, can convey more precise and higher-density information[22]. Moreover, ionic and molecular signals are capable of modulating ion channels, thereby regulating cellular states and directing physiological processes. Currently, biotic iontronics still lags behind conventional electronics in terms of response speed, device compatibility, and integration level. Therefore, it is necessary to apply standard electronic theories and methods to achieve realistic, precise, and selective control of artificial ionic and molecular signals, as ionic-electronic transduction forms the basis of biotic iontronics. Ionic-electronic signal transduction occurs at the interface; thus, for biotic iontronic devices, biocompatibility, modulus matching, and adhesion stability of the bio-abiotic interface are essential[23]. Additionally, owing to the complexity of diverse physiological processes, the capability for multimodal signal detection and output should be further developed. Since the macroscopic behaviors of living organisms are often determined by rapid and efficient microlevel interactions, precise in situ regulation and monitoring are crucial for achieving desired functional outcomes, requiring devices that are functionally integrated, miniaturized, and highly compact.

APPLICATION IN THE COMMUNICATION WITH PHYSIOLOGICAL PROCESS

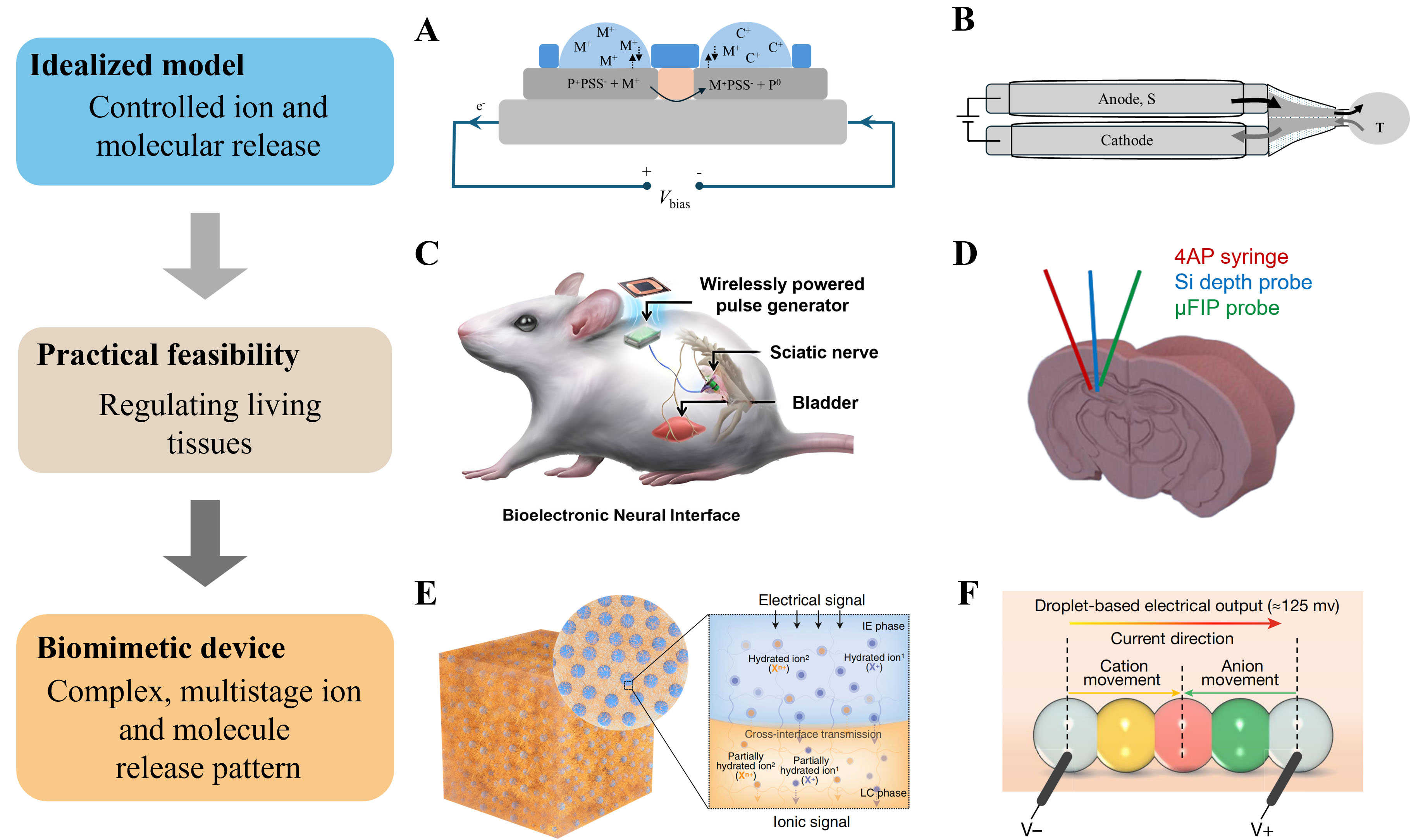

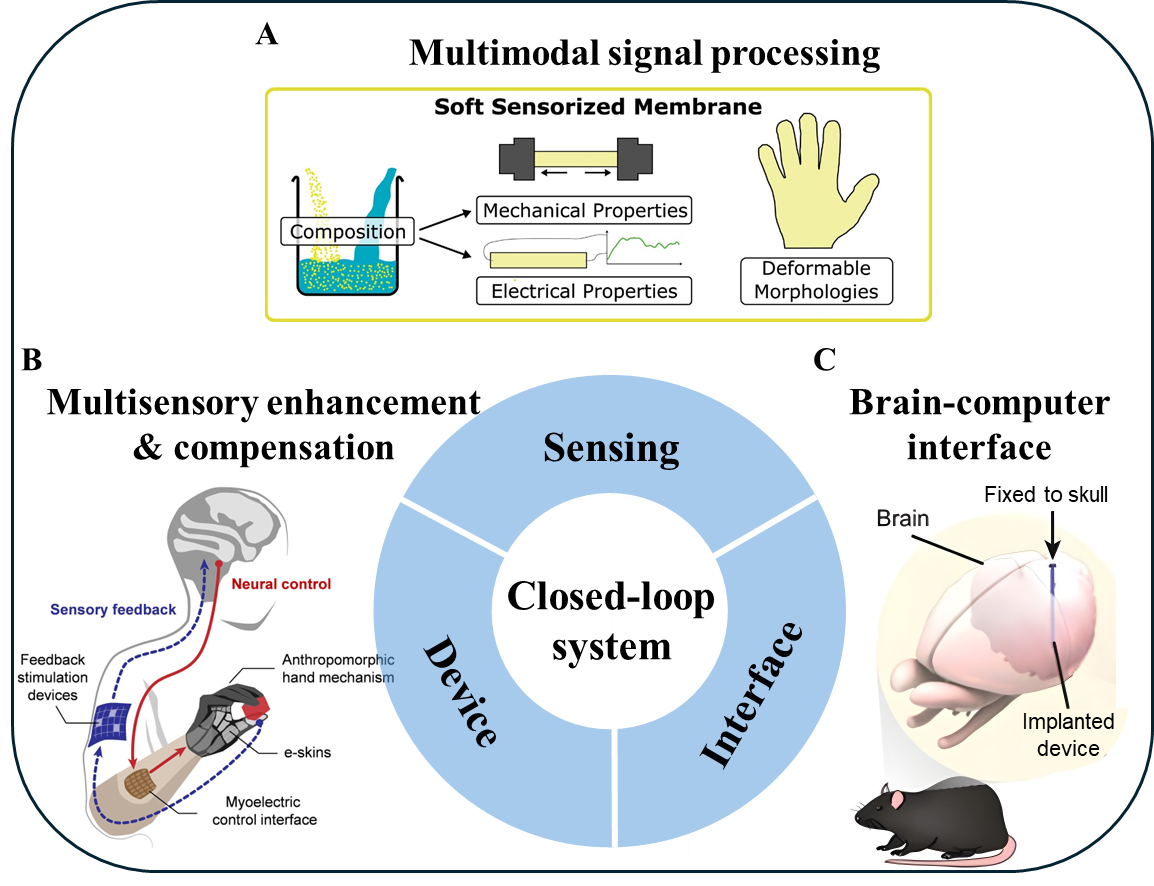

Biotic iontronics, as an emerging approach for information transfer and substance exchange between biological and abiotic systems, exhibits broad application prospects. Biotic iontronic devices can directly perceive, process, and output ionic and molecular signals, thereby enabling closed-loop therapeutic devices[24,25] that allow real-time monitoring and on-demand drug delivery, laying the foundation for future personalized medicine. Owing to the intrinsic complexity of ionic and molecular signals, as shown in Figure 3A, biotic iontronics can achieve perception of multimodal signals through device design - for example, monitoring muscle activity, pulse, and human metabolites - thereby supporting health management, disease prevention[26-29], environmental condition prediction, human touch localization, and proprioceptive data generation. Biotic iontronics also serves as a bridge connecting biological tissues with mechanical devices, showing promising potential in the fields of multisensory enhancement and functional compensation [Figure 3B], such as enabling and enhancing assistive devices including controllable prostheses[30-32], bionic eyes[33], and exoskeletons[34]. Particularly in the rapidly advancing field of BCIs[35,36], as shown in Figure 3C, biotic iontronics offers distinctive advantages in ultrahigh fidelity, biocompatibility, and enhanced information density and complexity, with ions and molecules serving as information mediators.

Figure 3. Applications of biotic iontronics in closed-loop signal processing systems. (A) Biotic iontronics enables multimodal signal sensing based on a hydrogel-based electronic skin, detecting thermal, mechanical, and chemical signals[26]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 26, Copyright 2025, The American Association for the Advancement of Science; (B) Prosthetic control system enhanced by gel-based electrodes, with further improvements possible through the application of biotic iontronics[30]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 30, Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society; (C) Hydrogel-based brain-machine interface achieving neural activity recording[36]; Reproduced with permission of ref. 36, Copyright 2021, Springer Nature under CC BY 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

OUTLOOK

Biotic iontronics is a promising and emerging field, yet it faces numerous unknowns and challenges. Current devices and methods still exhibit certain limitations. Although selective output of various ionic signals has been achieved, there remains a lack of integrated and controllable approaches for the simultaneous delivery of both ions and molecules, which is crucial for expanding the regulatory capabilities of biotic iontronics. Furthermore, constrained by limited reproducibility and high production costs, functional integration of devices remains inadequate. Biomimetic design offers inspiration for further development, drawing on the ultrahigh speed, specificity, complexity, and ultralow energy consumption of living systems to realize closed-loop medical devices, multimodal signal processing, multisensory enhancement, and advanced BCIs. With a deeper understanding of bionics and continued technological integration, sustained efforts in this area are expected to drive substantial advances and enable real-world applications.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the draft: Lei, C.; He, J.

Supervised, reviewed and edited the manuscript: Wen, L.; Chen, W.; Kong, X. Y.

Contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript: Lei, C.; He, J.

All authors discussed the review and agreed upon the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The research data are not publicly available.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22402077, 22122207, 21988102) and the Director’s Fund of the Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (E5A9Q10201).

Conflicts of interest

Wen, L. is an Associate Editor of Iontronics. Kong, X. Y. and Chen, W. are Editorial Board Members of Iontronics. Wen, L., Kong, X. Y. and Chen, W. were not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers' selection, manuscript handling or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

2. Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; et al. A chemically mediated artificial neuron. Nat. Electron. 2022, 5, 586-95.

3. Chantranupong, L.; Beron, C. C.; Zimmer, J. A.; Wen, M. J.; Wang, W.; Sabatini, B. L. Dopamine and glutamate regulate striatal acetylcholine in decision-making. Nature 2023, 621, 577-85.

4. Lei, D.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L. Bioinspired 2D nanofluidic membranes for energy applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 2300-25.

5. Yin, J.; Jia, P.; Ren, Z.; et al. Mechanically enhanced, environmentally stable, and bioinspired charge-gradient hydrogel membranes for efficient ion gradient power generation and linear self-powered sensing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2417944.

6. Qian, H.; Fan, H.; Peng, P.; et al. Biomimetic Janus MXene membrane with bidirectional ion permselectivity for enhanced osmotic effects and iontronic logic control. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx1184.

7. He, J.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhai, J.; Fan, X. Self-powered green hydrogen production via osmotic energy harvesting. Adv. Mater. 2026, 38, e14316.

8. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

9. Arwani, R. T.; Tan, S. C. L.; Sundarapandi, A.; et al. Stretchable ionic-electronic bilayer hydrogel electronics enable in situ detection of solid-state epidermal biomarkers. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1115-22.

10. Xin, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. A thermogalvanic cell dressing for smart wound monitoring and accelerated healing. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2026, 10, 80-93.

11. Cheng, L.; Zhuang, Z.; Yin, M.; et al. A microenvironment-modulating dressing with proliferative degradants for the healing of diabetic wounds. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9786.

12. Wang, Y.; Wustoni, S.; Surgailis, J.; Zhong, Y.; Koklu, A.; Inal, S. Designing organic mixed conductors for electrochemical transistor applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2024, 9, 249-65.

13. Isaksson, J.; Kjäll, P.; Nilsson, D.; Robinson, N. D.; Berggren, M.; Richter-Dahlfors, A. Electronic control of Ca2+ signalling in neuronal cells using an organic electronic ion pump. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 673-9.

14. Simon, D. T.; Kurup, S.; Larsson, K. C.; et al. Organic electronics for precise delivery of neurotransmitters to modulate mammalian sensory function. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 742-6.

15. Jonsson, A.; Sjöström, T. A.; Tybrandt, K.; Berggren, M.; Simon, D. T. Chemical delivery array with millisecond neurotransmitter release. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601340.

16. Zhang, Y.; Riexinger, J.; Yang, X.; et al. A microscale soft ionic power source modulates neuronal network activity. Nature 2023, 620, 1001-6.

17. Chen, W.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, S.; et al. Cascade-heterogated biphasic gel iontronics for electronic-to-multi-ionic signal transmission. Science 2023, 382, 559-65.

18. Zhao, S.; Tseng, P.; Grasman, J.; et al. Programmable hydrogel ionic circuits for biologically matched electronic interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1800598.

19. Uguz, I.; Proctor, C. M.; Curto, V. F.; et al. A microfluidic ion pump for in vivo drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29,.

20. Kim, J. S.; Kim, J.; Lim, J. W.; et al. Implantable multi-cross-linked membrane-ionogel assembly for reversible non-faradaic neurostimulation. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 14706-17.

21. Proctor, C. M.; Slézia, A.; Kaszas, A.; et al. Electrophoretic drug delivery for seizure control. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau1291.

22. Ro, Y. G.; Na, S.; Kim, J.; et al. Iontronics: neuromorphic sensing and energy harvesting. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 24425-507.

23. Ro, Y. G.; Chang, Y.; Kim, J.; et al. Ionic-bionic interfaces: advancing iontronic strategies for bioelectronic sensing and therapy. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 2025, e13985.

24. Leng, Y.; Sun, R. Multifunctional biomedical devices with closed-loop systems for precision therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2500860.

25. Huang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; et al. A skin-interfaced three-dimensional closed-loop sensing and therapeutic electronic wound bandage. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5782.

26. Hardman, D.; Thuruthel, T. G.; Iida, F. Multimodal information structuring with single-layer soft skins and high-density electrical impedance tomography. Sci. Robot. 2025, 10, eadq2303.

27. Song, S.; Zhang, M.; Gong, X.; Shi, S.; Fang, J.; Wang, X. Advances in wearable sensors for health management: from advanced materials to intelligent systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e18767.

28. Liang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; et al. A wearable multimodal health monitoring bracelet powered by high-power-density flexible thermoelectric generators. Device. 2025, 3, 100748.

29. Li, M.; Li, W.; Guan, Q.; et al. Sweat-resistant bioelectronic skin sensor. Device 2023, 1, 100006.

30. Gu, G.; Zhang, N.; Chen, C.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X. Soft robotics enables neuroprosthetic hand design. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 9661-72.

31. Dai, Y.; Wai, S.; Li, P.; et al. Soft hydrogel semiconductors with augmented biointeractive functions. Science 2024, 386, 431-9.

32. Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, W.; et al. Highly-stable, injectable, conductive hydrogel for chronic neuromodulation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7993.

33. Long, Z.; Qiu, X.; Chan, C. L. J.; et al. A neuromorphic bionic eye with filter-free color vision using hemispherical perovskite nanowire array retina. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1972.

34. Lee, J.; Kwon, K.; Soltis, I.; et al. Intelligent upper-limb exoskeleton integrated with soft bioelectronics and deep learning for intention-driven augmentation. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 11.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].