Perovskite solar cells for low earth orbit space applications

Abstract

Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are a promising next-generation photovoltaic (PV) technology for space applications. Their high power-to-weight ratio, mechanical flexibility, and tunable optoelectronic properties make them particularly attractive for Low Earth Orbit (LEO) applications. PSCs demonstrate favorable behavior under low light and partial shading, as well as a unique self-healing response under certain space conditions. They also achieve specific power densities of 23-30 W g-1, representing a 10-15× improvement over conventional silicon arrays (0.5-2 W g-1) and 4-6× improvement over III-V multijunction cells (5.5 W g-1), while maintaining > 92% efficiency retention under 1 × 1016 e cm-2 electron irradiation. The key challenges and opportunities for PSCs in the LEO environment arise from intense ultraviolet radiation, vacuum exposure, thermal cycling, and proton irradiation. In this review, a comprehensive understanding of PSCs in the space environment is presented, including recent strategies to improve efficiency, as well as thermal and mechanical durability, while also addressing performance optimization and space PV analysis. This overview highlights the potential of perovskite photovoltaics for satellite power systems by enabling high-efficiency energy harvesting with minimal mass and processing constraints, positioning PSCs as a promising new PV paradigm for the coming decade.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

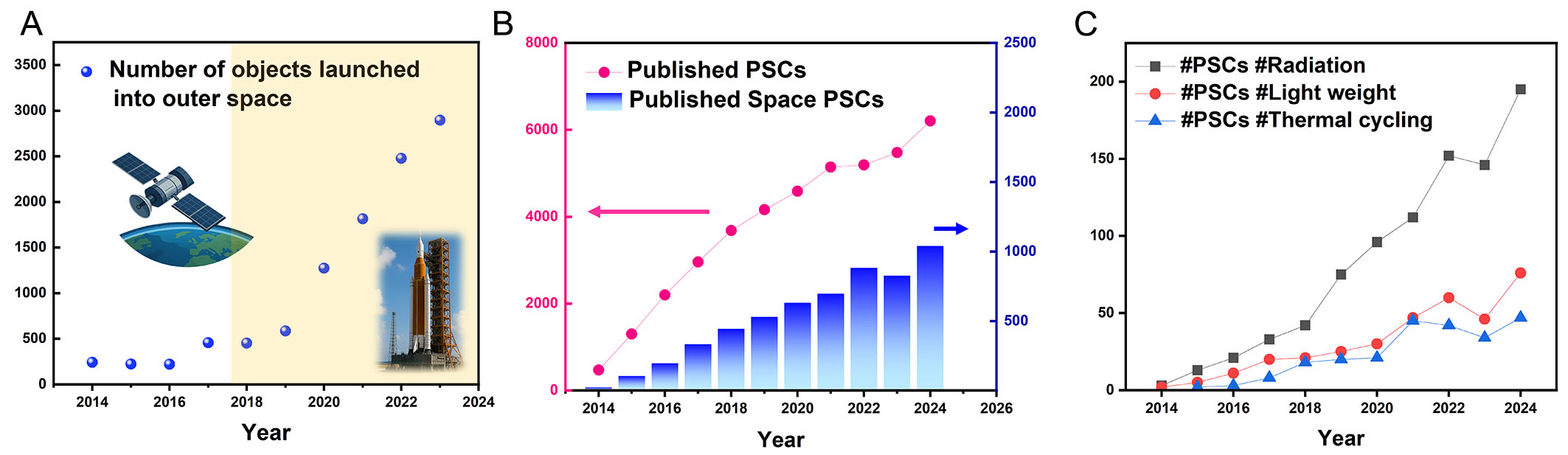

Since the Apollo lunar landing in 1969[1], human interest in space exploration and aerospace technology has expanded dramatically. This milestone catalyzed sustained efforts to advance space science and engineering. A key achievement is the establishment of the International Space Station (ISS), symbolizing international collaboration and technological progress in long-term space habitation and experimentation[2,3]. In recent decades, governmental space agencies (e.g., National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)[4,5], The European Space Agency (ESA)[6], Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)[7], etc.) and private companies (e.g., Space X[8], Blue Origin[9], etc.) have invested heavily to accelerate space exploration and to enhance spacecraft technologies [Figure 1A][10]. This global effort has intensified, with remarkable developments for long-duration missions, from orbital platforms to interplanetary travel. To support such missions, an understanding of the space environment, including radiation, thermal cycling, vacuum, and micrometeoroid exposure, is essential. Equally critical is the development of efficient energy systems for spacecraft and satellites, which directly influence mission longevity and functionality. In our solar system, solar energy is the most abundant and accessible power source, with photovoltaics as a key energy-harvesting technology.

Figure 1. (A) Annual number of objects (CubeSat, satellite, etc.) launched into outer space[10], reproduced under a Creative Commons license. (B) Increasing number of journal publications on PSCs and space-related PSCs, retrieved from the Web of Science on 15 September. (C) Number of journal publications for selected keyword combinations retrieved from the Web of Science on 15 September: PSCs + Radiation, PSCs + Lightweight, and PSCs + Thermal cycling.

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) missions require photovoltaic (PV) systems that are efficient, lightweight, and durable in harsh space environments. Conventional space PV technologies, primarily crystalline silicon (c-Si) and multi-junction III-V cells (e.g., Gallium arsenide (GaAs)[11,12]), provide proven performances but are limited by heavy and rigid panels, high manufacturing costs, and sensitivity to radiation. In contrast, metal-halide perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have emerged as a groundbreaking thin-film PV technology, exceeding 27% power conversion efficiency (PCE) in lab-scale devices[13,14]. Since PSCs can be fabricated as ultralight flexible films with remarkable power-to-weight ratios, and their defect-tolerant crystal structure enables remarkable radiation resistance. These features establish perovskites as a next-generation power source in satellites and space systems [Figure 1B][15], potentially enabling large deployable solar arrays while reducing launch mass and cost.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of PSC technology specifically for LEO applications. As shown in Figure 1C, detailed studies on space PSCs have been actively reported in recent literature. Considering this, we examine key aspects such as the radiation tolerance, material stability, structural design for lightweight and flexible modules, performance under space irradiation, and a comparison with conventional space photovoltaics. Based on a technically grounded perspective, this work aims to support near-term LEO demonstrations and future standardization efforts for PSC-based space power systems.

RADIATION TOLERANCE AND STABILITY OF PEROVSKITES IN SPACE CONDITIONS

Intrinsic radiation damage mechanisms and self-healing

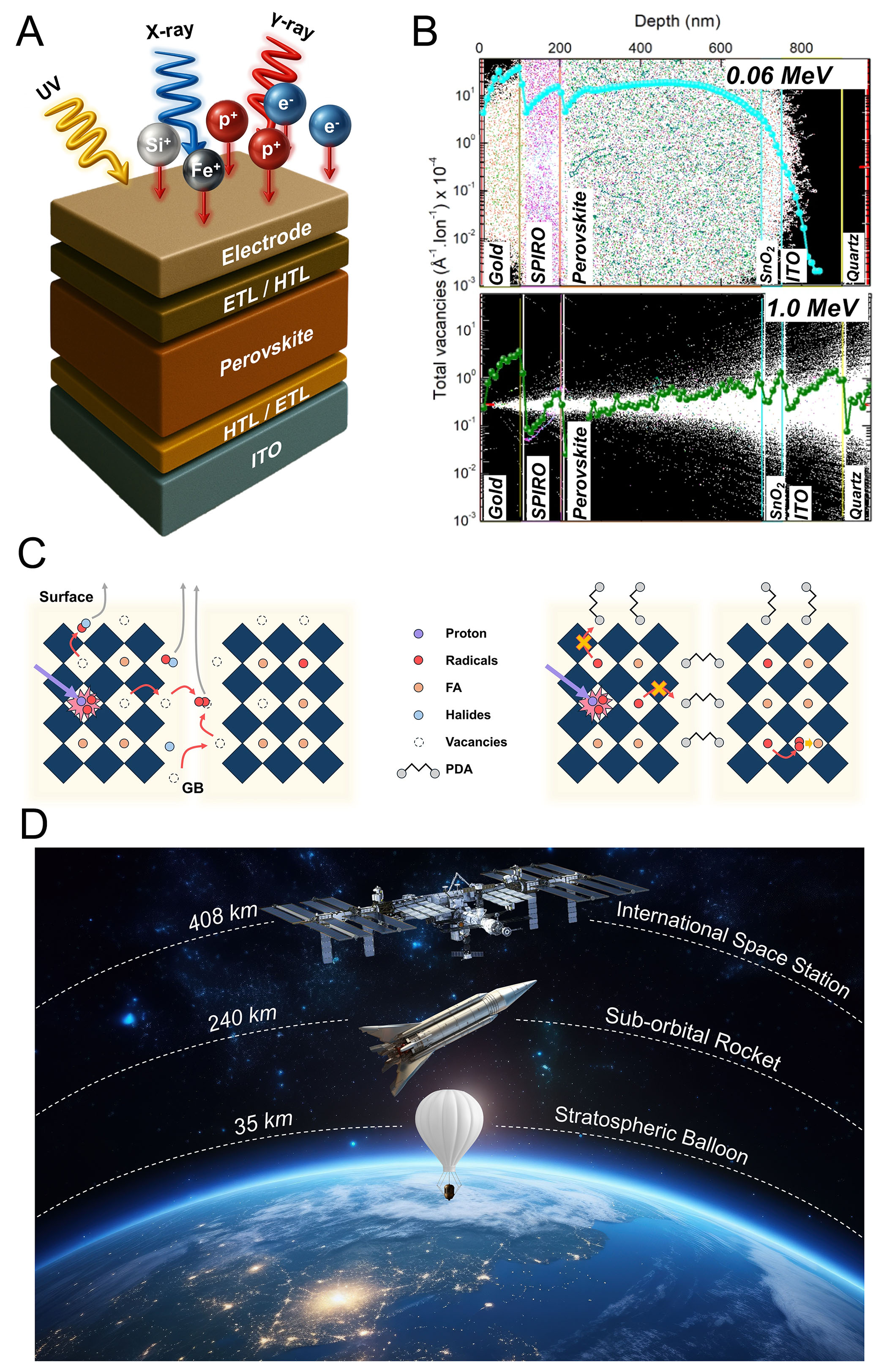

Unlike terrestrial environments, solar cells in LEO are exposed to a broad spectrum of high-energy radiations such as protons, electrons, heavy ions, Ultraviolet (UV) and X-rays, and γ-rays[16], which induce severe degradation through lattice-defect formation and increased charge trapping, permanently damaging conventional solar cells [Figure 2A][17,18]. While Si and GaAs accumulate irreversible dislocations under such irradiation[19-21], metal-halide perovskites exhibit inherent defect tolerance and self-healing properties[22,23]. Their soft ionic lattice can absorb and dissipate radiation energy via lattice vibrations and ion rearrangements. Radiation-induced Frenkel-type defects such as vacancies or interstitials in perovskite are readily annealed due to low formation energies (0.1-0.5 eV), which is much lower than those in Si

Figure 2. (A) Schematic illustration of perovskite solar cells (PSCs) exposed to various cosmic radiation sources, including protons, electrons, heavy ions, and UV, X-ray, and γ-ray. (B) Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM) simulations of proton penetration of PSCs[26]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature. (C) Schematic diagram for the degradation mechanism and degradation suppression by passivating the perovskite surface[37]. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier. (D) In-orbit demonstrations of PSCs, from stratospheric balloon flights to sub-orbital rockets and extended operation aboard the International Space Station.

Tolerance to protons, electrons and gamma radiation

Empirical studies have shown that PSCs maintain high performance under proton, electron, and gamma irradiation. Miyazawa et al. reported that Formamidinium Methylammonium Lead Iodide-Bromide (FAMAPb(IBr)3) PSCs subjected to 50 keV protons at fluences up to 1 × 1015 p cm-2 exhibited only modest performance degradation[28], whereas Si[29], Copper Indium Gallium Selenide (CIGS)[30], and GaAs[31] solar cells showed significant degradation under comparable conditions. Similarly, they reported that Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT)- Methylammonium Lead Iodide (MAPbI3)PSCs exposed to 1 MeV electron irradiation at fluences of 1 × 1016 e cm-2 retained 92% of their initial PCE, compared to 60% retention for Si solar cells[32]. Even at higher-energy proton irradiation (~68 MeV), PSCs exhibited minimal external quantum efficiency (EQE) degradation and no observable PbI2 formation, indicating limited structural damage. Perovskites have also demonstrated robustness under gamma irradiation. Studies have shown that PSCs maintain excellent performance up to 1,000 kilorad (kRad) - equivalent to approximately 20 years of cumulative LEO exposure[33]. Boldyreva et al. showed negligible MAPbI3 degradation, attributing most losses to substrate darkening rather than active layer deterioration and reported reversible decomposition related to volatile species release[33]. All-inorganic perovskites such as CsPbI3 and CsPbBr3 showed no photoluminescence (PL) degradation under gamma radiation doses up to 500 kRad. The lack of PbI2 formation is attributed to the absence of volatile organic components. These findings confirm the sustainability of PSCs for LEO regions exposed to intense proton and electron flux including the South Atlantic Anomaly and polar orbits[34].

While systematic investigations are still limited, several routes to enhanced radiation tolerance have emerged. Mixed-halide perovskites (FA0.8Cs0.2Pb1.02I2.4Br0.6Cl0.02, where FA = formamidinium) showed defect formation dependent on proton energy, followed by performance recovery via lattice self-healing under dark conditions, with radiative recombination remaining dominant over nonradiative pathways[35]. All-inorganic vacancy-ordered double perovskites Cs2CrI6 have also shown remarkable robustness, retaining 90% of initial PCE after 50 keV proton irradiation of 5 × 1013 p cm-2 and withstanding fluences up to 1016 p cm-2[36]. The absence of hygroscopic and volatile organic cations, combined with the high mobility of Cs2CrI6, contributed to long-term stability by suppressing charge-carrier recombination at vacancy sites. Surface passivation has emerged as another effective strategy. Moreover, surface passivation has proven effective: propane-1,3-diammonium iodide (PDAI2)-treated (Cs0.22FA0.78)Pb(I0.79Br0.17Cl0.04)3 devices exhibited reduced ion migration, suppressed volatile species formation, and mitigated δ-phase CsPbI3 and PbI2 generation after proton irradiation [Figure 2C][37-39].

In-orbit tests and long-term stability

Beyond laboratory experiments in controlled environments, several studies have successfully tested the durability of PSCs in real space environments [Figure 2D][40]. The stratosphere, the second-lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere (20-50 km altitude), can be reached by high-altitude balloons[40]. Cardinaletti et al. launched a balloon incorporating PSCs based on MAPbI3 to 32 km for over 3 h, where the temperature varied from -53.2 to 16.9 °C[41]. The devices retained 64% of initial PCE, showing degradation due to phase transition from the cubic phase to the tetragonal phase at temperatures below 57 °C and increased interfacial recombination at the electron-selecting contact.

In another experiment, PSCs based on MA0.17FA0.83Pb(I0.17Br0.83)3 (MA = methylammonium,

Most impressively, perovskite films were subjected to continuous LEO conditions at an altitude of 408 km for 10 months on the ISS in 2020-2021[15]. The samples, fabricated with the structure of borosilicate/encapsulant/SiO2/MAPbI3/borosilicate, exhibited partial degradation: borosilicate turned yellow under electron radiation, while bubbles trapped in the encapsulant induced perovskite decomposition into PbI2. In addition, extreme thermal cycling (> 200 °C swings per orbit) induced strain in the perovskite lattice. But intriguingly, upon re-illumination on Earth, the accumulated stress gradually relaxed under sunlight, leading to effective recovery of the initial structure, reduced defects, and increased charge carrier lifetime. Overall, these in-orbit demonstrations confirm that, with proper encapsulation, perovskites can remain stable for extended durations in LEO, supporting their feasibility for multi-year satellite missions. The next steps will be multi-year orbital tests of fully operational perovskite solar arrays.

LIGHTWEIGHT AND FLEXIBLE DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS FOR LEO APPLICATIONS

Ultra-high specific power and power-to-weight ratio

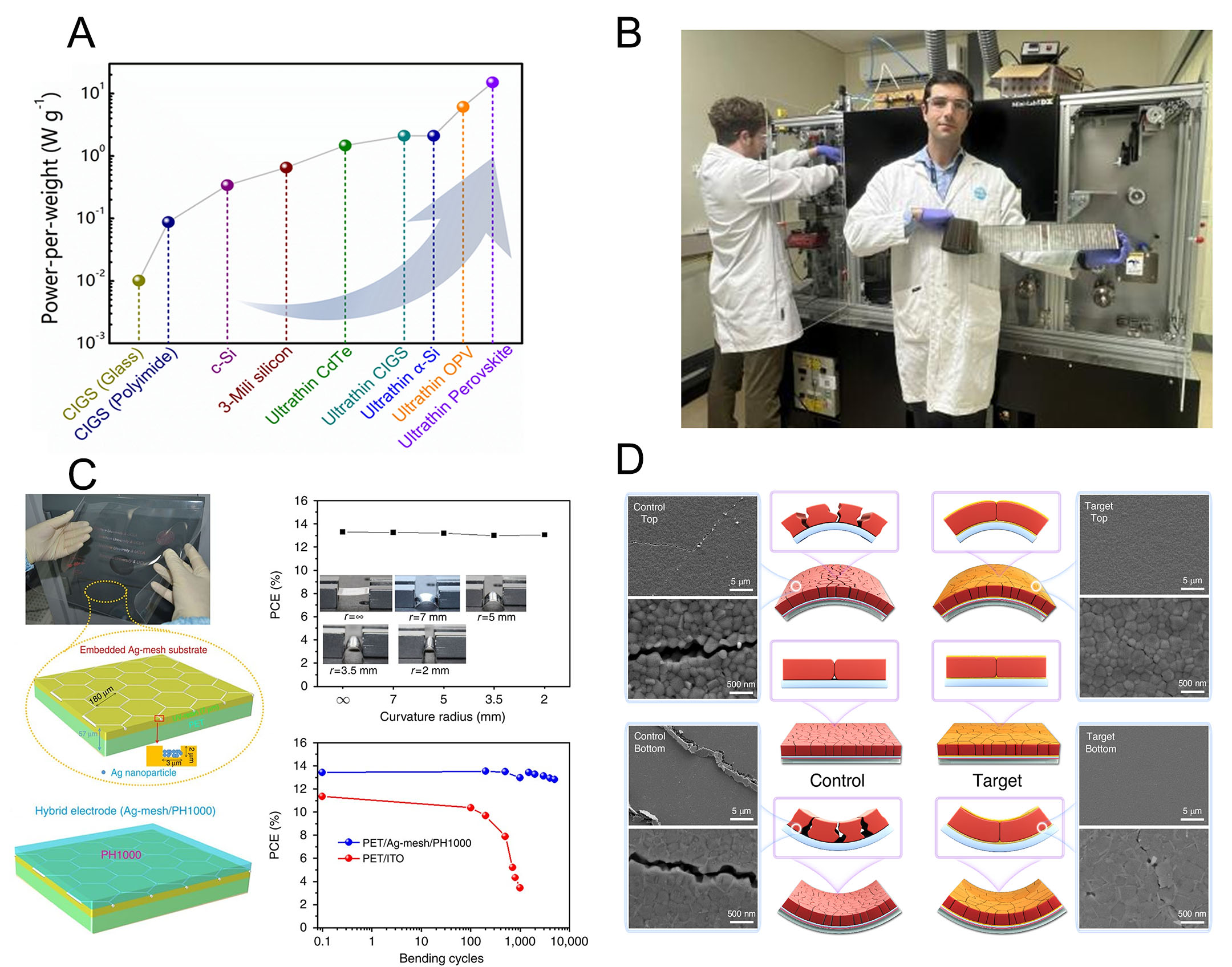

PSCs can be fabricated with an extremely thin active layer of a few hundred nanometers[43], and devices can be built on ultralight substrates such as plastic films, thin metal foils, or 10-50 µm glass[44-47]. Consequently, the power output per unit weight of PSC devices is higher than that of today’s space solar panels. State-of-the-art flexible PSCs have demonstrated specific powers on the order of

Figure 3. (A) Comparison of the power-to-weight ratios of various photovoltaics[58] Copyright © 2023, Springer Nature. (B) Photograph of a researcher holding a roll of printed PSCs on a plastic substrate (CSIRO, Australia)[71]. (C) PSC based on PET/Ag mesh/PH1000 and its bending test, reported by Li et al.[76] Copyright © 2016, Springer Nature. (D) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the top and bottom surfaces of a control perovskite film and a bifacial 2D-capping-layered perovskite film after 10,000 convex and concave bending cycles, reported by Jin et al.[80] Copyright © 2025, Springer Nature.

Flexible substrates and mechanical robustness

Another advantage of perovskites is that they can be fabricated on flexible substrates using low-temperature processes. Unlike III-V multi-junction solar cells, which are grown on rigid wafers, PSCs can be fabricated at temperatures below ~150 °C[48,59], using polymer films, metal foils, or thin glass as substrates. Polyimide (Kapton) substrates tolerate space temperatures up to ~400 °C and have excellent mechanical strength[60-62], as well as PET[63-65]/polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) films[66,67] for low-cost roll-to-roll manufacturing. Ultrathin (< 1 mm) flexible glass is another attractive substrate, offering flexibility along with superior barrier properties against moisture and oxygen ingress. Metal foils, such as titanium or aluminum, can serve as both substrate and encapsulant, providing mechanical robustness and thermal management[68-70]. The integration of flexible substrate-based solar cells indicates that the entire solar arrays can be designed for folding, rolling and stowing compactly during launch and then deploying to large areas in orbit. This is ideal for small satellites or deployable structures such as roll-out solar blankets. Figure 3B shows a flexible perovskite PV module[71]. Thus, the mechanical durability of PSCs under bending and vibration has recently attracted attention and shown promising results. Typically, flexible PSCs maintain high performance under tight bending radius and repeated flexing[72-75]. Li et al. reported that the PSCs on PET/Ag-mesh/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS, PH1000) substrates retained over 95.4% of their original efficiency after 5,000 bending cycles of 5 mm radius. Additionally, PSCs endured with a few mm curvature (r = ∞, 7, 5, 3.5 and 2 mm), retaining 98.1% of the original PCE value [Figure 3C][76]. One strategy to improve the flexibility of PSCs is to incorporate 2D/3D perovskite interfaces or strain-relieving additive microstructures, which act as micro-shock absorbers in the film[77-79]. Accordingly, introducing a bifacial 2D capping layer that cushions grain boundaries has recently been reported to achieve ~80% PCE retention after 10,000 bending cycles at a 3 mm radius [Figure 3D][80]. The thin device is capable of being bent or rolled while continuing to generate power. The ability of PSCs to endure high vibration during launch and flexural stress during deployment without cracking is a critical prerequisite for space solar panels.

Space-grade encapsulation and thermal management

Operating in LEO exposes solar cells not only to radiation but also to vacuum, extreme temperatures, and atomic oxygen. Notably, the exposure of perovskite photoactive layer to oxygen with light results in superoxide (O2-) species, enabling deprotonate the cation of photo-exited perovskite, leading to the formation of PbI2, water, methylamine and iodine[81]. Furthermore, atomic oxygen can cause corrosion, surface texturing, or the formation of metal oxides in the metal electrode contacts, all of which contribute to the degradation of PSCs in LEO[82]. Therefore, an effective encapsulating technology is vital to protect perovskite devices and ensure long-term stability. Space PV encapsulation must have multiple roles, including sealing the cell from vacuum and oxygen, maintaining transparency to radiation, withstanding thermal cycling, and blocking UV and atomic oxygen[83-85]. Traditional space solar cells use rigid cover glasses fused silica with anti-reflective coating for bonding over the cell, which results in significantly increased mass. Although the traditional encapsulated glasses have high transparency, UV radiation absorption and high durability, they are not suitable enough for space perovskite photovoltaics. From these reasons, more innovative lightweight encapsulations are being developed for PSCs[82,86-88]. A common approach is to use ultra-thin barrier films composed of multilayer inorganic/polymer coatings, often deposited by atomic layer deposition (ALD). For example, an ALD-grown Al2O3 layer of a few nanometers in thickness on a polymer sheet can dramatically reduce moisture and oxygen permeation, with negligible added weight[89]. Edge sealing with low-outgassing epoxies or thermoplastics is used to prevent vacuum ultraviolet penetration and isolate the cell’s edges[83,90]. Flexible glass or polyimide/fluoropolymer sheets can act as the outer layers, offering both mechanical protection and atomic oxygen resistance[91-94]. The PV encapsulation must also minimize optical loss. Therefore, the encapsulation materials are required to be transparent across the solar spectrum to avoid attenuating the incoming sunlight.

A corresponding challenge for fully flexible perovskite photovoltaics is managing thermal stress. Perovskite cells in orbit cycle through temperatures from roughly -150 °C (night side) to +150 °C (sun side). Such thermal cycling can induce expansion mismatch between the different layers of the cell, causing mechanical issues. To address this, researchers are incorporating stress-relief elements into the module stack. A practical strategy is to match the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) of the substrate and transport layers with that of the perovskite layer, thereby reducing differential strain[95-97]. Alternatively, introducing an elastic buffer layer or adhesive within the encapsulation can absorb some of the expansion and contraction, such as a silicon-based encapsulant that remains pliable at low temperatures[93]. Careful optimization of material selection and device engineering allows perovskite panels to tolerate repeated thermal cycling without cracking or delamination. Notably, in ISS experiments, employing a specialized encapsulation architecture comprising a thin glass superstrate and edge sealant enabled the devices to endure nearly one year of orbital cycling without degradation[98].

PERFORMANCE OPTIMIZATION UNDER SPACE IRRADIATION CONDITIONS

Adapting to the AM0 space solar spectrum

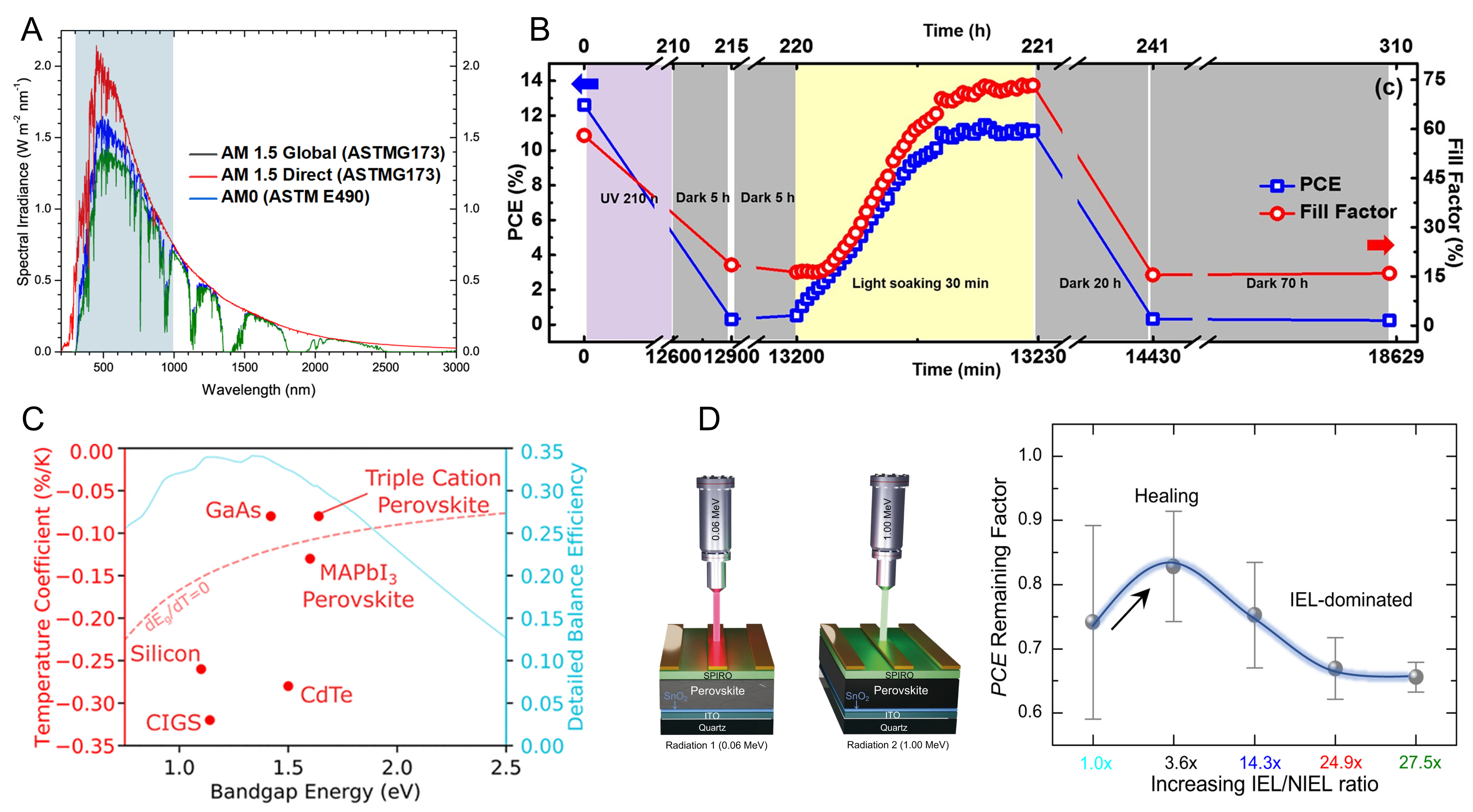

In space, solar cells are exposed to unfiltered sunlight characterized by the Air Mass 0 (AM0) spectrum, which has higher light intensity and a distinctly different spectral shape compared to the standard AM1.5G spectrum commonly used on Earth. Key differences include: (i) Higher UV flux: The UV photon flux is significantly higher under the AM0 spectrum, representing approximately 8% of the total photon power compared to about 4% under AM1.5G, since there is no atmospheric filtering to absorb a large portion of incoming UV radiation; (ii) No atmospheric absorption bands: The spectrum is continuous from 250 to 2,500 nm; (iii) Over 36% higher intensity: Sunlight intensity is up to 1,366 W m-2 in space compared to around 1,000 Wm-2 at Earth’s surface[99]. These differences indicate that solar cells in LEO must withstand high UV conditions while also utilizing a broader irradiance range in the UV-Blue region [Figure 4A].

Figure 4. (A) Solar irradiation spectra under different air mass conditions (AM0, AM1.5 direct, AM1.5 G). (B) Light-IV characteristics of PSCs showing PCE and FF under the indicated illumination conditions[103]. Copyright © 2016, Springer Nature. (C) Temperature coefficients of major photovoltaic technologies overlaid on the detailed balance limit of photovoltaic efficiency at 290 K; dashed lines indicate TPCE at AM 1.5 under 1 sun and for the case without bandgap shift with temperature[117]. Copyright © 2021, American Chemical Society. (D) Irradiation of PSCs with elastic non-ionizing energy loss (NIEL)-dominated 0.06 MeV proton beam (red) and 1.0 MeV proton beam (green), and remaining PCE for PSCs irradiated at various inelastic ionizing energy loss (IEL)/NIEL ratios[26]. Copyright © 2024, Springer Nature.

Effective utilization of UV-Blue photons is one of the critical issues for PSCs in LEO[100-102]. PSCs that absorb the UV-Blue region can be optimized through compositional tuning of perovskite materials and device architecture engineering. Promising approaches include employing slightly wide-bandgap perovskites (1.8-2.0 eV) and fabricating tandem device architectures to more effectively harvest UV-Blue photons. CH3NH3PbI3-based PSCs have recently been reported to demonstrate improved UV stability and effective absorption of high-energy UV photons without rapid device degradation [Figure 4B][103]. Tandem solar cells based on perovskite/silicon[104,105] or all-perovskite[106,107] have also been explored as potential candidates for LEO applications. These devices are generally configured with a top perovskite sub-cell featuring a wide bandgap of 1.7-1.8 eV to harvest high-energy photons, and a bottom Si or narrow-bandgap perovskite sub-cell (1.1-1.2 eV) to absorb longer-wavelength photons extending into the infrared region. Such tandem solar cells could maximize performance under the AM0 environment in space, potentially achieving efficiencies beyond the single-junction limit of 30%-35%[108]. In addition, another important strategy in device engineering is the introduction of integrated UV filters or UV-tolerant charge transport layers, since photo-induced degradation of perovskite thin films occurs at short wavelengths, including the UV range[109]. For example, metal-oxide electron transport layers, such as TiO2 or SnO2, were widely used to filter out the most damaging UV wavelengths and protect the chemical bonds in the perovskite film from direct exposure to high-energy UV light due to their wide bandgap and cutting UV region[110]. In addition, recent studies have raised concerns that oxygen-vacancy-related Ti ions of TiO2 under UV illumination can lead to photocarrier losses[100], and SnO2 often exhibits more severe charge recombination due to its lower conduction band[111], along with degradation during high-temperature processes[112]. Accordingly, emerging research efforts are underway to develop innovative charge transport materials with improved UV durability[113,114]. Thus, compositional engineering of perovskites allows their absorption to be tuned for the space solar spectrum, while PSCs can selectively absorb a broad range of wavelengths with high device stability through appropriate choice of materials and device architecture.

Temperature coefficients and thermal cycling performance

Due to unpredictable solar phenomena, such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections, as well as the orbital motion of spacecraft alternating between light and dark environments, thermal fluctuations become more intense. The space temperature range of -185 to -150 °C, as specified by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in AIAA S-111A-2014, “Qualification and Quality Requirements for Space-Qualified Solar Cells”[115], requires that solar cells possess high thermal tolerance across a broad operational range (-150 to +120 °C) to maintain stable and reliable performance in orbit. The temperature coefficient (TPCE) is an important parameter for evaluating and improving the thermal cycling performance of PSCs. It is defined as the change in efficiency or voltage with temperature. For example, c-Si solar cells have a relatively low TPCE of about -0.4 to -0.25%°C-1, indicating a significant efficiency drop with increasing temperature due to their high sensitivity to thermal effects. GaAs-based solar cells, commonly used in current space applications, have a TPCE of approximately 0.1 ~ -0.05%°C-1 [Figure 4C]. PSCs generally exhibit a less negative TPCE of around -0.2%°C-1[116]. Notably, Moot et al. reported a significantly improved TPCE of -0.08%°C-1 for PSCs, achieved through compositional engineering of the perovskite and optimization of the charge transport layers[117]. This interesting result can be attributed to the unique properties of perovskites, as discussed below. (1) The bandgap of lead-halide perovskites typically increases with temperature, resulting in an improvement in the open-circuit voltage (Voc) of PSCs or a smaller Voc drop compared to other solar cells. Consequently, PSCs exhibit reduced thermal voltage losses upon heating, partially offsetting the performance degradation commonly observed in any commercial solar cells; (2) Although the carrier density in perovskites varies depending on film engineering, device architecture[118,119], and application, high-quality MAPbI3 perovskites have a lower carrier density[120] compared to Sn-based narrow-bandgap, highly doped perovskites[121]. This lower carrier density contributes to suppressed charge recombination and reduced performance loss with increasing temperature. From a practical view, PSCs have high potential for thermal tolerance with increased environmental temperatures[122,123], such as prolonged sunlight exposure up to

Basically, the perovskite PV materials undergo phase transitions in response to temperature variations, leading to changes in crystal structure, structural disorder, and charge-carrier dynamics. For example, MAPbI3 undergoes well-known phase transitions from the orthorhombic (γ) phase below ~-115 °C, to the tetragonal (β) phase between -115 and ~60 °C, and finally to the cubic (α) phase above ~60 °C[127,128]. As temperature increases, lattice symmetry increases, leading to enhanced dynamic disorder and stronger electron-phonon coupling[129]. This enhances ionic mobility and can lead to increased non-radiative recombination. At low temperatures (below -100 °C), carrier mobility is reduced due to localized states and suppressed lattice motion[130], while at high temperatures (> 80 °C), thermal degradation and MA+ instability become dominant concerns. FAPbI3 tends to undergo phase transitions from tetragonal (β phase, below ~-140 °C), to hexagonal (-140 to ~30 °C), and then to cubic (α phase, above ~30 °C)[127]. Under high-temperature conditions below ~150 °C and in the presence of moisture, FAPbI3 exhibits instability, with structural distortion involving transformation from the α phase to the non-perovskite δ phase, because the FA+ cation size leads to dynamic fluctuations at intermediate temperatures[131,132]. At temperatures above

Consequently, the thermal cycling endurance of PSCs can be enhanced through interface engineering between 2D and 3D perovskite layers, the introduction of self-healing compositions, and suppression of phase transitions via compositional engineering of perovskite materials[133,134]. In addition, it has been reported that the use of 2D capping layers and strain-relieving buffer layers prevents light-induced phase segregation in mixed-halide perovskites under high-temperature conditions. These studies suggest promising strategies for enhancing the thermal endurance of PSCs in space environments. On the other hand, to prevent device degradation caused by extremely high and low temperatures, it is also essential to develop thermally robust materials and to consider additional thermal management strategies, such as reflective coatings, thermal straps, and heat-insulating films.

Low-light and partial illumination performance

In dark space environments encountered during deep-space exploration, eclipses, and on planetary surfaces beyond direct sunlight, solar cells are required to operate under low-light conditions. Notably, PSCs can perform efficiently at low irradiance while maintaining relatively high Voc and efficiency, owing to their superior electronic properties, such as low non-radiative recombination rates and high charge-carrier mobility[135-137]. Corresponding to the characteristics of PSCs, Glowienka et al. investigated a light-intensity-dependent analysis of current density-voltage (J-V) parameters to identify the mechanisms in PSCs, such as bulk or interfacial recombination and series or shunt resistance[138]. Glowienka and

Radiation-induced performance enhancements

The response of perovskites to space radiation, including protons, electrons, γ-rays, and neutrons, demonstrates their promising tolerance and unique self-healing characteristics. The intriguing and unique recovery phenomenon about perovskite is that device performance can be temporarily improved under certain radiation exposure. This has been attributed to radiation-induced defects passivating pre-existing trap sites in the material. For example, some studies reported that PSCs exhibited a slight increase in fill factor (FF) and efficiency immediately after exposure to a low, followed by a higher fluence of proton irradiation (0.9 × 1013-3.8 × 1013 cm-2) [Figure 4D][26]. The proposed hypothesis is that ionizing radiation can displace halide ions into vacancy sites and relieve lattice strain, effectively “healing” certain defects. In particular, Lang et al. demonstrated the proton robustness of MAPbI3 by investigating the positive-intrinsic-negative (p-i-n) solar cells, resulting in stable Voc and FF at high proton energy of

In the case of γ-rays, which are highly penetrating and difficult to shield[146], Cs0.15MA0.10FA0.75Pb(Br0.17I0.83) exhibits PL enhancement and red-shift under up to 5,000 gray (Gy), with Hoke effect indicating halide segregation and bandgap formation under illumination. Boldyreva et al.[147] also reported a reversible mechanism in perovskites: upon irradiation, MAPbI3 decomposes into methylammonium iodide (MAI) and PbI2, with MAI further breaking down into NH3 and CH3I. γ-rays cleave the C-I bond, producing CH3+ and I-, which may passivate iodine vacancies or reform MAI via reactions with NH3I-, ultimately restoring the perovskite phase[147-149].

Fast neutrons with energy > 10 MeV are generated through collisions between incoming plasma or cosmic rays and the atmosphere’s constituents or materials comprising the spacecraft[150,151]. Paternò et al. demonstrated MAPb(I3-xClx)-based p-i-n PSCs using a spallation neutron source at the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source facility (Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, UK), simulating ~80 years of fast neutron exposure equivalent to levels experienced on the ISS (1.5 × 109 particles cm-2s-1)[152]. The PSCs exhibited more stable PV performance under neutron irradiation than under illumination, due to neutron bombardment[152].

This counterintuitive self-healing under radiation does not occur in conventional semiconductors, which typically suffer cumulative damage under such conditions. Although applying radiation to enhance PSC performance is impractical, this phenomenon highlights the unique radiation response of perovskites, including a radiation-annealing threshold beyond which degradation begins. Identifying the optimal radiation dose window that triggers beneficial defect healing without causing additional damage is currently under investigation. By exploiting these unique properties, PSCs can be refreshed during service via natural background radiation or controlled radiation. Overall, the self-healing of perovskites under radiation provides potential for their long-term performance in space.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS WITH CONVENTIONAL SPACE PHOTOVOLTAIC TECHNOLOGIES

Radiation hardness and reliability

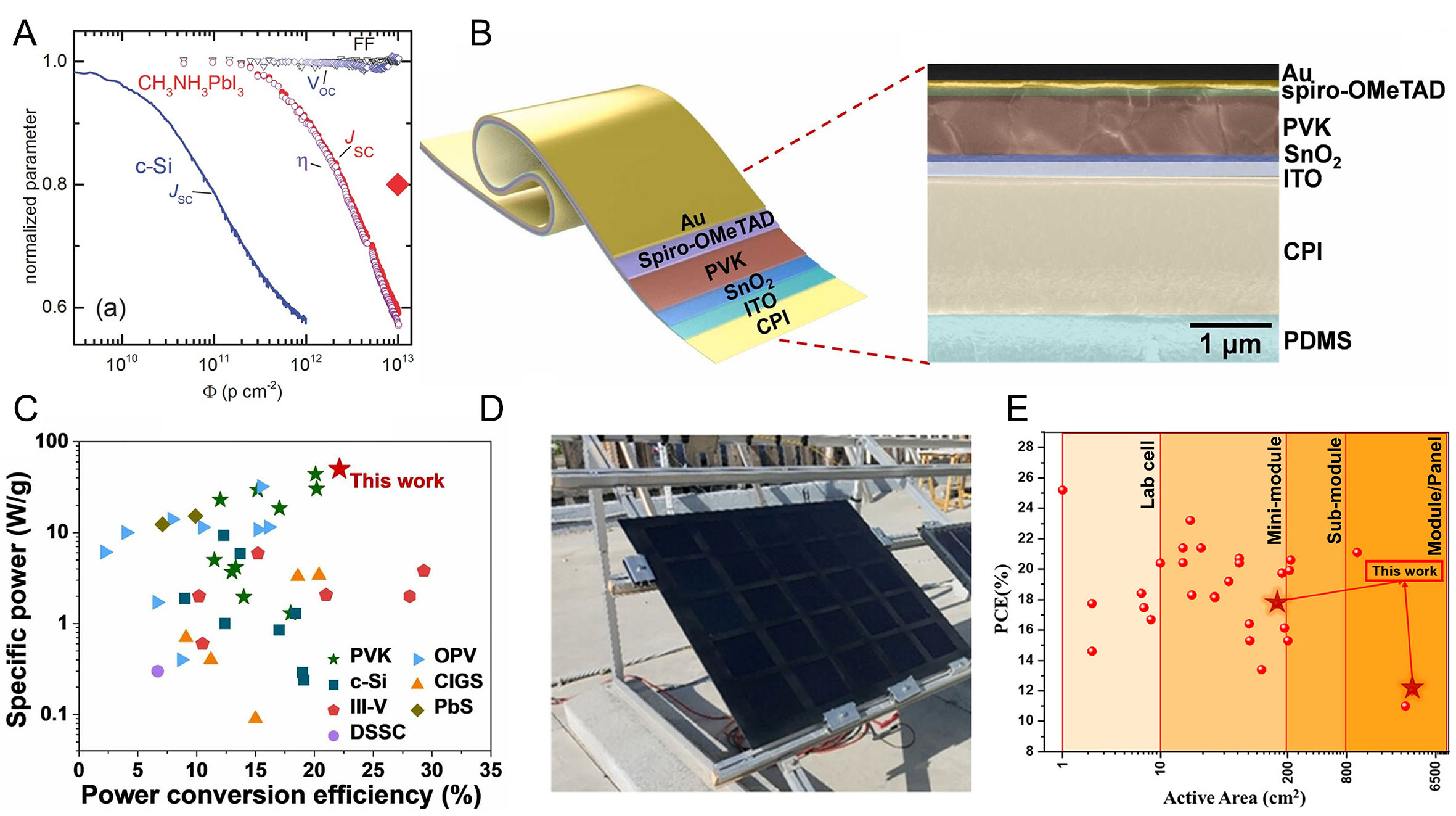

To withstand prolonged radiation exposure in space, solar cells require physical protection such as cerium-doped glass[153] or fused silica[154]. Even with such shielding, ionization and lattice displacement gradually degrade device performance and shorten PV lifetimes. PSCs exhibit exceptional intrinsic radiation hardness compared with conventional silicon or III-V based photovoltaics [Figure 5A]. For instance, Si solar cells typically lose 50%-80% of their output under proton irradiation at doses as low as ~1 × 1010 p cm-2, due to defect formation[23]. GaAs solar cells show similar vulnerability, with maximum power reduced by 50%-60% under fluences of ~ 1 × 1016 e cm-2 or 1 × 1012 p cm-2[17], and pronounced degradation of electroluminescence and Voc arising from nonradiative recombination centers induced by electron irradiation, even at fluence as low as 3 × 1013 e cm-2[155]. By comparison, PSCs have maintained their initial performance even under higher proton fluences reaching 1 × 1015 p cm-2. This inherent radiation hardness suggests that PSCs could potentially operate in orbits or mission durations without the need for heavy shielding, enabling lighter and simpler arrays with improved specific power. However, it is important to note that the long-term reliability of PSCs remains unproven over multi-year timescales, especially compared with the extensive flight heritage accumulated over decades for Si and III-V solar cells[156,157]. Therefore, extensive qualification testing for PSCs is essential to validate that no unexpected failure modes arise, including extended thermal cycling or micrometeoroid impacts on thin films. Nevertheless, the remarkable radiation tolerance of perovskites highlights their promise as candidates for more robust spacecraft power systems.

Figure 5. (A) Proton radiation tolerance of CH3NH3PbI3-based PSCs compared to a c-Si photodiode as a function of the proton dose, ϕ[23]. Copyright © 2016, Wiley. (B) Device architecture and cross-sectional SEM images of an ultra-thin flexible PSC achieving a specific power of 50 W g-1[159]. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier. (C) Summary and comparison of PCE and weight-specific power density of ultra-thin solar cells[159]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier. (D) Photograph of a realized perovskite panel installed for outdoor characterization[171]. Copyright © 2025, Wiley. (E) Summary of PCEs for perovskite-based photovoltaics across various device sizes[171]. Copyright © 2025, Wiley.

Specific power and deployability

In terms of specific power, PSCs already surpass conventional solar cells. State-of-the-art multi-junction panels based on gallium indium phosphide/gallium indium arsenide/germanium (GaInP/Ga(In)As/Ge) triple junctions[57] can achieve a specific power of 1.3 W g-1 by reducing the cell thickness from 150 to 50 μm. By comparison, silicon arrays typically provide less than 0.1 W g-1[158]. In contrast, ultra-thin PSCs on

Efficiency and power output

Single-junction perovskite cells have achieved record efficiencies of 27.0%[14,166] at the lab scale, comparable to silicon (~27%)[15,167] and approaching those of state-of-the-art triple-junction GaAs cells (~39% under 1 sun, AM1.5G[168]). Although GaAs multi-junctions still maintain extremely high efficiencies of ~34% under the AM0 space spectrum[168], the performance gap can narrow - or even reverse - after radiation exposure and thermal cycling, as GaAs cells are expected to degrade by nearly 25% over several years in orbit[169]. Beyond single-junction devices, tandem PSCs have shown remarkable progress, with efficiencies of 29.1% for two-terminal perovskite-perovskite[106] and 34.85% for perovskite-silicon tandem devices[14]. The latter is comparable to III-V solar cells, while offering the potential for much higher specific power due to the lightweight nature of perovskites. However, scaling PSCs from laboratory-scale devices to large-area modules (> 100 cm2) without significant efficiency loss remains a challenge[170]. Recently, perovskite panels with an aperture area of 0.73 m2 and 12.0% efficiency were demonstrated by interconnecting 156 cm2 modules with individual efficiencies of 16.3% [Figure 5D and E][171]. These advances highlight the rapid progress toward large-area PSCs, although they still lag behind III-V multijunction panels with proven meter-scale fabrication[172]. Continued improvements in perovskite efficiency, combined with their inherent radiation tolerance, could substantially reduce the cost of space-grade solar power.

Cost and manufacturing

One of the most compelling advantages of PSCs for space applications is their potential for dramatic cost reduction. Conventional space-grade III-V multi-junction solar cells remain extremely expensive - typically several hundred to over one thousand USD W1 - due to epitaxial growth on costly substrates and limited mass production[173]. c-Si modules are cheaper at terrestrial module levels (0.2-0.4 USD W-1), but radiation-hardened silicon architectures adapted for space also incur elevated costs because of specialized processing[174]. PSCs, in principle, can be fabricated using scalable solution-based or roll-to-roll techniques[175], with preliminary estimates suggesting module manufacturing costs below 0.1 USD W-1 once stabilized high-efficiency modules are realized[176-178]. More recent technoeconomic modeling studies indicate that, under favorable stability and scale-up scenarios, the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) for PSCs could fall in the range of 0.04-0.25 USD kWh-1, making them competitive with c-Si and III-V PVs in applications such as satellite mega-constellations, where deploying large quantities of solar panels renders traditional PV economically unfeasible[179]. Lower PV costs could also expand mission design options, enabling concepts such as expendable solar arrays or increased on-board power availability for electric propulsion systems[180]. However, these projections remain theoretical in the space context. The transition from laboratory-scale devices to qualified space-grade modules will require extensive testing for encapsulation, radiation hardening, and long-duration operation. Initial deployments are therefore likely to be expensive, mirroring the early trajectory of other PV technologies. Nonetheless, the ability to leverage terrestrial thin-film manufacturing infrastructure, combined with the intrinsic advantages of PSCs in mass per watt, presents a credible pathway toward cost breakthroughs in space photovoltaics.

Challenges and considerations

Sections "Adapting to the AM0 space solar spectrum"-“Radiation-induced performance enhancements” have highlighted the performance characteristics of PSCs relevant to space applications. As summarized in

Quantitative comparison of photovoltaic (PV) technologies for space applications

| PV technology | Initial efficiency (%) | Specific power (W g-1) | Radiation tolerance | 10-year performance retention1 | Manufacturing cost (USD W-1) | TRL[186]2 |

| c-Si | 22-27[167] | 0.1-0.4[158] | Low (severe degradation > 1012 p cm-2)[23] | 70%-85%[157] | 0.2-0.4[174] | 9 |

| III-V (GaAs, multi-junction) | 30-39[168] | 0.3-1.5[57] | Medium (significant degradation > 1013 p cm-2)[155] | 80%-90%[157] | 150-1,000[173] | 9 |

| Perovskite | 25-27[166]; 34.8[14] (tandem) | 2-50[159] | High (tolerant up to ~1016 p cm-2)[28] | Unvalidated | < 0.1 (target)[176] | 4, 5 |

Thermal tolerance represents another limitation. PSC materials and device architectures have yet to demonstrate stability under sustained high-temperature operation (> 150 °C), where phase transitions or decomposition are likely to occur. In contrast, Si and GaAs solar cells can endure higher temperatures, albeit with some efficiency loss[184]. Effective thermal management - through optical reflectors or sun-tracking to avoid overheating - will be indispensable in PSC array design. Integration and scalability also remain unresolved. The reliable interconnection of many thin-film cells into deployable arrays is an engineering challenge. Furthermore, fabricating large-area modules (> 100 cm2) without performance loss remains a work in progress and must be addressed before operational deployment can be realized[185].

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Overall, PSCs combine high efficiency, exceptional specific power, and intrinsic radiation tolerance, positioning them as strong alternatives to conventional Si- and GaAs-based solar cells for space PV applications, particularly in LEO. Experimental studies consistently indicate that PSCs experience less severe radiation-induced degradation than traditional photovoltaics, with partial performance recovery enabled by defect-tolerant lattice dynamics. However, the lack of comprehensive device-level validation under fully representative LEO conditions highlights the early stage of technological maturity. Progress toward space deployment will therefore depend on coordinated efforts to establish robust encapsulation, thermal management, and space-qualification pathways through targeted demonstration missions.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to the conception of this mini-review and proposed its topic: Kim, G. H.

Conducted the literature survey and prepared the manuscript: Song, S.; Cho, H. W.

Collected literature and summarized the reports: Kim, H.; Kim, M.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2023-00301974 and RS-2023-00246901), and by the Human Resources Development program of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of Korea (RS-2024-00398425).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Jolliff, B. L.; Robinson, M. S. The scientific legacy of the Apollo program. Phys. Today. 2019, 72, 44-50.

2. Chen, M.; Goyal, R.; Majji, M.; Skelton, R. E. Review of space habitat designs for long term space explorations. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2021, 122, 100692.

3. Martinelli, A.; Buzzaccaro, S.; Galand, Q.; et al. An advanced light scattering apparatus for investigating soft matter onboard the International Space Station. NPJ. Microgravity. 2024, 10, 115.

4. NASA Home page. https://www.nasa.gov/humans-in-space/space-launch-system/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed 2026-02-4).

5. Kraft, R. H. NASA progresses toward artemis II moon mission. https://www.nasa.gov/missions/artemis/artemis-2/nasa-progresses-toward-artemis-ii-moon-mission/ (accessed 2026-02-4).

6. Arianespace Home page. https://newsroom.arianespace.com/with-ariane-6-arianespace-successfully-launches-copernicus-sentinel-1d-satellite?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed 2026-02-4).

7. Yamaguchi, M. Japan successfully launches new cargo spacecraft to deliver supplies to International Space Station. https://apnews.com/article/japan-space-rocket-h3-iss-6b4384acb177c6b8f9c41fa7005b6691 (accessed 2026-02-4).

8. Robinson-Smith, W. SpaceX to launch 4 Falcon Heavy rockets as part of newest U.S. national security missions award. https://spaceflightnow.com/2025/10/04/spacex-to-launch-4-falcon-heavy-rockets-as-part-of-newest-u-s-national-security-missions-award/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed 2026-02-4).

9. Dunn, M. Blue origin launches huge rocket carrying twin NASA spacecraft to Mars. https://apnews.com/article/blue-origin-mars-nasa-new-glenn-bezos-4e3e6c380b8294b557618a6fea92282b (accessed 2026-02-4).

10. Data Page: annual number of objects launched into space. https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250909-093708/grapher/yearly-number-of-objects-launched-into-outer-space.html (accessed 2026-02-4).

11. Alta sets flexible solar record with 29.1% GaAs cell. https://optics.org/news/9/12/19?utm (accessed 2026-02-4).

12. Conway, E. J.; Walker, G. H.; Heinbockel, J. H. GaAs solar cells for space applications. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19800064033 (accessed 2026-02-4).

13. Min, H.; Lee, D. Y.; Kim, J.; et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on SnO2 electrodes. Nature 2021, 598, 444-50.

14. Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart. https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html (accessed 2026-02-4).

15. Delmas, W.; Erickson, S.; Arteaga, J.; et al. Evaluation of hybrid perovskite prototypes after 10-month space flight on the international space station. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2203920.

17. Hisamatsu, T.; Kawasaki, O.; Matsuda, S.; Nakao, T.; Wakow, Y. Radiation degradation of large fluence irradiated space silicon solar cells. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 1998, 50, 331-8.

18. Raya-Armenta, J. M.; Bazmohammadi, N.; Vasquez, J. C.; Guerrero, J. M. A short review of radiation-induced degradation of III-V photovoltaic cells for space applications. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 2021, 233, 111379.

19. Inguimbert, C.; Messenger, S. Equivalent displacement damage dose for on-orbit space applications. IEEE. Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2012, 59, 3117-25.

20. Messenger, S. R.; Summers, G. P.; Burke, E. A.; Walters, R. J.; Xapsos, M. A. Modeling solar cell degradation in space: a comparison of the NRL displacement damage dose and the JPL equivalent fluence approaches. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2001, 9, 103-21.

21. Neitzert, H.; Ferrara, M.; Kunst, M.; et al. Electroluminescence efficiency degradation of crystalline silicon solar cells after irradiation with protons in the energy range between 0.8 MeV and 65 MeV. Phys. Status. Solidi. 2008, 245, 1877-83.

22. Durant, B. K.; Afshari, H.; Singh, S.; Rout, B.; Eperon, G. E.; Sellers, I. R. Tolerance of perovskite solar cells to targeted proton irradiation and electronic ionization induced healing. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 2362-8.

23. Lang, F.; Nickel, N. H.; Bundesmann, J.; et al. Radiation hardness and self-healing of perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8726-31.

24. Nie, W.; Blancon, J. C.; Neukirch, A. J.; et al. Light-activated photocurrent degradation and self-healing in perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11574.

25. Yuan, Q.; Chen, J.; Shi, C.; Shi, X.; Sun, C.; Jiang, B. Advances in self-healing perovskite solar cells enabled by dynamic polymer bonds. Macromol. Rapid. Commun. 2025, 46, e2400630.

26. Kirmani, A. R.; Byers, T. A.; Ni, Z.; et al. Unraveling radiation damage and healing mechanisms in halide perovskites using energy-tuned dual irradiation dosing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 696.

27. Brus, V. V.; Lang, F.; Bundesmann, J.; et al. Defect dynamics in proton irradiated CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cells. Adv. Elect. Mater. 2017, 3, 1600438.

28. Miyazawa, Y.; Ikegami, M.; Chen, H. W.; et al. Tolerance of perovskite solar cell to high-energy particle irradiations in space environment. iScience 2018, 2, 148-55.

29. Keleş, D. G.; Karadeniz, H.; Karadeniz, S. A study of proton radiation effects on a silicon based solar cell. Gazi. Univ. J. Sci. Part. A. Eng. Innov. 2023, 10, 105-12.

30. Lin, T.; Hsieh, C.; Kanai, A.; et al. Radiation resistant chalcopyrite CIGS solar cells: proton damage shielding with Cs treatment and defect healing via heat-light soaking. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 7536-48.

31. Anspaugh, B. E.; Downing, R. G. Radiation effects in silicon and gallium arsenide solar cells using isotropic and normally incident radiation. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19840026722 (accessed 2026-02-4).

32. Yamaguchi, M.; Taylor, S. J.; Matsuda, S.; Kawasaki, O. Mechanism for the anomalous degradation of Si solar cells induced by high fluence 1 MeV electron irradiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 3141-3.

33. Boldyreva, A. G.; Frolova, L. A.; Zhidkov, I. S.; et al. Unravelling the material composition effects on the gamma ray stability of lead halide perovskite solar cells: MAPbI3 breaks the records. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2630-6.

34. Ginisty, F.; Wrobel, F.; Ecoffet, R.; et al. South Atlantic anomaly evolution seen by the proton flux. JGR. Space. Phys. 2024, 129, e2023JA032186.

35. Afshari, H.; Chacon, S. A.; Sourabh, S.; et al. Radiation tolerance and self-healing in triple halide perovskite solar cells. APL. Energy. 2023, 1, 026105.

36. Zhao, P.; Su, J.; Guo, Y.; et al. A new all-inorganic vacancy-ordered double perovskite Cs2CrI6 for high-performance photovoltaic cells and alpha-particle detection in space environment. Mater. Today. Phys. 2021, 20, 100446.

37. Shim, H.; Seo, S.; Chandler, C.; et al. Enhancing radiation resilience of wide-band-gap perovskite solar cells for space applications via A-site cation stabilization with PDAI2. Joule 2025, 9, 102043.

38. Akbulatov, A. F.; Frolova, L. A.; Dremova, N. N.; et al. Light or heat: what is killing lead halide perovskites under solar cell operation conditions? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 333-9.

39. Juarez-Perez, E. J.; Hawash, Z.; Raga, S. R.; Ono, L. K.; Qi, Y. Thermal degradation of CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite into NH3 and CH3I gases observed by coupled thermogravimetry-mass spectrometry analysis. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3406-10.

40. Tu, Y.; Xu, G.; Yang, X.; et al. Mixed-cation perovskite solar cells in space. Sci. China. Phys. Mech. Astron. 2019, 62, 9356.

41. Cardinaletti, I.; Vangerven, T.; Nagels, S.; et al. Organic and perovskite solar cells for space applications. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 2018, 182, 121-7.

42. Reb, L. K.; Böhmer, M.; Predeschly, B.; et al. Perovskite and organic solar cells on a rocket flight. Joule 2020, 4, 1880-92.

43. Lee, M. M.; Teuscher, J.; Miyasaka, T.; Murakami, T. N.; Snaith, H. J. Efficient hybrid solar cells based on meso-superstructured organometal halide perovskites. Science 2012, 338, 643-7.

44. Hu, Y.; Niu, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Flexible perovskite solar cells with high power-per-weight: progress, application, and perspectives. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 2917-43.

45. Wang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yan, Y.; et al. Al2O3 nanoparticles as surface modifier enables deposition of high quality perovskite films for ultra-flexible photovoltaics. Adv. Powder. Mater. 2024, 3, 100142.

46. Li, Z.; Jia, C.; Wan, Z.; et al. Boosting mechanical durability under high humidity by bioinspired multisite polymer for high-efficiency flexible perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1771.

47. Lee, M.; Jo, Y.; Kim, D. S.; Jeong, H. Y.; Jun, Y. Efficient, durable and flexible perovskite photovoltaic devices with Ag-embedded ITO as the top electrode on a metal substrate. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 14592-7.

48. Kaltenbrunner, M.; Adam, G.; Głowacki, E. D.; et al. Flexible high power-per-weight perovskite solar cells with chromium oxide-metal contacts for improved stability in air. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1032-9.

49. Kang, S.; Jeong, J.; Cho, S.; et al. Ultrathin, lightweight and flexible perovskite solar cells with an excellent power-per-weight performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019, 7, 1107-14.

50. Zhang, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, D.; et al. Perovskite films: toward all room-temperature, solution-processed, high-performance planar perovskite solar cells: a new scheme of pyridine-promoted perovskite formation (Adv. Mater. 13/2017). Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, adma.201770091.

51. Zhang, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, D.; et al. Toward all room-temperature, solution-processed, high-performance planar perovskite solar cells: a new scheme of pyridine-promoted perovskite formation. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1604695.

52. Panagiotopoulos, A.; Maksudov, T.; Kakavelakis, G.; et al. A critical perspective for emerging ultra-thin solar cells with ultra-high power-per-weight outputs. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2023, 10, 041303.

53. Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; et al. High weight-specific power density of thin-film amorphous silicon solar cells on graphene papers. Nanoscale. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 324.

54. Jeong, S.; McGehee, M. D.; Cui, Y. All-back-contact ultra-thin silicon nanocone solar cells with 13.7% power conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2950.

55. Kim, J.; Hwang, J.; Song, K.; Kim, N.; Shin, J. C.; Lee, J. Ultra-thin flexible GaAs photovoltaics in vertical forms printed on metal surfaces without interlayer adhesives. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 253101.

56. Cho, S.; Jung, D.; Kim, J.; Seo, J.; Ju, H.; Lee, J. Ultrathin GaAs photovoltaic arrays integrated on a 1.4 µm polymer substrate for high flexibility, a lightweight design, and high specific power. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2200344.

57. Algora, C.; Reboreda, D. G.; Palacios, P. F.; et al. Flexible GaInP/Ga(In)As/Ge triple-junction space solar cells with a simple fabrication process based on Ge substrate thinning demonstrate power-to-mass ratios of 1.3 kW/kg. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 2025, 292, 113817.

58. Li, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, Z.; et al. Progress and challenges toward effective flexible perovskite solar cells. Nanomicro. Lett. 2023, 15, 206.

59. Gao, Y.; Huang, K.; Long, C.; et al. Flexible perovskite solar cells: from materials and device architectures to applications. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 1412-45.

60. Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, F.; Chen, C. Research of aging test on high Tg colorless polyimide. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55286.

61. Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D. Synthetic strategies for highly transparent and colorless polyimide film. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52604.

62. Fang, Y.; He, X.; Kang, J.; et al. Colorless transparent and thermally stable terphenyl polyimides with various small side groups for substrate application. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 202, 112640.

63. Lee, G.; Kim, M.; Choi, Y. W.; et al. Ultra-flexible perovskite solar cells with crumpling durability: toward a wearable power source. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3182-91.

64. Bu, T.; Li, J.; Zheng, F.; et al. Universal passivation strategy to slot-die printed SnO2 for hysteresis-free efficient flexible perovskite solar module. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4609.

65. Bu, T.; Shi, S.; Li, J.; et al. Low-temperature presynthesized crystalline tin oxide for efficient flexible perovskite solar cells and modules. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 14922-9.

66. Duan, M.; Yang, J.; Li, T.; et al. Mechanically stable screen-printed flexible perovskite solar cells via selective self-assembled siloxane coupling agents. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 407.

67. Yeo, J.; Lee, C.; Jang, D.; et al. Reduced graphene oxide-assisted crystallization of perovskite via solution-process for efficient and stable planar solar cells with module-scales. Nano. Energy. 2016, 30, 667-76.

68. Lee, M.; Jo, Y.; Kim, D. S.; Jun, Y. Flexible organo-metal halide perovskite solar cells on a Ti metal substrate. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 4129-33.

69. Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, W.; et al. TiO2 nanotube arrays based flexible perovskite solar cells with transparent carbon nanotube electrode. Nano. Energy. 2015, 11, 728-35.

70. Kumar, A.; Rani, S.; Sundar, Ghosh. D. Kitchen-grade aluminium foil as dual-purpose substrate-cum-electrode for ultrathin, ultralight, and bendable perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 2024, 268, 112737.

71. Peleg, R. Printed flexible solar cells by CSIRO launched on Space Machine Company’s Optimus-1 satellite, as part of Space X’s Transporter-10 mission. https://www.perovskite-info.com/printed-flexible-solar-cells-csiro-launched-space-machine-company-s-optimus-1 (accessed 2026-02-4).

72. Ma, Y.; Lu, Z.; Su, X.; Zou, G.; Zhao, Q. Recent progress toward commercialization of flexible perovskite solar cells: from materials and structures to mechanical stabilities. Adv. Energy. Sustain. Res. 2023, 4, 2200133.

73. Sears, K. K.; Fievez, M.; Gao, M.; Weerasinghe, H. C.; Easton, C. D.; Vak, D. ITO-free flexible perovskite solar cells based on roll-to-roll, slot-die coated silver nanowire electrodes. Sol. RRL. 2017, 1, 1700059.

74. Lu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S.; Choy, W. C. Room-temperature solution-processed and metal oxide-free nano-composite for the flexible transparent bottom electrode of perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 5946-53.

75. Jung, H. S.; Han, G. S.; Park, N.; Ko, M. J. Flexible perovskite solar cells. Joule 2019, 3, 1850-80.

76. Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Yang, Y. M.; et al. High-efficiency robust perovskite solar cells on ultrathin flexible substrates. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10214.

77. Liu, D.; Bi, J.; Xu, W.; et al. Strain relaxation in halide perovskites via 2D/3D perovskite heterojunction formation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu3459.

78. Tang, G.; Chen, L.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tai, Q. A review on recent advances in flexible perovskite solar cells. Solar. RRL. 2025, 9, 2400844.

79. Li, Y.; Yan, S.; Cao, J.; et al. High performance flexible Sn-Pb mixed perovskite solar cells enabled by a crosslinking additive. NPJ. Flex. Electron. 2023, 7, 253.

80. Jin, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ming, Y.; et al. Spontaneous bifacial capping of perovskite film for efficient and mechanically stable flexible solar cell. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 90.

81. Aristidou, N.; Eames, C.; Sanchez-Molina, I.; et al. Fast oxygen diffusion and iodide defects mediate oxygen-induced degradation of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15218.

82. Seid, B. A.; Sarisozen, S.; Peña-Camargo, F.; et al. Understanding and mitigating atomic oxygen-induced degradation of perovskite solar cells for near-earth space applications. Small 2024, 20, e2311097.

83. Wang, Y.; Ahmad, I.; Leung, T.; et al. Encapsulation and Stability testing of perovskite solar cells for real life applications. ACS. Mater. Au. 2022, 2, 215-36.

84. Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Yang, J.; Shi, T. A review of encapsulation methods and geometric improvements of perovskite solar cells and modules for mass production and commercialization. Nano. Mater. Sci. 2025, 7, 790-809.

85. Zhang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, M.; Lan, Z.; Wu, J.; Ye, L. Electrostatically sprayed flexible encapsulation for high-performance III-V solar cells. Solar. RRL. 2024, 8, 2300836.

86. Bush, M. E.; Sims, J. D.; Erickson, S. S.; et al. Space environment considerations for perovskite solar cell operations: a review. Acta. Astronaut. 2025, 235, 235-50.

87. Zheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Z.; et al. Advancing perovskite photovoltaics for space: critical stability testing guidelines. Adv. Photon. 2025, 7, 030502.

88. Kirmani, A. R.; Ostrowski, D. P.; Vansant, K. T.; et al. Metal oxide barrier layers for terrestrial and space perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Energy. 2023, 8, 191-202.

89. Ajdič, Ž.; Jošt, M.; Topič, M. The effect of Al2O3 on the performance of perovskite solar cells. Solar. RRL. 2024, 8, 2400247.

90. Li, J.; Xia, R.; Qi, W.; et al. Encapsulation of perovskite solar cells for enhanced stability: structures, materials and characterization. J. Power. Sources. 2021, 485, 229313.

91. Huang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Hu, N.; Wei, Q. Advances in atomic oxygen resistant polyimide composite films. Compos. Part. A. Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 168, 107459.

92. Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Zou, L.; Ayubi, B. I.; Wang, Y. Mechanism analysis and potential applications of atomic oxygen erosion protection for kapton-type polyimide based on molecular dynamics simulations. Polymers 2024, 16, 1687.

93. Mariani, P.; Molina-García, MÁ.; Barichello, J.; et al. Low-temperature strain-free encapsulation for perovskite solar cells and modules passing multifaceted accelerated ageing tests. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4552.

94. Wang, T.; Yang, J.; Cao, Q.; et al. Room temperature nondestructive encapsulation via self-crosslinked fluorosilicone polymer enables damp heat-stable sustainable perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1342.

95. Xue, D. J.; Hou, Y.; Liu, S. C.; et al. Regulating strain in perovskite thin films through charge-transport layers. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1514.

96. Dailey, M.; Li, Y.; Printz, A. D. Residual film stresses in perovskite solar cells: origins, effects, and mitigation strategies. ACS. Omega. 2021, 6, 30214-23.

97. Wu, J.; Liu, S. C.; Li, Z.; et al. Strain in perovskite solar cells: origins, impacts and regulation. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwab047.

98. Vansant, K. T.; Kirmani, A. R.; Patel, J. B.; et al. Combined stress testing of perovskite solar cells for stable operation in space. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2023, 6, 10319-26.

99. Balan, M. C.; Damian, M.; Jäntschi, L. Preliminary results on design and implementation of a solar radiation monitoring system. Snesors 2008, 8, 963-78.

100. Ji, J.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; et al. Two-stage ultraviolet degradation of perovskite solar cells induced by the oxygen vacancy-Ti4+ states. iScience 2020, 23, 101013.

101. Farooq, A.; Hossain, I. M.; Moghadamzadeh, S.; et al. Spectral dependence of degradation under ultraviolet light in perovskite solar cells. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2018, 10, 21985-90.

102. Berhe, T. A.; Su, W.; Chen, C.; et al. Organometal halide perovskite solar cells: degradation and stability. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 323-56.

103. Lee, S. W.; Kim, S.; Bae, S.; et al. UV degradation and recovery of perovskite solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38150.

104. Gao, J.; Sahli, F.; Liu, C.; et al. Solar water splitting with perovskite/silicon tandem cell and TiC-supported Pt nanocluster electrocatalyst. Joule 2019, 3, 2930-41.

105. Liu, J.; He, Y.; Ding, L.; et al. Perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells with bilayer interface passivation. Nature 2024, 635, 596-603.

106. Liu, Z.; Lin, R.; Wei, M.; et al. All-perovskite tandem solar cells achieving >29% efficiency with improved (100) orientation in wide-bandgap perovskites. Nat. Mater. 2025, 24, 252-9.

107. Lin, R.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; et al. All-perovskite tandem solar cells with 3D/3D bilayer perovskite heterojunction. Nature 2023, 620, 994-1000.

108. Al-Ashouri, A.; Köhnen, E.; Li, B.; et al. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell with >29% efficiency by enhanced hole extraction. Science 2020, 370, 1300-9.

109. Quitsch, W. A.; deQuilettes, D. W.; Pfingsten, O.; et al. The role of excitation energy in photobrightening and photodegradation of halide perovskite thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 2062-9.

110. Roose, B.; Wang, Q.; Abate, A. The role of charge selective contacts in perovskite solar cell stability. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2019, 9, 1803140.

111. Dong, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Discontinuous SnO2 derived blended-interfacial-layer in mesoscopic perovskite solar cells: minimizing electron transfer resistance and improving stability. Nano. Energy. 2017, 38, 358-67.

112. Dong, Q.; Shi, Y.; Wang, K.; et al. Insight into perovskite solar cells based on SnO2 compact electron-selective layer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015, 119, 10212-7.

113. Arora, N.; Dar, M. I.; Akin, S.; et al. Low-cost and highly efficient carbon-based perovskite solar cells exhibiting excellent long-term operational and UV stability. Small 2019, 15, e1904746.

114. Zhang, M.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Simple route to interconnected, hierarchically structured, porous Zn2SnO4 nanospheres as electron transport layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. Nano. Energy. 2020, 71, 104620.

115. Standard: qualification and quality requirements for space solar cells (AIAA S-111A-2014). Washington: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc, 2014. https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/book/10.2514/4.102806 (accessed 2026-02-4).

116. Dong, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; et al. High-temperature perovskite solar cells. Solar. RRL. 2021, 5, 2100370.

117. Moot, T.; Patel, J. B.; McAndrews, G.; et al. Temperature coefficients of perovskite photovoltaics for energy yield calculations. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 2038-47.

118. Qin, J.; Liu, X.; Yin, C.; Gao, F. Carrier dynamics and evaluation of lasing actions in halide perovskites. Trends. Chem. 2021, 3, 34-46.

119. Alnuaimi, A.; Almansouri, I.; Nayfeh, A. Performance of planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells under light concentration. AIP. Advances. 2016, 6, 115012.

120. Saidaminov, M. I.; Adinolfi, V.; Comin, R.; et al. Planar-integrated single-crystalline perovskite photodetectors. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8724.

121. Nishimura, K.; Kamarudin, M. A.; Hirotani, D.; et al. Lead-free tin-halide perovskite solar cells with 13% efficiency. Nano. Energy. 2020, 74, 104858.

122. Mavlonov, A.; Hishikawa, Y.; Kawano, Y.; Negami, T.; Hayakawa, A.; Minemoto, T. Investigating the stability of flexible perovskite solar cell modules in heat and damp-heat environments. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2025, 282, 113410.

123. Mavlonov, A.; Hishikawa, Y.; Kawano, Y.; et al. Thermal stability test on flexible perovskite solar cell modules to estimate activation energy of degradation on temperature. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2024, 277, 113148.

124. Philippe, B.; Park, B.; Lindblad, R.; et al. Chemical and electronic structure characterization of lead halide perovskites and stability behavior under different exposures - A photoelectron spectroscopy investigation. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 1720-31.

125. Kim, K.; Yang, S.; Kim, C.; et al. Non-volatile solid-state 4-(N-carbazolyl)pyridine additive for perovskite solar cells with improved thermal and operational stability. Nat. Energy. 2025, 10, 1427-38.

126. Dong, B.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Self-assembled bilayer for perovskite solar cells with improved tolerance against thermal stresses. Nat. Energy. 2025, 10, 342-53.

127. Kim, B.; Kim, J.; Park, N. First-principles identification of the charge-shifting mechanism and ferroelectricity in hybrid halide perovskites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19635.

128. Whitfield, P. S.; Herron, N.; Guise, W. E. Structures, phase transitions and tricritical behavior of the hybrid perovskite methyl ammonium lead iodide. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35685.

129. Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, H. Phase transition kinetics of MAPbI3 for tetragonal-to-orthorhombic evolution. JACS. Au. 2023, 3, 1205-12.

130. Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Evolved photovoltaic performance of MAPbI3 and FAPbI3-based perovskite solar cells in low-temperatures. Energy. Mater. 2024, 4, 400034.

131. Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Mohtar, M. N.; et al. Advances in multi-phase FAPbI3 perovskite: another perspective on photo-inactive δ-phase. J. Semicond. 2025, 46, 051804.

132. Liang, Y, Li, F, Cui, X. Toward stabilization of formamidinium lead iodide perovskites by defect control and composition engineering. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1707.

133. Grancini, G.; Nazeeruddin, M. K. Dimensional tailoring of hybrid perovskites for photovoltaics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 4-22.

134. Wang, B.; Iocozzia, J.; Zhang, M.; et al. The charge carrier dynamics, efficiency and stability of two-dimensional material-based perovskite solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4854-91.

135. Asada, T.; Raifuku, I.; Murata, F.; Hayashi, K.; Sugiyama, H.; Ishikawa, Y. Influence of the electron transport layer on the performance of perovskite solar cells under low illuminance conditions. ACS. Omega. 2024, 9, 32893-900.

136. Yang, G.; Ren, Z.; Liu, K.; et al. Stable and low-photovoltage-loss perovskite solar cells by multifunctional passivation. Nat. Photon. 2021, 15, 681-9.

137. Gu, Y.; Du, H.; Li, N.; Yang, L.; Zhou, C. Effect of carrier mobility on performance of perovskite solar cells. Chin. Phys. B. 2019, 28, 048802.

138. Glowienka, D.; Galagan, Y. Light intensity analysis of photovoltaic parameters for perovskite solar cells. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2105920.

139. Raifuku, I.; Ishikawa, Y.; Ito, S.; Uraoka, Y. Characteristics of perovskite solar cells under low-illuminance conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016, 120, 18986-90.

140. Guo, Z.; Jena, A. K.; Miyasaka, T. Halide perovskites for indoor photovoltaics: the next possibility. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2023, 8, 90-5.

141. Vieira, R.; de, Araújo. F.; Dhimish, M.; Guerra, M. A comprehensive review on bypass diode application on photovoltaic modules. Energies 2020, 13, 2472.

142. Tayagaki, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Murakami, T. N.; Yoshita, M. Effects of partial shading and temperature-dependent reverse bias behaviour on degradation in perovskite photovoltaic modules. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2025, 279, 113229.

143. Bartusiak, M. F.; Becher, J. Proton-induced coloring of multicomponent glasses. Appl. Opt. 1979, 18, 3342-6.

144. Gusarov, A. I.; Doyle, D.; Hermanne, A.; et al. Refractive-index changes caused by proton radiation in silicate optical glasses. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 678-84.

145. Lang, F.; Jošt, M.; Bundesmann, J.; et al. Efficient minority carrier detrapping mediating the radiation hardness of triple-cation perovskite solar cells under proton irradiation. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1634-47.

146. Daly, E. J.; Drolshagen, G.; Hilgers, A.; Evans, H. D. R. Space environment analysis: experience and trends. In: Environment modeling for space-based applications, Symposium Proceedings (ESA SP-392). ESTEC Noordwijk, 18-20 September 1996. https://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1996ESASP.392...15D (accessed 2026-02-4).

147. Boldyreva, A. G.; Akbulatov, A. F.; Tsarev, S. A.; et al. γ-ray-induced degradation in the triple-cation perovskite solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 813-8.

148. Unger, E. L.; Kegelmann, L.; Suchan, K.; Sörell, D.; Korte, L.; Albrecht, S. Roadmap and roadblocks for the band gap tunability of metal halide perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017, 5, 11401-9.

149. Hoke, E. T.; Slotcavage, D. J.; Dohner, E. R.; Bowring, A. R.; Karunadasa, H. I.; McGehee, M. D. Reversible photo-induced trap formation in mixed-halide hybrid perovskites for photovoltaics. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 613-7.

150. Koshiishi, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Chishiki, A.; Goka, T.; Omodaka, T. Evaluation of the neutron radiation environment inside the International Space Station based on the Bonner Ball Neutron Detector experiment. Radiat. Meas. 2007, 42, 1510-20.

151. Armstrong, T. W.; Colborn, B. L. Predictions of secondary neutrons and their importance to radiation effects inside the International Space Station. Radiat. Meas. 2001, 33, 229-34.

152. Paternò, G. M.; Robbiano, V.; Santarelli, L.; et al. Perovskite solar cell resilience to fast neutrons. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2019, 3, 2561-6.

153. Kim, S.; Choi, M.; Park, J. Cerium-doped oxide-based materials for energy and environmental applications. Crystals 2023, 13, 1631.

154. Wilt, D.; Snyder, N.; Jenkins, P. Novel flexible solar cell coverglass for space photovoltaic devices. In 2013 IEEE 39th Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), 16-21 June, 2013; pp. 2835-9.

155. Yan, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, R.; Wang, R. Electroluminescence analysis of VOC degradation of individual subcell in GaInP/GaAs/Ge space solar cells irradiated by 1.0 MeV electrons. J. Lumin. 2020, 219, 116905.

156. Bertotti, L.; Flores, C.; Garner, J. The ASGA experiment on EURECA platform: testing of advanced GaAs solar cells in LEO. In Conference Record of the Twentieth IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, September 26-30, 1988; pp. 1002-6.

157. Aburaya, T. Analysis of 10 years' flight data of solar cell monitor on ETS-V. Solar. Sol. Energy. Mater. Sol. Cells. 2001, 68, 15-22.

158. Verduci, R.; Romano, V.; Brunetti, G.; et al. Solar energy in space applications: review and technology perspectives. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2200125.

159. Jia, C.; Li, Z.; Wan, Z.; et al. Ultra-thin perovskite solar cells with high specific power density based on colorless polyimide substrates. Nano. Energy. 2024, 131, 110259.

160. Hailegnaw, B.; Demchyshyn, S.; Putz, C.; et al. Flexible quasi-2D perovskite solar cells with high specific power and improved stability for energy-autonomous drones. Nat. Energy. 2024, 9, 677-90.

161. Liu, P.; Wang, H.; Niu, T.; et al. Ambient scalable fabrication of high-performance flexible perovskite solar cells. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7069-80.

162. Lee, J. H.; Nocerino, J. C.; Hardy, B. S. On-orbit characterization of space solar cells on nano-satellites. In 2016 IEEE 43rd Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), 5-10 June, 2016; pp. 1331-6.

163. Leipold, M.; Eiden, M.; Garner, C.; et al. Solar sail technology development and demonstration. Acta. Astronaut. 2003, 52, 317-26.

164. Chamberlain, M. K.; Kiefer, S. H.; Lapointe, M.; Lacorte, P. On-orbit flight testing of the roll-out solar array. Acta. Astronaut. 2021, 179, 407-14.

165. Yun, Y.; Moon, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J. Flexible fabric-based GaAs thin-film solar cell for wearable energy harvesting applications. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. Cells. 2022, 246, 111930.

166. Gao, D.; Li, B.; Sun, X.; et al. High-efficiency perovskite solar cells enabled by suppressing intermolecular aggregation in hole-selective contacts. Nat. Photon. 2025, 19, 1070-7.

167. Wang, G.; Su, Q.; Tang, H.; et al. 27.09%-efficiency silicon heterojunction back contact solar cell and going beyond. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8931.

168. France, R. M.; Geisz, J. F.; Song, T.; et al. Triple-junction solar cells with 39.5% terrestrial and 34.2% space efficiency enabled by thick quantum well superlattices. Joule 2022, 6, 1121-35.

169. Statler, R. L.; Walker, D. H. Three-year performance of the NTS-2 solar cell experiment. 1980. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19810009037/downloads/19810009037.pdf (accessed 2026-02-4).

170. Li, R.; Yao, L.; Sun, J.; et al. Challenges and perspectives for the perovskite module research. Chem 2025, 11, 102542.

171. Nikbakht, H.; Mariani, P.; Vesce, L.; et al. Upscaling perovskite photovoltaics: from 156 cm2 modules to 073 M2 panels. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2416316.

172. Yan, B.; Qin, L.; Tao, S.; Fang, G. Development and challenges of large space flexible solar arrays. SSPW 2025, 2, 33-42.

173. Horowitz, K. A. W.; Remo, T.; Smith, B.; Ptak, A. A techno-economic analysis and cost reduction roadmap for III-V solar cells. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2018. https://docs.nlr.gov/docs/fy19osti/72103.pdf (accessed 2026-02-4).

174. Woodhouse, M.; Smith, B.; Ramdas, A.; Margolis, R. Crystalline silicon photovoltaic module manufacturing costs and sustainable pricing: 1H 2018 Benchmark and cost reduction road map. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2019. https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy19osti/72134.pdf (accessed 2026-02-4).

175. Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; et al. Perovskite solar modules with high efficiency exceeding 20%: from laboratory to industrial community. Joule 2025, 9, 102056.

176. Cai, M.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Qiang, Y.; Han, L. Cost-performance analysis of perovskite solar modules. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1600269.

177. Sengupta, A.; Afroz, M. A.; Sharma, B.; et al. Commercialization of perovskite solar cells: opportunities and challenges. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2025, 9, 3999-4022.

178. Zhao, G.; Hughes, D.; Beynon, D.; et al. Perovskite photovoltaics for aerospace applications - life cycle assessment and cost analysis. Solar. Energy. 2024, 274, 112602.

179. Boley, A. C.; Byers, M. Satellite mega-constellations create risks in Low Earth Orbit, the atmosphere and on Earth. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10642.

180. Boretti, A. A narrative review of solar electric propulsion for space missions: technological progress, market opportunities, geopolitical considerations, and safety challenges. J. Space. Saf. Eng. 2025, 12, 549-59.

181. Shi, L.; Bucknall, M. P.; Young, T. L.; et al. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analyses of encapsulated stable perovskite solar cells. Science 2020, 368, eaba2412.

182. Papež, N.; Dallaev, R.; Ţălu, Ş.; Kaštyl, J. Overview of the current state of gallium arsenide-based solar cells. Materials 2021, 14, 3075.

183. Shin, G.; Kwon, S.; Lee, H. Reliability analysis of the 300W GaInP/GaAs/Ge solar cell array using PCM. J. Astron. Space. Sci. 2019, 36, 69-74.

184. Vaillon, R.; Parola, S.; Lamnatou, C.; Chemisana, D. Solar cells operating under thermal stress. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 2020, 1, 100267.

185. Angmo, D.; Yan, S.; Liang, D.; et al. Toward rollable printed perovskite solar cells for deployment in low-earth orbit space applications. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2024, 7, 1777-91.

186. Manning, C. G. Technology readiness levels. https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/somd/space-communications-navigation-program/technology-readiness-levels/ (accessed 2026-02-4).

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].