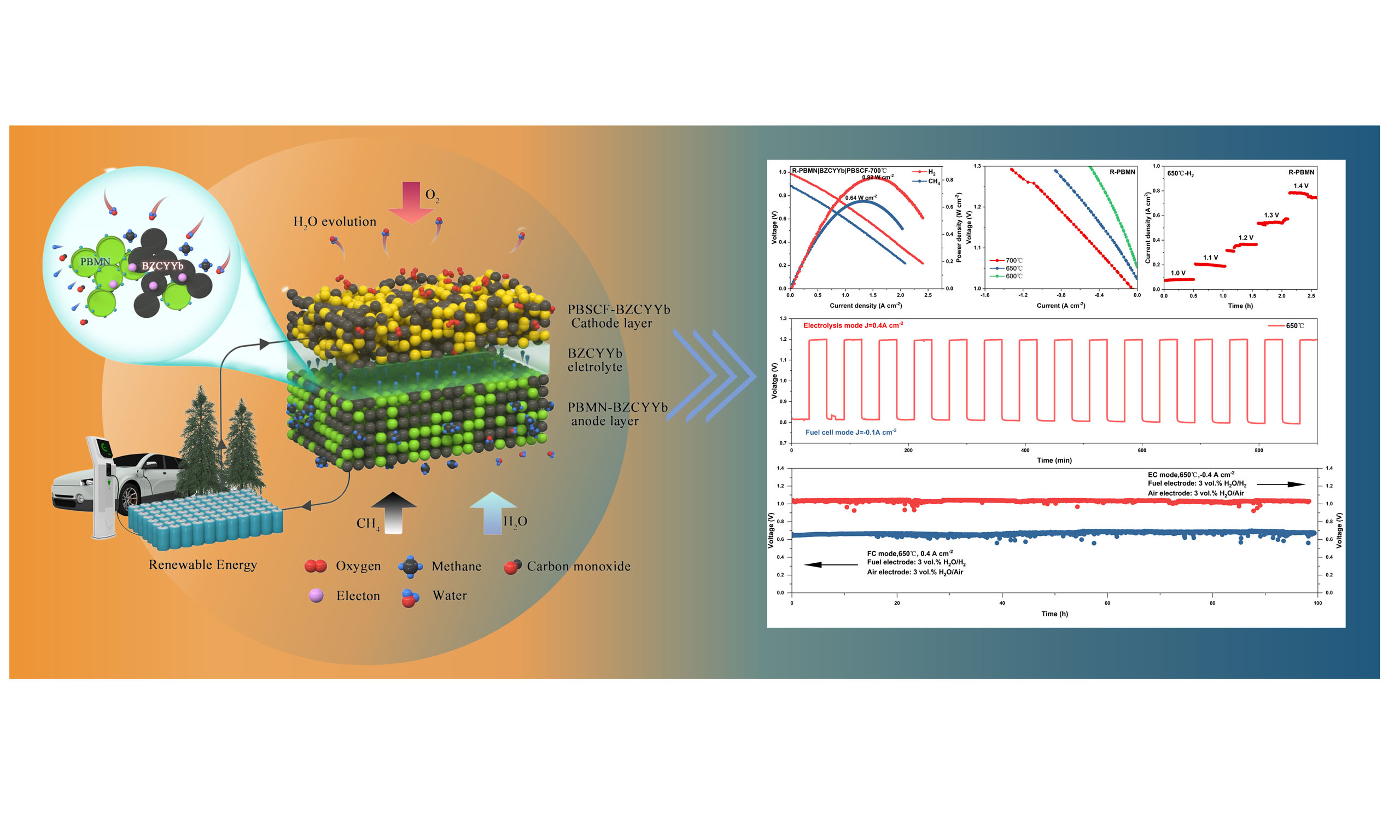

Synergistically enhanced anode performance of PrBaMn2O5+δ for proton ceramic fuel cells via nickel doping and exsolution

Abstract

Proton ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) are considered highly efficient energy conversion devices, yet their performance is strongly governed by the catalytic activity and stability of anode materials. Although PrBaMn2O5+δ (R-PBM) has demonstrated intrinsic tolerance to hydrocarbon fuels, its electrochemical activity at intermediate and low temperatures remains insufficient for practical reversible PCFCs (r-PCFCs) applications. Therefore, a Ni-doped R-PBM anode material, PrBaMn1.95Ni0.05O5+δ (R-PBMN), was studied in this work. The in situ exsolution of Ni nanoparticles after partial Ni substitution for Mn sites significantly improved the anode activity. The exsolved Ni nanoparticles effectively lower the activation energy for C-H bond cleavage, thereby enhancing methane activation and decomposition. Meanwhile, the R-PBMN lattice provides intrinsic hydrophilicity and high proton mobility, which enable cooperative CH4/H2O activation and facilitate the formation of CHxOH* intermediates that suppress carbon deposition. As a result, R-PBMN exhibits substantially enhanced electrochemical performance. At 650 °C, R-PBMN demonstrated substantially lower polarization resistance than R-PBM: 0.56 Ω cm2 in H2 and 3.38 Ω cm2 in CH4, representing a 90% and 55% reduction, respectively, while retaining a high impedance stability for 120 h in methane-steam atmosphere. At 700 °C, the peak power density of R-PBMN in H2 and CH4 reached 0.82 and

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Proton ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) offer the advantage of efficient energy conversion at lower operating temperatures (< 650 °C) compared to conventional solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs)[1,2]. Additionally, PCFCs exhibit remarkable fuel flexibility[3-6], allowing the direct utilization of hydrocarbons such as methane (CH4) instead of pure hydrogen, thereby significantly broadening their application potential[7].

However, several critical challenges must be overcome before PCFCs can be widely commercialized. The conventional Ni/electrolyte composite anode, commonly referred to as Ni cermet, exhibits high catalytic activity for fuel oxidation but suffers from deactivation due to carbon deposition arising from the incomplete oxidation of hydrocarbons in practical fuels[8]. Coke formation blocks the active sites of Ni, thereby reducing its catalytic activity and long-term stability[9]. Moreover, redox-induced volume changes and Ni particle coarsening during long-term operation further compromise the energy efficiency and durability of Ni-based ceramic anodes in PCFCs[10].

To address these challenges, extensive research efforts have been devoted to the development of novel anode materials and composite anode architectures for PCFCs[11,12]. For instance, Hu et al. developed a Ru@Ru-Sr2Fe1.5Mo0.5O6-δ (SFM)/Ru-Gd0.1Ce0.9O2-δ (GDC) anode[10]. This nano-heterostructure exhibited outstanding electrochemical performance, achieving peak power densities of 1.03 and 0.63 W cm-2 at 800 °C under humidified H2 and CH4 atmospheres, respectively. Moreover, it maintained stable performance for over 200 h in humidified CH4, indicating strong resistance to carbon deposition[10]. Separately, Liu et al. engineered a novel samarium (Sm)-doped CeO2-supported Ni-Ru (SCNR) catalyst for steam methane reforming (SMR)[13]. The optimized configuration achieved a peak power density of 0.733 W cm-2 at 650 °C, representing a 55% enhancement over conventional CH4 systems (0.473 W cm-2)[13]. In another study,

Double perovskite-structured materials provide highly tunable crystal structures and abundant active sites, rendering them promising candidates for anode materials in SOFCs. Among these, PrBaMn2O5+δ (PBM) has been extensively studied as an anode material in SOFCs because of its excellent electrochemical properties, redox stability, and methane tolerance. In particular, layered PBM-based anodes have shown great promise in methane dry reforming and sulfur-tolerant operation, as demonstrated in previous studies by

Despite their outstanding structural stability and intrinsic coking resistance, R-PBM-based perovskites suffer from insufficient electrochemical activity at intermediate and low temperatures, limiting their practical application in PCFCs. To address this challenge, we designed a Ni-modified derivative, R-PBMN, by minimally substituting Ni at the Mn sites of R-PBM, followed by in situ exsolution of Ni nanoparticles under reducing conditions. This cooperative strategy integrates the catalytic advantages of exsolved Ni with the lattice-driven hydrophilicity and oxygen mobility of R-PBM, thereby enhancing methane activation while retaining the intrinsic resistance to carbon deposition. Without Ni exsolution, the anode retains good carbon tolerance but exhibits much lower electrochemical activity, and without the Pr0.5Ba0.5MnO3-δ (PBM) host, the Ni nanoparticles would rapidly coke and deactivate, making their synergy essential for superior performance. Benefiting from this synergy, R-PBMN demonstrates significantly improved electrochemical performance and durability compared with pristine R-PBM, achieving peak power densities of 0.82 W cm-2 in H2 and

EXPERIMENTAL

Synthesis of powders

PBM and Pr0.5Ba0.5Mn0.975Ni0.025O3-δ (PBMN) powders were prepared using a sol-gel method. Pr(NO3)3·6H2O, Ba(NO3)2, Mn(NO3)2·4H2O, and Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (all Aladdin, > 98%) were dissolved in deionized water with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and citric acid as dual complexing agents (molar ratio of total metal ions: EDTA: citric acid = 1:1:2). The solution pH was adjusted to 7.0 ± 0.1 using NH3·H2O (25%) and heated at 90 °C under stirring (300 rpm) for 12 h to form a viscous gel. The gel was dried at 300 °C for 5 h and calcined in air at 950 °C for 10 h to obtain crystalline PBM and PBMN powders. The layered perovskite oxides R-PBM and R-PBMN were obtained by thermal reduction in H2 at 800 °C for 1 h (heating rate:

Cell preparation

The BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3-δ (BZCYYb) electrolyte powder was prepared via a solid-state reaction. Stoichiometric amounts of BaCO3 (≥ 99.5%), ZrO2 (≥ 99.9%), CeO2 (≥ 99.9%), Y2O3 (≥ 99.9%), and Yb2O3

A single anode-supported cell was fabricated with an R-PBMN-BZCYYb (60:40 wt.%) substrate containing 10 wt.% nanographite, pressed at 100 MPa. A ~10 μm anode functional layer (prepared from the same R-PBMN-BZCYYb composite as the anode support, with a R-PBMN:BZCYYb weight ratio of 6:4, but without pore former) and a ~20 μm BZCYYb electrolyte layer were sequentially deposited by spin-coating (4,000 rpm, 40 s per layer). The multilayer structure was co-sintered at 1,450 °C for 5 h (2 °C min-1) to obtain a dense electrolyte. Finally, a PrBa0.5Sr0.5Co1.5Fe0.5O5+δ (PBSCF) cathode was screen-printed and fired at 950 °C for 2 h to form a porous cathode (~30 μm thickness).

Characterization and electrochemical tests

The crystalline phases of R-PBM and R-PBMN powders were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, MiniFlex 600, Rigaku, Japan, Cu Kα, λ = 1.5406 Å) over a 2θ range of 20-80° (step size: 0.02°, 2 s per step). Rietveld refinement was performed using the General Structure Analysis System (GSAS) with EXPGUI, a graphical user interface for GSAS. High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were performed on an aberration-corrected

The methane adsorption/desorption capacity and hydrogen reduction behavior of R-PBM and R-PBMN were further evaluated by CH4-temperature programmed desorption (TPD), H2-temperature programmed reduction (TPR), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were recorded using an EMXplus EPR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). SMR activity was evaluated in a fixed-bed quartz reactor at 1 atm. Catalysts were reduced in 20% H2/Ar (50 sccm) at 600 °C for 30 min, then heated to 700 °C under an inert atmosphere. Methane (10 sccm) was introduced through a temperature-controlled bubbler to maintain a steam-to-carbon (S/C) ratio of 1:2. Effluent gases were analyzed online by micro gas chromatography (µGC) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). The system was stabilized ≥ 30 min before measurement, and methane conversion (XCH4) was calculated as:

where FCH4,in and FCH4,out represent the inlet and outlet methane flow rates, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal structure and microstructure characterizations

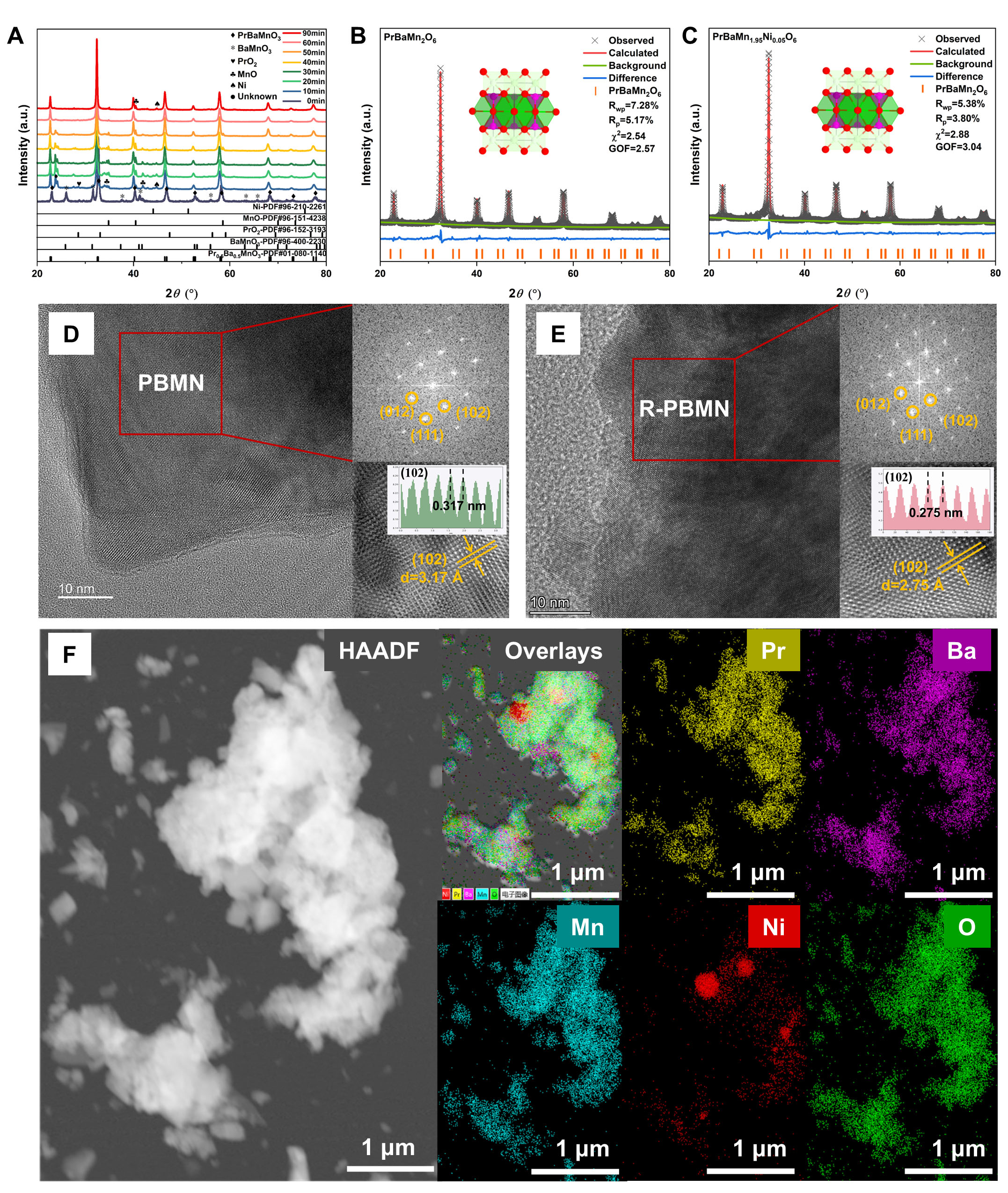

The XRD patterns of PBMN powder, calcined in air at 950 °C for 10 h and subsequently reduced in H2 at

Figure 1. (A) XRD patterns of PBMN and R-PBMN samples after reduction in H2 at 800 °C for 0-90 min, showing phase evolution. Rietveld refinement profiles of (B) R-PBM and (C) R-PBMN, demonstrating good agreement between experimental and calculated patterns; HRTEM images and corresponding FFT patterns of (D) PBMN grain and (E) R-PBMN grain (zone axis [100]); (F) STEM-EDS elemental mappings of Pr, Ba, Mn, Ni and O in an R-PBMN grain.

Rietveld refinements of the XRD data for R-PBM and R-PBMN were carried out, and the results are shown in Figure 1B and C, respectively. The refined lattice parameters of R-PBM and R-PBMN are presented in

To investigate the crystal structures of as-prepared PBMN and reduced R-PBMN, HRTEM was conducted along the [100] zone axis [Figure 1D and E]. Both images exhibit clear and continuous lattice fringes, confirming the high crystallinity of the perovskite framework at the atomic scale. The interplanar spacings of 3.17 Å for PBMN and 2.75 Å for R-PBMN correspond to the (102) planes, with the slight contraction in R-PBMN consistent with lattice reduction and the exsolution of Ni nanoparticles under reducing conditions. Additional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of R-PBM are provided in

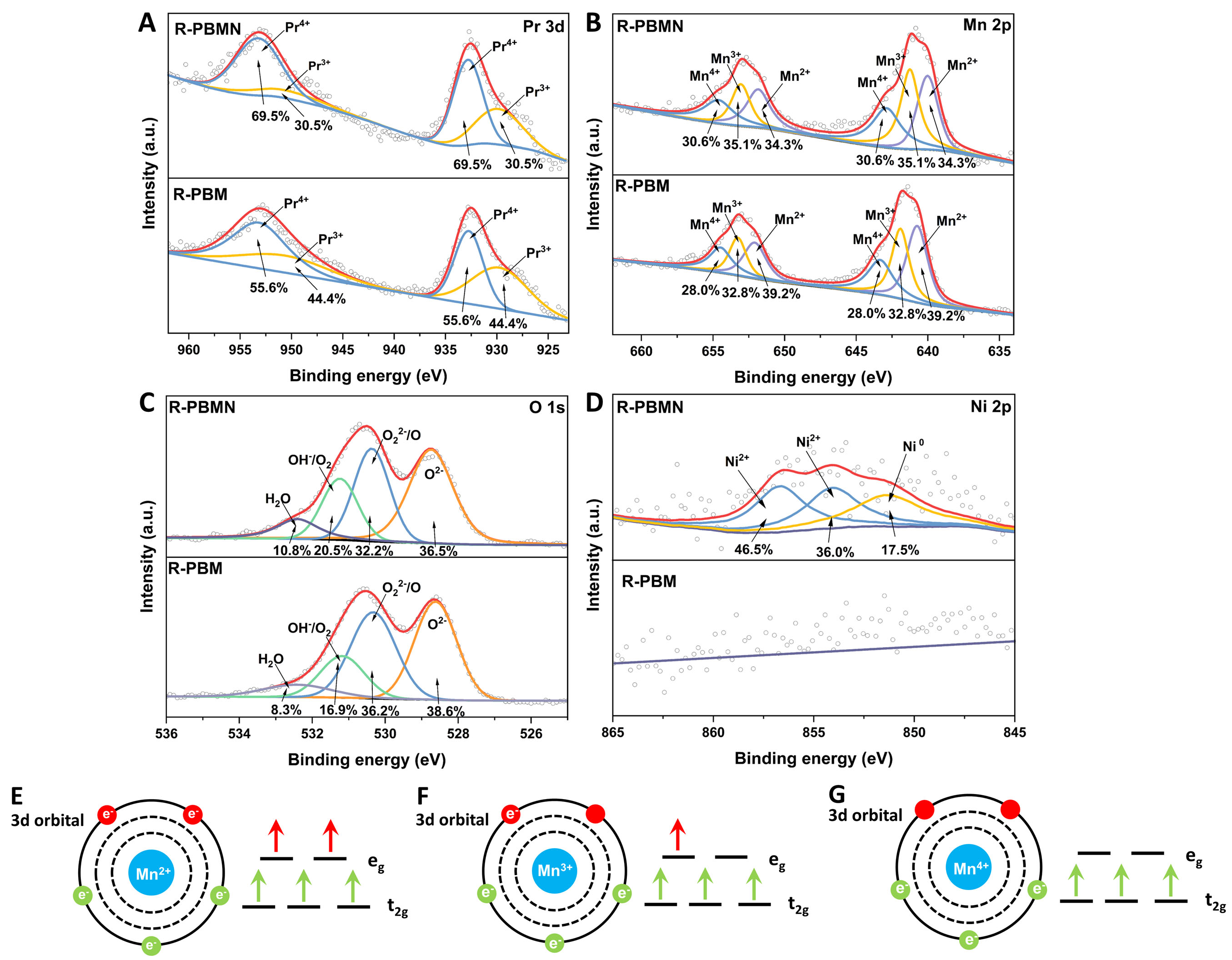

The valence state of elements

To elucidate the influence of Ni doping on the mixed-valence metal ions in double perovskite (R-PBM), XPS was conducted to examine the valence states of Pr, Mn, Ni, and O in both pristine R-PBM and R-PBMN [Figure 2]. The Pr 3d spectra [Figure 2A] exhibited two distinct peaks at 929.4 eV (Pr3+, 3d5/2)/949.5 eV (Pr3+, 3d3/2) and 933.4 eV (Pr4+, 3d5/2)/953.9 eV (Pr4+, 3d3/2). Upon Ni doping, the Pr4+ content increased markedly from 55.6% (R-PBM) to 69.5% (R-PBMN), corresponding to an ~20% relative increase. This result suggests that Ni incorporation promoted the oxidation of Pr3+ to Pr4+, likely through charge compensation or ligand-hole formation.

Figure 2. XPS spectra of R-PBM and R-PBMN: (A) Pr 3d; (B) Mn 2p; (C) O 1s; (D) Ni 2p (for R-PBMN only, no Ni signal detected in R-PBM). Schemes illustrate the degeneracy of (E) Mn2+; (F) Mn3+; (G) Mn4+ 3d orbitals.

The Mn 2p spectra [Figure 2B] revealed three oxidation states: 640.6 eV (Mn2+, 2p3/2)/652.8 eV (Mn2+, 2p1/2), 641.8 eV (Mn3+, 2p3/2)/653.7 eV (Mn3+, 2p1/2), and 642.9 eV (Mn4+, 2p3/2)/654.9 eV (Mn4+, 2p1/2). Ni doping increased the Mn4+ content from 28.0% to 30.6% (+8.5% relative) and the Mn3+ content increased from 32.8% to 35.1% (+6.6% relative). These results indicate that Ni doping not only substantially elevated the average oxidation state of Pr but also moderately increased that of Mn, likely due to electron transfer from Mn to Ni or local structural distortion.

In an octahedral crystal field, the 3d orbitals of transition-metal cations (e.g., Mn) are split into lower-energy t2g (dxy, dyz, and dxz) and higher-energy eg (

The O 1s XPS spectra of R-PBM and R-PBMN were deconvoluted into four components [Figure 2C], corresponding to lattice oxygen (O2-), highly oxidized oxygen species (O22-/O-), adsorbed oxygen (OH-/O2), and surface-adsorbed H2O. R-PBMN exhibited a significantly larger OH- contribution than R-PBM, suggesting a higher concentration of oxygen vacancies and enhanced proton uptake capacity. The increased surface-adsorbed H2O in R-PBMN further indicates enhanced water adsorption capability. The enhanced hydrophilicity of the anode not only improves its resistance to carbon deposition but also positively influences its electrochemical performance. A higher water uptake capacity facilitates the adsorption and activation of H2O molecules, which promotes steam reforming and carbon-water gasification reactions (C+H2O → CO+H2, C+2H2O → CO2+2H2). Increased water adsorption facilitates proton generation and transport, expands the effective triple-phase boundary, and accelerates surface redox kinetics.

The Ni 2p spectrum of R-PBMN [Figure 2D] revealed the coexistence of Ni2+ (82.5%) and Ni0 (17.5%), indicating predominant incorporation of Ni2+ into the bulk lattice with surface precipitation of metallic Ni. No Ni signal was observed in undoped R-PBM.

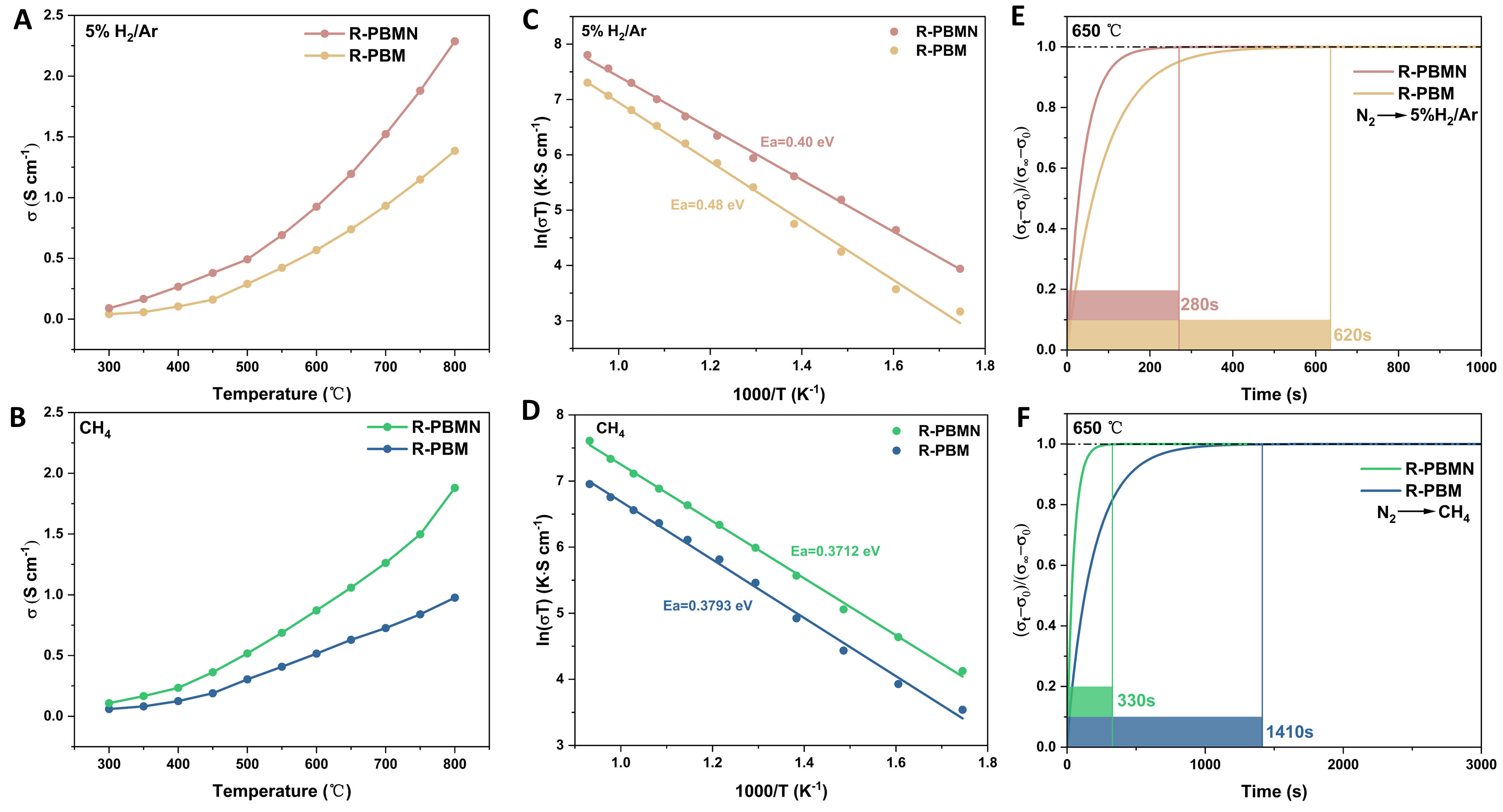

Electrical conductivity, oxygen surface exchange, and bulk diffusion

The electrical conductivity of R-PBM and R-PBMN was measured as a function of temperature in 5% H2/Ar and CH4 atmospheres [Figure 3A and B]. R-PBM exhibited p-type semiconducting behavior in the range of 300-800 °C. At 800 °C, the conductivities of R-PBM and R-PBMN were 1.38 and 2.29 S cm-1, respectively, in 5% H2/Ar, and 0.98 and 1.88 S cm-1, respectively, in CH4. In H2, the stronger reducing environment facilitates the reduction of Mn4+ to Mn3+, which enhances small-polaron hopping and thereby increases the electronic conductivity. In contrast, in CH4, the relatively weaker reducing power suppresses the extent of Mn reduction, leading to comparatively lower conductivity. These results demonstrate that Ni doping markedly enhanced conductivity under both atmospheres. The improvement was attributed to enhanced overlap between O 2p and Mn 3d orbitals in the perovskite lattice, which facilitated charge transfer through the Mn-O-Mn network. The conduction mechanism followed a small-polaron hopping process, as given in:

Figure 3. Electrical conductivity of R-PBM and R-PBMN as a function of temperature in (A) 5 %H2/Ar and (B) CH4 atmospheres. Arrhenius plots of electrical conductivity for R-PBM and R-PBMN in (C) 5 %H2/Ar and (D) CH4 atmosphere. Normalized conductivity relaxation profiles for R-PBM and R-PBMN during gas switching from (E) N2 to 5 %H2/Ar and (F) N2 to CH4.

Ni doping increased the average Mn valence state, broadened electron-transfer pathways, and improved both electronic/ionic conductivity and catalytic activity. The linear Arrhenius behavior further confirmed small-polaron hopping as the dominant conduction mechanism[22]. Notably, R-PBMN exhibits lower activation energy than R-PBM in both atmospheres [Figure 3C and D], indicating that Ni doping reduces conduction energy barriers and enhances charge transfer efficiency.

The oxygen surface-exchange coefficient (Kex) and bulk diffusion coefficient (Dchem) were determined by ECR [Figure 3E and F]. R-PBMN showed significantly shorter relaxation times than R-PBM, indicating superior catalytic activity for H2 and CH4 oxidation. Further analysis of the calculated Dchem and Kex values revealed that, at 650 °C in 5% H2/Ar, R-PBMN exhibited higher Dchem (8.87 × 10-5 cm2 s-1) and Kex (7.36 × 10-4 cm s-1) compared with R-PBM (Dchem = 8.22 × 10-5 cm2 s-1, Kex =3.29 × 10-4 cm s-1). Similarly, in CH4 at 650 °C, R-PBMN exhibited higher Dchem (1.83 × 10-5 cm2 s-1) and Kex (6.23 × 10-4 cm s-1) than R-PBM

Electrochemical performance and electrode reaction kinetics

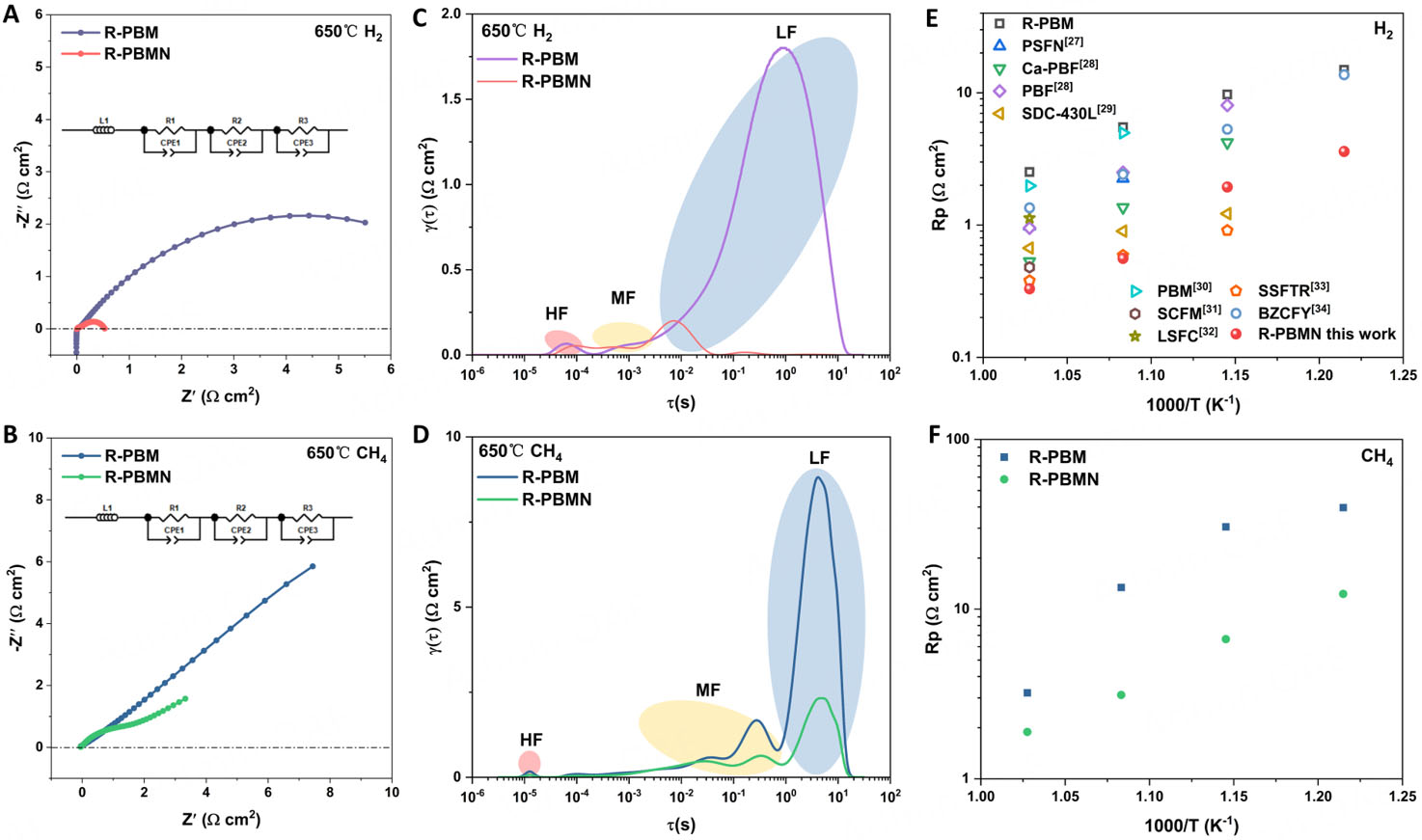

The electrode kinetics of the anodes were investigated at 650 °C by measuring the polarization resistance (Rp) of symmetrical cells (R-PBM|BZCYYb|R-PBM and R-PBMN|BZCYYb|R-PBMN) under varying partial pressures of H2 and CH4. EIS revealed that R-PBMN had a significantly higher catalytic activity than R-PBM in both H2 and CH4 atmospheres. At 650 °C, R-PBMN exhibited substantially lower Rp: 0.56 Ω cm2 in H2 (vs. 5.50 Ω cm2 for R-PBM) and 3.38 Ω cm2 in CH4 (vs. 7.49 Ω cm2 for R-PBM). The superior performance of R-PBMN originates from three synergistic effects: (1) Electronic structure modulation: Ni doping increases the Mn valence state. In an octahedral crystal field, Mn 3d orbitals split into lower-energy t2g and higher-energy eg orbitals. The eg orbitals participate in σ-bonding with adsorbates, where reduced electron occupancy enhances catalytic activity[23,24]. As shown in Figure 2E-G, the electronic configurations are Mn2+: (t2g)3(eg)2, Mn3+: (t2g)3(eg)1 and Mn4+: (t2g)3(eg)0. Decreasing eg occupancy correlates with stronger catalytic activity for H2 and CH4 oxidation; (2) Oxygen vacancy formation: The increased Pr4+ content promoted oxygen vacancy generation during reduction, creating additional active sites for fuel adsorption and oxidation; (3) Ni catalytic properties: Surface-precipitated metallic Ni (17.5%) exhibited high catalytic activity due to its partially filled 3d orbitals, low electronegativity (1.91), and relatively low first-ionization energy. These properties facilitated oxidative addition reactions critical for fuel reforming. This multifunctional enhancement accounts for the superior electrochemical performance of R-PBMN under both reducing atmospheres.

To further elucidate this performance enhancement, DRT was applied to deconvolute the impedance spectra and identify rate-limiting steps. Based on the frequency range, the overall reaction was deconvoluted into three electrochemical steps. The low-frequency (LF) region, associated with gas adsorption, dissociation, and surface diffusion, was identified as the dominant rate-limiting step. The medium-frequency (MF) region represents gas diffusion and surface exchange at the electrode-electrolyte interface, while the high-frequency (HF) region corresponds to charge transfer involving ionic species at the electrode-electrolyte three-phase boundary (TPB)[25,26]. The corresponding EIS and DRT results are shown in Figure 4A-D. The area under each peak was used to quantify the resistance of the corresponding process. Analysis showed that the LF peaks exhibited the highest intensity and largest area in both atmospheres, confirming that gas adsorption/dissociation is the rate-limiting process. Critically, R-PBMN showed significantly reduced LF peak intensities and smaller areas compared with R-PBM, indicating enhanced gas adsorption-dissociation kinetics. The improvement was most pronounced in CH4 atmosphere, suggesting enhanced C-H bond activation capability. This kinetic enhancement may be attributed to the increased oxygen vacancy concentration induced by Ni2+ doping, the in situ-formed Ni nanoparticles that provide additional active sites. In addition, optimization of the electronic structure - specifically, Mn eg orbital occupancy - enhances adsorbate interactions. The combined effects account for lower Rp and superior fuel adsorption-dissociation performance of R-PBMN under both reducing atmospheres compared to R-PBM and other materials reported in the literature

Figure 4. Electrochemical impedance spectra of symmetrical cells (R-PBM|BZCYYb|R-PBM and R-PBMN|BZCYYb|R-PBMN) measured at 650 °C in (A) H2 and (B) CH4 atmospheres. Distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis for (C) H2 and (D) CH4 at 650 °C. Temperature-dependent polarization resistance (Rp) in (E) H2 with other materials reported recently [27-34] and (F) CH4 from 550-700 °C.

Electrode kinetics and reaction mechanism analysis

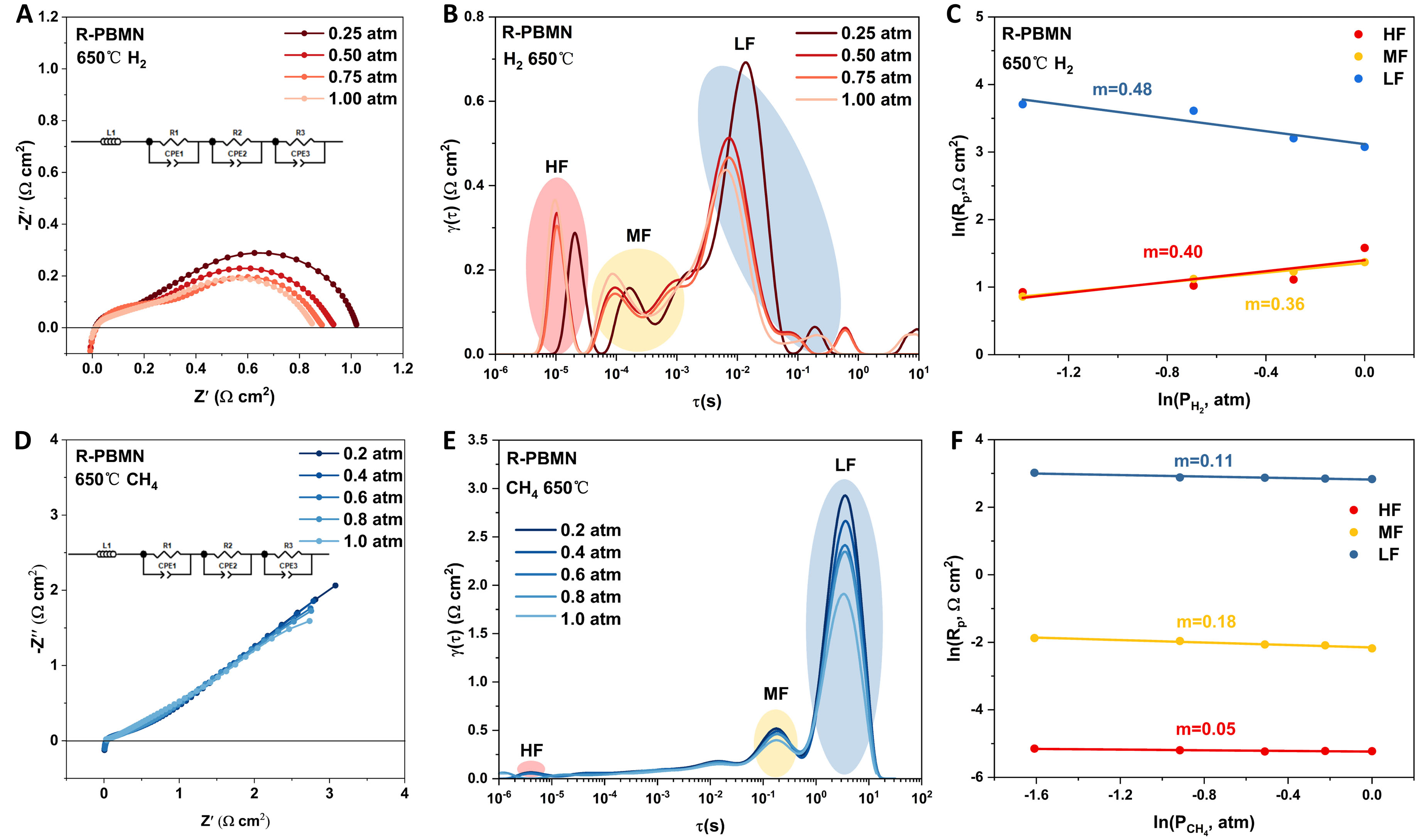

The electrode kinetics of the anodes were investigated at 650 °C by measuring the Rp of symmetrical cells (R-PBM|BZCYYb|R-PBM and R-PBMN|BZCYYb|R-PBMN) under varying partial pressures of H2 and CH4. The power-law relationships Rp = k(

Figure 5. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy of R-PBMN anode measured at 650 °C under varying partial pressures of (A) H2 and (D) CH4. Corresponding distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis for (B) H2 and (E) CH4 atmosphere. Polarization resistance (Rp) dependence on (C) H2 and (F) CH4 partial pressures.

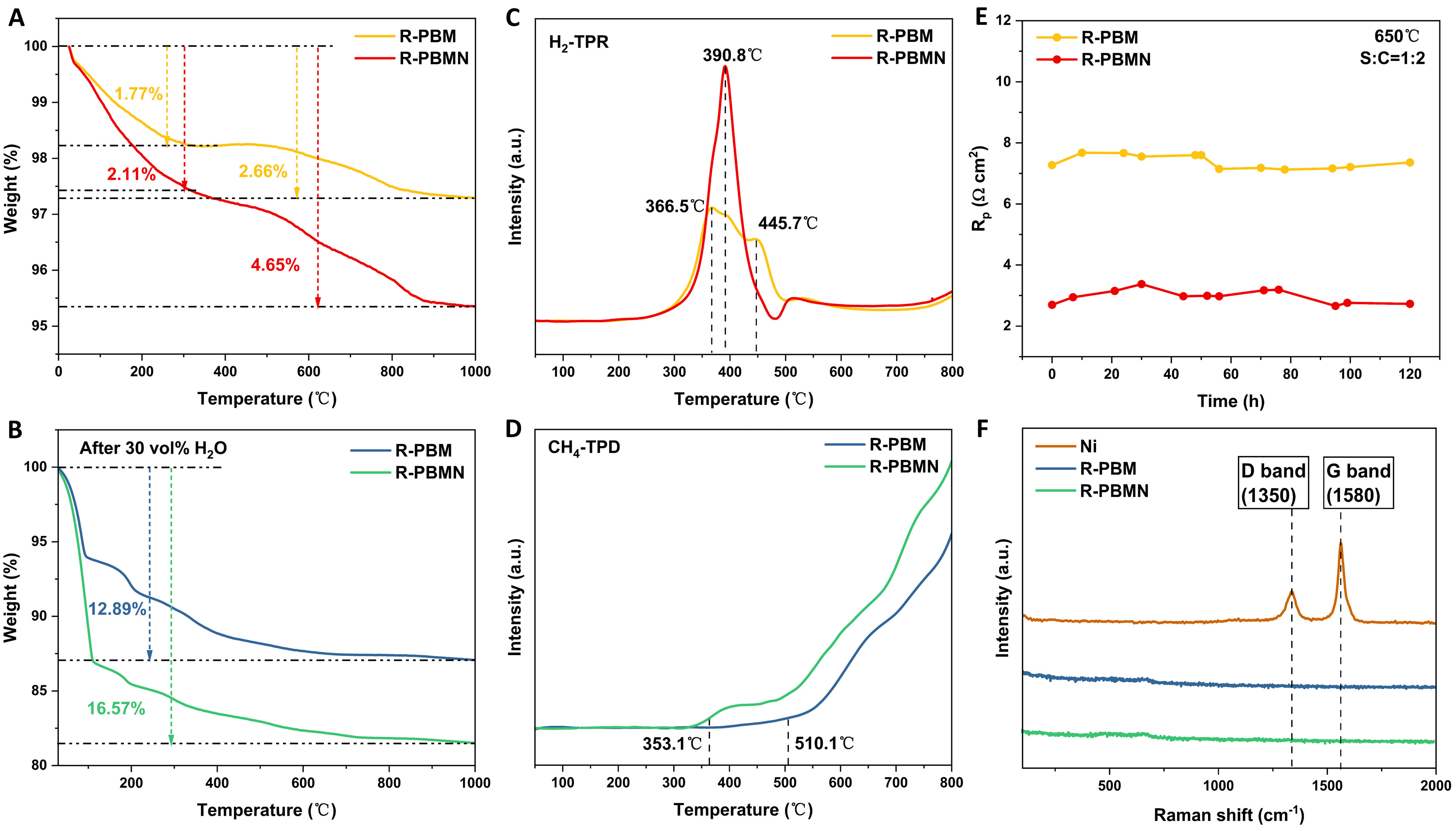

The water absorption capability of electrode materials plays a critical role in the reaction kinetics of SMR. TGA was conducted to evaluate this property [Figure 6A and B]. The comparative weight-loss profiles of R-PBM and R-PBMN revealed significant differences in hydration behavior. Oxygen-vacancy characterization [Figure 6A] showed that both materials gradually lost weight with increasing temperature. A distinct plateau at ~300 °C indicated lattice oxygen release, and R-PBMN exhibited greater total weight loss, confirming a higher oxygen-vacancy concentration. Water absorption analysis [Figure 6B] after pretreatment (600 °C, 3 h, 30 vol% H2O) showed rapid weight loss between 30 and 100 °C, attributed to desorption of surface-adsorbed water[37]. This was followed by progressive weight loss from 100 to 400 °C, associated with the release of lattice-incorporated water via the transformation

Figure 6. (A) Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of R-PBM and R-PBMN from room temperature to 1,000 °C. (B) TGA profiles after treatment in wet air (30 vol% H2O) at 650 °C for 3 h. (C) CH4-temperature programmed desorption (TPD) profiles. (D) H2-temperature programmed reduction (TPR) profiles. (E) Area-specific resistance (Rp) stability of symmetrical cells with R-PBM and R-PBMN electrodes at 650 °C in steam methane reforming (S/C = 1:2) for 120 h. (F) Raman spectra of R-PBM, R-PBMN, and reference Ni catalyst after steam methane reforming (S/C = 1:2) at 650 °C for 24 h.

CH4-TPD, H2-TPR, and EPR were used to further evaluate the methane adsorption/desorption capacity and hydrogen reduction behavior of R-PBM and R-PBMN. As shown in Figure 6C, H2-TPR results revealed the critical influence of Ni on reducibility. R-PBM exhibited two distinct reduction peaks near 400 °C, corresponding to the phase transition from single to double perovskite. In contrast, R-PBMN displayed a more intense low-temperature peak (~400 °C), attributable to both the perovskite phase transition and metallic Ni precipitation[39]. CH4-TPD analysis [Figure 6D] indicated significantly lower CH4 adsorption onset for R-PBMN (~360 °C) compared with R-PBM (~510 °C), demonstrating that Ni doping facilitates low-temperature CH4 adsorption for SMR. The larger peak area for R-PBMN further confirmed enhanced CH4 catalytic activity. EPR analysis detected signals of unpaired electrons in both materials, with R-PBMN showing higher intensity. Calculated free-radical concentrations (R-PBM: 3.112 × 1015 spins g-1; R-PBMN: 3.582 × 1015 spins g-1) correlated with oxygen-vacancy concentrations, confirming that R-PBMN had a higher defect density and stronger catalytic activity under reducing atmosphere.

Figure 6E illustrates the evolution of area-specific resistance (ASR, Rp) in symmetrical cells with R-PBM and R-PBMN electrodes during 120 h of operation at 650 °C under a steam-to-methane ratio of S/C = 1:2. Both materials maintained stable ASR, demonstrating excellent short-term stability and high coking tolerance under SMR conditions. To evaluate structural stability post-operation, Raman spectroscopy was conducted on catalysts exposed to S/C = 1:2 for 24 h [Figure 6F]. The characteristic D-band (~1,350 cm-1) and G-band (~1,580 cm-1) of graphitic carbon served as critical indicators of carbon deposition[40,41]. While a reference Ni catalyst exhibited prominent D- and G-bands, confirming carbon deposition, neither R-PBM nor R-PBMN showed detectable coke-related bands, demonstrating exceptional resistance to carbon formation.

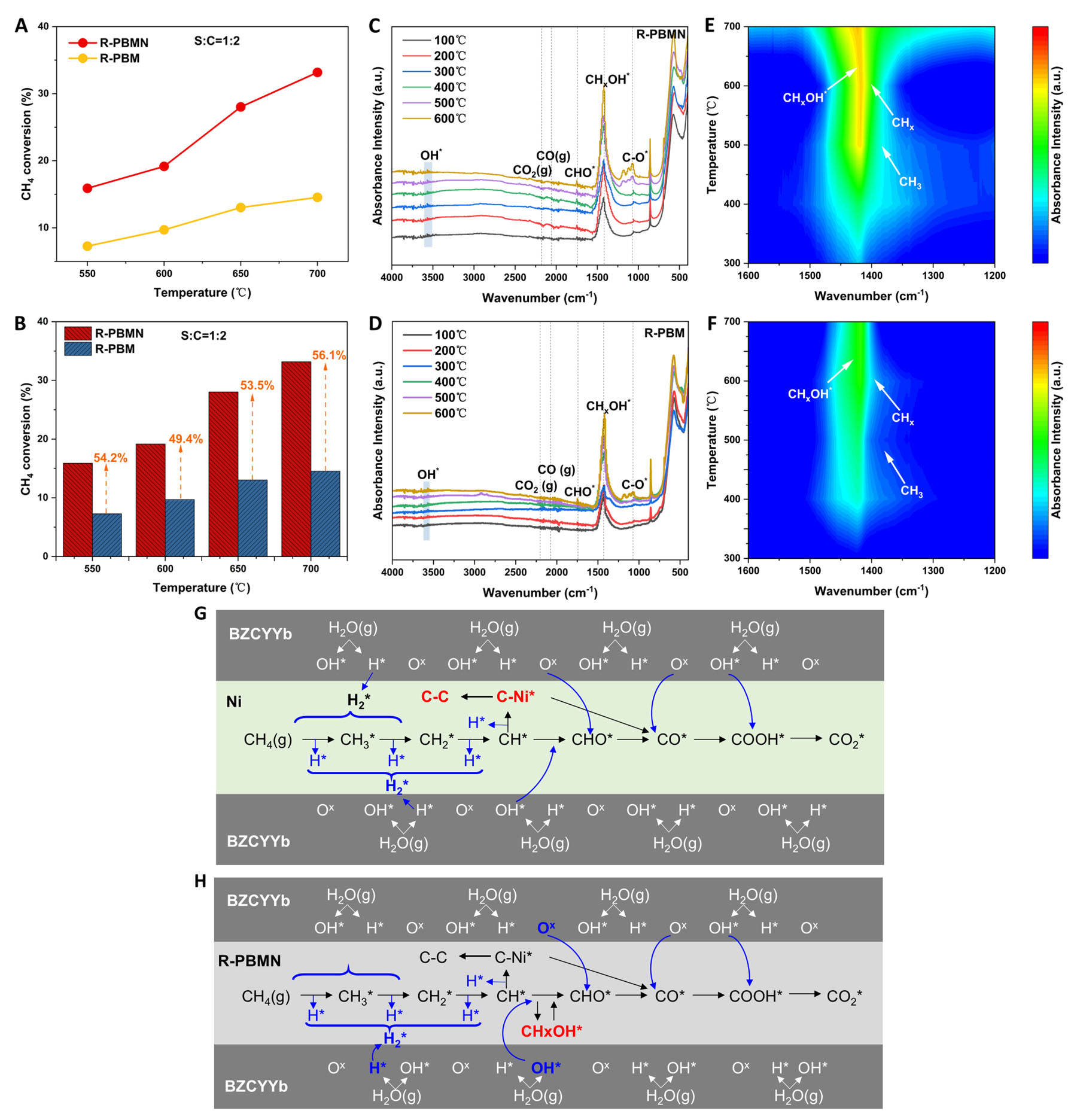

To systematically evaluate the catalytic performance of the newly developed SMR catalyst, comprehensive activity tests were performed in a packed-bed reactor (PBR) system under a S/C ratio of 1:2. As shown in Figure 7A, the R-PBMN catalyst exhibited superior catalytic activity, achieving the highest CH4 conversion efficiency over 550-700 °C. At 700 °C, R-PBMN achieved 33.2% CH4 conversion, a 56.1% increase compared with R-PBM. This performance advantage persisted at lower temperatures, with R-PBMN reaching 15.9% conversion at 550 °C compared with 7.3% for R-PBM [Figure 7B]. These results confirmed that Ni doping significantly enhanced CH4 conversion and SMR activity.

Figure 7. (A and B) CH4 conversion of R-PBM and R-PBMN in PBRs at S/C = 1:2. Semi-in-situ DRIFTs spectra for (C and E) R-PBMN and (D and F) R-PBM under steam methane reforming conditions (S/C = 1:2, 100-700 °C) probing intermediate species. (G and H) Proposed reaction pathways for steam methane reforming on (G) Ni and (H) R-PBMN derived from Semi-in-situ DRIFTS analysis.

To elucidate the SMR mechanism, Semi-in-situ DRIFTS analysis was employed to probe surface adsorbates under operando conditions [Figure 7C-F]. Steady-state spectra for R-PBMN [Figure 7C] and R-PBM

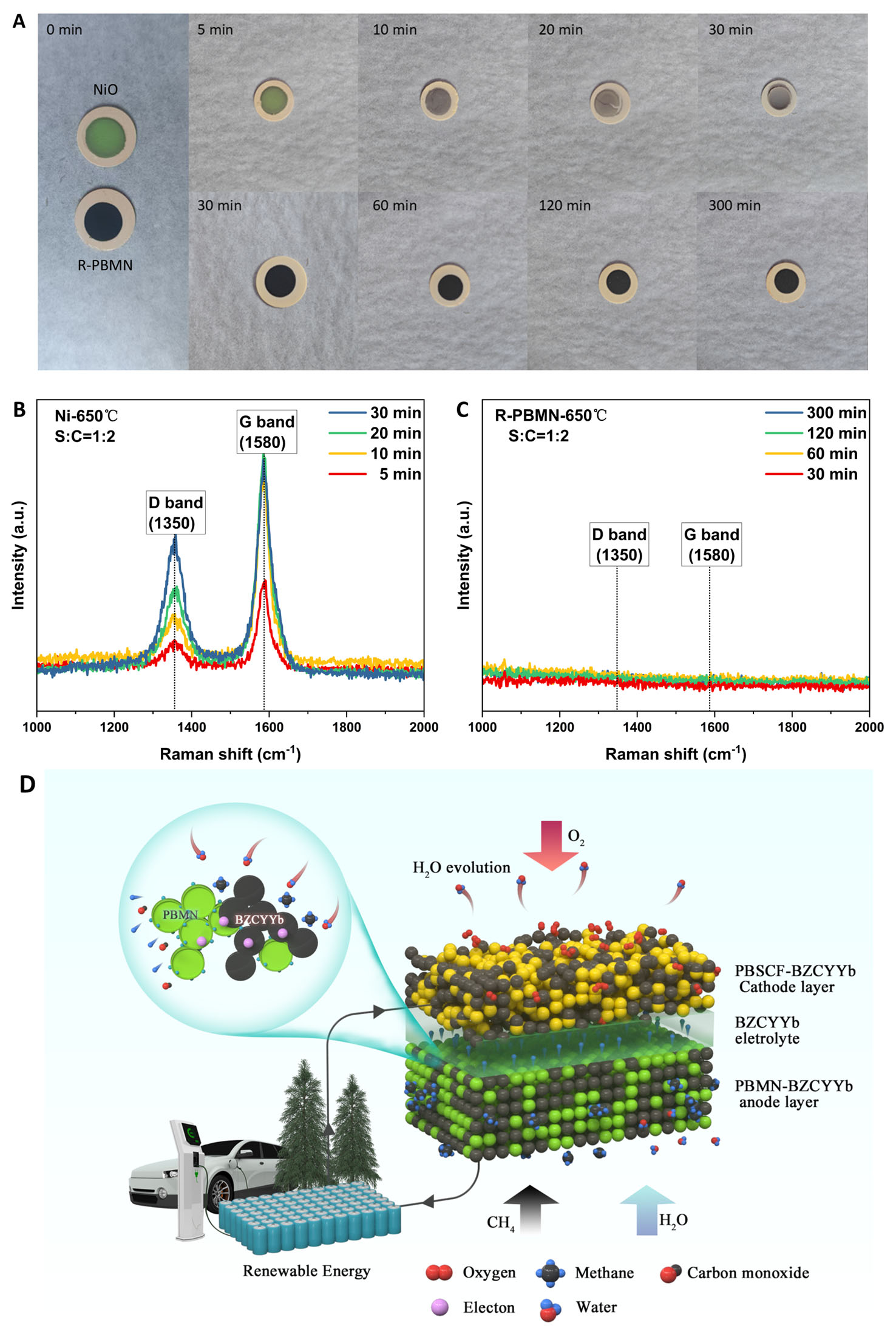

Figure 8A compares the morphological evolution of NiO and R-PBMN anodes under a S/C ratio of 1:2. The NiO anode darkened within 10 min, indicating the onset of carbon deposition accompanied by surface cracking, and was fully deactivated after 30 min due to severe coking. Conversely, the R-PBMN anode maintained structural integrity without detectable degradation throughout the test. Raman analysis

Figure 8. (A) Morphology evolution of NiO and R-PBMN fuel electrodes under steam methane reforming conditions (S/C = 1:2) at various exposure times. Raman spectra of (B) NiO and (C) R-PBMN fuel electrodes after S/C = 1:2 treatment for increasing durations. (D) Schematic diagram of steam methane reforming with R-PBMN as fuel electrode.

Electrochemical activity of r-PCFCs

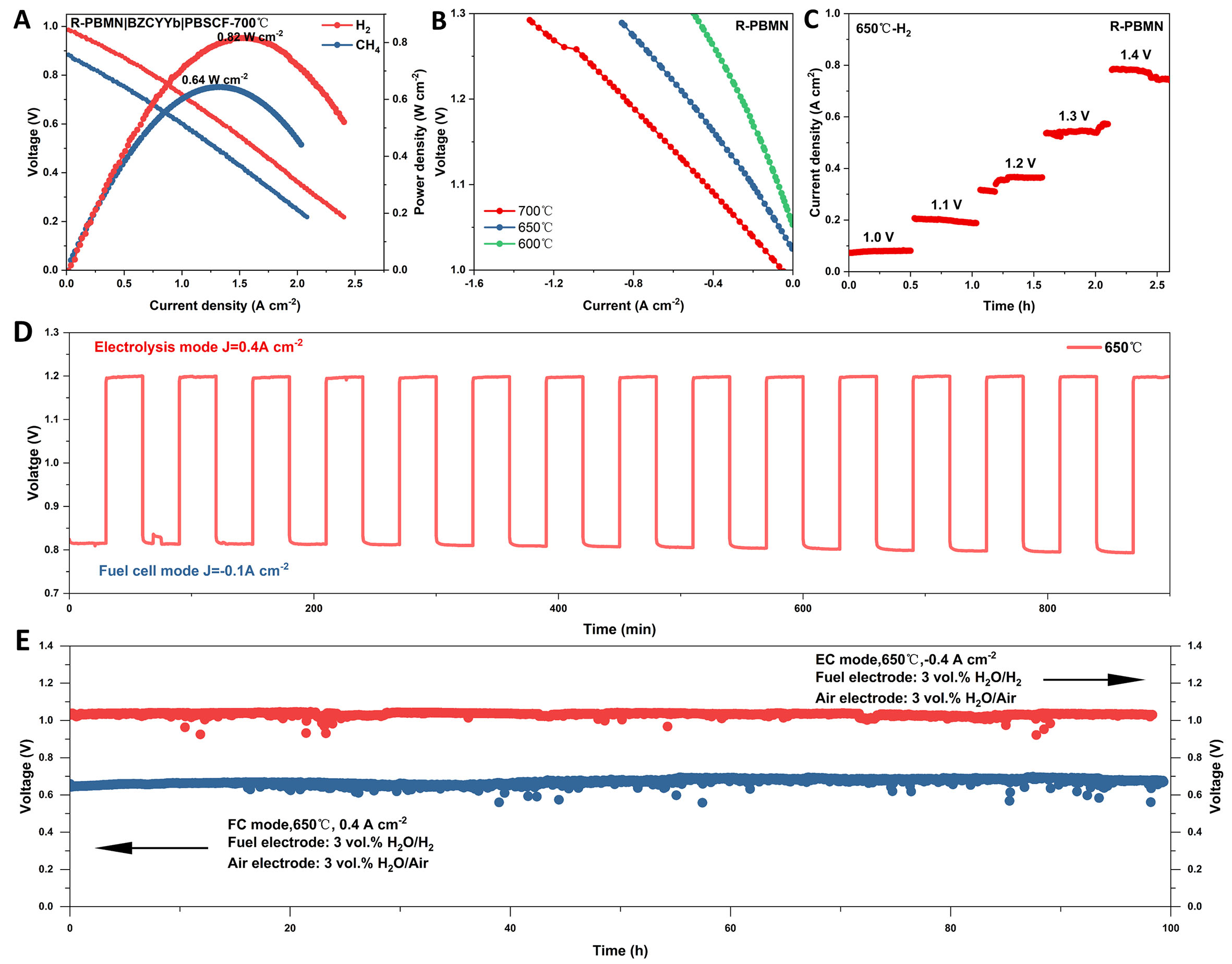

Laboratory-scale single cells with the configuration R-PBMN-BZCYYb|BZCYYb|PBSCF-BZCYYb were fabricated to evaluate the electrochemical performance of the R-PBMN anode. Figure 9A shows the current density-voltage (I-V) and power density (I-P) curves in fuel cell (FC) mode using H2 and CH4 as fuels at

Figure 9. (A) I-V and I-P curves in fuel cell (FC) mode at 700 °C with humidified H2 (3 vol.% H2O) or CH4 fuel. (B) I-V curves in electrolysis cell (EC) mode with humidified H2 fuel (3 vol.% H2O). Both for R-PBMN-BZCYYb|BZCYYb|PBSCF-BZCYYb cells. (C) Short-stability under stepped voltages. (D) Reversible cycling operation at 650 °C (current densities of 0.4-0.1 A cm-2). (E) Long-term operational stability at ±0.4 A cm-2 in FC/EC modes.

In electrolysis cell (EC) mode [Figure 9B], current densities of -1.30, -0.86, and -0.50 A cm-2 at 1.3 V were achieved at 700, 650, and 600 °C, respectively. Short-term stability tests under stepped-voltage conditions [Figure 9C] confirmed the cell’s robustness. Excellent cyclic stability was observed over 15 reversible FC/EC cycles lasting 15 h at 650 °C [Figure 9D]. The power density and current density of R-PBM under FC and EC modes were shown in Supplementary Figure 6. Long-term operation [Figure 9E] further demonstrated the stability and durability of the cell. These results indicated that the single cell with the R-PBMN anode exhibited remarkable stability. Under a current density of 0.4 A cm-2, the cell remained stable in FC mode for 100 h. The rate of performance degradation was calculated as 0.02% per hour, based on the change in power density over the cycling period. Similarly, in EC mode, the maintained stability for 100 h at a current density of -0.4 A cm-2, with a power density degradation rate of only 0.02% per hour over the 100-h cycling period. Additionally, high-resolution SEM (HR-SEM) images revealed no significant interfacial delamination between R-PBMN and BZCYYb after 100 h of single-cell testing, demonstrating the structural stability of the cell under operating conditions [Supplementary Figure 7]. The exceptional operational stability of the cell underscored the promising potential of R-PBMN as an anode material for reversible PCFCs (r-PCFCs).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, a high-performance anode material, R-PBMN, was successfully developed through partial Ni substitution at Mn sites followed by in situ exsolution of Ni nanoparticles. This cooperative design strategy effectively enhanced the electrochemical activity of the parent R-PBM perovskite material, particularly at intermediate and low temperatures where its intrinsic performance is insufficient for PCFC applications. The exsolved Ni nanoparticles lowered the activation barrier for C-H bond cleavage, accelerating methane activation and electrochemical oxidation, while the R-PBM lattice provided inherent hydrophilicity and oxygen mobility that facilitated CH4/H2O co-activation and intermediate formation. As a result, R-PBMN exhibited significantly improved power densities, achieving 0.82 W cm-2 in H2 and 0.64 W cm-2 in CH4 at

DECLARATIONS

Author’s contributions

Writing - original draft, visualization, investigation and data curation: Duan, X.

Investigation, and data curation: Tang, J.; Qu J.; Dai X.; Zhao Z.; Wang L.

Validation and investigation: Wang, W.

Writing - review & editing, project administration, funding acquisition, conceptualization: Zhao Y.; Yun S.; An S.; Wu F.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the results of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A2099, 52264046, 51974167); the Natural Science Research Project of the Guizhou Provincial Department of Education ([2022]041); the Guizhou High-Level and Innovative Talents Projects ([2022]009-1); the Guizhou Provincial Major Scientific and Technological Program ([2024]021, [2024]017); the Guizhou Science and Technology Planning Project (CXTD[2025]018); the First-Class Discipline Research Special Project of Inner Mongolia (YLXKZX-NKD-002); the Fundamental Scientific Research Funds for Universities Directly under Inner Mongolia (201-04060822030, 2023QNJS028); and the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (2023QN05038).

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Yun S. is Associate Editor of the journal Energy Materials. Dr. Yun S. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers' selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Xie, M.; Cai, C.; Duan, X.; Xue, K.; Yang, H.; An, S. Review on Fe-based double perovskite cathode materials for solid oxide fuel cells. Energy. Mater. 2024, 4, 400007.

2. He, F.; Liu, S.; Wu, T.; et al. Catalytic self‐assembled air electrode for highly active and durable reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2206756.

3. Bian, W.; Wu, W.; Gao, Y.; et al. Regulation of cathode mass and charge transfer by structural 3D engineering for protonic ceramic fuel cell at 400 °C (Adv. Funct. Mater. 33/2021). Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2170244.

4. Duan, C.; Kee, R. J.; Zhu, H.; et al. Highly durable, coking and sulfur tolerant, fuel-flexible protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nature 2018, 557, 217-22.

5. He, F.; Hou, M.; Liu, D.; et al. Phase segregation of a composite air electrode unlocks the high performance of reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 3898-907.

6. Bian, W.; Wu, W.; Wang, B.; et al. Revitalizing interface in protonic ceramic cells by acid etch. Nature 2022, 604, 479-85.

7. Hong, K.; Choi, M.; Bae, Y.; et al. Direct methane protonic ceramic fuel cells with self-assembled Ni-Rh bimetallic catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7485.

8. Sengodan, S.; Choi, S.; Jun, A.; et al. Layered oxygen-deficient double perovskite as an efficient and stable anode for direct hydrocarbon solid oxide fuel cells. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 205-9.

9. Wang, W.; Su, C.; Wu, Y.; Ran, R.; Shao, Z. Progress in solid oxide fuel cells with nickel-based anodes operating on methane and related fuels. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 8104-51.

10. Hu, F.; Chen, K.; Ling, Y.; et al. Smart dual-exsolved self-assembled anode enables efficient and robust methane-fueled solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2306845.

11. Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. W.; Li, S.; Shao, Z. Bifunctional electrocatalysts Pr0.5Sr0.5Cr0.1Fe0.9-xNixO3-δ (x = 0.1, 0.2) for the HOR and ORR of a symmetric solid oxide fuel cell. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023, 11, 21839-45.

12. Song, L.; Chen, D.; Pan, J.; et al. B-site super-excess design Sr2V0.4Fe0.9Mo0.7O6-δ-Ni0.4 as a Highly active and redox-stable solid oxide fuel cell anode. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 48296-303.

13. Liu, F.; Deng, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Synergistic effects of in-situ exsolved Ni-Ru bimetallic catalyst on high-performance and durable direct-methane solid oxide fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 4704-15.

14. Liu, F.; Diercks, D.; Hussain, A. M.; et al. Nanocomposite catalyst for high-performance and durable intermediate-temperature methane-fueled metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 53840-9.

15. Bahout, M.; Managutti, P. B.; Dorcet, V.; Le, Gal. La. Salle. A.; Paofai, S.; Hansen, T. C. In situ exsolution of Ni particles on the PrBaMn2O5 SOFC electrode material monitored by high temperature neutron powder diffraction under hydrogen. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 3590-7.

16. Song, Y.; Kim, H.; Jang, J.; et al. Pt3Ni alloy nanoparticle electro‐catalysts with unique core‐shell structure on oxygen‐deficient layered perovskite for solid oxide cells. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2302384.

17. Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Py, B.; et al. DRTtools: freely accessible distribution of relaxation times analysis for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. ACS. Electrochem. 2025, 1, 2680-9.

18. Wan, T.; Saccoccio, M.; Chen, C.; Ciucci, F. Influence of the discretization methods on the distribution of relaxation times deconvolution: implementing radial basis functions with DRTtools. Electrochim. Acta. 2015, 184, 483-99.

19. Yin, Y.; Dai, H.; Yu, S.; Bi, L.; Traversa, E. Tailoring cobalt‐free La0.5Sr0.5FeO3‐δ cathode with a nonmetal cation‐doping strategy for high‐performance proton‐conducting solid oxide fuel cells. SusMat 2022, 2, 607-16.

20. Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, R.; et al. In situ exsolved CoFe alloy nanoparticles for stable anodic methane reforming in solid oxide electrolysis cells. Joule 2024, 8, 2016-32.

21. Yao, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. High flux and stability of cationic intercalation in transition-metal oxides: unleashing the potential of Mn t2g orbital via enhanced π-donation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 26699-710.

22. Li, W.; Guan, B.; Yang, T.; et al. Layer-structured triple-conducting electrocatalyst for water-splitting in protonic ceramic electrolysis cells: Conductivities vs. activity. J. Power. Sources. 2021, 495, 229764.

23. Wang, N.; Tang, C.; Du, L.; et al. Advanced cathode materials for protonic ceramic fuel cells: recent progress and future perspectives (Adv. Energy Mater. 34/2022). Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2270145.

24. Ding, H.; Wu, W.; Jiang, C.; et al. Self-sustainable protonic ceramic electrochemical cells using a triple conducting electrode for hydrogen and power production. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1907.

25. Zhou, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, D.; et al. New strategy for boosting cathodic performance of protonic ceramic fuel cells through incorporating a superior hydronation second phase. Energy. Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12660.

26. Shao, S.; Li, X.; Cai, Y.; et al. Interfacial metal ion self-rearrangement: a new strategy for endowing hybrid cathode with enhanced performance for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141698.

27. Yao, X.; Cheng, Q.; Bai, X.; et al. Enlarging the three-phase boundary to raise CO2/CH4 conversions on exsolved Ni-Fe alloy perovskite catalysts by minimal Rh doping. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 5639-53.

28. Bang, S.; Kim, J. G.; Wen, Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, W. Equalized oxygen partial pressure for carbon coking-free dry reforming of methane in intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163163.

29. Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Li, C.; et al. BaCe0.8Fe0.1Ni0.1O3-δ-impregnated Ni-GDC by phase-inversion as an anode of solid oxide fuel cells with on-cell dry methane reforming. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 834-41.

30. Wang, H.; Cui, G.; Lu, H.; et al. Facilitating the dry reforming of methane with interfacial synergistic catalysis in an Ir@CeO2-x catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3765.

31. Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; et al. Enhanced photothermal methane dry reforming through electronic interactions between nickel and yttrium. Nanoscale. Horiz. 2025, 10, 905-14.

32. Li, Y.; Yao, L.; Li, J.; et al. GaN nanowire-supported NiO for low-temperature and durable dry reforming of methane toward syngas. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 366, 125051.

33. Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Highly efficient transformation of tar model compounds into hydrogen by a Ni-Co alloy nanocatalyst during tar steam reforming. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3540-51.

34. Han, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Barnett, S. A. Highly efficient perovskite-based fuel electrodes for solid oxide electrochemical cells via in-situ nanoparticle exsolution and electron conduction enhancement. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 361, 124676.

35. Wang, S.; Ye, X.; Zhou, Y. All symmetrical metal supported solid oxide fuel cells. J. Inorg. Mater. 2016, 31, 769.

36. Gu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Ge, L.; Guo, L. PrBaMn2O5+δ with praseodymium oxide nano-catalyst as electrode for symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2019, 257, 117868.

37. Wang, S.; Zheng, H.; Wu, Y.; et al. Characterization of Pr0.5A0.5Fe0.9W0.1O3-δ (A = Ca, Sr and Ba) as symmetric electrodes for solid oxide fuel cells. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2022, 6, 4741-8.

38. Li, X.; Li, R.; Tian, Y.; et al. Tuning Pr0.5Ba0.5FeO3-δ cathode to enhanced stability and activity via Ca-doping for symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 60, 650-6.

39. Zhang, W.; Meng, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Meng, J. Co-incorporating enhancement on oxygen vacancy formation energy and electrochemical property of Sr2Co1+xMo1-xO6-δ cathode for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cell. Solid. State. Ion. 2018, 316, 20-8.

40. Zhou, J.; Shin, T.; Ni, C.; et al. In situ growth of nanoparticles in layered perovskite La0.8Sr1.2Fe0.9Co0.1O4-δ as an active and stable electrode for symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2981-93.

41. Fan, W.; Sun, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wu, K.; Cheng, Y. Highly stable and efficient perovskite ferrite electrode for symmetrical solid oxide fuel cells. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 23168-79.

42. Yu, Y.; Yu, L.; Shao, K.; et al. BaZr0.1Co0.4Fe0.4Y0.1O3-SDC composite as quasi-symmetrical electrode for proton conducting solid oxide fuel cells. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 11811-8.

43. Escudero, M.; Aguadero, A.; Alonso, J.; Daza, L. A kinetic study of oxygen reduction reaction on La2NiO4 cathodes by means of impedance spectroscopy. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2007, 611, 107-16.

44. Liu, X.; Huang, L.; Xi, X.; et al. Regulating the d-p orbital hybridization in BaCo0.4Fe0.4Zr0.1Y0.1O3-δ via Cu doping for high-performance solid oxide fuel cells cathode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162958.

45. Cao, X.; Ke, L.; Zhao, K.; Yan, X.; Wu, X.; Yan, N. Surface decomposition of doped PrBaMn2O5+δ induced by in situ nanoparticle exsolution: quantitative characterization and catalytic effect in methane dry reforming reaction. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 10484-94.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].