Super-slow charging dynamics of water-in-salt electrolytes in subnanopore

Abstract

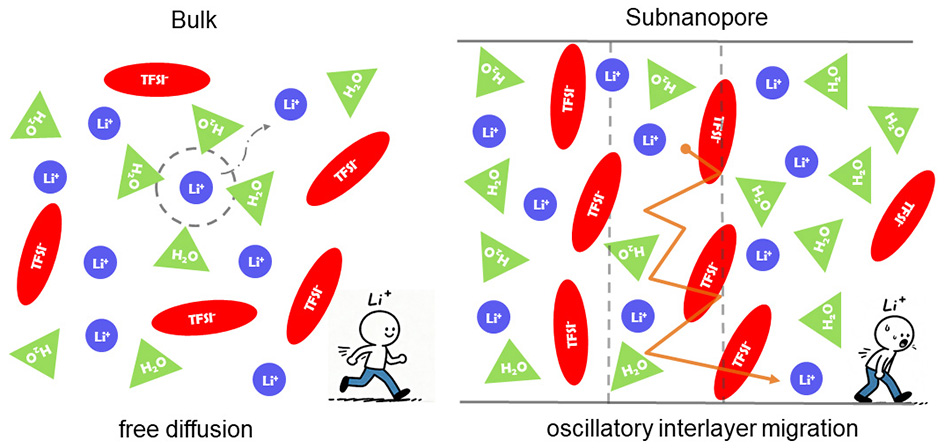

Water-in-salt electrolytes have attracted significant interest as high-performance electrolytes for electrochemical energy storage owing to their expanded electrochemical stability windows and enhanced safety. However, the mechanisms of ion transport and charging dynamics of water-in-salt electrolytes under nanoconfinement remain poorly understood. Here, we employed constant-potential-based molecular dynamics simulations to investigate ion transport and charging dynamics of water-in-salt electrolytes within subnanopore. In contrast to dilute solutions, an anomalous solvation-enhancement phenomenon was observed for highly concentrated electrolytes in subnanopore. Further analysis reveals that, contrary to bulk behavior, ion transport with enhanced solvation is strongly suppressed, ascribable to a transition in the transport mechanism from free diffusion to oscillatory interlayer migration. Additionally, in highly concentrated electrolytes within subnanopore, the distinctive layered structure restricts ion adsorption and desorption to the pore entrance during charging, ultimately yielding pronounced ion blockage. As a result, the charging rate of high-concentration electrolytes is reduced by nearly an order of magnitude relative to dilute solutions. These findings provide valuable insight into ion transport in water-in-salt electrolytes under nanoconfinement and offer theoretical guidance for the design of next-generation electrochemical energy storage systems.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Electric energy storage serves as a critical foundation for meeting the rising demands of electric vehicles and portable electronics[1-3]. Electrolytes are regarded as the lifeblood of electrochemical devices as they provide ion-conduction pathways between electrodes[4]. Aqueous electrolytes have attracted widespread attention because of their high safety and environmental friendliness[5,6]. However, their practical application is constrained by a narrow electrochemical stability window[7]. Water-in-salt (WIS) electrolytes, also termed high-concentration aqueous electrolytes, have emerged as promising candidates for next-generation energy storage systems due to their ability to expand the electrochemical stability window[8-12]. Despite these advantages, ion transport in WIS is significantly reduced, which severely limits the power performance of energy storage devices[13,14].

In recent years, the solvation structure and ion diffusion of WIS have been extensively investigated[15-18]. Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) is commonly selected as the reference salt because it can disrupt the hydrogen-bond network in water, thereby strengthening the stability of the electrolyte[19]. For instance, as suggested by a study combining molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with spectroscopic techniques, a fraction of cations in 10-21 m (kg mol-1) LiTFSI were dissociated from ion pairs owing to weakened Coulombic interactions and arranged into a three-dimensional Li-H2O network spanning

Ion transport under nanoconfinement exhibits marked deviations from bulk behavior[22-26]. For example, within the two-dimensional nanochannels, the WIS electrolytes are organized into an ordered, stratified architecture that substantially enhances ion transport[27]. Mesoporous materials similarly contain an interconnected network of continuous ion-conduction channels that promotes ion transport rate; however, their specific and volumetric capacitances are still limited[28]. Subnanometer pores have attracted considerable attention as supercapacitor electrodes because they can deliver conspicuous improvements in both capacitance and energy density[29-32]. However, the underlying ion transport mechanisms in such confined spaces remain poorly understood. Therefore, it is essential to develop a comprehensive understanding of ion transport and charging dynamics within subnanopore, so as to establish design principles for safe and high energy density supercapacitors.

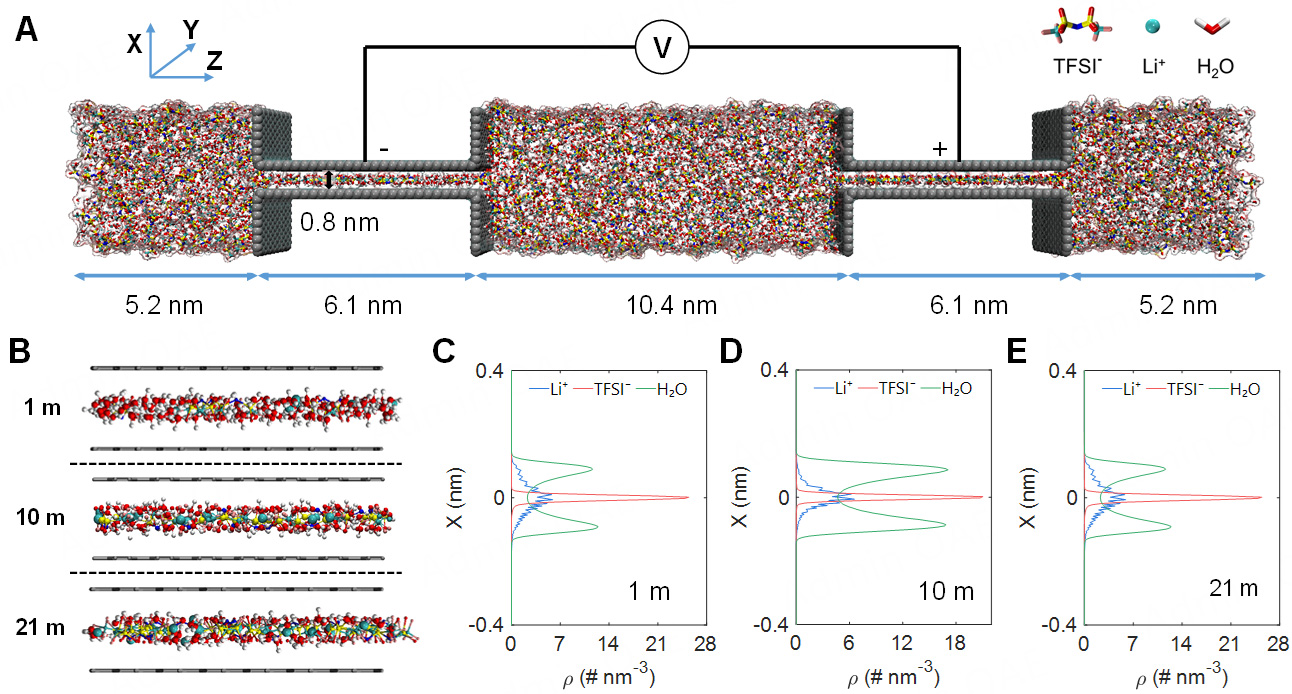

In this work, we used constant-potential molecular dynamics (CPM-MD) simulations to investigate the microstructure, ion transport and charging dynamics mechanisms in LiTFSI electrolytes confined within subnanopore [Figure 1A]. The simulations employed electrolytes with concentrations of 1 m, 10 m, and

Figure 1. Molecular dynamics model and electrolyte distribution in subnanopore. (A) Schematics of MD simulation; the electrodes are modeled as slit pores with a pore width of 0.8 nm, and the electrolyte comprises Li+, TFSI- and water molecules (H2O); (B) Simulation snapshot along the pore length; (C-E) The number density distributions of electrolytes along the X-direction of the pore width. The water number density in (C) is scaled by 1/6 to illustrate component distributions better.

EXPERIMENTAL

All MD simulations in this work were performed using the GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulations (Gromacs) 2020.2 software package[33]. The electrolyte system consisting of Li+, TFSI-, and H2O was prepared at concentrations of 1 m, 10 m, and 21 m. Specific particle numbers for each electrolyte concentration were listed in Table 1. As demonstrated in Figure 1A, each simulation system had a pair of slit pores with a width of 0.8 nm and a length of 6.1 nm as the electrodes, and the bulk region on each side was 4 × 3 × 5.2 nm3. Porous structure of electrodes was generated by using the Cornell force field[34]. Water molecules were described by the Simple Point Charge-Extended (SPC/E) model[35], and parameters about bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide anions (TFSI-) and Li+ were adopted from Doherty et al.[36] and

The number of particles in the LiTFSI electrolyte at each concentration

| Concentration | NLi | NTFSI | Nwater |

| 1 m | 160 | 160 | 7,384 |

| 10 m | 648 | 648 | 3,544 |

| 21 m | 848 | 848 | 2,248 |

The electrodes were kept fixed throughout the simulation. A Nosé-Hoover thermostat was employed to maintain temperature with a coupling constant of 1 ps, and pressure was regulated at 1 bar using a Parrinello-Rahman barostat. Van der Waals and short-range electrostatic interactions were truncated at

We employed CPM-MD to simulate the charging dynamics of the electrolyte systems. A 2 V potential discrepancy was imposed between the positive and negative electrodes during charging. In view of the differing charging times at each concentration, simulations were run for 100 ns (1 m), 300 ns (10 m), and

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The microstructure in subnanopore

We first focused on the microstructure in subnanometer pores. As shown in Figure 1B, the ions and water molecules were preferentially accumulated at the pore center. This distribution can be explained by the finite length of subnanopore, which produces local minima in the free-energy landscape that confines ions and water molecules in the central region[41]. In particular, water molecules exhibited an intermediate distribution between monolayer and bilayer, whereas Li+ cations and TFSI- anions were both characterized by monolayer distributions within the pore [Figure 1C-E]. As the electrolyte concentration increased, the ion population at the pore center correspondingly rose. Thus, water molecules were repelled to the electrode surface owing to the hydrophobic nature of TFSI-, resulting in a more pronounced bilayer distribution. It has been established that the transition of the confined electrolyte from a monolayer to a bilayer configuration significantly enhances ion transport within subnanopore[42]. Our findings suggested that electrolyte concentration could modulate the spatial distribution, which may in turn alter ion solvation and transport mechanisms.

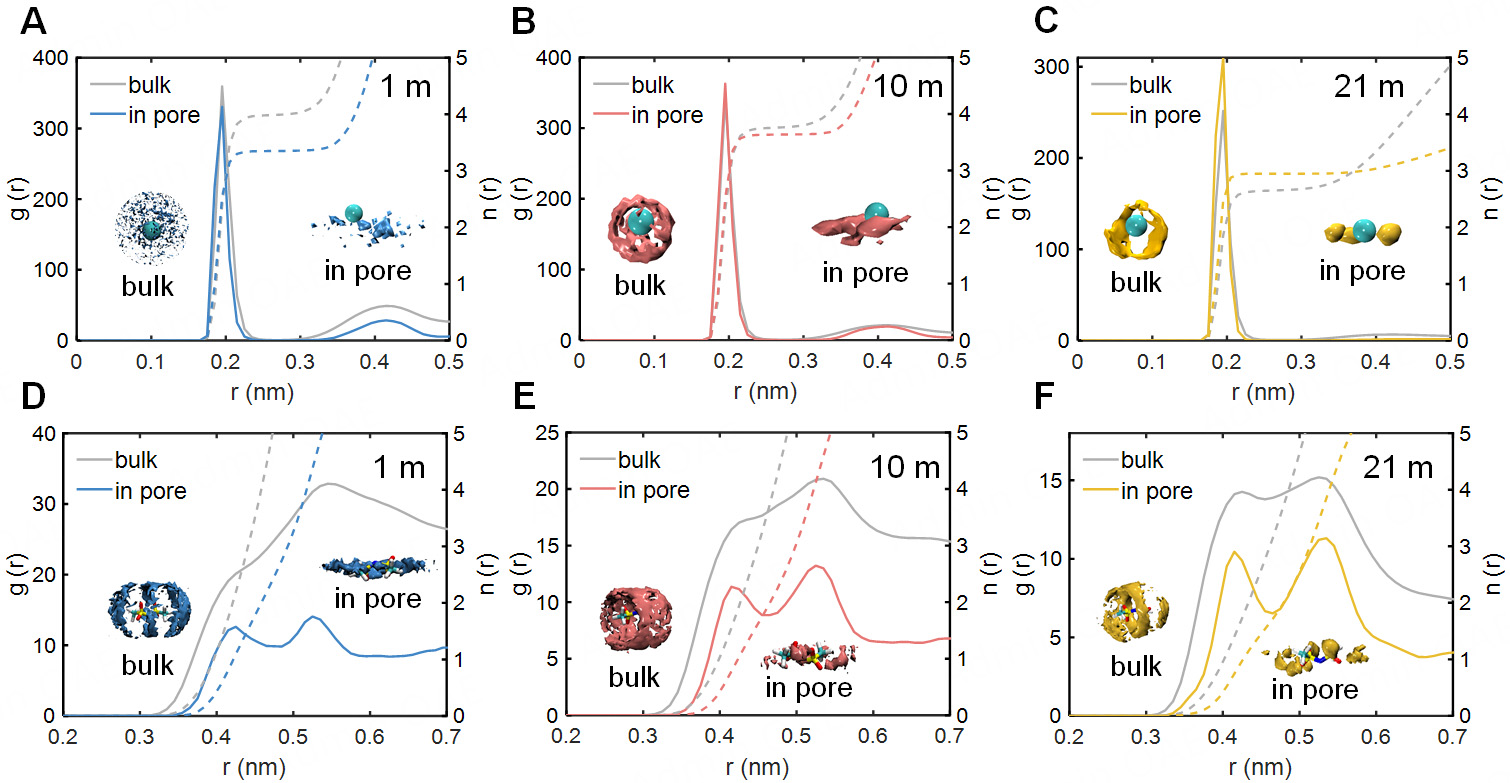

The spatial distribution function (SDF) provides direct evidence for the reorganization of the solvation shell around ions upon their entry into the subnanopore. Figure 2A and B shows that Li+ solvation structure inside the pore was annular rather than spherical in the bulk, which indicated a disruption of the hydration shell. When Li+ cations moved from the bulk into the pore, their coordinating water molecules were stripped away by the electrode surface due to the spatial constraint[43,44]. This process ultimately formed a Li+-centered annular solvation structure. Therefore, as illustrated in the coordination number, Li+ cations within the pore were less solvated by water than those in the bulk at concentrations of 1 m and 10 m. Despite the diminished solvation of Li+ in dilute solutions, a solvation‐enhancement phenomenon was observed in 21 m [Figure 2C and Supplementary Figure 1]. This behavior could be attributed to the fact that, in the bulk electrolyte at high concentrations, a portion of TFSI- anions penetrated the Li+ solvation shell and thereby replaced the solvated water molecules associated with Li+. In contrast, the TFSI- anions that coordinate with Li+ in the bulk were excluded from the subnanopore due to spatial confinement, resulting in enhanced solvation of Li+.

Figure 2. The ion solvation structures in the bulk phase and under nanoconfinement. (A-C) Radial distribution functions (RDF) and coordination numbers of relative water molecules surrounding Li+ in electrolyte systems at concentrations of 1 m, 10 m, and 21 m, with spatial distribution function (SDF) as insets; (D-F) The RDF, coordination numbers, and SDF of relative water molecules surrounding TFSI- at the same concentration.

As shown in Figure 2D-F, the radial distribution function (RDF) of water around TFSI- anions inside the pore exhibited a more pronounced two-peak profile compared to that in the bulk. This revealed that nanoconfinement promoted a more ordered solvation structure of TFSI-. Similar to Li+, TFSI- anions were desolvated upon entering the subnanopore. Ascribable to their chain-like molecular structure, the solvation shell of TFSI- underwent a transition from an ellipsoidal to an annular shape.

Interlayer oscillation transmission mode in subnanopore

In bulk electrolytes, Li+ cations are often characterized by a vehicular mechanism, wherein the ions diffuse within their stable solvation shells. The enhanced solvation can reduce the migration resistance and facilitate the diffusion rate of Li+[45-49]. Our results demonstrated that Li+ cations were preferentially solvated by water molecules as they moved from bulk into the pore in 21 m [Figure 2C]. This might facilitate Li+ transport within subnanopore, thereby increasing ionic conductivity and improving the power density of supercapacitors.

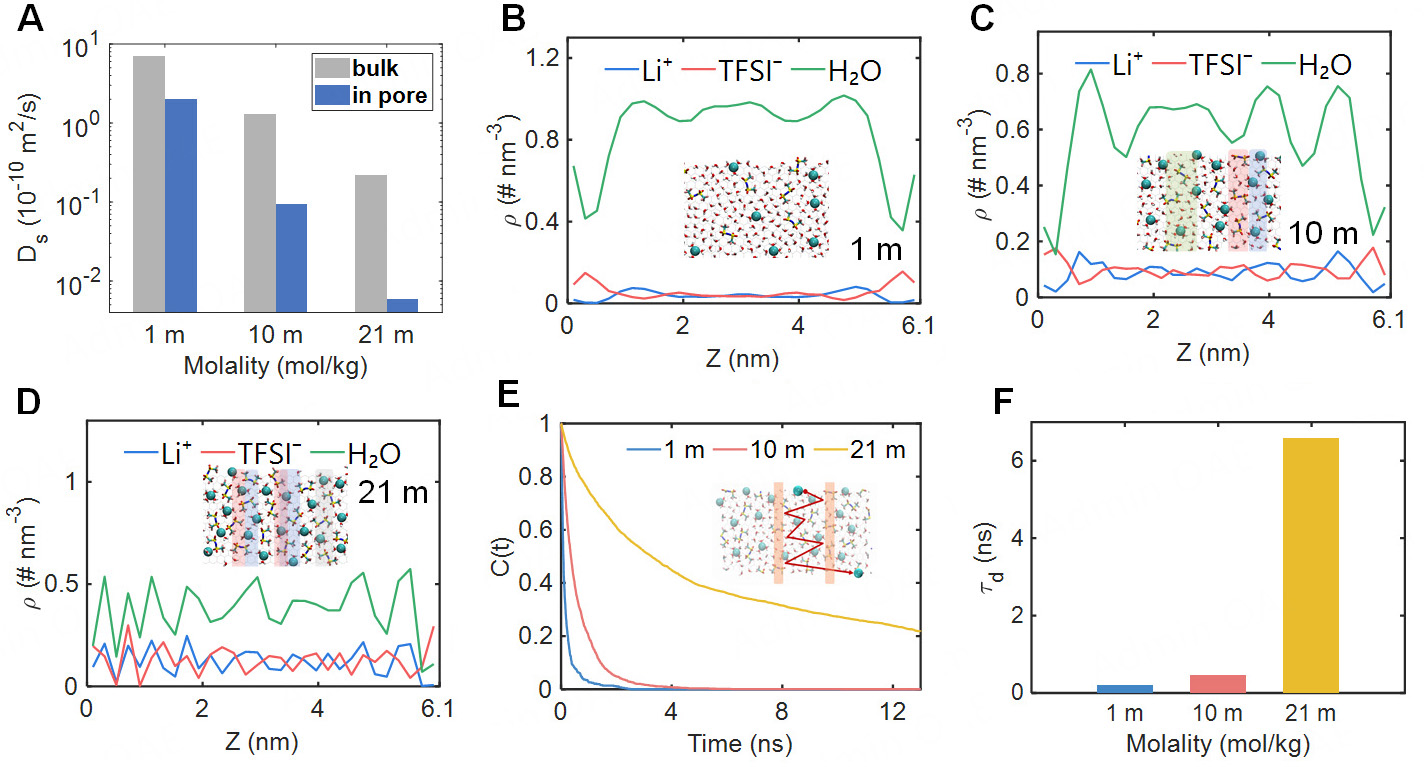

To validate this hypothesis, we computed the diffusion coefficients of Li+ using:[42]

where ri(t) refers to the position of the ion i at time t, ri(0) is the position of the ion i at initial moment, and n denotes the degree of freedom which is 3 in bulk phase and 2 within subnanopore. The diffusion coefficients of Li+ in pore were reduced to about one-quarter of their bulk values at concentrations of 1 m and 10 m [Figure 3A]. This originated from the desolvation of ions as they moved into the pore, which strengthens ionic interactions and retards ion diffusion. Surprisingly, despite the solvation enhancement of Li+, ion diffusion plummeted to approximately 1/50 of the bulk value in 21 m. TFSI- anions and water molecules were observed to follow a similar trend to that of Li+ [Supplementary Figure 2]. The drastic reduction in ion mobility was correlated with the evolving composition of ion clusters. The proportion of contact ion pairs (CIP) within the subnanopore was lower than the bulk value in 1 m and 10 m. Nonetheless, a reversal was observed at the concentration of 21 m [Supplementary Figure 3]. This indicated that a fraction of TFSI- entered the Li+ solvation shell in highly concentrated electrolytes within subnanopore. Hence, the Coulomb interaction between ions was strengthened, which obstructed ion transport inside the pore.

Figure 3. Ion transport mode of LiTFSI electrolyte in subnanopore. (A) The cations diffusion coefficients, Ds, of the electrolyte at the concentration of 1 m, 10 m, 21 m, with red bars representing in-pore values and gray bars representing bulk values; (B-D) The electrolyte number-density distributions along the pore axis (Z-direction) at concentrations of 1 m, 10 m and 21 m, with simulation snapshots at the corresponding concentrations shown as illustrations. (E) Time correlation function, C(t), for Li+ leaving the interlayer region, with schematic diagram of Li+ transport within the interlayer; (F) Average residence time, τd, of Li+ leaving the interlayer region.

We further calculated the number density distribution along the pore axis (Z-direction) to uncover the underlying mechanism behind the deceleration of Li+ in the enhanced solvation environment. The electrolyte distribution within subnanopore exhibited a uniform profile in the central region with a concentration of

Since the continuous ion transport network was fragmented in the highly concentrated electrolyte within subnanopore, ions can no longer undergo bulk-like free diffusion. This motivated an investigation into the distinctive layered structure to elucidate the underlying ion transport mechanism. The motivation energy for Li+ moving through interlayers is quantified by the potential of mean force (PMF), calculated as:[42]

where T is the temperature, kb is the Boltzmann constant,

where t is the time required for cations to escape from their interlayer region. Li+ cations required about 3 ns to complete interlayer migration with the concentrations of 1 m and 10 m

Super-slow charging dynamics

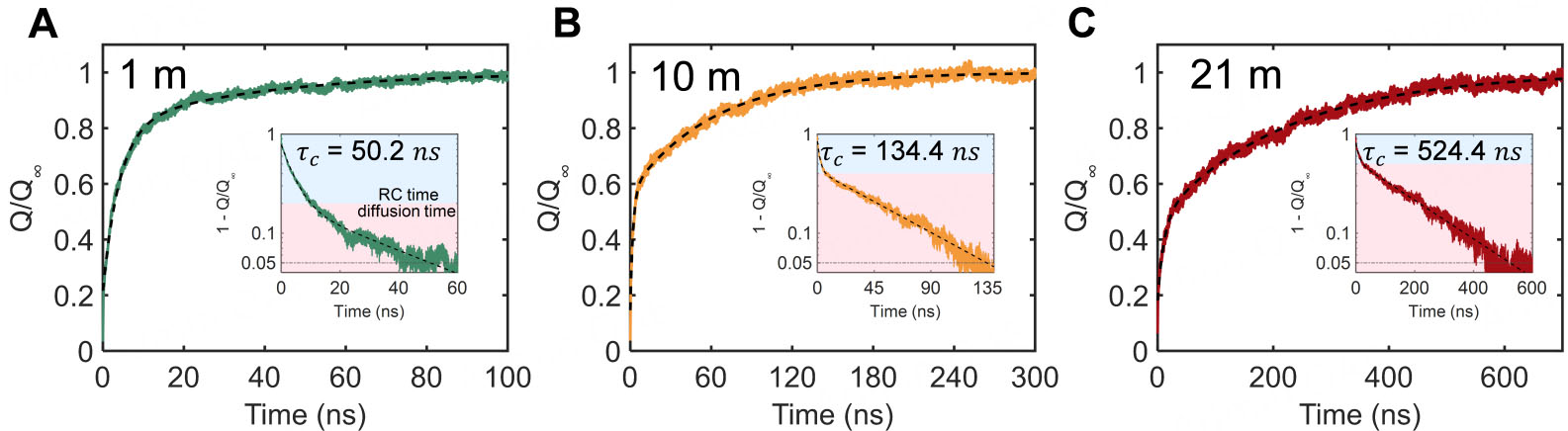

We next evaluated the charging performance of LiTFSI electrolytes within subnanopore. According to charging curves, the charging process was characterized by two stages: resistance capacitance (RC) time and diffusion time [Figure 4]. Therefore, a two-exponential function is employed to model the charging dynamics:[50]

Figure 4. The charging dynamics. (A-C) Normalized charging dynamics and charging time with the concentrations of 1 m, 10 m, and 21 m. Charging completion is defined as the point when Q/Q∞ attained 95%, and the time of this criterion is reported as τc.

where Q(t) denotes the charge on the electrode surface as a function of time; t is the charging time, and e is the base of the natural exponential (Euler’s number). Q∞ is the surface charge on the electrode when it is fully charged. A1 and A2 are proportional coefficient. τ1 and τ2 represent electromigration time and diffusion time, respectively. Figure 4A-C reveals that RC time decreased with increasing concentration, suggesting the charging process is mainly controlled by ion diffusion. Furthermore, the RC time was unexpectedly extended in 21 m, likely derived from the increased concentration discrepancy between the pore interior and bulk region. The charging time τc was defined as the time required for the electrode charge to reach 95% of its equilibrium value Q∞ in this work. The τc increased from 50.2 ns (1 m) to 524.4 ns (21 m), exhibiting that charging kinetics were slowed by approximately one order of magnitude at high concentration. This molecular-scale observation can be associated with macroscopic device behavior via a scaling law:[51]

where τnano repersents the charging time of the sub-nanopore and lnano is the radial length of subnanopore in the molecular dynamics simulations. τmaco denotes the charging time of the experimental device, and lmaco is the thickness of the electrode. The charging time in our simulation represented the dynamics within a single idealized subnanopore with width lnano = 6.1 nm. For electrodes with a thickness of 25 μm, τmaco with pore sizes of 0.8 nm will be 8.8 s. This aligns with the experimental data with the order of magnitude 10 s[52]. The trend of slowed dynamics is further corroborated by supercapacitor experiments, which show a substantial extension of the charging time at elevated concentrations[23,52].

The pronounced increase in charging time implied a transition in the underlying charging mechanism. The charging mechanism in supercapacitors can be categorized into three primary types: counter-ion adsorption, co-ion desorption, and ion exchange. In practice, the overall charging process often comprises a combination of these mechanisms. Forse et al. introduced a charging mechanism parameter, X, to establish a unified metric for quantifying their contributions. It is defined by:[53]

where N and N0 represent the total number of ions inside the pore after and before the electrode is charged, respectively. Ncounter and Nco stand for the number of counter-ions and co-ions. X = +1 represents charging solely by counter-ion adsorption, while the value of X = 0 means ion exchange, and X = -1 for co-ion desorption. X is a continuous variable. For example, X = 0.4 suggests that both ion exchange and counter-ion adsorption occur during charging, with ion exchange dominating since the value is closer to 0.

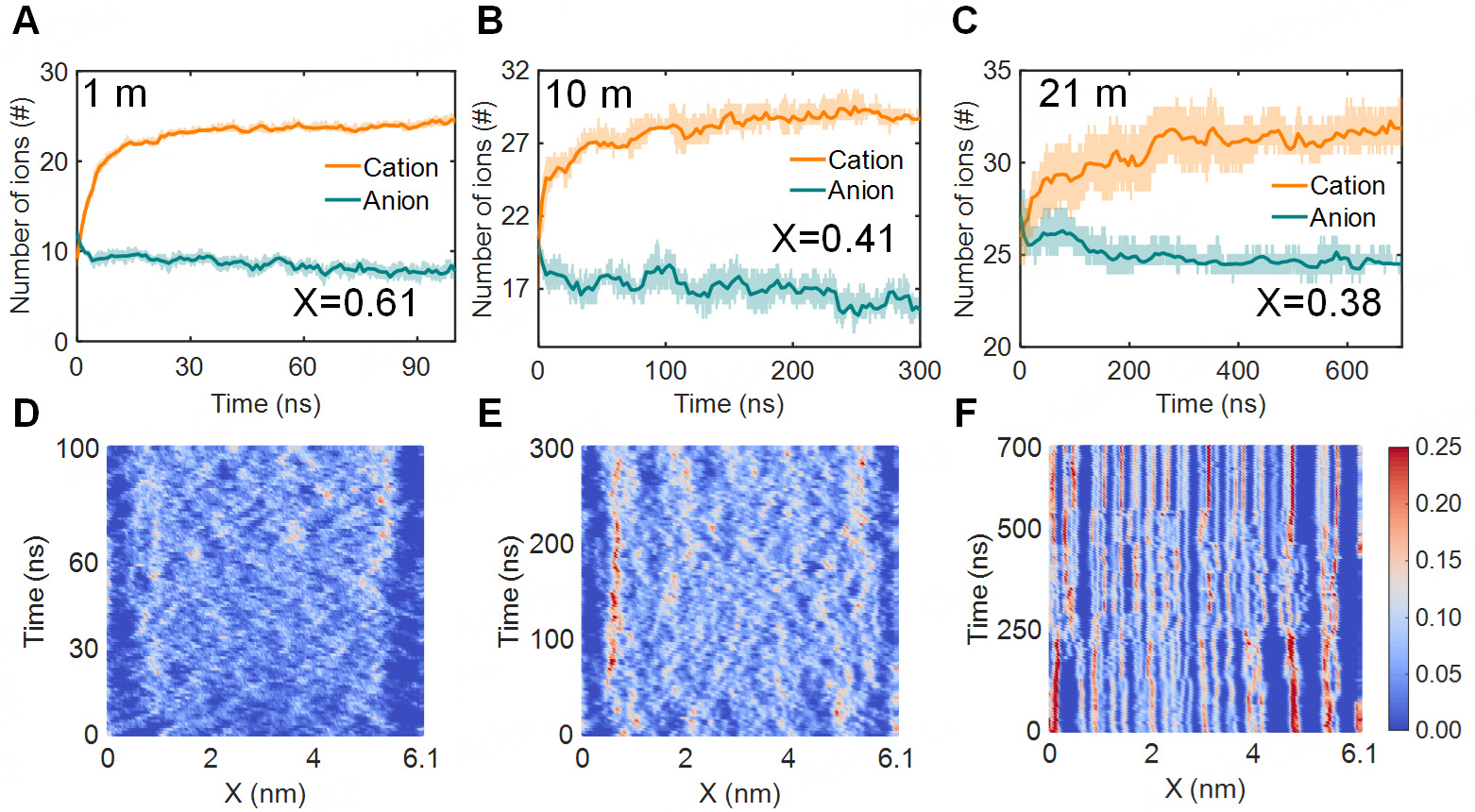

As shown in Figure 5A-C, Li+ cations were attracted by the negatively charged electrode, which led to an increase in the Li+ population within the subnanopore. In dilute solutions, ion transport was essentially unhindered, allowing the number of Li+ to rise rapidly [Figure 5A]. The charging mechanism was dominated by counter-ion adsorption (X = 0.61) in this case. For highly concentrated electrolytes, the layered structure confined ions between adjacent layers, thereby markedly extending the time for ions to reach equilibrium and the overall charging time. Figure 5C illustrates that the difference in counter-ion population between the charged and discharged states was markedly reduced for the 21 m electrolyte relative to the 1 m. This indicated a diminished capacity of the electrode surface to adsorb counter-ions. As a result, the dominant charging mechanism shifted from counter-ion adsorption to ion exchange (X = 0.38).

Figure 5. The ion number and ion motion path of negative electrode. (A-C) Variation of ion number within subnanopore in 1 m, 10 m, 21 m. (D-F) Time evolution of Li+ in subnanopore along the Z-direction of the pore length at 1 m, 10 m, and 21 m concentration, respectively. Unit of color bar: #/nm3.

On this basis, we presented a time-evolution analysis to provide a clearer illustration of ion motion during charging. As evidenced by the research findings, Li+ cations were trapped in a highly ordered and layered structure that persists throughout the charging process [Figure 5D-F]. The TFSI- anions occupied layers that alternate with those of Li+ [Supplementary Figure 6], which coincides with the conclusion drawn from the number density distribution analysis. As ions were confined between adjacent layers from the layered structure, the ion transport mechanism shifted from free diffusion to oscillatory interlayer migration. This transition rendered ions in the central region largely immobile. Consequently, adsorbed ions were driven to accumulate at the pore entrance, obstructing subsequent ion insertion into the pore center and resulting in pronounced ion blockage. The pore-entrance ion blockage closely resembles the “overfilling” behavior observed during the initial charging of ionic-liquid supercapacitors[54,55], which is proven to slow the charging kinetics. From another perspective, ion adsorption and desorption were restricted to the pore entrance during charging, significantly hindering the expulsion of co-ions from the pore center. These effects confined ion exchange to the pore entrance and inhibited ion diffusion into the pore center. As a result, the oscillatory interlayer migration of ions, combined with pore-entrance ion blockage, led to extended charging times in highly concentrated electrolytes.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we used CPM-MD simulations to investigate the ion transport and charging dynamics mechanisms in LiTFSI electrolytes within subnanopore. Our results suggested that the electrolyte in subnanopore was compressed from a three-dimensional bulk phase into a two-dimensional arrangement on account of the confined space. Thus, the coordination number of solvated water surrounding Li+ and TFSI- in dilute solutions was reduced by nanoconfinement. With increasing concentration, the electrolyte within subnanopore was progressively organized into an ordered and layered structure. Due to the pronounced layering that reduced the spacing between Li+ and surrounding water molecules, enhanced solvation of Li+ was observed at a concentration of 21 m. To be more specific, this layered structure confined ions between interlayers, requiring them to overcome energy barriers for migration. The ion transport mechanism thereby shifted from free diffusion to oscillatory interlayer migration, which severely suppressed ion mobility within the subnanopore.

Ions were drawn into the subnanopore by Coulombic interaction with the charged electrode during charging. However, in highly concentrated electrolytes, ions became trapped and immobilized between adjacent layers within subnanopore, hindering subsequent ions from entering the pore. Therefore, counter-ions were compelled to accumulate at the pore entrance and produced distinct pore-entrance ion blockage. This behavior triggered a shift in the dominant charging mechanism from counter-ion adsorption to ion exchange, as evidenced by the charging mechanism parameter X decreasing from 0.61 to 0.38. Driven by the synergistic effects of oscillatory interlayer migration and pore-entrance ion blockage, the charging rate of the 21 m solution inside the pore was nearly one order of magnitude lower than that of the 1 m solution.

Our study provided valuable theoretical guidance for selecting electrode materials with optimized pore-size distributions. In particular, we recommend that experimental efforts prioritize synthesizing electrodes with pore-size distributions to minimize the pore-entrance ion blockage. Furthermore, our findings offered a comprehensive understanding of ion transport mechanisms and charging performance in WIS electrolytes within subnanopore, thereby laying a foundation for the rational design of next-generation aqueous energy-storage systems. These results established guiding principles for developing aqueous batteries that combine high power density with environmental safety.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Data validation, writing of the original draft, revising the manuscript, software: Zhu, B.

Conceptualization, software, data curation, writing of the original draft: Zhou, J.

Software, information gathering, revising the manuscript: Jia, Y.

Supplementary experiments, procuring required materials: Fu, J.

Revising the manuscript, software: Liang, C.

Methodology, writing-review & editing, resources, project administration, funding acquisition: Mo, T.

Availability of data and materials

Some results of supporting the study are presented in the Supplementary Materials. Other raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52406226), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (No. 2025GXNSFBA069396), the Opening Project of Guangxi Key Laboratory of Petrochemical Resource Processing and Process Intensification Technology (No. 2024K009), and the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCSW2025114) for their support.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G. The Li-ion battery industry and its challenges. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2025, 9, 497-8.

2. Xie, Z.; Sun, L.; Sajid, M.; Feng, Y.; Lv, Z.; Chen, W. Rechargeable alkali metal-chlorine batteries: advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 8424-56.

3. Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Yoo, J.; Kwon, G.; Ko, Y.; Kang, K. Organic batteries for a greener rechargeable world. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 8, 54-70.

5. Xie, J.; Lu, Y. C. Designing nonflammable liquid electrolytes for safe Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2312451.

6. Chen, S.; Zhang, M.; Zou, P.; Sun, B.; Tao, S. Historical development and novel concepts on electrolytes for aqueous rechargeable batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 1805-39.

7. Dong, D.; Zhao, C. X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Aqueous electrolytes: from salt in water to water in salt and beyond. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2418700.

8. Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Hasa, I.; Passerini, S. Challenges and strategies for high-energy aqueous electrolyte rechargeable batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 598-616.

9. Hsieh, Y.; Tuan, H. Emerging trends and prospects in aqueous electrolyte design: elevating energy density and power density of multivalent metal-ion batteries. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2024, 68, 103361.

10. Suo, L.; Borodin, O.; Gao, T.; et al. "Water-in-salt" electrolyte enables high-voltage aqueous lithium-ion chemistries. Science 2015, 350, 938-43.

11. Wei, J.; Zhang, P.; Sun, J.; et al. Advanced electrolytes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 10335-69.

12. Supiňková, T.; Zukalová, M.; Kakavas, N.; et al. Electrolyte effects and stability of Zn/Li dual-ion batteries with water-in-salt electrolytes. J. Power. Sources. 2025, 655, 237983.

13. Jaumaux, P.; Yang, X.; Zhang, B.; et al. Localized water-in-salt electrolyte for aqueous lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 19965-73.

14. Xie, J.; Lin, D.; Lei, H.; et al. Electrolyte and interphase engineering of aqueous batteries beyond "water-in-salt" strategy. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2306508.

15. Khan, Z.; Kumar, D.; Crispin, X. Does water-in-salt electrolyte subdue issues of Zn batteries? Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2300369.

16. Dong, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Shen, L.; Zhang, X. Niobium tungsten oxide in a green water-in-salt electrolyte enables ultra-stable aqueous lithium-ion capacitors. Nanomicro. Lett. 2020, 12, 168.

17. Gomez Vazquez, D.; Pollard, T. P.; Mars, J.; et al. Creating water-in-salt-like environment using coordinating anions in non-concentrated aqueous electrolytes for efficient Zn batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 1982-91.

18. Jiang, L.; Liu, L.; Yue, J.; et al. High-voltage aqueous Na-ion battery enabled by inert-cation-assisted water-in-salt electrolyte. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1904427.

19. Flores, L.; Martin, J.; Toudret, P.; Bayle, P.; Martinet, S. A comprehensive study of highly concentrated Lithium‑ion aqueous electrolytes: from structural characterizations to electrochemical properties. Electrochim. Acta. 2025, 536, 146680.

20. Borodin, O.; Suo, L.; Gobet, M.; et al. Liquid structure with nano-heterogeneity promotes cationic transport in concentrated electrolytes. ACS. Nano. 2017, 11, 10462-71.

21. Goloviznina, K.; Serva, A.; Salanne, M. Formation of polymer-like nanochains with short lithium-lithium distances in a water-in-salt electrolyte. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 8142-8.

22. Liu, K.; Epsztein, R.; Lin, S.; Qu, J.; Sun, M. Ion-ion selectivity of synthetic membranes with confined nanostructures. ACS. Nano. 2024, 18, 21633-50.

23. Quan, T.; Härk, E.; Xu, Y.; et al. Unveiling the formation of solid electrolyte interphase and its temperature dependence in "water-in-salt" supercapacitors. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 3979-90.

24. Cheng, C.; Jiang, G.; Simon, G. P.; Liu, J. Z.; Li, D. Low-voltage electrostatic modulation of ion diffusion through layered graphene-based nanoporous membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 685-90.

25. Raidongia, K.; Huang, J. Nanofluidic ion transport through reconstructed layered materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16528-31.

26. Iamprasertkun, P.; Ejigu, A.; Dryfe, R. A. W. Understanding the electrochemistry of "water-in-salt" electrolytes: basal plane highly ordered pyrolytic graphite as a model system. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6978-89.

27. Qin, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, G.; et al. High and stable ionic conductivity in 2D nanofluidic ion channels between boron nitride layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6314-20.

28. Wang, P.; Zhang, K.; Liao, J.; et al. Mesoscale dynamics of electrosorbed ions in fast-charging carbon-based nanoporous electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 1228-36.

29. Kondrat, S.; Pérez, C. R.; Presser, V.; Gogotsi, Y.; Kornyshev, A. A. Effect of pore size and its dispersity on the energy storage in nanoporous supercapacitors. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6474.

30. Wang, Y.; Hao, X.; Kang, Y.; et al. Enhanced ion conductivity of “water-in-salt” electrolytes by nanochannel membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023, 11, 1394-402.

31. Liu, X.; Lyu, D.; Merlet, C.; et al. Structural disorder determines capacitance in nanoporous carbons. Science 2024, 384, 321-5.

32. Mo, T.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, L.; et al. Energy storage mechanism in supercapacitors with porous graphdiynes: effects of pore topology and electrode metallicity. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2301118.

33. Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2008, 4, 435-47.

34. Cornell, W. D.; Cieplak, P.; Bayly, C. I.; et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 117, 5179-97.

35. Berendsen, H. J. C.; Grigera, J. R.; Straatsma, T. P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 2002, 91, 6269-71.

36. Doherty, B.; Zhong, X.; Gathiaka, S.; Li, B.; Acevedo, O. Revisiting OPLS force field parameters for ionic liquid simulations. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2017, 13, 6131-45.

37. Jensen, K. P.; Jorgensen, W. L. Halide, ammonium, and alkali metal ion parameters for modeling aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2006, 2, 1499-509.

38. Martínez, L.; Andrade, R.; Birgin, E. G.; Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2157-64.

39. Gingrich, T. R.; Wilson, M. On the Ewald summation of Gaussian charges for the simulation of metallic surfaces. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 500, 178-83.

40. Kondrat, S.; Feng, G.; Bresme, F.; Urbakh, M.; Kornyshev, A. A. Theory and simulations of ionic liquids in nanoconfinement. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6668-715.

41. Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33-8.

42. Mo, T.; Bi, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Ion structure transition enhances charging dynamics in subnanometer pores. ACS. Nano. 2020, 14, 2395-403.

43. Liu, P.; Song, Z.; Miao, L.; Lv, Y.; Gan, L.; Liu, M. Boosting spatial charge storage in ion-compatible pores of carbon superstructures for advanced zinc-ion capacitors. Small 2024, 20, e2400774.

44. Chmiola, J.; Largeot, C.; Taberna, P. L.; Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Desolvation of ions in subnanometer pores and its effect on capacitance and double-layer theory. Angew. Chem. Int. 2008, 47, 3392-5.

45. Liu, X.; Lee, S.; Seifert, S.; et al. Revealing the correlation between the solvation structures and the transport properties of water-in-salt electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 2088-94.

46. Kim, J.; Koo, B.; Lim, J.; et al. Dynamic water promotes lithium-ion transport in superconcentrated and eutectic aqueous electrolytes. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 7, 189-96.

47. Chen, Y.; Atwi, R.; Nguyen, D. T.; et al. From bulk to interface: solvent exchange dynamics and their role in ion transport and the interfacial model of rechargeable magnesium batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 12984-99.

48. Hou, T.; Fong, K. D.; Wang, J.; Persson, K. A. The solvation structure, transport properties and reduction behavior of carbonate-based electrolytes of lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14740-51.

49. Li, C. Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, S.; et al. Unconventional interfacial water structure of highly concentrated aqueous electrolytes at negative electrode polarizations. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5330.

50. Breitsprecher, K.; Holm, C.; Kondrat, S. Charge me slowly, I am in a hurry: optimizing charge-discharge cycles in nanoporous supercapacitors. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 9733-41.

51. Péan, C.; Merlet, C.; Rotenberg, B.; et al. On the dynamics of charging in nanoporous carbon-based supercapacitors. ACS. Nano. 2014, 8, 1576-83.

52. Zhang, Q.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Dou, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yan, X. Temperature-dependent structure and performance evolution of “water-in-salt” electrolyte for supercapacitor. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2023, 55, 205-13.

53. Forse, A. C.; Merlet, C.; Griffin, J. M.; Grey, C. P. New perspectives on the charging mechanisms of supercapacitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5731-44.

54. Kondrat, S.; Wu, P.; Qiao, R.; Kornyshev, A. A. Accelerating charging dynamics in subnanometre pores. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 387-93.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].