Ion sieving function of MoS2 and Alg-Zn hybrid coating endows high stability of Zn anode for aqueous Zn-ion batteries

Abstract

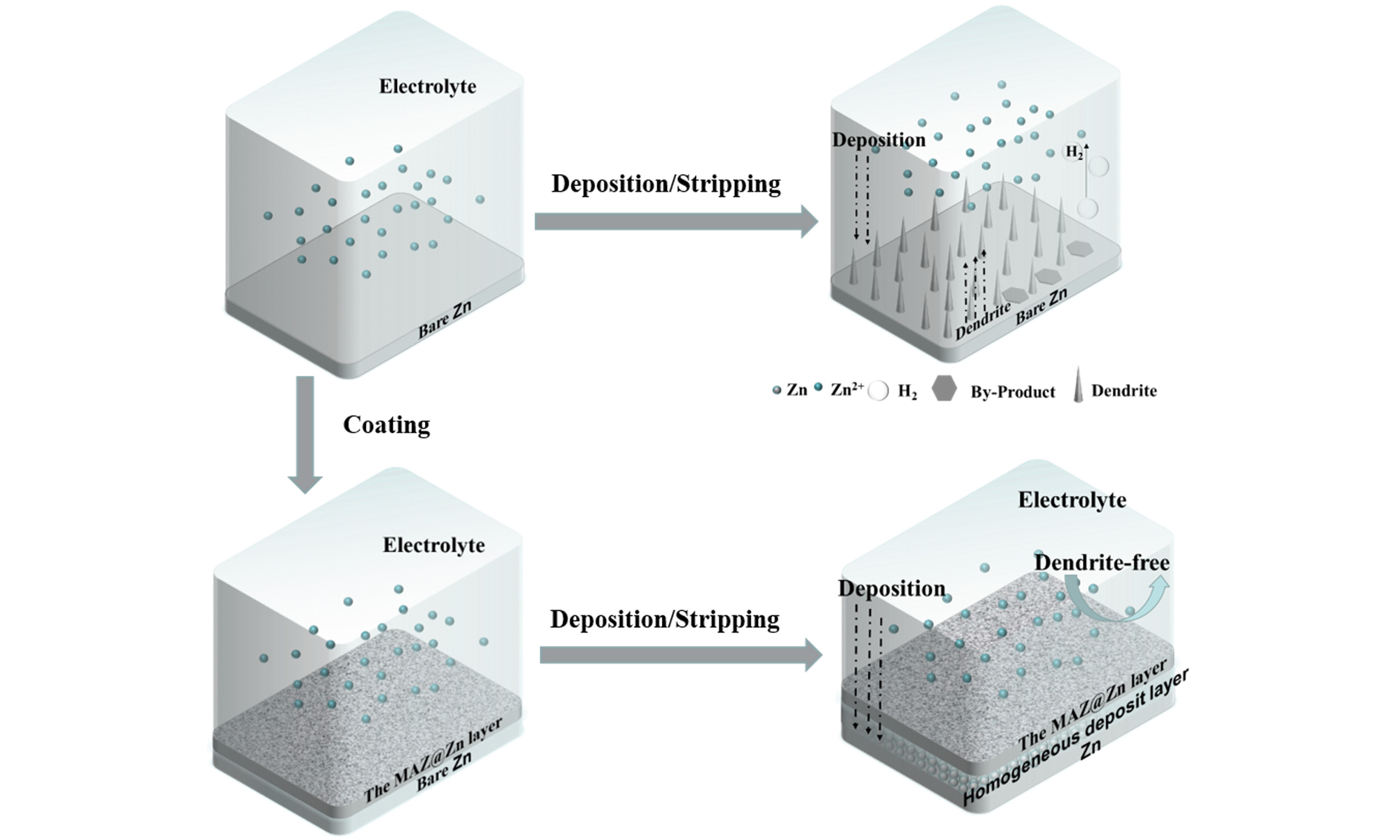

Aqueous Zn-ion batteries (AZIBs) have emerged as promising energy storage systems due to their high safety, low cost, and environmental friendliness. However, the practical application of zinc metal anodes is hindered by challenges such as Zn dendrite growth and side reactions, which degrade the cycle performance and energy efficiency of AZIBs. To address these issues, a facile and functional coating composed of zinc alginate gel (Alg-Zn) and 2H-molybdenum disulfide (2H-MoS2) was used to modify the Zn anode (MAZ@Zn). Combined experimental and theoretical investigations reveal that, in addition to the Zn2+ guiding effect of ion conductive Alg-Zn, the 2H-MoS2 functions as an ion sieve. This facilitates the fast Zn2+ migration and even distribution because of the lower ion migration energy along the MoS2 surface, ensuring fast Zn2+ diffusion in the MAZ@Zn coating and uniform Zn deposition. Moreover, the barrier effect of MoS2 against H2O helps suppress side reactions such as hydrogen evolution, thereby further enhancing the interfacial stability of the Zn anode. As a result, the MAZ@Zn symmetric cells exhibit excellent cyclic stability, achieving a lifespan of 880 h at 1 mA cm-2 and 1 mAh cm-2, with low voltage polarization and low charge transfer energy. In contrast, the bare Zn anode only sustains 150 h of cycling under identical conditions. In Zn//sodium vanadate full batteries, the MAZ@Zn anode demonstrates outstanding performance, retaining 88.4% of its capacity after 1,000 cycles at 4 A g-1. This work offers a simple and effective strategy for developing high-performance Zn anodes for long-life AZIBs.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Aqueous Zn-ion batteries (AZIBs) are promising candidates for next-generation energy storage devices, owing to the inherent advantages of zinc-metal anodes[1,2]. These advantages include low cost[3], abundant resource availability, compatibility with aqueous electrolytes, high theoretical capacity (820 mAh g-1)[4], and an appropriate redox potential (-0.76 V vs. the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE))[5]. This specific potential window effectively inhibits hydrogen evolution reactions (HERs) at the Zn/electrolyte interface, thereby ensuring electrochemical stability[6]. Despite these benefits, the practical use of zinc metal anodes remains challenging, such as the formation of Zn dendrites during the electroplating process[7], side reaction with water, which can deteriorate the battery performance[8,9].

In response to these challenges, great efforts have been made to enhance the performance of AZIBs[10-12]. Strategies include designing three-dimensional Zn anodes and Zn alloys[13,14], employing gel or solid-state electrolytes[15-18], and introducing electrolyte additives[19-21]. Among these, the development of artificial coatings to inhibit the growth of Zn dendrites has emerged as an effective and practical solution[22-25].

The coating surface reported in the literature can be simply classified into inorganic and organic coatings. Inorganic coatings mainly consist of metals[26,27] (In, Ag, etc.), metal oxides[28-31] (TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3, etc.) and carbon materials[32,33]. They can inhibit dendrite growth but tend to increase the resistance at the electrolyte-electrode interface[34], adversely affecting overall battery performance. Organic materials with polar groups[35-38] (meta-organic frameworks, polyamide, poly (2-vinylpyridine)) - although capable of guiding Zn2+ migration - often suffer from high polarization. This significantly affects the rate performance of the batteries[39,40]. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore the surface coating of the Zn anode in order to reduce the disadvantages of inorganic coating or organic coating with facile preparation.

Zinc alginate (Alg-Zn) demonstrates potential as an effective organic coating material, exhibiting high ionic conductivity (1.83 × 10-2 S cm-1)[41]. By binding with free water molecules, it significantly improves electrolyte wettability. Furthermore, the Zn-affinity carboxyl and ether groups within its polyanionic framework enable guided two-dimensional Zn2+ diffusion[41,42]. In our prior study, an engineered mixed ionic-electronic conductive coating (Alg-Zn + AB@Zn) - comprising Alg-Zn gel and acid-treated carbon black (AB) - was developed to enhance Zn anode stability[43]. The prepared mixed coating not only promoted uniform Zn nucleation, but also effectively reduced the nucleation overpotential of Zn. The Alg-Zn + AB@Zn symmetrical cell exhibited a low polarization voltage (47 mV) and achieved long-term cycle stability for

MoS2 demonstrates a strong capability for promoting the homogeneous deposition of Zn2+ and inhibiting dendrite formation. Wang et al. prepared a large-area quasi-single-crystal 2D material (molybdenum disulfide, MoS2) as a substrate using an epitaxial phase-conversion method[44]. The results showed that the edge of 2H-MoS2 exhibited a stronger Zn deposition induction effect than the base plane, which inhibited the growth of Zn dendrites. Bhoyate et al. developed a 2D MoS2 coating on a Zn anode via electrochemical deposition[45]. The coated MoS2 layer formed a vertically oriented structure that facilitated the easy flow of Zn2+ and ensured a uniform electric field distribution on the anode. This led to uniform stripping and plating of Zn2+, preventing dendrite growth and complex side reactions. When tested at a current density of

Here, we use a simple drop-coating method to obtain a hybrid gel-conductive coating consisting of 2H-MoS2 and Alg-Zn (MAZ@Zn). When sodium alginate is immersed in the 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte, it interacts with Zn2+ to form Alg-Zn, which can transfer Zn2+. This creates a “channel” where Zn2+ migration is guided and confined by the carboxylate groups of alginate[43-46]. The superimposed or cross-linked flexible channels formed by MoS2 facilitate rapid Zn2+ transfer and guide the homogeneous deposition of Zn2+ on the surface of zinc foil beneath the coating[47]. First-principles calculation reveals that Zn2+ exhibits reduced migration energy on the 2H-MoS2 (002) interface, making this surface an adept sieve for these ions. Such a design guarantees the homogeneous distribution of Zn2+ on the electrode surface, curbing the emergence of Zn dendrites effectively. In addition, the barrier effect of MoS2 against H2O may help suppress side reactions such as hydrogen evolution, further enhancing interfacial stability. The symmetric cell constructed with MAZ@Zn achieves a cycle life of 880 h at a current density of 1 mA cm-2, while the unmodified bare Zn anode only shows a cycle life of 150 h. Compared with previous studies [Supplementary Table 1], the MAZ@Zn anode exhibits competitive cyclic stability (880 h), which can be attributed to the uniform distribution of Zn2+ on the electrode surface, effectively inhibiting the formation of Zn dendrites. In addition, the full MAZ@Zn//Zn// sodium vanadate (NVO) battery retained 88.4% of its capacity after 1,000 cycles at a current density of 4 A g-1.

EXPERIMENTAL

Preparation of Zn anode modified with a composite layer of Alg-Zn and MoS2

First, sodium alginate and commercial MoS2 powder were initially blended in deionized water at room temperature (25 °C). The mass ratios for the sodium alginate and MoS2 powder were varied as 3:7, 1:1, and 7:3, while the sodium alginate-to-deionized water mass ratio was maintained at 1:50[43]. This blend was then subjected to magnetic stirring for a duration of 12 h to ensure thorough mixing. Leveraging sodium alginate's properties as a binder, the slurry was carefully mixed until it achieved a viscous yet flowable consistency. Following this, the slurry was meticulously drop-cast and uniformly spin-coated onto a polished and smooth Zn plate to ensure even distribution. The coated Zn plate was subsequently immersed in 2 M ZnSO4 solution, which facilitated the ion-exchange process between sodium alginate and zinc alginate in the coating. Specifically, Zn2+ ions replaced Na+ ions in the carboxylate groups of the alginate chains, forming coordination bonds that give rise to the characteristic “egg-box” structure of Zn alginate. This crosslinking with divalent Zn2+ significantly enhances the stability of the alginate matrix compared with monovalent Na+, thereby reducing solubility and improving resistance against swelling or dissolution in aqueous electrolytes. Upon removal from the solution, a composite coating comprising Zn alginate and MoS2 was formed on the Zn surface. This resulted in the formation of three distinct coated materials: M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and M3AZ7@Zn, each indicating the respective ratios of MoS2 to Alg-Zn in the coating.

Preparation of sodium vanadate (NVO) cathode material

Initially, 1.5 g of commercial V2O5 powder was mixed into 50 mL of 2 M NaCl solution. This mixture was then subjected to ultrasonication to achieve a uniform dispersion. Following this, the solution was continuously stirred for 72 h. When the solution acquired an orange hue, it was filtered, and the resulting residue was meticulously rinsed with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol. The next step involved vacuum drying the residue at 80 °C for 12 h. For the composition of the active material, NVO, conductive carbon black, and binder PTFE were proportionally weighed in a mass ratio of 7:2:1. These components were then ground together and dissolved in anhydrous ethanol to form a slurry, which was subsequently exposed to a baking lamp. The obtained material was then pressed onto a stainless-steel mesh current collector using a roller press, with the areal loading of the active material controlled at approximately 4.5 mg cm-2.

Electrochemical measurements

In the electrochemical tests for Zn/Zn symmetric cells, two polished Zn foils, each 100 μm thick and 15 mm in diameter, were used as electrodes. To assemble the battery, 70 μL of a 2 M ZnSO4 electrolyte solution was added into a CR2025 button cell using a pipette. A glass fiber separator (GF/A, Whatman) was used to separate the electrodes in the battery. For the Zn/Cu asymmetric cells, the process was the same as for the Zn/Zn cells. However, one Zn foil was replaced with a Cu foil, which was 32 μm thick and 15 mm in diameter. For the Zn//NVO full batteries, a Zn foil was used as the anode, and NVO material was used as the cathode. A glass fiber membrane was used as the separator, similar to the other battery types. The electrolyte was a mixture of 70 μL of 2 M ZnSO4 and 1 M Na2SO4. All parts were carefully assembled into a CR2025 button battery format for testing. The ionic conductivity (σ) of the electrolytes was derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) data collected over 10 mHz-100 kHz on Zn//Zn symmetric cells. A custom-designed fixture maintained a fixed electrode gap to ensure reproducible conductivity estimates. The conductivity was calculated using:[48]

where Rb is the bulk resistance taken from the high-frequency intercept on the real axis of the Nyquist plot, L denotes the coating thickness, and S is the effective electrode-electrolyte contact area. The contribution of the MAZ coating (RMAZ) was isolated by subtraction: RMAZ = Rtotal - Rglass-fiber.

The Zn2+ transference number (t+(Zn2+)) was obtained using the Evans method:[49]

where ∆V is the applied polarization voltage, Io and Is are the initial and steady-state current densities, respectively, and Ro and Rs are the charge-transfer resistances measured before and after polarization. Chronoamperometry was conducted under a constant 25 mV bias, which corresponds to ∆V.

The desolvation activation energy (Ea) was determined by fitting the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) measured at different temperatures to an Arrhenius-type relation:[50]

where Rct is the interfacial charge-transfer resistance, A represents the pre-exponential factor, T denotes the absolute temperature, R indicates the gas constant, and Ea signifies the activation energy for desolvation.

Characterization

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) data were collected using a Nicolet IS50 spectrometer with an Attenuated Total Reflection attachment. The crystal structure was analyzed with an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D/MAX-IIA, Rigaku) using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) and a scanning angle (2θ) range from 10° to 90°. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images were taken at 10 kV or 15 kV using a Phenom XL-70 instrument. An optical microscope was used to examine the samples at a microscopic level. All samples were analyzed using the YM520R optical microscope from Yueshi Company in Suzhou, China. The cycling performance of the batteries was tested using the LAND battery test system (CTA2001A, Wuhan Land Electronics Co., Ltd., China). Cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD), and EIS tests were conducted with the CHI660E electrochemical workstation (Shanghai, China). The EIS range was 0.01-100 kHz.

Computational details

In the density functional theory (DFT) calculation, we initially optimize the geometry structures of Zn (002) surface and 2H-MoS2 (002) surface until the force on each atom is reduced to less than 1 × 10-4 eV Å-1 and obtain the total energy of the Zn and MoS2 surface. Then, Zn atoms are put on each selected adsorption site. Following the geometry optimization of Zn (002) [or MoS2 (002)] surface with adsorption atoms, the total energy of the adsorption system is obtained. We then calculate the adsorption energy using:[51]

where E(Zn) indicates the total energy of a Zn atom. E(surface) is the total energy of the clean surface, and E(surface + Zn) is the total energy of the surface with the adsorbed Zn atom.

All the DFT calculations are performed using the CP2K code package. In these calculations, the molecular orbitals of the valence electrons were expanded using a hybrid double-zeta valence polarisation (DZVP)-Molecular Optimization(MOLOPT)-Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) Gaussian basis set, with plane waves expanded to a cutoff of 500 Rydberg[52]. The GTH pseudopotentials within the framework of the local density approximation functional are employed to describe the atomic core electrons, while the DFT-D3 method accounts for van der Waals interactions[53,54].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

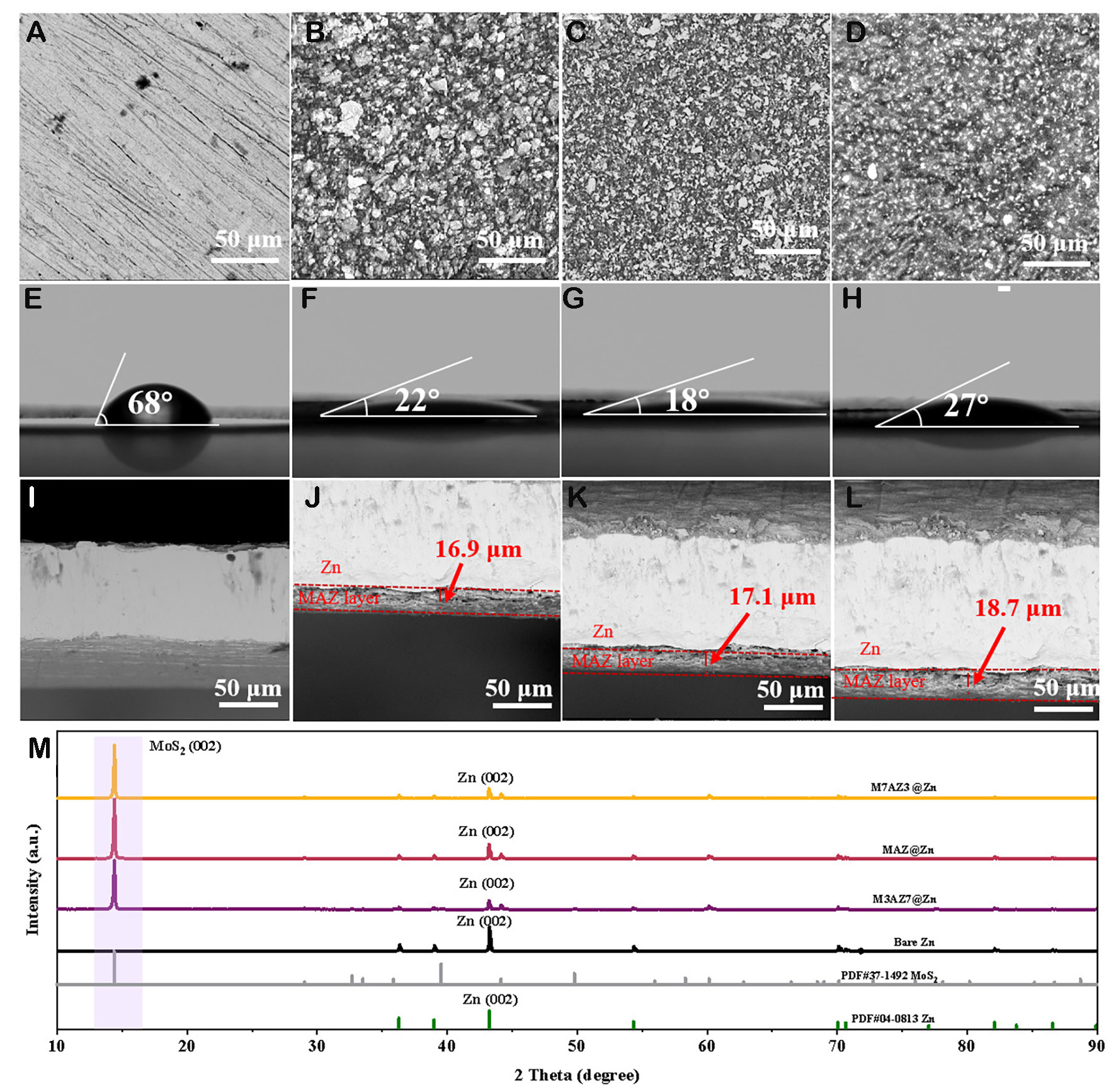

This study investigated the impact of Alg-Zn to MoS2 mass ratios on the performance of Zn anode electrodes. Raman spectroscopy [Supplementary Figure 1A] confirmed that the experimental MoS2 was in the 2H phase[55]. Different compositions of Alg-Zn and MoS2 coatings were prepared, with mass ratios of 3:7 (M3AZ7), 1:1 (MAZ), and 7:3 (M7AZ3). The surface morphology of these coatings, along with that of bare Zn, was examined using SEM. As shown in Figure 1, bare Zn exhibits a relatively flat surface interspersed with fine scratches, likely resulting from the polishing process of the Zn foil [Figure 1A][56]. However, M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn and M3AZ7@Zn consist of irregular aggregated particles with dense surfaces and uniform distribution of MoS2 particles [Figure 1B-D], which are conducive to electrolyte penetration and provide an improved interface for electrochemical reactions[43].

Figure 1. Physical property characterization of Zn anodes. SEM images of (A) bare Zn, (B) M7AZ3@Zn, (C) MAZ@Zn, and (D) M3AZ7@Zn. Contact angle measurements of (E) bare Zn, (F) M7AZ3@Zn, (G) MAZ@Zn, and (H) M3AZ7@Zn. Cross-sectional SEM images of (I) bare Zn, (J) M7AZ3@Zn, (K) MAZ@Zn, and (L) M3AZ7@Zn. (M) Initial XRD patterns of bare Zn, M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and M3AZ7@Zn.

The efficacy of the MAZ@Zn coating is further evaluated through contact angle measurements conducted in 2 M ZnSO4 aqueous solution, as depicted in Figure 1E-H. Remarkably, while the bare Zn sample exhibits a contact angle of 68° [Figure 1E], the coated samples of M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and M3AZ7@Zn demonstrate significantly lower contact angles of 22°, 18°, and 27°, respectively [Figure 1F-H]. The contact angles of M7AZ3@Zn and M3AZ7@Zn are larger than that of MAZ@Zn, but for different reasons. For M7AZ3@Zn, the higher contact angle is due to its larger fraction of hydrophobic MoS2. For M3AZ7@Zn, despite having more Alg-Zn, the contact surface with the electrolyte is insufficient, leading to a similarly higher contact angle. For MAZ@Zn, the homogeneous mixing of MoS2 with Alg-Zn creates a hybrid structure that facilitates electrolyte penetration, thereby resulting in a smaller contact angle. Further cross-sectional SEM observations reveal that the coating thicknesses of M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and M3AZ7@Zn are 16.9 μm, 17.1 μm, and 19.7 μm, respectively, as shown in Figure 1J-L.

To gain a deeper understanding of the structural composition of the MAZ@Zn coating, X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of bare Zn and MAZ@Zn samples were recorded, as shown in Figure 1M. In addition to the diffraction peaks similar to those of Zn (PDF#04-0813), the MAZ@Zn sample displays additional peaks that align with the characteristics of MoS2 (PDF#37-1492)[57]. This observation confirms that the MAZ@Zn coating has been successfully applied to the Zn foil. Furthermore, the diffraction peaks of M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and M3AZ7@Zn are similar. FTIR analyses provide additional verification of the presence of Alg-Zn in the coatings, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 1B. The peak at 3,112 cm-1 is indicative of the O-H stretching vibration in the hydrogen bonds of the alginate salt polymer chain, the peak around 1,593 cm-1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of the -COO- group on the alginate salt chain, and the peak near 1,011 cm-1 is likely attributed to the C-O stretching vibration[43].

XRD analyses of coated samples and bare Zn after a five-day immersion in a 2 M ZnSO4 solution were conducted, to investigate the stability of different Zn anodes [Supplementary Figure 2]. For the bare Zn electrode, besides the diffraction peaks of Zn (PDF#04-0831), two peaks appear at 16.25° and 24.47°, which correspond to irreversible formation of Zn4(SO4)4(OH)6·5H2O (PDF#39-0688), indicating that severe passivation occurred during deposition[58]. In contrast, for M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn and M3AZ7@Zn electrodes, no trace of the by-product is observed. These observations highlight the stability of the MAZ coating in ZnSO4 electrolytes and its ability to shield the Zn anode from direct contact with the electrolyte, which effectively inhibits potential side reactions. In [Supplementary Figure 3], EIS shows that the impedances of M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn and M3AZ7@Zn are lower than those of bare Zn. Compared with

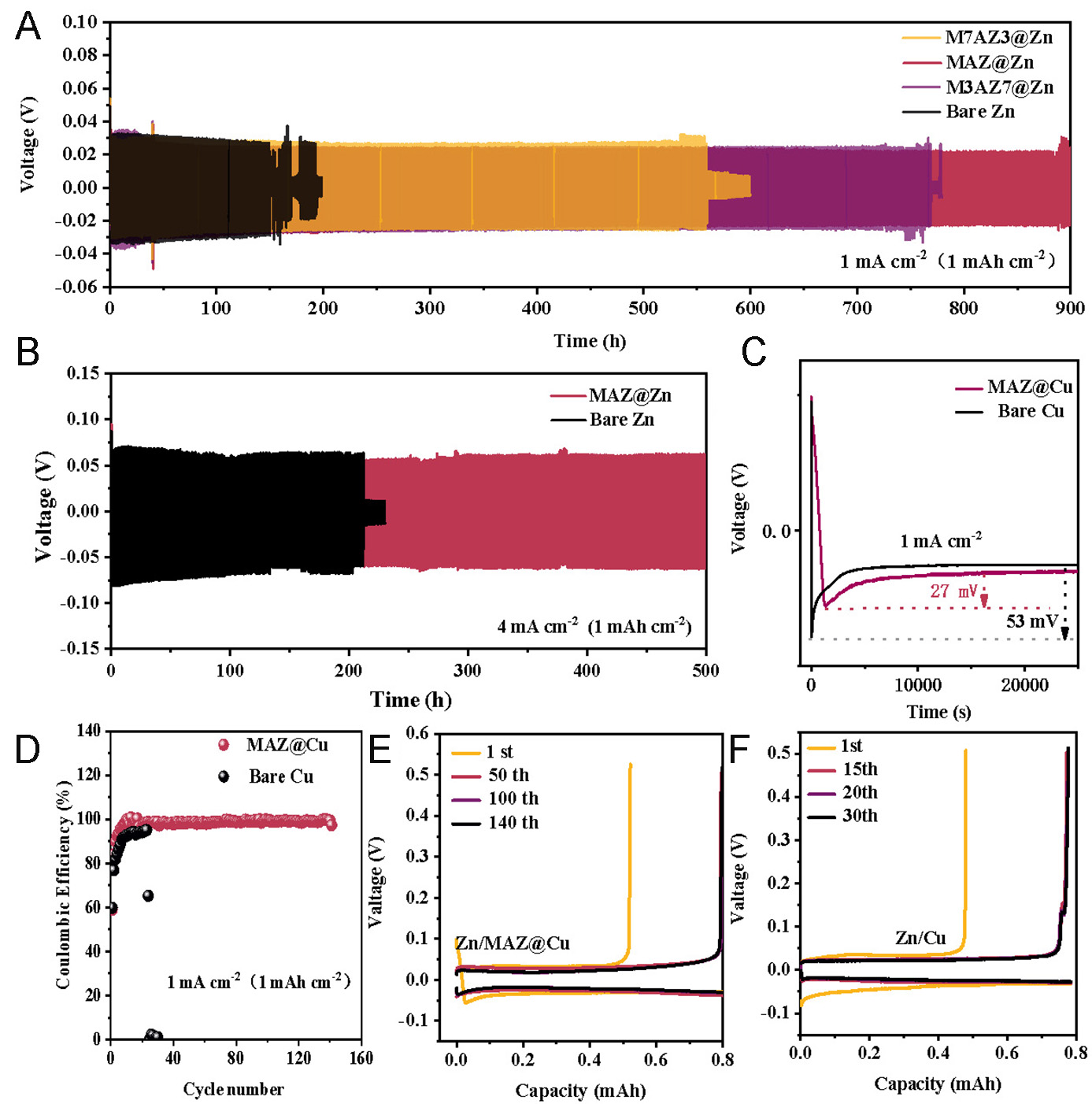

In assessing the electroplating/stripping stability of bare Zn, M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn, and

Figure 2. Electrochemical performance in Zn/Cu cells and Zn/Zn cells. Constant current charge and discharge curves of symmetric cells of bare Zn, M7AZ3@Zn, MAZ@Zn and M3AZ7@Zn: (A) at 1 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2); (B) 4 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2). (C) Nucleation overpotential in Zn/Cu and Zn/MAZ@Cu in asymmetric cells. (D) CE of Zn plating/stripping in Zn/Cu and Zn/MAZ@Cu half-cells. GCD curves of (E) Zn/MAZ@Cu and (F) Zn/Cu half-cells.

Further charge-discharge test was executed with a higher current density of 4 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2), as shown in Figure 2B. The results reveal that bare Zn encounters a short circuit after approximately 200 h [Figure 2B]. In sharp contrast, MAZ@Zn exhibits a cycle life of more than 500 h, with a nucleation overpotential of 107 mV compared to 137 mV for bare Zn, showing a considerable reduction in polarization [Supplementary Figure 4B]. These results finally confirm that MAZ@Zn coating significantly enhances the stability of Zn stripping and plating processes. Compared with most previously reported interfacial modification strategies [Supplementary Table 1], the MAZ@Zn anode exhibits superior cyclic stability and cumulative capacity, although there is still room for further improvement in overall electrochemical performance.

Under a discharge current density of 1 mA cm-2 [Figure 2C], the measured nucleation overpotential of Zn/Cu is 53 mV. In contrast, for Zn/MAZ@Cu, the nucleation overpotential is significantly lower, measured at 27 mV, which is smaller than that of the bare Zn. To better understand the effect of the MAZ coating on the Zn electroplating/stripping process, we measured the Coulombic efficiency (CE) of Zn/Cu and Zn/MAZ@Cu half-cells at a current density of 1 mA cm-2 and an area-specific capacity of 1 mAh cm-2. As depicted in Figure 2D-F, the Zn/Cu half-cell exhibits voltage fluctuations after only 30 cycles due to the formation of Zn dendrites, which can lead to internal short circuits. In contrast, the Zn/MAZ@Cu half-cell maintains stable CE even after 140 cycles, demonstrating excellent reversibility in Zn stripping and electroplating. This result not only underscores the efficacy of the MAZ coating in preserving the electrochemical reversibility of Zn, but also signifies its role in effectively mitigating side reactions and curtailing dendritic growth of Zn.

To further validate the ion-transport characteristics of the Alg-Zn/MoS2 hybrid coating, EIS was conducted to evaluate its intrinsic ionic conductivity. Nyquist plots were recorded at open-circuit potential over

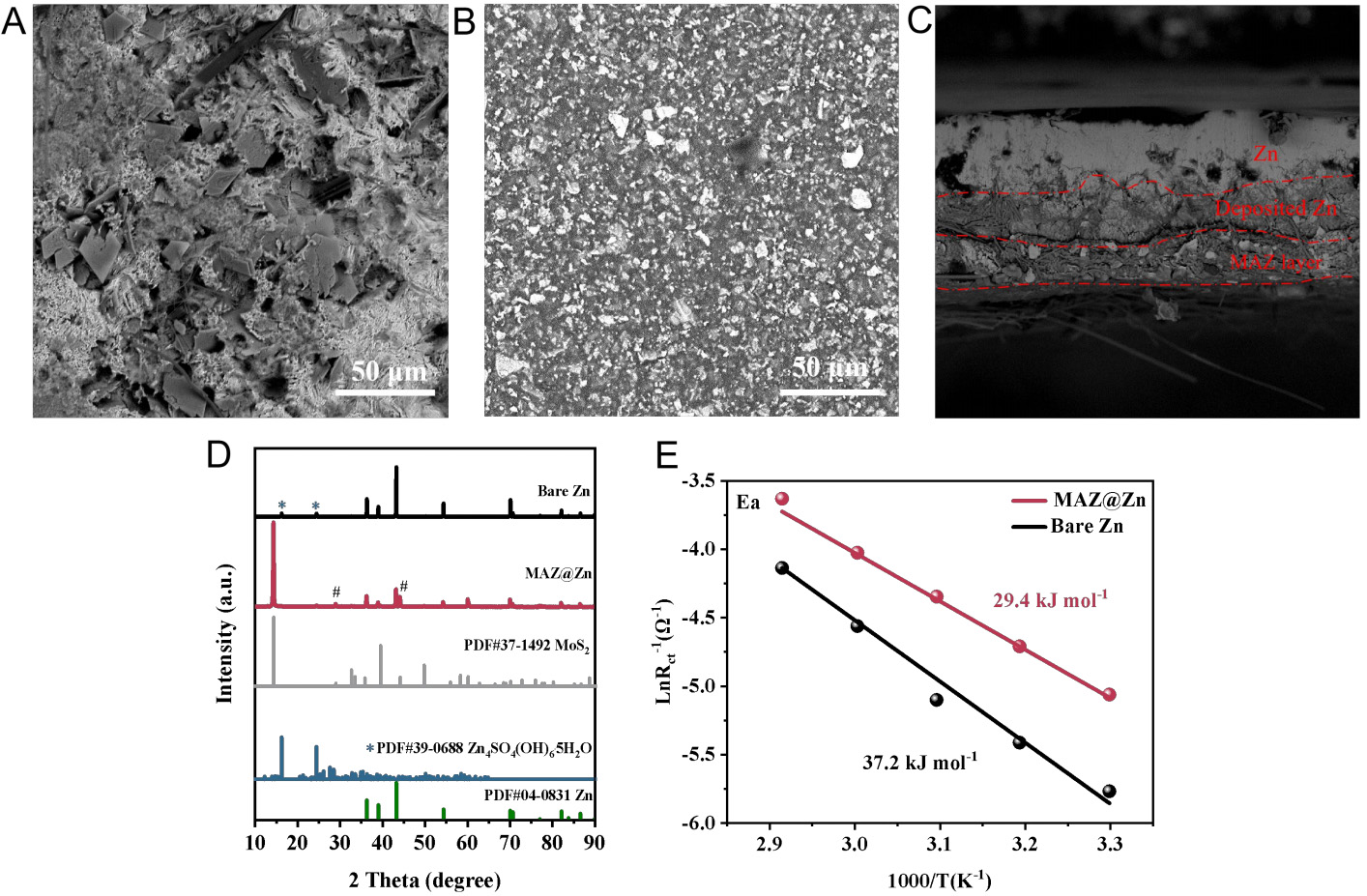

SEM and XRD investigations were conducted for the bare Zn and MAZ@Zn after cycling in symmetric cells. These cells underwent 50 cycles at a current density of 1 mA cm-2 and area-specific capacity of 1 mAh cm-2. The bare Zn electrode displays a rough and uneven surface, characterized by a dense array of dendritic structures and non-uniform deposition of Zn [Figure 3A][60]. In sharp contrast, the surface of the MAZ@Zn electrode remains smooth and uniform, with no signs of Zn dendrite formation or cluster aggregates

Figure 3. Structural and electrochemical analysis of Zn-based cells. SEM images of (A) bare Zn, (B) the top surface, and (C) the cross-section of MAZ@Zn in symmetric cells after 50 cycles at 1 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2). (D) XRD patterns of bare Zn and MAZ@Zn in symmetric cells after 50 cycles at 1 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2); (E) Corresponding Arrhenius plots and comparison of activation energies between bare Zn and MAZ@Zn.

In addition, when the MAZ coating was removed from the cycled MAZ@Zn electrode for XRD analysis [Supplementary Figure 7], only the diffraction peak of MoS2 (PDF#37-1492) was observed in the coating material, while no peak of Zn (PDF#04-0831) was detected. This indicates that, under the regulation of the MAZ coating, Zn is uniformly and effectively deposited beneath the coating at the interface between the coating and the Zn substrate, which is consistent with the cross-sectional results shown in Figure 3C. Furthermore, to further elucidate the deposition behavior, a single Zn deposition test was conducted using a MAZ@Cu substrate [Supplementary Figure 8]. The use of Cu foil eliminates the influence of the Zn base electrode, enabling direct observation of Zn deposition morphology. Both the cross-sectional and top-view SEM images (before and after coating removal) confirm that Zn is deposited beneath the coating, forming a uniform and compact interfacial layer. Temperature-dependent EIS measurements [Supplementary Figure 9] and the corresponding Arrhenius analysis [Figure 3E] revealed a lower desolvation activation energy for MAZ@Zn symmetric cells (29.4 kJ mol-1) compared with bare Zn cells (37.2 kJ mol-1). This reduced energy barrier indicates that the MAZ coating enables more efficient Zn2+ desolvation and accelerates interfacial charge transfer.

In-situ optical microscopy was used for real-time observation of the Zn electroplating and stripping processes. As shown in Supplementary Figure 10, under a current density of 0.3 mA cm-2, bare Zn displays an uneven surface Zn deposition even after applying the current for 15 min. In contrast, under the guiding effect of the MAZ coating, the MAZ@Zn electrode demonstrates a much more uniform deposition at the same time interval. The difference becomes even more pronounced after 60 min. The surface of the bare Zn electrode is covered by extensive and irregular Zn deposits. On the other hand, the MAZ@Zn electrode exhibits a remarkably uniform deposition. The ability of the MAZ coating to promote uniform deposition of Zn is a key factor in enhancing the longevity and efficiency of Zn electrodes for AZIBs.

To further evaluate the suppression of side reactions, Tafel and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements were carried out [Supplementary Figure 11]. The LSV curves reveal that the MAZ@Zn electrode exhibits a higher HER overpotential, while the Tafel plots show a lower corrosion current density compared with bare Zn, confirming that the coating effectively inhibits both HER and corrosion. These findings further validate the proposed “ion-sieve” function of MoS2: while the low migration energy barrier facilitates Zn2+ transport, the barrier effect against H2O helps to suppress parasitic reactions, thereby enhancing the interfacial stability of the Zn anode.

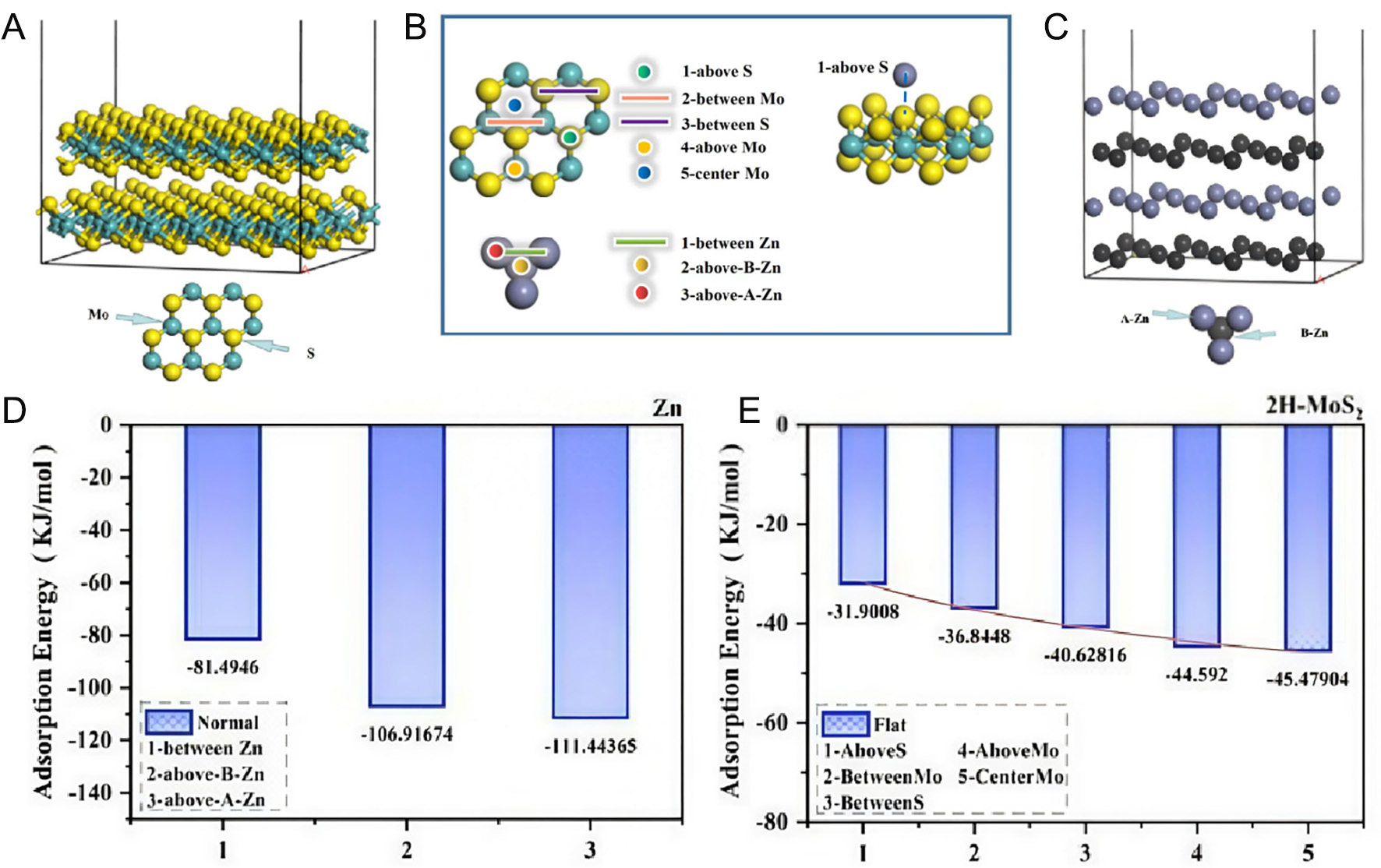

Ab initio DFT calculations were performed to investigate the adsorption behavior of Zn atoms on both 2H-MoS2 and Zn surfaces. Figure 4A shows the lattice model of the 2H-MoS2(002) surface, which corresponds to the most intense XRD peak in Figure 1I and possesses superior chemical stability[61,62]. A supercell consisting of two MoS2 layers with a 40 Å vacuum in the z-direction to mimic the 2H-MoS2 (002) surface. Five possible Zn adsorption sites were examined on the 2H-MoS2 surface, as illustrated in Figure 4B: atop a Mo atom (site 1), atop a S atom (site 2), nestled between two Mo atoms (site 3), between two S atoms (site 4), and at the nexus of three Mo atoms (site 5). As a benchmark, the adsorption of Zn atoms on a Zn (002) surface was also studied [Figure 4C][63]. The Zn (002) facet was selected because it is the most thermodynamically stable plane of hexagonal Zn, exhibiting the lowest surface energy among the exposed facets[64-66]. Therefore, it is widely used as a benchmark surface for modeling Zn adsorption and diffusion behavior in both theoretical and experimental studies. The Zn layers are categorized as either the “A” or “B” layer based on their geometric configurations, represented by gray and black spheres in Figure 4B. To systematically explore Zn adsorption, three typical sites were considered on the Zn (002) surface: directly above a Zn atom from the A layer (between-Zn), directly above a Zn atom from the B layer (above-B-Zn), and interstitially between two surface Zn atoms (above-A-Zn). The calculated adsorption energies are -81.5, -106.9, and -111.4 kJ mol-1 for the above-A-Zn, above-B-Zn, and between-Zn sites, respectively, as presented in Figure 4D. Notably, the between-Zn site exhibits the least exothermic adsorption energy, indicating that Zn adsorption at this position perturbs the intrinsic hexagonal close-packed (HCP) structure of the Zn surface due to its interstitial configuration. In contrast, the above-A-Zn and above-B-Zn sites show comparable, more negative adsorption energies, suggesting a small diffusion barrier for Zn migration between these two energetically favorable sites. As summarized in Figure 4E, the adsorption energies of Zn atoms on the 2H-MoS2 (002) surface range from -31.9 to -45.5 kJ mol-1, which are significantly weaker than those on the Zn (002) surface. Combined with the smaller energy differences among the adsorption sites, this suggests a reduced diffusion energy barrier for Zn migration on 2H-MoS2, enabling homogeneous Zn distribution, suppressed dendritic growth, and improved interfacial stability.

Figure 4. Lattice structure and adsorption of Zn atoms on 2H-MoS2 and Zn surfaces. Lattice structure of 2H-MoS2 (002) surface (A) and with Mo and S atoms plotted as green and yellow spheres, respectively. (B) Selected adsorption sites on the MoS2 (002) and Zn (002) surfaces. (C) Lattice structure of Zn (002) surface, with Zn atoms plotted as gray(black) spheres. (D) Adsorption energy of Zn atom at different sites of Zn (002) surface and (E) 2H-MoS2 (002) surface.

In addition to the theoretical analysis of Zn adsorption on the MoS2 surface, we further examined whether Zn2+ ions could also be intercalated into the MoS2 interlayers. Interlayer insertion of Zn2+ is strongly dependent on the MoS2 phase (1T/2H), interlayer chemistry/spacing, defect characteristics, and the testing protocol[67-71]. In this study, commercial, pristine 2H-MoS2 was used as a surface-modifying layer without further modification, and limited Zn-storage activity is therefore expected. To substantiate this, pure MoS2 electrodes were evaluated in 2 M ZnSO4. CV and GCD measurements [Supplementary Figure 12] show nearly no reversible capacity within the selected potential window, indicating no measurable Zn2+ intercalation into the S-Mo-S galleries. This observation is consistent with reports that pristine 2H-MoS2 requires defect engineering to effectively accommodate Zn2+[69]. Accordingly, in this study, MoS2 primarily regulates Zn2+ adsorption and guides uniform Zn deposition, rather than serving as a Zn2+ storage host.

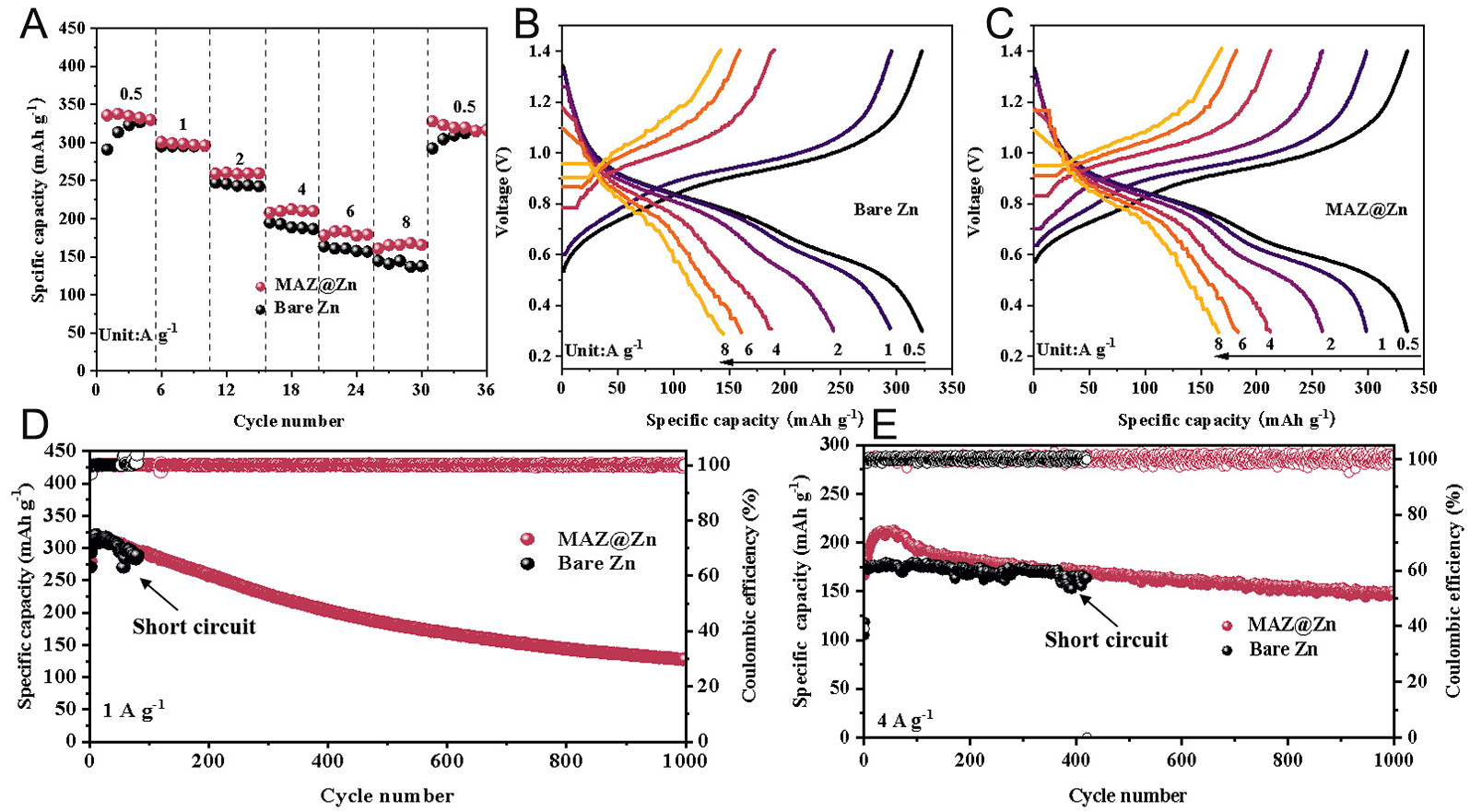

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of MAZ@Zn in full cells, NVO was employed as the cathode material. As shown in Supplementary Figure 13, the NVO displays a nanowire-like morphology, and its crystalline phase matches well with PDF#16-0601. The electrolyte consisted of a mixed solution of 2 M ZnSO4 and 1 M Na2SO4. Bare Zn and MAZ@Zn were used as the anode electrodes, respectively. Preliminary CV tests were conducted at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s-1, with a working voltage window set at 0.3-1.4 V. The results of the second cycle test, as shown in Supplementary Figure 14, indicate that in the NVO full battery, whether MAZ@Zn or bare Zn is used as the anode, the CV curve exhibits two pairs of redox peaks. Specifically, the redox peaks for bare Zn are at 0.59/0.77 V and 0.83/1.0 V, while those for MAZ@Zn are at 0.58/0.78 V and 0.82/1.02 V, which are similar to those of bare Zn[72]. The similarity of the electrochemical reaction processes between MAZ@Zn and bare Zn anodes in NVO full batteries was further confirmed. The electrochemical performance of Zn//NVO and MAZ@Zn//NVO batteries at different current densities was further evaluated [Figure 5A]. At current densities of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 A g-1, the discharge specific capacities of the MAZ@Zn//NVO full battery are 332.8, 302.3, 262.8, 215.2, 183.6, and 166.3 mAh g-1, respectively, higher than those of the bare Zn//NVO battery, which are 322.9, 295.3, 243.4, 188.7, 160.7 and 144.7 mAh g-1 at corresponding current densities. When the battery returns to a current density of 0.5 A g-1 from 8 A g-1, the MAZ@Zn//NVO battery shows an excellent capacity retention rate. The results suggest that MAZ@Zn//NVO exhibits better rate performance in comparison to Zn//NVO, which is attributed to the enhanced charge transfer process, as indicated by the EIS results [Supplementary Figure 15]. Figure 5B and C shows the constant current charge and discharge curves of the two batteries from 0.5 A g-1 to 8 A g-1. The results are consistent with the CV curve, with two obvious voltage platforms and the average working voltage reaching 0.83 V (vs. Zn2+/Zn). In addition, MAZ@Zn//NVO shows a superior cycle performance compared with bare Zn//NVO at 1 A g-1 and 4 A g-1 [Figure 5D and E] For MAZ@Zn//NVO, the specific discharge capacity remains 130.6 mAh g-1 at 1 A g-1 over 1,000 cycles with a capacity retention of 45.7%. For bare Zn//NVO, it can only be cycled for 80 times. At 4 A g-1, the discharge capacity of MAZ@Zn//NVO is

Figure 5. Comparison of electrochemical performance between bare Zn//NVO and MAZ@Zn//NVO batteries. (A) Rate performance (charge-discharge curves at a current density from 0.5 A g-1 to 8 A g-1); GCD curves of (B) bare Zn//NVO; (C) MAZ@Zn//NVO; (D) cycling test at 1 A g-1; (E) cycling test at 4 A g-1.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, facile MAZ@Zn hybrid coating composed of Alg-Zn and MoS2 is effective in suppressing Zn dendrite formation and enhancing the cycle stability of Zn anodes for AZIBs. The Alg-Zn guides the Zn2+ ion diffusion in the coating; in addition, first-principles calculations reveal that the 2H-MoS2 (002) surface significantly reduces the migration energy barriers for Zn2+, functioning as an efficient ion sieve that promotes fast migration and uniform distribution of Zn2+ ions across the electrode surface. The hybrid coating effectively suppresses the formation of Zn dendrites and lowers the charge transfer energy of the Zn anode. The MAZ@Zn anode demonstrates remarkable electrochemical performance. In symmetric cells, the MAZ@Zn anode achieves a cycle life of 880 h at a current density of 1 mA cm-2 (1 mAh cm-2), significantly outperforming bare Zn electrodes. The high ionic conductivity and Zn2+ transference number of the Alg-Zn/MoS2 coating further confirm its capability to facilitate rapid and uniform Zn2+ transport at the electrode interface, which contributes to the improved cycling stability. Moreover, the MAZ coating effectively suppresses the HER by impeding H2O access to the Zn surface, further improving interfacial stability and prolonging the cycle life of Zn anodes. In full Zn//NVO batteries, the MAZ@Zn anode maintains a discharge capacity of 130.6 mAh g-1 after 1,000 cycles at 1 A g-1, and a capacity retention rate of 88.4% after 1,000 cycles at 4 A g-1. For the bare Zn anode, the full battery cycles only 80 times at 1 A g-1 and 420 times at 4 A g-1. The MAZ hybrid coating offers a practical and effective solution to improve the performance of Zn anodes for high-performance and long-life AZIBs.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Changzhou Jiulian Battery Materials Co., Ltd. for providing the fiberglass separators used in this study.

Authors’ contributions

Investigation, methodology, writing-original draft: He, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, K.

Data curation, formal analysis, visualization: Sun, Z.; Fan, W.; Yuan, W.

Conceptualization, supervision, project administration: Yuan, X.; Han, P.; Fu, L.; Wu, Y.

Funding acquisition, writing-review & editing: Yuan, X.; Han, P.; Fu, L.; Wu, Y.

Availability of data and materials

Supplementary Material is available from the authors.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52122209, 12174270, 52131306, 52073143 and 52403001).

Conflicts of interest

Prof. Wu, Y. is Editor-in-Chief of Energy Materials. He was not involved in any part of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Shang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J. Solvation structure regulation of zinc ions with nitrogen-heterocyclic additives for advanced batteries. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 2121-9.

2. Tang, L.; Peng, H.; Kang, J.; et al. Zn-based batteries for sustainable energy storage: strategies and mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 4877-925.

3. Du, M.; Miao, Z.; Li, H.; Sang, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Strategies of structural and defect engineering for high-performance rechargeable aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 19245-81.

4. Mao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Bai, J.; Wang, P.; Zhu, X.; Sun, Y. Recent progress in critical electrode and electrolyte materials for flexible zinc-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 5042-59.

5. Zhu, Y.; Liang, G.; Cui, X.; et al. Engineering hosts for Zn anodes in aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 369-85.

6. Lv, W.; Liu, J.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, C. In situ hybridization of biomass carbon with layered hydroxide for dendrite-free aqueous zinc batteries. eScience 2025, 19, 100410.

7. Li, Y.; Musgrave, C. B.; Yang, M. Y.; et al. The Zn deposition mechanism and pressure effects for aqueous Zn batteries: a combined theoretical and experimental study. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 14, 2303047.

8. Ding, T.; Yu, S.; Feng, Z.; Song, B.; Zhang, H.; Lu, K. Tunable Zn2+ de-solvation behavior in MnO2 cathodes via self-assembled phytic acid monolayers for stable aqueous Zn-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 21317-25.

9. Jin, Y.; Jin, K.; Ji, W.; et al. Fabrication of a robust zinc powder anode via facile integration of copper nanopowder as a functional conductive medium. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2418503.

10. Wu, L.; Zhu, X.; Peng, Z.; et al. Electrode process regulation for high-efficiency zinc metal anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 30169-89.

11. Li, L.; Jia, S.; Cao, M.; Ji, Y.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, D. Research progress on modified Zn substrates in stabilizing zinc anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023, 11, 14568-85.

12. Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, B. Recent progress of MXenes in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Acta. Phy. Chim. Sin. 2023, 39, 2210027.

13. Wu, B.; Guo, B.; Chen, Y.; et al. High zinc utilization aqueous zinc ion batteries enabled by 3D printed graphene arrays. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2023, 54, 75-84.

14. Yin, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Dendrite-free zinc deposition induced by tin-modified multifunctional 3D host for stable zinc-based flow battery. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906803.

15. Yang, J.; Weng, C.; Sun, P.; et al. Comprehensive regulation strategies for gel electrolytes in aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 530, 216475.

16. Ye, B.; Wu, F.; Zhao, R.; et al. Electrolyte regulation toward cathodes with enhanced-performance in aqueous zinc ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2501538.

17. Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, J.; et al. Anisotropic and anti-freezing cellulose hydrogel electrolyte with aligned channels stabilizing Zn metal anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159950.

18. Qi, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrolyte regulation strategies for improving the electrochemical performance of aqueous zinc-ion battery cathodes. Acta. Phy. Chim. Sin. 2022, 39, 2205045.

19. Zhang, R.; Liao, Z.; Fan, Y.; et al. Multifunctional hydroxyurea additive enhances high stability and reversibility of zinc anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2025, 13, 5987-99.

20. Kim, H. J.; Kim, S.; Yu, J. H.; Lim, J.; Yashiro, H.; Myung, S. Unlocking long-term stability: electrolyte additives for suppressing zinc dendrite growth in aqueous zinc metal batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160017.

21. Yang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhi, C. Insights into the role of electrolyte additives for stable Zn anodes. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500021.

22. Chen, X.; Li, W.; Hu, S.; et al. Polyvinyl alcohol coating induced preferred crystallographic orientation in aqueous zinc battery anodes. Nano. Energy. 2022, 98, 107269.

23. Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Xu, L.; et al. High‐yield carbon dots interlayer for ultra-stable zinc batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2200665.

24. Li, Y.; Yang, S.; Du, H.; et al. A stable fluoride-based interphase for a long cycle Zn metal anode in an aqueous zinc ion battery. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 14399-410.

25. Song, B.; Lu, Q.; Wang, X.; Xiong, P. Promoted de-solvation effect and dendrite-free Zn deposition enabled by in-situ formed interphase layer for high-performance zinc-ion batteries. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500031.

26. Han, D.; Wu, S.; Zhang, S.; et al. A corrosion-resistant and dendrite-free zinc metal anode in aqueous systems. Small 2020, 16, e2001736.

27. Lu, H.; Jin, Q.; Jiang, X.; Dang, Z. M.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y. Vertical crystal plane matching between AgZn3 (002) and Zn (002) achieving a dendrite-free zinc anode. Small 2022, 18, e2200131.

28. Zhou, X.; Cao, P.; Wei, A.; et al. Driving the interfacial ion-transfer kinetics by mesoporous TiO2 spheres for high-performance aqueous Zn-ion batteries. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 8181-90.

29. Kim, J. Y.; Liu, G.; Shim, G. Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. K. Functionalized Zn@ZnO hexagonal pyramid array for dendrite-free and ultrastable zinc metal anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2004210.

30. Wang, R.; Wu, Q.; Wu, M.; et al. Interface engineering of Zn meal anodes using electrochemically inert Al2O3 protective nanocoatings. Nano. Res. 2022, 15, 7227-33.

31. Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, A. Tailoring the crystal‐chemical states of water molecules in sepiolite for superior coating layers of Zn metal anodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211088.

32. Zeng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, R.; et al. Dendrite-free zinc deposition induced by multifunctional CNT frameworks for stable flexible Zn-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1903675.

33. Zhou, J.; Xie, M.; Wu, F.; et al. Ultrathin surface coating of nitrogen-doped graphene enables stable zinc anodes for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2101649.

34. Wang, G.; He, P.; Fan, L. Z. Asymmetric polymer electrolyte constructed by metal-organic framework for solid‐state, dendrite‐free lithium metal battery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2007198.

35. Yang, H.; Zhu, K.; Xie, W.; et al. MOF nanosheets as ion carriers for self-optimized zinc anodes. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4549-60.

36. Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. Long-life and deeply rechargeable aqueous Zn anodes enabled by a multifunctional brightener-inspired interphase. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 1938-49.

37. Cai, X.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Polymer coating with balanced coordination strength and ion conductivity for dendrite-free zinc anode. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2307727.

38. Xie, K.; Ren, K.; Wang, Q.; et al. In situ construction of zinc-rich polymeric solid-electrolyte interface for high-performance zinc anode. eScience 2023, 3, 100153.

39. Geng, Y.; Pan, L.; Peng, Z.; et al. Electrolyte additive engineering for aqueous Zn ion batteries. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2022, 51, 733-55.

40. Zong, Q.; Lv, B.; Liu, C.; et al. Dendrite-free and highly stable Zn metal anode with BaTiO3/P(VDF-TrFE) coating. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2023, 8, 2886-96.

41. Tang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, H.; et al. Ion-confinement effect enabled by gel electrolyte for highly reversible dendrite-free zinc metal anode. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2020, 27, 109-16.

42. Li, C.; Xie, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Integrated 'all-in-one' strategy to stabilize zinc anodes for high-performance zinc-ion batteries. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9, nwab177.

43. Fan, W.; Sun, Z.; Yuan, Y.; et al. High cycle stability of Zn anodes boosted by an artificial electronic-ionic mixed conductor coating layer. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2022, 10, 7645-52.

44. Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, J.; et al. MoS2 - mediated epitaxial plating of Zn metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2208171.

45. Bhoyate, S.; Mhin, S.; Jeon, J. E.; Park, K.; Kim, J.; Choi, W. Stable and high-energy-density Zn-ion rechargeable batteries based on a MoS2-coated Zn anode. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 27249-57.

46. Malagurski, I.; Levic, S.; Pantic, M.; et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of Zn-mineralized alginate nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 165, 313-21.

47. Zhu, Z.; Mosallanezhad, A.; Sun, D.; et al. Applications of MoS2 in Li-O2 batteries: development and challenges. Energy. Fuels. 2021, 35, 5613-26.

48. Orazem, M. E.; Tribollet, B. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons, 2017. Available from: https://books.google.com.tw/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=KnNdDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR23&ots=nh1yNMJdDT&sig=rJwmIeqf-6E4Q602jveii8ngUTc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false. [Last accessed on 15 Jan 2026].

49. Bruce, P. G.; Evans, J.; Vincent, C. A.; et al. onductivity and transference number measurements on polymer electrolytes. Solid. State. Ion. 1988, 28-30, 918-22.

50. Bard, A. J.; Tribollet, L. R. Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications; Wiley, 1980. Available from: https://books.google.com.tw/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=4ShuEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR21&dq=Bard,+A.+J.%3B+Faulkner,+L.+R.+Electrochemical+Methods:+Fundamentals+and+Applications%3B+Wiley,+1980.&ots=SJGxEUSvwF&sig=SAYgU_kDw47kJDVAoO-GZ31o4mE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Bard%2C%20A.%20J.%3B%20Faulkner%2C%20L.%20R.%20Electrochemical%20Methods%3A%20Fundamentals%20and%20Applications%3B%20Wiley%2C%201980.&f=false. [Last accessed on 15 Jan 2026].

51. Martin, R. M. Electronic structure: basic theory and practical methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. Available from: https://books.google.com.tw/books?id=wvXvDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=zh-CN#v=onepage&q&f=false. [Last accessed on 15 Jan 2026].

52. VandeVondele, J.; Hutter, J. Gaussian basis sets for accurate calculations on molecular systems in gas and condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 127, 114105.

53. Hartwigsen, C.; Goedecker, S.; Hutter, J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B. 1998, 58, 3641-62.

54. Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104.

55. Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Y. Phase‐regulated active hydrogen behavior on molybdenum disulfide for electrochemical nitrate‐to‐ammonia conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 136, e202315109.

56. He, P.; Huang, J. Detrimental effects of surface imperfections and unpolished edges on the cycling stability of a zinc foil anode. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 1990-5.

57. Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Zhou, K.; et al. Fully printed and sweat-activated micro-batteries with lattice-match Zn/MoS2 anode for long-duration wearables. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2412844.

58. Zeng, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, L.; et al. Correction: Long cyclic stability of acidic aqueous zinc-ion batteries achieved by atomic layer deposition: the effect of the induced orientation growth of the Zn anode. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 2435.

59. He, H.; Liu, J. Suppressing Zn dendrite growth by molecular layer deposition to enable long-life and deeply rechargeable aqueous Zn anodes. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 22100-10.

60. Xie, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, Z.; Zhu, M.; Guo, S.; Du, P. Regulating horizontal lamellar Zn to uniformly deposit under and on the hollow porous carbon nanosphere coating for dendrite-free metal Zn anode. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149601.

61. Ramos, M.; López-Galán, O. A.; Polanco, J.; José-Yacamán, M. On the electronic structure of 2H-MoS2: correlating DFT calculations and in-situ mechanical bending on TEM. Materials 2022, 15, 6732.

62. Lee, C. H.; Zhang, Y.; Johnson, J. M.; et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of GaN on 2H-MoS2. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 117, 123102.

63. Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Regulating Zn(002) deposition toward long cycle life for Zn metal batteries. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 8, 372-80.

64. Cao, C.; Lu, H.; Yang, Z.; et al. Feather-effect-inspired superhydrophobic and zincophilic strategy for ultrastable Zn metal anodes. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 14384-94.

65. Liu, D.; Meng, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Seed-promoted patch-like deposition for dynamic protection and ion transport synergy to achieve stable zinc-powder anodes. Small 2025, 21, e06972.

66. Zhao, X.; Gong, Z.; Wang, G.; et al. Preferential texture of surface coating on Zn anodes for advanced aqueous batteries: small change but big gain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202509952.

67. Lee, W. S. V.; Xiong, T.; Wang, X.; Xue, J. Unraveling MoS2 and transition metal dichalcogenides as functional zinc-ion battery cathode: a perspective. Small. Methods. 2021, 5, e2000815.

68. Liang, H.; Cao, Z.; Ming, F.; et al. Aqueous zinc-ion storage in MoS2 by tuning the intercalation energy. Nano. Lett. 2019, 19, 3199-206.

69. Xu, W.; Sun, C.; Zhao, K.; et al. Defect engineering activating (Boosting) zinc storage capacity of MoS2. Energy. Stor. Mater. 2019, 16, 527-34.

70. Jia, D.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, W.; et al. Vertically stacked heterostructure in MoS2/rGO to accelerate ion diffusion kinetics for aqueous zinc ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156945.

71. Xin, C.; Yang, D.; Setyawan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, T. Engineering defects in MoS2 cathodes for high-performance aqueous zinc-ion batteries. J. Energy. Stor. 2025, 134, 118115.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].