Post-hybridization of MIL-101(Cr) with graphene oxide enhances its hydrogen storage and release capacities

Abstract

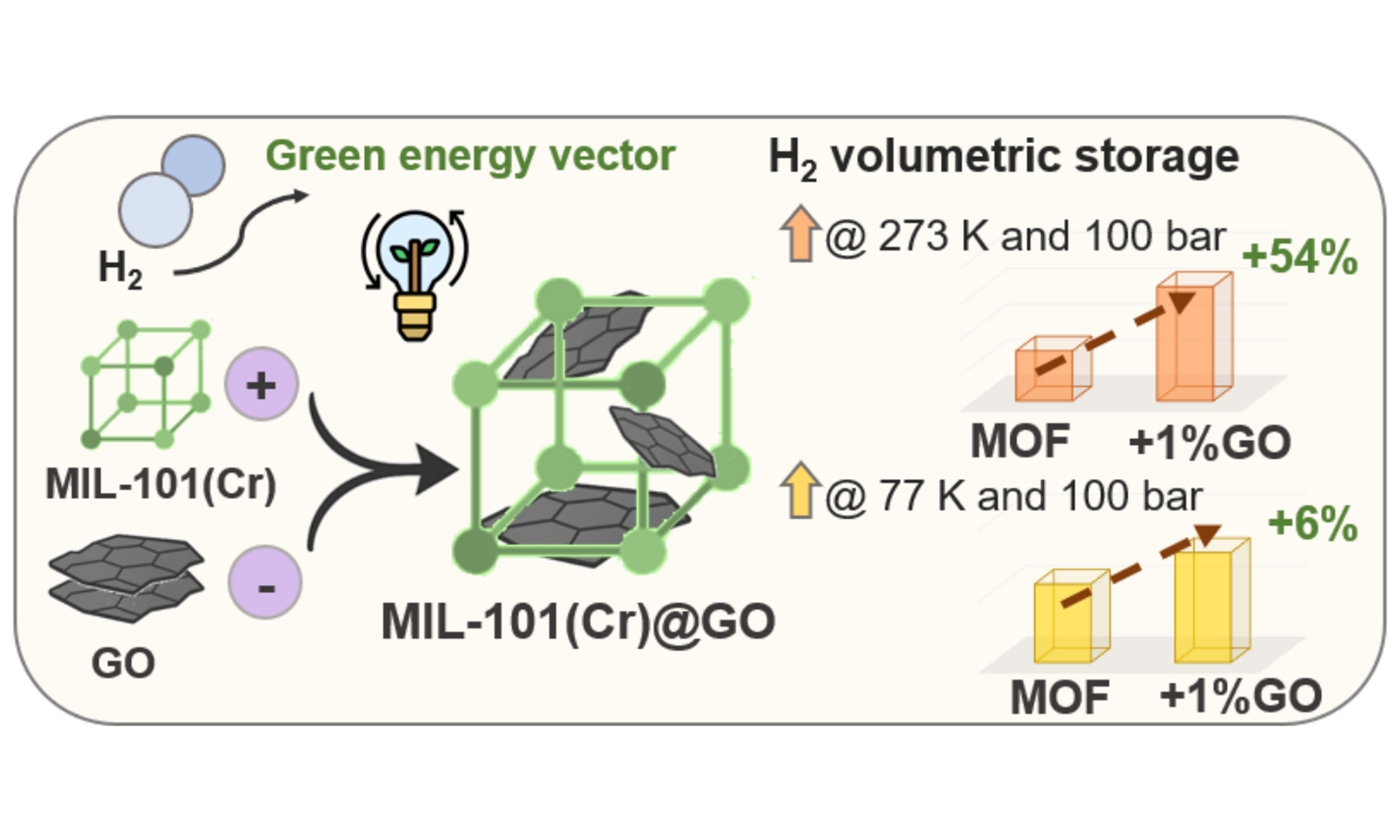

Hydrogen (H2) is a clean and high-energy carrier; however, its low volumetric energy density remains a major barrier to practical storage and transport. This study demonstrates that the hybridization of MIL-101(Cr) with graphene oxide (GO) effectively enhances H2 storage and release capacities. The integration of GO, with a density of 450 kg m-3, into MIL-101(Cr), a highly porous metal-organic framework (ABET ≥ 3,500 m2 g-1, Vpore ≥ 2.0 cm3 g-1 and 259 kg m-3 of density) was investigated through a post-synthetic hybridization strategy, leading to increased ultra-microporosity and enhanced density of the resulting hybrids. Although GO incorporation led to a reduction in gravimetric (wt.%) H2 storage at 77 K and 100 bar, ranging from 3% to 36% as GO content increased, it significantly improved H2 uptake at 273 K and 100 bar. The hybrid with 1 wt.% GO exhibited the most notable enhancement, achieving a 40% increase in gravimetric storage capacity (273 K, 100 bar) compared to pure MIL-101(Cr). This hybrid also demonstrated superior volumetric performance, reaching a 6% increase both in total H2 storage, 35.8 kg m-3 (77 K, 100 bar), and deliverable capacity, 34.2 kg m-3, under practical operating conditions (i.e., charging: 77 K and 100 bar; discharging: 160 K and 5 bar). These findings highlight the dual role of GO: densifying the composite while potentially introducing ultramicroporosity, particularly effective at elevated temperatures, offering a promising pathway toward practical, scalable, and efficient hydrogen storage systems.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Hydrogen (H2) is a key energy carrier in the transition toward sustainable energy systems[1] due to its clean combustion, which produces only water as a byproduct, making it a viable alternative to fossil fuels[2]. Despite its high energy density of 131.76 MJ kg-1, a major challenge lies in its low volumetric density[3], which is just 0.0108 MJ L-1 at 1 bar and 298 K[4]. One approach to increase H2 volumetric density is physisorption on porous materials. In this process, van der Waals interactions between H2 molecules and the material lead to reversible adsorption without altering the material’s structure or forming chemical bonds[5]. Efficient H2 storage through physisorption requires both high microporosity and large surface area, as well as adequate pore size distribution (PSD)[6-9].

Materials such as zeolites[10,11], carbon-based materials[12,13] and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are being extensively studied for this purpose, as their porous nature allows for H2 storage through physisorption. MOFs are crystalline materials composed of metal ions coordinated to organic linkers, forming an extended porous network[14,15] that offers exceptional structural versality and diverse topology through the judicious selection of their metal nodes and organic linkers[16]. This class of porous materials has shown promise in a wide range of applications[17] up to the industrial scales in some cases[18]. More particularly, they are promising for H2 storage due to their high surface area, tunable porosity, and abundant sites for reversible H2 adsorption[19,20]. Among them, MIL-101(Cr) is notable for its exceptional chemical and thermal stability, withstanding exposure to air, water, and acids. It also features high surface area (ABET ≥ 3,500 m2 g-1) and large pore volume (Vtot ≥ 2.0 cm3 g-1)[21]. This MOF consists of trimeric Cr3+ oxoclusters coordinated with six terephthalic acid ligands (1,4-benzenedicarboxylate, H2BDC), forming supertetrahedral secondary building units that assemble into a porous framework featuring pentagonal (1.2 nm) and hexagonal (1.4 nm) windows, which lead to mesoporous cavities measuring 2.9 and 3.4 nm in diameter[22,23]. Fluoride (F-) or hydroxide (OH-) ions and water molecules (if not activated) complete the coordination sphere[24,25]. Additionally, MIL-101(Cr) contains chromium sites with open coordination positions, generated by the removal of solvent or water, molecules by heating or vacuum drying. These open metal sites enhance H2 adsorption by increasing interaction strength[26-28].

Although MIL-101(Cr) shows significant potential for H2 storage[29], its conventional synthesis involves hazardous chemicals such as N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and hydrofluoric acid (HF), which raise environmental and safety concerns and hinder scalability for large-scale production[23,30]. Additionally, common challenges associated with MOFs (particularly when highly porous structures are required), including low density, poor thermal conductivity and limited structural stability, further restrict their practical applications. Hybrid MOFs thus offer a promising solution to overcome these limitations. Graphene oxide (GO) stands out among carbon materials for its ability to enhance MOF performance by increasing surface area[31-33], thermal conductivity[34] and ultramicroporosity development[34,35], all key to improving H2 storage performance.

MOF@GO hybrids can be synthesized through various approaches, including in-situ growth or ex-situ methods such as post-synthetic hybridization and physical mixing[36-38]. In the in-situ growth method, oxygen functional groups on GO act as nucleation sites for the metal clusters of the MOF[38-40]. Conversely, ex-situ approaches involve the pre-synthesis of MOFs, which are subsequently combined with GO, either via electrostatic assembly, taking advantage of oppositely charged surfaces at optimized pH[38], or through simple physical mixing. Ex-situ approaches offer better control over MOF properties, along with shorter synthesis times and milder conditions. MIL-101(Cr)@GO hybrids have been explored for a range of applications, including volatile organic compound (VOC) adsorption[41-43], gas separation[30] and water vapor adsorption[35]. However, to the best of our knowledge, only a few studies have investigated their performance for H2 storage. In that study, Zhang et al. developed MIL-101@Pt-doped GO nanocomposites using an in-situ self-assembly method[44]. They reported a significant enhancement in H2 storage capacities under moderate storage conditions (298 K, 10 bar), which they attributed to H2 spillover effects facilitated by the Pt/GO components within the hybrid structure. Following this approach, Lee et al. prepared Ni-doped GO/MIL-101 (Ni-GO/MIL) hybrid composites via an in-situ hydrothermal method to investigate their H2 storage performance at 77 K and 1 bar, demonstrating the potential of metal-doped GO to enhance the adsorption capacity of MIL-101[45]. It is worth noting that both studies were conducted at relatively low pressures, up to 10 bar for Zhang et al.[44] and 1 bar for Lee et al.[45], whereas our work focuses on high-pressure H2 adsorption (up to 140 bar), making direct comparisons between results difficult.

The present study evaluates the H2 storage performance of a green-synthesized MIL-101(Cr) - produced without toxic solvents such as DMF or HF- and its GO hybrids (MIL-101(Cr)@GO), produced by post-synthetic hybridization. The incorporation of GO aims to densify the material and enhance its volumetric storage capacity, addressing a key challenge in practical H2 storage. Comprehensive characterization was conducted using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), textural analysis by gas adsorption, and water affinity measurements. H2 storage and release capacities were assessed under high-pressure conditions (up to 140 bar) at three temperatures (77, 160 and 273 K), considering gravimetric, volumetric and usable storage metrics. These results offer valuable insights into scalable, environmentally friendly MOF-based systems for efficient hydrogen storage.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification: Cr(NO3)3·9H2O (Fluka (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 97%); 1,4 benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2BDC, Sigma-Aldrich (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), > 98%); absolute ethanol (VWR Chemicals®, Radnor, Pennsylvania, USA, ≥ 96%); and a 2 wt.% GO water dispersion (Graphenea SA, San Sebastián, Spain).

Synthesis

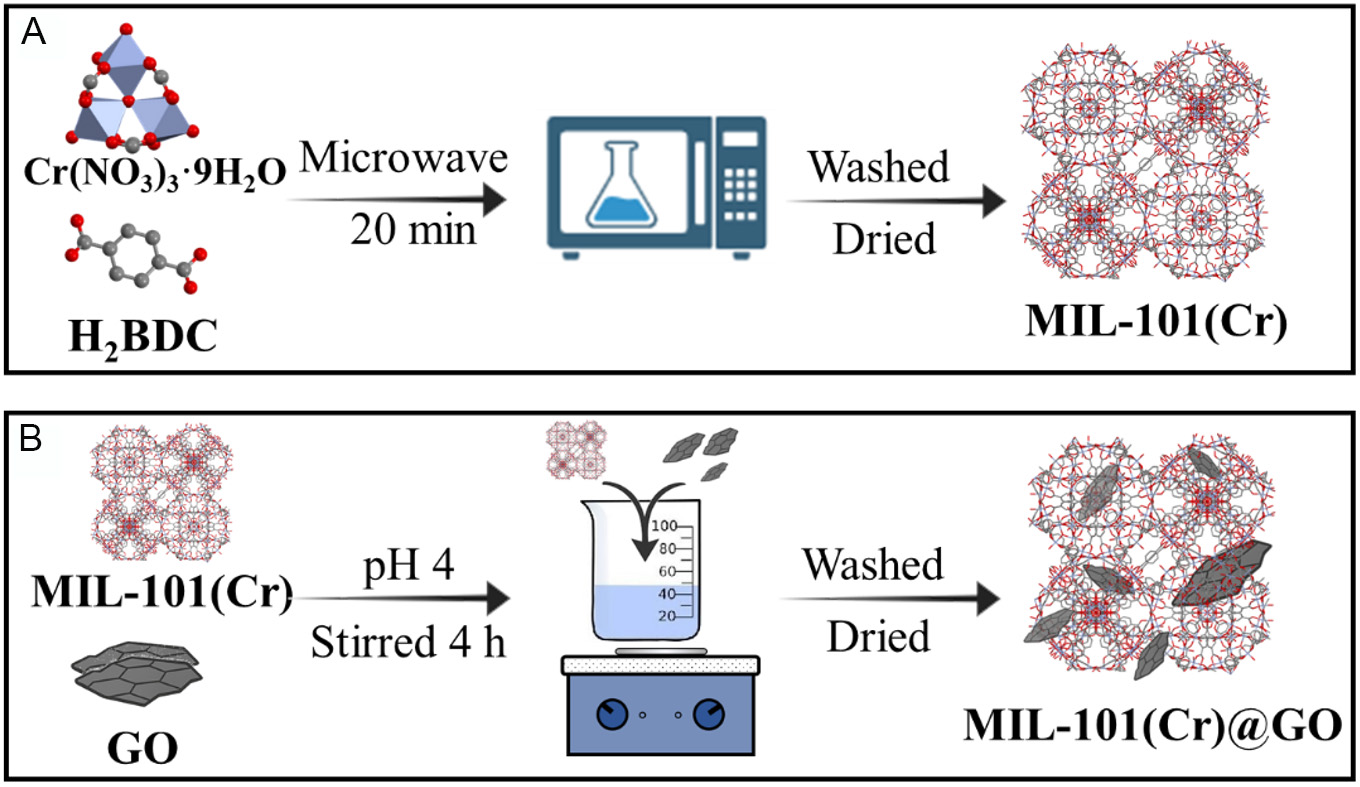

Synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) via microwave-assisted method [Figure 1A]. The synthesis was slightly adapted from a previously reported procedure[46]. A mixture of 2 g Cr(NO3)3·9H2O and 0.825 g H2BDC was dissolved in 25 mL water inside a 100 mL Teflon-lined reactor. The reaction mixture was heated up to 473 K and maintained for 30 min. After cooling, the resulting nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation. The solid was then re-dispersed in 50 mL water and refluxed for 20 min. Once cooled to room temperature, the material was separated by centrifugation at 19,000 rpm for 20 min at 298 K. The recovered solid was subsequently suspended in 50 mL ethanol and refluxed for 20 min, followed by recovery via centrifugation under the same conditions; this step was repeated three times. Finally, the clean product was dried in an oven at 363 K overnight.

Figure 1. (A) Microwave synthesis of ML-101(Cr). Left Cr-oxocluster of MIL-101(Cr) consisting of three Cr3+ ions arranged in a trimer with a central µ3-oxo, and linker BDC2- = 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate or terephthalate), right: crystal structure of the unit cell of MIL-101(Cr). Color code: Purple Cr, Red O, Dark grey H; (B) MIL-101(Cr)@GO hybrids synthetized via post-hybridization.

Synthesis of MIL-101(Cr)@GO hybrids via post-synthetic hybridization (Figure 1B, M101-GO 1; M101-GO 5 and M101-GO 10). To facilitate the post-synthetic hybridization of MIL-101(Cr) and GO, the zeta potential of each component was measured as a function of pH to determine its surface charge at different pH values [Supplementary Figure 1]. This analysis allowed the identification of the pH range in which MIL-101(Cr) and GO exhibit the greatest difference, an essential condition to promote electrostatic interaction. Next, 1 g MIL-101(Cr) was dispersed in 80 mL water. A predetermined amount of GO was then added to achieve the desired hybrid composition: 0.6 g for the 1 wt.% hybrid (M101-GO 1), 2.75 g for the 5 wt.% hybrid (M101-GO 5), and 6.75 g for the 10 wt.% hybrid (M101-GO 10). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for four hours, with the pH carefully adjusted to 4, and the resulting solid was recovered by centrifugation and dried at 363 K.

Physicochemical characterization

• XRD: The crystalline structure of the adsorbents was examined by XRD using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with a Cu Kα radiation source (40 kV, 40 mA). The diffraction patterns were collected over a 2θ range of 5°-30°. Bruker's DIFFRAC.EVA software was used for data analysis and phase identification. The simulated XRD pattern of the pure MOF was calculated using Mercury 3.0 software (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, CCDC) with the corresponding CIF file of MIL-101(Cr) (deposition number 605510)[47].

• FTIR: FTIR spectra were collected in transmission mode using a PerkinElmer Frontier 400 spectrometer over a wavenumber range of 650-4,000 cm-1. Prior to analysis, the powdered samples were degassed at 398 K for 12 h to eliminate water interference. The technique was used to identify the characteristic functional groups of the MOF and confirm the presence of key bonding interactions.

• Thermogravimetric analysis: TGA measurements were performed using a STA 449F3 Jupiter microbalance (Netzsch). Prior to analysis, samples were dried at 398 K for 12 h. A sample of mass 15-20 mg was heated at 10 K min-1 from room temperature to 1,173 K under an argon atmosphere. Data processing and derivative curve analysis were performed using the Proteus® software (Netzsch).

• Optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM): A NIKON LV100ND ECLIPSE polarized-light optical microscope, operating in either transmitted or reflected light and equipped with a 5 MPix CCD camera, was employed to obtain high-resolution images for accurate sample documentation and analysis.

Morphological and compositional analysis was carried out through SEM imaging, using a GeminiSEM 360 microscope. The primary objective was to assess the distribution of MOF and GO phases by employing elemental mapping. Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) was used to identify the elements present on the sample surface.

• Textural properties: Gas adsorption measurements using N2 (77 K), Ar (87 K) and H2 (77 K) as probe molecules were conducted using a 3Flex volumetric adsorption system (Micromeritics-Particulate Systems®, USA). Before analysis, MOF and hybrid samples (100 mg) underwent degassing under secondary vacuum for 12 h at 398 K using a SmartVacPrep unit (Micromeritics-Particulate Systems®, USA). In the case of pure GO, the water dispersion was dried using the same procedure as in the hybrid synthesis, degassed at 398 K, and subsequently subjected to N2 adsorption measurements at 77 K. This analysis aimed to reproduce exactly the same conditions as those experienced by the GO incorporated into the hybrid materials.

The textural properties of the samples were assessed by determining the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) area (ABET, m2 g-1), calculated with Microactive® software (Micromeritics) from N2 and Ar adsorption isotherms following Rouquerol’s criteria to ensure data reliability and comparability[48]. N2 and H2 adsorption isotherms were processed using SAIEUS® software (Micromeritics) with the two-dimensional non-local density functional theory for heterogeneous surfaces in carbon materials (2D-NLDFT HS). Due to the lack of specific kernels for MOF@GO hybrids and the limited number of available kernels for MOFs, the carbon-based 2D-NLDFT model was chosen to characterize the samples as it provided a better fit for both N2 and H2 adsorption isotherms. From these analyses, key textural parameters were obtained: PSD, 2D-NLDFT surface area (S2D-NLDFT, m2 g-1), total pore volume (Vtot, cm3 g-1), micropore volume (Vµ, cm3 g-1: pore width w < 2 nm), ultramicropore volume (Vuμ, cm3 g-1: w < 0.7 nm), supermicropore volume (Vsμ, cm3 g-1:

• Water affinity: Water adsorption experiments at 293 K were conducted using a BELL-SORP automatic adsorption analyzer from Microtrac (USA). Prior to measurements, samples (approximately 100 mg) were degassed under secondary vacuum at 398 K for 12 h with a SmartVacPrep system (Micromeritics-Particulate Systems®, USA) to remove any residual moisture or other adsorbed species. Water vapor isotherms were performed up to a relative pressure (p/po) of 0.4. The apparent water affinity constant was evaluated from the slope of the isotherms in the low relative pressure region (p/p° < 0.02).

• Thermal conductivity: The thermal conductivity of the powders was measured using a Transient Plane Source (TPS 2500) instrument (Hot Disk, Sweden), employing a special setup where the sensor is positioned between two layers of powder. This configuration allows for precise thermal measurements while preserving the powder form without the need for pelletization. Prior to the measurements, the samples were dried under secondary vacuum at 398 K for 12 h to ensure the removal of adsorbed moisture. The sensor was heated at a power of 50 mW for four seconds during each measurement.

Hydrogen storage performance

To evaluate the H2 storage performance, adsorption isotherms were measured at 77, 160 and 273 K, in a range of pressures up to 140 bars. These measurements were conducted using a high-pressure manometric adsorption system HPVA II (Micromeritics, USA), equipped with precise temperature control via a single-stage closed-cycle cryogenic refrigerator based on He compression (Micromeritics, USA). Prior to measurement, approximately 1 g of sample was thoroughly degassed overnight at 398 K in a vacuum oven to remove any residual adsorbates and ensure accurate adsorption data.

The excess H2 uptake (nexc) was automatically determined by the instrument using the Leachman equation of state, as recommended by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)[49]. Dead volume correction was performed using the skeletal density (ρskel) of the samples, which was determined by helium pycnometry (AccuPyc II 1340, Micromeritics) at room temperature. To ensure reproducibility, samples were degassed under vacuum at 398 K for 12 h prior to measurement. It is useful to recall here that H2 can be stored in two forms when using a specific adsorbent in a pressurized tank: (1) as an adsorbed phase on the surface of the material; and (2) as a free gaseous phase occupying the remaining voids, including inter- and intra-particle spaces. The total H2 uptake (ntot) must therefore consider nexc and the H2 compressed, which refers to the gas stored in the void space by compression, as given in[50]:

where ρtap is the tapped density of the adsorbent, and

Another key parameter to evaluate the performance of a porous material for H2 storage is the release capacity, which quantifies the amount of H2 effectively retrievable under operational conditions[51-53]. The release capacity was determined using

where (ntotal)storage represents the total H2 uptake under charging conditions, and (ntotal)release refers to the total H2 uptake under discharging conditions. Charging conditions were set at 77 K and 100 bar, consistent with the maximum refueling pressure for Type I metal tanks[51]. According to the Hydrogen Storage Engineering Center of Excellence[54], a minimum release pressure of 5 bar is required to ensure an effective H2 flow to an engine or fuel cell[55]. Consequently, 5 bar was selected as the discharge pressure in this study.

RESULTS

Physicochemical characterization

The zeta potential of each component was measured separately at different pH values

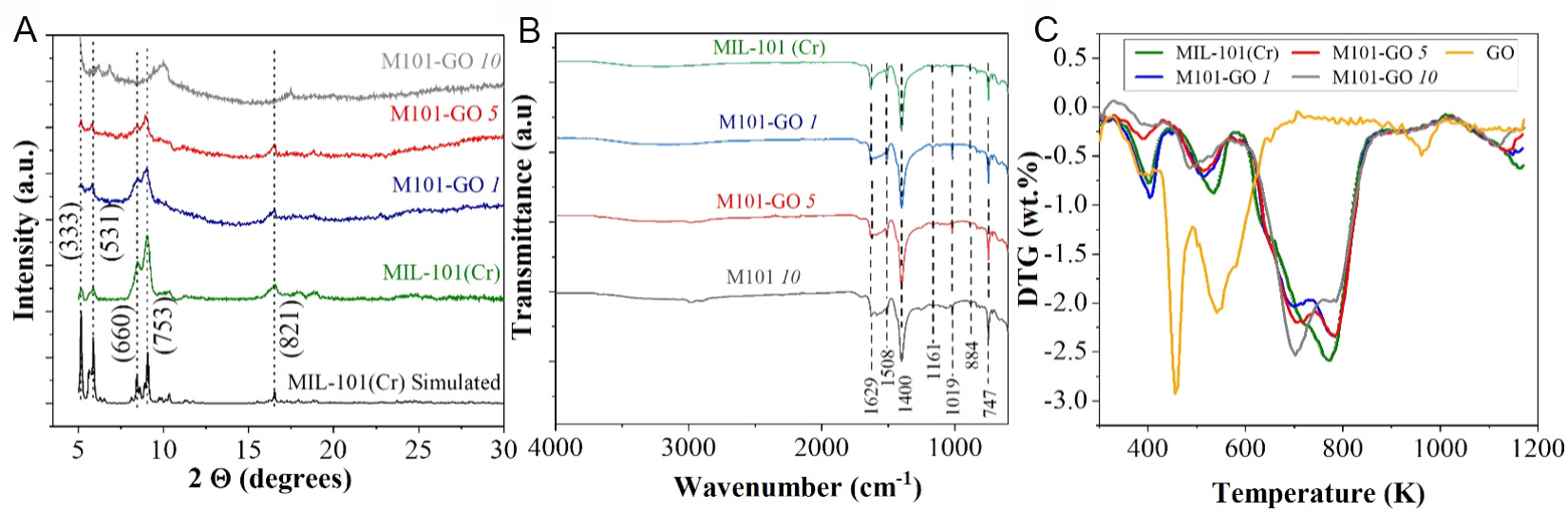

XRD patterns of the synthesized MIL-101(Cr) and its hybrids, containing varying weight fractions of GO and prepared via post-synthetic hybridization, are presented in Figure 2A. The diffraction pattern of MIL-101(Cr) matches the simulated XRD pattern, displaying characteristic peaks at 2θ = 5.16°, 5.88°, 9.06° and 16.54°[56]. The broader XRD peaks observed in MIL-101(Cr) samples can be attributed to the smaller particle size typically obtained via microwave synthesis, resulting from rapid nucleation and short reaction times. This agreement confirms the successful formation of the MIL-101(Cr) framework and indicates its structural integrity, thus providing a stable framework for GO incorporation.

Figure 2. (A) Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) experimental patterns of MIL-101(Cr) and its hybrids containing different wt.% of GO, compared with the MIL-101(Cr) simulated pattern; (B) FTIR spectra of MIL-101(Cr) and its GO-based hybrids; (C) Derivatives of the thermogravimetry (DTG) curves for pure MIL-101(Cr) and its hybrids with varying GO contents, measured under an argon atmosphere.

The incorporation of GO to MIL-101(Cr) results in peak broadening in the XRD patterns, which may indicate reduced crystallinity[57]. This effect becomes more pronounced with increasing GO content. Despite these changes, the diffraction peaks of the hybrids remain aligned with the simulated pattern of MIL-101(Cr), confirming that the overall framework structure is preserved following GO incorporation.

FTIR spectra were used to assess the impact of the hybridization process on the characteristic vibrational modes of MIL-101(Cr). Figure 2B shows that the band at 1,629 cm-1 in the spectrum of pure MIL-101(Cr) corresponds to adsorbed water[58]. The intense band at 1,400 cm-1 is attributed to the symmetric (O-C-O) stretching vibrations of the dicarboxylate groups within the MIL-101 framework[59]. Additional bands between 600 and 1,600 cm-1 are associated with benzene ring vibrations. Specifically, the band at 1,508 cm-1 corresponds to the (C=C) stretching vibrations, while those at 1,165, 1,019, 884 and 747 cm-1 are ascribed to C-H deformation[60]. The FTIR spectra of the GO-containing hybrids retain the same characteristic pattern as pure MIL-101(Cr), although with reduced band intensities. This decrease suggests a degree of interaction between GO and the MOF, yet the retention of key vibrational features confirms that the MIL-101(Cr) structure remains intact after the post-hybridization process. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies[30,44].

TGA profiles [Supplementary Figure 2] reveal the main three characteristic weight loss stages for MIL-101(Cr), in agreement with previous reports[31]. The first two mass losses are associated with the release of water molecules confined within the characteristic cages of MIL-101(Cr). The initial weight loss, occurring between 303 and 473 K, corresponds to the desorption of guest water molecules from the larger cages (diameter ≈ 3.4 nm), while the second stage, from 473 to 623 K, is attributed to the removal of water molecules located in the medium-sized cages (diameter ≈ 2.9 nm). Beyond 623 K, the final weight loss is attributed to the removal of linker degradation, ultimately resulting in the structural decomposition of the MIL-101(Cr) framework. These findings confirm the high degradation point of the linker in all samples, with decomposition temperatures exceeding 698 K under an argon atmosphere. The derivatives of the thermogravimetric curves (DTG) [Figure 2C] of MIL-101(Cr) and their GO-based hybrids show the two characteristic peaks of this MOF (660-725 and 770-786 K), associated with the release of structural water and the decomposition of organic moieties within the framework, respectively[61].

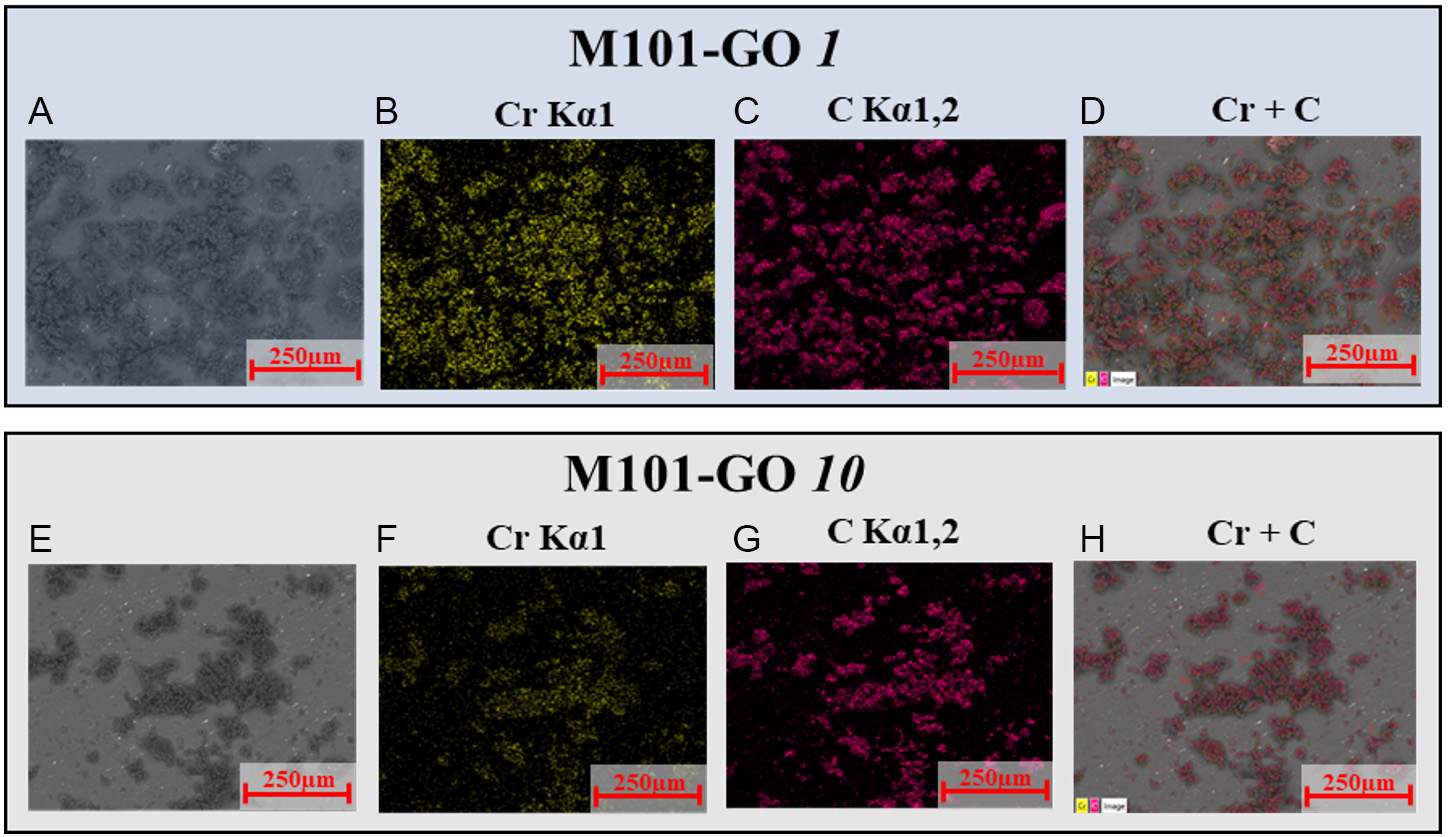

Optical microscopy images are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Supplementary Figure 3A displays the crystals of pure MIL-101(Cr), which exhibit a pale light blue color. Upon incorporation of GO

Figure 3. (A) SEM image of M101-GO 1, alongside its (B) chromium; (C) carbon mapping images; and (D) overlap between Cr and C mappings. (E-H) Same as (A-D), but for M101-GO 10.

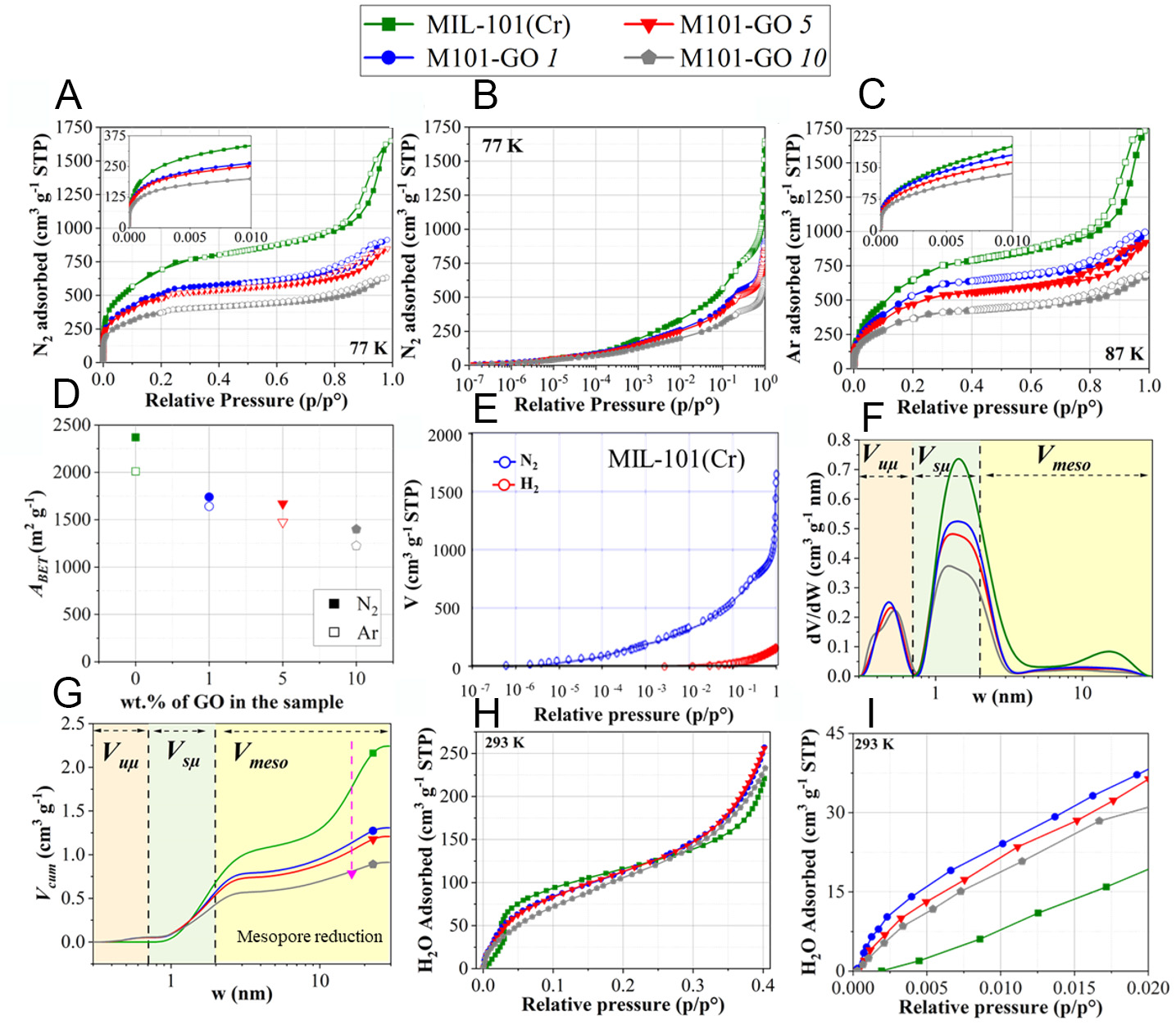

Figure 4A shows the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms for all samples. The isotherm of pure MIL-101(Cr) follows a Type I+ IV(a) pattern, according to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification[62], characteristic of micro-mesoporous materials. The presence of an H2(b) hysteresis loop in the isotherms suggests capillary condensation occurring within a non-rigid, complex pore structure. Upon incorporation of GO, both microporosity and mesoporosity are reduced, likely due to partial pore blockage or structural changes induced by GO sheets, an effect that becomes more pronounced with increasing GO content. These changes are more clearly observed in the semi-logarithmic representation of the N2 isotherms [Figure 4B].

Figure 4. Textural characteristics of pure MIL-101(Cr) and its GO-based hybrids: (A) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K (the inset shows a zoom at p/p < 0.01); (B) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K in semi-logarithmic scale; (C) Ar adsorption-desorption isotherms at 87 K (the inset shows a zoom tat p/p < 0.01); (D) ABET obtained from N2 and Ar isotherms; (E) 2D-NLDFT fitting for heterogeneous surfaces using N2 and H2 isotherms for bare MIL-101(Cr); (F) Pore size distribution and (G) cumulative pore volume as a function of pore width; (H) Water adsorption isotherms at 293 K for pure MIL-101(Cr) and its hybrids with various GO contents; (I) Zoomed-in view of (H) highlighting the water affinity region.

Argon adsorption-desorption isotherms at 87 K were performed to obtain a more accurate assessment of micropore characteristics, as argon’s inert nature and lack of quadrupole moment reduce specific interactions with surface functional groups, thereby offering more reliable data compared to N2[63]. Figure 4C illustrates that pure MIL-101(Cr) and MIL-101(Cr)@GO hybrids exhibit Ar isotherms of the same type observed in the N2 measurements, confirming consistent porosity features across gases. Figure 4D compares the ABET from Ar and N2 isotherms. A systematic reduction in ABET is observed when using Ar as the adsorbate. This reduction is the most significant for pristine MIL-101(Cr) (- 15%), followed by M101-GO 10 (-12%), M101-GO 5 (-11%) and M101-GO 1 (-6%). These differences can be attributed to the distinct gas-surface interactions: N2, possessing a quadrupole moment, may interact specifically with open metal sites (e.g., Cr) or polar functional groups, leading to a potential overestimation of specific surface area. In contrast, Ar, being nonpolar, provides a more neutral and physically accurate probe of the accessible surface. The more pronounced ABET reduction in pristine MIL-101(Cr) suggests that specific N2 interactions with the framework, possibly at Cr centers or linker sites, artificially enhance the measured specific surface area. In the GO-containing hybrids, the presence of GO functional groups may diminish these effects, moderating overestimation. Nevertheless, both Ar- and N2-derived ABET values consistently reflect the expected trend: a gradual decrease in specific surface area with increasing GO content, consistent with the negligible specific surface area measured for pure GO when dried from the water suspension.

Due to the structural diversity of MOFs, the availability of dedicated 2D-NLDFT models remains limited, and this challenge is further amplified in the case of hybrid materials. For the textural analysis of our samples, the 2D-NLDFT model for heterogeneous carbon surfaces was employed using both N2 [Figure 4A] and H2 [Supplementary Figure 5] isotherms. This model provided an adequate fit to the experimental data, as demonstrated in Figure 4E. The PSDs shown in Figure 4F reveal that the incorporation of GO into the MIL-101(Cr) framework induces the formation of ultramicropores (< 0.7 nm), which are not present in the pristine MOF. Additionally, the mesopore peak centered around 15 nm, prominent in pure MIL-101(Cr), is markedly diminished across all GO-containing hybrids. This trend is further corroborated by the cumulative pore volume (Vcum) [Figure 4G], where a progressive reduction in mesopore volume is observed with increasing GO content. While the parent MIL-101(Cr) exhibits substantial contributions from both supermicropores (0.7-2 nm) and mesopores, the hybrid materials show enhanced ultramicroporosity alongside a notable decrease in mesopore volume. These modifications in pore texture reflect the dual impact of GO incorporation: partial pore blockage and restructuring of the original MOF porosity. This structural alteration plays a significant role in increasing ρtap, as discussed in Section "Hydrogen storage and release capacities". A full summary of the textural parameters for all samples is provided in

Water affinity is a critical parameter in evaluating MOF performance, as it significantly influences the efficiency and capacity of gas adsorption processes under humid conditions[64-66]. Moreover, potential structural degradation in the presence of moisture emerges as a major limitation for the use of MOFs in H2 storage applications[67,68]. Therefore, understanding the interactions between water molecules and the MOF framework is essential for optimizing their functionality in real-world environments. Certain MOFs exhibit a characteristic steep increase in water uptake at specific relative pressures p/p° < 0.4, often manifesting as a sharp, step-like adsorption transition[69]. This behavior contrasts with the water adsorption mechanism observed in carbon-based materials, as described by the Dubinin-Serpinski model, where water adsorption initiates at high-energy primary sites, and progresses through the formation of molecular clusters acting as nucleation centers. In MOFs, water adsorption pathways are influenced by a broader range of factors, including the nature of the inorganic metal clusters, surface functional groups, and the geometry and dimensionality of the pore structure[70]. As relative humidity increases, water molecules continue to interact with the internal surface of the framework, progressively leading to pore filling and saturation of the porous structure[71,72].

Water adsorption isotherms at room temperature demonstrate that all hybrids have a strong water affinity, evidenced by the steep uptake at low relative pressures (p/p° < 0.1), as shown in Figure 4H. Additionally, the microporous structure of the samples further contributes to this high water uptake capacity[73]. However, this increase is more pronounced in the GO-containing hybrids. This enhancement may be attributed to the intrinsic hydrophilicity of GO, which arises from its sheet-like structure and the abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups that facilitate strong interactions with water molecules[74,75]. However, GO-containing hybrids underwent degassing under secondary vacuum at 398 K that should have considerably reduced their O content. To quantitatively assess the water affinity of the materials, the initial slopes of the isotherms up to p/p° = 0.02 [Figure 4I] were calculated under the assumption of linearity in this low-pressure range (Henry's regime)[76,77]. A steeper slope indicates a greater affinity for water. The results reveal a marked increase in water affinity upon GO incorporation. The slope for pristine MIL-101(Cr) was

Thermal conductivity is a critical factor in MOF-based gas storage, as the exothermic nature of gas uptake can lead to local temperature rises, "hot spots", potentially reducing the storage capacity if heat is not effectively dissipated[78]. One of the significant limitations of MOFs, including MIL-101(Cr), is their inherently low thermal conductivity. This drawback stems from their large pore size and high internal free space, which hinder efficient phonon transport[34]. The thermal conductivity of MOFs can vary significantly depending on measurement conditions. Typically, thermal conductivity assessments are performed on pelletized samples subjected to compaction pressures ranging from 60 to 200 bars for 20 s[34,79]. Reported values for MIL-101(Cr) in pelletized form range from 0.05 to 0.21 W·m-1·K-1[34,79-81]. Supplementary Figure 6 shows the thermal conductivity values obtained in this study. For pure MIL-101(Cr) in powder form, a thermal conductivity of 0.132 W·m-1·K-1 was measured, which is consistent with literature reports. The incorporation of GO at varying weight fractions via post-synthetic hybridization did not significantly alter the thermal conductivity of the resulting hybrid materials. The measured values were 0.124 W·m-1·K-1 for M101-GO 1, 0.126 W·m-1·K-1 for M101-GO 5, and 0.143 W·m-1·K-1 for M101-GO 10. These findings suggest that, despite the rather good thermal conductivity of GO, its relatively low content and potential localization within the hybrid matrix were insufficient to markedly improve heat transport within the MIL-101(Cr) framework.

The synthesis method employed for MOF-based hybrids, as well as the amount of GO, plays a crucial role in determining their thermal conductivity. Elsayed et al.[34] investigated the influence of the synthesis approach and the weight percentage of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) incorporated into the MIL-101(Cr) matrix. In the case of the ex-situ method (physical mixing), the addition of small amounts of rGO (< 2 wt.%) resulted in a decrease in thermal conductivity by approximately 10%. This reduction was attributed to the weak interfacial interaction between rGO and the MOF, which hinders efficient heat transfer across the composite. Conversely, a higher rGO content (5 wt.%) led to a significant increase in thermal conductivity of approximately 150%, suggesting enhanced transport due to improved interfacial contact and the formation of conductive pathways.

Hydrogen storage and release capacities

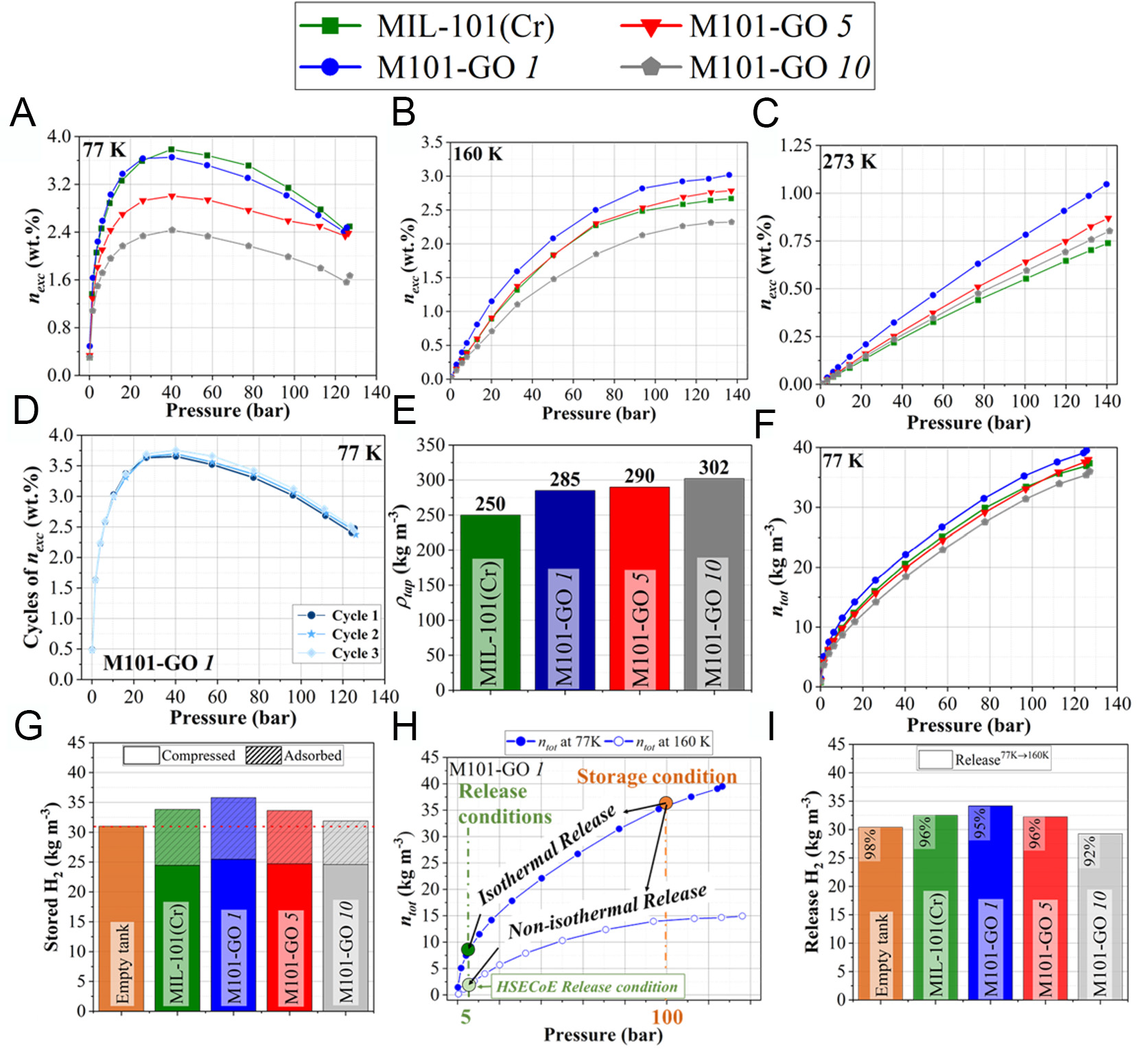

Figure 5A presents the excess H2 uptake (nexc, wt.%) for all synthesized samples. Pure MIL-101(Cr) shows the highest nexc (77 K and 40 bar), reaching 3.78 wt.%, which falls within the range of those previously reported in the literature (2.90-6.40 wt.%)[82-84]. Among the hybrids, M101-GO 1 shows a slightly lower value of 3.65 wt.%, representing only a 3.4% decrease relative to the pristine MOF. However, as the GO content increases, a marked decline in nexc is observed. M101-GO 5 and M101-GO 10 show nexc values of 3.0 wt.% and 2.43 wt.%, corresponding to reductions of 20.6% and 35.7%, respectively. Notably, the extent of nexc reduction exceeds theoretical expectation based on the percentage of GO introduced into the hybrids. This disproportionate decline can be attributed to the dual impact of reduced specific surface area and partial pore blockage, which may limit the internal diffusion and adsorption capacity of the MOF framework. Additionally, this may be attributed to the increased likelihood of aggregation as the amount of GO increases, resulting in more heterogeneous composites and a reduced formation of micropores at the MOF/GO interface.

Figure 5. Hydrogen adsorption performance of MIL-101(Cr) and GO-based hybrids under high-pressure conditions. Excess

At 77 K, nexc generally increases by approximately 1 wt.% for every 500 m2 g-1 increase in ABET, a well-established empirical relationship known as Chahine's rule[85]. Supplementary Figure 7A shows the nexc values of the materials in this study plotted against their ABET. While most samples follow a trend consistent with Chahine’s rule, their uptake values are slightly lower than predicted, with M101-GO 1 being the only sample closer to the expected correlation. Additionally, nexc was plotted as a function of specific surface area calculated via 2D-NLDFT model [Supplementary Figure 7B], and all samples exhibit higher-than-predicted values. This discrepancy may stem from the absence of 2D-NLDFT kernels really suitable for MOF structures, potentially leading to inaccuracies in textural property estimations. To address this, a modified correlation has been proposed in the literature[9,85,86], suggesting an increase of 1.25 wt.% in nexc at 77 K for every 500 m2·g-1 increase in 2D-NLDFT specific surface area. As shown in Supplementary Figure 7C, the samples in this study align more closely with this revised trend, supporting their suitability for evaluating MOF-based materials.

Figure 5B displays the H2 excess uptake at 160 K, showing a shift in the adsorption performance trend compared to the results at 77 K [Figure 5A]. At this intermediate temperature, M101-GO 1 achieves the highest uptake (2.86 wt.%), followed by M101-GO 5 (2.60 wt.%), which nearly matches the performance of pure MIL-101(Cr) (2.53 wt.%). In contrast, M101-GO 10 shows a reduced capacity (2.43 wt.%). These results may suggest that at 160 K, specific interactions between H2 and functional groups or defect sites at the interface created by GO incorporation play a more prominent role in the adsorption process. However, these contributions are still not sufficient to fully compensate for the reduction in specific surface area and porosity caused by GO incorporation, which remains the dominant factor influencing overall adsorption performance.

Figure 5C reveals a distinct behavior in H2 adsorption at 273 K and 100 bar: pure MIL-101(Cr) exhibits the lowest uptake (0.55 wt.%), whereas M101-GO 1 achieves the highest capacity (0.77 wt.%), followed by M101-GO 5 (0.64 wt.%) and M101-GO 10 (0.59 wt.%). This trend emphasizes the growing influence of GO when the temperature increases, as its functional groups and defect sites introduced into the MOF promote surface interactions[87]. These surface interactions enhanced by GO introduction are confirmed by comparing N2 and Ar adsorption at 77 K and 87 K, respectively (see Supplementary Figure 8). Upon GO incorporation, the relative pressure at which N2 adsorption begins decreases significantly, while it remains approximately unchanged for Ar. Since N2 has a non-zero quadrupole moment, it undergoes enhanced polarization effects and begins adsorbing at lower relative pressures due to the presence of GO and defects in the MOF structure. In contrast, Ar is a non-polarizable molecule, and the introduction of GO does not lower the relative pressure at which its adsorption starts. However, the reduction in performance at higher GO loadings, such as in M101-GO 10, likely stems from pore blockage and structural disruptions, which reduce accessible specific surface area. Taken together, the trends in Figure 5A-C suggest the existence of an optimal GO concentration that maximizes adsorption performance without significantly compromising the textural integrity of the parent MOF. To assess the cycling performance of the hybrids, H2 adsorption isotherms were measured over three consecutive cycles for the top-performing material in this study, M101-GO 1 (see Figure 5D). The negligible variation among the cycles confirms the material’s excellent adsorption stability under repeated use.

Total H2 uptakes (ntot, wt.%) at 77 K, calculated using Equation 1 and presented in Supplementary Figure 9, confirm that pure MIL-101(Cr) exhibits the highest uptake, following the same trend as observed for nexc uptake at this temperature. However, when considering the volumetric total H2 uptake (ntot, kg m-3) calculated using the values of ρtap of the materials [Figure 5E], M101-GO 1 outperforms MIL-101(Cr), while M101-GO 5 shows performance similar to the pristine MOF [Figure 5F]. This enhancement is directly linked to the higher ρtap of the hybrids, which enables greater packing density and, consequently, higher volumetric storage. Specifically, MIL-101(Cr) has a ρtap of 259 kg m-3, while M101-GO 1, M101-GO 5 and M101-GO 10 present increased values of 285, 290 and 302 kg m-3, respectively. GO alone demonstrates a significantly higher ρtap of 450 kg m-3 (see Supplementary Figure 10). The increased packing density effectively offsets the slight reduction in gravimetric H2 uptake of the hybrids by improving the amount of H2 stored per unit volume [Figure 5F]. The full set of density values (ρtap and ρskel) used for the calculations of ntot is provided in Supplementary Table 1, while the corresponding gravimetric and volumetric H2 uptakes are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

As shown in Figure 5G, the total H2 storage capacity of all evaluated materials exceeds that of an empty tank under identical conditions (77 K and 100 bar), confirming their viability for H2 storage applications. Notably, the inclusion of GO enhances the overall volumetric H2 storage capacity of the M101-GO 1 hybrid relative to pure MIL-101(Cr). While the addition of GO reduces the specific surface area of hybrid materials, the resulting increase in packing density compensates for this loss, enabling M101-GO 1 to achieve a total storage capacity of 35.80 kg·m-3, outperforming pure MIL-101(Cr), which reaches

Two different H2 release scenarios were examined in Figure 5H: one where the discharge takes place at the same temperature as the charge (77 K → 77 K, isothermal release), and the other where the discharge temperature is raised to 160 K (77 K → 160 K, non-isothermal release). As shown in Supplementary Table 3, at 77 K and 5 bar, the empty tank has a higher H2 release capacity (29.5 kg m-3) compared to the tanks filled with porous materials, including the best-performing material, M101-GO 1 (27.6 kg m-3). However, when the discharge temperature is raised to 160 K, the trend reverses: the porous materials outperform the empty tank [Figure 5I]. Under these conditions, M101-GO 1 exhibits the highest release capacity of 34.2 kg m-3, exceeding both MIL-101(Cr) and the empty tank with 32.5 and 30.4 kg m-3, respectively. The percentages in Figure 5I correspond to the amount of H2 released relative to the initially total stored amount. When the temperature increases to 160 K, the porous materials exhibit release efficiencies ranging from 92% to 96%. In contrast, maintaining a discharge temperature of 77 K results in lower efficiency, ranging from 77% to 89%. These results highlight the strong influence of temperature on H2 release efficiency. Because the H2 adsorption measurements carried out in this study are performed at cryogenic temperatures, effective thermal management during discharge is critical. H2 desorption is an endothermic process, and the Joule-Thomson (JT) cooling, due to gas expansion through a valve, can further lower the temperature. If not properly controlled, this cooling can reduce desorption efficiency and hinder overall H2 delivery performance[88].

A comparative summary of H2 storage performances for various MOFs reported in the literature, measured under similar conditions (77 K and 20-60 bar), is provided in Supplementary Table 4. This comparison includes 11 studies covering representative MOFs such as HKUST-1, MIL-100(Al), MOF-5, IRMOF-2, and several MIL-101(Cr) samples. From this analysis, the nexc values (wt.%) obtained in our work are above the average reported for these materials. Only three studies surpass our best result (3.78 wt.%), all based on MIL-101(Cr): two hybridized with activated carbon[82,83], and one with single-walled carbon nanotubes[84]. In all these cases, the pristine MIL-101(Cr) was synthesized using hazardous reagents such as HF or NH4F. In contrast, our approach deliberately accepted a slight reduction in the specific surface area typical of this MOF in favor of a greener synthesis route. By avoiding HF and DMF, the resulting framework did not achieve the highest surface areas reported, which accounts for the slightly lower values compared with those of the most optimized MIL-101(Cr)-based materials.

Considering the total H2 storage capacities (ntot, wt.%) under identical conditions (77 K and 120 bar), and comparing with the data reported by Chen et al.[51] for NU-1500-Al and NU-1501-Al, our best hybrid material, M101-GO 1, reaches 14.0 wt.% compared to 8.5 wt.% for NU-1500-Al, and is very close to the

CONCLUSIONS

This comprehensive study demonstrates that the hybridization of MIL-101(Cr) with GO through post-synthetic synthesis results in hybrid materials with enhanced volumetric H2 storage performance. While the addition of GO reduces the specific surface area (by 27% in the case of M101-GO 1) and leads to decreased gravimetric excess H2 adsorption, with reductions ranging from 3 to 36% at 77 K and 40 bars, the M101-GO 1 hybrid exhibits outstanding performance in virtually real-world conditions. Most notably, this hybrid material achieves 40% increase in gravimetric capacity, and a 54% increase in volumetric capacity at near-ambient conditions, 273 K and 100 bar, and achieves consistent 6% improvements in both total (35.8 kg m-3) and deliverable (34.2 kg m-3) volumetric capacities, at 77 K and 100 bar, compared to pure MIL-101(Cr). These enhancements are attributed to the dual role of GO, increasing the material’s tap density (ρtap) while introducing structural defects that promote ultramicroporosity and most likely create additional favorable adsorption sites. In addition, excellent cycling stability was observed for these hybrid materials. Overall, these findings demonstrate that GO hybridization is a very promising strategy for overcoming the challenge of balancing high porosity with high density in MOF materials, especially for H2 storage applications where volumetric efficiency is critical.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mr. Philippe Gardonneix (Université de Lorraine, M.Sc.) and Dr. Farid Nouar (Institut des Matériaux Poreux de Paris) for their invaluable assistance in the laboratory.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and, writing - original draft: Lopez, L. J.

Supervision, investigation, formal analysis, and, writing - review & editing: Ospino, R. M.

Investigation and, writing - review & editing: Pinto, R. V.

Formal analysis, and, writing - review & editing: Castro-Gutiérrez, J.

Writing - review & editing: Mouchaham, G.

Resources, writing - review & editing: Serre, C.

Supervision, and, writing - review & editing: Celzard, A.

Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, resources, and, writing - review & editing: Fierro, V.

Availability of data and materials

Supplementary Material is available from OAE Publishing Inc. or from the author. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by (i) SOLHYD project (ANR-22-PEHY-0007) funded by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche; (ii) FRCR HyPE project funded by Région Grand-Est; and (iii) TALiSMAN and TALiSMAN2 projects funded by FEDER.

Conflicts of interest

Fierro, V. an Editorial Board Member, and Christian Serre, an Advisory Editor, who are co-authors of this article, are current Editorial Board members of Energy Materials. They were not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewers' selection, manuscript handling and decision making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Squadrito, G.; Maggio, G.; Nicita, A. The green hydrogen revolution. Renew. Energy. 2023, 216, 119041.

2. Habib, M. A.; Abdulrahman, G. A.; Alquaity, A. B.; Qasem, N. A. Hydrogen combustion, production, and applications: a review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 100, 182-207.

3. Ilisca, E. Microporous materials for hydrogen liquefiers and storage vessels. J. Mater. Sci. Manuf. Res. 2022, 3, 1-10.

4. Ball, M.; Wietschel, M. The hydrogen economy: opportunities and challenges. Cambridge University Press; 2009.

5. Barbieri, C.; Ceglie, V.; Stefanizzi, M.; Torresi, M. Solid-state Hydrogen storage: influence of storage capacity in physisorption. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2893, 012057.

6. Rouquerol, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. Thermodynamics of adsorption at the gas/solid interface. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 25-56.

7. Sdanghi, G.; Schaefer, S.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Application of the modified Dubinin-Astakhov equation for a better understanding of high-pressure hydrogen adsorption on activated carbons. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2020, 45, 25912-26.

8. Ramirez-Vidal, P.; Sdanghi, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. High hydrogen release by cryo-adsorption and compression on porous materials. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2022, 47, 8892-915.

9. Ramirez-Vidal, P.; Canevesi, R. L. S.; Sdanghi, G.; et al. A step forward in understanding the hydrogen adsorption and compression on activated carbons. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 12562-74.

10. Weitkamp, J. Zeolites as media for hydrogen storage*1. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 1995, 20, 967-70.

11. Prasanth, K. Adsorption of hydrogen in nickel and rhodium exchanged zeolite X. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2008, 33, 735-45.

12. Hirscher, M.; Becher, M.; Haluska, M.; et al. Hydrogen storage in carbon nanostructures. J. Alloys. Compd. 2002, 330-2, 654-8.

13. Popov, V. Carbon nanotubes: properties and application. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2004, 43, 61-102.

14. Langmi, H. W.; Ren, J.; North, B.; Mathe, M.; Bessarabov, D. Hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks: a review. Electrochim. Acta. 2014, 128, 368-92.

15. Liu, X.; Sun, T.; Hu, J.; Wang, S. Composites of metal-organic frameworks and carbon-based materials: preparations, functionalities and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016, 4, 3584-616.

16. Paz, F. A.; Klinowski, J.; Vilela, S. M.; Tomé, J. P.; Cavaleiro, J. A.; Rocha, J. Ligand design for functional metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1088-110.

17. Achenbach, B.; Yurdusen, A.; Stock, N.; Maurin, G.; Serre, C. Synthetic aspects and characterization needs in MOF chemistry - from discovery to applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, e2411359.

18. Chakraborty, D.; Yurdusen, A.; Mouchaham, G.; Nouar, F.; Serre, C. Large-scale production of metal organic frameworks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309089.

19. Rojas-Garcia, E.; Castañeda-Ramírez, A.; Angeles-Beltrán, D.; López-Medina, R.; Maubert-Franco, A. Enhancing in the hydrogen storage by SWCNT/HKUST-1 composites: effect of SWCNT amount. Catal. Today. 2022, 394-6, 357-64.

20. Liu, S.; Sun, L.; Xu, F.; et al. Nanosized Cu-MOFs induced by graphene oxide and enhanced gas storage capacity. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 818.

21. Zorainy, M. Y. M. MIL metal-organic frameworks: synthesis, post-synthetic modifications, and applications; 2022. Available from: https://publications.polymtl.ca/10306/ [Last accessed on 15 Sep 2025].

22. Vallés-García, C.; Gkaniatsou, E.; Santiago-Portillo, A.; et al. Design of stable mixed-metal MIL-101(Cr/Fe) materials with enhanced catalytic activity for the Prins reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 17002-11.

23. Niknam, E.; Panahi, F.; Daneshgar, F.; Bahrami, F.; Khalafi-Nezhad, A. Metal-organic framework MIL-101(Cr) as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for clean synthesis of benzoazoles. ACS. Omega. 2018, 3, 17135-44.

24. Zorainy, M. Y.; Gar, Alalm. M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Boffito, D. C. Revisiting the MIL-101 metal-organic framework: design, synthesis, modifications, advances, and recent applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 22159-217.

25. Denysenko, D.; Grzywa, M.; Tonigold, M.; et al. Elucidating gating effects for hydrogen sorption in MFU-4-type triazolate-based metal-organic frameworks featuring different pore sizes. Chemistry 2011, 17, 1837-48.

26. Bromberg, L.; Diao, Y.; Wu, H.; Speakman, S. A.; Hatton, T. A. Chromium(III) terephthalate metal organic framework (MIL-101): HF-free synthesis, structure, polyoxometalate composites, and catalytic properties. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1664-75.

27. Sutton, A. L.; Mardel, J. I.; Hill, M. R. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as hydrogen storage materials at near-ambient temperature. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202400717.

28. Shi, W.; Jin, X.; Zhang, C.; et al. Recent advancement in metal-organic frameworks for hydrogen storage: mechanisms, influencing factors and enhancement strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 83, 432-49.

29. Bimbo, N.; Zhang, K.; Aggarwal, H.; et al. Hydrogen adsorption in metal-organic framework MIL-101(Cr)-adsorbate densities and enthalpies from sorption, neutron scattering, in situ X-ray diffraction, calorimetry, and molecular simulations. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2021, 4, 7839-47.

30. Taheri, A.; Babakhani, E. G.; Towfighi, Darian. J. A MIL-101(Cr) and graphene oxide composite for methane-rich stream treatment. Energy. Fuels. 2017, 31, 8792-802.

31. Jia, X.; Zhao, P.; Ye, X.; et al. A novel metal-organic framework composite MIL-101(Cr)@GO as an efficient sorbent in dispersive micro-solid phase extraction coupling with UHPLC-MS/MS for the determination of sulfonamides in milk samples. Talanta 2017, 169, 227-38.

32. Xia, X.; Li, S. Improved adsorption cooling performance of MIL-101(Cr)/GO composites by tuning the water adsorption rate. Sustain. Energy. Fuels. 2023, 7, 437-47.

33. Jia, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hou, X. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of sulfonamide antibiotics in aqueous solution on a novel MIL-101(Cr)@GO composite. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2019, 64, 1265-74.

34. Elsayed, E.; Wang, H.; Anderson, P. A.; et al. Development of MIL-101(Cr)/GrO composites for adsorption heat pump applications. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2017, 244, 180-91.

35. Yan, J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, C.; et al. Adsorption isotherms and kinetics of water vapor on novel adsorbents MIL-101(Cr)@GO with super-high capacity. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 84, 118-25.

36. Panchariya, D. K.; Rai, R. K.; Anil, Kumar. E.; Singh, S. K. Core-shell zeolitic imidazolate frameworks for enhanced hydrogen storage. ACS. Omega. 2018, 3, 167-75.

37. Dutta, A.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Kumar, A. Multicomponent isoreticular metal-organic frameworks: Principles, current status and challenges. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 214074.

38. Muschi, M.; Devautour-Vinot, S.; Aureau, D.; et al. Metal-organic framework/graphene oxide composites for CO2 capture by microwave swing adsorption. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021, 9, 13135-42.

39. Petit, C.; Bandosz, T. J. Engineering the surface of a new class of adsorbents: metal-organic framework/graphite oxide composites. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2015, 447, 139-51.

40. Qiu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Controlled growth of dense and ordered metal-organic framework nanoparticles on graphene oxide. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3874-7.

41. Sun, X.; Xia, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Synthesis and adsorption performance of MIL-101(Cr)/graphite oxide composites with high capacities of n-hexane. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 239, 226-32.

42. Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Xi, H.; Xia, Q. Adsorption performance of a MIL-101(Cr)/graphite oxide composite for a series of n-alkanes. RSC. Adv. 2014, 4, 56216-23.

43. Zhou, X.; Huang, W.; Miao, J.; et al. Enhanced separation performance of a novel composite material GrO@MIL-101 for CO2/CH4 binary mixture. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 266, 339-44.

44. Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, H.; Yan, X.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, A. Pt-doped graphene oxide/MIL-101 nanocomposites exhibiting enhanced hydrogen uptake at ambient temperature. RSC. Adv. 2014, 4, 28908-13.

45. Lee, S. Y.; Park, S. J. Hydrogen storage behaviors of Ni-doped graphene oxide/MIL-101 hybrid composites. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2013, 13, 443-7.

46. Gkaniatsou, E.; Sicard, C.; Ricoux, R.; et al. Enzyme encapsulation in mesoporous metal-organic frameworks for selective biodegradation of harmful dye molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16141-6.

47. Groom, C. R.; Bruno, I. J.; Lightfoot, M. P.; Ward, S. C. The Cambridge structural database. Acta. Crystallogr. B. Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171-9.

48. Rouquerol, J.; Llewellyn, P.; Rouquerol, F. Is the bet equation applicable to microporous adsorbents? Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2007, 160, 49-56.

49. Leachman, J. W.; Jacobsen, R. T.; Penoncello, S. G.; Lemmon, E. W. Fundamental equations of state for parahydrogen, normal hydrogen, and orthohydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 2009, 38, 721-48.

50. Morales-Ospino, R.; Jiménez-López, L.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Fuels - hydrogen - hydrogen storage | physical adsorption. Encyclopedia of Electrochemical Power Sources. Elsevier; 2025. pp. 319-29.

51. Chen, Z.; Li, P.; Anderson, R.; et al. Balancing volumetric and gravimetric uptake in highly porous materials for clean energy. Science 2020, 368, 297-303.

52. García-holley, P.; Schweitzer, B.; Islamoglu, T.; et al. Benchmark study of hydrogen storage in metal-organic frameworks under temperature and pressure swing conditions. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2018, 3, 748-54.

53. Schlichtenmayer, M.; Hirscher, M. The usable capacity of porous materials for hydrogen storage. Appl. Phys. A. 2016, 122, 9864.

54. DOE materials-based hydrogen storage summit: defining pathways for onboard automotive applications. Available from: https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/articles/doe-materials-based-hydrogen-storage-summit-defining-pathways-onboard [Last accessed on 15 Sep 2025].

55. Allendorf, M. D.; Hulvey, Z.; Gennett, T.; et al. An assessment of strategies for the development of solid-state adsorbents for vehicular hydrogen storage. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2784-812.

56. Zorainy, M. Y.; Titi, H. M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Boffito, D. C. Multivariate metal-organic framework MTV-MIL-101 via post-synthetic cation exchange: is it truly achievable? Dalton. Trans. 2022, 51, 3280-94.

57. Tan, S. C.; Lee, H. K. A hydrogel composite prepared from alginate, an amino-functionalized metal-organic framework of type MIL-101(Cr), and magnetite nanoparticles for magnetic solid-phase extraction and UHPLC-MS/MS analysis of polar chlorophenoxy acid herbicides. Mikrochim. Acta. 2019, 186, 545.

58. Liu, Q.; Ning, L.; Zheng, S.; Tao, M.; Shi, Y.; He, Y. Adsorption of carbon dioxide by MIL-101(Cr): regeneration conditions and influence of flue gas contaminants. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2916.

59. Karikkethu Prabhakaran P, Deschamps J. Doping activated carbon incorporated composite MIL-101 using lithium: impact on hydrogen uptake. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015, 3, 7014-21.

60. Mirsoleimani-azizi, S. M.; Setoodeh, P.; Samimi, F.; Shadmehr, J.; Hamedi, N.; Rahimpour, M. R. Diazinon removal from aqueous media by mesoporous MIL-101(Cr) in a continuous fixed-bed system. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4653-64.

61. Tourani, S.; Behvandi, A. Synthesis of MIL-101(Cr)/sulfasalazine (Cr-TA@SSZ) hybrid and its use as a novel adsorbent for adsorptive removal of organic pollutants from wastewaters. J. Porous. Mater. 2022, 29, 1441-62.

62. Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure. Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051-69.

63. Cho, H. S.; Yang, J.; Gong, X.; et al. Isotherms of individual pores by gas adsorption crystallography. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 562-70.

64. Ding, M.; Jiang, H. Improving water stability of metal-organic frameworks by a general surface hydrophobic polymerization. CCS. Chem. 2021, 3, 2740-8.

65. Burtch, N. C.; Jasuja, H.; Walton, K. S. Water stability and adsorption in metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10575-612.

66. Tóth, A.; László, K. Water adsorption by carbons. Hydrophobicity and Hydrophilicity. Novel Carbon Adsorbents. Elsevier; 2012. pp. 147-71.

67. Greathouse, J. A.; Allendorf, M. D. The interaction of water with MOF-5 simulated by molecular dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10678-9.

68. Terrones, G. G.; Huang, S. P.; Rivera, M. P.; Yue, S.; Hernandez, A.; Kulik, H. J. Metal-organic framework stability in water and harsh environments from data-driven models trained on the diverse WS24 data set. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 20333-48.

69. Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Kapteijn, F. Water and metal-organic frameworks: from interaction toward utilization. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 8303-77.

70. Canivet, J.; Fateeva, A.; Guo, Y.; Coasne, B.; Farrusseng, D. Water adsorption in MOFs: fundamentals and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5594-617.

71. Zeng, Y.; Prasetyo, L.; Nguyen, V. T.; Horikawa, T.; Do, D.; Nicholson, D. Characterization of oxygen functional groups on carbon surfaces with water and methanol adsorption. Carbon 2015, 81, 447-57.

72. Nguyen, V. T.; Horikawa, T.; Do, D.; Nicholson, D. Water as a potential molecular probe for functional groups on carbon surfaces. Carbon 2014, 67, 72-8.

73. Zhao, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M. Synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) and its water adsorption performance. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 2020, 297, 110044.

74. Liu, R.; Gong, T.; Zhang, K.; Lee, C. Graphene oxide papers with high water adsorption capacity for air dehumidification. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9761.

75. Lian, B.; De, Luca. S.; You, Y.; et al. Extraordinary water adsorption characteristics of graphene oxide. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 5106-11.

76. Castro-gutiérrez, J.; Canevesi, R.; Emo, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. CO2 outperforms KOH as an activator for high-rate supercapacitors in aqueous electrolyte. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2022, 167, 112716.

77. Liu, L.; Tan, S. J.; Horikawa, T.; Do, D. D.; Nicholson, D.; Liu, J. Water adsorption on carbon - A review. Adv. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2017, 250, 64-78.

78. Schlemminger, C.; Næss, E.; Bünger, U. Adsorption hydrogen storage at cryogenic temperature - Material properties and hydrogen ortho-para conversion matters. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2015, 40, 6606-25.

79. Fang, M.; He, R.; Zhou, J.; Fei, H.; Yang, K. Thermal conductivity enhancement and shape stability of composite phase change materials using MIL-101(Cr)-NH2/expanded graphite/multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Energy. Storage. 2024, 86, 111244.

80. Zhou, J.; Fang, M.; Yang, K.; et al. MIL-101(Cr)-NH2/reduced graphene oxide composite carrier enhanced thermal conductivity and stability of shape-stabilized phase change materials for thermal energy management. J. Energy. Storage. 2022, 52, 104827.

81. Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Gao, H.; Li, A.; Wang, C. Construction of CNT@Cr-MIL-101-NH2 hybrid composite for shape-stabilized phase change materials with enhanced thermal conductivity. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 350, 164-72.

82. Yu, Z.; Deschamps, J.; Hamon, L.; Karikkethu, Prabhakaran. P.; Pré, P. Hydrogen adsorption and kinetics in MIL-101(Cr) and hybrid activated carbon-MIL-101(Cr) materials. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2017, 42, 8021-31.

83. Somayajulu Rallapalli PB, Raj MC, Patil DV, Prasanth KP, Somani RS, Bajaj HC. Activated carbon @ MIL-101(Cr): a potential metal-organic framework composite material for hydrogen storage: A potential MOF composite material for hydrogen storage. Int. J. Energy. Res. 2013, 37, 746-53.

84. Prasanth, K.; Rallapalli, P.; Raj, M. C.; Bajaj, H.; Jasra, R. V. Enhanced hydrogen sorption in single walled carbon nanotube incorporated MIL-101 composite metal-organic framework. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2011, 36, 7594-601.

85. Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Storage of hydrogen by physisorption on carbon and nanostructured materials. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 803-8.

86. Sdanghi, G.; Sdanghi, G.; Maranzana, G.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V. Hydrogen adsorption on nanotextured carbon materials. In: Sankir M, Sankir ND, editors. Hydrogen Storage Technologies. Wiley; 2018. pp. 263-320.

87. Tyagi, C.; Kulriya, P.; Ojha, S.; Avasthi, D.; Tripathi, A. Investigation of graphene oxide-hydrogen interaction using in-situ X-ray diffraction studies. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2018, 43, 13339-47.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].