Tailored synthetic strategies for tetraphenylethylene-based metal–organic frameworks: design, construction, and control

Abstract

Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) derivatives have garnered considerable interest due to their unique characteristics, including distinctive aggregation-induced emission optical properties, flexible and rotatable π-structural subunits, inherent compressible elasticity, and the four-corner connection structure. Such attributes collectively render TPE derivatives as exceptional building blocks for the fabrication of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). The structural design flexibility and controllability inherent to TPE derivatives enable precise targeted design and synthesis of MOF materials, offering significant advantages in MOF research and application. Consequently, in recent years, MOFs constructed from TPE derivatives have showcased extensive and growing potential applications across diverse domains, including luminescence, gas adsorption and separation, photocatalysis, sensing technology, energy conversion and storage, and biomedical science. This review aims to provide an overview of the design and synthesis strategies, construction methods, and synthesis control techniques for TPE-based MOF materials tailored for specific applications. Throughout the discussion on design and synthesis strategies, the performance advantages of these materials and their promising application prospects in diverse fields are also explored.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) and its derivatives, with unique rotatable and twisted π-structural subunits, exhibit significant aggregation-induced emission (AIE) effects, thereby laying a solid foundation for the development of diverse functional materials[1-3]. This inherent property of TPE derivatives has not only enriched the family of AIE molecules but has also propelled the boundaries of AIE research forward. Consequently, numerous breakthroughs in the AIE field have been achieved, directly or indirectly, through the exploration of TPE and its derivatives[4-6]. Extensive and in-depth studies have been conducted on these compounds, leading to the design and synthesis of numerous molecules, supramolecular structures, and polymeric systems. The structural advantages have further broadened the application prospects of TPE derivatives in various domains[7,8].

Furthermore, when the ends of their rotatable arms are modified with groups capable of participating in coordination, covalent bond formation, hydrogen bonding interactions, and host-guest supramolecular interactions, TPE derivatives can serve as building blocks for assembling infinitely extended crystalline network frameworks. These include metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs), and supramolecular organic frameworks (SOFs), among others[9-14]. Each type of these crystalline framework materials possesses unique characteristics, collectively forming a versatile and widely applicable material platform with broad prospects for applications in various fields. Notably, TPE-based crystalline materials demonstrate multiple advantages. On the one hand, the crystalline structure endows the materials with highly ordered and precisely analyzable structural features, facilitating performance optimization and mechanism research[15,16]. On the other hand, in terms of luminescent applications, the solid form enhances the stability and maneuverability of the materials in practical optical applications. The inherent AIE characteristics of TPE ligands effectively overcome the challenge of weakened or quenched luminescence in the solid state encountered by traditional aggregation-caused quenching chromophores. This ensures the excellent luminescent performance, even when integrated into framework structures[17]. Additionally, the porosity of these materials offers an extra dimension for functionalization. It allows performance tuning through the adsorption of guest molecules and enables the exploration of novel structural systems, including mechanisms such as elastic structural compression[18,19].

MOFs, also known as porous coordination polymers (PCPs), represent a unique class of framework materials distinct from discrete metal–organic structures such as rings and cages[20-22]. Unlike the discrete structures, MOFs are crystalline solids with extended, periodic frameworks formed through precise coordination bonds between metal nodes [or secondary building units (SBUs)] and organic linkers[23,24]. The appeal of this structure lies in the varying organic linkers, diverse metal nodes, and the flexibility in coordination modes[25-27]. These factors have fueled the rapid design and development of MOF structures. Therefore, by skillfully incorporating TPE chromophores through ingenious coordination-driven self-assembly strategies, MOFs exhibit distinct properties and functionalities[28]. Recently, the embedding of AIE luminogens (AIEgens) into MOFs has emerged as a research hotspot, demonstrating exceptional performance in chemical sensing, white light-emitting diodes (LEDs), nonlinear optics, and external stimuli-responsive fluorescence switching[28,29]. Notably, the highly symmetrical structure of TPE allows it to fit perfectly into MOF frameworks, serving as a scaffold for construction with specific geometric and spatial arrangements[13,28]. Consequently, the majority of reported AIEgens-MOFs are based on TPE-based linkers[9,28]. The development of TPE-based MOF materials requires meticulous design and synthesis of ligands, guided by structure-activity relationships and tailored for target applications.

MOFs boast highly adjustable structures and widely designable properties, along with easily characterized microporous features. These characteristics endow them with extraordinary potential and unique advantages in numerous high-end applications. For example, the tunability and predictability of TPE-based MOF structures provide an ideal platform for exploring the intrinsic mechanisms of solid-state AIE phenomena[30,31]. Applications of TPE-based MOFs extend beyond luminescence. These materials, characterized by their well-defined structures, ease of characterization, porosity, and designability, also demonstrate tremendous potential in various fields such as adsorption and separation, catalysis, gas storage, sensors and detection, etc.[7,32]. For example, by finely tuning the pore size and chemical environment of the frameworks, MOFs can efficiently and selectively adsorb specific gases or organic molecules, enabling efficient separation and purification[33,34]. Moreover, their porous structures provide ideal active sites and reaction venues for catalytic reactions, contributing to improved catalytic efficiency and selectivity[35].

This review focuses on MOF materials constructed with TPE-derived coordination linkers, highlighting their extensive applications in luminescence and other fields. To date, many TPE-based ligands have been reported. As illustrated in Figure 1, they are typically synthesized by attaching coordination groups (such as carboxyl, pyridine, pyrimidine, imidazole, triazole, tetrazole, etc.) to the periphery of TPE core. By finely tuning the length, number, and position of substituents, a series of functional TPE-based ligands can be created, including:

H4TCPE (Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene)[30,36-69],

DPEB (4,4’-(2,2-diphenylethene-1,1-diyl)dibenzoic acid)[70],

H2BCTPE ((E)-4,4’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)dibenzoic acid)[71],

ETTC (4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)))[18,72-105],

m-ETTC (4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid)))[106-108],

H2DPDBP (4’,4’’’-(2,2-diphenylethene-1,1-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid))[109],

H4DPDBP (4’,4’’’-(2,2-bis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethene-1,1-diyl)bis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)))[33],

H8ETTB (4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3,5-dicarboxylic acid)))[32,110-120],

BCPPE ((E)-4’,4’’’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid))[121-123],

trans-BPYPE ((E)-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene)[124-126],

TPPE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene)[64,127-147],

TPPYE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl)ethene)[148,149],

TPBE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4’-(pyridin-4-yl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethene)[150-152],

TIPE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)ethene)[153-161],

TTPE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)ethene)[162-167],

H4TTPE (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethene)[35,168-171],

H4TPE4Pz (1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)phenyl)ethene)[172-175],

H8TPPE (1,1,2,2-Tetrakis[4-phosphonophenyl]ethylene)[176-187].

Figure 1. Ligands for AIEgens-MOFs based on TPE derivatives. Drawn using ChemDraw. AIEgens: Aggregation-induced emission luminogens; MOFs: metal–organic frameworks; TPE: tetraphenylethylene; H4TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; DPEB: 4,4’-(2,2-diphenylethene-1,1-diyl)dibenzoic acid; H2BCTPE: (E)-4,4’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)dibenzoic acid; ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); m-ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3-carboxylic acid)); H2DPDBP: 4’,4’’’-(2,2-diphenylethene-1,1-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid); H4DPDBP: 4’,4’’’-(2,2-bis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethene-1,1-diyl)bis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); H8ETTB: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3,5-dicarboxylic acid)); H8TDPEPE: tetrakis[4-(3,5-dicarboxyphenylethynyl)phenyl]ethylene; H4TPEEB: 4,4’,4’’-(((2-(4-((4-carboxyphenyl)ethynyl)phenyl)ethene-1,1,2-triyl)tris(benzene-4,1-diyl))tris(ethane-2,1-diyl))tribenzoic acid; BCPPE: (E)-4’,4’’’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid); trans-BPYPE: (E)-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; TPPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; TPPYE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyrimidin-5-yl)phenyl)ethene; TPBE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4’-(pyridin-4-yl)-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl)ethene; H4TATZTPE: 4,4’,4’’,4’’’-(4,4’,4’’,4’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayltetrakis(benzene-4,1-diyl))tetrakis(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4,1-diyl))tetrabenzoic acid; TIPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)ethene; TTPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)phenyl)ethene; H4TTPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(2H-tetrazol-5-yl)phenyl)ethene; H4TPE4Pz: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(1H-pyrazol-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; H8TPPE: 1,1,2,2-Tetrakis[4-phosphonophenyl]ethylene.

Additionally, more TPE-based ligands have been developed[188]. Furthermore, by replacing benzene rings with ethylene, acetylene, triazole, etc., the coordination arms of TPE-derived ligands can be extended, such as

H4TPEEB (4,4’,4’’-(((2-(4-((4-carboxyphenyl)ethynyl)phenyl)ethene-1,1,2-triyl)tris(benzene-4,1-diyl))tris(ethane-2,1-diyl))tribenzoic acid)[189],

H8TDPEPE (Tetrakis[4-(3,5-dicarboxyphenylethynyl)phenyl]ethylene)[31],

H4TATZTPE (4,4’,4’’,4’’’-(4,4’,4’’,4’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayltetrakis(benzene-4,1-diyl))tetrakis(1H-1,2,3-triazole-4,1-diyl))tetrabenzoic acid)[190,191].

Heteroatoms or functional groups for modification can also be skillfully introduced, such as in H4(tcbpe-F)[192-201], H4(tcbpe-OH)[34], thereby enriching their functionality and diversity. Innovative research has also reported novel ligands with TPE units as pendant groups[202,203].

In terms of synthetic strategies, leveraging reticular chemistry principles is essential[204,205]. These principles allow for the combination of meticulously designed ligands with various metal salts through hydrothermal methods and other synthetic pathways, facilitating the construction of diverse TPE-based MOFs. Metal nodes can also be designed as complex metal clusters[206]. The introduction of second ligands provides additional fine-tuning of the structural characteristics[100]. Furthermore, by regulating synthetic methods and various post-processing techniques, a variety of materials with specific functions can be prepared[57,99]. Therefore, this paper explores the following five dimensions: (1) innovative ligand design; (2) strategic metal nodes selection; (3) ingenious introduction of second ligands; (4) precise control of coordination modes; (5) post-treatment, nano-processing, and composite material preparation. Through the citation and summarization of typical literature cases, this review aims to provide a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the synthetic strategies for TPE-based MOFs, shedding light on the diverse approaches and innovative techniques employed in their preparation [Figure 2]. Furthermore, beyond merely focusing on synthesis, this review also delves into the remarkable breakthroughs and ongoing pursuits in terms of the properties and applications of TPE-based MOFs. A roadmap for TPE-based MOFs, illustrating the substantial development of this field, is also presented [Figure 3]. It not only showcases the historical progression but also hints at the promising future directions in optimizing their performance and expanding their practical uses.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the synthetic strategies for TPE-based MOFs[31,33,54,57,58,81,82,88,93,138,190,197,203,207]. Reproduced from Ref.[31], Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society; Ref.[33], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; Ref.[54], Copyright 2022, The American Association for the Advancement of Science; Ref.[57], Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; Ref.[58], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[81], Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society; Ref.[82], Copyright 2018, Elsevier; Ref.[88], Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society; Ref.[93], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[138], Copyright 2019, Chinese Chemical Society; Ref.[190], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[197], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; Ref.[203], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; Ref.[207], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. TPE: Tetraphenylethylene; MOFs: metal–organic frameworks.

Figure 3. Roadmap for TPE-based MOFs[35,36,38,39,42,59,70,72,75,79,80,82,85,86,93,110,122,127,138,141,202]. Reproduced from Ref.[35], Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society; Ref.[36], Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society; Ref.[38], Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society; Ref.[39], Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry; Ref.[42], Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[59], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[70], Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society; Ref.[72], Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society; Ref.[75], Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society; Ref.[79], Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[80], Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[82], Copyright 2018, Elsevier; Ref.[85], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[86], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; Ref.[93], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[110], Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society; Ref.[122], Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[127], Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society; Ref.[138], Copyright 2019, Chinese Chemical Society; Ref.[141], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; Ref.[202], Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry. TPE: Tetraphenylethylene; MOFs: metal–organic frameworks; VOCs: volatile organic compounds; WLEDs: white light-emitting diodes; MPEF: multi-photon excited fluorescence; 2PEF: two-photon excited fluorescence.

INNOVATIVE LIGAND DESIGN

Length regulation of coordination arms

The pioneering synthesis of TPE-based MOFs was reported by Shustova et al. in 2011, utilizing coordination reactions between H4TCPE and d10 metal ions Zn and Cd [Figure 4A][36]. The activated ZnMOF displayed notable fluorescence color changes upon exposure to chemicals such as ethylenediamine, cyclohexanone, and acetaldehyde. Further investigation was conducted utilizing deuterated ligands and employing comprehensive analyses through variable-temperature X-ray diffraction (XRD), solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and density functional theory (DFT) calculations[30]. The results revealed that torsion of the alkene bonds and rotation of the benzene rings could lead to fluorescence quenching. However, the rigid lattice and coordination constraints of the MOF effectively blocked these non-radiative pathways, triggering intense fluorescence emission.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic illustration of AIE fluorescence turn-on via coordination in the rigid MOF matrix of TCPE-Zn/Cd[30,36], Copyright 2011,2012 American Chemical Society; (B) PCN-94 constructed by rigidifying H4ETTC into the MOF matrix and their PLQY[72], Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society; (C) Molecular structure and design features of H8TDPEPE and the shortest chromophore-chromophore contacts of the MOF[31], Copyright 2012, American Chemical Society; (D) Single- and two-photon absorption dual-way excited white-light emission in dye@LIFM-WZ-6 systems[190], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; (E) Estimated HOMO–LUMO energy gaps of the ligands[74], Copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry; (F) PL images and wavelength shift of lasing modes in the TPBE-Cd microwire under alternate exposure to air and acetone[150], Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. AIE: Aggregation-induced emission; MOF: metal–organic framework; TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; PCN: porous coordination network; H4ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); PLQY: photoluminescence quantum yield;

In 2014, Wei et al. skillfully rigidified the extended AIE chromophore, ETTC, into a Zr-based MOF, named porous coordination network (PCN)-94, successfully prepared porous and highly luminescent crystal materials [Figure 4B][72]. This MOF emits yellow fluorescence in air with an absolute quantum yield of 30%, and deep blue fluorescence in argon with a 99.9% ± 0.5% quantum yield. The significant increase in luminescence is primarily attributed to the fixation of ligands within the framework, which restricts intramolecular motion and reduces energy dissipation pathways.

These two classic cases of TPE-based MOFs highlight the importance of reducing non-radiative energy dissipation pathways for improving emission energy utilization, making such materials promising for optical-related applications. However, for some specific applications such as turn-on fluorescence sensing, materials with lower luminescent efficiency are required[208]. By lowering the torsion barrier for benzene ring flipping in MOFs, a deeper understanding of the AIE effect can be achieved. Based on this, Shustova et al. designed an acetylene-extended octacarboxylic acid ligand, H8TDPEPE, and successfully obtained the yellow crystalline MOF product [Figure 4C][31]. XRD analysis revealed that the crystal was formed by connecting paddlewheel-like Zn2(O2C-)4 SBUs via TDPEPE8- ligands, resulting in a three-dimensional MOF structure. In this structure, the distance between the benzene rings connected by acetylene groups in two adjacent TPE cores was sufficiently large (10.24 Å), leading to more rotatable benzene rings in the TPE units and a reduced fluorescence quantum yield of only 9%. Both DFT calculations and experimental studies indicated that the decrease in quantum yield is due to the reduction in the torsion barrier for benzene ring flipping.

In 2019, Wang et al. synthesized a highly porous MOF, [(Zn2(TATZTPE)Bpy·8DMA)]n [Lehn Institute of Functional Materials (LIFM)-WZ-6], by using a TBE-based ligand with triazole groups[Figure 4D][190]. Owing to the abundant electron-accepting sites within its pore structure, this material is capable of selectively adsorbing cationic organic dyes. The resulting dye@MOF system demonstrates excellent white light emission performance after either single- or two-photon absorption, achieved through flexible adjustment of the composition ratio and excitation wavelength. This work expanded design strategies for white light-emitting materials and multi-path optical conversion.

The two aforementioned cases, reporting alkyne and triazole group incorporation into ligand arms, fully demonstrate the potential of the ligand design approach for framework expansion. The successful implementation of this design concept can be primarily attributed to the crucial role played by the steric hindrance and other weak interactions of the ligand’s rotor portion in modulating the overall properties of MOFs.

In 2015, Hu et al. investigated the luminescent properties of LMOF-231 (LMOF: luminescent MOF) constructed from ETTC ligands and zinc metal [Figure 4E][74]. They used DFT calculations to explore the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energies, as well as the HOMO-LUMO gap, of a series of chromophores containing a TPE core with varying extended arm lengths. They discovered that the energy gap gradually decreases as the length of the extended coordination arm increases, leading to a red shift in fluorescence. However, the overall luminescent behavior of these MOFs is also influenced by how the MOF structure confines the ligands. Another typical example is the work by Lv et al., where they assembled a MOF using a TPE-based ligand, TPBE, with an extended coordination arm length via benzene rings [Figure 4F][150,152]. They applied it to multifunctional micro-nano lasers with dual-wavelength reversible switching. The detachment of guest molecules reduced steric hindrance around the AIE connector, enhancing rotational emission and causing a red shift. Guest molecule adsorption/desorption dynamically altered emission, allowing flexible switching of the gain region.

Currently, there is a lack of systematic summary regarding the influence of the rotor portion’s length in the coordination arm of TPE ligands on material properties. Therefore, there is an urgent need for comprehensive analysis from multiple dimensions, including the energy levels of coordination compounds, framework structures, torsion barriers of coordination arm rotors, the impact of guest molecules on radiative transitions, non-radiative energy dissipation, etc.

Regulation of coordination group type, quantity, and position

The selection of coordination groups is crucial for developing novel MOF structures. Different coordination group modifications have their unique advantages in constructing various MOF structures. On the other hand, based on the Hard and Soft Acids and Bases (HSAB) theory, stable MOFs are typically constructed by combining carboxylic acid ligands (as hard Lewis bases) with high-valent metal ions (as hard Lewis acids), or nitrogen heterocyclic ligands (as soft Lewis bases) with low-valent transition metal ions (as soft Lewis acids)[23,209].

In 2021, Kang et al. reported a MOF structure named ZJU-X8 (ZJU-X: Zhejiang University, Xiao’s group), which was constructed using pyrimidine-functionalized TPE derivative ligands with accessible silver sites

Figure 5. (A) Fluorescence photographs, emission spectra, and the CIE color space chromaticity diagram of ZJU-X8 in the presence of various anions, showing the fluorescent recognition toward TcO4-/ReO4-[148], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (B) The proposed mechanism of O3 degradation by ZZU-281[35], Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society; (C) CAU-54’s optical properties, responses to stimuli 1-5, and photophysical process diagram (stimuli 1, 4)[187], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (D) Synthesis of PCN-922 using PCN-921 as a template[110], Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society; (E) Schematic illustration thermo-/piezofluorochromic properties of DEF∈ZnETTB[115], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; (F) Dinuclear ZnII2 cluster linearly bridged by CO2[106], Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. CIE: International Commission on Illumination; TcO4-: pertechnetate; ReO4-: perrhenate; ZZU-281: [Mn3(μ3-OH)2(TTPE)(H2O)4]·2H2O; Zhengzhou University, ZZU; CAU: Christian-Albrechts-University; PCN: porous coordination network; DEF: N,N-diethylformamide; Zn: zinc; ETTB: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3,5-dicarboxylic acid)); UV: ultraviolet.

In recent years, various new TPE-based ligands have been developed by grafting novel coordinating groups onto TPE molecules. A typical example is the tetradentate phosphonate ligand H8TPPE, which can assemble with a wide range of metal ions to form MOFs with unique advantages in specific applications. For instance, in 2022, Chakraborty et al. constructed a MOF using manganese ions and H8TPPE, demonstrating high selectivity for “turn-on” fluorescence detection of L-arginine in aqueous solutions[183]. In the same year, they also developed a MOF using divalent copper ions and H8TPPE, which exhibited high stability, reactive oxygen species generation capability, and antibacterial performance[184]. These characteristics indicate its potential for use in anticancer photodynamic therapy and bacterial eradication. In 2024, Steinke et al. constructed a TPE-based MOF, CAU-54 ([La2(H2O)5(H2TPPE)]·3H2O; Christian-Albrechts-University, CAU), using H8TPPE and La3+ ions [Figure 5C][187]. This material exhibited a reversible white-to-red photochromic transition under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, attributed to free radical formation. It was also confirmed as low quantum yield red phosphorescence, which marks the only currently reported case of a TPE-MOF emitting phosphorescence. Furthermore, it showed photoluminescence self-quenching and multi-stimuli photoresponsive properties, responding with turn-on photoluminescence to various external stimuli such as pressure changes, solvent exchange, and temperature variations. These unique photophysical phenomena highlight the enormous potential of this material in the study of luminescence mechanisms and applications of TPE-based MOFs.

Tetrakis(4-ethynylphenyl)ethene (T4EPE), featuring alkyne groups as the functional coordinating moieties, represents a novel ligand. In 2022, Sun et al. successfully constructed a Cu(I)-bridged aggregate MOF nanophotocatalyst using T4EPE and monovalent copper ions[210]. This material demonstrated light-modulated generation of 1O2 and O2∙-, enabling selective photocatalytic aerobic oxidation. It exhibited exceptional photocatalytic performance in Glaser coupling and benzylamine oxidation reactions. Such MOFs, constructed through metal-carbon coordination bonds, are rarely reported. Apart from the above case, in 2024, Jiang et al. reported a novel class of two-dimensional (2D) MOFs based on isocyanide-silver bonds[211]. Among them, SJTU-102 (SJTU: Shanghai Jiao Tong University) is constructed via C–Ag–C coordination between TPE-isocyanide ligands and silver(I) ions. These materials exhibit good activity in the electrocatalytic application of reducing CO2 to CO.

Increasing the number of coordination groups can theoretically enhance the stability of constructed MOF materials. Although most TPE derivatives naturally possess four coordinating arms, more efforts are needed to enhance the stability of TPE-based MOFs. Because the TPE-based framework structures are prone to dissociation due to the strong tendency for torsion of the alkene bonds and rotation of the four benzene rings. In 2013, Wei et al. synthesized the stable MOF material PCN-222 with large pores and high gas adsorption using H8ETTB and template synthesis/metal exchange [Figure 5D][110]. In 2022, Zhu et al. prepared ZnETTB, which leverages its twisted rotor structure, elastic framework, suitable pore size, and host-guest interactions to achieve fluorochrome recognition of N,N-diethylformamide (DEF)

By adjusting the positions of the coordinating groups, typically exemplified by m-ETTC, the symmetry of the ligand is effectively reduced. This, coupled with the rotational properties of terminal phenyl groups, gives rise to a multitude of potential bonding orientations, greatly facilitating the exploration of novel MOF structures. In 2019, Wang et al. pioneered the use of m-ETTC ligands to construct two zinc-based MOF materials, one featuring SBUs linearly bridged by CO2 [Figure 5F][106]. Subsequently, in 2021, Hurlock et al. synthesized two MOFs, WSU-30 (WSU: Washington State University) and WSU-31, using Cd2+ and m-ETTC linkers, both with novel topological structures[107]. These achievements demonstrate the significant expansion of TPE-based MOF diversity through this ligand design strategy.

In 2019, Johnson et al. studied the self-assembly of non-planar aromatic carboxylic acids [BCPPE, ETTC, tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene (TCPE)] on Au(111) and highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) surfaces [Figure 6A-C][123]. This marked the first step in developing a new strategy for creating 2D surface MOFs (SURFMOFs), holding significant research value. They discovered that the combination of molecules and substrates played a crucial role in monolayer formation and final surface linker structures. In 2023, Zou et al. also utilized scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) to investigate MOFs constructed via Ullmann-type reactions of C2-symmetry TPE derivatives (p-BrTBE) on Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces [Figure 6D][212]. They found that substrate type, molecular coverage, and catalytic activity were key factors influencing the formation and ordering of MOFs, and provided mechanistic insights through DFT calculations. These studies open new avenues for precisely controlling the growth of SURFMOFs and their applications in electronic devices or nanomaterials.

Figure 6. (A) Schematic diagram of the self-assembly forms of the ligands on the substrate. High-resolution images of TCPE (a), BCPPE (b), and ETTC (c) solutions in heptanoic acid deposited on HOPG (B) and Au(111) (C)[123], Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society; (D) Reaction pathways of p-BrTBE on Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces[212], Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. TCPE: Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; BCPPE: (E)-4’,4’’’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid); ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); HOPG: highly oriented pyrolytic graphite; p-BrTBE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4’-bromo[1,1’-biphenyl]-4-yl) ethene; TPE: tetraphenylethylene.

Heteroatoms or functional groups grafting

In addition to grafting functional groups directly into the coordination arms in the rotor section of TPE derivatives, with examples of H8TDPEPE and H4TATZTPE, functional atoms or groups can also be cleverly attached to the sides of these coordination arms. A typical example is shown in the lower left corner of Figure 4E, where the substituent group R can be halogen atoms, hydroxyl groups, amino groups, methyl groups, etc.[74].

In 2016, Lustig et al. constructed two novel MOF structures, LMOF-302 and LMOF-304, with fluorinated ligand 4’ ,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(3-fluoro-[1,1’ -biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid (H4tcbpe-F)[192]. The ortho-position fluorine substitution reduced carboxyl electron density, facilitating Zn2+ coordination with pyridine lone pairs. This rotor arm functionalization strategy significantly influenced MOF luminescence, HOMO-LUMO energy levels, coordination modes, pore size, and host-guest interactions. MOF structures constructed using this ligand also show unique advantages in areas such as white LED (WLED) lighting[194], efficient copper ion detection[195], and two-photon absorption[197]. In 2024, Liang et al. synthesized two zirconium-based MOFs, the non-interpenetrated PCN-1001 and the doubly interpenetrated PCN-1002, using 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(3-hydroxy-[1,1’biphenyl]−4-carboxylic acid) (H4tcbpe-OH), functionalized with hydroxyl groups[34]. PCN-1002 not only exhibits high stability but also demonstrates efficient adsorption capacity of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) up to

Desymmetrized ligand design

Reducing the symmetry of ligands has a profound impact on the structure and performance of MOFs, as evidenced by m-ETTC. For TPE derivatives, another two common strategies to reduce symmetry include modifying the structure of the two coordination arms on one side of the central alkene bond to form butterfly-shaped ligands, or altering the structure at the diagonal positions to create ligands with trans-/cis- isomerization. These ligands, designed with reduced symmetry in mind, offer unique benefits in constructing novel MOF structures.

In 2014, Zhang et al. pioneered the use of a desymmetrized DPEB ligand, lacking two carboxyl groups compared to H4TCPE, to construct a MOF with a special pore structure, NUS-1 (NUS: National University of Singapore)[Figure 7A][70]. The two pendant phenyl rings in this ligand have relatively less spatial restriction, enabling effective interactions with volatile organic compound (VOCs) analytes and thus activating fluorescence turn-on detection. Single crystal structure analysis and gas adsorption-desorption experiments have confirmed its wide-channel and flexible pore structures. In 2022, Wang et al. synthesized two MOF materials [Lehn Institute of Functional Materials (LIFM)-102 and LIFM-103] with dense packing structures and low porosity using a symmetry-reduced TPE-based AIEgen ligand H2DPDBP and alkaline earth metals via a hydrothermal method

Figure 7. (A) Crystal structure of activated NUS-1 viewed along [010] direction and [001] direction[70], Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society; (B) H2DPDBP, and the packing views of LIFM-102 and LIFM-103[109], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; (C) H4DPDBP, the two types of metal nodes, and the packing views along the a-axis and c-axis[33], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (D) Structural presentation of compound [Cu4I4(cis-bpype)3(trans-bpype)]·3DMF[125], Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society; (E) Scheme depicting the process of ligand exchange from bio-MOF-101 to bio-MOF-101-BCPPE[121], Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry; (F) Simulated SURMOF-2 structure and oxidative photocyclization reaction of trans-BCPPE in SURMOF-2[122], Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. NUS: National University of Singapore; H2DPDBP: 4’,4’’’-(2,2-diphenylethene-1,1-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid); LIFM: Lehn Institute of Functional Materials; H4DPDBP: 4’,4’’’-(2,2-bis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethene-1,1-diyl)bis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); bpype: 1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; bio-MOF: biological metal–organic frameworks; BCPPE: (E)-4’,4’’’-(1,2-diphenylethene-1,2-diyl)bis([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid); SURMOF: surface grown metal–organic framework.

In 2017, Tao et al. pioneered the use of a trans-disubstituted TPE derivative, trans-BPyPE, to synthesize a pillar-layered interpenetrated MOF with an exceptionally high fluorescence quantum yield (99%)[124]. Since then, this type of linear trans-TPE-based ligand has been widely applied in the construction of novel MOFs[71]. In the same year, Zhao et al. prepared a novel MOF using a mixture of cis- and trans- derivative ligands of BPyTPE, featuring a sugar gourd shape network structure connected by coordination cages and trans-ligands [Figure 7D][125]. Compared to MOFs constructed with purely cis- ligands, it exhibits unique thermally induced fluorescence color-changing behavior, showing potential for application in temperature sensor devices. In 2018, Zhao et al. introduced H2BCPPE into the bio-MOF-101-archetype structure through solvent-assisted ligand exchange (SALE) and successfully applied it to WLEDs [Figure 7E][121].

In 2018, Haldar et al. adopted a supramolecular approach by incorporating carboxylic acid-functionalized ligand, H2BCPPE, as a bidentate linker into SURFMOFs [Figure 7F][122]. This approach enabled precise control over oxidative photocyclization pathways and kinetics, achieving ~96% selectivity for a specific phenanthrene isomer. The constrained rotation of C=C double bonds within the crystalline framework enhanced product selectivity and accelerated reaction rates. Therefore, the emergence of novel MOF structures, facilitated by such desymmetrized ligand design, also positively influences the development of reliable platforms for studying reaction kinetics and mechanisms at the supramolecular level.

TPE units as pendant groups

An innovative strategy for ligand design involves grafting TPE units as pendant groups onto the ligand backbone. However, synthesizing MOFs using such ligands can be relatively challenging. Typically, they need to be mixed with ligands without pendant groups for synthesis or employ the post-synthetic ligand exchange method. In 2016, Li et al. employed a clever approach by using azole-linked TPE pendant group-modified triphenyl dicarboxylic acid derivative ligand, 4,4’-(2-(4-(1,2,2-triphenylvinyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4,7-diyl)dibenzoic acid (H2-etpdc), mixed with methyl-modified triphenyl dicarboxylic acid ligand, 2’,5’-dimethyl-[1,1’:4’,1’’-terphenyl]-4,4’’-dicarboxylic acid (H2-mtpdc), to hydrothermally synthesize the target MOF, UiO-68-mtpdc/etpdc

Figure 8. Schematic diagram for (A) the synthesis of mixed strut MOF UiO-68-mtpdc/etpdc[202], Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry; (B) the synthesis of AIE-responsive MOFs with different ratios of H2-tppetdc ligand[203], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. MOF: Metal–organic framework; AIE: aggregation-induced emission; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; NUS: National University of Singapore.

In 2020, Dong et al. also adopted a mixed ligand strategy to construct multivariate ligand-MOFs

STRATEGIC SELECTION OF METAL NODES

Despite the significant influence of ligand modulation on MOF properties, the selection of metal nodes remains equally critical, as there is a close correlation between the types of metals in MOFs and their properties and applications[26]. To improve the performance of TPE-based MOF materials, metal nodes have been extensively modified for precise control targeting specific applications, beyond adjusting organic linkers. According to HSAB theory, hard acids tend to bind with hard bases, while soft acids prefer to bind with soft bases. In MOFs, metal ions can be regarded as acids, and organic ligands as bases, providing important guidance for constructing stable MOFs. However, MOF collapse under specific external environmental conditions also holds significance for certain specific applications.

In 2020, Guo et al. successfully assembled two novel MOFs, Sr-ETTB and Co-ETTB, using H8ETTB with SrII and CoII cations [Figure 9A][112]. Sr-ETTB exhibited stimuli-responsive luminescence properties within a certain range of temperature and pressure. While the non-emissive Co-ETTB possessed fluorescence turn-on detection capability for histidine, attributed to ligand release and reorganization due to competitive coordination, resulting in AIE behavior with low detection limits and high selectivity.

Figure 9. (A) Fluorescence spectra of single crystalline Sr-ETTB at various pressures from 1 atm to 11.96 Gpa[112], Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH; (B) Temperature dependence of magnetic moments for various solvation states of {[Fe(L)-(TPPE)0.5]·3CH3OH}n (1·3CH3OH) and luminescence intensity at 460 nm relative to 300 K for 1 and TPPE[137], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; (C) Structure and topology of NKU-200-Ln[58], Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH; (D) The structure of Ag8 cluster and Ag12 cluster, and the gradual fluorescence changes of the corresponding MOF sample[136], Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH; (E) Metal–organic nanotube Ni-TCPE for the carbon dioxide cycloaddition to cyclic carbonates[38], Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society; (F) ECL Emission of TPPE and AgMOF[145], Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society; (G) HIAM-111 with 8-connected Na4 clusters for purifying C2H4 directly from C2H4/C2H2/C2H6[32], Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. ETTB: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-3,5-dicarboxylic acid)); TPPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; NKU: Nankai University; MOF: metal–organic framework; TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; ECL: electrochemiluminescence; AgMOF: novel silver metal–organic framework; HIAM: Hoffmann Institute of Advanced Materials; DMAC: N,N-dimethylacetamide.

Recently, materials with interactions or synergistic effects between two or more properties have attracted considerable attention. However, the correlation between spin crossover (SCO) and luminescence has been rarely studied due to their independent existence or mutual cancellation. In 2019, Ge et al. constructed a 2D iron(II) coordination polymer where luminescence is influenced by the spin state of FeII ions during thermal spin transitions[Figure 9B][137]. The spin state of FeII ions and the luminescence of TPPE can be mutually traced. This allows for the modulation of the emission characteristics of luminescent groups by switching spin states, while utilizing reliable and practical optical signals as probes for spin state changes, representing the first example in 2D coordination polymers.

Metal clusters, used as nodes in MOFs, offer advantages such as enhanced structural stability, increased functional diversity, and more flexible pore size and porosity control, compared to individual metal ions. MOFs based on zirconium clusters, aluminum clusters, lanthanide clusters, and other high-valent metal ion clusters demonstrate exceptional stability due to their robust Zr–O and Al–O bonds, as well as the strong connectivity between highly linked polynuclear clusters and multiple ligand coordination sites. TPE-based MOFs centered around zirconium clusters have been widely reported, with their stability and multifunctionality being well-recognized[85,206].

In 2024, Yu et al. reported a rare TPE-based MOF constructed from aluminum ions and ETTB ligands, designated as HIAM-330 (HIAM: Hoffmann Institute of Advanced Materials)[119]. This MOF features two distinct types of cavities, exhibiting high adsorption capacity, reversible adsorption, and high selectivity for sulfur dioxide (SO2), plus excellent recyclability due to its chemical and thermal stability. In 2023, Pang et al. synthesized a MOF (NKU-200-Eu, NKU: Nankai University) assembled from a Eu9 cluster and TCPE

Certain transition metal ions, such as copper, zinc, and cobalt, can easily form uncoordinated metal centers in MOFs, making them more likely to exhibit catalytic activities. These metal centers act as Lewis acid sites or coordination-unsaturated sites, effectively promoting chemical reactions. Additionally, the metal ion type also influences the pore size, shape, and chemical environment of MOFs, further regulating their catalytic performance.

In 2015, Zhou et al. pioneered TPE-based MOFs for organic catalysis by synthesizing Ni-TCPE1, a single-walled metal–organic nanotube MOF [Figure 9E][38]. Its open Ni active sites within pores function as Lewis acid sites to activate epoxy rings and as charge-dense binding sites for efficient CO2 capture, enabling stable and robust catalytic CO2 cycloaddition. This highlights the promise of metal–organic nanotubes in heterogeneous catalysis.

Subsequently, numerous cases of TPE-based MOFs for heterogeneous catalysis have been reported. For example, in 2019, Yang et al. constructed a porous Ag(I)-based coordination polymer using H4TCPE and silver ions, achieving high yields in CO2 carboxylation cyclization[41]. Its large pores facilitated rapid interaction and transport of substrate molecules, and the Ag(I) chains played a crucial role in the π-activation of internal alkynes. In 2020, Zheng et al. synthesized two novel 2D MOFs, 2D-M2TCPE (M = Co or Ni)[42]. These MOFs exposed more active sites through weakly coordinated paddle-wheel-like units with water molecules, thereby promoting CO2 adsorption and catalytic conversion. Under visible light, they can be exfoliated in situ to form nanosheets. Thereby, the electron transfer path is significantly shortened. Meanwhile, the separation and transfer of photogenerated charge carriers are facilitated. Based on this synergistic effect of dual regulation, MOFs served as efficient heterogeneous photocatalysts for CO2 reduction to CO.

MOF materials, with their high porosity, functional organic ligands, adjustable framework structures, and straightforward synthesis processes, have become ideal candidates for solid-state proton conduction across a wide temperature range. Two literature cases of MOFs constructed with TPE-based ligands and rare earth ions for proton conduction have fully demonstrated the feasibility of designing and preparing highly proton-conductive MOFs[90,114]. Hydrogen-bond networks formed by water molecules or charge-balancing ions within MOF pores are favorable for proton transport. Additionally, the inherent high stability of MOFs is leveraged in their design and preparation process.

Certain TPE-based MOFs, formed with specific metal ions, have also shown exceptional electrochemiluminescence (ECL) performance. For instance, in 2020, Huang et al. utilized Hf-ETTC as a novel ECL emitter[86]. Compared to H4ETTC monomers and aggregates, Hf-TCBPE exhibited significantly enhanced ECL intensity, attributed to restricted intramolecular rotation and MOF’s enrichment effects. Subsequently, they anchored ferrocene-labeled phosphate-terminated hairpin DNA (Fc-HP3) onto Hf-TCBPE to form a signal probe, constructing a novel “off-on” ECL sensor for ultrasensitive mucin 1 detection. This matrix coordination-induced ECL (MCI-ECL) enhancement strategy provides a fresh perspective for developing new ECL emitters for biosensing and clinical applications. In 2022, Xiao et al. prepared a novel silver MOF (AgMOF) as a self-enhanced ECL emitter [Figure 9F][145]. By combining aggregation-induced ECL (AIECL) emission of ligands with silver-catalyzed generation of more SO4•- from S2O82-, the AgMOF achieved strong and stable ECL signals. An ECL resonance energy transfer (ECL-RET) biosensor based on this MOF enabled sensitive and selective miRNA-107 detection, highlighting the potential of silver nanomaterials for ECL-based nucleic acid sensing.

The versatility of TPE-based MOFs in designing tailored structures for ECL applications highlights their potential. However, their performance is critically influenced by stability and electrical conductivity, which can be optimized through strategies such as incorporating cross-linkers, doping with conductive materials and optimizing pore structures.

Over the past two decades, the number of MOF structures has grown significantly, yet most are based on transition metals or lanthanides. In contrast, alkali metal-based MOFs, with their lower density, offer notable advantages in adsorption and separation. However, they have been scarcely reported due to the challenge of achieving stable structures and the relative complexity of their preparation processes.

In 2021, Yang et al. made a groundbreaking move by co-utilizing TPE-based ligands with alkali metal ions to construct MOF materials[91]. The synthesized anionic potassium organic framework, UPC-K1 [UPC: China University of Petroleum (East China)], possesses excellent chemical stability. In this novel structure, protonated dimethylamine (Me2NH2+) resides within the rhomboid channels. Based on the cation exchange and pore size selectivity, UPC-K1 demonstrates outstanding performance in the selective removal of planar cationic dyes and UO22+. In 2023, Miao et al. achieved a breakthrough by constructing a microporous MOF, HIAM-111 [Figure 9G][32]. With 8-connected Na4 clusters as metal nodes, HIAM-111 provides a Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area of up to 1,561 m2/g. Due to its stronger adsorption for C2H2 and C2H6 over C2H4, it enables one-step separation of C2H2/C2H4/C2H6, efficiently purifying C2H4.

In conclusion, by finely tuning the organic linkers and exploring diverse metal nodes, remarkable strides have been made in enhancing the performance of TPE-based MOF materials for tailored applications.

Replacing metal ions or metal cluster nodes with organic cations can sometimes yield stable periodic framework structures. In recent years, crystalline porous organic salts (CPOSs) have gained significant attention due to their rapid development[213,214]. They are porous materials formed by the self-assembly of organic acids and organic bases through ionic bonds, with extended periodic network structures. Although not MOFs, we briefly describe them here.

In 2024, Wang et al. successfully prepared two types of supramolecular ionic nanomaterials (SINs)

Figure 10. (A) Synthetic route to SIN-1 and SIN-2[215], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (B) Structural composition, emission wavelength, and the absolute quantum yields (Φf) of the organic salts[219], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (C) The zwitterionic strategy in constructing CPOSs by TPE-NS-Z and TPE-NS-E[220], Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. SIN: Supramolecular ionic nanomaterial; CPOS: crystalline porous organic salt; TPE: tetraphenylethylene; NS: amino group and sulfonic acid group; Z: Zusammen; E: Entgegen.

A new preparation strategy by employing zwitterionic strategies to construct CPOSs has been recently explored. This strategy simplifies the preparation process and achieves precise control over the structure and performance of CPOSs by introducing isomer compounds containing both anionic and cationic groups as single building units. In 2024, Wang et al. proposed the Zwitterionic strategy, using stereoisomers of 4,4’-(1,2-bis(4-ammoniophenyl)ethene-1,2diyl)dibenzenesulfonate (TPE-NS-Z and TPE-NS-E) isomers, to form CPOS-Z and CPOS-E via poor solvent induction [Figure 10C][220]. Especially, CPOS-E exhibited flexible pore characteristics, ensuring multiple controllable releases of high-polarity chemicals in different solvents. This work demonstrates the potential of zwitterionic strategies for constructing CPOSs for storage and controlled release.

INGENIOUS INTRODUCTION OF THE SECONDARY LIGAND

In the process of constructing MOFs, the introduction of second ligands is a common and crucial strategy for regulating the structural characteristics such as framework flexibility, pore size, and BET specific surface area[26,221,222]. It also endows MOFs with specific functionalities, including stimulus responsiveness, hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity modulation, and even enhanced framework stability. This approach is particularly prevalent in the construction of TPE-based MOF materials. Below are several classic cases and their applications.

Notably, in 2014, Gong et al. pioneered the use of benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid as a second ligand, along with TPPE ligand and zinc ions, to create a novel yellow phosphor without rare-earth elements[127]. This achievement demonstrated the potential of TPE-based MOFs in phosphor conversion for WLEDs. The following year, Hu et al. designed and synthesized a luminescent MOF (LMOF-241) using the second ligand biphenyl-4,4’-dicarboxylic acid (bpdc) and TPPE ligand, which effectively and selectively detected mycotoxins through a luminescence quenching mechanism[128].

TPE-based MOFs, as common sensing materials, possess porous structures that efficiently adsorb analytes. Thereby, the detection sensitivity and rate were enhanced, and the detection limit was significantly lowered. Their detection scope is broad, encompassing nitro explosives, metal ions, toxic gases, toxic ions, VOCs, antibiotics, mycotoxins, and pesticides[223-227]. Due to their high fluorescence brightness, TPE-based MOFs can achieve signal turn-off via stimulus-induced fluorescence quenching, primarily through photoinduced electron transfer (PET) and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), with PET being dominant[28]. Other mechanisms include the restriction of intramolecular motion and fluorescence turn-on resulting from framework dissociation. In 2025, Jiang et al. designed a MOF integrating two synergistic AIE linkers, TCPE and TPPE, for ultrasensitive and quantitative visual sensing of pesticide residues, achieving highly sensitive detection of 2,6-dichloro-4-nitroaniline (DCN) on fruit surfaces and contaminated soil[64].

The introduction of a second ligand strategy often leads to pillar-layered MOFs with flexible frameworks that are responsive to external stimuli. In 2018, Chen et al. employed a one-pot two-step synthesis method to construct a MOF material, named LIFM-66W, with anisotropic piezofluorochromic response

Figure 11. (A) Schematic illustration of the one-pot two-step synthesis of LIFM-66W and switch to LIFM-66Y[82], Copyright 2018, Elsevier; (B) Synthesis and structures of the Zinc-AIEgen MOFs[93], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; (C) Schematic illustration of the construction and the linker installation strategy of Zr-TCPE; The simplified illustration of anisotropic flexibility of Zr-TCPE and the rigidified MOFs[57], Copyright 2023, Springer Nature; (D) structure of FJU-94[59], Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH; (E) Illustration of the chiral reticular self-assembly strategy[140], Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. LIFM: Lehn Institute of Functional Materials; AIEgen: aggregation-induced emission luminogen; MOFs: metal–organic frameworks; TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; DLI: dual linker installation; FJU: Fujian Normal University; H4ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); UV: ultraviolet; H4TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; FRET: fluorescence resonance energy transfer; TSCT: through-space charge transfer; CPL: circularly polarized luminescence.

In 2020, Mayer et al. investigated the two-photon absorption properties of MOFs constructed with two TPE-based ligands as layers and bipyridine ligands as pillars[197]. They found that framework contraction introduced additional steric hindrance, enhancing the material’s single- and two-photon absorption properties. Notably, while the crystallinity of the coordination network was disrupted during compression, the improved performance indicated that coordination crystallization was not a prerequisite for performance enhancement. In 2022, Liu et al. constructed a densely packed luminescent TPE-based MOF structure and four pillar-layered MOFs with added pillar ligands [Figure 11B][93]. However, the incorporation of the pillar ligands significantly reduced the materials’ nonlinear optical properties. In 2024, Lv et al. successfully constructed a series of pillar-layered MOFs, named FJU-666 ([Zn2(DPBD)(TCPE)2]; Fujian Normal University, FJU), FJU-667 ([Zn2(DPA)(TCPE)2]), and FJU-668 ([Zn(DPBD)(TCPE)])[60]. These MOFs were utilized by TCPE and second ligands with varying numbers of electron-donating groups. Leveraging the high lattice matching among these MOFs, they further employed a seed-mediated epitaxial growth technique to build a series of multicolor MOF heterostructures. Within these MOFs, varying degrees of spatial twisting of second ligands enabled distinct responsive emissions upon subtle stimuli, generating tunable color patterns ideal for smart anti-counterfeiting labels. In summary, the introduction of second ligands is crucial for luminescent color regulation in MOFs, enhancing external stimulus responsiveness due to flexible frameworks but reducing luminescent efficiency because of decreased framework density.

By adopting the innovative post-synthetic modification strategy of dynamic spacer installation (DSI), researchers can effectively prepare mixed-ligand MOF materials. Zr-MOFs exhibit significant advantages in post-synthetic ligand insertion due to the highly adjustable coordination number of zirconium clusters and unique dynamic chemical properties, enabling rich structural transformations[228]. In 2023, Meng et al. synthesized a Zr-MOF, Zr-TCPE, with anisotropic flexibility [Figure 11C][57]. They employed post-synthetic modification to introduce secondary ligands into specific pockets, precisely controlling framework flexibility and TCPE ligand motion. Heat treatment experiments further confirmed the reversible anisotropic flexibility of Zr-TCPE. When L1 is inserted into site A, it partitions pores and inhibits benzene ring rotation in TCPE ligands, while L2 at site B suppresses intramolecular motion, collectively enhancing the fluorescence performance and structural stability. Stepwise ligand insertion produced Zr-TCPE-DLI (dual linker installation) with exceptional stability, offering new strategies for designing luminescent materials and separation media. A similar work was conducted by He et al. in 2025[99]. They achieved modulation of crystal packing density and ligand conformation by installing linkers within an interpenetrated TPE-based MOF and combining thermal activation, thereby enhancing the material’s single- and two-photon excited fluorescence properties.

In 2024, Xiong et al. used dipyridyl boron dipyrromethene (BDP) and TCPE as organic ligands to successfully construct a double-dipole MOF, FJU-94, with a unique pillar-layered structure [Figure 11D][59]. Its 2D rectangular microcrystals minimized scattering losses, while regulated photogenerated radicals enabled energy transfer from TCPE to BDP, inducing anisotropic photonic transport and modified reabsorption patterns in FJU-94L. This finding promotes the development of smart photonic regulatory devices based on MOFs.

The introduction of functional second ligands has also been attempted to impart targeted applicability to MOF materials. In 2020, Shang et al. made a breakthrough by combining the circularly polarized luminescence (CPL)-active pillar ligand camphoric acid (Cam) with TPPE, assembling MOF materials that respond to external stimuli and exhibit dual mechanical switching chirality-luminescent properties

There are many similar cases involving the introduction of functional secondary ligands for regulatory control. Not long ago, Wu et al. reported a novel method that utilizes pillar[5]arene-functionalized MOFs as supramolecular docking platforms for the efficient determination of single crystal structures of molecules containing long alkyl chains and complex mixtures through host-guest recognition[100]. In 2022, Xue et al. constructed a dual-ligand MOF using ETTC ligand and 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DN2H2) for the ECL bioassay of microRNA-141[94], where ordered heterogeneity restricted ETTC rotation and spatially arranged DN2H2 to significantly enhance excitation and electron transfer efficiencies.

In 2024, Lyu et al. conducted an intriguing study, skillfully constructing cationic, neutral, and anionic inverse Hofmann-type SCO MOF materials using TPPE ligands and cyanometallates with varying charges[146]. The cationic and neutral frameworks exhibited single-step thermally induced spin transition behaviors, while the SCO capability of the anionic framework was activated by partial desolvation. This innovative strategy offers valuable guidance and inspiration for introducing diverse metal nodes, counterions, guest molecules, and modulating the pore environment.

REGULATION OF SYNTHESIS CONDITIONS

By adjusting the synthetic strategy, one can prepare TPE-based MOFs with varying structures and properties using the same ligands and metal nodes. These changes may be as subtle as the formation of crystal defects or alterations in ligand conformation, or as significant as adjustments in the arrangement of TPE-based chromophores, changes in coordination modes, and variations in crystal size and morphology. Synthetic strategy regulation includes aspects such as feed ratio, solvent selection, pH adjustment, reaction temperature and time, reaction pressure, synthetic pathway, post-treatment processes, etc.

In 2019, Chen et al. studied the one-, two-, and three-photon excited fluorescence (1/2/3PEF) color-changing properties of five Zr-MOFs (including PCN-94, PCN-128, LIFM-66, LIFM-114, and LIFM-223) based on the ETTC ligand before and after pressure treatment [Figure 12A][85]. The fluorescence color-changing behavior of MOFs is closely related to their structural characteristics and pressure-induced deformations. Pressure treatment tightens ETTC chromophore arrangement in MOFs, enhancing intermolecular/intramolecular interactions and subsequently improving 1/2/3PEF performance. For convenience, a statistical comparison of multi-photon absorption properties of the reported TPE-based MOFs is provided [Table 1]. In 2020, Lv et al. skillfully adjusted the coordination mode by varying HCl concentration and synthesized MOF materials with 1D microwires and 2D microplate morphologies using TPBE ligands and Cd ions [Figure 12B][151]. Both single-crystalline microwires and microplates exhibit strong light confinement, making them excellent low-threshold MOF microlasers. In 2024, Liu et al. synthesized a single crystal, FJU-222, using a tetrazole-TPE ligand with elongated arms[229]. By altering synthesis conditions, they obtained an amorphous microsphere material, aMOF-1. Its size can be finely tuned by varying ligand concentration, a phenomenon induced by coordination defects. The size-dependent luminescent properties of aMOF-1 hold great promise for the construction of anti-counterfeiting devices.

Figure 12. (A) Structural characteristics of the five Zr-MOFs (PCN-94, PCN-128, LIFM-66, LIFM-114, and LIFM-223)[85], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; (B) Synthesis routes, microscopy images, and the structures of the FJU-96 microwires and FJU-97 microplates[151], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; (C) Schematic illustration of [M+–L–M-–L–M]∞ configured AIE MOFs for HCl vapor induced reversible luminescence and magnetic switch, and the fluorescence responsiveness of CoMOF towards different amino acids[50], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (D) Synthesis of Zr-TCPE-FA(x), monitoring spectral diffusion in Zr-TCPE-FA(50) and Zr-TCPE-FA(200), and images of Zr-TCPE samples with UV light on[56], Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. MOFs: Metal–organic frameworks; PCN: porous coordination network; LIFM: Lehn Institute of Functional Materials; FJU: Fujian Normal University; AIE: aggregation-induced emission; HCl: hydrogen chloride; CoMOF: cobalt-based metal–organic framework; TCPE: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; FA: formic acid; UV: ultraviolet; BTB: benzene tribenzoate; ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); DMF: N,N-dimethylformamide; AA: acetic acid; BA: benzoic acid.

Comparison of reported multi-photon absorption performance of TPE-based MOFs

| Materials | Two-photon absorption action cross-section (GM) | Ref. |

| (DMA)[In(TCPE)](sol)x | 3,072 | [79] |

| (DMA)[Zn(HTCPE)] | 1,053 | [79] |

| [Zr6O4(OH)4(TCPE)3] | 1,035 | [80] |

| [Hf6O4(OH)4(TCPE)3] | 292 | [80] |

| [Zr6O4(OH)6(H2O)2(CO2CF3)2(TCPE)2] | 3,582 | [80] |

| [Zr6O4(OH)6(H2O)2(OH)2(TCPE)2] | 2,590 | [80] |

| [Hf6O4(OH)6(H2O)2(CO2CF3)2(TCPE)2] | 1,984 | [80] |

| [Hf6O4(OH)6(H2O)2(OH)2(TCPE)2] | 1,823 | [80] |

| PCN-94 | 266 | [85] |

| PCN-94-pressed | 453 | [85] |

| PCN-128 | 153 | [85] |

| PCN-128-pressed | 1,897 | [85] |

| LIFM-66 | 31 | [85] |

| LIFM-66-pressed | 229 | [85] |

| LIFM-114 | 210 | [85] |

| LIFM-114-pressed | 2,217 | [85] |

| LIFM-223 | 1,383 | [85] |

| LIFM-223-pressed | 2,200 | [85] |

| C27H16O4Zn | ≈1.2 × 106 - 7.4 × 107 | [93] |

| C74H48N2O8Zn2 | ≈14-86 | [93] |

| C78H50N2O8Zn2 | ≈127-307 | [93] |

| C82H52N2O8Zn2 | ≈10-296 | [93] |

| C84H52N2O8Zn2 | ≈0.36-0.43 | [93] |

| SIFE-5 | 3,483 | [99] |

| SIFE-6 | 3,758 | [99] |

| SIFE-7 | 3,571 | [99] |

| SIFE-5a | 4,895 | [99] |

| SIFE-6a | 6,768 | [99] |

| SIFE-7a | 1,037 | [99] |

| LIFM-102 | 231.2 | [109] |

| LIFM-102a | 1,912.3 | [109] |

| LIFM-103 | 404.7 | [109] |

| LIFM-103a | 2,301.8 | [109] |

| [Zn2(TCPE)(bpy)] | 13.2 | [197] |

| [Zn2(TCPE)(bpy)]-contracted | 20.2 | [197] |

| [Zn2(TCPE-F)(bpy)] | 11.4 | [197] |

| [Zn2(TCPE-F)(bpy)]-contracted | 111.7 | [197] |

In 2021, Zhu et al. synthesized novel AIE MOFs (3D Zn/Co-MOF-Solv) with ligands in unique geometries and three coordination modes [Figure 12C][50], forming alternating [M+-L-M--L-M]∞ structures with metal clusters in +1, 0, and -1 charge states. This unique structure and HCl’s strong dipolar effect grant the material high sensitivity and selectivity in detecting HCl vapor. Meanwhile, CoMOF also showed a ferromagnetic to antiferromagnetic switch upon HCl adsorption. Non-emissive CoMOF also exhibits fluorescence turn-on upon encountering histidine. This research offers new insights into AIE MOF topological design and stimulus-responsive fluorescent sensing.

In 2023, Halder et al. synthesized a series of robust Zr-based MOFs using TCPE ligands [Figure 12D][56]. Taking these MOFs as platforms, how the precise arrangement of chromophores and MOF defects determines the material’s photophysical properties was investigated. Their study revealed that defects can be introduced through the regulation of acid modulator concentration, with a positive correlation between defects and spectral broadening; that is, more defects lead to wider spectral diffusion. In the work by Yin

POST-TREATMENT, NANO-PROCESSING, AND PREPARATION OF COMPOSITE MATERIALS

Post-treatment

Post-treatment is a common and crucial method for modifying the properties of MOFs. Previously, we mentioned the application of post-treatment in compressing MOF frameworks through pressure to alter their properties[228,230]. Additionally, strategies such as metal node substitution[110], ligand substitution[121], and post-synthetic modification using DSI[57], can also yield MOFs with new structures. In recent years, some novel and creative post-treatment methods have emerged. For instance, in 2021, Gong et al. constructed a MOF with silver ions as metal nodes, then replaced them with iodine cations using an iodine methanol solution [Figure 13A][141]. Iodine cations were introduced as connecting elements to form a stable, linear three-center four-electron [D···X+···D] halogen bond interaction, successfully creating an innovative 2D halogen-bonded organic framework (XOF). Various characterizations confirm that this XOF not only exhibits a well-ordered 2D crystal structure in the solid state but also maintains a stable 2D periodic structure in solution. This research expands the scope of organic framework structures and is significant for the development of new framework materials.

Figure 13. (A) Schematic diagram of the construction of [N···I+···N]-bridged XOF-TPPE[141], Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH; (B) Schematic diagram of the tailoring luminescence in the mesoporous MOF by encapsulation of different guest molecules[138], Copyright 2019, Chinese Chemical Society. XOF: Halogen-bonded organic framework; TPPE: 1,1,2,2-tetrakis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; MOF: metal–organic framework; CIE: International Commission on Illumination.

Another common post-treatment method for modifying MOF properties is adsorbing guest molecules. In 2019, Wu et al. synthesized a MOF based on silver-chalcogenolate clusters and TPPE, featuring extra-large pores with cubic cages up to 32 Å in diameter [Figure 13B][138]. By adjusting functional guest molecules, various luminescent effects such as CPL, white light luminescence, and room-temperature phosphorescence can be easily achieved, showcasing the MOF’s adaptability for customized luminescent applications. In fact, there are many studies on utilizing the large pores of TPE-based MOFs to adsorb dyes for the preparation of WLEDs, further proving the importance and wide application prospects of post-treatment techniques in MOF modification[49,143,190].

Nano-processing

Nanoscale MOFs offer several advantages. First, they significantly increase the material’s specific surface area, enhancing performance in adsorption, separation, and sensing. Second, they exhibit better biocompatibility and are more readily taken by cells, presenting broader biomedical applications, such as in drug delivery systems, multimodal imaging, and synergistic therapy[231-233]. On the other hand, AIE nanomaterials exhibit unique luminescent properties, maintaining high emission efficiency in the aggregated state while enhancing photostability. This characteristic makes AIE nanomaterials particularly suitable for bioimaging, biosensing, and theranostics, where high sensitivity and specificity are crucial[234,235]. By integrating TPE derivatives with AIE characteristics into nanoscale MOFs, one can leverage the structural advantages of MOFs with the luminescent properties of AIE, creating hybrid nanomaterials that excel in both performance and functionality[236].

In 2016, Wang et al. successfully prepared the first TPE-based nanoscale MOF material, Zr-TCPE NCPs (nanoscale coordination polymers) [Figure 14A][39]. The type and amount of acidic regulator in the synthesis conditions played a crucial role in determining nanoparticle size and morphology. Furthermore, the fluorescent emission characteristics of the material were closely related to the morphology of the nanoparticles. Owing to its high crystallinity, strong fluorescence, and good biocompatibility, this material demonstrated excellent performance in drug delivery and bioimaging.

Figure 14. (A) Schematic presentation of Zr-TCPE NCPs synthesis[39], Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry; (B) Schematic illustration of the synthesis and quencher-delocalized emission strategy of Cu-tpMOF in living cells for profiling of subcellular GSH. And SEM and HR-TEM images of Cu-tpMOF[139], Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH; (C) Schematic of the formation of the MOF nanotubes with hollow nanostructure and the application in self-indicating drug delivery. And SEM and TEM images of the MOF nanotubes[88], Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. TCPE: Tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)ethylene; NCPs: nanoscale coordination polymers; Cu-tpMOF: tetra(4-pyridylphenyl)ethylene (TPPE)-based metal–organic framework; GSH: glutathione; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; HR-TEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; MOF: metal–organic framework; AIE: aggregation-induced emission; FL: fluorescence; TCBPE: ETTC (4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid))); DOX: doxorubicin hydrochloride.

In 2022, Ren et al. synthesized the nanostructured MOF material HBU-20 (HBU: Hebei University) using zirconium ions and TCPE ligands[52]. With a BET surface area of 1,551.1 m2/g, HBU-20 exhibits exceptional SO2 adsorption capacity, efficiently capturing and separating trace SO2 from flue gas and natural gas. In the same year, Zhang et al. systematically investigated the regulation of Zr-TCPE’s morphology and particle size by adjusting various parameters, including acetic acid as a regulator for slow deprotonation, water as a co-regulator to alter MOF surface polarity, the mass ratio of TCPE to ZrCl4, and the addition of surfactants[54]. These adjustments aimed to enhance the detection performance of the material. Ultimately, this nano-MOF material was applied in the preparation of hydrogel composites and the development of point-of-care (POC) biochemical sensors.

In 2024, Geng et al. developed a solution-processable magnesium-based MOF (NKU-Mg-1)[62], where reversible COO-Mg coordination bonds enable dynamic control over nanocrystal size and aggregation via self-assembly. The resulting micrometer-sized MOF can be processed in solution to form a sol system. Based on this solution-phase regulation of aggregation states, the authors achieved modulation between CPL signals and fluorescence signals. This demonstrates how varying regulatory approaches can tailor nanoparticle size/morphology using identical metal nodes and ligands, significantly broadening their applications.

Recent studies have confirmed that TPE and its derivatives exhibit intrinsic delayed fluorescence properties and excellent scintillation performance in their organic single crystal forms[237,238]. Moreover, they also possess the potential to retain these photophysical characteristics when incorporated into nano-MOFs. In 2024, researchers achieved microsecond-scale long-lived emission in TPE-based MOFs through defect engineering strategies[65]. In 2025, Wang et al. conducted a deeper mechanistic investigation, uncovering a unique T1-blocked thermally activated delayed fluorescence (TADF) pathway in MOFs constructed from the TPE derivative H4TCPE and tetravalent metals (Zr, Hf, Th)[66]. This mechanism enables high-lying T2-state excitons to efficiently convert to the S1 state via a high-lying reverse intersystem crossing (hRISC) process, emitting delayed fluorescence, rather than through the conventional reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) process from the T1 state to the S1 state. This significantly enhances the utilization efficiency of triplet excitons, endowing M-TCPE with excellent scintillation performance under X-ray excitation.

Additionally, there are numerous other nano-MOF materials constructed based on TPE ligands. For example, in 2019, Zhu et al. assembled a non-emissive MOF nanoprobe using copper ions and TPPE ligands [Figure 14B][139]. This probe exhibits green fluorescent emission in a neutral environment upon excitation, due to partial delocalization of Cu ions through competitive binding with glutathione (GSH). In acidic environments, ligand protonation and MOF dissociation shift the emission to yellow, enabling sensitive subcellular GSH detection through this dual-emission, quencher-delocalized mechanism.

In 2021, Chen et al. synthesized a hollow hexagonal nanotube nano-MOF using Zr ions and ETTC ligands via a one-pot method [Figure 14C][88]. This unique morphology was formed through self-templated growth and a concave process. This pH-responsive MOF shows excellent biocompatibility, optical stability, and strong drug-loading capacity, with inherent fluorescence enabling real-time drug release tracking. Its pH-dependent release mechanism prolongs tumor cell killing through sustained delivery, highlighting the potential of TPE-based nano-MOFs for biomedical applications.

Composite processing

The construction of MOF composites effectively integrates the advantages of other materials, enhancing stability and imparting multifunctional properties, which significantly benefits the practical application of MOFs[239-242]. In 2022, Tan et al. prepared a novel composite by exfoliating 2D TPE-MOF crystals into ultrathin nanosheets and combining them with seaweed cellulose nanofibrils (CNFs) [Figure 15A][53]. The resulting transparent film exhibits enhanced fluorescence, good UV shielding capability, excellent optical transmittance, and improved mechanical properties, making it suitable for humidity sensing and UV protection. In the same year, Zhang et al. finely tuned a nanoscale MOF material (as mentioned above in the nano-processing section) and composited it with commercial red-emissive quantum dots and hydrogels to develop a hydrogel digital sensor [Figure 15B][54]. This material can directly absorb antibodies to form fluorescent-labeled particles, making it highly suitable for lateral flow immunoassay with ultra-high sensitivity and portability.

Figure 15. (A) Illustration for the exfoliation of the bulk MOF crystals into ultrathin 2D nanosheets and the process to prepare CNF/MOF assembly[53], Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH; (B) Fabrication of MAFs@QDs-PVP hydrogel complex[54], Copyright 2022, The American Association for the Advancement of Science. MOF: Metal–organic framework; 2D: two-dimensional; CNF: cellulose nanofiber; MAFs: metal-AIEgen (aggregation-induced emission luminogen) frameworks; QDs: quantum dots; PVP: polyvinylpyrrolidone; TOCNF: 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) free radical oxidized cellulose nanofibrils; AIEgen: aggregation-induced emission luminogen.

Incorporating guests into TPE-based MOFs via a host-guest strategy is a common method for composite material construction[138,143,147,190]. In 2025, Li et al. utilized this strategy by pre-incorporating guests into the synthetic precursors, instead of post-treatment, thereby encapsulating three different viologen derivatives in situ within the TPE-MOFs[63]. Variations in the viologen derivative guests led to differences in single crystal structures and morphologies. The three prepared photochromic MOFs show potential in organic amine detection and anti-counterfeiting applications.

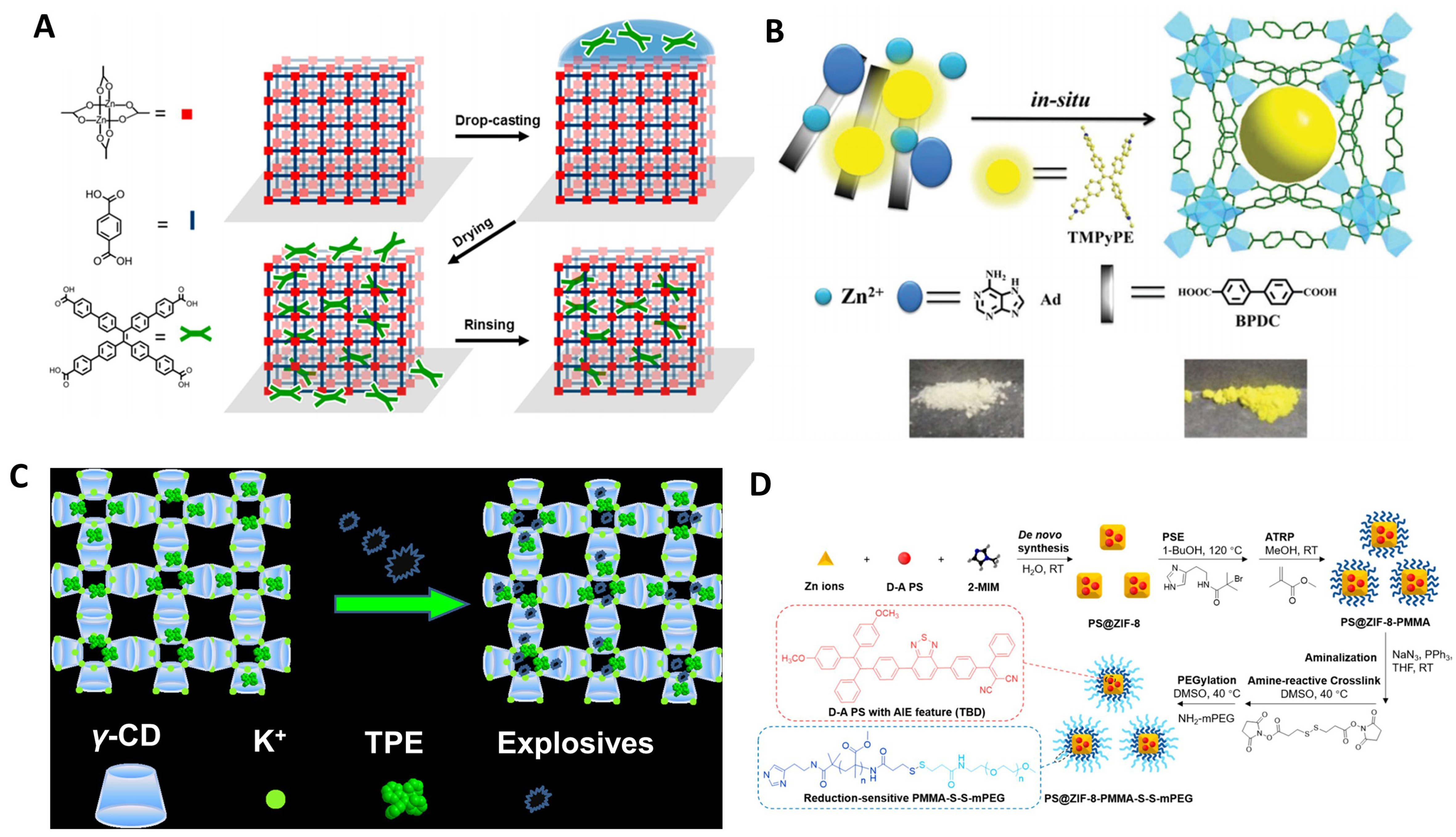

Additionally, synthesizing MOF-TPE derivative composites by coating or adsorbing TPE derivatives onto MOFs is also an effective strategy for preparing MOF composites with high fluorescence emission performance. The framework structure of MOFs can stably support the stacking environment of TPE derivatives, and the restrictions on rotors imposed by crystallization and various intermolecular forces further enhance the fluorescence emission effect. In 2018, Baroni et al. skillfully utilized a surface anchoring technique to firmly attach ETTC chromophores to the surface of a MOF material [Figure 16A][81]. Through precise adjustment of the chromophore concentration, they successfully identified the key concentration for achieving optimal luminescent efficiency.

Figure 16. (A) The process of postfabrication SURMOF loading by drop-casting with ETTC[81], Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society; (B) Schematic illustration of the encapsulation of TMPyPE into bioMOF-1, and photographs showing the change of colours before and after encapsulation[243], Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry; (C) Schematic illustration of the TPE@γ-CD-MOF-K with explosive detection properties[244], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; (D) Synthetic schemes to PS@ZIF-8-PMMA-S-S-mPEG[207], Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. SURMOF: Surface-anchored metal–organic framework; ETTC: 4’,4’’’,4’’’’’,4’’’’’’’-(ethene-1,1,2,2-tetrayl)tetrakis(([1,1’-biphenyl]-4-carboxylic acid)); TMPyPE: tetrakis[4-(1-methylpyridin-4-yl)phenyl]ethene; bioMOF: biological metal–organic framework; TPE: tetraphenylethylene; γ-CD: gamma-cyclodextrin; MOF: metal–organic framework; K: potassium; PS: polystyrene; ZIF: zeolitic imidazolate framework; PMMA: polymethyl methacrylate; S-S: disulfide bond; mPEG: methoxy polyethylene glycol; BPDC: biphenyl-4,4'-dicarboxylic acid; 2-MIM: 2-methylimidazole; RT: room temperature; PSE: postsynthetic exchange; ATRP: atom-transfer radical polymerization; TBD: 2-((4-(7-(4-(2,2-bis(4-methoxyphenyl)-1-phenylvinyl)phenyl)benzo[c][1,2,5]thiadiazol-4-yl)phenyl)(phenyl)methylene)malononitrile; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide; THF: tetrahydrofuran.