Functional fluorescent probes for efficient identification and detection of mercury ions based on fluorescence emission, quenching, and resonance energy transfer processes

Abstract

The issue of water pollution caused by heavy metal ions has been receiving increasing attention, particularly in the case of Hg2+ ions, which can significantly amplify their biological toxicity through bioaccumulation and stepwise magnification in the food chain. This review systematically summarizes and discusses common construction strategies for functional materials along with their applications in mercury ion recognition and detection. In addition to exploring the construction strategies, this review also delves into the diverse applications of these materials in mercury ion recognition and detection. Whether in environmental monitoring, where rapid and accurate detection of Hg2+ is critical for preventing contamination, or in biomedical research, where sensitive detection methods are essential for understanding the role of mercury in biological systems, these materials have demonstrated their versatility and effectiveness.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Mercury, as a common heavy metal, is commonly found in human activities and daily routines in various forms, including organic mercury compounds (e.g., methylmercury), inorganic salts, and elemental mercury[1]. Its presence can be attributed to natural cycles, industrial processes, and experimental research, resulting in a range of mercury compounds. However, mercury poses significant threats to living organisms, particularly mammals, causing numerous environmental concerns[2]. Studies reveal that mercury can infiltrate animals and humans via respiratory, dermal, or digestive routes. It can also accumulate in the environment and enter the human body through the food chain, ultimately causing irreversible harm to the immune or endocrine systems[3]. All stable forms of mercury can lead to central nervous system poisoning in various animals and humans, affecting organs such as the liver, heart, and brain. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the maximum permissible limit for Hg2+ ions in drinking water is 2 ppb. Exceeding this limit poses considerable risks to human health and the environment[4].

Hence, there is an urgent need to develop practical and reliable probes for Hg2+ detection, offering excellent selectivity and sensitivity to distinguish it from other metal ions or hazardous substances. This is crucial for protecting human health and the environment. Currently, some Hg2+ detections still heavily rely on instrumental analysis, such as atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), cyclic voltammetry, and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography[5-9]. Nevertheless, these methods often demand expensive and precise instruments, along with complex sample preparation and operation. Therefore, simple, precise, and cost-effective detection strategies for Hg2+ ions are essential for environmental conservation.

In recent years, researchers have sought alternative methods to address these challenges. Fluorescent probes, also known as fluorescent chemical sensors, convert biological and chemical events into analyzable fluorescent signals. Typically, these probes consist of functional groups with recognition sites, chromophores or fluorescent groups, and communication linkers. Since the advent of fluorescence-based chemosensing technology, considerable progress has been made in selectively detecting Hg2+ ions using small molecule fluorescent probes. This not only reduces detection costs but also simplifies the operation[10]. However, current research still faces challenges, such as limited photostability and solubility, small Stokes shift, and strong background fluorescence interference, restricting their practical applications. Thus, developing fluorescent probes for Hg2+ ions with easy accessibility, rapid response, high selectivity, and sensitivity remains a priority.

In this context, we provide an overview of the synthesis and applications of various functionalized two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) fluorescent probes (and their limitations) for selective Hg2+ detection and removal. We also discuss the underlying detection mechanisms to foster the development of simple, efficient, high-performance materials for Hg2+ detection. This is vital for the sustained growth of this emerging field. Furthermore, we offer a detailed explanation of each detection strategy and holistically evaluate various Hg2+ detection techniques by comparing different molecular structures and analyzing the distinct mechanisms of individual fluorescent probes.

This review distinguishes itself from other syntheses in the field through its focused and multi-faceted approach to the analysis of fluorescent probe technologies tailored for mercury ion detection. Notably, this review contributes unique insights by comprehensively examining not only traditional 2D fluorescent probes but also emerging 3D structures, thereby expanding the scope of discussion to encompass the latest advancements in material science and nanotechnology. A key difference lies in its integration of diverse fluorescence mechanisms (emission, quenching, and resonance energy transfer) within a unified framework for the efficient identification and quantification of mercury ions. Furthermore, the review underscores the practical implications of these functional probes by discussing their sensitivity, selectivity, and applicability in real-world environments, which is often overlooked in broader or more theoretical overviews, and it stands out for its nuanced exploration of both established and novel fluorescent probe designs, its rigorous examination of multiple fluorescence-based mechanisms, and its practical emphasis on performance metrics and environmental relevance, thereby offering a forward-looking perspective that is both comprehensive and innovative.

FLUORESCENT PROBES BASED ON AGGREGATION-INDUCED EMISSION PROPERTY

In 2001, Hong et al. discovered a unique luminescent phenomenon based on aggregation-induced emission (AIE). More specifically, they noticed that certain silole derivatives appeared non-emissive in dilute solutions but exhibited significantly enhanced luminescence when aggregated in concentrated solutions. This phenomenon is known as AIE[11]. The fluorescence or phosphorescence emitted in the aggregated state is due to restricted intramolecular rotation (RIR), which facilitates the release of energy from the excited state. Furthermore, numerous structures with AIE characteristics have been successfully employed in the creation of various functional materials. Leveraging these advancements, diverse molecules have been meticulously designed, developed, and implemented for the recognition and detection of mercury ions[12-21].

Recently, the fluorescent probe H based on benzothiazole structure was developed by Huang et al., and this material was successfully applied to Hg2+ detection based on excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) and AIE mechanism [Figure 1A][10]. The established fluorescent probe was proven to endow the merits of lower detection limit and a larger Stokes shift in a N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) mixed system with a water content of 60%; the material exhibits a lower detection limit and a larger Stokes shift. In addition, it also exhibits outstanding selectivity and excellent anti-interference ability. The author studied the mechanism of the interaction between the probe and Hg2+ by ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectroscopy and fluorescence spectroscopy of HBT-CHO and H + Hg2+. As expected, the UV-vis absorption and fluorescence spectra of these two substances are very similar. Moreover, probe H showed that the corresponding phenolic hydroxyl signal based on the HBT-CHO precursor disappeared. Based on the above mechanism verification experiments, it is not difficult to infer that the hydroxyl group of the modified probe is a functional group directly involved in mercury ion complexation [Figure 1B]. As shown in Figure 1C, the gradual addition of Hg2+ to a solution containing probe H under 380 nm excitation results in a notable enhancement of fluorescence emission at 550 nm. Moreover, in the presence of additional interfering factors, the introduction of a specific Hg2+ concentration (2 × 10-5 M) leads to a pronounced increase in fluorescence intensity across all samples, without any external interference. To further validate the effectiveness of this approach, probe H has also exhibited excellent cell biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity in live cells. Consequently, it holds significant potential for detecting and identifying Hg2+ residues within live cells [Figure 1D]. In summary, Huang et al. successfully designed and developed a novel benzothiazole-derived fluorescent probe H, which exhibited excellent performance in Hg2+ detection with high selectivity, low detection limit, and good cell biocompatibility[10]. The probe’s mechanism of action and interaction with Hg2+ were thoroughly investigated through spectral analysis, demonstrating its potential for practical applications in detecting Hg2+ in biological systems.

Figure 1. (A) Proposed mechanism of Hg2+ detection; (B) 1H NMR spectra of HBT-CHO, H + Hg2+ and H; (C) Fluorescence spectra of different metal ions and Fluorescence intensity (at 550 nm) of H + Hg2+ solution in the presence of various cations; (D) Fluorescence images of MCF-7 cells incubated with probe H[10]. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

The structure containing tetrastyrene units is a common AIE-emitting group, and a variety of AIE-active luminescent materials based on this basic structure have been designed and developed[22-31]. However, due to the narrow emission wavelength of tetraphenylethene (TPE) skeletons, the research on fluorescence Hg2+ probes based on tetraphenylethylene moiety is not abundant. In 2019, a new tetrastyrene-derived fluorescent probe, named TPE-M, was proposed and synthesized by Tang et al. This probe exhibited an enhanced fluorescence behavior by detecting the presence of Hg2+ [Figure 2A][32]. The recognition of Hg2+ by this developed fluorescent probe possessed the merits of rapid reaction kinetics, exceptional selectivity, heightened sensitivity, robust resistance to interference, and a remarkably low limit of detection. In order to verify the mechanism of Hg2+ induced probe TPE-M hydrolysis leading to the release of aldehyde compounds, the author conducted a detailed comparative 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis of the separated products of tetraphenylethenal and Hg2+ reacting with TPE-M. As shown in Figure 2B, the proton (Hb) signal of methylene in TPE-M appears at 5.31 ppm, and the chemical shift disappears after interacting with Hg2+. Notably, a chemical shift signal of 10.04 ppm can be clearly observed, which could be assigned to the aldehyde proton (Ha) of tetraphenylvinyl aldehyde. In addition, the 1H NMR spectra of the isolated product exhibited a high degree of similarity to that of tetraphenylvinyl aldehyde compound, thereby confirming that the interaction between TPE-M and Hg2+ resulted in the liberation of aldehyde structure. The fluorescence emission band located at 538 nm presented a progressive enhancement as the solution of the Hg2+ source was gradually added to the detection system, and emission intensity reached a stable state when the concentration of Hg2+ reached 1.5 equivalents [Figure 2C]. The obtained titration findings suggested that the TPE-M probe endowed a favorable sensing characteristic to mercury ions. Furthermore, the author systematically studied the detection and recognition of other metal ions by the probe TPE-M in order to further verify the specific recognition ability of TPE-M for Hg2+ [Figure 2D]. Unlike the phenomenon observed in Hg2+ detection, detection based on other metal ions did not exhibit significant fluorescence emission or quenching, and the results indicated that the selectivity of Hg2+ detection was higher than that of other metal ions detected. Therefore, TPE-M could be well applied not only under chemical conditions, but also in the detection of Hg2+ in real foods such as shrimp, crabs, and tea. The detailed mechanistic study confirmed the interaction between TPE-M and Hg2+, resulting in the liberation of aldehyde structure. The probe’s high selectivity for Hg2+ and its applicability in real food samples make it a promising candidate for Hg2+ detection in various conditions.

Figure 2. (A) Proposed mechanism; (B) 1H-NMR spectra analysis of compound 4, TPE-M with Hg2+ and TPE-M (DMSO-d6 as a deuterated reagent); (C) Fluorescence spectrum of TPE-M on incremental addition of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence spectrum of probe

AIE luminescence behavior is also applied in many fields, such as biological detection, bioimaging, etc.[33-45]. Besides, peptide probes are widely used in biological detection and sensing due to their excellent biocompatibility, low biological toxicity, and high water solubility[46-48]. In this content, functionalized tetrastyrene skeletons are easily attached to the peptide skeleton. For instance, a peptide fluorescent TP-2 was developed by Li et al., which was utilized in the mercury ion recognition and detection with high selectivity based on AIE phenomena[49] [Figure 3A]. This fluorescent probe was proved to possess the advantages of being characterized by high biocompatibility and excellent for bioimaging based on live cells. The response of the fluorescent probe with Hg2+ was investigated via 1H NMR titration experiments. As shown in Figure 3B, the amino group in TP-2 presented an obvious signal at a chemical shift of δ 8.23 ppm in the absence of Hg2+. The chemical shift intensity of -NH2 protons gradually decreases with the continuous addition of Hg2+, and this trend continues until the addition of 1.0 equivalents of Hg2+, accompanied by the corresponding disappearance of the chemical shift of amino protons. In addition, the molar binding ratio of TP-2 with Hg2+ was confirmed by Job’s plot method. Subsequently, spectral properties of TP-2 were also determined by using UV-vis absorption and fluorescence spectrum analysis. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to study the microscopic morphology of aggregates before and after the binding of TP-2 to the target metal ions [Figure 3C]. The fluorescence intensity of TP-2 at 470 nm gradually increased about 30 times with rising Hg2+ concentration [Figure 3D]. In anti-interference experiments, it has been proven that other metal ions have almost no effect on the fluorescence of TP-2 [Figure 3E]. It can be seen that combining functional molecules with AIE groups with mercury ion detection sites can not only effectively solve the problem of efficient recognition and detection of mercury ions from this work, but also successfully apply them to imaging applications in living organisms. This work enabled qualitative and quantitative detection of Hg2+ and could be used for live-cell imaging due to the effective cell permeability of TP-2.

Figure 3. (A) Molecular simulation diagram; (b)The 1H NMR titration experiment of TP-2 with different concentrations of Hg2+ in DMSO-d6 (left) and Job’s plot for determining stoichiometry of TP-2 with Hg2+ in buffer system (right); (C) TEM image of TP-2 in the absence and presence of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence emission spectrum analysis; (E) Specific detection and recognition experimental results[49]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; TEM: transmission electron microscopy.

In 2021, a fluorescent probe TPE-BTA bearing a TPE derivative as the mercury-binding fragment was designed and synthesized by Selvaraj et al.[50] [Figure 4A]. The fluorescent probe TPE-BTA demonstrated a relatively high quantum yield when immersed in a solution with a water content of 70%. Additionally, this fluorescent probe presented a unique AIE behavior, favorable photochromism, a large Stokes shift (178 nm), exceptional sensitivity, and an impressive detection limit (10.5 nM). The proposed interaction mechanism was systematically investigated through 1H NMR spectroscopy analysis. With the continuous addition of Hg2+ ions, the 1H NMR proton shifts of the methylene thiophene group’s protons Ha, Hb, Hc, and Hd show a significant upfield shift [Figure 4B]. In addition, the Hg2+ binding site was also fully characterized by comparing the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis [Figure 4C]. The fluorescence spectrum of TPE-BTA exhibited an obvious peak (550 nm), while the fluorescence emission peak intensity of the probe was significantly enhanced after introducing Hg2+ [Figure 4D]. Moreover, in the study of selective recognition and detection of several metal ions, the author found that when different metal ions were introduced into the probe solution, their fluorescence intensity remained unchanged. The established fluorescence probe exhibited low cytotoxicity below 50 mM, and it was easy to penetrate live HeLa cells, making it promising as a fluorescent biological imaging agent. In summary, the fluorescent probe TPE-BTA designed by Selvaraj et al. in 2021 showed excellent performance in detecting Hg2+ ions with high sensitivity and selectivity, as well as low cytotoxicity and good cell permeability, making it a potential candidate for fluorescent biological imaging[50]. Its unique AIE, favorable photochromism, and substantial Stokes shift further enhance its applicability in this field.

Figure 4. (A) Synthetic route towards fluorescence probe; (B) 1H NMR spectra analysis of probe with different equivalents of Hg2+ in DMSO-d6; (C) FT-IR spectra analysis of probe and probe with Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence emission spectra analysis of probe and probe with Hg2+[50]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier B.V. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; FT-IR: Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy.

Recently, Lei et al. designed and developed size-tunable and uniform AIE-activated materials with homogeneously functionalized AIE-activated tetraphenylethylene motifs and Hg2+ capturing thymidine groups [Figure 5A][51]. The results showed that the nanoplatelets displayed solvent-responsive fluorescence emission and exhibited excellent performance for detecting Hg2+ with a lower detection limit and excellent selectivity. To elucidate the reaction mechanism of the probe towards Hg2+, Lei et al. also tested the fluorescence spectra of AIE activated 2D nanoplates with different contents of mercury ion addition[51]. As shown in Figure 5B, a significant change in fluorescence was observed within about 10 s after the addition of Hg2+ sources. In addition, three samples were observed with repeated and subsequently unchanged responses within 10 min. This uniformly distributed AIE active TPE and Hg2+ capture thymine structure, which can form T-Hg2+-T cross-linking, thereby inducing a collective RIM effect throughout the corona segment, leading to fluorescence “turning on” through a synergistic mechanism. The modular functionalization of thymine units in corona formation blocks may be the reason why this material can effectively recognize and detect Hg2+. Subsequently, the selectivity of hybrid nanoplatelets was explored by testing aqueous solutions of various metal ions such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, Li+, Ni2+, Al3+, Fe3+, Hg2+, Co2+, Cr3+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Ag2+, and Mg2+ (added as chlorides) [Figure 5C]. The modular functionalized corona-forming blocks, containing uniformly distributed AIE-active TPE and Hg(II)-capturing thymine units, played a crucial role in the detection mechanism by forming T-Hg2+-T cross-links, which induced a collective RIM effect and led to fluorescence “turn-on”. The nanoplatelets showed high selectivity for Hg2+ ions even in the presence of various other metal ions, further highlighting their potential for specific Hg2+ detection applications.

Figure 5. (A) Mercury ion detection diagram based on functionalized AIE activated tetraphenylene motifs material; (B) Fluorescence spectrum analysis of AIE-activated materials and AIE-activated materials with Hg2+; (C) Fluorescence emission (λmax = 480 nm) analysis of AIE-activated materials and AIE-activated materials with Hg2+[51].Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. AIE: Aggregation-induced emission.

The fluorescent biopro based on peptidyl structure was successfully developed by coupling AIE unite (tetraphenylethylene) peptide receptors, and this bioprobe was proved to present a highly selective On-Off stimulus response to mercury ions [Figure 6A][52]. The established fluorescent probes have good selectivity, low detection limits and are useful in understanding how buffers are involved in aggregation of fluorescent probe and the complex formation. NMR hydrogen spectroscopy studies explained the way fluorescent probe 1 binds to Hg2+. As shown in Figure 6B, an upward shift of H1 and H2 corresponding to the imidazole proton was observed after adding Hg2+, indicating the corresponding coordination of Hg2+ with imidazole moiety. The small shifts of H4 and H7 indicate that the two carboxylic acid groups of 1 have chelated with Hg2+. Subsequently, dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements and TEM were employed to observe the interaction between the developed probe and Hg2+. These studies revealed the rapid formation of aggregates upon binding with Hg2+, which explains the significant enhancement in fluorescence emission intensity. Hg2+ fluorescence titration experiments were conducted on probe 1 in both phosphate-buffered aqueous solution and distilled water at pH 7.0 [Figure 6C]. The results showed that the addition of Hg2+ to distilled water led to a notable increase in emission intensity at 470 nm, reaching saturation at about 1.5 equivalents of Hg2+. In contrast, in the phosphate buffer solution, approximately three equivalents of Hg2+ were required to saturate the emission intensity change, resulting in a 100-fold increase at 470 nm. Moreover, this fluorescent probe demonstrates an On-Off stimulus response to mercury ions in both distilled water and phosphate buffer solution at pH 7.0. The probe exhibits a highly selective response to Hg2+ and does not show significant color changes in the presence of other metal ions [Figure 6D]. This work utilizes the AIE process to achieve selective detection of Hg2+ in aqueous solutions, with a detection limit that surpasses the maximum allowable content of Hg2+ in drinking water as specified by the EPA. The fluorescent peptidyl bioprobe 1, developed by conjugating tetraphenylethylene with a peptide receptor (AspHis), demonstrated a selective Off-On response to Hg2+ ions, and the probe showed high selectivity for Hg2+ ions and a low detection limit, making it suitable for the selective detection of Hg2+ in aqueous solutions, including distilled water and phosphate buffer solution at pH 7.0. This bioprobe has potential applications in monitoring Hg2+ levels in drinking water, ensuring compliance with EPA regulations.

Figure 6. (A) Proposed binding mechanism of fluorescent peptidyl bioprobe with Hg2+; (B) 1H NMR spectra analysis of peptidyl bioprobe with Hg2+; (C) Fluorescence spectra of peptidyl bioprobe with different concentration of Hg2+ in distilled water (left), and phosphate buffered aqueous system (right); (D) Fluorescence spectra of peptidyl bioprobe with different kinds of metal ions in distilled water (left), and phosphate buffered aqueous system (right)[52]. Copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

In 2022, Cheng et al. developed a practical fluorophore material with AIE properties based on ESIPT mechanism via a concise synthetic strategy. An efficient “turn-on” probe by connecting an ESIPT-type fluorophore [3-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-4′-(diphenylamino)-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-ol (HTO)] with a thioformate phenyl ester group with photoinduced electron transfer (PET) effect was successfully obtained [Figure 7A][53]. The probe showed good selectivity for Hg2+ with a rapid response performance and low detection limit. In order to study the interaction mechanism between the probe and Hg2+, a systematic study was conducted on the changes in reaction time and fluorescence spectra based on the probe and mercury ions. As shown in Figure 7B, the reaction of heavy and transition metal (HTM) with different concentrations of Hg2+ shows that the fluorescence intensity reaches its maximum value within

Figure 7. (A) Proposed binding mechanism of fluorescent of HTM with Hg2+; (B) Time dependent fluorescence intensity analysis of probe with Hg2+; (C) The fluorescence spectrum of HTM with different concentrations of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence spectra of HTM with different kinds of metal ions[53]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. HTM: Heavy and transition metal.

Over the past few decades, supramolecular polymers have received increasing attention in chemical sensors, drug delivery, biomaterials, and organic light-emitting diodes (OLED)[54-60]. Supermolecular self-assembly is a process of material self-assembly at the molecular level, typically involving intermolecular interactions such as electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, etc. Through these interactions, structures can spontaneously organize into materials with ordered structures that exhibit various properties, such as high strength, high toughness, conductivity, magnetism, optical properties, etc. Supermolecular self-assembly has broad application prospects and can be used to prepare various materials with specific functions, such as high-strength materials, magnetic materials, optical materials, sensors, drug carriers, etc. In addition, supramolecular self-assembly can also be used to prepare complex nanostructures, such as molecular machines, nanotubes, nanowires, nanopores, etc. These structures have important application value in fields such as nanotechnology, biomedicine, chemistry, and physics[61-65]. Supermolecular compounds with important functions can be prepared from small molecules with sizes ranging from nanometers to micrometers. Among them, macrocyclic structures are crucial in supramolecular chemistry due to their unique ability to bind guest structures. Based on these achievements, diverse functional macrocycles, including crown ethers[66,67], cyclodextrins[68,69], calixarenes[70], and cucurbiturils[71], are successfully developed for exploring advanced materials. In this context, pillar[5]arenes, which are composed of hydroquinone units connected by methylene bridges, have gained attention. Due to their unique symmetrical and rigid skeleton structure, low synthesis cost, and ease of functionalization, they are often used in the synthesis and modification of functional materials. In addition, various supramolecular assembly drivers based on columnar aromatic hydrocarbons, such as π-π, cations-π, C-H-π, hydrophobic interactions, etc., thus providing a new platform for the development of various interesting supramolecular stimulus responsive smart polymers[72].

In 2017, a new supramolecular system was successfully generated by Cheng et al. by using the TPE and thymine-substituted copillar[5]arene as the starting materials for efficient mercury ion recognition and detection. The current protocol was established under the mechanism of AIE to facilitate the subsequent mercury ion containing nanoparticles detection and the removal process[73] [Figure 8A]. Significantly, the host-guest complex could be successfully recovered through a straightforward process involving the use of sodium sulfide in a mixed solvent system of dichloromethane and acetone. As shown in Figure 8B, the fluorescence intensity exhibited a progressive increase upon the addition of Hg2+ at a wavelength of 460 nm. The TEM and SEM characterizations in Figure 8C depicted the morphology of the 2⊂1@Hg2+ complex, while DLS confirmed that the diameter of the spherical aggregates is approximately 250 nm. 1H NMR experimental results indicated that the imide proton signal diminished as the concentration of Hg2+ increased, which provided confirmation of the generation of T-Hg2+-T pairs between copillar[5]arene and Hg2+ [Figure 8D]. Moreover, the changes in UV-vis spectra in the presence of Hg2+ supported this conclusion. With the gradual addition of 1.0 equivalent amount of Hg2+, the absorption intensity of copillar[5]arene in acetone increased notably, and the absorption maximum underwent a slight shift from 326 to 329 nm. Furthermore, the detection and removal of Hg2+ were not interfered with by other metal ions [Figure 8E]. This study provided a method for detecting and removing other environmental pollutants in the future by constructing supramolecular polymers containing metal ions to perceive and remove heavy metal ions in water.

Figure 8. (A) Proposed formation of supramolecular polymer process for Hg2+ removal; (B) Partial spectra of 1H NMR titration of 1 with Hg2+; (C) Characterization of the supramolecular complex 2⊂1@Hg2+. TEM and SEM images of 2⊂1@Hg2+. DLS study of 2⊂1@Hg2+ ([1] = [Hg2+] = 0.50 mM; [2] = 0.25 mM); (D) Fluorescence spectral analysis of 2⊂1 with different concentrations of Hg2+; (E) Fluorescence intensity of 2⊂1 in the presence of various metal ions[73]. Copyright 2017 American Chemical Society. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscope; DLS: dynamic light scattering.

Recently, Yang successfully synthesized fluorescent supramolecular polymers by leveraging supramolecular host-guest interactions. This achievement was attained through the innovative design of a biphenyl-linked pillar[6]arene hydrocarbon, featuring two thymine sites as the arms (H), and a tetraphenylethylene bis-quaternary ammonium guest (G) that possesses AIE properties. The resulting system, through the formation of host-guest complexes between H and G, demonstrates the potential for the creation of novel fluorescent materials with supramolecular architectures, which were effectively applied to recognition and detection of Hg2+ [Figure 9A][74]. These supramolecular polymers were proven to possess the merits of rapid response, exceptional selectivity, and a high rate of adsorption. Furthermore, these polymers could be effectively regenerated and reused through direct treatment with Na2S without experiencing any material loss. The association and binding between the cations G and H were also examined through 1H NMR exploration. 1H NMR results exhibited distinct upfield shifts in the resonances of H1, H2, and H4 protons in phenyl and biphenyl groups, while the resonances of H3 and H5 protons experienced downfield shifts [Figure 9B]. These observations provided additional evidence to support the occurrence of host guest encapsulation, which was promoted by the electrostatic interaction between the electron rich cavity of H and electron deficient quaternary ammonium group of G. As shown in Figure 9C, a spherical supramolecular assembly known as G⊂H@Hg2+ could be formed when the supramolecular polymer G⊂H was introduced into the aqueous solution, and this component exhibited significant fluorescence enhancement under 312 nm UV irradiation. Moreover, other metal ions did not turn on fluorescence despite the same conditions presented in Figure 9D. This study provided a practical and reliable tactic for selective detection and rapid removal of toxic Hg2+, offered promising potential for addressing environmental remediation of heavy metal ion contamination, and stimulated new ideas in adsorbent material design.

Figure 9. (A) Schematic representative of regeneration−recycling process for Hg2+ removal; (B) 1H NMR spectra of (1) G, (2) The equimolar mixture of G and H, and (3) H; (C) Fluorescence spectral analysis of G⊂H, H, and G with different concentrations of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence intensity of G⊂H in the presence of various metal ions[74]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

THE DETECTION OF HG2+ BY THE FLUORESCENCE QUENCHING METHOD

Fluorescence detection has become a convenient and cost-effective detection method, whereas traditional detection methods are not only expensive but also lack portability. Carefully designed probes can eliminate interfering substances and display unique fluorescence signal changes, which can be divided into fluorescence enhancement, fluorescence discoloration, fluorescence quenching, etc.[75]. In 2018, two fluorescent probes, DFBT and DFABT, and their corresponding water-soluble forms WDFBT and WDFABT based on the benzo[2,1,3]thiadiazole (BT) moiety were synthesized by Cui et al., and the luminescence behavior of these fluorescent probes on Hg2+ was also studied through absorption and emission spectra analysis [Figure 10A][2]. These fluorescent probes exhibited specific detection behavior for Hg2+ in solution with a maximum detection limit (10-7 M). Additionally, by altering the bridging mode between functional units from a C≡C triple bond to a C–C single bond, the probe type can be transformed from irreversible to reversible[76,77]. In order to elucidate the underlying chemical mechanisms involved in the detection process, the reversibility of both probes was examined through the assessment of the reproducibility of the fluorescence signal. A clear fluorescence quenching was observed after adding Hg2+ ions to the aqueous solutions of WDFBT and WDFABT [Figure 10B]. Upon the subsequent addition of an excessive amount of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to the mixed solution, WDFABT exhibited almost no emission recovery. This lack of recovery can be attributed to the mercury ions catalyzed acetylene hydration reaction, commonly known as the Kucherov reaction. In addition, mass spectrometry was also utilized to reveal the comprehensive examination of the structural modifications occurring upon the introduction of Hg2+ and EDTA. The binding ratio between the probes and Hg2+ ions was determined to be 2:1 for DFBT and WDFBT. This coordination reaction resulted in a fluorescence quenching, which was attributed to the partial transfer of the excited state charge from the electron-rich BT to the electron-deficient Hg2+ ions. Both DFABT and WDFABT had a binding ratio of 1:1 with Hg2+ ions. An irreversible decomposition reaction took place, causing fluorescence quenching. This quenching was primarily attributed to the disruption of the conjugated framework within the probe molecule. The emission band intensities of DFBT and DFABT at 547 and 525 nm gradually decreased after adding Hg2+, and the fluorescence intensities of WDFBT and WDFABT also reduced with the increase of Hg2+ concentration

Figure 10. (A) Potential mechanism by which probes WDFBT and WDFABT detect mercury ions; (B) Spectral emission variations in probes’ buffer solutions prior to and following the addition of Hg2+ and EDTA, specifically for WDFBT and WDFABT; (C) Alterations in fluorescence spectra for DFBT (left) and DFABT (right) dissolved in dichloromethane; (D) Changes in fluorescence spectra of WDFBT (left) and WDFABT (right)[2]. Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry. EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

So far, various sensors utilizing fluorescent organic nanoparticles (FONs) have been documented, primarily created through methods such as core-shell structure design[78-82], self-assembling nanoparticle engineering[83-88], and the sol-gel technique[89-95]. Recently, a FONs-based sensor was devised by incorporating 3-perylenecarboxaldehyde (PlCA) as the fluorophore and L-methionine (Met) as the recognition element through a straightforward hydrothermal process, specifically tailored for the detection of mercury ions. The detection of Hg2+ by this probe might involve a process of photoelectron transfer, which was caused by specific coordination interactions [Figure 11A][96]. This study introduced the advancement and successful implementation of a unique visual detection tool leveraging FONs for the semi-quantitative assessment of Hg2+ ions. It was worth noting that this was the first time this device had been developed and utilized for visual inspection. In addition, this sensor could effectively detect the presence of Hg2+ in various sample types, including environmental samples, water samples, tea samples, and apple samples. To elucidate the mechanism of the mercury ion recognition and detection, the UV-vis absorption spectra of the PlCA-M system with and without Hg2+ addition had also been systematically studied. As shown in Figure 11B, the peak near 250 nm showed a significant increase with the addition of Hg2+, indicating that PET may be the mechanism for obtaining PlCA-M-based sensors. Due to the abundant C=N, -OH, and -S sites in PlCA-M, these electron rich parts could effectively form coordination bonds with electron deficient Hg2+ with the addition of mercury ions. The fluorescence intensity of PICA-M changed significantly only after adding Hg2+, indicating that the prepared PICA-M had a high specificity for Hg2+ [Figure 11C]. As illustrated in Figure 11D, the fluorescence intensity variations triggered by Hg2+ alone or Hg2+ complexed with interfering ions were nearly identical. This demonstrates that the existence of interfering ions did not influence the capacity of PlCA-M to sense and discern Hg2+. The aforementioned experimental outcomes show that the PlCA-M sensor exhibits excellent selectivity and resistance to interference for the target metal ions, along with strong selectivity, high sensitivity, and precise accuracy. More importantly, a secure card based on fons FPBT@PlCA-M was successfully developed for the first time in this study; it expanded the application of FON materials.

Figure 11. (A) Schematic representation of the synthesis of PICA-M and the potential quenching mechanism of Hg2+ on PlCA-M, along with its application; (B) UV-vis absorption spectra of PlCA-M, PlCA-M under acidic conditions (pH = 3.07), and PlCA-M with the addition of Hg2+ under neutral solubility; (C) Changes in fluorescence intensity of PlCA-M before and after the addition of various metal ions; (D) Interference from other ions by PlCA-M[96]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. UV-vis: Ultraviolet-visible.

In 2014, Hu et al. designed and synthesized a novel non-sulfur simple fluorescence chemical sensor for mercury, named L, which was based on the benzimidazole group and featured the quinoline group as the fluorescence signal group [Figure 12A][97]. By observing fluorescence spectral variations in a H2O/DMSO (1:9, v/v) solution, this receptor exhibited the ability to instantly detect Hg2+ cations specifically and with high sensitivity, as opposed to other cations such as Ca2+, Cu2+, Cd2+, Fe3+, Ag+, Ni2+, Cr3+, Pb2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, and Co2+. As depicted in Figure 12B, the fluorescence color of the solution containing sensor L underwent a noticeable transition from blue to colorless only in the presence of mercury ions in the aqueous medium, whereas other cations did not induce a significant color shift. Furthermore, sensor L demonstrated specific selectivity, high sensitivity, and a remarkably low detection limit of 9.56 × 10-9 M. This threshold is considerably below the maximum permissible level of 0.01 M mercury in drinking water, as per EPA guidelines. Additionally, a mercury ion test strip was developed based on sensor L, offering a convenient and efficient means for mercury ion detection. Consequently, this probe holds promise for potential applications in monitoring mercury in aquatic environments [Figure 12C and D].

Figure 12. (A) Possible sensing mechanism; (B) 1H NMR spectra of L with different concentrations of Hg2+; (C) Fluorescence titration spectra of L with different concentrations of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence spectra of L with the addition of various metal ions[97]. Copyright 2015, Royal Society of Chemistry. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

In 2019, Liu et al. introduced a novel detection mechanism based on the orbital interaction between the detector L and Hg2+[75]. By examining the excitation process and the deactivation of the excited state in organic metal compounds formed by L and mercury ions, they identified two non-emissive channels: intermolecular electron transfer and system crossing. The combined effect of these two channels resulted in significant fluorescence quenching of L [Figure 13A]. Initially, the strong orbital coupling between the mercury ion and L ensured the presence of the mercury ion during both excitation and relaxation processes, leading to the formation of intermolecular electron transfer states between S0 and S2. Secondly, the heavy atom effect of mercury ions opened up an additional channel for non-emissive deactivation. The synergistic action of these two mechanisms led to pronounced quenching of the L probe, enabling precise and selective detection of mercury ions. This article presented a new approach for designing Hg2+ fluorescence probes [Figure 13B], providing valuable insights for future probe development and mercury ion detection methods.

Figure 13. (A) FO interactions L with Hg2+; (B) Starting geometry and optimized geometry for tetra-coordinated Hg-L[75]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. FO: Fragment orbital.

Wang et al. achieved the successful synthesis of Tb-L0.2P0.8 metal-organic gels (MOGs) through a straightforward mixing process involving Tb salts, luminol, and Phen. This novel dual-ligand material, featuring a 2D structure, was created via gelation at room temperature [Figure 14A][98]. The developed ratiometric fluorescence probe simplified and enhanced the monitoring process of Hg2+ levels in both porphyra and tap water. According to Figure 14B, it is evident that as Hg2+ concentrations escalated, the fluorescence intensity at 424 nm underwent a notable decrease. Conversely, the fluorescence intensity at

Figure 14. (A) The synthetic route towards MOGs and a schematic illustration of ratiometric fluorescence detection for Hg2+ are presented; (B) Fluorescence emission spectra show the response of MOGs when exposed to various concentrations of Hg2+ under 290 nm excitation; (C) FT-IR spectra demonstrate the characteristics of MOGs both without and with the presence of Hg2+; (D) Competitive interfering experiments[98]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. MOGs: Metal-organic gels; FT-IR: Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy.

Liu et al. developed a range of π-conjugated macrocycles featuring shape-persistent structures, adaptable backbones, and AIE characteristics by replacing butadiynylene connectors with ethylene ones

Figure 15. (A) Synthesis of TPEMCS; (B) NOESY spectrum (aromatic region) of TPEMCS and the proposed rotation of thiophene rings in shape-persistent macrocyclic backbone; (C) Photoluminescence spectra analysis of TPEMCS with different concentrations of Hg2+; (D) Photoluminescence spectra analysis of TPEMCS with the addition of various metal ions[99]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. NOESY: Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscop.

Fluorescent self-assembled materials with advanced structural and supramolecular host-guest interaction stimulus-response properties have also attracted the attention of various researchers[100-107]. Columnar aromatic hydrocarbons represent a novel category of macrocyclic host molecules, succeeding established classes such as crown ethers, cyclodextrins, and calyxarenes (commonly known as gourd seeds). Columnar aromatic hydrocarbons have a unique columnar structure and exhibit significant binding properties. In addition, their low synthesis cost and ease of functionalization contribute to their widespread applications in various fields, such as chemical sensors, transmembrane channels, molecular mechanics, and supramolecular polymers.

In 2022, Cao constructed a fluorescent supramolecular system in pure water through the self-assembly of carboxylatopillar[5]arene sodium salts (H) and diketopyrrolopyrrole-bridged bis(quaternary ammonium) guest (G). This system could effectively trigger a fluorescence burst in H and G through synergistic action upon the addition of Hg2+ [Figure 16A][3]. The established fluorescent supramolecular system showed good selectivity for Hg2+ with low detection limit (LOD = 7.17 × 10-7 M), and fluorescence of H⊃G@Hg2+ burst could be restored after post-treatment with the addition of Na2S. The author also conducted a 1H NMR analysis of H and G in the presence of Hg2+ in D2O to gain insights into the mechanism behind Hg2+ detection. Their findings revealed that the proton signals corresponding to the thiophene groups (Ha, Hb, and Hc) from J exhibited a slight upshift. Notably, the signals for H2, H3, and H1 from H showed a considerable upshift in the presence of Hg2+ [Figure 16B]. Furthermore, the disappearance of the split peak for H1 suggests complex interactions occurring between H, G, and Hg2+. The fluorescence emission intensity at 560 nm decreased with increasing Hg2+ content [Figure 16C]. However, adding other metal ions induced different degrees of enhancement of the fluorescence intensity [Figure 16D]. Anti-interference experiments showed that other competing cations did not affect the response of H, G to Hg2+. The construction of this fluorescent supramolecular system provided supramolecular fluorescent materials based on column aromatic hydrocarbons, which could not only fluorescently detect Hg2+ with high selectivity but also efficiently remove Hg2+ and realize reversibility [Figure 16E]. Besides, H and G could effectively detect Hg2+ concentration in real samples (tap water and lake water). The developed 100% in-water supramolecular system possessed remarkable potential for the detection and removal of Hg2+, aligning perfectly with the goals of environmental sustainability. Its unique ability to operate entirely within an aqueous environment eliminated the need for harmful solvents, thereby minimizing environmental impact. This innovative approach not only offered a new method for efficient Hg2+ detection and removal but also contributed significantly to promoting environmentally friendly practices and ensuring long-term ecological sustainability.

Figure 16. (A) Synthetic route. The host molecule H and the guest molecule G were synthesized through a series of chemical reactions, carefully controlled to ensure purity and efficiency; (B) The partial 1H NMR titration spectra of the H⊃G complex were recorded with varying equivalents of Hg2+ to observe the chemical shifts and interactions between the host-guest complex and the mercury ions; (C) Fluorescence spectra were obtained for the self-assembled H⊃G complex in the presence of increasing concentrations of Hg2+ to investigate the fluorescent response and sensitivity of the system to mercury ions; (D) The emission spectra of the H⊃G self-assembly were measured in an aqueous solution after the addition of 50 equivalents of various metal ions to assess the selectivity and specificity of the system towards different metals; (E) Photographs were taken of H⊃G-loaded filter paper exposed to Hg2+ and then treated with S2-, illuminated with 365 nm UV light, to visually demonstrate the system’s response to these specific ions[3]. Copyright 2022, MDPI. UV: Ultraviolet.

Recently, an allyl- and hydroxyl-functionalized covalent organic framework (COF) material, named AH-COF, has been developed for the detection and removal of mercury ions [Figure 17A][108]. The developed AH-COF material was confirmed to have good uniqueness, high sensitivity, easy visualization, and real-time response and could be efficiently recirculated in NaBH4. The author studied the 1H NMR spectra of allyl and hydroxy groups reacting with mercury ions further to understand the reaction mechanism of AH-COF in detection and effectively removing mercury ions. As shown in Figure 17B, the

Figure 17. (A) Synthetic route towards AH-COF; (B) 1H CP/MAS NMR spectra analysis; (C) Fluorescence titration experiments show the response of AH-COF dispersed in acetonitrile upon gradual addition of Hg2+; (D) Competition experiments were conducted to assess selectivity. In (B), the green bars represent the fluorescence response of AH-COF upon the addition of competing ions (2.0 equivalents), while the purple bars indicate the fluorescence response upon subsequent treatment with Hg2+ in the aforementioned systems[108]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier B.V. COF: Covalent organic framework; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance.

In 2023, Li et al. modified cellulose substrates using the AIE properties of DNS-Cl to prepare a multifunctional adsorbent material, DFCA, while detecting and removing mercury ions from aqueous solutions. This fluorescent probe has excellent selectivity and a low detection limit [Figure 18A][109]. DNS-Cl exhibits green emission at 505 nm in water due to its AIE [Figure 18B]. As shown in Figure 18C, the interaction between DFCA and metal ions in water was studied using fluorescence sensing technology. Adding mercury ions to an aqueous solution of 0.1-8.0 mg/L gradually quenches the sample’s fluorescence. To understand the possible interaction mechanism between DFCA and Hg (II), the author verified through density functional theory (DFT) calculations and XPS analysis that O, N, and S atoms participate in the adsorption of Hg (II), and the sensing site coordinates with Hg (II) ions, resulting in a reversal of the structure of the naphthalene ring unit [Figure 18C]. The aggregation of the danoyl moiety is disrupted by the contraction of the carbon chain. Therefore, AIE is efficiently quenched by metal ion recognition. DFCA only showed significant fluorescence quenching when adding Hg (II) in the metal competitive titration experiment. In contrast, other metal ions showed almost no change during the continuous titration process [Figure 18D]. At the same time, the relative changes in fluorescence intensity of all tested metal ions during the titration process can be observed in Figure 18E, where the fluorescence emission of DFCA decreased by 87% on Hg (II). In contrast, the other metal ions showed little change. The integration of fluorescent sensors onto cellulose, a solid adsorbent material, holds promise for their application in the aqueous phase, thereby broadening their potential usage scenarios.

Figure 18. (A) The synthesis pathway of the multifunctional adsorbent DFCA; (b) DFCA’s fluorescence sensing capability for mercury ions in an aqueous environment, with insets showing the fluorescence quenching effect upon the introduction of mercury ions; (C) The proposed mechanism of interaction between DFCA and mercury ions; (D) The fluorescence response exhibited by DFCA in the presence of various metal ions in water; and (E) the fluorescence quenching ratio observed in the adsorbent material when exposed to different metal ions in water, accompanied by photographs of the DFCA sample in natural light and under 365 nm UV illumination, as well as images showing metal ion-treated DFCA in water under 365 nm UV light[109]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V. UV: Ultraviolet.

In a recent study, Song et al. reported a controllable synthesis of magnetic carbon dots (M-CDs)

Figure 19. (A) The synthesis of GSH-CDs, Fe3O4 NPs and M-CDs; (B)Schematic mechanism for the binding of M-CDs to Hg2+; (C) The fluorescent intensity ratio I/I0 of M-CDs with various metal ions (100 μM) vs. Hg2+ (100 μM); (D) FL spectra of M-CDs exposed to different concentrations of Hg2+ (0-100 μM); (E) The linear fitting of I0/I vs. the Hg2+ concentration (0.008-0.08 μM, R2 = 0.999). Inset in (D): corresponding sample image under UV light[110]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V. FL: fluorescence emission; UV: ultraviolet.

THE DETECTION OF HG2+ BY FLUORESCENCE RESONANCE ENERGY TRANSFER

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a process by which light energy transfers from one molecule to another, causing the fluorescence signal to increase in intensity[111-119]. It is a fundamental process in molecular biology and has numerous applications in fields such as molecular medicine, biotechnology, and chemistry[120-129]. In addition, FRET goes through a process called fluorescence activation energy transfer (FAET), where the energy of the light is transferred to the protein or DNA, causing it to become activated and emitting a fluorescence signal. Moreover, FRET is usually triggered by an external signal, such as a photon or reaction, and can be used to detect the presence of a specific protein or measure the amount of a particular compound in a sample. In recent years, FRET has been used in many experiments in molecular biology, including the detection of disease-related proteins, the analysis of chemical reactions, and the development of new drugs. In addition, FRET is also being used in biotechnology to develop new materials and devices, such as biosensing and artificial cells[118,129-138].

Based on the many advantages of FRET, many fluorescent probes have been reported in recent years for designing Hg2+ systems. Luxami used an ethylenediamine spacer to connect naphthalimide derivatives with rhodamine B and developed a FRET-based sensor for the proportional detection of Hg2+. The FRET chemical sensor comprised a 1,8-naphthalimide donor and a rhodamine thiosemicarbazide receptor, which was successfully developed by Guo et al. In 2015[139], a pair of 1,8-naphthalimide-Rhodamine based chemosensors R6G-NA and RB-NA with high selectivity and sensitivity for Hg2+ detection were designed and synthesized by Fang et al. [Figure 20A][140]. This chemical sensor could not only be used for quantitative and reversible detection of Hg2+ but also had the characteristics of high sensitivity and short response time. The R6G-NA system exhibited a characteristic emission band belonging to the 1,8-naphthalimide fluorophore only at 520 nm when excited at 450 nm in the presence of Hg2+. With the increase of Hg2+ concentration (0-6 equivalent), the fluorescence intensity at 520 nm gradually weakened, and the fluorescence band centered at 550 nm became prominent, forming a fluorescence emission point at 532 nm [Figure 20B]. The fluorescence intensity ratio at F550 nm/F520 nm varied between 0.71-6.44, which was enhanced by a factor of 9.07, suggesting that R6G-NA could be used for the detection of Hg2+ in an extensive dynamic range for quantitative analysis of Hg2+. This spectral property is indicative of FRET behavior. It occurs due to the Hg2+-induced chelation and ring-opening of the spirolactam, facilitating energy transfer from 1,8-naphthalimide (the donor) to Rhodamine 6G (the acceptor). Subsequently, the UV spectrum of R6G-NA was titrated with Hg2+ in pure acetonitrile, as shown in Figure 20C. With the increase of Hg2+ addition (0-6 equivalent), new absorption bands were formed at 350 and 525 nm, and the absorption coefficient significantly increased at 525 nm, which belonged to the characteristic absorption wavelength of Rhodamine 6G. Furthermore, a notable transition in solution color from yellow to orange was evident, suggesting that R6G-NA has potential as a visual (“naked-eye”) indicator for Hg2+ detection [Figure 20D].

Figure 20. (A) Proposed mechanism of R6G-NA with Hg2+; (B) Fluorescence titration spectra analysis of R6G-NA in the presence of different concentrations of Hg2+ Inset: the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 550 and 520 nm as a function of Hg2+ concentrations; (C) UV-vis absorption spectra of R6G-NA (M) with different contents of Hg2+; (D) An image exhibiting both the color shift (left) and fluorescence transformation (right) of R6G-NA prior to and following its interaction with Hg2+[140]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier B.V. UV-vis: Ultraviolet-visible.

In 2015, Cheng et al. successfully developed a novel intramolecular FRET and PET system, which was based on the dendritic compound perylene bisimide-dipyrromethene boron difluoride (PDI–BODIPY)

Figure 21. (A) The potential bonding mechanism of probe with mercury ions; (B) Alterations in the 1H NMR spectra of PDI-BODIPY upon titration with mercury ions at molar ratios ranging from 0 to 3 equivalents; and (C) Fluorescence spectra of probe in relation to varying mercury ions concentrations; (D) Anti-interference experiment[140]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier B.V. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

Recently, Tonsomboon et al. reported the creation of a fluorescent electrospun fiber strip incorporating a cutting-edge mercury-responsive organic dye known as NF06. This dye demonstrates fluorescence amplification through FRET mechanism, specifically designed to detect Hg2+ [Figure 22A][142]. The combination of this mercury-sensitive sensor with chemically compatible polymeric fibers has led to the development of a strip platform capable of detecting Hg2+ at concentrations as low as the sub-nanomolar level (0.309 ppb) in aqueous solutions, with an impressively brief assay duration of just 1 min. The results obtained from 1H-NMR and FT-IR analyses lend support to the ring-opening mechanism exhibited by NF06 during Hg2+ chelation, both in its free and immobilized states. As illustrated in Figure 22B, in the absence of Hg2+, the 1H-NMR spectra of NF06 distinctly reveal three proton signals corresponding to 5H (labeled c, d, and e) and five signals associated with the protons located on the aromatic ring of thio-R6 GH (labeled a, b, f, g, and h). However, upon the introduction of Hg2+, there is a negligible alteration in the proton signals of the 5H moiety. Conversely, the proton signals from the rhodamine derivative moiety undergo a significant downfield shift, indicating structural rearrangements within the thio-R6 GH moiety as a result of the Hg2+-induced spirolactam ring opening. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 22C, the fluorescence intensity progressively intensifies with an increasing concentration of Hg2+. In terms of selectivity, the fluorescence spectrometer’s spectrum exhibits a distinct emission wavelength of 560 nm solely in the Hg2+ band, remaining absent in all other bands. This observation underscores the selective responsiveness of the NF06 band towards Hg2+ [Figure 22D]. Given its remarkable sensitivity, scalability, cost-effectiveness, and user-friendliness, the newly developed NF06-Hg2+ test strip holds substantial promise as a standardized tool for regulatory and certifying bodies to conduct safety evaluations of consumer products.

Figure 22. (A) Proposed mechanism of NF06 for mercury ions detection; (B) 1H-NMR spectra analysis of NF06 for mercury ions detection; (C) The corresponding fluorescence spectra of NF06 after adding different contents of mercury ions; (D) Fluorescence spectra of NF06 with different metal ions[142]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier B.V. NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance.

Dey designed bishydrazone derivatives of 2,5-furandicarboxaldehyde (R1) with perfect heteroatomic cavities and synthesized them for Hg2+ sensing by FRET mechanism [Figure 23A][143]. The fluorescent probe has a low detection limit and excellent selectivity. As depicted in Figure 23B, upon complex formation with Hg2+, the imine protons of R1 experienced a significant shift from δ = 7.74 ppm to the higher downfield region at δ = 8.20 ppm, representing a ∆δ of 0.46 ppm. Additionally, there was a noticeable downfield shift in the furan ring proton, moving from δ = 6.65 ppm to δ = 6.83 ppm (∆δ = 0.18 ppm). In the mass spectra analysis, distinct molecular ion peaks were identified for R1 and the R1:Hg2+ complex, appearing at 1001.5095 (M+H+) and 1202.4 (M+Hg2+), respectively. Both spectroscopic analyses provided compelling evidence for the formation of a complex between R1 and Hg2+. Adding Hg2+ to the non-fluorescent solution of R1 immediately turned into bright red fluorescence [Figure 23C]. After introducing 1 equivalent of Hg2+, a peak shift from λmax = 450 to 589 nm (∆λ = 139 nm) was observed. An isotropic point was formed at

Figure 23. (A) Proposed Hg2+ induced FRET mechanism; (B) 1H-NMR spectrum of R1: Hg2+ complex; (C) Fluorescence emission spectra of R1 with Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence emission spectra of R1 with Hg2+ and other metal ions; (E) Overlap spectra of furan and rhodamine[143]. Copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V. FRET: Fluorescence resonance energy transfer; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance.

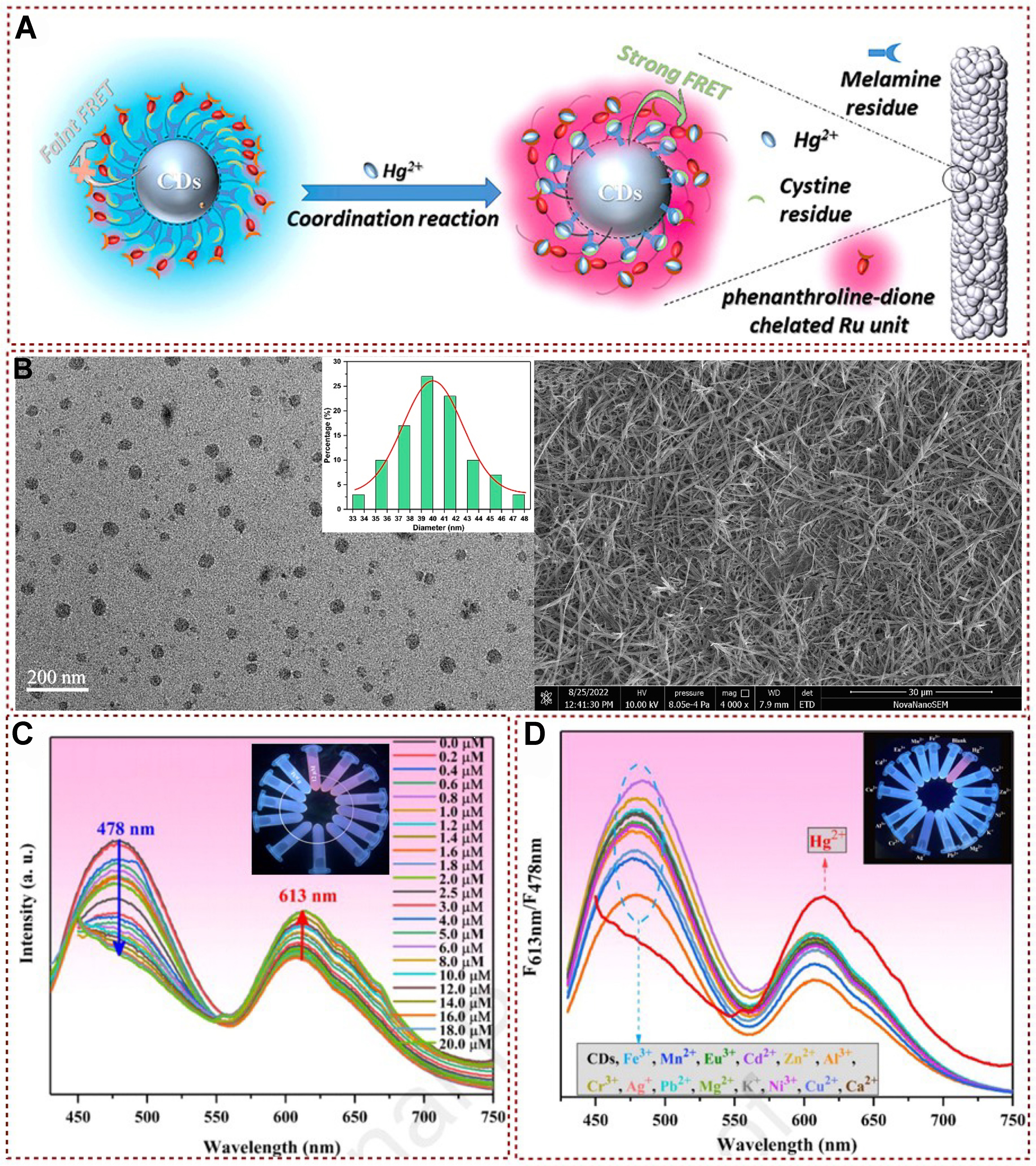

Recently, a platform with simultaneous visual sensing and efficient Hg2+ removal was developed using melamine and L-cystine as N/S sources and high-density Hg2+ binding sites [Figure 24A][144]. To further understand the efficient mercury ion recognition and detection processes, Figure 24B shows the TEM and SEM images of the N, S-CDs/Ru materials. The rapid introduction of Hg2+ ions promoted the self-assembly process of N, S-CDs/Ru surfaces containing functional groups, forming nanofibers with uniform structures. In addition, the author also analyzed XPS, and FT-IR to reveal additional evidence supporting the assertion that the introduction of Hg2+ formed stable compounds through the complexation of nitrogen (N), sulfur (S), and oxygen (O) with Hg2+ [Figure 24C]. With the gradual increase of Hg2+ concentration, the fluorescence intensity at 613 nm could be increased. In comparison, the fluorescence intensity at 478 nm decreased and saturated at the concentration of Hg2+ of about 16 μM, and the visible fluorescence color gradually changed from blue to red. In anti-interference experiments, the interference of various metal ions on N, S-CDs/Ru nanocomposites was very small and could be ignored [Figure 24D].

Figure 24. (A) Schematic illustration of Hg2+ detection based on N, S-CDs/Ru materials; (B) TEM image showing the detailed structure and size distribution of N, S-CDs/Ru nanocomposites. Additionally, an SEM image illustrates the morphology of N, S-CDs/Ru nanofibers after the introduction of Hg2+; (C) Fluorescence spectra of N, S-CDs/Ru in B-R buffer solution demonstrate changes in fluorescence intensity with varying amounts of Hg2+. The inset image provides a visual representation of how the fluorescence of N, S-CDs/Ru varies in the buffer at different concentrations of Hg2+; (D) Fluorescence spectra of N, S-CDs/Ru in the presence of different metal ions reveal its selectivity. The inset image offers a visual comparison of the fluorescence response of N, S-CDs/Ru to various metal ions[144]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier B.V. TEM: Transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscope.

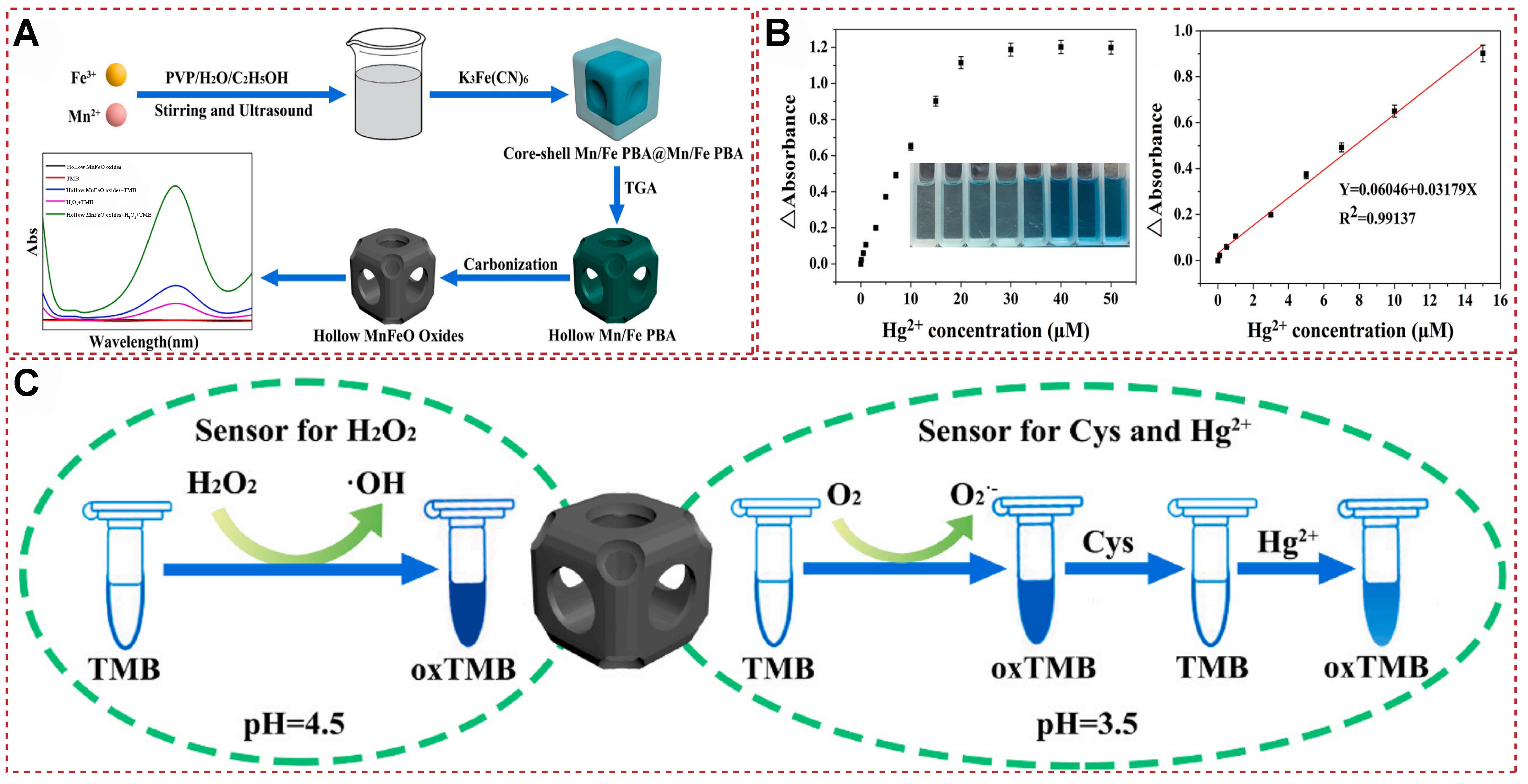

In 2021, Lu et al. synthesized a novel hollow MnFeO oxide nanomaterial, which is a derivative of metal-organic frameworks (MOF)@MOF with multiple enzyme-like activities [Figure 25A][145]. Under specific pH conditions, this material can mimic the activity of oxidase and react with the substrate 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) to produce a color change. Cys, as an antioxidant, can bind to MnFeO oxide, thereby inhibiting the oxidation process of TMB, leading to a decrease in absorbance. However, when Hg2+ is introduced into the reaction system containing MnFeO oxide, TMB, and Cys, Hg2+, due to its high affinity for Cys, binds to Cys to form a stable Hg–S bond. This process releases the hollow MnFeO oxide from its binding with Cys, restoring its catalytic activity and consequently increasing the absorbance. By monitoring this change in absorbance, the concentration of Hg2+ can be accurately determined [Figure 25B and C]. This novel approach utilizing the hollow MnFeO oxide nanomaterial offers a promising method for the sensitive and selective detection of Hg2+ in various samples.

Figure 25. (A) Synthesis of hollow MnFeO oxide; (B) Hg2+ Detection Dose-Response Curve and Calibration Curve; (C) a scheme for colorimetric detection of biomolecules and Hg2+ based on its simulated enzyme activities[145]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier B.V.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

The field of functional fluorescent probes for the efficient identification and detection of mercury ions has garnered significant attention in recent years due to the urgent need for sensitive and selective analytical tools in environmental monitoring and biological research. These probes leverage a variety of mechanisms, including fluorescence emission, quenching, and FRET processes, to provide robust platforms for mercury ion detection. Current research has seen remarkable advancements in the design and synthesis of fluorescent probes tailored to respond specifically to mercury ions. Two-dimensional materials and 3D structures have demonstrated the ability to amplify detection signals and improve the selectivity towards mercury ions through well-engineered photophysical processes. Fluorescence emission and quenching mechanisms have been extensively explored in these probes. By incorporating specific mercury-binding moieties, researchers have been able to engineer probes that undergo significant changes in their fluorescence properties upon mercury ion binding, leading to highly sensitive and selective detection. Additionally, FRET-based probes have offered an alternative route by utilizing the energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores, which can be disrupted or enhanced in the presence of mercury ions, thus providing a quantitative readout of ion concentration.

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. One critical area is the development of probes with enhanced sensitivity and selectivity in complex environmental and biological matrices, where interfering ions and background fluorescence can hinder accurate detection. Efforts are ongoing to refine probe designs through the incorporation of novel chelating agents and surface modifications that can improve binding affinity and reduce non-specific interactions. Furthermore, the integration of these fluorescent probes into practical analytical devices remains a challenge. Looking ahead, the field is poised for exciting developments. Continued innovations in materials science and synthetic methodologies will likely lead to the discovery of new fluorescent probes with superior properties. Additionally, advancements in nanotechnology and microfluidics could enable the miniaturization and integration of these probes into high-throughput analytical platforms. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms will further enhance the capabilities of these systems by enabling real-time data analysis and prediction, thereby improving the accuracy and reliability of mercury ion detection.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Writing the manuscript, and being responsible for the whole work: Shi L, Li B

Revising the first draft of the manuscript: Wu D, Zhu Y, Go Y, Wang L

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22101267 and 82103686), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (202300410477 and 242300421123), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Nos. 2021M692905 and 2024T170832).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; et al. A small molecule fluorescent probe for mercury ion analysis in broad low pH range: spectral, optical mechanism and application studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127701.

2. Cui, T.; Yu, S.; Chen, Z.; et al. Rational design of fluorescent probe for Hg2+ by changing the chemical bond type. RSC. Adv. 2018, 8, 12276-81.

3. Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Ran, X.; Tang, H.; Cao, D. Green, efficient detection and removal of Hg2+ by water-soluble fluorescent pillar[5]arene supramolecular self-assembly. Biosensors 2022, 12, 571.

4. Ding, Z.; Dou, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, C.; Xie, J. Nanoscale semiconducting polymer dots with rhodamine spirolactam as fluorescent sensor for mercury ions in living systems. Talanta 2023, 259, 124494.

5. Vil’pan, Y. A.; Grinshtein, I. L.; Akatov, A. A.; Gucer, S. Direct atomic absorption determination of mercury in drinking water and urine using a two-step electrothermal atomizer. J. Anal. Chem. 2005, 60, 38-44.

6. Moreton, J. A.; Delves, H. T. Simple direct method for the determination of total mercury levels in blood and urine and nitric acid digests of fish by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 1998, 13, 659-65.

7. Liu, S. J.; Nie, H. G.; Jiang, J. H.; Shen, G. L.; Yu, R. Q. Electrochemical sensor for mercury(II) based on conformational switch mediated by interstrand cooperative coordination. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81, 5724-30.

8. Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, G.; et al. Development of ELISA for detection of mercury based on specific monoclonal antibodies against mercury-chelate. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2011, 144, 854-64.

9. Krishna MV, Castro J, Brewer TM, Marcus RK. Online mercury speciation through liquid chromatography with particle beam/electron ionization mass spectrometry detection. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2007, 22, 283-91.

10. Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhong, K.; Tang, L. An “AIE + ESIPT” mechanism-based benzothiazole-derived fluorescent probe for the detection of Hg2+ and its applications. New. J. Chem. 2023, 47, 6916-23.

11. Hong, Y.; Lam, J. W.; Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: phenomenon, mechanism and applications. Chem. Commun. 2009, 4332-53.

12. Cheng, X.; Li, Q.; Qin, J.; Li, Z. A new approach to design ratiometric fluorescent probe for mercury(II) based on the Hg2+-promoted deprotection of thioacetals. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2010, 2, 1066-72.

13. Niu, C.; Liu, Q.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ouyang, J. Dual-emission fluorescent sensor based on AIE organic nanoparticles and Au nanoclusters for the detection of mercury and melamine. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 8457-65.

14. Yang, J.; Yang, B.; Wen, G.; Liu, B. Dual sites fluorescence probe for H2S and Hg2+ with “AIE transformers” function. Sensor. Actuat. B. Chem. 2019, 296, 126670.

15. Wang, Y.; Mao, P.; Wu, W.; et al. New pyrrole-based single-molecule multianalyte sensor for Cu2+, Zn2+, and Hg2+ and its AIE activity. Sensor. Actuator. B. Chem. 2018, 255, 3085-92.

16. Li, S.; Wan, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Pi, F.; Liu, L. A competitive “on-off-enhanced on” AIE fluorescence switch for detecting biothiols based on Hg2+ ions and gold nanoclusters. Biosensors 2022, 13, 35.

17. Liu, B.; Liu, J.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Gao, C. A novel red-emitting fluorescent probe for the highly selective detection of Hg2+ ion with AIE mechanism. Chem. Phys. 2020, 539, 110944.

18. Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kan, X.; et al. Tripodal aroyl hydrazone based AIE fluorescent sensor for relay detection Hg2+ and Br- in living cells. Dyes. Pigments. 2021, 191, 109389.

19. Wu, Y.; Wen, X.; Fan, Z. An AIE active pyrene based fluorescent probe for selective sensing Hg2+ and imaging in live cells. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 223, 117315.

20. Wang, K.; Li, J.; Ji, S.; et al. Fluorescence probes based on AIE luminogen: application for sensing Hg2+ in aqueous media and cellular imaging. New. J. Chem. 2018, 42, 13836-46.

21. He, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Du, B.; Liang, L. A naphthalimide functionalized fluoran with AIE effect for ratiometric sensing Hg2+ and cell imaging application. Spectrochim. Acta. A. Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 296, 122672.

22. Nie, X.; Huang, W.; Zhou, D.; et al. Kinetic and thermodynamic control of tetraphenylethene aggregation-induced emission behaviors: nanoscience: Special Issue Dedicated to Professor Paul S. Weiss. Aggregate 2022, 3, e165.

23. Tong, F.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. Supramolecular nanomedicines based on host-guest interactions of cyclodextrins. Exploration 2023, 3, 20210111.

24. Qi, Q.; Jiang, S.; Qiao, Q.; et al. Direct observation of intramolecular coplanarity regulated polymorph emission of a tetraphenylethene derivative. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 2985-7.

25. Kim, D.; Thuy, H. T. T.; Kim, B.; et al. Synergistic enhancement of luminescent and ferroelectric properties through multi-clipping of tetraphenylethenes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2208157.

26. Docker, A.; Shang, X.; Yuan, D.; et al. Halogen bonding tetraphenylethene anion receptors: anion-induced emissive aggregates and photoswitchable recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19442-50.

27. Zheng, J.; Ye, T.; Chen, J.; et al. Highly sensitive fluorescence detection of heparin based on aggregation-induced emission of a tetraphenylethene derivative. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 90, 245-50.

28. Tian, W.; Lin, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, W. Configuration-controllable E/Z isomers based on tetraphenylethene: synthesis, characterization, and applications. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019, 11, 6302-14.

29. Schultz, A.; Diele, S.; Laschat, S.; Nimtz, M. Novel columnar tetraphenylethenes via McMurry coupling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2001, 11, 441-6.

30. Ma, X.; Chi, W.; Han, X.; et al. Aggregation-induced emission or aggregation-caused quenching? Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1790-4.

31. Ma, X.; Hu, L.; Han, X.; Yin, J. Vinylpyridine- and vinylnitrobenzene-coating tetraphenylethenes: aggregation-induced emission (AIE) behavior and mechanochromic property. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 1489-92.

32. Tang, L.; Yu, H.; Zhong, K.; Gao, X.; Li, J. An aggregation-induced emission-based fluorescence turn-on probe for Hg2+ and its application to detect Hg2+ in food samples. RSC. Adv. 2019, 9, 23316-23.

33. Li, H.; Lin, H.; Lv, W.; Gai, P.; Li, F. Equipment-free and visual detection of multiple biomarkers via an aggregation induced emission luminogen-based paper biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112336.

34. Geng, Z.; Cao, Z.; Liu, J. Recent advances in targeted antibacterial therapy basing on nanomaterials. Exploration 2023, 3, 20210117.

35. Lv, W.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Li, F. Quaternary ammonium salt-functionalized tetraphenylethene derivative boosts electrochemiluminescence for highly sensitive aqueous-phase biosensing. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11747-54.

36. Huang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Yang, Y.; et al. Tuning proapoptotic activity of a phosphoric-acid-tethered tetraphenylethene by visible-light-triggered isomerization and switchable protein interactions for cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202208378.

37. Zhang, C. J.; Feng, G.; Xu, S.; et al. Structure-dependent cis/trans isomerization of tetraphenylethene derivatives: consequences for aggregation-induced emission. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 6192-6.

38. Ma, L.; Li, C.; Yan, Q.; Wang, S.; Miao, W.; Cao, D. Unsymmetrical photochromic bithienylethene-bridge tetraphenylethene molecular switches: synthesis, aggregation-induced emission and information storage. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 361-4.

39. Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Li, N.; et al. Multistimuli-responsive fluorescent organometallic assemblies based on mesoionic carbene-decorated tetraphenylethene ligands and their applications in cell imaging. CCS. Chem. 2022, 4, 732-43.

40. Xu, H.; Li, K.; Jiao, S.; Li, L.; Pan, S.; Yu, X. Tetraphenylethene based zinc complexes as fluorescent chemosensors for pyrophosphate sensing. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 877-80.

41. Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Hong, Y.; Tang, B. Z. Fabrication of fluorescent nanoparticles based on AIE luminogens (AIE dots) and their applications in bioimaging. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 283-93.

42. Hu, R.; Qin, A.; Tang, B. Z. AIE polymers: synthesis and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 100, 101176.

43. Liu, H.; Xiong, L.; Kwok, R. T. K.; He, X.; Lam, J. W. Y.; Tang, B. Z. AIE bioconjugates for biomedical applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000162.

44. Li, M.; Yin, B.; Gao, C.; et al. Graphene: preparation, tailoring, and modification. Exploration 2023, 3, 20210233.

45. Liu, W.; Yu, H.; Hu, R.; et al. Microlasers from AIE-active BODIPY derivative. Small 2020, 16, e1907074.

46. Pazos, E.; Vázquez, O.; Mascareñas, J. L.; Vázquez, M. E. Peptide-based fluorescent biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3348-59.

47. Malachowski, L.; Stair, J. L.; Holcombe, J. A. Immobilized peptides/amino acids on solid supports for metal remediation. Pure. Appl. Chem. 2004, 76, 777-87.

48. Schiering, N.; Kabsch, W.; Moore, M. J.; Distefano, M. D.; Walsh, C. T.; Pai, E. F. Structure of the detoxification catalyst mercuric ion reductase from Bacillus sp. strain RC607. Nature 1991, 352, 168-72.

49. Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Highly selective fluorescence probe with peptide backbone for imaging mercury ions in living cells based on aggregation-induced emission effect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 415, 125712.

50. Selvaraj, M.; Rajalakshmi, K.; Ahn, D. H.; et al. Tetraphenylethene-based fluorescent probe with aggregation-induced emission behavior for Hg2+ detection and its application. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2021, 1148, 238178.

51. Lei, S.; Tian, J.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Manners, I. AIE-active, stimuli-responsive fluorescent 2D block copolymer nanoplatelets based on corona chain compression. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 17630-41.

52. Neupane, L. N.; Hwang, G. W.; Lee, K. H. Tuning of the selectivity of fluorescent peptidyl bioprobe using aggregation induced emission for heavy metal ions by buffering agents in 100% aqueous solutions. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 179-85.

53. Cheng, X.; Huang, S.; Lei, Q.; et al. The exquisite integration of ESIPT, PET and AIE for constructing fluorescent probe for Hg(II) detection and poisoning. Chinese. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 1861-4.

54. Qin, B.; Zhang, S.; Song, Q.; Huang, Z.; Xu, J. F.; Zhang, X. Supramolecular interfacial polymerization: a controllable method of fabricating supramolecular polymeric materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 7639-43.

55. Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. Composite materials based on covalent organic frameworks for multiple advanced applications. Exploration 2023, 3, 20220144.

56. Kwon, T. W.; Choi, J. W.; Coskun, A. The emerging era of supramolecular polymeric binders in silicon anodes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2145-64.

57. Makam, P.; Gazit, E. Minimalistic peptide supramolecular co-assembly: expanding the conformational space for nanotechnology. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 3406-20.

58. Liu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Bao, Z.; Yan, X. Skin-inspired electronics enabled by supramolecular polymeric materials. CCS. Chem. 2019, 1, 431-47.

59. Tian, W.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Supramolecular hyperbranched polymers. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2531-42.

60. Hua, B.; Shao, L.; Li, M.; Liang, H.; Huang, F. Macrocycle-based solid-state supramolecular polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 1025-34.

61. Ishiwata, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Sugikawa, K.; Kokado, K.; Sada, K. Transformation of metal-organic framework to polymer gel by cross-linking the organic ligands preorganized in metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 5427-32.

62. Deng, X.; Njoroge, I.; Jennings, G. K. Surface-initiated polymer/ionic liquid gel films. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018, 122, 6033-40.