Sustainable fertilizers from wastes: a strategy to enhance soil carbon, improve soil quality, and mitigate emissions

Abstract

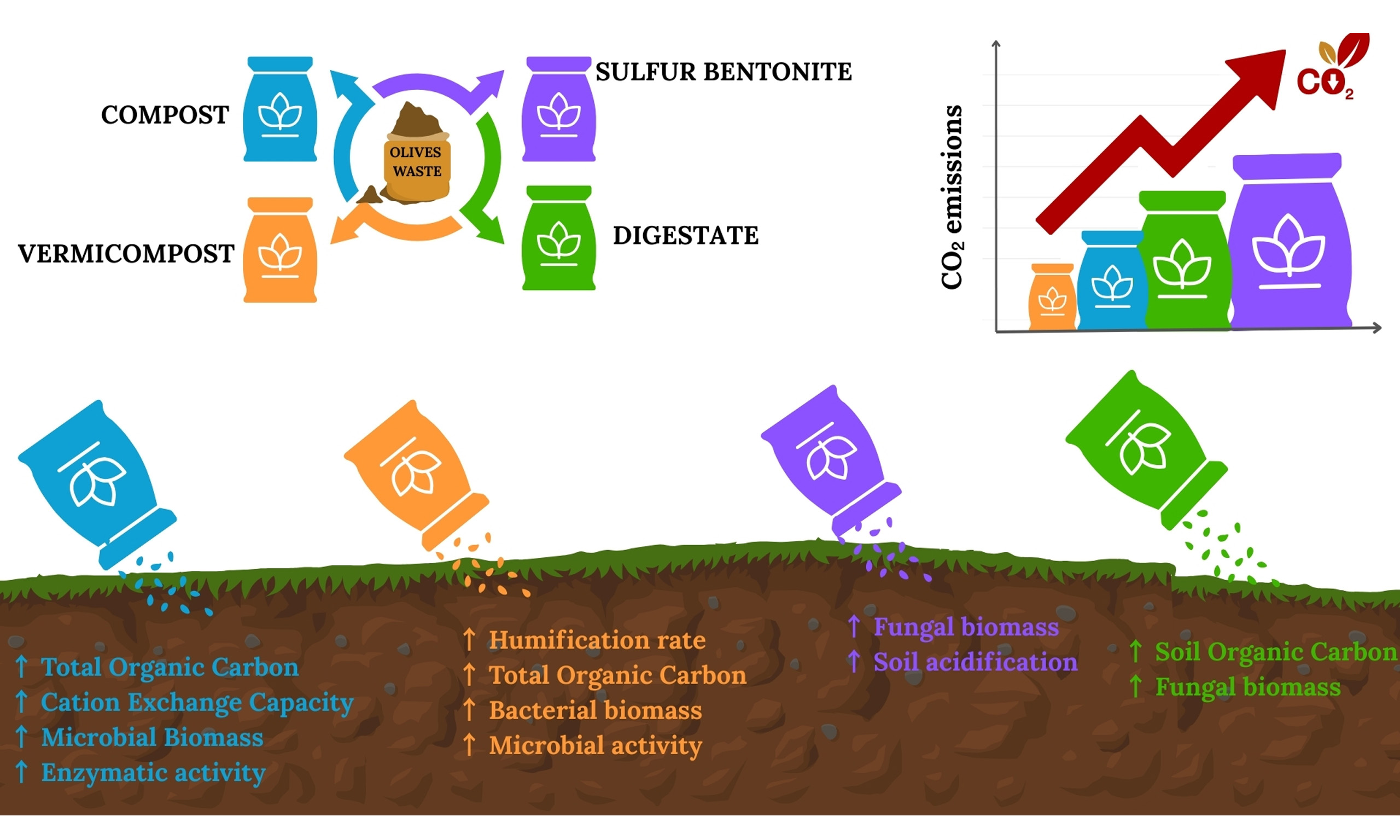

The transition to sustainable fertilization strategies is essential to reconcile agricultural productivity with soil health and climate change mitigation. This study assessed the agronomic and environmental performance of four waste-derived fertilizers - compost (C), vermicompost (V), olive-based digestate (D), and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO) - through integrated soil analyses and life cycle assessment (LCA). The results showed that compost and vermicompost exhibited the highest degree of organic matter humification, improving total organic carbon, cation exchange capacity, soil microbial biomass carbon, and enzymatic activity. Vermicompost provided the greatest increase in humification rate and bacterial biomass, while compost maximized fungal-to-bacterial ratios, soil enzymatic activities, and stable carbon pools. Digestate enhanced soil organic carbon and fungal biomass, although with lower humification indices and higher water-soluble phenols. SBO strongly acidified the soil and shifted microbial communities toward fungal dominance but contributed the highest greenhouse gas emissions due to sulfur processing. LCA confirmed vermicompost as the most climate-friendly amendment (25 kg CO2 eq ton-1), followed by compost (43), digestate (110), and SBO (167). These findings indicate that waste-derived organic fertilizers can simultaneously improve soil quality, promote carbon sequestration, and reduce emissions compared with synthetic inputs, with vermicompost and compost offering the greatest agronomic and environmental benefits.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Reducing the carbon footprint (CFP) of agri-food systems while sustaining soil health and improving productivity is a global priority in the context of climate change and food security. Two complementary research directions have emerged as central to this challenge: (i) robust CFP assessments, which quantify emissions across the life cycle of agricultural inputs and practices, and (ii) analyses of carbon dynamics in food production systems, which elucidate the mechanisms of carbon sequestration, stabilization, and turnover in soils. Against this background, waste-derived fertilizers represent a promising circular economy strategy, simultaneously addressing waste management, soil fertility, and climate mitigation. Recent studies[1-3] highlighted the potential of fertilizers produced from organic residues to significantly reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to conventional mineral fertilizers, increasing soil carbon sequestration. Anaerobic digestates, composts, and vermicomposts are particularly relevant as sustainable fertilizers. Over the past decade, anaerobic digestion has undergone substantial expansion on a global scale[4]. Within Europe, as of 2021, this development was reflected in the establishment of 1,023 industrial biomethane production plants in addition to approximately 20,000 anaerobic digesters of varying capacities[5]. Beyond its technological diffusion, anaerobic digestion provides dual environmental and agronomic functions: the generation of renewable biogas as an alternative to fossil-derived energy sources, and the production of nutrient-enriched digestate that can be utilized as an organic soil amendment. A recent study[6] showed that nutrient-rich digestate can benefit plant growth by slowly releasing nutrients, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. However, it should be used as fertilizer only after careful testing of its chemical composition and potential contaminants, as well as after conducting growth experiments. Composting stabilizes organic residues, reducing methane emissions otherwise associated with landfill disposal, while vermicomposting produces amendments rich in bioavailable nutrients and beneficial microbial communities[7]. These technologies, when assessed through CFP analysis, reveal significant mitigation potential when compared with synthetic fertilizers. For instance, a life-cycle perspective demonstrated that compost derived from municipal solid wastes could replace up to 71% of synthetic nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) fertilizers in urban and peri-urban agriculture, lowering eutrophication potential and mitigating GHG emissions[8]. Badewa et al.[7] found that, compared with other organic amendments (digestate and biosolids), compost had the greatest soil carbon sequestration potential. Similarly, a recent review emphasized that organic fertilizers and biowaste-based amendments can serve as key tools in Mediterranean agroecosystems to sustain soil fertility, enhance crop growth, control GHG emissions, and increase soil carbon[9]. Vermicomposting represents an environmentally sustainable bioconversion process in which earthworms facilitate the degradation of organic residues, resulting in a stabilized compost that is rich in nutrients and humic-like substances[10]. The incorporation of vermicompost into soil contributes to an increase in total soil carbon stocks by supplying organic matter and enhancing the formation of stable soil aggregates. These aggregates play a critical role in physically protecting organic carbon from microbial decomposition, thereby reducing carbon losses[11]. The stability of soil organic carbon (SOC) is further reinforced by the relatively high calcium content in vermicompost, which promotes aggregation through cation bridging mechanisms. Carbon that becomes physically and chemically stabilized within these aggregates exhibits lower turnover rates, resulting in greater long-term sequestration. Such processes not only improve soil structure and fertility but also represent an important strategy for enhancing soil health and mitigating atmospheric CO2 accumulation, with potential implications for climate change adaptation and mitigation. The addition of different amendments to the soil plays a key role in driving soil microbial diversity and, in particular, affects the fungi-to-bacteria ratio, thereby modulating soil carbon dynamics by governing the balance between stabilization and mineralization, largely through mechanisms of organic matter decomposition and soil aggregation[12]. Fungi allocate a greater proportion of assimilated carbon to their biomass compared to bacteria, largely due to the synthesis of structurally complex and decay-resistant compounds, such as chitin, melanins, and glucans[13]. This investment in recalcitrant biomass is considered an important pathway for the formation of stable SOC. However, recent studies highlight that long-term carbon stabilization is also strongly influenced by the formation and persistence of microbial necromass, particularly of bacterial origin. These two perspectives are not contradictory: fungal biomass contributes to the formation of aromatic and structurally complex intermediates during early decomposition, whereas bacterial necromass - often bound to mineral surfaces - constitutes a major component of mineral-associated organic matter. Thus, the relative importance of fungi and bacteria in soil carbon dynamics depends on the stage of decomposition and on environmental conditions. Soil management practices that promote a balanced or fungi-enhanced microbial community - such as reduced tillage, organic amendments, and diversified crop rotations - can therefore improve carbon sequestration by stimulating both fungal transformation pathways and bacterial necromass accumulation[14]. This functional divergence between fungi and bacteria underscores the importance of microbial community composition in regulating soil carbon dynamics and highlights the potential for microbiome-targeted management strategies to mitigate atmospheric CO2 accumulation. Waste-derived fertilizers - particularly compost, vermicompost, digestate, and sulfur - bentonite formulations enriched with olive pomace - are increasingly relevant in this context, as they are produced from abundant regional waste streams in southern Italy and reflect current circular economy objectives. Their contrasting stabilization levels, nutrient availability, and microbial activity provide an ideal framework for comparing multiple carbon sequestration pathways, from soil aggregation enhancement to microbial necromass formation. Understanding their effects is especially important in Mediterranean horticultural systems, where high temperatures and intensive management accelerate organic matter mineralization.

Integrating CFP assessment with a mechanistic understanding of soil carbon stabilization, this study evaluates the dual contribution of these regionally relevant amendments to climate mitigation and soil health. Specifically, we investigate how compost, vermicompost, digestate, and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO) influence soil carbon accumulation, microbial activity, and the balance between fungal- and bacterial-mediated pathways of organic matter transformation.

METHODS

sulfur bentonite with olive pomace

SBO was produced in tablet form (3-4 mm) by Steel Belt System srl (Varese, Italy), following the method described by Muscolo et al.[15,16]. Elemental sulfur (S, 80%), a residue of hydrocarbon refining processes, was combined with bentonite clay (B, 10%) as a support and carrier, and olive pomace (OP, 10%), a by-product of the olive oil industry. Elemental sulfur represented the main component of the fertilizer[17]. Prior to use, the fertilizer was tested for potential contaminants, including pathogenic microorganisms (total coliforms, faecal coliforms, Salmonella spp., and Escherichia coli) and heavy metals, to ensure its environmental safety and suitability for soil application[16]. Analyses confirmed the absence of both pathogens and heavy metals[16].

Compost

Compost was produced using specialized electric composters designed to promote efficient organic matter decomposition. These composters contained separate chambers, which prevented the mixing of fresh and decomposing material and allowed independent temperature regulation to optimize microbial activity. Each composting process was carried out in triplicate and followed three controlled phases: (i) an initial mesophilic phase of 8 days at 29 °C, (ii) a thermophilic phase of 20 days at 50 °C, and (iii) a prolonged mesophilic phase of 92 days at 27 °C[18]. Following these phases, all composts underwent a 30-day stabilization stage at a constant temperature of 20 °C to ensure adequate maturation. Throughout the composting process, temperature, moisture, and oxygen levels were monitored daily using a centrally placed probe. Water was added when necessary to maintain optimal moisture content, and daily mixing ensured proper aeration and oxygenation, thereby enhancing microbial activity and promoting the breakdown of organic matter into stable humus. At the end of the composting cycle, the composts were air-dried, finely ground to pass through a 2 mm sieve, and homogenized for uniformity. Both compost types reached full maturity within six months[19].

Vermicompost

Vermicomposting was conducted in a 50 L capacity worm bin (Vevor, 5-Tray Worm Composter, model WB25101). The feedstock mixture consisted of 45% olive residues, 45% organic food waste, and 10% straw, to which 20% earthworm biomass was added. Red wigglers (Eisenia fetida) were introduced at a density of approximately 1,000 individuals (≈1 lb) per square foot of surface area. The bedding was kept loose to enhance aeration, and moisture was maintained at a level that was damp but not waterlogged. Over a period of four months, the organic material was progressively decomposed by the worms, resulting in stable and mature vermicompost[20].

Olive-based digestate

Olive-derived digestate was sourced from a biogas plant operated by the Fattoria della Piana cooperative (Candidoni, Calabria, Italy). The facility has a total digester volume of 3,260 m3 and an installed capacity of 998 kWe. The feedstock used for anaerobic digestion consisted of 50% olive residues combined with 50% animal manure and maize silage. The plant was operated under mesophilic conditions at 40 °C, with a daily feed input of 120 m3 and a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 60 days. The minimum guaranteed retention time (MGRT) was 16 h at 40 °C. After production, the digestate was sampled and analyzed to determine its chemical and biological characteristics, with the aim of evaluating its suitability as a humus-rich soil amendment.

Humic substance detection

Humic substances (HSs) were extracted from air-dried samples using 0.1 mol L-1 KOH (sample-to-solution ratio of 1:20, w/v). Extractions were performed at room temperature under a nitrogen atmosphere for 16 h. The suspensions were centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 20 min to separate the supernatant containing soluble HS from residual solids[21]. The resulting extracts were analyzed to determine total organic carbon (TOC), total extractable carbon (TEC), concentrations of humic acids (HA) and fulvic acids (FA). The corresponding fraction of carbon (FC) were expressed as C_HA and C_FA, respectively. These measurements were used to calculate several humification parameters, including humification rate (HR%), humification index (HI), humification degree (HD, DH%), and the ratio of the absorbances at 465 and 665 nm (E4/E6)[22].

Characterization of HS functional groups was carried out by Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFT). Measurements were conducted with a Nicolet Impact 400 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrophotometer (Nicolet Instruments, Madison, WI, USA) equipped with a diffuse reflectance accessory (Spectra-Tech, Stamford, CT, USA). For each spectrum, 200 scans were collected at a resolution of 4 cm-1 and processed using Omnic software (Version 3.1, Nicolet Instruments, USA). Analytical samples were prepared by homogenizing 2 mg of dried extract with 148 mg of spectroscopic-grade potassium bromide (KBr) (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI, USA). Absorption bands were identified according to standard assignments described in previous studies[23-25]. Carboxylic and total acidic functional groups were quantified following the CaOAc and Ba(OH)2 titration methods[26], with filtrates passed through 0.45 μm membrane filters as recommended by Ritchie and Perdue[27]. Phenolic acidity was calculated as the difference between total acidity and carboxylic acidity. The degree of humification (DH%)[21] was expressed as:

DH% = [(C_HA + C_FA) × 100 / TEC] (1)

while humification rate (HR%)[21] was calculated as:

HR% = [(C_HA + C_FA) × 100 / TOC] (2)

Soil experiments

The experiment was carried out in Motta San Giovanni (LAT:38°0′15″12 N; LONG: 15°41′45″24 E) in Reggio Calabria, southern Italy, an agricultural area representative of Mediterranean horticultural systems. The region has a typical Mediterranean climate, characterized by mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers, with a mean annual temperature of approximately 17-18 °C and annual precipitation of 600-700 mm, concentrated mainly between autumn and early spring.

A sandy-loam soil (11.85% clay, 23.21% silt, 64.94% sand)[19] was used for the trial, which was carried out from December to June. The experimental field was divided into two main plots of 0.5 hectares each, and subsequently into smaller subplots. Four fertilizer treatments were tested, applied on a nitrogen-equivalent basis of 30 kg N ha-1:

• SBO (476 kg S ha-1): sulfur bentonite with olive pomace amendment;

• CTR: unfertilized control;

• CTR0: soil at initial state;

• Compost: 2,123 kg/ha;

• Vermicompost: 1,769 kg/ha;

• Digestate: 2,123 kg/ha.

The trial followed a randomized complete block design with three replicates per treatment. Each replicate consisted of three subplots, and six soil samples were taken per subplot for analysis. The experiment lasted two consecutive years, with results presented as the mean of three independent trials. Irrigation was managed at 70% of field capacity, monitored using a direct-read pH/moisture probe (R181). The application rate of SBO was determined based on published references, which recommend elemental sulfur inputs ranging from 2,200 kg S ha-1 to 3,300 kg S ha-1 depending on soil characteristics[15-20]. After 180 days, soil samples were collected for chemical and biological analyses. Samples were air-dried, sieved to < 2 mm, and stored at 4 °C for no longer than 24 h before microbial and enzymatic assays. Chemical and biochemical properties were analyzed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

Soil chemical analysis

The following soil properties have been detected. Soil texture with the hydrometer method[27]; electric conductibility (EC) in 1:5 soil/water suspension, after stirring at 15 rpm for 1 h, was measured with a Hanna instrument conductivity meter; pH was determined in soil/solution ratio 1:2.5 with a glass electrode. Organic carbon was detected with the Walkley and Black method[28]. Total nitrogen (TN) was assessed with the Kjeldahl method[29]. C/N was quantified as a carbon:nitrogen ratio. Water-soluble phenols were extracted and analyzed as described by Kaminsky and Muller[30] and monomeric and polyphenols were determined with Box method[31], using tannic acid as standard. The concentration of water-soluble phenolic compounds was expressed as tannic acid equivalents (μg TAE g-1D.W.). Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was analysed with barium chloride method[32]. Cations and anions were detected using ion chromatography (Dionex ICS-1100, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sunnyvale, CA, USA)[29].

Soil biological analysis

Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) was assessed with the chloroform fumigation-extraction procedure[33] on fresh soil. Fumigated and unfumigated soil sample extracts were used to detect soluble organic carbon[28]. Fluorescein diacetate hydrolase (FDA) activity was determined according to the method of Adam and Duncan[34]. Dehydrogenase (DHA) activity was assessed with the method used by Von Mersi and Schinner[35]. The decrease in the absorbance was measured at 240 nm, using the extinction coefficient of 39.4 M-1 cm-1. Protease activity was detected as reported in Muscolo et al.[15]. Urease activity was determined as described by Kandeler and Gerber[36]. Ammonium concentrations were determined at 690 nm by using a calibration curve. The results are reported as μg N-NH4 g-1 d-1 3 h-1.

Percentage CFU (%)[15] = (CFU of the group / Total CFU) × 100 (3)

where:

• CFU of the group = colony-forming units of fungi, bacteria, or actinomycetes;

• Total CFU = sum of CFU of all groups[15].

The biomass of each group is calculated using[15]:

μg C g-1 = fraction of each group × total MBC (4)

where:

• Fraction of the group = CFU of the group / Total CFU;

• MBC = microbial biomass carbon (µg C g-1).

Environmental impacts based on life cycle assessment

The environmental impacts of fertilizers were evaluated using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approach, following the ISO 14040:2006 (Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Principles and framework) and ISO 14044:2006 (Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Requirements and guidelines) standards[37,38]. The methodological framework was applied in accordance with ISO 14025:2006 (Environmental labels and declarations - Type III environmental declarations - Principles and procedures) and the Product Category Rules (PCRs). Since no specific PCRs currently exist for organic fertilizers derived from organic matrices, PCR 2010:20 (EPD, 2010)[39], which refers to fertilizer production, was adopted, as suggested by Egas et al.[40].

According to ISO 14040:2006[37], an LCA consists of four phases:

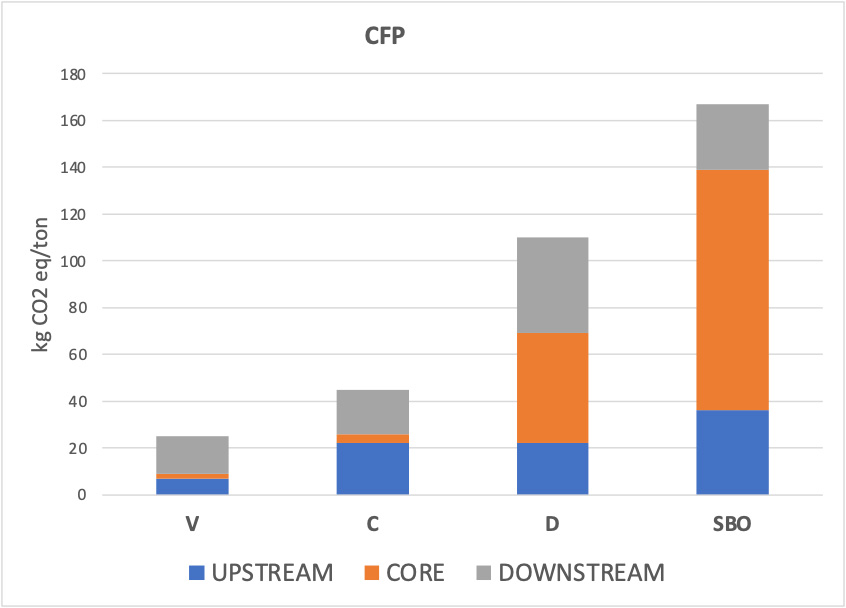

I. Goal and Scope Definition: The aim of this study was to assess the contribution of different fertilizers to climate change by quantifying their Global Warming Potential (GWP, 100 years), expressed as kg CO2 eq per ton of fertilizer. A cradle-to-gate approach was applied, which considered the environmental impacts from raw material extraction up to the factory gate. The system boundaries were divided into three modules: upstream, core, and downstream. The upstream module included the production of raw materials for the fertilizers. The core module comprised transportation, production processes (dosing, homogenization, granulation, drying), and related emissions. The downstream module covered the use phase, in which emissions to air and water following fertilizer application were calculated. The functional unit (F.U.) was set as 1 ton of fertilizer.

II. Inventory Analysis (LCI): Data were collected for all inputs and outputs related to the production of one ton of fertilizer. Primary data from field measurements were used for the core module, while upstream processes were modeled using the Ecoinvent 3.9 database, complemented with supply chain information. Emissions during the downstream phase were estimated following PCR 2010:20 (EPD, 2010). For waste management in the core module, the scenario followed Legislative Decree 152/2006, distinguishing between recovery and disposal operations. During composting and related processes, gaseous emissions such as CO2, CH4, and N2O were considered, representing the main GHGs. As reported in previous studies[41-44].

III. Impact Assessment (LCIA): The environmental impact assessment was carried out using SimaPro v.9.01 software (PRé Consultants, 2015). In this study, only the GWP (100 years) was considered, since it directly quantifies the CFP of fertilizers. This category integrates the contributions of CO2, CH4, and N2O emissions, allowing their comparison on a common basis (kg CO2 eq).

IV. Interpretation: The characterization of emissions enabled the quantification of the CFP for each fertilizer treatment. No normalization or weighting procedures were applied, as the analysis focused exclusively on the GWP indicator.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP software (version 14, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for all datasets, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was applied to evaluate differences among treatments. Student’s t-test was used where appropriate. The effects were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to analyze the relationships among fertilizer treatments and environmental impact analysis.

RESULTS

The degree of humification of different fertilizers can be estimated using the HA/FA ratio [Table 1]. A higher HA/FA ratio corresponds to a greater degree of humification of organic material, and this is further supported by the calculated humification indices.

Chemical and humic properties of compost (C), vermicompost (V), digestate (D), and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO)

| C | V | D | SBO | |

| TOC | 44b ± 1.4 | 53a ± 2.4 | 45b ± 1.5 | 6.3c ± 0.5 |

| TEC | 17b ± 1 | 24a ± 1.1 | 18b ± 1 | 1.8c ± 0.5 |

| HA + FA | 14a ± 1 | 14a ± 1.2 | 11b ± 1 | nd |

| HA | 9a ± 0.5 | 8a ± 0.9 | 3b ± 1 | nd |

| FA | 5b ± 0.3 | 6b ± 1.0 | 8a ± 0.2 | nd |

| HA/FA | 1.8a ± 0.4 | 1.3b ± 0.4 | 0.35c ± 0.2 | nd |

| HR | 30a ± 1.8 | 28a ± 1 | 24b ± 1.4 | nd |

| HD | 81a ± 1.9 | 65b ± 2.5 | 61b ± 1.9 | nd |

| HI | 0.37b ± 0.01 | 0.22c ± 0.04 | 0.63a ± 0.06 | nd |

| E4/E6 | 3.3b ± 0.9 | 4b ± 0.8 | 9.1a ± 1.0 | nd |

| WSP | 2.3b ± 0.06 | 2.1b ± 0.03 | 5a ± 1 | nd |

Among the tested materials, compost and vermicompost showed the highest HA/FA ratio. Compost showed the greatest values of HI and HD, while vermicompost had the highest HR. Vermicompost contained the largest amount of TOC and TEC. The E4/E6 spectral ratio, which reflects the aromaticity and condensation of organic matter and is indicative of molecular size, also varied across the treatments. The lowest E4/E6 ratio - signifying the highest degree of organic matter polymerization - was observed in compost, while the highest ratio was detected in digestate, which also contained substantial amounts of water-soluble phenols. SBO contained a small amount of TOC and TEC, and did not contain humified material. Soil analysis showed that, compared to the initial soil, untreated soil maintained the same pH, whereas pH decreased with all treatments, with the greatest reduction observed in the presence of SBO. Conversely, EC increased relative to the initial soil state, with the largest increase observed for compost and digestate. Water Content, Water Soluble Phenols, Total Organic Carbon , and Total Nitrogen also increased compared to CTR0 and CTR.

Soil analysis further revealed significant differences among treatments [Table 2]. Soil texture remained unchanged (data not shown); however, pH decreased under all treatments compared to CTR0 and CTR, with the most pronounced reduction observed for SBO.

Chemical properties of soil at the beginning of the experiment (CTR0), untreated soil (CTR), and soil treated with compost (C), vermicompost (V), digestate (D), and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO)

| CTR0 | CTR | C | V | D | SBO | |

| pH (H2O) | 8.3a ± 0.55 | 8.2a ± 0.52 | 7.6b ± 0.80 | 7.6b ± 0.40 | 7.2c ± 0.40 | 5.2d ± 0.40 |

| EC (dS/m) | 310d ± 10 | 350c ± 12 | 433a ± 9 | 375b ± 12 | 421a ± 12 | 120e ± 11 |

| WC (%) | 21b ± 2.6 | 22 b ± 2.1 | 27a ± 1.7 | 28a ± 1.70 | 24a ± 1.70 | 25a ± 1.70 |

| WSP (µg TAE g-1 d.s) | 16c ± 2.0 | 18c ± 2.8 | 44a ± 2.7 | 40a ± 3.3 | 41a ± 3.2 | 28.8b ± 2.8 |

| TOC (%) | 1.0bc ± 0.16 | 0.9c ± 0.16 | 1.7b ± 0.15 | 2.1a ± 0.25 | 1.3b ± 0.25 | 1.54b ± 0.19 |

| TN (%) | 0.13c ± 0.01 | 0.14c ± 0.01 | 0.30a ± 0.02 | 0.22b ± 0.04 | 0.21b ± 0.03 | 0.14c ± 0.02 |

| C/N | 7.6ab ± 0.35 | 6.4b ± 0.4 | 5.7c ± 1 | 9.5a ± 0.6 | 6.2b ± 0.5 | 11a ± 0.9 |

| SOM (%) | 1.72c ± 0.3 | 1.55c ± 0.27 | 2.92b ± 0.25 | 3.6ab ± 0.13 | 2.24cb ± 0.13 | 2.64b ± 0.23 |

| HC (%) | 0.50b ± 0.06 | 0.55b ± 0.03 | 0.63b ± 0.02 | 0.70a ± 0.01 | 0.60b ± 0.01 | 0.62b ± 0.01 |

| FC (%) | 0.40c ± 0.06 | 0.39c ± 0.08 | 0.26d ± 0.05 | 0.38b ± 0.03 | 0.55a ± 0.03 | 0.59a ± 0.02 |

| HC/FC | 1.25b ± 0.05 | 1.41c ± 0.09 | 2.42a ± 0.8 | 1.84a ± 0.9 | 1.09d ± 0.04 | 1.05d ± 0.04 |

| MBC | 899d ± 5 | 789e ± 7 | 1,087a ± 12 | 999b ± 11 | 957c ± 13 | 932c ± 14 |

| CEC [cmol(+) Kg-1] | 18.9b ± 1 | 18.7b ± 0.9 | 22a ± 1.1 | 23a ± 1.2 | 22a ± 1 | 19.9b ± 0.9 |

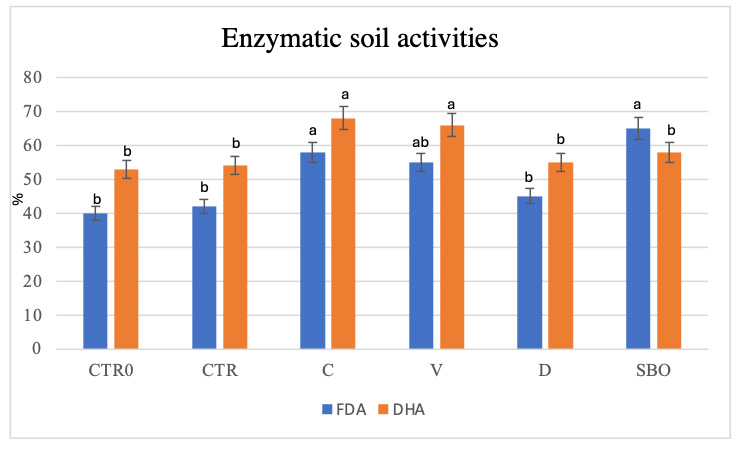

An increase in EC values and water-soluble phenols was recorded, particularly in soils treated with compost, relative to both controls. Water content, TOC, TN, and soil organic matter (SOM) also increased in compost-treated soils, and indicators of active soil life - FDA, and DHA - reached their highest levels with compost application, followed by vermicompost, SBO, and digestate [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Fluorescein diacetate (FDA, μg fluorescein g-1 d.s.) and dehydrogenase activity (DHA, μg TTF g-1 h-1 d.s.) in soil at the initial state (CTR0), untreated soil (CTR), soil treated with compost (C), vermicompost (V), digestate (D) and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO). Data are the mean of three replications ± standard deviation. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Humic carbon (HC) and FA were quantified to assess the relative contribution of humic and fulvic fractions to soil organic matter stabilization.

The HC/FC ratio and CEC were likewise elevated with compost treatment. Vermicompost produced similar effects, with increases in most parameters. HC increased with all treatments, with the greatest rise observed with vermicompost. FC increased with digestate and SBO, but decreased under compost treatment compared to controls. No changes in FC were observed between vermicompost and control soils. The HC/FC ratio increased only in compost- and vermicompost-treated soils [Table 2]. CEC increased under all treatments compared with the controls, except for SBO, where no significant effect was detected. MBC increased with the treatments; the ranking of increase was C > V > D = SBO > CTR0 > CTR.

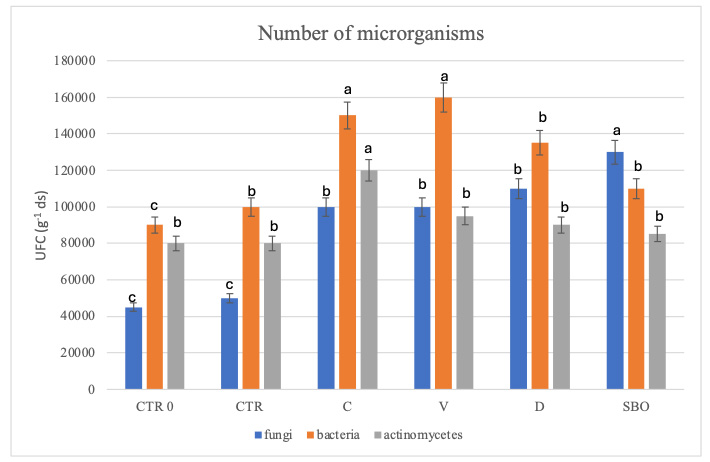

In all soils, both treated and untreated, except for SBO, bacteria were the dominant microorganisms. Actinomycetes were most abundant in compost-treated soil, while in CTR0 and CTR, and in vermicompost-treated soil, fungi and actinomycetes were present in comparable amounts. In soils treated with digestate, fungi prevailed over actinomycetes. SBO altered the microbial composition, increasing the abundance of fungi more than other microorganisms [Figure 2].

Figure 2. Unit forming colonies per gram of dry soil of fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes in soil at the initial state (CTR0), untreated soil (CTR), soil treated with compost (C), vermicompost (V), digestate (D), and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO). Data are the mean of three replications ± standard deviation. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among the treatments according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Considering the percentage of fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes with respect to the total MBC and for each treatment, SBO was the treatment that mostly increased the amount of fungi, vermicompost mostly increased the bacteria percentage unexpectedly, and the actinomycetes were decreased by treatments compared to the control 0. The Fungi biomass expressed as microgram C per gram of soil was increased by SBO, and the ranking was SBO > D > C > V > CTR0 > CTR. The highest amount of bacterial biomass was detected in vermicompost and compost. Actinomycetes were the greatest in soil treated with compost [Table 3].

Number of fungi, bacteria and actinomycetes in relation to the total microbial biomass C in soil at the initial state (CTR0), untreated soil (CTR), and soil treated with compost (C), vermicompost (V), digestate (D) and sulfur bentonite with olive pomace (SBO)

| % Fungi/MBC | % Bacteria /MBC | % Actinomycetes/MBC | FBC | BBC | ABC | |

| CTR0 | 20.9d ± 0.9 | 41.9b ± 1.4 | 37.2a ± 0.9 | 188.2d ± 8 | 376.3b ± 8 | 334.5b ± 5 |

| CTR | 21.7d ± 0.8 | 43.5a ± 1.2 | 34.8b ± 0.8 | 171.6d ± 9 | 343.1c ± 5 | 274.3c ± 7 |

| C | 27.1c ± 1.1 | 40.5b ± 0.9 | 32.4c ± 0.6 | 293.6c ± 7 | 440.4a ± 9 | 353.0a ± 8 |

| V | 28.2c ± 0.9 | 45.1a ± 1.5 | 26.8d ± 0.8 | 281.5c ± 6 | 450.2a ± 7 | 267.3cd ± 9 |

| D | 32.8b ± 1.3 | 40.3b ± 1.1 | 26.9d ± 1 | 314.5b ± 8 | 385.9b ± 7 | 257.6d ± 6 |

| SBO | 40.0a ± 1.2 | 33.9c ± 1 | 26.2d ± 0.9 | 372.8a ± 5 | 315.5d ± 8 | 243.7e ± 5 |

A dedicated focus was placed on the GWP (100a), considered here as the CFP of each fertilizer system, since it represents the most widely recognized indicator for climate change. The results showed that vermicompost had the lowest impact (25 kg CO2 eq ton-1), followed by compost (43 kg CO2 eq ton-1) and digestate (110 kg CO2 eq ton-1), while SBO recorded the highest emissions (167 kg CO2 eq ton-1) [Figure 3]. This ranking reflects the different energy requirements and input materials: vermicompost benefits from a biologically driven process with limited energy demand, while digestate and especially SBO are penalized by high fossil fuel use, electricity consumption, and sulfur processing. When emissions were broken down by life cycle modules, the core stage, and particularly the fertilizer manufacturing process, emerged as the dominant hotspot. SBO displayed the largest contribution due to the transformation of sulfur and bentonite, while vermicompost confirmed its favourable performance. In the upstream module, raw material recovery was more relevant than transport, especially for digestate and SBO, whereas in the downstream module, field application generated higher CO2 emissions than distribution. Focusing on GWP is particularly relevant because CFP is a key metric in evaluating the climate sustainability of agricultural practices, directly linked to global mitigation targets. The findings highlight that reducing energy consumption in fertilizer manufacturing and minimizing emissions during field application are critical steps toward lowering the CFP of fertilization systems.

DISCUSSION

The experimental evidence indicates that compost and vermicompost not only improve the chemical, physical, and biological properties of soil, but also strongly enhance humification processes, i.e., the transformation of fresh organic matter into more recalcitrant and stable fractions. This mechanism is crucial for carbon sequestration, since HSs represent the most stable pools of SOC, with residence times ranging from decades to centuries. Compost and vermicompost treatments showed the highest values of TOC and TEC, along with superior humification indices such as the HC/FC ratio, humification rate and HD. These parameters indicate that a larger share of organic matter is converted into humic fractions, which are more resistant to microbial mineralization. In particular, the highest HC/FC ratio with compost and vermicompost reflects an enrichment of larger, more aromatic, and condensed molecules, typical of stable organic matter. Together, these findings show that compost and vermicompost do not simply add carbon to soils, but also transform it into more stable forms, thereby strengthening the long-term sequestration potential. Microbial roles in carbon stabilization. The microbial community shifts observed under different treatments further explain the pathways of carbon sequestration and humified material formation: Fungi, particularly stimulated under digestate and SBO treatments, are central players in the decomposition of plant residues because of their ability to degrade lignocellulosic materials through extracellular oxidative enzymes such as laccases and peroxidases[45]. Their filamentous growth allows them to penetrate plant tissues and initiate the breakdown of recalcitrant organic matter, releasing soluble compounds that can be further metabolized by other microorganisms[46,47]. Although fungi efficiently transform complex polymers into aromatic precursors, recent research indicates that their biomass contributes less to persistent humus formation than previously assumed. Instead, bacterial necromass represents a large and stable fraction of soil organic matter[48,49]. This emerging view aligns fungal activity with early-stage decomposition and precursor formation, while assigning bacteria a leading role in long-term carbon stabilization via the “microbial carbon pump”. Bacteria - particularly enriched under vermicompost - decompose labile substrates and generate cell wall residues and extracellular polysaccharides that bind to minerals and persist in soil. Actinomycetes, enriched in compost and vermicompost soils, bridge fungal and bacterial functions: they degrade cellulose and hemicellulose while also producing metabolites that serve as humus precursors. Their slow turnover further enhances organic matter stabilization.

These complementary microbial functions reconcile seemingly conflicting findings in the literature: fungi dominate transformation processes and generate aromatic intermediates, whereas bacteria contribute disproportionately to humification and to mineral-associated carbon. Our results support this framework, showing that treatments fostering diverse and active microbial communities - such as compost and vermicompost - enhance both precursor formation and stable carbon accumulation. Long-term fertilization studies show strong correlations between SOC and humic fraction with a coefficient of determination up of 98%[50], reflecting the formation of resistant aromatic-aliphatic humic structures and their stabilization through mineral interactions[51,52].

The microbial patterns observed here are consistent with these mechanisms: fungal activity enhances aromatic condensation (lower E4/E6), while bacterial and actinomycete contributions promote necromass stabilization and soil aggregation. The results indicate that compost and vermicompost represent the most effective amendments for promoting stable carbon sequestration. By increasing humification indices and stimulating diverse microbial communities, they foster the buildup of humic pools with slower turnover rates. This is particularly relevant for Mediterranean agroecosystems, where climatic stressors (high temperatures, drought) accelerate the mineralization of labile carbon pools. In contrast, digestate contributed to SOC accumulation but with lower humification indices and microbial diversity, suggesting a more transient carbon contribution. SBO, while stimulating fungal dominance and potentially enhancing aggregate-associated carbon, showed limited benefits in terms of humification indices and carried a larger environmental burden due to sulfur processing.

A more detailed examination of the LCA modules provides insight into the origin of the observed differences among treatments. The core module, corresponding to fertilizer manufacturing, represented the dominant emission hotspot across all amendments. SBO showed the highest core-stage contribution due to energy-intensive sulfur activation and bentonite processing, whereas compost and vermicompost required substantially fewer external energy inputs. In the upstream module, the recovery and pre-treatment of raw materials contributed disproportionately for digestate and SBO, while transport played a minor role for all fertilizers. The downstream module was primarily driven by field application, which generated higher CO2 emissions than distribution. These module-specific patterns clarify the drivers of CFP variability and highlight that reducing energy demand during manufacturing and application represents a key mitigation strategy for future waste-derived fertilization systems.

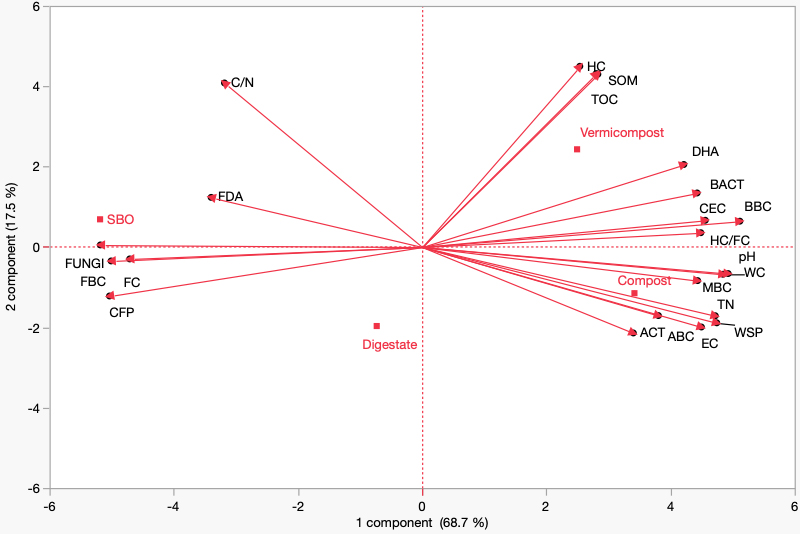

PCA was performed to integrate the CFP with the main chemical, microbiological, and enzymatic parameters of the soil, highlighting clear patterns of correlation. CFP was located on the left side of the biplot, in close association with the fungal fraction (FUNG), the respiratory fraction [Fungi Biomass C (FBC)], and the easily decomposable FC [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) integrating the Carbon Footprint (CFP, kg CO2 eq ton-1) with the main chemical, microbiological and enzymatic soil parameters under treatments with Compost, Vermicompost, Digestate, and SBO (sulfur bentonite with olive pomace). Variables included: TOC (Total Organic Carbon, %), TEC (Total Extractable Carbon, %), HA (Humic Acid carbon, %), FA (Fulvic Acid carbon, %), HA+FA (Humic + Fulvic Acid carbon, %), HA/FA (Humic to Fulvic Acid ratio, dimensionless), HR (Humification Rate, %), HD (Humification Degree, %), HI (Humification Index, %), E4/E6 (absorbance ratio at 465/665 nm, dimensionless), WSP (Water Soluble Phenols, mg TAE g-1 d.w.), SOM (Soil Organic Matter, %), TN (Total Nitrogen, %), C/N (Carbon to Nitrogen ratio, dimensionless), pH (H2O, 1:2.5 ratio), EC (Electrical Conductivity, dS m-1), WC (Water Content, %), CEC [Cation Exchange Capacity, cmol(+) kg-1], MBC (Microbial Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), FBC (Fungal Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), BBC (Bacterial Biomass Carbon,

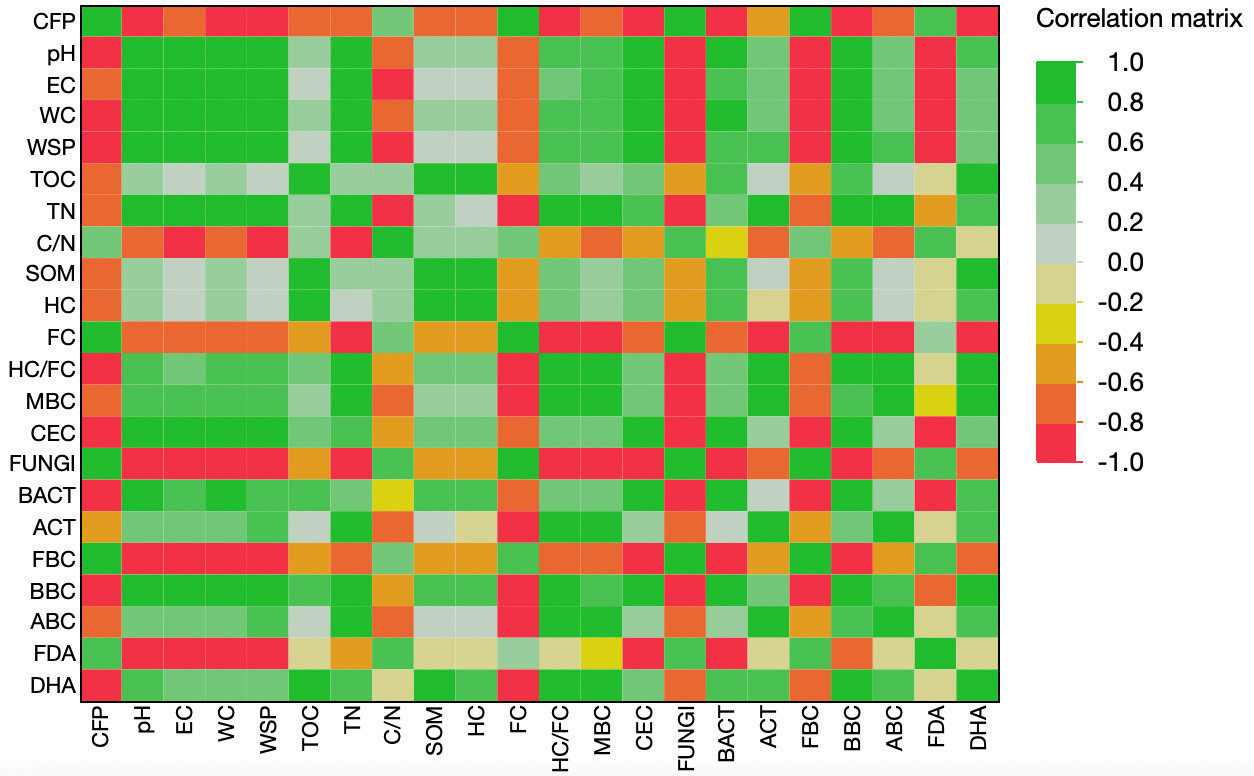

This result suggests that CO2 emissions are higher in the presence of greater mineralization of organic matter and a dominant fungal activity, which favors the rapid degradation of organic compounds. In contrast, CFP was positioned opposite to variables such as TOC, soil organic matter, humified carbon, total nitrogen, pH, electrical conductivity, MBC, and CEC. This indicates a negative correlation, meaning that soils richer in stable organic matter, nutrients, and microbial biomass exhibited a lower CFP, due to their greater capacity to sequester carbon. From the perspective of treatments, SBO was located in proximity to CFP, confirming its contribution to higher CO2 emissions. Compost and Vermicompost, on the other hand, were strongly associated with soil quality and stability parameters, confirming their ability to reduce CFP and enhance carbon sequestration. Digestate showed an intermediate position, exerting some positive effects on fertility but without the same efficacy in mitigating emissions. Overall, the first principal component (PC1), which explained 68.7% of the variance, clearly represented the gradient between soils with higher emissions and those with greater carbon accumulation potential. These results emphasize that the application of high-quality organic amendments can be an effective strategy to improve soil fertility while simultaneously mitigating the CFP. The correlation matrix heatmap further supports these findings by providing a global overview of the pairwise relationships among soil parameters and CFP. CFP showed strong negative correlations with TOC, SOM, HC, MBC, CEC, DHA and pH, confirming that higher soil fertility and organic matter stability are linked to lower emissions [Figure 5]. Conversely, positive correlations were observed between CFP and variables such as Fungi, FBC, and FC, highlighting the role of fungal-driven mineralization and labile carbon pools in promoting CO2 release. This multivariate visualization reinforces the conclusion that a soil system enriched with stable organic carbon and balanced microbial communities is more efficient in sequestering carbon and mitigating the CFP, while treatments dominated by labile pools and fungal activity contribute to higher emissions [Figure 5]. When translating these results into future policy actions, scalability and waste availability must also be considered. While vermicompost showed the most favorable agronomic and environmental performance on a per-ton basis, its global production capacity remains far smaller than that of agricultural waste compost and food-waste compost. Composting is currently the dominant technology capable of processing millions of tons of organic residues annually, including agricultural by-products, pruning residues, and municipal food waste. Therefore, although vermicompost represents a high-quality amendment, compost is the option with the greatest scalability for climate policy frameworks. Integrating estimates of regional waste availability into policy design would support realistic deployment scenarios for waste-derived fertilizers. A methodological limitation of this study is that the compost was produced using an electrically assisted system based on a traditional, slower three-phase process. In recent years, however, composting technology has advanced substantially. Novel microbial-driven systems are able to shorten the initial mesophilic phase to less than one day, rapidly reach higher thermophilic temperatures (up to 70 °C), and complete thermophilic stabilization within 7-10 days without the need for external energy inputs. These new process configurations - driven primarily by optimized aeration, moisture control, and microbial community engineering - enable faster decomposition, lower energy consumption, and reduced GHG emissions during composting[53,54].

Figure 5. Correlation matrix among the Carbon Footprint (CFP, kg CO2 eq ton-1) and the main chemical, microbiological and enzymatic soil parameters. Variables included: pH (H2O, 1:2.5), EC (Electrical Conductivity, dS m-1), WC (Water Content, %), WSP (Water Soluble Phenols, mg TAE g-1 d.w.), TOC (Total Organic Carbon, %), TN (Total Nitrogen, %), C/N (Carbon to Nitrogen ratio, dimensionless), SOM (Soil Organic Matter, %), HC (Humified Carbon, %), FC (Fraction of Carbon easily decomposable, %), HC/FC (Humified Carbon to Fraction of Carbon ratio, %), MBC (Microbial Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), CEC [Cation Exchange Capacity, cmol(+) kg-1], FUNGI (Fungi, % of total microbial biomass), BACT (Bacteria, % of total microbial biomass), ACT (Actinomycetes, % of total microbial biomass), FBC (Fungal Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), BBC (Bacterial Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), ABC (Actinomycetes Biomass Carbon, µg C g-1), FDA (Fluorescein Diacetate hydrolase activity, µg fluorescein g-1 h-1), and DHA (Dehydrogenase activity, µg TPF g-1 h-1). The scale ranges from -1 (strong negative correlation, red) to +1 (strong positive correlation, green).

Beyond their experimental performance, these results have important implications for future GHG mitigation and soil management policies. The strong humification capacity and low CFP of compost and vermicompost indicate that these waste-derived fertilizers can simultaneously support agronomic productivity and climate-smart nutrient management. By recycling regional organic residues and promoting the formation of stable carbon pools, these amendments reduce dependence on synthetic fertilizers, enhance soil resilience under Mediterranean climatic stressors, and contribute to long-term carbon neutrality goals. Integrating such circular bio-based fertilizers into agricultural policy frameworks could therefore provide a dual benefit, improving soil quality while mitigating GHG emissions. These outcomes are also consistent with the goals of the “4 per 1000” Initiative launched at the 2015 Paris Climate Conference (COP21)[55], which promotes increasing global SOC stocks by 0.4% per year to offset anthropogenic GHG emissions. The substantial gains in humification observed under compost and vermicompost suggest that these amendments can meaningfully contribute to meeting this global target, particularly in vulnerable Mediterranean soils.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that organic amendments derived from agro-industrial wastes have strong potential to improve soil fertility, enhance humification, and contribute to climate change mitigation. Compost and vermicompost emerged as the most effective strategies, showing the highest humification indices (HA/FA, HC/FC, HR%, HD%) and fostering the formation of stable carbon pools. These treatments also promoted balanced microbial communities, where fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes acted synergistically to transform organic inputs into persistent HSs. Digestate played an intermediate role, increasing TOC and fungal biomass but with lower humification efficiency, suggesting that its contribution is more relevant for short-term nutrient recycling than for long-term carbon sequestration. SBO significantly influenced microbial composition by stimulating fungal dominance and acidifying the soil; however, its environmental footprint, largely due to sulfur processing, limits its suitability as a climate-smart amendment. Life cycle assessment further confirmed the advantages of compost and vermicompost, which showed the lowest CFPs compared with digestate and SBO. By combining agronomic, biochemical, microbial, and environmental evidence, this work highlights how waste-derived fertilizers can replace or reduce the use of synthetic inputs, contributing simultaneously to soil quality, resource efficiency, and GHG mitigation.

Overall, compost and vermicompost represent the most sustainable solutions for promoting stable carbon sequestration and long-term soil health in Mediterranean and similar agroecosystems. Future studies should focus on long-term field trials, deeper humic fraction characterization, and microbial functional profiling to strengthen predictive models of carbon stabilization under different climate and management scenarios.

Although this study provides strong evidence of carbon stabilization via humification, the experimental period (two years) limits conclusions about long-term persistence. Future research will focus on: (1) extending monitoring to 5-10 years to evaluate the stability of HA and humin fractions; (2) including humin characterization, as it is often the most stable component of HSs; and (3) exploring how HA/FA and E4/E6 ratios evolve under different cropping systems, soil management practices, and climatic conditions, and how these indices correlate with deep-soil carbon sequestration.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Orfei Farm for providing both their land and personnel for the open field experiments.

Authors’ contributions

Methodology, data collection and analysis, writing - original draft: Muscolo, A.; Maffia, A.

Conceptualization, writing - review and editing: Maffia, A.; Muscolo, A.; Marra, F.

Project administration, supervision, and funding acquisition: Muscolo, A.

Methodology: Maffia, A.; Battaglia, S.; Marra, F.; Mallamaci, C.

Data collection, writing - review and editing: Maffia, A.; Battaglia, S.; Marra, F.; Mallamaci, C.

Data collection, writing - original draft: Muscolo, A.; Maffia, A.

Review and editing: Muscolo, A.; Maffia, A.; Marra, F.;

Availability of data and materials

Data in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry for University and Research (MUR) under Project CN_00000022, “National Research Centre for Agricultural Technologies - Agritech” and “Solutions for Soil Quality Assessment and Protection” 3.2.1.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Reis, S. D. D. S. D.; Junior, M. A. P. O.; Tomazi, M.; Orrico, A. C. A.; Cunha, S. D. S.; Amaral, I. P. D. O. Feasibility of organic fertilization for reducing greenhouse gas emissions compared to mineral fertilization. Grasses 2025, 4, 26.

2. Subedi, S.; Dent, B.; Adhikari, R. The carbon footprint of fruits: a systematic review from a life cycle perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 12-28.

3. He, Z.; Ding, B.; Pei, S.; Cao, H.; Liang, J.; Li, Z. The impact of organic fertilizer replacement on greenhouse gas emissions and its influencing factors. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 905, 166917.

4. Akhiar, A.; Ahmad Zamri, M. F. M.; Torrijos, M.; et al. Anaerobic digestion industries progress throughout the world. IOP. Conf. Ser. Earth. Environ. Sci. 2020, 476, 012074.

5. O'connor, S.; Ehimen, E.; Pillai, S.; Black, A.; Tormey, D.; Bartlett, J. Biogas production from small-scale anaerobic digestion plants on European farms. Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2021, 139, 110580.

6. Chojnacka, K.; Moustakas, K. Anaerobic digestate management for carbon neutrality and fertilizer use: a review of current practices and future opportunities. Biomass. Bioenergy. 2024, 180, 106991.

7. Badewa, E. A.; Yeung, C. C.; Whalen, J. K.; Oelbermann, M. Compost and biosolids increase long-term soil organic carbon stocks. Can. J. Soil. Sci. 2023, 103, 483-92.

8. Polo, J. D.; Toboso-Chavero, S.; Adhikari, B.; Villalba, G. Closing the nutrient cycle in urban areas: the use of municipal solid waste in peri-urban and urban agriculture. Waste. Manag. 2024, 183, 220-31.

9. Badagliacca, G.; Testa, G.; La Malfa, S. G.; Cafaro, V.; Lo Presti, E.; Monti, M. Organic Fertilizers and bio-waste for sustainable soil management to support crops and control greenhouse gas emissions in mediterranean agroecosystems: a review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 427.

10. Enebe, M. C.; Erasmus, M. Mediators of biomass transformation - a focus on the enzyme composition of the vermicomposting process. Environ. Challenges. 2023, 12, 100732.

11. Aksakal, E. L.; Sari, S.; Angin, I. Effects of vermicompost application on soil aggregation and certain physical properties. Land. Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 983-95.

12. Shu, X.; He, J.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Organic amendments enhance soil microbial diversity, microbial functionality and crop yields: a meta-analysis. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 829, 154627.

13. Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms and implications of bacterial-fungal competition for soil resources. ISME. J. 2024, 18, wrae073.

14. Soares, M.; Rousk, J. Microbial growth and carbon use efficiency in soil: links to fungal-bacterial dominance, SOC-quality and stoichiometry. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2019, 131, 195-205.

15. Muscolo, A.; Papalia, T.; Settineri, G.; Romeo, F.; Mallamaci, C. Three different methods for turning olive pomace in resource: benefits of the end products for agricultural purpose. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 662, 1-7.

16. Panuccio, M. R.; Marra, F.; Maffia, A.; et al. Recycling of agricultural (orange and olive) bio-wastes into ecofriendly fertilizers for improving soil and garlic quality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200083.

17. Bouranis, D. L.; Gasparatos, D.; Zechmann, B.; Bouranis, L. D.; Chorianopoulou, S. N. The Effect of granular commercial fertilizers containing elemental sulfur on wheat yield under mediterranean conditions. Plants 2018, 8, 2.

18. Hao, Y.; Mao, J.; Bachmann, C. M.; et al. Soil moisture controls over carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions: a review. npj. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 16.

19. Wang, F.; Pan, T.; Fu, D.; et al. Pilot-scale membrane-covered composting of food waste: Initial moisture, mature compost addition, aeration time and rate. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 926, 171797.

20. Majlessi, M.; Eslami, A.; Najafi Saleh, H.; Mirshafieean, S.; Babaii, S. Vermicomposting of food waste: assessing the stability and maturity. Iranian. J. Environ. Health. Sci. Eng. 2012, 9, 25.

21. Nardi, S.; Pizzeghello, D.; Reniero, F.; Rascio, N. Chemical and biochemical properties of humic substances isolated from forest soils and plant growth. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 639-45.

22. Chang, Y.; Lee, C.; Hsieh, C.; Chen, T.; Jien, S. Using fluorescence spectroscopy to assess compost maturity degree during composting. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1870.

24. Stevenson, F. J. Humus chemistry: genesis, composition, reactions, 2th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ed072pA93.6 (accessed 2026-01-27).

25. Francioso, O.; Sánchez-cortés, S.; Casarini, D.; Garcia-ramos, J.; Ciavatta, C.; Gessa, C. Spectroscopic study of humic acids fractionated by means of tangential ultrafiltration. J. Mol. Struct. 2002, 609, 137-47.

27. Ritchie, J. D.; Perdue, E. M. Analytical constraints on acidic functional groups in humic substances. Organic. Geochemistry. 2008, 39, 783-99.

28. Walkley, A.; Black, I. A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil. Sci. 1934, 37, 29-38.

29. Kjeldahl, J. Neue methode zur bestimmung des stickstoffs in organischen Körpern. Fresenius. Z. Anal. Chem. 1883, 22, 366-82.

30. Kaminsky, R.; Müller, W. H. A recommendation against the use of alkaline soil extractions in the study of allelopathy. Plant. Soil. 1978, 49, 641-5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42933627 (accessed 2026-01-27).

31. Box, J. Investigation of the Folin-Ciocalteau phenol reagent for the determination of polyphenolic substances in natural waters. Water. Res. 1983, 17, 511-25.

32. Hendershot, W. H.; Duquette, M. A simple barium chloride method for determining cation exchange capacity and exchangeable cations. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1986, 50, 605-8.

33. Vance, E.; Brookes, P.; Jenkinson, D. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703-7.

34. Adam, G.; Duncan, H. Development of a sensitive and rapid method for the measurement of total microbial activity using fluorescein diacetate (FDA) in a range of soils. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 943-51.

35. Mersi, W.; Schinner, F. An improved and accurate method for determining the dehydrogenase activity of soils with iodonitrotetrazolium chloride. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1991, 11, 216-20.

36. Kandeler, E.; Gerber, H. Short-term assay of soil urease activity using colorimetric determination of ammonium. Biol. Fert. Soils. 1988, 6, 68-72.

37. ISO 14040. Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Principles and framework. International Organization for Standardization,2006. https://www.cscses.com/uploads/2016328/20160328110518251825.pdf (accessed 2026-01-27).

38. ISO 14044. Environmental management - Life cycle assessment - Requirements and guidelines. International Organization for Standardization, 2006. https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed 2026-01-27).

39. EPD, 2020.PCR Mineral or chemical ferilizers 2010:20- Version 3.0. International Environmental Product Declaration system. https://www.environdec.com/pcr-library/pcr2010-20 (accessed 2026-01-28).

40. Egas, D.; Azarkamand, S.; Casals, C.; Ponsá, S.; Llenas, L.; Colón, J. Life cycle assessment of bio-based fertilizers production systems: where are we and where should we be heading? Int. J. Life. Cycle. Assess. 2023, 28, 626-50.

41. Amlinger, F.; Peyr, S.; Cuhls, C. Green house gas emissions from composting and mechanical biological treatment. Waste. Manag. Res. 2008, 26, 47-60.

42. Beck-friis, B.; Smårs, S.; Jönsson, H.; Eklind, Y.; Kirchmann, H. Composting of source-separated household organics at different oxygen levels: gaining an understanding of the emission dynamics. Compost. Sci. Util. 2003, 11, 41-50.

43. Pagans, E.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Emission of volatile organic compounds from composting of different solid wastes: abatement by biofiltration. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 131, 179-86.

44. Pergola, M.; Persiani, A.; Pastore, V.; et al. Sustainability assessment of the green compost production chain from agricultural waste: a case study in Southern Italy. Agronomy 2020, 10, 230.

45. Baldrian, P. Forest microbiome: diversity, complexity and dynamics. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 109-30.

46. Kögel-knabner, I. The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 139-62.

47. Six, J.; Frey, S. D.; Thiet, R. K.; Batten, K. M. Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 555-69.

48. Whalen, E. D.; Grandy, A. S.; Geyer, K. M.; Morrison, E. W.; Frey, S. D. Microbial trait multifunctionality drives soil organic matter formation potential. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10209.

49. Bölscher, T.; Vogel, C.; Olagoke, F. K.; et al. Beyond growth: the significance of non-growth anabolism for microbial carbon-use efficiency in the light of soil carbon stabilisation. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2024, 193, 109400.

50. Zhang, J.; Chi, F.; Wei, D.; et al. Impacts of long-term fertilization on the molecular structure of humic acid and organic carbon content in soil aggregates in black soil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11908.

51. Canellas, L. P.; Olivares, F. L. Physiological responses to humic substances as plant growth promoter. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3.

52. Sedlář, O.; Balík, J.; Černý, J.; Suran, P.; Kulhánek, M.; Bihun, T. Soil organic matter quality and carbon sequestration potential affected by straw return in 11-year on-farm trials in the Czech Republic. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1277.

53. Hoang, H.; Lin, C.; Nguyen, M.; Bui, X.; Vo, D. N.; Tran, H. The microbiology of food waste composting. In Food waste valorisation. WORLD SCIENTIFIC (EUROPE); 2023. pp. 105-24.

54. Lin, C.; Cheruiyot, N. K.; Le, T.; Hussain, A.; Nguyen, D.; Kuo, C. Food waste composting: current status, challenges, and opportunities. In Food waste valorisation. WORLD SCIENTIFIC (EUROPE); 2023. pp. 125-47.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].