Disrupting resistance: novel therapeutic approaches to combat multidrug resistance in fusion-negative rhabdomyosarcoma

Abstract

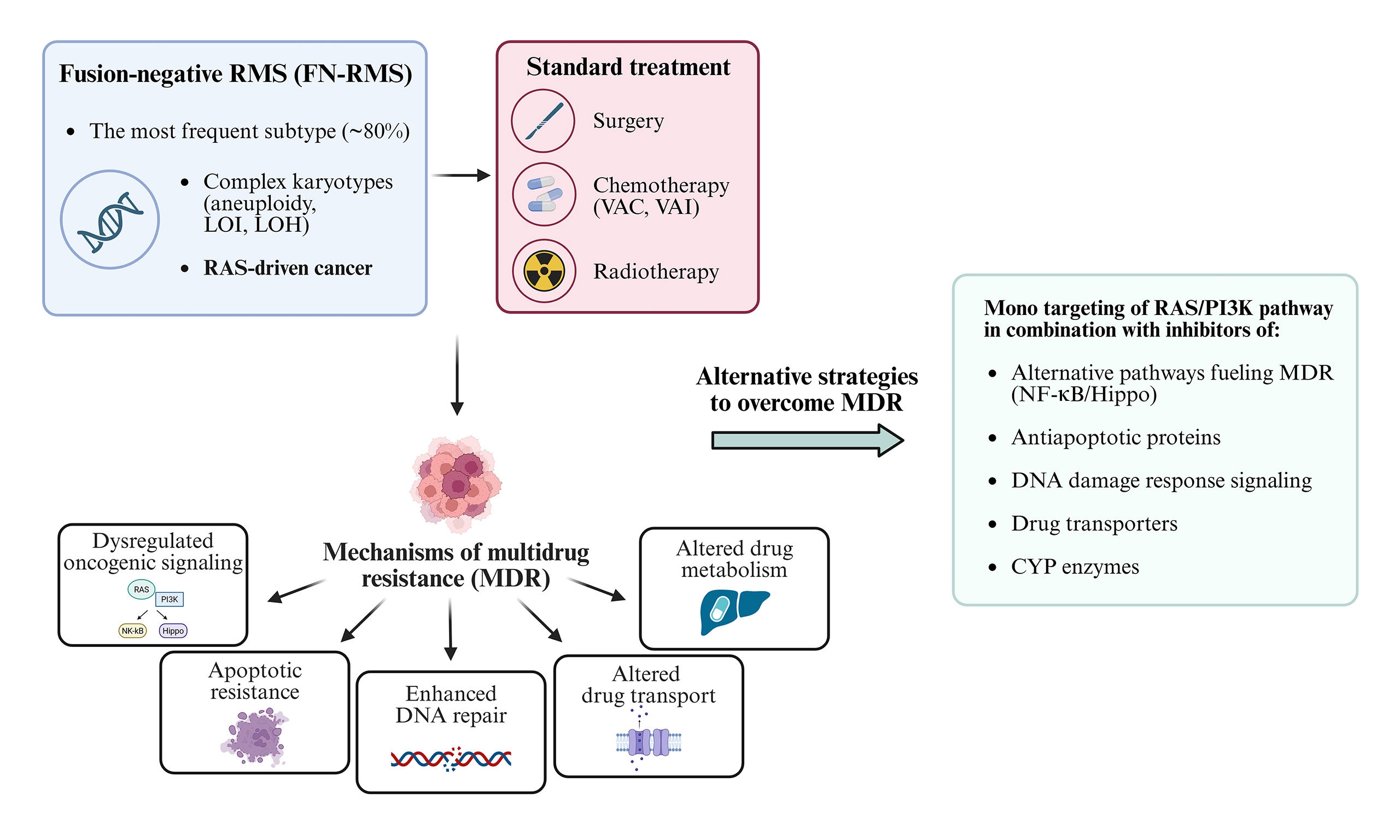

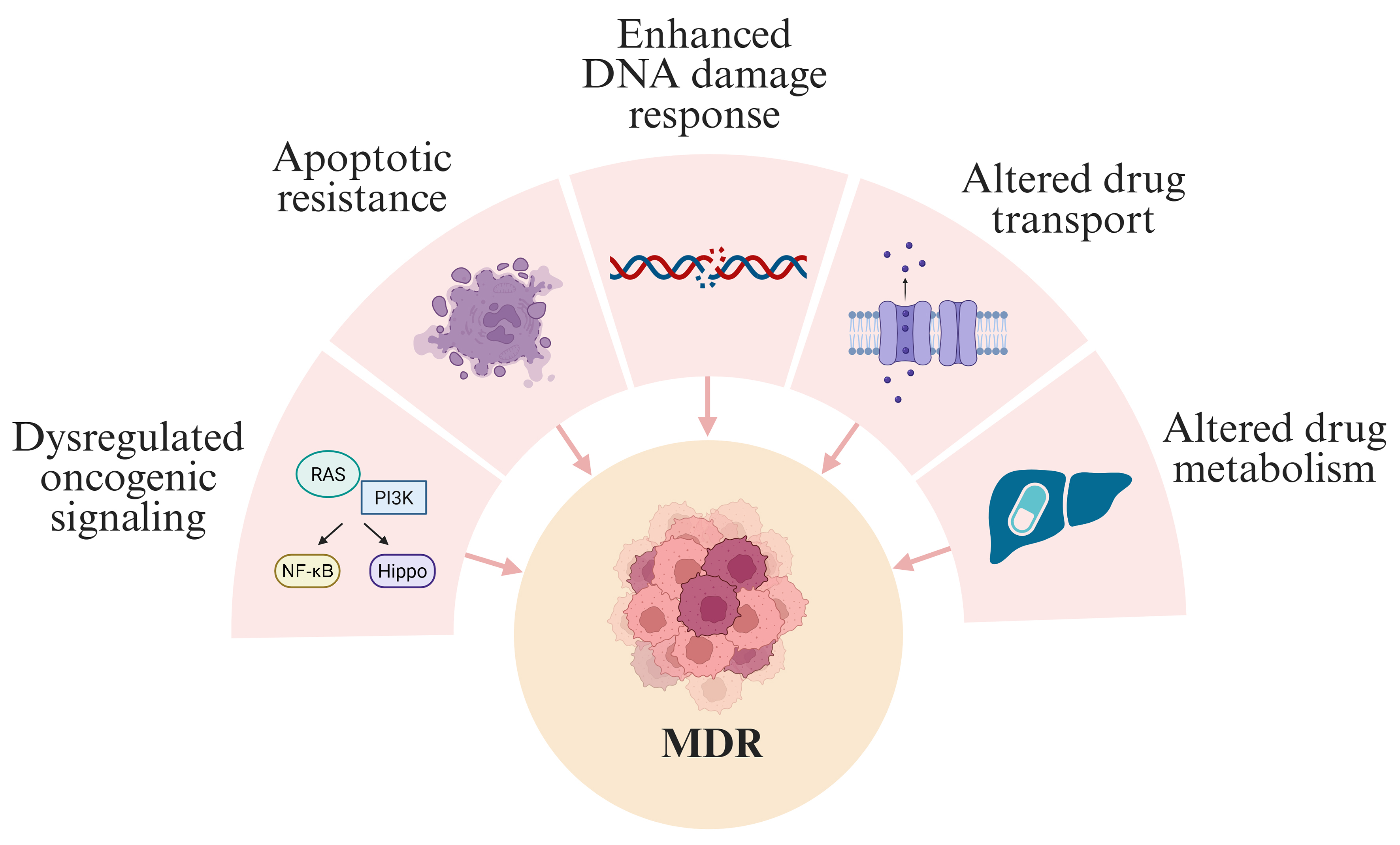

Rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) are aggressive pediatric soft tissue tumors. The fusion-negative subtype (FN-RMS) is characterized by RAS pathway mutations and genomic instability. While standard chemotherapies - vincristine, actinomycin D, and alkylating agents - are effective against localized disease, multidrug resistance (MDR) often leads to treatment failure in relapsed and metastatic RMS. Key drivers of MDR in FN-RMS include dysregulated RAS/PI3K signaling, enhanced DNA repair, evasion of apoptosis, and alterations in drug transport and metabolism. Preclinically, vertical inhibition of the RAS/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways shows promise but is limited by toxicity and compensatory feedback. Combination strategies targeting MEK, IGF1R, and PI3K, as well as epigenetic regulators and metabolic pathways, demonstrate synergistic effects. BH3 mimetics can restore apoptotic sensitivity, especially in FBW7-deficient tumors. Radiotherapy resistance is mediated through the DNA-PK–mTORC2–AKT axis, while drug transporters such as ABCB1 and SLC7A11, along with age-dependent CYP enzyme expression, affect drug bioavailability. Targeting these convergent mechanisms offers a promising therapeutic strategy to overcome resistance in FN-RMS.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

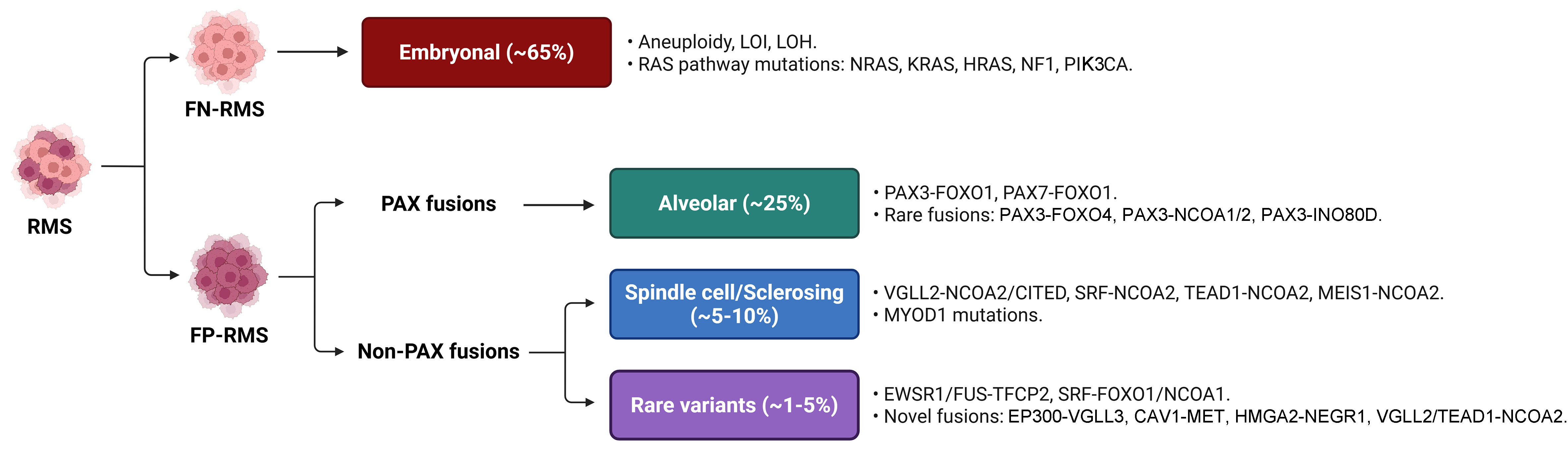

Rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS) are high-grade malignant tumors exhibiting partial myogenic differentiation due to aberrant expression of muscle regulatory factors (MRFs) such as myogenic factor 5 (MYF5), myoblast determination protein 1 (MYOD), and myogenin (MYOG)[1]. Although rare in adults, RMS accounts for roughly 50% of pediatric soft tissue sarcomas, primarily affecting children, adolescents, and young adults. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies pediatric RMS into three main histologic subtypes - embryonal, alveolar, and spindle cell/sclerosing - which display diverse morphologies and are driven by distinct genetic alterations [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Molecular and genetic features of RMS. Primary genetic alterations and fusion oncoproteins associated with the RMS subtypes. RMS: Rhabdomyosarcomas; WHO: World Health Organization; FN-RMS: fusion-negative RMS; LOI: loss of imprinting; LOH: loss of heterozygosity; RAS: rat sarcoma; NRAS: neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog; KRAS: Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; HRAS: Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; NF1: neurofibromin 1; PIK3CA: phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3 kinase catalytic subunit alpha; FP-RMS: fusion-positive RMS; PAX: paired box gene; PAX3/7: paired box 3/7; FOXO1/4: forkhead box O1/4; NCOA1/2: nuclear receptor co-activator 1/2; INO80D: INO80 complex subunit D; VGLL2/3: vestigial-like family member 2/3; CITED: Cbp/P300 interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp rich carboxy-terminal domain 1; SRF: serum response factor; TEAD1: TEA domain family member 1; MEIS1: myeloid ecotropic viral integration site 1 homolog; MYOD1: myogenic differentiation 1; EWSR1: EWS RNA binding protein 1; FUS: fused in sarcoma; TFCP2: transcription factor CP2; CAV1: caveolin 1; MET: mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor; HMGA2: high-mobility group AT-hook 2; NEGR1: neuronal growth regulator 1.

Embryonal and alveolar RMS are the most common, representing approximately 65% and 25% of cases, respectively. Modern classification stratifies RMS into fusion-negative (FN-RMS) and fusion-positive (FP-RMS) based on the absence or presence of characteristic chromosomal translocations. FN-RMS typically exhibits complex karyotypes, aneuploidy, and somatic mutations, most commonly in rat sarcoma (RAS) pathway genes such as neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS), Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (HRAS), neurofibromin 1 (NF1), and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA)[2]. Consequently, FN-RMS is considered a prototypical RAS-driven cancer[3], a notion supported by the increased RMS risk in genetic syndromes such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and various RASopathies[4]. In contrast, FP-RMS is defined by recurrent translocations, most commonly generating paired box 3 (PAX3)-forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) or paired box 7 (PAX7)-FOXO1 fusion oncoproteins, which are associated with a poorer prognosis[2]. It is important to note that many rare variant fusions involving PAX3/7 or FOXO1 with novel partner genes are being discovered in FP-RMS[5]. As reviews on FP-RMS and its therapeutic management are available elsewhere[6,7], this review will focus primarily on novel therapeutic strategies for FN-RMS, although the rationale for some treatments may overlap across histotypes.

MECHANISMS OF STANDARD CHEMOTHERAPY IN RMS

Multimodal treatment - combining chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery - achieves durable remission in over 90% of children with low-risk, localized RMS. Standard chemotherapy regimens include VAI [vincristine, actinomycin D, ifosfamide (IFO)] or VAC [vincristine, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide (CFO)], which demonstrate comparable efficacy in Europe and North America[8]. These agents act through distinct mechanisms. Vinca alkaloids (e.g., vincristine) are derived from Catharanthus roseus or synthesized semi-synthetically. These drugs depolymerize microtubules and destabilize the mitotic spindle, causing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. However, resistance to vincristine often develops, making combination therapies more effective than monotherapy[9].

Actinomycin D (Dactinomycin) is an antibiotic that intercalates into DNA at GpC-rich sites, inhibiting replication and blocking RNA polymerase activity, thereby impairing transcription and DNA repair. Tumor cells resistant to vincristine often show cross-resistance to actinomycin D and doxorubicin.

Alkylating agents (IFO and CFO) are prodrugs that form covalent DNA crosslinks, causing DNA damage. They require metabolic activation by cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (mainly CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 for IFO)[10]. Consequently, co-administration of CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, sorafenib) can reduce their efficacy.

Despite the success of these regimens in localized disease, outcomes for metastatic or relapsed RMS remain poor due to multidrug resistance (MDR)[11-13]. This review focuses on MDR in FN-RMS, driven primarily by dysregulated oncogenic signaling [RAS/phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)], apoptotic resistance, enhanced DNA repair, and altered drug transport and metabolism [Figure 2].

OVERCOMING MDR IN RMS

Vertical RAS targeting

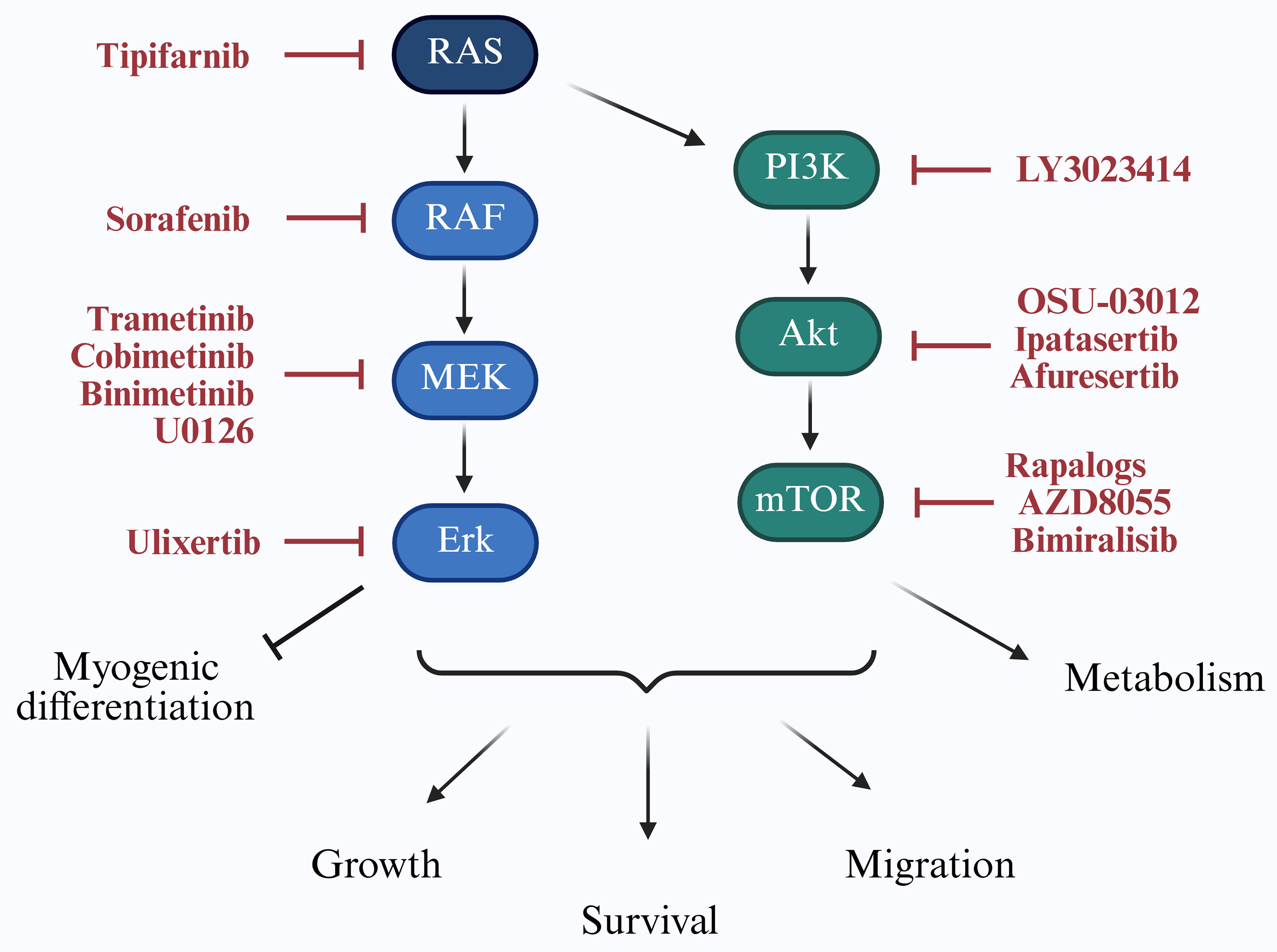

As illustrated in Figure 3, targeting the RAS/PI3K axis is a key strategy to improve RMS therapy.

Figure 3. Targeting RAS/PI3K signaling in RMS. The RAS/PI3K signaling cascade regulates key cellular processes including proliferation, survival, migration, myogenic differentiation, and metabolism. Downstream effectors contribute to tumor progression and therapy resistance in RMS. Specific inhibitors targeting components of this pathway, which have been investigated in RMS models, are indicated in red. RAS: Rat sarcoma; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RMS: rhabdomyosarcomas; RAF: rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; Erk: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; Akt: protein kinase B; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin.

The RAS family of small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases), including HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS, regulates critical cellular functions. Oncogenic RAS mutations, which cause constitutive activation of downstream signaling, are found in approximately 25% of human cancers[14]. In FN-RMS, 29 distinct RAS mutations have been reported[2], with isoform prevalence varying by age: HRAS in neonates, KRAS in younger children, and NRAS in adolescents[2]. Notably, RAS pathway activation may also be therapeutically relevant in FP-RMS[15]. Direct targeting of RAS has been challenging due to its compact and smooth protein structure[16], leading to strategies that interfere with its membrane localization, such as with the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib[17].

Upon activation, RAS-guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP) stimulates the rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF)/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) cascade. Pan-RAF inhibitors such as sorafenib are sometimes preferred to avoid paradoxical ERK activation[18]. In NRAS-mutant FN-RMS models, combined RAF and MEK or ERK inhibition has induced tumor regression[18] [Table 1], though sorafenib monotherapy showed limited clinical efficacy[19].

Combined treatments employed in preclinical RMS models

| Drug targets | Drugs | Basis for combination | Model | Endpoints | Risks | Ref. |

| RAFi + MEKi | LY3009120 + trametinib | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | RAS-mutated FN-RMS lines and tumor xenografts | Cell cycle arrest, myogenic differentiation, apoptosis, reduced tumor growth in vivo | Normal tissue toxicity | [18] |

| RAFi + Erki | LY3009120 + LY3214996 | |||||

| MEKi + Erki | trametinib + LY3214996 | |||||

| IGF1Ri + MEKi | BMS-754807 + trametinib | Partial response to trametinib monotherapy | RAS-mutated FN-RMS lines and tumor xenografts | Apoptosis, reduced tumor growth in vivo | Intolerance in murine models | [20] |

| IGF1Ri + MEKi | Ganitumab + trametinib | Improved tolerability compared to previous study | RAS-mutated FN-RMS lines and PDX tumor | Inhibition of cell proliferation, reduced tumor growth in vivo | Hematologic and metabolic side effects | [21] |

| MEKi + PI3Ki | MEK162 + BYL719 | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | NRAS-mutated FN-RMS lines | Apoptosis, reduced clonogenic capacity | Metabolic side effects | [22] |

| Erki + MCL-1i | Ulixertinib + S63845 | Apoptosis restoration | RMS lines | Apoptosis, reduced clonogenic capacity | / | [26] |

| MEKi + PI3Ki | U0126 + PI103 | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | RMS lines | Apoptosis | / | [38] |

| FGFRi + HSP90i | LY2874455 + NVP-AUY922 | Folding of FGFR4 V550L protein may depend on HSP90 | RMS559 harboring FGFR4 V550L mutation and RH30 lines | Reduced cell viability | / | [39] |

| MEKi + Akti | BI-847325 + afuresertib | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | RAS-mutant PDX-derived cells and RMS tumors | Apoptosis, reduced tumor growth in vivo | / | [41] |

| PI3Ki + BCL-2i | NVP-BKM120 + ABT-737 | Apoptosis restoration | RMS lines | Apoptosis | / | [42] |

| mTORi + BCL-2i | AZD8055 + ABT-737 | |||||

| PI3Ki + IGF1Ri | Buparlisib + NVP-AEW541 | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | RMS lines | Apoptosis | Cytotoxicity | [45] |

| PI3Ki + MEKi | Buparlisib + trametinib | |||||

| PI3Ki + mTORi | Buparlisib + rapamycin | |||||

| BCL-2i + NF-κBi | Navitoclax + BAY 11-7082 | Apoptosis restoration | FP-RMS lines | Cytotoxic effect | / | [59] |

| BCL-2i + HDACi | ABT-199 + NJ-26481585 | Apoptosis restoration | Primary PDX cells | Apoptosis, inhibition of long-term survival | / | [67] |

| MEKi + MCL-1i | trametinib + S63845 | Single treatment displays little efficacy and cross-activation of compensatory pathway | PDX tumor cells | Reduced tumor growth in vivo | / | [68] |

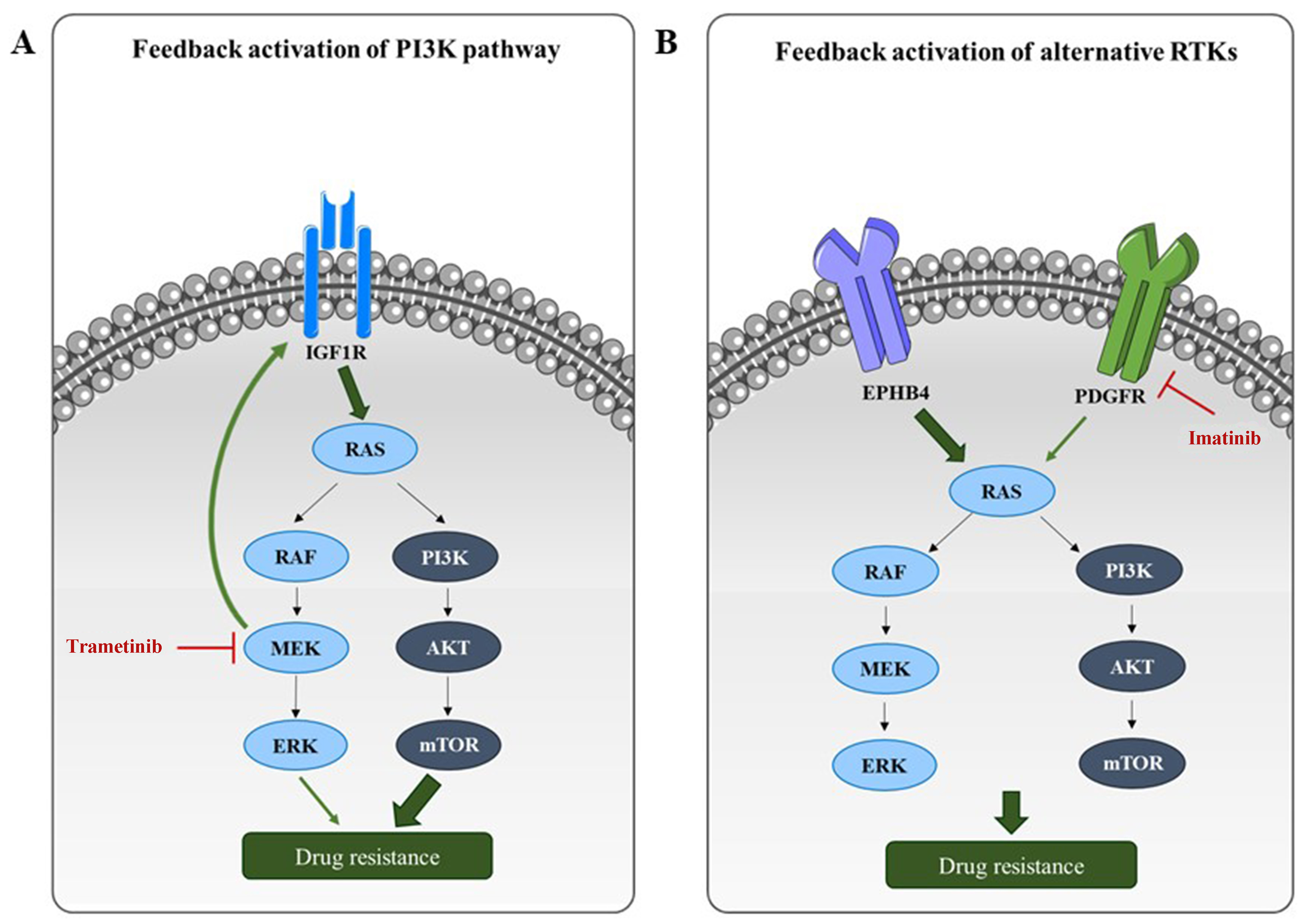

MEK inhibitors (e.g., trametinib) often elicit transient responses due to compensatory activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and the PI3K/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway [Figure 4]. Dual inhibition of MEK and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R)[20,21] or PI3K[22] has shown synergistic effects in xenograft models [Table 1].

Figure 4. Resistance mechanisms to RAS/PI3K pathway targeting in RMS. (A) Monotherapies targeting RAS or PI3K pathway components often induce compensatory feedback mechanisms, resulting in reactivation of RAS/PI3K signaling or upstream RTKs. For example, MEK inhibition by trametinib leads to upregulation of IGF1R, which in turn reactivates the PI3K pathway; (B) Inhibition of a specific RTK can also lead to compensatory signaling through alternative RTKs. For instance, PDGFR inhibition by imatinib may be bypassed through alternative activation of the RAS/PI3K axis via EPHB4. RAS: Rat sarcoma; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; RMS: rhabdomyosarcomas; RTKs: receptor tyrosine kinases; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; IGF1R: insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor; PDGFR: platelet-derived growth factor receptor; EPHB4: ephrin type-B receptor 4; RAF: rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin.

Furthermore, combining trametinib with CDK4/6 inhibitors reduces viability in RAS-mutant RMS by counteracting upregulation of the cyclin D–CDK4/6–RB–E2F axis[23]. Resistance can also involve activation of the Hippo pathway effector yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1)[24]. While RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway inhibition has been explored with radiotherapy[25], ERK inhibition alone is insufficient for apoptosis due to survival pathways such as myeloid cell leukemia-1 (MCL-1) overexpression. Combining ulixertinib (ERK inhibitor) with the MCL-1 antagonist S63845 restores apoptosis preclinically[26] [Table 1], though clinical translation has so far been limited[27].

Beyond proliferation and survival, the RAS/MAPK pathway suppresses myogenic differentiation[20,28,29]. Its pharmacological inhibition can restore differentiation and reduce tumorigenicity in preclinical models[18,20,30].

Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway

Aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway in RMS is linked to poor short-term survival and therapy resistance[2,31]. Among the PI3K classes, class I - comprising heterodimers of a catalytic subunit (p110α, β, γ, or δ) and a regulatory p85 subunit - is most strongly implicated in cancer. RMS frequently harbor activating mutations in PIK3CA (encoding p110α) and exhibit overexpression of all four class I catalytic isoforms (p110α, β, γ, and δ). Combined inhibition of p110α (alpelisib) and p110δ (idelalisib) induces apoptosis in RMS models[32,33]. This axis contributes to radioresistance[34], hypoxia adaptation[35], and DNA repair[34], and enhances the transcriptional activity of PAX3-FOXO1 in FP-RMS[36].

Similar to RAS pathway inhibition, PI3K monotherapy triggers compensatory MAPK activation[37], necessitating dual PI3K and RAS/ERK inhibition[38,39] [Table 1], though often with dose-limiting toxicity. Combining MEK inhibitors with AKT pathway inhibitors [e.g., the 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) inhibitor OSU-03012] has shown promise in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models[40,41] [Table 1].

Newer agents such as dual PI3K/mTOR or isoform-specific PI3K inhibitors are being evaluated. The dual mTOR inhibitor AZD8055 synergized with the MEK inhibitor selumetinib[37] and the B-cell lymphoma 2 homology 3 (BH3) mimetic ABT-737[42] [Table 1].

mTOR functions through two distinct complexes: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1, rapamycin-sensitive), which regulates proliferation via ribosomal p70 S6 kinase (p70S6K) activation and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2, rapamycin-insensitive), which controls cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular invasion[43]. As mTORC2 predominates in primary RMS[44] and is rapamycin-insensitive, it represents a critical node in disease progression.

Despite strong preclinical data, clinical trials of combinations such as PI3K/IGF1R or PI3K/MEK have shown only modest benefit[45] [Table 1].

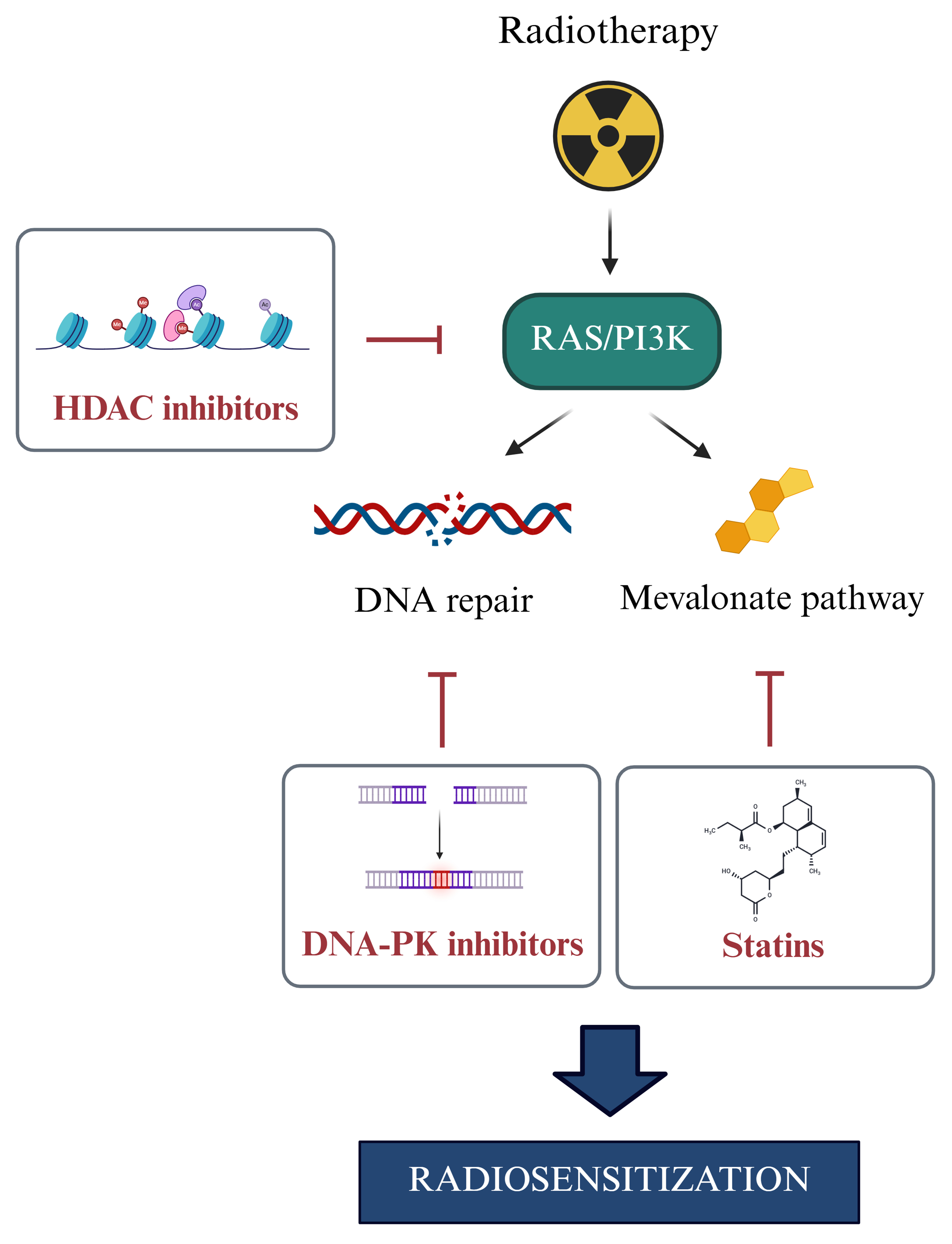

As schematized in Figure 4, inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR or RAS/MEK/ERK often triggers feedback upregulation of IGF1R [Figure 4A][46] or alternative receptors such as ephrin type-B receptor 4 (EPHB4) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)[47,48] [Figure 4B], supporting the need for dual targeting. New insights suggest vulnerabilities: histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors[49] and mevalonate pathway inhibitors[50,51] can achieve radiosensitization by targeting this axis, revealing new druggable targets [Figure 5].

Figure 5. Impact of RAS/PI3K signaling on radiotherapy response. Ionizing radiation activates the RAS/PI3K signaling pathway, resulting in downstream effects that promote MDR by enhancing DNA repair and stimulating the mevalonate pathway. The use of HDAC inhibitors, DNA-PK inhibitors, or statins to target key components of this axis holds promising potential when combined with radiotherapy. RAS: Rat sarcoma; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; MDR: multidrug resistance; HDAC: histone deacetylase; DNA-PK: DNA-dependent protein kinase.

Exploring alternative pathways driving MDR

Although dual PI3K and MAPK inhibition shows superior efficacy preclinically[52], its clinical use is limited by toxicity[53]. As RMS progresses, the PI3K–AKT axis integrates with other networks, including nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and Hippo pathways[54].

The NF-κB pathway is a key regulator of survival and inflammation[55]. Oncogenic RAS activity is known to drive hyperactivation of NF-κB[56], and this interaction plays a prominent role in the development of MDR. In RMS, NF-κB upregulates glycolytic enzymes such as hexokinase 2 (HK2), promoting the Warburg effect[57].

Its inhibition (e.g., with curcumin) increases cytotoxicity by modulating AKT/mTOR, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and p53 pathways[58] and sensitizes sarcomas to navitoclax, a B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family inhibitor[59] [Table 1].

The Hippo pathway, a tumor suppressor cascade, is often inactivated in RMS[60,61]. Its disruption leads to unchecked YAP1/TAZ (transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif) activity, promoting growth and resistance. Restoring Hippo pathway activity is therefore a viable strategy to overcome chemoresistance.

To die or not to die: apoptotic evasion

The RAS/PI3K pathways promote therapy resistance by upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCL-2, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), and MCL-1[62], as seen in RMS[63]. BH3 mimetics, which inhibit these anti-apoptotic proteins, can overcome this resistance[64]. They show preclinical efficacy in RMS[42,65,66], especially when combined with HDAC inhibitors or standard chemotherapies[67,68] [Table 1].

Resistance to MEK1/2 inhibition has been linked to phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 (PMAIP1, known as NOXA) depletion. Co-treatment with the MCL-1 inhibitor S63845 restores sensitivity to MEK inhibitors[69] [Table 1].

MDR in RMS is also driven by mutations in genes such as BCL-2, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), PIK3CA, tumor protein p53 (TP53), and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette (ABC) transporters[70]. A key regulatory node in this network is the tumor suppressor F-box and WD repeat domain-containing protein 7 (FBW7), a tumor suppressor that targets oncoproteins such as cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene (c-Myc) and MCL-1 for degradation. FBW7 loss stabilizes MCL-1, conferring resistance to vincristine[71]. As FBW7 mutations occur in ~7.4% of FN-RMS cases[72], they represent a potential biomarker for predicting response to MCL-1 inhibitors or vincristine.

DNA damage response and therapy resistance

Radiotherapy is a cornerstone of RMS treatment, but radioresistance can arise through enhanced DNA damage response (DDR). Activated AKT promotes cell survival after irradiation by facilitating repair of double-strand breaks (DSBs)[73]. Upon DNA damage, DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) phosphorylates the mTORC2 subunit Sin1, leading to AKT activation and promoting survival and resistance[74,75].

Both radiation and topoisomerase inhibitors can activate this DNA-PK–mTORC2–AKT axis. The PI3K/AKT and RAS/ERK pathways also contribute to DDR and resistance[25,34].

Inhibiting DNA-PK catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs) shows promise in enhancing radiosensitivity and overcoming MDR by preventing efficient DSB repair[76].

Molecular barriers to chemotherapeutic efficacy

Chemotherapy failure often results from mechanisms that limit intracellular drug accumulation or activity, involving drug transporters and metabolic enzymes. In particular, membrane transporters from the ABC, solute carrier (SLC), and solute carrier organic anion (SLCO) families play a central role in drug disposition[77]. While SLC and SLCO transporters mediate drug influx, ABC transporters function as efflux pumps, reducing intracellular drug concentrations and contributing significantly to MDR.

Efflux transporters

The human genome encodes 48 ABC transporter genes, classified into seven subfamilies (ABCA–ABCG) based on sequence homology[78]. Among these, ABCB1 [also known as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) or MDR1], ABCC1 [multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1)], and ABCG2 [breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)] are most strongly implicated in chemoresistance[79].

P-gp is a 170-kDa transmembrane efflux pump capable of exporting a wide range of chemotherapeutic agents - including vinca alkaloids, anthracyclines, and taxanes - thereby reducing their intracellular accumulation and cytotoxicity[80]. P-gp expression in RMS is linked to poor prognosis and actinomycin D resistance[81,82]. MRP1 and MDR3 (ABCB4) are upregulated post-chemotherapy, with MDR3 correlating with PAX fusions in FP-RMS[83]. The non-ABC transporter lung resistance-related protein (LRP) - also known as major vault protein (MVP) - also contributes to resistance by drug sequestration[81].

Influx transporters

The SLC superfamily comprises 65 subfamilies and 458 individual transporters, which mediate the cellular uptake of ions, nutrients, and xenobiotics, including several chemotherapeutic agents[84]. The SLCO superfamily, consisting of six subfamilies, is responsible for the uptake of larger molecules (> 300 Da) such as bile acids, hormones, and certain chemotherapeutic drugs[85]. However, their role in RMS is poorly characterized, except for SLC family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) (xCT), a cystine/glutamate antiporter that maintains glutathione synthesis and redox homeostasis, supporting resistance to oxidative stress. Often overexpressed in tumors, SLC7A11 contributes to ferroptosis resistance[86]. In RMS models, pharmacological inhibition of SLC7A11 triggers ferroptotic death[87].

Drug metabolism and detoxification

Many drugs are metabolically activated or inactivated by CYP enzymes. The expression of CYP enzymes varies with age, tissue type, and developmental stage, making drug metabolism especially complex in pediatric cancers such as RMS[88].

The human genome encodes 57 CYP genes across 18 subfamilies that metabolize a wide array of xenobiotics[89]. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, for instance, detoxify vincristine[90,91]. The activity of these enzymes is age-dependent, affecting efficacy in pediatric patients.

Co-administration of CYP3A4 inhibitors can impair the activation of prodrugs such as IFO and CFO.

Notably, RMS tumors often overexpress the fetal-type CYP2W1, a fetal-type monooxygenase typically silenced after birth[92,93], a potential therapeutic vulnerability.

Therapeutic strategies co-targeting CYP enzymes, transporters, and oncogenic pathways may help overcome these resistance mechanisms.

CONCLUSIONS

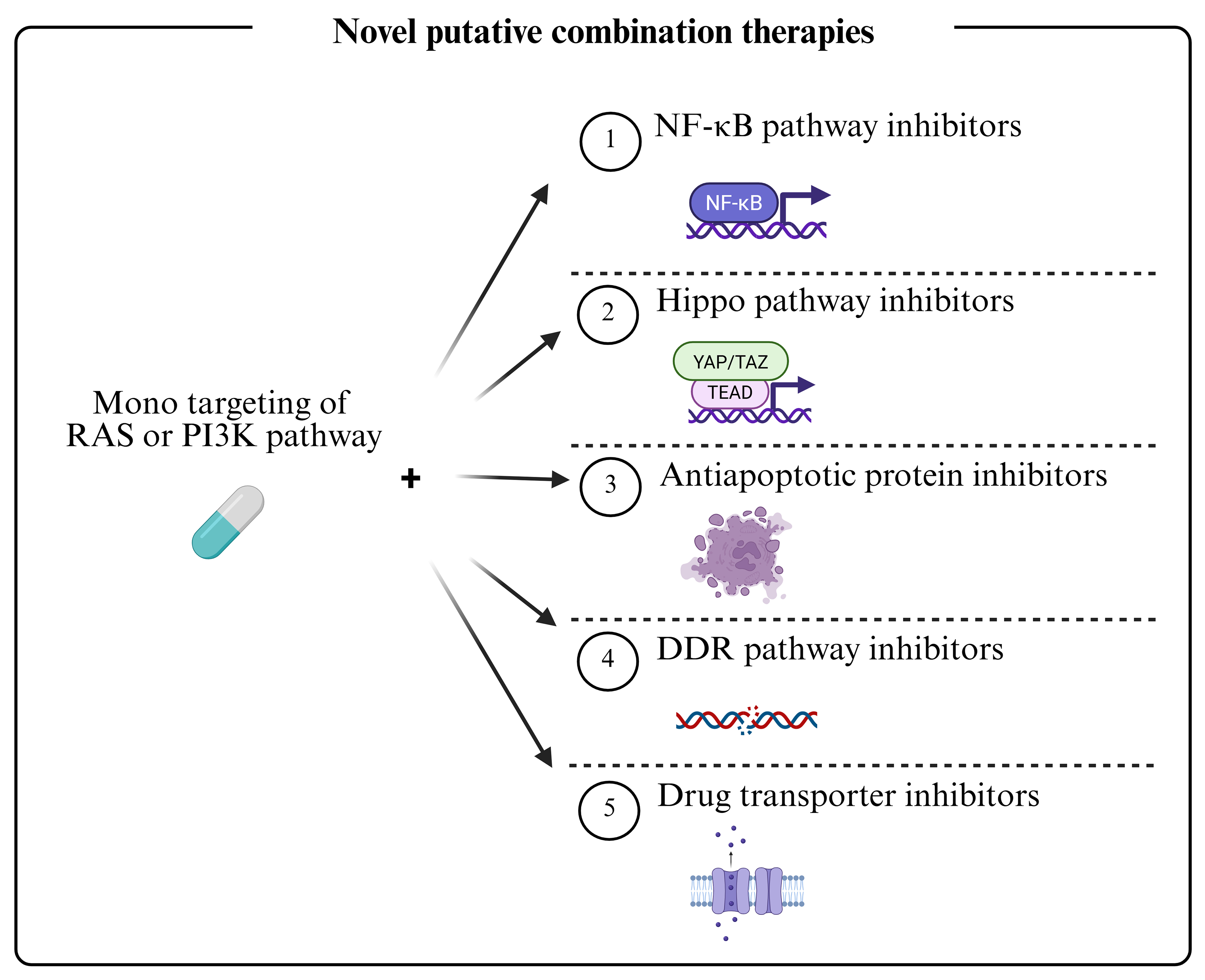

Dysregulation of the RAS and PI3K pathways is central to therapy resistance in FN-RMS. While current chemotherapy is effective for localized disease, MDR causes failure in metastatic and relapsed cases. Vertical inhibition of these pathways can restore sensitivity but is limited by toxicity and compensatory feedback loops. Combination strategies targeting multiple resistance mechanisms, including signaling feedback, apoptotic evasion, DDR, and drug transport, are therefore essential [Figure 6]. For instance, BH3 mimetics or FBW7-targeting approaches can reverse apoptotic resistance. Inhibiting DNA-PK or mTORC2 can enhance radiosensitivity. Epigenetic and metabolic modulators (e.g., HDAC inhibitors, statins) show efficacy as radiosensitizers. Furthermore, efflux pumps (ABCB1, MRP1) and influx transporters (SLC7A11) significantly impact drug bioavailability, while age-dependent CYP metabolism and tumor-specific isoforms such as CYP2W1 represent metabolic vulnerabilities. To advance the field, future efforts should focus on identifying novel biomarkers[94,95], developing robust preclinical models[96], and leveraging machine learning for integrative analysis and predictive modeling[97]. A multi-faceted approach is crucial to overcome MDR and improve outcomes for patients with high-risk RMS.

Figure 6. Combined therapeutic regimens against RMS. Dual inhibition of the RAS and PI3K pathways has generally proven ineffective due to the emergence of MDR mechanisms and is further limited in clinical settings by toxicity. More promising therapeutic approaches involve monotargeting of either the RAS or PI3K pathway in combination with agents targeting downstream effectors - such as those involved in alternative oncogenic signaling, apoptotic resistance, DDR and drug transport. These combined strategies, aimed at overcoming MDR in RMS, include both ongoing therapies and emerging experimental approaches. RMS: Rhabdomyosarcomas; RAS: rat sarcoma; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; MDR: multidrug resistance; DDR: DNA damage response; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa B; YAP: yes-associated protein; TAZ: transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif; TEAD: TEA domain family member.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the review, drafted the manuscript, and secured funding: Fanzani A

Contributed to conceptualization, prepared the figures and tables, and critically revised the manuscript: Codenotti S

Performed the literature search: Cattaneo CG

Critically reviewed and revised the manuscript: Megiorni F, Gastaldello S, Pozzo E, Sampaolesi M, Rota R, Keller C

Critically revised the manuscript and secured funding: Marampon F

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) under Investigator Grant 2020 (ID. 24696; Principal Investigator: Marampon F). Codenotti S was supported by the Fondazione Umberto Veronesi.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

2. Shern JF, Selfe J, Izquierdo E, et al. Genomic classification and clinical outcome in rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from an International Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2859-71.

3. Chen X, Stewart E, Shelat AA, et al.; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital–Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Targeting oxidative stress in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:710-24.

4. Martin-Giacalone BA, Weinstein PA, Plon SE, Lupo PJ. Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma: epidemiology and genetic susceptibility. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2028.

5. Sankhe CS, Hall L, Kendall GC. Fusion oncogenes in rhabdomyosarcoma: model systems, mechanisms of tumorigenesis, and therapeutic implications. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1570070.

6. Marshall AD, Grosveld GC. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma - the molecular drivers of PAX3/7-FOXO1-induced tumorigenesis. Skelet Muscle. 2012;2:25.

7. Turco GM, Oberoi S, Ladle B, et al. Towards directed therapy for fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma. Pharmacol Ther. 2025;276:108931.

8. Miwa S, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Igarashi K, Tsuchiya H. Recent advances and challenges in the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers. 2020;12:1758.

9. Martino E, Casamassima G, Castiglione S, et al. Vinca alkaloids and analogues as anti-cancer agents: looking back, peering ahead. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2018;28:2816-26.

10. Willits I, Price L, Parry A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of ifosfamide in relation to DNA damage assessed by the COMET assay in children with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1626-35.

11. Bergeron C, Jenney M, De Corti F, et al.; European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG). Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma completely resected at diagnosis: the European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group RMS2005 experience. Eur J Cancer. 2021;146:21-9.

12. Zarrabi A, Perrin D, Kavoosi M, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma: current therapy, challenges, and future approaches to treatment strategies. Cancers. 2023;15:5269.

13. Vaidya FU, Sufiyan Chhipa A, Mishra V, et al. Molecular and cellular paradigms of multidrug resistance in cancer. Cancer Rep. 2022;5:e1291.

14. Muñoz-Maldonado C, Zimmer Y, Medová M. A comparative analysis of individual RAS mutations in cancer biology. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1088.

15. Danielli SG, Porpiglia E, De Micheli AJ, et al. Single-cell profiling of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma reveals RAS pathway inhibitors as cell-fate hijackers with therapeutic relevance. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eade9238.

17. Odeniyide P, Yohe ME, Pollard K, et al. Correction: Targeting farnesylation as a novel therapeutic approach in HRAS-mutant rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncogene. 2022;41:3037.

18. Garcia N, Del Pozo V, Yohe ME, et al. Vertical inhibition of the RAF-MEK-ERK cascade induces myogenic differentiation, apoptosis, and tumor regression in H/NRASQ61X mutant rhabdomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022;21:170-83.

19. Kim A, Widemann BC, Krailo M, et al. Phase 2 trial of sorafenib in children and young adults with refractory solid tumors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1562-6.

20. Yohe ME, Gryder BE, Shern JF, et al. MEK inhibition induces MYOG and remodels super-enhancers in RAS-driven rhabdomyosarcoma. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaan4470.

21. Hebron KE, Wan X, Roth JS, et al. The combination of Trametinib and Ganitumab is effective in RAS-mutated PAX-fusion negative rhabdomyosarcoma models. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29:472-87.

22. Dolgikh N, Hugle M, Vogler M, Fulda S. NRAS-mutated rhabdomyosarcoma cells are vulnerable to mitochondrial apoptosis induced by coinhibition of MEK and PI3Kα. Cancer Res. 2018;78:2000-13.

23. Stewart E, McEvoy J, Wang H, et al.; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital - Washington University Pediatric Cancer Genome Project. Identification of therapeutic targets in rhabdomyosarcoma through integrated genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic analyses. Cancer Cell. 2018;34:411-26.e19.

24. Slemmons KK, Crose LE, Rudzinski E, Bentley RC, Linardic CM. Role of the YAP oncoprotein in priming Ras-driven rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140781.

25. Marampon F, Gravina GL, Di Rocco A, et al. MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 increases the radiosensitivity of rhabdomyosarcoma cells in vitro and in vivo by downregulating growth and DNA repair signals. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:159-68.

26. Winkler M, Friedrich J, Boedicker C, Dolgikh N. Co-targeting MCL-1 and ERK1/2 kinase induces mitochondrial apoptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Transl Oncol. 2022;16:101313.

27. Vo KT, Sabnis AJ, Williams PM, et al. Phase II study of Ulixertinib in children and young adults with tumors harboring activating mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway alterations: APEC1621J of the National Cancer Institute-Children’s Oncology Group pediatric MATCH trial. JCO Precis Oncol. 2024;8:e2400103.

28. Tenente IM, Hayes MN, Ignatius MS, et al. Myogenic regulatory transcription factors regulate growth in rhabdomyosarcoma. Elife. 2017;6:e19214.

29. Pomella S, Cassandri M, D’Archivio L, et al. MYOD-SKP2 axis boosts tumorigenesis in fusion negative rhabdomyosarcoma by preventing differentiation through p57Kip2 targeting. Nat Commun. 2023;14:8373.

30. Di Rocco A, Camero S, Benedetti A, et al. Anti-oncogenic and pro-myogenic action of the MKK6/p38/AKT axis induced by targeting MEK/ERK in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Oncol Rep. 2022;48:151.

31. Ramadan F, Fahs A, Ghayad SE, Saab R. Signaling pathways in rhabdomyosarcoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39:287-301.

32. Piazzi M, Bavelloni A, Cenni V, et al. Combined treatment with PI3K inhibitors BYL-719 and CAL-101 is a promising antiproliferative strategy in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Molecules. 2022;27:2742.

33. Vanhaesebroeck B, Perry MWD, Brown JR, André F, Okkenhaug K. PI3K inhibitors are finally coming of age. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:741-69.

34. Codenotti S, Zizioli D, Mignani L, et al. Hyperactive Akt1 signaling increases tumor progression and DNA repair in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma RD line and confers susceptibility to glycolysis and mevalonate pathway inhibitors. Cells. 2022;11:2859.

35. Kilic-Eren M, Boylu T, Tabor V. Targeting PI3K/Akt represses Hypoxia inducible factor-1α activation and sensitizes rhabdomyosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma cells for apoptosis. Cancer Cell Int. 2013;13:36.

36. Gallo-Oller G, Pons G, Sansa-Girona J, et al. TRIB3 silencing promotes the downregulation of Akt pathway and PAX3-FOXO1 in high-risk rhabdomyosarcoma. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13:38.

37. Renshaw J, Taylor KR, Bishop R, et al. Dual blockade of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (AZD8055) and RAS/MEK/ERK (AZD6244) pathways synergistically inhibits rhabdomyosarcoma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5940-51.

38. Guenther MK, Graab U, Fulda S. Synthetic lethal interaction between PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Ras/MEK/ERK pathway inhibition in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:200-9.

39. Fiorito E, Szybowska P, Haugsten EM, et al. Strategies to inhibit FGFR4 V550L-driven rhabdomyosarcoma. Br J Cancer. 2022;127:1939-53.

40. Cen L, Hsieh FC, Lin HJ, Chen CS, Qualman SJ, Lin J. PDK-1/AKT pathway as a novel therapeutic target in rhabdomyosarcoma cells using OSU-03012 compound. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:785-91.

41. Manzella G, Schreck LD, Breunis WB, et al. Phenotypic profiling with a living biobank of primary rhabdomyosarcoma unravels disease heterogeneity and AKT sensitivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4629.

42. Preuss E, Hugle M, Reimann R, Schlecht M, Fulda S. Pan-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor AZD8055 primes rhabdomyosarcoma cells for ABT-737-induced apoptosis by down-regulating Mcl-1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:35287-96.

43. Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;169:361-71.

44. Felkai L, Krencz I, Kiss DJ, et al. Characterization of mTOR activity and metabolic profile in pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers. 2020;12:1947.

45. Anderson JL, Park A, Akiyama R, Tap WD, Denny CT, Federman N. Evaluation of in vitro activity of the class I PI3K inhibitor buparlisib (BKM120) in pediatric bone and soft tissue sarcomas. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133610.

46. Wan X, Harkavy B, Shen N, Grohar P, Helman LJ. Rapamycin induces feedback activation of Akt signaling through an IGF-1R-dependent mechanism. Oncogene. 2007;26:1932-40.

47. Abraham J, Prajapati SI, Nishijo K, et al. Evasion mechanisms to Igf1r inhibition in rhabdomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:697-707.

48. De Giovanni C, Landuzzi L, Palladini A, Nicoletti G, Nanni P, Lollini PL. HER tyrosine kinase family and rhabdomyosarcoma: role in onset and targeted therapy. Cells. 2021;10:1808.

49. Marampon F, Di Nisio V, Pietrantoni I, et al. Pro-differentiating and radiosensitizing effects of inhibiting HDACs by PXD-101 (Belinostat) in in vitro and in vivo models of human rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2019;461:90-101.

50. Codenotti S, Sandrini L, Mandracchia D, et al. Statin-sensitive Akt1/Src/Caveolin-1 signaling enhances oxidative stress resistance in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers. 2024;16:853.

51. Codenotti S, Asperti M, Poli M, et al. Synthetic inhibition of SREBP2 and the mevalonate pathway blocks rhabdomyosarcoma tumor growth in vitro and in vivo and promotes chemosensitization. Mol Metab. 2025;92:102085.

52. Cao Z, Liao Q, Su M, Huang K, Jin J, Cao D. AKT and ERK dual inhibitors: the way forward? Cancer Lett. 2019;459:30-40.

53. Shimizu T, Tolcher AW, Papadopoulos KP, et al. The clinical effect of the dual-targeting strategy involving PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MEK/ERK pathways in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2316-25.

54. Ghomlaghi M, Hart A, Hoang N, Shin S, Nguyen LK. Feedback, crosstalk and competition: ingredients for emergent non-linear behaviour in the PI3K/mTOR signalling network. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6944.

55. Godwin P, Baird AM, Heavey S, Barr MP, O’Byrne KJ, Gately K. Targeting nuclear factor-kappa B to overcome resistance to chemotherapy. Front Oncol. 2013;3:120.

56. Tago K, Funakoshi-Tago M, Ohta S, et al. Oncogenic Ras mutant causes the hyperactivation of NF-κB via acceleration of its transcriptional activation. Mol Oncol. 2019;13:2493-510.

57. Londhe P, Yu PY, Ijiri Y, et al. Classical NF-κB metabolically reprograms sarcoma cells through regulation of hexokinase 2. Front Oncol. 2018;8:104.

58. Salucci S, Bavelloni A, Stella AB, et al. The cytotoxic effect of curcumin in rhabdomyosarcoma is associated with the modulation of AMPK, AKT/mTOR, STAT, and p53 signaling. Nutrients. 2023;15:740.

59. Cleary MM, Mansoor A, Settelmeyer T, et al. NFκB signaling in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10:1109-15.

60. Crose LEC, Galindo KA, Kephart JG, et al. Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma-associated PAX3-FOXO1 promotes tumorigenesis via Hippo pathway suppression. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:285-96.

61. Mohamed A, Sun C, De Mello V, et al. The Hippo effector TAZ (WWTR1) transforms myoblasts and TAZ abundance is associated with reduced survival in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pathol. 2016;240:3-14.

62. Adams JM, Cory S. The BCL-2 arbiters of apoptosis and their growing role as cancer targets. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:27-36.

63. Armistead PM, Salganick J, Roh JS, et al. Expression of receptor tyrosine kinases and apoptotic molecules in rhabdomyosarcoma: correlation with overall survival in 105 patients. Cancer. 2007;110:2293-303.

64. Montero J, Letai A. Why do BCL-2 inhibitors work and where should we use them in the clinic? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:56-64.

65. Meister MT, Boedicker C, Klingebiel T, Fulda S. Hedgehog signaling negatively co-regulates BH3-only protein Noxa and TAp73 in TP53-mutated cells. Cancer Lett. 2018;429:19-28.

66. Faqar-Uz-Zaman SF, Heinicke U, Meister MT, Vogler M, Fulda S. BCL-xL-selective BH3 mimetic sensitizes rhabdomyosarcoma cells to chemotherapeutics by activation of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 2018;412:131-42.

67. Heinicke U, Haydn T, Kehr S, Vogler M, Fulda S. BCL-2 selective inhibitor ABT-199 primes rhabdomyosarcoma cells to histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2018;37:5325-39.

68. Alcon C, Manzano-Muñoz A, Prada E, et al. Sequential combinations of chemotherapeutic agents with BH3 mimetics to treat rhabdomyosarcoma and avoid resistance. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:634.

69. Alcon C, Martín F, Prada E, et al. MEK and MCL-1 sequential inhibition synergize to enhance rhabdomyosarcoma treatment. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8:172.

70. Emran TB, Shahriar A, Mahmud AR, et al. Multidrug resistance in cancer: understanding molecular mechanisms, immunoprevention and therapeutic approaches. Front Oncol. 2022;12:891652.

71. Wertz IE, Kusam S, Lam C, et al. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature. 2011;471:110-4.

72. Shern JF, Chen L, Chmielecki J, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:216-31.

73. Toulany M, Lee KJ, Fattah KR, et al. Akt promotes post-irradiation survival of human tumor cells through initiation, progression, and termination of DNA-PKcs-dependent DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:945-57.

74. Liu L, Dai X, Yin S, et al. DNA-PK promotes activation of the survival kinase AKT in response to DNA damage through an mTORC2-ECT2 pathway. Sci Signal. 2022;15:eabh2290.

75. Shin S, Walker KA, Yoon SO. The PIKK-AKT connection in the DNA damage response. Sci Signal. 2022;15:eabm6211.

76. Fok JHL, Ramos-Montoya A, Vazquez-Chantada M, et al. AZD7648 is a potent and selective DNA-PK inhibitor that enhances radiation, chemotherapy and olaparib activity. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5065.

77. Roberts AG. The structure and mechanism of drug transporters. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2342:193-234.

78. Fruci D, Cho WC, Nobili V, Locatelli F, Alisi A. Drug transporters and multiple drug resistance in pediatric solid tumors. Curr Drug Metab. 2016;17:308-16.

79. Xiao H, Zheng Y, Ma L, Tian L, Sun Q. Clinically-relevant ABC transporter for anti-cancer drug resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:648407.

80. Ahmed Juvale II, Abdul Hamid AA, Abd Halim KB, Che Has AT. P-glycoprotein: new insights into structure, physiological function, regulation and alterations in disease. Heliyon. 2022;8:e09777.

81. Komdeur R, Klunder J, van der Graaf WT, et al. Multidrug resistance proteins in rhabdomyosarcomas: comparison between children and adults. Cancer. 2003;97:1999-2005.

82. Seitz G, Warmann SW, Vokuhl CO, et al. Effects of standard chemotherapy on tumor growth and regulation of multidrug resistance genes and proteins in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:431-9.

83. Citti A, Boldrini R, Inserra A, et al. Expression of multidrug resistance-associated proteins in paediatric soft tissue sarcomas before and after chemotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:117-24.

84. Rashid K, Ahmad A, Liang L, Liu M, Cui Y, Liu T. Solute carriers as potential oncodrivers or suppressors: their key functions in malignant tumor formation. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26:1689-701.

85. Roth M, Obaidat A, Hagenbuch B. OATPs, OATs and OCTs: the organic anion and cation transporters of the SLCO and SLC22A gene superfamilies. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:1260-87.

86. Koppula P, Zhuang L, Gan B. Cystine transporter SLC7A11/xCT in cancer: ferroptosis, nutrient dependency, and cancer therapy. Protein Cell. 2021;12:599-620.

87. Codenotti S, Poli M, Asperti M, Zizioli D, Marampon F, Fanzani A. Cell growth potential drives ferroptosis susceptibility in rhabdomyosarcoma and myoblast cell lines. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:1717-30.

88. Picher EA, Wahajuddin M, Barth S, Chisholm J, Shipley J, Pors K. The capacity of drug-metabolising enzymes in modulating the therapeutic efficacy of drugs to treat rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers. 2024;16:1012.

89. Manikandan P, Nagini S. Cytochrome P450 structure, function and clinical significance: a review. Curr Drug Targets. 2018;19:38-54.

90. Dennison JB, Kulanthaivel P, Barbuch RJ, Renbarger JL, Ehlhardt WJ, Hall SD. Selective metabolism of vincristine in vitro by CYP3A5. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:1317-27.

91. Yao D, Ding S, Burchell B, Wolf CR, Friedberg T. Detoxication of vinca alkaloids by human P450 CYP3A4-mediated metabolism: implications for the development of drug resistance. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:387-95.

92. Molina-Ortiz D, Camacho-Carranza R, González-Zamora JF, et al. Differential expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in normal and tumor tissues from childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93261.

93. Molina-Ortiz D, Torres-Zárate C, Cárdenas-Cardós R, et al. Aberrant expression of CYP2W1 in pediatric soft tissue sarcomas: clinical significance and potential as a therapeutic target. Curr Oncol. 2025;32:131.

94. Hettmer S, Linardic CM, Kelsey A, et al. Molecular testing of rhabdomyosarcoma in clinical trials to improve risk stratification and outcome: a consensus view from European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group, Children’s Oncology Group and Cooperative Weichteilsarkom-Studiengruppe. Eur J Cancer. 2022;172:367-86.

95. Pacenta HL, Allen-Rhoades W, Langenau D, et al. Prioritization of novel agents for patients with rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) New Agents for Rhabdomyosarcoma Task Force. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1416.

96. Ghilu S, Morton CL, Vaseva AV, Zheng S, Kurmasheva RT, Houghton PJ. Approaches to identifying drug resistance mechanisms to clinically relevant treatments in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022;5:80-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].