From large language models to AI agents in energy materials research: enabling discovery, design, and automation

Abstract

Fragmented knowledge and slow experimental iteration constrain the discovery of energy materials. We trace the evolution of artificial intelligence (AI) in materials science, from large language models as knowledge assistants to autonomous agents that can reason, plan, and use tools. We introduce a two-path framework to analyze this evolution, distinguishing architectural innovation (agent collaboration) from cognitive innovation (learning and representation). This framework synthesizes recent progress in AI-driven discovery, design, and automation. By examining challenges in reliability, interpretability, and physical grounding, we outline a roadmap toward physics-informed, human-AI systems for autonomous scientific discovery.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The discovery of advanced materials is essential for solving global challenges in energy and the environment, from high-efficiency batteries to catalysts for green chemistry. While materials innovation has evolved from trial-and-error to a sophisticated integration of theory, computation, and experiment (the “fourth paradigm”)[1], progress is throttled by two bottlenecks.

First, we face a paradox of knowledge. The exponential growth of scientific literature has created a vast ocean of data, yet the majority of this knowledge remains “dormant” in unstructured PDF documents, inaccessible to systematic analysis[2]. For complex fields such as materials design, where a breakthrough might require synthesizing insights from hundreds of disparate papers, this task severely limits the scale, speed, and scope of human-led discovery[3]. Traditional data-driven methods, in turn, are limited by their dependence on large-scale, high-quality structured training data, which is precisely what is lacking[4,5].

Second, at the computational level, we face a representation gap. While graph neural networks (GNNs) have achieved great success[6-10], they often focus on geometry while neglecting physical principles. They struggle to encode critical information such as crystal symmetry, which can be the deciding factor for a material’s functional properties[11,12]. This fundamental limitation in how we describe materials to artificial intelligence (AI) has prompted a search for more expressive representations. AI for science (AI4Science) shows great potential, yet its use in discovering new scientific principles remains limited, representing a critical gap[13].

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) have emerged as a powerful technology to address these challenges. Initially applied to scientific comprehension and literature review[14], their role is rapidly evolving. On one front, to tackle the “knowledge paradox”, multi-agent systems (MAS) are being constructed. Systems such as SciAgents[3], a multi-agent framework utilizing ontological knowledge graphs for scientific reasoning, and collaborative networks for electrolyte discovery, along with Cat-Advisor, an intelligent system for automated catalyst optimization, for MgH2 dehydrogenation catalysts[15], demonstrate how multiple specialized agents can reason over ontological knowledge graphs or vast text corpora, automating the mining and generation of scientific hypotheses at an unprecedented scale[5,16]. This marks a shift from a ‘Machine Learning-Guided Synthesis’ paradigm to a broader ‘LLM-Driven Synthesis’, where the LLM acts as a cognitive orchestrator coordinating hypothesis generation, simulation, and experimental planning[17].

On another front, to bridge the “representation gap”, works such as LLM-Prop, a framework capable of predicting crystal properties from textual descriptions, are pioneering a revolution in how materials are described to AI. By representing crystals with rich textual descriptions instead of graphs, and fine-tuning lightweight language models, this approach has shown performance competitive with, or in some cases superior to, state-of-the-art GNNs on certain property prediction tasks[18]. This suggests that natural language processing (NLP) is a powerful complementary approach. However, it is crucial to recognize that for tasks requiring explicit geometric reasoning and physical equivariance, such as predicting interatomic forces, equivariant GNNs and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) remain the superior approach.

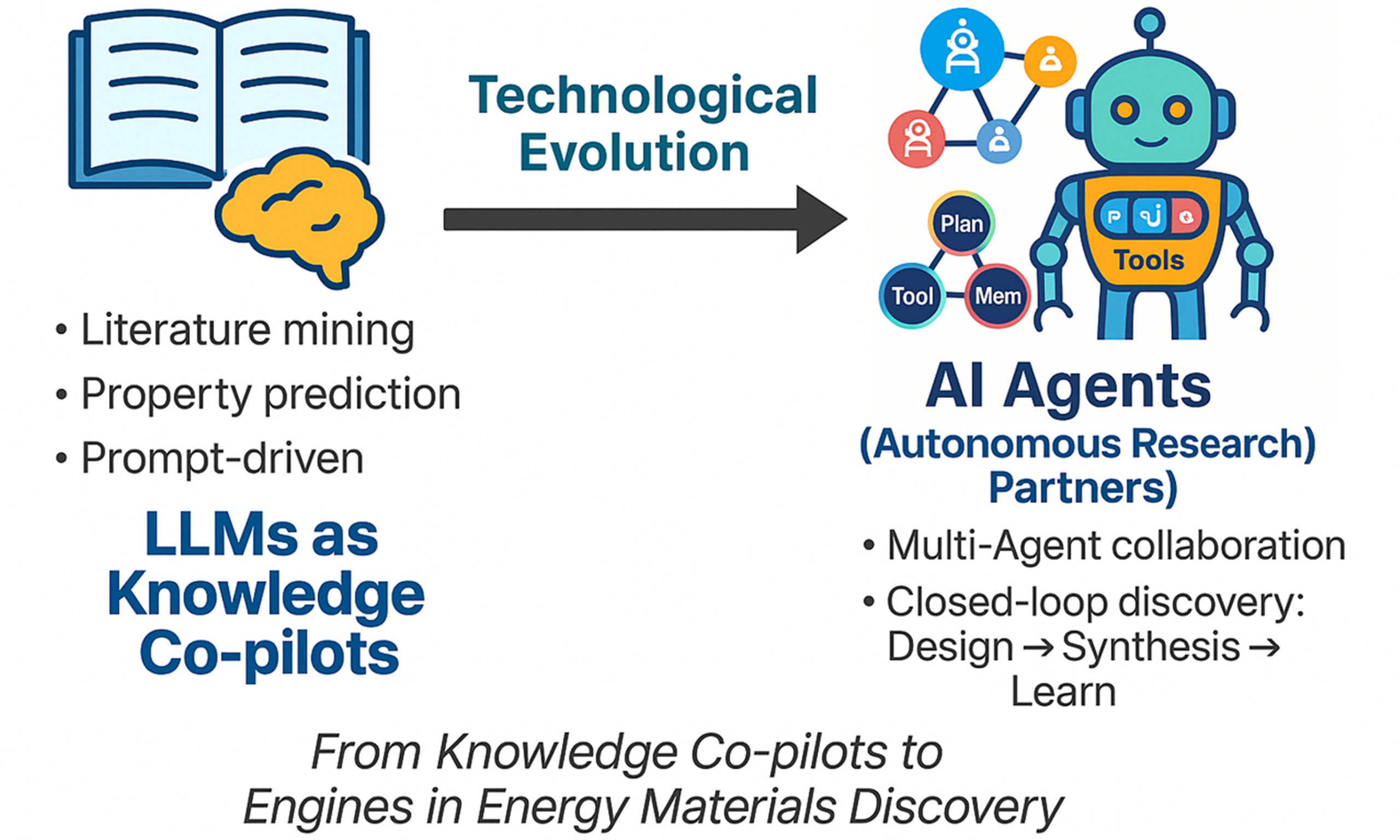

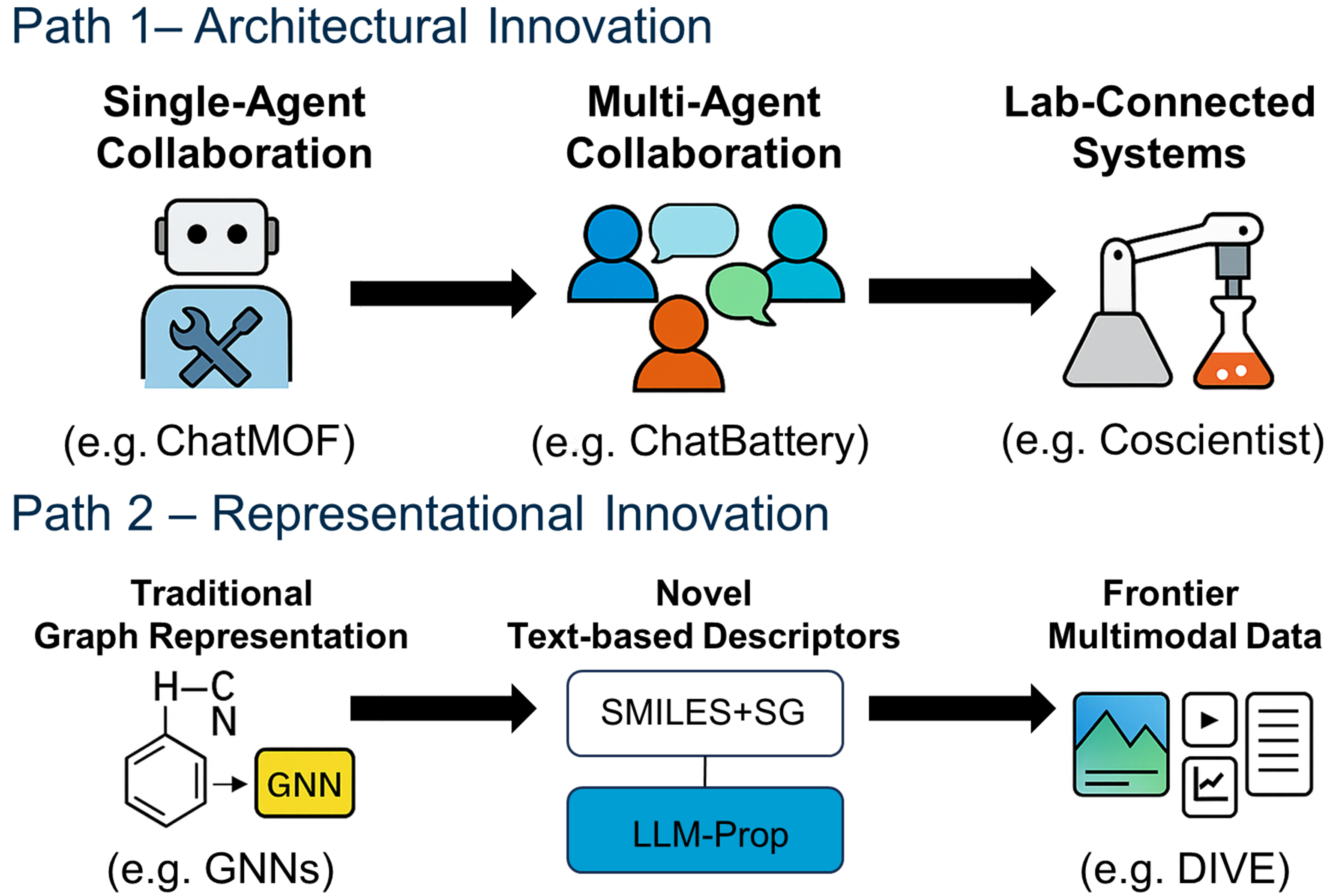

In this review, we examine how AI is reshaping R&D (Research and Development) in energy materials and trace its evolution from auxiliary tools to autonomous agents. We propose and apply a “two-path” framework that distinguishes Architectural Innovation (agent system design, tool-use, orchestration) and Cognitive/Representational Innovation (reasoning, planning, memory, and scientific representations). We use this framework to systematically organize disparate advances and use it to analyze developmental patterns in materials-focused AI. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work to define and apply these two trajectories in materials science. This framework helps identify challenges and guide future research. The macroscopic view of this evolution is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Evolution from LLMs to AI Agents in Energy Materials Research. Phase 1 depicts large language models (LLMs) acting as knowledge-augmentation tools, where human researchers employ prompt-based interaction for data extraction, literature mining, and property prediction, functioning as a “Knowledge Co-pilot”. Phase 2 illustrates an AI-driven human-robot collaboration, in which an AI Agent with an LLM-driven core autonomously plans, executes, and analyzes experiments. Robotic systems carry out experimental tasks under human supervision, closing the loop from hypothesis generation to data validation. AI: Artificial intelligence.

FOUNDATIONAL ENABLEMENT: LLMS AS RESEARCH AUGMENTATION TOOLS

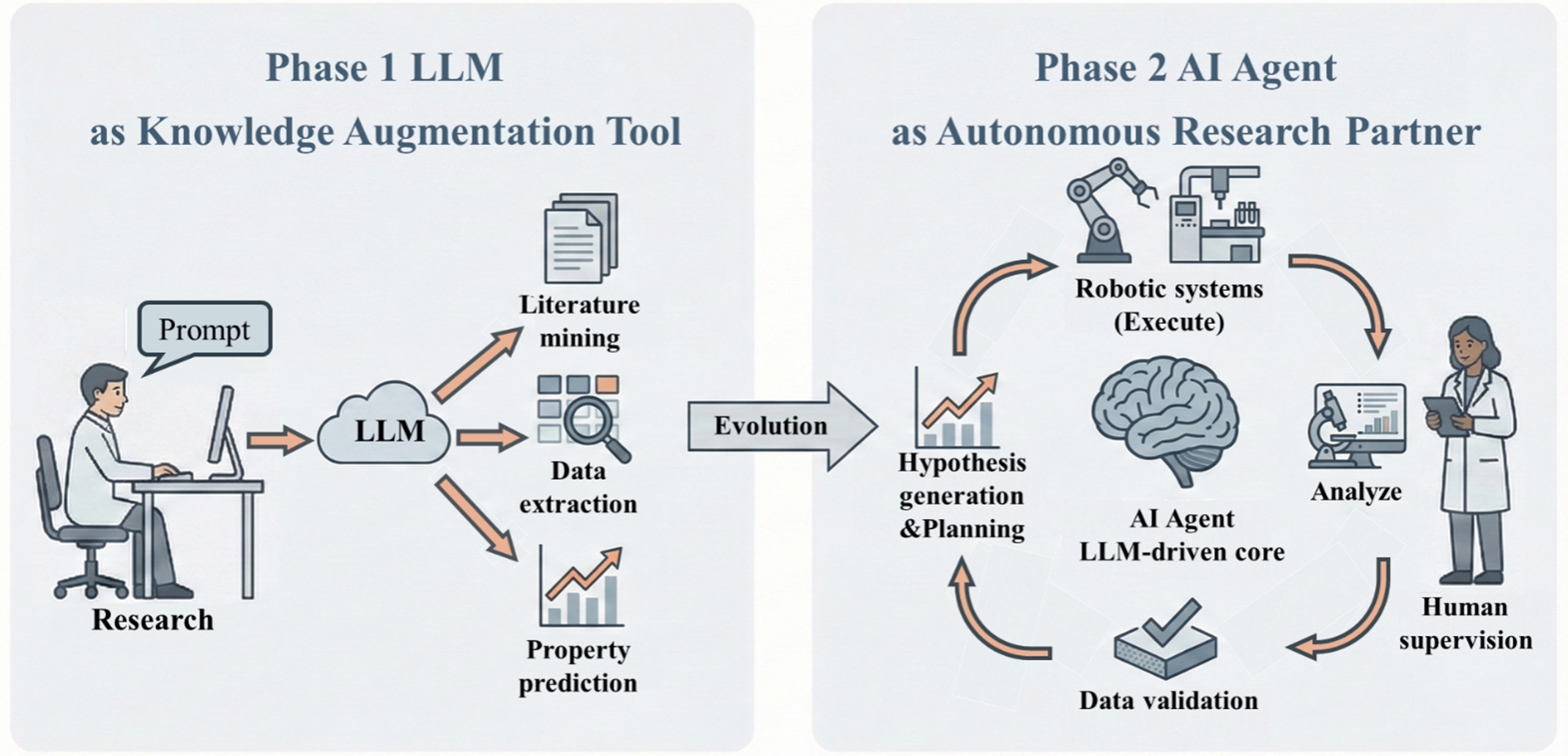

Before evolving into autonomous agents, LLMs first serve as powerful auxiliary tools, augmenting various stages of energy materials research. Understanding their core capabilities and how they have evolved is crucial. Figure 2 details this developmental trajectory, from foundational architectures to the emergent multimodal and agentic reasoning that powers modern AI systems. The application of these capabilities can be broadly understood through two primary functions: scientific comprehension and preliminary scientific discovery.

Figure 2. Milestones in the development of LLMs, highlighting architectural advances, multimodal integration, and the emergence of agentic reasoning for scientific automation. LLMs: Large language models; RLHF: reinforcement learning from human feedback; AI: artificial intelligence; BERT: bidirectional encoder representations from transformers; GPT-2: generative pre-trained transformer 2; API: application programming interface.

AI for scientific comprehension

Scientific comprehension is the starting point of all research activities, with its core being the efficient and accurate extraction of knowledge from vast amounts of literature. Liu et al. provide an excellent example of this process. They developed a tool named LMExt, an LLM-based automated literature review and data extraction pipeline specifically designed to build datasets required for machine learning[19]. The successful development of LMExt demonstrates an automated workflow for constructing thermodynamic datasets using LLMs[19]. Similarly, the creation of Perovskite-R1 was also based on the deep integration of extensive domain knowledge: researchers systematically mined and organized 1,232 high-quality scientific papers on perovskites and combined them with a library of 33,269 candidate compounds to build a large, domain-specific instruction-tuning dataset[1]. These efforts highlight the core capability of LLMs in transforming unstructured scientific literature into structured, AI-usable knowledge. A recent example is the Cat-Advisor system, which automatically curated a large, high-fidelity dataset for MgH2 catalysts from 759 scientific papers using a prompt-engineered LLM[15]. Such automated data curation lays the groundwork for subsequent data-driven discovery.

Text and knowledge graph extraction

LLMs can efficiently extract structured information from unstructured text. For example, tools such as ChatExtract[20] achieve high-precision extraction of material property triplets through conversational prompts. Furthermore, systems such as SciAgents[21] enhance the accuracy and depth of knowledge extraction by constructing scientific knowledge graphs or introducing fact-checking tools. At the same time, PaperQA2[22], an agentic system for automated scientific literature synthesis, can even match or exceed expert performance in literature review tasks without internet access[14]. The successful application of the LMExt tool demonstrates this by autonomously extracting stability constants of metal cation-ligand interactions and thermodynamic properties of minerals[19]. This work directly confronts the core challenges of materials science literature mining: processing old documents with inconsistent formats and specialized terminology. To address optical character recognition (OCR) errors from low-quality scans, they innovatively adopted a “PDF → high-resolution image → Markdown” conversion workflow, using the Mistral OCR model to bypass text encoding issues, significantly improving the fidelity of raw data from pre-2000 literature[19].

Advanced techniques for extraction accuracy

Simple prompt engineering often struggles with complex scientific texts. Liu et al. found that when extracting thermodynamic data, especially from intricately formatted tables, conventional prompts were ineffective. To address this, they introduced an “evidence-based prompting” strategy, requiring the LLM to cite evidence from the original text along with the extracted values. This Chain-of-Thought-like method forces the model to reason more deeply, which significantly improves extraction accuracy and can turn failed extractions into successful ones[19]. Their results also highlight the challenges: for well-formatted modern literature, the success rate of extraction can reach 84.2%. In contrast, for pre-2000 literature, even with optimization, the success rate is only 43.8%, quantifying the difficulty of processing legacy scientific data.

Multimodal comprehension: charts and figures

Energy materials research relies highly on graphical data [e.g., performance curves, XRD (X-ray diffraction) patterns, SEM (scanning electron microscopy) images]. Although the work of Liu et al. focuses mainly on text and tables, traditional NLP tools remain ineffective for such visual information. Recently, multimodal LLMs and benchmarks such as Table-LLaVA[23], for table interpretation, and ChartQA[24], for visual reasoning on scientific charts, have been developed to enable AI to directly “read” and reason about graphical data. These models can answer questions such as “After how many cycles does the battery capacity decay to 80%?”, enabling deep analysis of multimodal scientific data crucial to the energy materials field[14]. A prime example of this is the “Descriptive Interpretation of Visual Expression” (DIVE) workflow. Applied to solid-state hydrogen storage materials, this MAS extracts and interprets experimental data directly from graphical figures, improving extraction accuracy by 10%-15% over commercial models and enabling a rapid inverse-design process based on a large curated database[25]. In parallel with these advances, large-scale data mining has begun to yield tangible breakthroughs in materials science. A recent study analyzed over four decades of literature on magnesium-based solid-state electrolytes (SSEs), constructing a structured Mg-ion database that revealed composition-structure-conductivity relationships critical for the rational design of divalent ion conductors[26].

A paradigm shift in representation: from graphs to text

From graphs to text: a paradigm shift in material representation. Wang et al. demonstrate the synergy of integrating diverse data sources by combining a hydride SSE database with LLM analysis and ab initio simulations[27]. This multimodal approach not only identified materials with low Mg2+ migration barriers but also provided new insights into ion migration mechanisms, demonstrating how AI can integrate textual, numerical, and simulation data to generate deeper scientific insights[27]. Traditionally, crystalline materials are represented as graphs, with atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges, and their properties are predicted using GNNs[10]. However, this representation method has inherent difficulties in encoding complex crystal information such as periodicity and space group symmetry. LLM-Prop offers a different approach: representing materials with text, which can be more expressive and flexible than graphs[18]. Its core advantages are:

(1) High Expressiveness: Text can easily and directly incorporate key information that is difficult to encode in graph representations, such as space groups, bond angles, and lattice parameters.

(2) Rich Information: By pre-training on vast scientific literature, LLMs can learn rich chemical and structural knowledge about crystal design principles and fundamental properties[28-31].

(3) More Direct Modeling: Instead of designing complex GNN architectures to capture crystal symmetries, one can directly input symmetry information (such as space group labels) as text to the LLM, which greatly simplifies the modeling process.

LLM-Prop validated this idea with a simple and efficient strategy: they used only the encoder part of a pre-trained language model (T5) and fine-tuned it on a dataset containing textual descriptions of crystals. The results demonstrated that this approach not only outperformed state-of-the-art GNN models such as ALIGNN (atomistic line graph neural network) but also achieved comparable accuracy with substantially fewer parameters, without relying on large-scale domain-pretrained models [e.g., MatBERT[32], a BERT-based model pre-trained on materials science literature, (BERT = bidirectional encoder representations from transformers)]. This work indicates that the “understanding” of materials is shifting from structured graph reasoning to more expressive natural-language comprehension.

Preliminary exploration of AI for scientific discovery

In the core stage of scientific discovery, LLMs have also shown great potential as creativity boosters and experimental assistants. The capabilities of these AI systems are directly tied to the power of their underlying foundational models. Table 1 summarizes a representative selection of these state-of-the-art systems and their applications in materials science and chemistry, highlighting the base models they are built upon, their specific application domains, and their key achievements.

Representative AI systems and applications in materials science and chemistry research

| System | Base model | Domain |

| Coscientist[33] | GPT-4 | Chemical synthesis |

| ChemCrow[34] | GPT-4 | Organic chemistry |

| ChatMOF[35,36] | GPT-4/GPT-3.5 | Metal-organic frameworks |

| MOF-Reticular[37] | GPT-4 | Metal-organic frameworks |

| LLM-RDF[38] | GPT-4 | Chemical synthesis |

| ChatBattery[39] | GPT-4/GPT-3.5 | Battery cathodes |

| Perovskite-R1[1,40] | QwQ-32B | Perovskite solar cells |

| Perovskite-LLM[41] | Llama-3.1-8B, Qwen-2.5-7B | Perovskite materials |

| Solar Cell IE[42] | Fine-tuned LLaMA | Perovskite solar cells |

| DARWIN | Llama3.1/GPT-4 | Materials |

| aLLoyM[43] | Mistral-Nemo-Instruct-2407 | Alloy phase diagrams |

| LLM-Prop[18] | T5 Encoder | Crystal properties |

| SciAgents[3] | GPT-4 | Biomaterials |

| RetroDFM-R[13] | ChemDFM-v1.5 (RL) | Retrosynthesis |

| Electrolyte-MA[16] | GPT-4 | Zinc-ion batteries |

| Cat-Advisor[15] | GPT-4o, DeepSeek-Rl-Distill-Llama-8B | Hydrogen storage |

| DIVE[25] | Gemini-2.5-Flash, Deepseek-Qwen3-8B | Hydrogen storage |

| LMExt[19] | GPT-4 | Thermodynamics |

| MaScQA[44] | GPT-4/LLaMA-2-70B | Materials Q&A |

Hypothesis generation and idea mining

LLMs can generate novel hypotheses from existing knowledge. Their primary contribution is the ability to simulate human reasoning, allowing them to mine novel scientific hypotheses from a vast knowledge space. For example, the dZiner framework, an agent for rational inverse material design, generates entirely new molecular structures from natural language requirements by learning design rules from literature[45]. Systems and benchmarks such as HypoGen[46], for automated hypothesis generation, and ResearchBench[47], for evaluating scientific discovery capabilities, are also specifically designed to evaluate and drive AI’s hypothesis generation capabilities[14]. This process can operate in multiple modes: generation based on the LLM’s internal knowledge, or generation combined with databases and experimental feedback, which lays the foundation for autonomous AI agents.

LLMs can generate novel hypotheses from existing knowledge. Their primary contribution is the ability to simulate human reasoning, allowing them to mine novel scientific hypotheses from a vast knowledge space. For example, the dZiner framework, an agent for rational inverse material design, generates entirely new molecular structures from natural language requirements by learning design rules from literature[45]. Systems and benchmarks such as HypoGen[46], for automated hypothesis generation, and ResearchBench[47], for evaluating scientific discovery capabilities, are also specifically designed to evaluate and drive AI’s hypothesis generation capabilities[14]. This process can operate in multiple modes: generation based on the LLM’s internal knowledge, or generation combined with databases and experimental feedback, which lays the foundation for autonomous AI agents.

The main goal of LMExt is data extraction. However, the large, structured dataset it creates also provides a foundation for data-driven idea mining, such as inferring stability relationships among minerals[19]. Domain-specific LLMs are becoming powerful idea engines. For instance, Perovskite-R1, fine-tuned on massive perovskite data, can intelligently generate and screen innovative precursor additives for defect passivation in perovskite solar cells (PSCs)[1]. This marks a shift for AI from general reasoning to goal-oriented hypothesis generation guided by chemical intuition.

Theoretical analysis and experimental planning

LLMs can assist in generating standard operating procedures (SOPs) and simulation code. For example, frameworks such as ChemGraph[48], an agentic framework for computational workflows, and LLaMP[49] (large language model made powerful), can automatically generate Python code for DFT calculations or molecular dynamics simulations from natural language instructions. Systems such as AI Co-Scientist[50], an autonomous research partner, and ChemCrow[34], a tool-augmented chemistry agent, can autonomously plan multi-step organic synthesis routes, which have direct implications for designing organic linkers for MOFs or polymer electrolytes[14].

Synergy with traditional machine learning and optimization

LLMs can create a powerful synergy with traditional machine learning by acting as “data engineers.” For instance, Liu et al. demonstrate this by using a thermodynamic dataset automatically constructed by LMExt to train a CatBoost model[19], a high-performance gradient boosting algorithm, connecting unstructured knowledge to a predictive model.

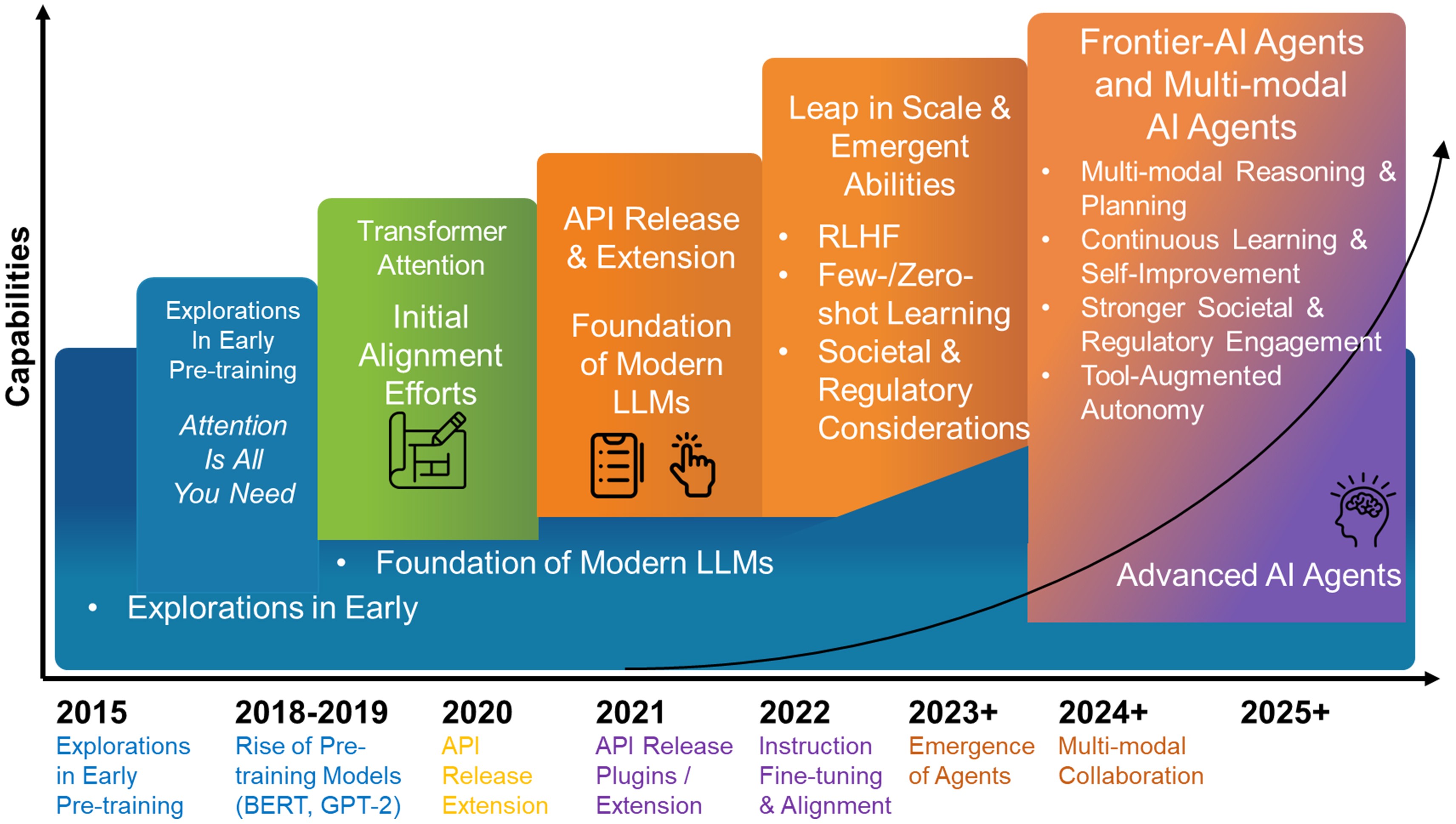

The Cat-Advisor framework extends this synergy by creating a workflow that links literature curation with design[15]. After using GPT-4o (generative pre-trained transformer 4 omni), OpenAI's multimodal large language model, to curate a high-fidelity dataset from 759 PDFs on MgH2 catalysts, machine learning models were trained, achieving an R2 (coefficient of determination) value of 0.91. This model was integrated with a genetic algorithm (GA) for inverse design. Notably, this automated process uncovered multi-metal synergy principles that align with recent experimental findings in high-entropy alloy catalysts. As shown in Figure 3, Cat-Advisor represents a comprehensive pipeline that integrates LLM-assisted data curation, predictive modeling, and AI-driven optimization to derive practical catalyst candidates directly from the literature.

Figure 3. Schematic of the LLM-driven machine learning framework for MgH2 catalyst design. (A) Data preprocessing pipeline. Depicts the workflow converting 759 publications into a structured dataset via OCR and GPT-4o. P1 (catalyst performance), P2 (category), P3 (Q&A pairs), and P4 [Chain-of-Thought (CoT) data] represent information types extracted and integrated with the Materials Project API; (B) Prompt engineering. Details the four specific prompt strategies: P1 for parameter extraction; P2 for catalyst classification; P3 for Q&A pair generation; and P4 for CoT dataset construction; (C) Multi-Agent System (CatalystAI). Illustrates the integration of Agent 1 (Machine Learning) utilizing Genetic Algorithms for candidate prediction, and Agent 2 (Fine-tuned LLM) enhanced by LoRA and RAG for advisory tasks. Function-calling techniques connect the two agents to enable interactive catalyst design. Adapted with permission from Yao et al.[15] (© 2025, Chongqing University); change made: no changes made. LLM: Large language model; OCR: optical character recognition; Q&A: question and answer; API: application programming interface; RAG: retrieval-augmented generation; GPT-4o: generative pre-trained transformer 4 omni.

FROM LLMS TO AI AGENTS: A NEW PHASE IN AUTONOMOUS DISCOVERY

The transition from LLMs to AI agents marks a fundamental shift in the role of AI in scientific research, from an “auxiliary tool” to an “autonomous partner”. To better understand the breadth and depth of this evolving ecosystem, it is crucial to first define what constitutes an AI agent and how it differs from a conventional LLM.

What are AI agents? The leap from LLMs to agents

An AI agent is a system with an LLM at its cognitive core, endowed with the capabilities of planning, tool use, and memory[51]. Its core working mechanism is often based on frameworks such as ReAct (Reason + Act), which completes tasks through a “think-act-observe” cycle[52]. Such systems are becoming crucial because LLMs alone are often not robust enough for complex scientific tasks that require multiple steps or autonomous exploration[13]. Agents compensate for these deficiencies by integrating external tools and environments. A step beyond individual agents is the MAS, where multiple specialized agents solve complex problems through conversational, iterative interactions. The key to this collaborative approach lies in the strategic decomposition of tasks. Instead of a single agent handling everything, a complex workflow is broken down into manageable sub-tasks, with each assigned to an agent possessing a specific role and expertise. The SciAgents framework is a key example of this approach: an Ontologist agent defines concepts from a knowledge graph, a Scientist agent crafts a hypothesis, and a Critic agent rigorously evaluates the proposal[3].

This division of labor, combined with iterative feedback, creates a system of checks and balances that enables the system to handle greater complexity and lead to breakthroughs difficult for a single agent to achieve[34,53-55]. Crucially, this collaborative model has been shown to effectively mitigate the problem of error accumulation common in the long-chain reasoning of a single LLM, thereby producing more reliable and creative results, as also demonstrated in conversational agent networks for tasks such as electrolyte discovery[16].

The key shift is from “passive answering” to “active execution”, where AI agents can break down grand objectives, autonomously call upon tools, and reflect and iterate based on the results. In terms of “tool use”, a revolutionary advancement is the use of structured knowledge bases to manage and orchestrate a vast number of tools. For example, the core of the SciToolAgent framework, an agentic system for orchestrating scientific tools, is a “Scientific Tool Knowledge Graph” (SciToolKG), which encodes the functions, input/output formats, and interdependencies of hundreds of tools spanning biology, chemistry, and materials science. This structured representation enables compositional planning across heterogeneous simulation environments, allowing the agent to move beyond simple tool invocation toward intelligent design of multi-step workflows, which serves as a key enabler of large-scale, cross-domain automation[56].

The role of AI agents in the closed-loop of autonomous discovery in energy materials

The goal of AI agents in energy materials research is an autonomous discovery process that integrates design, synthesis, and testing within a continuous closed loop[14]. This vision is being advanced by systems capable of performing increasingly complex tasks, spanning computational modeling, experimental design, and laboratory automation. The development of standardized benchmarks such as ScienceAgentBench[57,58], for evaluating data-driven scientific tasks, and DiscoveryBench, for assessing end-to-end discovery capabilities, are helping to evaluate and accelerate this progress. Within this framework, agents play three essential roles: generating and optimizing material designs, planning feasible synthesis routes, and coordinating automated laboratory execution. Together, these capabilities point toward a new paradigm of data-driven, self-improving materials discovery.

Optimizing the loop: agentic planners vs. traditional methods

At the core of every self-driving lab is the policy that determines which experiment to perform next. Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Active Learning (AL) remain standard approaches because of their high sample efficiency for costly experiments[59,60]. BO constructs a surrogate model (often a Gaussian Process) and selects new candidates through acquisition functions such as Expected Improvement (EI)[61] for single-objective tasks or q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement (qEHVI)[62] for multi-objective, batch optimization targeting Pareto trade-offs. Constrained BO further incorporates feasibility, toxicity, or cost constraints[63,64], while sequential and batch modes account for sensor or actuator noise to ensure robust convergence[65].

In contrast, LLM-based agentic planners conduct heuristic, knowledge-driven searches by leveraging literature priors, calling external simulators, and composing multi-step experimental workflows. These systems offer flexibility and contextual reasoning but currently lack quantitative benchmarking against BO in terms of sample efficiency. A hybrid framework that combines the strategic reasoning of LLM agents[16] with the statistical rigor of BO provides a promising direction for reliable and efficient closed-loop discovery.

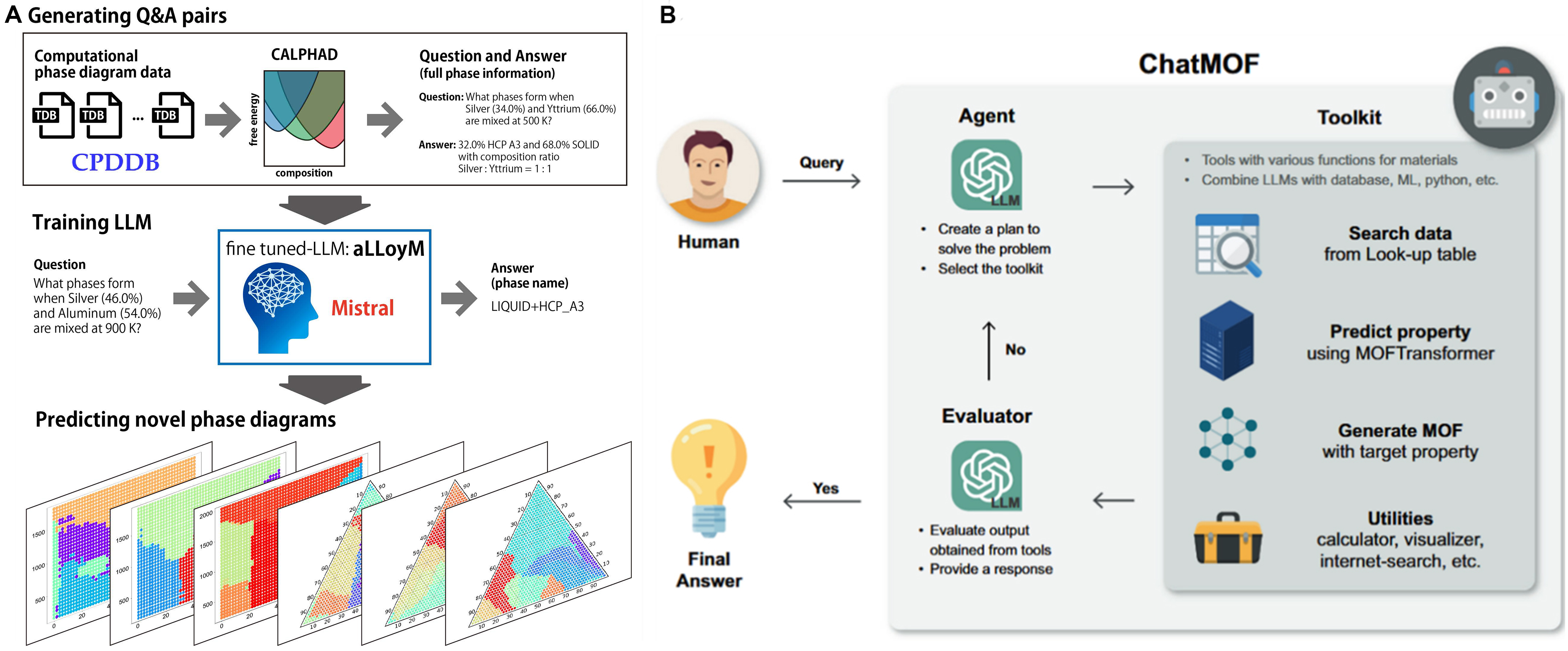

Autonomous discovery and design

At the design stage, AI agents can autonomously generate and evaluate novel material hypotheses. Early prototype systems demonstrated end-to-end capabilities from hypothesis generation to result analysis[66,67]. This has evolved into specialized agents capable of tackling fundamental materials science problems. A primary exemplar is the aLLoyM model, an LLM specialized for alloy phase prediction, which, after being fine-tuned on vast CALPHAD (calculation of phase diagrams)-generated datasets, can accurately predict complex alloy phase diagrams, a task traditionally requiring immense experimental or computational effort[43]. This showcases an agent’s ability to internalize deep domain knowledge and serve as a powerful design tool. Other systems such as the one developed by Liu et al., while not fully autonomous, represent a preliminary discovery loop where an LLM extracts data from literature to build a knowledge base, which then informs a predictive ML model[19].

Beyond general design frameworks, recent studies report task-level advances with explicit objectives, constraints, and lab readouts in batteries and electrolytes. Below, we highlight three concise cases that reflect how these systems operate under practical performance metrics.

To further illustrate domain-specific progress, several representative cases demonstrate how AI-driven systems address practical challenges in energy-materials discovery. In electrolyte formulation, closed-loop workflows that combine Bayesian optimization with high-throughput electrochemistry optimize compositions under multiple constraints, including ionic conductivity, viscosity, and electrochemical stability window; such pipelines have identified solvent-salt combinations with improved conductivity-stability trade-offs[16]. In cathode design, agent-assisted modeling integrates redox-potential prediction and lattice-strain penalties to balance phase stability, volumetric energy density, and mechanical integrity, yielding candidates with reduced expansion and improved cycle life; recent agentic frameworks also report end-to-end identification and validation of new Li-ion cathodes[33]. For SSEs, models trained on both experimental and computational data perform Arrhenius-type analysis to estimate ionic conductivity and assess chemical stability against electrodes. Reliability is further enhanced by incorporating uncertainty-aware screening and dendrite-suppression considerations in sulfide and oxide systems[26,27]. Together, these cases illustrate a shift from general AI frameworks to physically grounded, constraint-aware workflows for energy-materials discovery.

Autonomous synthesis planning

A crucial link from a digitally designed material to its physical realization is the generation of a feasible synthesis route. This complex chemical reasoning task, known as “retrosynthesis”, has seen significant progress with specialized AI agents. For instance, RETRODFM-R, a retrosynthesis agent trained via reinforcement learning, exemplifies this capability. It not only predicts viable precursors for target molecules but also generates a detailed, interpretable “Chain-of-Thought” reasoning process, explaining the chemical logic behind its decisions[13]. This function is essential for automating the “synthesize” step in the discovery cycle.

Autonomous automation: the “Self-Driving Lab”

In the final stage, AI agents act as the core of a “Self-Driving Lab,” connecting virtual design with the physical world in a “design-synthesize-test-learn” loop[68,69]. Pioneering systems from chemistry, such as Coscientist, an autonomous system for robotic chemical experimentation, provide a powerful blueprint, demonstrating how an LLM can plan an experiment, write code to control robotic hardware (such as liquid handlers), and execute the synthesis in a real-world laboratory[33].

This paradigm is being actively applied to energy materials. The ChatBattery framework, a multi-agent system for battery cathode discovery, stands as a landmark example in which a MAS automates the entire discovery process for battery cathodes, from conceptualization to wet-lab validation and characterization[39]. The successful, accelerated discovery of novel cathode materials within this framework highlights the transformative potential of fully integrated autonomous science. A complete autonomous workflow can thus be envisioned as a synergistic collaboration between specialized agents (see Supplementary Table 1 for more examples, including ChemCrow and SciToolAgent): a design agent proposes a material, a planning agent devises the synthesis route, and an automation agent executes the experiment, completing the discovery loop. This entire process can be abstracted as a “hypothesis-experiment-observation” cycle, in which AI contributes at every stage to enhance efficiency and creativity[13,17].

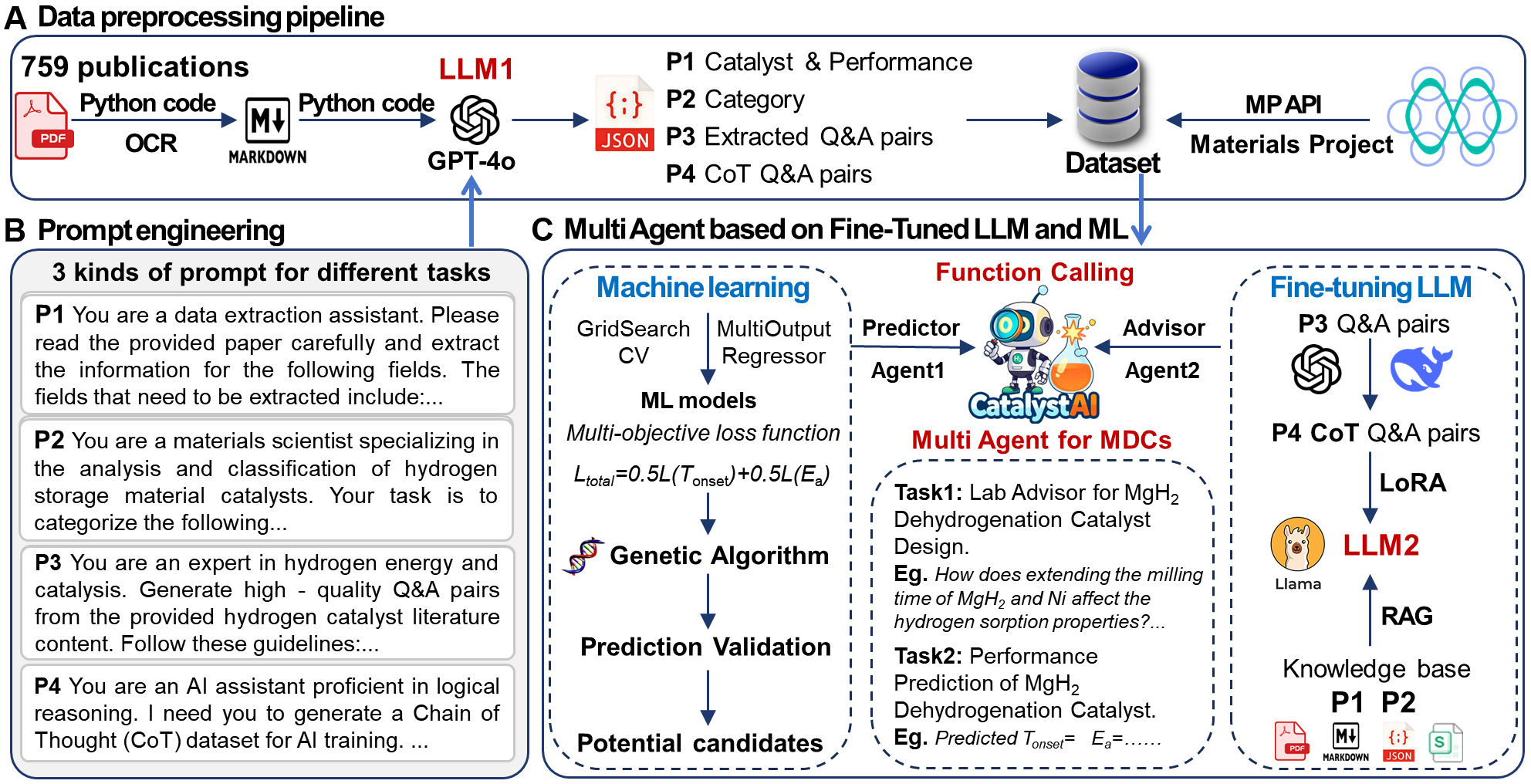

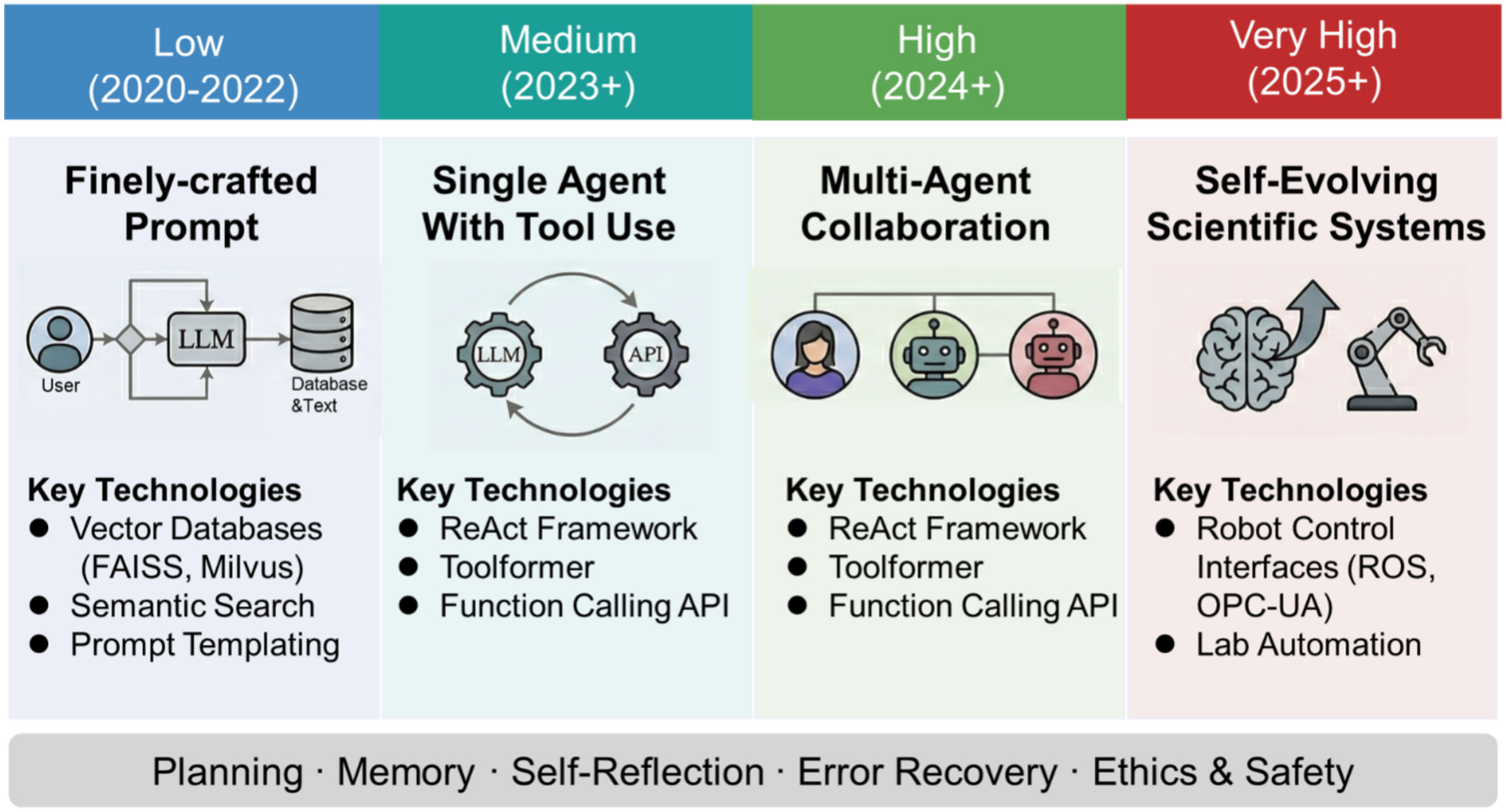

The development of AI agents is reflected not only in the breadth of their applications but also in the increasing complexity of their architecture and their growing autonomy. Figure 4 illustrates the evolutionary path of AI agent architecture and its positioning on the autonomy spectrum.

Figure 4. Architectural evolution and autonomy spectrum of AI agents, from single-agent tool use to multi-agent collaboration and fully autonomous self-driving laboratories. AI: Artificial intelligence; LLM: large language model; FAISS: Facebook AI similarity search; API: application programming interface; ROS: robot operating system; OPC-UA: open platform communications unified architecture.

Frontier case studies: AI agent-driven closed-loop discovery

The practical implementation of AI agents for autonomous discovery is rapidly evolving, giving rise to a variety of sophisticated architectures and workflows. Examining these frontier case studies provides a concrete understanding of how AI is being deployed to tackle complex scientific challenges.

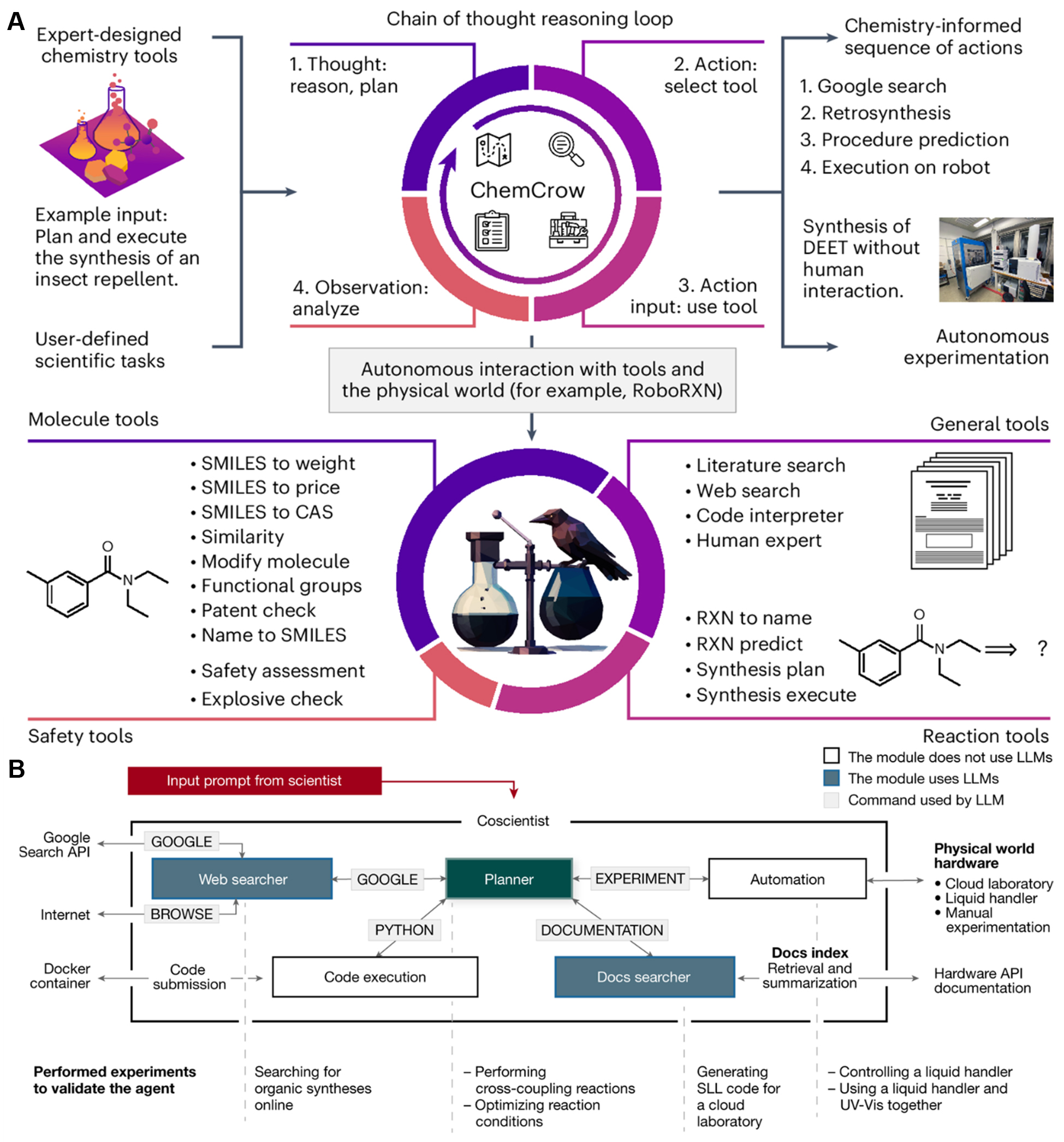

A foundational architecture for AI agents is the integration of a cognitive core with a diverse set of tools and a connection to the physical world. Pioneering systems from chemistry, such as ChemCrow[34] and Coscientist[33], provide excellent blueprints [Figure 5]. ChemCrow showcases the “thought-action-observation” reasoning loop of the agent for task execution [Figure 5A], while Coscientist demonstrates how such an agent can be integrated into a larger system to control laboratory hardware, thereby closing the loop from digital hypothesis to physical experimentation [Figure 5B].

Figure 5. Core architectures of AI agents for autonomous discovery. (A) ChemCrow workflow demonstrating chain-of-thought reasoning with tool use. Adapted from Bran et al.[34] (CC BY 4.0); change made: no changes made; (B) Coscientist system integrating LLM planners with robotic control for closed-loop experiments. Adapted from Boiko et al.[33] (CC BY 4.0); change made: cropped. AI: Artificial intelligence; RoboRXN: robotic reaction; CAS: Chemical Abstracts Service; SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; API: application programming interface; LLM: large language model; SLL: Scilligent laboratory language; UV-Vis: ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.

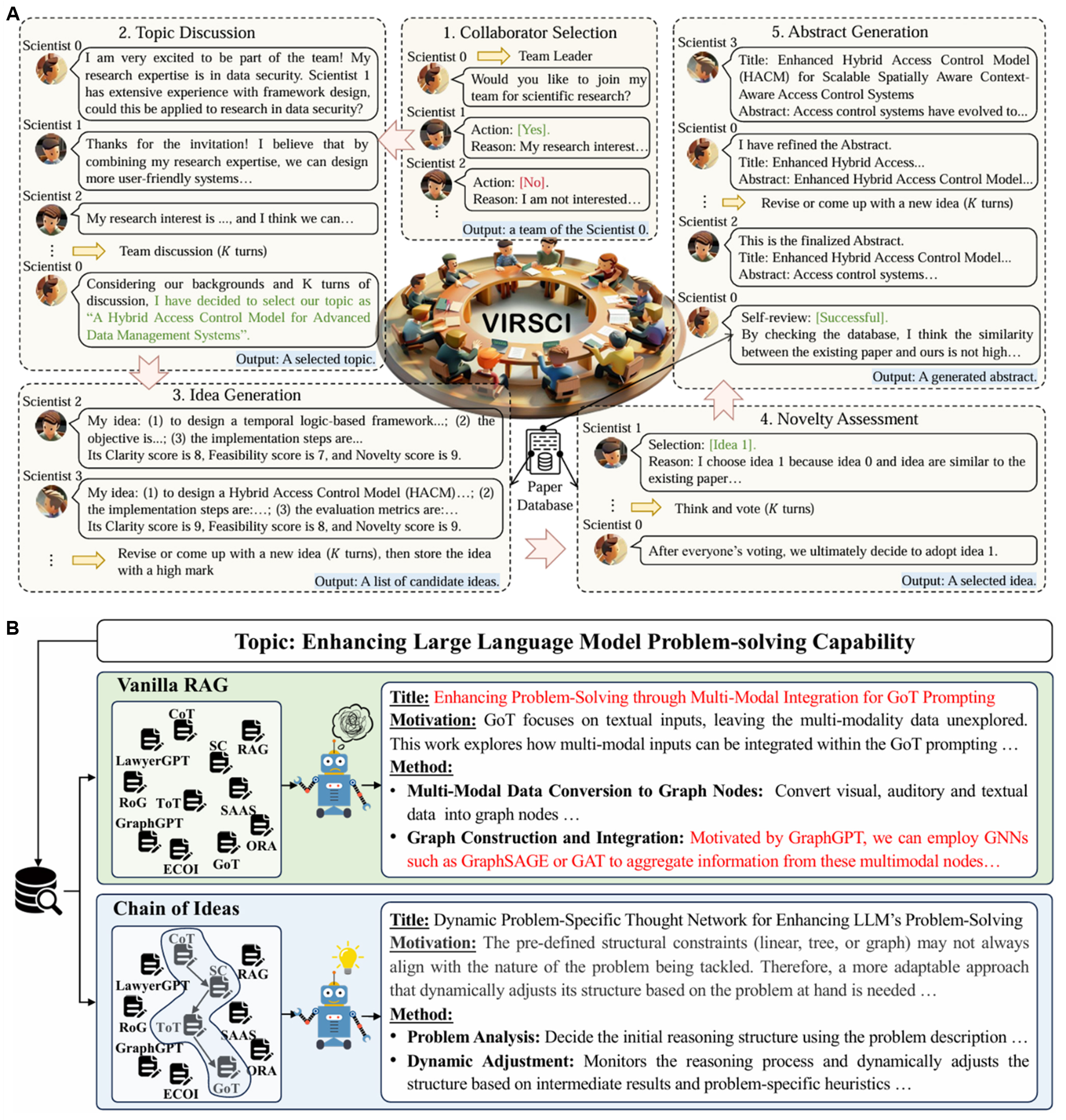

Building upon these foundational concepts, a key frontier is enhancing the ability of the agent to generate novel scientific ideas. This often involves more complex multi-agent collaboration frameworks. As illustrated in Figure 5, two distinct strategies have emerged. The VirSci system, a collaborative platform for virtual scientific research, simulates a virtual research team, leveraging social collaboration dynamics among agents to foster creativity[70] [Figure 6A]. In contrast, the Chain-of-Ideas (CoI) agent focuses on optimizing the cognitive process itself, by structuring retrieved knowledge into coherent chains to enable deeper reasoning[71] [Figure 6B].

Figure 6. Advanced frameworks for AI-driven idea generation. (A) VirSci multi-agent collaboration simulating research teams. Adapted from Su et al.[70] (CC BY 4.0); change made: no changes made; (B) Chain-of-Ideas (CoI) agent structuring retrieved knowledge into coherent reasoning chains. Adapted from Li et al.[71] (CC BY 4.0); change made: no changes made. AI: Artificial intelligence; VORSCI: virtual interactive research for scientific collaboration and innovation; RAG: retrieval-augmented generation; CoT: Chain-of-Thought; GPT: generative pre-trained transformer; SC: self-consistency; RoG: recall-augmented generation; ToT: tree of thought; SAAS: self-alignment augmented search; GraphGPT: graph-based generative pre-trained transformer; ECOI: ensemble of contextualized output interpretation; GoT: Graph-of-Thought; ORA: output refinement augmentation.

These architectural and cognitive patterns are now being successfully applied to create end-to-end discovery platforms in energy materials, achieving a complete loop from “AI hypothesis” to “real material”.

ChatBattery stands as a paragon of the multi-agent collaborative model for end-to-end materials discovery[39]. Instead of a single monolithic LLM, it employs seven specialized agents (including LLM, Search, Domain, and Human Agents) working in concert. Through this intricate process, the team successfully discovered and synthesized three new lithium-ion battery cathode materials, including LiNi0.7Mn0.05Co0.05Si0.1Mg0.1O2 (NMC-SiMg), derived from the widely used NMC811 (LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2). The evaluation protocol detailed in the original work confirms these materials were experimentally validated in coin cells cycled between 2.6-4.3 V. The results demonstrated reversible capacity improvements of up to 28.8% over the NMC811 baseline after three charge-discharge cycles. Although minor impurity phases were noted, reflecting the preliminary nature of the synthesis, the entire process - from AI-driven hypothesis to wet-lab validation - was completed in just a few months, representing a dramatic acceleration compared to traditional research timelines.

In contrast to the multi-agent architecture, another successful path involves transforming a general-purpose LLM into a domain expert. Perovskite-R1 exemplifies this for designing novel PSC additives[4]. By fine-tuning a model on a vast dataset of perovskite literature, the resulting “expert agent” autonomously recommended new additives that were experimentally validated to significantly outperform those selected by human experts. Similarly, the aLLoyM agent, created by fine-tuning on computationally generated CALPHAD data [Figure 7A], concentrates on “predicting system behavior”. Its remarkable ability to extrapolate and generate plausible phase diagrams for unseen alloy systems showcases the value of AI agents in fundamental scientific research[43].

Figure 7. Representative workflows of AI agents in materials science. (A) The aLLoyM workflow for alloy phase prediction. Adapted from Oikawa et al.[43] (CC BY 4.0); change made: no changes made; (B) The ChatMOF architecture for agent-tool integration in MOF design. Adapted from Kang et al.[72] (CC BY 4.0); change made: no changes made. AI: Artificial intelligence; LLM: large language model; Q&A: question and answer; aLLoyM: aLLoy large language model; LIQUID: liquid phase; HCP_A3: hexagonal close-packed, strukturbericht A3; MOF: metal-organic framework; ML: material library.

Two paths of agent evolution: architectural and cognitive innovation

The case studies presented above, despite their varied technical approaches, collectively show a clear evolutionary path for AI agents. This landscape is defined by two parallel and complementary macro-strategies: the “horizontal scaling” of architectural innovation and the “vertical deepening” of cognitive innovation.

The first path, “horizontal scaling” of architectural innovation, focuses on building more complex and capable agent systems to simulate and enhance collective intelligence. This is evident in the evolution from the simple “single-agent + toolkit” model of ChatMOF [Figure 7B], an autonomous agent for metal-organic framework generation, to the intricate multi-agent collaboration seen in VirSci [Figure 6A] and the end-to-end ChatBattery platform. This path also includes the development of conversational “idea generators” for tasks such as electrolyte discovery, as demonstrated by Robson et al. using the AutoGen framework[16], a platform for building multi-agent LLM applications, and multi-expert frameworks such as MOOSE-Chem[73], designed for focused chemical reasoning, where each agent plays a distinct, specialized role within the chemical domain. In these systems, multiple specialized agents collaborate through dialogue, critique, and RAG (retrieval-augmented generation)-powered knowledge retrieval to brainstorm novel solutions. The goal of this architectural evolution is to overcome the limitations of a single LLM by enabling internal discussion and role-playing, effectively transforming the AI from an independent executor into a “virtual research team”.

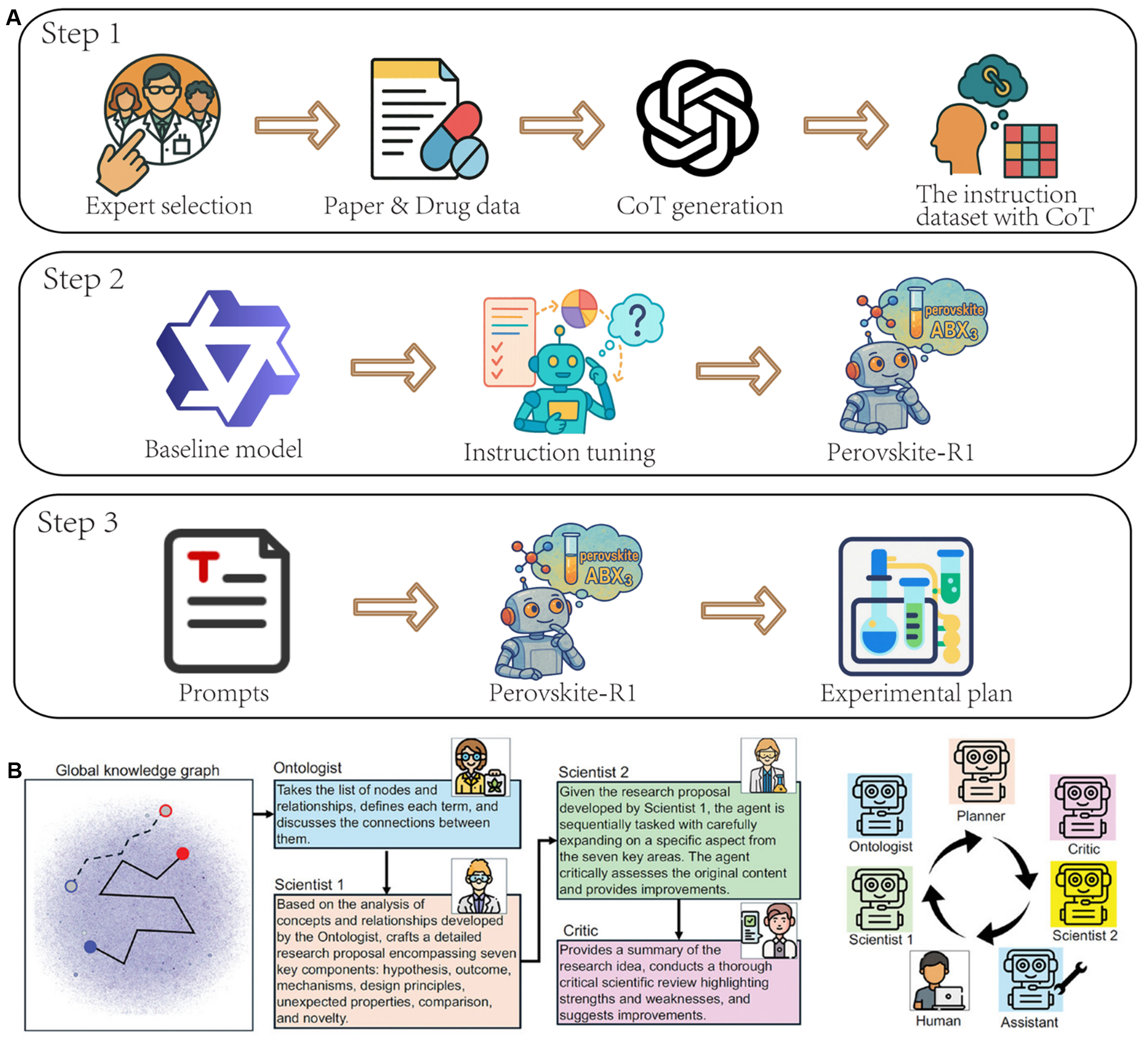

The second path, “vertical deepening” of cognitive innovation, focuses on the root of the problem: fundamentally enhancing the “understanding” of the agent with respect to specific domain knowledge. A key technique here is domain-specific fine-tuning, as exemplified by the aLLoyM [Figure 7A] and Perovskite-R1 workflows. A more profound approach, showcased by the construction of Perovskite-R1, involves creating high-quality, Chain-of-Thought (CoT)-enhanced instruction datasets from unstructured literature to instill deeper reasoning capabilities [Figure 8A]. This path culminates in systems such as SciAgents, which tightly integrate multi-agent collaboration with a large, structured Ontological Knowledge Graph (OKG)[3]. By anchoring agent reasoning to an external, verified knowledge structure [Figure 8B], this method provides a solid basis for reasoning. It is a key path toward overcoming the “hallucination” and knowledge limitations of LLMs[74].

Figure 8. Technologies enhancing agent cognition. (A) Perovskite-R1 instruction-tuning pipeline for domain specialization. Adapted with permission from Wang et al.[40]. This figure is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0) license; no changes made; (B) SciAgents framework anchoring reasoning to an ontological knowledge graph. Adapted from Ghafarollahi et al.[3] (CC-BY-NC 4.0); change made: cropped. CoT: Chain-of-Thought.

These two paths are not mutually exclusive but form the core of the future autonomous science toolkit. An ideal future system will likely combine a sophisticated collaborative architecture (Path 1) with agents that possess a deep, well-grounded understanding of their domain (Path 2).

KEY TECHNOLOGIES, CHALLENGES, AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

Key technologies driving the evolution

The evolution from LLMs to AI agents is driven by several key technologies across the system stack. These technologies can be broadly categorized along the two evolutionary paths identified in this review: architectural innovation, which builds more capable systems, and cognitive innovation, which endows them with deeper understanding.

Technologies for architectural innovation

Architectural innovation focuses on enhancing the ability of an agent to plan, collaborate, and interact with its environment. Key enabling technologies include:

(1) Knowledge Graph-driven Tool Integration: As the number of available computational tools grows, enabling agents to effectively “learn” and “use” them is a core challenge. The foundational role of well-structured databases and knowledge graphs in AI-driven science is becoming increasingly evident, as they provide the essential substrate for fine-tuning LLMs and developing robust machine learning models, particularly in complex fields such as electrocatalysis[27]. The SciToolKG proposed by SciToolAgent provides a scalable solution by modeling the functions and dependencies of tools in a structured way. This allows agents to perform graph-based reasoning to dynamically plan and combine tools to solve complex, multi-step tasks that were previously intractable[56].

(2) Multi-Agent Conversational Frameworks: To transcend the limitations of a single LLM, frameworks such as AutoGen are essential for achieving higher-level collective intelligence[40,75]. As demonstrated by Robson et al., these frameworks allow multiple agents to iterate through dialogue, enabling them to integrate diverse perspectives, perform cross-validation, and self-correct. This collaborative reasoning is crucial for enhancing problem-solving on complex scientific issues[16].

(3) Reliable Physical World Interfacing: The bridge connecting the virtual agent to the real world relies on reliable tool-calling interfaces and dynamic experimental control. This is a prerequisite for achieving the “dynamic real-time optimization of scientific experiments”, a cornerstone of the autonomous lab vision[14].

Technologies for cognitive and representational innovation

Cognitive innovation focuses on deepening the core understanding of an agent with respect to scientific knowledge. Advanced techniques for knowledge acquisition, reasoning, and representation are central to this endeavor, as highlighted in Figure 8.

(1) Domain-Specific Foundation Models and Fine-tuning: A core strategy to create “expert” agents is to instill deep domain knowledge. This begins with foundation models pre-trained on scientific literature, such as MatSciBERT (Materials Science BERT) and BatteryBert (Battery BERT), which provide a high-quality knowledge base[9,76]. Subsequently, as demonstrated by the success of Perovskite-R1 [Figure 8A], a general-purpose LLM can be transformed into a specialist by fine-tuning on high-quality, domain-specific instruction datasets. For domains where experimental data is scarce, the aLLoyM project showcases a powerful alternative: using high-throughput computations (e.g., CALPHAD) to generate vast, structured training datasets, effectively creating a “computational simulation empowering AI training” paradigm. Similarly, recent work by Wang et al. demonstrates a hybrid approach, where LLMs are employed to construct comprehensive databases from literature, which are then augmented with ab initio simulation data to build high-fidelity predictive models for solid-state hydride electrolytes[9].

(2) Advanced Reasoning and Training Paradigms: To move beyond simple imitation, advanced training methods are crucial. The success of the retrosynthesis agent RETRODFM-R, for instance, is due to its innovative use of reinforcement learning. This allows the model to discover better chemical paths through “trial and error”, enhancing its advanced reasoning capabilities[13]. Furthermore, to mitigate issues such as hallucination, agents are increasingly being anchored to external knowledge bases. The SciAgents framework [Figure 8B] pioneers this with Knowledge Graph-Enhanced In-Context Learning, where structured information is strategically extracted from an ontological knowledge graph to provide richer, more logically layered context for the reasoning of the LLM[3,77-79].

(3) Multimodal and Cross-Modal Integration: Scientific data is inherently multimodal. Future agents must move beyond text to understand images, spectra, and graphs to achieve comprehensive data fusion[14]. This involves cross-modal integration, for example, combining LLMs with spectral data or quantum chemical calculations, to ground the decisions of the agent in solid physical insights rather than merely in text patterns[9,80].

(4) Novel Material Representations: A disruptive technological path involves innovating not the model architecture, but how we describe the physical world to the model. The LLM-Prop project further illustrates this approach by representing crystalline materials using rich textual descriptions rather than traditional graphs, as discussed in Section 2.1[18].

Foundational capability enhancement

Underpinning both paths is the rise of general-purpose “foundation models” for science. A key trend is to move away from designing narrow models and instead train large models on massive, multimodal scientific data. This approach “encapsulates” the knowledge of a broad scientific domain[13]. The success of Evo[81], a genomic foundation model, and ChemBERT[82], a pre-trained language model for chemical structures, demonstrates the power of this strategy. In the future, the “brains” of AI agents will increasingly be driven by these powerful scientific foundation models.

These key technologies illuminate the two parallel and complementary evolutionary paths for AI agents, as summarized in Figure 9. “Architectural Innovation” focuses on building smarter collaborative systems, while “Representational and Cognitive Innovation” enhances the core intelligence of each agent. Understanding the interplay between these paths is crucial for fully grasping the potential of AI in future scientific discovery.

Figure 9. The two evolutionary paths of AI in materials science: architectural innovation through multi-agent collaboration and representational innovation via text-based material representations. AI: Artificial intelligence; MOF: metal-organic framework; SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; LLM: large language model; GNN: graph neural networks; SG: summarized graph; DIVE: descriptive interpretation of visual expression.

Integration with physical knowledge and uncertainty quantification

Purely data-driven AI agents may generate results that violate physical laws or lack interpretability. To ensure scientific reliability, two foundations are essential: physics-based learning and uncertainty quantification (UQ).

Physics-informed methods introduce governing equations and constraints directly into the model. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) embed differential equations, such as diffusion or Schrödinger forms, into the loss function, forcing predictions to obey physical laws[83]. For atomistic systems, E(3) (Euclidean group in 3 dimensions)-equivariant neural networks such as NequIP (neural equivariant interatomic potentials)[84] maintain translation and rotation symmetries, producing consistent force and energy predictions. Combining low- and high-fidelity data, together with explicit physical constraints such as charge balance or energy conservation, further improves robustness and interpretability.

Reliable autonomy also requires agents to assess their own confidence. Deep ensembles estimate predictive variance from multiple trained models and provide calibrated uncertainty through temperature scaling[85]. Conformal prediction (CP) produces statistically valid confidence intervals without assuming data distributions[86]. These techniques enable agents to make risk-aware decisions, such as avoiding experiments with low confidence or switching to safer conditions when uncertainty is high.

Embedding these principles into closed-loop workflows enables continuous self-correction. During planning, high-uncertainty actions are flagged for human review; during execution, deviations between predictions and measurements trigger adaptive updates. Incorporating physical priors and calibrated uncertainty allows AI agents to make safer experimental decisions and maintain interpretability during autonomous research.

Core challenges from LLMs to AI agents

Despite the promising outlook, the practical application of AI agents faces significant challenges across three interconnected levels: internal technical limitations, practical application hurdles, and broader ethical and societal concerns.

Internal technical challenges

Internal technical challenges stem from the inherent limitations of current AI technology, especially LLMs:

(1) Reliability and Error Propagation: The “hallucinations” of LLMs can lead to erroneous calculations or unsafe experimental procedures, and errors are particularly prone to accumulate in long-chain reasoning[87]. To ensure the robustness and controllability of agent behavior, researchers are exploring multiple strategies. For example, SciToolAgent identifies potential risks by introducing an integrated “safety check module” to prevent harmful operations[56]. MAS effectively mitigates error accumulation in the chain of propagation of LLMs through iterative feedback and mutual validation among agents[16]. Furthermore, a core strategy is to ensure that AI-generated content is “firmly rooted in a comprehensive knowledge framework”[3], as SciAgents enforces that its reasoning is based on an ontological knowledge graph, significantly improving the accuracy and reasonableness of the generated hypotheses. It is worth noting that researchers are beginning to reconsider the role of “hallucinations,” exploring their potential as a source of novel ideas during hypothesis generation[88]. This suggests the possibility of designing a workflow in which AI freely generates ideas, which are then rigorously screened and validated by humans or other systems.

(2) Fundamental Limitations in Reasoning and Planning: While proficient at pattern recognition, current LLMs exhibit fundamental deficits in robust logical and causal reasoning. This is evidenced by persistent issues such as the “reversal curse”[89] and failures in non-trivial planning tasks[90]. In the context of scientific discovery, this limitation is critical. An agent might, for instance, correctly identify a correlation between a material’s feature and its performance but fail to reason about the underlying physical cause, leading to spurious or chemically implausible hypotheses. Consequently, for the foreseeable future, human supervision remains indispensable, not merely as a safeguard but as the primary source of rigorous logical validation and strategic oversight.

(3) Interpretability and Transparency: The “black-box” decision-making process of AI agents is a major obstacle to gaining the trust of human scientists. Efforts to address this challenge generally fall into two categories: “white-box analysis”, which involves studying the internal mechanisms of the model, and “black-box analysis”, which infers behavior from input-output relationships. A significant issue is the lack of a standardized explanatory framework to unify these approaches[14].

However, new agent architectures are actively addressing this challenge. RETRODFM-R is a prime example, transforming “black-box” predictions into transparent, “white-box” reasoning. Its detailed chemical logic not only enhances the credibility of the results but also provides valuable insights and inspiration to human chemists[13]. Additionally, researchers are exploring hybrid architectures - such as combining GNNs and LLMs - to enhance interpretability, while developing ‘explainability engines’ that clearly convey decision-making logic in natural language[17].

Practical application challenges

Practical application challenges focus on the practical difficulties encountered when deploying AI technology in real research environments:

(1) Gap in Physical World Interaction: Physical experiments are full of uncertainties. How to make agents understand and cope with the complexities of the real world, such as sensor noise and variations in reagent purity, is a huge gap[5]. Especially when dealing with legacy data, even with carefully designed processes, the success rate of extracting data from low-quality scanned documents from before 2000 may be less than 50%[19]. This indicates that AI agents must have strong robustness to cope with imperfect, noisy data sources in the real world.

(2) Constraints of Data and Computational Resources: Many advanced AI methods rely on large models that are secondarily pre-trained on massive domain literature, which requires huge computational resources[18]. In addition, high-quality, labeled downstream task data is also very limited. The work of LLM-Prop provides a solution: by using innovative representation methods (text instead of graphs) and efficient model utilization strategies (fine-tuning only the encoder), it is possible to achieve or even surpass the performance of existing SOTA (state-of-the-art) methods without relying on large-scale pre-training and huge model parameters, which is crucial for promoting the inclusive application of AI in materials science. In addition, existing chemical databases (such as USPTO, the United States Patent and Trademark Office database) generally suffer from data sparsity, incomplete annotation, and a bias towards “star reactions”, which limits the ability of the model to explore novel chemical spaces[17,91].

Ethical and societal challenges

Ethical and societal challenges involve the profound impact of AI technology on research practices, the academic community, and society at large.

(1) Ethics and Academic Integrity: The comprehensive survey by Chen et al. on AI4Research (AI for scientific research) specifically points out the ethical risks that AI may bring, such as data bias and intellectual property disputes. Their work even proposes the concept of a “plagiarism singularity”[92], where an overabundance of AI-generated content leads to a decline in originality, all of which require the establishment of corresponding ethical frameworks to avoid[14].

(2) “Dual-Use” Risk: AI agents could be used to design regulated or dangerous compounds. Therefore, it has become crucial to develop integrated “safety gates,” such as the ChemSafetyBench (Chemistry Safety Benchmark)[93] benchmark and frameworks such as Guardian-LLM[94], which are designed to audit synthesis pathways before execution to prevent potentially dangerous operations[17].

(3) Human-AI Relationship and Goal Alignment: A deeper issue is the extent to which the scientific community is willing to trust and empower AI to drive scientific discovery. This challenge is multifaceted and extends beyond simple acceptance of AI as a tool.

A primary barrier is the “black-box” nature of many AI models, which fosters skepticism. For AI to be a true partner, it must not only produce results but also offer transparent, interpretable, and verifiable reasoning. Without this, researchers cannot fully validate AI-generated hypotheses, making it difficult to build genuine trust. Furthermore, there is a significant risk of “automation bias,” a cognitive tendency where human researchers may uncritically accept AI’s suggestions, potentially stifling the critical thinking, creativity, and serendipity that are hallmarks of human-led discovery.

Another critical concern is goal misalignment. An AI agent, instructed to optimize a material for a single metric such as efficiency or stability, might propose solutions that are theoretically optimal but practically unfeasible, unsafe, or scientifically uninteresting. For example, it might suggest a synthesis pathway involving highly toxic or rare precursors, ignoring the broader scientific context of sustainability and cost. True alignment requires embedding complex, multi-objective human values into the AI’s reward function, which remains a formidable challenge. Finally, an over-reliance on AI-driven discovery could fundamentally alter the training of future scientists, potentially de-emphasizing the development of deep theoretical intuition and hands-on experimental skills. Therefore, navigating this new paradigm requires not just technological innovation, but also a profound discussion within the scientific community about how to foster a collaborative, rather than purely delegative, relationship with AI.

To strengthen the quantitative grounding of this review and address benchmarking gaps across the AI-driven materials discovery workflow, we summarize representative systems and their performance in Table 2. Following the structure suggested by recent evaluation protocols, Table 2 organizes tasks by pipeline stage, covering literature mining, design, simulation, optimization, and agentic reasoning. Each entry lists reported metrics, datasets, and representative baselines from peer-reviewed sources. The full extended version with additional systems, metrics, and references is provided in Supplementary Table 2 [Supplementary Materials] to ensure transparency and completeness. Where quantitative results were not available, we indicate Not Reported (N/R) to highlight areas that require standardized benchmarks in future studies.

Representative quantitative comparison of AI systems and baselines across the materials discovery pipeline

| Pipeline stage | Task | Representative AI system | Key metric(s) | Reported performance/outcome | Baseline(s) |

| Literature mining | Structured data extraction | LMExt[19] | Extraction accuracy (%) | 84.2 (modern)/43.8 (legacy PDFs) | Manual curation |

| Design & prediction | Band-gap prediction | LLM-Prop[18] | MAE (eV) | 0.23 | CGCNN (0.29); ALIGNN (0.25) |

| Simulation | Formation-energy prediction | ALIGNN/MEGNet[10,11] | MAE (eV/atom) | 0.026/0.028 | DFT ground truth |

| Optimization/automation | Closed-loop electrolyte optimization | Robson[16] | Cycle time (weeks); sample efficiency | Novel electrolytes in ≈ 4 weeks | BO; human DoE |

| Agentic systems | Hypothesis generation | SciAgents[3] | Long-horizon task success | Qualitative success reported | Single LLM prompt |

The data summarized in Table 2 provide a unified view of how modern LLM-based and agentic systems compare with established materials-informatics methods across the research pipeline. These benchmarks demonstrate measurable progress in efficiency and automation while revealing uneven maturity among stages. Collectively, they underscore the need for standardized datasets, reproducible evaluation protocols, and clearly defined baselines to enable consistent head-to-head assessment of future AI agents.

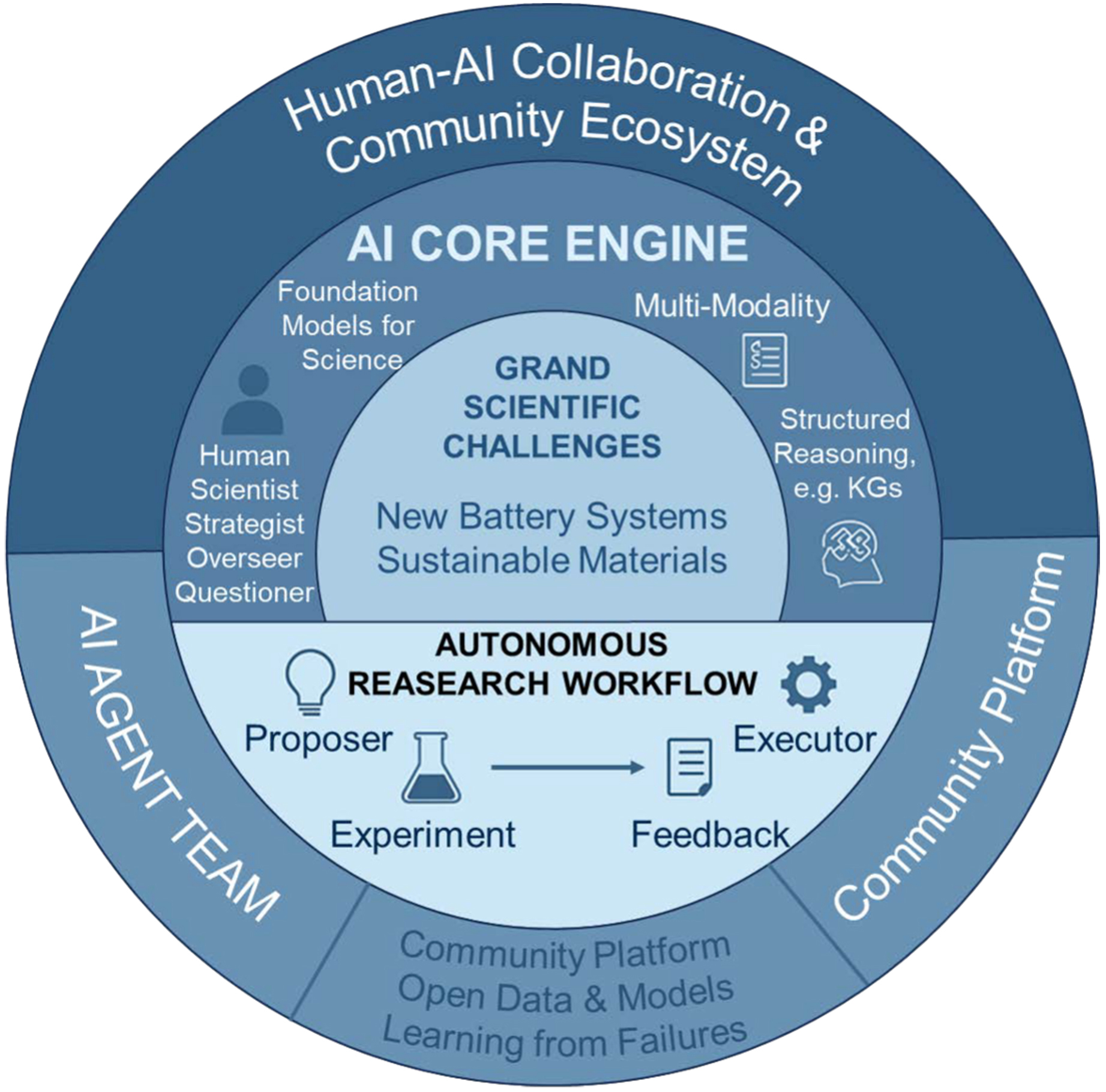

Future outlook: a new era of human-AI collaborative autonomous science

In the future, AI agents will be integrated into scientific research, leading to more human-AI collaboration and autonomous science. This will reshape the tools, the roles of researchers, and the scientific ecosystem.

New models of human-AI collaboration

The role of human scientists is set to evolve from direct execution to that of strategic planners and final decision-makers. Researchers will be responsible for defining grand scientific objectives and formulating creative, high-level concepts, while AI agents will serve as powerful execution tools, handling the heavy lifting of broad exploration and validation[41,95]. This approach is exemplified by the “Expert-Guided LLM Reasoning” methodology developed in the ChatBattery project, where AI-driven data exploration operates under expert supervision, producing a synergistic effect that substantially enhances discovery efficiency[1,39].

This evolution signifies that the future role of AI is not as a “replacement” but as an “augmenter” and “collaborator.” Ultimately, this partnership will mature to a point where AI agent systems become indispensable creative partners. The ultimate goal is to develop AI into a “creative engine” capable of discovering new scientific principles and posing novel, profound questions on its own[13]. By deeply integrating theory, experiment, and computation, these AI partners will subvert the traditional linear research model, revolutionizing the R&D cycle of energy materials and heralding a true fourth paradigm in scientific discovery[76,96].

Open and collaborative research ecosystems

Future research will be carried out by multiple highly specialized agents (synthesis agents, characterization agents, computational agents) collaborating to form an efficient, distributed “virtual research team”[14]. The multi-agent network constructed by Robson et al. for electrolyte discovery is an early prototype of this vision[16]. At the same time, it is crucial to build an open and democratic research ecosystem, including establishing open benchmarks, developing open-source AI models[17], and embracing failure to learn systematically: that is, using the powerful text processing capabilities of LLMs to systematically share, analyze, and learn from “negative results”, valuable information that is often underestimated and ignored in the current research culture[97-99].

Broader scientific and educational implications

AI agents will become powerful tools for promoting green chemistry and sustainable materials design. For example, the EcoSynth system[100], an automated planner for green chemistry synthesis, can encode green chemistry metrics into the optimization objectives of LLMs, thereby prioritizing solvents and schemes with less environmental impact when designing synthesis routes[17]. This has profound significance for developing environmentally friendly energy materials.

Beyond its impact on specific research domains such as green chemistry, this technological wave also places new demands on researchers. Future materials scientists will need not only solid domain knowledge but also new skills for efficient collaboration with AI. This includes: (1) the ability for precise questioning and prompt engineering to effectively guide the thinking direction of AI; (2) the ability for critical evaluation of AI-generated results to discern their reliability and innovation; and (3) the ability to design and manage human-AI collaborative workflows to maximize the efficiency of the entire research team. The role of researchers will gradually shift from being “producers of knowledge” to “orchestrators and validators of wisdom”.

To depict the future scientific landscape of human-machine collaboration, Figure 10 presents the vision of a new autonomous science paradigm.

Evaluation and reproducibility standards for agentic science

Reproducibility and standardized evaluation remain major challenges for AI agents in scientific discovery. To promote transparency and comparability, several community initiatives are establishing shared benchmarks and artifact standards. Representative examples are summarized in Supplementary Table 3 [Supplementary Materials], which compiles datasets and task types relevant to materials science, including literature-extraction corpora such as SciREX (scientific information extraction) and MatSciBERT, property-prediction datasets with in- and out-of-distribution (OOD) splits such as the Materials Project, JARVIS (Joint Automated Repository for Various Integrated Simulations), and AFLOW (Automatic-FLOW for materials discovery), as well as multi-tool planning and automation benchmarks such as ScienceAgentBench and DiscoveryBench.

Meanwhile, reproducibility can be improved through standardized agent checklists that specify prompt templates, tool registries and schemas, trace logging, error taxonomies, random seeds, and environment configurations. Making these components openly available, together with model outputs, agent trajectories, and safety controls, will facilitate independent validation of research outcomes and accelerate community-wide progress. Furthermore, encouraging the publication of benchmark scores, reproducibility metadata, and agent traces can help transform conceptual demonstrations into measurable and verifiable scientific contributions.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This study explores the evolution from LLMs to AI agents in energy materials research. While LLMs offer significant value for understanding science and supporting design, the key breakthrough lies in transforming them into autonomous research partners equipped with planning, tool use, and memory. This shift advances automation from routine execution toward genuinely collaborative science.

Two complementary paths are highlighted: architectural innovation (e.g., multi-agent systems) and cognitive innovation (e.g., domain-specific fine-tuning). The former enhances collective intelligence for complex challenges, while the latter strengthens domain knowledge and reasoning. Together, these advances show that AI agents can now manage complete workflows, from hypothesis generation to material realization.

Challenges related to reliable reasoning, trustworthiness, and alignment with human goals remain; however, emerging approaches - such as expert-guided collaboration and transparent reasoning frameworks - are steadily addressing these issues.

Ultimately, integrating specialized AI agents with human experts will establish collaborative networks that transform materials research. In this partnership, discovery will accelerate as AI not only executes complex tasks but also helps generate new scientific insights.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing: Yang, W.; Yao, T.

Data curation, methodology, software, validation: Yao, T.; Huang, J.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.

Investigation, formal analysis, visualization: Yang, Y.; Shao, X.

Resources, project administration: Gao, Z.

All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei (E2023502006) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (grant numbers 2025JC008 and 2025MS131).

Conflicts of interest

Yang, W. is an Associate Editor of the journal AI Agent. Yang, W. was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve language clarity and check grammar. After using this tool, the authors carefully reviewed and edited all materials as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Wang, W. Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, G.; et al. Artificial intelligence enabled smart design and manufacturing of advanced materials: the endless Frontier in AI+ era. Mater. Genome. Eng. Adv. 2024, 2, e56.

2. Dagdelen, J.; Dunn, A.; Lee, S.; et al. Structured information extraction from scientific text with large language models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1418.

3. Ghafarollahi, A.; Buehler, M. J. SciAgents: automating scientific discovery through bioinspired multi-agent intelligent graph reasoning. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2413523.

4. Chen, X.; Yi, H.; You, M.; et al. Enhancing diagnostic capability with multi-agents conversational large language models. NPJ. Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 159.

5. Sendek, A. D.; Ransom, B.; Cubuk, E. D.; Pellouchoud, L. A.; Nanda, J.; Reed, E. J. Machine learning modeling for accelerated battery materials design in the small data regime. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2022, 12, 2200553.

6. Chen, C.; Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2022, 2, 718-28.

7. Chen, C.; Ye, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ong, S. P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3564-72.

8. Choudhary, K.; Decost, B. Atomistic line graph neural network for improved materials property predictions. npj. Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 185.

9. Schütt, K.; Kindermans, P. J.; Sauceda, H. E.; Chmiela, S.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K. R. SchNet: a continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.08566. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.08566 (accessed 12 December 2025).

10. Xie, T.; Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301.

11. Kaba, S. O.; Ravanbakhsh, S. Equivariant networks for crystal structures. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.15420. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.15420 (accessed 12 December 2025).

12. Yan, K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Ji, S. Periodic Graph Transformers for Crystal Material Property Prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.11807. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.11807 (accessed 12 December 2025).

13. Zhang, Y.; Khan, S. A.; Mahmud, A.; et al. Exploring the role of large language models in the scientific method: from hypothesis to discovery. npj. Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 14.

14. Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; Qin, L.; et al. AI4Research: a survey of artificial intelligence for scientific research. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.01903. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.01903 (accessed 12 December 2025).

15. Yao, T.; Yang, Y.; Cai, J.; et al. From LLM to Agent: a large-language-model-driven machine learning framework for catalyst design of MgH2 dehydrogenation. J. Magnes. Alloys. 2025.

16. Robson, M. J.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Ciucci, F. Multi-agent-network-based idea generator for zinc-ion battery electrolyte discovery: a case study on zinc tetrafluoroborate hydrate-based deep eutectic electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2502649.

17. Lohana Tharwani, K. K.; Kumar, R.; Sumita; Ahmed, N.; Tang, Y. Large language models transform organic synthesis from reaction prediction to automation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.05427. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.05427 (accessed 12 December 2025).

18. Niyongabo Rubungo, A.; Arnold, C.; Rand, B. P.; Dieng, A. B. LLM-Prop: predicting the properties of crystalline materials using large language models. npj. Comput. Mater. 2025, 11, 186.

19. Liu, J.; Anderson, H.; Waxman, N. I.; Kovalev, V.; Fisher, B.; Li, E.; Guo, X. Thermodynamic prediction enabled by automatic dataset building and machine learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07293. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.07293 (accessed 12 December 2025).

20. Polak, M. P.; Morgan, D. Extracting accurate materials data from research papers with conversational language models and prompt engineering. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1569.

21. Ma, Y.; Gou, Z.; Hao, J.; Xu, R.; Wang, S.; Pan, L.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Sun, A.; Awadalla, H.; Chen, W. SciAgent: tool-augmented language models for scientific reasoning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.11451. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.11451 (accessed 12 December 2025).

22. Skarlinski, M. D.; Cox, S.; Laurent, J. M.; et al. Language agents achieve superhuman synthesis of scientific knowledge. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.13740. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.13740 (accessed 12 December 2025).

23. Zheng, M.; Feng, X.; Si, Q.; et al. Multimodal table understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.08100. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.08100 (accessed 12 December 2025).

24. Masry, A.; Long, D. X.; Tan, J. Q.; Joty, S.; Hoque, E. ChartQA: a benchmark for question answering about charts with visual and logical reasoning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.10244. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.10244 (accessed 12 December 2025).

25. Zhang, D.; Jia, X.; Hung, T. B.; et al. “DIVE” into hydrogen storage materials discovery with AI agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.13251. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.13251 (accessed 12 December 2025).

26. Yang, F.; Sato, R.; Cheng, E. J.; et al. Data-driven viewpoint for developing next-generation Mg-ion solid-state electrolytes. J. Electrochem. 2024, 30, 3.

27. Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. Unraveling the complexity of divalent hydride electrolytes in solid-state batteries via a data-driven framework with large language model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2025, 64, e202506573.

28. Beltagy, I.; Lo, K.; Cohan, A. SciBERT: a pretrained language model for scientific text. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.10676. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.10676 (accessed 12 December 2025).

29. Gupta, T.; Zaki, M.; Krishnan, N. M. A. Mausam. MatSciBERT: a materials domain language model for text mining and information extraction. npj. Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 102.

30. Huang, S.; Cole, J. M. BatteryBERT: a pretrained language model for battery database enhancement. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 6365-77.

31. Trewartha, A.; Walker, N.; Huo, H.; et al. Quantifying the advantage of domain-specific pre-training on named entity recognition tasks in materials science. Patterns 2022, 3, 100488.

32. Song, Y.; Miret, S.; Liu, B. MatSci-NLP: evaluating scientific language models on materials science language tasks using text-to-schema modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, Canada, July 9-14, 2023; Rogers, A.; Boyd-Graber, J.; Okazaki, N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; pp 3621-39.

33. Boiko, D. A.; MacKnight, R.; Kline, B.; Gomes, G. Autonomous chemical research with large language models. Nature 2023, 624, 570-8.

34. M Bran, A.; Cox, S.; Schilter, O.; Baldassari, C.; White, A. D.; Schwaller, P. Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 525-35.

35. Choi, J. Y.; Kim, D. E.; Kim, S. J.; Choi, H.; Yoo, T. K. Application of multimodal large language models for safety indicator calculation and contraindication prediction in laser vision correction. NPJ. Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 82.

36. Kang, Y.; Kim, J. ChatMOF: an autonomous AI system for predicting and generating metal-organic frameworks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.01423. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.01423 (accessed 12 December 2025).

37. Zheng, Z.; Rong, Z.; Rampal, N.; Borgs, C.; Chayes, J. T.; Yaghi, O. M. A GPT‐4 reticular chemist for guiding MOF discovery. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202311983.

38. Ruan, Y.; Lu, C.; Xu, N.; et al. An automatic end-to-end chemical synthesis development platform powered by large language models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10160.

39. Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Ai, Y.; Li, H.; Bengio, Y.; Guo, H. Expert-guided LLM reasoning for battery discovery: from AI-driven hypothesis to synthesis and characterization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16110. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.16110 (accessed 12 December 2025).

40. Wang, X. D.; Chen, Z. R.; Guo, P. J.; Gao, Z. F.; Mu, C.; Lu, Z. Y. Perovskite-R1: a domain-specialized LLM for intelligent discovery of precursor additives and experimental design. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.16307. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.16307 (accessed 12 December 2025).

41. Liu, X.; Sun, P.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Dong, P.; You, H.; et al. Perovskite-LLM: knowledge-enhanced large language models for perovskite solar cell research. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12669. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.12669 (accessed 12 December 2025).

42. Xie, T.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Creation of a structured solar cell material dataset and performance prediction using large language models. Patterns. 2024, 5, 100955.

43. Oikawa, Y.; Deffrennes, G.; Abe, T.; Tamura, R.; Tsuda, K. aLLoyM: a large language model for alloy phase diagram prediction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.22558. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.22558 (accessed 12 December 2025).

44. Zaki, M.; Jayadeva; Mausam; Anoop Krishnan, N. M. MaScQA: a question answering dataset for investigating materials science knowledge of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09115. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.09115 (accessed 12 December 2025).

45. Ansari, M.; Watchorn, J.; Brown, C. E.; Brown, J. S. dZiner: rational inverse design of materials with AI agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.03963. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.03963 (accessed 12 December 2025).