How geometry drives innovation in aortic valve repair

Abstract

Understanding the geometry and thus the possibility of repairing the aortic valve (AV) has evolved over time thanks to the integration of historical insights and technological advances. The aortic root geometry has proven to be central to understanding valve function. Today, with modern finite element models and flow studies supported by

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In Latin, the ability to abstract from observation and perceive the unapparent connection between phenomena was defined as “Intus legere”, meaning “to see inside”, which is the root of the word “intelligence”. Thus, the idea that understanding a shape (and its intrinsically connected function) provides an opportunity to manipulate and enhance a device, whether natural or artificial, has a long history. However, heart surgery is a very young branch of medicine, and the application of this paradigm to the reconstructive surgery of the aortic valve (AV) is an even younger, yet fascinating, topic. In this chapter, we will attempt to walk through the milestones that led to the development of the relationship between geometry and function in the repair of an incompetent AV.

Overview

The surgical community has historically pursued AV competence through two main strategies: direct leaflet repair or aortic root reconstruction. AV repair (AVR) seeks to restore normal morphology and function by symmetrically repositioning the leaflets to align their free margins at a uniform level. Conversely, aortic root correction aims to restore valve form and function by normalizing root dimensions - a concept advanced through the procedures of Sarsam and Yacoub[1] and David and Feindel[2]. While Sarsam and Yacoub[1] relied on intraoperative visual assessment of geometry, David and Feindel introduced graft sizing to define fixed dimensional boundaries for valve function, though leaflet configuration remained evaluated by inspection alone[2].

Despite improvements in surgical management, these procedures still resulted in a considerable rate of late valve failure. Analysis of failed repairs led to the introduction of the “effective height” (eH), an anatomical-functional parameter[3]. Subsequent studies on normal anatomy and its variations established reference cusp dimensions, integrating geometric principles into AVR. The Brussels school introduced coaptation height (cH), another anatomical-functional parameter, and validated its predictive value for valve competence through large cohort analyses[4]. More recently, four-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging (4D MRI) has enabled investigation of root geometry in relation to flow dynamics[5]. Although individualized flow modeling remains under development, ongoing advances in computational and artificial intelligence (AI) methods may soon refine repair standards further.

HISTORICAL OBSERVATIONS

Geometry as a tool

As in many scientific fields, Renaissance humanism advanced anatomical understanding. Leonardo da Vinci’s descriptions of the AV and orifice remain strikingly accurate and relevant today[6]. He observed that no human invention, however ingenious, can surpass nature’s designs, which are inherently complete, efficient, and purposeful.

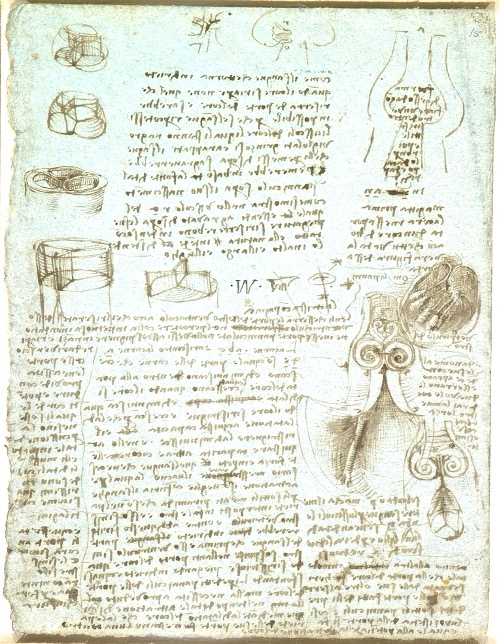

Leonardo’s observations led to early hypotheses on the physiology of aortic leaflet coaptation and margin length. He recognized that flow turbulence facilitated valve closure and validated these concepts through experiments based on empirical observation and rational analysis, anticipating the modern principle of experimental reproducibility centuries before Galileo. For example, Leonardo injected molten wax into an ox heart to model the aortic root and reconstructed it in glass, through which he pumped water mixed with grass seeds. Observing vortical flow within the sinuses, he concluded that these vortices facilitated AV closure following each heartbeat [Figure 1].

Figure 1. Leonardo’s depiction of the aortic valve and root, highlighting flow vortices in the sinuses of Valsalva and the geometric precision of the root. c.1512-13. Reproduced with permission of the Royal Collection Trust[6].

Leonardo questioned the triangular shape of the aortic orifice, reasoning that obtuse angles confer greater strength than right angles. He further noted that three cusps are structurally superior to four, as their central angles lie closer to the base, concluding that the triangular orifice offers greater load resistance through shorter geometric spans [Figure 2]. After Leonardo’s death, his anatomical drawings remained undiscovered for a century, limiting their contemporary influence. The inability to study the living heart for centuries thereafter caused his insights to be largely forgotten until modern times.

Figure 2. Royal Library, Windsor 19117v. Leonardo’s study of a tricuspid valve within a circular orifice, shown open and closed. Reproduced with permission of the Royal Collection Trust[6].

EARLY SURGICAL APPLICATIONS

Defining key anatomical parameters

The “Geometry Era” of AVR began with the establishment of an assessment framework based on eH, cH, and geometric height (gH). Subsequent classification of bicuspid AV (BAV) phenotypes enabled tailored repair strategies, driven by the parallel contributions of the Homburg and Brussels schools toward standardization.

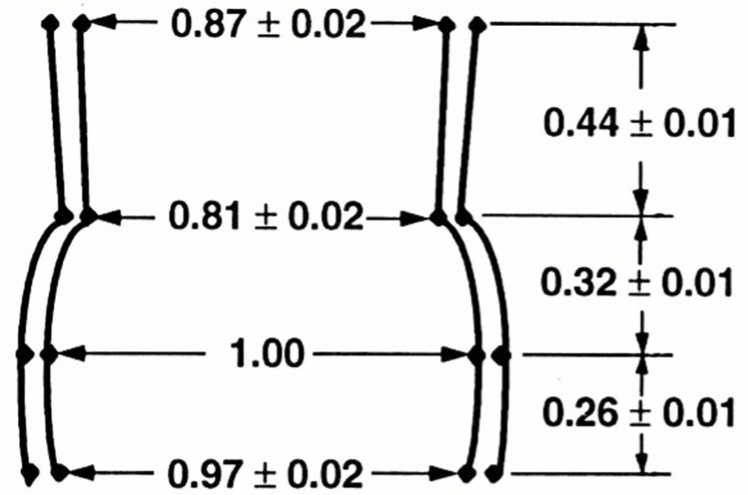

From the 1970s onward, studies by Thubrikar et al.[7] advanced understanding of aortic root geometry and its correlation with valvular disease, particularly stenosis. Their canine studies demonstrated that the AV is a dynamic structure, with geometric parameters varying throughout the cardiac cycle in response to aortic and ventricular pressures and geometry. While early studies established the link between valve geometry and function, Kunzelman et al., in the early 1990s, advanced the field by defining the AV-root complex in relative rather than absolute terms. Using the mid-root (sinus of Valsalva) diameter as a reference, they expressed all other dimensions proportionally, enabling more refined geometric analysis [Figure 3][8].

Figure 3. Shape of Valsalva sinuses with arbitrary size. Values are unitless. Reproduced from Ref.[8] with permission from Mosby, Inc. © 1994.

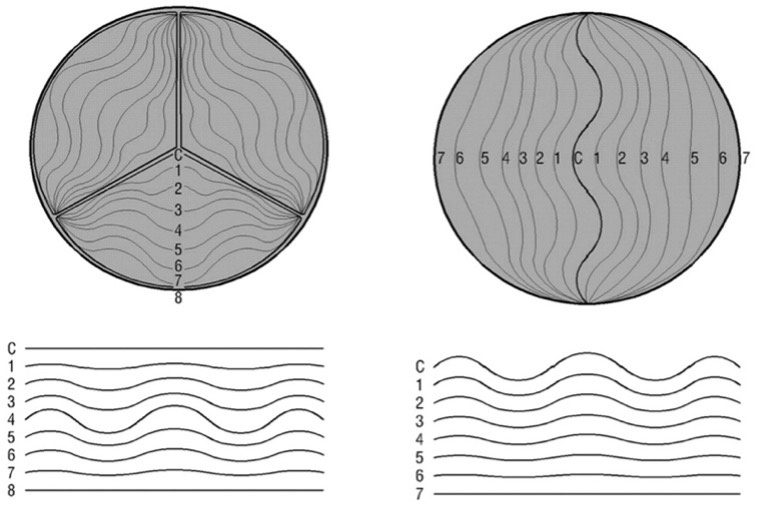

A decade later, Robicsek et al. advanced from two-dimensional (2D) long-axis models to a three-dimensional (3D) representation, emphasizing geometric differences between tricuspid AVs (TAVs) and BAVs[9,10]. They demonstrated how the 3D geometry of the leaflets and root governs valve dynamics, and how congenital BAVs employ distinct geometric adaptations to mimic TAV function[10]:

• Functional flexibility of the margins: The leaflets fold to aid valve motion, though excessive or incomplete folding may persist throughout the cardiac cycle [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Comparison of TAV (left) and BAV (right) dynamics: differing degrees of opening and closure necessitate distinct leaflet folding patterns; when closed, TAV free edges linearize, unlike those of the BAV. Abbreviations: BAV: Bicuspid aortic valve; TAV: tricuspid aortic valve. Reproduced from Ref.[10] with permission from The Society of Thoracic Surgeons © 2003, published by Elsevier Inc.

• Limited valve opening: In BAVs, incomplete opening relative to the annular area produces a morphologically narrowed orifice. Although this lessens the need for leaflet folding, excessive folds can induce high stresses and tissue damage [Figure 4].

• Increased leaflet bulging (“belly cambering”): Enhances coaptation by expanding the contact area through upward convex curvature.

• Asymmetric coaptation line: Leaflets meet laterally rather than centrally, resembling a unicuspid configuration; effective closure requires folding or upward bulging.

• Elliptical orifice: The oval BAV shape facilitates coaptation of unequal leaflets, improving functional competence.

• Commissural “pull-and-release” mechanism: In TAVs, progressive aortic expansion maintains leaflet tension and flatness throughout opening - a dynamic behavior first described by Thubrikar et al. in canine models[11,12] and later elaborated by El-Nashar et al.[13] and other researchers.

Robicsek et al., along with other early 20th-century researchers, highlighted the role of AV and root histology in normal and pathological states, linking abnormal geometry in BAV and connective tissue disorders to corresponding histological and functional changes[9].

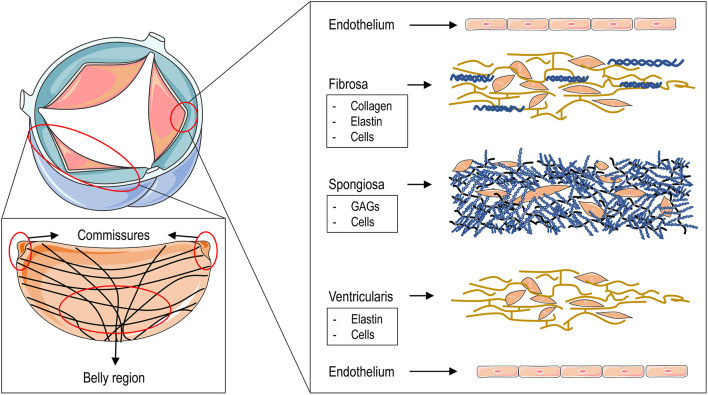

Histologically, valve leaflets consist of a central fibrous core flanked by fibroelastic layers beneath the endothelium - an arterial layer facing the aorta and a ventricular layer facing the ventricle. The fibrous core includes a spongiosa layer on the ventricular side, characterized by a loose proteoglycan-rich matrix, abundant elastin, and loosely organized collagen fibers[14,15]. Near the free margin and lunula, subendothelial thickness increases, particularly at the node of Arantius, which contains an elastic core. Elastin facilitates the recoil of collagen to its original configuration[16]. The fibrous layer continues into the aortic wall along the hinge lines, where localized thickening forms semilunar ridges that elevate as the leaflets open [Figure 5].

Figure 5. Aortic valve structure and leaflet layers. The red area illustrates the circumferential arrangement of collagen fibers within an aortic leaflet, with crossovers emerging centrally from the commissures. The microstructure of the three layers - fibrous, spongiosa, and ventricular - extends from the aortic to the ventricular surface, each characterized by distinct cellular and extracellular components. Both surfaces are lined by valvular endothelial cells adherent to the basement membrane. Reproduced from Ref.[14] with permission from Rizzi, Ragazzini and Pesce © 2022. GAGs: Glycosaminoglycans.

The walls of the sinuses of Valsalva are predominantly fibrous, with elastic fiber density increasing toward the tubular aorta, where they merge seamlessly with the elastic tissue and smooth muscle of the media.

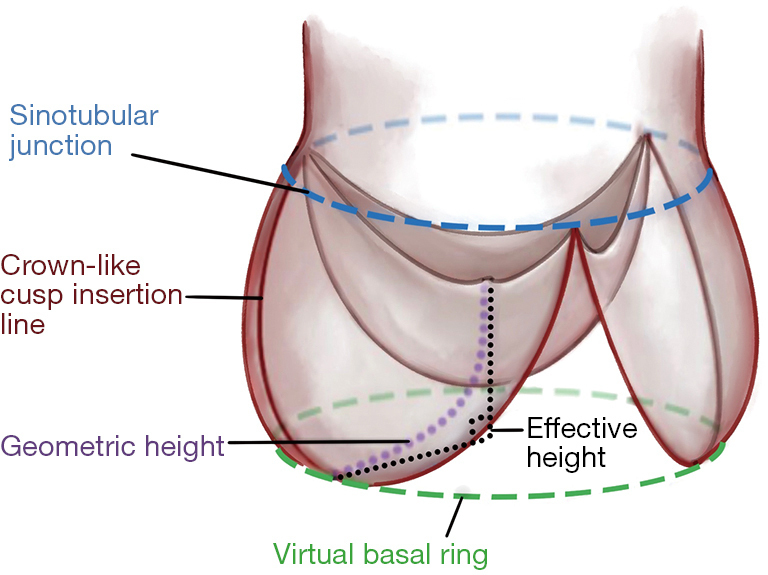

Macroscopically, the sinuses and tubular aorta are delineated by the sinotubular junction (STJ), a thickened ridge following a cloverleaf contour. Owing to sinus height asymmetry - highest on the right and lowest on the left - the sinotubular plane is inclined by approximately 11° relative to the sinus base[17,18]. The aortic annulus is not a discrete anatomical structure but a virtual plane connecting the basal attachment points of the leaflets, lacking a fibrous ring separating ventricle and aortic wall. The only true histological landmark is the ventriculoarterial junction, which does not coincide with the leaflet origin.

In essence, the AV consists of three cusps anchored to the aortic wall by crown-shaped fibrous rings that define the sinuses of Valsalva and the intervalvular trigones. The commissures form the vertices of these rings and mark the boundary with the STJ [Figure 6][3,19,20].

Figure 6. Proposed nomenclature for the aortic root components. Reproduced from Ref.[20] from open access.

The search for surgical parameters useful in clinical practice soon led to the description of new entities and their respective geometric properties, ranges, and relationships.

In the early 2000s, Bierbach et al. introduced eH and gH as fundamental parameters for assessing and guiding AVR[3]: eH is defined as the distance between the central cusp free edge and the ventriculoarterial junction, whereas gH represents the distance from the nadir to the cusp center, quantifying total cusp tissue. Pre- and postoperative analyses, along with studies in healthy subjects, showed a strong correlation between eH and body size parameters (body surface area, weight, height), as well as annular, sinus, and sinotubular diameters - particularly an almost linear relationship with sinus dimensions. Bierbach et al. concluded that aortic root geometry follows consistent proportional patterns across body sizes, and that restoring normal eH is closely associated with optimal AV function after repair[3].

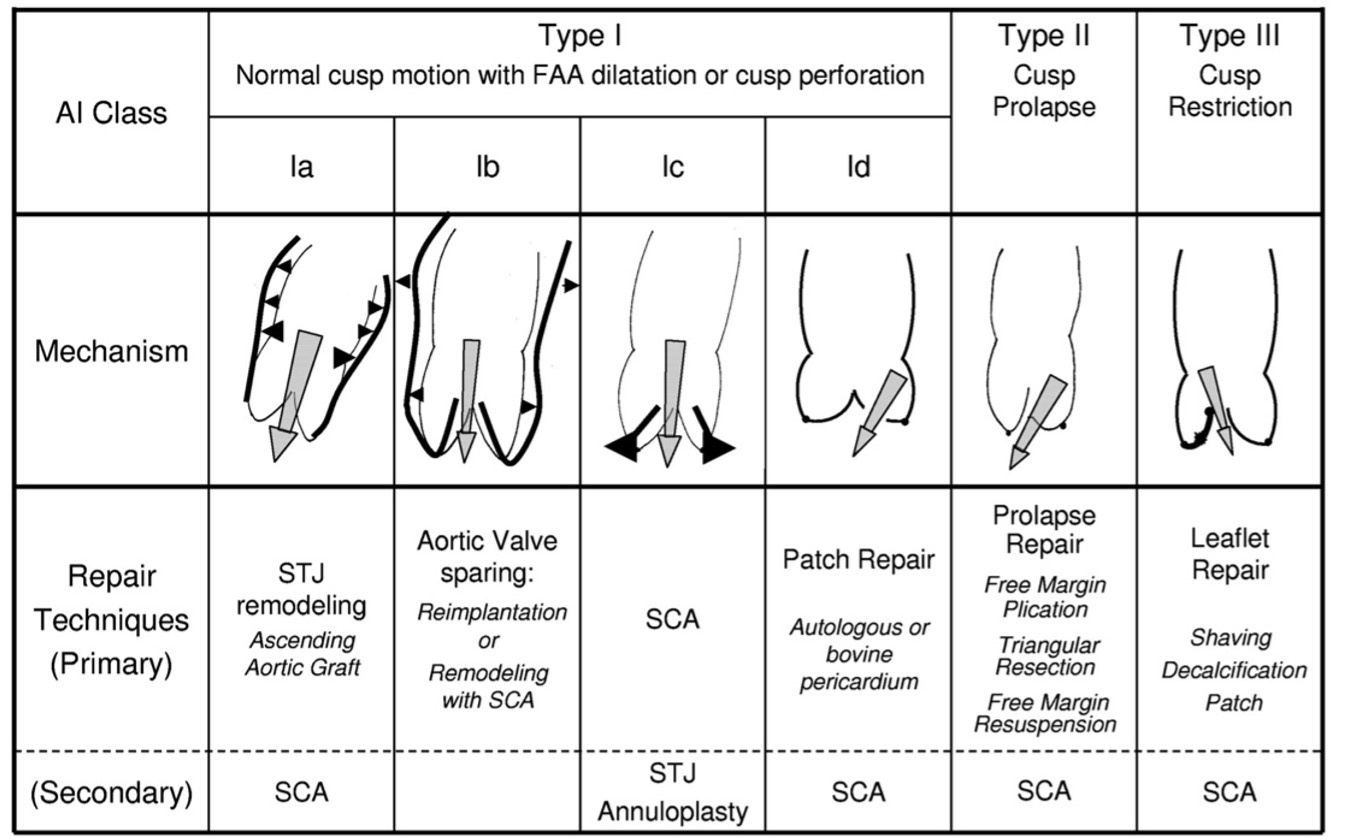

Bierbach et al.[3] demonstrated that aortic root geometry maintains consistent proportionality across body sizes and that restoring normal eH correlates with optimal postoperative valve function. The Brussels school, led by El Khoury, was the first to integrate this parameter clinically, termed the “distance from the tips to the annulus”. Building on Carpentier’s mitral framework, Boodhwani and El Khoury developed a classification of aortic insufficiency linking anatomical lesions to corresponding repair strategies[21]. This classification, summarized below, provides a foundational framework for advancing AVR [Figure 7].

Figure 7. Classification of pathological mechanisms underlying aortic insufficiency and corresponding repair techniques[21]. Type 1 indicates normal cusp motion, Type 2 excessive motion, and Type 3 restricted motion, as seen in rheumatic or bicuspid valves. Reproduced from Ref.[21] with permission. AI: Aortic insufficiency; FAA: functional aortic annulus; SCA: subcommissural annuloplasty; STJ: sinotubular junction.

DEVELOPMENT OF MEASURABLE PARAMETERS

The advent of caliper and effective height

The introduction of an intraoperative caliper for assessing post-repair dimensions marked the shift from subjective reconstruction to geometry-based valve repair. Holubec et al. systematically developed, validated, and disseminated this tool, establishing a new standard in AV surgery[4].

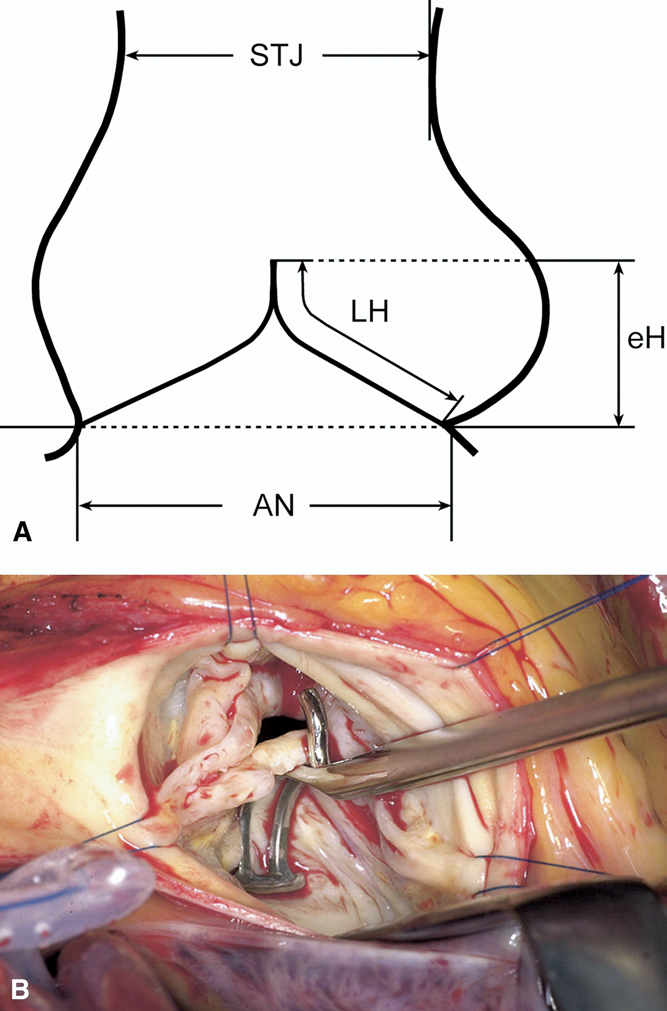

As noted, eH represents the vertical distance between the central free margin and the aortic insertion line. Intraoperatively, it is measured with a caliper, positioning the longer limb at the cusp nadir and the shorter curved limb along the free margin to ensure tangential contact [Figure 8]. While sinus dimensions can be reliably measured preoperatively by echocardiography, accurate assessment of cusp geometry remains difficult, and intraoperative measurements of cusp height, insertion length, or free margin are technically demanding. These interdependent parameters have limited individual diagnostic value. Cusp prolapse may occur as an isolated lesion - usually of a single cusp in BAV or TAV - or in association with root dilatation or sinotubular reduction. Diagnosis becomes challenging when multiple cusps are affected, as reference points are distorted. This is critical in generalized prolapse, native or postoperative, where valves with initially satisfactory competence may fail within a few years[22,23]. Schäfers et al. observed that valves with lower preoperative eH were more prone to progressive regurgitation and eventual reoperation[24]. In aortic regurgitation, eH typically measures around 4 mm, reaching 0 mm in severe cases, whereas postoperative restoration to ≥ 8 mm is consistently associated with stable valve geometry and ≤ grade I regurgitation. Kunihara et al. therefore integrated intraoperative eH measurement into valve-sparing repair as an objective means to quantify cusp prolapse and evaluate surgical outcomes[25].

Figure 8. (A) Schematic representation of effective height (eH) measurement using an aortic caliper, defined as the vertical distance between the central free margin and the aortic insertion line[24]; (B) Intraoperative assessment of eH with a caliper, positioned with the longer limb at the nadir of cusp insertion[24]. AN: Aortic anulus; eH: effective height; STJ: sinotubular junction; LH: leaflet height. Reproduced from Ref.[24] with permission.

The computer simulation additions

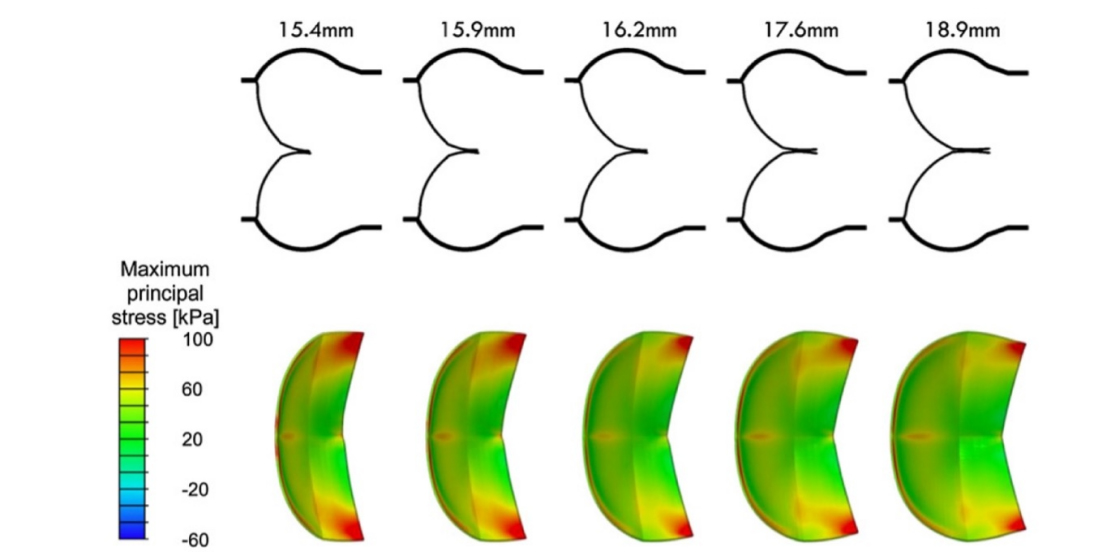

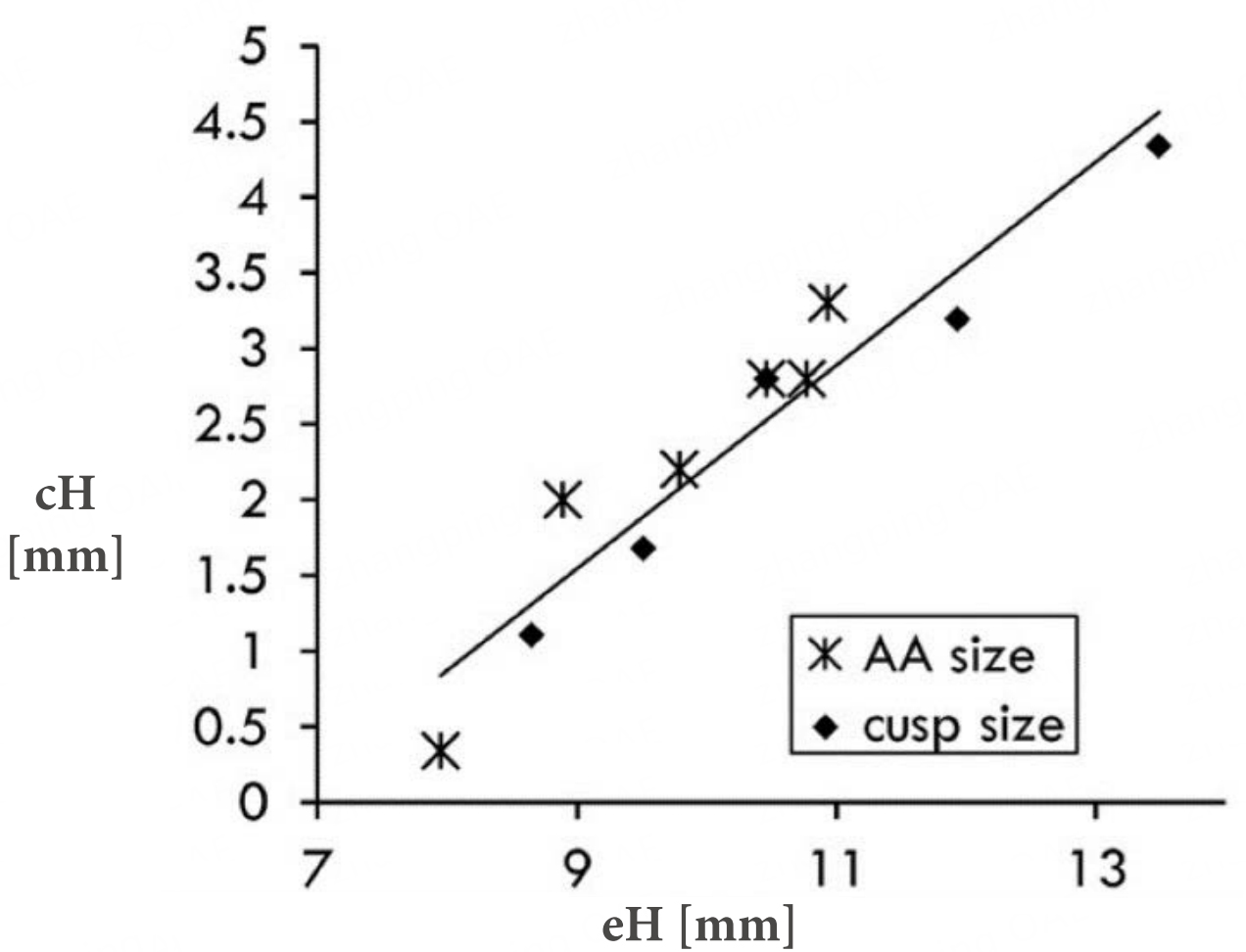

Advances in computing enabled in silico simulations to investigate how root dimensions affect cusp geometry. Over the past decade, these models have refined our understanding of the interdependence between anatomical and functional components of the aortic root-valve complex. The quantification of cH and its prognostic relevance for valve repair feasibility was later formalized through surgeon-engineer collaboration. Finite element simulations demonstrated that greater cH provides a safety margin against regurgitation and reduces cusp mechanical stress[26] [Figures 9 and 10].

Figure 10. Relationship between average coaptation height and effective height, demonstrating a direct positive correlation: higher eH values correspond to increased cH. AA: Aortic anulus; eH: effective height; cH: coaptation height. Reproduced from Ref.[26] with permission.

In this study by Marom et al., mean cH increased proportionally with gH, reflecting effective cusp size. An almost linear correlation between cH and eH was observed; when eH ≤ 9 mm, diastolic regurgitation occurred with a wider stress distribution [Figure 10]. As noted by Marom et al., valves with low eH are associated with reduced durability; thus, increasing eH during repair enhances cusp coaptation and overall valve performance[26].

COMPUTATIONAL/ENGINEERING INSIGHTS

In the early 2000s, the shift from 2D to 3D computational modeling of the aortic root enabled detailed correlation of geometry with hemodynamic forces and wall stress. Grande-Allen et al. were among the first to document the role of mechanical stresses in valve closure and root dynamics[27].

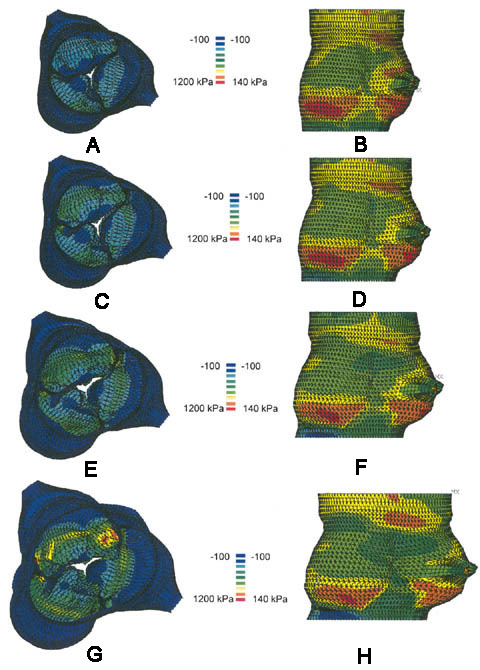

Grande-Allen et al. employed finite element modeling to simulate the aortic root in Marfan syndrome across four degrees of dilation. Progressive dilation increased wall stress and leaflet deformation, particularly along the anterior and central regions, reducing leaflet coaptation by 8% at 30% dilation and 17% at 50%. Thus, greater dilation heightens leaflet stress, impairs closure, and promotes central orifice persistence[27] [Figure 11].

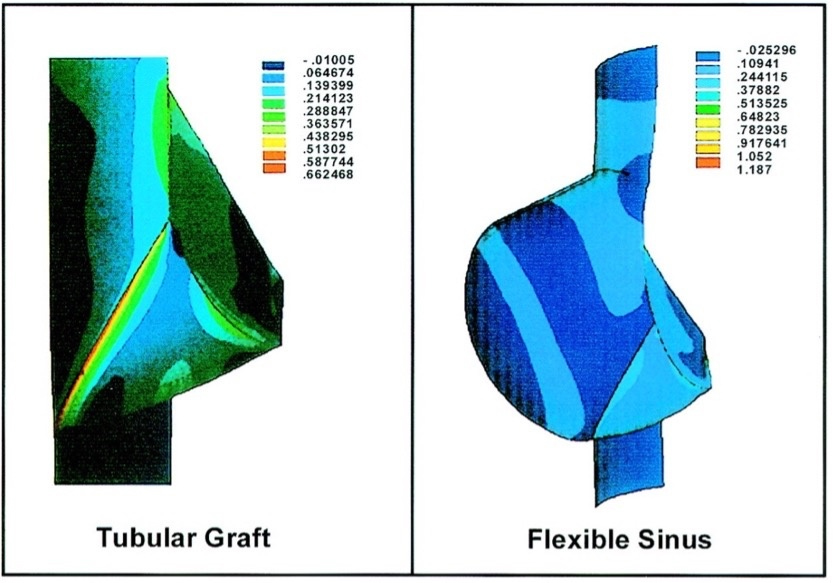

Analysis of wall stress at the sinus level led to the concept of the sinus-cusp functional unit and prompted investigation into the consequences of absent Valsalva sinuses in straight graft root replacements. Robicsek et al. demonstrated that in tricuspid roots, loss of sinus elasticity markedly increases aortic wall stress

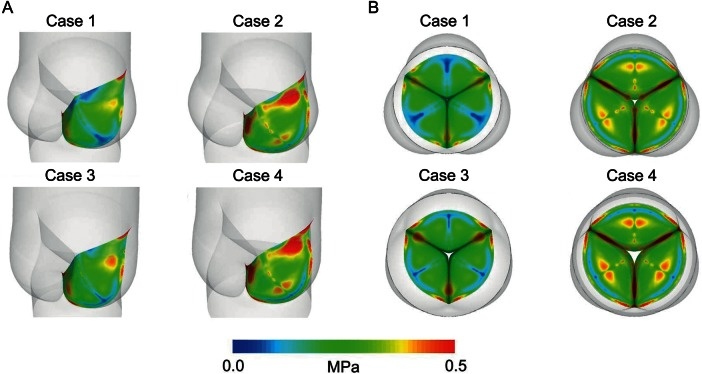

Advances in computational modeling have enabled simulation of complex aortic root–leaflet interactions. By selectively altering components (annulus, STJ, or root dimensions), it is now possible to predict effects on leaflet stress and valve function. Weltert et al. (Italy), in collaboration with Tor Vergata University Hospital and Polytechnic engineers, investigated virtual annular and sinotubular “rings” to assess leaflet durability and stress distribution[28]. They analyzed four aortic root configurations - normal, annular dilation, STJ dilation, and combined dilation - using Computer-Aided Design (CAD) modeling and finite element analysis

Figure 13. Projected deformed leaflet configurations for the four aortic root models. The normalized cusp coaptation area (NCCA) - defined as the coaptation area relative to total leaflet area - measured 30.6% in the healthy model and 13.3%, 28.2%, and 13.5% in Cases 2-4, respectively. Optimal coaptation occurred in the healthy root. Loss of the sinotubular junction had minimal impact, whereas annular dilation, alone or combined with STJ loss, markedly reduced coaptation and accentuated the leaflet belly region. (A) Top view; (B) Top view. Reproduced from Ref.[28] with permission. STJ: Sinotubular junction.

Annular dilation emerged as the principal determinant of increased leaflet stress (up to +70%), while isolated STJ dilation produced a modest rise (+15%) and minimal additional effect when coexisting with annular dilation[28].

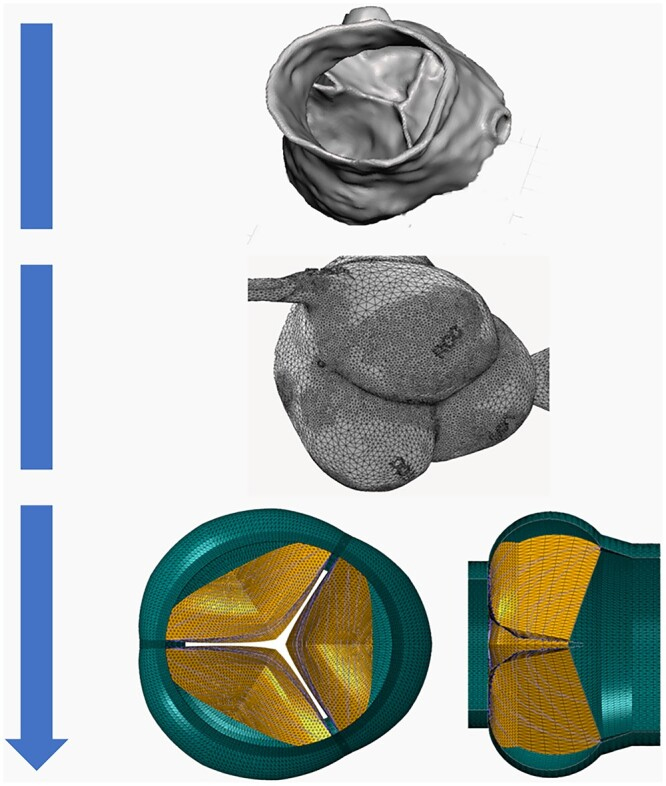

Clinically, AVR was advancing without a standardized geometric framework to ensure reproducibility. The introduction of gH as a reference parameter addressed this gap. Marom et al. (Hamburg and Rome groups) developed a computational TAV model maintaining constant gH while varying annular and STJ diameters, simulating 125 virtual anatomies [Figure 14]. Optimal surgical results were achieved when the STJ exceeded the annulus by 2-4 mm, yielding greater eH, normal cH, reduced stress, and no stenosis, even with a small annulus[29].

Figure 14. Schematic representation of finite element model generation for the aortic root and valve, from computed tomography reconstruction to geometric meshing. Reproduced from Ref.[29] with permission.

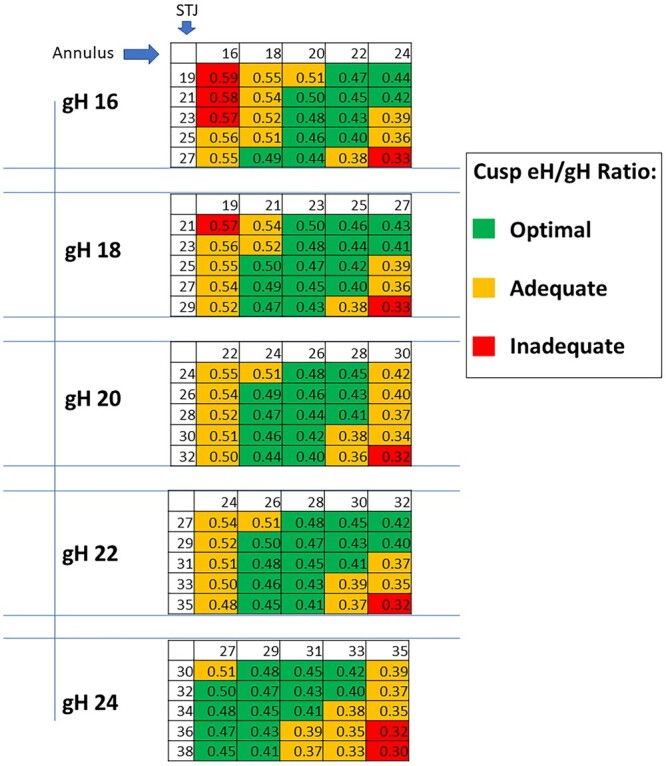

In TAV, gH enables prediction of ideal post-repair annular and STJ dimensions to achieve optimal valve configuration and reduced cusp stress. To standardize this approach, the Repair Aortic Index (RAI), defined as the ratio of eH to gH, was introduced as a size-independent metric [Figure 15]. Marom et al. established threshold values for eH, gH, cusp stress, and RAI, classifying repairs as optimal (RAI > 0.4), suboptimal (0.35-0.4), or inadequate (< 0.35)[29]. Practical intraoperative spreadsheets were developed to guide annulus and STJ sizing relative to gH, complemented by caliper-based post-repair assessment to correct asymmetry. This structured, geometry-driven method provides a predictive framework for successful TAV repair. Building on these principles, Jahanyar et al. emphasized the necessity of detailed anatomical understanding - particularly of bicuspid valve variants - for effective valve-sparing surgery[30].

Figure 15. Expected eH-to-gH ratios (Repair Aortic Index, RAI) for each combination of annular and STJ dimensions at a given gH. eH: Effective height; gH: geometric height; STJ: sinotubular junction. Reproduced from Ref.[29] with permission.

The role of Valsalva sinuses: clinical translation and current practice

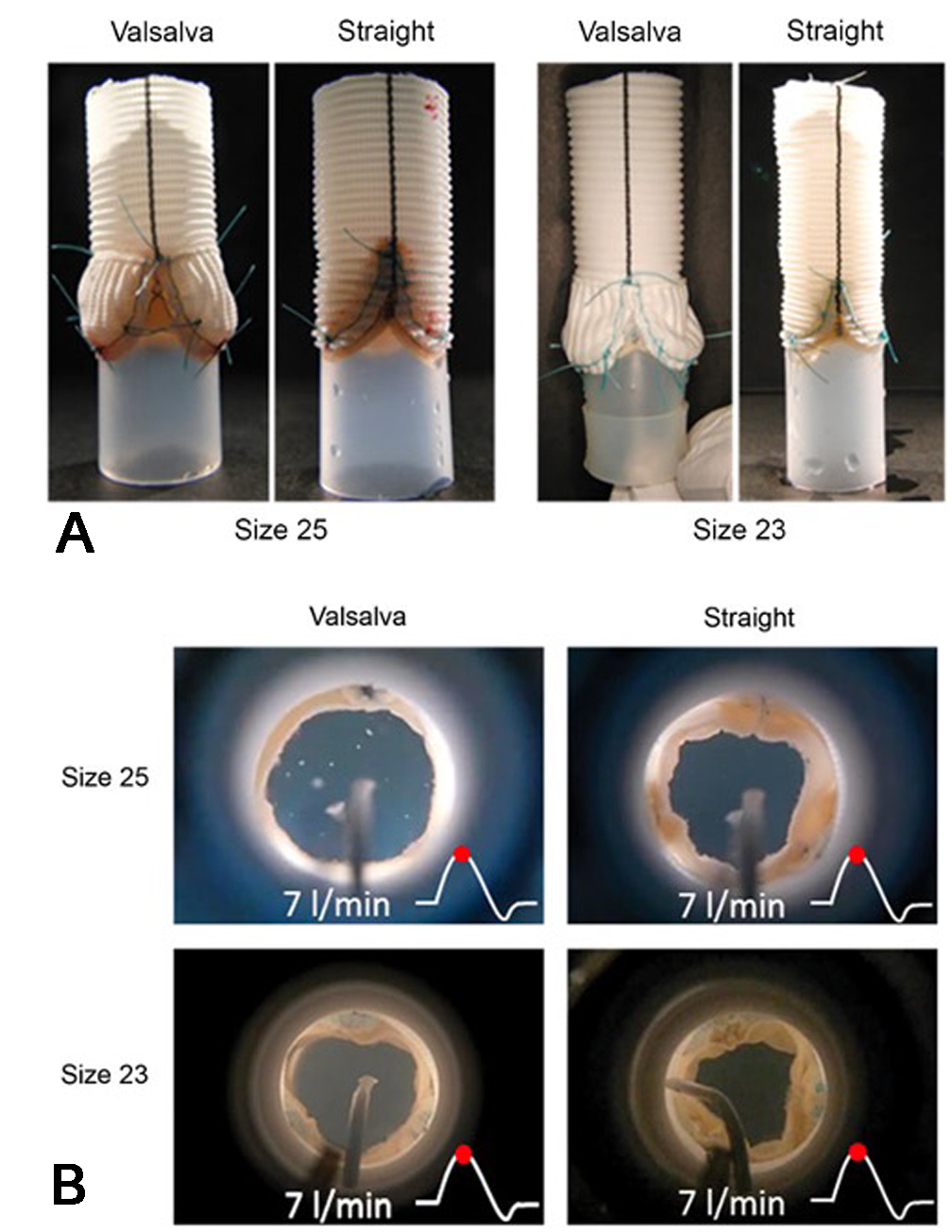

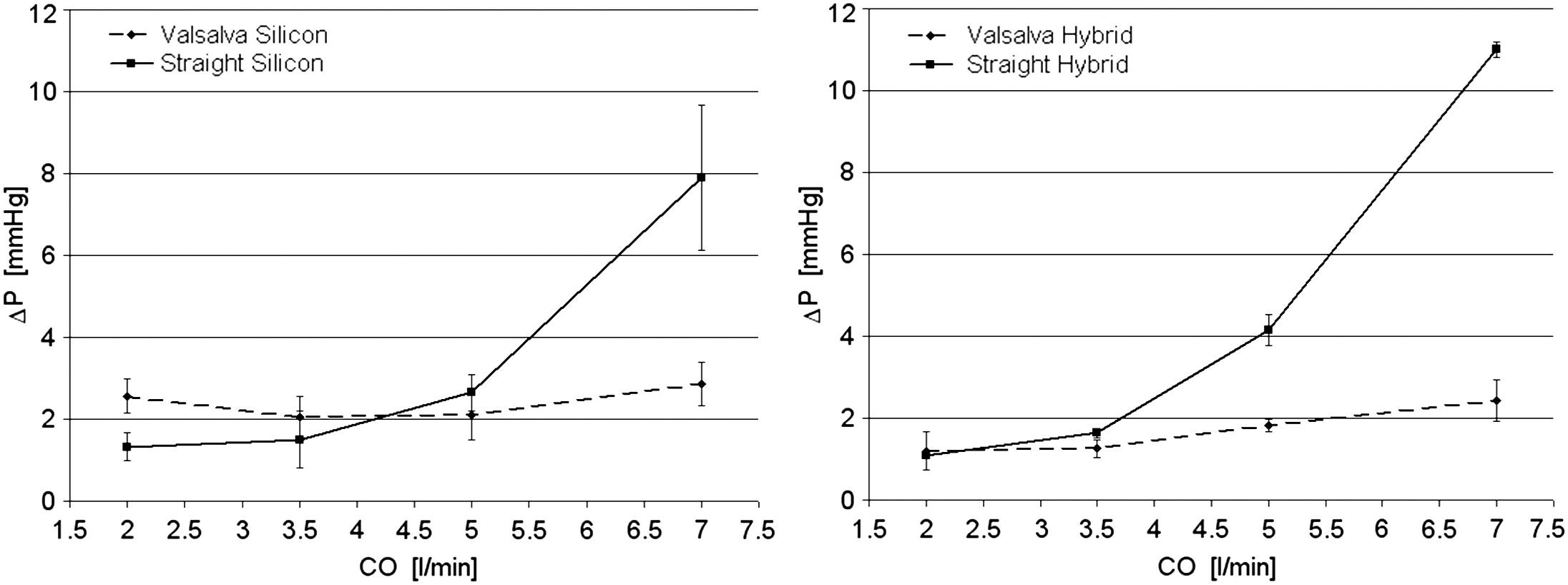

The role of the sinuses of Valsalva in AV dynamics -recognized since Leonardo da Vinci and later by Bellhouse -was conclusively elucidated through active flow studies, initially using pulse replicator systems and later in vivo 4D MRI. Early flow experiments with artificial roots demonstrated marked functional differences between cylindrical and sinus-containing models [Figure 16A], confirming the hemodynamic relevance of the sinuses. These insights led to the development and widespread adoption of sinus-containing prostheses, particularly the Valsalva Graft introduced by De Paulis in the early 2000s. An Italian group investigated the hemodynamic role of the sinuses of Valsalva[31,32], demonstrating that their presence reduces intra-aortic pressure during systole by increasing the effective orifice area (EOA), thus minimizing flow obstruction at high cardiac output[31] [Figures 16B and 17]. During diastole, sinus expansion and vortex redirection facilitate leaflet bulging and valve closure, consistent with prior findings[7,12].

Figure 16. (A) Experimental aortic root configurations for valve sizes 25 and 23; (B) Visualization of valve function at peak systole within the two root models (sizes 25 and 23) under pulsatile flow at 7 L/min. Reproduced from Ref.[31] with permission.

Figure 17. Pressure gradients across the valve in Valsalva and straight silicone models (left) and in Valsalva-hybrid and straight-hybrid configurations (right)[32]. Increasing cardiac output (CO) from 5 L/min to 7 L/min produced higher pressure drops only in roots lacking sinuses. Reproduced from Ref.[32] with permission.

Advances in computational technologies have enabled detailed investigation of the geometry of the sinuses of Valsalva and the AV through computational fluid dynamics and fluid-structure interaction (FSI) analyses. Early 2D models, based on angiographic[33] and echocardiographic data[34], were followed by several 3D reconstructions from 2003 onward[35], refining Thubrikar’s original cusp geometry. A key advancement was the 3D finite element model by Soncini et al.[34], integrating Thubrikar-derived cusp equations with root geometry extrapolated from limited 2D measurements.

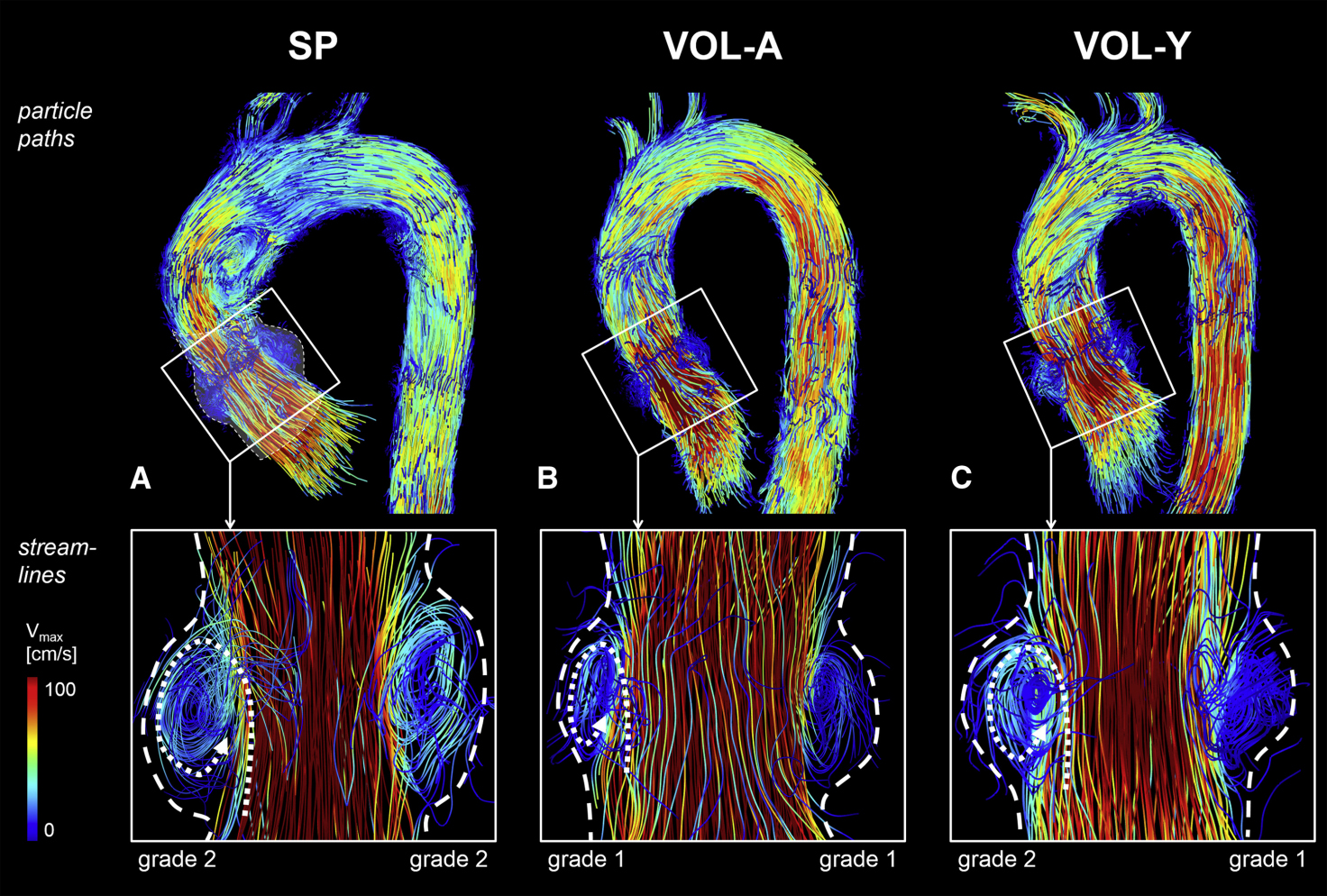

The study of aortic flow regained prominence with the advent of 4D cardiac MRI, which enables temporal tracking of blood flow particles in four dimensions. This technology allows direct visualization of helicity, vortices, and eddy currents generated by the sinuses of Valsalva, confirming their multifaceted hemodynamic role within the aortic root. These flow patterns may influence valve function and repair long-term durability, as demonstrated by Oechtering, who compared sinus flow in healthy subjects, patients with Valsalva grafts, and those with straight grafts [Figure 18]. Oechtering et al. demonstrated that sinus prostheses effectively replicate the physiological flow patterns of native sinuses of Valsalva, thereby supporting more natural valve function and mitigating the long-term deterioration observed with straight grafts[5].

Figure 18. Sinus vortices visualized by 4D flow MRI. Top row: particle pathlines at peak systole in a 60-year-old patient with a sinus prosthesis (SP, A), a 53-year-old age-matched volunteer (VOL-A, B), and a 30-year-old young volunteer (VOL-Y, C). Bottom row: instantaneous streamlines showing right and left coronary sinus vortices, forming behind the open cusps during systole and persisting into early diastole. Vortex configuration in patients closely resembled that of healthy volunteers. Dashed lines indicate sinus borders, and dotted lines indicate vortex direction.. SP: Sinus prosthesis; VOL-A: age-matched volunteer; VOL-Y: young volunteer; Vmax: peak velocity. Reproduced from Ref.[5] with permission.

This observation prompted further investigations into the hemodynamic impact of bicuspid valves on aortic arch flow, notably the study by Chandra et al.[36]. Using FSI with the arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian method, Chandra et al. analyzed TAV and BAV models with 10% and 16% asymmetry, evaluating valve function and cusp wall shear stress[36]. Shear stress was consistently higher and more pulsatile on the ventricular surface and lower with oscillatory patterns on the fibrous side. Marked differences in stress magnitude and pulsatility were observed between TAV and BAV cusps, supporting a mechanical contribution of abnormal shear stress to calcific AV disease in BAV. Recent studies in cardiac fluid dynamics, such as those by Kaiser et al.[37], have demonstrated that AV morphology - particularly bicuspid configuration - significantly influences hemodynamics. Distinct BAV phenotypes produce localized flow disturbances and shear stress within the ascending aorta, accounting for the asymmetric pattern of aortic dilation and supporting a predominantly mechanical etiology for aneurysm formation.

While Chandra et al.[36] and Kaiser et al.[37] investigated stenosis and aneurysm, respectively, Guo et al. expanded this research by developing a fully automated system for BAV segmentation in 4D computed tomography (CT) imaging[38]. Using a deep learning algorithm, Guo et al. achieved accurate frame-by-frame measurements of cusp gH, commissural angle, and annular diameter with minimal deviation from reference values[38]. This technique holds promise for improving surgical planning, guiding intraoperative decisions, and reducing procedural risk in AVR.

TODAY AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Contemporary AV surgery builds upon these geometric foundations, though future directions remain under exploration. Guided by these principles, surgeons have pursued techniques that restore native valve geometry and function. Early debates largely centered on the reproducibility and standardization of repair methods.

Today, young cardiac surgeons benefit from improved training resources, including the use of calipers and eH measurement, detailed step-by-step publications, instructional videos, and observerships in high-volume centers. Although the learning curve remains long, repair techniques are becoming progressively standardized and more widely adopted across cardiac surgery institutions.

Current debate centers on the long-term durability of AVR and the associated risk of reoperation. Boodhwani and El Khoury reported a 10-year overall survival of 89% and freedom from reoperation of 86% following repair[39]. Three years later, Zeeshan et al. reported improved outcomes for AVR. In a 2017 cohort of 1,124 patients (41% with BAV) from a high-volume center, early mortality and morbidity were comparable to valve replacement, with a 10-year reoperation rate of ~10% and first-year survival nearly equivalent to that of the general population[40]. A 2020 expert review led by Ehrlich et al.[41] on isolated repair of regurgitant BAVs reported a 10-year freedom from reoperation of 90% and survival comparable to age- and sex-matched controls, highlighting superior outcomes relative to conventional valve replacement[41]. The most recent review by De Paulis et al.[42] provides an updated overview of AVR and valve-sparing surgery. When performed by experienced surgeons, these procedures achieve an in-hospital mortality of ~1%, with 10-year survival rates of 85%-92% and freedom from reoperation of 91% at 10 years and 88% at 20 years, based on a meta-analysis of over 7,800 patients[43]. Favorable outcomes have also been achieved in lower-volume centers with careful patient selection. For TAV repair with cusp prolapse, operative mortality is < 1%, 10-year survival ~80%, and freedom from reoperation 72%-80% at 10-15 years. BAV repair demonstrates up to 91% freedom from reoperation at 10 years, consistent with previous studies, though with a higher risk of recurrent regurgitation owing to technical complexity and variability in surgical technique and follow-up.

These authors emphasized that durable, reoperation-free outcomes depend on appropriate patient selection and technique choice, underscoring the importance of key geometric parameters, including eH, commissures, leaflets, annulus, sinuses, and the STJ. For this reason, the potential key priorities for the near future may include:

• Optimize surgical timing through comprehensive preoperative imaging of the aortic root to anticipate intraoperative challenges.

• Tailor repair strategies to each patient’s anatomy and pathology to achieve durable, individualized outcomes.

• Establish a standardized, reproducible, and clinically applicable framework for aortic anatomy assessment to guide surgical indications and contraindications for valve repair.

• Standardize and streamline surgical techniques using clear, evidence-based protocols to ensure consistency and improve outcomes.

• Refine approaches addressing both the sinotubular and ventriculoaortic junctions - analogous to valve-sparing techniques - and evaluate novel devices such as durable pericardial patches and intranular aortic root rings (such as the Corcym intranular ring called HAART).

• Integrate AI-assisted surgery for 3D preoperative analysis, patient-specific repair planning, and virtual simulations to enhance procedural prediction and precision.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding of AV geometry - and consequently of repair feasibility - has evolved through the interplay of historical insight and technological progress. Leonardo da Vinci first recognized the geometric basis of valve function, observing that the triangular cusp shape optimizes efficiency and structural integrity. His concepts remained theoretical until modern advances transformed surgery from a visually guided practice to a quantitative discipline. The introduction of parameters such as eH and cH standardized repairs, improving precision and reproducibility, while intraoperative tools such as calipers further refined geometric assessment.

Aortic geometry is fundamental to valve function. The TAV configuration demonstrates greater mechanical stability and resistance than bicuspid or quadricuspid forms, owing to superior stress distribution and coaptation. Computational models have further confirmed that annular junction and STJ dimensions critically influence cusp stress and overall valve durability. Modern finite element models and 4D MRI supported flow studies have clarified the role of the sinuses of Valsalva in blood flow dynamics. These studies confirm that the presence of sinuses reduces cusp stress and improves repair durability, supporting the use of sinus-containing prostheses.

Future efforts should focus on integrating advanced technologies to individualize AVR according to patient-specific anatomy. Emerging tools, such as AI-driven surgical simulations, may enhance procedural planning, while ongoing research into novel materials and devices aims to optimize and standardize outcomes without compromising adaptability.

Ultimately, the integration of early insights into form-function relationships with modern technological advances has transformed AVR into a precise, reliable, and durable procedure, embodying the guiding principle of our mentors: Ars imitatur naturam in sua operatione (“art imitates nature in its operation”).

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Led the conception and design of the study: Ciccarelli G, Weltert L, Schäfers HJ, De Paulis R

Responsible for data analysis: Weltert L, Ciccarelli G

Contributed to data interpretation and provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ciccarelli G, Weltert L, Schäfers HJ, De Paulis R

Availability of data and materials

Data are not publicly available due to the nature of the subject matter. The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

De Paulis R is the Guest Editor of the Special Issue “Innovations in Aortic Surgery and Valve Repair” of the journal of Vessel Plus. De Paulis R was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Sarsam MA, Yacoub M. Remodeling of the aortic valve anulus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:435-8.

2. David TE, Feindel CM. An aortic valve-sparing operation for patients with aortic incompetence and aneurysm of the ascending aorta. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;103:617-21.

3. Bierbach BO, Aicher D, Issa OA, et al. Aortic root and cusp configuration determine aortic valve function. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:400-6.

4. Holubec T, Žáček P, Tuna M, et al. Aortic valve repair in patients with aortic regurgitation: experience with the first 100 cases. Cor Vasa. 2013;55:e479-86.

5. Oechtering TH, Hons CF, Sieren M, et al. Time-resolved 3-dimensional magnetic resonance phase contrast imaging (4D Flow MRI) analysis of hemodynamics in valve-sparing aortic root repair with an anatomically shaped sinus prosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:418-427.e1.

7. Thubrikar M, Piepgrass WC, Shaner TW, Nolan SP. The design of the normal aortic valve. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:H795-801.

8. Kunzelman KS, Grande K, David TE, Cochran R, Verrier ED. Aortic root and valve relationships: impact on surgical repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:162-70.

9. Robicsek F, Thubrikar MJ, Fokin AA. Cause of degenerative disease of the trileaflet aortic valve: review of subject and presentation of a new theory. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1346-54.

10. Robicsek F, Thubrikar MJ, Cook JW, Fowler B. The congenitally bicuspid aortic valve: how does it function? Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:177-85.

11. Robicsek F, Thubrikar MJ. Mechanical stress as cause of aortic valve disease. Presentation of a new aortic root prosthesis. Acta Chir Belg. 2002;102:1-6.

12. Thubrikar M, Bosher LP, Nolan SP. The mechanism of opening of the aortic valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1979;77:863-70.

13. El-Nashar H, Sabry M, Tseng YT, et al. Multiscale structure and function of the aortic valve apparatus. Physiol Rev. 2024;104:1487-532.

14. Rizzi S, Ragazzini S, Pesce M. Engineering efforts to refine compatibility and duration of aortic valve replacements: an overview of previous expectations and new promises. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:863136.

17. Choo SJ, McRae G, Olomon JP, et al. Aortic root geometry: pattern of differences between leaflets and sinuses of Valsalva. J Heart Valve Dis. 1999;8:407-15.

18. Charitos EI, Sievers HH. Anatomy of the aortic root: implications for valve-sparing surgery. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:53-6.

19. Sievers HH, Hemmer W, Beyersdorf F, et al.; Working Group for Aortic Valve Surgery of German Society of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. The everyday used nomenclature of the aortic root components: the tower of Babel? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:478-82.

20. Giebels C, Ehrlich T, Schäfers HJ. Aortic root remodeling. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;12:369-76.

21. Boodhwani M, El Khoury G. Aortic valve repair. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;14:266-80.

22. Van Dyck M, Glineur D, de Kerchove L, El Khoury G. Complications after aortic valve repair and valve-sparing procedures. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:130-9.

23. le Polain de Waroux JB, Pouleur AC, Robert A, et al. Mechanisms of recurrent aortic regurgitation after aortic valve repair: predictive value of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:931-9.

24. Schäfers HJ, Bierbach B, Aicher D. A new approach to the assessment of aortic cusp geometry. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:436-8.

25. Kunihara T, Aicher D, Rodionycheva S, et al. Preoperative aortic root geometry and postoperative cusp configuration primarily determine long-term outcome after valve-preserving aortic root repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:1389-95.e1.

26. Marom G, Haj-Ali R, Rosenfeld M, Schäfers HJ, Raanani E. Aortic root numeric model: correlation between intraoperative effective height and diastolic coaptation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:303-4.

27. Grande-Allen KJ, Cochran RP, Reinhall PG, Kunzelman KS. Mechanisms of aortic valve incompetence: finite-element modeling of Marfan syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;122:946-54.

28. Weltert L, de Tullio MD, Afferrante L, et al. Annular dilatation and loss of sino-tubular junction in aneurysmatic aorta: implications on leaflet quality at the time of surgery. A finite element study. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17:8-12.

29. Marom G, Weltert LP, Raanani E, et al. Systematic adjustment of root dimensions to cusp size in aortic valve repair: a computer simulation. Interdiscip Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2024;38:ivae024.

30. Jahanyar J, Tsai PI, Arabkhani B, et al. Functional and pathomorphological anatomy of the aortic valve and root for aortic valve sparing surgery in tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;12:179-93.

31. Salica A, Pisani G, Morbiducci U, et al. The combined role of sinuses of Valsalva and flow pulsatility improves energy loss of the aortic valve. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49:1222-7.

32. Pisani G, Scaffa R, Ieropoli O, et al. Role of the sinuses of Valsalva on the opening of the aortic valve. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:999-1003.

33. Reul H, Vahlbruch A, Giersiepen M, Schmitz-Rode T, Hirtz V, Effert S. The geometry of the aortic root in health, at valve disease and after valve replacement. J Biomech. 1990;23:181-91.

34. Soncini M, Votta E, Zinicchino S, et al. Finite element simulations of the physiological aortic root and valve sparing corrections. J Mech Med Biol. 2006;6:91-9.

35. Weinberg EJ, Kaazempur Mofrad MR. Transient, three-dimensional, multiscale simulations of the human aortic valve. Cardiovasc Eng. 2007;7:140-55.

36. Chandra S, Rajamannan NM, Sucosky P. Computational assessment of bicuspid aortic valve wall-shear stress: implications for calcific aortic valve disease. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2012;11:1085-96.

37. Kaiser AD, Shad R, Schiavone N, Hiesinger W, Marsden AL. Controlled comparison of simulated hemodynamics across tricuspid and bicuspid aortic valves. Ann Biomed Eng. 2022;50:1053-72.

38. Guo Z, Dong NJ, Litt H, et al. Towards patient-specific surgical planning for bicuspid aortic valve repair: fully automated segmentation of the aortic valve in 4D CT. In: 2025 IEEE 22nd International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI); 2025 April 14-17; Houston, TX, USA. IEEE; 2025. pp. 1-5.

39. Boodhwani M, El Khoury G. Aortic valve repair: indications and outcomes. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16:490.

40. Zeeshan A, Idrees JJ, Johnston DR, et al. Durability of aortic valve cusp repair with and without annular support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105:739-48.

41. Ehrlich T, de Kerchove L, Vojacek J, et al. State-of-the art bicuspid aortic valve repair in 2020. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:457-64.

42. De Paulis R, Chirichilli I, de Kerchove L, et al. Current status of aortic valve repair surgery. Eur Heart J. 2025;46:1394-411.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].