Controlled attenuation parameter factors and steatosis grading in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

Abstract

Aim: To identify factors influencing liver-controlled attenuation parameter (CAP, dB/m) and establish its optimal diagnostic thresholds for hepatic steatosis grading in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

Methods: A total of 758 prospectively enrolled MASLD patients at Zhongshan Hospital, Shanghai, China (September 2022-June 2023) were randomized into a training cohort (n = 619) and a validation cohort (n = 139), stratified by body mass index (BMI: normal-weight < 25 kg/m2; overweight ≥ 25 kg/m2). Demographics, laboratory parameters, CAP, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) proton density fat fraction (PDFF) were recorded. Using MRI-derived PDFF (MRI-PDFF) as the reference, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to establish CAP thresholds for steatosis grades.

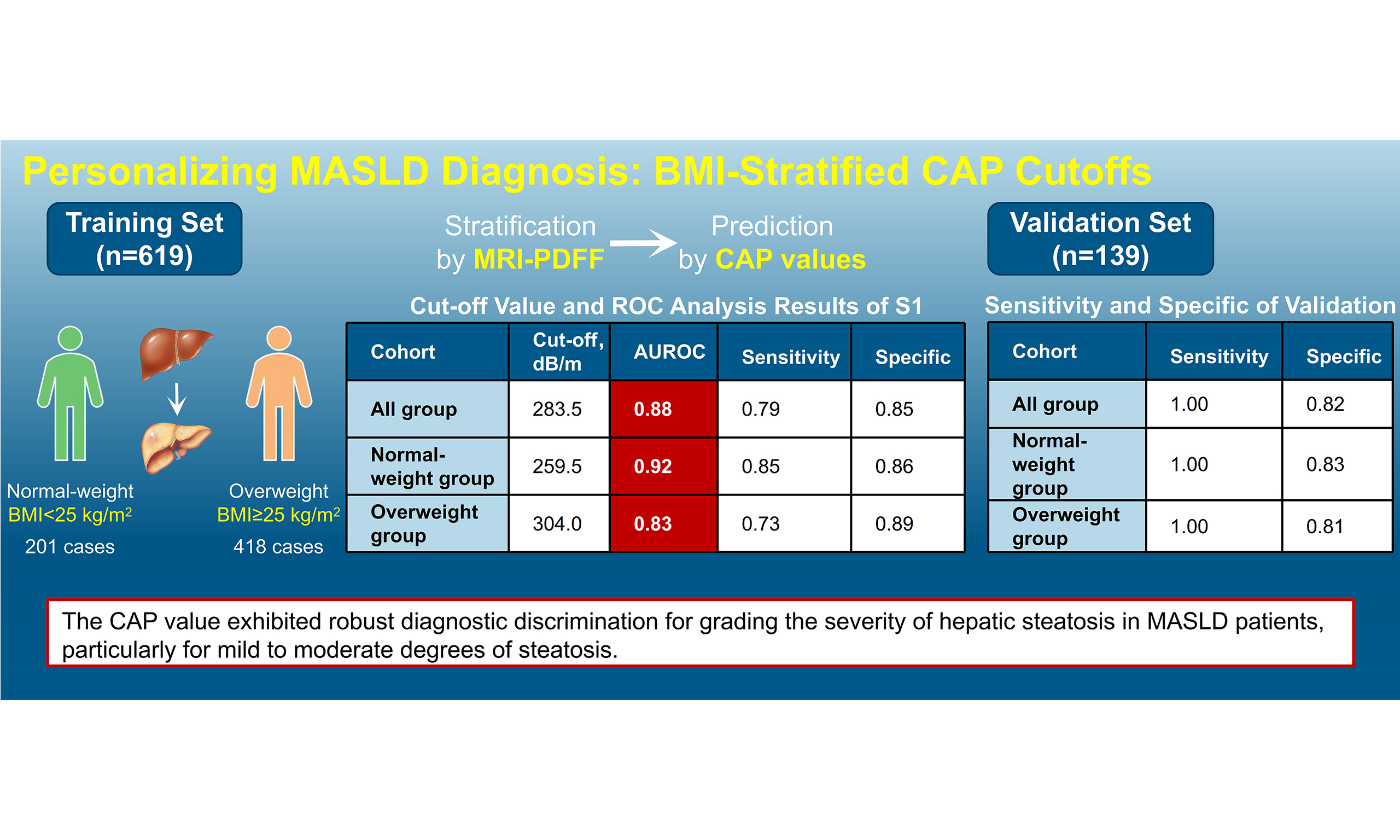

Results: In the training cohort, multivariate analysis showed that CAP was correlated with uric acid, glucose, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in normal-weight patients, and with alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total cholesterol (TC), and BMI in overweight patients. Overall cohort CAP thresholds were: S1, 283.5 dB/m [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.880]; S2, 311.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.712); S3, 328.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.799). Normal-weight thresholds: S1, 259.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.922); S2-3, 323.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.779). Overweight thresholds: S1, 304.0 dB/m (AUC = 0.829); S2, 311.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.677); S3, 328.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.767). Validation confirmed robust diagnostic performance.

Conclusion: CAP correlates significantly with metabolic factors (glucose, HDL) and shows a trend toward association with uric acid (P = 0.073) in normal-weight MASLD patients, and with liver markers/metabolic factors (BMI, ALT, TC) in overweight patients. CAP demonstrates good diagnostic accuracy for grading the severity of hepatic steatosis in MASLD, particularly for mild to moderate steatosis.

Highlights

1. Study of 758 MASLD patients stratified by BMI to identify factors influencing CAP and its diagnostic value for hepatic steatosis, using MRI-derived PDFF as reference.

2. CAP correlates with glucose, HDL, and uric acid in normal-weight patients, and with ALT, total cholesterol (TC), and BMI in overweight patients.

3. BMI-specific CAP thresholds were established, with the highest diagnostic performance in normal-weight individuals (AUC = 0.922 for S1).

4. Validation confirmed robust diagnostic accuracy (Youden index 0.81-0.83), supporting CAP as a practical non-invasive tool for grading mild-to-moderate steatosis.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a clinicopathological syndrome characterized by diffuse lipid accumulation in hepatocytes. It can progress to marked steatosis and hepatic inflammation, occurring in the absence of alcohol consumption, viral infection, or other known hepatotoxic factors[1]. Currently, MASLD has superseded hepatitis B virus infection as the predominant etiology of chronic liver disease worldwide, with epidemiological studies demonstrating a global prevalence of 30% in adults[2]. Notably, it is emerging as the most frequent contributor to end-stage liver disease, including MASLD-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The escalating global obesity pandemic has driven a parallel increase in MASLD prevalence, with recent epidemiological data revealing a concerning trend toward earlier disease onset, particularly in China, where this metabolic disorder poses a significant public health challenge. Beyond inducing varying degrees of hepatic injury, MASLD is strongly associated with multisystem morbidity, including but not limited to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular accidents, and malignancy development, as evidenced by recent cohort studies[3,4]. These pathophysiological insights underscore the clinical imperative for accurate disease stratification, timely diagnosis, and targeted therapy. Of particular translational significance is the development of reliable noninvasive assessment modalities for monitoring MASLD progression.

The scientific exploration of noninvasive stratification and evaluation methodologies for MASLD has witnessed exponential growth, with systematic reviews identifying three principal technical domains: biochemical marker profiling, advanced imaging modalities, and multimodal integrated approaches[5,6]. In routine clinical settings, B-mode ultrasonography remains the first-line imaging modality for detecting hepatic steatosis, particularly sensitive for assessing moderate to severe fatty liver disease[7]. However, this technique exhibits limited diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing between histological grades of steatosis (S1-S3) and fails to reliably quantify fibrosis stages (F0-F4). Histopathological evaluation of liver biopsy specimens continues to serve as the reference standard for MASLD staging. It allows comprehensive assessment of key histological features, including steatosis severity (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3), hepatocyte ballooning (0-2), and fibrosis stage (0-4), based on the metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) Clinical Research Network criteria. Nevertheless, diagnostic accuracy may be compromised by sampling variability and interobserver variability among pathologists. Furthermore, the invasive nature of liver biopsy carries inherent risks, including postprocedural pain, hemorrhage, and rarely pneumothorax, leading to suboptimal patient compliance that substantially limits its utility in longitudinal monitoring[8]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) demonstrates superior sensitivity and diagnostic accuracy for detecting mild steatosis, establishing it as a robust quantitative imaging biomarker for hepatic triglyceride (TG) quantification[9]. However, clinical implementation faces challenges, including substantial cost burdens, prolonged acquisition times, stringent breath-holding requirements, and specialized postprocessing needs, collectively restricting its scalability in resource-constrained settings. Vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE, FibroScan®), a validated ultrasound-based shear wave elastography technique, was originally developed for noninvasive evaluation of liver fibrosis stiffness (measured in kPa) in chronic hepatopathies. Technological evolution has enabled concurrent measurement of the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP, dB/m), which quantifies ultrasound signal attenuation and correlates with hepatic fat content. CAP offers distinct advantages, including rapid acquisition, excellent reproducibility, and a noninvasive nature, positioning it as a practical point-of-care tool for steatosis surveillance in high-risk populations[10]. Nevertheless, CAP measurements demonstrate variable reliability due to technical confounders, including subcutaneous fat, ascites, and hepatic venous congestion[11]. In this prospective cohort study, MRI-PDFF was employed as the reference standard to stratify hepatic steatosis severity (S0-S3) according to the MASLD Activity Score.

METHODS

Study population

This prospective cohort study consecutively enrolled 758 treatment-naïve MASLD patients (mean age 44.3 ± 12.8 years, 67.5% male) at the Hepatology Clinic of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China) between September 2022 and June 2023. Using computer-generated block randomization with an allocation ratio of approximately 80:20, participants were stratified into derivation (n = 619) and validation (n = 139) cohorts. Randomization was stratified by body mass index (BMI) group (normal-weight vs. overweight) to ensure balanced representation across both cohorts. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Asian criteria, participants were stratified into normal-weight (BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI >

Inclusion criteria:

(1) Comprehensive clinical documentation including anthropometrics (BMI, waist-hip ratio), serological profiles, FibroScan® parameters [CAP and liver stiffness measurement (E)], and MRI-PDFF quantification.

(2) Confirmed hepatic steatosis, defined by MRI-PDFF ≥ 5%.

(3) Presence of at least one of the following cardiometabolic risk factors, in accordance with the current international definition of MASLD:

· BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 (using Asian-specific criteria);

· Fasting plasma glucose ≥ 5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dL) or diagnosed type 2 diabetes or use of antihyperglycemic agents;

· Blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or use of antihypertensive drugs;

· Plasma TG ≥ 1.70 mmol/L (150 mg/dL) or use of lipid-lowering medication;

· Plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) < 1.0 mmol/L (40 mg/dL) for men and < 1.3 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) for women.

Exclusion criteria:

(1) Secondary hepatic steatosis due to:

· Significant alcohol consumption (> 30 g/day for men or > 20 g/day for women);

· Use of steatogenic medications;

· Positive serological markers for chronic viral hepatitis, specifically hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or hepatitis C virus antibody (anti-HCV).

(2) Any stage of liver cirrhosis (including compensated Child-Pugh A cirrhosis), as diagnosed by clinical, imaging, or histological criteria, or the presence of HCC.

(3) Systemic comorbidities (autoimmune disorders, decompensated diabetes mellitus).

(4) Technical failure in imaging acquisitions.

Methodology

Demographic, anthropometric, and biochemical parameters were systematically collected through electronic medical records. Central adiposity was defined by waist circumference thresholds (male > 90 cm, female >

CAP quantification

CAP measurements were obtained using FibroScan® 502 Touch (Echosens, France) with M-probe (3.5 MHz), following European Association for the Study of the Liver-European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EASL-EFSUMB) guidelines[14]. Ten valid measurements were acquired with a success rate > 80% and interquartile range/median (IQR/M) ≤ 30% as quality criteria.

MRI protocol

All patients included underwent abdominal MRI-PDFF examinations on a Siemens Magnetom Avanto MRI system with software version VB15. The Siemens Healthcare multi-echo Dixon sequence technique was used to detect liver fat and iron content, all performed by an experienced magnetic resonance physician. Select three 30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm voxels to locate in different regions of the liver, namely the region of interest (ROI), avoiding large blood vessels, bile ducts, and liver edges, and measure the liver fat fraction value.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc version 20.1 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Continuous variables underwent Shapiro-Wilk normality testing. Parametric data [mean ± standard deviation (SD)] were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni correction, and non-parametric data [median (IQR)] were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. To mitigate the influence of extreme outliers, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) values were winsorized at the 99th percentile prior to analysis. Variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were incorporated into a stepwise multivariable linear regression model to identify independent factors associated with CAP values. Multivariable regression incorporated variables with P < 0.1 in univariate analysis. Model performance was assessed by receiver operating characteristic-area under the curve (ROC-AUC) with DeLong’s method. The assumptions of the regression model were validated using a standardized residual scatter plot (|residuals| < 3) and Levene’s test for homogeneity of variance (P > 0.05).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of the study cohort

The derivation cohort (n = 619) had a mean age of 43.7 ± 13.2 years, with male predominance (68.5%, 424/619). Overweight prevalence (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) was 67.5% (418/619) [Supplementary Table 1]. Males accounted for 56.2% (117/201) and 72.0% (307/418) of the normal-weight and overweight groups, respectively (P < 0.001). Waist-hip ratio (0.90 ± 0.12 vs. 1.00 ± 0.64, P = 0.185) and comorbidities (diabetes: 5.0% vs. 6.2%; hypertension: 20.9% vs. 24.6%; both P > 0.05) showed no intergroup differences. Overweight patients exhibited elevated ALT (77.0 ± 58.9 vs. 49.0 ± 41.8 U/L) and AST (43.1 ± 31.7 vs. 32.7 ± 22.3 U/L) (all P < 0.001). CAP (317.9 ± 45.0 vs. 289.2 ± 54.3 dB/m) and MRI-PDFF (23.7% ± 15.3% vs. 15.9% ± 12.8%) were significantly higher in overweight patients (P < 0.001).

The validation cohort (n = 139) demonstrated comparable characteristics: mean age 45.1 ± 11.8 years, 64.0% males (89/139), and 66.9% overweight (93/139) [Supplementary Table 2]. The distribution of fatty liver grades was: S0 (n = 19), S1 (n = 111), and S2 (n = 9). Due to the small sample size of the S2 group, its diagnostic performance was not reported separately; instead, it was combined with the S1 group for analysis. The results showed that CAP maintained good diagnostic performance for detecting steatosis ≥ S1.

CAP values progressively increased with steatosis severity [Supplementary Figure 1]: S0, 212.0 ± 24.6 dB/m; S1, 262.2 ± 24.2 dB/m; S2, 336.8 ± 5.3 dB/m; S3, 358.6 ± 11.8 dB/m. Pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between S0 and S1 (P = 0.003) and S1 and S2 (P < 0.001), but not between S2 and S3 (P = 0.27), based on ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test.

Univariate analysis related to CAP values

Univariate linear regression analyses were performed separately in normal-weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2) and overweight (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) cohorts to identify CAP-associated determinants. In the normal-weight cohort, CAP was significantly associated with BMI (β = 6.28), erythrocyte count (β = 28.14), soluble interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) (β = -0.14), fasting glucose (β = 9.89), uric acid (β = 0.12), prealbumin (β = 0.27), TG (β = 21.37), and HDL-C (β = -32.52) (all P < 0.05; Table 1). In the overweight cohort, stronger associations were observed with BMI (β = 1.89), procollagen type III N-terminal peptide (PIIINP) (β = 1.38), ALT (β = 0.11), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (β = 0.19), prealbumin (β = 0.12), uric acid (β = 0.09), total cholesterol (TC) (β = 8.98), TG (β = 7.79), HDL-C (β = -22.96), and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) (β = 36.07) (all P < 0.05; Table 1).

Univariate linear regression

| Cohort | Variable | β | S.E | t | P | β (95%CI) |

| Normal-weight group | BMI | 6.28 | 3.00 | 2.10 | 0.038 | 6.28 (0.41-12.15) |

| RBC, 1012/L | 28.14 | 12.82 | 2.20 | 0.032 | 28.14 (3.01-53.27) | |

| IL-2R, U/mL | -0.14 | 0.06 | -2.38 | 0.020 | -0.14 (-0.26-0.02) | |

| Prealbumin, mg/L | 0.27 | 0.08 | 3.22 | 0.002 | 0.27 (0.11-0.43) | |

| FBG, mmol/L | 9.89 | 3.42 | 2.89 | 0.005 | 9.89 (3.19-16.59) | |

| TG, mmol/L | 21.37 | 5.83 | 3.67 | < 0.001 | 21.37 (9.94-32.79) | |

| HDL, mmol/L | -32.52 | 14.62 | -2.22 | 0.028 | -32.52 (-61.18-3.86) | |

| UA, μmol/L | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.15 | 0.034 | 0.12 (0.01-0.23) | |

| PLT, 109/L | 0.16 | 0.09 | 1.81 | 0.076 | 0.16 (-0.01-0.34) | |

| Overweight group | BMI | 1.89 | 0.57 | 3.32 | < 0.001 | 1.89 (0.77-3.00) |

| PIIINP, ng/mL | 1.38 | 0.41 | 3.35 | < 0.001 | 1.38 (0.57-2.18) | |

| ALT, U/L | 0.11 | 0.04 | 2.87 | 0.004 | 0.11 (0.04-0.19) | |

| LDH, U/L | 0.19 | 0.06 | 3.40 | < 0.001 | 0.19 (0.08-0.30) | |

| Prealbumin, mg/L | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.13 | 0.034 | 0.12 (0.01-0.24) | |

| UA, μmol/L | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.51 | < 0.001 | 0.09 (0.04-0.14) | |

| TC, mmol/L | 8.98 | 2.52 | 3.56 | < 0.001 | 8.98 (4.04-13.93) | |

| TG, mmol/L | 7.79 | 2.03 | 3.83 | < 0.001 | 7.79 (3.80-11.78) | |

| HDL, mmol/L | -22.96 | 9.13 | -2.51 | 0.012 | -22.96 (-40.86-5.07) | |

| ApoB, g/L | 36.07 | 10.97 | 3.29 | 0.001 | 36.07 (14.58-57.56) |

Multivariate analysis related to CAP values

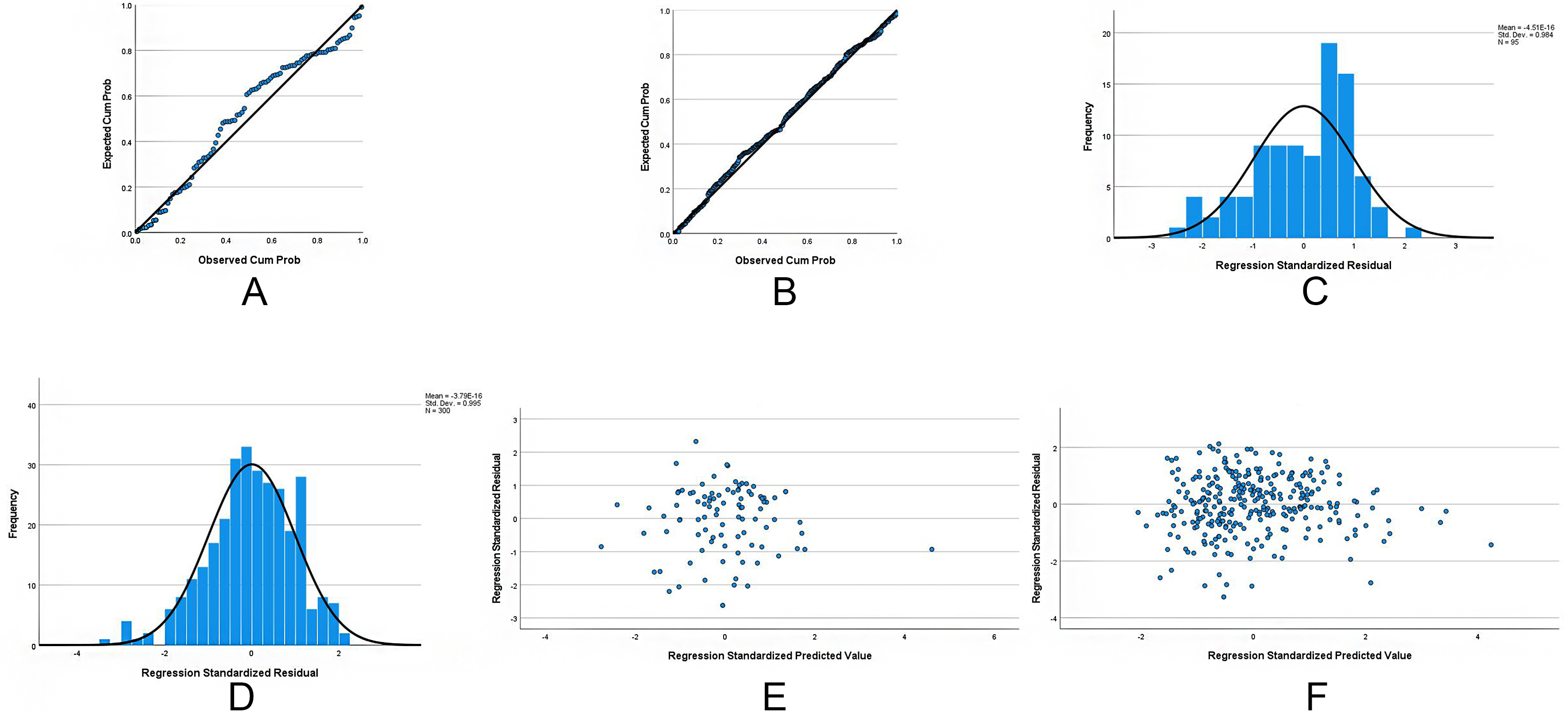

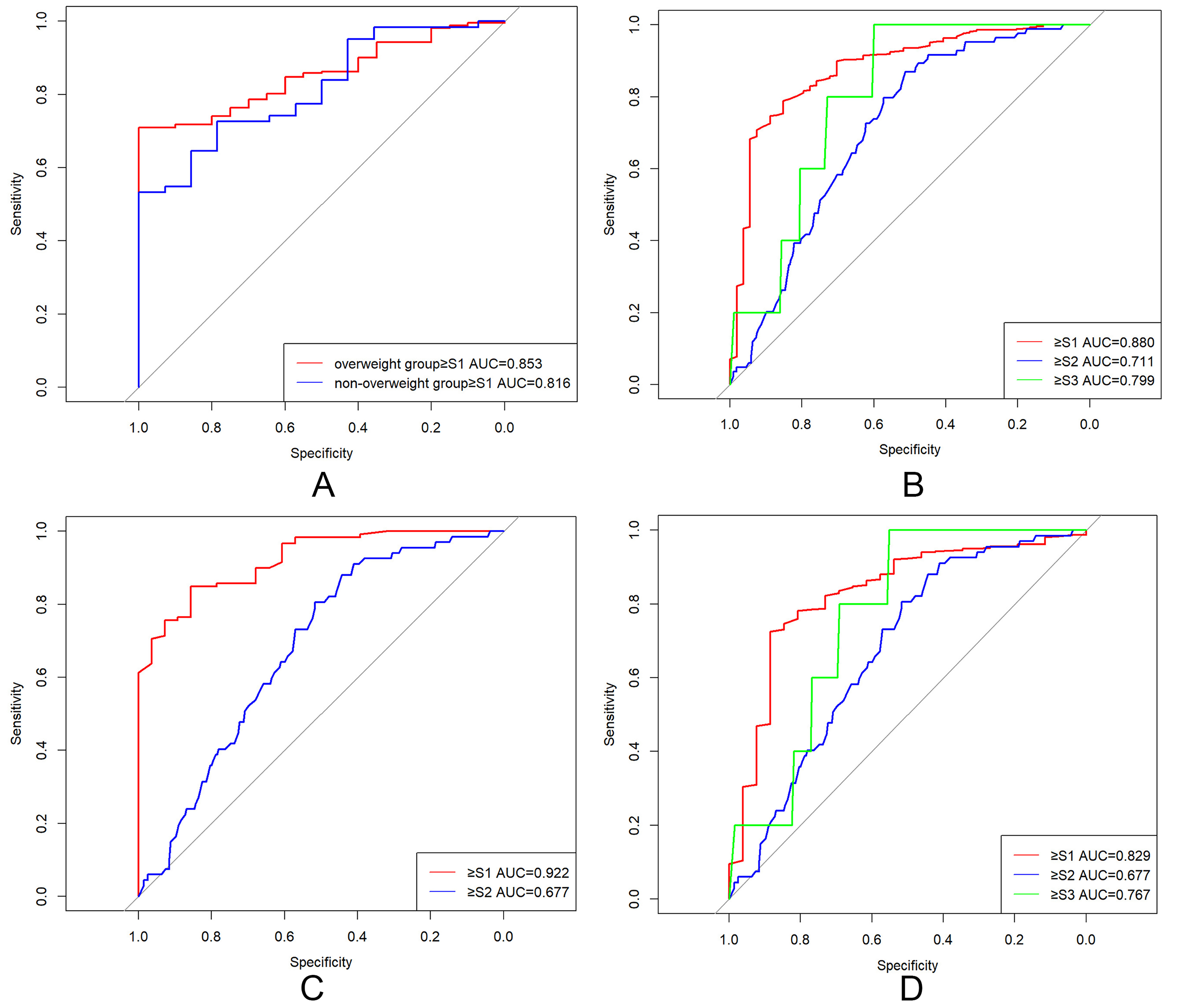

Variables demonstrating marginal significance (P < 0.10) in univariate analyses were entered into stepwise multivariate linear regression models (entry α = 0.05, removal α = 0.10). The normal-weight multivariate model identified serum (β = 0.11, P = 0.073), fasting glucose (β = 13.76, P < 0.001), and HDL-C (β = -45.47, P = 0.003) as independent CAP determinants [Table 2]. The overweight model revealed stronger associations with BMI (β = 2.47, P = 0.006), ALT (β = 0.16, P = 0.004), and TC (β = 8.41, P = 0.006) [Table 2]. To validate the assumptions of the linear regression models, residual analyses were performed. Normal probability plots (P-P plots) of standardized residuals for both groups closely approximated the diagonal line [Figure 1A and B], indicating approximate normality. This was further supported by residual histograms, which displayed near-normal distributions for both groups [Figure 1C and D]. Residual scatter plots revealed that standardized residuals were randomly distributed above and below zero with no discernible pattern [Figure 1E and F], supporting the assumption of homoscedasticity. Residual diagnostics yielded Durbin-Watson statistics of 2.01 (normal-weight) and 2.02 (overweight), suggesting the absence of autocorrelation. Variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis confirmed no significant multicollinearity, as all independent variables had VIF values < 5. Residual diagnostics confirmed model validity: Durbin-Watson statistics of 2.010 (normal-weight) and 2.024 (overweight) [Supplementary Table 3] fell within the ideal range (1.5-2.5), ruling out significant autocorrelation (P > 0.05). ROC analysis validated clinical utility: AUC = 0.816 for the normal-weight group and 0.853 for the overweight group [Figure 2A], with both models achieving P < 0.001 and sensitivity/specificity > 80%.

Figure 1. Diagnostic plots assessing assumptions of the multivariable linear regression models for CAP values. (A) Residuals closely follow the diagonal line, supporting normality in the normal-weight model; (B) Residuals approximate the diagonal line, validating normality in the overweight model; (C) Histogram showing a near-normal distribution of residuals for the normal-weight model; (D) Residuals are approximately symmetrical and unimodal in the overweight model, supporting normality; (E) Residuals are randomly dispersed around zero, indicating homoscedasticity for the normal-weight model; (F) Random scatter of residuals confirms homoscedasticity in the overweight model. Collectively, plots (A-F) validate key regression assumptions - normality, homoscedasticity, and independence - for both BMI subgroups. Durbin-Watson statistics (2.01 and 2.02) and VIF values < 5 confirm absence of autocorrelation and multicollinearity, respectively. CAP: Controlled attenuation parameter; BMI: body mass index; VIF: variance inflation factor.

Figure 2. ROC curves for CAP in diagnosing hepatic steatosis grades. (A) Multivariable linear regression models predicting CAP. Normal-weight group AUC = 0.816 (95%CI: 0.713-0.927); overweight group AUC = 0.853 (95%CI: 0.798-0.907); (B) CAP diagnostic performance in the overall cohort. ≥ S1: cut-off = 283.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.880 (95%CI: 0.831-0.910); ≥ S2: cut-off = 311.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.712 (95%CI: 0.659-0.764); ≥ S3: cut-off = 328.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.799 (95%CI: 0.628-0.917); (C) CAP performance in the normal-weight group. ≥ S1: cut-off = 259.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.922 (95%CI: 0.875-0.968); ≥ S2: cut-off = 323.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.779 (95%CI: 0.628-0.876); (D) CAP performance in the overweight group. ≥ S1: cut-off = 283.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.829 (95%CI: 0.744-0.915); ≥ S2: cut-off = 311.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.677 (95%CI: 0.613-0.740); ≥ S3: cut-off = 328.5 dB/m, AUC = 0.767 (95%CI: 0.635-0.898). ROC: Receiver operating characteristic; CAP: controlled attenuation parameter; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; S1: mild hepatic steatosis; S2: moderate hepatic steatosis; S3: severe hepatic steatosis.

Results of multiple linear regression analysis

| Cohort | Variable | β | S.E | t | P | β (95%CI) | VIF |

| Normal-weight group | Intercept | 229.83 | 41.41 | 5.55 | < 0.001 | 229.83 (148.68-310.99) | |

| UA, μmol/L | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.82 | 0.073 | 0.11 (-0.01-0.23) | 1.056 | |

| FBG, mmol/L | 13.76 | 3.87 | 3.56 | < 0.001 | 13.76 (6.18-21.33) | 1.039 | |

| HDL, mmol/L | -45.47 | 19.11 | -2.38 | 0.020 | -45.47 (-82.91-8.02) | 1.065 | |

| Overweight group | Intercept | 189.31 | 28.212 | 6.710 | < 0.001 | 189.31 (134.91-244.71) | |

| ALT, U/L | 0.164 | 0.056 | 2.910 | 0.004 | 0.164 (0.054-0.274) | 1.030 | |

| TC, mmol/L | 8.411 | 2.996 | 2.807 | 0.006 | 8.411 (2.527-14.295) | 1.033 | |

| BMI | 2.469 | 0.895 | 2.760 | 0.006 | 2.469 (0.712-4.226) | 1.036 |

Grading efficiency of CAP for hepatic steatosis and cut-off values between different diagnostic grades

Stage-stratified analysis revealed progressive CAP elevation: S0 vs. S1 (P < 0.001), S1 vs. S2 (P < 0.001) in all cohorts, preserved in BMI subgroups (all P < 0.005; Supplementary Table 4) after Bonferroni correction. These findings validate CAP’s discriminative capacity for early to moderate steatosis (S0-S2), with reduced efficacy in advanced stages (P > 0.05).

ROC curve analysis established BMI-adaptive diagnostic thresholds [Figure 2B-D and Table 3]:

· Overall cohort: ≥ S1: 283.5 dB/m (AUC = 0.880), S2: 311.5 (0.712), S3: 328.5 (0.799);

· Normal-weight: ≥ S1: 259.5 (0.922), S2-3: 323.5 (0.779);

· Overweight: ≥ S1: 304.0 (0.829), S2: 311.5 (0.677), S3: 328.5 (0.767).

Limited S3 cases in the normal-weight subgroup necessitated merging S2-3 categories. BMI stratification enhanced diagnostic accuracy: normal-weight AUC = 0.922 vs. 0.880 overall (+4.8% improvement), outperforming overweight cohorts.

ROC analysis results

| Cohort | AUROC (95%CI) | Cut-off, dB/m | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| All group | S1 | 0.880 (0.831-0.910) | 283.5 | 0.789 | 0.852 |

| S2 | 0.712 (0.659-0.764) | 311.5 | 0.869 | 0.514 | |

| S3 | 0.799 (0.628-0.917) | 328.5 | 1.000 | 0.599 | |

| Normal-weight group | S1 | 0.922 (0.875-0.968) | 259.5 | 0.849 | 0.857 |

| S2-S3 | 0.779 (0.628-0.876) | 323.5 | 0.765 | 0.723 | |

| Overweight group | S1 | 0.829 (0.744-0.915) | 304.0 | 0.725 | 0.885 |

| S2 | 0.677 (0.613-0.740) | 311.5 | 0.881 | 0.444 | |

| S3 | 0.767 (0.635-0.898) | 328.5 | 1.000 | 0.552 | |

Performance of obtained cut-off values in the validation cohort

Current Chinese consensus thresholds (S1: 248 dB/m, S2: 268 dB/m, S3: 294 dB/m), based on the 2021 Chinese national guidelines, showed suboptimal validation performance in our cohort [area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) = 0.76-0.82][14]. External validation quantitatively compared BMI-stratified thresholds with the Chinese guidelines using standardized metrics. Sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index were analyzed [Tables 4 and 5]. The results showed that the cut-off values derived from this study maintained higher sensitivity in the validation cohort (overall: 1.00 vs. 0.53; normal-weight: 1.00 vs. 0.50; overweight: 1.00 vs. 0.44), indicating superior diagnostic efficiency for grading MASLD. These findings support revision of Chinese MASLD screening protocols to incorporate BMI-adjusted CAP thresholds, which may be particularly beneficial for resource-limited preliminary screening settings.

Relevant values of the study cutoff in the validation cohort

| Validation cohort | Normal-weight group in the validation cohort | Overweight group in the validation cohort | |

| Sensitivity | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Specificity | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

| Youden index | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.81 |

Relevant values of the domestic study cutoff values in the validation cohort

| Validation cohort | Normal-weight group in the validation cohort | Overweight group in the validation cohort | |

| Sensitivity | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.44 |

| Specificity | 0.94 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| Youden index | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.37 |

DISCUSSION

The global burden of MASLD has reached pandemic proportions, affecting 32.4% of adults worldwide, with accelerated progression in Asia (46.1 per 1,000 person-years incidence) and China demonstrating the highest documented prevalence surge (29.6% pooled prevalence, 2000-2020). China has emerged as the epicenter of this epidemic, exhibiting the world’s highest MASLD incidence (59.4 per 1,000 person-years) and a 210% increase in prevalence since 2000. Obesity is a major driver of this progression, with 51.3% of Chinese MASLD patients meeting WHO obesity criteria (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2)[15,16]. MASLD encompasses a clinicopathological spectrum from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, acting as a hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome that accelerates progression to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and HCC[14]. It seriously threatens human health, causes a significant medical burden, and has become one of the major public health problems, urgently requiring population-level interventions. Precise non-invasive staging is pivotal for MASLD management, enabling (1) disease trajectory mapping; (2) personalized therapy optimization; (3) treatment response monitoring; and (4) prognostication. VCTE with the CAP (VCTE-CAP) has emerged as a cost-effective point-of-care tool, requiring less than 5 min per measurement. VCTE-CAP demonstrates superior diagnostic accuracy compared with ultrasound for detecting ≥ S1 steatosis, providing immediate quantification (CAP range: 100-400 dB/m) with excellent intra-observer concordance[17,18]. It has strong potential for early diagnosis and treatment of MASLD in clinical practice.

This multicenter study established BMI-stratified CAP thresholds in 758 consecutively enrolled Chinese MASLD patients (derivation cohort, n = 619; validation cohort, n = 139), optimizing diagnostic accuracy for steatosis grading using MRI-PDFF as the reference standard. The normal-weight subgroup (BMI < 25 kg/m2) thresholds were S1 = 259.5 dB/m and S2-3 = 323.5 dB/m, while the overweight subgroup (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) thresholds were S1 = 304.0 dB/m, S2 = 311.5 dB/m, and S3 = 328.5 dB/m (all AUROC: 0.71-0.92). Compared with the diagnostic cut-off values currently used in clinical practice in China, the overall cut-off values identified in this study were higher, while the Youden index in the validation cohort increased significantly, suggesting improved diagnostic accuracy of the proposed thresholds in the validation cohort [Tables 4 and 5]. It is speculated that the differences in cut-off values may be related to differences in study cohorts and detection errors. We searched for relevant studies on the application of CAP in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis ≥ S1 from 2021 to 2024. In the study by Beyer et al., the cut-off value was 268.5 dB/m and the AUROC was 0.95. The study found that CAP performed well in identifying individuals with low levels of fat in hepatic steatosis ≥ S1, but had poor diagnostic performance for higher levels of fat in hepatic steatosis ≥ S2 and ≥ S3, which is consistent with the results of this study[19]. In the study by Ferraioli et al., the cut-off value was 273 dB/m with an AUROC of 0.85, but the sample size was too small (n = 72), leading to poor representativeness[20]. In the study by Petroff et al., the cut-off value was 294 dB/m with an AUROC of 0.80. It was found that the critical value of CAP varies depending on disease etiology and can effectively identify severe steatosis in patients with viral hepatitis. CAP cannot fully classify steatosis in patients with MASLD, but its value in the screening setting for MASLD needs further study[21]. The Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (Version 2024) adopted the cut-off values proposed by Karlas et al. in 2017, with the optimal critical values for M-probe detection of S0, S1, and S2 being 248, 268, and 294 dB/m, respectively[11]. However, our study establishes CAP thresholds that are systematically higher than those recommended in earlier Chinese guidelines. This upward shift is not an isolated finding, as it aligns with trends observed in several recent investigations [Supplementary Table 5][19-21]. We posit that this phenomenon is multifactorial. First, technological evolution of VCTE: the FibroScan® device and its proprietary CAP algorithm have undergone continuous refinement, and newer software versions and hardware optimizations may affect the dynamic range and absolute CAP values, directly influencing diagnostic thresholds. Second, the shifting epidemiological landscape: the MASLD patient population in China is evolving, with increased prevalence and severity of metabolic risk factors. Our cohort, recruited between 2022 and 2023, may therefore differ from historical cohorts in metabolic characteristics and body composition. Third, reference standard and population stratification: the use of MRI-PDFF as the reference standard may allow more precise CAP threshold calibration, particularly for lower grades of steatosis. In addition, the BMI-stratified approach used in this study may better reflect the CAP values required for diagnosing steatosis in patients with increased abdominal adiposity, which was not fully accounted for in earlier studies. Further research is needed to clarify the specific reasons. The advantages of this study include the large sample size (n = 619), the use of recent data, and the exclusive inclusion of Chinese patients, which better reflects the characteristics of the Chinese population. At the same time, an independent validation cohort was used for effective validation, and it will be further expanded to verify the rationality of the optimal critical values, providing guidance for the non-invasive clinical diagnosis of MASLD.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the small number of S2 patients in the validation cohort (n = 9) may have reduced the reliability of diagnostic performance estimates for this subgroup. This limited sample size particularly affects the stability and generalizability of the proposed S2 cut-off (311.5 dB/m) for overweight patients. The point estimates of diagnostic accuracy (e.g., AUC, sensitivity, specificity) derived from such a small sample are prone to substantial uncertainty and may vary widely in different populations. Therefore, this specific threshold should be interpreted with caution and is best viewed as a preliminary finding that requires confirmation in larger, prospective validation studies. Although we attempted to increase statistical power by combining S1 and S2 stages for analysis, future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to confirm the optimal threshold specifically for the S2 stage. Second, for S3 steatosis, we observed exceptionally high sensitivity (100%) but relatively low specificity (59.9%). This indicates that while our threshold (328.5 dB/m) effectively avoids missing severe steatosis cases (minimizing false negatives), it may misclassify a substantial proportion of non-severe cases as positive (increasing false positives). Therefore, this threshold is more suitable for screening purposes, and positive cases should undergo further confirmation with MRI or liver biopsy. Third, as the validation cohort was derived from a single center, future multi-center studies using external cohorts are necessary to validate the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, for quality control of CAP measurements, we adhered to the commonly accepted criteria of a success rate > 80% and an IQR/M ratio ≤ 30%. While these criteria ensure the technical feasibility of measurements in a broad clinical cohort and are widely used in the literature, it is noteworthy that some recent guidelines and studies advocate for stricter thresholds (e.g., IQR/M ≤ 20%) to further minimize measurement variability. The use of a more lenient criterion in our study could potentially introduce additional variability into the CAP values, which might, in turn, affect the precision of the established diagnostic thresholds. Future studies employing these stricter quality criteria would be valuable to confirm the robustness of our findings.

In other related studies, CAP has shown good performance in diagnosing hepatic steatosis ≥ S1 grade, with an AUROC of 0.79-0.89. However, for grades ≥ S2 and S3, the AUROC decreased to 0.72-0.79 and 0.70-0.76, respectively[22-25]. In this study, CAP also demonstrated good diagnostic performance for liver steatosis ≥ S1 in the overall cohort, normal-weight group, and overweight group, with AUROCs of 0.880, 0.922, and 0.829, respectively. Its diagnostic performance for liver steatosis ≥ S2 and S3 was consistent with most previous clinical studies[22,26]. According to the research of Chan et al.[26], the reduced performance of CAP in grading steatosis may be related to substantial data overlap among S1, S2, and S3, as shown in Supplementary Figure 1. As the grade of hepatic steatosis increases, the upward trend in CAP becomes less pronounced, highlighting significant limitations in diagnosing patients with moderate to severe fatty liver.

CAP performance is significantly influenced by BMI. This study found that CAP values were independently correlated with BMI, and the ability of CAP to estimate hepatic steatosis was significantly reduced in overweight subjects compared to normal-weight subjects. The degree of hepatic steatosis is positively correlated with BMI, which is also significantly correlated with the thickness of the abdominal fat layer in patients[27]. Abdominal fat can interfere with VCTE. Individuals with high BMI have thicker subcutaneous fat layers, which can affect ultrasound penetration, leading to reduced CAP accuracy and subsequently diminished classification efficacy. This suggests that using a single cutoff value for patient classification has limitations. After differentiating patient populations by BMI, the diagnostic efficacy of CAP for steatosis grading in normal-weight patients can be significantly improved. Future validation with larger sample sizes is required, and it is recommended that different CAP diagnostic cutoffs be used for MASLD patients with different BMIs. In addition, probe type can affect CAP measurement accuracy. Our study exclusively utilized the M-probe for CAP measurements across all patients, providing internal consistency for our dataset and derived thresholds. However, CAP performance can be influenced by body habitus. Research has shown that the M-probe’s efficacy may be reduced in individuals with high BMI, as a thicker subcutaneous fat layer can attenuate ultrasound signals. In such cases, the extra-large (XL) probe is recommended to improve measurement success and accuracy. Therefore, while our findings define M-probe-specific thresholds, future studies should consider BMI-adapted probe selection (M or XL) to further optimize diagnostic performance across the MASLD spectrum. This represents an important direction for standardizing and refining the clinical application of CAP[28]. Another study indicated that different operators or different measurement times for the same operator can inevitably introduce variability in CAP values. Although inter-operator differences are not significant, small gaps between cutoff values can lead to inconsistent classification of liver steatosis and reduced diagnostic efficacy of CAP[29].

In short, this study further demonstrates that CAP can effectively and rapidly assess liver steatosis noninvasively, with superior performance in detecting significant steatosis. CAP also performs better when applied in BMI-stratified diagnosis and is worthy of clinical adoption. Future studies with larger clinical samples and diverse population compositions are needed to refine the assessment of significant steatosis in MASLD patients, further improve CAP’s diagnostic efficacy across different steatosis grades, and enhance its standardized clinical application. Moreover, ongoing technological advances in detection instruments provide greater opportunities for the efficient clinical use of CAP in the future.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the participants who took part in this study. We also thank the clinical and research staff at the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, for their invaluable assistance in patient recruitment, data collection, and technical support.

Authors’ contributions

Collected and organized the data: Su N, Jin Z, Huang D, Fang Y, Liu T

Took charge of data analysis and processing and drafted the initial manuscript: Su N, Jin Z, Zhou D

Responsible for reviewing and revising it: Zhou D, Fang Y

Availability of data and materials

The clinical and imaging data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available, as they contain information that could compromise research participants’ privacy. However, these data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to approval by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China [Approval No. (B2020-085R)]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018;24:908-22.

2. Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77:1335-47.

4. Targher G, Tilg H, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a multisystem disease requiring a multidisciplinary and holistic approach. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:578-88.

5. Masoodi M, Gastaldelli A, Hyötyläinen T, et al. Metabolomics and lipidomics in NAFLD: biomarkers and non-invasive diagnostic tests. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:835-56.

6. Tincopa MA, Loomba R. Non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:660-70.

7. Saadeh S, Younossi ZM, Remer EM, et al. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:745-50.

8. Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, et al; LIDO Study Group. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1898-906.

9. Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:729-49.

10. Sirli R, Sporea I. Controlled attenuation parameter for quantification of steatosis: which cut-offs to use? Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:6662760.

11. Karlas T, Petroff D, Sasso M, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) technology for assessing steatosis. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1022-30.

12. Jan A, Weir C. BMI classification percentile and cut off points. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337153906_BMI_Classification_Percentile_And_Cut_Off_Points. [Last accessed on 6 Jan 2026].

13. Li Y, Hu Z, Xie T, et al. The correlation of body mass index (BMI) and transient elastography parameters. Journal of Rare Diseases. 2022;29:101-3. (in Chinese).

14. Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of metabolic dysfunction-associated (non-alcoholic) fatty liver disease (Version 2024)]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2024;32:418-34. (in Chinese).

15. Duan Y, Pan X, Luo J, et al. Association of inflammatory cytokines with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:880298.

16. Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69:896-904.

17. Rinella ME, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Siddiqui MS, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on the clinical assessment and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2023;77:1797-835.

18. Eslam M, Sarin SK, Wong VW, et al. The Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2020;14:889-919.

19. Beyer C, Hutton C, Andersson A, et al. Comparison between magnetic resonance and ultrasound-derived indicators of hepatic steatosis in a pooled NAFLD cohort. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0249491.

20. Ferraioli G, Maiocchi L, Savietto G, et al. Performance of the attenuation imaging technology in the detection of liver steatosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40:1325-32.

21. Petroff D, Blank V, Newsome PN, et al. Assessment of hepatic steatosis by controlled attenuation parameter using the M and XL probes: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:185-98.

22. Myers RP, Pollett A, Kirsch R, et al. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a noninvasive method for the detection of hepatic steatosis based on transient elastography. Liver Int. 2012;32:902-10.

23. Kumar M, Rastogi A, Singh T, et al. Controlled attenuation parameter for non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis: does etiology affect performance? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1194-201.

24. Chon YE, Jung KS, Kim SU, et al. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) for detection of hepatic steatosis in patients with chronic liver diseases: a prospective study of a native Korean population. Liver Int. 2014;34:102-9.

25. Masaki K, Takaki S, Hyogo H, et al. Utility of controlled attenuation parameter measurement for assessing liver steatosis in Japanese patients with chronic liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:1182-9.

26. Chan WK, Nik Mustapha NR, Mahadeva S. Controlled attenuation parameter for the detection and quantification of hepatic steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1470-6.

27. Zhou Y, Sun Y, Qiao Q, et al. Correlation between body fat distribution measured by quantitative CT and body mass index in adults receiving physical examination. Chin J Health Manag. 2024;18:354-60. (in Chinese).

28. Sporea I, Șirli R, Mare R, Popescu A, Ivașcu SC. Feasibility of Transient Elastography with M and XL probes in real life. Med Ultrason. 2016;18:7-10.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].