Chronic inflammation and immune response in hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive literature review

Abstract

Chronic inflammation is an established driver of tumorigenesis across multiple organs, including the liver. Yet, the precise mechanisms linking persistent inflammatory signaling to tumorigenesis remain unclear. While classic tumor immunology focuses on immune-mediated tumor eradication, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), growing evidence highlights a paradoxical immune capacity to foster malignant growth. HCC is a major health burden, most often arising in the setting of chronic inflammatory liver disease and cirrhosis. Nonetheless, some HCC cases occur in patients lacking cirrhosis or its traditional triggers, underscoring gaps in our mechanistic understanding. The immune system orchestrates a highly regulated defense network; however, neoplastic cells can subvert this network by sculpting an immune-modulating milieu that mimics protective inflammation while promoting tumor survival and expansion. In HCC, immune influences are bidirectional and stage dependent. As liver disease evolves to cirrhosis, the interplay among the inflammatory response, immune response, cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction syndrome, and the tumor microenvironment becomes increasingly intricate. This review delineates these overlapping but distinct processes, dissects their individual contributions to HCC pathogenesis, and highlights immune-cell compositional changes across disease stages. We contrast protective immune-inflammatory responses that contain early chronic liver injury with the pro-tumorigenic environment characteristic of cirrhosis. Finally, we propose that mapping stage-specific biomarker signatures could transform inflammatory staging into a precision modality, informing immune-based prevention strategies and guiding individualized systemic therapies for HCC.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for about 90 % of primary liver cancers and is projected to surpass one million cases annually by 2025[1,2]. Regardless of etiology, repeated hepatocyte injury elicits immune and inflammatory reactions that shape every stage of hepatocarcinogenesis, from early protective immune surveillance to the protumor milieu of cirrhosis[3].

Traditional tumor-immunology emphasized the immune system’s capacity to eliminate transformed cells[4]. Yet chronic, dysregulated inflammation can do the opposite: foster angiogenesis, genomic instability, and immune evasion, ultimately accelerating HCC[5-8]. Understanding when inflammation switches from guardian to accomplice is therefore paramount.

In this review, we aim to:

• Differentiate immune processes across the disease continuum (protective surveillance, unresolved chronic inflammation, and immune exhaustion) and clarify their respective molecular cues.

• Dispel the notion of “one-size-fits-all” inflammation by mapping stage-specific pathways and biomarker patterns linked to distinct risk profiles.

• Highlight therapeutic implications, arguing that modulating harmful inflammation - rather than blanket immunosuppression - offers a more precise route to HCC prevention and personalized systemic therapy.

By tracing how the liver’s inherently tolerogenic environment, robust regenerative capacity, and lifelong antigen exposure interact with chronic injury, we present a framework for distinguishing beneficial immunity from tumor-promoting inflammation. This perspective is essential for advancing biomarker-guided strategies that match the right anti-inflammatory or immune-activating interventions to the right patient at the right disease stage.

PATHOLOGICAL INFLAMMATION: THE GATEWAY TO HEPATIC IMMUNE DYSREGULATION

Acute immune-inflammatory reactions usually subside within days; however, when dysregulated, they undermine host defense, ushering in a state of immune dysregulation. This is defined as chronic self-propagating inflammatory activation that overrides normal regulatory brakes[9]. The liver is uniquely vulnerable to repeated hepatocyte injury from metabolic, viral, or toxic insults, generating a self-perpetuating loop of cell death, danger signaling, and maladaptive repair.

Stressed hepatocytes provoke Kupffer-cell cytokines that recruit neutrophils and monocytes, while hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) deposit collagen[10]. Fibrosis stiffens sinusoids and heightens oxidative stress[11]. Importantly, the precise cytokine and cellular profile that follows is dictated by the upstream trigger, whether persistent viral antigens or lipotoxic metabolic stress, setting two divergent tracks of immune dysregulation.

As cirrhosis advances, patients frequently develop cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction syndrome (CAIDS), a downstream consequence of the fibrotic process. CAIDS is marked by the paradoxical coexistence of sustained systemic inflammation and profound immune paresis. This dual dysfunction heightens susceptibility to infection and enables tumor immune escape through impaired antigen presentation and T-cell anergy[12]. The resulting micro-environment fosters genomic instability, angiogenesis, and immune escape, accelerating hepatocarcinogenesis[12,13].

UNDERSTANDING THE UNIQUE CONTRIBUTION OF INFLAMMATION ON HCC: A FIVE-STAGE EVOLUTION FROM CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE TO CANCER

Chronic Liver Disease (CLD) represents a spectrum of progressive liver injuries that result from sustained inflammation and immune dysregulation, often leading to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ultimately HCC. Unlike acute liver injury, CLD progresses through multiple distinct yet interrelated pathogenic pathways, reflecting the complex biology of liver tissue and its unique immunological environment[14].

A proper understanding of the immune system’s role in CLD and HCC pathogenesis requires an appreciation of the liver’s distinctive immunological features and how they respond to specific inflammatory insults over time. Each inflammatory milestone (whether triggered by metabolic, infectious, toxic, or autoimmune factors) elicits a characteristic immunopathological response that shapes disease progression differently[15,16]. For clarity and structure, this review categorizes CLD progression into two major, interlinked pathways:

• Fibrosis-Driven Progression, which encompasses the transition from liver injury to fibrosis, and eventually to cirrhosis; and

• Oncogenic-Driven Progression, which focuses on the transformation of chronically inflamed liver tissue into a tumor-permissive microenvironment and malignant state.

Within these two overarching pathways, five key inflammatory and immunological processes will be examined. Although these processes are described distinctly, they often occur concurrently or in overlapping patterns during the course of the disease. This layered complexity underlines the importance of dissecting each process individually while recognizing their interactions in the broader context of CLD evolution.

Pathway 1: CLD progression via fibrosis and cirrhosis (3 Key processes)

Process 1: initial exposure, acute inflammation, and initial immune response

The liver is uniquely positioned at the interface between the gut and systemic circulation, continuously exposed to dietary antigens and low levels of endotoxins such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from commensal gut microbiota. Approximately 30% of the liver's function is immunological in nature[17]. To cope with this constant antigenic load, the liver has evolved specialized self-defense mechanisms mediated by a diverse array of hepatic immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T (NKT) cells, γδ T cells, and liver-resident macrophages known as Kupffer cells[18]. These immune cells act as frontline sentinels, surveilling hepatic tissue and eliminating potentially harmful agents such as pathogens, toxins, and even early-stage malignant cells[19].

During acute inflammation, proinflammatory mediators are released to coordinate this immune defense, supporting the clearance of exogenous pathogens, infected hepatocytes, and precancerous lesions[20].

The liver maintains a uniquely high level of immunological tolerance despite the abundance of cytotoxic immune cells. Regulatory T cells (Tregs), primarily characterized by the expression of CD4, CD25, and the transcription factor Forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3), are essential for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing autoimmunity[21]. This is critical in preventing unnecessary immune activation against autoantigens (such as debris from normal cell turnover) and dietary or commensal-derived antigens. The programmed death receptor, also known as PD-1, is a transmembrane protein found on the surface of T cells and B cells. It plays a crucial role in regulating the immune system, acting as an immune checkpoint that prevents excessive T cell activity. PD-1 interacts with its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are expressed on various cells, including tumor cells and antigen-presenting cells[22]. This interaction leads to the suppression of T cell activity, helping to maintain self-tolerance and prevent autoimmunity. The liver achieves this balance through its enrichment of immune cells functionally linked to adaptive immune regulation, which preserves tolerance while still enabling effective pathogen elimination[23].

Furthermore, the liver sinusoidal endothelium cells (LSECs) form the first immunological barrier between circulating blood and liver parenchyma. These endothelial cells express a range of adhesion molecules - such as intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), ICAM-2, vascular adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I and II antigens - that facilitate the selective recruitment and interaction of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes with antigen-presenting cells in the liver. This interaction can lead to either immune activation or the induction of tolerance through the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, notably interleukin (IL)-10 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)[24].

Interestingly, LPS, a microbial product from gut flora, plays a paradoxical role by suppressing hepatic endothelial cell activation and reducing the generation of novel antigens against T lymphocytes[25].

The liver is also home to 5-10 million lymphocytes per gram of tissue, predominantly cytotoxic subsets such as NK and NKT cells, with relatively fewer T and B lymphocytes. NK cells, in particular, exert natural cytotoxicity (without requiring prior antibody sensitization) by releasing key cytokines such as interferons (IFN-α, IFN-β), IL-12, IL-18, and IL-21, contributing to the early elimination of virus-infected and transformed cells[18,26].

In addition to its cellular immune arsenal, the liver serves as a major source of proteins essential to both innate and adaptive immune responses. It synthesizes complement components, acute-phase proteins (e.g., C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, procalcitonin), and a variety of Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), including Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Upon activation, these components drive opsonization, inflammation, and cytotoxic responses, thereby playing a pivotal role in shaping the immune outcome during early hepatic immune challenges[18].

Process 2: chronic exposure-triggered chronic inflammatory response

Prolonged exposure to harmful stimuli leads to sustained liver injury and progressively disrupts the liver's tightly regulated immune equilibrium[27]. As chronic injury persists, a pro-inflammatory microenvironment is established, altering interactions between immune and stromal cells within the hepatic tissue. This environment facilitates exposure-associated chronic inflammation and promotes hepatocellular changes, including unchecked activation of immune cells such as NK cells, which contribute to both viral and autoimmune-driven hepatic inflammation.

The liver contains a distinct subpopulation of γδ T cells that represents approximately 35% of hepatic T cells. These cells, equipped with γδ T-cell receptors (TCRs), produce both Th1(IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) and Th2 (IL-4) cytokines and exert potent cytotoxic effects that can be major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent. Their ability to recognize stress-induced ligands, phosphoantigens, alkylamines, and heat-shock proteins enables them to target infected or transformed cells effectively. In addition to their cytolytic functions, γδ T cells contribute to immunoregulation, particularly through the secretion of IFN-γ[28-30].

HSCs, sometimes previously mischaracterized as Kupffer cells, reside along the sinusoidal walls and constitute approximately 80% of the liver’s macrophage population. These cells act as antigen-presenting cells and, upon activation by microbial or inflammatory stimuli, secrete acute-phase proteins and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α. These cytokines amplify immune responses by stimulating NK cell activation and promoting Th1-type immunity[31]. Hypoxia is the most obvious stimulus for angiogenesis, commonly detected in progressive CLD, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), and angiogenesis may have a major role in sustaining and potentially driving liver fibrogenesis. Hepatic myofibroblasts (MFs), regardless of origin, are critical cells in governing and modulating the interactions between inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrogenesis[32].

Process 3: apoptosis-induced fibrogenesis (cirrhosis)

Persistent exposure to damaging factors drives hepatocyte apoptosis and fibrogenesis, ultimately leading to cirrhosis. Initially, fibrotic scarring serves as a protective mechanism to compartmentalize injury and preserve functional liver tissue[11,13]. While healthy hepatocytes can regenerate and compensate, the immune system begins to exhibit paradoxical responses at this stage. Cirrhosis-associated chronic inflammation simultaneously attempts to eliminate pathogens while recruiting and activating monocytes and lymphocytes. This process activates a maladaptive cycle of inflammation, tissue remodeling, angiogenesis mediators namely vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibrosis[13].

Cirrhosis fundamentally disrupts the liver's architecture, compromising both its metabolic and immune functions. Damage to the reticuloendothelial system impairs antigen clearance and protein synthesis which may lead to weakened innate immunity. CAIDS manifests as a combination of systemic inflammation and immunodeficiency, a dynamic imbalance that evolves as disease progresses from compensated to decompensated stages[13,33,34].

Early cirrhosis is marked by a strong innate immune response, with pro-inflammatory neutrophils (N1-type) and macrophages (M1-type) releasing large quantities of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. However, as cirrhosis advances, there is a shift toward immune exhaustion and dysfunction. Monocytes downregulate activation markers (e.g., human leukocyte antigen, isotype DR (HLA-DR)) and fail to produce TNF-α in response to stimuli such as LPS. Lymphopenia, specifically affecting T and B cells, coupled with NK cell depletion, further exacerbates immune surveillance failure. Hyperproduction of immunoglobulin (Ig)A and impaired synthesis of IgG erode immunological memory, while Kupffer cells decline in number and function, increasing susceptibility to endotoxemia and infections[35-38]. Compounding these cellular abnormalities, the liver's synthetic failure results in disrupted production of acute-phase proteins, complement factors, and PRRs, weakening defenses against pathogens. Serum cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and their soluble receptors increase, indicating dysfunctional cytokine signaling, exemplified by resistance to IL-6 through elevated soluble glycoprotein 130 (sgp130) levels[39,40]. Systemic inflammation in cirrhosis is driven by continuous exposure to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from increased gut permeability and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from necrotic hepatocytes. PRR signaling in gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), mesenteric lymph nodes, and peripheral blood activates immune cells and propagates inflammation beyond the liver[11,33,35].

Pathologic liver angiogenesis diverges sharply from the brisk, self-limited neovascularization that supports physiologic regeneration. Chronic hypoxia in progressive liver disease stabilizes HIFs and drives sustained secretion of VEGF, PDGF, and other atypical pro-angiogenic signals from hepatocytes and macrophages. Critically, chronic hypoxia also activates HSCs that have transdifferentiated into contractile, pericyte-like MFs. These HSC/MFs coordinate with LSECs and release profibrogenic microparticles, linking inflammation, sinusoidal remodeling, and fibrogenesis. Meanwhile, C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2)-dependent recruitment of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)-responsive lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C (Ly6C)+ monocytes expand a macrophage pool that amplifies cytokine release, angiogenesis, and extracellular-matrix deposition, accelerating fibrosis, portal hypertension, and the transition to cirrhosis. The resulting maladaptive vascular network both sustains fibrogenesis and establishes a microenvironment conducive to HCC, emphasizing how the same angiogenic machinery that enables physiologic repair becomes pathologic when chronically activated[32].

In addition to structural damage, cirrhotic patients experience qualitative changes in albumin that impair its antioxidant and immunomodulatory functions, further weakening systemic immunity and exacerbating inflammation.

In summary, fibrogenesis not only crystallizes as a pathological endpoint but actively modulates the immune system. Cirrhosis represents a critical tipping point in liver disease progression. Meanwhile, the early stages of cirrhosis are characterized by excessive immune activation and inflammation. Advanced cirrhosis exacerbates systemic inflammation, disrupts vascular homeostasis, exhausts immune mechanisms, and fosters a paradoxical immunosuppressive state. CAIDS exemplifies the complexity of cirrhosis pathophysiology and underscores the urgent need for targeted immunomodulatory therapies.

Pathway 2: CLD-driven HCC development (2 key processes)

Process 4: cell mutations and the pro-tumorigenic pathway

In parallel with the processes of apoptosis, fibrogenesis, and cirrhosis, liver injury caused by chronic risk factors also initiates a distinct carcinogenic pathway[34]. While initially separate, this pathway progressively converges with fibrogenesis and cirrhosis during the advanced stages of liver disease, establishing a complex interplay between immune dysregulation, inflammation, and tumorigenesis.

The development of HCC involves a dynamic interaction between tumor cells and the host immune system, a process known as cancer immunoediting. This unfolds in three phases: Elimination, Equilibrium, and Escape[41]. In the Elimination phase, the immune system uses both innate and adaptive mechanisms to actively identify and destroy transformed cells. Cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes are the principal effectors in this process, guided by transcription factors, cytokines, and chemokines that direct their differentiation and activity. CD4+ T helper cells support this function by sustaining CD8+ T cell responses and preventing their exhaustion[42].

At early stages of tumorigenesis, particularly before the onset of cirrhosis, the immune system remains competent, and immune surveillance effectively suppresses malignant transformation. The inflammatory response during this phase is largely antitumorigenic, exerting protective effects with minimal contribution to the pathogenesis of HCC[43].

Process 5: tumorigenesis and the promotion of a harmful inflammatory response (TME)

As liver injury progresses and cirrhosis develops, immune evasion mechanisms are increasingly activated. The tumor microenvironment (TME) shifts toward immunosuppression, allowing mutated hepatocytes to escape immune detection and promoting tumor growth. This immunological transition marks a critical shift in the disease course and links the fibrotic and pro-tumorigenic pathways[7].

During cancer immunoediting, sporadic tumor cells that evade immune destruction may enter an equilibrium phase where selective pressure by the immune system continues to shape their properties. Eventually, these immunologically sculpted tumor cells may progress to the "escape" phase (characterized by unchecked proliferation, clinical manifestation, and the establishment of carcinogenesis-associated inflammation). This process leads to the infiltration of immune cells into the tumor and surrounding tissues, contributing to tissue remodeling and dysfunction[34,35]. The collection of immune and non-immune cells surrounding the tumor, such as T lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), constitutes the TME. The TME plays a dual role in tumor progression. On one hand, it supports immune surveillance and immunoediting; on the other, it facilitates tumor growth, metastasis, and immune escape[44]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) contribute significantly to tumor progression by promoting cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis, dissemination, and immune evasion. In addition to classical stromal and immune components, recent work has shown that intratumoral bacterial, fungal, and viral communities constitute a further layer of TME heterogeneity[45-47], reshaping myeloid polarization, checkpoint expression, and metabolic signaling and thereby influencing both tumor progression and responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors[47-49]. In HCC, chronic inflammation leads to elevated expression of cytokines and chemokines, such as PD-L1, PD-L2 and CCL2 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1), which recruits monocytes that differentiate into immunosuppressive macrophages (M2-type) within the TME[50]. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are both ligands that bind to the PD-1 receptor, but they differ in their expression and function. PD-L1 is widely expressed on various cell types, including hematopoietic, non-hematopoietic, and tumor cells; PD-L2 is primarily expressed on dendritic cells and macrophages[51]. This shift heralds immune dysfunction, a phase distinct from earlier dysregulation and characterized by exhausted T- and NK-cell phenotypes, tolerogenic TAMs, and ineffective antigen presentation, collectively crippling anti-tumor surveillance.

Numerous studies confirm that interactions between tumor cells and their microenvironment inhibit anti-tumor immunity by activating and recruiting immunosuppressive cells. This promotes tumor immune evasion and reprograms immune cells to support malignancy. The resulting dysregulated cytokine and chemokine profiles, along with increased reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS, RNS), promote fibrosis, cirrhosis, and malignant transformation. These changes within the TME are key drivers of HCC development, progression, and therapy resistance[52].

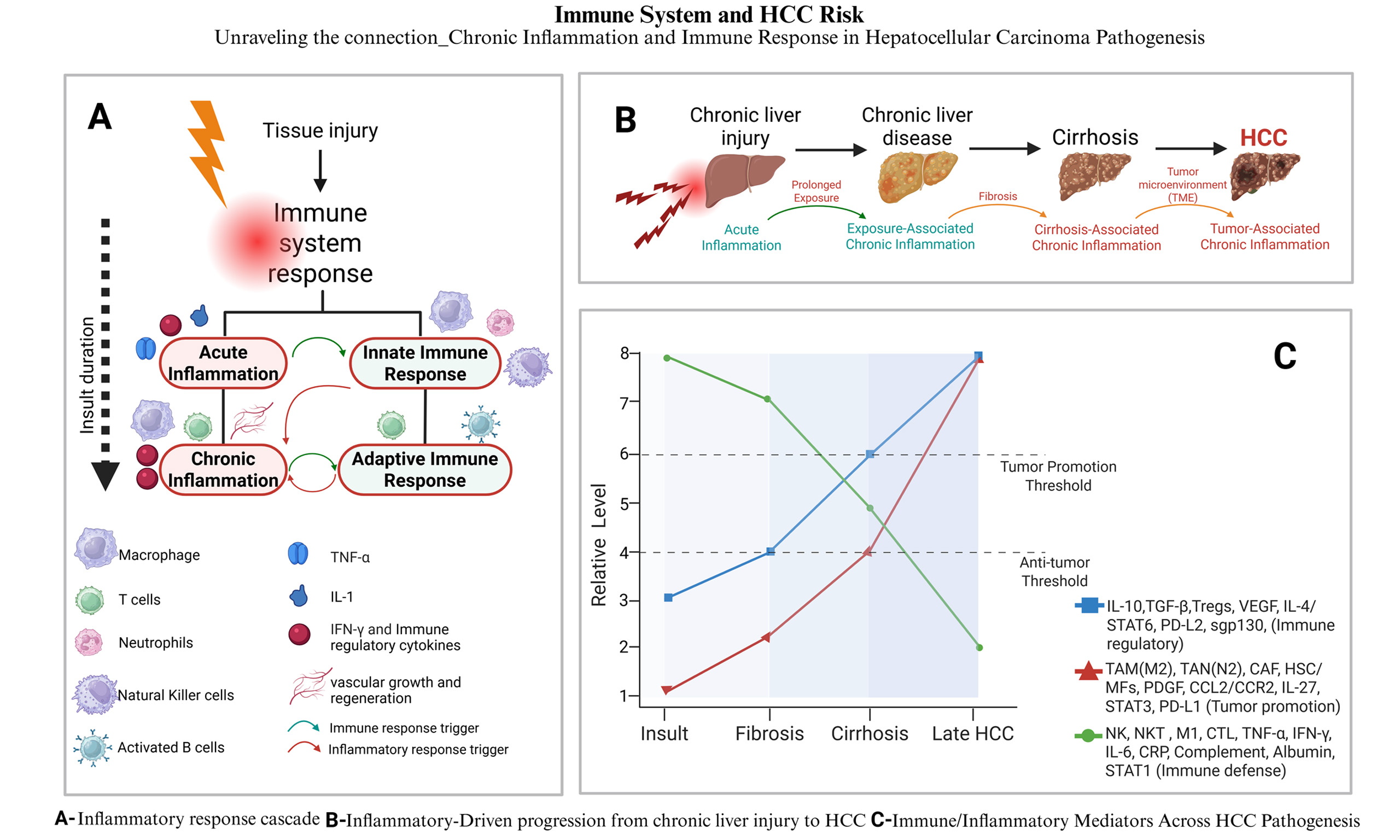

In summary, the pathogenesis of HCC involves a dynamic interplay between chronic liver inflammation and an increasingly immunosuppressive TME. Chronic injury activates HSCs, which stimulate fibrogenesis and angiogenesis, while immune cells such as TAMs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and Tregs secrete immunosuppressive mediators and express checkpoint molecules (IL-10, TGF-β, PD-L1/PD-L2, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) ligands). Within this environment, CD8+ T cells acquire a PD-1 high exhausted phenotype and are physically excluded from tumor nests by aberrant vasculature and dense, CAF-rich stroma. High densities of PD-L1+ TAMs and Tregs further limit the pool of effector cells that can be re-invigorated by PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, contributing to both primary and acquired resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Dissecting and therapeutically targeting this cellular and molecular crosstalk, including TAM recruitment and polarization, stromal remodeling, and co-inhibitory signaling, is therefore essential not only for reducing HCC risk but also for improving the depth and durability of responses to immunotherapy[53,54] (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual roadmap linking liver injury, inflammation, and immune dysregulation to either cirrhosis or HCC: Chronic liver injury can diverge into two mechanistically distinct yet overlapping trajectories once acute inflammation becomes persistent. In the fibrogenic axis (blue, Pathway A), ongoing injury sustains exposure-associated chronic inflammation that matures into cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction (CAIDS) and ultimately cirrhosis (timeline cues 1 → 2 → 3)[55]. In parallel, the same chronic insult can trigger a mutation-driven, immunosuppressive axis (red, Pathway B): DNA damage and progressive immune exhaustion create a tumor-promoting micro-environment (TME), allowing hyperplasia, dysplasia, and progression to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (cues 4 → 5). The “fork” after step 2 represents the point at which repair-dominant (fibrogenic) vs. mutation-dominant (oncogenic) programs dictate whether cirrhosis, HCC, or both emerge from the shared inflammatory milieu. CAIDS: Cirrhosis-associated immune-dysfunction syndrome; TME: tumor micro-environment. Created in BioRender. Alsudaney, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/uvlt8j2.

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION AND HCC RISK: TRIGGER-BASED STRATIFICATION

In CLD, three distinct inflammatory processes evolve, each with different mechanisms and immunological contributions to HCC risk, depending on the underlying trigger and stage of disease:

Exposure-associated (acute and chronic) inflammation

In response to infectious or toxic insults, the liver initiates a pro-inflammatory microenvironment characterized by hepatocellular changes that alter immune and stromal cell interactions. This environment promotes the destruction of infected or damaged cells and counters carcinogenic transformations, while simultaneously preserving immunological tolerance and preventing autoimmunity.

Key features of this response include activation of NK and NKT cells, which produce Th1 (IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α) and Th2 (IL-4) cytokines, as well as a mixed Th0 profile (co-expression of IFN-γ and IL-4). Additionally, γδ T cells contribute by producing both Th1 and Th2 cytokines. HSCs also play a role by acting as antigen-presenting cells that secrete acute-phase proteins and cytokines (particularly IL-12 and TNF-α), thereby promoting Th1-type immune responses and NK cell activation. Beyond resident Kupffer cells, acute hepatic injury rapidly mobilizes CCR2+ bone marrow-derived monocytes from the circulation. Once recruited to the liver, these monocytes differentiate into effector macrophages that can adopt either pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotypes, characterized by high production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and reactive oxygen species, or reparative M2-like phenotypes, secreting IL-10, TGF-β, and matrix-modifying factors. The dynamic balance between these bone marrow-derived macrophage states helps determine whether exposure-associated inflammation resolves and restores homeostasis or instead becomes self-perpetuating and fibrogenic, predisposing to cirrhosis and HCC[10,32,33] (See Table 1).

Exposure-associated (acute & early-chronic) inflammation

| Principal actors | Hallmark mediators/markers | Net effect on liver & HCC risk |

| NK/NKT cells | IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α (Th1); IL-4 (Th2)[17,18,20,26,28-33] | Rapid cytotoxic clearance of infected/damaged hepatocytes while preserving tolerance |

| γδ T cells | Mixed IFN-γ + IL-4 (Th0) profile[17,18,20,26,28-33] | Bridging innate-adaptive immunity; amplifies early antiviral/antitumor defense |

| Kupffer cells | Pattern-recognition (TLR4) activation → TNF-α, IL-1β[17,18,20,26,28-33] | Orchestrate neutrophil recruitment; initiate acute‐phase response |

| Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) | IL-12, acute-phase proteins (e.g., CRP, fibrinogen, procalcitonin)[17,18,20,26,28-33] | Antigen presentation, bolster NK-cell activation and Th1 deviation |

| Soluble components | Complement, ROS/RNS bursts[17,18,20,26,28-33] | Pathogen opsonization and initial tissue repair |

However, when infectious, metabolic, or toxic insults persist, this initially protective program becomes chronically engaged, leading to unresolved cell death, sustained DAMP/PAMP exposure, and progressive skewing of innate and adaptive responses toward the cirrhosis-associated CAIDS phenotype described in the next subsection.

Cirrhosis-associated chronic inflammation

Cirrhosis induces a paradoxical inflammatory state characterized by simultaneous immune activation and immune deficiency (CAIDS). This condition results from widespread abnormalities in both cellular and soluble immune components, affecting liver and systemic immune responses. In early cirrhosis, neutrophils dominate the inflammatory milieu (N1-type), producing large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and expressing activation markers such as CD11b and CD62L. Macrophages at this stage typically display an anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotype, contributing to tissue repair. However, both quantitative and qualitative lymphopenia and albumin abnormalities are also observed.

In advanced cirrhosis, macrophages undergo phenotypic switching toward a pro-inflammatory (M1) state, persistently releasing TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and their soluble receptors (e.g., sgp130). Additional hallmarks include increased IgA production, reduced IgG levels, and upregulation of innate immune receptors such as TLRs, NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and PRRs (See Table 2).

Cirrhosis-associated chronic inflammation (CAIDS)

| Principal actors/stage | Hallmark mediators/markers | Net effect on liver & HCC risk |

| Early cirrhosis (N1 Neutrophils) | TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; CD11b↑, CD62L↑[13,32-40,55] | Persistent pro-inflammatory drive; ROS-mediated hepatocyte injury |

| Early cirrhosis (M2 Macrophages) | IL-10, TGF-β[13,32-40,55] | Tissue-repair bias, but seeds fibrogenesis |

| Progressive fibrosis | TLR/NLR/PRR upregulation; sgp130[13,32-40,55] | Heightened PAMP/DAMP sensing, systemic cytokine spill-over |

| Advanced cirrhosis (M1 switch) | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β (sustained)[13,32-40,55] | Hyper-inflammation plus immune exhaustion; angiogenic VEGF surge |

| Humoral/systemic changes | IgA↑, IgG↓, oxidized albumin; lymphopenia[13,32-40,55] | Compromised antigen clearance, weakened adaptive memory, portal hypertensive environment |

These cirrhosis-related defects in innate killing, antigen presentation, and lymphocyte trafficking directly set the stage for the final, tumor-associated inflammatory state, in which an immunosuppressive, pro-angiogenic TME consolidates immune escape and supports clinically overt HCC, as summarized in the following section.

HCC-associated chronic inflammation

In HCC, cancer-driven inflammation creates an immunosuppressive tumor environment that supports tumor growth. This environment suppresses effective anti-tumor immunity by recruiting and reprogramming immune cells with immunosuppressive phenotypes. Tumor cells exploit these conditions to evade immune detection and support their own growth and survival.

Components of the TME in HCC:

• CAFs: CAFs are defined by a combination of their morphology, association with cancer cells, and lack of lineage markers for epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and hematopoietic cells. CAFs secrete growth factors (epidermal growth factor (EGF), PDGF), immunomodulatory cytokines, chemokines (e.g., C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 11 (CXCL11)), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), driving inflammation and tumor progression. CAFs express proangiogenic factors such as VEGF and angiopoietin-1, facilitating tumor vascularization. CAFs inhibit NK cell activity by producing Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO), and blocking activating receptors (e.g., NK cell p30-related protein (NKp30)). NK cells, which ordinarily mediate cytotoxicity via natural killer group 2, member 2 (NKG2D) and Fas ligand (FasL), are suppressed within the TME due to CAF-derived signals and immune checkpoints such as PD-1/PD-L1[56-59]. Clinically, dual PD-L1 and VEGF blockade with atezolizumab + bevacizumab improved recurrence-free survival in high-risk patients in the phase III IMbrave050 adjuvant trial, reinforcing the pathogenic role of VEGF-driven immunosuppression in HCC[60].

• Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs): LSECs are fenestrated cells forming a barrier between hepatocytes and sinusoidal blood. In chronic disease, they lose fenestration (capillarization), contributing to fibrosis and TME remodeling. LSEC trans differentiation and the loss of several LSEC markers are hallmarks of HCC[61]. HCC tumor progression is associated with phenotypic changes in peri-tumoral LSEC and increased production of angiogenic factors (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, VEGF, and PDGF)[61]. LSECs can cross-present antigens and induce CD8+ T cell tolerance, facilitating immune evasion. In HCC, LSECs overexpress PD-L1, further suppressing cytotoxic T cell activity.

• TAMs and Monocytes: Recruited by chemokines such as CCL2, monocytes differentiate into TAMs (predominantly M2-type), which suppress anti-tumor immunity and promote tumor growth. In addition to driving NK-cell dysfunction through CD48/2B4 interactions, TAMs directly inhibit CD8+ effector T cells by expressing high levels of PD-L1/PD-L2 and other co-inhibitory ligands and by secreting IL-10, TGF-β, arginase and adenosine. These signals reduce CD8+ T-cell infiltration, proliferation and cytotoxicity within the tumor bed. TAMs also release adenosine, which sustains a Ki67 high macrophage population linked to poor prognosis, further consolidating an immunosuppressive TME[62-67].

• T Cell Dysfunction and Exhaustion: Chronic inflammation, metabolic byproducts (kynurenine, S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA)), and immune checkpoints (PD-1, CTLA-4) contribute to T cell exhaustion. These molecules impair T cell proliferation and cytokine production. PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4/CD80-86 interactions suppress mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/extracellular signal–regulated kinase signaling pathway (ERK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/(protein kinase B) signaling pathway (AKT) pathways, crucial for T cell function[68-71]. Reversing this exhaustion translates to a durable benefit: the STRIDE regimen (single-dose tremelimumab + durvalumab) delivered a 5-year overall-survival advantage vs. sorafenib in the phase III HIMALAYA (NCT03298451) update, confirming the therapeutic value of simultaneous CTLA-4 and PD-L1 blockade[72]. Other dual-checkpoint strategies, such as nivolumab plus ipilimumab, likewise exploit complementary PD-(L)1 and CTLA-4 blockade and achieve higher objective response rates than PD-1 monotherapy in advanced HCC, albeit with increased immune-related toxicity. Together with PD-(L)1/VEGF and PD-1/tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) combinations described in other sections, these regimens illustrate how rationally designed immunotherapy combinations are reshaping first-line treatment and are being tested in peri-operative and intermediate-stage trials[73]. Among intratumoral lymphocytes, tissue-resident memory (Trm) CD8+ T cells have emerged as key orchestrators of local immune surveillance. These CD69+CD103+ cells persist long-term within the liver and can rapidly produce effector cytokines and cytolytic molecules upon antigen re-encounter, amplifying antigen spreading through cross-priming of dendritic cells and contributing to durable tumor control[73]. High intratumoral Trm signatures correlate with improved responses to immune checkpoint blockade across several solid tumors and have been proposed as biomarkers of immunotherapy benefit[74]. Conversely, in chronically inflamed livers, persistent antigen stimulation and immunosuppressive mediators such as TGF-β, IL-10 and adenosine can drive Trm cells toward an exhausted, PD-1 high state with impaired cytotoxicity. Pre-clinical work indicates that skewing memory differentiation toward functional Trm-like populations enhances liver cancer immunotherapy efficacy[75]. Thus, microenvironmental factors that govern Trm differentiation and maintenance constitute an important component of the HCC TME and a promising target for future stage-specific immunomodulatory strategies. We support this with a recent comprehensive review on combination checkpoint strategies in HCC that summarizes dual-ICI (PD-1/PD-L1 + CTLA-4) and multi-target regimens with curative potential.

• Tregs: Tregs are key immunosuppressive components of the TME[76]. Tregs accumulate in both peripheral blood and tumor tissues, correlating with poor prognosis and advanced disease stages. Mechanistically, Tregs inhibit cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and NK cells via cell-cell contact and secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β. They also modulate dendritic cell function, impairing effective antigen presentation[77]. By fostering an immunosuppressive milieu, Tregs facilitate immune evasion and support tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis in HCC[78].

• Tumor-Associated Neutrophils (TANs): TANs can exist in either a pro-inflammatory or an anti-inflammatory state, known as N1 and N2, respectively. TANs polarize into pro-tumor N2 phenotypes under the influence of TGF-β, TNF, and cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF)-derived factors. N2 TANs express PD-L1, suppress T cells, and release NETs containing MMP-9 and cathepsin G, promoting metastasis. High TAN infiltration correlates with poor prognosis[79-82].

• Cytokines and Chemokines in HCC Progression: IL-6 promotes HCC through trans-signaling via Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT)3/sgp130 factors[83]. IL-27 signals through STAT1 and STAT3. While STAT1 promotes immune activation and tumor suppression, STAT3 acts as an oncogene in hepatocytes, enhancing survival, motility, and immune tolerance[84]. TGF-β initially suppresses tumors but promotes progression in later stages. HCC cells can evade TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition through epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling. TGF-β also promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis, reinforcing tumor development[85]. Complementing systemic cytokine re-wiring, the ongoing phase III LEAP-012 study evaluated pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib in combination with Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE) for intermediate-stage disease[76]; although the regimen improved progression-free survival, the trial was stopped early after interim analysis indicated a low probability of overall survival benefit, underscoring the challenges of intensifying immunotherapy in this setting[86].

Although all chronic liver injuries eventually converge on an immunosuppressive TME, the nature of that suppression differs by etiology. Viral hepatitis (hepatitis B virus (HBV) > hepatitis C virus (HCV)) supplies a constant stream of viral antigens and type I/III interferon signaling, driving early Th1-skewed inflammation that later collapses into PD-1 high, CD28 low exhausted CD8 T cells and FOXP3 + Tregs. Hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) and core proteins up-regulate PD-L1 on Kupffer cells, and HBV can even demethylate the PD-1 promoter, deepening T-cell exhaustion[87]. Autoimmune liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cholangitis lie at the opposite end of this spectrum: they are characterized by numerical and functional defects of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Tregs, reflecting a breakdown of self-tolerance rather than Treg-driven immune suppression. Meta-analytic data confirm that HCC incidence in cirrhosis due to autoimmune etiologies is lower than in HBV- or HCV-related disease, with the lowest risk observed in autoimmune liver diseases even at the cirrhotic stage (new refs). These opposing patterns of Treg abundance and function underscore that the immunosuppressive TME in viral-related HCC is fundamentally distinct from that in HCC arising from autoimmune liver diseases[88]. In contrast, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), formerly termed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), represents a sterile lipotoxic insult. Free cholesterol crystals, saturated fatty acids, and mitochondrial DNA activate the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain–containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and STAT3, recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), polymorphonuclear TANs and STAT3-activated macrophages while depleting effective CD8 T/NKT surveillance. Spatial-proteomics confirms an MDSC-TAM tandem that wires MASH-HCC (historically NASH-HCC) for primary resistance to PD-(L)1 blockade[89]. These distinct immune circuits help explain why HBV-HCC often retains some responsiveness to PD-(L)1-based combinations, whereas MASH-HCC requires additional TAM/MDSC- or STAT3-targeted strategies.

STAT1/STAT6 axis is a pivotal rheostat that determines which PD-1 ligand predominates in the inflamed liver and, by extension, in the HCC TME. IFN-γ-rich, Th1-biased signals activate STAT1 and drive a sharp upsurge of PD-L1 on resident and recruited macrophages, toning down cytotoxic T-cell activity yet permitting controlled tissue repair. In contrast, IL-4/IL-13-dominated, Th2 milieus engage STAT6, selectively imprinting macrophages with PD-L2 and curbing excessive humoral-type inflammation[51]. These mutually exclusive, cytokine-polarized circuits continually reshape checkpoint-ligand geography as chronic hepatitis evolves into cirrhosis and early HCC. Crucially, disrupting this equilibrium with systemic PD-1 blockade can backfire in gastric cancer[90]; the therapy amplified PD-1+ Ki67+ effector T-regs and triggered hyper-progressive disease (a mechanism now being implicated in HCC). In this context, STAT1-high, PD-L1+ TAM clusters correlate with profound T-cell exhaustion and poor prognosis. Integrating STAT-directed PD-L1/PD-L2 dynamics into Process 5 underscores how the shifting Th1/Th2 balance in the liver TME dictates immune-editing outcomes, and why checkpoint-targeted strategies must consider the underlying inflammatory polarity to avoid paradoxical tumor acceleration[66,67] (See Table 3).

HCC-associated chronic inflammation (TME)

| TME component | Hallmark mediators/markers | Tumor-promoting actions |

| Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) | VEGF, PDGF, angiopoietin-1, CXCL11, PGE2, IDO, EGF, MMPs[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Angiogenesis; ECM remodeling; NK-cell inhibition |

| Capillarized LSECs | PD-L1, ICAM-1, VCAM-1[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Antigen cross-presentation that induces CD8+ tolerance; enhances vascular supply |

| TAMs/M2 macrophages | CCL2, PD-L1, PD-L2, adenosine[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Recruit monocytes, exhaust T/NK cells, support tumor metabolism |

| Exhausted T cells & T regs | PD-1, CTLA-4, IL-10, TGF-β[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Suppress effector responses; foster immune escape |

| N2 TANs | PD-L1, NET-derived MMP-9, cathepsin G[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Facilitate invasion and metastasis |

| Cytokine polarity circuits | IL-6/STAT3, IL-27/STAT1, IL-4/STAT6[7,45-52,56-82,86-89] | Dictate PD-L1 vs. PD-L2 dominance; influence response to checkpoint blockade |

Taken together with the preceding stages, this framework therefore depicts a stepwise erosion of immune surveillance, from exposure-associated defense, through cirrhosis-associated CAIDS, to a fully immunosuppressive HCC TME, which provides a rationale for matching immunomodulatory strategies to the dominant immune phenotype at each stage of disease.

CONCLUSION

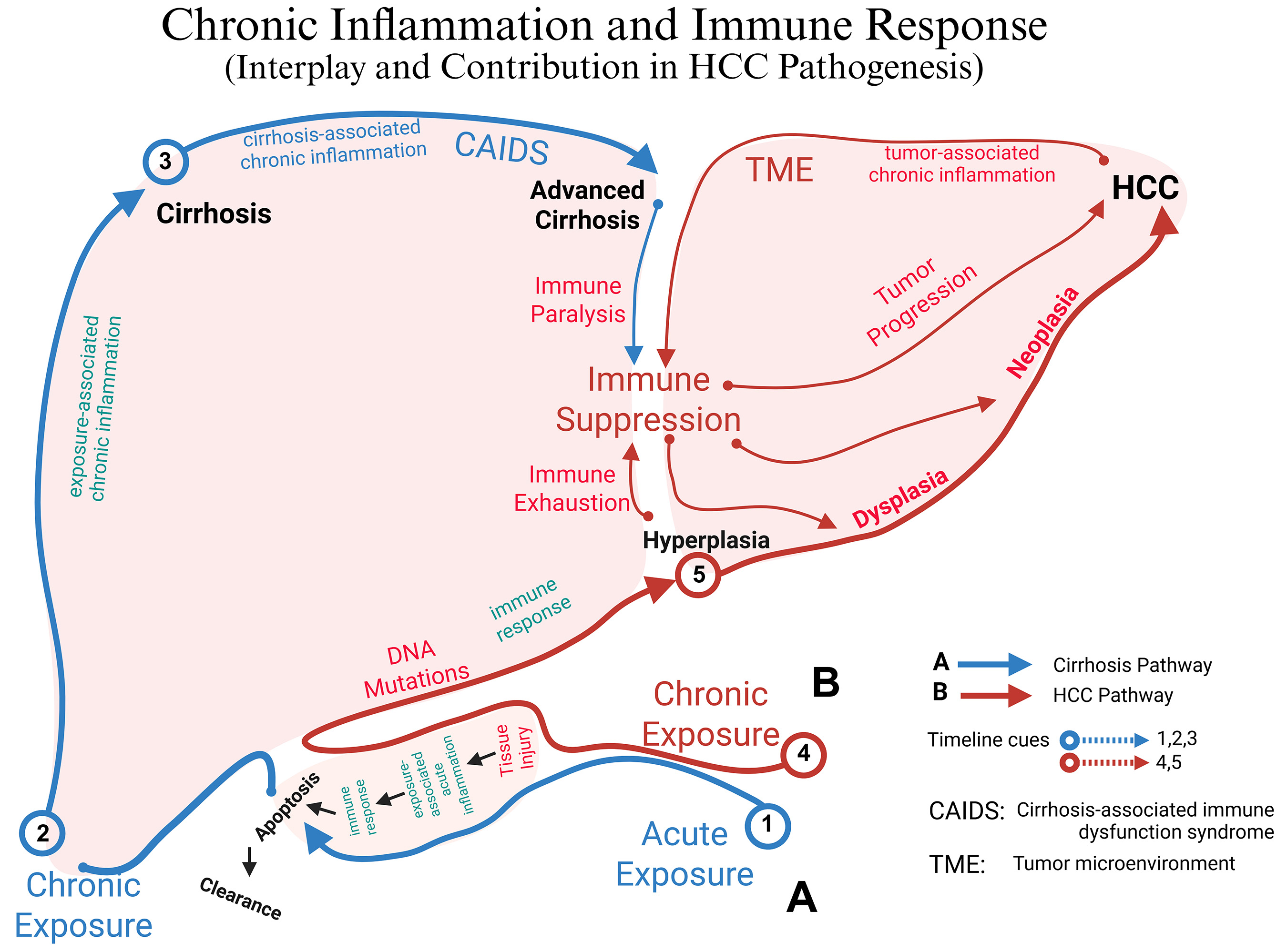

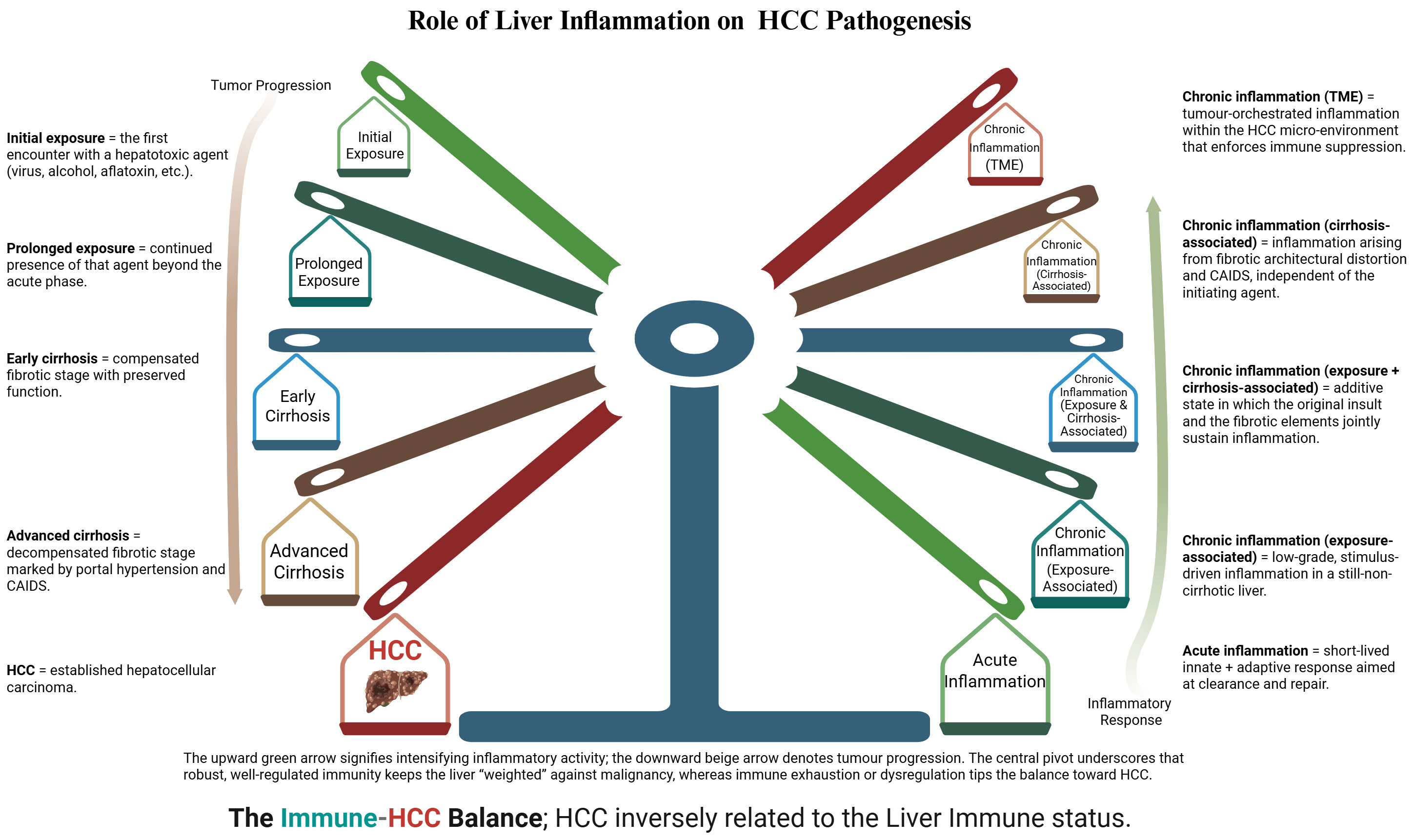

HCC emerges where immune surveillance fails, and chronic inflammation persists. Tumor cells use checkpoints such as PD-1/PD-L1 to silence cytotoxic responses, exploiting mechanisms intended to maintain self-tolerance[34]. In parallel, genetic or acquired immunodeficiencies and (most prominently) advanced cirrhosis, drive CAIDS, eroding antigen presentation and fostering oncogenesis. We recognize three immune/inflammatory stages along this trajectory: (i) exposure-associated inflammation, initially protective and anti-tumorigenic; (ii) cirrhosis-associated inflammation, in which sustained hepatocyte death and fibrosis accelerate HCC initiation; and (iii) tumor-associated inflammation, where the TME entrenches immune escape (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stylized balance illustrating the inverse relationship between hepatic immune competence and HCC risk. The right-hand spokes (shaded green → brown → red) depict the graded inflammatory/immune response to hepatic injury, ranging from acute inflammation through successive layers of chronic inflammation (Exposure-associated, cirrhosis-associated, and tumor-micro-environment-associated). As immune tone weakens and chronicity deepens, the balance tips leftward. Left-hand spokes trace the clinical consequences of that shift - progressing from early to advanced cirrhosis and, ultimately, overt HCC. The opposing arrows reinforce the concept that heightened, effective immune surveillance restrains tumorigenesis, whereas prolonged or dysregulated inflammation erodes immunity and accelerates tumor progression. Created in BioRender. Alsudaney, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/5td954s.

Chronic hypoxia in progressive liver disease locks the liver into a vicious cycle of pathologic angiogenesis: HIF-driven VEGF and PDGF secretion, together with trans-differentiated, pericyte-like HSCs, orchestrates sustained sinusoidal remodeling and fibrogenesis. CCR2-mediated influx of Ly6C monocytes further amplifies cytokine release, extracellular matrix deposition, and aberrant neovascularization, accelerating portal hypertension and cirrhosis. The maladaptive vascular network that emerges not only perpetuates fibrosis but also creates a tumor-permissive microenvironment, directly linking chronic angiogenic signaling to heightened HCC risk.

Cytokine polarity further modulates these stages: IFN-γ/STAT1-driven Th1 signals up-regulate PD-L1 to curb excessive cytotoxicity, whereas IL-4/STAT6-biased Th2 cues induce PD-L2 to temper humoral responses. Unselective PD-1 blockade can therefore expand PD-1 effector T-regs, tilting the TME toward immune evasion and rapid tumor growth.

Effective prevention and therapy must be stage-specific immunomodulation along the exposure-cirrhosis-HCC pathways. In the exposure-associated phase, the priority is removal of inciting viruses, toxins, and metabolic factors and reinforcement of short-lived, pathogen-clearing responses. In cirrhosis, where CAIDS emerges, therapeutic goals shift toward dampening sterile inflammation and portal-hypertension-driven cytokine release while partially restoring antigen presentation and T-cell trafficking; candidate approaches under investigation include CCR2/C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) antagonists, gut-targeted and anti-fibrotic therapies, and interventions such as long-term albumin or non-selective β-blockers that modulate systemic inflammation. In established HCC, rational immune-checkpoint-based combinations that simultaneously target pro-angiogenic signaling, immunosuppressive myeloid subsets, or TGF-β and other stromal barriers are needed to overcome primary resistance, as illustrated by the survival benefits achieved with atezolizumab-bevacizumab, the STRIDE regimen (tremelimumab plus durvalumab), and other PD-1/TKI regimens. Defining and validating biomarker panels that capture these stage-specific immune phenotypes should therefore be a priority for future studies, both to refine HCC risk stratification and to design trials of preventive and therapeutic immunomodulation in chronic liver disease.

DECLARATION

Acknowledgment

The Graphical Abstract is created with BioRender. Alsudaney, M. (2026) https://BioRender.com/638ovlt.

Author contributions

Data acquisition and/or interpretation, critical revision, concept and design: Alsudaney M, Abdulhaleem MN, Attia AM, Liu J, Adetyan H, Khattab O, Hendifar A, Kuo A

Drafting the manuscript: Alsudaney M, Abdulhaleem MN

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was internally supported by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6.

2. Hwang SY, Danpanichkul P, Agopian V, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: updates on epidemiology, surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:S228-54.

3. Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O'Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:222-32.

4. Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331:1565-70.

5. Yu LX, Ling Y, Wang HY. Role of nonresolving inflammation in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2018;2:6.

6. Pinto E, Pelizzaro F, Farinati F, Russo FP. Angiogenesis and hepatocellular carcinoma: from molecular mechanisms to systemic therapies. Medicina. 2023;59:1115.

7. Chen C, Wang Z, Ding Y, Qin Y. Tumor microenvironment-mediated immune evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1133308.

8. Yang YM, Kim SY, Seki E. Inflammation and liver cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:26-42.

11. Roehlen N, Crouchet E, Baumert TF. Liver fibrosis: mechanistic concepts and therapeutic perspectives. Cells. 2020;9:875.

12. Yin Y, Feng W, Chen J, et al. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the progression, metastasis, and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: from bench to bedside. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024;13:72.

13. Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: distinctive features and clinical relevance. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1385-96.

14. Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver-from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:88-110.

15. Robinson MW, Harmon C, O'Farrelly C. Liver immunology and its role in inflammation and homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:267-76.

16. Sharma A, Nagalli S. Chronic liver disease. StatPearls Publishing, 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554597/ [Last accessed on 22 Jan 2026].

18. Gao B, Jeong WI, Tian Z. Liver: an organ with predominant innate immunity. Hepatology. 2008;47:729-36.

19. Ronca V, Gerussi A, Collins P, Parente A, Oo YH, Invernizzi P. The liver as a central "hub" of the immune system: pathophysiological implications. Physiol Rev. 2025;105:493-539.

22. Pedoeem A, Azoulay-Alfaguter I, Strazza M, Silverman GJ, Mor A. Programmed death-1 pathway in cancer and autoimmunity. Clin Immunol. 2014;153:145-52.

23. Hann A, Oo YH, Perera MTPR. Regulatory T-cell therapy in liver transplantation and chronic liver disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:719954.

24. Knolle PA, Wohlleber D. Immunological functions of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:347-53.

25. Schildberg FA, Hegenbarth SI, Schumak B, Scholz K, Limmer A, Knolle PA. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells veto CD8 T cell activation by antigen-presenting dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:957-67.

27. Gufler S, Seeboeck R, Schatz C, Haybaeck J. The translational bridge between inflammation and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cells. 2022;11:533.

28. Sajid M, Liu L, Sun C. The dynamic role of NK cells in liver cancers: role in HCC and HBV associated HCC and its therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2022;13:887186.

29. Gu X, Chu Q, Ma X, et al. New insights into iNKT cells and their roles in liver diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1035950.

30. Zakeri N, Hall A, Swadling L, et al. Characterisation and induction of tissue-resident gamma delta T-cells to target hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1372.

31. Mehrfeld C, Zenner S, Kornek M, Lukacs-Kornek V. The contribution of non-professional antigen-presenting cells to immunity and tolerance in the liver. Front Immunol. 2018;9:635.

32. Bocca C, Novo E, Miglietta A, Parola M. Angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in chronic liver diseases. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1:477-88.

33. Clària J, Stauber RE, Coenraad MJ, et al. Systemic inflammation in decompensated cirrhosis: Characterization and role in acute-on-chronic liver failure. Hepatology. 2016;64:1249-64.

34. Alsudaney M, Ayoub W, Kosari K, et al. Pathophysiology of liver cirrhosis and risk correlation between immune status and the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2025;11:7.

35. Guan H, Zhang X, Kuang M, Yu J. The gut-liver axis in immune remodeling of hepatic cirrhosis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:946628.

36. Maini AA, Becares N, China L, et al. Monocyte dysfunction in decompensated cirrhosis is mediated by the prostaglandin E2-EP4 pathway. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100332.

37. Balazs I, Stadlbauer V. Circulating neutrophil anti-pathogen dysfunction in cirrhosis. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100871.

38. Wheeler MD. Endotoxin and Kupffer cell activation in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:300-6.

39. Tuchendler E, Tuchendler PK, Madej G. Immunodeficiency caused by cirrhosis. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;4:158-64.

40. Lemmers A, Gustot T, Durnez A, et al. An inhibitor of interleukin-6 trans-signalling, sgp130, contributes to impaired acute phase response in human chronic liver disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:518-27.

41. Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:329-60.

42. Sun L, Su Y, Jiao A, Wang X, Zhang B. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:235.

43. Roderburg C, Wree A, Demir M, Schmelzle M, Tacke F. The role of the innate immune system in the development and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Oncol. 2020;7:HEP17.

44. Argentiero A, Delvecchio A, Fasano R, et al. The complexity of the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma and emerging therapeutic developments. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7469.

45. Cao Y, Xia H, Tan X, et al. Intratumoural microbiota: a new frontier in cancer development and therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:15.

46. Xu J, Cheng M, Liu J, Cui M, Yin B, Liang J. Research progress on the impact of intratumoral microbiota on the immune microenvironment of malignant tumors and its role in immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1389446.

47. Wang N, Wu S, Huang L, et al. Intratumoral microbiome: implications for immune modulation and innovative therapeutic strategies in cancer. J Biomed Sci. 2025;32:23.

48. Tan Q, Cao X, Zou F, Wang H, Xiong L, Deng S. Spatial heterogeneity of intratumoral microbiota: a new frontier in cancer immunotherapy resistance. Biomedicines. 2025;13:1261.

49. Gao Z, Jiang A, Li Z, et al. Heterogeneity of intratumoral microbiota within the tumor microenvironment and relationship to tumor development. Med Res. 2025;1:32-61.

50. Li X, Yao W, Yuan Y, et al. Targeting of tumour-infiltrating macrophages via CCL2/CCR2 signalling as a therapeutic strategy against hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66:157-67.

51. Loke P, Allison JP. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are differentially regulated by Th1 and Th2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5336-41.

52. Li Y, Yu Y, Yang L, Wang R. Insights into the role of oxidative stress in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Front Biosci. 2023;28:286.

53. Tong J, Tan Y, Ouyang W, Chang H. Targeting immune checkpoints in hepatocellular carcinoma therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025;14:65.

54. Sen D, Bisht S, Gupta S. Unravelling inflammation-driven mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma: therapeutic targets and potential interventions. Egypt Liver J. 2025;15:446.

55. McGettigan B, Hernandez-Tejero M, Malhi H, Shah V. Immune dysfunction and infection risk in advanced liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2025;168:1085-100.

56. Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:174-86.

57. Butti R, Khaladkar A, Bhardwaj P, Prakasam G. Heterotypic signaling of cancer-associated fibroblasts in shaping the cancer cell drug resistance. Cancer Drug Resist. 2023;6:182-204.

58. Zhang Q, Peng C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate the biological behavior of cancer cells and stroma in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:691-8.

59. Mao X, Xu J, Wang W, et al. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:131.

60. Yopp A, Kudo M, Chen M, et al. LBA39 Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave050: Phase III study of adjuvant atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) vs active surveillance in patients (pts) with resected or ablated high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Onco. 2024;35:S1230.

61. Wilkinson AL, Qurashi M, Shetty S. The role of sinusoidal endothelial cells in the axis of inflammation and cancer within the liver. Front Physiol. 2020;11:990.

62. Kadomoto S, Izumi K, Mizokami A. Roles of CCL2-CCR2 axis in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8530.

63. Chen Y, Song Y, Du W, Gong L, Chang H, Zou Z. Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26:78.

64. Wu Y, Kuang DM, Pan WD, et al. Monocyte/macrophage-elicited natural killer cell dysfunction in hepatocellular carcinoma is mediated by CD48/2B4 interactions. Hepatology. 2013;57:1107-16.

65. Wang J, Wang Y, Chu Y, et al. Tumor-derived adenosine promotes macrophage proliferation in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;74:627-37.

66. Hao L, Li S, Deng J, et al. The current status and future of PD-L1 in liver cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1323581.

67. Sas Z, Cendrowicz E, Weinhäuser I, Rygiel TP. Tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities for new treatment options. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3778.

68. Patsoukis N, Brown J, Petkova V, Liu F, Li L, Boussiotis VA. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra46.

69. Hung MH, Lee JS, Ma C, et al. Tumor methionine metabolism drives T-cell exhaustion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1455.

70. Basson C, Serem JC, Hlophe YN, Bipath P. The tryptophan-kynurenine pathway in immunomodulation and cancer metastasis. Cancer Med. 2023;12:18691-701.

71. Zhang H, Dai Z, Wu W, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of immune checkpoints PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in cancer. J Exper Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:184.

72. Rimassa L, Chan SL, Sangro B, et al. Five-year overall survival update from the HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable HCC. J Hepatol. 2025;83:899-908.

73. Menares E, Gálvez-Cancino F, Cáceres-Morgado P, et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells amplify anti-tumor immunity by triggering antigen spreading through dendritic cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4401.

74. Damei I, Trickovic T, Mami-Chouaib F, Corgnac S. Tumor-resident memory T cells as a biomarker of the response to cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1205984.

75. Wang S, Xu N, Wang J, et al. BMI1-induced CD127+KLRG1+ memory T cells enhance the efficacy of liver cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2023;571:216336.

76. Gao Q, Qiu SJ, Fan J, et al. Intratumoral balance of regulatory and cytotoxic T cells is associated with prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2586-93.

77. Zhang CY, Liu S, Yang M. Regulatory T cells and their associated factors in hepatocellular carcinoma development and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3346-58.

78. Du G, Dou C, Sun P, Wang S, Liu J, Ma L. Regulatory T cells and immune escape in HCC: understanding the tumor microenvironment and advancing CAR-T cell therapy. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1431211.

79. Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: "N1" versus "N2" TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183-94.

80. Yajuk O, Baron M, Toker S, Zelter T, Fainsod-Levi T, Granot Z. The PD-L1/PD-1 axis blocks neutrophil cytotoxicity in cancer. Cells. 2021;10:1510.

81. Chen Q, Zhang L, Li X, Zhuo W. Neutrophil extracellular traps in tumor metastasis: pathological functions and clinical applications. Cancers. 2021;13:2832.

82. Teo JMN, Chen Z, Chen W, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils attenuate the immunosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Med. 2025:222;e20241442.

83. Rose-John S, Jenkins BJ, Garbers C, Moll JM, Scheller J. Targeting IL-6 trans-signalling: past, present and future prospects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:666-81.

84. Dusi S, Bronte V, De Sanctis F. IL-27: overclocking cytotoxic T lymphocytes to boost cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:126.

85. Giarratana AO, Prendergast CM, Salvatore MM, Capaccione KM. TGF-β signaling: critical nexus of fibrogenesis and cancer. J Transl Med. 2024;22:594.

86. KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab) Plus LENVIMA® (lenvatinib) in Combination With Transarterial Chemoembolization Significantly Improved Progression-Free Survival Compared to TACE Alone in Patients With Unresectable, Non-Metastatic Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Available from: https://www.merck.com/news/keytruda-pembrolizumab-plus-lenvima-lenvatinib-in-combination-with-transarterial-chemoembolization-significantly-improved-progression-free-survival-compared-to-tace-alone-in-patients-w/ [Last accessed on 26 Jan 2026].

87. Ji Z, Li J, Zhang S, Jia Y, Zhang J, Guo Z. The load of hepatitis B virus reduces the immune checkpoint inhibitors efficiency in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1480520.

88. Granito A, Muratori L, Lalanne C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in viral and autoimmune liver diseases: role of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the immune microenvironment. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2994-3009.

89. Li M, Wang L, Cong L, et al. Spatial proteomics of immune microenvironment in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2024;879:560-74.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].