Functional significance of miR-218 in lung cancer

Abstract

Lung cancer remains one of the most prevalent and lethal malignancies worldwide, characterized by a poor prognosis and high mortality rates. Although therapeutic strategies targeting oncogenic signaling cascades, such as receptor tyrosine kinases, have shown promising outcomes by regulating cellular functions such as survival and proliferation, their long-term effectiveness is often limited by mechanisms, including tumor resistance, drug toxicity, and adverse events. These challenges underscore the urgent need to identify new molecular targets and develop alternative therapeutic approaches. One promising avenue lies in the exploration of microRNAs (miRs) and their significance in cancer biology. Among them, miR-218 has drawn significant attention for its tumor-suppressive properties. Multiple experimental studies have emphasized the role of miR-218 as a key regulator of cell signaling pathways critical to cancer progression, including proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and apoptosis. Notably, miR-218 has been investigated as both a diagnostic biomarker and a therapeutic target. Importantly, clinical evidence further supports its relevance, showing an inverse correlation between miR-218 expression levels and tumor aggressiveness, reinforcing its translational significance. This review logically consolidates the functional significance, mechanistic insights, and experimental and clinical findings that emphasize the pivotal role of miR-218 in regulating molecular pathways involved in lung cancer growth.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the major cause of cancer-related mortalities across the globe, accounting for 18.7% of all cancer deaths in 2022, followed by colorectal cancer (9%)[1]. Notably, the cancer statistics estimate that in 2025, new lung cancer cases represent 11% of all cancer cases[2]. In terms of gender-based mortality, lung cancer has a mortality rate of 20% in both males and females[3]. Histologically, lung cancer is categorized into small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[4]. NSCLC accounts for 80% of total pulmonary malignancies and is mainly subdivided into three major subtypes, namely, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and large-cell carcinoma (LCC)[5,6], and rare subtypes such as sarcomatoid carcinoma[7]. NSCLC involves dysregulation of signaling pathways responsible for cell control, apoptosis, and immune responses, resulting in tumor progression with major mutations observed in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog (KRAS), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), mesenchymal-epithelial transition Factor (MET), and c-ROS Oncogene 1 (ROS1)[8,9].

Despite significant advancements in the understanding of pathogenic pathways, the exact mechanisms responsible for carcinogenesis and metastasis of NSCLC are still unknown[10,11]. In addition, NSCLC is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, which remains one of the major challenges in the treatment of this cancer type[12-14]. In fact, the five-year survival rate of NSCLC patients (< 28%) remains relatively unchanged, owing to delayed detection during the early stage of the disease and subsequent progression to an advanced stage before any therapy can be applied[15-18]. Although multiple therapeutic strategies are available, including surgical resection for localized tumors, platinum- or taxane-based chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, their efficacy is often reduced when the disease is detected at an advanced stage[19-21]. In recent years, the introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as targeted therapies directed against oncogenic drivers such as EGFR, has expanded the treatment landscape and provided clinical benefit to selected patient subgroups[22-25]. These modalities, together with neoadjuvant and adjuvant approaches, are increasingly being combined to enhance treatment response and improve overall outcomes[26-28].

Lung cancer arises from the uncontrolled proliferation of epithelial cells within the respiratory tract, with tobacco smoking being one of the major risk factors for lung cancer[29-31]. Other risk factors include exposure to outdoor air pollution, occupational exposure, radon (especially in non-smokers), family history, and genetic alterations[8,32-34]. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying its development and progression is critical for improving outcomes[35]. To that end, substantial emphasis on ongoing research has been focused on identifying specific molecular players, such as microRNAs (miRs), which regulate gene expression and play a role in carcinogenesis and chemoresistance[36,37].

miRs are single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules comprising 19-25 nucleotides that regulate post-transcriptional gene expression[38,39]. The biogenesis of miRs involves the transcription of microRNA (miRNA) coding genes into primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), which are then processed to produce precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs)[40]. The pre-miRNAs are then cleaved to form the miRNA duplex, which involves the integration of various enzymes such as Drosha and RNase Dicer[40]. miRs are able to recognize their target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and by binding to the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) of complementary sequences, they regulate their protein expression[41]. This typically results in either translational repression or mRNA cleavage[42]. miRs have been found to regulate various key cellular processes, including regulation of the cell cycle[43,44], growth and differentiation[45], migration[46], apoptosis[47,48], and stress response[49].

In cancer, miRNAs can exhibit different functions - namely, tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting -depending on their target genes, regulatory networks, and ability to regulate cellular processes such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)[50-52]. Over the last few decades, studies have identified numerous miRNAs that are associated with lung cancer and regulate cellular and chemotherapeutic responses[53-55]. Among these, miR-218 has drawn significant attention for its tumor-suppressive properties[56]. The focus of this review is to highlight the role and mechanistic insights of miR-218, as well as its impact and implications on the efficacy of therapeutic agents in NSCLC.

ROLE AND MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF MIR-218

miR-218 is a highly conserved miRNA encoded by its host genes: Slit Guidance Ligand 2 (SLIT2) and Slit Guidance Ligand 3 (SLIT3) from two distinct loci, miR-218-1 and miR-218-2, which are located on chromosomes 4p15.31 and 5q35.1[57-59]. miR-218 is produced from these intronic loci, both of which are frequently deleted or transcriptionally silenced in NSCLC, resulting in decreased expression of miR-218[58]. It is predominantly expressed in normal tissues. However, in cancerous tissues, miR-218 is frequently downregulated, contributing to the dysregulation of its target genes and associated pathways[60-63]. Beyond canonical transcription and processing, miR-218 is also regulated through non-canonical mechanisms involving its genomic context and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) networks. Structural loss or epigenetic silencing of SLIT2/SLIT3 decreases intronic miR-218 transcription, while lncRNAs such as CCAT1 (colon cancer-associated transcript 1) act as miR-218 sponges, thereby derepressing B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog (BMI-1) and promoting tumor growth and drug resistance in lung cancer[64,65].

Experimental evidence suggests that miR-218 functions as a tumor suppressor in various malignancies, such as breast cancer[66], colorectal cancer[67], retinoblastoma[68], cervical cancer[69], thyroid cancer[70] and lung cancer[71]. In lung cancer, miR-218 has been found to regulate several key oncogenic pathways, including the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway, the interleukin-6/Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (IL-6/JAK/STAT3) pathway, and IκB (inhibitor of κB), a key component of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway, all of which play critical roles in tumor progression[56,72]. Alongside that, it directly targets genes such as EGFR, BMI-1, and B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2), which are critical in tumor development and metastasis[72,73]. The loss of miR-218 expression in lung cancer correlates with aggressive tumor phenotypes, tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) stages, and poor patient prognosis[73]. Below, we logically discuss the in vitro studies, in vivo studies, clinical evidence and bioinformatics evidence exploring the functional significance of miR-218 alone or its combination with therapeutic agents in lung cancer models, with major focus on NSCLC.

IMPLICATIONS OF MIR-218 IN LUNG CANCER

Evidence from the in vitro studies

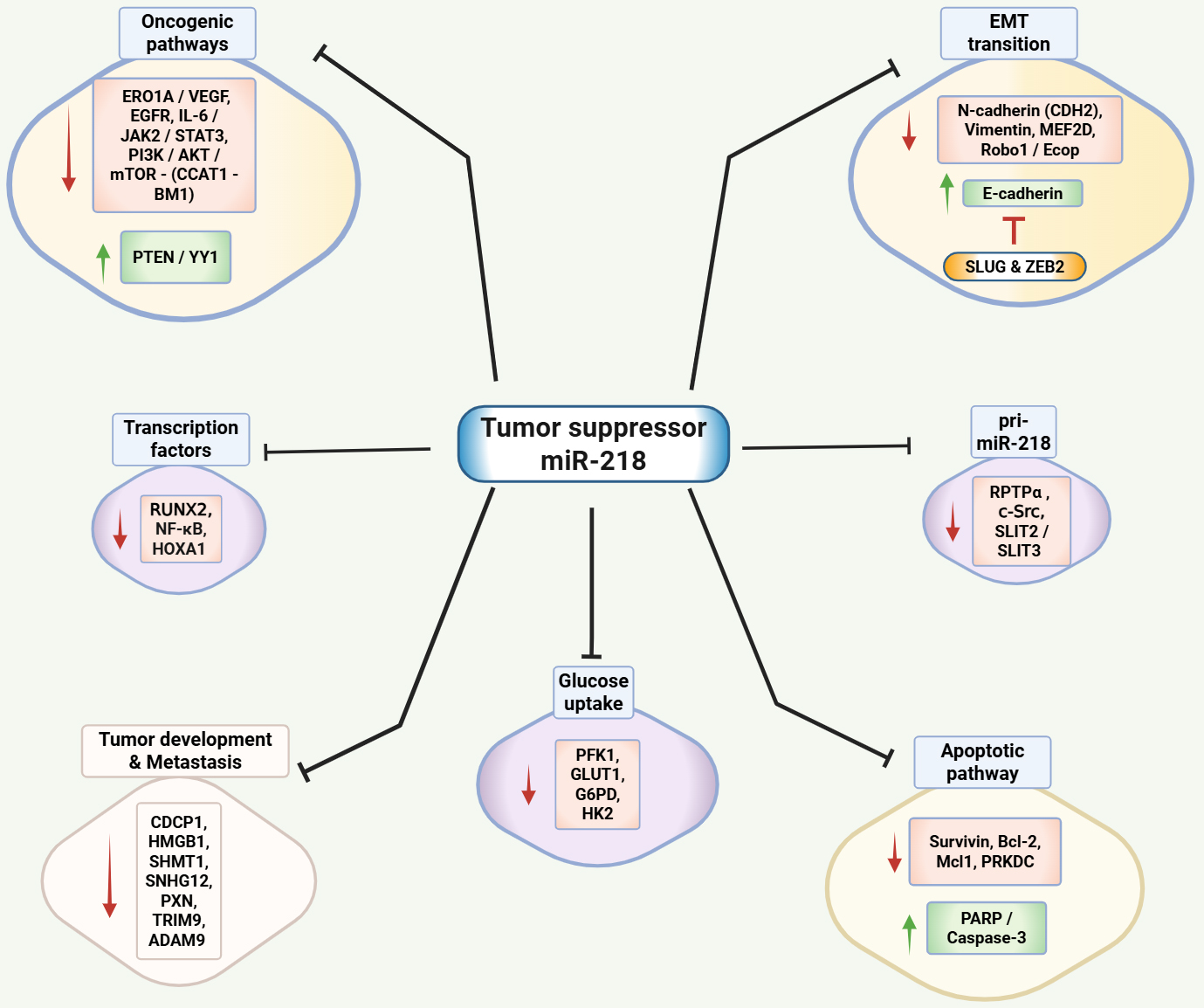

Several studies have utilized in vitro culture models to define the mechanism and functional significance of miR-218 in NSCLC. One of the first studies to correlate miR-218 with NSCLC was conducted by Wu et al.[74]. The study focused on determining the impact of miR-218 on the proliferative and invasion ability of NSCLC cells. The researchers initially used a wide panel of lung cancer cell lines, including A549, H1299, Ch27, H460, Calu-1, H661, CL1-0, and CL1-5. However, upon analyzing the miR-218 expression levels in these cell lines, the authors performed further studies primarily using CL1-0 and CL1-5 cell lines. The data demonstrated that overexpression of miR-218 inhibited the growth and invasive potential of lung cancer cells, while its inhibition enhanced these aggressive phenotypes. Additionally, they also discovered an inverse correlation in miR-218 expression and paxillin (PXN) mRNA and protein levels, which are associated with poor overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS). The comparative summary of the in vitro studies is given in Table 1, and the schematic representation of miR-218 targets is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of miR-218 mechanisms of action. miR-218 targets multiple oncogenic cascades, transcription factors, apoptotic pathways, and cellular properties such as tumor development and metastasis, glucose uptake, and EMT, as well as reduces its own synthesis by inhibiting pri-miR-218. ERO1A: Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 alpha; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; PI3K/AKT/mTOR: phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin; IL-6/JAK/STAT3: interleukin-6/Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; CCAT1: colon cancer-associated transcript 1; BMI-1: B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog; PTEN/YY1: phosphatase and tensin homolog/Yin Yang 1; PARP: poly-ADP ribose polymerase; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma; Mcl1: myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1; HOXA1: homeobox A1; RUNX2: runt-related transcription factor 2; PRKDC: protein kinase, DNA-activated, catalytic subunit; RPTPα: receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase alpha; SLIT2/SLIT3: Slit Guidance Ligand 2/3; TRIM9: tripartite motif 9; SNHG12: small nucleolar RNA host gene 12; SHMT1: serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1; CDCP1: CUB-domain-containing protein 1; ADAM9: disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 9; HMGB1: high mobility group box-1; PXN: paxillin; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; NF-κB: Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PFK1: phosphofructokinase 1; GLUT1: glucose transporter 1; G6PD: glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HK2: hexokinase 2; MEF2D: myocyte enhancer factor 2D; Robo1: roundabout homolog 1; Ecop: EGFR-coamplified and -overexpressed protein; CDH2: N(Neural)-cadherin; ZEB2: zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Created in BioRender Thyagarajan A (2025).

Comparative summary of in vitro studies investigating miR-218 function in lung cancer

| Mechanistic category | Targets | Comparative summary of miR-218 function in NSCLC cells | References |

| Apoptosis and cell-survival signaling | Bcl-2, BMI-1, YY1, PTEN, Mcl-1, Survivin, PARP, Caspase-3, Bax | Across these studies, miR-218 overexpression reduces the expression of multiple anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, BMI-1, Mcl-1, Survivin) while increasing pro-apoptotic markers (cleaved PARP, Caspase-3, Bax), leading to reduced cell viability and enhanced apoptosis. Conversely, loss of miR-218 has the opposite effect, supporting its consistent pro-apoptotic and tumor-suppressive roles | [64,72,75] |

| JAK-STAT proliferative signaling | IL-6R, JAK3 | miR-218 decreases IL-6R and JAK3 levels, resulting in suppressed cytokine-driven proliferation. This links miR-218 to the inhibition of IL-6/STAT-type growth signaling in NSCLC | [56] |

| Growth-factor receptor signaling | EGFR | By targeting EGFR, miR-218-5p reduces receptor expression and downstream signaling, thereby suppressing cell migration and proliferation | [73] |

| Cell motility and structural support | PXN, RPTPα, CDCP1 | PXN, RPTPα, and CDCP1 are proteins that promote cancer cell adhesion, motility and dissemination. Across these studies, miR-218 overexpression decreases their expression, leading to reduced migration, invasion and, in some models, diminished tumor growth and colony formation | [74,76-78] |

| EMT, invasion and metastasis | Robo1, Ecop, TRIM9, HMGB1, CDH2/N-cadherin, Slug, ZEB2, Robo1, CDCP1, HS3ST3B1 | Multiple independent studies demonstrated that miR-218 downregulates EMT drivers at different levels, including surface receptors (Robo1, CDCP1, HS3ST3B1), transcriptional regulators (Slug, ZEB2), mesenchymal markers (CDH2) and pro-invasive factors (Ecop, HMGB1, TRIM9). Across these targets, miR-218 consistently reduces EMT marker expression as well as cell migration and invasion, indicating that inhibition of EMT and metastatic potential is a central function of miR-218 in NSCLC | [76,77,79-85] |

| Transcriptional growth control | MEF2D | By suppressing MEF2D, miR-218 inhibits lung cancer cell growth, supporting its broader role in limiting cancer progression | [86] |

| Metabolic regulation and stress response | SHMT1, ERO1A, GLUT1 | miR-218 affects several metabolic pathways: it reduces GLUT1-mediated glucose uptake, interferes with folate/one-carbon metabolism through SHMT1, and disrupts oxidative and ER stress responses via ERO1A. Across these pathways, miR-218 consistently limits metabolic activity, reduces tumor growth, and suppresses angiogenesis | [87-89] |

| Chemotherapy sensitivity (platinum agents) | RUNX2, Bcl-2/BMI-1/Mcl-1/Survivin axis | miR-218 improves the response to cisplatin by downregulating RUNX2 and enhances carboplatin-induced cell death by reducing survival-related proteins. Overall, miR-218 acts as a sensitizer to platinum-based drugs by weakening resistance pathways | [64,72,75,90] |

| Targeted therapy resistance (EGFR-TKI) | HOXA1 | In gefitinib-resistant NSCLC, restoration of miR-218 levels decreases HOXA1 levels, reducing proliferation and promoting gefitinib-induced apoptosis, indicating that loss of miR-218 contributes to resistance to EGFR-TKIs | [65] |

| Radiation response and DNA-damage repair | PRKDC | miR-218 directly suppresses PRKDC, a key DNA repair enzyme, leading to increased unrepaired DNA damage, enhanced apoptosis, and greater radiosensitivity, including in radiation-resistant models | [91] |

Wang et al. conducted a study focusing on the effect of miR-218 in restricting cell proliferation and metastasis by targeting TRIM9, a member of the tripartite motif (TRIM) family[80]. This protein has been associated with tumorigenesis in several cancers[92,93]. The data demonstrated that while miR-218-5p was significantly downregulated, TRIM9 was upregulated in 95D and H1299 NSCLC cell lines[80]. This suggested a negative correlation between the expression levels of miR-218-5p and TRIM9, which was confirmed using the luciferase reporter assay. In addition, overexpression of miR-218-5p led to a significant reduction in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in NSCLC cells. The same effects were documented following the knockdown of TRIM9, suggesting that TRIM9 acts as an oncogene in NSCLC[80]. Furthermore, overexpression of TRIM9 reversed the suppressive effects of miR-218-5p, reinforcing the notion that TRIM9 is a downstream target of miR-218-5p[80]. The study thus revealed that since TRIM9 is associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer, targeting the miR-218-5p/TRIM9 axis could offer a novel therapeutic strategy for NSCLC.

As mutations in the EGFR gene contribute to nearly one-third of all NSCLC cases, especially in regions such as Asia[94]. This makes EGFR a potential target to determine the mechanistic insights and explore its impact on the treatment strategies in NSCLC. To that end, Zhu et al. conducted a study to explore correlation between miR-218 and EGFR expression levels using the LUAD A549 and H1975 cell lines[73]. They found that miR-218 directly targets EGFR protein in NSCLC cells, with miR-218 overexpression leading to reduced cell proliferation and migration. This correlation with EGFR provides the rationale for exploring miR-218 application in the treatment strategies of NSCLC.

EMT is a biological process in which epithelial cells lose their cell-cell adhesion and epithelial markers, and acquire mesenchymal characteristics such as increased motility and invasiveness, enabling metastasis[95]. Since EMT is a key characteristic of NSCLC, Zhang et al. investigated the role of miR-218 in NSCLC cell migration using the A549 and H1299 cell lines[81]. The study showed that overexpression of miR-218 using mimetics resulted in the reduction of cell migration and invasion. Furthermore, the study also identified high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) as a direct target of miR-218. Given that high HMGB1 levels have been associated with poor clinical outcomes and metastasis in lung cancer, exploration of the mechanisms involved in its regulation such as miR-218 has potential significance[96]. A similar finding was reported by Sher et al., using BM7 cell model (BM7 cell line was a brain-metastatic clone derived from a high metastatic subline F4, which had higher invasion capability than its parental cell line), where miR-218 was found to target N-cadherin (CDH2), which is a mesenchymal marker of the EMT process[82]. The studies primarily focused on a disintegrin and metalloprotease 9 (ADAM9), which was found to upregulate N-cadherin via suppressing miR-218 level, thus promoting metastasis in NSCLC.

Moreover, to evaluate the significance of miR-218 in EMT and metastasis, Shi et al. conducted a study using EMT markers such as E-cadherin and vimentin[83]. They selected a panel of lung cancer cell lines - A549, H1299, PC9 and SPCA-1, and first assessed the expression levels of miR-218, and then chose H1299 and A549 cells for further experiments. During EMT, E-cadherin expression decreases, leading to loss of cell-cell adhesion and epithelial characteristics, while Vimentin increases, promoting cell motility and structural reorganization[97]. Interestingly, the study found that miR-218 overexpression reversed this pattern, increasing E-cadherin and decreasing Vimentin. Furthermore, miR-218 transfection was able to induce morphological changes in NSCLC cells. Additionally, the transcription factor, Slug and zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2), which typically represses E-cadherin, were identified as direct targets of miR-218. This study holds great significance as it demonstrated the potential of miR-218 to prevent metastasis in lung cancer.

Furthermore, a study conducted by Li et al. demonstrated that miR-218 exerts its action on inhibiting EMT by targeting several key components such as Roundabout homolog 1 (Robo1) and EGFR-coamplified and -overexpressed protein (Ecop)[79]. Robo1 is an axon guidance receptor gene that has been shown to enhance migratory capacity in breast cancer[98]. Ecop is a novel oncogenic protein that directly regulates NF-κB transcriptional activity, thereby promoting cancer cell survival through suppression of apoptosis[99]. The study provided compelling evidence that the expression levels of miR-218 are negatively correlated with those of Robo1 and Ecop in A549, H2228, H1975, HCC4006, H23, Calu-3, H1435 and H1793 LUAD cell lines. Furthermore, miR-218 repressed cancer cell invasion and migration by inhibiting Robo1 and Ecop expression, reinforcing the notion that miR-218 plays a critical role in suppressing tumor progression. In fact, similar findings were reported by Chen et al., where the researchers experimented only on Robo1 expression and found that miR-218 transfection significantly reduces the expression of Robo1, affecting cell migration and invasion in A549 cells[84].

Along similar lines, Wang et al. conducted a study to delve further into the mechanisms of the EMT pathway and determined the effects of miR-218 in the same context, using A549 and H1299 NSCLC cell lines[100]. They identified small nucleolar RNA host gene 12 (SNHG12), a lncRNA with functions in tumor progression and treatment resistance of NSCLC[101], as a key regulator of miR-218 in EMT. The authors found that SNHG12 was overexpressed in NSCLC tissues with significant correlations with advanced tumor stages and poor OS rates and that silencing SNHG12 led to a marked decrease in cell viability, proliferation, migration, and invasion. They further found that SNHG12 acts as a molecular sponge for miR-218, sequestering and preventing its regulatory effects on target genes. However, the knockdown of SNHG12 resulted in the upregulation of miR-218 followed by downregulation of the Slug/ZEB2 signaling pathway known to regulate EMT and metastasis.

A study by Song et al. focused on the miR-218 effect on NSCLC via myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2D (MEF2D) regulation using A549 lung carcinoma cell line[86]. MEF2D functions as an oncogene in lung cancer by inducing EMT and promoting tumor cell proliferation and motility[102]. The researchers found that mimic transfection of miR-218 directly targets the MEF2D expression resulting in decreased cell proliferation, survival, and invasion. Additionally, the use of miR-218 inhibitors had the opposite effect, enhancing the malignant traits, suggesting an inverse correlation between miR-218 and MEF2D expression levels.

The role of miR-218 in cancer metastasis was further explored where ADAM9 and CUB domain-containing protein 1 (CDCP1) were used as the main targets of the study[76]. ADAM9 is known for promoting metastasis and CDCP1 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that plays a significant role as a driver of oncogenic signaling in tumor progression and metastasis in various cancers[103-105]. In the study, the researchers found that miR-218 directly targets the 3’-UTR of CDCP1 mRNA, which resulted in the inhibition of the migration ability of A549 and F4 lung cancer cells. Furthermore, it was found that ADAM9 enhances CDCP1 expression by suppressing miR-218 levels, thus creating a feedback loop where ADAM9 promotes CDCP1 expression, which in turn facilitates cancer cell migration and metastasis. Similarly, Zeng et al. also identified CDCP1 as a direct target of miR-218 using the A549 cell line[77]. The study demonstrated that overexpression of miR-218 resulted in a reduction in CDCP1 expression, suggesting that miR-218 exerts its tumor-suppressive effects in NSCLC by down-regulating CDCP1 expression.

A study conducted by Zarogoulidis et al. found that miR-218, when upregulated, resulted in reduced cell viability and induced apoptosis in A549 and H1975 lung cancer cell lines[75]. The authors explored the effects of miR-205 and miR-218 on apoptosis and their roles in the chemoresistance of carboplatin, a platinum-based medication used to treat lung cancer. The researchers found that while miR-205 promotes chemoresistance, miR-218 upregulation inhibited that by reducing the expression of specific anti-apoptotic proteins, namely survivin and Myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1). Mcl-1 is known to promote cell survival by inhibiting apoptosis, while survivin plays a critical role in apoptosis regulation[106]. Furthermore, miR-218 also promoted the expression of apoptotic proteins, including poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), Bax and Caspase-3 resulting in the induction of apoptosis. Along similar lines, Zhao et al. found that downregulation of miR-218 increases cell proliferation and decreases apoptosis[64]. They conducted a study focused on the significance of CCAT1/mir-218 on cell proliferation and apoptosis in NSCLC using A549 and H1975 cell lines and patient tissues. The authors found that patients with high expression levels of CCAT1 had a lower survival rate and poor prognosis than those with lower expression. In NSCLC cells, CCAT1 knockdown led to a decrease in cell proliferation and an increase in apoptosis. However, this effect was reversed when miR-218 was downregulated. The authors also identified a new target of miR-218, BMI-1, which is a member of the polycomb group proteins (PcG) and has been shown to be involved in tumorigenesis[107]. BMI-1 was found to be downregulated with CCAT1 knockdown and targeted by miR-218.

Chen et al. conducted a study to examine the effects of miR-218 in NSCLC. However, unlike other studies, they used an adenocarcinoma cell line, XWLC-05 (Xuanwei lung adenocarcinoma cell line-05), named after Xuanwei county in China[72]. The researchers found that miR-218 is significantly downregulated in lung cancer cells compared to normal lung epithelial cells. In addition, overexpression of miR-218 significantly inhibited the proliferation, invasion, and migration in XWLC cells, while also inducing apoptosis. Furthermore, miR-218 overexpression led to a significant accumulation of cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle, suggesting that it induces G2/M phase arrest. Additionally, miR-218 overexpression downregulated the levels of Bcl-2 and BMI-1, which are known to promote cell survival and proliferation. In addition, increased expressions of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and Yin Yang 1 (YY1) were noticed by miR-218 overexpression, which is associated with tumor suppression and cell cycle regulation. Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein and PTEN is a tumor suppressor and a negative regulator of the PI3K/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) oncogenic signaling pathway[108]. This study provided insights into the possible roles of miR-218 in NSCLC treatment. Chen et al. explored the effect of miR-218 on serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 (SHMT1), a cytoplasmic enzyme involved in one-carbon metabolism in NSCLC cells[87]. SHMT1 is known to play a significant role in cancers due to its involvement in cellular metabolism and DNA synthesis[109]. Treatment with recombinant miR-218 resulted in a significant decreased level of the SHMT1 protein in both A549 and H1975 NSCLC cell lines, which led to disruptions in the folate one-carbon metabolism, primarily in the incorporation of the methylene bridge from serine into the folate cycle[87]. Furthermore, the downregulation of SHMT1 was also associated with reduced cell viability and proliferation among NSCLC cell lines[87]. This interaction between miR-218-5p and SHMT1 elucidates a mechanism by which miR-218-5p functions as an antimetabolite, disrupting key metabolic pathways that NSCLC cells rely on for growth and survival[87].

As vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key mediator of angiogenesis, which plays a critical role in NSCLC by supplying oxygen and nutrients to rapidly growing tumors, facilitating tumor progression, and metastasis[110]. Heparan sulfate D-glucosamine 3-O-sulfotransferase 3B1 (HS3ST3B1) is an enzyme involved in the sulfation of heparan sulfate which plays a role in enhancing VEGF signaling in leukemias and NSCLC[111]. A study by Zhang et al. found that HS3ST3B1 is upregulated in NSCLC tissues compared to matched normal tissues, with higher mesenchymal phenotype expression in CALU6, H460, H1975, A549, HCC827, and H358 NSCLC cell lines[85]. While its knockdown reversed the EMT-induced responses, it was found that transfection with miR-218 mimics also led to decreased protein levels of HS3ST3B1 in NSCLC cell lines, which inhibited the EMT process. Along similar lines, Chen et al. determined the effect of miR-218 on VEGF secretion, focusing on endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase 1 alpha (ERO1A), which was identified as a potential target of miR-218 using bioinformatics software[88]. ERO1A is an oxidoreductase in the endoplasmic reticulum, known to promote angiogenesis by enhancing the secretion of VEGF. Using a luciferase assay, the authors confirmed that ERO1A was a direct target of miR-218 in PC-9 and A549 cell lines. In addition, while high expression of ERO1A in LUAD correlates with aggressive tumor behavior, miR-218-5p was found to exert its tumor-suppressive effects by targeting ERO1A. These findings suggest the possibility of a regulatory axis where miR-218-5p inhibits LUAD progression by downregulating ERO1A.

Moreover, miR-218’s tumor suppressor activity was found to be mediated via its ability to target various other pathways in NSCLC. One of those is the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway, which is responsible for promoting cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and resistance to apoptosis[112]. Yang et al. found that miR-218 directly targets the IL-6/Janus kinase 3 (JAK3)/STAT3 pathway in A549 and H1975 cell lines, which resulted in reduced cell proliferation and invasive behavior of cancer cells[56]. Additionally, the authors also compared the miR-218 expression with disease prognosis and found that decreased levels of miR-218 were associated with poorer prognosis in NSCLC patients. Lai et al. also elucidated the molecular mechanisms of miR-218, though primarily focusing on the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase α (RPTPα)-c-Src signaling pathway using A549 cells as an NSCLC model[78]. In general, the RPTPα activates c-Src through dephosphorylation of its inhibitory tyrosine residue (Tyr527), leading to increased c-Src kinase activity. In lung SCC, elevated RPTPα expression correlated with poor prognosis and cell cycle dysregulation, as RPTPα overexpression was shown to accelerate the G1/S transition by upregulating cyclin D3 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), resulting in increased cancer cell proliferation[113]. In addition, the researchers demonstrated that miR-218 directly targets RPTPα mRNA, leading to decreased activation of c-Src as evidenced by lower levels of phosphorylated c-Src. This indicates a negative feedback loop where miR-218 inhibits RPTPα, which in turn reduces c-Src activity. Moreover, c-Src was found to suppress miR-218 expression by downregulating its host genes, SLIT2 and SLIT3, which encode pri-miR-218. This indicates a feedback loop where c-Src not only acts downstream of RPTPα but also negatively regulates miR-218, promoting a pro-tumorigenic environment. Overall, this study had significant implications as the identification of miR-218 as a regulator of the RPTPα-c-Src signaling pathway opens new avenues for targeted therapies that could improve patient outcomes.

Glucose metabolism is essential for cancer progression because it provides the substrates required for tumor growth and metastasis[114]. Tian et al. studied the effects of miR-218 on glucose consumption, using the NCI-H23 and A549 human NSCLC cell lines and miR-218 mimics[89]. The authors found that miR-218 overexpression significantly reduced glucose consumption and led to a decrease in glucose uptake and lactate production in NSCLC cells. In addition, the ratio of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (reduced form) (NADPH) to Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (oxidized form) (NADP+), a measure of pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) activity, was also reduced in cells expressing higher levels of miR-218. Furthermore, the authors determined the expression levels of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), hexokinase 2 (HK2), phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD), and identified GLUT1 as a direct target of miR-218 in NSCLC cells. Further analysis revealed that miR-218 can inhibit glucose uptake by downregulating GLUT1 expression. Moreover, miR-218 significantly decreased the phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 in NSCLC cells, suggesting that the miR-218-induced inhibition of glucose metabolism was mediated by the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Chemotherapeutic agents represent viable treatment options for human cancers and miRs are being evaluated for their impact on drug resistance. To that end, Xie et al. conducted a study to elucidate the function of miR-218 on cisplatin chemoresistance using parental A549 and A549/DDP (cisplatin-resistant) cell lines[90]. The researchers found that expression levels of miR-218 were significantly downregulated in cisplatin-resistant A549/DDP NSCLC cells compared to their parental A549 cells. Restoring the miR-218 levels led to an increased sensitivity of cisplatin-resistant cells to cisplatin. Furthermore, the study identified Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) as a direct target of miR-218. RUNX2 is a transcription factor known to be involved in various cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in various cancer models[115]. The study demonstrated that the restoration of miR-218 levels may be a potential therapeutic strategy for reversing the chemoresistance to cisplatin.

Given the intriguing role of miR-218 in the regulation of NSCLC growth, Jin et al. determined the effect of miR-218 and lncRNA CCAT1 in drug resistance in NSCLC focusing on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, gefitinib[65]. To that end, they used HCC827 and PC9 cell lines and generated gefitinib-resistant cell lines, HCC827GR and PC9GR. The authors found that CCAT1 expression was higher in gefitinib-resistant NSCLC cell lines compared to gefitinib-sensitive counterparts and that its knockdown enhanced gefitinib sensitivity in NSCLC cells. Furthermore, the authors found that CCAT1 acts as a molecular sponge of miR-218 and reduces its expression levels. The study further identified homeobox A1 (HOXA1) as a direct target of miR-218. HOXA1 is upregulated in NSCLC and promotes tumorigenesis[116]. The study suggested that CCAT1 reduces the expression of miR-218, enabling the upregulation of HOXA1, which promotes chemoresistance. This study established that restoring miR-218 levels could be a promising therapeutic strategy to overcome resistance to gefitinib and improve treatment outcomes for patients with NSCLC.

Moreover, radiation therapy has been used for decades to manage NSCLC; however, patients often develop resistance to this therapy[117]. To that end, Chen et al. explored whether miR-218 could be used to enhance the sensitivity of radiation-resistant lung carcinoma cells[91]. For that, A549 and H1299 cell lines were irradiated with a 2 Gy daily fraction size administered 30 times for a total dose of 60 Gy. The authors found that overexpression of miR-218-5p in radiation-resistant NSCLC cell lines led to a significant reduction in cell viability and increased apoptosis following X-ray irradiation. These findings indicate that miR-218-5p enhances the sensitivity of these NSCLC cell lines to radiation therapy. Furthermore, the study identified protein kinase, DNA-activated, catalytic subunit (PRKDC) as a direct target of miR-218-5p. The inhibition of PRKDC expression was found to be associated with increased DNA damage[118]. This suggests that miR-218-5p may sensitize cancer cells to radiation by impairing their ability to repair DNA damage. Overall, these findings suggest that by modulating miR-218-5p levels, it may be possible to enhance the efficacy of radiotherapy and improve patient outcomes in NSCLC.

Although most studies have characterized miR-218 as a tumor-suppressive miR in lung cancer, a contrasting report by Yang et al. demonstrated that miR-218 can exert a pro-tumorigenic effect within the immune microenvironment[119]. The authors investigated the immunomodulatory role of miR-218-5p in LUAD, focusing on its impact on the cytotoxic activity of natural killer (NK) cells through targeting SHMT1. They found that miR-218-5p was significantly upregulated in NK cells isolated from LUAD patients, whereas SHMT1 expression was markedly reduced, suggesting an inverse relationship between the two molecules. This negative regulatory interaction was confirmed via luciferase reporter assays, which validated SHMT1 as a direct downstream target of miR-218-5p[119]. Functionally, overexpression of miR-218-5p in interleukin 2 (IL-2)-activated NK-92 cells led to a pronounced reduction in Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) secretion, accompanied by significant suppression of NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity against A549 LUAD cells. Conversely, knockdown of miR-218-5p or overexpression of SHMT1 restored cytokine production and enhanced NK-cell killing capacity. Taken together, these findings indicate that, unlike its tumor-suppressive effects reported in lung cancer epithelial cells, miR-218-5p exerts a pro-tumorigenic, immune-evasive role within NK cells mediated by downregulation of SHMT1 and impaired NK-cell cytotoxicity[119].

While the majority of studies discussed in this section consistently demonstrate a tumor-suppressive role for miR-218 in lung cancer cells - mediating inhibition of proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT, and oncogenic signaling pathways, the findings by Yang et al. revealed a critical context-dependent divergence[119]. Unlike the epithelial cell-intrinsic effects described throughout the preceding studies, miR-218-5p can exert a pro-tumorigenic influence in immune cells by impairing anti-tumor immunity. This discrepancy underscores the cell-type specificity of miR function and emphasizes that the effects of miR-218 are highly dependent on biological context. Therefore, therapeutic strategies targeting miR-218 must account for these dual roles to avoid inadvertently compromising immune-mediated tumor control.

Evidence from the in vivo studies

While in vitro studies provide mechanistic insight into miR-218-mediated signaling, many investigations have utilized in vivo mouse models to establish the functional significance of miR-218 in NSCLC. To explore the therapeutic potential of miR-218 in modulating lung tumor metastasis, Chiu et al. utilized severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice and injected intracardially with human lung cancer cells (Bm7brmx2) that had inducible miR-218 expression[76]. Mice were treated with doxycycline to induce miR-218 expression. Results showed that induction of miR-218 significantly reduced tumor metastasis to the brain, as evidenced by bioluminescent imaging and histological analysis. In addition, survival analysis demonstrated that mice receiving miR-218 treatment had a significantly longer survival time than the control group, highlighting the potential of miR-218 as a therapeutic agent. The study highlighted the potential of miR-218 as a candidate for therapeutic intervention to combat lung cancer metastasis, which remains a major challenge in oncology. Table 2 lists the summaries of the in vivo studies in chronological order of their publication.

Summary of the in vivo studies defining the role of miR-218 in lung cancer

| Model/Experimental design | Treatment groups | Timeline/Endpoint | Key findings | References |

| Intracardiac injection of metastatic NSCLC cells with tetracycline-inducible pri-miR-218; SCID mice | Doxycycline vs. control; pri-miR-218 ON/OFF | Metastasis was monitored at approximately 4 weeks; and survival was followed until endpoints | miR-218 overexpression reduced metastatic burden and improved survival | [76] |

| Subcutaneous xenografts using A549 cells with RPTPα mutation ± miR-218 modulation; BALB/c nude mice (n = 4/group) | A549-RPTPα mutation ± miR-218 manipulation | Tumor growth was monitored every 2 days starting at week 2, with the endpoint at approximately 5 weeks | miR-218 suppressed RPTPα expression and inhibited tumorigenesis | [78] |

| Subcutaneous xenografts with H1975 cells stably overexpressing miR-218; nude mice (n = 10/group) | miR-218 mimic vs. control | Tumors were measured on days 7, 9, 11, and 13; and the animals were sacrificed thereafter | miR-218 overexpression suppressed NSCLC xenograft growth | [73] |

| H1299 and A549 cell lines were injected into the posterior flanks; BALB/c nude mice (n = 6) | miR-218 overexpression vs. NC; anti-miR-218 vs. anti-NC | Tumors were measured every 2 days after Day 12, and the animals were sacrificed after Day 22 | Overexpression of miR-218 suppressed Slug and ZEB2 expression and inhibited tumor growth and metastasis | [83] |

| Orthotopic lung implantation of tumor fragments from subcutaneous xenografts; BALB/c nude mice | miR-218 overexpression vs. control | Tumor growth and metastasis were assessed 7 weeks post-implantation | ||

| Subcutaneous A549 xenografts; BALB/c nude mice (n = 5/group) | miR-218-LV vs. control-LV | Tumor volume was measured weekly, and the animals were sacrificed at week 5 post-injection | miR-218 overexpression inhibited tumor growth by targeting STAT3 | [56] |

| Subcutaneous xenografts using A549 cells; 10 BALB/c nude mice (n = 8) | miR-218 inhibitor vs. control | Tumor volume was measured every other day after reaching 50mm3, with the endpoint at 30 days | miR-218 inhibition promoted NSCLC xenograft growth | [79] |

| Subcutaneous A549R xenografts; BALB/c nude mice (n = 3/group) | miRNA-NC, miR-218 mimic; each ± 12 Gy X-ray | Tumor volume was measured every 3 days, with the endpoint at 25 days | miR-218-5p increased radiosensitivity in vivo | [91] |

Along similar lines, Lai et al. conducted in vivo studies to assess the role of miR-218 in inhibiting NSCLC tumor growth using BALB/c nude mice[78]. To that end, stable A549 cell lines were engineered to overexpress miR-218, while cells without miR-218 expression served as controls, and were then injected subcutaneously into the flanks of male nude mice. Results indicated a significant reduction in tumor growth in mice receiving the miR-218 overexpressing cells compared to the control group, suggesting that miR-218 acts as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC. Further analysis revealed decreased levels of RPTPα protein in the tumors harvested from the group of mice implanted with miR-218-overexpressing cells, which correlated with increased phosphorylation of c-Src at Tyr530 (tyrosine (Tyr) is located at 530 amino acid residue), indicating reduced c-Src activity. Notably, re-expressing RPTPα rescued tumor growth, while a mutated version of RPTPα (RPTPαY789F) failed to show similar effects. These findings demonstrate that miR-218 inhibits tumorigenesis by targeting RPTPα and downregulating c-Src activity, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target in lung cancer treatment strategies.

Another study by Zhu et al. evaluated the effects of miR-218 on tumor growth using nude mice[73]. Mice were implanted subcutaneously with human NSCLC H1975 cells, infected with a lentivirus for miR-218 overexpression or a control lentivirus. Following 1 week of implantation, it was found that tumors in the miR-218 overexpressing group exhibited significantly retarded growth compared to the control group. After 13 days, tumors were excised and analyzed for size and weight. Tumors from the miR-218 group were substantially smaller, confirming the tumor-suppressive effect of miR-218. Furthermore, miR-218-overexpressing tumors had higher levels of miR-218 and lower levels of EGFR, reinforcing the notion of direct inhibition of EGFR by miR-218. Immunohistochemical staining revealed reduced cell proliferation in miR-218 overexpressing tumors. Overall, the study demonstrated that miR-218 functions as a tumor suppressor in NSCLC by negatively regulating EGFR and could offer therapeutic potential for lung cancer treatment.

In a study, Shi et al. elucidated the role of miR-218 in NSCLC growth, utilizing two distinct in vivo experiments in BALB/c nude mice[83]. In the first experiment, researchers created stable cell lines in which H1299 cells overexpressed miR-218, while A549 cells had reduced expression. These cells were then injected subcutaneously into the flanks of the mice. After 22 days, the authors observed that miR-218-overexpressing tumors were significantly smaller compared to control tumors, while tumors with reduced miR-218 expression exhibited larger sizes and accelerated growth, suggesting that miR-218 inhibits tumor growth. Histological assessments showed reduced expression of Slug and ZEB2 in the smaller tumors, reinforcing the idea that miR-218 inhibits EMT. Meanwhile, the tumors harvested from reduced miR-218 expression had increased levels of Slug and ZEB2, which are markers of EMT. The second experiment aimed to investigate the effects of miR-218 on metastatic behavior. For that, tumor tissues from the first experiment were transplanted into the lungs of mice to analyze metastasis. The results indicated that mice harboring miR-218-overexpressing tumor cells exhibited significantly fewer metastatic lesions and less extensive invasion into lung tissue than controls. Histological staining again showed reduced levels of Slug and ZEB2 in these tumors, underscoring the role of miR-218 in inhibiting not only tumor growth but also metastatic spread. Overall, this study highlighted the critical function of miR-218 in inhibiting both tumor growth and metastatic spread in NSCLC, suggesting it as a potential therapeutic target.

Yang et al. conducted a study to evaluate the tumor-suppressive effect of miR-218 using A549 LUAD xenograft model in nude mice[56]. They utilized lentiviral vectors to stably express miR-218, or a control miRNA in A549 cells, which were then injected into the mice subcutaneously. The data demonstrated that tumors expressing miR-218 were significantly smaller than those in the control group, indicating the antitumor effects of miR-218. Furthermore, histological analyses of the tumors showed reduced Ki67 staining, signifying decreased cell proliferation, and lower levels of phosphorylated STAT3 were noticed in miR-218-expressing tumors. These findings confirmed that miR-218 inhibits activation of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway.

Similarly, a study conducted by Li et al. assessed the effects of miR-218 on the growth and proliferation of a human LUAD model using female BALB/c nude mice[79]. To that end, A549 cells were administered subcutaneously into the right and left flanks of mice and once the tumors reached palpable size, a miR-218 inhibitor was injected into one flank, with a control miR sequence on the opposite flank, allowing for direct comparison. Through this approach, the study aimed to understand how inhibiting miR-218 affected tumor proliferation. After the treatment, the weights of the tumors were recorded and the results indicated that tumors treated with the miR-218 inhibitor exhibited a significantly greater volume and weight compared to the control group. This suggested that downregulation of miR-218 allowed for enhanced proliferation of malignant cells, indicating its role in suppressing tumor growth. The study highlighted the potential of miR-218 as a therapeutic target, demonstrating its regulatory role in inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis in LUAD, while paving the way for future miRNA-based cancer therapies.

Chen et al. aimed to assess the effects of miRNA-218-5p on radiation sensitivity in NSCLC using male BALB/c nude mice[91]. Researchers implanted radiation-resistant A549R cells and categorized the mice into control and experimental groups: miRNA-218-5p mimics, miRNA-negative control (miRNA-NC) + 12 Gy X-ray radiation, and miRNA-218-5p mimics + 12 Gy X-ray radiation. Following 2 days of treatment, tumor volumes and weight were measured. The data demonstrated that the mice receiving miRNA-218-5p mimics combined with X-ray radiation exhibited significantly smaller tumor volumes compared to the other groups, indicating enhanced radiosensitivity in combination with miR-218. Overall, the study suggests that targeting miRNA-218-5p could be a potential therapeutic strategy to improve radiotherapy outcomes in NSCLC, particularly for resistant cases, and highlights the promise of miRNA-based treatments in personalized cancer therapy.

While the preceding in vivo studies demonstrate that elevating miR-218 within tumor cells suppresses lung cancer growth and progression, the work by Yang et al. highlights a clear deviation from this trend[119]. In their xenograft model, maximal anti-tumor effects were achieved not by enhancing miR-218, but by inhibiting miR-218-5p in NK cells. Specifically, A549 cells were implanted subcutaneously into the nude mice, followed by treatment with IL-2-activated LNK cells transfected with either a miR-218-5p inhibitor or a negative control. Consistent with their mechanistic findings, suppression of miR-218-5p significantly reduced tumor growth, accompanied by increased SHMT1 expression in tumor tissues, indicating enhanced NK-cell activity in vivo. These results contrast with the majority of in vivo studies, in which upregulation of miR-218 inhibits tumor growth; in this case, downregulation of miR-218-5p in immune cells produced the anti-tumor effect. This discrepancy underscores that the in vivo role of miR-218 is context-dependent, varying across cellular compartments, and that therapeutic manipulation may have opposing consequences depending on whether the target is a tumor cell or an immune effector cell.

Across the in vivo studies assessed, several investigations of miR-218 in lung cancer relied on small, single-cohort sample sizes (in some cases, n < 10), which may limit the robustness and generalizability of the findings. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution and warrant further validation in larger, independent cohorts. In addition, the use of different mouse strains introduces important model-specific limitations that influence the interpretation of miR-218 functions in NSCLC. Nude mice, which lack functional T cells, permit efficient engraftment of human tumor cells but cannot model miRNA effects that depend on intact immunity[120,121]. BALB/c nude mice, although similarly immunodeficient, differ slightly in baseline tumor growth kinetics and inflammatory responses, which may alter microenvironmental influences on tumor progression[122,123]. SCID mice, with combined T- and B-cell deficiencies, provide an even more permissive setting for tumor establishment, yet their severely compromised immune surveillance restricts evaluation of miR-218’s potential immune-modulatory roles[120,124]. These inherent differences in immune competence complicate direct comparison across studies and underscore the importance of considering strain-specific limitations when interpreting in vivo miR-218 data.

Evidence from clinical studies

Several studies have investigated the functional significance of miRNA-218 in NSCLC patients. In one study, Davidson et al. determined the expressions of miR-218 and its host genes, SLIT2 and SLIT3, in tumor samples and compared them to paired normal lung tissue[58]. For that, they collected lung tissue from 39 patients [18 SCC and 21 Adenocarcinoma (AC)] with or without smoking status. The analysis revealed that miR-218 was downregulated in 85% (33/39) of patients, and SLIT2 and SLIT3 downregulation was also observed in 97% (36/37) and 92% (34/37) of NSCLC tissues, respectively. Further analysis showed that miR-218 and SLIT2/3 downregulation were co-regulated as a concordant downregulation of miR-218 and SLIT2 was observed in 81% (30/37) of tissue samples. Moreover, miR-218 expression was found to be significantly reduced in the tissue samples of current smokers (14/39) and former smokers (19/39), and not in the samples of patients who had no history of smoking (6/39). These findings indicate a potential link of miR-218 expression with tobacco exposure, which is one of the major causes of lung cancer. The summaries of the clinical studies are given in Table 3 in the chronological order of their publication.

Summary of clinical studies defining the role of miR-218 in lung cancer

| Study design | Patient characteristics/sample size | miR-218 expression levels | Findings | References |

| To study the expression of the host genes SLIT2 and SLIT3, and miR-218 in NSCLC patient samples | Samples were collected from 39 lung cancer patients | miR-218 expression was downregulated by 4-fold in NSCLC samples | SLIT2/3 and mir-218 expressions were significantly downregulated in NSCLC samples. Furthermore, smokers (current and former) had significantly decreased levels of miR-218 expression | [58] |

| To determine the association of PXN with miR-218 expression | Samples were collected from 124 patients with primary lung cancer | miR-218 levels decreased as lung cancer progressed through its stages | PXN expression was significantly elevated and miR-218 expression was downregulated in tumor samples relative to normal tissues | [74] |

| To determine whether EGFR expression is associated with miR-218 expression | Samples were collected from six lung cancer patients | miR-218 expression was nearly 2-fold higher in normal lung samples compared to NSCLC tissues | EGFR mRNA and protein levels were consistently higher in tumor samples, relative to normal tissues; miR-218 expression was downregulated | [73] |

| To determine the association of Slug/ZEB2 with miR-218 expression | Samples were collected from 60 NSCLC patients | miR-218 levels were downregulated in NSCLC and declined significantly with advancing TNM stages | Slug/ZEB2 expression was markedly elevated and miR-218 expression was downregulated in tumor samples relative to normal tissues | [83] |

| To determine the association of TRIM9 with miR-218 expression | Samples were collected from 50 NSCLC patients who did not receive any prior treatments | miR-218 expression was downregulated by 2-fold in NSCLC samples | TRIM9 expression was markedly higher and miR-218 expression was downregulated in tumor samples relative to normal tissues | [80] |

| To determine whether miR-218 synergistically enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy | Samples were collected from 42 patients with NSCLC who received radiotherapy | miR-218 levels were nearly 2-fold higher in the serum of control patients compared to lung carcinoma patients | miR-218 level in the serum of LC patients after radiotherapy was evidently higher than pre-radiotherapy. PRKDC expression was negatively correlated with miRNA-218-5p levels in the serum of LC patients | [91] |

In another study, Wu et al. examined the association between miR-218 and PXN expressions and their correlation with tumor stages using tissue samples that were collected from 124 patients diagnosed with primary lung cancer[74]. The results showed that miR-218 levels were further downregulated in Stage III patients in comparison to Stage I and II patients. In contrast, the PXN mRNA and protein levels were found to positively correlate with tumor stages, suggesting that PXN expression in lung tumors is negatively associated with miR-218 expression. In addition, the high expression of miR-218 was also positively correlated with OS and RFS in lung cancer patients.

In addition, Zhu et al. conducted a study using NSCLC and normal adjacent tissues (NATs) from 6 patients, to assess the EGFR expression in lung cancer patients[73]. They found that EGFR mRNA and protein levels were significantly higher in NSCLC tissues in comparison to the NATs. The next study analyzed the expression of miR-218 in the same samples and found it to be negatively correlated with the EGFR expression, indicating that EGFR is a direct target of miR-218. These findings hold great significance considering the prevalence of EGFR mutations in NSCLC.

Shi et al. conducted a study to determine miR-218 expression in NSCLC across different TNM stages using tissue samples from 60 lung cancer patients[83]. The results showed that miR-218 expression was significantly downregulated in the NSCLC samples. Furthermore, the downregulation was inversely correlated with histological grade, and miR-218 levels were found to be drastically decreased in metastatic samples compared with non-metastatic NSCLC tissues. In addition, the researchers studied the expression levels of Slug/ZEB2 in the same tissues and found that they correlate negatively with the miR-218 expression, indicating miR-218’s potential against NSCLC metastasis.

In another study, Wang et al. studied the association of miR-218 with TRIM9 using 30 pairs of tumor tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues collected from NSCLC patients[80]. The results revealed downregulation of miR-218 and upregulation of TRIM9 expression in NSCLC tissues. In addition, using immunohistochemical staining, the authors also confirmed increased levels of TRIM9 protein in NSCLC tissues. These findings suggested a negative association between TRIM9 and miR-218 in NSCLC patients.

Moreover, Chen et al. conducted a study to determine the effects of radiotherapy on miR-218 levels in NSCLC patients using blood samples collected from 42 patients before and after they received 60 Gy/30 min of radiotherapy[91]. The results showed that while the miR-218 levels were initially lower in the serum of patients, compared to healthy control, following radiotherapy, miR-218 expression increased significantly. In addition, they also tested the PRKDC levels in the same samples and found a negative correlation with the miR-218 levels. These findings indicate that miR-218 may target PRKDC and potentially enhance radiotherapy outcomes.

Bioinformatics and large-cohort evidence

Multiple large-scale datasets and integrative bioinformatic analyses have independently validated the tumor-suppressive role of miR-218 in NSCLC. Early genome-wide mapping using array comparative genomic hybridization in 132 NSCLC tumors demonstrated that the host loci of miR-218, miR218-1 and miR218-2, reside within regions of recurrent copy-number loss, with matched expression profiling confirming significant downregulation of mature miR-218 in tumor tissues compared with adjacent normal lung[58].

Subsequent bioinformatic studies further reinforce these observations. A multi-dataset integrative analysis identified FANCI (FA Complementation Group I) as a key gene inversely associated with miR-218 expression[125]. Notably, FANCI overexpression correlated with larger tumor size, lymph-node involvement, metastatic behavior, and poorer survival in LUAD[125]. The same study confirmed the miR-218-FANCI regulatory axis through TargetScan prediction and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)-based expression validation. Similarly, inverse correlations between miR-218 and oncogenic drivers such as CDCP1, RUNX2, PRKDC, and EGFR have been observed across public bioinformatics databases and tools such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and TargetScan[73,77,90,91].

Clinical cohort-level evidence parallels these findings. In a prospective serum study of advanced NSCLC, 76.7% of patients exhibited miR-218-5p downregulation at diagnosis, with suppression persisting after multiple cycles of chemotherapy[126]. This circulating miRNA pattern mirrors the downregulation reported in tumor tissues and across public datasets[126]. Collectively, evidence from genomic copy-number mapping, multi-cohort bioinformatic analyses, and clinical plasma profiling converges to show that miR-218 is consistently and robustly downregulated across both major NSCLC subtypes, reinforcing its tumor-suppressive role in disease progression[58,125,126].

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The role of miR-218 in the context of lung cancer has provided significant insights into its multifaceted roles as a tumor suppressor, prognostic indicator, and therapeutic target, offering a window into future research possibilities. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these effects remain incompletely understood. For instance, while several miR-218 targets, such as Robo1, SLIT2, and pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR and EMT regulators have been identified, their integrated network and specific roles require further elucidation. Furthermore, given that lower miR-218 expression is strongly associated with poor prognosis and decreased OS in NSCLC patients, therapeutic approaches aimed at restoring or enhancing miR-218 levels hold promise in reversing malignant phenotypes. This could include developing efficient miR-218 mimics, nanoparticle-based delivery systems, or viral vector therapy strategies to achieve targeted overexpression in tumor tissues while minimizing off-target effects[127,128]. However, significant challenges remain in optimizing the stability, specificity, and systemic delivery of such miRNA-based therapeutics[129].

Another critical future direction is the evaluation of miR-218’s role in resistance to existing chemotherapeutic or targeted therapies. Investigating whether miR-218 modulation can sensitize tumor cells to conventional treatments could open new combinatorial therapeutic approaches for NSCLC management. In addition, integrating miR-218 expression profiling into existing diagnostic and prognostic models may enhance early detection strategies and treatment stratification for lung cancer patients. Future research should focus not only on validating these findings in large-scale, multicenter clinical cohorts but also on initiating early-phase clinical trials to assess the safety, pharmacodynamics, and efficacy of miR-218-targeted therapies in humans.

Beyond NSCLC, miR-218 may exhibit divergent roles in other lung cancer subtypes. In lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), miR-218-5p expression progressively decreases from normal to tumor tissue, correlating with larger tumors, higher T stage, and enhanced migration and invasion, supporting a tumor-suppressive function in this context[130,131]. In SCLC, although data are limited, the lncRNA Linc00173 has been shown to act as a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) that sponges miR-218, reducing its inhibitory effect on targets such as Etk and thereby promoting proliferation and chemoresistance [132]. These observations highlight that miR-218’s function is context-dependent, influenced by tumor histology, transcriptional programs, and microenvironmental cues, and underscore the need for studies beyond NSCLC to fully elucidate its therapeutic potential across lung cancers.

In conclusion, although significant progress has been made in understanding the tumor-suppressive roles of miR-218, comprehensive mechanistic investigations and well-designed translational studies are essential to fully harness its potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target. In addition, challenges such as delivery stability, off-target effects, and clinical standardization must be addressed before therapeutic application can be realized. By bridging these gaps, miR-218-directed interventions could contribute meaningfully to improving the clinical management and outcomes of NSCLC patients.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conception: Sahu RP

Writing the first draft: Aggarwal D

Generating the figure: Thyagarajan A

Reviewing and editing: Aggarwal D, Thyagarajan A, Sahu RP

Supervision: Sahu RP, Thyagarajan A

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R21 grant ES033806 (to Sahu RP).

Conflicts of interest

Sahu RP is an Editorial Board Member of Journal of Cancer Metastasis and Treatment. Sahu RP was not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-63.

2. Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin. 2025;75:10-45.

4. Inamura K. Lung cancer: understanding its molecular pathology and the 2015 WHO classification. Front Oncol. 2017;7:193.

6. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al.; WHO Panel. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of lung tumors: impact of genetic, clinical and radiologic advances since the 2004 classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1243-60.

7. Yendamuri S, Caty L, Pine M, et al. Outcomes of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the lung: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database analysis. Surgery. 2012;152:397-402.

8. Hendriks LEL, Remon J, Faivre-Finn C, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10:71.

9. Chevallier M, Borgeaud M, Addeo A, Friedlaender A. Oncogenic driver mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: past, present and future. World J Clin Oncol. 2021;12:217-37.

10. Xie S, Wu Z, Qi Y, Wu B, Zhu X. The metastasizing mechanisms of lung cancer: Recent advances and therapeutic challenges. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;138:111450.

11. Li W, Li M, Huang Q, et al. Advancement of regulating cellular signaling pathways in NSCLC target therapy via nanodrug. Front Chem. 2023;11:1251986.

12. Alamri S, Badah MZ, Zorgi S, et al. Disease prognosis and therapeutic strategies in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a 6-year epidemiological study between 2015-2021. Transl Cancer Res. 2024;13:762-70.

13. Gildea TR, DaCosta Byfield S, Hogarth DK, Wilson DS, Quinn CC. A retrospective analysis of delays in the diagnosis of lung cancer and associated costs. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:261-9.

14. Kocher F, Hilbe W, Seeber A, et al. Longitudinal analysis of 2293 NSCLC patients: a comprehensive study from the TYROL registry. Lung Cancer. 2015;87:193-200.

15. Samson JS, Parvathi VD. Prospects of microRNAs as therapeutic biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2023;40:345.

16. Shimamura SS, Shukuya T, Asao T, et al. Survival past five years with advanced, EGFR-mutated or ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer-is there a “tail plateau” in the survival curve of these patients? BMC Cancer. 2022;22:323.

17. Garon EB, Hellmann MD, Rizvi NA, et al. Five-year overall survival for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with pembrolizumab: results from the phase I KEYNOTE-001 study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2518-27.

18. Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:943-53.

19. Kneuertz PJ, Ferrari-Light D, Altorki NK. Sublobar resection vs lobectomy for stage ia non-small cell lung carcinoma-takeaways from modern randomized trials. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;117:897-903.

20. Matsuda A, Yamaoka K, Kunitoh H, et al. Quality of life with docetaxel plus cisplatin versus paclitaxel plus carboplatin in patients with completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: quality of life analysis of TORG 0503. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:2629-37.

21. Schneider BJ, Daly ME, Kennedy EB, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: American Society of clinical oncology endorsement of the American Society for radiation oncology evidence-based guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:710-9.

22. Brozos-Vázquez EM, Díaz-Peña R, García-González J, et al. Immunotherapy in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: current status and future prospects for liquid biopsy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70:1177-88.

23. Lu Y, Zeng T, Zhang H, et al. Nano-immunotherapy for lung cancer. Nano TransMed. 2023;2:e9130018. Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2790676023000365 [accessed 5 February 2026].

24. Hsu PC, Jablons DM, Yang CT, You L. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway, yes-associated protein (YAP) and the regulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3821.

25. Tran TO, Lam LHT, Le NQK. Hyper-methylation of ABCG1 as an epigenetics biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Funct Integr Genomics. 2023;23:256.

26. Wu Y, Lu S, Zhou Q, et al. Expert consensus on treatment for stage III non‐small cell lung cancer. Medicine Advances. 2023;1:3-13.

27. Saw SPL, Ong BH, Chua KLM, Takano A, Tan DSW. Revisiting neoadjuvant therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:e501-16.

28. Thyagarajan A, Gajjar V, Sahu RP. Are metformin-based combination approaches beneficial for non-small cell lung cancer: evidence from experimental and clinical studies. Mil Med Res. 2025;12:61.

29. Pesch B, Kendzia B, Gustavsson P, et al. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer--relative risk estimates for the major histological types from a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1210-9.

30. Le Calvez F, Mukeria A, Hunt JD, et al. TP53 and KRAS mutation load and types in lung cancers in relation to tobacco smoke: distinct patterns in never, former, and current smokers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5076-83.

31. Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma: a study of six hundred and eighty-four proved cases. J Am Med Assoc. 1950;143:329-36.

32. Krewski D, Lubin JH, Zielinski JM, et al. Residential radon and risk of lung cancer: a combined analysis of 7 North American case-control studies. Epidemiology. 2005;16:137-45.

33. Boffetta P, Autier P, Boniol M, et al. An estimate of cancers attributable to occupational exposures in France. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:399-406.

34. Lissowska J, Bardin-Mikolajczak A, Fletcher T, et al. Lung cancer and indoor pollution from heating and cooking with solid fuels: the IARC international multicentre case-control study in Eastern/Central Europe and the United Kingdom. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:326-33.

35. Ling B, Liao X, Huang Y, et al. Identification of prognostic markers of lung cancer through bioinformatics analysis and in vitro experiments. Int J Oncol. 2020;56:193-205.

36. Thyagarajan A, Tsai KY, Sahu RP. MicroRNA heterogeneity in melanoma progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;59:208-20.

37. Hamdy NM, Basalious EB, El-Sisi MG, et al. Advancements in current one-size-fits-all therapies compared to future treatment innovations for better improved chemotherapeutic outcomes: a step-toward personalized medicine. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40:1943-61.

39. Chauhan SJ, Thyagarajan A, Sahu RP. Effects of miRNA-149-5p and platelet-activating factor-receptor signaling on the growth and targeted therapy response on lung cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6772.

40. Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363-6.

41. Walayat A, Yang M, Xiao D. Therapeutic implication of miRNA in human disease. In: Sharad S, Kapur S, editors. Antisense therapy. IntechOpen; 2018.

42. O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y, Peng C. Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9:402.

43. Wang F, Fu XD, Zhou Y, Zhang Y. Down-regulation of the cyclin E1 oncogene expression by microRNA-16-1 induces cell cycle arrest in human cancer cells. BMB Rep. 2009;42:725-30.

44. Sun F, Fu H, Liu Q, et al. Downregulation of CCND1 and CDK6 by miR-34a induces cell cycle arrest. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1564-8.

45. Luo J, Zhu C, Wang H, Yu L, Zhou J. MicroRNA-126 affects ovarian cancer cell differentiation and invasion by modulating expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:5803-8.

46. Lang Y, Kong X, Liu B, Jin X, Chen L, Xu S. microRNA-651-5p affects the proliferation, migration, and invasion of lung cancer cells by regulating calmodulin 2 expression. Clin Respir J. 2023;17:754-63.

47. Qin W, Shi Y, Zhao B, et al. miR-24 regulates apoptosis by targeting the open reading frame (ORF) region of FAF1 in cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9429.

48. Cui F, Zhou Q, Xiao K, Ma S. The microRNA hsa-let-7g promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in lung cancer by targeting HOXB1. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61:210-7.

49. Tüfekci KU, Meuwissen RLJ, Genç Ş. The Role of MicroRNAs in biological processes. In: Yousef M, Allmer J, editors. miRNomics: microRNA biology and computational analysis. Totowa: Humana Press; 2014. pp. 15-31.

50. You J, Li Y, Fang N, et al. MiR-132 suppresses the migration and invasion of lung cancer cells via targeting the EMT regulator ZEB2. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91827.

51. Li J, Song Y, Wang Y, Luo J, Yu W. MicroRNA-148a suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting ROCK1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;380:277-82.

52. Thyagarajan A, Shaban A, Sahu RP. MicroRNA-directed cancer therapies: implications in melanoma intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;364:1-12.

53. Cortez MA, Valdecanas D, Zhang X, et al. Therapeutic delivery of miR-200c enhances radiosensitivity in lung cancer. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1494-503.

54. Zhao Z, Zhang L, Yao Q, Tao Z. miR-15b regulates cisplatin resistance and metastasis by targeting PEBP4 in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:108-14.

55. Yu S, Qin X, Chen T, Zhou L, Xu X, Feng J. MicroRNA-106b-5p regulates cisplatin chemosensitivity by targeting polycystic kidney disease-2 in non-small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2017;28:852-60.

56. Yang Y, Ding L, Hu Q, et al. MicroRNA-218 functions as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer by targeting IL-6/STAT3 and negatively correlates with poor prognosis. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:141.

57. Tatarano S, Chiyomaru T, Kawakami K, et al. miR-218 on the genomic loss region of chromosome 4p15.31 functions as a tumor suppressor in bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:13-21.

58. Davidson MR, Larsen JE, Yang IA, et al. MicroRNA-218 is deleted and downregulated in lung squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12560.

59. Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004;14:1902-10.

60. Charostad J, Nakhaei M, Azaran A, et al. MiRNA-218 is frequently downregulated in malignant breast tumors: a footprint of epstein-barr virus infection. Iran J Pathol. 2021;16:376-85.

61. Shi J, Yang L, Wang T, et al. miR-218 is downregulated and directly targets SH3GL1 in childhood medulloblastoma. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:1111-7.

62. Guan B, Mu L, Zhang L, et al. MicroRNA-218 inhibits the migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell properties of prostate cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:1821-6.

63. Hu L, Ai J, Long H, et al. Integrative microRNA and gene profiling data analysis reveals novel biomarkers and mechanisms for lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:8441-54.

64. Zhao L, Wang L, Wang Y, Ma P. Long noncoding RNA CCAT1 enhances human nonsmall cell lung cancer growth through downregulation of microRNA218. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:1045-52.

65. Jin X, Liu X, Zhang Z, Guan Y. lncRNA CCAT1 acts as a MicroRNA-218 sponge to increase gefitinib resistance in NSCLC by targeting HOXA1. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:1266-75.

66. Wischmann FJ, Troschel FM, Frankenberg M, et al. Tumor suppressor miR-218 directly targets epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression in triple-negative breast cancer, sensitizing cells to irradiation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:8455-65.

67. Lun W, Wu X, Deng Q, Zhi F. MiR-218 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer via targeting CTGF. Cancer Cell Int. 2018;18:83.

68. Li L, Yu H, Ren Q. MiR-218-5p suppresses the progression of retinoblastoma through targeting NACC1 and inhibiting the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:6959-67.

69. Cruz-De la Rosa MI, Jiménez-Wences H, Alarcón-Millán J, et al. miR-218-5p/RUNX2 axis positively regulates proliferation and is associated with poor prognosis in cervical cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6993.

70. Han M, Chen L, Wang Y. miR-218 overexpression suppresses tumorigenesis of papillary thyroid cancer via inactivation of PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway by targeting Runx2. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:6305-16.

71. Guo P, Sheng M, Liu H, Ju L, Yang N, Sun Y. Effects of miR-218-1-3p and miR-149 on proliferation and apoptosis of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:96.

72. Chen Y, Yang JL, Xue ZZ, et al. Effects and mechanism of microRNA218 against lung cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23:1-1.

73. Zhu K, Ding H, Wang W, et al. Tumor-suppressive miR-218-5p inhibits cancer cell proliferation and migration via EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28075-85.

74. Wu DW, Cheng YW, Wang J, Chen CY, Lee H. Paxillin predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer by microRNA-218 targeting. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10392-401.

75. Zarogoulidis P, Petanidis S, Kioseoglou E, Domvri K, Anestakis D, Zarogoulidis K. MiR-205 and miR-218 expression is associated with carboplatin chemoresistance and regulation of apoptosis via Mcl-1 and Survivin in lung cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1576-88.

76. Chiu KL, Kuo TT, Kuok QY, et al. ADAM9 enhances CDCP1 protein expression by suppressing miR-218 for lung tumor metastasis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16426.

77. Zeng XJ, Wu YH, Luo M, Cong PG, and Yu H. Inhibition of pulmonary carcinoma proliferation or metastasis of miR-218 via down-regulating CDCP1 expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:1502-8. Available from https://www.europeanreview.org/article/12517 [accessed 5 February 2026].

78. Lai X, Chen Q, Zhu C, et al. Regulation of RPTPα-c-Src signalling pathway by miR-218. FEBS J. 2015;282:2722-34.

79. Li YJ, Zhang W, Xia H, et al. miR-218 suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by targeting Robo1 and Ecop in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Future Oncol. 2017;13:2571-82.

80. Wang Z, Wang B, Wang K. Targeting TRIM9 by miR-218-5p restricts cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2023;53:106-15. Available from https://www.annclinlabsci.org/content/53/1/106.short [accessed 5 February 2026].

81. Zhang C, Ge S, Hu C, Yang N, Zhang J. MiRNA-218, a new regulator of HMGB1, suppresses cell migration and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2013;45:1055-61.

82. Sher YP, Wang LJ, Chuang LL, et al. ADAM9 up-regulates N-cadherin via miR-218 suppression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94065.

83. Shi ZM, Wang L, Shen H, et al. Downregulation of miR-218 contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis in lung cancer by targeting Slug/ZEB2 signaling. Oncogene. 2017;36:2577-88.