Congenital nasal deformities: advances in early surgical intervention

Abstract

Congenital nasal deformities represent a diverse group of structural anomalies present at birth, often resulting in significant functional impairments and aesthetic challenges. Historically, surgical correction has been deferred until adolescence due to concerns about disrupting facial growth; however, emerging evidence supports earlier intervention, prompting a reevaluation of traditional paradigms. This review provides a comprehensive overview of major congenital nasal deformities, with a particular focus on cleft nasal deformities and frontonasal dysplasia. We explore evolving trends in surgical timing and techniques, key anatomical considerations, and reported outcomes. Special attention is given to the balance between early aesthetic and functional normalization and the preservation of midfacial growth. Advances in surgical planning, including individualized approaches, have improved outcomes and minimized risks associated with early intervention. Comparative data suggest that appropriately timed early correction may offer psychosocial and developmental benefits without significantly compromising facial growth. Overall, the management of congenital nasal anomalies is undergoing a paradigm shift toward earlier, more tailored surgical approaches. This evolution reflects a growing consensus that strategic early intervention can address both functional deficits and psychosocial impacts during critical developmental periods, while still safeguarding long-term facial growth and aesthetics.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Congenital nasal deformities comprise a diverse group of structural anomalies present at birth that can significantly impact nasal airway function, facial symmetry, and psychosocial development[1]. These deformities may occur in isolation or as components of broader craniofacial syndromes, ranging from subtle nasal asymmetries to extensive midline clefts involving multiple facial subunits. The developmental and clinical implications of these deformities are profound, as the nose plays a central role in both respiratory physiology and social identity from an early age[1]. Beyond functional impairment, children with conspicuous nasal deformities are at increased risk for adverse psychosocial outcomes, including diminished self-esteem, social withdrawal, and peer victimization, which may have lasting effects on emotional and behavioral development[1-3].

Historically, surgical intervention for many congenital nasal deformities was deferred until late adolescence due to concerns that early operative manipulation could disrupt normal facial development[1,4]. The cartilaginous nasal septum, particularly the septodorsal cartilage, acts as a major growth center influencing both vertical and anteroposterior development of the nose and midface[4,5]. Disruptions of this structure, whether by trauma or surgery, have been associated with lasting deformities such as saddle nose or midfacial hypoplasia[5]. Nasal growth is most rapid during adolescence, occurring between ages 12-14 years in girls and 13-17 years in boys[5]. These growth patterns led surgeons to delay nasal operations until after skeletal maturity. This conservative approach was supported by animal studies, primarily in rabbits, that demonstrate that surgical interventions on the nasal septum during growth can disrupt cartilage development and nasal morphology[5]. However, recent evidence suggests that conservative, well-planned early interventions may not significantly impair nasal development[6]. In fact, these interventions may provide psychosocial and functional benefits during critical periods of childhood development, including improved nasal patency and sleep, reduced mouth breathing and incidence of sleep apnea, and lowered risk of malocclusion and dental pathology[1,6,7]. This evolving perspective has prompted reconsideration of surgical timing, particularly in cases where deformity impairs breathing or contributes to social stigma[2,6,7].

This review categorizes major types of congenital nasal deformities including cleft nasal deformities, Tessier craniofacial clefts, and frontonasal dysplasia (FND). Certain congenital lesions, such as nasal dermoids and hemangiomas, although they may alter nasal contour, are excluded from this discussion due to their distinct pathology and treatment paradigms, which focus more on lesion excision and management than on structural reconstruction.

Each deformity presents unique reconstructive challenges that require careful consideration of surgical timing, technique, and preservation of facial growth potential. Emphasis is placed on evolving trends in early surgical intervention and technical innovations tailored to specific deformity subtypes. As the field shifts toward more proactive and personalized approaches, a nuanced understanding of early intervention strategies is essential for optimizing long-term functional and aesthetic outcomes.

CLEFT NASAL DEFORMITIES

Cleft nasal deformities result from incomplete fusion of the medial and lateral nasal prominences during embryogenesis, most commonly in association with cleft lip and/or palate[8,9]. These deformities involve both the overlying soft tissue envelope and the underlying skeletal and cartilaginous framework of the nose[10].

Unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity is characterized by lateral displacement and collapse of the alar cartilage, deviation of the nasal septum toward the non-cleft side, asymmetry of the nasal sill, and flattening of the nasal dome[7,10]. In contrast, bilateral cleft lip nasal deformities typically present with a shortened columella, broad nasal base, splayed lower lateral cartilages (LLC), and a poorly projected nasal tip[10]. While bilateral cleft lip nasal deformity tends to be more symmetric, nasal reconstruction remains equally complex[10]. Both deformities often require staged reconstruction to comprehensively address both functional and aesthetic concerns[10].

Cleft nasal deformities represent some of the most challenging aspects of cleft lip and palate management due to their three-dimensional complexity and their impact on nasal form and function[11]. Effective management requires a longitudinal treatment strategy, with careful consideration of timing, technical approach, and the balance between early intervention and facial growth[11,12].

Principle of early intervention

Recent advances in early cleft rhinoplasty have focused on minimally invasive, cartilage-sparing techniques, including primary septal repositioning, to enhance nasal symmetry, improve airway patency, and reduce the need for future revision procedures[13]. These interventions are typically performed at the time of primary lip repair, between 3 and 12 months of age, and are designed to address both the functional and aesthetic components of the cleft nasal deformity. While concerns persist regarding potential impacts on midfacial growth[5], current evidence supports the safety and efficacy of early intervention when growth centers are preserved. However, the evaluation of surgical techniques should include long-term assessment of facial development. Table 1 outlines key surgical principles in congenital rhinoplasty that support safe, anatomically restorative intervention while minimizing the risk of growth disturbance.

Key surgical techniques for congenital nasal deformities

| Key surgical techniques in congenital rhinoplasty for safe outcomes |

| Perform meticulous dissection with careful preservation of natural tissue planes |

| Prioritize cartilage repositioning and suture contouring, and avoid cartilage resection |

| Preserve midfacial growth by avoiding incisions through critical growth and supporting zones - especially the sphenodorsal and sphenospinal regions of the nasal septum |

| Use cartilage grafts as needed to reinforce structural support and to accommodate expansion of the soft tissue envelope during facial growth |

| Prevent vestibular stenosis by designing incisions and repairs that preserve or enlarge the nasal vestibule, ensuring adequate airway patency and long-term function |

Presurgical orthopedics

Presurgical infant orthopedic (PSIO) therapy is widely used to optimize alveolar and nasal alignment prior to cleft lip and palate repair, with nasoalveolar molding (NAM) being the most common technique in North America[14]. Historically, PSIO encompassed both active (invasive) and passive methods. Active techniques, such as the Latham appliance, mechanically reposition alveolar segments using surgically anchored devices, but concerns regarding invasiveness, caregiver burden, and limited evidence for long-term benefit have led to a decline in their use[14-16]. Passive PSIO methods - now the mainstay of presurgical care - include NAM, which utilizes an intraoral molding plate combined with extraoral taping and nasal stents to gradually approximate alveolar segments and enhance nasal symmetry. Systemic reviews and meta-analyses show that NAM significantly reduces alveolar gap width and enhances nasal form with minimal risk to midfacial or dental development[17-22]. Presurgical orthopedic plates without nasal stents, such as the passive alveolar molding (PAM) approach using a modified Hotz appliance, guide maxillary growth without nasal stenting. Comparative studies demonstrate that both NAM and PAM reduce the anterior cleft, though NAM produces greater segment narrowing and rotation, whereas PAM permits more transverse and sagittal maxillary growth[16,23,24]. Long-term outcomes, particularly facial growth and nasolabial aesthetics, are comparable among passive and active NAM approaches, as well as between NAM and PAM, although NAM may offer superior short-term nasolabial form[20,24,25].

PLANA (Presurgical Lip, Alveolus, and Nose Approximation) is an emerging passive orthopedic therapy that employs nasal stenting to improve nasolabial alignment before surgery. PLANA is a non-intraoral approach that uses an external adhesive device to gently approximate nasolabial structures without interfering with feeding or requiring frequent clinic visits. A 2025 comparative study showed that PLANA reduces caregiver burden substantially, cutting office visits by 61% and transient side effects by 72%, while achieving nasolabial outcomes comparable to traditional NAM[26]. PLANA produced greater improvement in columellar length ratio, whereas NAM provided slightly greater gains in nostril height, with no significant differences in other nasal symmetry measures[26]. Its ease of use and suitability for both unilateral and bilateral clefts make PLANA particularly advantageous for families living far from cleft centers[27].

Surgical techniques in primary cleft rhinoplasty

The Tajima reverse U incision technique is a surgical approach designed to address the inferior displacement and distortion of the alar rim by providing direct and controlled access to the LLC[28]. This approach allows for precise mobilization and repositioning of the LLC, correcting alar rim asymmetry and improving nostril shape[29,30]. The incision itself is cartilage-sparing and is frequently combined with suture techniques to maintain the new position of the cartilage. Modified Tajima techniques, including the use of buried polydioxanone sutures, have demonstrated reliable repositioning of the LLC and improved tip symmetry, with minimal complications and durable results[31].

Tse and Fischer introduced a foundation-based approach to primary rhinoplasty, emphasizing early structural correction of the nasal base to promote favorable long-term growth and aesthetics[13,32]. Rather than masking deformities, this method aims to reconstruct the nasal foundation by repositioning the ala and septum, thereby improving tip projection and overall nasal form. This method avoids nasal tip dissection and instead targets the underlying skeletal and cartilaginous support, aiming to upright the nose and establish a balanced foundation for long-term growth and aesthetics. Presurgical NAM is frequently used alongside this foundation-based strategy, as it helps mold the LLC and align nasal and alveolar segments, enhancing the effectiveness of the surgical correction. Preservation of tissue planes is a key principle, facilitating easier secondary revision if necessary and minimizing disruption to nasal growth.

Suture contouring and suspension sutures are central to modern primary cleft rhinoplasty. Mattress sutures are used to approximate the alar domes and medial crura[30], while suspension sutures secure the LLC to the upper lateral cartilage or septum, often through the reverse U incision[31]. These cartilage-preserving maneuvers effectively contour and stabilize the nasal tip and alar base, promoting long-term nasal symmetry. Sandwich suturing of the skin, cartilage, and mucosa further reinforces the correction and supports the nasal framework[33]. The Melbourne technique combines septal repositioning with upper lateral cartilage suspension to achieve overcorrection and long-term symmetry[34].

Composite grafting, typically using auricular or costal cartilage with overlying skin or mucosa, may be employed to increase columellar length and improve tip projection in cases with significant columellar deficiency. While more commonly described in secondary or revision settings[35], composite grafting can be used in primary cases with severe deformity. These grafts augment rather than resect native structures, maintaining the cartilage-sparing philosophy.

Recent adaptations of preservation rhinoplasty principles to cleft nasal surgery have highlighted the importance of ligament release and reconstruction, particularly of the Pitanguy ligament, to alleviate tension on the nasal tip, expand the skin envelope, and facilitate precise midline alignment of the LLCs[36]. This approach is inherently cartilage- and ligament-sparing, focusing on restoring normal anatomy and function.

Across all these techniques, the literature consistently supports a cartilage-sparing, repositioning, and suture-based approach, with cartilage or skin resection generally reserved for complex or secondary cases. A critical element of early intervention is minimizing trauma to the delicate infant cartilage and soft tissue envelope. Scar tissue can impede growth, particularly within the nasal vestibule, leading to functional compromise. Thus, meticulous, conservative dissection and surgical designs that preserve or expand the nasal vestibule are essential for maintaining long-term nasal development and airway patency.

Postoperatively, multiple forms of nasal conformers or nasal retainers are frequently employed after primary cleft lip and nasal repair to maintain surgical correction and reduce relapse. Evidence from clinical studies and systematic reviews demonstrates that postsurgical nasal conformers improve nasal symmetry and decrease cleft-non-cleft side discrepancies compared with no postoperative device use[37-40].

Primary septal repositioning

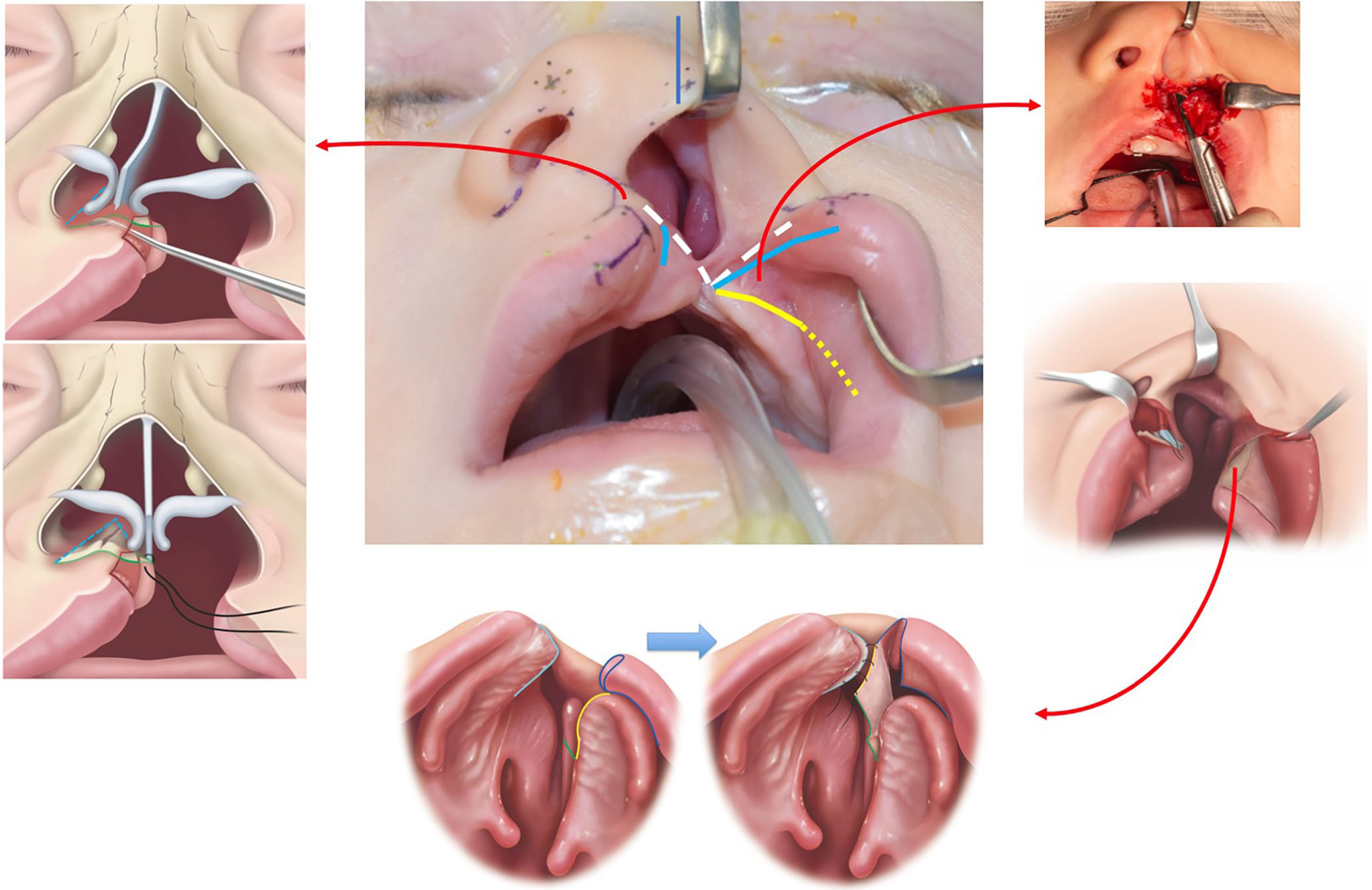

There is a growing trend toward incorporating primary septal repositioning during cleft lip repair [Figure 1]. Studies have demonstrated that early septal repositioning can significantly improve nasal airway function and aesthetic outcomes without adversely affecting midface growth[1,41]. Unlike adult septoplasty, primary cleft septal repositioning is typically limited to the anterior caudal septum and nasal spine, with no cartilage excision. Septal repositioning is sometimes referred to as a “primary septoplasty”, but this term can be misleading, as it may suggest a similarity to adult septoplasty procedures, where extensive cartilage excision is typically performed; if such excision were carried out in children as it is in adults, it would carry a higher risk of disrupting nasal growth centers. To reflect the unique characteristics of this technique,

Figure 1. Illustration of the concepts for septal repositioning in a foundation-based primary rhinoplasty. The septum is released from the anterior nasal spine and nasal floor and repositioned to midline. An upper buccal sulcus incision with supraperiosteal dissection over the anterior maxilla and subperiosteal dissection along the lateral nasal sidewall. A back cut in the mucoperiosteum allows the flap to be advanced en bloc with the ala. The flap is inset into the septum to produce a nasal floor. Copyright © 2022 Tse RW and Fisher DM. Reprinted with permission from Sage Publications[32].

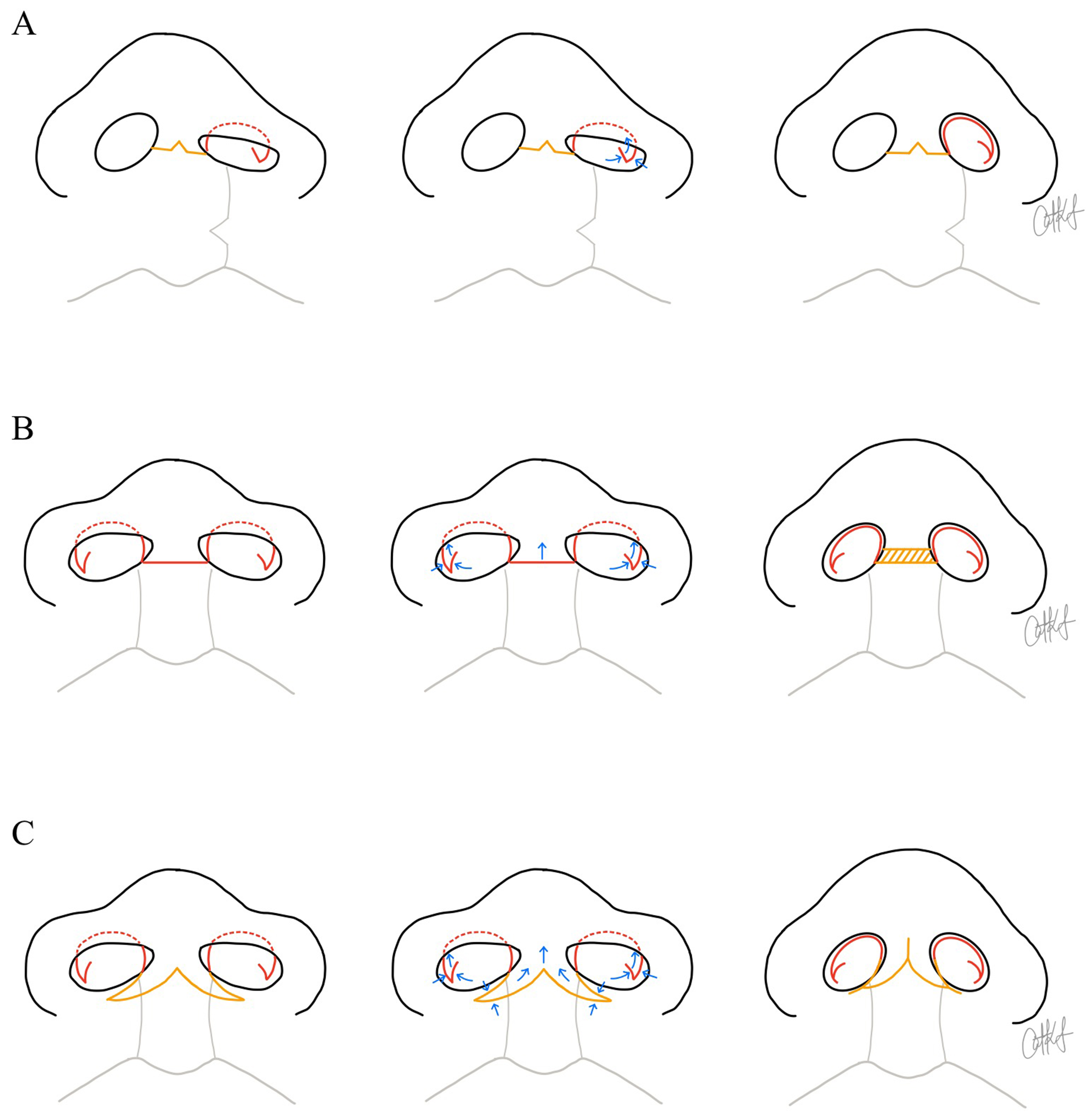

When residual deformities persist, intermediate rhinoplasty in childhood and definitive or secondary rhinoplasty in adolescence or adulthood may involve more extensive cartilage release or structural grafting. The use of autologous cartilage grafts, such as rib and ear cartilage for columellar support, has been associated with a reduced need for further rhinoplasty in both intermediate and definitive stages[43]. Allogeneic cartilage and alloplastic implants are recognized alternatives to autologous tissue in cleft rhinoplasty, with limited available data suggesting comparable safety and efficacy, whereas xenografts are not established in this setting[44-46]. Intermediate cleft rhinoplasty focuses on component restoration, repositioning and reinforcing individual nasal structures such as the LLC and nasal lining. The component technique has been shown to improve nasal tip support, symmetry, and aesthetic outcomes in both bilateral and unilateral cleft patients with sustained results lasting for at least 18 months in bilateral cases and over 3 years in unilateral cases[47,48]. Figure 2 offers a schematic diagram of the incisions often used for primary, intermediate and definitive cleft rhinoplasty in both unilateral and bilateral cleft lip.

Figure 2. Schematic illustrations demonstrating surgical techniques used to increase tip projection and columellar length during primary, intermediate, or definitive rhinoplasty procedures. Yellow lines indicate trans-columellar incisions, while red lines depict additional incisional designs that may be performed with or without a trans-columellar approach. Blue arrows represent the direction of tissue advancement. The yellow hatched region denotes a composite chondrocutaneous auricular graft. (A) Left unilateral cleft lip and nasal example. From left to right, the illustrations show the planned intraoperative incisional design, including an inverted-V trans-columellar incision and a reverse-U Tajima alar incision combined with a lateral crural steal maneuver. This maneuver is performed using a composite mucosal-chondral V-to-Y advancement; (B) Bilateral cleft lip and nasal example. From left to right, the illustrations show the planned incisional design, including a horizontal columellar incision and bilateral reverse-U Tajima alar incisions, combined with lateral crural steals to increase columellar and tip projection. Columellar lengthening is achieved with insertion of a composite graft; (C) Bilateral cleft lip and nasal example. From left to right, the illustrations show the planned incision design, including a W-to-Y columellar incision and bilateral reverse-U Tajima alar incisions, also combined with lateral crural steals. The W-to-Y columellar incision allows creation of forked flaps from the nasal sill or lower columella to recruit tissue superiorly. Illustrations designed by Dr. Catharine Kappauf.

Long-term outcomes and growth impact of primary cleft rhinoplasty

Overall, the literature supports that early, anatomically precise intervention - including primary rhinoplasty and septal repositioning - improves long-term nasal form and function while reducing need for future surgeries, without compromising nasal or midfacial growth[1,49-51]. Systemic reviews and meta-analyses further demonstrate that both unilateral and bilateral cleft patients benefit from these early approaches, with aesthetic and functional outcomes sustained into adolescence and adulthood[1,52-54].

In a large systematic review and meta-analysis, Alanazi et al. evaluated primary rhinoplasty outcomes in 2,964 unilateral and 1,012 bilateral cleft lip patients[53]. Success was defined as achieving nasal symmetry and function without the need for revision surgery. The procedure met these goals in 73.6% of unilateral and 88% of bilateral cases, with only 14% of unilateral patients requiring secondary interventions. The analysis of 65 studies emphasized the importance of long-term follow-up, concluding that early rhinoplasty does not significantly affect nasal or midfacial growth. While the review did not report a pooled average follow-up duration, individual studies ranged from several months to over 15 years.

Similarly, a systematic review by Zelko et al. supports the effectiveness of primary rhinoplasty during initial unilateral cleft lip repair[52]. Most of the subjective and objective studies reviewed reported favorable aesthetic and functional outcomes, and eight out of nine growth studies found no impairment in nasal or midfacial development. Additionally, five long-term studies with follow-up periods of six years or more reported that between 43% and 100% of patients avoided revision rhinoplasty[7,11,13,21,29,52]. This wide range reflects variability in surgical technique, patient selection, follow-up duration, and outcome measures, underscoring the need for standardized protocols and higher-quality, long-term research to optimize patient selection and surgical timing. Di Chiaro et al.’s systematic review, which included 12 studies primarily focused on bilateral cleft lip repair, found that nine studies supported primary rhinoplasty at the time of lip repair[54]. Eight studies assessing nasal growth reported no restriction over time, and four studies following 158 patients for an average of 15 years demonstrated that 77% did not require secondary rhinoplasty.

Furthermore, two high-level studies using three-dimensional morphometric analysis provide strong evidence that primary rhinoplasty in unilateral cleft lip does not impair nasal growth and results in stable, symmetric nasal outcomes over time. Seo et al. showed that most nasal measurements at skeletal maturity were comparable to normal controls, with only minor differences in nasal bridge length and tip projection that did not indicate growth restriction[55]. Similarly, Tse et al. found that primary correction of the nasal foundation led to stable and symmetric nasal base correction over a 5-year follow-up, without evidence of recurrent deformity or adverse nasal changes regardless of cleft type[11]. Together, these findings robustly support early nasal intervention, which preserves normal nasal development and achieves lasting, symmetric outcomes.

Tessier clefts

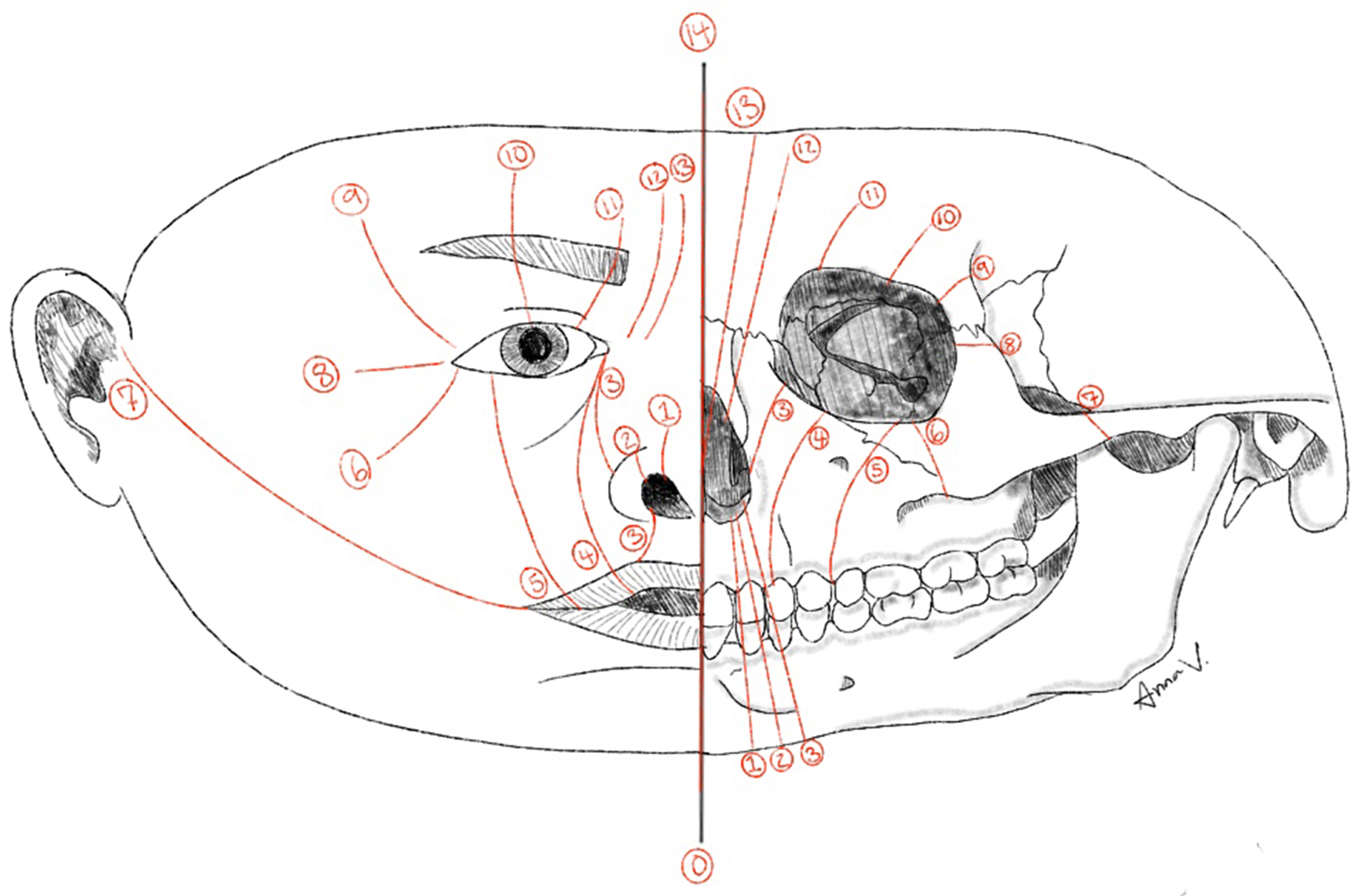

Tessier clefts are a rare group of craniofacial anomalies classified using a system introduced by Paul Tessier in 1976[56]. This system assigns cleft numbers ranging from 0 to 14 based on the cleft's anatomical location, arranged in a radial pattern around the orbit, using the orbit as a central reference point [Figure 3]. The overall incidence of craniofacial clefts is extremely rare and estimated to be between 1.4 and 4.9 per 100,000 live births[57]. In this discussion, we focus on Tessier clefts 0 through 3, as these involve the oro-nasal structures.

Figure 3. Diagram illustrating the soft-tissue and skeletal locations of the Tessier craniofacial clefts (numbers 0-14). Illustration designed by Anna Virginia DeMarco.

Tessier number 0 cleft

Tessier number 0 cleft lies in the true midline and involves the center of the upper lip and nose, potentially extending superiorly to the forehead. The Tessier number 0 cleft is the most common of the craniofacial clefts, occurring in approximately 60% of cases[57]. Tessier 0 clefts present with a midline nasal cleft, often accompanied by a bifid nasal tip, columella deficiency, and potential involvement of the nasal septum. Based on the patient’s age, severity, and extent of the defect, correction often requires excision of redundant midline skin and soft tissue, anatomic approximation of the LLC, and, when present, repair of associated midline cleft lip or alveolar defects [Figure 4]. Techniques such as local skin flaps, expanded forehead flaps, split M-shaped flaps, and combined intraoral and nasal approaches have been described[58-60].

Figure 4. An example of techniques employed for a Type 0 Tessier. (A) Preoperative frontal view (B) Immediate postoperative frontal view. Surgery included lateral and medial nasal bone osteotomies; (C) Preoperative lateral view (D) Immediate postoperative lateral view. Surgery included an on-lay graft composed of autologous minced costal cartilage and fibrin glue. The excess skin/SMAS generated from medializing the nasal bones and upper/lower lateral cartilages created a potential space to place the on-lay graft and project the nasal dorsum and tip; (E) Preoperative base view; (F) Immediate postoperative base view; (G) Schematic illustrating the planned trans-columellar incision with excision of intra-tip skin excess; (H) Schematic illustrating closure of the incisions. The asterisk denotes where there is a purposeful standing cone at the end of the elliptical excision to allow for more tip projection. SMAS: Superficial musculoaponeurotic system.

Local skin flaps are generally performed after infancy, typically between 3 and 6 years of age, and are indicated for mild-to-moderate soft-tissue deformities. Timing is individualized based on psychosocial impact, airway function, and nasal growth potential. Forehead flap reconstructions are reserved for more severe nasal deficiencies or when local tissue is insufficient, typically performed at school age (> 6 years) and often combined with costal cartilage grafts to provide structural support.

Wang et al. introduced the use of a split M-shaped flap, typically applied in early childhood (median age 5-7 years), for the correction of bifid nose deformities associated with Tessier type 0 clefts[60]. This technique involves transposing an M-shaped flap to reconstruct the nasal dorsum and alar structures. In a series of 26 patients, the approach resulted in increased nasal length, improved nasal appearance, and high patient satisfaction, with complications including mild nostril deformities and temporary breathing difficulties.

The 2023 retrospective review by Wang et al. provides a comprehensive analysis of the surgical management of Tessier type 0 clefts with a bifid nose, focusing on both aesthetic and functional outcomes[59]. The surgical approach emphasized involves staged reconstruction, beginning with repositioning of the alar rims and columella to establish a central nasal axis. Subsequent procedures aim to reconstruct the nasal septum and support the nasal dorsum, utilizing autologous grafts such as costal cartilage, typically performed after 6-8 years of age, when sufficient donor tissue is available. Outcomes from the cohort indicate significant improvements in nasal symmetry and airway function postoperatively. However, the study also notes the challenges associated with these complex reconstructions, including the need for meticulous surgical technique and long-term follow-up to monitor for potential complications such as graft resorption or airway obstruction.

Tessier number 1 and 2 clefts

Tessier number 1 cleft is located just lateral to the midline, affecting the area between the philtrum and the nasal ala, and often presents as a subtle notch in the medial one-third of the nasal ala. Tessier number 2 cleft is positioned more laterally than cleft 1, involving the lateral aspect of the nasal ala and adjacent maxilla, with greater disruption of the nasal contour. Surgical correction of Tessier type 1 and 2 nasal clefts - characterized by notches in the medial one-third of the nasal ala - has been addressed through various innovative techniques aimed at restoring both form and function. These procedures are typically performed after infancy, often between 1 and 5 years of age.

Rashid et al. proposed a rotation-transposition method involving a composite muco-chondro-cutaneous lateral alar flap to recreate the alar rim[61]. The resulting defect on the lateral nasal wall is then covered with a transposition flap from the dorsum. An alar rim Z-plasty is added in cases where notching is evident. This technique has demonstrated satisfactory results with minimal scarring in a series of 13 patients.

Chapchay et al. introduced a single-stage procedure performed in early childhood (median age 2-4 years), using local tissue rearrangement to restore nasal anatomy[62]. The technique involves a laterally based rotational alar flap, a medially based triangular flap, and a nasal wall advancement flap, all derived from existing nasal tissue near the cleft. This approach has shown excellent aesthetic outcomes with no postoperative complications in a series of five pediatric patients.

Yu et al. introduced the alar rim triangular flap, a local flap technique involving two triangles of existing nasal tissue near the cleft[63]. Performed in patients aged 2-5 years, this approach aims to cover the alar rim defect through local tissue rearrangement. In a study of 10 pediatric patients, all cases were successfully reconstructed with no flap loss, alar retraction, nasal obstruction, or step-off deformities.

Tessier number 3 Cleft

Tessier number 3 cleft is even further lateral. It follows an oblique course from the philtrum of the upper lip, through the nasal ala, and toward the medial canthus of the eye, involving both soft tissue and underlying bony structures. Current surgical management of Tessier number 3 craniofacial clefts involves an individualized, staged approach that targets both soft-tissue and skeletal deformities. Procedures typically begin in infancy (6-12 months) and are staged throughout growth. The primary objectives are to restore facial symmetry and function, particularly in the lip, nasomalar, and eyelid regions.

Soft tissue correction typically includes local flaps such as the dorsal nasal Rieger flap for alar repositioning, cheek advancement flaps, medial canthal repositioning, and a modified Millard technique for cleft lip repair. Eyelid colobomas and canthal displacement are addressed through direct repair in infancy, while nasal deformities are managed with rotation and advancement flaps. Skeletal intervention may involve pre-surgical orthopedics, bone grafting, or osteotomies and is typically delayed until at least 8-10 years of age. These procedures are reserved for cases with significant bony malposition or midfacial hypoplasia.

In the review by Golinko et al., two infants with Tessier number 3 clefts underwent a four-step, top-down surgical approach: (1) Rieger flap; (2) cheek advancement; (3) medial canthal repositioning; and (4) modified Millard repair[64]. Early complications included scarring, lagophthalmos, lower lid retraction, and under-correction of alar position, though medial canthal positioning was satisfactory. Long-term follow-up with imaging was planned to monitor facial growth and guide future interventions. These insights underscore the importance for multidisciplinary, staged care and long-term surveillance in managing these complex clefts.

FND

FND is characterized by a spectrum of midline facial anomalies with the clinical diagnosis made by the presence of two or more of the following cardinal features: ocular hypertelorism, a broad nasal root, median facial clefts involving the nose and/or upper lip, bifid or absent nasal tip, and anterior cranium bifidum occultum (a midline defect of the frontal bone covered by skin)[65-67]. Additional manifestations may include a long philtrum, V-shaped frontal hairline, cleft palate, anophthalmia or microphthalmia, eyelid malformations, ptosis, midline dermoid cysts, and agenesis of the corpus callosum[66,67]. Intellectual disability and systemic anomalies such as congenital heart defects, choanal atresia, and upper limb abnormalities may occur, particularly in severe forms or specific subtypes[67]. The phenotypic variability in FND is significant, even among patients with the same genetic subtype[66].

FND has traditionally been considered a sporadic condition, though familial cases have recently been described[65,68]. Mutations in the ALX (Aristaless-Like Homeobox) gene family - comprising ALX1, ALX3, and ALX4 - are now recognized as key contributors to the etiology of FND subtypes[66,69]. These genes encode transcription factors that are essential for the development and fusion of the frontonasal, maxillary, and branchial arch-derived facial structures[66]. Based on these mutations, FND is now classified into three ALX-related subtypes:

- FND1 (ALX3 mutation): typically present with milder facial features such as bifid nasal tip and hypoplastic columella[66];

- FND2 (ALX4 mutation): often includes severe hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, cleft or hypoplastic nasal alae, bifid nasal tip, short, broad columella, alopecia, and parietal bone defects[66,67];

- FND3 (ALX1 mutation): the most severe form, marked by bilateral cleft lip and palate, widened philtrum with prominently defined philtral columns, hypoplastic alae nasi, wide nasal bridge, extreme orbital malformations, and agenesis of the corpus callosum[66,67].

Intervention

Surgical intervention for FND-associated nasal anomalies is typically staged, with initial procedures reserved for urgent functional and psychosocial indications. Treatment planning must account for the variability in midline anomalies and craniofacial involvement, with early neuroimaging essential to exclude intracranial extensions prior to nasal reconstruction. More definitive nasal reconstruction is often performed in conjunction with hypertelorism repair, orbital box osteotomies, or facial bipartition around 5 to 6 years of age or delayed until after skeletal maturity (over 14 years) to minimize interference with craniofacial growth[65]. Although definitive nasal reconstruction is traditionally delayed, early intervention may be appropriate in infants or young children when severe nasal deformity causes airway or other functional impairment[4].

Fujisawa et al. reported a case of rhinoplasty with costochondral grafting performed at 16 months in a patient with FND and significant airway compromise, resulting in improved nostril patency and nasal contour without evidence of impaired growth[69]. Similarly, Song et al. described a case of early rhinoplasty performed at parental request in a 2-year-old child with FND who presented with a broad nasal root, bifid nasal tip, and hypertelorism[70]. The procedure addressed complex anatomical challenges, including a short columella, widened alar base, and separation of the lower and upper lateral cartilages. A V-Y transcolumellar incision allowed access and mobilization of the LLC. Conchal cartilage grafts were used for septal extension and tip derotation, while dorsal augmentation was achieved with acellular dermal matrix. Interdomal and transdomal sutures refined tip contour and definition. Redundant dorsal soft tissue was de-epithelialized and transposed to further enhance the nasal dorsum. At six months, the patient underwent minor scar revision and dorsal contouring. At two-year follow-up, nasal growth was normal, with no additional surgery required. The authors emphasized that, despite conventional deferral of nasal surgery until adolescence, early correction of severe nasal deformities may offer psychosocial benefits and support adaptation during early childhood.

Lopez et al. described a full-term infant with FND who presented with a severe midline facial mass, absent nose, and bilateral cleft lip and palate[68]. The patient underwent staged reconstruction beginning at 3 weeks of age, including mass excision and primary nasal soft tissue creation using a glabellar graft, followed by cleft lip and palate repair at 9 months and revision rhinoplasty at 14 months to address nasal tip bifidity. Despite the severity of the deformity and absence of normal nasal subunits, the patient exhibited no breathing or feeding difficulties and demonstrated normal nasal growth at 28 months of age, supporting the feasibility of staged early intervention in select cases. Nevertheless, these reports should be interpreted with caution, as long-term outcomes extending into adolescence were not reported.

Surgical techniques

Nasal deformities in FND are characterized by a short, broad, and often bifid nasal tip, necessitating structural support to achieve a more normalized contour[65]. Reconstruction commonly involves autologous cartilage grafting, harvested from the rib or upper lateral cartilages, to augment the nasal dorsum, lengthen the columella, and enhance tip projection[46]. Osteotomies are frequently used to narrow the widened nasal bones, while interdomal and intradomal suturing techniques allow for medialization of the LLC.

In a retrospective review of 17 patients with FND, Kim et al. reported favorable outcomes using a septal extension graft and L-strut technique with autologous costal cartilage[71]. The patients, aged 6 to 13 years at the time of surgery, underwent open rhinoplasty to correct the deficient nasal framework, with grafts sculpted to provide both dorsal augmentation and columellar support. No significant intraoperative or postoperative complications were reported, and all patients demonstrated substantial improvements in nasal shape and projection.

In skeletally mature patients with FND, structural rhinoplasty can be an effective approach for addressing complex nasal deformities involving both bony and cartilaginous components. One case by Chaisrisawadisuk described a 19-year-old male with a broad nasal root, bifid tip, and hypoplastic septum who underwent reconstruction using a costochondral cantilever graft, dorsal augmentation with Kirschner wire fixation, septal extension, and columellar strut placement[72]. The V-Y advancement technique was employed for columellar lengthening due to its versatility and aesthetically favorable outcomes[73]; however, significant advancement and tension on the columellar flap led to partial skin necrosis at the suture line, which healed conservatively but ultimately resulted in scar contracture, rightward tip deviation, and external nasal valve collapse at seven-month follow-up. Secondary revision was planned following scar maturation. This case highlights several critical considerations in FND reconstruction, including the limitations of soft tissue advancement, the risk of scar contracture and distortion when tip grafting is overextended, and the frequent need for staged surgical correction.

Ultimately, the complex and variable nature of FND underscores the importance of a comprehensive, phenotype-driven approach to reconstructive planning[69]. Advances in surgical techniques and understanding of the genetic underpinnings continue to refine treatment paradigms in order to improve long-term outcomes in this patient population.

Maxillonasal dysplasia

Maxillonasal dysplasia or Binder Syndrome is characterized by a hypoplastic nasomaxillary skeleton resulting in a retruded midface, shortened columella, flattened nose tip, and absent or deficient anterior nasal spine[3,74]. Other associated anomalies include cervical spine malformations, cleft lip and palate, and class III malocclusion[75-77]. It is estimated to occur in approximately 1 in 10,000 live births, with no significant sex predilection. While most cases are considered sporadic, familial recurrence has been reported in 15%-35% of cases, suggesting a possible underlying genetic contribution[75,76].

Correction of maxillonasal dysplasia anomalies is surgically challenging, with outcomes frequently limited by soft tissue constraints and the potential for graft resorption, resulting in multiple surgical procedures to achieve desired results[74-77]. Nasal reconstruction in this population typically occurs between 16-18 years of age, but this delay leaves patients with persistent psychosocial distress[3,74]. In a 2022 systematic review, most studies reported augmentation of the nasal dorsum and reconstruction of the columella and nasal spine, often in combination with grafting to the premaxillary and paranasal regions[78]. Of the 14 clinical studies included, 12 employed rhinoplasty techniques using autologous grafts, most frequently costal cartilage or bone, to achieve greater nasal projection and midfacial contour. In contrast, few studies utilized alloplastic materials such as silicone or expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE), which were associated with long-term complications including calcification and extrusion. Collectively, these findings suggest that autologous cartilage grafts may offer superior long-term structural and aesthetic outcomes compared to synthetic alternatives. However, due to the rarity of this condition, a standardized surgical approach has yet to be established.

Recent data supports a staged treatment strategy beginning in childhood. In a 27-year longitudinal study of 31 patients, early expansion resulted in reduced rates of graft resorption and more satisfactory nasal projection compared to patients who underwent post-pubertal, one-stage reconstruction[74]. Customized L-shaped silicone implants were inserted during early childhood, typically between 7-9 years of age, and exchanged serially to accommodate growth. These implants expanded both the nasal lining and external soft tissue, particularly the columella, which is crucial for ultimate nasal lengthening. Definitive rhinoplasty following puberty employed a one-piece costochondral graft cantilevered to the frontal bone. The technique preserved the dorsal periosteum, which was sutured to the upper lateral cartilages to support the internal nasal valves and minimize resorption. This approach not only reduces visible scarring from traditional nasal lengthening flaps and the number of future surgeries, but provides the psychosocial benefit of early aesthetic correction, highlighting the importance of initiating treatment in childhood[3,74].

Complementary findings were reported in a 2022 case series of five children aged 8 to 15 years who underwent augmentation rhinoplasty using autologous cartilage[3]. All patients demonstrated improved nasal contour and projection, with no intraoperative complications or postoperative graft resorption. Furthermore, subjective assessments and Rhinoplasty Outcome Evaluation scores reflected enhanced self-image, greater social confidence, and high satisfaction with aesthetic outcomes. Notably, performing surgery at a younger age facilitated easier release of tight nasal skin and mucosa, which is a common limiting factor in older patients[79]. The use of autologous cartilage avoided complications often associated with alloplastic materials, such as infection, extrusion, or stiffness[3].

Taken together, these findings favor earlier surgical intervention for those affected with maxillonasal dysplasia, offering the advantage of more compliant soft tissues and the potential to positively impact psychosocial development[79]. A treatment strategy that combines early augmentation to enable soft tissue envelope expansion with planned secondary procedures after skeletal maturity provides a flexible, patient-centered approach aimed at optimizing both short- and long-term outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Congenital nasal deformities encompass a broad and complex spectrum of anomalies that significantly impact both function and facial aesthetics from an early age. Historically, concerns regarding interference with facial growth led to delayed surgical correction; however, a growing body of evidence now supports the safety and efficacy of earlier, anatomically precise interventions. This shift reflects improved understanding of nasal development, advances in surgical techniques, and greater emphasis on psychosocial well-being during critical developmental periods.

Early intervention with primary cleft rhinoplasty and septal repositioning is now generally accepted as safe and effective, with a shift toward more comprehensive and anatomically precise techniques to optimize long-term outcomes. Early correction in cleft congenital noses has demonstrated consistent improvements in nasal symmetry, airway patency, and patient satisfaction while minimizing the need for extensive revision procedures later in life.

Beyond concerns about restricted facial growth, most surgeons recognize that early-life surgery inevitably creates scar tissue, which can distort natural tissue planes and complicate future procedures. Therefore, conservative and meticulous dissection is essential to minimize unpredictable scarring. Early interventions should focus on repositioning and recontouring underlying structures while avoiding unnecessary tissue resection. Augmentation with grafts supports gradual expansion of the nasal soft tissue envelope, potentially reducing the need for more extensive reconstructive flaps later in life.

Across various deformity types - including cleft nasal deformities, Tessier clefts, FND, and maxillonasal dysplasia - tailored, phenotype-driven approaches allow for timely and effective treatment, aligning both functional and aesthetic goals with developmental considerations.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Anna Virginia DeMarco for her outstanding work in illustrating Figure 3.

Authors’ contributions

Contributed substantially to the conception and design of the work, conducted the literature review, drafted the manuscript, and made critical revisions: Hullfish H

Contributed to the acquisition and analysis of relevant literature and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript: Williamson L, Close M

Preparation and creation of the published work, specifically visualization/data presentation and participated in drafting and revising the manuscript: Kappauf C

Provided oversight throughout the writing process, critically revised the manuscript, ensured the accuracy and integrity of the work, and contributed expert guidance throughout the writing process: Patel K

All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to accountability for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for the use of clinical photographs in this publication. The guardian was informed that the images may be published in print and online and may be used for educational and research purposes.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Bins GP, Dourado J, Tang J, Kogan S, Runyan CM. “Primary correction of the cleft nasal septum: a systematic review”. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2024;61:373-82.

2. Afifi T, Saleh D, Shaker A. Our strategy in management of maxillonasal dysplasia in pediatric patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1037-41.

3. Baser B, Singh P, Surana P, Roy PK, Chaubey P. Early surgical intervention for nasal deformity in Binder’s syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 2022;136:146-53.

4. Kopacheva-Barsova G, Nikolovski N. Justification for rhinoseptoplasty in children - our 10 years overview. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4:397-403.

5. Verwoerd CD, Verwoerd-Verhoef HL. Rhinosurgery in children: developmental and surgical aspects of the growing nose. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;9:Doc05.

6. Gary CC. Pediatric nasal surgery: timing and technique. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25:286-90.

7. Pinto V, Piccin O, Burgio L, Summo V, Antoniazzi E, Morselli PG. Effect of early correction of nasal septal deformity in unilateral cleft lip and palate on inferior turbinate hypertrophy and nasal patency. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;108:190-5.

8. Smarius B, Loozen C, Manten W, Bekker M, Pistorius L, Breugem C. Accurate diagnosis of prenatal cleft lip/palate by understanding the embryology. World J Methodol. 2017;7:93-100.

9. Hammond NL, Dixon MJ. Revisiting the embryogenesis of lip and palate development. Oral Dis. 2022;28:1306-26.

10. Kaufman Y, Buchanan EP, Wolfswinkel EM, Weathers WM, Stal S. Cleft nasal deformity and rhinoplasty. Semin Plast Surg. 2012;26:184-90.

11. Tse RW, Knight R, Oestreich M, Rosser M, Mercan E. Unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity: three-dimensional analysis of the primary deformity and longitudinal changes following primary correction of the nasal foundation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:185-99.

12. Kalmar CL, Carlson AR, Patel VA, et al. Cleft rhinoplasty: does timing and utilization of cartilage grafts affect perioperative outcomes? J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:1762-8.

13. Tse RW, Mercan E, Fisher DM, Hopper RA, Birgfeld CB, Gruss JS. Unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity: foundation-based approach to primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:1138-49.

14. Avinoam SP, Kowalski HR, Chaya BF, Shetye PR. Current presurgical infant orthopedics practices among American Cleft Palate Association-Approved Cleft Teams in North America. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:2522-8.

15. Owens WR, Mohan VC, Bonanthaya K, Figueroa AA. Cleft presurgical infant orthopedics: evolution from analog to digital appliances-will it increase accessibility? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025;156:72S-80.

16. Winnand P, Ooms M, Heitzer M, et al. Defining biomechanical principles in pre-surgical infant orthopedics in a real cleft finite element model. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2025;54:904-13.

17. Dunworth K, Porras Fimbres D, Trotta R, et al. Systematic review and critical appraisal of the evidence base for nasoalveolar molding (NAM). Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2024;61:654-77.

18. Desale M, Tamchos R, Kapur A, Jaiswal M, Chauhan A. Effectiveness of presurgical orthopedic interventions in infants with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

19. Bayan L, Nordahl E, Huynh K, et al. Grayson’s technique for presurgical nasoalveolar molding (PNAM) in unilateral cleft lip and palate: a systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

20. Padovano WM, Skolnick GB, Naidoo SD, Snyder-Warwick AK, Patel KB. Long-term effects of nasoalveolar molding in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59:462-74.

21. Rau A, Ritschl LM, Mücke T, Wolff KD, Loeffelbein DJ. Nasoalveolar molding in cleft care--experience in 40 patients from a single centre in Germany. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118103.

22. Esenlik E, Gibson T, Kassam S, et al. NAM therapy-evidence-based results. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020;57:529-31.

23. Parhofer R, Rau A, Strobel K, et al. The impact of passive alveolar molding vs. nasoalveolar molding on cleft width and other parameters of maxillary growth in unilateral cleft lip palate. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27:5001-9.

24. Gibson E, Pfeifauf KD, Skolnick GB, et al. Presurgical orthopedic intervention prior to cleft lip and palate repair: nasoalveolar molding versus passive molding appliance therapy. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:486-91.

25. Chang FC, Huang JJ, Wallace CG, et al. Comparison of facial growth between two nasoalveolar molding techniques in patients with unilateral complete cleft lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:1078-83.

26. Multani N, Plana NM, Staffenberg DA, Flores RL, Shetye PR. An early comparative analysis of presurgical lip, alveolus and nose approximation (PLANA) and nasoalveolar molding (NAM). Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2025.

27. Shetye PR. An innovative technique of presurgical lip, alveolus, and nose approximation (PLANA) for infants with clefts. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;35:e357-9.

28. Tajima S, Maruyama M. Reverse-U incision for secondary repair of cleft lip nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60:256-61.

29. Lu TC, Lam WL, Chang CS, Kuo-Ting Chen P. Primary correction of nasal deformity in unilateral incomplete cleft lip: a comparative study between three techniques. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:456-63.

30. Byrd HS, Salomon J. Primary correction of the unilateral cleft nasal deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:1276-86.

31. Rottgers SA, Jiang S. Repositioning of the lower lateral cartilage in primary cleft nasoplasty: utilization of a modified Tajima technique. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:691-5.

32. Tse RW, Fisher DM. State of the art: the unilateral cleft lip and nose deformity and anatomic subunit approximation. Plast Surg. 2024;32:138-47.

33. Madaree A. Primary nasal correction in unilateral cleft lip: an ongoing journey. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:2354-7.

34. Wilkes C, Burge J, Chong DK. Primary unilateral cleft lip rhinoplasty technique: the melbourne technique. J Craniofac Surg. 2023;34:1347-50.

35. Cho BC, Lee JW, Lee JS, et al. Correction of secondary unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity in adults using lower lateral cartilage repositioning, columellar strut, and onlay cartilage graft on the nasal tip with open rhinoplasty combined with reverse-U incision. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:1077-86.

36. Tanikawa D, Sá Á, Figueroa Á, Chong D, Ishida LC. Introducing preservation rhinoplasty principles to cleft nasal surgery: unveiling the role of nasal ligaments in infant anatomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2026;157:79e-83.

37. Nguyen DC, Myint JA, Lin AY. The role of postoperative nasal stents in cleft rhinoplasty: a systematic review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2024;61:1941-50.

38. Bhutiani N, Tripathi T, Verma M, Bhandari PS, Rai P. Assessment of treatment outcome of presurgical nasoalveolar molding in patients with cleft lip and palate and its postsurgical stability. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020;57:700-6.

39. Yeow VK, Chen PK, Chen YR, Noordhoff SM. The use of nasal splints in the primary management of unilateral cleft nasal deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1347-54.

40. Al-Qatami F, Avinoam SP, Cutting CB, Grayson BH, Shetye PR. Efficacy of postsurgical nostril retainer in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate treated with presurgical nasoalveolar molding and primary cheiloplasty-rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:623-9.

41. Kim YC, Yoon I, Min JC, Woo SH, Kwon SM, Oh TS. Primary cleft rhinoplasty with custom suture needle for alar cartilage repositioning in unilateral cleft lip patients: 3d nasal analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2024;61:1593-600.

42. Park JJ, Rodriguez Colon R, Arias FD, et al. “Septoplasty” performed at primary cleft rhinoplasty: a systematic review of techniques and call for accurate terminology. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2023;60:1645-54.

43. Ng JJ, Cheung L, Massenburg BB, et al. Long-term surgical outcomes of intermediate cleft rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2025;156:455-64.

44. Insalaco LF, Karp E, Zavala H, Chinnadurai S, Tibesar R, Roby BB. Comparing autologous versus allogenic rib grafting in pediatric cleft rhinoplasty. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;138:110264.

45. Jenny HE, Siegel N, Yang R, Redett RJ. Safety of irradiated homologous costal cartilage graft in cleft rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:76e-81.

46. Hoang TA, Lee KC, Dung V, Chuang SK. Augmentation rhinoplasty in cleft lip nasal deformity using alloplastic material and autologous cartilage. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:e883-6.

47. Dang BN, Pfaff MJ, Jain NS, et al. Component restoration in the bilateral intermediate cleft tip rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148:243e-7.

48. Ayeroff JR, Volpicelli EJ, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Component restoration in the unilateral intermediate cleft tip rhinoplasty: technique and long-term outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:572e-80.

49. Murali SP, Denadai R, Sato N, et al. Long-term outcome of primary rhinoplasty with overcorrection in patients with unilateral cleft lip: avoiding intermediate rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;151:441e-51.

50. Nicol M, de Boutray M, Captier G, Bigorre M. Primary cheilorhinoseptoplasty using the Talmant protocol in unilateral complete cleft lip: functional and aesthetic results on nasal correction and comparison with the Tennison-Malek protocol. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;51:1445-53.

51. Lam T, Munns C, Fell M, Chong D. Septoplasty during primary cleft lip reconstruction: a historical perspective and scoping review. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;35:1985-9.

52. Zelko I, Zielinski E, Santiago CN, Alkureishi LWT, Purnell CA. Primary cleft rhinoplasty: a systematic review of results, growth restriction, and avoiding secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;151:452e-62.

53. Alanazi F, Alonazi M, Hazazi MT, AlQahtani SM, Alenezi M. Effectiveness and outcomes of primary rhinoplasty in cleft lip surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

54. Di Chiaro B, Santiago G, Santiago C, Zelko I, Choudhary A, Purnell CA. A systematic review of primary rhinoplasty in patients with bilateral cleft lip. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:2406-10.

55. Seo HJ, Denadai R, Vamvanij N, Chinpaisarn C, Lo LJ. Primary rhinoplasty does not interfere with nasal growth: a long-term three-dimensional morphometric outcome study in patients with unilateral cleft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:1223-36.

56. Tessier P. Anatomical classification facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg. 1976;4:69-92.

57. Kalantar-Hormozi A, Abbaszadeh-Kasbi A, Goravanchi F, Davai NR. Prevalence of rare craniofacial clefts. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:e467-70.

58. da Silva Freitas R, Alonso N, Shin JH, Busato L, Ono MC, Cruz GA. Surgical correction of Tessier number 0 cleft. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:1348-52.

59. Wang X, Wang H, You J, et al. A ten-year surgical experience in patients of Tessier No.0 cleft with a bifid nose. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;164:111399.

60. Wang Y, Yu B, Dai C, Wei J. Surgical correction of a bifid nose deformity with a split M-shaped flap. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2023;25:238-43.

61. Rashid M, Islam MZ, Tamimy MS, Haq EU, Aman S, Aslam A. Rotation-transposition correction of nasal deformity in Tessier number 1 and 2 clefts. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009;46:674-80.

62. Chapchay K, Zaga J, Billig A, Adler N, Margulis A. Surgical technique for nasal cleft repair. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;82:289-91.

63. Yu BF, Wei SY, Dai CC, Wei J. Alar rim triangular flap for congenital nasal cleft repair in pediatric patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:183-6.

64. Golinko MS, Pemberton JD, Phillips J, Johnson A, Hartzell LD. The arkansas tessier number 3 cleft experience: soft tissue and skeletal findings with primary surgical management: four-step approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:1834-41.

65. Lee SI, Lee SJ, Joo HS. Frontonasal dysplasia: a case report. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2019;20:397-400.

66. Vargel I, Canter HI, Kucukguven A, Aydin A, Ozgur F. ALX-related frontonasal dysplasias: clinical characteristics and surgical management. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59:637-43.

67. Umair M, Ahmad F, Bilal M, Arshad M. Frontonasal dysplasia: a review. J Biochem Clin Genet. 2018;1:2-14.

68. Lopez A, Lyle DA, Brennan TE, Bennett E. Rhinoplasty in a 3 week old: surgical challenges in the setting of severe congenital frontonasal dysplasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022;131:1409-12.

69. Fujisawa K, Watanabe S, Kato M, Utsunomiya H, Watanabe A. Costochondral grafting for nasal airway reconstruction in an infant with frontonasal dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2019;30:200-1.

70. Song SY, Choi JW, Lew HW, Koh KS. Nasal reconstruction of a frontonasal dysplasia deformity using aesthetic rhinoplasty techniques. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:637-9.

71. Kim YB, Nam SM, Park ES, Choi CY, Cha HG, Kim JH. Nasal reconstruction of a frontonasal dysplasia via septal l-strut reconstruction using costal cartilage. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022;59:1306-13.

72. Chaisrisawadisuk S, Chaisrisawadisuk S. Structural rhinoplasty as an effective surgical approach for frontonasal dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;Epub ahead of print.

73. Agrawal K, Shrotriya R. Columellar lengthening in primary and secondary rhinoplasty for binder’s syndrome: a fresh perspective. Indian J Plast Surg. 2023;56:78-81.

74. Holmes AD, Lee SJ, Greensmith A, Heggie A, Meara JG. Nasal reconstruction for maxillonasal dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:543-51.

75. Goh RC, Chen YR. Surgical management of Binder’s syndrome: lessons learned. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34:722-30.

76. Siddiqui HP, Sennimalai K, Samrit VD, Bhatt K, Duggal R. Binder’s syndrome: a narrative review. Spec Care Dentist. 2023;43:73-82.

78. Kerbrat A, Ferri J. Surgical treatment for patients with binder syndrome, clinical features and associated symptoms: a systematic review. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:530-3.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].