Surgical approaches to diabetic foot ulcers: an algorithm for applying the reconstructive ladder

Abstract

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) affect over 18 million people worldwide and account for more than 70% of lower-limb amputations in the United States, emphasizing the need for effective limb-preservation strategies. This narrative review synthesizes current evidence on the algorithmic surgical management of DFUs using the reconstructive ladder to provide a practical decision guide for multidisciplinary teams. Scientific papers, society guidelines, and orthoplastic experience are integrated to outline surgical treatment recommendations, including preoperative optimization, serial debridement, wound conditioning with reconstructive adjuncts, and definitive closure techniques aligned with the reconstructive ladder. Early radical debridement combined with vascular optimization, tight glycemic control, and infection eradication forms the foundation for surgical success, while the reconstructive ladder provides the algorithm for closure, from secondary intention or tension-free primary closure for small superficial wounds, to split-thickness skin grafts for larger well-granulating defects, and to local or regional pedicled flaps for larger defects. Knowledge and application of this algorithm have the potential to reduce major amputation rates while restoring durable ambulation in complex DFU cases.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic foot disease is a debilitating health condition and remains one of the most common complications in patients with diabetes, affecting approximately 15% of the 200 million people diagnosed with diabetes worldwide[1-3]. Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) influence 18 million people globally, including 1.6 million individuals in the United States[4].

Diabetic foot ulcerations start from acute injury or repeated trauma from the lack of protective sensation secondary to peripheral neuropathy, concomitant peripheral artery disease, and impaired wound healing secondary to diabetic microcirculatory disease[3,5,6]. The sequelae of DFUs include recurrent ulceration, deep infections, osteomyelitis, and the potential need for partial or complete foot amputation. It is estimated that 50% of DFUs will become infected and at least 20% will result in a lower extremity amputation[4,7]. These complications not only lead to significant morbidity and functional impairment but also contribute to increased mortality rates in diabetic populations, with a 5-year mortality rate of approximately 30%-40%[4,8]. Out of the 185,000 lower limb amputations performed a year in the United States, 70% occur in diabetics, and the incidence of a major amputation (below/above the knee) is correlated with an increased 5-year mortality of 61%-74%[3].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant healthcare burden and economic costs associated with managing DFUs, as well as their detrimental impact on patient quality of life[2,4,5,8,9]. Patients with DFUs often have prolonged hospitalizations, frequent medical interventions, and long-term rehabilitative care placing immense strain on the individual and healthcare systems. However, timely diagnosis, comprehensive wound management, and appropriate surgical interventions can play a crucial role in reducing chronicity, preventing severe complications, and ultimately lowering the rate of major amputations. A multidisciplinary approach incorporating glycemic control, optimization of other medical comorbidities, early surgical intervention, and advanced wound care modalities is essential in optimizing patient outcomes and preserving limb function[8]. Several studies have demonstrated that implementation of a diabetic multidisciplinary service resulted in reductions of major amputations between 62%-82%[10-13].

This article aims to summarize the advanced and modern surgical techniques currently used in the treatment and management of diabetic foot wounds. It discusses the indications for surgical debridement, reconstructive procedures, and offloading techniques, while outlining a comprehensive approach to optimize patient outcomes and reduce the risk of complications.

SURGICAL INTERVENTIONS

Surgical reconstruction of the diabetic foot plays a crucial role in managing DFUs and has been increasingly utilized over the past two decades. Despite the favorable outcomes associated with diabetic foot surgery, it is not without risks. However, selective surgical treatment can significantly improve patient outcomes, particularly for those with persistent foot ulceration.

Surgical interventions for DFUs include both vascular and non-vascular procedures, with some cases requiring foot amputation. Non-vascular foot surgery in diabetic patients is classified into three categories: prophylactic, curative, and emergency surgery, each performed with the goal of correcting deformities, relieving pressure, and preventing complications that contribute to ulcer formation.

Prophylactic procedures aim to correct structural foot deformities before ulceration occurs and address high-risk foot conditions to prevent future complications. Curative procedures focus on active ulcer management, including debridement and wound reconstruction, whereas emergency surgery is reserved for infections, gangrene, or critical ischemia requiring urgent intervention.

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT

The etiology of diabetic foot wounds is typically due to acute or repeated trauma that persists because of loss of protective sensation resulting from diabetic peripheral neuropathy along with physiologically impaired wound healing.

A well-conducted preoperative assessment ensures that patients undergo appropriate interventions tailored to their wound severity, vascular status, and infection risk, ultimately improving surgical outcomes and limb preservation. Proper evaluation helps identify factors that may influence wound healing, infection control, and postoperative recovery. The assessment process includes patient evaluation, wound classification, vascular assessment, and infection assessment/control. Before initiating reconstructive surgery, modifiable factors should be addressed and optimized via a multidisciplinary approach.

Patient evaluation

A thorough medical history and physical exam are essential for evaluating diabetic patients. Key factors include:

• Duration and severity of diabetes

• Glycemic control [Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels]

• Previous and current ulcers, infections, or amputations

• Peripheral neuropathy assessment (monofilament testing/vibration perception)

• Comorbid conditions [e.g., peripheral artery disease (PAD), renal insufficiency, cardiovascular disease]

Foot examination

According to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, United Kingdom), annual foot exams in diabetic patients are recommended[6]. Not only should each exam include assessment of presence of ulcerations, calluses, and deformities, but also include monofilament and vibration testing for sensation and pulse examination [Table 1]. Regular diabetic foot exams can lead to early identification of diabetic neuropathy and diabetic foot complications.

Clinical examination of the diabetic foot

| Clinical examination | Components |

| Visual foot exam | Ulcerations, calluses, corns, skin breaks, nail abnormalities, infection |

| Palpation of foot pulses | Dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial |

| Sensation | Monofilament, vibration |

| Footwear examination | Condition, fit |

DFU classification

Proper classification of DFUs aids in determining the appropriate treatment strategy. Common classification systems include:

• Wagner Classification System [Table 2] - Grades wounds based on depth, infection, and presence of gangrene

• University of Texas Diabetic Wound Classification [Table 3] - Considers depth, infection, and ischemia

• SINBAD System [Table 4] - Focuses on ulcer site, ischemia, neuropathy, bacterial infection, and depth

Wagner classification system

| Grade | Description | Clinical features |

| 0 | No open lesion | Intact skin; may have deformity or pre-ulcerative lesion (callus) |

| 1 | Superficial ulcer | Localized superficial ulceration limited to the epidermis and dermis; no underlying deep tissue involvement |

| 2 | Deep ulcer | Deep ulceration, extending into subcutaneous tissue, involving tendon, bone, or joint capsule; no abscess or osteomyelitis |

| 3 | Deep ulcer with infection | Extensive ulceration with presence of abscess, osteomyelitis, or joint sepsis |

| 4 | Localized gangrene | Partial foot gangrene (toes or forefoot) with necrosis |

| 5 | Extensive gangrene | Gangrene involving the entire foot; often requires major amputation |

The University of Texas wound classification system

| Grade | |||||

| Stage | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| A | Pre-ulcerative lesions No skin break | Superficial wound No penetration | Wound penetrating tendon or capsule | Wound penetrating bone or joint | |

| B | With infection | With infection | With infection | With infection | |

| C | With ischemia | With ischemia | With ischemia | With ischemia | |

| D | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia | With infection and ischemia | |

SINBAD system

| Category | Definition | Score |

| Site | Forefoot | 0 |

| Midfoot and hindfoot | 1 | |

| Ischemia | Pedal blood flow intact: at least one palpable pulse | 0 |

| Clinical evidence of reduced pedal flow | 1 | |

| Neuropathy | Protective sensation intact | 0 |

| Protective sensation lost | 1 | |

| Bacterial infection | None | 0 |

| Present | 1 | |

| Area ulcer | Ulcer < 1 cm2 | 0 |

| Ulcer ≥1 cm2 | 1 | |

| Depth | Ulcer confined to skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0 |

| Ulcer reaching muscle, tendon or deeper | 1 | |

| Total possible score | 0-6 | |

These different classification systems help guide treatment decisions, with lower grades/scores often managed conservatively and higher grades/scores requiring surgical intervention, including debridement or amputation.

Vascular assessment

Approximately half of those with diabetic foot wounds have peripheral artery disease[4,7]. Because of the increased likelihood of concomitant vascular disease, all patients with DFUs should also undergo vascular evaluation, as it may be critical in determining whether revascularization is necessary before surgery. Vascular assessment of patients with DFUs includes palpation of the lower extremity pulses, assessment of skin temperature, and other skin changes. Imaging should also be considered in obtaining a complete vascular assessment.

Common imaging methods include:

• Ankle-brachial index (ABI)

• Toe-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcPO2s)

• Doppler ultrasound and duplex scanning

• Plain film radiography

• Computerized tomography (CT) angiography or magnetic resonance (MR) angiography

As many diabetics have noncompressible vessels due to calcification, ABIs may not be able to provide accurate results on the patient’s peripheral vascular disease[7]. Therefore, TcPO2s and Toe-brachial indices may be preferred.

If concomitant peripheral vascular disease is suspected or diagnosed, prompt referral to vascular surgery is recommended to assist in optimizing the patient’s wound healing ability and evaluate for the need for surgical revascularization of critically ischemic limbs.

Infection assessment

Infection control is a key determinant of surgical success in DFU management. Assessing infection severity involves:

• Clinical signs - Redness, warmth, swelling, purulent drainage, or systemic signs of sepsis

• Laboratory tests - White blood cell count (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and procalcitonin (PCT)

• Deep wound tissue cultures - Identify causative microorganisms for targeted antibiotic therapy

• Imaging studies - X-rays to detect osteomyelitis, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if diabetic-related osteomyelitis remains uncertain despite clinical, X-ray, and lab results

According to the 2023 updated International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, diabetic foot infections are diagnosed with the presence of at least two of the following: swelling, induration, erythema around the wound, localized pain/tenderness, increased warmth, or purulent discharge[14].

The IWGDF/IDSA further classifies by severity of the infection into uninfected, mild, moderate, and severe.

Table 5 is adapted from the 2023 updated guidelines, further describing characteristics for each classification.

IWGDF/IDSA classification system for defining the presence and severity of foot infection in a person with diabetes[14]

| Clinical classification of infection, definitions | IWGDF/IDSA classification |

| No systemic or local symptoms or signs of infection | 1/Uninfected |

| Infected: At least two of these items are present: • Local swelling or induration • Erythema > 0.5 but < 2 cma around the wound • Local tenderness or pain • Local increased warmth • Purulent discharge And, no other cause of an inflammatory response of the skin (e.g., trauma, gout, acute charcot neuro-arthropathy, fracture, thrombosis, or venous stasis) | 2/Mild |

| Infection with no systemic manifestations and involving: • Erythema extending ≥ 2 cma from the wound margin, and/or • Tissue deeper than skin and subcutaneous tissues (e.g., tendon, muscle, joint, and bone)b | 3/Moderate |

| Infection involving bone (osteomyelitis) | Add “(O)” |

| Any foot infection with associated systemic manifestations (of the SIRS), as manifested by ≥ 2 of the following: • Temperature, > 38 °C or < 36 °C • Heart rate, > 90 beats/min • Respiratory rate, > 20 breaths/min, or PaCO2 < 4.3 kPa (32 mmHg) • WBC > 12,000/mm3, or < 4 G/L, or > 10% immature (band) forms | 4/Severe |

| Infection involving bone (osteomyelitis) | Add “(O)” |

Patient education

Patient education has been shown to be essential in delaying the onset of, reducing the severity of, and preventing the recurrence of DFUs[6,15,16]. Patients should be educated about their condition and potential complications of their diabetes and DFUs. They should be advised to undergo regular foot inspection, foot care, and glycemic control. Patients will need to follow up closely with their primary care physician, and possibly a podiatrist, in order to reduce their Hemoglobin A1C (HgbA1c) and for foot exams and assistance in finding appropriate shoes that reduce the risk of pressure injury on their plantar surfaces. Several studies have shown that tight glycemic control can prevent and slow down the progression of diabetic neuropathy[8]. They should also be advised to maintain foot hygiene by washing the feet daily with warm water - checking the temperature with their hand - towel-drying thoroughly, and applying moisturizer. They should be advised to avoid wearing shoes that may cause pressure over areas of their plantar surface. Moreover, patients should understand the importance of professional foot inspections, as regular self-inspection - even using a mirror to view all areas, particularly the soles - is essential for proper foot care. Patients should not overlook any sign of skin redness, swelling, cracking or callus formation. Table 6 provides a summary of patient education topics.

Various important patient education topics

| Education topic | Key points |

| Diabetes and glucose control | Maintain tight glycemic control (target HbA1c per provider); monitor blood glucose regularly; adhere to medication, dietary, and exercise plans |

| Foot hygiene | Wash feet daily with warm (not hot) water; dry thoroughly, especially between toes; apply moisturizer (avoid between toes) |

| Daily inspection | Inspect feet for redness, swelling, cracks, or calluses using a mirror or with assistance |

| Shoe selection | Wear well-fitted, cushioned footwear; avoid barefoot walking, tight shoes, or high heels |

| Signs of infection | Look for increased redness, warmth, drainage, foul odor, or pain; seek prompt medical attention |

| Routine follow-up | Maintain regular appointments with your primary care physician and podiatrist for monitoring and preventive care |

SOFT TISSUE SURGICAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE DIABETIC FOOT

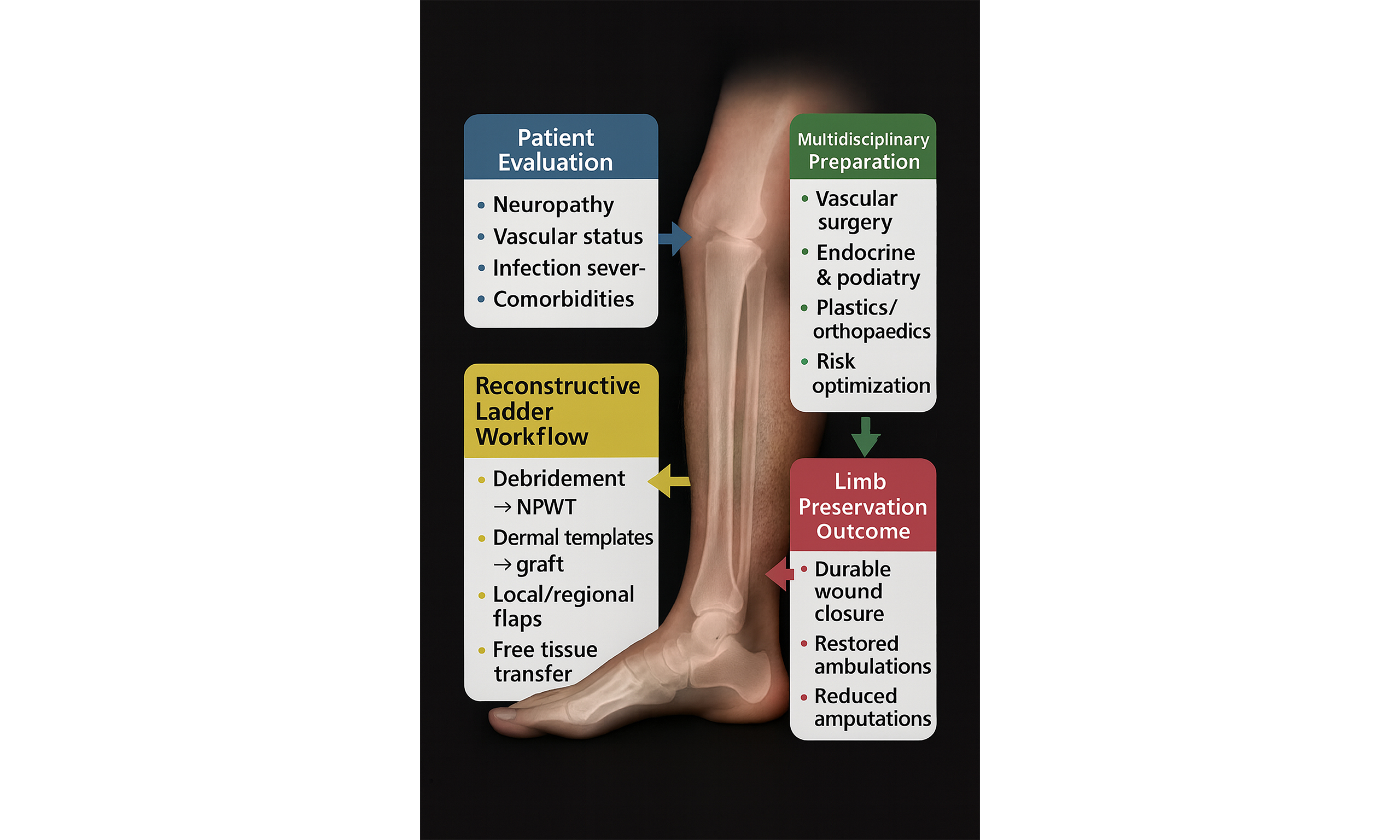

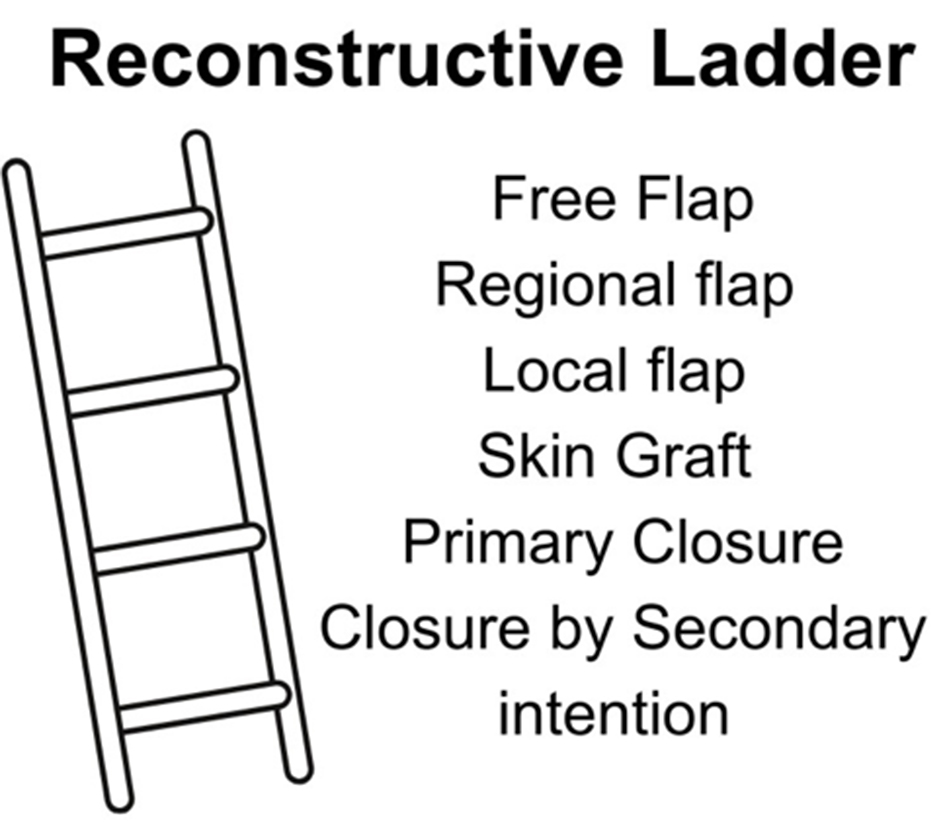

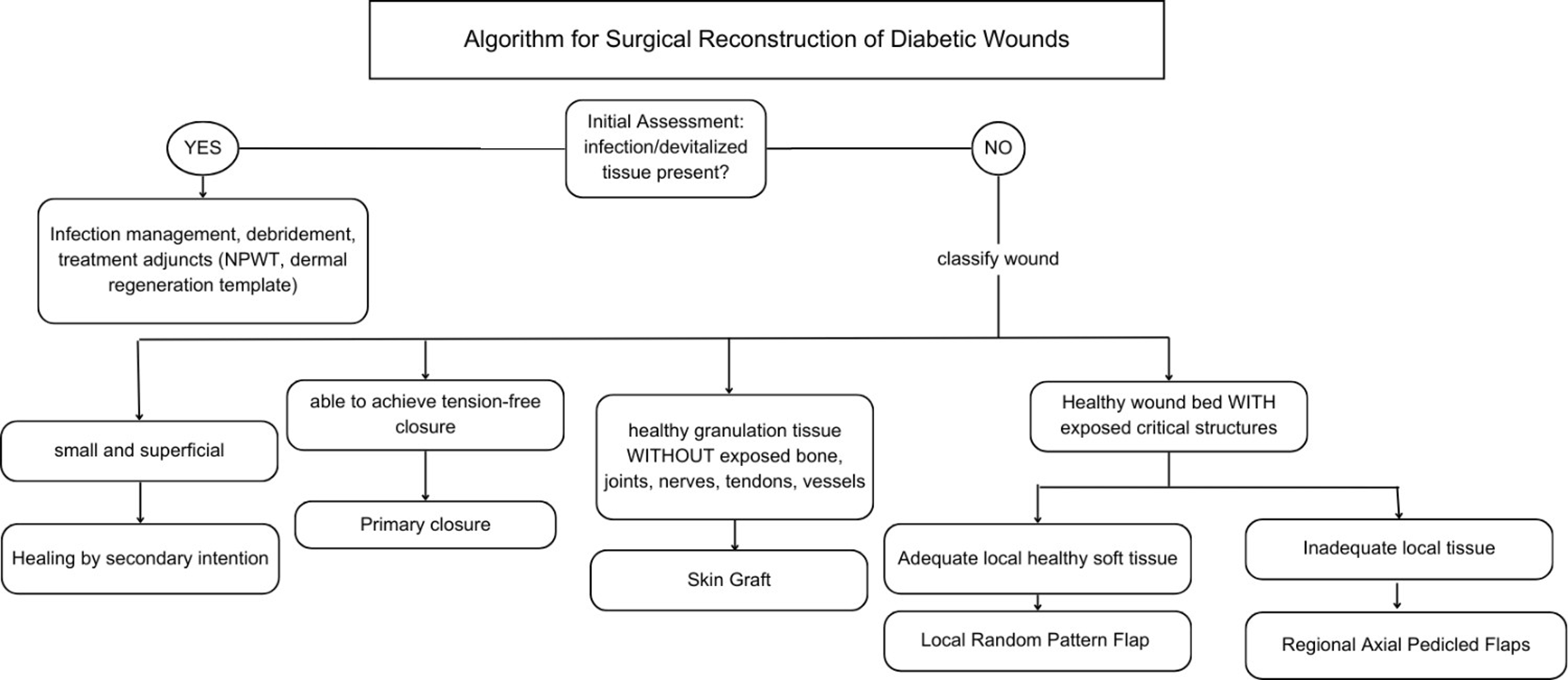

Obtaining a functional, strong, and durable wound closure is integral in limiting re-ulceration, infection, and amputation in patients with DFUs[9]. Planning for coverage of wounds requires a multidisciplinary team approach, which includes addressing the multiple comorbidities found in diabetic patients, controlling blood glucose levels, and addressing factors that may compromise the surgical outcome such as infection, bony prominences, and vascular insufficiency[6]. Once the wound is ready for coverage, the decision regarding the type of surgical modality to be used is tailored to the individual and type of wound and is oftentimes based on the reconstructive ladder [Figure 1]. The reconstructive ladder is a stepwise algorithmic approach used by plastic surgeons for surgical wound closure management[9,17,18]. Each increasing rung of the ladder represents a more complex closure technique, usually reserved for more complex wounds.

Oftentimes, the surgical management of diabetic foot wounds requires multiple steps rather than one large operation. Surgical debridement is often the initial stage, followed by wound care and the use of reconstructive adjuncts prior to definitive closure and coverage.

Surgical debridement

Necrotic tissue may impede wound healing by obstructing cellular migration across the wound bed, becoming a nidus for infection, and preventing the formation of granulation tissue[3]. Therefore, debridement is a critical component in the management of DFUs, aiming to remove necrotic, devitalized tissue and biofilm that impede the natural healing process and pose a risk of infection[19]. By eliminating these barriers, debridement reduces microbial load and stimulates the formation of healthy granulation tissue, thereby facilitating wound closure.

Sharp surgical debridement allows for the rapid and thorough removal of devitalized tissue, allowing for healthy tissue with healing potential to remain[5]. This can be done at either an inpatient or outpatient setting. Sharp debridement also creates a “new acute wound”, thereby restarting the phases of wound healing to acute healing and restimulating the immune response to growth factors[5].

Reconstructive adjuncts

After initial surgical debridement of the DFU, there is a period of wound conditioning. This phase can be characterized by local wound care, antibiotics, additional debridement, and reconstructive adjuncts.

Adjunctive therapies are increasingly used in the surgical management of DFUs to improve healing and optimize the success of reconstructive procedures. Among the most well-established adjuncts are negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) and bioengineered skin substitutes, both of which can be instrumental in wound bed preparation, postoperative support, and bridging the gap to definitive reconstruction.

In the context of surgical reconstruction, NPWT is particularly valuable as a bridge to closure. NPWT employs negative pressure in order to promote wound healing through the following mechanisms:

- reducing edema and exudate

- enhancing perfusion

- promoting wound contraction and formation of granulation tissue

Several studies have demonstrated that the use of NPWT was associated with significantly higher ulcer healing rates and shorter healing times[20-22].

Dermal regeneration templates (DRTs) are bioengineered skin substitutes that consist of a dermal matrix and a silicone outer layer[23]. These skin substitutes are designed to mimic the structure and function of native skin and can serve both as definitive coverage and as a temporary bridge to surgical reconstruction. They promote wound healing by providing a scaffold for cellular infiltration and neovascularization and within 2-3 weeks of application of the DRT, the neodermis revascularizes and matures[23]. At that point, a split-thickness skin graft can be applied, or it can be allowed to completely re-epithelialize.

Primary closure

After the option of allowing a wound to heal by secondary intention, the bottom of the reconstructive ladder is primary closure. Debridement of tissues followed by primary closure remains the simplest and least invasive method of wound management. Noninfected, small DFUs may be excised and closed tension-free, usually by excision with a 3-to-1 ellipse and closure along resting skin tension lines[2]. Oftentimes, primary closure may not be feasible due to the size and location of the wound, limited skin and soft tissue redundancy, along with the reduced pliability in the foot and ankle[2,9].

Skin grafts

For wounds that are not amenable to primary closure, skin grafting may be considered as the next option. Skin grafts are tissue without their own blood supply and rely on vascularization from the recipient site for integration[17]. Skin grafts are indicated for coverage of wounds with healthy granulation tissue without infection, or exposed tendon, bone, vessels, or joints[1]. Skin grafting over granulated wound beds offers rapid and accelerated wound closure, as once the graft revascularizes and adheres to the recipient bed, the graft then functions as the recipient site’s skin[18]. Skin grafts are also relatively minimally invasive and can be repeated if additional coverage is needed. Relative contraindications of skin graft use are in infected wounds, wounds without granulation tissue, exposed bone, tendon, vessels, and weight-bearing areas of the foot.

Skin grafts consist of epidermis and varying thicknesses of dermis. There are two types of skin grafts:

- Split-thickness skin grafts: include epidermis and partial dermis

- Full-thickness skin grafts: include the entire depth of epidermis and dermis

Split-thickness skin grafts are oftentimes harvested with a dermatome over a nondescript area, such as the upper lateral thigh, at a depth of 0.008 to 0.015 inches. The grafts are then meshed to allow for greater surface area coverage and to allow for drainage of hematoma and seroma, preventing them from interfering with contact over the recipient site. The donor site is allowed to heal and epithelialize by secondary intention.

Full-thickness skin grafts can be harvested from many locations on the body with laxity in a 3:1 length-to-width ratio to allow for primary closure of the donor site.

Skin grafts are ideally used to cover superficial wounds with adequate granulation tissue and without exposed structures. They may be used for coverage of deeper wounds, though the resulting healed area may be concave compared to the rest of the foot due to the lack of underlying subcutaneous tissue. Because of this, deeper wounds and weight-bearing areas over the plantar foot are relative contraindications to skin grafting due to the lack of adequate subdermal soft tissue between the skin graft and the underlying bone[1].

Local random-pattern flaps

When the size, location, or exposure of important structures in a wound precludes the use of skin grafting, local random-pattern flaps may be used. These flaps use soft tissue adjacent to the wound for coverage and are based on a random-pattern blood supply[13]. Unlike grafts, flaps are surgically transferred with an intact vascular supply, ensuring better survival and function as revascularization from the recipient site occurs[17]. These flaps can either be advanced, rotated, or transposed over the wound[24]. They can incorporate skin, subcutaneous tissue, and occasionally, fascia[2]. Local flaps, in general, are the preferred coverage modality for plantar defects, which necessitates using “like with like” tissue due to the need to bear weight[2,9,24]. Table 7 describes types of random pattern local flaps, their definition, and studies where they have been described.

Examples of local random-pattern flaps

| Local flap | Anatomic mechanism | Study described in |

| Advancement flap | Use of two parallel incisions adjacent to and away from defect and advancing over defect along single axis | Patel[24], Blume et al.[18] |

| V-Y advancement flap | Creation of a V-shaped incision adjacent to defect and advancement over the wound, resulting in Y-shaped closure | Patel[24], Bharathi et al.[25], Hayashi and Maruyama[26], Onishi and Maruyama[27], Roukis et al.[28], Colen et al.[29], Blume et al.[18] |

| Rotation flap | Uses a semicircle or arched incision to rotate adjacent area around a fixed pivot point through arc of rotation to cover defect | Patel[24], Boffeli and Hyllengren[30], Boffeli and Peterson[31], Feng et al.[32], Blume et al.[18] |

| Bilobed flaps | Transposition flap using two adjacent triangular flaps to redistribute tension and cover defect with the first lobe filling the defect and the second lobe filling the donor site of first lobe. Ideal for defects < 1.5 cm diameter | Patel[24], Bouche et al.[33], Yetkin et al.[34] |

| Rhomboid/limberg flap | Creation of a rhomboid shaped defect with 60° and 120° with a limb of the flap bisecting the 120° angle away from the defect and of the same length and another parallel limb at a 60-degree angle. This is transposed into the defect | Patel[24], Zgonis et al.[35], Blume et al.[18] |

Regional axial pedicled flaps

Regional pedicled flaps differ from local flaps in that they require the identification and isolation of a vessel in the transfer of the flap[9]. In contrast, random-pattern flaps only provide fasciocutaneous coverage, these flaps can be fasciocutaneous, adipofascial, muscular, or musculocutaneous[36]. They are indicated when there is not enough healthy, pliable tissue abutting the wound to adequately cover it and deeper wounds in which there is exposed bone or hardware. They are elevated while remaining partially attached to their vascular pedicle and transferred onto the wound, allowing them to survive and integrate into the wound without requiring microsurgical intervention. The donor defect is then either closed primarily or skin grafted. Some common examples of pedicled flaps for the foot are the reverse sural artery flap, medial plantar artery flap, and dorsalis pedis flap, which are further detailed in Table 8.

Types of regional axial pedicled flaps

| Regional flap | Anatomic basis | Study described in |

| Medial plantar artery flap | Fasciocutaneous flap that can be used to cover medial side of foot and ankle, medial or plantar heel | Li et al.[36] |

| Lateral calcaneal flap | Fasciocutaneous flap used to cover posterior heel defects | Balakrishnan et al.[37] |

| Reverse sural flap | Fasciocutaneous flap based on perforator of sural artery from peroneal to cover posterior heel/ankle, dorsal/plantar midfoot, ankle | Assi et al.[38], Yammine et al.[39] |

| Peroneus brevis muscle flap | Pedicled peroneus brevis muscle flap used to cover the lower third of leg, malleolar, posterior ankle, and proximal foot and heel defects | Megevand et al.[40] |

NAVIGATING THE RECONSTRUCTIVE LADDER

The reconstructive ladder promotes a staged treatment philosophy that is well-suited to the protracted nature of DFU care. It is common to perform serial debridement and utilize intermediate therapies (such as NPWT or temporary skin substitutes) as precursors to definitive closure - essentially climbing the ladder one rung at a time. This allows for continuous re-evaluation at each stage and ensures the wound is optimally conditioned for the next step. Such an approach is algorithmic but not inflexible: if a wound demonstrates improvement at a given stage, one might continue that course; if it deteriorates or stalls, one ascends to a more advanced intervention [Figure 2]. The end result is an efficient yet prudent utilization of surgical modalities, where the patient receives neither under-treatment nor over-treatment. By embedding the reconstructive ladder into clinical decision-making, multidisciplinary teams can systematically deliver escalating care that is commensurate with wound complexity and patient tolerance, leading to more consistent outcomes and a clear rationale for each therapeutic move.

Adopting the reconstructive ladder as a guiding paradigm in the surgical management of DFUs carries significant benefits for patient outcomes and interdisciplinary care. This conceptual framework reinforces the principle of thoughtful escalation of care - ensuring that interventions are intensified in step with wound severity and patient needs, rather than in a haphazard or overly aggressive manner. Such prudence is rewarded in clinical outcomes: when the right level of intervention is delivered at the right time, patients experience higher rates of wound healing, limb preservation, and functional recovery. By systematically addressing simple wounds with simple solutions and reserving complex reconstructive techniques for truly advanced lesions, clinicians can avoid the morbidity of unnecessary major surgeries while still achieving high limb salvage rates[41]. Notably, studies have reported that with diligent multidisciplinary management, the majority of diabetic foot wounds can heal without resorting to free flaps, while those severe cases that do require microvascular reconstruction can be approached proactively rather than as a last-ditch effort[41]. The net effect is a more efficient allocation of surgical resources and improved patient-centric outcomes such as healed wounds that are durable, restore ambulation, and reduce recurrence and amputation.

The ladder provides a common language and clear milestones for this team. At each rung, different experts may take the lead - for instance, vascular intervention precedes a graft, or an orthopedic stabilization coincides with a flap - but all understand how their contributions integrate into the overall treatment algorithm. This encourages parallel planning (e.g., performing a tendon release to facilitate flap inset) and helps avoid siloed decision-making. The result is a coordinated care plan where each escalation is deliberate and collaborative. As the patient’s wound evolves in complexity, so does the level of care, with the team collectively deciding when to ascend the ladder or when to consider alternative endpoints. Through this cooperative, stepwise escalation, the patient receives holistic care that not only closes the wound but also optimizes limb function and general health.

The reconstructive ladder embodies a philosophy of judicious advancement in wound management. It reminds clinicians that successful outcomes in DFUs come from neither rushing to the most complex solution nor remaining complacent with inadequate measures, but from choosing the right intervention at the right time. By reinforcing this disciplined yet flexible approach, the reconstructive ladder improves the likelihood of durable wound healing and limb preservation. It underscores that every “rung”, whether a simple closure or a free flap, has its rightful place in the treatment algorithm when aligned with patient factors. In embracing the reconstructive ladder, clinicians commit to a principled, patient-tailored escalation strategy that maximizes healing while minimizing harm, ultimately translating into better patient survival, enhanced quality of life, and more efficient care delivery for this challenging patient population.

CONCLUSION

DFUs are complex and often debilitating wounds, which require an individualized, staged, and algorithmic treatment approach. When considering the reconstruction of DFUs, one must do a thorough assessment of the wound and medically optimize the patient prior to surgical intervention. There are various surgical approaches towards DFU reconstruction, including the use of adjuncts, primary closure, skin grafts, and flaps. To guide treatment choice, surgical reconstruction is based on the reconstructive ladder which encourages clinicians to match the wound’s needs with the least invasive and most effective approach. Figure 2 demonstrates an algorithmic approach towards the reconstructive ladder in which at each decision node, the wound’s size, depth and response to previous treatment are considered in order to determine the next route towards reconstruction. With this approach based on the reconstructive ladder, each DFU can be approached in an individualized, patient-centered manner to maximize healing while minimizing risk and harm.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, review and revision of the manuscript: Gupta S

Preparation and creation of the original draft, review and revision of the manuscript: Myint J

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Akhtar S, Ahmad I, Khan AH, Khurram MF. Modalities of soft-tissue coverage in diabetic foot ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28:157-62.

2. Capobianco CM, Stapleton JJ, Zgonis T. Soft tissue reconstruction pyramid in the diabetic foot. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010;3:241-8.

3. Dayya D, O’Neill OJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Habib N, Moore J, Iyer K. Debridement of diabetic foot ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 2022;11:666-86.

5. Sorber R, Abularrage CJ. Diabetic foot ulcers: epidemiology and the role of multidisciplinary care teams. Semin Vasc Surg. 2021;34:47-53.

6. Lim JZ, Ng NS, Thomas C. Prevention and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J R Soc Med. 2017;110:104-9.

7. Gallagher KA, Mills JL, Armstrong DG, et al.; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Current status and principles for the treatment and prevention of diabetic foot ulcers in the cardiovascular patient population: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149:e232-53.

8. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411:153-65.

9. Zgonis T, Stapleton JJ, Roukis TS. Advanced plastic surgery techniques for soft tissue coverage of the diabetic foot. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007;24:547-68, x.

10. Driver VR, Madsen J, Goodman RA. Reducing amputation rates in patients with diabetes at a military medical center: the limb preservation service model. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:248-53.

11. Driver VR, Goodman RA, Fabbi M, French MA, Andersen CA. The impact of a podiatric lead limb preservation team on disease outcomes and risk prediction in the diabetic lower extremity: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2010;100:235-41.

12. Larsson J, Apelqvist J, Agardh CD, Stenström A. Decreasing incidence of major amputation in diabetic patients: a consequence of a multidisciplinary foot care team approach? Diabet Med. 1995;12:770-6.

13. Krishnan S, Nash F, Baker N, Fowler D, Rayman G. Reduction in diabetic amputations over 11 years in a defined U.K. population: benefits of multidisciplinary team work and continuous prospective audit. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:99-101.

14. Senneville É, Albalawi Z, van Asten SA, et al. IWGDF/IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes-related foot infections (IWGDF/IDSA 2023). Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024;40:e3687.

15. Ang L, Jaiswal M, Martin C, Pop-Busui R. Glucose control and diabetic neuropathy: lessons from recent large clinical trials. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:528.

16. Callaghan BC, Little AA, Feldman EL, Hughes RA. Enhanced glucose control for preventing and treating diabetic neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012:CD007543.

17. Pehde CE, Bennett J, Kingston M. Orthoplastic approach for surgical treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2020;37:215-30.

18. Blume PA, Donegan R, Schmidt BM. The role of plastic surgery for soft tissue coverage of the diabetic foot and ankle. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2014;31:127-50.

19. Lebrun E, Tomic-Canic M, Kirsner RS. The role of surgical debridement in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:433-8.

20. Monami M, Scatena A, Ragghianti B, et al.; Panel of the Italian Guidelines for the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Syndrome, SID and AMD. Effectiveness of most common adjuvant wound treatments (skin substitutes, negative pressure wound therapy, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, platelet-rich plasma/fibrin, and growth factors) for the management of hard-to-heal diabetic foot ulcers: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for the development of the Italian Guidelines for the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Syndrome. Acta Diabetol. 2025;62:1081-95.

21. Dalmedico MM, do Rocio Fedalto A, Martins WA, de Carvalho CKL, Fernandes BL, Ioshii SO. Effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy in treating diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Wounds. 2024;36:281-9.

22. Hu X, Meng H, Liang J, et al. Comparison of the efficacy of 12 interventions in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a network meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2025;13:e19809.

23. Gupta S, Moiemen N, Fischer JP, et al. Dermal regeneration template in the management and reconstruction of burn injuries and complex wounds: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:e5674.

25. Bharathi RR, Jerome JT, Kalson NS, Sabapathy SR. V-Y advancement flap coverage of toe-tip injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;48:368-71.

26. Hayashi A, Maruyama Y. Lateral calcaneal V-Y advancement flap for repair of posterior heel defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:577-80.

27. Onishi K, Maruyama Y. The dorsal metatarsal V-Y advancement flap for dorsal foot reconstruction. Br J Plast Surg. 1996;49:170-3.

28. Roukis TS, Schweinberger MH, Schade VL. V-Y fasciocutaneous advancement flap coverage of soft tissue defects of the foot in the patient at high risk. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:71-4.

29. Colen LB, Replogle SL, Mathes SJ. The V-Y plantar flap for reconstruction of the forefoot. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:220-8.

30. Boffeli TJ, Hyllengren SB. Unilobed rotational flap for plantar hallux interphalangeal joint ulceration complicated by osteomyelitis. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2015;54:1166-71.

31. Boffeli TJ, Peterson MC. Rotational flap closure of first and fifth metatarsal head plantar ulcers: adjunctive procedure when performing first or fifth ray amputation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2013;52:263-70.

32. Feng J, Thng CB, Wong J, et al. Outcome of rotation flap combined with incisional negative pressure wound therapy for plantar diabetic foot ulcers. Arch Plast Surg. 2025;52:169-77.

33. Bouché RT, Christensen JC, Hale DS. Unilobed and bilobed skin flaps. Detailed surgical technique for plantar lesions. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1995;85:41-8.

34. Yetkin H, Kanatli U, Oztürk AM, Ozalay M. Bilobed flaps for nonhealing ulcer treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:685-9.

35. Zgonis T, Stapleton JJ, Rodriguez RH, Girard-Powell VA, Cromack DT. Plastic surgery reconstruction of the diabetic foot. AORN J. 2008;87:951-66; quiz 967-70.

36. Li KR, Lava CX, Lee SY, Suh J, Berger LE, Attinger CE. Optimizing the use of pedicled versus random pattern local flaps in the foot and ankle. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:e5921.

37. Balakrishnan TM, J L, Karthikeyan A, Madhurbootheswaran S, Sugumar M, Sridharan M. Lateral calcaneal artery perforator/propeller flap in the reconstruction of posterior heel soft tissue defects. Indian J Plast Surg. 2025;58:38-50.

38. Assi C, Samaha C, Chamoun Moussa M, Hayek T, Yammine K. A comparative study of the reverse sural fascio-cutaneous flap outcomes in the management of foot and ankle soft tissue defects in diabetic and trauma patients. Foot Ankle Spec. 2019;12:432-8.

39. Yammine K, Eric M, Nasser J, Chahine A. Effectiveness of the reverse sural flap in covering diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Surg. 2022;30:368-77.

40. Mégevand V, Scampa M, Suva D, Kalbermatten DF, Oranges CM. Versatility of the peroneus brevis muscle flap for distal leg, ankle, and foot defects: a comprehensive review. JPRAS Open. 2024;41:230-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Special Topic

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at [email protected].